Special Section: Dusk Discovering another side of architectural design during magic hour.

Explore: Visibility Now Menehune revel in mystery, and queer creatives light up the dance foor.

Features: Edge of Darkness Manta rays swim in uncertain waters,

and

The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I Theme: Nights Volume 9 Issue 1 0 01 > 09281 $14.95 US $14.95 CAN 25489 8

overworked locals push onward,

surfers seek solace.

ROYAL HAWAIIAN SHOPPING CENTER ALA MOANA CENTER F EN D I . COM

SCAN WITH THE FENDI APP TO SEE EXCLUSIVE CONTENT

58 | Manta Rays

The multi-million-dollar manta ray tour industry on Hawai‘i Island is a beast of its own. riter i an ill loo s eneath the sur ace o this popular activity that’s never been regulated.

68 | Overtime Shifts

Though unemployment is at its lowest, the cost of living forces some Honolulu residents to give up their nights for a second shift. Photographer Marie Eriel Hobro and writer Eunica Escalante visit these workers to gather their trials.

80 | Night Surfing

An antidote to crowds is to paddle out beneath a ell lit oon. ur er and scientist li apono and photographer John Hook share the thrill of sur ng a ter the sun sets.

92 | BDSM

Delve into the vast and diverse world of BDSM, a universe unto its own of sexual and nonsexual kinks. Writer Martha Cheng speaks with individuals to better grasp this continuum of preference.

TABLE OF CONTENTS | FEATURES | 22 NIGHTS Editor’s Letter Contributors FLUX PHILES 24 | Film Analog Sunshine Recorders 32 | Environment Dark Skies 40 | Animals Native Bats 46 | Community Late-night Diners A HUI HOU 176 | Newborns

FEATURES

TABLE

OF CONTENTS | SECTIONS |

SPECIAL SECTION

DUSK

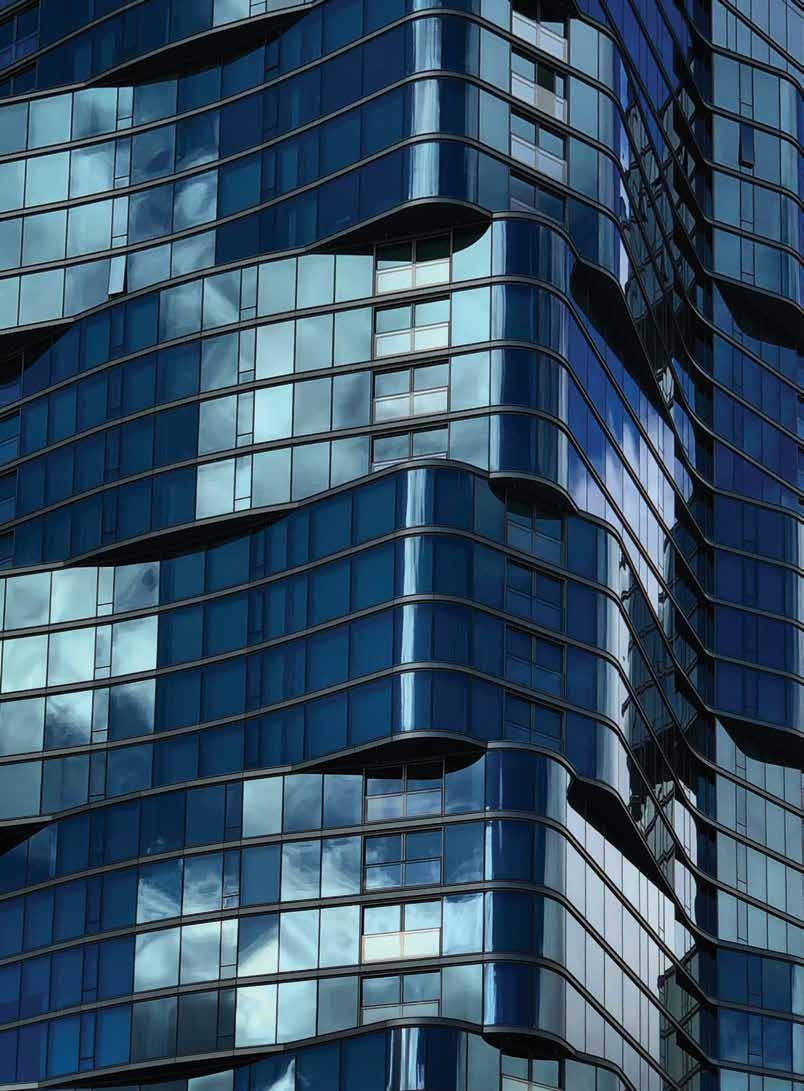

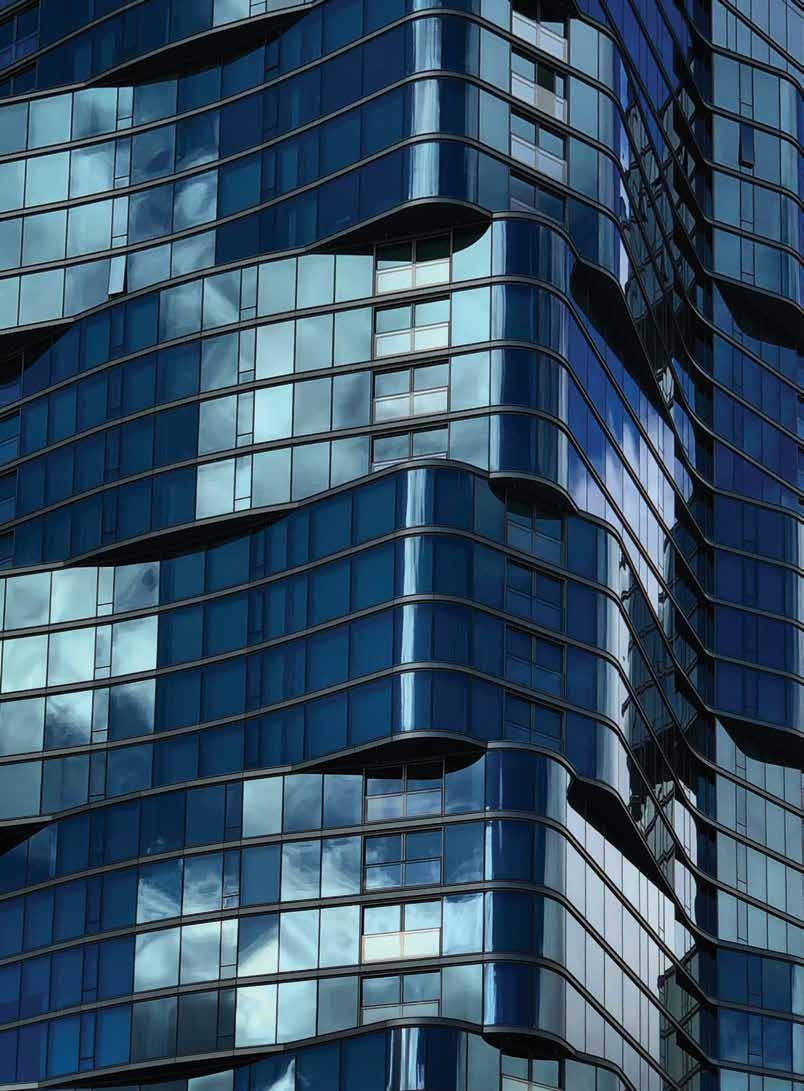

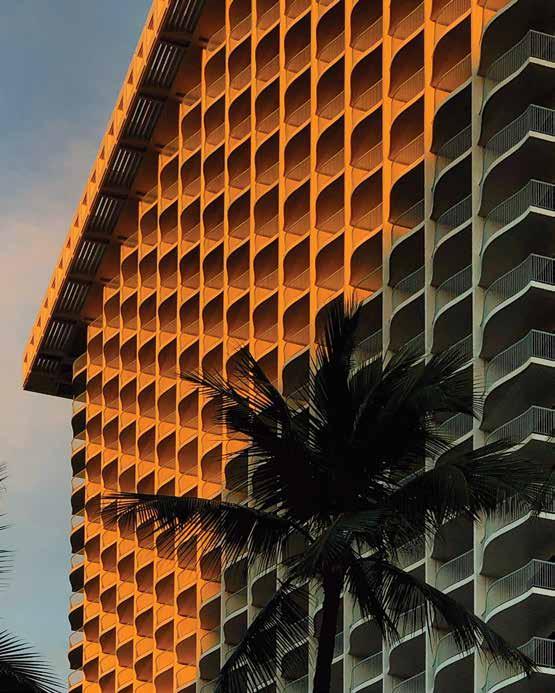

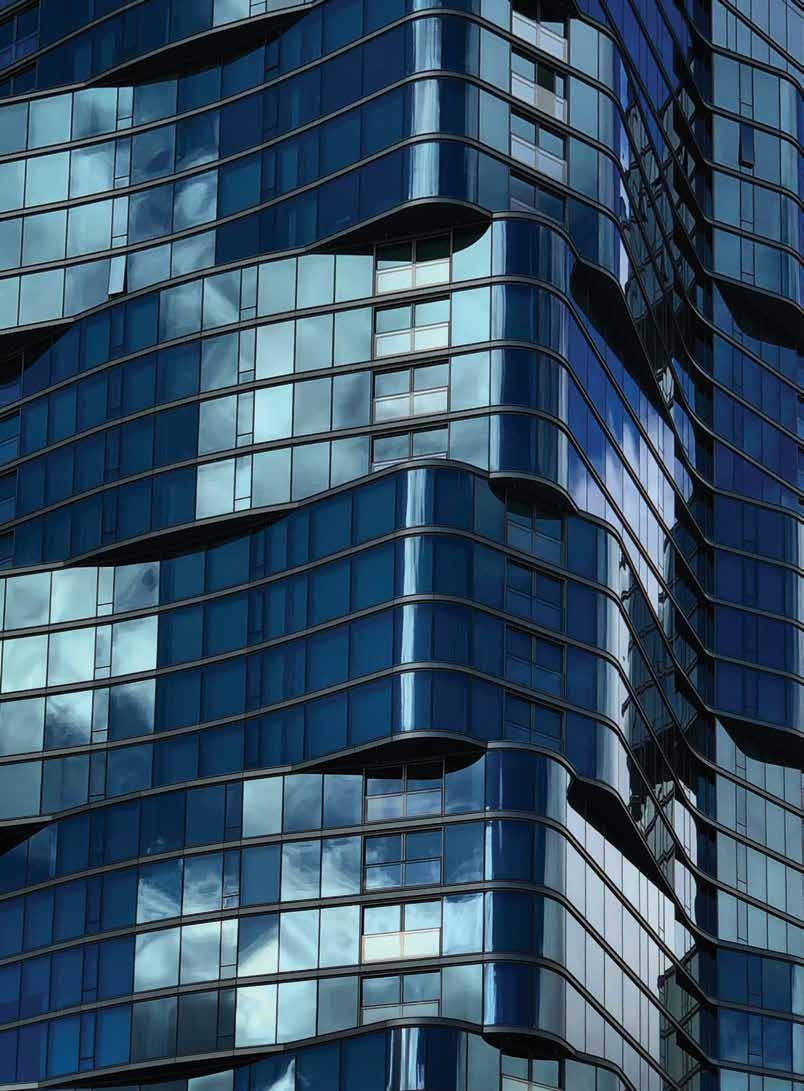

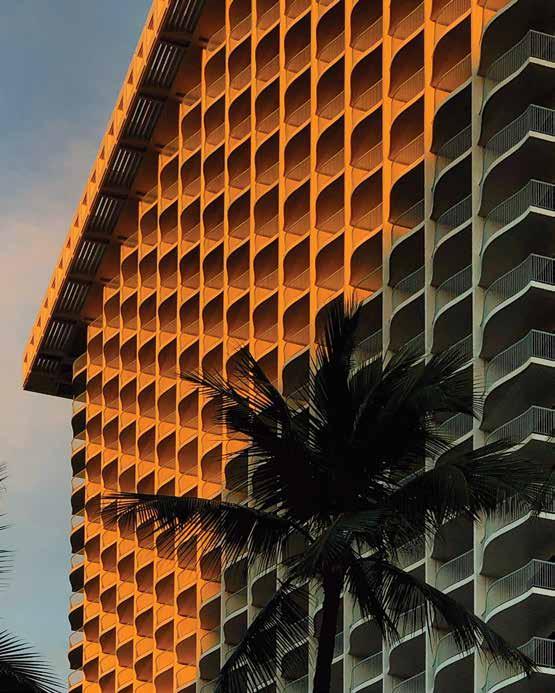

Golden hour, also called magic hour, the period of daytime shortly after sunset or before sunrise, allows one to observe the Honolulu cityscape in its best light.

Designer Caleb Bennett catalogs the architectural details and patterns of O‘ahu’s buildings via his iPhone to capture a graphic sense of place.

138

ANYWHERE ALOHA ® OLUKAI.COM MIKI LĪ

TABLE OF CONTENTS | SECTIONS | 152 LIVING WELL 154 | Media Michelle Broder Van Dyke 160 | Ferns hala otanicals 104 EXPLORE 106 | Legends Menehune 116 | LGBTQ Bubble_T 128 | Lava Tubes a u ura ave

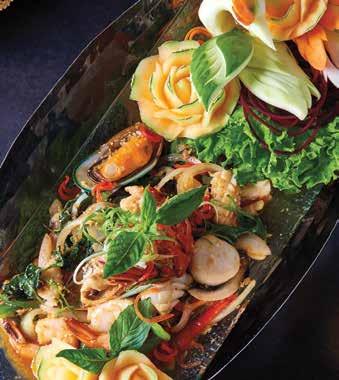

LATE NIGHT LIBATIONS, DESIGNER COCKTAILS AND FINE FOODS. COMPLIMENTARY PARKING www.halekulani.com | 855.738.4966 | 2199 Kalia Road, Honolulu

TABLE OF CONTENTS | FLUX TV |

Stay current on arts and culture with us at:

fluxhawaii.com

/fluxhawaii

@fluxhawaii

@fluxhawaii

FLUX TV

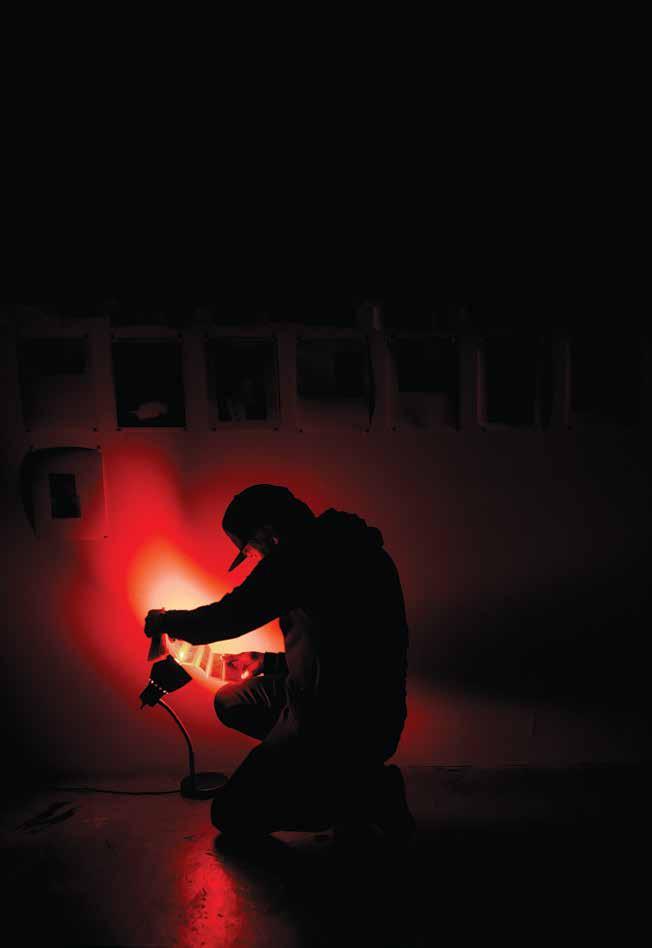

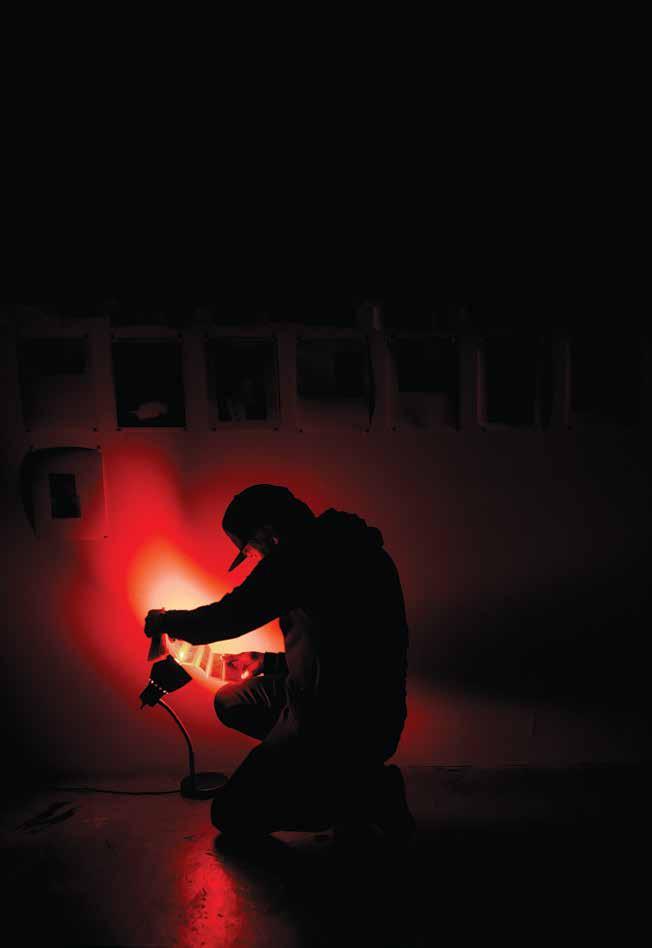

Process: Premiere

In the debut episode of this new series on Hawai‘i creatives, follow Barrio Vintage owner and stylist Bradley Rhea as he prepares to unveil his otherworldly fashion show, “Protea,” at the Hawai‘i State Art Museum.

We represent more luxury listings and sell more luxury properties than any firm in Hawai‘i. Find out why. HawaiiLife.com 800-667-5028 | RB-19928

Pictured: Kailua Kona, Hawaii Island MLS # 619204 Represented by Steve Hurwitz R(B)

Our senses are sharpened in the dark.

Of course, that typically isn’t what we first notice in spaces that are, either figuratively or literally, devoid of light. Often, our first encounters with anything uncertain—say a poorly lit room or a lofty, obscure topic—provoke anxiety, doubt, confusion, fear, or, if you’re me, a bit of impatience. (In my case, the night generally represents a despairing state of immobility. I’d rather do anything else after nightfall than work, which might be why I consume more bowls of cereal for dinner in a state of procrastination and lethargy than for breakfast.) But then, after inching your way through shrouded environments, you get acclimated. Unable to rely only on your sight, you engage other senses or follow thoughts you wouldn’t have otherwise considered. These are worthy skills for a reporter or photographer to exercise. Whether you’re developing prints in a darkroom, descending into a lava tube, surfing at night, or beginning to write, you have to feel your way.

Trekking through uncertainty to see something more clearly— what a paradox to embrace! In her book The Faraway Nearby , Rebecca Solnit ruminates on this subject elegantly. “Darkness is generative, and generation, biological and artistic both, requires this amorous

engagement with the unknown, this entry into the realm where you do not know what you are doing and what will happen next,” she writes. “Ideas emerge from edges and shadows to arrive in the light, and though that’s where they may be seen by others, that’s not where they’re born.” Darkness giving way to creation is a theme that echoes across ancient cultures worldwide. In Hawai‘i, the principal genealogy chant, the u ulipo egins in the cos ological real o p dar and lingers there for almost half of its 2,101 verses: Not only is the dark the source of everything—it is worth settling into and spending time with.

This theme of welcoming discovery in the dark resulted in a surprisingly sensuous issue. Some of the stories are charming, others are challenging. Rather than individually highlight the stories contained in this issue, as an editor’s letter expectedly, if resourcefully, does for its readers, I’ll let you feel them out on your own. They don’t always provide answers, but each are delicately traced with speci cit to people and place. he show that among tumultuous days, a single night can, in fact, hold us steady.

For me, this was revealed to me in a single visual from the visits I made to diners over multiple evenings for this issue: a carousel of pancake

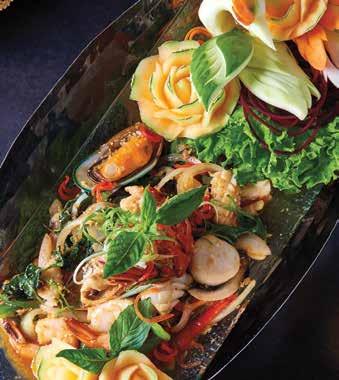

syrups, salt and pepper shakers, and red-capped shoyu bottles. They greeted me at every diner, at any table, at whatever hour, and began to feel oddly reassuring and dependable. In the strangest way, all of their spaces seemed to hinge on their presence. It brought me back to a sentence from one of Patti Smith’s memoirs that I find myself returning to whenever I feel like we’re all just floating through this world or feeling uncertain about the role of art in our lives. She writes, “Life is at the bottom of things and belief at the top, while the creative impulse, dwelling in the center, informs all.” Each of the contributors in this issue, with their senses finely attuned and attentions paid to minute details, managed to ground themselves and find their footing in the dark, to share with us something concealed about Hawai‘i and where it fits in our understanding of this place. They remind us we’re all here dwelling at the center.

With

aloha, Matthew Dekneef EDITORIAL DIRECTOR @mattdknf

|

|

EDITOR’S LETTER

NIGHTS

174 LAHAINALUNA ROAD LAHAINA , MAUI , HI 96761 WWW . THEPLANTATIONINN . COM 1-808-667-9225 discover island tranquility

MASTHEAD | NIGHTS |

“Usually it was about food... because the clubs have just closed.”

They say the best talks happen at 4 a.m. What’s a memorable late-night conversation you’ve had?

“In college I had a conversation about why we only acknowledge that certain emotions exist.”

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

EDITOR

Lisa Yamada-Son

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Ara Laylo

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Matthew Dekneef

SENIOR EDITORS

Anna Harmon

Rae Sojot

DESIGNERS

Michelle Ganeku

Skye Yonamine

PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR

John Hook

PHOTO EDITOR

Samantha Hook

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Eunica Escalante

IMAGES

evin rani ar olina

Caleb Bennett

Nainoa Ciotti

Christian Richard Cook

Minü Han

Andrew Richard Hara

Marie Eriel Hobro

rendan eorge o

Michelle Mishina

Chris Rohrer

“My friend went on a rant about string theory. In the lobby of a karaoke club. In Korea.”

CONTRIBUTORS

Travis Hancock

i an ill

Christine Hitt

a a a a i itchell uga

Timothy A. Schuler

athleen ong

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley VP SALES mike@NMGnetwork.com

Helen Chang

Chelsea Tsuchida

MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVES

lee a ata SALES ASSISTANT

unter apo a MARKETING & SALES COORDINATOR

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock CHIEF REVENUE OFFICER joe@NMGnetwork.com

Francine Beppu NETWORK STRATEGY DIRECTOR francine@NMGnetwork.com

Gary Payne VP ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE

Courtney Miyashiro OPERATIONS ADMINISTRATOR

CREATIVE SERVICES

Tammy Uy VP CREATIVE DEVELOPMENT

Shannon Fujimoto CREATIVE SERVICES MANAGER

Gerard Elmore LEAD PRODUCER gerard@NMGnetwork.com

le osa i PRODUCER

Shaneika Aguilar

VIDEO EDITOR

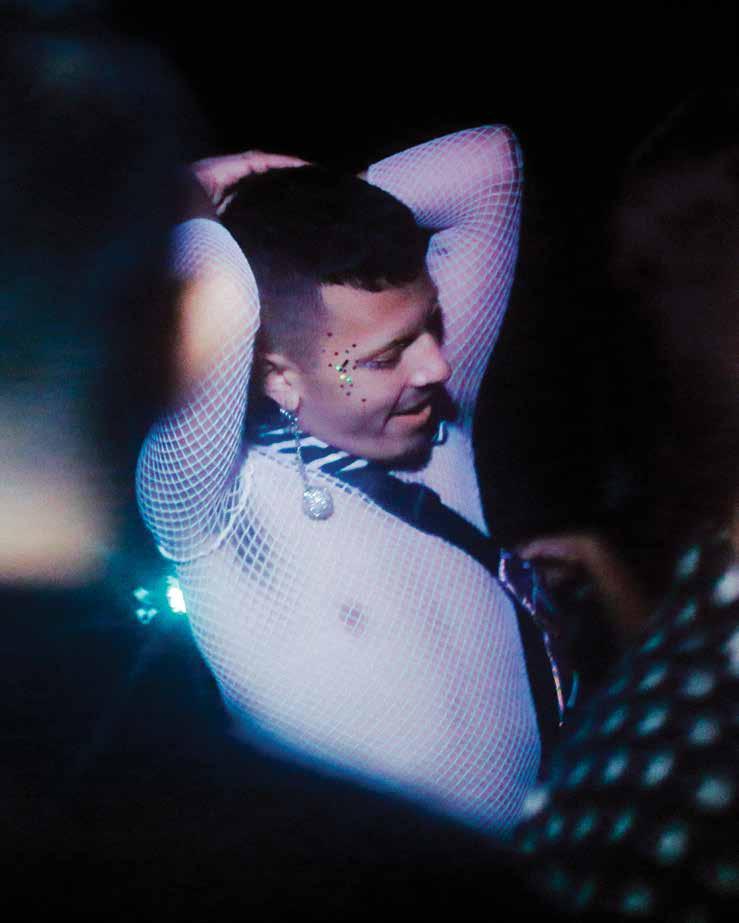

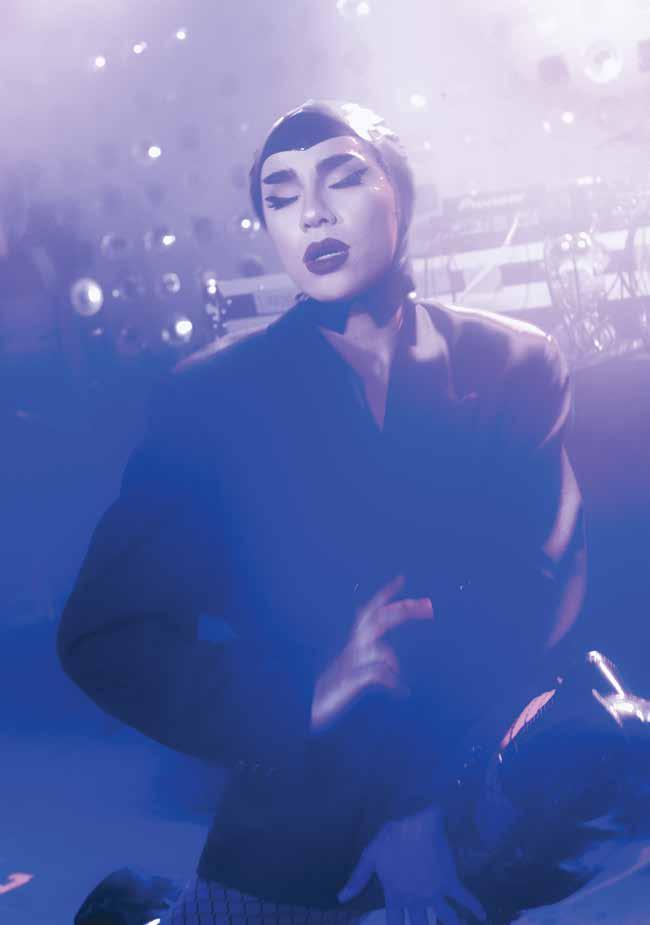

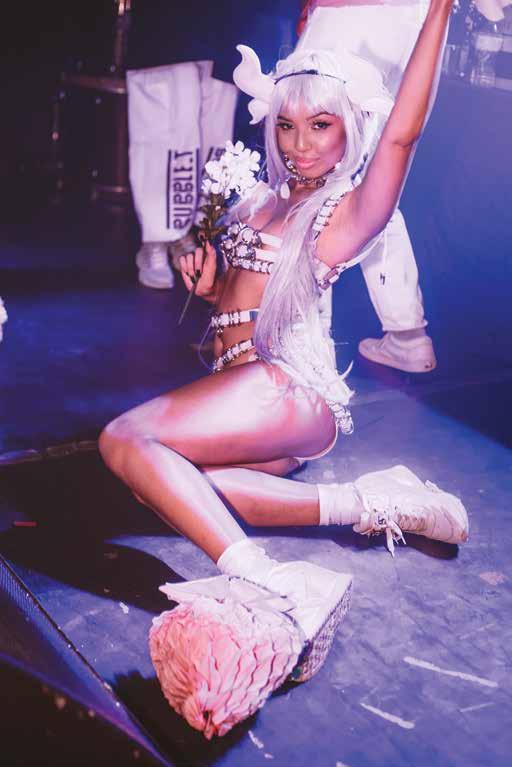

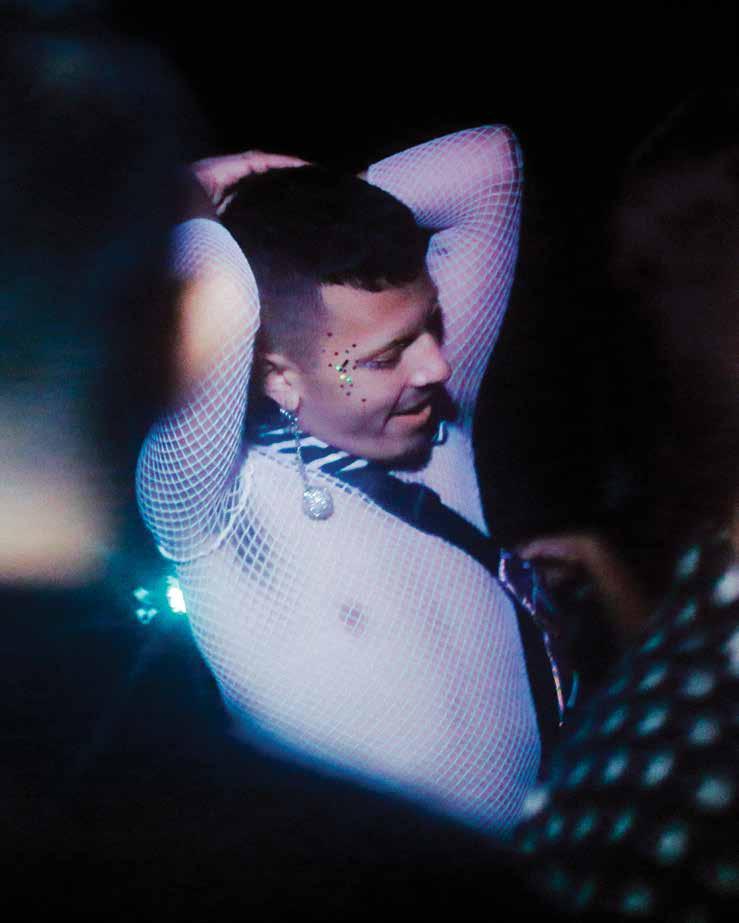

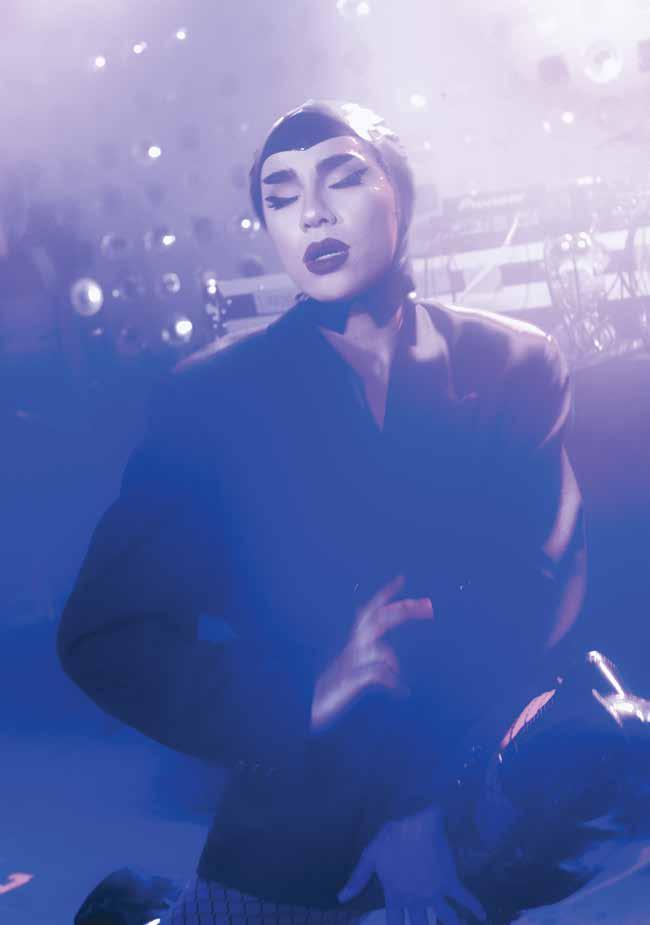

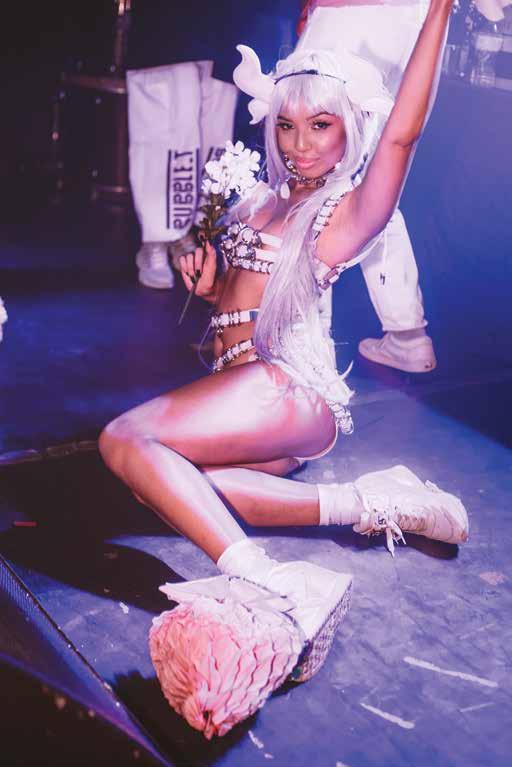

Aja Toscano NETWORK MARKETING COORDINATOR

i i ung WEB DEVELOPER

INTERNS

Romina Escano enneth o Rena Shishido Hillary Stratton

General Inquiries: contact fu ha aii.co

PUBLISHED BY: Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel St., Ste. A Honolulu, HI 96817

©2008-2019 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher.

FLUX Hawaii assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. FLUX Hawaii is a triannual lifestyle publication. ISSN 2578-2053

“Those late-night/ early morning talks about life with a new love interest always give great insight to relationship possibilities.”

As physicians, Jon and Toni Narimasu enjoy peace of mind knowing their private banker is going above and beyond to help their family achieve their financial goals. For this generation and the next. Learn how our wealth management advisors can do the same for you. Call 544-3542. centralpacificbank .com 808-544-0500 1-800-342-8422 Planning Investments Insurance Investments are not insured by FDIC or any government agency. Not a deposit or obligation of or guaranteed by Central Pacific Bank. Subject to investment risks, including loss of principal invested. Looking ahead and going beyond. WEALTH MANAGEMENT

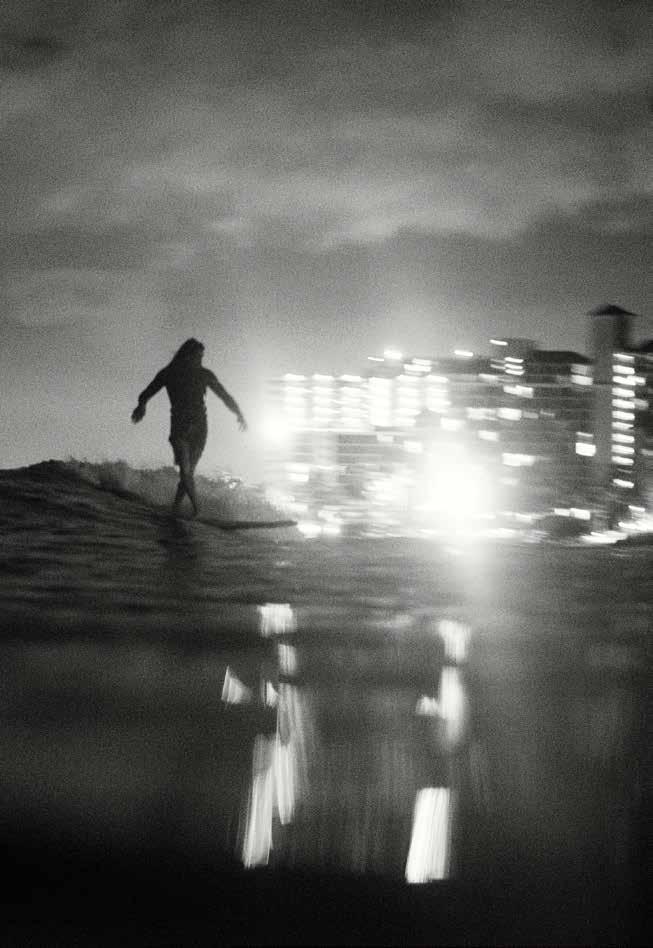

On the Cover

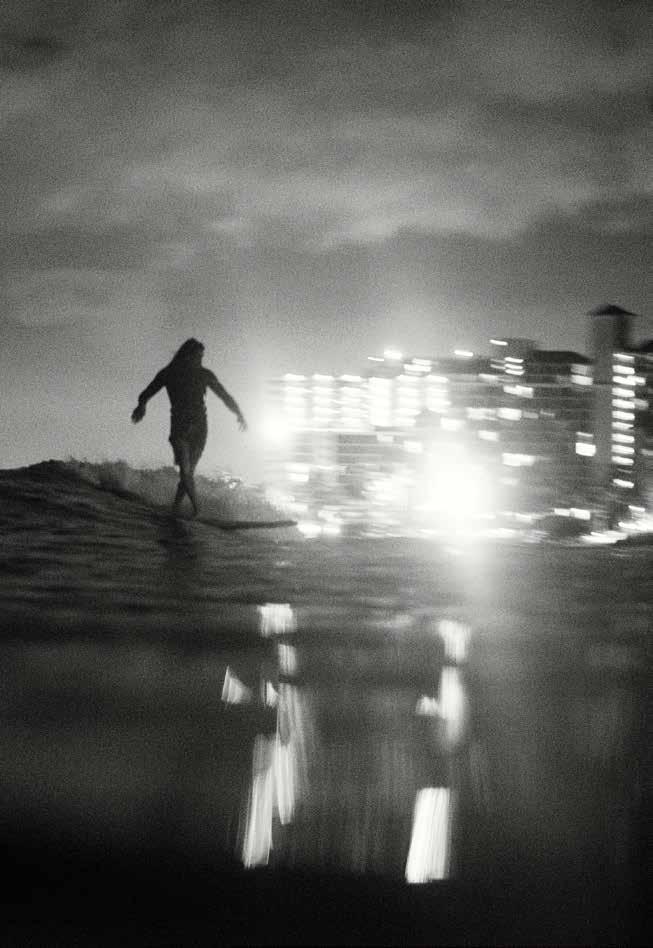

sur er foats in the aters o ai . hotographer John Hook took this portrait, and the series of equally tranquil and adrenalinelled i ages that co prise the photo essay for the story “Night Riders” on page 80. “Taking photos in the ocean, in the dark, is a whole other level of weirdness and excitement,” says Hook. “The streets o ai provide just enough light to make it possible. Even without a full moon, I’ve had a few sessions out there with no moonlight and have seen stars refecting on the hori on in the lulls between sets.”

Caleb Bennett

Caleb Bennett

Originally from Del Rio, Texas, Caleb Bennett is a freelance art director, designer, and consultant with a passion for editorial. He formerly served as design director for Condé Nast Traveler, where he produced a story about hula with lau e uhi in ilo during the Merrie Monarch Festival. He previously held art and design titles at Wired, The New York i es aga ine and e as Monthly. While traveling, Bennett is most drawn to the graphic representation of a place. “Hawai‘i certainly provides many idyllic visuals, but also presents a unique challenge to try and discover it a di erent way,” he says, on capturing Honolulu’s architectural character on page 140. He also credits his network of local friends in Hawai‘i for enriching his visits.

“I've grown to admire the islands through them and am generally inspired by the respect for culture and familial connection that a ai i o ers.

Mitchell Kuga

Mitchell Kuga

Moanalua High School graduate itchell uga is a Brooklyn-based writer whose work has appeared in The Village Voice, GQ, u eed e s he ader ut aga ine and ei. n his essay on page 116, he refected on so e o the parallels between queer nightlife in Hawai‘i and New York, where there’s been a shift towards centering queer people of color. In January, two New York-based collectives, Bubble_T and Papi Juice, threw a duet of day and night parties in Honolulu. “The pool party at Surfjack Hotel was really cute, as a family moment in the sun. Lots of pool looks!” he says. “The party six hours later at Aupuni Space, dubbed Mahu_Mix, felt really surreal and transformative, like being at your favorite aunty’s garage party—but gay. It felt special to have these really di erent parts o li e that felt separate congeal in a seemingly natural way. I literally couldn’t stop dancing that night.”

Born and raised in the ona region o a ai i Island, Michelle Mishina is a photographer based in Honolulu. She attended Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California where she studied journalism and communications while honing her interest in photography. Her work has appeared in publications including the New York Times, Hana Hou!, as well as travel titles in the NMG Network. Mishina shot two stories for this issue—her images of late-night local diners appear on page 46, and of an expedition on Maui following the practice of fern foraging on page 160.

“As I worked on these night projects, I became aware of how even without sunlight, Hawai‘i is unmistakable in its warmth,” Mishina says. She recalls the mood of it most. “In the early hours of morning, everything slows down,” she says. “There’s a stillness that heightens the senses, and interactions seem to have more weight and meaning.”

Michelle Mishina

| NIGHTS |

CONTRIBUTORS

A streelight on Hawai‘i Island against a lavender sky. Image by Michelle Mishina.

A streelight on Hawai‘i Island against a lavender sky. Image by Michelle Mishina.

NIGHTS

“I am alone, just as I had hoped.”—Cliff Kapono

With the Grain

Film isn’t dead, and it isn’t really dying either. What was once thought to be an obsolete medium is in focus again thanks to a growing global community of photographers who refuse to be ruled by megapixels.

TEXT BY NAZ KAWAKAMI

IMAGES BY CHRIS ROHRER & COURTESY OF ANALOG SUNSHINE RECORDERS

For the Analog Sunshine Recorders, a Honolulu photography collective devoted to capturing images the old-fashioned way, film’s legitimacy was never under threat. In 2010, when film labs and darkrooms were being shuttered left and right and it appeared digital technology had finally choked out its photographic predecessor, Analog Sunshine Recorders was beginning to take shape.

The original members of the collective took advantage of the mass exodus from analog to digital to buy top-of-the-line film photography equipment—everything from enlargers to cameras to film itself—for pennies on the dollar. “All this stuff that used to be too expensive to own was getting tossed out,” says Chris Rohrer, one of its founding members. “We were all in the right place at just the right time.”

Other founding members include Natalie Nakasone and Travis Sasaki, but it’s important not to get caught up in who is in and who is out. Analog Sunshine Recorders is intentionall ithout or ali ed leadership or direction and has a constantl shi ting membership with numbers ranging anywhere from 10 to 100 at any given moment or in an given photograph sho . t acts li e a hive ind organi ation that an od can qualify to join simply by indulging in a love for emulsion. If you can’t help but keep loading rolls of film into that old camera, Analog Sunshine Recorders is for you. If you love to pass countless hours in the darkroom, you’re in. However, the real induction ceremony for incoming members is helping put on or contributing work to one of its many photography exhibits.

Analog Sunshine Recorders’ anonymous collective presence is one of its integral characteristics, and its most unique. Most art shows center around a single artist, while in group shows, the works are often separated by creator. For its shows, the collective combines members’ photos into a single massive work and leaves them void of title cards or labels, making it impossible to discern ownership of one piece from another. In this way, viewers are signaled to focus on the collective work instead of a photo-by-photo experience.

At the Analog Sunshine Recorders recent show, “Tourist,” members set up a community darkroom at Aupuni Space, an art gallery in Kaka‘ako.

24 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUX PHILES | FILM |

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 25

For the collective’s December 2018 event “Tourist,” members pooled together their darkroom resources and transformed a a a o galler upuni pace into a community darkroom for a week. Anyone could sign up for a slot to print tourismthemed photos in a wet lab for free. The online sign-up sheet was almost immediately full and was eventually disregarded entirely as word got out that there was a place for nocturnal analog weirdos to print their old negatives. For a week, it was a late-night, chemical-soaked haven. Some photographers who had never seen a darkroom were able to learn the process of printing (all the way from exposing a negative to developing to the rinse bath) from more experienced photographers. By the end of the week, 39 photographers had printed 125 images, which were then mounted in straight rows and columns in the gallery, spreading across the walls from floor to ceiling. There was no room for name tags or title cards, of course.

Built into one gallery wall was the very darkroom that the photos were printed in, which Analog Sunshine Recorders decided to leave on display to reintroduce the public to wet-lab photo printing and maybe inspire curiosity in folks who had thought the process a little too intimidating or perhaps too nerdy to give it a chance.

Members of Analog Sunshine Recorders aren’t exactly sure what the collective is all about. It doesn’t have a mission statement or a goal or a hierarchy to decide one. It isn’t for profit, considering money is usually lost on its shows. It’s not even about promoting film as a medium. “You can shoot whatever you want,” one member says, “We just happen to like film.” Oddly enough, when forced to describe what Analog Sunshine Recorders is about— what all the effort and money and late nights amount to—more than a few members answer, “Good times.”

Analog Sunshine Recorders is without formalized leadership and maintains an anonymous membership base.

To see more work from the film collective, visit analogsunshinerecorders.com.

28 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Your Livable Sculpture

THIS IS NOT INTENDED TO BE AN OFFERING OR SOLICITATION OF SALE IN ANY JURISDICTION WHERE THE PROJECT IS NOT REGISTERED IN ACCORDANCE WITH APPLICABLE LAW OR WHERE SUCH OFFERING OR SOLICITATION WOULD OTHERWISE BE PROHIBITED BY LAW. WARD VILLAGE IS A PROPOSED MASTER PLANNED DEVELOPMENT IN HONOLULU, HAWAII THAT DOES NOT YET EXIST. PHOTOS AND DRAWINGS AND OTHER VISUAL DEPICTIONS IN THIS ADVERTISEMENT ARE FOR ILLUSTRATIVE PURPOSES ONLY AND DO NOT REPRESENT AMENITIES OR FACILITIES WHOLLY WITHIN WARD VILLAGE AND SHOULD NOT BE RELIED UPON IN DECIDING TO PURCHASE AN INTEREST IN THE DEVELOPMENT. FURTHER, ANY RENDERINGS, PHOTOS, DRAWINGS OR OTHER REPRESENTATIONS AS TO UNITS OR OTHER ELEMENTS OF THE PROJECT THAT ARE DELIVERED OR SHOWN TO PROSPECTIVE PURCHASERS MAY NOT ACCURATELY PORTRAY SUCH UNITS AND OTHER ELEMENTS, AND DO NOT CONSTITUTE A REPRESENTATION BY THE DEVELOPER. THE DEVELOPER MAKES NO GUARANTEE, REPRESENTATION OR WARRANTY WHATSOEVER THAT THE DEVELOPMENTS, FACILITIES OR IMPROVEMENTS DEPICTED WILL ULTIMATELY APPEAR AS SHOWN. THIS IS NOT INTENDED TO BE AN OFFERING OR SOLICITATION OF SALE. EXCLUSIVE PROJECT BROKER WARD VILLAGE PROPERTIES, LLC. COPYRIGHT ©2019. EQUAL HOUSING OPPORTUNITY.

The Limits of Light

Darkness is the least appreciated natural resource on the planet. For scientists and practitioners, saving the night sky is as important as preserving Hawai‘i’s native forests or its coral reefs.

TEXT BY TIMOTHY A. SCHULER

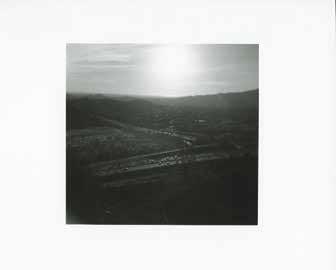

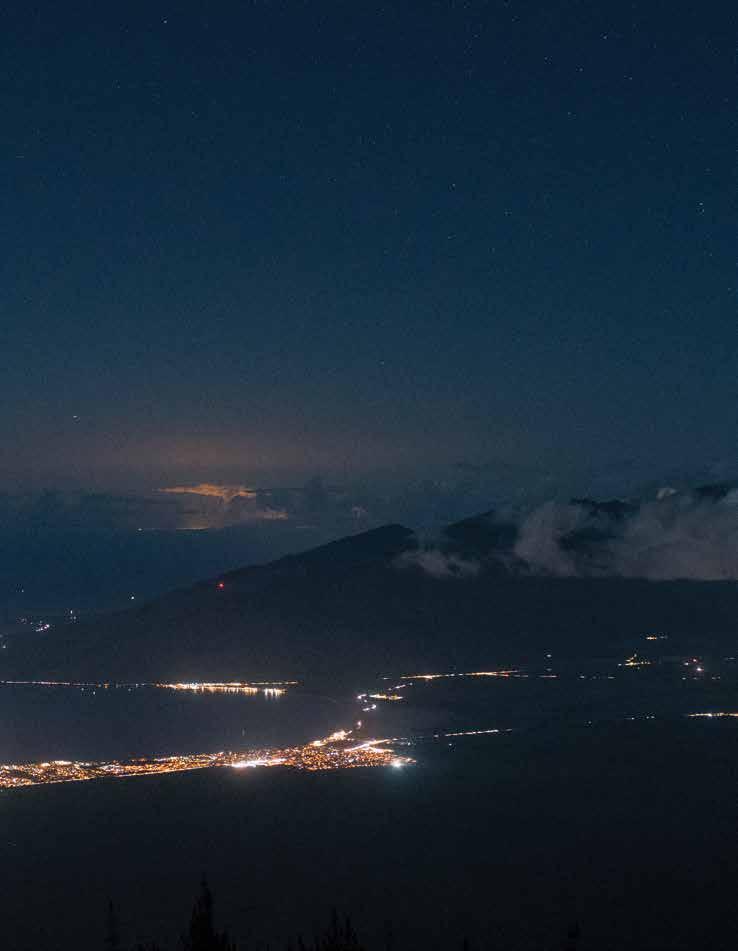

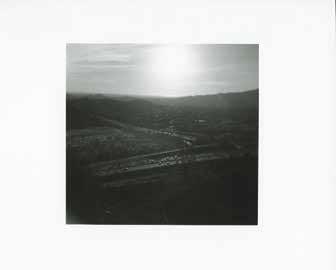

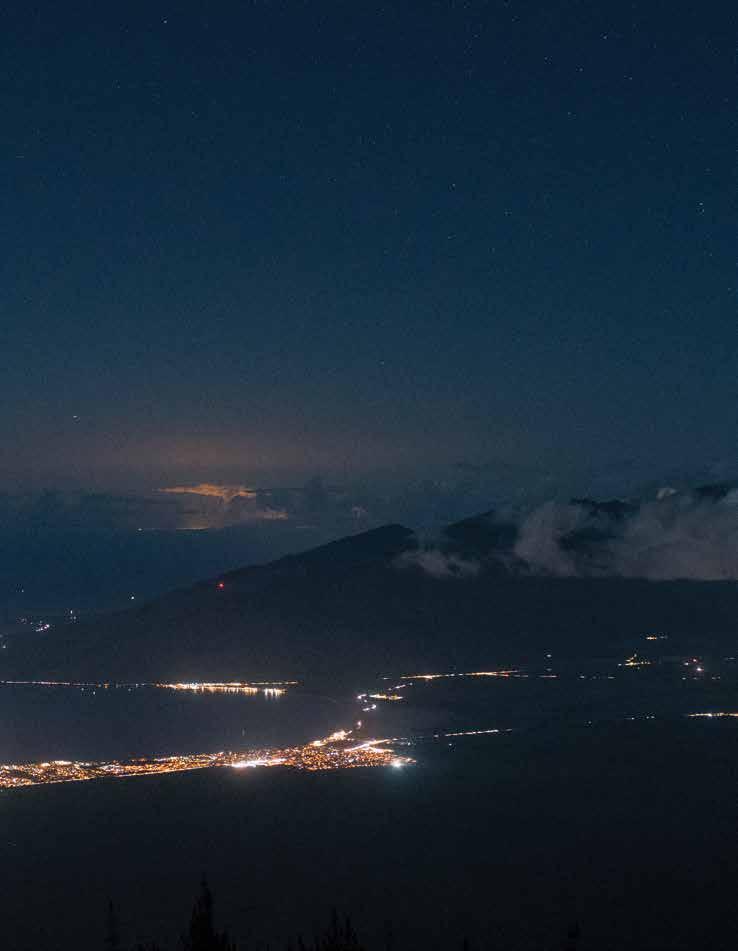

IMAGES BY BRENDAN GEORGE KO

For much of human history, light and dark have served as shorthands for good and evil. This enduring dichotomy has convinced us, with the help of evolutionary instincts, that nighttime is something to be feared. But night is not so much the opposite of day as part of a continuous and balanced cycle. A river does not stand in opposition to the sun. Each sustains us.

Because we spend so little time in the dark—since the invention of the arc lamp in the mid-1800s, we’ve grown accustomed to ever-present light—its centrality to the web of life tends to elude us. As a result, we treat the night sky like the endless void we mistake it for: Darkness is immaterial. What is there to pollute? In recent decades, however, a growing number of scientists, doctors, astronomers, and conservationists have raised the alarm about the loss of darkness, about the erosion of this once-plentiful and vital resource.

In the evening, for instance, when light levels dip low enough, our brains know to release melatonin, a hormone that helps us sleep and regulates our circadian rhythms and immune systems. Melatonin also has been shown to suppress cancer growth. In a study funded by the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences, melatonin-rich blood, produced after two hours of complete darkness, actively slowed the growth of a breast cancer tu or. lood lo in elatonin ro e posure to arti cial light sti ulated gro th.

Electric light also bleeds into the atmosphere in ways that firelight doesn’t, through a phenomenon known as Rayleigh scattering, in which shorter-wavelength light (such as blue light) is made visible by particulate matter in the atmosphere. It emanates from bedrooms, street lamps, airports, parking lots, military bases, and more, the aggregation of which creates an ashen glow over densely populated areas. Astronomers were some of the first to notice the phenomenon, which blotted out all but the brightest stars and made far-off objects like asteroids and comets hard to see, even with high-powered telescopes. It was as if the lens of the Earth’s atmosphere had been smudged. Today, Honolulu’s s glo can e seen ro the su it o alea al on aui.

Electric light is a cause of ecological concern in Hawai‘i. Following spread, the Honolulu skyline glows on the horizon from the slopes of Maui.

FLUX PHILES | ENVIRONMENT | 32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Electric light—particularly that of LEDs, which often are rich in blue light (the same kind that suppresses melatonin production)—has also wreaked ecological havoc in Hawai‘i. Thousands of Hawaiian petrels and Newell’s shearwaters have been victims of what is known as “fallout,” when a blinded bird flies into a building or becomes so disoriented by lights that they crash to the ground. “I’ve actually had them fall at my feet,” says Jay Penniman, project manager of Maui Nui Seabird Recovery Project.

Scientists aren’t sure why lights affect seabirds this way. It may be because some of the ocean creatures they eat are bioluminescent or because their celestial navigation system is short-circuited. Either way, on the ground, the birds are far more likely to be eaten by cats or run over by cars. The Hawaiian petrel population has fallen by 78 percent since 1993, according to the aua i ndangered ea ird ecover

Project. Newell’s shearwaters decreased in number by 94 percent over the same period.

In response to Hawai‘i’s ebbing night, authorities have attempted to rein in excess illumination. In 2012, the state passed a law requiring that all lighting along state roadways or on state property be shielded to avoid shining into the sky and have a correlated color temperature of no more than elvins. he lo er a light s color temperature, the “warmer” or more candle-like its hue.) Richard Wainscoat, an astronomer at the University of Hawai‘i at noa s nstitute or strono ishes the law went further, limiting the color te perature to as lo as elvins and mandating blue-light filters, which render short-wavelength light invisible, creating a more yellow glow.

Hawai‘i County, which Penniman says has one of the most progressive lighting ordinances in the world, has installed blue-light filters on the lights illuminating

Parts of Hawai‘i can offer a rare sanctuary from the glow of modern life, a place to see the night sky as previous generations saw it.

36 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

most of its public roadways. The island also created a special one around auna ea where lights must be shielded and dimmed so as not to interfere with the astronomy taking place at the observatories above.

As a result, Hawai‘i Island is a rare sanctuary from the glow of modern life, a place to escape the light and see the night sky as previous generations saw it. For alei u uhi a a researcher at the dith ana a ole oundation and an e pert on the Hawaiian moon calendar, preserving this refuge is as important as preserving Hawai‘i’s native forests or its coral reefs. To her, erasing the stars means the loss of culture and knowledge. “Sure, I can read about [a constellation] in a book,” she says, “but until I actually stand in a spot and see it, it doesn’t become part of my inner core being.”

For early Hawaiians, and many still today, the night sky contains entire encyclopedias of information. The moon is a celestial planting guide, while the stars act as an exact, never-failing GPS and dictate the seasons. The constellation

Makali‘i, for instance, marks Makahiki, the beginning of the Hawaiian new year.

Nu‘uhiwa says the nine stars of Makali‘i are growing fainter, however. Already, except in the darkest skies, two are nearly invisible. As the stars change, so do the stories. Makali‘i is the same star cluster as Pleiades, or the Seven Sisters from Roman mythology; if only seven stars are visible, the Roman story becomes more legible, easier to grasp. What will Hawaiians call Makali‘i when there are only a few stars left?

Penniman says that our fear of the dark dates back millennia. “In the human psyche, there is a fear of the unknown, the dark, and what is hidden there,” he says. “I think it’s our responsibility to try and help others reali e that the dar is not a ad thing. It’s a good thing, an essential thing.”

In response to Hawai‘i’s light pollution, authorities have attempted to rein in excess illumination through legislation.

38 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Mon–Sat 9:30am to 9pm Sun 10am to 7pm • 808.955.9517 • 1450 Ala Moana Blvd., Honolulu, HI 96814 • FREE WI-FI AlaMoanaCenter.com • Download the Ala Moana Center App from the App Store for iPhone MORE THAN 350 STORES AND RESTAURANTS INCLUDING AMERICAN EAGLE OUTFITTERS • BLOOMINGDALE’S • BOXLUNCH • CRAZY SHIRTS • DIESEL • ESCADA • GAP • GUESS KIEHL’S • L’OCCITANE • LULULEMON • MACY’S • MAMA PHO • NEIMAN MARCUS • NORDSTROM • PLANET BLUE PREMIER BARBERSHOP • SAKS OFF 5TH • TARGET • THE BRILLIANT OX • THE NORTH FACE • UNIQLO • & MANY MORE Celebrating 60 years of shopping, dining & entertainment.

Gone with the Wind

As wind farms slice up the island skies that Hawaiian hoary bats call home, advocates for the nocturnal creatures hunt for solutions on different sides of the night.

TEXT BY TRAVIS HANCOCK

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

s the lashing lades o ahu s ind tur ines s oop through the cool morning air on December 5, 2018, attorney Maxx Phillips stands in Honolulu’s first circuit court, directing Judge Jeff Crabtree’s attention to an i hone si ed ple iglass o perched at the edge o her podiu . nside it is a li eless pe ape a or a aiian hoar bat, the state’s official, and only endemic, land mammal.

From his bench, Crabtree can hardly discern the tiny specimen’s features, like its namesake streaks of hoary fur. At least that’s what Phillips is counting on, since her opponents ali ornia ased ind energ co pan Pua Makani Power Partners and the Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources, had sought to assure ra tree o ua a ani s a ilit to spot all ats its proposed wind turbines will “take,” the legal term for kill.

Bat deaths increasingly occur via wind-turbine strikes and barotrauma—lung explosions caused by sudden changes to proximal air pressure. Since 2012, the collective lades o the hite onoliths on ahu and Maui have already killed far more than the officially allowed total of 92 bats over 25 years, leading every wind company to request higher take licenses. Should the state grant all pending requests, the total number of bats that could legally be killed would increase to nearly 500. Meanwhile, everyone involved is flying blind, moving forward without even a clear estimate of how many pe ape a e ist in the ild. n esti ated the population could be just upwards of a few thousand or as low as a few hundred.

“On a 700-acre parcel, you're not going to find the bats,” Phillips tells me after the hearing. She is appealing s approval o ua a ani s plan to uild up to ind tur ines in ahu u hile the co pan unds bat research and long-term habitat conservation plans to make up for its expected take. This plan is unacceptable to many North Shore residents including Phillips, who is

or ing pro ono and her client the nonpro it eep the North Shore Country.

Phillips borrowed her courtroom bat from Molly age ann verte rate oolog collections anager at Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum. Hagemann tracks the institution s collection o pe ape a ith a spreadsheet which inadvertently records the many ways American development has intruded on the bats through the years. Donated carcasses trace their deaths to the Mauna Lani a otel olo a i irport a alaea o er lant the ilitar s ha uloa raining rea and the ences enclosing alea al ational ar . he oldest speci en in the collection a s ull and s in ro aua i as given to the fledgling museum by expat rancher George Campbell Munro in 1893—the same year white businessmen ousted ueen ili uo alani. hile on house arrest in her o n palace the ueen translated the u ulipo a a aiian creation chant which describes “hairy bats” and Pe‘ape‘a, “the great god of bats,” who gets his eight eyes scratched out by the demigod Maui.

oda native narratives ith the po er to sacrali e pe ape a stories that once su cientl accounted or and protected the ani al in an energ independent a ai i have been pushed to the wings of public discourse. Taking center stage are empirical news of turbine take, archaeological nds o su species clades and geneticall veri ed arrival dates o the earl pe ape a that igrated in two waves, 10,000 and then 800 years ago. Meanwhile, Bishop’s collection grows at a steady clip. Nearly all its new specimens come from wind farms, including eight from a ailoa ind ar iles ro ahu u.

The Vertebrate Zoology Collection at Bishop Museum records data of how development has harmed the native bat population.

FLUX PHILES | ANIMALS | 40 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

he a ailoa ind ar has taken far more bats than any other ind ar hillips sa s. n court Pua Makani argues there is an upside to this increase in specimens for study. “They’re like, ‘Well, if it wasn’t for all the bats that we’re killing, you guys wouldn’t know anything about the bats,’ which I kind of want to challenge.” Underpinning Phillips’ challenge are the state and federal endangered species acts, which require violators to make up for animal deaths in real time.

“It’s really rare that research will qualify as mitigation in state and federal endangered species law,” hillips sa s. n its o cial state ent allo ing ua a ani to uild its ind ar in ahu u declared the priority of “helping Hawai‘i achieve its self-imposed target of 100 percent of its electric power from renewable energy by 2045, set by Governor Ige in June of 2015.” The statement also contradictorily added that “the project will spend up to $4.6 million dollars to assure there will be no negative impacts to Hawai‘i’s environment and native and protected species.”

“More dead bats doesn’t equal more bats,” says Phillips. “Our community includes the plants and animals that were there before us. And, so, when I thin a out the pe ape a on ahu those are pe ape a. have a kuleana to them, as a community we have a kuleana to them. What are we doing if we’re not taking care of our own community members?”

The same day that Phillips presents her bat in court, over on Maui, wildlife ecologist Dave Johnston packs headlamps, poles, and nets. “We’re going to go mist-netting this evening,” he tells me over the phone, referring to a technique that involves stretching mesh between wide poles like a giant volleyball net. “We’re trying to catch

more bats in the winter right now so that we can get a handle on what their home ranges are.”

Johnston works for H.T. Harvey and Associates, a Monterey-based ecological consulting firm that has studied bat-fatality mitigation for several Hawai‘i wind-energy companies, including SunEdison and First Wind. Johnston got involved eight years ago. “My recommendation at that point was to study the bat so that we knew what insects it ate, and once we knew that, we could figure out presumably which plants are hosts to those insects,” he says. In theory, when all of these insects, and the plants that they eat, have been identified, the wind-energy companies will then be able to start planting restoration sites to support pe ape a. Through a mix of lures that emit high-pitched bat calls and detectors that record the chirps and squeaks of passing bats, Johnston has gotten a feel for their favorite haunts. When his three-person team manages to catch a bat, the dirty work begins. “We collect some fecal pellets if we can,” he explains, “and this has insect parts that we then run through a DNA barcode analysis.”

While some distrust a plan that is, well, bat shit, Johnston and other researchers are making gamechanging discoveries. Maui bats, for example, were once presumed to hi ernate in alea al rater during the winter. That changed when Johnston drove to the summit in 2017. he hole road up to alea al was just iced over, black ice, and they closed the road,” he says. “Once it cleared and I got up there, there were all these shrubs in bloom, and when we started catching bats, they went right up to the top, and they were foraging on a lot of insects—in the middle of winter!”

Determining bat behavior and range is vital to effective mitigation, specifically “curtailment,” a method which entails slowing or shutting off wind turbines when the bats are especially active. Smart curtailment represents a good fix for Maxx Phillips. “We have a way that we can ini i e ho an ats are eing killed, which is what the law requires,” she says, “and the wind farms aren’t doing it. And this new project isn’t doing it.”

Though Johnston is confident in his holistic mitigation plan, he also reali es that it ight e est suited to the current scale of wind-farm operations and the current climate. “There is going to be more and more pressure here in a ai i and on the Mainland to put up more wind turbines, all of which will take more bats,” he says. “I’m worried for the Hawaiian hoary bat, but I’m also worried about bats around the world.”

Johnston’s team fails to net any bats on this trip. Undeterred, he heads toward reliable bat activity at a eha eha chools aui ca pus in Pukalani, where he started the pe ape a lu ith school counselor e aula a p ell. ach ee clu members conduct outreach, study the Hawaiian cultural significance o pe ape a and research their ecology. In the spring of 2018, the club presented a research poster at the a ai i onservation on erence in Honolulu. A far cry from the spectacle playing out in America’s federal courts, the students’ extracurricular efforts signal a small return to homegrown ste ardship. hould a ai i eet its goal of energy independence, these kids will be around, in the nights beyond 2045, taking stock of what it took to get there.

44 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 45

In Good Company

The late-night diner doubles as a place for patrons to eat and somewhere to conveniently remove yourself from the world and enter a sanctuary of strangers.

TEXT BY MATTHEW DEKNEEF

IMAGES BY MICHELLE MISHINA

The most opportune hour to visit your local diner must be sometime between 3 and 5 a.m. certain solitude can e ound there in the inutes ou can t con dentl call night but wouldn’t pin down as day. Often, that solitude is literal, straightforward, and bare— meaning there is not another soul to tally, aside from your blank-faced self, dining there. You place your ready-set order after reading blindly from a menu glossy with daily specials that rarely, if ever, change.

ther ti es ou a e in the presence o other e e ru ing deni ens their el o s resting atop laminate tabletops, the mirror image of you, weighing whether they are in the ood or ried rice or a a e recipe that hasn t een odi ed in ages. ou re not alone yet a chasm of a solace still exists, only now it’s shared between the unplanned party of t o or ve or nine o ou all sitting there lan as alloons. ho are these statuar people spread thin across the diner during these hours? What could they possibly be doing here? When we tuck ourselves away into a booth, I suspect we all spend a sliver of our time asking ourselves these sorts of questions.

onight there happens to e an elderl gentle an the t pe to read a aga ine delicately, page by page: Why isn’t he doing that on his living-room chaise? The waitress lling our ater glass ho ends all her phrases ith s eetheart oes she have one Two haole men in cowboy hats chatting with a sistah in a tita bun: What’s … happening there? Open the aperture on this scene slightly to allow in light from the hours leading up to and following this two-hour window, and more individuals enter the frame. We have construction workers before construction-working, little-league baseball players after baseball-playing, gossiping aunties gossiping about someone else’s aunty—is it your aunty? Someone is shouting, someone is mumbling. What’d they say? Young folks, old ol s ne ol s. aces refected in glass indo s and pastr cases e pressions lit up rief the lights o passing vehicles and lin ing cellphone screens. aces elonging to so eone ou ight recogni e and so eone ou re destined to orget ho no s I adore these public questions posed by entering my local diner. More than the lu e ar ion co ee and iliha a er s radioactive right ell i onl to re ind us that the ordinary people in our midst are so much more mysterious than anything we could ever re and a e up. t s this catholic cast o characters so speci c ut inno inate that captures my imagination—they are so plain and convincing! Diners at late-early hours hold the same air of wonder and melancholy that understandably makes Edward Hopper’s painting Nighthawks his most renowned. Though Hopper has claimed this painting as not consciousl eant to e a refection on hu an isolation and ur an loneliness

Twenty-four hour diners across the islands are home to local comforts.

FLUX PHILES | COMMUNITY | 46 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

his view of a Greenwich Avenue diner in downtown New York can easily be a stand-in for whatever might unfold at Zippy’s along i it igh a or en s House of Pancakes on the outskirts of Hilo Bay.

Diners at nighttime prove to be a natural canvas. There’s a tenet across creative endeavors, from oil paintings to retail window displays, that by isolating something, you illuminate it. This notion is melded with voyeurism, another essentialism for ost gurative art a ing which happens constantly among us in the heightened con nes o the diner. hen there s the ene t o ho time tends to operate in them—how it allows you to observe the eloquence in human fatigue, to pick up on the poetry of so eone s pro le or their posture, the caress of a leg wrapped around a vinyl stool, a rubber slipper dangling o a oot. t s a world that moves at an entirely alternative pace. here the fush o orders coming and going mingles with the sound of clinking dishes and just-out-of-reach chatter. Twenty-four-hour diners: the crinkly radio static between FM radio stations, the white noise o eats si ling on the grill. red e e fight ith its minimal demands, only asking you to sit there breathing until you land back on solid ground.

Unlike the tangle of human storylines that crisscross in places like shopping malls or the DMV, the diner is more akin to a public park. Or an underfunded aquarium. What restaurants are to fash the e par s diners are to sh tan s. ctuall diners are most aligned with churches. Tables traded for pews, menus treated like a biblical text, their contents trusted and e ori ed devoted regulars. Our diner, who art in iliha or alihi on e eau o u or i i oi. ver consider how their aproned waitresses are dressed like nuns? The way they stride through aisles, always in sandals that never seem to s uea foating a out like angels? If you arrive alone, as one sometimes does, during those ungodly hours between night and day, to join the nave of the diner and break bread by yourself, not knowing what to do with your hands, you mindlessly hold them together as if in prayer.

The late-night diner: It can occasionally feel spooky, but in the most subterranean and indelible and con dential a . ere among the company of strangers, you sense you are also your own individual person, glowing with your own insecurities and imaginations, going about a secret and uncertain path in the lighted dark.

[“Ei Nei” by Lena Machado plays in the background]

Wailana Coffee House

[“Ei Nei” by Lena Machado plays in the background]

Wailana Coffee House

“No mountains, no trees. Just buildings.”

Waik ī k ī , O‘ahu

“You know, you look just like my friend from back when.”

Liliha Bakery

“More coffee?”

Kalihi, O‘ahu

“More coffee?”

Kalihi, O‘ahu

“We don’t have that here, my dear.”

Ken’s House of Pancakes

“Someone should be joining me soon.” Hilo, Hawai‘i

“Someone should be joining me soon.” Hilo, Hawai‘i

U nru l y Waters

The multi-million-dollar manta ray tour industry is a beast of its own. Named one of the “top 10 things to do in your lifetime,” snorkeling or diving with these creatures o ff the Kona coast at night has become immensely popular over the last three decades. It’s also an activity that’s never been regulated.

FLUX FEATURE

TEXT BY TIFFANY HILL

IMAGES BY NAINOA CIOTTI AND JOHN HOOK

Magical. An underwater ballet. Gentle giants.

These are oft-repeated praises used to describe manta rays and the experience of snorkeling and diving with the large, docile creatures o the ailua ona oast. There are only a handful of locations around the globe where humans can get up close ith anta ra s. n a ai i Island, the action takes place at night, as divers and snorkelers shine lights in the water to attract the mantas’ food source, ooplan ton. iving ith anta ra s is one of the top-five rated activities on rip dvisor and elp or a ai i sland. arrive at ono hau ar or at p. . It is dim and nearly empty. I sign a liability waiver with Hawai‘i Oceanic, a small ocean activity company started in 2013, and then slip on a wetsuit before climbing aboard ueo ai. he neon lit passenger oat is captained by Dusty, who also works as a beach lifeguard. Fifteen minutes later, we’re at the manta feeding site at Makako a near the ona airport. e re the onl boat out, having avoided the crowds who took the earlier twilight tour. Facemasks on, we slip into the sea. Something feels unnatural about being in the water at night. But within a minute, I forget this thought when a manta glides gracefully only inches from us, somersaulting as its cavernous mouth filters plankton-saturated water. It’s easy to see why people pay more than $100 dollars for this experience. It’s also easy to see why there are so many operators in the waterlogged market. no n in a aiian as h h lua the manta alfredi are the type of manta ray species we see in Hawai‘i. They have a wingspan that can reach up to 20 feet and they often weigh around 1,600 pounds. While manta rays have always existed

in the Hawaiian Islands, it wasn’t until the late 1980s that they became a tourist attraction. his is hen the ona ur otel no the heraton eauhou a Resort—beamed spotlights into the water at night to draw plankton as a lure for manta rays, and in turn, spectators.

People watching from shore were es eri ed the antas cavorting as they dined on the plankton. Divers soon reali ed the e perience as in initel ore magical when viewed from the water right alongside the animals. They also quickly reali ed this ne ho o theirs could e oneti ed. hus a ne co ercial industry was born.

In the last 30 years, manta ray tours have become an annual multimilliondollar industry in Hawai‘i. But unlike the surf-lesson industry and the kayakrental business in Hawai‘i, unlike even shark diving tours and dolphin cruises along the coast o ahu ona s anta ray industry is only now in the process of being regulated. Most companies who offer the manta ray tours abide by do-noharm guidelines tour operators created for themselves in the early 1990s, but these rules are self-imposed. The state’s main involvement has been the issuing of 240 commercial boat permits to tour operators for ocean activities, which includes manta tours. (The Hawai‘i State Department of Land and Natural Resources placed a cap on permits in 1994. There is currently a waitlist to receive permits in both harbors.) The state doesn’t have statistics on the number of human injuries resulting from manta ray tours, but as of yet, no one has died as a result of one. Mantas, however, have been hurt. In 2018, two manta rays were injured in the span of two months,

Manta ray tour companies know following the rules de ned operators is optional, with virtually no consequences for breaking them.

State officials considered regulating businesses in 2012, largely because of complaints within the industry. “People weren’t getting along,” says Jason Thurber, owner of Hawai‘i Oceanic.

60 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

both likely hit by boat propellers. (The boat owners responsible weren’t found out, and there was no motivation for anyone to come forward.)

Starting around 4:30 p.m., boats ranging in capacity from six to 40 passengers ferry eager visitors out of ono hau and eauhou har ors. There are two prime spots for these nighttime tours: Makako Bay, also known as “Manta Heaven,” near the ona airport and eauhou a dubbed “Manta Village,” adjacent to the Sheraton. During the summer and winter holidays, it’s common to see captains drop off people from sunset tours and then immediately load up new passengers for twilight tours.

“I first did the manta ray night dive in 1991 down at what’s now the heraton sa s eller aros. “It kind of completely changed my life. I was blown away by the manta rays.” Laros is the founder of Manta Pacific Research Foundation and an owner of Jack’s Diving Locker, one of the oldest and biggest manta-ray tour operators. He says those initial dives made him ditch law school and become a certified professional scuba instructor. According to Laros, in the early ’90s, fewer than 10 commercial dive co panies e isted in ona. ut around 2007, the fledgling manta ray tour industry rapidly expanded when snorkel operators began adding manta tours to their itineraries.

Manu Powers, who owns Sea Quest a ai i ith her hus and ia says the manta ray snorkeling tours are their most popular tours. In fact, their business has doubled since they purchased the company from another couple in 2015. “A great portion of that is due to the manta tours,” she says. ea uest a ai i has si oats and operates out o eauhou oat ar or.

Powers says there are about 10 other companies that make use of the bay.

Eleven miles away, at Honokohau Harbor fronting Makako, Jason Thurber opens the upstairs office of a ai i ceanic. orn and raised on Hawai‘i Island, Thurber started his company in 2013 with a 12-passenger boat, the Pueo Kai . He says the manta ra snor eling tours are a ai i Oceanic’s top bookings, beating out swimming with dolphins or watching humpback whales. Overall, manta ray tours generate about 70 percent of its annual income. “The manta tours have been good for the community and for di erent ona usinesses hur er says. “A lot of companies are small companies and there’s a lot of growth potential. But because of that, there’s competition and overcrowedness.”

According to Thurber, there are more than 40 companies doing tours out of Honokohau Harbor.

Owners like Powers and Thurber are part of a small community of commercial operators, many of whom are industry veterans, who know each other well and keep tabs on each other’s business practices. Over time, operators have finetuned their manta ray tour standards. They provide swimmers with wetsuits to keep them warm and prevent human and manta contact, anchor on a mooring to protect the reef, and group their boats together in a single spot for safer manta viewing.

Everyone also knows that following the rules defined by the operators is optional, with virtually no consequences for breaking them. Some operators take advantage of that. Everyone I interviewed had anecdotes of tours gone wrong, but they declined to name names. Stories included guides seen fishing while their guests

were snorkeling 15 feet away, captains leaving people unsupervised in the water, and underwater photographers confusing mantas with their lights.

“Those are the people that are giving us a bad name,” Powers says. “Those are the people that are bringing these regulations down on this industry.”

State officials admit that policing an unregulated industry is challenging. DLNR first considered regulating manta tours in 2012, in large part because operators started complaining about each other. “People weren’t getting along,” Thurber says. “Some companies felt like maybe they’d have something to gain from [state regulation] because they had been doing things right. I would say that a lot of the companies that were complaining to the state years ago, you know, would take it all back now if they could.”

After two years of inaction, in 2014, Hawai‘i state legislature nudged the department to again look into regulation with a measure urging DNLR to adopt rules to manage the dive sites. “We knew it was becoming a booming activity,” says Edward Underwood, an administrator with DLNR’s Division of Boating and Ocean Recreation. “It was starting to get to the point where there were so many people in the water that it was becoming a safety issue.”

Over the past four years, the state has met with tour operators to get their input on ho to standardi e manta tours. While tour owners want their fellow operators to be safe in the ater the also recogni e that the state’s involvement will change how their business has been done for the past three decades. Most contentious for the operators are the installation of propeller guards, which are costly,

62 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

the first-come-first-use of 12 commercial moorings at each site and the permitting process. The current draft of the manta tour rules specify that 30 permits will be issued for each manta site. That means that 50 operators won’t receive a permit. To be eligible for a permit, operators must prove they were in business on or before June 1, 2015.

“We’re never gonna make everybody happy,” says Meghan Statts, the state Division of Boating and cean ecreation ahu district manager, who also or s on a ai i sland. “We’re resigned to that.”

In all this, curiously little is mentioned about the mantas themselves. The majority of the 36-page proposed rules are about managing the humans, not preserving the underwater animals they take boatloads of visitors out to see each night. Many of my conversations were about the industry above the surface.

“I think mantas are much more comfortable with people now than they were back in the day,” Laros says. “If there’s plankton attracted to the diver’s lights and the resort lights, the mantas will be there. If there’s no plankton, the mantas don’t hang out there. So have we impacted the mantas? No more so than the resorts shining lights into the water.”

Our impact to the manta rays, though, for better or worse, is what is finally prompting regulation. As of January 2019, the rules

were sitting at the office of the Hawai‘i Department of the Attorney General. According to Underwood, it will be at least a year before any rules for the industry are approved, but it will likely take longer. In the meantime, hundreds of

visitors jump into the inky water each night to witness the gentle giants.

More than 40 businesses conduct snorkeling and diving tours outside Honokohau Harbor. With growth potential for small Kailua-Kona businesses, there’s also the issue of overcrowding.

66 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUX FEATURE

A n Over t i me St ate

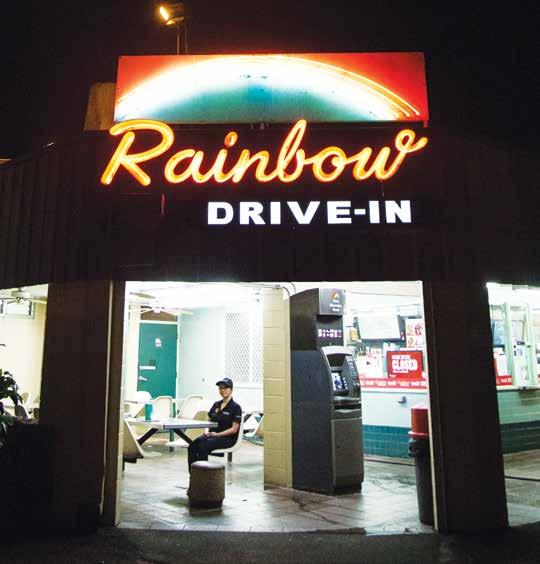

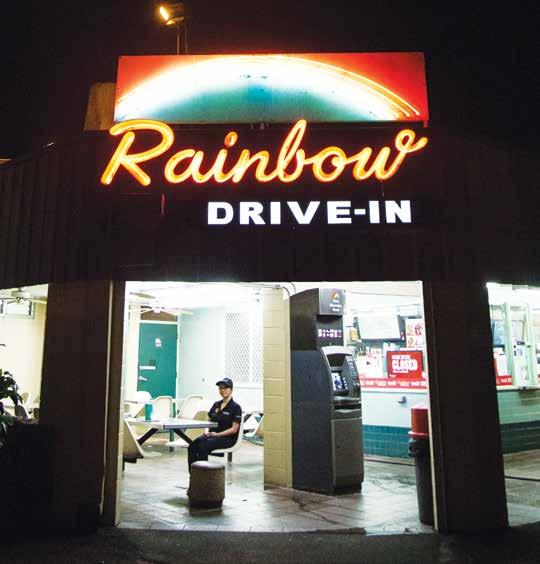

A hidden labor force of Honolulu residents toil their nights away at their second shifts in order to survive living in paradise.

TEXT

BY

EUNICA ESCALANTE

IMAGES BY MARIE ERIEL HOBRO

The picture painted by recent statistics is a rosy one. Tourism is flourishing. In 2018 alone, visitors to Hawai‘i hit the 9 million mark with the Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism projecting that arrivals will surpass 10 million visitors in 2019. Unemployment is the lowest it has been since 1976. Hawai‘i’s household and family income continues to rise, remaining as one of the highest in the nation.

But the cost of living is rising too— and at a more rapid rate. Housing prices are reaching a peak. To afford a twobedroom rental, renters need to earn an average of $36.13 an hour. Hawai‘i’s minimum wage remains at $10.10. Today, a yearly salary of $96,000 is considered low-income for a family of four. It seems that Hawai‘i’s workers are always one step behind, and often will resort to multiple jobs to get ahead.

Courtnie Tokuda

Courtnie Tokuda

“Teaching has always been the dream. There’s a misconception that being a preschool teacher means just playing with kids all day. But we’re teaching them things like empathy and compassion how to be a decent human being. I have a master’s degree and 10 years of teaching experience, and, still, I take in more money per hour being a server than being a teacher. If I didn’t have to work two jobs then I could devote more time and energy to helping my students. There’s just not enough investment in education. But this is our future. These kids are our future.”

Age: 32 60 hours per week

Day job: Lead teacher at St. Philomena Early Learning Center

Second job: Server at Tanaka Saimin for 3 years, 5 to 11 p.m.

Income: second shift, $27,000, total gross, $67,000

James Orlando

James Orlando

“I’ve lived in Hawai‘i for eight years. The cost of living has always been too much. For young adults, achieving our dreams means needing to overwork ourselves. After working 15-hours at my day job, I’ll devote whatever time I have left to my small business. I always feel like I’m at the edge of burning out. This is just part of the lifestyle we need to live now, otherwise it wouldn’t be sustainable. But I don t thin could ever stop. ve een a ing pi as since I was 14-years-old. This is all I’ve ever wanted to do.”

Age: 26 80 hours per week

Day job: Lead baker at Kokua Market, Pizzaiolo at Brick Fire Tavern

Second job: Baker, owner of Fatto A Mano, 11 p.m. to 3 a.m.

Income: second shift, $50,000, total gross, $100,000

Madeline Escalante

“Being a single mom is hard. Hawai‘i is already expensive enough, but when you’re on your own with two sons, one of them going through college, it gets tough. I’ve been a single mom for 8 years. No income, no help, nothing from their father. Going through college, I was a single mom. I would wake up at 5 in the morning, take the kids to school, go to work, pick them up, and study after they’ve gone to bed. But I’m luckier than most because my family is a great support system. Even though Hawai‘i is so unaffordable, I could never move. Leaving Hawai‘i means leaving my family. I’ve never had the thought that this is too much. Everything I do is for my kids.”

Age: 49

55 hours per week

Day job: Accountant at Elite Mechanics

Second job: Driver for Lyft and Uber for the past year, 6 to 9 p.m.

Income: second shift, $20,000, total gross, $68,000

Virginia Lin

Virginia Lin

parents and e igrated ro ong ong in . They wanted to retire in Hawai‘i. They got a house in apahulu. he ortgage as over . had to work four jobs to help them with their payments. At one point, I worked 109 hours per week, every week for four years. Now, I have my own mortgage and a 1-year-old. It’s tiring being a single mom and working over 60 hours a week. My days are either working, preparing food for the baby, or catching up on sleep. I don’t get much time to play with her, but I hope she understands. Even if Hawai’i is so expensive, I could never leave. My parents are over 70-years-old. If I move away, who’s going to take care of them?”

Age: 38

62 hours per week

Day job: Sales associate at HMSA

Second job: Server at Rainbow

Drive-In for 4 years, 5 to 9:30 p.m.

Income: second shift, $10,000, total gross, $60,000

Lindsey Paresa

Lindsey Paresa

“Everyone that’s born and raised here dreams of one day owning a place where they grew up. But it’s nearly impossible nowadays. I don’t want to rent for the rest of my life. I want to own a home, more so now that I have a ne orn. as orn in ailua. and as a orda le there at one point, but today? Gentrification is everywhere. There’s all this talk of growth, and it’s good, but everyone else is being pushed out. I love Hawai‘i, have always wanted to live and work on O‘ahu. But with how the cost of living is now, that dream is looking increasingly difficult.”

Age: 30

70 hours per week

Day job: Bartender at The Laylow Hotel

Second job: Bartender at The Manifest, 6 p.m. to 2 a.m.

Income: second shift, $20,000, total gross, $60,000

ON VIEW MARCH 2 – JULY 14, 2019 THIS EXHIBITION IS MADE POSSIBLE BY Lynne Johnson and Randy Moore, Linda and Robert Nichols, Judy Pyle and Wayne Pitluck, and The Taiji and Naoko Terasaki Family Foundation. MAJOR SPONSORS MEDIA SPONSOR HOTEL SPONSOR ‘Alohilani Resort Waikiki Beach FREE Waikiki Shuttle 808.532.8700 honolulumuseum.org

FLUX FEATURE

Night

R iders

Without sun, the crowds disperse and leave an abandoned lineup for surfers to show evenings are prime time for unforgettable sessions.

TEXT BY CLIFF KAPONO

BY JOHN HOOK

IMAGES

80 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

I’ve been waiting for these conditions for quite some time. A perfect tide, just the right swell direction, and offshore winds that will light up the coast with long-overdue surf. Sitting in front of my computer screen, my excitement slo l ades as reali e that a not the only one who has been clued into such a favorable event. Hundreds, if not thousands, of like-minded surfers have also been digitally notified of the rapidly approaching swell through surf-report subscriptions, mobile devices, and push alerts.

I take a moment to digest the reality of the entire island finding out that the swell of the season will be arriving early Friday morning and will last through the weekend. I frantically look at my calendar. Just as I feared, Friday is a holiday. Sinking into my chair, my excitement completely faded, I accept one of the most difficult realities of surfing on O‘ahu’s south shore: the crowds.

Putting my hands behind my head, I lean back in my chair. I begin strategi ing ho ight ind a ave to myself. Maybe I’ll go at first light, I think. Perhaps lunchtime will be my window. If I wait for the end of the day, maybe everyone else will be too tired to paddle out. Multiple scenarios play out in my head, but each inevitably reveals that it will be packed all day.

I call a close friend to seek counsel only to have my fears confirmed with doomsday advice. “From sunup to

sundown, you ain’t gonna find an e pt one this s ell he replies. Suddenly, it dawns on me. It is going to be packed from sunup to sundown, but what about sundown to sunup? I know what I have to do. I need to begin my session at dusk.

I open my internet browser to search the moon phase. It’s a full moon tonight. I check the tides. Perfect. I calculate the precise time necessary to enjoy the conditions. I set my alarm for 2 a.m. and try my best to get a few hours of sleep, but my excitement keeps me awake. Opting out of a quick nap, I begin packing my truck.

Driving to the beach, I watch the moon rise over Wa‘ahila Ridge. I’m curious as to just how much will be visible out in the lineup. I contemplate taking my headlamp with me. After a few seconds, I laugh at such a stupid idea. At the parking lot, I am welcomed by a plethora of open stalls. I waste no time in taking the one closest to the shower. Giggling with excitement, I pull out my board and run across the empty lot.

I am alone, just as I had hoped. Without waxing my board, I run to the water’s edge. I can faintly see hite ater on the hori on. he s ell must have come early, I think. Within seconds, I dive into the darkness. It is surprisingly warm, much warmer than I expected. As I paddle out to the breakers, the current pulls me to the lineup. With each stroke, I watch as tiny fluorescent creatures get sucked into whirlpools left in my wake. The

moon is now directly overhead, and there is not a cloud in sight.

It isn’t long before I reach the lineup and see a set approaching. Instinctually, I look around to see who may want the wave. There isn’t a soul in sight, but it doesn’t stop me from shouting with laughter got it push o the rails of my board, stand up, and begin a ride directed more by feeling than by sight. nli e sur ng during the da hen I’m typically focused only on the wave, eco e h per ated on ever thing around me. I see myself sliding across refections o the cit . eel the gentle sting of the cool wind on my face. I take notice of the sound of the tumbling whitewater. It is as if my senses have een a pli ed the night.

I make my way back to the lineup and take a moment between sets to think about all the people who would appreciate this experience as much as me. Strangely, I begin to feel alone. And in those fading moments of midnight bliss, I wish there were a few more people to share this moment. I catch my last wave all the way to shore and slowly walk up the sand. Startled, a young couple ask if I was out in the sea. I pause a moment to think and then respond. “Night sur ing is prett a a ing tell the . “If you go, make sure to take a friend.”

82 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 83

FLUX FEATURE

FLUX FEATURE

Con sent of K in k

Delving into the vast and diverse world of BDSM, a universe unto its own of sexual and nonsexual kinks opens up a continuum of preferences.

`

TEXT BY MARTHA CHENG

IMAGES BY CHRIS ROHRER

92 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Each kink—and there are so, so many—has its own language, its own universe within it. For impact play, the vocabulary is in a variety of implements, from floggers to paddles to whips. For rope, there are different dialects in ties for humiliation, pain, restraint. The acronym BDSM references for more than one thing, like the world it describes. It can mean bondage and discipline, domination and submission, sadism and masochism. It is a vast and diverse world, encompassing seemingly infinite combinations of sexual and nonsexual kinks, gender, and sexual orientation, as well as a continuum of preferences.

But for the most part, these languages have been kept hidden or suppressed. It’s been less than a decade since BDSM behaviors were removed from the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. For some fetishists, their desires are something they’re born with— how else to explain the deep urges before they even discovered sex? How to explain, as a child, looking up the definition of “spank”—so often that the dictionary would fall open to that page—and feeling strange flutters and desires?

There is still a stigma, however, associated with BDSM, despite the popularity of Fifty Shades of Grey. But to kinky people, having that movie represent BDSM is like having Basic Instinct illustrate a typical romance. It’s difficult to find any accurate depiction of healthy BDSM relationships in media. Vanilla (what kinky people call the non-kinky) people have been misrepresenting BDSM stories for too long.

Here, four Honolulu residents tell their own stories of what draws them to BDSM. In their own words (interviews condensed for clarity), they share some of what they enjoy: their complicated relationship to pain; the intense connection, intimacy,

and vulnerability with others; the explicit communication and consent. Some incorporate aspects of BDSM mostly in sex, while for others it is a lifestyle. None of them wished to be identified by name, for fear of repercussions socially and professionally—pseudonyms are used to ensure anonymity.

Emily, she/her, late 30s, in public relations and marketing

Who knew that I was such a masochist? But maybe I’m not. I don’t enjoy pain simply for the sake of pain. I enjoy it if it gets me somewhere. If it makes me feel stronger. If it means I can do something I didn’t think I could do before. If it brings me closer to someone. And I suppose I like testing my limits. The only way for me to know where they are is to cross them, break them.

I was introduced into the BDSM world about a year ago by someone I was seeing. It started out pretty gradually. A playful spanking, and as he put it, I responded well. Eventually, we were talking about safe words, the importance of communication, and I was bent over his knee, and he was hitting my ass with his hand and then a wooden spoon. We graduated to a leather strap, belts, paddles. And I loved it. He perverted so many household objects that these days I get aroused by the sight of backscratchers, belts, long-handled spoons.

It felt like suddenly all the desires I’d had as long as I had been interested in sex—all the ones I had suppressed and been ashamed about—were given an outlet. I’m pretty independent in the rest of my life, I just like being submissive in the bedroom. I’d had fantasies about being tied up and dominated for as long as I can remember. When I was a kid I’d strip my Barbies naked and bind them and have my way with them and pretend it was happening to me.

GLOSSARY

Vanilla – non-kinky

Top – a dominant, generally only in scenes

Bottom – a submissive, generally only in scenes

Switch – someone who can take on either a top or bottom role

Scene – a BDSM interaction, which can range from building anticipation to a full-fledged roleplay, public or private, include or not include sex

Impact – when one person is struck by another, with a hand or implements

94 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Thirty years later, I discovered that there was someone willing to indulge my fantasies, not judge me for them, and still treat me respectfully before and after. It blew my mind open. I dove in deep. reali ed that it s not ust a out se ual submission. I love BDSM for the intimacy, excitement, creativity, and intense attention to sensory details. I love the buildup. I love how a good dominant will know how to read my body. I rarely ever have to say stop because even though we both may like to push things, see how far we can go, he knows before I do when my body, and mind, have had enough. I like the juxtaposition, too ho so eone can e fogging e and then stop and e li e ait are ou Do you need a break? I like the contrast of domination and tenderness.

I like how leather feels very different from stiff plastic, from wood—some things sting, others inflict a blunt pain. I like the marks left on my skin, the welts and bruises, private little reminders of the fun I had. And I love rope. Being bound feels helpless, but it also feels like being taken care of. When I’m being bound, I’m in tune with my senses—hearing rope sliding through someone’s fingers, feeling the softness of cotton versus the slight scratchiness of jute, being physically close to my top as they tie. With a top I trust, I am relaxing into their care.

Too many people think being dominant is just rough sex. There’s no buildup, there’s no intimacy, there’s no aftercare, it’s just someone doing whatever the fuck they want without paying attention to me. In the bedroom, I may want to be treated like I don’t matter or exist only for your pleasure, but I don’t want you to actually believe that. That’s the funny thing: It’s as much about the bottom as it is the top. I love the paradox.

Tango, she/her, early 30s, in the tech industry

It’s all about balance in my life. Until I joined the kink community, I felt dominant in all aspects of my life, at work, in my personal relationships and friendships. I felt I needed to find a space

where I could not have to be in control, not have to lead, not have to make decisions. I needed it so strongly—that’s how I found the in co unit . in ind o ills the gap. I can switch into a more submissive or dominant role.

My relationship with my husband has allowed me to explore relationships with other people where I’m the dominant. Right now my interests in kink are topping rope. My husband and I maintain a monogamous relationship—I do nonsexual rope. Sex was never really the interesting part of kink to me. It was always about the intimacy and the honesty. Sex is not a requirement for that. I think that I had kinky inclinations as early as 13 years old. The few times I expressed them, they were met with negativity. I went into my early 20s suppressing that side. My first fantasy was about being tied up in a chair. Later I had fantasies about having my clothes cut off of me and some consensual non-consent stuff. Definitely all my fantasies were as a recipient up until the last couple years.

As a bottom, I think I really enjoyed being challenged. Rope is oftentimes a challenge—learning how to process and sustain things and really listen to your body. Being able to do something for someone that you really trust, being able to go through it for them, is very gratifying. And the feeling of success, of being able to do things that other people cannot do.

I wouldn’t say that I’m necessarily a sadist, but I find that it’s difficult to be dishonest when you’re experiencing pain. Being with somebody as they’re experiencing true pain is really interesting to me. I’ve always liked to make people uncomfortable. I enjoy watching people. I enjoy seeing how people respond to things. Does this rope make you feel relaxed? Does this scene make you feel sensual? Do you really want to do something for me? Everyone responds differently. If you hand somebody a cup that’s full of water and you say, this is my water, don’t spill it, and ou antagoni e the ever od s going to feel differently. A person who accidentally drops that water might cry. A person might intentionally drop that water.

It’s a subculture that endures a complicated relationship to pain, intense intimacy, and vulnerability.

“It was a very peaceful feeling to be able to be so open and not have to hide any part of you,” one anonymous person admits.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 97

In the scenes I’m interested in, there’s no faking, there’s no pretense. I think in a lot of our interactions with people we pretend we’re happy. We don’t say the things we want to say. We don’t behave the way we truly want to behave. Because kink is out of bounds, it allows the participants to express emotions they wouldn’t normally express. How often in your normal life do you just scream? Screaming can be very cathartic. How often in your normal life do you get to just cry and that s

Fear is a constant. It’s part of the reason I don’t play with a lot of people. I don’t play with people that I don’t trust. Having been both a top and a bottom, trust plays into it in different ways. As a bottom, you’re trusting that this top doesn’t intentionally cross your boundaries. One of my biggest fears as a top is unintentionally crossing somebody’s boundary and not being able to properly make up for it and resolve the issue. If I do something to somebody and I trigger them, or I make them feel unsafe—there is always that risk. I think there’s a lot of risk from both sides. You want to play with people who you believe wouldn’t do something out of malice.

One of my favorite things I’ve seen out of the community the last couple of years is an accountability circle, where you pick several people from the local community who are respected and independent and can be trusted to not be swayed. If I play with somebody and something goes wrong and they don’t feel comfortable talking to me about it, they potentially have somebody in my accountability circle who they can talk to anonymously or non-anonymously to help come to a resolution on what boundaries are crossed.

In the vanilla world, everything is about interpreting non-verbal communication, and one of the best things about kink is explicit communication and explicit

negotiation from the start. One of my favorite things is that people would as s it i touch ou hose things are so big. I wish the vanilla community had more of that. In fact, it’s weird to me when it doesn’t happen. What do you mean you didn’t ask what they want? There are pieces of the kink world that can benefit everyone like open discussion, explicit communication, explicit consent.

T.J., he/him, mid-30s, in the health field

I was 17 years old the first time I had a planned exploratory kinky session with a girl I was dating at the time. I spanked her for hours. It turned out she had an extraordinarily high pain threshold and she had more than just a little bit of liking to have her ass spanked. I used my hand for a while and then I used a slipper I had in the car. It was extraordinary.

After that, I went on some spanking chat room. I started talking to an older lady in New York City, about an hour away. We talked for two or three years on Yahoo messenger and emailing back and forth. When I was 22, she brought me to a party on the Upper West Side. I was so nervous. But it was a pretty normal, non-intimidating situation— people wearing cargo shorts, a barbecue going on. Then you hear an unmistakable slapping sound. It just became a kind of normal thing to hear. I was introduced to a girl who said, “Let’s go play.” We went into a room and I just spanked her. And then we hugged. It was fun, and it was the weirdest feeling in the world. I hadn’t told any of my friends about this, and yet I was sitting there with a bunch of strangers that I felt so much more comfortable with than people I had known for 22 years at that point.

Being able to relate to someone with your deepest, darkest desire, knowing they’d probably been through similar self-identity

struggles, it was a very peaceful feeling to be able to be so open and not have to hide any part of you. They were normal people, with normal jobs, and normal problems, and yet they had this very specific thing that held them together. Maybe it’s like with country clubs or extreme surfers, that same shared experience. But this one is around an innate, weird, hidden desire. I started to meet more people in that scene. Started going to parties and bigger parties—in New York City, Atlantic City, Vegas, Pennsylvania, Philly—and making more friends.

A lot of times, when I am drained of energy, sadism is more appealing because it’s less taxing. Sometimes being a dominant can be taxing. A good dom should always be attentive and aware of what’s happening and be on. Read body language, read breathing patterns. Read through moans. You can tell a good whimper from a bad whimper. When you start to get to know someone, they give you signals, too. Breathing patterns is a really big one. Watch if someone’s going into a trance, someone’s relaxing into it, or someone’s just stressed out.

There’s a deeper emotional aspect to kink in my eyes. One, you’ve found someone that shares this desire, this very deep part of you. Two, it’s the trust involved in it. If you think about anything pain-related—bondage, suspension, caning, degradation— you are trusting each other so deeply to not let it go awry, for either of you to be harmed. That goes so much deeper to me than like, “We’re going to have sex for the 57th time in the same position.” Obviously, the sex feels good. But the dance of kink, that delicate partner swing dance or whatever you want to call it, is so powerful that it seems to kind of transcend sex.

Aftercare is super important. Being able to build back up I think is imperative. It’s not an option.

100 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 101

Subs might want to be broken—they’re bratty and sassy until they’re broken. There might be degradation, humiliation. But giving up that much to someone, giving up that control can make you feel low. As a top or dom, you are building them back up, telling them, it was a scene. You are a respected, wonderful human being and you are not the worthless little slut that I was saying you are. How deep you take the person is how equally high you should build them back up when you’re done. Otherwise they’re left with this broken type of feeling. One, it’s emotional. Two, if you think about the serotonin, dopamine, and the huge amount of endorphins that are released, when those leave, you have a really hard drop. Making sure you hold the person, comfort the person, wrap them in a blanket and surround them with positivity can make that drop a lot less severe.

One of the most fun scenes I’ve had was after I was playing with a girl and we had just had funishment (playful punishment) during the party. She was telling me she was supposed to be taking a medication but kept ignoring it. I got really upset and started lecturing her. She started to tear up. She was kind of cowering in front of me. I stopped and said, “Oh no, I’m sorry.” And she said, “No, keep going. Do not stop.” So I went back to lecturing. “I am upset by this. I don’t want to have to talk to you again about this. I’m going to leave something in your mind that should remind you how severely you messed up.” And I spanked her really hard. “Tomorrow I want you to tell me when you took your pill.” And she did, and she continued to take it after that. I’d probably like to explore the discipline thing more. There’s a helping side to it.

Warren, he/him, mid-60s, in construction

I remember when I was in 7th grade, in the ’60s, and the theaters would have illustrations for horror movies—dungeons, men and women being tortured. At that time, it was fascinating. It didn’t get arousing until the 8th grade as I was hitting puberty. I had access to All Man aga ine it al a s see ed to eature