Theme : TIME { 48 } Seeking the Source { 56 } Age of Consequence { 148 } Carving Traditions 0 03 > 0928 1 $14.95 US $14.95 CAN 2548 98 10 The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I

26 | Climate Tradewinds

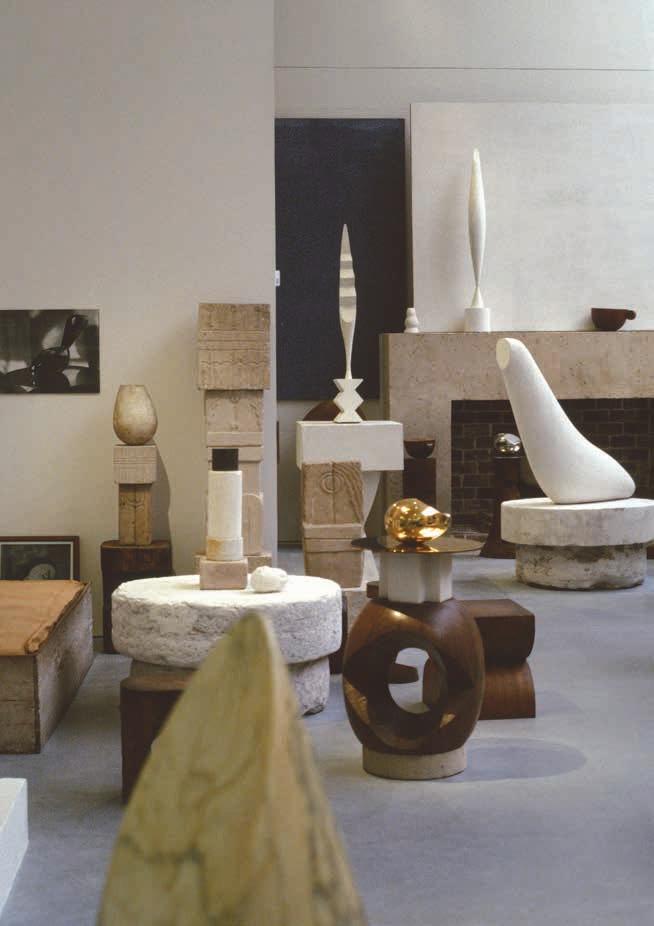

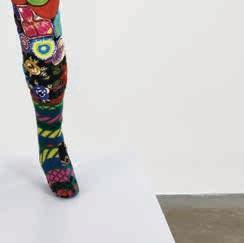

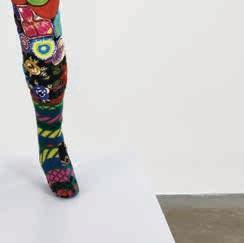

32 | Sculpture Tom Sewell

44 | Language Island Time

48 | Mo‘okū‘auhau Genealogy A HUI HOU

184 | Procrastination

FEATURES

56 | The Plastic Age

Journey to one of the islands’ most polluted beaches with managing editor Lauren McNally. In her piece, she seeks to uncover truths about plastic, a material made to last forever but typically only used for a short period of time.

76 | The Odd Couple

Writer Timothy A. Schuler assumes the role of willing third wheel to explore the love story between best friends Richard Lowe and Bundit Kanisthakhon, two men whose unlikely bond transcends generations.

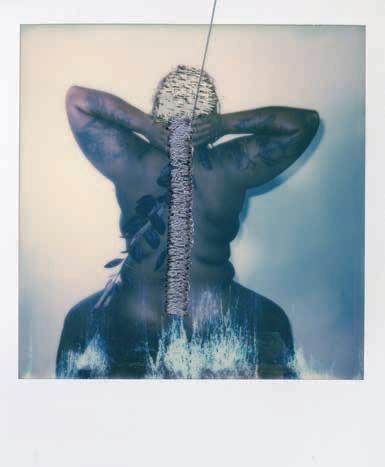

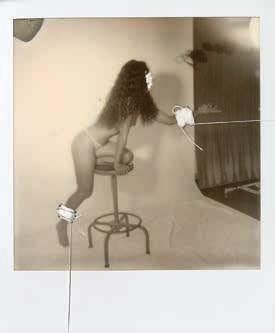

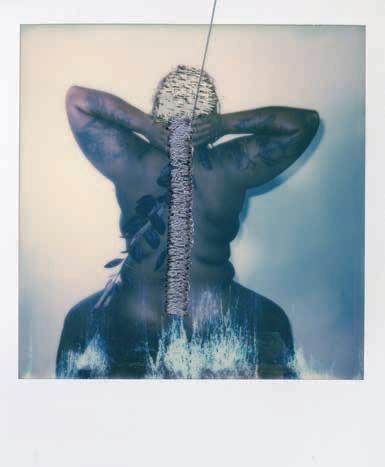

92 | Aperture Everlasting

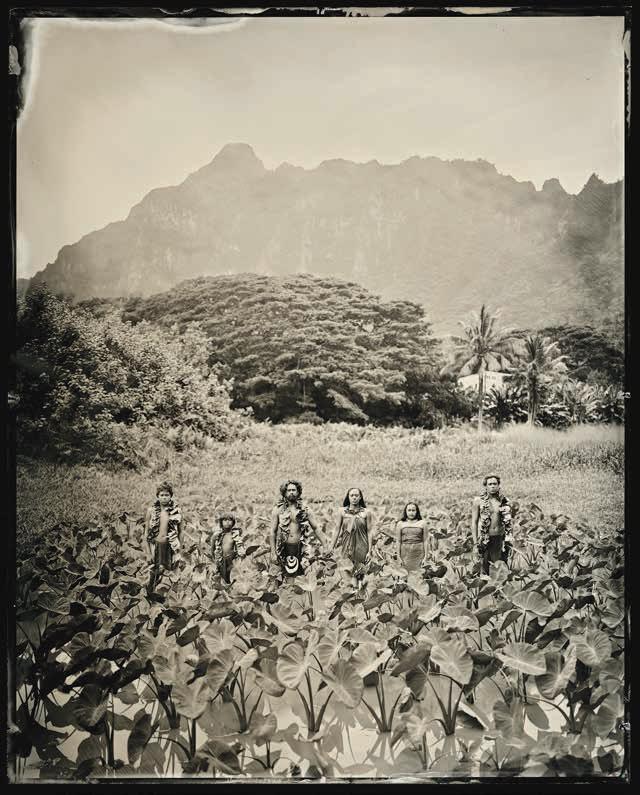

Three local arts writers and curators respond to the works of three Hawai‘i-based photographers who capture modern life in oldfashioned analog formats. Kenyatta Kelechi resurrects an early wet-plate photographic process, Nakemiah Williams heals her trauma with cathartic Polaroids, and Mark Kushimi presents dreamy meditations on life below and above the ocean surface.

TABLE OF CONTENTS | FEATURES | 16 TIME Letters Contributors FLUX PHILES

Image by Brenden George Ko

TABLE OF CONTENTS | DEPARTMENTS |

113

SPECIAL SECTION

TEN-YEAR ANNIVERSARY

In these essays, Flux writers grapple with and reflect on age-old topics that affect the daily fabric of Hawai‘i, from land conservation to the public education system.

Lisa Yamada-Son, founder and former editor-inchief of Flux Hawaii, guest edits this special section, complete with reports from staff writers and regular contributors. Image by John Hook.

BRANCH AND BLOSSOM

The Legend of ‘Ōhi‘a & Lehua

Limited Release in collaboration with Hawaiian designer Brandy Serikaku.

Visit us at Whalers Village on Maui and at Hilton Hawaiian Village on O‘ahu

Visit us at Whalers Village on Maui and at Hilton Hawaiian Village on O‘ahu

164 EXPLORE 166

176

146 LIVING WELL 148

156

TABLE OF CONTENTS | DEPARTMENTS |

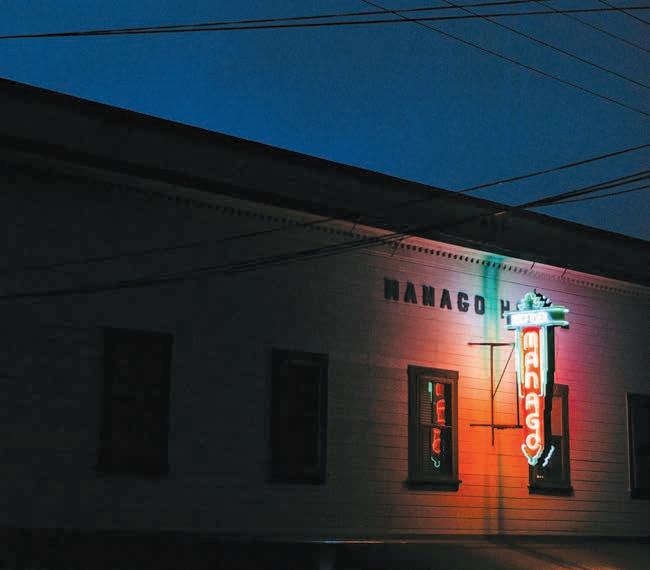

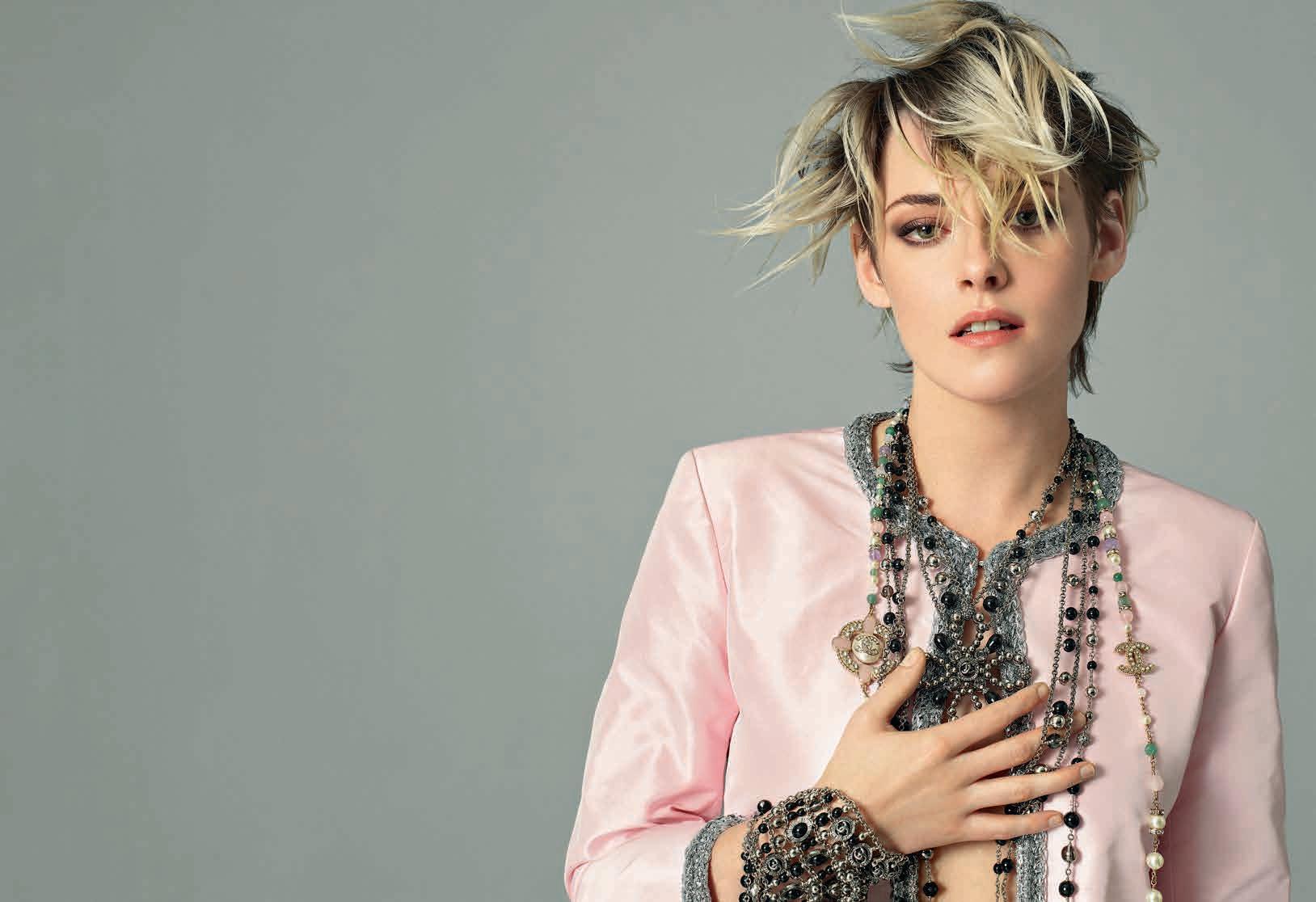

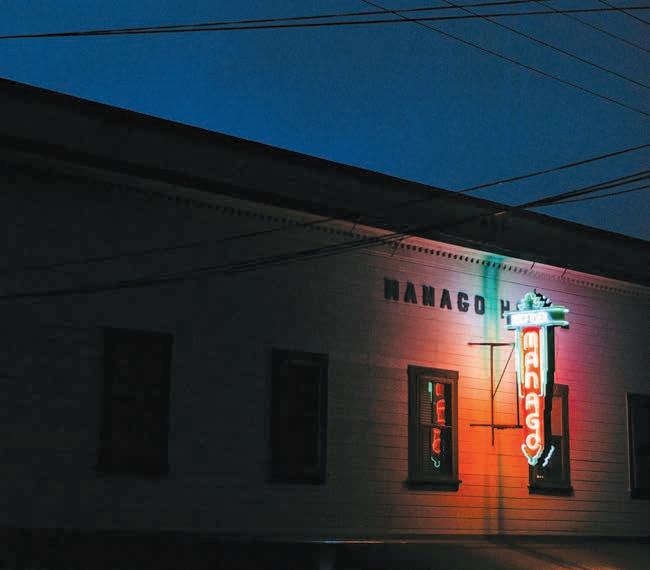

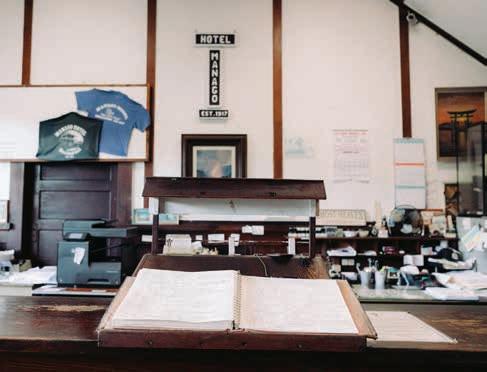

| Kona Manago Hotel

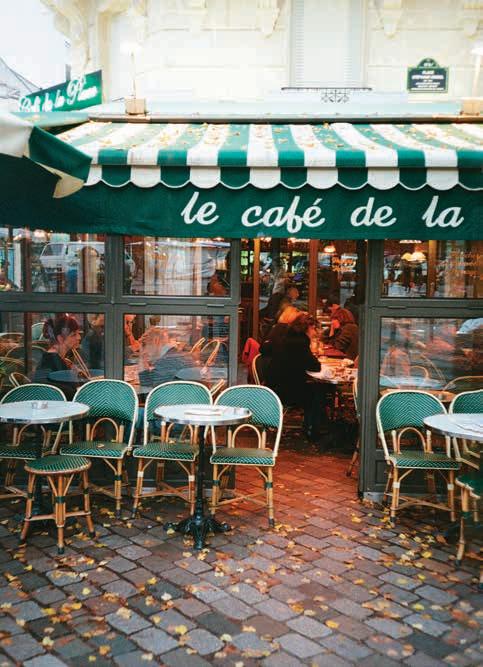

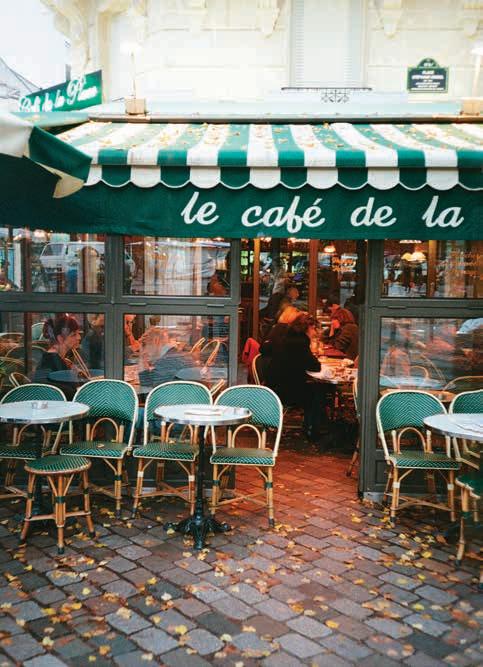

| Paris Le

Marais

| Surfing The Stones

| Preserves Ohana Jam

Image by Michelle Mishina

Image by Michelle Mishina

WAIKELE

HYATT REGENCY WAIKIKI

ALA MOANA CENTER

KOKO MARINA

WINDWARD MALL

WAIKELE

HYATT REGENCY WAIKIKI

ALA MOANA CENTER

KOKO MARINA

WINDWARD MALL

LocalMotion com H A W AI

LAHAINA GATEWAY

FLUX TV

Modern Age

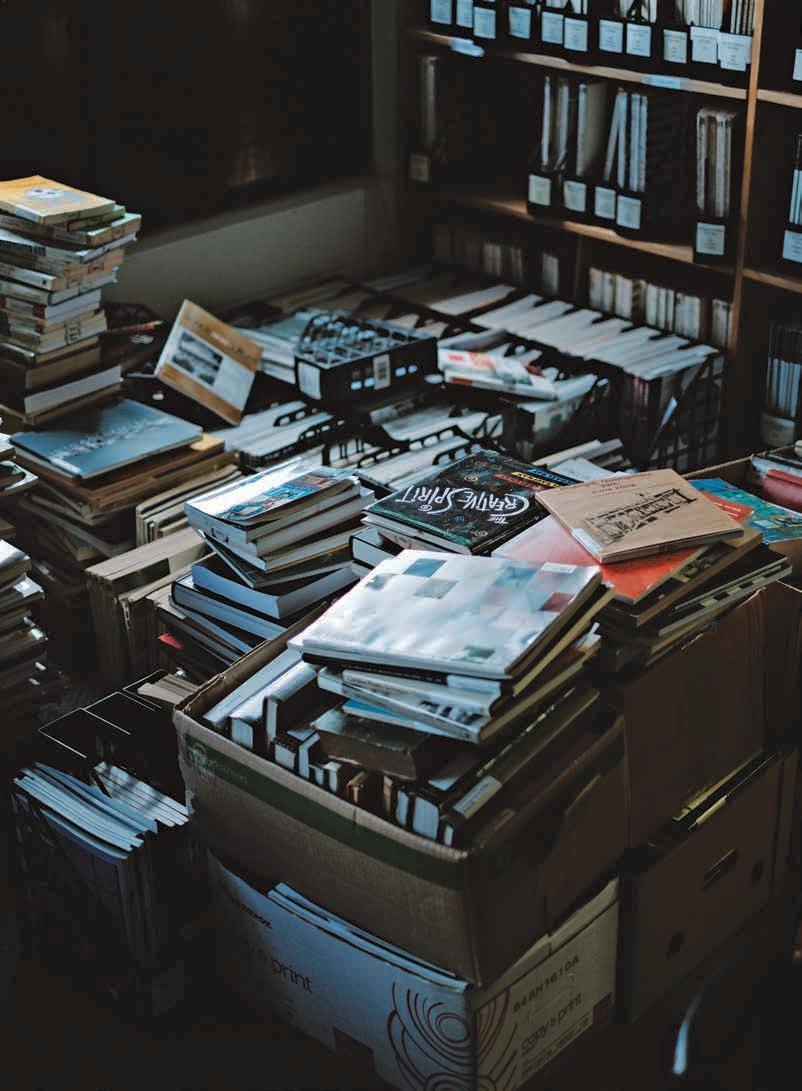

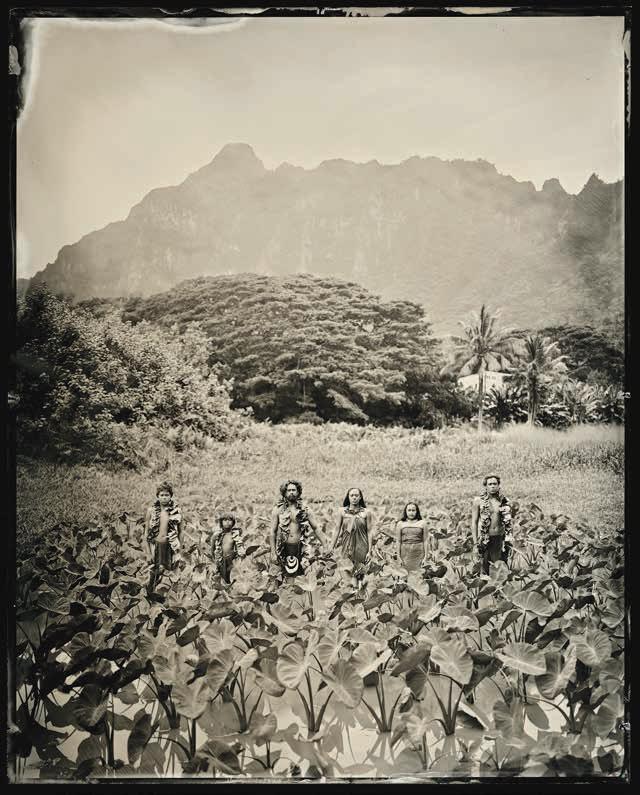

Though laborious, wet-plate photography remains Kenyatta Kelechi’s medium of choice. “I think people are interested in it because it takes you out of this moment in time. It puts you somewhere ambiguous,” says Kelechi, one of the only Hawai‘ibased artists utilizing the method. His photographs of Hawai‘i natives and locals also work to subvert the medium’s problematic history.

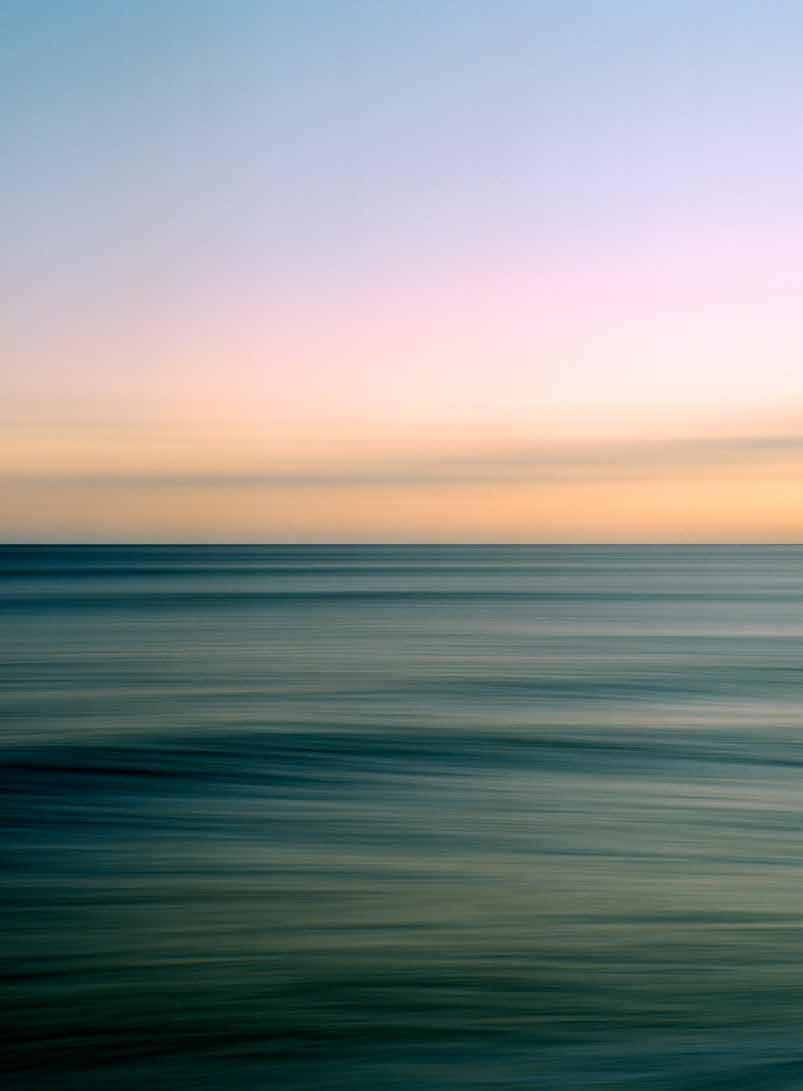

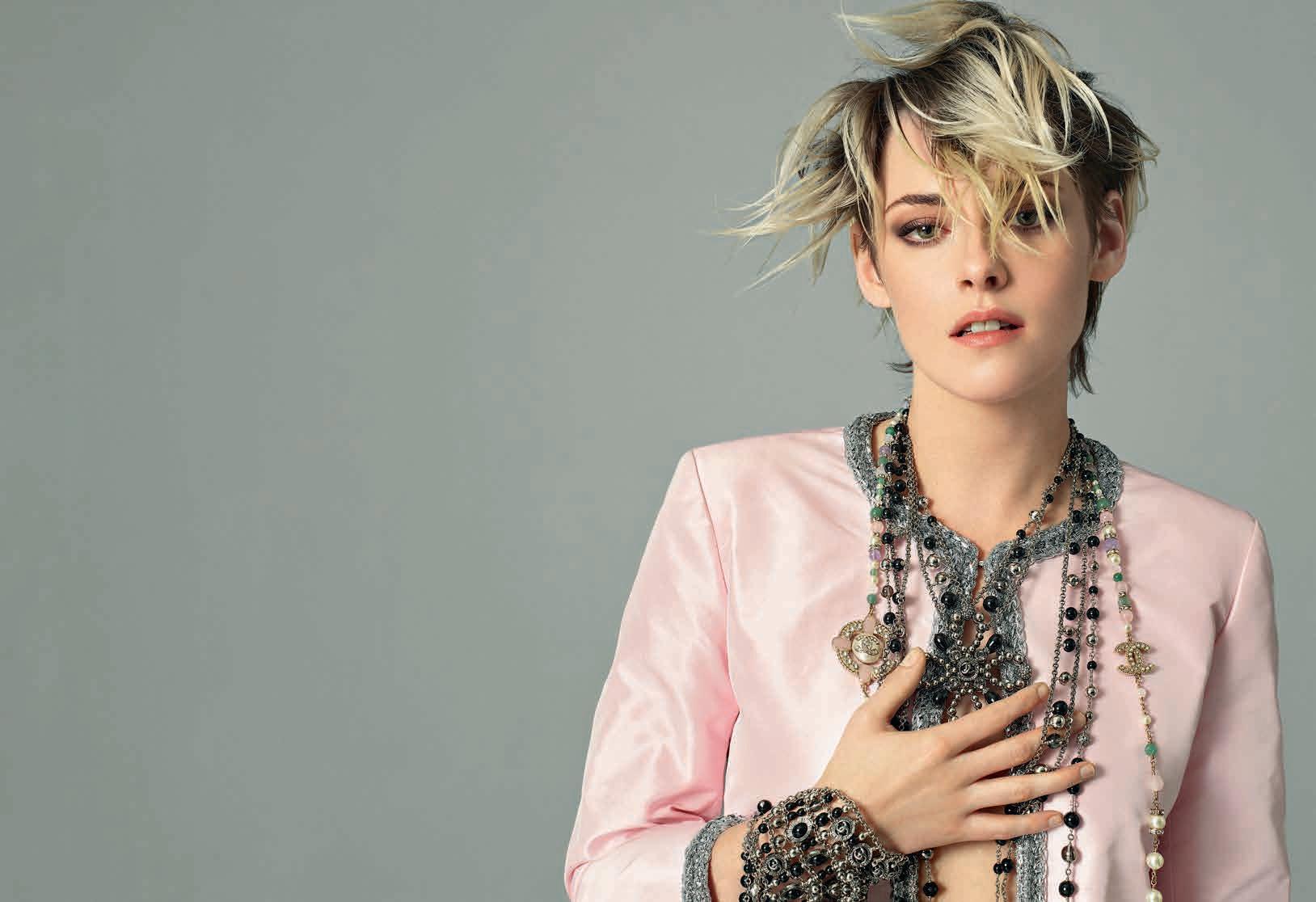

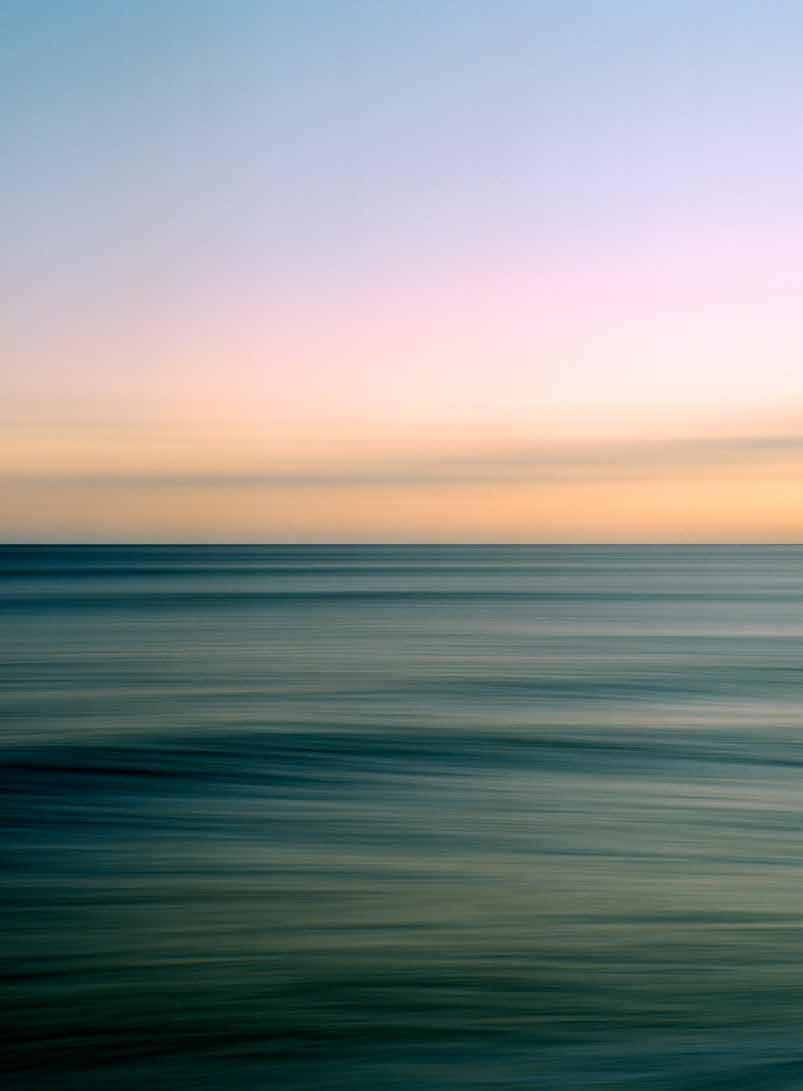

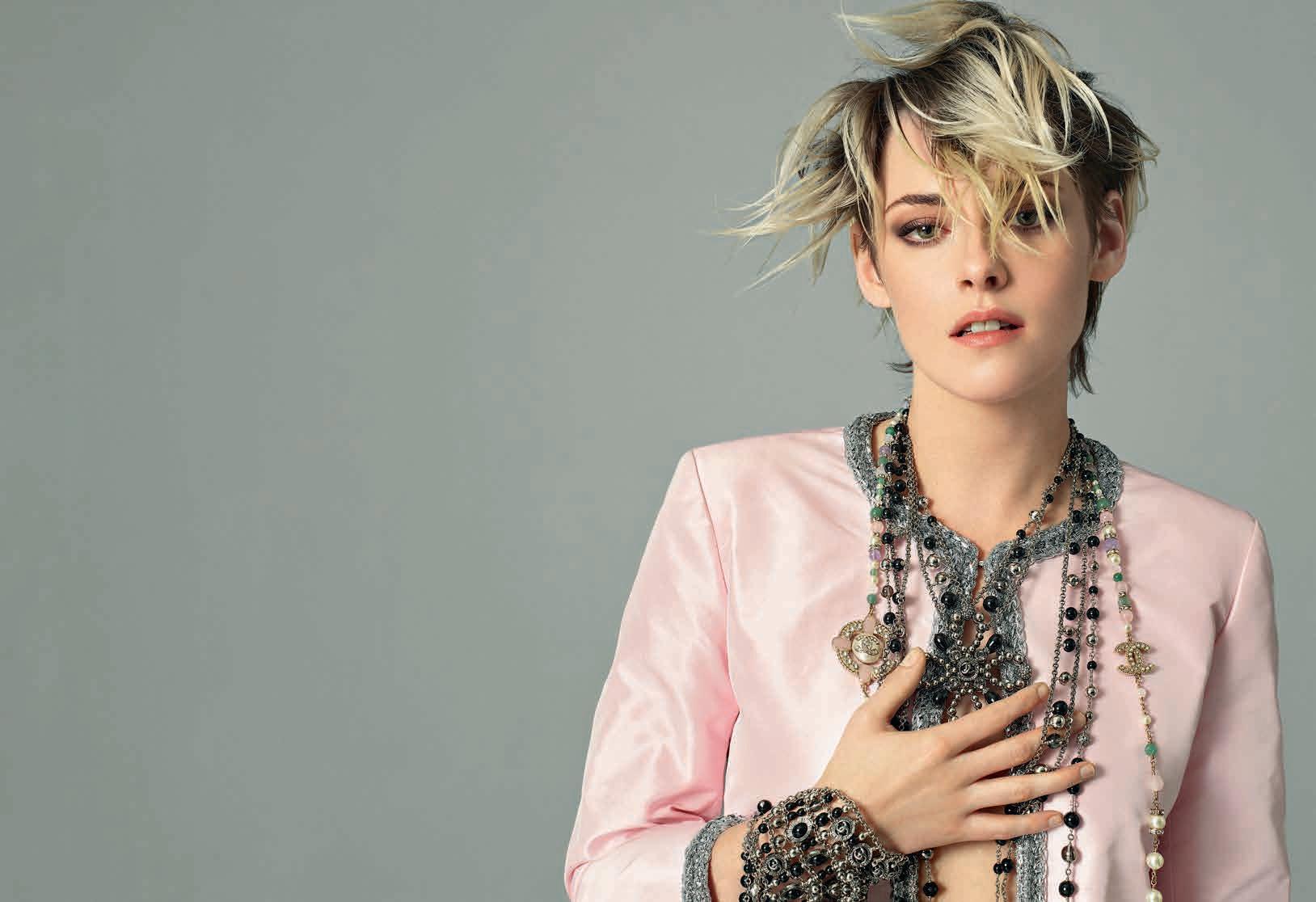

On the Cover

An oceanscape by photographer Mark Kushimi is featured on the cover of the Time Issue. This long-exposure image is part of a larger series by the photographer, “Forever Drowning,” capturing Hawai‘i’s surf breaks at sunset. Kushimi’s formal approach to this subject matter is contextualized by writer and artist Noe Tanigawa in the photo feature, “Aperture Everlasting,” on page 106.

Stay current on arts and culture with us at:

fluxhawaii.com /fluxhawaii @fluxhawaii

@fluxhawaii

TABLE

| FLUX TV |

OF CONTENTS

TREBLE AWAITS... Halekulani’s destination for live music, late night libations, designer cocktails and fine foods. COMPLIMENTARY PARKING 8 55 – 738–4966 2199 Kalia Road, Honolulu Halekulani.com

Remember where you started…

Ten years ago, a recent college graduate named Lisa Yamada handed me a flyer outside of Aloha Tower. The flyer read “FLUX Hawaii Coming Soon.” She introduced herself to me and explained that she was starting her own local magazine, uninterested in joining any existing publishing houses or newspapers. Her hungry ambition reminded me of New Yorkers like myself, and so I volunteered to sell ads for her. Soon enough, Lisa and I became business partners, since my own newly formed brand, NMG Network (Nella Media Group, at the time), was in need of editorial direction for its stories of Hawai‘i.

Together, we hoped to create a dynamic vision for Flux and hoped to amplify modern and local voices in Hawai‘i on a global scale. There are art, culture, fashion, and social scenes here that are less seen by the rest of the world. Through our stories, we wanted to give visibility to local people and foster learning.

I’m honored to say the Flux brand continues to accomplish its vision. It has evolved from a beautiful print magazine to a multimedia platform also featuring breathtaking documentary videos, informative social media content, and global events. Lisa has moved on from NMG to build her family, but her vision and voice will always remain with the brand.

In this period of reflection, I am proud that while we’ve gained new channels and formats, our storytelling is the same. Flux is a brand that embraces the tides of change, but it will always dive into the vast ocean that is Hawai‘i’s voice.

Stay humble and always move forward,

Jason Cutinella CEO, PUBLISHER @jcut @nmgnetwork

PUBLISHER’S LETTER | TEN-YEAR ANNIVERSARY |

702 SOUTH BERETANIA STREET, HONOLULU, HI 808.543.5388 | CSWOANDSONS.COM

EDITOR’S LETTER

Hours structure our days. Days become our months. Months congeal into our years.

In life, this constant churn of time is inevitable, though it does not always move at the same clip. There is an elasticity that feels unique to time’s passage, in how it can crunch forward heavyfooted or speed by in a blur. What we do in this lair of time ultimately matures as meaning about our priorities, how we square away our worlds, who we are. As Annie Dillard wrote, with alarming simplicity: “How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.”

The state a reader is in when they happen upon this magazine, whether in a frenzied frame of mind (“Time is of the essence!” the clock’s hand screams) or a mode of relaxation (“Oh, you have all the time in the world,” it coos), is unknowable for us, the crew of editors, writers, photographers, and designers who put each issue together while feeling the anxiety-inducing press of time as we tick closer to strict deadlines. But our underlining approach is always the same: not to waste a minute of anyone’s efforts. Time is a precious commodity (perhaps the most precious) and we’re well aware we must honor a reader’s rapt and warm attention with pages that aim to inform, challenge, and touch you.

For storytellers, the trappings of time have their benefits. Time can clarify what needs to be told and how to tell it. A writer who has only seven pages or seven days to realize an idea will negotiate these constraints with their narratives. One of the ways this expresses itself is in the scaffolding of the story. I’m often struck by how the structure of a piece of writing can also inform its content, its tenor and tone; how it can add a surprising texture to its subject. Writer Timothy A. Schuler’s feature on a platonic, generation-spanning romance, on page 76, is strung together as if told in bursts of consciousness, holding a mirror to how memory can play out when looking back on a life. Managing editor Lauren McNally holds a microscope to the millions of pieces of plastic that wash up on our shores, on page 56, oscillating between research on the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and her personal trek to Hawai‘i Island to participate in a volunteer cleanup of one of Hawai‘i’s most plastic-polluted beaches. Organized in such a way on the page, this problem’s double consciousness, literally at our feet while also feeling out of reach, emphasizes the overwhelming toll the topic has on our collective psyche. The familial themes that emerge from stories about ancestral surfing knowledge passed on from grandfather to granddaughter and a century-old hotel maintained by the next generation of caretakers reminds us that time isn’t necessarily linear, that it circles back to where it originated.

The Time Issue also ushers in the 10th anniversary of Flux Hawaii. This milestone gave us a chance to collaborate with the title’s founder and former editor-in-chief, Lisa Yamada-Son, who thoughtfully steered the editorial tone and interests of this publication through all kinds of waters. She guest-edited a special section, which starts on page 113, that features reflections on how the islands’ cultural landscape has changed over the past decade. If you’re familiar with Flux, you might also notice creative director Ara Laylo modified the look and feel of the cover layout: the obsidian-esque foil on the masthead, the simplified text, and the alluring, full-bleed cover photo, artfully shot by Mark Kushimi. The intention is to draw you in, just as the magazine did when it appeared on the scene in 2010. To create a space that allows you to linger and engage. To contemplate where we’ve been, where we are now, and where we’re going. Time and again.

With aloha,

Matthew Dekneef EDITORIAL DIRECTOR @mattdknf

| TIME |

MASTHEAD

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Ara Laylo

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Matthew Dekneef

MANAGING EDITOR

Lauren McNally

NATIONAL EDITOR

Anna Harmon

SENIOR EDITOR

Rae Sojot

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Eunica Escalante

SENIOR PHOTOGRAPHER

John Hook

PHOTOGRAPHY EDITORS

Samantha Hook

Chris Rohrer

DESIGNER

Skye Yonamine

CONTRIBUTORS

Michelle Broder Van Dyke

Beau Flemister

Christine Hitt

Healoha Johnston

Mitchell Kuga

Roland Longstreet

Leilani Marie Labong

Cameron Miculka

Natalie Schack

Timothy A. Schuler

Noe Tanigawa

Josh Tengan

Lisa Yamada-Son

IMAGES

Kenyatta Kelechi

Brendan George Ko

Mark Kushimi

Lila Lee

Michelle Mishina

Nikki Oka

Josiah Patterson

Kiki Williams

CREATIVE SERVICES

Shannon Fujimoto CREATIVE SERVICES MANAGER

Gerard Elmore LEAD PRODUCER gerard@NMGnetwork.com

Aja Toscano CREATIVE PRODUCER

Shaneika Aguilar

Kyle Kosaki

Rena Shishido FILMMAKERS

Chloe Ma

Hazuki Ritchie

Kanani Smull INTERNS

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley VP SALES mike@NMGnetwork.com

Phil LeRoy NATIONAL SALES DIRECTOR

Chelsea Tsuchida KEY ACCOUNTS & MARKETING MANAGER

Helen Chang MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

Hunter Rapoza DIGITAL NETWORK ANALYST

Jackie Tu SALES ASSISTANT

Taylor Kondo FASHION MARKETING COORDINATOR

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock CHIEF RELATIONSHIP OFFICER joe@NMGnetwork.com

Francine Beppu NETWORK STRATEGY DIRECTOR francine@NMGnetwork.com

Gary Payne VP ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE

Courtney Miyashiro OPERATIONS ADMINISTRATOR

General Inquiries: contact@fluxhawaii.com

PUBLISHED BY:

Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel St., Ste. A Honolulu, HI 96817

©2008-2020 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. FLUX Hawaii is a triannual lifestyle publication. ISSN 2578-2053

| TIME |

FEB 22–JUN 21, 2020 Honolulu Museum of Art honolulumuseum.org #30Americans

by the

The exhibition 30 Americans is made possible with generous support from Sharon Twigg-Smith, Elizabeth Rice Grossman, Priscilla and James Growney, and Lynne Johnson and Randy Moore. Additional funding provided by the Conley Family Foundation, Judy Pyle and Wayne Pitluck, The Schulzman-Neri Foundation, The Taiji & Naoko Terasaki Family Foundation, and Hawai‘i Council for the Humanities & the National Endowment for the Humanities. Special thanks to corporate sponsors Christian Dior, Halekulani, and Honolulu Star-Advertiser.

1959). SOUNDSUIT 2008. FABRIC, FIBERGLASS AND METAL. COURTESY RUBELL MUSEUM, MIAMI. © NICK CAVE.

NICK CAVE (B.

Organized

Rubell Museum, Miami.

HISTORY IN THE MAKING

THE MOST INFLUENTIAL CONTEMPORARY AFRICAN AMERICAN ARTISTS

FEATURING WORKS BY 30 OF

Broder Van Dyke

Michelle Broder Van Dyke is a feature and news writer based in Hawai‘i. Her work has been published in The New York Times, NBC News, the Guardian, BuzzFeed, Gizmodo, the San Francisco Chronicle, and NMG Network. She was formerly the night editor for BuzzFeed News, where she reported and edited breaking international news from Honolulu. In this issue, Broder Van Dyke reports on the effect of a warming climate on the islands’ famed tradewinds. “Growing up in Hawaiʻi, I’ve experienced the effects of climate change, some of which are not seen as much as they are felt,” she says. Since returning to her home in Tantalus after moving away for college, she’s had a chance to enjoy the trades, while also reflect on how the ecosystem functions as a whole. “As the trade winds change, so will the rain, and the flora and fauna that it supports.” When Broder Van Dyke isn’t writing, she’s working at her and her husband’s backyard flower farm, Tantalus Botanicals.

Christine Hitt

Christine Hitt

Kamehameha Schools and University of Hawai‘i graduate Christine Hitt is a Los Angeles-based freelance writer whose work has appeared in the LA Times, Yes! magazine, Hana Hou!, and Honolulu Magazine. Prior to moving to Southern California, she served as editor-in-chief of Mana and Hawai‘i magazines. She has previously written for NMG Network’s titles, including a piece on Hawai‘i’s legendary Menehune for Flux. For this issue, Hitt guides readers through the process of uncovering Native Hawaiian genealogies on page 48. “I’ve been a fan of genealogy since I was a kid, and when I discovered that there were barely any resources about how to research Hawaiian roots, I wanted to help as many people as possible,” Hitt says. “It was a passion project for a good chunk of my life, and I’m happy to share what info I know with others.”

Cameron Miculka

Cameron Miculka

Cameron Miculka is a freelance journalist based in Kealakekua, Hawai‘i Island, where he was most recently a reporter at West Hawaii Today. Miculka’s work in journalism has focused on rural communities across the continental United States and Pacific. He has also worked as a journalist at the Pacific Daily News, a daily publication on the island of Guam, as well as The Weimar Mercury in Colorado County, Texas. For this issue, Miculka wrote about Manago Hotel, which is located just down the road from his home in South Kona on Hawaiʻi Island. “Writing about the hotel and restaurant challenged me to consider why we form the relationships we do with places in our community,” he says. “Places like Manago Hotel continue to thrive because they continue to be good—it has loyal customers because it is loyal to them in return.” The piece, “Checking In,” on page 166, is Miculka’s first piece for the publication.

Lisa Yamada-Son is the founder of Flux Hawaii and its former editor-in-chief. After a decade of tending to the magazine that first held her heart, she stepped down in 2019, following the birth of her first child. “Flux was my first baby,” she says, “and I’m proud that many of the topics we covered in our early years are still as relevant today as ever.” To mark its 10-year anniversary, she resumed the editorial mantle, curating a special section on page 113 that revisits topics that drove the magazine’s first year in print. “Flux is what it is today because of the courage and passion of our writers, whose voices were more than just words on the page: Flux has been cited to pass legislation and used in school curriculum. I can only hope that Flux will continue to be a platform that pushes Hawai‘i forward.” Currently, she is shaking up the construction world at A-1 A-Lectrician, an electrical contracting company that was started by her grandfather in 1957.

Michelle

Michelle

| TIME |

CONTRIBUTORS

Lisa Yamada-Son

The Maui sky through a steel sculpture by artist Tom Sewell. Image by Michelle Mishina.

The Maui sky through a steel sculpture by artist Tom Sewell. Image by Michelle Mishina.

“If

TIME

you don’t get up on time and plant those seeds, your harvest is not going to feed you.”—James

Viernes

Up in the Air

The northeast trade winds play a huge role in providing Hawai‘i with some of the best weather on the planet, but that might be changing.

TEXT BY MICHELLE BRODER VAN DYKE

IMAGES BY BRENDAN GEORGE KO

The air in the Koʻolau mountains is still this morning. With no wind to rustle the trees, the chatter of birds, the whirl of a helicopter, and the beeping of a garbage truck fill the silence. The air feels thick with humidity, making me not want to move, except I do dance around to fend off mosquitoes. In the distance, the ocean shimmers like glass, reflecting the cloudless sky. On days like this, everyone knows there are no northeast trade winds.

When the islands’ famous northeast trade winds are present, they arrive on the windward side of Hawaiʻi, where they wrap around the shoreline, creating small waves, cool breezes, clouds, and rain, which feeds the watershed. A sublime breeze persists and the air is clean, as any volcanic haze or industrial pollution is blown off shore. Everything feels right.

It’s easy to take for granted something we don’t necessarily “see,” but the northeast trade winds affect the everyday reality of locals, inviting keiki to ride waves at Makapuʻu Beach, encouraging us to eat lunch outside, and providing much of the water that comes out of the tap. Commonly known as Hawaiʻi’s “natural air conditioner,” the northeast trade winds hav e a powerful

Trade winds are fundamental to every aspect of Hawai‘i’s climate.

FLUX PHILES | CLIMATE | 26 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

cooling effect as they blow across your skin.

Trade winds also figure largely into the idealized version of Hawaiʻi: Palm trees sway, hula skirts flutter, and a surfer is seen through the perforated mist dashing off a wave.

Northeast trade winds blow more frequently in the summer, cooling the islands down when the temperature starts to heat up. Native Hawaiians recognize two seasons: kau, from May to October, when the sun shines directly overhead and the trade winds are more reliable, and hoʻoilo, from November to April, when the weather is cooler and the trade winds are less reliable. This aligns closely with the two seasons determined by modern climatologists, although the hotter season is shorter by a month.

But there has been a significant decline of northeast trade winds in the past four decades. Climatologist and University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa professor Pao-Shin Chu, along with other researchers, published a study in 2012 that found the frequency

and intensity of northeast trade winds had decreased between 1973 and 2009. Data collected at Honolulu’s airport showed that in 1973, northeast trade winds occurred 291 days per year, but by 2009, the number had dropped to only 210 days. Chu called the findings “really alarming” and said it was not good for Hawaiʻi’s future.

These discoveries are consistent with what would be expected as climate change causes the planet to heat up. The study indicates fewer days were cooled off by northeast trade winds. It also found slightly increased frequency of easterly trade winds, which don’t bring the same amount of cool air to Hawaiʻi.

This phenomenon seemed obvious over the long, hot summer of 2019. It was evident in the headlines on the local news—“Hawaii has broken or tied more than 120 heat records since April” (Hawaii News Now) and “NE Trade wind days nearly cut in half” (KITV). It was also clear in the extra-tense conversations people had about things that happen every

In the past four decades, climatologists have noted a significant decline in Hawai‘i’s trade winds.

28 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

summ er, like mango thieves. My auntie, who lives in Mānoa, decided to buy an airconditioning unit. There was a shave-ice shortage, as the machines that make the large ice blocks overheated.

European sailors, who followed the winds’ consistent paths from Europe to the Americas and then across the Pacific Ocean to Hawaiʻi and Asia, named them the trade winds. These early sailors figured out that the best route was not necessarily in a straight line, but instead in a sort of circular pattern that follows the winds. Polynesians also used the winds to explore the seas, and Hawaiians have hundreds of names for the winds on each island that flow across, away, or toward the islands.

“The trade winds are created by an atmospheric circulation system that basically takes heat away from the tropics and distributes it to the north and south of the tropics,” explained Chip Fletcher, a professor at the UH at Mānoa’s School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology. Hawaiʻi’s proximity to the equator means that the sun is often shining overhead, heating up the land and in turn warming the air. This warm air rises into the atmosphere and is pulled into cooler parts of the Earth in the form of high-altitude jet streams. To replace the hot air, cool air then flows from the northeast along the surface of the Earth, collecting moisture and creating trade winds. This cycle operates as Hawai‘i’s natural ventilation system.

Without the blissful northeast trade winds in Hawaiʻi, we will feel the warmth and we will notice that trade wind rainfall has decreased, according to Chu. “We depend very much on trade-wind rainfall for agriculture, tourism, water resources, and all kind of things,” Chu said.

The trade winds are fundamental to the climate of Hawaiʻi, influencing the different environments from makai to mauka and windward to leeward. By shaping the dense cloud banks that surround the ridge tops in Hawaiʻi, the winds create what is known as

a cloud forest. Water droplets are deposited on leaves and branches, then drip onto the ground and travel down into the islands’ aquifers. The flora and fauna that live in the upper watersheds along Hawai‘i’s windward slopes have evolved in these moist conditions. The extraction of moisture as the air is lifted over or around the windward slopes leads to a “rain shadow” on the leeward slopes, creating dry mountains. This is why a drive from cloudy Kailua on Oʻahu through the Nuʻuanu Pali tunnels to Honolulu is often like sliding into a parallel land where it is very sunny.

Each Hawaiian island interacts with the trade winds in different ways. On Oʻahu and Kaua‘i, the trade winds flow over the mountains. The taller peaks on Hawaiʻi Island and Maui force the clouds to go around them, creating dry, desert conditions at the highest elevations. But an increase in eastern tradewinds means the mountains are getting different windy results that produce fewer trade showers and fewer clouds, according to Fletcher.

“The phenomena of global warming is expanding the tropics and it is changing atmospheric circulation,” Fletcher said. Hawaiʻi does see more extremes, he said, and it will continue to see changes. “I’m saying ‘changing’ because there’s so much about how climate change influences the atmosphere and ocean that we just don’t understand.”

I have lived close to the top of O‘ahu’s Mount Tantalus, also known as Puʻu ʻŌhiʻa, for most of my life, so I’ve grown up embedded in the upper watershed ecosystem. Misty days that blocked the sunlight used to be fairly common, but now they feel infrequent enough that I am delighted when they arrive. Many of my neighbors still have working fireplaces, and the smell of burning embers fills the air on these days. Cloudy trade wind weather is an excuse to stay home and to feel cozy, like how the Danish do hygge, but tropical style with slippers and socks.

Trade winds have figured largely into the idealized image of Hawai‘i.

30 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 31

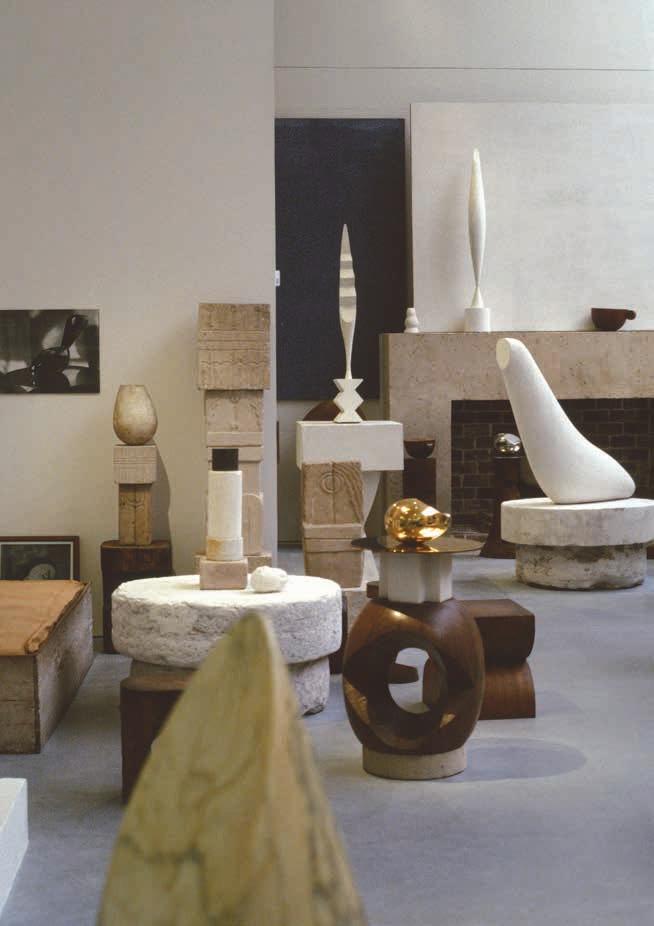

Breaking the Mold

Over six decades, Tom Sewell has found, filmed, and sculpted a hefty body of work. Much of it originated with Maui’s bygone sugar mills.

TEXT BY RAE SOJOT

IMAGES

BY MICHELLE MISHINA

Tom Sewell delights in documentation. Each morning, the artist hands over his iPhone to his assistant, Ines Gurovich, who downloads the photos he took the day before and selects highlights to print. She then assembles the prints into a montage that she pastes into an oversized journal. It’s an ambitious approach for a diary, but Sewell’s zeal for all things creative is insatiable. “There’s at least a hundred photos a day,” says Gurovich, a Peruvian painter and sculptor who has been working with Sewell since 2018. “Sometimes it’s hard to pick which ones.” Sewell’s images capture the miscellany of his daily life—a tree or shadow or building might catch his fancy— though most shots are of people. “He talks to everyone,” she says. “A lot of beautiful women,” Sewell quips. The two laugh.

A multimedia artist and photographer based on Maui, Sewell believes one can find art anywhere and in any form. He certainly does. Now 80 years old, he has spent a lifetime collecting and creating, cultivating and celebrating experiences, places, sculptures, and friends. His specialty, however, is objet trouvé, or “found art.”

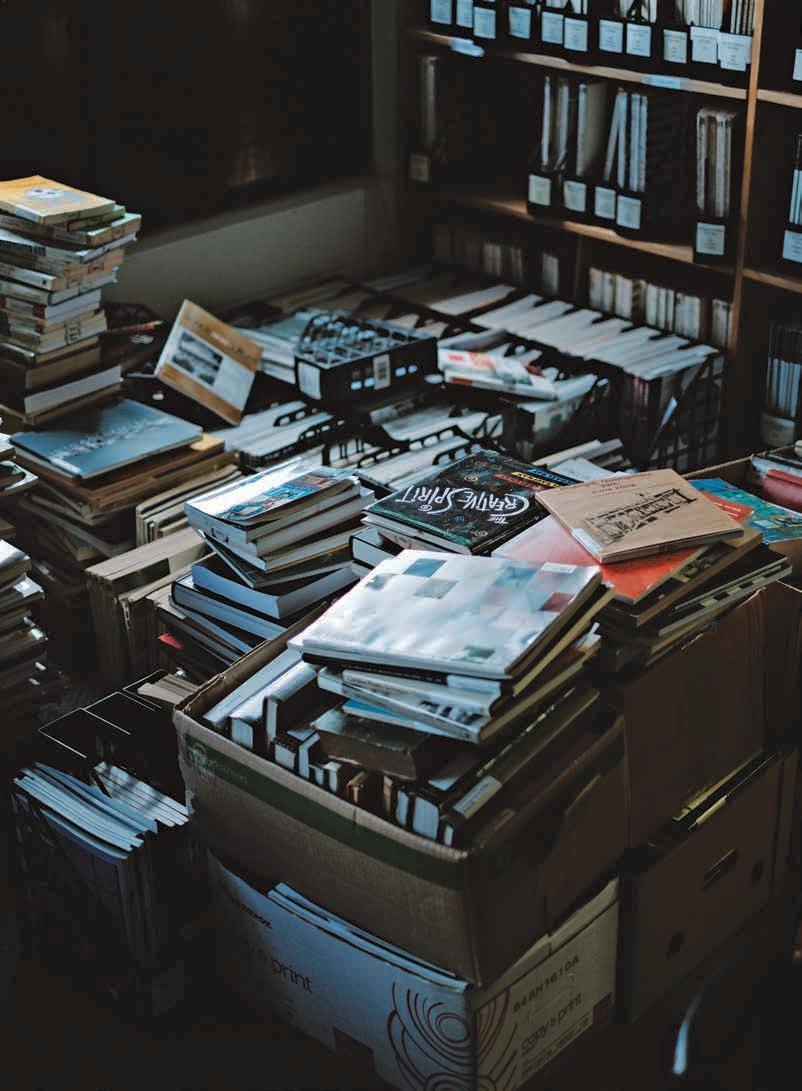

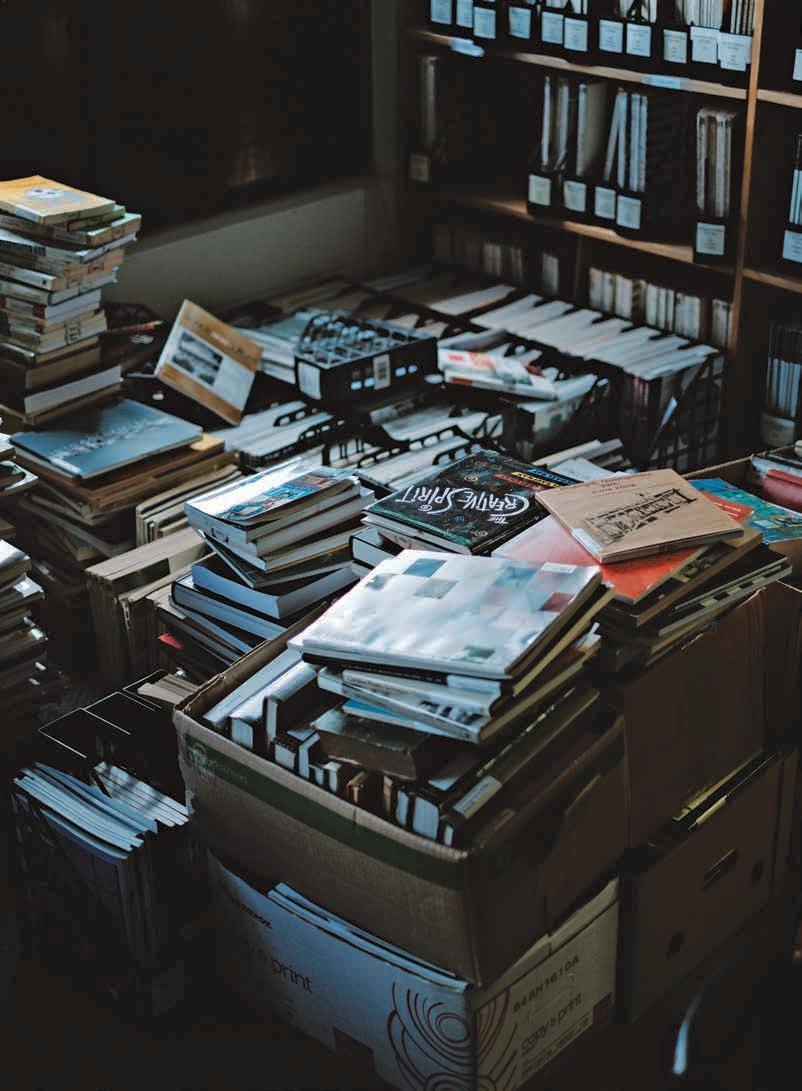

Throughout Sewell’s 17-acre estate in the cool, green uplands of Ha‘ikū are such treasures. Along the rolling grounds, massive steel gears from Maui’s now-defunct sugar mills return to life as delightful window frames. Enormous industrial drills serve as building posts. The magic continues indoors where, in a tidy, side office of his art studio, boxes of Kodachrome slides, photography binders, and film cassettes line an entire wall, all neatly named and numbered. Many are accompanied by miniature snapshots depicting their contents. There are troves of letters from friends and mentors (he names Basil Langton among them) which he lovingly reads and re-reads. Nearby, in his library, a collection of worn tomes— Sewell’s dream journals—sits on cozy rows of shelves. Each morning for the past few decades, Sewell has sketched the remnants of his dreams. Some become blueprints for reality, like a Japanese rock garden he created for his wife, Michelle Sewell, an interior designer.

If the estate seems a merry reflection of his character, the artist is quick to note that life hasn’t been and isn’t always easy. Fortunately, he has managed life’s ups and downs—bad breakups, health issues, financial difficulties—with his signature optimism. “There were times I had to go to the pawn shop with my camera in

Tom Sewell spent a lifetime refining the craft of objet trouvé or “found art,” celebrating the beauty in objects often overlooked.

32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM FLUX PHILES | SCULPTURE |

order to pay the rent,” Sewell says. “But my middle name is Serendipity. I wake up each morning and think, ‘What miracle is going to happen today? Is something going to be in the mail? Will somebody come to visit?’”

Growing up in Minnesota, Sewell was a tall, skinny kid, calm and a little self-conscious. His mother affectionately referred to him as “rug head” because of his mop of curls. As a teenager, he developed a flair for the illicit. Robbing gas stations and stealing tires became his forte. “I think I might have had some kind of attention deficit disorder,” Sewell muses. “That crime stuff was really exciting.” It wasn’t long before he was caught. “I managed to escape jail time by the skin of my teeth,” Sewell says. “I went straight then.” By 19 years old, Sewell had come into a more positive outlet for his energy, trimming windows at Dayton’s Department store in Minneapolis. There, he met Joe Wright, an “educated,

elegant, and stylish” gentleman who was the head of the display department. Wright left an indelible impression on Sewell, who began to emulate the dapper men of downtown—the cut of their suits, the polished shoes, their knowledge of art and design. “I’d wear a suit and tie and fedora hat and go to jazz clubs,” Sewell recalls. “I loved the idea of being grown up.” He chuckles in mild amusement at the follies of youth. “I even started smoking.”

Sewell’s immersion in art and culture laid the groundwork for a lifetime of creativity. He went on to run an art gallery in Minneapolis, work at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and start a design magazine called Main. In the 1960s, down on his luck and ready for change, Sewell moved to Southern California. In Venice, he began converting derelict industrial buildings into sought-after real estate. The endeavor proved lucrative, but for Sewell,

Sewell’s talent for transforming derelict objects into found art has generated a unique body of work. The artist lives and works at his estate on the hillsides of Ha‘ikū, Maui.

34 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

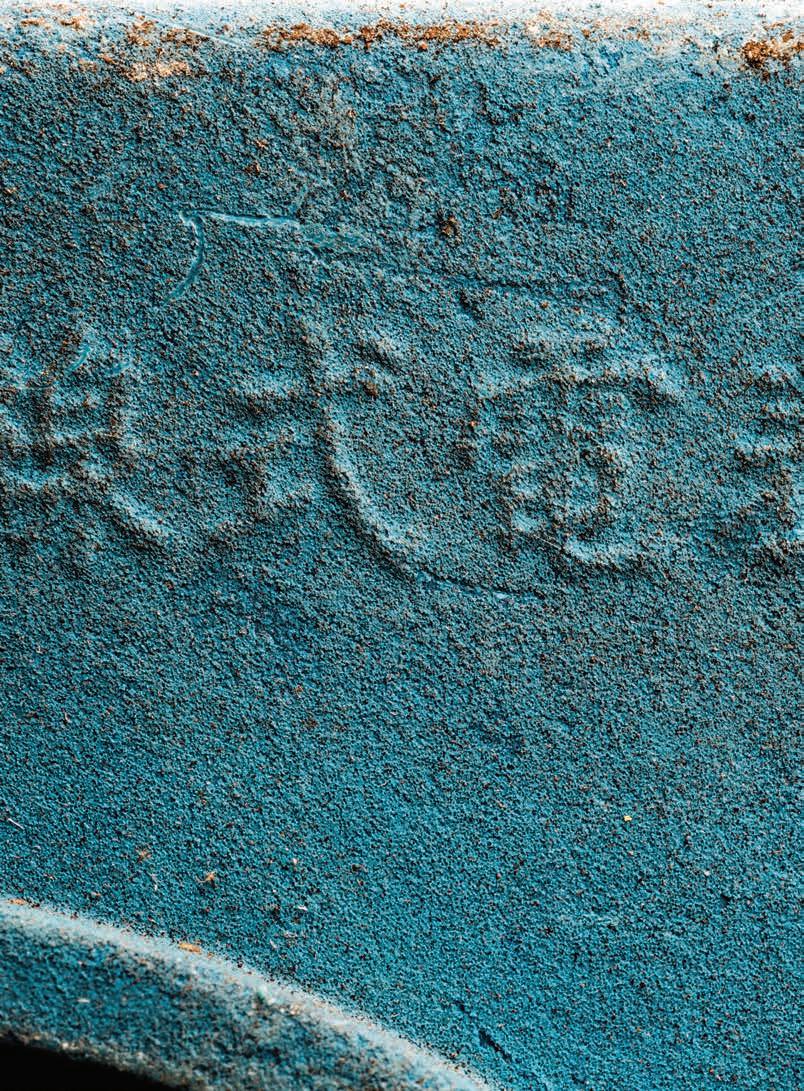

“I was so interested in the colors and patina, design and decay, the juxtaposition of objects,” Sewell says.

it was the process of transforming nothing into something that enlivened him.

This leitmotif surfaced anew when Sewell settled on Maui in the ’90s. Here, he found inspiration in the most unlikely of scenes: the island’s declining sugar empire. “The sugar mills were some of the ugliest, loudest places on Maui,” Sewell says. Stepping into the industry’s rusting mechanical belly, Sewell marveled at the beauty in its brutality. Ideas surrounding duality of light and shadow, weight and lightness, decay and growth sprang to mind.

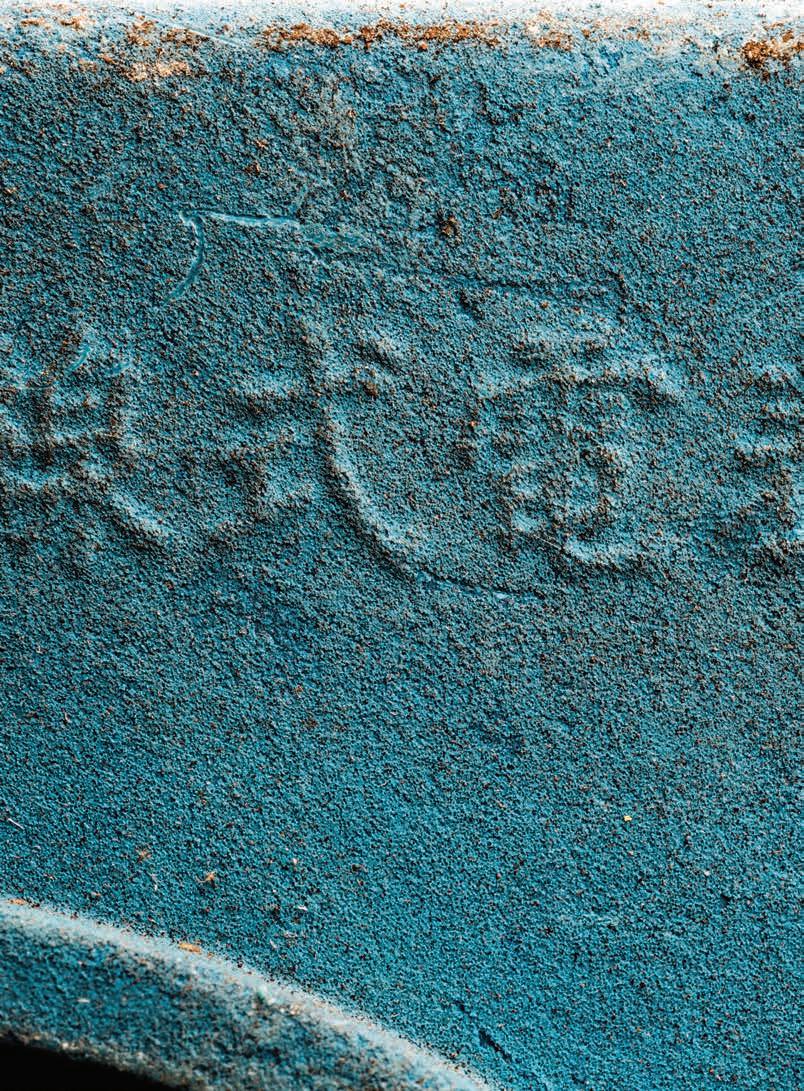

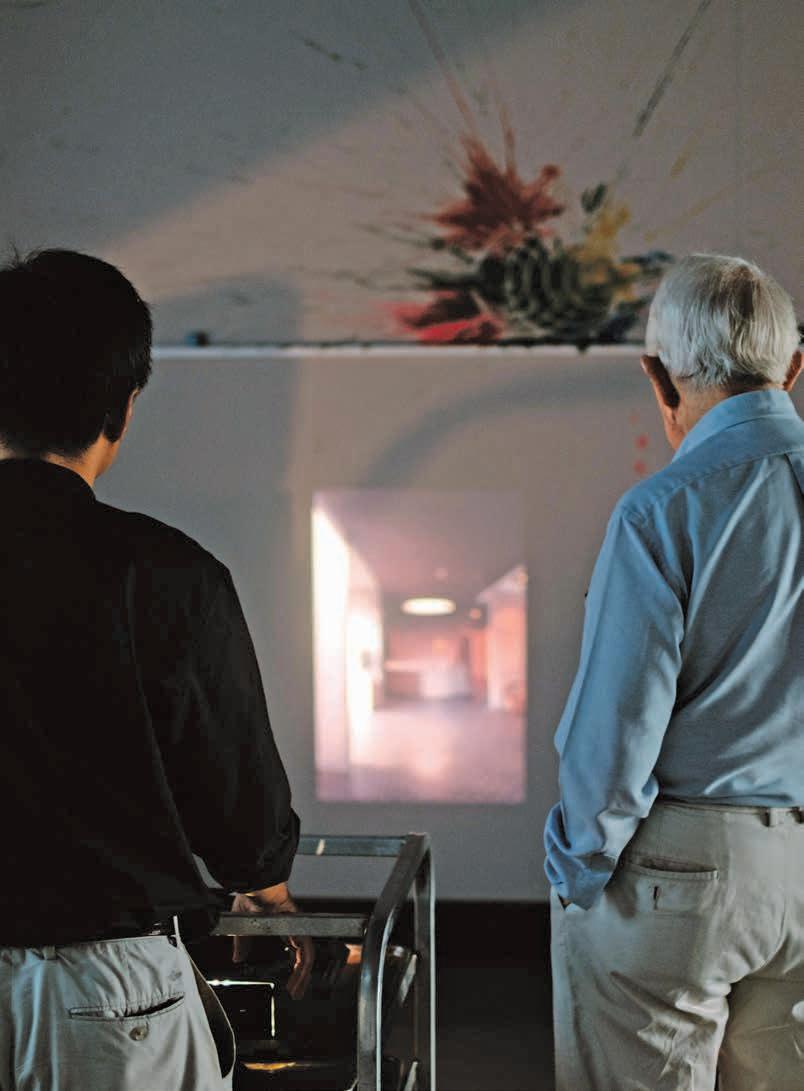

For more than a decade, Sewell regularly visited the sugar mills and documented their activity. “I was so interested in the colors and patina, design and decay, the juxtaposition of objects,” he says. In 2006, he debuted “The Enigma of the Mill,” a grand art installation featuring giant giclée photo prints, panning video,

and audio recordings. It was a mesmerizing panoply of sight, sound, and movement: thick streams of molasses pouring into vats; wet steaming pipes; close-ups of sprockets, cogs, and gears. The custom musical score, including pieces by Kronos Quartet and Xploding Plastix, was dominated by rhythmic clanging metal, its jarring notes woven alongside a stirring melody. To this day, even speaking about the installation stirs something wondrous within Sewell. “The sugar mill is really my soul,” he says. His eyes glint as if he were a schoolboy with a gleeful secret. “Again, it’s that finding of art in the most unexpected places.”

The art-making continues at the Ha‘ik ū estate. Here, elements collected from the island’s sugar mills find place in Sewell’s home and heart. Dotting the property are his large-scale sculptures, crafted from scrap bulk steel sheets

Sewell’s Ha‘ikū estate is punctuated by remnants from the Pā‘ia sugar mill. Their rusting structures create a thoughtprovoking contrast to the surrounding natural environment.

38 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Stepping into the sugar mill’s rusting mechanical belly, Sewell marveled at the beauty in its brutality.

Stepping into the sugar mill’s rusting mechanical belly, Sewell marveled at the beauty in its brutality.

salvaged from the Pā ‘ia mill. The sheets, arranged together vertically onto concrete slabs, are perforated with series of shapes: crescents and chevrons, triangles and trapezoids. Originally, the cut-outs were utilized as pieces for mill machinery, items such as blades, guides, and seals. Today, their remaining negative spaces are whimsical plays on form and light. Sewell invites guests to sit, walk, and even dance within the sculptures. “You should see what it’s like at night,” Sewell says. “It’s just beautiful.”

On a summer afternoon on the artist’s property, two men use a telehandler to maneuver a large sheet of steel—another retrieved sugar-mill gem—flush against a building wall. It’s a painstaking process of stop-and-go because the sheet, though pierced throughout with geometric forms, still weighs half a ton. Under Sewell’s careful instruction, the duo inch the sheet into its

dedicated space. Their brows are furrowed in consternation and concentration. Sewell, however, grins from ear to ear. “I love this,” he says. To Sewell, it is art in motion. It is also an irresistible opportunity to employ large machinery. His wife appears and greets him with a kiss on the cheek. “You get to see the whole show today,” she says to me as I watch the piece being assembled. “Tom and his Tonka trucks.”

Later, Sewell takes a stroll on the grounds. The day has begun to cool, and the late afternoon sun etches the airy, steel sculptures with thin veins of gold. Suddenly, Sewell hoists himself up onto one of them. He locates a foothold in a circular cutout, and then another and another. Higher and higher Sewell climbs, the artwork transformed into a piece of play, an impromptu jungle gym. Upon reaching the top, his face shines with joie de vivre. From his perch, he scans the sky above him, ready for the day’s next miracle.

Inspired by the junkyard aesthetic of the sugar mills, the latter half of Sewell’s oeuvre meditates on the duality of light and shadow, decay and growth.

42 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

The Tick of Island Time

Behind the humor and tropical scenesetting, what does it really mean to be on Hawaiian time?

TEXT BY MITCHELL KUGA

IMAGE BY LILA LEE

Growing up, the concept of “Hawaiian time”—that locals possess a more lax attitude toward punctuality—felt as emblematic of local humor as Lie Hagi and four-tu-tu, tu-tu-tu-tu. Thirty minutes late for the dentist? Hawaiian time. Cruising into the party two hours after it started? Hawaiian time. Missing a deadline for an essay about Hawaiian time? Hawaiian time. In 2018, T&C Surf Designs even trademarked the phrase “I NOT LATE I STAY ON HAWAIIAN TIME,” which they’ve printed on tank tops, stickers, hoodies, and license-plate frames: a good-natured way of symbolizing what it means to get along on an island chain that ranks first in the country for racial and ethnic diversity, and in the case of Honolulu, within the top 20 for worst traffic in 2019.

But the concept can also be weaponized. My mother, who works at a department store at Ala Moana Center, recently re called an interaction her co-worker had with an associate from Boston. “I know you’re on Hawaiian time,” the associate huffed over the phone regarding an incoming package, “but we need it ASAP.” Her implication was clear: You lazy islanders, lounging around with your mai tais and rubber slippers, lack initiative—and by extension, a sense of purpose.

I’ve tilted toward this bias. When people on the continent ask why I moved to New York from Hawai‘i— as if I’d foolishly ejected myself out of a postcard from paradise—my typical response is that life in Honolulu felt too slow. This lethargy felt cultural, the way the belated arrival of an Abercrombie and Fitch store or an NSYNC concert still elicited waves of 7th-grade shock. But it also

felt baked into the architecture of the city itself: escalators lagged, yellow traffic lights dawdled, the seasons stretched into one long eternal summer. As a teenager, I’d watch the ball drop in Times Square through the fuzz of my television, while outside my window the sun had just set. It was 7 p.m. We were five hours late to the party, stuck forever in the past.

Hawaiian time is an inflection of “island time,” a term that gained colloquial traction during the U.S. military’s invasion of the Pacific post-World War II. Westerners accustomed to frigid winters and a rigid clock romanticized the idea of an island paradise, where time seemed to melt into a soothing drip. But beneath that fantasy simmered traces of cultural friction. According to professor Davianna Pōmaika‘i McGregor, a founding member of the ethnic studies department at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, this friction was most pronounced during the rise of Hawai‘i’s first corporate industry: the sugarcane plantation. Plantation owners, who were mostly descendants of missionaries, enforced stringent 10-hour work days that defied the Native Hawaiian approach to planting, which centered around the cycles of the sun and moon and the two seasons, kauwela (the hot season from May to October), and ho‘oilo (the wet season from November to April).

An inquiry into the origins of “island time” reveal longstanding biases about the Pacific.

FLUX PHILES | LANGUAGE | 44 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

McGregor also points out that capitalistic wage labor contradicted uku pau, a Native Hawaiian system that compensated agricultural workers per job rather than per hour. As a result, journals kept by Kaua‘i’s Ladd and Co., the first commercial sugarcane plantation in Hawai‘i, characterized Native Hawaiian workers as lazy and unmotivated, a stereotype McGregor says erroneously persists today. “It’s not at all a sense of laziness,” she says. “It’s just a different approach to work, a different orientation to planting and cultivating the land.”

James Viernes, a Chamorro scholar from Guam, where the vernacular is “Chamorro time,” stresses the importance of islander urgency. “Whether it’s Hawai‘i or Guam or Samoa, our ancestors really did live and die by time,” he says. “I mean, if you don’t get up and get in that canoe at the right time, you’re going to miss the currents that are going to take you on a successful journey. If you don’t get up on time and plant those seeds, your harvest is not going to feed you.” That understanding of time, dictated by the cycles of nature, is the reason many indigenous cultures see time as circular rather than a straight line. As the outreach director for the Center for Pacific Islands Studies at UH Mānoa, Viernes supervises a lot of students—“all islanders like me”—who shrug off deadlines and show up late for meetings, claiming they’re on island time. He’s grown frustrated with the excuse, calling unexamined usage of the phrase, with its ties to imperialism, “dangerous.”

But he also sees employing “Hawaiian time” as a form of “everyday peasant resistance,” to borrow a phrase from the anthropologist James C. Scott; as a gesture of protest, however small. “I think the reason

we take so much pride in this ‘island time’ is that yeah, it’s funny, but if you really look at it, there is a level of resistance in that term—in saying that, despite all this history of outside influence coming in and dominating us, we’re still insisting on our Hawaiian time, our Chamorro time, our Fijian time,” Viernes says. “An insistence on island time is a way of maintaining island identity.” Through this lens, he continues, embracing Hawaiian time becomes a way for the 50th state to stand outside of an “artificial nationalist American identity where it never existed.” In short, it is a claim to sovereignty.

As expected, since I moved to New York nine years ago, my life has moved considerably faster, dictated by the demands of a city that feels single-mindedly oriented toward bigger, shinier, faster. I learned to walk like a New Yorker, lunging perpetually forward despite often not knowing where I was headed, yet feeling guilty anytime I slowed down, guilty anytime I wasn’t participating in the city’s ambient rat race, which was really just a way of staying vaguely afloat. What I mean to say, in the most New York way possible, is that I like it here.

But after returning to New York following a month in Hawai‘i, I can feel myself trying to inhabit two opposing time frames simultaneously—Hawaiian time and a New York minute—as if conducting dueling orchestras, willing them to be one. Pausing an entire hour, even a day, before responding to difficult work email? Island time. Walking the Williamsburg Bridge instead of taking the train? Island time. Seeking spaces that permit reflection in a city forever honking, shuffling, and churning? Island time. After all, Manhattan is an island too.

46 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

174 lāhaināluna road lāhainā , maui , hawai ’ i 96761 www . theplantationinn . com 1-808-667-9225

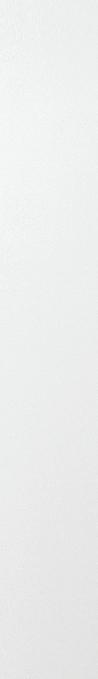

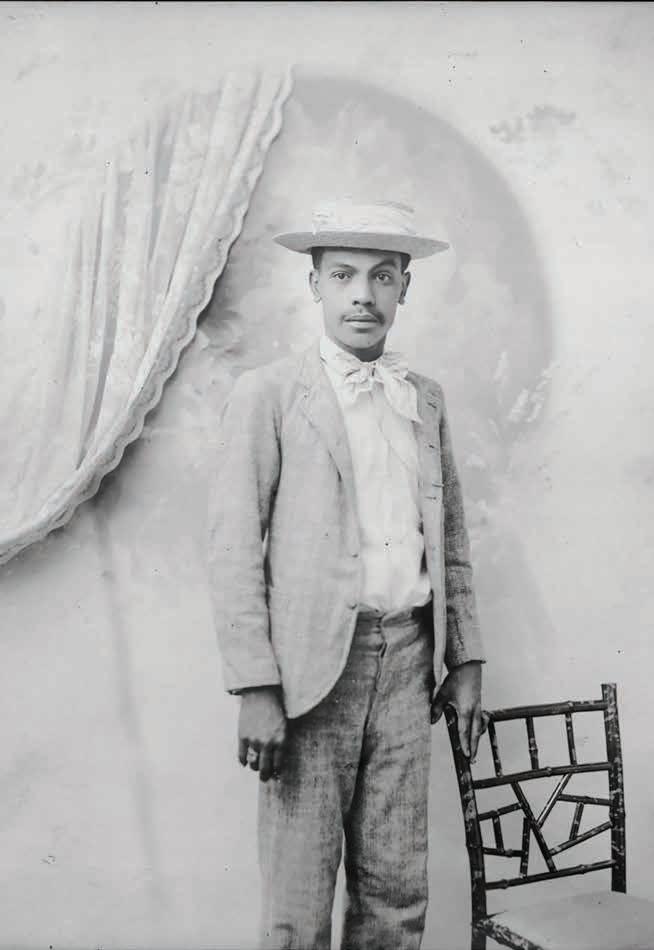

Tracing the Past

Native Hawaiian genealogy presents an idiosyncratic slew of challenges and familial puzzles to solve.

TEXT BY CHRISTINE HITT

IMAGES FROM HAWAI‘I STATE ARCHIVES

It’s the aha! moments that make researching genealogy so satisfying. Like finishing a 500-piece jigsaw puzzle or filling in the last word of a crossword, finding the biological parents of my client’s hānai (adopted) greatgrandmother gave me the feeling of elation.

After finding a 1985 obituary with my client’s great-grandmother’s maiden name at University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa’s Hamilton Library, and then coming across a 1910 census with her listed under her adoptive father’s name on Ancestry.com, I looked into her marriage records by searching the genealogy indexes at Ulukau.org, a Hawaiian electronic library. There I discovered that she had been married twice. When I visited the Hawai‘i State Archives and pulled the two marriage licenses, my eyes could have lit up the room. The first license I found listed her adoptive parents. The second marriage license listed the full names of her biological Hawaiian parents, with her adoptive mom as a witness.

Not everyone has such luck in their family-history searches. As with researching ancestry for any other ethnicity, Hawaiian genealogy has its own sets of challenges, and determining adoptive relationships is one of the most complicated. It’s also one of the many things that make Hawaiian genealogy unique. There are a few types of

Hawaiian adoptions to consider: ho‘okama (adopting another person’s child, usually by the desire of the child and older adult, looked negatively upon by the biological parents), ho‘okāne or ho‘owahine (an adoptive platonic marital relationship between persons of opposite sex), and hānai (a child reared in another household as their own). Hānai adoptions were almost always of children from within one’s family, with first-born males considered to belong to the father’s side and the first female child said to belong to the mother’s side; if a grandparent asked for a grandchild, it was impossible to refuse the request.

Many of the resources and much of the documentation regarding genealogy only go back to the 1800s, and unless the family line has a link to an ali‘i (chief) whose lines are preserved, the information stops there. And, as is the case in some of my own family lines, you have to learn to be OK with that. Records can get lost or burned in fires, kūpuna might not have participated in the Territory of Hawai‘i census nor claimed land during its redistribution in the Māhele, when the concept of privately-owned property was instated by the government. Unless personal family records were kept or stories of the past were passed down, that knowledge is lost in time.

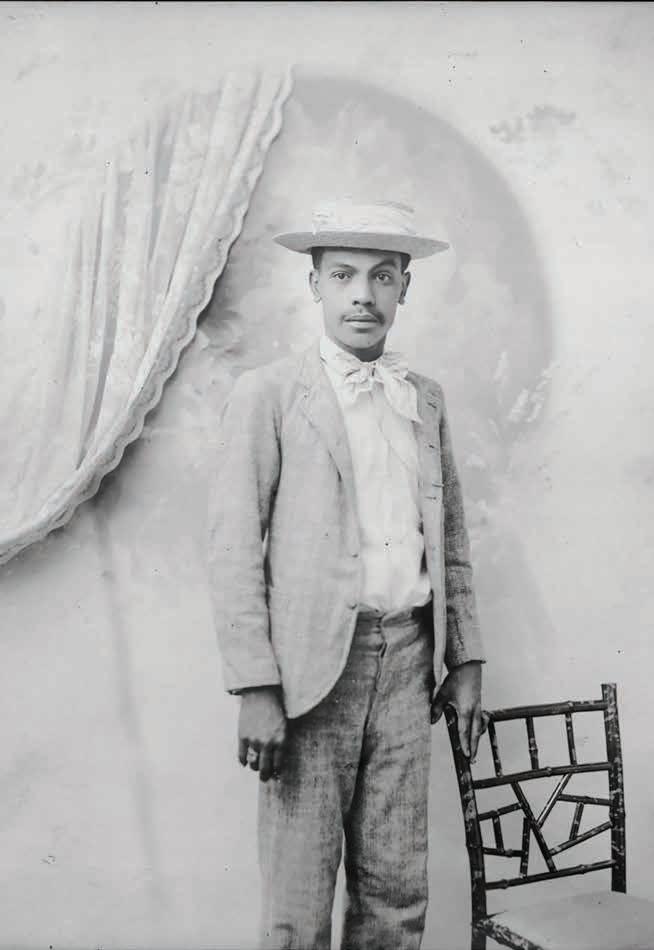

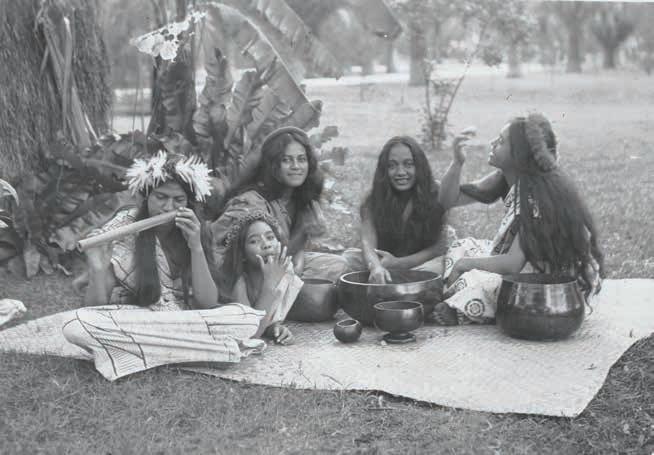

Understanding cultural practices of the time help researchers uncover one’s roots. Pictured right, portrait of a Hawaiian girl.

FLUX PHILES | MO‘OKŪ‘AUHAU | 48 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“I think a lot of people get really angry towards their kūpuna that they didn’t record information,” says Sarah Tamashiro, who has been a professional researcher since 2014. She, along with professional genealogist Ami Mulligan, led a series of genealogy workshops at the Waiwai Collective earlier this year. “Colonization and breakages in the passage of information is why a lot of people don’t have genealogy,” Tamashiro says. “It’s also due to certain choices that people made within their own family. They said, ‘This isn’t for you,’ or ‘This isn’t important for you to move forward and so I’m not going to say anything.’ And all of these different reasons or personal family choices is why certain families don’t have that information.”

With blood-quantum requirements to apply for Hawaiian Home Lands and documented proof of Native Hawaiian ancestry needed for admission to Kamehameha Schools, scholarships, and financial aid, Hawaiian families are trying their best to gather information and create their own genealogical charts. Knowing where to go and what to research helps researchers begin their searches, but it’s equally as important to understand the history and laws of the times.

“It’s easy to put what your understanding of the current law is on the past and to just assume that it’s the same, but in reality, you really can’t,” says Mulligan, who owns Discover Your ‘Ohana, which offers professional genealogical services. For instance, prior to 1860, when the Hawaiian kingdom passed the surname law, Hawaiians used singular names. There was no patrilineal surname passed down to children. Also, prior to 1911, many people didn’t have birth certificates and didn’t file for one, until it was a requirement for jobs, government benefits, and so on.

Looking at documentation through a lens of social and cultural practices of that time period also helps make sense of what you find. In some cases, when Chinese

immigrants and Hawaiians married, surnames would be Hawaiianized, such as Ah Kam becoming Akamu or Wai becoming Awai. Some Hawaiians also found it more prestigious during the 1920s and ’30s to claim to be half Caucasian or half Chinese, even when the family was pure Hawaiian, and claim Caucasian-sounding names. Going back another generation in searches should show what family names were before the changes.

Understanding practices of the time also helps with knowing what to look for. Traditionally, Hawaiians had many types of names, such as a spiritual name, a secret name, a nickname, or a name inspired by an event. Usually only one name was used for legal documents, but even so, it’s important to search all names known for a person when researching genealogy.

It is also essential to keep an open mind when researching. Stories that are passed down may not always be accurate or proven, such as relations to ali‘i. “I think that you can’t dismiss anything, but when you’re researching, you shouldn’t have this specific goal in mind,” says Mulligan, adding that you can’t shove square sources into round holes. “You have to go with the sources.”

Tamashiro thinks the desire to be linked to ali‘i is the product of our historiography. “The types of books we have about Hawaiian history is largely about ali‘i. And we don’t have books about, you know, everyday people, about commoners or about maka‘āinana,” Tamashiro says. “But if your family was the best sweet-potato farmer in rural east side Moloka‘i, that’s awesome. And I think that needs to be celebrated just as much as being able to claim an ali‘i.”

No doubt, the research that goes into building a genealogy chart takes time and may not be completed in your lifetime. But the sources and stories that you document today are lasting gifts to future generations, who can continue connecting pieces of the puzzle.

Many resources and documentation regarding Hawaiian genealogy only go back to the 1800s. Pictured right, portrait of a Hawaiian man.

50 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

HOW TO BEGIN

1. Gather as much information as possible about your family, including surnames and maiden names of your parents, your grandparents, their parents, siblings, spouses, and children. If dates of births, marriages, or deaths or where they lived is unknown, try to approximate.

2. Start with online resources, including Ulukau.org, Ancestry.com, Hawai‘i State Archives Digital Collections, and Familysearch.org. Look up family names in the indexes, and record any findings. Note: While Ancestry.com’s searchable census database is unmatched, Hawaiian names are often misspelled in it, so you should doublecheck the documents.

3. Once you’ve exhausted online resources and know what you want to research, decide where you want to visit. If you found a name in an index, retrieve those documents.

RESOURCES

Birth, Marriage, and Death Certificates

The Hawai‘i State Department of Health holds certificates of birth, marriages, and death records from the early 1900s to present. For records prior to 1929, the Hawai‘i State Archives has a collection of these also. Indexes to these can be found online at Ulukau.org. The Hawai‘i State Public Library also has an index to births, marriages, and deaths from 1909 to 1949.

Certificates of Hawaiian Birth

From 1911 to 1972, the Certificate of Hawaiian Birth program registered all births that occurred in Hawai‘i and weren’t certified. The Territory of Hawai‘i asked each person to testify and produce witnesses to their birth in Hawai‘i, making this an invaluable resource. The LDS Mormon Family History Centers have an index to these, and certain locations have testimonies as well. Certified copies of birth certificates and transcribed testimonies are available through the Hawai‘i State Department of Health. Be sure to order the testimony when requesting the certificate.

Hawaiian families do their best to create their own genealogical charts. Knowing where to go and what to look for helps researchers begin their searches, but it’s equally as important to understand the history and laws of the times.

Pictured above, grass house at Moanalua Gardens, circa 1900.

52 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 53 FREE WIFI WHERE 110 RENOWNED RETAILERS & 30 DINING DESTINATIONS CREATE ONE TIMELESS PARADISE. THIS LAND IS OUR LEGACY. THIS IS HELUMOA AT ROYAL HAWAIIAN CENTER. Apple Store | Fendi | Harry Winston | Hermès | Jimmy Choo | Kate Spade New York | Leather Soul | Loro Piana | Omega

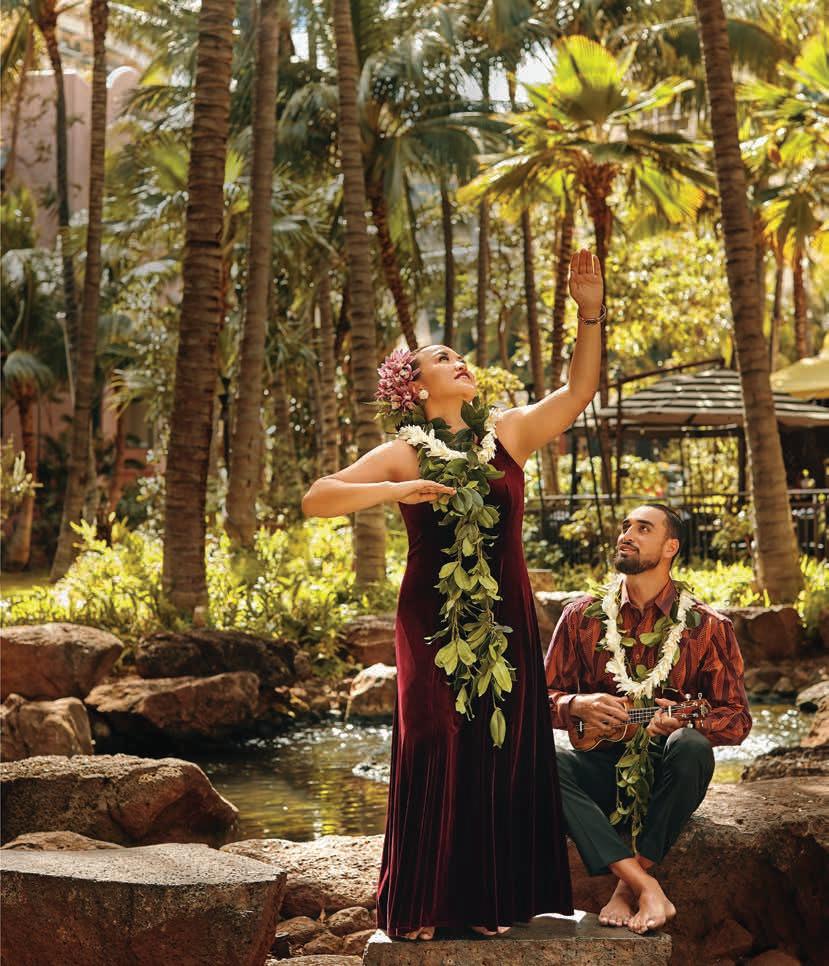

Rimowa | Salvatore Ferragamo | Tiffany & Co. | Tory Burch | Tourneau | Valentino | Doraku Sushi | Island Vintage Wine Bar | Noi Thai

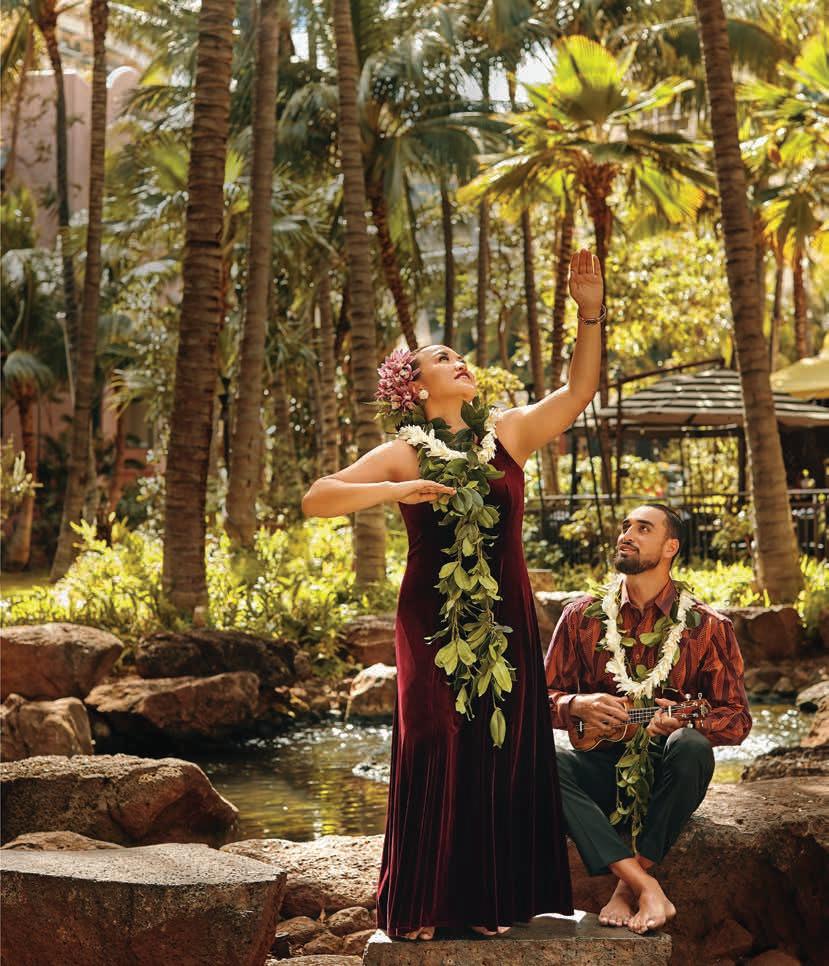

Restaurant Suntory | The Cheesecake Factory | Tim Ho Wan | TsuruTonTan Udon Noodle Brasserie | Wolfgang’s Steakhouse Hula | Keiki Hula | ‘Ukulele | Hawaiian Entertainment | Presented in The Royal Grove | RoyalHawaiianCenter.com Open Daily 10am–10pm | Kalākaua Avenue and Seaside, Waikīkī | 808.922.2299 BE CONNECTED TO THIS LAND. WHERE OUR PAST IS YOUR PARADISE. WHERE YOUR ARRIVAL MAKES A DEFINING STATEMENT. WELCOME TO OUR LEGACY.

Boutique

Cuisine

Census Records

Race, relationships to head of household, ages, marital statuses, and birthdates are some information found in census records. The Hawai‘i State Archives has census records for 1866, 1878, 1890, and 1896. The Hawai‘i State Library holds copies of the U.S. Census from 1900 to 1930.

Probates & Wills

Probate records from 1847 to 1917 are located at the Hawai‘i State Archives, with an index available at Ulukau.org. These records link parents to children, which is especially handy for adoption searches, and include an inventory of property. Often, probates and land deeds are in Hawaiian.

Church Records

Once the kapu system was abolished, Hawaiians joined Christian churches. Church documentation may help push back genealogical charts. Hawaiians were mostly converts to Latter-Day Saints, Catholics, and Congregationalists.

Land Records

The Māhele required Hawaiians to explain their rights to own property. Native and Foreign Testimony can be found at the Hawai‘i State Archives and LDS Family History Centers.

Court Records

Circuit court divorce records from 1849 to 1915 are available at LDS Mormon Family History Centers. Divorces (1848-1915), equity files (1851-1914), criminal cases (1848-1914), minutes (1848-1960), and civil cases (1848-1916) can be found at the Hawai‘i State Archives. Divorce indexes are found on Ulukau.org.

Newspapers & Obituaries

Genealogies, births, marriages, deaths, and obituaries were sometimes printed in Hawaiian newspapers. A partial index from 1850 to 1950 can be found at LDS Mormon Family History Centers, the Hawai‘i State Archives, and Hamilton Library. Hamilton also has an index of 1929-1985 newspaper clippings on microfiche.

Writer Christine Hitt worked professionally as a Hawaiian genealogist from 2002 to 2014 as the founder of Hawaiian Roots. Visit the organization’s Instagram at @hwnroots. Pictured above, Hawaiian girls eating poi, circa pre-1900.

54 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 55 Royal Hawaiian Center has a storied past that connects to Chief Kākuhihewa who once ruled O‘ahu, Kamehameha I who became Hawai‘i’s first monarch, and Princess

last of his royal line to reside on these grounds. Since we opened as Waikīkī’s premier shopping center in 1980, we’ve been sharing our history and culture with the world. Our hula lesson, once taught on the sidewalk flanking Kalākaua Avenue, now has a home in the center’s beautiful Royal Grove. Our suite of complimentary cultural lessons, seven in all, will ensure you take Hawai‘i home with you. Hula | Keiki Hula | ‘Ukulele | Hawaiian Entertainment | Presented in The Royal Grove | RoyalHawaiianCenter.com CONNECT TO OUR STORY . UNEARTH THE LEGENDS OF ITS WONDER. BE IMMERSED IN THIS HISTORIC PARADISE. WELCOME TO OUR LEGACY.

Pauahi,

The Plastic Age

Engineered to stick around for decades—and potentially thousands of years or more—plastic continues its journey long after we throw it away.

TEXT BY LAUREN MCNALLY

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

FLUX FEATURE

TEXT BY LAUREN MCNALLY

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

FLUX FEATURE

There’s something curiously perverse about the soap dispenser sitting by the sink in the guest bathroom of my parents’ house: I can tell by the sunrise shell glued to the front of the bottle that the scrap of nylon netting around it is meant to resemble a miniature fishing net. It’s charming and beachy, probably a DIY gift from a crafty acquaintance. But it begs the question, how did seashells and trash become so inextricably linked?

Humans have been fishing for tens of thousands of years, but only in the last 50 years or so has the practice left such a pervasive spectacle of marine debris on our shorelines. Once made from natural, biodegradable fibers, like the olonā bark and ‘ie‘ie vine that Native Hawaiians favored, today’s nets, lines, and traps are made from synthetic materials to weather the elements like never before. As with so many other things in our lives, we devised a cheaper and more durable alternative to the organic stuff, and now wayward plastic is piling up in our oceans at an alarming pace. At this rate, if we’re to believe predictions from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, plastic will outweigh fish in the sea within the next 30 years. Meaning tiny plastic fishing nets will make perfect sense as decorative accents if you’re looking to conjure reveries about the ocean.

beaches. Less clear, perhaps, is how it earned that sorry nickname. Later, in a different car headed back to Kona, my driver wonders aloud, “Why is there so much trash at Kamilo?"

Kamilo Beach is the unfortunate dumping ground for trash from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a vast expanse of marine debris dispersed an indeterminate distance across the surface and upper water column of the north Pacific Ocean. Comprised of two distinct garbage patches weighing an estimated 80,000 tons, it’s the largest and most notorious of the trash heaps accumulating in our planet’s five major ocean gyres, which help circulate water around the globe like giant, slowmoving whirlpools, pulling objects such as buoyant plastic toward their centers.

Though all of the islands act like sieves for this swirling junkpile of marine debris, Kamilo’s location at the southeastern tip of the Hawaiian archipelago puts it in the crossfire of onshore winds and plastic-laden surface currents, which together dump 10 to 20 tons of trash onto its half-mile stretch of coastline every year. This combination of circumstances is why, despite cleanup efforts by local conservation groups, an unpopulated beach in Hawai‘i has come to be known as one of the most plastic-littered places on Earth.

Early one morning in December, I step off a plane on my way to visit ground zero of Hawai‘i’s plastic-pollution crisis. “Going to Wai‘ōhinu?” my Lyft driver asks as I climb into the backseat of his Subaru Forester at Kona International Airport. Then, after a pause: “What are you going to do there?” I’m guessing his airport pickups don’t usually lead him to the small town of Wai‘ōhinu in Hawai‘i Island’s rural Ka‘ū district. I tell him I’m meeting a group to pick up trash at Kamilo Beach.

“You been there before?” he asks. “It’s bad.” Apparently, everyone here is well aware of Kamilo’s reputation as Plastic Beach, made infamous by news outlets declaring it one of the world’s dirtiest

In Wai‘ōhinu, I gather with 20 others in a semi-circle around Megan Lamson, a marine biologist who has been leading beach cleanups with the nonprofit Hawai‘i Wildlife Fund for more than a decade. She instructs us to prioritize large pieces of litter over small ones, presumably in the interest of efficiency and due to their risk for animal entanglement, and before long, we split up into different cars for the drive to Kamilo. I find myself sandwiched between two volunteers in the backseat of a heavy-duty pickup truck, the bed of which has been outfitted with a ramp, winch, 150foot cable, and logging hook for the express purpose of hauling derelict fishing nets from the shoreline.

Though our journey is only nine miles, it takes us nearly two hours to navigate the coast’s rugged terrain. The dried bozu lei hanging from the rearview mirror swings

Researchers suspect the majority of all plastic ever produced persists in the environment as waste—either in landfills, in the ocean, or hiding in plain sight as microplastic.

Overzealous media has painted the Great Pacific Garbage Patch as a nightmarish island of trash twice the size of Texas, but in reality, you might not notice this vortex of plastic waste unless you passed right through it.

58 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

wildly as we crawl five miles per hour down the rough, unpaved road to Kamilo, which takes us through groves of invasive kiawe, former cattle runs with crumbling rock-wall enclosures, and jagged lava fields littered with fallen albizia trees swept south along the coast after the 2018 volcanic eruption in lower Puna. The smell of sulfur fills the car as we near the ocean. At one point, we’re bouncing up and down along the rocks at the water’s edge, only a few feet from the churning waves of Ka‘alu‘alu Bay.

We veer left and follow the bay to Kamilo Point, where fierce winds tear down the coast. The beach is blanketed in gnarled driftwood that was carried ashore by the same powerful currents that inspired early inhabitants to call the place Kamilo, meaning “swirling currents.” Massive evergreen logs, which still regularly wash in from the Pacific Northwest, were once gathered here by Native Hawaiians as building material for dugout canoes. Kamilo is said to be where bodies would turn up following accidents at sea, where travelers could send lei from up the coast to let those back home in Ka‘ū know they had safely arrived at their destinations.

Due to storm events, wind, currents, and other factors affecting ocean dynamics, I’m told the winter season is a clean time of year for Kamilo Beach, but as usual, the worst problems are the ones you can’t see. At first glance, I hardly notice the vibrant confetti of plastic scattered among the tidewrack, but looking closer, I realize the stuff is everywhere—strewn about the rocks, mixed in the sand, swirling in the shallows like flakes in a snow globe. I duck into an opening in the sprawling thicket of beach heliotrope lining the shore and find a trove of plastic debris lodged in the dense tangle of branches: waterlogged shoes, broken clothes hangers, tattered fishing net, foam fishing floats, a set of kid’s costume fangs. There’s a small tire from Japan, a scrap of plastic lined with Chinese characters, the lid from a Nestlé container, and a weathered bottle of Boots UK shower gel (in the scent of “sea minerals,” ironically enough).

Next I come across a hard, flat wad of plastic curled in on itself like the folds of a brain. I later learn that this perplexing specimen is known as plastiglomerate, likely formed by the heat of a campfire melting plastic trash in the dirt and sand, fusing it into a composite of plastic and natural sediment. Geologists predict that these plasticsediment hybrids will persist in the fossil record as a marker of the Anthropocene, an unofficial but commonly used term for the current geological age, of which plastic will be one of humanity’s most lasting legacies.

Little research has been done to quantify the microplastics accumulating in terrestrial environments, but the handful of studies out there suggest they’re as ubiquitous on land as they are in our oceans and waterways.

contrary to popular belief, the jury's out on whether or not plastic ever biodegrades. “Those numbers are good, in a way, to raise awareness among consumers, but from a scientific perspective, they aren’t necessarily accurate,” says Sarah-Jeanne Royer, a postdoctoral research fellow studying plastic and microfiber degradation at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego. “Scientists have found very few organisms using plastic as a source of nutrients. Plastic degrades due to several degradation processes, fragmenting into smaller and smaller pieces until it is invisible to the naked eye, but how much of it is actually transforming into something useful for nature, we have no idea.”

Estimates for how long it takes different plastics to break down range from decades to hundreds of years, but

What we do know is that microplastic is turning up in the most remote reaches of the planet, from the peaks of the Pyrénées mountains to the depths of the Mariana Trench. Plastic has found its way into sea ice in the Arctic, rainwater samples in the Rocky Mountains, soil and groundwater systems the world over, and, most alarming

60 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 61

Marine debris collected from Kamilo Beach, Hawai‘i Island on December 22, 2019.

“It’s easy for people to detach from the problem,” says Megan Lamson, president of Hawai‘i Wildlife Fund. “It’s hard for people to relate their everyday lives to the marine debris they’re seeing wash up on the shore.”

of all, our bodies. A new study commissioned by the World Wildlife Fund revealed we may be consuming a credit card’s worth of plastic every week, and not just those of us with a taste for seafood. “We probably ingest more microfibers in five minutes at home than in the flesh of the fish we eat,” Royer says.

Royer’s work in this area follows a groundbreaking study she led during her time at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa’s Center for Microbial Oceanography Research and Education, which discovered that plastics increasingly produce climate-warming methane, ethylene, and other greenhouse gases as they degrade, even more so on land than at sea. “To know if it has a significant contribution to climate change, we need better numbers [for the amount, surface area, and types of plastic out there],” Royer says, though she and other researchers are working with the European Space Agency to quantify the problem via satellite. In fact, little is known about the potential impacts of plastic pollution anywhere other than the marine ecosystem, but suffice it to say, plastic in the ocean isn’t the only kind we should be worried about.

Most of us are aware of plastic’s capacity for physical damage—that image of the turtle with a straw stuck in its nose is a hard one to forget—but plastic has also proven to leach toxic chemicals and act as a vehicle for persistent organic pollutants it attracts from the surrounding environment. That’s bad news, seeing as plastics are fragmenting into particles small enough to bypass wastewater-treatment plants and to be mistaken for food by organisms that form the basis of the marine food web; it’s worse news if those microplastics are crossing cell membranes, as Royer’s latest research suggests.

The day after the cleanup at Kamilo Beach, I meet Megan Lamson of the Hawai‘i Wildlife Fund at a cafe in Keauhou. She informs me our group collected 886 pounds of debris, including 60 pounds of “ghost gear,” or abandoned nets, lines, and other fishing equipment. As she explains how the ocean acts like a sorting device—buoyant plastic can travel far distances on the ocean surface, while denser plastic typically sinks at the source—the barista hands us our drinks. To my chagrin, mine comes in a plastic cup. I awkwardly call attention to this fact once the barista is out of earshot, eyeing Lamson’s latte in its ceramic mug. “Guilt is natural,” Lamson says, unfazed. “But it’s important for people to not be so overwhelmed by the scale of the problem that it spurs inactivity. It doesn’t have to be all or nothing, every small step matters.”

Trash consumes at least two-thirds of Lamson’s time as president and Hawai‘i Island program director for the Hawai‘i Wildlife Fund. The organization cleared some

56,000 pounds of it from the shores of Hawai‘i Island in 2019 alone and has been using data from its monthly debris surveys for environmental education and to support prevention efforts like the Styrofoam and plastic bag bans on Hawai‘i Island and Maui. To confront an issue as complex as plastic pollution, I imagine it helps to understand it first.

When it comes to plastic in the environment, misconceptions abound. Overzealous media has painted the Great Pacific Garbage Patch as a nightmarish island of trash twice the size of Texas, but in reality, you might not notice this vortex of plastic waste unless you passed right through it. When long-distance swimmer Ben Lecomte swam 300 nautical miles through the eastern portion of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in 2019, he and his support crew spotted one plastic fragment every other second and a piece of larger debris once every three minutes on average— hardly the trash swamp of lore but rather a plastic smog lurking below the surface. Yet it’s the image of a floating

68 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Nearly half of the 300 million tons of plastic we make every year is thrown away after a single use.

landfill that’s galvanized initiatives to clean up some of the mess we’ve made in the 70 years since we began mass-producing plastic, the most high-profile being The Ocean Cleanup helmed by 25-year-old Dutch inventor Boyan Slat.

Billed as “the largest cleanup in history,”

The Ocean Cleanup is developing the prototype for a passive trash-catching system designed to work like an artificial coastline to collect marine debris drifting on the surface of the ocean. In deploying a fleet of these floating barriers, the organization estimates it will be able to capture, collect, extract, and recycle half of the plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in five years and 90 percent of the plastic in all of the ocean’s gyres by 2040. The project has roused its fair share of skeptics: conservationists concerned about its impact on wildlife, oceanographers dubious of its efficacy, and plastic-pollution experts who contend that our efforts would be more productive upstream.

“Once plastic gets to the gyres, much of the damage to marine life through ingestion and entanglement has been done,” writes environmental scientist Marcus Eriksen in his book Junk Raft, a chronicle of Eriksen’s three-month voyage from California to Hawai‘i on a raft made of plastic trash. “Plastic is largely not making it to the gyres [intact], unless it’s something designed to last, like fishing gear. ‘Gyre cleaners’ typically underestimate how quickly plastic is torn apart, fragmenting from macroplastic to microplastic. If you’re hellbent on cleaning up the gyres, the science of current movements suggests the best place to be effective is very close to shore or at river mouths. Focus on gyre cleanup and you’ve missed the boat.”

Part of Eriksen’s beef with The Ocean Cleanup has to do with a discrepancy between the 270,000 tons of plastic believed to be drifting in the world’s oceans and the 8.8 million tons leaving our coastlines every year. A 2019 study by Slat and his team accounts for the disparity by proposing it can take decades for plastic

hanging out at the coasts to migrate in measurable quantities into the open ocean. Previous studies, however, have mostly led Eriksen and other experts to presume that the majority of the plastic entering the ocean isn’t floating on the surface like we thought, but landing back on our beaches, being ingested by wildlife, sinking to the seafloor, and splintering into a growing haze of microplastic.

“When I first spoke with The Ocean Cleanup, I had my doubts,” admits Royer, now one of The Ocean Cleanup’s go-to oceanographers and a science advisor to brands and nonprofits addressing the plastic crisis closer to the source, including Parley for the Oceans, Hydroflask, Icebreaker, and European textile giant Lenzing. “But if you think about it,” Royer says, “beach cleaners do the same thing. They remove plastic that’s been trashed. These are different organizations with different purposes, and we are trying to solve the issue from different sides. One organization can’t do it all.”

It turns out The Ocean Cleanup had, in fact, been devising another method to rid the world’s oceans of plastic: The Interceptor, an autonomous, solar-powered river barge designed to catch trash before it enters the ocean. As for where on Earth they plan to put the thing, Slat and his team investigated the world’s top polluting rivers and determined that 1 percent of them are responsible for 80 percent of the plastic entering the ocean by way of our river systems. An earlier study out of Germany’s Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research attributed as much as 95 percent of the problem to 10 rivers in Asia and Africa.

Numbers aside, both reports have made it easy to point the finger at developing nations, inadequate waste management, and the habits of a growing consumer population. “There’s a lack of infrastructure in general to deal with the waste that we generate today as a society, and that’s what we’re trying to tackle,” stated Jim Fitterling, CEO of plastics manufacturer The Dow

“No species hangs on to its trash like ours does. And now thanks to the resilience of its chemistry, trash exceeds our lifespans.”

Marcus Eriksen, environmental scientist

70 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

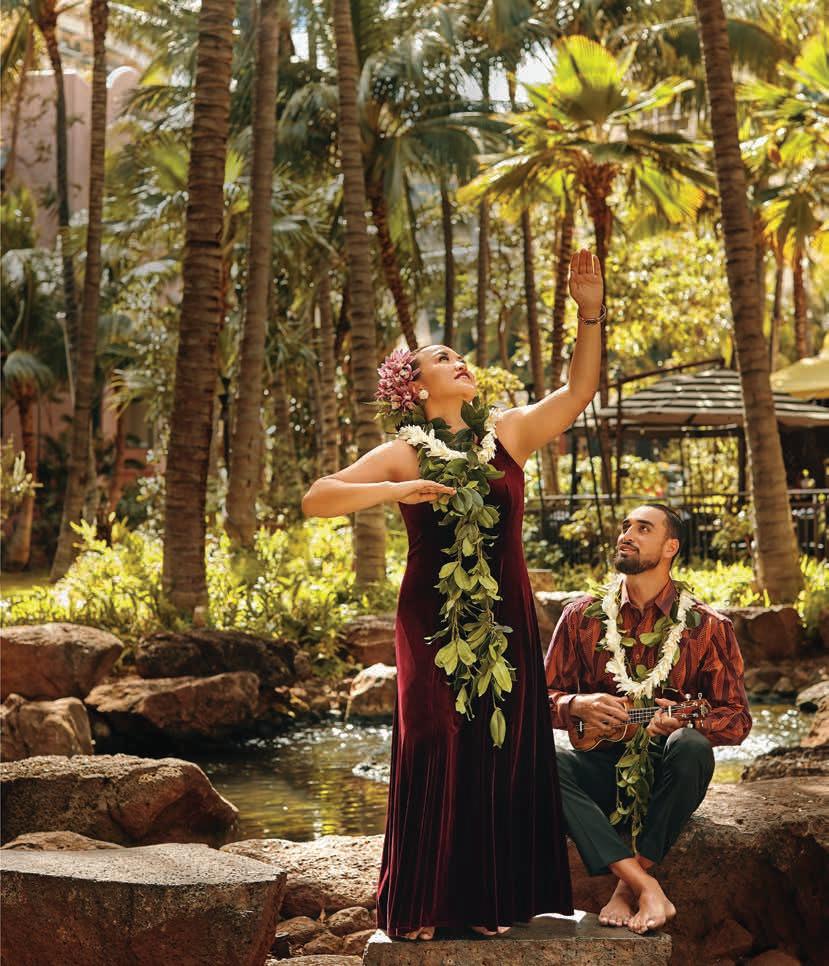

First discovered at Kamilo Beach in 2006, plastiglomerates are plasticrock hybrids formed when molten plastic fuses with natural sediment.

First discovered at Kamilo Beach in 2006, plastiglomerates are plasticrock hybrids formed when molten plastic fuses with natural sediment.

Some experts believe these future “technofossils” will endure in the geological record as evidence of our anthropogenic influence on the environment.

Chemical Company, during a talk at the inaugural Fortune Global Sustainability Forum in China in September 2019.

“Anyone tells you it’s a waste-management problem, they’re lying,” countered Tony Faddell, creator of the Nest smart thermostat, father of the iPod, and one of the early designers of the iPhone. Fadell delivered that zinger at the close of a presentation in which he dismissed recycling, incineration, and even bioplastics as palliative and misguided, proposing instead that products come in consumer-compostable packaging made of biowaste. Still, deflecting blame has proved an effective strategy for those with a vested interest in maintaining the status quo. Anti-litter campaigns of the ’50s and ’60s—initiated largely by plastic industry groups—implored the public, “don’t be a litterbug,” all the while enticing them with the luxury and convenience of products meant to be thrown away after use.

plastic pollution in our own backyards. Coastal advocacy nonprofits like Sustainable Coastlines Hawai‘i and the Surfrider Foundation O‘ahu Chapter have long set their sights upstream, engaging the public through civic action and citizen science in addition to organizing large-scale beach cleanups in hopes that seeing what’s drifting in the ocean will inspire people to change what they do on land. Programs and organizations championing a zero-waste ethos of wasting less, not just recycling more, have sprung up on most of the major Hawaiian Islands, including Hawai‘i Island, O‘ahu, Maui, and Kaua‘i. Together these organizations have succeeded in rallying support for measures like Bill 40, the nation’s most comprehensive regulation of single-use plastics, which was signed into law in December 2019.

Today, single-use plastics account for half of the 300 million tons of plastic produced every year. Considering most of the material value of that kind of plastic is lost after its first use, it’s no wonder that a dismal 9 percent of plastic waste has lived a second or third life, leaving the majority to hang around in landfills or in the natural environment long after use. “We can’t continue to justify bad behavior by upping our recycling programs or relying on an ocean cleanup in the middle of the Pacific. We need to bring the issue home and stop buying this crap in the first place,” Lamson says. “We’re part of the problem, but it’s harder to see. Even the stuff washing in from Asia— where do you think we’ve been sending our trash?”

China was buying 70 percent of the world’s contaminated and poorly sorted plastic waste before its National Sword policy took effect in early 2018, banning imports of certain waste materials, enforcing stricter contamination standards in others, and sending the global recycling market into a tailspin. In Hawai‘i, our distance and small scale puts us at a disadvantage in the recycling game, even more so in a dwindling market. Now that Hawai‘i County has stopped accepting all plastic and most paper recyclables, it’ll be that much harder for us to claim the moral high ground when it comes to waste. In the wake of this development, along with one of Hawai‘i Island’s two landfills recently hitting capacity, grassroots groups are working harder than ever to reduce

But you don’t need to spend the day at Plastic Beach stuffing feed bags with discarded bottles, net, and plastic scraps of every color, shape, and size to realize there are flaws in the system. A good look around at all the plastic filling our supermarkets, pantries, refrigerators, and bathroom cabinets will tell you that. But until the Tony Faddells out there fundamentally overhaul the way stuff is made, used, and packaged, we each have a choice to make (and remake, ad infinitum).

Whether you turn off the tap or go with flow, things have a way of coming around. Back on O‘ahu, on a shoreline much closer to home, I watch the waves carry a flurry of plastic in and out of the tide pools at my feet before finally dragging the specks into deeper waters, out of sight but never truly gone.

Plastic has found its way into sea ice in the Arctic, rainwater samples in the Rocky Mountains, soil and groundwater systems the world over, and, most alarming of all, our bodies.

74 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 75

FLUX FEATURE

The Odd Couple

Here is a portrait of an unconventional friendship at life’s end. Meet Richard and Bundit.

TEXT BY TIMOTHY A. SCHULER

IMAGES BY JOSIAH PATTERSON

“I don’t think it’s going too far to say that we love each other.”

Richard Lowe, a 91-year-old retired urban planner, real estate broker, and pianist, is reflecting on the unlikely relationship that has defined the past five years of his life. The other person in this collective “we” is Bundit Kanisthakhon, a 49-year-old architect and university professor who also lives in Honolulu.

“I didn’t know I was going to fall in love with this 91-year-old man,” Bundit tells me later. “But I do love him.”

If it surprises some people that both men, separately and unbidden, use that word—love—it’s understandable. After all, they are neither family nor romantic partners. And yet this is a love story. It is a story about a relationship that expands conventional notions of love and family and friendship. About loving across generations, across race and culture, and across a deepening political divide.

Most of all, it is a story about showing up. Again and again. Occasionally with chocolate cake.

Before I tell you Bundit and Richard’s story— and it’s a story I will never tire of hearing or telling—I have to explain why I’m telling this story at all, how I fit into all of this.

I first met Bundit in 2016, one year after my wife, Allison, and I moved to Honolulu. He and his wife, Janice Li, who is also an architect, run the small but eminently creative office Tadpole Studio, which in 2014 was honored by Dwell for its Honolulu Museum of Art parking attendant station, built primarily out of repurposed bed frames. After I interviewed the couple as part of a survey of contemporary architecture in Hawai‘i, they invited Allison and me over for dinner. Bundit, who grew up in Thailand and is as curious and versatile a chef as he is an architect, made curry and a host of other dishes,

which he prepared one by one in the galley kitchen of his and Janice’s Punchbowl apartment, a spare, concrete-floored loft where every piece of furniture came with a story: the airline beverage carts, the Linda Yamamoto sculpture, the Holoholo cab sign.

Most amusing were the apartment’s white walls, which served as a living and lived-upon canvas. Everywhere were doodles in black china marker: a rough trace of the couple’s dog, Dhut Dhut; a black circle that circumscribed the glow of a lamp, creating the appearance that the wax had corralled the light. The most eyebrow-raising doodle appeared on the wall behind the dining table. It was a cartoon speech bubble. Inside it said, “WE ARE ALL GOING TO DIE.”

My memory of meeting Richard is fuzzier. It was a year or two after that dinner at Bundit and Janice’s, and it must have been through Bundit, perhaps at a party or a lecture at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, where Bundit teaches. I can’t recall the exact moment, and past emails and text messages are no help. In some ways, it felt as if Richard were simply suddenly there, omnipresent. He and Bundit seemed to go everywhere together—to class, to Bundit’s office, to parties and networking events. I began to expect that if Bundit was somewhere, Richard was nearby.