FOR KOOLINA Hale

In the Hawaiian language, hale (pronounced huh’-leh) translates to “house” or “host.”

Hale is an intimate expression of the aloha spirit found throughout the islands and a reflection of the hospitality of Ko Olina.

In this publication, you will find that hale is more than a structure, it is a way of life.

Ko Olina celebrates the community it is privileged to be a part of and welcomes you to immerse yourself in these stories of home.

SOME ENCOUNTERS YOU WEAR FOREVER RINGS AND EARRINGS IN 18K BEIGE GOLD, 18K WHITE GOLD* AND DIAMONDS.

FEATURES

58 Dancing Queen

Miss Aloha Hula Taizha Keakealani Hughes-Kaluhiokalani and her kumu hula reflect on her triumphant journey.

74

Back to ‘Āina Ka‘ala Farm digs deep to reconnect with land and community.

88

Remembering Rell

In her lifetime, Mākaha legend Rell Sunn set a gold standard for surfing and community outreach.

100

Of Plants and Progeny

More than just a staple food, kalo (taro) is a source of cultural and spiritual nourishment and identity.

Aloha!

I am continually inspired by the resilience of our resort ‘ohana.

We successfully navigated the challenges of a global pandemic and re-opened our doors with a renewed commitment to ensuring the good health and well-being of our residents, employees, and guests. We enhanced cleaning guidelines, redesigned employee work spaces, and emphasized the importance of personal safety and responsibility when gathering together. Our efforts and your understanding and cooperation assure the longevity and continued success of Ko Olina Resort.

As travel reopens throughout the world, we are humbled you chose Ko Olina as one of your first destinations—welcome to our island home. We also take a moment to celebrate the collective efforts of our resort partners in caring for you during your time with us.

We applaud the victories and joys of our West Side community... a community that perseveres and thrives despite adversity. This issue of Hale pays homage to a diverse group of artists, teachers, chefs, and surfers who are preserving local culture and creating fellowship. We invite you to share these stories and experiences with your ‘ohana.

Our commitment to responsible stewardship of this ‘aina, this land, is unwavering. We will continue to care for this special place and its abundant resources; to perpetuate the unique culture of Hawai‘i through ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i, music, and dance; and to embrace Hawai‘i’s common values of mālama and aloha in all we do. Our hope is for you to walk alongside us on this journey.

With much aloha,

Jeffrey R. Stone Master Developer,Ko Olina Resort

At Big Island Candies, it’s “Aloha at rst sight.” Behold fabulous displays of products, plus gorgeous gifts that celebrate Hawaii’s beauty. At our Hilo Flagship Store, watch dedicated artisans create our signature dipped shortbreads—and more—right before your eyes! Shopping for gifts? Our store associates are happy to help you nd the right ones for those you love.

Big Island Candies: the go-to destination for Hawaii’s nest cookies, chocolates and confections, since 1977.

Hilo Factory & Retail Gift Shop - 585 Hinano Street - Hilo, Hawaii Open daily: 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.; Factory Viewing: Monday – Friday (except holidays): 9:00 a.m. – 3:30 p.m. Ala Moana Center, Street Level 1, Center Court - Oahu 1-808-935-8890 / 1-800-935-5510

Hale is a publication that celebrates O‘ahu’s leeward coast—a place rich in diverse stories and home

to

Ko Olina Resort.

On the West Side of O‘ahu, there is an affinity for community. In this issue, we feature stories that exemplify this interconnectedness. Begin mauka, at a community farm founded in the ’70s. Discover spaces that nurture knowledge within their neighborhoods, from a learning center rooted in Native Hawaiian values to a library three decades in the making. Then journey makai to meet a renowned surfer who championed change in her hometown. Also, learn how rediscovering her heritage helped the reigning Miss Aloha Hula dance the most important performance of her life. Come and meet the people of the Leeward coast and, in turn, learn of the place they call home.

ABOUT THE COVER

The cover image of hula dancer Taizha HughesKaluhiokalani was photographed by IJfke Ridgley, a Honolulu-based photographer.

FRESH POKE & TEMPURA BOWL

CEO & Publisher

Jason Cutinella

Creative Director

Ara Laylo

Editorial Director

Advertising

VP Sales

Mike Wiley mike@nmgnetwork.com

Partnerships & Media

Aulani, A Disney Resort & Spa aulani.com

Four Seasons Resort O‘ahu at Ko Olina fourseasons.com/oahu

Marriott’s Ko Olina Beach Club marriott.com

Beach Villas at Ko Olina KoOlina.com/accommodations

Oceanwide Resort

Ko Olina Golf Club koolinagolf.com

Ko Olina Marina koolinamarina.com

Ko Olina Station + Center koolinashops.com

The Resort Group theresortgroup.com KoOlina.com

Lauren McNally

Editor-At-Large

Matthew Dekneef

National Editor

Anna Harmon

Senior Editor

Rae Sojot

Associate Editor

Eunica Escalante

Photography Director

John Hook

Designer

Skye Yonamine

Translations

Yuzuwords

N. Ha‘alilio Solomon

Creative Services

VP Global Content

Marc Graser

Creative Services Manager

Shannon Fujimoto

Lead Producer

Gerard Elmore

Filmmakers

Blake Abes

Romeo Lapitan

Brand Production Manager

Kaitlyn Ledzian

Brand Production Coordinator

Taylor Kondo

Executive

Chris Kelly

Marketing & Advertising

Executive

Courtney Asato

Operations

Partner/GM-Hawai‘i

Joe V. Bock joe@nmgnetwork.com

VP Special Operations

Rob Mora

VP Accounts Receivable

Gary Payne

Operations Administrator

Courtney Miyashiro

©2021 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of Hale are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. Hale is the exclusive publication of Ko Olina Resort. Visit KoOlina.com for information on accommodations, activities, and special events.

ONLY MINUTES AWAY FROM KO OLINA!

100 Shops

20 Restaurants & Eateries

Luxury movie theatres

Local Farmers Market

Cultural Events & Entertainment

KA MAKANA ALI‘I

West O‘ahu’s largest shopping center

Visit Ka Makana Ali’i – it’s just a few minutes from Ko Olina! See a movie, celebrate a special occasion, enjoy lunch, shop for yourself or discover some one-of-a-kind gifts.

Ask your concierge about transportation options between the shopping center and the resort.

91-5431 Kapolei Pkwy, Kapolei, HI 96707 808.628.4800 | kamakanaalii.com

Image by Josiah Patterson

Image by Josiah Patterson

“

We know Hawai‘i is special. Hopefully people will have more appreciation and respect for the land and the sea.”

Pauline Sato, founder of Mālama Learning Center

Image by Josiah Patterson

Nature’s Stage

Text by Rae Sojot Images by Josiah PattersonKolekole Pass, a lean and exclusive trail in Wai‘anae, ascends to a plateau with sweeping views all around.

‘O Kolekole ka nuku e waiho ala ma waena o ke kula ‘o Leilehua me nā kahakai o Wai‘anae, a he nui wale kona mau mo‘olelo kahiko.

ワイアナエの隠れたハイキングスポット、コレコレ峠。オア フ島中央部の広々とした景観が望めるトレイルです。

I grew up in Wahiawā, a sleepy plantation town surrounded by fields of pineapple and bookended by O‘ahu’s two mountain ranges. To the east, the distant Ko‘olau Mountain Range was dusky, mysterious, and often covered in clouds. I preferred looking west, to the bright ridgeline of the Wai‘anae Mountain Range, which children were often told was a woman lying down in leisure repose. Romanced by the idea,

私はワヒアワで育った。かつては砂糖プランテーションがあったひ なびた町で、まわりをパイナップル畑が取り囲み、その両側をオア フ島の2大山脈にはさまれている。遠く東側に見えるコオラウ山脈 はいつも謎めいてほの暗く、雲がかかっていることが多い。子どもの 頃、私は西の空にくっきりと明るく聳えるワイアナエ山脈を見るの が好きだった。親戚のおじいちゃんやおばあちゃんが私といとこた ちに、あの山は女の人がゆったり寝そべっている姿なんだよ、と教 えてくれた。その考えが気に入って、私たちは稜線やなだらかな山

we imagined the ridges and slopes as the curves of the feminine form, a sleeping woman draped in a kapa of mountain forest. Anyone who couldn’t see it was offered a tip: See the lowest spot in the ridge, where it makes a V? That is her hip. Start there.

The dip is Kolekole Pass, a natural cleft in the nearly 4-million-year-old range, which links Wai‘anae to O‘ahu’s central plains. The area is rich with cultural and historical significance: The pass provided a path to the Kūkaniloko birthing stones, served as a battleground for warring chiefs, and was a route for cattle transit during O‘ahu’s burgeoning ranching industry. In 1937, the U.S. Army Third Engineer Battalion constructed a road linking Schofield Barracks and Lualualei Naval Magazine, O‘ahu’s primary military munitions depot. Old Hawaiian stories tell of a mysterious woman who guarded the pass and of a large, fluted boulder rumored to be an ancient sacrificial stone. Interestingly, Kolekole translates to “red” or “raw.”

Today, the area is a training ground for the military, but the trail is open to military ID holders and their guests on select days. It’s a short hike but one I

すそを女性の優雅な体のラインなのだと想像した。森の木々をカパ (木の繊維でつくった布)のようにまとって眠っている女の人の姿。

その姿を見るには、山稜がVの字を描いているところを見つければ よい。そこが腰の部分にあたる。

寝そべった女性のウェストにあたるこのV字の部分が、コレコレ 峠。400万年前に生まれた山脈に自然にできた鞍部で、ワイアナエ とオアフの中央平野の間を結ぶ、文化的にも歴史的にも重要な意 味をもつ峠だ。コレコレ峠はクカニロコ・バースストーンへの道でも あり、酋長たちの戦いの場ともなり、オアフ島で牧畜が盛んだった 時代には家畜の移動経路としても使われた。1937年には、米国陸 軍の第3工兵大隊が陸軍基地のスコフィールド・バラックスからオ アフ島最大の海軍弾薬庫だったルアルアレイまでの道路を建設し た。伝説はコレコレという名の神秘的な女性がこの峠を守っている と伝え、峠にある縦長の大きな岩は、その昔生け贄が捧げられたと ころだという噂もある。興味深いことに、「コレコレ」はハワイ語で「 赤」または「生の」を意味する。

現在、峠の付近は陸軍の演習場になっているが、軍人や軍属とその ゲストは、許可されている日にはハイキングトレイルを利用できる。 私にはとても馴染み深い、短いハイキングだ。私が子どもの頃父は スコフィールド・バラックスに勤務していたので、私は週末になると 何度となくコレコレ峠に行った。森で聴こえる物音と、そこでの静か な時間が大好きだったのだ。

Nature’s Stage

Sitting at an elevation of approximately 1,725 feet, Kolekole Pass is made even more exclusive by the military, which uses the area surrounding it as a training ground.

know well. In my youth, I spent countless weekends visiting Kolekole Pass, drawn to the forest song and the solace to be found there.

I returned to Kolekole Pass one winter morning after nearly 20 years. It was chilly when I arrived at the trailhead. I followed the series of stairs—dug into the earth and fortified with wood stubs—that wound upwards, following the pitch and yaw of the terrain. Then I started upon the wellworn track that wove further into the forest. The trail felt intimate and familiar: a path hedged with tall guinea grass and shrubs beneath a canopy of ironwoods and sweet-smelling eucalyptus. It was largely silent, save for the rushing wind. ある冬の朝、私は20年ぶりくらいにコレコレ峠を再訪した。トレイ ルヘッドに到着すると、空気はひんやりしている。コースの最初には いくつも階段がある。半分土に埋もれ、木の板でまわりを補強され た階段が斜面を巻くように登っていき、その先は上り下りがしばら く続いたあとで、よく踏み固められたトレイルは森の奥深くへと入っ ていく。森の中の小道はほっとする親しみやすさを感じさせてくれ る。道の両側にはアイアンウッドや甘い香りのユーカリの木々の下 に背の高いギニアキビや灌木が茂り、風が吹き抜けていく音のほ かには何も聞こえない。

Nature’s Stage

Nestled in the 4-millionyear-old Wai‘anae range, Kolekole Pass is a short hike with rewarding views, lush foliage, and a storied past.

A few moments later, the trail emerged onto a windswept plateau. An amphitheater of cliffs rose, majestic against a misty sky. To the east, the Leilehua plains unrolled like a bolt of green velvet. To the west, the leeward coast glittered gold and blue. I turned my face to the wind, feeling the same breathlessness and wonder I did as a child. It’s easy to feel the power, or mana, that resonates at Kolekole Pass. It’s easy to feel its raw beauty.

少し歩くとすぐにひらけた場所に出て、靄を含んだ空を背景にま るで野外劇場のような壮麗な崖がそびえているのが望める。東 にはレイレフア台地が緑色のベルベットのように広がり、西には リーワードの海岸が金色と青に輝いている。子どものときのよう に風の吹く方向に顔を向けて、息が止まりそうな感じを楽しむ。 コレコレ峠の上では、そこに満ちている力、「マナ」を感じとること ができる。ありのままの自然の美しさを感じることができるのだ。

ふるさとの味 Life

Served with Love

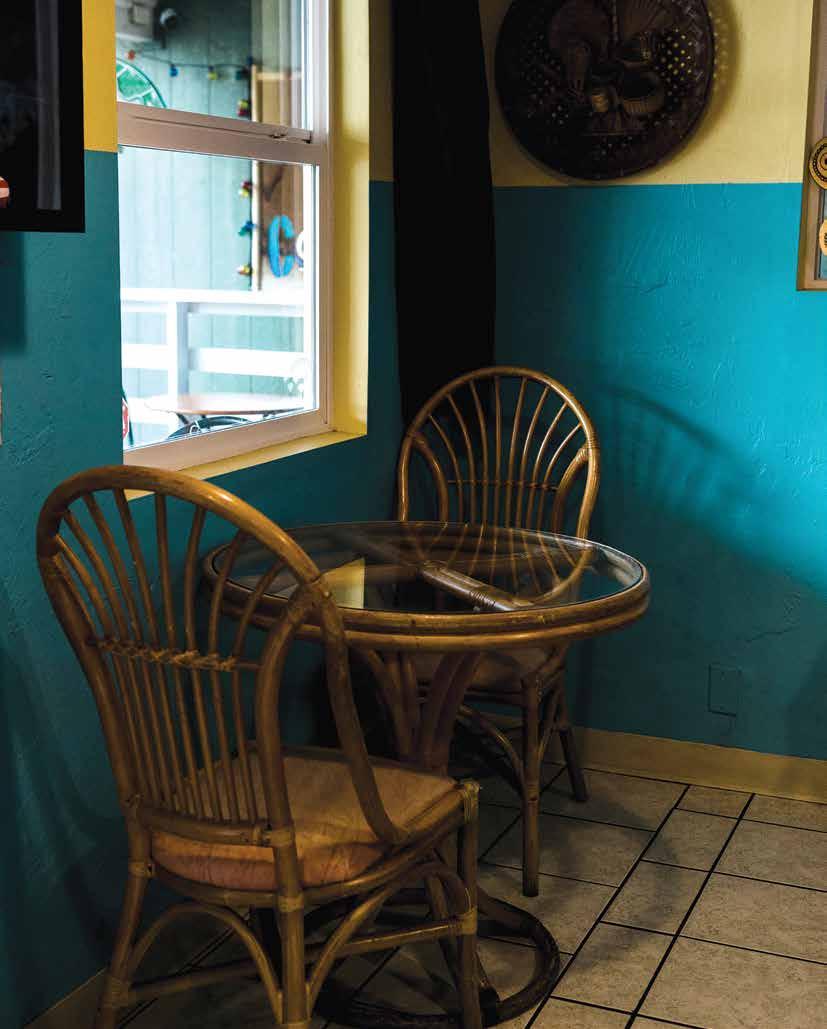

Text by Rae Sojot Images by John HookA restaurant owner bridges her twin love for Puerto Rico and Hawai‘i with a Latin-inspired menu.

Kāwili ‘ia e kekahi mea ‘ona hale ‘aina kona make‘e ‘āina no Pokoliko a me Hawai‘i ma o nā ‘ai kū i ka Lākina.

カリブ海の島から太平洋の島へ。ウエストオアフの小さな レストランが、プエルトリコの本場の味を伝えています。

Stevina Kibuya is an island girl, and she can call two islands home to prove it.

Originally from Puerto Rico, Kibuya came to O‘ahu in 2010 to spend time with her sister, whose husband had been deployed to Afghanistan. Her plan was to stay only a year. But life had other ideas: She met Fred Kibuya, a local guy of Puerto Rican heritage from the leeward side. The two fell in love, got married, and settled in his hometown of Wai‘anae.

Prior to arriving on O‘ahu, Kibuya, who trained at the Culinary Institute of America in New York, was immersed in the restaurant industry on the East Coast, working as a pastry chef, restaurant consultant, and trainer. “I was raised by parents who taught me to follow my dreams,” Kibuya says.

It wasn’t long after her wedding that she felt the familiar entrepreneurial itch and decided she would open a bakery. One afternoon, while driving along Farrington

ステヴィナ・キブヤさんは、二つの島を自分の「ホーム」と呼ぶ、生粋 の「アイランド・ガール」だ。プエルトリコ出身のキブヤさんは、2010 年に妹を訪ねてオアフ島にやって来た。妹の夫がアフガニスタンに 派遣されているあいだの1年間だけ滞在するつもりだったが、人生 は思わぬハプニングを用意していた。オアフ島のリーワードに住む プエルトリコ系のローカル男性、フレッド・キブヤさんと出会ったの だ。二人は恋に落ち、結婚して、彼のホームタウン、ワイアナエに落 ち着いた。

キブヤさんはニューヨークのキュリナリー・インスティチュート・オ ブ・アメリカで技術を磨いたあと、ハワイに来る前はペストリーシェ フ、レストランのコンサルタント、トレーナーとして働き、米国東海岸 の外食産業を知りつくしていた。「両親から、夢を大切にしなさいと 教えられて育ったのです」

結婚してすぐにまた事業を始めたくなり、ベーカリーを開業しよう と心に決めた。ある日の午後、ファーリントン・ハイウェイを運転し ていたときに、プランテーション様式の小さな家が商業区画の中に

Served with Love

Coquito’s has become La Casita to many Puerto Ricans who are here in Hawai‘i,”

Stevina Kibuya says. “And to be able to offer a piece of Puerto Rico here in Hawai‘i has been an honor.”

Highway, she noticed a plantation-style house sitting on a small, commercial lot. It was up for lease. “I knew it was the place for me,” Kibuya says. Some market research led her to determine a swanky dessert shop would be a mismatch for the neighborhood. “Wai‘anae isn’t like New York,” Kibuya laughs, referring to diehard foodie urbanites who make an art out of waiting in line for fancy sweets. So instead of high-end desserts, Kibuya went homespun, inspired by the dishes of her childhood.

In 2012, she debuted Coquito’s, bringing flavors of the Latin American and Caribbean diaspora—from Columbian and Cuban to Mexican and Argentinian— to O‘ahu’s West Side. The Puerto Rican dishes remain its star attractions.

ぽつんと建っているのを目にした。貸出中の物件だった。「これがわ たしの店だ、とピンと来たんです」とキブヤさん。でも市場を少しリ サーチしてみて、その地区にはおしゃれな高級デザートショップは 向かないことが分かった。「ワイアナエはニューヨークじゃありませ んから」と、キブヤさんは笑う。高級スイーツの店にグルメたちが並 ぶ都会とは違う戦略が必要だった。そこで、ハイエンドのデザート の代わりに、子ども時代に親しんだ味にヒントを得た料理を出すこ とに決めたのだという。

2012年、キブヤさんの店「コキート」が開業し、ラテンアメリカとカ リブ海、コロンビア、キューバ、メキシコ、アルゼンチンの味をオアフ 島ウエストサイドに持ちこんだ。なかでも主役はプエルトリコ料理。 すべて手作りにするのは時間もかかるし、輸入食材(たとえば、モフ

Although making everything from scratch is time-consuming and requires the expensive importation of many ingredients, like plantains for mofongo, Kibuya believes it’s worth the effort. “Having people eat my food and then wanting to meet me to tell me it reminds them of their abuelita’s cooking fills me with joy,” Kibuya says.

In the near decade since opening its doors, Coquito’s has become more than just a place to grab pastele stew or alcapurrias. The little green plantation house has become exactly what Kibuya had hoped for: a festive, gathering space that welcomes all. Inside, guests are treated to a kaleidoscope of colors and sounds. Walls painted lemon yellow and blue channel the tropics, and upbeat Latin music plays on the stereo. Puerto Rican pride is displayed via decorative flags, maps, and patriotic tchotchkes. Holding court in the center of the restaurant is a wooden table —a collaboration between Kibuya and Yelenys Calabrese, an artist and friend—inlaid with a vibrant depiction of a Puerto Rican landscape and shells collected from neighboring beaches. If it’s not being used for eating, it’s a favorite place to play dominos.

Having the restaurant allows Kibuya to feel closer to Puerto Rico, at least in spirit. “Coquito’s has become La Casita to many Puerto Ricans who are here in Hawai‘i,” Kibuya says. “And to be able to offer a piece of Puerto Rico here in Hawai‘i has been an honor.”

ォンゴに使うプランテンなど)は高くつくが、キブヤさんはそれだけ の価値があると考えている。「うちの店の料理を食べたお客様がわ ざわざ私に会いに来て、おばあちゃんの味を思い出したよ、と言って くれると、嬉しさでいっぱいになります」

オープンから約10年。コキートの魅力は、パステレシチューやアル カプリアだけではない。小さな緑色のプランテーションハウスのレ ストランは、キブヤさんが思い描いたとおりの、にぎやかで、誰もが 歓迎される集いの場になった。店内は明るい色と音でいっぱいで、 レモンイエローとブルーの壁がトロピカルな気分を引き立て、ステ レオからはアップビートなラテン音楽が響く。プエルトリコの旗や 地図、こまごました愛国的モチーフの小物が並び、故郷への熱い誇 りを示している。店の中央に置かれた木製のテーブルには鮮やかな 色彩でプエルトリコの風景が描かれ、近くのビーチで拾い集めた貝 殻が埋め込まれている。キブヤさんと友人でアーティストのイェレ ニス・カラブレーゼさんとの共同作品だ。このテーブルは食事のた めではなくて、ドミノ遊び用に使われている。

この店のおかげで、キブヤさんはプエルトリコを身近に感じること ができるという。「コキートは、ハワイに住むプエルトリコ人にとって 『ラ・カシータ』(小さな家)になりました。ハワイの人たちに小さな プエルトリコを紹介できて光栄です」とキブヤさんは語る。

A Community Connects

Text by Laurel Dudley Images by

Josiah PattersonNative Hawaiian values and island traditions inspire the ethos behind Mālama Learning Center, where the concepts of mālama (to take care) and mālamalama (enlightenment) are celebrated through hands-on craft workshops and programs.

Na ke kū‘auhau Hawai‘i e ho‘oulu i ka mākia no ka Mālama Learning Center, ‘o ke kaulona i nā papahana no ka hana no‘eau, akeakamai, ho‘omauō, a me ka mo‘omeheu.

マラマ・ラーニングセンターは、実践的なプログラムを通し て、マラマ(大切に育む)とマラマラマ(啓発)という理念を 育て、ハワイの伝統を伝えています。

“Watch out for bubbles,” Sayo Costantino tells a woman who is dipping a scrunched white tea towel into a bucket of blackish liquid. Others watch, awaiting their turns, holding towels they’ve secured with pebbles, wrapped with string, or clipped with clothespins. Costantino is teaching shibori, the traditional Japanese handicraft of dyeing fabrics, of which tie-dye is one of many styles. The liquid is indigo, grown and made by Costantino. And the bubbles, she explains, are to be avoided because they indicate oxygen, which can impede the color adhering to the fabric.

「泡に気をつけてね」と、サヨ・コンスタンティノさんが注意する。 生徒の女性は、きゅっと絞った白いティータオルをバケツの中の黒 っぽい液体に浸けようとしているところだ。順番を待つほかの生徒 も、小石を入れて包んだり、紐で結んだり、洗濯バサミであちこちを 留めたティータオルを手に順番を待っている。コンスタンティノさ んが教えているのは、日本に伝わる多くの染色技術の一つ、絞り染 めだ。使うのは彼女が自ら育てた藍(インディゴ)の染料。泡を避け る理由は、泡の中の酸素が布地への染料の浸透を妨げることがあ るからだそうだ。

The workshop is part of Mālama Learning Center’s program Without Walls, or WOW. Held monthly and open to all, its workshops take place at locations determined by topic—a garden for planting, a kitchen for cooking, a community room for weaving. But the goal remains the same: to bring the community together for hands-on learning about sustainable living. For Costantino, shibori is a personal passion and also a neat way to repurpose things. “I think of it as expanding our knowledge on how to do things,” she tells the attendees. “In doing that, we learn how to look at our resources differently.”

Taking care of resources is a shared theme among all programs of Mālama Learning Center, which was founded in 2004. The center’s primary goal is to bring middle and high school students, mostly from Waipahu to Wai‘anae, to nearby destinations to learn about science, conservation, art, and culture. Activities include lauhala weaving, hau cordage making and braiding, and wetland restoration.

Just a short walk from the shibori workshop, the center’s founder and executive director, Pauline Sato, shows me one of its native reforestation sites. Wire fencing surrounds the two acres, which look small amid swaths of open land. They also look different—the weeds and tall grass that span the hillside are absent inside the fence. Instead, clustered together are plants and young trees which Sato identifies: wiliwili (Hawaiian coral tree); ‘a‘ali‘i (Hawaiian hopseed bush); lonomea (O‘ahu soapberry tree), and ‘ilima (a native Sida). Students and volunteers planted each one.

このクラスは、マラマ・ラーニングセンターのプログラム「ウィズア ウト・ウォールズ(WOW)」の一部として毎月1回開催されるワー クショップの一つ。開催場所は内容によりさまざまで、植物につい てのクラスなら庭園で、料理教室ならキッチンで、手織りならコミ ュニティルームで、という具合だが、サステイナブルな暮らしの技 術を通してコミュニティをつなげるという目的はどのクラスにも共 通している。コンスタンティノさんにとって絞り染めは情熱であり、 同時に不要なものを再利用する気の利いた方法でもある。「いろ いろな生活の技術をより多く知るための方法だと思います。資源 の使い方についても違う視点から見られるようになりますし」 資源を大切にするというのは、2004年に開設されたマラマ・ラー ニングセンターの全プログラムが共有する課題だ。センターは主 にワイパフとワイアナエに住む中学生と高校生が、科学、環境保 全、アート、文化について近隣のさまざまな場所に行って学ぶ機 会を提供することを第一の目標としている。アクティビティにはラ ウハラ編み、ハウの木の繊維を使ったロープ作り、湿原の復元作 業などがある。

絞り染めのワークショップが行われている場所のすぐ近くにある 植生復元中の一画へ、センターの創設者でありエグゼクティブ・デ ィレクターのポーリーン・サトウさんが案内してくれた。針金のフェ ンスで囲われた8,000平方メートルほどの保護緑地は広い草地 の中ではごく小さな一画だが、まわりとは様子が違う。草地にたく さん生えている丈の高い雑草はフェンスの中には一本もなく、そ の代わりに一群の若木が育っている。サトウさんは、あれがウィリ ウィリ、アアリイ、ロノメア、イリマ、と指さして教えてくれる。どれも ボランティアや学校の生徒たちが植えた木だ。

「この木々は皆それぞれにハワイ文化につながる物語や用途を 持っているのです」と、コアの苗木にかがみ込み、葉を検分しな がらサトウさんは言う。規模こそごく小さいが、目標は人びとにハ ワイ原生植物について知ってもらい、復元の可能性を示すことだ という。

A

Community Connects

Through Mālama Learning Center’s site-restoration projects, students and volunteers can join the effort to remove invasive species and reforest the landscape with native plants.

“All of these have a cultural story and a purpose,” Sato says, bending down to examine the leaves of a koa sapling. The site is a speck among the mountain, but the goal is to teach people about native plants and demonstrate that reforestation is possible.

“We know Hawai‘i is special,” Sato says of the inspiration behind the center’s programming. “By building these connections, hopefully people will have more appreciation and respect for the land and the sea and the culture that they come from.”

「ハワイは、とても特別な場所です」。サトウさんは、センターのプ ログラムを支えるインスピレーションについてそう語る。「こうして つながりを築いていくことで、人々がもっと土地や海に、そしてそ こから生まれた文化に、理解と敬意を抱くようになってほしいと 願っています」

「ハワイは、とても特別な場所です」。サトウさんは、センターのプ ログラムを支えるインスピレーションについてそう語る。「こうして つながりを築いていくことで、人々がもっと土地や海に、そしてそ こから生まれた文化に、理解と敬意を抱くようになってほしいと 願っています」

Image by Josiah Patterson

Image by Josiah Patterson

by John Hook “

We had to learn, especially if we wanted to restore this place.”

Eric Enos, director of Ka‘ala FarmImage

A U T R E E S

Dancing Queen

Miss Aloha Hula Taizha Keakealani

Hughes-Kaluhiokalani and her kumu hula reflect on her triumphant journey.

Text and images by IJfke Ridgley

Ma ka ‘ao‘ao o kāna mau kumu hula, hō‘ike mai ‘o Taizha Keakealani Hughes-Kaluhiokalani i kona ho‘oikaika ‘ana iā Merrie Monarch, me ka nalu ‘ana ona i ka lanakila hanohano he Miss Aloha Hula.

2019年ミス・アロハ・フラ優勝者、テイザ・ケアケアラニ・ヒュ ーズ=カルヒオカラニさんがフラと共に歩んだ軌跡を語ります。

As she dances along the shoreline of Diamond Head Beach, her pleated skirt dipping in the water and her hair catching the light like spun gold, hula dancer Taizha Keakealani Hughes-Kaluhiokalani radiates strength and grace. She moves under the watchful eyes of one of her kumu hula (hula teachers), Ke‘ano Ka‘upu, who stands nearby in the strong setting sun. He and his partner, Lono Padilla, lead Hālau Hi‘iakaināmakalehua, the hula troupe Hughes-Kaluhiokalani has been a member of since 2016.

“I’m surprised he’s lasted this long,” Hughes-Kaluhiokalani says about Ka‘upu, giggling conspiratorially. “He hates being in the sun.” It is clear the three have a familial bond, the result of years dancing together and intense hours spent preparing Hughes-Kaluhiokalani for her debut solo act at the 2019 Merrie Monarch Festival, a week-long competition that celebrates Hawaiian art, music, culture, and dance. Held annually in Hilo since 1971, the competition is considered paramount in the hula world. Only the most elite hālau (hula schools) from Hawai‘i and beyond are invited to compete. Each hālau spends months preparing to perform the requisite kahiko, a solemn, traditional dance performed to a chant and percussive beat, and ‘auana, a charming, modern dance performed to a song accompanied by contemporary

スカートの裾を波が洗い、髪は夕陽を受けて黄金の糸 のように輝く。ダイヤモンドヘッド・ビーチの波打ち際 で踊るテイザ・ケアケアラニ・ヒューズ=カルヒオカラ ニさんの姿は、力強さと優雅さを放っている。沈みか かった太陽が投げかける強い光の中で踊る彼女を見 守るのは、彼女のクム・フラ(フラの師)の一人、ケアノ・ カウプさんだ。カウプさんがパートナーのロノ・パディ ラさんと共に率いるハーラウ・ヒイアカイナマカレフア に、ヒューズ=カルヒオカラニさんは2016年から所属 している。

「こんなに長い時間つきあってくれると思わなかっ たわ」と、クスクス笑いながらクムの方を見る。「日光 に当たるのが嫌いなのに」。この三人が親しい絆で 結ばれているのは一目瞭然。師弟は何年も一緒に踊 り、2019年のメリー・モナーク・フェスティバルでの ヒューズ=カルヒオカラニさんのソロパフォーマンス のために、長時間にわたる厳しい練習を共に重ねてき た。メリー・モナークはハワイ島のヒロで1週間にわた って繰り広げられる、ハワイのアート、音楽、文化、そし てフラの祭典で、1971年に始まったコンペティショ ンはフラの世界で最高の権威があり、ハワイ、そして世 界中からよりすぐりのハーラウ(フラ教室)が集い、技 を競う。それぞれのハーラウは「カヒコ」(チャントとパ ーカッションのリズムだけを伴う荘重な古典フラ)と「 アウアナ」(スティールギターやウクレレなど現代の楽 器の伴奏による優美なモダンフラ)を何か月もかけて

hula is a part of me because that ’ s where i found my identity. ”

instruments like steel guitar and ‘ukulele. It was here, too, that Hughes-Kaluhiokalani was crowned Miss Aloha Hula.

“I like to say that hula is a part of me, because that’s where I found my identity,” says Hughes-Kaluhiokalani, who grew up in Wai‘anae. When Hughes-Kaluhiokalani was three, her mother enrolled her in Tahitian dance lessons as a means to focus the toddler’s energy while she cared for Hughes-Kaluhiokalani’s younger brother, who was born with special needs. By 8 years old, Hughes-Kaluhiokalani had turned her focus to hula.

Although winning the title of Miss Aloha Hula is a great honor, it was never HughesKaluhiokalani’s primary intention. Instead, it was about learning as much as she could from her kumu hula, who both come from strong hula traditions. Ka‘upu danced from a young age on Hawai‘i Island, and Padilla grew up in a family of kumu hula on Maui. In 2008, the pair completed their ‘ūniki (graduation) ceremonies to become kumu hula under Padilla’s mother, Hōkūlani Holt. That same year, the duo started Hālau Hi‘iakaināmakalehua, which means “Hi‘iaka in the eyes of the lehua,” with just four girls. Today, the hālau has around 250 members in Hawai‘i and 125 members in Japan.

練習し、磨き上げるのだ。ヒューズ=カルヒオカラニさ んは昨年、その競技会のソロ部門で見事優勝し、「ミ ス・アロハ・フラ」の称号を手にした。

フラは私の一部です。私は自分自身をフラの中に見つ けたのですから」。ワイアナエ出身の彼女は、3歳のと きタヒチアンダンスのクラスに通い始めた。障害を持 つ弟が生まれたばかりで、母は幼い娘のありあまるエ ネルギーを何かに集中させたいと思っていたのだ。8 歳の頃にはフラに熱中するようになっていた。

ミス・アロハ・フラに優勝したのは大きな栄誉だけれ ど、それは究極の目標ではなく、それよりも、何代にも わたるフラの伝統を受け継ぐ二人のクム・フラからで きる限り多くを学びたいと考えているそうだ。カウプ さんは少年時代からハワイ島でフラを踊り、パディラ さんはマウイ島のクム・フラの家系に生まれた。2008 年、二人はパディラさんの母でありクム・フラでもある ホクラニ・ホルトさんのもとでウニキ(卒業)の儀式を 終え、同じ年にハーラウ・ヒイアカイナマカレフア(「レ フアの目に映るヒイアカ」という意味)を設立した。当 時の生徒は4人の少女だけだったが、現在ではハワイ に250名、日本に125名の生徒を持つハーラウに成 長している。

In readying the hālau for Merrie Monarch, both Ka‘upu and Padilla believe that an alignment of purpose and values is paramount. The kumu hula help the haumana (student) with music, choreography, and costume design. All decisions are made by the kumu, as each dancer “is the vehicle to carry forth the vision of the kumu,” Ka‘upu says. They also aren’t driven by a need to win: “We don’t train for competition, we train to be good hula dancers,” Padilla says. Adds Ka‘upu, “We look at training as 24-7, year-round, from the time you start your hula journey to the time you end.”

二人のクム・フラは、メリー・モナークに向けての準備 にあたり、ハーラウの目的と価値観を整えることが最 優先だと考えた。クム・フラは、ハウマナ(生徒)を音 楽、振り付け、コスチュームデザインの面で助け、すべ ては最終的にクムが決定する。踊り手は「クムのビジ ョンを運ぶ乗り物」だから、とカウプさんは説明する。 クム・フラたちも、競技会で勝つことを目的とはしてい ない。「コンペティションのための訓練ではなく、良い フラダンサーになるための訓練なのです」とパディラ さんが言うと、カウプさんがつけ加える。「毎日24時間 が訓練なのですよ。フラを始めた瞬間から、最後のと きまでね」。

Months earlier, while choreographing the dances that would serve as HughesKaluhiokalani’s solo performances, Ka‘upu and Padilla had asked about her native lineage. They were impressed by her family’s ample documentation and the importance of the people mentioned. Though her family knew about their royal ancestry, they were protective of the information and hadn’t taught HughesKaluhiokalani about it while she was growing up. For Hughes-Kaluhiokalani, the opportunity to learn about her heritage through her kumu was a blessing. “I’ve learned a lot about those people in my documents. They are in my chant, in my mele, and being able to dance about them and present about them on that stage was a magical thing to do,” she says. “For the first time it felt like I know who I am not just as a Hawaiian but as a descendent of them.”

On the night of the soloists’ competition in April 2019, Hughes-Kaluhiokalani carried the weight of her ancestors’ stories with her. She introduced her kahiko performance with an oli (chant) about the royal lineage of Līloa, an ancestor of hers from Waipi‘o Valley on Hawai‘i Island. Her ‘auana was danced to a mele (song) about the love story between Līloa and ‘Akahikuleana, a woman of a much lower status, and the son, ‘Umialīloa, who was a product of their love. Hughes-

数か月前、ヒューズ=カルヒオカラニさんのソロパフォ ーマンスの振付をしていたとき、二人のクムは彼女の ネイティブハワイアンの血筋について尋ね、その家系 に多くの記録が残されていること、そして祖先に重要 な人物がいたことに驚いたという。彼女の家族は先祖 に王族がいたことを知っていたが、それをあまり口外 しようとしなかったので、彼女自身もそのときまで知ら なかった。自分の祖先についての事実をクムたちから 聞いたというのは祝福だった、と、ヒューズ=カルヒオ カラニさんは語る。「その記録を読んで、自分の祖先に ついて多くを学びました。私の先祖が、私が詠唱する チャントに、メレに歌われているのです。先祖の物語を 舞台で表現できるとは、魔法のような経験でした。自 分がハワイアンというだけでなく彼らの子孫だという ことを知って、生まれてはじめて、自分が誰なのかを知 った気がします」。

昨年4月のメリー・モナークの舞台に、彼女はその先 祖たちの物語の重みを担って立ち、カヒコのパフォー マンスの前には自分の祖先の一人で、ハワイ島のワイ ピオ渓谷に住んだ王族、リロアについてのオリ(詠唱) を披露した。そしてアウアナでは、リロアと身分の低い 女性アカヒクレアナ、そしてその二人の間の息子ウミ アリロアの物語を歌ったメレ(歌)にあわせて踊った。 ソロパフォーマンスの間、彼女の存在感は舞台いっぱ

Kaluhiokalani’s presence during those performances filled the stage and reached 5,000 people in that stadium—a talent, explains her kumu, that takes “a special kind of dancer.”

To know she had a purpose beyond winning is music to her teachers’ ears, because, as Ka‘upu points out, winning Miss Aloha Hula is a lot about luck, as all contestants at that level are exemplary. But he is quick to define the most noteworthy characteristic of HughesKaluhiokalani’s dancing. “The thing that grabs me is that she’s expressive,” he says. “Hula is nothing if there is no emotion.”

いに力強くあふれ、スタジアムを埋める5,000人の観 客の心を動かした。「特別なダンサーにしかない才能 ですよ」と彼女のクムたちは賞賛する。

ヒューズ=カルヒオカラニさんは、クムの言葉に熱心に 耳を傾け、自分で話すときには慎重に言葉を選びなが ら雄弁に語る。クムによると、ステージで感情を大きく 表現するのと裏腹に、実生活の彼女は「とてもシャイ」 なのだそうだ。1年にわたりメリー・モナークを代表し てさまざまな場に出席するというミス・アロハ・フラの 責任ある立場は、内気な彼女にとっては大きなチャレ ンジとなった。「皆が私の一挙手一投足を常に観察し ているのに気づきました。踊りだけでなく、私の存在が インスピレーションになっていれば嬉しいのですが。 ミス・アロハ・フラであるというのは、踊り手であると いう以上の意味があると思います。自分がどんな人間 か、人生に何を見、何を目的として生きているかという ことも問われるのです」 Dancing Queen

Hughes-Kaluhiokalani listens attentively when her kumu speak. When she speaks, she’s measured and eloquent. Contrary to what her emotional stage presence may imply, in person, she’s a “shy violet,” as her kumu say. As Miss Aloha Hula, she serves as an ambassador for Merrie Monarch for the year, a challenge for such a private person. “I realized that everyone was watching and I am constantly under a microscope,” she says. “I hope to inspire not just with my dancing but in life as a person. I think there is so much more to being Miss Aloha Hula than being a dancer. It starts with who you are as a person and what your outlook is on life and what your purpose is.”

優勝するよりも大切な目的があるという彼女の言葉 は、クムにとっては美しい音楽のように響く。なぜな ら、候補者たちはいずれも実力では抜きん出ているの で、ミス・アロハ・フラに選ばれるかどうかは運の要素 も大きいからだ、とカウプさんは言う。彼女の踊りの持 つ魅力について、カウプさんはこう語る。「表現が豊か なところに惹きつけられますね。踊りに感情がこもって いなければ、フラにはなりませんから」。

Back to ‘Āina

Ka‘ala Farm digs deep to reconnect with land and community.

Text by Eunica Escalante

Images by IJfke Ridgely

He kanakolu makahiki aku nei, ua ‘imi a loa‘a he lo‘i i waiho wale ‘ia iā Eric Enos, nāna ‘o Ka‘ala Farms i ho‘okumu, ua ‘ike mua nō ‘o ia i ka waiwai o ia mea.

ウエストサイドのカラフルな壁画が、文化と歴史に 対する人びとの誇りを育む役割を果たしています。

Eric Enos is shin-deep in a taro patch. From my spot across the field, I watch as he marches alone through the bed of thick mud. A rich layer of clay coats his legs and hands, his face bronzed from hours working under the Wai‘anae sun.

Before Enos found this stretch of ancient taro patches in 1976, he had little experience with farming. Today, he oversees the more than 100 acres in Wai‘anae Valley occupied by Ka‘ala Farm as its co-founder and director. “I gardened, but never taro,” he says as he washes off the mud with a makeshift faucet. “But we had to learn, especially if we wanted to restore this place.” He nods toward the rolling hills that surround us.

In 1976, Enos was working at the Rap Center, a substance-abuse rehabilitation program for students from Wai‘anae and Nānākuli high schools. The program’s ethos was to reconnect the youth to the ‘āina (land). “It was the ’70s, you know,” Enos says. “There were all of these indigenous peoples’ movements saying that we need to get back to the traditional practices that are taking care of the land.”

In Hawai‘i, it was the height of a Hawaiian renaissance, a period of Native Hawaiian activism and renewed interest in Hawaiian culture. The crew of Hōkūle‘a , a traditional Back to ‘Aina

エリック・イノスさんは、ふくらはぎまで泥に埋めてタ ロ畑に立っている。深いぬかるみの中を一人でこちら に向かってやってくるイノスさんは手も脚も粘土質の 泥にまみれ、ワイアナエの日ざしの下で長年畑仕事を してきた顔はブロンズ色に日焼けしている。

1976年にここに古代のタロ畑を見つけた時、イノス さんはほとんど農作業を経験したことがなかったが、 今日ではカアラ農園の共同創設者兼ディレクターと して、ワイアナエ渓谷の40ヘクタールを超える畑を監 督している。「庭仕事はしてたけど、タロを植えたこと はなかった。でも学ばなくちゃならなかった。ここを復 元したかったからね」畑の簡易蛇口で手を洗いながら そう語り、畑を取り囲むゆるやかな丘陵にむかってう なずく。

1976年、イノスさんは、ワイアナエとナナクリの高校 生を対象とする薬物依存症リハビリテーションプログ ラム「ラップ・センター」で働いていた。プログラムの目 的は、若者とアイナ(土地)のつながりを取り戻すこと だった。「70年代でね、当時はあちこちで、先祖と同じ やり方に還って土地を大事にしようという先住民運動 が盛んだった」とイノスさん。

ハワイではその頃、ネイティブハワイアンの活動家た ちが勢いを得、ハワイ文化に新たな関心が向けられ て、第二次ハワイアンルネッサンス運動が最盛期を迎 えていた。ホクレア号が西洋の技術を使わずポリネシ

Polynesian voyaging vessel, completed its first voyage without Western sailing instruments. The Kaho‘olawe Nine landed on Kaho‘olawe in protest of the U.S. Navy’s use of the island as a bombing range. And deep in Wai‘anae Valley, Enos was bringing a band of youths to the land that their ancestors lived off of centuries before.

It was on a group camping trip on Mount Ka‘ala that Enos and the students stumbled upon stonework reminiscent of ancient kalo lo‘i systems. “We discovered all of these walls underneath all the grass,” he says. They were rock terraces that once functioned as irrigation systems for fields of kalo, also known as taro, a primary source of food for Native Hawaiians.

It turned out to be possibly the most intact agricultural system on O‘ahu, Enos believes, though far from its former glory. According to Enos, Wai‘anae was once the poi bowl of the Leeward side, yielding more taro—which would go on to be pounded into the staple Hawaiian starch poi, among other preparations— than what is produced in all of Hawai‘i today. From our vantage point at the edge of the farm, he gestures toward the hundreds of acres of wilderness beyond. “This whole valley,” he marvels. “Bishop Museum showed us a map—it used to be all taro production.”

アの伝統的な航法だけで遠洋航海を終え、「カホオラ ヴェの9人」と呼ばれた活動家たちは米国海軍が爆撃 演習に使っていたカホオラウェ島に抗議のため体を張 って上陸した。それと同じ頃、イノスさんは若者たちを 連れて、ワイアナエ渓谷の奥まった場所、彼らの祖先 が何世紀も生活の糧を得ていた土地へ出かけた。そし てカアラ山へのキャンプ旅行の途中で、古代のカロ・ ロイ(タロ畑)跡を発見したのだ。「草の下にすっかり 埋もれていた石の壁を見つけたんだ」。その石組みは ネイティブハワイアンが主食としていたタロ畑の灌漑 システムの一部だと分かった。

イノスさんの考えでは、その遺跡は農業設備のものと してはおそらくオアフ島で最も完全な形で遺されてい たものだが、往年の栄光は見る影もなかった。イノス さんによれば、ワイアナエにはかつて豊かにタロ畑が 広がり、現在ハワイ州で栽培されているタロを全部合 わせたよりも多くのタロが収穫されていたはずだとい う。ハワイアンたちはタロをすりつぶして主食のポイ を作った。ワイアナエはいわば、リーワードの「ポイ・ ボウル」だったというわけだ。イノスさんは畑の縁に立 ち、何十ヘクタールも広がる野山を指して言う。「この 渓谷がみんな、一面のタロ畑だったんだよ。ビショッ プ博物館で見せてもらった地図にもその記録が残っ ているんだ」

a rich layer of clay coats his legs and hands, his face bronzed from hours working under the wai ‘anae sun.

For decades, Western colonization disrupted traditional Native Hawaiian ways of living, including the maintenance of the lo‘i. Wai‘anae was one of the last strongholds of taro farming, due in large part to its robust Native Hawaiian community, but in the 1800s, a burgeoning cattle industry cleared the valley, turning taro patches into pastureland. Sugar plantations dealt a final, devastating blow, diverting streams that had fed the lo‘i systems to water fields of sugarcane. With its lifesource cut off, the valley dried up. The remaining taro patches that hadn’t been bulldozed sat fallow, and the surrounding forest crept in.

By the time Enos discovered the system, it was nothing more than stones buried under a thick bramble of haole koa trees. Yet he couldn’t ignore its cultural significance. Taro was among the first plants brought by the Polynesians who settled in the islands. For Native Hawaiians, taro is also more than just a plant. Hawaiian mythology tells of how Wākea (sky father) and Papahānaumoku (earth mother) planted the body of their stillborn first son in the earth, and it grew into the first taro plant. Taro is seen as a direct ancestral connection to the divine powers of nature.

ネイティブハワイアン伝統の暮らしは植民地化により 何十年もの間途絶え、タロ畑の手入れも過去のものと なっていた。ワイアナエには活気あるハワイアンのコミ ュニティがあったため、ハワイでも最後までタロの栽 培が続けられていたが、1800年代に牧畜産業が渓谷 に進出し、タロ畑を牧草地に変えてしまった。さらに砂 糖産業が追い打ちをかけた。タロ畑に注がれていた水 がサトウキビ畑の用水に転用されてしまったのだ。命 の源である水を失い、渓谷は干上がった。壊されなか ったタロ畑にも作物が植えられることはなくなり、や がて少しずつ森に覆われていった。

再発見された灌漑システムは、うっそうとしたコア・ハ オレの藪に埋もれた石垣でしかなかったが、イノスさ んはその文化的重要性を見過ごすわけにはいかなか った。タロは、最初にハワイに渡ったポリネシア人たち がカヌーで持ち込んだ植物の一つであり、ネイティブ ハワイアンにとってはたんなる植物以上の意味を持 つ。ハワイの神話が伝えるところでは、空の父なる神ワ ケアと大地の母なる神パパハナウモクの間の最初の 息子が死産だったので、その亡骸を埋めたところ、タロ となって育ったという。ハワイアンにとってタロは自然 の崇高な力に直接つながっているのだ。 Back to ‘Aina

Enos and his group hiked into the valley in search of water to feed the land and discovered some trickling from a leak in a pipe that been built to feed the nowdefunct Wai‘anae Sugar Plantation but was now being used as a general conduit by the Honoulu Board of Water Supply. The rivulets weren’t to be used as a public water supply, since they were already escaping into the open environment. Enos applied for a permit to irrigate the taro using this source but was denied.

Enos decided to use the water anyway. In the summer of 1978, Enos, with the help of Wai‘anae community members, built a PVC pipe system from the leak to where Ka‘ala Farm stands about one mile away. When charged by the state for illegal water diversion six months later, Enos appeared before the Board of Land and Natural Resources to make his case. He brought all of the research he used for his original permit application as well as binders of paperwork outlining the area’s cultural legacy and the work the youth had been doing in restoring it. In the end, Enos explains, the board decided that the water “was outside of the state’s jurisdiction.” He pauses for dramatic effect: “But they didn’t say no!” The board allowed the water to flow, and it hasn’t stopped since.

イノスさんたちは渓谷に分け入り、水源を探した。そし て、かつてそこにあった砂糖プランテーションのため に造られ、現在はホノルル水道局が導管として使用し ているパイプからちょろちょろと水が漏れ出している のを見つけた。パイプの裂け目からの小さな流れは、 自然環境の中に流れていくだけで水道水としては使 われていなかった。その水をタロ畑の灌漑に使う許可 を申請したところ却下されてしまったが、イノスさんは 構わずに水を使うことにした。

1978年、イノスさんとワイアナエの人びとはポリ塩化 ビニールのパイプで取水システムを造り、導管から漏 れ出した水を1.6キロ先の現在カアラ農園がある場所 まで引いた。その半年後、違法に取水をしたとして罪 に問われたとき、イノスさんはハワイ州土地天然資源 局に対して言い分を主張した。それまでに行ったすべ ての調査の資料、最初に取水を申請した時の書類、そ してこの土地の文化的遺産についての資料と、若者た ちがそれを再建するために行ってきた作業について概 要を説明したバインダーを何冊も持ちこんだのだ。結 局、取水権は「州の司法管轄外にある」というのが資 源局の結論だった、とイノスさんは語り、ドラマチック にひと息置いてから言葉をついだ。「でも、駄目だとは 言われなかったんだよ!」。資源局は取水を認め、水は それ以来今も流れ続け、畑をうるおしている。

Back to ‘Aina

In the four decades since Enos and his group planted the first taro root, Ka‘ala Farm has become a pillar of the Wai‘anae community. Schools throughout O‘ahu take their students to the farm. Some like Nānākuli High and Intermediate School, have incorporated it into curriculae. The school’s ‘A‘ali‘i program allows struggling students to make up credits by learning how to grow Hawaiian staples such as ‘ulu (breadfruit) and taro on their own plots of land. Program directors Kathryn Fisher and Jewelynn Kirkland take students to the farm every week. “We’re learning to take more care of our ‘āina,” said program participant Kam Arrington. “When we came here, it changed us a lot.”

Enos believes that Ka‘ala Farm can act as a model for systemic change for other organizations (its success inspired Ka Papa Lo‘i ‘o Kānewai at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa) and the Wai‘anae community itself.

“He wasn’t just trying to reclaim the ability to grow food,” Enos’ son Kamuela Enos recalled of his father’s efforts in a 2018 PBS Hawai‘i interview. “He was trying to reclaim the ability to grow people, and therefore, the ability to regrow community.”

イノスさんたちが最初にタロを植えてから40年。カア ラ農園は、ワイアナエのコミュニティにとって大きな柱 のような存在となった。現在はオアフ島中の学校から 生徒たちが農園を見学にやって来る。ナナクリ中学・ 高校では教科にこの農園での実習を組み込んでいる。

学科の成績がふるわない生徒がウル(ブレッドフルー ツ)やタロなどハワイアンの主食を育てる方法を学ぶ 実習で単位を得られる「アアリイ・プログラム」がそれ で、プログラムのディレクター、キャサリン・フィッシャ ーさんとジュエリン・カークランドさんが毎週生徒たち を農園に連れて行く。生徒の一人、カム・アーリントン

さんは「私たちのアイナを大切にする方法を学んでい ます。この農園は、私たちを大きく変えました」と語る。

イノスさんは、カアラ農園がハワイのほかの組織やワ イアナエの地域社会そのものに変化を起こすモデル になると信じている。この農園の成功はハワイ大学マ ノア校のカ・パパ・ロイ・オ・カネワイ(タロ畑を中心と する文化庭園)設置のヒントにもなった。

「父は、ただ食料生産の場を復活させようとしている だけではないのです」。イノスさんの息子カムエラ・イ ノスさんは、2018年に放映されたPBSハワイの番組 でそう語っている。「人を育て、地域社会を再び育てる 力を取り戻そうとしているんです」

Remembering Rell

In her lifetime, Mākaha legend Rell Sunn set a gold standard for surfing and community outreach.

Text by Kylie Yamauchi

Images by Greg Ambrose and courtesy of Bess Press

‘A‘ole ma kona ‘ano wale iho nō he wahine kaulana i ka he‘e nalu, mahalo ‘ia ‘o Rell Sunn, ka mea i hala akula, no kona ho‘okino ‘ana i ka māhiehie a me ka mauli o ia hana ho‘onanea.

オアフ島ウエストサイドのマカハビーチは、何世代にもわたるワヒ ネ(女性)サーファーたちのホームグラウンド。彼女たちは互いに 学び合い、刺激を与え合いながら、コンペティションの世界で頭角 を現してきました。

The sport of surfing is like the tide: always in flux. With each competitive season, fresh-faced rookies are ushered in and legends retire. Boards are reinvented to be lighter, faster, and more maneuverable. This summer, surfing will even debut as an Olympic sport. But making a name for oneself in the ebb and flow of the surfing world is about more than winning competitions. It’s about creating a legacy. It’s about creating a better future for the surfing community. There is no better example of this than the First Lady of Surfing, the Queen of Mākaha, Rell Kapolioka‘ehukai Sunn.

It was in 1954 that 4-year-old Sunn rode her first wave at Mākaha Beach, an increasingly popular surf break among surfers across the globe. In the 2002 documentary Heart of the Sea: Kapolioka‘ehukai , Sunn said, “Before I could read, I could read the ocean. I knew the tides; I could read the wind on the ocean. I thought I knew everything I ever needed to know just from being on the beach every day.” Her commitment to the ocean made her into a skilled surfer, bodysurfer, spearfisher, and outriggercanoe paddler. In 1975, she helped start the Women’s International Surfing Association and competed with a handful of women. A couple years later, she was

ケアヌエヌエ・デソトさんとプアマカマエ・デソトさん の姉妹が子どものころから住んでいるオアフ島ウエス トサイドの家には、ワールド・サーフィン・リーグのロゴ が刻まれたゴブレット型のトロフィーが輝いています。

二人が6歳と4歳だった2010年、父デュエイン・デソ トさんはワールド・サーフィン・リーグの男子ロングボ ード部門で初優勝を果たし、頭上に高くこのトロフィ ーを掲げました。ケアヌエヌエさんは、シャンパンのし ぶきが父親とトロフィーの上に降りそそぐ光景をよく 覚えているそうです。家族一同、そして見物に来た地 域の人びとも、そろってデュエインさんの勝利に歓声 をあげました。デソト家はウエストサイドのサーファ ーたちの間で敬意を集めるファミリーなのです。

今ではティーンエイジャーとなったケアヌエヌエさ 二人が父デュエインさんと母マリア・カアイフエさんの 手引きでサーフィンをはじめたのはそれぞれ生後5ヶ 月のころ。まだ小さすぎたので、最初に乗った波は記 憶にありません。しかし、家族のメンバーが増えるに つれ、初めて波に乗る妹や弟たちを見守りながら、二 人は自分たちが幼かったころの海での様子を想像して みるようになりました。「(弟や妹の)ホヌアのときもホ クヴェロのときもワイラナのときも、パパはいつも赤ち ゃんをSUP(スタンドアップパドルボード)に乗せてワ イキキの海に漕ぎ出してました」とケアヌエヌエさん。 妹や弟たちを見守りながら、二人は自分たちが幼かっ たころの海での様子を想像してみるようになりました。 「(弟や妹の)ホヌアのときもホクヴェロのときもワイ

rell sunn’s surfing

style was that of a dancer, her graceful hands and sweeping arms exuding fluidity.

named Hawai‘i’s first female lifeguard, proving that wāhine were just as capable as kāne of handling rough currents and sizable waves. Unfortunately, after becoming a pioneer of both surfing and lifeguarding, Rell was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1983. However, this did not stop her from surfing professionally.

Sunn’s style was that of a hula dancer, her graceful hands and sweeping arms exuding fluidity whether she was on a shortboard or longboard. A focused and competitive athlete in the water, Sunn always resumed her genuine smile and welcoming spirit on land.

“Professionalism is an attitude,” she said in the documentary. “How you feel good about yourself, how you represent your country, how you present yourself to other people, and how you represent your sport. You know, the honor of being a surfer.”

Before she became a perennial favorite on surfing’s world stage, Sunn was adored by groms in her hometown of Mākaha. She was the cheering auntie on the beach, offering praise to all the keiki vying for her attention. In 1976, she started the Menehune Surf Contest for contestants under 13 years old, an annual event still held in her honor. It was the chance for keiki to win surfboards, leashes, backpacks, and most prized of all, official congratulations from Sunn herself.

ラナのときも、パパはケアヌエヌエ・デソトさんとプア マカマエ・デソトさんの姉妹が子どものころから住ん でいるオアフ島ウエストサイドの家には、ワールド・サ ーフィン・リーグのロゴが刻。

今ではティーンエイジャーとなったケアヌエヌエさん とプアマカマエさんは、これまで何百回とそうしてきた ように、リビングルームに飾ってある父親の記念トロフ ィーにちらりと目を向けてからサーフィンに出かけま す。二人の前にも勝つべきコンテストがあり、そのた めのトレーニングが待っているのです。二人が父デュ エインさんと母マリア・カアイフエさんの手引きでサー フィンをはじめたのはようになりました。「(弟や妹の) ホヌアのときもホクヴェロのときもワイラナのときも、 パパはいつも赤ちゃんをSUP(スタンドアップパドル ボード)に乗せてワイキキの海に漕ぎ出してました」と ケアヌエヌエさん。

らりと目を向けてからサーフィンに出かけます。二人 の前にも勝つべきコンテストがあり、そのためのトレ ーニングが待っているのです。二人が父デュエインさ んと母マリア・カアイフエさんの手引きでサーフィンを はじめたのはようになりました。「(弟や妹の)ホヌアの ときもホクヴェロのときもワイラナのりました。「(弟 や妹の)ホヌアのときもホクヴェロのときもワイラナの ときも、パパはいつも赤ちゃんをSUP(スタンドアップ パドルボード)に乗せてワイキキの海に漕ぎ出してま した」とケアヌエヌエさん。ケアヌエヌエ・デソトさんと

One of Sunn’s protégés was Jenny Van Gieson. In 1997, 11-year-old Van Gieson won her division of the Menehune Triple Lei of Surfing, a three-part contest on O‘ahu hosted by Sunn. Sunn invited the winner of each division to travel with her to France for the Biarritz Surf Festival. Among the travelers were surf standouts Freddy Patacchia, Melanie Bartels, Joel Centeio, and Jamie Sterling, all of whom later became professional surfers. For Van Gieson, the trip cemented her relationship with Sunn, who gave her surfing tips, handled her sponsors, and arranged photoshoots. The mentor and mentee also both danced hula and thus had similar surfing styles. Sunn called Van Gieson her ‘opihi, because one could not be found without the other. At the time, Van Gieson didn’t realize how famous Sunn was. She just knew Sunn as “the coolest person ever,” who taught her how to pick limu, left her voicemails while she was in school, and invited her over for sleepovers.

It was during the trip to France that Sunn learned that her breast cancer, which she had been battling for nearly 15 years, had returned once more. But, Sunn continued to wear a bright smile. “I feel like [Sunn] always wanted to be around people,” Van Gieson said. “Most people withdraw. Kids made her want to live, and I feel like that’s another reason she wanted to keep me around.”

プアマカマエ・デソトさんの姉妹が子どものころから 住んでいるオアフ島ウエストサイドの家には、ワール ド・サーフィン・リーグのロゴが刻まれたゴブレット型 のトロフィーが輝いています。二人が6歳と4歳だった 2010年、父デュエイン・デソトさんはワールド・サーフ ィン・リーグの男子ロングボード部門で初優勝を果た し、頭上に高くこのトロフィーを掲げました。ケアヌエ ヌエさんは、シャンパンのしぶきが父親とトロフィーの 上に降ルド・サーフィン・リーグの男子ロングボード部 門で初優勝を果たし、頭上に高くこのトロフィーを掲 げました。ケアヌエヌエさんは、シャンパンのしぶきが 父親とトロフィーの上に降りそそぐ光景をよく覚えて いるそうです。家族一同、そして見物に来た地域の人 びとも、そろってデュエインさんの勝利に歓声をあげ ました。デソト家はウエストサイドのサーファーたち の間で敬意を集めるファミリーなのです。

今ではティーンエイジャーとなったケアヌエヌエさん とプアマカマエさんは、これまで何百回とそうしてきた ように、リビングルームに飾ってある父親の記念トロフ ィーにちらりと目を向けてからサーフィンに出かけま す。二人の前にも勝つべきコンテストがあり、そのた めのトレーニングが待っているのです。

Remembering Rell

On January 2, 1998, the Queen of Mākaha passed away at the age of 47, leaving behind a legacy almost impossible to fill. Hundreds gathered at Mākaha Beach for her memorial, bringing with them surfboards and paddles. Together, the crowd paddled out to the surf line-up in her honor. Though it was peak season for large surf, the ocean was unusually flat that day, a sparkling, blue lake. Those on the water formed a lei by holding hands, saying their last goodbyes as Rell’s ashes sank into the deep. As the crowd dispersed and began to paddle in, a perfect cresting wave formed out of nowhere for everyone to share and ride into shore—Auntie Rell’s final push of encouragement.

ボードの上に乗せる正しい方法、救助した人をパドリ ングして岸に連れ戻す方法をもう一度説明します。も う1人のインストラクター、チャド・ケアウラナさんは、 「レスキューのテクニックを教えていますが、いよい よレスキューが必要という状態になる前にできること も教えるよう努めています」と話します。「海に飛び込 むのは最後の選択肢であって欲しいわけですが、その 一方で、何もできず呆然としているのではなく、助けと なれる人になって欲しいという狙いがあります。その ためには型にはまらない柔軟な思考が必要です。だっ て、自分がたった12歳で、大柄で重い男性が助けを求 めていたらどうしますか?」

Of Plants and Progeny

More than just a staple food, kalo is a source of cultural and spiritual nourishment and identity.Text

by

Rae SojotImages by John Hook

Mai ka wā iō kikilo mai e mahalo ‘ia ai ke kalo i mea nui na ka Hawai‘i, no kona mo‘olelo, a no ka ho‘omo‘a ‘ai nō ho‘i.

カロは、文化的にもスピリチュアルな面でもハワイ アンのアイデンティティに深いつながりをもつ、滋 養あふれる植物です。

In Hawaiian legends, nature is also family. In the Hawaiian creation story, Papahānaumoku (earth mother) and Wākea (sky father) created the islands of Hawai‘i. Their daughter, Ho‘ohōkulani, became pregnant and gave birth to a stillborn son named Hāloanakalaukapalili. He was buried and from his body grew a kalo plant. When Ho‘ohōkulani gave birth to a second child, a healthy baby boy, she named him Hāloa (everlasting breath) in honor of his older brother, kalo. Hawaiians are descendants of Hāloa, the first Hawaiian, and recognize the plant as an older brother.

ハワイの伝説では、自然も家族の一部だ。ハワイの創世記によると、大地の 母神パパハナウモクと空の父神ワケアが島々をつくったという。パパハナウ モクは身ごもり、ハロアナカラウカパリリという息子を生むが、死産だった。 その亡骸を埋めるとそこからカロ(タロイモ)が育ってきたのだという。2番 めに生まれたのは元気な男の子で、兄の名をとってハロア(「長くつづく呼 吸」という意味)と名づけられた。ハワイアンはみなハロアの子孫だといわ れている。だから、カロはハワイの人びとにとっては兄なのだ。

Kalo, or taro, has been integral to the Hawaiian diet. Alongside mai‘a (banana), niu (coconut), and ‘ulu (breadfruit), kalo was one of the canoe plants, the original plants brought to the Hawaiian Islands by the first Polynesian settlers. It is estimated that they cultivated over 50 varieties.

カロはハワイアンの食生活の中で重要な位置を占めてきた。マイア(バナナ)、 ニウ(ココナツ)、ウル(ブレッドフルーツ)と同じく、カロもその昔ポリネシア人 が海を越えて移住したときにハワイに持ち込んだ「カヌー植物」のひとつ。カロ には50種類以上の品種があるといわれている。

The plant’s primary parts include the lau (leaf), hā (leaf stalks) and kalo (corm). The main hā is surrounded by smaller ‘oha, or offshoots. In ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i, the word ‘oha is connected to the word ‘ohana, meaning family. Kalo that is ready to be harvested is known as the makua, or parent. The remaining ‘oha is removed and can be planted anew and the next generation of kalo continues.

カロは、ラウ(葉)、ハ(茎)、カロ(塊茎)からなる。主茎のまわりには、小さな「オ ハ」(新芽)がついている。ハワイ語で「オハ」は「オハナ」(家族)につながる言葉 だ。収穫できるまでに育ったカロは「マクア」(親)と呼ばれる。収穫したあとに 残ったオハは切り取られて植えられ、次の世代のカロが育っていく。「それを知 ったら、きっとつながりを感じられることでしょう。カロは家族なんです」とカポ イさんは言う。

Though the demands of working in a lo‘i (kalo field) are physically taxing, Sam Kapoi and Daniel Anthony, who are both from Wai‘anae, find its efforts worthwhile, both culturally and spiritually. “Put your feet in the dirt an’ feel ‘em,” Anthony says, scanning the lo‘i. “This is who we are.” Kapoi and Anthony consider kalo a form of food sovereignty and they want to bring kalo back as a staple Hawaiians eat on a regular basis.

ロイ(タロ畑)での仕事は厳しい肉体労働だ。だが、ワイアナエ出身のサム・ カポイさんとダニエル・アンソニーさんは、文化的にもスピリチュアルな面で もやりがいのある仕事だと感じているという。「泥のなかを歩いて、足にそれ を感じる。そのとき、これこそが僕たちなんだ、と思うんです」とアンソニーさ ん。カポイさんとアンソニーさんは、カロは食糧主権の方法の一つとみなし、 ハワイアンの日常的な食事の主役に復権させたいと考えている。

Once kalo is cooked or steamed, it is ready for pounding. The two mainstay tools of the trade remain simple and traditional: a papa ku‘i‘ai (food striking board) often fashioned from hard woods such as ‘ulu and kamani and a knobbed stone pounder called pōhaku ku‘i ‘ai. The kalo is first pounded into pa‘i‘ai, a thick, starchy, stretchy paste. Pounders must use both finesse and strength in their stroke. “It’s a push-pull movement,” Kapoi says.

カロは茹でるか蒸すかしてからつぶすのが伝統の料理法だ。主な 道具は二つ。どちらもシンプルな、昔ながらの形のものが使われて いる。パパクイアイと呼ばれる、ウルやカマニなどの木材でできた 板と、ポハク・クイポイと呼ばれる石のパウンダーだ。まず、カロを つぶしてしっとりと重く粘り気の強いペースト状の「パイアイ」にす る。この作業には細やかな技工と力強いストロークが必要だ。「押 して引く動きなんです」とカポイさんは説明する。

Poi is then made by adding water to the pa‘i‘ai to a desired consistency. “I want to re-introduce Hawaiians to their original native food and remind them of their identity,”

Kapoi says. “Ho‘olu i ka Lāhui. Grow the nation, in every way possible.” このパイアイに水を加えて、好みの粘度に調整する。「ハワイアンの 皆に、祖先から伝わった食べものを紹介しなおして、自分たちのル ーツを思い出してもらいたいのです」とカポイさん。「ホオルイ・カ・ ラフイ、つまり『あらゆる面から、国を育てる』というわけです」

Image by Josiah Patterson

Image by Josiah Patterson

“

When I surf Mākaha, I’m connected to my ancestors and flooded with peace, joy, and happiness.”

Jordan Maka‘alanalani Iaea Patterson, tandem surferImage by Mark Kushimi

Fred “Pops” Pereira: The Boxing Coach

As told to Rae Sojot Images by Mark Kushimi

Ma kona ‘ano ‘ālapa, ‘ōlohe, a kumu ‘ike loa ho‘i, he puni ke ku‘iku‘i na Fred ‘Pops’ Pereira, ka mea i kono ‘ia a‘e nei e komo kona inoa i ka Golden Gloves of American Coaches Hall of Fame.

Growing up in Mā‘ili there was 11 of us cousins and we all learned to box from my mother’s brother, my Uncle Nick. He helped coach boxing greats like Frankie Fernandez and Carl “Bobo” Olsen. We liked watching wrestling—this was when it was still blackand-white TV. Uncle Nick would tell us, “Box!” and then we’d just go at it like those wrestling guys, throwing blows, throwing each other down. He then taught us how to throw punches.

As soon as I graduated high school, I wanted to go to the mainland. I didn’t have any money, the only way was to join the Army. I was sent to Fort Benning, Georgia, to become a paratrooper. After 16 weeks of basic training, the Army put my unit on a ship and sent us straight to Japan. This was during the Korean War. I spent almost 10 years in Japan.

フレッド・「パップス」・ペレイラ: ボクシング・コーチ

わたしはマイリ育ちで、いとこが11人いた。みんなそろって、母の 弟、ニック叔父さんからボクシングを教わったんだ。ニック叔父はフ ランキー・フェルナンデスやカール・「ボボ」・オルセンといった名選 手たちをコーチした人なんだよ。みんな、レスリング観戦が好きだ った。テレビがまだ白黒だった時代だよ。ニック叔父さんが「ボック ス!」と合図すると、みんなでレスリングの選手たちみたいに取っ組 み合いをする。パンチをくり出し、お互いを投げ飛ばす。そのあと、ニ ック叔父さんがパンチの出し方なんかを教えてくれた。

高校を卒業したらすぐに本土に行きたいと思っていたんだが、お 金がなかったから、唯一の手段は陸軍に入隊することだった。ジ ョージア州のフォート・べニングに送られて、落下傘部隊に所属 した。16週間の基礎訓練が終わったあとで、部隊はまっすぐ日本 に送られた。朝鮮戦争の最中だった。結局10年近く日本で過ごし たんだ。

In Japan, it was those times with Uncle Nick that gave me the idea to jump into coaching. I even set up a boxing match between Japanese fighters and American fighters. They had a different style, but I knew how to hit somebody and get away with it. A “hit and run,” something I teach my boys even now. After that first tournament, the Japanese organizers wanted to do another, where they put Judo fighters against American boxers. I said to them, “Wait a minute, this doesn’t make sense. Do they have gloves on? How is this going to work?” I didn’t want to fight but I couldn’t find anybody, so I volunteered. I had the whole Army cheering for me but let me tell you, I got the licking of my life!

I opened up the Wai‘anae Boxing Club in 1972. Back then there was a lot of drugs in Wai‘anae—kids were stealing tires and breaking into farms and bothering tourists at the beach. I worked with PAL [Police Athletic League] at the time, so I went down to talk to the kids who got caught. That month, maybe 25 kids started coming to the gym, checking it out. They started shaping up, started to listen.

日本にいるあいだに、ニック叔父さんに教わったときのことを思い 出して、ボクシングのコーチをやってみようと思い立った。日本の選 手とアメリカの選手との対戦も企画したよ。日本のボクシングはス タイルが違ったが、わたしはパンチの出し方とかわし方をよく知っ てたからね。いまでも、その「ヒット・アンド・ラン」の方法をここに来 る子たちに教えているよ。最初のトーナメントのあと、日本側の主 催者が柔道の選手とアメリカ人ボクサーを対戦させようと言い出 した。わたしは言ったよ、「ちょっと待ってくれ、わけがわからない。 グローブはどうする? どうやって戦わせるつもりなんだ?」って ね。やりたくなかったんだが、ほかに誰もいなかったので、仕方なく わたしが自分で対戦した。陸軍のみんなが総出で応援してくれたん だが、実をいうとこてんぱんにされたんだよ! ワイアナエ・ボクシング・クラブを開いたのは、1972年のことだ。当 時のワイアナエはドラッグが蔓延していて、子どもたちがしょっちゅ うタイヤを盗んだり、農園に押し入ったり、ビーチの観光客を襲っ たりしてた。わたしはその当時、PAL(ポリス・アスレチック・リーグ: 警察が運営するスポーツリーグ)に携わっていたので、補導された 少年たちに会って話をした。最初の月だけで25人くらいの少年た ちがジムを見に来てくれて、ジムに来はじめた子どもらはだんだんし ゃんとして、悪さもしなくなっていった。

I’m here every day, Monday through Friday. I love working with kids. I teach my boys and girls how to move from side to side, left to right. Show them step this way and fake, step that way and strike. I tell them that to become a good fighter you gotta train hard. You gotta listen. You gotta pay attention. And you gotta do what you have to do in order to survive. I put it to the kids straight: Whatever I teach you, if you ever use it at school, I’m going to have to let you go. I’m not teaching you to go pick on somebody else.

In 2004 the Wai‘anae Boxing Club brought home its first World Championship title belt. I felt like I was 10 feet tall. I love what I am doing. I wouldn’t know what to do with myself if I didn’t have this. I don’t know why Wai‘anae produces so many good fighters. Maybe Jesus is helping me a lot because he sees what I’m doing and thinks that it is good. I’m 87 years old now. I don’t know if I’m leaving a legacy, but I know that I sure am enjoying myself.

Fred “Pops” Pereira is the Wai‘anae Boxing Club founder and 2019 Golden Gloves of America Coach Hall of Fame inductee.

わたしは月曜から金曜まで、毎日ここにいるよ。子どもたちにかかわ っているのが好きなんだ。少年たちや少女たちに、横移動のステッ プを教える。左、それから右。こっちに踏み出してフェイクを入れ、こ っちに踏み出してパンチ、ってね。子どもらには、いい選手になりた ければ一生懸命トレーニングしなきゃ駄目だ、と教えてる。人の話 に注意を払い、ちゃんと耳を傾けろ、と。この世界で生き残るために は、努力が大事だ。それから、もう一つ、がつんと言っておくのは、こ こで教えたボクシングを学校で一度でも使ったら破門だ、ていうこ とだ。人を痛めつけるためにボクシングを教えてるんじゃないんだ。

2004年には、ワイアナエ・ボクシング・クラブの選手が初めて世界 チャンピオンベルトを持ち帰った。こんなに誇らしいことはなかった ね。ここで自分がやっていることに、生きがいを感じているよ。これ がなかったら自分は何をしていたのか、想像もつかない。ワイアナ エからなぜこんなにいい選手が次々に出てくるのか、正直わからな い。ここでわたしがやっているのがいいことだと認めてくれて、神様 も力を貸してくれているのかもしれない。今年で86歳になって、何 かを残せたかどうかはわからないが、人生を楽しんでいることだけ は間違いないよ。

フレッド・ペレイラさんはワイアナエ・ボクシング・クラブの創設 者。2019年、ゴールデン・グローブス・オブ・アメリカのコーチ・ホ ール・オブ・フェイムに選ばれた。

All Booked Up

As told to Eunica Escalante

Images by Josiah Patterson

Kūkulu ‘ia i ka makahiki 2018, ‘o ko Nānākuli

Hale Waihona Puke kahi ho‘okahi i lako i nā

hō‘ailona ‘ōlelo haole a Hawai‘i nō ho‘i, lako pū i

kekahi ke‘ena ‘oki leo no nā ‘ohana e mālama i ko lākou kū‘auhau.

12 pm: Hemo

Each day starts with turning the entrance sign over from “Closed” to “Open”—or, rather, from “Pa‘a” to “Hemo.” All signage at Nānākuli Public Library show both the English and ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i versions of each word. It is the first library in the state to do so and a way for the Nānākuli and Mā‘ili communities, which are predominately Native Hawaiian, to claim ownership of this space, says branch manager Kelsey Faradineh. There’s a substantial Hawaiian literature section; every month, there are ‘ukulele lessons held in the keiki section. There’s even a collection of ‘ukulele available to borrow with a Hawai‘i state library card.

3 pm: School’s Out

The library is filled with the usual afterschool crowd. The hallmarks of parenthood unfold as a father teaches his daughter how to read. A group of high schoolers post up on a table, seemingly just to charge their phones, but one by one they get up to find a book. Outside, the weekly farmers market is setting up. Booths of fresh produce hauled in from the nearby farms entice passersby.

ナナクリ公共図書館の分館長、ケルシー・ファラディネさんの本に 囲まれた一日をご紹介します。

正午:ヘモ

毎日の仕事は、入り口の表示を「閉館」から「開館」に替えることか ら始まる。「閉館」には「パア」、「開館」には「ヘモ」というハワイ語も 添えられている。ナナクリ公立図書館の館内表示にはすべて英語と ハワイ語が併記されているのだ。これはハワイ州でも初の試み。特

にネイティブハワイアンの住民が多いナナクリ地区とマイリ地区の 人々が、図書館という場所を自分たちのものと感じられるようにす るための試みだと分館長のケルシー・ファラディネさんは説明する。

ハワイ文学の蔵書も多く、ケイキ(子ども)コーナーでは毎月ウクレ レ教室も開催されている。ハワイ州の図書館カードがあれば、ウク レレを借りることだってできるのだ。

3 pm:放課後 学校が終わると、図書館は放課後の子どもたちでいっぱいになる。 お父さんが小さな娘に読み方を教えている姿があり、テーブルには 高校生のグループが陣取っている。高校生たちはただ携帯電話を 充電しに来ているようにも見えたが、中の一人は席を立って書棚 に本を探しに行った。外では、週一回のファーマーズマーケットの 開店準備が進んでいる。近隣の農家が出店する新鮮な野菜の屋台 が、通る人の目を惹きつける。

6 pm: Settling In

On Mondays and Thursdays, the library opens later to give people who work during the day a chance to enjoy it. A man approaches the front desk, inquiring about the genealogy section, and he’s led to a bookcase of binders and leather-bound books. Instead of having ancestry resources buried in their reference shelves, Faradineh has given them their own place, so that they’re easier to find. It’s quickly become one of the library’s most used resources.

8 pm: Closing Time

There are the usual late-nighters. College students frantically typing away, their faces lit by a laptop screen’s soft glow. Or a parent and child taking advantage of the keiki section to spend some quality time reading together. Before Nānākuli Library opened in April 2018, this community would have to drive to Kapolei or Wai‘anae for a library. Now they have this space, placed squarely amidst their own neighborhood. It‘s been over 30 years in the making, but finally this community has a library they can call their own.

Library hours, services, and activities are subject to change due to Covid-19 safety measures. For the most up-to-date information, visit librarieshawaii.org.

6 pm:夜間の調べもの 月曜日と木曜日、図書館は開館時間を延長して、日中働いている人 も利用できるようにしている。フロントデスクに男性が近づいてき て、系図学の資料はどこかと尋ね、バインダーと革張りの書物がお さめられた書棚に案内される。ファラディネさんはここに就任して から、ハワイアンの先祖についての文献を資料室の棚に埋もれさせ る代わりに専用の場所を設け、目的の資料を探しやすくした。「コミ ュニティとのつながりを築く方法の一つです」とファラディネさん。 系図コーナーはたちまち、この図書館で最もよく利用されるリソー スの一つとなった。

8 pm:閉館

いつも遅くまで残っている利用者たちがいる。真剣に課題に取り 組み、ノートパソコンの画面の光に顔をぼうっと浮き上がらせな がら必死でキーボードを叩いている大学生たちや、ケイキコーナ ーで一緒に本を読んでいる親子連れ。2018年4月にナナクリ図 書館がオープンするまで、ここの住民はカポレイかワイアナエの図 書館まで行かなかればならなかった。今では町の真ん中に図書館 がある。30年以上の年月を経て、ようやく町に図書館がやって来 たのだ。

新型コロナウイルス感染症予防対策を実施中のため、図書館の営 業時間、サービスやアクティビティの内容が変更になる場合があり ます。最新情報はlibrarieshawaii.orgをご覧ください。

Jordan Maka‘alanalani Iaea Patterson: The Tandem Surfer

As told to Rae Sojot Images by

Josiah Patterson‘O ka nalu ‘ana kēia o ke kaikunāne a me ke kaikuahine i ko lāua kūlana nalu kama‘āina.

ジョーダン・マカアラナラニ・イアエア・パターソン: タンデム・サーファー

When we were really young, my uncles would bring my brothers and me to Mākaha Beach. They would take us far in the ocean and make us swim all the way back in. It was sort of trial by fire, we had to learn the hard way! Later, my dad taught me how to surf on an old 9-foot single fin Hansen board that he had used himself as a kid. It had a little rocker and it made me feel like I was flying on the waves. Even now, my fondest memories are of waking up early in the mornings when it was still dark and walking from Charlie’s Reef to Mākaha to surf with my brothers.

I spent my early childhood in Mākaha, and then later in Maine while my father went to seminary. We lived on Kaua‘i for a few years before moving back to Mākaha when I was in high school. My grandmother’s family is from Mākaha since the late ’40s, so my roots here are deep.

まだほんの小さい頃、おじたちがよく僕たち兄弟をマカハビーチに 連れていってくれた。ずっと沖まで連れていかれて、浜まで泳いで帰 らされる。スパルタ式でしごかれたよ!もう少し大きくなると、父が 9フィートのシングルフィンのボードでサーフィンを教えてくれた。父 が自分で子どものときに使っていた、ハンセンのボードだった。ちょ っとロッカーがあり、波の上を飛んでいるような感覚が味わえた。

今でも頭に浮かぶ子ども時代のいちばん楽しい思い出は、兄弟そ ろって朝まだ暗いうちから起き出して、チャーリーズリーフからマカ ハまで歩いて波乗りをしに行ったことだ。

小さい頃はマカハで過ごし、その後、父が神学校に入ったので家族 でメイン州に引っ越した。そのあとカウアイ島に移って数年暮らし、 僕が高校生の頃にまたマカハに戻った。祖母の家族は1940年代 からマカハに住んでいるから、僕のマカハでのルーツは深い。

I got into tandem surfing 9 years ago through my baby sister Keala. She wanted to try it out—I’m always down to do fun stuff with my sisters. We surfed together for about 4 years both for fun and in amateur contests. In 2016 she encouraged me to find a professional level partner and to try and go pro.

For people who have never seen tandem surfing, I describe it as an art form like ice dancing or ballet, except we are in the water. You have two people on one board: a graceful, flexible woman, and a man who does the surfing. The man guides the dance, lifting his partner into beautiful acrobatic poses while still surfing the wave. It takes a lot of skill and training. We have to put in the time and work, first on land practicing lifts, then executing the moves in the water while surfing a wave. I’ve gotten a lot of coaching and advice from Mākaha’s tandem greats: my uncle Jason Patterson and his wife, Kelly, my uncle Mel Pu‘u, and my uncle Brian Keaulana and aunty Kathy Terada, who are former tandem world champions.

Tandem surfing is also one of the most competitive forms of surfing. There are weight rules: the woman must be half the man’s weight, no less, otherwise you get point deductions for every pound the team is off weight. Points are docked if you aren’t able to hold the moves for a certain amount of time, or for something as small as my partner’s toes not being pointed

タンデムサーフィンをはじめたのは8年前。妹のケアラがやりたが ったんだ。妹たちとは仲がよくて、一緒にいろんなことを楽しんでき た。4年ほどアマチュアのコンテストに出場しながら趣味として続け てきたが、2016年に、プロレベルのパートナーを探してプロの世界 でやってみたらどうかとケアラがすすめてくれた。

タンデムサーフィンを見たことがない人には、海の上で行われる点 を除けばアイスダンスやバレエとよく似たアートだと説明する。ひと つのボードにふたりで乗る。優雅で体のやわらかい女性と波に乗る 男性。男性は波に乗りながら美しくアクロバティックなポーズをとる パートナーを支え、ダンスをリードする。高度な技と訓練を要する スポーツだ。練習には時間をかける。まず、陸でリフトの練習をして、 次に海に出て波に乗りながらひとつひとつの動きをやってみる。こ れまで、マカハ出身の偉大なタンデムサーファーたちからさまざま なアドバイスを受けてきた。ジェイソン・パターソンと奥さんのケリ ー。メル・プウおじさん。タンデムの元世界チャンピオンであるブラ イアン・ケアウラナとキャシー・テラダにもコーチしてもらっている。

タンデムサーフィンは、競技サーフィンのなかでももっとも熾烈な種 目のひとつだ。体重制限もある。女性の体重は男性の半分以上な ければならず、それより少ないと1ポンド(約450グラム)につき1ポ イントずつ減点される。ポーズを一定時間保てなかったり、女性の つま先が特定の角度に向いていなかったりという細かいことも減 点の対象になる。スコアは波の乗り方にも左右される。ただまっす ぐ波に乗ってもだめなんだ。ポーズをキープしたままで、高度なライ ディングが求められる。フランスで行われるコンテストでは、観客の 熱狂ぶりがすごい。ビーチに詰めかけた観客がポーズを決めるたび に大声援を送ってくれるんだよ。

in a certain way. A score also depends on how well we surf. We can’t just go straight. We have to hold position and surf the hell out of the wave at the same time. At the contests in France, the crowds are insane, they gather on the beach to watch and cheer for the different moves.

In 2016 the International Tandem Surfing Association World Championship was held here in my hometown. I wanted to enter and Uncle Mel recommended his old partner, Angelee Homma. We practiced twice and decided to go for it. With contests, I always feel a rush, a sense of anticipation and excitement, right before I go out onto the water. Then, when surfing there’s a sense of calm and focus. I’m not worried about the actual competition, I’m focused on the wave, my partner, and nailing the moves while keeping us safe. That day, we placed 7th overall in the World Championships! Top ten in the world! I was stoked.

I’ve surfed in France, Australia, and all over the continental U.S. and the ocean is beautiful everywhere. But nothing compares to Mākaha. From 2 feet to 15 feet, from the beautiful obstacles that keep you on your toes to the different sections and backwash, you get it all. When I surf Mākaha, I’m connected to my ancestors and flooded with peace, joy, and happiness. I can feel it in my bones. It’s the best wave in the world.

2016年、国際タンデムサーフィン協会の世界選手権が僕のホーム タウン、マカハで開催された。出場を考えていた僕に、メルおじさん が自分の長年のパートナーだったアンジェリー・ホンマを紹介して くれた。二度ほど練習して、僕とアンジェリーは出場を決めた。コン テストのときはいつも、海に出る直前まで不安と期待で気持ちが高 ぶっている。でも実際に波に乗ると、心が静まり、集中できるんだ。

勝敗にはこだわらず、波とパートナーに意識を集中する。お互いの 安全を確保しつつ、ポーズを決めることしか頭にない。その日、僕 たちは世界第7位の成績をおさめた。世界のトップ10入りだよ! 最高の気分だった。

これまでフランス、オーストラリア、全米各地でサーフィンをしてき た。世界中どこに行っても海は美しいものだけど、マカハ以上のビ ーチはどこにもないよ。2フィートの波から15フィートの波まで。近 寄りがたくて緊張させる美しいフェイスから、ほかのセクション、そ してバックウォッシュまで、波乗りのすべてがそこにある。マカハで サーフィンするときは先祖とのつながりを感じるし、安らぎと喜び や幸福感で胸がいっぱいになる。それを骨の奥に感じるんだ。世界 一の波だよ。

Jordan Maka‘alanalani Iaea Patterson is a professional surfer who spent his formative years in Mākaha, where he resides with his family today.

ジョーダン・マカアラナラニ・イアエア・パターソンはマカハで生 まれ育ったプロサーファー。現在も家族でマカハに暮らしている。

Ko Olina Center 92-1047 Olani Street. Ko Olina, HI. 96707 ▪ Ko Olina Station 92-1048 Olani Street. Ko Olina, HI. 96707

Ko Olina Center 92-1047 Olani Street. Ko Olina, HI. 96707 ▪ Ko Olina Station 92-1048 Olani Street. Ko Olina, HI. 96707

FIND YOUR PLACE OF JOY

Shops, Restaurants, and Services to indulge your senses.

DINING

Starbucks Coffee

Black Sheep Cream Co.

Eggs ‘n Things

Island Country Market

Island Vintage Coffee Company

Monkeypod Kitchen By Merriman

Mekiko Cantina

Pizza Corner

Tropic Ohana Poke Bar

APPAREL

Bikini Bird

Crazy Shirts

Honolua Surf Co.

Coconene

Mahina

Pineapples Boutique

Pineapples Kids

Tommy Bahama

ART

The Plantation

Things Unique - Na Mea Laha‘ole SERVICES

SOHO New York

Ko Olina Medical

Ko Olina Visitor + Sales Center

Ko Olina Resort Executive Offices

Hours: 6AM-11PM; Open Daily. Across from Four Seasons Resort O‘ahu and Aulani, A Disney Resort & Spa.

働き蜂たち Life

Busy Bees

Text and images by Michelle Mishina

Burrowed in the back of a valley, a local ‘ohana has been quietly producing the island’s most unique honey.

Aia i uka loa o Lualualei, ke ho‘omākaukau akula nō ka ‘ohana nona ka ‘ahahui ‘o Tolentino Honey Co. i meli laha ‘ole ma O‘ahu nei. Ma ka hala ‘ana o ke kau a hiki mai ka ho‘oilo, a me nā wā e pua aku ai nā kumu lā‘au kūloko, ‘o ia ‘ike ka mea e maopopo ai nā loli ‘ana o ke au i ua mau kahu nalo meli lā.

渓谷の奥にひっそりと抱かれた農園で、地元のオハナ(家 族)がオアフ島随一のユニークなはちみつを生産してい ます。

On O‘ahu’s leeward coast, miles of skykissed sand meander alongside the twolane highway. Cars slow as drivers, in no hurry to make their turns, crawl through Nānākuli, Mā‘ili, Wai‘anae. The pace of life on the West Side, like the traffic, is languid. It’s as if the heat makes everything as slow as syrup. Or honey.

Tucked in the back of Lualualei Valley, Tolentino Honey Co. has been quietly producing some of the most unique honey on O‘ahu. Raw and only coarsely filtered, it retains more pollen and enzymes than its heat-treated and pasteurized counterparts. The resulting honey’s flavor is richer. It will also often crystallize within a month, turning from smooth, golden liquid to creamy, white frosting.

オアフ島のリーワード海岸。

2車線の道路沿いに日に灼けた砂浜 がうねうねと続く。ナナクリ、マイリ、ワイアナエといった町を通っ ていく車のドライバーたちは、せかせかと急がない。ウエストサイ ドでは生活のペースそのものも車の流れと同じくのんびりしてい て、暑い空気のなか、何もかもが濃いシロップのようにゆるやかに 流れる。

または、はちみつのように。

ルアルアレイ渓谷の奥にひっそりと抱かれたトレンティーノ・ハニ ー・カンパニーは、オアフ島で最もユニークなはちみつを作ってい る。目の粗いフィルターで濾過しただけのローハニー(生はちみ つ)だ。熱処理や低温殺菌したはちみつに比べ、花粉や酵素をより 多く含み、より豊かな風味を持ち、1か月ほどで結晶化して、黄金色 のなめらかな液体から白いクリーム状になる。

Four Seasons Resort O‘ahu at Ko Olina

Aulani, A Disney Resort & Spa

Beach Villas at Ko Olina

Marriott’s Ko Olina Beach Club

WEDDING CHAPELS

Ko Olina Chapel Place of Joy Ko Olina Aqua Marina

RESIDENTIAL COMMUNITIES

Kai Lani

The Coconut Plantation

Ko Olina Kai Golf Estates & Villas

The Fairways at Ko Olina

Ko Olina Hillside Villas

AMENITIES

Ko Olina Marina Shop and Activity & Dive Center

Ko Olina Golf Club

Ko Olina Station

Ko Olina Center

Laniwai, A Disney Spa & Mikimiki Fitness Center

Four Seasons Naupaka Spa & Wellness Centre; Four Seasons Tennis Centre

Lanikuhonua Cultural Institute

Grand Lawn

The Harry & Jeanette Weinberg

Campus Seagull School, The Stone

Family Early Education Center

Hawaiian Railway Society Railroad

It will remind you of absolutely nowhere else in the world.

Ko Olina is a luxurious world unto itself on O‘ahu’s sunniest shoreline. Where crystal clear lagoons invite you in, and miles of seaside pathways encourage exploration. Restaurants are duly awarded, and the golf course, tested by champions. It’s an extraordinary and uncommon place. Away from it all.

Celebrating 30 years.

Aulani, A Disney Resort & Spa Beach Villas at Ko Olina Four Seasons Resort O‘ahu at Ko Olina Marriott’s Ko Olina Beach Club

Image by John Hook

Image by John Hook