F/W 2023

ART & DESIGN: SHINGO YAMAZAKI, MEGAN KAMALEI KAKIMOTO, AND GOOD LAMP CO. CULTURE: KĀ‘EO IZON, KALEINOHEA CLEGHORN, LANAKILA MANGAUIL, AND MELEANA ESTES. SOCIETY: MOKAUEA ISLAND, KALAPANA, AND WĀHINE SURFING. LIVING WELL: JOHNSON HOUSE, AND LEI MAKING. EXPLORE: NYC WITH EMILY MAY JAMPEL, AND OBON DANCES. STYLE: AUNTY NANI, AND PĀ‘Ū RIDERS. PORTFOLIO: NANI WELCH KELI‘IHO‘OMALU. POETRY: KRISTINE PONTECHA.

FLUXHAWAII.COM NO. 45

The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I $14.95 US $14.95 CAN COVER: 1/5

TABLE OF CONTENTS

20 | Painting

Shingo Yamazaki

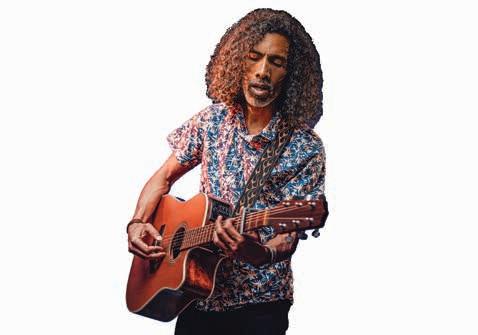

32 | Maoli

Kāʻeo Izon

38 | Style @hirokolele

44 | Literature Megan Kamalei Kakimoto

A HUI HOU

158 | Mangosteen

FEATURES

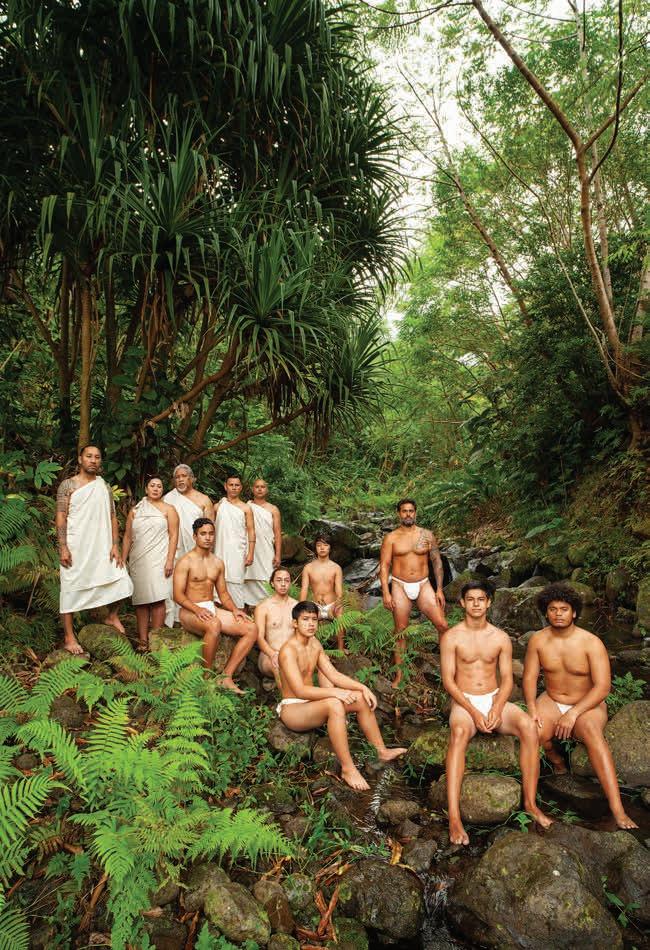

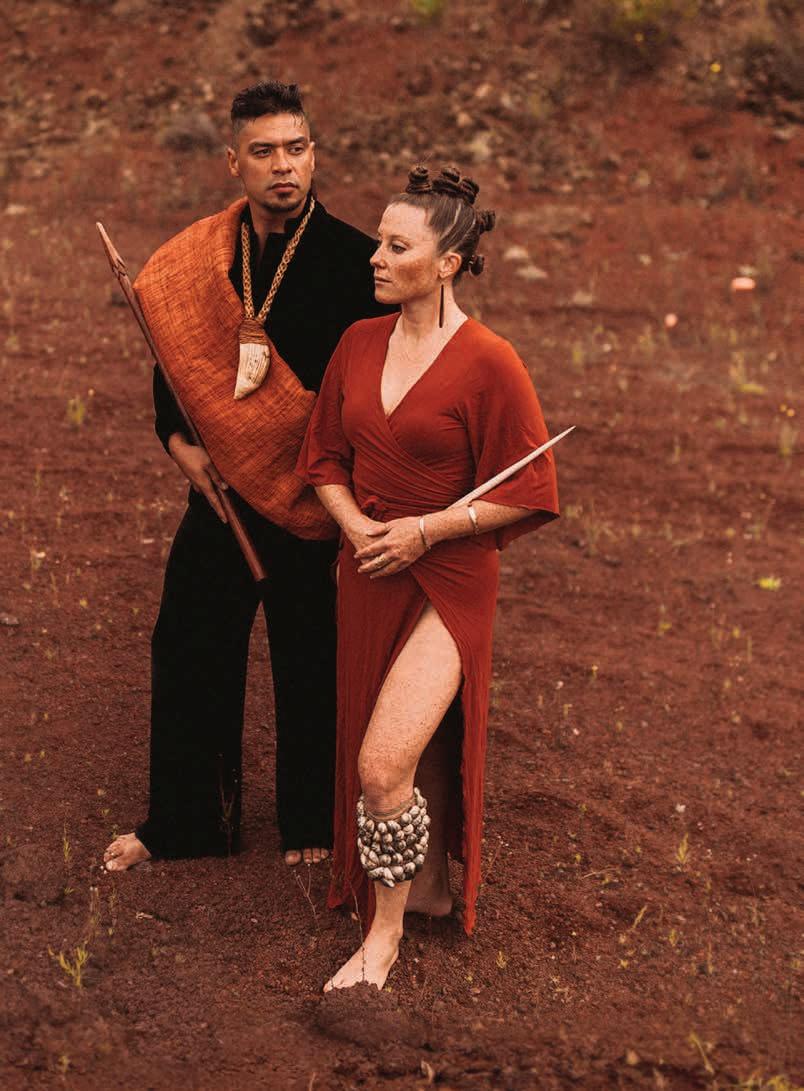

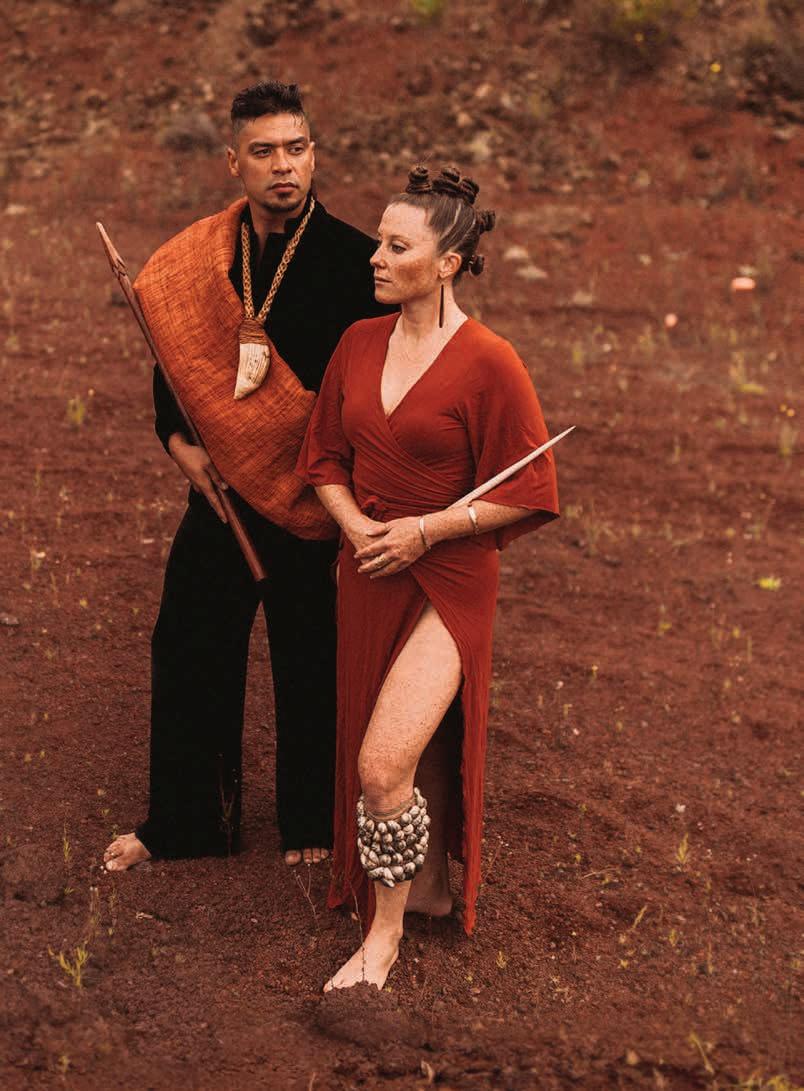

52 | Ceremonial Shifts

For two Hawai‘i Island ceremonialists, reindigenizing a people to their homeland begins with marking the seasonal transitions that Kānaka Maoli have formalized for centuries.

66 | She Go

Over the last few years, waves of change have rocked the surfing world, especially for Hawai‘i and women athletes.

80 | To Build After Fire

On Mokauea Island, the site of O‘ahu’s last traditional fishing village, families have fought for decades to preserve their traditional way of life.

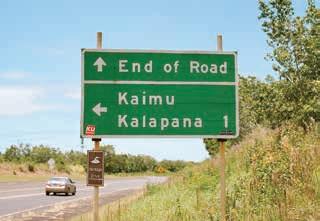

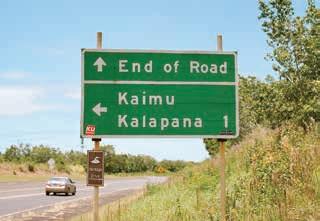

92 | A t the End of the Road

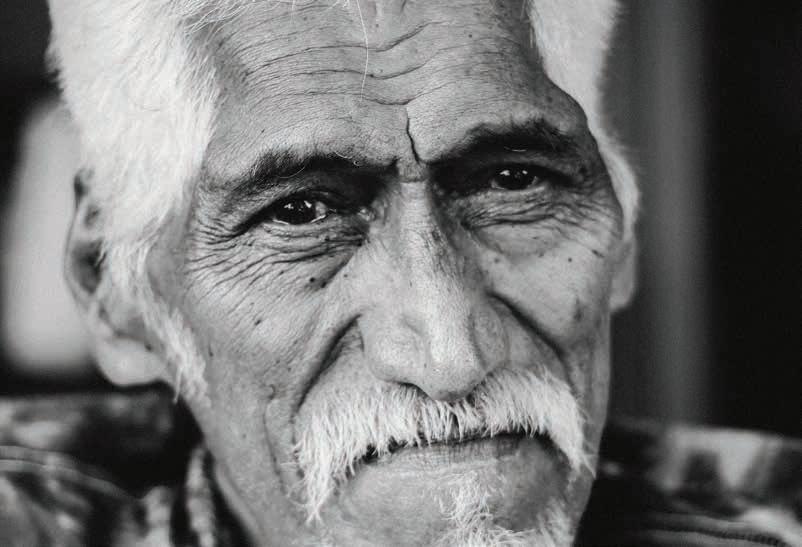

Photographer Nani Welch Keli‘iho‘omalu’s work revolves around the documentation of the contemporary Native Hawaiian experience. Through analog and digital photography, she recreates the multifaceted and layered histories that she finds herself placed within.

|

F/W 2023

FEATURES |

FLUX PHILES

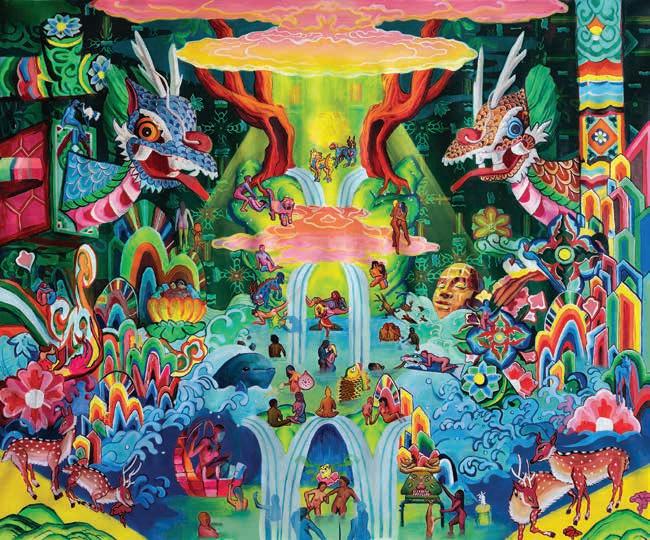

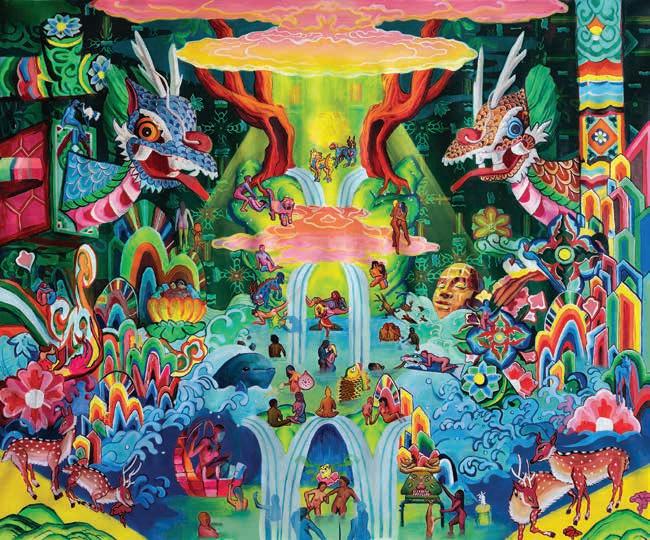

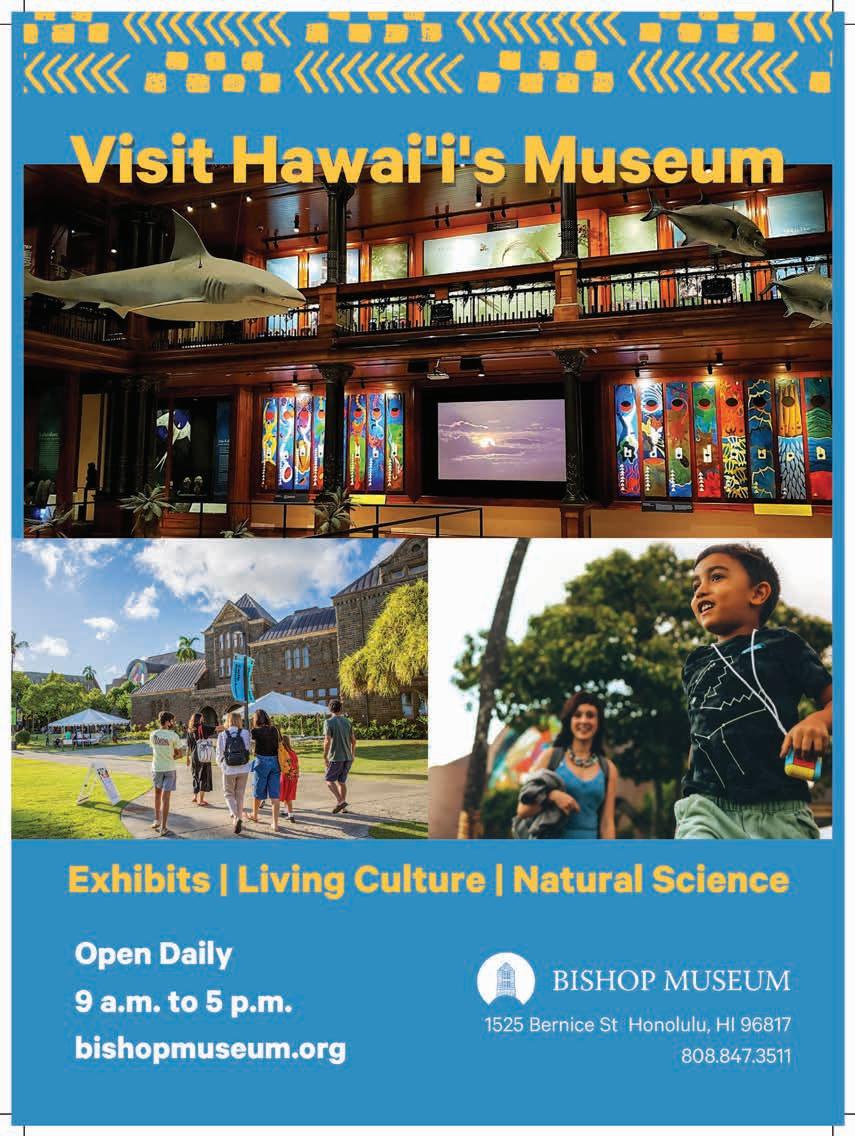

Warm Lights, 2022 . Art by Shingo Yamazaki.

6 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

ROYAL HAWAIIAN CENTER ALA MOANA CENTER 808 427 3780 FENDI.COM

128 EXPLORE 130 | New York City Emily May Jampel 140 | Honolulu Obon 152 | History Pāʻū Riders 108 LIVING WELL 110 | Hana Lei Meleana Estes 116 | Design Johnson House & Good Lamp Co. TABLE OF CONTENTS | DEPARTMENTS |

Image by Michelle Mishina

8 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Image by Viola Gaskell

JEWELS THAT TELL TIME © 2023 Harry Winston SA. HARRY WINSTON OCEAN DATE MOON PHASE AUTOMATIC ALA MOANA CENTER 808 791 4000 ROYAL HAWAIIAN CENTER 808 931 6900 HARRYWINSTON.COM

Lei Making

Meleana Estes

Surfing

Kelis Kaleopa‘a

Stay current on arts and culture with us at: fluxhawaii.com /fluxhawaii @fluxhawaii @fluxhawaii INFLUX TV

TABLE OF CONTENTS | VIDEO | Still from IN FLUX Still from IN FLUX 10 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Streaming Videos, Newsletters, Local Guides, & More

We’ ve refreshed the website for Flux Hawaii with a more dynamic viewing experience. Watch all the original episodes from our themed seasons, find ways to support local small businesses, and sign up for our weekly newsletters curated with fascinating reads. You can also browse past issues of the print magazine for purchase.

On the Covers

Reflecting the dynamism of stories in every issue, we redesigned Flux Hawaii’s covers to express the kaleidoscopic and shifting landscape of these islands. This seismic burst of energy arrives with five original covers to captivate, inspire, and connect.

Clockwise from right:

1. Image by Sam Muller

2. Image by Michelle Mishina

3. Image by Nani Welch Keli‘iho‘omalu

4. Image from Hawai‘i State Archives

5. Image by Tahiti Kulia Huetter

TABLE OF CONTENTS | ONLINE | FLUXHAWAII.COM

12 | FLUXHAWAII.COM NO. 45 2023 KĀ‘EO KALAPANA, AND WĀHINE SURFING. AND PĀ‘Ū RIDERS. The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I NO. 45 2023 The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I $14.95 US $14.95 CAN NO. 45 2023 IZON, KALEINOHEA CLEGHORN, LANAKILA MANGAUIL, AND MELEANA MOKAUEAISLAND, KALAPANA, AND WĀHINE SURFING. EMILY MAY JAMPEL, AND OBON AUNTY NANI, The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I $14.95 US $14.95 CAN FLUXHAWAII.COM NO. 45 F/W 2023 ART DESIGN: SHINGO YAMAZAKI, MEGAN KAMALEI KAKIMOTO, AND GOOD LAMP CO. CULTURE: KĀ‘EO IZON, KALEINOHEA CLEGHORN, LANAKILA MANGAUIL, AND MELEANA MOKAUEA ISLAND, KALAPANA, AND WĀHINE SURFING. LIVING WELL: JOHNSON HOUSE AND EMILY MAY JAMPEL, AND OBON DANCES. STYLE: AUNTY NANI, AND PĀ‘Ū RIDERS. PORTFOLIO: $14.95 US $14.95 CAN The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I SHINGO YAMAZAKI, MEGAN KAMALEI KAKIMOTO, AND IZON, KALEINOHEA CLEGHORN, LANAKILA MANGAUIL, AND MELEANA MOKAUEAISLAND, KALAPANA, AND WĀHINE SURFING. EMILY MAY JAMPEL, AND OBON DANCES. STYLE: AUNTY NANI, AND PĀ‘Ū RIDERS. PORTFOLIO: NANI WELCH KELI‘IHO‘OMALU. POETRY: KRISTINE PONTECHA. FLUXHAWAII.COM NO. 45 F/W 2023 The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I

MASTHEAD

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

EDITORIAL

Brian McManus

GLOBAL EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Lauren McNally

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Matthew Dekneef EDITOR IN CHIEF

EDITORIAL VIDEO DIRECTOR, HAWAI‘I

Eunica Escalante MANAGING EDITOR

Rae Sojot SENIOR EDITOR

N. Ha‘alilio Solomon ‘ŌLELO HAWAI‘I EDITOR

Taylor Niimoto MANAGING DESIGNER

Eleazar Herradura

Coby Shimabukuro-Sanchez DESIGNERS

John Hook

SENIOR PHOTOGRAPHER

Samantha Hook

PHOTOGRAPHY EDITOR

CONTRIBUTORS

C. Kawohikūkahi Adversalo

Alexis Cheung

N. Kamakaokalani Gallagher

Sonny Ganaden

Viola Gaskell

Nicole Naone

Mindy Pennybacker

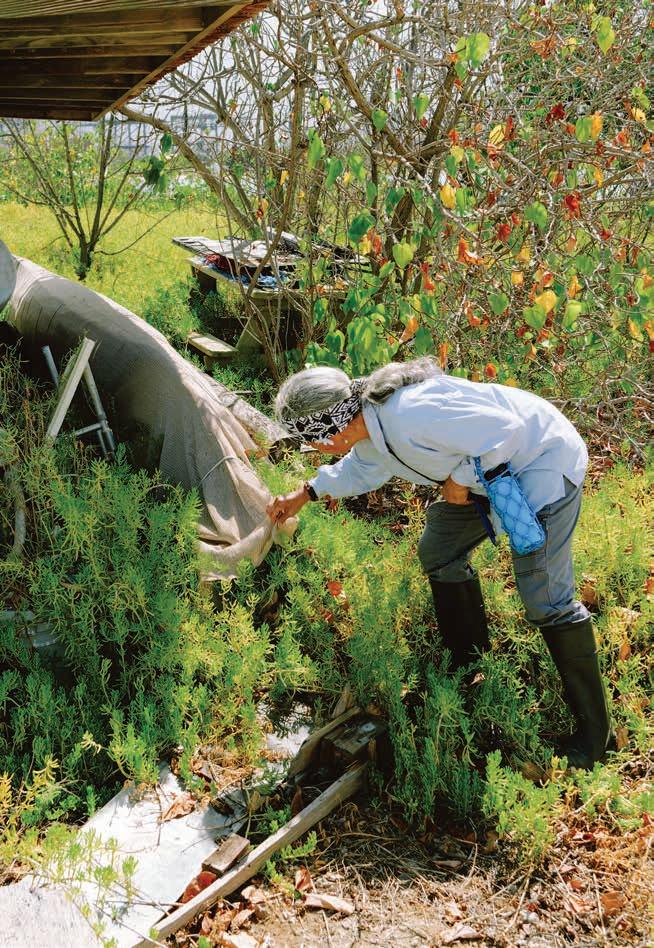

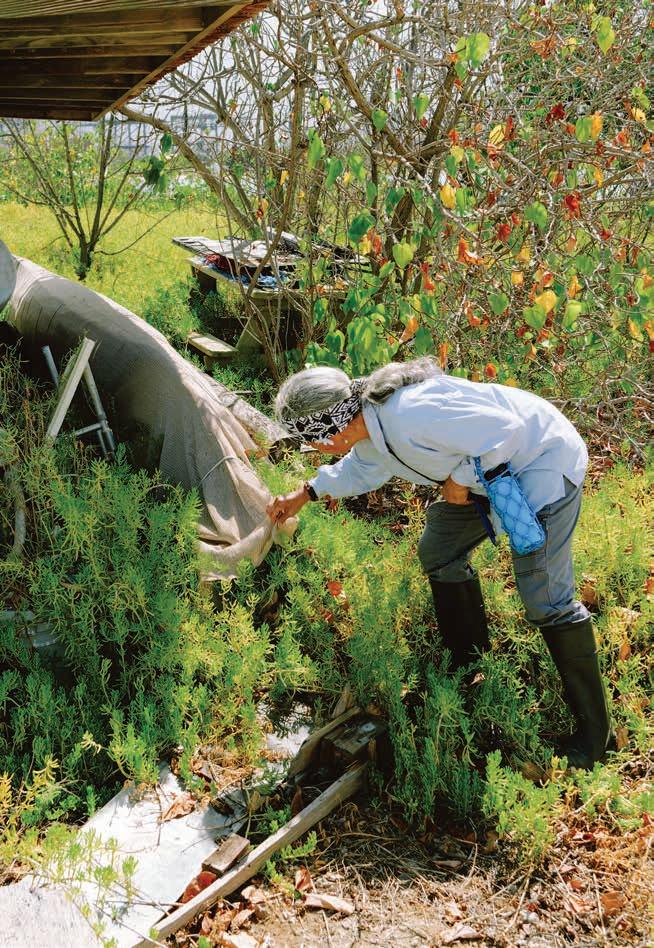

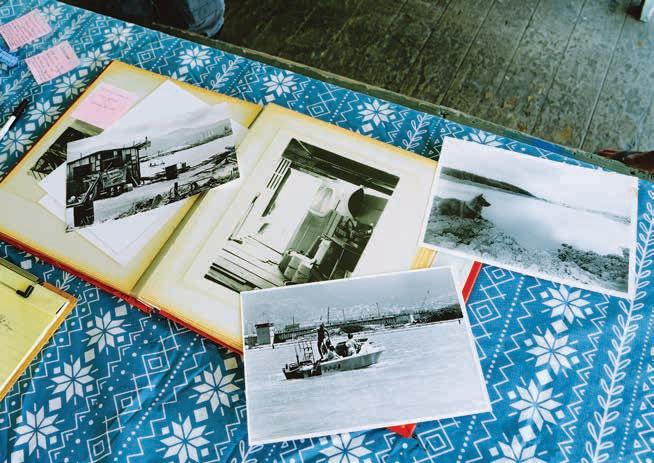

Kristine Pontecha

Jasmine Reiko

Kylie Yamauchi

IMAGES

Ruben Carrillo

Mahina Choy-Ellis

Christa Funk

Viola Gaskell

Tahiti Kulia Huetter

Kā‘eo Izon

Nani Welch Keli‘iho‘omalu

Hiroko Letman

Brandyn Liu

Michelle Mishina

Sam Muller

Nicole Naone

Josiah Patterson

Meagan Suzuki

Michael Vossen

Shingo Yamazaki

CREATIVE SERVICES

Marc Graser VP GLOBAL BRAND STORYTELLING

Gerard Elmore VP FILM

Blake Abes

Romeo Lapitan

Erick Melanson FILMMAKERS

Jhante Iga VIDEO EDITOR

Kaitlyn Ledzian STUDIO DIRECTOR/ PRODUCER

Taylor Kondo PRODUCER

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock PARTNER/GENERAL MANAGER, HAWAI‘I

Kristine Pontecha CLIENT SERVICES DIRECTOR

Gary Payne VP ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE

Sheri Salmon PEOPLE AND CREATIVE SERVICES DIRECTOR

Sabrine Rivera OPERATIONS DIRECTOR

Brigid Pittman

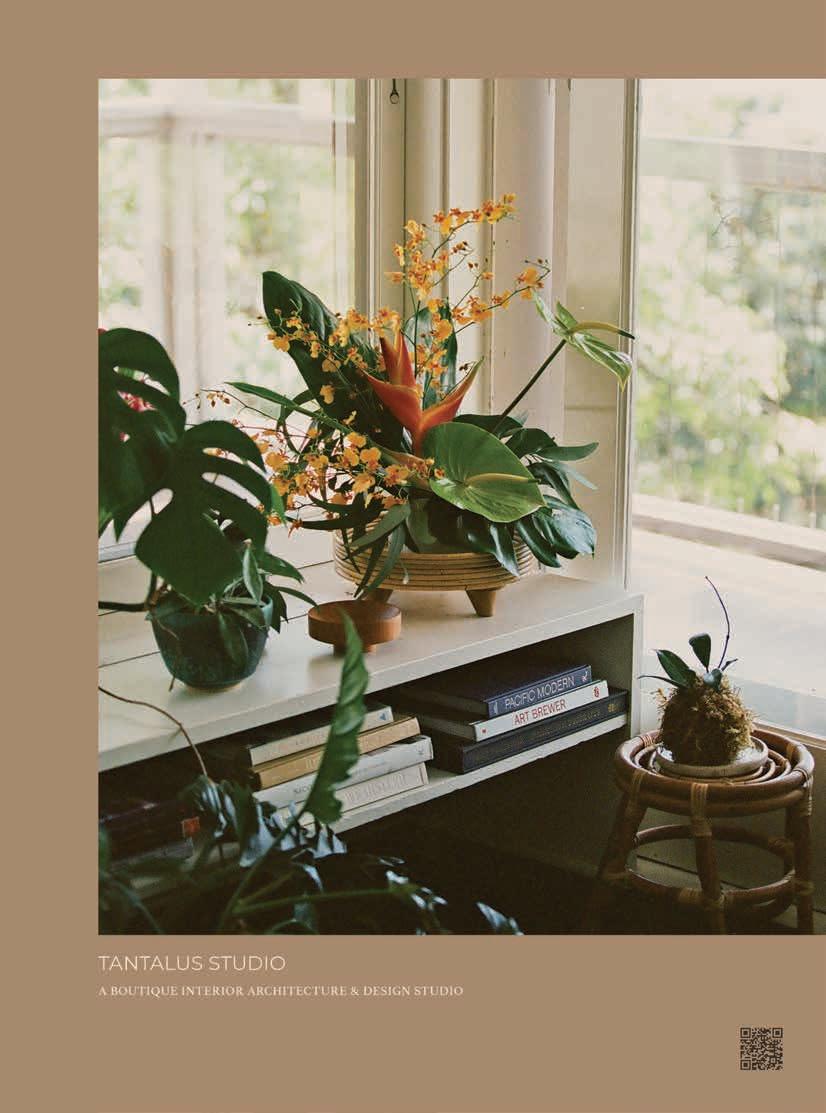

DIGITAL CONTENT & SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER

Arriana Veloso

DIGITAL PRODUCTION DESIGNER

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley VP SALES

Alejandro Moxey SENIOR DIRECTOR, SALES

Francine Beppu INTEGRATED MARKETING LEAD

Courtney Asato MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

General Inquiries: contact@fluxhawaii.com

PUBLISHED BY: NMG Network

36 N. Hotel St., Ste. A Honolulu, HI 96817

©2023 NMG Network. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. ISSN 2578-2053.

| FALL/WINTER 2023 | 14 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

2023 |

C. Kawohikūkahi

Adversalo

No ka ʻāina e pā mai ana ka makani Hoʻeʻo, no ka ʻāina ʻo Moanalua kēia kanaka nei, ʻo Kawohikūkahi Adversalo. ʻO kāna hana nui ka ulana lau hala. Eia naʻe, ʻo kahi pahuhopu āna ka lilo ʻana i kumu ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi no kahi kula kiʻekiʻe. Ke hoʻokō ʻia nei nā kekelē lae pua he ʻelua ma lalo o ka Hālau ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi ʻo Kawaihuelani a me ka Hālau ʻIke Hawaiʻi ʻo Kamakakūokalani ma ke Kulanui ʻo Hawaiʻi ma Mānoa. Ma hope, e holomua ana no ka palapala PostBaccalaureate ma lalo o ke Kula Hoʻonaʻauao ma ua kulanui nei. ʻO ka moʻolelo ʻo “Nā Kama a Ohiohikupua Lāua ʻo Lauhuki,” ma ka ʻaoʻao 32, no nā hui ulana lau hala ka mua loa āna i kākau ai no Flux Hawaiʻi. A he hoihoi ia hana ma muli o ko ia nei pilina ma ke ʻano he lālā o ia hui ulana. “He pono nō ke aʻo pū ʻana i ka ʻōlelo me ka moʻomeheu Hawaiʻi ʻoiai e aʻo ana i mea Hawaiʻi. Pēlā e maopopo leʻa ai a e lau aʻe ai ko kākou ʻike,” wahi a Adversalo i ʻōlelo ai.

Alexis Cheung

Alexis Cheung is a writer from O‘ahu currently living in New York City. Her journalism, interviews, and essays have been published in Vanity Fair, T: The New York Times Style Magazine, The New York Times, The Cut, The Sewanee Review and The Believer, among others. After graduating from Punahou School, she attended New York University and later obtained her MFA in Creative Nonfiction from Hunter College. For this issue, she profiled the Hawai‘i-born artist Shingo Yamazaki, page 20, and the Instagram account of @hirokolele which features a woman known as Aunty Nani, page 38. “Hawai‘i might be small, but there’s no shortage of talent in and coming from the islands,” she says. “Every time I report a story, I’m reminded of how its unique blend of so many communities from various countries cannot help but inspire creativity. It’s heartening to watch people perpetuate Hawai‘i’s history and culture through their chosen mediums, but in a way that complicates existing narratives and notions about the state, too.”

Jasmine Reiko

Nicole Naone is a Kanaka Maoli, Korean cultural producer with practices spanning film, sculpture, and virtual reality. Naone’s cinematic credits include producing short film Lahaina Noon and the multi-award winning scripted feature Waikiki As a writer-director she created the short film installations Mauna Fuji (2014), Kalaoke o Mākua (2019), and PIKO: Virtual Reality (2021). Naone has contributed her mastery of visual communication to spaces of Native Hawaiian resistance, including the fight to protect Maunakea and the repatriation of ʻiwi kūpuna. Naone moderated a conversation for this issue on the relevance of oli in contemporary society. “Spending time with Lanakila and Kaleinohea is always a blast. My cheeks and abs hurt from laughing,” Naone says of her time with the two Hawaiʻi Island cultural practitioners, on page 52. “They makawalu it in a super cool way. More than anything they’re good fun, and make me excited for the future while giggling through the present.”

Descended from grandparents born in Kaua‘i and O‘ahu, Jasmine Reiko is a fourth-generation writer and painter with roots in Pālolo and Kaimukī. Raised with a little sister, the two explored abandoned houses full of termites, the tops of hills, and dry, forested deadends in a neighborhood full of children from varying multigenerational households who all told very different stories and who all collectively avoided Waiʻalae Avenue because it was “too city.” Finding resonance in the quiet and slow, Reiko corresponds conversations that honor their own contours, ground place, and extend identity out through in. Concerned with beauty and shape through storytelling, Reiko engages personal and broader myths with dreams and hypotheticals, exploring the layers of truths already present. For this issue, she profiles the photographer Nani Welch Keliʻihoʻomalu, on page 92. “Engaging acts of compassion and gratitude through art with one’s culture is essential to perpetuating community,” Reiko says, “something Nani does by taking photos of the changing while keeping past and present in mind.”

CONTRIBUTORS | FALL/WINTER

Nicole Naone

16 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

KULEANA

‘Āina... it’s also the old word for ‘ohana, for family. And that’s because it was recognized that the land is us.”

Kahealani Acosta BS, Tropical Plant & Soil Sciences, UH Mānoa, 2019 Current master’s student in Tropical Plant & Soil Sciences

At the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, we help you develop a sense of purpose beyond yourself. Be among the innovators who are creating, rethinking and reinventing our world. Where will your learning take you?

MANOA.HAWAII.EDU The University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa is an equal opportunity, affirmative action institution.

n. right, privilege, concern, or responsibili

PICTURED: KAHEALANI AT MAʻO ORGANIC FARMS, WAIʻANAE, HAWAIʻI

“

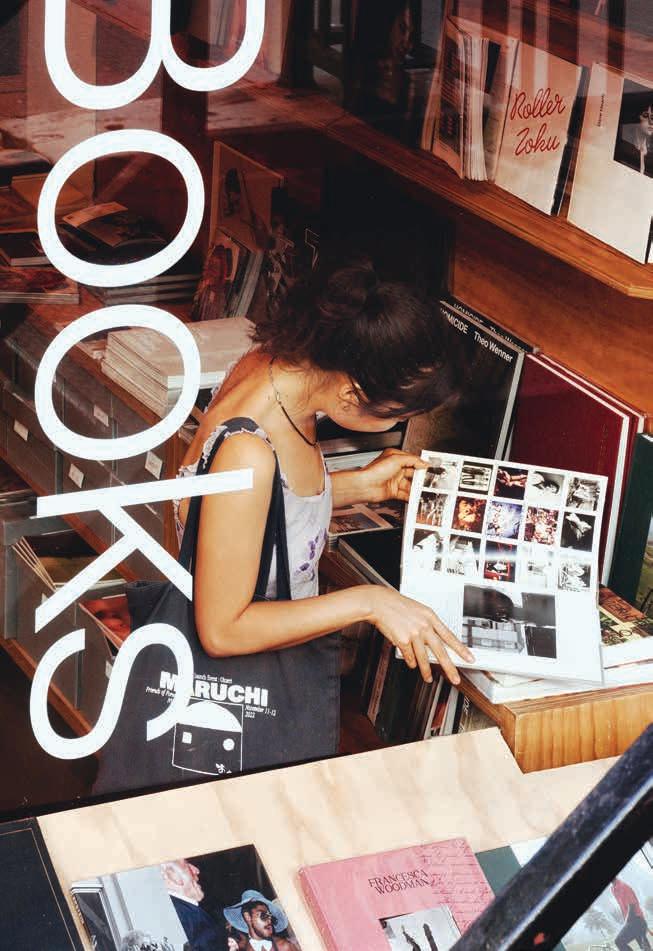

The author Megan Kamalei Kakimoto at Nu‘uanu Pali. Image by Meagan Suzuki.

The author Megan Kamalei Kakimoto at Nu‘uanu Pali. Image by Meagan Suzuki.

ARTS & CULTURE

“Akā nō na‘e, iā kākou, ‘o nā loina, nā hua‘ōlelo, ka ‘ike ku‘una, nā ka‘ao, a me ka lawena i loa‘a mai mai ke kumu mai a i ka haumāna aku, ‘o ia nō nā mea i Hawai‘i ai kā kākou nala ‘ana.”—Pueo Pata

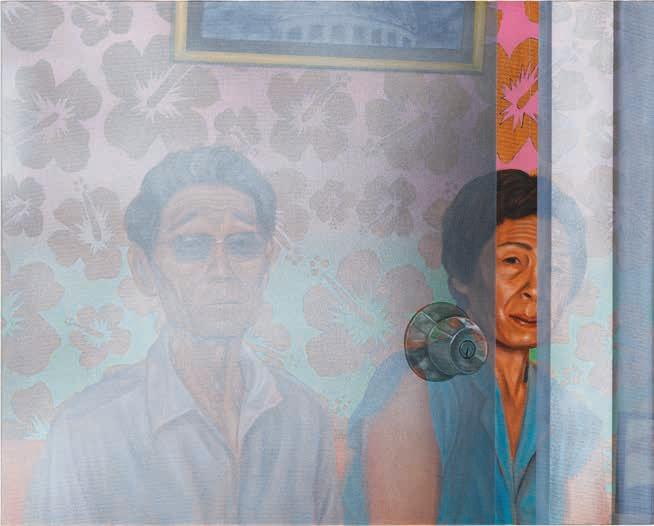

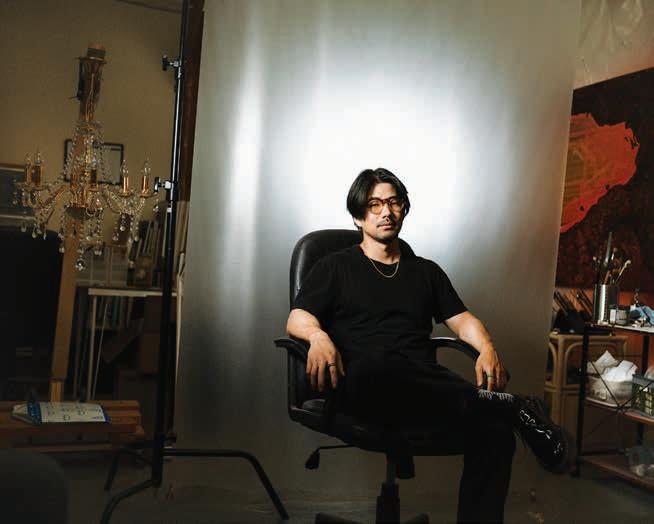

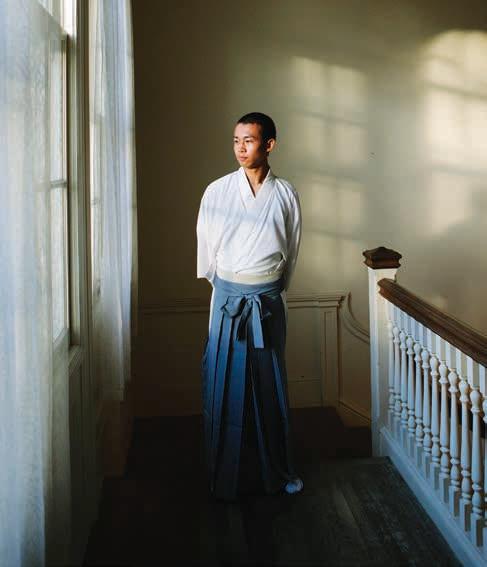

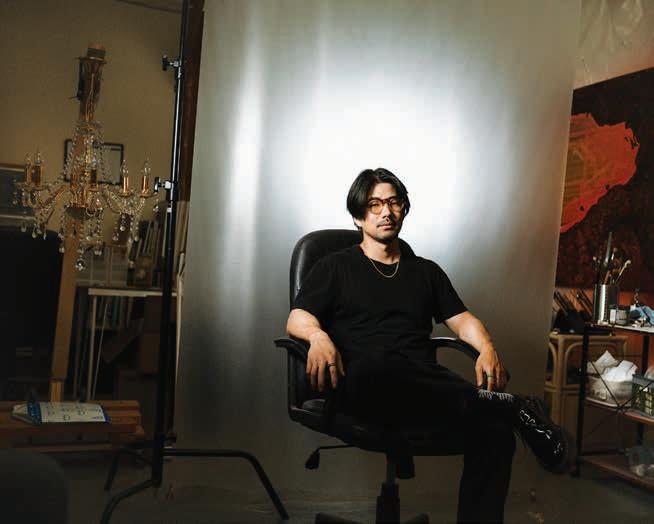

Layered Histories

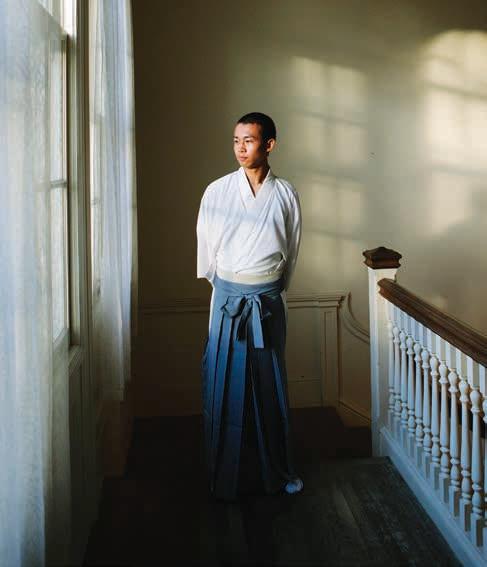

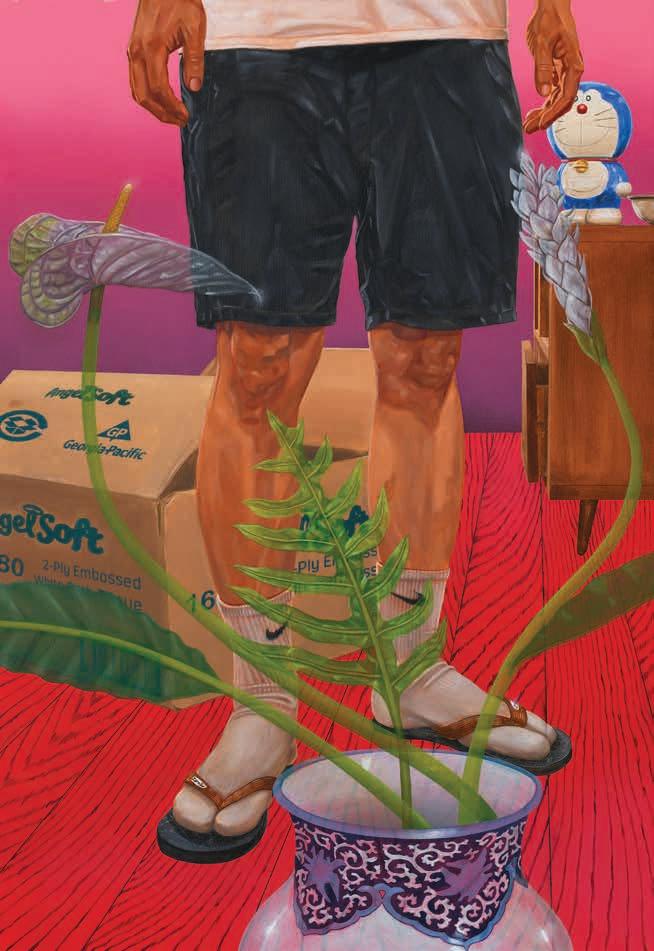

The L.A.-based Shingo Yamazaki paints a multicultural Hawai‘i upbringing steeped in meditations on identity and memory.

TEXT BY ALEXIS CHEUNG

IMAGES BY SAM MULLER

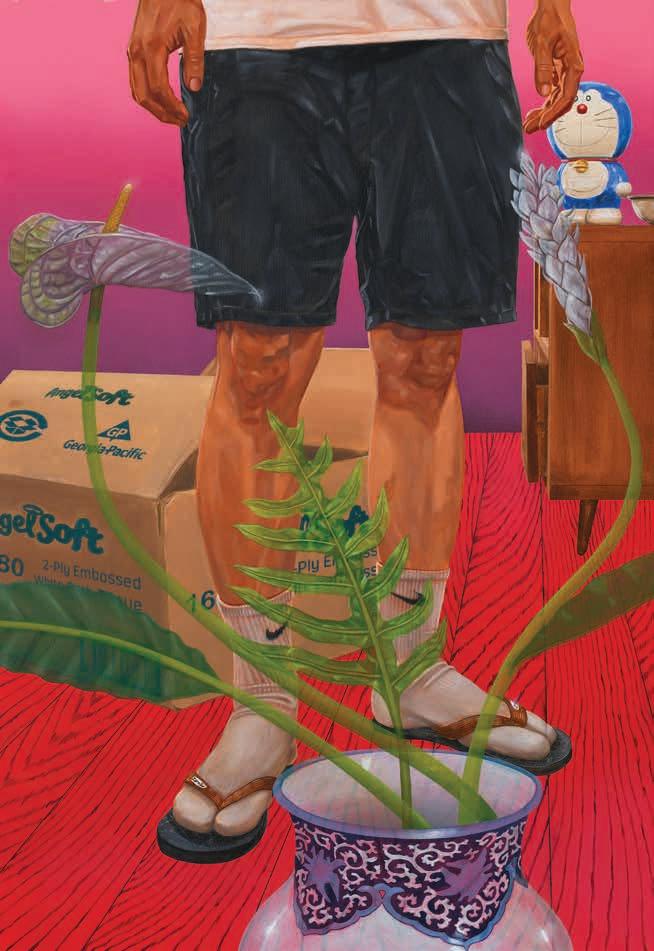

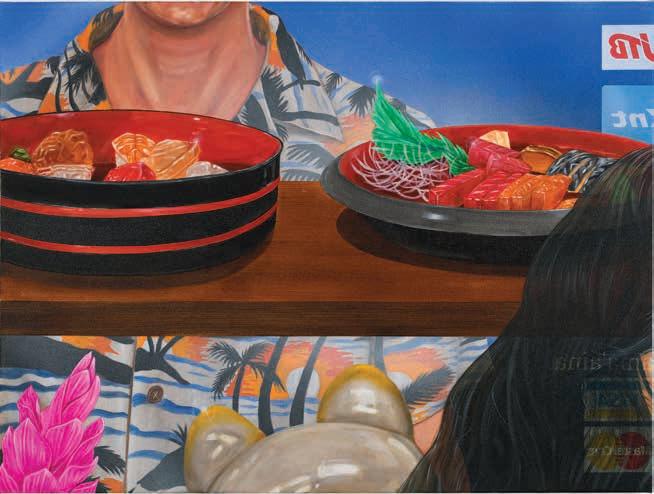

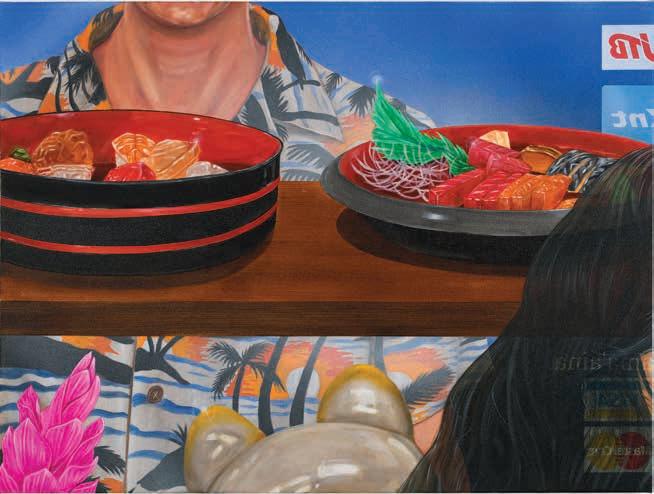

A couple sits down to dinner. On the table there’s a Budweiser for him (bottled, not canned), a water for her (tap, not bottled), and a plate and two bowls between them. The booth behind them is cherry red and the walls are covered in wallpaper patterned with anthuriums.

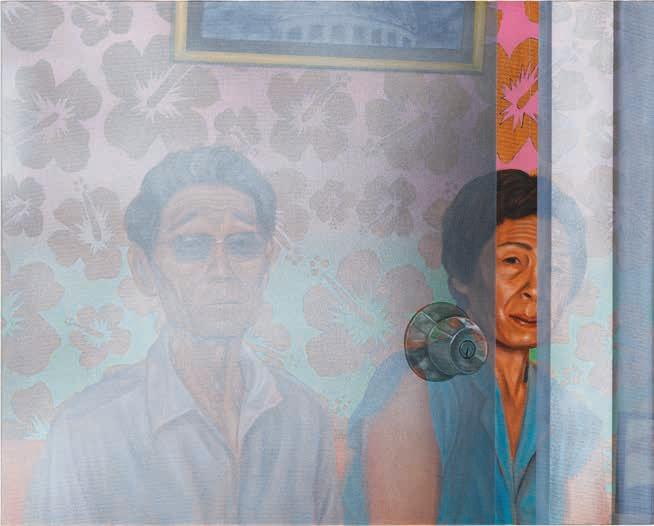

The painting, Remember to Forget, by Honolulu-born artist Shingo Yamazaki captures an intimate moment, only there’s a scrim separating we, the onlookers, and the two eaters in the frame. Translucent yet opaque brush strokes cover the entire canvas, obscuring certain details, which makes the act of gazing feel like spying on someone through a dirty window pane.

“I call them interjections,” says Yamazaki, whose portraits explore the nuances of identity, multiculturalism, home, and belonging. The technique is actually called “glazing,” where transparent oil paints are painstakingly layered to create a full image, and they’re a consistent presence in Yamazaki’s work for their ability “to simultaneously allow and deny access.”

In Transient Veil, a straightforward portrait of a man — the same one at the dinner table: aged, handsome, wearing wire-rimmed glasses — is interrupted by what appears to be a hanging aloha shirt, unbuttoned and forest green with pink and yellow plumeria. It partially obscures his face from his forehead to nose.

“I was really thinking about how we self identify, or personhood, and how those interactions create relation to reality and psychological space,” Yamazaki explains of his fondness for glazing. His late grandmother lived with dementia and the method worked as a metaphor for

FLUX PHILES | PAINTING | 20 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

memory and the self. By precisely controlling the distance between his viewers and his subjects, often his family members or friends and inspired by old photographs, Yamazaki can spotlight or shroud each figure, creating presence or absence, and “instill a sense of in-betweenness at the same time.”

This “in-betweenness” could be spatial too. In In Transit, a young boy sits with his mother in a minivan as a gate rises, about to enter a parking garage; in Beyond the Pacific, his grandparents are seen behind a pellucid door that’s ajar. These interstitial themes extend to cultural representations as well. As a Japanese Korean born and raised in Hawai‘i, Yamazaki is acutely aware of both the hybridity and intersectionality of his own body and the islands’ melting pot society, which is why in his art, “I try to embed different iconographies and cues from my upbringing,” he says.

Across his oeuvre, there are recurring motifs. Hawai‘i’s flora — spindly

anthuriums, scaly ginger, elongated bird of paradise — are often composed in ikebana arrangements as a nod to his family who practices the artform. Local clothing from vivid aloha shirts to slouchy T&C tees adorn the subjects. Island foods like portable Spam musubi and glistening chirashi bowls also appear.

“When I paint, I can embed different things within the work in a really subtle way where they’re coexisting,” says Yamazaki. Remnants of Nostalgia shows a figure from the thighs down, wearing purple shorts and Nike socks tucked into Locals rubber slippers, intimating a crossover between Hawai‘i, Japanese, and American style.

The idea of coexistence became central to Yamazaki’s paintings after moving from O‘ahu to Los Angeles in 2018. Despite the large Asian population in California, he found the communities were often isolated. Asian restaurants were clustered in Koreatown or Japantown or

Shingo Yamazaki uses “glazing,” a technique where transparent oil paints are layered to create a full image. “I call them interjections,” he says. Above, Outside Looking In. Previous page, Intersections of a Wandering Mind , all oil and acrylic on canvas.

22 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

In Transit , oil and acrylic on canvas.

In Transit , oil and acrylic on canvas.

Above, Beyond the Pacific . Opposite page, Looking Glass , oil and acrylic on canvas.

Above, Beyond the Pacific . Opposite page, Looking Glass , oil and acrylic on canvas.

Chinatown. Items he’d find in any local Hawai‘i supermarket — sushi rice, fish sauce, kimchi — he’d have to purchase from an Asian-specific grocery store instead.

The differences in language (“soy sauce” instead of “shoyu”), driving (aggressive honking instead of throwing shakas), and mindset (individualism over community) became a clear contrast to Hawai‘i, prompting Yamazaki to think more deeply about how cultures come to exist and their histories. “It’s such a rich mixture, that you don’t even realize what it is,” he says of Hawai‘i. “If you’re eating a plate lunch,” a dish that originated on the plantations where Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, and Portuguese immigrants labored, “you’re not pointing out the origins of each item.”

Distance from home and the ability to paint during the pandemic (his day job as a flight attendant for Hawaiian Airlines was paused during lockdown) gave Yamazaki the space to create a coexistence of identities, cultures, and personhood on the canvas. The work “speaks to a broader conversation on identity and being very specific and accurate about trying to depict those complexities,” he says, “because historically certain kinds of identities were not typically addressed.”

Yamazaki speaks from personal history here. His mother, who is half Korean, partially grew up in Hiroshima, Japan.

His maternal Korean grandfather, who had lived there for decades, experienced the atomic bombing in 1945. Japan was — and to some extent still remains — notoriously hostile to Koreans. As a result, Yamazaki, 38, didn’t learn he was also Korean until he was 17 years old.

“My mom doesn’t generally like talking about being Korean having grown up in Japan,” he explains. Yet the news wasn’t a

total shock. “I already had a feeling because my grandma had all this Korean paraphernalia around the house.”

Yamazaki understands that the immigrant’s refusal to talk about generational trauma doesn’t necessarily replace the underlying, unspoken knowledge their offspring possess.

Painting for him then is, as he puts it, an “uncovering process.” Interjections, with their ability to conceal

For Lack of Better Words , oil and acrylic on canvas. Across Yamazaki’s oeuvre, there are recurring motifs like tropical flora found in Hawai‘i, often presented in ikebana arrangements.

28 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

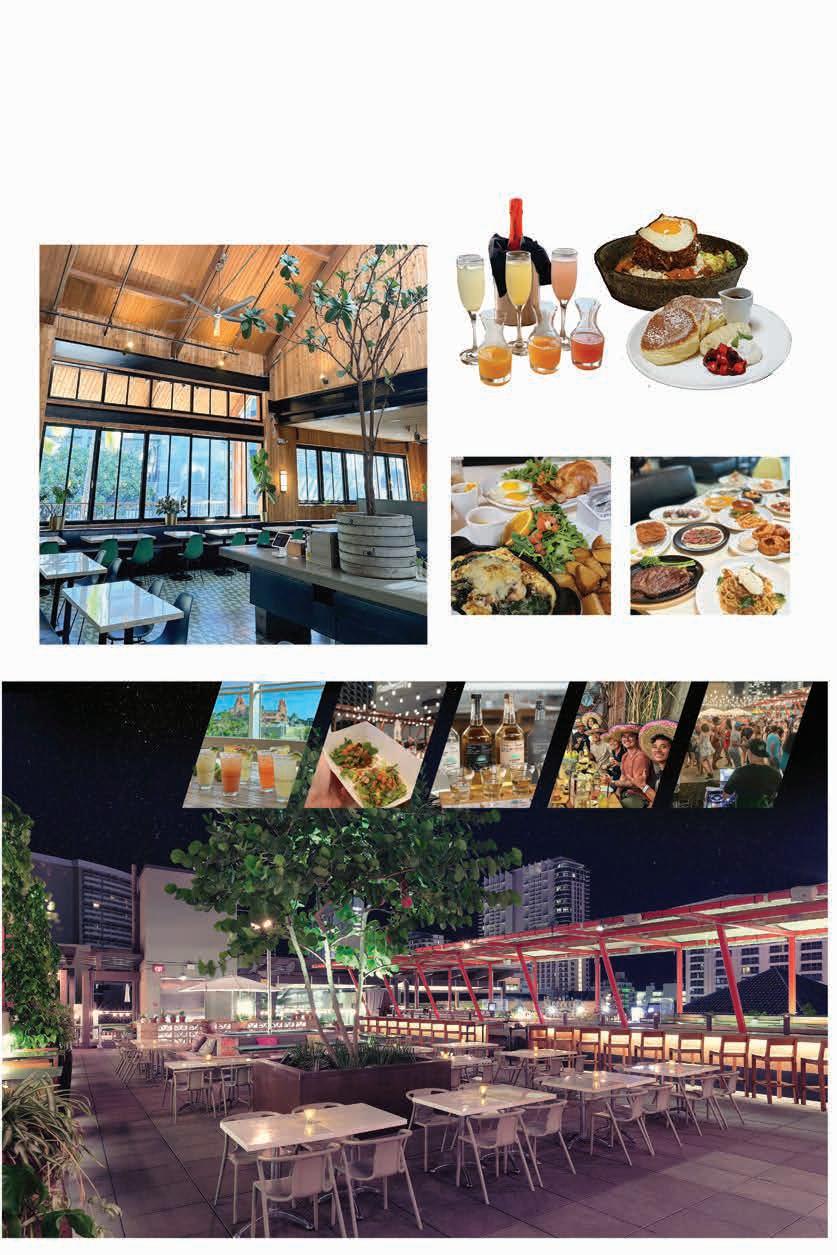

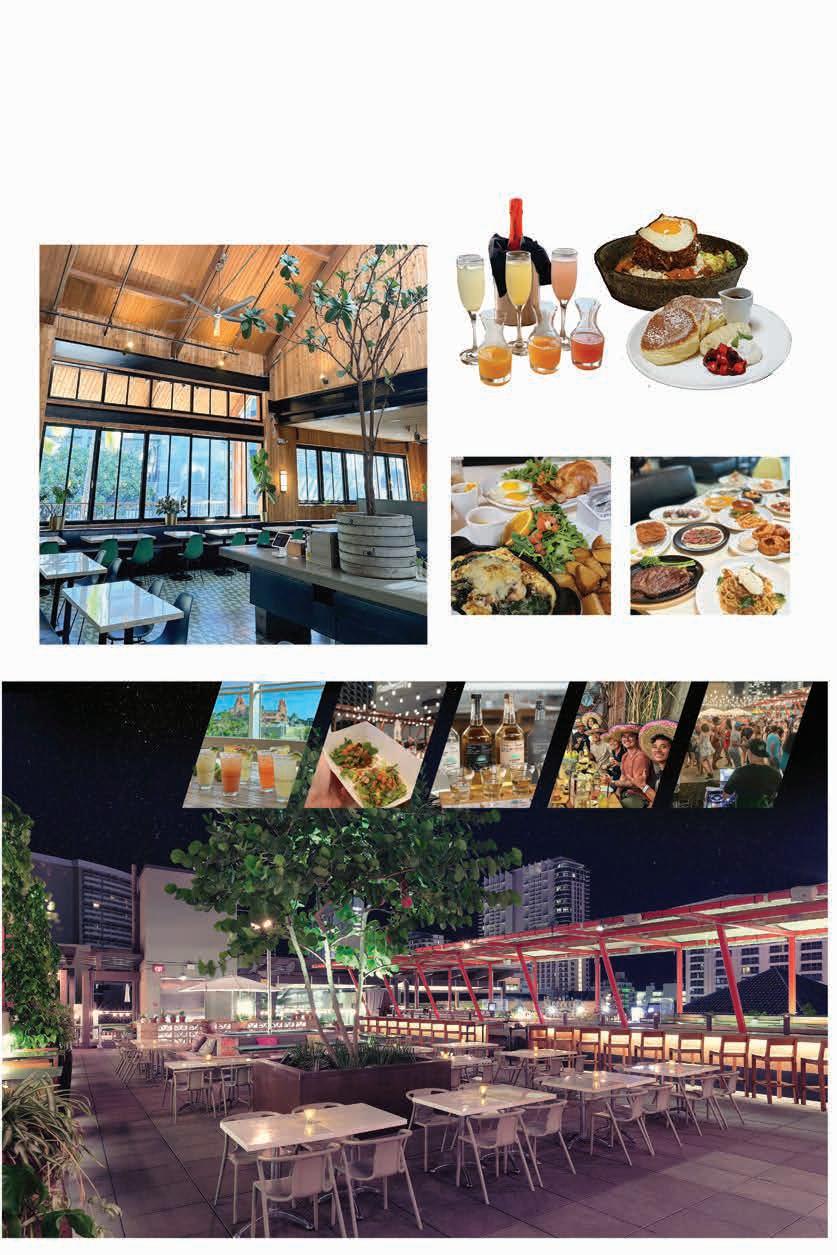

ELEVATE YOUR MORNING OPEN AT 7AM FOR BREAKFAST, LUNCH & DINNER - OUTDOOR DINING AVAILABLE ROYAL HAWAIIAN CENTER | VALIDATED PARKING | 808.922.3600 OR OPENTABLE.COM

and reveal simultaneously, mirror the process Yamazaki continually finds himself undergoing with respect to his own identity, heritage, and family history. In preparation for several upcoming group shows and one solo show, he’s been “working with the idea of filling in the blanks as a way of trying to reconnect with this lack of generational knowledge.”

Lately, Yamazaki has been contemplating the history of objects and traditions, how certain ones have been adopted or changed from movement and migration. In his Boyle Heights studio now, there are hanafuda cards, the Japanese playing card game, and Pogs, the stack and slam game popularized on Maui by the passion fruit, orange, and guava juice manufacturer. Both are “originally from Japan but popularized in Hawai‘i and then the mainland, so they’ve gone through this

whole traveling and migration process,” he says. “That’s really applicable to how we self identify and shift, the way we live our lives and continue our paths.”

Yamazaki’s desire to fill in the blanks is personal but also universal. All the major characters in his work, which include his grandparents and family, classify as what the novelist Min Jin Lee has called “minor characters in history”: the everyday, ordinary people who are frequently underappreciated and overlooked, their stories left unrecorded.

“We cannot help but be interested in the stories of people that history pushes aside so thoughtlessly,” the author has said, which can explain the appeal of Yamazaki’s art. As viewers, we cannot help but admire the artist who places his family’s own, unknown histories front and center, deserving of the light to be seen.

His artwork “speaks to a broader conversation on identity and being very specific and accurate about trying to depict those complexities,” Yamazaki says.

Learn more about the artist and his work at shinyamazaki.com.

30 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Opened as a small Liliha Street market by Wilfred and Charlotte Young, Young's Fish Market was originally what its name implies: a store that sold fish.

As time passed, they adapted the store to survive slow fishing seasons. Today, Young's Fish Market specializes in local staples and is known for their Laulau, Kalua Pig and Beef Stew.

Come visit us in Kapolei or Kalihi, and try it for yourself!

FLUX PHILES

| MAOLI |

Na Kama a Ohiohikupua Laua ‘o Lauhuki

Alaka‘i ‘ia a a‘o ‘ia nā hui ulana ‘o Hui ‘Ala Hīnano lāua ‘o Hui Waianuhea o Ka Pua Hala e Kā‘eo Izon i nui a‘e ai ko nā haumāna ‘ike ma ka ulana lau hala, ka ‘ike Hawai‘i, a me ka ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i.

KĀKAU ‘IA E C. KAWOHIKŪKAHI ADVERSALO

PA‘I KI‘I ‘IA NA MICHAEL VOSSEN

HO‘OPONOPONO ‘IA E N. HA‘ALILIO SOLOMON

Huki ʻia ka lau o ka hala a ulana mikioi ʻia e ka lima a lilo i mea paʻa e hoʻohana ʻia ai. He moena paha, he peʻahi paha, he pāpale paha a pēlā aku. Aia i ka mākaukau o ka lima. Nui nā hui e hoʻomau ana i ua hana noʻeau nei, ʻo ka ulana lau hala. Eia mai ʻelua o ia mau hui. Hoʻokumu ʻia ka Hui ʻAla Hīnano ma ka makahiki 2019 ma lalo o ke alakaʻi a me ke aʻo ʻana a ke kumu, ʻo Kāʻeo Izon, a me ka mālama pū ʻana a ke kahu, ʻo Pueo Pata. He hui ulana lau hala ia no nā kāne. Hoʻokumu ʻia nō hoʻi ka Hui Waianuhea o ka Pua Hala no nā wāhine i ka makahiki 2022. Ma ia poʻe hui ʻelua e mālama ʻia ai nā kama a Ohiohikupua lāua ʻo Lauhuki ma ka hoʻomau ʻana i ka ulana lau hala, me ka mālama pū ʻia hoʻi o ka ʻike a me ka ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi. Ua komo ʻo Kāʻeo i kēia hana ma kahi o ka makahiki 2010 ʻoiai ʻo ia e noho ana me kekahi o kāna kumu, ʻo Ipolani Vaughan. Ma kona hale, ua ʻike ʻia e ua Kāʻeo nei nā mea nani āna i ulana ai me ka lau hala. ʻO kāna noi akula nō ia i kāna kumu e ulana ʻia mai kekahi o ua mau mea kāhiko nāna. Eia kā, ʻo ka hōʻole maila nō ia me ka pane ʻana aʻe, “ʻO ia kou makemake, nāu e ulana nāu iho.” ʻO kā Kāʻeo ulana nō a kupu maila kekahi pilikia ma ka ulana ʻana i

maopopo ʻole ai ka hoʻoponopono kūpono ʻana iā lāua. Lawe ʻia kāna pūpū mauʻu i mua o ke kumu a Ipolani, ʻo Gladys Grace kona inoa. I nānā aku kāna hana i kā Kāʻeo mea i ulana ai, pane aʻela ka loea, “Maikaʻi kou lima. E ulana ʻoe.” Ua aʻo ʻia ʻo Kāʻeo e Ipolani Vaughan, Evva Lim, Suzi Swartman a me Margaret Lovett. No Pueo, ʻoiai ʻo ia e noho haumāna ana ma kona wā ʻōpio ma ka hālau hula a Nona Mahilani Kaluhiokalani, ua hoʻokuleana ʻia nā haumāna e hana lima i nā mea like ʻole no ke kūʻai ʻana aku ma ka wā Kalikimaka. Pēlā ʻo ia i komo mua ai i ka nala lau hala a no laila, ʻo Nona a me nā kūpuna o kāna hālau nō kāna poʻe kumu nala mua. Ma ia manawa, ʻaʻole i makemake iki ʻia ka nala e Pueo. I ka makahiki 2016, ua paipai ʻia ʻo ia e nala i peʻahi. Eia kā, he maʻalahi, ʻaʻohe hemahema o ka lima. I ka makahiki 2017, noi akula ʻo ia iā Kāʻeo e aʻo mai i ka nala maka liʻi. He nui loa kona aloha i ka nala. ʻO kona lilo aʻela nō ia, ʻo ia ka haumāna mua a Kāʻeo. Eia nō ma lalo ke ʻano i nīnauele ʻia ai ʻo Kāʻeo lāua ʻo Pueo e pili ana i nā hui ulana, ʻo ka Hui ʻAla Hīnano me ka Hui Waianuhea o ka Pua Hala.

32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

33

C. KAWOHIKŪKAHI ADVERSALO Aloha mai e Kāʻeo ʻolua ʻo Pueo. No ke aha i hoʻomaka ʻia ai ka Hui ʻAla Hīnano?

KĀ‘EO IZON ʻO ke kumu i hoʻokumu ʻia ai ka hui, ʻo ke noi ʻana a kekahi hoa i ke aʻo ʻana i kāna keikikāne. He ʻumikūmākahi ona makahiki ma ia wā a ʻaʻole au i aʻo mua i nā keiki a kānalua nō kēia. Ua hele maila ia keiki a kāhāhā wau i kona ʻeleu.

KA ʻOkoʻa ke ʻano o ke aʻo a nā kumu ulana, ʻokoʻa nō hoʻi kāu, e Kāʻeo. E wehewehe mai i ke ʻano o ke aʻo ʻia ʻana o ko kāu poʻe hui.

KI ʻO kekahi mea, ke aʻo ʻia kekahi maka, kekahi piko paha a huikau paha ka haumāna, ʻaʻole i hāʻawi wale ʻia ka pane. Hāpai ʻia nā nīnau ma mua ona e hōʻeuʻeu iā ia a kūkākūkā māua ā maopopo. Aia a maopopo, nāna nō e wehewehe aku i kekahi haumāna a paʻa ka manaʻo iā ia.

PUEO PATA ʻO ka ʻōlelo noʻeau ʻo: Paʻa ka waha, nānā ka maka, hana ka lima. He mea nui ia ma nā hui. Eia kā, ʻaʻole nō ʻo Kāʻeo e kāohi iki mai iā mākou ke kupu kekahi poʻe nīnau. Paipai nui ʻia nā nīnau. Eia hoʻi, aia a hemahema a hewa paha ka hana, hōʻole mai paha ʻo Kāʻeo a hoʻolale ʻia ka wehe aku a hana hou. Aia a kūpono, mea mai ʻo ia, "ʻĒ, ʻē, kēnā.” A, ʻo kekahi, nānā nui mākou i kona mau lima ma ka nala ʻana i mau laʻana no ka hana kūpono.

KA No kēia hui, he aʻo ʻia nō ka moʻolelo o ka hala, ua haku pū ʻia hoʻi he mau pule e Pueo. Pehea e kōkua ai ka ʻike o lākou i ke aʻo a me ka hoʻopaʻa ʻike ʻana o nā haumāna, a me ko lākou pilina me ia hana he ulana?

PP No ke kaʻao o Ohiohikupua i loaʻa iā Fornander, he waihona nō ia no ka ʻike o kēlā me kēia ʻano o ka pū hala, o ka lau hala, no ka hoʻomākaukau ʻana i nā lau, a he mau mea waiwai aku. No nā pule aʻu i haku ai, ua hoʻokomo wau i nā loina kūpono no ko ka Hui ʻAla Hīnano a me ko ka Hui Waianuhea o ka Pua Hala, a me ka moʻokūʻauhau o kā Kāʻeo mau kumu. Aia nō a hoʻopuka ʻia kēia mau pule, ua hoʻopili ʻia mai kēia mau mea o ke au i hala me mākou i kēia au e holo nei. Penei kekahi, ua nui loa nā lāhui e nala ana i ka lau hala a me nā ʻano mauʻu ʻē aʻe a puni ka honua. Ua like a like nā maka. Akā nō naʻe, iā kākou, ʻo nā loina, nā huaʻōlelo, ka ʻike kuʻuna, nā kaʻao, a me ka lawena i loaʻa mai mai ke kumu mai a i ka haumāna aku–ʻo ia nō nā mea i Hawaiʻi ai kā kākou nala ʻana. No laila, ʻo ia nō kekahi o nā mea aʻu i hoʻokomo ai i loko o kaʻu mau pule a mele.

He pāpale nona ka maka manu o kū na Kā‘eo Izon. Ua haku ‘ia ua maka nei ma muli o ka lele ‘ana o ia po‘e manu maoli e ‘ike ‘ia ana ma waho o kona hale ku‘i i kēlā me kēia lā. Maluna, ki‘i ‘ia na Kā‘eo Izon. ‘Ākau, ki‘i ‘ia na Ruben Carrillo.

KA Ma nā hui, ʻaʻole no ke kumu hoʻokahi iho nō ke kuleana ʻo ka mālama ʻana i kēlā me kēia haumāna. Paipai ʻia nō naʻe ka mālama aku a mālama mai, ke kōkua aku a kōkua mai hoʻi o nā haumāna, me he ʻohana lā. No ke aha i lilo ai kēia ʻano he mea nui no ka hui, pehea hoʻi ia e kōkua ai i nā haumāna ma ko lākou ʻimi ʻike i ka ulana lau hala?

KI Ua hū ka nui o nā haumāna a hiki ʻole iaʻu ke kōkua iā lākou a pau ma ka manawa hoʻokahi. No laila, he kūpono ke kākoʻo a kōkua ʻana kekahi i kekahi. Pēlā nō e hoʻopaʻa ʻia ana nā mea a lākou i aʻo ai.

PP Ua kumu nō nā hui i ka pilina me ka manaʻo ʻo “Aloha kekahi i kekahi.” No ko mākou kaukaʻi nui ʻana kekahi i kekahi, ua ʻike mākou he ikaika ko laila. A, he ʻano laʻana kēia no ka pono o nā hana ma ka nala lau hala a no ka pono o ka nohona.

34 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

KA E Kāʻeo, kaulana loa nō ʻoe ma TikTok a me Instagram hoʻi. Ma nā mea āu e hōʻike ai ma luna o laila, he aha kāu mea e makemake nei e ʻike mai ka lehulehu?

KI Makemake nui ʻia nā mea like ʻole i ulana ʻia me ka lau hala. Hoʻokahi naʻe pilikia i ka poʻe o kēia wā, maopopo ʻole iā lākou ka nui o ka hana. ʻIke ʻia ka hopena wale nō. Ke ʻike ʻia ke kumukūʻai, namunamu kekahi, “He lau wale nō. ʻAʻole makepono. Pipiʻi.” He ʻoiaʻiʻo nō, he lau hala. Eia naʻe, pehea ka lima? He maiau? He hōlona? ʻO ia ka mea nui. ʻO ia ke kumu i hoʻokau ʻia ai nā wikiō ma laila, i hiki i ka lehulehu ke ʻike maka i ka hana nui o ka poʻe ulana a hiki ke mahalo i kēia hana lima noʻeau.

KA He aha kā ʻolua pahuhopu no ka poʻe haumāna ma kēia mua aku? Pehea hoʻi kā ʻolua makemake no ia loina

KI

he ulana lau hala, a no ka mau ʻana hoʻi o nā loina a kuanaʻike paha e aʻo ʻia nei ma nā hui?

E hoʻopākela, e hoʻokāʻoi, a e hoʻomau aku.

PP ʻO ka hoʻomau ʻana o nā haumāna me ka lokomaikaʻi nui i hoʻoili ʻia ma luna o mākou maiā Kāʻeo mai. E hoʻomau nō me ke aloha ʻana o kekahi i kekahi, a me ka ʻaui ʻole ʻana mai ke ala aku o ka hana kūpono.

Ho‘okumu ‘ia ka Hui ‘Ala Hīnano ma ka makahiki 2019 ma lalo o ke alaka‘i a me ke a‘o ‘ana a ke kumu, ‘o Kā‘eo Izon, a me ka mālama pū ‘ana a ke kahu, ‘o Pueo Pata. Ua komo ‘o Kā‘eo i kēia hana ma kahi o ka makahiki 2010 ‘oiai ‘o ia e noho ana me kekahi o kāna kumu, ‘o Ipolani Vaughan.

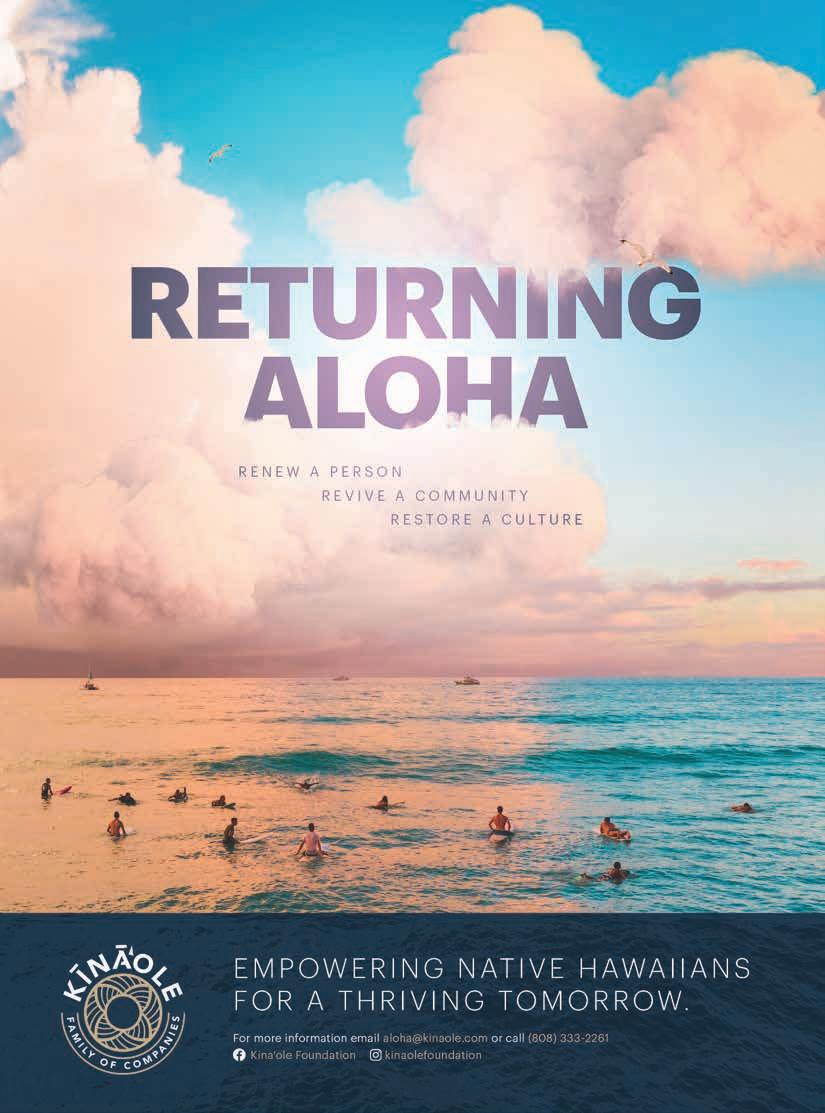

This story is from Flux Hawaii’s Hawaiianlanguage reporting series featuring articles conceived, commissioned, and produced all in ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i, in partnership with Kīnā‘ole Foundation. Visit fluxhawaii.com/ section/olelo-hawaii to read this story in English.

36 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Nature’s Crown

The beauty and brio on display in a Kaua‘i aunty’s floral headpieces captivate social media.

TEXT

BY

ALEXIS CHEUNG

IMAGES BY HIROKO LETMAN

We never see her face, not really. The portraits are taken at elevated angles so we glimpse a corner of tanned forehead, the crinkle of under eye smile lines, an ear graced with a delicate hoop or pearl earring. If anything we see her profile at most, from the left side with its strong cheekbones. What’s always on view are the flowers, arranged artfully in her pulled back, silvering hair.

This is the Instagram account of @hirokolele. The woman in the photographs is known simply as Aunty Nani. We, the 14,300+ followers, understand this because the captions always follow the same convention: “Aunty Nani with…” insert whichever florals (with a hashtag) she happens to be peacocking that day, and there have been many since the first post of her in 2016.

The flowers themselves range from minimalist — a single-stem white lily as large as an open palm; a solo sherbet-colored hybrid hibiscus with ruffled petals tucked into a neat bun — to maximalist: tusk-like blue jade with tī leaves are pinned to stand upright, like a toothy crown; a Turks cap lei is folded over and flanked by a phalanx of carnations, chrysanthemums and ferns, like a blooming bonnet. Some arrangements aren’t even flowers. Scroll back to 2018. There’s a cluster of orange eggplant and fern dangling in her hair, a clutch of handmade coconut palm frond roses speared to touch edges so they look like a shield, or kauna‘oa, the stringy, yellow-orange endemic vine, coiled around her bun.

How did I find the account? A repost, probably, some time in 2022. Yet scrolling it from bed felt more like strolling through a botanical garden or national park: calming because the beauty of nature awes you at every turn. Her flowers, their design, were so beautiful. The feeling I had was distinctly different from most emotions the social media app inspires — covetousness, jealousy, insecurity, inattention — probably because it

38 | FLUXHAWAII.COM FLUX PHILES | STYLE |

39

40 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

IMAGES COURTESY OF @HIROKOLELE

MINIMALIST TO MAXIMALIST

From anthuriums and lilies to blue jade and hibiscuses, Aunty Nani delights tens of thousands online with her bold and beautiful adornments.

lacks the pretense and perfection that runs rampant across people’s grids.

“I just take the photo in the setting where I happen to run into Nani, even if it is in front of a parked car, outside of the restroom, next to a rubbish bin or by an old truck,” says Hiroko Letman, the woman behind the account, in an email. As a landscape architect on Kaua‘i, Letman was drawn to Aunty Nani for the same reasons tens of thousands on the internet are enamored with her now: for her bold, beautiful flowers. The two work together at a plant nursery on the island, and everyday, she would spot Aunty Nani sporting a new hairdo, ergo the impulse to document it.

Even more striking to Letman though was the confidence with which Aunty Nani, in her late eighties, styled herself. Originally from Japan, “we don’t have this custom to wear flowers in our hair every day. At first I thought this was something that young women do,” explains Letman. “But I saw Nani wearing these very large, gorgeous flowers so beautifully, it changed my

impressions about beauty and age. I realized it’s okay for older women to be very bold and expressive just like young women.”

Letman’s instinct was prescient given the “lei-naissance” of late. From lei and tastemaker Meleana Estes’ Lei Aloha recent book to Island Boy shop owner Andrew Mao’s statement necklace-like creations, lei are no longer viewed as celebratory tokens but everyday expressions of personal style and design sensibilities. Aunty Nani, with her singular styling, is the ultimate ambassador for taking the ancient tradition of adorning yourself with flowers — hers come from many places: her garden, the nursery, the sale section of the supermarket — and making it wholly your own.

Though we never see her face, Aunty Nani feels familiar, as if she could be your own tūtū or aunty or kumu or woman you see daily at the grocery store. She’s a grounding, assured presence, reminding us that beauty is ubiquitous and adornment available to everyone, if only we go outside and look.

The woman in the snapshots is known simply as Aunty Nani. Since 2016, a social media account broadcasts whichever flora her hair is adorned with that day.

Follow on Instagram at @hirokolele.

42 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

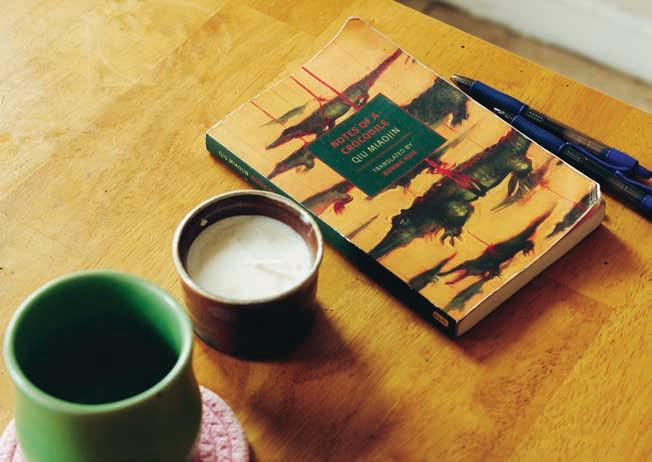

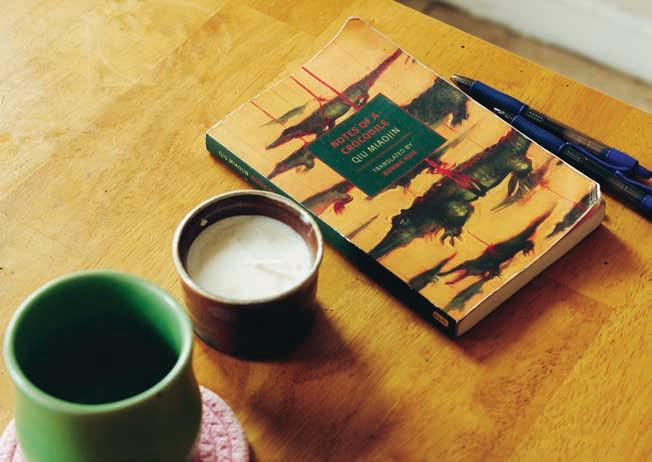

Sticky Obsessions

Megan Kamalei Kakimoto embraces the macabre and ghostly side of Hawai‘i in her debut short story collection.

TEXT AND

INTERVIEW

BY KYLIE YAMAUCHI

IMAGES BY MEAGAN SUZUKI

A thrilling examination of the psyches of Native Hawaiian women, Megan Kamalei Kakimoto’s debut collection of eleven short stories Every Drop is a Man’s Nightmare is as haunting and titillating as its title suggests. The Hawaiian Japanese writer from Honolulu muses on ancient moʻolelo and a tragic history of colonization and exploitation, in order to conjure a present-day Hawaiʻi where cunning menehune appear on one’s doorstep, military strikes shower the island of Kauaʻi, deadly night marchers are summoned through kapu words, and bringing pork down Old Pali Road has dire, atavistic consequences.

The collection drastically veers from popular literature about the islands, which tend to set their narratives against a soothing tropical background. Kakimoto, however, prioritizes penetrating the intimate lives and troubled minds of her characters as they contend with motherhood, lust, ambition, and grief. Kakimoto’s women aren’t mad, but they aren’t “all right” either. The stories that result are unsettling, touching, absurd, and humorous, an ode to the complexities of Hawaiian femininity.

Despite the book’s serious subject matter, Kakimoto herself is naturally lighthearted and joyful, eager to discuss her love of Hawaiʻi and the women she admires. The 30-year-old has had her stories published in Granta, Conjunctions, and Joyland; Every Drop has been reviewed by Publishers Weekly, selected by independent booksellers as an Indies Introduce title, and featured by Book Riot as an excellent short story collection by an Asian author. We sat down with Kakimoto to talk story about her women, the kuleana of writing about Hawaiʻi, and the drop that is every man’s nightmare.

KYLIE YAMAUCHI Let’s start with the story which lends its title to the entire collection. What led you to write about menstrual blood and Old Pali Road? How’d you even begin to bring them into conversation with each other?

MEGAN KAMALEI KAKIMOTO Blood captures the beauty and horror of the female body, and it’s always been something that I knew in all my stories I’d be interested in exploring. I get excited when I see other fiction that unabashedly celebrates menstruation and talks about it in a very casual way because it’s a part of normal life.

As for Old Pali Road, so many superstitions that I grew up being warned about and am still reminded of by my family figures into historic sites. The Pali is so rich in moʻolelo, like the familiar story of not traveling with pork in the car. The Pali was part of the trek that I would make as a kid from here in Makiki to Gram and Papa’s place in Waikāne Valley. No matter how often we went, my mom always brought that story up. It really stuck in my head.

I was interested in taking a sacred site, figuring it as a central place where there’s so much heat already in terms of its history and moʻolelo, and zeroing in on one story of a girl: Tracing her from the moment of her first maʻi in this monumental place and chronicling her life as she contends with what it is to be a woman and to have a physical body, and to be concerned with things like bleeding and weight. It felt like a great intersection to start that story.

KY Speaking of places, in the entire collection, there’s not a single image of Hawaiʻi as a paradise. The images that we’re so used to from tourist advertisements

44 | FLUXHAWAII.COM FLUX PHILES | LITERATURE |

like white sand beaches, none are in your collection. In “Every Drop,” a lot of it takes place in private and grimy spaces. When it’s not in these spaces, it’s at Old Pali Road. What fascinated you about portraying this darker side of Hawaiʻi that people aren’t used to?

MKK A lot of that decision was subconscious. But maybe there was also my awareness of mainstream media’s depiction of Hawaiʻi. There’s, on the one hand, a real gut reaction of excitement that these [depictions] produce, from seeing your people and culture portrayed in art. But the consequence of our lack of representation in media is that when we are afforded entry and allowed to take up space, gratitude occludes the larger questions: Are these depictions respectful, are they authentic, are they thoughtful? A lot of times, contemporary portrayals of Hawaiʻi don’t let these questions enter into the conversation. With this collection, one of the biggest things I struggled with was fear. I resisted writing about Hawaiʻi for so long. I had this big fear of failing to do right by this place and the pressure of that silenced me. When I decided to lean in and force myself to write into that fear, that’s when these stories came alive and I was able to meet the women who charge through this collection. It didn’t become a question of whether or not to write about Hawaiʻi because at that point Hawaiʻi was inextricable from the characters. And these women don’t live in glamorized portrayals of Hawaiʻi. It was a pleasure to explore a very different side of Hawaiʻi that I hope is still recognizable to Native Hawaiians and people who live here as well.

KY It sounds like you felt a heavy kuleana when writing this book. That’s not just something that Native Hawaiian writers face but all writers of color share. You touch on this anxiety in the story of “Aiko, the Writer.” How there’s an expectation of writers of color to only write about their race and their own racial experience. As someone who works in publishing, I can say that’s how a lot of writers get pigeonholed. Do those concerns cross your mind ever?

MKK There’s this Carl Phillips quote I love so much pinned on my desk. He talks about how he writes from a place where his gender, race, and sexual identity are never outside of his consciousness but they’re not the forefront of his consciousness either. It’s about allowing space to explore other interests as well. I really love exploring women’s bodies, the violence that’s visited upon them, and the immense power of them. I’m also interested in questions of isolation and questions of belonging. A lot of these passions extend outside of Native Hawaiian identity. What I’ve come

to terms with is being okay with following whatever obsession is in front of me and not letting questions of readership or audience or representation enter into, at least, the first draft phase.

KY In the short story “Aiko the Writer” there’s that great quote from her tūtū about the white gaze: “There are ways to tell Hawaiian stories and ways to make Hawaiian stories vulnerable to the white hand. And you’ll need to be extremely careful with your choices.” I assumed this is directly applicable to your writing process. When does the white gaze come into play?

MKK I think it only comes into play in revisions, for me. I also don’t know if it’s helpful at all to think about. I’m often overcome with anxiety: Will white readers read this and pull from this only the negative? Will they think I’m depicting a particular character as a villain? I have to remind myself that I know what readers I want to be reaching and what readers are going to resonate with these stories. I also understand there are certain things out of my control, in terms of how some stories are read and interpreted, especially by people outside of my lived experience. Having to come to terms with that has been a bit of a process, but it’s been important to keeping my sanity [laughs].

KY I think you did a really good job in this book of not explaining too much to white readers.

MKK That’s good to know.

KY That you don’t define or italicize every Hawaiian word, that they’re spelled with ʻokina and kahakō makes a difference. What also struck me was how the women in this collection were far from perfect. Sadie is the first Kanaka woman that we meet and she’s not what we expect her to be. She’s sickly, kind of a pushover, silent. What went into the construction of this character and not someone who is more traditionally feminist, if that’s even the right word?

MKK I love a messy protagonist. Starting with her maʻi, the story tracks monumental moments in Sadie’s womanhood. These are also moments when anyone would be really vulnerable and probably making bad decisions. I appreciate fiction that affords women the space to make mistakes and be messy, while also being rebellious and strong. Sadie’s a really great example of a messy woman and a silent one, like you said. She has moments of silence that feel incredibly frustrating to me but also deeply human.

So much of the story for me was tracking Sadie’s relationship with her body, which then becomes her pregnant body, and then it becomes the body that has

46 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

housed a baby and has lost a baby, simply by giving birth. I actually don’t know if she’s in a different place by the end of the story as she was in the beginning.

KY Just to be clear, what even happens in the end?

MKK [Laughs] It’s super ambiguous. I know it’s a weird, open-ended ending. I hope it feels like one of those endings where there’s a whole other life to be lived beyond where the story ends. I really don’t think there’s a wrong way to read it. One could wonder, Is it even a baby?

KY All the mothers in the book have really troubled or ambivalent relationships with their children. A question that I’m sure will upset some readers: How do you think motherhood factors into “madness,” or to put it less controversially, into a shared struggle?

MKK I am not a mother, so my perspective is going to be incredibly different. But I am a daughter and so much of my upbringing has been wonderfully influenced by my mom. But I have a lot of fear and anxiety of ever becoming a mom, because it feels like the most pivotal responsibility. Something that has drawn me to writing about motherhood has been investigating the different ways to be a mother and ways to care for a life. A lot of times, in my own experience as a non-mother, as a woman, there’s so much expected from me all of the time. I think it’s often hard to even conceive of what my life would look like with a child. It keeps me up at night sometimes. Some of my biggest obsessions are my biggest anxieties. So having the space on the page to explore what it means to be a mother is almost therapeutic. It doesn’t take away the anxiety, but it gives me an outlet to consider what being a mother even looks like.

KY I like the specificity to Hawaiian women, too. What makes the “madness” of Hawaiian women distinct?

MKK When conceiving of this book, I was interested in locating the intersection of Indigenous women’s bodies and the wounds of colonization. How do Native women respond to this violence and what is the horror that’s innate in possessing a body already rooted in a history of violence? Seeing these women in the collection react messily or horrifically was just as thrilling as when they chose camaraderie or compassion. Affording that range of responses was really important to me.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Kakimoto’s debut collection was released in August 2023. The stories that result are unsettling and touching, and an ode to the complexities of Hawaiian femininity.

MEGAN’S OWN OBSESSIONS

We asked the author what books, music, and snacks have sustained her recently during the writing process.

Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer

The question of discomfort and of how to handle art made by monstrous individuals is one that’s constantly on my mind, and Dederer’s book-length negotiation with it speaks to all my interests.

Walking on Cowrie Shells by Nana Nkweti

What I consider a must-read collection. Truly impossible to finish it unchanged.

“Not” by Big Thief

Lately I’ve been listening to this song on repeat while writing fun flash pieces. I’m obsessed with the idea of an entire song made up of negations.

PopCorners, Kettle Corn flavor chips

I ordered these salty-and-sweet treats in bulk while working on revisions to the collection and novel-in-progress. If anyone deserves to be in their acknowledgements, it’s PopCorners.

48 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

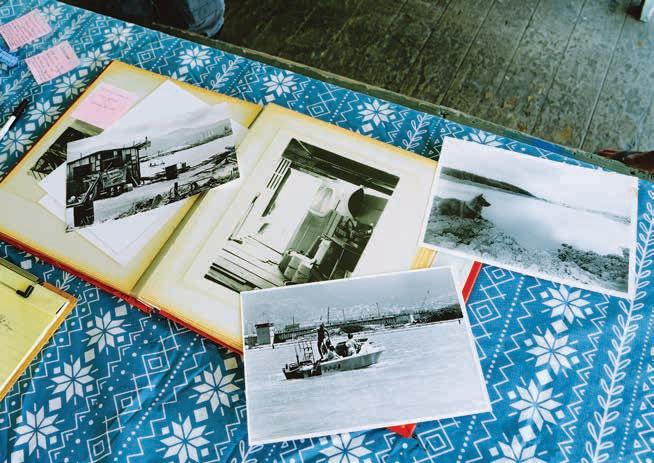

Kalapana-Kapoho Road, Hawai‘i Island. Image by Nani Welch Keli‘iho‘omalu.

Kalapana-Kapoho Road, Hawai‘i Island. Image by Nani Welch Keli‘iho‘omalu.

FEATURES

“We want to continue this, our way of life. We want people to know about this place, to be educated about it, to see what should be preserved.”—Joni

Bagood

FLUX FEATURE

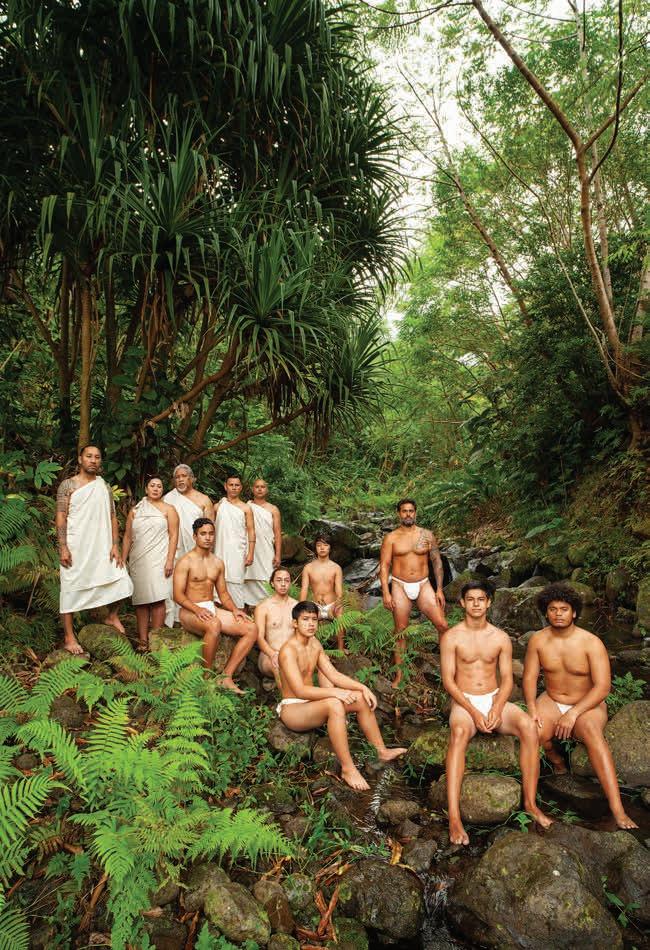

Ceremonial Shifts

For two Hawai‘i Island ceremonialists, re-indigenizing a people to their homeland begins with marking the seasonal transitions that Kānaka Maoli have ritualized for centuries.

TEXT BY NICOLE NAONE

IMAGES BY TAHITI KULIA HUETTER

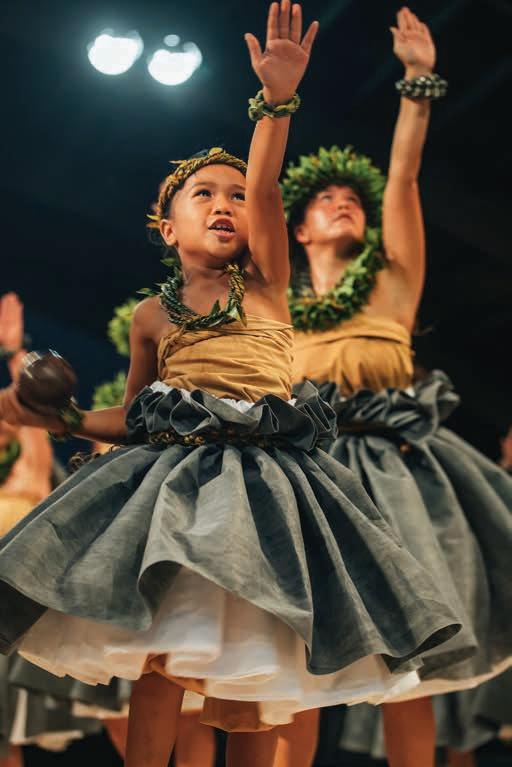

‘Ai kamumu kēkē, nakēkē pāhoehoe, kē” travels through the home, carried by the little bravado of four-year-old Uluao, as he assists his seven-year-old sister, Pilali, in retrieving paʻi ʻai from the kitchen counter. The gentle taps of Waimea rain on the kitchen windows harmonize with the earthly scents of ‘alaea and ‘a‘ali‘i, emanating from an artisanal salve simmering on the stove.

Kaleinohea Cleghorn, the children’s mother, gracefully navigates the space, exuding a profound serenity that belies her extensive training in hula, most recently with Hālau O Kekuhi. With over a decade of active participation in sacred ceremonies atop Maunakea, guided by the revered Pua Case, Kaleinohea’s presence as a prominent figure in the resurgence of Hawaiian indigeneity comes as no surprise. Drawing strength from her lineage, which features a trailblazing mother who was the first Native Hawaiian to achieve an MA in Hawaiian Archeology, and her ancestral connection to Princess Kaʻiulani Cleghorn, she emerges as a driving force in the reclamation of Hawaiian identity and connection to ‘āina. As she tends to Uluao and Pilali, and engages in conversation, her unwavering dedication to research and encyclopedic knowledge of Hawai‘i is both evident and mesmerizing. Kaleinohea’s words flow with a captivating calmness, conveying a profound depth of understanding. This quality, it becomes apparent, has been inherited by her remarkable children, as they absorb her wisdom and carry it forward with them.

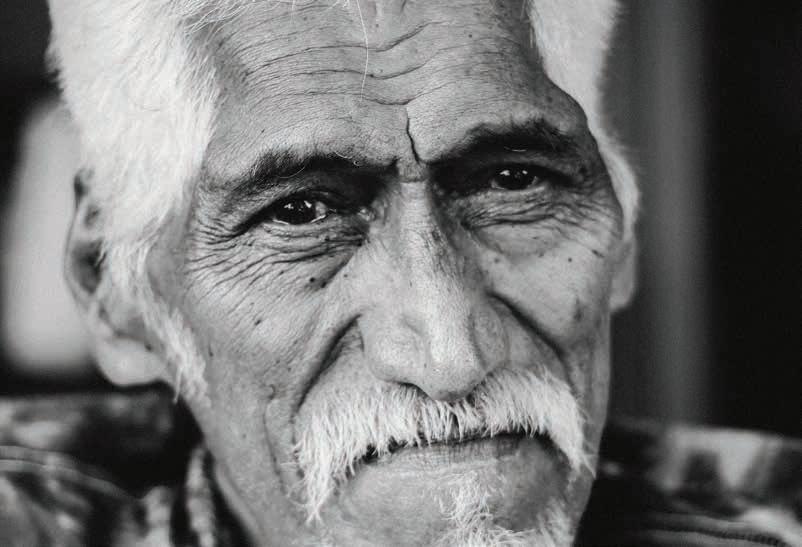

The tranquility of this dreamy morning is jolted awake by the arrival of Lanakila Mangauil. True to form, Lanakila bursts through the front door, accompanied by nature itself — in this case, wind and rain. He enters with his bombastic voice, an espresso, and an energetic puppy named Luka, honored with a name inspired by the resilient and resolute protector, Princess Ruth Keʻelikōlani Keanolani Kanāhoahoa. Ordinarily, his audacious reputation as a disruptor instills fear in the hearts of those who cling tightly to the fruits of colonization, but here amongst family, it unleashes a heartwarming chaos. Through his mere presence, Lanakila defies the notion that disruption is a binary concept confined to the reductive realms of “good” or “bad.” Rather, he unveils its intrinsic importance to the realm of Hawaiian activism. Reared by ʻĀhualoa rain, Waipiʻo Valley wind, and the kumu who came before him, he is best known for his leadership in the protection of Maunakea.

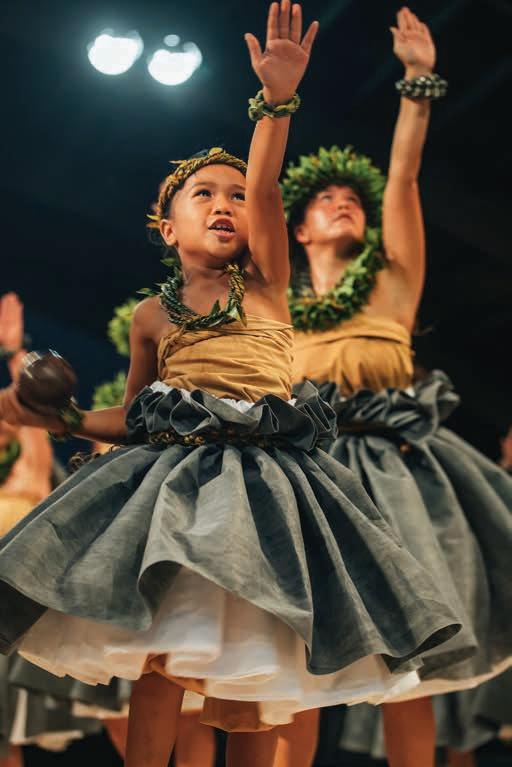

In their respective artistic expressions and unwavering commitment to the pae ‘āina, Kaleinohea and Lanakila beckon us to embark on a transformative journey, where the boundaries of traditional ceremony, art, and activism converge seamlessly. Recently, the pair launched Kū Mai and Ha‘ialono, a duet of oli-centric workshops that are now entering their second year. Kū Mai explores the

Lanakila Mangauil is executive director of HŌ‘Ā, a Native Hawaiian enrichment organization. Kaleinohea Cleghorn is the founder of E Ala Ea, a site-specific wellness brand. Images, above and opposite page, by Nicole Naone.

application of Kū during the Kū season, which is loosely considered to be during spring and summer; Haʻialono explores the application of Lono during the Lono season which falls loosely from the end of autumn through winter. Together, seated at the kitchen table, we nourish our bodies while recounting moments of the previous evening. Kū Haʻaheo, a hula drama performance by Kanu o Ka ʻĀina was the first in-person performance from the Hawaiian charter school since the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. As music teacher for the school, Lanakila approaches education with the same hands-on dedication he devotes to activism and ʻāina. He allows no room for superfluous essays or dwelling within oppressive academic structures. Instead, these students were taught the history of their existence and the stories of their deities with a night that culminated in hula, oli, and mele.

As we all settle into our comfy chairs to discuss nation building, embodying culture, and the spiritual depths of Kū and Lono, Lanakila declares, “OK, we go talk story about our workshops.”

54 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

ON AKUA

LANAKILA MANGAUIL Pele, Kū, Kāne, Kanaloa, Lono: these are not “gods” as perceived from a Western space. They’re more like categories, processes, descriptions, archetypes. They’re not necessarily external spirits outside of us, but instead they are manifestations that we see within ourselves. That we can reflect with, to what we’re experiencing. They have and are specific functions. They are also elements. I look into ecological understanding of our environments because they’re intertwined with the historical documentation of our people. We are a key species to the environment because we don’t just see nature as resources. They are us. They are people, they’re family, they’re kūpuna. They’re akua.

KALEINOHEA CLEGHORN

My first experience in decolonizing a monotheistic perception of akua was from the Kanakaʻole family. They would use of both “Pele” as in Pelehonuamea (Pele of the red earth) or Peleʻaihonua (Pele who devours the earth), as well as “the pele,” lower case “p,” as in volcanism as a whole, general lava, magma. So many thousands of years we’ve been in this relationship and have built this love. This love has created a poetry that kūpuna in every culture all over the world can recognize and speak. I see our myth as a poetic understanding of ecology. It’s all poetry, but it’s also science — it’s both.

ON LONO AND KŪ

KC We’re currently in a collective exploration of Kū and Lono. Today, we talk so much about how to create a sovereign nation. In order to have a sovereign nation the individuals have to be free. Kū and Lono become a path toward that individual responsibility and individual sovereignty. It’s about inspiring the individual to be in the right relationship with themselves, to

be in the right relationship with ʻāina, and to be in the right relationship with others.

Hāwane [Rios, daughter of Pua Case] and I for many years traveled to Kahoʻolawe together and participated in Lonoikamakahiki ceremony. A lot of what I know of Lono comes from that — a sisterhood which comes from Aunty Pua Case’s teachings, which is not only her lineage but her dream. Her audacity to be so loving and her ability to listen and trust what she hears, you can see it in the way that their whole family speaks, the way they show up in space. There’s a gentleness to it. There’s a grace to it. There’s such a powerful balance of the Kū and the Lono.

LM As Lono is having time to reflect and always looking back into the internal reflection, Kū is self discipline, self regulation — disciplining oneself to discipline oneself. The Kū and the Lono are the internal and external. The Lono, the balance from within to connect with a depth of understanding and listening and feeling. The Kū is keeping order and function with everything around you.

Kū has to do with human societal structures. This includes politics, governance, farming practices, fishing practices, etcetera. Kū is the one who upholds kapu. Nation building and defending is a kūleana of Kū. Yet there is only one iteration of Kū that has been popularized: war. Kū as in Kūkaʻilimoku was called upon by Kamehameha The Great to unite the Hawaiian Islands. It is no wonder then that the colonizers of Hawaiʻi put a very targeted effort to demonize Kū. Separating us from our concepts of empowerment, taking action, holding firm, and organizing.

KC When you really dig deep into researching Kū, there are so many facets beyond “God of War.” Kū, as in Kūkauakahi, who defended and protected the makaʻāinana, the

common farmers, from overbearing aliʻi, or chiefs. Kū is the one who connects, the one who protects, the one who actualizes, the one who manifests, the one that follows through and gets it done. Kū is the energetics of the body that makes a reality out of the dream. It is time we reframe the fear of Kū with function and approachability.

LM This kiʻi (he points to a carving of Kū used in ceremony during the Maunakea protest) was risen, stood up, and took action. We saw what happened within our lāhui, our nation, when calling for Kū. The utterance “Kū Kiaʻi Mauna” activated our entire nation for the betterment of keeping the stones of a mountain in place.

KC People rose to Kū. People Kū-ed. We saw the effects of Kū energy. “Kū Kiaʻi Mauna”: That’s Kū energy.

ON KŪ MAI AND HA‘IALONO WORKSHOPS

KC What we’re doing [with the Ku Mai and Haʻialono courses] is getting to the root not only of practice, but also the root of language, of loving and living our culture. What has become most relevant in our lives today is a need for pause. To listen, reflect, so that you can release some of what’s not serving you. Then you’re able to move into Kū season with a fresh skin and sharp manifestation. My intention when we first started this was to touch the Kānaka who don’t feel a belonging to any school, hālau, movement, or even the lāhui. The way in which our teaching is unconventional is intentional, so that we include those who have felt so displaced and feel comfortable enough to engage. There is a specific intention in the teaching. It is not for entertainment or for those curious about our culture. Participating in these courses is giving your consent to evolve these words

58 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

and feelings. You’re here to digest, integrate, and have them move with and live through you. This is so that your place and your soil and the leaves on your trees are changed because your frequency has shifted based on your attunement to the season you’re in. Acknowledging and participating in the changing of season. The reestablishment of the Kānaka into the environment by resurrecting an active role in the shift of season. That comes by way of ceremony, consciousness, chant. It comes from how I walk and speak and listen to the environment.

LM We’re teaching this because we want to see some returned results. Not necessary for us, but we want to see something sparked from this.

KC The baseline of our curriculum is inspired by our Kumu Kekuhi Kanakaʻole herself because it’s so fun and playful. And that’s why we have

chant as the curriculum because it gets you out of your head. It gets you in your body. And we give the deepest, darkest Pelehonua ʻAikamumu chants, and then we bust out in laughter and it’s the highest feeling you ever had. I want every Kānaka to feel that. We’ve learned that from these audacious families. The Kanakaʻoles, the Pua Cases, the Lims. It is important to note that of these ‘ohana, none of them have been displaced from their ʻāina. That’s why I believe they can embody so powerfully. How do you make a sorceress? Don’t remove her from her forest.

ON MODERN HAWAIIAN CEREMONIAL PRACTICE

LM I define indigeneity as peoples who are so of a place, that after so many centuries, they have achieved mutual symbiosis with said environment. They have become such

a unique key species to a place that we actually are essential to its existence. It really is about standing in a natural part of this world again. We’re part of this world, of this rain, wind, animals and plants. Being here, and not within the construct that we can only exist within the context of some colonial dogma, is the ecological balance of indigeneity. And yet, there’s so much of that feeling of “not being Hawaiian enough” or “I don’t know, so I shouldn’t participate” in our community.

KC We are not artifacts. Pick up your body and move. Listen, touch, and taste and feel. How do you reindigenize a people to their place? Discernment is so important. There are aspects of colonization that we have dubbed Hawaiian. It is so dangerous.

LM The condemnation of leaning into the new comes from fear and the pain

62 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

of loss. As a people we really did lose so much, and thus we desperately cling to what little specific texts still exist. However, these texts only give us tiny glimpses of what once was. We must hoʻāla hou. We resurrect these things the best that we can. We have to keep it rolling. You don’t have to be an expert to take the first step.

KC Our kūpuna slowly over the generations have simplified what was so complex. We’re anchored in this knowledge, understanding, relationship, and every year our modern ceremonial practice is going to be a little different.

LM It better be! If not, what is this? I hope that we’ve grown. Back in 2014, ʻAha Pule ʻĀina Holo [a six-day-straight run around the circumference of Hawaiʻi Island ushering in Lono season] began as a prayer for the health of the land. When I first brought the medicine of ceremonial running here from the Pitt Rivers tribe, it was through this process that Kekuhi and Taupōuri Tangarō taught me to hoʻohawaiʻi, to make it Hawaiian. Since its inception, this ceremony has done amazing work in changing lives and igniting our people. That is the actual measurement of ritual and the only reason I’ve continued to conduct ceremonies like ʻAha Pule ʻĀina Holo or Wehe Kū.

KC Why would we not continue to evolve it in wider ways to touch and activate even more of our people so it doesn’t become static? That is what we are doing with Kū Mai and Haʻialono.

knowledge that no scholarly article can fully embody and the complementary natures between these two luminaries generates something greater than the sum of their individual parts. Their voices resound like echoes of our forebears. Their dances breathe life into our cultural resilience and ignite the brilliance of our artistic spirit. Through every melodic note and rhythmic movement, they manifest a profound veneration for our Hawaiian heritage and the power of community.

Enraptured by the Kū Haʻaheo performance from the evening prior, I beheld a remarkable sight: children, who were as young as five years old, fervently chanting words that once resided solely within the domain of impassioned activists. The realization that this next generation possesses a normalization — an intimate familiarity — with these profound concepts, akin to the very breath that sustains them, stirred an indescribable surge of emotion. The scene served as a poignant reminder that activism transcends the boundaries of protest lines, permeating the very fabric of our community on multiple levels.

In Kaleinohea and Lanakila, we bear witness to a convergence of two ceremonialists from diverse backgrounds, illuminating the multifaceted nature of Hawaiian identity. They share ancestral

As the grand crescendo of their voices reverberated through the hallowed space, the entire school convened upon the stage, uniting their voices in a harmonious symphony of “Hawaiʻi Aloha.” Generations intertwined, as elders and youngsters alike rose from their seats to join the students in song. In that sacred moment, the division between performer and spectator dissolved, replaced by an overwhelming sense of unity. Kaleinohea swayed gracefully alongside her two children, while Lanakila harmonized with his devoted students. Past, present, and future converged, in a profound intergenerational symbiosis. Enveloped by the gentle caress of Waimea rain, we nurtured the seeds that would carry forth our ancestral wisdom for generations yet to come.

“We are not artifacts. Pick up your body and move. Listen, touch, and taste and feel. How do you re-indigenize a people to their place?”

—Kaleinohea Cleghorn

The two ceremonialists stand firm on the sacred ‘āina of Hawai‘i Island.

64 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Over the last few years, waves of change have rocked the surfing world, especially for Hawai‘i and women athletes.

TEXT BY MINDY PENNYBACKER

She

FLUX FEATURE

IMAGES BY CHRISTA FUNK

Go

Born and raised in the ahupua‘a of Waikīkī, near the fabled shoreline once graced by the beach homes of Hawaiian chiefs, I took up surfing in the late 1960s as a young teen and have been obsessed with it ever since. If I’d had any real athletic talent, not been so averse to cold water that I quit my Northern California college surf club, and been able to find work in Hawai‘i instead of having to move to New York City, I could easily have become my family’s worst nightmare: a surf bum.

After all, I went surfing in a Kamehameha Day swell the morning of my wedding, and got back so late, I walked down the aisle with dripping hair. While living for decades in NYC, writing and editing for a living, I swam in city pools to stay in shape for the two weeks a year my husband, Don Wallace, our son, Rory, and I spent visiting family on O‘ahu. Sometimes we’d arrive at the end of a big swell and leave just as a new one was rolling in for me to gaze upon with frustration as our airplane dipped a wing towards Diamond Head for a farewell look.

Although we lived in Lower Manhattan without a car, once in a while our uptown writer friend William Finnegan, author of Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life, would load our boards and fins into his station wagon and drive to Long Island, where we’d tackle the dirty gray waves breaking off the rock groins of Long Beach, or the clean, turquoise cylinders rolling over the sandbars of East Hampton and Montauk. A couple times, Don and I even took the subway to the crowded Rockaways.

I was never as obsessed with surf as Bill, who chased big waves from Fiji to Madeira. But when I met him for the first time (he and Don had been classmates at U.C. Santa Cruz), I learned we shared surfing origins. Bill had, for a time in his teens, lived in my Honolulu neighborhood and surfed the same stretch of breaks: Suis, Graveyards, Radicals, The Winch, Ricebowls, Tongg’s. Although we had

somehow never met at the time, he had known and surfed with my friends and mentors, the boys of the Tongg’s Gang.

During the ‘60s, I would hear about Hawai‘i female surfers who were competing on the nascent amateur and professional circuits of the time, but we never saw them surfing in magazines or films. In 1963, Californian Linda Benson was the first woman to appear on a surf magazine cover, but it didn’t show Benson riding a wave. It’s a portrait shot of the petite but powerful blonde, her hair in a Jean Seberg pixie cut, holding her board as she stands on land.

As a teenager, I assumed that surfing, like most other sports and professions, had always been maledominated. I was hopeful that, as the feminist movement gained momentum and won demands for equal opportunity, there would soon be as many women surfing as men. I was wrong.

After more than 30 years on the continent, I moved home to Hawai‘i in 2009, and for the first time since high school, I have the joy of surfing yearround without sadly counting the days left in my visit every time an outwardbound jet flies overhead. I began writing a newspaper column on surfing, which grew into my book, Surfing Sisterhood Hawai‘i: Women Reclaiming the Waves. I have been happy to see more females in the lineup than when I was a girl, but alarmed to witness far more overt, gender-based intimidation and insulting, dismissive behavior from males. A booming sport since the mid-20th century, surfing, even in its everyday, supposedly “fun” form, has gotten exponentially more crowded and competitive, which stokes some men’s frustration and aggression.

Worldwide, as of 2016, there were an estimated 33 million surfers, with males outnumbering females by 4-1, according to the International Surfing Association. But in Hawai‘i, the average ratio that I and other women observe is more like 8-1. Meanwhile, competitive surfing allots places to half as many female as male contestants, from

amateur keiki events to the elite big wave and world championship pro tours. Only surfing’s Olympic debut in the 2020 Tokyo Summer Games, where Hawai‘i’s Carissa Kainani Moore won gold — has fielded equal numbers of women and men.

Hawai‘i’s women surfers are reclaiming our traditional rights in the waves and shredding chauvinist myths that we can’t execute advanced maneuvers, such as getting tubed or exploding into the air above the tops of the waves or ride big waves, as well as men. “When I was a little girl, I was told that women can’t surf,” said Keala Kennelly, the first woman to win the open-gender, Pure Scot Barrel of the Year Big-Wave Award, in 2016, “and I was told this about getting barreled, surfing big waves, surfing Pipeline, paddling in at Jaws, and the list goes on.”

Over the last few years, waves of change have rocked the surfing world, especially for Hawai‘i and women athletes. In response to women surfers’ demands for equal opportunity, the World Surf League began paying equal prize money to women and men in 2019; and, following passage of a “surf equity bill” by the Honolulu City Council in 2020, the city’s Department of Parks and Recreation is revising its permitting rules for surf meets at O‘ahu beach parks, adding gender equity as a criterion. In 2022, the World Surf League Championship Tour began fielding men’s and women’s events at the same venues, including O‘ahu’s Pipeline and Sunset Beach. Last January, women competed for the first time, alongside the men, in the 37 years of the Eddie Aikau Big-Wave Invitational at Waimea Bay.

This article is excerpted from Surfing Sisterhood Hawai‘i: Wahine Reclaiming the Waves by Mindy Pennybacker, published by Mutual Publishing. Pennybacker is a surf columnist for the Honolulu Star-Advertiser and former editor of The Honolulu Weekly.

68 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

OPENING SPREAD: RED BULL CONTENT POOL

Women recreational surfers are also fast overcoming the discrimination that has held us back since Westerners invaded the islands, decimating the original population with introduced disease; illegally overthrowing and annexing the sovereign Hawaiian nation; causing impoverishment and starvation through the taking of lands and fishing rights; and suppressing the language and traditional practices, including surfing, which Protestant missionaries tried to ban. For more than 50 years, since the Hawaiian Renaissance of the 1960s and ‘70s, Native Hawaiians have been working to revive, restore, and steward their history, culture, health, prosperity, lands, and natural resources — and women surfers have been reclaiming the waves.

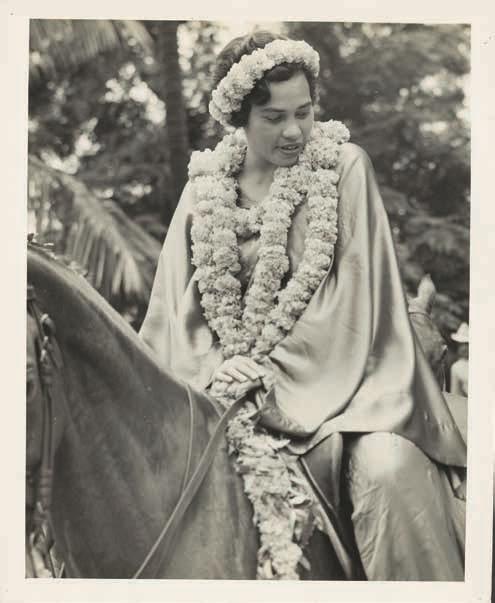

In Hawaiian history, legends, and 19th-century newspapers, women not only surfed in great numbers, but often ruled the waves. Although they weren’t allowed to eat with men and faced other gender-based restrictions under the traditional kapu system, when they got out in the ocean, Hawaiian women were free.

“The entire female population of Kealakekua plunged entirely naked into the waves” atop six- to eight-feet-long pointed boards and rode “upon the foaming crest of the surges,” writes Theodore-Adolphe Barrot in his Visit of the French Sloop of War Bonite, to the Sandwich Islands, in 1836. “Women not only surfed, but surfed as well as men,” or better, according to Hawaiian waterman and historian John Clark in Hawaiian Surfing: Traditions from the Past.

Clark cites a newspaper account of a Kamehameha Day surf contest at Lahaina, Maui, on June 11, 1887, in which a man named Poepoe was favored to win. His wife Nakookoo also competed. As her husband rides a wave, Nakookoo “shoots like a flying fish through the whitening foam, jostles the champion on his wonted plank of victory, and came in foremost amid the outcries of a delighted multitude glad that the woman had won.” The writer added that Nakookoo, while still beautiful, was not in her first youth, so it’s also a win against ageism. “As far as I know, this is the first description in English of a surfing contest, and it was won by a woman,” Clark told me. He points out that women also got barrelled, as observed by Barrot: “The least movement of their body gave to the plank the desired direction, and disappearing for a moment in the midst of the breakers, [the women] very soon arose from the foam.” Clark calls this “the earliest description by a Westerner of tube-riding, the radical maneuver that is commonly assumed to be a 20th-century invention.”

Many of the most famous surfers in Hawaiian legend and history were female, starting with volcano goddess Pele and her sister Hi‘iaka, goddess of the hula, the traditional dance closely linked to surfing. Many Hawai‘i women today practice both.

70 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“We know from mo‘olelo and history that Hawaiian women surfed,” says U‘ilani Macabio, a Hawaiian cultural adviser from Hawai‘i Island. Macabio grew up hearing stories about Queen Ka‘ahumanu, the favored wife of King Kamehameha, surfing Maliu in Kalaoa and the heavy waves at Lighthouse in Kohala. Ka‘ahumanu was the daughter of another famous surfer, the Maui chiefess Nāmāhana, “reckoned one of the most expert at that diversion,” according to Peter Puget, a lieutenant who sailed aboard the Discovery circa 1795.

“My favorite story is of Kelea, the surfing princess goddess from Maui, the best ocean woman ever,” Macabio says. Kelea lived near the Hāna sea, writes Samuel Mānaiakalani Kamakau, who set down her legend in 1865. “Surfing was her greatest pleasure,” Kamakau writes. “She enjoyed surfing so much that at night she dwelt upon the morrow’s surfing and awakened to the murmuring of the sea to take up her board. The early morning, too, was delightful because of its coolness, and so she might go at dawn.”

I found it both thrilling and reassuring to read that this heroine of old Hawai‘i preferred glassy, windless conditions and did the occasional dawn patrol session, just like me. These details humanized and enlivened the past with a sense that Hawai‘i’s people and waves haven’t changed much, despite all the upheavals and loss they have suffered. Reading Kamakau, I could imagine that Kelea and I might one day find ourselves riding the same wave through time. The story and the way Kamakau wrote it confirmed my long-held feeling that riding a wave serves up a slice of eternity.

Famous for her beauty and he‘e nalu skills, Kelea was kidnapped by an O‘ahu chief named Lo-Lale, of Līhu‘e, an inland district on that island. She lived with him in the highlands for a decade, bearing three children and never once getting down to the ocean. Finally, she asked his permission to visit the nearest seashore in ‘Ewa. He agreed, guessing he might never see her again. His guess was correct. From ‘Ewa, Kelea kept following the shoreline east to Waikīkī,

During the ‘60s, I would hear about Hawai‘i female surfers competing on the amateur and professional circuits, but we never saw them surfing in magazines or films.

“Women not only surfed, but surfed as well as men,” or better, according to John Clark in Hawaiian Surfing: Traditions from the Past

72 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

ABOVE: RED BULL CONTENT POOL

and when she arrived and saw the chiefs surfing its perfect waves, she asked to borrow a board, “and perhaps because she was so beautiful a woman, someone gave her one.”

Like a pilgrim entering a sacred place, she rubbed the red dirt of ‘Ewa from her feet at the water’s edge before she entered the sea, dipped herself in it before getting on the board, and paddled out to the break where she sat a courteous space apart from the local surfers and waited for the fourth wave. While riding, “she showed herself unsurpassed in skill and grace” and all the people “burst out in cheering.”

The ali‘i nui of Waikīkī, the high chief Kalamakua, ran down to the water’s edge to greet her, took her off to his kapu place, and they were married.

Kelea’s surfing is a proud part of the heritage all island daughters share. She’s an inspiration to us all, that inner voice who sets us free from the nagging ties of duty to fling care to the winds and just go for it when the surf is good.

Another legendary Hawaiian surfer was the namesake of the sea of Māmala, the great bay whose waters stretch from Lēʻahi through Waikīkī to Honolulu Harbor. Author William Westervelt wrote of her in his 1913 “A Surfing Legend.” “Very skillfully she danced on the roughest waves. The surf in which she most delighted rose far out in the rough sea, where the winds blew strong and white-caps were on waves which rolled in rough disorder into the bay of Kou [Honolulu].”

Surfing mele and chants were dedicated to Hawaiian royalty, including the Kingdom of Hawai‘i’s last monarch, Queen Lili‘uokalani, born Lydia Lili‘u Loloku Walania Wewehi Kamaka‘eha in 1838. She fought to restore the integrity of the constitutional monarchy after American residents in the kingdom forced her late brother, King Kalākaua, to sign the 1887 Constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, notoriously known as the “Bayonet Constitution” by where an armed militia was used to obtain

his signature and prevented Native Hawaiians from voting, placing his government under their control. When Lili‘uokalani gained power, however, she dismissed her brother’s “reform cabinet” and rewrote the constitution. She also wrote many songs, most famously “Aloha ‘Oe” and “Ke Aloha O Ka Haku (Queen’s Prayer).” “Halehale Ke Aloha,” a surfing chant composed in her honor, celebrates how “Kamaka‘eha on the crest, Rides the surf to shore,” writes John Clark, who notes a parallel meaning of the lyrics describes the queen as both the foundation and top of the state, providing guidance and stability. She only reigned for three years, however, before her government was illegally overthrown at gunpoint by the Americans in 1893.

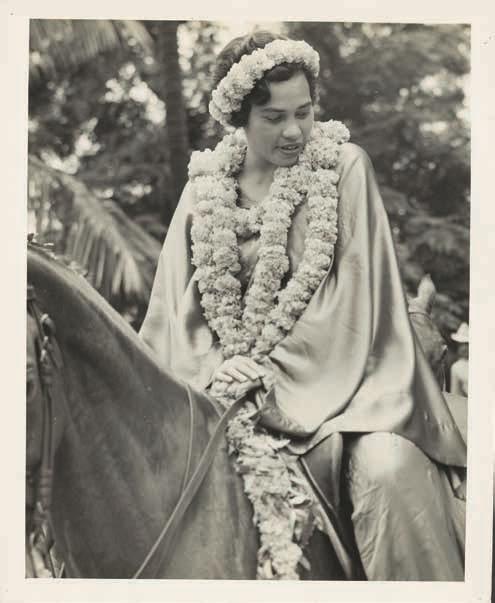

The Waikīkī surfbreak Queen’s is named for Lili‘uokalani, who is believed to have written her song “Ahe Lau Makani” (“the soft, gentle breeze”) at Hamohamo, her cottage on the beach. In 1896, her niece and heir to the throne, Princess Victoria Kawēkiu Lunalilo Kalaninuiahilapalapa Ka‘iulani Cleghorn, traveled to Washington, D.C. with her aunt and met with President Grover Cleveland, petitioning but ultimately unable to prevent the illegal annexation of Hawai‘i by the U.S. in 1898.

Raised in Waikīkī at her family’s estate, ‘Āinahau, Ka‘iulani loved to swim and surf; one of her surfboards, a slender alaia model made of koa, seven-foot, four-inches long, is in the collection of the Bishop Museum. The princess also loved to surf in outrigger canoe, and in June 1898, following a beach luncheon, travel writer Burton Holmes found himself riding waves with Ka‘iulani in a canoe surf session off Waikīkī. As the boat raced shoreward at 30 miles per hour, Holmes recounted, “There before me is the Princess Kaiulani, her faced aglow with excitement, shouting and paddling frantically, her eyes flashing with the wild pleasure of it all.”

Less than a year later, in March 1899, Ka‘iulani fell ill after being caught in a rainstorm while riding horseback in the mountains of Hawai‘i Island, and died soon after at age 24. One of the many kanikau, or lamentations, written for her evokes the surf site Kalehuawehe as “a poetic symbol of great loss.”

Kalehuawehe, then, is at once the happy place where a surfer lost his lehua lei to a wahine, and the sorrowful place where the loss of Kai‘ulani, who shone in the waves of Waikīkī and white lehua lei, will always be deeply felt. But her joyful presence, too, can be felt in the waves, as evoked in the mele “Lei No Kai‘ulani,” just as the rediscovery of this surfing lineage the ancient tales, the storied history from Kelea to Kennelly, from Māmala to Moore — reaffirms women’s presence in the ocean today.

As longboarder Jenny Van Gieson told me, “I feel when I’m surfing, I’m surfing with Aunty Rell, and other uncles and aunties I’ve lost.” Mentored as a child by Rell Sunn, the late, beloved Mākaha surfer, lifeguard, and children’s advocate, “When my life gets super hectic, the ocean is the place I go to for release, to feel that connection with the past,” she said.

In the surf, like the queens and commoners of old, we can escape gender-based restrictions and celebrate who we are, and who we are becoming.

The kai is the first playground for Hawai‘i’s children.