0 92 > $14.95 US 71486 29217 3

A symbol of love, friendship, appreciation, and aloha.

For generations, the people of Hawai‘i have used lei to express these emotions, strengthen relationships, and show gratitude. Our roots are set in the islands and, as in the human gesture of gifting someone a lei, extend outward.

FOR THE LGBTQ TRAVELER

Publisher

JOE V. BOCK

joe@nmgnetwork.com

Creative Director

ARA LAYLO

Editorial Director

MATTHEW DEKNEEF

Senior Editor

ANNA HARMON

Designers

MICHELLE GANEKU

SKYE YONAMINE

Photography Director JOHN HOOK

Network Marketing Coordinator

AJA TOSCANO

Editorial Assistant

EUNICA ESCALANTE

Contributors

CALLA CAMERO

MARIE ERIEL HOBRO

MITCHELL KUGA

JADE SNOW

KYLIE YAMAUCHI

Images

KEVIN ARANIBAR-MOLINA

CHRIS BEHROOZIAN

RAMSEY CHENG

JASON CHU

SAM FEYEN

LILA LEE

MICHELLE MISHINA

IZIK MORENO

JA TECSON

MELANIE TJOENG

President & CEO

JASON CUTINELLA

VP Creative Development

TAMMY UY

VP Sales

MIKE WILEY mike@nmgnetwork.com

Network Strategy Director

FRANCINE NAOKO BEPPU

Marketing & Advertising Executives

HELEN CHANG

CHELSEA TSUCHIDA

Sales Assistant

KYLEE TAKATA

Advertising Operations & Digital Marketing Coordinator

HUNTER RAPOZA

Creative Services Manager

SHANNON FUJIMOTO

Operations Administrator

COURTNEY MIYASHIRO

VP Accounts Recievable

GARY PAYNE

Digital Marketing Manager

MUTYA BRIONES

Web Designer & Developer

KIMI LUNG

Lead Producer

GERARD ELMORE

Video Producers

SHANEIKA AGUILAR

KYLE KOSAKI

Destination

Marketing Hawaii

DEBBIE ANDERSON

Published by 36 N. Hotel St., Suite A Honolulu, HI 96817 nmgnetwork.com

© 2019–2020 by Nella Media Group, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted without the written consent of the publisher. Opinions are solely those of the contributors and are not necessarily endorsed by Nella Media Group.

ISSN 2578-210X

MASTHEAD 6

For guest room reservations and information, call 855.738.4966 | www.halekulani.com ARE WORTH REMEMBERING SOME MOMENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS 8 ARTS & DESIGN 20 Cut to the Feeling 30 Celestial Utopia 38 As They Are 46 Illustrating Change 54 Finding His Voice FASHION 66 Love & Honesty CULTURE 76 The Advocate 86 Papi Party 98 Spoken Words EXPLORE 110 Rising Queens 122 Girls on Film 134 Tastes Like Home

Stories

Shot from the street level of Honolulu Pride, a photographer’s uplifting photo essay gives visibility to Hawai‘i‘s LGBTQ community. Learn how the Aloha State sparked the legal movement toward marriage equality in the 1990s. Read about the inspiring cultural landscape of the islands today, on our site.

Itineraries

DJ and jetsetter Kim Ann Foxman splits her life between New York City, music festivals around the world, and her childhood home of O‘ahu. Follow in her footsteps with an adventurous itinerary from air to sea, online.

Experience

Mark dates and activities with monthly calendars highlighting fun and relaxing happenings across the islands.

instagram: @leiculture

twitter: @leiculture

facebook: /leiculture

ONLINE 10 Want to stay in the know on the latest in Hawai‘i? Find more stories online at leiculture.com

PILIAINA ‘

WHERE 110 STORES & 30 RESTAURANTS CREATE ONE TIMELESS PARADISE. THIS LAND IS OUR LEGACY. THIS IS HELUMOA AT ROYAL HAWAIIAN CENTER. Apple Store | Fendi | Harry Winston | Hermès | Jimmy Choo | Kate Spade New York | Loro Piana | Louis Vuitton | Salvatore Ferragamo Tiffany & Co. | Tory Burch | Tourneau | Valentino | Doraku Sushi | Island Vintage Wine Bar | Noi Thai Cuisine | Restaurant Suntory The Cheesecake Factory | Tim Ho Wan | TsuruTonTan Udon Noodle Brasserie | Wolfgang’s Steakhouse Hula | Lei Making | ‘Ukulele | Lauhala Weaving | Offered daily in The Royal Grove | RoyalHawaiianCenter.com Open Daily 10am–10pm | Kalākaua Avenue and Seaside, Waikīkī | 808.922.2299 FREE WIFI BE CONNECTED TO THIS LAND. BE IMMERSED IN THIS PARADISE. WHERE A LEGENDARY EXPERIENCE AWAITS YOUR ARRIVAL. WELCOME TO OUR LEGACY.

Aloha, and welcome to Lei, our voice for the LGBTQ traveler.

This issue our theme is Togetherness, something we think the world needs a little more of today. In many ways, we’re united more than ever before, connected through mediums and platforms one couldn’t have imagined only a few years ago. But we’re also more divided, segmented into micro-communities, even within our LGBTQ sphere.

What better time to think about our community more expansively than as we approach the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots and the launch of Pride as a global movement and phenomenon that brings us all together? Our strength lies in our individuality, yet also in our community and our support for one another.

We encourage all our viewers and readers to express themselves, support Pride movements in their own locales,

and hopefully travel to ours and others so we can continue building our bonds between cities, across oceans, and around the world.

We hope you enjoy this issue and also our exciting new video series, The Lei Over, Lei Exchanges, and Lei Escapes, where we bring attention to artists and advocates alike. View our latest content at leiculture.com as well as at hotels and in the air through our valued travel partners.

Aloha, Joe Bock Publisher @leiculture

leiculture.com

PUBLISHER � S LETTER 12

WHERE 110 STORES & 30 RESTAURANTS CREATE ONE TIMELESS PARADISE. THIS LAND IS OUR LEGACY. THIS IS HELUMOA AT ROYAL HAWAIIAN CENTER. Doraku Sushi | Island Vintage Wine Bar | Noi Thai Cuisine | Restaurant Suntory | The Cheesecake Factory | Tim Ho Wan TsuruTonTan Udon Noodle Brasserie | Wolfgang’s Steakhouse | Dean & Deluca | Il Lupino Trattoria & Wine Bar P.F. Chang’s Waikīkī | Uncle Tetsu Japanese Cheesecake | Kokoro Café | Kulu Kulu Honolulu | Island Vintage Coffee Hula | Lei Making | ‘Ukulele | Lauhala Weaving | Offered daily in The Royal Grove | Discover more at RoyalHawaiianCenter.com Open Daily 10am–10pm | Kalākaua Avenue and Seaside, Waikīkī | 808.922.2299 FREE WIFI HE ‘ONO WHERE CRAVINGS ARE SATISFIED. WHERE PARADISE IS SERVED. WHERE YOU CONNECT TO OUR WORLD WITH EVERY BITE. WELCOME TO OUR LEGACY.

Lei TV offers a curated guide to Hawai‘i for the discerning LGBTQ traveler. Its episodic series take viewers into the hearts, minds, and passions of the people who are shape the culture today.

EXCHANGES

Kapa

New York-based decor designer Nicholas Andersen learns about the art of kapamaking from artist Dalani Tanahy.

WATCH ONLINE AT: nmgnetwork.com/leitv

Lei TV is also available on Hawaiian Skies, the inflight video magazine for Hawaiian Airlines.

EXCHANGES

Tattoos

Los Angeles tattoo artist Ruby Croak and Hawaiian kākau practitioner Keli'i Mākua share their approach to body art.

CULTURE

Madame Gandhi

The musician and activist spends the week in Honolulu to perform and assemble an all-girl band of local musicians.

ESCAPES

Bubble_T & Papi Juice

Explore the sunny sights and local eats sprinkled throughout the North Shore of O‘ahu with two Brooklyn party collectives, Bubble_T and Papi Juice.

TV NMGNETWORK.COM/LEITV 14

Discover our elegantly packaged premium shortbread cookies. Indulge in Aloha with island-inspired flavors like Pineapple, Mango, Kona Coffee, and much more! For the Very Best, Look for the Pineapple Shape® honolulucookie.com 1-866-333-5800 18 LOCATIONS The pineapple shape of the cookie is a federally registered trademark of the Honolulu Cookie Company.June 2019-May 2020. Lei Magazine. ©2019 Honolulu Cookie Company. All Rights Reserved. OAHU Ala Moana Center Hilton Hawaiian Village Hyatt Regency Waikiki International Market Place OHANA® Waikiki Malia by Outrigger® Outrigger Waikiki Beach Resort Royal Hawaiian Center Sand Island Retail Store Waikiki Beach Marriott Waikiki Beach Walk® MAUI Front Street The Shops at Wailea Whalers Village LAS VEGAS The Forum Shops at Caesars Palace® Grand Canal Shoppes at The Venetian | The Palazzo The LINQ Promenade GUAM Micronesia Mall The Plaza Shopping Center

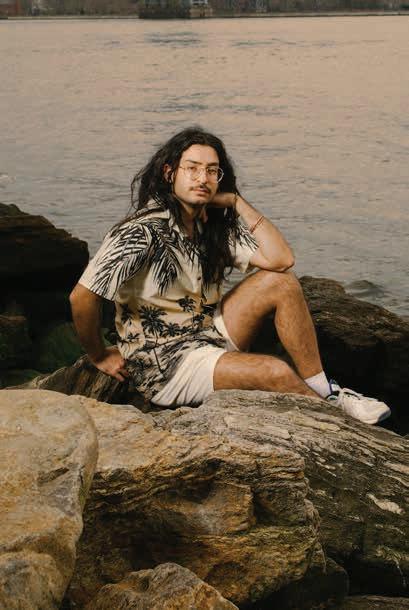

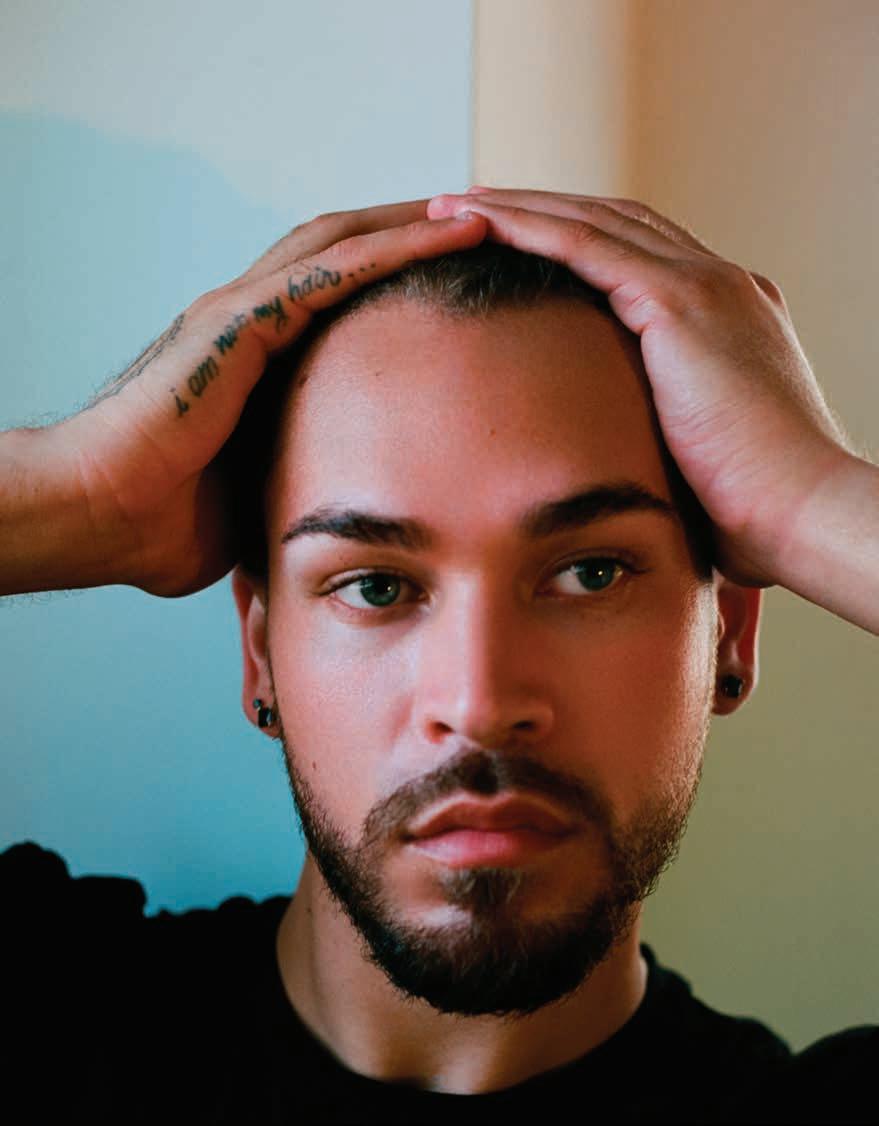

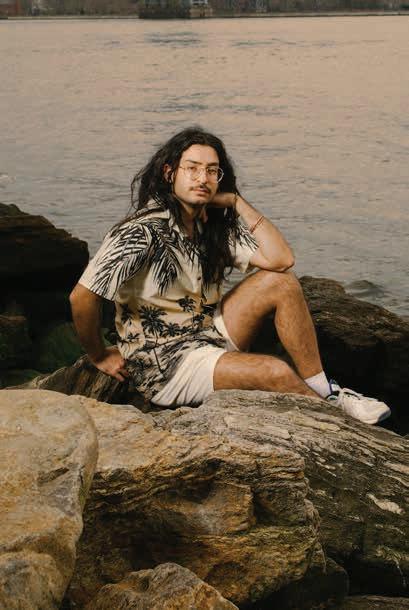

KEVIN ARANIBARMOLINA

A photographer and visual artist born and raised in New York City, Kevin holds a BFA in photography from Parsons School of Design. His work evinces a sharp eye for the points where forces that have shaped his life and practice intersect. Experiences of religion, gentrification, sexuality, displacement, masculinity and cultural identity meet in his portfolio. He photographs friends, strangers, and himself as characters in a nonlinear narrative.

Based in Brooklyn, Calla is a writer from Honolulu, Hawai‘i. During her time studying at San Francisco State University, she was able to develop a passion for storytelling. She reports on minority groups whose identities are often misunderstood by the uninformed. Through her work, she intends to challenge society’s narrow presumptions to create a more empathetic and tolerant society.

A graduate of Moanalua High School, Mitchell is a Brooklynbased writer whose work has appeared in The Village Voice, GQ, BuzzFeed News, The Fader, Out, and Flux Hawai‘i. His writing largely centers on LGBTQ culture, food, and identity. He has spoken on panels and readings at The Guggenheim, The Asian American Writers’ Workshop, Soho House, McNally Jackson, and the School of Visual Arts.

Born and raised in the Kona region of Hawai‘i Island, Michelle is a photographer based in Honolulu. She attended Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California where she studied journalism and communications while honing her interest in photography. Her work has appeared in publications including the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Hana Hou!, Flux Hawai‘i, alongside the arts, culture, and travel titles in the NMG Network.

Utah born, Hawai‘i raised, Izik Moreno is a singer-songwriter based on O‘ahu. He released his debut album, Obsidian, in 2016 and is working on his sophomore album. A Nā Hōkū Hanohano Award nominee, Izik has performed in venues across Hawai‘i, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and Japan. He was featured in Lei Issue 5.

CONTRIBUTORS 16

CALLA CAMERO

MITCHELL KUGA

MICHELLE MISHINA

IZIK MORENO

I. Arts & Design

Inside the lives of creatives intent on fostering a sense of place and belonging

TO THE FEELING TEXT

20

CUT

BY

MITCHELL KUGA IMAGES BY MICHELLE MISHINA

From

touring with Lady Gaga to Insta-celebrity, choreographer Mark Kanemura dances to his own beat.

When he was about 10 years old, dancer Mark Kanemura saved his allowance for months to buy a strobe light from Radio Shack. “I loved anything that would contribute to my theatrical vision,” Mark says over the phone from his Los Angeles apartment. “I really wanted a fog machine, but I don’t think I ever saved enough.”

The strobe light was for homespun productions of Broadway musicals that he and his younger sister, Marissa, performed in the living room of their ‘Aiea home. Their typical audience consisted of their parents, but that didn’t stop Mark from selling handmade merchandise—sequined cardboard magnets shaped like cat eyes—after their livingroom production of Cats. For their recreation of Phantom of The Opera, he remembers cutting out a cardboard chandelier and making it fall on top of Marissa’s head at the end of act one, “because that’s what happens in the show,” he explains.

More than 20 years later, in the summer of 2017, Mark reconnected with this childlike wonder via Instagram. He was crashing at a friend’s apartment in Los Angeles, heartbroken after the end of a long-term relationship, when he first heard Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Cut to the Feeling.” For 3 minutes and 28 seconds, the song made him feel “ridiculously happy.” Like lip-synching-shirtless-in-your-friend’skitchen-while-wearing-a-blonde-wig-revealinga-shock-of-red-confetti happy. He filmed with his iPhone doing exactly this before posting it on Instagram. The video went viral with nearly 100,000 views on his social media and landed on a segment of Entertainment Tonight.

A year later, to celebrate Pride month, he amplified the concept. Filmed in the West Hollywood bedroom of his new apartment, the weekly video series, dubbed #CutToTheFeelingFridays, approximated the sensation of a gay piñata bursting, unleashing a medley of wigs, balloons, confetti, and rainbow flags (which he repurposed into nearly every conceivable garment). In each stand-alone clip he choreographs these elements into a campy fantasia of precision. Till this day, he admits the process can be somewhat of a nightmare, a series of prop malfunctions, near injuries, and multiple takes that test the limits of his patience. Most importantly, they’ve connected Mark to his 421,000 Instagram followers (as of this writing), giving them the permission to be as free and playful as the guy pulling a cloud of confetti out of his rainbow-striped Speedo.

Mark, who is 35 years old and describes his offline personality as “shy and introverted,” wasn’t a stranger to the spotlight. In 2008, he competed in the fourth season of Fox’s television franchise So You Think You Can Dance, and starting in 2009, he toured internationally with Lady Gaga’s The Monster Ball Tour. Mark was born on O‘ahu to a family that indulged his flair for the theatrical, signing him up for classes at Hawaii Theater for Youth and taking him to Broadway shows at the Neal Blaisdell Center. “I just knew I had to be involved in that world somehow,” he says. “I didn't know how exactly, but I knew that that was where I felt a lot of excitement.”

After graduating from Castle High School, where he immersed himself in the school’s illustrious theater program, Mark taught at Kāne‘ohe’s 24-7 Danceforce, a training ground for Hawai‘i’s top dancers. Itching to break out of his comfort zone, he flew to Los Angeles on a whim when he was 24 to audition for So You Think You Can Dance. He remembers the jitters he felt waiting in line at 4 a.m. next to dancers who were more technically trained and further along in their careers. “To this day,

24

I think the reason I got on is I brought something that was a little different, a little unique,” he says. He describes his style of dance as a patchwork of his upbringing: the emphasis on ballet and modern at Mid Pacific Institute, where he attended middle school; the concentration on jazz and hip-hop at Castle; the shades of Polynesian he picked up from Tau Dance Theater; and his lifelong obsession with musicals. “When I started choreographing, all those things sort of naturally blended together,” he says, “and created whatever it is that I do.”

Mark finished in the top six of the competition, but the exposure didn’t safeguard him from the uncertainties of life as an artist. “After the show, I moved to LA and was back auditioning with every other dancer that lives here,” he says. “If I'm being really honest, I remember there was a month or two where I was so broke that I was living off of cereal and ramen. I had a really hard time asking for help.”

Then a chance meeting with choreographers Laurieann Gibson and Richard Jackson landed Mark a dream gig: dancing in Lady Gaga’s 2009 performance at the MTV Video Music Awards, regarded as a turning point in her career. His genre-melding dance style made him a natural fit for the singer, who was positioning herself as pop music’s avant enfant terrible. He toured with her for the next four years as a principal dancer and appeared in her “Telephone” music video.

“She fulfilled all my dreams of wanting to tour with an artist,” he says.

Today, Mark travels regularly to teach his choreography at dance conventions, dabbles in video work (he directed visual content for Selena Gomez’s tour), and occasionally models and acts. But he always budgets time for elaborate Instagram productions, inspired by that first one in his friend’s apartment, which allow him to tap into his inner child, the 10-year-old who made a cardboard chandelier. “That’s my playtime,” he says. “When I’m not working, I make sure to do those videos because they bring me a lot of joy.”

They’ve also brought Mark opportunities. In August 2018, Carly Rae Jepsen’s team invited him to perform “Cut to the Feeling” during her set at the San Francisco music festival Outside Lands. A video taken by Marissa shows Mark sashaying on stage in a rainbow Speedo and cape before rhythmically snatching off each of his seven wigs and sending them soaring in high-arching lobs. The video is shaky with excitement, and over the roar of the audience, Marissa’s screams are ecstatic: “That’s my brotherrrrr!”

“To this day, there's something about that video that makes me want to cry,” Mark says. “Because I grew up with a sister who never questioned me, she never called me any names, she was always just down for the ride—that encouraged my creativity. Being able to play and create as a child is why I am able to freely do that now.”

28

THE CHAIRS ARE NEW. THE VIEW, TIMELESS.

We kept all the best things.

Our spectacular views of Diamond Head. The blue Pacific as far as the eye can see. Great surf at our famous sun-soaked beaches. A legacy of art and tradition. Cocktails at twilight. Aloha everywhere. Things that age well, and things that don’t age at all.

Everything else is brand shiny new.

Welcome to the newly renovated Queen Kapi‘olani Hotel.

Where Diamond Head Meets Waikīkī

150 Kapahulu Avenue, Honolulu, Hawai‘i

Book your shiny suite: Call: 808-922-1941

QueenKapiolani.com

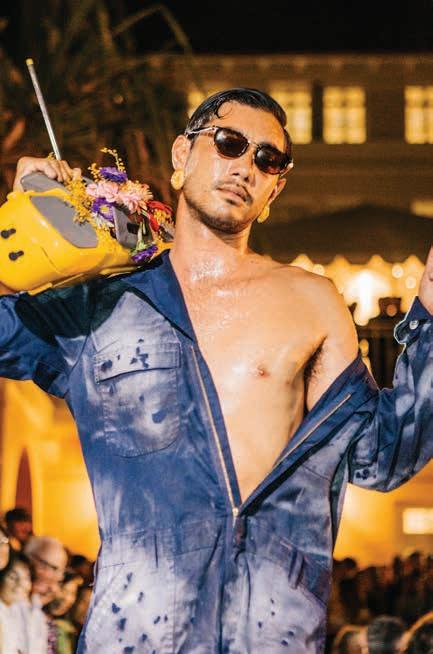

With Protea, stylist and Barrio Vintage owner Bradley Rhea showcases the diversity and daringness of his Honolulu community.

A psychedelic, space-funk beat set the tempo as ethereal beings floated across the dimly lit courtyard of Hawai‘i State Art Museum in downtown Honolulu. Their ensemble of kaleidoscopic prints and vintage retro garb make them seem unearthly, as if unbound by the laws of our time. No, this was not a science-fiction odyssey; this was Protea. The outer space-themed fashion show was the latest vision from Bradley Rhea, the brain behind Barrio Vintage. It was a celebration of courage and transformation as exhibited not only by the clothes—rare, vintage finds culled by Bradley himself–but by the models, many of whom were chosen for their individuality and rebellious spirits. To see how Bradley brings his creative vision to reality, watch the premier episode of Process at nmgnetwork.com.

CELESTIAL UTOPIA IMAGES BY JASON CHU & LILA LEE 30

AS THEY ARE TEXT

BY EUNICA

ESCALANTE

38

IMAGES BY AJA TOSCANO & SKYE YONAMINE

Artfully crafted and implicitly political, Maganda by jewelry designer

Bayebette Lacar aims to inspire beauty, pride, and self-worth.

In my native tongue of Tagalog, the main language of the Filipino people, to be maganda means to be beautiful. Yet the compliment often extends to features that do not quite resemble mine. Through centuries of colonization, first by the Spaniards then by Americans, the definition of ganda, or beauty, in the Philippines was warped, becoming dominated by Eurocentric aesthetics: porcelainwhite skin, high-bridged noses, and thin, angular faces—features that are a far cry from those of my indigenous ancestors.

I grew up striving for this version of beauty. I recall aunties in the Philippines advising me when I was as young as 6 years old to pinch my nose bridge with a clothespin so that, magically, the bones could grow into a slimmer, Caucasianlooking nose. To this day, my mother hoards stacks of skin-whitening soap, shipped from the Philippines, in her bathroom cupboard.

But identity politics are shifting. Movements by people of color and the LGBTQ+ community are challenging who and what is considered beautiful. For Bayebette Lacar, embracing her Filipino heritage is a pillar of her Hawai‘i-based jewelry line, Maganda. The designer realized from the start that the brand was “more than just selling accessories,” she said. “It’s about empowering my brown girls and anyone else who might not fit into what society ‘traditionally’ considers beautiful.”

Maganda began as a happy accident for Bayebette. Stuck at home with a two-monthold daughter, she began experimenting with polymer clay, molding and baking the versatile material into customized jewelry pieces. She wore the earrings out, and they caught the eyes of friends who encouraged her to turn the hobby into a business.

“I honestly never planned for them to blow up like this,” she said. “It all came out so organically.” Since its launch in late 2017, Maganda has grown into a locally beloved brand known for its sweet, minimal style. The earrings now span a multitude of materials, from clay to wicker and beads. Her designs call back to Bayebette’s Filipino roots, their aesthetics inspired by jewelry worn by Filipino indigenous tribes.

“It’s about sharing my identity and heritage,” she said. “My Filipino culture is a part of who I am. And, in a way, my creations are an extension of my identity.”

Many of the people that Bayebette chooses to model her creations, including myself, are “her fellow brown girls,” she said, an effort to promote a brand image that is relatable for her and her demographic. Representation and visibility are important to Bayebette, and she understands the power that her jewelry has in promoting a more inclusive idea of beauty, one that is not constricted by Eurocentric ideals.

On Instagram, she shares images explaining facets of Filipino culture and of strong Filipinos who have inspired her. One striking post included a photo of Whang-od Oggay, a 102-year-old Filipina tattoo artist from the Kalingga tribe. In the photo, she faces the camera head-on, her body covered in tribal markings, still magnificent in her old age.

40

The latest collection of jewelry on Maganda designer Bayebette Lacar (left) and writer, Eunica Escalante (right)

The latest collection of jewelry on Maganda designer Bayebette Lacar (left) and writer, Eunica Escalante (right)

For Bayebette, the type of beauty Whang-od Oggay embodies is more than skin deep. It is a beauty of selfworth rather than self-scrutiny, a beauty that is confident in the power of one’s uniqueness. “No one is you,” reads an illustration by fellow Filipinx creative Roselle Julian that Bayebette shared on Maganda’s Instagram at @ma.ga.nda. “That is your power.”

44

Sometimes unplugging can make you feel a whole lot more connected.

Timeless happens here.

MAUNAKEABEACHHOTEL.COM

Visual

artist

Ashley Lukashevsky’s work doubles as a love letter to the community and a spirited call to action.

The warm Los Angeles light dances across the drawing nook that serves as Ashley Lukashevsky’s makeshift studio space. This afternoon, she sits in front of her stylus, doodling away. Displayed above her are pieces by other women artists, many of whom have inspired Ashley’s own work. Among these works hangs one of her own featuring a radiating woman in a power stance with her hands behind her head and the words “Believe in Yourself.”

It’s a creed that speaks to Ashley’s quest as an illustrator and visual artist. She spells it out proudly on her Instagram bio: “Illustrating to dismantle patriarchal nonsense + systemic racism.” For this Hawai‘i-born artist, systemic issues such as homelessness, poverty, and unemployment were realities she witnessed while growing up in Honolulu. She always knew that she wanted to create an impact in her community, but expressing her voice through illustration wasn’t always her vision. While attending University of Southern California, Ashley studied international relations and political science. Back then, she was convinced that pursuing a “serious” career was the only way to create the change that she hoped to achieve. “I didn’t understand the power that art has to shape change at the time,” Ashley says. “I thought I had to do research or writing in order to create change.” During her last semester at USC, Ashley decided to take an elective course in graphic design and found that design came naturally to her.

ILLUSTRATING CHANGE TEXT BY AJA TOSCANO IMAGES BY JA TECSON 46

After graduating, she worked as a graphic designer for a start-up company for a year. Commissions done on her own time were what kept her excited. In 2017, Ashley decided to break free from the mundane and became a freelance illustrator. Since then, she has been creating works that critique and comment on societal issues, encouraging discourse among her active community of supporters both online and off. “I want my art to feel affirmative to people of all identities, specifically to queer and trans people of color,” Ashley says.

Ashley’s works are easy to spot; they feature queer, full-figured, ethnic women who evoke power and poise within the same pen stroke. Though these women are two-dimensional, it’s easy to see that each of them are comfortable in their illustrated skin. Whether they’re drawn in a power stance or in a calm state of self-care, each subject portrays a specific emotion that viewers relate to.

What ties each piece together are the dynamic words and voices that these works aim to represent. Ashley’s project in collaboration with Planned Parenthood of New York illustrated a variety of topics from sexuality to self care paired with catchphrases. “Whenever I get to work with an organization or a company that is asking me to create something that really resonates with me, that’s my favorite project,” Ashley says.

Ashley shares her artwork on Instagram, and thousands of fans have reposted her illustrations. Her work even resonates with celebrities. During the 2018 election, Ariana Grande shared Ashley’s post encouraging people to vote with intersectionality in mind to her 148 million Instagram followers.

I caught Ashley for a FaceTime call while she was between projects. We talked about home, her community, her recent vibrator collaboration, and more.

48

How did home (Honolulu) influence your work?

I think my work is impacted by where I grew up in ways that I don’t even notice. My work is really colorful and has a lot of botanical, beautiful plants and flowers because that was the environment that I grew up in. There’s also something really nostalgic and comforting about that. I miss that a lot in LA. because I feel like everything here is so dry. People are like, “Do you wanna go on a hike?” and I’m like, “No, it’s just dirt.” I miss the landscape of home. And the people in my art are typically always people of color because that’s who I grew up around. And I think that I also miss that. Being in such white circles when I went to college, now I’m wanting to fully embrace diversity and the multicultural communities that I grew up in.

How do you support your local LGBTQ community in LA?

I have done work for organizations that serve all kinds of populations. I did a limited-edition print run of my “SISTERS NOT CIS-TERS” print. I sold them and donated 100% of the proceeds to the TransLatin@ Coalition. That organization is really incredible, and they work with a lot of trans people in Los Angeles. And it’s led by Bamby Salcedo, who I’m a huge fan of! I also do most of my pro bono work for immigration-related issues, which is definitely something that impacts LGBTQ people. A lot of the immigrants at the border who are trying to have a safer life are often running from persecution based on their sexual identity or gender identity.

When you’re working at your favorite coffee shop, do people ever come up to you or peek over and ask about your work? Honestly, that’s one of my biggest pet peeves (laughs). The things I draw often have nudity and different topics, sexual things. This happened a few weeks ago! I was drawing two nude women and it read “LOVE THY SELF.” It was very sensual, and this older white man sitting next to me was just like “Oh, I like that,” and I was just so uncomfortable, and kept having to do other things so he wouldn’t keep looking.

Speaking of sensuality, I saw your recent collaboration with the Le Wand Massager for International Women’s Day. What a fun project!

Yes! That was really cool because my pattern is all over the vibrator and they have this illustration of me on the back of the box. And I was like, “All these people have to think about me every time they pull out their vibrator!”

What’s your dream art commission or collaboration?

I think that my dream art collaboration would be something surrounding public art, working in collaboration with a community to create a visual manifestation of their dreams. I think that we all need something physical, a picture to aim towards. With everything happening right now, it’s easy to feel disengaged or hopeless. We need to be able to continue to dream, and that’s a really big role that art plays. To create public art is so powerful. And it would be

50

amazing to see the way people interact with art in that space, instead of just online where my work usually is.

Is it cooler seeing your work online or offline?

Definitely offline. My work is on billboards right now sponsored by Why We Rise, an ongoing project of the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health. I see it often online but rarely see it in person. Sometimes I’ll be driving or in an Uber, and I see a billboard of my work—and it’s giant—I get really excited!

Your Uber driver is looking at you in the rear view mirror like “Uhh…”

And I’ll be like “That’s mine! I made that!” The first time I saw it at LAX I was really excited because it’s on a rotating screen. I would just stand next to it and wait for it to come on again so I could take a picture (laughs).

What do you hope your illustrations will create for others?

I hope that my work, at the very least, gives someone a glimmer of hope that they’re not alone, and that they’re cared for and have community wherever they are.

52

888-282-0918 | paradisecopters.com Departing from Kona, Hilo, Waimea, Lana‘i, Turtle Bay, and Kapolei (West O‘ahu) Hawai‘i’s Premier Helicopter Company Unparalleled Charters & Exceptional Tours

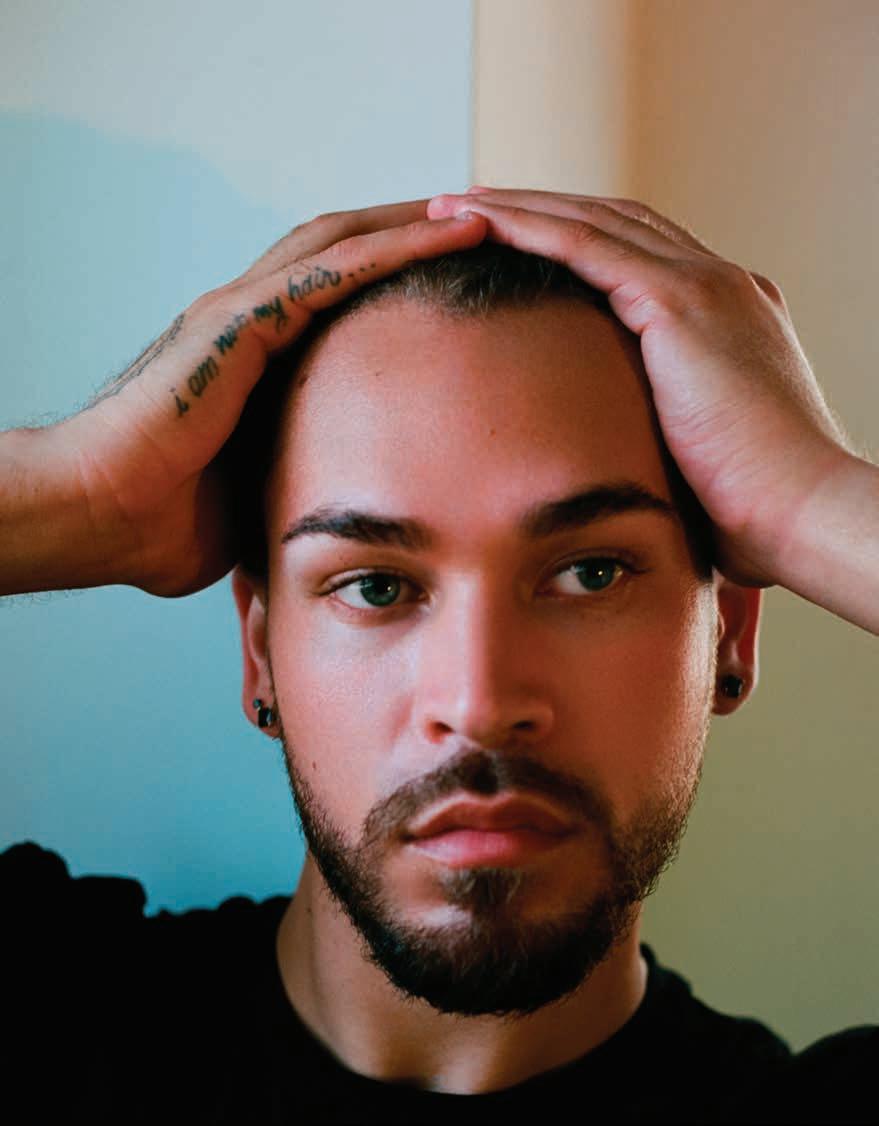

With his debut album, singer-songwriter DeAndre reveals his soul-searching journey with exquisite lyrics and melodies.

FINDING HIS VOICE TEXT BY JADE SNOW IMAGES BY IZIK MORENO 54

At a time when many artists are searching for the quickest shortcut to success, DeAndre has been journeying down a path of self-discovery. Displaying wisdom beyond his 24 years, he has ignored the temptation to chase the trappings of the music industry, focusing instead on honing his craft and finding himself in the process. Though he rose to fame on American Idol in 2011, DeAndre may be recognized by many in Hawai‘i as a hula dancer and falsetto singer known as “Kamele,” his given Hawaiian name. Now, eight years after Idol, DeAndre has hit his stride with the release of his debut R&B album, Black Denim.

DeAndre’s upbringing included a varied cultural and musical landscape. Born in San Jose, California, he realized his vocal ability at an early age because his family and friends insisted he sing. The sounds of his youth were diverse: His father exposed him to soul classics like Sam Cooke and Teddy Pendergrass as well as hip-hop favorites like Nate Dogg and Warren G, while his mother introduced him to rock and alternative music like Nirvana and Evanescence. Through his hānai grandparents, the classic Hawaiian voices of Genoa Keawe and the Ho‘opi‘i Brothers became nostalgic sounds of his childhood. Because of these grandparents, he was heavily immersed in Hawaiian music and culture throughout his youth, and he naturally progressed to dancing hula. He began performing at 11 years old in a San Jose-based Polynesian performance group, learning a variety of Polynesian traditions including Samoan, Tongan, and Kapa Haka dance forms. Ultimately, he fell in love with hula and the captivating stories of Hawaiian culture. Four years after his first kāholo (a foundational hula step), his passion was further ignited when he joined the California branch of Hālau Ka Liko Pua O Kalaniākea under the direction of kumu hula Kapua Dalire-Moe. DeAndre steeped himself in hula through travel and competitions with the hālau, which culminated in three years of group performance at the prestigious Merrie Monarch Festival and, in 2010, the solo title of Master Iā ‘Oe E Ka Lā at the oldest hula competition and festival held outside of Hawai‘i in Pleasanton, California.

Though hula was DeAndre’s main focus as a teenager, he continued to find his singing voice both in and out of the hālau. His naturally high tone was akin to that of Motown legend Smokey Robinson, which lent itself perfectly to leo ki‘eki‘e (Hawaiian falsetto). “My range was high because all I did was sing leo ki‘eki‘e growing up, so I had no comprehension of how to use my full voice,” he said. When he was 15, he auditioned for American Idol at the insistence of his mother, where he was encouraged by judges to hone his skills and return. DeAndre did just that, earning a spot a year later and awing spectators and judges alike with his unique sound, drawing comparisons to R&B legend Maxwell. However, it didn’t take long for him to feel the tremendous pressure of sudden fame. “When I got to the big stage on American Idol, I was told to just ‘do you,’ and I wasn’t sure what that was because most of my performance training was in hula,” he explained. Being thrust into the limelight amid sky-high expectations was overwhelming for a young singer just beginning to discover himself and his sound. Despite the challenges, DeAndre still made it to top eight in the competition. His time on Idol also garnered him attention and curiosity around his sexual identity. “There was speculation at the time because I had long hair, I was skinny, singing falsetto, and was lowkey effeminate,” he said. “At that point I was still figuring my sexuality out, but it wasn’t cut and dry. I’m bisexual—I like humans. I’m not the norm, I walk around in heels, that’s just me.” His mother’s acceptance was exemplary of the close-knit bond he shares with his family. “She was like, ‘You’re DeAndre and that’s it. You can like guys, you can like girls, just because you have an interest in one thing doesn’t mean that’s all that you are.’”

58

Life is a journey. Get comfortable. Proud to be the Premier Airline of HONOLULU PRIDE™

Some are thick, some are worn, and some are really fine. They’ve been woven together to make me strong and to make me into the fabric that I am now.”

“

Though navigating identity as a young adult is often a challenge, DeAndre has identified himself as a powerhouse vocalist hitting his stride. He moved to Honolulu in 2014, where he became the first member of his family to graduate college. In 2018, he moved to Melbourne, Australia, where he poured himself into his debut album. Titled Black Denim, it is an emotional snapshot of his journey and all that he has endured. Its eight original songs showcase his vocal style as well as his poetic songwriting, each referencing moments of challenge or triumph. The title song, “Black Denim,” was inspired by a time of darkness in his life. “I went through a period of depression and was anorexic and bulimic,” DeAndre explained. “I wasn’t strong enough to handle my own saboteur.

Black Denim is one of the more poetic songs I’ve written—it’s a statement about where I was and a benchmark of where I’ve come.” Through heartfelt lyrics, he explores personal stories, such as the dissolution of his parents’ marriage in “Love Was The Excuse.” “I.D.n.Y.L,” stands for “I Don’t Need Your Love” and encourages empowerment and self-love.

Black Denim explores the highs and lows of DeAndre’s journey thus far, illustrating his profound emotional depth and lyrical maturity. “Denim is composed of threads of different consistencies,” he said of the album’s name. “Some are thick, some are worn, and some are really fine. They’ve been woven together to make me strong and to make me into the fabric that I am now.” A new chapter of his musical journey is beginning with the release of Black Denim, and DeAndre will continue to strengthen the weave of his artistic story.

62

II. Fashion

The latest formal wear bridging a divide between runway and reality

LOVE & HONESTY IMAGES BY MELANIE TJOENG 66

Mikko & Lucas

When photographer Melanie Tjoeng gathered her friends Mikko Puttoan and Lucas Ruska Martin for a shoot, she knew that the concept would be more than just a fun, fashionable jaunt through London. Their love story was typical enough, of finding “the one” after years of loss and heartbreak. “It’s about love and healing,” Melanie says. “It was important for us to just show an intimate and honest portrait of two people.”

III. Culture

Face to face with those who hope to open up the conversation on identity and community

With 25 years of stomping in the streets and championing change, Kim Coco Iwamoto continues fighting for disenfranchised communities.

Kim Coco Iwamoto knows she cuts a formidable figure in Hawai‘i politics. “My presence in a room makes sphincters tighten,” she says, before breaking out in laughter. “In Hawai‘i, I’m such a known entity that people aren’t going to say anti-trans rhetoric in front of me. I never have to discuss being trans, I never have to out myself or speak as an out person.”

That respect is largely based on her more than 25 years of advocating for the most vulnerable communities. She started rallying in the ’90s, stomping in the streets of New York City with The Transexual Menace, a grassroots organization protesting anti-transgender violence. After earning a law degree from the University of New Mexico, she leveraged her radically progressive beginnings into legislative action, serving on the Hawai‘i State Board of Education, where she amended policies to protect LGBTQ students from bullying; the Hawai‘i Civil Rights Commission, where she expanded the rights of LGBTQ families; and the Victory Institute, a national organization dedicated to elevating LGBTQ leaders.

After running for lieutenant governor in 2018 as a democratic socialist, Kim Coco continues fighting for causes that elevate people over profit, like increasing the state’s minimum wage, halting the development of the proposed Thirty-Meter Telescope on Maunakea, and funding cleaner energy alternatives to fossil fuels. In 2013, the Obama White House recognized Kim Coco as a Champion of Change, a title honoring those who have helped “our country rise to meet the many challenges of the 21st century.”

THE ADVOCATE TEXT BY MITCHELL KUGA IMAGES BY JOHN

76

HOOK

In 2006, Kim Coco made history as the highest-ranking openly-transgender elected official in the country after winning a seat on the Hawai‘i State Board of Education. The swell of national media attention she received in the aftermath, though framed as celebratory, often felt “very othering and objectifying,” she says, a fixation on her identity at the expense of her merits. “I don’t know if I feel proud to be trans, or proud to be Japanese American—I just am,” says Kim Coco, who was born on Kaua‘i and raised on O‘ahu. “I'm not ashamed, you know what I mean? But it has nothing to do with my achievements.”

When we spoke over the phone in March 2019, Kim Coco, 50, was by turns candid and astute. As she shepherded her 6-yearold daughter home from the chaos of her school’s ho‘olaule‘a (celebration), Kim Coco opened up about being the class president of her all-boys school, the transition she made from fashion to politics, and being a single mother.

What were you like as a kid?

Um, I guess I was really irritating. (Laughs) I was not shy. I was super flamboyant and put myself out there. I remember once the dean of our class tried to ask me to tone it down. Apparently, at a high school dance a parent who was chaperoning pointed at me

like, What is going on there? This was the early ’80s, so it was a lot of androgynous makeup, Norma Kamali shoulder pads, a cinched waist. I was so femmed out that the boys who came over from Damien High School would ask me to dance—they didn't know I was the class president of Saint Louis [an all boy’s school].

How did you respond to being told to tone it down?

Very dramatically. I went home right after he spoke to me and—this is back when we had typewriters—wrote this letter of resignation that said my class voted for me exactly as I am. The next day, I gave a copy of this letter to the principal, the board of trustees, and to every single administrator. Everyone got a copy, it was so overly dramatic.

Did it work?

By the end of the afternoon the dean apologized to our class advisors for the comments he made to me and said I should be exactly who I am and stay on as class president. I was like, yeah, and the next time a parent raises concerns you’ll be prepared. (Laughs) I was a total diva by the age of 14.

So it sounds like you were popular? Mmmm…

78

Well, I guess being class president doesn’t necessarily mean you were popular, but it means people voted for you. Well, they knew who I was. (Laughs)

After graduating you moved to New York to study and work in fashion. How did you transition into politics?

Well, I got terminated from a job in fashion. I graduated from the Fashion Institute of Technology and worked for this small boutique design house in New York City—my dream job. One day, my employer told me that her largest corporate client was not comfortable working with me because I’m trans, that I was basically a liability to her. It was a constructive termination: She started denying me certain benefits and stuff.

So I went to a community legal clinic at the LGBT center and sought counsel. I discovered there were no protections for me in the law at the time. In fact, I found out I could even be counter-sued for slander. It shifted the whole awareness I had about who the laws were set up to protect. That’s when I realized that instead of fashion I needed to go to law school.

Prior to being terminated, were you engaged with LGBTQ issues?

Well, truthfully, when I was working in the fashion industry, I just saw my life on a trajectory of fabulousness, you know? (Laughs) Like that was the life I was striving for. I wasn’t striving to make a positive impact in the world or for my community. In fact, I didn’t even know that the trans community even needed any kind of support, because my father—who ran the family company, Roberts Hawaii Tours—employed trans people. And they were in positions of leadership, they were supervisors. Growing up in Hawai‘i, it wasn’t a big deal. It felt like you could achieve things.

80

START WATCHING. VISIT NMGNETWORK.COM WE ARE A PLATFORM FOR LGBTQ TRAVELER S

Speaking to The Advocate, you said “Here in Hawai‘i, the LGBT movement is often seen as an outsider issue.” Can you elaborate on that?

For those of us who were born and raised here, we had a lesbian auntie, a gay uncle. We worked with trans people. The roles we play in the community are based on relationships: relationship to place, to community, to what school you grad. All that stuff contextualizes us. LGBTQ civil rights issues, in general, are framed as individual rights and liberties, not familial rights. A lot of people relocate here from the mainland and their identity is strongly connected to being away from family and feeling this independence. As a result, you saw a disproportionate number of LGBT non-locals in the formal movement.

We also have to recognize that certain cultures feel much more comfortable asserting verbally, so unless we make room for those quieter voices, the media loves picking up on the assertive ones. We have to be conscious that this is a concept being imposed on Hawai‘i by mainland people and the media.

What made you decide to run for elected office?

I was a foster parent and my kids, who are on the spectrum of trans and queer, were being bullied in school. These kids were from Wai‘anae, Kalihi, Kāne‘ohe, and one was sort of abandoned in Hawai‘i by parents on the mainland. They were picked up for truancy and forced to go to school, yet no one was keeping them safe from bullying and harassment, so they asked me to testify to the Board of Education. After doing so, I realized they needed someone on the inside.

“

I discovered there were no protections for me in the law at the time. I found out I could even be counter-sued for slander. It shifted the whole awareness I had about who the laws were set up to protect.”

82

HNL NON-STOP LAX B747-400 All Cargo Ships Six Days/Week Next Day Service VIP Pet Service Oversize Items From Aston Martins and Outsize Cartons, to Polo Ponies and Man’s Best Friend. PACIFICAIRCARGO.COM 808-834-7977 cameronbrooksart.com ALWAYS STRESS FREE WHEN YOU P.A.C. IT

Growing up, was it always Kim Coco?

My one uncle used to call me Coco Palm, because I was named after the Coco Palms Resort. That was my nickname.

The fact that your parents named you Kim Coco is almost too good to be true. It’s funny because to all the Cocos I meet who are trans, I’m like, “I think I might be the only one who was born Coco—sorry!”

And now you’re a full-time mother?

Yes, I adopted Rory three years ago, from China. I basically came home from a party drunk and saw her on Facebook, and then nine months later she was in my arms— kind of a subversion of that person who drunkenly gets knocked up. (Laughs) But, no, a friend of mine works at one of the international adoption agencies here in Hawai‘i and sent me Rory’s photos.

What is it like being a single mother?

It’s a lot, but I’m so grateful that I'm doing it at this age. I’m just calmer. I feel like it’s the right time for me to do this. And she happens to be so smart and funny and quite a delight. She loves sports, singing, and travel. Today is her first day of spring break, so we’re going to be traveling to some of the other islands.

Growing up, was there ever a period in your life when you felt like you had to hide who you were?

This was always me. That’s why when people ask, “When did you transition?” I’m like, “You know what? I don’t actually see my life like that. I feel like I’ve always been me.” Who I am has always been different. I have four brothers and I’ve always looked different. Having the name Kim Coco set me apart from my brothers.

NORTH SHORE OCEANFRONT FIELD MATCHES & MUSIC EVERY SUNDAY

To buy tickets or for more information, visit HAWAIIPOLO.COM T-RX ENTERTAINMENT, LLC POSTER ARTWORK BY: RYAN BRANT HAWAII POLO CLUB, CELEBRATING SPORT & COMMUNITY OCEANFRONT IN MOKULEIA - 56 YEARS STRONG Beach

Polo

Live

APRIL 14 TH THRU SEPTEMBER 1 ST

Bar, Ono Eats, Tailgating

Matches (2-5pm)

Music (5:30-7pm)

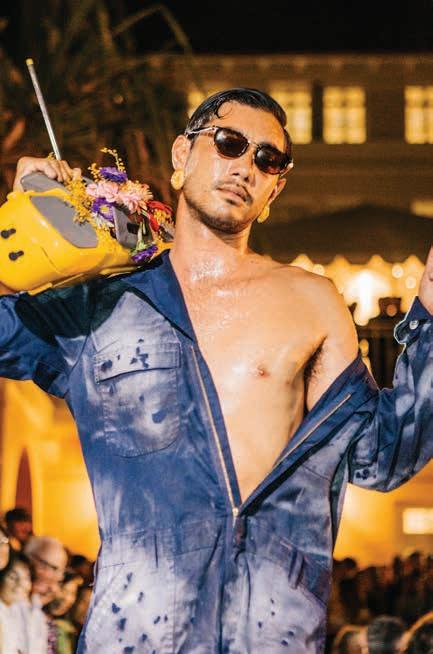

PAPI PARTY TEXT BY CALLA

86

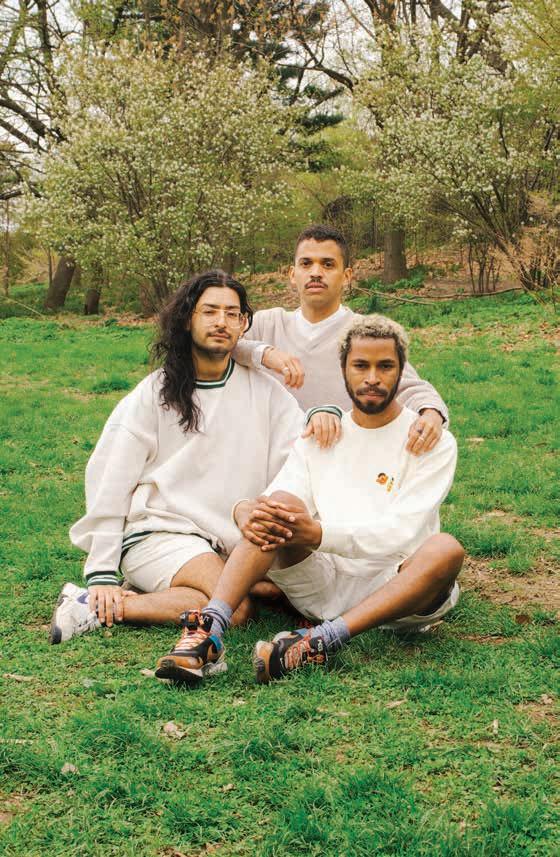

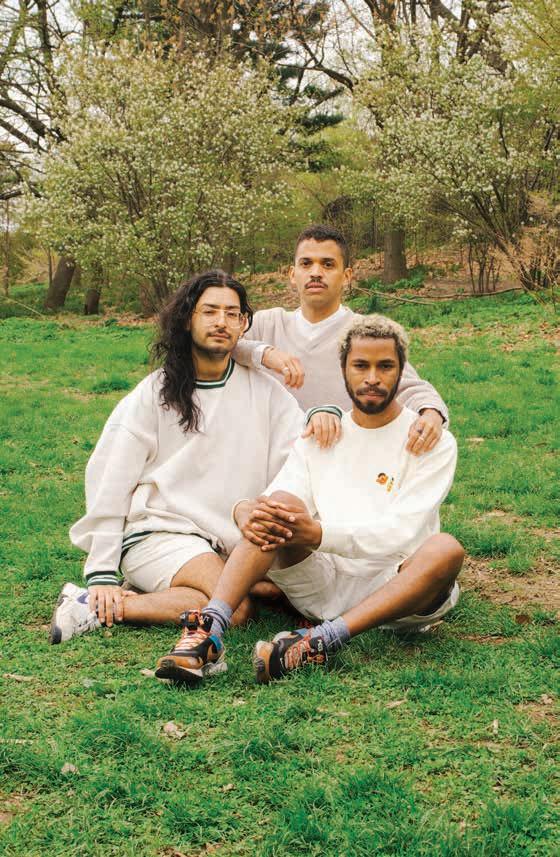

CAMERO IMAGES BY KEVIN ARANIBAR-MOLINA

The New Yorkbased collective Papi Juice turns up the volume on representation and gets down in solidarity.

A typical Papi Juice dance party starts like no typical party at all. Diverse groups of ethnicities and gender expressions pour into the room as the dance floor sways with bodies dressed in colorpopping club looks as unique as the personalities of those wearing them. The DJ turns the music up as the beat transitions to “Thotiana” by Blueface, cueing the crowd to shout “Ayyyye!” and drop it down even lower. It’s 10:15 p.m., and Papi Juice has only just begun.

“Someone mentioned that Papi felt like a house party, and it’s become one of my favorite descriptions,” says Papi Juice co-founder Adam Rhodes. “Wherever we go, individually and as a group, we always bring that with us and make it feel that way. Even as we grow bigger, we try to keep that intention.”

Ultimately, what sets this party apart from any other club night is the intention Papi Juice establishes to create a space that affirms and celebrates the lives of queer and transgender people of color. The collective, which is now a platform for artists of color, was started in 2013 by Adam and his close friend Oscar Nuñez, both Brooklyn-based DJs who were frustrated with New York City’s traditional gay spaces, which were composed of mostly white and cisgender men.

“We felt invisible, like our cultures weren’t being represented, or our beauties, or our creativity wasn’t ever really valued,” says Oscar, who is from Honduras but has lived in New York for 10 years. “We weren’t seeing ourselves, not only in the community or the audiences, but also in the art [world], so that translated into nightlife as well. That’s when we were like, we should start our own night.”

After a couple successful parties with increasing attendance, Adam and Oscar welcomed Brooklyn-born illustrator Mohammed Fayaz into the Papi Juice family. Six years after its first party, held at Bed-Stuy’s sinceshuttered One Last Shag with a maximum capacity of 75 people, Papi Juice has turned into a global artistic movement that reaches beyond the nightlife scene. The collective also organizes daytime sober events, group discussions, and art and musical collaborations for the LGBTQ+ community.

Successes aside, building the perfect party from the ground up proved a painful and difficult feat for the trio. In those earlier years, they experienced a lot of racist, homophobic, and transphobic discrimination from venue owners. “We would be looking at a venue spot and they would be like, ‘Oh, you’re a little bit too niche for us,’” Adam says. Venues would pigeonhole Papi Juice as a “gay party” and deny the event, claiming they didn’t “wanna be known as the gay bar.” For the founders, such experiences only confirmed the need for their events.

88

Today, peers doing similar work around the city, and in other cities, make for good company for the Papi Juice crew. Part of that community is Bubble_T, a New York-based collective celebrating queer Asian visibility. To ring in 2019, Oscar and Mohammed joined Bubble_T in Honolulu, Hawai‘i, to throw a daytime pool party for Lei at the Surfjack hotel in Waikīkī.

As fun as the pool party was, Oscar and Mohammed also wanted to share with Hawai‘i what they do best: nightlife. So together with Bubble_T, Hawai‘i friends, and connections made on the trip, the crew threw another party just three days later. The event, Mahu Mix, was held at Aupuni Space in Kaka‘ako.

“We really wanted to plug into the scene there and see the kind of spaces and what kind of things people were doing,” Oscar says. “It was the perfect place to do this nightlife event.”

They gathered local DJs in Aupuni’s exposed gallery space—think a local garage, but with contemporary artwork lining the walls—to create an indoor-outdoor experience, which made the party feel more inclusive to Hawai‘i’s community. The music was amplified out onto the street, with people spilling out to the sidewalk, dancing through projected visuals, and conversing with one another. The turnout, while smaller in numbers than their usual Brooklyn events, left a lasting impression on Oscar and Mohammed because of the people they met and the relationships that were cemented.

92

Honolulu Pride Parade & Festival is a project of the Hawaii LGBT Legacy Foundation. Join us to continue the celebration at our Lei Over Pool Party on Sunday, October 20, 2019 at ‘Alohilani Resort Waikiki Beach presented by NMG Network. #LeiOver PARADE & FESTIVAL HONOLULUPRIDE.COM @HONOLULUPRIDE

Mohammed recalls meeting a cute guy at Mahu Mix who was there with his cousins. “They were just really excited to go out together,” he says. “And that’s so tapping into the way that you grow up there—just him being open to bringing family to this party. So exciting.”

“That’s the thing, we’re all from these cultures where that’s the norm,” Oscar says of finding common ground with Hawai‘i’s family-oriented culture. “If we were in Honduras, I’d have 25 cousins I’d want to bring. And it makes so much sense because we’re all kinda cousins. We’re all people of color.”

Outside of the local party scene, Oscar and Mohammed found time to explore O‘ahu. They ate shave ice on the North Shore; swam at Keawa‘ula Beach (also known as Yokohama Bay) on the west side; danced at gay bars in Waikīkī; toured Shangri La Museum of Islamic Art, Culture, and Design in Kāhala; and hiked the famously steep stairs of Koko Crater in Hawai‘i Kai. “I think it was one of the most productive vacations I’ve ever had in my life, because we literally trolled the island of O‘ahu,” Oscar laughs. “We went everywhere.”

For Oscar and Mohammed, their visit to Hawai‘i was especially memorable because of the people who helped them see what the culture is all about by opening their homes, cooking food, showing them around, supporting Papi Juice, and overall demonstrating the spirit of the islands and its LGBTQ+ community.

“My friends said to me, and this is corny, but home is really wherever your family is. And we had like 12 people there that were really like my family, and we met so many new people in Hawai‘i that became my family,” Oscar says.

“And also it’s in the name,” Mohammed adds. “Anyone can be a Papi.”

Disposable film from Papi Juice's escapades on O‘ahu. See more at leiculture.com.

Poet and scholar Jamaica Osorio draws on the intricate framework of Native Hawaiian relationships to construct more inclusive ways of activism and being.

SPOKEN WORDS TEXT BY MATTHEW DEKNEEF IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK 98

Jamaica Heolimeleikalani Osorio jokes that she peaked at 18 years old when she was invited to read a poem at the White House. It was for the first-ever Poetry Jam in 2009, and she performed a piece titled “Kumulipo,” a searing lamentation for her Hawaiian roots, to a standing-room-only crowd. “There is a culture, a people somewhere beneath my skin that I’ve been searching for,” she recited, as Barack and Michelle Obama and their two daughters, Malia and Sasha, watched on in spellbound silence. In its final verses, she recited her native lineage in that successive style of a storytelling tradition which gives credit to each generation prior, an outpouring of ancestral names in Hawaiian echoing within the walls of the White House, that iconic and complicated symbol of America.

In the decade since, Jamaica has continued to honor those names with rigor and creativity. Indigenous epistemology, generational trauma, and cultural resilience have also remained themes in her work. Her intellectual energies revolved around researching the story of Hi‘iakaikapoliopele, an epic pan-island journey of the sister of the goddess Pele. Through it, Jamaica examined the heroine’s relationship to another female character, her lover, Hōpoe. It culminated in an intersectional doctoral dissertation for which she coined the term “‘upena of intimacy” (‘upena meaning net or web). Her study calls for a radical decolonial future in how to acknowledge relationships to one another and the land, where “intimacy is many bodied and overflowing,” she writes. It is a poetic rebuke of “settler logics” of heterosexism, cishetero-partriarchy, and heteronormativity, and in its construction shows how weaving together the values of a pre-colonial Hawaiian world can simultaneously dismantle the systemic inequities of the current order.

Like the women in the stories she recounts, Jamaica has many dimensions: poet, scholar, author, doctor, paddler, activist. In an office at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, where she is an associate professor of political science, she spoke with Lei about relationships of all kinds—to writing, to family, and to new methodologies for exploring identity through literature.

I loved that you opened your dissertation, ”(Re)membering ‘Upena of Intimacies: A Kanaka Maoli Mo‘olelo Beyond Queer Theory,” with a poem. Originally, I thought I was going to write a creative dissertation, which is just a fancy way of saying a book of poetry. It was going to be a translation of the Hi‘iakaikapoliopele mo‘olelo (story) through a series of poems from Hi‘iaka to Hōpoe, and telling that story. Then it became clear early on that while the poetry part was important, that’s not all I wanted to do. That opening poem [“He Mele No Hōpoe: A Dedication”] is the first I wrote for that series, which I wrote during my honors thesis at Stanford. It just seemed like the most genuine way to acknowledge where this project started; it began because I love poetry, because I fell in love with Hi‘iaka and Hōpoe. It just made sense. It’s the genesis.

Do you always start exploring topics through poetry?

I don’t necessarily think about something first through poetry and then have it change into this more “critical work.” The poetry in this sense just speaks to the fact that one of the most important things I think we do with the Hi‘iakaikapoliopele story is continue to tell it in new ways. One of the things I really struggled with while I was working on the dissertation is when people would ask me what it’s about. I didn’t have a clear sense about almost anything until I was done writing it.

That’s what made it so unique to me. It doesn’t have the sense of trying to argue a point. You also interweave vignettes about your family, growing up in Pālolo, your father. It’s like you hold those personal memories as equal to the academic research.

One of the big arguments I'm making about Hawaiian literature—and it’s not even really my argument, I'm just reassessing the argument we’ve been talking about in Hawai‘i for a while—is the need to understand the multiple versions of our stories and not reduce them to a single idea of fact or history. I didn’t want to write a dissertation that said, “This is the only way you can think about it.” I wanted to write a book that says, “This is one brilliant, beautiful way we can think about this, it’s a part of our larger story, and there are so many other stories a part of said larger story I’m hoping you will go look into.” That's really the call towards the end of the dissertation, that so much of our concept of who we are as Hawaiians, especially when we talk about sovereignty and governance, is based in our Kingdom history. Our Kingdom history is really interesting and vibrant and powerful, but it’s such a short period of time and such a small part of our people’s narrative. I hope by the end it gets the reader to think, “This showed me a method of investigation through literature that I find valuable, and now I’m going to do my own investigation of mo‘olelo that I am in love with and see what lessons are there for us.”

100

You utilize memory in an interesting way in your work, almost like a strategy or a weapon.

I think of the act of remembering and insisting on remembering in the face of the way that colonialism systematically works to make us forget is an act of resistance. Everything that we come to remember, even if they contradict each other, is valuable in the struggle against erasure and the struggle against forgetting. In that way, I use memory as a weapon, for sure.

There was a verse in the poem that caught me off guard: “writing us into stillness.” That resonated with me, as someone who places a certain weight on Hawaiian texts in regard to education. There’s also the side of me completely aware of honoring oral histories. Did you grapple at all with this—of taking this sprawling, shifting mode of storytelling, and then locking it into a text?

Oh, man, you’ve just pointed out all my insecurities. One of the things our kūpuna grappled with, and we continue to, is how do we tell these oral stories in a way that can do different things when you’re speaking them, but in a written form. How do we still honor the movement of the tale and the movement of the story on the page? I think I’m going to be figuring that out for the rest of my life, how to tell a story in a way that leaves room for the story to not just transform the reader, but transform itself. In the poem, “writing us into stillness” is followed by “into silence / how it seems through them, we have been forgotten.” That’s a response not to the Hawaiians writing about the mo‘olelo, but these guys like Emerson, Thrum, and Westervelt who basically took these stories and wrote them in

their own tradition and fixed people like Hi‘iaka, Hōpoe, and Pele into these onedimensional caricatures. I think a lot of our work today is trying to undo and unlearn that.

What challenges do you face in accomplishing that?

Accessing our mo‘olelo is complicated because of the relationship between colonialism and the erasure of our language—that most Native Hawaiians don’t speak Hawaiian. The ultimate goal is that we continue to learn our language and continue to access the Hawaiian written by our ancestors. We’re also lucky enough that we have newer translations of these texts that we can read instead of these haole (foreign) people who really didn’t understand the story that they were telling. I’m not going to have my students’ first exposure to a story come from someone on the outside looking at us.

That’s something I’ve had to reckon with too, when it involves Hawaiian stories— the idea of an authoritative story. Because we’re taught to think about stories in that way. As this linear thing. That there is an original version of the story and everything else is a deviation after that. I was working through that even at my time at Stanford—trying to separate the thinking of what is the most authoritative version of the story versus what is each version of a story trying to teach me based off of when and where it was published, who authored it. There’s a reason the stories are different. There’s a reason they have different focuses. If you can make space for that, the world opens up in a really beautiful way.

102

Endless conversation starters. MUSEUMS • CAFÉS • THEATER • SHOPS 900 S Beretania St • 808.532.8700 2411 Makiki Heights Drive • 808.526.1322 honolulumuseum.org

Antonin Mercié (French, 1845–1915), David Vainqueur (David the Conqueror), c. 1889 Bronze. Gift of Steven H. Levinson, 2013 (2013-13-01)

You’re from a family of storytellers. What was that upbringing like?

I tell people I hit the jackpot with my parents. My gender expression was always different. It was always a point of contention for other people. But I grew up in this family that was not just openminded—they really fiercely celebrated different ways to think about love. That said, it was still hard to face the fact that I was going to love differently than what society expected of me. Most gay kids hope that their parents will accept them and still love them, but my parents celebrated it.

I often wonder about the stories our parents tell us in our youth, and how those stories shape us. Your dad, Jonathan Osorio, has such a noteworthy intellect. What stories were you being told as a child that most affected you? The most meaningful and transformative story I grew up with was the mo‘olelo of the illegal overthrow of Hawai‘i. That characterized my childhood and it came to form the center of my identity: I’m Native Hawaiian, I’ve been wronged by the United States; I see a relationship between this

violence and the trauma that my people continue to go through, and therefore I am an activist. That was the story I was told over and over, and believed—I make it sound like I was indoctrinated—but really that’s what I was surrounded with at a Hawaiian immersion school, and then at home. The interesting thing is my dad is this professor and musician and an activist, but I don’t actually remember him feeding me those lines. My dad was just there to answer questions. I was really lucky that as I was growing up, he also treated me like a peer. That started to shape my identity as a Hawaiian, as someone who seeks sovereignty in Hawai‘i.

The other thing about my dad is how he allowed me to figure things out for myself, while providing support on the way. By virtue of who made up the sovereignty movement, my dad put me in a position to see a lot of really powerful women, to grow up around Haunani-Kay Trask, Mililani Trask, Terri Keko‘olani, Moanike‘ala Akaka, and Lilikalā Kame‘eleihiwa, to see them being fierce. My dad was a giant to me, and yet these women somehow seemed even larger than this giant.

104

A Poem for Moving Water

... Give her a name for every morning you wake up thinking of her smile

Ho‘ohokulani: for the way she seems to put stars in every single one of your skies

Haumea: for the ways she makes you wish you were more of a woman

Pele: for the way she can burn every inch of you with her gaze and her silence

Papa: for how she seems to have given life to everything around you

La’ieikawai: for how you’d travel all the islands to find her because you have heard of her beauty and you trust it

Take every mo’olelo you have ever read or heard and find a place for it on the breath between your bodies learn its purpose through her kiss because you know now that this kind of memory is embodied and when you are sure call her Hi’iaka hold her in your chest make sure she is the one you will keep the one who will stay

When you run out of names of women of oceans of trees of roots call her something heavier call her Vaihere for the parts of her that always move you

When you re-introduce her to your father

use the pronoun ku’u because it fits tell him that she is every moon you have carved on your skin and you are every tide that follows

Tell him:

she is the morning you’ve been waiting to name that most nights you are kept awake just by the thought of your lips on her temple and that somehow you found every single one of your gods in the melody of her breath tell him that she is real and that you are ready that she is Hi’iaka and you are Hōpoe writing poems for every part of her body about how you would burn under the weight of her mistakes while planting songs in the form of yellow lehua trees hoping that the salt water between you might grow something worthy of your love

–Jamaica Heolimeleikalani Osorio

What’s your sense of where the next generation of Hawaiians are, as a people?

I think we’re brewing a revolution. I imagine the way that I feel to be similar to folks who were involved in the Protect Kaho‘olawe movement. The opportunity and the pain and the privilege of being in that moment. And I say that not to say that I feel as instrumental in change as those folks felt, but like I wonder what they saw when they looked around in that time, 1975, 1976, in this reawakening. Because I look around here, and I hear the way students are talking, I see people speaking Hawaiian out

in the streets—when I grew up, you only spoke Hawaiian at your immersion school. That’s the only place you could speak. But now I hear it walking around campus. We’re in this really powerful moment, and Maunakea and the conflict against the Thirty Meter Telescope is going to characterize my generation in the same way that Kaho‘olawe characterized my father’s generation. This is our struggle and it is important, not just because Maunakea is important, but because it symbolizes our struggle and this moment. That is equally important for us.

106

Experience

the new

bar,

modern Aloha at

Hyatt Centric Waikiki Beach Restore your senses in our contemporary island-inspired rooms overlooking vibrant Waikiki. Relax at our splash lounge pool and enjoy craft cocktails from the Lanai Lobby

located on the 8th Floor. Enjoy weekly musical entertainment and special events for travelers and locals alike. Book your stay at hyattcentricwaikikibeach.com.

III. EXPLORE

Connect with locals who see their cities as maps to self-discovery

ERIEL HOBRO

ERIEL HOBRO

RISING QUEENS TEXT and IMAGES BY

110

MARIE

Remember their names: Shezzy.

Anna Mei. Boujie. This trio of nextgeneration drag queens find life and love in their communities and their art, on and off the stage.

Drag in Hawai'i is always evolving. The queens who were considered “new” two years ago have since elevated their craft, and a fresh generation of newcomers are trickling onto the scene. The following photo essay follows three of those newcomers, Shezzy, Anna Mei, and Boujie, as they learn who they are and where they belong in drag. The following profiles are paired with quotes from each queen, in their words.

As an ally, I love supporting this incredible community from the sidelines. When I first moved home two years ago, I was struggling with immense trauma. I felt like a shell of my former self, too afraid to connect with people or pick up my camera. That all changed when I began photographing the local drag scene in 2017. In this time, I've documented the evolution of drag families while also finding a drag family of my own. Their genuinity and kind-heartedness helped me find myself and a sense of safety again and I will forever be grateful for that.

DRAG NAME : Anna Mei

NAME : Sean Ramsey

AGE : 25

FROM AND RESIDES IN : ‘Aiea, O‘ahu

OCCUPATION : Sales associate at BoxLunch

Anna Mei is the nerdy girl in those movies that didn’t know she was pretty until she took off her glasses and let her hair down. I am gender-fluid, and Anna Mei is a way for me to express my female side while also having the opportunity to perform.

I first started doing drag in a play at Mānoa Valley Theatre called The Legend of Georgia McBride. It was such a wonderful experience performing as a drag queen in the play. I decided I wanted to continue doing it after the show ended. My now drag mother, Candi Shell, watched our opening night and helped me get my first gig at Hula’s Bar and Lei Stand for her show, Mimosas and Marys. I love her kindness and support. She really is one of the sweetest queens on the island.

Everyone I’ve met has been such a big influence in my drag. I think the biggest

supporters are my drag queen mentors and sisters who helped guide me and venues like Scarlet Honolulu, Hula’s, Wang Chung’s, who give me a chance to perform by booking me. There’s also everyone that comes to my shows and enjoys my performances enough to tip.

The thing I love the most about drag is performing. Every chance I can I get on the stage. Connecting with people I’ve never met, the lights, the music—they’re all incredible experiences.

Drag is very expensive. Regardless of what kind of drag you do, it costs a lot of money. Makeup, hair, outfits, they all cost a lot. If you’re at a drag show and see a queen performing, make sure you tip them!

112

DRAG NAME : Scheherazade “Shezzy” Springs

NAME : Seth Ives-Hubin

AGE : 19

FROM : Lāna‘i City, Lāna‘i

RESIDES IN : Salt Lake, O‘ahu

OCCUPATION : Beauty consultant at Longs Drugs

A huge struggle for me as an arising queen is wanting to be accepted. I want the experienced queens that I’ve looked up to for so long to validate me as a queen. I guess when it comes down to it, I fear their judgement. There’s also the issue of self-destruction. You truly are your worst saboteur.

My drag family is the Haus of Shell. They constantly push me to do the best I can and help me work on advancing myself. The local queens are also a huge support system for me and so much of them believe in me and my ability to perform. They all make me feel super talented and welcomed. Outside of drag, the first ones to uplift me are my boyfriend, Brenden Clowe, my biological mother, Sherilynn Hubin, my Nana,

Lenora Fabrao-Wong, and my close friends who constantly go to every single performance possible and help me emotionally with my gender identity. They never turn their backs on me. I’m so grateful for them because they support me not only as Seth, but as Shezzy. What I love the most about doing drag is the feeling of being whole. It brings so many people together as a community to just celebrate life no matter who you are. It also allows me to feel a sense of self-love and security in who I am—celebrating what makes me unique in this world.

I started drag at the end of high school. At first, I saw drag as something of disgust due to my Christian, Catholic background. Doing it made things very difficult

for me. But as soon as I was in drag, this feeling of confidence, poise, and courage flourished through my veins and that’s where it all started. When my grandma on my dad’s side told me the story of One Thousand and One Thousand Nights, it inspired me to name myself Scheherazade “Shezzy” Springs.

I see Shezzy as a Pandora’s box because when you open her, you never know what you’re going to get. I like to keep people on their toes whenever they come see me perform. I like doing things that are campy, fierce, and frightening! There’s so much more room for improvement and I’m so excited for the future.

DRAG NAME : Boujie

FULL NAME : Tkani Finau

AGE : 21

FROM : Reno, Nevada

RESIDES IN : Honolulu, O‘ahu

OCCUPATION : Assistant operations manager at UFC Gym

I got into drag through Emma Gration, a queen here in Hawai‘i. When we first met, Emma asked if we could hang out at Scarlet—what I didn’t know was that Emma was performing. Before that, I honestly didn’t know anything about drag. After realizing that there was nothing wrong with it and that it was another art form, I really wanted to try it out. I’ve always wanted to be an entertainer, so I figured why not? My friend Ron used to work at Scarlet and encouraged me to compete in the Miss Scarlet competition last year. He gave me the biggest push and kept motivating me to follow through with it.

I’m still trying to find an appropriate way to integrate my Tongan and Native American culture into my drag. It’s important for me because I feel like I don’t know any Tongan or Native American drag queens—they’re out there, but I don’t know them. When I was younger, I would sometimes wish that I’d see someone like me on the big screen in acting and politics. I try to incorporate that into my drag because I don’t know who’s out there in the crowd watching.

Outside of drag, I want to run for office one day. I grew up very involved in my Native American culture and I’m very conscious about the issues affecting my people. I want to get into politics not only to help them, but everyone.

The hardest thing is the idea of belonging somewhere. I’ve heard of drag mothers and families, but I don’t have one. I feel like I have to do it on my own. When I first got into drag, the only person that helped me was a drag queen I used to talk to back home in Reno. He showed me how to do my makeup through FaceTime. Drag is another form of art. I feel like stepping out into the world in drag is an inspirational sight for anybody to witness. When I think back about going to a drag show at Scarlet for the first time, there was this feeling inside of me. As soon as I saw the queens, I was obsessed. Seeing how alive they were during their performances, I was like, “Wow. I wanna go up there dance to some ‘Boogie Shoes.’” I felt like I was at home—not only with the idea of drag, but with other LGBTQ+ people and people of color. It felt like a safe space.

120

Photographers

Ramsey Cheng and Sam Feyen discuss their approaches to the female form, balancing commercial and personal projects, and how their creative processes are always developing.

You might think it easy to make a living as a photographer in Hawai‘i, with its supply of endless beaches as a backdrop, a melting-pot demographic to pluck beautiful faces from, and, at the right hour, all that diffused natural light. But if you’re of a mindset like Ramsey Cheng and Sam Feyen, two photographers born and raised in the islands, you would much prefer to take those postcard-ready images with more grain and grit. Often working in 35-millimeter film, the two operate at opposite ends of the sensibility spectrum: Ramsey’s reels capture a sprezzatura sense of place, with images that feel ripped out of a self-published zine; Sam’s construct a tropical, honey-soaked world peppered with muses that channel a free-spirited confidence. But they both share a thrill for the unexpected final product that results from shooting film. At Fishcake, an interior design store and art gallery space in Kaka‘ako, O‘ahu, Ramsey and Sam met up for bright cups of clover-brewed coffee to chat about cameras, photography, and the images that most resonate with them.

GIRLS ON FILM IMAGES BY RAMSEY CHENG & SAM FEYEN 122

Sam Feyen

Ramsey Cheng

Sam Feyen

Ramsey Cheng

Ramsey: I can’t even remember the last time I actually touched my digital camera. It’s been a long time.

Sam: That’s crazy. I think about bringing disposable cameras with me everywhere, but usually I’m so in the moment wherever I am that I forget to take them out. (Laughs)

Ramsey: I’ve just been obsessed with film recently. But it comes in waves, for sure. For instance, I don’t like that I only take the opportunity to really, actually shoot when I travel. One of my New Year’s resolutions was to keep my film camera on me at all times. I’m a little, like, obsessed with not knowing how it’s going to turn out.

Sam: It’s an adrenaline rush.

Ramsey: That feeling of, like, this is going to turn out so amazing or a waste of a frame.

Sam: I know! I hate the feeling of a wasted frame.

Ramsey: When it comes out right or you got that one lucky shot, nothing can beat that feeling.

Sam: It’s like a victory. (Laughs) What else do you enjoy about the process?

Ramsey: One thing I love is that it’s always going to be an outlet of happiness, you know?

Sam: That … was cute. (Both laugh.)

Ramsey: How did you get into photography?

124

Ramsey and Sam photographed DJ and friend Nara Nellis at Honolulu Museum of Art Spalding House.

Ramsey and Sam photographed DJ and friend Nara Nellis at Honolulu Museum of Art Spalding House.