18 | ARTS & CULTURE

The cosmically Black figures of Mark “Feijão” Milligan II, Joseph Han’s debut voice, and weaving legacies with Kekai Naone.

62 | FEATURES

How cartography secretly shapes politics, Josiah Patterson’s spectral images, and the keepers of Kaiser’s.

122 | EXPLORE

Where the kua‘āina lifestyle persists, and an enlightening journey to Kumukahi.

FALL/WINTER 2022 0 03 > 09281 $14.95 US $14.95 CAN 254898 The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FEATURES|

FLUX PHILES

20 | Painting

Mark “Feijão” Milligan II

30 | Literature

Joseph Han

38 | Lau Hala

Kekai Naone

48 | Film

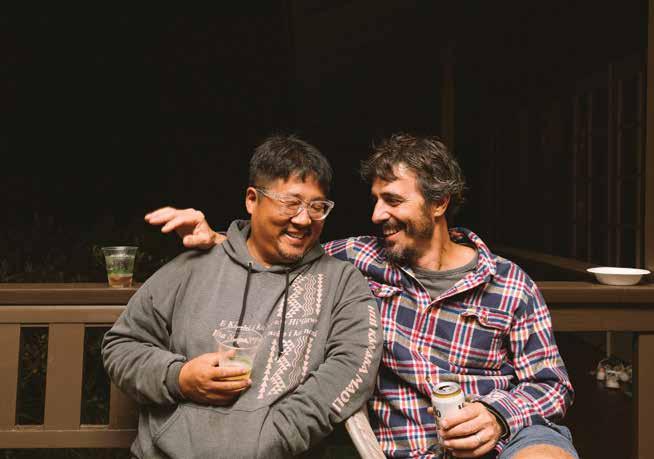

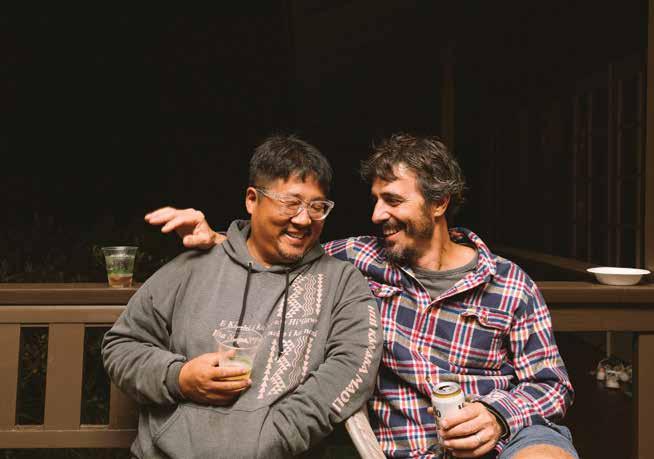

Christopher Makoto Yogi

A HUI HOU

150 | Cerulean

FEATURES

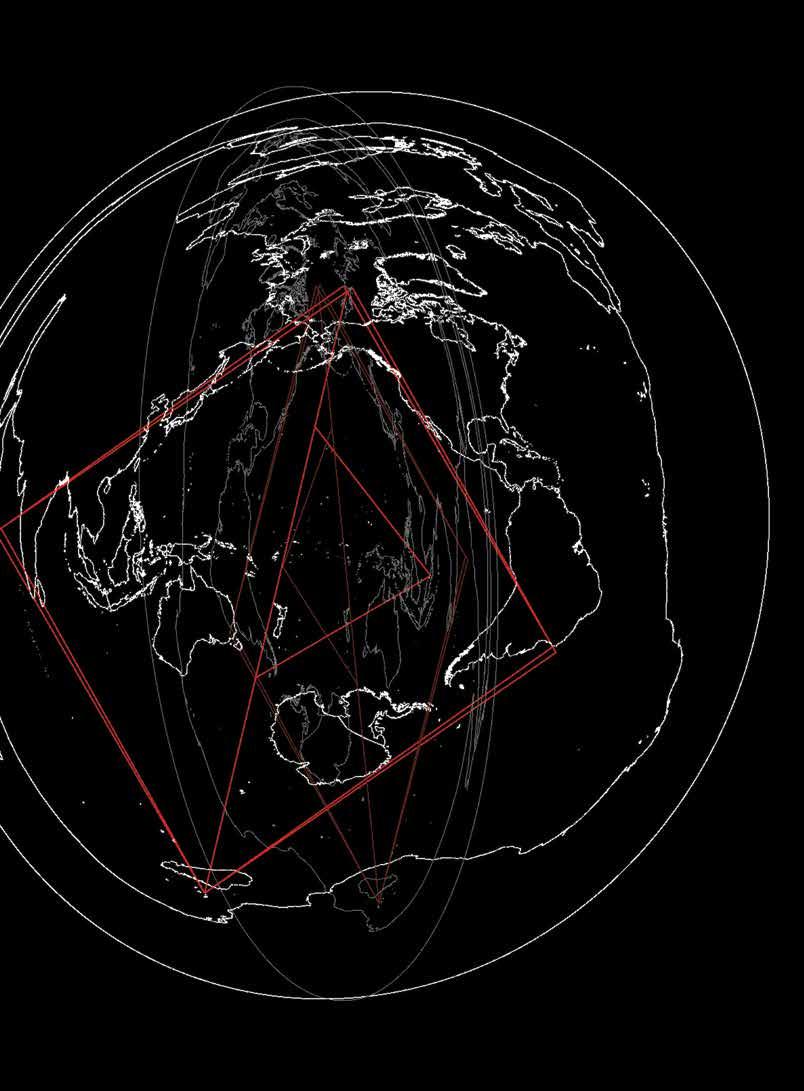

62 | Unsettling Cartographies

Political change depends on getting others to see a story the same way. Writer Jack Truesdale examines the fuel leak at Red Hill fuel and the land the crisis is situated on to reflect on how this stubborn truth frustrates local residents, activists, and Kanaka Maoli seeking justice.

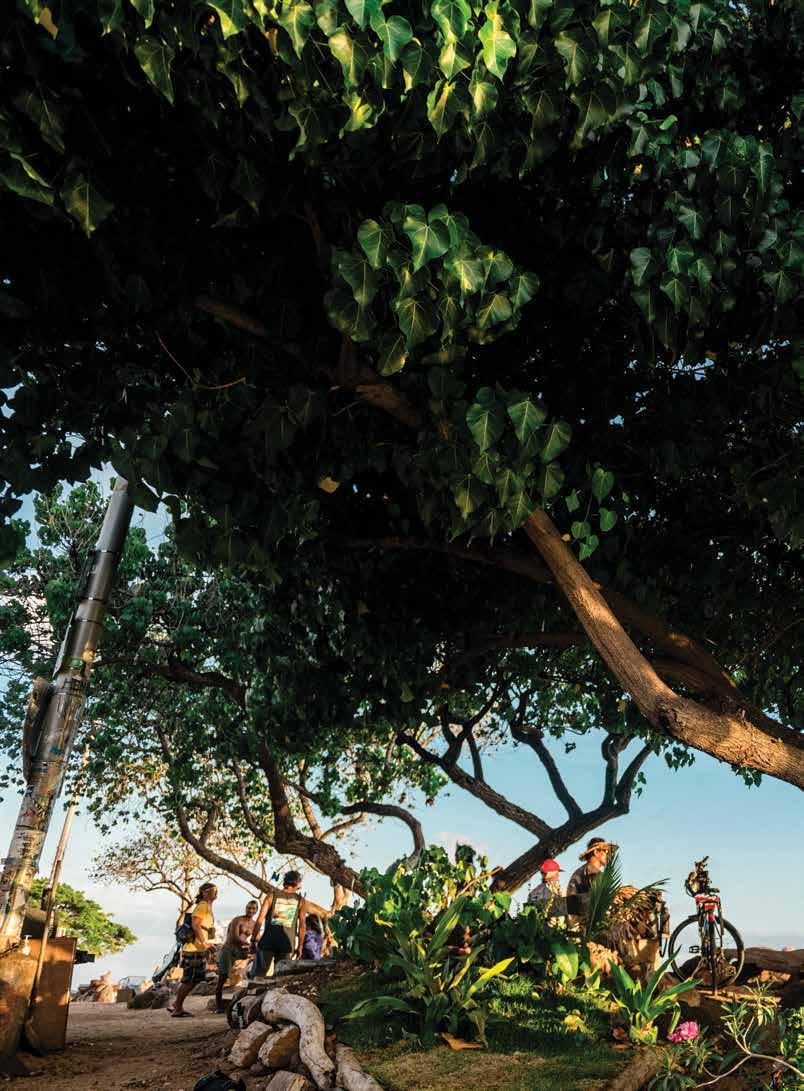

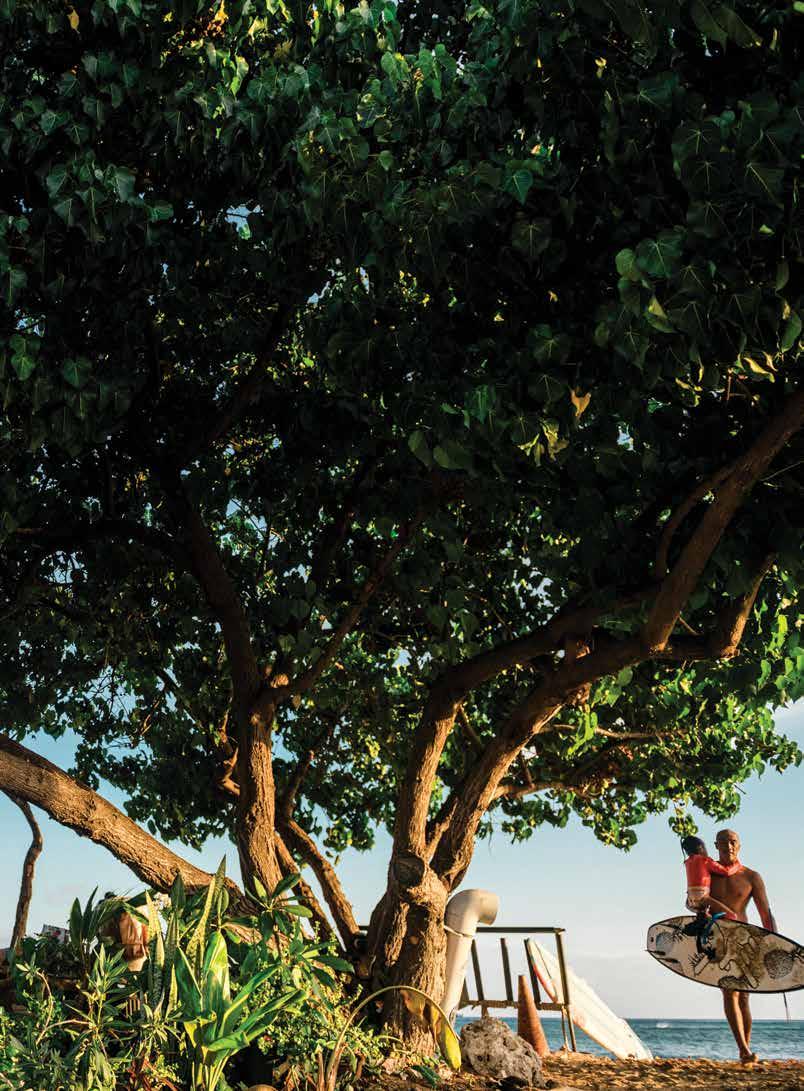

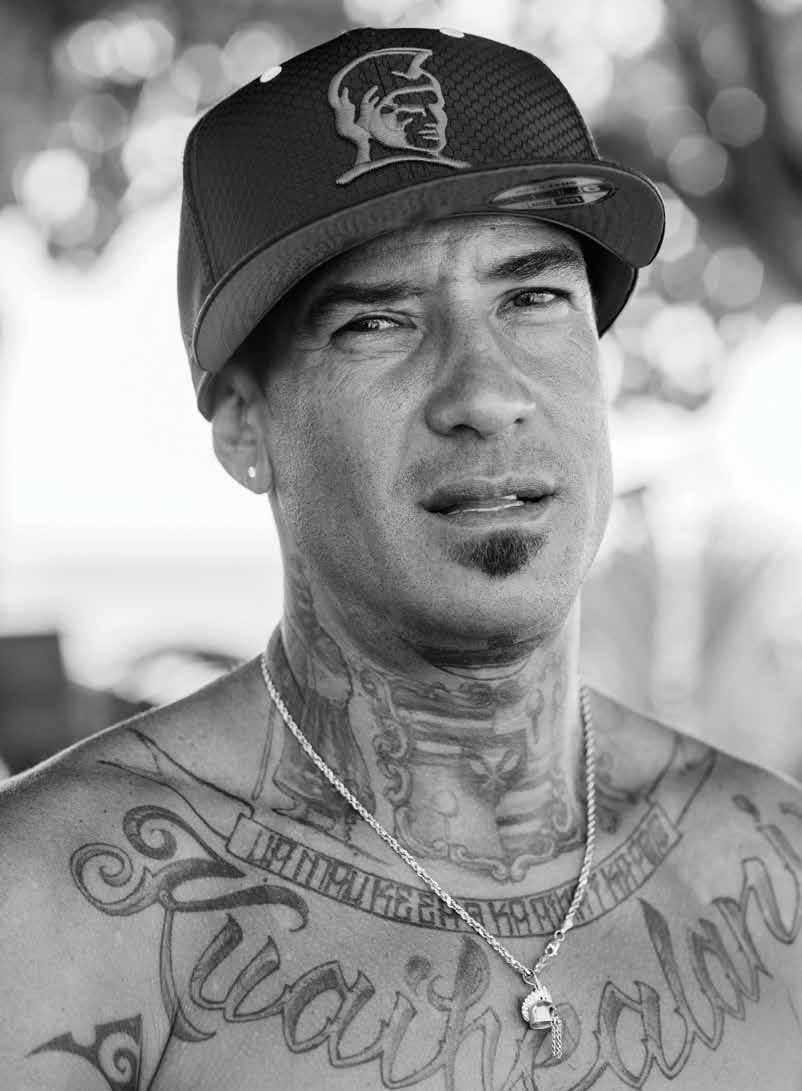

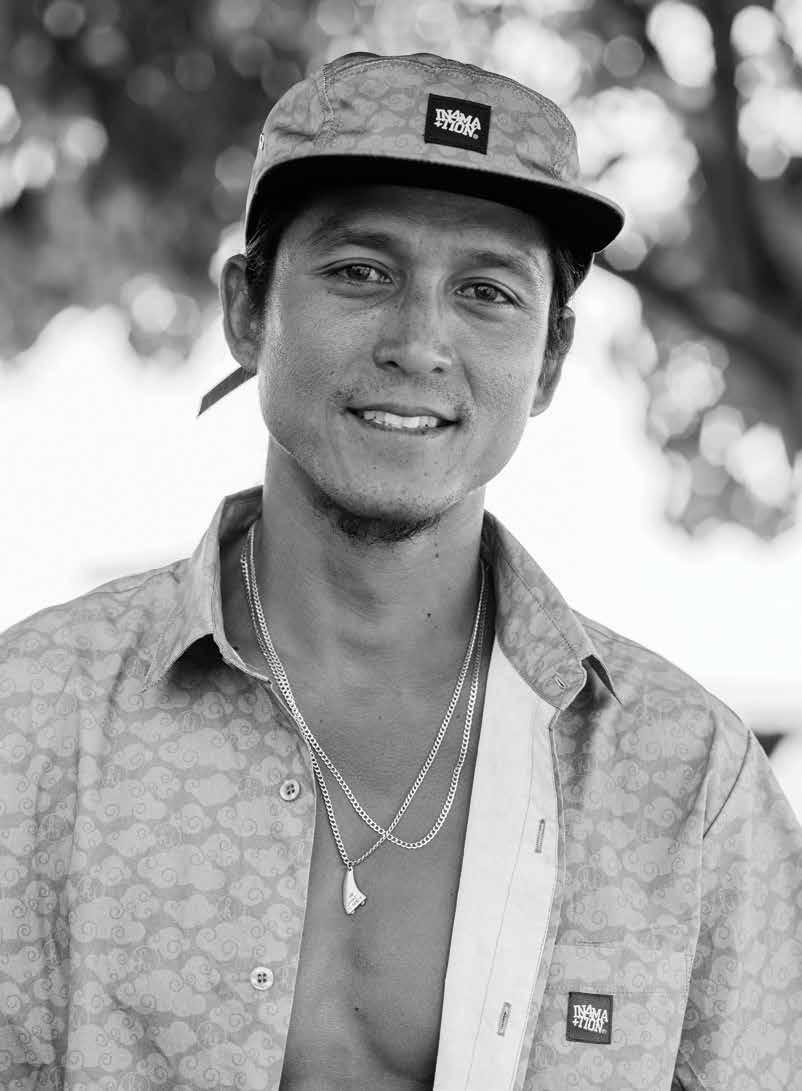

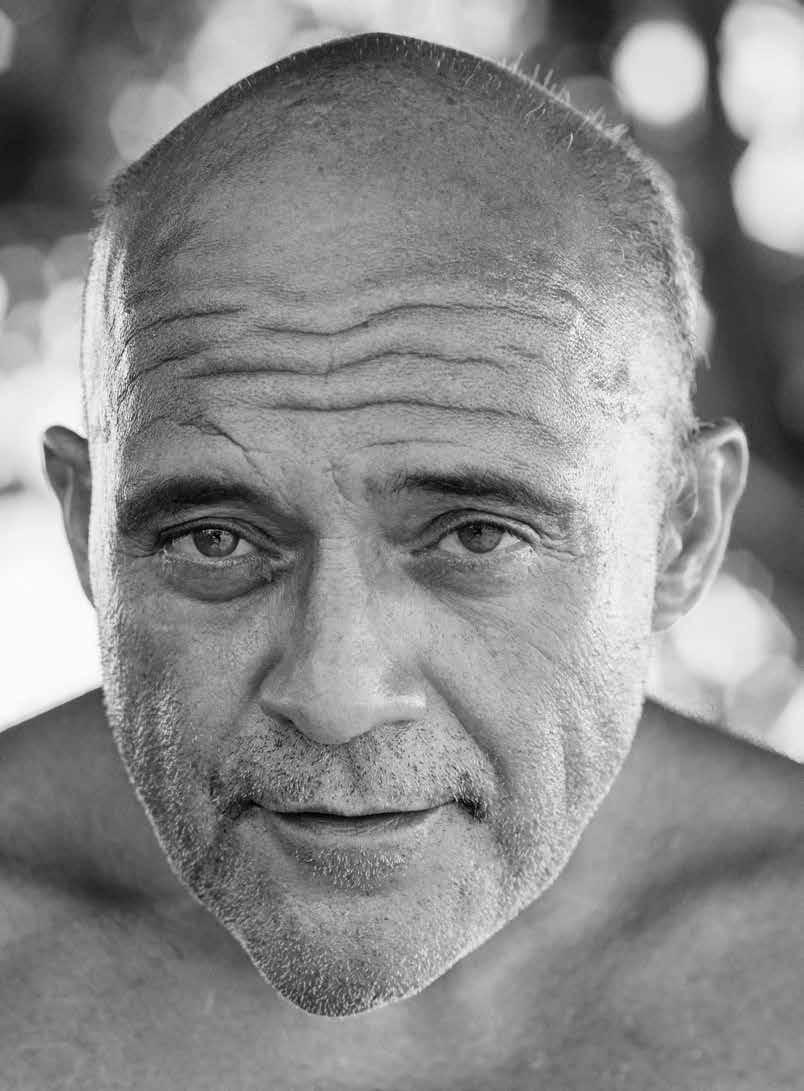

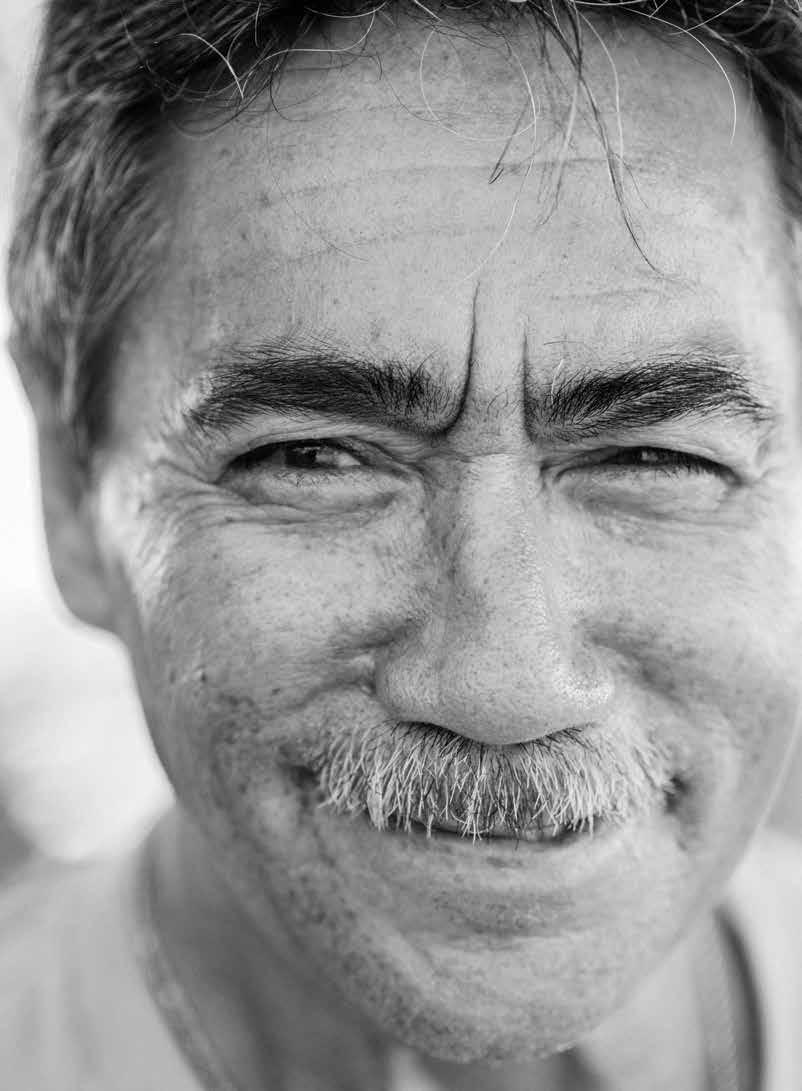

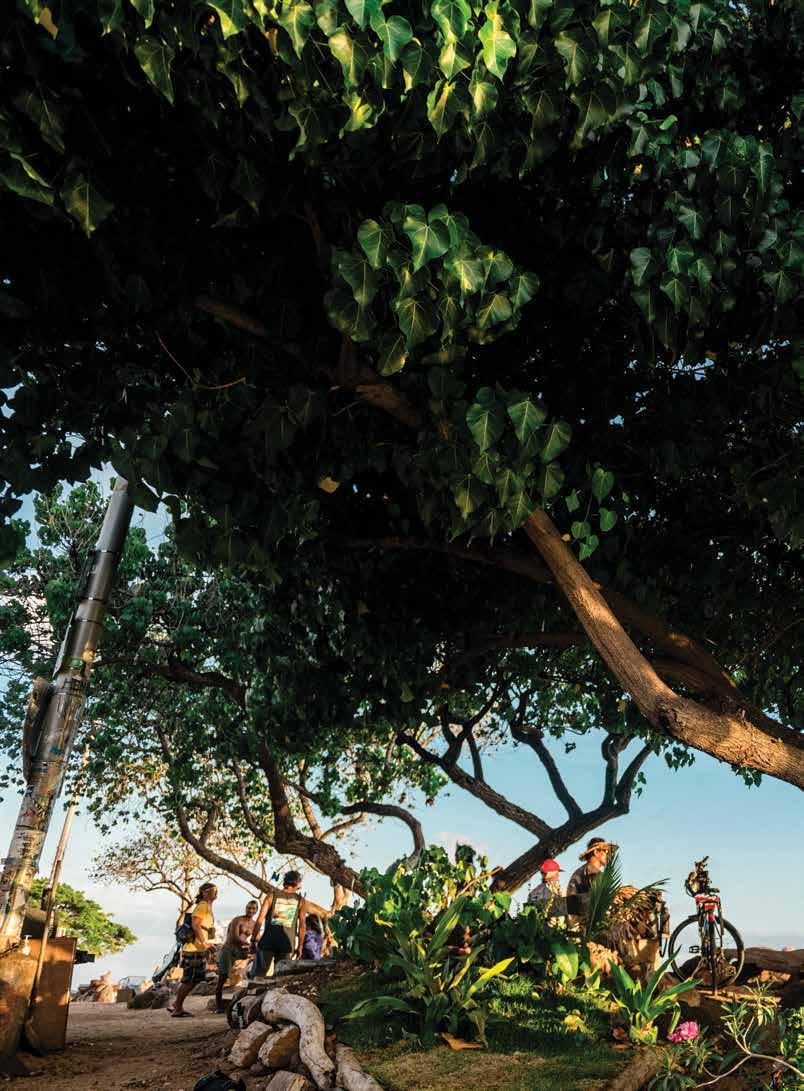

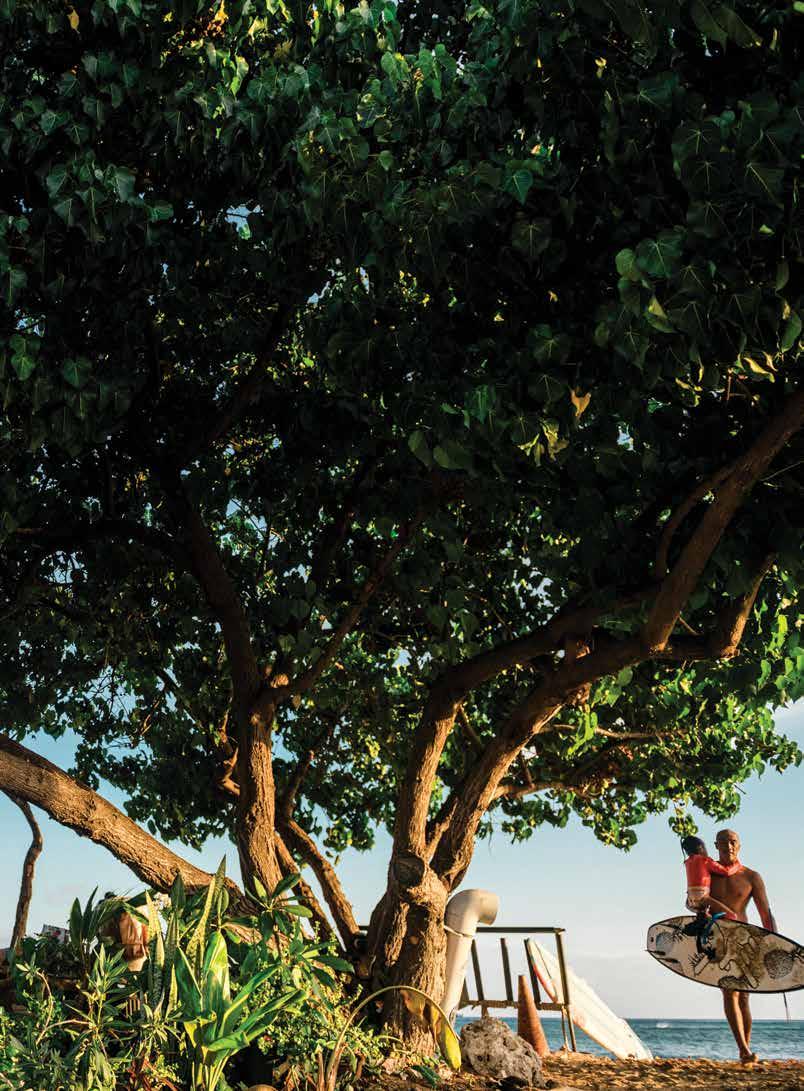

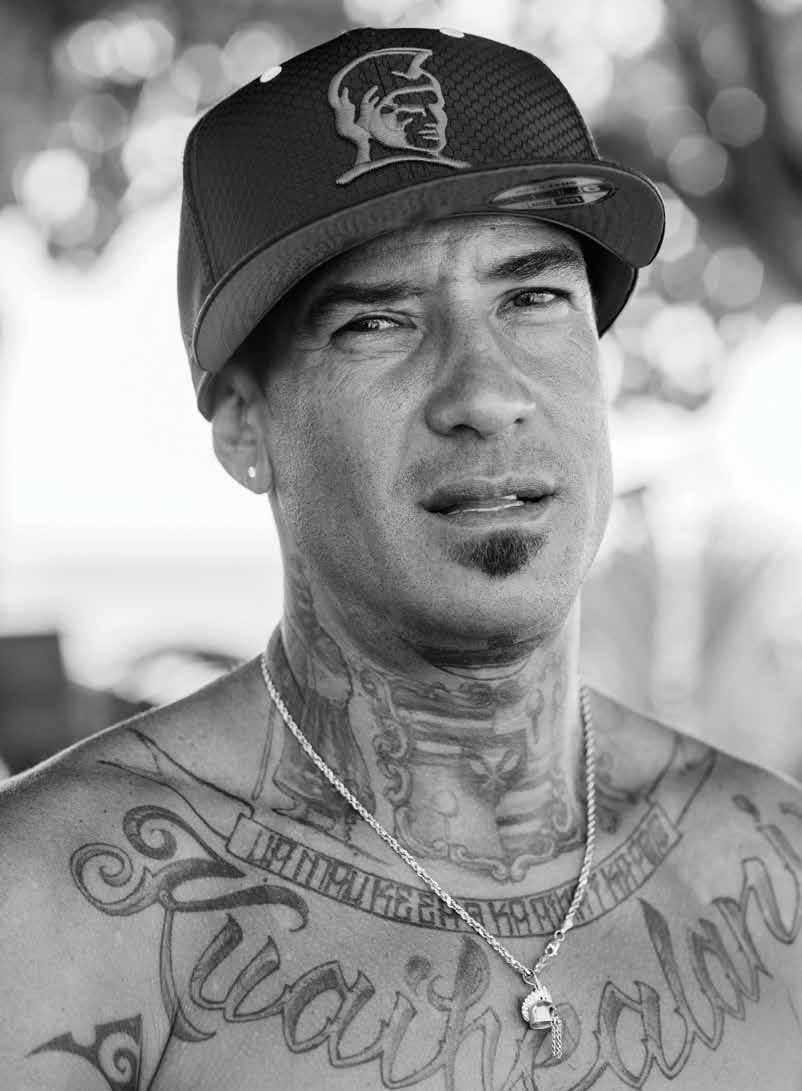

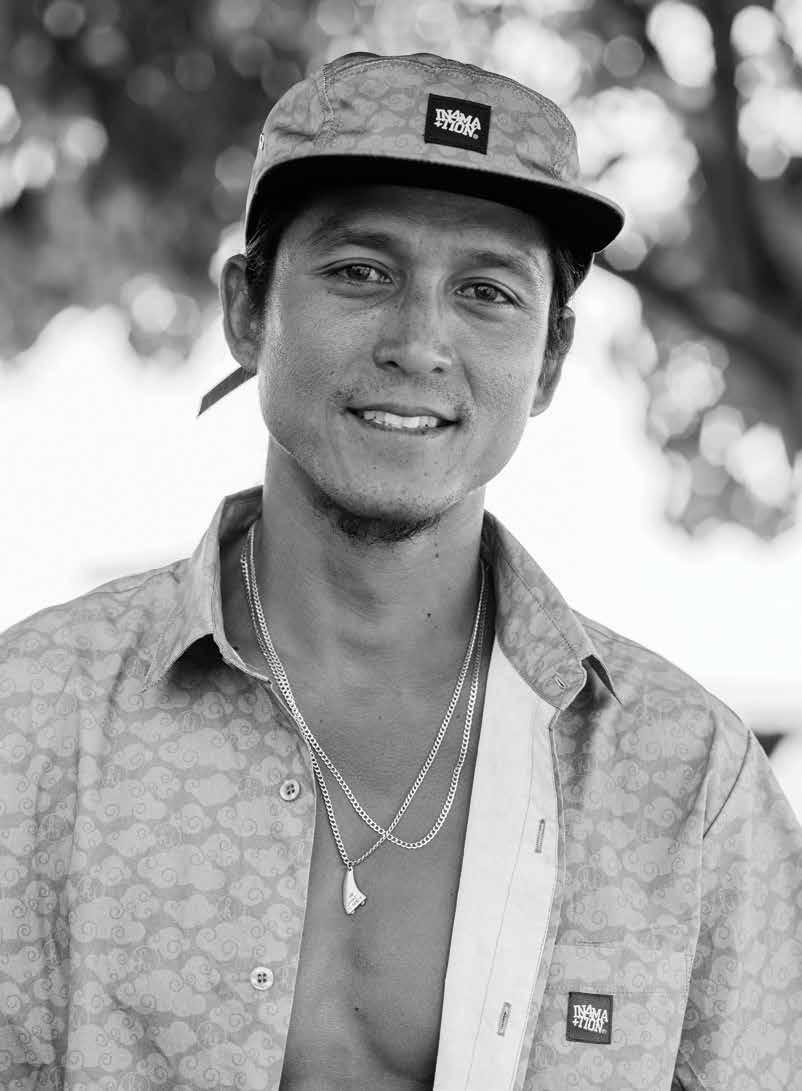

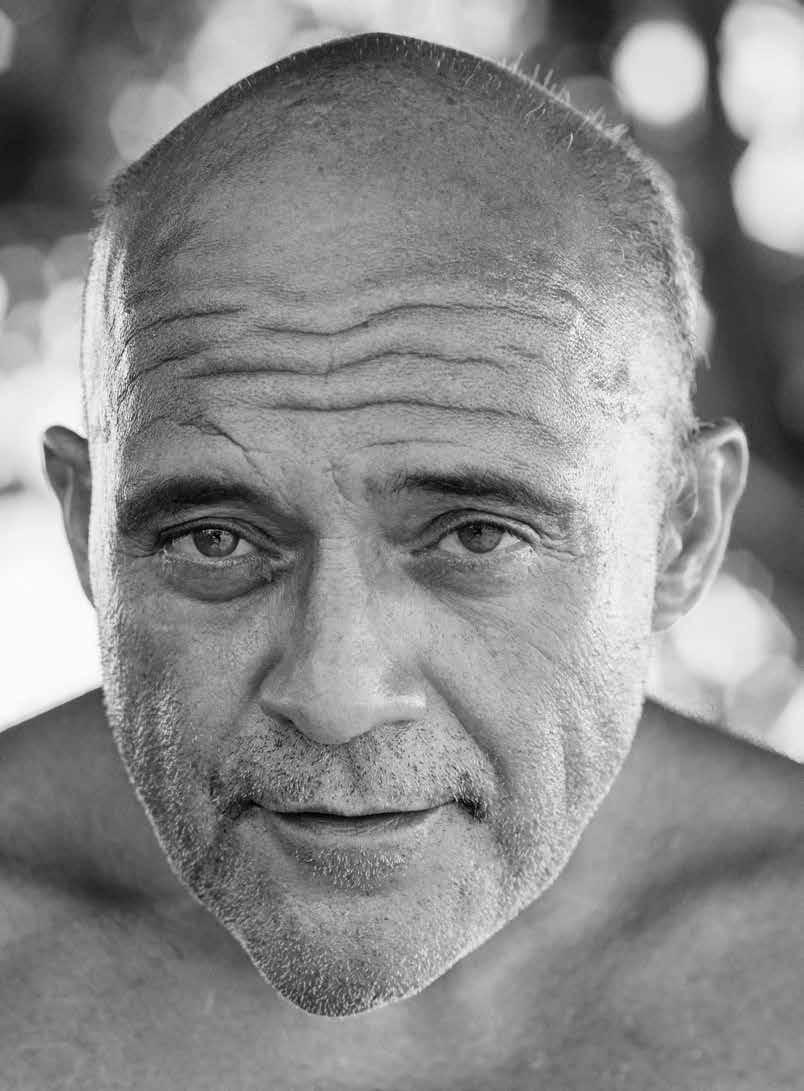

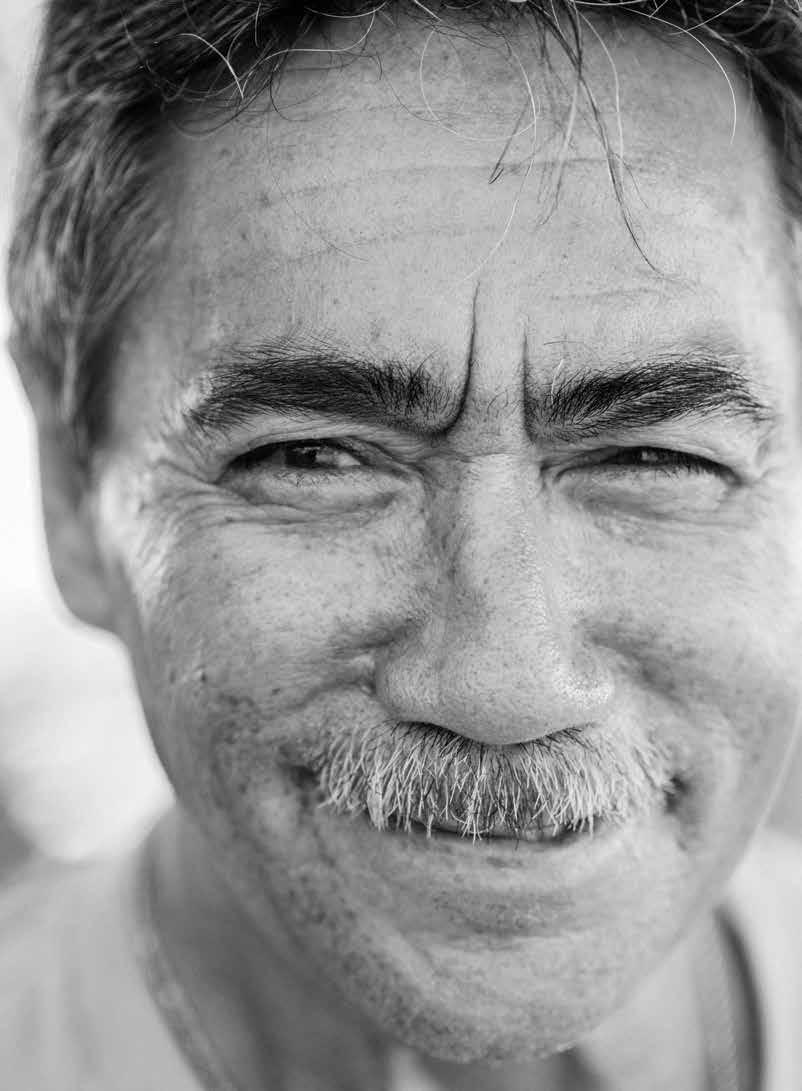

70 | Keepers of Kaiser’s

For generations, a group of local surfers known as the Kaiser Surf Crew—friends, brothers, fathers and sons—have established a presence in and out of the water. Senior editor Rae Sojot gathers their stories.

96 | Making It in Mō‘ili‘ili

In learning a neighborhood’s labor history and modern-day eccentricities, writer Sarah Burchard manages to cope with loss and find the resilience to move forward.

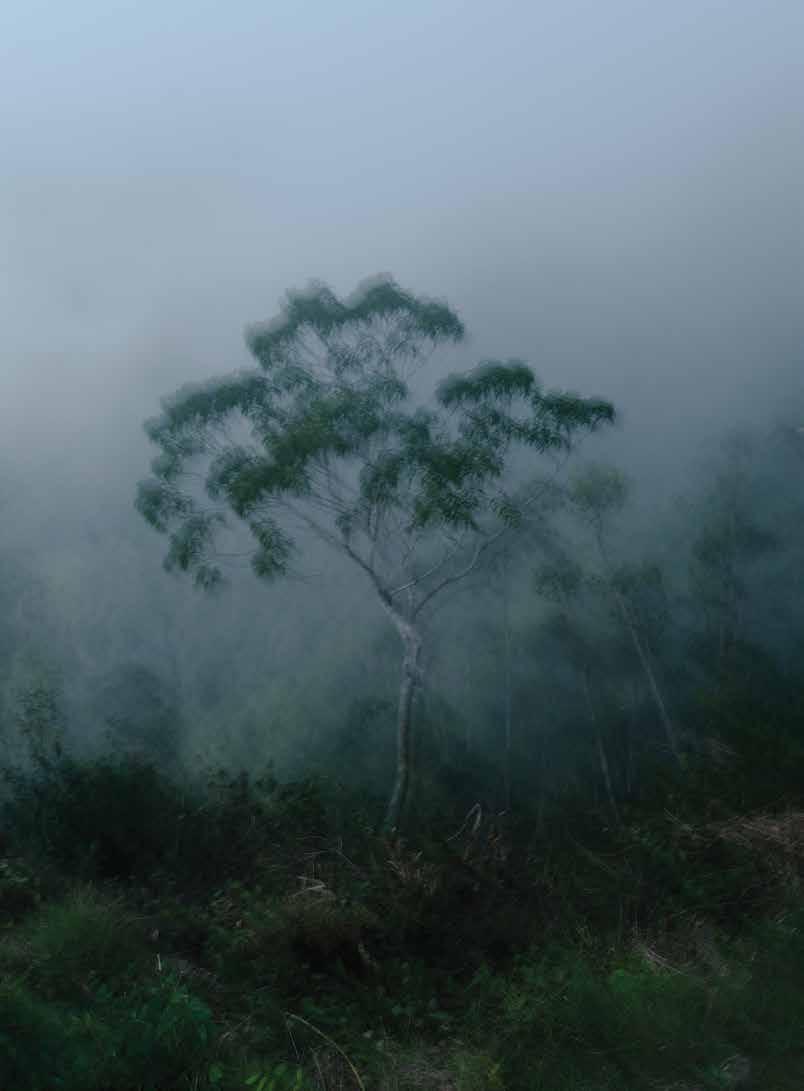

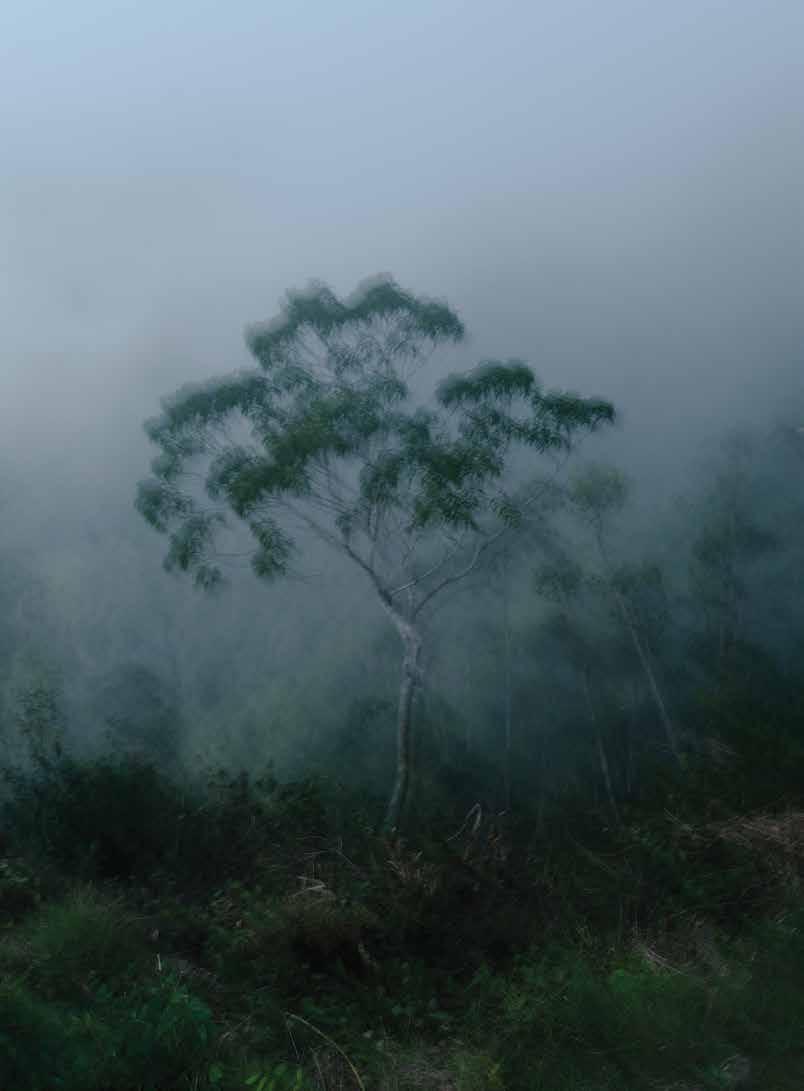

110 | Island Gaze

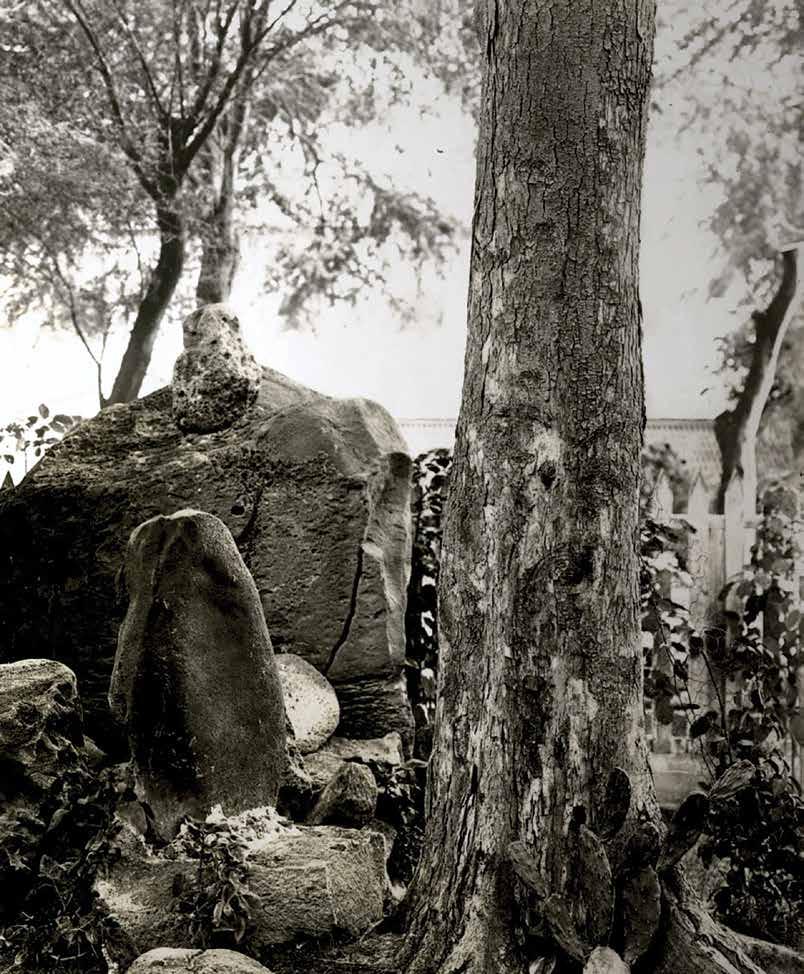

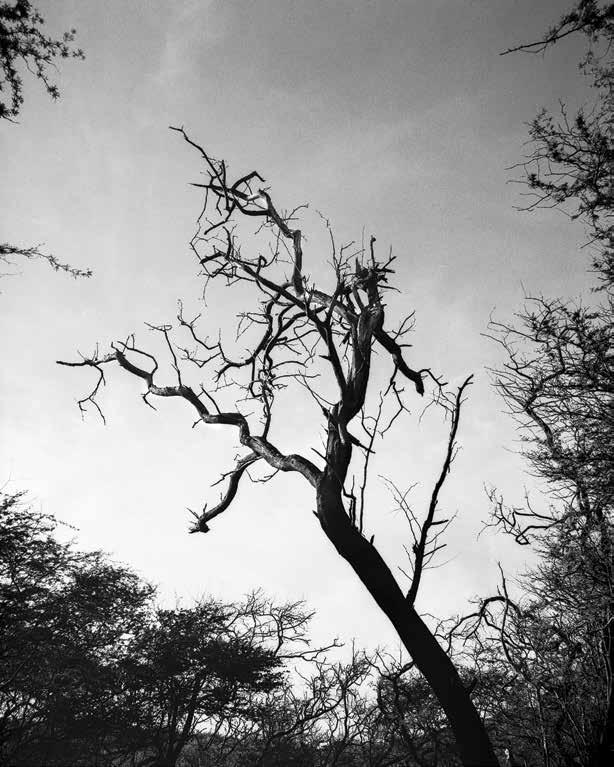

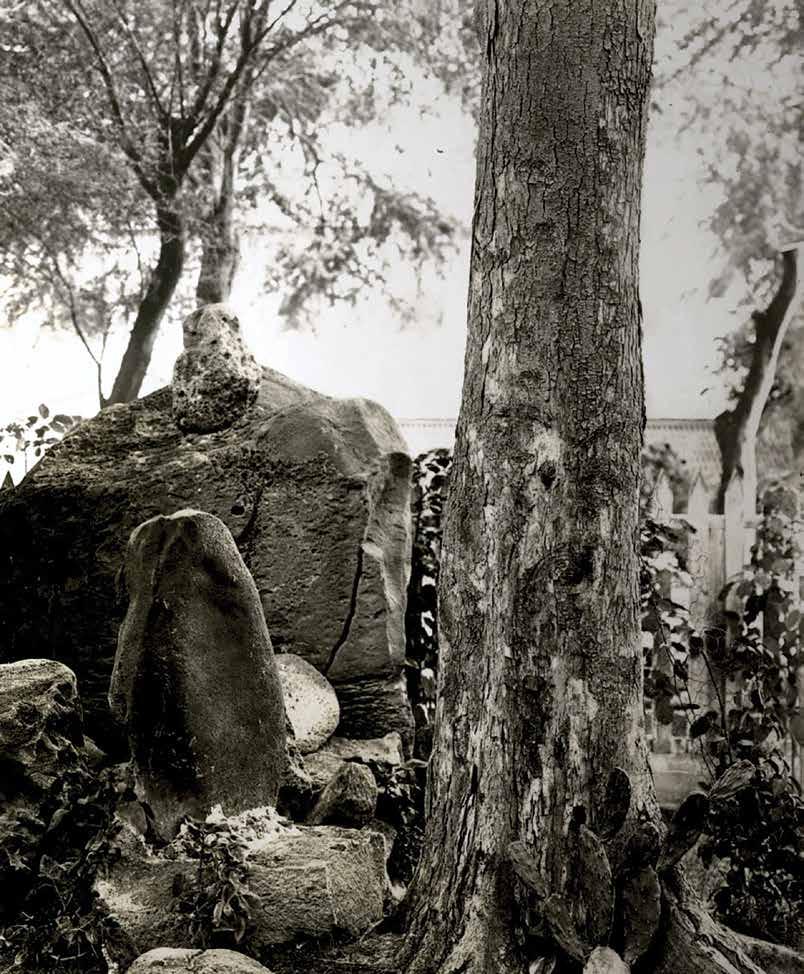

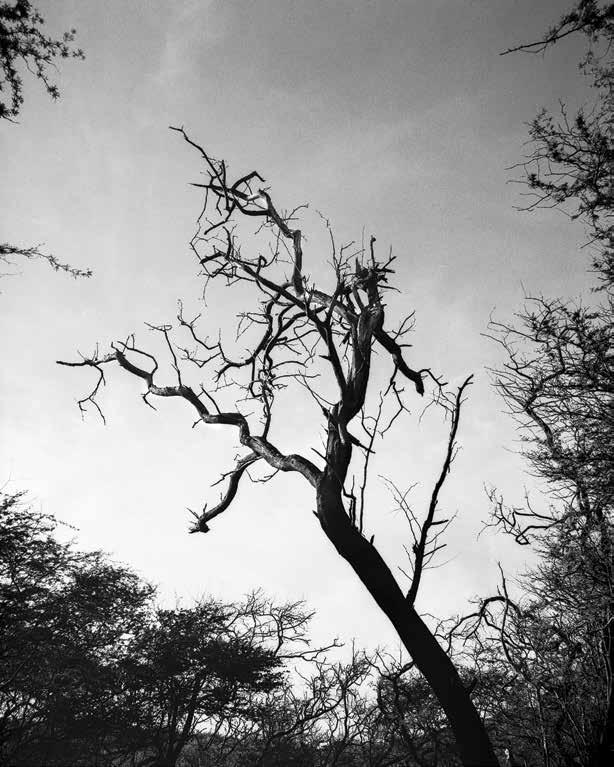

In the images of Kanaka Maoli photographer Josiah Patterson, a portfolio that speaks to the enigmatic nature of his O‘ahu home.

|

F/W 2022

Still from Christopher Makoto Yogi

6 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

142 LIVING WELL 144 | Kapaemahu Healing Stones 122 EXPLORE 124 | Food Hana

132 | ‘Ōlelo Kumukahi TABLE OF CONTENTS | DEPARTMENTS |

Kū

Image by Josiah Patterson

8 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Image by Viola Gaskell

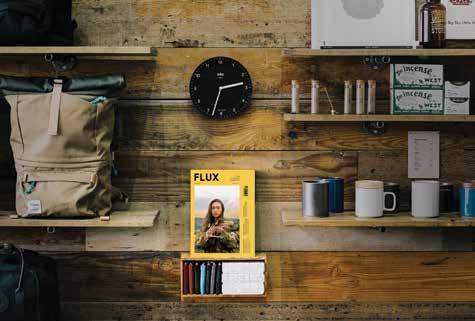

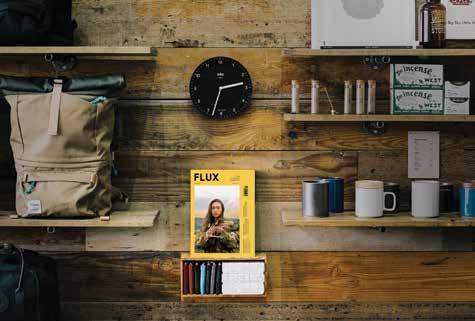

Stay current on arts and culture with us at: fluxhawaii.com /fluxhawaii @fluxhawaii @fluxhawaii INFLUX TV Sweetly Homegrown ‘Ulu and Kalo Bakery TABLE OF CONTENTS | VIDEO | Still from IN FLUX Still from IN FLUX 10 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Streaming Videos, Newsletters, Local Guides, & More

We’ ve refreshed the website for Flux Hawaii with a more dynamic viewing experience. Watch all the original episodes from our themed seasons, find ways to support local small businesses, and sign up for our weekly newsletters curated with fascinating reads. You can also browse past issues of the print magazine for purchase.

On the Cover

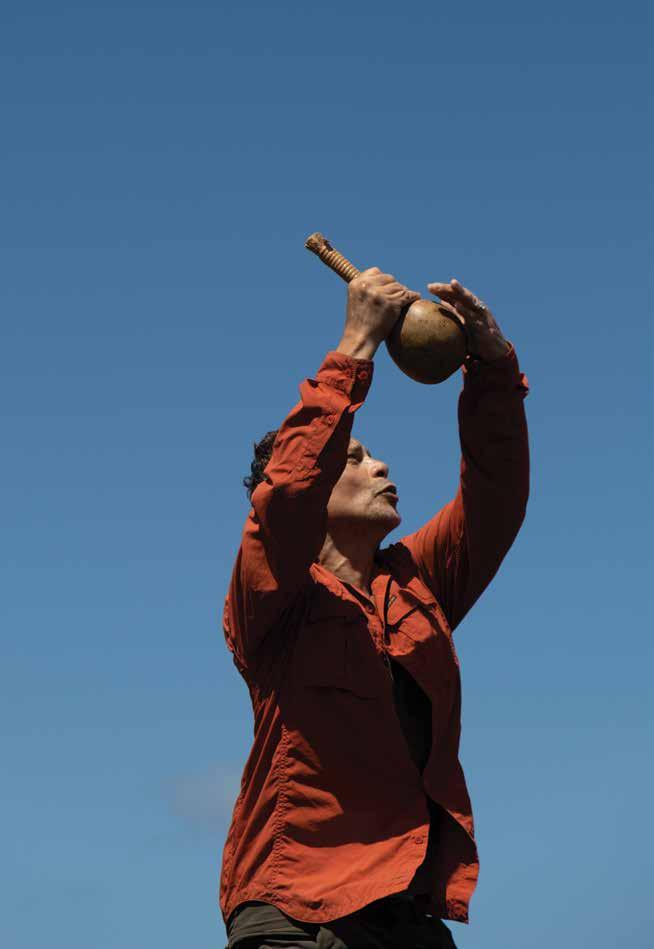

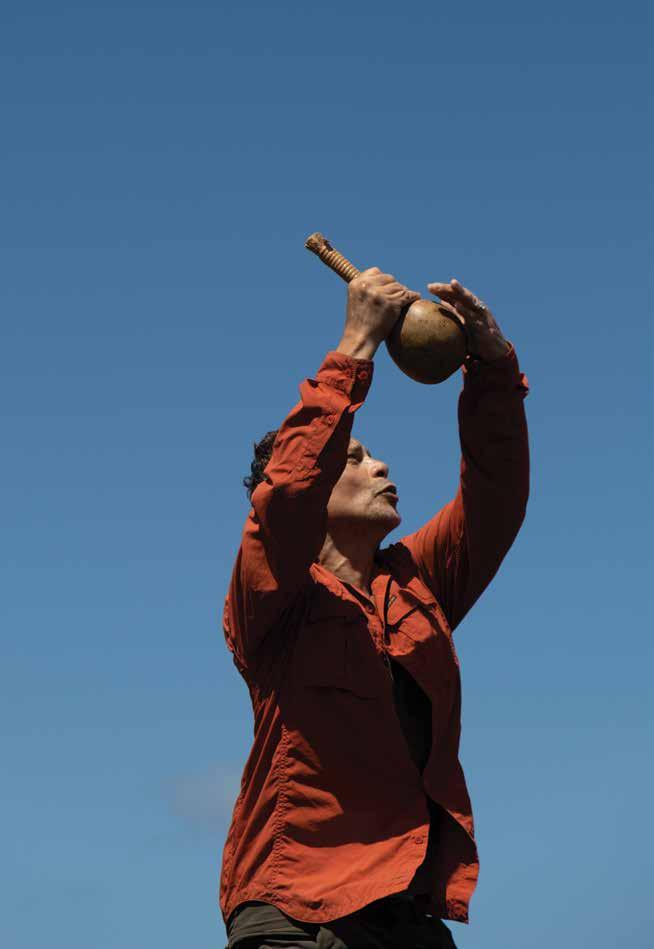

Three images highlighting stories from inside the issue. Clockwise from right: 1.) Portrait of Iosua Stevens at the beach, photographed by Josiah Patterson; 2.) the hands of Kekai Naone, gathering lau hala, and 3.) kumu hula Taupōuri Tangarō, in protocol at Kumukahi, both on Hawai‘i Island and photographed by Keatan Kamakaiwi.

| ONLINE | FLUXHAWAII.COM

TABLE OF CONTENTS

12 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

VP BRAND DEVELOPMENT

Ara Laylo

GLOBAL EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Brian McManus

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Lauren McNally

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Matthew Dekneef

SENIOR EDITOR

Rae Sojot

DIGITAL EDITOR

Eunica Escalante

SENIOR PHOTOGRAPHER

John Hook

PHOTOGRAPHY EDITOR

Samantha Hook

DESIGNERS

Nico Enos

Taylor Niimoto

CONTRIBUTORS

Vincent Bercasio

Sarah Burchard

M. Kaleipumehana Cabral

Frank E. Ka‘iulani Damas

Viola Gaskell

Krystal Hope

Mitchell Kuga

Jackie Oshiro

N. Ha‘alilio Solomon

Jack Truesdale

Kylie Yamauchi

IMAGES

kekahi wahi

Kevin Brock

Mahina Choy-Ellis

Sean Connelly

Viola Gaskell

Keatan Kamakaiwi

Josiah Patterson

Pūlama Long

Mark “Feijão” Milligan II

Christopher Makoto Yogi

CREATIVE SERVICES

Marc Graser VP GLOBAL BRAND

STORYTELLING

Gerard Elmore VP FILM

Blake Abes

Romeo Lapitan

Erick Melanson FILMMAKERS

Jhante Iga VIDEO EDITOR

Kaitlyn Ledzian BRAND & PRODUCTION MANAGER

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock PARTNER/GENERAL MANAGER – HAWAI‘I

Francine Beppu VP INTEGRATED MARKETING francine@NMGnetwork.com

Gary Payne

VP ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE

Brigid Pittman

DIGITAL CONTENT & SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER

Sheri Salmon CREATIVE SERVICES MANAGER

Sabrine Rivera OPERATIONS MANAGER

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley VP SALES mike@NMGnetwork.com

Courtney Asato MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

Nicholas Lui-Kwan ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE

Taylor Kondo BRAND PRODUCTION COORDINATOR

General Inquiries: contact@fluxhawaii.com

PUBLISHED BY: Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel St., Ste. A Honolulu, HI 96817

©2008–2022 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. ISSN 2578-2053

MASTHEAD | FALL/WINTER 2022 | 14 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

CONTRIBUTORS

Mahina Choy-Ellis

Born and raised in Kalihi Valley, Mahinahokukauikamoana Choy-Ellis is a Kanaka photographer who picked up a camera at 12 and never put it down. With a curiosity that knows no bounds, Choy-Ellis and her camera can be found spending time photographing professors to drag queens, and is grateful for every journey. After eight years in New York City, she felt the call to return back home to Hawaiʻi and has since found creative support from the Lāhui and Māhūi, finding her main inspirations from both. She finds joy in capturing local artists, performers, and beyond. In this issue, she photographed Joseph Han for a profile on page 30. “It was a joy to simply talk story with a brilliant author like Joseph,” she said. “It was only fitting that we spent our time together at the Hawai‘i State Art Museum, surrounded by works with strong connections to Hawaiʻi. I loved listening to the inspirations behind his latest novel and can’ t wait for the world to hear more from this storyteller.”

Krystal Hope

Krystal Hope is an AfroGuyanese American woman raised between Guyana and New York City. She is a subversive, pro-Black feminist who examines the intersections of culture to identify opportunities for collective liberation. Her interest in decentering Western ideologies brought her to Oʻahu to complete her master’s degree in Communication at UH Mānoa. Her work critiques homogeneity and encourages subaltern representation in media. In 2020 she founded KHopeacetic, a digital communications and marketing consulting company that helps missiondriven entities achieve their goals. When not practicing her craft, she consumes an inordinate amount of books, watches terrible reality TV, practices photography, and wanders around art spaces. She interviewed artist Mark “Feijão” Milligan II on page 20. “I am struck by how Mark uses his imagination and curiosity to capture the finer details of Blackness,” Hope said. “ Viewing his artwork is like seeing yourself through the eyes of someone who already loves you as you are.”

Jack Truesdale

Keatan Kamakaiwi is a photographer born on the Island of Hawaiʻi and raised on Oʻahu. Growing up, he had always known that he wanted to pursue the creative arts and just happened to discover photography. Kamakaiwi started taking photographs in high school, then took a break, but the 2019 protests on Maunakea reignited his practice. A friend and contemporary of his, the photographer Marie Eriel Hobro, asked if he could help photograph and interview some of the people involved on the mauna. Since then he has made images of local people, small businesses, and island-based programs. Kamakaiwi photographed two stories in this issue. For a profile on lau hala weaver Kekai Naone, on page 38, Kamakaiwi said witnessing “the amount of patience it takes really changes your perspective when you see a pāpale or anything handwoven.” On his journey to Kumukahi, for the story on page 132, he added, “to learn about the moʻolelo of the stones, then to see it in person gave me chills.”

Neither born nor raised in Hawaiʻi, Jack Truesdale hails from the icy hinterlands of Massachusetts. Family, William Finnegan’s Barbarian Days, and a fascination with Hawaiʻi’s history, both past and present, brought him to the islands. He initially was based on Maui, where he wrote for local newspapers and now contributes to surf magazine Stab. In August 2022, he moved to Oʻahu and joined the Honolulu Star-Advertiser as a reporter. He holds a bachelor’s degree in English Literature from Brown University. For this issue, on page 62, Truesdale reflected on the Red Hill fuel leak crisis at Kapūkakī and how reimagining and recontextualizing the landscape might reshape the ongoing narrative.

“I was surprised to learn how much conventional mapping obscures Hawaiʻi’s history and culture, and how conversation and a little digging can resurface those old but not out-ofdate stories,” Truesdale said. “These stories live on, and re-enliven the land, if you know where to look.”

|

| FALL/WINTER 2022

Keaton Kamakaiwi

16 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Scene from I Was a Simple Man . Still from Christopher Makoto Yogi.

Scene from I Was a Simple Man . Still from Christopher Makoto Yogi.

ARTS & CULTURE

“Fiction became a home for me, a place where I can return to articulate the important connections that continue to shape who I am and what I live for.”—Joseph Han

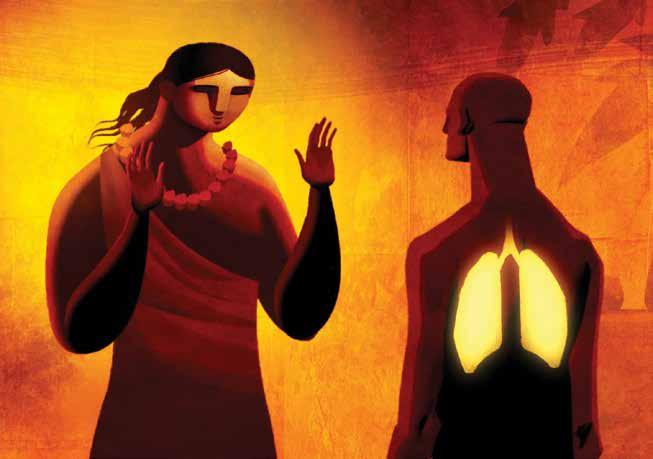

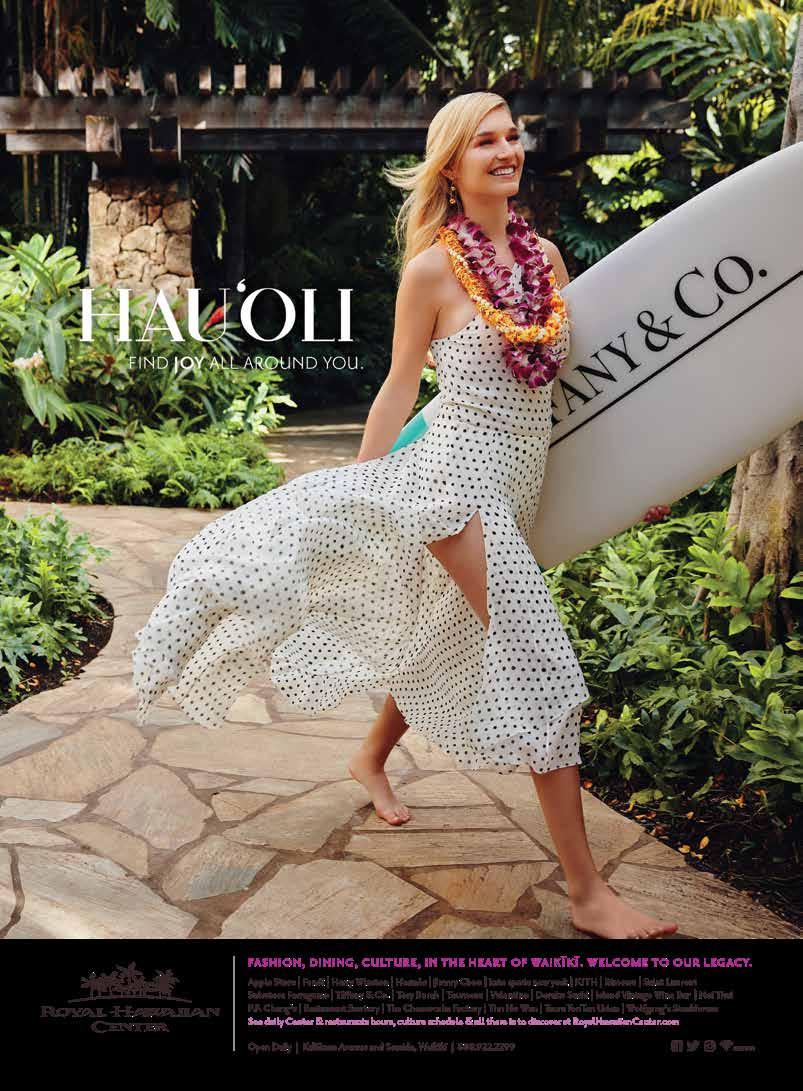

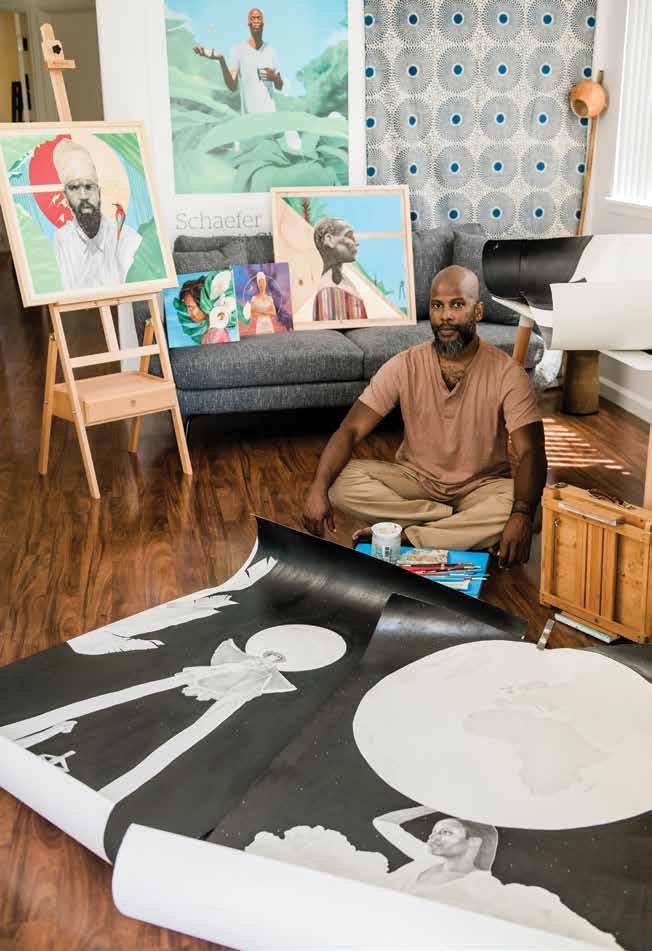

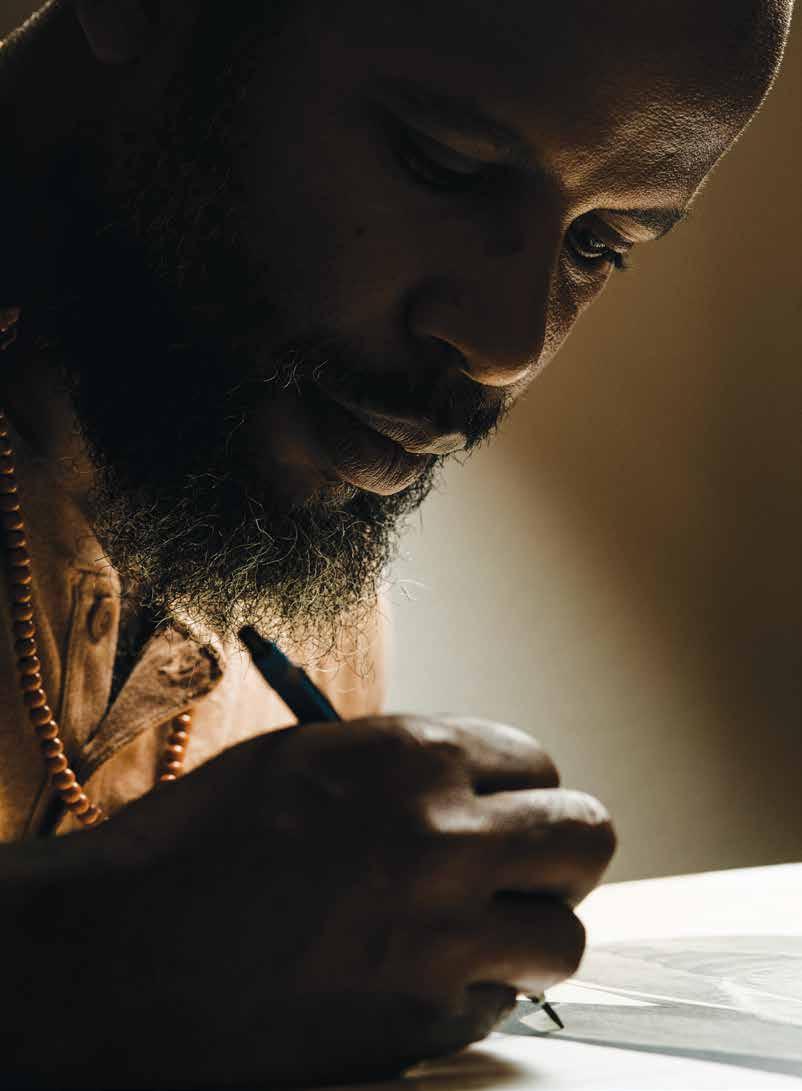

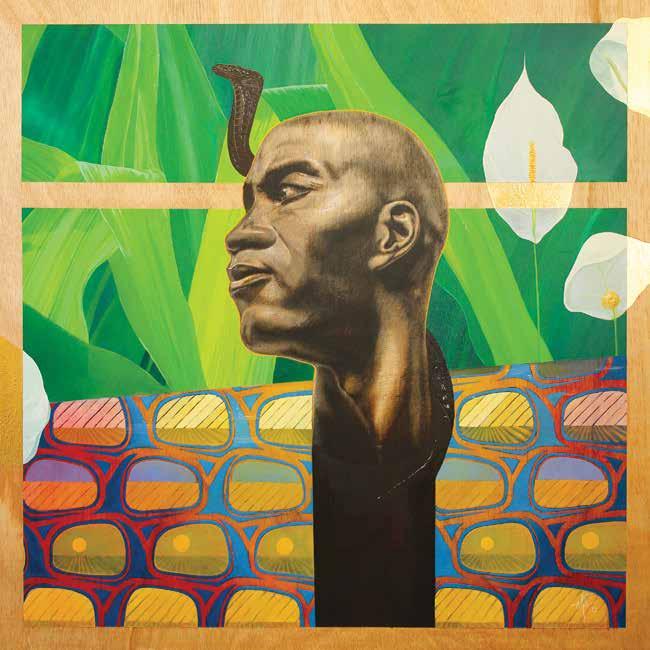

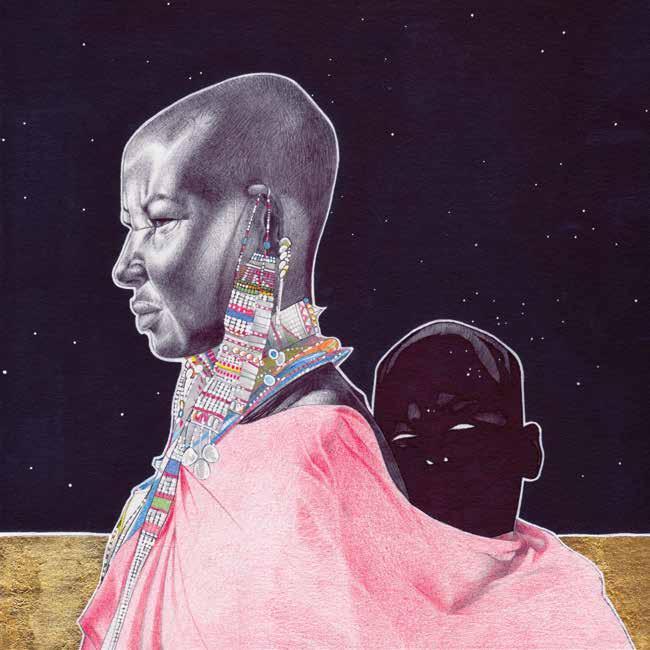

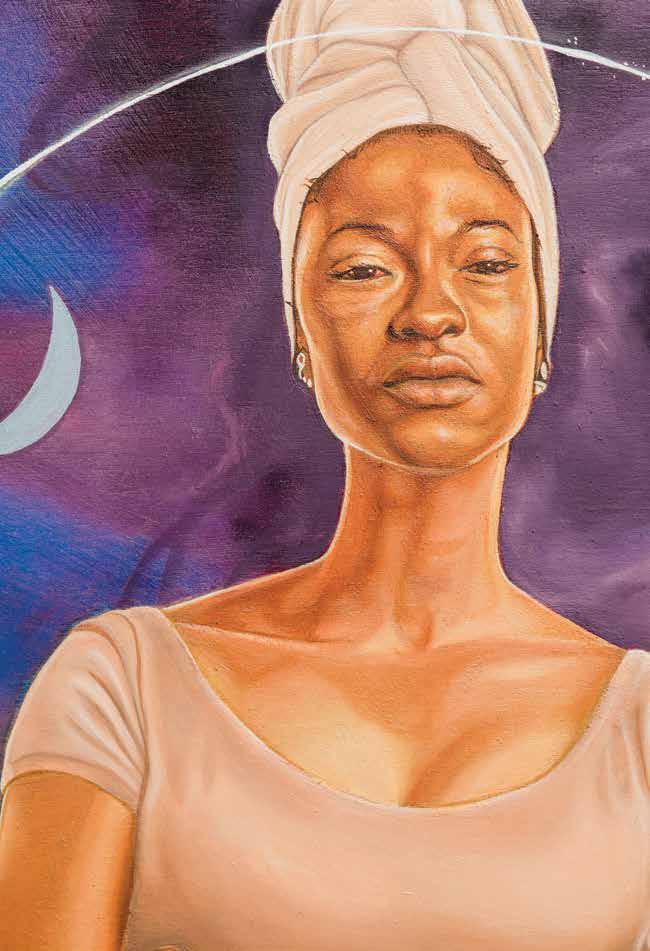

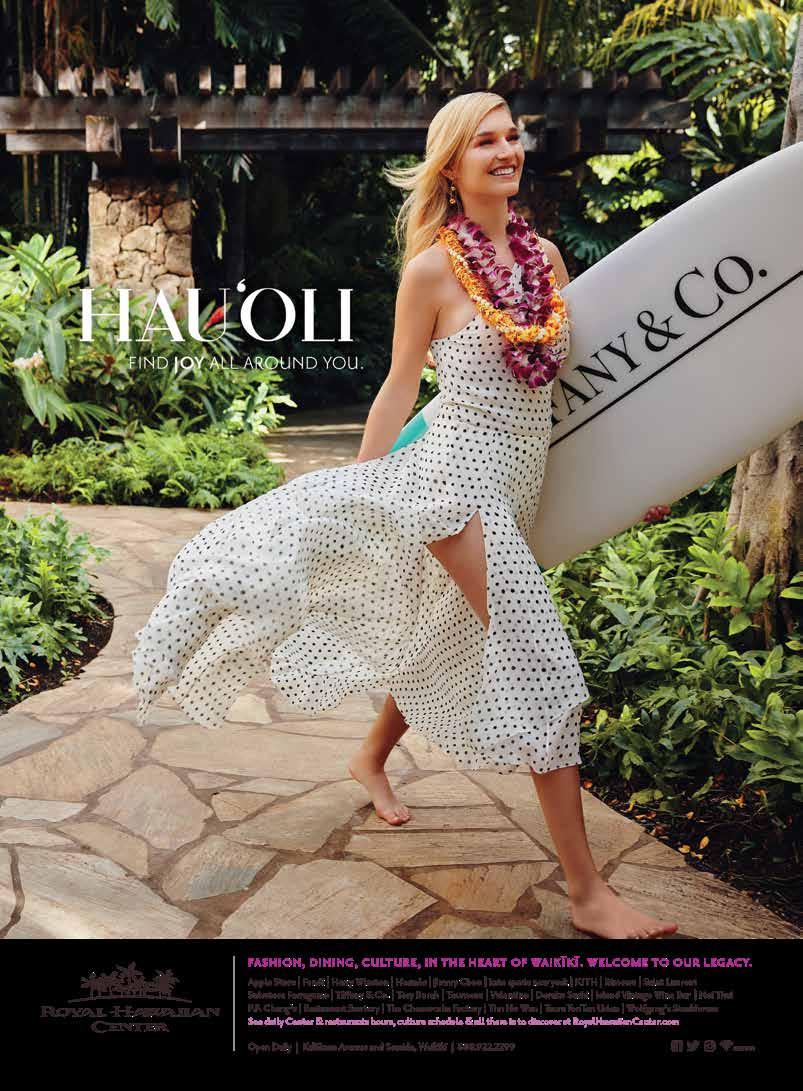

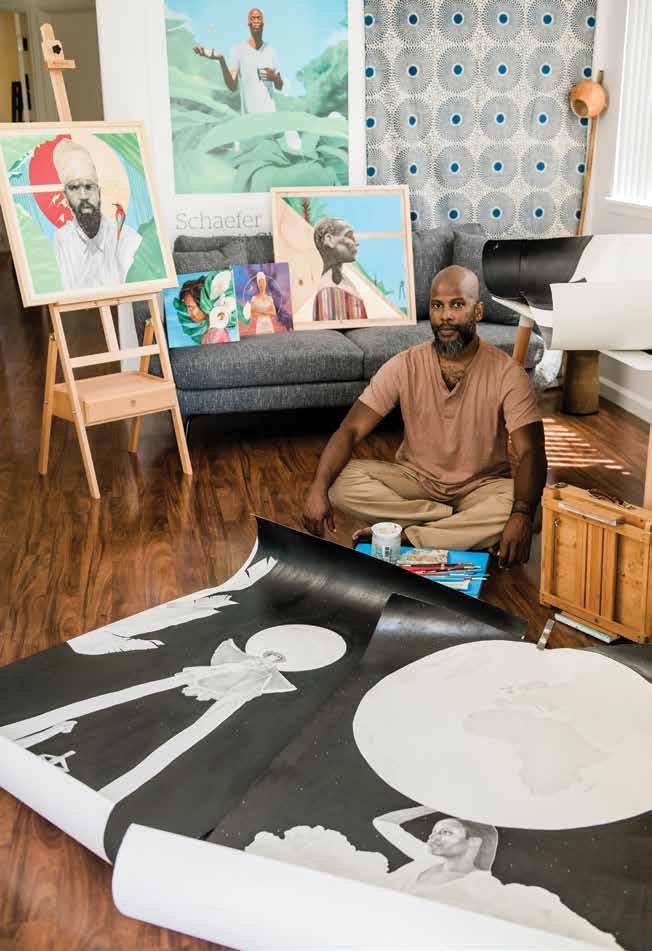

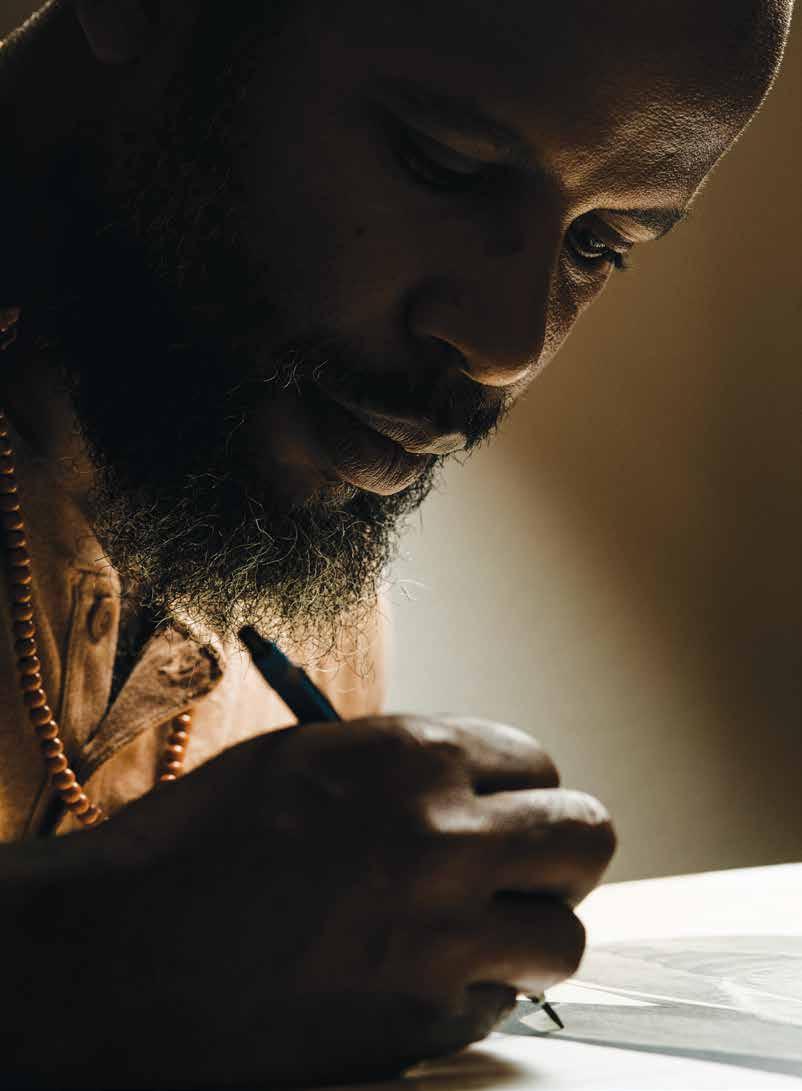

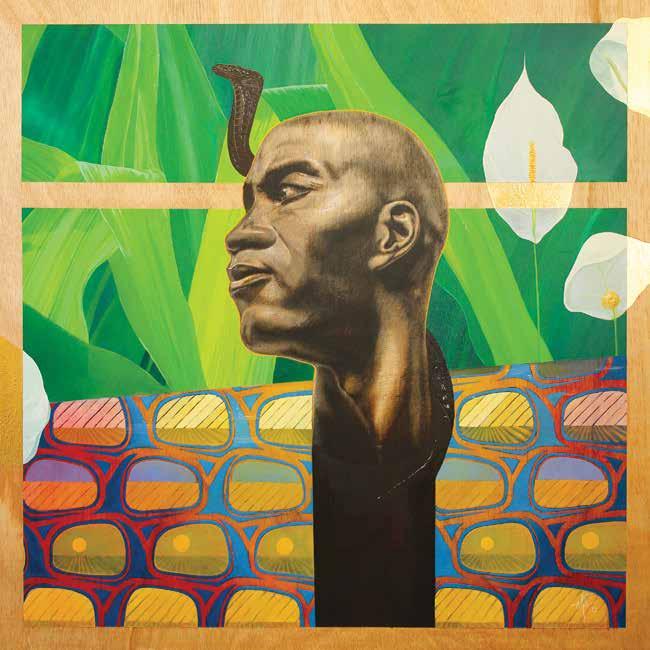

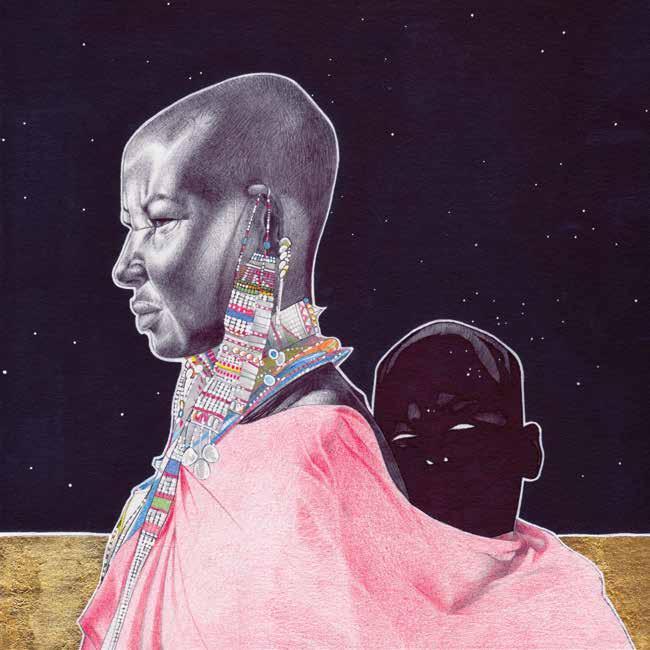

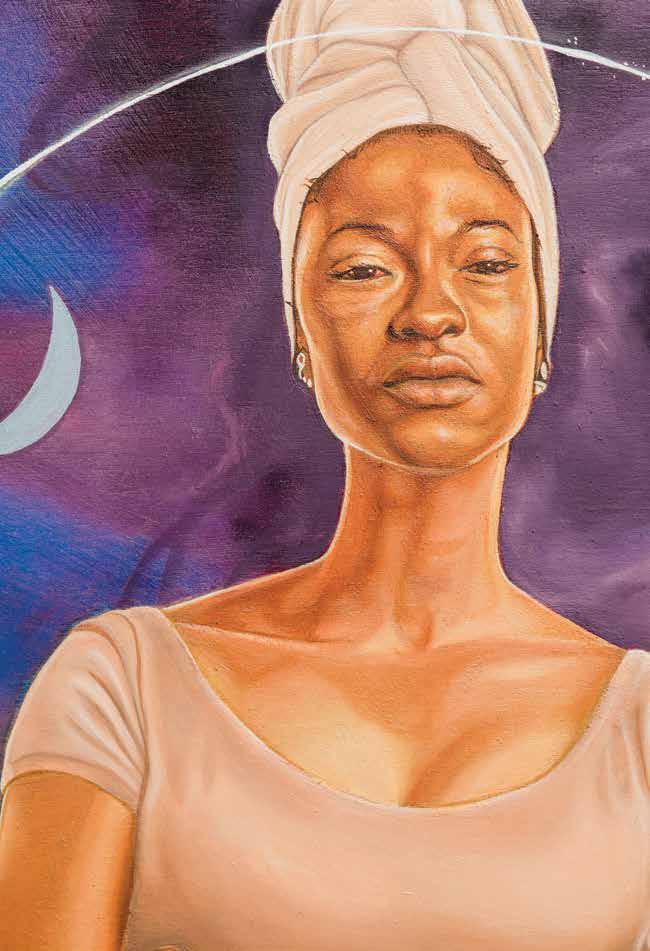

Black Abundance

The artwork of Mark “Feijão” Milligan II richly humanizes the African diaspora with the majesty of Black joy and abundance.

TEXT BY KRYSTAL HOPE

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

Mark “Feijão” Milligan II is a child of St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands, and is a contemporary Hawai‘i-based artist who is imagining and creating abundantly powerful representations of Blackness. He works in figurative painting and drawing to invite conversations that reveal the humanity of Black people across the diaspora.

Pay attention to its finest details and viewers will notice intentionally integrated influences of the Hawaiian Islands reflected in the stories he tells.

As a child of St. Croix, Virgin Islands, how does your identity play a role in how you express yourself through your art?

From an early age, I found identity to be very important. That was the catalyst for a lot of what I continued to do even today.

When I was 11 or 12, I was leaving our house, walking up the street to catch a bus. I was passing by all our neighbors, and I remember how much of an impression it made on me, seeing all these beautiful households of people of African descent, people who are Afro Latino, and people from Puerto Rico. You also have different faiths too. I was very present in that moment, taking it in with a lot of pride.

I remember feeling like, not necessarily making a comparison to anything else, but feeling very full. Like, “Wow, this is like such a beautiful community.” I’m leaving my house, but I’m still in a community that’s so strong. We pass by each other, hail each other up, greet each other— this was all just in a walk from my house. I remember

at that moment also thinking about the portrayal of my community and this area that I lived in and all these neighbors in mainstream media, and seeing how different it was, how twisted and one-sided, and foreign their perspective of our community was.

I knew at that point that I had art inside of me. I knew that even as one person, I’m going to do what I can to affect some kind of change. If I’m not seeing it outside of me and I’m feeling all of this within me, I’m going to be a creator. A part of it was for myself and for other people too.

What does your creative process look like?

Oftentimes my work tends to be a response either to something that I’m feeling internally or something that I’m seeing. Typically, I’m seeing portrayals that are very different from my experience. What I started to do in those moments is to tell the story myself. It becomes a situation where I just kind of sit and think of things that move me. I think in something of icons.

For example, a couple of years ago, I was in church and I was sitting in the pews and I was seeing these images of Caucasians portrayed as Jesus Christ, as Mary, portrayed with reverence and respect. But then, we’re also going into the text and we’re talking about Egypt and the Middle East. Then when you see these places in National Geographic or other travel publications to reference the geography, the people that I’m seeing on the walls are not matching up. I really started to play with that. Fast forward a couple of years later, I actually got a little bit of trouble during my religious teachings because I would

FLUX PHILES | PAINTING | 20 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

bring it up quite often. [Laughs] For my process, I see something that needs to be adjusted and I do a piece that kind of responds to it. It’s a conversation against untruths that need to be corrected. Then it just flows from there.

What dialogues are you hoping to inspire? Is there a certain conversation that you think folks should be having around your art? The main thing I want the viewer to do is recognize the humanity of the African diaspora. Because I find that so often we are treated as something different. There is a lack of empathy by the mainstream media.

It’s really important for there to be a humanization to realize that our stories are real, that our stories are not always this one-sided portrayal of pain, of a lack of history, of impoverishment, of sickness. There’s so many things that are sometimes associated with the Black experience, but coming from my situation, there was abundance, there was a strong social structure. I had a strong family around me. I grew up very healthy. I grew up understanding my history and realizing that my history did not begin with enslavement, and realizing that my history is actually the history of everyone.

Because if you really look at it, all people’s history connects to Africa, our history is long. We come from a culture that really needs to be celebrated in a certain way. So that’s what I try to capture within the pieces because I feel like oftentimes we only get little snippets in time.

But if you look down the line, if you look over the years, you can see the continuity and these moments are forming a sentence, they’re forming a structure. The larger story is that there’s so much more to us than we are given credit for.

So if the credit isn’t going to be given, I’m going to become a vehicle for telling this story. The question that I want people to have when they see it,

if they’re not from the community, is to express a certain amount of curiosity without an immediate prejudice. I would like to inspire them to kind of realize that our story runs deep.

I love that. I do get that. I can see that you want us to see ourselves. That’s something I’ve been interested in and has inspired a lot of my research and work in communications because I don’t like the way I see myself portrayed. I often ask myself how I can influence that. You’re asking that as an artist. What do you think we lose or gain by seeing ourselves or not seeing ourselves?

By not seeing ourselves there’s a diminishing of a person. By not seeing ourselves, I think there’s a lot of questioning. By not seeing ourselves, we are leaving ourselves exposed to our story being narrated by someone else. Telling our stories is empowering. Oftentimes when I think about that, I’m not thinking about the adults. I think about the children because there is such an impression that can be made when a child looks at images that celebrate them. You’re propping them up and to have that within a community, it does so much.

Totally. I have heard you talk about the people in your life who you have painted or drawn. What do your muses think of your work? How do they respond to you? Or, rather, how do they respond to seeing themselves through you?

Everyone’s reaction is a little different, it’s never exactly the same. Sometimes I can tell they feel very flattered. Some say nothing [laughs]. But in general, I’ve always had a good experience when I work with folks.

Because I personally enjoy the process. I enjoy creating art where it’s collaborative, where I’m able to go to someone and we pose and we do these different things. I think the people have enjoyed it too.

Regarding the symbols that you use

in your art, particularly foliage, water, the stars, what do they mean to you? Why incorporate these natural elements?

I love richness. For instance, with food, I love dishes that have a lot of different elements. One of my favorites growing up back home was callaloo (taro leaves). It’s not exactly the same, but one could compare it to gumbo because it’s this rich mix of the callaloo leaf and different meats and sometimes you even put a little fungi or fufu in there. It’s mixed, it’s layered. That’s kind of how I like to create my artwork. Very layered.

A lot of what the symbolism really boils down to it is actually religious or spiritual. I find that icons already have, within our culture, been given a certain amount of weight. People have certain associations of the sun or the moon, regardless of where you’re from—that’s global, that’s almost genetic. When you see the sun, generally people will think of brilliance, wisdom, growth.

If I want to bring in a different kind of vibe, maybe I'll reference the moon, to create a sense of solitude and the wisdom associated with that. Oftentimes it’s about creating that right balance, you know?

Absolutely. How has your art evolved, shifted, or surprised you since living in Hawai‘i?

I have not shifted my art a lot, but there’s a reasoning behind that. I did not want to come to the islands, not know about the culture, and start feeling like I can include all kinds of imagery, acting like I am in a place where I can start to speak for the Native Hawaiian culture. I take that very seriously. If I’m going to be a vehicle, I want there to be some kind of knowledge base there. I want there to be time.

I intentionally have not tried to take on that kind of voice until recently with the mural Tapestry in 2020. I had this huge wall for Pow Wow Hawaii, it was the size of a

22 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“Gordon in Flora.”

“Gordon in Flora.”

“Dibujo Nocturno.”

“Dibujo Nocturno.”

tennis court. It was in the Salt complex at Kakaʻako and there was a connection with Kamehameha Schools too. I requested to have two students from KS join me and work on the wall together. I could almost mentor them throughout the process, and give back in a way that I remember being given back to when I was a child. I went to a teacher and I asked questions because I knew, in that instance, I wanted to create a piece that spoke to the native experience. I wanted to use that public platform as a vehicle for that portrayal, but I did it with research and seeking permission.

That mural was already influenced by the foliage there too it seemed.

Oh, yeah, without question. A lot of what my experience has been living in Hawai‘i is seeing a the strong connection between the West Indian and Caribbean experience in the environment. I’ll go out on the west side in Waiʻanae and be like, “Oh, that’s kasha (buckwheat).” Even the plumeria, we have plumeria back home, we just call it something different.

So there’s so many connections and I do bring that to the pieces. For example, in Yeshua/Horus and Madonna/ Isis, the foliage is Hawaiian. If you have the eye, like you do, you can see the connection, you can see that there’s a dialogue with the Hawaiian experience and the West Indian experience just through the inclusion of the foliage. That I definitely can do. There’s so many conversations that can be had there. The political connections, the experience of the Native Hawaiian culture here and the experience of us back home.

Can you be more specific? What do you mean by the experience?

I’m speaking to the experience of colonization. We’re both cultures that have histories of colonization. I think that’s one of the reasons why I also approach the culture with a certain reverence and respect because I know what it’s like to come from a culture where people colonize a place and bring their perspectives of who we need to be and impose that on us. Almost with like martial law. I know what it’s like.

I come from St. Croix, which is the furthest east possession within the United States, Point Udall, as far as I know. Then to be here in the furthest west, there’s a whole dialogue there. And, so many different similarities, even the way that we speak. There’s a resurgence of ‘ōlelo Hawaiʻi, which I think is beautiful, taking on your language and taking it on with pride. Back home, we have different Creole. I come from a culture where we speak Cruzan and sometimes one would refrain from speaking it because it may not be the “proper” way to speak. I remember going to school and sometimes they would tell us not to speak Cruzan.

I’ve seen your artwork in so many different phases and I’ve just developed a new relationship with your artwork. What are you creating these days?

I did a really cool collaboration with Solomon Enos left me very inspired. I always appreciated his work before, but to actually do a collaboration … we gave each other sketches and then completed them. So he completed a sketch that I did, I completed a sketch that he did.

With something like that, you actually have to kind of get into the person’s mind a little bit. It’s like you starting a sentence and then me finishing it, but we actually did it without actually meeting each other. We were kind of familiar with each other—we had seen each other’s artwork—but we had not actually even had a conversation. So to have that kind of dialogue, you have to like, you know, do a little research, you have to get into their head.

That was really inspiring for me because he’s an amazing artist, has an amazing portfolio — in actually working on his piece and completing it certain things kind of to re-bubble up within me. It had my mind thinking in different ways. A lot of what I’m gonna start working on now has threads of that experience in it. There’s a certain amount of surrealism in it, it is gonna have a little element of a native Hawaiian experience in it. I actually have models that are gonna be posing and there’s a new series that’s gonna be coming out that.

Who are you inspired by or who are you looking forward to seeing grow? Anyone you want to shoutout or uplift? One person that is really amazing is Jules Arthur. I don’t think I even tell him this that often, but he is an amazing artist. We went to school together and I just knew him more as a person. He’s really warm and little did I know he is a genius. Over the years from college to now, we continue to have some dialogue over social media. He is very inspiring to me personally. He might be actually surprised to hear that, but that’s the truth right there.

If I would like to be some place, I would love to be at a level where I’m working like Kehinde Wiley because he has really revolutionized the whole concept of what it means to be a Black artist. The way that he has been able to establish himself has been fantastic. He is just working with such high autonomy, it’s just amazing.

Local artists, too, like I mentioned before Solomon Enos. His prolific ability, like, when you look at the breadth of his work and what he creates, he is able to do so much with the amount of detail he has in there.

La Vaughn Belle, she’s an artist from St. Croix. Seeing the way that she works with the narrative of the culture that we come from and then kind of references past historical instances. She just created this beautiful sculpture that was displayed in Northern Europe that is a dialogue between the West Indian and European cultures and colonization called I Am Queen Mary. It’s really

26 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

beautiful to see the way that she’s growing within her artwork too.

Where can we find your art these days?

I just recently had, surprisingly, two of my pieces on national television. One was on NCIS: Hawaii. Another on Lizzo’s show, Lizzo’s Watch Out for the Big Grrrls, one of my pieces is in that too. My work just recently got included in the personal collections of a couple substantial people. I’m gonna honor their privacy, I’m not gonna name names. But, you know, one is a former president of the United States of America. Another one is the current governor of the US Virgin Islands.

I love to hear that you’re being celebrated in the way that you should be celebrated. I love that your art is reaching the people who need to see it. Thank you. I love what I do. I love the opportunity that I’m being given, our conversation, I love this. I just want to continue to grow and to better myself.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. For an in-depth discussion on the origins, references, and in-depth symbology behind more of Milligan’s work, visit fluxhawaii.com.

Milligan II is a figurative painter whose work concerns the Black diaspora.

Explore his portfolio at markmilliganart.com.

28 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

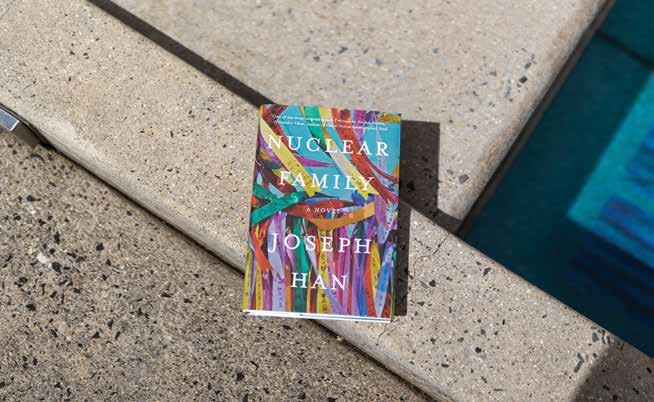

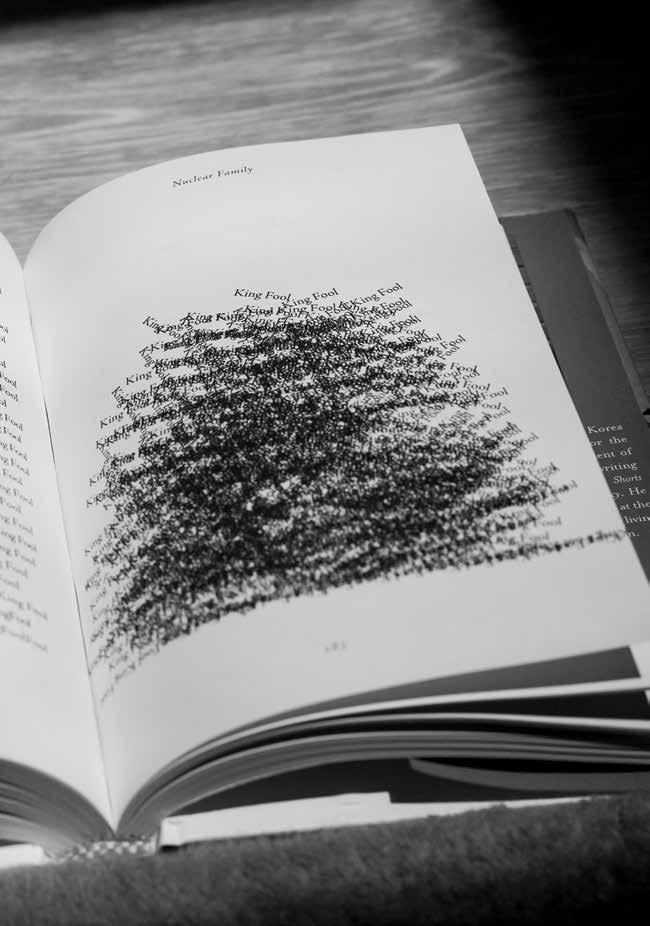

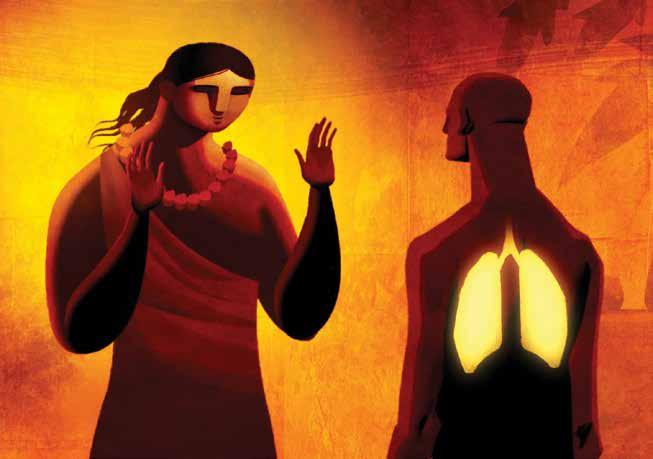

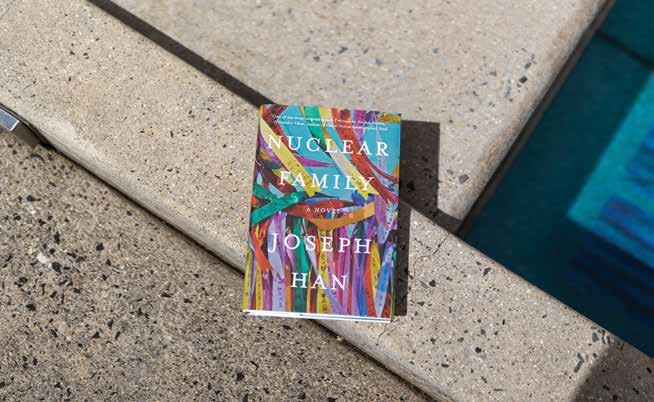

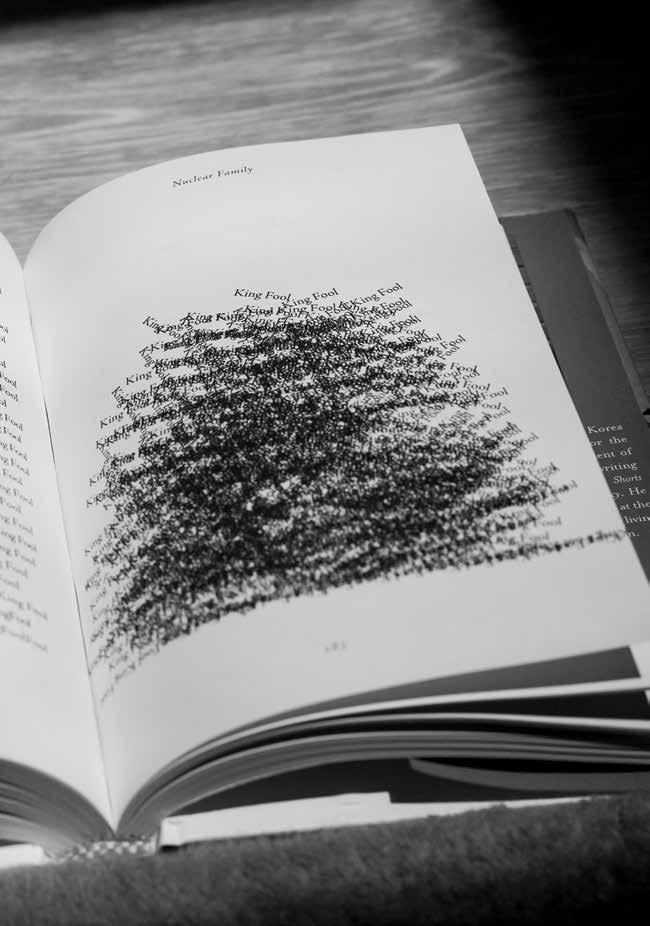

Culture Clash

In Joseph Han’s debut novel, imperial legacies in Hawai‘i and Korea are confronted with humor and heart.

TEXT BY MITCHELL KUGA

IMAGES BY MAHINA CHOY-ELLIS

Nuclear Family, the debut novel by Joseph Han, is many things: a ghost story embedded into a multigenerational Korean family saga; a typographical experiment utilizing elements of concrete poetry; a reckoning with the U.S. military; a lowbrow stoner comedy. But don’t call the book, which takes place largely in Hawai‘i, a beach read, with all the genre’s connotations of escapism. Han, a National Book Foundation “5 Under 35” honoree, says he thought a lot about the words readers use to describe their favorite books: It was so immersive; I felt transported; I escaped into the text. But that impulse felt complicated by writing about a place so often framed as an idyllic escape for tourists. Or, as Han explains, “I was very wary of allowing readers to visit the Hawai‘i in their imaginations.”

So instead of Hale‘iwa, or Waikīkī, or Kailua—places that favor the postcard image of Hawai‘i—Nuclear Family takes readers to Ke‘eaumoku Street, where “somewhere in the middle,” Han writes, “between a strip club and Ala Moana Center on the other end, bloated with a Target, a Walgreens, and a Walmart on each block,” sits Cho’s Delicatessen. It’s an unremarkable Korean plate lunch spot, with styrofoam plates that squeak under the weight of banchan, until it’s anointed by a visit from Guy Fieri, America’s “diner troll,” Han pans. Fieri’s co-sign elevates Cho’s Delicatessen into a bustling franchise, with lines suddenly out the door. But many years later, Umma, the family matriarch, still harps on one detail from his visit: “He didn’t even pay for his food.”

It’s funny, but at its heart Nuclear Family is about the many fractures, fallouts, and fissures caused by war. The Cho family—Umma and Amma and their children, Joseph and Grace—are Korean immigrants living in working class Honolulu. When Joseph, a closeted 25-year-old, leaves Hawai‘i for South Korea to teach English, his parents are elated. “You’re Korean is going to get so good!” Umma exclaims. But then Joseph gets possessed by the spirit of his dead grandfather (hate when that happens) who’s desperate to reunite with the family he abandoned in North Korea. A viral video of a possessed Joseph unsuccessfully attempting to cross the demilitarized zone into North Korea sends shockwaves across the Pacific, bringing shame to the Cho family. Business slows, as Grace, a 21-year-old senior at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, tries her best to remedy the PR crises. She copes

30 | FLUXHAWAII.COM FLUX PHILES | LITERATURE |

primarily through smoking an increasing amount of weed, which leads to one particularly extravagant meal at Zippy’s.

Throughout the book, O‘ahu’s housing crises, Red Hill’s jet fuel leak, and development on Kānaka Maoli burial grounds are all alluded to, grounding Nuclear Family in a socio-political present that places the concerns of Hawai‘i residents at its core.

“You’d have to visit Cirque du Soleil to see someone juggle as much as Han with such effortless dexterity and tenderness,” writes a critic for The New York Times. But for Han, that balancing act felt instinctual. He sees parallels to the structure of the plate lunch, a culinary mishmash often posited as a metaphor for local culture: the best of everything. “And that kind of informed how I approached writing the book, offering a little bit of everything in terms of style, and point of view, and also different genre registers,” Han says. “In writing in all these different genres, I was really just trying to create the language that I needed to survive as an artist.”

He was also inspired by the Korean ceremony known as jesa, in which a large

table is set with an overflowing assortment of foods as an offering to those who’ve passed. “So much of the novel is about how our nourishment is so conditioned on how well fed our spirits are,” Han says. He’s come to think of the writing of Nuclear Family as its own elaborate ceremony, a table he’s returned to over and over again to bear the weight of his ancestors, and to offer them something in return. “I needed the novel to structurally be able to hold as much as it could,” he says.

Han, 30, was born in Seoul and moved to O‘ahu with his grandmother, a devout Christian, when he was a baby (his parents eventually followed as he was about to start high school). Because he was born prematurely and prone to sickness as an infant, “my grandmother frames my life as having been saved by God,” Han says, with a chuckle. “And that’s why they needed to protect me, by finding a healthier environment for me [in Hawai‘i].” He grew up in Honolulu, in low-income housing on Vineyard Boulevard, feeling like an outsider. At Hawai‘i Baptist Academy, where Han graduated, he was bullied, his Koreanness most legible either through the

In writing about Hawai‘i, a place so often framed as an idyllic escape for tourists, Han explains that he was “very wary of allowing readers to visit the Hawai‘i in their imaginations.”

32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

specter of North Korea or food. Though his mostly Japanese classmates “loved meat jun, they ridiculed me for being Korean, for my appearance and my flat face,” Han writes, in an essay recently published in LitHub titled “Making Meat Jun, Facing History: Flattening Korean Tradition in Hawaiʻi.”

It wasn’t until college, at UH-Mānoa, that Han began to conceive of himself as a writer. Up until that point, he describes his attitude towards the themes guiding his work today—reckoning with the U.S. military occupation globally; the histories shaping the Korean diaspora—as “totally detached, oblivious, and indifferent.” But during his sophomore year, Han’s father, a taxi driver at the time, was assaulted by a soldier in the military who refused to pay his fare. “That was a really formative moment for me,” Han says. “That anger that I felt and seeing my dad in the hospital really started to feed a lot of my wanting to learn more about military violence, both here in Hawai‘i and Korea.”

Reading scholars like Haunani-Kay Trask and Grace M. Cho radicalized Han, shattering the narrative he was taught growing up of the U.S. as the world’s savior. Just as enlightening was discovering the world of Asian American literature, and Korean American literature in particular. These books oriented Han

towards the possibilities of using fiction to illuminate histories that were either silenced in his family or distorted by the weight of American exceptionalism. In this way, Han’s project is somewhat of an ouroboros: “That’s what I have to offer,”

he says, “to use fiction to write back against fiction.”

Nuclear Family, which Han began conceiving in 2017, towards the end of his research as a PhD student (also at UH-Mānoa) comes at the tail of what he calls a “huge learning curve.” He

is both realistic about and resistant towards what it means to be a writer from Hawai‘i who’s writing about Hawai‘i within a national framework. He intentionally wrote Guy Fieri into the book as a hook for readers from the

34 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

continental United States, “which really worked out, as I'm seeing now,” Han says, referring to the book’s Fieri-heavy press coverage. “Maybe a little too well.” And yet the book rarely panders to an outsider’s gaze, referencing menehune, Puck’s Alley, and iwi kūpuna without an explanatory comma in sight. Foremost, though, Han says he felt “a huge responsibility” to write for a diasporic Korean audience.

It’s a responsibility he’ll carry into his forthcoming book titled Monster Ball. Han describes the collection of short stories as even more personal than Nuclear Family, while taking a broader look at the Korean diaspora in Hawaiʻi. In the meantime, he has shifted into more of a mentor role, serving as an editor for the West region of Joyland Magazine, a literary journal that publishes by time zone, and teaching a fiction workshop this summer at Antioch University’s MFA program, where he was paired with five mentees.

Writing fiction, though, continues to be Han’s primary focus, grounding him in a

sense of place—a respite for someone who’s “always felt in-between in a way, neither of Korea or Hawai‘i,” he says. Rather than fight that in-betweenness, Han has learned to see it as a unique vantage point for his work, a kind of homecoming. “Fiction became a home for me, a place where I can return to articulate the important connections that continue to shape who I am and what I live for,” Han says, “and a lot of that comes back to living for the opportunity to reconnect with those we’ve lost or forgotten.”

Reading scholars like Haunani-Kay Trask and Grace M. Cho left an influence on Han.

Find Han’s debut novel Nuclear Family at local booksellers like Da Shop.

36 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

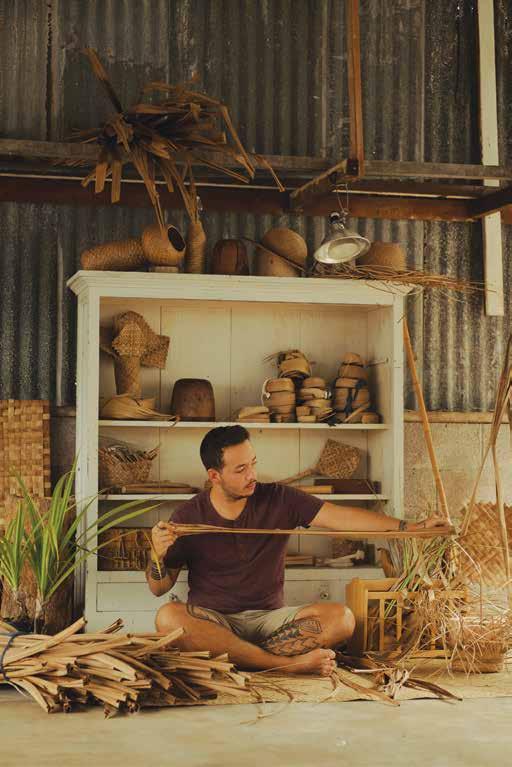

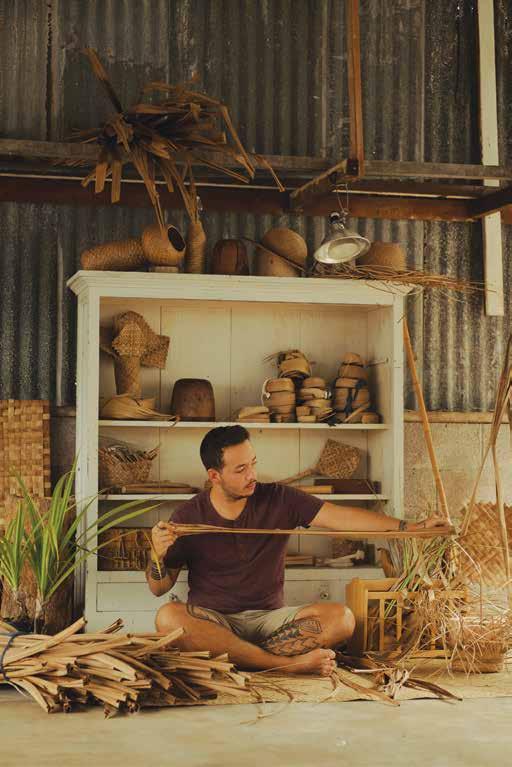

Interlocking Legacies

Through ulana lau hala, Kekai Naone weaves time together, connecting past to future with purpose, pragmatism, and personality.

TEXT BY JACKIE OSHIRO

IMAGES BY KEATAN KAMAKAIWI

In a quiet neighborhood in Hilo, a small stool stands in the middle Kekai Naone’s living room, its seat wrapped in an elegant twist of alternating patterns comprised of thin strips of light and dark lau hala. Like much of Naone’s work, the stool cover is beautiful, playful, and practical— an embodiment of the 26-year-old weaver’s approach to ulana lau hala, which is the weaving of dried pandanus leaves by hand. Chatting with a friend recently about how to best describe work like this, he was struck by her appraisal of his practice: “‘You don’t make culture for art. You make art for culture,’” he recalls, gesturing towards the stool. “It’s utilitarian, but it’s beautiful at the same time. And that was definitely a focal point for Hawaiians,” Naone explains. “We don’t want to have ugly things in our houses, so weaving wasn’t necessarily art—it was functional beauty.”

Functional is almost an understatement. Prior to Western contact, items made from lau hala—the leaves of the hala tree—were ubiquitous in everyday life. Floor mats, sleeping pads, baskets, cordage, and house thatching were all made from lau hala, and weaving was held as a point of pride as each family often had carefully guarded techniques. Over time, however, with the rapid decline of the Hawaiian population post-contact and imported materials becoming more commonly used, lau hala goods came to be seen as works of art meant to be treasured, not regularly used.

Naone’s dedicated lau hala Instagram account, @pikohinano, delights followers with a fresh take on the traditional practice. Intricately woven stools, water bottle sleeves, pāpale (bowties, even!) of all shapes and sizes, Naone’s creations are designed to be seen, loved,

Kekai Naone views Hawaiian weaving as a craft that needs to be practiced, stretched, pushed, and played with in order to remain healthy.

38 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Naone was introduced to weaving as a teenager in the Nā Pua No‘eau cultural enrichment program run by the University of Hawai‘i. Opposite, Piko Hīnano pāpale on Keanu Wilson

Naone was introduced to weaving as a teenager in the Nā Pua No‘eau cultural enrichment program run by the University of Hawai‘i. Opposite, Piko Hīnano pāpale on Keanu Wilson

and used often, inviting you to rethink your perspective on what constitutes mea lau hala, or lau hala objects, and how to embrace it. “A lot of people only wear their lau hala to church or parties. They don’t really know what they’re supposed to do with it, and I think that adds to the relegation of it to being super sacred or only for special occasions,” Naone says. “But, actually, wearing it is what keeps it in a healthy condition. It’s when you put it to the side that it can get bugs or it dries out and gets brittle.”

Naone views the craft of weaving itself in a similar light. It needs to be practiced, stretched, pushed, and played with in order to remain healthy. “In previous generations there was this sense of urgency focused on preservation,” he says, explaining that before the Hawaiian Renaissance of the 1970s, the knowledge of weaving was in decline, and those who practiced ulana lau hala were focused on preserving traditional methods and maintaining the foundation of lau hala. Learning how to weave meant mastering the exact way it was taught, which was important at the time, but ensuring the future of weaving requires growth. “Now, people love to do Hawaiian things. It’s not so sparse in the community, and I get to think of random things to make, like stool covers. So, I think my own sense of urgency is focused on expansion or living it.” In other words, it’s time to get building.

For Naone, thinking of ways to push the boundaries comes very naturally, perhaps because of his less traditional background. His childhood years on Oʻahu weren’t spent cleaning leaves for his tūtū or watching his mother weave. After he was first introduced to weaving as a teenager in the Nā Pua Noʻeau cultural enrichment program run by UH, he spent years teaching himself through books. Though he credits the only class he’s taken with helping him fill in some knowledge gaps—and introducing him to his kumu Michele Zane-Faridi—much of Naone’s work is characterized by the same figure-it-out attitude today.

“I like to take a lot of naps and that’s usually where I figure things out,” he says. “I kind of just envision it in my mind. I’m like, ‘Oh, that’s how it works.’ And then I get up and I’m like, ‘Okay, let me try this.’ But even

Prior to Western contact, items made from lau hala, which are the leaves of the hala tree, were ubiquitous in everyday life. Opposite, Piko Hīnano pāpale on Kai‘anuilālāwalu Andaya.

42 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 43

if I don’t know how to do it, I figure it out as I go. I’m very inspired by the spirit in that way.”

But Naone’s seemingly casual, inspiration-driven approach is not without intention. “I feel like Hawaiians always had a reason to do something, and there was always a meaning behind it,” he says. “We didn’t do things just to do it. I always keep that in my mind. What larger things am I speaking about by creating this? And even if it’s just for me, does this change the way I view the world?”

Naturally, Naone hopes to contribute to a future where more people have more lau hala things in their homes, where lau hala goods are part of one’s everyday life. Reaching that point is going to require many more hands, and while it may be daunting to start learning as an adult or without any personal connections, Naone points to his own journey as an example. “Whether you have ancestral connections or not, by learning to weave you’re making ancestral connections,” he says. “I think

people forget that back in the day everyone had weavers in their family. It wasn’t only special people. It was very utilitarian. If you didn’t know a weaver, I don’t know how you’re going to sleep—no pillow, no mat—it’s going to be a pretty junk life. It’s just about seeing what you’re good at, what you’re pulled to, and just going with it.”

Naone’s creations aredesigned to be seen, loved, and used often, inviting you to rethink your perspective on what constitutes mea lau hala, or lau hala objects, and how to embrace it.

Visit @pikohinano on Instagram to peep more of his designs.

46 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Cinematic Poetry

Memory, sorrow, and colonial fantasies continue to cycle anew in the filmmaker’s oeuvre with startling artfulness.

INTERVIEW BY VINCENT BERCASIO

IMAGES COURTESY OF CHRISTOPHER YOGI

In March 2022, the Hawai‘i-born filmmaker Christopher Makoto Yogi’s feature film I Was a Simple Man (2021) saw its streaming premiere exclusively on the Criterion Channel. Plaintively described as a “ghost story,” its programming on the platform was also joined by another subdued achievement, his Hawai‘i Island feature August at Akiko’s (2018), and a selection of seven shorts from the past thirteen years. Collectively, they compose perhaps the largest body of Hawai‘i-related cinema from a single filmmaker yet on the American streaming service. Vincent Bercasio spoke with Yogi about the maturation of his practice, how local politics surface in his filmography, and the outsized influence of the Taiwanese New Wave.

VINCENT BERCASIO Hello, Chris!

CHRISTOPHER MAKOTO YOGI Hi, Vincent. It’s nice to see you again.

VB Firstly, I hope you and your family are doing well.

CMY Yeah, we’re doing great!

Christopher Makoto Yogi is a filmmaker from O‘ahu. Overleaf, still from Layover, on the Shore (2009).

48 | FLUXHAWAII.COM FLUX PHILES | FILM |

VB I’m happy to be talking and to get an opportunity to revisit your work. It’s beautiful seeing the common threads, repeating motifs, and even some of the same actors in your films, and how they grow and evolve throughout the years. One thing that stood out to me in particular were the repeated shots of [tower] cranes.

CMY You know, there’s that old joke, the crane is the state bird of Hawai‘i [laughs]. Everywhere you look, there’s a crane, there’s some kind of development going on. Hawai‘i is a place that’s being pulled in two different directions, and the crane is a really great encapsulation of that.

VB It’s especially emblematic of this idea of Hawai‘i as a construction, both literal and figurative. Layover, on the Shore (2009) concludes with ambient sounds of construction. In I Was a Simple Man, they open the film with an almost aggressive loudness. How have those ideas evolved for you between the two films?

CMY I actually hadn’t watched Layover, on the Shore in many years, and only just recently took a look at it because I had forgotten what a lot of the film was. There’s a theme that runs through both works, of buildings, concrete, development. While producing Simple Man, so much of what I was thinking about was this idea of the land being covered up. The concrete being this mud that envelops everything. Over the course of the film, nature breaks through in spite of that. Before shooting, Akiko [Masuda, an actor in August at Akiko’s] was telling me how she grew up in Kalihi before moving to the Big Island in the ’80s. I asked her if she ever came back. She said, “No, I never go back. When I go back, it’s just concrete…that’s all I see, everywhere.” And when I got back, that’s all I ended up seeing too. But sometimes I would be walking around and I’d see roots busting through the concrete, or a plant emerging through the cracks in the wall. Akiko is right that there’s concrete everywhere now, but over time, if you were to take a more geological view of time, I think nature wins.

VB Nature eventually reclaims itself.

CMY Exactly, given time. Simple Man is essentially telling that story. In regards to the soundwork, that was something we found in post-production. We knew there would be some kind of industrial sound at the beginning, but we didn’t know we were gonna go that big until we were in the mix. I just love this idea of confronting the audience upfront with an

abrasive wall of sound that they must pass through. It’s something like an entrance or a cleansing. You have to pass through this grinding barrier, then the film starts in earnest, becoming a much quieter experience onward.

VB Sound in general plays a beautiful role in your films. I grew up in an area that had relatively little development, then came a Wal-Mart, a few shopping centers, and then the rail, so those construction sounds ended up becoming very familiar to me.

CMY Yes, and that’ll continue, cause the rail will definitely make noise, even though they say it’s supposed to be pretty quiet. It’ll be like living by a subway in New York, just a constant sonic interruption in daily existence.

VB I wanted to mention the role that Hawai‘i and Hawaiian politics plays in your films. They’ve always been present in your work, but Simple Man defines its presence more clearly.

CMY It’s important that Hawai‘i’s political dimensions are incorporated into the work on a more subtle level. They aren’t necessarily making up the narrative of the film, but they are integral to the tellings of the stories. The production of Simple Man was a really interesting experience because we started shooting in the midst of the TMT protests, which rippled out to the rest of the islands. We were in this production bubble on the North Shore, and it wasn’t until the first weekend of shooting that I figured out through social media what was going on at the mauna. Throughout Hale‘iwa, we saw all these flags coming up, and there were protests going on that were impossible to ignore in this very exciting, energizing way. We were seeing the movement awaken, the nation rise, it was so beautiful. Meanwhile, here we were shooting this movie, which suddenly started to feel totally unimportant [laughs]. At one point, I asked myself, “Should we stop shooting?” The statehood elements were already integrated into the script, but during production, it felt even more important that Hawai‘i’s colonial history was incorporated in a way that hopefully inspires those unfamiliar to seek out, to learn more. It touches upon it enough, I hope, that it will motivate viewers to educate themselves.

VB The political potential of films should never be doubted, I think, even if their function is more reflective than propulsive. I saw Occasionally I

52 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Saw Glimpses of Hawai‘i (2016) and Anthony Banua-Simon’s Cane Fire (2020) around the same time, which made it click for me that there are ways, even through recontextualized imagery alone, to politically subvert the narrative imposed on Hawai‘i. Both are a sort of destruction of images, a catharsis.

CMY When I made Occasionally it was never supposed to be a film project. It started off as me just saying, “I’m gonna sit down and watch these images that I’ve avoided for my entire life.” Growing up in Hawai‘i, I thought, “Why should I waste my time watching these movies? They’re not for me. They’re for the outside world.” I eventually came to think I should at least be in dialogue with them and educate myself on what these images are. So I started to watch everything. I started to see films quoting films quoting films, artifice upon artifice upon artifice. The most interesting part, though, was when it played at HIFF. Most of Occasionally came from a very angry place. Then at the screening, people would come up to me and say, “That film was so beautiful, it reminded me of my childhood, it took me back to the good old days.” Cinematic images become memory in this way that’s almost indistinguishable from our personal memories. It becomes the lens in which we look through our own lives. It remotivated me about the importance of producing images that counteract that narrative, not only for the rest of the world, but for people who have lived in the islands their entire lives.

VB There’s a certain comfort in those colonial fantasy Hawai‘i depictions that a lot of people I know find warmth in. It’s unfortunate that it takes up a large bulk of what we have to work with.

CMY I guess in a way I shouldn’t have been surprised at their reactions. For me, growing up with the version of Hawai‘i that’s sold to the world created a real cognitive dissonance. I’m still questioning what a real Hawai‘i is. Of course, my experience of everyday life there differs from that of my friends, people I don’t know, other parts of the islands, the outer islands…these questions were always spinning in my head. For me, the reaction was a sense of detachment from Hawai‘i as a young person. I felt very alienated from the place in which I was living. Now, I look back and think, “That’s really unhealthy.”

VB Would you say it took leaving the islands to gain that renewed connection?

CMY When I left the islands to move to LA, I was in this very disorienting period of my life. My father had just passed away, and at the same time, I was living outside of the islands for the first time of my life. It was a period that was full of grief and longing which channeled itself into a deep sense of homesickness. Every time I sat down to write, the pieces would be set in Hawai‘i. I was already interested in telling stories from a local perspective, but it didn’t really crystallize until after I had left.

VB Did the films you watch over the years shape your idea of what’s possible within Hawai‘i?

CMY One-hundred percent. The biggest influence was the Taiwanese New Wave. It wasn’t until I started watching films by Hou Hsiao-Hsien, Tsai Ming-liang, and Edward Yang that I started to understand cinema’s ability to capture the history of a place in a way that’s both personal and incredibly artful. They’re all touching upon the history of colonialism in Taiwan, often not so overtly, and it opened my brain to the possibility to tell stories about home that are simultaneously localized, personal, political, and cinematically progressive.

VB Layover felt a little like a Tsai Ming-liang film to me. [Yogi laughs.] I really appreciated those shots of the Chinatown streets at night for that reason, and another, more incidental one—you were capturing an era of Chinatown that doesn’t really exist anymore. So much of it looks and feels different today.

CMY Yeah! That goes back to what we were talking about earlier in how film can incidentally capture a specific window of time.

VB Have you seen Los Angeles Plays Itself? There’s a quote from it that goes, “If we can appreciate documentaries for their dramatic qualities, perhaps we can appreciate fiction films for their documentary revelations.”

CMY That’s amazing. When I think of fiction and documentary, it’s more of a spectrum than it is a binary. Obviously, hybrid filmmaking is really in vogue now, but even creating fiction films, you can’t control everything, and every documentary film has elements of fiction in it.

VB Even towards the beginning of the documentary form, you have stuff like Nanook of the North, the city symphonies, it’s all very deliberately constructed.

54 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

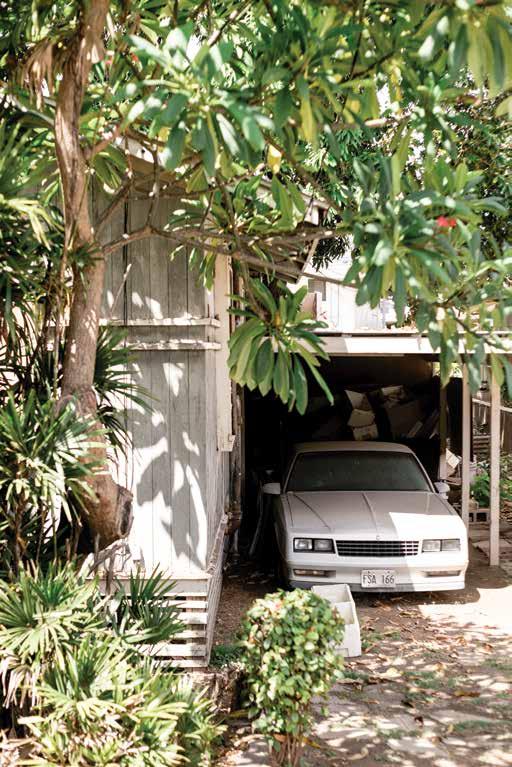

I Was A Simple Man , written and directed by Christopher Makoto Yogi, is set in the pastoral countryside of the north shore of O‘ahu, Hawai‘i. Told in four chapters, an elderly man facing the end of his life is visited by the ghosts of his past.

I Was A Simple Man , written and directed by Christopher Makoto Yogi, is set in the pastoral countryside of the north shore of O‘ahu, Hawai‘i. Told in four chapters, an elderly man facing the end of his life is visited by the ghosts of his past.

CMY It’s funny that where cinema started was more or less operating in that hybrid form, then somewhere along the way it got barricaded off into a binary when they crossover more than we would like to think.

VB On the other hand, you have stuff like the shorts of Lumière and Edison that are incredibly pure. Technologically, it was a miracle to document a baby eating, people shuffling around, the waves crashing, things like that. There’s a certain purity of vision. In your films, the way you and [cinematographer] Eunsoo Cho film plants, the mountains, the sky—I feel that same sense of wonder. Sometimes it really is just about pointing your camera and shooting.

CMY Getting back to that sense of beginner’s mind, that purity, was basically the goal. Before I start every film, I try to forget everything and start from zero to see what we can come up with. Leaving Hawai‘i gave me an ability to more easily inhabit that emptied state of mind. For example, I’ll come back and be completely blown away by the clouds. When the sound of rain in Hawai‘i is no longer a thing I’m hearing every day, upon returning, it becomes this incredibly evocative music that I haven’t heard for so long, and I’m like, ‘Oh my god, I’ve missed this so much!’ I’m glad you mentioned that because, for me, that’s the intention. To see the everyday anew.

VB The beauty of Hawai‘i is undeniable. It’s also, unfortunately, the tourism industry’s most valuable commodity. How do you respond to this contradiction and represent its beauty in a way that feels new, subversive, or pure to you?

CMY If you asked me this when I first started to think about cinema, I would’ve thought to reject those images completely and be like, “We’re not gonna interface with that at all,” and that would be the radical statement. Now, I feel like that would be a bit dishonest because the beauty is certainly there. I find emotion out of the nature, the ocean, the mountains. It’s not about refusing to engage with that grammar at all, but finding a way to personalize it. With Layover, on the Shore, the city and the country are split in a way that makes their differences apparent. Like, here’s the city, which is supposedly more gritty and real, and here’s the country, which is supposed to be more fanciful and constructed and based on the presumed ideas of Hawai‘i. The fact that they are split up in that way shows where my brain was at the time, whereas now I don’t think I would be as didactic. Each

part is both imagined and real at the same time. Cinema is one of the great art forms where we can interrogate these tensions. Now that there are more artists telling their personal stories here, it complicates the entire narrative in a way I think is healthy and beautiful.

VB I’m definitely excited for the future and how it seems the local film scene is cross-pollinating. The first batch of graduating classes from UH Manoa’s film program are now mature enough to be producing features. You have professors coming to these students with an explicitly Indigenous perspective.

CMY What was really important was that I was able to be a part of a filmmaking community in Hawai‘i. Up until that point, I didn’t know a lot of filmmakers or people who were interested in cinema. It was really only our small group of friends who were just screwing around and having fun creating things. But then to contextualize it amongst this diverse group of people who are all interested in film and all telling their specific stories, we were encouraged to look at Hawai‘i as a legitimate place to create films. It’s strange that it should seem like a radical thing, but if you’re growing up here, there isn’t really much of an arthouse scene or cinephile culture. A lot of the films we were watching were big Hollywood movies, and it wasn’t until I watched those Taiwanese New Wave films where I was like, ‘Oh, this is possible!’ To couple that with a community of filmmakers, it’s like, if this continues to grow, then this could be a thing. Fast forward a decade later, it has become a thing. It really is exciting. At the most recent Hawai‘i Shorts program at HIFF, I was almost gonna cry, it was so beautiful. The ambition of the filmmakers there, their craft, every year it just seems to level up.

VB It feels like local filmmakers are more in dialogue with each other’s work than ever.

CMY When I was at Mānoa, it seemed like the only avenue people were trying to enter was Hollywood filmmaking because that was how limited our scope was. Now there’s cross-pollination, the work is in dialogue with one another, and the craft is evolving much faster now than it ever seemed to be before.

VB My last question is more practical. For those who would like to tell non-traditional stories such as yours, what was the process of procuring funds for your films like for you, and is it any more easy or difficult from when you first started making films to now?

56 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

CMY It’s definitely still difficult. Every independent filmmaker would say that raising funds is the hardest part of the development process. You can have a great idea, you can have tons of passion, but you really do need the resources. We were trying to make Simple Man for a very long time and found it impossible to get the financing. We took a break from raising the money to make August at Akiko’s simply because we were kind of burnt out trying to get the film made. We created it for a shoestring budget and a very small crew, which was like a palate cleanser for us. There was a laboratory-type atmosphere that allowed us to try things, play around, to have fun, to do what we want and not be beholden to anybody. That freedom reinvigorated my own love for filmmaking. After making that film and coming back to Simple Man, I came back with a renewed confidence. The success of August

at Akiko’s proved to investors it was possible for us to make a film that is embraced by people all around the world, and that there is an audience for it. Raising money still wasn’t easy [laughs]. But it was easier. We could now say, “Here, this is another film we made for much less money, it premiered at a great festival, it has acclaim…” Financiers could trust us more with something a little bit bigger.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Search online to find the most current streaming options for

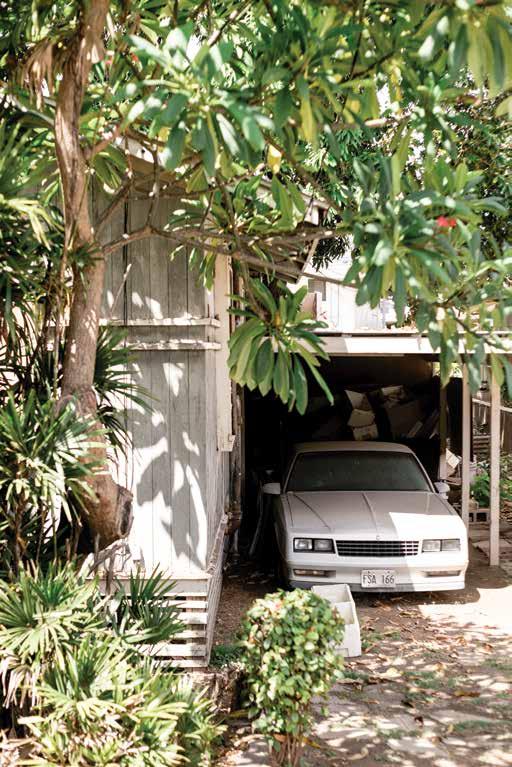

The exterior of Masao Matsuoshi’s home feataured in I Was a Simple Man

58 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

the film.

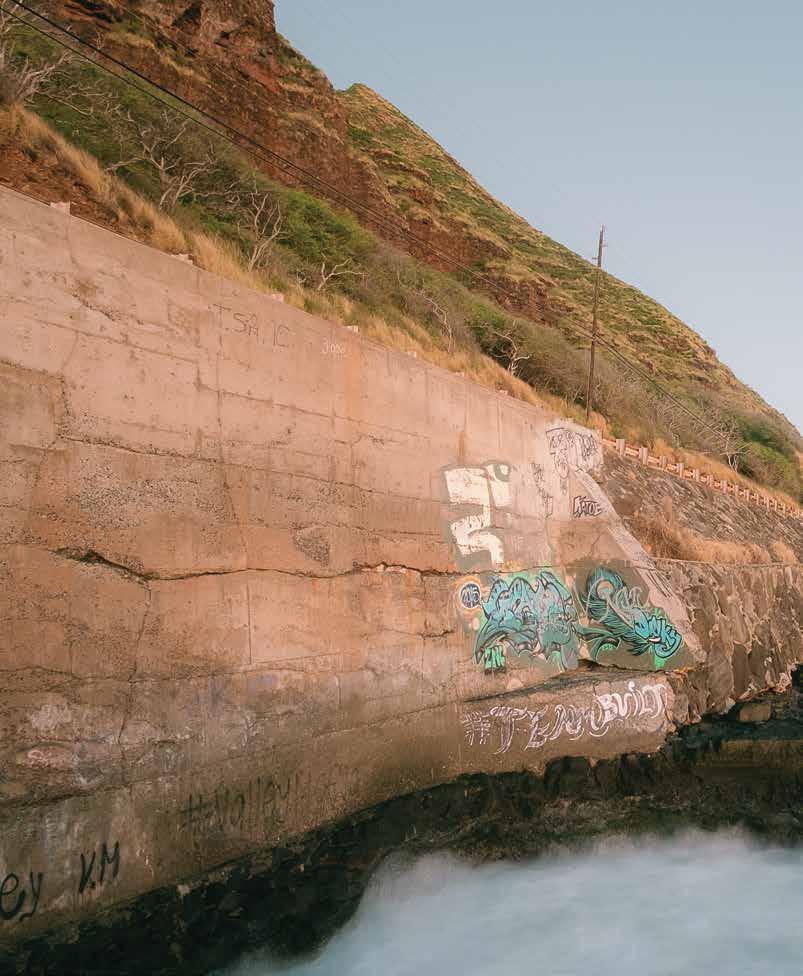

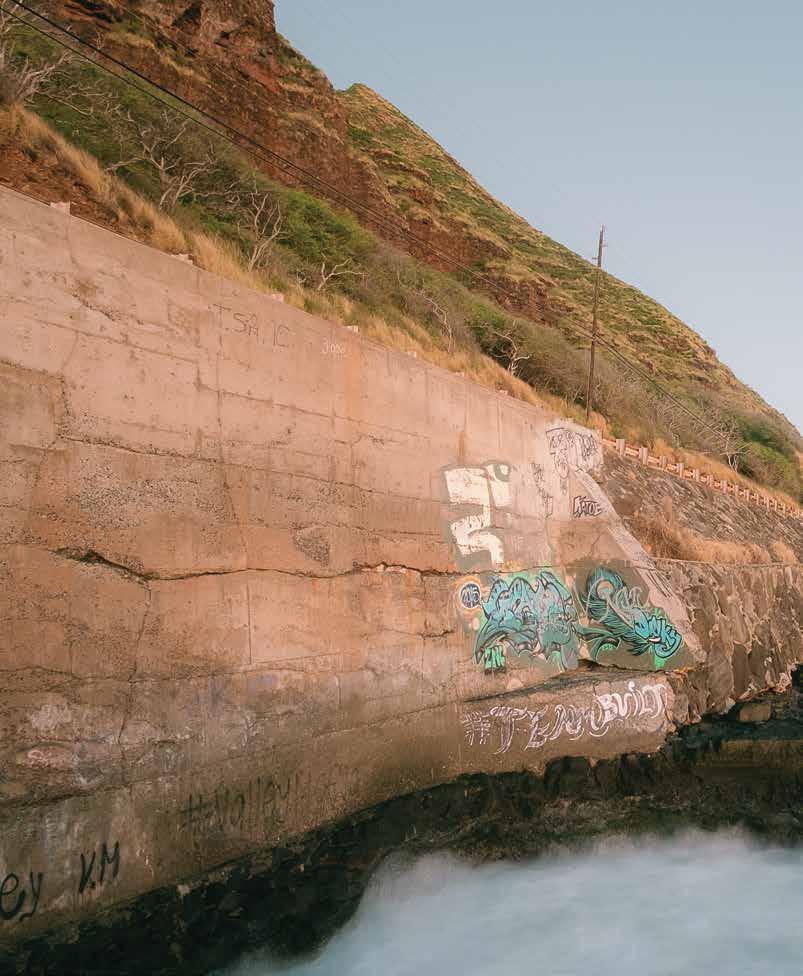

A view of O‘ahu’s west side. Image by Josiah Patterson.

A view of O‘ahu’s west side. Image by Josiah Patterson.

FEATURES

“There it was, a danger of forgetting.”—W. G. Sebald

FLUX FEATURE

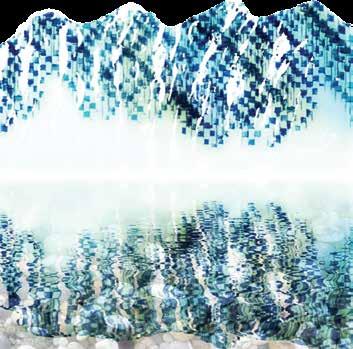

Unsettling Carto g ra p hies

Political change depends on getting people to see a story the same way. This stubborn truth frustrates activists who seek justice by reimagining and reclaiming Hawai‘i’s maps.

TEXT BY JACK TRUESDALE

ART BY SEAN CONNELLY & KEKAHI WAHI

TEXT BY JACK TRUESDALE

ART BY SEAN CONNELLY & KEKAHI WAHI

Two weeks after the 80th anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy announced that 19,000 gallons—5,000 more than an earlier figure—of fuel mix spilled downhill from its Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility in Honolulu. The facility’s 20 underground fuel tanks, built 100 feet above a major aquifer during the Second World War, were known to leak. Military and civilian families alike were turning on their taps and smelling fuel. Those who drank or showered in the water suffered rashes, sores, stomach aches, and nausea—about 2,000 people reported falling ill. More than 3,000 military families left their homes for temporary lodging in hotels. Honolulu shut down three drinking wells, fearing contamination. In March 2022, following mounting criticism, and after the Navy vacillated on whether to fight the state in court, the Pentagon announced it would close the facility permanently. By April, however, there was still no consensus between the Navy, academics, and regulators about where the contamination was moving.

The plot advanced in numbers. The setting was infrastructure—underground pipes, wells—and the characters were bureaucrats, institutions, and victims. Ours is a purportedly secular society, and drinking fuel-contaminated water harms people no matter what they believe. But throughout the fuel leak crisis at Red Hill, the area originally known as Kapūkakī, a necessary context seemed absent. The landscape of Hawai‘i is woven with mo‘olelo, or orally transmitted stories, that store generations of knowledge and patient, detailed observations of the natural world.

I hoped one of these stories might reveal what more was at stake, and the mo‘olelo of Keaomelemele presented an image of a miles-long path packed bumper-to-bumper with 30-foot-long lizard deities, known as mo‘o, migrating from the North Shore to Honolulu. The story of mo‘o migration was a record of a changing climate, according to University of Hawai‘i Mānoa English professor Candace Fujikane. “The arrival of the mo‘o signals a historic moment when Kānaka Maoli began to pay greater attention to the care and conservation of water and the cultivation of fish,” Fujikane writes

in Mapping Abundance for a Planetary Future: Kanaka Maoli and Critical Settler Cartographies in Hawai‘i. With that new concern for water, Kānaka Maoli could imagine in the migration of the mo‘o a network of waterways above and below ground, connecting the land’s far-flung ecosystems. These deities became known as guardians of streams, springs, and fishponds. “Today, it is at Kapūkakī that the mo‘o engage in battle with monsters that lie beneath the surface of the land,” Fujikane writes.

I first encountered Fujikane’s work in college. Asian Settler Colonialism, a collection of essays she co-edited and wrote the introduction to, explored how Asians have helped develop Hawai‘i as a “U.S. colony” through the state legislature, prisons, the military, and the arts. Fujikane, who was born on Maui, calls herself a “fourthgeneration Japanese settler aloha ʻāina.” I followed Fujikane’s output since reading the collection, and I thought that Mapping Abundance, published in 2021, might illuminate the Red Hill spill.

In Mapping Abundance, Fujikane recounts the past decade of activism in Hawai‘i, chronicling attempts by developers and the occupying settler state to “wasteland” the ‘āina—framing it as lacking all but a potential for development—while activists including herself fought to reveal those lands’ abundance. Yet she finds opportunity in others’ apocalypse. The current way of seeing land through “cartographies of capital”—expedient abstractions of complex lands for profit—facilitates the extraction and pollution driving climate change, she writes. And yet, climate change heralds the end of capital, she further explains, “making way for Indigenous lifeways that center familial relationships with the earth and elemental forms.”

In several episodes where capital— developers, the state—depicted lands as scarce, the activists deployed “Kanaka Maoli and critical settler cartographies” to find what the land could provide in not only food and water but also wonder and hope. Sometimes that’s literal, but sometimes that’s less obvious, identifying

Mo‘olelo are rife with double meanings and double entendres. They aren’t always what they appear to be.

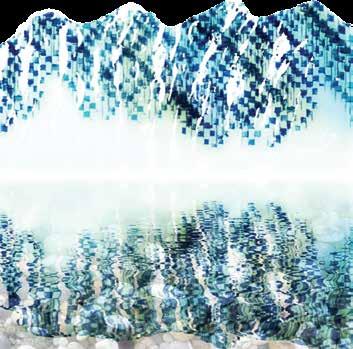

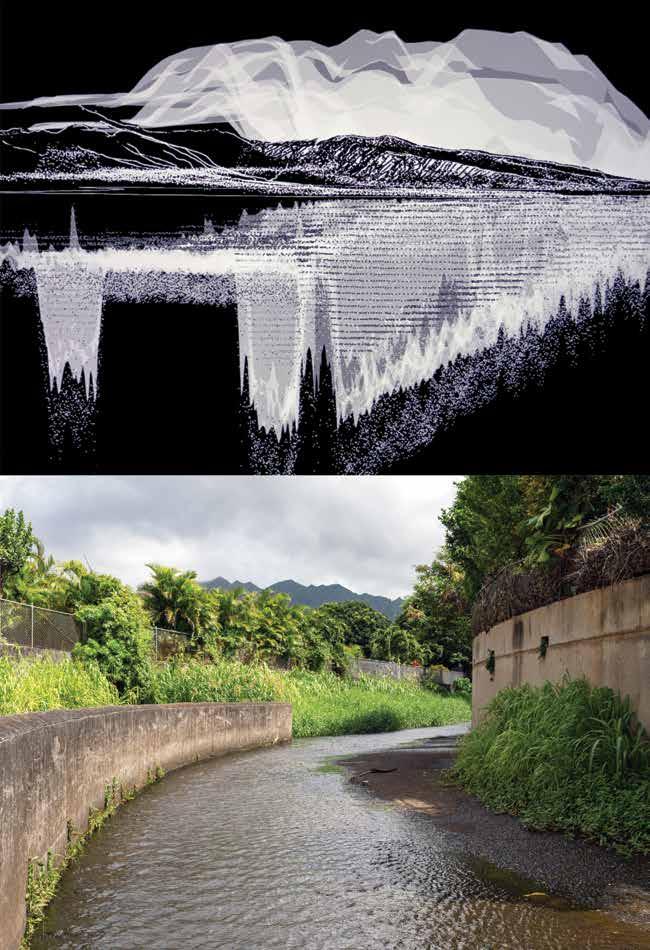

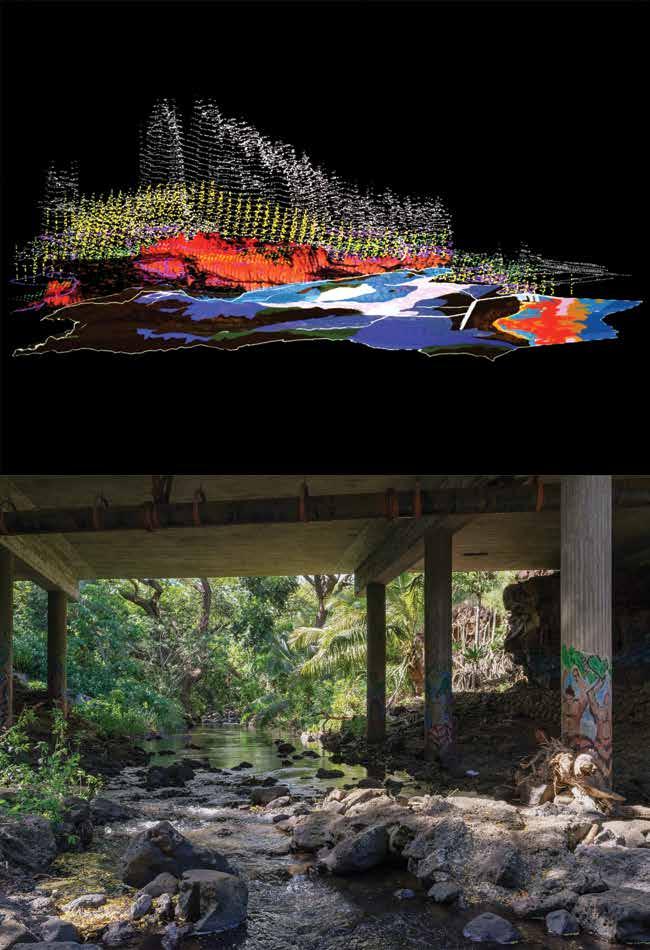

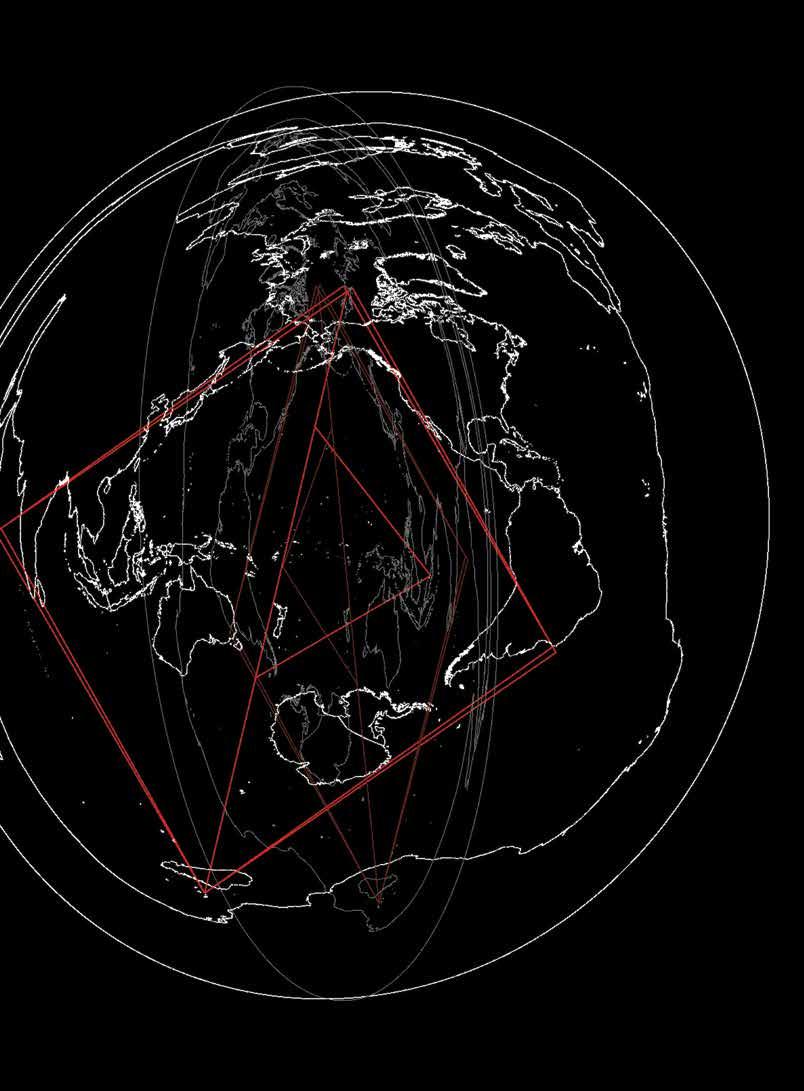

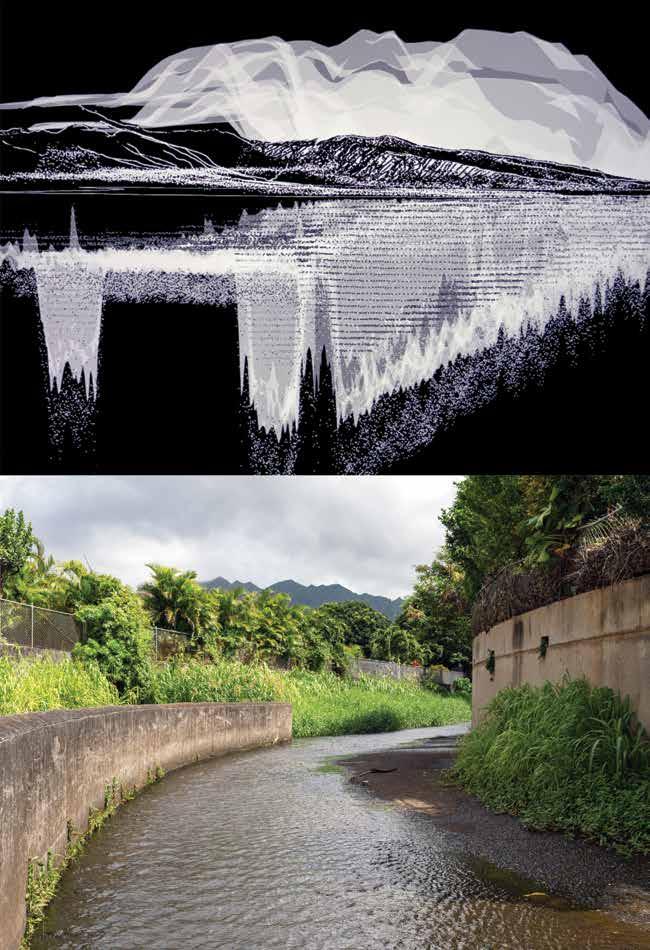

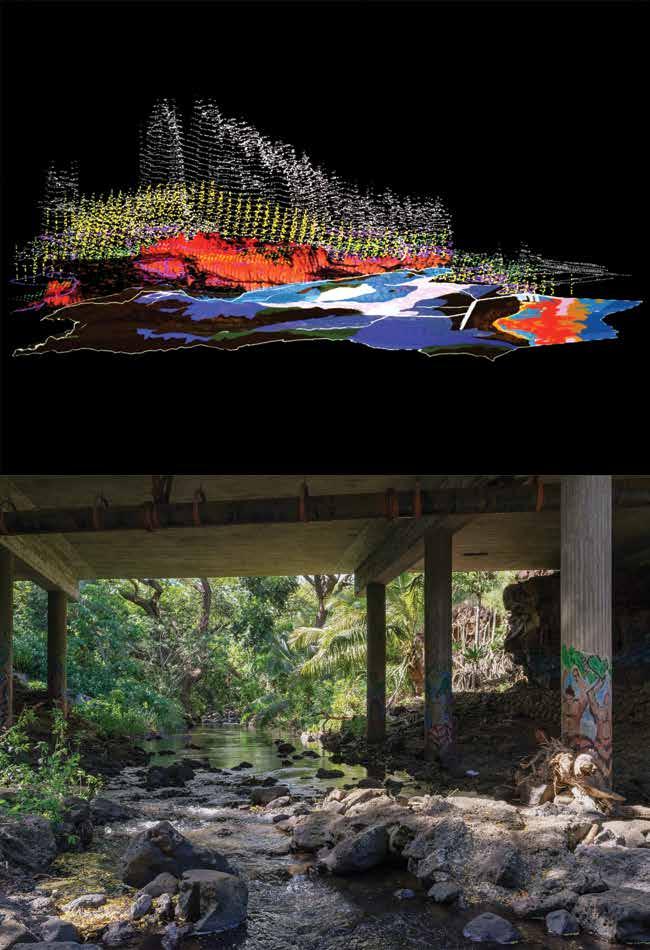

Opposite, digital architecture model taken beneath Mānoa stream comprising abstracted GIS rainfall and wind data. Still facing mauka, near Mānoa Shopping Center, Mānoa, O‘ahu, Hawai‘i. Opening spread, from AFRICA-PACIFIC (2014), a digital mapping project by Sean Connelly.

64 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

the elemental forms of nature, the akua, which, Fujikane writes, “were identified and named based on the ancestral insights into the optimal workings of interconnected ecological webs.” Just as the developer tells a story of a purported wasteland to develop it, activists tell a story of abundant land to preserve it.

Learning from mo‘olelo, like any story, requires some to suspend disbelief. Mo‘olelo are rife with double meanings and double entendres. They aren’t always what they appear to be. Seeing these stories come to life in the landscape requires some degree of imagination. One story Fujikane calls a “genre of wonder” encourages “listeners to challenge the limits of our conceptions of what is possible and to deepen our imaginative capacities.”

And yet political change depends on getting other people to see a story the same way. Fujikane devotes a chapter to demonstrating how this stubborn truth frustrates her careful methods. In 2010, local activists protested the proposed development of an industrial park in Wai‘anae. Locals argued the development, ignominiously named the Purple Spot, opened the door for yet more development, inevitably eroding their agricultural district. They also worried it would desecrate the storied birthplace of Māui, the supernatural being who pulled the islands from the ocean’s depths with a fish hook.

The dispute evolved into a contested case before the state Land Use Commission. In the commission hearing room, the developer’s attorney presented a five-gallon-bucket of the land’s rocky soil to suggest that it wasn’t good for farming. In Fujikane’s eyes, he reduced complex, storied lands to merely “dirt held in suspension, isolated away from the histories, stories, material practices, and people of the place from which the dirt was taken.”

The developer’s view of the land relied on “stark line drawings paralyzed in time” that “abstract, compartmentalize, and encode the intimacies of land into a ‘parcel’ and a ‘project area.’”

As a counterpoint, the activists projected onto the wall of the hearing room photographs from 1968 of the land’s bounty: farmers held watermelons in green fields. In her own testimony, Fujikane presented maps issued by the Land Study Bureau in 1972 that show the land in rows of green. The visuals suggested that the developer assessed the land in its unirrigated state to prove it was “unproductive.”

The developer was also required to commission “cultural impact assessments,” which resulted in an 11-page evaluation for the property itself and a 145-page evaluation for the surrounding land that contains places described in the Māui mo‘olelo. Comparatively, according to the developer’s reductive argument, the page numbers of these assessments—11 versus 145—suggested the proposed development was less culturally relevant than its neighboring plots. But in isolating the land from its surroundings, the developer was practicing what Fujikane calls “a settler mathematics of subdivision.”

Testifying against the development, one local asserted, “These boundaries were not known to our ancestors.” In her own research outside of the hearing room, Fujikane had been sifting through maps of land commission awards from 1851, where she noticed the term “mo‘o” cropping up. It was a shorthand for “moʻoʻāina,” smaller land sections connected within a larger land base, “genealogically connected to one another across ahupuaʻa, as the long iwikuamoʻo (backbone) formed by the moʻo akua in Moʻoinanea’s genealogical line,” Fujikane writes. Like the waters coursing away with fuel spilled from Red Hill, these lands too were connected.

The developer’s attorney asked for documentation of Māui’s exact birthplace. The meaning of the mo‘olelo, however, is not always forthcoming from text alone, Fujikane writes. On a kūpuna-led bus tour through Wai‘anae, Fujikane witnessed the Māui mo‘olelo

come alive as she moved through the landscape. Driving along Farrington Highway, an elder located Māui’s evolution—hatching from an egg as a chicken then evolving into a man in the landscape. The elder identifies Pu‘u Heleakalā as “an egg lying on its side,” then “two peaks that form a beak emerge as a chick hatches from the egg,” Fujikane writes. Turning up toward the mountains, “the silhouette of a beaked man with a wattle” appears, she writes.

“As we continue up Hakimo Road, the silhouette finally transforms into the rugged facial planes of a handsome man.” Māui’s exact birthplace, in other words, was all around, visible in full only by traversing the land.

The elder explains, “One thing about Waiʻanae is we want to save our viewplanes because that’s where our stories are.” With her cultural memory stored in the mountains themselves, each glance renews the mo‘olelo told long before. One night, under a full moon, the elder took Fujikane to Hakimo Road to look at Māui’s profile. “Oh, look at him!” the elder says. “He is one handsome brotha, you know what I mean?”

The development was eventually called off over an issue about an easement rather than the cultural grounds the activists argued. A Judas had emerged in the form of a cultural practitioner who stood to profit from a community benefits package and claimed that the land was, in fact, a wasteland. “And because of this testimony the land use commissioners asserted that there was ‘no consensus’ on the significance of that land,” Fujikane writes.

Legally, the state isn’t built to buy in either. Fujikane later describes the contested case against the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope on Maunakea, when activists attempted to make Mo‘oinanea, the mo‘o matriarch deity, a legal party. They claimed she dwelt on Maunakea and therefore had a vested interest in the land. The Bureau of Land and Natural Resources denied the request. “The information provided

66 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 67

indicated that Moʻoinanea is a spirit, not a person, and as such does not meet the requirements of Haw. Admin. R. §13-1-31 and 13-1-2 to be admitted as a party,” the bureau wrote in a resolution. (According to the latter law, “person” includes corporations and other organizations. Four decades ago, another non-human resident of Maunakea, the palila, an endangered native bird species, sued the Department of Land and Natural Resources for letting goats and sheep eat the last of its habitat. The bird, represented by the Sierra Club, won.)

On a Tuesday in December 2021, I took a bus to Hickam Air Force Base, where the water was reported to be contaminated. The bus slowed to a halt at a checkpoint, and a man in uniform stepped aboard and asked me for my military identification (non-existent). I flashed my driver’s license, he shook his head, and I shrugged and walked out of the checkpoint. I was there reporting a story about Red Hill’s fuel contamination crisis, trying to get a feel for the scope of the issue, but also its more lasting environmental, cultural, spiritual— call it what you will—impact on the island. Pinching my way through Google Maps, though, I could see no subterranean network of water running throughout Honolulu, no obvious signs of meaning that others before me had found in the land.

The date—still alive in infamy, depending on whom you ask—was December 7th. The same day 80 years before, Japan attacked American territories throughout the Pacific including, infamously, Pearl Harbor. That morning I walked around the memorial, which was populating with visitors in veteran’s hats. Although the attacks occurred on the same day, the Pacific Ocean straddles the international date line: December 7 in Hawai‘i was December 8 in other regions that Japan targeted. In an earlier draft of the speech he would give to Congress, President Franklin Roosevelt framed the main attacks as a “bombing in Hawaii and the Philippines.” I had originally learned this from the historian Daniel Immerwahr’s book, How to Hide an Empire. Now there it was on an 80-year-old typewritten draft in a

glass case at the memorial: Roosevelt drew a pencil through the two names and wrote “Oahu.” By the time he spoke, he called it “the American island of Oahu.” It was a presidential act of cartography—zooming in and cropping to a limited geography and chronology—that determined what would be remembered to this day. Perhaps remembering the same-day attacks on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines and Midway Island and Wake Island and Guam (and a host of British colonies including Hong Kong) would have proven cumbersome, or just narratively inconvenient. The rest of that morning, I walked through an old submarine and chatted with dewy-eyed veterans. In the gift shop sat a stack of facsimile St. Louis Star-Times newspapers dated Monday, December 8, 1941. The headline: “WAR DECLARED.”

Two months later, I spent a night on Hawai‘i Island, on the black lava fields south of Pāhoa. Lava undulated from the volcano to the water thirty years before, and now only spare ʻōhiʻa and other shrubs grew from the soilless, newborn land. I stayed in a plywood bed and breakfast on stilts over bare rock, in a neighborhood of other Burning Man-esque hippie cottagecompounds. I was chuffed to find W. G. Sebald’s novel Austerlitz on a communal bookshelf, sandwiched between a perplexing combination of woo-woo tomes on magical thinking and Ayn Rand.

I couldn’t help imagining the land of Red Hill, missing its context and memory, as I read Sebald’s narrator recall a map of a Nazi prison camp. He contemplates that “everything is constantly lapsing into oblivion with every extinguished life, how the world is, as it were, draining itself, in that the history of countless places and objects which themselves have no power of memory is never heard, never described or passed on.” There it was, a danger of forgetting.

Later in the novel, the titular character imagines what existed where a London train station stands: “The little river Wellbrook, the ditches and ponds, the crakes and snipe and herons, the elms and mulberry trees … had all gone … and gone now too are the millions and millions of people who passed through … day in, day out, for an entire century.” Dwelling in that place, recollecting,

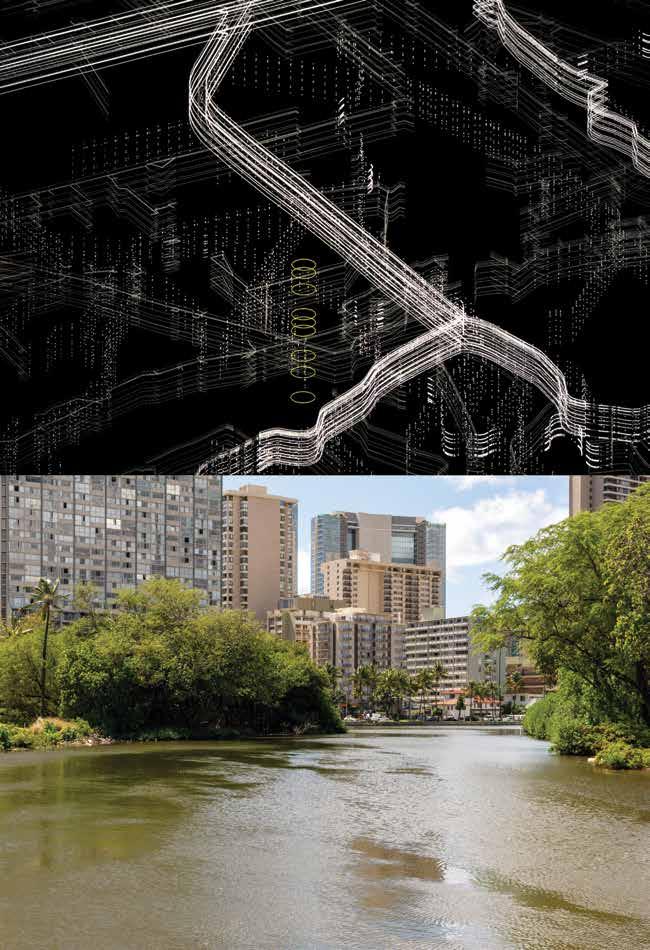

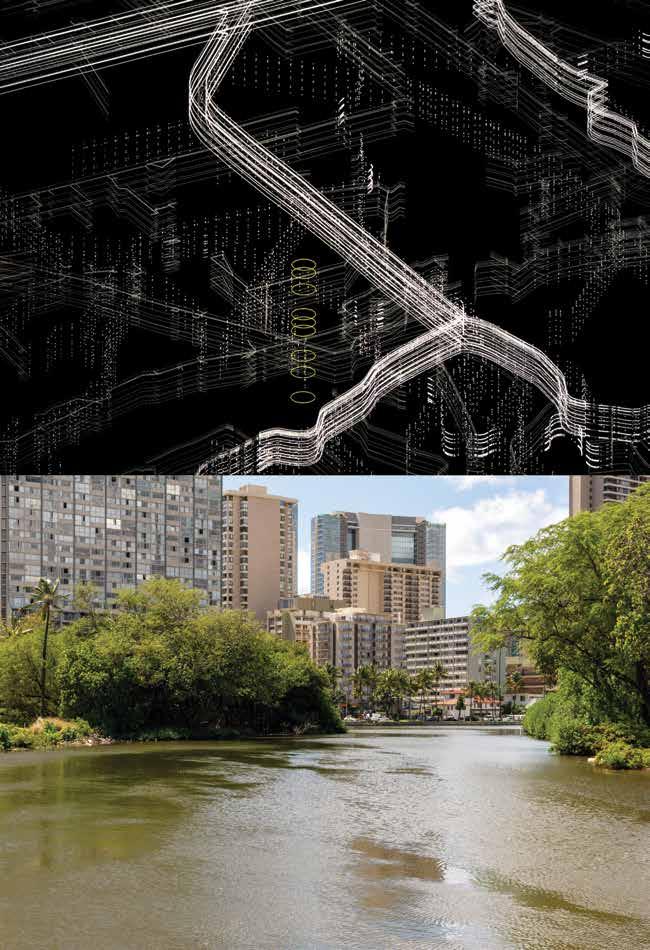

Opposite, digital architecture model of above MānoaPālolo drainage ditch comprising abstracted GIS streamflow data and storm water drainage network. Still facing makai, near Market City Shopping Center, Waikīkī, O‘ahu, Hawai‘i. Previous, digital architecture model of Mānoa Valley looking toward Wa‘ahila Ridge, comprising abstracted GIS cloud cover and aquifer data. Still facing mauka, near Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies, Mānoa, O‘ahu, Hawai‘i.

About the artwork

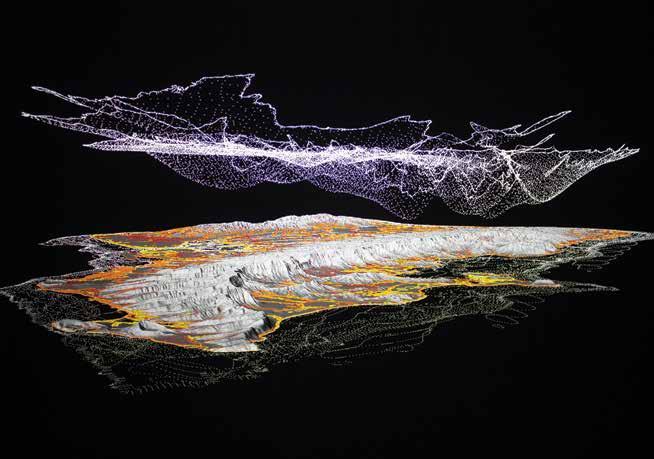

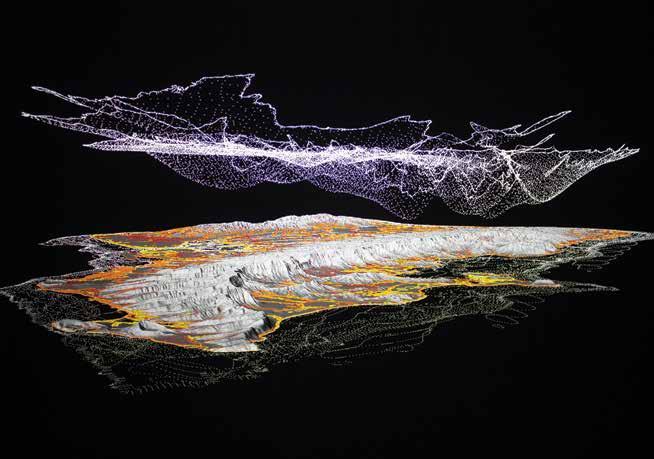

All digital architecture models by artist Sean Connelly, who works primarily in architecture, sculpture, and experimental cartography. All stills by film collective kekahi wahi (Sancia Miala Shiba Nash and Drew Kahu‘āina Broderick), who document stories of transformation across Hawai‘i.

68 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

he says, “I felt at this time as if the dead were returning from their exile and filling the twilight around me with their strangely slow but incessant to-ing and fro-ing.”

Back on O‘ahu in December, I left the Pearl Harbor memorial in an Uber headed downtown. The driver asked why I was in town and then offered a detour. He pulled up to the entrance to the Aliamanu Military Reservation, a housing development downhill from the leaking fuel tanks, where the water was later found to contain levels of petroleum hydrocarbons three times the state limit. Its resident military families were relocating to hotels in Waikiki. A guard stopped the car (“unusual,” the driver said). A few dozen yards inside, an electronic sign was flashing: “Do Not Use The Water!” The guard turned the valiant driver away, and back we went down into Honolulu.

Beyond the military complex’s carbon copy housing, the barbed wire, the pavement, and the city buildings, I wasn’t sure I could make out what came before, what was lost and being lost. I couldn’t make out the stories of the land’s former Hawaiian

inhabitants, while another story—nationalist and grandiose—was already shaping the people here. The dead, albeit of a different demographic, were returning now too. I stayed on in Honolulu until evening to watch the hullabaloo before a commemorative parade at Kapi‘olani Park: Hundreds of red-white-and-blue cheerleaders flown in from the mainland, grade-schoolers-in-uniform, slack-jawed and dozing nonagenarians-in-uniform receiving yet more medals on stage. (“Everybody is still receiving a medal!” the master of ceremonies said, after thanking the event sponsor, the History Channel.) On the grass sat a two-story inflated Purple Heart float, a blow-up Navy jet bigger than a bus, a 20-foot-tall eagle with stars-and-stripes wings, and 12-foot balloons for the military’s branches. Here was a narrative complete with characters and gods, a mythology all its own. I wouldn’t know where to begin reconstructing what came before, but I could almost imagine the raw land and the people passing through here long ago, in the time between pure lava and this.

Above, from HI-ATLAS (2015) by Sean Connelly featuring O‘ahu’s annual rain data as a cloud combined with solar data representing the island’s aquifer. Opposite, digital architecture model of Waikīki comprising abstracted GIS soil type/ permeability/fertility data. Still facing makai, near Ala Wai Canal, Waikīkī, O‘ahu, Hawai‘i.

70 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 71

Keepers of Kaiser ’ s

For generations, the Kaiser Surf Crew has established a presence in and out of the water. For them, Kaiser’s is more than a surf break: It’s community. It’s family. It’s Hawai‘i.

TEXT BY RAE SOJOT

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

In 1954, when industrialist Henry J. Kaiser built his signature hotel, The Hawaiian Village, the property featured a lagoon, a boating facility and a docking area for water craft. Wanting to provide beach access for catamarans, Kaiser also dredged a channel through the reef. The action produced a prized surf break—a predominate righthander with two highlight sections: the deep, long shot at the top of the reef shelf and a shallower, more compact area with a highly desirable “bowl,” or bend to the wave. Eventually, the property was sold and the hotel’s name changed. But the break’s name—Kaiser’s— stuck, and around it, a local surf community grew.

Kaiser’s feels local because it is local. Because Hawaiʻi’s surf demographics are shifting, these uniquely local pocket communities are in decline. Strongholds at breaks like Mākaha, Point Panic, Sandys, Kaiser’s remain: Each of these communities embody and embrace the culture unique to that surf spot and often serve as their most vigilant keepers.

I met the Kaiser Surf Crew like most do, through a shared love for the ocean. This summer I spent some time with them—sharing waves of course, and meals and stories too. What follows is a collection of profiles, rules, and personal anecdotes from members of this special community.

Tony Ikaika Teves

37, FROM MĀNOA