24 | ARTS & CULTURE

The colorful canvases of Jack Soren, the reign of Carissa Moore, and the water protectors of Kapūkaki.

70 | FEATURES

How modern kapa straddles binaries, Michelle Mishina’s eye for island light, and the power of Pe‘ahi.

124 | EXPLORE

Lei making with sustainability in mind, and the role of Hawaiian language in contemporary media.

SPRING/SUMMER 2022 0 03 > 09281 $14.95 US $14.95 CAN 254898 The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FLUX PHILES

24 | Surfing

Carissa Moore

34 | Activism

Women Cross DMZ

40 | Cuisine

Merienda

46 | Maoli

Kapūkaki

56 | Arts

Jack Soren

64 | Environment

Mā‘ona Community Garden

A HUI HOU

FEATURES

168 | Rooftop 102 N. Hotel 72 | A Written Movement

Delve into the origins and generational influence of Bamboo Ridge Press, which continues to nurture Hawai‘i writers and preserve their literary legacies.

80 | Creators of Kapa

Nanea Lum and Lehuauakea, two creative contemporaries who bring a modern lens to their respective artforms, discuss kapa making, colonial institutions, and the hardbitten truths of being a contemporary Kanaka Maoli artist.

92 | Sliding Giants

The monstrous waves at Pe‘ahi are not for the faint of heart. But for those who find the courage and strength, a sense of triumph and euphoria follow in their wake.

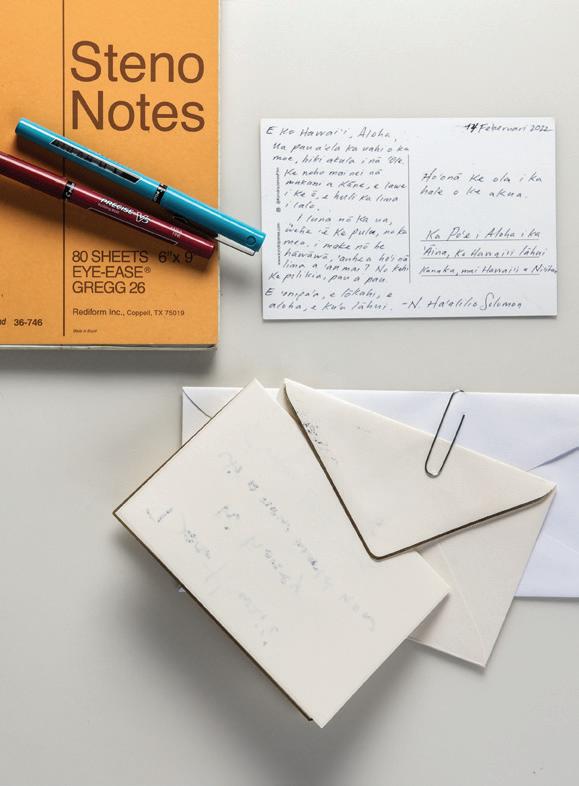

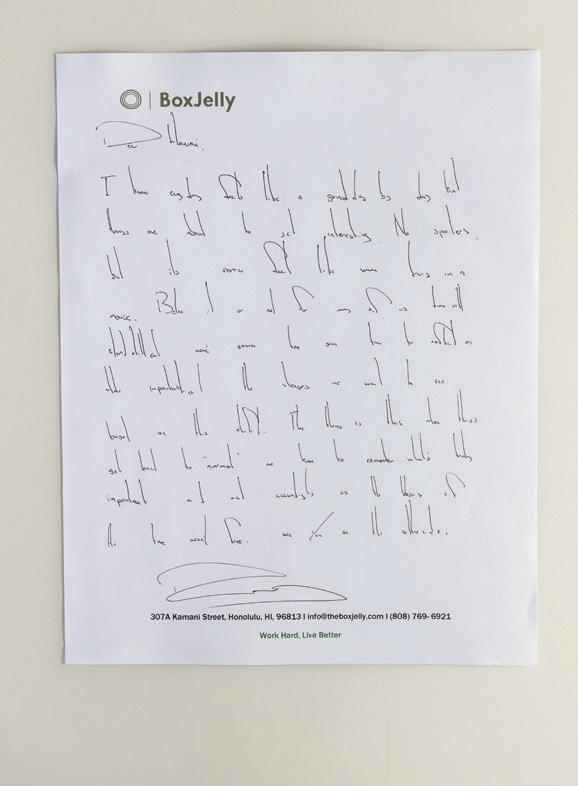

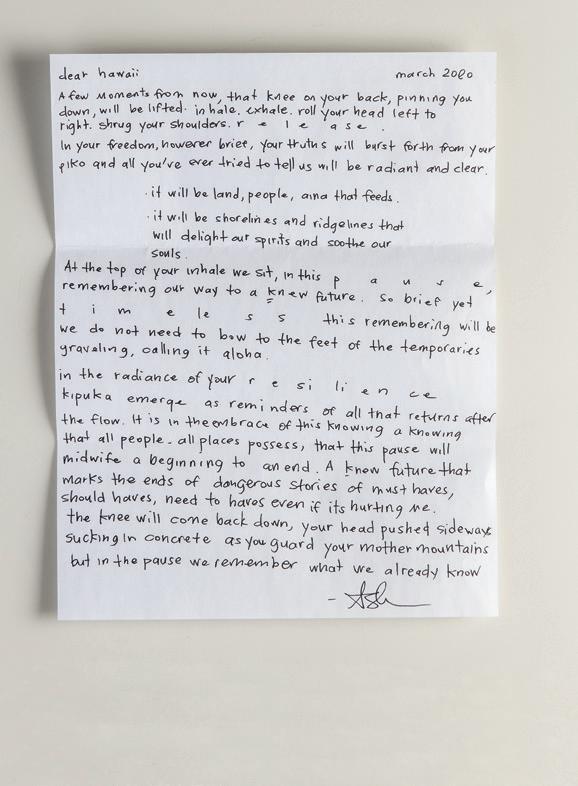

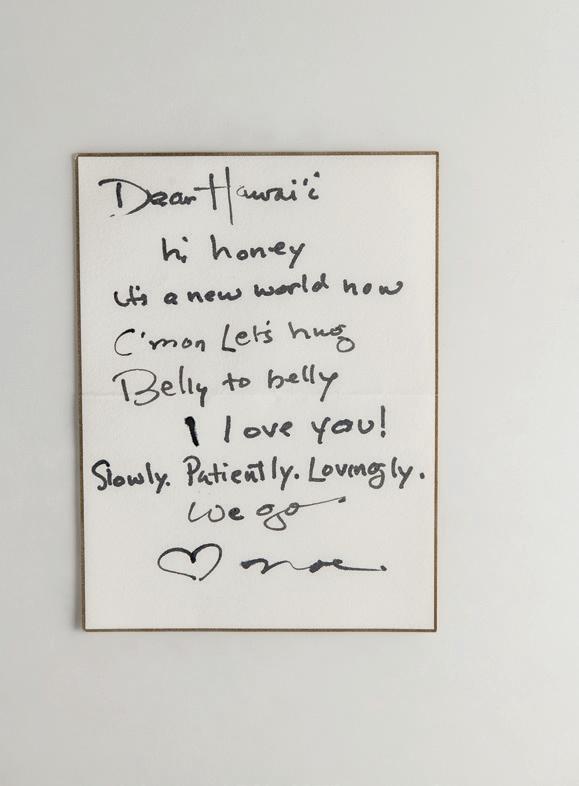

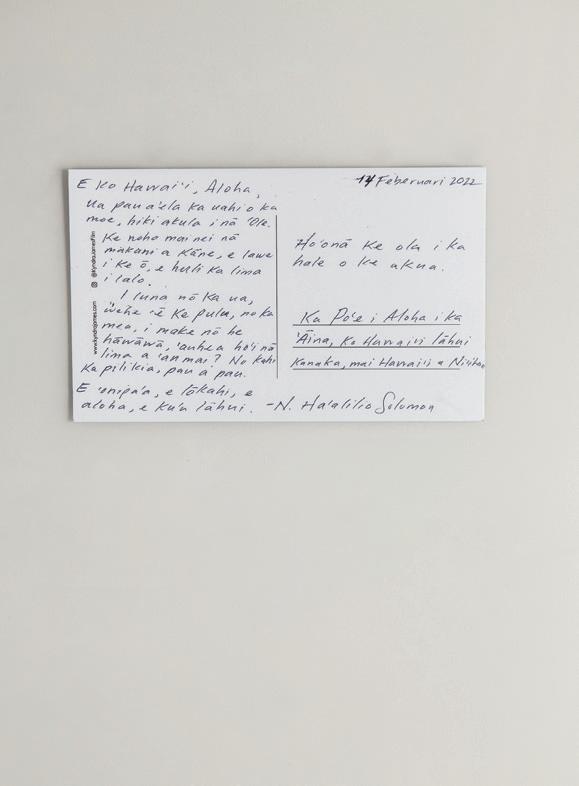

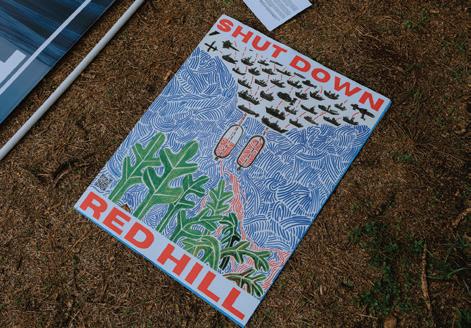

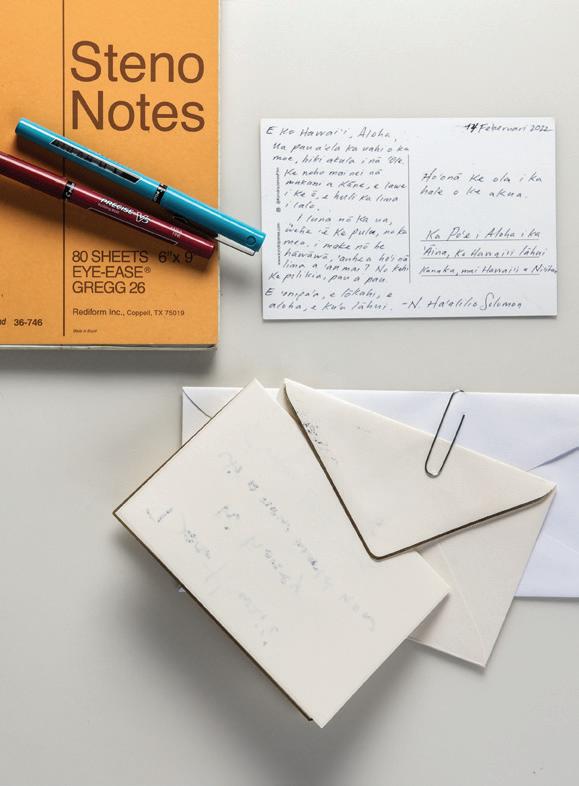

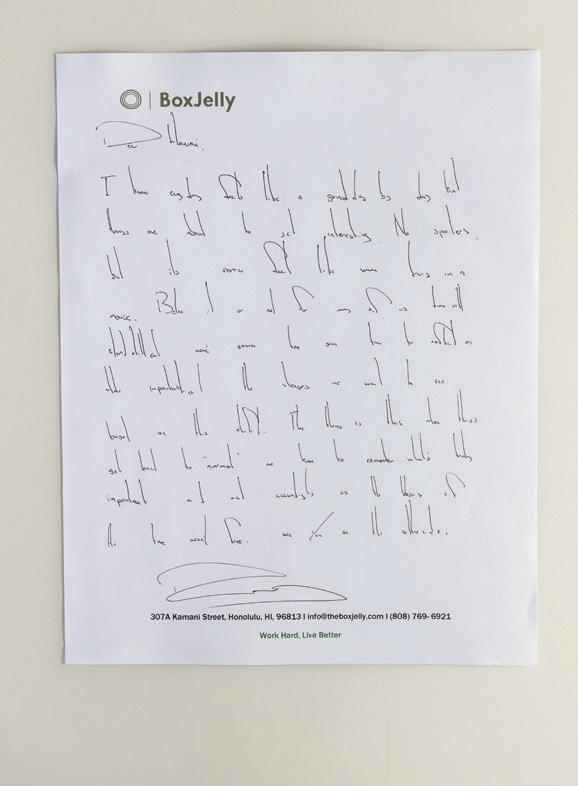

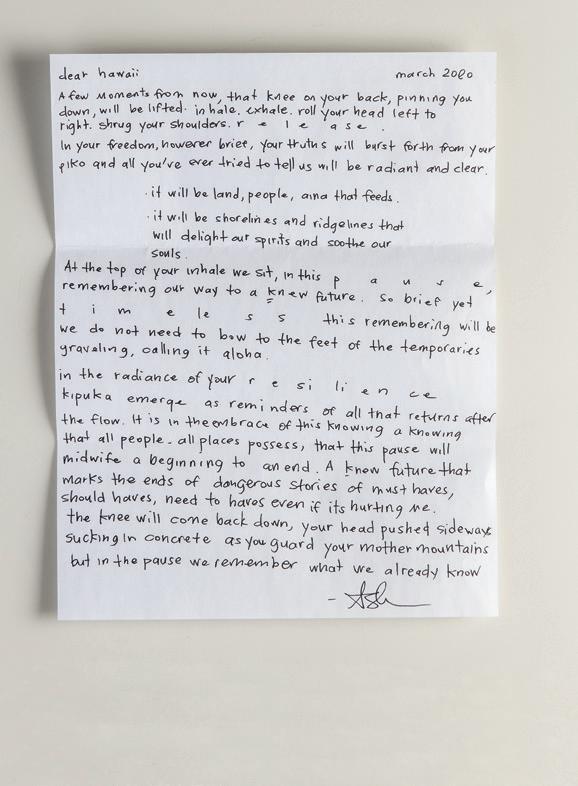

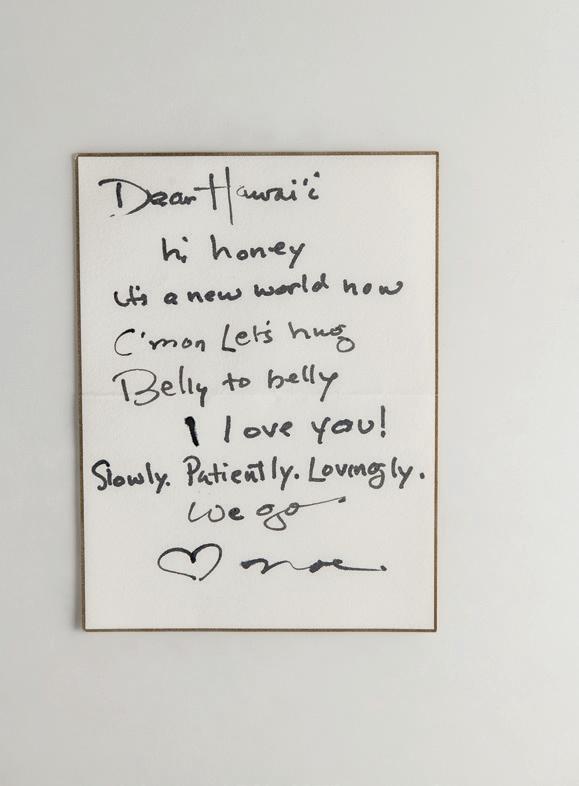

104 | Letters to Paradise

If you could send a message back in time to the year 2020, what would you write? We asked local luminaries to offer handwritten words of comfort and insight to a Hawai‘i just at the start of the pandemic.

112

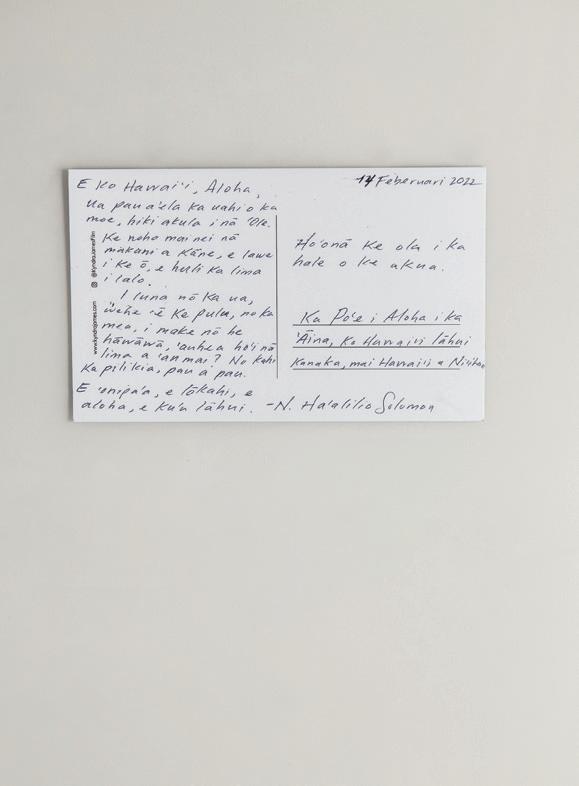

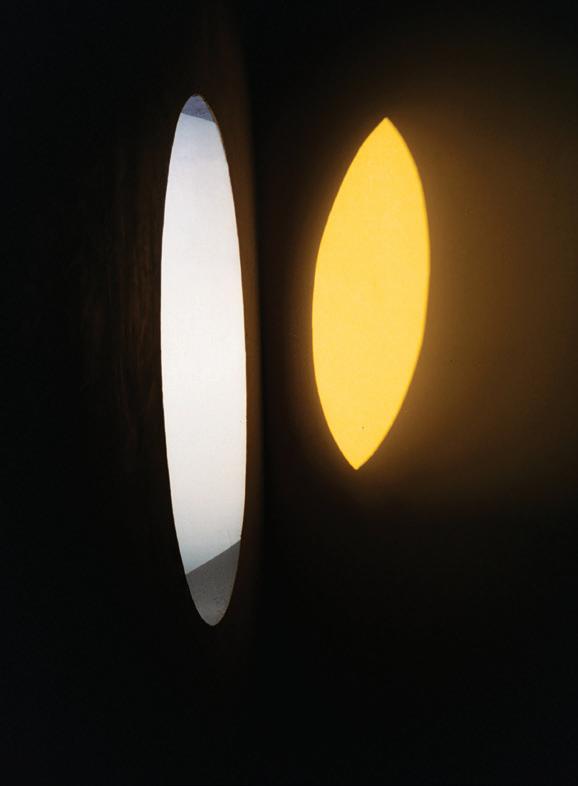

| This Elusive Light

A bright narrative of the islands shines through in the imagery of photographer Michelle Mishina.

|

|

FEATURES

S/S 2022

10 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Image courtesy of Lehuauakea

152 LIVING WELL 154 | Architecture Hawai‘i Non-Linear 162 | Ceremony Chado 124 EXPLORE 126 | Dining Okazuya and Vinyl 134 | Media Nūpepa 142 | Culture Lei Makers TABLE OF CONTENTS | DEPARTMENTS |

Image by Mark Kushimi

12 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Image by John Hook

Stay current on arts and culture with us at: fluxhawaii.com /fluxhawaii @fluxhawaii @fluxhawaii INFLUX TV

TABLE OF CONTENTS | VIDEO | Still from IN FLUX Still from IN FLUX 14 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Renko Floral Alien Arrangements

On the Cover

Three images highlighting stories from inside the issue. Clockwise from right: 1.) Hāehu Masau Lee at Honokea Loko I‘a, at Waiuli in Keaukaha, Waiākea Ahupuaʻa, Hawaiʻi Island, photographed by Michelle Mishina; 2.) Hawaiianlanguage editor N. Ha‘alilio Solomon at Hawaiian Mission Houses in Honolulu, photographed by Mahina Choy-Ellis; 3.) Kapa artist Lehuauakea, photographed by Moriel O’Connor.

Streaming Videos, Newsletters, Local Guides, & More

We’ ve refreshed the website for Flux Hawaii with a more dynamic viewing experience. Watch all the original episodes from our themed seasons, find ways to support local small businesses, and sign up for our weekly newsletters curated with fascinating reads. You can also browse past issues of the print magazine for purchase.

FLUXHAWAII.COM

TABLE OF CONTENTS | ONLINE |

16 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

VP BRAND DEVELOPMENT

Ara Laylo

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Lauren McNally

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Matthew Dekneef

DIGITAL EDITOR

Eunica Escalante

SENIOR PHOTOGRAPHER

John Hook

PHOTOGRAPHY EDITOR

Samantha Hook

DESIGNERS

Nico Enos

Mai Lan Tran

CONTRIBUTORS

Sarah Burchard

Kahikina de Silva

Viola Gaskell

Naz Kawakami

Lindsey Kesel

Tony Kile

Kai Lenny

Jon Letman

Timothy A. Schuler

Rae Sojot

N. Ha‘alilio Solomon

Kylie Yamauchi

IMAGES

Kara Akiyama

Mahina Choy-Ellis

Ronit Fahl

Mitchell Fong

Viola Gaskell

Mark Kushimi

Niana Liu

Michelle Mishina

Taylor Oishi

Jen May Pastores

Josiah Patterson

Chris Rohrer

CREATIVE SERVICES

Marc Graser VP GLOBAL CONTENT

Gerard Elmore VP FILM

Blake Abes

Romeo Lapitan

Erick Melanson FILMMAKERS

Jhante Iga VIDEO EDITOR

Kaitlyn Ledzian BRAND & PRODUCTION MANAGER

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock PARTNER/GENERAL MANAGER – HAWAI‘I joe@NMGnetwork.com

Francine Beppu VP INTEGRATED MARKETING francine@NMGnetwork.com

Gary Payne

VP ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE

Tim Didjurgis OPERATIONS DIRECTOR

Brigid Pittman DIGITAL CONTENT & SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER

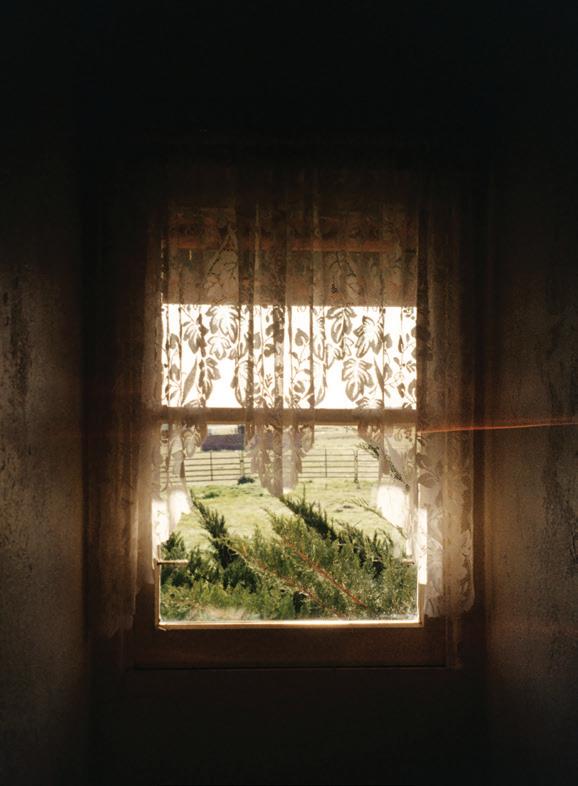

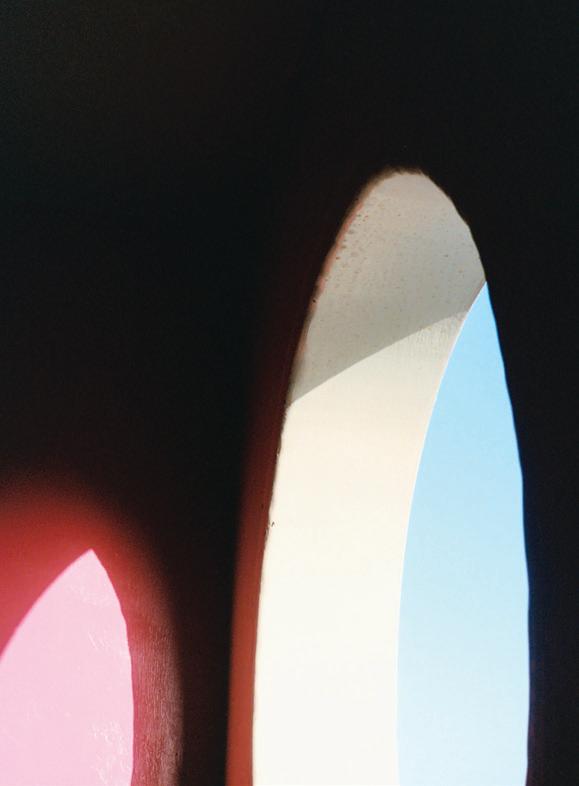

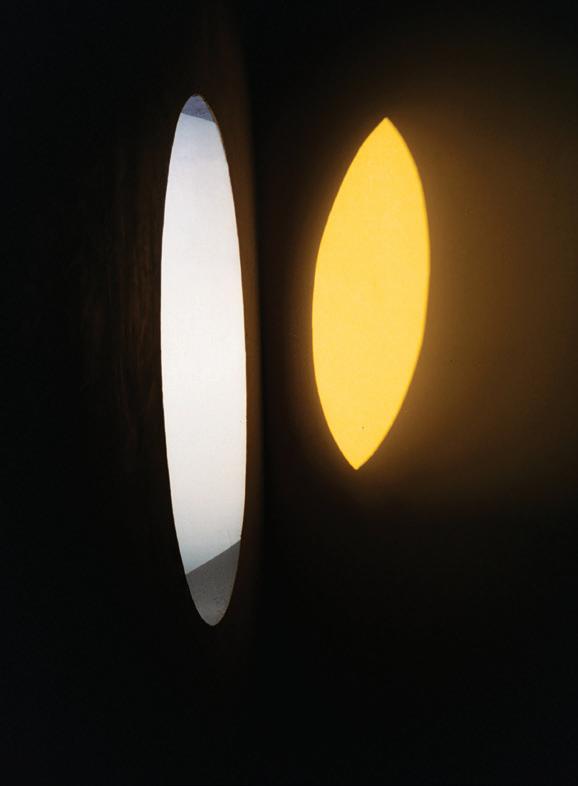

Sheri Salmon CREATIVE SERVICES MANAGER

Codey Mita SALES & MARKETING COORDINATOR

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley VP SALES mike@NMGnetwork.com

Kristine Quine SALES STRATEGY DIRECTOR

Courtney Asato MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

Nicholas Lui-Kwan ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE

Taylor Kondo BRAND PRODUCTION COORDINATOR

General Inquiries: contact@fluxhawaii.com

PUBLISHED BY:

Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel St., Ste. A Honolulu, HI 96817

©2008–2022 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. ISSN 2578-2053

MASTHEAD | SPRING/SUMMER 2022 | 18 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Mitchell Fong

Mitchell Fong is an artist, designer, and illustrator raised on the windward side of Oʻahu. He attended the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, where he received his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in graphic design and served as associate design editor at the student-run newspaper Ka Leo. He has a background in editorial design, drawing, and marketing, and has done work for places including Uniqlo and NMG Network. For this issue, on page 72, Fong created the illustrations for a feature on the origins of the beloved local literary journal Bamboo Ridge. “When I was making my drawings, I envisioned the existing local narratives that Bamboo Ridge was cataloging as interwoven of fishing lines,” he says. “This was both a nod to the journal’s fisherman namesake and something that I believe captured what Bamboo Ridge was doing— untangling the stories from the talk-story ether.”

Viola Gaskell

Viola Gaskell

Viola Gaskell grew up in Hāna, a rural town in remote East Maui, where her family grew macadamia nut and banana trees and kept chickens. Over the last seven years, she worked as a multimedia journalist in the U.S. and Asia, mostly in Hong Kong, where she reported on the city’s protest movement for an international press agency and publications like The Independent, Vice, and Al Jazeera. For others, she produced stories on a wide range of subjects, from Japan’s bread fandom to design preservation in China. In 2021, she returned to Maui, where she is now a freelance writer, photographer, and editor. Gaskell is thrilled to be reacquainting herself with her home and writing about Hawaiʻi’s moves towards selfsufficiency and reclamation of culture. In her first story for Flux Hawaii, Gaskell covered a triad of sustainable lei makers, on page 140. “For me, lei means love — that I love the person I am bestowing with lei, and that I am loved when I am given lei,” she says. “When I moved home after 12 years away and had my first art show on Maui, I was covered with lei from friends and family and it truly felt like an embrace made from the plants they’d grown and foraged, imbued with their ingenuity and affection. It really set that show apart for me.”

Lindsey Kesel

Lindsey Kesel

Naz Kawakami is a 26-yearold Hawaiian journalist based in New York City, and specializes in the culture and economics of music, film, and social issues relating to the Central Pacific. He graduated with a bachelor’s in creative writing from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, where he served as a programmer and news director for radio station KTUH. For a couple of glorious, unadulterated years circa 2017, he was the editor in chief of NMG Network’s creepy little cousin, Chinatown Now, where he showcased artists, musicians, and institutions of the historic district, as well as throw elaborate parties under the guise of “editorial research.” In this issue, Kawakami spoke with artist Jack Soren, on page 56. “I was refreshed by his sense of confidence and comfort in admitting that he isn’t perfect and is confronted by these contradictions without having a formalized answer for how to reconcile them,” Kawakami says, of interviewing Soren. “Where most seem to feel the need to have arrived at cultural postcolonial enlightenment, Jack is interested in learning and being on that journey and seems to view it as a never ending process. He is working on it, and he is okay with that. I liked that.”

Based in Bora Bora, French Polynesia, Lindsey Kesel keeps a strong connection to Hawai‘i through storytelling for publications by NMG Network. In 15 years of living in Honolulu, Kesel parlayed her experience creating content for agencies, businesses, and nonprofits into a new iteration of writing career: exploring the souls and spaces that enrich local landscapes. Her favorite topics are sustainability and nature, the arts and artists, Hawaiian and Pacific Island culture, makers and changemakers. Her past stories for Flux Hawaii include a feature on O’ahu’s female lifeguards and a review of legendary artist Ai Weiwei’s canon. On page 64, she shares the journey of a Hawai‘i Island community garden. The shift in mindset that happens to many garden visitors left a lasting impression on the writer. “Here’s this modest 5-acre space where a small group of volunteers are rallying the community around massive waste diversion efforts like shredding a ton of cardboard a month,” Kesel says. “People learn that the go-to option of recycling involves a fossilfuel-eating boat ride to Asia, and instead they get to see their scraps being used right here, right away as fertilizer. That stays with them forever.”

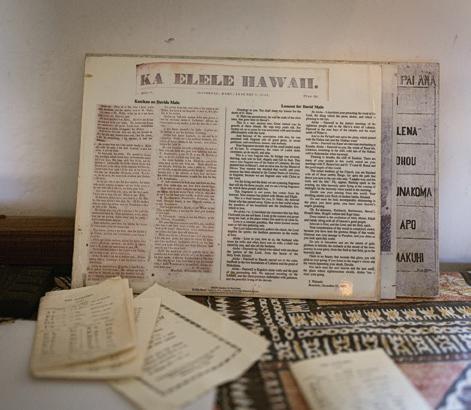

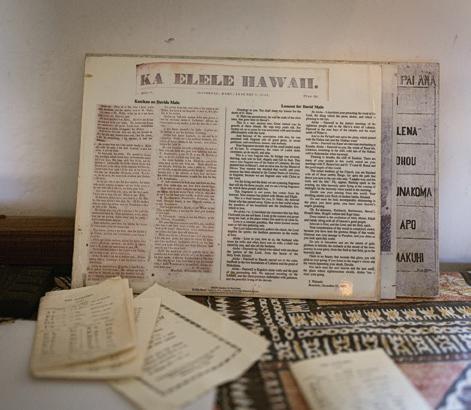

CONTRIBUTORS |

SPRING/SUMMER 2022 |

Naz Kawakami

20 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Carissa Moore is the first female Olympic gold medalist for surfing. Image by Steven Lippman.

Carissa Moore is the first female Olympic gold medalist for surfing. Image by Steven Lippman.

ARTS & CULTURE

“We want to give people permission to look around at their community and ask, ‘How can we do better with what we have?’ Because no one is more powerful than you and I.”—Chantal Chung

The Reign of Carissa Moore

The Kānaka ‘Ōiwi athlete didn’t just witness Duke Kahanamoku’s wish of seeing surfing become an Olympic sport: she won gold. Now, as surfing’s first female Olympian to medal, Carissa Moore reflects on what’s next.

TEXT BY KYLIE YAMAUCHI

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK AND STEVEN LIPPMAN COURTESY OF RED BULLETIN

In July 2021, Carissa Moore found herself far from the world-class, crystalline waves she’d come to love and master in her hometown of Honolulu. More than 4,000 miles away in Chiba, Japan, the 28-year-old professional surfer represented the United States in the 2021 Olympics and its debut surfing competition.

An impending typhoon, gloomy skies, and angry currents at Tsurigasaki Beach served as constant reminders that Moore was out of her comfort zone on finals day, as she went up against Bianca Buitendag from South Africa.

To add to the pressure, Moore, who is Native Hawaiian, was following in the footsteps of another homegrown icon Duke Kahanamoku, a three-time Olympic gold medalist in swimming and the father of modern-day surfing. With all of Hawai‘i cheering her on, Moore won her heat, becoming the first woman to win Olympic gold in surfing.

Now back home on O‘ahu, and on the heels of a newly unveiled 150-foot Honolulu mural by artist Kamea Hadar that depicts Moore alongside Kahanamoku, she recounts that historic day, everything that has transpired since, and the meaning of aloha.

Carissa Moore started surfing with her dad at Waikīkī, where she would pass by Duke Kahanamoku’s statue daily. Right, image by Steven Lippman.

FLUX PHILES | SURFING | 24 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 25

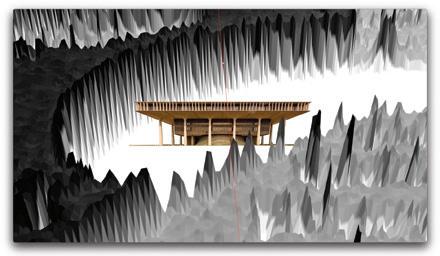

First off, I want to say congratulations on your Olympic gold medal. Thank you so much!

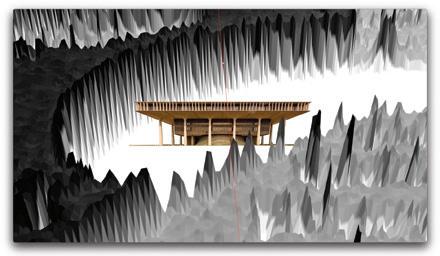

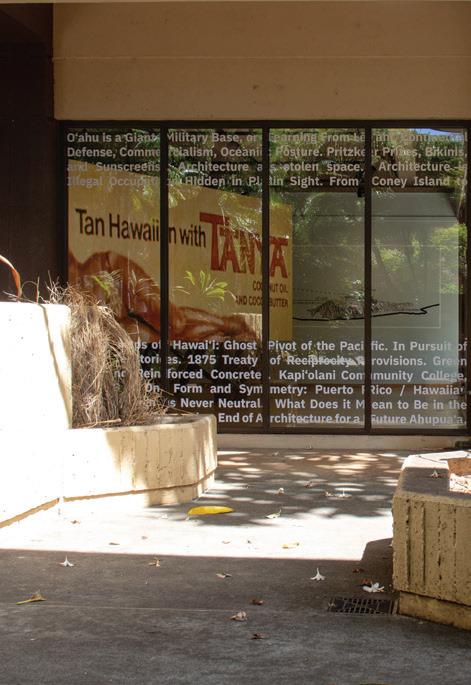

I was rewatching your finals heat and saw that you had the biggest smile on your face, even before you got into the water. What was that day like for you? The whole Olympic experience was new and uncharted territory. For me, it was finding that balance between wanting to do well in the contest and giving everything I had, and letting go and enjoying the experience.

On final’s day, there were crazy conditions because of the typhoon—a lot of water moving, a lot out of my control. So I surrendered to the universe: Whatever’s going to be is going to be. I’ll give my very best and surf from my heart and we’ll see what happens. I’m very grateful, because I felt very present in that moment and enjoyed every second of it.

Did it feel any different from when you competed on the World Surf League Championship Tour?

All I’ve ever known is competing on the

Championship Tour (CT), so I didn’t know what this [Olympic event] would be. It did feel different in the fact that the contest setup was massive and without fans. Also, there’s different luxuries that come with the CT. Sometimes when there’s a lot of water moving, we get jetski assistance.

I feel like the first twenty minutes of the final’s heat was just you and Bianca paddling out.

(Laughs) I just get exhausted thinking about it. I was so tired! Before paddling out, I remember having a conversation with my dad and he said, “It may not feel like things are going your way, but just keep going, because something will work out.”

Having competed with Caroline Marks, John Florence, and Kolohe Andino on tour, what was it like to represent Team USA together?

I really enjoyed being a part of the team spirit, because surfing, for the most part, is an individual sport. Caroline is one of my biggest competitors, normally. I

From O‘ahu, Moore represented the United States in the 2021 Olympics and the event’s debut surfing competition. Above, image by Steven Lippman. Opposite and overleaf, images by John Hook.

26 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

honestly thought she was the one to beat in the Olympics, especially when the conditions were smaller because that’s what she grew up surfing in Florida. I was literally staying and living in the house with the surfer I wanted to beat the most. (Laughs.)

Having surfed on tour since 2010 and with five women’s world titles under your belt, you’re no stranger to competing and competing well. Going into this prestigious, international sports event, did your mindset and goals shift in any way?

I definitely drew inspiration from my normal formula. One of the things that was unique to this event was the wave. [Surfing in Chiba] took calmness and simplicity. For the most part, you’re not worrying about your opponent; you’re playing your own game.

As a Kānaka ‘Ōiwi Olympian, you’ve been compared to the legendary Duke Kahanamoku. Going into the Olympics, how did his legacy influence you? It’s a lot to be mentioned in the same sentence as Duke, because he’s a legend and he’s been one of my role models. I grew up surfing Waikīkī and passing by his statue every day. His legacy is beautiful. It’s about treating people with kindness and sharing what you have without wanting anything in return. He had the biggest heart. I think he was an incredible athlete, Olympian, and waterman as well.

It’s neat because before the Olympics, I had the chance to watch a documentary on him. Watching his backstory helped me to realize what it means to be a Native Hawaiian and to represent our people the best I can. This was his dream for surfing to be in the Olympics. I wanted to make Hawai‘i proud. I wasn’t going into any normal surfing event. It was about something bigger than me.

I saw on Instagram that you were able to view Kamea Hadar’s mural of you and Duke up close and personal. Despite your fear of heights, what was your reaction to seeing the mural? Honestly, just blown away. They told me this was happening, but I didn’t realize it until I was standing in front of it. It’s such an honor to have someone paint my face on a giant wall and next to one of my heroes. I definitely want to do the best that I can with my platform to send my love and hopefully continue Duke’s legacy of the aloha spirit.

Kamea did an absolutely stunning job. I can’t even grasp how he’s able to translate a small picture on a paper to a wall that size. I’m afraid of heights, he’s afraid of heights! (Laughs.) How does he stand up there all day and paint?

It was really cool getting to know Kamea too. He puts so much effort into his work. He did a lot of research into Duke’s medal. He even looked up the ribbon that the medal hung on, which is different from mine. There are so many different meaningful things in what he did. So much research, love, and time he put in. I’m blown away all around by the love from my community. It’s been heartwarming and special.

Being from Hawai‘i, my dad and I love watching you surf especially because you always show the aloha spirit both on and off camera. What does aloha mean and look like to you? It’s a big question. I think aloha to me is love. I feel so fortunate to have grown up in Hawai‘i surrounded by the aloha spirit. My family goes beyond my blood. It’s the people I see every day in the water, the people who say hello or ask how I’m doing. Those little interactions

30 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

I have found really make a difference. My biggest heroes have definitely done incredible things in their sport or achieved great things in their life, but it’s who they are as people—that they’re real, tangible, and caring. That’s the stuff that lasts. You can win an event, but tomorrow it’s on to the next thing. I’ll always remember how people made me feel. So, that’s love, that’s aloha.

Can you speak more on Moore Aloha and where this idea came from?

I started my charitable foundation Moore Aloha three years ago. I was inspired by Hurley Surf Club, which organized events at local beaches and invited the community of kids to come down. They’d have one of their pro surfers do a session and mentor. I did one at Kewalos. There were 30 girls with big wide eyes, ready to absorb any sort of information. As much as it was about giving to them, I felt that I got so much more in return from their smiles and joy and excitement. It was so refreshing and beautiful. I always wanted

to find a way to give back, so this felt like my aha moment.

I know how hard it is as a young woman in this day and age. There is so much that can take away from us being our most authentic self. So how could I make a day where girls feel inspired to be themselves, share, create, and encourage? I’ve been at the top before where I haven’t had any friends and it’s really lonely. The goal is to help these girls do what they love and give love along the way.

Now that you’re an Olympic gold medalist, what goals do you have yet to accomplish?

I’m actually in the midst of my brainstorming and goal setting right now. There’s a lot of performance goals I have with surfing, and I’d like to continue with my non-profit. At some point — I don’t know when it will happen — I’d love to be a mom one day! That’s definitely a goal for the future.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

A 12-story mural by Kamea Hadar in honor of Moore and Kahanamoku is located at King and Pensacola streets. Above and previous page, images by Steven Lippman.

Learn more about Moore Aloha and its empowering surf camps at moorealoha.com.

32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Breaking Borders

In the documentary film Crossings, international activists mobilize the charge toward peace on the Korean peninsula. A Honolulu organizer highlights how Hawai‘i can play a key role.

TEXT BY JON LETMAN

IMAGES BY NIANA LIU AND JEN MAY PASTORES

On our war-wounded planet, some conflicts are acute, some chronic, and still others defy simple diagnosis. Nowhere is this truer than the Korean peninsula where, for more than 70 years, a divided nation remains in a state of war.

From 1950 to 1953, a brutal war took place on ground and air between the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in the north, backed by China, and the Republic of Korea in the south, backed by the United States. This war inflicted death and destruction, causing millions of mostly civilian casualties. A 1953 armistice signed by the United Nations Command, China, and North Korea halted active fighting, but a formal peace treaty was never concluded, leaving Korea in a technical state of war.

Today the Korean peninsula remains divided by a demilitarized zone, or DMZ, which is, in fact, one of the most militarized places on Earth. Previous attempts to cross the DMZ have been met with immediate arrest or death, but a 2015 crossing by a group of 30 women from 15 countries suggests another future is possible.

This peace effort is documented in Crossings, a 2021 documentary directed by Deann Borshay Liem had its world premiere at the Hawai‘i International Film Festival. The film follows the transnational feminist group, now known as Women Cross DMZ, as they travel from Beijing to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea to meet with North Korean women, then cross into the Republic of Korea to meet their counterparts in the south.

After multiple visits to North and South Korea, Christine Ahn, a Korean American peace activist based in Honolulu and founder of Women Cross DMZ, concluded that the participation and leadership of women was key to bringing peace to the peninsula. That required meeting with the people who were “supposed to be her enemy.”

Informed and inspired by decades of work by Korean women on both sides of the divide, Ahn points to studies that prove women-led peace efforts are stronger and more durable. Women Cross DMZ had three ambitious goals: replace the armistice with a peace treaty; reunite Korean families; and elevate women’s leadership in the peace process.

In May of 2015, the 30 women, accompanied by filmmaker Liem and a crew of three, flew to Pyongyang to seek dialogue, understanding, and a chance to end the so-called “forgotten war.” The group was comprised of women from South Korea, Asia, Africa, Oceania, the Americas, and Europe. Delegates included Nobel Peace laureates Mairead Maguire and Leymah Gbowee, feminist organizer Gloria Steinem, members of CODE PINK, activists, educators, and leaders who could work across ideological and political lines.

While in North Korea, the group met women in a textile factory, a kindergarten, a maternity hospital, as well as at formal meetings and a symposium. In one scene, a Korean war survivor wept as she described both her hands being shot off by an American soldier during the war, her bitter

From the documentary Crossings , directed by Deann Borshay Liem. Still by Niana Liu.

FLUX PHILES | ACTIVISM | 34 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

memories still raw and mercilessly vivid.

Liem said her crew was allowed to film almost without restriction. They documented women working to dispel years of mistrust and fear, sharing their struggles and aspirations, and recognizing their common humanity. In a moment of striking candor, one young North Korean woman— an interpreter—told the women, “We are against [the U.S.] hostile policy towards the DPRK. We are not against the U.S. people.”

The visit took place during the administration of South Korea’s thenconservative president Park Geun-hye, and not everyone appreciated their efforts at rapprochement. As news of the trip spread, the women were vilified by some in South Korea as “North Korean sympathizers,” “propogandists,” and worse. They were chided for being naïve despite their collective decades of addressing war and conflict from Northern Ireland and Liberia to Okinawa, Zimbabwe, Colombia, Gaza, Iran, and elsewhere.

On May 24, 2015, the day the women crossed the DMZ, they received an ebullient

sendoff by throngs of North Korean women wearing Chosŏn-ot (Hanbok), traditional dresses of plum pink, sky blue, and golden yellow, and waving bright red floral wands. Large banners read “Let us reunify the divided country as soon as possible!” But tensions at the DMZ were high and the air was heavy with uncertainty about what awaited them to the south.

Initially, the women planned to walk across the border at the Joint Security area (Panmunjom) where Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un stepped over the military demarcation line in 2019, but crossing on foot was politically sensitive and the US-led UN Command, which controls the South Korean side of the DMZ, insisted they enter by bus at the nearby Kaesong border crossing.

Upon arriving in South Korea, the women were met by reporters, some of whom challenged their motives. Several in the group were threatened with deportation, and all faced right-wing protesters, many of them North Korean defectors, with signs reading “Return to North Korea!” and “Women Cross go to hell.” That didn’t stop

The film follows the transnational feminist group, now known as Women Cross DMZ. Still by Niana Liu.

Learn more about the organization and their efforts at mufilms.org.

36 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

the group from crossing Tongil (Unification) Bridge where they were welcomed by South Korean supporters waving balloons and singing songs. South Korean committee member Jin Ok Lee said of the peace walk, “I think [it] sparked the revitalization of women’s peace movement in South Korea.”

Recalling her visit to North Korea in Crossings, Liberian Nobel Peace laureate Leymah Gbowee said, “This is a place in my mind where there was no life, but you see the yearning for greater connection with the rest of the world. Five thousand women showed up and saw 30 international women. I believe it gave them hope.”

Six years after that trip, following Trump’s whiplash diplomacy which jerked between “fire and fury” and “love letters,” U.S.-Korean diplomacy is more muted. But the Biden administration has retained policies Ahn calls “regressive and draconian,” such as sanctions and a travel ban.

Speaking from her home in Honolulu, Ahn said, “I do feel like Hawai‘i can play a really critical role in ending the 70-year-old

conflict, moving the U.S. from this stuck, broken, failed policy of maximum pressure, sanctions, and military aggression towards a different approach.”

She pointed to the Korean War Divided Families Reunification Act, co-introduced by Hawai‘i’s Sen. Mazie Hirono in 2020 and again August 2021, and Rep. Kai Kahele’s co-sponsorship of a U.S. House resolution calling for peace on the Korean peninsula. Ahn hopes all of Hawai‘i’s congressional delegation will play a more active role promoting peace for Korea. Ahn also hopes the film will encourage people to join a movement of those who recognize that peace in Korea offers security for Hawai‘i too. For all who experienced the 2018 false ballistic missile scare, that connection is not an abstraction.

If the DMZ is a place of separation and tragedy, Crossings shows it can also be a place of hope and one from which the healing from the sickness of war and division that has beset Korea can begin.

Protests were held around the United States in response to the spike in violence against the Asian American community. Image by Jen May Pastores.

Read an op-ed by Christine Ahn, the founder and executive director of Women Cross DMZ, on addressing the long legacy of imperialism and ending anti-Asian violence at fluxhawaii.com.

38 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Afternoon Delights

How the nostalgic ritual of merienda, a midday snack-break and Filipino favorite, satiated one writer’s inner child.

TEXT BY EUNICA ESCALANTE

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

As a kid there was no other time of day that I cherished as deeply as merienda, the point in the afternoon specially reserved for a midday nosh. In the Philippines, it’s usually comprised of a light meal, practically a snack, taken at some point between lunch and dinner. But don’t let merienda’s casual nature fool you. Blasé it may be, irrelevant it is not. It is the country’s unofficial fourth meal, as well-established as breakfast, lunch, and dinner. And with a category of dishes all its own, they claim some of Filipino cuisine’s greats, from street food to desserts.

It may seem frivolous, perhaps even infantile, to hold snacking in such high regard. And yet! In my formative gastronomic memory, merienda brings the main character energy: a perfectly caramelized turon on the way home from the market; a warm and pillowy pan de sal for an after-school snack; a cup of halo-halo as a reprieve from the summer heat.

None of these dishes were essential for sustenance. Unlike its meal-time contemporaries—the more legitimate trio of breakfast, lunch, and dinner—merienda isn’t necessary for a day of well-rounded nutrition. So, the question arises: If not for survival, what higher purpose does merienda serve? Why is it so ubiquitous and beloved that it’s not only bequeathed a name, distinguishing it from the day’s other meals, but also bears its own distinctive cuisine?

Merienda isn’t exclusive to the Philippines. It came to the islands by way of Spanish conquistadores, who in turn inherited it from their Roman predecessors. It can be found in some form across countries and cultures. In Portugal and Italy, it’s known as merenda; in Brazil, lanche. Then, there is the French goûter, Swedish fika, Russian poldnik. Let’s not forget the Brits and their afternoon tea. In an age when no one can seem to agree on anything, the urge to snack may be among the last that we have in common.

Merienda’s etymology traces its roots to merere , the Latin for “to earn or deserve.”

FLUX PHILES | CUISINE | 40 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Across centuries and cultures, the conditions of a merienda are mutable. The time of day, length, and dish can vary based on the particular needs and wants of the merienda taker. But, its basic conceit remains the same. While not depended on for physical nourishment, the practice still satiates a hunger of a different kind: It is a comestible respite. A moment of rest and relaxation presented on a platter. An intermission from the grueling production that is daily life—pūpū and drinks provided. I’m being melodramatic, I know. But, why else is the concept so universal?

Now, this is the point when I reveal the third-act plot twist of this piece. For all my endless pontificating about merienda, it has only recently become a part of my own daily routine. While I vividly remember afternoons spent meriendaing, it encompassed just a fraction of my childhood. Upon emigrating to the United States at the age of nine, merienda became a vestige of my former life in the Philippines, one of the relics washed away amid the wave of cultural assimilation.

Besides, the modern-day American workplace has no stomach for an act as leisurely indulgent as merienda. To take another hour away from one’s work for a simple snack-break feels like a repudiation of the grind for the American Dream. To be successful you must be productive. To be productive you have to be efficient. And to be efficient means to favor output above all else, ignoring even your most basic human needs for company, for contentment, for a moment to breathe. At no point has this been more prominent than today, when the pandemic has blurred the boundaries between work and everything else.

One afternoon in January, I took a tasting with chef Jo Seoung, the one-woman team behind Wow Baguio, an all-vegan shop for handcrafted snacks that in the year since its inception rapidly became a local purveyor of authentic Filipino treats. A fellow journalist recommended that I try her Taste of Cordillera menu, an intimate tasting experience that Soeung offers alongside her ready-made treats, inspired by her childhood in the Philippines’s Benguet

Merienda isn’t necessary for a day of well-rounded nutrition, but some might argue it serves a higher purpose.

42 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 43

Province. To my delight, the three-course affair consisted entirely of—wait for it— merienda dishes. Right then and there, that little word, “merienda,” ignited an instant response in me, like a child hearing the tinny melody of an ice cream truck. At the tasting, each bite was a Proustian experience, triggering nodes of childhood memories. There I am, five years old and on my father’s lap as he delicately peels the thin banana leaf wrapping off of suman malagkit, a sweet sticky rice and coconut milk confection, before dipping it into a bowl of sugar, coating its glutinous exterior with a thousand sparkling crystals. I am eight and freshly home from school, a daily pilgrimage that requires my mother and I to pack ourselves into a cramped jeepney, our skins sweaty and sticky from exhaustion amid the humidity. For our efforts, she rewards the two of us with a spread of pan de sal, each light and airy bun packed with a tangy mayonnaise spread, a tantalizing cup of Coca-Cola always within reach. There is something comforting about preparing a platter of snacks for oneself—

and I don’t mean grabbing a handful of nuts on the way back to your desk or swiping a bag of chips to mindlessly munch on while working. The nostalgic ritual of a midday break itself feels like a return to my childhood, when the day’s idle moments could be delightfully interrupted by a conspiratorial whisper of, “Tara, merienda tayo.” Come on, let’s have merienda. An invitation to leave the day as it lays, at least for a little while, and enjoy an unbidden moment of respite.

Merienda’s etymology traces its roots to merere, the Latin for “to earn or deserve.” Growing up, merienda was seen as a treat, doled out to children who behaved, which might explain my almost Pavlovian response to it. These days, as the clock ticks over to the afternoon, I’ll feel the siren song of merienda calling to adult-me. The crushing expectations of the day lessens, albeit marginally. And my inner child reassures me: “Go on, have some merienda. You deserve it.”

Chef Jo Seoung is the onewoman team behind Wow Baguio, an all-vegan shop for handcrafted snacks that became a local purveyor of authentic Filipino treats.

Learn more about this pasalubong shop at wowbgo.com.

44 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“He Kaua Kuana‘ike Kēia”: E Kū Ana ma nā Lālani Mua Loa me Kalehua Krug

Ke ho‘okikina mai nei kekahi alaka‘i lāhui Hawai‘i i nā hoa make‘e pono—i “nā mea a pau ho‘i e aloha nei iā Hawai‘i”—e maka‘ala mau.

NĪNAUELE ‘IA NA N. HA‘ALILIO SOLOMON

PA‘I KI‘I ‘IA NA JOSIAH PATTERSON

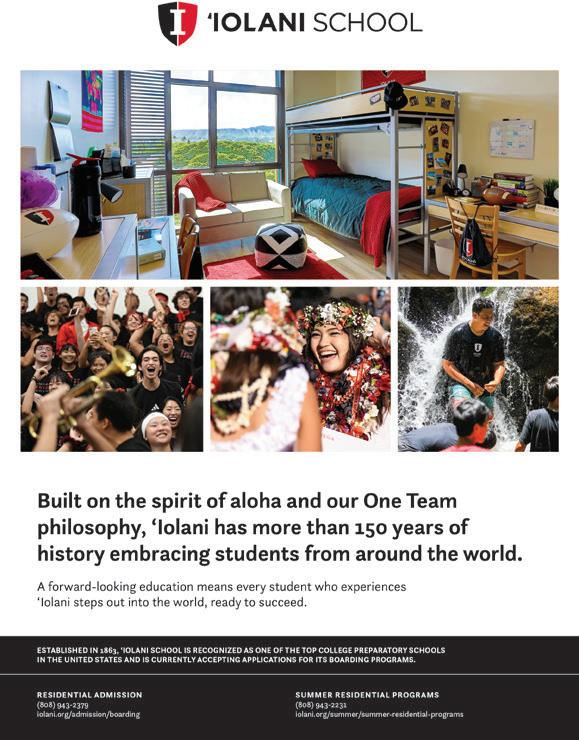

ʻOiai he mau makahiki lōʻihi ke kūʻē ʻana i ko Red Hill

Bulk Fuel Storage Facility o kekahi mau ʻahahui kūloko e ʻimi mau ana i ka pono o ka ʻāina, ʻaʻole naʻe i ulele mai nā keʻena mana o ka mokuʻāina i ka hana hoʻoponopono ʻana a hiki i ka wā i maʻi ai kekahi o nā kamaʻāina, me ke hoʻokomo pū ʻia i loko o ka haukapila. E like me ia kūʻē

ʻana, he lōʻihi ke kānalua ʻana iho o kekahi mau ʻahahui makeʻe ʻāina i ke ʻano a ko ʻAmelika Huipūʻia pūʻali koa e hana nei i ka ʻāina. No laila i ʻeu aʻe ai ʻo Kalehua Krug i ka hoʻolaha ʻana aʻe nei he kuanaʻike Hawaiʻi i wahi e alakaʻi ai i ka mālama pono ʻana i ka ʻāina; ʻo ke Poʻo Kula ʻo Krug no Ka Waihona o Ka Naʻauao, he kula hoʻāmana Hawaiʻi; he kākau uhi; he hoʻokani pila, puʻukani, a he haku mele hoʻi. He lālā pū hoʻi ʻo Krug no Kaʻohewai, ka hui nāna i kūkulu he koʻa ma ka ʻīpuka mua o ka Headquarters Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, kahi a lākou e lawelawe mau ana he mau ʻaha hoʻomanamana Hawaiʻi, i loaʻa ai he kuanaʻike Hawaiʻi ma ona lā hoʻi e kūʻē ai i nā pahu kakalina nui a ka ʻOihana Moku he iwakālua e waiho nei ma lalo o ka ʻāina.

I Dekemaba nei, ua noho ʻo Krug me Flux Hawaii ma Pauao, e kūkā kamaʻilio ai no ka huliamahi ʻana o ka poʻe he mau makahiki lōʻihi ma ka ʻaoʻao o ka pono, aia hoʻi ma Kapūkaki, e kapakapa mau ʻia nei ʻo Red Hill, a no ka hoʻolana ʻana hoʻi i ko kākou mau manaʻo.

Ke kūpa‘a nei kekahi po‘e ma hope o ka pono o ka ‘āina ma Kapūkaki (Red Hill), no ka ho‘oma‘ema‘e ‘ia ‘ana o ka wai ma laila i haumia ma muli o ka hana hāwāwā na‘aupō o ka ‘Oihana Moku o ‘Amelika Huipū‘ia.

46 | FLUXHAWAII.COM FLUX

| MAOLI |

PHILES

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 47

HA‘ALILIO SOLOMON Aloha mai, e Kalehua. E wehewehe iki mai ʻoe i kā ʻoukou hana ma Kapūkaki. He koʻa, ʻōlelo mai nei ʻoe, he koʻa, a, he aha kona ʻoihana?

KALEHUA KRUG ʻĀ ʻoia, maopopo iā kākou i ka nānā ʻana i ka puke wehewehe ʻōlelo a Pūkuʻi i waiho maila na kākou, ʻo ke koʻa, he ʻano ahu pōhaku, pōhaku poepoe a koʻa nō hoʻi, a kūkulu ʻia no ka hoʻomāhuahua ʻana i ka iʻa a manu paha. Kūkulu pū ʻia ʻo ia ma kaʻe o kahawai i ka hapa nui o ka manawa, a i ʻole ma kahi o ke kai, a ua loaʻa m aila nō kēlā, ʻoiai kūkulu ʻia kēia i mua o ka pāpū ʻoihana moku, ma ka puka mua o ka pāpū ʻoihana moku ma Kapūkaki. No laila, kūkulu ʻia kēlā koʻa ma laila, no ka mea i ka puka mua, ʻike mau ʻia he kia hoʻomanaʻo kēlā na ka poʻe kāʻalo aku no ka hihia e holo aʻe nei i kēia manawa he hihia ia o kānaka. ʻO ka mea wale nō e pōmaikaʻi ai kona kūkulu ʻia ʻana ma laila, he kahawai ko laila kekahi. No laila ke mālama ʻia nei ke ʻano o kona kūkulu ʻia ʻana, e like me ka ʻike i loaʻa iā kākou i kēia manawa. Akā, ʻaʻohe iʻa e ʻume ʻia ana, ʻaʻohe manu, inā

ʻaʻole kākou kiʻi ma ke kaona ʻo ka manu he kanaka, a ʻo ka iʻa, he kanaka. No ka mea ʻo kēlā koʻa, he mea ʻume kanaka, ʻume ola ke ʻano. E ʻumeʻume i ka hoihoi o nā kānaka e kū nō ma ka ʻaoʻao kūpono o kēia hihia e kākoʻo ai no ka holo ʻana o ke kakalina i loko o ka wai ma lalo o ka ʻāina, e puka mai ana ma nā kahawai, ma nā paipu wai, i loko o nā hale e noho ʻia nei e kekahi o nā pūʻali koa i kēia manawa. He 90,000 nā kānaka i pilikia i kēia wai i hoʻohaumia ʻia, a no laila ʻo kēlā koʻa, he koʻa kēlā e ʻume ai i ka ʻike, e ʻume ai i ka noʻonoʻo a me ka ʻālawa o ko ka lehulehu mau maka no kēia hihia, e ʻume ai i ka lāhui e kū pū me ka poʻe nāna i uhauhumu i kēlā koʻa, a kū pū ma ka ʻaoʻao … a hoʻōla ma ka ʻaoʻao e hoʻoponopono ai i kēia hihia.

HS ʻO wai ka poʻe e kū ana i mua o ka ʻaha hoʻokolokolo, e haʻiʻōlelo ana? ʻOukou, Sierra Club?

KK ʻĒ. Na kekahi mau lālā mai ke kula nui kekahi. Akā, ʻo ka poʻe aloha ika ʻāina.

Penei ke kū‘ē ‘ana o ka po‘e kūpa‘a ma hope o ka ‘āina, me ka ho‘omā‘ike‘ike pū ‘ana aku i kekahi mau hō‘ailona.

Visit fluxhawaii.com/ section/olelo-hawaii to read this story in English. This piece is part of Flux Hawaii’s Hawaiianlanguage reporting series featuring articles conceived, commissioned, and produced all in ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i, in partnership with Google News Lab.

48 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

HS ʻAe. Ma laila ka mea ʻāpiki, he mau makahiki ka hoʻolaha nui ʻia ʻana no kēia pilikia a, huli ʻia mai ʻoukou e ka pepeiao kulikuli.

KK Maʻamau naʻe. ʻO kekahi hui i hānau i loko o keia kūkulu ʻana, ʻo ia hoʻi ʻo Kaʻohewai. He hui kēnā i hui ai nā ʻano ʻoihana like ʻole, ka poʻe, kekahi mau kula, kekahi mau ʻoihana, e alu like, e hōʻike ai i ka poʻe i ke alu like ʻana ma ka ʻaoʻao lāhui Hawaiʻi no kēia hihia. No ka mea, ma mua o kēia kūkulu ʻana, uhauhumu ʻana i kēia koʻa, ʻaʻole nō i nui loa ko ka Hawaiʻi ʻōlelo ʻana e like me ka ʻōlelo ʻana no Maunakea. No laila, kini a lehu ka poʻe i kipa i ka mauna, he mauna hou kēia, ʻo Kapūkaki, e hui ai nā ihu, e hui ai nā kānaka i ke aloha i ka ʻāina.

HS I ka Pōʻalima nei, ua hālāwai ʻoukou me kekahi luna o ka ʻoihana moku?

KK He hālāwai pōkole wale nō e hōʻike aku ai iā lākou i ko mākou mau manaʻo. E like me ka maʻamau, nui ka minoʻaka, nui ka hoʻomalimali, ma ko lākou ʻaoʻao. ʻAʻole lākou — makemake wau e hilinaʻi, ua ʻoiaʻiʻo kā lākou i hōʻike mai ai, akā, i loko o ke ʻano o ko lākou hoʻomalimali ʻana, he hana nui ka hilinaʻi ʻana. A ua hana nui ka manaʻo ʻana e hilinaʻi iā lākou, ua hana nui ma mua o ka hōʻea ʻana i kēlā hālāwai. He hālāwai wale aku nō kēlā e hōʻike ai iā lākou, ʻaʻole mākou makaʻu i ka hui ʻana me lākou, mau ko mākou hoʻohuoi ʻana i ko lākou.

HS Pehea, he akua anei nona kēia koʻa?

KK ʻĀ ʻoia. No laila, ua kūkulu ʻia he kiʻi na Andre Perez mā i kālai, nani loa, e kū ana i ke kino kiʻi o kekahi mea no Kāne, i loaʻa ma Kauaʻi. Akā, ʻo ia kiʻi ke kiʻi wale nō i maopopo iā kākou ma ka Hale Hōʻikeʻike o Bīhopa, a e kū ana i ke kino i kapa ʻia no Kāne. A, no laila, ua hoʻohana ʻia kona aka, kona ʻano i mea e kū hou ai ʻo Kāne. Kāne — Kāneikawaiola. ʻO ia kēia. A loaʻa kona kahu, e kahu mau ai, ā hiki i ka hopena o ke ola. Akā, ʻo ia ʻano, loaʻa kēlā ʻano, ʻaʻole ana e mea, pahuʻa kona mālama ʻia ʻana ma hope o kēia. E mālama maikaʻi ʻia ana ʻo ia. ʻĒ, Kāneikawaiola, e kū ana ʻo ia i waena o ke koʻa, a ma kona ʻaoʻao hema, he ipu pōhaku i kālai ʻia. He pola, ʻūmeke. ʻŌlelo kekahi poʻe he ʻūmeke, ʻōlelo wau he ipu — ipu wai. Ma laila kahi i waiho ʻia ai, hānai ʻia ai ka wai. No laila, ʻo ka mea e waiho ai nāna, he wai, he hoʻohāinu.

Welo ka hae Hawai‘i ma mua iho o ke ko‘a i kūkulu ‘ia ma kahi a ka po‘e e huliāmahi nei.

50 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

HS ʻŌlelo mai nei ʻoe he kahawai ko laila?

KK ʻĒ, Hālawa. ʻAʻole nō i nui loa ka nānā ʻia o kēia hihia. A no laila ʻo ia koʻa, inā he leo kāhea ko ke koʻa, e kāhea ana ʻo ia i ko ka poʻe ʻaoʻao ʻike, no kēia hihia. A hoʻohana ʻia kēlā ma kahi o ke ahu no ka mea, ʻo ke ahu, i kekahi manawa, pono kūkulu ʻia ke ahu me ka mālama ʻole ʻia me ka maikaʻi, a ʻo ke ahu, kohu heiau lā kona ʻano, i kekahi manawa. A no laila, ua kiʻi ʻia ke koʻa no ka mea ʻo ke koʻa, he mea e ʻumeʻume ai i ke kumu waiwai, he iʻa, he manu, kēlā ʻano. Mai kahiko mai, ua manaʻo mākou ma ko mākou kūkā ʻana no ka mea e kū ai, ʻoi aku ke koʻa ma mua o ke ahu, no ka mea, ʻo ia ʻano, he aha lā hoʻi, ke ahu pōhaku hoʻomanamana, e like me ka mea e kū mau ana he māka ia no ke ahupuaʻa, a ʻo kona ʻano o ka hoʻomanamana ʻia, kohu heiau. ʻAʻole kēlā kā mākou i makemake ai. ʻOkoʻa kēia. A Kānekoʻa, ʻo ke koʻa, he kinolau na Kāne. He kino na Kāne kekahi. I ke kālailai ʻana i kekahi o ko Kāne mau inoa. No laila, ua kū i kēlā, i ka wai a Kāne, koʻa, wai. No laila holo aku nō me kēlā ko mākou noʻonoʻo ʻana ma mua o ka hoʻoholo.

HS Auē hoʻi kēia nīnau, pehea kou ʻimi ʻana i ka mea e lana ai ka manaʻo o kānaka no kēia mua aku. E walaʻau ana wau me kekahi hoa aloha no KAHEA. ʻŌlelo ʻo ia, “Easy to feel powerless,” ʻeā, he wahi komo wale kēlā e pau loa ai ka mana o ke kanaka hoʻokahi. Pehea ʻoe e hoʻolana ai i kou manaʻo?

KK ʻO ka mea wale nō, hoʻolana ʻia koʻu naʻau, koʻu noʻonoʻo ma ka mau ʻana o ka paio me ke kū ma ka ʻaoʻao pono. A no laila, wehewehe wau i ka poʻe, ʻo ia koʻa, hoʻomaka kēia ʻaoʻao o ka ʻike ma koʻu nānā ʻana i nā kiʻi akua, nā kiʻi no Kū i hoʻohele ʻia, i nauane ʻia i waena o ke anaina, ma luna o ka mauna, ma Puʻuhuluhulu, a i waena o nā wāhine, keiki, wāhine hāpai, luahine, ʻelemākule, nā mea like ʻole. A ma ka ʻike o ko kākou mau kūpuna, ua paʻa akula, ʻaʻole kēlā ka mea pololei. ʻAʻole kēlā ka mea pono. Akā, ke kiʻi nei au i kēia manawa, e kala mai, no ka poʻe heluhelu a hoʻolohe, ʻaʻole wau e hoʻohalahala nei. Ke ʻōlelo wale nei nō. He waha ʻōlelo ʻana no ka hana i hana ʻia. Ua hana ʻia kēlā, heluhelu ʻia ka moʻolelo, ʻaʻole pēlā. ʻAʻole kūlike i ka mea a Malo mā, a Kamakau mā i ʻōlelo ai.

ʻAʻole kūlike. Eia nō naʻe, ma ke kuanaʻike o ke kanaka, i mea aha ke kuanaʻike? I mea aha ka nohona Hawaiʻi? A ʻo koʻu ʻaoʻao kēia, a kaʻu e ʻōlelo mau ai i ka poʻe, ʻo ka mea nui o ka ʻōlelo, ka ʻike, ke aʻo ʻana, ka naʻauao ma kēia mau mea a pau, ma ka ʻike Hawaiʻi, ʻo ia hoʻi, ke kū ʻana o ke kanaka he lālā

no ka honua. ʻAʻole ʻokoʻa ke kanaka, ʻaʻole ʻokoʻa ka iʻa, ka makani, ka pōhaku. ʻO kēlā ʻano hoʻokanaka ʻana, ke kūkulu hoʻopili ʻana i nā mea a pau, i ia mea he kanaka — kapa inoa, walaʻau, ʻo kēlā mau mea a pau, he papahana ia e ulu ai ke kuanaʻike. A i loko nō o kaʻu mea e ʻōlelo nei, pololei, pololei ʻole, ʻaʻole wau e ʻōlelo nei i kēlā. Ke ʻōlelo nei wau, he papahana kēlā e pili ai ke kanaka i ka ʻāina. A no laila, ma koʻu kālailai ʻana i ka mea i hana ʻia ma luna o Puʻuhuluhulu, inā ʻo kēlā hana he hana Hawaiʻi, ah… ʻaʻole i like me ka mea a kūpuna mā i waiho ai na kākou, eia nō naʻe, ke nīnau aku wau i ka nīnau, inā ua ʻoi aku ka pili o kānaka i ka ʻāina ma hope o kēlā, ʻōlelo wau, “ʻAe.” He mea i ʻume i ka poʻe, a i hoʻoulu i ke aloha i nā akua, i nā kūpuna, i nā ʻaumākua, i nā mea Hawaiʻi kahiko loa. A ke loaʻa kēlā ʻano ʻike kapukapu, ah, e ʻoi aku ai ka pilina o kānaka i ka honua. E manaʻo ana au, ma laila ka lanakila. No ka mea, aia kākou ma waena o ke kaua, a ʻo ke kaua, he kaua kuanaʻike. Ke ʻano o ka noho ʻana o ʻaneʻi nei, me ka poʻe ma mua. ʻO ka poʻe ma mua, ua kūkulu lākou i ko lākou nohona no ka pono o nā mea a pau. ʻAʻole wale nō lākou i kālele ma luna o ka pono o… ka pono kānaka. A ke hoʻoholo ʻia kēlā, a he nīnau paʻakikī kēia e ʻauamo mau ai, ma nā mea a pau e hoʻoholo ai, inā kākou e pākuʻi aku i kēlā nīnau ʻana inā he mea no ke kanaka wale nō, a i ʻole no ka honua holoʻokoʻa. Noʻu nei, hoʻolana ʻia koʻu naʻau ma ia ʻano o ka noʻonoʻo ʻana. No ka mea, ʻike wau i ka hihia, ah, maʻalahi loa ka minamina i nā hana i hana ʻia aku nei, nā mea i hoʻoholo ʻia e nā aliʻi ma mua. Ah, ʻo ka hāʻule ʻana o ka ʻAikapu, noʻu, he keʻehina. Ah, ka ʻae ʻana i ka mikioneli, he keʻehina. Ah, hiki iaʻu ke wehewehe i nā mea a pau, mea, ke aupuni palapala, he keʻehina. ʻO ka Māhele, he keʻehina. Ah, mea, ka hoʻokahuli aupuni, he keʻehina. Nui nā keʻehina e ʻike aku ai i ka wāhi ʻia o ko kākou kuanaʻike a me ka noʻonoʻo. Ah, i loko o ka makemake ʻole e hoʻohalahala i kekahi ʻaoʻao o ka ʻike, ke ʻōlelo nei au ma ka wāhi ʻia o kēlā kuanaʻike, wāhi pū ʻia––moku ka pilina o kānaka i ka ʻāina. E like me ka mea i kūkulu ʻia e ka poʻe hope loa i pili i ka ʻāina nei. ʻApo ʻoe?

HS ʻAe.

‘O Kalehua Krug, ‘o ia pū kekahi ke ho‘oikaika nei i nā hana kū‘ē‘ē i ke ‘ano e hana ‘ia nei ka wai e ka ‘Oihana Moku.

52 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 53

KK Aia i loko o kekahi puke aʻu i heluhelu ai, he puke i kōkua iaʻu ma ka — ke kūkulu ʻana i kēia ʻano manaʻo ʻana. Ah, ma ka hopena o ka puke, nīnau ʻia ka nīnau — me ia manaʻo e ʻano hoʻoluʻuluʻu ai iā loko, pehea e holomua ai. A ʻo ka haʻina, lilo ʻoe, ʻo ʻoe ka waha ʻōlelo e moʻolelo ai i kēia moʻolelo. No laila ma ka moʻolelo ʻana e hoʻolana ai i kēia. No laila ma ke kū ʻana i mua o ka poʻe, a kēlā ʻōlelo ʻana i mua o kēlā mau kānaka i nīnauele mai iaʻu — hoʻolana ʻia koʻu naʻau, no ka mea, lohe ka poʻe. A ʻo ia wale nō ka mea i hiki ai iā kākou.

ʻO Sitting Bull kekahi. ʻO ia kāna i ʻōlelo ai. A no laila, e ʻōlelo ana ʻo Sitting Bull i kekahi mea maikaʻi loa e hoʻolana ana i ka poʻe i kēlā manawa, a e haʻalele ana ka poʻe, a nui ka hala loa o ka pāpulō, ka poʻe, nui ka maʻi, hoʻoneʻe ʻia lākou, kīpeku ʻia mai ko lākou ʻāina aku, a hoʻolana ʻia ʻo ia, no ka mea nīnau ʻia ʻo ia, “No ke aha ʻoe e hulahula mau ai? No ke aha ʻoe e oli mau ai? No ke aha ʻoe e hoʻolauleʻa mau ai? No ke aha ʻoe e ʻakaʻaka mau ai?” A ʻōlelo ʻo ia, he mau māhele kēlā no ka ʻIlikini ʻana — no kona lāhui. A ʻōlelo ʻo ia, inā hoʻokū ʻo ia i kēlā, hōʻoki ʻo ia i kēlā mau mea a pau, pau kona ʻōiwi ʻana, a no laila, hoʻolana ʻia koʻu manaʻo me kēnā.

HS Me he mea lā, hoʻolana pū ʻia kou manaʻo ma kou kāhea nui ʻana i ka poʻe e komo pū mai. Ah, ua nānā wau i kekahi wikiō i paʻi ʻia. ʻO ʻoe, e walaʻau ana. Nīnau ʻia ana ʻoe e ka mea hoʻolaha nūhou. He aha kāna mea i nīnau aku ai iā ʻoe? A ʻo kāu pane, ʻo “Join us.” Pehea kou manaʻo no ka poʻe i hiki ke huliāmahi mai i ʻaneʻi me ka poʻe e huliāmahi ʻole? Pehea kou manaʻo ma laila?

KK E like me kaʻu ma mua, ʻaʻole kēia he kūʻē ʻana i kekahi kanaka — i kekahi lāhui kanaka. He kūʻē ʻana kēia i kekahi kuanaʻike. A no laila, ʻo ia ʻōlelo ʻana e hoʻopili pū mai nā kānaka a pau. Ah, ʻo ia ʻano ʻōlelo e hoʻopili pū mai ai i ka poʻe i ka mea e hōʻike aku ai, ʻaʻole ʻo ke ʻano o ka ʻili ka mea e kono ʻia ai ke kanaka. ʻAʻole kā lākou ʻōlelo kekahi mea e kono ʻia mai ai lākou. ʻO ka mea wale nō, inā lākou lohe i ke kuanaʻike he — a e ʻōlelo ana wau he kuanaʻike ʻōiwi, kuanaʻike Hawaiʻi, he aha lā — ulu ʻo loko, pili pū mai. A ke ʻume ʻia ka ulu o loko, ʻo ia ka mea nui. ʻO ia ka pahuhopu nui. E kiʻi i ka poʻe a hoʻāʻo, e hoʻāʻo wale nō — e kūkulu i kuanaʻike hou aku, e pono ʻole ai kā kākou mau moʻopuna e hopohopo no ka mau a me ka ʻole o ke ola ʻana. A no laila, ke kono ʻia nei nā kānaka a pau e pili pū mai i kēia kuanaʻike.

HS A ulu ʻo loko, pili pū mai. Nani maoli. ʻO kaʻu e manaʻo nei, ʻo ka mea waiwai loa o kā kāua kamaʻilio ʻana, ʻo kou wehewehe ʻana mai i kēia manaʻo he kaua no ke kuanaʻike kēia. No ka mea lohe mau ʻia ma ka ʻōlelo haole, he culture war, kēlā ʻano. He hukihuki ko kēia lāhui me kēlā lāhui. He kuanaʻike nō. He ʻelua kuanaʻike e hukihuki ana, ʻeā.

KK ʻĒ. Well, ʻaʻole pili wale nō iā ʻAmelika kekahi. No ka mea, ke hana nei nā kānaka ma Kina i ka mea like. Ke hana nei ka poʻe ma ʻĪnia i ka mea like. A ke manaʻo nei kākou i kēia manawa, ʻo ia kuanaʻike ke kuanaʻike e kū ai ke kanaka, ʻo ia ke aliʻi o ka honua. A poina akula, he aliʻi ka ʻāina. ʻAe. ʻO ia ia kaua.

Ua hoʻoponopono ʻia kēia nīnauele i kūpono kona lōʻihi, i mōakāka hoʻi.

54 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 55

Jack of All Trades

Meet Jack Soren, the 26-year-old wave-surfing, graffiti-spraying, mural-painting Native Hawaiian artist inspired by where he was born, raised, and resides: O‘ahu’s North Shore, where culture and commerce collide daily.

TEXT BY NAZ KAWAKAMI

IMAGES BY CHRIS ROHRER

ARTWORK COURTESY OF THE ARTIST

Jack Soren is pensive. He thinks. Hard. When you speak to him, you can see the cogs turning in his head as he sorts out the answer to whatever you have just asked. He thinks intently about what is important to him: Surfing. Dirt biking. Art. Being Hawaiian.

As a child, Soren spent most of his time at the beach, due to his family’s deep connection to the ocean, particularly surfing. Then, as a teenager, he spent most of his time in ditches, spray painting its walls and falling in love with the painted figure. As an adult, Soren parlayed the lessons and techniques he learned in that guerilla classroom into a professional career creating diverse, multifaceted artworks.

Working primarily with paint, Soren’s work has been commissioned for major branding and marketing campaigns by the Vans Triple Crown and Hawaiian Airlines; he has also produced large-scale pieces for clients such as International Market Place and Bloomingdale’s. Given his expertise producing on a grand scale, Soren has been a featured muralist in art events around the globe, including Pow Wow Hawaii and SprayseeLA. Soren believes in sharing aspects of his Hawaiian culture with these outside audiences through his work. In 2021, at a mural festival in Washington D.C., Soren inscribed over his piece, “Ka lā hiki ola,” a phrase about optimism, hope, and looking toward the new day.

Being Hawaiian is very important. For Soren, working as a native artist in Hawai‘i is an incredibly complex position to be in, with many points to be considered, all

of which surface in his paintings. There is responsibility, obligation, passion, and fulfillment in applying his lineage to the work that he creates. In reworking idyllic, postcard depictions of “vintage” Hawai‘i, he attempts - in some small part - to reclaim colonized imagery and make it his own, bringing it back into Hawaiian hands, denying the foreign commercialization of Hawaii, while retaining their depiction of Hawai‘i’s beauty and culture, with recognizable figures and a strong, smooth color palette.

Being the reflective, casually critical artist he is, we asked Soren about being a painter, a thinker, a doer, a studier, a designer, a surfer, a learner, as well as the selfwork needed to learn about himself, his culture, his place, and making art that speaks.

How exactly does one become a professional pretty-picture painter. Did you go to art school?

I graduated with a degree in graphic design from BYU and a minor in entrepreneurship. I think I’ve always known that I wanted to do art because we grew up painting graffiti, but there was never really a plan. Me and my friends would do murals for people every now and then, but not really canvasses. Canvas is a new thing for me.

Were you just tagging?

We would all do lettering, but I was always more drawn to characters and figures. It made it easy to transition from graf to legal murals because I was already used to painting figures on a large scale.

FLUX PHILES | ARTS | 56 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Why’d you stop?

Well, I got married. That’s something. I didn’t want her to have to come get me from a police station or whatever, but I wanted to keep making art, so I made this style as a test run and it took off. Now I make a living off of it.

Wait, what? This whole signature style was made on a whim?

I mean, I guess that’s one way to put it. I just have a lot of different tastes and preferences. My friends said to pick a style, paint five paintings, and see how that goes. I showed it to the Green Room Gallery, and it went from there. Now I’m trying to develop my style based on all of my preferred tastes. My colors are strong, I think. If I paint something in my color palette then my customer base seems to like it and it does well.

A serious question.

Do you like your stuff?

That’s a good question. I ask myself that every day. I think I just get bored quickly. Getting stuck to surf paintings — I want to try different things already. I wanted to go paint a giant walrus in D.C., which I am lucky enough to do, and I appreciate that. I am lucky that I can produce what I want, and it’ll be appreciated by one audience or another. I’m less worried about what the market is going to do or what my audience will think.

You’ve built up a base?

I’ve built up my style and portfolio enough. I think in the beginning I was worried about whether things will sell or will people like this, but I don’t feel that pressure quite as much anymore. I think my style is also just very applicable to branding or apparel or whatever, and that’s given me a lot of great opportunities. I love what I do and I’m grateful that I get to make art for a living.

I might be reading into the language too much, but it sounds like you’re saying that your style is strong and you’re grateful for the opportunities and you love what you do. I asked you if you like your art, and your answer was that you love what you do, which is not really an answer. Maybe I’m overstepping.

No, I’m interested in this rabbit hole. This is an interesting thought.

Well, I’ve seen your character graffiti style of art, and it’s so different from the stuff that you’re making commercially. Maybe you are putting that entrepreneurship degree to use and are putting forward what you think will sell best, and it’s working. But do you like what you’re selling? Man, you really caught me in my words. I’m asking myself a lot of things, which is great! That has value to me. I’ve recently realized that as I talk to people who I admire or look up to for advice, my instinct is usually right, but my mind doubts it and complicates it, so I make the other decision sometimes. Or I’m procrastinating on those instinct decisions. A lot of the time I’ll ask an artist that I admire for advice and he will tell me the same thing that I thought was right a few weeks ago, but am doubtful of, or maybe scared of?

It seems like people who know you for your surfing art, don’t know you for your walrus art, and vice versa. Both of your styles are great, and I can see that they’re beginning to blend into each other a little more. I can see that Hawaiian-ness is important and incorporated. Is there a way to balance those two styles and combine them fully? Or do I need to make an alter ego. Do you know MF Doom? I love MF Doom. He has multiple albums under multiple egos and identities and he kills them all! I love that. It’s a

whole personality and world that he’s building out over and over. I think, for me, the mountain of creating a whole other ego and running two businesses is so daunting that I don’t want to do that, so I’ve been trying to think about how to blend them.

What are your goals with the surf style? Not even professionally, necessarily. What do you get out of it?

I think it’s come from a younger dream to be a part of the surf industry because I was never good enough to go pro like my friends. I grew up on the North Shore and all my friends were sponsored and had all the cool shit sent to them, but I was never good enough for that. I think I found this other route to be a part of that industry. I did the Vans Sunset Pro contest and that was crazy! That was a dream come true. I didn’t get to compete, but I got to decorate the whole thing!

“Decorate” is an interesting word for that.

Well, my art is all over the scaffolding, the street, the apparel, it was great!

Yeah, decorating is just such a sweeter word. I expected a more corporate word, like branding. Ah, yeah, maybe branding is more appropriate. But I made the event look beautiful. I don’t like the business words as much. I think as I get older, I’m realizing that I want to create artwork that’s more consistent. In graffiti, there are no narratives, really, we just paint whatever looks sick. As I get older, I think I want to think more conceptually without overthinking. That’s tough. I overthink.

Soren has been commissioned by clients such as the Vans Triple Crown, Hawaiian Airlines, and Bloomingdale’s.

58 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Soren spent most of his time at the beach as a kid, and spray painting in ditches as a teenager. As an adult, Soren parlayed the lessons and techniques he learned in that surf-street classroom into a career creating diverse, multifaceted artworks.

“I don’t want to be another Hale‘iwa surf artist. I don’t want to be grouped into these sunset-surfer paintings,” Soren says. “That’s why I’m trying to develop more, combine my street style with my surf style to create something more interesting and obscure.”

It’s interesting that you’re an overthinker because I’d describe your art as modest. Not overly detailed, not complicated, very unified.

I think that sort of reflects my surfing — there aren’t a lot of surfers that I’ve painted who are ripping or surfing too aggressively. What I’d like in my surf paintings is to develop a softer palate, not so obnoxious, something more stylistic in my figures. That’s what I’ve been aiming for. I don’t want to be another Hale‘iwa surf artist. I don’t want to be grouped into these sunset-surfer paintings. That’s why I’m trying to develop more, combine my street style with my surf style to create something more interesting and obscure. I like this creative therapy that’s happening here. It’s fun to untangle all of this stuff out loud.

We’ve talked about how important Hawaiian culture and being Hawaiian is to you. Can you speak a little about that? Yeah, it’s important to me. It’s mostly to do with learning and trying to incorporate lessons or values or really any sort of Hawaiian-ness into my daily life because I think that reconnection is really important as a Hawaiian person living in Hawai‘i in the modern day. I also want it to show through in my art. I’ll try and learn one new thing about kalo in order to have a better understanding of the image that I’m painting. Growing up, I wanted to play Playstation and be really involved and assimilated with what Western culture had to offer, but now as an adult, I wish I had taken more of an interest in Hawaiian culture when I was young.

I think that I’m seeing it get diluted and begin to recede, and that scares me, and I want to preserve it as best I can. Like, I’d love for my kids to go to Hawaiian immersion school and get them involved and interested at a younger age and sort of invest forward. Most of this just means doing a lot of research on my end and trying to know as much as I can, trying to understand and appreciate and have a deeper respect and appreciation for Hawaiian culture daily, but especially when I apply it to my artwork.

How do you reconcile that with your postcard-esque Hawai‘i subject matter? It can be seen as a sort of colonized imagery.

Yeah, I can see that. I took this nostalgic look and reimagined it in a more modern way. Deep down, there is

a lot of contradiction. All those postcards, I like the style and the nostalgia, but I wasn’t thinking about the impact of those things on Hawaiian culture at that time, because those are the postcards that sold Hawai‘i. It’s difficult because it’s the style that I like, and I put a lot of my own thought and research, my own self into the subject matter of what I’m painting, but it is referencing this sort of imagery that was detrimental to Hawaiian culture.

You’re a Hawaiian artist painting Hawai‘i. Maybe this is a reclamation of that imagery?

It’s really complicated. I mean, if I’m being honest, I’m an overthinker, but maybe I should be thinking this hard about these things, and I do. I think so much about this contradiction and what things mean and my impact and what my art is saying or doing and how I relate to it and the world that I live in. I’m trying to find it still. I’m trying to find answers and understanding about what I’m doing. I don’t really know yet, and that’s fine, I’m okay with that. I am working toward understanding. I’m trying to be patient and do work and do research and trying really hard, and I know that this is a long game.

I think a lot of artists these days — well, people in any creative field — have a hard time admitting that they aren’t correct or knowing, or sort of without any contradiction at all times. It’s hard for people to not instinctually go, “Well actually I’m right because of this” or “Yes I already knew that.”

Have you read The Four Agreements? You should. It’s a really good book. It taught me to be okay with myself and okay with being on the journey as long as you’re really working at it. I always ask people what they think about what I’m doing or what I’m making and I think it’s a very nice thing to do, but the only answers I ever get are, “Oh you’re doing great!” It’s nice to have someone be real with me and bold enough to ask me about these contradictions because this is the stuff I think about already, and I think there needs to be more discussion and criticism.

I’m pretty good at criticizing. I mean productive criticism.

This interview has been edited by length and clarity.

62 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

The Little Garden That Could

From modest food forests to worm composting, Mā‘ona Community Garden’s hardscrabble efforts take a sustainable stand against food insecurity on Hawai‘i Island.

TEXT BY LINDSEY KESEL

IMAGES BY RONIT FAHL

The 5.4 acres in South Kona where Hawai‘i Island’s first community garden now sits was once a virtual wasteland, degraded by years of neglect and illegal dumping. As a little girl, Chantal Chung would visit a beautiful botanical garden in the very same spot. In 2007, Chung was recruited to help set up a nonprofit that planned to build a multimilliondollar civic center on the Kamehameha Schools-leased land. “I just had a nagging feeling that it should be something else, something better,” she says.

At the time, Chung was working as an ‘Ohana Advocate for Keiki Steps, a Hawaiian culture-based preschool, where she and another mother had recently planted a 3-feet-long, raised garden bed that successfully grew corn and bell pepper. “It’s down closer to the ocean so we really felt like we accomplished something,” she says.

In a twist of fate, several investors backed out of the civic center project when the 2008 recession hit, and Chung set a new plan in motion for a communal garden space that could host farming and conservation ventures. With her longtime friends Lovey Simmons and Hala Medeiros, the trio founded Mā‘ona Community Garden, named for the Hawaiian word meaning “full or satisfied

Co-founder Chantal Chung hopes to empower Hawai‘i residents to create their own economically viable solutions to environmental and social challenges.

FLUX PHILES | ENVIRONMENT | 64 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

after eating.” By growing nutrient-dense, locally grown food through sustainable techniques, they hoped to encourage better physical and mental health among local families, especially Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders affected by chronic disease, and spark cultural connection and entrepreneurship in the process.

But, it would take a laborious grassroots effort to realize their vision. In the four years it took to transform the grounds into arable land, volunteers rem oved 55 tons of rubbish, and recycled and composted much of it. Neighbors offered hauling services, and donated excavator and backhoe equipment. “My friends and I were stripping copper in the bushes,” Chung recalls, “that’s how we made our first few h undred dollars to put gas in the machines and purchase large containers to take away what we couldn’t compost.”

With help from community partners and grants, they planted breadfruit trees and taro, and experimented with composting methods. One of the acres became an experimental food forest and fruit germplasm repository, a valuable resource for Hawaii Tropical Fruit Growers to store and study fruit seeds and genetic material. After six years of groundwork, the garden officially opened to the public in 2014.

Then, in 2016, the garden began the Community Composting Project with Hawaii ‘Ulu Producers Cooperative. Unable to find vermicasting systems, a method of using earthworms to process organic waste, in the United States for less than $10,000, Chung replicated a model from India that cost $500 to build. The 40-by-4-feet bin is populated with Indian blue worms working around the clock to turn thousands of pounds of food and paper waste into organic fertilizer with no effluent or air

Mā‘ona Community Garden offers family and individual garden plots, growing and composting workshops, food plant giveaways and volunteer workdays.

66 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 67

pollution. “These worms have great power,” Chung says. “They eat waste products and output gold!” Sprinkling a single cup of the vermicast around the base of a fruit tree will inoculate the soil around the tree’s entirety. The composting project has been so successful, the garden is now able to offer its worm-made fertilizer to schools and organizations free of charge, and to farmers and gardeners by donation.

In 2021, the garden completed an expanded aquaponics system, comprising four grow areas inside a 3,500-gallon tank. Thanks to the off-grid water catchment and a solar-powered ebb-and-flow pump setup, the closed loop system sustains plants and fish using less water and space than traditional soil gardening techniques. Food plants such as watercress and ong choi thrive next to swimming guppies, which will soon be replaced by awa, ‘ama‘ama, and other fish traditionally farmed by Native Hawaiians.

Currently, Mā‘ona Community Garden offers family and individual

garden plots, growing and composting workshops, food plant giveaways and volunteer workdays. They host a monthly Community Cardboard Shredding Day, where residents can bring in their boxes or pick up freshly shredded cardboard to feed their compost. Plans for expansion include adding two additional worm bins, upgrading the solar electrical system, and building a certified kitchen with attached farmers market, expected to break ground in late 2022.

A goal is to eventually get the community garden’s composting and aquaponics models to turn a profit and create living wage jobs. Chung hopes to empower Hawai‘i residents to create their own sustainable, economically viable solutions to environmental and social challenges. “The idea is to get the template of problem solving out there,” she says. “We want to give people permission to look around at their community and ask, ‘How can we do better with what we have?’ Because no one is more powerful than you and I.”

In 2016, the garden began the Community Composting Project with Hawaii ‘Ulu Producers Cooperative.

Follow Mā‘ona Community Garden on Instagram at @maonacommunity.

68 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

WATCH NOW ONLINE NMGnetwork.com/FLUXTV

‘Ohe kāpala, or bamboo stamps, are used in stamping kapa. Image courtesy of Lehuauakea.

‘Ohe kāpala, or bamboo stamps, are used in stamping kapa. Image courtesy of Lehuauakea.

FEATURES

“I was in love with the word ‘aloha’ … which is getting so hard to say.”—Eric Chock

A Written Movement

After nearly 45 years, Bamboo Ridge Press continues to nurture Hawai‘i writers and preserve their words. Its first issue is a story in and of itself.

TEXT BY KYLIE YAMAUCHI

ARTWORK BY MITCHELL FONG

FEATURE 72 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUX

Iwas in love with the word ‘aloha’ … which is getting so hard to say,” Eric Chock pens in “Poem for George Helm: Aloha Week 1980.” In this elegy, Chock mourns the late Native Hawaiian activist and singer, who disappeared at sea in 1977 while protesting the military bombing of Kaho‘olawe. The local Chinese-Japanese poet conjures a nightmarish yet recognizable image of Hawai‘i: malihini who swarm the islands, commodified expressions of aloha at every turn, an occupied nation plundered of its culture and land. Helm flickers in and out of Chock’s prose — ghostlike, silent, and irredeemable. “There is no chance of seeing him walk up to the stage / pick up his guitar and smile the word at you across the room,” Chock bewails.

Local literature like “Poem for George Helm” depicts a real Hawai‘i — narratives that are typically censored by travel brochures and magazines, unseen by ingenuous tourists, and yet realer than ever. As playwright Darrell H.Y. Lum wrote, “This isn’t standing-in-awe-of or ain’t-it-beautiful nature writing that we’re talking about. It’s chemicals in the milk and water, it’s not washing the car or watering the lawn when there’s a water shortage; it’s volcanic ash in the air from an eruption two islands away or the sky gray with ash from burning sugar cane.” This is the Hawai‘i that he and Chock know from experience. Generations of writers before knew a Hawai‘i bound by colonialism, grown in the plantation fields, and stricken by war. Local literature uncovers every palimpsest of Hawai‘i, no matter how harsh or how beautiful.

Yet prior to the 1970s, Hawai‘i’s local literature was stigmatized and largely went unpublished. Whereas on the continent, an Asian American literary movement was blossoming, sparked by the incendiary words of Frank Chin, Jeffery Paul Chan, Lawson Fusao Inada, and Shawn Wong, the editors of Aiiieeeee!: An Anthology of Asian-American Writers published in 1974. Inspired by the Black Power and Chicano movements of the ’60s, this new movement complicated Asian American

identity and distinguished it from the immigrant identity of their ancestors. “I had the conscious idea that literature of different kinds was essential to different social movements,” Chock recounts. With this as their compass, he and Lum would establish a Hawai‘i-centered literary press, Bamboo Ridge Press, and galvanize a local literary awakening.

Today, the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa’s English department boasts a variety of courses in Hawaiian and Pacific literatures and a faculty stacked with kama‘āina professors. But in 1973, when Chock was a first-year graduate student, the department was strikingly haole. The curriculum eschewed local narratives and local leadership in classrooms in favor of the literary “canon” and transplant professors. The sole Pacific Literature course centered on European stories of the Pacific, like those written by Mark Twain, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Jack London. Such stories, as we know today, perpetuate harmful stereotypes about Hawai‘i, particularly natives, as infantile, idyllic, and savage. Ironically, these were the ideas being taught to local students about their own communities.

The English department of Chock’s time also hosted a visiting writers program which, at first glance, was impressive. Notable American writers such as Allen Ginsberg, Margaret Atwood, and Adrienne Rich led workshops and gave talks to students. But an ignorance of local culture created an undeniable gap between the mentors and students. (According to Chock, one visiting writer urged students to dedicate themselves to European texts.) Meanwhile, at Hawai‘i Board of Education meetings, some residents petitioned against speaking Pidgin in public schools.

Erasing Pidgin, formally known as Hawaiian Pidgin English, would mean cutting out the shared tongue of Hawai‘i’s diverse population and erasing a part of history. We, locals, know the story well because our ancestors lived it. When thousands of Japanese, Chinese, Korean,

The idea to start Bamboo Ridge Press materialized on porch steps one evening in 1977 over beers and card games.

“We realized that theories about literature need to be supported by a critical substructure of scholars, who would write reviews and actual analyses of the work that would bear out some of the theories or contradict them,” Chock explains.

74 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“

Portuguese, and Filipino immigrants flocked to Hawai‘i to work on the profitable sugarcane plantations, a dialect was born. Despite being segregated by plantation rules, immigrant and Hawaiian workers sought to communicate, picking up certain words and phrases from each other’s homelands, eventually forming a dialect that crossed racial lines. Like any language or dialect, Pidgin evolved with each new generation and has become a defining trait of local culture and identity. Yet some residents in Hawai‘i viewed Pidgin, compared to the aspirationally “posh” English language, as atavistic and, thus, detrimental to Hawai‘i’s youth.

“In all these factors, the main underlying point is that we in Hawai‘i are expected to believe that we are subordinate to the Mainland,” Chock posited in 1980 at the Writers of Hawai‘i Conference. “At best, we are expected to believe that we are really no different here and can even be like the mainland if we try hard enough. We are asked to reject the feeling that Hawai‘i is special.”

But as anyone who has lived here has come to know, Hawai‘i is distinct in numerous cultural ways from the continent, not to mention isn’t legally a part of the United States. One only has to read Muriel M. Ah Sing Hughes’s poem “Bebe You Can Be” to understand (or not understand). In one stanza, the poem’s speaker, a mother, urges her daughter, “Be da Grace Kelly you wen see at da movies / So what if you get daikon legs, and lolo Jacob call you spastic / You can always look pretty, and dance good cuz ‘as Hollywood.’” Hughes’s Pidgin rolls off the tongue sweet like li hing mui and savory in its delivery. She doesn’t explain to malihini readers what “daikon” is or what “lolo” means, nor will I attempt to. Every line is an inside reference, with minor Western influences scattered throughout, whether it be Grace Kelly or Evening in Paris perfume. There’s a certain

satisfaction that comes with such poems — in being able to perfectly understand and fluidly recite words that a continental reader would stumble over. The “broken” English feels no longer broken.

Clearly, then, the issue wasn’t that local narratives didn’t exist. It was that local narratives weren’t being included in classrooms or the published page. (Little to no poetry by an Asian writer from Hawai‘i was published from the mid-1930s to mid-’60s.) Local narratives, real and fictitious, manifested predominately in “talk story”—casual conversations told around fishing poles and in the surf lineup, over the dinner table and atop futons, at recess and while in line for Foodland’s poke bar. For Native Hawaiians, these oral narratives are also called mo‘olelo and it can range from an inherited story about one’s genealogy to a supernatural legend of deities. Framed by tradition and spirituality and tinged by the traumas of colonialism, the Native Hawaiian literary tradition of the 21st century underwent its own revival in the late ’60s and ’70s, a period known as the Second Hawaiian Renaissance. Following in the wake of his influential essay “On Being Hawaiian” in 1964, hapa Hawaiian writer John Dominis Holt IV published short story collections and fiction, including his 1976 novel Waimea Summer. Meanwhile, Wayne Kaumuali‘i Westlake experimented with Hawaiian, Western, and Eastern forms in his poetry, reflective of his mixed heritage. Along with both writers participating in local literary circles, Native Hawaiian mele, oli, and mo‘olelo significantly influenced the way local narratives were composed.

In a community abundant with stories, Chock had to dismantle classroom walls to allow for more representation in literature, which was no easy feat. In his first-year of graduate school, he was hired as Hawai‘i’s coordinator for Poets in

the Schools, a national initiative to introduce public school students to poetry writing through visiting poets. He taught students and teachers about the importance of local literature, referencing works by friends and peers, which at the time only existed as drafts or mimeographs.

His colleague, Cathy Song, whose 1983 collection Picture Bride would join the canon of Asian American literature, used crisp and quiet language to reflect on her KoreanChinese upbringing in Hawai‘i, paying homage to her parents and ancestors. Meanwhile, Lum inundated his short stories and plays with boisterous, unapologetic Pidgin, which according to Chock, were favorites among public school students. Then there was Wing Tek Lum, the most published Hawai‘i poet in Asian American poetry collections throughout the ‘70s, who ventured beyond his own experiences in Hawai‘i, New York, and Hong Kong to write about the larger Asian diaspora. If nothing else, Chock’s own poetry nostalgically reentered his dreams and childhood, often musing about his beloved father, as well as fishing. There was no shortage of writers that he could invite into the classroom.