Editor’s Letter

Contributors FLUX PHILES

24 | Music

Twelvenoon & Midnite

28 | Plants

Silverswords

36 | Poetry

Merwin

44 | Culture

A Hua He Inoa

A HUI HOU

192 | Homecoming

50 | Human Nature

Faced with a warming climate, coral researchers in Kāneʻohe are working to reverse engineer the future through “assisted evolution.” Writer Timothy A. Schuler follows their scientific crusade and the queries their work poses for all of us.

In a weekend camping excursion on Moloka‘i, children learn how to live off the land. Senior editor Rae Sojot channels her inner keiki to chronicle the experience.

Ten photographers across Hawai‘i document the quiet corners of their daily lives. In the mundane and majestic, this photo essay unfolds to reveal life in the islands within the span of a single day.

After seven months spent on Kure Atoll, photographer and conservationist Zachary Pezzillo shares reflections on the constant field work happening on the northernmost island in the Hawaiian archipelago.

In the late 1970s, the infamous commune known as Taylor Camp was burned to ash. Writer Christian Cook recollects its free-spirited ascent and fall from grace.

CONTENTS

These conversations with Pacific creatives, who are exhibiting work with a sense of urgency and thoughtprovoking timeliness, speak to issues surrounding colonial histories, disenfranchised narratives, and stereotypes about Hawai‘i.

Aotearoa artist Lisa Reihana ambitiously animates, examines, and challenges the imperialist gaze on indigenous peoples and cultures. Her exhibition Emissaries was recently on view at the Honolulu Museum of Art. Image by Meagan Suzuki.

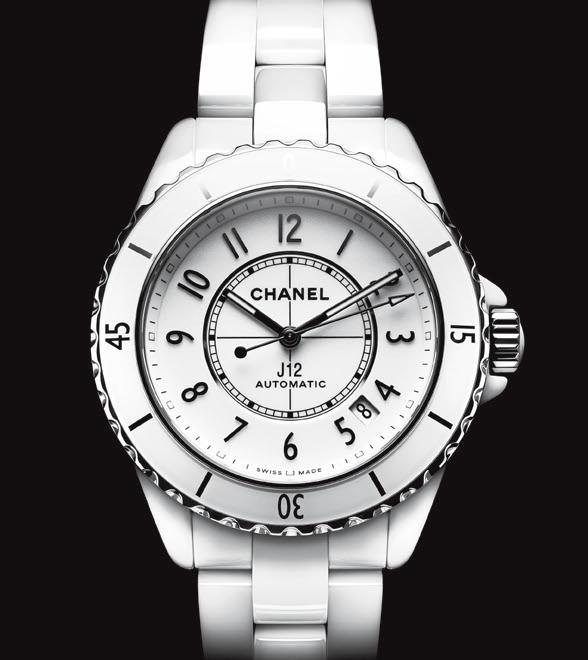

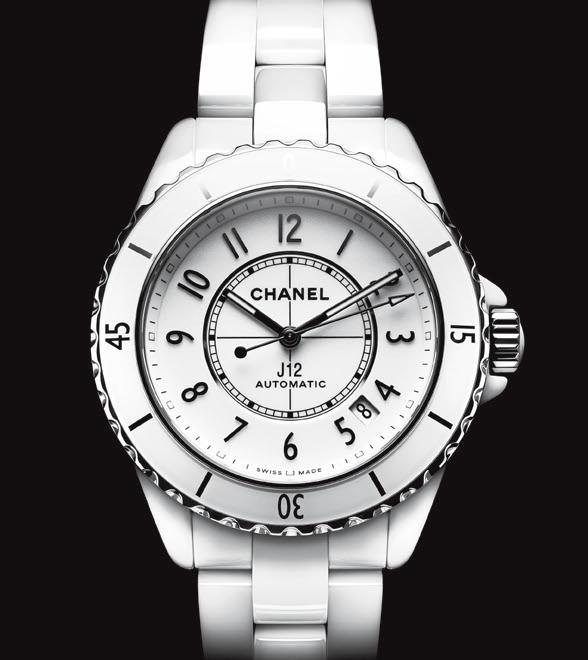

Scientists predict only 10 percent of the planet�s corals will live past the year 2050. Dive into the Gates Coral Lab, at the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology, where a research team is making strides to fight climate change by developing resilient coral reefs. The restoration effort is one of the first to use corals selected specifically for thermal tolerance. “We might not be putting out the most biomass of any restoration project,” the lab’s principal investigator Crawford Drury said, “but what we are putting out, we hope is still going to be there in 75 years.”

Deep in Pālolo Valley, children zipline through the acreage of a family home built around sustainability. Seventy-five percent of the house’s building materials are salvaged or repurposed, including this postwar cauldron found buried on a Maui property. Photographer and writer IJfke Ridgley captured this whimsical scene for the piece, “The Build Up,” on page 150, about architect Aaron Ackerman and his dream to create a green living space in sync with its environment.

fluxhawaii.com /fluxhawaii @fluxhawaii @fluxhawaii

EDITOR’S LETTER

The night after the last presidential election, I met up with a couple of friends to eat Mexican food in Chinatown.

We were in immediate shell shock upon learning whom this country’s leader was about to be. Being in Hawai‘i, diverse and loyally blue, we admitted our casual ignorance of the reality that there is a very real voting block of very real people forcible enough to bring such a man into office. We ate our tacos, talked story over cheap beer, felt despondent and defenseless, but comforted by each other’s company. Eventually, the conversation turned to art. As citizens in creative industries—both of the friends are curators for galleries and museums—we chatted about what we could contribute in our small ways to this pressing moment, about where the intersections between our day jobs and resistance might meet. Editors, creative directors, and curators are often viewed in the community as gatekeepers (though I would campaign for a less possessive and hierarchical term, such as custodian or steward), and part of the job is to have a historical and instinctual sense for the current zeitgeist, where it’s been, where it is, and more importantly, where it should go. The fortunate consequence of unfortunate times is that it often produces a formidable stream of art across disciplines. I remember relishing the opinions of my friends about what we might demand of our artists moving forward. We came to a consensus that the work doesn’t require an explicit political message, but if you’re not going to magnify, decentralize, or challenge a point of view, if your reflex is to remain pedestrian and not be deeply personal, then why even do it? As individual rights come

under daily assault by this administration, it is not a time for artists to be shy about who they are, what they feel, what they think. This is certainly not the time for painting rainbows over mountains and calling it art.

Since art by its nature is in pursuit of some kind of ideal, for this issue on Utopias, it felt necessary to share who we consider to be vanguards in this regard. As producers of conversation-sparking pieces in their own rights, we wanted to present working artists in conversation (page 116) to illustrate the expansive and imaginative ways we can approach, navigate, and think about our world.

This issue also reaffirms that we need to broaden our definition of an artist. If the role of one is to shift another’s consciousness, then Hawai‘i’s scientists engineering super corals (page 50), Hawaiian language speakers naming interstellar discoveries (page 42), and an uncle teaching the next generation how to cleave closer to the land (page 66) are also artists. Whether they succeed or fail, there is something utopian about a world where people are endlessly striving.

With aloha,

Matthew Dekneef EDITORIAL DIRECTOR @mattdknf

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Ara Laylo

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Matthew Dekneef

MANAGING EDITOR

Lauren McNally

SENIOR EDITORS

Anna Harmon

Rae Sojot

PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR

John Hook

PHOTOGRAPHY EDITORS

Samantha Hook

Chris Rohrer

DESIGNERS

Michelle Ganeku

Skye Yonamine

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Eunica Escalante

CONTRIBUTORS

Lindsay Arakawa

Noelani Arista

Emily A. Benton

M. A. Chavez

Christian Cook

Naz Kawakami

Ashley Lukashevsky

Zachary Pezzillo

IJfke Ridgley

Timothy A. Schuler

Shannon Wianecki

Kathleen Wong

Kylie Yamauchi

IMAGES

Vincent Bercasio

Elyse Butler

Lenny Kaholo

Lila Lee

Wayne Levin

Dino Morrow

Kenna Reed

Bailey Rebecca Roberts

Meagan Suzuki

John Wehrheim

CREATIVE SERVICES

Tammy Uy VP CREATIVE DEVELOPMENT

Shannon Fujimoto CREATIVE SERVICES MANAGER

Gerard Elmore LEAD PRODUCER gerard@NMGnetwork.com

Shaneika Aguilar

Kyle Kosaki

Rena Shishido FILMMAKERS

Mutya Briones

DIGITAL MARKETING MANAGER

Aja Toscano

NETWORK MARKETING COORDINATOR

Kimi Lung

WEB DESIGNER & DEVELOPER

David Efhan

Romina Escano

WEB PRODUCTION

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley VP SALES mike@NMGnetwork.com

Phil LeRoy NATIONAL SALES DIRECTOR

Chelsea Tsuchida KEY ACCOUNTS & MARKETING MANAGER

Helen Chang MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

Kylee Takata SALES ASSISTANT

Hunter Rapoza

AD OPERATIONS & DIGITAL MARKETING COORDINATOR

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock

CHIEF REVENUE OFFICER joe@NMGnetwork.com

Francine Beppu NETWORK STRATEGY DIRECTOR francine@NMGnetwork.com

Gary Payne VP ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE

Courtney Miyashiro OPERATIONS ADMINISTRATOR

General Inquiries: contact@fluxhawaii.com

PUBLISHED BY:

Nella Media Group

36 N. Hotel St., Ste. A Honolulu, HI 96817

©2008-2019 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. FLUX Hawaii is a triannual lifestyle publication. ISSN 2578-2053

Born and raised in ‘Aiea, O‘ahu, Lindsay Arakawa has lived and worked on the west and east coasts of the continental U.S. She was formerly a social media strategist and creative for Refinery29, and has since consulted for Vice Media, Girlboss, and Women’s Health Japan. With 10 years of industry experience, Arakawa has developed a deep understanding of the different facets of social media while learning how to navigate the more personal benefits and setbacks it has on our daily lives, which she reflects on in her piece on page 172. “Having lived in and worked in major cities like San Francisco, New York City, and Tokyo, the chances of me being more dependent on my phone might be higher than most,” Arakawa says. “Because so much of my work revolves around me being on my phone, it’s been interesting for me to navigate my feelings towards this dependency.” Arakawa resides in Tokyo, Japan.

Emily A. Benton is a poet, writer, editor, and coorganizer for MIA Honolulu, a monthly reading series for Hawai‘i writers. Her poems have appeared in journals such as Southern Poetry Review, Bamboo Ridge: Journal of Hawai‘i Literature and Art, and ZYZZYVA: A San Francisco Journal of Arts & Letters. She has also contributed to outlets such as Honolulu Magazine and The Charlotte Observer. Her tribute to the late American poet W.S. Merwin, on page 36, is her first piece for the magazine.

“Merwin was one of our few contemporaries capable of adopting the idyllic poet’s life,” she says. “Who wouldn’t want to ditch the day job, move to the country, till the earth, and read and write for the rest of their lives?” Benton also edited a series of poems by local writers inspired by the photo essay on page 78 in this issue, published exclusively on Instagram at @fluxhawaii.

Wayne Levin is an oceanic photographer whose subject matter has ranged from surfers to shipwrecks. He was an instructor at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and later founded the photography program at La Pietra, Hawaii School for Girls. Levin’s photography, published in the story “Human Nature” on page 50, is fueled by his passion for conservation. His 2001 project Other Oceans documented aquariums throughout the United States and Japan where he implied that more resources are attributed to “hi-tech mini oceans” than our natural oceans. Levin continues to focus his work on conservation matters. “My goal is to show a very real and visible effect of climate change,” he says. “Not only did El Niño of 2014 to 2016 have a devastating effect on Hawaiʻi’s ecosystem, but it was one of many ‘canaries in a coal mine’ warnings of the disaster humanity faces, unless we do something about it now.”

Zachary Pezzillo

Zachary Pezzillo

Photographer and conservationist Zachary Pezzillo grew up on Maui with a deep appreciation for native species and the biodiversity found throughout Hawai‘i. In April 2019, he returned from his second winter season on Kure Atoll and works full time for the Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project. Pezzillo wrote about his recent visit to Kure, published with images he shot while there, on page 96. “Despite Kure’s sheer remoteness, this once utopian habitat has struggled against both invasive species and an ongoing salvo of discarded trash and debris carried to its pristine reefs and shores by currents from faraway places,” Pezzillo says. “It was a privilege to spend time there and I am optimistic about its future. It was a life-changing experience and left me with a profound and deep appreciation of the important role we all play as caretakers of this extraordinary planet on which we live.”

The otherworldly landscape of Haleakalā. Image by Bailey Rebecca Roberts.

The otherworldly landscape of Haleakalā. Image by Bailey Rebecca Roberts.

“If you don’t get heaven right, you can’t get earth right.”—Brother Noland

In their debut musical release, two singersongwriters reflect on their experiences with depression and faith.

TEXT BY KYLIE YAMAUCHI IMAGES BY MEAGAN SUZUKIIt was the morning after Christmas when Gabriel Miller and Freddy Leone, the singersongwriters behind Twelvenoon & Midnite, herded me toward a white SUV in a Starbucks parking lot. I had only just met them for coffee to ask them about Season , their new EP, but Miller and Leone preferred I listen to it instead. “Should I sit shotgun or in the back?” I asked. Miller pondered before answering. “Backseat,” he said, “then you can get surround sound.” Leone took the driver’s seat and turned on the car. Once we were settled, Miller swiveled around to look at me. A kolohe grin spread across his face. Leone fidgeted in his seat with a smile just as wide. “OK, you ready?” Miller asked.

Our meeting marked two weeks before the release of Season . From the way they acted, it may have well been the first time a public listener would hear their collection of five songs. Miller pressed play on his phone and a track titled “Sin” filled the car.

The song, which Miller wrote, began with wind chimes and ambient noise. The peaceful instrumental drew me into a spiritual space. I envisioned myself surrounded by nature. “I can’t believe these words you said to me,” Miller sang on the track. “Smoking, drinking, wash it down slowly.” He sang each line carefully, pausing between every couple words as if they were drawn out of him in religious confession, or like someone in a drunken stupor. Either was a possibility, considering the song juxtaposed themes of Christian faith and intoxication. “Every time I choose to do this, it’s a sin,” he continued defeatedly.

Miller wrote “Sin” as a testimony to the darker moments of his depression. Having been abused as a youth, he became addicted to drugs and alcohol. According to Miller, his depression grew over the years, eventually driving him to attempt suicide. “And many times, I’ve been looking to get away from here,” he sang in “Sin.” “And many times, I’ve been searching for a way out of here.” After his attempt, Miller found himself on the floor, still alive, the presence of God lingering in the room. Miller refocused his life on growing his Christian faith, a decision that alleviated his depression.

The haunting song came to a peaceful end, and Miller caught my eye in the rearview mirror. “You like it, yeah?” he laughed. Then it was Leone’s turn to play a song he wrote and composed.

Freddy Leone and Gabriel Miller form the duo Twelvenoon & Midnite.

“Two-thirty” transitioned us into a rhythm and blues mood. There was an immediate distinction between the singers’ voices, aside from their natural tones. In “Two-thirty,” Leone didn’t treat his words cautiously but declared them defiantly. “Not myself, can’t recognize me,” he sang. “Zero confiding, there’s nothing guiding.” “Twothirty” is also about depression, which Leone developed a couple years back.

According to Miller, Leone could hardly imagine himself writing and performing music. After Leone attended a live public performance by Miller and friends, Miller encouraged Leone to join them next time. “Nah, it’s not for me,” Leone said. At that moment, Miller recognized the symptoms of depression in his childhood friend. Leone’s voice intensified through the speakers: “It’s so loud in here, yet I don’t want to leave, I crave your air so bad and I just want to breathe.”

It was hard to reconcile that the singers behind these songs filled with hurt and struggle were the duo in front of me, two men throwing out goofy dance moves.

“Two-thirty” faded to an end, and like “Sin,” its finishing lyrics avoided closure. I found myself wanting more of their stories, to find out how Miller and Leone had gotten to a point where they could move forward from their darkest moments. Miller turned to face me and asked, “OK, how about one more?” The next song, titled “Beautiful Life,” started with the lyric, “peace like a river,” and was sung by both of them.

Season shares the mentalhealth journeys of the musicians and how they found healing in their religious faith.

For more information on upcoming shows, visit twelvenoonandmidnite.com.

Before the arrival of humans, the Hawaiian archipelago was a radical laboratory sequestered in the center of Earth’s largest ocean.

TEXT BY SHANNON WIANECKI IMAGES BY BAILEY REBECCA ROBERTSAround five million years ago, a tiny California tarweed seed blew out to sea. Perhaps it was swept up by a jet stream. Maybe it clung to the feathers of a migrating plover or rode the marine currents on a sturdy bit of flotsam. Somehow, this wee speck traveled more than 2,000 miles across the Pacific Ocean to land on a fresh slab of lava: most likely the brand new island of Kaua‘i.

Rains came and watered the seed. The sun fed it, and it grew. In this wholly unfamiliar landscape, it bloomed, unfurled a scant, daisy-like flower and produced seeds of its own. With each successive generation, the tarweed’s descendants warped to their home. The mutants survived and thrived. Their genes bent in directions better able to tolerate the tropical sun, salt air, and volcanic soil. They bent until they weren’t tarweeds anymore but something new. Amazingly, they didn’t all bend in one direction. That single seed gave rise to a multitude of novel species: the 30-plus shrubs, trees, and vines known as the Silversword Alliance.

If this sounds like a superhero origin story, well, it kind of is. The pioneer species that found their ways here could endlessly perfect themselves, honing their compatibilities to the Hawaiian archipelago’s precise microclimates. Had Darwin sailed to these shores after the Galapagos, the pages of Origin of the Species would have burst with examples of endemic Hawaiian splendor: happy-faced spiders, 50-plus types of honeycreeper birds, and 800 drosophila flies, each with an identifiable stained-glass wing pattern. Hawai‘i would’ve blown Darwin’s mind.

The Hawaiian Islands were an evolutionary utopia for two reasons: isolation and height. Once a species arrived here, it couldn’t easily mix with others of its kind a few counties over. The Pacific was too great a moat to cross for casual encounters. Each new recruit had to forge its own tribe. And the height of Hawai‘i’s volcanoes—the planet’s tallest mountains when measured from their bases at the sea floor—meant that new arrivals had a plethora of climates to inhabit: coastal dunes, lava plains, rainforests, dry forests, sub-alpine forests, and mountaintops sometimes capped in snow. The diversity of terrain signaled both opportunity and challenge. A species that flourished at sea level had to reinvent itself in order to endure the frigid, wind-blasted atmosphere found at the 13,800-foot summit of Maunakea.

Prior to human contact, the Hawaiian archipelago offered an ideal location for pioneer species to develop.

Hawai‘i offered its first inhabitants just about everything, but what it lacked was equally important. Reptiles, amphibians, social insects like ants and termites—entire taxonomies couldn’t survive the type of journey the tarweed endured. There are only two endemic Hawaiian mammals: the monk seal, because it could swim here, and the hoary bat, because it could fly. Every other furred creature came later and had the help of humans.

And so, as the islands emerged one by one out of the sea, they were populated by the humbler half of the food chain: plants, insects, and birds. Free from the pressure of grazing buffalo, deer, or giraffes, plant species shed their thorns, toxins, and means of long-distance travel. Birds became fat and flightless, swelling to fill niches of missing beasts. Two caterpillars turned carnivorous—the sole examples of meat-eating moth larvae in the world. The ecosystems that emerged here over the millennia were … weird.

Which brings us back to the Silversword Alliance. That solo tarweed hit the Hawaiian Islands running. It didn’t just

morph into new species, but three new genera. The most famous of its descendants is, of course, the silversword. The spikyleafed rebel chose the archipelago’s most extreme environment as its home: the parched peaks of Haleakalā and Maunakea. The silversword is almost alone in its ability to withstand the intense solar radiation and spiking temperatures found on Hawaiian summits, though it looks a bit like a giant metallic hedgehog snuffling around the red volcanic cinders.

The silversword’s succulent leaves are covered in silver reflective hairs that keep the plant from frying in the sun or freezing at night. It can live more than 50 years. Before dying, it produces a single magnificent inflorescence that towers up to six feet tall, bearing tiny fuchsia blossoms that resemble those of its distant progenitor. The plant’s powerful perfume lures Hawaiian hylaeus bees, who bury their faces in its pollen. Native drosophila flies pay visits, as do native tephritid flies, who feed on its fruit. In an otherwise stark terrain, the flamboyant silversword is an ecosystem unto itself.

The eye-catching silversword is protected by silver reflective hairs which allow it to thrive on mountainous summits.

Less famous than its cousin, the greensword possesses equal superpowers. It dwells in some of the wettest spots on Earth, such as Pu‘u Kukui bog. The soil here is so saturated and acidic that tree species are dwarfed, growing only one or two feet tall. The greensword looms over this miniature canopy, dangling a chandelier of blossoms in the ever-present mist. Over on Kaua‘i, the iliau resembles a greensword on stilts, but belongs to a separate genus. Other members of the alliance include the koholāpehu (Dubautia latifolia), a ropey vine found only on Kaua‘i, and the na‘ena‘e (Dubautia reticulata), a tree in the east Maui rainforest. If it weren’t for their shared genus name, one might never know they are related.

All these idiosyncratic species sprang from a single pioneer many eons ago, and all are now imperiled by habitat loss, invasive species, and climate change. When humans finally found Hawai‘i, the fertile era of isolation ended. The laboratory was flooded with newcomers. An army of nibblers and grazers—rats, cows, pigs,

goats, deer—descended on the natives, which no longer had armor with which to defend themselves. Scores of species went extinct, some disappearing before humans even laid eyes on them.

Early Hawaiians did not often travel up to the high-elevation forest, known as Wao Akua, realm of the gods. But rats did. They jumped out of Polynesian canoes and beelined up the mountain to feast on the juiciest fruits. As a result, numerous species vanished before even receiving a Hawaiian name. Some are known only from the pollen record, or their fossilized bones. Consider the po‘ouli, a forest bird first discovered and named in the 1970s. It was only by chance that biologists found this species before it, too, succumbed to extinction in 2004.

And yet Hawai‘i’s peculiar endemic paradise is not altogether lost. Successful restoration projects on each island are not only preserving what’s left but also reviving degraded habitats and bringing them back to life. Pockets of the mystery remain for us to investigate, fall in love with, and fight for.

Perfume released by the silversword attracts an array of native bees and flies to feed on its fruit.

Kō‘ula seamlessly blends an innovative, indoor design with spacious, private lanais that connect you to the outdoors. Designed by the award-winning Studio Gang Architects, every home will feature exceptional views of the ocean. Kō‘ula also offers curated interior design solutions by acclaimed, global design firm, Yabu Pushelberg, making your move turn-key and stress-free. Outside, Kō‘ula is the first Ward Village residence located next to Victoria Ward Park. This unique, central location puts you in the heart of the vibrant Ward Village neighborhood. This holistically designed, master-planned community is home to Hawaii’s best restaurants, local boutiques and events, all right outside your door.

1, 2 & 3 bedroom homes available. Contact the Ward Village Residential Sales Gallery to schedule a private tour.

808.824.4857 | koulaward.com 1240 Ala Moana Blvd. Honolulu, Hawaii 96814

The prolific poet W.S. Merwin leaves behind a treasured legacy of letters, lore, and his blooming love for the natural world.

TEXT BY EMILY A. BENTON IMAGES BY CHRIS ROHRERThe late poet William Stanley Merwin, who spent 40 years turning an 18-acre Maui plantation into a lush palm forest, began his ode “Trees” in this way: “I am looking at trees / they may be one of the things I will miss / most from the earth.” The lines are fitting for a poet who lived by a daily ritual: write a poem, plant a tree.

However, to carry his meditative practice to the northern slopes of Maui, he first had to shed the Western attachments that came with being an established American poet.

Unlike his contemporaries in the early 1970s, Merwin held no permanent position at a university, though he’d given readings on campuses and protested the Vietnam War alongside students. Upon receiving a Pulitzer Prize in 1971, he had stated he was “too conscious of being an American to accept public congratulation with good grace, or to welcome it except as an occasion for expressing openly a shame which many Americans feel.”

While his New England predecessors had walked a mile outside town to Walden and his Beatnik peers drove On the Road , Merwin continued, throughout his life, to step into a more isolated existence reminiscent of earlier poets. Specifically, Merwin studied 12th century troubadours—poets who traveled on foot throughout Europe orating verse for peasants and the king’s court. As Ezra Pound once advised him to do, Merwin learned languages, and plenty of them: Latin, Greek, Spanish, Japanese, Sanskrit, Quechua, Occitan. He translated medieval epics including Dante’s Divine Comedy and many other longform, narrative poems in his lifetime.

Merwin also departed from his father’s Presbyterian church in favor of Eastern spirituality, sidestepping commune culture for a more solitary study of Zen Buddhism. Not one for city life, the poet left the urban New Jersey of his childhood to reside in an abandoned farmhouse in the French countryside. In between writing and translating poems, he studied gardening in old French-language manuals and learned how to live off the land.

“When I first saw farmland and woods as a child, I wanted to be there, to get out of the car or the train and be surrounded by what I saw,” Merwin wrote in a piece later published in The Kenyon Review. “I was learning to read about people who did not read or write but who lived all the time in the woods. I said that was what I wanted to do.”

So when his friend and Zen teacher Robert Aitken introduced him to a fallow, offthe-grid pineapple farm on Maui in 1976, Merwin saw an opportunity. There, he began another garden, this time with a few pots of palm trees.

Merwin, one of American literature’s most decorated poets, made his home on the island of Maui.

“I had long dreamed of having a chance, one day, to try to restore a bit of the earth’s surface that had been abused by ‘human improvement,’” he wrote. Planting a tree each day for four decades, from seeds gathered all over the world, Merwin established more than 2,000 palms and a home for many endangered plants and birds under their towering canopy. (Visitors would later recount the blind, aged poet feeding berries to birds out of his hand, knowing each species by its song.)

As Merwin connected with the land more deeply, his poetry ascended to new heights. On one of his first visits to Hawai‘i, he had given a reading at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa alongside San Francisco poet Gary Snyder. Among the students in the room was Frank Stewart, who later published Merwin’s work as editor of Mānoa: A Pacific Journal of International Writing. “Merwin was always friendly, always charming, but his work was thought of as rather formal,” Stewart recalled of Merwin’s earlier poetry, published in his

first four books. “Of course, that was a big contrast to Gary Snyder, to Galway Kinnell, and others.”

But the antiquated language and tight stanzas Merwin fished out of translated epics soon broke free from their nets. Over time, verse without punctuation and meter, in lines of varying length, became his signature style.

“I think Hawai‘i really got into his sensibility,” Stewart said. “I remember one of the first books where I felt that was called The Compass Flower , which was more sensual and more like the islands, whatever that means—less like the mainland.” In this 1977 book written against the backdrop of a rainforest replanted palm by palm, a place once inhabited by Hawaiians long before his stewardship, Merwin’s poems captured his appreciation for what had come before him.

“Hawai‘i enriched him as much, or more, than he enriched Hawai‘i,” Stewart said. “Even a very sparse style can have a flavor, a taste, and an aroma that’s drawn out of

Merwin showed a deep appreciation for Hawai‘i’s landscape and people with his epic The Folding Cliffs. Right, Robert Becker, the poet’s cousin and vice president of the Merwin Conservancy.

the environment it’s written in. Merwin’s gentleness and inwardness are things that were elaborated upon in him because of Hawai‘i. I think it was under the influence of him really beginning to love the people.”

Moved by the islands’ history and voices of the Hawaiian Renaissance, Merwin wrote The Folding Cliffs in 1998, a 350-page narrative in verse about Kaluaikoolau, or “Koolau the Leper,” and the many Hawaiians endangered by Hansen’s disease and 19th century laws that sought to exile them. The book was informed by 12 years of research, including Merwin’s study of the Hawaiian language. In a 2010 article in the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, Hawaiian educator Pualani Kanaka‘ole Kanahele, a close friend of Merwin’s, praised The Folding Cliffs for how Merwin “got into the head” of characters and captured the emotions behind the story.

With his wife, Paula, Merwin established the Merwin Conservancy in 2010, a nonprofit that hosts visitors and runs an “arts and ecology” salon that invites guest artists and writers to speak at events on

Maui and O‘ahu. In 2018, the conservancy also invited 15 Hawai‘i teachers to the palm forest for a week to kick off a oneyear collaboration with Merwin and visiting poet Naomi Shihab Nye to infuse creative curricula into Hawai‘i schools. The conservancy is also developing a multidisciplinary residency that will host artists in the poet’s old home, an almost mythic place for today’s writers.

By the time he died in his sleep at his Maui home on March 15, 2019, Merwin had won a second Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and the Lannan Lifetime Achievement Award. He had served as the U.S. Poet Laureate under President Obama. He’d published more than 50 books of poetry, translation, and prose. For each page he wrote, for each tree he planted, he tried to give back a little to what a dying world had given him, from the most storied place he could find.

The Merwin Conservancy hosts literary events. Above, Sonnet Kekilia Coggins, executive director.

For more information on the Merwin Conservancy, visit merwinconservancy.org.

Inspired by a creation chant and an image of the once unseeable, astronomers and a Hawaiian language expert named one of history’s most captivating discoveries.

TEXT BY EUNICA ESCALANTEIMAGES BY DINO MORROW

On a balmy morning in March 2019, three scientists, two Hawaiian cultural experts, and a communications consultant sat around a conference table. Moments before, two of the scientists had sworn the rest to secrecy. The information they were about to discuss was strictly confidential, “under heavy media embargo and guarded like Fort Knox,” as Doug Simons, one of the scientists and the director of the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope on Maunakea, explained to me months later. The other two scientists, Jessica Dempsey, deputy director of the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope, and Geoffrey Bower, lead scientist of Academia Sinica Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics’ Hawai‘i operations, were members of the Event Horizon Telescope consortium, a project involving eight telescopes and more than 200 scientists around the globe.

The consortium had found something. Or more accurately, had seen what was once unseeable, Dempsey and Bower told the group. There, at the heart of nearby galaxy Messier 87, was a glowing ring of light descending into the deepest, darkest abyss. The photographs that Dempsey and Bower presented were blurry, but there was no contending what they showed: a black hole.

“I had a hard time sleeping that first night,” Simons said. It was so bizarre, he recalled, seeing something that no one had seen before. “As an astronomer, I never thought I would live to see such an image.”

In two weeks’ time, these images would be disseminated to media organizations and scientific journals. The news would permeate the globe. An astrophysicist in the Netherlands and member of the consortium would passionately announce at a press conference, “We have seen the gates of hell.” Memes would be made with the

historic images, like one equating the black hole with the Eye of Sauron, signifying how much it had captured the public’s attention. It would be heralded as one of the most important discoveries of the decade, if not the century.

Yet on that spring day, as Dempsey and Bower presented the images of the black hole to the shellshocked group, the world was yet to know of its existence. And, more importantly for the people in that room, the discovery was yet to be named.

On April 10, at exactly 9 a.m. Eastern time, six press conferences across four continents would simultaneously unveil the images. Except, because of its time zone, Hawai‘i was at a disadvantage. “No one was going to come to a press conference at 3 a.m.,” Simons said. As the representatives for the Event Horizon Telescope’s two Hawai‘i-based telescopes, Dempsey and Bower didn’t want their team to get lost in the noise. They needed a media kit unique from the others.

Enter A Hua He Inoa. Directed by Leslie Ka‘iu Kimura, who runs the program under her post as executive director of ʻImiloa Astronomy Center, A Hua He Inoa has become well known among the astronomical community, having named celestial objects with the assistance of Larry Kimura, a Hawaiian language professor and pioneer of the language’s revitalization (and Leslie’s uncle).

Two years prior, the program and its concept of modernday Hawaiian celestial nomenclature was just an abstract idea conceived by John De Fries, a Hawaiian entrepreneur. In March 2017, he sent a memo to Kahu Kū Mauna,

Hawaiian language professor Larry Kimura has been tapped to name tremendous cosmological findings.

a cultural advisory group for the Maunakea Management Board. Familiar with the group’s influence, he proposed a novel concept: to bestow every discovery made on Maunakea with a Hawaiian name. Prior to that, discoveries were only labelled with a system of acronyms and numerical codes. Except for those of key astronomical objects, names were little more than coordinates.

The memo made waves in the astronomy scene and arrived on Simons’ desk at the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope on recommendation from some members of Kahu Kū Mauna. Intrigued, he reached out to De Fries. Yet other members of the observatory community were skeptical, unsure of the concept’s viability and how the astronomical society would react.

Then, on October 2017, Haleakalā’s network of telescopes, the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System, detected an interstellar object hurtling past the sun. It was the first time that an object from another solar system was observed passing through ours. In the months after its publication, the discovery was linked to everything from the formation of solar systems to proof of extraterrestrial life.

Pan-STARRS astronomer Richard Wainscoat phoned Simons, asking for permission to use the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope for further observations. As Wainscoat described the significance of the observation, Simons’ thoughts turned to De Fries’ memo. “That’s when it clicked,” he said. “This was the big astronomical discovery that John and I had been waiting for.”

Proving its potential through a highprofile discovery would “give it a shot of confidence,” Simons said. He phoned Kaʻiu Kimura, a long-time colleague who he knew could connect him to Larry Kimura. The language professor, having helped perpetuate the Hawaiian language’s renaissance in the 1980s by founding one of the first Hawaiian language immersion schools, was the only person who could credibly name the discovery, according to Simons.

Larry was alerted and given 72 hours to come up with a name. They only had one chance to do so. The Pan-STARRS research team was wrapping up a paper that would announce the discovery in the science journal Nature, with or without a Hawaiian name. Once a discovery was made public, Simons said, “there would be no reeling it back.”

The first-ever photo of a black hole, named Pōwehi, was released on April 10, 2019. Image courtesy of Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration.

PRESENTING SPONSOR MAJOR SPONSORS MEDIA SPONSORS

Larry didn’t need 72 hours. The name was ‘Oumuamua, meaning a scout or a warrior sent ahead of the pack to discern the strength of the opposing force. “It was coming from someplace sort of mysteriously, from another realm, so to speak,” Larry said. The salient characteristics that made it a unique and scientifically important discovery served as Larry’s inspiration. “It was checking us out in a way,” he said. “That would be something like a spy, like a scout.”

Though it was an interesting project, Larry didn’t anticipate that the name would leave the scientific community. But upon its unveiling, the Hawaiian word was everywhere: splashed across global headlines and on newscasts, albeit often mispronounced. Soon after, it was approved by the International Astronomical Union, the official designating body for celestial objects, making ‘Oumuamua the official distinction. The magnitude of the name’s reach—having “gone viral,” as Simons described— proved A Hua He Inoa’s potential.

Yet, upon the name’s publication, some Native Hawaiians disagreed with this use of their language, especially amid continued tensions surrounding the Thirty Meter Telescope on Maunakea. For activist and Ph.D. student Iwakelii Tong, bestowing discoveries made on Maunakea and Haleakalā with Hawaiian names felt like “fabricating consent from Native Hawaiians,” he said. By aligning Hawaiian language and culture with their observatories, which have been a source of frustration for some Hawaiians for decades, it was as if these organizations “were sweeping everything under the rug,” according to Tong, rather than directly addressing issues brought up by activists like him.

For members of A Hua He Inoa, however, the Hawaiian language’s presence in the scientific sphere was progress. It was a step forward for a language that three decades ago was on the edge of extinction.

“There were stories from my mother about not being able to speak Hawaiian at school,” De Fries said, “not even in Kamehameha Schools,” an institution founded by Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop for Native Hawaiian children. Federal policies banned Hawaiian in schools. Native speakers stopped speaking to their children in Hawaiian. Use waned to elders and the island of Niʻihau. By 1984, there were only 32 speakers under the age of 18.

That same year, Pūnana Leo, a Hawaiian immersion school Larry founded with a group of ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i experts, opened its doors. The school and its Hawaiian mode of

instruction became a part of a movement to restore the language by instilling it in the next generation. In the years since, the use of the language spread, revitalized by immersion schools and a larger Hawaiian renaissance. By 2016, Hawaiian speakers numbered more than 18,000.

De Fries cites ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i’s near extinction as partially having inspiring his concept for A Hua He Inoa decades later. Larry also sees A Hua He Inoa as an extension of this revitalization. When he saw the coverage that ‘Oumuamua attracted, he said, “I realized the opportunity we had to pick up where we left off.” Preserving the Hawaiian language is crucial to preserving Hawaiian culture. “Every language has a different perspective of living through this world,” and holding on to one’s native language, Larry said, “is crucial in preserving who we are as Hawaiians.”

Learning from ‘Oumuamua’s success, Dempsey and Bower invited Ka‘iu and Larry to join the black hole’s media team. Larry knew the name would involve pō, the “profound dark source of unending creation” as described in the Kumulipo. “But there were many types of pō, of darkness,” Larry said, estimating that pō was mentioned over a hundred times in the Kumulipo. “Which one would this be?” Dempsey described the image’s basic anatomy to Larry. “Ah, then I knew,” he said.

That orange halo amid the darkness reminded Larry of “wehiwehi,” meaning “honored with embellishments.”

Within the Kumulipo, one such pō was described to be adorned, as if wearing a crown. As far as Larry understood it, the black hole could only be named “Pōwehi,” the pō he had learned about in the Kumulipo.

Though the other telescopes were notified, it was slightly too late. Unlike with ‘Oumuamua, the black hole’s discovery papers were already in the final proofing stage. “Sometimes timing really is everything,” Simons said. All the Hawai‘i team could do was disseminate their press kit to as many media organizations as possible and hope that the name would catch.

The day had come. At the strike of 10 a.m., every major news organization in the world released the images. As expected, the joint press conference captured worldwide attention. And there, among the headlines, was a name. The black hole was everywhere, and everywhere, it was being called Pōwehi.

Members of A Hua He Inoa turn to Hawaiian chants, stories, and writings for guidance.

Faced with a warming climate, coral researchers are working to reverse engineer the future through “assisted evolution.” What if nature isn’t what needs to evolve?

TEXT BY TIMOTHY A. SCHULER IMAGES BY LENNY KAHOLO & WAYNE LEVIN

The Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology occupies several bland, bunker-like buildings near the center of Coconut Island, which sits a quarter mile offshore of Kāne‘ohe. It’s not the easiest place to reach. You don’t just drive up and park. Instead, to visit the institute, which is home to a series of research laboratories affiliated with the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, you must take at least two shuttle rides: the first in an aging, gray Honda CR-V, which ferries you from a parking area near Windward Mall to Lilipuna Pier; the second via a skiff with a makeshift shade canopy that collects you from the end of the pier and takes you the rest of the way.

Earlier this spring, I made the multileg journey to Coconut Island to visit the Gates Coral Lab. Founded in 2003 by Ruth Gates, a Cyprus-born marine biologist, the lab has produced some of the world’s most important coral research. Gates gained international recognition earlier this decade when she issued a clarion call for the world’s coral. Earth’s coral reefs were in serious trouble, Gates insisted in interviews with National Public Radio, National Geographic, and VICE News. The oceans were warming, and corals couldn’t keep up.

Like most living things, corals are capable of adapting to environmental conditions, but Gates explained that the Earth’s oceans are warming too rapidly for most coral species. Already, over the past century, average ocean temperatures increased 0.13° Celsius per decade, and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change experts have projected the world’s oceans will warm anywhere from 1° to 4° Celsius by 2100. In 2015, in the aftermath of a violent heat wave, coral reefs along the Kona coast of Hawaiʻi Island saw mortality rates of up to 90 percent. In 30 years, it is likely that 90 percent of the world’s coral species will be extinct.

Gates saw an urgent need for scientists to intervene. In 2013, she began to experiment with something she called “assisted evolution.” The idea was to artificially accelerate the process of natural selection and engineer “super coral” that could withstand the predicted increases in ocean temperatures. Engineering, of

course, had little to do with it. The work consisted of old-fashioned selective breeding, the same technique used to create everything from golden delicious apples to golden doodle puppies. Gates and her team took samples of reef-building corals found in Kāne‘ohe Bay that exhibited higher than average thermal tolerance and bred them with other corals, with the goal of producing more resilient offspring.

Gates’ work made international headlines. The Economist and Netflix produced documentaries about her research, and she was a fixture on Hawai‘i Public Radio. Then, on October 25, 2018, at the age of 56, Gates died of complications related to surgery for diverticulitis.

“The Fight for Corals Loses Its Great Champion,” ran the headline in The Atlantic. “Ruth was magnetic,” Judy Lemus, the interim director of the institute, told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser. “People were drawn to her.”

The scientists at the Gates Coral Lab grieved the loss of their charismatic leader, even as they endeavored to continue her groundbreaking research. Taking over as principal investigator was a young, squarejawed, surfer type named Crawford Drury whom everyone called Ford. When we first met outside the lab, he wore shorts and sunglasses and a backwards baseball cap. Neither he nor the institute were what I expected. I had imagined someone older, maybe wearing a white lab coat. And the island, well, it felt less like a place that produced world-class research than a science experiment that had gone awry, a Frankenstein of dredged earth and mysterious ruins held together by fossilized bags of Quickcrete.

Coconut Island, known also as Moku o Lo‘e, or the land of Loʻe, was named after one of four siblings who, stories say, traveled from Wai‘anae to make their home on O‘ahu’s windward shore. In the early 20th century, the island was purchased by an entrepreneur and heir named Christian Holmes, who for much of the 1930s, used the island for a tuna cannery as well as a private retreat. He dredged the bay to expand the island, cutting trenches in the reef and building long, spindly fingers of land that stretched out as if to touch Kāne‘ohe. He added a house, a

As the Earth’s atmosphere and oceans warm, bleaching events are predicted to become more frequent.

The research process begins with collecting samples of coral that exhibit a tolerance to higher than average ocean temperatures.

bowling alley, a shooting range, even a saltwater swimming pool.

Everywhere I looked, Holmes’ follies peeked through the foliage: large lava rock walls, stairs that led to nothing but jungle. Just inland from the now-abandoned swimming pool, a low-slung building housed a series of guest rooms, one of which was being cleaned by a young woman. She said the rooms were used by visiting researchers. When I mentioned all the strange ruins, she explained that the island used to be a zoo. “The elephant ponds were down there,” she said, pointing over the hill.

Indeed, Holmes had a thing for animals. He imported monkeys, a giraffe, a baby elephant to the island. When he died in 1944, the animals became some of the first residents of the Honolulu Zoo. For a few years following, the island was used for R&R for Marine officers, which is how the barracks came to be built. A group of five oil and gas executives then bought the island in 1947, after which one named Edwin Pauley became the sole owner. Pauley hosted renowned guests including presidents Harry Truman and Richard Nixon on Coconut Island, and he also helped establish a marine research lab there. The facility eventually evolved into the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology, an independent research station of UH Mānoa’s School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology. In 1995, Pauley’s family donated $2 million to the University of Hawai‘i Foundation to help it purchase the island outright.

Coconut Island was still a menagerie of sorts when I arrived, though one with more scientific purpose than Holmes had in mind. Its most dramatic residents were the sharks, which cruised a small pond on the east side of the island, their tails flicking in a way that seemed almost feline. Just down the road was the Gates Lab, with its hundreds, if not thousands, of corals. I saw baby corals smaller than the spores on the frond

of a fern and adolescent corals that resembled shelled walnuts. One tray was full of a shape-shifting species that grew just as often into tall, spiky turrets as broad, flat plates. More than one specimen could have passed for fried chicken.

Most of the corals growing in the lab’s tanks were part of current experiments. Drury showed me how the researchers were implanting coral specimens with radio-frequency identification chips to track them more easily. In November 2018, less than a month after Gates’ death, the Gates Coral Lab received $1 million from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to test some of the researchers’ ideas in situ, in the water. The aim, Drury explained, was to understand the ecological implications of introducing more thermally tolerant corals into an existing reef ecosystem. The researchers would work with a team from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and volunteers from Mālama Maunalua to outplant nearly 12,000 baby corals at three sites around O‘ahu, in Maunalua Bay, Kāne‘ohe Bay, and offshore of Daniel K. Inouye International Airport.

The restoration effort would be unique, one of the first to use corals selected specifically for thermal tolerance. “We might not be putting out the most biomass of any restoration project, but what we are putting out, we hope is still going to be there in 75 years,” Drury said, “as opposed to the current restoration framework, which is get some corals, propagate as many as you can, however you can, and put ’em back on the reef. Maybe just dump a cooler over the side of the boat.”

Drury explained that when coral reefs are subjected to abnormal temperatures for extended periods of time, the corals expel their zooxanthellae, a type of symbiotic algae, which turns the reef a ghostly white. This is what’s known as coral bleaching. Without the zooxanthellae, which provide corals with food and

oxygen in exchange for shelter, the organisms are far more susceptible to disease and stress. It was something the scientists had seen firsthand. Between 2014 and 2015, more than half of Hawai‘i’s reef-building corals bleached. It was unprecedented. And it endangered not only Hawai‘i’s reefs but also the many hundreds of marine creatures—and human livelihoods— that depended on them.

As the Earth’s atmosphere and oceans warms, bleaching events are predicted to become more frequent.

“There’s a growing recognition in restoration that if you plant something out and it just turns around and dies a couple of years later, that’s a huge amount of wasted effort,” Carlo Caruso, a postdoctoral researcher at the Gates Coral Lab, told me.

I met Caruso, who previously worked for the National Park Service in American Samoa, as he was building the infrastructure for an upcoming research project, a massive experimental setup involving computer-controlled solenoids and commercial-grade chillers behind the Gates Lab’s research facility. He had erected a large shade structure to protect the corals from excess sunlight. A giant computer chip encased in plexiglass sat on a folding table. Caruso explained that it was a Raspberry Pi, an extremely simple type of computer that could run basic programs. He planned to use it to replay historic bleaching events. The Raspberry Pi would control the temperature of the water in the tanks, following a set pattern based on actual recorded ocean temperatures in locations around Hawai‘i.

“We can look back at bleaching events that happened here in Kāne‘ohe Bay and replay a segment that we’re interested in,” Caruso said, “like leading up to when we saw corals bleaching in the field, and essentially recreate that profile in tanks, but also tweak that, maybe have it go a little bit higher, to replicate what would happen in a more intense bleaching event.”

In lieu of any meaningful action taken by U.S. lawmakers, scientists were being forced to take the lead on averting a climate catastrophe, Drury said, and there had been a noticeable shift in how researchers approached a subject like coral bleaching. Historically, scientists simply wanted to know how things were. Increasingly, they advocated for how they should be.

“It’s very much a triage situation,” Drury said of Hawai‘i’s coral reefs. “This is urgent and going to get worse.” At the same time, he said, when it came to bleaching and coral die-offs, “on the fine scale, we don’t understand a whole lot about how it works. I feel like that’s a very non-scientist thing to say. Everyone always wants to seem like we know what we’re talking about. But we’re still very early in understanding what’s happening.”

Drury’s team didn’t know why some corals were more thermally tolerant than others. But on some level, it didn’t matter. If they could build coral reefs that would survive the coming conditions, that was what they were going to do.

Over the past 10 years, the tone of the conversation around climate change has darkened dramatically. What once was full of cautious but ultimately confident manifestos about clean energy and sustainability now overflows with bleak accountings: a million species threatened with extinction, thousands of humans dead from extreme weather in 2018. In May, researchers at Hawai‘i’s Mauna Loa Observatory made history when they reported that the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere had reached 415 parts per million, the highest point in recorded history. (When atmospheric carbon dioxide began being tracked in 1958, the number was 316 parts per million.) The first few months of 2019 brought a slew of new books by leading voices in the climate discussion. Their titles were not optimistic: The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming; Losing Earth: A Recent History; Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out?

Psychologists have begun to recognize the profound emotional toll that these doomsday predictions are taking on humans. Earth is our species’ native habitat. We might live in towns and cities that feel manmade, but our home—the thing that meets the vast majority of our needs—is the natural world. Without oceans, valleys, forests, and soils, our bodies cannot function. The question, then, is what does it do to us to watch these natural systems falter and the birds we once saw outside our windows vanish? What sort of psychological wound is made when we dive beneath the water and see a pale landscape of dead and dying corals?

In 2018, a pair of Australian researchers published a paper in the journal Nature on a relatively new condition they termed “ecological grief.” “Climate-related weather events and environmental changes have been linked

Scientists are still in the process of understanding how bleaching and coral die-offs work. Some are more focused on planting reefs made to handle the coming conditions.

to a wide variety of acute and chronic mental health experiences,” it read. Among the symptoms being reported were “elevated rates of mood disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and pre- and post-traumatic stress; increased drug and alcohol usage; increased suicide ideation; … and threats and disruptions to sense of place and place attachment.”

Ecological grief, as the researchers defined it, was “grief felt in relation to experienced or anticipated ecological losses, including the loss of species, ecosystems, and meaningful landscapes due to acute or chronic environmental change.” To this definition, they added a troubling observation: “We consider ecological grief to be a form of ‘disenfranchised grief’ or a grief that isn’t publicly or openly acknowledged. Indeed, ecological grief, and the associated work of mourning, experienced in response to ecological losses are often left unconsidered, or entirely absent, in climate change narratives, policy and research.”

Shortly after my visit to the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology, I attended a Honolulu Biennial panel discussion on the subject of “ecological grief and optimistic nihilism.” A stage was set up in the old Famous Footwear space, surrounded by dozens of art installations that tackled

themes of identity and ecological trauma: an epic graphic novel that presupposed no contact between Polynesia and European culture, found toys suspended in plastic molds. The panel comprised a mix of artists and scientists, including Chip Fletcher, associate dean for academic affairs at UH Mānoa and vice-chair of the Honolulu Climate Change Commission. Each panelist spoke of the personal despair they had felt when contemplating the coming decades. Fletcher said it was rare these days to get through a presentation without bursting into tears.

The event was organized by Ava Fedorov, a Honolulubased artist whose spring 2019 solo show, “Haunted Landscapes,” explored some of the same topics through large-scale abstract paintings.

“These landscapes are more than mere topographical geographies,” Fedorov wrote in her artist statement. “They are the overlaid arrangements of non-human and human life, translucent histories, and the physical tracings of space-time. They are intricately and indelibly woven into every aspect of the world as we know it, haunting our memories alongside our visions of the future.”

A few days after the panel, I met up with Fedorov, who arrived to our meeting wearing shorts and a tank top and carrying a bicycle helmet under one arm. Over coffee, I asked the 37-year-old if, given that a certain amount of warming is inevitable, the framework of grief, namely the five stages—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance—could help society process the impending losses.

She said yes, insofar as grief requires an explicit acknowledgement of the coming reality. “We have to change the way we embrace that future, and I think that’s the function of ecological grief,” she said. “It’s better than denial, whether it’s ‘We can still stop climate change,’ or ‘Climate change is not real.’ Those are both not as useful as, ‘OK, the shit’s gonna hit the fan—the shit is hitting the fan. It just hasn’t splattered across us yet.’”

She added that certain segments of humanity will experience the stages of grief very differently. Developing countries, which are likely to bear the brunt of climaterelated destabilization, “are going to be feeling the rage,” she said. “Because they are falling victim to behavior before they even have the luxury to adopt that behavior themselves.”

At the lab on Coconut Island, I asked Drury and Caruso if they experienced grief when they saw corals struggling to survive, or when they ran simulations meant to replicate end-of-century conditions. I wanted to know what the scientists who were on the front lines of climate change felt when they took stock of the situation. “For me, I end up not stopping. If I stop, I don’t think I can keep going,” Caruso said. But he said he didn’t get angry “because that would be to assign blame to some other entity, when really, as humans, we just stumbled down this path of being clever creatures that were trying to survive.”

If he felt anything, it was frustration. “I have two daughters, and they’re going to grow up in this era,” he said. “It’s still a beautiful world, but it’s changing, and

Initially developed as a private retreat during the 1930s, Coconut Island is the current location of the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology.

it’s hard to know how it’s all going to turn out. And I’m frustrated that we can’t do a better job as a species of making it turn out as a utopia.”

I thought about the tiny corals in the lab, RFID chips ready to transmit signals back to the scientists, and the term “assisted evolution.” Ruth Gates wanted to help corals survive. She devoted her life to it. Now, her colleagues were carrying the mantle, working tirelessly, despite the projections, despite the headlines, to ensure that at least some corals lived into the next century. Drury and Caruso, and the rest of the team at the Gates Lab, I decided, really were more like triage nurses, more like caregivers, than scientists. And I couldn’t help but feel that Hawai‘i’s coral reefs were lucky to have them. Because who would be there to assist us when humans began to decline? Where was the giant scientist in the sky who would help us evolve?

“In a way, assisting the evolution of a reef is assisting our own evolution,” Caruso said. “We’re taking responsibility for this ecosystem around us. We’re making a vision of, what do we want this to be? And how do we get there?”

Healthy coral. Coral reefs support 25 percent of all ocean life. The resilience offered to island communities like Hawai‘i by coral reefs is just one reason restoration efforts are important and the Gates Lab team hopes its super coral survive.

Bleached coral. Ecological grief, as the researchers have defined it, is a “grief felt in relation to experienced or anticipated ecological losses, including the loss of species, ecosystems, and meaningful landscapes due to acute or chronic environmental change.”

How do you mourn losses that have yet to manifest but that you can do little to prevent? When a loved one dies, it is the finality of the event that allows us to eventually accept the loss. But there is no finality with climate change or mass extinction, only degrees of horror.

In this way, ecological grief feels insufficient. All of us have played a role in poisoning the planet. Most of us did not intend it. We did not choose our culture or our economic system. Nonetheless, we share at least a fraction of the responsibility for the current crisis. Is there a word for this guilt-laden grief? This mixture of mourning and shame?

In 2017, journalist Alice Gregory profiled a group of men and women in the New Yorker who all had one thing in common: each had accidentally killed someone. Gregory described the unique, often debilitating mix of sorrow and shame these individuals carried around with them and the complete lack of resources contemporary society provided. “There are no self-help books for anyone who has accidentally killed another person. An exhaustive search yielded no research on such people, and nothing in the way of therapeutic protocols, publicly listed support groups, or therapists who specialize in their treatment,” Gregory wrote. What the individuals shared was a sense of responsibility, an ever-present awareness that no matter how they sliced it, they had played a role in taking a person’s life. A woman who had hit and killed a motorcyclist told Gregory, “At the end of the day ... I took his life. No matter how much you want to dismiss it as an accident, I still feel responsible for it, and I am.”

This is what many of us will soon feel. A grief curdled by a morbid sense of responsibility. An overwhelming tide of loss, anger, guilt. Guilt for sins we aren’t sure we committed but from which we know there is no escaping. Guilt that brings a new level of grief.

One way to deal with such feelings may be to process them collectively. Gregory cites the Old Testament, in which God instructs Moses to designate six cities as places of refuge for those who have accidentally caused a death. Their purpose, a rabbi explained to Gregory, was to allow these haunted individuals to process their pain with others like them.

“In the collective grief,” the rabbi said, “the individual’s grief is assuaged.”

If there is one thing I have learned in 10 years of writing about nature, it’s that humans are the beneficiaries of a mindboggling array of symbiotic relationships, a constantly regenerating network of plants, animals, bacteria, and fungi, entire webs of living things that, most of the time, go completely unnoticed. Without the mycorrhizal fungi in the soil, we wouldn’t have food. Without bacteria inside our bodies, we wouldn’t be able to turn that food into energy.

Corals reefs are vital not only to the health of the marine ecosystem—singlehandedly supporting 25 percent of all ocean life—but to coastal communities around the globe, including in Hawai‘i. A coral reef is a natural defense against large waves and storm surges, which could otherwise destroy beaches, houses, and coastal infrastructure. When a reef dies, it doesn’t take long for the underlying structure to degrade. If it collapses entirely, any coastal protection provided by the reef goes with it. Surf breaks could disappear, along with beaches. Rising sea levels would become all the more menacing.

The resilience offered to island communities by coral reefs is just one reason restoration efforts are important and the Gates Lab team hopes its super coral survive. And there are reasons to be optimistic. “Our colleagues in Australia are modeling end-of-century bleaching events, and replaying those in tanks, and corals are surviving,” Drury said. “I mean, it’s a natural system that has flexibility and capacity to adapt to change, right? We don’t have a very good grip on the rate of change for the corals or for temperature and how it interacts with all those other factors, but it’s not a hopeless situation.”

In the end, none of this—the Gates Lab’s work, Fedorov’s paintings, even these words—is about coral. It’s about noticing. It’s about looking around and seeing not an island or an ocean but our collective home. It’s about acknowledging the interminable complexity that undergirds our world, that bright cord that binds us to Earth and to one another. It’s about our species’ endless quest for reciprocity, for symbiosis, for a way of life that leads not to grief but gratitude.

Historically, scientists simply wanted to know how things were. Increasingly, they advocate for how they should be.

Coral

reefs are vital to the health of the marine ecosystem and coastal communities around the globe, including Hawai‘i, offering protection from large waves and storms.

On Hō‘ea Initiative’s weekend camping excursions, keiki learn how to fend for themselves and live off the land.

TEXT BY RAE SOJOT

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

Camouflage is the first thing I notice debarking from the plane at the airport on Moloka‘i. From T-shirts and pants to duffle bags and trucker hats, nearly every local person I see is sporting or carrying an item of camo. A little girl, no older than three, scampers to the waiting area in a pink camo-patterned skirt. Though it is a short 30-minute flight from O‘ahu, Moloka‘i is a world apart from its neighboring glittering urban island. Residents cleave proudly to traditional, subsistence-style living. Fashion follows function here, hence the camo.

I have come to Moloka‘i to join the latest cohort of Hō‘ea Initiative, a wilderness survival and cultural appreciation program created by Hawai‘i musician Noland Conjugacion, better known as Brother Noland. Unlike the tropical girl wooed by the high-fashion world of Hollywood in his 1983 breakout hit “Coconut Girl,” Brother Noland’s inner compass has always drawn true to his first love: the ‘āina. Nature, Brother Noland believes, is God’s original classroom. Since 1996, the expert survivalist and animal tracker has utilized Hōʻea Initiative as a platform to connect children back with nature and teach lessons that go beyond the outdoors.

Brother Noland greets me at baggage claim. Tanned and easygoing, with a gleaming shock of white hair pulled back into a ponytail, he channels equal parts shaman and surfer, samurai and sage. His insouciance is misleading. Those who know his tracking skills say nothing escapes his keen eye.

Surrounding him are the six kids signed up for this season’s three-day camp, a cheery group of five boys and one girl ranging from 10 to 15 years in age. Palakiko Yagodich, a former student turned Hō‘ea Initiative staff, is here to assist. A parent has come along too. We make a brief stop at Kanemitsu Bakery and Cafe in the sleepy town of Kaunakakai where Brother Noland’s relationship to the tight-knit Moloka‘i community is evident in the generous rounds of shakas and warm hugs exchanged at the diner. Midway through breakfast, Brother Noland approaches the kids’ table with a merry glint in his eye. “Enjoy your last meal,” he portends. “From this point on, we catch what we eat … and if we don’t catch, we don’t eat.” The children, momentarily shocked into silence, study their plates piled with steaming pancakes, eggs, and sausage. Brother Noland breaks into a broad smile and throws his head back in laughter.

Heading southeast along the highway, we make our way to Keawanui Fishpond, where we will be camping. Scores of fishponds, some dating as far back as the early 13th century, once flourished in this region. According to legend, the moon goddess Hina gave birth to Moloka‘i and afterwards took a stroll along the island’s southern stretch. Everywhere she stepped, pūnāwai (freshwater springs) sprang forth, delivering the sweet, cold water necessary for aquaculture. By the late 1950s, many of these fishponds had fallen into disrepair, suffocated with thick mangrove and kiawe growth. In

1989, restoration efforts revitalized Keawanui, and over the course of the following decade, life was slowly breathed back into the 800-year-old fishpond, inviting the return of fish, plants, and people.

Hanohano Naehu welcomes us in front of the twin lava-rock mounds that mark the entrance to Keawanui. A stout and hearty man, he is a kia‘i loko, or caretaker of the fishpond. The children remove their shoes and stand barefoot in the grass. They perform an oli of introduction and respect, requesting permission to enter the sacred space. Uncle Hanohano accepts, and then greets each child as they pass single-file through the entry. “Nature is chief. We are servants,” he says solemnly, looking each in the eye. Inside, Keawanui’s energy is enigmatic and palpable. Large swaths of grassy lawn serve as gathering spaces. Gardens of delights abound: useful hala trees and pili grass, noni and ti. There are fruits of all kinds: tangerine, mango, papaya. Waxy, cream-colored pua kenikeni blossoms release a heady scent. Beyond, the fishpond shimmers with a thousand points of white light.

Uncle Hanohano leads our group to a small pavilion sitting over the water. Ancient Hawaiians were shrewd scientists and engineers, he informs us, directing our gaze to the fishpond. He points out its three critical elements: the crescent shaped rock and coral kuapā (wall) that serves as the fishpond’s protective border; the sluice gate, called mākāhā (eye and breath), that gazes into the pond and out to the ocean, breathing in the tide twice daily; the puna (spring water) that provides the essential, brackish

mix of phytoplankton and zooplankton. Because nutrients from cultivated kalo fields upstream fed into water systems that made their way makai (to the ocean), fishponds often served as a barometer of what was happening mauka: A problem in the fishpond could indicate a problem upland. “Our ancestors were akamai,” Uncle Hanohano says to the children, tapping his head with his forefinger. “They knew everything was connected.”

In today’s technology-driven world, convenience and instant gratification are the norm rather than luxuries, and children are less inclined to spend time outside. “Kids are more preoccupied than previous generations, and they end up limiting themselves,” says Brother Nolan, who spent his childhood hunting, fishing, and diving. “Each generation becomes further and further removed from nature.”

Hō‘ea Initiative aims to mend that disconnect. Though Brother Noland and his staff teach the “fun survival stuff” like how to shoot a bow and arrow or make fire, he also emphasizes skills considered the hardest to master: the ability to sit still, to observe, to listen. The ability to do so allows the children to better connect with the world around them. In many indigenous cultures, co-existing with nature becomes a spiritual endeavor. Cultivating such mindfulness is not a skill just for the outdoors, Brother Noland explains. It’s a skill critical to an individual’s internal journey, helping to unveil the path to who we are.

That afternoon we take to the road again, hugging the empty, rugged coastline. To our left, the striated beiges and grays of exposed karst offer respite from the brilliant blue of the ocean. Through the first half of 2019, the kids have been learning to cast net at Hō‘ea Initiative’s monthly meetups on Oʻahu. Today they are eager to test their abilities. We’re instructed to scan waters for telltale shadows and splashes. La‘a and Noah, two of the older and more experienced boys, let out a whoop: they’ve spotted a promising cove. As we pull over, the two boys tumble out, hurriedly put on their tabi, and grab a net. “Throwing net” is an excellent way for the children to lōkahi (work together), or what Brother Noland likes to call “practicing the village.” In other words, it requires teamwork. Making their way to the water, one works as a spotter while the other cautiously steps to the reef’s edge. The boys nod to each other as an incoming wave surges and suddenly a translucent web arcs high and then unspools, graceful and swift. We collectively hold our breath as the net is pulled up. A couple fish thrash about, glinting sliver in the sun. Triumph. Brother Noland gives a nod of approval. I’m simultaneously impressed and relieved: We caught something. We can eat.

When we return from fishing, the children are dispatched to set up camp. They descend upon the designated area with boisterous glee. Some 30 minutes later, the scene resembles a Greek comedy turned hilariously tragic: Amid heaps of nylon and scattered tent

Initiative, inspiring lōkahi while also providing food.

poles, a couple kids sit hapless and morose. Excitement, it seems, does not translate to execution. With Brother Noland and Uncle Palakiko remaining conspicuously absent, the kids are forced to take stock of their situation. Moments like these are prime for catchy survival codes they’ve been taught: The “Two E’s,” Endure and Embrace, and the “Two A’s,” Adapt and Adjust. Eventually, frustration gives way to resolve and a collective effort ensues. Working together, the children build their village. That evening, after lights out, I can hear some of the boys goofing around in a tent. When Brother Noland issues a stern, guttural warning, the shenanigans abruptly stop and the guilty culprits shuffle back to their sleeping quarters. All is quiet in Keawanui. The stillness is broken when a boy named E.B calls out goodnight, his voice slightly wavering, to no one in particular. It’s a self-comforting gesture, I suspect, and my heart twinges. I wonder if this is his first time sleeping alone, away from home.

The next morning, the children gather in a wide circle. It’s time for Opening Words, a Haudenosaunee invocation of greetings and gratitude to the natural and spiritual world. As Uncle Palakiko guides the children through the prayer of thanks, the children acknowledge the integral parts that make up the web of life—from the Earth Mother to the waters to the animal nations and the stars above. Each passage of the prayer is concluded with a simple statement, spoken together: “And now we are One.” An advocate of native knowledge, Brother Noland has long incorporated a rich mix of indigenous cultures’ practices, philosophies, and traditions into Hō‘ea Initiative’s curriculum, including Hawaiian, Native American, Aboriginal Australian, and Japanese. This mélange is intentional, mirroring the myriad cultural practices inherent in Hawai‘i’s ethnic diversity. “I’m teaching them aloha,” he says, “embracing culture and nature.”

Afterward, the children perform a regimen of stretching exercises. “Taking care of the body is bush medicine,” Brother Nolan reminds them. “The way to stay in shape is never to get out of shape.” There are multiple references to beasts—the students shake their bodies like a “dragon coming out of a mist,” balance on a single leg like a crane, and imitate a deer’s cautious step in the wood. “We can learn a lot from animals,” Brother Noland tells me as I crouch down low to the ground like a turtle in an effort to mimic the reptile’s slow, methodic breathing.

Later that afternoon, we drive west into the hinterlands, the pitch and yaw of the rough road revealing dusty patches of haole koa and kiawe and swaths of

dark-green gullies deep within. We are on private land owned by Billy Buchanan, a friend of Brother Noland. Uncle Billy is a man of few words. “Animals are all around us,” he says as we set off on our explorations. “They are watching you.”

Two by two, we walk in silence through the forest, pausing at intervals to glean information from our surroundings. We see trees with portions of their trunks rubbed smooth, an indication that it is the season when young bucks are growing antlers and jockeying for supremacy in the herd. We inspect scat for freshness. We scrutinize a deer track. Even a single hoof print can provide a wealth of information to an animal tracker, explains Brother Noland, pointing out the hallmark feature called the pressure release. Hidden within it is a cache of clues: Was the deer injured? Did it stop abruptly and change direction? What time of day did the deer cross this way? My mind wanders to something he said while telling a story about tracking bear in New Mexico: If you step into a bear track, that bear, wherever it is, will pause too.

The thickets give way to a wide, flat expanse. We have arrived at the mudflats, an area dubbed The Boneyard, which is used by local hunters to discard the skeletal remains after dressing their quarry. Thousands of bones of beasts, mostly deer, blanch white under a scorching sun. It’s a sobering and eerie place, and the children move about with curious deference. Finn, a wiry and quick-witted boy, remarks on the difference between bones: the older the bones, the whiter and cleaner they are, while newer bones retain scraps of fur and skin. Brother Noland asks for volunteers to assemble a skeleton for an impromptu, hands-on lesson in anatomy. When one child loosens a tooth from a jawbone to