The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I Theme: Power Volume 8 Issue 3 Features:

a

Explore:

fight for

rights,

new

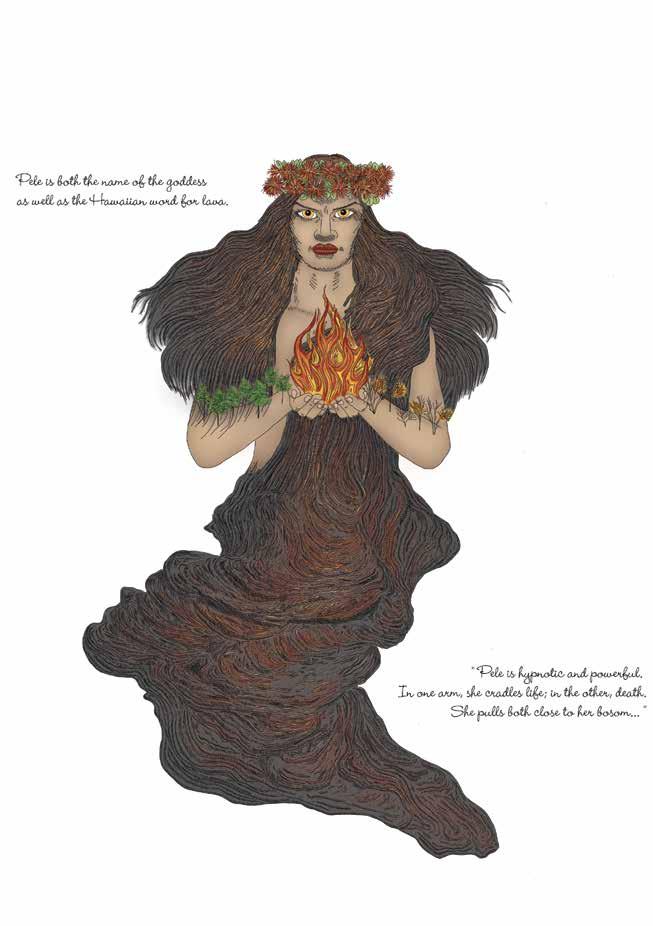

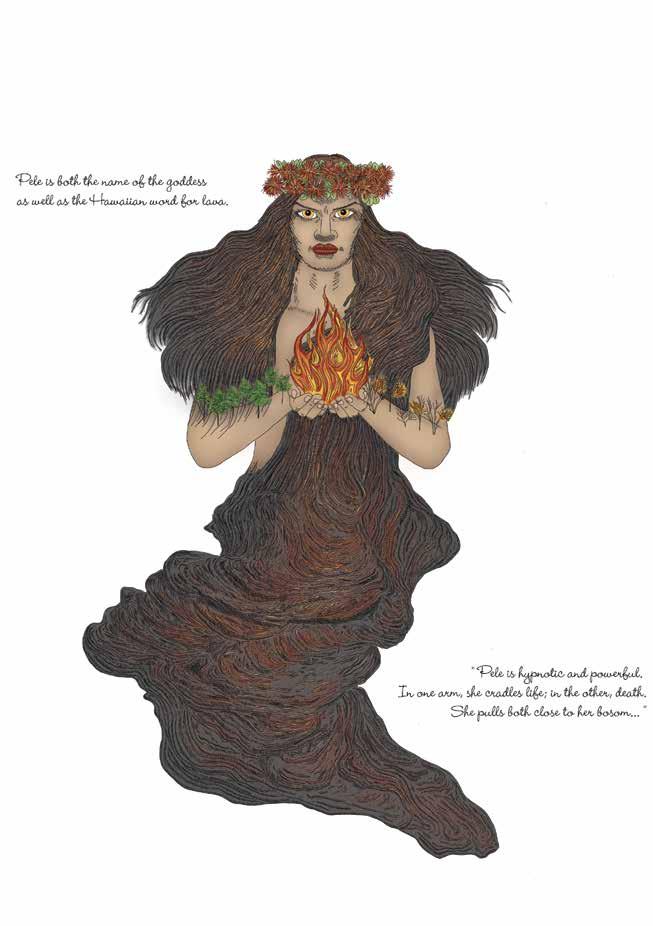

Special Section: Pele In the path of lava, the land and its people continue forward on fresh earth. 0 03 > 0928 1 $14.95 US $14.95 CAN 2548 98

Fierce Forces Kaua‘i faces

severe storm, female lifeguards stand vigilant, and expecting parents reconnect with their roots.

Decolonizing Space Activists

Maui’s water

and historic statues take on

meaning.

22 | Arts

Sally Lundburg & Keith Tallett

30 | Community Craig Hanaumi 36 | Technology

| Arts

192 | Campaign Refections

48 | In the Wake of Water

Christian Cook recounts the record-breaking rainfall, fash fooding, and mudslides that devastated Kaua‘i’s north shore.

62 | The Guardians

Lindsey Kesel shares insider stories from O‘ahu’s active sisterhood of lifeguards, who are some of the most elite and respected waterwomen in the world.

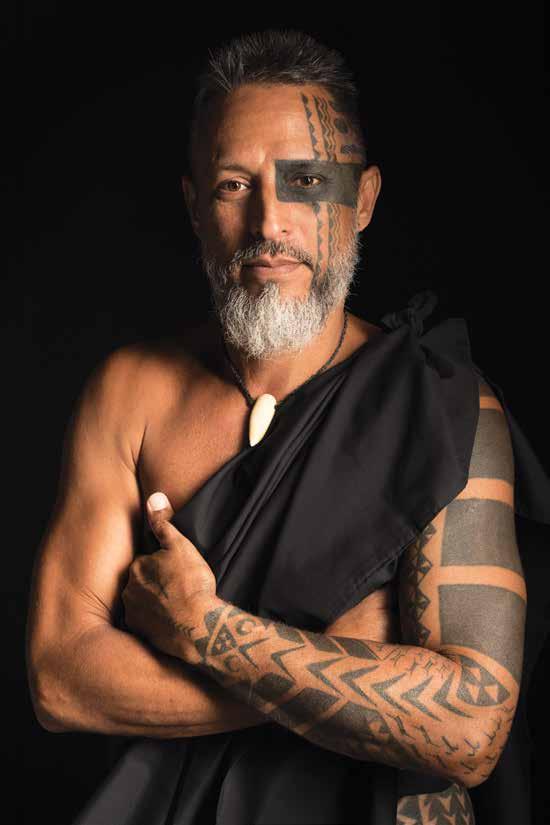

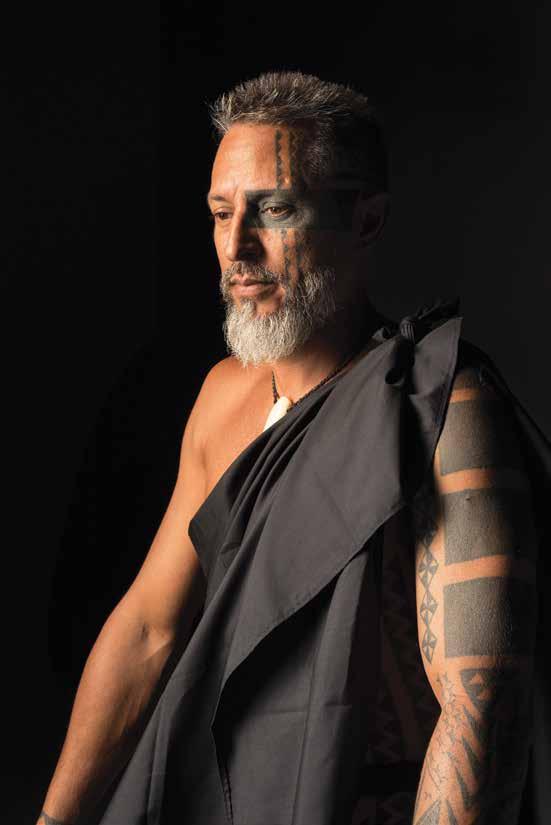

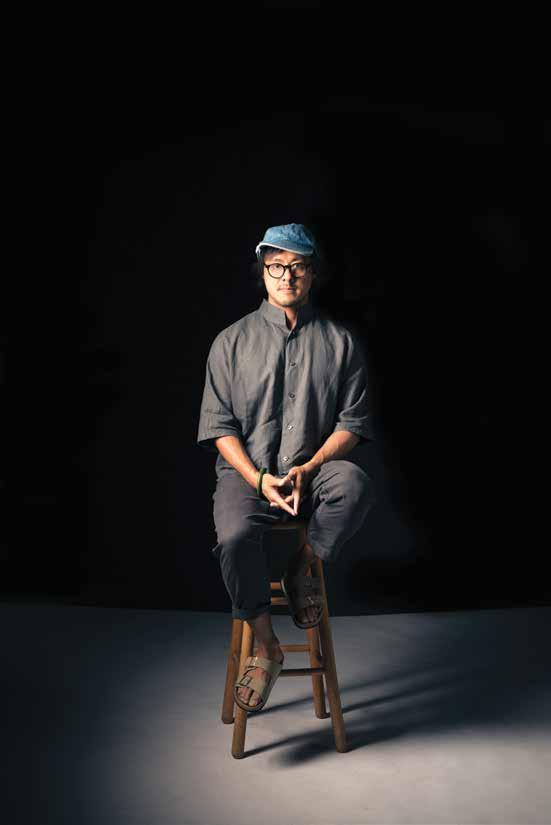

76 | Enclothed Cognition

There is more to what we wear than meets the eye. Chris Rohrer photographs individuals dressed in their most self-afrming garments.

92 | Birth Rights

From a landmark legal case to changing health care protocols concerning placenta, Rae Sojot covers indigenous birthing rights, traditions, and wellness here on the islands.

TABLE OF CONTENTS | FEATURES | 20 POWER Editor’s Letter Contributors FLUX PHILES

Data

A

Archives 40

Masculinity

HUI HOU

FEATURES

TABLE OF CONTENTS

102 SPECIAL SECTION

PELE

The Hawaiian Islands are forged by fire. Recent events at K ī lauea bring this understanding to the surface with breathtaking intensity.

Shown above is Leilani Estates, a subdivision in Puna that was at the center of the media’s international coverage of Hawai‘i Island’s disastrous lava flows in 2018. Photos by John Hook.

| SECTIONS |

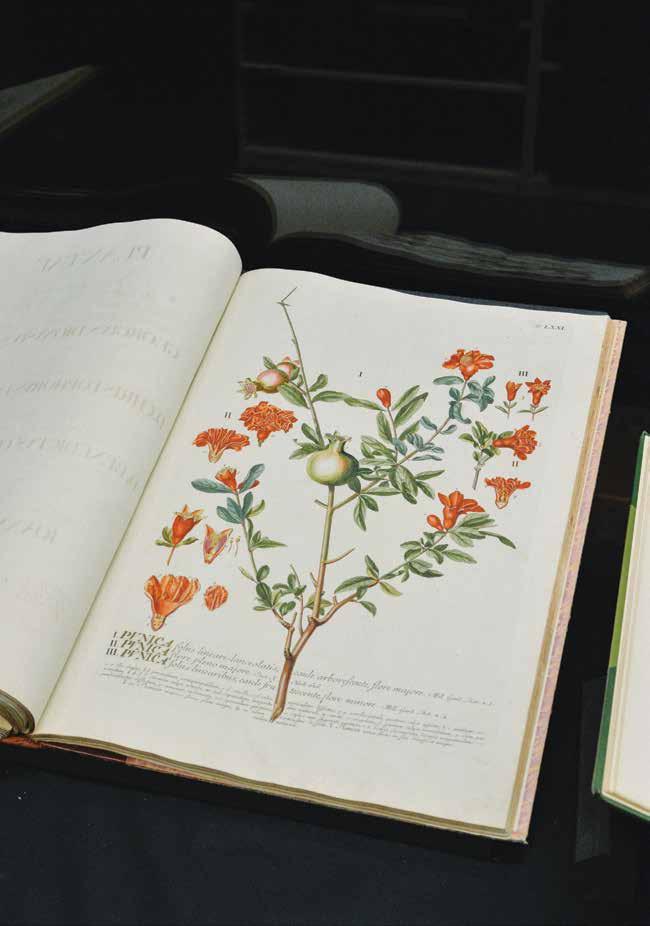

TABLE OF CONTENTS | SECTIONS | 160 LIVING WELL 162 | Nature Sandalwood 172 | Architecture Ward Village 130 EXPLORE 132 | Maui Water Rights 144 | Sculpture Historic Statues 152 | Plants Botanical Library

Who What Wear

In this video essay, diverse modes of dress display a range of attitudes, contextual clues, and ways the world is navigated. “It’s about signaling a meaning to those around you and to yourself,” says Joni Sasaki, an assistant professor of cognitive psychology at the University of Hawai’i at noa, not ust as individuals but also who they are in connection to the community around them.”

ON THE COVER:

An explosion of rock in the glow of lava at Kamokuna, Hawai‘i Island in 2017, photographed by Elyse Butler. The event occurred after a section of the lava delta collapsed into the ocean on New Year’s Eve. Butler visited the dramatic and unforgettable spectacle by boat just after daybreak. “I came away with a deeper sense of wonder about volcanoes and how the islands are created,” Butler says. “As the daughter of a seismologist, I’ ve gro n up around scienti c data about how the Earth moves, but seeing lava up close gave me a fuller understanding.” Read more about the eruptions at lauea on page .

Stay current on arts and culture with us at:

fluxhawaii.com

/fluxhawaii

@fluxhawaii

@fluxhawaii

@fluxhawaiitravel

FLUX

TV

| FLUX TV |

TABLE OF CONTENTS

“An ability to act or produce an effect.”

If you turn to the Merriam-Webster dictionary and look up the word po er, this is the rst entr listed. The next reads “possession of control, authorit , or infuence o er others. he most performati e de nition of “physical might”—the meaning that can be most easily observed in others—doesn’t appear until three entries do n. nd it telling that our main understanding of power is built around recognizing that it is largely felt over seen. That, with power, we sense its potential before the actual fact.

As 2018 progressed, Hawai‘i’s natural forces made the vagaries of power that inspired this issue all the more clear and potent. Fire and water, and what these elements left in their wakes, ended up as building blocks for this issue of FLUX. In Christian Cook’s field account and film photos of the storm that shook Kaua‘i’s north shore on page 48—made all the more haunting considering the images were tainted by the torrential rains after water seeped into his camera gear—disaster allowed room for deep reflection. Lava allowed similar sentiments to surface for the writers and photojournalists who brought to life our special section on Pele that begins on page 102. Nothing is permanent, these stories reveal, no matter how solid the foundation under your feet may seem. We can climb our way to higher levels of power, yet we are also not in control.

lauea is still erupting, and as Coo states, “Floods will come again.”

Following my first year as an editor, I’ve been deliberating on what this

role means, on what power it yields. I’ve learned there are many things required of editors beyond managing words, assigning photography, and making them stick coherently to the page. There are responsibilities that occur off paper that require an editor’s devotion, too, like fostering a creative environment and upholding spaces where we feel free to be expressive and take risks with our work. Being an editor involves analyzing structure—breaking sentences apart, bridging passages together—in a written story, but also the structural dynamics of one’s relationships with a team. I like that if you walk into our Chinatown office, you might find it hard to discern who is in charge. That there aren’t insulated, corner offices where our publisher, creative director, or editors sit in rooms separate from individuals divided by cubicles. We share desks and resources in an open floor plan where anyone can raise a thought or ask for feedback, out loud, at any time. We all have a window view.

This framework and access is essential to producing a composite of voices and perspectives every issue. The themes of FLUX reflect our interests and what is on our minds, but, more specifically, they materialize in the form of questions: What does it mean when...? What would it look like if...? How can this story be more of that or less of this, and what could that say? It’s what I’m struck by most about our team’s process, from conception to execution, and what I appreciate above all: the constant

stream of consideration, of inquiry. I’m so enthralled by this issue’s cover image of lauea photographer Elyse Butler because, for me, it captures this same attitude: In its overwhelming magnitude, it forces you to look hard and make sense of what it even is

When I discuss ideas with Lisa Yamada-Son, FLUX’s editor in chief, and we’re uncertain about whether they belong in an issue, we often return to whether or not they are in service to the publication’s mission: to show Hawai‘i as a place that is dynamic, not static; to inspire thought and conversation, not apathy; to activate prose and photography in ways that engage rather than pacify readers. To transfer whatever creative influence we’ve used into shaping a story out to the reader.

So, once you’ve finished reading a piece—seen its ultimate photo, followed it to its final word, and hopefully, been expanded on something you previously knew little about—you won’t feel it’s enough to merely be made more aware of it: You might feel empowered. You may feel “an ability to act,” even if that action is to put forth more questions. You may ask yourself, Now that I know about this, what will I do with it?

With aloha,

Matthew Dekneef EDITORIAL DIRECTOR @mattdknf

| POWER |

EDITOR’S LETTER

MASTHEAD

“A passage from Virginia Woolf’s journals that reads, ‘The future is dark, which is the best thing the future can be, I think.’ For myself, it’s a constant reminder to embrace uncertainty and have no fear of the future.”

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

EDITOR

Lisa Yamada-Son

What’s the most powerful advice you’ve received recently?

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Ara Laylo

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Matthew Dekneef

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Anna Harmon

SENIOR EDITOR

Rae Sojot

DESIGNERS

Mitchell Fong

Michelle Ganeku

JUNIOR DESIGNER

Skye Yonamine

PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR

John Hook

PHOTO EDITOR

Samantha Hook

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Eunica Escalante

CREATIVE ASSISTANT

Naz Kawakami

IMAGES

Elyse Butler

Christian Cook

Andrew Richard Hara

Michelle Mishina

IJfke Ridgley

Bailey Rebecca Roberts

Chris Rohrer

Jenny Sathngam

Lauren Trangmar

CONTRIBUTORS

Diane Ako

Christian Cook

Sonny Ganaden

Lindsey Kesel

Joshua Iwi Lake

Meghan Miner Murray

Timothy A. Schuler

Shannon Wianecki

Kylie Yamauchi

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley GROUP PUBLISHER mike@NMGnetwork.com

Francine Beppu

NETWORK STRATEGY DIRECTOR francine@NMGnetwork.com

Helen Chang

Chelsea Tsuchida MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVES

Kylee Takata SALES ASSISTANT

“An Amy Poehler quote: ‘Great people do things before they are ready.’”

PUBLISHED BY:

Nella Media Group

36 N. Hotel St., Ste. A Honolulu, HI 96817

Hunter Rapoza MARKETING & SALES COORDINATOR

OPERATIONS Joe V. Bock

CHIEF REVENUE OFFICER joe@NMGnetwork.com

Gary Payne VP ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE gpayne@NMGnetwork.com

Courtney Miyashiro OPERATIONS ADMINISTRATOR courtney@NMGnetwork.com

MEDIA Gerard Elmore LEAD PRODUCER gerard@NMGnetwork.com

Kyle Kosaki PRODUCER

Shaneika Aguilar JUNIOR VIDEO EDITOR

Aja Toscano NETWORK MARKETING COORDINATOR

Kimi Lung WEB DEVELOPER

INTERNS

Erin Kushimaejo Christian Navarro

General Inquiries: contact fu ha aii.com

“I heard a thought at Adobe Max from Kristy Tillman, the Head of Global Experience Design for Slack, that I liked: ‘The moment you decide to create opportunities without asking for permission is when it’s time to invite yourself to new possibilities.’”

©2008-2019 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. FLUX Hawaii is a triannual lifestyle publication.

ISSN 2578-2053

| POWER |

Christian Cook

Born on Kaua‘i and raised there by journalist parents, Christian Cook grew up around the island’s historians, ecologists, farmers, and conservationists. With a background in computer science, Japanese language, and world travel, Cook writes about futurism, culture, and the relationship between humans and the natural environment. Returning to his home island in early 2018, Cook found himself faced ith historic fooding on the north shore and the looming threat of a destructive hurricane in the feature, “The Wake of Water,” page 48. “My life was thrown into chaos after my childhood home was destroyed in Hurricane Iniki in 1992 with my family inside of it,” he says. he analei food rought ac apocalyptic visions of what it’s like to survive without modern resources.”

Joshua Iwi Lake

Joshua Iwi Lake is an artist, graphic designer, photographer, and lmma er. n riting a out Hawai‘i’s data archiving systems and public statues of historic heroes, on pages 36 and 144, respectively, a e contemplates the signi cance of crafting a collective memory and identity. “Hawaiian culture has struggled to maintain its language, history, and knowledge base due to rapid religious, political, and economic changes in the islands,” he says. “From this change, Hawaiians have been marginalized and underrepresented in leadership roles only to be used in decorative or super cial a s. hrough continuous e orts in education, archi ing, and placemaking, Hawaiians will hopefully regain agency as stewards of the islands, avoiding irrelevance and extinction in the process.” As an indigenous designer, Lake’s lifelong goal is to assist Hawaiian culture into the 21st century and beyond.

Bailey Rebecca Roberts

Bailey Rebecca Roberts is a photographer who was born and raised on Maui. She earned degrees in photography and cultural anthropology at Parsons School of Design in New York City, where she lived and worked for nearly a decade before returning to Hawai‘i. For the feature, “An Upstream Battle,” page 132, Roberts covered Maui’s Ke‘anae region to visit the home and lo‘i kalo of water rights activists Ed and healani endt. Ro erts as most struck by their dedication to their cause. eople li e d and healani are not fueled by popularity or social media likes, but by the reclamation of their power and collective power of their community. Their hearts are rooted in conviction and dedication to their culture and lineage, and to the gift that is their home.”

CONTRIBUTORS | POWER |

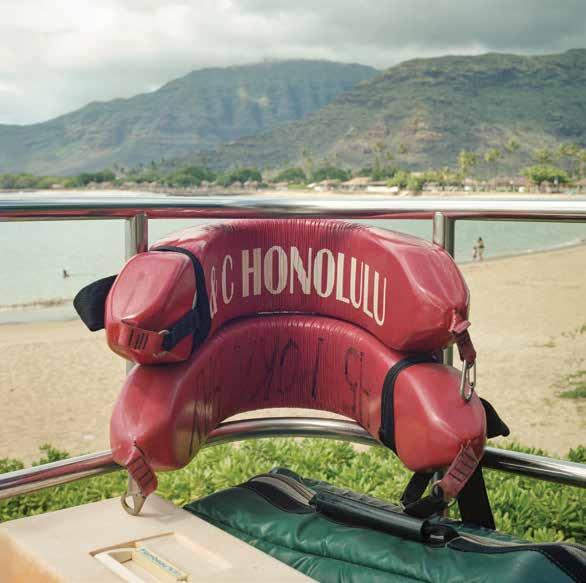

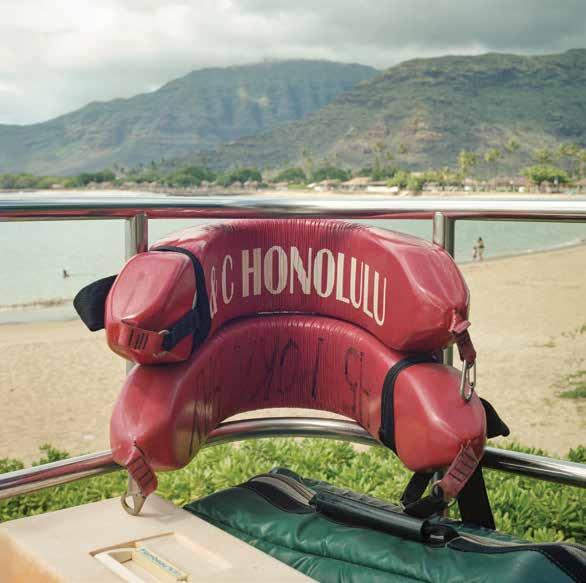

During Kaua‘i’s flash floods, the north shore received nearly 50 inches of water in a 24-hour period. Image by Christian Cook.

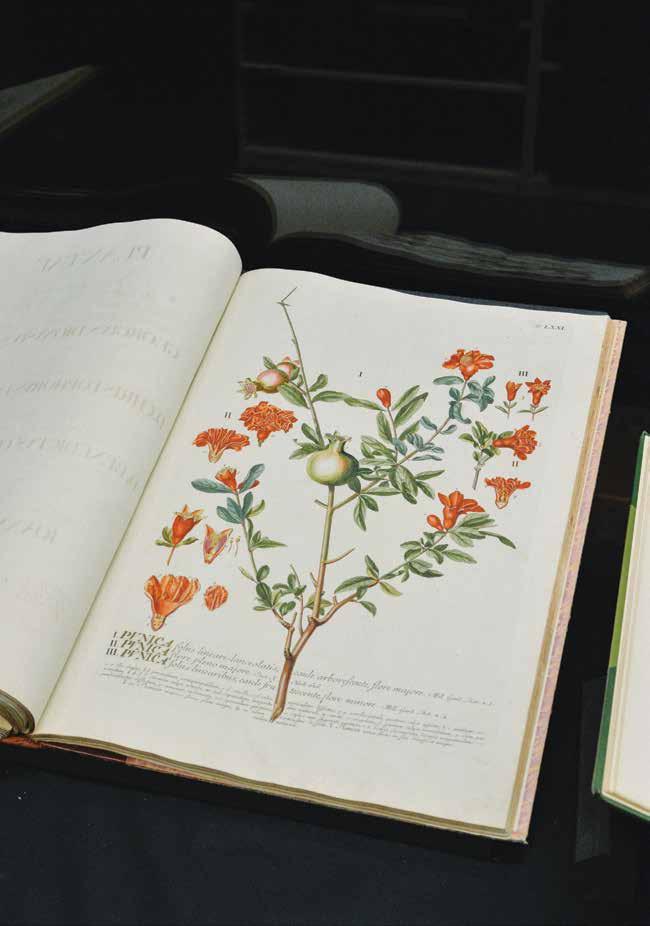

POWER

“Looking weak takes tremendous courage.”—Timothy A. Schuler

The Burdens of Artmaking

The latest commissions of artists Sally Lundburg and Keith Tallett comment on Hawai‘i families’ trying times.

TEXT

BY

RAE SOJOT

IMAGES BY MICHELLE MISHINA

It’s a warm summer morning and artist Sally Lundburg is not getting dressed for work. Rather, she s getting undressed for it. hile al ing past stands of oa and hia on the four-acre Pa‘auilo homestead she and her husband, Keith Tallett, call home, Lundburg strips down from her jeans and T-shirt and into a black swimsuit.

Nearby is a small pond, its still surface reflecting the deep greens of the surrounding forest. Lundburg slips into the water soundlessly and lines of inky water unfurl around her in languid, concentric circles. A few meters away, a floating piece of cordwood from a 2012 Honolulu Academy of Arts installation Lundburg created of koa logs, inkjet prints, silk, and epoxy resin reveals a sepia image of a man from Hawai‘i’s bygone plantation era. His gaze is stoic amid the rise and fall of the incoming eddies. Camera in hand, Lundburg examines the log with interest. It rests partially submerged at a curious slant, its exposed surface now textured with thin, white, raised wrinkles. It has no doubt been affected by its time in the pond.

The piece is one of 37 logs used in Sink or Swim , Lundburg’s mixed-media installation commissioned as part of a collaboration between the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center and Aloha United Way. In this work, Lundburg examines concepts of fragility and resilience—all-too familiar themes in Hawai‘i, where the struggle for financial security resembles a path along the razor’s edge. Living expenses in Hawai‘i are on average nearly two-thirds higher than the rest of the United States, and almost half of all residents live paycheck to paycheck, according to the Aloha United Way “ ALICE Report a ai i . ” According to this report’s findings, financial hardship is especially felt by a segment of the population termed as ALICE, an acronym for Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed. These are households with working adults who struggle to cover basic necessities such as food, housing, transportation, healthcare, and childcare and yet remain ineligible for government relief programs. In other words, households that are poor, but not poor enough.

Keith Tallett and Sally Lundburg in their home and studio space in Pa‘auilo, Hawai‘i Island.

FLUX PHILES | ART | 22 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Lundburg and Tallett, who is also an artist, were both commissioned to create a piece in response to the Aloha United Way’s findings. The two were given carte blanche to transform the report’s sheer volume of research and complex analytics into something alive: art. “It’s this giant, almost overwhelming document full of data, graphs, and numbers,” Lundburg says. The report struck a personal chord with the couple, too. In reading about struggling families, they recognized their own. “I remember thinking, ‘Whoa,’” Lundburg says. “We fit into that category.”

Upon reading the report, Lundburg recalls being drawn to the idea of buoyancy: the ability to rise or sink depending on one’s internal and external circumstances. Observing cordwood’s interactions in nature undergirded what Lundburg describes as interconnectedness—how each decision we make in turn affects other decisions, an endless ripple effect influenced by personal strengths and

weaknesses, resources or the absence of them, and the people individuals surround themselves with. Lundburg says, “All of these factors affect how we collectively or individually rise or become submerged.”

With achieving financial stabilty in Hawai‘i often a Sisyphean task, the “starving artist” who strikes gold and now lives comfortably off her art alone is the exception rather than the rule. “When you go to art school, you’re told the odds are stacked against you,” Tallett says.

For Lundburg and Tallett, being artists requires a twin mindset of creativity and pragmatism. Though long-established and active as artists, both still hold full-time jobs in order to support their family, which includes their teenage daughter, Kia‘i. But making ends meet is no easy task, and it is made more challenging by their decision to live in a rural area on Hawai‘i Island where creative career opportunities are scarce and tough decisions arise at the intersection of priorities, passions, and paycheck.

Lundburg’s installation, Sink or Swim , addresses familiar themes for Hawai‘i families who are struggling with financial security.

24 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

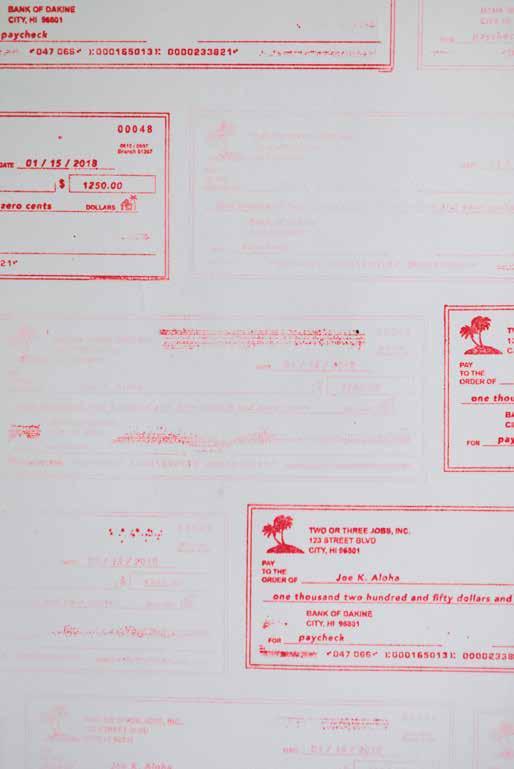

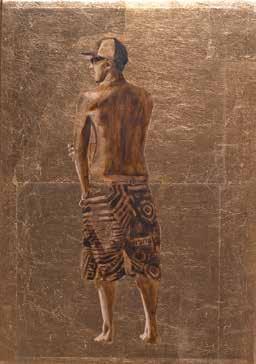

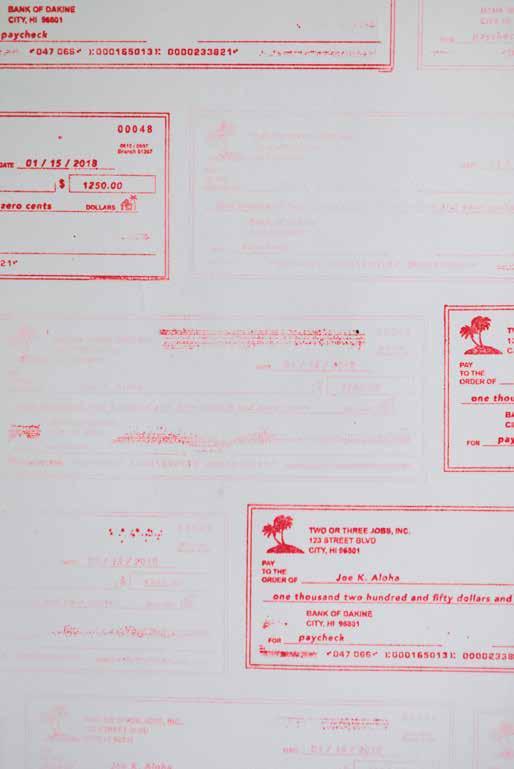

A detail shot of Tallett’s Paycheck 2 Paycheck , which sources data from the ALICE Report to create a stamped pattern that highlights the high cost of living in Hawai‘i.

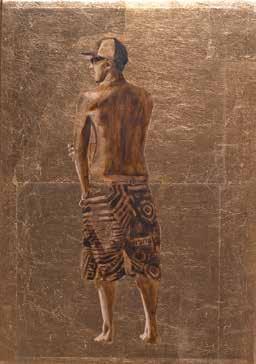

Both artists tackle contentious topics in their art careers. Tallett’s 2017 piece “Vamos Amigo” addressed the immigration policies of the United States.

These sentiments are confronted in Tallett’s piece titled Paycheck 2 Paycheck At the couple’s studio on their property, a massive roll of white cotton rag paper hangs near the ceiling’s edge and unspools to the floor like a massive receipt. It is systematically stamped with an unusual design: custom-made, large-scale images of paychecks. Covered with rows upon rows of crimson paychecks—Tallett chose the color red to speak to being “in the red,” fiscally— the piece looms like a formidable brick wall. Upon closer scrutiny, each stamp is a cryptograph of sorts that reveals a cache of information. The graphics reflect the sobering data found in the ALICE Report, which include everything from housing needs to income statistics to the ongoing pressures of having to stretch one paycheck long enough to meet the next. The mixedmedia piece showcases how a limited income is not just a disadvantage but a palpable barrier to financial security. In

the most trying times, Tallett muses, it feels like an insurmountable wall.

Creating art inspired by the stark nancial realities so man a ai i households face has struck home for Lundburg and Tallett. But it has also reminded them that their choices refect their purposeful decision to live as artists regardless of income stability. “We are kind of further away from the sun,” Tallett concedes. However, wealth can be framed in variety of ways, including what one chooses to do. “Our heads and minds are rarely still,” Lundburg says. “We want to be doing this. We imagine the life we want to live, and then gure out ho e ma e it happen.

Tallett and Lundburg with their daughter, Kia‘i.

To learn more about the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, visit smithsonianapa.org.

28 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Humanizing the Badge

As a member of the Bellevue Police Department, an ‘Aiea local aims to change the way the community he serves views ofcers in uniform.

TEXT BY KYLIE YAMAUCHI

IMAGES BY IJFKE RIDGLEY

Officer Craig Hanaumi likes to joke that of any job, police officers have the closest one to being Batman. “We have a car that has special equipment, we have a uniform with armor and a belt full of tools, and we get to fight crime,” Hanaumi says. “There’s no other job like that.”

But the masked vigilante and blue-clad law enforcement ofcers share more similarities than gadgets and goals. oth face intense scrutiny, tend to keep their personal identities private, and are seen as enforcers of the law. They’re de ned their uniforms, not ho the are underneath.

In recent years, Hanaumi has worked to combat this by “humanizing the badge,” he says. Today, the Bellevue police officer uses his personal interests and hobbies to redefine how the community perceives him, creating personalized forms of outreach in his Washington community. News outlets such as Today and ABC News have featured him as the “skateboarding cop,” presenting atypical coverage of a police officer. The 42-year-old visits skateparks, schools, and community centers and shares it on his Instagram with an audience of 34,000 followers, creating relationships in person and over social media. “It’s neat to see good acts every once in a while,” Hanaumi says. “Because [the media] is usually just negative stories, which is unfortunate.”

ac on ahu, the iea igh chool graduate patrolled District Four, which spans Kahuku to aim nalo, after oining the police force in . hile he had been attracted to the job for its promise of job security,

In response to growing anti-police sentiment nationwide, Craig Hanaumi builds trust and improves relationships with Bellevue’s youth by appealing to their interests.

FLUX PHILES | COMMUNITY | 30 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

its wages weren’t enough for him to ignore a ai i s rising cost of li ing. n , Hanaumi moved to Washington after being hired by the Bellevue Police Department.

On May Day, which made him think of lei, he learned of protests in Seattle. In the Northwest, the day had long been marked by demonstrations for labor rights, but that year there was a heavy focus on police brutality. He was surprised by the antipolice sentiment and militaristic response. As he acclimated to his settings and settled into his community, Hanaumi learned of the four city-run skate parks. This news of a thriving skate scene excited the police officer, who had lived and breathed the sport in his childhood. The classic skate film The Search for Animal Chin featuring the iconic trio the Bones Brigade—Tony Hawk, Steve Caballero, and Mike McGill—engrossed Hanaumi when he was 10 years old. The film featured Wallows, a gulch in O‘ahu’s Niu Valley, which gave him every reason to assume a skater persona. But increasing amounts of

time spent in school and at work put his skateboard into retirement. It wasn’t until 2015 that he decided to return to the familiar landscape of concrete and Masonite slopes. He hadn’t skated for nearly two decades, but praises of Bellevue’s four skate parks increased his longing to get back on the board. Not wanting to draw attention, he visited Bellevue Indoor Skate Park one evening after work, during the park’s slower hours. To his relief, only an employee and a 6-year-old were there. The pair greeted the uniformed police officer with some confusion, since cops were usually only present for events or camps. When Hanaumi asked if he could join the action, their confusion became skepticism. Assuming Hanaumi had no experience, Akash Rishi, the worker on duty, handed over the necessary skate equipment and began to instruct him on the basic skating stance: Stand on the bolts, bend your knees, stay low. Hanaumi dropped in on the ramp with ease.

The 42-year-old officer approaches his job with humility and a smile. His motto is “Serving and protecting with aloha.”

A thriving local skate scene excited the police officer, who had lived and breathed the sport during his upbringing in Hawai‘i.

32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Impressed, Rishi asked for a picture with Hanaumi to post on Instagram. “Seeing the amount of positivity that came out of Akash’s reaction, I thought ‘I can use this activity as an outreach,’” Hanaumi says. “And then I realized there are camps here with two dozen kids coming out for a week at a time. Every single one of those kids probably has never had any interaction ith the police, and their rst one can e of me skateboarding with them.”

From then on, Hanaumi kept a skateboard in his police car. “Anything done in uniform gets more notice,” he explains. “But I’m the same person whether in uniform or not. It’s just weird to see an officer doing normal things, because people aren’t thinking officers are human beings or have hobbies.” When given slower work assignments in mellow areas, Hanaumi experimented on his skateboard, which drew curious observers, as he hoped. He also teaches jiu jitsu at community

centers like the YMCA and Boys and Girls Clubs as part of his job as a police officer. In his spare time, he continues to hone his skating skills, and he also volunteers teaching students low-brass instruments at Tillicum Middle School. He is almost always in uniform.

Hanaumi became a police officer in 2003 for District Four on O‘ahu, which spans Kahuku to Waim ā nalo. Three years later, he was hired by the Bellevue Police Department.

Officer Hanaumi is on Instagram at @craighanaumi.

34 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Data Loss

Local television, newspapers, and radio stations build bodies of work that preserve the history of places and their communities. But these institutions are shrinking.

TEXT

AND IMAGES BY

JOSHUA IWI LAKE

In the spring of 2010, I stood ankle-deep in colorful wires that lay in twisted piles on the floor of KGMB studio’s master control room. The oldest surviving television station in Hawai‘i, KGMB had hosted many locally produced programs, including Hawaii’s Superkids , Hawaiian Moving Company , Rap Reiplinger’s Rap’s Hawaii , and Checkers and Pogo . But this station that had provided Hawai‘i families with authentic local programming for more than 50 years had finally succumbed to the realities of an internet world, merging with local stations KFVE and KHNL a few months earlier. It was relocating to a new shared home in Kalihi, and what was left of its former location was a maze of lifeless rooms filled with boxes, old furniture, and forgotten technology.

As I wandered the empty offices and hallways with Mike May, a friend and former KGMB news cameraman, we found one room that stood out from the rest: a small office space lined with mismatched bookshelves and oddly shaped boxes. It was the tape room. Typical of television studios, this room was a climate-controlled space that held broadcast-ready versions of programs and any reusable raw footage. Typewritten labels on cases denoted episodes of Hawaii Superkids , Hawaiian Moving Company , and nightly newscasts.

ll legac media, including these lm reels, was to be donated and digitized at the Henry Ku‘ualoha Giugni Moving Image Archive of Hawai‘i at the University of Hawai‘i’s West O‘ahu campus, part of plans to protect KGMB’s archives and make it available to future generations. This is important because newspapers, radio stations, and local television outlets like KGMB build bodies of work that preserve the history of a place and its people in perpetuity. Analog technology has portrayed our communities through stories, photographs, news segments, and children s tele ision sho s, and e are the ene ciaries.

Unfortunately, all technology is not created equal for doing so. For example, prior to the 1980s, almost all of the station’s content was shot on 16mm film. To reduce production costs demanded by the film, the station transferred its back catalog into newly emerging videotape technology and sent the original film to the city dump. But the videotapes deteriorated until they were unplayable. As these institutions disappear, we trade antiquated trappings of in on paper and light on lm for still ne er technology like Facebook posts and live television for Twitter updates. In doing so, we begin to undermine the archival services these legacy institutions provide. It is unknown if our investment in the internet and social media is building something similar. Our collective data represents who we are as a community and a culture. Without proper access to our shared stories, memories, and hopes, we undermine our own identities and self-determination.

According to Sree Sreenivasan, a technology journalist who served as chief digital officer for the Metropolitan Museum of Art and New York City, archives are a huge part of history. It is important to have an accurate historical record of everything and being able to access such archives enables this. However, paywalls, poor website design, and disregard for how the internet works have contributed to the demise of legacy institutions that generate this information even as they have attempted to go online. Furthermore, Sreenivasan continued, online platforms and individuals increasingly store everything digitally with cloud computing. “What happens if we lose access to the cloud?” Sreenivasan said to me during

Inside KGMB studios, from the writer’s visit in 2010. It relocated to shared facilities following a local merger, and all its legacy media was donated.

FLUX PHILES | TECHNOLOGY | 36 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

a phone conversation. “Everything’s in the cloud, great, but what if the cloud is gone one day? What would happen to all the collected memory that we have?”

This scenario is more common than we think. In 2012, Twitter went down for a few hours, costing advertisers an estimated loss of $25 million per minute. In 2015, Facebook caused self-inflicted downtime for nearly an hour, sending the website, apps, and dependent services like Instagram and Tinder grinding to a halt. These websites affect billions of internet users. Then consider the hypothetical downtime of internet service providers, domain registrars and website hosts, government and education services, and the millions of websites that depend upon them. We may have traded our boring but stable solutions for a virtual house of cards.

The internet also has another flaw. “You know the old adage, ‘History is told by the winner?’ In this case, history may be told by the hacker,” Sreenivasan said. “Many years ago, the front page of the New York Times was hacked. … But that kind of vandalism you can tell has happened. What is much more insidious [is if hackers] go in and change the [earned run average] of a pitcher

from a baseball game of the ’40s or ’50s. No one would ever notice or check those records. That kind of tampering is huge.”

Hawai‘i, with its over-dependence on importation that has normalized out-ofstate purchasing decisions and influenced our internet habits, stands to lose the most from a rapid adoption of cloud-based services and increasing reliance on social media as an archival tool. The state’s investment in social media and internet web services place the majority of the data generated by its residents in servers on the mainland and beyond.

There is no local version of Google, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or YouTube, and likely never will be. The idea of instant connectivity in your pocket is a highly effective illusion that only exists if the islands’ power stays on. This issue gets increasingly dystopian when you consider nearly every popular service is a publicly traded company that sells your data for profit. Do we trust these companies to protect our heritage and keep our memories safe forever? Can we verify our data hasn’t been tampered with? Will there be anything to show to future generations?

KGMB provided Hawai‘i families with authentic local programming for more than 50 years before finally succumbing to the realities of an internet world.

38 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Hard Look

In art, as in life, men are constrained by old notions of masculinity. How do we break the mold?

TEXT BY TIMOTHY A. SCHULER

The men are alone. That’s the first thing I notice. Despite their differences—for they are old, young, black, brown, Czech, Hawaiian, heavy, slender, muscular, soft, real, symbolic, and fictional—almost all of the figures in MEN , an exhibition that debuted in September 2018 at the Hawai‘i State Art Museum, are depicted solo.

This isn’t so unusual. A portrait is, almost always, the study of an individual. Many artists begin by drawing the human od , and that od , too, is often a lone gure in a room. And yet there is something profound in the bodies of the men here, not least because, besides being alone, many of their faces are obscured. They show us their backs.

The second thing I notice is that, again with exceptions, the men are all doing something. They dive beneath the waves or bend over fishing nets. They hunt or surf or plant rice in dark paddies. Elizabeth Baxter, the show’s curator, said she didn’t select such images intentionally, but that’s the beauty of art: Even in a collection as small as the museum’s Art in Public Places collection, from which the exhibit was assembled, one can start to see patterns. That so many of the men in MEN are frozen in action says something about us.

The question is: What? What does it say that when we look at men, we largely see them as archetypes concerned with age-old tasks of hunting and gathering?

The exhibit, which spans the century between 1910 and 2010 and features work by Francis Haar, Carol Bennett, James Surls, and Jean Charlot, among others, leaves the question largely unanswered. Only a few pieces, such as Melinda Morey’s series on young men’s public posturing or Rick Allred’s La Bouche , address the topic of masculinity directly. And yet somewhat inadvertently, the show

joins a much larger conversation. In the past few years in the United States, there has been an explosion in the number of people trying to answer a very basic yet very complicated question: What does it mean to be a man?

New York Magazine devoted an entire recent issue to the topic, as did the podcast Death, Sex, and Money, while Devin Friedman published a meditation—in GQ of all places—on the sad lack of intimacy in male friendships. In the wake of #MeToo, discussions of toxic masculinity now can be found in the unlikeliest of places, such as Playboy, which published an exploration of the science of extremism featuring the work of Michael Kimmel, the executive director of Stony Brook University’s Center for the Study of Men and Masculinities.

It can also be found in think pieces about the Harry Potter spin-off Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them , whose highly sensitive, deeply human protagonist, Newt Scamander, has been praised for existing outside the macho mold of the typical Hollywood hero. Or in the national conversation surrounding the death of Anthony Bourdain, who publicly called out chefs who harassed women but also examined his own role in perpetuating the restaurant industry’s toxic culture. “Bourdain’s death is the loss of an ally,” penned one female writer.

Understanding what men are being taught has become an urgent task, and not just because every day seems to bring new sexual assault allegations. There is also a

Masaji Kobayashi by photographer Brian Sato. On display in MEN , a group exhibition focused around artistic depictions of masculinity at the Hawai‘i State Art Museum.

FLUX PHILES | ART | 40 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

IMAGES COURTESY OF HAWAI‘I STATE ART MUSEUM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 41

growing awareness that we are poisoning ourselves. According to a 2018 poll of 1,000 kids aged 10 to 19 in the United States by PerryUndem for PLAN International USA, while the definition of what it means to be a girl has gradually expanded—the result of decades of hard work by women—boys continue to be taught that the number one thing a man should be is “tough.”

“Too many boys are trapped in the same su ocating, outdated model of masculinit , where manhood is measured in strength, where there is no way to be vulnerable without being emasculated, where manliness is about having power over others,” Michael Ian Black wrote in a New York Times op-ed in early 2018. “They are trapped, and they don’t even have the language to talk about how they feel about being trapped, because the language that exists to discuss the full range of human emotion is still viewed as sensitive and feminine.”

Black was responding to the mass shooting in Parkland, Florida. As of September 2018, there had been 104 mass shootings in the United States since 1982, and all but three of them were committed by men. Men are also responsible for the vast majority of rapes, sexual assaults, and instances of domestic violence in this country. Our violent rage is also aimed inward. Men commit suicide at more than triple the rate of women; in the United States, roughly 80 men kill themselves every day.

At least part of why men are prone to violence is because we are taught that vulnerability is a sign of weakness. As a result, as men get older, our relationships, especially with other men, tend to fade.

Our social circles become smaller and smaller until we find ourselves more or less alone. This sort of social isolation, we’re learning, can be just as deadly as physical violence. Researchers now believe that loneliness is a much greater public health epidemic than obesity, able to increase mortality risk by as much as 50 percent. If men are struggling, we have only ourselves to blame. We mistook our power for strength. We believed our own hype. We couldn’t see the warning signs, or if we did, we largely ignored them. In our silence, we forced women to do our emotional thinking for us. We outsourced to women any question about how we ought to behave in the world. We rely on women to tell us, “This is OK. That is not.” We ask women not only to su er our oorishness ut to it too.

Art and film have romanticized the image of the lone male hero, but rugged individualism is less rosy in real life. It comes at a price. While men retain the power in a patriarchy, we are also imprisoned by it, taught to assert ourselves but only in ways that do not threaten the system. Like war, patriarchy maims even the victors.

Standing in the gallery at the Hawai‘i State Art Museum, I think about the ways that I’ve internalized messages about shame, weakness, vulnerability. I never bought into the idea of machismo; I’ve been the shy, sensitive guy for as long as I can remember. Still, it seeps in. Like a muscle, our ability to be emotionally honest can atrophy. It’s taken three years of therapy to decode the breadth of my own feelings and learn how to access them in real time. And I still have a long way to go.

The exhibit asks a very basic yet very complicated question: What does it mean to be a man?

Above, Query Abjection by Allen Hori.

Photographer Robin Kaye’s portrait of a L ā na‘i resident from the 1970s titled Jonathan Mano

42 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

A series by Melinda

displays the backsides of its subjects, a common posture and motif that appears throughout creative expressions of men in contemporary art.

Morey

In the past few years, more Americans are trying to answer a basic yet complicated question: What does it mean to be a man?

From La Bouche , a series by Rick Allred.

Clearly, more than ever, there is a need for men to listen to the women in their lives—at home, at work, in school, on the eld. ut men also need to see out one another, not for empowerment, but for help. We have to unlearn what we were taught as boys and instead remind each other that it’s OK to be vulnerable, to look “weak.” Looking weak takes tremendous courage.

After I leave the exhibit, I find myself meditating on one image in particular, a black and white photograph by Robin Kaye, ho documented na i throughout the 1970s. The work is named for its subject, Jonathan Mano, who in the photograph wears a loose-fitting T-shirt and smiles proudly as he leans on the carcass of a huge pig, which is stretched out on a table, its skin sagging in huge, long folds.

At first glance, the image is full of all the old symbols: physical strength, violence, death. But then we read that the pig was not wild. Mano raised it for the occasion, a l au that as a out to ta e place. he circumstances of the animal’s death are a clue to something else as well: Mano is part of a communit . l au is not a solo event but a raucous, often celebratory feast,

full of uncles, aunties, cousins, friends. In his book, Lāna‘i Folks , Kaye wrote that the preparations for one l au too months and, during those days beforehand, “It was as if the party had already begun.”

We know very little about Jonathan Mano and nothing of his wellbeing in the moment that Kaye made his picture. But his is one of the only smiles in the exhibit. And at least a portion of his happiness seems to come from his participation in this communal ritual. I wonder: How can men recover this kind of community? To start, we’ll have to admit that community requires human connection and human connection requires vulnerability. A lot of men are learning this. I’m learning it. As I do, life gets a little bit easier, for me and for those around me.

Shortly after Mano posed with his pig, the animal would have been hauled to the imu. It would have been set on a bed of kiawe wood and red-hot stones, itself the result of much hard work performed by dozens of hands. What we see in the photo is a solitary man, but Mano is not alone. A party is about to begin. The feast is imminent.

Art and film have romanticized the lone male hero, but rugged individualism can be less rosy in real life. Spear Fisherman by Louis Pohl.

MEN , on display at the Hawai‘i State Art Museum, runs through January 2019. Free and open to the public.

46 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUX FEATURE

FLUX FEATURE

In the Wake of Water

Home to one of the wettest places in the world, Kaua‘i is blessed with an overabundance of rainfall. But the people who live there also know how unstoppable and destructive water can be.

TEXT

AND IMAGES

BY CHRISTIAN COOK

Growing up on Kaua‘i, water was all we knew. Every free second we had we spent playing in the tossing shore break at Lumaha‘i Beach, swimming in the frigid waters of cold ponds, or kayaking up a river to a waterfall. The water was always there, and always on our minds. At Hanalei Elementary School, every kid was obsessed with the surf and everyone constantly sketched perfect waves on school notebooks. Rain, floods, and landslides were also part of life growing up on Kaua‘i. I spent the night at my best friend’s house in Wainiha Valley every Wednesday, and the drive there, which took us over steep ridges on narrow two-lane roads with no guard rails, gave me recurring nightmares about landslides taking us over the edge. We would be free from school for weeks at a time when the typically placid Hanalei River would swell with the heavy rains of Mount Wai‘ale‘ale and spill over its banks, covering the road and even the bridge that connected Hanalei with the rest of Kaua‘i. These small natural disasters were normal, and we relished them. We shared the same insight as Hemingway in For Whom the Bell Tolls : “This was a big storm and he might as well enjoy it. It was ruining everything, but you might as well enjoy it.” The change a storm brought, those moments of uncertainty and unknowing were exciting and different, and they brought an element of danger to our everyday, idyllic life.

Then came Hurricane Iniki. Kaua‘i was demolished, and my life was never the same. My family lived in a small condominium, and in the second half of the hurricane, the roof of a nearby tower flew right into our condo. We were in the bathroom, and death missed us by only inches. I could tell you of other storms after that hurricane, about the time we saw ball lightning rolling around in the yard of

our off-the-grid home in Pila‘a, about when my uncle was lost at sea, about what it’s like to see a steadfast and strong coconut tree break out of the ground and fly in the air and the aquamarine blue of swimming pools transform into a deep green, about encountering massive sinkholes that opened in the middle of the road and swallowed swathes of asphalt. But these childhood memories could never prepare me for the destructive power of water that the people of Kaua‘i were yet to witness.

In mid-April 2018, I was an enjoying warm, sunny day on the west side of Kaua‘i. Sitting in the shade of my brother’s garage, I absentmindedly checked Instagram and saw the live feed of my friend Timothy Hamilton, who works at an upriver Hanalei tour boat yard on the island’s lush north shore. What he was broadcasting shocked me: Hanalei River as wide as the Amazon, its distant shore shrouded in rain.

Tim continued to live-stream through the morning, first from the boat yard and then from the mouth of Hanalei River. Floodwaters inched over the banks, up to his heels. Then, over the next hour, the water surged to head-high and reached as wide as a football field, washing away everything in its path. Tim filmed as he clung precariously to an areca palm to avoid being swept away in a deluge of foaming, chocolate-brown river water. Then, out of the maelstrom, a jet ski raced up to him. Tim reached out, and the ski delivered him to safety.

The gentle rain and waters of Kaua‘i had shown their darker side. They also revealed unlikely heroes.

On that day, the rain-saturated rivers and streams of Hanalei and Wainiha poured over their banks, flooding to levels beyond what anyone could remember. A rain gauge measured nearly 50 inches of rainfall in a 24-hour period, a world record. The raging rainwater soaked the land, causing landslides that moved homes off their foundations, undermined roads and In the aftermath of historic flash flooding and mudslides, Hanalei Bay on the north shore was rendered unrecognizable to those who lived there.

50 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

i ak ana a iā ‘o

ia i a ka ai a ān

ia i lalo i ka on a i ka ai

ka ai ka a ān analoa

He waipuna, he wai e inu

He wai e mana, he wai e ola ola n a

One question I ask of you

o s a o ān

Deep in the ground, in the gushing spring

n s o ān an analoa

ll s in o a a a o a a o o a o li

Li Lon a i li

l o ān

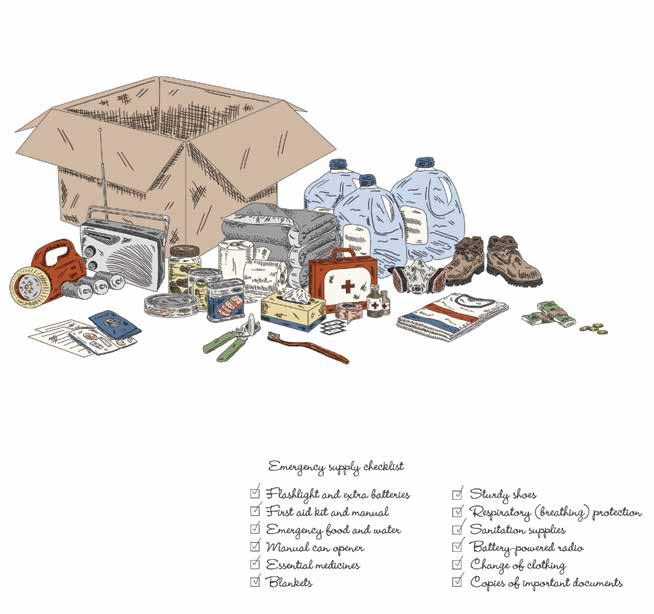

buried them with red dirt. Early on April 15, determined to help, I set out for Princeville, a resort town sitting high on a plateau overlooking flood-ravaged Hanalei to the west. The road into Hanalei was closed by a police blockade, with officers in their blue uniforms waving traffic back and away from the destruction zone. I walked around to a side entrance. Even at Princeville, far above the low-lying flood plain of Hanalei, the extreme rain had broken the road in places. One section I had crossed countless times on my way to Foodland as a child was completely washed away, a gaping sore in the otherwise smooth roadway.

Making my way to the east bank of the Hanalei River, I came upon a flow of evacuees from the populated valleys of analei, ainiha, and ena ho had een rescued by boat and ski. Huge hands of green bananas, cans of gasoline, bottles of water, and other supplies packed by volunteers were piled up on the shore. Among them was a group of campers who had fled from the famous Kalalau Valley. The Kalalau Trail is renowned as a beautiful hike, but also as one of the world’s most dangerous. They had tra ersed this precarious trail to ena after the storm s rains lifted and then made their a do n flooded hi Highway to Hanalei. They recounted hiking through wash-outs on a narrow, slippery trail carved into a pali thousands of feet above the ocean, one slip away from a deadly plummet. They told of arriving back to civilization at a andoned each, utterl in shoc as the encountered apocalyptic scenes of downed telephone poles and abandoned vehicles littering the roads. I flagged down a friend on a jet ski. He dropped me upriver on a dock in the backyard of the home of big-wave surfer Laird Hamilton. The day before, Hamilton had tirelessly trekked up and down the river, rescuing people from second-story windows and delivering food and water to stranded people in Wainiha. A quarter-mile downriver, the home of retired longtime Hanalei boat captain and surfer Ralph Young lay in ruin, pushed aside effortlessly by a muddy landslide. The classic plantation-era home was nearly 100 feet from its foundation. The flood left behind a muddy outline of the house littered with his possessions. Ralph’s home lay peeled open like a tin can. A hole torn in a wall revealed a beautifully renovated bathroom exposed to the elements. I joined in retrieving glass balls, surfboards, and memorabilia from the mud.

Then I caught passage on a boat headed west to Wainiha Valley, which along with its adjoining valleys were the most heavily flooded areas. In earlier times, Wainiha was a kalo-farming valley, the longest-lasting on Kaua‘i. The waters of Wainiha, which make it prime for wetland taro farming, flow from the table-top plateau of ount ai ale ale, hich is a out , feet a o e sea level, and then pass through the valley on a 14-mile path to the Pacific Ocean. Rock walls were strategically erected to turn the wild waters of the stream into a precise irrigation system. Hawaiian planters at Wainiha fed a large

Suffering major damage to roads and bridges, many communities were completely cut off from one another.

The majority of homes affected were in Hanalei, Wainiha, H ā‘ena, and Anahola.

population on taro, ananas, olon , s eet potatoes, a a, and noni. The name of the ahupua‘a translates to “angry waters” or “unfriendly waters,” perhaps a reference to both its flowing streams and its dangerous shoreline.

Growing up, I spent days with my best friend, Makana, exploring upper Wainiha Stream near his family home. We would wander barefoot under blue skies and brilliant sunlight through verdant fields, crossing streams by clinging to slippery stones. I remembered the dappled light filtered by the shade of overhanging choke plum trees, patches of light reflecting on the fast-moving mountain water. We would catch Tahitian prawns with our hands and sometimes even manage to score a sucker-bellied, slimy o‘opu. Those pleasant days belied the extreme power of the Wainiha streams. In the aftermath of the flood, I barely recognized the valley. Homes, brand new Toyota Tacoma trucks, and the possessions of entire lives were washed away on April 14. The flood forever transformed the landscape and the lives of families who were now bereft of houses, of dry clothes, of drinkable water, of any of the typical comforts we take for granted.

54 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Returning to the beaches of Hanalei, the verdant mountain backdrop stood in stark contrast to the dilapidated and collapsing fooded lu ur homes that sell for double-digit millions along its coast. These mansions, twisted and waterlogged, stood in testament to the arrogance of man. Houses built upon sand had collapsed as the land under their foundations was swept away. I saw wrecked vehicles and pieces of once vainly glorious homes degrading into standing water and sediment. Walking through Black Pot Beach Park was the most shocking. I had spent so much of my youth at this beach. I had been umping o its pier for as long as I could remember, and relieving myself in its always sandy public restroom for just as long. I still have a scar on my back from being slammed into the parking lot’s ironwood hedge on my 14th birthday. Now this landscape that I

had considered ed and permanent, somewhere I could always relive my childhood exploits, was irrevocably transformed. Water had consumed the land around the pier, and the restroom lay squished on the ground nearly eight feet lower than where it was originally. Looking down into its ruins and seeing tilapia swimming around a sink where I had washed my hands for more than 30 years gave me the strangest feeling, one I can only describe as cognitive dissonance.

A flood tears everything apart. It also brings everything together and creates renewal and growth in the wake of its destructive path. Nine days after the flood, the townspeople of Wainiha, Hanalei, and Ha‘ena gathered at Hanalei Colony Resort to discuss plans for ongoing rescue and aid efforts and how to move forward. There still wasn’t enough drinking water. Standing water

A preliminary assessment from the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency estimated nearly $20 million in damage to public properties from the severe storm.

56 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

throughout Wainiha contained disease-carrying microbes. Officials from the Department of Health and other government agencies took turns sharing their instructions and guidance. People, justifiably exhausted and frustrated, still managed to smile at one another across the room. Many people had lost their homes and were unable to work but remained cool and neighborly. A haunting mele had begun the town meeting, and its ethereal melody engendered thoughts of the countless generations who had come before, of Hawaiians traveling on foot and by canoe to meet around puna ho offered advice and support for ama ina ho ere ust as traumatized by the storms of ancient Hawai‘i.

The gentle and nourishing rain and waters of Kaua‘i had shown their darker side, a destructive force, unstoppable and unknowable. But they also revealed unlikely heroes. Talitha Byram, general manager of Hanalei Big Save, and her staff of two worked a 56-hour shift to keep residents and tourists fed and comfortable while they were trapped in Hanalei. The Robinson family landed a barge with supplies and Polaris UTVs for residents to navigate the transformed landscape. Volunteers immediately brought in excavators and worked to remove the debris from 12 landslides that blocked the roads. Water, that substance that we use so much of and

think of so little, showed its true power to destroy and divide, but also to dissolve the barriers between landowner and resident, tourist and shopkeeper, na a maoli and haole. Floods will come again. There will be storms and wind, lightning and rain.

Way out in the Pacific, our islands are the most remote in the world, completely exposed to the powerful forces of nature. Everything can change in an instant, and if we remain inflexible, we will be washed away just as easily as tears in the rain.

More than 150 people were evacuated and rescued by helicopter and more than 120 by bus and watercraft from floodstricken areas.

60 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUX FEATURE

T he

Gua rd ians

O‘ahu’s female lifeguards are some of the most elite and respected waterwomen in the world.

Every day, these fearless first responders test their power to save lives against the formidable Pacific Ocean.

TEXT BY LINDSEY KESEL

IMAGES BY JENNY SATHNGAM

She sits alone in a white tower before a sea of bobbing surfers waiting for the next set, capped swimmers following imaginary perpendicular lines, bodyboarders flirting with pounding shorebreak. She is tracking every silhouette in her line of sight, searching for the harbingers of trouble—the child ignoring his mother’s warning to stay close, the snorkeler inching closer to the current, the stand-up paddler with a beginner’s stance. While O‘ahu’s locals and visitors enjoy another day at the beach, she waits vigilant as bodyguard and guardian angel, ready to risk her own life to keep the sea from claiming the lives of those she protects.

“You go into tunnel vision,” says Kawehi Namu‘o, a 39-year-old lifeguard stationed at a a each ar on the island’s west side. “You’re running from the tower, your shades are flying off, you don’t see nothing around you. It’s just you against the ocean in that moment.”

he sta of cean Safety and Lifeguard Services, a division of the City and County of Honolulu Emergency Services Department, can’t a ord to tear their e es from the sea for longer than a few seconds at a time. Lifeguards are on duty seven days a week, including holidays, typically for eight-hour shifts, or longer if there’s high surf. The 42 towers on O‘ahu are split into

four districts: South Shore, Windward, North Shore, and Leeward—each with a captain and two or three lieutenants, plus two teams of eight personal rescue watercraft operators. Of the 126 lifeguards, only nine are women, and there’s never been a woman in a supervisor or watercraft position.

Hawai‘i is one of the few places in the world where lifeguarding is a year-round and full-time job. It’s also one of the most dangerous places to be a lifeguard, mixing inexperienced swimmers with hazards like strong currents, high surf, and sharp rocks. These risks are compounded by the growth

Above, Kawehi Namu‘o, at Pō ka‘ ī Bay Beach Park. She is the west side’s lone female lifeguard and the only one with EMT certification. Previous spread, Ka‘iulani Bowers, a lifeguard stationed on O‘ahu’s east side.

64 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

of stand-up paddling, kayaking, hydrofoiling, and kitesurfing—sports that have high percentages of beginners. In 2017, local lifeguards assisted in 3,340 rescues, according to Shayne Enright, public information officer for the Honolulu Emergency Services Department. These included responding to 1,300 major medical cases (traumatic injuries, near drownings, and other calls requiring emergency medical services on the scene) and 16 drownings.

In 2018, O‘ahu will likely surpass the 23 million beach visits it saw the previous year—and more visitors means a greater potential for injuries, even fatalities. Ocean Safety continues to fortify the best defense it has in minimizing collateral damage from ocean recreation nding and recruiting rst responders like Namu‘o. As a kid, she was always on the beach near her home in n uli learning how to dive for tako (octopus) with her grandpa and teaching herself to surf. Working with the sea was all she ever wanted to do. On

her da s o , she surfs her favorite west side breaks or leads paddling crews as the head coach of aha Canoe Club. The only female lifeguard with EMT certi cation, she sa s it gi es her more con dence in caring for victims of severe injuries.

When Namu‘o first began lifeguarding, she rotated through the west side beaches and fell in lo e ith a a , a one-tower beach tucked in from Farrington Highway. She requested it as her permanent assignment. Having spent most of her 15-year career here, she has watched it go from a sleepy local hangout to what she calls the “West Side Ala Moana,” a location popular with tourists and locals like Ala Moana Beach in Honolulu. Today, the majority of her rescues involve visitors who are stand-up paddling. “It’s definitely higher stress,” she says. “A lot of stand-up paddlers have a false sense of confidence. They’re following dolphins and heading out in the surf now instead of staying in the flat water.”

Lifeguard Chelsea Bizik mentors young girls in the Junior Lifeguards program. She says, “A lot of women care about looking skinny and petite, but that’s not us, we’re strong women.”

66 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Lifeguards are on duty seven days a week, including holidays, typically for eight-hour shifts, or longer if there’s high surf. The 42 towers on O‘ahu are split into four districts: South Shore, Windward, North Shore, and Leeward—each with a captain and two or three lieutenants, plus two teams of eight personal rescue watercraft operators.

In 2018, O‘ahu will likely surpass the 23 million beach visits it saw the previous year, and more visitors means a greater potential for injuries, even fatalities. Ocean Safety continues to fortify the best defense it has in minimizing collateral damage from ocean recreation by finding and recruiting first responders.

When it comes to getting the job, Ocean Safety holds everyone to the same high standards of performance, regardless of age or gender. Candidates participate in two-day tryouts packed with physical strength, stamina, and skills tests. High-ranking recruits are invited to apply for employment, and if they are hired, intense training begins: two weeks of accelerated medical instruction in the classroom culminating in an emergency medical responder certification exam followed by two weeks of water-based exercises. Instructors incorporate training scenarios based on real-life situations former lifeguards have faced. Emergency Services department director Jim Howe says these methods help guards overcome the barriers of fear. “When you’re presented with a situation that is life-threatening, the normal human response is fight or flight, and neither of these responses is appropriate in a rescue situation,” he says.

Ocean Safety training hits all the fear points: deep water, rough surf, confined spaces, sharks. Exercises might entail scaling a coral bench in surging water at Witches’ Brew in Hanauma Bay or jumping into a cove at na i oo out and then s imming the coastline to the area designated for pulling victims out of the water. The new hires are taught highly technical survival and safety maneuvers. One day they might learn how to move a victim of a spinal injury onto a 12-foot rescue board in dangerous shorebreak, and the next they might execute mock rescues in both small and big surf. Freediving is also integrated, including diving a minimum of 30 feet to retrieve a weighted dummy posing as an unconscious swimmer. They do open-ocean swims and sit in the impact zone where waves break to practice maintaining clarity in high-stress environments. They learn how to effectively communicate with hearing-impaired and non-Englishspeaking guests. For the final test, the lifeguards must reach a flag in the back of Moi Hole—a jagged lava cave in Wai‘anae that is the site of one of the most dramatic rescues in Ocean Safety history.

What O‘ahu’s lifeguard inauguration lacks in comfort it makes up for in camaraderie. Surviving the grueling training and working together in the field creates a strong, lifelong bond—because saving lives largely depends on trusting your colleagues. United in this high-stakes role, the guards have each others’ backs. “I don’t go out of my way to prove myself, but over time you earn respect, then you’re tight,” Namu‘o says. “We all hang out outside of work. It’s one big family.”

Exceptional water skills aside, the women lifeguards all share a deep love for the ocean. “Most of us just do it because we’re most comfortable when we’re in the water,” says east side lifeguard Elizabeth Bradshaw. “We all feel that connection. I couldn’t tell you the last day I didn’t go jump in the water.”

At age 15, Bradshaw watched her brother try out for the lifeguard program in Crystal Cove State Park, California.

“I remember being so upset because I wanted to be able to jump in on it, thinking I totally could have done that,” she says. A year later, in 2013, she became a lifeguard at Crystal Cove. After moving to O‘ahu for college, at age 19, Bradshaw was hired by the Ocean Safety division. The island’s strong currents ere challenging at rst, and she had ne er used a rescue board before, but the men and women in her district helped her get acclimated.

In June 2018, Bradshaw saved 70-year-old snorkeler Lawrence Gambone at Hanauma Bay by performing CPR for eight minutes. Along with the EMTs and other guards who responded to the incident, she reunited with Gambone in his hospital room two weeks later to celebrate his dramatic rescue. This deep-rooted team dynamic is what makes the victories possible—and carries the guards through the tragic losses as well. “It’s like having a second family. When you have incidents that are heavier or harder, you have 50-plus brothers and sisters who are around,” Bradshaw says. “Everyone will come together and jump in the water and check on each other.”

Successfully manning 198 miles of O‘ahu coastline and near-shore waters out to a mile also hinges on the Ocean

70 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Elizabeth Bradshaw, a lifeguard on O‘ahu’s east side.

“Most of us just do it because we’re most comfortable when we’re in the water,” says Bradshaw. “We all feel that connection. I couldn’t tell you the last day I didn’t go jump in the water.”

Safety crew following a very precise code of conduct. “Before we go out on a rescue, we have to alert the neighbor towers,” explains south shore lifeguard Marianna Pires, who is stationed at la oana and ai . “They watch the rescue and wait for hand signals—it can either be, ‘It’s all good,’ ‘I need assistance,’ or ‘unconscious person.’” hen it s up to the guards to focus on lling in the gaps of what happened and wait with the victim until the paramedics arrive, o ering life support if necessar . The rescues tend to get all of the glory, but the guards actually spend most of their time on preventive action and administering medical attention for emergencies like heat exhaustion, stroke, cardiac arrest, seizures, and Portuguese man-o’-war encounters. Lifeguards are constantly talking to beachgoers about the day’s conditions and hunting for behaviors that could put people at greater risk for injury. Says Bradshaw, “At Sandy’s, sometimes I’ll see people walking up carrying floaties and I have to tell them, ‘That’s not a good idea.’”

Behind the scenes are the lifeguards manning the Safety Dispatch Center in ai , here a team of four ta e and emergency calls from tower guards and then coordinate with Honolulu Fire Department, Honolulu Emergency Medical Services Department, Honolulu Police Department, and Honolulu Department of Parks and Recreation to get them the support they need. “It’s just like on the beach, some days everything goes well, and some days everything is going wrong,” says lifeguard Chelsea Bizik, who left her east-side post to join dispatch in February 2018, when she was seven months pregnant. “You get a call from the east side—a broken neck—and then two minutes later a possible drowning on the North Shore. It’s crazy to see the teamwork side of it all.”

Bizik returned to dispatch after maternity leave, but she hopes to resume her beach post soon. “I’m seeing all the different situations the tower guards go through and it’s made me more confident,” she says. “But the feeling of saving someone is priceless. I wouldn’t mind being

a lieutenant, and maybe even a captain one day—how amazing would that be?”

Mentoring Ocean Safety hopefuls in the Junior Lifeguards program, Bizik encourages young girls to focus on developing their strength. “A lot of women care about looking skinny and petite, but that’s not us, we’re strong women,” she says. “You need the muscle, and you need to be able to pull somebody onto your board and swim them in past a three- to five-foot shorebreak.” She advises them to get in the water as much as possible to swim, surf, and practice quick turns on a longboard. Sitting and watching people interact with the ocean is also important, she says, to start developing an eye for spotting trouble.

“After a few years, you see the patterns of people who know how to swim and people who don’t—you can pick them out just like that,” Bizik says. She and the other guards have a saying, “lifeguards for life,” that speaks to this notion of “the eye” as an ingrained response. It’s not something you can turn off or age out of.

Former south shore lifeguard Helene Phillips saw a lot of changes over her 33 years of service, but one thing that never wavered was the close relationships formed among the guards. “We were a lot smaller then—about 50 of us—and everybody knew everybody,” she says. “I always felt it was a brother-sister relationship with male lifeguards. The competitiveness was a bonus to the job; it was so cool to be inspired by each other and push each other to get better.” She retired from Ocean Safety in 2014 after lifeguarding alongside respected waterwomen Rell Sun, Pua Moku‘au, and Marie McCauley, who went on become Honolulu Police Department’s first female deputy chief.

Looking back, Phillips feels grateful for the opportunity to spend her days right next to the sea, and for the fitness habits she parlayed into a lifelong training regimen. About five days a week, she heads to Ala Moana Beach to exercise and reflect. “The sprints are getting harder, but the run-swim still feels natural to me today,” she says. “Then I’ll sit on the bench near my old tower and think, I’m home.”

Helene Phillips, a retired south shore lifeguard.

OF THE 126 PART - TIME AND FULL- TIME LIFEGUARDS, 9 ARE WOMEN.

District I – South Shore

Kristin Acerra

Megan Jones

Marianna Pires

Leslie Roberts

District II – East Side

Chelsea Bizik

Ka‘iulani Bowers

Elizabeth Bradshaw

Shannon Clancey Tuinei

District IV – West Side

Kawehi Namu‘o

74 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 75

Enclothed Cognition

The drape of a kīhei. A family heirloom handed down. A body-hugging dress. In the following portraits, we gathered people from all walks of life and disciplines to look at the diverse array of garments that most empower them.

IMAGES BY CHRIS ROHRER

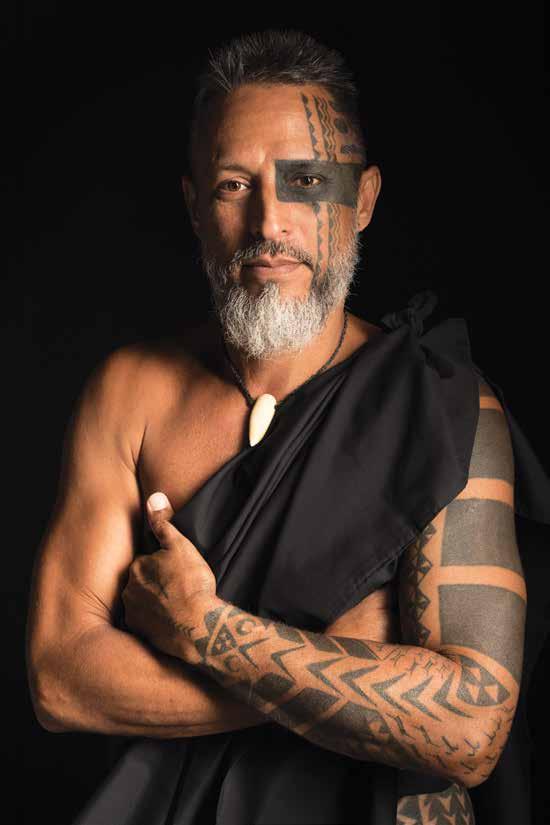

Throughout history, humans have used clothing to signal power and prestige. In a ai i, items li e n hulu ali i, or ro al featherwork, functioned as more than adornment. They signaled status, genealogy, and a right to rule. Take, for example, the ei, or feathered cordon, that elonged to loa, a legendar ali i of a ai i sland. t measured just under three meters in length and was generously covered on both sides with crimson and gold i‘iwi feathers— an undertaking that necessitated that thousands of individual feathers be carefully plucked from the necks and wings of birds and sewn to the garment’s fabric. Bordering the ends were yellow feathers from the prized and elusive o‘o bird. Along its cross section at the bottom edge, arranged in neat little rows, were human teeth. This arrangement of feathers and teeth was a show of power. Only the elite could don such plumage. The teeth contained the mana of ancestors and fallen warriors.

Today, researchers have found a psychological function to how we dress. Referred to as enclothed cognition, their theory is that clothing can affect how we think and behave.

“It’s about signaling a meaning to those around you and to yourself,” says Joni Sasaki, an assistant professor of psychology at the ni ersit of a ai i at noa. “Clothes are something that people really find deeply meaningful in terms of what it says about them,” Sasaki says. “Not just as individuals but also who they are in connection to the community around them.”

In the following portraits, we gathered members of Honolulu’s community to explore which items of clothing are their most empowering.

— Eunica Escalante

FLUX FEATURE

Bradley Rhea Owner, Barrio Vintage Clothed in: 1970s rice bag kimono

Bradley Rhea Owner, Barrio Vintage Clothed in: 1970s rice bag kimono

“I am always looking for the most original pieces to add to my closet items that played an important role in very specific moments in history. Most of my favorite pieces have been personalized by someone long ago, and this kimono is an incredible representation of this. It’s recycled from rice bags in the ’70s, a trend somewhat prolific during the time. Though you can find wonderfully done reproductions, there’s something about donning the original that is incredibly insurmountable.”

Clothed in: On-stage persona

“The idea of Cocoa Chandelier is empowering in itself: She is bold, courageous, cheeky, and camp. Being a role model is not something I aspired to be, but when you are out there living your truth, people look up to you just for being yourself. My mana comes from the people I surround myself with, and they have helped cultivate who Cocoa Chandelier is today.”

Cocoa Chandelier

Entertainer

Clothed in: Everyday work attire

“When I worked as an art installer at Spalding House, I used to wear the same outfit just because it’s the easiest to work in. Over time, it’s turned into something that’s recognizable. I didn’t consciously think about branding myself, but it’s just kind of turned into something that people associate me with.”

John Koga Artist

Ara Laylo

Creative director, NMG Network

Clothed in: Vintage jacket

Ara Laylo

Creative director, NMG Network

Clothed in: Vintage jacket

“I found this jacket at a flea market. The vendor was selling her mother’s vintage jacket for basically nothing. There’s something about finding value in things that others don’t.”

Summer Chong Dermatologist

Clothed in: Doctor ’s coat

“The first time that I put on this coat after receiving my PhD, I felt proud, accomplished, and honored. Wearing my white coat does empower me. For me, it stands for professionalism and reminds me of my commitment to my patients and the community.”

Brian Lam

Brian Lam

“My father gifted these to me and my brothers. I chose the one with the dark green tint and giant chip, and my father said that’s the damaged one with immature color. I guess it was meant to be! I like feeling the gravity of it sitting on my wrist, and I like to imagine it bringing me the tiniest bit closer to my ancestors.”

Founder, The Wirecutter

Clothed in: Jade bracelet

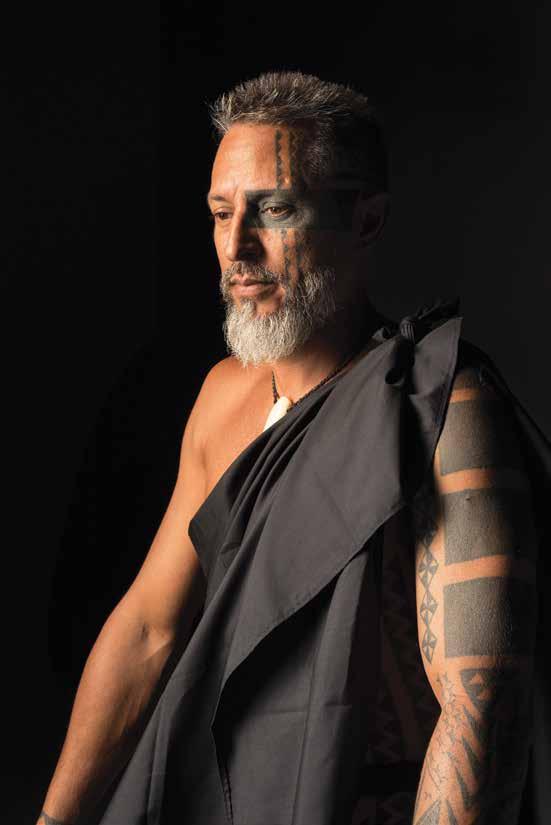

Keli‘iokalani Mākua

raditional tattooist, a n h n holani Clothed in hei and au uhi tattoos

“I got into k ā kau uhi while dancing hula for my cousin Keone Nunes. Elders passed information to him in his younger years on the priestly practice. I would assist him and became his apprentice. My sixth-generation grandfather was the last tattooist in my direct lineage—I’m following in my ancestors’ path. The patterns I wear are some of the same they wore. We mark our bodies to strengthen them, and to show who and where we are from. My ancestors will recognize me after I pass and guide me along the long red path of K ā ne because I wear their markings.”

FLUX FEATURE

Birt h

R ig ht s

More than a decade ago, Hawai‘i became the first state in the nation to give mothers the right to take home their placentas after childbirth. This has helped revitalize indigenous birthing rights and traditions and enabled holistic maternity practices on the islands.

TEXT BY RAE SOJOT

IMAGES BY MARIE ERIEL HOBRO AND JOHN HOOK

The placenta is a study in both substance and sustenance. With a name derived from “plakous,” Greek for “flat cake,” the placenta is hefty and oblong, averaging nine inches wide and one inch thick. It is dense and spongey and slab-like, with a rich vein system that radiates outward in myriad root-like lobes. Though no two placentas look alike, most subscribe to a palette of deep, meaty reds and dusky blue-purples, with large surface areas that outpace placentas of other mammals due to the human fetus’ enormous nutrient demand. Engorged with blood and attached to the interior wall of the mother’s uterus, the placenta is an organ of consequence during pregnancy. For nine months, it plays many critical roles: a conduit for nutrients and hormones, a filter against toxins, a sensor determining the needs of the fetus, a manufacturer of hormones for both fetus and mother. Once the mother gives birth, the placenta is expunged, hence the term, “afterbirth.” However, outside the womb, the placenta’s mystique remains in two arenas: cultural practices and the wellness industry.

I.ea eo ap ha u ichael to as orn in the hushed, early morning hours of a rising autumn moon. On a day marked by another rising moon, two months later, the infant’s family gathered in a quiet ceremony to bury his ‘iewe, or placenta, on his father’s ancestral homelands in Hilo on Hawai‘i Island. Doing so would spiritually lin the child to his ina, or land. o the first-time parents, this Hawaiian birthing

practice concept felt more than just pono, or right. It felt destined.

The preparations for the ceremony were simple and intentional. A small pit was dug and lined with compost and ash and then bordered with rocks that had been gathered from a waterfall on the family’s property. Nearby, a young niu, or coconut sapling, awaited planting. The selection of the niu was purposeful: the tree was a inolau, or em odiment, of , a masculine deity in the Hawaiian pantheon. Throughout its years, it would produce prized nuts; over the child’s lifetime and beyond, it would serve as a ceremonial marker and living testament to the ‘iewe’s resting place.

What was earthly was transcended into something otherworldly as the ‘iewe, dark and flushed with blood, was gently placed into the ground by the child’s father. With the ‘iewe’s return to the earth, the consecration was complete: The child as fore er lin ed to the ina and his ancestors. The child’s parents felt a sense of peace wash over them. Their son, ea eo ap ha u ichael to, ould ne er be lost.

The relationship between man and ina is a crucial one in a aiian culture. “Our origin stories have us coming from the land as kalo,” explains Malia NobregaOlivera, a Native Hawaiian cultural specialist and a director at the University of a ai i at noa s a ai inui ea School of Hawaiian Knowledge. By burying a child’s ‘iewe, one pays homage to that sacred link. “It’s usually done in a special place, often near a tree that holds meaning to the family or planted alongside a tree sapling,” NobregaOlivera says. For some practitioners, that connection carries significant weight, an

“We empower couples that want to employ cultural practices into their birthing plans.”

—Ka‘iulani

Odom, director of the clinic’s Roots Project

Right, at Kokua Kalihi Valley health center, participants gain knowledge from Native Hawaiian cultural practitioners in an eight-week family birthing program.

94 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

almost non-negotiable spiritual responsibility that, if not recognized, puts the child at spiritual risk. “Some believe that if a child’s ‘iewe is neglected and not given a proper burial,” Nobrega-Olivera says, “the child will grow up disconnected from its ancestors.”