Special Section: Beauty Stylish interpretations of local fashions from the past, present, and near future.

Explore: Treasure Hunts Seeking riches at the islands’ largest swap meet, spiritual zen from a radical temple, and home away from home in Madeira.

Features: Costs of Prosperity Houseless families settle into experimental dwellings, faces lost to history resurface, and activists stand firm to protect a sacred mountain.

The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I Theme: Wealth Volume 9 Issue 3 0 03 > 0928 1 $14.95 US $14.95 CAN 2548 98

KEIRA KNIGHTLEY WEARS A COCO CRUSH RING AND BRACELETS IN 18K WHITE GOLD* WITH DIAMONDS AND 18K BEIGE GOLD.

ALA MOANA CENTER LUXURY ROW ©2019 CHANEL ,® Inc.

*White gold plated with thin layer of Rhodium for color.

KEIRA KNIGHTLEY WEARS A COCO CRUSH RING AND BRACELETS IN 18K WHITE GOLD* WITH DIAMONDS AND 18K BEIGE GOLD.

ALA MOANA CENTER LUXURY ROW ©2019 CHANEL ,® Inc.

*White gold plated with thin layer of Rhodium for color.

Editor’s Letter

Contributors

24 | Community Waihe‘e Valley Country Club

36 | Vintage @fotoaloha

42 | Finance Parental Leave A HUI HOU

184 | In the Wai

FEATURES

46 | Promised Land

Kahauiki Village has been heralded as a disruptive model for solving homelessness. But is it actually putting a vulnerable population at risk? Writer Timothy A. Schuler reports on the project’s path to completion and the potential hazards of its built environment to residents.

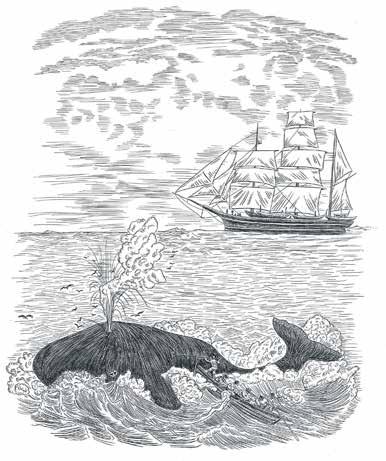

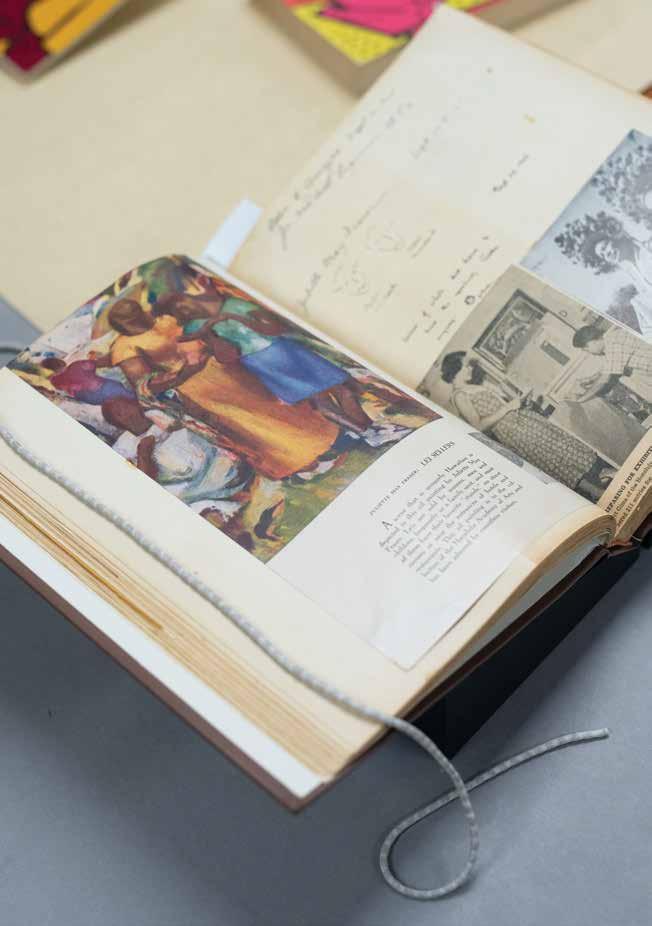

60 | The Hunt for George Gilley

The uncharted tale of history’s only Native Hawaiian whaling captain, culled from an archival abyss of explorer logs, scholarly mentions, and aging newsprint. Writer Travis Hancock pieces together Gilley’s historic and hidden biography.

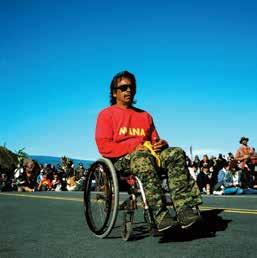

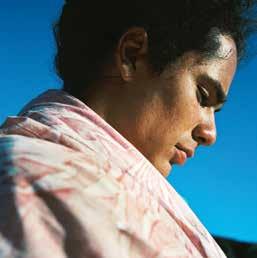

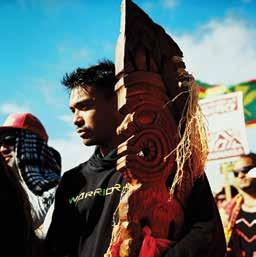

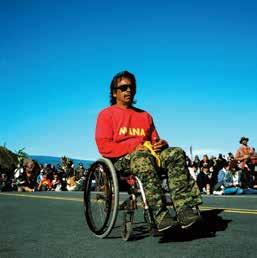

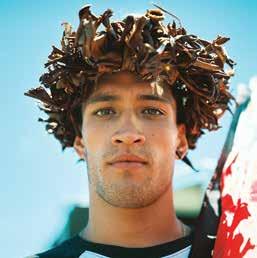

74 | For the Love of Lāhui

At the base of Maunakea, the work of kia‘i, both old and young, are electrifying a new generation to reclaim their identities and culture. Writer and activist Jamaica Osorio shares an insider’s perspective tracking the growth of the movement, and original poetry inspired by the mauna.

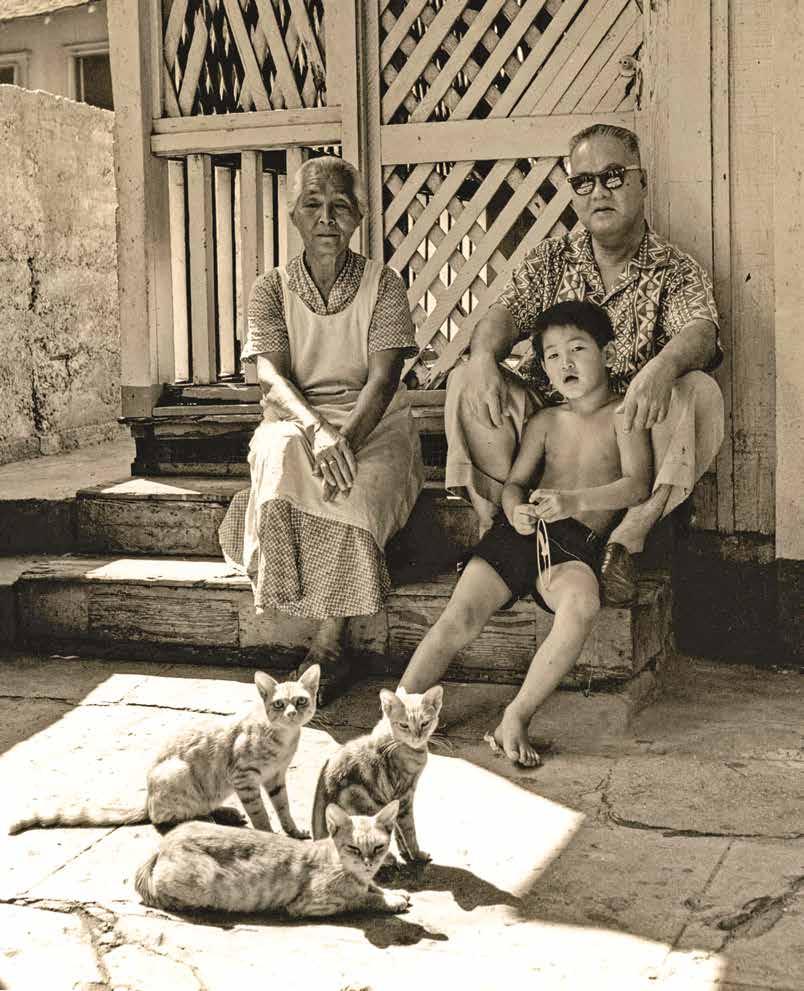

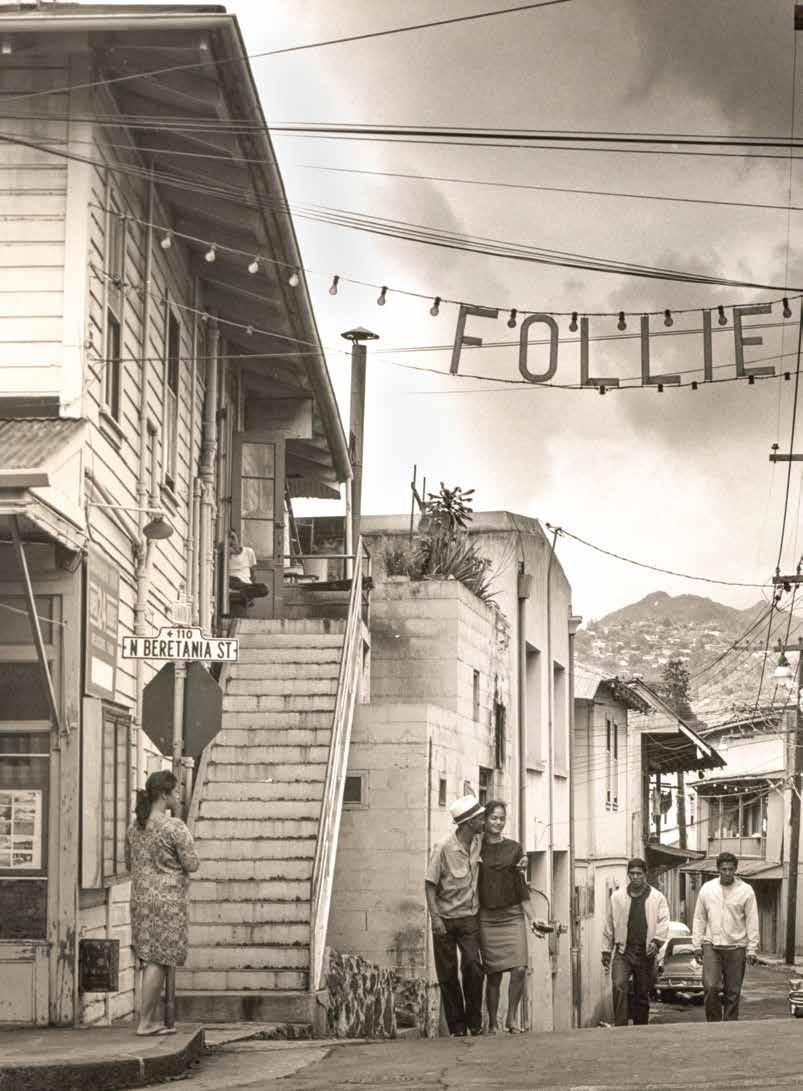

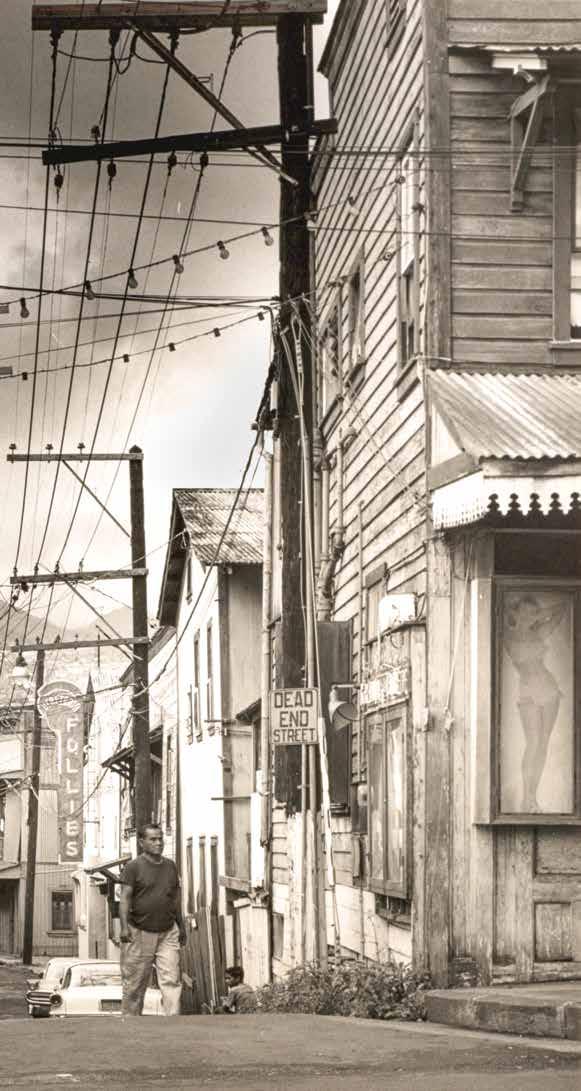

92 | From the Rubble

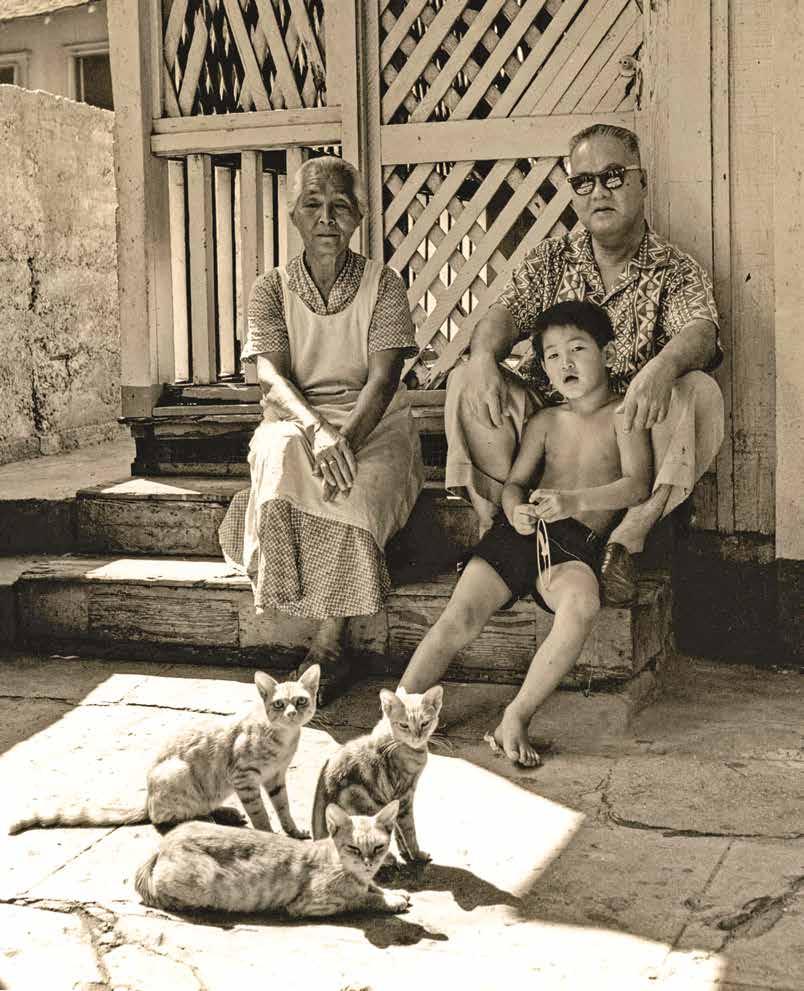

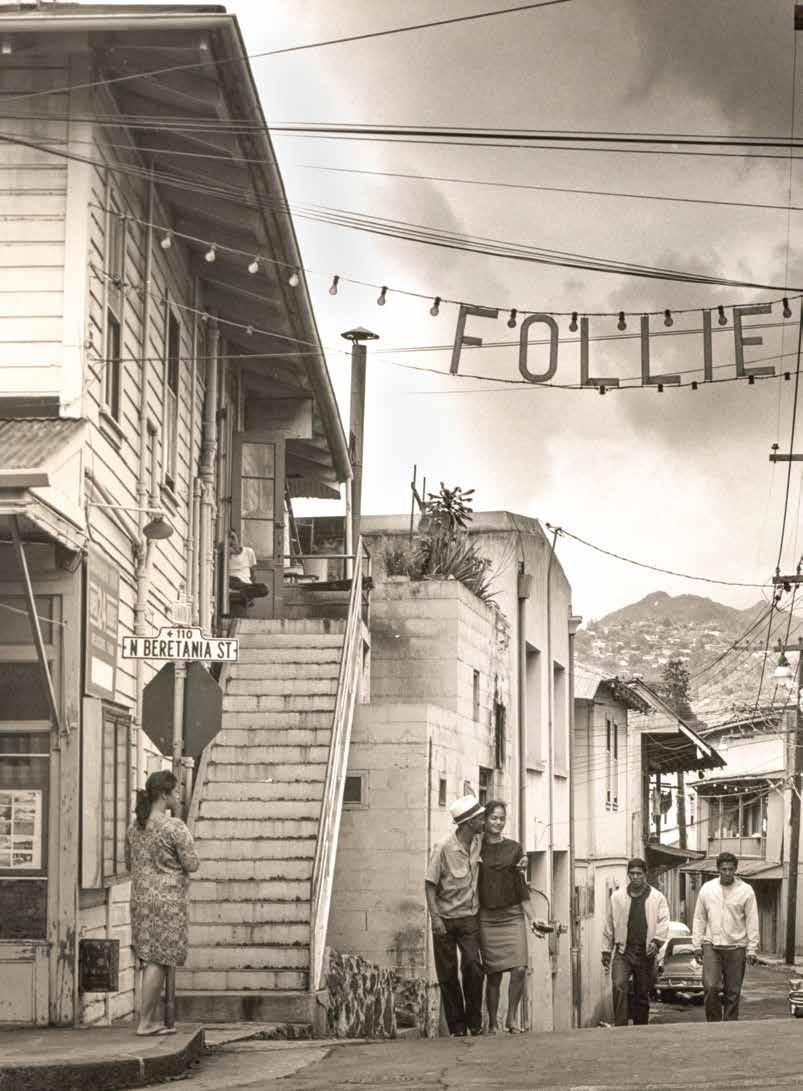

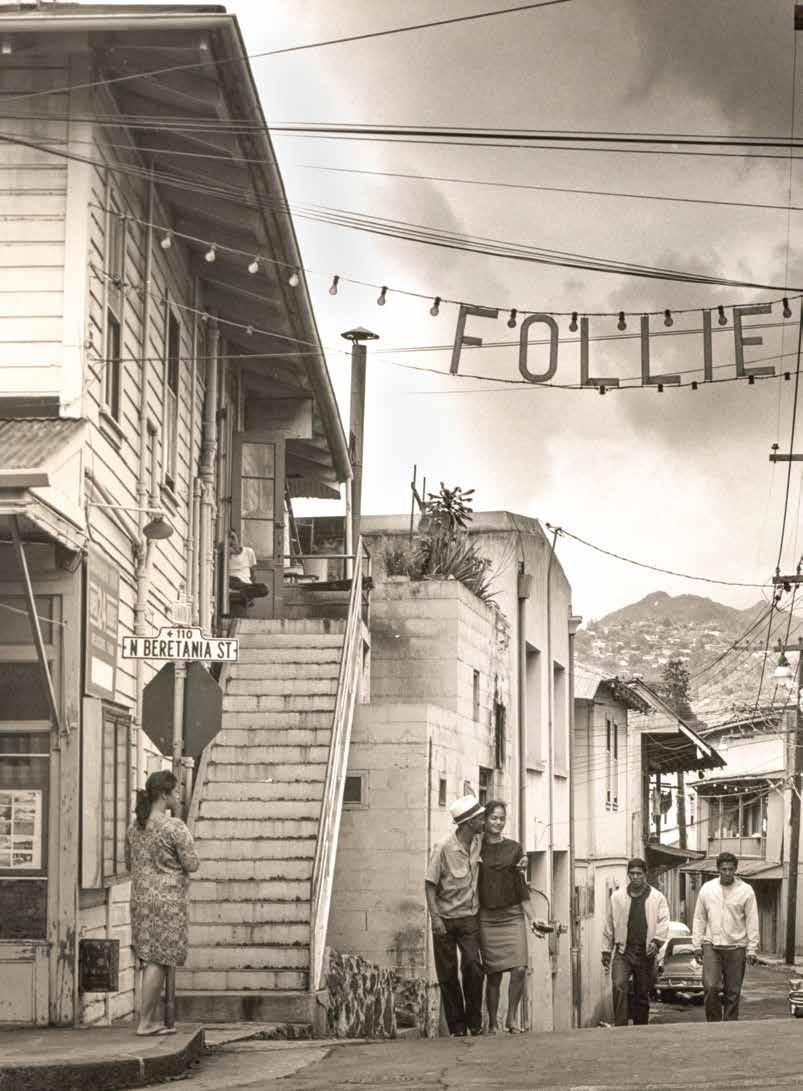

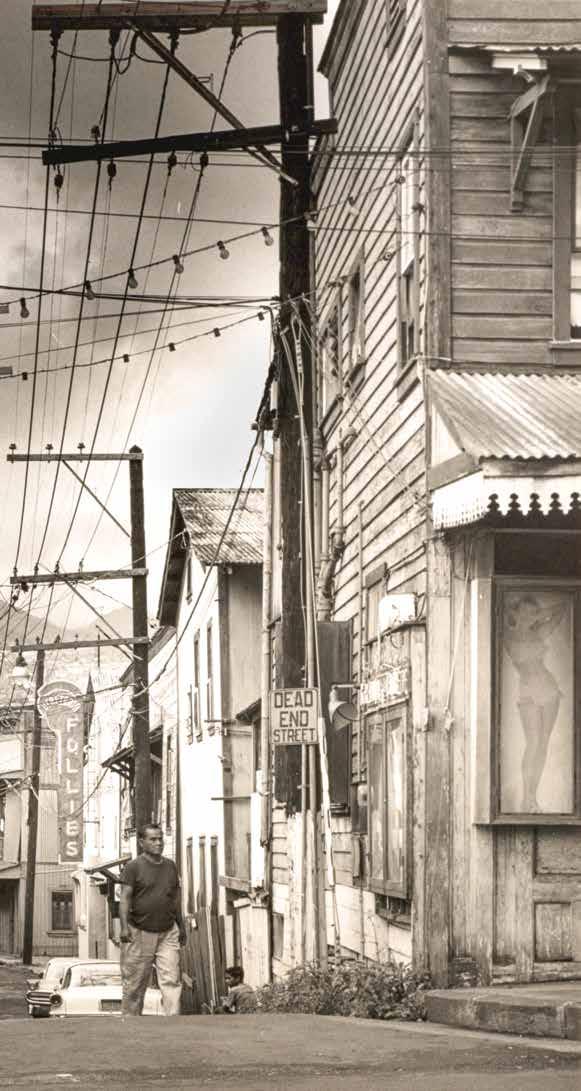

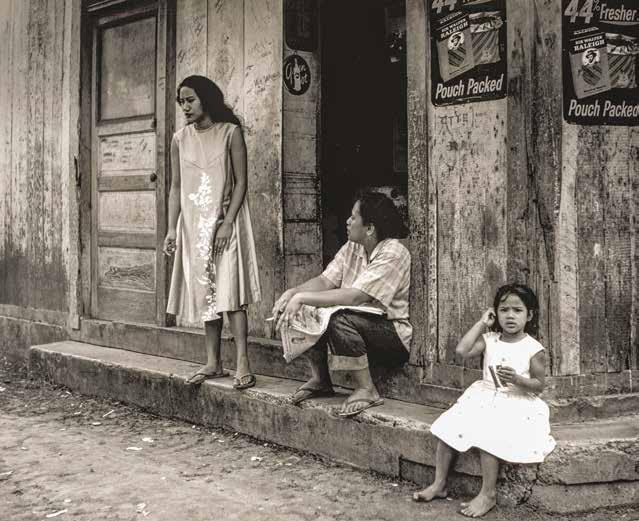

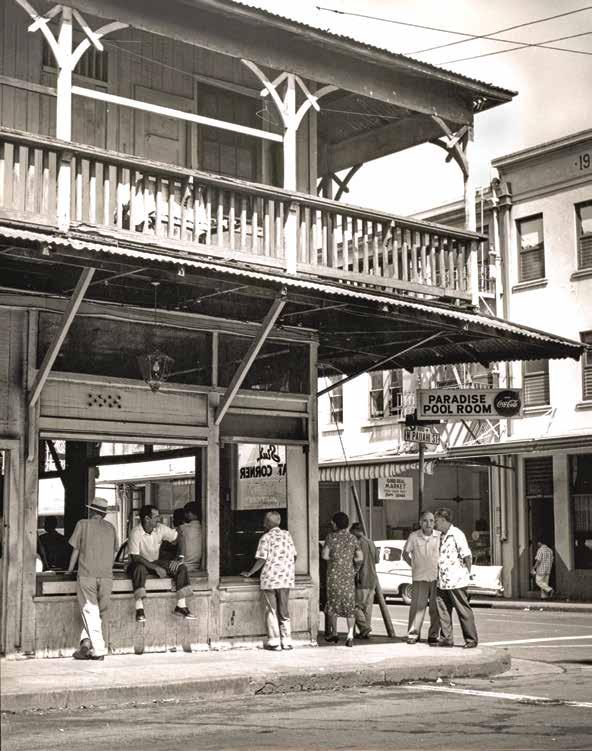

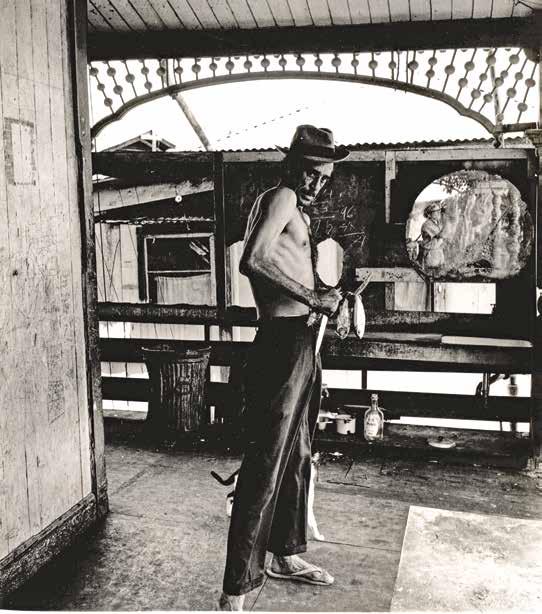

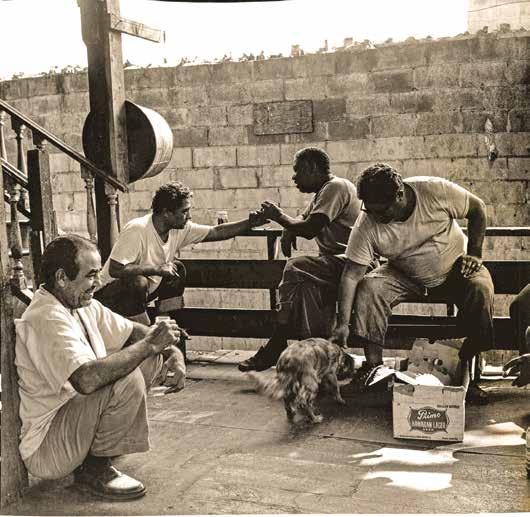

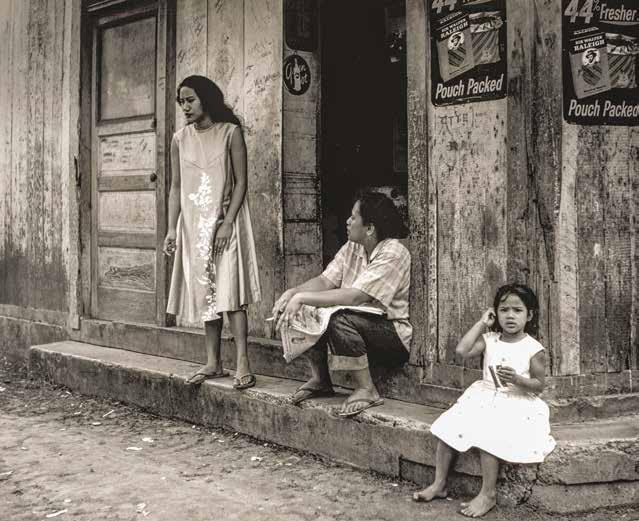

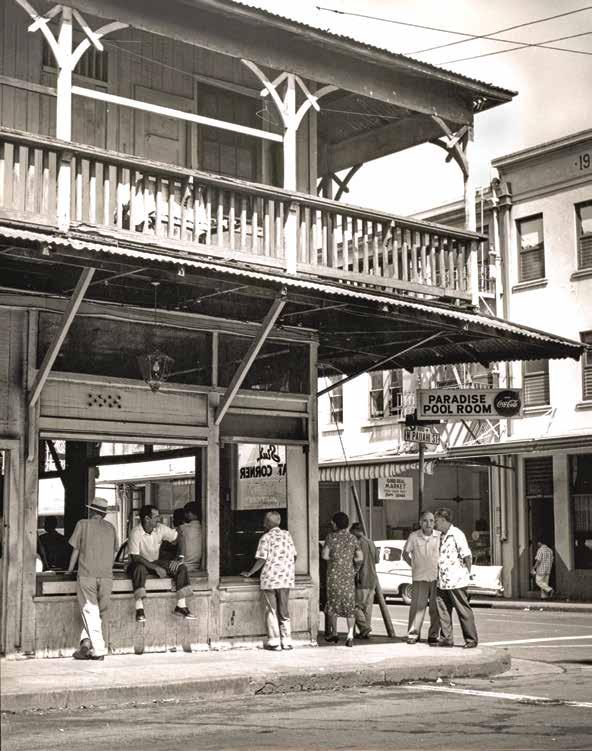

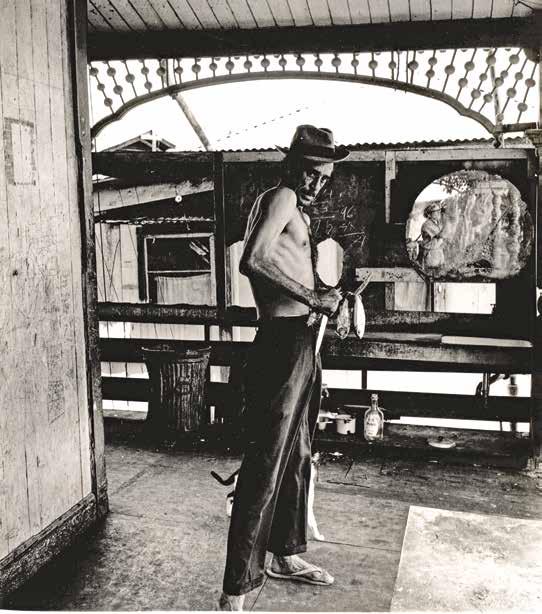

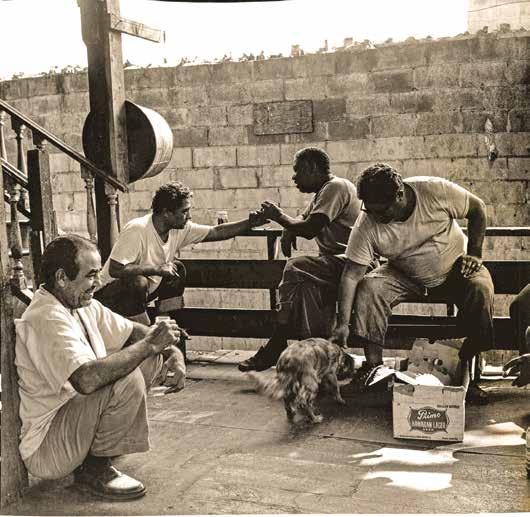

Photographer Francis Haar documented parts of Chinatown and Pālama, known as ‘A‘ala in the 1960s, while they were being demolished. Writer Michelle Broder Van Dyke recontextualizes Haar’s final and lasting images of a Honolulu that has since disappeared.

TABLE

| FEATURES | 22

OF CONTENTS

WEALTH

FLUX

PHILES

Image by Marie Eriel Hobro.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SPECIAL SECTION

BEAUTY

In these explorations of local fashions from our historic past and an imagined future, creatives across the spectrum prove that beauty truly is in the eye of the beholder.

Oakland-based artist Tiare Ribeaux draws on the biomorphic and natural shapes of her Hawaiian upbringing to fashion a living, breathing alternative to the single-use plastics polluting Pacific ecosystems. Image by Peter Prato.

106

|

DEPARTMENTS |

TREBLE AWAITS... Halekulani’s destination for live music, late night libations, designer cocktails and fine foods. COMPLIMENTARY PARKING | 855.738.4966 | 2199 KALIA ROAD, HONOLULU | WWW.HALEKULANI.COM

160 EXPLORE 162

174

134 LIVING WELL 136

| Madeira Funchal

| Swap Meet Aloha Stadium

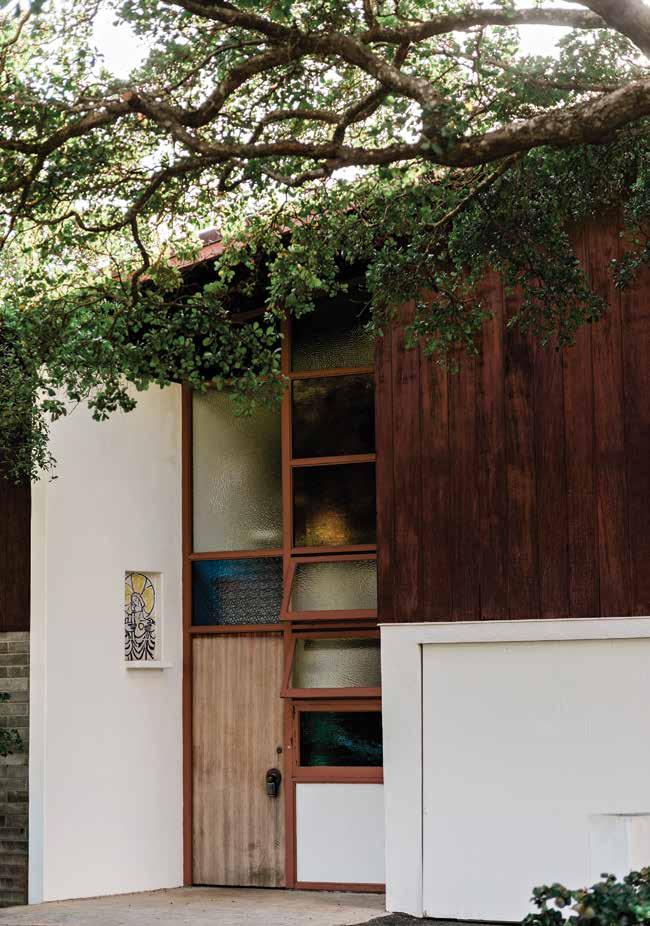

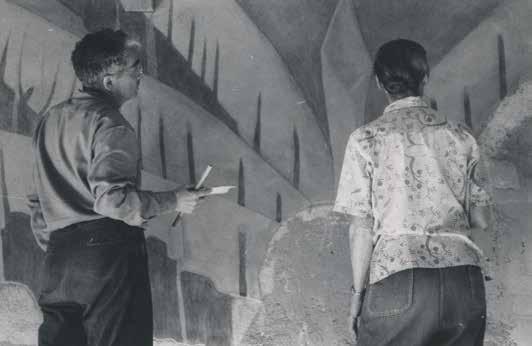

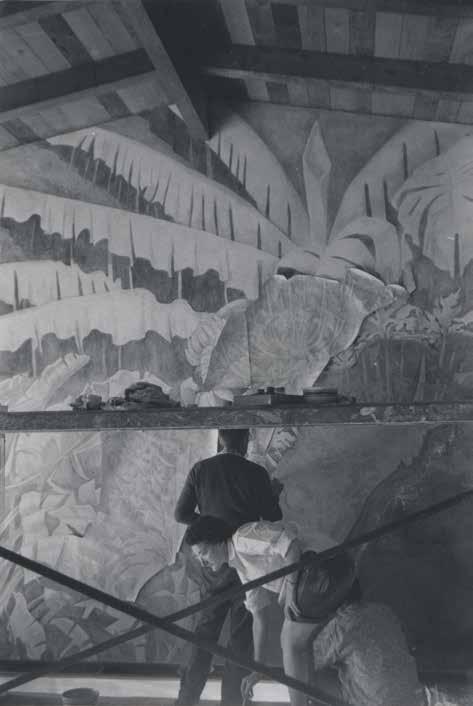

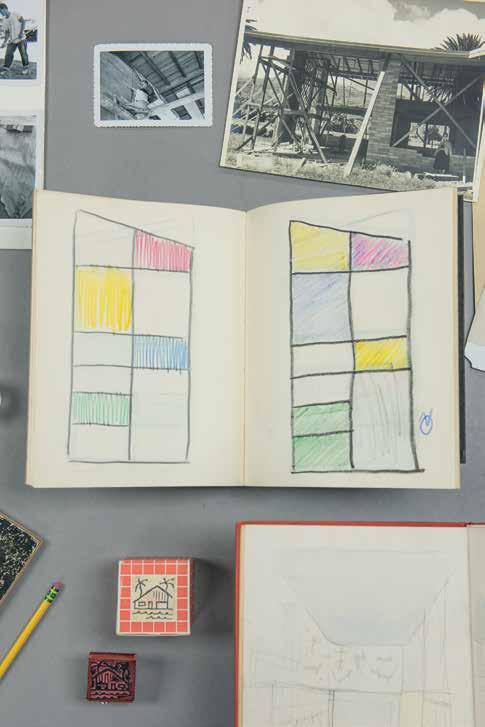

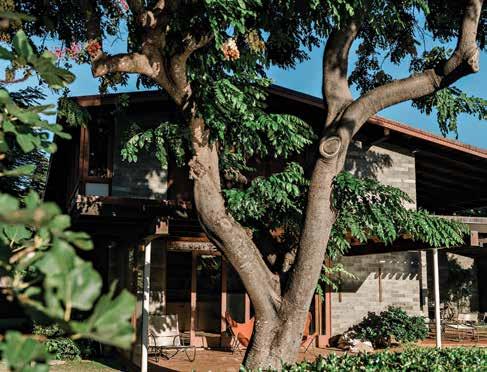

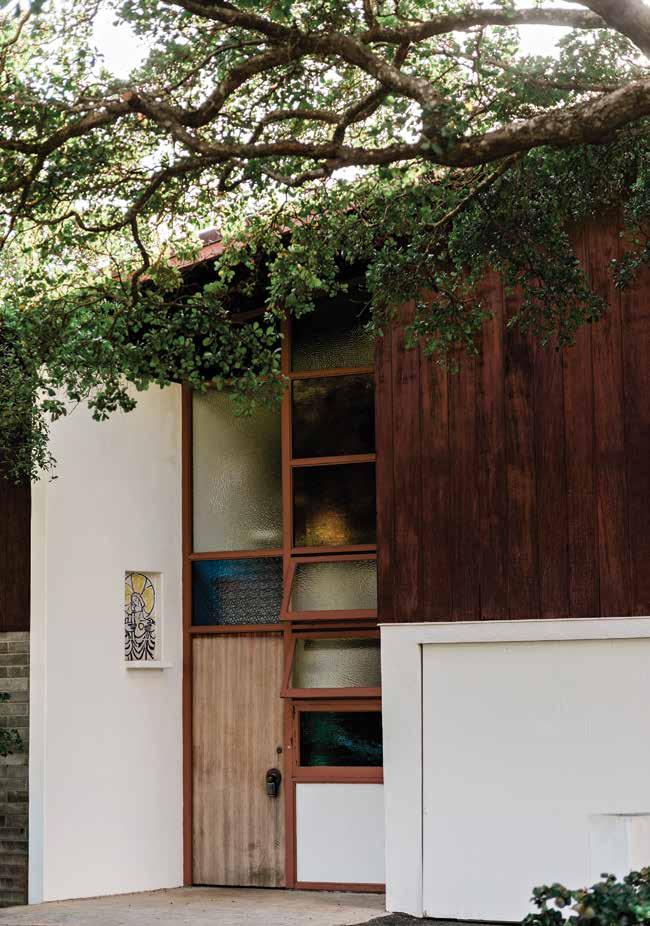

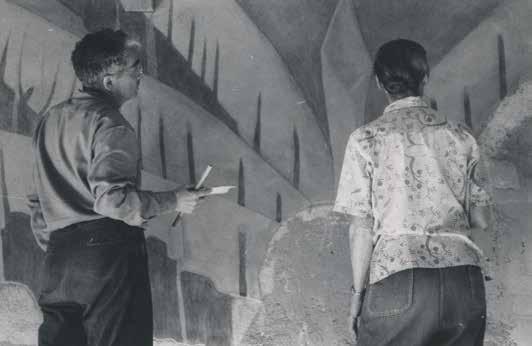

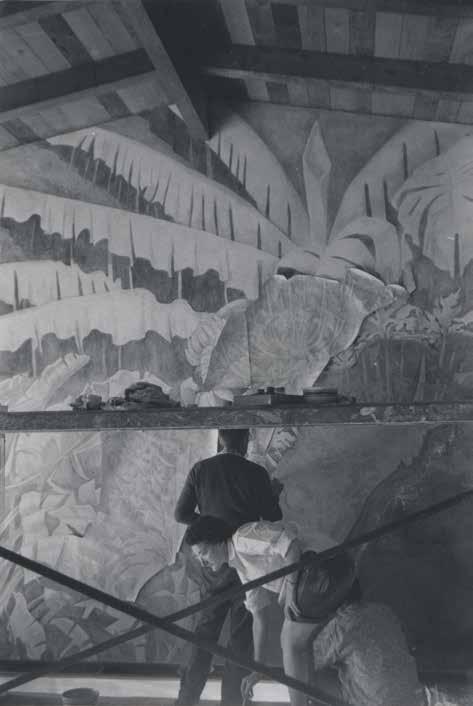

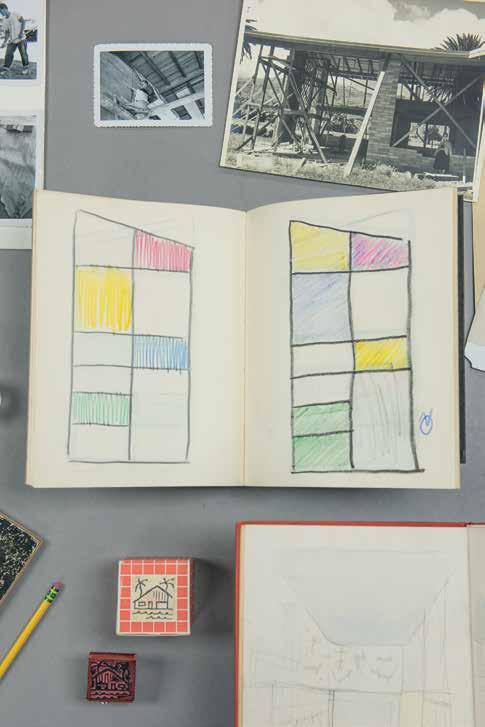

| Design Charlot House

TABLE OF CONTENTS | DEPARTMENTS |

148 | Rinzai Chozen-ji

Image by Colin Watts.

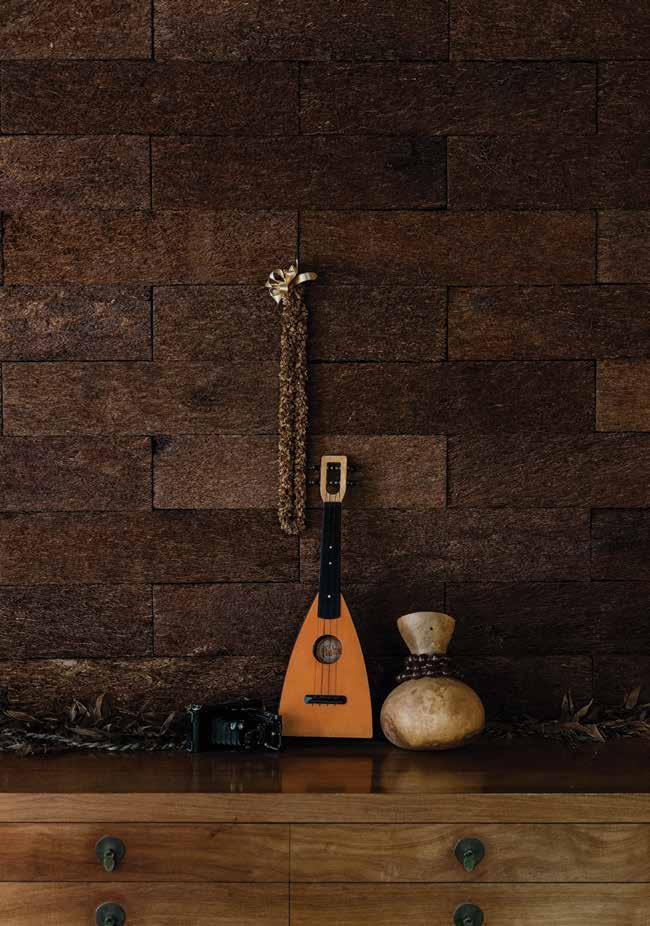

Image by John Hook.

Walk to ownyourbeat.

Introducing the Huaka‘i Collection, designed for voyaging city currents.

OLUKAI.COM / #ANYWHEREALOHA

HUAKA‘I LĪ

Visit us at Whalers Village on Maui and at Hilton Hawaiian Village on O‘ahu

Heavy Metal

Multi-media artist Tom Sewell sees art where others see decay. In one of his most ambitious installations, he repurposed massive metal plates discarded by Maui’s last sugar mill and assembled them into large-scale sculptures that are sprinkled across his 17-acre estate in Ha‘ikū. This sprawling work of land art is “all about finding art in unexpected places,” Sewell says, and serve as a tribute to the “magnificence of the mundane and the art of industry.”

Where the Wild Foods Grow

Through education in foraging, harvesting, and cooking wild plants, Sunny Savage shares how to identify edible plants in one’s backyard, at the park, and around the planet. “Hawai‘i is magical in so many ways—it’s a foraging paradise,” Savage says. “There are so many beautiful ways of tasting the land.” Her philosophy around integrating weeds into one’s daily diet breaks down preconceived notions about invasive species and food nutrition.

fluxhawaii.com

/fluxhawaii

@fluxhawaii

@fluxhawaii

TABLE

| FLUX TV | FLUX TV

arts

culture

us at:

OF CONTENTS

Stay current on

and

with

HYATT REGE NCY WAIKIKI

ALA MOANA CE NTE R KO KO MARI NA WI NDWARD M ALL

GAT E WAY

WAIKELE

LocalMotion .com HAWAI

LAHAINA

It can often feel like the only time you truly own something is when you can’t put a price on it.

Perhaps it was the invigorating country-hopping travels you embarked on recently, or just a film you watched that was so illuminating it cracked open your world view. Of course you likely anteed up some dollars and cents for those flights, for the ticket of admission, but what it actually afforded you, and you alone, was the way in which it left a part of you transformed. It’s in that unquantifiable exchange which managed to shift something in your own personal chemistry where you might feel a sense of belonging.

To my fortune, I find myself careening a similar train of thought near the close of each issue of this very magazine: Editing it is a source of my income, but it’s in the lessons learned about the people and places they feature where I feel I’ve really profited. The process of production itself proves to be a personal and collective reward: When our team of writers and designers are entrenched in the process of shuffling through pages of revisions, debating photography and layouts, marrying copy to art, eventually a peculiar creative alchemy takes over, unannounced, where the content begins to resemble a shape and cohere—the relief in seeing something reflected back in relief!— and it is in those unsuspecting strokes of surprise and inspiration where putting this publication together always feels worth it.

In this issue on Wealth, we wanted to focus on those moments of fulfillment. To take a look at the motivating factors that produce them and their repercussions. These stories pinpoint crossroads in which new models contending with everything from economic inequity to political sovereignty are being tried and tested right here in our own backyards. In that spirit, this edition aims to reflect a commerce of ideas, peddled by writers with an unwavering allegiance to truth and art and the wellbeing of their greater communities. And for that we are all richer.

With aloha,

Matthew Dekneef EDITORIAL DIRECTOR @mattdknf

| WEALTH |

EDITOR’S LETTER

As physicians, Jon and Toni Narimasu enjoy peace of mind knowing their private banker is going above and beyond to help their family achieve their financial goals. For this generation and the next. Learn how our wealth management advisors can do the same for you. Call 544-3542. Investments are not insured by FDIC or any government agency. Not a deposit or obligation of or guaranteed by Central Pacific Bank. Subject to investment risks, including loss of principal invested. Looking ahead and going beyond. centralpacificbank .com 808-544-0500 1-800-342-8422 WEALTH MANAGEMENT

MASTHEAD

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Ara Laylo

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Matthew Dekneef

MANAGING EDITOR

Lauren McNally

SENIOR EDITORS

Anna Harmon

Rae Sojot

SENIOR PHOTOGRAPHER

John Hook

PHOTOGRAPHY EDITORS

Samantha Hook

Chris Rohrer

DESIGNERS

Michelle Ganeku

Skye Yonamine

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Eunica Escalante

CONTRIBUTORS

Michelle Broder Van Dyke

Alexis Cheung

Sonny Ganaden

Travis Hancock

Spencer Kealamakia

Brendan George Ko

Leilani Marie Labong

Jamaica Osorio

Natalie Schack

Timothy A. Schuler

Shannon Wianecki

IMAGES

Jonathan Canlas

Francis Haar

Marie Eriel Hobro

Cheyne Kalai

Nani Welch Keli‘iho‘omalu

Michelle Mishina

Dino Morrow

Josiah Patterson

Peter Prato

Melanie Tjoeng

Lauren Trangmar

Shar Tuiasoa

CREATIVE SERVICES

Tammy Uy VP CREATIVE DEVELOPMENT

Shannon Fujimoto CREATIVE SERVICES MANAGER

Gerard Elmore LEAD PRODUCER gerard@NMGnetwork.com

Aja Toscano CREATIVE PRODUCER

Shaneika Aguilar

Kyle Kosaki

Rena Shishido FILMMAKERS

Kimi Lung

WEB DESIGNER & DEVELOPER

Romina Escano

DIGITAL DESIGNER

Chloe Ma Tomy Takemura INTERNS

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley VP SALES mike@NMGnetwork.com

Phil LeRoy NATIONAL SALES DIRECTOR

Chelsea Tsuchida KEY ACCOUNTS & MARKETING MANAGER

Helen Chang MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

Kylee Takata SALES ASSISTANT

Hunter Rapoza

AD OPERATIONS & DIGITAL MARKETING COORDINATOR

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock CHIEF REVENUE OFFICER joe@NMGnetwork.com

Francine Beppu NETWORK STRATEGY DIRECTOR francine@NMGnetwork.com

Gary Payne VP ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE

Courtney Miyashiro OPERATIONS ADMINISTRATOR

General Inquiries: contact@fluxhawaii.com

PUBLISHED BY:

Nella Media Group

36 N. Hotel St., Ste. A Honolulu, HI 96817

©2008-2019 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. FLUX Hawaii is a triannual lifestyle publication. ISSN 2578-2053

| WEALTH |

702 SOUTH BERETANIA STREET, HONOLULU, HI 808.543.5388 | CSWOANDSONS.COM

CONTRIBUTORS

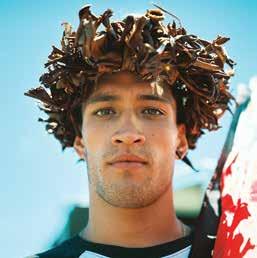

On the Cover

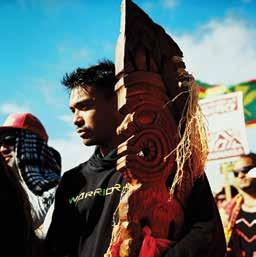

Nineteen-year-old student Pumehana La, whose full name is Mekealohapumehanahemolele Howard, holds her hands in the shape of a triangle, a symbol of resistance and solidarity in the Protect Maunakea movement. Photographer Melanie Tjoeng took this portrait of La during a visit to Hawai‘i Island in October 2019. Through her love of music and land, La, a sophomore at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa in ethnic studies, political science, and Hawaiian studies, says she is driven to “finding solutions for our kānaka to ho‘i, or return, back to being on the ‘āina and with ‘ohana.” Like many others, she is spending several months at Pu‘uhonua o Pu‘uhuluhulu to preserve what Hawaiians consider to be the sacred piko of the islands.

Travis Hancock

Travis Hancock

Originally from Paumalū, on Oʻahu's North Shore, Travis Hancock resides in Salt Lake City, where he is a doctoral student in history at the University of Utah. He has previously written for FLUX Hawai‘i about the decline of native bat populations due to wind turbines. For this issue, Hancock reconstructs the biography of George Gilley, a Native Hawaiian whaler, on page 60.

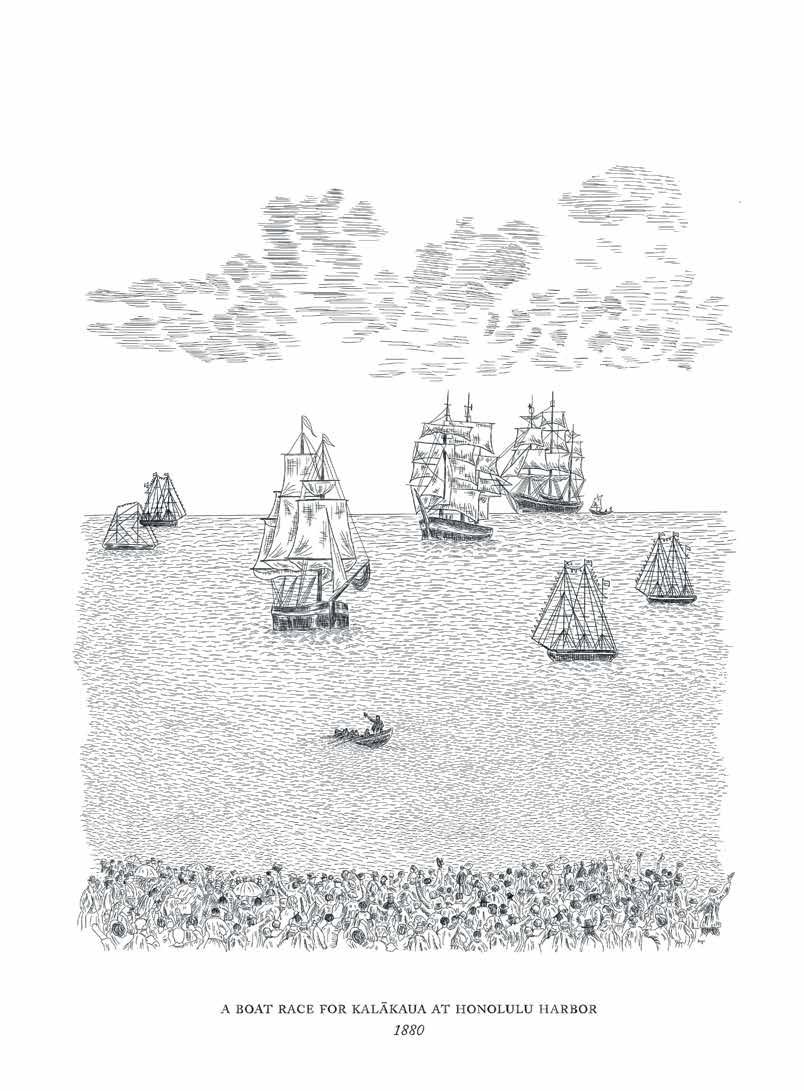

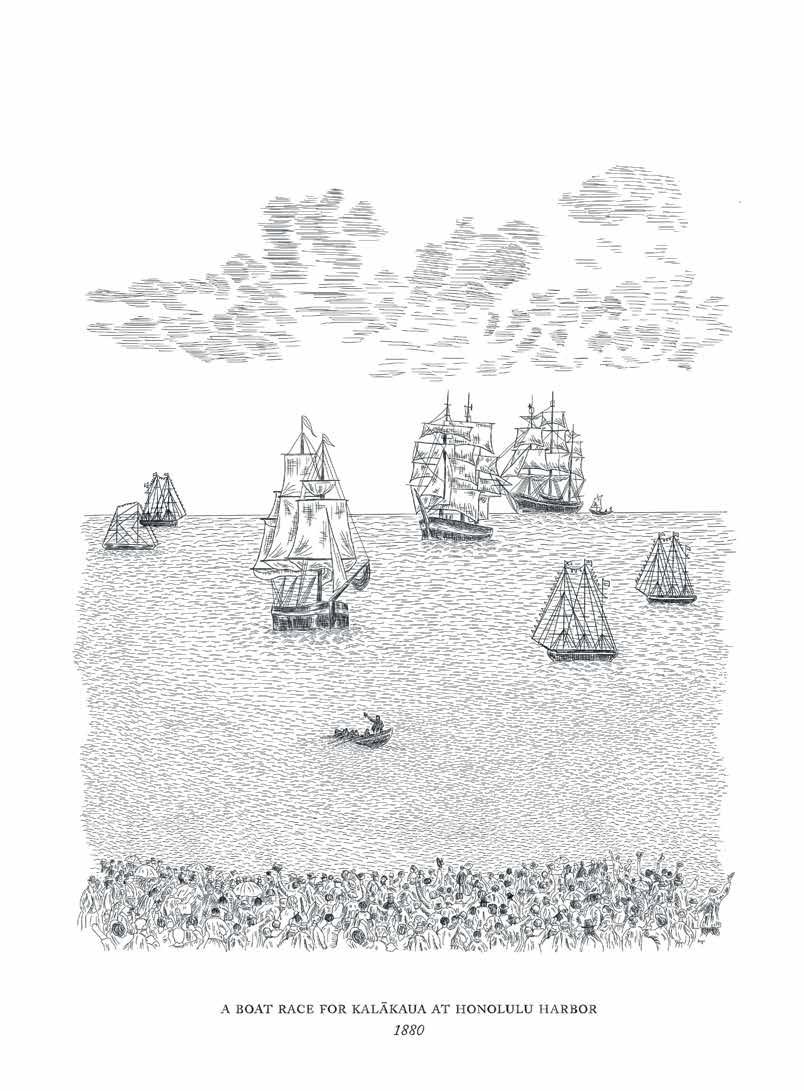

“Working on this story felt poignant, given the current climate in the islands. The opening image of 5,000 Hawaiian subjects gathered at the wharf for Kalākaua's birthday yacht race, proudly waving national flags, was duplicated this past October, when 10,000 hae-waving island protectors marched on Waikīkī,” Hancock says.

“What a role the media played in depictions of these events, past and present. And what a failing it was that Hawaiʻi’s newspapers failed to report Gilley’s death in 1900. I like to think, in a small way, this article brings his story home.”

Leilani Marie Labong

Based in San Francisco, Leilani Marie Labong writes about design, art, fashion, and travel for magazines and newspapers. Her featurelength work has appeared in Sunset, House Beautiful, San Francisco Chronicle, C Magazine, Coastal Living, Luxe Interiors + Design, 7x7 Magazine, and California Home + Design. Her travel memoirs have been published in such book anthologies as The Best Travel Writing 2005 and A Woman’s Asia. She received an MFA in Writing from the University of San Francisco in 2004 and is the former editor in chief of Habitat, the SF Chronicle's home and style magazine, and the Season 1 host of 7x7’s podcast, People Will Talk, featuring interviews with Bay Area mavericks. Labong’s first piece for the magazine, “Fabric of Life,” on page 128, profiles artist Tiare Ribeaux’s work with bioplastics.

Timothy A. Schuler

Timothy A. Schuler was born and raised in rural Kansas. An award-winning journalist whose work focuses on the built and natural environment, his writing has appeared in the Atlantic, Metropolis, Vox Media, and Places Journal. For this issue, he wrote about the experimental housing project Kahauiki Village, on page 46. “Housing is one of the biggest challenges Hawai‘i faces, and inseparable from issues of race, income inequality, and environmental justice. A key moment in reporting this piece came when I discovered that the word for air in the Hawaiian ‘ōlelo can also mean sovereignty. It was a reminder that language and culture are powerful frames through which to view contemporary issues.” Based in Honolulu, he is a contributing editor at Landscape Architecture Magazine and frequent contributor to NMG Network.

| WEALTH |

An offering of water at Pu‘uhonua o Pu‘uhuluhulu beneath the slopes of Maunakea. Image by Dino Morrow.

WEALTH

“Breakdown is our epistemic and experiential reality. What we really need to study is how the world gets put back together.”—Shannon

Mattern

The Journey Home

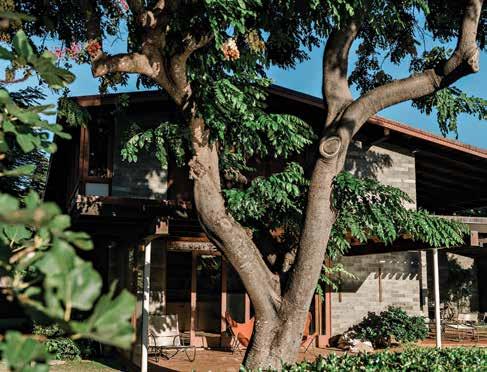

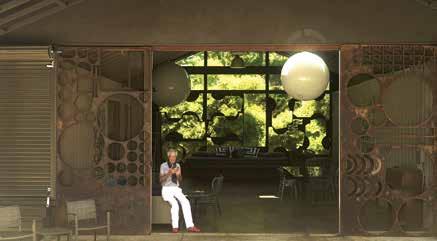

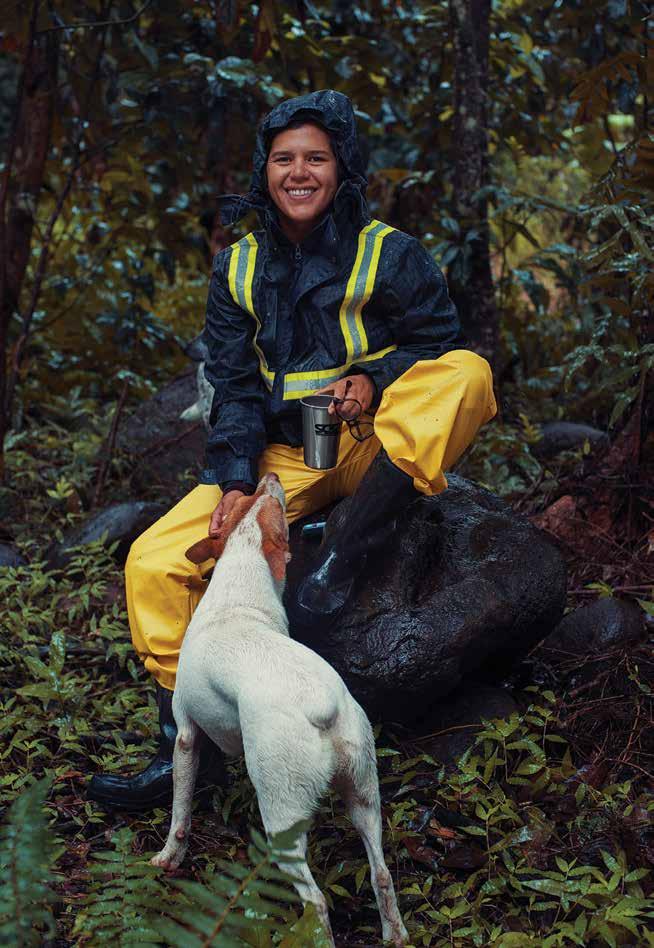

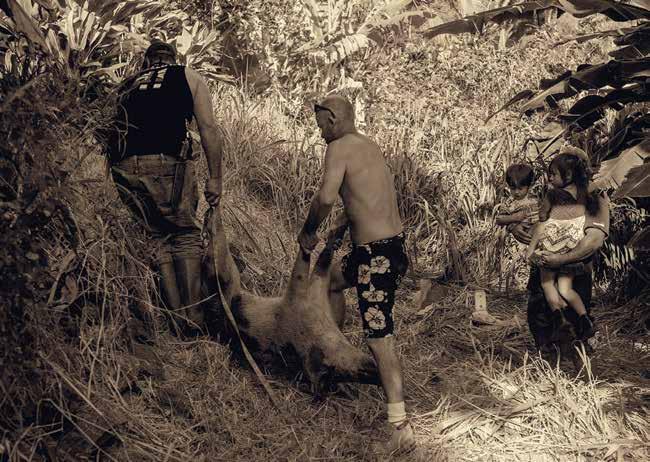

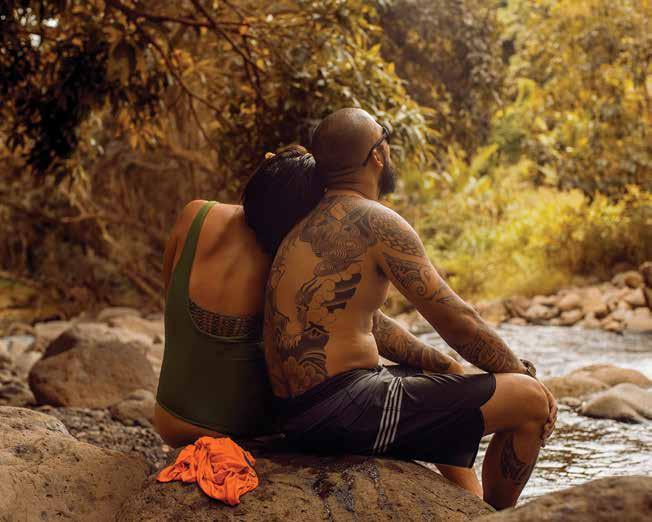

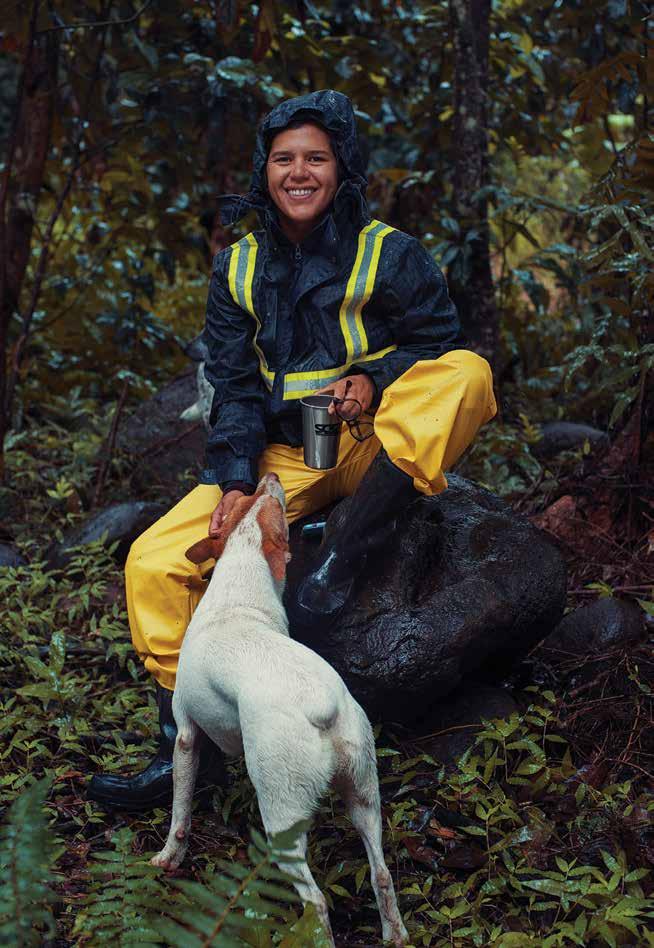

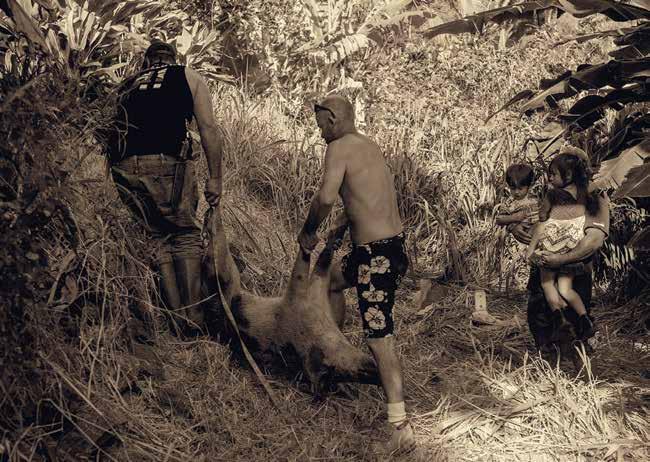

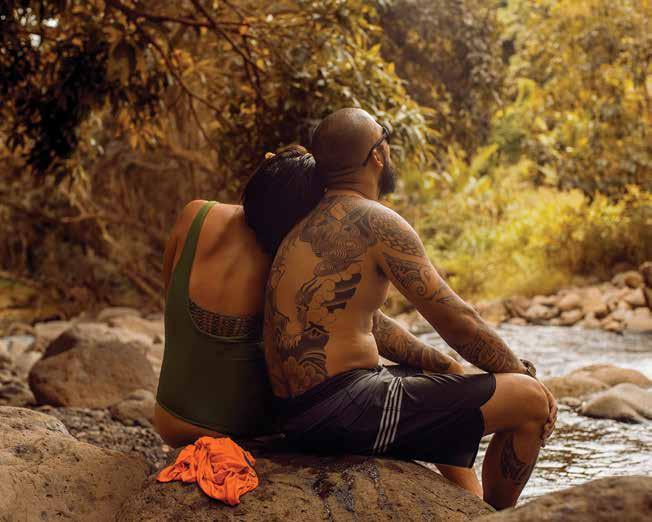

By returning to a backcountry lifestyle in Waihe‘e, Maui, a group of friends reconnect with their ancestors to further understand who they are.

TEXT AND IMAGES BY BRENDAN GEORGE KO

Legend and tradition grew up about the hills and valleys of Hawaii. The urge for deep-sea adventure decreased and interest narrowed to the coastal seas. Voyaging canoes ceased to sail out from the channel of Ke Ala-i-Kahiki (The Road-to-Tahiti) and trim their course for the Equator. The long sea voyages of the northern rovers had ended—Hawaii had become home.

– Te Rangi Hīroa, Vikings of the Sunrise, 1938

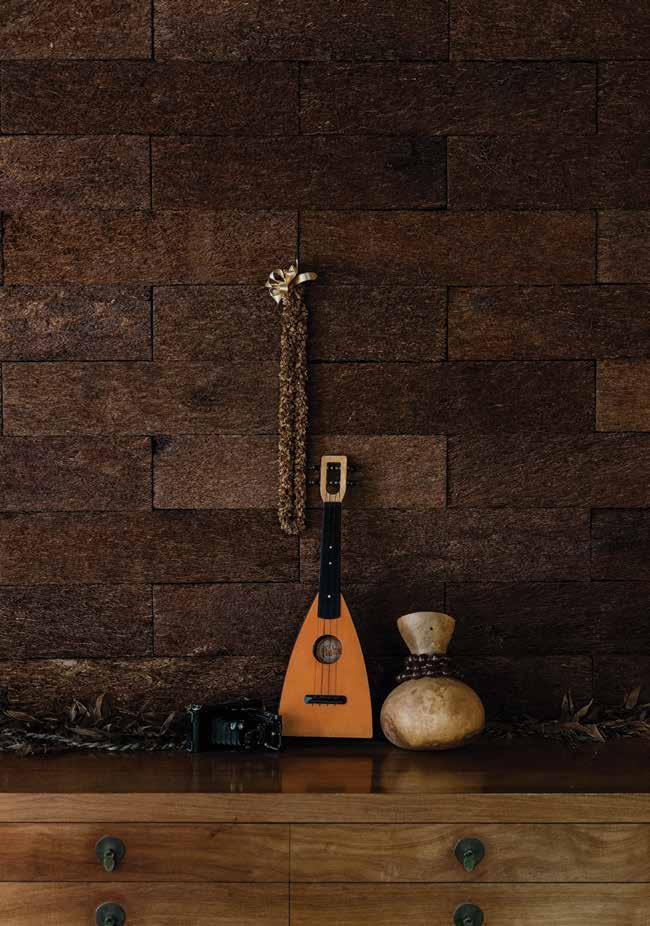

“We are trying in any way possible to get back to how our ancestors had lived and flourished,” Miki‘ala Pua‘a Freitas says one night in her valley home, the subtle sound of the river flowing in the background. In December 2018, she had moved from her farm into the valley where her father and kūpuna had lived and left behind a shack, lo‘i kalo, choke mosquitos, overgrown cane grass, and an ineffable peace. She jokingly calls it the Waihe‘e Valley Country Club, a place on Maui where friends of hers from throughout Hawai‘i gather to work, share, appreciate, learn, see, and value the world like those who understood this place better than anyone else. A sign from the defunct country club from which the name originated is nailed to the entrance of the shack.

Before arriving in Hawai‘i, Polynesians were largely defined by their oceanic courage and ingenuity. Their homes and cultures revolved around the ocean. The god of the ocean, Kanaloa, was one of the highest gods in the Polynesian pantheon, and canoes as well as paddles were dedicated to him. But after long voyages from Henua Enata (Marquesas), Samoa, Tahiti, and Ra‘iātea, the settlers in the Hawaiian archipelago found something that made them dig into the valleys and turn their eyes, once drawn to the ocean-lined horizon, to that of mountain ranges. The god of the land and forest, Kāne, and of peace and agriculture, Lono, grew in importance as the people’s roots grew deeper into this ‘āina. As a result, wa‘a moana (deep-sea ocean canoes) disappeared until the Hawaiian Renaissance inspired the construction of the Hōkūle‘a in 1975.

The life-nourishing promise of Hawai‘i heavily influenced the ancestors who decided to stay here. They introduced kalo, ‘ulu, and ‘uala, which grew plentifully in the rich volcanic soils. Individual tribes transitioned into families within districts, and entire islands came to be ruled by powerful chiefs. Nā maka‘āinana (the commoners) worked the land in exchange for free places to live and grow with the trees and change as the rivers slowly shaped the valleys. This pace of life existed for so long that, even with European contact and the rapid change in Hawai‘i Nei that followed, it was kept deep in the memory of nā maka‘āinana. Through the surviving stories and practices and the persistence of genetic memory, the ways of old survived.

After traveling across the world, the Polynesians who settled on Hawai‘i abandoned their deep-sea ocean canoes and began to cultivate the lush land of their new home.

FLUX PHILES | COMMUNITY | 24 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

In the modern era, commoners were removed from their ancestral valleys from the results of The Great Māhele, and later by private development and the tourism industry. They worked the plantations, and then hotels, airports, and other Western occupations for monetary subsistence. Many moved off-island to places throughout North America due to housing shortages and an ever-increasing cost of living. Buried were the ways of old, in which no money was exchanged and the word mahalo didn’t exist (for to receive is to have earned already, no need to say thanks). Those who descended from Polynesian voyagers survived to see their way of life replaced by a system of capitalism and landownership completely foreign to these islands. Their population became the minority and their cultural identity was on the brink of extinction.

At Waihe‘e Valley Country Club, some of us are learning, and some of us are relearning, what is deeply ingrained in our DNA—that deep memory unbroken from the great change that has happened.

Many of us simply drop by to work or bring things for family dinners, or simply to say hi to Freitas and her dog, Mo‘o, the permanent fixtures of the club. One night, a friend of Freitas, a young fisherman named Mikey, came by with freshly caught fish and ‘opihi. We started a fire, drank some beers, and ate the fruits of the sea as the moon crept from makai to mauka. Holding an empty shell of an ‘opihi took Freitas back to her childhood, when she would find shells buried in the ground by previous generations. “When I was a little kid, cleaning the yard or planting a tree, we were so inland that whenever I would find ‘opihi shells, whether it was my grandparent, or my great-grandparent, or great-great-great-grandparent, whoever it was, somebody was enjoying them in this exact spot and chucked it out. That always made me giggle,” she said as she threw the shell into the fire.

Now in her 30s, Freitas is returning to her roots after living abroad and working as a personal trainer. By returning to that kua‘āina (backcountry) lifestyle

Freitas is returning to the kua‘āina lifestyle of her kūpuna and discovering her ancestral roots along the way.

26 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 27

The life-nourishing promise of Hawai‘i heavily influenced the ancestors who decided to stay here.

“We are trying in any way possible to get back to how our ancestors lived and flourished,” Freitas says.

A window looking out to a field of sugarcane.

A window looking out to a field of sugarcane.

Relaxing by the stream.

Relaxing by the stream.

reminiscent of her kūpuna, she wants to further understand who she is. She wants to work with her hands in the very valleys they once worked. The spirit of those ancestors imbue their mana in the valley and look after her as she makes this journey. The signs of their presence are uncanny, as are the challenges they set forth to transform those who seek their ways of life and their perspectives. Those of us who come here from other occupations imagine maka‘āinana working the lo‘i kalo, cutting down the cane, and bathing in the cool rivers with a romance of a bygone era. When we visit, we get muddy and shed some blood and sweat. But to live this life daily is far from romantic.

What made those seafaring people find home here? To look back to those ancient times is to realize our ancestors never needed anything from the outside world, and so they ceased to voyage beyond the horizon. The fortunate few who still have land left to them can dig their roots in those backcountry lots and return to the ways of the old, acting as conduits to the past.

As Freitas gazes upon the ‘opihi shells among the glowing embers, she says, “I wanted to put them back into the ground, and maybe in 30, 40, 50, 80 years from now, someone will find them and say, ‘Oh, these are some nice-size ‘opihi, they were eating good!’”

Freitas moved from her farm into the valley to join the community she and friends have dubbed the Waihe‘e Valley Country Club.

32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Your Trusted Neighborhood Expert RB-17095 At Locations we look beyond zip codes to give our clients one of a kind neighborhood insights to help them make the most informed real estate decisions. LocationsHawaii.com/50years

THIS IS NOT INTENDED TO BE AN OFFERING OR SOLICITATION OF SALE IN ANY JURISDICTION WHERE THE PROJECT IS NOT REGISTERED IN ACCORDANCE WITH APPLICABLE LAW OR WHERE SUCH OFFERING OR SOLICITATION WOULD OTHERWISE BE PROHIBITED BY LAW. WARD VILLAGE IS A PROPOSED MASTER PLANNED DEVELOPMENT IN HONOLULU, HAWAII THAT DOES NOT YET EXIST. PHOTOS AND DRAWINGS AND OTHER VISUAL DEPICTIONS IN THIS ADVERTISEMENT ARE FOR ILLUSTRATIVE PURPOSES ONLY AND DO NOT REPRESENT AMENITIES OR FACILITIES WHOLLY WITHIN WARD VILLAGE AND SHOULD NOT BE RELIED UPON IN DECIDING TO PURCHASE AN INTEREST IN THE DEVELOPMENT. FURTHER, ANY RENDERINGS, PHOTOS, DRAWINGS OR OTHER REPRESENTATIONS AS TO UNITS OR OTHER ELEMENTS OF THE PROJECT THAT ARE DELIVERED OR SHOWN TO PROSPECTIVE PURCHASERS MAY NOT ACCURATELY PORTRAY SUCH UNITS AND OTHER ELEMENTS, AND DO NOT CONSTITUTE A REPRESENTATION BY THE DEVELOPER. THE DEVELOPER MAKES NO GUARANTEE, REPRESENTATION OR WARRANTY WHATSOEVER THAT THE DEVELOPMENTS, FACILITIES OR IMPROVEMENTS DEPICTED WILL ULTIMATELY APPEAR AS SHOWN. THIS IS NOT INTENDED TO BE AN OFFERING OR SOLICITATION OF SALE. EXCLUSIVE PROJECT BROKER WARD VILLAGE PROPERTIES, LLC. COPYRIGHT ©2019. EQUAL HOUSING OPPORTUNITY.

Curated design inside. Ocean views outside.

In the center of Ward Village.

Kō‘ula seamlessly blends an innovative, indoor design with spacious, private lanais that connect you to the outdoors. Designed by the award-winning Studio Gang Architects, every tower floor plan has been oriented to enhance views of the ocean.

Kō‘ula also offers curated interior design solutions by acclaimed, global design firm, Yabu Pushelberg. Outside, Kō‘ula is the fi rst Ward Village residence located next to Victoria Ward Park. This unique, central location puts you in the heart of Ward Village, making everything the neighborhood has to off er within walking distance. This holistically designed, master-planned community is home to Hawaii’s best restaurants, local boutiques and events, all right outside your door.

1, 2 & 3 bedroom homes available. Contact the Ward Village Residential Sales Gallery to schedule a private tour.

808.824.4857 | koulaward.com 1240 Ala Moana Blvd. Honolulu, Hawaii 96814 Ward Village Properties, LLC | RB-21701

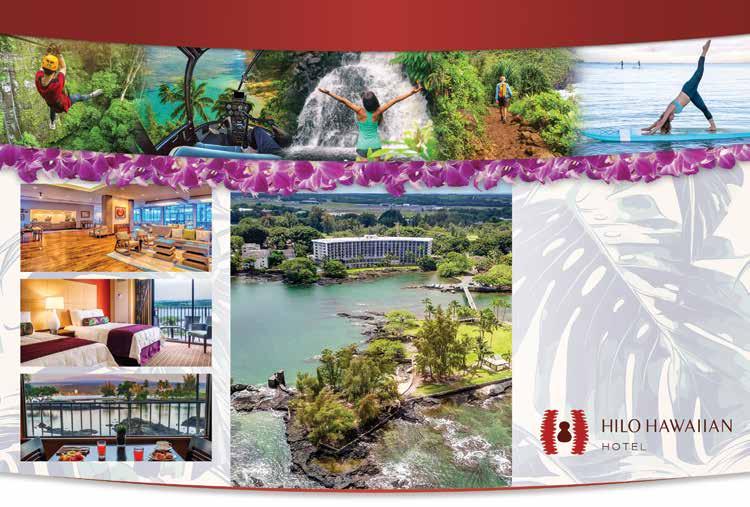

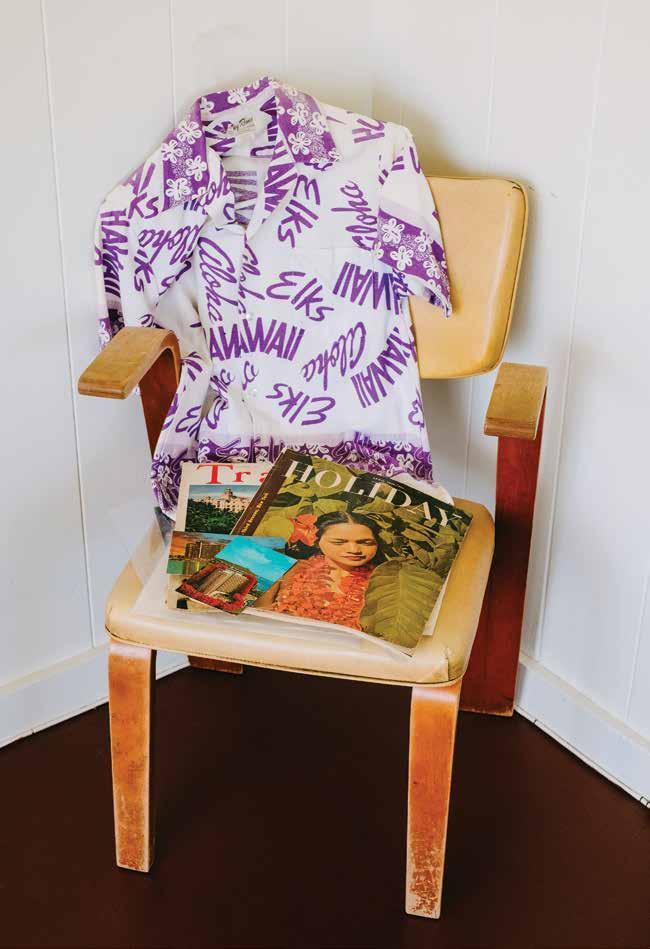

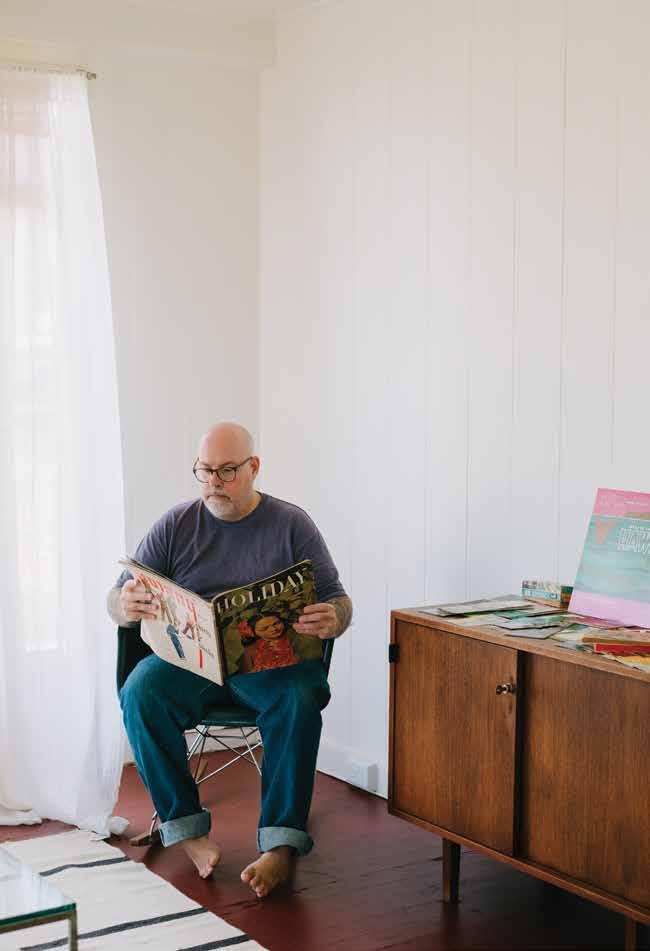

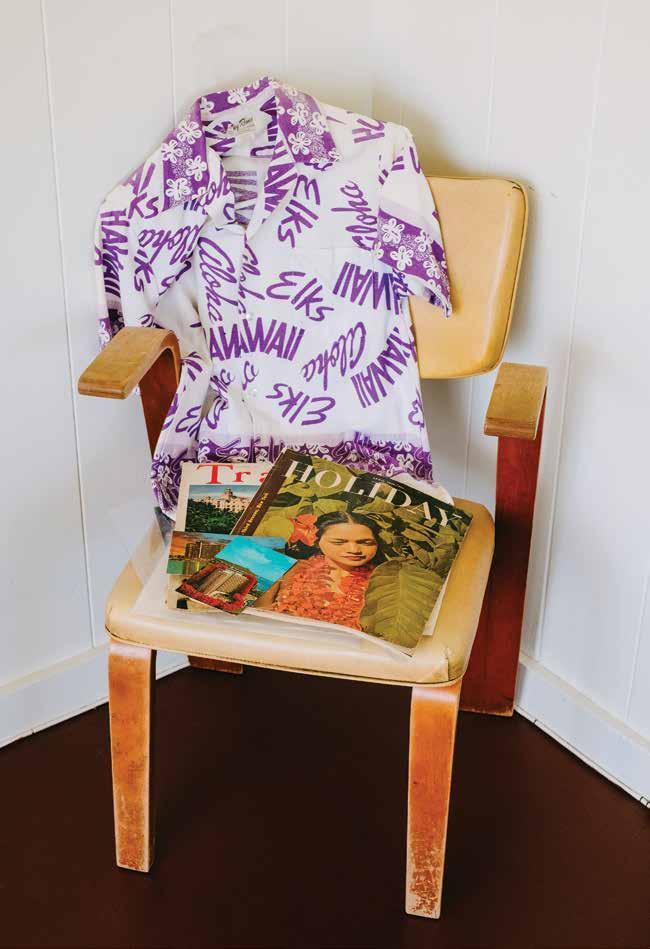

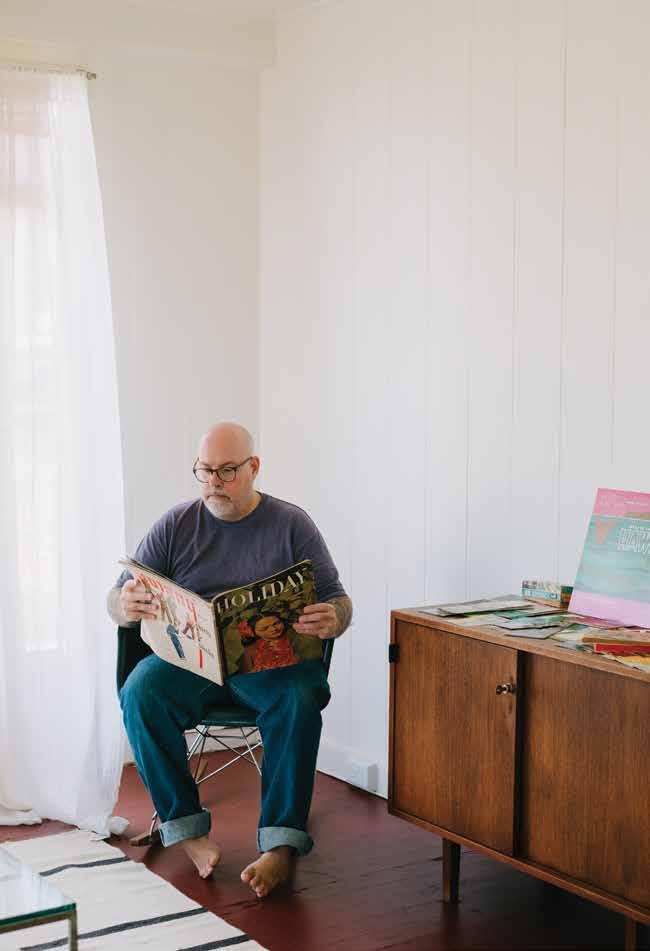

Picture-Perfect Paradise

Through postcards and hotel brochures, a collector endlessly pursues the golden age of Hawai‘i travel.

TEXT BY SPENCER KEALAMAKIA

IMAGES BY JOSIAH PATTERSON

There’s always something the collector wants but doesn’t have, never mind all the things the collector would want but hasn’t yet seen. In the case of Spencer Tolley, he began searching out vintage Hawai‘i ephemera in 2012, when work as a travel agent brought him from Miami to the Wai‘anae coast of O‘ahu. “I’ve been a collector of things all my life,” says Tolley, whose pursuits include first-edition books, midcentury housewares and furniture, and postcards of New York City’s Rockefeller Center. “Collecting postcards has been a constant.”

Postcards also played a part in shaping Hawai‘i’s reputation as a paradise of the Pacific. Local companies like Hawai‘i and South Seas Curio Co.; Wall, Nichols and Co.; and Island Curio Co. produced lithographic postcards that played up Hawai‘i’s sensuousness, its traditional and regal cultures, its landmarks and landscapes.

Tolley is especially interested in locally produced cards from between 1901 and 1907, the first time in U.S. Postal Service history that private companies could print postcards. Sites like eBay, where Tolley’s watchlist is maxed out at 100 items, make finding these antiques much easier, though collectors are more educated now.

Hunting down postcards has also helped Tolley learn about his new home and entertain folks online. As his collection grew, he began sharing his finds on Instagram under the name @fotoaloha. Through the account, Tolley has cultivated a vision of the islands he refers to as the golden age of Hawai‘i travel, between the turn of the 20th century and late 1941, when the United States entered World War II. In this phase of its tourism history, Hawai‘i was a hard-to-reach and expensive destination. Seats aboard Matson luxury liners and propeller planes headed to the islands were reserved for the well-heeled and adventurous. According to Tolley, ’60s jet travel and mass-marketed tourism brought that era to a close, though Hawai‘i continued to attract visitors looking for an exclusive place of retreat, isolatation, and freedom through the 1950s.

A mid-’50s Hotel Hana Maui brochure posted by Tolley sneaks us a glance, through hala and naupaka leaves, of a Hāmoa Beach scene with bathers, umbrellas, and a pink longboard arranged just so. “Every day of your stay at Hana Maui,” the copy promises, “will be pleasure-filled and exciting ... The full facilities are yours to enjoy exactly as you wish.”

For the sophisticated traveler, @fotoaloha is a time machine, a return ticket to what many consider to be the golden age of Hawai‘i tourism.

FLUX PHILES | VINTAGE | 36 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Lately, Tolley has been posting images of of Hawai‘i’s unique architecture, past and present. A postcard of the Waikikian, “Hawaii’s Most Beautiful Hotel,” shows off its wild architecture. The shape of the hotel’s “hyperbolic paraboloid” lobby roof and the ornamentation of its adjacent suites conjure the seduction and dread of attending a Skull Island sacrifice, but with cocktails shortly to follow.

“I try to think about what will be most meaningful and exciting and focus on the places that are mostly gone,” Tolley says about how he curates the Instagram account. He strives to strike a balance in what is presented rather than focusing solely on the hospitality industrial complex. “It’s not only about places tourists care about,” he says. “It’s about the lives of people who live here now, or were stationed here during

World War II, or during Korea—anyone who’s crossed paths with Hawai‘i.” Tolley is always adding to his collection and posting new items to @fotoaloha on Instagram as he gets things in the mail. And, as he says, it’s never ending.

For more than 150 years, Hawai‘i has been marketed as a vacation getaway, a fantasy, and an isolated locale, producing endless memorabilia for collectors.

Follow Tolley’s account @fotoaloha to add a dash of vintage Hawai‘i to your Instagram feed.

40 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

The Parent Trap

Hawai‘i is often considered the most progressive state in the country. But the state’s parental-leave policies and their overwhelming checklists and loopholes lead to little support for those considering welcoming new life.

TEXT BY ANNA HARMON

As a child, I loved Choose Your Own Adventure books, though I quickly tired of the starting sections and skipped ahead to the middle, where adventures really picked up speed. As soon as I saw where one choice would lead, I would flip back to where the path diverted and try the other direction. What decision got characters to which endings? The plotline mattered less to me than knowing how choices impacted the rest of the story, and what ending followed.

As an adult, parental-leave policies have begun to read like the footers of those Choose Your Own Adventure books, only based on past decisions. I had always wondered how parents made it work. But when I began to consider having a baby as I approached turning 31, the paths ahead began to look foggy and foreboding. Does your employer have a statutory plan? Have you had at least 14 weeks of employment in Hawai‘i during which you were paid at least $400 each week? Did you complete Part A of the claim form and have disability certified by a doctor in Part C? Are you a domestic worker or insurance agent? Did you reside in two states in the last two years? Are you a contracted employee? Can you truly afford to have a child? How can you measure a child’s life in dollars, see their future through the lens of lost opportunity? A child is a blessing, no matter the cost, right?

In the United States, there is no federal paid parental leave policy. There is only an unpaid one, the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993, for parents who work for a public agency such as federal or state government, a private company with at least 50 employees (within 75 miles), or an elementary or secondary school. The lucky souls who have followed this path of employment for at least 1,250 hours in the past year and at least 12 months

overall are given 12 weeks of job security in the form of time off without pay to nourish their newborns or bond with their adopted or fostered child, to begin to heal their bodies and adjust to new sleep schedules and lives. Can you take this path? Add up your fellow employees, measure their distances from you, calculate hours and months worked in the past, cross your fingers that your stockpiles of paid sick and vacation leave add up to the money otherwise lost by taking that time off. Toss the policy out the window if you just graduated, work in the gig economy, or have only a handful of coworkers.

For the sake of alternative life adventures, take Australia and Japan. In Australia, paid maternity leave policy pays women minimum wage for up to 18 weeks and men for up to 2 weeks as long as they earn under $150,000 annually and have been doing the same work for 10 months of the 13 months prior to birth or adoption. In Japan, mothers get time off before and after birth, and receive their salary through social insurance for 8 weeks; after that period, labor insurance covers two-thirds of the salaries of both parents for around 1 year after (with minor variation).

In Hawai‘i, often deemed the most progressive state in the country, federal policy is paralleled by the Hawaii Family Leave Law and the Hawaii Temporary Disability Law. The first mandates four weeks of unpaid leave for employees who have worked for six consecutive months for the state government or a Hawai‘i-based company with more than 100 employees. (This may only be used once in

42 | FLUXHAWAII.COM FLUX PHILES | FINANCE |

“My Soul It Is Mine” by Jene Ballentine. Oil painting, 1972. Courtesy of Hawai‘i State Foundation on Culture and the Arts.

a calendar year, so don’t have back-to-back babies.) In place of this time off, employees can use up to 10 days of accrued sick leave as well as paid vacation or personal leave—if their employers even offer any. Are you still following the footers? What if you would prefer to save paid leave for when your baby catches a fever at the new daycare? Time to do some savings account math. The second law, which applies only to biological mothers, views pregnancy as a disability and requires employers (with exceptions) to pay accordingly, though this depends on the insurance plan the employer chooses and the wages the employee was earning. Footer: The woman must have worked more than part-time for at least 14 of the past 52 weeks, must immediately notify her employer, and must file the appropriate form within 90 days. Postpartum recovery is defined by what the woman’s doctor signs off on, usually six weeks for a vaginal birth and eight weeks for a C-section, though doctors can decide this should be shorter.

In early 2019, my spouse and I were wrapping up two years in Arizona, where we had moved so I could get a master’s degree in sustainability, and were debating returning to Hawai‘i, where he was born and raised and we had lived prior. Tentative about having a child, I had decided I wanted to do it soon or not at all. When we added up the cost of living on O‘ahu, the complete absence of parental leave at the University of Hawai‘i, where he would be getting a PhD, and my truncated work history in the islands, we couldn’t justify the sacrifices—like my health or our time with a newborn—a move back would require. I wondered how anyone afforded being a parent, from the single moms I had waited tables with to my former boss. We stayed on the continent, moving to a different state instead. Yet we haven’t yet

ventured into the world of parenthood. As societal expectations loom, and I work contract-to-contract, I still can’t fathom how we can afford to bring a child into this world. People make it work, I’m told. It will all be fine. But will it?

In 2019, the ki‘ai at Maunakea briefly demonstrated a different model when they offered free childcare to those protecting the mountain. It was surely informal, a volunteer basis kind of thing. But in tightknit communities, people often pitch in, and those connections are turned to when formalized structures fall short. For those without strong communities or inherited wealth, in a patriarchal society in which social support has been institutionalized, the struggle is real. Not all is lost—in 2018, Hawai‘i’s legislature passed a bill recognizing that “Hawaii’s working families are not adequately supported during times of caregiving and illness” and dedicating funds to producing a report and proposed legislation on paid family leave by September 2019. Then it passed a measure to extend the deadline to November 2019. What will it do when it finally has that report?

Paid parental leave is important. It has been found to promote gender equity and improve the health of children. It helps new parents survive financially, emotionally, and physically during an upheaval in their lives. But by tying it to employment, its underlying message is still this: Your bonding time with your child, your body’s recovery, is only worth funding if you’re economically viable; if you’ve adequately paid into the system; if leaders say so. You can only have as much as your provider can afford, regardless of your needs as a single parent. It is only worth what retaining you is worth. If you do not meet all the qualifiers or have chosen a different path, you are on your own.

Tying parental leave to employment sends the message that bonding with your newborn is only worth funding if you’re economocially viable.

44 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

174 lahainaluna road lahaina , maui , hi 96761 www . theplantationinn . com 1-808-667-9225

FLUX FEATURE

FLUX FEATURE

Prom ised

L and

Kahauiki Village has been heralded as a disruptive model for solving homelessness. But is it putting a vulnerable population at risk?

TEXT BY TIMOTHY A. SCHULER

IMAGES BY MARIE ERIEL HOBRO

A MODEL COMMUNITY

Every so often, a person will pull into Kahauiki Village off Nimitz Highway in Honolulu and ask if any of the cheery, solar-powered houses are for rent. Each time, employees have to explain that the residential development is only available to formerly homeless families. “That happens weekly,” said Kimo Carvalho, the director of community relations and development at the nonprofit Institute for Human Services, one of Hawai‘i’s largest homeless service providers and a partner at Kahauiki Village, as he toured me around the development.

Kahauiki Village, which everyone calls KV, is a novel approach to alleviating homelessness in Hawai‘i, which in 2018 had the largest homeless population per capita in the nation, tying with New York. Since it opened in January 2018, KV has been called a “dynamic community,” the “first of its kind in the country,” an “unprecedented affordable housing project for previously homeless families.” In June 2018, Duane Kurisu, a local real estate investor and KV’s originator, published an essay on Zócalo Public Square, a nonprofit media outlet, under the headline, “The New Kahauiki Village Is Rekindling the Communal Values of Old Plantation Towns.” “At Kahauiki,” he wrote, “we believe that a sense of community should be the starting point in addressing the day-to-day needs of those seeking comfort and shelter, and for providing long-term solutions for homelessness.”

Spearheaded by the Aio Foundation—the charitable arm of Kurisu’s family of companies, which includes PacificBasin Communications—and supported by the City and County of Honolulu and the State of Hawai‘i, the 11acre, multiphase development along Honolulu’s industrial waterfront will eventually house 144 families who previously had nowhere to go but one of O‘ahu’s handful of family shelters. For IHS, it was a unique opportunity to collaborate with the private sector. “Housing developers rarely come to us and ask what a population needs,” Carvalho says.

The community is located on a peninsula built from soil, sand, and rock leftover from the construction of Interstate H-1 that, prior to KV, housed a paintball course. That the property became what it is today was something of a fluke. The way Kurisu tells it, he was flying to Honolulu from Hawai‘i Island when he and his friend, Lloyd Sueda, a local architect, spotted the peninsula from the air. The two already had been discussing plans for a housing project for formerly homeless families, so Kurisu decided to look into who owned the property. As it happened, the paintball course was closing, and the parcel was public land owned by the state. After months of discussion, the state gave Kurisu the green light and

Shown above is Dolores, a resident of Kahauiki Village, with her two youngest children. The housing construction is a public-private partnership that began with a community of 30 formerly homeless families.

transferred the land to the city, which leased it to the Aio Foundation for $1 per year. From a developer’s perspective, a person couldn’t have asked for a better deal.

The project is being built in five phases, two of which are now open. It’s made up of what look like small, singlefamily houses but in fact are prefabricated, modular disaster-relief units that previously housed Japanese families left homeless by 2011’s catastrophic earthquake and tsunami. The units were purchased by the Aio Foundation, deconstructed, refurbished, and stacked into piles of constituent parts—steel trusses, insulated wall panels, plywood ceilings—and shipped to Hawai‘i to again house families who have nowhere else to go. Except this time, the catastrophe wasn’t grinding tectonic plates, but the grinding forces of a global economy: record-high rents, stagnant wages, a fraying social safety net.

Structurally, KV is a hybrid, occupying a rare zone between homeless shelter, public housing, and marketbased “affordable” housing. Residents at KV can stay as long as they want, as long as they pay rent. Those rents

48 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

I.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 49

are subsidized, but not in the same way as federal programs like Section 8 in which monthly rents are often income-based. At KV, rents are fixed at $725 for a one-bedroom unit, including utilities, and $900 for a two-bedroom unit, less than half of what a family would pay on the open market. (Although an income-based system seems more equitable—a person making minimum wage would pay less in rent than a person making $20 per hour—Carvalho says it can disincentivize residents from pursuing better-paying jobs.)

From the beginning, KV was designed to create a base level of stability as well as an incentive to work. November Morris, IHS’s employment program manager, says childcare and transportation are often listed by homeless families as two of the biggest barriers to steady employment. KV is located within walking distance of several major employers, including United Laundry, Love’s Bakery, and Honolulu International Airport, and along a major bus route that connects the village to downtown Honolulu and Waikīkī. The community offers onsite daycare for just $100 a month, with a free half-day program, a major financial relief in a state where childcare can cost anywhere from an average of $640 a month to more than $2,000.

KV gets several things right when it comes to livable environments. Inspired by Kurisu’s childhood, which was spent in a plantation town on Hawai‘i Island’s Hāmākua coast, the homes in KV’s first phase are painted brick red or teal green, their colorful metal roofs (a custom add-on designed by Kurisu’s team) pitched to rid the buildings of their cheap boxiness. Although one could accuse the project of romanticizing plantation culture— Hawai‘i’s sugar plantations were structured around a ghastly system of segregation and oppression—from a design perspective, these details

elevate the secondhand housing units to photogenic cottages, complete with Victorian-style wall lights mounted above the front doors. The result is a feeling of quaintness.

The village’s first phase is also planned to encourage interactions among its neighbors. The 30 houses are tightly grouped, with landscaped paths winding between them rather than roads. There is a post office and a communal laundromat, and Palama Market recently opened a Palama Express not far from the daycare center. Residents have organized a parent hui to address community concerns, and on Saturdays, Ken Miyasato, the director of strategic planning and human resources at Aio Foundation, runs a pop-up dojo in the IHS office behind the Palama Express. KV even has its own micro-grid and is a zero-net-energy community, meaning it produces more energy than it consumes.

Most importantly, though, KV seems to be succeeding in giving formerly homeless families a genuine stepping stone to increased housing security and higher-wage jobs. IHS partners with various Hawai‘i companies to identify job openings before they are posted and prescreens candidates. “Companies are always approaching us, and one of the conversations I have with them is, ‘What do you pay?’” Morris said. “That’s important because our people are at risk. We need to place them in employment that pays a higher rate than minimum wage.” Within one year of KV’s operation, two families transitioned to more traditional housing.

Still, KV is far from edenic. Although technically it’s built on a peninsula, it’s actually more of an island. The property is cut off from the rest of the city by an imposing tangle of concrete onramps, offramps, viaducts, and surface roads, making it accessible by car only from the west— hardly a place a person would choose to live. I visited the village

several times in September 2019, shortly after it welcomed another 30 families to the community. On one visit, I met a woman named Althea, who was working as the cashier at the Palama Express. (She requested that her last name not be used.) Althea had grown up in the Marshall Islands but attended high school in ‘Aiea. She eventually worked at Pu‘uhale Elementary School as an aide to students for whom English was a second (or third) language. About four years ago, after her father died, Althea found herself physically and emotionally incapable of working. Unable to pay their rent in Kalihi, Althea, her husband, and their three kids, two of whom are grown, moved into the Holomua Na ‘Ohana family shelter in Waimānalo. Shortly after, they moved into KV.

I asked Althea how KV compared to other places she had lived. She said the rent was affordable, and that she appreciated KV’s sense of community—the parent hui, the monthly tenant meetings. The twobedroom house that she and her family shared was smaller than the one they had lived in in Waimānalo. It was hotter, too. KV’s housing units have fans but not air-conditioning. But the main difference, Althea said, was the noise. The family’s house sits fewer than 100 feet from Nimitz Highway. The traffic barreling past is constant. Trucks and tour buses tumble from the H-1 onto Nimitz Highway in an unceasing riot of clanging, humming, grinding noise. This was one of the first things I noticed too. On my first visit, the village reverberated with the persistent clamor of construction. KV’s third and fourth phases were under construction, and the property was also being used by the Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transit to store construction materials. The result was a cacophony of voices, beeping trucks, and grumbling machinery. Woven through it was the deep yet shrill

50 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 51

roar of commercial airliners taking off from the airport. In 2018, Time Magazine published a report on the dangers of noise pollution, citing a connection between noise pollution and cardiovascular disease.

“High decibel levels from road traffic and airplanes, for example, has been linked to high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, stroke and heart failure—even after controlling for other factors like air pollution and socioeconomic status,” wrote Amanda MacMillan.

Carvalho is aware of the dangers that high decibel levels pose to human health. As an undergraduate student at Tulane University in New Orleans, he studied the relationship between heart disease and excess noise. “It’s a real thing,” he said, adding that noise was the number-one complaint at KV.

With the noise, I knew, came other dangers: the possibility of being struck by a vehicle, and poor air quality, which increasingly is linked to serious respiratory problems, particularly in children. The more time I spent at KV, the more concerned I became. Yes, the village provided immediate relief to O‘ahu’s network of overcrowded shelters as well as a potential a stepping stone out of homelessness. But it also exposed residents to environmental dangers that we are only now fully understanding.

A MATTER OF SOVEREIGNTY

There was a reason, besides being a design writer, that I was sensitive to the quality of the built environment at Kahauiki Village. I had written about the project before, when it was still under construction. In that article—published in Next City, a nonprofit publication focusing on urban issues—I had tried to paint a picture of the less-thanideal environment KV occupied, cut off from even the industrial parts of Honolulu by overpasses and on-ramps. But I didn’t explicitly explore the potential dangers that the location posed to soon-to-be residents, and so a commenter wrote, “No mention of the pollution from the highway and the airport—pollution those banana trees and vegetable gardens will absorb, & that will

cause that community’s children and elderly & adults too health problems … This seems to be the perfect example of environmental discrimination becoming entrenched.”

The comment was merited. Despite technological advancements that have produced cleaner automobile emissions, air quality concerns have ratcheted up in recent years as researchers have learned more about the dangers posed by fine and ultrafine particulate matter—the technical term for much of the air pollution associated with traffic. According to the American Lung Association, exposure to particulate matter can cause or exacerbate respiratory illnesses such as asthma and pneumonia and put individuals at greater risk for cardiovascular disease. Because these particles can enter our bloodstream, they can also lead to increased cell loss in the brain, resulting in neurodegeneration and enhancing the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Even autism has been linked to air quality. A 2014 study published by researchers at Harvard University’s School of Public Health found that the risk of a child developing autism doubles if the mother is exposed to fine particulate pollution late in her pregnancy.

Scientists used to think that particulate matter came strictly from a car’s exhaust pipe. But it turns out our vehicles are perpetually shedding bits and pieces of themselves. Disc brakes release a steady stream of metals such as iron, copper, and manganese into the atmosphere, which can mingle with sulfate to become soluble before entering our lungs. Rubber tires release microparticles of potentially harmful compounds, such as carbon black, a possible carcinogen. We’re only now realizing how dangerous these sources may be, and these aspects of car manufacturing are not regulated the way emissions are, which means even electric vehicles will not solve all our air-pollution problems.

The most dangerous places, when it comes to air pollution and traffic, are areas within 1,500 feet of busy roadways, which is the case for all of Kahauiki Village. It’s easy to write off air quality as a secondary concern, but Hawai‘i’s homeless population is disproportionately Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and Native Hawaiians in turn are disproportionately afflicted with heart disease, diabetes, and obstructive

Kahauiki Village is being built in five phases. It’s made up of what look like small, singlefamily houses, but in fact are prefab disasterrelief units.

By the time the first phase opened, more than 200 local businesses, nonprofit organizations, and government agencies had donated time to help realize the project.

52 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

II.

lung conditions such as asthma, bronchitis, and emphysema. Quite frequently, it is a health issue that puts a family on the streets in the first place. One of the other residents I met at KV is Dolores (who also requested her last name not be used). Dolores is middle-aged, Chuukese, a mother of three. Two years ago, she was living in Kansas City, Kansas, when she became severely ill. She couldn’t work. She could barely move. Doctors had no idea what was ailing her; tests revealed high blood pressure but little else. “I was sick for eight months,” she told me. She moved to Hawai‘i for treatment on the recommendation of a cousin, who knew a woman who practiced nontraditional medicine. Her two youngest children, who are 13 and 12, came with her. But without a job or savings, she couldn’t afford her own apartment, so she went to IHS, which found her a house in KV.

After several months of treatment, Dolores recovered enough to be able to work again—she recently got a job in security at the airport—but her story is a common one. Unexpected health problems, and the resulting medical bills, are one of the main reasons Americans lose their jobs or file bankruptcy. Once a person becomes homeless, sufficient healthcare can be even more difficult to acquire.

Unfortunately, putting our most vulnerable populations in harm’s way is a common thread in American history. In 1970, Congress passed the Clean Air Act, which, like the Clean Water Act before it, made a healthful environment a civil right, regardless of ethnicity or income level. Beginning in the 1980s, however, a series of protests and reports made clear that many communities in the United States still lacked clean air or water and that, worse, the level of toxicity strongly correlated with race. Minority communities, often low-income, were far more likely to be exposed to various forms of environmental pollution, leading to the term

“environmental racism” and birthing the environmental justice movement. I find it striking that in the Hawaiian language, the word for air, “ea,” is also the word for sovereignty. Ea refers to breath and respiration, as in the phrase “ho‘opuka ea,” which means “exhaust fumes.” But it also connotes sovereignty, whether of a nation or of a person’s mind or body.

Elizabeth Kapu‘uwailani Lindsey, a Hawaiian voyager and National Geographic Society fellow, has described ea as her favorite word in the Hawaiian language. “Ea means a personal sovereignty, a sovereignty where no one can hold you back or keep you down,” she once said. This etymological link between sovereignty and the physical, earthly environment suggests an innate relationship between our wellbeing and the health of the planet—our air and water. An environment that endangers us is another form of subjugation. If we want to free families from the burdens created by poverty and homelessness, the environments we create are essential to that project.

The dangers posed by the knotted roadways near KV are not limited to noise or air pollution. I’ve taken the number 19 bus from Waikīkī to Kahauiki Village. Although the city added a bus stop in front of the community, it only serves eastbound traffic. Coming from the other direction, I had to get off at Pu‘u Hale Street and walk the remaining halfmile to KV. It’s a harrowing journey, even for an able-bodied 33-year-old. There’s no shade and no buffer between pedestrians and the speeding cars. Where Sand Island Access Road intersects Nimitz Highway, drivers are given a wide, curving right-turn lane so that they don’t have to stop. The only way to reach KV is to dash across, keeping your eyes on the road to ensure a semi-truck doesn’t barrel around the turn and crush you.

At one point during my trek, a dump truck going at least 45 miles per hour hit a steel plate in the road

as it passed me, causing a bang so loud that I flinched. Several minutes later, my ears were still ringing. Loud noises trigger our bodies’ natural “fight or flight” response, flooding our bodies with stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol. In these situations, our bodies are doing what they’re designed to do. But repeated or chronic exposure to stress-inducing environments, such as overly noisy ones, can lead to unhealthy cortisol levels, which can put people at risk for increased blood pressure, cholesterol, and heart disease.

The scariest moment came just after crossing Kalihi Stream. By this point, the sidewalk had disappeared, so I was forced to walk along Nimitz with not so much as a curb to protect me from the speeding traffic. Eventually, I found my way blocked by a huge, diamond-shaped traffic sign warning drivers of a steel plate ahead. With a ditch full of debris falling steeply away from the other side of the sign, I had no choice but to scurry around it when there was a slight break in traffic. By the time I reached KV, I was soaked in sweat—mostly from the sun and the way it bounced off the metal buildings that lined the road, but also from the stress of the noise and navigating so many hazards.

KV’s developers highlight the community’s proximity to jobs and schools. And it’s true that some of IHS’s partners, including Love’s Bakery and United Laundry, are within walking distance, as are public elementary, middle, and high schools. But the routes to many of these places are downright hostile, lacking shade or sidewalks or both, and, in the case of the walk to Farrington High School, passing directly by O‘ahu Community Correctional Center, a three-block-long stretch of chain-link fencing and razor wire. In general, pedestrian safety in the U.S. seems to be trending in a troubling direction: 2018 saw the highest number of pedestrian deaths since 1990, and Hawai‘i consistently ranks among the deadliest states for elderly persons.

54 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

One afternoon, I saw a couple and their young son walking along Nimitz Highway. I recognized the boy from KV’s afterschool program, where kids had worked on homework or colored pictures of Naruto characters. Framed by a seemingly endless expanse of asphalt, this family seemed small, vulnerable, as if they didn’t belong in this alien environment of roaring, smog-spewing machines. In that moment, Nimitz seemed like a death trap, designed to maim.

Were there quieter, better protected locations to build Kahauiki Village? It’s hard to say. Communities often resist supportive housing projects in their neighborhoods. The reality is that our reliance on—or rather addiction to—cars affects all of us. Many O‘ahu residents are forced to make the same tradeoff: To escape the everyday assault of noise and smog is to be trapped in the everyday assault of bumper-to-bumper traffic— that is, if they can afford a car in the first place. If we’re serious about protecting people’s health, we have to think bigger than housing, bigger than jobs. Those are important. But so is clean air. So is ea.

III.

AN ETHIC OF EA

One of the big storylines of Kahauiki Village is the leading role played by the private sector. “We’re just a bunch of guys who wanted to give back,” Lloyd Sueda, the architect who designed the plantationstyle embellishments on KV’s houses, told Midweek in April 2019. “Obviously, this wasn’t something any of us had to do, but it was a passion of ours and it came from the heart.” By the time the first phase of KV opened, more than 200 local businesses, nonprofit organizations, and government agencies had donated time to help realize the project.

Kahauiki Village was built in record time. This was possible in part because of private-sector collaboration but mainly because of a proclamation made by Governor David Ige, which declared the state’s homelessness crisis a state of emergency. An emergency proclamation

allows the government to bypass certain regulations in the actions it takes to respond to a crisis. In the case of KV, it meant Aio Foundation and its primary government partner, the City and County of Honolulu, could forego certain bureaucratic processes—such as zoning and permitting—that typically add months to construction schedules. It also allowed them to experiment with prefab structures that otherwise wouldn’t meet local building codes. KV, in other words, was disruptive.

To what extent was this revolutionary process responsible for the largely invisible dangers residents face on a daily basis?

When I interviewed Duane Kurisu two years ago, he told me that Aio Foundation went through all the regular steps when it came to assessing the environmental impact of the project; they simply didn’t have to wait for building permits. I’m not sure which would be worse: if the assessment was never completed, or if it was and the potential noise and air quality impacts to residents somehow were deemed insignificant.

The problem with treating the private sector as a benevolent hero that swoops in to save the day is that such a story relies on an imbalance of power, on public institutions so emaciated that when private money is on the table they are all but forced to leap through whatever hoops are placed before them. But private money can be fickle. Cities around the world got a taste of this in April 2019 when the Rockefeller Foundation, a tax-exempt organization with assets exceeding $4 billion, announced the termination of its 100 Resilient Cities program, which since its launch in 2013 had invested $164 million in helping city governments, including Honolulu’s, undertake long-term climate resilience planning.

The foundation’s decision to pivot away from the program stemmed, in part, from a change in leadership. “As it existed, 100RC had grown too costly, and its model no longer aligned with Rockefeller’s goals,” Laura Bliss wrote in CityLab. Josh Stanbro, Honolulu’s chief resilience officer, said the dissolution of the program won’t impede his office’s work. From the outset, Stanbro said he and his staff worked to ensure that the office was supported by the city and

Housing alone cannot address the larger forces that left families homeless in the first place.

Minority communities, often low-income, are far more likely to be exposed to various forms of environmental pollution.

56 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

had financial support from outside the Rockefeller Foundation. They did this, he said, precisely because private funding can be unpredictable. “That’s the nature of philanthropy,” he said.

On my last visit to Kahauiki Village, I noticed what seemed to be a sign of this sort of slow, financial evaporation. Tucked behind the first group of homes, KV’s second phase looked different. The homes were still painted cheery colors, but they lacked the pitched roofs that the Aio Foundation proudly points to in its marketing materials and that did the heavy lifting in making the first-phase homes feel less like factory-built boxes and more like plantation-style homes. Comparing the two, the second-phase houses felt cheaper, more temporary, more like the emergency housing units they were.

The Aio Foundation nixed the custom roofs because they accounted for nearly 40 percent of the cost of each unit. I wasn’t surprised. Maintaining support for nonprofit endeavors is notoriously hard. Capital projects such as new museum wings garner millions of dollars in one-time gifts, while the upkeep for those spaces must be funded from a fixed and often meager budget. “In philanthropy, it’s the die-off effect,” Carvalho said. In the lead up to opening Kahauiki Village, he said the project reached “peak momentum and contributions and assistance. That has definitely tapered. But I wouldn’t say it’s completely lost.”

Kahauiki Village is designed to be self-sustaining. Revenue from tenants’ rents support daily operations and long-term maintenance. But because maintenance has little to no value, its actual cost is often underestimated. It’s not hard to imagine returning to the community 15 years from now to find paint chipping, trees spindly and undernourished, public spaces spoiled by years of neglect. For projects like KV, under the current paradigm, entropy is the rule, not the exception.

We need a new paradigm, just as we need new stories. In her essay, “Maintenance and Care,” Shannon Mattern writes, “Values like innovation and newness hold mass appeal—or at least they did until disruption became a winning campaign platform and a normalized governance strategy. Now breakdown is our epistemic and experiential reality.” Maintenance, meanwhile, is overlooked, deferred, or relegated to the domestic realm (traditionally the jurisdiction of housewives, whose everyday labor has no market value). What we need, Mattern says, is to better understand “how the world gets put back together” through the “everyday work of maintenance, caretaking, and repair.”

In any situation, it’s worth asking what exactly is being disrupted. Housing alone cannot address the larger forces that left families homeless in the first place, or the entrenched car culture that pollutes our islands and disproportionately harms low-income families. Will the business leaders who helped build KV also push Hawai‘i’s lawmakers to pass legislation raising the minimum wage or expand their companies’ family leave policies and benefits packages to decrease housing insecurity? In April 2019, while KV’s second phase was getting its final coat of paint, a bill that would have raised the minimum wage to $15 per hour by 2023 died on the House floor.

A lot of people say KV is a model for addressing homelessness in Hawai‘i, maybe even around the world. But Kahauiki Village is still an experiment. And like all experiments, we should track the results closely, not only the standard metrics—number of families housed or average household income—but also the health and wellbeing of those families, their longterm financial stability, the strength and longevity of social ties established while part of the community. We should not shy away from the project’s

failings or its imperfections, but rather hold them up in the spirit of improving the lives of those it is meant to serve.

While writing this, I’ve been worried that in critiquing Kahauiki Village I am implicitly setting myself against the welfare of the families who call it home, or invalidating the tireless labor of the hundreds of workers and volunteers who sustain it: the case managers, daycare providers, landscapers, and construction crews; the security guards and the students who volunteer after school; the residents who serve on KV’s parent hui.

More than that, I worry that by reporting on the potential health impacts of living there, I am adding an undue burden on the shoulders of mothers, fathers, and children who already have experienced various traumas. But to look the other way feels unjust. We all deserve the best information we can get about our health. And we, the public, need to examine the results of social endeavors with humility and an eye toward our own biases and blind spots.

Kahauiki Village is an attempt to prioritize the dignity and autonomy of people who so often are deprived of both. But we rob people of their personal sovereignty when we infringe on their rights to clean air and safe streets and a quiet refuge to call their own. To continue to build cities with insufficient regard to human health and wellbeing is to rob ourselves of the ea we need to survive. We need alternatives that prioritize maintenance and care, that are imbued with an ethic of environmental sovereignty. A clean and safe community should be a right, not a privilege.

58 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

©2019 MARRIOTT INTERNATIONAL, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MARRIOTT BONVOY™ AND ALL OTHER NAMES, MARKS AND LOGOS ARE THE TRADEMARKS OF MARRIOTT INTERNATIONAL, INC., OR ITS AFFILIATES, UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED.

Waikiki ALOHA ANYWHERE Discover your piece of paradise in Hawaii. Immerse yourself in the rich cultures, traditions and stunning natural beauty of these tropical islands. We invite you to explore Marriott International’s collection of distinctive hotels and resorts, where family getaways, romantic escapes and unforgettable adventures await. BOOK NOW AT MARRIOTTHAWAII.COM

Sheraton

FLUX FEATURE

T he Hunt for Geor ge Gil ley

The uncharted tale of history’s only Native Hawaiian whaling captain, culled from an archival abyss of explorer logs, scholarly mentions, and aging newsprint.

TEXT BY TRAVIS HANCOCK

ILLUSTRATIONS BY LAUREN

TRANGMAR

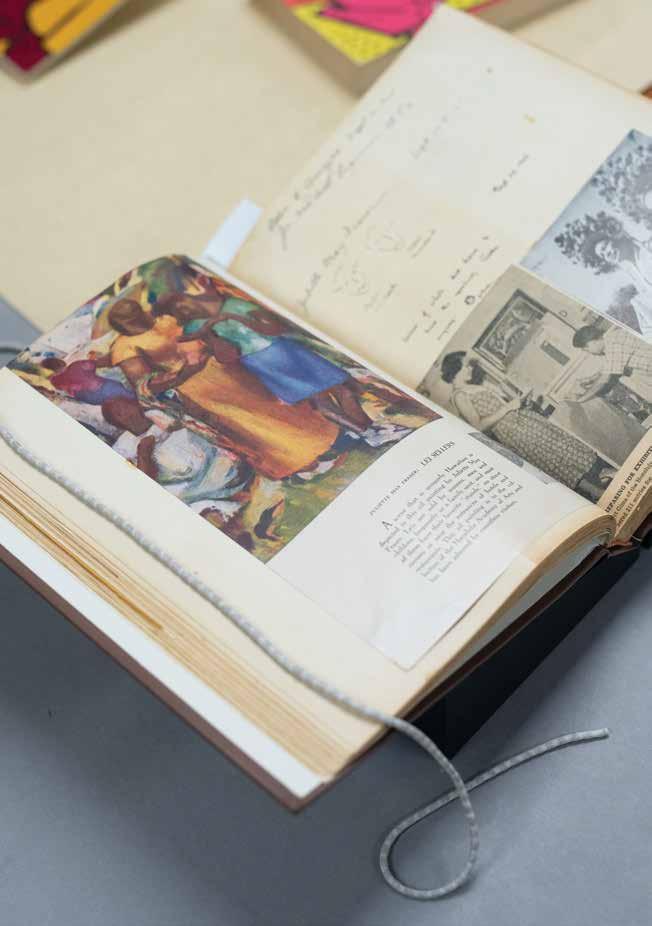

The only existing portrait of George Gilley, a Native Hawaiian whaler, in 1887. Photograph by Herbert L. Aldrich. Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

The only existing portrait of George Gilley, a Native Hawaiian whaler, in 1887. Photograph by Herbert L. Aldrich. Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum.

Nā pe‘a i ka makani THE SAILS IN THE WIND

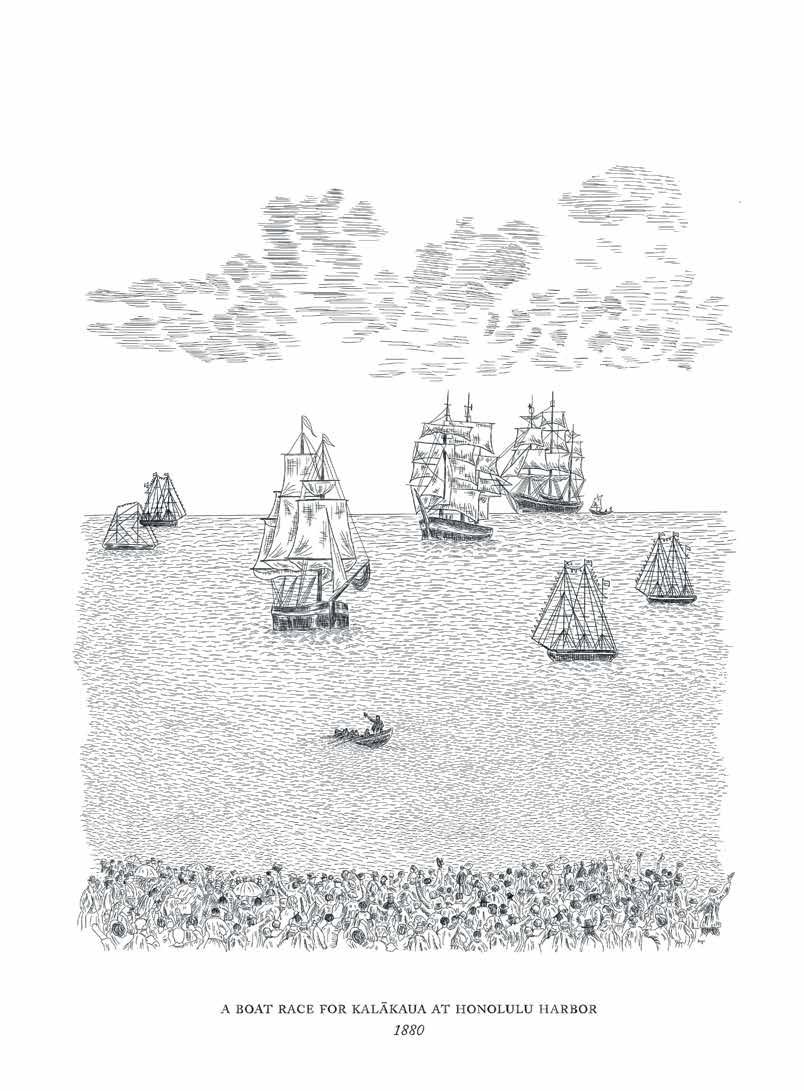

With the wind freshening toward morning’s end, George Gilley’s little whaleboat held its lead. The sharpset prows of the larger ships Sarah, Kapiolani, and Mokuola nipped at his wake as he rounded the flag-boat at Waikīkī, sprinted westward to a buoy near the Pearl River mouth, and then beat back through the early afternoon to the finish line at Honolulu Harbor. There at the wharf, where Aloha Tower would stand half a century later, a crowd of 5,000 revelers thronged the esplanade, cheering as Gilley sailed first through the flagfestooned channel.

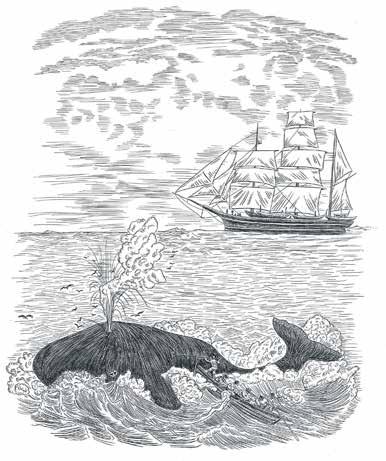

The race launched the sporting festivities for King Kalākaua’s 44th birthday, November 16, 1880. Reporting on the celebration, the Pacific Commercial Advertiser described a collective “spontaneity of spirit, an enthusiasm, and at the same time, a peacefulness of demeanor; proving a widespread loyalty ... prevails among all races of our population.” But it is hard to say if such feelings were stirred in George Gilley. The whaleboat that he had rigged with a sail likely came from the schooner Julia A. Long, which had just completed the final whaling expedition undertaken by any Hawaiian-registered ship. As its captain—the only known Native Hawaiian whaling captain in history— Gilley was out of work. Was he driven to win the race for king and country? Or was it for the $50 prize, a hefty payday for a whaleman without prospects?

Gilley’s life story, which has never been told in full, is rife with such questions. But one thing we might reasonably infer, after weaving together the scattered mentions of his name—spelled Gilley, Gilly, Gillie, Gelley, or Kele—in newspapers, letters, and explorer accounts, is that a festive day spent riding island breezes around buoys was much easier than his average foray. In the years well before

and after that day, Gilley navigated Arctic storms and treacherous fields of coral, ice, and thrashing leviathans that shivered the timbers of all who braved the North Pacific in the great blubber rush of the 19th century. Propelled by a jetstream of sheer talent, Gilley was an exemplar of the Native Hawaiian initiative, skill, and fearlessness that rendered a small island kingdom a player in the global economy.

When 18th-century Kānaka Maoli, or “real people” in Hawaiian, applied the word for their islands, moku, to the foreign ships arriving at their birth sands, they implicitly continued a deep-routed tradition of Polynesian migration and island colonization. This semantic act soon translated into real Kānaka seamen making gains throughout the floating archipelago of ships built by nations seeking economic footholds in their islands. Navigating his way to the top of this movement, and furthest beyond the West’s maritime color lines, George Gilley led his predominantly Pacific Islander crews into a novel form of sovereignty in the post-contact era.

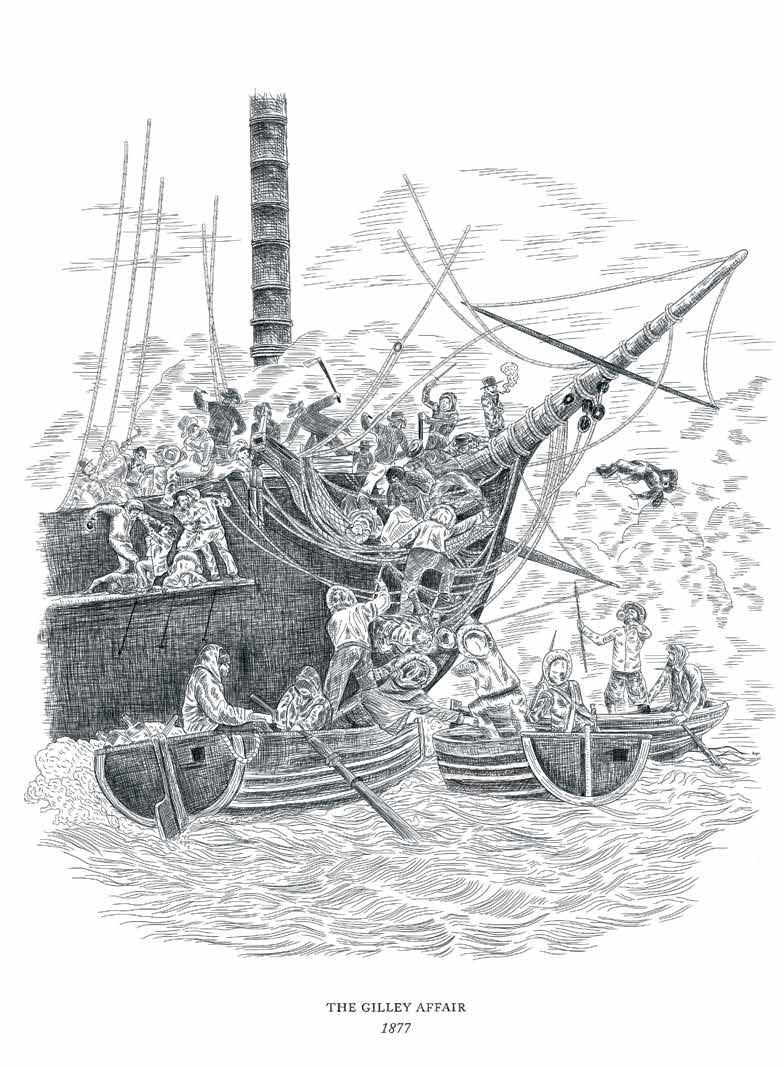

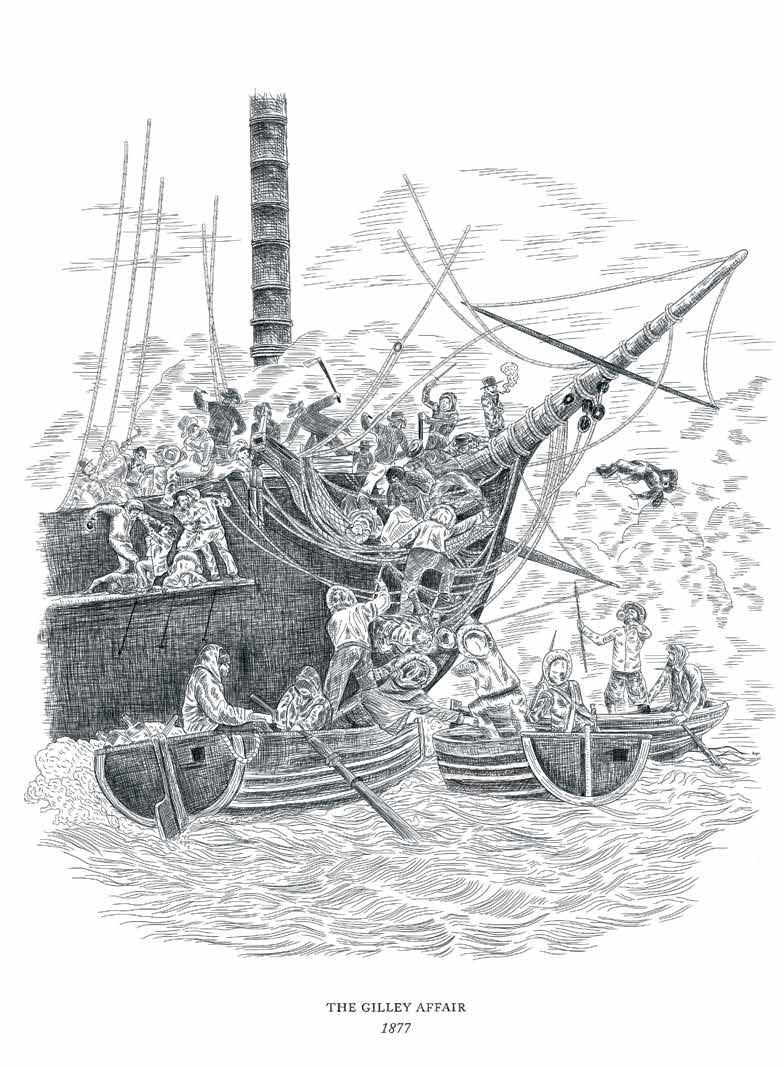

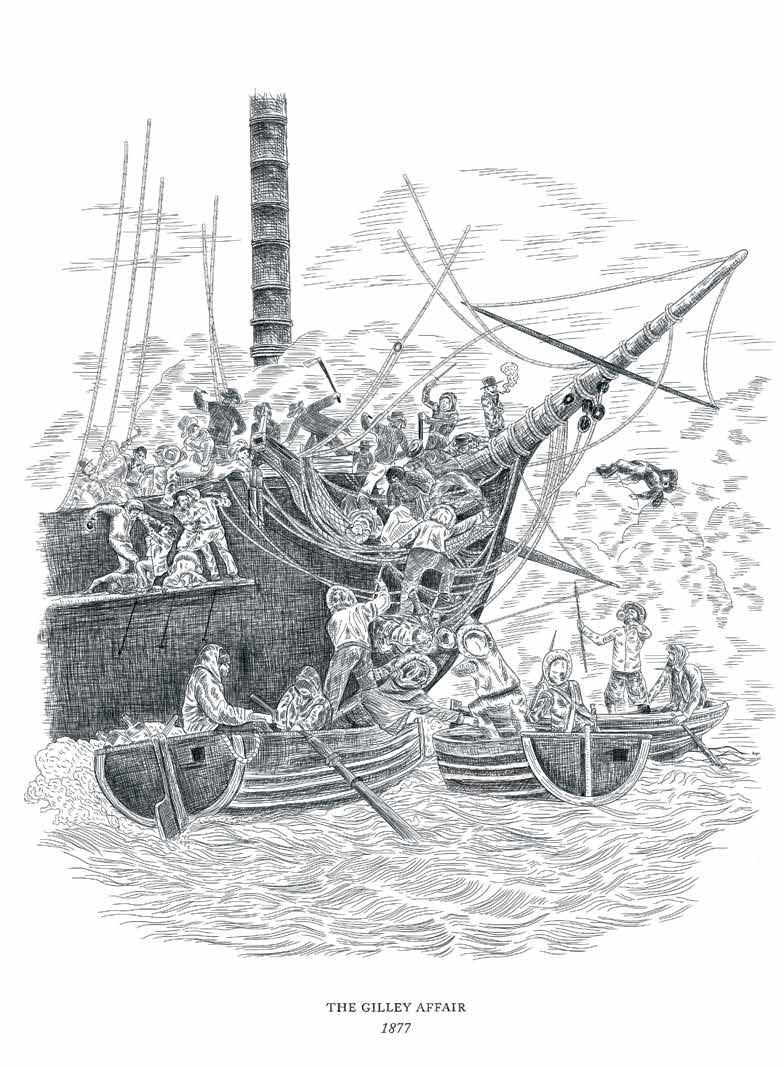

Yet when a moth-eaten memory of Gilley is occasionally brought forth in whaling histories, it rarely highlights his dynamism. Most often, writers cite the so-called “Gilley Affair” that transpired just three years before Kalākaua’s birthday race, when a close shave with the westernmost tip of North America resulted in Gilley’s crew swabbing the decks clean of blood that belonged not to whales but to Iñupiat—“real people” in the Iñupiaq language. But taking a brief, telescopic view of that gruesome picture denies Gilley the full scope of his unrivaled life, which began decades earlier, several seas away.

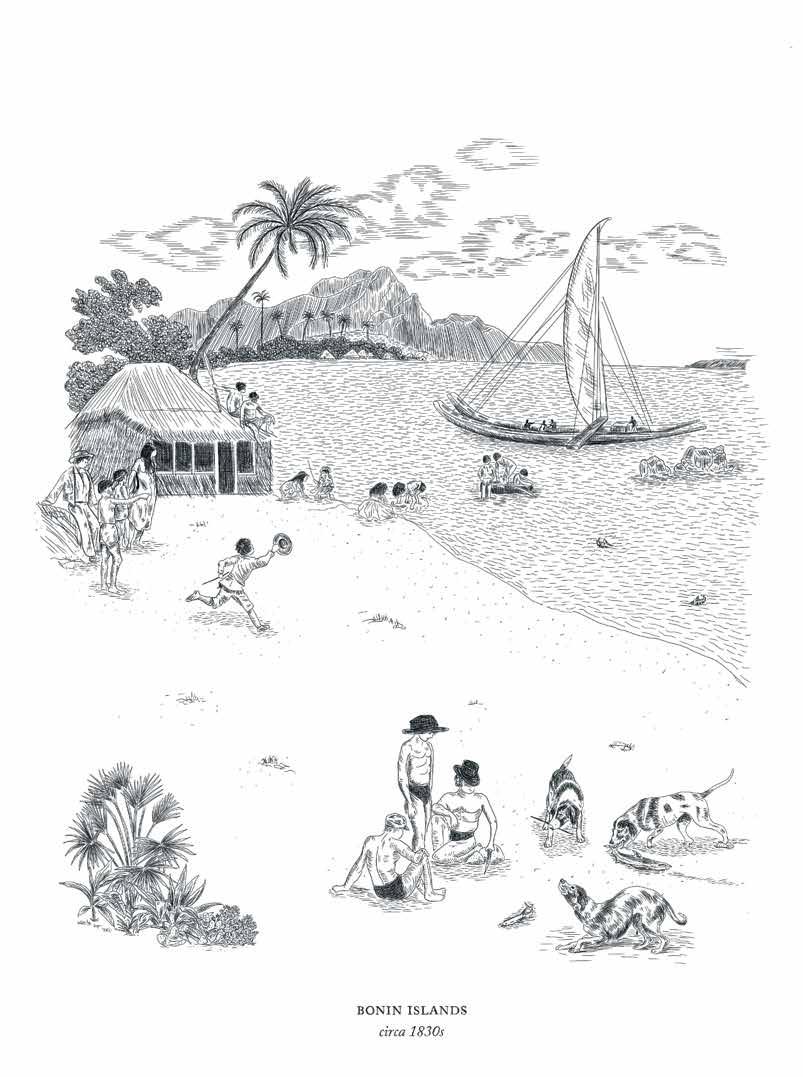

E komo ʻĀkia GONE TO ASIA

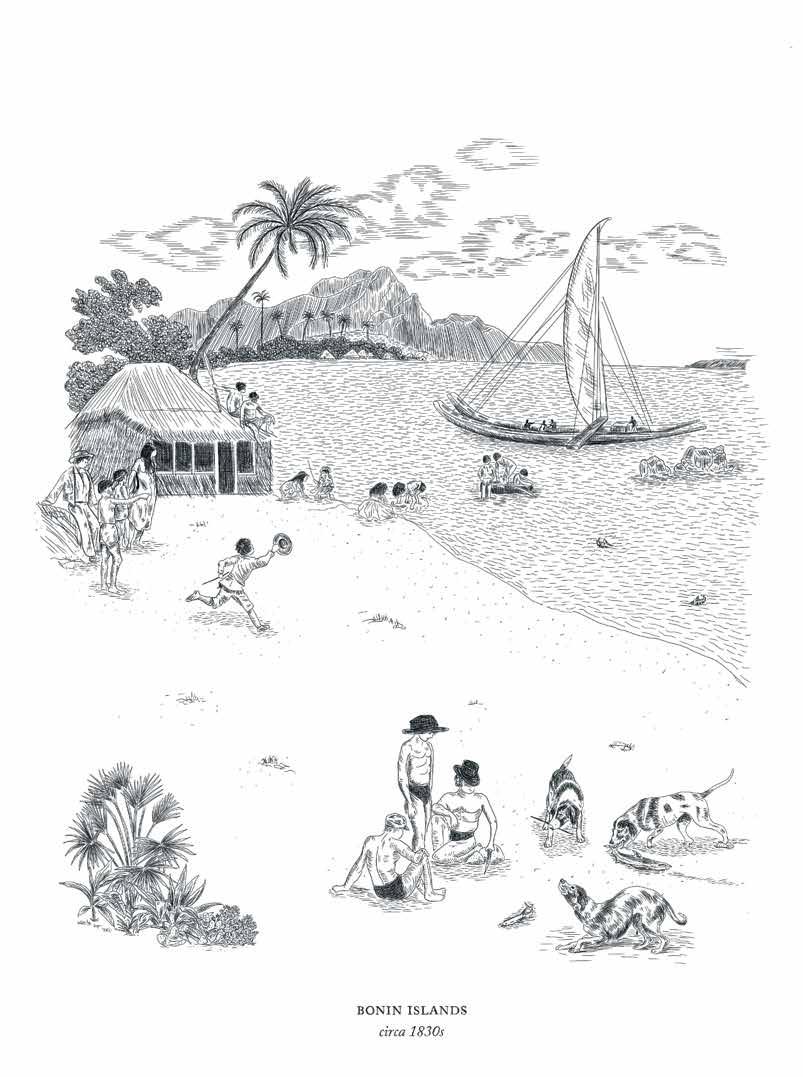

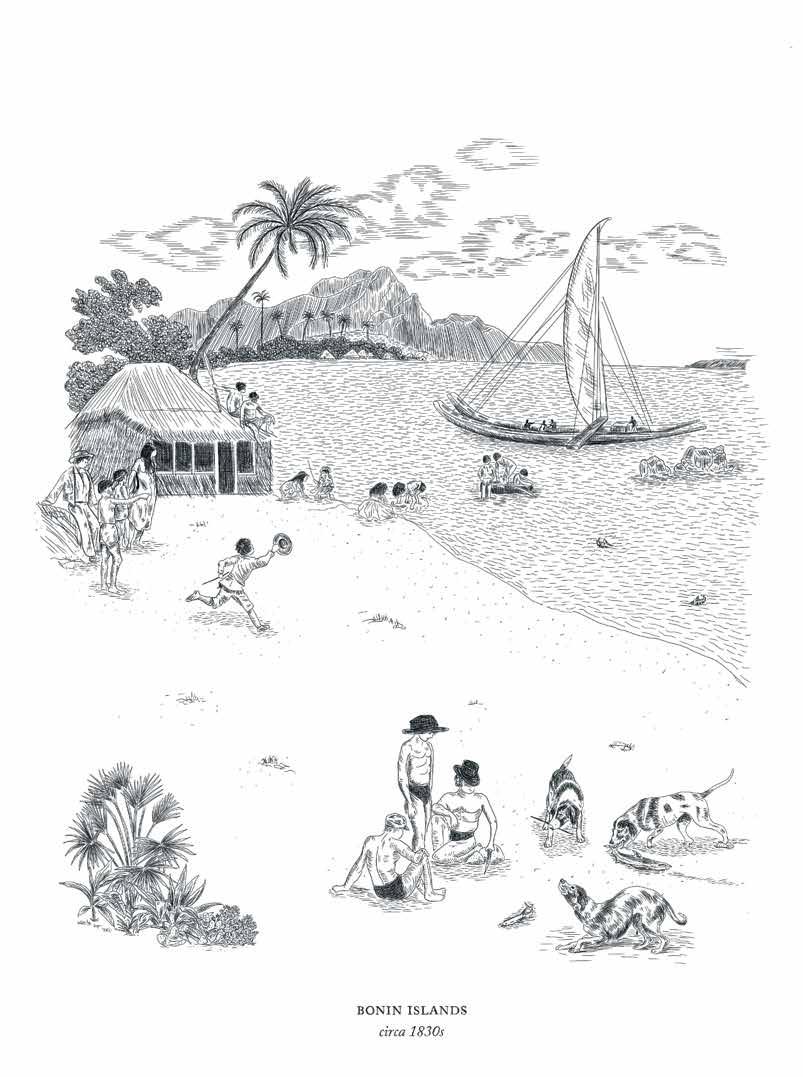

In 1830, a British ship captained by Samuel Dowsett carried 13 pioneering Kānaka Maoli from Hawai‘i nearly 4,000 miles westward to the uninhabited Bonin Islands, 600 miles

south of Tokyo. Accompanying them were five white men—their indenturers and in a few cases husbands—who intended to colonize the island group for England. They settled on Peel Island, now known as Chichijima. By 1835, their grass-hut settlement attracted at least six more enterprising wāhine and several other disaffected Westerners, including Englishman William Gilley. One of the colony’s 16 wāhine bore children who took his name—among them William Jr., Michael, Lizzie, and around 1840, George.

Growing up in this distant microcosm of colonial Hawai‘i, young George thrived on Hawaiian staples, from fresh fish and wild pig to sweet potatoes and sugarcane. His life was defined by the sea. He learned to sail on outrigger canoes made for interisland travel and, at first, likely hunted turtles. In 1837, visiting British captain Michael Quin observed the settlers’ efficient use of island resources, including its many sharks, which he saw “the dogs frequently chase in shoal water, capture and drag high and dry on the sandy beach.” Other supplies came by way of roving whalers that occasionally appeared on the eastern horizon. As a teenager, George Gilley jumped at the first opportunity to leave on one, arriving in Hawai‘i via a whaling ship and sticking around. An 1855 letter, sent to the Bonin Islands from a family friend in Honolulu, mentioned that “George has been here 2 or 3 times but I could not persuade him to go home and see his mother. He seems to like this place so much.”

Through the mid-19th century, Honolulu and Lahaina were the de facto dispatch hubs for ships en route to the cold, whale-rich waters off Japan. Most of these ships hailed from Nantucket and New Bedford, Massachusetts, and brought to the islands everything from bricks to syphilis to Christian missionaries. They also presented opportunities for Kānaka Maoli. In 1840, Richard Henry Dana Jr.’s bestselling sailing memoir Two Years Before the Mast

62 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

broadcast the enviable talents of “Sandwich-Islanders” who made their way from whaling into the fur trade on California’s coast. “Ready and active in the rigging,” wrote Dana, these “complete water-dogs” schooled their New England counterparts in the art of landing small boats through the Santa Barbara surf.

Small-craft skills were vital to the whaling industry, which partly explains for the quick rise of Pacific Islanders to the coveted, harpoonwielding position of boatsteerer—a trend caricatured by Herman Melville’s Queequeg in Moby-Dick. However, Hawaiians ascended well beyond token status on board, and often manned the full span of positions available on a single ship. Even as outsourced laborers, they gleaned competitive seasonal wages ranging from $5 to $200. Between the roughly 5,000 Kānaka Maoli who signed onto whaleships between 1842 and 1867 alone, the profits Hawai‘i skimmed off the American market stacked up. The real booty, however, lay in selling oil to the burgeoning empire, which needed it to light and lubricate its industrial revolutions. As early as 1832, Hawai‘i’s financiers began flipping used ships and assembling a local whaling fleet. Fitted with high-flying Hawaiian flags proclaiming the monarchy’s might, the budding flotilla was loaded with homegrown talent and launched into the wind.

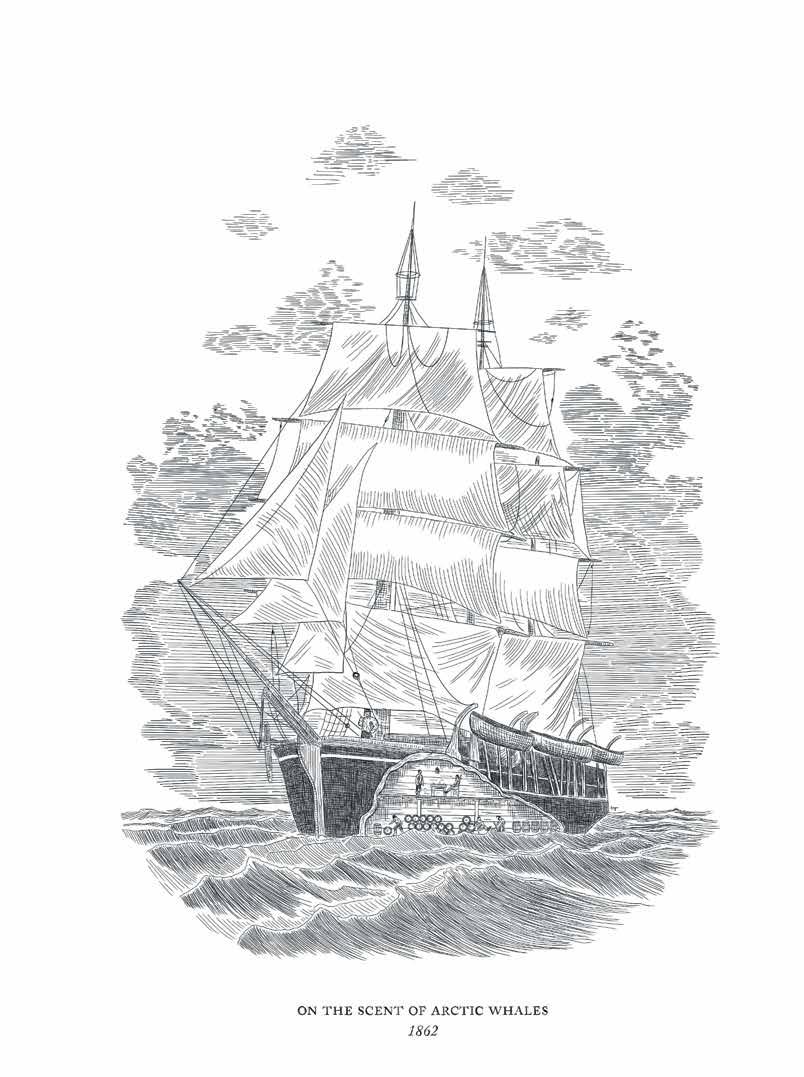

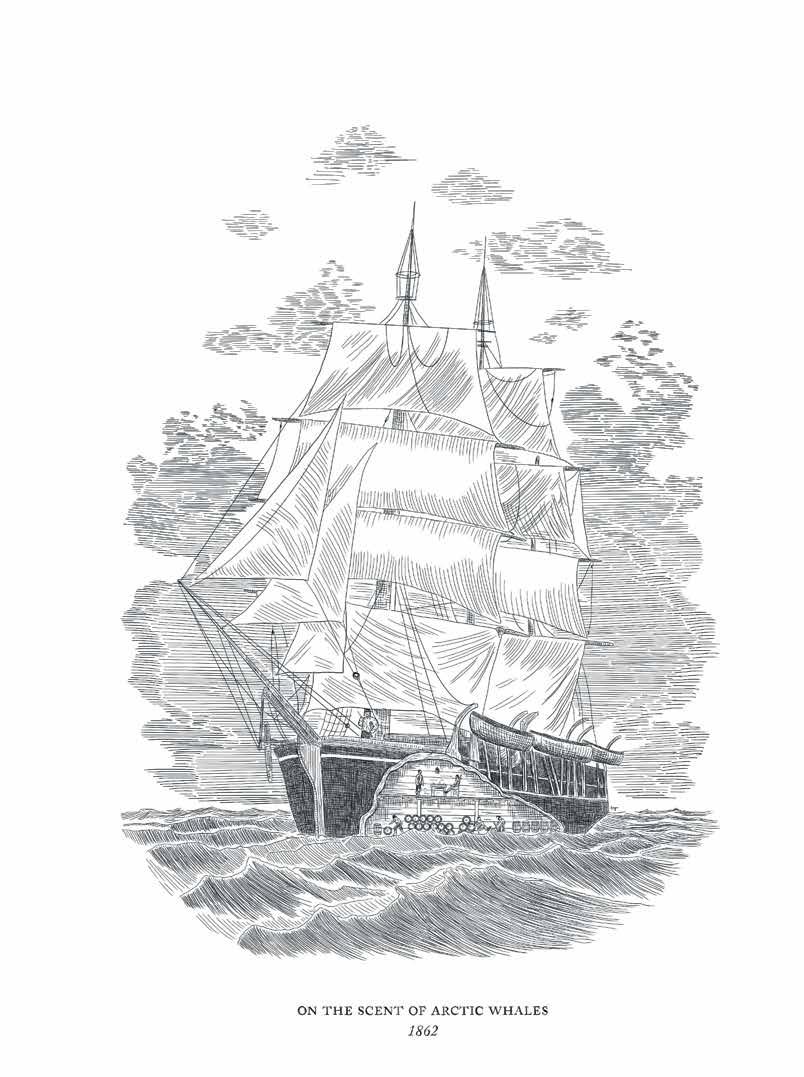

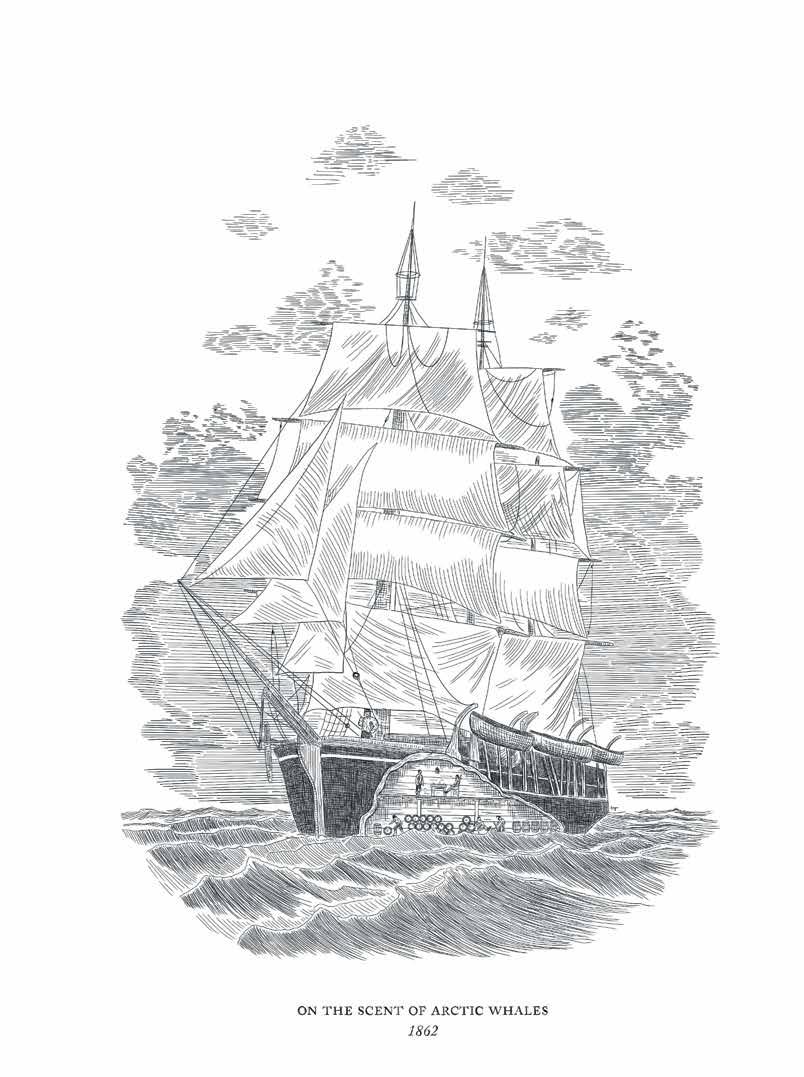

Ke kōā o Pēlina THE BERING STRAIT

According to one newspaper, young George Gilley was on the scent of Arctic whales by 1862, aboard the Hawaiian-registered Kohola under Captain Brummerhop. This could have included his first “wintering over” in the Bering Strait, at eastern Siberia’s St. Lawrence Bay. If he was there, locked in sea ice awaiting the spring hunt, he surely marveled when Siberian Yupik traders emerged from the white landscape to deliver vital deer meat to the crew. The favor,

however, backfired on one such visitor, Capatchou, who became trapped on the ship during a gale. Desperate to see his family, Capatchou futilely begged Brummerhop for help ashore, jumped overboard to attempt the frigid swim, and disappeared.

Later, Gilley would have heard gunshots echo across the ice as the captain tried to defend himself from the vengeful arrows and spears of Capatchou’s relatives at their village. The crew were only returned Brummerhop’s clothing, but never his body. When the Kohola resumed its methodical decimation of the Yupiks’ source of whale meat and muktuk (a skin and blubber dish) in the spring, five of Gilley’s fellow Kānaka died of scurvy, followed by three more from other diseases. Sailed by first mate Bernard Cogan, the Kohola returned to Honolulu in the fall of 1863 with 600 barrels of bowhead whale oil and 10,000 pounds of baleen, which equates to about six kills. Between 1847 and 1867, whalers would remove more than 18,000 bowheads from the Arctic—more than the entire population in the region today.

In 1863, Gilley’s father (or possibly brother), William, was reportedly murdered, which might explain why an 1870 letter written by Lizzie suggests that Gilley had returned to the Bonin Islands. But by February 14, 1872, the Hawaiian Gazette listed a sailor named “Gillie” on the Honolulu yacht Henrietta who is “counted among the most expert whalemen that belong here.” Although the Henrietta was slated for a two-month shark hunt, the Advertiser reported on February 24 that “the crew of the Henrietta have struck three whales since leaving here; one sunk and was lost; one they secured and tried out at Ukumehame, to the westward of Lahaina, and they were fast to another when last seen, on Monday, in the channel between Molokai and Lanai.” But was this our Gilley? The Advertiser confusingly identified this whaler as “R. Gillie,” a name found nowhere else in Hawai‘i’s

whale-related press. By contrast, misinformation and misspellings abound in these papers— Brummerhop’s name, for example, was rarely spelled the same way twice. In any case, Gilley would have needed exactly the kinds of experiences gained on the Kohola and Henrietta to explain how by 1875 the approximately 35-year-old was listed as captain of the brig Onward, becoming the only known Kanaka Maoli to achieve that title on a whaleship. Owned by Honolulu businessman James Dowsett, son of the Captain Dowsett who ferried the first settlers to the Bonin Islands, the Onward was a force in the kingdom’s whaling fleet. In Gilley’s first recorded season as a captain, he proved his worth. Following a successful spring hunt, the Advertiser reported in November that the brig Onward sailed into port with her casks brimming with oil, thanks to Gilley’s winning gamble on a once-popular whaling ground near Alaska’s Kodiak Island.

Ke liolio nei ke kaula likini THE RIGGING LINES TIGHTEN

In December 1876, Dowsett hired Gilley again, to captain the William H. Allen for a short hunt along the equator—a late-season trip likely intended to recoup some of the year’s Arctic losses. That summer, at least 12 ships, including the Honolulu barks Arctic and Desmond, had been lost to rogue ice floes off Nuvuk, or Point Barrow, on the north coast of Alaska. It seems that delays in fitting out the William H. Allen spared Gilley the hardship faced by the 300 seamen stranded on the ice, though there is a chance he had been present for the even greater disaster of 1871, five years prior, which had claimed 33 ships, including the Kohola and three other Hawaiian-registered vessels. When not listed as a captain, a whaler’s story is difficult to track—unless they wrote it down.

Such was the case for Kanaka seaman Charles Edward Kealoha,

64 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

whom Gilley saw hurtling toward him over the ice dunes near Tangent Point, Alaska in early August 1877. Gilley was again at the helm of the William H. Allen, having embarked from Honolulu on April 21. Kealoha, on the other hand, had been on Alaska’s north slope for almost a year. He and a Mā’ohi whaler named Kenela, both of the Desmond, were the last survivors of at least 50 men who had stayed behind in Alaska when others took their chances on a few crowded ships that escaped the ice. These two Pacific Islanders persevered by the grace of Iñupiat who brought them to their warm caves and fed them fatty fish and orca meat.