Ulrich Krauer

General Manager Halekulani

Ulrich Krauer

General Manager Halekulani

Culture and the arts are at once reflections of our roots and stages for reinvention. The notions of preservation and transformation unite with special force in Hawai‘i, a place of convergence for so many different traditions.

This edition of Living explores the dynamics between change and tradition. In these stories, cherished links back to the islands’ ancestors and bygone eras reveal what makes this place uniquely Hawai‘i.

As a leading proponent of the arts in the Hawaiian Islands, Halekulani highlights the islands’ most veritable institutions to experience its history and culture. The Honolulu Museum of Art’s reorientation of artwork created during King Kalākaua’s reign is informative and groundbreaking. At the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, get a detailed look at exquisite Hawaiian featherwork with a back-of-thehouse reveal of designs formerly displayed at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Also featured are textile artists Donna Miyashiro and Tokunari Fujibayashi of the Honolulu-based brand Hawaiian Blue. The two devotedly develop indigo with plants grown in the islands and employ this to make end products found only in Hawai‘i.

In the beauty scene, the ancient wisdom of botanical healing is reimagined by Hawai‘i-based skincare brands JK7 and Pure Mana. The luxuriousness of their products is reminiscent of that of our own spa, SpaHalekulani.

Halekulani’s history is also one of preservation and transformation. While, over more than a century, Halekulani has grown from a two-story bungalow into a 453-room property and has grown into a splendid enterprise, we aim to maintain the genuine hospitality. Please take this complimentary copy of Living with you to keep.

We hope that you enjoy your time at Halekulani and feel both rooted and renewed.

Warmly,

Ulrich Krauer General Manager Halekulani文化と芸術は、私たちのルーツの表れであり、自己再発見の過程でも あります。独自の多民族文化を持つハワイでは、歴史や伝統を継承し、 進化させていく様々な取り組みが行われています。

今号のハレクラニリビングでは、伝統と時代の変化についてその関 係を探求しています。これらのストーリーを通して、過ぎ去った時代や 島々の祖先たちとの絆が今も大切にされているハワイならではの魅力 に触れられることでしょう。

ハレクラニは、様々な芸術、文化や歴史に触れることのできるハワイ の優れた美術・文化施設を積極的に支援しています。現在、ホノルル美 術館で開催中の展示は、カラカウア王時代の芸術品を通じて、激動の 時代を迎えていた当時のハワイ王国に新しい視点を与える非常に興味 深く画期的な内容となっています。またビショップ博物館では、これまで ロサンゼルス郡立美術館で展示されていた美しいハワイアン・フェザー ワークをご覧いただけます。本誌ではその芸術的なデザインに秘められ たストーリーについてもご紹介しています。

またホノルルを活動拠点とするドナ・ミヤシロさんとトクナリ・フジバ ヤシさんが手がける藍染めブランド「ハワイアンブルー」についてもフィ ーチャーしています。日本で何百年も続く藍染めの技法とハワイ産の藍 を原料に用いたハワイならではのユニークな藍染めを作り出すハワイ アンブルーの商品は現在、ハレクラニ ブティックでも数量限定にて取 り扱っています。

美容についてのストーリーでは、古代から伝わる植物由来成分によ るヒーリングや美容効果を用いたハワイ生まれのスキンケアブランド、 「JK7」と「ピュア・マナ」に焦点を当て、伝統と安らぎに満ちた美と健康 のオアシス、スパハレクラニを彷彿とさせるこれらの贅沢なスキンケア 製品についても詳しくご紹介いたします。

ハレクラニの歴史もまた伝統の継承と進化の賜物といえます。2階 建てのバンガローであった時代から、453室を擁するハワイを代表する 一流リゾートへと生まれ変わった現在に至るまで、ハレクラニでは1世 紀以上にわたり一貫して変わらないエレガンスとおもてなしの心でお 客様をお迎えしています。ご帰国の際には是非、ハワイの旅の思い出と して本誌をお持ち帰りください。

ハレクラニでのご滞在が、安らぎと癒しに満ちたひとときとなります ようスタッフ一同心から願っております。

ハレクラニ総支配人 ウーリック・クラワー

HALEKULANI CORPORATION

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER

PETER SHAINDLIN

CHIEF EXECUTIVE ADVISOR

PATRICIA TAM

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER

JASON CUTINELLA

CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER

LISA YAMADA-SON

LISA@NMGNETWORK.COM

GENERAL MANAGER, HALEKULANI

ULRICH KRAUER

DIRECTOR OF SALES & MARKETING

GEOFF PEARSON

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

ARA LAYLO

CHIEF REVENUE OFFICER

JOE V. BOCK

JOE@NMGNETWORK.COM

HALEKULANI.COM

1-808-923-2311

2199 KALIA RD. HONOLULU, HI 96815

PUBLISHED BY

NMG NETWORK

36 N. HOTEL ST., SUITE A HONOLULU, HI 96817 NMGNETWORK.COM

© 2018–2019 by Nella Media Group, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted without the written consent of the publisher. Opinions are solely those of the contributors and are not necessarily endorsed by NMG Network.

The artisans of Hawaiian Blue infuse island-style indigo into hand-dyed creations.

ハワイアンブルーの職人は 藍染めにハワイ産の藍を 使用している。

ARTS

Re-exposing Kalākaua

Mood Indigo

CUISINE 44

Merry Mochi-Making

CULTURE 56

Plume of Time

WELLNESS 72

Stay Blessed 84

The Alchemists

At the Liljestrand House, masterful design and bronzetoned fashions converge.

リジェストランドハウスの 卓越したデザインに映える ブロンズ系のファッション

CITY GUIDES 100

Fashion: A Day at Liljestrand 114

Explore: For the ‘Ohana 126

Explore: Man About Town 134

Spotlight: Hildgund

Daylight spills through the Liljestrand House. Model Sophie Wall, photographed by Mark Kushimi.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

目次

In search of wholeness and good fortune, a writer visits three distinct temples on O‘ahu.

心の安らぎと幸運を求め、

オアフ島にある3つの 仏教寺院を巡る

72

56

ARTS

24

明かされるカラカウア王の真実 34

魅惑のインディゴ CUISINE 44

幸運を呼ぶ餅つき

CULTURE 56

時を超えた羽 WELLNESS 72

清められて

84

錬金術士

ABOUT THE COVER: 表紙について:

From its grand and resplendent capes to brilliant bands for woven hats, the Hawaiian art of featherwork endures.

豪華なマントから色鮮やかな ハットバンドまで、継承される ハワイのフェザーワークの伝統

午後の木漏れ日が降り注ぐリジェストランドハウスにて、モデルのソフィー・ウォールさん。マーク・クシミ氏撮影。

CITY GUIDES

100

ファッション:リジェストランド で過ごす一日

114

家族で楽しむ 126

街を愛する人

134

スポットライト:ヒルガンド

Halekulani

Living TV is designed to complement the understated elegance enjoyed by Halekulani guests, with programming focused on the art of living well. Featuring captivating imagery and a luxurious look and feel, Living TV connects guests with the arts, style, food, and people of Hawai‘i.

客室内でご視聴いただけるリビング TVは、ハレクラニでのご滞在をお楽し みいただくため、より豊かで健康的な ライフスタイルをテーマにした番組を ご提供しています。魅力的な映像と豪 華な演出を通して、アートやファッショ ン、食文化、ハワイの人々について紹介 しています。

watch online at: halekulaniliving.tv

MOOD INDIGO

The artisans of Hawaiian Blue infuse island-style indigo into hand-dyed creations.

魅惑のインディゴ ハワイ産の藍を使った職人技の手染め「ハワイアンブルー」

MERRY MOCHI-MAKING

幸運を呼ぶ餅つき

Whether created at home or purchased from a shop, mochi binds families together in the islands.

家族の絆を深めるハワイの餅文化

PLUME OF TIME

時を超えた羽

From its grand and resplendent capes to brilliant helmets, the Hawaiian art of featherwork endures.

豪華絢爛なマントからヘルメットまで、ハワイアンに 受け継がれる羽毛の芸術

MAGNIFICENT MEZZO

麗しのメゾソプラノ

Hawai‘i’s own opera star Blythe Kelsey dazzles audiences with her captivating vocals.

魅惑のヴォーカルで観客を圧倒するハワイのオペラ歌手、 ブライス・ケルシー

HOUSE ON A HILL

丘の上の家

Perched above Honolulu, the Liljestrand House is regarded as the pinnacle of architect Vladimir Ossipoff’s work.

建築家ウラジミル・オシポフ氏によるモダン建築の傑作、 ホノルルを見渡す高台に建つリジェストランドハウス

文=トラヴィス・ハンコック

写真=ホノルル美術館提供

明かされるカラカウア王の真実

right: Kingdom telephones circa the late 19th century and Kalākaua’s Around the World medal. Photo by Jesse W. Stephen, Bishop Museum; Bishop Museum Archives.

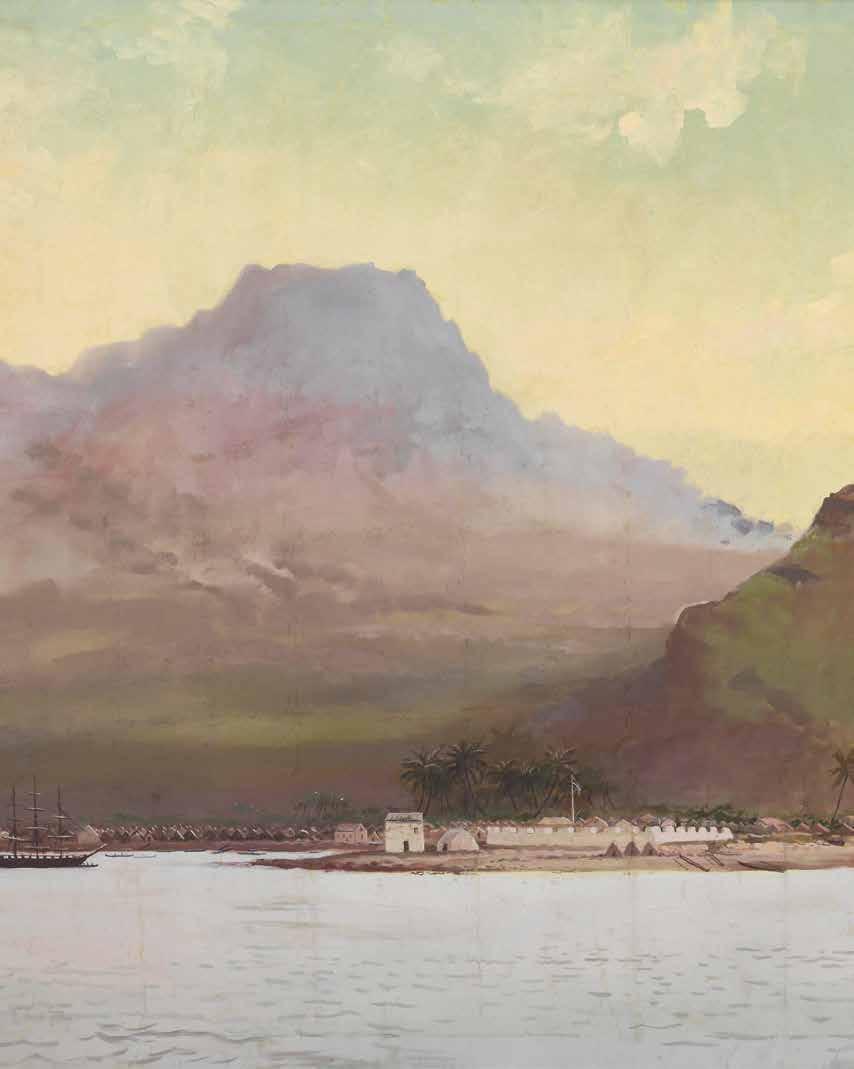

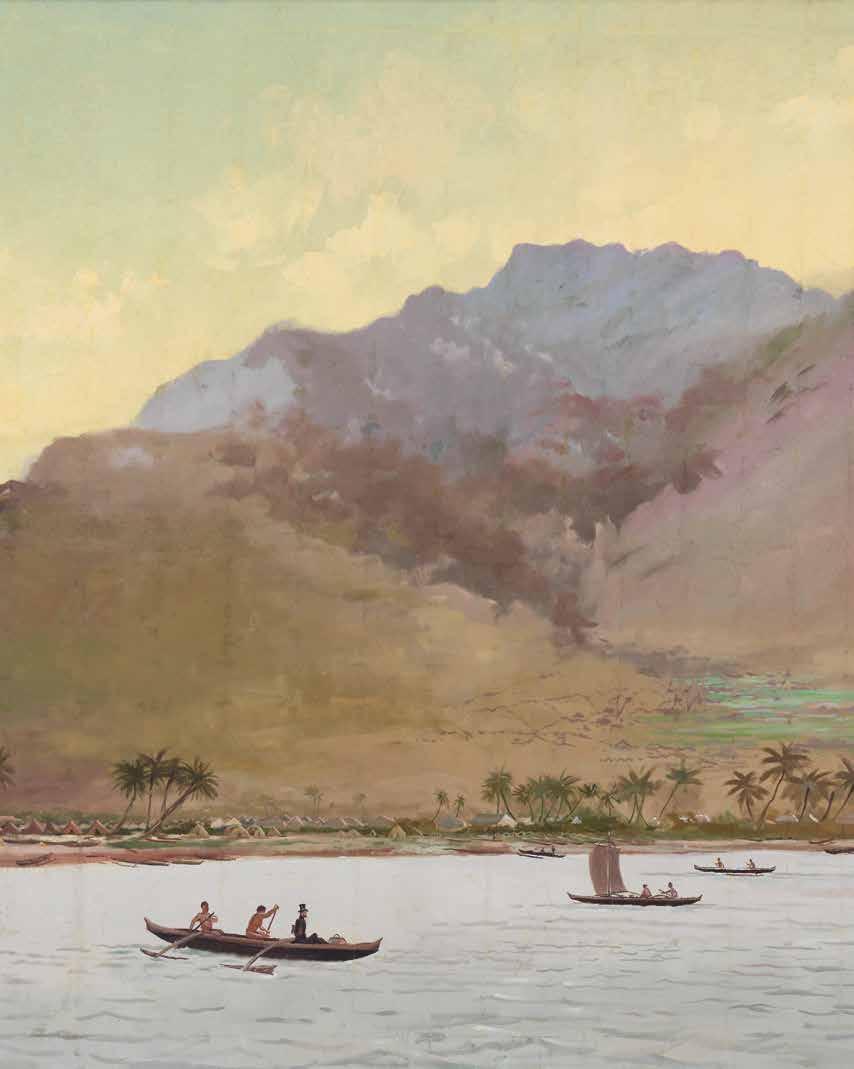

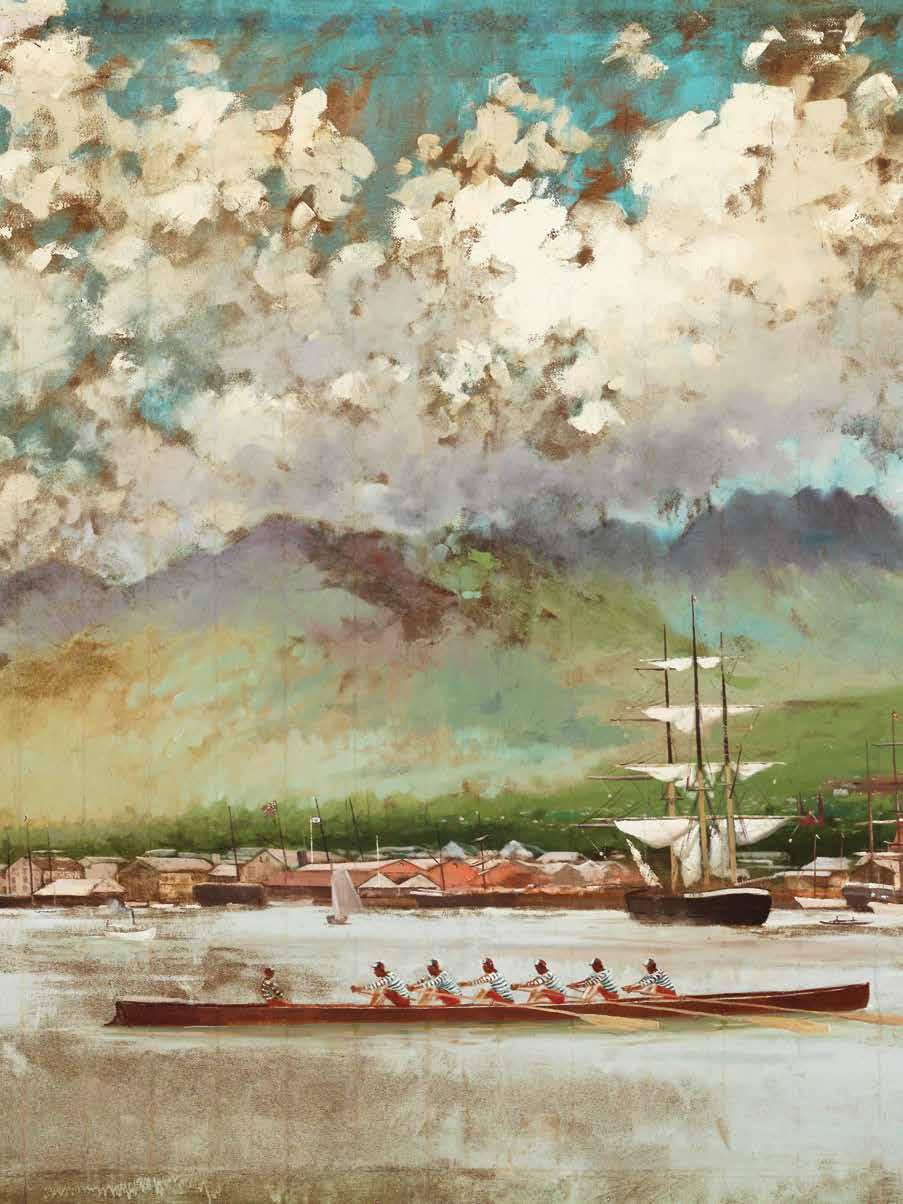

previous spread: Honolulu Harbor, 1836 by Joseph Strong. This oil on canvas was painted in 1886 to depict the year of Kalākaua’s birth.

Photo by Shuzo Uemoto, Hawai‘i State Archives.

右: ハワイ王国で使用されてい

た電話機(19世紀後半)とカラ カウア王の世界一周メダル。

写真:ジェシー・W・スティーブ

ン、© Bishop Museum

ビショップ博物館古文書館 前ページ見開き:1836年の ホノルル・ハーバー。ジョセフ・ ストロング作。1886年にキャン バスに油絵でカラカウア王の 誕生年の風景を描いた作品。

シュウゾウ・ウエモト撮影、 ハワイ州立資料館

A groundbreaking exhibition at the Honolulu Museum of Art pushes viewers to ho‘oulu, or increase, their scope of admiration for Hawai‘i’s most recent king.

近代を生きたハワイ王の名誉を取り戻す『ホオウル・ハワイ:カラカウア王の時代』展 ホノルル美術館にて開催中 RE-EXPOSING KALĀKAUA

Unthink everything you think you know about King Kalākaua. That was the advice of Native Hawaiian scholar Keanu Sai to his cousin Healoha Johnston when she told him that her master’s thesis would focus on the king. Sai feared the young scholar would be misled by the archive of colonialist propaganda that famously distorted Kalākaua’s image—framing him as a tyrant, a drunk, a spendthrift, a blemish on his kingdom. But when Johnston explained that she thought Kalākaua was brilliant, Sai exclaimed, “OK, then keep thinking!”

Ten years later, in 2015, Johnston found herself sitting at the Honolulu Museum of Art across from then-director Stephan Jost, interviewing to be the first Arts of Hawai‘i curator in the museum’s 90year history. Jost asked her, “If you could curate any exhibition, what would it be?” She answered that it would be an exhibition of works from King Kalākaua’s

カラカウア王について今まで教えられたことは全て忘れたほうがいい。 それはネイティブハワイアンの学者のケアヌ・サイさんが、カラカウア 王を修士論文の題材にしようとしていた従兄弟のへアロハ・ジョンス トンさんに与えた忠告だった。サイさんは若い学者のジョンストンさん が、植民地主義のプロパガンダによって 、酔っ払いの暴君で浪費家 であり、ハワイ王国の汚点であったかのように歪められた一般的に知 られるカラカウア王のイメージに惑わされるのではないかと危惧した のである。カラカウア王は聡明な君主だったと思う、というジョンストさ んの言葉を聞いたサイさんは「それならやってごらん!」と諸手を挙げ て賛同してくれた 。

それから10年後の2015年、ジョンストンさんは90年におよぶホノ ルル美術館の史上初のアート・オブ・ハワイ・キュレーターになるため、 当時の館長であったステファン・ジョスト氏と面接することとなった。

Halekulani Living

opposite: Lantern slide of King Kalākaua of Hawai‘i, c. 1880. Photo by Shuzo Uemoto, Honolulu Museum of Art.

向かいのページ:カラカウア王 のスライド写真、1880年。

シュウゾウ・ウエモト撮影、

ホノルル美術館

reign, from 1874 to 1891. Jost was surprised but intrigued, and when he ultimately handed her the job, he asked, “So that Kalākaua show—when do you want to do it?”

Sipping an Americano in her office in 2018, Johnston looks over a paper mockup of the museum’s largest exhibition space, filled with cut-out miniatures of the eclectic works that make up the exhibition Ho‘oulu Hawai‘i: The King Kalākaua Era. “Everything I love about contemporary art was happening at that time,” she says. “It was experimental. It was fearless.”

She opens the book that tandems with the exhibition, flips past images of oil paintings and Hawaiian featherworks, and lands at a photograph from Kalākaua’s 1886 birthday jubilee. The king, styled in a cool white suit, strides down the steps of ‘Iolani Palace, Queen Kapi‘olani at his side, followed by his sister Lili‘uokalani and her husband John Dominis. The photographer, one of many working in the nation, framed the royal procession between a background of decadent Corinthian columns festooned with masterful textiles, including a monumental Hawaiian flag and coat of arms, and a foreground prominently featuring an electrified lamp post containing an Edison light bulb. “It’s all these symbols of ali‘i, nationhood, and technology,” Johnston says.

Throughout the gallery, photography refracts and magnifies the meaning of older media. On the frontmost wall of the gallery hangs a large quilt that features an image of Queen Emma. For the first time, the quilt is paired with the photograph it is based on—a tiny three-and-a-half-inch-wide lantern slide that Johnston excavated from the museum’s vaults. “It shows how these artists, these creatives, were using all these different forms of image-making and reappropriating them within their given practice,” she explains.

During his unprecedented worldwide voyage, Kalākaua consistently donned his full regalia and

その席でジョスト氏に「もしあなたが美術展を企画するとしたら、どん なテーマにしますか?」と尋られた彼女は、1874年から1891年にかけ てのカラカウア王時代のアート展だと答えた。その答えに驚きながらも 関心を持ったジョスト氏は、結果的にジョンストンさんを採用し、開口 一番に「それで、カラカウア王の展示はいつにしようか?」と聞いた。

そして2018年の今、ジョンストンさんはオフィスでコーヒーを飲みな がら、中に沢山の作品の縮小版の切り抜きが並べられている美術館最 大の展示スペースの紙模型を眺めている。「この時代には、私が大好き な現代アートの全てがありました。それは実験的であると同時に、とて も大胆な表現でした」。

ジョンストンさんは、今回の展示の内容と連動している歴史資料を開 くと、さまざまな油絵やハワイアンの羽細工といった写真に続いて、カラ カウア王の誕生日を祝う1886年撮影の祝賀会の写真で手を止めた。 涼しげな白のスーツに身を包み、カピオラニ女王とともにイオラニ宮殿 の階段に降り立つ王に、妹のリリオオカラニと夫のジョン・ドミニスが続 く。当時の王国には多くの写真家がいたが、この写真に写っている王族 たちの背後には、ハワイの旗や紋章といった立派な装飾品が並べられ たコリント様式の柱、前景にはエジソン発明の電球がついた電柱が堂 々と捉えられている。ジョンストンさんはこの写真家の意図について「こ れらは全てハワイの王族と国家を象徴するもので、当時のハワイ王国の 洗練された文化と高度な技術を周知させるために意図的に映されてい るのです」と教えてくれた。

ギャラリーの各所に展示されている写真からは、レイやキルト、勲章 や油絵といった当時の芸術に込められた作者の意図を汲み取ることが できる。ギャラリーの一番手前の壁には、エマ女王の姿が縫いこまれた 大判のキルトが掛けられている。その横には、キルトのデザインの元と なった初公開の女王の写真が並んでいる。その写真は幅9センチに満 たない小さなスライドで、美術館の書庫からジョンストンさんが見つけ たものだ。「これは当時のアーティストや職人たちが、独自の芸術手法 を使ってさまざまな形で自由かつ大胆に表現していたことを表していま す」と説明する。

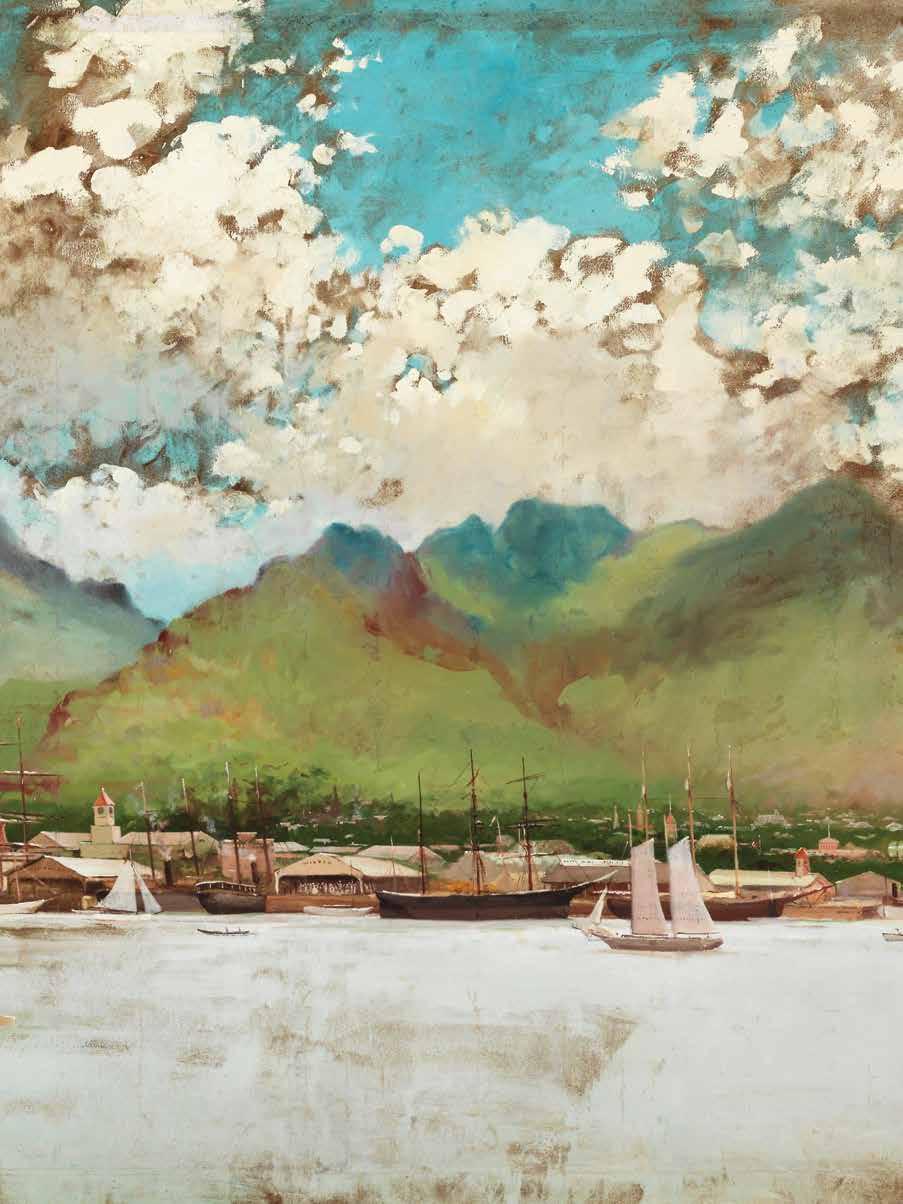

opposite: Two female hula dancers; Hawai‘i, c. 1858, Bishop Museum Archives.

previous spread:

Honolulu Harbor, 1886 by Joseph Strong. Photo by Shuzo Uemoto, Hawai‘i State Archives.

反対ページ:ハワイの女性フ ラダンサーの二人。

1858年、ビショップ博物館 古文書館

前ページ見開き:1886年の ホノルル・ハーバー。

ジョセフ・ストロング作。

シュウゾウ・ウエモト撮影、

ハワイ州立資料館

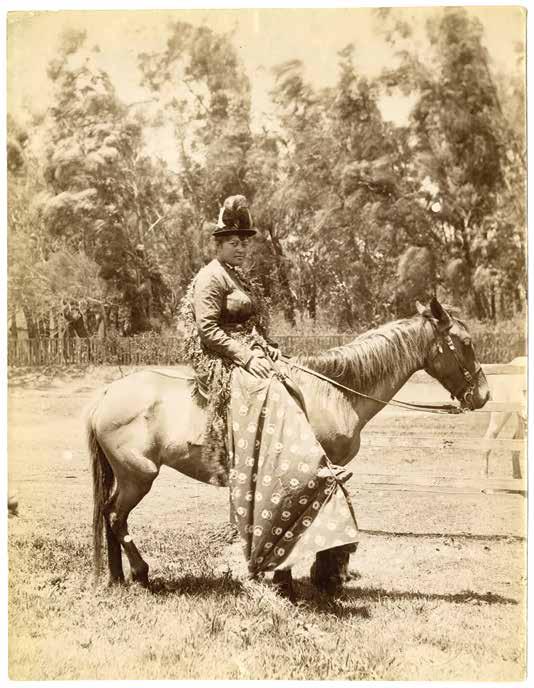

royal orders to sit for photographers, effectively disseminating visions of his power to international audiences. On the gallery walls, these photographs become historic windows with the shutters blown open as the eye connects his kingly accoutrements to the staggering, glimmering display of medals and royal orders nearby. As in his domestic parades, the Merrie Monarch’s culturally fortified optics in the gallery are augmented by the attendant visions of proud hula dancers and strong wāhine equestrians, known as pā‘ū riders for their bloomer-like skirts. Dropped into this dynamic milieu, visitors discover a fully formed, prismatic Kalākaua suffused with the brilliant light and color of his time. And they can leave with a piece of this light, too, by stepping into an in-gallery photobooth that mimics the textures and colors of fin-de-siècle development process.

Ho‘oulu Hawai‘i might be the first exhibition ever to put equal emphasis on Hawaiian-language text. In putting together this exhibition, Johnston espoused the distinctly Hawaiian ethos of community reliance, gathering a large number of works from ‘Iolani Palace, Hawai‘i State Archives, and Bishop Museum. This unprecedented collaboration mirrors the spirit of experimentation of Kalākaua’s era. “It represents a shared vision across these museums to interrogate the way Hawaiian history has been interpreted,” Johnston says.

Collaboration with the Hawai‘i State Archives led to the inclusion of two long-cloistered panoramic oil paintings of Honolulu Harbor by Joseph Strong, also produced for the king’s 1886 jubilee. A kind of beforeand-after diptych, the set first depicts the harbor in 1836, imagined as a calm, placid space. “Then in the 1886 [painting] it’s this hustle-bustle port city,” Johnston says. “The sky is very busy, and it’s the artist’s way of portraying Hawai‘i as an epicenter of commerce within the Pacific. Kalākaua’s narrative of growth over his lifetime is depicted in a way that empires would understand.”

当時、一国の長としては初の世界航海に出たカラカウア王は、どの写 真にも王族の礼服や勲章を身につけた正装で写っている。これには国 際社会へ王の権威を示す狙いがあった。ギャラリーの壁に飾られたこ れらの写真や王の衣服と並んで飾られたメダルや勲章が輝くディスプ レイからは、これまで明かされてこなかった歴史の一面を察することが できる。メリーモナーク(陽気な王様)として親しまれ、伝統文化の復興 に尽力したカラカウア王が、ハワイという王国の文化水準の高さを世界 に知らしめる目的で開催した王国内のパレードや、誇らしげなフラダン サーやパウ(ブルマ風のスカート)を履いた颯爽とした女性騎馬隊のパ ウライダーを撮影した写真も展示されている。

会場には、プリズムの光と色で当時の姿を見事に再現したカラカウ ア王の姿もある。来館者は、ギャラリー内にあるフォトブースでは、世紀 末の渦中にあった激動の時代を感じさせる写真を撮影して持ち帰るこ とができる。

『ホオウル・ハワイ』展は、英語と同等にハワイ語を使った初の展示で あるかもしれない。監修にあたりジョンストンさんは、イオラニ宮殿やハ ワイ州立資料館、ビショップ博物館から多数の展示品を集めた。コミュ ニティの中で助け合うハワイアンの理念に基づいた未だかつてない規 模のコラボレーションは、カラカウア時代の実験的かつ大胆な表現の 精神を象徴している。「それはこれまでのハワイの歴史的解釈を問い正 そうというこれらの博物館が共有するビジョンの表れなのです」。

今回の展示には、ハワイ州立資料館の協力により、1886年のカラ カウア王の誕生日の祝賀パーティーのためにジョセフ・ストロング氏が ホノルル港の風景を描いた2枚のパノラマの油絵が公開されている。長 い間眠っていたこの二連画の一枚目には静かで落ち着いた雰囲気の 1836年の港の風景、そしてもう一枚には1886年の賑やかな港町が描 かれ、近代化の前と後で大きく姿を変えた港の様子が分かる。「このア ーティストは、賑やかな空を描写することで、ハワイを太平洋の商業の 中心として描いています。そこにはカラカウア王の治世下における王国 の繁栄を帝国主義の列強諸国に知らしめる狙いがあったのです」とジ ョンストンさんは説明する。

ハワイのリロア王の羽で

作られた王族の綬章。

1890年、エラ・スミス・

コーウィン、ビショップ

博物館古文書館

Passing these two paintings and exiting the gallery, the visitor inevitably steps into the complex tableau of concrete, steel, and palm trees that is modern Honolulu, a crown jewel in America’s empire. And perhaps it is only at this point that one feels the oppressive weight of the elephant in the room— the forceful shuttering of the House of Kalākaua in 1893. In Johnston’s grand, restorative vision, this rupture was intentionally cropped out. “To understand how bad the overthrow was, you have to know how great it was before,” she says. “This is really looking at Kalākaua with an incredible amount of pride and honor.”

この2枚の絵を通り過ぎギャラリーを出ると、そこにはコンクリートと 鉄筋とヤシの木の混在する世界が待っている。それは現代のホノルル であり、アメリカの資本主義帝国に輝く宝石のようである。来館者はこ こで初めて、1893年にカラカウア王が強制的に退位させられるまでに 至った、当時の資本主義による弾圧を実感できるであろう。カラカウア 王の名誉回復を図るジョンストンさんの画期的な展示からその歴史は 意図的に省かれている。その理由についてジョンストンさんは「ハワイ王 朝の転覆がいかに悲惨な歴史であったかを知るためには、それ以前の ハワイがどれだけ素晴らしいものであったかを知る必要があります。今 回の展示は、カラカウア王の生涯と歴史に誇りと名誉を取り戻すもの なのです」と語った。

BY

TEXT NATALIE SCHACK BY MARIE ERIEL HOBRO文=ナタリー・シャック

写真=マリー・エリエル・ホブロ

MOOD INDIGO魅惑のインディゴ

The artisans of Hawaiian Blue infuse island-style indigo into hand-dyed creations.

ハワイの藍にこだわった藍手染の「ハワイアンブルー」

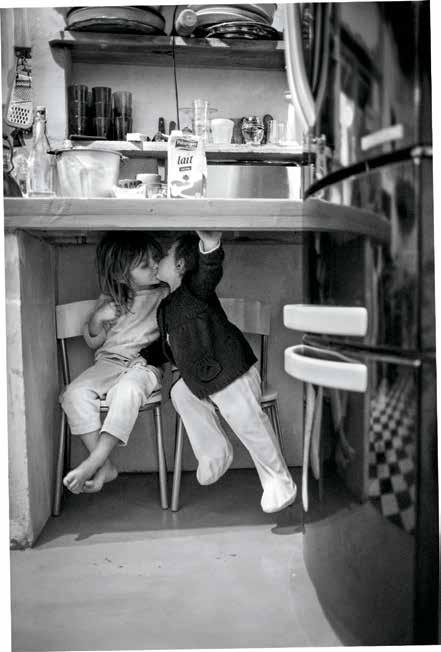

The water in the pail is a heavy, moody blue. It is deep and opaque. Effervescent like oil, its multitude of shades shimmer and pool outward like rings within a dynamic cobalt tree. Donna Miyashiro peers into it with a practiced eye, occasionally poking at the mixture with a wooden stick stained halfway up with overlapping layers of ever-deepening blues. Hovering over the scene is the unapologetically earthy scent of fermentation, the virile stench of plants becoming something entirely new.

“Toku and I are so funny smelling it, like, ‘Ooooh,’” Miyashiro says. “Because sometimes when it’s smelly, it means you got a good batch. At Lana Lane, we would drive people crazy. They’d be like, ‘What is that smell?’”

Miyashiro and Tokunari Fujibayashi are the two halves of Hawaiian Blue, a Honolulu-based brand that produces organic Hawaiian indigo-dyed creations out of Lana Lane, an artists’ collective in Kaka‘ako. “I actually met Tokunari at a weaving workshop,” Miyashiro says. “He’s from like 13 generations of a textile family in Japan. He had come here and wanted to do an indigo dye that was just from here.”

When Fujibayashi found indigo growing wild and unnoticed in the Hawai‘i mountains, he collected it and started propagating it. “This is really different from the Japanese indigo,” Miyashiro explains. “Japanese you get a really deep blue, and he wanted an indigo that reflected the sky and the ocean in Hawai‘i.” In contrast to the deeply pigmented drama of the rich indigo dye in the pail, the colors of Hawaiian Blue bags and pouches are the soft, dreamy hues of a light beryl or lilting baby blue.

Today, Miyashiro is working from her home in ‘Aiea. Buckets of mesmerizing fresh-leaf dye are set against the sliding door to her lānai, the watery excess separating from the concentrated, thick pigment in the sun of her courtyard. Miyashiro is an artist, and she takes her work home. Before indigo creations, she was making wedding dresses and clothing, and the loom from her foray into Japanese weaving sits in her back room. Textiles hang on her walls, a Haruki Murakami novel peeks out from one of the piles of tomes scattered about, and a multicolored, painted chair reminiscent of Frida Kahlo’s artwork rests by the front wall.

バケツの中には、どろっとした深みのある紺色の液体が入っている。オイ ルのように艶やかで濃淡のあるコバルト色が年輪のように何層にも広 がっている。ドナ・ミヤシロさんは慣れた目つきで中の液体を覗き込み、 青い線が何重にも染みついた木製の棒で、時折その液体を掻き混ぜ る。そこには腐敗し発酵した植物の鼻をつくような臭いが漂っている。

「トクと私はこういう匂いを嗅いでは『いいねー』と言って喜ぶの。臭 いが強ければ強いほどいい染料ができていたりするのよ。ラナ・レーン の工房のみんなはいい迷惑よね。何の匂い?とよく聞かれるわ」とミヤ シロさんは笑う。

ミヤシロさんとトクナリ・フジバヤシさんは、オーガニックのハワイ産 藍を使った手染め製品を製作するホノルル発のブランド「ハワイアンブ ルー」を手がける職人だ。カカアコで活動するアーティストグループのス タジオ「ラナ・レーン」が彼らの作業場となっている。ミヤシロさんは「ト クと初めて出会ったのは織物のワークショップだったわ。彼は京都で伝 統織物業を営む家系の13代目で、ハワイならではの藍染めを作るため に来ていたの」と話す。

ハワイの山中にひっそり生えている野生の藍を見つけたフジバヤシさ んは、それを持ち帰り、栽培し始めた。ミヤシロさんは、「ハワイの天然の 藍は、濃い紺色に染まる日本の藍とは全く違ったの。トクは、ハワイの空 や海のような色に染まる藍を作りたいと考えていたのよ」と説明する。

濃く濁った紺色をしたバケツに入った染料とは対象的に、ハワイアンブ ルーのバッグやポーチは優しいアクアマリンやベビーブルーのうっとり するような色合いだ。

今日、ミヤシロさんはアイエアの自宅で作業をしている。強い匂いを 放つ植物の葉を使った染料の入ったバケツが、ベランダのスライドドア の前に並べられている。中庭に差し込む太陽にあたって濃縮された色 素から余分な水分が分離し、上澄みができている。アーティストのミヤ シロさんの自宅はアートスタジオのようだ。藍染を作る以前は、ウェディ ングドレスや洋服を作っていたという彼女の部屋には、日本の織物をし ていた頃の名残りで織機が置かれている。部屋の壁には織物が吊るさ れ、村上春樹の小説がそこらじゅうに積み上げられた書物の中から顔 を覗かせる。正面の壁にはフリーダ・カロの作品を連想させるカラフル な椅子が置かれている。

Halekulani

“ “

You can never reproduce the color. It’s always a surprise,” Miyashiro says of the indigo-dying process. There are no constants.”

藍染についてミヤシロさんは、 「同じ色を再現することはでき ないの。不確定要素ばかりで常 に驚きの連続よ」と語る。

Miyashiro demonstrates how to plunge the scarves into the dye just so to create a bokashi, or fade effect. She bounces from spot to spot in her home: the dining room table, with its bundles of cloth and buckets of dye ready for dipping; the patio, with its precious heater that keeps persnickety fermenting indigo at just the right temperature; the side yard, where she points out unassuming indigo bushes that in two months grow from seed to harvest. Her nails have a pleasant, denim-like wash to them from dipping linen and silk in and out of the dye, over and over and over.

Indigo is all about fermentation, which is a timeconsuming process. Miyashiro makes the dyes slowly and deliberately, plumbing the depths of the scrubby little plant to create something brilliant, vivid, and bursting with potential. There are two processes that can be used to create indigo dye, she explains. One, the fresh-leaf technique, which is quick but fleeting,

ミヤシロさんは、色あせたように見える“ぼかし”と呼ばれる手法を使 ったスカーフの染め方を見せてくれた。彼女は仕事場となっている自宅 の中を行ったり来たりする。布の束と染めの準備ができている染料の入 ったバケツが並ぶダイニングテーブルから、扱いの難しい発酵中の藍の 染料を適温に保つためのヒーターがあるパティオへ移動し、勝手口か ら外に出ると今度はわずか2ヶ月で種から収穫できるまでに成長すると いう低木のタデ科の植物の藍を見せてくれた。麻や絹の染色を何度も 繰り返す彼女の爪もまた美しいデニム色に染まっている。

藍の性質を左右するのは何と言っても発酵である。それは時間のか かる工程で、ミヤシロさんはゆっくりと時間をかけて丹念に染料を作 る。この植物の葉に秘められた色素を最大限に引き出し、独特の輝きを 放つ鮮やかな色合いを生むためだ。藍染め染料を生成するには2つの 方法があるという。まず一つは、新鮮な葉を使った方法で、作業に要す る時間は短いが、一度しか使うことができない。葉が完全に水に浸かっ た状態で24時間置いて作る染料は、吸収性のある生地に適していて、

requires fully submerging the leaves in water and leaving them to soak for 24 hours, and is appropriate for lighter effects and more absorbent fabrics. The other is a long fermentation in a warm-water bath that takes 10 days to 14 days, depending on conditions, to form a foamy, blossom-like puff Miyashiro says is called an aibana , the Japanese word for flower. When the foam and bubbles come together to form this dense, deeply colored bloom, which sometimes has a coppery sheen, the indigo is ready. This fermented dye can be used on any fabric, but it needs constant nurturing. “They’re like children,” says Miyashiro of the indigo vats. She “feeds” them sake and honey to encourage the fermentation process. Her current vat is named Aita, inspired (as their vat names always are) by the Japanese word for indigo, ai

She dips and dips cloth in Aita, then rinses and rinses, then dips and dips again, over and over, until she gets the depth of color she wants. The shade, however, is always changing, sometimes an airy sky blue, sometimes a steely slate. “You can never reproduce the color. It’s always a surprise,” Miyashiro says. “There are no constants.”

Hawaiian Blue bags, pouches, and scarves are sold at Fishcake. The company’s output is small due to the time and labor it takes to sew and do the numerous rounds of rinsing and dyeing for each piece. But that hasn’t stopped people from hunting the duo down every now and then to place a large order, propose a collaboration, or even invite them to work on a new product. Sometimes they have taken these offers on—they partnered with Kaka‘ako café Arvo to create two-tone netted bags and shoe company OluKai to make dyed-canvas slip-ons— but generally, for Miyashiro, the risk of sacrificing quality for quantity makes her content to keep things as small as possible.

“I like the slow process, because, when you look at life, everything is so fast,” she says. “Look at the Japanese and their sense of how everything takes time: The person who makes bentos, they’ll make 15 bentos, and make them perfect. And when they’re sold out, they’re gone. There’s something about that slow, focusing-on-the-details mentality.”

淡い色合いに仕上がるのだそうだ。もう一つは、葉を温かい水に長時間 つけて、日本では「藍花」と呼ばれる花の蕾のような泡ができるまで発 酵させる方法だ。気候などの条件によって10日から2週間かかる。泡と 泡が合わさって濃くて深い色の花を咲かせるのだが、この花が艶やかで 鈍い輝きを帯びて来ると藍染の染料ができた証拠である。この発酵染 料はあらゆる生地に使用できるが、常に手入れをし、育てていかなくて はならない。「染料は子供のようなもの」というミヤシロさんは、発酵過 程を促進させるため、染料に酒や蜂蜜を与える。現在彼女が今育てて いる染料には、全ての染料に共通で使用している藍染の“藍”を含んだ「 アイタ」という名前がつけられている。

彼女は布をアイタにつけては取り出しすすぐという工程を、理想の濃 さになるまで何度も繰り返す。同じ染料を使っても仕上がりは常に変化 に富んでいて、時には透き通るような空の青やグレーがかったクールな ブルーに染まる。「同じ色を再現することはできないの。不確定要素ば かりで常に驚きの連続よ」とミヤシロさんは語る。

ハワイアンブルーのバッグやポーチ、スカーフはカカアコにあるセレク トショップ「Fishcake」で販売されている。一つ一つ手作りされている ハワイアンブルーの製品は、縫製に時間と労力がかかり、染めとすすぎ の工程を何度も繰り返すので、生産量が限られている。それでもこの二 人の作品を求め、大量の注文をする人やコラボレーションや新しいプロ ジェクトを提案する人が後を絶えない。二人はこれまでにカカアコのカ フェ「Arvo」と組んで2色使いのネットバッグを作ったり、靴メーカーの 「OluKai」と藍染のキャンバス生地を使ったスリッパなどを製作してき た。だが基本的に、量産のために質に妥協したくないと考えるミヤシロ さんは、このビジネスを小規模のまま維持したいのだという。 「私は時間をかけて何かをすることが好きなの。日々の生活では全て があっという間に過ぎてしまうでしょう? 」とミヤシロさんは言う。「日 本の人たちは時間を惜しまず丁寧な物作りをするわね。お弁当屋さん 一つをとってもそうよ。15個の弁当を細部までこだわって完璧に作り、 それが売り切れたら終わり。時間をかけて丹念に仕事をする彼らの精 神って本当に素晴らしいと思うの」。

The dyes produced from Hawai‘i-grown indigo are a dreamy, light blue intended to reflect the sky and ocean of the island landscape.

BY

TEXT CATHERINE TOTH FOX IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK文=キャサリン・トス・フォックス 写真=ジョン・フック

MERRY MOCHI-MAKING幸運を呼ぶ餅つき

Mochi binds families together at the start of a new year. Gathering around its chewy goodness, whether to make it or to eat it, is a tradition for many in the islands.

ハワイのローカル家庭で家族の絆を深める伝統となっている正月の餅つきや餅を食べる習慣

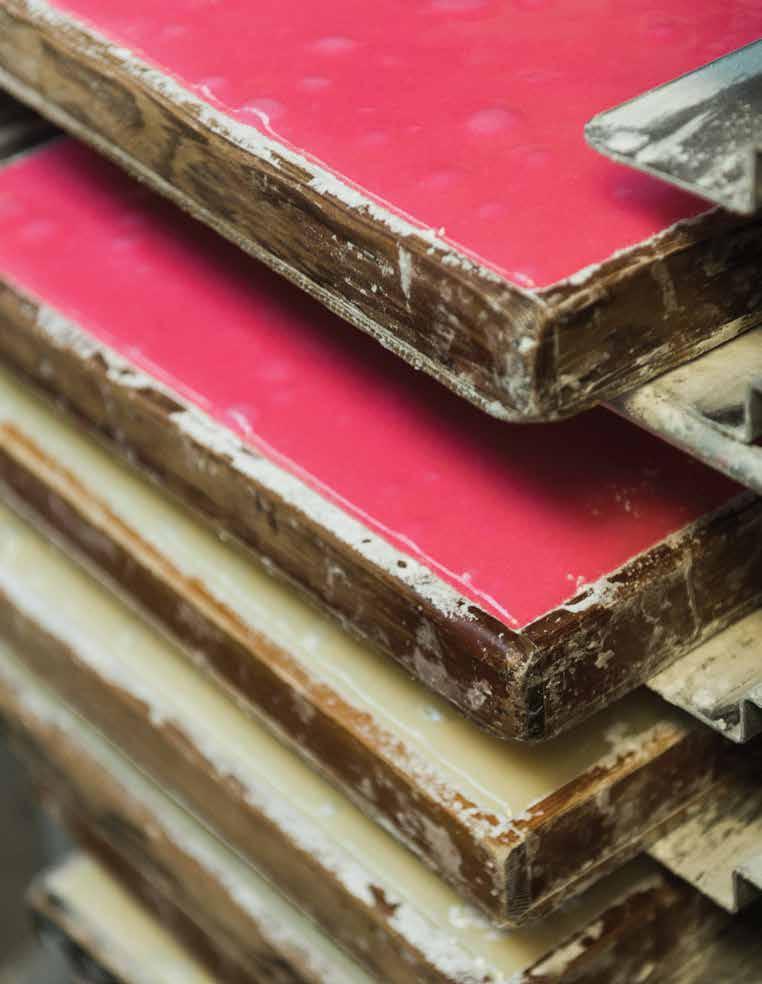

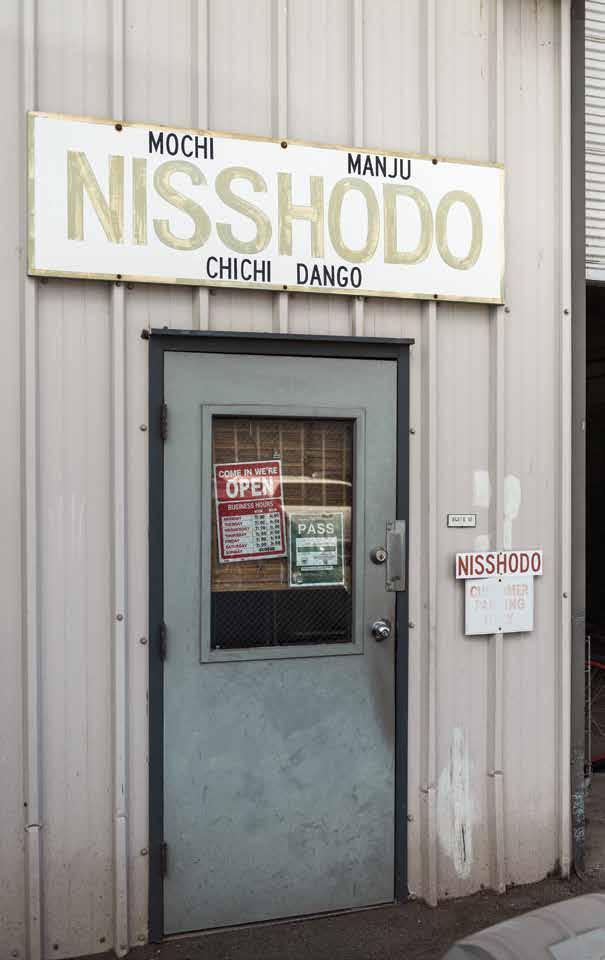

The Nisshodo Candy Store nears its 100th year of serving mochi to the Hawai‘i community.

ハワイで餅を作り続けている ニッショードー・キャンディ・

ストアは、もうすぐ創業100年 を迎える。

Just after 6 a.m. on a chilly December morning in Wahiawā, a rural community in the middle of O‘ahu that was once the pineapple capital of the world, a few older men dressed in short-sleeved happi coats and hachimaki (Japanese headbands) steam sweet mochi rice in bamboo boxes over propane stoves in a backyard. Others set up the tables in the garage. In a few hours, dozens of members of the local Uesugi family will gather to shape the cooked and pounded rice, or mochi, into balls of various sizes, filling them with tsubushian (azuki bean paste), chocolate-hazelnut spread, and even cookie butter.

12月の冷え込んだある朝、かつてパイナップルの世界的な生産地とし て栄えたオアフの中心にある田舎町のワヒアワでは時計が午前6時を まわったところだ。裏庭では半袖の法被を羽織り、鉢巻をした初老の男 性たちが、ガスコンロの上に積まれた竹製の蒸し器でもち米を蒸してい る。ガレージの中にテーブルを並べている人たちもいる。数時間後には、 ここに地元に住むウエスギ家の親戚が数十人集まり、餅つきが始まる。 炊きたてのもち米をつき、できた餅をさまざまな大きさに丸め、つぶしあ んやチョコレート、ヘーゼルナッツクリーム、クッキーバターなどを中に 詰めていく流れ作業だ。

Once eaten solely by Japanese emperors and nobles, mochi is now often enjoyed by the masses as a casual snack.

日本では季節の変わり目やお祝 い事に縁起の良い食べ物として 食べられていた餅は、今日のハ ワイでは日常的なおやつとして 食べられている。

Making mochi, by hand and at home, is a New Year’s tradition that goes back generations in Hawai‘i, though very few families still prepare mochi this way. Older folks in the Uesugi family remember pounding hot glutinous rice using kine (wooden mallets) in an old stone usu (large mortar), but the usu has long been missing. Today, young boys pound the freshly steamed rice with kine as it enters a stainless-steel machine that churns and massages it until it’s a soft and pliable paste. When this process is complete, the rest of the family takes the mochi and shapes it into smooth discs. These will be used as offerings or put into ozoni , a soup full of ingredients that have significance in Japanese culture like konbu (seaweed) for long life and mochi for good fortune and strength.

“My family has been doing this for as long as I can remember,” says Shawn Uesugi Nakamoto. Her two sons have pounded mochi every new year since they were teenagers. “It’s just always been our family tradition that nobody wants to let go of. It’s a fun time for our kids. We all really look forward to it.”

自宅で餅を手作りする習慣は、ハワイでは何世代も前から続く正月 の伝統であるが、今ではごく少数の家庭でしか見られない光景となっ た。ウエスギ家の年配の人たちによれば昔は木製の杵と石臼のみを使 って餅をついていたそうだが、今日では蒸したてのもち米をステンレス 製の機械を通して柔らかいペースト状にしてから杵でつく。若い男性た ちがついた餅を、残りの家族が手に取って平たい丸形に整えていく。 できあがった餠は、鏡餅にして供えたり、力のつく縁起物として昆布とと もに雑煮に入れて食べる。

2人の息子が10代の頃から毎年決まって正月に餅をついているとい うショーン・ウエスギ・ナカモトさんは、「私の一家は、私の知る限りずっ と餅つきを続けています。我が家の餅つきの伝統は、これからも大切に 守り続けたいと思います。子供たちにとっても楽しい経験で、家族全員 が毎年楽しみにしているのですから」。

During the holiday season, Nisshodo goes through more than 500 pounds of mochi rice.

ホリデーシーズンになると、 ニッショードーでは230キ ロ近くの餅米を使い切る。

In Hawai‘i, mochi is as much a part of New Year’s celebrations as fireworks and champagne toasts. The food comes from Japan, where it has been made for at least 13 centuries. Once eaten exclusively by emperors and nobles, mochi came to be used in religious offerings at Shinto rituals and, during the Japanese New Year season, took on the symbol of long life and wellbeing.

Today, no matter the time of year, mochi is dropped in soups, dusted in kinako (soybean flour), grilled and dressed in a sugary shoyu sauce, or stuffed with a variety of fillings ranging from lima bean paste to peanut butter to whole strawberries. In Hawai‘i, mochi is also consumed year-round, found on shelves in convenience stores and atop bowls of shave ice.

But the mochi made for New Year’s celebrations is special: It is always left white, the color of the rice, and shaped into discs. Often, two large ones are stacked and then topped with a mikan (Japanese orange) with its leaf attached. This is kagami mochi (mirror mochi), an offering to the gods, which is placed on the family altar or somewhere in the home to bring good fortune in the coming year.

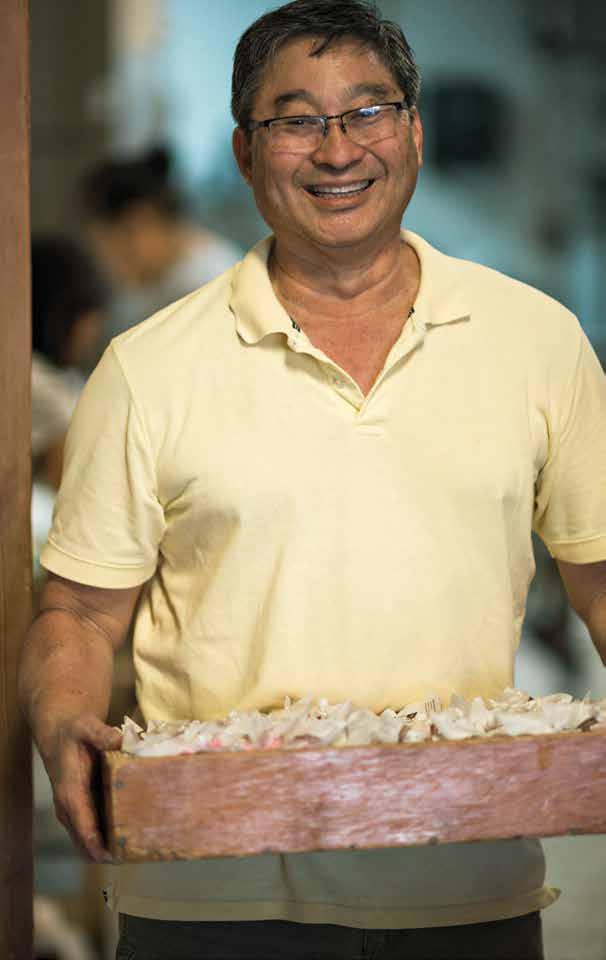

Traditional daifuku mochi (mochi stuffed with sweet filling), which is too difficult for most people to make at home the way the Uesugis do, is what people clamor for at the 97-year-old Nisshodo Candy Store housed in an unassuming warehouse in Kalihi. Each year, it churns out thousands of pieces of fresh mochi for New Year’s alone, going through more than 500 pounds of mochi rice during the holiday. At the peak of the season, its workers clock in at 5 a.m. to try to meet everyone’s needs. Even this is sometimes not enough. “The line goes out the door and there’s a lot of complaining,” says Mike Hirao, 68, a retired banker and third-generation owner of the family-run store. “But cannot help.”

Though the shop is busiest on the days leading up to New Year’s, its best-selling mochi is chichi dango, a soft, sweet confection made fresh daily onsite. The shop sells around 40,000 pieces of the pink and white mochi—made from scratch and mostly by hand—every week. The shop is also one of the few on O‘ahu that makes the specialty

ハワイでは、餅は花火やシャンパンと同様、新年のお祝いに欠かせな いものである。少なくとも13世紀以上前から日本で作られている餅は、 かつては皇族や貴族の間でしか食べられていなかったが、神道の儀式 に使われるようになって普及し、日本の正月に長寿と健康のシンボルと して食べられるようになったという。

今日、ハワイでは餅の入ったスープやきなこ餅、磯辺焼き、あんこやピ ーナッツバター入りのものやいちご大福など様々な餅が一年を通して 食べられている。コンビニエンスストアでも売られているし、ローカルが 大好きなシェイブアイスのトッピングになっているほど身近な食べ物で ある。だが新年のお祝いに作られる餅ほど特別なものはないだろう。丸 くて平たい白餅を2つ重ね、葉の付いたみかんがのった鏡餅は、神々へ の供え物として祭壇や家の中に飾ると新年に幸運を招くとされている。 ウエスギ家の人たちのように、伝統的な大福餅を普通の家庭で作る のは至難の技である。故に地元の人たちは、カリヒにある倉庫街にひっ そりと店を構える創業97年のニッショードー・キャンディ・ストアに足 を運ぶのである。この店では毎年、正月だけでも何千個もの餅を作って いる。ホリデーシーズンには230キロ近くの餅米を使い切り、ピーク時 には、客からの需要に応えるため、スタッフは朝5時に出勤するが、それ でも間に合わないという。「繁忙期には店の外まで行列ができ、お客様 から不満の声もあがるのですが、どうすることもできないのです」と説明 するのは銀行を定年退職し、家族経営のニッショードーを3代目オーナ ーとして支えるマイク・ヒラオ(68歳)さんだ。

繁忙期は年末から正月にかけてであるが、一年を通してニッショー ドー・キャンディ・ストアで一番の人気を誇る商品は「ちちだんご」だ。求 肥を使った柔らくてほの甘いピンクと白の餅は、店内で毎日ほぼ全て手 作業で作られ、週に4万個ほど売れるという。またこの店は、オアフ島で 今もひな祭り用の菱餅を作っている数少ない店でもある。

餅には様々な味や食感、トッピングやフィリングの入ったものがある。

Hand-pounding mochi is a New Year’s custom in Hawai‘i with origins in Japan. Kagami mochi, a two-tiered variety, is traditionally set out in the home as an offering to the gods in exchange for good fortune in the coming year.

日本の餅つきは、ハワイの新年 の習慣として定着している。

地元の家庭でも新年の幸福を 祈り、鏡餅を神々への供え物と して祭壇や家の中に飾る。

hishi mochi, a three-layer, diamond-shaped mochi dessert, for Girl’s Day, or Hinamatsuri , in March.

Still, the busiest holiday for Nisshodo Candy Store is New Year’s. Hirao understands the sentiment. He grew up placing mochi on family altars and eating it in soup on New Year’s Day. Though he doesn’t have an altar in his own home, he still honors the custom, placing the kagami mochi on the stove in his kitchen. “This is how we grew up, it’s what we do,” he says. “And to this day, we still do that. It’s tradition.”

ニッショードー・キャンディ・ストアが一年で一番忙しいのは何といっ ても新年だ。祭壇に餅を飾り、元旦にお雑煮に入れて食べる習慣の中 で育ったヒラオさんは今も、正月になると自宅の台所のカウンターの上 に鏡餅を飾ってその伝統を守っている。「僕たちが子供の頃から続いて いる習慣を今も大切にしています。それは我が家の伝統ですから」とヒ ラオさんは語る。

TEXT BY NATALIE SCHACK

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK & SKYE YONAMINE

TEXT BY NATALIE SCHACK

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK & SKYE YONAMINE

文=ナタリー・シャック 写真=ジョン・フック&スカイ・ ヨナミネ

PLUME OF TIME

時を超えた羽

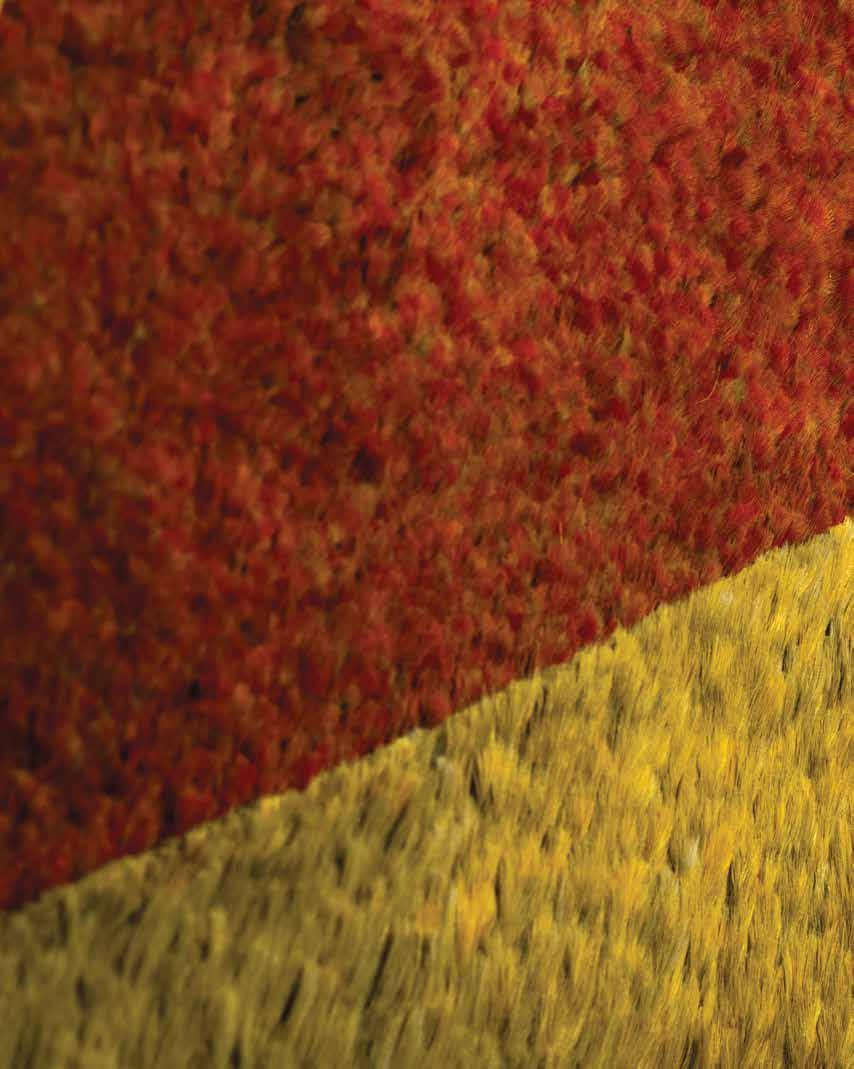

From its grand and resplendent capes to brilliant bands for woven hats, the Hawaiian art of featherwork endures.

豪華絢爛なマントから帽子を粋に彩るハットバンドまでハワイアンに脈々と受け継がれる羽毛を使った芸術、フェザーワーク。

Early Hawaiian settlers brought the art of featherwork with them from older parts of Polynesia. Previous: The mahiole (helmet) of Kalani‘ōpu‘u.

Opening spread: A detail of the feathered ‘ahu ‘ula (cape) of Kalani‘ōpu‘u on display at the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum. The impressive garment is made of 4 million feathers.

鳥の羽を使ったフェザーワー クは、初期のハワイ入植者たち が古くからあるポリネシアの島 々から持ち込んだ。前ページ: カラニオプウの使用したマヒオ レ(ヘルメット)。最初ページの 見開き:バーニース・パウアヒ・ ビショップ博物館に展示され ている羽でできたカラニオプウ のアフウラ(マント)。400万本 の羽毛でできている。

The 19th century was in its infancy. Princess Nāhi‘ena‘ena, descended from the ali‘i and most elite echelons of Maui and Hawai‘i Island society, was still only a child when she was gifted a feather pā‘ū so magnificent that its fame lives on today. Creating the pā‘ū was a massive undertaking. The skirt consists of 1,000,000 tiny feathers bundled and tied to a netted base by the people of Lahaina over what could have been a mere year, says Marques Marzan, the cultural advisor at the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, where the skirt now lies. Especially remarkable is its color, which is almost entirely yellow. This hue required the rarest of the feathers to be taken from a small tuft of golden plumage at the neck of the now extinct ‘ō‘ō. The sheer volume of plumage required kia manu, or bird catchers, to venture in groups into the forests for days to pluck precious, wee feathers from the evasive honeyeaters.

19世紀初期のことであった。マウイ島とハワイ島における上流階級で あり、アリイ(王族)の子孫のナヒエナエナ王妃は、今日までその美しさ が語り継がれるほど豪華な羽毛でできたパウ(スカート)を贈られた当 時、まだ幼い子どもであった。

このパウの製作は壮大なプロジェクトであったという。ラハイナの人 々が一年かけて集めた100万本もの小さな羽毛を束ね、網状の生地に 結びつけて作られたスカートなのだと、現在この美術品が収蔵されてい るバーニス・パウアヒ・ビショップ博物館の文化顧問、マルケス・マルザ ン氏は教えてくれた。何より見事なのはその鮮やかな色である。全体が 黄色に輝くこのスカートには、すでに絶滅しているオーオーと呼ばれる ハワイ固有の鳥の首の部分から採取される最も希少な金色の羽毛が 使われている。膨大な数の羽が必要とされるため 、「キア・マヌ」と呼ば れる鳥捕獲隊は、この小さくて貴重な羽を求め、臆病で森の中に隠れて いるミツスイを何日もかけて探し回らなければならなかった。

Today, lei from the practitioners of Kahailimanu are comprised of feathers like Chinese golden pheasant, peacock, and chicken.

今日、カハイリマヌの文化継承者が作るレイには、キジや孔雀、鶏など の羽が使われている。

The feathers of the mamo, ‘ō‘ō, and ‘i‘iwi were gathered by skilled hunters. This lei, right, from the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, features yellow feathers of the mamo bird, a now-extinct black honeycreeper with small tufts of goldenrod feathers beneath its wings. These feathers were some of the rarest.

マモやオーオー、イイヴィといっ

た鳥の羽は熟練した捕獲者た ちによって集められた。バーニー ス・パウアヒ・ビショップ博物館

にある写真右のレイには、ハワ イ島のマモの黄色の羽が使用 されている。すでに絶滅している 黒いミツドリのマモの翼の下側

に生えている鮮やかな黄色をし た小さな羽の房は、最も希少な 羽のひとつである。

Featherwork can actually be seen all across the Pacific and the world. Early Hawaiian settlers brought the art with them from their homes in older parts of Polynesia, says Marzan, and over time the practice evolved in slight, distinct ways. The type of net backing used in traditional Hawaiian handiwork, for example, was made of olonā, a fiber found only in Hawai‘i. Originally, he explains, both making featherwork, as well as wearing it, was reserved for the chiefly class. The Bishop Museum’s collection houses everything from magnificent cloaks in royal yellow and red shades and iconic, crescent-shaped feathered helmets, to elegant lei and fierce, feathercoated god effigies.

Today, mother-and-son team Lehuanani and Kaimana Chock, who craft traditional feather lei and hat bands under the name Kahailimanu, are part of a small community of artisans carrying on this artistic legacy of their ancestors.

“I learned when I was 16, dancing hula, loved it, and always kept making lei,” says Lehuanani. Everyone in her hālau had to make their own

鳥の羽を使ったフェザーワークは、実は太平洋や世界全域でみられ る。マルザンさん曰く、その芸術は初期のハワイ入植者たちによってポリ ネシアに古くからある彼らの故郷から持ち込まれ、時代とともに独自の 進化を遂げてきたという。たとえば、伝統的なハワイの手工芸品の網状 の裏地には、“オロナ”というハワイにしかない繊維が使われている。もと もとフェザーワークを作り、身につけることは王族階級のみが許されて いた。ビショップ博物館のコレクションには、王族の象徴である黄色と 赤の豪華なマントや三日月形の羽の装飾が施されたヘルメット、上品な フェザーレイ、羽毛で覆われた神像などがある。

カハイリマヌというフェザーワーク工房を手がける親子のレフアナニ さんとカイマナ・チョックさんは、伝統的な手法でフェザーレイと帽子に つけるハットバンドを作っている。二人は、先祖代々伝わるハワイアンの 芸術を今日へと受け継ぐ数少ないフェザーワーク職人である。

カハイリマヌのクム(講師)のレフアナニ・チョックさんは、伝統的であり ながらモダンなデザインのハワイアンフェザーレイ作りを教えている。

We very much still make them in the same manner that it was made for generations. We’re not learning from a book—we learn from a kupuna. That’s what makes it Hawaiian to me.”

— Kaimana Chock, lei hulu practitioner of Kahailimanu

「先祖代々伝わる方法で今も作り続けています。フェザーレイ作りは、本から学ぶのではなく、先祖から習い、人から人へ伝えていくもので す。僕にとっては、それが本当の意味でのハワイアンの伝統なのです」 ー カハイリマヌのレイ・フル職人のカイマナ・チョックさん

The Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum houses everything from magnificent cloaks to elegant lei in royal yellow and red shades.

バーニース・パウアヒ・ビショッ プ博物館のコレクションには、 王族の象徴である黄色と赤の 豪華なマントや上品なフェザー レイなどがある。

lei sets—thus proving their commitment and dedication—in order to participate in the Merrie Monarch Festival. “Then, when I got married, my husband’s grandmother would make lei with her sisters. As each sister passed away, I would inherit all of their feathers. She wanted me to keep on. She wanted to make sure the art didn’t die.”

Now, as interest in Hawaiian culture grows, so does interest in feather making, according to Kaimana. “I think there’s a resurgence,” he says. “There was a time period when it was only a really small community making the lei.” Lehuanani teaches feather-making classes at their home in Pearl City, bringing together groups of women and the spare man for two hours a week to devote themselves to slow-going work and tiny stitches.

The Chock home is filled with the fruits of lifetimes spent doing such work: kāhili (handheld standards); hakupapa-style hat bands; lei kāmoe, which features feathers that lie flat, like they would on a bird; and lei poepoe, which feature feathers standing up, making for a fluffier effect.

「フラを踊っていた私は16歳のとき、レイの作り方を習いました。その 素晴らしさに魅了されて以来、ずっと作り続けています」とレフアナニさ んは言う。彼女のハラウ(フラスクール)の誰もがメリーモナークフェス ティバルに出場するため、自ら身につけるレイ一式を手作りしなければ ならなかったのだそうだ。レイ作りは、フラへのコミットメントと献身の 証でもある。「私が結婚した時、夫の祖母は、彼女の姉妹たちと一緒に 私たち二人のためにレイを作ってくれました。姉妹が亡くなると、彼女た ちの持っていたフェザーレイを全て私に譲ってくれたのです。祖母はフ ェザーレイ作りの伝統が途切れることのないよう、私に受け継いでほし いと願っていました」と語った。

ハワイ文化への関心が高まっている今日、フェザーアートに興味を持 つ人も増えているという。カイマナさん曰く、「一時はフェザーレイを作 る人の数がほんの一握りになったこともありましたが、今では復活の兆 しを見せています」。レフアナニさんは、パールシティの自宅でフェザー レイ作りのレッスンを開催している。女性が大半のグループが週一回2 時間のクラスに集まり、細かい縫い目を繰り返す時間のかかる作業に 熱心に取り組んでいる。

Halekulani Living

The mother and son team Lehuanani and Kaimana Chock are part of a small community of artisans carrying on this artistic legacy of their ancestors.

親子のレフアナニさんとカイマ ナ・チョックさんは、先祖代々伝

わるハワイアンの芸術を今日へ と受け継ぐ数少ないフェザーワ ーク職人である。

The feathers of ancient times, gone with the endangered or extinct birds, have been replaced by others such as pheasant, with its almond-like pattern, or brilliant peacock, with its iridescent sheen. The Chocks even source feathers from homeraised chickens.

While the materials have changed since the princess received her pā‘ū, the methods of creating featherwork pieces remain the same. “We very much still make them in the same manner that it was made for generations,” Kaimana says. “There’s that person-to-person transmittal of the practice. We’re not learning from a book—we learn from a kupuna. That’s what makes it Hawaiian to me.”

They still process, cut, and tie or stitch every single feather with intention and purpose, infusing it with a bit of themselves. “In old Hawaiian thought, because lei is something that goes on your body, it automatically gets your mana and part of your energy,” Kaimana says. “Think how much of you goes into the final product—you've tied each of the thousand feathers, taken three stitches or three

チョック家の自宅には、膨大な時間を費やして手作りされたフェザー ワークの作品がところ狭しと飾られている 。そこには王族の象徴である 「カヒリ」とよばれる羽飾りのついたポールや帽子につける「ハクパパ」 というハットバンド、羽を平らに寝かせたデザインの「レイ・カモエ」と羽 を立ち上げてふわふわに仕上げた「レイ・ポエポエ」の2種類のフェザー レイなどがある。昔は絶滅種あるいは絶滅に瀕した鳥たちの羽が使用 されていたフェザーレイに、現在では、アーモンドのような模様のキジ の羽や、鮮やかな孔雀の羽が使用されている。チョック家では、自宅で 飼っている鶏の羽を使うこともあるという。

ナヒエナエナ王妃がパウを贈られた頃のフェザーワークはその材料 こそ変わったものの、作り方は昔と変わらない。「先祖代々伝わる方法 で今も作り続けています。フェザーレイ作りは、本から学ぶのではなく、 先祖から習い、人から人へ伝えていくものです。僕にとっては、それが本 当の意味でのハワイアンの伝統なのです」とカイマナさん。

一枚一枚の羽を処理し、切って、結びつけたり、縫い付けたりする一 連の工程が今も全て手作業で行われるフェザーワークには、目的と意 識を持って作業する作り手の心が込められてる。

Lei poepoe feature feathers standing up, whereas lei kāmoe are composed of feathers that lie flat. These lei, shown here, were created by Kahailimanu.

フェザーレイには、羽を立たせてふんわりと仕上げた「レイ・ポエポエ」 と羽を平らに寝かせたデザインの「レイ・カモエ」がある。写真はカハイ リマヌ製作の作品。

The rare design of this cloak features upturned feathers and is the only one of its kind. 上向きの羽を使った珍しいデ ザインのマント。この世に一つ しかない。

times around with your piece of thread—all of that.” Adds Lehuanani, “So that when you’re giving it, it’s almost like giving them a little bit of you.”

What featherwork represents today has changed considerably, according to Marzan. In the past, the material culture produced served as a visually understood symbol, a vestment of the chief and their station. “Today, it serves more of a purpose of holding onto cultural practices,” Marzan explains, a symbol of your commitment to preserving this knowledge. “It’s about committing your time and energy to the creation of a piece and observing all of the things you see in the process.”

The intention behind modern-day featherwork practitioners is still to celebrate and honor, but it’s now not just to uplift a social class of people, but instead an entire people.

「古くからのハワイアンの間では、体に身につけるレイには、その人のマ ナやエネルギーが自然に入り込むと考えられています。手作りしたレイ に作り手の心がどれだけ込められているか考えてみてください。1000 枚の羽を一枚ずつ結んでは3針縫ったり、糸を3回巻いたりする作業を 繰り返すのですから」とカイマナさんは言う。レフアナニさんは「自分で 作ったレイを人に贈るということは、あなた自身の一部を捧げているの と同じなのです」と加えた。

マルザン氏によれば、今日のフェザーワークが意味するものは以前と は違っているという。ネイティブ文化に根付くこれらの芸術は、昔は王 族とその側近を象徴する視覚的なシンボルであった。マルザン氏は「今 日のフェザーワークは、伝統文化を守るために受け継がれるべき芸術 として、ハワイの人々のコミットメントのシンボルとなっています」と説明 する。「制作に多くの時間やエネルギーを費やすことで、色々なことを感 じ、考え、見えてくるプロセスこそが大切なのです」。フェザーワーク職 人たちが伝統を受け継ぎ、讃えることに今も変わりはない。ただ昔と違 うのは、それが一部の特別階級の人たちのためではなく、すべての人た ちのためであるということなのだ。

Uniform of Walter Murray Gibson 19th century (detail)

Cotton, wool, gold thread, and metal buttons

Hawai‘i State Archives 210

MARCH 1–JULY 14, 2019

Lisa Reihana, detail in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015–17, Ultra HD video, colour, 7.1 sound, 64 min.

Image courtesy of the artist and New Zealand at Venice. With support of Creative New Zealand and NZ at Venice Patrons and Partners.

BY

TEXT EUNICA ESCALANTE IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK文=ユーニカ・エスカランテ 写真=ジョン・フック

STAY BLESSED

清められて

In search of wholeness and good fortune, a writer visits three distinct Asian temples on O‘ahu.

心の安らぎと幸運を求め、オアフ島の3つの仏教寺院を訪れる

Buddhism was brought to the Hawaiian Islands in the late 1800s with the wave of Asian immigrants coming to work at sugarcane plantations.

仏教は1800年代後半、ハワイ のサトウキビ農園で働くため に海を渡った多くのアジア移

民によってハワイ諸島へもたら された。

It’s a Saturday afternoon and I’m deep in Pālolo Valley learning how to breathe. About 10 of us are gathered in a room at Mu-Ryang-Sa Temple for a session on vipassanā meditation. Leading the class is a slight, bald man by the name of Gregory Pai. He has been the temple’s resident meditation instructor for a decade. He sits with his back straight, eyes closed. If inner peace exists, I’m sure this man has found it.

Pai begins by striking a tuning fork against the ground. Its tinny note centers our focus. “Feel the sensation of your breath in your body,” he says as we draw in air. “Use it as an object to ground you.” His measured tone guides us deeper into the calm. A soft breeze filters through the doors. Incense sweetens the air.

土曜日の午後、パロロ渓谷の奥深くにあるムリャンサ寺院に呼吸法を 学びに来ている。10人ほどが集まった部屋では、ヴィパッサーナ瞑想 のセッションが行われている。この寺院で10年間、瞑想のインストラク ターを務めているという細身で髪の薄いグレゴリー・パイさんが指導し てくれる。彼は背筋をまっすぐに伸ばし、目を閉じたまま座っている。心 の平穏というものがあるとすれば、パイさんはとっくの昔に見つけてい るに違いない。

パイさんが音叉を地面に打ちつけると、レッスンは始まった。その甲 高い音色が私たちの意識を集中させてくれる。深呼吸する私たちに向 かって「体の中で呼吸を感じてください。呼吸に意識を集中して、心を 落ち着かせましょう」彼の規則的な口調が私たちを穏やかな気分にさ せてくれる。ドアを抜けて入ってくるそよ風に乗って、線香の香りがほの かに漂う。

Tokens of good fortune located around the grounds.

The anticipation of spiritual renewal draws visitors to Hawai‘i’s Buddhist temples each new year.

毎年、新年になると祈祷やお祓 いのために多くに人がハワイの 仏教寺院を訪れる。

Once dismissed as a hokey New Age notion, meditation’s popularity is experiencing a reawakening through digital upgrades and the self-care movement that makes it appealing to millenials. Mindfulness gurus liken its effects to other buzzy wellness methods like crystal healing and digital detoxes. But at Mu-Ryang-Sa, meditation isn’t just another trend—it is a practice steeped in the history of Buddhism. And as I sit cross-legged, surrounded by its sacred design, I feel the weight of centuries of culture.

It’s an experience that I thought required traveling—perhaps to a monestary atop Nepal’s misty peaks or to ruins deep in the jungle. But the authentic does not always have to be exotic. An Eat, Pray, Love journey to spiritual self-discovery can be found right here in Hawai‘i.

Buddhism was brought to the Hawaiian Islands in the late 1800s with the wave of Asian immigrants coming to work at Hawai‘i’s sugarcane plantations.

宗教的なイメージがあり敬遠されつつあった瞑想は、テクノロジーの 進化とセルフケアへの関心の高まりにより、最近では特にミレニアル世 代の間で人気だ。マインドフルネス(意識を集中させ心をこめて物事を 行える状態)を謳う人たちの中には、その効果をクリスタルヒーリングや デジタルデトックスのような話題の健康法に例える人もいる。だがムリ ャンサで体験する瞑想は単なる流行ではなく、仏教の伝統に根付いた 習慣である。神聖な神器に囲まれて座禅を組めば、誰もが何十世紀に もおよぶ歴史と文化の重みを肌で感じることができるだろう。

それは霧に包まれたネパールの山頂にある僧院や、ビルマのジャ ングルにある秘境の地などに旅しなければ得られない経験だと思って いた。だが本物は必ずしもエキゾチックである必要はないのだ。『Eat, Pray, Love(食べて、祈って、恋をして)』という2010年公開のアメリカ 映画に出てくるようなスピリチュアルな自己探求の旅はここハワイに あった。

Byodo-In Temple on O‘ahu’s windward side is a small-scale replica of a 950-year-old temple in Uji, Japan that has been designated a United Nations World Heritage Site.

オアフ島のウィンドワード側にある平等院テンプルは、950年の歴史を 誇りユネスコの世界文化遺産に登録されている日本の宇治市にある 平等院を縮小したスケールモデルである。

The first temples were just single-story, wooden structures built within the plantations. Some, like the Honpa Hongwanji Mission along Pali Highway, which is more than 100 years old, are still in operation today. Over the years, as the religion’s popularity grew, so did its temples.

Mu-Ryang-Sa’s sprawling estate is the largest Korean Buddhist temple outside of Korea. Ensconced at the end of a winding, climbing drive, the temple boasts a view of the lush valley below. Through its gate, which is guarded by the towering statues of the Four Heavenly Kings, the tumult of town life dissipates. As one of the lesser-known temples on O‘ahu, Mu-Ryang-Sa is often devoid of crowds. One can roam its picturesque courtyard and intricately decorated halls in solitude.

For visitors hesitant about meditation sessions, insight can still be garnered from the temple’s unique architecture. After exceeding the City and County of Honolulu’s limits on building height, its ridge, meant to be pointed in the typical Buddhist style, had to be leveled. Soon after, it was renamed Mu-Ryang-Sa, which roughly translates to “Broken Ridge Temple.”

It’s an anecdote taken directly from Buddha’s teachings, says Dohyun Gwon, Mu-Ryang-Sa’s abbot. “Buddha teaches that in order to reach the true heights of enlightenment, we must shatter our own structures of ignorance,” he says. “Much like the shattering of our temple’s ridge.”

On a summer afternoon, crowds flock to another O‘ahu temple. Tucked at the foot of the Ko‘olau mountain range, Byodo-In, a nondemonimational Buddhist temple, is one of Hawai‘i’s most popular sites. On an average day, hundreds of visitors tour the temple grounds. And tonight is no exception, as it is the eve of Obon, a Buddhist festival celebrating the return of ancestors from the spirit world.

A string of glowing lanterns light the bridge at the temple’s entrance. Stands lined across the courtyard offer good luck charms and fried snacks. Attendees dance to the beat of taiko drums. Other visitors stroll its meandering pathways, hoping for a chance encounter with the temple’s resident black swans or possibly even its elusive peacock. Alcoves beckon them to explore off the beaten path, like the corner behind the temple that hides a miniature

仏教は1800年代後半、ハワイのサトウキビ農園で働くために海を渡 った多くのアジア移民によってハワイ諸島へもたらされた。最初の寺院 は、プランテーション内に建てられた1階建ての木製の建物であった。 築100年を超えるパリ・ハイウェイ沿いにある本派本願寺をはじめ、い くつかの寺院は今も健在である。仏教は年を経てハワイに広まり、寺院 の数も増えていった。

広大な敷地のムリャンサ寺院は、韓国国外で最大の韓国仏教寺で ある。曲がりくねった坂を登りきった先にひっそりと佇む寺院の目下に は、青々とした谷が広がっている。四天王像が両脇に立つ門をくぐって 中に入ると、街の喧騒が一気に遠のく。オアフ島でもあまり知られてい ないこの寺院は閑散としていて、美しい中庭や優美に装飾された回廊 を一人静かに歩き回ることができる

瞑想には抵抗があるという人でも、韓国独自の建築形式を楽しめる この寺院は十分に訪れる価値があろう。ホノルル市郡の建築基準に基 づく規定の高さを越えてしまったこの寺院は、仏教様式では通常尖っ ているはずの屋根の棟が削られて平らになっている。それに由来して この寺院は、「壊れた棟の寺」を意味する「ムリャンサ」と呼ばれるよう になった。

「それは仏の教えにもある逸話です」とムリャンサの住職であるドゥヒ ョンさんは教えてくれた。「ブッダは悟りの境地に達するためには、私た ち自身の内にある無知の砦を打ち砕かなくてはならないと教えていま す。この寺の棟を壊さなければならなかったこともそれと同じです」。

ある夏の午後、オアフ島にあるもう一つの寺院には大勢の人が集ま っている。コオラウ山脈のふもとのカネオヘにある無宗派の仏教寺院、 平等院テンプルは、ハワイで最も人気のある観光スポットの一つであ る。1日あたり何百人もの訪問者がこの寺院を見学しに訪れる。先祖の 霊を迎えて供養する迎え盆にあたる今夜も例外ではない。

寺院の入り口にある橋に沿って一列に吊るされた提灯が灯ってい る。中庭には、揚げ菓子やお守りの出店がたくさん並んでいて、太鼓のリ ズムにあわせて踊る人たちや、寺の池に生息する黒鳥や孔雀を一目見 ようと敷地内を散歩する人たちで賑わっている。寺の敷地の角には、山 から水が流れ出る水が小さな滝となって注ぐ鯉の泳ぐ池があり、人里 離れた風情のある小道を散策することができる。

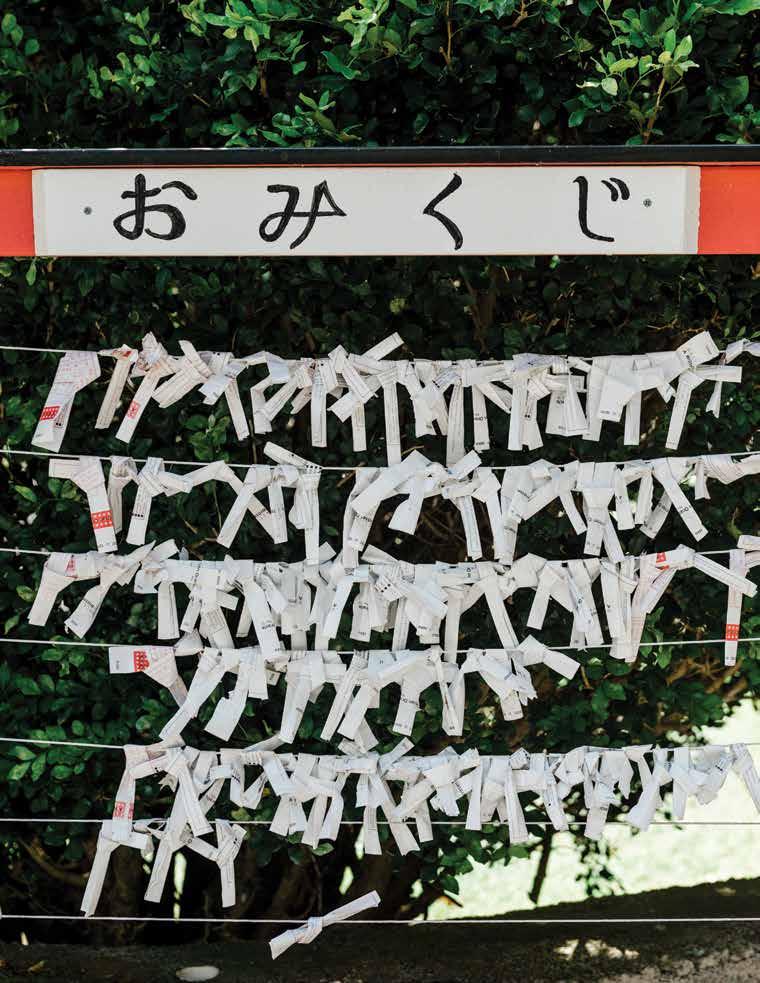

visitors divine

luck by drawing omikuji, or randomly drawn fortunes written on pieces of paper, and secure it by buying omamori, or good-luck amulets.

ハワイの神社でも参拝者の多くは、おみくじを引いたり、お守りを買って 開運を祈願する。

Luck is a subject in which Daijingu, a temple on the leeward side, specializes.

オアフ島のリーワードにある

ハワイ大神宮は幸運の神様 として知られる。

waterfall emptying fresh mountain water into a koi pond.

Byodo-In was built in 1968 within the Valley of the Temples, a memorial park home to various other theologies, in commemoration of the 100year anniversary of the first Japanese immigrants’ arrival in Hawai‘i. From its bell house to the main structure housing the nine-foot Buddha statue, it is a small-scale replica of a temple in Uji, Japan. In 2018, the temple celebrated its 50th anniversary. As the sun disappeared behind the mountains, dozens of attendees placed lanterns on the waterway that winds through the grounds. Their flames illuminated the water as they floated around the temple. Amid dusk’s waning light, Byodo-In appeared to be ablaze.

Nestled on the leeward side of the Ko‘olau mountain range is Daijingu Temple. Humble in appearance, Daijingu is one of Hawai‘i’s oldest

平等院テンプルは1968年、ハワイの日系移民100周年を記念し、 宗教や宗派を問わないメモリアルパークの「バレー・オブ・ザ・テンプル ズ」に建立された。鐘楼から2メートル70センチの仏像を収めた本堂ま で全てが、日本の宇治市にある平等院を縮小したスケールモデルであ る。2018年にこの寺院は建立50周年を迎え、記念イベントが開催され た。山の向こうに夕日が沈み、数十人の拝観者が敷地内に廻らされた水 路に灯篭を流すと、水面を照らす灯篭の灯りで平等院はまるで暗闇の 中で燃え立っているかのようであった。

コオラウ山脈のリーワード側にあるハワイ大神宮。質素な外見の大 神宮は、ハワイで最も古い神社の一つである。1900年代に建立され、 激動の時代を経た今もハワイで神道を信仰する人々の拠り所となって いる。第二次世界大戦中、日系移民が強制収容された際には、大神宮 の元の建物も押収され、米国政府によって競売にかけられたという。そ れでも神主たちの信仰心が揺らぐことはなかったとハワイ大神宮の岡 田章宏宮司はいう。戦後、大神宮は現在のヌウアヌ渓谷に再建された。

the largest Korean Buddhist temple outside of Korea, is nestled in lush Pālolo Valley.

“Buddha teaches that in order to reach the true heights of enlightenment, we must shatter our own structures of ignorance.”

— Dohyun Gwon, abbot of Mu-Ryang-Sa 「ブッダは悟りの境地に達するためには、私たち は自身の内にある無知の砦を打ち砕かなくては ならないと教えています」 ー ムンリャサ住職のドゥヒョンさん

temples. Established in the 1900s, the temple has remained a stronghold for Hawai‘i’s Shinto practitioners even through tumultuous times. During the Second World War, as people of Japanese ancestry were forcibly interned, Daijingu’s original temple was seized and auctioned off by the U.S. government. But according to the temple’s reverend, Akihiro Okada, the faith of the monks was never shaken. After the war ended, they rebuilt the temple in Nu‘uanu Valley, where it stands today.

Within the local community, the temple has garnered a devoted following. Residents flock to its grounds during the holiday season when the temple provides blessings for the new year. Luck is something in which Daijingu specializes. Its tables and shelves are lined with omamori , or amulets, for everything from having a lucky love life to blessing a new car. During hatsumode , the first shrine visit of the new year, visitors shed a year’s worth of bad luck through a purification ceremony.

“It is very important to be mindful,” Okada says. “If they miss the purification, they must wait one whole year until the next one. Then it is double the bad luck!”

Some may dismiss the temples’ beliefs as mysticism, but within their walls, it is hard not to indulge. As I bid farewell to Okada, he stops me to ask if he can give me a blessing. I nod yes and watch wide-eyed as he wields his onusa (wand) to cleanse me of my bad luck. His chants flow into one another until they become a collective hum. It ends as suddenly as it began. I walk away lighter in spirit and, hopefully, better in luck.

地元のコミュニティに信心深い氏子のいるハワイ大神宮は、年末年 始には新年の祈祷やお祓いに大勢の住民で賑わう。幸運の神様として 知られる大神宮の境内のテーブルや棚には、縁結びから交通安全まで あらゆるご利益のあるお守りが並ぶ。年始の初詣に厄除け祈願に訪れ る人も多い。

岡田宮司は「マインドフルになることは大切です。一年の終わりにお 祓いをしないと次は1年後まで待たねばなりません。すると悪運は倍に なるのです」という。中にはこのような考えを受け入れがたいと考える人 もいるかもしれないが、実際にこの場所を訪れたのなら、そのご利益に あやからずに去ってしまうのは惜しい。岡田宮司は別れを告げようとす る私を呼び止め、お祓いしてくれるという。大麻(おおぬさ)を振ってお 祓いする宮司をじっと見つめる私の心に、何重にも重なって聞こえる祈 りの声が次第に一つの和音になって響く。祈りは前触れもなく始まり、 終わった。そして私は心が軽くなったような気分で歩き出した。運が良 くなっていることを祈りながら。

Mu-Ryang-Sa is often devoid of crowds. One can roam its picturesque courtyard and intricately decorated halls in solitude.

ムリャンサ寺院は閑散としていて、美しい中庭や優美に装飾された 回廊を一人静かに歩き回ることができる。

文=レイ・ソジョット

写真=ジョン・フック、

ピュア・マナ提供

THE ALCHEMISTS

錬金術士

By dipping into bountiful botanicals that bestow dewy glows and promises of eternal youth, two Hawai‘i skincare lines are creating treasured cosmetics.

植物の効能を最大限に引き出し、艶やかで若々しい肌へと導くハワイの極上スキンケアブランド

At all-natural and local beauty companies like JK7 and Pure Mana, laboratory, science and the dreaminess of alchemy converge.

上:JK7や ピュア・マナのような

ハワイの天然化粧品メーカーで

は、研究、科学、そして錬金術の 夢が一つになる。

Ancient Egyptians celebrated beauty as a pleasure, a responsibility, and a direct link to the divine. As the world’s original skincare enthusiasts, they were well-versed in harnessing nature’s healing properties: pressing sumptuous oils from olives and almonds to keep skin supple or extracting essences from rose, lotus, and myrrh to elevate the spirit. Five thousand years later, the power of plant-based botanicals endures. In Hawai‘i, two companies tap into nature’s bounty.

古代エジプト人は喜び、責任、神との繋がりとして「美」を崇めた。世界 で最も古くからスキンケアにこだわっていた彼らは、オリーブやアーモ ンドを絞って皮膚を保湿するオイルを作ったり、バラや蓮、没薬などか ら精神力を高めるエッセンスを抽出するといった自然に秘められた癒 しの効果を引き出す方法を熟知していた。それから5千年以上たった今 も、植物由来の成分が持つ豊かな力は変わっていない。ここで自然の恵 みを活かしたスキンケア製品を提供しているハワイの天然化粧品ブラ ンド2社を紹介する。

“We like to say our products are from our soil to your soul,” says Pure Mana founder Kollette Stith.

「『私たちの大地からあなたの心へ』が私たちの製品のコンセプトです」 とプア・マナ創設者のコレット・スティスさん。

turning botanicals to gold

Jurgen Klein’s laboratory is an exercise in eclectic, scientific delight. Housed in a vintage carriage house on his hillside estate on O‘ahu’s North Shore, the working space channels apothecary, fairytale cottage, and proper chemistry lab all at once. Atop sleek countertops, beakers and flasks find tidy place among burettes and burners, scales and stills. An array of laboratory equipment lines exterior shelves while an imposing steel apparatus holds court in a far corner.

Across the room, a softer side of science emerges. Orderly rows of glass jars reveal botanical curiosities of all kinds: dried yarrow flower and clover blossoms, powdered spikenard root and nettle leaf. On a nearby shelf, vials with hues ranging from pale honey to deep amber glow with the liquid gold of essential oils. Each distillate is cataloged in neat shorthand and prepped for possible inclusion in JK7, one of the most exclusive —and expensive—luxury skincare lines in the world.

Growing up in Germany, Klein was enthralled by nature, often exploring the forests near his home. It was through his grandparents that young Klein discovered the medicinal power of plants. “I used to help my grandmother process veggies from our gardens and herbs for folk medicine,” Klein recalls. “My grandfather could heal large wounds and broken bones on horses with comfrey and calendula.” Though a chemist by profession, Klein remains an alchemist at heart. “No chemist would exist today without the curiosity and endless trials and errors of alchemists working and discovering nature,” Klein says, citing the works of scholars such as Paracelsus, Jan Baptist van Helmont, and Avicenna who laid groundwork for modern medicine and chemistry.

In creating JK7, Klein has again embraced a botanical challenge: developing an organic skincare line that maximizes a plant’s life force. Having founded the successful organic skincare line Jurlique decades earlier, Klein is no stranger to the meticulous, laborious process required. His dedication to quality in research, ingredients, and sourcing practices remains paramount. Drawing upon his chemistry expertise, Klein scrutinizes a plant’s bioavailability and the ways its derivative interacts with those of other plants. He experiments with these results until a refined, potent product emerges.

植物を金に変える オアフ島ノースショアにある丘の中腹の広大な敷地に、ユルゲン・クラ インさんの邸宅は建っている。その豪華なエステートの一角にあり、薬 局と本格的な化学実験室を兼ね合わせたおとぎ話に出てくるコテージ のような趣のある研究室では、科学に基づいた様々な実験が日々行わ れている。カウンターの上には、ビュレットやバーナー、秤や蒸留器に混 ざって、沢山のビーカーとフラスコが並ぶ。壁を一周する棚の上には様 々な実験器具が所狭しと置かれ、部屋の隅には巨大な鉄製の実験装 置が構えている。

部屋の向こう側では、様々な種類の植物を使った実験が行われてい る。干したノコギリソウやクローバーの花、粉末状の甘松の根やイラク サの葉などが入ったガラスの瓶が整然と並び、その近くの棚には淡い蜂 蜜色や深い琥珀色をした金の液体のエッセンシャルオイルの入ったい くつもの小瓶が置かれている。蒸留液には簡略化された識別ラベルが それぞれ貼られ、「JK7」の成分に適しているかテストされる。JK7は世 界で最もエクスクルシブで高価な高級スキンケアラインの1つである。 ドイツ出身のクラインさんは、森の近くに住んでいたこともあり、幼い ことから森の中を探検し、自然に触れて育った。彼が自然療法を初めて 学んだのは祖父母からであった。「私は幼い頃から、祖母が庭で採れた 野菜やハーブを使って民間療法の薬を作るのを手伝っていました。私 の祖父は馬が負った大きな傷や骨折をヒレハリソウやキンセンカで治し ていました」という。クラインさんは化学者であるが、化学的な手段を用 いて様々な物質をより完璧なものに精錬しようと試みる錬金術師でも ある。「現代医学と化学の基礎を築いたパラケルススやヤン・バプティス タ・ファン・ヘルモント、アヴィセンナといった学者による功績をはじめ、 歴代の錬金術師による自然への探求心と数え切れない試みと失敗なし では、現在の化学者は存在しません」と彼は力説する。

錬金術や生物科学に基づき、科学的にも証明された効能の高いハー ブをベースにしたこれまでになく贅沢な自然化粧品のJK7を開発する ため、クラインさんは再び植物への挑戦に取り組んだ。数十年前に 高 品質のオーガニックスキンケア製品「ジュリーク」を開発し、自然療法分 野のパイオニアとして成功させた経験を持つクラインさんは、そのよう な製品の開発は、気の遠くなるほど几帳面で手間のかかるプロセスで あることを誰より理解していた。研究、原料、調達における品質管理に 徹底してこだわるクラインさんは、化学的専門知識に基づき、植物の持 つバイオアベイラビリティー(生物学的利用能)や、その成分が他の植 物の成分とどのように相互作用するかを精査する。こうして出来上がっ た成分の実験を何度も繰り返すことで完成度を高め、有効とみなされ たものを製品化していく。

Essential oils and extracts are vital components to the rejuvenating products found at HalekulaniSpa.

Creators of Pure Mana, Sue Mandini and Kollette Stith, are involved with every level of production, from farm to the customer’s hands.

ピュア・マナを手がけるスー・マ ンディーニさんとコレット・ステ ィスさんは、農場での栽培から 商品が顧客の手に渡るまで、 全工程に携わっている。

Today, Klein, with the help of his wife, Karin, has curated a collection of 21 products. Capturing nature’s power in a bottle is expensive, and potency does come with a price. The signature JK7 Rejuvenating Serum Lotion, a cult favorite among those with tastes for luxury beauty, is priced at $1,800 for a 30-milliliter bottle.

It’s not uncommon to find Jurgen tinkering away late into the night when he and Karin are at their North Shore estate. That’s what alchemists do. Recently, he received a call about his natural skincare from an Australian colleague. “Jurgen, you have not made gold from crude metals,” he recalls the modern alchemist telling him. “But you have made gold from water and natural oils.”

現在、クラインさんは妻のカリンさんの助けを借りて、21種類の製 品からなるスキンケアコレクションをプロデュースしている。自然の力 をボトルに閉じ込めるため、多大な労力と時間を費やして開発された 製品は、高い効能と価格にも反映されている。最高級化粧品を嗜好す る女性たちの間で絶大な支持を得ているシグネチャー製品、「JK7リジ ュビネーティング・セーラム・ローション(30ml)」の価格は一本1,800 ドルである。

ノースショアのエステートではユルゲンさんとカリンさんの二人が夜 遅くまで研究を続けていることは珍しくない。それが錬金術師というも のだ。JK7のスキンケアについて知った同じく錬金術師のオーストラリ アの友人からの電話で、「ユルゲン、君は粗金属から金を作れなかった けど、水と天然油から金を作ることに成功したね」と言われたとユルゲ ンさんは話す。

the promise of the land

An experience is a collection of a thousand details. For Sue Mandini and Kollette Stith, creators of luxury skincare line Pure Mana, it’s about the intention behind these details.

“We are involved at every level of production, from farming and harvesting to processing and packaging,” Stith explains. At her farm, Mahina Mele Farm, the bounty of its macadamia orchards is transformed into the primary base of Pure Mana’s elixirs. During twice-yearly macadamia nut harvests, the two women can be found under the orchard’s leafy canopy, combing the ground for tawny, spherical nuts. Once sorted, the nuts are painstakingly husked, cracked, dehydrated, and pressed for oil—all by hand. The farm, nestled in the tropical uplands of Kealakekua on Hawai‘i Island, is the only certified organic macadamia nut farm in the United States.

“We like to say our products are from our soil to your soul,” Stith says. Macadamia nut oil is recently in vogue in the cosmetics industry due to its significant amount of squalene, an organic compound that protects and nourishes the skin. Found in both plants and animals, it is used as a moisturizing base in cosmetics.

“Strangers would ask what we were using,” Mandini recalls of the early days when she and Stith began using home-pressed oil as part of their daily beauty regimes. “Our friends noticed our ‘glow.’” As the compliments continued, the pair realized that the shared interests that had shaped their friendship—motherhood, homesteading, sustainable island living—could also support the creation of a dream business: an organic, Hawai‘ibased luxury skincare line.

Pooling their skills, time, and talents, Mandini and Stith debuted Pure Mana in 2015 as a respite from synthetic, mass-made cosmetics. Instead of artificial binders, emulsifiers, and colors, the collection takes inspiration—and ingredients— directly from nature.

大地の恵み 無数のディテールが作り上げるもの。ハワイのラグジュアリースキンケ アブランド、「ピュア・マナ」を手がけるスー・マンディーニさんとコレッ ト・スティスさんは、一つ一つのディテールに込められた思いを大切に している。

「私たちは栽培から収穫、加工、包装まで、すべての生産工程に携わ っています」とスティスさんは説明する。彼女の所有するマカダミア農園 「マヒナ・メレ・ファーム」で収穫されるナッツが、ピュア・マナ製品のベ ースに欠かせない原料となっているのだ。年2回のマカダミアナッツの 収穫期には、2人は緑の葉に覆われた木の下に落ちた黄褐色で丸いマ カダミアナッツを拾う。実の選別が終わると殻をむき、割って中身を取 り出して乾燥させ、圧搾してオイルを取り出す。ここまで全ての工程が手 作業である。ハワイ島ケアラケクアの熱帯高地にあるこの農場は、米国 で唯一オーガニック認定されているマカダミアナッツ農園だ。

「私たちの製品のコンセプトは、『私たちの大地からあなたの心へ (From our soil to your soul)』です 」とスティスさん。マカデミアナ ッツオイルは、皮膚を保護して栄養を与える有機化合物の美容成分で あるスクワランを豊富に含むため、化粧品業界で最近注目を集めてい る。スクワランには植物性と動物性の両方があり、化粧品の保湿剤とし て使用されている。

マンディーニさんとスティスさんが、毎日の肌の手入れに自宅で搾っ たオイルを使い始めた頃のことだ。「初めて会う人たちから、肌に何を使 っているの?と聞かれるようになったんです。友人たちも私たちの肌の 輝きに気づきました」とマンディーニさん。しばらく同じようなことが続 き、子育てや家事、ハワイでの環境に配慮したサステイナブルなライフ スタイルといった価値観を共有する二人は、共通の夢であったビジネス を立ち上げることにした。こうして生まれたのが、ハワイ産の高級オーガ ニックスキンケアライン「ピュア・マナ」だ。

マンディーニさんとスティスさんは、これまでに培ったスキルと才能 を発揮し、多くの時間を費やして2015年、大量生産された合成化粧品 ではない「ピュア・マナ」をデビューさせた。人工的な結合剤や乳化剤、 色素は一切使用しない製品ラインナップは、自然から直接インスピレー ションと原料を得ているという。

Botanicals function as anti-aging, brightening, luminizing, and cleansing agents. They eschew artificial ingredients, opting instead for organics.

植物由来成分は、アンチエイジングや美白、角質ケアやクレンジングに 効果がある。彼らは人工的な成分を使用せず、オーガニックな原料を 使用している。

ピュア・マナは、米国で唯一 オーガニック認定されている マカダミアナッツ農園のナッツ

から採れるオイルを原料に 使用している 。

Today, the recursive beauty of a mandala is found on the collection’s elegant packaging. Specialty violet-flame glass bottles preserve the vitality of the oils. Inside the Soul Serum, ethereal notes of tuberose and Hawaiian sandalwood surround a single, delicate crystal. Such details are among the multitude that go into creating Pure Mana products. For the two friends, each facet is part of a lovely process.

コレクションの上品な包装には、美しい曼荼羅模様がデザインされ、容 器にはオイルの生命力を保つために特殊なバイオレットフレームと呼ば れるガラス製のボトルが使用されている。「ソウル・セーラム」は、優れた 浄化作用とエネルギーを高めるクリスタルの効能を含み、月下香とハワ イアンサンダルウッドの優美な香りが特徴のセーラムだ。ピュア・マナの 製品に込められた多くの手間やディテール、その全てが2人にとっては 愛しいプロセスなのだという。

Dress, The Row; Tiffany HardWear ball hook earrings and graduated

link necklace in 18k gold, all from Tiffany & Co.

Dress, The Row; Tiffany HardWear ball hook earrings and graduated

link necklace in 18k gold, all from Tiffany & Co.

TEXT BY KYLIE YAMAUCHI

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

TEXT BY KYLIE YAMAUCHI

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

TEXT

TEXT