Hale FOR KOOLINA

In the Hawaiian language, hale (pronounced hah’-lay) translates to “home” or “host.” Hale is an intimate expression of the aloha spirit found throughout the islands and a reflection of the hospitality of Ko Olina. In this publication, you will find that hale is more than just a structure, it is a way of life. Ko Olina celebrates the community it’s privileged to be a part of and welcomes you to immerse yourself in these stories of home.

FEATURES

58

Standing Guard

Each summer, thousands of youth line up to learn ocean rescue skills from the best lifeguards in the world.

74

Roaming Pālehua

The rich historical and ecological significance of the ranchlands of Pālehua reveals the power of place.

90

Hometown Heroes

MMA heroes Max Holloway and Yancy Medeiros speak about their unbreakable bond with Wai‘anae.

104

Blessings Bestowed

A woman connects with mothers past and present on the plains of Kūkaniloko and in the waters of Anianikū.

LETTER FROM JEFFREY R. STONE

Storytelling is an art.

It is with great pleasure I introduce Hale, a collection of essays that defines the diverse cultural landscape of our home here on the west side of O‘ahu.

There has truly never been a more exciting time at Ko Olina. Our resort partners are enjoying an incredible year, creating extraordinary experiences for our visitors on a daily basis and hosting more new and returning guests than ever before. It is these successful partnerships that allow us to continue our stewardship of this special place and remain a model of sustainability for destinations around the world.

Our commitment to this community is also stronger than ever. As we expand our Ko Olina ‘ohana, we strive to provide sustainable livelihoods for our employees and their families and offer greater opportunities to those who live and work here.

We are also proud to be able to continually contribute to local organizations that serve a greater role in caring for our keiki, ensuring many have access to much needed educational and social support services.

A sincere mahalo to the numerous hands who created this piece. As you browse through our stories, we invite you to get to know some of our special friends and neighbors, and explore the experiences that make our Hale, our home, like nowhere else in the world.

Enjoyment and enrichment for our guests, and opportunity for our employees and our business partners, is the dream of Ko Olina being fully realized. It has always been my vision for this to be a singular place, even in our islands of many very special places. A place for both kama‘āina and visitors to enjoy, and one our community takes great pride in. A place to gather, celebrate and rejuvenate. A place to breathe easy and feel at home by the sea.

A place of joy.

With much aloha, Jeffrey R. Stone Master Developer, Ko Olina Resort

Hale is a publication that celebrates O‘ahu’s leeward

side—a place rich in diverse stories and home to Ko Olina Resort.

In this inaugural issue, we gaze mauka, or toward the mountains, to explore the many facets of Pālehua Ranch, including its reverent past and relevance to the future. Heading makai, or toward the ocean, we take a look at a youth lifeguarding program held annually at world-renowned Mākaha beach. As you follow along, learn about a golden food produced with the seed pods of kiawe, a tree found abundant along the coast, and listen in on a conversation between two mixed martial art champions proud to call Wai‘anae home. These stories, along with others, are intimate glimpses of west O‘ahu, and the people and places at its heart. We invite you, dear traveler, to sit down, relax, and take in the view.

ABOUT THE COVER

The cover image, of a West Side sunset, was photographed by Josiah Patterson, a self taught contemporary photographer from Mākaha. “The people of Wai‘anae exhibit a unique cultural pride, and they stick together and uplift others in the community,” Patterson says. “Through my photographs, I hope readers will come away with a sense of respect for the host culture, the land, and the ocean.” To see more of Patterson’s work, follow him on Instagram @siahpatterson.

KoOlina.com

Aulani, A Disney Resort & Spa aulani.com

Four Seasons Resort O‘ahu at Ko Olina fourseasons.com/oahu

Marriott’s Ko Olina Beach Club marriott.com

Beach Villas at Ko Olina KoOlina.com/accommodations

Oceanwide Resort oceanwidehawaii.com

Ko Olina Golf Club koolinagolf.com

Ko Olina Marina koolinamarina.com

Ko Olina Station + Center KoOlina.com/experiences

The Resort Group theresortgroup.com

CEO & Publisher

Jason Cutinella

Chief Creative Officer

Lisa Yamada-Son lisa@nellamediagroup.com

Creative Director

Ara Feducia

Managing Editor

Matthew Dekneef

Senior Editor

Rae Sojot

Associate Editor

Anna Harmon

Photography Director John Hook

Photo Editor

Samantha Hook

Designers

Michelle Ganeku

Mitchell Fong

Editorial Assistant

Eunica Escalante

Digital Content Coordinator

Aja Toscano

Translations

Yuzuwords

Advertising

Group Publisher

Mike Wiley mike@nellamediagroup.com

Marketing & Advertising Executives

Chelsea Tsuchida

Ethan West

Operations

Chief Revenue Officer

Joe V. Bock joe@nellamediagroup.com

VP Accounts Receivable

Gary Payne gpayne@nellamediagroup.com

Operations Administrator

Courtney Miyashiro

©2009-2017 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of Hale are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. Hale is the exclusive publication of Ko Olina Resort. Visit KoOlina.com for information on accommodations, activities and special events.

Image by John Hook

Image by John Hook

“The way we care for the most vulnerable members of our society determines our mark as a people and a nation.”

Rachel LaDrig, manager of agritourism, Kahumana Organic Farm

Image by Josiah Patterson

花開いた才能 Life

At Full Bloom

Text by Eunica Escalante Images by Molly CaskeyFloral artist Pamakane

Pico’s eye-catching

creations

demand attention.

フローラルアーティスト、パマカネ・ピコさんの色鮮やかで目立つ作品には、誰もが見入 らずにはいられません。

On a warm summer morning, Pamakane Pico glides through a garden. With one hand, she holds an overflowing bouquet of flowers in bright hues of yellow and red. With the other, she reaches into a tangle of stems nearly as tall as her, and plucks a magnolia at full bloom. When she does so, she utters a quiet prayer of thanks to the land.

It’s gathering day, and Pico has traveled from her Kailua home to Wai‘anae to browse one of her favorite garden enclaves. As she collects flowers, she keeps an eye

温かい夏の朝、パマカネ・ピコさんはゆるやかな足取りで庭を歩き 回ります。片手に溢れるほど抱えているのは、明るい赤や黄色の花 を集めた大きな花束。そしてもう片方の手を伸ばすと、自分の背丈 ほど高さのからみあった茎から満開のマグノリアの花を摘みとりま す。花を摘みながら、ピコさんは大地に捧げる感謝の祈りの言葉を 静かにつぶやいています。

その日は素材集めの日で、ピコさんはカイルアの自宅からワイアナ エへと車を走らせ、あちこちにあるお気に入りの場所でこれはと いう花を探していました。さまざまな花を集めながら特に目を配っ て探すのは、日当たりの良い乾燥したオアフ島風下側の海岸にた

Pamakane Pico, who has been making lei since age 5, specializes in lei po‘o, which slip onto one’s head like a crown crafted from fresh flowers and leaves.

out for ‘ilima, a golden blossom that grows in abundance on the sunny, dry leeward coast. The floral fruits of her labor will be wound into adornments at an upcoming lei-making workshop at the Four Seasons Resort O‘ahu at Ko Olina.

No matter the moment, Pico never stops perusing. She scans roadsides for any flora that catches her interest. “I love to use anything I can’t usually get my hands on,” Pico says. “If I see something, I’ll stop to check it out and try to make a lei out of it.” At the end of days spent gathering for lei orders, she hauls her loot home and begins hand-weaving for the next few days. It is a ritual that must be done twice a week if Pico wants to satisfy the demand for her creations.

くさん自生している黄金色の花「イリマ」です。集めた花々は、フォ ーシーズンズ・リゾート・オアフ・アット・コオリナでピコさんが教え ているレイ作りのワークショップで編み合わされ、美しい首飾りと なります。

ピコさんは片時も花探しをやめません。車を走らせながら、興味を ひかれる植物がないかどうか、道路の脇にも目を走らせます。「ふだ ん手に入らないような素材を使ってみるのが大好きなんです。何か が目にとまったら車を止めて調べ、その植物を使ってレイを作って みます」とピコさん。注文を受けたレイに使う素材を集め終わった ら、それを自宅に持ち帰って編む作業に取りかかり、数日間没頭し ます。作品の需要に応えるには、ピコさんはこのルーティンを週に2 回こなさなくてはなりません。

ピコさんはフローラルアーティストです。ピコさんが5歳の時、レイ 職人だったお母さんがティーの葉を使ってバラの花の形を作る方 法を教えてくれて以来、花飾りを作り続けてきました。やがて、マウ

Pico is a floral artist. She has been since the age of 5, when her mother, a lei-maker, taught her how to make a rose out of ti leaves. Soon, Pico began helping her mother create lei for her shop on Maui. Then, she started crafting them for friends, until what began as favors for fun blossomed into a full-time business. Her success is a surprise to no one except for Pico, who never realized how popular her lei could become. Now, they have graced the likes of Kourtney Kardashian and recording artist Kehlani, and garnered her 60,000 Instagram followers. “I was scared at first, because I didn’t really want anyone to see them,” Pico says. “But I began to embrace it. I felt alive. It lit this fire within me.”

Pico specializes in lei po‘o. They slip onto one’s head like a crown crafted from fresh flowers and leaves. Lei po‘o have grown in popularity in recent years, making their ways to weddings, music festivals, and even SnapChat filters. Despite this oversaturation, Pico’s creations stand out.

Even as a child, Pico had her own aesthetic. “When my mom gave me something to do, I always did it different,” she says. “I always tried to make it bigger than it was.” Her lei are a mixture of traditional and modern styles. She takes influences from her Tahitian roots, inspired by the grand lei worn by her relatives at family functions. Then, Pico, unabashed in her use of the brightest tropical blooms she can find, adds punctuations of color. “Some people don’t like to use a lot of colors, but I do,” Pico says. “It can be wild, and I’ll love it.”

For more information on Pico’s workshops at Four Seasons O‘ahu, visit fourseasons. com/oahu. To see Pico’s creations on Instagram, follow her account @ocean_dreamerr.

イ島でお母さんが商っていたレイの店を手伝うようになり、その後 友だちのためにもレイを作り始め、そしていつしか楽しみのために 始めたことがフルタイムのビジネスへと成長していました。ピコさん の成功に一番驚いているのは彼女自身で、自分が作ったレイがこれ ほど好評を博すことになるとはまったく予想していなかったそうで す。今ではコートニー・カーダシアンやR&Bシンガーのケラーニと いったセレブたちがピコさん作のレイを身につけ、ピコさんのインス タグラム・アカウントは57,000人のフォロワーを獲得しています。 「本当は誰にも作品を見せたくなかったので、最初のうちは怖かっ たんですが、次第に嬉しく思うようになりました。自分が本当に生き ていると感じられたんです。私の中に眠っていた情熱に火をつけて くれたのですね」とピコさんは語ります。

ピコさんが得意とするのはレイ・ポオ。摘みたての花や葉で編まれ、 冠のように頭にかぶるレイです。レイ・ポオは最近人気が高まり、ウ エディングやミュージックフェスティバル、さらにはSnapChatのフ ィルターにも登場するようになりました。これだけよく見かけるよう になったレイ・ポオですが、ピコさんの作品はひときわ目立ちます。

ピコさんは子どもの頃でさえ独自の審美眼を持っていました。「母 から何かを作るように言われると、いつも教えられたのとは違うや り方をしたものでした」とピコさんは回想します。「最初に教えられ たものよりもっと大きなものを作ろうとしたんです」と語るピコさん のレイには、伝統的なスタイルとモダンなスタイルが混ざり合って います。タヒチの血をひくピコさんは、そのルーツに影響を受け、家 族の行事で親戚の人たちが身につける豪華なレイにインスピレー ションを得ているそうです。そして、ピコさんは、見つけられる限り できるだけ鮮やかな色の熱帯の花々を臆せず使い、レイに色でアク セントをつけます。「あまり多くの色を使いたがらない人もいますけ ど、私は使います。かなりワイルドな作品が出来上がることもありま すが、私はそういうレイが好きなんです」とピコさんは語りました。

ピコさんが講師を務めるフォーシーズンズ・リゾート・オアフ・アッ ト・コオリナのレイ作りワークショップの詳細は fourseasons. com/oahuでご覧ください。ピコさんの作品は、インスタグラム@ ocean_dreamerrで見ることができます。

癒しの菜園へようこそ Life

Healing Garden

Text by Kate Mykleseth Images by Josiah PattersonOn 50 acres in Lualualei Valley, Kahumana Organic Farm and Community grows more than just greens.

ルアルアレイの渓谷に、約20ヘクタールにわたって広がるカフマ ナ・オーガニック・ファーム・アンド・コミュニティ。ここで育つのは、 野菜だけではありません。地域社会を育む、学びと癒しの場です。

At Kahumana Organic Farm, which is hidden within Lualualei Valley at the base of Mount Ka‘ala, monkeypod and mango trees tower over buildings alongside fields of produce, an aquaponics system, and quiet, lush areas marked by small temples. Rachel LaDrig, Kahumana’s manager of agritourism, guides me through the farm’s grounds and explains the decades-old ethos behind its name: Those who contribute to Kahumana are “kahu,” or guardians, nurturing “mana,” the spirit and soil.

カアラ山の麓に広がるルアルアレイ渓谷にひっそりと抱かれたカフ マナ・オーガニック・ファーム。その敷地にはアメリカネムノキやマン ゴーの木が建物に覆いかぶさるように繁り、農作物が植えられた 畑とアクアポニクスと呼ばれる魚の養殖と野菜の水耕栽培を融合 させた施設があり、いくつもの小さな聖堂が豊かな緑の中に静かに 佇んでいます。この農園でアグリツーリズム部門のマネージャーを 務めるレイチェル・ラドリグさんに敷地内を案内してもらう間、この 農園の名が表す、数十年にわたって受け継がれてきた精神につい て教えてもらいました。カフマナ農園に貢献する人々は、マナ(魂と 土地)を育むカフ(保護者)だというのです。

The staff at Kahumana Organic Farm see themselves as guardians of the spirit and the soil and work to improve food sustainability, as well as the health of the community.

Founded in 1974 as a holistic place to help adults with special needs, the nonprofit Kahumana has expanded to include 50 acres in the leeward valley where it hosts a variety of services for the community, including its organic farm, as well as a café, transitional housing, a retreat, a learning center for adults with intellectual disabilities or autism, and a commercial kitchen. “Part of the mission is to serve a holistic, farm-based, community approach to healing,” LaDrig says. “The way we care for the most vulnerable members of our society determines our mark as a people and a nation.”

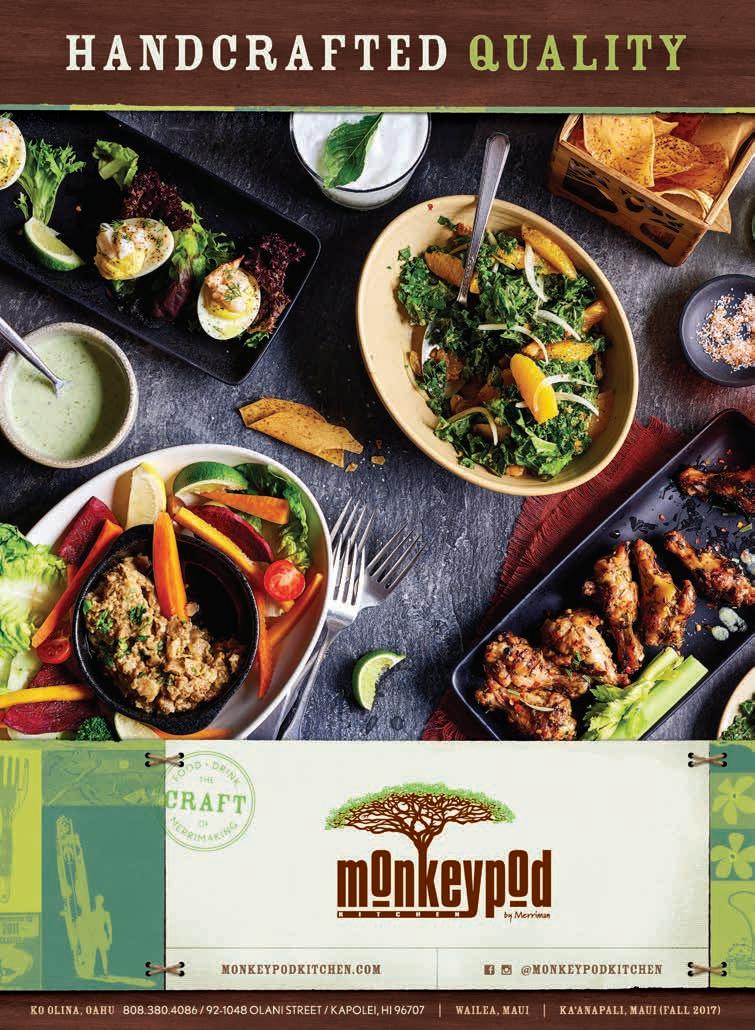

Despite its hidden location, Kahumana opens its land to the community through guided tours, annual seed exchanges and festivals, and the Farm Hub, at which Kahumana buys excess produce from Wai‘anae residents. The farm also produces bountiful harvests of kale, collards, fennel, and parsley—favored by upscale O‘ahu restaurants like Roy’s and Monkeypod Kitchen. As we walk by a small plot set aside for salad mix, LaDrig points out the farm’s Organic Keiki Greens, popular with such restaurants. She shares a dragon fruit, picked from an adjacent cactus, and explains the farm’s use of cover crops, which aid in protecting unused soil, and trap crops, which distract pests.

In addition to promoting food sustainability, the farm serves groups from all walks of life: Interns tend to the farm acreage while learning about time management and meal preparation; adults from the nearby Kahumana Learning Center pitch in at the market store; and residents living at one of Kahumana’s two transitional housing programs work in the farm’s café, serving dishes made with produce sourced just a stone’s throw away.

カフマナは、特別な支援が必要な成人をサポートするためのホリス ティックな場として1974年に設立された非営利団体ですが、現在 ではオーガニックファーム、カフェ、社会復帰をめざす人々のための 住居、リトリート施設、知的障害や自閉症を持つ成人のための学習 センター、業務用キッチンなど、コミュニティー支援のための様々な 施設が備わった約20ヘクタールの土地をリーワード渓谷内に所 有するまでに成長しています。「農場をベースとして、コミュニティー としての包括的な癒しへのアプローチを提供するというのが、私た ちのミッションのひとつです」とラドリグさんは言います。「社会の中 で最も弱い立場にある人々をどう支援していくか。それが人間とし て、そして共同体としての私たちのあり方を決定づけるのです」 人里離れた場所にあるカフマナですが、彼らはその土地をガイドつ きツアー、毎年恒例の種の交換会、フェスティバル、そしてワイアナ エ地域の住民から余剰の農産物を買い取る「ファーム・ハブ」を通 じてコミュニティーに開放しています。また、農園でたくさん栽培さ れているケール、コラード、フェンネル、パセリといった野菜は、「ロ イズ」や「モンキーポッド・キッチン」といったオアフ島の高級レスト ランで使われ、好評を博しています。サラダ用の野菜が植えられた 小さな区画のそばを通りながら、ラドリグさんはそうしたレストラン で人気の「オーガニック・ケイキ・グリーン」として出荷されるとりど りの野菜を指さしました。そして、その隣に植えられているサボテン からドラゴンフルーツをもぎ取って手渡してくれ、被覆作物を利用 して使っていない土壌を守る方法や、「トラップ作物」を使って害虫 を防ぐ方法を説明してくれました。

農園では食料の持続可能性を推進するほか、様々な立場の人々を 支援する取り組みが行われています。インターン生たちは農園の仕 事に従事しながら時間管理や調理の技術を学び、カフマナ学習セ ンターの成人学生たちはマーケットストアを手伝います。カフマナ に2つある、社会復帰をめざす人のための住宅プログラムの参加 者は農場のカフェで働き、カフェの目の前にある畑で採れる農作物 を使って調理された食事を給仕するのです。

カフマナには、オアフの貧困家庭を支援する「オハナ・オラ・オ・カフ マナ」と「ウル・ケ・ククイ」という2つのプログラムがあります。そう した家庭の多くはワイアナエ沿岸の住民です。カフマナは、彼らに

Kahumana Organic Farm produces bountiful harvests of kale, collards, fennel, and parsley— favored by upscale O‘ahu restaurants like Roy’s and Monkeypod Kitchen.

These programs, Ohana Ola O Kahumana and Ulu Ke Kukui, support O‘ahu’s struggling families, the majority of which are from the Wai‘anae Coast, by providing transitional housing and wraparound services. “You don’t just hand someone a house and their problem is solved,” LaDrig says, noting that the residents at the facilities can also take part in workshops for resume writing, money management, and computer training. Some stay on with Kahumana afterward, working at homesteads that are rented out for retreats, in the café, or on the farm.

“There is so much growth happening all the time here,” LaDrig says, noting that the Organic Keiki Greens are thriving and will soon be ready for harvest. “This is a model for a healthy community and healthy relationships, between food and people.”

For more information, visit kahumana.org.

社会復帰のための住宅施設や「ラップアラウンド」と呼ばれる巻き 込み型の福祉サービスを提供しています。「困っている人々に住む 場所を提供するだけでは問題の解決にはなりません」とラドリグさ んは語ります。施設の住民は履歴書の書き方やお金の管理法を学 んだり、コンピューターのトレーニングを行うワークショップに参加 することもできます。プログラムの期間が終了した後もカフマナに 住み続け、リトリート用に貸し出される住居施設やカフェ、農園で 働く人々もいるそうです。

「ここではいつでもたくさんの成長を目にすることができます」とラ ドリグさん。彼女はそう語りながら、まもなく収穫の時期を迎える オーガニック・ケイキ・グリーンがすくすくと育っているところを見せ てくれました。「カフマナは、食べ物と人間の間に成り立つ健康な関 係と、すこやかなコミュニティの優れたモデルだと思います」

カフマナについて詳しくはkahumana.orgへ。

恵みの木 Life

The Giving Tree

日照豊かな乾燥したオアフ島西部で、ヴィンス・ドッジさんは思いが けない食料源を見つけました。

Text by Martha Cheng Images by John HookAmong the sunny, dry setting of O‘ahu’s leeward side, an unexpected food source is flourishing.

“Kiawe is the mother tree of the desert,” says Vince Dodge at his home in Wai‘anae, where he is making kiawe-flour pancakes. He spoons the thick batter mixed with kiawe and ‘ulu (breadfruit) flour into a hot castiron pan greased with a bit of coconut oil. As he flips the fluffy, golden-brown rounds, the aroma of sweet, toasted coconut tinged with molasses wafts from the stove.

In Hawai‘i, locals have a love-hate relationship with kiawe (mesquite)—it is prized for its long-burning wood, which is perfect for grilling and smoking meat, but is cursed at for its thorns, which pierce slippers and feet. For Dodge, however, it’s all love. “People view it as a nuisance, but it’s because people don’t understand it,” he says.

Hawai‘i’s first kiawe tree was planted in Honolulu in the late 1820s by Catholic priest Alexis Bachelot, who brought a seed from the royal garden in Paris. That seed is thought to have come from Peru, where

「キアヴェは、砂漠の母なる木です」と語りながら、ヴィンス・ドッジ さんはワイアナエの自宅でキアヴェ粉のパンケーキを作っていま す。キアヴェとウル(ブレッドフルーツ)の粉を混ぜ合わせて作った もったりとしたたねをスプーンですくって、少量のココナッツオイル をひいて熱した鋳鉄のフライパンに落とし、やがてきつね色に焼け たふわふわの丸いパンケーキをひっくり返すと、糖蜜とココナッツ の甘い香りがレンジから立ち上ります。

ハワイの住民は、キアヴェ(メスキート)に対して愛憎半ばする気持 ちを抱いています。キアヴェの木は肉を焼いたり燻製にするのに最 適な長く燃え続ける薪として珍重される一方、サンダルの底や足に 刺さるトゲが嫌われています。でも、ドッジさんにとってキアヴェは もっぱら愛すべき存在。「邪魔者扱いする人もいるけれど、それはこ の木のことをよく分かっていないからですよ」と言います。

ハワイで最初のキアヴェの木は、1820年代後半に、カトリック教 会の司祭だったアレクシス・バシェロがパリの王立植物園から持ち 込んだ種をホノルルに植えたものでした。その種は、キアヴェの木 々が砂丘にしがみつくように自生しているペルーから渡来したもの と考えられています。ふんだんな日光を必要とする一方で水は少な

Restaurants across Hawai‘i have incorporated Wai‘anae Gold flour into their dishes, from the marinated tomatoes drizzled with kiawe molasses at the Grand Wailea on Maui to the kiawe brownies topped with sesame gelato at Mud Hen Water in Honolulu.

The Giving Tree

kiawe trees cling to sand dunes. Requiring much sun but little water, the species also grows widely on the dry leeward coasts of the Hawaiian Islands, even earning the title of invasive species. Its scientific name, Prosopis pallida, hints at either its prolific capacities, or its practical riches: “Prosopis” is ancient Greek for “toward abundance.”

For Dodge, every part of the kiawe tree is useful—its canopy provides shade; its wood creates fire and shelter; its leaves serve as a poultice for wounds; its flowers have reserves of nectar for bees. But he is most interested in its bean pods, for food.

Once upon a time, Dodge only knew of the kiawe tree for its pesky thorns, and its pods for their use as livestock feed. Then he had a chance meeting in 2006 with a couple from Arizona, who told him he was sitting on a health-food gold mine. Kiawe is a naturally sweet, diabetic-friendly food and a staple of Southwestern U.S. tribes, they said.

“Seriously?” Dodge recalled thinking. “Could it be that the most common wild tree on our coast, where we have the most diabetes of the entire archipelago, is diabetic friendly? Mama ‘āina’s got our backs like that?”

He traveled to Tucson, Arizona, where he learned to mill kiawe beans. Then he headed to northern Argentina, where a Wichí community showed him how they ate raw kiawe-bean flour. From this, he derived his Wai‘anae Gold ‘Āina Bar, a dense energy bar of kiawe flour, peanut butter, and honey.

Last year, he produced about 1,700 pounds of the flour, which he sells under the Wai‘anae Gold label. In the summer season, he and his team of pickers gather bean pods along the leeward coast, from Kalaeloa to Mā‘ili. The pods are dried in a solar dryer until

くても育つこの木は、ハワイ諸島のリーワード(貿易風の風下にあ たる島の南西側)の乾燥した沿岸地帯にもたくさん生えており、侵 入種とさえ呼ばれるようになっています。「プロソピス・パリーダ」と いう学名の「プロソピス」は古代ギリシャ語で「豊富さに向かって」 という意味で、たくさんの実をつける性質または用途の豊富さにち なんで命名されたのではないかといわれています。ドッジさんにとっ ては、キアヴェの木のどの部分も役に立つもの。樹冠は木陰を作っ てくれ、材木は燃料と住居となり、葉は傷を癒やす湿布として使え、 花は蜂のための蜜をたたえています。でも、ドッジさんの最大の関 心は、食料になる豆のサヤにあります。

とはいえ、2006年にアリゾナからハワイを訪れていた夫婦に偶然 出会い、この木が素晴らしい健康食品になる資源だと聞かされる までは、厄介なトゲがあって昔はサヤが家畜の飼料に使われてい た木としてしか知りませんでした。この夫婦は、キアヴェのサヤには 自然の甘味があり、糖尿病によい食品で、米国本土南西部の原住 民が主食としていたことをドッジさんに教えたのです。

その話を聞いたドッジさんは、「本当だろうか?ハワイ諸島でも一番 糖尿病患者が多いこの地域に一番よく生えている木が、糖尿病に いいだなんて。ママ・アイナ(母なる大地)は、そんな形で私たちを助 けてくれるのかな?」と思ったそうです。

ドッジさんはアリゾナ州ツーソンを訪れ、キアヴェのサヤを製粉す る方法を学びました。その後アルゼンチン北部に向かい、ウィチ族 のコミュニティーで、彼らが生のキアヴェ豆の粉をどのようにして食 べるのかを見せてもらいました。こうして学んだ知識をもとに、キア ヴェ粉、ピーナツバター、蜂蜜でできたどっしりとしたエナジーバー 「ワイアナエ・ゴールド・アイナ・バー」を作り出したのです。

ドッジさんは昨年1年間で約770kgのキアヴェ粉を生産し、「ワイ アナエ・ゴールド」というブランドで販売しています。夏季には、自ら 摘み手のチームを率いてカラエロアからマイリまでのオアフ島南 西沿岸一帯で豆のサヤを集めます。集めたサヤは指先で簡単に折 れるようになるまで太陽熱乾燥機で乾燥させます。この段階のサヤ は、バターとシロップで作るお菓子、トフィー・ブリトルに繊維をたく さん入れたような味がします。

Vince Dodge is turning pesky kiawe, cursed by locals for its thorny branches that pierce slippers and feet, into sweet golden flour.

they can be snapped in half. At this stage, they taste like fibrous toffee brittle. Restaurants across Hawai‘i have incorporated Wai‘anae Gold flour into their dishes, from the marinated tomatoes drizzled with kiawe molasses at the Grand Wailea on Maui to the kiawe brownies topped with sesame gelato at Mud Hen Water in Honolulu.

Back home, Dodge slides the last of the pancakes onto a plate and serves it with kiawe honey, though the pancakes don’t really need it, since the kiawe flour already lends the sweetness and flavor of brown sugar. The stack in front of him melds ancient staples of two native cultures— kiawe, or huarango, from South America, and ‘ulu, from Polynesia—which he has combined to create something unique for the Hawai‘i of now, and, he hopes, its future.

For more information, visit waianaegold.com.

ハワイ各地のレストランもワイアナエ・ゴールドの粉をさまざまな 料理に取り入れています。たとえば、マウイ島「グランド・ワイレア」 のキアヴェ糖蜜をかけたトマトマリネや、ホノルルの「マッド・ヘン・ ウォーター」の、ごまのジェラートをトッピングしたキアヴェ・ブラ ウニーなど。

自宅のキッチンで、ドッジさんは焼きあがったパンケーキを皿に積 み重ね、キアヴェ蜂蜜を添えてテーブルに出しました。キアヴェ粉に はもともと甘味とブラウンシュガーの風味があるので、蜂蜜はなく てもよいほどです。このパンケーキは、南米で「フアランゴ」と呼ばれ ているキアヴェと、ポリネシアのウルという、二つの先住民文化を古 代から支えてきた主食が融合した、現代ハワイのための食品といえ ます。ドッジさんは、自分が創り出したこのユニークな製品が未来 のハワイのためにも役立つことを願っています。

詳しくはwaianaegold.comをご覧ください。

歴史の中を歩く Life

Plantation Stroll

Text by Timothy Schuler Images by

Jonas Maonワイパフにあるハワイ・プランテーション・ビレッジは、昔のサトウキビ農園での暮らし を垣間見ることができる場所。

At Hawai‘i’s Plantation Village in Waipahu, visitors get a glimpse of a bygone life among sugarcane fields.

“Thank you for coming to Hawai‘i’s best kept secret,” Ken Kaneshige, a docent, tells the group standing near the entrance to Hawai‘i’s Plantation Village. Up the hill, lined along a narrow lane, are replicas of a traditional Japanese furo (bathhouse), general store, saimin stand, Chinese social hall, and a half-dozen types of plantation dwellings, including a Filipino dormitory. Towering over the buildings are trees and plants that workers would have brought from their home countries: tamarind from the Philippines, yucca from Puerto Rico, pomelo from China, bong seon hwa from Korea.

This outdoor museum, tucked away in Waipahu on former farmland, was founded in 1992 to take visitors back to the time between 1850 and 1950, when sugar dominated the islands. Commercial exploitation of Hawai‘i—first for sandalwood, then for whales—began immediately after Western explorers arrived on its shores, but few industries reshaped the archipelago the way sugar did, leading to the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy and to a dramatic change in the demographics of the population. Following the establishment of the first sugar

ハワイ・プランテーション・ビレッジの入り口付近。ガイドのケン・カ ネシゲさんは一群の入場者に向かって「ハワイの隠れた名所にお いでいただきましてありがとうございます」と挨拶します。丘の上に は、狭い道の両側に、復元された日本の伝統的な風呂屋(公衆浴 場)や雑貨屋、サイミンの小店、中国人労働者たちの社交場、そし て、フィリピン人労働者寮をはじめ、6種類のプランテーション住 居を再現した家が並んでいます。建物の周りには、フィリピンのタ マリンド、プエルトリコのユッカ、中国のザボン、韓国のホウセンカ など、労働者たちが祖国から持ち込んだであろう木や草が丈高く 伸びています。

この野外ミュージアムは、以前は農地であったワイパフの奥まった 一角にあり、砂糖がハワイの主な産業だった1850年から1950年 の生活の様子を紹介するため、1992年に創設されました。ハワイ の資源の商業利用は、まず白檀、そして捕鯨と、西欧の探検者たち が上陸してから直ちに始まりましたが、砂糖産業ほどハワイのあり ようを変えた産業はほかにありません。砂糖産業の興隆はハワイ 王国の転覆につながり、人口構成の劇的な変化をもたらしました。 初めてのサトウキビ農園がカウアイ島に作られたのは1835年。そ れ以降、ヨーロッパ、アジア、南北アメリカから数十万人の移民労 働者がハワイにやって来ました。労働人口は34の民族グループか らなり、そのうち多数を占めていたのは中国人、日本人、沖縄出身 者、フィリピン人、韓国人、ポルトガル人、プエルトリコ人、ハワイ先 住民でした。

Tucked away in Waipahu on former farmland, Hawai‘i’s Plantation Village was founded in 1992 as a way to take visitors back to the time between 1850 and 1950, when sugar dominated the islands.

At this outdoor museum, visitors can see replicas of a traditional Japanese bathhouse, a Chinese social hall, and a half-dozen types of plantation dwellings, including a Filipino dormitory.

plantation on Kaua‘i in 1835, hundreds of thousands of immigrant workers arrived from Europe, Asia, and the Americas. The workforce consisted of 34 ethnic groups, the most numerous of which were the Chinese, Japanese, Okinawans, Filipinos, Koreans, Portuguese, Puerto Ricans, and Native Hawaiians.

Without these workers, and their traditions, Hawai‘i would be unrecognizable today. It was in plantation camps where the plate lunch, that staple of contemporary island cuisine, was born. But these are well-worn narratives of plantation life. After being told that I would “experience the real Hawai‘i,” according to the Plantation Village’s tagline, I worried the tour would peddle a saccharine tale of neighborliness and aloha. The sugar industry enabled multiculturalism, but it also imposed inhumane conditions and racial discrimination—the lighter your

こうした労働者たちと彼らが持ち込んだ伝統がなければ、現在の ハワイの姿はまったく違ったものになっていたでしょう。現代ハワイ 料理の定番であるプレートランチが生まれたのもプランテーション の居住区でした。でも、こうした事柄はプランテーションでの生活 を語る上ですでに語りつくされています。私はプランテーション・ビ レッジの「本当のハワイを体験できる」というキャッチフレーズを聞 いて、見学ツアーでは隣人愛とアロハ精神のフワフワした話を聞か されるのではないかと懸念していました。砂糖産業は多文化共存 主義を育みもしましたが、その一方で労働者たちに非人道的な労 働生活環境や人種差別も強いていました。肌の色が明るい民族ほ ど高い賃金をもらえるのが普通だったのです。

このミュージアムでは、そうした面も含め、当時の生活のあらゆる 側面を知ることができます。ビレッジの中を歩き回り、ポルトガル式 のフォルノ(オーブン)や土でできたかまどにかけられた巨大な中 華鍋を見ていくうちに、移民労働者たちの体験がいっそうの現実 味をもって伝わってきます。時には、そうした遺物を見て心が痛むこ ともあります。「バンゴー」と呼ばれ労働者たちが身分証明証として 首から下げていた金属製の番号札を見た時には、胃が締め付けら

ethnicity’s skin color, the better your wages generally were.

Visitors to the museum, however, get the whole story. Walking through the village, I pass a Portuguese forno, or oven, and a giant earthen wok, which make the experiences of such immigrants feel all the more real. At times, these encounters are painful. I feel a knot in my stomach when I see the metal bango tags that laborers wore around their necks as forms of identification. Even practices that seem generous often had ulterior motives: Plantation owners gave workers land for temples and language schools not primarily out of respect, but rather to segregate ethnic groups. “If you keep people in different camps, and if you discourage communication between them, you can control them,” Kaneshige explains.

After the tour, we return to the visitor center, and to present day. It’s a Friday afternoon, and the museum is celebrating its latest addition: a Chuukese utteirek, a thatch-roofed structure similar to a Hawaiian hale. Built by volunteers and students as a place for community events, the utteirek is not part of the museum’s plantation history, but rather its general effort to preserve the heritages of Hawai‘i’s many peoples. At the dedication ceremony, there are speeches, prayers, songs, dances, and a Chuukese feast including roasted pig, taro, and Spam and noodles. I get the sense the men and women who run Hawai‘i’s Plantation Village, many of them volunteers, firmly believe that Hawai‘i’s past has something important to tell us about who we are—and how we should live today. I watch young kids run in and out of the utteirek as Chuukese families talk story with longtime Waipahu residents, and think that, indeed, maybe this is the real Hawai‘i.

れるような気持ちになりました。一見寛大に思える処置の多くにさ え、その裏には別の動機があったことも知りました。農園主は労働 者たちに寺院や言語教室を建てる土地を与えましたが、それは主 に彼らの文化を尊重する心から出たものではなく、異なる民族を隔 てておく目的があったのです。「出身国別に居住区を分け、相互のコ ミュニケーションを妨げれば、人々をコントロールできるからです」 とカネシゲさんは説明します。

見学ツアーの後、私たちはビジターセンターへ向かい、現代に戻り ます。金曜日の午後で、ミュージアムは最新の施設であるチューク 諸島の「ウテイレク」の落成を祝っていたところでした。ウテイレクと いうのは、ハワイのハレに似た椰子ぶき屋根の小屋です。コミュニ ティーのイベントのための施設としてボランティアと学生の手で建 てられたもので、このミュージアムが紹介するプランテーションの 歴史の一部ではありませんが、ハワイに住む多様な民族の伝統を 保存する活動の一環として作られたものです。落成式では、スピー チや祈祷が行われたほか、歌や踊りも披露され、豚の丸焼き、タロ イモ、スパムやヌードルなどチュークのご馳走もふるまわれました。 ハワイ・プランテーション・ビレッジを運営している人たちの大半は ボランティアです。彼らは、ハワイの過去には私たちのルーツと、私 たちが現在をいかに生きるべきかを教えてくれる大切な何かがあ ると強く信じているようです。幼い子どもたちが走り回ってウテイレ クから出たり入ったりし、チュークの家族たちが昔からのワイパフ 住民と語り合っている光景は、まさに本当のハワイそのものでした。

Image by Josiah Patterson

Image by Josiah Patterson

“At the end of the day, the people here will give you the shirt off their back— if you show nothing but aloha, you’ll only get aloha back. Wai‘anae is a special place.”

Max “Blessed” Holloway, UFC featherweight champion

Image by John Hook

Each summer, thousands of youth learn ocean rescue skills from the best lifeguards in the world.

An afternoon in Mākaha with the Junior Lifeguard program.

毎夏、世界最高のライフガードから海での救助スキル を学ぶために何千人もの少年少女たちが集まります。

Text by Beau Flemister

Images by John Hook

As I head deep into the west side of O‘ahu, past the sun-faded towns of Nānākuli and Mā‘ili, the roadside minimarts and family homes disappear and the beaches turn vast and quiet. It’s a Tuesday morning, so the weekend crowds haven’t set up shop in the countless parks lining the sand, but the silence is still suspect. The coastline is listless and serene.

Suddenly, idyllic Mākaha Beach presents itself like a crown jewel. I park near a pop-up tent covering a dozen soft-top surfboards and other lifeguard equipment. On the glimmering golden sands, no one is in sight. I trudge through the thick west side grains, the electric blue Pacific Ocean in the backdrop, searching for the Mākaha Junior Lifeguard program, until I hear cheering and yelling. Just beyond a sharp drop in the sand are about 40 kids lined up, sprinting toward the sea, swimming around a buoy, and sprinting back to shore.

Created by the City and County of Honolulu’s Ocean Safety Division in 1990, the program provides ocean safety and awareness education and teaches first aid and surf-rescue techniques. Free of charge and open to all 12- to 17-year-olds who have some swimming experience, each site

白っぽく日焼けした建物が並ぶナナクリとマイリの町 を過ぎ、オアフ島の西側深く進んでいくにつれていつし か道路脇の小さな商店や民家もまばらになり、その代 わりに広々としたビーチが次々と現れ、静けさが深まっ ていきます。火曜の朝なのでビーチ沿いに無数にある 公園に陣取る週末客の姿がないのは当然ですが、それ にしても静けさは不思議なほどです。海岸線は物憂げ でうららかです。

突然、珠玉のように美しいマカハ・ビーチが目の前に 現れます。1ダースほどのソフトトップサーフボードやそ の他のライフガード用具が置いてあるポップアップテ ントの近くに、私は車を駐めました。陽光にきらめく金 色の砂の上に人の姿はありません。目の覚めるような ブルーの太平洋を前に、ウエストサイド特有の粒の大 きな砂を踏んで「マカハ・ジュニア・ライフガード」プロ グラムの人たちを探して進んでいるうちに、歓声とかけ 声が聞こえてきました。砂浜が急な傾斜で切れ込んで いる向こうで、40人ほどの少年少女たちが並んで海に 向かって走り、泳いでブイの周りを回ってから岸に駆け 戻っています。

1990年にホノルル市郡の海上安全局が創設したこの プログラムは、海での安全と意識向上のための教育を 提供するもので、応急手当とサーフレスキューの技能 を教えています。参加費は無料で、ある程度の水泳経 験がある12歳から17歳までの若者なら誰もが参加 でき、6週間にわたって各会場で毎週約40名の参加 者を受け入れています。多くの若者たちにとってこのプ ログラムは夏の一大行事であり、マウイ島、ハワイ島、 カウアイ島、オアフ島の各指定訓練会場で合わせて 2,000人近くが参加します。

enrolls approximately 40 participants per week for six consecutive weeks. For many, this program is the hallmark of summer. Nearly 2,000 youth participate in the program throughout designated sites on Maui, Hawai‘i Island, Kaua‘i, and O‘ahu.

O‘ahu has four beach sites for the program, one on each shore—Ala Moana to the south, ‘Ehukai to the north, Kalama to the east, and Mākaha to the west. From Monday to Friday, morning to afternoon, youth learn skills from county lifeguards, many of whom are legendary watermen in their own rights, having honed their ocean skills in the same waters where they are now teaching.

“The Junior Lifeguard program is important on so many levels,” says Bryan Phillips, O‘ahu director of the Junior Lifeguard program and president of the North Shore Lifeguard Association. “It’s a safe environment for the kids to come, it’s healthy, keeps them active, and it teaches them some really useful lifesaving skills.” For instance, kids are taught the same rescue techniques that lifeguards use on the beach: the cross-chest carry, the use of fins and a tube, the rescue board, and rescues with the jet ski. They also learn basic first aid and CPR.

オアフ島では、南岸のアラモアナ、北岸のエフカイ、東 岸のカラマ、西岸のマカハの4つのビーチがプログラム 会場です。訓練生たちは月曜から金曜の朝から午後ま で、郡のライフガードからスキルを学びます。講師のラ イフガードの多くは高い実績を持つ有名な人たちです が、彼らもかつて同じ場所で同じように技術を磨いて きたのです。

「ジュニア・ライフガード」プログラムのオアフ島担当 ディレクターであり、ノースショア・ライフガード協会の 会長でもあるブライアン・フィリップスさんは「このプロ グラムにはいろいろな面で重要な意義があります。若 者たちにとって安全な環境であり、健康的で運動にも なりますし、実際に役立つ救命スキルをいくつか学べ ます」と語ります。たとえば、参加者は、クロスチェスト・ キャリーや、フィン、チューブやレスキューボードの使 い方、ジェットスキーでの救助法など、ライフガードが ビーチで実践しているのと同じ救助テクニックを教わ ります。さらに、基本の応急手当とCPR(心肺蘇生法) も学びます。

ブイを回って戻って来るスプリントを終えたマカハ・ジ ュニア・ライフガードの訓練生たちは、ポップアップテ ントに向かい、水分を補給してから、ブランドン・マー ティンさんの周りに集まります。たくさんの少年少女た ちに囲まれてひときわ大きく見えるマーティンさんは、 「ジュニア・ライフガード」プログラムのインストラクタ ーを務める3人のうちの1人です。マーティンさんは、見 本役を買って出た訓練生に、サーフボードを使って溺 れかけている人を救助する正しい方法をやってみせる ように言います。そして、溺れている人に近づき過ぎる のを避ける方法、救助する人を上手にスライドさせて

Having finished their sprints around the buoy, the Mākaha Junior Lifeguards in training head to the pop-up tents to hydrate. They gather around Brandon Martin, a hulking man in a sea of kids. One of the three Junior Lifeguard program instructors, Martin asks for a volunteer to demonstrate how to properly rescue a drowning victim using a surfboard. He reiterates how to avoid approaching someone, the correct way to efficiently slide someone onto the board, and how to paddle the person in.

“We’re teaching rescue techniques, but we’re also trying to teach kids what

ボードの上に乗せる正しい方法、救助した人をパドリ ングして岸に連れ戻す方法をもう一度説明します。

もう1人のインストラクター、チャド・ケアウラナさんは、 「レスキューのテクニックを教えていますが、いよいよ レスキューが必要という状態になる前にできることも 教えるよう努めています」と話します。「海に飛び込む のは最後の選択肢であって欲しいわけですが、その一 方で、何もできず呆然としているのではなく、助けとな れる人になって欲しいという狙いがあります。そのため には型にはまらない柔軟な思考が必要です。だって、自 分がたった12歳で、大柄で重い男性が助けを求めて いたらどうしますか?」

オアフ島西岸のビーチで受け継がれてきた豊かな伝

they can do in a situation before it comes to that,” says instructor Chad Keaulana. “We want jumping into the ocean to be the last option for them, but at the same time, we want them to be helpful instead of helpless. That requires thinking outside of the box, because if you’re just 12 years old and a big heavy guy needs help, what are you gonna do?”

The west side beach’s rich heritage dovetails with Keaulana’s family history. In 1954, Mākaha Beach served as the site of the world’s first international surf competition, the Mākaha International Surfing Championships, which Chad’s grandfather, Richard “Buffalo” Keaulana, won in its seventh year. An acclaimed waterman and professional surfer, Buffalo also served as head lifeguard at Mākaha for more than 25 years, during which he organized the Buffalo Big Board Classic—an event that still draws crowds to Mākaha’s broad white beach every year.

Mākaha is also where ocean safety and lifeguarding methods took a quantum leap. Chad’s father, Brian Keaulana, Buffalo’s son and a former Mākaha lifeguard, is the cofounder of Hawaiian Water Patrol. Along with his partner, Terry Ahue, and with the

統は、ケアウラナさんの家族の歴史とも重なりあって います。1954年、マカハ・ビーチは世界で初めての国 際サーフ競技会「マカハ国際サーフィン選手権」の会 場となりました。祖父のリチャード・「バッファロー」・ケ アウラナさんは、その7回目の大会で優勝したのです。 海の男として名を馳せプロサーファーでもあったバッフ ァローさんは、マカハで25年間以上にわたってライフ ガード長を務め、その間に「バッファロー・ビッグボー ド・クラシック」を主催しました。このイベントは、今で も毎年たくさんの人をマカハの白砂のビーチに呼び寄 せています。

マカハは、海での安全確保とライフガードの技術が大 きな進歩を遂げた場所でもあります。バッファローさん の息子でチャドさんの父であり、やはりマカハでライフ ガードを務めていたブライアン・ケアウラナさんは、「ハ ワイアン・ウォーター・パトロール」の共同創立者でも あります。ブライアンさんは、パートナーのテリー・アフ エさんと共に、メルヴィン・プウやデニス・ゴウヴェイア などのビッグウェーブサーファーやライフガードの協力 を得て、海での救助へのジェットスキーの活用を世界 各地で推進してきました。

各週の最終日には、ケアウラナさんとそのチームは参 加者にトレーニング修了証を授与します。修了を祝っ て、ケラウラナさんたちは新米ジュニア・ライフガード たちをジェットスキーに乗せて海に連れ出し、地元の 先駆者が編み出したジェットスキーによる救助法を実 演してみせます。

このプログラムはハワイの将来のライフガードを育て る訓練場のようなものですか、と私が尋ねると、ケアウ

help of big-wave surfers and lifeguards like Melvin Pu‘u and Dennis Gouveia, Brian spearheaded the use of jet skis for ocean rescue around the world.

On the final day of each week, Keaulana and his crew award certificates of completion to the participants. They celebrate by taking the newly minted junior lifeguards out on jet skis to demonstrate water craft rescue techniques invented by their local forefathers.

When I ask Keaulana if this program is like a training ground for Hawai‘i’s future lifeguards, he nods. “On the west side specifically, I’d say over 60 percent of our lifeguards came from Junior Lifeguards programs. I came from Junior Guards, these other guys did too, even that lifeguard over there.” Keaulana points to a man wearing the telltale uniform of red shorts and a yellow shirt, his eyes fixed on the sea and shoreline.

I also look to the water, to where kids practicing board-rescue techniques are picking up the skill with astonishing speed. If these are the future guards that will be protecting our communities, we will be in good hands.

ラナさんはうなずき、「特にウエストサイドでは、うちの ライフガードの60%強がジュニア・ライフガードのプ ログラム修了生なんですよ。私自身もそうですし、ここ にいる他のライフガードたちもです。向こうにいるあの ライフガードもそうですよ」と答え、一目でライフガー ドと分かる赤いショーツと黄色のシャツのユニフォー ムを着て、海と海岸線をじっと見つめている男性を指 さしました。

私も海に目を移すと、少年少女たちがボードレスキュ ーのテクニックを練習中でした。彼らが技術を習得す る速さは驚くばかりです。この子たちが将来コミュニテ ィーを守るライフガードになるのなら、私たちも安心と いうものです。

Roaming Pālehua

Spanning swaths of the mountain range and grasslands inland of Ko Olina, Pālehua Ranch is more than just a ranch.

Ride into the remote area rich in culture, history, and ecological significance with this photo essay.

コオリナ内陸部の山岳地帯と草原に広がるパレフア・ランチは、ただの牧場ではあり ません。「パレフア」という地域の名を冠するこの牧場は、豊かな文化、歴史、そして 生態学上の意義を持ち、場所が持つ力が顕れる土地のただ中にあります。

Text by Rae Sojot Images by Josiah Patterson

At 25 years old, Ed Olson, left, now the owner of Pālehua Ranch under the Edmund C. Olson Trust II, launched a profitable career in specialty concrete. Today, 60 years later, the 86-year-old is one of Hawai‘i’s largest landowners. Over the last decade, Olson has gifted millions of dollars to entities that champion land stewardship. In 2009, land purchases brought the Edmund C. Olson Trust II to its current 3,000 acres of ranch, agricultural, and conservation land at Pālehua. Working with the Hawaiian Islands Land Trust, the Edmund C. Olson Trust II dedicated 1,200 acres as a conservation easement, protecting the land from residential or commercial development.

エドマンド・C. オルソン・トラストの管理下にあるパレフア・ランチ の現在のオーナーは、エド・オルソンさん。25歳で吹きつけ用コン クリート「ガナイト」の事業を始めて並外れた収益を上げ、その後 60 年にわたって建設や商業施設の開発で確固たるキャリアを築 き、86歳となった今ではハワイで最大級の土地所有者の一人に 数えられます。オルソンさんは過去10年間にわたり、土地の管理 保全を推進する諸団体に数百万ドルを寄付してきました。エドマン ド・C. オルソン・トラストは2009年に行った土地買収により、パレ フアに現在の1,200ヘクタールの牧場、農業、保全を目的とする土 地を保有することになりました。エドマンド・C. オルソン・トラスト は、ハワイアン・アイランズ・ランド・トラストと協力し、宅地開発や 商業地開発から土地を守るために485ヘクタールの保全地役権 を設定しました。

Because of the discovery of a large heiau, or place of worship, underscored by oral traditions that speak of the area, cultural scholars believe Pālehua served as a training ground for warriors in ancient times. In Hawaiian, pā means “a stone enclosure.” Lehua refers to the ‘ōhi‘a tree, known for both its bright flower and sturdy wood— the latter prized by warriors in crafting weaponry. As such, Pālehua translates to “enclosure of the warrior.”

大規模なヘイアウ(祈りの場所)の遺跡が発見され、この地域についての昔からの言 い伝えもあることから、文化学者たちはパレフアが 古代に戦士たちの訓練場として 使われていたと考えています。ハワイ語で「パ」とは「石に囲まれた場所」を意味し、「レ フア」は真紅の花と丈夫な木材になる硬い性質で知られるオヒアの木をさします。オ ヒアの木材は武器の材料として戦士たちに珍重されていました。ですから、パレフアと は「戦士たちの囲い地」と訳せます。

McD Philpotts was raised at Pālehua Ranch. As a boy, he roamed its ridges, valleys, and grasslands—often on horseback and often alone. As a man, he serves as the ranch caretaker. Philpotts’ ties to the land are myriad and rich. He’s both kanaka maoli (Native Hawaiian) and a descendent of James Campbell, a prominent Hawai‘i land developer and industrialist of the 1800s. Though his dual ancestry informs his understanding of the importance of land stewardship, the ranch’s real significance lies closer to his heart: Pālehua is home.

McD・フィルポッツさんはパレフア・ランチで育ちました。少年時代にはよく馬に乗って一人で尾根や谷 や草原を自由に駆け回っていたそうです。大人になった今は牧場の管理人を務めています。フィルポッ ツさんとこの土地との間には、たくさんの豊かな絆があります。彼はカナカ・マオリ(ハワイ先住民)であ ると同時に、1800年代にハワイの土地開発者として、また実業家として名を馳せたジェームズ・キャン ベルの子孫でもあるのです。二つの民族の子孫であるおかげで土地を管理し守っていくことの重要性 を深く理解しているフィルポッツさんですが、もっと身近な理由からもこの牧場を大切に思っています。 彼にとって、パレフア は故郷なのです。

At the same time that the Wild West emerged in America in the 19th century, Hawaiian paniolo, or cowboys, honed a distinct island tradition in the middle of the Pacific. Though prominent on Hawai‘i Island, paniolo culture continues in small, vibrant pockets on O‘ahu. Ranch horses, like the American paints and buckskins at Pālehua, are adept at navigating the area’s various terrains. When flushing out errant cows, the horses nimbly maneuver through forest trails and craggy outcroppings, gulches and grasslands. But the best times come when work is done, and they can run wild and free.

19世紀にアメリカ西部の開拓時代が始まったのと同じ頃、ハワイ のパニオロ(カウボーイ)たちは太平洋の真ん中で独自の文化を創 り上げました。パニオロ文化が色濃いのはハワイ島ですが、オアフ 島各地でも小規模ながらいきいきと受け継がれています。パレフア で飼われているアメリカン・ペイント種やバックスキン種といった馬 たちは、この地域の多様な地形の中をやすやすと歩き回ることがで きます。迷い牛を追い立てて連れ戻すとき、馬たちは森の中の小径 も、ゴツゴツした岩だらけの場所も、峡谷も草原も器用に動き回り ます。でも、馬たちが一番好きなのは一日の仕事が終わった後。好 きなだけ自由に駆け回ることができるからです。

Hawai‘i’s geographic isolation enabled the development of unique flora and fauna, but it has also served a role in their decline: Native plants are especially vulnerable to introduced diseases and competing, invasive species. Pālehua Ranch partners with entities like Mālama Learning Center to establish reforestation and education programs. At an onsite nursery, the nonprofit grows seedlings, and soon, students from nearby high schools will be able to learn firsthand the importance of mālama ‘āina, or taking care of the land, and safeguarding it for the next generation.

他の陸地から遠く隔離されているハワイの地理的条件は、独特な 植物相と動物相の形成に役立ちましたが、その一方で原生種の植 物相と動物相の衰退にも一役買うことになりました。原生植物は、 外から持ち込まれた病気や侵入種との競争に特に弱いのです。パ レフア・ランチ は、マラマ・ラーニング・センターなどの団体と提携 し、森林再生・教育プログラムを創設しています。このNPOは牧場 内にある育苗場で苗を育てています。まもなく、近くの高校の生徒 たちがマラマ・アイナ(土地を大切にすること)の重要性を直に学 び、次世代のために守っていくことになるでしょう。

Most of Pālehua Ranch’s 40 head of cattle are of the Brahman breed, and like the kiawe tree they seek refuge beneath, their tolerance for arid conditions suits them well on the dry leeward lowlands. Throughout the year, cattle roam a patchwork quilt of grassland parcels. Rotation of these grazing areas is critical. During drought season, uneaten grass transforms from feed into something much more dangerous: fuel. It serves as easy tinder during electrical storms, or worse in negligent human hands. In 2014, children playing with a lighter set off a fire that ripped through the landscape, scorching 500 acres.

パレフア・ランチに40頭いる牛の大半はブラーマン種で、ちょうど その木陰が憩いの場所となっているキアヴェの木々と同じく乾いた 気候に強いので、リーワード地区の乾燥した低地に合っています。 牛たちはパッチワークのように区切られた草地で一年中放牧され ます。こうした放牧地のローテーションはきわめて重要です。日照り が続く季節には、食べられずに生い茂った牧草は飼料でなく、もっ と危険なもの、つまり燃料と化します。落雷を伴う嵐や、さらに悪い ことには人間の不注意をきっかけに、乾いた草が燃えやすい焚きつ けとなって山火事になってしまいます。2014年には子どもたちがラ イターで遊んでいたのが原因で草地に燃え広がり、約200ヘクター ルが焼けてしまいました。

though prominent on hawai‘i island, paniolo culture continues in small, vibrant pockets on o‘ahu.

Dirty and hot, ranch work is often tedious: tending to animals, checking water troughs, mending fences, maintaining roads. Duties begin at sunrise with little set routine. Cattle may breach a fence, requiring an impromptu roundup; a tractor might break down, demanding an immediate fix. It’s not an easy life, explains Philpotts with a wry smile. But there is an upside: “I have a bigger office than most.”

家畜の世話、水桶のチェック、柵の修繕、道路のメンテナンスなど、 牧場の作業は暑い中での汚れ仕事が多く、えんえんと続く単調な 作業も多いそうです。牧場の一日は日の出と同時に始まり、決まっ た順序はほとんどありません。牛が柵を破って出れば即刻捕まえに 行かなくてはなりませんし、トラクターが故障すれば直ちに修理が 必要です。楽な生活ではないですよ、とフィルポッツさんは苦笑いし ます。でも長所もあります。「私ほど広々した職場で働いている人は あまりいないでしょう」とフィルポッツさんは自慢します。

Hometown Heroes

「僕たちの故郷は誇り高い町」

Our town has so much pride.”

Mixed martial artists Max Holloway and Yancy Medeiros speak about their unbreakable bond with O‘ahu’s West Side and giving something for their community to rally around.

MMAのヒーロー、マックス・ホロウェイさんとヤンシー・メデイロスさんが、オア フ島ウエストサイドの固い絆について、そして故郷のコミュニティに誇りを提供す ることについて語ってくれました。

Text by Matthew Dekneef Images by Josiah Patterson

When Max “Blessed” Holloway knocked out José Aldo in the final bout of the Ultimate Fighting Championship 212 event in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, cheers rang out like firecrackers across the Hawaiian Islands. The 25-year-old mixed martial artist from Wai‘anae had claimed his title as the undisputed UFC featherweight champion.

Between that win in June 2017 and a welterweight victory for another native son, Yancy Medeiros—who opened the night’s main card event with a crisp left hook to his opponent, Erick Silva—their stomping grounds of West O‘ahu, a rumbling ocean away, felt like the epicenter of the sports world.

It’s been a rapid-fire year for the two since those career-defining wins abroad. We visited Holloway and Medeiros during a late-afternoon training session at Wai‘anae Boxing Gym, which is just a short drive from Medeiros’ childhood home, and where Holloway still regularly trains. The duo appeared more focused and relaxed than ever.

マックス・ホロウェイさん(通称「ブレスト」)がブラジ ル、リオデジャネイロでのアルティメット・ファイティン グ・チャンピオンシップ 212王座統一戦でジョゼ・ア ルドをKOした時、ハワイ中で歓声が爆竹のように響き 渡りました。ワイアナエ出身の25歳の総合格闘技家 は、紛れもないUFCフェザー級王者のタイトルを獲得 したのです。

ホロウェイさんが収めたその2017年6月の勝利につ づき、今年、もう一人のハワイ出身選手ヤンシー・メデ イロスさんがメインカードイベントだったウェルター級 マッチで対戦相手のエリック・シウバに歯切れの良い 左フックを打ち込んで勝利。両選手の地元ウエストオ アフははるか大海の彼方でしたが、まるでMMAの中 心地のように感じられました。

海の向こうでキャリアを決定づける勝利を収めたこの 二人にとって、この1年間は目まぐるしく過ぎていきま した。本誌取材班はワイアナエ・ボクシング・ジムで午 後遅くトレーニング中のホロウェイさんとメデイロスさ んを訪問しました。メデイロスさんが子どもの頃住んで いた家から車ですぐの所にあり、ホロウェイさんが今で もよくトレーニングに来ているジムでもあるそうです。 二人は今まで以上に目標が定まり、またリラックスして もいるようでした。

Your careers have taken you traveling all over the world. What does your hometown have that nowhere else has?

MAX: The air. It’s different. There’s nothing like the West Side air, I’ll tell you that much. People always think I’m kidding, but there’s something in the air, man, that makes us a different breed. The West Side is a very “you get what you give” kind of a place. At the end of the day, the people here will give you the shirt off their back—if you show nothing but aloha, you’ll only get aloha back. Wai‘anae is a special place.

YANCY: Our town has so much pride. I feel that not just in myself, but everyone around me. Everything we do, we do it with all our heart. This place has so much harmony and love. People outside of Wai‘anae don’t always see that, they see our stereotyped life.

Which is?

YANCY: Growing up, you hear, “Oh, you’re from Wai‘anae?” They see tattoos, they hear you’re a fighter, and then you’re seen as a bad guy from a rough neighborhood. I don’t feel that way about us at all. I wanted to change that aspect of how we’re perceived.

お二人は世界中を旅されていますよね。お二人の故郷 にあって、他所にないものは何でしょう?

ホロウェイ:空気ですね。他所とは違います。本当の 話、ウエストサイドのような空気は他にないです。そう 言うと僕が冗談を言っていると思う人が多いけど、こ この空気には、僕らをひと味違った人間にする何か があります。ウエストサイドは「人は自分が与えた分 だけ手に入れることができる」という精神が生きてい る場所です。地元の人たちは、相手が必要としている なら、しまいには自分が着ている服さえ脱いであげて しまうような人たちです。純粋なアロハの心を見せれ ば、純粋なアロハの心が返ってくる。ワイアナエは特 別な町です。

メデイロス:僕たちの故郷は誇り高い町です。自分自身 にだけじゃなくて、周りの人たち皆にそれを感じます。

何に取り組むにせよ、一生懸命にやるんです。ここは調 和と愛でいっぱいなんです。でもワイアナエの外の人た ちには、あんまりそれが見えないようです。型にはまっ た見方でしか見ようとしないんですよ。

それはつまり、どんなことでしょう?

メデイロス:子どもの頃、「ああ、お前はワイアナエ出身 か?」って言われたものでした。タトゥーを見て、ファイ ターだと聞くと、荒っぽい地域出身の悪い奴だと思わ れるんです。自分ではそんな風には全然思わないし、僕 らがそういう見方をされるのを変えたかったんです。

ホロウェイ:メディアは悪いことばかりに飛びつくから ね。出身地がネガティブに報道されるんだ。

MAX: The media jumps all over the bad stuff. Where we’re from gets a bad shake in that way.

Have you ever felt that being where you’re from, Wai‘anae and Mākaha, people underestimate you?

MAX: I’ve felt people try to hold me to a lesser standard, telling me I’m not supposed to do this and that. But, that’s not me, that’s not Wai‘anae, period. I always say that if society tries to suppress the people here, it’s because they see greatness in us, and there’s lots of it on the West Side. They’re just scared to see us trying and succeeding.

YANCY: I’ve never tried to prove anything to anyone. I just try to show people exactly the person I am, that I’m no different than anybody. Being where we’re from, being tough is like, that’s the big thing. But, even as a kid, I’ve always been totally fine with backing down from a fight. This is the town where I was born and raised, so my home is a sanctuary, that’s my outlook.

At the gym today, the owner hung up a banner of you, Max, right next to your championship belt. And, Yancy, one of the kids asked you to sign his headgear. How does that make you both feel—to

ワイアナエやマカハ出身だということで、軽く見られて いると感じたことがありますか?

ホロウェイ:こうすべきじゃないとかああすべきじゃな いとか言われて、他の人よりも低い基準に当てはめよ うとされていると感じたことはあります。でも断じて僕 はそうじゃないし、ワイアナエだってそうじゃない。これ は僕がいつも言っていることなんですけど、社会がここ の人たちを押さえつけようとしているのなら、それは彼 らが僕たちの中に優れたものを見出しているからで、ウ エストサイドには優れた所がたくさんあるからです。僕 たちが挑戦して成功するのを見るのが怖いんですよ。

メデイロス:僕は、誰に対しても何かを証明しようとし たことはないですね。ありのままの自分と、自分が他の 人とちっとも違わないことを見せようとしているだけで す。僕らが育った所では、タフであることは大事なこと です。でも、僕は子どもの頃から、ケンカを避ける選択 をしても全然構わなかった。ここは自分が生まれ育っ た町だから、自分にとって大切な安らぎの場でもある。 それが僕の見方かな。

今日このジムで、オーナーが、チャンピオンシップベルト のすぐ脇にホロウェイさんのための横断幕を掲げまし たね。それから、自分のヘッドギアにサインして欲しい とメデイロスさんに頼んだ子がいました。コミュニティ 全体が老いも若きもお二人をとても誇りに思っている ことを知って、どのように感じますか? ホロウェイ:夢のようです。故郷のコミュニティと州の ためになにか良いことができている自分は幸運だと思 います。小さい子どもたちに希望をあげられるし、年上

know the whole community, old and young, is so proud of you?

MAX: It’s surreal. I’m blessed to do something good for my community and the state. All these little kids, you give them hope. Older people, too—a lot of my fans are grandmas and grandpas—they come up to me and say, “Eh, you’re the fighter kid, yeah?” [Laughs] As for the young ones, it’s about giving them hope, showing them that I came from here, I’m rooted here, graduated from the schools here.

YANCY: That’s the best thing about it, the kids look up to you. It brings balance to the job, this barbaric sport, creating that positive outlook for them. It motivates me to do what I do. Look, in the ring, I’m over here trying to take heads off, but not outside it. I’m a martial artist, that’s my profession, and I know when to turn it on and off. That’s what kids need direction on, especially in our community. They need positive influences around them—that’s what we can do. You can be a peaceful person and still do this sport.

MAX: When I was in middle school they’d bring successful people not from Wai‘anae to speak to our classes, but, for me, it was always in one ear,

の人たちにも。僕のファンの多くはおじいさんやおばあ さんたちなんです。僕を見ると近づいてきて「ああ、あん たがあの戦う子だね?」って言うんですよ(笑)。子ども たちには、希望を与えられることが大事です。僕はここ の地元の出身で、地元にルーツがあって、地元の学校 を卒業しているんですから。

メデイロス:それが一番嬉しいことですね。子どもたち が僕らを目標にしてくれる。野蛮なスポーツだけど、子 どもたちにとってポジティブな見本となることで、自分 の仕事にもバランスが生まれる。僕にとっては頑張る 動機にもなります。リングの中では対戦相手を徹底的 に打ちのめそうとするけど、リングの外ではそうじゃな い。僕は格闘家で、それが僕の仕事です。戦闘モード をオンにするときとオフにするときを心得ている。子ど もたちに指導が必要なのもその点です。特に僕らのコ ミュニティでは大切なことなんです。子どもたちの周り にはポジティブな影響を与える大人が必要で、僕らに はそれができる。平和を愛する穏やかな人であっても、 こういうスポーツが可能なんだということを見せられ るんです。

ホロウェイ:僕が中学生だった時、ワイアナエ出身じゃ ない成功した人たちが学校に来て話をしてくれました が、そういう話はいつも耳を素通りするだけでした。こ こで育つことがどういうことか、何を知っているという んだ、と思ってました。僕は、大人の言うことを聞きたく ない頑固な子どもだったんです。でも今じゃ、ここの子 どもたちは、僕やメデイロスや、僕の兄のサム・カポイ など、実際にウエストサイドで育った大人たちの話を 聞ける。次世代の人たちにインスピレーションを与え

out the other. What did they know about growing up here? I was one of those stubborn kids who didn’t want to listen. Now, the kids out here have people who are actually from the West Side—myself, Yancy, my older brother, Sam Kapoi. I want to inspire the next generation and be that difference.

Max, what’s something most people don’t know about Yancy?

MAX: A lot of people think Yance is just this funny guy. You’d never think this guy is a fighter. We’re kind of like the same person, we’re from the same hood, we joke around, this and that, but when it’s time for business, he gets down to it. He’s a hard worker.

And, Yancy, what about Max?

YANCY: Max is a kid at heart. That’s what I love about the guy. People don’t realize he’s just a typical kid from a small town who has all this belief and confidence in himself. He’s a prideful person who’s also very humble and modest. He hardly goes out. He loves video games. He’s a fat kid stuck in a skinny body—he loves to eat. [Laughs] Put it this way, he can eat over 10 churros at Disneyland. I get off one churro and feel like I’m going to have a heart attack, but he’s over there in the corner of the park grindin’. Unreal, brah.

て、ポジティブな変化をもたらす存在になりたいです。 マックスさん、メデイロスさんのことで、大半の人が知 らないことは何ですか?

ホロウェイ:ヤンシーはただ愉快な奴だと思っている 人が多いですね。ちょっと見には格闘家だとは思えな いんです。僕たちは同じような人間で、同じ地域の出 身だし、よく冗談は飛ばすし、あれこれ似た点がありま す。でもいざ仕事となると彼は真剣になります。努力の 人ですよ。

では、メデイロスさん、ホロウェイさんについてはどう でしょう?

メデイロス:ホロウェイは子どもの心を持つ人です。だ から僕はこいつが好きなんです。他の人には、彼が信 念と自信を持っている小さな町出身の典型的な若者 だということが分からない。誇り高い人であると同時 に謙虚で慎み深い人でもあるんです。滅多に出かけな いし、ビデオゲームが大好きだし。まるで細い体に閉じ 込められた太った子どもみたいで、食べることが大好 きなんですよ(笑)。たとえば、ディズニーランドでチュ ロスを10本もたいらげられる。僕なんか1本食べただ けで心臓発作を起こしそうになるのに、彼はディズニ ーランドの一角でまだ食べ続けてるんです。信じられな いでしょう?

Blessings Bestowed

A woman connects with mothers past and present on the plains of Kūkaniloko and in the waters of Anianikū.

At Lanikūhonua, a traditional Hawaiian ceremony cleanses and protects all who partake.

Text by Rae Sojot

Images by Josiah Patterson

A little baby sat quiet and brave along the shoreline of Anianikū, one of Lanikūhonua’s three lagoons, her petite frame cocooned by folds of warm sand. Her eyes wide, she drank in an intimate scene: The serene waters of the lagoon were gilded gold in the afternoon sunlight, and her parents, flanking her on either side, had their heads bowed. A kahu, or spiritual advisor, was knelt before the small child, deep in prayer. The girl, just shy of 2 years old, was about to receive her pī kai, a sprinkling of saltwater that would purify and protect her. In essence, a blessing.

Oceans of time have passed since the ali‘i, or Hawaiian royalty, regularly journeyed to what is now known as Ko Olina for rest, recovery, and recreation. Travel to this area was dictated by the elemental calendar, in accordance to the moon and stars, and upon arrival, the royal families found respite in the calm, healing waters. They relaxed along the shores, swam in the sheltered lagoons, and feasted on the plentiful white fish found in the coves. When Alice Kamokila Campbell, the daughter of a Native Hawaiian mother and a Scottish industrialist, settled in the area in the 1930s, the mana, or life force, of the place spoke to her. She gifted her new home a name: Lanikūhonua, “where heaven meets Earth.”

小さな子どもが一人、砂浜の上に静かに座っています。 ここはラニクホヌアにある3つのラグーンの一つ、アニ アニク。子どもの小さな身体は、温かな砂で覆われてい ます。子どもは目をみはり、この親密さに満ちた場面を 心に刻んでいるようです。ラグーンの澄み切った水が 午後の陽射しを受けて黄金色に輝く前で、子どもの両 脇には両親が座り、頭を下げています。「カフ」と呼ばれ るスピリチュアル指導者が、このもうすぐ2歳になろう としている小さな女の子の前に膝をつき、一心に祈り をささげています。子どもの上に振りかけられる「ピ・カ イ」という浄めの塩水は、彼女を悪いものから守る、祝 福のしるしです。

現在コオリナとして知られるこの場所にハワイの王族 「アリイ」たちが静養やレクリエーションのために定期 的に訪れていたのは、もう遥かな昔です。この場所を訪 れるべき時は、月と星の運行にもとづく自然暦によって 定められていました。王家の人々は、癒しの力を持つ静 かな水の中に平安を見出し、海辺でくつろぎ、木陰のあ るラグーンで泳ぎ、入江で豊富に捕れる白い魚のご馳 走を楽しみました。ネイティブハワイアンを母に、スコッ トランド人の実業家を父に持つアリス・カモキラ・キャ ンベルが1930年代にこの地に家を構えた時、この場 所のマナ(生命の力)が彼女に語りかけたといいます。

彼女は自分の新しい家に「天と地が出会う場所」とい う意味の「ラニクホヌア」という名をつけました。

この地域のカフは、祝福を授けてほしいというリクエ ストを昔から頻繁に受けていたそうです。ラニクホヌ アを訪れる人は、癒しの力を持つここの水にスピリチ ュアルに共鳴するのだといいます。現在、そうした祝福 を授けるのは多くの人から「アンティ(おばさん)」とし

The kahu of the area were regularly requested to give blessings here, since those who visited Lanikūhonua often felt a spiritual resonance with its healing waters. Today, such occasions are conducted by Lynette Tiffany, who is known by most as “Auntie Nettie.” The honor of serving as Lanikūhonua’s spiritual advisor was bestowed on her by her mother, Leilani, a kahu and friend to Campbell. Over the years, Auntie Nettie has administered thousands of pī kai—most often for children, like the toddler on the beach—to cleanse them of harmful energies and offer prayers for a fruitful life.

Only a few years earlier, this baby, Ada, was only a dream of her parents, Ara and AJ Feducia. After months of trying to conceive with no success, Ara had wondered if the universe was refusing her a child due to her wild, unrestrained past. Fear and doubt crept their ways into hushed conversations. She stowed this shame in a small corner of her heart until a friend told her about Kūkaniloko. Located in the cool, windswept plains of neighboring Wahiawā, Kūkaniloko once served as the sacred birthing grounds for ali‘i. For centuries, royal processions traveled to the ancient site in order to give birth to future chiefs

て親しまれているネティ・ティファニーさん。ラニクホヌ アで儀式を行うスピリチュアルな指導者としての立場 は、カフでもあり、アリス・キャンベルの友人でもあった 母のレイラニさんから受け継ぎました。ネティおばさ んは、長年にわたり、ピ・カイの儀式を何千回も行って きました。多くの場合、祝福を授ける相手は冒頭で紹 介した女の子のような小さな子どもたちで、悪いエネ ルギーを浄めて払い、実りある人生となるよう祈りを 捧げます。

ほんの数年前、両親であるアラさんとAJさんにとって、 エイダという名のこの赤ちゃんは夢の中にしかいない 存在でした。子どもを得ようと何ヶ月も試みた後、アラ さんは、自分の過去の野放図な行いのために、宇宙の 意思が自分に子どもを与えるのを拒否しているのでは ないかと考え始めました。小声での会話の中に恐れと 疑いが忍び寄り、アラさんは心の片隅に、自分を恥じる 気持ちをしまいこんでいました。そんな時、友人の一人 がクカニロコのことを教えてくれたのです。クカニロコ はワヒアワの風が吹き抜ける冷涼な野原にある、かつ てアリイたちが出産する場所であった聖域です。何世 紀にもわたり、王族の女性たちはこの古い聖域に旅し て、未来の王や女王たちを産んだのです。ここには全部 で184の大きな「ポハク」(岩)があり、そのすべてが、 出産の苦しみを和らげる力を持っているとされ、ハワイ 語で「内から苦しみの声を抑える」という意味のクカニ ロコという名前がついています。

クカニロコは長年にわたり、太古と現在の数多くの母 親たちにつながりたいと願う人々をひきつけてきまし た。アラさんも、ユーカリの香りが漂い、風がささやくこ の聖なる場所を沈黙のうちに散策しました。アラさん

and chiefesses. It was believed that the large pōhaku, or rocks, numbering 184 in total, were imbued with the power to lessen labor pains, hence the area’s name, which means, “to withhold the cry from within.”

Over the years, Kūkaniloko has become a place for seekers hoping to connect with mothers past and present. Ara explored this sacred ground in silence, the wind whispering through stands of sweet-scented eucalyptus. She brought with her a ho‘okupu, or gift, an homage to women who had come before her. The small bundle held an assortment of items: a piece of kalo, or taro, for nourishment and fertility; kukui nut oil for its ability to burn clear and long into the night; pa‘akai, or salt, for its cleansing properties; laua‘e fern for its beauty. It also contained Ara’s own prayers and wishes. On a small piece of paper, she drew her hopes: a treehouse overlooking the water, AJ surfing, a baby playing.

This part would need no formal guidance, her friend had explained. Ara’s heart would serve as her spiritual compass. Sitting near an oblong stone, its surface a greenish brown mottled with white lichen, Ara presented her ho‘okupu. Under the wide sky, she thought of Kūkaniloko’s powerful

はかつて生きていた女性たちのために「ホオクプ」(捧 げ物)を持参していました。滋養と豊穣の象徴である カロ(タロ)、夜を明るく照らすククイナッツオイル、浄 めの力を持つパアカイ(塩)、そして美しさの象徴であ るラウアエの葉を、小さな包みにまとめたものです。こ の包みには、アラさんの祈りと願いもこめられていまし た。小さな紙に描いたアラさんの望みとは、水辺を望む ツリーハウス、サーフィンをするAJさん、そして遊んで いる赤ちゃんの姿でした。

この祈りには正式な手順は必要としないと、アラさん は友人から聞いていました。自分の心がスピリチュア ルな磁石の役割を果たすのだと。緑がかった茶色の地 衣類にところどころ覆われた長方形の岩のそばに座 り、アラさんは持参したホオクプを捧げました。広々と した空の下で、アラさんはネイティブハワイアンの文化 にとってクカニロコがどれほど強力な存在であったか について、新しい生命を生み出すことについて、そして、 畏敬の念を抱いてここを尋ねた無数の女性たちについ ても思いを馳せました。背景にはオアフ島の中央に位 置する平原から立ち上がっているワイアナエ山脈があ り、その谷と山稜の形が休んでいる妊婦の姿になぞら えられています。

その2か月後、アラさんは友人に電話で嬉しいニュース を伝えていました。アラさんは妊娠していたのです。

それから約3年。エイダちゃんはまだ儀式の意味を理 解するには小さすぎますが、そこにある厳かさと誠実 さを感じ取っているようです。カフがそっと肩と顔、そし て頭のてっぺんにさわる間、アイナ(土地)とのつながり を象徴する砂に抱かれたままじっとしていました。

significance in Native Hawaiian culture, the bringing forth of new lives, and of the many women who make pilgrimages here out of reverence. In the background, rising up from the central plains, was the Wai‘anae Range, with its sloping ridges and valleys thought to form the profile of pregnant woman in repose.

Two months later, Ara telephoned her friend with the news: She was pregnant.

Nearly three years later, little Ada, still too young to understand the ceremony, sensed its solemnity and sincerity. Ensconced in the sand—a symbolic connection to the ‘āina, or land—she remained still as the kahu lightly touched her shoulders, her face, and the crown of her head.

When the kahu drew forth a ti leaf and an ‘umeke, or bowl, filled with seawater from the lagoon, Ada watched with curiosity. Chanting softly, the kahu skimmed the ti along the water’s surface. Its swirling eddies proved irresistible, and Ada stretched her hand out to touch. With childish delight, she splashed the holy water with her fingers, and a tiny curl of laughter escaped her lips.

Gazing down, the kahu smiled upon the blessed child.

カフがティーの葉とラグーンで汲んだ海水を満たした ウメケ(ボウル)を差し出すと、エイダちゃんは興味深そ うに見守ります。カフは静かにチャントをつぶやきなが ら、ティーの葉を海水の表面につけます。水の面に現 れた渦巻きに好奇心をかられて、エイダちゃんは小さ な手を伸ばしました。指先で聖なる水に小さなしぶき を上げ、可愛らしい唇から笑い声を上げます。

カフも微笑みをたたえて、この祝福された子どもを見 下ろしていました。

Image by Josiah Patterson

Image by Josiah Patterson

“I want to have an opportunity to go out and teach everyone weaving because I want it to come back and be a normal occurrence. I have so much pride in keeping the culture alive—this is what it means to be Hawaiian and to be an islander.”

Jordan Koko Kroger, coconut weaver

Image by Josiah Patterson

Sam Kapoi: My Journey to Voyaging

航海者:サム・カポイさん

John Hook

I grew up in Wai‘anae and, on paper, I’m nine generations deep—I’m sure there’s more prior to that. I went to public school: Wai‘anae Elementary, Intermediate, and High School. In 10th grade you selected your career pathway, and I selected Hawaiian studies and natural resources.

I was really interested in a side program in voyaging. The school had a canoe called E Ala that was built in Wai‘anae in ’81, right after Hōkūle‘a in ’76. I gravitated toward that because of my love for the water. At the time, I was part of archaeology. I saw myself doing that for the rest of my life, until I started to get my feet wet with voyaging. Once I started doing that, I realized that this could be a viable thing for the rest of my life as well.

With E Ala we got to sail every day, going to the beach and getting credit for it. I remember one time we were at Sand Island, at the Marine Education Training Center, and Hōkūle‘a and Hawai‘iloa pulled up. They had just come back from a training session, and we were there doing some work on E Ala. I told Nainoa Thompson, “I want to sail on this canoe. This is the mother of canoes.

私はワイアナエ育ちです。記録に残っている限りでは9世代目です が、うちの家族がもっと前の代からワイアナエ住民だったのは間違 いないと思います。私は小学校から高校まで、ワイアナエの公立校 に通いました。10年生になって進路を選ぶ時、私はハワイアンスタ ディーズと天然資源について学ぶことを選択しました。

そして、その授業の一環で航海に触れて、深い興味を持ったので す。私の通ったワイアナエ高校には「エ・アラ」という名のカヌーが ありました。1976年にホクレアが建造された後、1981年に作ら れたカヌーです。私は海が大好きなので、自然にそのカヌーに惹き つけられました。その当時は考古学を真剣に学んでいて、考古学を 一生の仕事にしようと思っていましたが、カヌーの航海を始めてか ら考えが変わりました。航海も、一生をかける仕事になるのだと気 づいたのです。

私たち生徒は、毎日エ・アラ号で海に出ました。ビーチに行くことで 単位がもらえたんです。一度、クラスの皆とサンドアイランドの海洋 教育訓練センターにいる時に、ホクレア号とハワイロア号が入港し てきました。2艘の航海カヌーは、私たちがエ・アラで作業をしてい るところへ、航海訓練を終えて戻ってきたのです。その時、私はナイ ノア・トンプソンに尋ねたのです。「僕はホクレアで航海したいです。 このカヌーはすべてのカヌーの母ですから。どうしたら参加できま すか?」と。

How can I get involved?”

I was only 15. He was like, “OK, let’s go.”

I was like, “What?!”

It was that simple.

That summer was my first time that I remember sailing Hōkūle‘a, from Sand Island to Ko Olina to Pōka‘ī, and then we would sail back. That’s when the hook set in for Hōkūle‘a for me—the voyaging family.

When I was in college in California studying digital filmmaking and production, I had this wild dream. It was basically like the canoes were calling me back home. We were in a bay with canoes from all over the world—I had never seen them ever in my life. When I woke up I was asking myself, “What was that all about?”

When I moved back to Hawai‘i and got reconnected with the Polynesian Voyaging Society, we started training in 2008 for this thing called the Worldwide Voyage. We were going to run across all these canoes, and then come back with canoes from all over the world, creating this convoy back home. It was kind of a trip—the dream came true.

Sam Kapoi is an entrepreneur and filmmaker from Mākaha Valley who serves as a media specialist for the Polynesian Voyaging Society. He shares his dual passions for Hawaiian studies and media production on Instagram at @samkapoi.

私はその時、たったの15歳でした。そうしたら、トンプソンは「オー ケー、じゃあ行こう」と言ってくれたんです。

私は「ええっ?」と聞き返しました。

それほど簡単だったんです。

その夏、私はホクレア号でサンドアイランドからコオリナへ、そして ポカイへと航海し、また同じ航路を戻りました。それ以来、私はホク レアにしっかり結び合わされたのです。ホクレアは航海するファミリ ーのようなものです。

カリフォルニアの大学でデジタル映像制作を勉強している時、はっ きりとした面白い夢を見ました。カヌーたちが私を故郷に戻るよう に呼びかけているかのような夢でした。夢の中で私たちは、とある 湾にいました。そこには、世界中からカヌーが集まっていました。そ んなカヌーはそれまで見たこともありませんでした。目が覚めてか ら、一体これはどういう夢なんだろう、と不思議に思いました。

ハワイに戻って、ポリネシア航海協会と再びつながりを持ち、2008 年の航海「ワールドワイド・ボヤージュ」のために訓練を始めまし た。この航海では世界中で様々なカヌーに出会い、そのカヌーたち を船団のように引き連れて、ハワイに戻ったのです。まるで、私の夢 が現実になったような航海でした。

サム・カポイさんは、マカハ・ヴァレー出身の映像作家で、ポリネシ ア航海協会のメディアスペシャリストを務めています。ハワイ文化と 映像制作の両方に情熱を傾けるカポイさんの日常は、インスタグラ ム@samkapoiで。

Jordan Kroger: The Weaver

島の文化を織る人:ジョーダン・クルーガーさん

As told to Natalie Schack Images by Jonas

Maon

The first time I saw coconut weaving was in the Polynesian Club in Kapolei High School, where they race to see who can make the fastest basket. In this club, I felt that I belonged. My mom is Micronesian, but we were never around that family a lot and I didn’t know what it meant to be Micronesian. I didn’t really know what it meant to be Hawaiian either. It’s something I was struggling with.

After high school, my mom sent me to Micronesia, and it was one of the best things I ever did. Micronesia is a whole different world! The culture there is so laidback. Everyone’s farming their own land. And at funerals or weddings or big parties, everyone would come with pigs or food carried in coconut baskets. The baskets looked so perfect and so nice. I thought, “Ho! I want to learn how to do that.”

Later, I got a Polynesian dance contract to go to Guam. The people there are

私がココナッツの葉を織る技を初めて目にしたのは、カポレイ高校 のポリネシアンクラブに所属していた時のことでした。そこでは誰 が一番早くバスケットを織れるかを競うのです。このクラブで活動 している時、自分の居場所はここだと感じることができました。私の 母はミクロネシア人なのですが、母方の家族とはあまり交流がな く、私はミクロネシア人であるとはどういうことなのかをあまり理解 できていませんでした。もっとも、自分がハワイアンであるというこ との意味もよく分かってはいなかったのです。当時はそういったこと を理解するのに苦労しました。

高校を卒業した私は母に勧められてミクロネシアへ渡りました。そ してそれは私の人生で最高の経験のひとつになったのです。ミクロ ネシアはまったくの別世界です!その文化はとてものんびりしてい て、皆が自分の土地を耕して暮らします。お葬式や結婚式、大きな パーティーがあれば、誰もが豚やら食べ物を詰めたココナッツの 葉のバスケットを手にしてやってきます。そのバスケットがどれも 完成度が高く、とても素敵で、私は「わあ、作り方が知りたい!」と思 ったのです。

その後私はグアムでポリネシアンダンスを踊る契約を得ました。グ アムの人々はココナッツ織りがとても上手です。ある村はビーチに

really good at weaving coconut. There’s a village right on the beach, and every day, Chamorro people would demonstrate to tourists how to weave headbands or fish toys. I’d never tried to weave before. I thought it was so awesome, but I was too scared to ask. But by the time I left Guam, I learned how to make all the little stuff.

When the contract was done, I came back to Hawai‘i and was without a job. I thought, “How can I make money quick? Something that I would love to do?” I love Polynesian dancing, but at that time, nothing had come up. Then, I noticed every beach park had something in common: coconut trees. I cut down a few leaves and started playing around. I tried making hats first. My first hundred were so ugly that I was too ashamed to sell them.

Eventually, I started getting a lot of encouraging comments. People would say, “I remember doing this! But now I don’t because I’m too old to climb the tree,” or, “My grandma used to do that, but she never taught me.” Hearing these stories from people encouraged me to keep trying, because I liked to see the joy in their faces when they see that I’m doing something they used to love. Old men would come up to me and say, “I’ll give you some tips.” After their lessons, my hats came out perfect every time. They taught me what kind of trees to look for, which leaves on

あって、そこでは毎日チャモロの人々がココナッツ織りのデモンスト レーションとして観光客にヘッドバンドや魚のおもちゃの作り方を 披露します。私はそれまでココナッツ織りにチャレンジしようとした ことがありませんでした。素敵だと思ってはいたものの、織り方を教 えて欲しいと頼むのが怖かったのです。でも、グアムを去る頃には小 さい物ならなんでも織れるようになっていました。

契約が終了してハワイに戻った私は仕事を探す必要がありました。 そこで、「自分のやりたいことで、すぐにお金を稼ぐにはどうすれば いいだろう?」と考えました。ポリネシアンダンスを踊るのは大好き でしたが、その当時はダンスの仕事が見つからなかったのです。そ んな時、ビーチに隣接する公園には必ずココナッツの木が生えてい ることに気づきました。私はその葉をいくつか切り落として織り始 めてみました。最初に試してみたのが帽子作りですが、最初の百個 は見ばえもひどく、恥ずかしくて売り物にはできませんでした。

それでも、やがて少しずつ褒めてもらうことが多くなりました。人び とが、「私も昔はやっていたんだ!年を取って木に登れなくなってし まったからもうやらなくなったけれど」とか、「私のおばあちゃんが ココナッツ織りをしていたわ。でも織り方は教わらなかったの」など と声をかけてくれるのです。そういう話を聞くことがココナッツ織り を続ける励みになりました。昔自分たちが好きだったことを、私が 今もやり続けているのを見て人びとが喜ぶ顔を見るのが楽しかっ たのです。「コツを教えてやろう」とお年寄りの方がやってくること もありました。そうやって教えを受けるごとに、私が織る帽子の品 質は上がっていったのです。彼らは良い木の選び方や、どの部分の 葉を使えば良いか、前処理のしかた、織り方の向きなどを教えてく れました。

the tree you want, how to prepare them, which way to weave it.

I want to have an opportunity to go out and teach everyone weaving because I want it to come back and be a normal occurrence. I have so much pride in keeping the culture alive—this is what it means to be Hawaiian and to be an islander. You used to depend on things like this. Me, I’m in love with everything about island culture. If someone can teach me other islander things, I’m always down. And I’m always ready to teach someone how to make hats or baskets.

Jordan Koko Kroger is an O‘ahu-born coconut-frond weaver who lives in Mā‘ili. Kroger gathers leaves by hand to weave everyday items like hats and headbands. Follow him on Instagram @naulanalauniu.

私の希望はココナッツ織りを皆に教える機会を得ることです。ココ ナッツ織りが再び日常的なものになって欲しいのです。私は自分が この文化を守り続けていることをとても誇りに思います。これこそ ハワイアンであること、そして島の民であるということなのです。昔 は皆、こうした資源に頼って暮らしていたのですから。私は島に関 係するあらゆる文化を愛しています。もし誰かが私がまだ知らない 島の文化を教えてくれるなら喜んで教わりに行きますし、私も帽子 やバスケットの織り方を習いたい人にはいつでも喜んで教えたい と思います。

ジョーダン・ココ・クルーガーさんはオアフ生まれ、マイリ在住のコ コナッツ織りの織り手です。自らの手でココナッツの葉を集め、帽子 やヘッドバンドといった日常品を製作しています。クルーガーさんの インスタグラムは@naulanalauniu。

Aloha Salads

Bank of Hawaii

BIC Tacos

Coldwell Banker

Cookies Clothing Co.

DB Grill

Denny’s Down to Earth

Dunkin' Donuts - COMING SOON

Eating House 1849

Genki Sushi

Gyu-Kaku

Hawaiian Island Creations

Inspiration Furniture

La Tour Cafe

Massage Envy

Menchie’s Frozen Yogurt

Office Max

Petco

Pier 1 Imports

Ramen-Ya

Regal Kapolei Commons 12

Ross Dress For Less Royal Nails

Ruby Tuesday

Sally Beauty

Subway

Supercuts

Target T.J. Maxx

T-Mobile

Verizon Wireless

Vitamin Shoppe www.thekapoleicommons.com

Blaine Tolentino: Upward from Here

ここから上へ

詩:ブレイン・トレンティーノ

Poem by Blaine

TolentinoImage by

AJ FeduciaThere is a spot in the sky where your body knows to surge toward heavenly things.

Mapping the heights— ka ho‘oku‘i, ka ho‘ohālāwai, ka maku‘ialewa the juncture, the meeting, the sky connection.

There are these familiar terms for that place. There are clouds and weather systems to dress the moment when you arrive. You will not know at what part of infinity you are stopped.

These are terms for the spot in the sky between man and the cosmos where the body knows.

There, we are revised— watch the sky shimmer with news of your beauty.

空にあるひとつの場所 そこから天上のものたちへ向かって 舞い上がることを身体は知っている

高さをはかりながら カ・ホオクイ、カ・ホオハラワイ、カ・マクイアレヴァ 接点、出会い、空とのつながり。

その場所には耳慣れた名前がある 雲たちと気圧団が あなたの到着する瞬間をいろどる 無限の中のいったいどこに 自分がとどまっているのか あなたが知ることはなく

空にあるあのひとつの場所をさす言葉がある 人と宇宙の間にある場所を 身体は知っている。

その場所で、私たちは新しくなる。 空をごらん、あなたの 美しさゆえに、輝きわたる空を。

About

Blaine TolentinoBlaine Namahana Tolentino works at the University of Hawai‘i Press in Mānoa and lives in Kaimukī. Her great-grandmother and grandmother have consecutively lived at Lanikūhonua in Ko Olina (the ahupua‘a of Waimānalo) for more than six decades.

Portrait image by Kelii Heath Cruz

Photographer AJ Feducia took inspiration from Blaine Tolentino’s poem, photographing these images of the sky and everything in between.

Pizza Corner

(808) 380-4626

92-1047 Olani Street

Ko Olina, HI 96707

Inspired by legendary New York City pizzerias, this family owned restaurant specializes in hand-tossed thin crust pizza with ingredients made fresh on premises daily. Pizza Corner offers traditional and not so traditional toppings for visitors and residents for dine-in, take-away or delivery. Convenient drive up area for prepaid online orders.

shopmahina.com

Mahina evokes a feeling of shopping your most fashion-forward friend’s closet: a perfectly edited collection of soft, breezy sundresses, stylish tops and subtle-yet-striking accessories. We firmly believe in the philosophy of good vibes and the spirit of aloha, which to us means that the more positive energy we radiate into the world, the more love, kindness, and happiness comes back in return. We put our words into practice by charging a fair price for our merchandise, by treating our employees and customers with kindness and friendliness, ultimately considering them our ‘ohana, or family. Stop by your local Mahina to experience this unique shopping experience. Located on Maui, O‘ahu, Hawai‘i Island, and Kaua‘i. Mahina

Lanikūhonua

A

HAWAIIAN PARADISE WHERE DREAMS WERE REALIZED, LIVES WERE LIVED AND TIMES WERE SHARED.

Located in Ko Olina, or “Place of Joy,” Lanikūhonua was known to be a tranquil retreat for Hawai‘i’s chiefs. It was said that Queen Ka‘ahumanu, the favorite wife of King Kamehameha I, bathed in the “sacred pools,” the three ocean coves that front the property.

In 1939, Alice Kamokila Campbell, the daughter of business pioneer, James Campbell, leased a portion of the land to use as her private residence. She named her slice of paradise, “Lanikūhonua,” as she felt it was the place “Where Heaven Meets the Earth.”

Today, across 10 beautiful acres, Lanikūhonua continues on as a place that preserves and promotes the cultural traditions of Hawai‘i. It allows visitors from around the world an opportunity to experience the rich, cultural history and lush, natural surroundings of this beautiful property.

Lanikūhonua is also a place where memories are made of milestone occasions like weddings, birthdays, anniversaries, and special family gatherings. The stunning landscape is also a superb setting for corporate events and as a tropical backdrop for films, videos and photography.

The possibilities are endless.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, CALL 808-674-3360 OR VISIT LANIKUHONUA.COM.

Image by John Hook

Image by John Hook