Theme: MEMORY 0 02 > 09281 $14.95 US $14.95 CAN 25489 8 The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I { 24} Framing Identities { 66} Black Lives Matter { 126} Modernist Origins

MAXMARA.COM WAIKIKI 2186 K A l AKA u A Avenue 808 926 6161

Editor’s Letter

Contributors

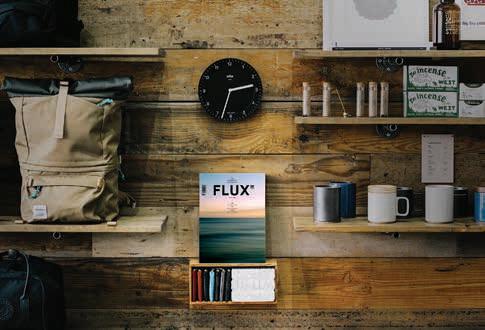

FLUX PHILES

24 | Portraiture Nikkeijin

32 | Childhood Hanafuda

42 | Activism Wāhine Koa

A HUI HOU

168 | Isolation

FEATURES

52 | The Gravity of Inoa ‘Ā ina

Due to the islands’ colonial history, the Hawaiian place names of common landmarks and regions have faded in the public consciousness. N. Ha‘alilio Solomon writes of how industrial development and militarization have silenced inoa ‘āina, and as a result, Hawaiian stories, knowledge, and values, and the incremental ways they are being reclaimed.

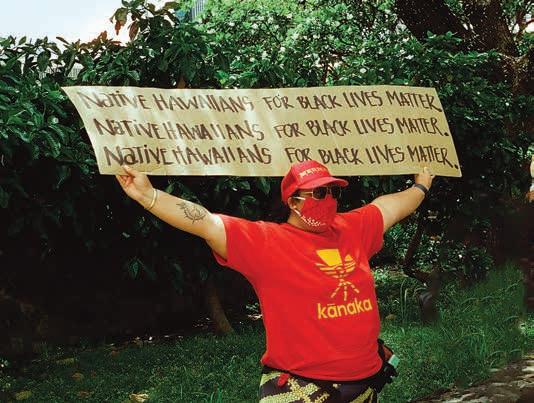

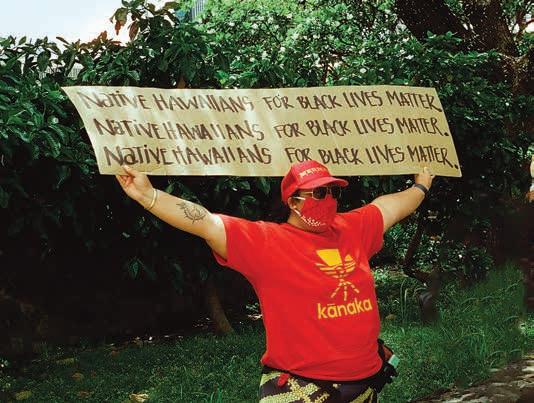

66 | Black Lives Matter in the Hawaiian Kingdom

In this illuminating essay, Joy Lehuanani Enomoto contextualizes the B.L.M. movement in the Pacifc. Referencing ancient mo‘olelo, the islands’ monarchy past, and 21st-century events, she traces why Hawai‘i and the lāhui must stand with Black liberation.

78 | The Pandemic Diaries

Written in the unnerving times of the novel coronavirus, these four pieces by writers Noelani Arista, Marika Emi, Tina Grandinetti, and Shannon Wianecki attempt to make sense of the complicated range of emotions and societal issues that have surfaced since Hawai‘i’s frst lockdown order.

TABLE

| FEATURES | 14

OF CONTENTS

MEMORY

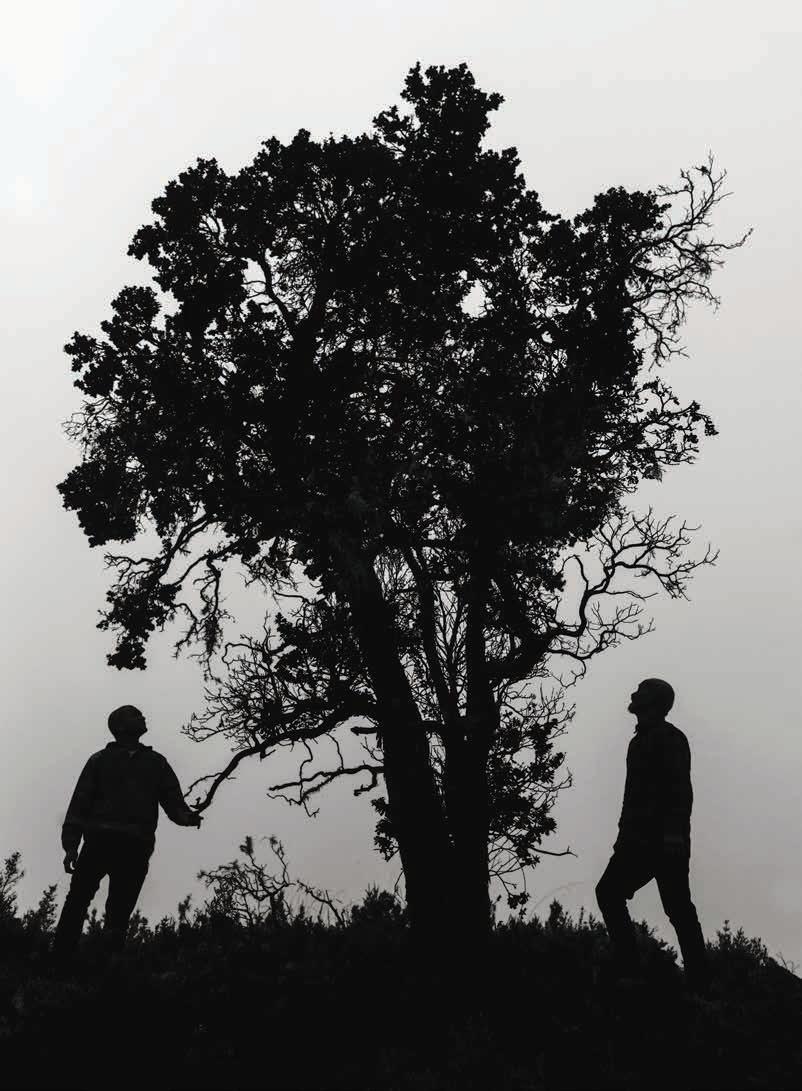

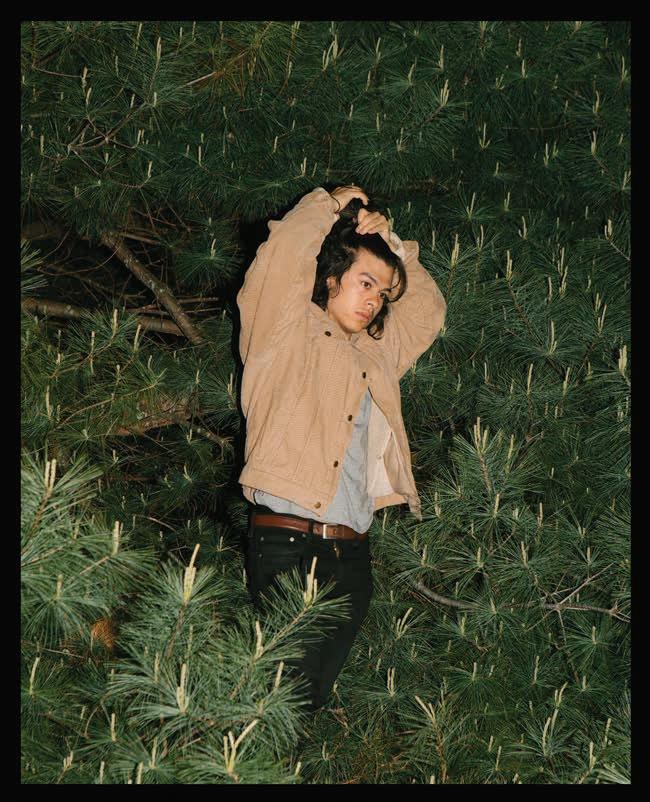

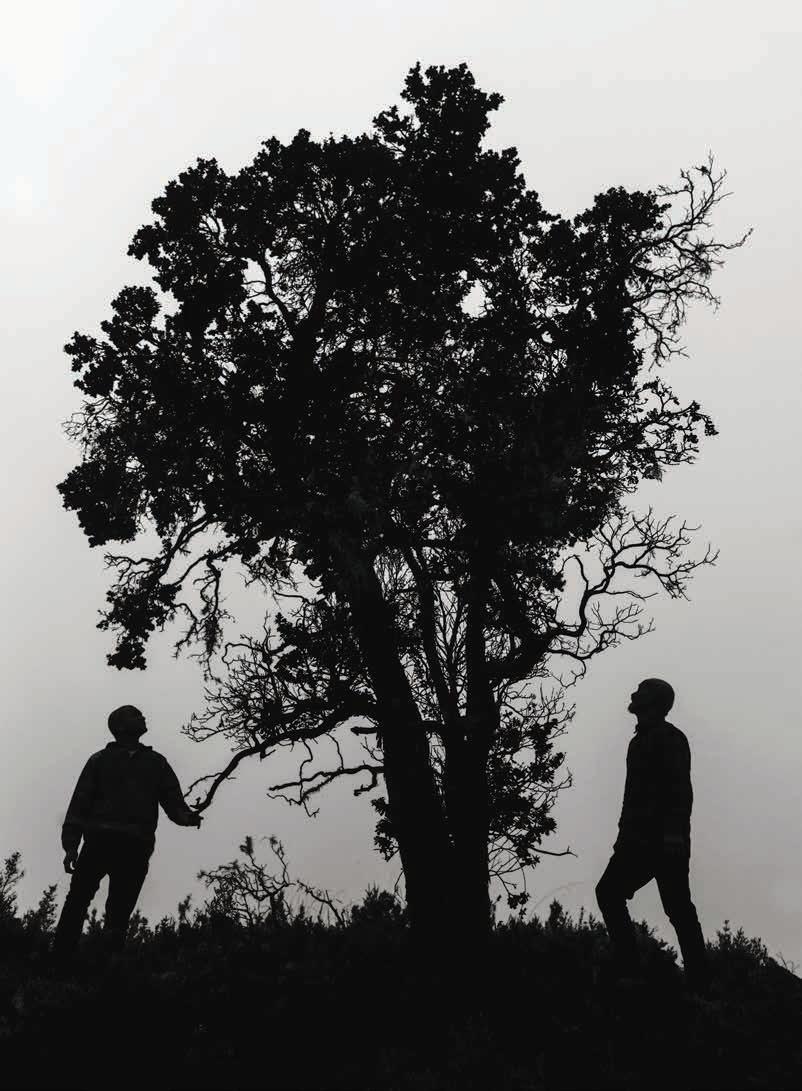

Image by Vincent Bercasio

TABLE OF CONTENTS | DEPARTMENTS |

SPECIAL SECTION

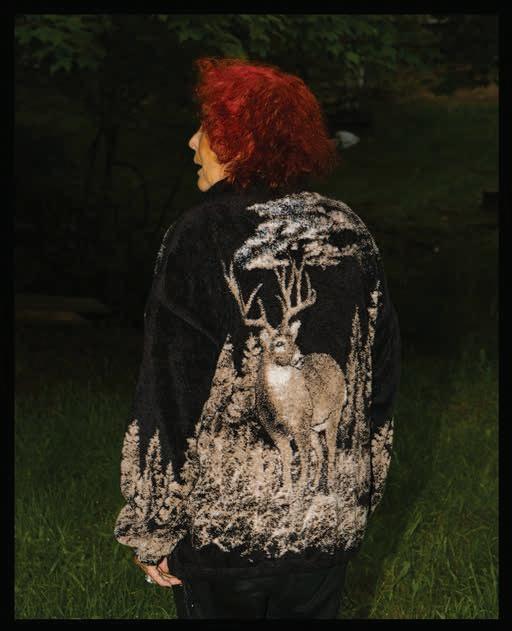

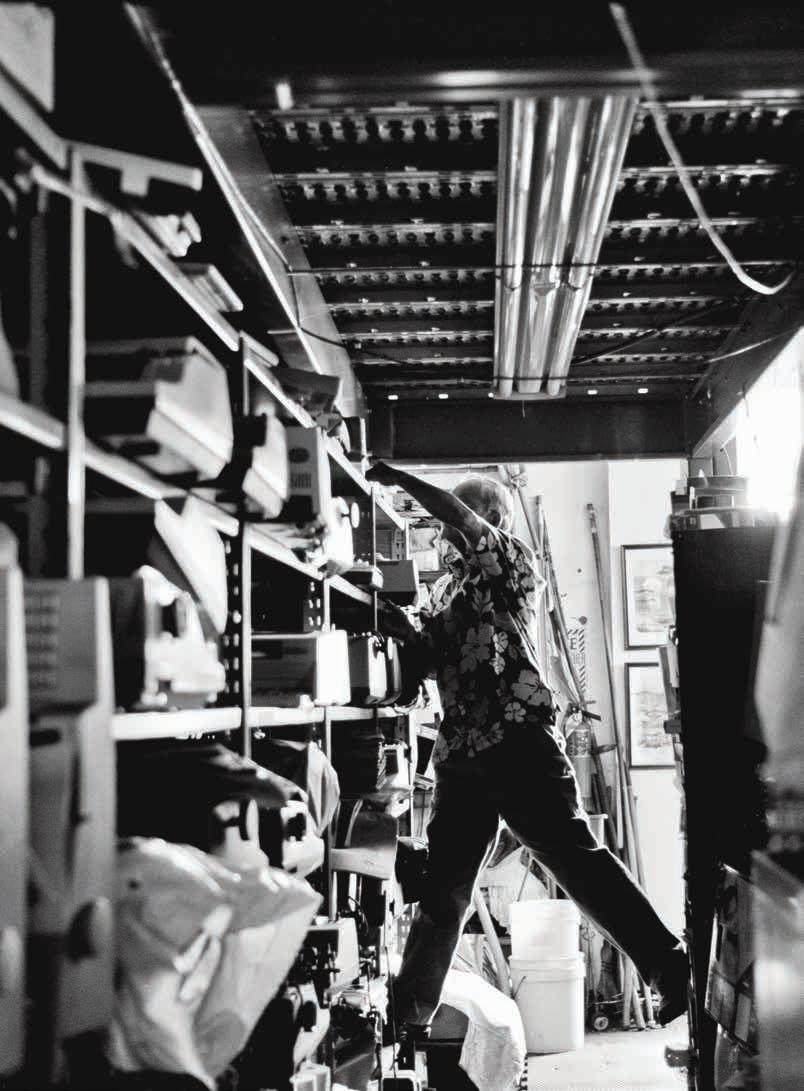

TEN - YEAR ANNIVERSARY

In this photography retrospective, revisit some of the most compelling visual moments published in the pages of Flux Hawai‘i.

Senior photographer John Hook, creative director Ara Laylo, national editor Anna Harmon, and founding editor Lisa Yamada-Son reminisce over a decade of memorable images.

90

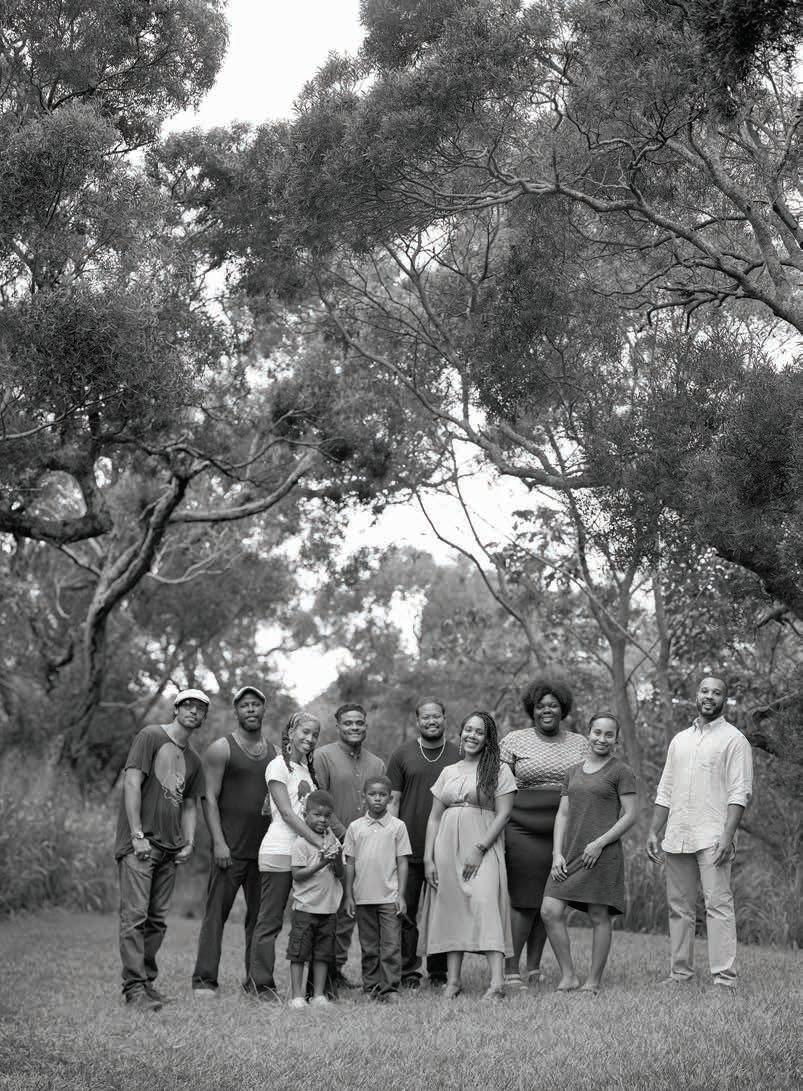

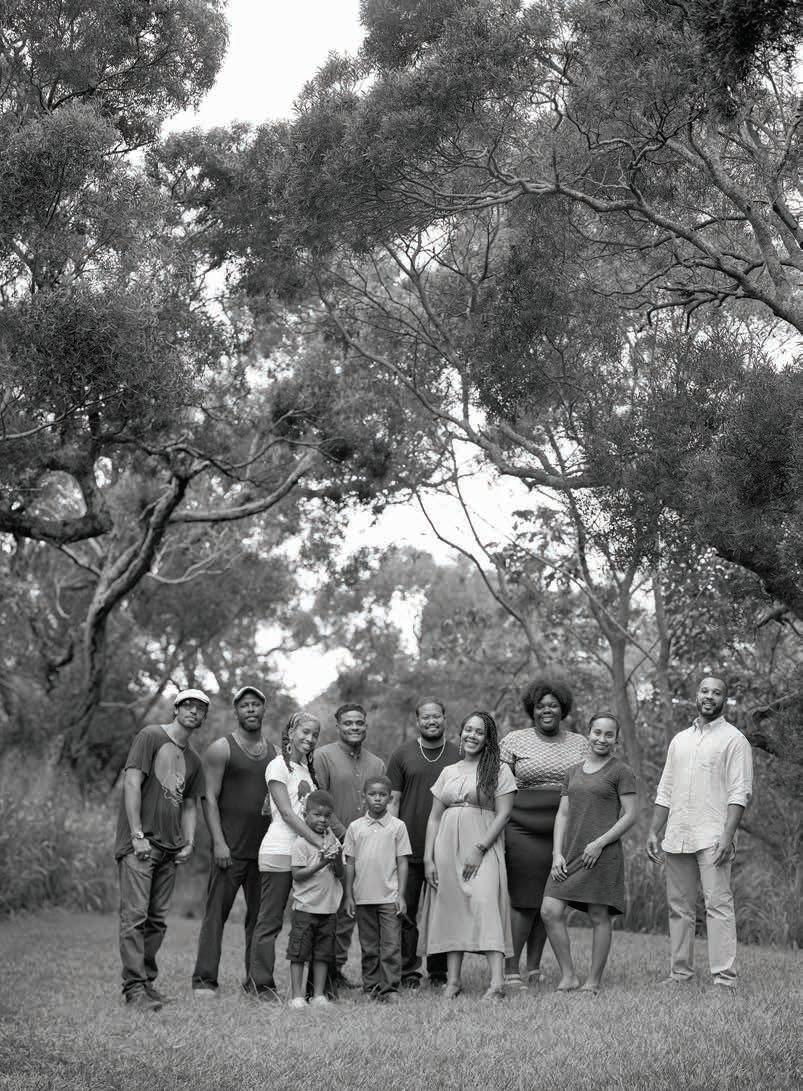

Image by Mark Kushimi

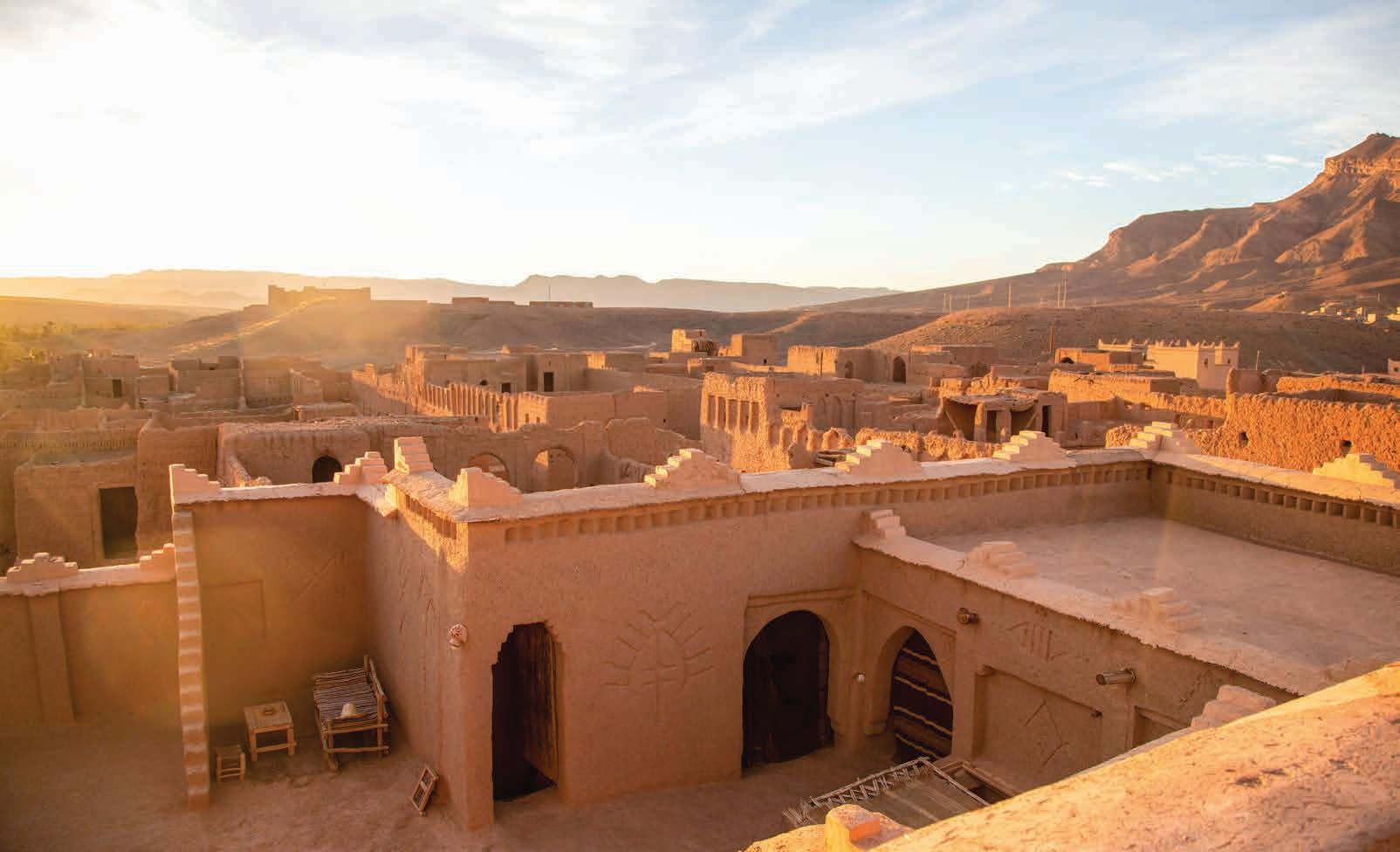

126 | Design Pālehua

136 | Travel Postcards

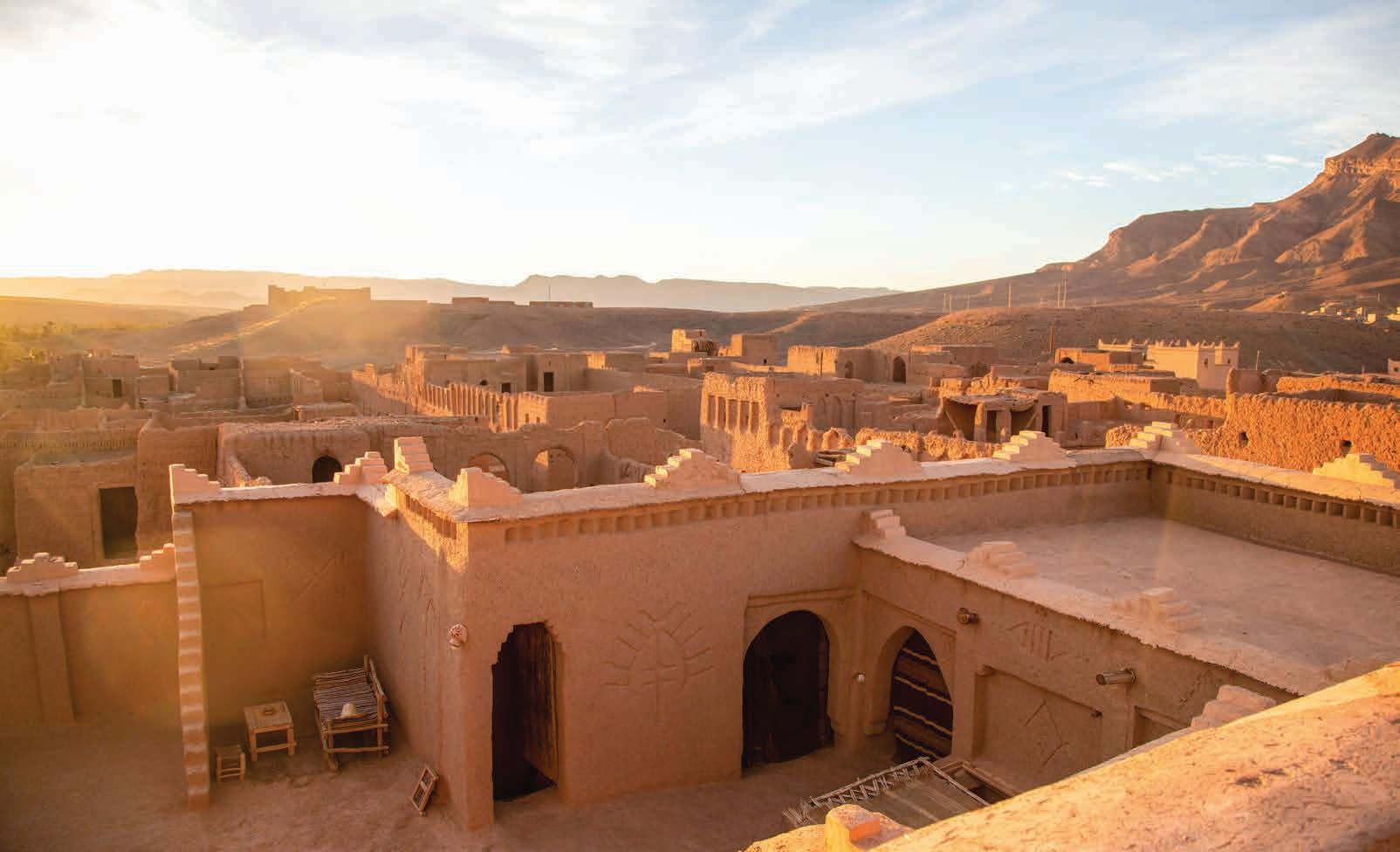

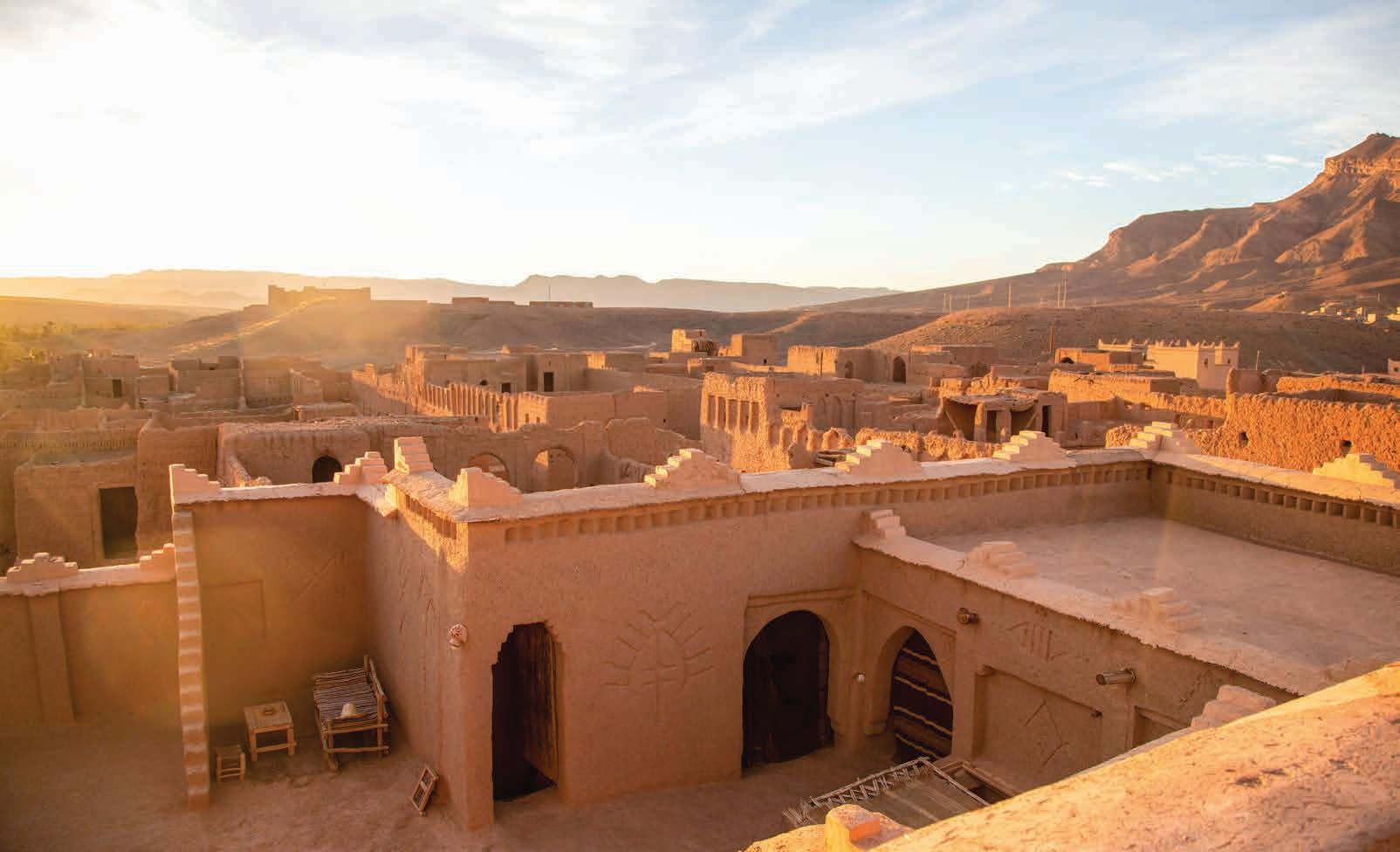

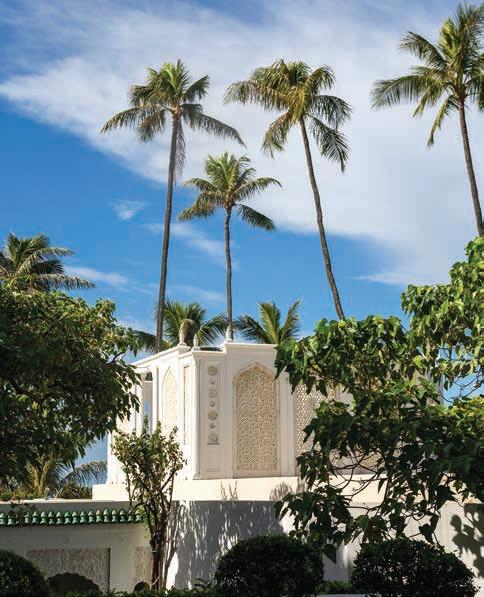

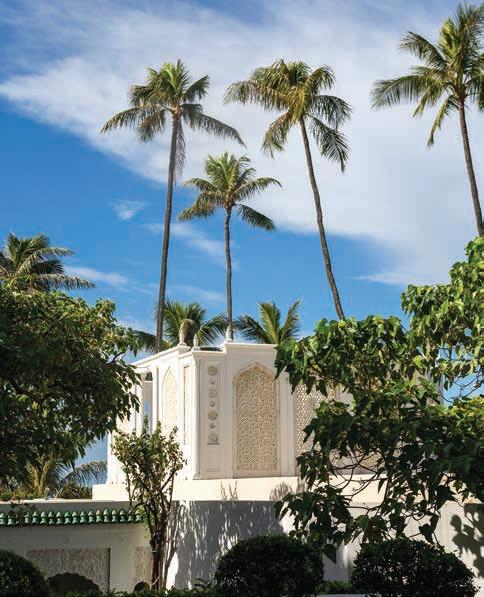

146 | Wahi Pana Kūkaniloko 156 | Morocco Shangri La

144 EXPLORE

124 LIVING WELL

TABLE

| DEPARTMENTS |

OF CONTENTS

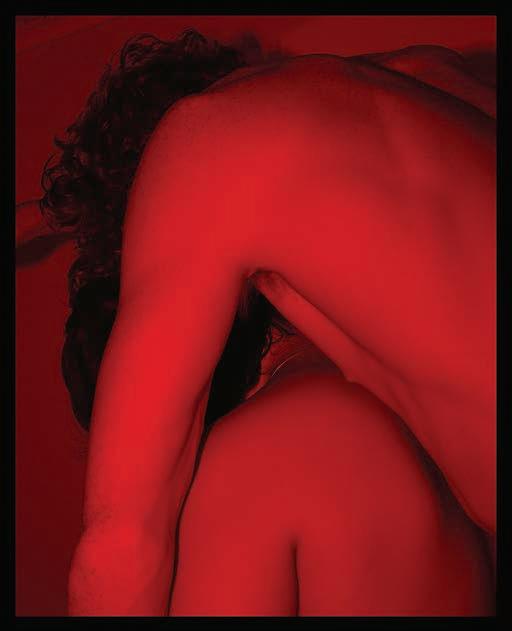

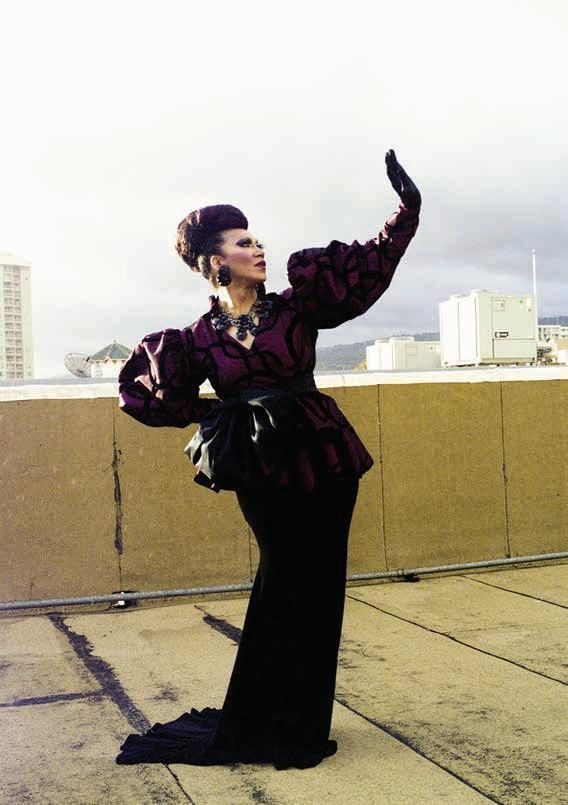

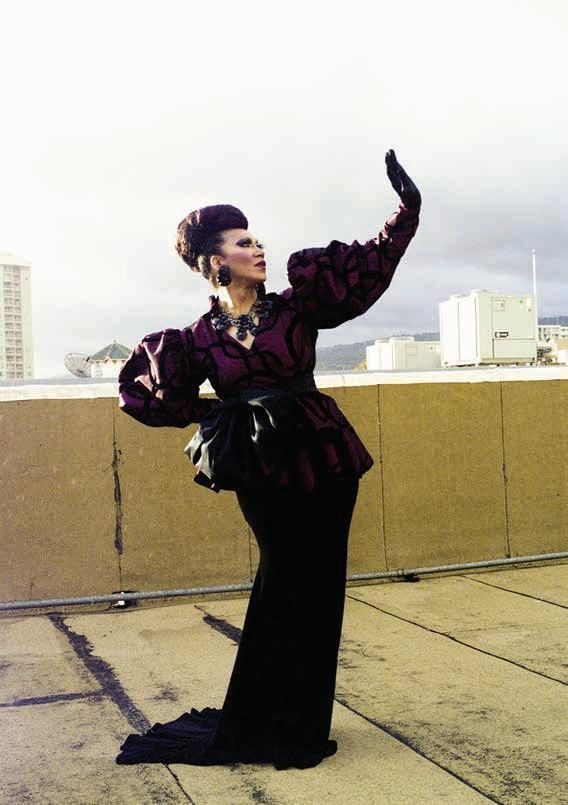

Image by Sera Lindsey

Image by John Hook

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Food Sustainability

As Covid-19 continues to upend modern society, Hawai‘i ’ s local food systems attempt to adjust to the new normal. In this season of In Flux , confront the trials and tribulations facing the islands ’ farmers and suppliers.

FLUXHAWAII.COM

Streaming Videos, Newsletters, Local Guides, and More

We’ ve refreshed the website for Flux Hawai‘i with a more dynamic viewing experience. Watch all the original episodes from our themed seasons, fnd ways to support local small businesses, and sign up for our weekly newsletters curated with fascinating reads. You can also browse past issues of the print magazine for purchase.

|

FLUX TV | FLUX TV

ARE WORTH WAITING FOR SOME MOMENTS HALEKULANI RENEWED OPENING 2021 RESERVATIONS

WWW.HALEKULANI.COM

For an unprecedented time,

as this collective one we’re living through has been so widely referred to, there is a stilling comfort in knowing perhaps there is already an ‘ōlelo no‘eau that suits it. Here, a popular and applicable one: “I ka wā mamua, ka wā mahope.”

Translation: “In the past, the future,” more commonly understood to mean, “The future is in the past.” Somewhat of a proverbial ouroboros in both speech and translation, its rotund construction was clarifed best by Hawaiian scholar Lilikalā Kame‘eleihiwa when she wrote, “In Hawaiian, the past is referred to as ka wā mamua, or ʻ the time in front or before.’ Whereas the future, when thought of at all, is ka wā mahope, or ʻ the time which comes after or behind.’ It is as if the Hawaiian stands frmly in the present, with his back to the future, and his eyes fxed upon the past, seeking historical answers for present-day dilemmas. Such an orientation is to the Hawaiian an eminently practical one, for the future is always unknown, whereas the past is rich in glory and knowledge.”

This retroftted reasoning to resituate your relative position as you navigate this year is not a panacea for the dueling diseases—Covid-19 and racism—that are ravaging lives across the country, but, if anything, it’s a salve. In the climate of anxiety and uncertainty that beclouds this moment, gathering your bearings is a viable way to keep from keeling over. The systemic inequities that the pandemic has exposed in these swift if glacial six months since the frst known cases of the virus emerged in the United States and Hawai‘i have upended our days with pressing questions, one being: How did we get here? Improving on how to answer that question is key to combating being negligent to the present, because “if you understand your condition,” another Hawaiian scholar, HaunaniKay Trask, once suggested, “you’re in a better position to interact with it, to change it, to increase your participation in it.”

This issue of Flux is inspired by the subject of memory, that slippery and vulnerable device. The stories within concern themselves with this gesture of looking back to look forward, whether in art, design, travel, or allyship. At their most intimate, like in our feature from four local writers, “The Pandemic Diaries,” on page 78, they create a record for posterity of the challenges we are facing at this date; at their most impassioned, like artist-activist Joy Lehuanani Enomoto’s essay, “Black Lives Matter in the Hawaiian Kingdom,” on page 66, they are attempts to organize through a foggy and imposed collective memory of Hawai‘i—itself a byproduct of the state’s own colonial baggage—to strike greater degrees of clarity: historical, political, and moral. At their best, the stories display how memory can transmogrify an abstract, solitary account into a wieldy weapon. Miming memory can equip us with the consciousness we’ll need when we can once again step outside without a care over this virus, but with all the cares in the world for everything else plaguing us, whenever that will be.

With Aloha,

Matthew Dekneef EDITORIAL DIRECTOR @mattdknf

EDITOR’S LETTER | MEMORY |

Handcrafted Classic Aloha Wear www.davidshepardhawaii.com

MASTHEAD

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Ara Laylo

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Matthew Dekneef

MANAGING EDITOR

Lauren McNally

NATIONAL EDITOR

Anna Harmon

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Eunica Escalante

SENIOR PHOTOGRAPHER

John Hook

PHOTOGRAPHY EDITORS

Samantha Hook

Chris Rohrer

DESIGNER

Skye Yonamine

CONTRIBUTORS

Noelani Arista

Martha Cheng

Marika Emi

Joy Lehuanani Enomoto

Christine Hitt

Noelani Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua

Tina Grandinetti

Sera Lindsey

Timothy A. Schuler

N. Ha‘alilio Solomon

Tori Toguchi

Shannon Wianecki

Lisa Yamada-Son

Kylie Yamauchi

IMAGES

Vincent Bercasio

Alexis Cheung

Mitchell Fong

Ed Greevy

Graham Hart

Greg Hatton

Brendan George Ko

Sera Lindsey

Will Matsuda

Michelle Mishina

@misterver

Chris Rohrer

Franco Salmoiraghi

CREATIVE SERVICES

Marc Graser VP GLOBAL CONTENT

Shannon Fujimoto CREATIVE SERVICES MANAGER

Kaitlyn Ledzian

ART & PRODUCTION MANAGER

Gerard Elmore LEAD PRODUCER

Aja Toscano CREATIVE PRODUCER

Shaneika Aguilar FILMMAKER

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock CHIEF RELATIONSHIP OFFICER

joe@NMGnetwork.com

Francine Beppu NETWORK STRATEGY DIRECTOR francine@NMGnetwork.com

Gary Payne VP ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE

Courtney Miyashiro OPERATIONS ADMINISTRATOR

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley VP SALES mike@NMGnetwork.com

Phil LeRoy NATIONAL SALES DIRECTOR

Chelsea Tsuchida KEY ACCOUNTS & MARKETING MANAGER

Helen Chang MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

Jackie Tu SALES ASSISTANT

Taylor Kondo FASHION MARKETING COORDINATOR

General Inquiries: contact@fuxhawaii.com

PUBLISHED BY:

Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel St., Ste. A Honolulu, HI 96817

©2008-2020 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. ISSN 2578-2053

| MEMORY |

On the Cover

A raised fst during a Black Lives Matter rally at the Hawai‘i State Capitol by photographer Greg Hatton is featured on the cover of the Memory Issue. This image was captured at one of three organized protests that took place in Honolulu following the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020. “In my childhood I remember seeing images and hearing stories of the civil rights movement, the Black Panthers, police brutality, lynchings, strange fruit swinging in them trees … the pain of the struggle and the feeling of pride knowing my people endured so much,” says Hatton, who was born and raised in Los Angeles, and is now based in Hawai‘i. An enduring visual of that era is the raised Black fst, “a symbol that was not just an idea of strength, but a reality of it. After all, that Black fst was and is attached to a strong Black person, standing up to violence, discrimination, hatred, bigotry and fear to show that we are here and worthy of respect.”

Joy Lehuanani Enomoto

Joy Lehuanani Enomoto

Joy Lehuanani Enomoto is a Kanaka Maoli, African American, Japanese, Caddo Indian, Punjabi, and Scottish visual artist, archivist, social justice activist, and kiaʻi of Mauna Kea. Her work engages with mapping climate justice, extractive colonialism, saltwater conversations that occur within the diaspora, the policing of black and brown bodies, anti-Blackness in Oceania, demilitarization, and other issues currently afecting the peoples of Oceania. Her artwork and scholarship have been featured in Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawaiʻ i, Na Wahine Koa: Hawaiian Women for Sovereignty and Demilitarization, Amerasia Journal, and Bamboo Ridge. In January 2020, Enomoto collaborated with poet and climate activist Kathy JetnilKijiner for the exhibition Inundation at UH Mānoa Art Gallery. Enomoto wrote the piece “Black Lives Matter in the Hawaiian Kingdom,” on page 66, in conversation with the Hawaiian and Black community living in Hawai ʻi and hopes that readers will recognize the value and necessity of solidarity in these difcult times.

N. Ha ‘ alilio Solomon

N. Haʻalilio Solomon is a Hawaiian language instructor at the University of Hawai ʻi at Mānoa, where he is also a PhD candidate in the department of linguistics. He is a translator of ‘ōlelo Hawai ʻi with Awaiaulu and Hoʻopulapula. He is the author of “Rescuing Maunalua: Shifting Nomenclatures and the Reconfguration of Space in Hawaii Kai,” a chapter in the forthcoming book Migrant Ecologies: Environmental Histories of the Pacifc World (2021). For this issue, he wrote the feature “The Gravity of Inoa ‘Āina,” on page 52, examining the erasure of Hawaiian place names. “Losing our place names does more than we may realize in the way of obscuring our past and distancing us from it,” Solomon says. “One way to reconcile with Hawai‘i’s colonial history is to keep Hawaiian place names alive by speaking them to children and reclaiming them in everyday speech. At this point, this is an act of resistance in itself.”

Raised in Kāne ʻohe, Oʻahu, Kylie Yamauchi is passionate about telling the stories of her local community. After earning a B.A. in English Literature from the University of San Francisco, she returned home to continue studying the junctures of language, gender, and race. Since interning at NMG Network in 2018, she’s contributed multiple articles to Flux, particularly pieces about Hawaiian and local history. In “Hanafuda Redux,” page 32, she refects on a photography series inspired by one of her childhood pastimes. “The game of hanafuda through Will Matsuda’s lens allowed me to see the larger signifcance of this card game,” Yamauchi says. “His attempt to conjure Japanese images in an American environment represented the plight of many Japanese immigrants. As a yonsei, I was reminded of my family’s history of displacement and adaptation upon moving to Hawai‘i.”

CONTRIBUTORS | MEMORY |

Kylie Yamauchi

INTRODUCING KRISTIE FUJIYAMA KOSMIDES

Hilo-born artist, Kristie Fujiyama Kosmides, has been quietly painting away in her Hawaii studio since returning from Los Angeles in 2017. Some may be familiar with her oversized pieces and murals that grace the Honolulu International Airport, Straub Medical Center - Ward Village Clinic & Urgent Care, and the Sheraton Maui, Kaanapali, to name a few. Upcoming projects include 50 original paintings for the new Straub Medical Center - Kahala Clinic & Urgent Care at Kū‘ono Marketplace and an 825-square foot art installation for an airport lobby. A visual storyteller, Kristie is inspired by experiences, connections, and reflections of daily life. Collectors around the world connect to her art which captures energy both serene and powerful. Kristie’s latest collection, Works on Linen, is presented here. Originals and prints available.

To see all projects, please visit www.kf.art or @kristiekosmides.

LEFT: STRAUB MEDICAL CENTER, WARD VILLAGE | PC - ROXY FACER

ABOVE: STRAUB MEDICAL CENTER, KAHALA | PC - TRACEY NIIMI

RIGHT: RESIDENCE COMMISSION, MAUNA LANI

LEFT: STRAUB MEDICAL CENTER, WARD VILLAGE | PC - ROXY FACER

ABOVE: STRAUB MEDICAL CENTER, KAHALA | PC - TRACEY NIIMI

RIGHT: RESIDENCE COMMISSION, MAUNA LANI

an

Studies

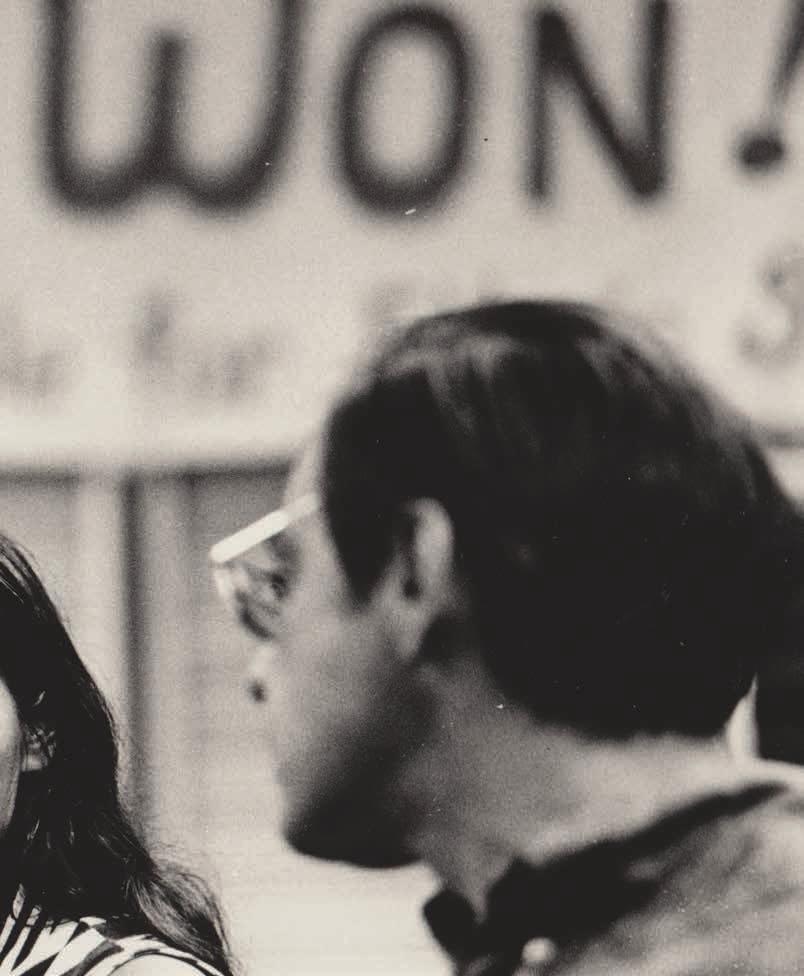

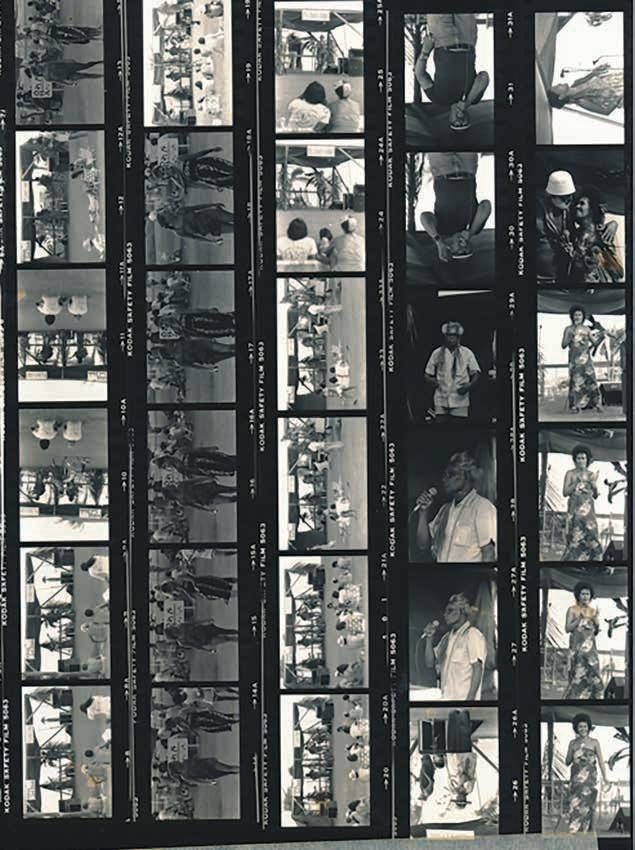

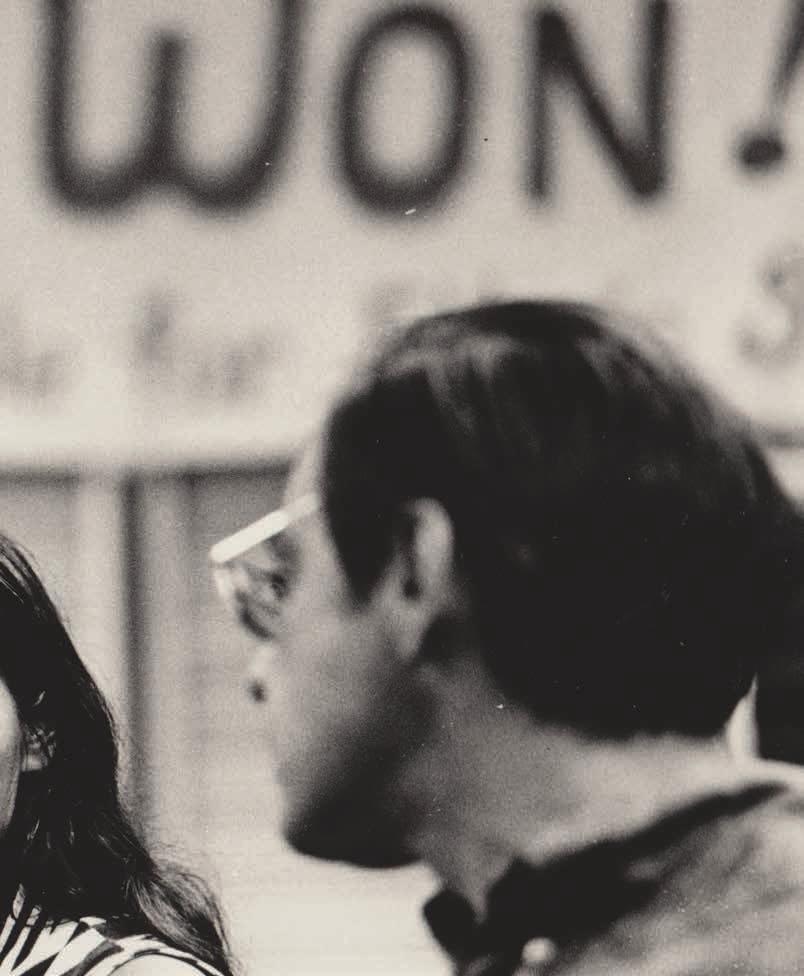

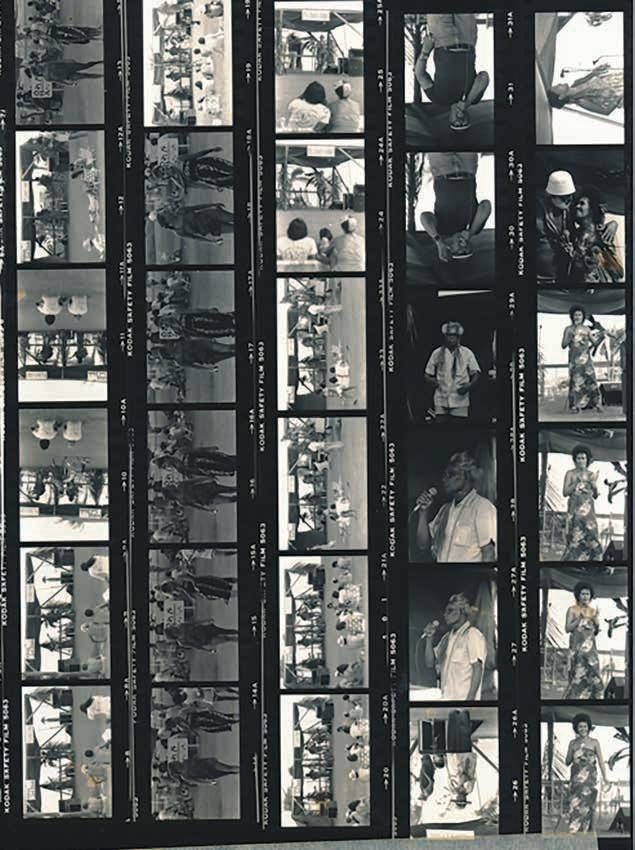

Activist Terrilee Keko‘olani-Raymond at

Ethnic

meeting at the Kaimuk ī library, 1972. Image by Ed Greevy.

Activist Terrilee Keko‘olani-Raymond at

Ethnic

meeting at the Kaimuk ī library, 1972. Image by Ed Greevy.

MEMORY

“I listened to the tide roll onto shore, a global heartbeat that mimicked my own.”—Shannon Wianecki

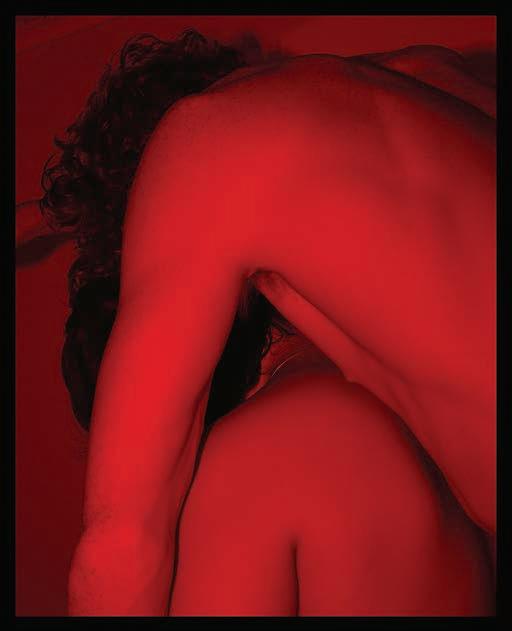

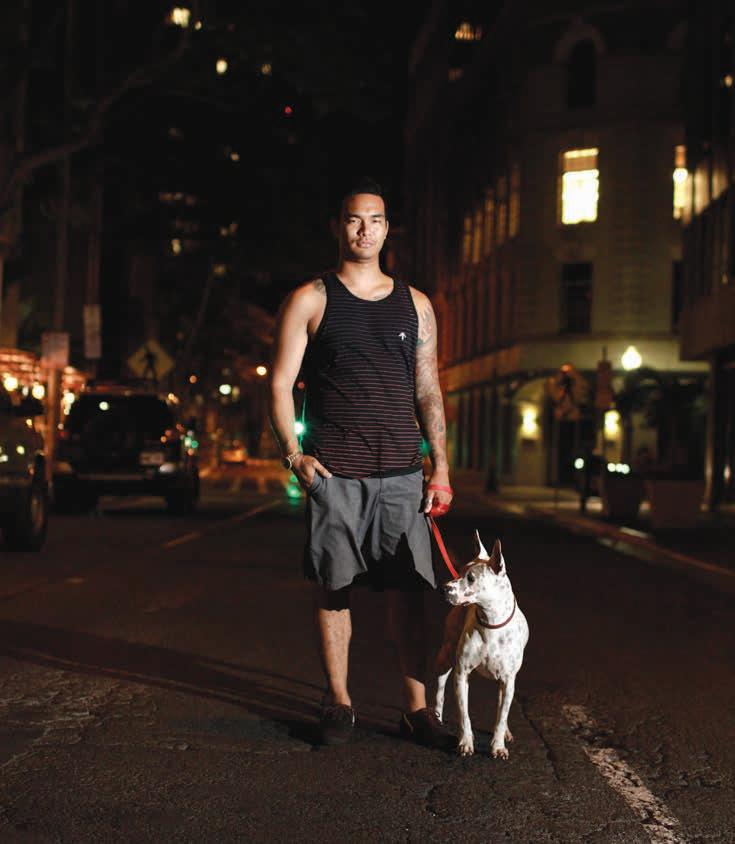

Framing Identities

The lived nikkei experience is difcult to define in the world, let alone in a single photograph. With her portraits, photographer Tori Toguchi aims to create space to explore multiple meanings.

TEXT BY ALEXIS CHEUNG

IMAGES BY TORI TOGUCHI

They’re known as nikkeijin, emigrants of Japanese descent and their descendants who permanently live abroad. It’s a defnition for the otherwise undefnable, for most nikkeijin resist neat classifcation. Collectively, their backgrounds and experiences are anything but uniform.

One nikkeijin could be Okinawan, Mexican, and Black. Another could be hāfu—someone who is half Japanese— born in Aomori to a Japanese mother and white American father but resettled in the United States. Another might have a Dutch mother and a Japanese father yet have lived as a British citizen in London her whole life. All are nikkeijin, or nikkei, a popular abbreviation of the term, and all are subjects of Nikkeijin 日系人, a portrait series by photographer Tori Toguchi.

Born and raised in Honolulu, Hawai‘i, Toguchi is ethnically Japanese and Okinawan. In other words, nikkeijin. Her mother’s family came from Okinawa to Hawai‘i, starting with Toguchi’s great-great-grandfather in the early 1900s, and her father’s family hails from Japan. Her interest in nikkeijin began in 2014, the same year that she moved to New York City to pursue photography at the School of Visual Arts.

Suddenly unmoored from her community in Hawai‘i, where a majority

of residents are of solely Asian descent or multiracial, Toguchi began to question her identity, heritage, and ethnicity. She started talking to people about their sense of belonging or disconnection from being nikkeijin. She spoke with friends, acquaintances, schoolmates, even strangers who were tagged #nikkei or #hāfu on Tumblr.

“A few of the people I met would talk about being mixed race, not being monoracial, feeling discriminated against and left out of the communities they grew up around or in,” she says. Hearing others’ thoughts on belonging or lack thereof was the push that made her pursue the project.

Nikkeijin 日系人 shows nine young adults alone in their bedrooms. Her subjects are a mix of friends, acquaintances, and nikkei she met on Tumblr or social media. Almost everyone is seated on their beds, their belongings framing them. The bedroom setting was deliberate. “I chose to portray them in their rooms because, apart from ethnic or physical identity, a room represents personality in a way that I can photograph,” Toguchi says.

At frst glance, little seems to unite the photographs aside from the domestic spaces. Although everyone is nikkeijin, none of them could be accused of that all-too-familiar

Through connections made on the internet, photographer Tori Toguchi sought to document the experience of the descendants of Japanese emigrants. Opposite, “Kiani,” Brooklyn.

FLUX PHILES | PORTRAITURE | 24 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

stereotype: Asians all look the same. But the longer your eyes linger over each image, the more similarities start to emerge: Each person shares a quiet confdence, an absence of pretense. They look like people settled in their skin, willing to be seen.

Toguchi allowed each of her subjects to pick their favorite image of themselves, which might explain their comfort in front of the camera. Accompanying the series are a few candid video interviews in which Toguchi asked her subjects specifc questions about their identities. Wataru Yonaiyama, one of the series’ subjects, also drew a small self-portrait and wrote some thoughts in Japanese and English. His words read: “I am from Aomori. I am hafu, I am proud.” In the future, Toguchi wants to expand the series to include more written elements, inspired by photographer Jim Goldberg, who often asked his subjects to scribble about the self (or selves) they saw in his images.

The multimedia approach mimics identity and its many facets. “Part of the project was about perception, either by outsiders or even within the community,”

Toguchi says. Since nikkeijin are a minority ethnic group, she was hyperaware of accurately representing people as they saw themselves and dispelling any stereotypes.

“I didn’t want to speak over or talk for other groups or diasporas,” she explains.

During our conversation, Toguchi referenced the photographer Matika Wilbur, whose Project 562 is dedicated to photographing members from more than 562 Native American tribes in the United States. At a University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa talk by Wilbur, which Toguchi attended, Wilbur raised critiques of Edward S. Curtis, an American photographer at the turn of the 20th century who often exaggerated the noble savage trope in his photographs. Similarly, the photographer Jimmy Nelson exoticized subjects from indigenous groups

“A few of the people I met would talk about being mixed race, not being monoracial, feeling discriminated against and left out of the communities they grew up around or in,” Toguchi says. Above, “Mieko,” Bronx (from Indiana). Opposite, “Emma,” Brooklyn (from Hawai‘i).

26 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

27

“Wataru,” Brooklyn (from Ohio)

“Wataru,” Brooklyn (from Ohio)

“Melody,” Brooklyn (from Hawai‘i)

“Melody,” Brooklyn (from Hawai‘i)

he believed to be disappearing in his 2013 book Before They Pass Away, including Māori, whom he often placed in settings where they wouldn’t normally be found.

For better or worse, photographer and subject are inevitably entwined in a portrait’s making—namely, the question of who gets to be remembered and how. Toguchi’s sensitivity to her subjects’ visual representation serves as a corrective to the approach of many documentary photographers, often white and male, who presented groups of people as they imagined them, not as they actually existed.

By allowing nikkeijin individuals to choose their photographs and articulate their thoughts, Toguchi restores their agency.

“It gives them the power to say, ‘This is who I am, this is how I think about this situation, my identity, and how I connect,’” Toguchi says. It’s a simple but radical stance to take, that the underrepresented can speak for themselves and be celebrated for their glorious specifcity instead of dismissed as another sweeping stereotype.

Toguchi asks her subjects to participate in how they are represented by allowing them to choose their photographs and articulate their own thoughts. Above, “Amara,” Manhattan (from Hawai‘i).

View more of the photographer’s work at toritoguchi.com.

30 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Hanafuda Redux

A beloved Japanese card game inspires a curious body of work that conjures paradoxical feelings of familiarity and displacement.

TEXT BY KYLIE YAMAUCHI

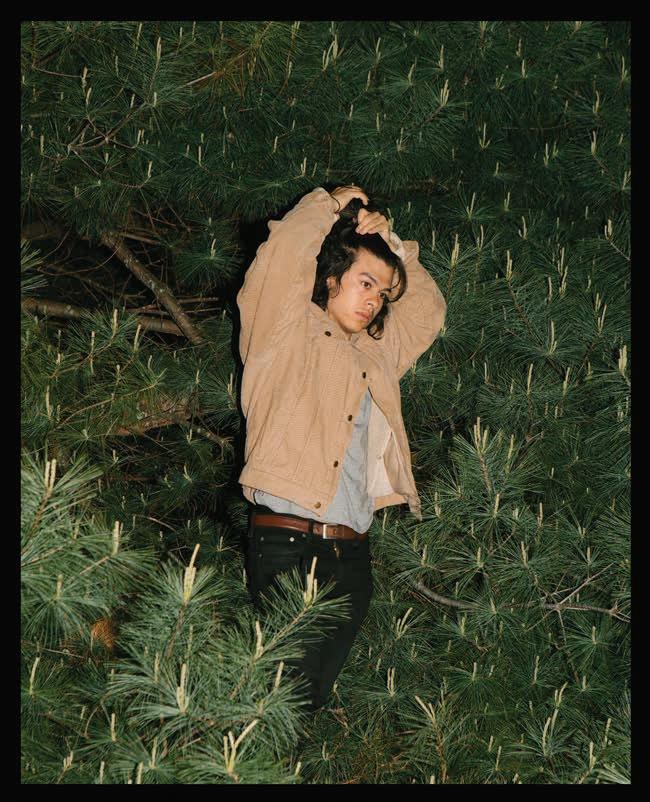

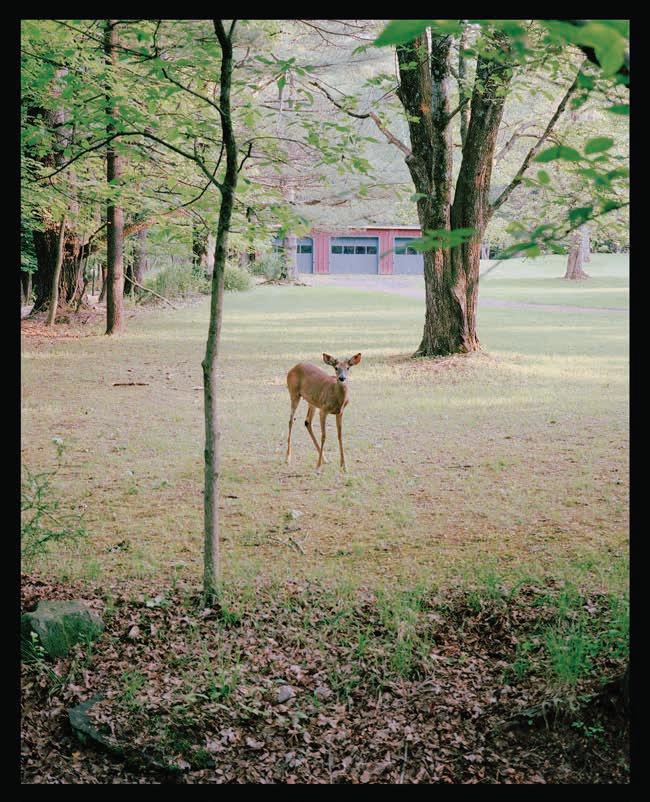

IMAGES BY WILL MATSUDA

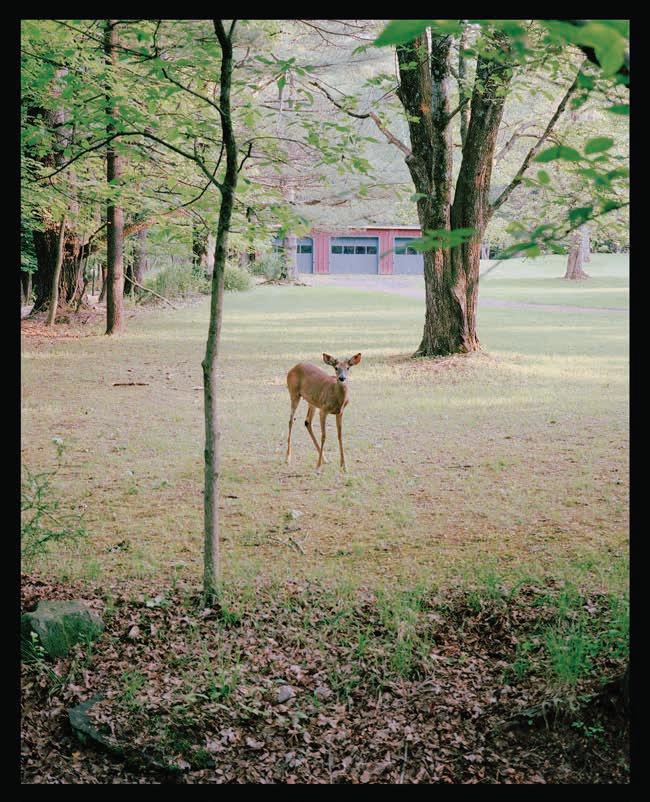

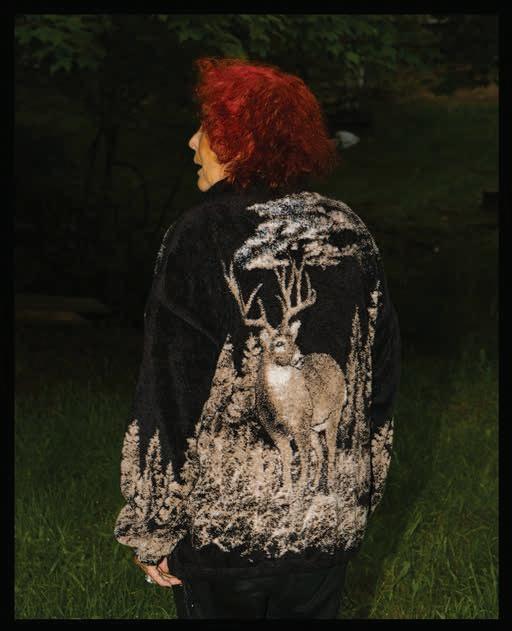

Will Matsuda’s photo project Hanafuda is a test of memory and recognition. Scanning the series of photographs, I identify a crumpled iris blossom, a pale pink peony, a darkened hillside, and a nimble doe. To anyone unfamiliar with the Japanese card game, these images are nothing more than fora and fauna. But to Japanese Americans like me, they coincide with the faces of hanafuda cards and also recall childhood memories of friendly competition with one’s obachan. I don’t remember at what age I learned to play, but I do know every visit to granny’s house prompted multiple rounds of hanafuda. The desirable gaji card always incited squeals of delight and the beautiful sakura cards were worn from handling.

Matsuda’s Hanafuda treads a fne line between reimagining and recreating the timeless prints of the beloved game. Unlike Western playing cards, hanafuda is void of numbers or conventional suits, instead depicting fower and animal prints representing the 12 months in a calendar year. Matsuda, who learned how to play at a young age from his Grandma Amy, still doesn’t understand all the rules. Growing up in Portland, Oregon, he only played hanafuda once a year when he and his immediate family visited his grandma on O‘ahu for the holidays. He fondly remembers losing to her, claiming she didn’t hold back in leveraging her years of experience. It was this nostalgia that prompted Matsuda to create 25 vertical photographs of scenes reenvisioning hanafuda prints.

“I was thinking of these cards as a metaphor and vehicle to think about Japanese American culture and identity,” photographer Will Matsuda says.

FLUX PHILES | CHILDHOOD | 32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

At the time, Matsuda was living in New York for a residency at The Center for Photography at Woodstock. While on a leisurely stroll in the Catskill Mountains, he recognized a variety of the same plants, such as wisteria and iris, depicted on the hanafuda cards he played in childhood. Intrigued, he learned that Woodstock is on the same latitude as northern Japan, which would account for the similarity in foliage. Consequently, Hanafuda ended up being shot at an unconventional Western location with Japanese subjects.

Matsuda knew he wanted the series to have a human presence, and as one of the few Japanese Americans in the area, he often cast himself as the subject. “I was thinking of these cards as a metaphor and vehicle to think about Japanese American culture and identity,” he says. “If I put myself in the photos, I fnd it to be an easier way to access these more complicated ideas.” As a result, the series conjures paradoxical feelings of familiarity and displacement.

Matsuda’s Asian features are a familiar sight in Hawai‘i or Japan, but as he poses among North American pine trees, against a black sheet, and below a starry sky in upstate New York, he creates a universal space neither distinctly Japanese nor American. There is a sense of longing for Japanese culture, an attempt to “fnd the bits we can latch onto or belong to, wherever we are,” Matsuda says. Throughout the process, Matsuda worried less about imitating the hanafuda prints exactly and more on ofering his own interpretations. This artistic choice points to the way the game evolved over time. The cards date back to the 17th century, when the Tokugawa shogunate, a military dictatorship, implemented a ban on foreign playing cards. Gamblers responded by creating new cards that coyly imitated Western cards. These imitation decks were still banned, leading to the production of hanafuda, which was distinctly domestic in appearance by its popular Japanese images. Nevertheless, the game was played

Unlike Western playing cards, hanafuda is void of numbers or conventional suits, instead depicting flowers and animals.

36 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

37

in secret in gambling circles. Eventually it evolved from a gambling game to a household pastime and was brought over to Hawai‘i by Japanese immigrants during the 19th century.

As a Japanese American with ties to Hawai‘i, Matsuda was in a unique position to conceive of and photograph his series. Within a canon of primarily white men, the photography industry has done little to diversify its community of photographers, photo editors, and critics. History has often been told through the lens of white people and not by those who experienced it frsthand. For Matsuda, Hanafuda was a

way to help rewrite history by telling a story of Japanese identity from the perspective of a Japanese American.

If hanafuda tells the story of issei Japanese in America, Matsuda’s Hanafuda represents the generations to follow, who navigate traditional and modern identities. It’s telling that he had to reference the original prints to produce new images suitable to him. For Japanese Americans, our identity is inevitably shaped by history, culture, and traditions. But this need not stop us from re-inventing what it means to be a Japanese American today.

Throughout the process, Matsuda worried less about imitating the hanafuda prints exactly, instead offering up his own interpretations.

View more of the photographer’s work at willmatsuda.com.

40 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

41

Unwavering W ā hine

The women in Nā Wāhine Koa, a look at history’s overlooked aloha ‘āina advocates, shares the journeys behind their boldest and most courageous actions.

TEXT BY NOELANI GOODYEAR - KA‘ Ō PUA

IMAGES BY ED GREEVY, FRANCO SALMOIRAGHI, AND COURTESY OF THE RITTE ‘OHANA

On January 13, 1976, Loretta Ritte kissed her two daughters and signed temporary power of attorney to her mother-in-law.

“It was a good day to die,” she says. Ritte and three others were heading out to protect the sacred Hawaiian island of Kaho‘olawe, which the U.S. Navy had been using as a live-fre target since World War II. They aimed to stop the military’s weapons testing and training by placing their bodies between the earth and the bombs the military planned to detonate on it. The group described their actions as aloha ‘āina, love of the land.

Ritte left her home on Moloka‘i by boat with her husband, Walter, her sisterin-law, Scarlett, and their friend Emmett Aluli. They slipped onto Kaho‘olawe at dusk and laid low until the morning. Then they hiked to the top of the island.

“It was just shattered rocks and red, open wounds,” Ritte writes in Nā Wāhine Koa: Hawaiian Women for Sovereignty and Demilitarization, published in 2018.

“It was all bare at the top. And yet it was really beautiful too. We were able to see Maui and L āna‘i, and there was a calming efect, because we had nothing else. Everything else was stripped away. It was just you and her. You and her, and everything that came with her.”

Loretta Ritte is one of many women who emerged as activists for aloha ‘āina in Hawai‘i in the 1970s. Yet far too often, their stories have gone untold and unrecognized. We sought to remedy this gap in popular memory with Nā Wāhine Koa, a book I edited featuring stories by Loretta Ritte, Moanike‘ala Akaka, Maxine Kahaulelio, and Terrilee Keko‘olani-Raymond.

Loretta Ritte, a lifelong activist for Native Hawaiian rights, at Maunakea in 2019. Image by Michelle Mishina.

FLUX PHILES | ACTIVISM | 42 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Loretta Ritte often talks of freedom, “the kine freedom when everyone takes care of each other, when everyone takes care of the ‘ā ina.”

In the late 1970s, she and her family moved to the uninhabited northern valley of Pelekunu on Moloka‘i, where they lived off-grid for almost two years. Images courtesy of the Ritte ‘ohana.

Maxine Kahaulelio made the ffth landing on Kaho‘olawe with 13 others from O‘ahu in August 1977. At the time, Kahaulelio was a single mother of fve working in a public-school cafeteria. She had also organized with local communities fghting eviction by large landowners and with women fghting for the dignity of their families while on welfare. “I will never forget the feeling of walking through the gun shells,” Kahaulelio writes in her chapter of Nā Wāhine Koa. “You could hear them: shack-shack, shack-shack. And every time I walk, my tears would fall, because every bullet was like, ‘Wow, can you imagine?’ We could have built beautiful schools.

We could have restored beautiful fshponds and given our children food. Real food. Real education. Hospitals. We could break down the prisons and give restoration to our people, our brothers. Instead, millions and millions of dollars just to destroy the land. That’s what I saw on the ground. That’s what I was walking through.”

Nā Wāhine Koa features four Hawaiian women elders who participated in the early Kaho‘olawe movement and spent the better part of the next fve decades working for the health and wellbeing of Hawai‘i’s lands and people. Maxine Kahaulelio, Loretta Ritte, Moanike‘ala Akaka, and Terrilee Keko‘olaniRaymond are wāhine koa, courageous

Terrilee Keko‘olaniRaymond, a staunch advocate against militarization, began her activism as a teenager.

Images by Ed Greevy.

46 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

women warriors. Each shares her story of coming into activism, of battles won and lost, of sustaining commitments to justice and aloha ‘āina. Between the four of them, they have protected freshwater supplies, Hawaiian burial sites, pristine rainforests, traditional fshing access trails, and more. They have resisted the use of toxic pesticides and weapons on Hawaiian lands, the construction of telescopes on sacred summits, and the eviction of multiethnic communities by wealthy developers. They have asserted the importance of Hawaiian independence, demilitarization, and nuclear-free zones in Hawai‘i and the Pacifc. Each has ofered visions of peaceful and sustainable ways of living that honor

the self-determination of Hawaiians and the humanity of diverse but oppressed peoples in the islands.

When we began the process of co-creating this book, these four ferce aunties welcomed me into their circles of memory. At their kitchen tables, on lānai, in restaurants and grocery stores, at cofee shops and bars, they poured out oceans of love for ‘āina, for extended families, for people who struggle. They shared stories over suitcases flled with water-damaged photos in Ziploc bags. They entrusted me with folders full of newspaper clippings and event fyers. They shared memories and analyses over food favored with laughter, heartache, hope, and kuleana.

Above, Moanike‘ala Akaka, 1972. Image by Franco Salmoiraghi. Opposite, Akaka, seen at far right of contact sheet, speaks at a local gathering. Images by Ed Greevy.

48 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

49

When Haunani-Kay Trask wrote of “fne baskets of resilience to carry our daughters in,” she must have known this kind of love. These four wāhine koa are not the only women to have fought such battles or led Hawaiian movements for justice. Rather they exemplify the powerful and diverse roles that Hawaiian women have played in ongoing expressions of aloha ‘āina.

When I asked Aunty Loretta why she continues to be active in her community on Moloka‘i, she talked about freedom, “the kine freedom when everyone takes care of each other, when everyone takes care of the ‘āina.” In the book, Loretta writes about experiencing an intensifed version of this freedom when she and her family, along with four other couples, moved to the uninhabited northern valley of Pelekunu on Moloka‘i, where they lived of-grid for almost two years in the late 1970s.

One week, when she was alone with the kids in the valley, a huge storm engulfed them from sky and sea. Massive waves rolled into the beach. She and her children ran to the back of the valley. The heavens poured down heavy rains, thunder, and lightning. Roaring waterfalls lined the clifs. And yet, Loretta felt empowered to protect her kids and survive the storm. “I don’t think I was ever afraid, because the valley was like a womb. A mama. A teacher. A protector,” she writes. “It was a good place, if you listened. It could be a bad place, if you nevah.”

Maxine Kahaulelio made the fifth landing on Kaho‘olawe with 13 others from O‘ahu in August 1977. At the time, Kahaulelio was a single mother of five. Image by Ed Greevy.

N ā Wā hine Koa: Hawaiian Women for Sovereignty and Demilitarization is available at N ā Mea Hawai‘i.

50 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

1450 Ala Moana Blvd., Honolulu, HI 96814 • 808.955.9517 • AlaMoanaCenter.com • FREE WI-FI MORE THAN 350 STORES, INCLUDING OVER 160 DINING OPTIONS AJA

&

• BLOOMINGDALE’S • BRUG • BUFFALO WILD WINGS • EGGS ‘N THINGS • FOODLAND FARMS JADE DYNASTY SEAFOOD RESTAURANT • LONGS DRUGS • MACY’S • NEIMAN MARCUS • NORDSTROM SEARS APPLIANCES & MATTRESSES • TANAKA OF TOKYO • TARGET • VIM N” VIGOR HEALTH & FITNESS • & MANY MORE

SUSHI

BENTO

FLUX FEATURE

FLUX FEATURE

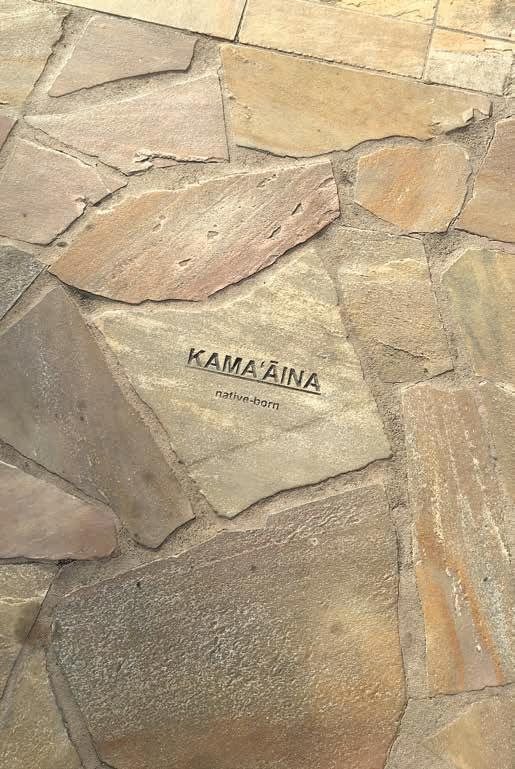

The Gravity of Inoa ‘Āina

Ambivalently understood, the phrase “Hawaiian sense of place” is heard everywhere from the tourism industry to design sector. The islands’ traditional place names, however, often remain silenced. Can one truly honor places without acknowledging the importance of inoa ‘āina?

TEXT BY N. HA ʻ ALILIO SOLOMON

IMAGES BY VINCENT BERCASIO

“ALAHULA PU ‘ ULOA, HE ALAHELE NA KA ‘ AHUP Ā HAU.” EVERYWHERE IN PU ‘ ULOA IS THE TRAIL OF KA ‘ AHUP Ā HAU.

In the mid-20th century, Mary Kawena Pukui wrote that “Hawaiian place names are on everyone’s tongue.”

Even if various pronunciations exist, with their meanings obscured or histories faded, these inoa ʻāina, or traditional place names, still exist in dialogue on maps, street signs, and in the public consciousness. Hawai ʻi is unique in this way because many other locations enduring colonial aftermath face the burying of their traditional place names beneath layers of re-inscription of foreign names that re-write the space. Yet, while it seems, at least to some extent, like our Hawaiian place names survive today, certain changes going on across Hawai ʻi caution us against taking their endurance for granted.

The saying above is an ʻōlelo noʻeau, a well-known adage among Hawaiians that is usually proverbial and didactic, often uttered as metaphor or allegory. Such adages speak of deities, people, places, events, and stories as references to Hawaiian lore, society, origin, and history. This one, about the trail in Pu‘uloa, reveals the extent to which shark deity Kaʻahupāhau is familiar with her home, such that it is, or at least was, her alahula, a well-known path.

The name change from Puʻuloa to Pearl Harbor coincides with the Kuʻikahi Pāna ʻi Like, or the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875, which aforded the United States tax-free access to the market of products such as sugar and other Hawaiian-grown goods. In turn, this treaty led to the acquisition of the lagoon and adjacent coastal areas by the United States, as well as the area’s conversion to an American naval base.

Many Hawaiians at the time opposed the treaty, expressing opposition to the impending large-scale American investment in local industry and the increasing control the United States was gaining in Hawai ʻi. Hawaiian political leader, lawyer, and patriot Joseph Nāwahī referred to it as “a nation-snatching treaty” as he defended against the cession of any sovereign land to foreigners, but by the end of 1884, modifcation of the treaty granted exclusive use of the harbor to America.

Such preemptive foresight on the Hawaiian Kingdom’s behalf is justifed by the sociopolitical maneuvers that dispossessed Hawaiians of sovereign land for use by the military, secured the economic futures of the United States, and ultimately led to the overthrow and illegal annexation. The ongoing militarization and occupation of Hawai‘i has turned it into the tip of America’s spear, while U.S. economic stake-holding maintains its supremacy in the islands. If we correlate the shift in names to transfers of power throughout Hawai ʻi’s history, we see a pattern that should not surprise us: The name changes occur alongside

Through the literal reinscription of Hawaiian spaces, new and foreign place names receive privilege and pave way to replace the lands’ networks of meaning and value systems.

some of the most egregious examples of an out-with-theold re-inscription of a new order, in a new language, atop a repurposed space, anointed with a new name.

It is an unfortunate irony, then, that even though the ‘ōlelo no‘eau about Kaʻahupāhau endures, the place to which it refers has been largely modifed and repurposed. Puʻuloa, now often called Pearl Harbor, is a wahi pana, a historical place, that survives today under mounting layers of development, militarization, and industrial use. In light of so much transformation, does Kaʻahupāhau still have her alahula, and if so, where is it?

Fortunately, the answer lies, at least to some degree, in the place name. Puʻuloa literally means “long hill” and delineates the geography and scope of Kaʻahupāhau’s abode. Like many other inoa ʻāina in the Hawaiian universe, Puʻuloa is topographical and encodes information about the physical features of the area from a feet-on-the-ground perspective. In diferent ways, Hawaiian place names

54 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

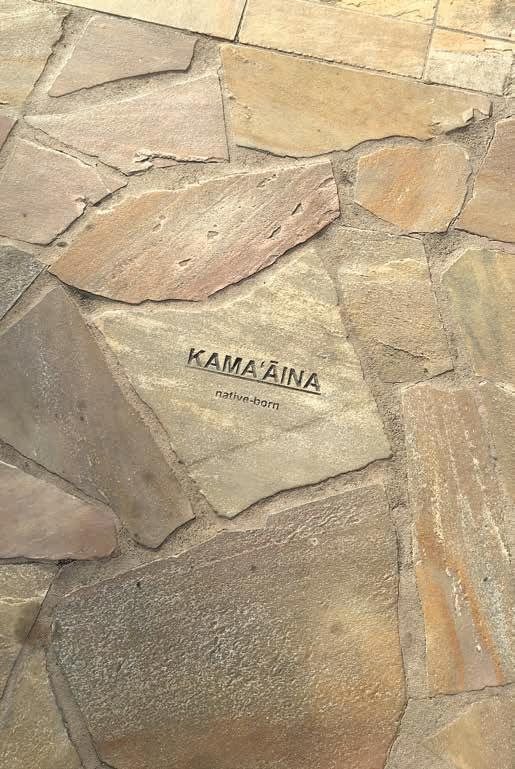

capture localized knowledge, mapping the lived experiences of people upon the ʻāina and the intimate relationships that tie us to it. The names are constructive intersections between the cognitive, imaginative, and spatial dimensions by which kamaʻāina make sense of our world, arrange the events of our existence, and embed value and meaning in these islands.

“KAI PAK Ī O MAUNALUA.”

THE SPRAYING SEA OF MAUNALUA.

Besides denoting topography, Hawaiian place names are informative in other ways, such as mapping natural resources. For example, place names that include “wai” indicate fresh water in that region. This is identifed in Oʻahu’s Wai ʻanae district, as are the ʻanae (mullet) that swim in the waters ofshore so frequently that they deserve mention in the area’s name.

Some inoa ʻāina are spiritually or religiously signifcant. Mōkapu, a peninsula on the windward side of Oʻahu, is a shortening of “moku kapu,” which literally translates to “taboo district.” The name demarcates the sacred lands that belonged to Kamehameha I. There are also older accounts in primary sources that tell of Mōkapu as the location where the frst humans were created to populate Hawai ʻi.

Other inoa ʻāina commemorate signifcant events, such as Kohelepelepe, meaning “vaginal fringe,” which calls to mind when shapeshifter Kamapuaʻa, true to his kolohe nature, chased Pele across the archipelago, and her sister Kapo sent her ma‘i, her genitalia, to the top of Koko Crater to distract Kamapuaʻa and give Pele a moment to rest and escape. According to lore, Kapo’s ma ʻi left an indentation on the lip of Koko Crater that is still visible from Awāwamalu, also known as Sandy Beach.

In recounting these examples, we might recognize a problem: All the inoa ʻāina

mentioned so far have English substitutes that usually supplant the original names, or have alternate pronunciations of the Hawaiian names that have become so widely used that the original sounds foreign, unrecognizable, and obscure. The local pronunciation of Wai ʻanae usually omits the ʻokina and changes its meaning, even if inadvertently. After World War II, Mōkapu became referred to as “North Beach,” and it has since devolved into the “Marine Corps Base,” or its more convenient acronym, MCBH. Kohelepelepe and the crater atop which it lies have been lumped together and subsumed by today’s common misnomer, “Koko Head.” These examples are a handful among hundreds of shifts that have already occurred, and at this rate, they foreshadow many more to come.

The erasure of Hawaiian names and the imposition of new and foreign ones is dangerous, even if the traditions by which the new names are created are similar to Hawaiian ones. The name Pearl Harbor is commemorative, but it celebrates American conquest, occupation, and militarization the same way MCBH does. The epithet “Sandy Beach” is topographical but hardly hearkens to a Hawaiian environment the way Awāwamalu does, referring to the shaded valley inland of the shoreline where ʻuala (sweet potato) was farmed. The name Kohelepelepe faded after Maunalua was massively developed into modern-day Hawaii Kai on the heels of Statehood in 1959, and the Koko Head “Stairs of Doom” further overwhelmed the name as the summit hike became a popular recreational activity and tourist destination.

We are witnessing the literal reinscription of Hawaiian space, with new and foreign names receiving privilege. When names are replaced, so are their senses of place, their networks of meaning, their value systems. The underlying reasons for such shifts are manifold but not always free of ulterior

The renaming process is the symbolic and fgurative accompaniment to the physical and literal gesture of breaking ground.

Beyond militarization and economization, residential development in the islands is often accompanied by the introduction of new names in subdivisions that overwrite traditional Hawaiian names in use prior to their development.

56 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“To change the place name drapes a veil over it,” writes N. Ha‘alilio Solomon. “The new names are stanchions that usher in a modern era of place-making, marking a new purpose for these places by resetting their history of habitation and use.”

The erasure of Hawaiian names and the imposition of new and foreign ones is dangerous, even if the traditions by which the new names are created are similar to Hawaiian ones.

motives such as the claiming of territory. For some, the English name is easier to pronounce than the Hawaiian. In other instances, a new name could actually be more appropriate to ft the way the place has since been manipulated. But mostly, we should consider this reinscription as a distancing of our Hawaiian place names from us, and by extension, an imposition of new cultural norms, values, and meaning.

“OLA KA INOA.”

THE NAME LIVES.

Beyond militarization and economization as motivations to stamp new names atop the land, other industries have also led to the establishment of exonyms, or names given by outsiders, at the expense of endonyms, the names given by locals. Residential development in the islands is often accompanied by the introduction of new names, such as the subdivisions of Pearl City, St. Louis Heights, and Chinatown, which have become widely used appellations over the last few decades. While these names are an inseparable part of local culture, they do overwrite older, traditional Hawaiian names that were in use prior to their development.

Usually, it is easy to spot an exonym—a foreign name, a non-Hawaiian designation—because, well, they are not Hawaiian. But sometimes, looks (and sounds) can be deceiving. Consider names like Hawaii Kai and Lanikai. Both are Hawaiian, in the sense that they use Hawaiian sounds in sequences that do not violate any orthographic rules. But their respective histories of place reveal collisions of tenure and best practice.

As early as 1924, the name Kaʻōhao began to recede under processes of place re-making and its development into Lanikai. In the 1960s, new Statehood legislation aided industrialist Henry Kaiser in his urban transformation of the

area known as Maunalua into presentday Hawaii Kai, and his conversion trophy is that the former half of his last name (Kaiser) forms the latter half of his subdivision (Kai). The case for both endonyms is that they conceptualize the space through precontact perspectives: Kaʻōhao means “the tying” and maps a noteworthy historical event where two women were tied together at the neck after losing a game of kōnane; Maunalua has “Ke-ahu-pua-o-Maunalua” (now Koko Marina) whose traditional name translates to “The Shrine of Young Mullet of Maunalua” and maps the region’s natural resources. Their ambiguous exonyms, however, are semantically neither here nor there, and not only obfuscate the environmental history, but their English translations also violate some linguistic rules. Lanikai, for example, is incorrectly translated as “heavenly sea”—with lani, meaning heavenly, preceding kai, meaning sea—except in ʻōlelo Hawai ʻi, adjectives follow nouns. Such tensions between traditional stewardship and contemporary planning serves as a micro-level metaphor for the macro-level coexistence among us living in Hawai ʻi.

To change the place name drapes a veil over it. The new names are stanchions that usher in a modern era of place-making, marking a new purpose for these places by resetting their history of habitation and use. The renaming process is the symbolic and fgurative accompaniment to the physical and literal gesture of breaking ground. Unsurprisingly, there is great dissimilarity in the stewardship of these new places, such that the modern and imposed nomenclatures seem to prefgure their transformation.

But there is hope in the small victories of traditional place names being reclaimed by local communities. For instance, in 2017, Lanikai School changed its name to Kaʻōhao School to identify the area’s name

Inoa ‘Ā ina

The traditional place names of the more commonly used ones around O‘ahu.

Ka‘ō hao = Lanikai

Keawa‘ula = Yokohama Bay

Kohelepelepe = Koko Head

Le‘ahi = Diamond Head

M ā nana = Rabbit Island

Maunalua = Hawai‘i Kai

Moku‘ume‘ume = Ford Island

Mokoli‘i = Chinaman’s Hat

P ū owaina = Punchbowl

Pu‘uloa = Pearl Harbor

Wā w ā malu = Sandy Beach (also known as Aw ā wamalu)

62 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

before development began in 1924. There also seems to be a push in the media to standardize the spelling of place names while including proper diacritic markings. All around O‘ahu, signage identifying the ahupuaʻa land divisions of larger moku districts is now visible, a project so successful that similar ones have begun on neighbor islands.

We know what makes Hawai ʻi beautiful and unique. We know the reasons behind the popular “lucky we live Hawai ʻi” notion. We know the values that make Hawai ʻi meaningful to us—our connection to our home and its history, to our shared heritage, and to our sense of place. Deeply embedded in all those things are our place names. It is up to us to know them, speak them, and pass them on.

64 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Mahalo to our NMG Network advertising partners for making a donation to the Hawai`i Resilience Fund. The Hawai‘i Resilience Fund at the Hawai‘i Community Foundation deploys resources to community nonprofts and health care providers who are working on the ground to address the COVID-19 pandemic in Hawai‘i. hawaiicommunityfoundation.org/coronavirus

FLUX FEATURE

Black Lives Matter in the Hawaiian Kin g dom

By supporting Black liberation, we do not lose Hawaiian ways of resistance and knowing. We do not stop perpetuating our culture or lose our language.

By supporting Black lives, our ea is enhanced.

TEXT BY JOY LEHUANANI ENOMOTO

The origin of the Kanaka Maoli universe begins with Pō, the deep, rich Blackness found at the bottom of the sea and from which all life begins. Pō is the night and the realm of the gods. Mai ka pō mai–of divine origin. One of Maui’s fercest chiefs, Kahekili, tattooed half of his body black just like his namesake, the god of thunder. Pāʻele kūlani—the chiefy blackening. Pele is the chiefess of both sacred darkness and sacred light—ʻO Pele ia ali ʻi o Hawai ʻi, he ali ʻi no laʻa uli, no laʻa kea. We did not begin by fearing Blackness, but by revering its power, its sacredness, and its importance to our origins and our strength.

So how did Kānaka, whose origins are rooted in such beautiful, opulent, and powerful Blackness arrive in a world that has reduced Blackness to something marked inferior, criminal, flthy, lazy, unintelligent, and evil? How has Blackness become synonymous with state-sanctioned homicide, lynching, and enslavement?

How could Hawaiians ever take their cues about Blackness from the very people who overthrew our kingdom? Everyone from the whalers who gave us venereal disease, to the missionaries who called us heathens and savages and introduced the word “nika” into our vocabulary, to the plantation owners who stole our kingdom at gunpoint. These sugar barons enslaved millions of Africans, then came to Hawai ʻi and applied their white supremacist ideologies to Kānaka Maoli. They forbade our language and suppressed our culture in the same violent manner as those of African descent.

And yet so often, some of the most racist views on Blackness come from the mouths of Kānaka Maoli, who claim they believe in liberation and are opposed to oppression. What a powerful gift to give to your oppressor: to turn against the very people to whom you would otherwise be in natural solidarity.

They turned Blackness into a thing unpure, unclean, violent, and inferior, by ranking the “purity” of our skin tone and adherence to Christianity. European men such as Jules Dumont d’Urville from France created the false cartographic divisions of Polynesia, Micronesia, and Melanesia, and placed Polynesians closest to whiteness. They marked Melanesians as black and convinced us that this was something that we should do too. We must rank each other in our proximity to Blackness. We must remove the “stain” of Blackness and push it far from us, although we can never escape its taint. This became the language used to justify genocide, lynching, and segregation. That violence and shame became so attached to Blackness that all the colonizers had to do was to simply imply the mark of Blackness onto our cultures, to convince us to say, “but we are not that.” That is the insidiousness of colonization. But you know this.

Opening spread and opposite, from a Black Lives Matter rally in Honolulu on May 25, 2020. Images

We must understand the context of how Hawaiians got here. In the mid-19th century, Hawaiians were more than aware of the way America slaughtered Native tribes and enslaved Africans. So much so that, in 1852, Hawaiians outlawed slavery in their constitution and decreed that any slave who arrived in Hawai ʻi would be emancipated. A few years earlier, in 1845, Prince Alexander ʻIolani Liholiho and his brother Prince Lot Kapuāiwa experienced American racism frsthand by nearly being thrown of of a train by a conductor because he assumed they were Black. It was his memory of this experience that later enhanced his opposition to annexation. This shows that we knew we did not want to act as Americans, but as a free people who afrmed the liberation of others. BLACK LIVES MATTER. But between the time of Liholiho and Queen Lili ʻuokalani, American theories of racialization had begun to take root in Hawai ʻi.

In the quote by Lydia K. Aholo, she recounts a trip to Washington, D.C., in 1899. Prince Kūhiō advised her and her siblings to “speak Hawaiian,” “sit where the white people sit and tell them you’re not Negroes.” I believe this advice was given to prevent and protect the Hawaiian youth from being racialized and treated as inferior in a segregated America. It was an act of trying to retain their autonomy and resist Jim Crow. A gesture to say we are not inferior, we are the same as you and uncolonizable. I cannot know what fears and threats of violence they faced from

68 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

by Greg Hatton. Nature images by Brendan George Ko.

white Americans during those years surrounding the Overthrow, but the choice made by ali ʻi to consistently separate themselves from Blackness, even as a tactic for survival, has had far-reaching implications.

In 1901, Queen Liliuʻokalani was turned away from four hotels in New York that mistakenly assumed her to be an “uppity” Negro. Had it not been for the makaʻāinana porter working at one of the hotels recognizing her and running ahead to the next hotel to tell them that the “Queen of Hawai ʻi is coming,” who knows how many more hotels would have denied her. The humiliation does not rest in the fact that the Queen was assumed to be Black, the humiliation comes in a society that determined that Black and Queen could not inhabit the same body. That a black body was not even worthy of entering the front door.

The makaʻāinana who went out into the diaspora on whaling ships and as migrant labor did not travel frst class on steamers and trains across North America as the ali ʻi did. Kānaka Maoli, unless traveling with white missionaries, were living among Native American, Black, and working-class immigrant communities. In the 19th century, to be a Hawaiian commoner in the United States aforded you no protections. This meant that many Hawaiian workers, far from Hawai ʻi, were often taken in and fed by other Native and Black communities. It also meant they faced the same dangers of racialization, segregation, imprisonment, or possible enslavement or lynching that Black folks faced.

But when Hawaiians are taught about our history, it is not flled with mo ʻolelo regarding the lives of the makaʻāinana who lived abroad and had to negotiate life under Jim Crow. In fact, we rarely discuss the true depth of anti-Black and anti-Native racism that any of our ancestors and ali ʻi nui had to face. Instead we would rather talk about our fully functioning government, our envoys to Europe, and treaties and letters of recognition

from European nations afrming that we were sovereign. This is true; this is important to know. But we must also ask where were those nice countries when American businessmen stole our country at gunpoint? How much did traveling and dining with white elites slow our overthrow? How diferent would it have been if, while traveling, the ali ʻi insisted that Blacks on the train be allowed to sit with them as a sign of solidarity to show their disgust with the American system? Impossible to imagine, but what if?

If we fast forward, after nearly a century of imposed Americanization and the attempted obliteration of our language and our culture, the Hawaiian Renaissance became a part of the global uprisings demanding decolonization and civil rights. In Hawai ʻi and throughout the Pacifc, you see people inspired by and learning from the Black Power movement and applying their strategies and tactics to their own movements. The frst time that I ever heard Haunani-Kay Trask speak in person was at an Empowering Women of Color Conference in 1997. She quoted Malcolm X, Toni Morrison, and Angela Davis, to name only a few of the African Americans who informed her politics. For me she was a game changer because she was the frst Kanaka Maoli I had ever heard stress the importance of internationalism and intersectionality in our struggles. She was the frst mana wahine I had ever heard call out the police violence aimed at Black communities. In fact, in a speech she gave in 1994, she stated, “…it is everywhere now. The violence of a police state protecting itself and its white citizens. The violence of a political system dependent on mass exploitation. Looking into the heart of whiteness, I do not see a willingness to change, only a ferocious determination to keep the black masses at bay.”

Listening to her as a young woman of both African American and Hawaiian ancestry, I learned from Dr. Trask all the ways that Hawaiian Sovereignty could be something more

than narrow nationalism. Because rather than distance Hawai ʻi from Black Liberation, she aligned the Hawaiian Sovereignty movement with Black Liberation. She was clear that although our struggles are distinctly diferent, we need solidarity to have true sovereignty. She spoke of women at the center of liberation movements worldwide—in Palestine, the Americas, Aotearoa, Papua Niugini, the Marshall Islands, and Australia. She spoke out against the nuclear testing in Micronesia and demanded a nuclearfree Pacifc. Her ability to “weave ropes of resistance,” as my friend Noʻu Revilla recently said, showed all of us the kind of nation we could build together.

So, now it is 2020. There is a fascist in the white house who has no respect for humanity and who is being funded by the Ku Klux Klan. Countless Black lives have been killed by the state, and now this killing will intensify with little to no consequence. But we are also in a world whose eyes are fnally opening to what we have been saying about the lies of the U.S. all along. The streets are fooded by those who want to build a movement for liberation that is intersectional, powerful, and flled with love. It is our turn to speak, to rise up, to dismantle, to change, and to build. We no longer live in a world that allows us the luxury of ranking oppressions. Our liberation is tied to the liberation of all oppressed peoples—this includes women, refugees, queer and transgender people—and I mean all oppressed peoples. As Bryan Kamaoli Kuwada wrote, “the idea that we can create a safe space, a puʻuhonua, here in Hawai ʻi is still something worth imagining.” We must not only imagine it. We must be a place of rest and healing and sanctuary within each other. We cannot survive otherwise.

By supporting Black Lives Matter, we do not lose Hawaiian ways of resistance and knowing, we do not stop perpetuating our culture or lose our language. By supporting Black lives, our ea is enhanced. As a sovereign

70 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

people we are saying we will stand as an example to those that would do us all harm, that their old tricks can no longer divide us. There is nothing more threatening to the state than mass solidarity across race, class, and gender diferences because there are far more of us. As long as we let the label of Blackness be seen as something less than beautiful, we are consenting to white supremacy.

But when we embrace Blackness in all its forms, we no longer let the mark of Blackness hurt us. If we instead say, “Thank you, I am proud to stand in resistance with my sisters and brothers in the struggle,” then we can be better than we were yesterday. Onipaʻa ana ka pono—let the right stand frm. Let us stand up for Blackness and protect Black lives. BLACK LIVES MATTER IN THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM.

Furthermore, the frst people of the Pacifc were Black. Hawai‘i belongs to the Pacifc. And so we must act against the genocide that is happening in West Papua being imposed by the Indonesian Army to protect mining interests, we must support the Kanak liberation struggle of New Caledonia as they continue their struggle for independence from France, we cannot forget the islands threatened by climate change in Vanuatu, Fiji, the Cook and Solomon Islands. BLACK LIVES MATTER IN OCEANIA.

As people with powerful histories of resistance, Hawaiians and Black folks have so much to learn from each other, and we welcome you with all of our aloha. However, that aloha comes with certain expectations of mutual respect. That means when Hawaiians stand up for Black lives, you show up for Hawaiian lives and Pacifc lives, you

show up for us as many times as you want us to show up for you. It means we all must expand our defnitions of Blackness to include our Pacifc sisters and brothers whose lives have been marked as Black while respecting how they defne themselves. I say all this to mean that undoing the impacts of our colonization is a process of reciprocity, but the result is our freedom.

This piece was originally published by Ke Kaʻ upu Hehi ʻAle, a collective of indigenous Pacifc and allied scholarpoet-activists. It is also featured on The Pōpolo Project, a Hawai‘i-based nonproft that redefnes what it means to be Black in Hawai‘i.

72 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Images, this spread and previous, by Greg Hatton

Where will you be?

A variation to Black lesbian activist Pat Parker’s poem, as a parting thought

By Joy Lehuanani Enomoto

Where will we all be when they come?

And they will come — they will come because we are defned as opposite perverse and we are perverse.

Every time we watched a queer hassled in the streets and said nothing — It was an act of perversion.

Every time we did not interrupt racism — It was an act of perversion.

Every time we heard, someone say that Muslims are all extremist terrorists and said nothing — It was an act of perversion.

Every time we let a Black mother lose her child and did not fll the courtroom fll the streets take over buildings shut down cities — It was an act of perversion.

Every time we let our friends and family accuse Micronesians of being welfare burdens and say nothing — It was an act of perversion.

Every time we hear the State proclaim that there is no such thing as a climate refugee and refuse to open our our borders our homes — It is an act of perversion.

Every time we heard a transgender woman lost her life and the killer is set free and we did not take to the streets — It was an act of perversion.

Every time we made excuses for rapists for misogynists for transphobia and homophobia — It was an act of perversion.

Every time we watched Zionist expansion, Israeli checkpoints and the genocide of Palestinians and did nothing — It was an act of perversion.

Every time they build and expand military bases in Hawai ʻi Guam Puerto Rico the Philippines Okinawa and do not fll the islands with bodies of resistance — It is an act of perversion.

Image by Royce Hui

Images by Greg Hatton

Images by Greg Hatton

And they will come. They will come for the perverts & it won’t matter if you’re homosexual, not a faggot lesbian, not a dyke gay, not queer

It won’t matter if you own your business have a good job or are on S.S.I.

It won’t matter if you’re Black Hawaiian Tongan Samoan Okinawan Chamorro

Chicano

Native American Asian or White

It won’t matter if you’re from New York or Los Angeles Galveston or Standing Rock

It won’t matter if you’re Butch, or Femme

Not into roles

Monogamous

Non-Monogamous

It won’t matter if you’re Catholic Baptist Atheist

Jewish or Mormon They will come They will come to the cities and to the land to your front rooms and in your closets. They will come for the perverts and where will you be When they come?

Eō.

Above, image by Royce Hui. Opposite, image by Greg Hatton

FLUX FEATURE

The Pandemic Diaries

Written in the wake of the coronavirus outbreak, these personal essays by a native historian, visual artist, urban researcher, and travel writer stitch together the complicated emotions and societal issues that affect everyday island living.

Image by @misterver

Text by Noelani Arista

Image by @misterver

Text by Noelani Arista

As news of Covid-19 began to spread in early March, my son and I enjoyed iced tea and cofee one late afternoon in the open, airy cool of a café in Chinatown. The photo I took of him then, smiling in his high school uniform, is now a marker of the number of days since we have set foot in a local establishment to eat or drink without apprehension. Months later, after his big band concert, choral competition, and junior prom had been cancelled, a deepening, premature sadness began to set in, fed by the fear of losing anticipated memories and not sharing time with graduating seniors and exacerbated by forced, 24/7 family time.

One evening, my son said he found a way to “degrease” his hair. He took me to the bathroom, sat down on the lip of the tub, and handed me the shampoo. “Can you work this into my hair and scalp using a minimum amount of water?” he asked. Moving my fngers through his lengthening, soapy hair felt good. Washing someone’s hair is an intimate act, which we have unfortunately surrendered to strangers. It made me think, when was the last time I washed my son’s hair? When is it acceptable in our culture to show care for others like this? I wondered. Only with our children when they’re babies or elders with Alzheimer’s, as in mainstream society? We fall out of these routines unconsciously and inadvertently lose connection with each other.

As graduation time neared, we prodded our son to make lei for one of his friends. We made three kinds of lei: plumeria, candy, and paper. Enlisting the help of his 9-year-old brother and various aunties with supplies of cellophane and ribbon, we sat down as a family to prepare them. It was my son’s idea to write YouTube URLs on each fower, so that the lei became a soundscape of songs shared between friends who could no longer bike from Nānākuli to Mākaha or jump into the ocean together. We had a fght before we went to the drive-through graduation ceremony. I said, “Remember, you can’t get too close to people, you can’t hug face to face.” He broke down into tears of frustration and screamed at me, “Wot! You like me throw da lei out da window?!”

When my world contracted to the point of a keyboard, many of the vital connections I had made through work and the friends I had prioritized receded. What emerged was a more vital inner life of connection to my family and pilina with my sons. My heart ached that day for my son and his friend. I will never again take for granted the ambient caress of an anonymous crowd in a restaurant or movie theater. Nor the ability to hug my parents, to give lei, or oli.

For years I felt that aloha was on life support. One day, in parting, I said “aloha” to a friend, and he replied dismissively, “Aloha—that word doesn’t mean anything. It’s overused.” In the Hawaiian language the word means more than “hello,” “goodbye,” and “I love you.” But in Hawai ʻi we have been saturated by these meanings and can only hear the word in English as marketing tool, as perennial invitation, as metonymy for a Hawai ʻi we do not inhabit.

Soon after, in 2015, I started the Facebook group 365 Days of Aloha as a way to foster deeper understandings of aloha using examples from Hawaiian language mele, oli, and positive imagery of Hawai ʻi and Hawaiians. I thought to reach people like my friend with these Hawaiian songs and chants to familiarize them with the beauty and aesthetics of Hawaiian poetics beyond haole imaginaries and unburdened by manufactured colonial nostalgia that sells Hawai ʻi to tourists the world over.

In the summer, my son and I woke up early and drove to Keawaʻula. We parked our car and ventured onto the beach, two of only three people there as far as our eyes could see. He planted himself fush against one of the towering dunes heaped up by the evening’s high tide and relaxed. He walked into the clear waves and said, “I love this, I love this so much.”

Noelani Arista is a historian and the author of The Kingdom and the Republic: Sovereign Hawai‘i and the Early United States

80 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FINDING ALOHA IN THE TIME OF COVID

Image by Matthew Dekneef

Text by Marika Emi DISRUPTING THE SYMBOLIC ORDER ( OR NOT )

Image by Matthew Dekneef

Text by Marika Emi DISRUPTING THE SYMBOLIC ORDER ( OR NOT )

Quarantine Island was a small, muddy islet on Kahololoa reef outside Honolulu Harbor. Established under King Kamehameha V in 1869, it was here that ships entering in the harbor with sick passengers docked to treat and isolate. This was during a time when deadly diseases in Hawai ʻi were rampant as settlers arrived, partially in response to the growing plantation industry and demands for labor. Kānaka, whose bodies were susceptible to foreign diseases, sufered at devastating rates. Quarantine Island was eventually flled in and expanded into what is now known as Sand Island, a continuation of this area’s complex history.

I can imagine myself as an island; connected to oceans, with shores of skin, permeable. Of the coast, there is my own Quarantine Island where I put things, material and immaterial, I deem unsafe for some amount of time in hopes that their temporary isolation will make them less dangerous to me. Sometimes I visit this island, activating and deactivating my sense of danger, gloves peeking out of the back pocket of my jeans, a mask tied hastily to my head, tangled with strands of bleached hair. My phone is never far away. My psychological state is amplifed by social media and breaking news of daily Covid-19 case counts, my physical life ritualized by a procession of safety: mask up, stay back, use a shield, sanitize your hands, follow the arrows. We straddle these experiences, we lose our balance, slip, and we fnd ourselves immersed when we least anticipate. It is ftting that we refer to the spread of this virus in waves—that which swells and inundates bodies. As if we aren’t already swimming.

One day I’m standing at the concrete clifs of Keehi Transfer Station overlooking mountainous heaps of trash against the backdrop of the Wai‘anae Range. Waste neither originates here nor stays for long, this is just one stop along the journey of mass disposal, an interrogation of the conditions of the present. I’m with a friend and we’ve borrowed a truck, it’s flled with bulk items we couldn’t dispose of elsewhere. The air is still and thick with the scent of things someone didn’t want anymore. A couch they used to relax on with

their three best friends from college, a wall constructed from quarter-inch ply that didn’t prevent sound from traveling between bedroom and living room in a studio-converted one-bedroom apartment. A lampstand with no shade. A gigantic teddy bear (once a grand gesture) tacked to a beam, like a beacon, 30 feet of the cavernous foor of discarded stuf. Huge things seem tiny when thrown over the railing here, as they scatter into shards dutifully swept up by a bulldozer. I am allowed to participate, briefy. I enter and exit this industrial ecosystem of exposure and contamination. I begin wondering what other waste I should have brought. Magic Island is a place I fnd myself at dusk. Four months into the pandemic, walking through Ala Moana Park is an exercise in chaos that quiets my mind, and arriving at this peninsula usually rewards me with my choice of benches angled to face the ocean. I’m reminded that this constructed landscape was once slated to be a resort complex, before public opposition spurred its use as recreational grounds. There are groups of friends lounging on the sand, families of all sorts under tents, aunties, uncles, single white men on hoverboards, fruit fies, joyful and hysterical children, ladies exercising, fshermen spaced six feet apart, shallow water lapping around their calves. The refective glass walls of the high-rises are shades of ocean and sky blue. The streetlights glow orange, casting shadows around patches of wet sand, and the industrial lights from Kakaʻako form a second sunset as they begin to hum. Little dogs pull on their little leashes as they trot in little circles with their masters. A group of twentysomethings ride by on Biki bikes; one exclaims, “I feel like I’m living life!”

There are systems in place, alienation, disconnection, coping mechanisms. There is movement as there has always been, and with it, a sense of calm. All the grinding away, overheating, but then this: the littoral zone in twilight flled with imported sand.

Marika Emi is the founder of nonprofit publishing imprint Tropic Editions, the editor of Tropic Zine, and the co-director of Aupuni Space.

82 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Image by Marika Emi

Image by Marika Emi

Images by @misterver SURVEILLING THE NEW NORMAL

Images by @misterver SURVEILLING THE NEW NORMAL

Text by Tina Grandinetti QUESTIONING HOME IN THE ARCHIPELAGO

Text by Tina Grandinetti QUESTIONING HOME IN THE ARCHIPELAGO

In the years before the current pandemic, we talked of a housing crisis. We created a river of numbers and fgures: 64,700, the defcit in housing stock; 70, the percentage of demand coming from low-income households; $835,000, the median price of an Oʻahu home. But no matter how much we talked or how many numbers we conjured, the crisis only intensifed.

Now, caught in the pandemic’s undertow, the housing crisis has been compounded by an impending eviction crisis, a food of displacement, bodies cast out of homes, nameless faces on the streets. Again, the fgures pile up: 21,500 families at risk of losing housing; 7,500 of those at extreme risk. No matter how much we talk, nothing seems to change. At best, an eviction moratorium buys us a month or two at a time while the waters continue to rise behind the foodwalls.

I am a doctoral student writing my dissertation on home and housing in Hawai ʻi. It feels like a painfully useless exercise in a pandemic, like writing about a world that no longer exists. But as everything around us changes at a dizzying pace, I’ve started to look for continuities and clues to how we got here. One of them is that people in Hawai ʻi have been talking about a “housing crisis” since as early as 1945 during the Territorial Era. Despite decades of unchecked development, we have never seemed to be able to provide housing for the working people of Hawai ʻi. Over the islands’ post-Statehood history, developers have taken more and more ʻāina, promising they can save us. We held our breath and have been left with a Hawai ʻi that is increasingly unrecognizable, not just in its changing landscape, but in its ethos—Kānāwai Māmalahoe (the Law of the Splintered Paddle) now replaced with sit-lie bans and sidewalk ordinances.

I moved back into my childhood home in late 2019, two days before my 30th birthday, and just in time to experience the joys and anxieties of navigating a pandemic with my parents. This past summer, I locked down in a multigenerational home, and needing a break from competing Zoom calls, I escaped the privileged irritations of a stay-at-home order and drove through Honolulu to my favorite surf break. On the way, I watched a police ofcer hand a citation to a man living on a grassy median along Ala Moana Boulevard. Later, while out on the water, I looked back toward the Honolulu skyline. In Kakaʻako, construction on yet another luxury tower continued—“essential work”

in Hawai ʻi, apparently. I was struck by the cruelty of a system that pushes people to the margins and then blames them for needing to exist somewhere. Sweeps and sidewalk ordinances have always been sadistic, but in the pandemic, they border on homicidal: Our local government continues to sweep houseless folks from now quiet streets, deliberately ignoring CDC guidelines that say sweeps spread the virus and put lives at risk.

In March, during the frst few weeks of the shutdown, things were even worse. The City and State shuttered public restrooms and callously told our houseless ‘ohana to fnd other facilities. An absurd amout of community energy was spent convincing our leaders to reopen bathrooms at the very moment when access to something as simple as a running faucet had become a matter of life or death.

I am just a couple chapters away from fnishing my dissertation. But the pandemic changed things. During the stay-at-home order, I sat down in my childhood bedroom-turned-makeshift workspace, and line by line, deleted every single reference to the “afordable housing crisis,” beginning with the one in the title. The truth, I think, is that we are not dealing with a crisis of housing, but a crisis of power. Not a crisis of supply, but a crisis of meaning—a fundamental struggle over the value of land and life that began with the greed of capitalism (a system that taught us to see land as property) and the violence of colonialism (a system that taught us that where there is no ownership, there is no personhood). How else do we make sense of a society that is so alarmingly adept at creating the opulence of blue-glass luxury towers and the abandonment of bluetarp tent cities, each a product of the other, only one so cruelly criminalized?

Now that the pandemic has laid bare the cruelties of this system, perhaps we are ready to think beyond the limits it has placed on who we are. As the food of evictions approaches, we can each hope that its current spares our house, that it rushes down a diferent street. Or we can meet it together, with a rising tide of humanity, recognizing that home is not a privilege to be earned, but something we all deserve on account of being here, being human.

Tina Grandinetti is a PhD candidate at RMIT University’s Center for Urban Research and a lecturer in Political Science at UH M ā noa.

86 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Image by @misterver

Text by Shannon Wianecki MANAGING THE COLLECTIVE SILENCE

Image by @misterver

Text by Shannon Wianecki MANAGING THE COLLECTIVE SILENCE

Aconfession: I enjoyed the initial days of the pandemic. The shelter-in-place order reminded me of my frst silent retreat in 2005, an experience that profoundly recalibrated my worldview.

In the days leading up to the retreat—a 10-day immersion into yoga and Ayurveda—I fretted about food. Never mind the silence, how would I survive without cafeine, sugar, or meat? I imagined sneaking across the highway to the snack shop. As it turned out, having fresh, nourishing food prepared for me three times a day was an extraordinary luxury. I didn’t miss chocolate at all.

Prior to the Covid-19 shutdown, I worried about food again. How long would this crisis last? Would grocery stores run out of supplies? In a panicked fog, I flled my pantry with things I’d never eaten before: four kinds of kimchi, two whole chickens, and broccoli “rice.” Again, as it turned out, I relished cooking new recipes and trading homemade salsa and sauerkraut with neighbors.

The frst day of the silent retreat felt like stepping of a moving sidewalk. Suddenly I wasn’t propelled by external forces; the only forward motion was my own. Retreat attendees had been instructed to leave behind cellphones, books, and any contact with the outside world. We were encouraged to avoid eye contact with one another. This felt alienating at frst, but gave us permission to turn wholly inward—an almost guilty pleasure in a world that demands constant interaction.