S/S 2024 FLUXHAWAII.COM NO. 46 $14.95 US $14.95 CAN COVER: 1/4 The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I ART & DESIGN: HO‘OMAU NĀ MAKA O KA ‘ĀINA, ADAPTIVE REUSE, AND KEOLA RAPOZO’S PILLARS. CULTURE: MAHJONG NIGHTS, MALA ‘ULU ‘O LELE, HAWAIIAN DRY ROCK MASONRY, AND SHARED DRIVEWAYS. SOCIETY: LAHAINA’S RECOVERY, GEN Z & HOUSING, AND KAILAPA HAWAIIAN HOMESTEADS. LIVING WELL: REFRAMING SPACE WITH THE BENNETTS, TANTALUS, AND PĀHONU POND. EXPLORE: O‘AHU WITH KĀNAKA CLIMBERS, AND WAIALUA. POETRY: KALEHUA FUNG.

56 _ PAST MEETS PRESENT

If placelessness plagues communities in the struggle to create affordable, dignified housing, can adaptive reuse rescue our histories?

68 HOUSING GEN Z

The youngest generation in the local workforce, who struggle to find their footing on a path toward homeownership in Hawai‘i, expresses their hopes, fears, and aspirations around the unaffordable real estate market.

90 A PEOPLE DESERTED

Hawaiian Home Lands are meant to generate Native Hawaiian self-sufficiency, yet one community on Hawai‘i Island is awfully overcharged for freshwater. What went wrong?

TABLE OF CONTENTS 10 _ DEPARTMENTS S/S 2024 PHILES 24 _ FILM Ho‘omau Nā Maka o ka ‘Āina 32 _ CULTURE Mana and Kalehua Caceres 38 _ COMMUNITY Shared Driveways 42 GAMES Mahjong 48 _ MAOLI Keola Rapozo A HUI HOU 192 BACKBONE OF PARADISE FEATURES

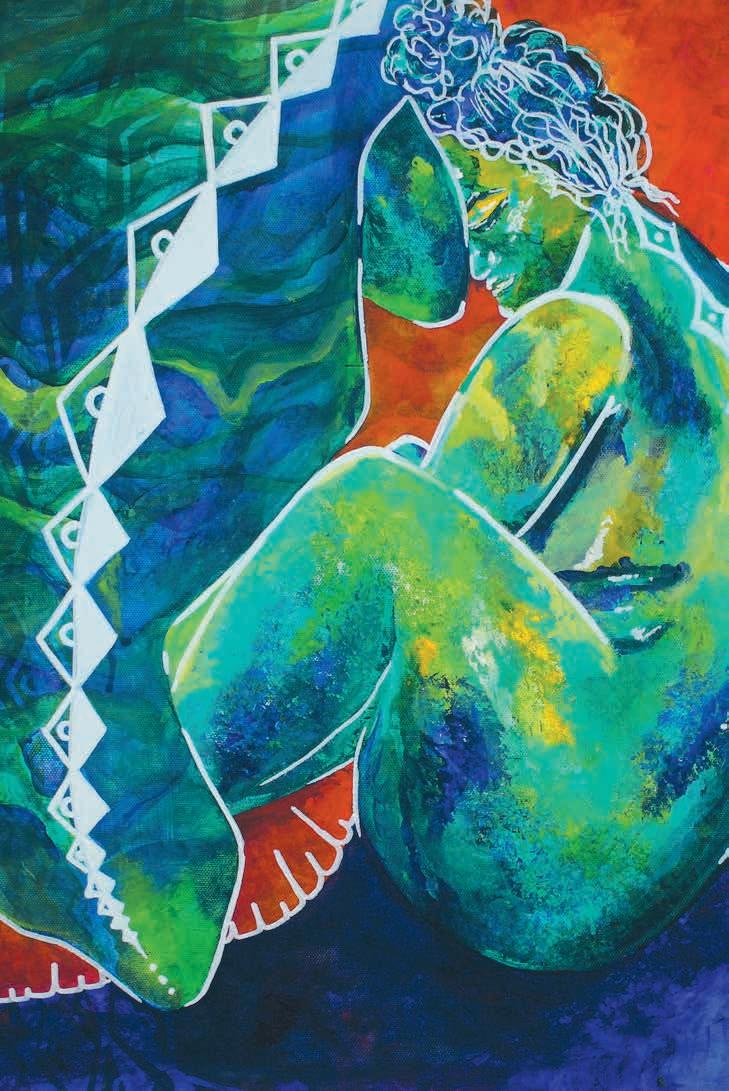

IMAGES BY _ VINCENT BERCASIO FACING PAGE, IMAGE BY _ ERICA TANIGUCHI

NO. 46 FLUXHAWAII.COM 11

110 HE LEI NO KA MALU ‘ULU O LELE

A storied description of Lahaina’s many historical modes of shelter, built and defended by the region’s maka‘āinana.

116 _ VOICES IN THE DARK

From grassroots support to coordinated efforts, Maui’s Filipino community finds it footing in the aftermath of the devastating wildfires.

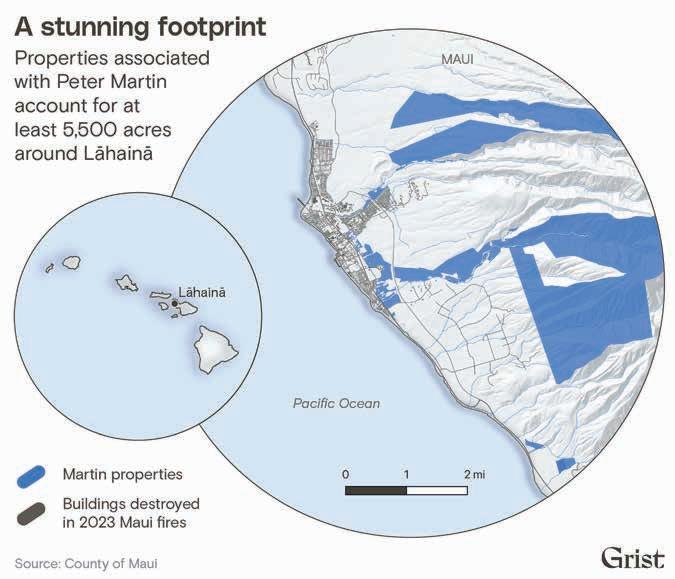

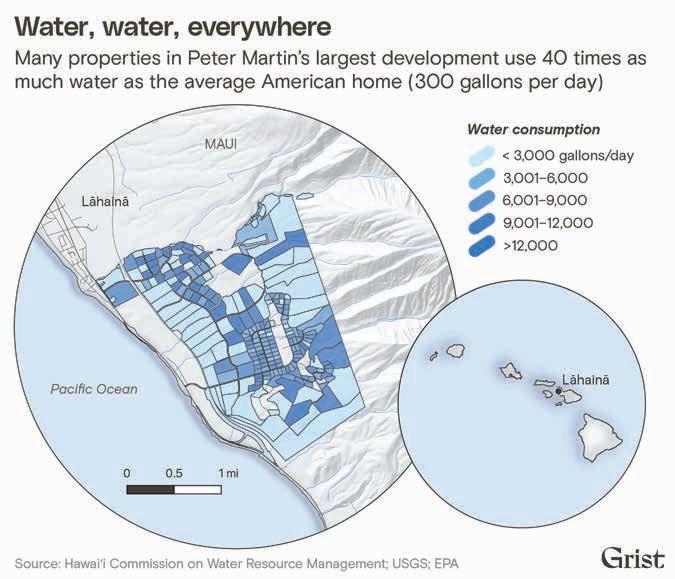

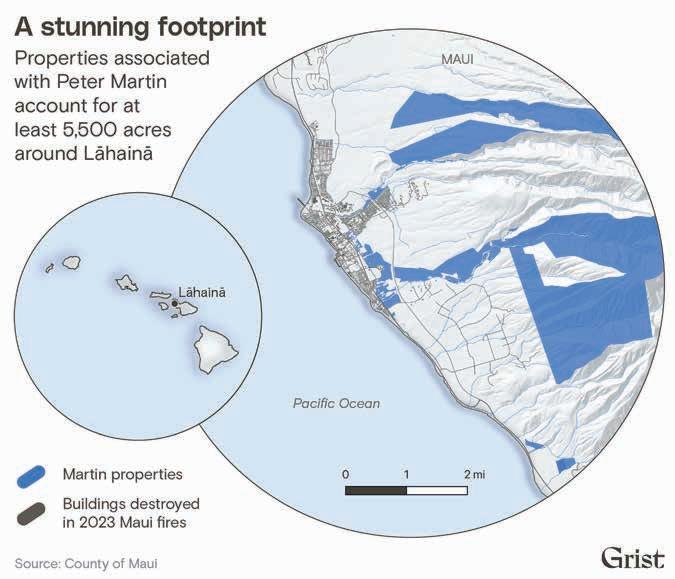

124 _ THE PEOPLE VERSUS THE WEST MAUI DEVELOPER

Controversial developer Peter Martin spent decades guzzling water around Lahaina. Then came the fire.

LIVING

Kimeona Kane

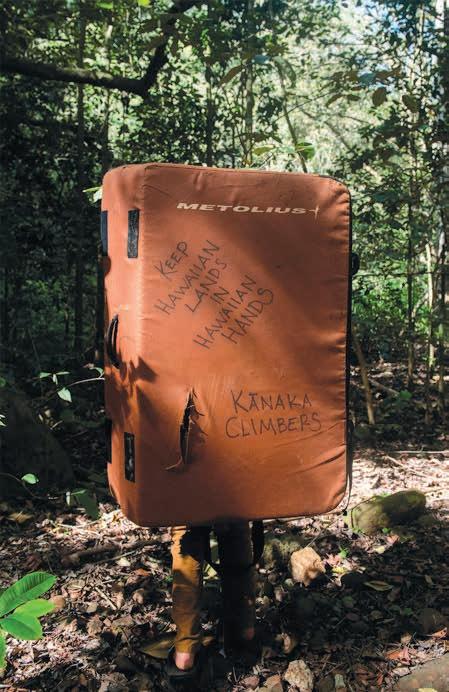

Kānaka Climbers 178 _ NORTH SHORE

Waialua

ART & DESIGN

CULTURE

SOCIETY

SUSTAINABILITY

STYLE

POLITICS

12 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM _ DEPARTMENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS

SPECIAL SECTION: LAHAINA

DESIGN

152

WELL 136 _

The Bennetts

UHAU HUMU PŌHAKU

EXPLORE

CLIMBING

168 _ ROCK

S/S 2024

BY _ MARK KUSHIMI AND ELYSE BUTLER

IMAGES

CONTENT _ VIDEO STILLS FROM IN FLUX IN FLUX TV Stay current on arts and culture with us at: FLUXHAWAII.COM @ fluxhawaii @ fluxhawaii / fluxhawaii FASHION _ KEOLA RAPOZO DRY STONE MASONRY _ KIMEONA KANE LEI MAKING _ MELEANA ESTES WEAVING _ K Ā ‘EO IZON 14 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM

STREAMING VIDEOS, NEWSLETTERS, LOCAL GUIDES, & MORE

We’ve updated Flux Hawaii for a more dynamic viewing experience. Watch all the original episodes from our themed seasons, find ways to support local small businesses, and sign up for our weekly newsletters curated with Pacific-related reads. You can also browse past issues of the print magazine for purchase.

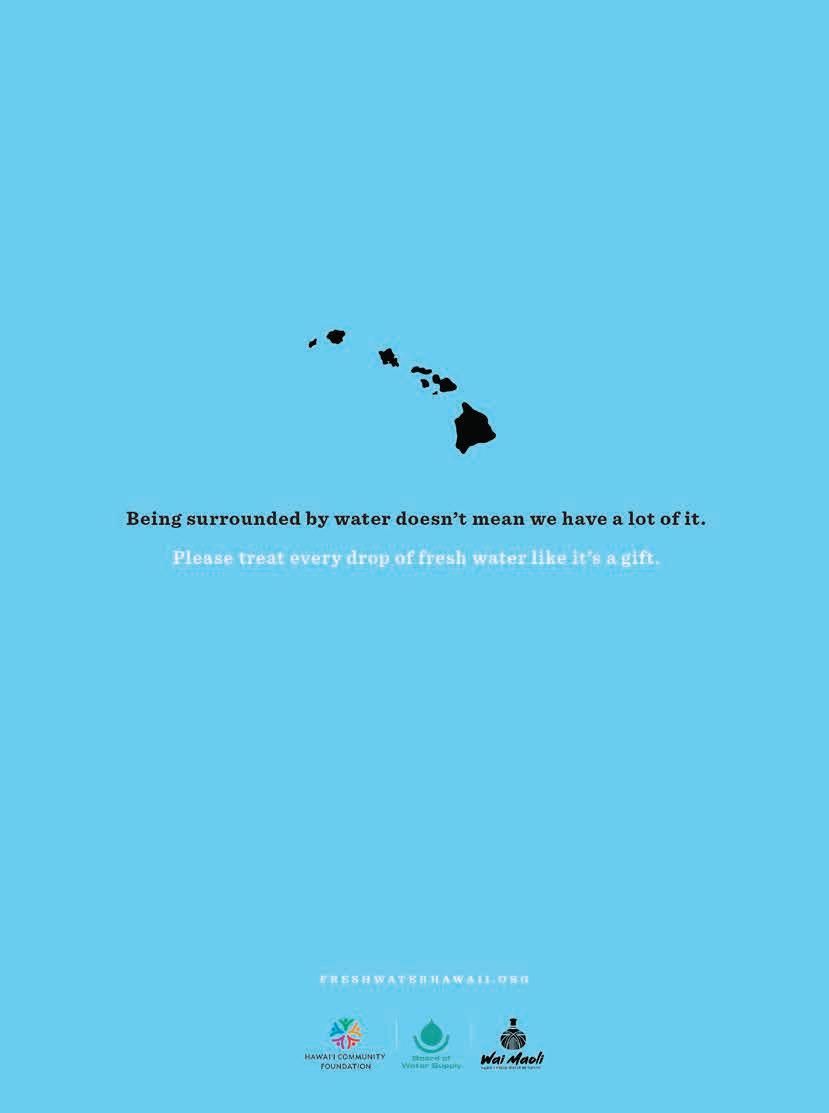

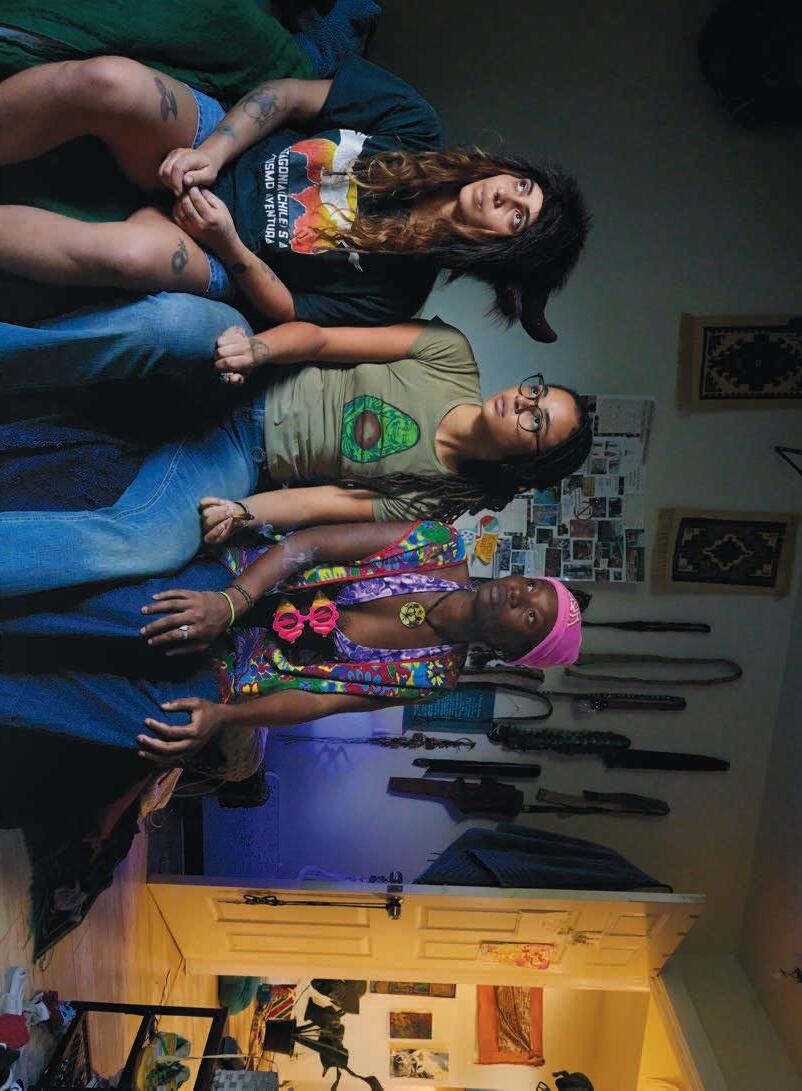

ON THE COVERS

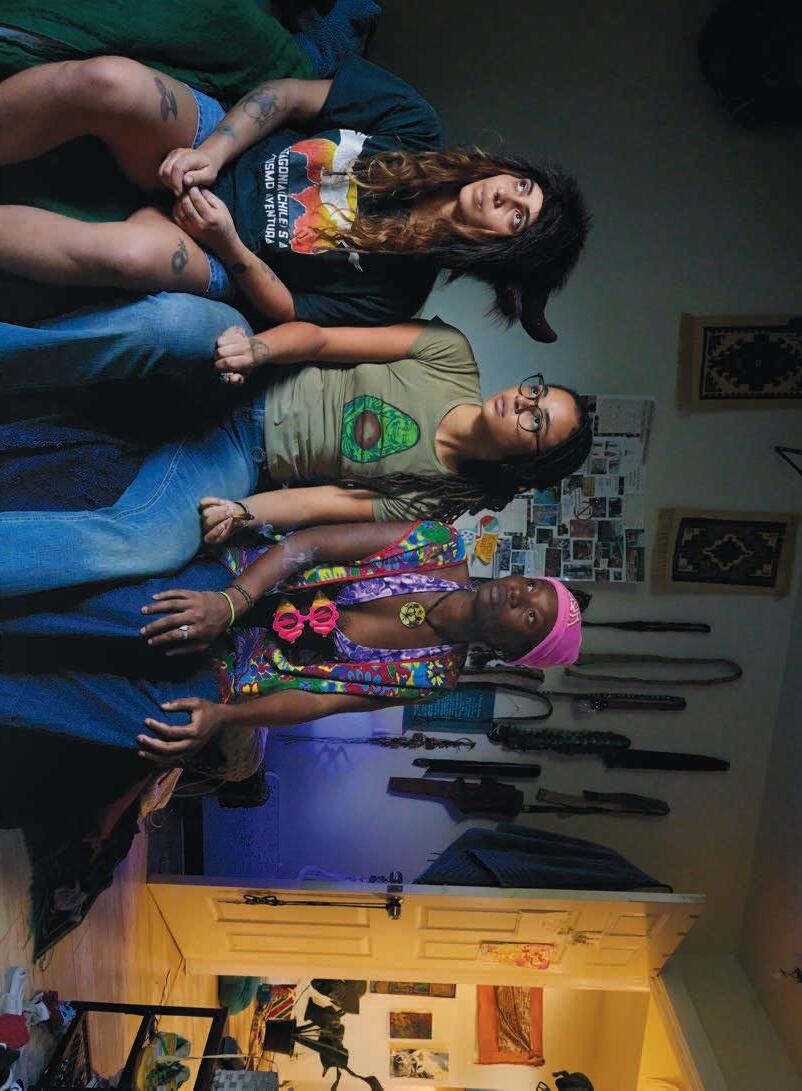

Reflecting the dynamism of stories in every edition, our new issues are released with multi-cover runs to express the kaleidoscopic and shifting landscape of the islands. L to R: 1. Gen Z-ers share their housing situations; 2. An afternoon with the Bennetts; 3. Bad Luck Club mahjong nights at Native Books; 4. Documentary footage captured by filmmakers Joan Lander and Puhipau.

Images, L to R, by:

ka

4.

_ ONLINE CONTENT 16 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM

1. Desmond Centro

2. Michelle Mishina

3. Vincent Bercasio

Stills from Nā Maka o

‘Āina

FLUX HAWAII

_ JASON CUTINELLA PUBLISHER/CEO

_ JOE V. BOCK

PARTNER/GENERAL MANAGER, HAWAI‘I

EDITORIAL

_ MATTHEW DEKNEEF

EDITOR IN CHIEF/EDITORIAL VIDEO DIRECTOR, HAWAI‘I

_ LAUREN MCNALLY

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

_ EUNICA ESCALANTE MANAGING EDITOR

_ N. HA‘ALILIO SOLOMON ‘ŌLELO HAWAI‘I EDITOR

_ RAE SOJOT

SENIOR EDITOR

_ TAYLOR NIIMOTO MANAGING DESIGNER

_ ELEAZAR HERRADURA

_ COBY SHIMABUKURO-SANCHEZ DESIGNERS

_ JOHN HOOK

SENIOR PHOTOGRAPHER

_ KAHŌKŪ LINDSEY-ASING HAWAIIAN CULTURAL ADVISOR

_ ANNA HARMON

_ LISA YAMADA-SON CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

_ AJA TOSCANO MAUI PRODUCER

_ KAIA STALLINGS INTERN

CONTRIBUTORS

_ SARAH BURCHARD

_ MARTHA CHENG

_ BEAU FLEMISTER

_ KALEHUA FUNG

_ N. KAMAKAOKALANI GALLAGHER

_ VIOLA GASKELL

_ MARIA KANAI

_ ANNABELLE LE JEUNE

_ D. KAUWILA MAHI

_ NICOLE NAONE

_ TIMOTHY A. SCHULER

_ KEALI‘I THOENE

IMAGES

_ VINCENT BERCASIO

_ ELYSE BUTLER

_ DAEJA FALLAS

_ MITCHELL FONG

_ JOSHUA GALINATO

_ SAVANNAH GLASGOW

_ PEKUNA HONG

_ LILA LEE

_ AUBREY KE‘ALOHI MATSUURA

_ MICHELLE MISHINA

_ SHANDELLE NAKANELUA

_ JOSIAH PATTERSON

_ CHRIS ROHRER

_ ERICA TANIGUCHI

_ NANI WELCH KELI‘IHO‘OMALU

CREATIVE SERVICES

_ GERARD ELMORE

VP FILM

_ KRISTINE PONTECHA

CLIENT SERVICES DIRECTOR

_ KAITLYN LEDZIAN

STUDIO DIRECTOR/PRODUCER

_ TAYLOR KONDO PRODUCER

_ BLAKE ABES

_ ROMEO LAPITAN

_ ERICK MELANSON

FILMMAKERS

_ JHANTE IGA

VIDEO EDITOR

_ BRIGID PITTMAN

GLOBAL DIGITAL CONTENT & COMMUNICATIONS MANAGER

_ ARRIANA VELOSO DIGITAL PRODUCTION DESIGNER

OPERATIONS

_ GARY PAYNE ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE

_ SABRINE RIVERA OPERATIONS DIRECTOR

_ SHERI SALMON TRAFFIC MANAGER

ADVERTISING

_ ALEJANDRO MOXEY SENIOR DIRECTOR, SALES

_ FRANCINE BEPPU INTEGRATED MARKETING LEAD

_ SIMONE PEREZ ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

_ TACY BEDELL DIRECTOR OF SALES

_ RACHEL LEE ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE

_ WILL FORNI SALES COORDINATOR

GENERAL INQUIRIES: CONTACT@FLUXHAWAII.COM

©2024 NMG NETWORK. CONTENTS OF FLUX ARE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT AND MAY NOT BE REPRODUCED WITHOUT THE EXPRESSED WRITTEN CONSENT OF THE PUBLISHER.

FLUX ASSUMES NO LIABILITY FOR PRODUCTS OR SERVICES ADVERTISED HEREIN. ISSN 2578-2053.

18 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM PUBLISHED BY: NMG NETWORK

MASTHEAD _ S/S 2024

RoyalHawaiianCenter.com • Waikīkī • Open Daily • 808.922.2299 FROM SUN UP TO SUN DOWN, THERE’S MAGIC AROUND EVERY CORNER. Fashion.

from day to night

Dining. Culture.

I Ka Pō Me Ke Ao

Fendi | Harry Winston | Hermès | Tiffany & Co. | Jimmy Choo | Stüssy | Rimowa | Saint Laurent | Ferragamo KITH | Tory Burch | Valentino | Tim Ho Wan | Doraku Sushi | Island Vintage Wine Bar | Restaurant Suntory

P.F. Chang’s | The Cheesecake Factory | TsuruTonTan Udon | Wolfgang’s Steakhouse | Noi Thai | Partial Listing

DESMOND CENTRO is a Native Hawaiian photographer born and based in Honolulu. Raised in the suburbs of Dallas, Texas, his childhood was full of Lone Star State experiences. While his upbringing was marked by exemplary public education, five-star Texas baseball, and frequent visits to indie cinemas, he always felt a deep pull toward his island roots. His choice of attending Hawai‘i Pacific University led him to O‘ahu. As he pursued a degree in Business Marketing, his passion for photography flourished during travels across Asia. With an Olympus Mju II, he interpreted his worldview through the lens, the camera is his tool to connect with people from place to place. The spectrum and

ANNABELLE LE JEUNE’s journey into storytelling stems from her islander roots. Born and raised in a primarily hispanic Miami, surrounded by enclaves of coastal nations, and coupled with her mother’s Indonesian-Chinese background, Annabelle finds home in many different ways. As a third culture kid and global citizen, she works around the world to bridge the gap for marginalized voices to equally obtain access to resources, rights, and representation as seen in Hana Hou!, Nonprofit Quarterly, Trip Savvy, and more. She is inspired by community-led initiatives that support stewardship and look to innovative ways for places, like Hawai‘i, to connect, protect, and live in harmony with the

KAIA STALLINGS, born in Nashville, Tennessee, found her artistic home in Hawai‘i after relocating at a young age. A recent college graduate, she has quickly found her place in the creative writing scene by utilizing her degree to craft live typewritten poetry at events like Art and Flea and Kaka‘ako Night Market. Inspired by the personal narratives shared by attendees, Kaia infuses her poetry with authentic emotions and vivid imagery drawn from these interactions. Her journey into journalism began during her undergraduate years at The Sentry, a student-led newspaper production. Her reporting and writing in this issue marks Kaia’s first contribution to Flux, adding to her

KEALI‘I THOENE is a native born son of Hawai‘i who grew up mostly barefoot, slurping from the garden hose, and slipping underneath Parker Ranch’s barbed wire fences. Keali’i graduated from Kamehameha Schools Kapālama, and the University of San Francisco with a BA in Media Studies. He has written for Living, Hualālai Magazine, and Big Island Traveller Magazine. He also coauthored a 2024 report on the state of next-generation work-based learning opportunities on Hawai’i Island called “Bridging Gaps, Building Futures.” He wrote the feature exploring water issues at Kailapa, on page 90. Set in Kawaihae, his ahupua‘a neighbor to the north, the story hits close to home for him. “I was

intricacies of the human face and food are common camera bait for him. Today, Desmond collaborates with local fashion brands and publications, blending the tropical essence of island life with the vibrant realm of fashion. In his first assignment for Flux, he shot portraits of local Gen Z residents, on page 68. “It’s an intimate experience being allowed into somebody’s home, and then being able to photograph it for a magazine is a feat of vulnerability,” he says. “I am constantly challenging myself to capture images of daily or what some might consider ordinary moments in unique light and unexpected angles. Photography is all about perspective.”

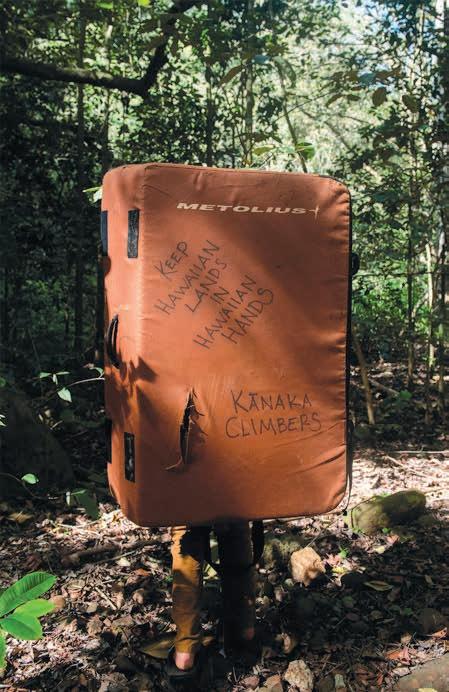

waters, lands, and life they nurture. She wrote about Kānaka Climbers, her first piece for Flux, on page 168. “At first, it seemed funny that a rock climbing organization would gather climbers and trek through a trail laden with climbing opportunities only to do a clean up,” she says. “But when I stood in the middle of Kīpapa Gulch and faced a series of petroglyphs, I understood why. Hearing about the mo‘olelo of the place, its mana and the aloha that the once-upon-a-time dwellers laid out for future generations made me think, if more organizations had a model to inspire stewardship and connection like Kānaka Climbers, Hawai‘i’s ‘āina and its resources would be in a much better place.”

portfolio, which includes works featured in the denver underground, a showcase of underground culture produced by the collective FreeMusicForFreePeople. Through her writing and poetry, Kaia continues to explore intersections of memory, identity, and the human experience. She contributed writing and reporting for the Gen Z photo essay on page 68. “Being able to sit down with members of my generation and delve into how their living situations are shaped by Hawai‘i’s current housing climate was an incredible opportunity,”she says. “It was a privilege to explore the shared sentiments and varied experience of those we interviewed.”

baffled when I found out how much the residents were paying for water, but more confused after I asked around and found out that no one really seemed to know about the injustice that was happening,” he says, considering himself fortunate. “I am grateful that Flux could publish my words, but mine are not special. All Hawaiians are storytellers. This piece is just one more article added to the Kānaka mo‘olelo mosaic. There are so many talented Hawaiians out there with stories untold.”

CONTRIBUTORS _ S/S 2024 20 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM

“ Where did we get this beautiful word, this magical word, this word that imparts life

“ Where did we get this beautiful word, this magical word, this word that imparts life

FLUX PHILES 23 IMAGE BY _ VINCENT BERCASIO

called aloha? ” — Frank Kawaikapuokalani Hewett

The installation for “Ahupua‘a, Fishponds and Lo‘i,” despite a spartan title that conjures impressions of agricultural abundance, was sparsely furnished. No framed works or large sculptures decorated Koa Gallery, the arts space at Kapiʻolani Community College. In a corner, a pair of small video monitors played outtakes from the 1992 documentary which shared the exhibit’s name. Inside a dimly lit alcove, the film’s full 90-minute runtime was projected on a loop. Placed modestly at the room’s center were two desks; one held an iMac, the other a pair of binders labeled “Hoʻomana Logs/Transcripts Oʻahu.” To the unacquainted they would have seemed like footnotes to the exhibit. For those familiar with the work

Reel Resonance

FOR THE PAST THREE YEARS, FILMMAKERS JOAN LANDER AND SANCIA MIALA SHIBA NASH HAVE BEEN DIGITIZING AND CATALOGING HALF A CENTURY’S WORTH OF INVALUABLE NATIVE HAWAIIAN FOOTAGE.

KANAI VINCENT BERCASIO

of documentarians Joan Lander and Abraham “Puhipau” Ahmad Jr., however, their contents were a revelation of utility.

The binders housed a stack of transcripts two inches thick, meticulously cataloged by Lander and Puhipau as they filmed the Oʻahu segment of Ahupuaʻa, Fishponds and Loʻi (1992), their seminal Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina documentary on Hawaiian aqua and agricultural practices across the islands. The installation made the film’s unabridged transcripts and outtakes public for the first time in 30 years, showcasing more than 80 unedited hours of oral histories on traditional Kānaka knowledge, storied places, and Hawaiian history.

One scene followed Marion Kelly, an activist and ethnohistorian credited with reorienting academia’s view on Native Hawaiian history, as she and educator Charles Kupa toured Ka Papa Loʻi o Kānewai, Mānoa Valley’s last intact taro patch. In another interview, omitted from the film’s final cut, kumu hula Frank Kawaikapuokalani Hewett traced his ancestral origins to Puʻu Hawaiʻi Loa, a wahi pana, or storied place, made inaccessible by the creation of Kāneʻohe

SANCIA MIALA SHIBA NASH, WHOSE EXPERIMENTAL FILMMAKING IS INFLUENCED BY ORAL HISTORIES, WAS ENLISTED TO DIGITIZE TRANSCRIPTS FROM NĀ MAKA O KA ‘AINA'S ARCHIVE OF DOCUMENTARY FOOTAGE AND TO ORGANIZE PUBLIC PROGRAMMING OPPORTUNITIES.

FLUX _ PHILES _ FLUXHAWAII.COM 24

_ FILM

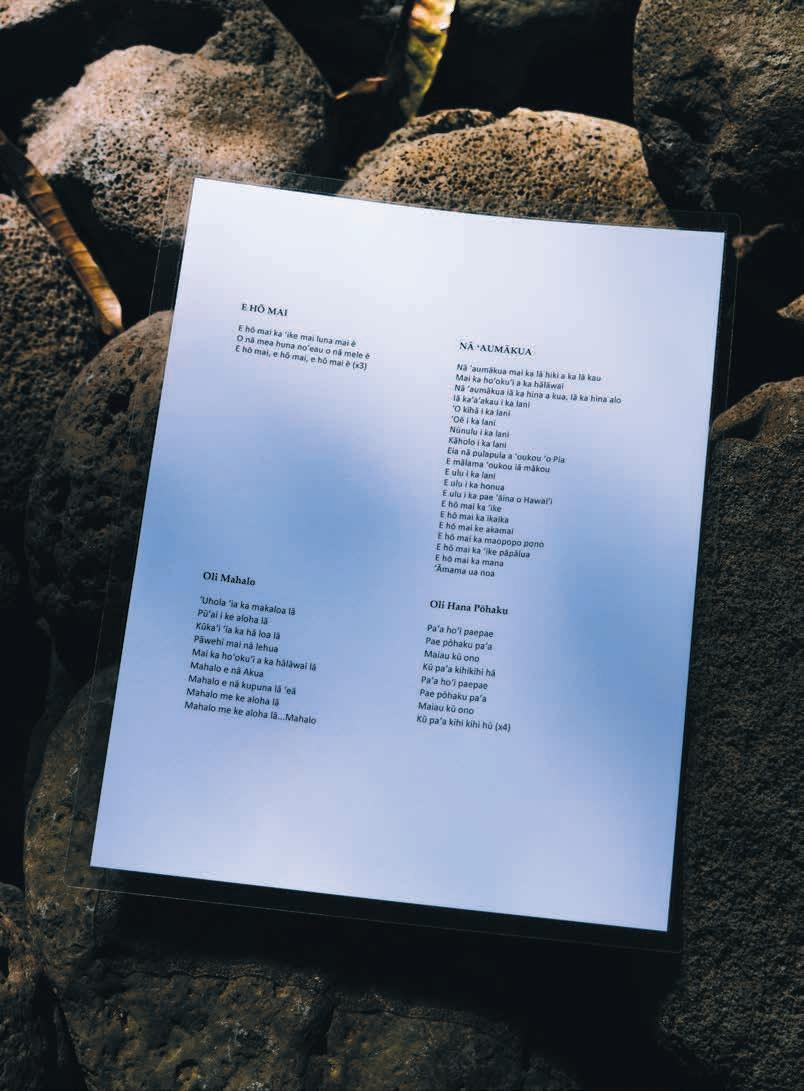

TEXT BY IMAGES BY MARIA

Marine Corps Base. “Where did we get this beautiful word, this magical word, this word that imparts life called aloha?”

Hewett asks, standing in ankle-deep water with his homelands in the background. “Believe me when I say, and I truly believe this, that the Hawaiian people or Hawai‘i are truly blessed because of that.”

The installation was the culmination of a three-year collaboration between Lander and filmmaker Sancia Miala Shiba Nash, enlisted by the Native Hawaiian non-profit Puʻuhonua Society to help catalog and digitize Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina’s vast moving picture archive. Lander and Puhipau founded the inde-

25

pendent video production company in 1981 after meeting in the post-production process for Victoria Keith and Jerry Rochford’s The Sand Island Story, which documented the state’s forceful eviction of a largely Native Hawaiian community on Mauiola (Sand Island). Lander was the editor; Puhipau, as one of the residents facing eviction, was asked to narrate. The pair’s serendipitous beginning was a portent of the work they would accomplish in the ensuing years.

It was the 1980s, the decade after the Second Hawaiian Renaissance, which had heralded a political and cultural

rebirth. There was a renewed focus on Native Hawaiian history and art. Political resistance called for a return to sovereignty. Lander and Puhipau turned their lens to the social movements occurring around them: evictions, land and water rights protests, and aloha ʻāina marches. It was all, according to the Hawaiian-Palestinian Puhipau, “for one purpose only, and that purpose is to speed up the process towards sovereignty.”

For more than 40 years, the duo covered traditional and contemporary Hawaiian culture, history, and politics, producing the resulting footage into

award-winning programs. By 2006, Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina had amassed over 8,000 videotapes, stored in Lander’s Kāʻū home. The recorded materials were fragile, the technology used to play them facing obsolescence. To avoid losing the archive, Lander and Puhipau began cataloging, digitizing, and archiving. They transferred most of their edited programs online. Then, in 2016, Puhipau passed away, making Lander the archive’s sole proprietor.

The next four years Lander continued alone. Yet, digitizing thousands of hours of footage proved to be a mon-

26 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM

PHILES _ FILM

27

FILM STILLS FROM MAUNA KEA TEMPLE UNDER SEIGE (2005), KAHO‘OLAWE ALOHA ‘ĀINA (1992), AND PACIFIC SOUND WAVES (1986).

umental project to undertake solo. In 2020 she began working with Puʻuhonua Society, a Native Hawaiian nonprofit who provided funding for additional equipment and manpower. Nash was enlisted to digitize the transcripts — applying precise metadata like names and locations — and to organize public programming opportunities.

Nash, who studied film and anthropology at Bard College in New York, moved back to Hawaiʻi in 2020. A family friend, kahu and musician Aaron Kamauna, took her to storied sites

across Maui upon her return, recalling the moʻolelo tied to the land. Among them was Honokahua, an ancient burial site reinterred in 1987 to make way for a Ritz-Carlton resort. Shortly after, she watched Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina’s Na Wai E Ho‘ōla I Nā Iwi—Who Will Save the Bones? (1998) about the desecration. The pivotal moment soon led to her collaboration with Lander. Their partnership was named Ho‘omau Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina, ho‘omau meaning to continue. They first tackled the more than 86 hours of footage filmed in 1989 to

FOR MORE THAN 40 YEARS, JOAN LANDER & PUHIPAU COVERED TRADITIONAL AND CONTEMPORARY HAWAIIAN CULTURE, HISTORY, AND POLITICS.

1990 that became Ahupuaʻa, Fishponds and Loʻi. “We had to go through the dozens of stories left on the cutting room floor, identifying the subjects and distributing the footage to families,” says Lander. “Puhipau and I believed that the people on the tape had as much right to the footage as we do. The most satisfying thing has been to put a copy of the tapes in the hands of the people who were on it or relatives of those who have passed.” With the permission of the families, certain tapes were made available to the public via installations

28 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM PHILES _ FILM

like the one at Koa Gallery, which featured interviews done on Oʻahu.

“It’s one of these programs that you are both absolutely honored to be part of and completely overwhelmed by the sheer amount of work that it requires,” says Emma Broderick, executive director at Pu‘uhonua Society, which also provided funding for the public programming.

The most interactive aspect of the exhibit was the iMac set up in the middle of the room, which housed the transcripts digitized by Nash along with an archive of previously unseen Oʻahu tapes. The metadata in Nash’s transcripts made the hours of footage easily searchable. One could type in “taro” and find where among the tapes it was discussed. Instantly, there Kelly would be, explaining how the sugar industry diverted water away from the taro patches. Or kalo farmer Charles Reppun showcasing the traditional irrigation methods of his Waiāhole farm. The tapes provided invaluable knowledge, made available to journalists, researchers, students, teachers, and cultural practitioners.

In a way, the program isn’t merely to create a historical archive for researchers or future documentarians. It presents a tangible link to Native Hawaiians’ past, proof of the ways in which Kānaka Maoli have fought and continue to fight for the rights of their people and land.

“I feel like many grassroots documentary filmmakers of Hawaiʻi would

agree that Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina left a vital resource for generations to come,” says Nash. “We still look to their educational programs and video archives for insight, as many of the issues they recorded still persist today.” In documenting the stories of ka pae ʻāina, the Hawaiian archipelago, Nash believes that Lander and Puhipau’s legacy played a critical role in educating the people of Hawai‘i.

Eventually, the Ahupua‘a, Fishponds and Lo‘i installation will travel to the various islands in which the documentary was filmed. The next island will be Maui, where the Maui portion of the tapes will be on display. Although the Oʻahu exhibit closed in 2024, the digitized footage and transcripts remain housed at Arts & Letters in Chinatown and, accessible by appointment, the Kualoa-Heʻeia Ecumenical Youth Project in Kāneʻohe.

“I appreciate the ho‘omau, the continuity piece that spans across generations with Nash and Joan. Not only are they able to continue the work as it exists and honor it as a source, they can evolve the work,” says Broderick. “It is beautiful to have a filmmaker working with a filmmaker, and not necessarily a filmmaker working with an archivist, as Nash brings her perspective to the project, as we can see with the exhibits.”

The project has made a mark on Nash and her experimental filmmaking, which is influenced by oral histories. The

Hawaiian proverb “i ka wā ma mua, ka wā ma hope,” meaning the future is in the past, is particularly inspiring for her work. “The stories that we record are important because they can offer solutions for the future of Hawai‘i,” she says.

There’s much more work still to be done. Lander and Nash continue their collaboration with the next set of 256 tapes from Nā Ki‘i Hana No‘eau Hawai‘i, a 30-part series on Native Hawaiian culture created for the Department of Education. Once all the tapes from Nā Maka o ka ʻĀina’s archives are digitized and cataloged, the raw materials and transcripts will be deposited at ʻUluʻulu: The Henry Kuʻualoha Giugni Moving Image Archive of Hawaiʻi, the official state archive for moving images, to ensure their future preservation.

“As I grow older, I feel such a responsibility and urgency to get the tapes out there and accessible,” Lander says, “and I’m so grateful to have the partnership of Pu‘uhonua. They’re treating my and Puhipau’s work with such respect and have seen its value.”

THE AHUPUA‘A, FISHPONDS AND LO‘I INSTALLATION WILL TRAVEL TO THE VARIOUS ISLANDS IN WHICH THE DOCUMENTARY WAS FILMED.

30 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM

PHILES _ FILM

(808) 593-1864 synlawnhawaii com always green lower water bills . zero maintenance

1 The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act became law on November 16, 1990. NAGPRA requires federal agencies and institutions that receive federal funding to return Native American cultural items to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated American Indian tribes, Alaska Native villages, and Native Hawaiian organizations. The act also establishes procedures for said items’ inadvertent discovery on federal or tribal lands.

2 Ayau was the first manager of the Burial Sites Program at the State of Hawai‘i Historic Preservation Division that formally established the island burial councils, and was the principal drafter of the State laws that remain in use to this day.

3 Two hui repatriated a total of 55 iwi kūpuna, 30 lauoho (hair of the head), and seven moepū from Übersee-Museum Bremen, Stuttgart State Museum of Natural History, Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg, and others.

‘Ike in Iwi Kūpuna

IN THE RELENTLESS MARCH OF URBAN EXPANSION, MANA AND KALEHUA CACERES ARE STEADFAST IN THEIR COMMITMENT TO PROTECTING AND DEFENDING THE BONES OF HAWAI‘I.

TEXT AND INTERVIEW BY IMAGES BY

In 1987, despite the Native Hawaiian community’s assertions that the site was a burial ground, construction commenced anyway on the Ritz-Carlton Hotel at Honokahua, Maui. The subsequent desecration: more than 1,100 human remains. This horrific event prompted Pualani Kanakaʻole Kanahele and Edward Lavon Huihui Kanahele to found Hui Mālama I Nā Kūpuna ‘O Hawai‘i Nei, a nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting iwi kūpuna, the ancestral bones of Hawaiian natives. Its members went on to repatriate and rebury over 6,000 iwi kūpuna, moepū (burial objects), and mea kapu (sacred objects), and in collaboration with other Indigenous communities, established the federal laws 1 used today to protect our ancestors. Edward Halealoha Ayau2, an original member and former executive director, established the successor organization Hui Iwi Kuamoʻo in 2015.

In April 2023, I had the privilege of joining Hui Iwi Kuamo‘o on a mission to reclaim our ancestors’ stolen bones from three German museums 3. Through Kalehua, I learned that tears serve as a powerful testament to our shared humanity, while Mana taught me that

NICOLE NAONE LILA LEE

laughter holds the key to building resilience. It was their balanced understanding of both sorrow and joy that made clear why our kūpuna entrusted them with such important work.

As haumāna of Ayau and alakaʻi with Hui Iwi Kuamoʻo, Mana and Kalehua Caceres are the latest fruits of this geneology of ʻike. Following a couple talk story sessions with the Cacereses4, Flux learned about the latest updates, challenges , and best practices surrounding Hawaiian burial grounds and development, a critical topic to all residents of Hawai‘i.

defining ancestral remains

Mana Caceres: Everybody in your parents’ generation was considered your mākua, your parent. Everybody in the generation before that was your kūpuna. So, for us, the very definition of human remains is iwi kūpuna 5 , it literally is the bones of my grandparents. Thankfully, we’re living in an age now where we have revitalization of the Hawaiian language. We’re getting whole generations of our ʻōpio, our youth, who are young adults now who have grown up in our language, who have rewired their brains to think like our kūpuna.

32

FLUX _ PHILES _ CULTURE _ FLUXHAWAII.COM

common misconceptions

MC: One of the things we battle, as far as the construction industry itself, is that there’s a stigma that the construction project will be terminated. So, we have a lot of open dialogue on projects that we are involved in and it’s basically trying to teach everybody what they’re missing. We’ve had instances where iwi is found on construction sites where the people are trying to hide it because if they find iwi they think they’re going to get fired or something. So, it’s not like they’re trying to hide it to be ‘ino (immoral, disrespectful).

They’ll try and dig fast sometimes so that the archeologists and the other monito r 6 won’t be able to see if iwi is present. The worst case scenario is they’re digging with no monitor, or by the time a kūpuna is found, they don’t know where it originated. Some of these construction sites, by the time we’re contacted there are huge piles of dirt that they’ve had on site for months, which then requires an investigation that is going to take months because now they have to find out where on-site that dirt came from. We’ve seen cases where the state has required half a dozen to a dozen archeologists sitting there with screens, screening truckloads of dirt, trying to find all the kūpuna because nobody was there when they were digging.

when iwi are found

MC: If iwi kūpuna are found, the entire job doesn’t get shut down. When bones are found and the process is stuck to, you’re looking at something as short and as simple as a 24-hour shut down of a 20 foot area7. Finding a kūpuna as carefully as you potentially can, pays off in the long run, not only for the kūpuna because it’s safer and it’s less impactful, but for the developer also. The safer you go, the safer it is. The safer and more careful you do the excavation, obviously the kūpuna is going to be safe. Sometimes we are able to find kūpuna before the machines even touch them. If we know what kūpuna

was buried, like the material or the layer of dirt that they’re associated with in that area, once we reach that depth or we see that type of dirt, we usually go in and we check with our literal hands. And if that’s the case, then you can find kūpuna before anything touches the kūpuna.

a relationship-based methodology

Kalehua Caceres: The way we approach anything ‘ohana-related, our business, or any endeavors that we are partaking in, is that we use the ceremonial protocols for everything. It is super important for us to recognize people’s kūlana (rank or title) and kuleana.

For us, we know it’s about relationships. That is our value system. As Hawaiians, we’re trying to accept everybody at their value and treat them respectfully. Because when we do, we model the way we want our ancestors to be treated. And we want those we work with to know that if we show them respect, they can show our ancestors respect.

We want people to know that they’re more than just a company to us. Even if we don’t agree sometimes, we recognize they’re real people doing real jobs. Maybe they struggle like us, maybe they don’t. But if we want a better Hawai‘i, not just for kūpuna, but for all of us, that’s what it’s going to take: changing people’s mindsets. And if we get to be at the table in any capacity, that’s what we always do. For me, that’s why Hale always says that you got to bring some ‘ike (accurate knowledge) to the table. Which is different than manaʻo (thought, opinion) or maopopo (understanding). If you can bring ‘ike to the table, at least that’s a starting place, right?

interpretation of law

MC: When you read the rules, it’s quite clear. When there’s a find of iwi kūpuna, you’re supposed to look at it from a lens of, “We’re preserving the kūpuna in place.” It’s supposed to be preserved in place until you absolutely have proven that it can’t be done. If we had people in positions of authority at the state level that’s in

A DEVELPOMENT IN PROGRESS AT WARD VILLAGE, KAKA‘AKO. THE HALA TREE HERE MARKS THE PRESENCE OF IWI KŪPUNA THAT WERE PROTECTED FROM DISTURBANCE BY THE CACERES FAMILY.

4 They also operate ‘Ohana Kūpono Consulting, a family owned cultural consultation firm that specializes in providing highly qualified cultural monitors and cultural monitor training.

5 Hawai‘i state law defines “inadvertently discovered remains" as remains that are unexpectedly exposed or disturbed in a place not known to be a place of burial. “Remains” being all or part of a dead human body or corpse, exclusive of ashes, cremated remains, or waste.

6 Safeguarding iwi kūpuna hinges greatly on the quality of the archaeological reports prepared during the planning stages of any development. If a permitting agency determines a project may affect burial sites, a “qualified archaeologist,” who must have a graduate degree in the field or related area and years of experience, conducts an archaeological inventory survey. When done properly, they are an excellent tool to prevent the disturbance of iwi kūpuna by construction.

7 Reporting a burial site disturbance is required by law, according to DLNR’s website, and severe penalties could result when SHPD is not notified of such disturbance.

34 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM _ CULTURE PHILES

charge of monitoring the State Historic Preservation Division 8 or Department of Land and Natural Resources, and apply the rules as they were intended to be applied 9, kūpuna would be safer tomorrow. It’s as quick as that. It’s as easy as just having somebody there that’s looking at it from an angle of, “OK, let’s protect kūpuna today.” Not “let’s protect the developer,” not “let’s protect the building.”

KC: We’ve been in burial council meetings and they’ll be like, “In the spirit of the law…,” and Hale will say, “No, that is not the spirit of the law. I wrote it. I can tell you what it meant.”

relocating kūpuna

KC: Sometimes that’s the only alternative that we have to keep them safe. There are

times when we agreed or we advocated for them to be moved from one place to the other, but we make those decisions knowing the gravity of it and taking on the responsibility. If we cannot get a developer to agree to ways to keep the kūpuna safe, then the safest thing is to move them to another location that’s safer. They’re under all the roads. They’re under all the buildings. Chances are those are the ones you never find. They’re the safest ones right now. So you have to weigh the risks and the benefits. And for us, we know the risk, so we just pule (pray). We let the kūpuna know every step of the way.

MC: This is Hawaiʻi. Everywhere you go, you’re going to have kūpuna. Is it OK to leave my grandpa’s iwi under a sewage

line that might break? Is it OK to leave my grandpa’s iwi under a road? They were there before the road, now there’s a road. Is it more Hawaiʻi, more Kanaka, to dig them out because the road is there? Or leave them alone where they were purposely planted? Those kinds of questions are a little bit easier if you’re looking at it from the lens of, “That’s my grandpa’s iwi.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity from two conversations.

8 According to the DLNR website, SHPD is comprised of three branches: Architecture, Archaeology, and History and Culture. Together they collectively strive to preserve and protect Hawaiʻi’s historic identity.

9 A 2021 op-ed by Kēhaunani Abad and Edward Halealoha Ayau in Ka Wai Ola contends that for the past 25 years SHPD has chronically failed in this regard, mentioning its inability “to produce consistently rigorous, timely reviews of reports required of those undertaking projects, resulting in projects going forward that should have paused for more careful study and community involvement.”

AS HAUMĀNA OF AYAU AND ALAKA‘I WITH HUI IWI KUAMO‘O, MANA & KALEHUA CACERES ARE THE LATEST FRUITS OF THIS GENEAOLOGY OF ‘IKE.

36 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM _ CULTURE PHILES

On Shared Driveways

FOR RESIDENTS, THERE ARE DAILY SPLENDORS, SOMETIMES SPATS, AND A BURGEONING SENSE OF COMMUNITY THAT NATURALLY BLOSSOMS WHERE PATHS CONVERGE.

TEXT BY ART BY ANNA HARMON MITCHELL FONG

When I moved to Salt Lake City in 2019, I was lonely. Fresh off a master’s degree, I had followed my spouse there for his academic pursuits. We rented a one-bedroom apartment in a six-unit complex centered around a courtyard that had been built in the flurry of postWWII housing. Out our front door and kitchen window was a unit with an identical floor plan in reverse.

I had a remote job, so I spent a lot of time at home, during which I got to know the neighbor across the way. Her cats bathed in the sun on the low wall fronting the courtyard while I sat on my steps. She told me stories of the restaurant she had owned around the corner, her career aspirations. I looked on as she fell in love. Eventually, we also got to know the quiet, brilliant woman who lived in the back unit and walked by with her bike every day. We spent sun-soaked conversations talking about studies, the weather, the zucchini plants we were growing, which she watered when we were away. We became a small community. Then, one by one, we all moved out.

Upon moving back to Hawai‘i, my spouse and I found a rental with a surprisingly similar setup: a two-bed-

room house in Pālolo Valley oriented around a single driveway shared by nine residential dwellings. Across this drive-way is a nearly identical house to ours, with the same small yard and a plumeria tree.

Similarly to the Salt Lake City move, I arrived here lonely — far from my parents and siblings’ families and spending most of my time at home with my one-year-old daughter. Also similarly, living across the way was a couple quick to welcome us. The husband spent afternoons in his covered driveway, listening to country music one day, Hawaiian the next. My daughter learned that if she brought him a flower from our tree, he would say, “Just wait!” and go inside, returning with a sweet treat for her. Slowly, he became one of our quotidian joys, a burst of conversation after a stressful tantrum, a bright moment in isolated days. His wife waved to us as she fed the birds when she got home from work and gave our daughter gifts on her birthday and holidays. My child, in turn, would stand at our open front door, waving and yelling “hi” to them as soon as she learned the word. One day when I was chatting with my neighbor, he shared that he had wanted to buy the place because

_ FLUXHAWAII.COM 38

FLUX _ PHILES _ COMMUNITY

it reminded him of his childhood home, a strikingly similar house among eight identical houses on a pīkake farm in Kaimukī. He fondly recounted spending afternoons roaming the area with the neighbor boys.

We also have more neighbors, of course. Along our shared driveway, there’s the man we speculate is a mechanic who always waves when he walks up the driveway from work or with his kids, who will play basketball with the entertaining, roaming toddlers of the woman residing next door to him; the lady who lives catty-corner and owns a café down the street; an enterprising, middle-aged duo who have lived the longest on our side of the driveway and bring us bananas from their yard; and our fence-sharing neighbors, who are wary of strangers and have two dogs they adore. Other faces blur, or are soon replaced by new residents.

Our home in Pālolo was built in 1927, according to Redfin. I imagine it was housing for people moving out of plantations into the city. The shared driveway setup is common, if not dominant, in the neighborhood. I have friends who live at the back of another such four-house, eight-residence setup a block away, and years ago, I briefly lived three streets away with a friend in a small house behind her parents’ house, behind which were two more houses where her aunty and grandma lived.

The orientation around a shared driveway creates a sense of intimacy, guaran-

teeing a limited number of neighbors you’ll see more frequently than those along a busy street like 10th Avenue, which we also abutt. You can’t help but recognize everyone who lives there and learn some of their quirks. It requires those who reside deeper to pass everyone on their way out to walk their dogs or to head to work, and those at the front to become a sort of sentry. Living along a shared driveway is a blessing, a curse, and a commitment.

“Cluster developments group dwellings together in order to make efficient use of infrastructure, provide common areas that foster unity, and preserve the natural landscape and open space,” contends a recent guidebook on planned development housing from the City and County of Honolulu. A compelling association it makes is with the kauhale concept, which a 2020 Puu Opae Homestead Settlement Plan prepared for Department of Hawaiian Home Lands identifies as a “cultural model of housing consisting of tiny home clusters and communal areas for cooking, farming, and gathering.” The primary benefits of kauhale, according to this plan, are contiguous open spaces that help conserve wildlife habitats and soil quality, reduced initial investment in roads and infrastructure and long-term maintenance costs, and proximity to neighbors, which means beneficiaries are more likely to coalesce as a community. (The concept is also reflected in the state’s Kauhale Initiative, a housing proposi-

tion for the islands’ homeless, inspired by community-based efforts like Puʻuhonua O Wai‘anae and Hui Mahiai ‘Āina.)

Of course, there is a legal responsibility of shared resources. Where we live, the mauka side of the driveway has a single, tight-fisted owner. On the makai side, each house is individually owned. When the time came to re-pave the shared driveway, our landlord refused. Just as community can blossom in these setups, grudges can build and suspicions can fester.

Yet, as a renter in Honolulu searching for shelter in an era of individualistic homeownership as a competitive investment, I fantasize about how this sort of housing lends itself to being more affordable and communal. Sure, there’s the dream of the home where you can’t hear or see anything by the waves and you aren’t bothered by others, but shared resources, whether a driveway, a courtyard, or farmland, could also make housing more accessible and manageable while encouraging a lifestyle of collaboration and communication. Shared property can, under a cooperative ownership model, even build resilient, independent communities. At the least, it can provide people who are often at home, from the elderly to the new parents, a sense of not being so alone. Life oriented around shared spaces cannot help but change as lives change. The splendor may fade, the familiarity wanes as people come and go. Or, perhaps, it can grow.

PHILES _ COMMUNITY 41

42 Fresh Faces, Classic Tiles

AT A MONTHLY MAHJONG GATHERING, A NEW GENERATION OF PLAYERS FINDS COMMUNITY THROUGH THE CENTURIES-OLD GAME.

TEXT BY IMAGES BY MARTHA CHENG VINCENT BERCASIO

On a recent Tuesday evening, as I drove to Arts & Letters Nu‘uanu in Chinatown, I told my mom over the phone that I was going to play mahjong. There was a pause on the line.

“What?” she asked.

“Mahjong!” I said.

“Why?”

“Why not?”

She didn’t ask any more questions. Of all the activities that she hopes to hear I’m doing when I call her — studying investment strategies, cooking dinner for a prospective husband, reading Eleanor Roosevelt’s biography — mahjong has likely never crossed her mind.

I am slightly worried myself, partly because I’ve never played, but also because of the mahjong event’s name: Bad Luck Club. I am my parents’ daughter and I may have internalized some of their superstitions. The name, says Cassie Louie, co-founder of the monthly gathering, is in some ways a pushback against the philosophy in many Asian families where “everything has to be prosperous and fortuitous and good fortune and all the good things. But this is a space to just mess up. It’s fine.” She continues, “we’re playing [mahjong] probably not as perfectly as our ancestors would have loved it, but it’s OK. We play

FLUX _ PHILES

_ GAMES _ FLUXHAWAII.COM

it kind of shitty, but this space is safe for everyone to play in their own way.”

Inside Arts & Letters’ long and narrow space, with Cantonese pop from the ’80s and ’90s playing, Louie arranges a table laden with snacks and takeout from Mei Sum, the dim sum restaurant next door. Six square tables, each for four players, have been laid out, with the beginner tables in the front, the more experienced towards the back. As the novices, including me, take our seats hesitantly, people in the back are already shuffling their tiles, and the room fills with the soft clicking of the pieces against each other.

Usually, about 40 people turn out. Its organizers never expected this word-ofmouth event to be this popular. Louie says it all started on New Year’s Eve, when her friend and former co-worker Dane Nakama, came to her house and they began to play with her grandmother, an avid player — Louie drops her grandmother off at friends’ homes in Chinatown for weekly mahjong dates, where Louie guesses her grandmother plays about 200 games from 9 to 5 p.m. “I’ve always wanted to learn, but I couldn’t because my grandma can only speak Cantonese, and my Cantonese is so broken.” Nakama was able to explain the rules in English and “I was finally able to bridge the language and understand how to play.”

In March, inspired by the massive mahjong parties in LA hosted by the

Mahjong Mistresses, boasting guest lists hundreds of people long, Louie and Nakama launched their own gathering at Fishcake, the dual interior design store and art school where they both worked. But they quickly outgrew the space and moved to Arts & Letters in October. From the looks of it, they’ll soon outgrow this venue, too.

Louie thinks that coming out of the pandemic, “people don’t necessarily want to go out drinking or to restaurants, and this was an event where people could gather and socialize without spending a lot of money.” She’s been surprised at the turnout, but has found many people share similar stories as hers, of watching their families play but never learning themselves. For many, playing mahjong is “reconnecting with some part of their past,” she says.

Some, like Laura Zen, have been playing since they were young (in her case, since she was 10 years old). “We played more as my grandparents got older, to test their memory. It brought the family together,” she says. In addition to attending Bad Luck Club events, she plays every week at home, having introduced her friends to the game. “When you ask them do you want to play mahjong, they’re like, isn’t that for old people? Then you get them playing and you get them addicted.” But it’s more than the game itself. “I see my friends a lot more often, we’re not on

our phones, we’re not distracted. I have a lot of fun because we’re just laughing and talking, it’s very intimate.”

She plays with a mahjong set that she guesses is 50 years old, its resin tinged yellow with age. When she first started coming to Bad Luck Club, “it was shocking because every family we realize plays a little differently.” Mahjong, it turns out, like language, has many dialects, with variances among families and countries. Players in Singapore, for instance, play with different rules than those in Taiwan or the Philippines. Joy Sanchez, who organizes the events with Louie, plans on bringing her mahjong set to the Philippines and to play with family.

Others at Bad Luck Club have no familial or cultural connection to mahjong. They are propelled by a simple curiosity for the game — and, I hear a few times, inspiration from the pivotal mahjong scene in the movie Crazy Rich Asians. The most common refrain I hear among those who have not inherited the culture is that they played once and then immediately bought a set. And once you have a set, you need three more people to play, and so it spreads — to the Servco lunchroom where one attendee works, to an oil tanker where another spends 45 days at sea. To play at Bad Luck Club is to witness the virality of a physical game, its popularity measured in the people in front of me, the shouts of “pon” and “chi” and “mahjong”

44 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM _ GAMES PHILES

as matches and sequences are made and games won, followed by the clacking of tiles being reset.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Bad Luck Club and Mahjong Mistresses were started by creatives. More than card games, mahjong is such a tactile and visual game, each tile smooth and cool and pleasant to hold, and many sets striped like layered jello, in hues of jade green or lavender or a Tiffany’s-esque blue (for a real Tiffany’s blue, a Tiffany & Co. mahjong set is available for $15,000).

It’s these tactile qualities that draw me into mahjong, as someone in the middle

of the mahjong exposure scale — never having played it or even seen any of my family members play, but feeling the pull of my cultural heritage. And what keeps me here (and seeking my own mahjong set) is much the same as others in the room: a physical camaraderie that feels increasingly elusive in the world, and the game itself, wherein I can imagine infinite possibilities, of strategy, of joy, of luck, both good and bad. For how are you to ever recognize the good if you never know its counterpart?

“We’re playing mahjong not as perfectly as our ancestors would have, but it’s OK. ”

46 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM PHILES

PREVIOUS PAGES, BAD LUCK CLUB CO-ORGANIZERS CASSIE LOUIE AND JOY SANCHEZ

_ joy sanchez _ GAMES

THIS STORY WAS MADE IN PARTNERSHIP WITH

KĪNĀ‘OLE FOUNDATION FOR FLUX’S HAWAIIAN-LANGUAGE

REPORTING SERIES FEATURING ARTICLES PRODUCED ALL IN ‘ŌLELO HAWAI‘I.

TO READ THIS STORY IN

ENGLISH: FLUXHAWAII.COM/ SECTION/OLELO-HAWAII

Pāpale Lau Moʻolelo

NUI NĀ ‘ANO NO‘EAU A KEOLA I HO‘OPA‘A AKU, ‘O KA LOLE ‘OE, ‘O KA PĀPALE ‘OE, ‘O KA MĀKINI-IKI ‘OE, ‘O KA MĀLAMA LO‘I ‘OE.

KĀKAU ‘IA E

PA‘I KI‘I ‘IA E

Ma nā noʻeau like ʻole o ka Hawaiʻi ulana maiau ʻia ke kūʻauhau, ke kuleana, ka moʻolelo, a pēia pū ke kūlana i ka moena pāwehe hoʻokahi. Eia naʻe, ʻokoʻa ka ʻaʻala a ka lei maile lau liʻi o Koʻiahi i lei wili ʻia a ʻokoʻa pū ke kāʻeʻaʻeʻa pulu ʻole a ka heʻe nalu ma Kalehuawehe. A he nīnau wāhi pūniu ka hoʻopuka ʻana aku: Pehea lā hoʻi kākou e mau ai ka ʻike kūpuna? No Keola Nakaʻakahi Rapozo, ʻo ka hana noʻeau kekahi ala āna i pane aku ai i ia nīnau ma ka pono uhai kūpuna.

Nui nā ʻano noʻeau a Keola i hoʻopaʻa aku, ʻo ka lole ʻoe, ʻo ka pāpale ʻoe, ʻo ka mākini-iki ʻoe, ʻo ka mālama loʻi ʻoe, a he nui nā mea ma waho ʻo ia mau mea a ʻehā. He mea koʻikoʻi iā ia ka ʻī ʻana aku i mua o ka lehulehu na ka poʻe Kahaluʻu, Oʻahu i hoʻomaka i ka hoʻolei ʻana i nā mākini-iki ma nā aniani kilohi kaʻa i ke kekeke 1970. ʻIke ʻia kona hoʻohanohano i kona kulāiwi ʻo Kahaluʻu, Oʻahu eā? No kēia kui lei a Kākuhihewa, ʻo Fitted kekahi wahi e kui ai nā ʻilima kūpuna, ʻo ia hoʻi nā noʻeau a kona kūpuna ponoʻī, me nā ʻilima ʻōpiopio, ʻo ia hoʻi kona kahu hānai, i kekahi lei noʻeau milimili.

No Keola ʻo ka hana noʻeau kekahi ilina a kona mau kūpuna ponoʻī a me kona kahu hānai. He like kēia me kekahi moʻolelo Hawaiʻi e like me Kahinihiniʻula, Kalapana, me Kawelo. Ia wā a ia mau keiki ʻeu i māʻona i ka ʻono ʻo ka ʻike mai kō lākou mau kūpuna ponoʻī, lawe aku lākou i mau

D. KAUWILA MAHI PEKUNA HONG

kahu hānai e mau aku ai ke aʻo e pono ke ola. Pēlā kā Keola ma ʻOkana, Kahaluʻu, Oʻahu: aʻo ʻia nā noʻeau e like nō me ka hoʻomākaukau ʻana i mākini-iki ma lalo ʻo kona mākua a laila luʻu hohonu ʻo ia i nā moʻolelo Hawaiʻi ma ke kula paikini ma Windward CC, a lawe aku ʻo ia i kahu hānai e like me nā pāleoleo kaulana ʻo Maleka. Ma kekahi ʻano, ia wā ʻaʻahu kekahi i nā lei noʻeau a Fitted mā, ʻo ia nō ʻoe ʻo ka ʻiwa kīkaha i nā pali koʻolau e ʻaʻahu ana aku i ka moʻolelo Hawaiʻi.

ʻO wai a no hea mai ʻoe? ʻO au ʻo Keola Nakaʻahiki Rapozo. No Koʻolaupoko, ma ʻOkana. Kekahi alanui liʻiliʻi ma kahi ʻo ʻOkana Pl. a me ʻOkana Rd. e huli ai, i luna lilo, i ka wēkiu. Ma lalo ʻo ke kumulāʻau painaluhe, ʻo ia ka ʻōkuhi. He keikikāne Kahaluʻu nō au.

He aha kou moʻokūʻauhau hana noʻeau?

Hoʻina iā Kahaluʻu, nā mākua oʻu, i ka wā kamaiki, hana noʻeau mākou i nā mea Hawaiʻi, nā mea i hiki ai ke lawe aku i nā fea lima hana.

I ia manawa, koʻikoʻi nō ka hula i koʻu kaikuahine a me koʻu makuahine, no laila he maʻalahi ka hoʻokāʻoi. ʻOiai lōʻihi ka lauoho o oʻu mau mākuahine-ʻanakē hana mākou i mau ʻako lauoho a i mau lāʻau lomi kekahi. I koʻu wā kamaiki ʻo kō mākou kuleana ka hoʻomaʻemaʻe hua makani, ʻokiʻoki i nā lālā kuawa i mau lāʻau lomi, ke hoʻōne

48

FLUX _ PHILES _ MAOLI _ FLUXHAWAII.COM

ʻana aku i ka milo a me ke koa. Kālai aku koʻu makua kāne i kekahi pola nona ke kahua, a he ʻōmiomio ke nānā aku. He manomano nā ʻano mea a mākou i hana aku ai. Ma hope pono, halihali mākou i ia mea I nā fea lima hana me nā kumu paina iki e kaulaʻi aku ai. Ma nā makahiki ’80, ua hana mākini nō a nani ke kaulana, ʻo ia nō ʻoe ʻo ka paʻi nui! No laila hoʻomaka mākou e hana i mau mākini a ʻike ʻia nā mākini e kaulaʻi ʻia ʻana ma nā aniani. ʻAʻole au ʻike leʻa inā ʻo mākou ka poʻe mua i hana pēlā no ka hala ʻana I nā mākua a ʻelua lāua oʻu, eia naʻe ua kaulana aku ma waena ʻo nā makahiki 80. Me mauʻu ʻuki(ʻuki) a me ka pāʻā pāma i hana ʻia. I ia wā ʻaʻole au i ʻike i ka waiwai a i ʻole i ka lilo ʻana paha ʻo kēia noʻeau i kahua paʻa noʻu, akā i kēia manawa he 30 makahiki ma ka nohona haku mea noʻeau, he ʻōkuhi maʻalahi kēlā lama mau, a pēlā nō i ia wā.

Pehea lā hoʻi ʻoe e mau ai kēlā lama me ia mau makahiki āu ma lalo ʻo kau kāʻai ma ka nohona hana noeʻau? Na ka mākua i alakaʻi iā ʻoe?

Na oʻu mau mākua, māmā me pāpā. He hoihoi loa ʻo ia, he ʻeleu, he lehua holoholo. Ma kēlā ʻaoʻao ʻo ka mokupuni nei, ma kō mākou huʻa o Kahaluʻu, ʻo koʻu makua kāne kekahi ʻo ka heke ʻiuʻiu. Nīnīnau mau nā kānaka iā ia I kākoʻo. Ma Kaʻalaea kahi a mākou I noho ai, noho nō mākou ma kahi ʻo ke kapa kai a he moku kō mākou. Sela moku mākou I kēlā me kēia lā, a he ola lako a paʻa ʻo ka heʻe māloʻo a me ka iʻa ma ka pahu hau. He mau ka hoʻomaʻemaʻe me ka unaunahi. He naʻauao ia no kō mākou ola, ʻaʻohe wahi kamaʻāina i nā ola ʻē aʻe. He waiwai mākou i ka nohona ma kahi ʻo ke kahakai, he lako i ka ʻai. ʻAʻohe oʻu ʻike he puhikole a lako ʻole mākou-manaʻo au i loko ʻo koʻu naʻau he lako nō. ʻO kāna noʻeau ma kona mau hana he paepae ia [no koʻu hana noʻeau] - pēlā hoʻi, ma ka noʻonoʻo ʻana I ka wā ma mua, he ʻike leʻa koʻu ma laila hoʻi ka waiwai, no laila nō, ʻaʻole au i ʻike [i ia wā] e hoe hewa ʻia ana au. I koʻu wā kamaiki he ʻiʻini kaʻu e hana i mau noʻeau, a ma koʻu ulana ʻana I kēia mau mea, o ke mele ka lehua, a lohea mau iā Bob Marley a me The Smiths a me kekahi mau mele hoihoi ma nā makahiki 80- a

laila kuʻi ka pāleoleo iaʻu. Manaʻo au, ‘Eia iho, ʻO ke ola ma lalo ʻo ka pāleoleo he no ka hoʻopaʻa moʻolelo ʻana.’ He nui hewahewa nā haʻawina a me ka ʻike i aʻo ʻia mai ka pāleoleo mai ʻo ia wā a ʻo ia ihola ka paepae kapu ʻo koʻu ola, pēla au e pili mau I ka lāhui. ʻO nā puke [ma koʻu waihona] he paepae e hoʻopili aku ai i oʻu mau mākua, ka ʻikena waiwai ma loko he ala ia e pili paʻa i oʻu mau kūpuna. I kekahi lā, e lilo kō kākou hana i mau ʻike ma ka waihona ʻo ia nō ʻoe ʻo ka makila lei, ʻo ia ka pahu hopu nui.

No hea a ʻo wai mai nā kumu āu I uhai mau ai ma kēia ala āu e mākaʻikaʻi nei, a pili paʻa iā Fitted?

He nīnau maikaʻi nō kēlā, ma ke alahula ʻo koʻu ola ma luna aʻe ʻo ke kauna ka nui ʻo nā kānaka oʻu i makemake e mahalo aku ai. I ka wā kamaiki, ʻo Makua John, me Makua Pau mā. Kēlā manawa ma ka nohona i Waiāhole he koʻikoʻi nō. Ka nohona kānaka ma laila a me ka lāhui e ulu ana ma laila, he mau hāliʻaliʻa aloha milimili nō ia. Nā kumu a pau oʻu no ka pāʻani pōhili. Koʻu kumu Mrs. Goto I ke kula kiʻekiʻe, nāna i waele i kekahi ala aʻo noʻu, ʻo ia kai ʻā ke kukui-ʻaʻole au i manaʻo he kamaiki ʻakamai au, i ʻole i kākoʻo aku ai i ka lāhui. ʻAʻole au i paʻa i ke kī e hāmama aku ai i ka “lauele,” i kaʻu ʻanoʻano, i kaʻu ala e hoʻopaʻa ai i oʻu mau pahu hopu nui, ʻo Mrs. Goto, ʻo ia koʻu kahu hānai kamaiki. I ka wā kula nui, ma Winward Community College, na ke kahu puke ma laila i kena i koʻu make wai e aʻo. Hoʻomanaʻo au i koʻu kumu no ka papa logic nāna i kūkulu i kekahi manaʻo e ʻōlelo ai ka lolo-ʻo ia hoʻi ka manaʻo koʻikoʻi ma ke ke kamaʻilio ʻana, ka hoʻokaʻaʻwale ʻana i ke kamaʻilio ʻana ma ka makemakika, he mea ia e kāpiʻo ai I ka manaʻo. Moʻolelo, he mea leʻaleʻa ia noʻu. Ua ʻike au he ʻiʻini kaʻu e heluhelu a noiʻi noelo i nā mea i laha ʻole, e like me kekahi kaua i ʻole kekahi kāhuli ʻāina ʻana, he ʻike leʻa kaʻu he mea ia naʻu i aloha nui ʻia.

A he mea kēlā na kekahi oʻu kahu hānai i aʻo aku ai. ʻAʻole lākou i kamaʻāina iki iaʻu, eia naʻe, ʻo ke mele nō ia, ʻaʻole ʻanei? ʻO Nas, ʻo Jay-Z, ʻo Q-Tip, ʻo ia hoʻi nā haʻi moʻolelo ʻo ka wā ’90s. ʻO kēia mau poʻe nalukai me pāleo he keu a ka ʻeleu, he koʻikoʻi hoʻi kā

lākou ʻōlelo, kō lākou kui ʻana I nā ʻōlelo I ka lei hoʻokahi, ʻaʻole nō i aʻo ʻia, I like me ke kuanaʻike oʻu. A laila, ʻohiʻohi au I nā ʻike me nā hana I ulu ka hoi, ka hana noʻeau, ke kūkulu hale, ke kūkulu lako hale, ka hana noʻeau, a ma ia ala, lawe au i mau kahu hānai ʻoiai na kēia mau kānaka i waele ke ala e ʻololo aku ai, ka mua, kō lākou moʻolelo, ka lua, kō lakou ala I nuʻu aku ai I nā pōpilikia a loaʻa kēlā wahi hoʻīnana i kō lākou ola a noʻonoʻo pū i kēlā mea akaka ma koʻu ola. He kānaka au i noʻonoʻo me ka ʻikena, no laila he pono kaʻu ʻike ʻana i kekahi. No laila, ʻŌkē, pēlā lākou i hana, eia kaʻu kukū, ʻimi a loaʻa kēlā wahi kui a ʻike inā he hiki

KEOLA NAKA‘AHIKI RAPOZO, NO KO‘OLAUPOKO, MA ‘OKANA.

kaʻu e piʻi aʻe no loko mai. A ma koʻu nohona he ʻano kumu, ʻano kānālua au I kēlā no ka mea, ʻaʻole au i ʻike Inā nō he loea au a i ʻole, ʻaʻole au he loea ma kekahi mau mea. Papakū koʻu ʻike ma ka ka hana noʻeau ma luna ʻo kekahi mau kānaka – ka noʻonoʻo ʻana a me ka haʻina i kekahi mau mea he ʻokoʻa kaʻu ʻokoʻa pū kō kekahi kānaka a he mea saiwai kēlā. No laila, ʻike leʻa au i koʻu kuleana.

Pehea e lilo ai ka moʻolelo me ka makawalu i kūkulu ʻo kāu mau hana noʻeau?

Ma ka hoʻina ʻana aku i kaʻu wā kamaiki ma Kahaluʻu, ʻaʻole au i ʻike leʻa ʻo wai

50 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM _ MAOLI PHILES

kēia nei a i kēia manawa 30 makahiki o ka hana noʻeau he ʻo ia mau nō ka ʻiʻini e ʻimi i ka loina. No ka mea inā paʻa kēlā loina, he hiki nō ke kaʻana aku i ia pilina me kekahi kānaka. He hui lole wale nō ʻo Fitted, eia naʻe he ʻoni kō loko, he ʻiʻo kō loko. No mākou, ʻaʻole ia he waiho ana i ka hua ʻōlelo “aloha” ma kekahi pāpale. Manaʻo mākou ʻo “aloha” kekahi manaʻo i hele nō a manakā-palala, manaʻo mākou he pono ke aloha i “aloha.” E mau ka lama me ka mana ʻo ia ʻōlelo. E kaʻana like aku ai i ka hohonu-ʻike ʻoe, hoʻomaka ia me nā puke, ka noiʻi noelo, ka hoʻopaʻa ʻana i kō mākou kumu. Nā manaʻo i hoʻokomo ʻia i loko ʻo ka lole me ka pāpale he kū i ka hoʻokumu kuanaʻike I ʻole e hoʻopaʻa ai i ala e kaʻana like moʻolelo, e kū pili ai i kō kākou moʻo, i ka poʻe kūpuna. Pono kākou e noʻonoʻo I ala e pili pū ai i ka loina. A ʻo ʻoukou nō ia, nā hanāuna hou, a me nā hanāuna ma hope mai. A ke hoʻōia ʻiʻo ʻia nei, ʻo ia kaʻu manaʻo. Nui aʻe nā mea kūʻai i ʻī aku, palala, he makemake kō mākou i ka moʻolelo, he laha loa ia. Ma ka hoʻomaka ʻana, ʻaʻole pēlā kākaʻikahi ia ʻano hana. I kēia au ʻo nā poʻe kūʻai aku lole-ʻaʻole mākou wale [Fitted] ke ʻī aku nei naʻu nō, ua loli ka pōloli ʻo kekahi kānaka nāna i hoʻololi i ke ʻano ʻo nā wahi kumu kūʻai, a he kū i ka maikaʻi. Aloha nui ʻia.

He wahi nīnau kaʻu e uhai aku ai, he pili nō i ka makawalu, pehea mai kō aloha a ʻiʻini i ka pāleoleo e lilo ai i pono uhai ʻike kūpuna? Pehea ʻoe e hoʻololi iki i kēia moʻolelo a loli i noʻeau?

He nīnau maikaʻi nō kēlā. He ʻo ia ʻiʻo nō. [DJ] Premier, ke kānaka ʻoi kelakela ʻo ka uhai kūpuna. Nā pana a pau āna I hoʻokumu ai he panina. Nāna I hānai nā kānaka e like nō me Kanye West, a pēlā pū ʻo Pete Rock. A nāna nō i ulu aku i oʻu mau kahu hānai. No laila, manaʻo au ʻo ka pāleoleo me ka nohona I kēlā moʻo — ʻaʻole ia he wā aʻu i makemake e hāpai aku, eia naʻe ʻike au i ka waiwai ʻo ka nohona ma loko. Kekahi manaʻo nui ʻo kēia walaʻau ʻana, ʻo ia ke kānalua ʻo kekahi hana kaumaha, ʻeā?

He māka maʻalahi au, no ka hoʻāʻo ʻana I nā mea i kuhi kekahi kānaka he pono e hoʻokē aku. Me kēia loina kūpuna — aloha nui au i ka manaʻo e kau hou i inoa ma ka ulu ʻana.

51

Pēlā ka poʻe kūpuna. ʻO Paiʻea, ma kona naʻi aupuni ʻana, kau mai i inoa hou. A he waiwai luaʻole kēlā no ka hiki ke holomua. He like me ka ʻikena naʻu ke kahe koko, ke hou, a me nā hiolo maka a I kēia noho hiki ke kaʻana ʻike, a aʻo pū I kekahi mea. He like nō me ke kapa ʻana I kekahi inoa a me ke kau ʻana I inoa hou, a me ke kuanaʻike kūpuna ʻo ka hoʻopaʻa moʻolelo me ka ʻikena inoa, ka ʻohiʻohi ʻana I 300 inoa makani me ka ua. [ʻO kō kākou kūpuna] waiho lākou I kēia mau momi ʻo ke kilokilo mai ka pō mai a he hoʻoulu ia naʻu. He ulu nō kēia I nā mea a pau. He wili hou, a wili hou I lei e maikaʻi ai ke ola a e mau ka ui ma kaʻu hana. He hoʻoheno koʻu I ka wā ma mua o haki ke kaula hao, ʻo kaʻu kuleana nui ka haki ʻole ʻo ke kaula hao.

ana, kaʻapuni au i ia ʻike, pēlā ke ola. ʻAʻole au i manaʻo he mea ʻē ia. Ma koʻu neʻe ʻana a kokoke i ke kaona, ʻike iho la au, ‘Uao, palala. Nui nā kānaka I paʻa ʻole ka loina.’ ʻO ia hoʻi, ʻaʻole lākou i hele i kekahi loʻi ma mua, ʻaʻole i kamaʻāina i ka loko iʻa, i ʻole kekahi mākāhā. Kīkē ka ipu. He kōkua a koʻo ka nohona maʻaneʻi. ʻO au kekahi. Pēia e hoʻomaka hou ai e uhai kūpuna.

He pōpilikia paha. He pipiʻi ka nohona, ʻo ia kekahi kaumaha. Nui nā mea i hai ʻia e noho kūpaʻa i ke ola, ma Hawaiʻi nei. He mau kupa kāua a Oʻahu, a he kākoʻo haʻaheo au ʻo ka Moku o Kākuhihewa nei. A eia kekahi, he ʻokoʻa ka nohona maʻaneʻi, ʻokoʻa pū ka nohona Kauaʻi, ka nohona Maui, a me ka nohona Molokaʻi kekahi. E aʻo mākou mai kō mākou hoa hānau a noʻonoʻo pū no ka nohona ma lalo ʻo ka hale hoʻokahi. Kupaianaha ka nohona o kākou ma lalo ʻo hoʻokahi hale a e huliāmahi i paʻa ke kahua. ʻO ia mau nō ka pōpilikia, a he pono ka hoʻopaʻa. He keu nō a ka pipiʻi ka nohona Hawaiʻi maʻaneʻi. ʻAʻole e hiki paha kaʻu kamaiki e kūʻai ai i hale, a he mea koʻikoʻi kēlā. He pōpilikia kēlā i nā Kānaka ʻōpio me kō lākou loina. Inā e kuapo ʻia ka ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi ʻo ka poʻe kūpuna me ka ʻāina i lawe ʻia nei mai kō mākua-he akāka ke kuapo ʻana i nā manaʻo. Pono kākou e ʻimi i pane: He ʻaha kai hoʻi kākou i ka ʻāina? He aliʻi ka ʻāina, ʻo mākou ke kauā. Inā hoʻololi kākou I ka ʻāina me ka ʻike, ʻo ka ʻike kekahi manaʻo ākea ʻo ka ʻāina a me ka ʻāina momona. ʻO ka ʻike kō kākou kākālina. Kahi mea e hāmama ai ka puka. No

He manaʻo panina paha kāu? Pili i kēia a i ʻole iā ʻoe iho?

ʻAʻole ka ʻike kūpuna kekahi mea e waiho ai ma ka haka. ʻAʻole ia he kiʻi hoʻomanaʻo. ʻAʻole ia he mea e nānā aku me ka maka mānoanoa. Inā ʻoe he kānaka, inā nō. Waiho ka hilahila. Hoʻomanaʻo au I kaʻu wā kamaiki he hilahila nō au. Inā ʻaʻole I hiki mai koʻu mākua, ʻaʻole au I ʻai. Haʻi mai koʻu ʻanakē, “Palala, hilahila ʻoe, make pōloli.” Hāliʻaliʻa mau ia I koʻu lolo. “ʻAʻole, ʻanakē, ʻŌKē au.” “Kama, shua ʻoe? Hilahila ʻoe, make pōloli,” a he hāliʻaliʻa kūpono ia ma koʻu alahula. E mau i ke kūpaʻa Hawaiʻi.

Hoʻoponopono ʻia kēia kūkākūkā no ka pueko a me ka wali.

He ʻono ka pāleoleo i nā ʻai ʻo Hawaiʻi, hea ʻia ʻo Hawaiʻi ma nā mele (pāleoleo), a me kekahi ʻano like ʻole. He aloha paha kō kekahi i kekahi no ia ʻano walaʻau ʻana i ke ʻano o ke ea no ke Kānaka ma ka lole, ma ka pāleoleo, ma ka hana noʻeau, ma ka moʻolelo. ʻO kaʻu nīnau ma hope mai, pehea hoʻi ka hana noʻeau e koʻo i nā Kānaka e noho kupa ma Hawaiʻi nei? ʻO ka mua, ʻo kēia hānauna a me kēia mākeke, [noʻeau] ʻo ia ka lou. ʻIke au he nui a manomano nā mea e alakaʻi ai i nā kamaiki a me nā kānaka, ʻo ka hele nihi ka makamua. Ma hope mai ʻo ka lou he papakū mai i ka loina kūpuna, ma laila ka momi e hoʻomaka ai i ia ala pilina, ma nā ʻāina ʻē me maʻaneʻi nō kekahi. I kaʻu ulu aʻe nā ʻōpio e ulu mai nei, hamāma ka puka e noʻonoʻo me ke kuanaʻike Hawaiʻi, pēlā e kaʻi ai ma kēia honua. Me ke kapolena pena ʻole lākou e kaʻi ai ka honua a ʻike I kēlā ʻāina — na lākou paha e kilo a ʻike I kekahi manaʻo Waiwai hou, kūkulu I ʻoihana hou. No ka lani mai paha ia ʻike, mai nā kuahiwi e ʻīnāna ai I ka hanāuna. Paʻakikī ka hoʻopaʻa ʻana I ʻāina no kākou pākahi. ʻIke Hawaiʻi, Hawaiian IP. No mākou nō. Waiho ʻia no mākou. ʻO ia ke koko me ka hou a ka poʻe kūpuna i hiohio ai no mākou. Ke hoʻopāneʻe iki nei au I kēia mea maʻaneʻi [ma Fitted]. E noʻonoʻo pū i nā mea ma hope mai e hāmama mai ei.

52 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM

_ MAOLI PHILES

your favorite

kalapawaimarket.com 306 S Kalaheo Ave, Kailua, HI 96734 (808) 262-4359 kailua beach KAILUA TOWN 750 Kailua Road, Kailua, HI 96734 (808) 262-3354 41-865 Kalanianaole Hwy Waimanalo, HI 96795 (808) 784-0303

711 Kamokila Blvd #105, Kapolei, HI 96707 (808) 674-1700 KAPOLEI Our food is designed to fuel every local lifestyle Our classic favorites are inspired by home cooked meals, backyard BBQs & beachside picnics, because we know how Hawaii loves to eat.

stop in the neighborhood

WAIMANALO

“ After extensive investigation and survey

it was found that the only method in which to

FEATURES

on the part of various organizations organized to rehabilitate the Hawaiian race,

rehabilitate the race was to place them back upon the soil. ” —

55 IMAGE BY _

Jonah Kūhiō Kalaniana‘ole

JOHN HOOK

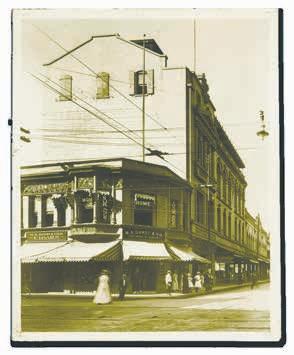

Past Meets Present

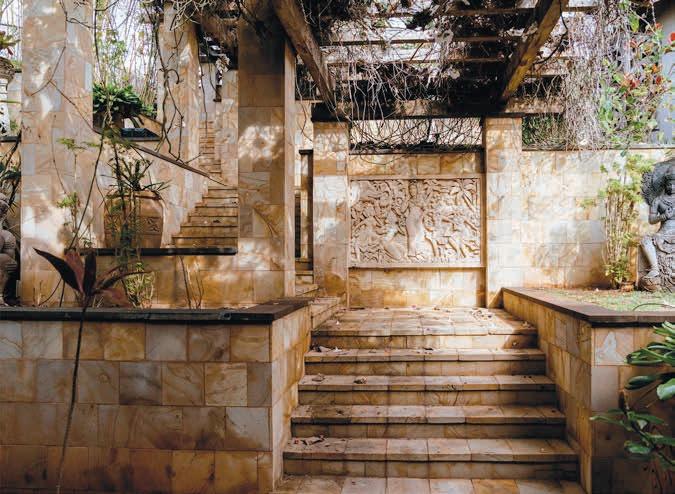

TEXT BY IMAGES BY _ TIMOTHY A. SCHULER _ JOHN HOOK

CHRIS ROHRER

TEXT BY IMAGES BY _ TIMOTHY A. SCHULER _ JOHN HOOK

CHRIS ROHRER

FLUX _ FEATURE 56 56 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM

PLACELESSNESS

PLAGUES

COMMUNITIES

IN THE STRUGGLE TO CREATE AFFORDABLE, DIGNIFIED HOUSING.

FEATURE _ ADAPTIVE REUSE

57

Afew years ago, I was invited to the opening of a new affordable housing development in Kakaʻako. Several hundred people mingled on the eighth floor rooftop, a carpet of synthetic turf underfoot. Television crews pointed their cameras up at the boxy tower, its lines of windows and yellow accents meant to evoke, according to the developer and its PR team, the patterns of Hawaiian kapa and the spirit of Keaomelemele, a kumu hula described in numerous moʻolelo who was said to have formed Nuʻuanu Valley. Later, we took the elevator up to one of the building’s two “sky lānai” on the 33rd floor, an open-air gathering space that was meant to democratize the 43-story building’s panoramic views. I stood at the glass railing, framed within the lānai’s mustard-yellow box, and wondered if this was the future of housing in Hawaiʻi. If it was, what did that future look like?

There are few topics in American culture more divisive than housing. Many people agree that the cost of housing has reached crisis-levels. In Hawaiʻi, and elsewhere, rents have skyrocketed, particularly during a global pandemic. In 2021, while my wife was pregnant with our son, our landlord raised the rent on our 1-bedroom apartment from $1,600 to $1,800.

Particularly controversial is the construction of new housing, which has become a bogeyman for residents across the political spectrum. For homeowners, contemporary housing developments can be seen as a threat to neighborhood character and, possibly, their property values. For renters, those same projects are often seen as a harbinger of gentrification. An overlooked thread in these

debates is the look of the housing, which, regardless of price point, tends toward large, squarish, flat-faced blocks punctuated by a pattern of colored panels.

The writer Jerusalem Demsas has documented the ways in which aesthetics and concerns about gentrification have become conflated, and not just among design critics. On TikTok, Demsas found that #gentrification brings up countless “posts criticizing modern homes for mostly aesthetic reasons.” One video, captioned “honestly, so ugly,” critiqued an affordable housing project in Camden, New Jersey, for being what the user assumed was a “gentrification building,” mostly based on its size and color scheme. Commenters piled on, with this quip collecting tens of thousands of likes: “why is it ALWAYS h&r block green?” Contemporary architecture and fears of gentrification have “simply become inextricable,” Demsas wrote in 2021.

Aesthetic-based opposition to new housing isn’t confined to TikTok. Throughout the country, historic preservation boards and design review panels regularly reject proposals for new apartment or condominium buildings on architectural grounds—the proposed building is too tall, or too large, or too contemporary to meld with the existing neighborhood.

The aesthetic in question has become so common that in 2023, the New York Times published an article titled “America, the Bland.” The style has birthed a whole array of derogatory descriptors, which fellow design writer Patrick Sisson compiled for Curbed in 2018: Minecraftsman, McUrbanism, developer modern, contemporary contempt, lo-mo (low modern), and, what CAN ADAPTIVE REUSE RESCUE OUR HISTORIES?

58 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM

_ ADAPTIVE REUSE FEATURE

ARCHITECTURE CRITIC KATE WAGNER HAS WARNED THAT OPPOSITION TO NEW HOUSING ON STYLISTIC GROUNDS IS AN EXAMPLE OF “AESTHETIC MORALISM,” THE BELIEF THAT ONE STYLE OF BUILDING IS BETTER SUITED OR MORE APPROPRIATE TO A PLACE THAN OTHER STYLES.

has arguably become the most enduring: fast-casual architecture. If you live or have spent time in Honolulu, you’ll recognize the style from Hale Mahana, the pixelated, gray-and-white-paneled apartment building at the intersection of University and King — or, yes, from Ke Kilohana, the condo tower with the yellow “sky lanai.”

I have a certain respect for the idea that animates Ke Kilohana’s high-altitude amenity spaces: the inversion of conventional developer logic, which typically reserves the highest floors for the highest-paying tenants. But I can’t in good faith argue that the building is beautiful. The not-quite-staggered, not-quite-straight lines of windows; the

59

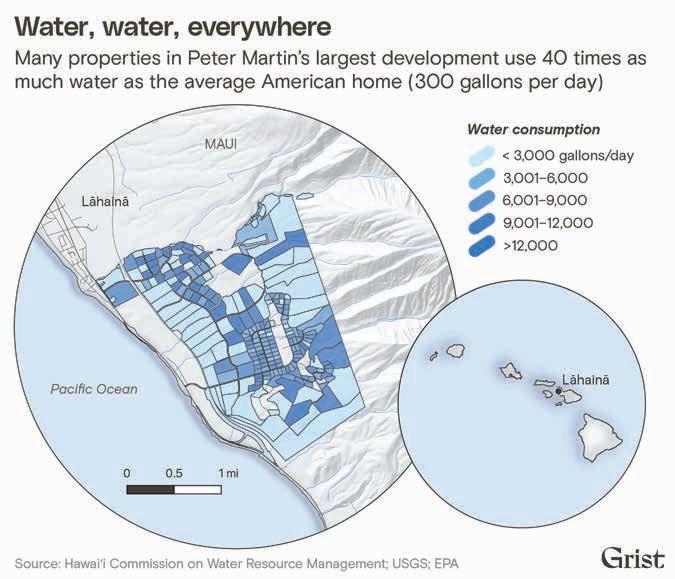

Opening spread, Modea Formerly Davies Pacific Center 841 Bishop St. Left, Ke Kilohana 988 Halekauwila St.

61

chaotic splatter of colors and materials; the deadening effect of a seven-story podium (most of which is parking) — the whole thing feels cheap and strange, like it was built in the sad, plasticky environs of the Metaverse. Honestly, Minecraftsman sounds better.

The architecture critic Kate Wagner has warned that opposition to new housing on stylistic grounds is an example of “aesthetic moralism,” the belief that one style of building is better suited or more appropriate to a place than other styles. This distracts us, she writes, from debating the underlying forces making housing unaffordable and, in a lot of places, unbuildable. But, if the war against new housing — par-

to be waged in aesthetic terms, then style matters. The look and feel of new housing can be either an ally or an enemy in its very materialization.

I’m not about to argue that kowtowing to residents’ (often petty) complaints should stop us from building new housing, and I’m not suggesting that politically difficult policy reforms — particularly on subjects like zoning and rent control — aren’t necessary if we’re to solve the affordability crisis, in Hawai’i and elsewhere. But I do think this moment offers a chance to invest in a building practice, and general design and urban development philosophy that can circumvent this kind of aes-

IN ARCHITECTURE, ADAPTIVE REUSE REFERS TO THE PROCESS OF RENOVATING AN EXISTING BUILDING, OFTEN VACANT HISTORIC STRUCTURES, FOR A NEW PURPOSE OTHER THAN ITS ORIGINAL INTENDED USE.

62 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM

FEATURE

917 Kokea St.

thetic opposition while also preserving layers of Hawaiʻi’s history and avoiding unnecessary carbon emissions: adaptive reuse.

Adaptive reuse is a wonky term that simply means converting a structure from one use — say, a warehouse — to another, such as condos or a coworking space. It’s basically recycling, but at the scale of entire buildings. The practice isn’t new, even in Hawaiʻi: The old circuit courthouse in Wailuku, Maui, was adapted into office space and a museum in the mid-1990s. Our old apartment building, Lili‘uokalani Gardens, began its life as vacation rentals marketed to Japanese tourists. And most of Kakaʻako’s galleries and artist studios occupy

spaces built for manufacturing or warehousing goods. But adaptive reuse is beginning to catch on in an even bigger way, in part due to the rise of remote work and the subsequent emptying out of offices. As of 2022, a majority of architectural billings come from renovations of existing buildings, not the design of new ones. A full quarter of that work is on adaptive reuse projects.

“The office vacancy issue happened even before the pandemic, with technology and just different lifestyles. The pandemic just sped up that trend,” said Janice Li, a Honolulu-based architect and studio director for Lowney Architecture, which also has offices in Oakland and Los Angeles. Li and her team

are currently working to convert the bulk of Davies Pacific Center, a Brutalist office building at the corner of Bishop and King streets designed by the late Honolulu architect Steve Au, into residences.

Li and other architects who have worked on adaptive reuse projects in Hawaiʻi say it offers a quicker, less costly pathway to more affordable housing for the islands because converting an office building into apartments avoids the time-consuming work of conducting an environmental assessment, preparing the building site, and erecting the structure. Some researchers have estimated that the construction costs of adaptive reuse projects can be as much

63

Maybe we already have what we need. Maybe what looks like an abandoned newspaper office is actually future workforce housing.

as 48 percent lower compared to new construction. These savings theoretically can produce housing that a wider swath of the population can afford. I say “theoretically” because our current system doesn’t guarantee that those cost savings will be passed on to potential buyers or renters. At Davies Pacific Center, for instance, all of the housing units will be sold at market rate.

The financial picture is just one benefit of adaptive reuse. Another is its ability to avoid the public handwring-

ing that often accompanies new housing. The struggle to create affordable, dignified housing isn’t confined to the spreadsheets of loan officers or the computer screens of architects. It plays out in the public sphere. Many of the barriers are social or political in nature, whether it’s basic NIMBY-ism or the understandable distrust residents have for real estate developers. But people rarely protest a building that’s already there. “I would say that that is one of the primary benefits of adaptive reuse,”

Jonathan Helton of the Grassroots Institute of Hawaiʻi told me. He points to Hocking Hale in Chinatown, which is currently being converted from office space to affordable housing. “I haven't heard of anyone who's coming out and complaining about it.”

Repurposing buildings from the past also guarantees a more heterogeneous urban landscape, avoiding the placelessness that people seem to associate with “fast-casual” architecture, and offers opportunities to preserve spaces

65

FEATURE _ ADAPTIVE REUSE

that hold important cultural memories. Not long ago I interviewed Brent Leggs, the executive director of the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, about the value of preserving the past. He told me that the loss and erasure of African American historic places is its own kind of trauma. Watching buildings and spaces that had served as safe gathering places, or had been places of great community pride or simply part of the background of everyday life, become derelict or disappear has psychological ripple effects on the communities who claim them.

For many residents of Honolulu, loss and erasure has been the defining experience of their relationship to the city, from the destruction of fishponds and loʻi kalo in the early 20th century to the intentional torching of Chinatown in response to fears of the bubonic plague. Despite government protections for the most significant places, in Hawai‘i, the wrecking ball still seems to swing with the regularity and precision of a pendulum, leaving gaps in communities’ collective memory.

As an architect raised in Honolulu, Dean Sakamoto has an intimate understanding of these effects. “When you clear a site, or you take something down that's been there for a long time, it's catastrophic change,” he told me recently. “There's not much difference between building demolition and a war[zone], when you think about it, physically. A bomb hitting a building or a building being knocked down — it’s catastrophic.” Sakamoto worries that history will continue to repeat itself unless we begin to see the built environment differently: as part of a cultural fabric that can either be tossed aside or rewoven into something even stronger and more beautiful, a tapestry that contains threads of both the present and the past. “I think part of our responsibility as architects is to help society see what's overlooked and to re-establish value,” he said.

Sakamoto has become something of a poster boy for adaptive reuse in Honolulu. He’s at work converting a former office building in downtown Honolulu into a teaching lab for Hawai‘i Pacific University and even recently purchased Chinatown’s Liberty Bank building, designed by Vladimir Ossipoff in 1952, which he plans to use as an office for his organization, SHADE Institute, as well as for cultural events and programs. His latest effort has been co-leading an architecture studio at Yale University that explores turning Hawaii Hochi building, designed by Pritzker Prize-winning architect Kenzo Tange for the Japanese-language newspaper in 1972, into workforce housing.

Sakamoto’s mother grew up in Kalihi just down the street from the building. “My grandmother used to read the Hawaii Hochi in Japanese religiously. She would say, ‘Where's my Hochi?’ and you’d have to go find it for her.” The paper, and its sister publication, the Hawaiʻi Herald, moved to a new building in 2022, and today the building sits vacant. Sakamoto is pushing Kamehameha Schools, which owns the building, not to tear it down. “I [told them], there’s three reasons why you gotta save this thing. Number one, you’ll look really bad, environmentally, because all that sequestered carbon gets thrown away. Number two, it’s going to cost you a lot of money to demolish this thing. And number three, this [area] was a Japanese-American enclave. There's a cultural memory of that.”

Adaptive reuse is not a cure-all for Hawai‘i’s housing woes. Despite its growing popularity, it remains a niche practice in a niche discipline, and not all buildings are well-suited to become housing. But the idea of recycling our buildings gestures toward a larger ethic of resourcefulness and circularity and even to ideas about abundance. Maybe we already have what we need. Maybe what looks like an abandoned newspa-

66 _ FLUXHAWAII.COM

FEATURE _ ADAPTIVE REUSE

per office is actually future workforce housing. Maybe we honor the past — good and bad — when we take the time to consider how a space might be given new life, rather than bulldozed into the ground.

Perhaps the word to describe this next century’s economic aspiration should not be “growth,” but “adaptabil-

ity.” In the same way that once-brittle systems must become more flexible and responsive in a time of climate chaos, perhaps our conception of housing must become equally malleable.

“THE OFFICE VACANCY ISSUE HAPPENED EVEN BEFORE THE PANDEMIC, WITH TECHNOLOGY AND JUST DIFFERENT LIFESTYLES. THE PANDEMIC JUST KIND OF AMPLIFIED OR SPED UP THAT TREND,” EXPLAINED HONOLULU-BASED ARCHITECT JANICE LI.

Building 2 North King St.

67

Hocking

FLUX _ FEATURE 68

“THE REALITY IS A LOT OF US WILL

NEVER

BE ABLE TO OWN A HOME, NO MATTER HOW HARD WE TRY HERE.”

Housing Gen Z

KAIA STALLINGS

JOHN HOOK

SHANDELLE NAKANELUA

TAYLOR NIIMOTO

ERICA TANIGUCHI

TEXT BY

IMAGES BY

_

MATTHEW DEKNEEF

_

DESMOND CENTRO