20 | ARTS & CULTURE

Bernice Akamine’s solemn artistry, the activism of Ai Weiwei, and the steely-soft adornments of Reise Kochi.

70 | FEATURES

On discovering the vitality of Honolulu’s fallow spaces, the hyperlocal lens of Phil Jung, and a modern-day mu‘umu‘u revival.

138 | LIVING WELL

Finding one’s center through pottery, and the communal origins of saimin.

SPRING/SUMMER 2021 0 01 > 09281 $14.95 US $14.95 CAN 25489 8 The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I

MAXMARA.COM

TABLE OF CONTENTS

S / S 2021

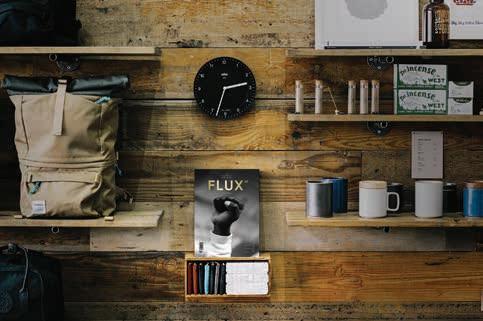

FLUX PHILES

22 | Painting

Roland Longstreet

32 | Fashion

Reise Kochi

40 | Activism

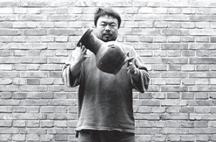

Ai Weiwei

50 | Maoli

Bernice Akamine

60 | Music

Ro

A HUI HOU

160 | Relationship

FEATURES

72 | On Weeds

Timothy A. Schuler spent a good portion of the coronavirus pandemic thinking about vacant lots—those weedy, overgrown spaces in our cities that seem to be contributing nothing. In his personal essay, he contemplates whether these fallow spaces might hold key lessons for our shared and present moment.

86 | A Movement in Mu‘umu‘u

The mu‘umu‘u: charming, nostalgic, occasionally awkward. Hawai‘i’s classic garment has found itself embraced by a new generation. Mitchell Kuga speaks with a loosely threaded cohort of islanders who are contributing to its stylish revival.

100 | A Sense of Place

The photographs of Phil Jung aim to explore the social landscapes and identity of Hawai‘i through personal spaces and locality. This photo essay predominately features select images from his series entitled O‘ahu.

|

FEATURES |

Image courtesy of Ai Weiwei

138 LIVING WELL 140 | Pottery Hawai‘i Potters’ Guild 150 | Food Saimin 116 EXPLORE 118 | Urban Forests Treehooo 128 | Design Album Art TABLE OF CONTENTS | DEPARTMENTS |

Image by Michelle Mishina

Image by Kenna Reed

Discover simplicity that surprises at Waikiki’s newest boutique hotel. Voted Hawaii’s Best Hotel 2020 by readers of Travel + Leisure and #1 Hotel in Hawaii by Condé Nast Traveler 2020 Readers’ Choice Awards. Visit Halepuna.com.

Hawaii’s Best

2020.

Voted

Hotel

On the Cover

Three images highlighting stories from inside the spring/ summer 2021 issue. Clockwise from right: 1.) Lise Michelle in a headpiece by Reise Kochi, photographed by John Hook; 2.) Still from “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn” (1995) by Ai Weiwei, courtesy of the artist; 3.) The overgrown facade of a home in Waikīkī, photographed by John Hook.

Streaming Videos, Newsletters, Local Guides, and More

We’ ve refreshed the website for Flux Hawai‘i with a more dynamic viewing experience. Watch all the original episodes from our themed seasons, fnd ways to support local small businesses, and sign up for our weekly newsletters curated with fascinating reads. You can also browse past issues of the print magazine for purchase.

TABLE

FLUXHAWAII.COM

OF CONTENTS | ONLINE |

KAUAI | OAHU | MAUI | HAWAII ISLAND | CORCORANPACIFIC.COM ©2020 Corcoran Group LLC. All rights reserved. Corcoran® and the Corcoran Logo are registered service marks owned by Corcoran Group LLC. Corcoran Group LLC fully supports the principles of the Fair Housing Act and the Equal Opportunity Act. Each Offce is independently owned and operated.

has your home in Hawaii.

2005.

of

service.

expertise.

Corcoran Pacific

Locally owned and operated since

A tradition

excellence. Impeccable

Peerless

| SPRING / SUMMER 2021 |

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Ara Laylo

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Lauren McNally

EDITOR - AT - LARGE

Matthew Dekneef

NATIONAL EDITOR

Anna Harmon

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Eunica Escalante

DESIGNER

Skye Yonamine

SENIOR PHOTOGRAPHER

John Hook

PHOTOGRAPHY EDITOR

Samantha Hook

CONTRIBUTORS

Roger Bong

Lindsey Kesel

Mitchell Kuga

Michelle Mishina

Natalie Schack

Timothy A. Schuler

Eric Stinton

Noe Tanigawa

Josh Tengan

Kylie Yamauchi

IMAGES

Roger Bong

Vincent Bercasio

Phil Jung

Mark Kushimi

Michelle Mishina

Dino Morrow

Kenna Reed

Chris Rohrer

Meagan Suzuki

CREATIVE SERVICES

Marc Graser VP GLOBAL CONTENT

Shannon Fujimoto CREATIVE SERVICES MANAGER

Gerard Elmore LEAD PRODUCER

Blake Abes

Romeo Lapitan FILMMAKERS

Kaitlyn Ledzian ART & PRODUCTION MANAGER

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock CHIEF RELATIONSHIP OFFICER joe@NMGnetwork.com

Francine Beppu NETWORK STRATEGY DIRECTOR francine@NMGnetwork.com

Rob Mora VP SPECIAL OPERATIONS

Gary Payne VP ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE

Courtney Miyashiro OPERATIONS ADMINISTRATOR

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley VP SALES mike@NMGnetwork.com

Phil LeRoy NATIONAL SALES DIRECTOR

Chris Kelly PARTNERSHIPS & MEDIA EXECUTIVE

Courtney Asato MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

Taylor Kondo FASHION MARKETING COORDINATOR

General Inquiries: contact@fuxhawaii.com

PUBLISHED BY:

Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel St., Ste. A Honolulu, HI 96817

©2008-2021 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. ISSN 2578-2053

MASTHEAD

Phil Jung

Phil Jung makes photographs of the American social landscape, exploring identity through personal space and locality. He was born and raised in the Lower Hudson Valley of New York. He currently lives and works in Honolulu, Hawai‘i teaching undergraduates at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. His work has been exhibited throughout the United States, and are in the collections of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Hawaii State Foundation on Culture and the Arts, and has been published and featured nationally and internationally. Jung’s images are featured in the photo essay “A Sense of Place,” on page 100. “Visual documentation is important for any community. It’s a way to critically look at what’s out there,” he says. “While I’m out photographing, I’m thinking about the types of information I can include in the frame that will tell something about contemporary culture. I’m examining the relationship between the people who inhabit O‘ahu and the landscape that binds them all together.” His frst monograph, Windscreen, will be released winter 2021 by TBW Books.

Natalie Schack

Natalie Schack

Natalie Schack grew up in O‘ahu’s central plains, playing in red dirt, eating too many Redondo’s hotdogs, and drinking in the stories that the islands had to ofer. Those stories continue to inspire her as a creative writing MA student and journalist today, who has contributed to publications like Honolulu Magazine, Curbed, Hawaii Business, Hana Hou! Magazine, and more. For the past decade, she’s crafted narratives around the people, places and legacies that give Hawai‘i shape, hopefully adding something meaningful (and, with luck, a little bit of beauty) to the conversations our communities are having.

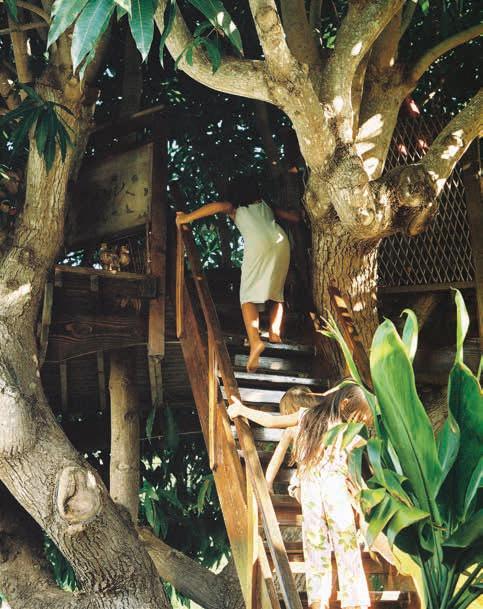

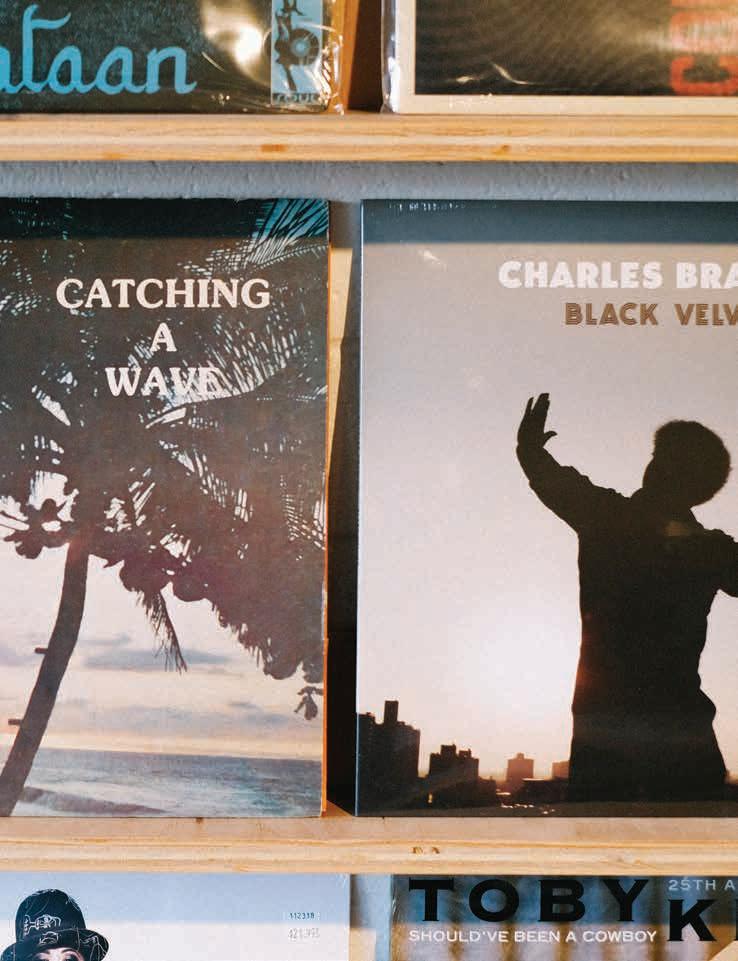

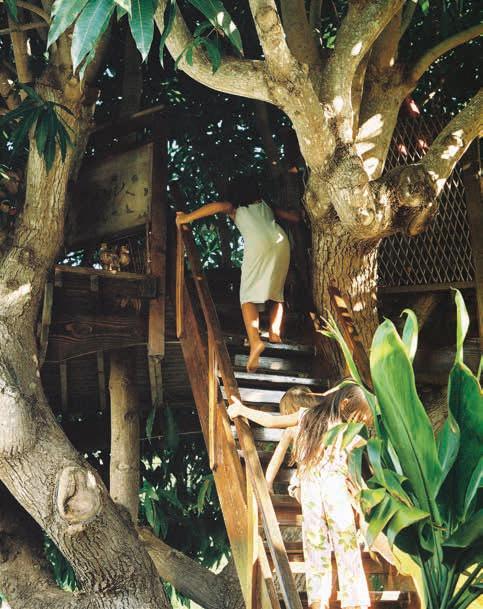

One of her pieces for this issue, on page 118, explores the Treehooo team’s eforts to foster Honolulu’s tree canopy.

“It’s a story about some of my favorite things: O‘ahu visionaries laboring to make a diference, with a spotlight on our island’s environmental gems,” she say. “This journey is an ode to all things arboreal–but at its roots, it’s also a testament to this city’s inspiring potential for community empowerment.”

Meagan Suzuki

Born and raised on O‘ahu, Meagan Suzuki studied environmental science and worked in the energy sector before pursuing a career in photography. She loves documenting stories and has contributed to NMG Network in various genres including pieces she wrote and photographed on the art scene in Paris, small town Hanapēpē, and the spiritual signifcance of Polihale. She is especially drawn to stories focusing on the environment, arts and culture, and travel. For this spring/summer issue, Meagan photographed women who are part of the vintage mu‘umu‘u renaissance on page 86. “It was fun to see gorgeous mu‘umu‘u prints and patterns given new life and exposure by a younger generation,” she says. “I loved hearing the stories behind special mu‘umu‘u—from heirlooms passed down through generations to a gift from a new elderly friend who heard about Mu‘umu‘u Month and wanted to share her own. As a sentimental person, I love the idea of wearing my grandmother’s mu‘umu‘u and imagining a day in her life way back when.”

Josh Tengan

Josh Tengan is a Hawai ʻiborn generational islander of Kānaka ʻŌiwi, Ryukyuan, and Madeiran descent. He is a contemporary art curator, writer, and NMG Network contributor with a focus on art and artists of Hawai ʻi. He is currently working on a publication project memorializing the annual thematic Hawai ʻicentric exhibition series, CONTACT, which ran from 2014 to 2019 in Honolulu. For this issue, Tengan profles senior Kānaka-artist, Bernice Akamine on page 50. “Bernice’s work always has a strong socio-political messaging. But one thing that stands out is her focus and attention to detail in both physical form and in concept,” he says. “Whether she is meticulously crocheting small wire sculptures or coordinating a procession of dozens of Kānaka for the installation of her work, every action is carefully considered.”

| SPRING / SUMMER 2021 |

CONTRIBUTORS

Yano

Compass is a licensed real estate broker and abides by Equal Housing Opportunity laws. All material presented herein is intended for informational purposes only. I’ve navigated to Compass. SEAN YANO | RS-61434 | 808.386.4487 | SEAN@YANOGROUP.COM

has partnered with Compass as a Founding Member to elevate the real estate experience for buyers and sellers all across Hawaii. Together, we are changing the tides with our exclusive programs and innovative tools. Allow me to guide you on your journey through this record-breaking market with a unique and strategic plan to reach your real estate goals.

Group

Face masks from a Covid-19 humanitarian project by Ai Weiwei. Image provided by Hawai‘i Contemporary.

Face masks from a Covid-19 humanitarian project by Ai Weiwei. Image provided by Hawai‘i Contemporary.

ARTS & CULTURE

“I was drawn in by the heat and the energy, the movement and spontaneity.”—Bernice Akamine

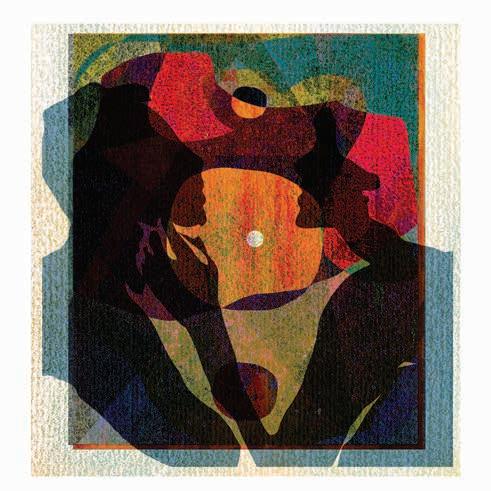

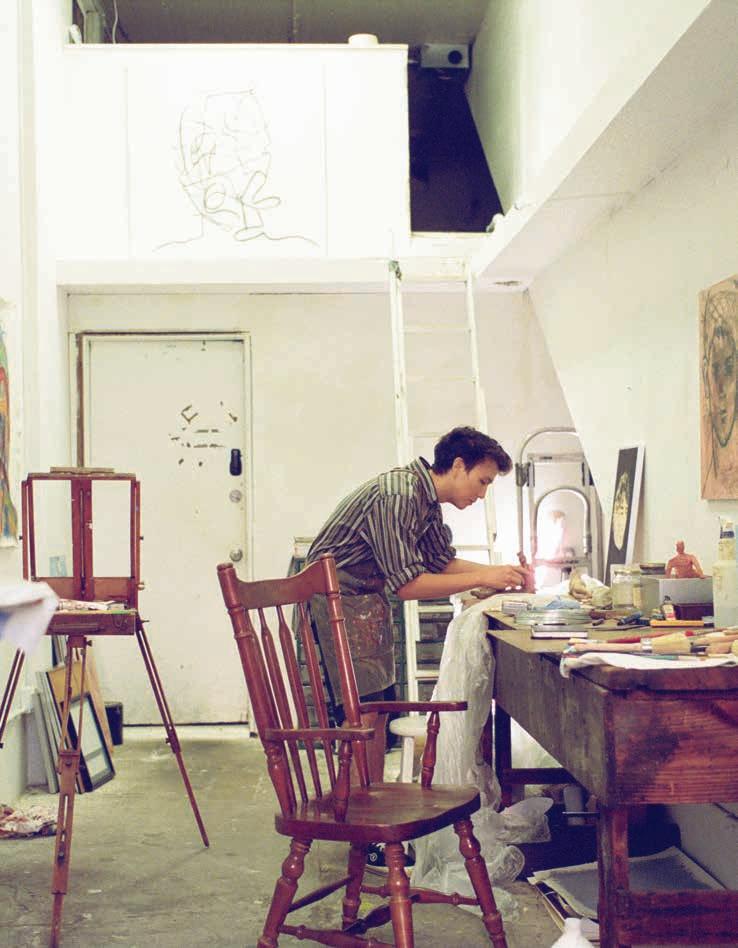

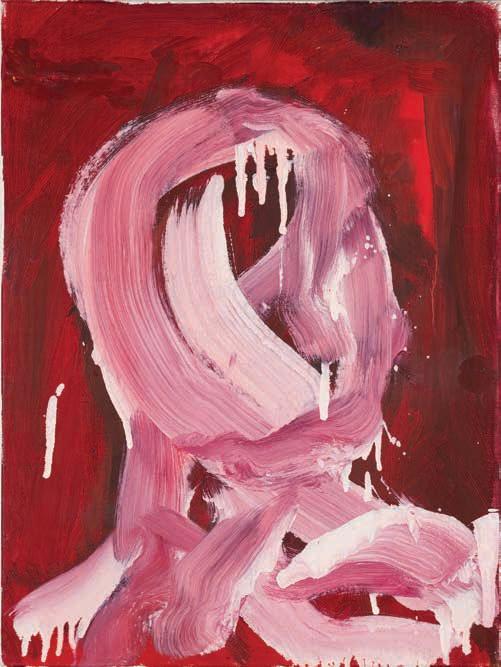

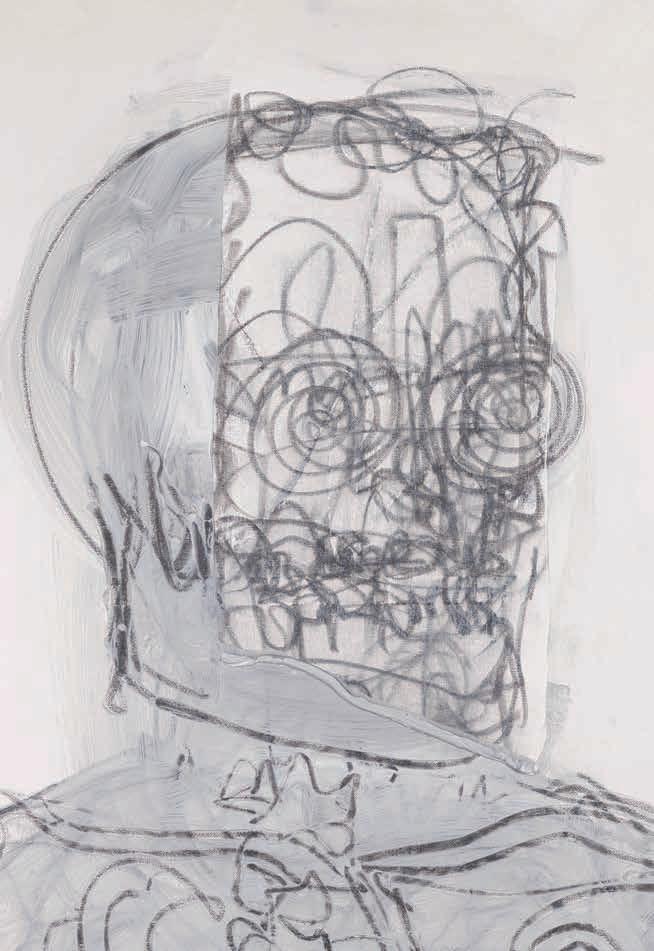

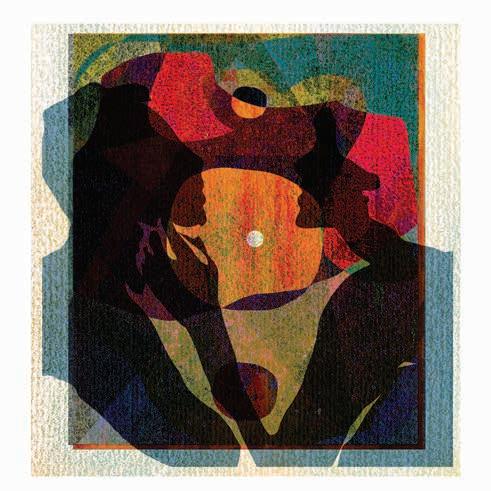

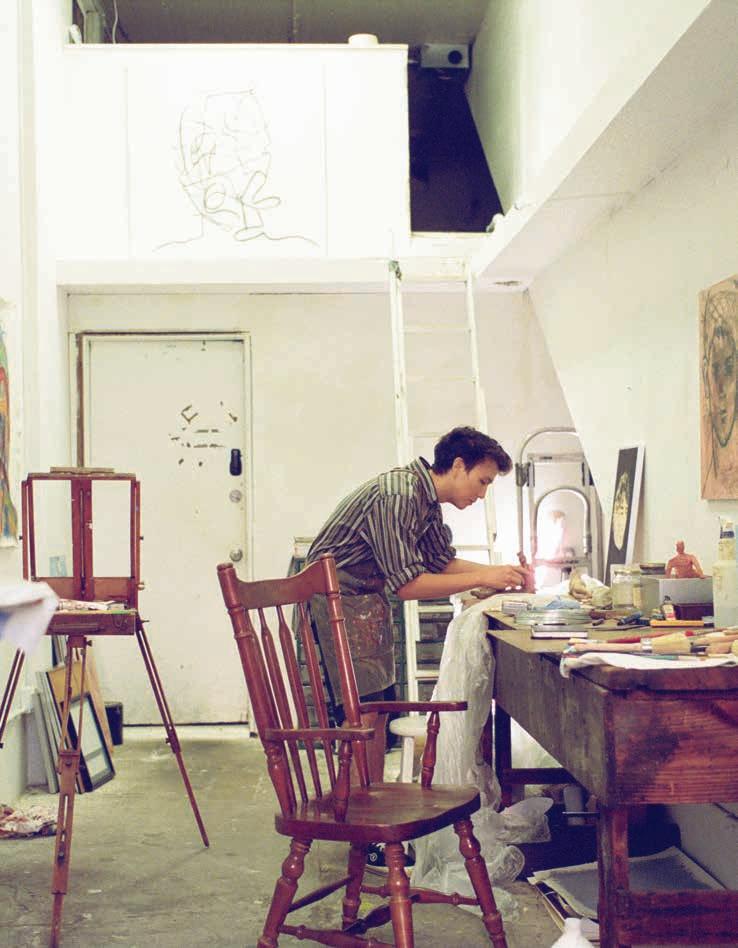

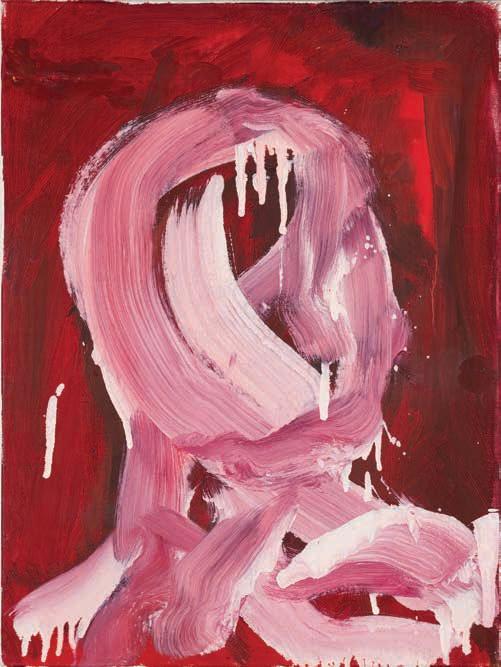

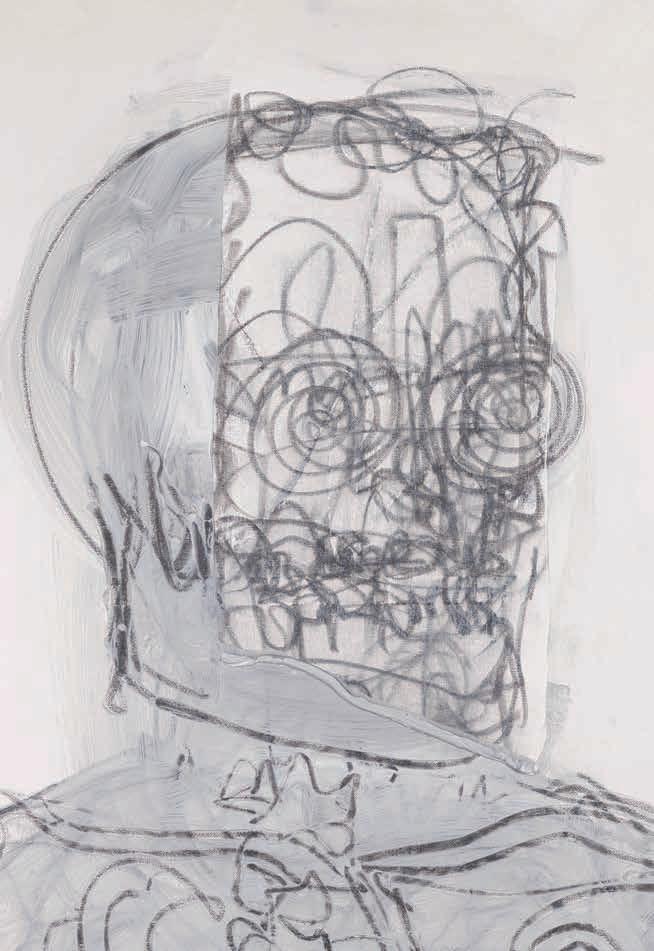

In His Own Head

The cerebral paintings of Roland Longstreet reflect an equally active and brainy creative process from the Honolulu-based artist.

TEXT BY NOE TANIGAWA

IMAGES BY MARK KUSHIMI AND CHRIS ROHRER

Roland Longstreet sounds like he is on the artist’s path when he tells me, “Just making work is where I’m trying to be mentally.” In October 2020, Longstreet procured a studio residency with Single Double, a boutique for chic, vintage island goods on Nu‘uanu Avenue in Chinatown. Coveted by artists, residencies provide what daily life cannot: time and space to work through ideas.

This residency, Longstreet’s frst, is a challenge to his commitment. “I know that I’m trying to scrape at something there’s no manual for,” says Longstreet, “It’s not like step one, step two, step three. I make my own steps in my head. But it’s an experience I’m exploring for myself for the frst time.”

Longstreet stands medium lanky, wearing a draftsman’s apron. Buoyant locks of hair top a friendly but often pensive face. After four years consumed by managing Ars Cafe, the cofeeshop-art gallery space near Waikīkī, he jumped into the art world in December 2019. He now installs art for corporate clients and others. In the Chinatown space, though, he is making time to paint.

The studio has a wide glass storefront and a loft in back. Nearly every inch of the room features his wet-looking, gestural fgure drawings and paintings. For Longstreet, the availability of walls, surfaces, and supplies is reason to paint as much as possible. Curious pedestrians can watch him do so from the sidewalk.

“If I stop myself from doing anything, it’s not going to go anywhere,” he says. “If I just keep making work, then that’s the work I maybe one day can destroy. Because it all sucks. But I’ll have done that to the point where I can make work that I think is good.”

“If I’m in the mode of being able to make a mess and use any material at my disposal, then I’m in the mode I should be,” Longstreet says, “starting to paint.”

FLUX PHILES | PAINTING | 22 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Logical deduction. So how does Longstreet start? “I gotta get loose and try to make a mess,” Longstreet says. “Because for me that’s a big part of it. That sounds obvious, but if I’m too timid about making a mess, then I’m not going to be able to start anything worthy of spending time on.” For Longstreet, the process involves sketching with large brushes and gobs of red ochre, blue, orange, green, brown, white, and feshcolored paint. Muscley brushstrokes sweep through the colors, blending them al fresco. A tangle of strokes and colors become a face, a head, a torso.

“If I’m in the mode of being able to make a mess and use any material at my disposal, then I’m in the mode I should be, starting to paint.”

Longstreet has a bachelor’s degree in art with a focus on sculpture and painting from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. He says he was one of those for whom the word “paintings” meant Renaissance art

and the Impressionism. Recently, he’s been diving into the Abstract Expressionists, those American bad boys of the 1950s: Pollock, de Kooning, Gottlieb, Rothko, Motherwell. Working large, for them the canvas is a record of heroic actions involving bold sweeps, pours, stains, spatters or interwoven drips of paint. Sometimes with dense activity, other times through expansive felds of color, the Abstract Expressionists removed recognizable subject matter and went straight for the phenomenological jugular.

“When I read into what they were trying to do, they were all a bunch of bad asses doing things that were never done before,” he says. “It seemed like they were trying to express the spiritual through abstract images, in a way where the viewer can feel the impact of what they’re doing.”

Their objective impressed Longstreet: to afect viewers viscerally, on a level above or below rational thought. “It made me look at

In October 2020, Longstreet procured a studio residency with Single Double, a boutique for chic, vintage island goods on Nu‘uanu Avenue in Chinatown.

26 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

27

my work diferently,” he says. “It made me realize there are some similar veins. But I put the fgure back into the composition, whereas they took everything out.”

He points to other more contemporary abstract expressionist fgures by Francis Bacon. There’s defnitely a resemblance.

Four small studies lie on a table. Paint, brushstrokes, and erasures writhe in the shape of a head. They’re largely all the same colors—olive, red ochre, pink, and grey—but each one gives of a distinctly diferent vibe. Longstreet is looking for the version that feels most alive.

“I’m going to be 31 this year,” Longstreet says. “It’s an ever-present sense of dissatisfaction with how much I’ve made or even the quality of the things I’ve made so far. When that gets pent up, eventually it makes me eliminate everything else and get here and make.”

Longstreet points out that an errand at Longs Drugs can derail the whole thing. Forget lunch with friends, food shopping, or a lazy morning scrolling through Instagram.

“That’s all it takes and you’re not in the studio,” he says. “I realized I was so fed up with the fact that I didn’t make much, so I spent seven hours in here. The next day I did the same thing. I felt great. I felt fantastic.”

Longstreet fips through a pile of newsprint fgure sketches. There’s a line drawing, another features gestural swipes using the side of a conte crayon, wax pencil cuts through gouache in another drawing. On one page, dry brushstrokes criss cross the surface insistently, and a sinewy person emerges. “That’s what it takes. The elimination of everything else in order to do this.” Longstreet is gunning for a fuller fgure now, life size or larger. Painting is his only way out.

Longstreet’s exhibition Embodied Reverence was on view at Above the Equator in April 2021. Learn more about the gallery space in historic, downtown Hilo at ategallery.com.

30 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

31

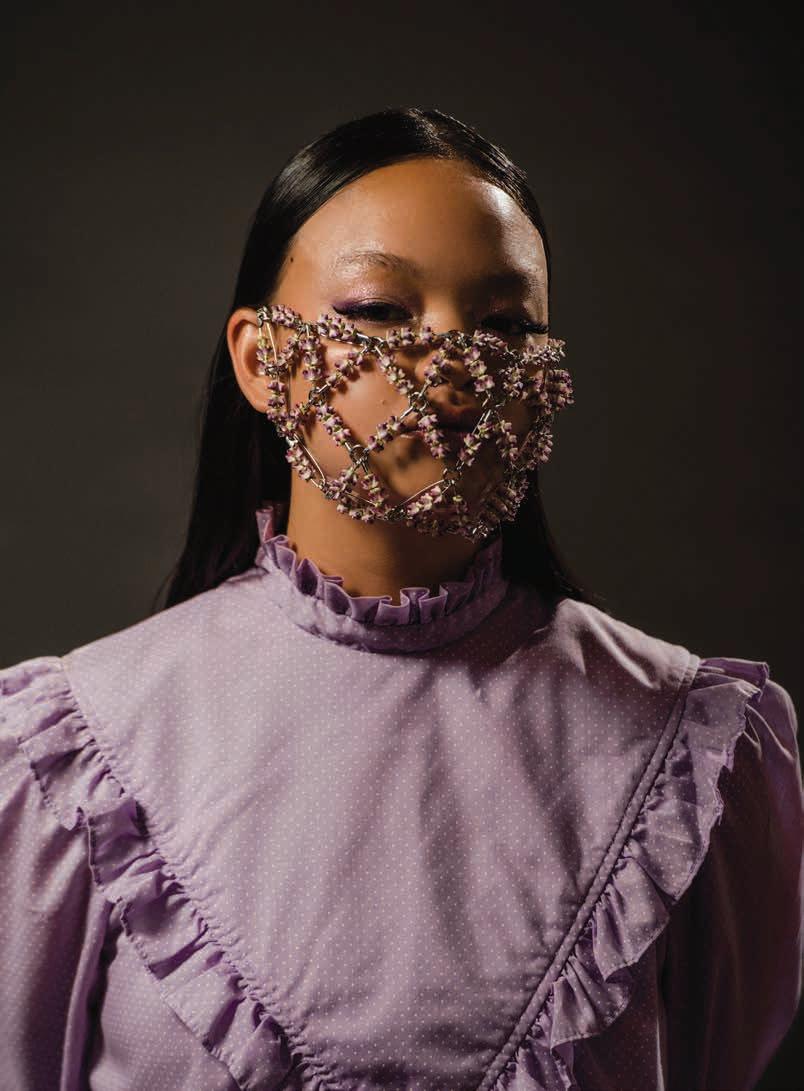

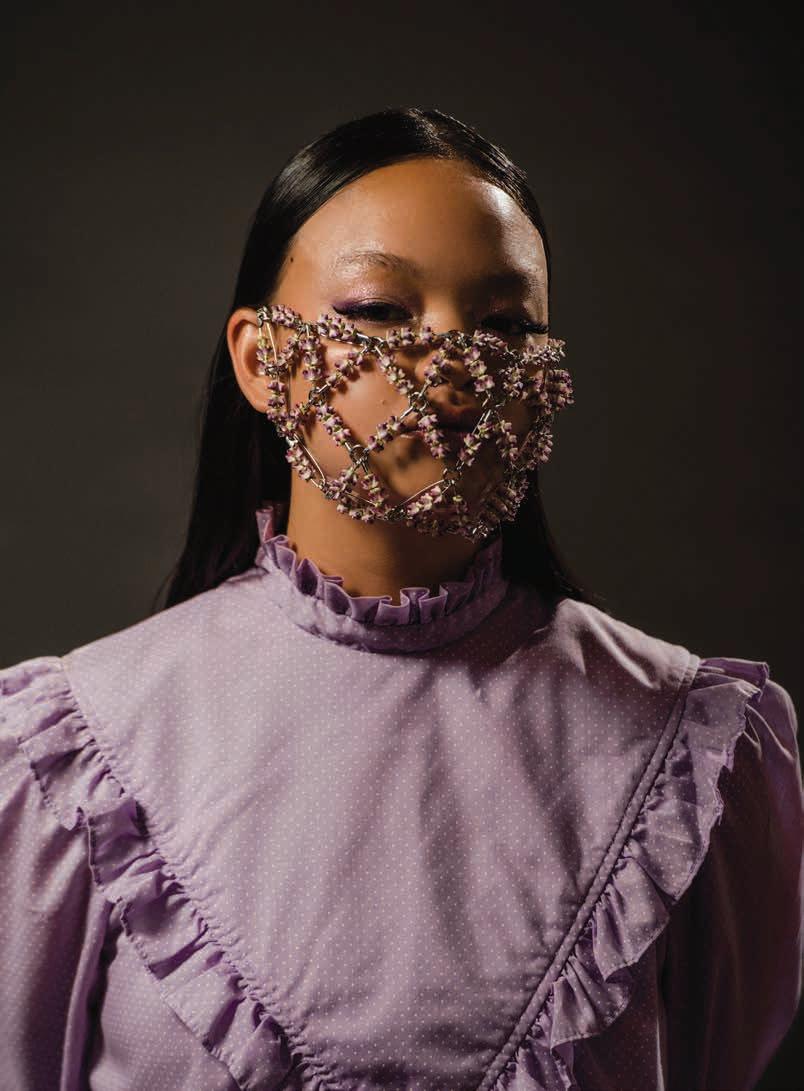

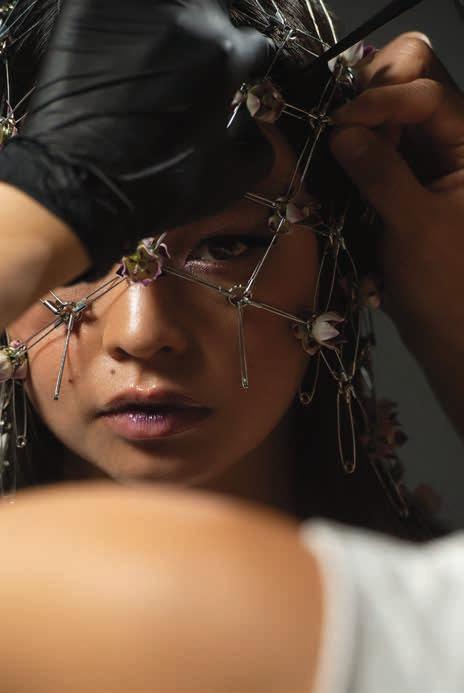

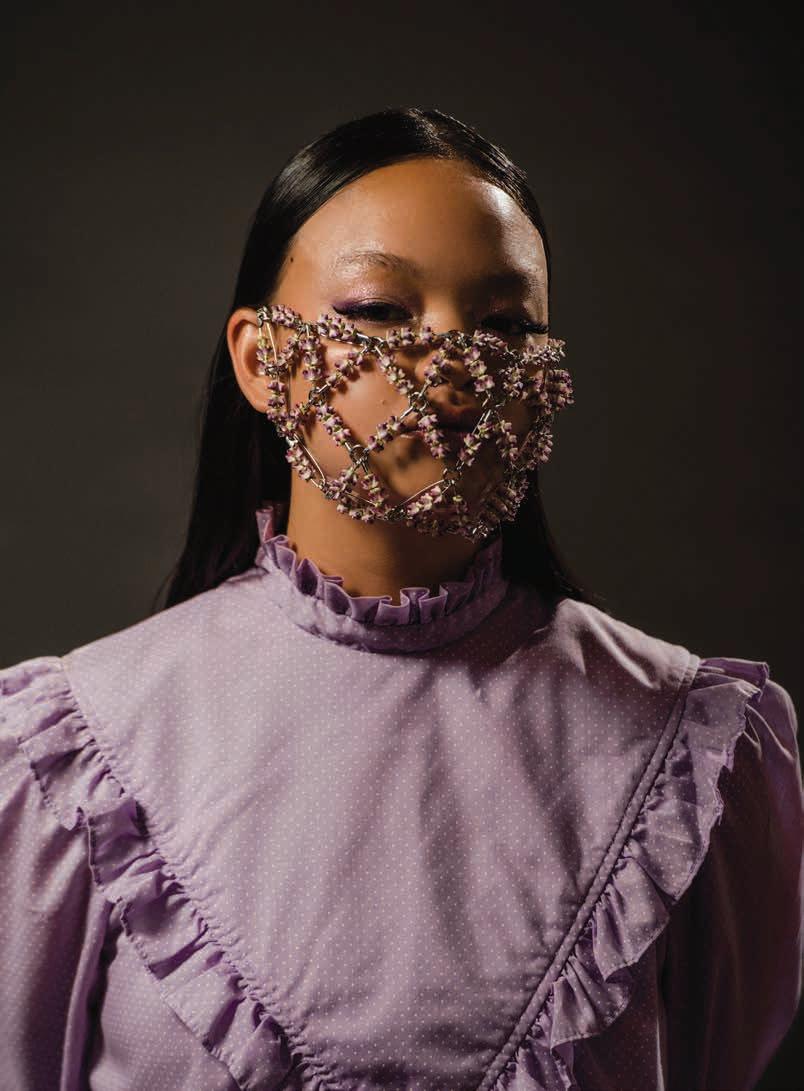

Reise Kochi’s Adornments

Make

a Statement

Pairing face chains and leather harnesses with long dresses and straw hats, the stylist and designer offers lessons on how to make the avant-garde work in Hawai‘i.

TEXT BY NATALIE SCHACK

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

HAIR AND MAKEUP BY RISA HOSHINO

MODELED BY LISE MICHELLE

Don’t bother looking for Reise Kochi creations at the mall. His hand-folded, origami-style paper purses, bespoke foral adornments, and leather harnesses are nowhere near retail-level production, which is sort of the point. “If I were just making the same thing again and again and again, that would kill my creative side,” says Kochi, who instead customizes each piece to the specifc project at hand, whether it’s a collaboration, editorial feature, commercial photoshoot, or runway show. “I make the patterns and do everything myself. That’s why it takes me a while on some projects. I’m literally working from scratch.”

While Kochi draws on his formal training in Honolulu Community College’s fashion program, as well as his selftaught skills in leather work, lately his inspiration has been coming from a more personal place: his heritage. The idea for Kochi’s signature leather harnesses—unique in the local fashion scene and perhaps the most recognizable of his creations—came about after he discovered a leather satchel that had been handmade by his grandfather.

Kochi’s more recent passion for utilizing tropical fowers and lei in his styling work has been an opportunity to dive into a part of his identity and culture that he hadn’t fully explored. When Kochi’s parents decided to sell the house he grew up in and move of island in early 2020, it awakened a sense of nostalgia and a desire for introspection that is

apparent in his work. “It’s funny, my life has been kind of bringing me back to my roots with my dad moving to the Big Island and really discovering and immersing himself in Hawaiian practice,” Kochi says. “And now, making my own lei for shoots and parties, I’m discovering a side of myself that I never really tuned into growing up.”

Reise Kochi’s edgy leather harnesses and chain work can be intimidating, especially in Honolulu’s relaxed fashion climate. Here are his tips for making these bold, stand-out pieces work for you.

OPPOSITES ATTRACT

“Try layering them over a piece that might be considered modest, like a mu‘umu‘u, a blouse, or an aloha shirt.”

THINK IN TEXTURES

“Layer it over or under mesh or something sheer. Add a cool pant or skirt or throw a cool, open, button-up shirt over it. Layer the harness over bare skin or a bralette and cover up with just a suit jacket.”

CONFIDENCE IS YOUR MOST ESSENTIAL ACCESSORY

“It’s a statement piece, so be ready for people to take notice. Remember: You are wearing the harness, don’t let the harness wear you.”

FLUX PHILES | FASHION | 32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

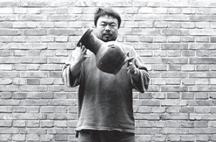

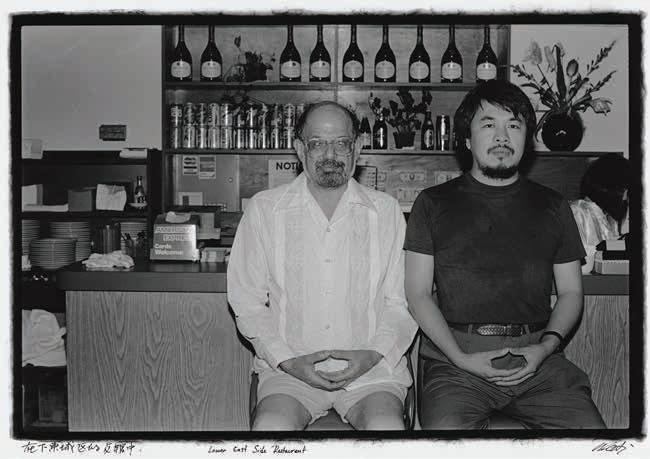

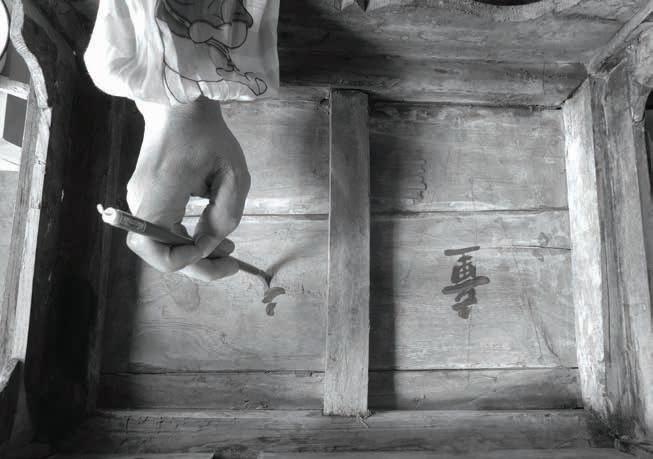

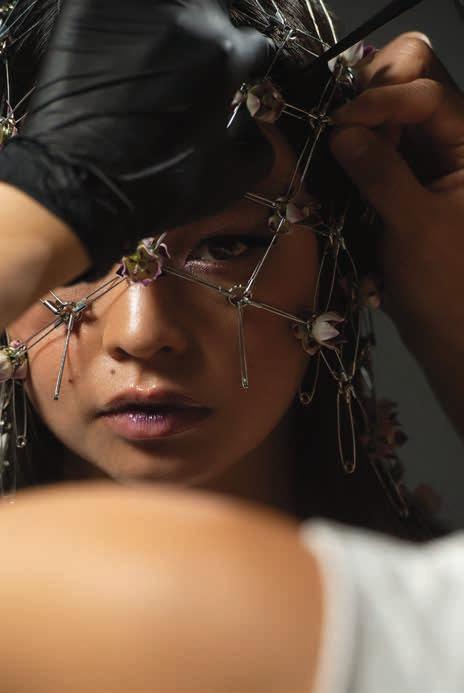

Artist at Large

Renowned for his powerful antiestablishment artwork, the iconoclast

Ai Weiwei is a relentless crusader for social and political justice.

TEXT BY LINDSEY KESEL

Ai Weiwei has been called a traitor, a hooligan, a lawbreaker, and an agent provocateur. Thanks to his subversive artworks, he lives with a permanent target on his back: In 2009, an assault by plainclothes police ofcers in Chengdu, China, sent him to the hospital with a cerebral hemorrhage; in 2011, Chinese authorities detained and imprisoned Ai for political dissidence, under the guise of tax evasion; in 2018, his Beijing studio was demolished without warning—the second art space of his to be razed. But for all the perils he has endured, Ai refuses to be silenced.

Ai’s multifarious body of work boldly defes agents of tyranny and transgression, including his motherland of China, branding him an antihero for the oppressed. His statements on the absurdity of what is—tackling heavy issues such as censorship, state surveillance, and human rights violations—are fueled by hope for what could be. “I’m an eternal optimist,” he says in Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry, the 2016 documentary about his life. “I think optimism is whether you are still exhilarated by life ... whether you are curious, whether you still believe there is possibility.”

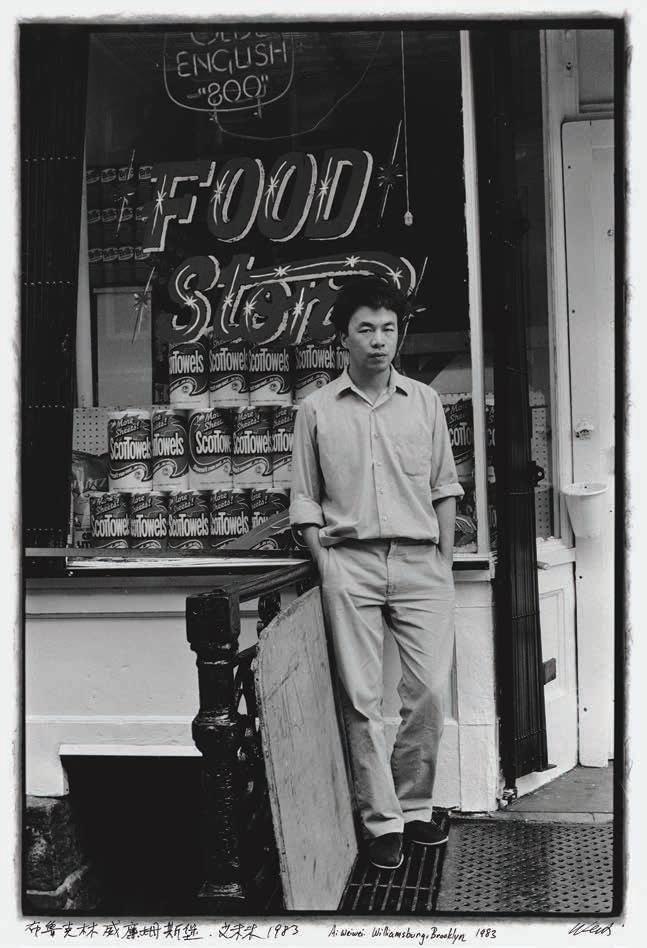

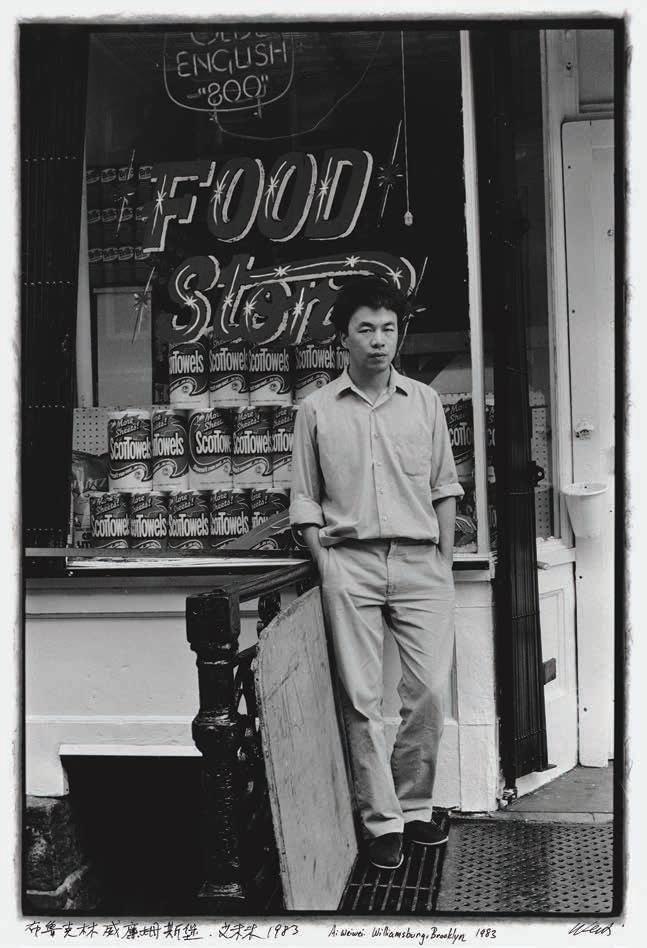

Disruption of the status quo is Ai’s birthright. His father, Ai Qing, was a famous poet, imprisoned and exiled to Western China shortly after his son’s birth in 1957 for his rightist views criticizing the Communist regime. Growing up in a labor camp, Ai’s front-row seat to displacement and sufering was the catalyst for his eventual life of activism.

A rare breed of artistic shapeshifter, Ai toggles among wildly diverse mediums dictated by the demands of his subject matter—everything from sculpture, architecture, and performance art to blogging, flmmaking, and heavy metal music. During a virtual appearance at the Hawai‘i

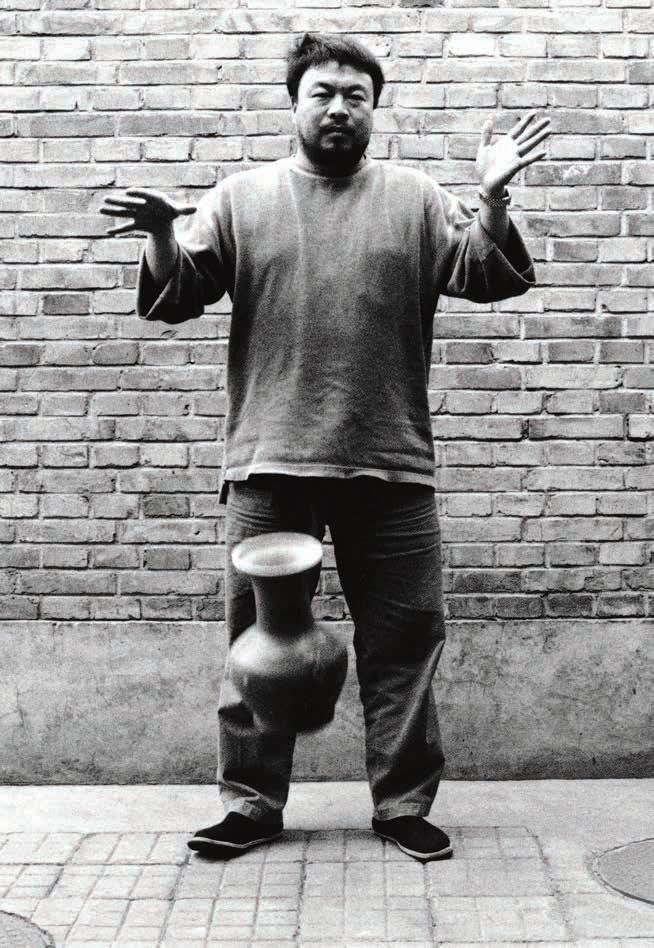

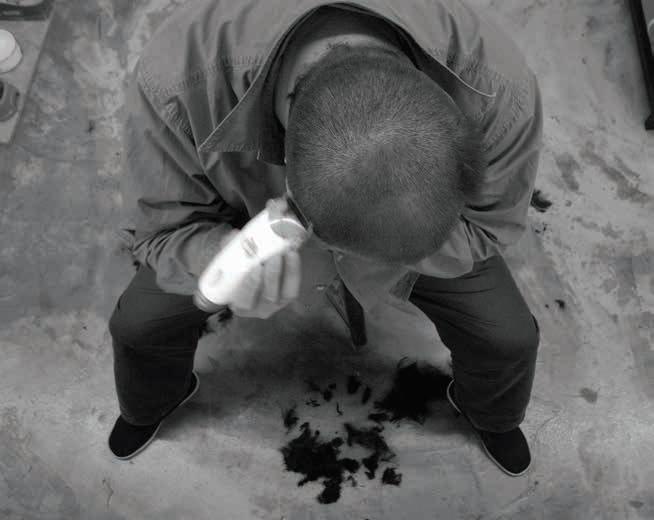

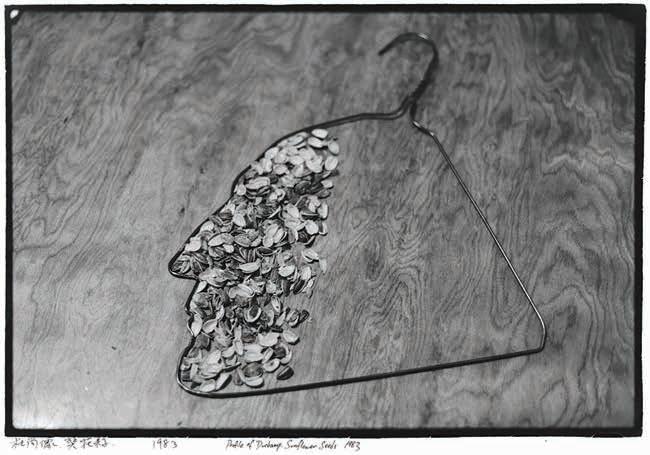

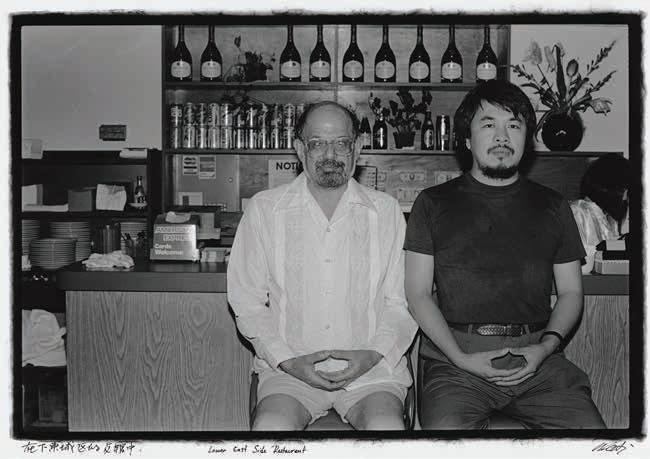

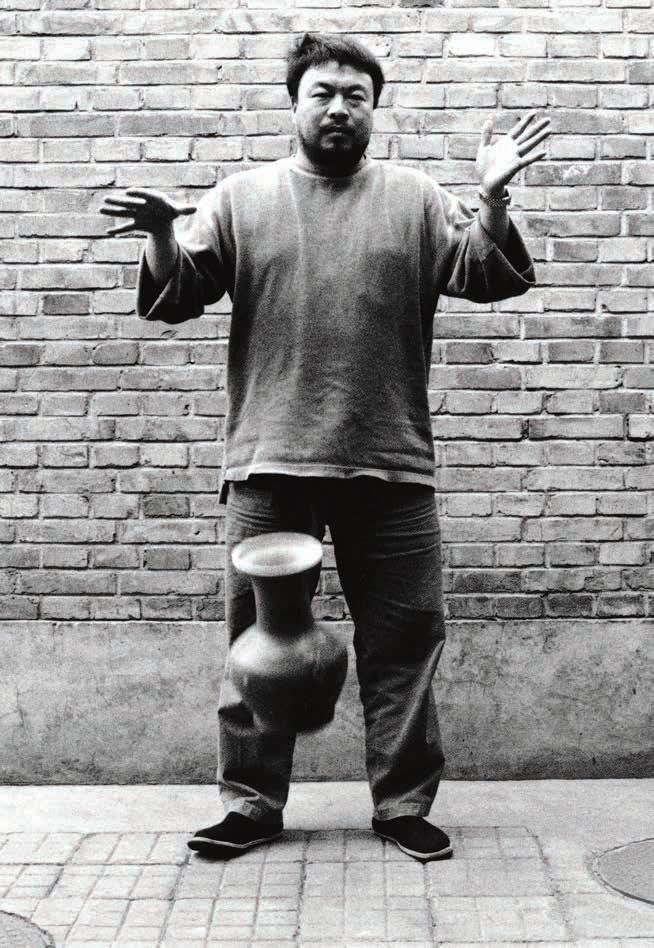

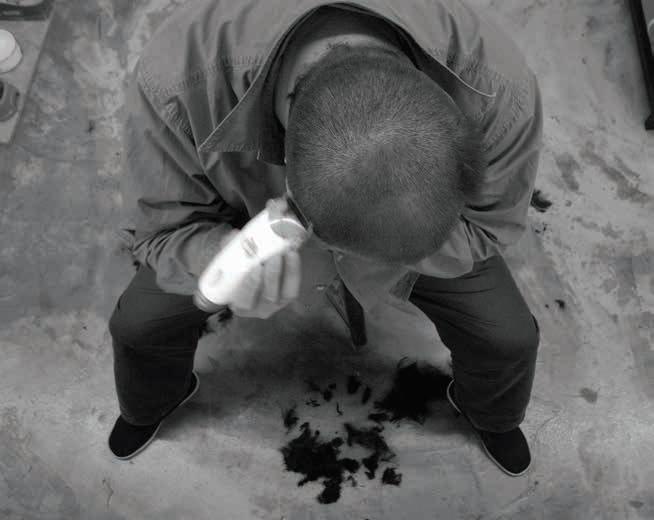

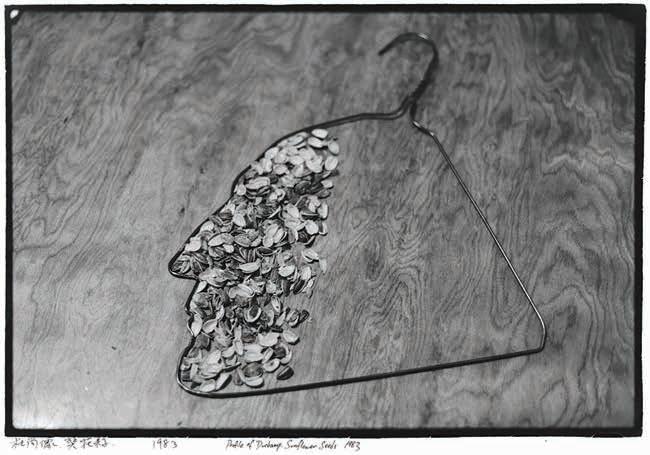

From sculpture to installation, Ai Weiwei toggles among wildly diverse mediums dictated by the demands of his subject matter. All images courtesy of the artist.

FLUX PHILES | ACTIVISM | 40 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Ai is often moved to include gestures of camaraderie for victims of political corruption.

At a Lower East Side restaurant in New York, 1988.

Contemporary Art Summit in February 2021, Ai spoke about the need for perpetual introspection and fresh challenges in making art: “If you know who you are, you’re not a real artist,” he said. “You have to put yourself in danger ... constantly in doubt about your fxed ideas.”

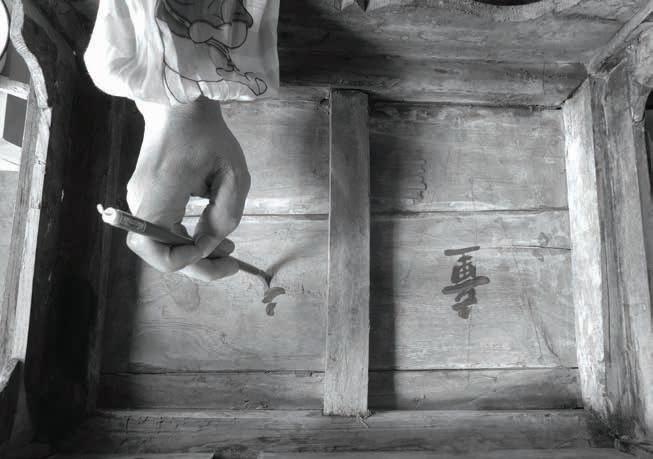

One of Ai’s frst big shockwave pieces is “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn” (1995), where he immortalized himself destroying a 2,000-year-old ceremonial artifact in photographs—a commentary on China’s clash of tradition versus modernization. Probably his most controversial work is the Study of Perspective (1995–2017), a series of photos featuring Ai’s middle fnger aimed at what he deems harbingers of censorship and suppression around the globe: the Eifel Tower in Paris, the White House in Washington, D.C., and Tiananmen Square Gate in Beijing. His Tiananmen Square image, a blatant reference to the 1989 massacre of peaceful student protesters, was a major focus of the interrogation that led to Ai’s 81-day incarceration in 2011.

Some of Ai’s most impactful works are those inspired by his experiences with imprisonment, invasion of privacy, and other forms of control: “I’ve been under restriction for a long time,” he says during the Hawai‘i Contemporary Art Summit talk. “And those obstacles only stimulate me or encourage me to respond, to act.”

A year after his arrest, Ai put himself under surveillance and invited the public to view a live feed of four webcams in his Beijing home for a cheeky piece titled “Weiwei Cam.” In the sculpture “Surveillance Camera” (2010), a likeness of a CCTV camera carved in marble—sourced from the same quarry as Chairman Mao’s mausoleum—taunts Chinese authorities who had him under 24-hour surveillance at the time.

Confned to China after his incarceration, in 2014 Ai coordinated more than 100 collaborators to execute the seven-part exhibition @Large: Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz from his Beijing studio. In one section of the former federal penitentiary, “Trace” featured

More recently, Ai has been busy making films that convey the gritty, intimate details of injustice, from the global refugee crisis to police brutality.

A still from one of his most famous pieces, “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn” (1995).

44 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

45

“I think optimism is whether you are still exhilarated by life...” Ai says.

“”...whether you are curious, whether you still believe there is possibility.”

portraits of 176 international prisoners of conscience, including Nelson Mandela and Edward Snowden, created entirely from Legos. During the seven-month show, guests were invited to write postcards carrying messages of hope and support to the prisoners.

Ai is often moved to include gestures of camaraderie for victims of political corruption and negligence. After an 8.0 earthquake hit China’s Sichuan province on May 12, 2008, he orchestrated “Straight” to spotlight government malfeasance in the form of shoddy school construction. The 90ton foor sculpture involved reclaiming 150 bars of mangled steel rebar from schools that crumbled in the disaster, and straightening them by hand. To honor the students who lost their lives that day, Ai led a volunteer efort to collect over 5,000 of their names and birthdays and posted the list to his blog on the earthquake’s oneyear anniversary.

More recently, Ai has been busy making flms that convey the gritty, intimate details of injustice, from the global refugee crisis to police brutality. For the 2020 flm Coronation, he directed a covert camera crew in Wuhan, China, during the militarystyle coronavirus lockdown of more than 10 million people. Whatever Ai Weiwei manifests next, it will be equal parts unexpected and meaningful, with a dash of goodwill. In 2017, Ai rekindled the spark of his Study of Perspective series by casting rhodium-plated models of his illustrious hand, middle fnger pointed high. Auctioned of to raise money for New York City’s Public Art Fund, the run of 1,000 mini sculptures sold out in a few hours.

Learn more about the artist at aiweiwei.com. Stay up to date with the Hawai‘i Triennial at hawaiicontemporary.org.

48 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

49

Called to Creation

The soulful and pertinent artworks of Bernice Akamine defy medium and description.

TEXT BY JOSH TENGAN

IMAGES BY DINO MORROW

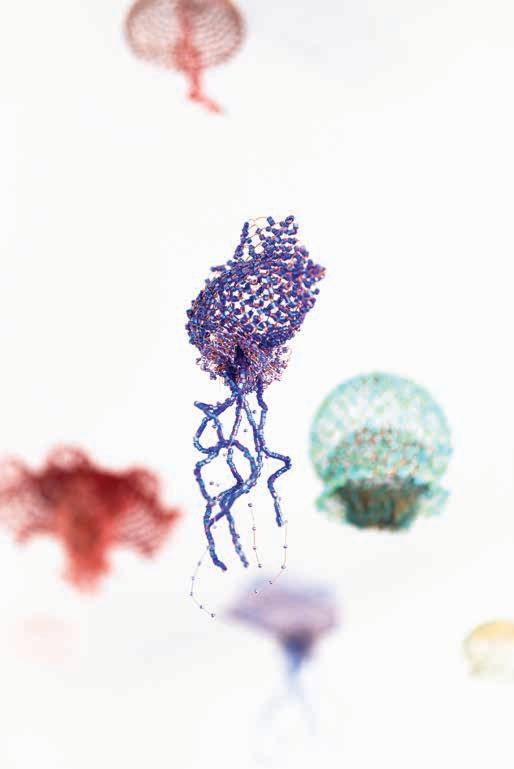

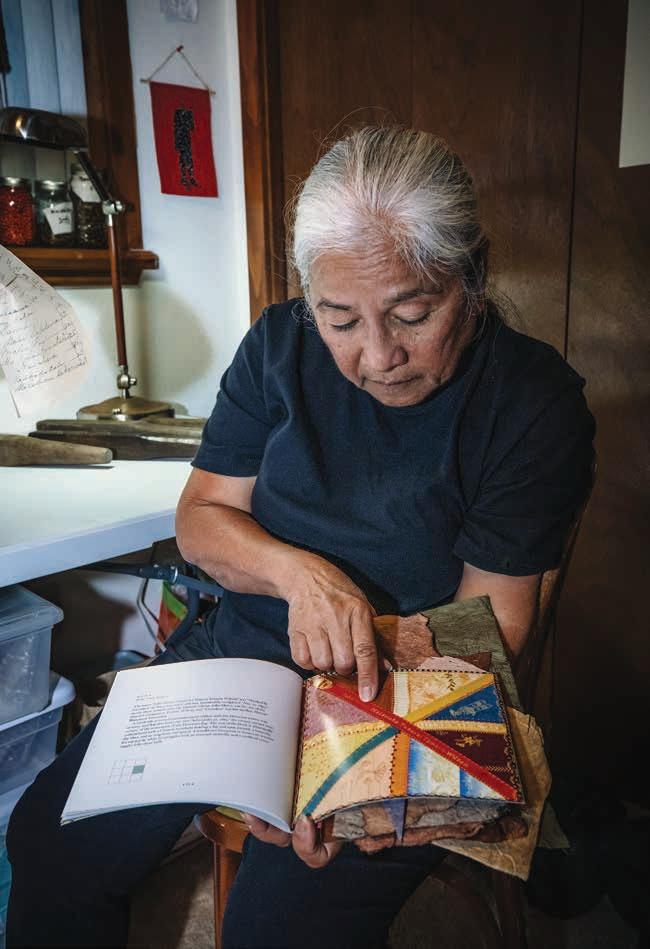

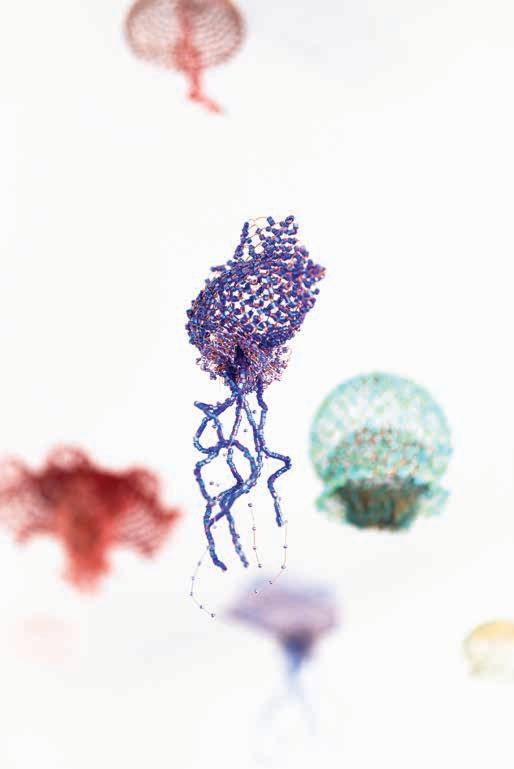

Bernice Akamine has found endless fascination in jellyfsh. For the 71-year-old artist, these mystic creatures are a symbol of ancestral connection as well as environmental imbalance. When I spoke with Akamine from her home in Volcano, Hawai‘i Island, she was fnishing Pololia, a series of 35 jellyfsh sculptures made of fnely crocheted copper wire and glass beads for Above the Equator, the new contemporary art gallery and project space in downtown Hilo.

Though best known for her socially engaged projects, it was during this past year of isolation that Akamine turned her focus back to making small, meticulously crafted art objects with nothing more than her two hands.

In the Kumulipo, life begins in a dark, primordial slime with the creation of a single foating coral polyp that anchors itself to the seafoor and begins to grow. (Genetically, these coral polyps are microscopic organisms closely related to anemone and jellyfsh.)

Recently, studies have shown large increases in jellyfsh populations around the world. Jellyfsh thrive in temperate and warm conditions, where they can reach sexual maturity quicker. When the conditions are right, jellyfsh can quickly spawn and multiply in a short period, especially when their populations are left unchecked by larger predators. These large and increasingly more common blooms are directly linked to an imbalance in marine ecosystems, as well as declining fsh populations, especially in already overexploited fsheries.

Like much of the work in Akamine’s oeuvre, her piece Kalo connects communities across the pae ‘ā ina, across time, and generations in aloha ‘āī na and ongoing resistance to American annexation.

FLUX PHILES | MAOLI | 50 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“We don’t think about how we’re impacting things,” says Akamine. And as waters continue to warm, jellyfsh blooms proliferate. Jellyfsh have unfortunately become an omen of future potential climate catastrophe even if it’s not their fault.

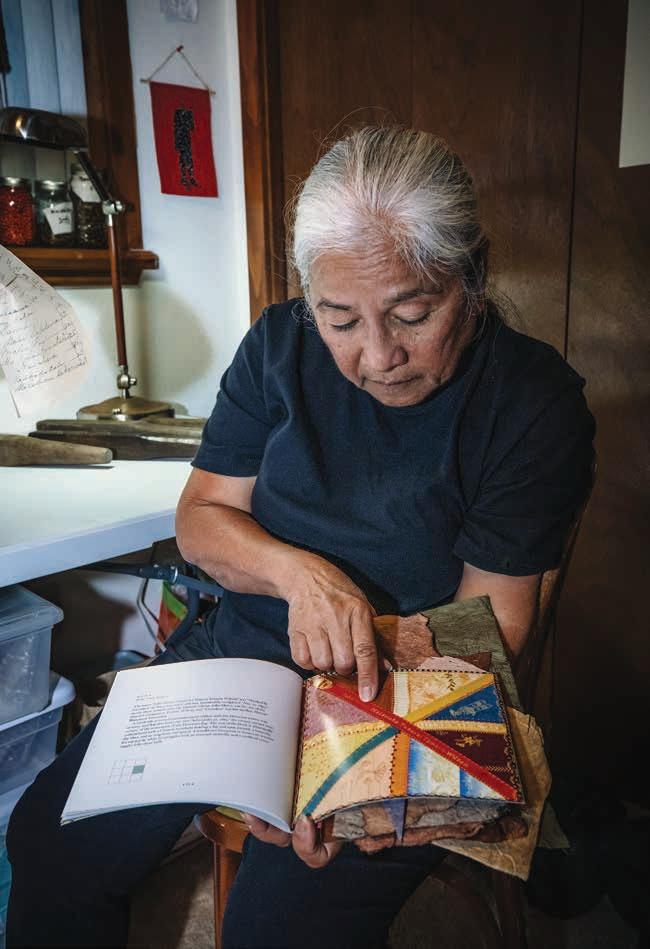

Born on Oʻahu in 1949 and raised in Waimānalo and Kalihi, Akamine, who holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts and Master of Fine Arts in sculpture from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, didn’t begin her formal Western art training until later in life after raising her family. Early in her studies, she took a glass-blowing class taught by longtime professor Rick Mills in the early 1990s. “From the moment I stepped into that studio, I was drawn in by the heat and the energy, the movement and spontaneity,” she said.

However, it was during her graduate studies in the late ’90s as an exchange student at California College of the Arts

in Oakland where she began to explore the possibilities of a socially engaged art practice. In Oakland, Akamine was an assistant to artist, feminist, and social practice pioneer Suzanne Lacy. At the time, Akamine was working with Lacy on a project called Expectations, which covered a spectrum of issues around teen pregnancy, from its impacts on the health and education of young women to its role in political stereotyping, lawmaking, and social policy. All of these new experiences sent her practice in a new direction.

Akamine moved home in 1999, to fnish her fnal semester of graduate school at UH-Mānoa. But before returning home, Akamine wrote Kahu Kaleo Patterson, a Hawaiian Episcopal minister and houseless community champion from Mākaha. She wanted to propose a project that would take her and members of the Hawai ʻi Ecumenical Coalition, a network

In Akamine’s piece, the leaves of the kalo plants were constructed from copies of the Hui Aloha ‘Ā ina Anti-Annexation Petitions of 1897 to 1898.

Best known for her largescale and socially engaged projects, it was during this past year of isolation that Akamine turned her focus back to making small, meticulously crafted art objects.

54 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

55

of ministers and churches from around the islands that Patterson founded, to diferent houseless encampments, most of which were found at beach parks and roadsides adjacent to Hawaiian Homestead communities.

The fnal work, Kuʻ u One Hānau, called attention to the rising rates of houselessness among Native Hawaiians in their homeland. As a part of the sculptural component of her thesis, Akamine created a tent structure whose roof was made of an oversize canvas Hawaiian fag. Finished in 1999, the work was most recently shown in 2019 as a fvepart iterative work during the Honolulu Biennial to highlight how Kānaka Maoli are still disproportionately represented in houseless statistics compared to other ethnic groups today.

That year’s biennial also featured another monumental community-centered work by Akamine entitled Kalo. The large-scale installation featured 87 kalo sculptures of paper, wire, and pōhaku. More than just a staple food of the Hawaiian diet, the kalo plant holds special signifcance in Kānaka Maoli cosmologies. (Hāloa, the frst Hawaiian, is the younger brother of Hāloanakalaukapalili, a stillborn from whose grave grew the frst kalo plant; kalo is thus considered an elder sibling to the Hawaiian people.) In Akamine’s piece, the leaves of the kalo plants were constructed from copies of the Hui Aloha ʻĀina AntiAnnexation Petitions of 1897 to 1898, which saw 21,269 Hawaiian Kingdom patriots

stand in frm resistance to American annexation. The corm of the kalo was made of a pōhaku sourced from communities in Oʻahu, Molokaʻi, Kauaʻi, Maui, and Hawai ʻi Island. For the biennial, the project was installed at Ali ʻiōlani Hale, the site of the 1893 overthrow.

On the morning that the project was installed, over 150 people from across the islands formed a procession from ʻIolani Palace to Ali ʻiōlani Hale, following the same route Queen Lili ʻuokalani would have traveled from her home to government ofces across the street. Each kalo sculpture was carried by kūpuna, ʻōpio, and descendants of those who signed the Kūʻē Petitions and placed in the central rotunda of the building.

Kalo, like much of the work in Akamine’s oeuvre, connects communities across the paeʻāina, across time, and generations, in aloha ʻāīna and ongoing resistance to American annexation and occupation in our islands.

Often, it’s the impactful projects of this scale that require months, sometimes years, of research, development, grant funding, and strong community partnerships to accomplish. But for now, Akamine is taking a pause and fnding satisfaction in the solitude of making small jellyfsh at her home studio. “I still make pieces, just to make, for joy. But I always try to balance that with work I feel that is important to give others a voice.”

Born on O‘ahu in 1949 and raised in Waim ā nalo and Kalihi, Akamine holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts and Master of Fine Arts in sculpture from the University of Hawai‘i at M ā noa.

For more on the artist, visit bernice-akamine.com.

59

Ro’s Moment

Through catchy beats inflected with local humor, the rapper breathes unapologetic fun into Hawai‘i hip-hop.

TEXT BY ERIC STINTON

IMAGES BY VINCENT BERCASIO

In February 2021, Ro told his grandma that he had a surprise waiting for her in the car. But when she hopped into the front seat of his Honda Civic, she found nothing out of the ordinary. Then her 21-year-old grandson turned the radio on, just as a DJ introduced the song coming up next, “Kodak Moment.”

On the breezy, nostalgia-tinged jam, Ro raps the frst verse and sings the hook; he’s the frst person you hear on the track, which also features producer Daju, guitarist Tyler Donovan and rapper Koins. It’s a song that evokes simpler times of chasing the sunshine and playful firtations—one you’ll be singing along with by the second chorus and unconsciously humming later that night. It’s the frst radio hit any of the artists have had.

“As soon as I heard it played back to me, I knew this was gonna be big for us,” Ro says. “I wasn’t shocked that it made it to the radio.”

He may not have been surprised, but his grandma— who he calls mom since she raised him—certainly was. “That’s you?” she asked when she heard her grandson’s voice crooning through the car speakers. “Oh my god!” She started moving her hands to the beat as if she were the one rapping, and a glowing smile lit up her face. If you’ve ever seen one of Ro’s many music videos, you’d recognize that smile—it’s the same one he has in virtually every one of them. It’s not just a genetic bequeathal from his grandma, either. It’s a refection of how she’s infuenced his life and his character.

When Ro was a kid in Mākaha Elementary School, he got in trouble for picking on a classmate. Ro’s grandma told him, “It’s better to go about life trying to make people

During his senior year at Waipahu High School, Ro started making his own music and messing around with music production software on his builtfrom-scratch computer.

FLUX PHILES | MUSIC | 60 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

smile.” He spent the next day trying to make his classmate smile, and they became best friends. “It was way better than being a bully,” Ro says.

Ro (an abbreviation of Myron) was born in 1999 in Sacramento, California to a Samoan mother and Black father. As an infant, his parents got into legal trouble, putting him and his two siblings in the care of their grandparents. They took the kids back to their home, the Samoan island of Savai ʻi, only to quickly realize there wasn’t much of a future for them there. Since the kids already had American passports, their grandparents moved the family to Hawai‘i, where they felt they could fnd the closest approximation to life in Samoa while taking advantage of the opportunities ofered in America. Ro was just over a year old.

Ro’s childhood was spent bouncing between diferent houses in Mākaha, Makakilo and Waipahu. Money is always a strain in Hawai‘i, especially for immigrants, but things got incalculably harder when Ro’s grandpa was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s

disease and could no longer work. Eviction notices and new landlords were regular occurrences.

But no matter what house they were in, music was a constant. “My mom [grandma] taught choir for her church. Samoans go hard in the vocal department, so we’d always be playing local music and American pop music,” he remembers. “That’s just the Samoan immigrant thing to do: you listen to catchy, simple stuf.”

Then he heard his frst hip-hop song: “Crazy Rap” by Afroman, often mistakenly called “Colt 45.” It taught him a lesson that informs his music today. “Rap doesn’t have to be serious. Here’s this guy walking us through how he’s smashing all these girls and all the repercussions he faces,” he says. “It’s hilarious.”

During his senior year at Waipahu High School in 2017, Ro started making his own music, trading rhymes with friends and messing around with music production software on his built-from-scratch computer when he wasn’t playing Minecraft. “Once I

“Pouring my heart into a single project just for it to shove me a centimeter isn’t worth my time,” Ro says. “I’m just focused on improving on the craft, putting out better visuals, and leaking singles until my music spreads around.”

64 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

65

started, I got that buzz,” Ro says. “I just got addicted to trying to make songs better and better.”

That addiction has led to a steady deluge of buoyant and ebullient music that Ro home-cooks in a makeshift studio in his bedroom. He released his frst EP, Haole, in August 2020, just to see if he could put a solo project together. “Pouring my heart into a single project just for it to shove me a centimeter isn’t worth my time,” he says. “I’m just focused on improving on the craft, putting out better visuals, and leaking singles until my music spreads around.”

Hawai‘i hip-hop has been a lot of things—a rallying cry for Hawaiian rights, a look at the underbelly of local street life—but it’s never been this unapologetically fun. It’s a big part of what makes Ro unique as a rapper and singer. But he wouldn’t call himself an artist just yet. “I’m just a brown boy trying to have fun. If I keep getting better, it will pay of,” he says. “I’m not worried about getting discovered. Talented people get discovered every day. I’m more worried about sucking when I get discovered. But when I learn what I do best and how to sound, it’s fucking over.”

Those were prophetic words. A few weeks after saying that, Ro signed a deal with the indie record label AWAL after someone there came across his music by chance. The deal gives Ro—who has since announced a name change to 8Ro8, though it’s still pronounced the same as Ro—complete ownership and creative control over his music, with access to the record label’s distributive and promotional muscle. “I’m not just a kid from Hawai‘i throwing shit into the ocean anymore,” he says. “Now I got a jet boat.”

On that note, “Kodak Moment” is ftting for his frst hit. It’s an infectious song from a promising talent, but it will no doubt be eclipsed in the coming years—probably sooner than later with how frequently Ro releases new music. In 10 years, we’ll remember it as the beginning of what will almost certainly be an established force by then. The melody will randomly return to us, and we’ll lapse into childhood daydreams of puppy love and sun rays peeking through palm leaves. We’ll look back on it as a memorable moment, but just that—a moment.

Ro signed a deal with the indie record label AWAL in spring 2021.

Listen to 8Ro8 at soundcloud.com/8ro8.

68 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

69

Along Kamehameha Highway, O‘ahu. Image by Phil Jung.

Along Kamehameha Highway, O‘ahu. Image by Phil Jung.

FEATURES

“To do the work, we need to rest, to read, to reconnect. It is the invisible labor that makes creative life possible.”—Bonnie

Tsui

FLUX ENVIRONMENT

On Weeds

Vacant and destitute to the eye, but upon closer approach brimming with much-needed lessons. During this past year of isolation, Honolulu’s fallow spaces can be our greatest classroom.

TEXT BY TIMOTHY A. SCHULER

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

Two blocks from the apartment my wife and I share in Waikīkī is a vacant lot surrounded by a chain-link fence. On a block otherwise crowded with high-rises and walk-up apartments, the lot sticks out. It’s big enough for three or four houses. And yet it is remarkable not only for what is absent but for what is present. Inside the fence, rows of steel rebar cut across the lot at right angles, like windbreaks made from tiny metal trees. The rebar is four feet tall in places and, in its orthogonal arrangement, creates the illusion of space, demarcating rooms in the bufelgrass. Perfect geometries overlaid onto a landscape of rubble.

I go out of my way to walk by this lot. It has the feeling of an art installation. In places, dirt has been mounded up into odd, grass-covered hillocks, leaving excavated areas that fll up with water when it rains, forming square, bedroom-sized ponds. In one corner is a solitary coconut palm. In the other, a dead mango tree. I imagine the artist’s statement, citing the record set in August 2020 when the median price of a house on O‘ahu climbed to $839,000 despite the pandemic. The installation is a commentary on housing insecurity in Hawai‘i, on all the families fnancially underwater.

I do not know who is responsible for this ghost house made of rebar, what it was intended to be, or when it was installed. Whether it is the remains of a structure or the opposite—its nascent, stalled beginnings. What I do know is that for the past six years, the lot has sat there. Empty but for its maze of steel. The phantom outline of a future that never was.

The pandemic has forced many of us to reevaluate our relationships to productivity. Weeds intrude on the narrative that we have it all together.

Vacant lots are omnipresent in cities. By one estimate, 15 percent of developable land in American cities is vacant. In Honolulu, excluding land too steep to build on, 590 acres are classifed as vacant. “Unimproved,” this land is called.

I’ve spent a good portion of the coronavirus pandemic thinking about vacant lots—these weedy, overgrown spaces in our cities that seem to be contributing nothing—and whether they might hold lessons for our present moment. A few years ago, I interviewed landscape theorist Jill Desimini about the phenomenon of vacancy in U.S. cities. Desimini doesn’t like the word “vacant.” She prefers “abandoned” or, better yet, “fallow,” a reference to the centuries-old practice in which a farmer leaves a feld unplanted for a season, allowing nutrients in the soil to be replenished. A lot with no house on it is rarely truly vacant, Desimini told me. There are myriad, often invisible activities taking place in such spaces. Weeds and volunteer trees, which spring from seeds dropped by birds or the breeze, can store carbon and flter air pollution. They can nourish denuded soils and absorb rainwater. Many play a

surprising role in supporting urban ecosystems. A study of “urban spontaneous vegetation” in Halifax, Nova Scotia, found that vacant lots were more biodiverse and attracted higher numbers of invertebrates such as butterfies than lawns or even urban forests. Some plant species we call “weeds” can even remove pollutants from contaminated soils, an act known as phytoremediation.

Our economic system places no value on these socalled ecosystem services, just as it places little to no value on activities that are not transparently productive, like recreation or rest. But the pandemic has taught me that, like weeds whose contributions to urban life largely go unrecognized, the hours we spend not producing may be more important than we realize.

In a 2019 op-ed for the New York Times titled “You Are Doing Something Important When You Aren’t Doing Anything,” writer Bonnie Tsui made a case for the necessity of fallow time as a regular part of a creative practice. “Fallow time is necessary to grow everything from actual crops to fgurative ones, like books and children,” she wrote.

74 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“To do the work, we need to rest, to read, to reconnect. It is the invisible labor that makes creative life possible.”

When I frst read these words, in the innocent days of summer 2019, I liked the idea of fallow time, felt the truth of it. Like Tsui, however, I struggled with the sense of guilt that can accompany fallow time activities: idly staring out the window, taking a walk or a nap during the workday, any of the small snatches of rest we reclaim from the busyness of life. Writing, my brain told me, meant putting words on a page. If I wasn’t doing that, was I really working?

Then a global pandemic sent me and hundreds of millions of other people into quarantine. For a lot of artists and writers, the fallout was immediate. Without the ability to travel, writing projects evaporated. Companies paused their ad-buys, hollowing out editorial budgets, and the overwhelming urgency of the crisis introduced new hierarchies for determining what was newsworthy. As a result, the amount of work I had on any given day dwindled. I applied for unemployment benefts and, in my more melodramatic moments, wondered what my next career would be. What kind of job was a plant nerd with zero hard skills qualifed for?

Forced into a fallow period, I began to give myself over to a slower pace. I flled my days with walks around my neighborhood, my nights with old movies. I started a journal, mostly a catalog of small joys, and got incrementally better at meditating, though many mornings I simply watched the terns wheeling over Kapahulu Avenue and envied their freedom. On my walks, I took a copy of Pratt’s Pocket Guide to Hawai‘i’s Trees and Shrubs and taught myself the name of any tree that was unfamiliar to me. The one whose large, almond-shaped seeds I dodged on my runs around Diamond Head was Terminalia catappa, or tropical almond, known variously as false kamani, ketapang, and story tree. The gangly one with the pink, tentacle-like fowers was Brassaia actinophylla, also known as octopus tree and classifed in Hawai‘i as a weed. Near the edge of Kapi‘olani Park were massive Ficus macrophyllas, or Moreton Bay fgs, their thick, magnolia-like leaves conjuring distant memories of a week spent wandering the streets of New Orleans. As I walked, some part of me—maybe it was my entire body?—began to unclench. I described the feeling to someone in book terms: Prepandemic life had felt like a page with only the thinnest of margins. In quarantine, paradoxically, life became a poem. Everything was white space.

I pictured these fallow-time activities as weeds colonizing a vacant lot, sprung from cracks pried open by quarantine, their worth masked by a culture that values only productivity. “Protecting and practicing fallow time is an act of resistance; it can make us feel out of step with what the prevailing culture tells us,” Tsui writes. This is, in essence, also the gospel preached by the Nap Ministry,

Our economic system places little to no value on activities that are not transparently productive, like recreation or rest. But rest is a political act, as is reclaiming our attention from an economic and political system that would commodify it.

an activist organization created by the Black performance artist and theologian Tricia Hersey, who frames rest as a “divine right” that people of color, specifcally Black people, have been denied for centuries.

The notion of lying fallow reminds us that our personal resources are limited. In arid areas, fallowing preserves the moisture in the soil for the season when crops are planted. We need to start acknowledging that our own energies—our mental, emotional, and spiritual resources—are fnite too.

The pandemic has forced many of us to reevaluate our relationships to productivity. I’ve come to see that our cultural and aesthetic preference for landscapes that are neat and tidy is part of a larger cult of order and optimization. Weeds intrude on the narrative that we have it all together. We may not always recognize what a particular fallow period—whether an afternoon, or the interminable pause in which we currently fnd ourselves—is providing. But claiming time for ourselves is, itself, an act of liberation. As the artist Anne Percoco put it, “Weeds serve their own purposes.”

78 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

79

At some point in the past year, reality and metaphor merged, and with the help of a newly downloaded plantidentifcation app called Seek, I began learning the names not only of the trees I passed but of the weeds too. There was scarlet spiderling and bellyache bush (which gets its name for toxic compounds that pervade every fber of the plant), old world diamond fower, and graceful spurge. I found winefower, tasselfower, and corkystem passionfower. Most were foreign to me, but a few, like cabbage and sorghum—both found along the edge of Kapi‘olani Park—were surprisingly common, and wouldn’t be considered weeds at all were they not growing on the side of the road. One day, I discovered a baby bodhi tree, that totem of enlightenment, no more than three inches tall and growing out of a black asphalt sea.

What we call a weed has always been a matter of culture, not botany. Recently, artists and ecologists have worked to rebrand these little-loved species. Books like Peter del Tredici’s Wild Urban Plants of the Northeast: A Field Guide recasts weeds as spontaneous urban vegetation, while the Next Epoch Seed Library, founded by Anne Percoco and Ellie Irons in 2015, is a genetic repository of “tough, highly adaptable” plant species “well-suited to live in close quarters with humans and their attendant landscape transformations.”

Poet Regan Good, who also spent quarantine cataloging the wild urban plants around her, writes that she could not help but admire the resilience of “plucky, scrappy, ingenious, tenacious” individuals growing out of wroughtiron fences, concrete curbs, and brick facades. In their adaptive ability to survive in hostile conditions, she found a kind of kinship. “In a weed’s natural calling to survive,” she writes, “one recognizes oneself.”

Fallow periods can feel like an end. If we’re lucky, we’ll have people in our lives who will counsel patience and remind us of the life-giving work happening below the surface.

The need to recognize the value of fallow time, individually and collectively, extends beyond our present moment or the needs of creative practice. One of the most disorienting aspects of the pandemic has been the need for those of us stuck at home (and without young kids) to square the languid pace of life in quarantine with the horrifying realities being lived by the doctors, nurses, farmers, delivery drivers, and all the other “essential” workers who make our fallow periods possible. Even now, with case counts falling in Hawai‘i and the daily tally of persons vaccinated inching upward, it is hard not to think of all that has been lost.

But rest is a political act, as is reclaiming our attention from an economic and political system that would commodify it. In How To Do Nothing, Jenny Odell argues that refusing to engage with the attention economy on its terms and instead retraining our attention on our

neighbors—be they the elderly couple downstairs or the white terns down the street—is one basis for collective action. “It is with acts of attention that we decide who to hear, who to see, and who in our world has agency,” Odell writes. “If it’s true that collective agency both mirrors and relies on the individual capacity to pay attention, then in a time that demands action, distraction appears to be (at the level of the collective) a life-and-death matter.”

In ecology, a sudden event that alters the underlying makeup of an ecosystem is known as a “disturbance.” Disturbance can come from wildfre, human development, disease. The ecology of a vacant lot is defned by disturbance, and the weeds that thrive there do so because they are uniquely adapted to degraded or even toxic environments. Writer and landscape architect Sean Burkholder speculates that it is these species that will form the backbone of tomorrow’s urban ecosystems. As urbanization causes plants and animals and bacteria to adapt and change, novel ecologies will form.

82 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

83

The past year brought incalculable loss. But the disturbance created by the coronavirus also gave rise to new physical and virtual networks—human ecosystems—of medical testing and contact tracing, political organizing and mutual aid. How many more novel ecosystems—made up of artists, organizers, educators, activists—will grow from the weeds of this forced fallow time?

Fallow periods can feel like an end. If we’re lucky, we’ll have people in our lives who will counsel patience and remind us of the life-giving work happening below the surface. For me, the slow days of early quarantine gave way to a vigorous crop of new ideas. The rough contours of a book idea germinated. Dormant memories surfaced, raising questions I resolved to explore in future writings. The roots of the weeds I had allowed to grow pried open new and larger cracks, creating space for yet more species, more fallow-time activities. As these things happened, I noticed the shape of my day changed in response. I was making more time to meditate, more time to rest. As Tsui promised, a period of “furious output” followed a period of “faithful input.”

Recently, I went back through the journal I’ve kept since last March. The word “fallow” frst appears on April 10, 2020. I’ve continued to gravitate to that word because, while it describes the present, it implies a future: a period of renewed vigor, fed by nutrients replenished over the course of the fallow season. Some days, it was hard to trust that such a period would come, as shock wave after shock wave of disease tore through communities and a callous president stood by. Some days, hope felt naive.

When I feel that way, because I still do some days, I turn to the page in my journal where I stuck a little, blue Post-It note. “Remember the value of weeds,” it reads. And I am reminded that it is from the cracks of a broken world that new realities and possibilities will sprout.

84 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

A Movement in Mu‘umu‘u

Charming, nostalgic, occasionally awkward, the classic island garment finds itself embraced by a new generation of islanders.

TEXT BY MITCHELL KUGA

IMAGES BY MEAGAN SUZUKI AND JOHN HOOK

FLUX STYLE

Iam reaching for a pint of blueberries at the Whole Foods in Kailua when, amidst the humdrum of athleisure, I see it: a classic mu‘umu‘u. The anklelength dress is faded, fowy, and foral— demure even, if the afect wasn’t so loud. It is the same style of mu‘u worn regularly by my kumu and tūtū, but seeing it on this twentysomething casually shopping for carrots feels destabilizing, a collision of references. I do a double take. She’s paired it with chunky sneakers and an insouciance I can only describe as punk, like she’s dressing at me. I smile behind my mask, the urgency of my to-do list temporarily consumed by memories of keiki hula competitions, the air fragrant with pīkake.

Chalk it up to the frequency illusion, but over the next few months I will see echoes of this woman—young, fashionable, and wearing old mu‘umu‘u—strolling the farmers market, picnicking at Magic Island, and flling gas. As a recent headline in The Times UK exclaimed: “The muumuu is back (yikes).” But don’t call it a trend, at least not in Hawai‘i. Instead, enthusiasts on Instagram are calling it a “muuvement,” one rooted in joy, sisterhood, and a reckoning with the garment’s colonialist past.

“Wearing mu‘u was my way of staying joyful in spite of the anxious energy that came from being in a pandemic,” says Annemarie Paikai, a 33-year-old Hawai ʻiPacifc resource librarian at Leeward Community College. “Lately, I’ve realized that it has become a type of armor for me. I’ll often put one on for the day when I’m feeling anxious or uncertain and just need to be surrounded by that muʻu comfort.”

Lise Michelle, a 23-year-old weaver, started collecting mu‘u after returning home to O‘ahu in 2016 from Marine Corps training in South Carolina. “Muʻu played a role in rebuilding my idea of self, which was lost while I was on the continent,” they say (Michelle uses they/them pronouns).

“The shapelessness of the muʻu allowed me to be whatever I wanted underneath it, and under my muʻ u were fve other sets of arms, hands working to ulana (plait) my healing and hurt.”

For others, the draw is more aesthetic. Meleana Estes, a 41-year-old lei maker and creative director in Honolulu, collects mu‘u for their bold, graphic prints, favoring those from the fower-power era of the 1960s and ’70s. “To me, wearing a mu‘u elevates you,” she says. Her collection numbers somewhere in the ffties, which causes “huge closet problems,” but she can’t let them go. “There is a mu‘u for every mood,” she says.

Today, local brands like Sig Zane, Kealopiko, and Manuheali‘i are making new, contemporary mu‘u. But for enthusiasts, the garment’s revitalized appeal lies primarily in looking backwards. Shadi Keehuweolani Faridi, 35, highlighted the eco-friendly, zero-waste ethos behind buying secondhand mu‘u, pointing to the superior quality of the old-school construction, along with the allure of stepping into a garment with history. This focus on sustainable fashion extends to a culture of giving. At Hana Hou, the boutique she co-owns in Hilo with her mother, Faridi started a mu‘u share rack where customers can take (or give) a free mu‘u, but as a sign on the rack notes, “You betta rock it!”

Mu‘umu‘u means to “cut of ” or “shorten,” referencing both the garment’s length, which traditionally ends around the ankles, and its absence of a yoke. Introduced to Hawai‘i by Christian missionaries in the 1820s, and initially constructed out of leftover sheets of muslin in monotone colors, the mu‘u was frst worn as a slip under the more formal holokū, a loose, seamed dress with a yoke and usually with a train. Before the arrival of Europeans, the predominant form of dress for Native

The muʻumu‘u as it’s worn today feels indebted to the spirit of streetwear, a garment meant to be contemporized, malleable, and seen.

Instead of retreating into merely comfort and fantasy, some enthusiasts are also taking to social media to wrestle with the garment’s colonial history.

88 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 89

Hawaiian women was the pā‘ū, a kapa skirt whose lack of coverage the missionaries believed not only “painful to the eye, but injurious to the soul,” according to Agnes Terao-Guiala’s book, Hawaiian Women’s Fashions. It wasn’t until the 1940s that the mu‘u started to be thought of as outerwear, and by the second Hawaiian Renaissance in the 1970s designers both local and foreign began approaching the mu‘u as a high-fashion garment, experimenting with colors and incorporating infuences from Japanese and Chinese apparel. From pākē mu‘u and pleated mu‘u, to party mu‘u and sunback mu‘u, “there was a muu for every fgure, a muu for every pocketbook and muu for every time of day,” declared a magazine article in Paradise of the Pacifc.

Today’s mu‘u renaissance is seemingly fanked by two adjacent moments: cottagecore and the pandemic. But unlike cottagecore—think teenagers on TikTok lounging in vintage prairie dresses that are meant to evoke the tranquility of the English countryside—wearing mu‘u in Hawai‘i doesn’t conjure the same sense of escapism. (Irony, too, feels beside the point.) Instead of retreating into fantasy, enthusiasts like Paikai are taking to Instagram to wrestle with the garment’s oppressive history.

On January 17, 2021, the anniversary of the illegal overthrow of Queen Lili‘uokalani and the Hawaiian Kingdom, Paikai expressed her feelings around the garment’s potential for shame and struggle. “While wearing muʻ umu ʻu may not be an obvious form of resistance, in many ways that’s what this movement does for me,” she wrote. “It allows me a space to push back on cultural norms, honor my people, and live in joy—which is an act of resistance too.”

The revitalization of the mu‘u also upends its popular perception as schlubby workfrom-home attire, as depicted in the 1995

episode of The Simpsons titled “King-Size Homer.” The episode follows Homer as he dons a mu‘umu‘u after gaining 61 pounds so he can qualify for disability and work from home. (The Westernized pronunciation of the garment, which bulldozes both ‘okina, doesn’t help either, evoking the mooing of a slovenly cow.) The muʻu as it’s being worn today feels more indebted to the spirit of streetwear, a garment that’s meant to be contemporized, malleable, and seen—and not just on social media.

Fueling the renaissance is Mu‘umu‘u Month, started by Shannon Hiramoto in 2014. Every day for the month of January, Hiramoto posted a photo of herself on Instagram wearing a diferent mu‘u—some days to work, other days to the bowling alley or the beach. It was a playful nod to the 40-year-old’s childhood growing up in Hanapēpē in the ’80s and ’90s, back when mu‘u were worn more frequently. Slowly but reverently an unexpected community of mu‘u enthusiasts developed, connecting through the #muumuumonth hashtag and emboldening each other through photos, comments, and likes.

Posts under the hashtag range from quippy to essaystic, with participants often sharing the labels, eras, and provenance of each mu‘u. Hana Hou co-owner Faridi, for her part, takes a playfully diaristic approach. In one post, a swirly lime and forest green mu‘u brought back memories of her family’s old ’70s Datsun pickup truck. Dubbed “Da green machine,” the truck had a “puka on the foor so when it rained you had to cover it with your slipper,” Faridi wrote. In another post Faridi, wearing a cinched teal mu‘u by Elsie Krassas, waxed refective, “These muʻ u teach me to stand up straighter (working on it), practice my grace (working on it), and slowwww down....” (“Broke da eye! ” user @kuumorningdew commented.)

Shadi Keehuweolani Faridi started a mu‘u share rack where customers can take (or give) a free mu‘u. But as a sign on the rack notes, “You betta rock it!”.

“The people who participated in Mu‘u Month this year are all badass ladies,” says Faridi, who started participating in earnest in 2019. She says fnding a digital community of fellow muʻu wearers felt galvanizing, a way of belonging to a tapestry of similarly minded women. “I noticed that a lot of us are introverts,” she says, which makes counting the actual number of Muʻ umu ʻu Month participants difcult— many of their profles are set to private, she points out, or have been deleted altogether. Through Instagram, “we kind of fed of of each other like a sisterhood,” she says.

Sometimes these relationships transcend the digital space. In January 2020, Hiramoto organized a mu‘umu‘u brunch at Gaylord’s, located on an old plantation in Kilohana, Kaua‘i. Muʻu designer Barabara Green spoke, and proceeds from a silent mu ʻu auction went to the Kaua‘i Historical Society. But the gathering was mostly a chance to talk story and connect with fellow mu ʻu lovers. Around 70 women showed up, all dressed in muʻ u.

In 2021, Hiramoto estimates that over 200 people participated in Mu‘umu‘u Month in some capacity, the largest number to date. “The frst year was just for fun,” she says. But each January, “more and more intention became attached to it, and things started to emerge—just new thoughts and new feelings and a new way of going through the world and bridging with other people that I didn’t expect. [Wearing mu‘u] continues to gift all these diferent ways of experiencing life.”

January just happened to be the month that Hiramoto, then the owner of the clothing store Machinemachine, was gifted an excess of vintage mu‘u. But Mu‘umu‘u Month turned out to be the perfect start to each year, she says, likening the 31

consecutive days of wearing mu‘u to a juice cleanse. “It wasn’t my intention, but every January I’m letting my armpit hair grow and my leg hair grow, because for the most part it’s covered up,” she says. “Like why am I doing those things? It’s a moment of pausing on a lot of those habits, and maybe some habitual thought patterns too.”

Even after seven years, Hiramoto sometimes has to give herself a pep talk before slipping on her mu‘u and stepping out the door. As everyone I spoke to mentions, casually wearing a mu‘u today takes guts, inviting wayward looks, sassy comments from that one coworker, and random conversations with strangers. But she’s learned to welcome these interactions, which have come to color her otherwise hermetic days as a craftsperson. “I like pushing out of my comfort zone,” she says, describing wearing mu‘u as a form of exposure therapy. “I gravitated towards the arts because of my introversion, but for me it got to the point where it was holding myself back from building community. And I desire community and people so much.”

Inspired by Mu‘umu‘u Month, Christy Werner has a collection of around 40 mu‘u—she’s lost track of the exact number at this point, giving and loaning mu‘u throughout the years to anyone who expresses interest. “I trust a mu‘u goes where it needs to,” she says, “even if sometimes I’m a little sad to no longer have it.”

The 41-year-old therapist and clinical social worker noticed that wearing mu‘u to work, a departure from her usual pants and shirt, sometimes served as a “portal into deeper conversations” with her clients, invoking discussions about their childhoods, older family members, or feeling diferent.

The revival of the mu‘umu‘u also upends its popular perception as schlubby workfrom-home attire.

“To me, wearing a mu‘u elevates you,” Meleana Estes says. Her collection numbers somewhere in the fifties, which causes “huge closet problems,” but she can’t let them go. “There is a mu‘u for every mood.”

Christy Werner has a collection of around 40 mu‘u. She’s lost track of the exact number at this point, giving and loaning mu‘u to anyone who expresses interest: “I trust a mu‘u goes where it needs to, even if sometimes I’m a little sad to no longer have it.”

Annemarie Paikai notes that wearing a mu‘u has been a way to stay joyful during the pandemic: “Lately, I’ve realized that it has become a type of armor for me. I’ll often put one on for the day when I’m feeling anxious or uncertain and just need to be surrounded by that mu‘u comfort.”.

For one client, the mu‘u was emblematic of Werner’s pregnancy, which brought up fears related to abandonment. For another, it led to a conversation around feeling like an outsider in Hawai‘i, despite an afnity and love for Hawai‘i culture. One client even became a fellow enthusiast. “She has the best mu‘u,” Werner says. “In January, I always fnd myself delighted and happily envious of her collection.”

She noticed her 3-year-old son also reacts diferently to her in mu‘u, cocking his head or petting her dress. Recently, he picked one of her mu‘u from the laundry and proclaimed that he wanted to put it on. “And he proceeded to have a dance party in it,” she says. “There really is just something about a mu‘u that is magical.”

Mu‘umu‘u Month takes place in January. Every day participants post photos on Instagram wearing a different mu‘u.

98 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

DREAMS, DELIGHTS, AND DELICACIES ALOHA CONFECTIONERY | BATH & BODY WORKS | KAY JEWELERS | LUPICIA | MACY’S SHOPPING & DINING AT THE HEART OF THE PACIFIC ALAMOANACENTER.COM

FLUX PORTFOLIO

A Sense of Place

The photographs of Phil Jung aim to explore the social landscapes and identity of Hawai‘i through personal spaces and locality.

IMAGES BY PHIL JUNG

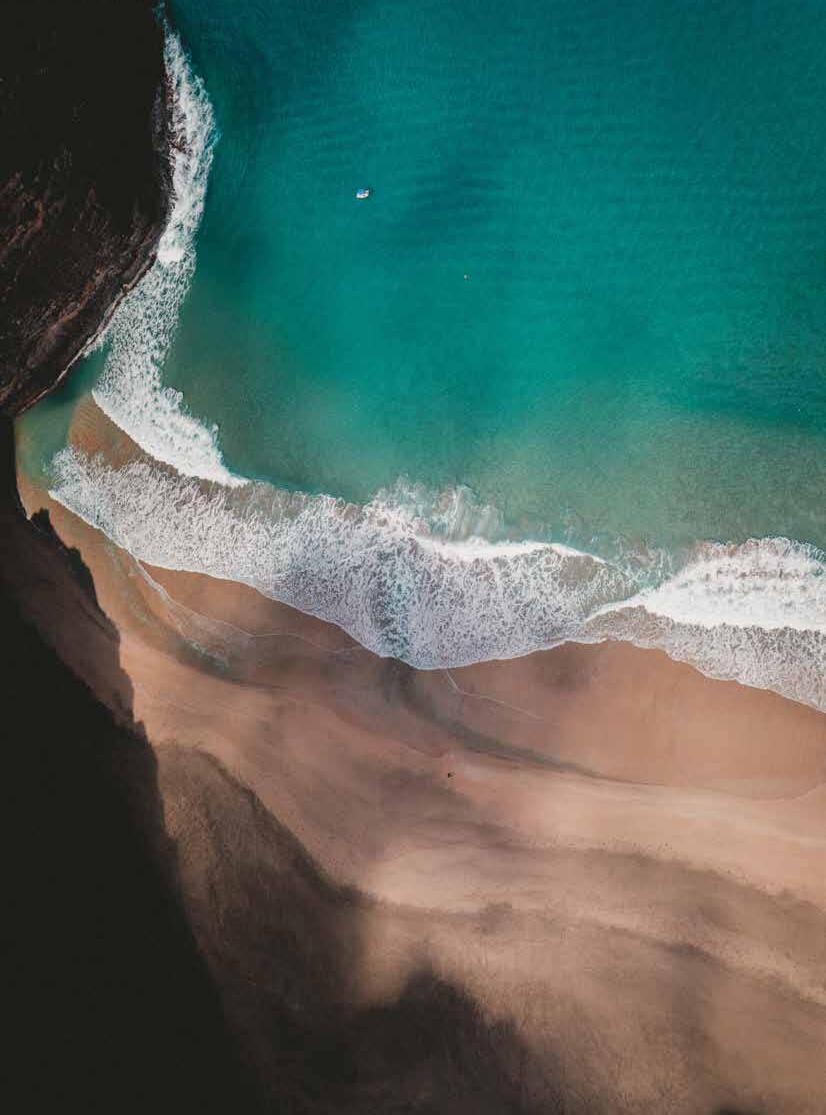

Electric Beach, Hawaii | Sharks Cove, Hawaii

From the series, O‘ahu

Electric Beach, Hawaii | Sharks Cove, Hawaii

From the series, O‘ahu

Water Canal, Hawaii

Water Canal, Hawaii

Couple Kissing, Hawaii

Couple Kissing, Hawaii

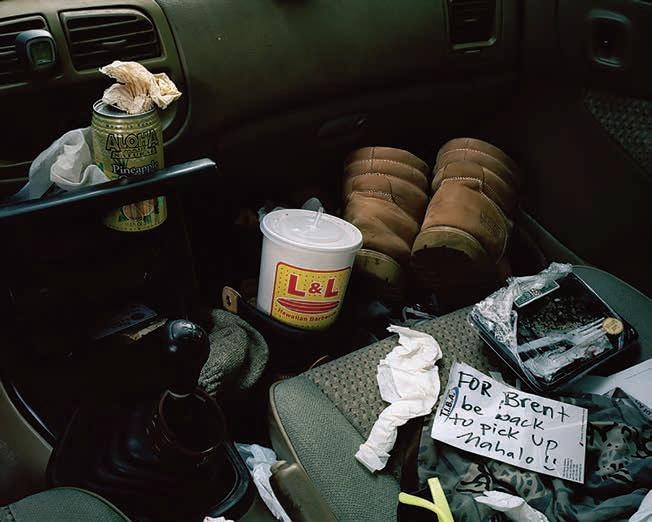

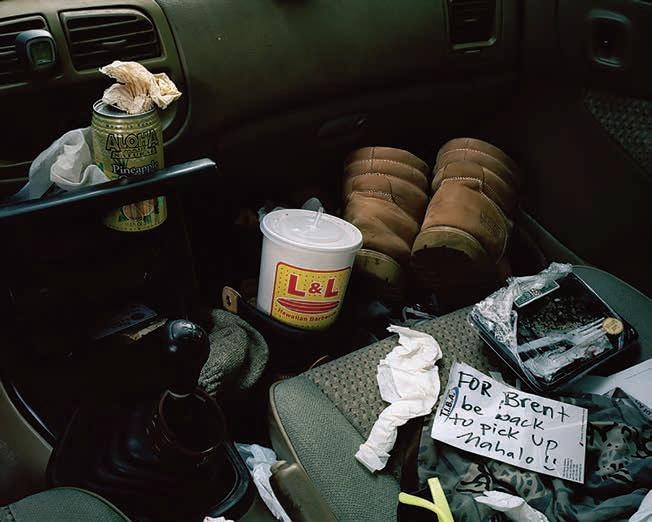

Ikaika’s Car, Hawaii

Ikaika’s Car, Hawaii

Children Swimming, Hawaii

#13, City of Refuge (2016) | Pu‘u Mahuka Heiau (Ceremonial Site), Hawaii

#13, City of Refuge (2016) | Pu‘u Mahuka Heiau (Ceremonial Site), Hawaii

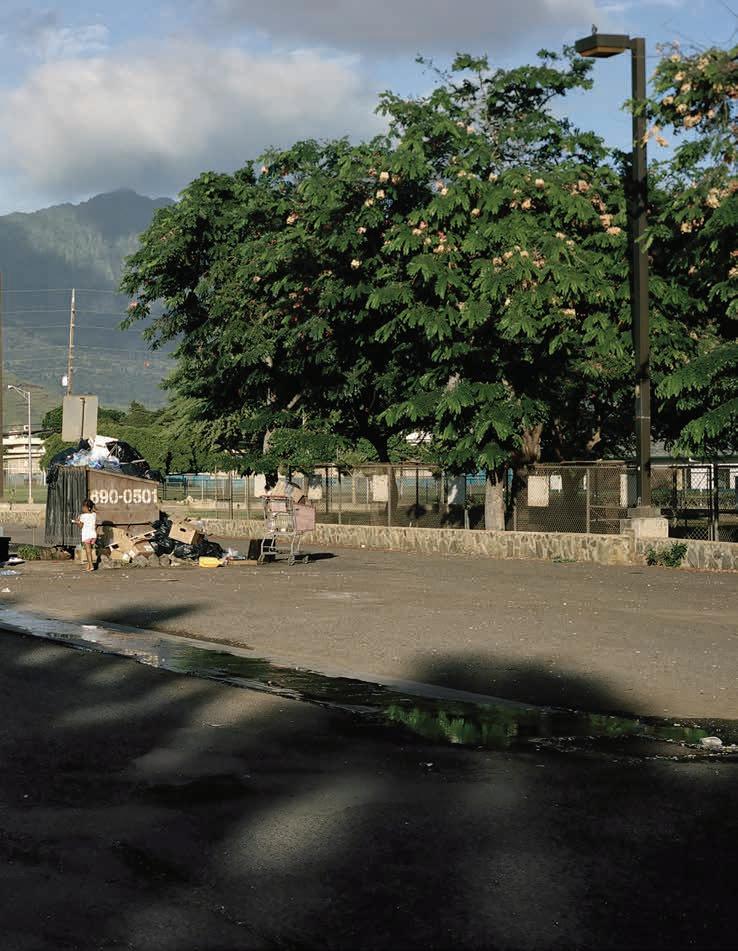

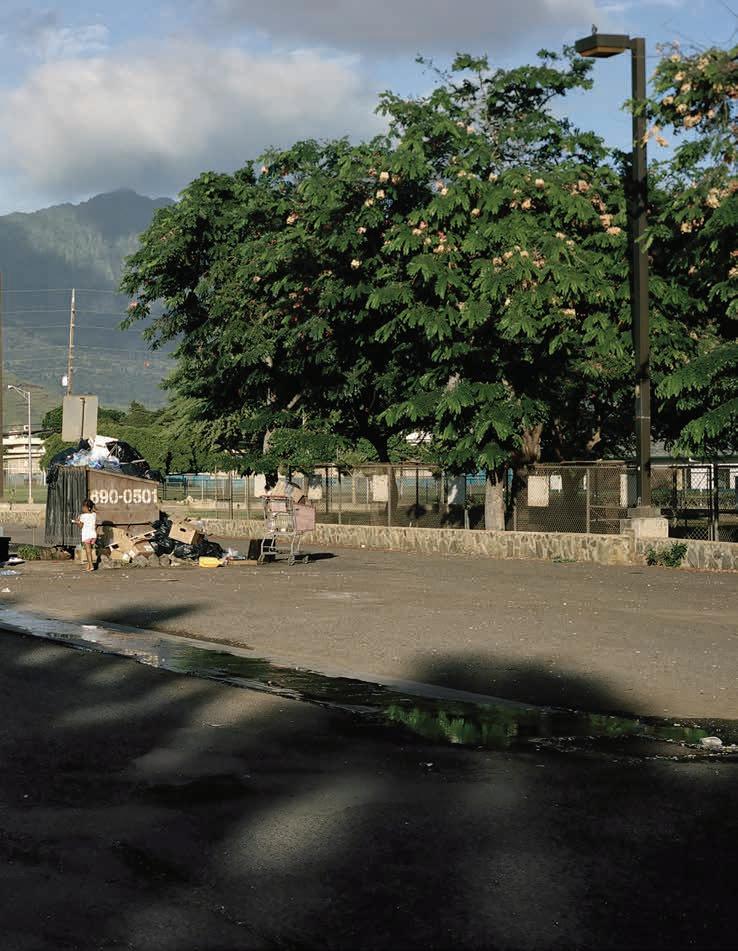

Parking Lot with Children, Hawaii

Parking Lot with Children, Hawaii

Untitled (Family on Westside), Hawaii

Untitled (Family on Westside), Hawaii

From the series, O‘ahu

From the series, O‘ahu

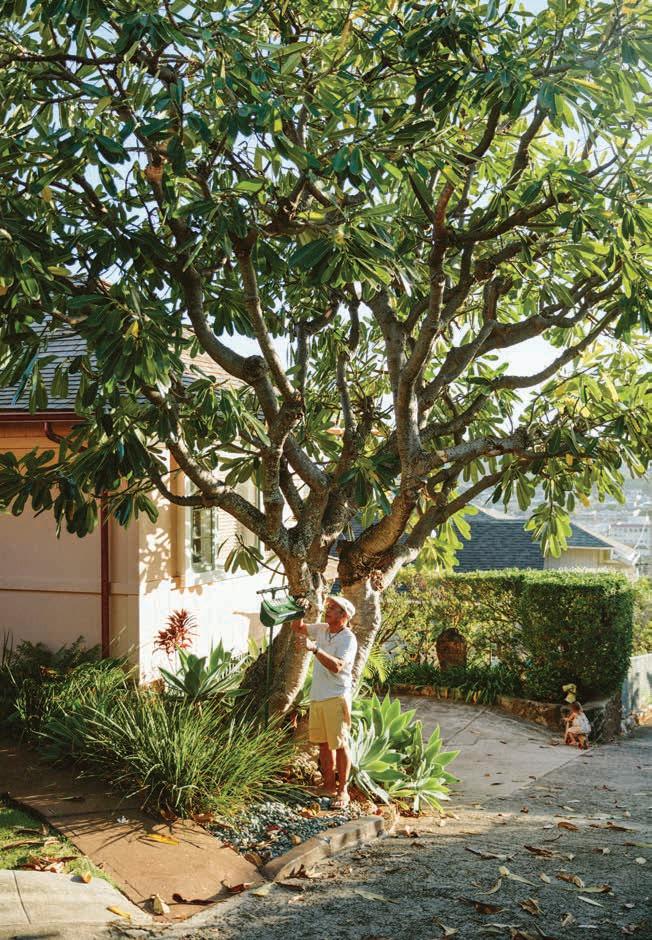

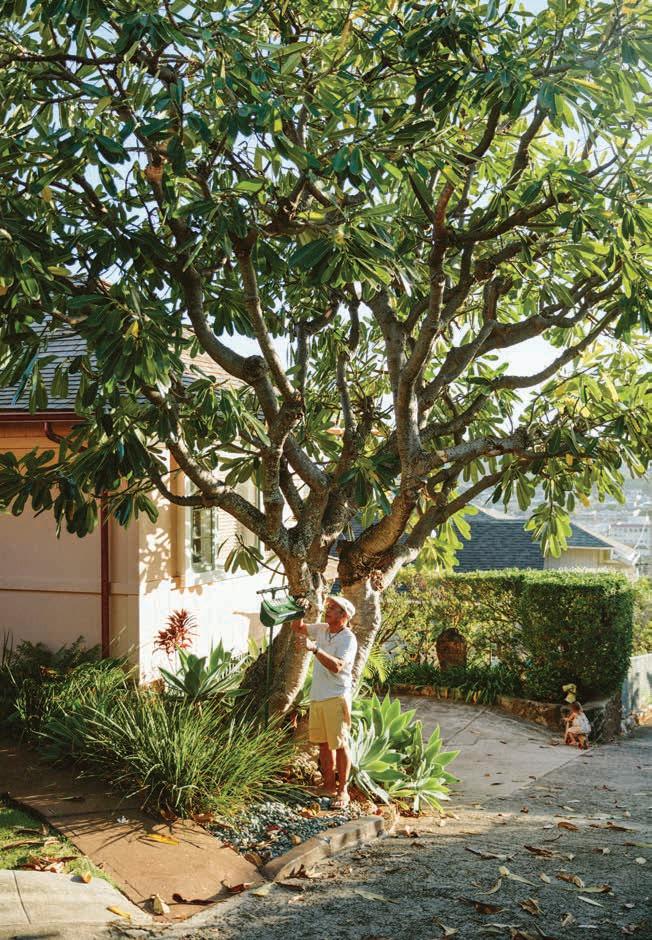

The welcome sight of a neighborhood tree from a driveway in Kaimuk ī . Image by Kenna Reed.

The welcome sight of a neighborhood tree from a driveway in Kaimuk ī . Image by Kenna Reed.

EXPLORE

“I'm catching a wave / Feeling the freedom flowing over me / Makes me feel so free.”—Steve & Teresa

Tree Huggers

Floral artist Tamara Rigney’s nonproft Treehooo is a love letter to—and a rescue plea for—Honolulu’s urban forests.

TEXT BY NATALIE SCHACK

IMAGES BY KENNA REED

Tamara Rigney is thinking about trees. There’s a dreamy, distant look in the botanical boutique owner’s eyes as she recalls times spent beneath the arching, enveloping embraces of Kapi‘olani Park’s gnarled kiawe. “I can get twice as much work done when I’m just at the park with my computer,” Rigney says, who runs the sister foral shops Paiko Hawai‘i and Pua Hana. Sometimes, she’ll head there for a morning jog along the shady tree tunnel of Paki Avenue. Or she’ll skip the ofce, or her shops, or whatever city errands she has on her too-full to-do list, and instead drive from her home in Pālolo to Waikīkī to lounge or work or just be. Immersed in the cooling calm of the park’s ethereal fora, alone in the dappled shadows cast by the foliage from who-knows-how-old branches, there’s a peace

The Treehooo Instagram celebrates the stories of beloved Honolulu trees.

118 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

EXPLORE | URBAN FORESTS |

119

found beneath the trees. What a wonderful world it would be, for all of us, if there were more of them.

Unfortunately, the opposite is happening: Honolulu’s trees are vanishing. A 2015 study, a dual efort by the Division of Forestry and Wildlife and nonproft Smart Trees Pacifc, found that 5 percent of Honolulu’s tree cover was lost between 2010 and 2015. The loss is even more signifcant if you consider that the city’s tree cover— that layer of branches and leaves that create a shady roof over the land and sidewalks—only covers about onethird of the space available for tree cover, which means there are more opportunities for trees to be planted, and more canopy-covered spaces created. Trees cool spaces with shade, release water through their leaves, and clean the air by absorbing pollutant gases and trapping particulates on their bark. But as lawns become driveways, yards are replaced for more

housing, and road verges grow weeds, direct sunlight hitting paved surfaces increases the heat of the city and the air becomes dusty. But, in some neighborhoods like Kalihi and Pālolo, sun-drenched sidewalks far from the comforting cover of nearby trees means a shady stroll is hard to fnd.

But tree lovers like Rigney have taken notice and are taking action.

For Rigney that meant applying to the Hawai‘i Urban and Community Forestry Program’s Kaulunani Grant Program. With the $10,000 grant award she founded Hawaii Neighborhood Forests, the ofcial community project of Paiko Hawai‘i that now boasts a budding partially volunteer staf of three (who overlap with the Paiko team). Better known as Treehooo, the name of the nonproft’s frst campaign, Hawaii Neighborhood Forests has a mission to spread awareness of the many benefts of urban trees, and to inspire residents

and homeowners to plant more, and cut down fewer.

The sprouting of Rigney’s idea started close to home, in Kaka‘ako, the rapidly developing neighborhood of her day job at Paiko Hawai‘i, where Rigney is co-founder and botanical designer. Working in the neighborhood day in and day out gave her a front-row seat to the recent rapid development. New buildings, new stores, new restaurants—but where were the new trees? In the midst of all this capital being spent and labor being invested to create a hip, urban oasis, Rigney wondered, shouldn’t that also include some shade? Noticing trees being overlooked in Kaka‘ako opened her eyes to it in the rest of the city, too.

“It just became really apparent to me how few trees Honolulu has,” Rigney says. “I was like ‘What’s up with this neighborhood? They spent all this money redeveloping this whole block and there’s no trees!’”

122 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

123

At the same time, Rigney noticed that people in diferent neighborhoods were cutting down their trees and not planting any new ones. She started attending board meetings of Trees for Honolulu’s Future, which she found was doing a great job through projects like working with the city to improve tree wells, helping to place more trees and planters, and mapping trees across the city in potential planting locations. While they were making some massive impacts, Rigney saw the opportunity for her to make a diference in a diferent way. “I realized there was no one really talking to the public or educating people about what was going on,” she says.

As part of the grant, the team seeded their frst project in the summer of 2020: a Treehooo advocacy campaign. Rigney knew she wanted to tackle residential tree loss cited, which the Smart Trees

study identifed as making up 40 percent of Honolulu’s total tree loss. That meant the campaign needed to reach residents and property owners. They launched radio ads as “the voice of trees” spouting the benefts of planting new ones and not chopping existing ones, which ended up reaching 900,000 listeners. They partnered with local artist Druscilla Santiago to produce charming video, branding, and web graphics. And, they built the Treehooo website into a one-stop shop for resources, like how to select and plant the right tree for your home, information on the benefts of trees, and tips on navigating city laws, street trees, and tricky root issues.

With the Kaulunani Grant period over, Rigney hopes to continue speaking directly to the public by running one outreach campaign or project a year. For 2021, the Treehooo team partnered with artist Wyatt

Hersey to create a vibrant, tree-centric mural above the Pua Hana shop in Kaimukī. The Treehooo Instagram account also regularly features facts and information from arborists and stories of trees beloved by Honolulu residents. Whether it’s showcasing a 100-year avocado tree in a Kaimukī backyard that provides shady space for its owners’ alfresco hangs or a small lemon tree in Nu‘uanu that brings joy to a home through the soothing sound of the wind in the leaves, the Treehooo focus is frmly rooted in an intention to inspire. Like the blooms and creations at Paiko and Pua Hana, the Treehooo team’s work reminds Honolulu of the beauty in nature—whether that be trees or fowers—and how much better everyone’s lives are because of them. “It’s uplifting to see that we can change public opinion,” Rigney says. “This is the frst step.”

126 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

127

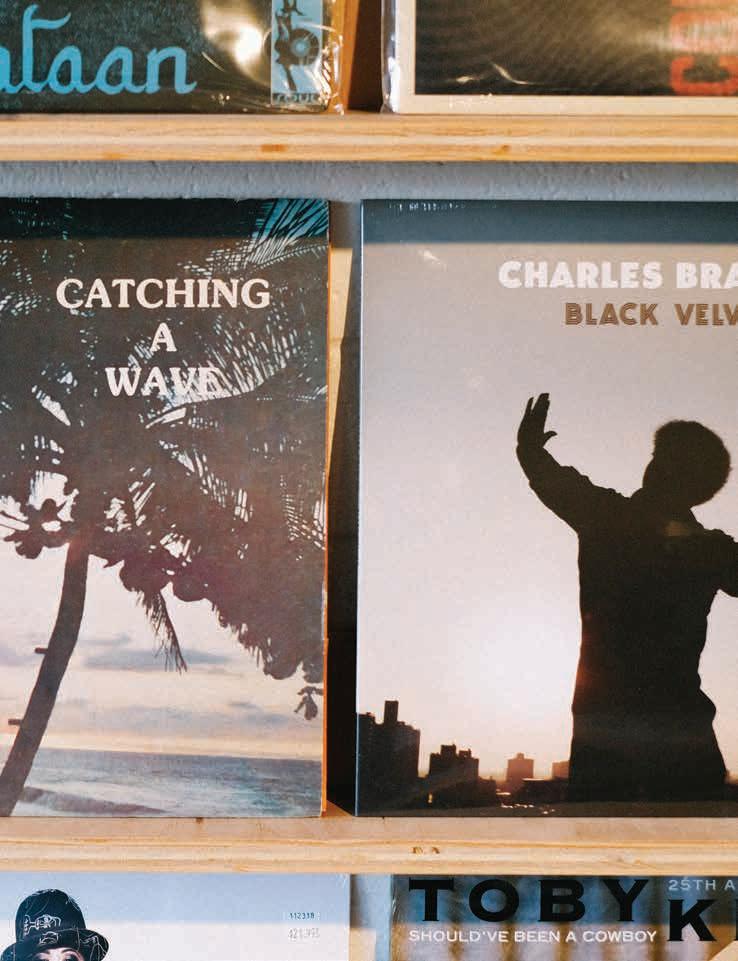

Sound & Vision

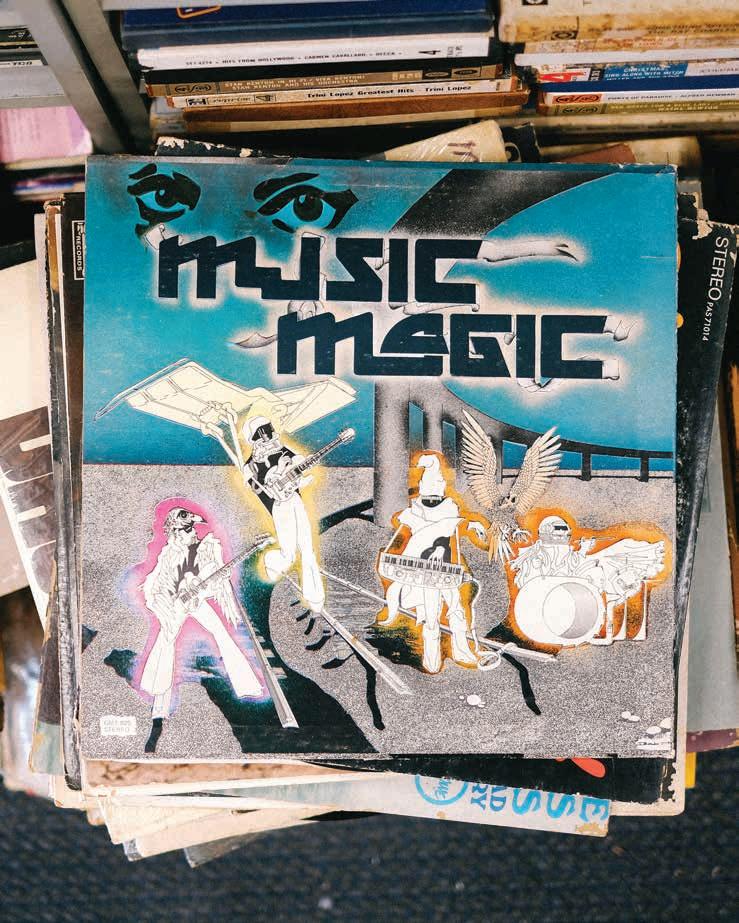

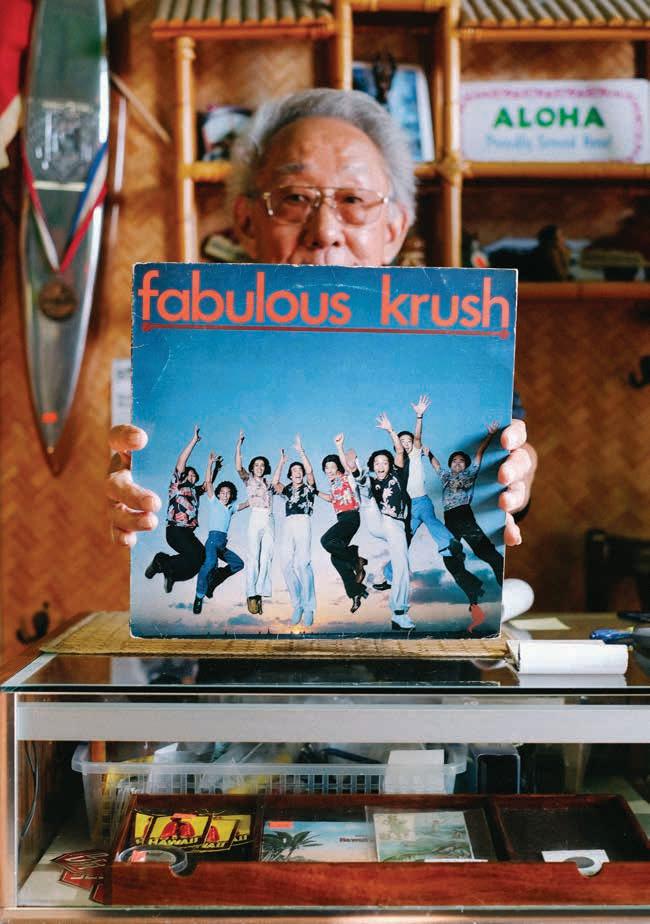

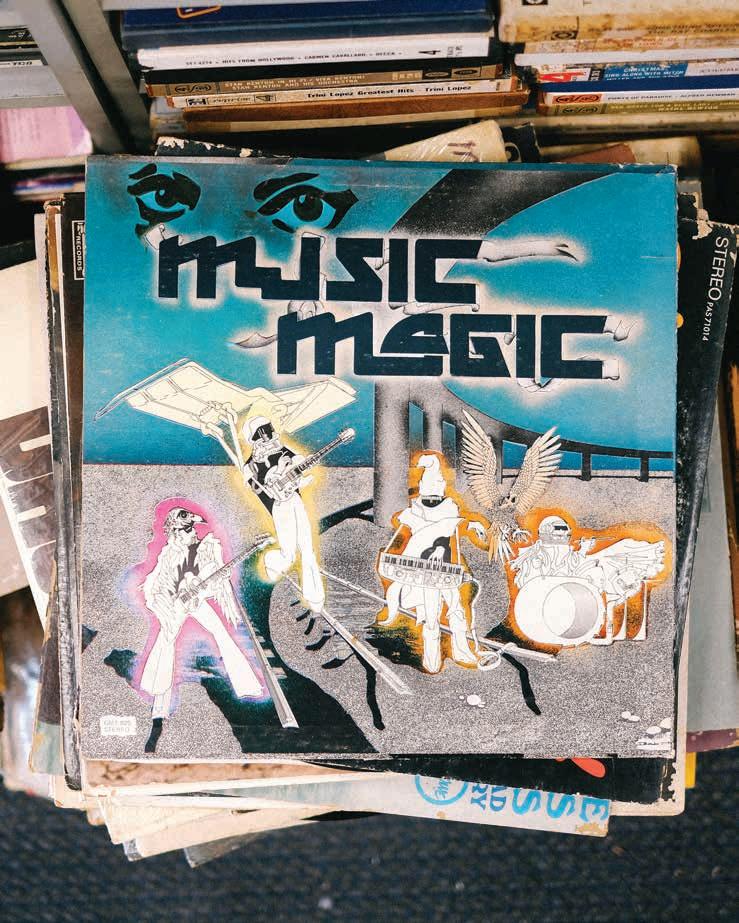

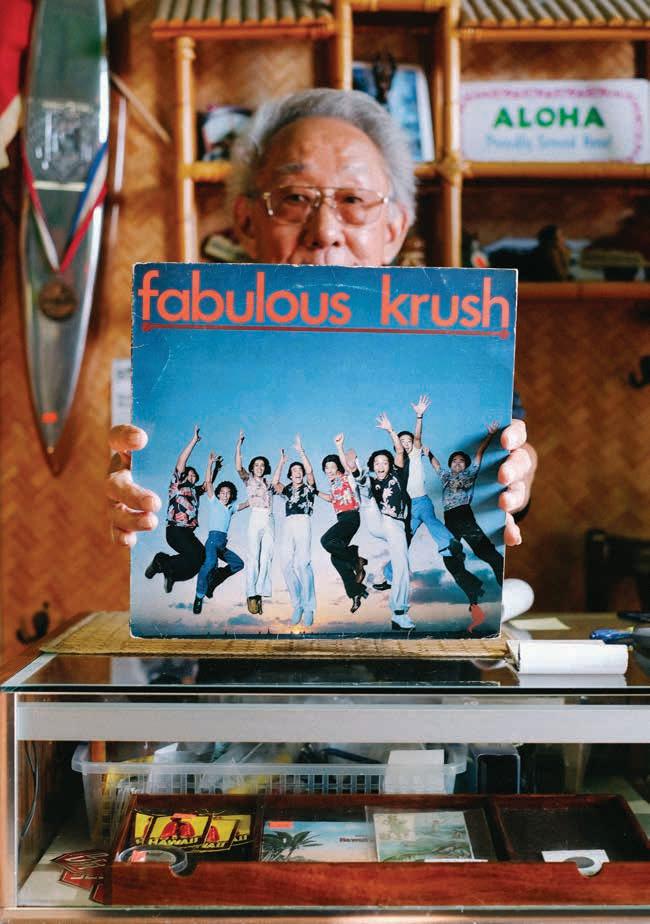

Every great album cover reveals a story beyond the music. Looking at the most iconic records from Hawai‘i’s golden age of music showcases the dreams of their musicians, the skill of its designer, and the hopes of the album’s producer.

TEXT AND IMAGES BY ROGER

BONG

Step into a record shop or antique store and you’ll encounter an artform now 80 years old: the album cover. To spend an hour at Hungry Ear Records or Idea’s Music and Books in Kaka‘ako is to dive into a rich landscape of visual stimuli designed for decades to pique your interest and, ultimately, convince you to buy the music behind the artwork.

Album cover design began with a desire to increase sales. In 1939, Columbia Records’ art director Alex Steinweiss convinced the vice president of sales to let him personally design covers to accompany records. Soon, records with covers sold ninefold better than those without. The industry was changed forever.

Hawai‘i-based record companies began popping up after the Second World War in tandem with increased tourism to the islands. These new local labels, including Hula Records, Waikiki Records, and 49th State Records, competed with the national labels that had been recording Hawaiian music since the early 20th century, like Columbia and Victor. At frst, they pressed music to fragile 10-inch shellac discs that held one song per side. Then, in the 1950s, the introduction of the 12-inch vinyl LP attracted a greater record-buying audience, providing the convenience and afordability of unbreakable discs that held 20 minutes of music per side. Local labels welcomed this era by transforming music they had already recorded into

The 1970s saw contemporary groups adopt custom-branded insignia and reinvent Hawai‘i’s marketing appeal.

128 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

EXPLORE |

ALBUM ART |

129

countless albums and then putting on the covers romantic phrases and idyllic images of Hawai‘i. The label 49th State compiled a series of albums titled Authentic Hawaiian Melodies Recorded In Hawai‘i and used stock photos like hula dancers entertaining malihini or a lone surfer at Hana Bay for artwork. Album titles like Enchanting Hawaiian Holiday unabashedly marketed to visitors.

This generic formula subsided in the 1960s when artists like Gabby Pahinui and Sonny Chillingworth released albums with down-to-earth images of themselves on the covers. Chillingworth’s frst album, Waimea Cowboy, shows the guitarist standing in a forest with the words “Hawaiian SlackKey.” His 1967 eponymous album used a photo from the same shoot and omitted any

text about Hawai‘i. Was it from Hawai‘i? It didn’t matter, at least for the album cover. Finally, musicians and art directors had the creative freedom to design covers rather than adhering to the often restrictive, wellworn marketing approach of attracting listeners by depicting Hawai‘i as an idyllic place of surf, sand, and enchanting sound. The 1970s saw contemporary groups adopt custom-branded insignia and reinvent Hawai‘i’s marketing appeal. The most recognizable logo of the era is that of Kalapana, which features an alllowercase, rolling typeface reminiscent of the ocean. The band has used it almost exclusively from its 1975 debut to its most recent 2018 Best Of collection. Fabulous Krush’s self-titled album featured alohashirted band members jumping above the

Many local artists during the 1970s and 1980s made original music to participate in the global music scene where R&B, rock, jazz, disco, and soul music topped charts.

130 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

131