FOR KOOLINA Hale

In the Hawaiian language, hale (pronounced huh’-leh) translates to “house” or “host.”

Hale is an intimate expression of the aloha spirit found throughout the islands and a reflection of the hospitality of Ko Olina.

In this publication, you will find that hale is more than a structure, it is a way of life.

Ko Olina celebrates the community it is privileged to be a part of and welcomes you to immerse yourself in these stories of home.

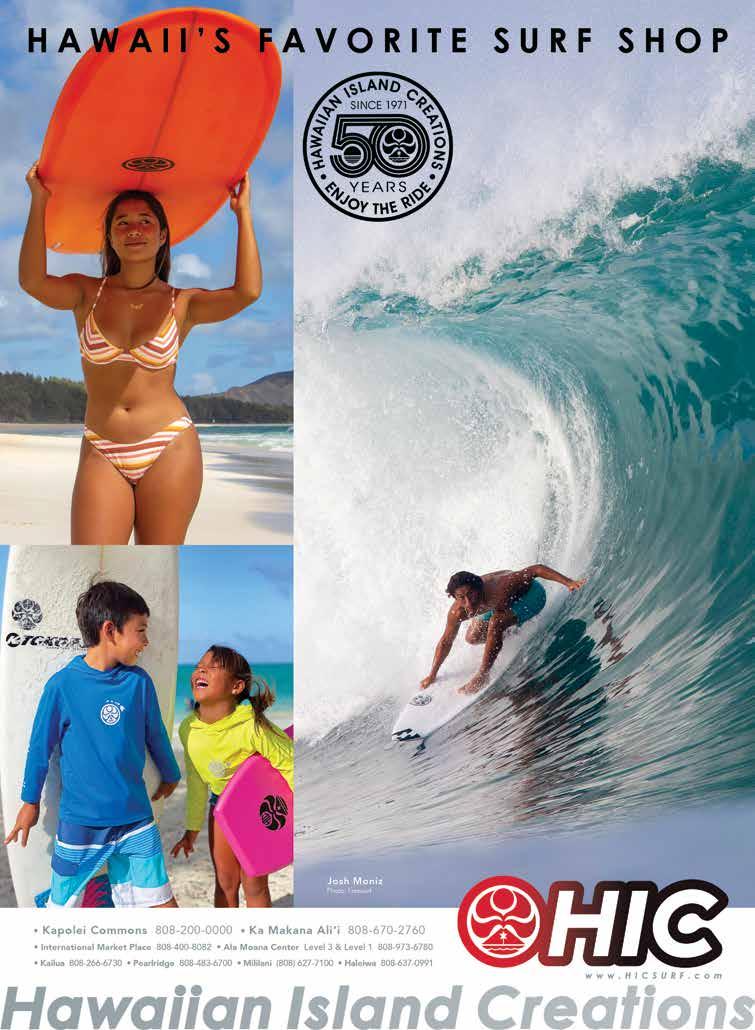

Ad

FEATURES

58

Mauka Bound

Whereas beach camping is popular in Hawai‘i, at Camp Pālehua, there’s mana (power) in the mountains.

80

Street Smarts

When a beloved skate park fell into disrepair, a group of teenagers inspired a community to help them restore it to its original glory.

96

Restorers of the Reef

The founders of Kuleana Coral Reefs are piloting a unique approach to restoration.

LETTER FROM JEFFREY R. STONE

LETTER FROM JEFFREY R. STONE

Aloha e,

The beginning of a new year provides an opportunity to reflect on how far we’ve come as a resort ‘ohana, an incomparable community of brand partners, employees, residents and guests, that continues to pave the way for the State’s robust recovery.

At Ko Olina, we faced the economic and social challenges presented by a global pandemic with urgency, and have emerged wiser and more committed to ensuring our home and the intrinsic values associated with living and thriving in a sustainable island setting are preserved for future generations.

We have a refreshed sense of purpose. We prioritize environmental consciousness and are keenly aware that the resort’s future is dependent on integrating the rich culture and unique environment of Hawai‘i with a holistic approach to health and wellness. Creating experiences to explore physical, mental and spiritual harmony is important to us and an integral part of Ko Olina’s future.

I’d like to recognize a profound community leader we celebrate in this issue of Hale, who, with a quiet, yet determined demeanor, accomplished much at the helm of Hale Kipa’s transitional home over 23 years. Mahalo Punky, for your selfless dedication and commitment to Hawai‘i’s youth; your voice will be truly missed. Enjoy the well-deserved years of retirement ahead!

There is much to cherish about the past year. We look ahead with optimism, determination and confidence in the breadth of our partnership with you, our extended resort ‘ohana, and remain focused on discovering opportunities that complement this special place and ensure a viable, regenerative future for Hawai‘i as a travel destination.

Thank you for choosing us. We are grateful of your belief in what Ko Olina and our West Side communities have to offer and hope our stories will inspire you to find simple ways to share aloha in your home.

E malama pono,

Jeffrey R. Stone Master Developer, Ko Olina Resort

Hale

is a publication that celebrates O‘ahu’s leeward

coast—a place rich in diverse stories and home to Ko Olina Resort.

The West Side is truly a special place, a bounty of nature and history, community and culture. In this issue, we celebrate the people and places that move us--from the cool, mountain forests surrounding Camp Pālehua to the turquoise depths of Ko Olina's shores, where critical coral restoration is underway. As you follow along, be inspired by a group of young skaters who rallied to save their local skatepark and a beloved community leader who dedicated his life to helping at-risk youth. These stories, along with others, provide intimate glimpses of West O'ahu and the reasons we are so proud to call this place home.

ABOUT THE COVER

The cover image of a coral head was photographed by Blake Thompson and provided courtesy of Kuleana Coral. In the past 30 years, approximately 50% of coral reefs around the world have been lost. Kuleana Coral's restoration efforts aim to recultivate coral populations and rebuild resilient marine ecosystems here in Hawai‘i. To learn more, visit kuleanacoral.com

CEO & Publisher

Jason Cutinella

VP Brand Development

Ara Laylo

Editorial Director

Advertising

VP Sales

Mike Wiley mike@nmgnetwork.com

Partnerships & Media

Aulani, A Disney Resort & Spa aulani.com

Four Seasons Resort O‘ahu at Ko Olina fourseasons.com/oahu

Marriott’s Ko Olina Beach Club marriott.com

Beach Villas at Ko Olina beachvillasaoao.com

Oceanwide Resort

Ko Olina Golf Club koolinagolf.com

Ko Olina Marina koolinamarina.com

Ko Olina Station + Center koolinashops.com

The Resort Group theresortgroup.com KoOlina.com

Lauren McNally

Editor-At-Large

Matthew Dekneef

National Editor

Anna Harmon

Senior Editor

Rae Sojot

Digital Editor

Eunica Escalante

Photography Director

John Hook

Designer

Mai Lan Tran

Translations

Yuzuwords

N. Ha‘alilio Solomon

Creative Services

VP Global Content

Marc Graser

VP Film

Gerard Elmore

Filmmakers

Blake Abes

Romeo Lapitan

Brand Production Manager

Kaitlyn Ledzian

Brand Production Coordinator

Taylor Kondo

Executive

Chris Kelly

Marketing & Advertising Executive

Courtney Asato Operations

Partner/GM-Hawai‘i

Joe V. Bock joe@nmgnetwork.com

VP Special Operations

Rob Mora

VP Accounts Receivable

Gary Payne

Distribution & Logistics Coordinator

Courtney Miyashiro

©2021 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of Hale are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. Hale is the exclusive publication of Ko Olina Resort. Visit KoOlina.com for information on accommodations, activities, and special events.

Image by John Hook

Image by John Hook

“People who are rooted and engaged in their community, they’re going to care for it.”

Miki‘ala Lidstone, executive director of Ulu A‘e Learning Center

Image by John Hook

自分の街を知る Life

Learn

Your Place

Textby

Kathleen Wong Imagesby

John HookAt Ulu A‘e Learning Center, students venture outside the classroom and into the community for lessons in Hawaiian culture, kinship, and aloha ‘āina (love of the land).

Ma Ulu A‘e Learning Center, he ‘a‘a nā haumāna i waho a‘e o ka lumi papa a komo i loko o ke kaiāulu no ke a‘o ‘ia i ka ‘ike no ka mo‘omeheu Hawai‘i, ka pilina ‘ohana, a me ke aloha ‘āina.

「ウル・アエ・ラーニング・センター」では、子どもたちは教室を 出てコミュニティのなかに身を置き、ハワイアンの文化、家族と の結びつき、そしてアロハ・アイナ(土地への愛)を学びます。

It’s an unusually cloudy October day at Hanakēhau Learning Farm, situated down a bumpy dirt road behind Leeward Community Center in Pearl City, or Pu‘uloa. It’s nearly impossible to find the farm on your own—there’s technically no address.

On this morning, nearly 20 keiki, ages 5 to 14, have gathered to tend to two lo‘i kalo, or taro patches. To prepare the areas, they hehi (stomp) to flatten the mud, pull out pink lotus plants and roots, and remove stray rocks. Barefoot and caked in mud, the children point out frogs and tiny fish in the lo‘i’s water-filled rows. There are no phones or computers in sight.

珍しく曇り空となった10月のある日。プウロア(パールシティ)のリ ーワード・コミュニティ・センター裏手に続く未舗装のでこぼこ道の 先に「ハナケハウ・ラーニング・ファーム」はある。この農園を自力で 探そうとしても、ほぼ不可能だ。正式な住所がないのだから。

この日の朝は5歳から14歳まで約20名のケイキ(子ども)たちが集 まり、ふたつの「ロイ・カロ(タロ芋畑)」の世話をしていた。準備とし

A grinning boy asks a ponytailed girl nearby, “Is there mud on my face?” She bursts into laughter. Mud is smeared all over his face—and hers too, in addition to their hands and legs.

The keiki here today are part of Ulu A‘e Learning Center’s Nene‘e intersession program. Executive Director Miki‘ala Lidstone founded Ulu A‘e in 2014 after years of being a Kapolei High School teacher. She had noticed her students didn’t feel rooted in Kapolei, as many had moved there from elsewhere. So she started after-school and, later, out-ofschool programs focused on perpetuating Hawaiian traditions, values, and practices that highlight the ‘Ewa moku (district) they live in.

In developing her curriculum, Lidstone incorporated mo‘olelo (storytelling) and had cultural practitioners train her staff in practices such as lauhala making. Hikes and workdays at ancient fishponds and lo‘i such as the one at Hanakēhau are among the popular student activities. The program has seen rising success: Last year alone, Ulu A‘e worked with about 400 kids who live across the West Side. In Ulu A‘e’s early days, Lidstone, who is from Kailua, knew that understanding the area where many of her students live was integral in helping her students become engaged members of their community. She dove deep into Kapolei’s rich past in order to gain a sense of place: Named after Kapo, a goddess of fertility, and “lei” for the ring of light seen around a volcanic hill, Kapolei has a history of

て、ケイキたちは「ヘヒ(足踏み)」をして泥をならし、ピンク色の蓮の 花や根を抜いて、そこここに落ちている石をどける。裸足で泥だらけ になりながら、子どもたちは水を張ったロイの畝にひそむカエルや 小さな魚たちを見つける。電話もコンピュータも見当たらない。 男の子がにやにや笑いながら近くにいたポニーテールの女の子に 尋ねる。「僕の顔に泥ついてる?」女の子はけらけらと笑う。男の子 はもちろん、女の子も顔じゅうが泥だらけなのだ。顔だけではなく、 手足にも泥がこびりついている。

この日、子どもたちは、ウル・アエ・ラーニング・センターの秋休みプ ログラム「ネネエ」に参加していた。エグゼクティブ・ディレクターの ミキアラ・リドストーンさんはカポレイ高校で長年にわたって教壇 に立った後、2014年にウル・アエを創設した。リドストーンさんは、 生徒たちが、自分たちが暮らすカポレイという街にちゃんと根を下 ろしていないことに気づいていた。ほかの場所から引越してきた生 徒が多いことも原因だった。そこで、生徒たちが暮らすエヴァ・モク (地域)の特色であるハワイの伝統や価値観、技能などを末永く伝 えていくことを目的としたプログラムを、まずは放課後、やがては学 校外で立ち上げるにいたった。

カリキュラムを作り上げる過程で、リドストーンさんは「モオレロ(語 り聞かせ)」を取り入れ、ラウハラづくりなどの技能は実際の作り手 を招いてスタッフに伝授してもらったそうだ。ハイキングや、ハナケ ハウにある古代のフィッシュポンド(養殖池)やロイでの農作業は 生徒たちに人気のアクティビティだ。プログラムは順調に発展して いて、ウル・アエは去年だけでもウエストサイドに住む約400人の 子どもたちを迎えた。

ウル・アエの発足当時、カイルア在住のリドストーンさんは、生徒た ちの多くが暮らす土地への理解を深めなければ、生徒たちが自分 たちの地域に根ざしたコミュニティの一員となる手助けなどできな いと考えたそうだ。そこで、カポレイの豊かな歴史をじっくり学ぶこ とにした。豊穣の女神の名「カポ」と、火山性の丘に見られる光の輪

Kalo, or taro, is an integral part of the traditional Hawaiian diet. It was one of several canoe plants brought to the Hawaiian Islands by the first Polynesian settlers.

sugarcane and pineapple industries. Now dubbed O‘ahu’s “second city,” Kapolei has witnessed booming commercial and residential development over the last few decades—and there’s no sign of that stopping any time soon.

“People who are rooted and engaged in their community, they’re going to care for it,” Lidstone says. Over the years, Ulu A‘e has hosted community efforts to clean graffiti and remove invasive plant species. Students are also encouraged to choose locally grown produce and support local restaurants.

「レイ」を合わせて名づけられたカポレイの街は、かつてサトウキビ とパイナップル産業を支えたエリアだった。今日ではオアフ島第二 の都市と呼ばれ、ここ数十年間で商業地域としても住宅地としても 爆発的に発展した。その勢いは当分おさまる気配がない。

「自分のコミュニティに深く根ざし、積極的に関わっている人は、 その地域を大切にするものです」リドストーンさんは語る。ウル・ア エはこれまで、落書きを消してきれいにしたり、外来種の植物を除 去するといった地域イベントを主催してきた。生徒たちにも、地元 でつくられた農産物を選び、地元のレストランを支援することを奨 励してきた。

Learn Your Place

At Ulu A‘e Learning Center, programs focus on perpetuating Hawaiian traditions, values, and practices, which help keiki feel connected to their home and ‘āina (land).

For the last three years, Ulu A‘e students have been helping out at Hanakēhau Learning Farm’s lo‘i to shatter the preconceived notion that the West Side is too dry to farm. “In their consciousness is the aloha ‘āina mindset,” Lidstone says. “So when they think of Kapolei, they think of abundance.”

For more information, visit uluae.org

過去3年間、ウル・アエの生徒たちはハナケハウ・ラーニング・フ ァームのロイで農作業に参加することで、乾燥したウエストサイ ドは農業には向かないという偏見の払拭に貢献してきた。「生 徒たちは、アロハ・アイナの考え方を常に意識しています」とリド ストーンさんは語る。「彼らは、カポレイといえば豊かさを思い浮 かべるのです」

地元から世界へ

Think Big, Shop Small

Text by Tracy Chan Images by John HookWhen lockdown measures took a toll on retailers across the islands, a West O‘ahu-based nonprofit launched an online marketplace to help local artisans and small businesses reach shoppers from afar.

Ma muli o nā hopena ‘ino i ili mai ma luna o nā hale kū‘ai li‘ili‘i a puni ka pae‘āina, ua wehe ‘ia e kekahi ‘ahahui ‘auhau ‘ole no Kapolei he mākeke kūpūnaewele i wahi e kōkua ai i nā mea hana no‘eau kūloko a pā‘oihana li‘ili‘i i ke kū‘ai pū ‘ana me ka po‘e kū‘ai e noho aku ana ma kahi mamao.

コロナ禍がハワイの小売業を直撃したとき、カポレイの非 営利団体が立ち上げたオンラインのマーケットプレイス が、地元の工芸家やスモールビジネスを世界中の顧客に 結びつけました。

From Hawai‘i-made cookies, seasoned salt, and coffee to clothing, jewelry, and handcrafted skin care—the best onestop shop for local products this year is online. The Pop-Up Mākeke (mākeke means “market” in Hawaiian) is a website that consolidates unique products from hundreds of Hawai‘i’s small businesses into one virtual hub for the world to discover and enjoy.

“It started as a means to help businesses survive when we were in a state of uncertainty,” says Kūhiō Lewis, president and CEO of the Kapolei-based nonprofit Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement (CNHA), which spearheaded the project.

ハワイ産のクッキー、シーズニングソルト、コーヒー、衣服、ジュエリ ー、手作りのスキンケア製品。さまざまなハワイローカルの製品が 一か所で手に入る、いま一番便利なスポットはオンライン上にある。

「ポップアップ・マケケ」(「マケケ」はハワイ語で「マーケット」の意) は、ハワイの何百ものスモールビジネスを一堂に集め、世界中の人 びとがハワイ産のユニークな製品を見つけられるようにしたバーチ ャルなハブ拠点だ。

「先が見えない状況の中で、スモールビジネスを支援するために 立ち上げました」と、このサイトの意図を説明するのは、カポレイを 拠点とする非営利団体ネイティブハワイアン・アドバンスメント評 議会(Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement 、CNHA) のプレジデント兼CEOであるクヒオ・ルイスさん。ポップアップ・マ ケケのプロジェクトは、CNHAの先導で始まった。

Launched in April 2020 during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Pop-Up Mākeke online commerce platform was put together quickly in response to an urgent reality: Malls were empty, craft fairs and festivals like Merrie Monarch were canceled, and small businesses were languishing. Initially funded by a grant from the Hawai‘i Community Foundation to help buoy the local retail industry, the mākeke soon became a partnership between the nonprofit, private, and government sectors.

When Hawai‘i state mandates ordered the closure of all restaurants in the spring of 2020, Lewis and his team got creative in order to raise awareness about the online marketplace. They partnered with Hawai‘i News Now and launched a weekly live show, broadcasted on television and Facebook Live. “We originally used a closed-down restaurant, the Moani Island Bistro & Bar, to film the show,” Lewis says. A set was created and local entertainers, musicians, and social media influncers were invited to host and tell the stories behind the products. “The response was incredible,” Lewis says. “It just blew up.”

The Pop-Up Mākeke’s success was incredible, and even overwhelming, for some small local vendors, who couldn’t keep up with the sudden demand. Now, the Pop-Up Mākeke has evolved into an entire support program, with CNHA offering business classes and a loan fund to help burgeoning small business owners form a plan of action and market their products online. The program has partnered with a local distribution warehouse in Kapolei, and, to date, it has put over $2 million into the pockets of hundreds of Hawai‘i-based small businesses and artisans and sold over 100,000 items to more than 20,000 customers worldwide.

2020年4月、ポップアップ・マケケのオンラインコマース・プラット フォームは、パンデミックの初期段階で緊急事態に対応すべく迅 速に構築された。ショッピングモールから人影が消え、メリー・モナ ーク・フェスティバルなどのお祭りやイベントも中止され、スモール ビジネスは息も絶え絶えの状況だった。当初は地元の小売業を支 援するためにハワイ・コミュニティ基金から資金を獲得して開始し た事業だったが、すぐに非営利団体、私企業、官庁間の提携事業と なっていった。

2020年春、ハワイ州がレストランの閉鎖を義務づけると、ルイスさ んと彼のチームはオンラインのマーケットプレイスに注目を集める ため、クリエイティブな案を打ち出した。ニュース番組「ハワイ・ニュ ース・ナウ」と提携して、テレビとFacebookライブの両方で毎週生 放送を放映したのだ。「最初は、閉店中のレストラン『モアニ・アイラ ンド・ビストロ&バー』で撮影していました」とルイスさんは振り返 る。セットを作って、地元の起業家、ミュージシャン、ソーシャルメデ ィアのインフルエンサーなどを招き、製品の裏話などを披露しても らった。「すごい反響で、まさに爆発的でした」とルイスさんは言う。

ポップアップ・マケケの成功はめざましく、圧倒的と言ってもいいほ どで、急増した注文に生産が追いつかなくなるベンダーもあった。 現在ではポップアップ・マケケはさらに進化し、ビジネス全般をサポ ートするプログラムとなっている。CNHAは、起業したスモールビジ ネスのオーナーを対象に事業計画の立て方やオンラインでの販売 方法を学べるビジネス教室を主催し、事業資金の貸し付けも行う ようになった。カポレイにある物流倉庫と提携していて、これまでに 世界各地の2万人を超える顧客に10万点以上ものアイテムを販売 し、数百ものハワイのスモールビジネスやアーティストに合計200 万ドルを超える売上をもたらした。

Think Big, Shop Small

A business development strategist for the Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement, Davis Price helps oversee warehouse operations for the Pop-Up Mākeke. “This provides an incredible opportunity for Hawai‘i-based merchants to market and sell their products,” he says. “It’s exciting to help these vendors grow their businesses.”

Lewis and his team are now looking to maintain a self-sustaining year-round online marketplace and adding more pop-up vendors for the holidays. “There’s so much more that Hawai‘i has to offer,” Lewis says. “We’re just scratching the surface.”

Shop online at popupmakeke.com.

Interested in becoming a vendor or partner? Visit hawaiiancouncil.org/popupmakeke for more information.

ルイスさんとチームの仲間たちは、年間を通して自律的に動くオン ラインのマーケットプレイスとしてポップアップ・マケケを今後も維 持するとともに、ホリデーシーズンに向けてさらにベンダーを増や そうとしている。「ハワイには、実にたくさん素晴らしいものがありま す。まだそのほんの一部を紹介しはじめたばかりなのです」と、ルイ スさんは語った。

Sprouting Change

Text by Tracy Chan

Imagesby

Josiah PattersonIn Mākaha Valley, a little indoor microgreen farm has discovered a recipe for growing success.

変化の芽 Life マカハ・ヴァレーの小さなインドア農場は、マイクログリー ンに成功へのレシピを見出しました。

Ho‘oulu ‘ia e Mākaha Mountain Farms nā hua‘ai a lau‘ai kemika ‘ole me ka ho‘oulu pū ‘ana i ka hanauna hou he po‘e ho‘oulu mea kanu ma American Renaissance Academy.

Step into one of the 360-square-foot shipping containers that house Mākaha Mountain Farms and you’ll see rows of neat, vertically stacked trays, each containing bright green sprouts of arugula, broccoli, kale, or radish. Nurtured in a controlled, indoor setting, these nutritious microgreens are grown without any chemicals, pesticides, herbicides, or fertilizers and then harvested at peak flavor, right before they are full grown.

In 2019, when Daimon Hudson, American Renaissance Academy’s (ARA) chairman of the board, was first introduced to the idea of a container farming program by an Academy staff member, his interest was piqued. Sustainability and food security were important issues for him, and Hudson believed container farming could add to the Academy’s agriculture program. Yurika Suzuki, who is now director of operations for Mākaha Mountain Farms and an

「マカハ・マウンテン・ファームズ」の農場は、約33平方メートルの 貨物コンテナの中にある。コンテナの一つに足を踏み入れると、垂 直にきちんと並んだ何列ものトレーが目に入る。それぞれのトレー には、ルッコラ、ブロッコリ、ケール、ラディッシュといった野菜の、明 るい緑色の芽が育っている。制御された屋内環境で育つこれらの マイクログリーンには、殺虫剤や除草剤や化学肥料をはじめ、化学 物質は一切使われておらず、成長しきる直前の最も風味豊かなと きに収穫される。

アメリカン・ルネッサンス・アカデミー(ARA)の理事長ダイモン・ハ ドソンさんは、2019年のある日、学校のスタッフの一人からコンテ ナ農場というものの話を初めて聞かされ、興味をそそられた。サス テナビリティと食料の安全保障に深い関心を持っていたハドソン さんは、コンテナ農場をアカデミーの農業教育プログラムに組み 入れられると確信したのだ。現在ではコンテナ農場の運営ディレク ターとARAの農業インストラクターを兼任するユリカ・スズキさん

ARA agriculture instructor, jumped in with the idea of a microgreen farm and spearheaded the buildout with her fiancé Derek, Hudson’s youngest son.

The team converted the first shipping container into a climate-controlled vertical microgreen farming operation and had it running by spring 2020. They began pitching the delicious new product to local restaurants, grocery stores, and produce distributors, and they also hosted stands at farmers markets.

“We didn’t know if it would be able to generate income, but we saw the potential,” Hudson says. “It is a revenue stream for the Academy—and it’s also, more importantly, showing the future of agriculture in the state of Hawai‘i.”

The farm uses the latest vertical farming techniques, cutting-edge technology, and surprisingly few resources. “We use such little water, it’s remarkable,” Suzuki says. Careful thought went into packaging the sprouts too: the farm sources plant-based, biodegradable packaging material from a company on Hawai‘i Island. The farm is also a part of the school’s regular curriculum, available as an elective for students eager to take an active role in growing food for their community. Coursework includes learning about microgreens and planting and caring for seedlings.

Given that nearly 90 percent of Hawai‘i’s food is imported, expanding local agriculture is an important focus at ARA. But how to get younger generations interested and involved? “Microgreens have such a short life cycle that the students can see the rewards of their efforts within two weeks, and the excitement stimulates their interest in agriculture,” Suzuki says.

も、マイクログリーンを育てる農場というアイデアに飛びつき、ダ イモンさんの末の息子でもある婚約者のデレクさんとともに農場 の構想を練った。

スズキさんのチームは、最初の貨物コンテナを空調システムを備 えた垂直マイクログリーン農場に改造して、2020年春に運営を 開始。美味しい野菜を地元のレストラン、食料品店、卸売業者に売 り込み、ファーマーズマーケットにも店を出した。

「収益を生むかどうかはわかりませんでしたが、ポテンシャルは あると思っていました。農場は学校の継続的な収入源になります し、もっと重要なことに、ハワイ州の農業の未来を示してもいます」 と、ハドソンさんは語る。

コンテナ農場には、最新の垂直農場の技法と最新鋭のテクノロジ ーが使われ、消費する資源は驚くほど少ない。「本当に使う水の量 がとても少なくて、驚きますよ」とスズキさん。梱包材にも配慮し、 ハワイ島の会社から仕入れた植物素材で生分解可能な素材を使 っている。農場は学校の通常カリキュラムに組み込まれ、自分たち のコミュニティのために食糧を育てる役割を担おうという意欲を 持った生徒たちが選択科目として履修できる。生徒たちはマイク ログリーンについて学び、種まきや苗の世話の実習をする。

ハワイ州は食糧の90パーセント以上を州外からの輸入に頼って いる。その現実を踏まえ、ARAは地元の農業を推進することを重 要な課題ととらえている。しかし、若者たちの関心をかきたて、参 加を促すにはどうすれば良いのだろうか。「マイクログリーンはライ フサイクルがとても短いので、生徒たちは2週間のうちに自分たち の努力の成果を目にすることができます。その喜びが農業への興 味につながるのです。生徒たちはスマートフォンが大好きですが、

Sprouting Change

Through Mākaha Mountain Farms’ partnership with American Renaissance Academy, students are offered hands-on experience in growing nutritious microgreens for their community.

“They love their phones, and we’re taking their interest in technology and putting it into something that benefits their family, their community, and will have an impact globally.”

The Academy has since retrofitted two more shipping containers, creating opportunities for increased production and student involvement. “We’re teaching keiki of the West Side how to sustainably grow food in a revolutionary manner,” Hudson says. “By doing this, we’ve been able to show them that it’s not only sustainable but economically feasible to do it here in Hawai‘i.”

For more information, visit makahamtnfarms.com

私たちは、彼らのそのテクノロジーへの興味を、家族やコミュニテ ィに役立ち、グローバルなレベルでも影響を及ぼすことに向ける ように促しているのです」とスズキさんは説明してくれた。

ARAでは、その後さらに2台の貨物コンテナを農場に改造し、生 産量も増え、生徒たちが参加できる機会も広がった。「私たちは、 ウエストサイドのケイキ(子ども)たちに、革命的な方法でサステ ィナブルに食糧を育てる方法を教えているのです」とハドソンさ んは語る。「実践を通して、農場がサスティナブルだというだけで なく、ここハワイでも経済的に実現可能だと証明することができ ています」

Image by John Hook “

There’s so much history to this place, and we get to share a piece of it.”

Eva Kahapea-Hubbard, director of Camp Pālehua

A U T R E E S

Mauka Bound

Whereas beach camping is popular in Hawai‘i, at Camp Pālehua, there’s mana (power) in the mountains.

Text by Rae Sojot

Images by John Hook ハワイではビーチでのキャンプが一般的ですが、「キャンプ・パレフ

Aia nō nā wahi ho‘omoana a ala pi‘i mauna ho‘i ma luna o nā ‘eka ‘āina ho‘okoe a mahi‘ai he 1,600, ke waiho ala ma Camp Pālehua kahi e ho‘ohanohano a ho‘okahukahu ana i nā kumu waiwai kālaimeaola, mo‘omeheu, a mō‘aukala no ka pae kuahiwi ‘o Wai‘anae.

Located on the upland slopes of the Wai‘anae Mountains, Camp Pālehua is one of few places on O‘ahu that permits mountainside camping. The area has seen many iterations: Originally the homestead of an early missionary family, it served as a telephone switching station before being repurposed in 1940 as Camp Timberline, a popular retreat for schools and business groups. Today the property, since renamed Camp Pālehua, is owned by Gill ‘Ewa Lands and serves as a recreation site focusing on Hawaiian culture and conservation. Featuring cabins, bunkhouses, and tent camping across 16 acres and hiking trails across an additional 1,600 acres of conservation land, Camp Pālehua is a working example of the Gill family’s overarching mission: to celebrate and steward the biological, cultural, and historical resources of the mountain.

ワイアナエ山脈の高地斜面にある「キャンプ・パレフア」は、オアフではめず らしく山の中でキャンプができる場所だ。この一画はさまざまな変転を見て きた。もとは初期の宣教師一家の居住地だったが、やがて電話交換局とな り、1940年には「キャンプ・ティンバーライン」として再出発し、長らく学校 や企業の保養地として人気を集めた。現在は私企業であるギル・エヴァ・ラ ンズが所有、「キャンプ・パレフア」と名前を改め、ハワイアン文化と環境保護 に力を入れたリクレーションサイトとなっている。約2万坪の敷地にキャビン やバンクハウス、テントサイトがあり、隣接する約200万坪の保護区域に続 くいくつものハイキングコースを抱くこのキャンプ場は、ワイアナエの山々の 生物学的、文化的、歴史的な資産を人々に伝え、守っていこうというギル一 族の大きな使命があらわれている。

For camp director Eva Kahapea-Hubbard and her staff, tackling the day’s to-do list is a Sisyphean task: There’s the housekeeping chores, the repair and maintenance of the camp’s cabins and bunkhouses, and plenty of landscape work too—from tree trimming and cutting grass to building and maintaining water dams that help fend off soil erosion. Kahapea-Hubbard, who first came to Pālehua in 2017, often acts as an impromptu carpenter, plumber, landscaper, and mechanic, all in a day’s turn. But she wouldn’t have it any other way. The mountain is special and holds mana (power). There’s something that speaks to her here. “When people come to Pālehua, they feel a natural connection, a healing,” Kahapea-Hubbard says. “For me, this has been my place to unplug.”

キャンプ・ディレクターのエヴァ・カハペア=ハバードさんとスタッ フの日常業務は、骨の折れる作業のくり返しだ。清掃や整備はも ちろんのこと、キャンプのキャビンやバンクハウスの修繕やメイン テナンスに加え、樹木の剪定、芝刈り、土壌の浸食を防ぐために水 を堰き止めるダムの造成や管理といった造園作業にも終わりがな い。2017年からパレフアの事業にたずさわってきたカハペア=ハ バードさんが果たす役割は、大工、配管工、造園師、修理工など、一 日のうちでもめまぐるしく変わる。それでも、それが気に入っている のだと彼女は言う。山には特別なマナ(パワー)がある。何かが彼女 に語りかけるのだ。「パレフアを訪れた人々は、自然なつながり、癒 やしを感じるのです。わたしにとって、ここは電源を切って、本来の 自分を取り戻す場所なのです」

Although the lovely, haunting calls of the pueo, or Hawaiian shorteared owl, can still be heard throughout Pālehua, deforestation and rising temperatures due to climate change have forced many native birds to seek refuge at higher elevations, prompting scientists to double down on efforts to save these species from extinction. The cool forests surrounding Mount Ka‘ala, the highest peak of the Wai‘anae Mountain, are home to endemic birds such as ‘apapane, ‘amakihi, and the ‘elepaio, whose lively chatter is the first to be heard in the morning and last to be heard at night.

パレフアのどこにいても、ハワイのコミミズク、プエオの物哀しくも耳に心地よ い鳴き声が聞こえてくる。しかし、伐採による森の消滅と気候温暖化により、ハ ワイ固有の鳥たちの多くはより標高の高い地域への移動を強いられるように なり、科学者たちはこうした固有種を絶滅から救うためにいっそうの努力を傾 けている。ワイアナエ山脈の最高峰カアラ山を取り巻く涼しい森を住処とする アパパネ、アマキヒ、エレパイオといった絶滅危惧種の鳥たちのにぎやかなさえ ずりは、パレフアでは朝早くから夜を迎えるまで一日中楽しむことができる。

The sandalwood trade of the 1800s and subsequent outplanting of invasive species in the 1920s decimated much of O‘ahu’s native forests. Yet today, reforestation work offers glimmers of hope.

Dotted throughout Pālehua’s dryland-mesic forests, small kīpuka (areas) feature carefully nurtured koa and ‘iliahi saplings and ‘a‘ali‘i (a native hardwood shrub). Kawika Shook, a former Pālehua camp director, believes such silviculture is critical: “The health of the mountain dictates the health of what’s below.”

19世紀の白檀貿易に続き、1920年代に侵略的な外来種を植えすぎたことに より、オアフ島固有の森の多くは失われた。だが、現在では、植林活動によりか すかな希望が見え始めている。「中湿性乾燥地域」であるパレフアの森のあちこ ちに、細心の注意を払って、コア、イリアヒ、アアリイといったハワイ固有種の広 葉樹の苗木を育成する小さな「キプカ(区画)」が点在している。パレフアのキャ ンプ・ディレクターを務めていたカビカ・シュックさんは、そうした林学にもとづ くアプローチが非常に重要だと語る。「山の健康状態は、山のふもとの健康状 態をそっくり反映しているのです」

Rich in cultural history, Pālehua offers clues to its vibrant past. Archeological findings point to communities living here, and an ancient pathway, the Kualaka‘i trail, is believed to have connected the people of Pālehua, ‘Ewa, and Pu‘uloa, today also known as Pearl Harbor. Because Hawaiians lived a subsistence lifestyle, the Kualaka‘i trail’s juncture served as a key meeting area. Valuable resources like salt and fish from ‘Ewa’s coasts, shellfish and oysters from Pu‘uloa’s brackish waters, and wood and meat from Pālehua’s forests could be bartered or shared.

文化的にも豊かな歴史を持つパレフアには、過去をいきいきと伝える手が かりがたくさんある。考古学的な発見により、ここにかつて人びとが住んで いたこと、そして「クアラカイ・トレイル」と呼ばれる古い道が通っていたこと もわかっている。この道を使って、パレフア、エヴァ、プウロア(現在のパール ハーバー)に住む人びとが行き来したと考えられている。自給自足の生活を 送ったハワイの人々にとって、クアラカイ・トレイルがまじわる場所は、重要 な交易の場だった。人々はエヴァの海岸で採れる塩や魚、淡水まじりのプウ ロアの海辺で採れる貝類やオイスター、そしてパレフアの森でとれる木材や 肉を交換し、分かち合った。

Winding through forests of eucalyptus and ironwood, a trail opens to offer sweeping views of Nānākuli Valley. Along its western flank, a natural cleft bends and curves into the distinct shape of a fishhook. Legend tells of Māui, whose mother appealed to him to find a way to delay the sun’s brisk sprint across the sky. To please her, Māui climbed to the top of Pu‘u Heleakalā, the Pathway of the Rising Sun, and lassoed the sun with his magical fishhook, Mānaiakalani. With his fiery prey’s daily passage now slowed, his mother could dry her kapa, or clothing, to her satisfaction. Afterward, Māui cast his fishhook aside, where it left a lasting imprint on the mountain’s wall, still visible today.

ユーカリとアイアンウッドの森を抜けてハイキングコースを進むと、やがて目の前に、 ナナクリの谷を見わたす広々とした景観が開ける。谷の向かい側の山々の西の斜面に は、自然が穿った溝が、くるりとカーブした釣り針のような独特のかたちを呈している。

ハワイの神話によれば、英雄マウイの母親が、空を全速力で駆けぬけていく太陽に腹 を立て、どうにかしてほしいと息子に頼んだという。マウイは母親を喜ばせようと「プ ウ・ハレアカラ(朝日の昇る道)」の山頂に登り、魔法の釣り針「マアナイアカラニ」で太 陽を捕らえた。捕らえられた太陽が空を横切る速度をゆるめたおかげで、マウイの母 親は満足のいくまで「カパ(服)」を乾かせるようになったという。その後、マウイがぽい と放り投げた釣り針の跡が山肌に刻まれ、今もくっきり見えるのだそうだ。

The discovery of a large heiau, or place of worship, along with oral traditions that speak of the area, lead cultural scholars to believe that Pālehua served as a training ground for lua, or hand-to-hand combat, in ancient times. In Hawaiian, pā means “stone enclosure.” Lehua refers to the flower of the ‘ōhi‘a tree, known for its sturdy wood, which was prized by warriors for crafting weaponry. As such, Pālehua translates to “enclosure of the warrior.”

この地域に語り伝えられている伝承に加え、ヘイアウ(聖所)の大規模な遺跡 が発見されたために、文化学者たちは、パレフアがあるこの一帯は古代に「ル ア」つまり格闘技の訓練の場だったと考えている。ハワイ語で「パ」は「石で囲ま れた」という意味で、「レフア」は戦士たちが武器を作るときに使った強靭な樹 木、オヒアに咲く花を指す。つまり、「パレフア」は「戦士たちのための囲われた 場所」という意味になる。

As the seasons change, so does the night sky above Pālehua. Against a black velvet backdrop, the winged constellation ‘Iwa Keli‘i, the Chief Frigate Bird, rises in the northeast and then glides a path over Hokupa‘a, the North Star. Polynesian voyagers rely on nature— constellations, ocean currents, and animals, especially birds—to help them navigate across the Pacific. Depicted in the center of the Hawaiian star compass, the manu (bird) is a traditional metaphor for a canoe. Wayfinders follow ‘Iwa Keli‘i to make sure they are within the latitude of the Hawaiian Islands, the ‘iwa safely guiding their way.

パレフアの上に広がる夜空は季節とともに変化する。黒いベルベットのような 北東の空に、翼を広げた「イヴァ・ケリイ(グンカンドリ)」の星座がのぼり、「ホ クパア(北極星)」の上をすべってゆく。ポリネシアの人々は自然に頼って航海し た。星座、海流、動物、特に鳥たちが、太平洋の旅の導き手となった。ハワイアン の星図の中心に描かれる「マヌ(鳥)」は、カヌーを象徴している。航海士たちは イヴァ・ケリイの位置で、自分たちのいる緯度がハワイ諸島の方角からはずれ ていないかを確かめた。イヴァが彼らを安全に導いたのだ。

Street Smarts

When a beloved skate park fell into disrepair, a group of teenagers inspired a community to help them restore it to its original glory.Text by Rae Sojot Images by Kuhio Vellalos

I ka pau loa ‘ana o ka pono o ka Pāka Holo Huila o ‘Ewa Beach, na kekahi hui ‘ōpiopio i hō‘eu‘eu a‘e i nā luna kūlanakauhale a lālā kaiāulu ho‘i i ka ho‘oponopono hou ‘ana i ia wahi e like me kona ‘ano hiehie o mua a‘e.

10代の若者たちの熱意が行政と地域の人びとを動かし、老朽 化していたスケートパークの再生につながりました。

“Kids downplay how much their voice really means,” Brandon Pagarigan says. “Your voice is more powerful than you think.” As a sophomore in high school in 2015, he hadn’t planned on being a community organizer. His passion for skating, however, proved otherwise.

Pagarigan grew up skating in ‘Ewa Beach. But the skate park at ‘Ewa Beach Community Park, originally built in 1992, had begun showing signs of serious wear and tear in the mid-2010s: derelict ramps, degrading asphalt, weeds growing rampant in the cracks. The facility had become unusable—so much so, claims Pagarigan, skaters had resorted to skating elsewhere, which included trespassing onto the nearby James Campbell High School campus. “The school absolutely hated us,” Pagarigan says. “It got so bad, there was after-hour security to watch out for us.”

During one particularly tense encounter in 2015, a police officer threatened arrest if the skaters were caught trespassing again. When Pagarigan admonished the officer, insisting they had nowhere else to skate, the officer’s reply was blunt: “Why don’t you do something about it?”

「若者は、自分たちが声を上げても意味がないと思っ ているんです」と、ブランドン・パガリガンさんは言う。「 でも僕らの声は、みんなが考えているよりもずっとパワ フルなんですよ」。2015年、高校生だったパガリガンさ んは自分が市民運動を率いるなどとは思ってもいなか った。だが、スケートボードへの情熱が、いつのまにか 彼をその役割へと駆り立てていった。

パガリガンさんはエヴァビーチで育ち、小さな頃からス ケボーを楽しんでいたが、1992年に完成したエヴァビ ーチ・コミュニティ公園のスケートパークは、2010年 代のなかばにはあちこちに傷みが目立つようになって いた。ランプは手入れもされず放置され、アスファルト はひび割れ、割れ目から雑草が生えていた。パークは もう使いものにならず、スケーターたちはほかの場所 を探すしかなくなっていた、とパガリガンさんは説明す る。ほかの場所とは、たとえば、パークの前にあるジェ イムズ・キャンベル高校のキャンパスなどだ。「高校は 僕らが校内でスケートボードをするのをすごく嫌って ました。僕らを追い払うために、放課後に警備員を配 置したくらいです」

2015年のある日、それまでにないほど緊張した場面 で、今度学校に入り込んだら逮捕すると警官に脅され たパガリガンさんは、ほかにスケートボードができる 場所がないのだと訴えた。警官は単刀直入に切り替 えした。「だったらなぜ、自分たちで何とかしようとしな いんだ?」

The officer’s remark hit a nerve. Pagarigan and his friends decided they would do something about it. And they would start with a pitch to the neighborhood board. The teenagers circulated a “Save ‘Ewa Beach Skate Park” petition at school, where it swiftly garnered 150 signatures. Pagarigan approached his chemistry teacher to sign, but the teacher declined, citing reluctance to support “a place where people did drugs.”

“That made me feel doubtful,” Pagarigan recalls. He was all too familiar with the reputation that skate kids unfairly carried—that they were outcasts, misfits, and troublemakers—but it still stung to hear, especially from his favorite teacher. “I remember thinking, ‘Am I doing something crazy?’”

But support for the petition snowballed on social media and soon dispelled Pagarigan’s doubt. Within days of appearing online, the petition gained traction among skate groups and on Internet forums, which led local streetwear brand In4mation to donate T-shirts for the cause and prompted skate shops to hold fundraisers. Eventually, the petition swelled to over 1,500 signatures, with support coming in from California and Oregon. To supplement the petition, the teenagers prepared a PowerPoint presentation outlining ‘Ewa Beach Skate Park’s critical need for repair and improvements.

警官の言葉は、痛いところを突いていた。奮起したパガ リガンさんと友人たちは、実際に自分たちでどうにか しようと決意した。手はじめに町の自治会に呼びかけ ることにして、学校内で「エヴァビーチ・スケートパーク を救おう」という署名を始めた。たちまち150人の署名 が集まったが、化学の教師に署名を求めたパガリガン さんは断られてしまった。「ドラッグをやる場所」など支 援したくないというのがその理由だった。

「そう言われて、疑念がわいてきました」とパガリガン さんは振り返る。スケーターははみだし者だとかトラ ブルメーカーだとかいった色眼鏡で見られることには 慣れていたが、一番好きだった教師に言われた言葉 は、ぐさりと心に突き刺さった。「自信を失い、自分は 馬鹿げたことをしてるんだろうか、と思ったのを覚えて います」

しかし、そんな疑念は、ソーシャルメディアを通して急 激に拡がった支援の輪が吹き飛ばしてくれた。インタ ーネットに掲載してから数日で、嘆願書はスケーター のグループやネットのフォーラムで注目を集め、やがて ストリートウェアブランドのIn4mationが運動を支援 するTシャツを寄付し、ショップでも資金集めが始まっ た。カリフォルニアやオレゴンからも署名が寄せられ、 署名の数は最終的に1,500を超えた。署名に加え、エ ヴァビーチ・スケートパークがどれほどひどい状態にあ り、修理と改善を必要としているかの現状を訴えるた め、10代のスケーターたちはパワーポイントのプレゼ ンテーションを作成した。

The night of the neighborhood board meeting, Pagarigan was gobsmacked by the turnout. Supporters of all ages arrived in shirts emblazoned with “Save ‘Ewa Beach Skate Park,” and the air reverberated with excitement for the cause. “We couldn’t fit everyone into the room,” Pagarigan says, estimating there were about 100 people in attendance. He was also impressed to learn that their PowerPoint presentation was part of the evening’s official agenda. Rather than patronizing or dismissing the young skaters, the board treated them as legitimate members of the community with a legitimate concern. “They really wanted to help us,” Pagarigan says.

The following morning, the realization truly hit. While in 7-Eleven grabbing snacks, Pagarigan and his friends noticed a newspaper on a nearby newsstand. A photo of the crowd of Save ‘Ewa Beach Skate Park supporters had made the front page. The friends looked at each other in disbelief, then celebration. The community was behind them.

Over the next two years, Pagarigan and his friends worked with city officials and community members to forge a public-private partnership to refurbish the skateboarding area. City Council Chair Ron Menor helped move a bill

自治会の役員会が開かれた夜、パガリガンさんは集ま った支援者の数に目をみはった。あらゆる年代の支援 者たちが「エヴァビーチ・スケートパークを救え」とい う色鮮やかなスローガンをつけたシャツを着てつめか け、会場は熱気に包まれていた。およそ100名の人び とが集まり、全員はとても部屋に入りきれなかった、と パガリガンさんは振り返る。自分たちが用意したプレゼ ンテーションが、その日の議題の一つとしてちゃんと組 み入れられていたことも嬉しかったという。役員会は、 若いスケーターたちの意見を上から見下したり、適当 に受け流すのではなく、同じコミュニティの一員の、き ちんとした意見として耳を傾けてくれた。「役員の人た ちは、心から僕らを支援してくれていたんです」とパガ リガンさんは言う。

自分たちの成し遂げたことに改めて気づいたのは、そ の翌朝だった。セブンイレブンでスナックを買おうとし ていたパガリガンさんと友人たちは、すぐそばにあった 朝刊に目をとめた。エヴァビーチ・スケートパークの支 援者たちの写真が一面を飾っていたのだ。信じられず に顔を見合わせたあと、喜びがこみあげた。コミュニテ ィは彼らの味方だった。

その後2年にわたり、パガリガンさんたちは、市当局や 町の人びととともに、スケートパーク改修に向けて官 民のパートナーシップを築くために働いた。市議会の ロン・メナー議長は、ホノルル市郡の予算から18万 3,000ドルを割り当てる法案を通すために尽力し、ハ ワイ・スケーターズ協会(ASH)の創設者であるチャッ ク・ミツイさんは、資金集めと物資の寄付、そしてボラ ンティアの組織と管理に協力した。お役所とのやり取

that allotted $183,000 from the City and County for improvements. Chuck Mitsui, the founder of Association of Skaters in Hawai‘i (ASH), helped to raise funds and in-kind donations for the project and coordinated the volunteer efforts. “These kids really took leadership with this,” Mitsui says of the teens’ willingness to work through the bureaucratic system. Under ASH’s guidance, the teens worked long, hot weekends and became a quick study in all things skate park construction: reading blueprints, deciphering dimensions, and building ramps.

りに積極的に取り組んだティーンエイジャーたちの活 動を振り返り、「この子たちは、しっかりリーダーシップ を発揮していました」とミツイさんは語る。ASHのサポ ートのもと、若者たちは暑い週末に長時間かけてプロ ジェクトに取り組み、設計図の読み方、寸法のとり方、 ランプの造成といったスケートパーク建設に必要なノ ウハウをたちまちのうちに学んでいった。

そして2017年、ランプが完成する。1年後、科学の授 業を受けていたパガリガンさんは、「外を見てごらん」 というテキストメッセージを受け取った。スケートパー クのひび割れたアスファルトを取り除き、コンクリート

Street Smarts

In 2017, the ramps were completed. A year later, Pagarigan was sitting in science class when he received a text message telling him to look outside. The City and County trucks had arrived to remove the skate park’s faulty asphalt and resurface it with concrete. Pagarigan sprinted to the principal’s office and asked permission to watch on site. It was a surreal moment. “Seeing the concrete being poured over the barriers…” Pagarigan says, pausing to search for the right words to describe the feeling. “We finally did it.”

Today, at age 21, Pagarigan works as a lab assistant but still finds time to skate. On a recent Saturday afternoon, he visited the skate park, which buzzed with activity. Young skaters glided by, the familiar purr of wheels resounding over the smooth pathways. Skaters congregated in small groups, their laughter punctuated with the pops and cracks of boards maneuvering tricks. There’s a new crop of skaters here, but for Pagarigan, the feeling of camaraderie spans generations. Nearby, along the hip of an obstacle, a list of names is etched into the concrete, a permanent tribute to those who helped make the skate park a better place for everyone. “In high school, you do stuff for a grade, but this was something that we truly cared about,” Pagarigan says. “Seeing it all come together was the best feeling in the world.”

で再舗装するために、ホノルル市郡のトラックが到着 していたのだ。パガリガンさんは校長室に駆け込み、パ ークでその様子を見守る許可を得た。現実とは思えな い、シュールな気分だったという。「囲いにコンクリート が流し込まれていくのを見ながら……」パガリガンさん はしばらく言葉を探してから続けた。「僕らはついにや ったんだ、と思いました」

21歳になった現在、パガリガンさんは臨床検査助手と して働きながら、スケートボードを楽しむ時間も確保し ている。ある土曜の午後、パガリガンさんが訪ねると、 パークはにぎやかな音と動きに満ちていた。年少のス ケーターがボードで通りすぎ、なめらかな表面をウィ ール(車輪)が滑っていくときに立てる、おなじみの滑 走音が響く。スケーターたちはパークのあちこちに数 人のグループで集まり、技を試みるたびにボードが立 てる破裂するような音の合間に笑い声がはじける。新 しい世代のスケーターたちも加わっているが、パガリ ガンさんは世代を超えた仲間意識を感じるという。パ ークに設置された障害物の一つには、土台のコンクリ ートに、このパークをよりよい場所にするために尽力し た人びとの名前が刻まれている。「高校では成績のた めに努力しますが、このパークは僕らにとって本当に 大切なものだったんです」とパガリガンさんは述懐する。 「そのための努力が実を結んだのを見届けられて、最 高に嬉しいです」

Restorers of the Reef

The founders of Kuleana Coral Reefs are piloting a unique approach to restoration.

Text by Timothy A. SchulerImages by John Hook and courtesy of Kuleana Coral

I ka huli ‘ana o ke alo i ka loli aniau, ka ‘oihana lawai‘a ‘oi‘enehana, a me ke kūkulu ‘ia ‘ana o kapa kai, ke ho‘omōhala ‘ia nei e Kuleana Coral Reefs he papahana kūkahi no ka ho‘oponopono hou ‘ana i nā wahi kohola a ‘āuna i‘a ho‘i no O‘ahu.

保護団体「クレアナ・コーラル・リーフス」の創設者たちは、ユニ ークな方法でサンゴ礁の再生を試みています。

“I used to take fish. Now I make fish,” says Alex “Alika” Peleholani Garcia. Garcia grew up fishing on the West Side of O‘ahu and worked as a commercial fisherman for 15 years. Now, he’s the co-founder of Kuleana Coral Reefs, a local nonprofit organization working to protect and restore Hawai‘i’s increasingly vulnerable coral reefs. He’s not against fishing or responsibly using marine resources—“We’ve been a fishing culture since pre-Western contact,” he says, referring to Native Hawaiians—he’s simply as interested in creating habitat for Hawai‘i’s native fish and eels as he is in snagging some for dinner.

Garcia founded Kuleana Coral alongside Daniel Demartini and Kapono Kaluhiokalani in 2019. The three of them had watched as coral reefs and native fish populations suffered as a result of climate change, industrial fishing, and coastal development.

“As we develop the coastline, we change the way the water has moved historically and the [amount] of runoff and sediment that is pouring into the ocean,” explains Demartini, a marine scientist and professor of chemistry at Brigham Young University on O‘ahu. “That sediment will cover sections of the reef after a major rainstorm and will choke out the coral.”

「以前は魚を獲る側にいましたが、今は育てる側にい ます」と語るのは、アレックス・「アリカ」・ペレホラニ・ガ ルシアさん。オアフ島西部で釣りをしながら育ち、漁師 の仕事に15年間就いていたこともある彼は、現在、地 元の非営利団体「クレアナ・コーラル・リーフス」の共同 創設者として、ますます脆弱化するハワイのサンゴ礁 の保護と再生に取り組んでいる。とはいえ、魚を獲るこ とそのものや、責任をもって海洋資源を利用すること に異を唱えているわけではない。ネイティブハワイアン の文化について「西洋の影響を受ける前から、ここには 漁業の文化がありました」と語るガルシアさんは、夕食 のために魚を捕まえることと同じくらい、ハワイ固有の 魚やウナギの棲みかをつくることにも関心をもってい るのである。

ガルシアさんがダニエル・デマルティーニさんとカポ ノ・カルヒオカラニさんとともにクレアナ・コーラルを設 立したのは2019年のこと。3人は、気候変動や商業漁 業、沿岸部の開発によって、サンゴ礁や在来魚の個体 数が減少していくのを目の当たりにしてきた。

海洋科学者であり、オアフ島にあるブリガム・ヤング大 学で化学の教授をしているデマルティーニさんは、こ う説明する。「海岸部の開発を行うと、海水の流れが それまでとは変わってしまうため、海に流れ込む水や 土砂、堆積物の量も変わります。大雨の後、その堆積 物がサンゴ礁の一部を覆い、サンゴを窒息させてしま うのです」

Garcia grew up in Waipahu and works full time as a firefighter with the Honolulu Fire Department. For years, he was part of the department’s dive unit, which is typically deployed for search and rescue missions. It was grueling and sometimes gruesome work, he says. At Kuleana Coral, he gets to apply some of the same skills, but for a more heartening purpose.

Kuleana Coral, whose name is centered around the Hawaiian word for responsibility, has a unique approach to coral restoration. Oftentimes, conservation groups will set up coral nurseries in the water—giant trays full of baby corals that they’ve propagated— then outplant the tiny creatures onto the reef. It’s an effective method with one big downside: It can take years for these small corals to get big enough to provide habitat for marine life or to reach sexual maturity and begin reproducing on their own. “And it has to survive the gamut of challenges that humans keep throwing at it to get to that size,” Garcia says.

ワイパフで育ち、現在はホノルル市消防局の消防士と してフルタイムで勤務しているガルシアさんは、長年に わたり、潜水部隊に所属していた。潜水部隊は捜索や 救助に出動することも多く、非常に過酷で、時に恐ろし い場面にも遭遇する任務だったという。彼はそこで培 った潜水スキルを、クレアナ・コーラルでは、希望に満 ちた活動に生かしている。

ハワイ語で「責任」を意味する「クレアナ」の名を冠した この団体は、独自の方法でサンゴの再生に取り組んで いる。サンゴを保護する団体は、多くの場合、水中にサ ンゴの苗床(繁殖させた稚サンゴが入った巨大なトレ イ)を設置し、その稚サンゴをサンゴ礁に移植するとい う方法をとっている。これは効果的な方法だが、ひとつ 大きな欠点がある。稚サンゴたちが海洋生物たちの棲 みかになるだけの大きさに成長するまでに、あるいは、 性的に成熟して自力で繁殖できるようになるまでに は、何年もかかるのだ。「しかも、そこまで成長するため には、人間たちのおかげで次つぎに降りかかるさまざ まな難関を乗り越えなければならないのです」とガル シアさんは語る。

Kuleana Coral’s method is to use dive teams to identify dislodged but otherwise mature and healthy corals and reattach them to the reef. The founders identify a restoration site, typically just offshore, where the ocean floor is 40 to 70 feet below the surface. Then they and a team of scuba-equipped volunteers scavenge the ocean floor for coral colonies that look healthy enough to be saved. Once they’ve assembled enough healthy corals, they reaffix them to the reef using standard marine epoxy.

It’s a bit like if conservationists were able to salvage mature trees that had been downed in a hurricane or tornado. Large trees are much more valuable than saplings. They provide shade to people and nesting and foraging opportunities for birds and other wildlife. Mature corals are similar. The ability to replant these large specimens— some of which represent 30 years of growth—is significant. “That’s immediate habitat,” Garcia says. Demartini adds, “You watch fish come back and take up residence the next day.”

一方、クレアナ・コーラルでは、ダイビングチームが「サ ンゴ礁から剥がれてしまっているものの、まだ健康な 状態の成熟したサンゴ」を見つけ出し、サンゴ礁にもう 一度定着させるという方法をとっている。創設者たち は、主に、海岸からそれほど遠くなく、海底までの水深 が12~20メートルのあたりに再生スポットを特定し、 スキューバの器材をつけたボランティアのダイバーチ ームとともに海底を探索して、救出できそうな健康な サンゴの群生を探す。十分な数の健康なサンゴが集ま ると、標準的な船舶用エポキシ樹脂を使い、集めたサ ンゴをサンゴ礁に再び定着させる。

この方法は、自然保護団体がハリケーンや竜巻で倒れ た巨木を救済するのに似ている。樹齢の高い大樹は、 人びとには木陰を、鳥などの野生動物たちには巣作り や採餌のための場所を提供するという意味で若木より も重要な存在だが、それは成熟したサンゴにも当ては まる。成熟した大きな標本(なかには30年かけて成長 したものもある)を再植えつけできれば、その意義は絶 大だ。「大きなサンゴは、すぐに生物たちの棲みかにな ります」とガルシアさんが言うと、デマルティーニさん が言葉を継ぐ。「魚たちが戻ってきて、翌日にはもう棲 みついているのが見られるのです」 Restorers of

Garcia summarizes Kuleana’s approach to restoration as, “You find something that’s broken, you fix it.” To date, the nonprofit has performed restoration work at four sites offshore of Ko Olina Resort on the West Side of O‘ahu, each measuring roughly 50 feet by 50 feet. The founders know it’s a drop in the bucket compared to what is needed to restore Hawai‘i’s degraded coral reefs. Statewide, cauliflower coral populations have declined by 90 percent. A 2018 report from the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration (NOAA) described the status of O‘ahu’s coral reefs as “impaired.”

The team hopes to scale up at some point in the future, but for now it’s focusing its energy on small-scale replanting efforts and studying those efforts to better understand why certain corals survive and others don’t. “That’s the importance of monitoring, to really understand what techniques are we using that make it effective?” Demartini says, adding that the group is collaborating with researchers at the Coral Resilience Lab and NOAA.

ガルシアさんは、クレアナの再生アプローチを「壊れて いるものを見つけて、それを直す」と端的に表現する。

彼らはこれまでに、オアフ島西部のコオリナ・リゾート の沖合にある4か所のスポットで、それぞれおよそ15 メートル四方の区域の再生を行った。ハワイの荒廃し たサンゴ礁全体から見れば、この再生プロジェクトが 焼け石に水のような微々たるものであることは、創設 者たちも承知している。たとえば、カリフラワーコーラル (ハナヤサイサンゴ)の個体数は州全体で90パーセン トも減少しており、米国海洋大気庁(NOAA)の2018 年の報告書には、オアフ島のサンゴ礁の状態は「悪化 している(impaired)」と記されている。

クレアナ・コーラルは、将来的には規模を拡大したいと 考えているが、現時点では小規模な再植えつけ作業に 力を注ぎ、なぜ特定のサンゴだけが生き残れるのかに ついて理解を深めるために調査研究を行っている。「 私たちが採用している技術のうちどの部分が効果を上 げているのかをしっかり理解する上で、モニタリングは 非常に重要です」とデマルティーニさん。コーラル・レジ リエンス・ラボやNOAAの研究者との共同研究も進ん でいるという。 Restorers of the Reef

For Garcia, an unexpected result of starting Kuleana Coral has been fostering a newfound connection to his Hawaiian heritage. “Personally, I’m not really involved in Hawaiian culture. I grew up in it, but I don’t speak it. I don’t hang out with practitioners or anything,” he says. “But this [work] has connected me to that community. I’m learning to speak a little bit. I’m learning about history. And I’ve grown a lot from it. It’s changed me.”

ガルシアさんにとって、クレアナ・コーラルの活動を始 めたことは、思わぬ収穫につながったそうだ。それは、 ハワイアンとして自らが受け継いだ文化との間に新た な絆を見出し、それを深めるきっかけを得られたこと だ。「ハワイアンの伝統文化には個人的にあまり関わ りがなく、ハワイアンの文化の中で育ったとはいえ、ハ ワイ語を話すわけでも、伝統文化を実践する人びとと のつき合いもありませんでした。ですが、この取り組み を通じて、そうしたコミュニティとのつながりをもつこ とができ、少しずつですがハワイ語も話せるようなり、 歴史も学んでいます。そこから多くのことを学び、成長 することができました。このプロジェクトが私を変えた のです」

Image by Josiah Patterson

Image by Josiah Patterson

“

You can be the fastest, greatest player in the world, but if you don’t have heart, you nothing.”

Kapono Lopes, steel guitaristImage by Josiah Patterson

Kapono Lopes: The Steel Guitarist

As told to Rae Sojot Images by John Hook

Ho‘ohāli‘ali‘a ‘o Kapono Lopes, he mea ho‘okani i nā ‘ano pila like ‘ole he nui, i nā kumu nāna ia i ho‘omōhala mai i kāna ho‘okani kīkā ‘ana me kona mana‘o‘i‘o i ka ‘ao‘ao ho‘oulu o ka mele.

Growing up, I spent a lot of time with my Tutu (grandmother) and her generation. We lived in Arizona then, and a couple of my favorite things to do were to ask questions about her childhood and family history and, of course, to play and listen to Hawaiian music. I still remember long car rides listening to Hawaiian music and sitting in my room with my CD player, playing ‘ukulele along with Gabby Pahinui. Tutu and my family began to notice my interest in music and instruments from when I was young. My training began at Phoenix Boys Choir, the largest boys’ choir in the U.S., in elementary orchestra at Shumway Elementary in Chandler, Arizona, and at home kanikapila (jam sessions) with Tutu and her sister, Aunty Kaliko. Eventually, I started to really enjoy playing upright bass and auditioned for Phoenix’s Metropolitan Youth Symphony, where I became first chair and grew a great appreciation for music.

マルチインストゥルメンタリスト、カポノ・ロペスさんが、ギターへ の愛情を育むきっかけとなった数々のインスピレーションと、人生 をも変える音楽のパワーへの信頼を語ってくれました。

子どもの頃、祖母をはじめ年配の人たちと過ごす時間が多かったん です。当時はアリゾナ州に住んでいて、僕はトゥトゥ(祖母)に祖母の 子どもの頃の話や家族の歴史について質問したり、ハワイの音楽を 聞かせてもらうのも大好きでした。ハワイアンミュージックを聞きな がらの長いドライブや、自分の部屋でCDを聞きながら、ギャビー・ パヒヌイの演奏に合わせてウクレレを弾いていたことを思い出しま す。トゥトゥも家族のほかの皆も、まだ僕が小さい頃から、音楽や楽 器に対する僕の関心の高さに気づいたようです。音楽への本格的 な取り組みは、全米最大の少年合唱団であるフェニックス少年合 唱団、それからアリゾナ州シャンドラーにあるシャムウェイ小学校 のオーケストラ、そして自宅でのトゥトゥや大叔母カリコとのカニカ ピラ(ジャム・セッション)で始まりました。やがてコントラバスの演 奏を心から楽しむようになり、フェニックスのメトロポリタン・ユー ス・シンフォニーのオーディションを受け、そこの首席コントラバス 奏者として、音楽の楽しさをますます深く知るようになりました。

When I turned 11, our family moved back home to Kaua‘i, where I was born. I was no longer playing bass and had very little interest in music until I went to Kamehameha Schools. There, I enjoyed singing in the well-known Kamehameha Schools Song Contest and played bass for several groups, including the school’s jazz band. It wasn’t until I graduated and began working at Polynesian Cultural Center that I fell in love with making music again.

At PCC, I was taught to play guitar and bass guitar by some of the most talented and humble Polynesian musicians in the world. I was also introduced to the first steel guitarist I’ve ever worked with, Steve Cheney. I was instantly fascinated with the beautiful, magical sounds that came out of his instrument. It was warm and familiar and brought me back to long car rides with my Tutu when I’d hear Benny Rogers play with Aunty Genoa Keawe, David “Feet” Rogers and the Sons of Hawai‘i, or Gabby Pahinui and his Hawaiian band. From then on, I wanted to take steel guitar lessons, but I didn't know where to begin.

A few months later, I was asked to be a part of Aulani’s premier show, the Ka Wa‘a Lū‘au, where I met some of Hawai‘i’s top musicians. A bass player from the show, Adam Asing, took me to a local restaurant called Dot’s in Wahiawa. That’s when I met steel guitar master Uncle Bobby Ingano.

After talking with him and sharing my appreciation for steel guitar, he invited me over to his house. For the first few visits, he showed me very little on the steel guitar. Mostly he taught me what he thought was more important than learning to play a few tricks: how to be humble, to be thankful, and, above all, to have aloha. He’d tell me things like, “You can be the fastest, greatest player in the world, but if you don’t have heart, you nothing.” This old, uniquely Hawaiian style of teaching has really resonated with me since the times when I was taught by my Tutu.

11歳のとき、生まれ故郷のカウアイ島に家族で戻りました。コント ラバスにも触らなくなり、カメハメハスクールに入学するまで音楽 のことはほとんど忘れていましたが、カメハメハスクールの有名な 合唱コンテストをきっかけにまた歌う喜びを思い出し、学校のジャ ズ・バンドも含め、いくつかのバンドでベースを弾くようになりまし た。そして卒業後にポリネシア・カルチャー・センターで働き始めて から、再び音楽に夢中になったのです。

ポリネシア・カルチャー・センターでは、才能にあふれ、それでいて 謙虚な世界屈指のポリネシアン・ミュージシャンからギターとベー スギターを教わりました。生まれて初めてスティール・ギタリストに 出会い、ともに仕事をしました。それがスティーブ・チェイニーでし た。耳にしたとたん、スティーブの楽器が奏でる魔法の音色の虜に なってしまったんです。温かく、懐かしく、トゥトゥとの長いドライブ の間に聴いていた、ベニー・ロジャースとアンティ・ジェノア・ケアヴ ェ、フィート・ロジャースとサンズ・オブ・ハワイ、ギャビー・パヒヌイ とハワイアン・バンドなどを彷彿とさせる音色でした。それ以来、ス ティール・ギターを習いたいと思うようになりましたが、どこから始 めたらいいのかわかりませんでした。

数か月後、アウラニのプレミアショー「カ・ヴァア・ルアウ」に参加し ないかと誘われ、ハワイのトップミュージシャンたちと出会いまし た。ショーに出演したベースプレイヤー、アダム・アシンがワヒアワ にある「ドッツ」というローカルなレストランに連れていってくれまし た。そこで、スティール・ギターの巨匠、アンクル・ボビー・インガノに 紹介されたのです。スティール・ギターに夢中だという話をすると、 家に招待してくれました。最初の数回は、訪れてもスティール・ギタ ーのことにはほとんど触れず、彼にとってギターのテクニック以上 に重要なことを教えられました。謙虚であること、感謝の気持ちを 忘れないこと、そして何より、つねにアロハの心を持つことです。よく こんなふうに言われましたよ。「世界で一番速く弾ける最高の腕が あっても、心がなければ、なんの価値もないんだよ」。その昔トゥトゥ に教わって以来、そういう昔ながらのハワイ流の教え方が、僕には しっくり来るのです。

スティール・ギターの音色は古くて、懐かしくて、僕にとっては、ハワ イそのものなんです。ハワイアン・スティール・ギタリストの奏でる 独特の音色を耳にした瞬間、ハワイにいる気分になれる。かつては ワイキキのすべてのショーにスティール・ギタリストが出演してい て、街中でもいたるところで演奏していたものですが、残念ながら 現在では若手のスティール・ギタリストは両手で数えられるほどし かいません。

To me, the steel guitar sounds old, nostalgic, and, in my opinion, Hawai‘i. When you hear the styling sounds of a Hawaiian steel guitarist, it instantly transports you. At one time, there were steel guitar players in every show and every corner of Waikīkī. Unfortunately, I can count on my fingers how many young steel guitarists we have today.

Whenever I perform, I think of all those who have mentored me: my Tutu and her siblings, Uncle Bobby Ingano, Dallin and Tia Muti, Milton Kaka, Uncle Kuki Among, Uncle Ainsley Halemanu, Kamuela Kimokeo, and anyone I’ve ever played music with. I’m blessed by all those people in my life who’ve contributed a story, a lesson, a small piece of themselves to me. And though I’ve had many mentors, they all shared with me one thing in common: Always play with feeling from the heart, and always be you.

Now, when I play with people, I really enjoy making music with, I feel full of aloha seeing people in the crowd dance and smile. I enjoy seeing how happy it makes our kūpuna (elders) feel. And when the kūpuna come up to me and share their appreciation, that means more to me than all the money in the world. Hopefully as I play more, it helps to encourage others in my generation to do the same.

In addition to the steel guitar, professional musician Kapono Lopes enjoys playing guitar, upright bass, and ‘ukulele. He performs with the Ka Wa‘a Serenaders at Aulani Resort.

演奏するときはいつも、今まで僕に教えてくれた人たちのことを思 い浮かべます。僕のトゥトゥとその姉妹たち、アンクル・ボビー・イ ンガノ、ダリンとティア・ムティ、ミルトン・カカ、アンクル・クキ・アモ ン、アンクル・エインズリー・ハレマヌ、カムエラ・キモケオ、そのほか これまで一緒に演奏してきたすべてのミュージシャンたち。これま で出会った人たち一人ひとりが、さまざまな物語や教訓、彼らの一 部を僕に授けてくれたのです。これまで大勢の人に教えてもらいま したが、すべての教えに共通するものがあるんですよ。それは、常 に心に感じたままに弾くこと、そして、常にありのままの自分でいる ことです。

人と演奏するときは楽しくてしかたがありません。お客さんが音楽 に合わせて踊ったり、笑顔になるのを見ていると、心からのアロハ を感じます。音楽がクプナ(年配の人々)を喜ばせているのを見るの も嬉しいです。クプナが近づいてきて感謝の言葉などかけられると、 どんなにたくさんお金をもらうよりも幸せな気分になれます。僕の 演奏を聞いて、同世代の人々もやってみようと思ってくれればいい なと思っています。

カポノ・ロペスさんは、スティール・ギターのほか、ギター、コントラ バス、ウクレレも手がけるプロのミュージシャン。カ・ヴァア・セレネ イダースとともにアウラニ・リゾートで演奏中。

Keānuenue DeSoto: The Fashion Designer

As told to Rae Sojot Images by Lucrezia Alcorn and courtesy of Keanuenue DeSoto

Ha‘i mai ‘o Kēanuenue DeSoto no nā lanakila me nā ‘īnea i hekau ihola ma luna o kona ala iā ia e puka a‘e ana i kona wā ‘ōpiopio ma ke ‘ano he haku lole.

When I was younger, there was a lot I was trying to figure out. But one thing was certain: I knew my ‘i‘ini (desire) was to create. I love to make stuff. I love painting, drawing, writing, music, and especially sewing—it’s so freeing and empowering. In elementary school, I remember wanting to make my own clothes, so I would just pick a fabric and see where my sewing took me. I made skirts, shirts, bags, everything. Later, I found myself glued to a sketch pad drawing every variation of any design I could think of. And just like that, I fell in love with design too.

In 2015, I debuted my first line, Mākaha Fierce, in my first fashion show. I had been working for months creating and planning for it. The night before the show, I needed to stay up late and finish my looks for the next day. I remember not even being tired. The show was a success, and the process taught me that even if something takes days, weeks, or years, it will all be worth it in the end.

10代にしてファッションデザイナーとしての成功をつかんだケア ヌエヌエ・デソトさんが、栄光と試練の道のりを振り返ります。

小さい頃、いろいろなことを理解しようとするなかで、わたしにとっ てひとつ確かだったのは、自分のイイニ(ハワイ語で「望み」)はもの を創ることだ、ということでした。創ることがとにかく好きだったの です。絵を描くのも、文章を書くのも、音楽も、そしてなにより縫うこ とが大好きでした。縫ってなにかを創っていると、心が自由になり、 力づけられるように感じました。小学校のときに服を自分で作って みたいと思い、布地を手に入れて、思うままに縫い合わせてみたの を覚えています。スカート、シャツ、バッグなど、何でも作ってみまし た。その後、スケッチブックにデザイン画を描きはじめ、考えつく限 りのデザインのバリエーションを描くようになりました。そうやって デザインにも惹かれていったのです。

2015年に最初のファッションショーを開催して、初めてのライン「 マカハ・フィアース」を発表しました。制作とプランニングには何か 月も前から取り組みました。ショーの前日にも夜遅くまで仕上げの 作業を続けましたが、まったく疲れを感じませんでした。ショーは成 功し、わたしはその準備を通して、何日も、何週間も、何年もかかる ことでも、やるだけの価値というものがあることを学びました。

As a young designer, I’ve faced some challenges too. In middle school I had to leave early one day, and I remember telling the office lady that I had something to do for my business. Her response was, “You’re too young to have that much responsibility.” And I just laughed because there was really no other way of responding politely. I’ve never forgotten that day. It makes me think about the limits we put on ourselves and how they can affect your life. But for me, my business has never been a burden. It is always an amazing opportunity.

Another challenge I faced was having to sew swimsuits for a pop-up event after my first show. I had sewn 100 suits, and I did not enjoy it. Afterwards, I decided that if my business was going to be successful, I needed to find a manufacturer. Finding a local manufacturer was important to me, and I thought it would be easy to do, but I was incredibly wrong. After looking for nearly 17 months, I was ready to give up. During this time I produced small lines, opened fashion shows for other designers, and worked a lot with my mentor Kini Zamora. I even traveled to New York for New York Fashion Week. When I received an email from my dad connecting me to his friend’s wife who owned a manufacturing company, I was so excited. She fell in love with my story and agreed to manufacture my suits. That was a huge stepping stone for my business, not only elevating the quality of my line but increasing my business capacity.

年少のデザイナーだからこそぶつかる壁もありました。中学時代の ある日、学校を早退しなければならないことがあって、事務室の人 に仕事があるからと言うと、「あなたはそんな責任を負うにはまだ 若すぎるでしょう」と言われたのです。これには笑うしかありません でした。ほかに無難に答える方法を思いつかなかったのです。その 日のことは忘れません。人は思い込みで自分の限界を決めてしま うものなのだと気づかされた出来事でした。でも、わたしにとって、 仕事はいつも素晴らしい機会を与えてくれるもので、少しも重荷で はありません。

最初のショーのあとでポップアップイベントのために水着をたくさ ん作らなければならなかったときも、壁にぶつかりました。自分でミ シンがけして100着作ったのですが、これは楽しいとはいえない経 験でした。その経験から、ビジネスを成功させたいなら、メーカーを 見つけなくてはならないと気づきました。どうしても地元のメーカ ーを見つけたかったし、簡単に見つかると思っていたのですが、とん でもない間違いでした。17か月近く探し回って、もうあきらめようか と思ったこともありました。その間は小さなラインで制作し、ほかの デザイナーたちとファッションショーを開いたり、わたしのメンター であるキニ・ザモラさんとたくさん仕事をしましたし、ニューヨーク のファッションウィークにも出かけました。そんなときに父からEメ ールが届き、父の友人の奥さんで衣服メーカーを経営している方と つながりを得ることができて大感激しました。その方はわたしのス トーリーに共感して、わたしの水着制作に同意してくれたのです。そ れはわたしのビジネスの大きな足がかりになりました。製品のクオ リティも上がり、ビジネスのキャパシティも広がったのですから。

Now, I am a freshman at Parsons School of Design in New York City. Studying fashion is invaluable to my career as a designer. I love going to school at Parsons. Imagine a kid in a candy store—that is exactly what it feels like for me. I enjoy every project, and some of my hardest classes are actually my favorite. Being at Parsons means being able to learn while being a part of the industry. I feel so lucky to be here.

Whenever I create, I find the purest form of who I am, and I can completely present myself as me. But I also see that designing has moved beyond just doing it for myself. To me, being a Hawaiian designer means to be pa‘a (steady) in the ways of our kūpuna (elders) and to design and create in ways that are responsible and sustainable.

Our kūpuna learned from the land, so I try to do the same. I continually draw inspiration from my culture and nature, and I give them new life through my designs. And now I get to share that with others too.

Keānuenue DeSoto is an 18-year-old fashion designer from Mākaha. Her swimwear brand, Anu Hawai’i, received the Small Business of the Year award by the Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement in 2017.

To learn more, visit anuhawaii.com

現在は、ニューヨークのパーソンズ・スクール・オブ・デザインで学 んでいます。ファッションを学ぶことはデザイナーとしてのキャリア を築く上でかけがえのない価値があることですし、パーソンズがと ても気に入っています。まるで、キャンディ屋さんにいる子どものよ うな気分です。どの課題も楽しいし、最も難しい教科が一番好きで す。パーソンズに通うということは、業界の中に身をおいて学べると いうことで、とても恵まれていると思います。

何を創るにしても、わたしは自分自身を最も純粋に表現する方法 を見つけ、ありのままの自分を偽りなく見せることにしています。で も、デザインとは、自分自身のためだけではなく、それを超えたもの でもあります。ハワイアンのデザイナーであるということは、わたし たちのクプナ(祖先)から受け継いだあり方をパア(着実)に保ち、 責任あるサスティナブルなやり方でものを創ることも意味します。

クプナたちが大地から学んだように、わたしも学んでいきたいので す。わたしはハワイの文化と自然から常にインスピレーションを受 けると同時に、わたしのデザインを通してハワイの文化にも新しい 生命を吹き込んでいます。そして、それを人びとと分かち合ってい きたいのです。

マカハ出身のファッションデザイナー、ケアヌエヌエ・デソトさんは 18歳。スイムウェアブランド「アヌ・ハワイ」は、ネイティブハワイア ン・アドバンスメント評議会により2017年の「スモールビジネス・ オブ・ザ・イヤー」に選出された。

Punky Pletan-Cross: The Community Beacon

As told to Timothy Schuler Images by Josiah Patterson

No‘ono‘o ‘o Punky Pletan-Cross i kona ‘oihana, ‘ane‘ane e piha he 52 makahiki, he alaka‘i ‘ana i nā ‘ahahui hana lawelawe pilikanaka no ka ho‘omaika‘i ‘ana i ka nohona o ka po‘e ‘ōpiopio a me ko lākou mau ‘ohana.

I grew up in Grand Forks, North Dakota, in a neighborhood where there was a lot of violence and a lot of trauma. I was incredibly aware of that early on. Over the course of high school and college, I had a series of jobs. I worked at a mission one summer as a truck driver and cook, dealing with homeless adults. I spent a year working nights in an emergency room. I became very committed to civil rights.

During the Vietnam War, I went into Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA), the domestic Peace Corps. VISTA sent me to Massachusetts, where I was originally a street outreach worker. There weren’t any resources for kids in the early ’70s, so we organized an agency and started a 24-hour drop-in center and crisis hotline.

In 1984, my dad died. Coming to Hawai‘i was on his bucket list, so as an homage to him, my wife and I came to Hawai‘i to fulfill that dream and returned every year for 13 years. Hawai‘i has always had a mystical quality for me. I used it as a healing place. I came back in ’97 and saw a posting for a position at Hale Kipa. I interviewed with the board, was offered the job, and we moved here in February of ’98.

パンキー・プレタン=クロスさんが、若者たちとその家族の生活を 向上させるためにに力を注ぐ非営利の社会福祉機関を率いた52 年間を振り返ります。

わたしはノースダコタ州グランドフォークスの、暴力やトラウマにあ ふれた地域で育ち、子どもの頃から、そういった状況に注意をひか れていました。高校時代から大学時代にかけてさまざまなアルバイ トをし、ある夏は、伝道団体でトラックのドライバー兼コックとして 働き、ホームレスの人たちとかかわりました。病院の緊急治療室で 1年間夜勤のアルバイトをしたこともあります。そして、人権問題に 強い関心を持つようになったのです。

ベトナム戦争のときは、国内向けの平和部隊である「ボランテ ィアズ・イン・サービス・トゥ・アメリカ(VISTA)」に参加しまし た。VISTAからマサチューセッツに派遣され、「ストリート・アウトリ ーチ・ワーカー」(政府機関と連携して主に路上生活をしている青 少年の支援をするソーシャルワーカー)として働きはじめました。そ のころ、1970年代初めには、青少年のためのリソースが何もありま せんでした。そこで、われわれが機関を立ち上げ、24時間いつでも 立ち寄れるセンターと緊急ホットラインを開設したのです。

1984年、父が他界しました。いつかハワイを訪れるのが父の夢で したので、供養代わりに妻とふたりでハワイを訪れ、以来13年間、 毎年訪れました。ハワイというのはわたしにとって常に神秘的な価 値を持つ場所で、わたしを癒やしてくれる場所でした。’97年に訪れ たとき、「ハレ・キパ」の人材募集の案内を目にして、理事との面接を 受け、採用されて、’98年2月にハワイに移ってきました。

Hale Kipa means House of Friendliness. Geared primarily, but not exclusively, to youth and young adults, we are an agency providing a range of services related to child welfare, juvenile justice, and children’s mental health. Services range from emergency shelter to foster care to family and individual therapy. We have a program for victims of commercial sexual exploitation and a street outreach program in Waikīkī that works with homeless adolescents and young adults.

I would describe our population as those who have experienced a significant and profound amount of trauma in their lives. Hale Kipa is a trauma-informed agency, which means we see almost everything we do through the lens of trauma and the way that trauma impacts people. We see people as their stories, not their behaviors. Twenty-five years ago, trauma was not at the core of any of the work any of us were doing. We were one of the early adopters of a trauma-informed approach here in Hawai‘i. We see behaviors as coping mechanisms. These are individuals who are trying to find a way to soothe the pain they have.

When I got to Hale Kipa, I implemented a paid-time-off plan because if you’re doing this really tough work, you’ve got to find a way to rejuvenate. Our primary tool for doing the work that we do is ourselves, so if we’re not healthy, we can’t be there for the people we’re supposed to serve. One of the people on my leadership team asked me last Friday, what keeps you up at night? And I said, “Nothing.” I developed an ability

「ハレ・キパ」とは「親しみの家」という意味です。限定してはいませ んが、主として青少年と若者を対象に、児童福祉、未成年者に対す る司法関連の支援、児童の心の健康などに関するさまざまなサー ビスを提供しています。活動の内容には、緊急シェルターの提供か ら里親の手配まで、それに家族単位または個人単位のカウンセリ ングなども含まれています。商業的性的搾取の犠牲者をサポート するプログラムや、ワイキキの若いホームレスたちに手を差し伸べ る路上プログラムもあります。

われわれの活動が対象として接するのは、重大かつ深刻なトラウマ を経験した人たちです。ハレ・キパは「トラウマインフォームド」な機 関、つまり、なにごともトラウマというレンズを通して見る努力をし、 トラウマが人びとにどんな影響を与えるかを理解した上で支援に 取り組む機関です。その人の行動ではなく、その人が抱える物語を 通じてひとりの人を理解しようと努力しています。25年前、社会福 祉の現場でトラウマが重視されることなどありませんでした。われ われはハワイでいち早くトラウマインフォームドのアプローチを取 り入れた機関のひとつです。人びとが取る行動は、トラウマに反応 する対処メカニズムです。私たちが見ているのは、痛みを抱え、それ をやわらげる方法を探し求めている人たちなのです。

ハレ・キパに来て、わたしは有給休暇制度を導入しました。過酷な 仕事をしているのですから、リフレッシュする方法を持たなければ なりません。われわれにとっておもな仕事道具は自分自身なので す。自分が健康でなければ人の力になどなれません。先週の金曜 日、リーダーのひとりにきかれたんです。夜、眠れなくなることはな いですか、と。わたしは「ない」と答えました。自分の力でできるこ ととできないことの見分け方は、ずいぶん昔に身につけましたから。

a long time ago to know what I can control. In January 2020, Hale Kipa moved into its new home in ‘Ewa Beach. Our goal for being in ‘Ewa is to be a player in the community. We want to be a partner to the schools. We want to be involved in meetings and advocacy efforts. The pandemic shut it all down. So when I retire, the thing that’s still on the table, the big unfinished goal that I would have had, is to do the outreach. I’m a community organizer by nature.

I will have spent almost 52 years as a CEO when I retire at the end of the year. There is a sense of responsibility that is fundamental to being a CEO. I don’t think you are ever not in that role. I have felt a very strong pull to spend the time I have left really enjoying life. COVID has really reinforced that. I have this intuitive sense that there are right times to do things. It’s not a matter of a plan but more of a gut feeling. We’re in a really good place as an agency, and that’s a great time to walk away.

Punky Pletan-Cross has served as CEO of Hale Kipa, a nonprofit agency that works with at-risk youth throughout the State of Hawai‘i, since 1998. He lives in Kailua with his wife, Cris Pletan-Cross, and their dog, Pearl.

To learn more, visit halekipa.org

2020年1月、ハレ・キパはエヴァ・ビーチの新しい場所に移転しま した。このエヴァで、コミュニティの一員として活躍したいのです。学 校と連携し、ミーティングに参加し、アドボカシー活動にも参画し たいと希望しています。パンデミックのおかげで、すべてが中断を余 儀なくされてしまいました。退職を前にしたわたしにとって、やりか けのまま残してしまったもの、果たせなかった最大の課題はアウト リーチ活動です。わたしは生まれついてのコミュニティオーガナイ ザーなんですよ。

今年の暮れに退職するとき、わたしはおよそ52年間にわたって CEOを務めてきたことになります。CEOという立場の基本にあるの は責任感です。CEOである以上、その責任からは一瞬たりとも逃れ られません。これから残された時間は、人生を謳歌するために使い たいと強く願っています。COVIDのおかげでその思いはいっそう強 くなりました。何ごとにもそのための絶好のタイミングというものが あると、私は直感しています。計画ではなく、本能的に感じるタイミ ングです。ハレ・キパが福祉団体として非常に良い活動をしている 今こそ、わたしが退職するときだと思うのです。

パンキー・プレタン=クロスさんはハワイ州の青少年を支援する非 営利機関ハレ・キパのCEOを1998年から務めてきた。妻クリス・プ レタン=クロスさん、愛犬パールとともにカイルア在住。

Four

Ko Olina Hillside Villas AMENITIES

Ko Olina Marina

Ko Olina Golf Club

Ko Olina Station

Ko Olina Center

Laniwai, A Disney Spa & Mikimiki Fitness Center

Four Seasons Naupaka Spa & Wellness Centre; Four Seasons Tennis Centre

Lanikuhonua Cultural Institute

Grand Lawn

The Harry & Jeanette Weinberg

Seagull School, The Stone

Image by John Hook

Image by John Hook