Ulrich Krauer

General Manager Halekulani

Ulrich Krauer

General Manager Halekulani

Hawai‘i’s cultures and traditions are as diverse as the people who live in the islands. Art is also expressed in many different ways—through paintings, sport, flower arrangement, dance, and even cuisine.

In this edition of Living, we bring you a story on Georgia O’Keeffe and the lush, vibrant works she created when she was commissioned 79 years ago to paint pineapples for Dole (then known as the Hawaiian Pineapple Company), but ended up painting the Hawaiian valleys and aquamarine seas. It was a departure from her signature desert landscapes that proved she could “make herself at home anywhere.”

Also featured is O‘ahu-based Japanese-American artist Masami Teraoka, who is famous for his woodcut prints and paintings influenced by the Ukiyo-e art of the Edo period. His creations blend reality with fantasy, history with the present.

All around Halekulani’s grounds, you will see unique displays of ikebana, which represent the calm tranquility for which the hotel is known. Meet Halekulani’s distinguished flower shop team that arranges these displays and learn how these living pieces of art establish a sense of oneness.

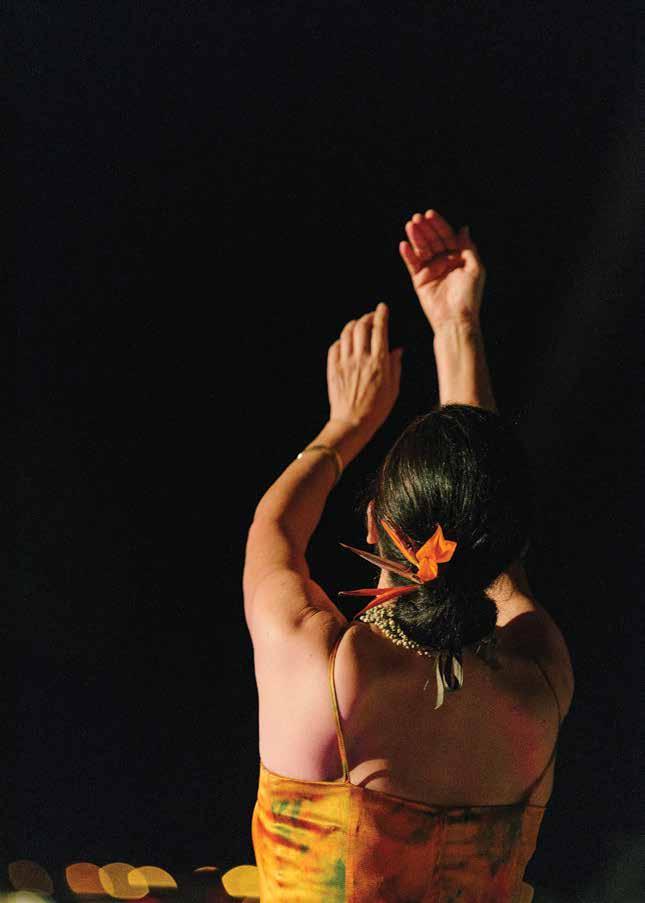

Dance is another form of artistic expression, and at Halekulani, hula is the time-honored tradition. At House Without A Key, meet graceful and esteemed performers as they share their stores of a cultural legacy recognized the world over. In Living’s photo essay, enjoy the captivating imagery and memories of these star performers and their oral history of hula. Please take this complimentary copy with you to keep so you can relive hula wherever your permanent residency may be.

We hope that you enjoy this small sampling of the diverse cultures that Hawai‘i has to offer.

Warmly,

Ulrich Krauer General Manager Halekulani多民族社会のハワイは、その文化や伝統も多様な魅力に満ちています。 絵画、スポーツ、フラワーアレンジメントから、ダンスや料理に至るまで、 芸術にはさまざまな表現方法があります。

今号のハレクラニリビングでは、ジョージア・オキーフさんについて のストーリーをお届けします。79年前、ドール社(当時のハワイアン・パ イナップル・カンパニー)に委託され、パイナップルの絵を描くためにハ ワイを訪れたオキーフさんは、ハワイの渓谷やアクアマリンの海をエネ ルギッシュで鮮やかに描いた作品を残しています。砂漠の風景に代表 される従来の彼女の作品とは異彩を放つこれらの絵は、であったことを 物語っています。

またオアフ島を拠点とする日系アメリカ人アーティストで、江戸時代 の浮世絵や木版画にインスパイアされたアートで知られる寺岡政美さ んについても紹介しています。彼は現実と幻想、過去と現在を融合させ た作品を多く手がけています。

ハレクラニの敷地内の各所には、当ホテルの安らぎと静けさの象徴 である美しい生け花が飾られています。本誌では、これらのアレンジメン トを手がけているハレクラニのフラワーショップのスタッフについて、ま た生きた芸術作品ともいえる生け花が空間に与える一体感についても 触れています。

踊りもまた芸術表現の一つです。ハレクラニにはフラの伝統が息づ いています。本誌のインタビューでは、優美な踊りで世界中の人々を魅 了し続けるハウス ウィズアウト ア キーのフラダンサーたちが、ハワイが 世界に誇る文化遺産のフラについて、それぞれの言葉で語っています。 リビングのフォトエッセイでは、彼女たちの魅惑的な写真や思い出を通 じて、語り継がれるフラの歴史に触れることができます。ご帰国の際に は是非、ハワイの旅の思い出として本誌をお持ち帰りください。

これらのストーリーを通して、ハワイの多様な文化の魅力に少しでも 触れていただければ幸いです。

ハレクラニ総支配人 ウーリック・クラワー

HALEKULANI CORPORATION

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER

PETER SHAINDLIN

CHIEF EXECUTIVE ADVISOR

PATRICIA TAM

GENERAL MANAGER, HALEKULANI

ULRICH KRAUER

DIRECTOR OF SALES & MARKETING

GEOFF PEARSON

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER

JASON CUTINELLA

CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER

LISA YAMADA-SON

LISA@NELLAMEDIAGROUP.COM

MANAGING EDITOR

MATTHEW DEKNEEF

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

ARA FEDUCIA

CHIEF REVENUE OFFICER

JOE V. BOCK

JOE@NELLAMEDIAGROUP.COM

HALEKULANI.COM

1-808-923-2311

2199 KALIA RD. HONOLULU, HI 96815

PUBLISHED BY

NELLA MEDIA GROUP

36 N. HOTEL ST., SUITE A HONOLULU, HI 96817

NELLAMEDIAGROUP.COM

© 2018 by Nella Media Group, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted without the written consent of the publisher. Opinions are solely those of the contributors and are not necessarily endorsed by Nella Media Group.

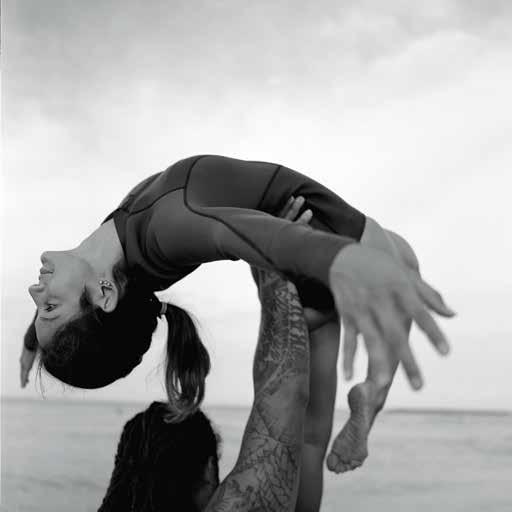

Surf the waters of Mākaha Beach with a champion brother-sister tandem surfing duo.

タンデムサーフィンのチャンピオ ン兄妹とマカハビーチの海でサ ーフィンを楽しもう。

Palette

and Serenity

The Form of Florals

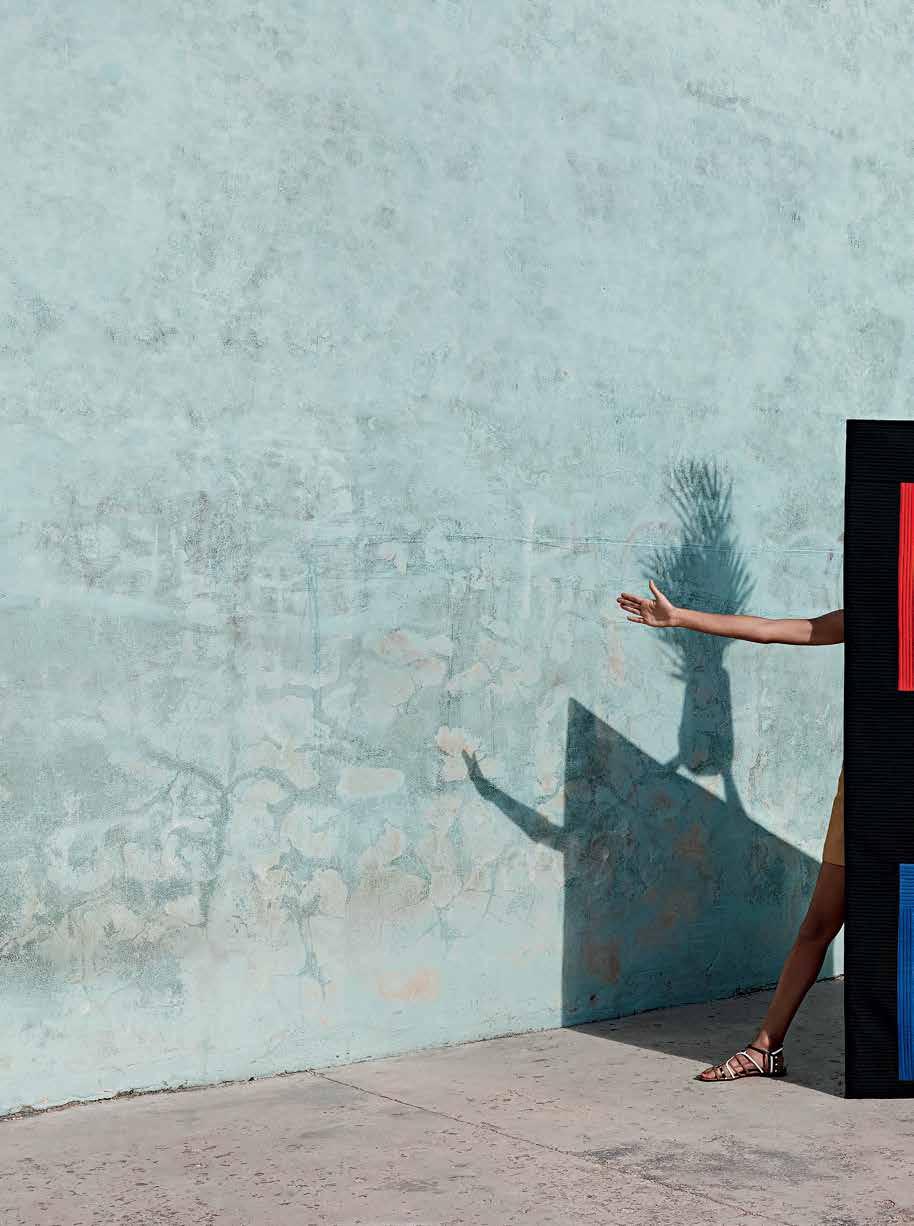

Fashion: Valley Deep

Magic Beside the Sea

The Pareu, Uncovered

Striking a Balance

Spotlight: Hildgund

Wander deep into Pālolo Valley with a fashionable afternoon of woven fabrics, silk gowns, and shell lei.

奥深いパロロヴァレーで、織布 と絹のガウン、貝殻のレイを纏 って、おしゃれな午後の散歩を 楽しもう。

The cover photograph, shot by Michelle Mishina, is dancer Kanoe Miller at House Without a Key. Every evening, soloists continue the Hawaiian tradition of hula at Halekulani. Learn more about its cultural significance in Waikīkī on page 50. ABOUT THE COVER:

The islands’ most famous hula soloists perform nightly at House Without a Key.

ハウス ウィズアウト ア キでは、 ハワイで最も有名なフラのソ ロダンサーたちが毎晩出演し ている。

TABLE OF CONTENTS

目次

ARTS 24

場所と色彩 32

花ざかりの狂詩曲 40

風刺と安らぎ CULTURE 50

海辺の魔法 66

パレオの知られざる歴史 72

驚異のバランス

32

Botanical artist Hadley Nunes in her studio in Kaka‘ako.

カカアコのスタジオにて撮影 したボタニカルアーティストの ハドレー・ヌネスさん。

WELLNESS 86

花のカタチ 98

地球の塩 CITY GUIDES 110

深い谷間に 118

ハワイのデザートブーム 134

スポットライト:ヒルガンド

ABOUT THE COVER:

表紙について

ミシェル·ミシナがハウス ウィズアウト ア キーで撮影した表紙の写真は、フラダンサーのカノエ· ミラーさん。ハレクラ ニでは毎夕、ソロのダンサーたちがハワイ伝統のフラを踊り続けている。ワイキキにおけるフラの文化的意義について 詳しくは50ページをご覧ください。

Living TV is designed to complement the understated elegance enjoyed by Halekulani guests, with programming focused on the art of living well. Featuring captivating imagery and a luxurious look and feel, Living TV connects guests with the arts, style, food, and people of Hawai‘i.

客室内でご視聴いただけるリビング TVは、ハレクラニでのご滞在をお楽し みいただくため、より豊かで健康的な ライフスタイルをテーマにした番組を ご提供しています。魅力的な映像と豪 華な演出を通して、アートやファッショ ン、食文化、ハワイの人々について紹介 しています。

watch online at: halekulaniliving.tv

BLOOMING BRUSHSTROKES

『花咲く絵筆』

Artist Hadley Nunes’s paintings whimsically evoke the tropical flowers they are inspired by.

アーティストのハドレー・ヌネスさんの作品には、彼女が感銘を 受けた印象的なトロピカルフラワーが描かれています。

HEART OF HULA

『フラの心』

The graceful hula soloists who perform at House Without a Key share their deeply-felt knowledge of the dance.

ハウス ウィズアウト ア キーで優雅にフラを踊るソロのダンサ ーたちがフラへの深い思いを語ります。

COASTAL FLAVOR

『浜の味』

The history and gathering practices of pa‘akai, Hawaiian sea salts, dates by centuries.

「パアカイ」と呼ばれるハワイアンシーソルト(海塩)の何世紀 にもおよぶ歴史と収穫方法について紹介しています。

TOGETHER IN TANDEM 『2人乗りサーフィン』

In its spectacular lifts and acrobatics, the sport of tandem surfing is poetry in motion.

生きている詩のようなスポーツ、ダイナミックなリフトや曲芸を 見せるタンデムサーフィン。

A BELOVED SOUND

愛しの音

The harmonious sound of an ‘ukulele is the result of dedicated craftsmanship.

ウクレレの奏でるハーモニーに富んだ音色は、丁寧な職人技に よるものである。

IMAGES COURTESY OF NEW YORK BOTANICAL GARDEN

文=レイ・ソジョット

写真=ニューヨーク・ボタニカ ル・ガーデン提供

OF PLACE AND PALETTE

場所と色彩

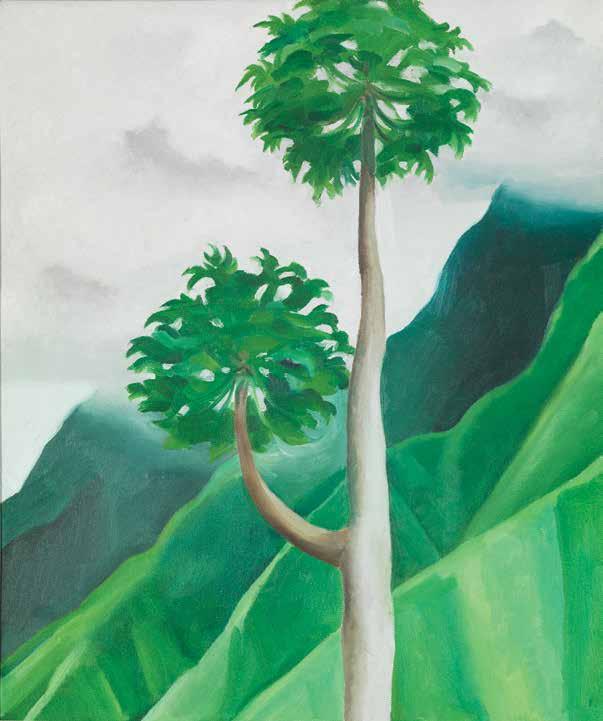

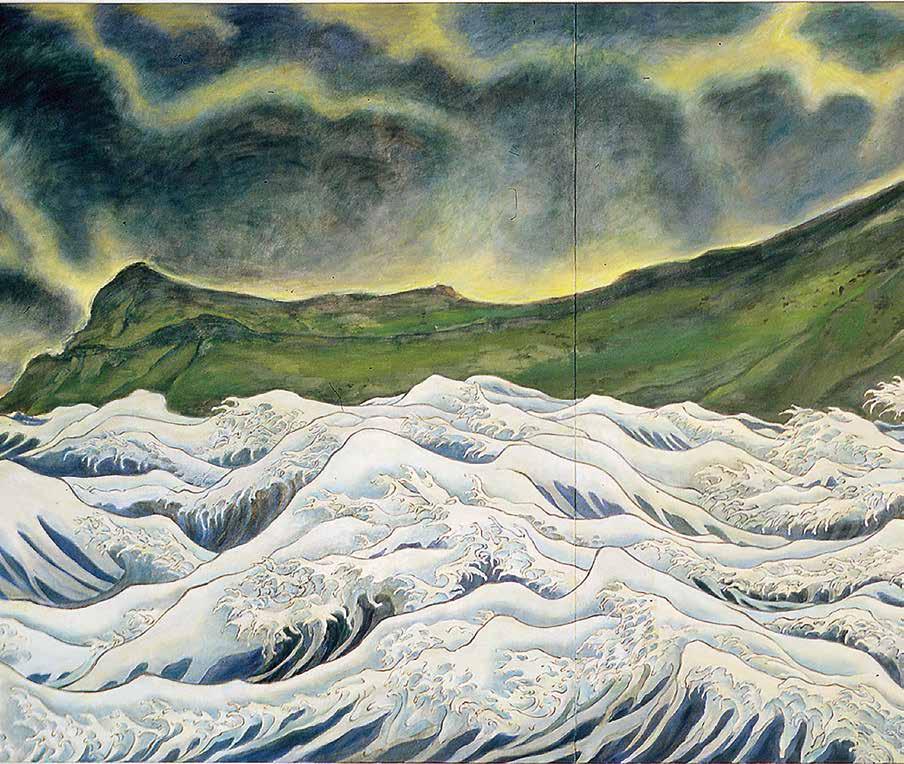

Nearly 80 years ago, artist Georgia O’Keeffe produced paintings inspired by the Hawaiian Islands, displaying her masterful ability to capture the spirit of her environment and make herself at home anywhere in the world.

それぞれの土地の奥深い魅力を伝え、ハワイでも数々の美しい絵画を残したアメリカの偉大な芸術家ジョージア・オキーフ

opposite: Georgia O’Keeffe Heliconia, Crab’s Claw Ginger , 1939. Oil on canvas, 19 x 16 in. Collection of Sharon Twigg-Smith. © 2018 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

右ページ:ジョージア・オキー フ作『ヘリコニア(クラブクロウ ジンジャー)』1939年。キャン バスに油絵。シャロン・ツウィッ グ・スミスのコレクション。

“One sees new things rapidly everywhere when everything seems new and different,” wrote American painter Georgia O’Keeffe in the statement for her exhibition at Alfred Stieglitz’s An American Place in New York City in 1940. At the gallery, widely considered the hub of avant-garde American art, guests anticipated the artist’s familiar iterations of austere Southwestern themes and city skylines. Instead they discovered an oeuvre of a different kind, one flush with exotic flora and vivid island landscapes from O’Keeffe’s nine-week sojourn in Hawai‘i the previous winter.

In 1939, the highly influential Modernist painter had accepted a proposal from the Hawaiian Pineapple Company (later known as Dole Food Company) to visit the Hawaiian Islands and produce two paintings for its national magazine advertising campaign. Commissioning established artists was a vogue marketing strategy in the 1930s: Fine art elevated products. Dole hoped O’Keeffe would capture the romance and allure of the islands—and therefore its pineapples—in her sumptuous imagery. For the famed artist, the invitation was a boon. O’Keeffe’s latest exhibits had received lukewarm reviews, with critics hinting that her work was stale and tiresome. Though O’Keeffe was reputed for being unmoved by such opinions, Dole’s offer may have served as a serendipitous opportunity for her to refresh and reset, both professionally and personally.

アメリカを代表する女性画家のジョージア・オキーフさんは、「人はどん な場所であっても、新しい環境に身を置くことで次々と新しいインスピ レーションが湧き上がってくるものです」と1940年にニューヨーク市 にある彼女の夫で写真家のアルフレッド・スティグリッツのギャラリー「 アン・アメリカン・プレイス」での個展について書き残している。アバンギ ャルドなアメリカの芸術の中心として知られていたこのギャラリーを訪 れる人々は、見慣れた質素な南西部の風景や都市のスカイラインとい った作品を想像していた。だが彼らが目にしたのは全く異なるアートで あった。それはオキーフさんがハワイで過ごした冬の9週間の滞在の滞 在中にエキゾチックな植物や鮮やかな島の景観の魅力を描いた美しい 作品集だった。

1939年当時すでに有名なモダニスト画家であったオキーフさんは、 ハワイアン・パイナップル・カンパニー(のちのドール・フード・カンパニ ー)から全国雑誌で展開する広告キャンペーン用に2枚の絵を制作して ほしいという依頼を受けてハワイを訪れた。1930年代には企業のマー ケティング戦略の一環として、著名なアーティストへのコミッション ワ ークの発注が流行していた。ドール社はオキーフさんに、独特のスタイ ルで ハワイのロマンチックな魅力を伝える瑞々しいパイナップルの絵を 描いてほしいと依頼した。オキーフさんにとっても、その誘いは願ったり 叶ったりであった。当時のアート展では批評家から新鮮さに欠けるとい った評価を受けていたこともあり、他人の評価に左右されないと言われ るオキーフさんではあったが、このドールのオファーは職業的にも個人 的にも新たなスタートを切るための格好の機会であったことだろう。

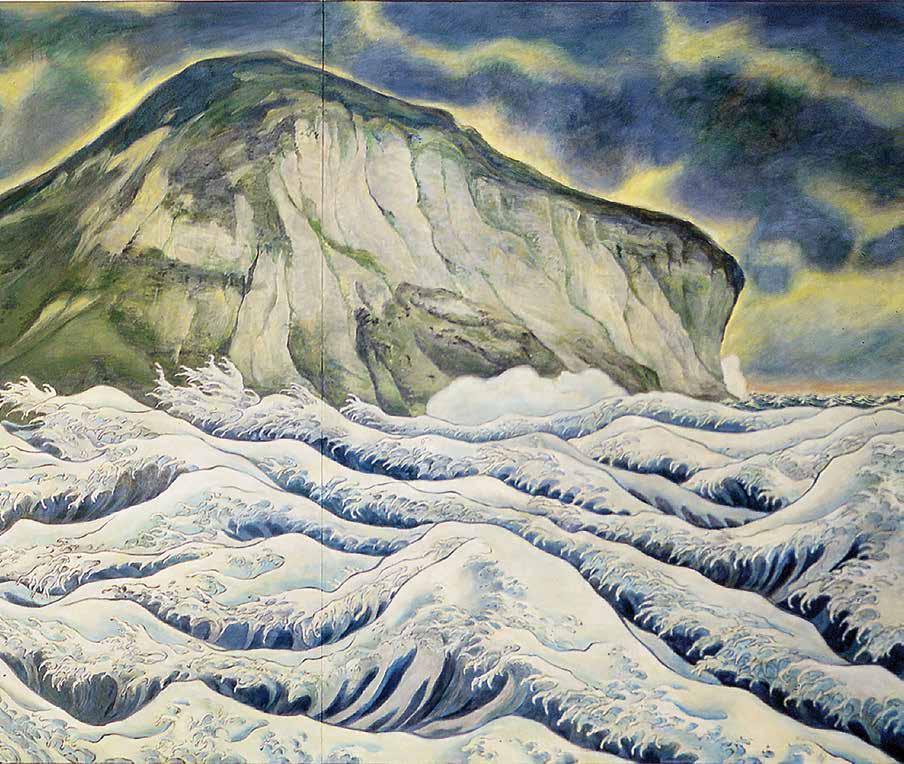

opposite : Georgia O’Keeffe Waterfall, No. I, ‘Īao Valley, Maui , 1939. Oil on canvas, 19 1/8 x 16 in. Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis, Tennessee. Gift of Art Today 76.7. © 2018 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

右ページ:ジョージア・オキーフ 作『ウォーターフォール、No. 1 、マウイのイアオ渓谷』キャンバ スに油絵。メンフィス・ブルック ス美術館。

Setting sail across the Pacific Ocean aboard the S.S. Lurline , 51-year-old O’Keeffe found warm welcome in the islands. Her arrival was celebrated in the local news, but subsequent public details of her activities remained scarce. Notoriously private and independent in equal measure, O’Keeffe eschewed social events in favor of a schedule that suited her personality—unfettered and unencumbered, and therefore free for painting.

Over the course of two months, O’Keeffe traveled throughout O‘ahu, Maui, Kaua‘i, and Hawai‘i Island, where she found new, lush expression in tropical landscapes and exotic flora. She marveled at O‘ahu’s pineapple fields, which she described as “all sharp and silvery stretching for miles off to the beautiful mountains,” and found heady inspiration along the Hāna coast, where “the lava washes into such sharp and fantastic shapes.” Loaned a private car on Maui, she found prodigious opportunities for exploration and solitude, and she roamed and painted at will. Through her signature use of form and color, O’Keeffe captured the resplendent drama of all that she encountered: the verdant, deep clefts and surrounding waterfalls of ‘Īao Valley; craggy lava outcroppings amidst a textured ocean; the sensuous, vermillion curves of heliconia against a twin backdrop of sea and sky.

The artist produced 20 paintings from her trip to the islands. Showcased at An American Place gallery the following year, they garnered critical acclaim for their freshness, excitement, and beauty. Henry McBride, a critic for the New York Sun, commented, “The landscapes, flower pieces and marines in this collection all testify to Miss O’Keeffe’s ability to make herself at home anywhere.”

Nearly 80 years later, 17 of these works are reunited at the New York Botanical Garden for an exhibit entitled Georgia O’Keeffe: Visions of Hawai‘i , held May 19 through October 28, 2018. Theresa Papanikolas, the curator of European and American art at the Honolulu Museum of Art, also curated the New York exhibit. Papanikolas, long a fan of O’Keeffe’s works, is delighted that the Honolulu Museum of Art is home to five of O’Keeffe’s Hawai‘i paintings. (All are on loan to the botanical garden through October.)

51歳のオキーフさんは、豪華客船のS.S. Lurlineに乗船して太平洋 を渡り、ハワイで温かい歓迎を受けた。彼女のハワイへの到着について は地元のニュースで流れたが、その後の滞在中の彼女の活動について は公にされることはなかった。プライベートな性格で単独行動を好むこ とで知られる彼女は、社交的なイベントを避け、自らの性格に合うスケ ジュールを優先した。ゆえに誰にも拘束や邪魔をされず、自由に絵を描 くことができたのだった。

オキーフさんは2ヶ月かけて、オアフ島、マウイ島、カウアイ島、ハワイ 島を旅し、熱帯の風景やエキゾチックな植物を描く中で、芸術的な新し い表現を見出した。彼女はオアフ島のパイナップル畑に驚嘆し、「鋭く銀 色に光るその畑は、美しい山々まで数マイルにわたって広がっている」と 賞賛し、マウイのハナ海岸沿いでは「溶岩がとても鋭く美しい形で海へ と流れ出ている」と心踊るような体験から多くのインスピレーションを 得ている。マウイ島ではレンタカーをし、探検と孤独の両方を楽しみな がら島内を自由に回って好きな絵を描くことに没頭した。フォルムと色 彩を生かし、目にしたもの全てを豊かで幻想的かつドラマチックに描い て ゆ く。青々とした険しいイアオ渓谷や滝、陰影のある海の中に覗くご つごつとした溶岩、空と海の背景に映える朱色のヘリコニアの官能的 な曲線などを描いた作品だ。

オキーフさんはハワイ滞在中に20枚の作品を製作した。翌年、アン・ アメリカン・プレイスでこれらの作品が展示されると、その新鮮さと豊 かな感性、美しさは大いに賞賛を浴びた。米紙『ニューヨーク・サン』の 批評家のヘンリー・マクブライド氏は、「このコレクションの風景や花の 描写、海の景色は、世界のどこでもその土地ならではの心地良さと魅力 を見い出すことができるオキーフさんの優れた才能が発揮されている」 と評価している。

それから約80年後、これらのうち17作品がニューヨーク植物園に集 められ、2018年5月19日から10月28日まで、『ジョージア・オキーフ: ビジョンズ・オブ・ハワイ展』が開催される。ニューヨーク植物園の展示 を企画したのは、ホノルル美術館でヨーロッパとアメリカ芸術のキュレ ーターを手がけるテレサ・パパニコラスさんだ。オキーフさんの長年のフ ァンでもあるパパニコラスさんは、ホノルル美術館にオキーフさんのハ ワイの作品が5つ収蔵されていることを嬉しく思っている。(現在、その 全てがニューヨーク植物園に貸し出されている)彼女は、オキーフさん がハワイで過ごした時間や作品はあまり知られておらず、多くの人たち がそれを知ると驚き、関心を抱くという。

opposite: Georgia O’Keeffe. Hibiscus with Plumeria , 1939. Oil on canvas, 40 x 30 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of Sam Rose and Julie Walters, 2004.30.6. © 2018 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

this page: Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986). Pawpaw Tree, Iao Valley , Maui , 1939. Oil on canvas. Gift of Susan Crawford Tracy, 1996 (7894.1). Honolulu Museum of Art.

左ページ:ジョージア・オキーフ作の『ハイビスカスとプルメリア』1939 年。キャンバスに油絵。スミソニアンアメリカ美術館、サム・ローズ&ジュ リー・ウォーターズ寄贈。ホノルル美術館

本ページ:ジョージア・オキーフ(米国1887-1986)作の『ポウポウツリ ー、イアオ渓谷、マウイ島』1939年。キャンバスに油絵。スーザン・クロ ーフォード・トレーシー寄贈。ホノルル美術館

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986). Black Lava Bridge, Hana Coast No. 2, 1939. Oil on canvas Gift of the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation, 1994 (7893.1)

Honolulu Museum of Art.

ジョージア・オキーフ作『ブラッ クラバ・ブリッジ、ハナコースト No.2』1939年。キャンバスに 油絵。ジョージア・オキーフ・フ ァンデーション寄贈。

“O’Keeffe is so often associated with New Mexico and the Southwest that to imagine her in a different place is strange,” notes Papanikolas about the surprise and then intrigue that many viewers experience upon learning of O’Keeffe’s littleknown time in Hawai‘i. “It’s hard to picture Georgia O’Keeffe, this ‘Priestess of the Desert,’ being in the islands.” But the artist’s keen ability to distill nature’s potent beauty regardless of geographic location was testimony to her lifelong desire to capture the spirit of her surroundings. “She loved Hawai‘i and always had hoped to come back,” Papanikolas says. “Critics reviewed her Hawai‘i work quite favorably, but what the critics really responded to was her response to Hawai‘i as a place.”

パパニコラスさんは、「オキーフさんは主にニューメキシコや南西部を 拠点にしていたイメージが強いので、それ以外の場所にいる彼女を想 像すると違和感を覚えます。『砂漠の巫女』であるジョージア・オキーフ さんのハワイでの姿はイメージし難いのです」。だが彼女には地理的な 場所に関わらず、それぞれの土地や自然の持つ美しさを最大限に引き 出す優れた能力があり、身を置いた環境の真髄を捉えたいという情熱 を生涯を通して抱いていた。「オキーフさんはハワイを愛し、いつか戻っ てきたいと望んでいました」とパパニコラスさんは言う。「批評家は彼女 のハワイでの作品を芸術的にも高く評価していますが、実際にはハワ イという場所でオキーフさんが感じた感受性溢れる表現を評価したの だと思います」。

ARTSTEXT BY NATALIE SCHACK IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK & IJFKE RIDGLEY

文=ナタリー・シャック

写真=ジョン・フック & イフカ・リッジリー

Plants and paintbrushes mix and mingle to spark artist Hadley Nunes’ whimsy in her workspace.

ヌネスさんの作業場には、アー ティストの創造力を沸き立たせ るさまざまな植物や筆が入り混 じっている。

RHAPSODY IN BLOOM

花ざかりの狂詩曲

Creation happens organically at the sun-kissed studio of botanical artist Hadley Nunes.

芸術が有機的に生まれる、ボタニカルアーティスト、ハドレー・ヌネスさんのアトリエ

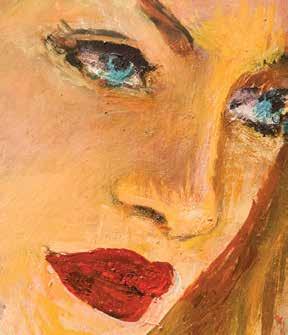

“It pleases me.” Hadley Nunes thoughtfully rests one finger on her bottom lip as she stares intently at a wall in her art studio. She is contemplating a triptych of a nude woman in dramatic repose she has painted, and trying to explain how she will add a vibrant abstraction of a king protea. The unworldly bloom with dynamic planes and piercing contours is her current fascination, and has become a repeating motif in her recent work—a saturated, striking signature of who and where Nunes is in this moment in time. It is to be the final addition to one of the first paintings she created a full year ago for a June 2018 show at Halekulani.

“My favorite is this collage element. It captures this lightness and this reflective quality,” she says, gesturing at the third panel, where bits of collaged found paper with magenta luminescence and lime 「見ていると楽しい気分になります」と話すのは、スタジオの壁に掛か った自らの作品に見入りながら思いに耽けるハドレー・ヌネスさん。大 胆なポーズをしたヌードの女性が描かれた彼女のトリプティック(三連 形式の絵画)に、鮮やかで抽象的なキングプロテアをどう描き加えるべ きか思索にふけっているのであった。平面と鋭い輪郭を持ったこの ドラ マチックで 美しい花に今彼女は夢中で、そのモチーフは彼女の最近の 作品に繰り返し使われている。それはヌネスさんがこの瞬間、アーティス トとして何を感じ、どう捉えているのかを示すサインのようである。ハレ クラニで6月に開催される展示会のためにヌネスさんが一年前から制 作している初期の作品のひとつにも、最後の仕上げにプロテアが加え られることになっている。

「私はこのコラージュの要素が大好きです。軽快なタッチで内面的な ものを上手く表現する ことができるから」と彼女は3つ目のパネルを指

Nunes’ paintings are bold expressions of color and form.

ヌネスさんの絵は色と形が大胆 に表現されている。

foliage stir dreamily at the subject’s feet. “If I put the drama of that flower, it would cancel out the poetry of what is only here that cannot be repeated. I can make paintings and paintings and paintings, but I cannot recreate that physical moment of poetry.” She pauses.

“No, I’m going to have the flower be in three tones, in a neutral palette that repeats the motif, but respects the cadence of what’s already there.”

Nunes moved to Hawai‘i with her family when she was 17 years old before heading off to Smith College and then the New York Studio School. It wasn’t until she met her husband, who is from Kaua‘i, that she returned. Eventually, she set up shop at Lana Lane Studios, a warehouse in Kaka‘ako that now serves as a shared space for 20 artists. Here, her studio is filled with potted cacti and monstera, canvases in various stages of completion, and artifacts that inspire her, like a bowed and buxom Venus figurine perched primly atop a wooden block. A History of the World in 100 Objects and tomes of historical paintings sit neatly on a shelf next to Nunes’ color palettes, which

差していう。そこには赤紫色の輝きとライム色の木の葉のような紙のコ ラージュがモデルの足元で夢のように混ざり合っている。「もしここにド ラマチックなプロテアを加えるとしたら、独特の詩的ニュアンスが消え てしまう。絵は何度でも描くことができるけれど、詩的な瞬間は再現す ることはできません」。しばらくして考え直した彼女は「いいえ、やっぱり 花をニュートラルなトーンの3色使いで描けばいいんだわ。この自由さ を尊重しながらね」と熱心に語る。

ヌネスさんは17歳の時に家族とともにハワイに移住した。その後、米 国本土のスミスカッレッジとニューヨークスタジオスクールに通い、カ ウアイ島出身の夫と出会ってハワイへ戻った。そしてカカアコ地区にあ る倉庫内に「ラナ・レーン・スタジオ」というショップを開いた。ここでは 共同スペースを使って、現在20名のアーティストが制作活動をしてい る。鉢植えのサボテンやモンステラ、製作中のキャンバスや、木製ブロッ クの上に立つ様々な女神像をはじめ、彼女のインスピレーションとなる オブジェや芸術作品が所狭しと並ぶ彼女のスタジオには、『100のモノ が語る世界の歴史』というタイトルの本や膨大な数の歴史的絵画がカ ラーパレットの隣の棚に綺麗に置かれている。重ねられた厚手の紙の

Nunes leads flowerarranging workshops at Paiko, a botanical boutique in Kaka‘ako.

ヌネスさんは、カカアコの花屋、 パイコでフラワーアレンジメント も担当する。

are captured in swatches of paint lined up in orderly little rows on stacks of heavy paper sheets.

All these things—nature, the old masters, her obsession with color—guide Nunes’ creative journey toward that ineffable thing she haltingly describes as her artist’s language. She speaks of aesthetic phases in artists’ work, such as Pablo Picasso’s Blue Period or her own protea, as she explores how to articulate a visual vernacular all her own. Nunes, who majored in art and got her graduate degree in painting, has worked as an artist in one way or another for her entire adult life, and she is still deep in the middle of that journey. At the moment, it has led her to proteas and abstraction. “I’m interested,” she says, slowly, “in discovering an image that I’ve never seen.”

上には、沢山の絵の具が何列にも整然と並べられている。

自然、芸術の巨匠たち、色へのこだわりといったもの全てが、ヌネスさ んを言葉では言い表せないものを表現する創作活動へと駆り立ててい る。それはアーティストである彼女にとって“言語”に等しいという。ヌネ スさんは彼女自身の視覚的表現を伝えるのに、パブロ・ピカソの“ブル ー・ピリオド”や彼女の絵のプロテアといった、芸術家が作品の中で表 現する美のフェーズについて語った。芸術を専攻し、絵画で大学院の学 位を取得したヌネスさんは、それ以来ずっと何らかの形でアーティスト として活動を続けている。その芸術活動の真っ只中にいる彼女が今取 り組んでいるのがプロテアと抽象画だ。「今まで見たことのないイメー ジを発見するのが楽しいんです」とヌネスさん。

芸術作品について他人に言葉で説明するのは難しいものだ。そこで ヌネスさんは「花」という媒体を使った別の表現方法を見つけた。カカ

An exhibition of Nunes’ work debuts at Halekulani this summer.

この夏、ハレクラニでヌネスさん の作品展が開催される。

It’s hard to explain to others, of course, as one’s oeuvre is wont to be. But for that, Nunes has found another tool in the medium of flowers. As the floral director at Paiko, a botanical boutique in Kaka‘ako, she does everything from order the blooms to design arrangements to arrange the wares for sale.

“Painting is the hardest thing I’ve ever done. Flowers are a more universal language,” she says, as she brings out a vase of cut stems and fingers the petals of a droopy variegated tulip affectionately. “I enjoy the placement and levels and flow, and the way there’s a rhythm. That’s what’s going on in the painting, space coming in front, space going in back. There’s negative space, just as important as the positive space. If I can use this as a bridge to the things that are important to me within the world of the painting, then it’s nice. It’s refreshing.”

She’s found that bridge in her flower-arranging group workshops, during which she invites visitors to her space, serves tea, shows her paintings, and then leads the ensemble in a collaborative floral design session. Participants select a single vase together, and then one at a time, different members add elements to the arrangement from buckets of botanicals. “It becomes the sum of its parts,” Nunes says. “It’s like a game. There’s an element of performance to it, but it’s definitely playful.”

The flower-arranging sessions have been successful, both as part of her workshop series, and as the focus of a collaborative film capturing the poetic group-arranging experience in a palm forest in Pālolo. This film is the seed for a larger artistic endeavor down the line. In the meantime, though, Nunes has that summer show and, of course, that fascinating king protea to keep her occupied.

That is, “Until I get bored with it,” she says with a grin. “Then, I’ll do something else.” For now, it’s the season of flowers.

アコにある植物ブティック「Paiko」のフラワーディレクターである彼女 は、花の注文からアレンジメントのデザイン、販売用の花器のディスプレ ーまで全てを行う。

「絵を描くことほど難しいことはないと思っています。それに比べて花 はより普遍的な言葉です」と彼女は切り花の入った花瓶を持ち出し、う なだれた色とりどりのチューリップの花弁を優しく撫でながら言う。「フ ラワーアレンジメントは、花の位置や高さや動きを考え、そこにリズムが 生まれるところが楽しいのです。絵の中でも同じことが起こっています。 前に出てくる空間、奥に広がる空間。そして正の空間と同じくらい大切 な負の空間があります。それが絵の中で、私にとって大切なものと繋が ることのできる架け橋になればと思っています。それはこれまでにない 新鮮なアプローチと言えます」。

ヌネスさんはその架け橋を自ら企画するフラワーアレンジメントのグ ループワークショップで見つけた。このワークショップは、彼女のスタジ オにゲストを招いてお茶を楽しみながら、彼女の絵を披露したり、共同 のフローラルデザインセッションを行うというものだ。参加者たちはグ ループで一つの花瓶を選び、一人一人がバケツに入った植物から選ん だものを一本ずつ生けていく。「それぞれのパーツが集まって一つの芸 術になるんです。毎回必ずうまくいくとは限りませんが、とても遊び心に 満ちていて、まるでゲームのような感覚です」とヌネスさんは言う。 グループで花をアレンジするこのセッションは、彼女のワークショップ シリーズの一環としてのみでなく、映画の主題としても話題になってい る。彼女はパロロにある椰子の森で行われた詩的なアレンジ体験の映 画を共同制作した。この映画は、今後さらに大きな芸術的インスピレー ションを生むであろう。それまでの間、彼女は夏に予定されているアー ト展をはじめ、彼女を魅了し続けるキングプロテアのアートの制作で忙 しい毎日を過ごすことになる。彼女は「しばらくはこの花の美を追求し 続けるつもりです。もし飽きたら、次の何かを見つければいいのですか ら」と笑う。彼女にとって今の季節は、「花」だ。

TEXT BY SONNY GANADEN

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

TEXT BY SONNY GANADEN

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

文=ソニー·ガナデン 写真=ジョン·フック

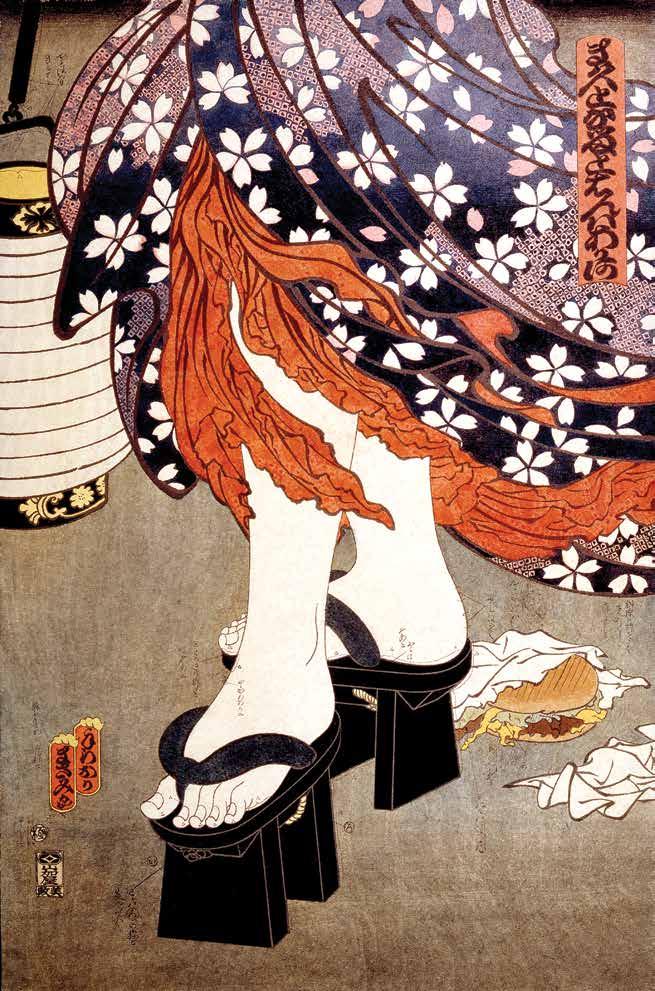

The artist Masami Teraoka is world-renowned for his politically charged paintings influenced by Japanese Ukiyo-e art techniques.

アーティストの寺岡政美氏は、

政治や社会問題を浮世絵で描 いた作品で世界的に有名だ。

SATIRE AND SERENITY

風刺と安らぎ

Masami Teraoka’s fantastically subversive artwork finds a surprising solace on the east side of O‘ahu.

オアフ島の自然に癒されながら、社会問題を風刺し続けるアーティストの寺岡政美

Masami Teraoka has all the idiosyncrasies one might imagine of a world-building artist. Although his studio is mere blocks away from the serene white sands of Waimānalo Beach on the eastern shore of O‘ahu, Teraoka’s paintings have never shied away from subject matter that addresses social and political issues of the day—many of which can be controversial and shocking for viewers. His latest series of paintings, which pit ski mask-wearing women in a battle royale against Catholic clergymen, was a response to sexual assault cases that were permeating the church.

Full of detail in gold and crimson, with hinged doors that open to reveal intense, fantastical scenes, the series began a decade ago and was shown in its explicit entirety at the Honolulu Museum of Art

寺岡政美さんは、奇抜で独創的な画風で知られるアーティストだ。オア フ東部のワイマナロビーチにある、白い砂浜から数ブロックというのど かな場所にスタジオを持つ彼だが、今でも現代の社会的、政治的問題 を題材とした制作活動に取り組み続けている。彼の作品の多くは、物議 をかもすような衝撃的な作品だ。最近の絵画シリーズは、カトリック牧 師を相手にバトルロイヤルに挑むスキーゴーグルで顔を覆われた女性 たちを描いたもので、教会に蔓延していた性的虐待に対する抗議の意 味が込められている。金色と紅色の豊かな色彩で細部まで詳細に描か れ、衝撃的かつ幻想的な場面を暴くかのように開いた扉が象徴的なこ のシリーズは、10年前からその制作が始まり、2015年にホノルル美術 館で開催された企画展『寺岡政美の三連祭壇画展』で発表された。 それぞれの作品には二つの球形をした閉じた扉が描かれている。そ れは芸術家としての寺岡さんを形成した彼自身のトラウマとなった過

opposite: Teraoka incorporates popular symbols into his work to comment on globalization and culture, such as the depicting of McDonald’s fast food in this screenprint McDonald’s Hamburgers Invading Japan/ Chochin-me (1982).

反対側のページ:寺岡さんは、 大衆受けするシンボルを作品 に取り入れ、国際化や文化に ついて意見している。『マクド ナルドハンバーガー、日本を侵 略』(1982)と題された版画が その例だ。

in 2015 under the title Feast of Fools: The Triptych Paintings of Masami Teraoka. Even when closed, the doors of each triptych reveal a traumatic past that inevitably shaped Teraoka as an artist today.

In 1945, Teraoka was a child survivor of the nuclear holocaust that was inflicted on Hiroshima, Japan. His uncle survived the blast under a collapsed house, and after severe injury, saved a friend in the rubble while bloody and naked, then walked for kilometers to his grandmother’s still-standing house for help. “It’s the kind of thing you don’t forget,” he says. “It’s etched in my brain forever.” Memory of the devastation had not shown in his previous work, but found itself on the exterior panels of the diptychs and triptychs of his recent work. When closed, the outside of the painted panels have twin orbs, which represent the sun, and on the opposite side of the horizon, the bomb. The sun hovers over Diamond Head and Koko Head—the famed promontories of urban Honolulu. Over the mountains is a floating peace gate of Hiroshima, and cherry blossom petals, set ablaze.

After the war, Teraoka earned a degree in Aesthetics at Kwansei Gakuin University in Kobe, Japan, and then moved to America in 1961. After attending Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles, Teraoka developed several print and painting exhibitions that satirized, condemned, and made surreal allusions to the commodification of bodies, globalization, capitalism, the AIDS epidemic, and most recently, sexual abuse in the Catholic Church.

His earlier work, more jovial in tone and subject, is held in several dozen institutions around the world. Teraoka’s East meets West style was inspired by techniques from artists who lived a century ago, like French impressionist Paul Cézanne. who was influenced by the compositions of Japanese woodblock prints, and Japanese printmaker Katsushika Hokusai, an Ukiyo-e painter and printmaker whose work depicted a whimsical world of history and folk tales, landscapes, and erotica. Since the 1990s, Teraoka’s paintings have bled toward surrealism worthy of comparison to Salvador Dalí.

Though entirely fictional, Teraoka’s work creates the kinds of juxtapositions found in the most compelling contemporary art, the most powerful of which does not merely reflect the current state of

去を示している。彼は8歳のとき、広島の原爆を経験している。彼の叔父 は原爆によって崩壊した家の下敷きになり重傷を負ったが、何とか逃 げ出して、瓦礫の中から友人を救った。叔父は裸で血まみれのまま、助 けを求めて彼の祖母の家まで何キロも歩いた。その時、原子爆弾の爆 心直下外にいた寺岡さんは「それは忘れることのできないものだ」と、離 れた場所から見た爆発の瞬間について語る。「その光景は私の脳裏に 永遠に刻まれています」。彼が描く二つの球の一つ目は太陽を表し、そ の水平線の向こうにあるもう一つの球は爆弾を表している。二つの球は ダイヤモンドヘッドとココヘッド、ホノルルの都市に広がる山々の尾根に 覆いかぶさり、ハワイの象徴的な景色と球の間には、宙に浮かんだ広島 の平和の門と桜の花びらが燃え上がっている。

寺岡さんは神戸にある関西外語大学美術科で学士号を取得 後、1961年に米国に移住した。ロサンゼルスでは、オーティス·カレッ ジ·オブ·アート·アンド·デザインに通い、ここでのちに世界的に知られる ようになる彼独特の画風と題材の原型を思わせる作品を生み出してい る。以来、彼は肉体の商品化、国際化、資本主義、エイズの流行、また最 近ではカトリック教会における性的虐待について言及、風刺し、非難す る絵画の制作と展示を続けてきた。ここ数十年間、彼の作品はシュール レアリズムに傾向していたが、彼の作品に見られる東西と西洋の混在す るスタイルは、日本の木版画の影響を受けたフランスの印象派のポー ル·スザンヌや、歴史、民話、風景、官能の世界を独特の作風で描いた日

31 Flavors Invading Japan/ Today's Special and McDonald's Hamburgers

Invading Japan/Burger and Bamboo Broom are examples of Teraoka's more cheeky and humorous pieces.

『サーティワンのフレーバー、日 本を侵略/本日のスペシャル』、 『マクドナルドのハンバーガー、 日本を侵略/バーガーと竹箒』 と題された水彩画は、寺岡さん によるユーモラスな作品。裏ペ ージ:『緑のラビットアイラ ンド』(1998)の、マナナ島の 風景は、彼のワイマナロの自宅 から見える景色だ。

affairs, but comments on societal issues at large.

“Pope Francis seems like a genuine human being. We would be friends. I feel comfortable depicting him,” says Teraoka, who says he attempted to reach the Pope via Twitter. On the other hand, he says, “I’d die if I had to paint Donald Trump.” Over the course of five decades, Teraoka has never slowed down, in life or art, and continues to show his work at the finest galleries throughout Hawai’i and the world.

“I must continue to present my work, as this is my form of poetry,” he says. “What I’m trying to say is that creative freedom and individual liberties must be protected.”

本の浮世絵師で版画家の葛飾北斎といった一世紀以上前のアーティ ストたちの技法にインスパイアされている。

寺岡さんの作品は架空でありながら、現代美術特有のある種の対比 を生み出している。中には、現代社会を映し出すだけでなく、社会全体 の問題について言及している作品もある。「フランシスコローマ教皇は 誠実な人に見えるし、友達にもなれるでしょう。彼を描くことに抵抗はあ りません」という寺岡さんは、Twitterで教皇に連絡を取ろうとしたこと もあるという。一方で彼は、「もしドナルド·トランプの絵を描くくらいなら 死んだ方がマシです」と言い放つ。ここ50年、生活面でも創作活動にお いても衰えをみせない寺岡さんは、ハワイや世界中の一流ギャラリーで 作品を披露し続けている。「私にとって世に作品を送り出すことは、詩を 書くようなものです。それは創造性の自由と個人の自由を守ることを意 味しています。だから続けなくていかなくてはならないのです」と語る。

IMAGE BY JOSIAH PATTERSON

IMAGE BY JOSIAH PATTERSON

CULTURE

BY

TEXT JADE SNOWIMAGES BY

MICHELLE MISHINA文=ジェイド・スノー 写真=ミシェル・ミシナ

MAGIC BESIDE THE SEA

海辺の魔法

Each evening, hula soloists grace a waterfront stage to recount melodic tales and transmit Hawaiian culture to watchful eyes through dance.

毎晩、ハレクラニのステージを華やかに彩るフラのソロダンサーたち。

From the nightly perspective of the resident hula dancers who move effortlessly across the House Without a Key stage, the dazzling view of Lē‘ahi (Diamond Head) to her right and the Waikīkī sunset to the left make it impossible for them not to dance: Inspiration is everywhere.

Though in hula the hands may tell the story of enchanted evenings and lovers adorned in fragrant floral lei, seasoned spectators know that it’s all in the eyes. Stylistic characteristics like the tap of a kāholo (hula step) or the sway of the hip may vary based on the hālau (hula school) or kumu (teacher) who taught the dancer her distinct techniques, but the eyes connect her to hula. An emboldened gaze can embody the strength of monarchs past, a flirtatious wink can quicken the heart, and a knowing glance can paint a picture of nostalgia reminiscent of Waikīkī’s golden era of travel. Many of these dancers have perfected their mele (songs) not only because they are practiced entertainers, but because they have lived these stories and breathed these mele through decades of hula study.

At Halekulani, a handful of its dancers—some of whom hold former Miss Hawaii and Miss HawaiiUSA titles or are the best hula ‘auana (modern style) soloists in Honolulu—perform at House Without a Key. We spent a week with dancers Kanoe Miller, Debbie Nakanelua-Richards, Jeanné Kapela, and Brook Māhealani Lee as they brought their distinct passions and prowess for hula to diverse onlookers, some who were witnessing hula in its native land for the first time. For these women, performing on this classic stage is a constant thrill and a familiar home for their hula. In their own words, they shared with us a varied testimony of hula: its beauties, its dedications, and what it means to dance in Waikīkī.

ハウス ウィズアウト ア キーのステージ上を優雅に舞うハレクラニ常勤 のフラダンサーたちの視界には、左手に立派なレアヒ(ダイヤモンドヘッ ド)、右手にはワイキキの美しい夕焼けの景色が広がる。そこには踊らず にはいられないほどのインスピレーションが溢れている。

フラでは、魅惑的な夜や香りのよいフラワーレイと恋人にまつわるス トーリーを繊細な手の動きで表現するが、フラについてよく知る観客 は、一番の語り手がダンサーの目であることを心得ている。カホロ(フラ のステップ)や腰の動きといった踊りのスタイルは、ハラウ(フラスクー ル)や独自の技を教えるクム(講師)によって異なるものの、フラを踊る ダンサーの心を一番表現しているのは目である。古代ハワイの王族の 強さを表現する力強い視線、心を踊らせる誘いかけるような目、ワイキ キの黄金時代を彷彿とさせるノスタルジックな眼差し。ダンサーの多く がこれらのメレ(歌)を完璧に美しく踊れるのは彼らが熟練した踊り手 であるだけでなく、何十年ものフラの研究を通じてこれらのストーリー を体現し、歌とともに歩んできたからである。

ハレクラニの ハウスウィズアウト ア キーに出演するダンサーの中に は、元ミスハワイのタイトル保持者やホノルルでトップレベルのフラ・ア ウアナ(現代フラ)のソロイストもいる。われわれは、カノエ・ミラーさん、 デビー・ナカネルア・リチャーズさん、ジャンヌ・カペラさん、ブルック・マ ヘアラニ・リーさんら、本場のフラを初めて観る人たちはもちろん世界 各国の観客とフラへの熱い想いと才能を共有するダンサーたちと1週 間をともに過ごした。由緒あるハレクラニのステージでフラを踊るのは 常に感動的な体験で、ダンサーにとってフラの故郷のようであるという 彼女たちに、フラの美しさ、ひたむきさ、ワイキキで踊ることの意味など、 それぞれにとってのフラの世界について聞いた。

“Being able to dance in Waikīkī, especially when there’s camaraderie with the other dancers like here, you’re a family. The clientele loves the hula, the scenery, they’ll come specifically just to see the dancers. If you get lucky enough to be invited and perform hula at the Halekulani, you have to know you’re engaging in a very special endeavor.” — brook māhealani lee

「ワイキキで踊るという機会に恵まれたダンサーたちの 間には、ここにいるメンバーのように家族のような絆が生 まれます。観客はフラとこの景色に魅了され、ダンサーた ちに会うために来てくださる方々も大勢います。光栄にも ハレクラニに招かれ、このステージでフラを踊れることは とても特別な - ブルック・マヘアラニ・リー

Halekulani Living

“Hula is a part of who we are as Native Hawaiian people. It’s how we learn and how we grow, it’s the art of storytelling and passing those stories down generation by generation. Today, it’s also an opportunity to share our culture. Hula is something that grounds me, to know who I was and am, and to be strongly rooted in that cultural heritage through dance.” —jeanné kapela

「フラは私たちネイティブハワイアンにとってアイデンティティの一部 です。私たち自身が学び、成長する方法であり、世代から世代へと歴 史や物語を伝える芸術でもあります。今日フラは私たちに、ハワイの 文化をより多くの人々と共有する機会を与えてくれています。フラは私 にとって心を落ち着けてくれるもの。私自身について知り、踊りを通し て伝統文化と深く繋がることのできるかけがえのない手段なのです」 - ジャンヌ・カペラ

“The audience at Halekulani has a far deeper appreciation of our Hawaiian culture and our music, and I believe it shows by the way they accept and appreciate our music. That is really important. It’s an engaged audience because they’re an educated audience— they’re knowledgeable and they’re respectful, and that’s the best thing about it.” —kanoe miller

「ハレクラニの観客がいかに私たちの音楽を受け入 れ、評価してくれているかを見れば、彼らがハワイの 文化と音楽をどれだけ深く理解しているかが分かり ます。それは本当に大切なことです。教養ある観客で あるがゆえに、強い関心を持ってくれるのです。私たち の文化に対する知識があり、尊重してくれる、それは 最高の観客と言えるでしょう」- カノエ・ミラー

“You really have to be at the top of your game, it isn’t a place to rehearse or practice. You really need to have the experience to be able to dance in this environment. You’re really close to the audience, and need to be able to communicate with them at another level, to really be in the space of a guest.”

debbie nakanelua-richards

「本当にトップレベルでなくては、この場所でフラを 踊ることはできないでしょう。リハーサルや練習はで きませんし、十分な経験を積んでなくては踊ることの できない環境ですから。観客との距離が非常に近く、 観客の空間に入って踊るため、普通のパフォーマン スとは違う次元でコミュニケーションをとらなくては なりません」- デビー・ナカネルア・リチャーズ

“To be a part of this legacy, to share my aloha with every single person that walks in the door and to be able to touch them with a sense of pride for our people and for hula itself is an incredible opportunity. It’s wonderful to be able to watch their eyes light up as they enjoy our hula.”

jeanné kapela「レガシーを受け継ぐ一人のダンサーとして、この場所を訪れる一人一人とア ロハの心を分かち合い、ハワイの人々の誇りである文化やフラに触れてもらえ る何より素晴らしい機会です。私たちの踊るフラを見て彼らの目が輝くのを見 ると、とても嬉しい気分になります」- ジャンヌ・カペラ

“Waikīkī is the ‘welcome mat’ to this place. I felt like if I was dancing here, I could be part of that welcoming feeling. That was the dream for me, to be a hula dancer who welcomes everyone to Hawai‘i. I wanted to express aloha to our visitors from all over the world and to tell the stories of our islands.” — kanoe miller

「ワイキキは、ハワイを訪れる人々を歓迎する玄関口です。ここで踊ることができたら、私に もその歓迎の気持ちを伝えることができるのではと思いました。ハワイを訪れる皆様を歓迎 するフラダンサーになることが私の夢でした。世界中からの旅行者の方々にアロハを表現 し、ハワイの物語を伝えたかったのです」 - カノエ・ミラー

“There are two things that dictate the dimension of hula. One is the music, and here at House Without a Key it’s traditional Hawaiian songs. That allows you to dance those hula mele you can’t always find other places. Another component that dictates what and how you dance is the venue. Oftentimes guests will say, ‘Wow, that was magnificent! Your dance!’ And I will always give credit to the place. Look how it surrounds you. You cannot wish or pray for a better stage and setting.”

debbie nakanelua-richards

「 フラを左右する2つのことがあります。一つは『音楽』。ハ ハウス ウィズアウト ア キーではハワイの伝統的な歌を演 奏するので、他の場所では聴くことのできない曲でフラを踊 ることができます。どのように踊るかを決めるもう一つの要 素は『場所』です。『あなたのダンスは素晴らしかった!感動 したわ!』とゲストが言ってくれるときにはいつでも、私はこ の場所のおかげですと言うのです。この場所はあなたを包み 込んでくれます。これほど素晴らしいステージと環境は他に ないでしょう」- デビー・ナカネルア・リチャーズ

“I love putting on the monarchy costume and dancing monarchy dances. But I just as easily love wearing a cellophane skirt and hearing that swishswish sound. I love that bounce and that feeling from the war days when the cellophane skirt was most prevalent. I also love the holokū (a formal Hawaiian gown style) of the 1930s because of that very gracious time—the golden years of Hawai‘i. And then, I really like dancing in a tī leaf skirt and doing implement dances because as a teenager that’s what I did.” —kanoe miller

「私はハワイの王族のような衣装を着て、王族の踊りを踊るのが好きです。セロハンスカートのたて るシュッシュッという音を聴きながら踊るのも同じくらい好きです。セロハンスカートが一番流行した 戦時中のフラを踊る感覚と躍動感に惹かれるのです。エレガントなハワイの黄金時代を彷彿とさせる 1930年代のホロクー(裾の長いハワイの正装ドレス)を着て踊るのも、10代の頃を思い出させてく れるティリーフの葉でできたスカートで楽器を使って踊るのも大好きです」- カノエ・ミラー

“Diamond Head is to the right, Waikīkī is behind you— you have the wind, the waves, and the sea spray. You look up and there’s Nu‘uanu, Pauoa, and Makīkī. You watch the mist come in and a rainbow comes out. You are just in the presence of inspiration. When I dance a mele like ‘Waikīkī’ by Andy Cummings here, it transports me to another space. Oftentimes I can’t remember the mele ending because I’m kind of transmitted somewhere else.”—debbie nakanelua-richards

「右手にはダイアモンドヘッド、後ろにはワイキキの景色が広がってい て、風、波、海の波しぶきを感じることができます。見上げると丘の向こ うにはヌウアヌ、パウオア、マキキがあり、霧が起こり、虹が出るのが見え るのです。それはインスピレーションそのものです。アンディー・カミング スの『ワイキキ』のような歌を踊ると、私は別の空間へと誘われてしまう ことがあります。トランス状態になって曲の最後を覚えていないこともよ くあるのです」- デビー・ナカネルア・リチャーズ

“I’m a big believer in fresh flowers and lei, so when I come to Halekulani I’m like an Aloha Week float, head to toe in plumerias in the summer, like Karen Keawehawai‘i! I’ve been brought up in the tradition of fresh lei—make your own lei, pick your own flowers. You put the love into it because it really pays off for the audience.” — brook māhealani lee

「私は新鮮な花とレイが大好きで常に身につけています。ハレクラニに来る時には、ま るでアロハウィークのフロートのように、夏にはプルメリアの花でつま先から頭まで飾 ります。カレン・ケアヴェハワイさんのようにね! 私は、自分で花を選んで、レイ(花輪) を作るというハワイのレイの伝統の中で育てられました。心を込めてレイを作るとその 想いは観客にも伝わるものです」- ブルック・マヘアラニ・リー

CULTURE

フラダンサーのカノエ・ミラー さんのシルエットと夕暮れ時の ハウス ウィズアウト ア キーの ステージからのダイヤモンドヘ ッドの眺め。

about the performers

debbie nakanelua-richards

Debbie Nakanelua-Richards has been performing every Sunday at House Without a Key for nearly 30 years.

A proud haumāna (student) of iconic hula master Ma‘iki Aiu Lake, Nakanelua-Richards acknowledges her kumu as the source of her passion. Many hold Nakanelua-Richards in high esteem as well, including Halekulani guests. Recently, a tearful woman even approached the dancer before she took the stage to thank her for the kindness she had shared with the guest and her husband 11 years earlier. Though her husband passed away since, the woman continued her annual pilgrimage to the hotel in his honor, and was touched to reconnect with the dancer who made such an impact on them. “I’ve been able to meet so many families who come here from generation to generation, whose grandparents and parents have been married here, so it’s really special to be a part of,” NakaneluaRichards says.

デビー・ナカネルア・リチャーズ

毎週日曜、ハウス ウィズアウト ア キーで30年近くにわたってフラを踊 っているデビー・ナカネルア・リチャーズさんは、ハワイを代表するフラマ スターのクムフラ、マイキ・アイウ・レイクの教え子の一人だ。フラへの情 熱の源は彼女のクムであるというナカネルア・リチャーズさんは、ハレク ラニのゲストをはじめ、多くの人が尊敬するフラダンサーだ。先日、ある 女性が涙を流しながら、ステージに上がろうとするナカネルア・リチャー ズさんに近づき、11年前に彼女がそのゲストと夫に親切にしたことへ の感謝の気持ちを伝えたという。夫に先立たれたその女性は、夫婦での 思い出に満ちたこのホテルを毎年訪れ、強く印象に残っていたダンサー との再会に感動したのであった。「私はこれまでに、この場所を訪れる多 くの家族と出会う機会に恵まれました。祖父母や両親がここで結婚し、 親子代々このホテルを訪れる家族の思い出の一部になれることはとて も光栄なことです」とナカネルア・リチャーズさんは語る。

kanoe miller

Kanoe Miller has been a mainstay dancer on the famed Halekulani grounds for 41 years. “I used to stand from the G Building of Roosevelt [High School] and look down at glittering Waikīkī, staring out at the ocean,” recalls Miller, who was crowned Miss Hawaii in 1973. “I wanted to be part of the fabric of what makes Waikīkī special.” Miller and her two sisters also studied under famed kumu hula Ma‘iki Aiu Lake of Hula Hālau O Ma‘iki. Miller has dedicated her life to sharing her passion for hula with a global audience as a performer and instructor. Having performed for four decades in Waikīkī, Miller is a renowned figure at House Without a Key.

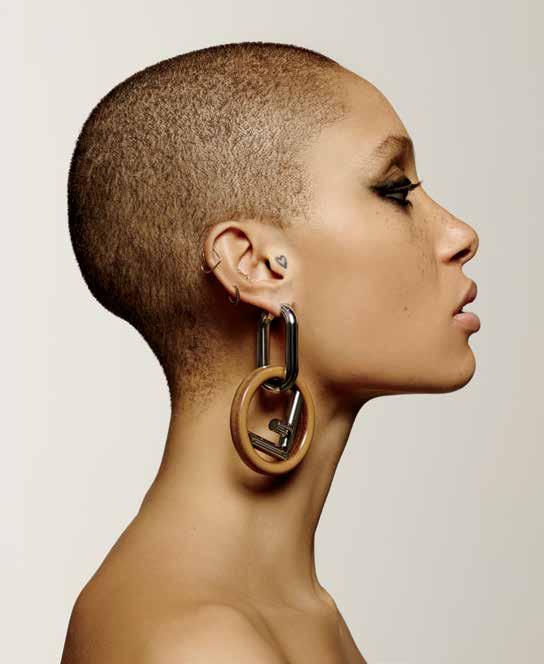

jeanné kapela

For Jeanné Kapela, performing at the House Without a Key for the past seven months has been as much about the performers as it has been about the venue. “A lot of the women that dance here are either a former or current Miss Hawaii,” says Kapela, who was crowned Miss Hawaii in 2015. “I like to think of it as a sisterhood.”

The ambitious 23-year-old learned to dance hula from her mother and uncle, both of whom were dancers for Tihati Productions in Kona, whose commercial dance troupe is highly respected for its style and skill. Kapela is running for Hawai‘i House Representative for District 5 and hopes to be the first female and first Native Hawaiian to earn the seat. She balances her campaigning schedule with hula, a way to connect to her roots.

brook māhealani lee

For Brook Māhealani Lee, dancing hula on the House Without a Key stage brings back memories of performing in the Waikīkī hula scene starting at the age of 20. Lee has lived in Los Angeles for 20 years, but returns home each Christmas and for other seasonal schedules to perform at Halekulani. Her early days of hula came from her mother, Toni Lee, who was also a pupil of Ma‘iki Aiu Lake. Lee continued her hula studies with various hālau, namely under kumu Suzanne Ka‘upu, Leinā‘ala Kalama Heine, and Randy Ngum. Even though Lee no longer lives on O‘ahu, her connections to her island home and her own hula history run deep.

カノエ・ミラー

41年にわたって由緒あるハウス・ウィズアウト・ア・キーのステージで踊 るカノエ・ミラーさんは、ハレクラニのフラダンサーを代表する人物だ。 「私は学生時代、ルーズベルト高校のG館から向こう側に広がる海を 眺め、光り輝くワイキキを見下ろしたものでした。ワイキキという場所の 魅力に惹かれ、自分もその一部になりたいと思いました」と1973年に ミスハワイに選ばれたミラーさんは振り返る。ミラーさんと彼女の二人 の姉妹は、フラ・ハラウ・オ・マイキの著名なクムフラ、マイキ・アイウ・レ イクのもとでフラを学んだ。ミラーさんは、パフォーマーとインストラク ターとして世界中の観客とフラへの情熱を分かち合うことに生涯を捧 げてきた。ワイキキで40年間踊り続けているフラダンサーのミラーさん は、ハウス・ウィズアウト・ア・キーの「華」である。

ハウス・ウィズアウト・ア・キーでフラを踊るようになって7ヶ月になるジ ャンヌ・カペラさんにとって、彼女が尊敬するフラダンサーと踊れること は、その場所と同じくらい特別な意味があるという。「ハレクラニでフラ を踊る女性の多くは、元あるいは現役のミスハワイです。それは姉妹を 持ったような感覚です」と2015年のミスハワイに選ばれたカペラさん は語る。23歳で野心家の彼女は、コナの「ティハティ・プロダクション」 の一流のダンサーである母親と叔父からフラを習った。ハワイを代表す るこのエンターテイメントグループは、踊りのスタイルと高いスキルで 定評がある。カペラさんは、第5地区のハワイ州下院議員選挙に出馬し ており、彼女のルーツと結びつく手段であるフラと選挙活動のバランス をとりながら、初の女性、かつ初のネイティブハワイアンとして議席の獲 得を目指している。

ブルック・マヘアラニ・リー ブルック・マヘアラニ・リーさんは、ハウス・ウィズアウト・ア・キーのステ ージで踊るたび、ワイキキでフラを踊り始めた20歳の頃のことを思い出 すという。リーさんはロサンゼルスに移住して20年になるが、ハレクラ ニでのクリスマスや季節毎のパフォーマンスのためにハワイに毎年帰 郷している。クムフラ、マイキ・アイウ・レイクの教え子であった母のトニ ー・リーさんから初めてフラを学んだリーさんは、その後も様々なハラウ で、スザンヌ・カウプ、レイナアラ・カラマ・ハイネやランディ・ナムといった クムからフラを学んだ。オアフ島に住んでいない今も彼女は、故郷であ るハワイとフラのルーツと深く繋がっている。

文=アレクシス·チョン 写真= カイノア·レポンテ & ジョサイア・パターソン

THE PAREU, UNCOVERED

パレオの知られざる歴史

Unraveling the Pacific garment’s surprising past beyond the beaches of Hawai‘i and Tahiti, all the way to Europe.

ヨーロッパからハワイとタヒチのビーチへと渡った太平洋を象徴する衣服

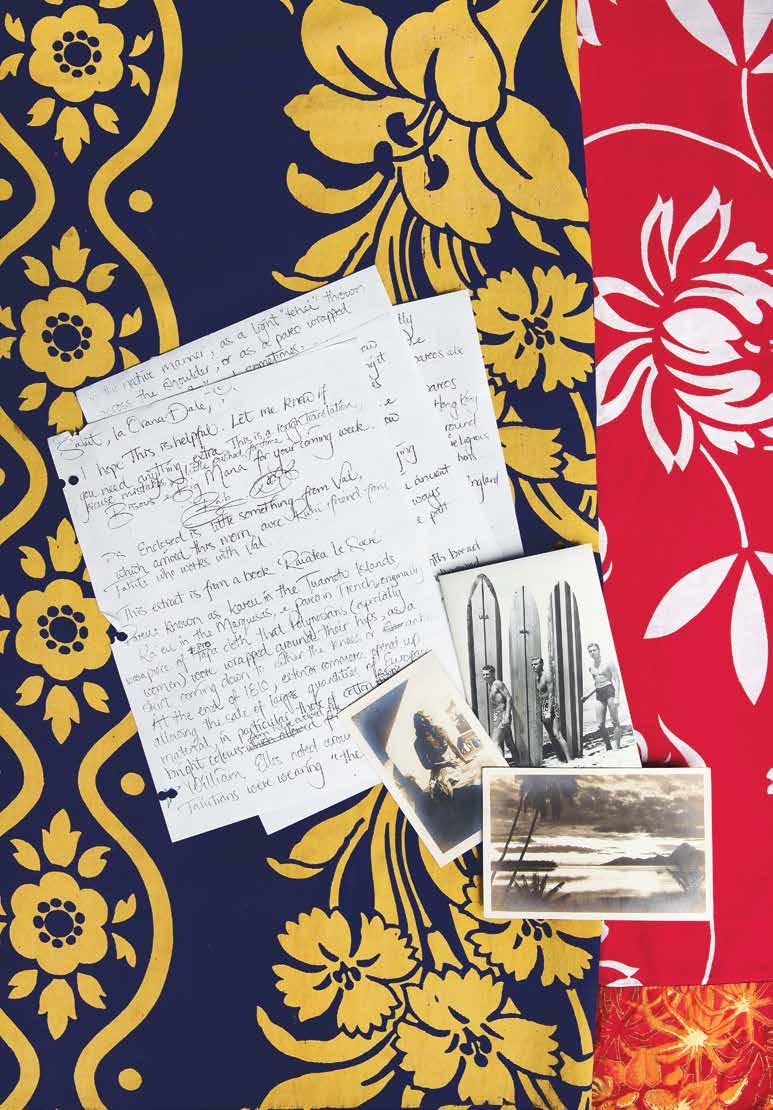

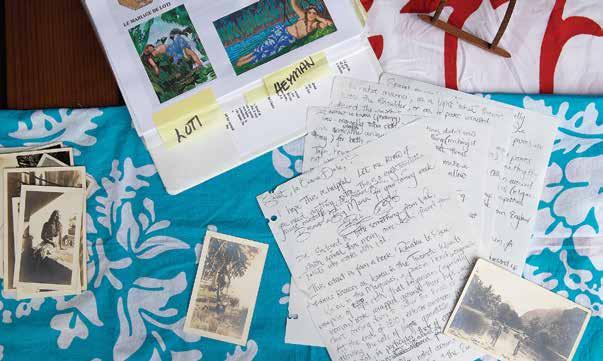

Fashion collector and historian Dale Hope is interested in following the pareu’s origins to its place in modern day Tahiti and sister islands like Hawai‘i.

ファッション収集家で歴史家の デール・ホープさんは、現代のタ ヒチとハワイのパレオの起源に 関心を持っている。

Knotted at the shoulders, wrapped around the waist, and tied taut at the chest, the pareu is a printed piece of fabric that is beloved for its endless versatility. Although ubiquitous across beaches in Hawai‘i, the pareu as we know it today actually hails from Europe and found its way to the South Seas with sailors in the 1800s.

What is now known as French Polynesia— which consists of five separate island groups that are culturally related but distinct—was colonized by France in the 1800s. At this time, European voyagers and colonists sought valuable commodities like vanilla and sandalwood, and even staples for survival like freshwater and citrus, so they came prepared with goods suitable for bartering.

While trading, they discovered that islanders, particularly those in Tahiti, appreciated the fabric printed with an abstract, white floral motif. This was an ideal trading good for Europeans since the Industrial Revolution was happening across Europe and the United States, making fabric much cheaper to produce.

According to the Tahitian and English dictionary, the word pareu is defined as “a garment worn as a petticoat, round the loins of both sexes.” (It’s also a verb that means “to put on a pareu.”) According to author Dale Hope, who is researching and writing a forthcoming book about pareu, “The pareu was accepted by the Tahitian people as something that was more indigenous for them to wear, rather than the missionaries’ clothing.”

In the island’s balmy heat, the pareu’s cotton fabric was cool and effortless. This appealed to islanders because, unlike traditional tapa fabric,

肩で結んだり、腰や胸に巻いたりと多様な使い道があり重宝されてい る布、パレオ。ハワイのビーチのあちこちで見かけるこのパレオは、実は もともとヨーロッパから持ち込まれ、1800年に船乗りたちとともに南 太平洋へとやってきた。

共通した文化を持ちつつ、それぞれに個性のある5つの諸島群で構 成されている現在のフランス領ポリネシアは、1800年代にはフランス の植民地であった。当時、ヨーロッパの航海士や入植者は、バニラやサ ンダルウッドのような貴重品を買い求め、飲料水や柑橘類といった必 要な食料を入手するため、物々交換できるものを持ち込んだ。

取引をするうちに、彼らはこれらの島の住民、特にタヒチの人々は抽 象的な白い花柄の布を好むことを知った。当時、ヨーロッパとアメリカ 全土で起こっていた産業革命のおかげで生地を安く生産できたため、 これはヨーロッパ人にとって理想的な取引であった。

タヒチ語と英語の辞書によると、パレオ(本来パレウと呼ばれていた) という言葉は「男女ともに腰巻のように身体に巻きつける衣服」と定義 されている。(「パレオをつける」という動詞としても使われる)。パレオに ついて研究し、パレオに関する本を出版予定の作家、デール·ホープさん によれば、「パレオはタヒチの人々の間で、宣教師の衣服というより、土 着のものとして受け入れられた」という。

熱帯の島では、パレオの綿素材は涼しく、着やすかった。樹皮を叩い て作られた伝統的な布のタパとは異なり、綿は長持ちし繰り返し洗うこ とができたため、島の人々に好まれた。宣教師は大抵パレオを洋服と組 み合わせて使い、スカートの上から巻きつけたり、ボタン付きのシャツ の上からスカーフのようにかけたりしていた。

初期のパレオはきまったデザインで、濃い赤や青の生地に白い葉や 花がプリントされていた。その柄は、南太平洋の人々にとっては見慣れ ないものであった。それらはヨーロッパの室内装飾品、カーテン、壁紙

which was made of beaten bark, cotton was longlasting and could be washed repeatedly. Missionaries often paired the pareu with their Western-style clothing, wrapping it around a skirt or draping it across a button-up shirt.

The earliest pareu had a specific design of white leaves and flowers printed on a darker background of red or blue. Nothing about those patterns were traditional to the South Seas region. As Bishop Museum historian DeSoto Brown explains, they were more akin to what might have been used for upholstery, curtains, or wallpaper in Europe. (Later, once pareu were produced in Tahiti, the motifs began to resemble indigenous flora and fauna from the region.)

European artists like Paul Gauguin captured the garment in its element. Through his lush paintings of local women, he telegraphed its leisurely practicality while imbuing it with an exotic allure. In an era of cumbersome clothing, seeing women in the South Seas minimally covered was enticing to Western men. Especially, as Brown says, “when the fabric was wet

などに使われる模様に似ていたと説明するのはビショップ博物館の歴 史家、デソト·ブラウン氏。その後、タヒチでパレオが生産されるように なると、その地域固有の花や植物がデザインに取り入れられるように なった。

ポール·ゴーギャンのようなヨーロッパの芸術家たちは、この衣服の ある風景を捉えている。島の女性たちが艶かしく描かれた彼の作品は、 パレオの汎用性と実用性を伝えながら、そのエキゾチックな魅力を存 分に感じさせる。華美な服装が主流であった時代に、最小限の布で体 を覆う南太平洋の女性たちの姿は、西洋の男性たちの目に魅力的に映 ったことであろう。「彼らは大抵泳ぐ時にパレオを着ていましたから、濡 れた布が体にまとわりついていることも多かったのです」とブラウンさ んは語る。

パレオはサロンにも似ているが、それらは異なるものである。サロン は、マレーシア語で男性がスカートのように腰に巻く生地を指す。この 二つが混同されるようになったのは、1936年に女優のドロシー·ラモー ルさんが初主演映画の「ジャングル·プリンセス」で体にフィットした布 を身に着けたのがきっかけであった。それは実際にはパレオだったのだ が、宣伝ツアー中に「サロン」と呼んでいたため、以来、何十年にもわた

CULTURE

In these detail shots of Hope’s research, archival photos and textiles show the variety of patterns and use of pareu in Polynesian society.

ホープさんの研究にまつわるこ れらの詳細な写真には、さまざ まな模様や島社会での用途を 明らかにする記録写真や生地 が写っている。

and clinging, which it often was, since the pareu was worn while swimming.”

Although similar to the sarong, the two are different. The sarong, or sarung, is the Malaysian word for a piece of fabric worn around the waist like a skirt, but by men. The confusion began in 1936 when actress Dorothy Lamour starred in her first film, The Jungle Princess. Her character wore a fitted pareu, but during the publicity tour, it was referred to as a sarong. The incorrect term was used for decades.

In Hawai‘i, the classic “Tahitian print” (which refers to the pattern that first appeared on the pareu) has graced everything from aloha shirts to mu‘umu‘u. In the late 1930s, local shirt makers like Kahala purchased pareu fabric from Tahiti, then made small runs of shirts, shorts, and bathing suits. By the 1960s and 1970s, the print was all the rage in Hawai‘i.

In the South Pacific, Hope has seen the pareu tied to bicycles and wrapped around torsos to carry newborns. He’s even heard stories of people strapping themselves to coconut trees with pareu to survive tremendous rain and wind storms. Although a pareu is slight in size, its importance cannot be overstated. “Whether you’re wearing it to the pool or walking down the beach,” Hope says, “it’s something you don’t want to be without.”

ってこの間違った名前が定着してしまったのであった。

ハワイでは、典型的なタヒチアンプリント(パレオに最初に使用され た柄)が、アロハシャツからムームーまであらゆるものに取り入れられ た。1930年代後半、カハラをはじめとする地元のシャツメーカーは、タ ヒチからパレオの生地を購入し、シャツやショーツや水着を少量ずつ 生産した。1960年代から70年代にかけて、このプリントはハワイで大 流行した。

ホープさんは、南太平洋ではパレオを自転車に結び付け、胴の周りに 巻きつけて新生児を運ぶのに使うのを見たことがあるという。さらには パレオでヤシの木に自らの体を括り付け、強風と雨の嵐に耐えたという 人々の話を聞いたこともあるという。パレオは小さな布であるが、その 重宝さは強調してもしきれない。「プールやビーチに行くときにも便利で 何かと使い回しの良いパレオは、一度使い方を覚えると手放せません 」 とホープさんは語る。

TEXT BY MATTHEW DEKNEEF

IMAGES BY JOSIAH PATTERSON

TEXT BY MATTHEW DEKNEEF

IMAGES BY JOSIAH PATTERSON

文=マシュー・デニーフ 写真=ジョサイア・パターソン

STRIKING A BALANCE

驚異のバランス

At

Mākaha Beach, a photographer captures the agility and eloquence of tandem surfing, an innovation of the sport that began in Hawai‘i.

写真家がマカハビーチで捉えた機敏かつ優雅なハワイ発祥の革新的なスポーツ、タンデムサーフィン。

Tandem surfing is defined as when two people, generally a man and a woman, ride together on a board. While the practice gained prominence in the 1930s in Waikīkī with beach boys and tourists, ancient Hawaiian legends reveal tandem surfing was common and popular in the islands long before. Mākaha is often considered the preeminent arena for its thrilling stunts, such as when the woman balances on one foot on her escort’s shoulder or encircles him in a round-the-world twist.

タンデムサーフィンとは、通常男女2人組で波に乗るス ポーツだ。1930年代にワイキキのビーチボーイズや 観光客の間で流行したタンデムサーフィンは、古代ハワ イの伝説によるとハワイではずっと昔から一般的に楽 しまれていたという。タンデムサーフィンのメッカとされ るマカハでは、女性がパートナーの肩の上に片足で立 ったり、彼の周りをくるっと一周するといったスリル溢 れる妙技が繰り広げられる。

One of tandem’s compulsory and most difficult rides is when the man extends the woman into the air and she strikes a swan position. “The girls deserve an earthquake of applause,” Duke Kahanamoku wrote in the his manual Duke Kahanamoku’s World of Surfing, “for their daring contributions to the bigger and better surfing meets.”

タンデムサーフィンにおいて必須かつ 難易度が高いのが、男性が女性の体を 空中に持ち上げ、女性が空を飛ぶ白鳥 のポーズをとる技だ。デューク・カハナ モクさんは著書『デューク・カハナモク のサーフィンの世界』の中で、「サーフィ ン大会の質を向上する女性たちの大 胆ともいえる貢献は高い評価に値す る」と書いている。

Jordan Patterson, who is ranked one of the top tandem surfers in the world, surfs with his sister Keala Patterson.

The multitude of manuevers of tandem surfing and how finely developed it has become over the decades illustrate the dedication and creativity of the sport’s performers. Tandem surf duos often take liberties with classic maneuvers to push limits and expectations, and in turn, wow the crowd.

選手の情熱と創造力が数多くの技を生むタンデムサーフィ ンは、ここ数十年で完成度の高いスポーツに成長した。タ ンデムサーフィンのデュオは、クラシックな技を独自にアレ ンジすることで競技の限界に挑み、観客を沸かせている。

TEXT BY JULIE ZACK

IMAGES BY KENNA REED

TEXT BY JULIE ZACK

IMAGES BY KENNA REED

文=ジュリー·ザック

写真=ケナ·リード

THE FORM OF FLORALS

花のカタチ

Ikebana, the art of living flowers, inspires and adorns the serene spaces of Halekulani, while soothing the minds of those who practice it.

ハレクラニの安らぎの空間を華麗に彩るいけばな

Irene Bacani, who manages the Flower Shop at Halekulani, learned the art of ikebana from Tanga Kamemoto.

ハレクラニのフラワーショップを 経営し、マサコ・カメモトさんか ら生け花を習ったアイリーン・バ カニさん。

Enter the lobby of Halekulani. There, in the center, is a sturdy set of Italian marble blocks stacked to withstand the wind that sweeps through the open-air space. It is easy to miss this sculpture. Though beautifully crafted, it is often overshadowed by crimson anthuriums, kelly green leaves, umber branches, and orange hanging heliconias that burst forth from it. For decades, this flower base has steadily supported dramatic weekly arrangements, Sogetsu design concepts inspired by the tradition of ikebana.

Ikebana, which roughly translates to “living flowers,” is the ancient Japanese art of floral arrangement. Its roots can be traced to flowers left on Buddhist altars after the religion arrived in Japan in the sixth century. In the intervening years, the art form developed into hundreds of schools with codified rules that evolved as different styles rose and fell. Traditional ikebana can be a rigid practice. Today, several older schools continue to adhere to a rule of representing heaven, human, and earth in each arrangement.

ハレクラニの正面玄関から中へ入ると、ロビーの中央にイタリア製大理 石のブロックを垂直に積み上げた彫刻が迎えてくれる。吹き抜ける風に 耐えられるようデザインされているこの芸術的なオブジェには、ここ数 十年間にわたり、真紅のアンセリウムや深緑色の葉、茶色の枝や前に突 き出したオレンジ色のハンギング·ヘリコニアといった草月風のいけば なを取り入れた美しいフラワーアレンジメントが毎週活けられている。 生きた花や植物を活けて鑑賞する日本の芸術、「いけばな」。仏教が 日本に伝来した6世紀頃、仏壇に献じられた供花が始まりとされてい る。それ以来、華道の芸術は、様々なスタイルが生まれては衰退しなが ら進化を遂げ、体系化されたルールのある何百もの流派が生まれた。 伝統的な生け花には厳格なルールがある。昔からある流派では、今で も天地人の3つの枝で花型の格を作る古来からの様式に従っていると ころもある。

草月流のいけばなは、形式にとらわれない自由なスタイルで知られて いる。勅使河原蒼風(てしがはら·そうふう)氏は1927年、個性と創造 性を重視した草月流いけばなを始めた。芸術家として活躍していた勅 使河原氏にとっていけばなとは、誰もがいつでもどこでも楽しむことの

For the ikebana displays, flowers are sourced from Hawai‘i to Holland. Materials are also salvaged from the hotel’s fallen kiawe tree.

生け花には、ハワイ島やオラン ダ産の生花が使用されているほ か、敷地内に横たわるハウス ウ ィズアウト ア キーのキアヴェの 木の枝なども素材として用いら れている。

The Sogetsu school of ikebana is known for breaking the rules. Sofu Teshigahara founded Sogetsu in 1927 to allow practitioners originality and creativity. An accomplished artist in his own right, Teshigahara saw ikebana as a creative art that could be enjoyed anywhere, anytime, by anyone. Teshigahara believed that any material could be used to construct an arrangement, and that ikebana shouldn’t be constrained by rules or location. Sogetsu defies convention by encouraging practitioners to embrace spontaneity and to make every arrangement an artistic endeavor.

“The important thing is lines and color and harmony and movement,” says Masako “Tanga” Kamemoto, the nonagenarian who brought Sogetsu design to Halekulani in 1984. Kamemoto is a slight woman with short brown hair styled in waves. She was born and raised in Japan, where she studied ikebana, earning her first Sogetsu teaching diploma at 20 years old, at which time she received the name “Tanga” from master Sofu Teshigahara. By the time she came to Halekulani, she had earned the highest teaching rank and was a celebrated practitioner.

できる芸術であった。勅使河原氏は、いけばなに使う材料は自由に好き なものを選んで、形式や場所に制限されるべきではないと考えていた。

草月流のいけばなは慣習にとらわれることなく、個人ののびやかで自由 な表現を求めるものである。

「いけばなで大切なのは、線と色、そして調和と動きです」と言うの は、1984年からハレクラニで草月流いけばなを活けてきたタンガ·カメ モトさんだ。90代のカメモトさんは、短くウェーブのある茶色の髪をし た小柄な女性だ。日本で生まれ育った彼女は、そこで生け花を学び、若 干20歳で草月流いけばなの師範の免状を取得し、華道家の勅使河原 蒼風氏から「タンガ」という雅号を授かる。ハレクラニのフラワーアレン ジメントを担当し始めた頃にはすでに最高位の一級師範証を持つ一流 のいけばな師範であった。

2004年に引退してからもホテルのスタッフの多くは彼女のことを覚 えていて、彼女が訪れると「ミセスカメモト」と呼んでは温かく迎える。彼 女と夫のキヨシさんは、20年にわたりハレクラニのロビーに欠かせない 存在であった。夫婦は決まって毎週金曜にハレクラニを訪れ、カメモト さんは新しいアレンジメントの制作に取り掛かる。キヨシさんは重い枝 を持ち上げるなどして彼女を手伝った。キヨシさんは2008年に他界し

Although she retired in 2004, much of the hotel’s staff still recognize her, warmly greeting her as “Mrs. Kamemoto” when she visits. She and her husband, Kiyoshi, were staples of the lobby for two decades. The couple would visit every Friday so that she could create new arrangements, while Kiyoshi helped with the heavier work. Kiyoshi, who passed away in 2008, also designed the timeless lobby sculpture that housed his wife’s ephemeral creations.

Before retiring, Tanga Kamemoto volunteered her time to impart some sense of the Sogetsu art of flower arrangement to the staff of the Halekulani Flower Shop. Irene Bacani, the manager of the Flower Shop, learned the trade from Kamemoto. Like her teacher and many Sogetsu practitioners before her, Bacani sees floral arranging as art. “Every time I make an arrangement, it comes from the heart,” Bacani says.

To form these living floral sculptures, Kamemoto and Bacani agree that it is imperative to use quality materials. Flowers are sourced from places including Hawai‘i Island, Holland, and South America. Materials salvaged onsite are used as well, such as branches from the beloved fallen kiawe tree that now grows on its side by House Without a Key. Each element is carefully examined and placed to maximize artistry and flow. To practice Sogetsu, as Kamemoto puts it, “You have to know how to use a flower.”

Sogetsu is an expression of the practitioner that requires focus and concentration. Bacani has taken to making her arrangements between 6 and 8 a.m. to avoid distractions. She also finds that Sogetsu is rarely far from her thoughts, as she often picks up twigs or other greenery throughout the day to feature in future arrangements. “We are using these natural materials to create beauty with our feelings,” Bacani says. By discovering and playing off the natural qualities and quirks of each plant—its color, durability, or texture, for instance—Bacani feels she learns from each new creation.

Back in the lobby of Halekulani, the flowers seem to move in stillness. Note the precision of each sweeping line. Take in the sculpture Kiyoshi Kamemoto lovingly made to support his wife’s art. The details of this scene change weekly, but the soul of the tableaux is constant.

ているが、カメモトさんの花の芸術を収めた、時代を感じさせないロビ ーの大理石彫刻をデザインしたのも彼である。

引退前、タンガ·カメモトさんはボランティアとして、草月流のいけばな の基本をハレクラニ·フラワーショップのスタッフに伝授した。フラワーシ ョップのマネージャーのアイリーン·バカニさんは、カメモトさんからそ の技を学んだ一人だ。師範のカメモトさんをはじめ、これまでに草月流 を習った人たち同様、バカニさんにとって花を活けることは芸術表現そ のものだという。「フラワーアレンジメントは、作り手の心から生まれるん です」とバカニさん。

これらの生きた花の芸術を作るためには、質の高い新鮮な材料を使 うことが何より大切、とカメモトさんとバカニさんは口を揃える。ハレク ラニで使用する花は、ハワイ島、オランダ、南アメリカなどから仕入れ、 ホテルの敷地内で育っている植物を使うこともある。例えば、ハレクラ ニの歴史とともに歩み、今ではハウス·ウィズアウト·ア·キーの傍に横た わってなお生き続けているキアヴェの木から出ている枝を使うことも ある。美しさと動きを最大限に引き出すため、全ての要素を十分に考慮 し、一本一本丁寧に活けていく。草月流いけばなを活けるためには、「そ れぞれの花の使い方を知る必要がある」とカメモトさんはいう。 草月流いけばなは、活ける人の心の表れであるがゆえに集中力を必 要とする。バカニさんは気が散らないよう、人気の少ない朝の6時から 8時までの間にアレンジメントを作るようにしている。日頃からアレンジ メントに使えそうな木の枝や葉などを集めたりと、いけばなが頭から離 れることがないというバカニさん。「このように自然の中にある材料を生 かし、自分たちの気持ちを表現しながら『美』を作り上げるのです」と語 る。色、日持ち、質感など、各植物の性質や特徴を見つけて、それを生か すことで、常に新しいことを学んでいるのだという。

ハレクラニのロビーに飾られた花には、静けさの中にも動きがあり、 伸びやかな線の一本一本が正確に配置されている。キヨシさんが妻の 芸術を生かすために心を込めて作った彫刻の魅力を味わってほしい。 ロビーのフラワーアレンジメントは毎週変わるが、そこには常に芸術家 の心意気が感じられる。

TEXT BY EUNICA ESCALANTE

IMAGES BY SKYE YONAMINE

TEXT BY EUNICA ESCALANTE

IMAGES BY SKYE YONAMINE

文=ユーニカ・エスカランテ 写真=スカイ・ヨナミネ

SALT OF THE EARTH

地球の塩

From the first Polynesian settlers to today’s gourmet saltmakers, pa‘akai has been an essential ingredient in Hawai‘i.

初期のポリネシア入植者が持ち込み、グルメなシーズニングへと進化した今も昔もハワイの文化に欠かせないハワイアンソルト「パアカイ」

Norman Berg traverses the coastline of O‘ahu’s east side.

オアフ島の東海岸をトラバース するノーマン・バーグさん。

In 1783, at the behest of Kamehameha I, European explorer Captain George Vancouver paid a visit to a favorite haunt of the monarch, the community of Kawaihae on Hawai‘i Island. Its cluster of huts hidden within a thick grove of coconut trees seemed to be a typical Native Hawaiian fishing village to Vancouver, until he stumbled upon a large pit dug out of the red earth.

Enclosed with a wall of mud and stone, this pit contained a reservoir of sea water, which seemed odd to Vancouver since the coast was mere feet away. Surrounding it were man-made earthen pans where, Vancouver was told, during the hottest months of the year the water would be transported and left to evaporate, leaving behind a layer of sparkling white crystals. This was pa‘akai, Hawaiian sea salt.

A decade after Vancouver first saw Kawaihae’s salt ponds, Hawai‘i had become the Pacific Northwest’s chief supplier of salt. Harbored fishermen traded for pa‘akai, preserving their salmon catches in it. (This is purported to be the origin of lomi lomi salmon, a popular local dish). Paniolos, Hawaiian cowboys, sold salt-cured meat to passing whalers and merchants. Hawaiian salt’s high quality and rich taste created a demand that exceeded supply from salt ponds, and salt mines, which pumped the mineral up from the earth, became an industry standard.

Today, small plastic bags heavy with the mineral labeled Hawaiian sea salt line supermarket shelves. There’s fine grain and coarse grain, ‘alaea red clay or black charcoal. If you want to go gourmet, there are sea salts infused with smoked kiawe or rum. Or stock up with a trusty five-pound bag that will last a decade. Surrounded by miles of pristine ocean,

1783年、ヨーロッパの探検家、キャプテン・ジョージ・バンクーバーは、 カメハメハ1世の命を受け、ハワイ島のカワイハエにある、王が好んで訪 れる村を訪ねた。ヤシの木の茂る森の中にいくつもの小屋が建つその 集落は、典型的なハワイアンの漁村のようであったが、よく見るとそこに は赤土を掘り出して作られた大きな穴があった。

泥や石でできた壁に囲まれたこの穴には、海岸線から離れているに もかかわらず、不思議と海水が貯まっている。それを囲むように、田んぼ のような四角い囲いがいくつも並んでいる。一年で一番暑い時期、ここ へ海水を運んで蒸発させると、表面に白く輝く結晶が残るのだと村人は バンクーバーに教えてくれた。これがハワイの海塩「パアカイ」であった。 バンクーバーが初めてカワイハエの塩田を訪れてから10年後には、 ハワイは太平洋岸北西部の塩の主な供給源となった。港に停泊した漁 師たちは、捕獲した鮭を保存するために必要なパアカイと物々交換し、 (これが人気の地元料理、ロミロミサーモンの起源とされる)、ハワイの カウボーイ「パニオロ」たちは、寄港する捕鯨船の乗組員や商人たちに 塩漬けの肉を売っていた。質が高く豊かな味わいのハワイアンソルトの 需要はやがて塩田からの供給量を上回り、地中からミネラルを汲み上 げる岩塩坑が主流となっていった。

今日では「ハワイアンシーソルト」というラベルのついた小さなビニー ル袋に、ずっしりと詰まった塩がスーパーマーケットの棚に並んでいる。 粒の細かいものと粗いもの、アラエア赤土塩と活性炭の入ったブラック シーソルトがある。キアヴェの燻製やラムの香りのするグルメなシーソ ルトなどもあり、10年はもつであろう2.5キロ入りの大袋も売られてい る。四方を美しい海に囲まれたハワイでは、普通の食塩よりも純粋な味 わいの塩ができる。アラエアは、ほのかに土の香りのするまろやかな味 が特徴だ。ブラックシーソルトは、パアカイに活性炭を混ぜることでスモ ーキーな味わいが楽しめる。

Modern day Hawaiian sea salt manufacturers hope to honor the traditional gathering techniques of pa‘akai.

今日のハワイアンシーソルトメ ーカーは、伝統的なパアカイの 収穫方法を受け継ぎたいと考 えている。

Hawai‘i produces salt that is purer in taste than the average table salt. ‘Alaea adds a mellow, earthy flavor while pa‘akai mixed with activated charcoal brings a smokey finish.

“Salt is inside us, it’s all around us,” says Norman Berg, lead chef for Sea Salts of Hawai‘i, which includes in its line-up a recent collaboration with Halekulani featuring their trio of classic salts: kona pure, ‘alaea rich red, and uahi black. “So when we use it in flavoring our food, we’re just returning to what we are.”

To see its influence, look no further than the dinner table. Local favorites like lomi lomi salmon, pipikaula (Hawai‘i’s take on beef jerky), and kalua pig cite pa‘akai as a main ingredient. Berg describes how Native Hawaiians would add it to poi for a pinch of flavor. In the past few years, artisanal salt has grown in popularity as local salt makers like Sea Salts of Hawai‘i carve out a niche with their versions of Hawaiian sea salt. Contemporary flavors like Maui onion or Hawaiian chili pepper have made flavoring with pa‘akai customizable.

「塩は私たちの中や身近にあるものです。私たちの体は、調理に塩を 使うことで本来あるべき状態に戻ることができるのです」と話すのは、 「シーソルト・オブ・ハワイ」の主任シェフのノーマン・バーグさん。この シーソルトメーカーのラインナップには最近、ハレクラニとのコラボレー ションにより、「コナ・ピュア」、「アラエア・リッチ・レッド」、「ウアヒ・ブラ ック」の3種類が新たに加わった。

ハワイの人々にとってパアカイがいかに大切なものであるかは、彼ら の食卓を見れば明らかだ。ロミロミサーモン、ピピカウラ(ハワイのビー フジャーキー)、カルアピッグなど、ローカル料理はどれもパアカイを主 原料とする。ネイティブハワイアンは、ポイにもひとつまみのパアカイを 加えるのだとバーグさんは教えてくれた。オリジナルフレーバーのハワイ アンシーソルトを販売し始めたシーソルト・オブ・ハワイのような地元の メーカーのおかげで、ここ数年、グルメなシーソルトが注目を集めてい る。マウイオニオンやハワイアンチリペッパーのようなシーズニングスパ イスが販売されるようになり 、パアカイの用途も広がった。

ハワイで海から塩を収穫するようになったのは、ハワイ諸島に最初に 到着したポリネシア人たちであった。彼らは太平洋を渡る航海中の食

Hawaiian sea salts both traditional and contemporary range in color, taste, and texture.

ハワイのシーソルトには、色、味 わい、食感が異なる様々な種類 のものがある。

Harvesting salt from the sea in Hawai‘i dates back to the Polynesians who first arrived in the Hawaiian Islands, and used salt to preserve food for their voyage across the Pacific. In Native Hawaiian culture, pa‘akai straddles the divide between the commonplace and sacred. As the physical manifestation of the ocean, the source of healing and purification, it is integral to wellbeing. Ancient stories speak of how the Hawaiian deity Kāne salted the ocean to preserve its purity. In imitation, saltwater (referred to as wai kuihala, or “water of forgiveness”) and its physical counterpart, pa‘akai, were prized for their purifying qualities. In pī kai, blessings conducted by kāhuna (Hawaiian priests), saltwater is essential. The sprinkling of saltwater, combined with invocations to Hawaiian gods or Christian prayers, is a common practice when ritually cleansing a space.

“Pa‘akai is a lifestyle,” says Malia NobregaOlivera as she dips a polished coconut shell into a onepound bag filled with large grains of salt. She holds the bowl out, encouraging me to have a taste. “You'll

べ物を保存するために塩を使っていた。ネイティブハワイアンの文化で は、パアカイは日常と神聖なものの間に存在すると考えられている。癒 しと浄化の源であり、海の恵みであるシーソルトは、人々の健康に欠か せないものである。ハワイの四大神の一人の「カネ」が、海水の純度を保 つために塩水にしたという古代の伝説もある。そのため海水(ハワイ語 ではワイ・クイハラと呼ばれる。許しの水という意味)やパアカイには浄 化作用があるとされ、重宝されていた。海水は「ピカイ」と呼ばれるカフナ (ハワイの司祭)が行う儀式には欠かせないもので、伝統的な儀式では 場所や空間を清める際、ハワイの神々やキリストへの祈りとともに、海 水を撒くことが一般的な習慣となっている。

「パアカイは人々の生活に根付いているの」とハワイ諸島で唯一、今も 伝統的な手法で塩を収穫しているハナぺぺのソルトメーカー、マリア・ ノブレガ・オリヴェラさんは語る。彼女は大粒の塩が入った1ポンドの袋 から、ピカピカに磨かれたココナッツの殻の器を取り出し、味をみるよう に勧めてくれた。「ここの塩は、塩田に生息する塩水エビのおかげで、他 のどの塩よりも甘いのよ」。

ノブレガ・オリヴェラさんは、ハワイに残る最後の塩田を保護する活

“THE ROOTS”

The very best of traditional and contemporary Italian flavors coupled with the best of local produce

LOCATED IN

From cuisine to cultural practices, “Salt was a big part of our life growing up,” says Malia Nobrega-Olivera, an expert on pa‘akai.

料理の味付けから文化的な習 慣まで、「塩は私たちの生活に欠 かせないものでした」と語るの はパアカイに詳しいマリア・ノブ レガ・オリヴェラさん。

find that it’s sweeter than other salt because of the brine shrimp that live in our salt pans.”

Nobrega-Olivera is a saltmaker from Hanapēpē, the last place in the archipelego where salt is still being harvested through traditional means. She is president of Hui Hana Pa‘akai, a group striving to preserve the last of the salt pans. Only 22 families claim stewardship over this corner of Kaua‘i. Many have been here for centuries, passing their land down through the decades. Nobrega-Olivera’s plot stretches back eight generations.

“Salt was a big part of our life growing up,” she says. In the summer months, they trekked down to the salt pans much like the ones that Vancouver visited. On their hands and knees in the clay and mud, they painstakingly scraped the wells so that only the purest salt water could enter. After a few weeks, when the water had turned white with froth, meaning its salinity has increased, they transferred it to smaller ponds where it remained until it had crystallized into pa‘akai.

Salt from Hanapēpē is particularly valued. For the families here, their salt is sacred—a link to the past rather than a mere commodity. This, coupled with Food and Drug Administration standards, means that Hanapēpē’s pa‘akai cannot be bought. It has to be gifted or bartered for. It is also becoming increasingly rare. Just a decade ago, a month’s harvest could yield several barrels full of salt, but the effects of climate change and development near the ponds have made harvesting nearly impossible. Nobrega-Olivera’s salt pans have not produced pa‘akai in five years.

‘Alaea salt, for which Hanapēpē is best known, is traditionally valued as medicinal. Salt is mixed with ‘alaea clay harvested from the Waimea mountains, producing pa‘akai that is red in color and rich in iron. Native Hawaiians believe that the clay imbues the salt with spiritual properties and can be used in treating all types of ailments. To this day, NobgregaOlivera swears by pa‘akai. “If ever I don’t feel pono (good), ” she says, gingerly placing a dab of salt on her tounge as if taking communion, “I just take a pinch of pa‘akai.”

動を行っている「フイ・ハナ・パアカイ」の代表だ。カウアイの南西部沿岸 にあるこの場所で今も塩田の管理に携わっているのはわずか22世帯 だ。その多くの家系が、何世紀にもわたってハナペペに住み、先祖代々 この土地を守ってきた。ノブレガ・オリヴェラさんはこの土地を受け継ぐ 8世代目だという。

「私たちが育った時、塩は私たちの生活においてとても重要なもので した」と彼女は言う。夏になると、彼らはバンクーバーが訪れたのと同 じような塩田まで歩き、純度の高い塩水を汲み出すための井戸の汚れ を、土と泥の中で四つん這いになって一生懸命取り除いた。数週間後、 塩濃度が高まって白い泡に変わった水を小さい塩田に移し、結晶化し てパアカイになるのを待つ。

ハナぺぺの塩はシーソルトの中でもとくに貴重とされる。ここに住む 家族にとって、塩は神聖なもので、それは単なる商品ではなく、先祖や 過去との繋がりでもある。食品医薬品局の規制により、ハナぺぺのパア カイは販売されることがない。誰かにもらうか交換してもらわなければ 手に入らないのである。最近では、ハナぺぺの塩はさらに希少になりつ つある。ほんの10年前までは一月分の収穫で樽数個分の塩が収穫で きたのが、気候の変化や塩田周辺の開発の影響により、今ではほとんど 収穫できなくなってしまった。ノブレガ・オリヴェラさんの塩田はこの5 年間、パアカイを全く生産していない。

ハナぺぺの名産品であるアラエアソルトは、昔から薬用効果のあるも のとして珍重されてきた。ワイメア山脈から採れたアラエア赤土を塩に 混ぜることで、色が赤く鉄分が豊富なパアカイができる。ネイティブハワ イアンは、土が塩に霊的な力を宿らせると考え、あらゆる病気の治療に 用いてきた。今もノブレガ・オリヴェラさんはパアカイに絶大な信頼を置 いている。彼女は、まるで聖体を拝領するかのように慎重な手つきで、 舌の上に塩を乗せて見せた。「体調が優れないと感じたら、パアカイを ひとつまみ口に入れるだけでいいのよ」。

ESCAPE THE ORDINARY, FIND THE CENTER OF PARADISE

Step into The Royal Grove and discover the rich legacy of Helumoa, Waikīkī’s historic coconut grove in the heart of Royal Hawaiian Center. We invite you to enjoy our celebration of dance, music and Hawaiian traditions while you shop our 110 distinctive stores and 30 unique dining destinations.

this page : Missoni waveknit dress, Saks Fifth Avenue; Shoes, stylist’s own.

opposite : Brunello

this page : Missoni waveknit dress, Saks Fifth Avenue; Shoes, stylist’s own.

opposite : Brunello