Ulrich Krauer General Manager Halekulani

Ulrich Krauer General Manager Halekulani

In Hawai‘i, a sense of gratitude and indebtedness for the past continue to be a source of inspiration. At Halekulani, we are committed to the timeless spirit of aloha as a way to care for our guests and honor all those who came before us. This gesture is most prevalent in how we interact with the trees of Hawai‘i that have been here generations before us, from kiawe to ‘ōhi‘a.

Within these pages of Living, learn about how we are paying tribute to the presence of both. In the Halekulani lobby and at Orchids, you may have noticed new sculptures crafted with salvaged branches from our beloved kiawe tree, an enduring symbol of our hospitality. These sculptures that welcome you to the grounds are a direct product of a collaboration between a master sogetsu ikebana artist and renowned local sculptor. Together, they transformed parts of the kiawe into a sogestu “flowork” displaying the harmonious blend of flowers and artwork. Please take a moment to visit them during your stay.

Also in this issue, we pay our respects to other iconic tropical trees. Turn to our feature on ‘ōhi‘a, considered the mother of the native forest. In the valley of Mānoa, not far from here, a revitalization of the tree is underway. Learn about how this tree is rooted in Hawaiian culture and tradition and what we can all to do support the species, especially as we travel among the island chain.

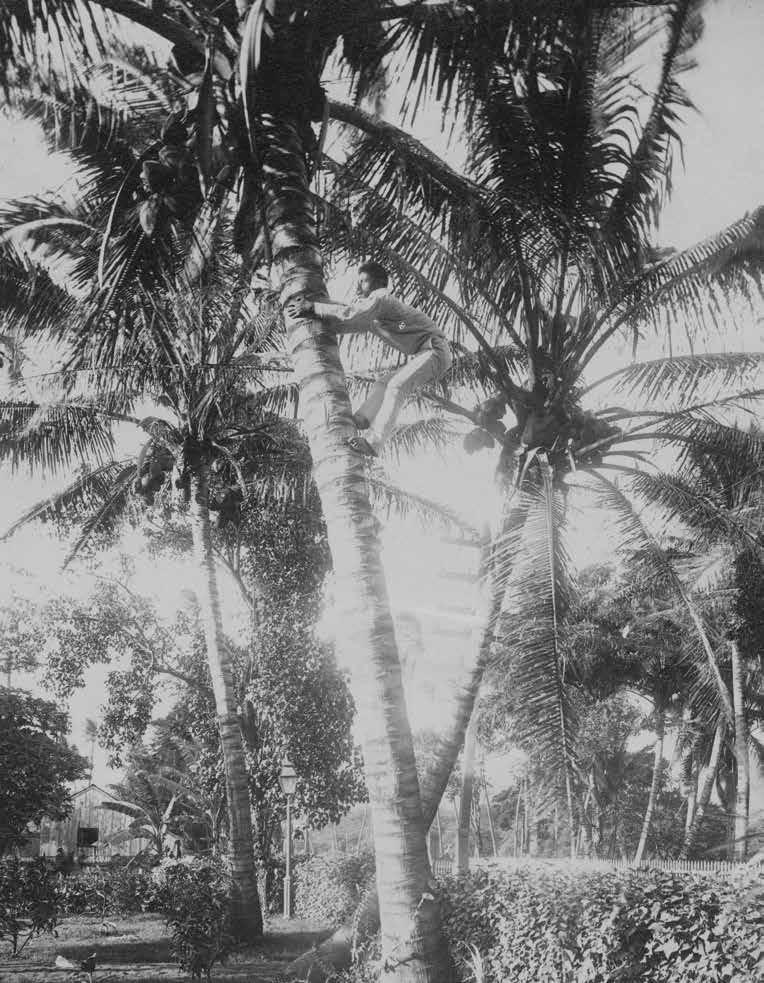

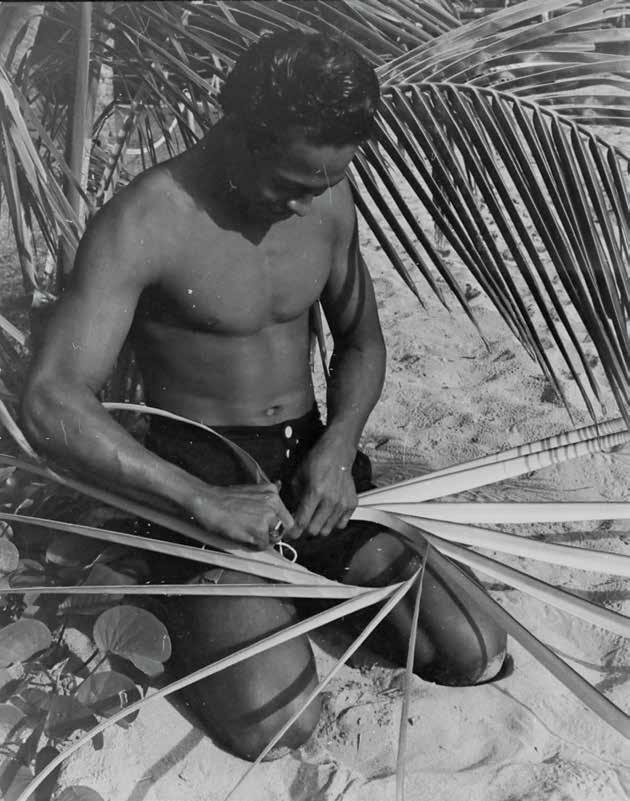

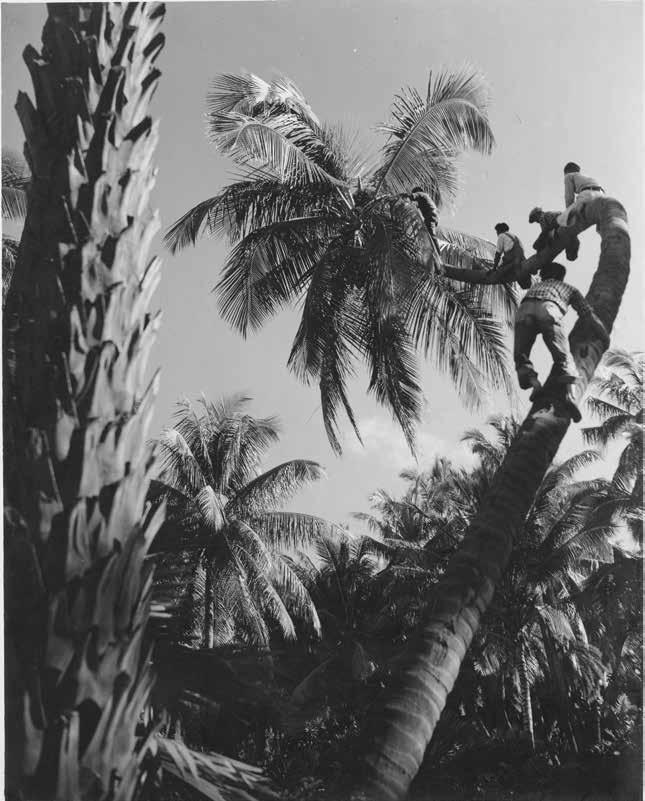

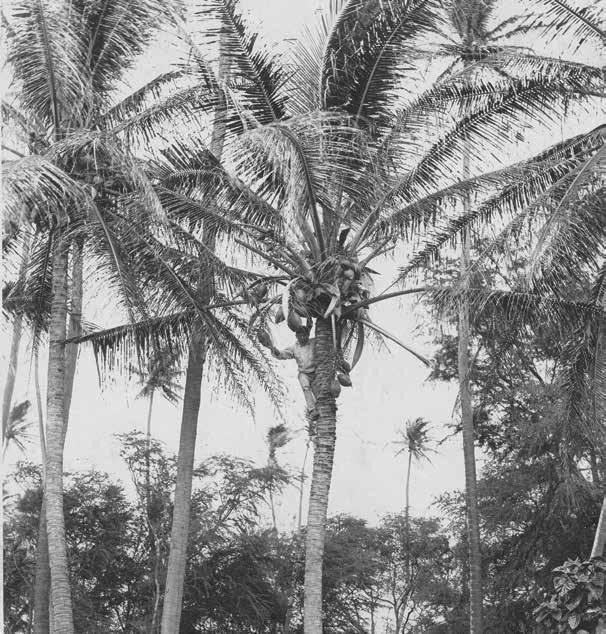

We also get to the roots of the once-robust harvest of the coconut palm, a canoe plant brought to Hawai‘i by the first settlers. We travel down its turn-of-thecentury past, when its cultivation in the islands was at its peak, to remember how its flavor rooted itself in our modern day palate, a taste of the islands we celebrate with our famous coconut cake.

Finally, in honor of Mother’s Day, we pay homage to the moms of our local creatives. Go inside their childhood homes to get a better understanding of their special kinships.

We hope this edition of Living offers a portrait of Hawai‘i unlike any other. Long after your stay in the islands ends, may it serve as an irreplaceable keepsake of your time here with us.

Warmly, Ulrich Krauer General Manager Halekulani現代においても、先祖への感謝と畏敬の念が人々の創造力の源となっ ているハワイ。ハレクラニでは、いつでも変わらぬアロハのこもったおも てなしでお客様をお迎えし、先人を敬うことを常に心がけています。私 たちの何世代も前からこの島に生育するキアヴェやオヒアといったハワ イの樹木に対する取り組みもまたハレクラニのこのような姿勢の現れ と言えるでしょう。

今号のリビングでは、当ホテルが取り組んでいるこれらの樹木にま つわるプロジェクトについてご紹介します。ハレクラニのロビーとオーキ ッズを飾る新しいオブジェにすでにお気づきの方もいらっしゃるかもし れません。お客様をお迎えするこれらの作品は、ハレクラニに根付くお もてなしの永遠のシンボルであるキアヴェの木の枝を大切に保存し、再 利用して作られたものです。草月流いけばな作家と地元の彫刻家のコ ラボレーションによって製作されたオブジェは、草月流の花と芸術が見 事に調和した空間創り「フラワーク」によって、キアヴェの木に新たな命 を吹き込んでいます。ご滞在中に是非一度ご覧いただければ幸いです。 この号では、ハワイを象徴する樹木「オヒア」についてもご紹介してい ます。ハワイの原生林の母とされるオヒア。現在、ワイキキからも遠くな いマノアの渓谷では、この木の植樹活動が進行中です。ハワイ文化と伝 統に根ざしたオヒアの木を守るために私たちに何ができるのか、ハワイ 諸島を巡る際に知っておくべきことについても触れています。

またかつてハワイの島々に茂っていたココヤシの木のルーツについ ても掘り下げてまいります。椰子の木は、初期の入植者たちによってカ ヌーでハワイへ持ち込まれた植物でした。島での栽培がピークだった頃 を振り返り、ハワイを象徴する食品となっているヤシの実が、美味しい ココナッツケーキはもちろん、現代のハワイの食文化にどのように根付 いているかを探ります。

最後に、ハワイで活躍するクリエイターの母親像に焦点を当てた母 の日因んだストーリーをお楽しみください。彼女たちの生まれ育った家 庭環境や特別な親子関係についてフィーチャーしています。

今号のリビングを通して、ハワイならではの魅力に少しでも触れてい ただけることを願っています。本誌はハワイの旅の記念に是非お持ち帰 りください。 ハレクラニ総支配人 ウーリック・クラワー

HALEKULANI CORPORATION

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER

PETER SHAINDLIN

CHIEF EXECUTIVE ADVISOR

PATRICIA TAM

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER

JASON CUTINELLA

CHIEF REVENUE OFFICER

JOE V. BOCK

JOE@NMGNETWORK.COM

GENERAL MANAGER, HALEKULANI

ULRICH KRAUER

DIRECTOR OF SALES & MARKETING

GEOFF PEARSON

CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER

LISA YAMADA-SON

LISA@NMGNETWORK.COM

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

ARA LAYLO

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

MATTHEW DEKNEEF

HALEKULANI.COM

1-808-923-2311

2199 KALIA RD. HONOLULU, HI 96815

PUBLISHED BY NMG NETWORK

36 N. HOTEL ST., SUITE A HONOLULU, HI 96817 NMGNETWORK.COM

© 2019 by Nella Media Group, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted without the written consent of the publisher. Opinions are solely those of the contributors and are not necessarily endorsed by NMG Network.

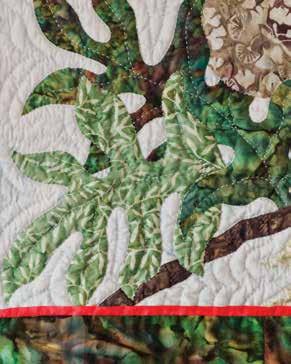

Quilter Patricia Lei Murray considers her work to be a meditative experience.

レイマレーさんにとって キルト作りは瞑想の ようなものだという

A Sense of Renewal

Reeling in Honua

Art of the Stitch

Along the Coconut Belt

WELLNESS

Hearty ‘Ōhia

Mother Knows Best

Creation of Kapa

Coffee & Pancakes

CITY GUIDES 118

Explore: Aloha for All 126

Explore: Travel in Tune 134

Spotlight: Hildgund

A species of the mesquite tree, kiawe can live for more than 1,000 years.

マメ科植物でメスキートの 一種のキアヴェの木は樹齢が 千年以上になるものもある。

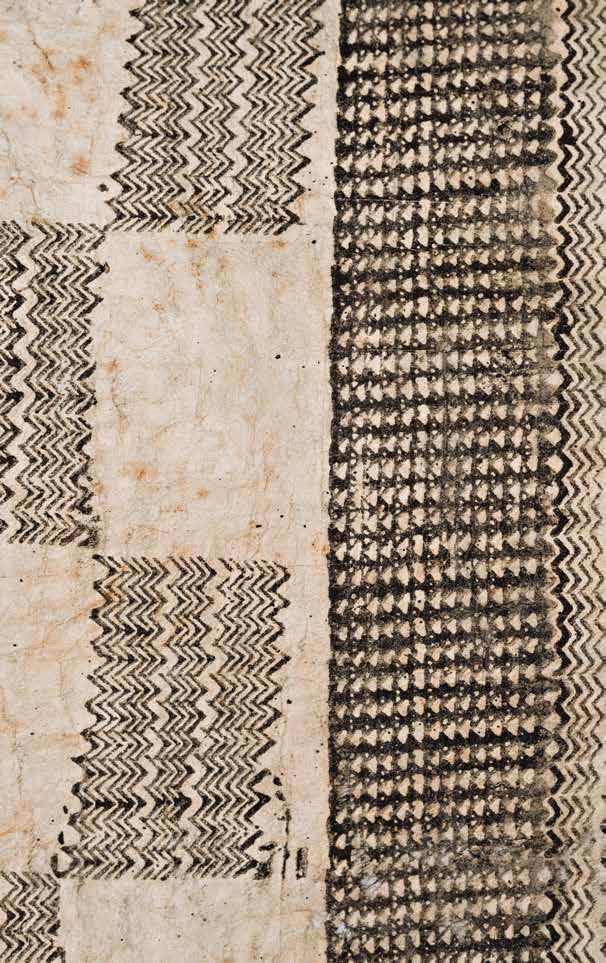

ABOUT THE COVER:

The cover image, shot by photographer John Hook, of a kapa design. Read about this Hawaiian artform on page 74. To learn more about the culture of kapa, view the video at halekulaniliving.tv.

Halekulani Living

At the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, its ethnology collections preserve ancient kapa.

バーニース・パウアヒ・ビシ ョップ博物館にある民族学 のコレクションには古代の カパが保存されている。

102 ABOUT THE COVER:

TABLE OF CONTENTS

目次

ARTS 22

新しい息吹 32

ホヌアの旅の記録 38 ステッチの芸術 CUISINE 50 ココナッツベルト CULTURE 60

母親が一番よく知っている 74

カパ作り

Splendid pastries are served with an assortment of coffee drinks and teas at the Veranda at Halekulani.

ハレクラニのベランダでは 各種コーヒードリンクや紅茶とともに 美味しいペイストリーが味わえる。

ジョン・フック氏撮影の表紙の写真は、カパのデザイン。このハワイの伝統工芸については74ページで紹介しています。 カパについて詳しくは、halekulaniliving.tv のビデオをご覧ください。

Halekulani Living 表紙について:

WELLNESS 92

オヒアの復活 FASHION 102

コーヒーとパンケーキ CITY GUIDES 118

すべての人にアロハを 126

音楽の旅 134

スポットライト:ヒルガンド

Living TV is designed to complement the understated elegance enjoyed by Halekulani guests, with programming focused on the art of living well. Featuring cinematic imagery and a luxurious look and feel, Living TV connects guests with the arts, style, and people of Hawai‘i. To watch all programs, tune into channel 2 or online at halekulaniliving.tv.

CREATION OF KAPA

カパ作り

Kapamakers continue to pass down, untangle, demystify, and reclaim this nearly forgotten practice.

長年の研究と鍛錬によって失われつつあるカパの神秘を 紐解き、復活させたカパ職人たち

A SENSE OF RENEWAL

新しい息吹

草月流いけばなの講師と彫刻家が共同制作した ハレクラニのロビーに新たな命を吹き込む花のオブジェ 客室内でご視聴いただけるリビング TVは、ハレクラニでのご滞在をお楽し みいただくため、より豊かで健康的な ライフスタイルをテーマにした番組を ご提供しています。魅力的な映像と豪 華な演出を通して、アートやファッショ ン、食文化、ハワイの人々について紹介 しています。 WHAT TO WATCH

An ikebana sensei and an acclaimed sculptor debut a floral centerpiece in the lobby of Halekulani.

watch online at: halekulaniliving.tv

COFFEE & PANCAKES

コーヒーとパンケーキ ホノルルの美味しいコーヒーと心地よいブランチを 心ゆくまで楽しむ

Sip and taste your way through the wonderful brunch offerings of Honolulu.

ART OF THE STITCH

針と糸の芸術

Hawaiian quilts embody treasured memories and remind us of the value of craftsmanship.

職人技の光る美しいハワイアンキルトは豊かな歴史や 思い出に満ちている

THE LIVING GUIDE TO TEMPLES

リビングの寺院ガイド

In search of wholeness and good fortune, a writer visits three distinct Asian temples on O‘ahu.

安らぎと幸運を求めて、オアフ島にある3つの寺院を訪ねた

TEXT BY MATTHEW DEKNEEF

IMAGES BY MARK KUSHIMI

TEXT BY MATTHEW DEKNEEF

IMAGES BY MARK KUSHIMI

文=マシュー・デニーフ 写真=マーク・クシミ

A SENSE OF RENEWAL

新しい息吹

An ikebana sensei and an acclaimed sculptor debut a floral centerpiece that breathes new life into Halekulani’s welcoming space.

草月流いけばなの講師と彫刻家が共同制作したハレクラニのロビーに新たな命を吹き込む花のオブジェ

Hours after the 129-year-old kiawe tree outside House Without A Key fell in the night, artist John Koga received a phone call. It was Halekulani’s executive team. They sought his advice for a looming task: What is a proper way to handle the deconstruction of its tremendous branches? Koga, who had regularly displayed artwork on the hotel’s grounds, suggested they try to save every bit of the timber. He didn’t know exactly what for, only that it would be wise to salvage and store all of it for the sake of art.

The first creation born of the idea to repurpose the kiawe’s lost branches into something new and lasting has taken shape as a vessel set before the hotel’s check-in counters. Koga worked with Hiromi Sugioka, a Sogetsu ikebana master, to create the living fixture that is now on view: a hollowed-out vase composed of reclaimed wood that bursts forth with a high-and-wide floral arrangement. One week, it features a gallant display of ferns among a delirium of white and red anthuriums punctuated by bubblegum pink-hued heliconia that dangle like crystals from a chandelier. The next week, this fountain of flowers is envisioned afresh. Here, in the center of the lobby at Halekulani, harmony constantly takes shape.

“I wanted to revive this kiawe in a new form,” said Sugioka, who conceived of the piece and directed its creation. Over the Thanksgiving holiday in 2018, Sugioka and Koga worked on the project at Koga’s Mānoa home. Though the two artists come from different disciplines, what they share is an obedience to organic forms and an exacting eye. Referencing the Sogetsu sensei’s hand-drawn design of the vessel, Koga labored to find practical ways to assemble it—cutting, fitting, stacking, and drilling stumps together on the floor of his studio. “He was able to construct and make into a reality exactly what I have envisioned for this project,” Sugioka said.

ハウス・ウィズ・アウト・ア・キーの前にあった樹齢129歳のキアヴェの 木が倒れたその夜。数時間のうちに芸術家であるジョン・コガさんの 電話が鳴った。それはハレクラニのエグゼクティブチームからの電話 であった。折れたキアヴェの巨大な枝をどう処理すべきかアドバイス を求められると、ホテルの敷地内に定期的にアートを展示している コガさんは、何らかの形でアートにできると考え、まずは一片も残さず 全ての木材を大切に保存すべきだと提案した。

このキアヴェの木に新しい命を吹き込み、永続的な形で再利用 するというユニークなアイディアから生まれた初の作品が現在、ハレク ラニのロビーに飾られている。コガさんと草月流いけばな講師の 杉岡宏美さんが共同で制作したこの生きたオブジェは、再生木材を 組み合わせたもので、花が活けられるよう中が空洞になっていて、背の 高く幅の広い生花のアレンジメントをより一層美しく引き立ててくれる。 ある週には、光沢のある白と赤のアンスリウムに青々としたシダ、シャン デリアのように揺れるピンク色の華やかなヘリコニアがアクセントとして 活けられていた。また次の週には、まるで花が沸いてくる泉のように新 しいディスプレイに入れ替わる。ハレクラニのロビーの中央には常に 「調和」というものが形として存在する。 「キアヴェの木を新しい形で蘇らせたかったのです」と、この作 品の発案と制作を手がけた杉岡さんは語る。2018年の感謝祭の休暇 中、二人はコガさんのマノアの自宅でこのプロジェクトに取り組んだ。 二人の芸術家は、専門分野は違っても、自然のありのままの形を生か す感性と厳格な芸術的視点を持っている点で共通している。杉岡さん が手描きした花器のデザインをもとに、コガさんは自らのスタジオで木 を伐採して穴を開け、試行錯誤を重ねながら積み木パズルのように 組み合わせて、実用性を兼ね備えた作品に仕上げた。杉岡さんは「彼 は実際に私がイメージした通りの作品を形にしてくれました」と満足 げだ。

The finished kiawe sculpture greets guests upon their arrival in the Halekulani lobby. It symbolizes balance, serenity, and the natural world.

バランスと安らぎ、ありのままの自然を象徴するキアヴェのオブジェは、 ハレクラニのロビーで到着するゲストを出迎えてくれる。

The finished shape honors the tree’s natural, woodsy character with soft and wavy edges that follow the curves of each branch. Contrasted with this are sawed surfaces left intentionally rough and unfinished. In an appeal to ikebana’s enthusiasm for balance and form, the chest-high sculpture is made to be conspicuous without being flamboyant. The vase is sturdy enough to physically support all sorts of arrangements, but fluid enough to become one with them. It should breeze over the guests like a “breath of fresh air,” Koga said, that “represents all of Hawai‘i’s nature and beauty coming together in one little object.”

With the kiawe sculpture complete and in place at the Halekulani lobby, Sugioka composed its first arrangement. She placed and moved stems in and about the vase slowly but with confidence, like a chess expert moving pieces around a chessboard. Every motion she made appeared clear in thought. By the time she placed the final stem, the sculpture had taken on a numinous air. For Koga, witnessing an artist of Sugioka’s caliber at work and experiencing her reverence for Halekulani’s kiawe was “the most beautiful part of this journey.”

Sugioka, as an ikebana practitioner, treats her usual medium—the islands’ tropical flora—with the same measured degree of deliberation that renowned classic artists have given plants and their blooms: van Gogh’s irises, O’Keeffe’s engorged petals, Manet’s prosaic attention to peonies in a

完成したオブジェは、枝の曲線に沿った柔らかい波状の輪郭を 持ち、木本来の自然な質感が生かされている。それとは対照的に、切り 出されたままの粗い断面が意図的に残され、作品にメリハリを与えて いる。バランスと形を大切にするいけばな独特の感性が生かされ、華 美すぎることなく控えめでありながら、目を引く存在感を放つ。豪華な アレンジメントを支えられるよう頑丈にできているが、生花や植物と一 体化するしなやかさも感じさせる。それはゲストを迎え入れる「新しい 息吹」のようだとコガさんは言う。「ハワイの自然と美しさを象徴するも のすべてがこの一つの作品に詰まっているのです」。

キアヴェのオブジェが完成し、ハレクラニのロビーに設置される と、杉岡さんはまるで将棋士が碁盤の上の駒を動かすようにゆっくりと した慣れた手つきで花器の内側と周りに茎を配置していった。彼女の 手の動きは優雅で自信に満ち、一本ずつ形を作り上げていく。最後の 茎を活け終わると、オブジェは華やかなオーラを放っているようにさえ 見える。コガさんにとって、杉岡さんという芸術家の仕事ぶりと彼女が ハレクラニのキアヴェの木に抱く畏敬の念を目の当たりにできたことは 「何より素晴らしい体験」だったという。 いけばな作家の杉岡さんは、日常的にハワイの熱帯植物を活け るときも一本ずつ熟考しながら丁寧に作業する。それはヴァン・ゴッホ のアイリスやオキーフの大胆な花びら、マネのクリスタつの花瓶に入っ た牡丹などに象徴されるアートの巨匠が描く植物や花のディテールと 同じだ。アートの主題としての花と葉は、いつの時代も芸術家や鑑賞す る者の心を落ち着かせ、考える機会を与えてくれるものだ。永続的に残 るキアヴェのオブジェの中で変化し続ける花のディスプレイも同じであ

“I wanted to revive this kiawe in a new form,” says ikebana master Sugioka, who conceived the overall sculpture.

「キアヴェの木を新たな 形で蘇らせたかったので す」と語るのはこの作品 の発案者の杉岡さん。

crystal vase. As subject matter, flowers and foliage graciously grant artists and observers reason to slow down, pause, and reflect. If one takes the time, one can see this in Sugioka and Koga’s piece, in the way its flowers change while the sculpture remains the same. At its most elemental, their collaboration is a reminder that a piece of art can be wrought from the quotidian earth.

る。杉岡さんとコガさんが共同制作したこの作品は、原点に回帰すれ ば、アートというものは私たちの生活を支える母なる大地から生まれ るものであると教えてくれている。

文=ソニー・ガナデン

写真=エリーゼ・バトラー

&ジョン・フック

REELING IN HONUA

ホヌアの旅の記録

After four years, Hōkūle‘a , the famed deep-sea sailing canoe, completed its circumnavigation of the globe. Nearly every moment of that odyssey was documented on film.

ハワイの航海カヌー、ホクレア号の世界一周の旅から4年を経て、全行程の貴重な瞬間を収めた映画が完成した。

Through filmmaking, a rare documentative opportunity of the voyaging canoe Hōkūle‘a arrives to the screen.

Running more than two hours, the documentary Moananuiākea: One Ocean, One People, One Canoe tracks the Hōkūle ‘ a ’s epic Mālama Honua Worldwide Voyage, which traversed more than 41,000 nautical miles to 23 countries, 150 ports, and eight UNESCO Marine World Heritage sites. Filmmakers followed the entire journey, from the training of the first crew and the departure from Hilo, Hawai‘i Island, through the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic oceans, to the canoe’s homecoming in Honolulu. Adventures and bonds were created that could not have been foreseen at its inception: Children were born; the last surviving founder of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, Ben Finney, passed away a month prior to the voyage’s completion in June of 2017. The voyage of Hōkūle ‘ a , and its story of oceanic adventure, indigenous resilience, and environmental activism, was retold around the world.

『モアナヌイアケア:一つの海、一つの民、一隻のカヌー』は、23カ国 150港と8つのユネスコ世界遺産を巡り、4万1千海里を旅した伝統 航海カヌー、ホクレア号の歴史的な世界一周航海「マラマホヌア」を記 録した2時間半におよぶドキュメンタリーだ。撮影隊は、第一陣の乗組 員のトレーニングから、ハワイ島ヒロ港での出帆、太平洋、インド洋、大 西洋の航海、母港ホノルルへの帰港まで、世界一周の全行程に同行し た。思いがけないほど多くの冒険や絆を生んだ壮大な旅。その間には 新しい命の誕生があり、2017年6月の旅の終了の一ヶ月前にはポリネ シア航海協会創始者の最後の一人であったベン・フィニー氏が逝去し た。ホクレア号の世界一周の旅は、オセアニア航海の歴史や先住民の 逞しさ、そして環境保護のメッセージを世界中に広めた。

「総勢8人でこの旅を記録しました」。地元の制作会社のオイヴ ィTVの共同創立者でCEOであり、ブライソン・ホエさんとマウイ・タウ オタハさんと共同でこの映画を制作した主任プロデューサーのナアレ フ・アンソニーさんは語る。生中継やウェブでのストリーミングを行い、 世界中のニュース番組へ提供する素材の撮影や編集を担当した オイ ヴィTVの撮影隊は、時にハワイアンのチャント(祈祷)やヘミングウェ イやメルヴィルの海洋小説に出てくるような悪条件下での作業を強い られたという。ホクレア号の双胴に打ち上げる波や、荒海の中、乗組員 たちが船体にしがみつくシーンが映画にも出てくる。1970年代に実現 したホクレア号の初航海についてアンソニーさんは、「ホクレア号の初 航海は全て映像に収められていたのです。2014年に私たちがこのドキ 航海カヌー、ホクレア号の旅を 記録した貴重なドキュメンタリ ー映画が完成し、公開された。

“Eight of us worked on the voyage,” says lead producer Nā‘ālehu Anthony, who co-produced the film with Bryson Hoe and Maui Tauotaha under local production company ‘Ōiwi TV, of which Anthony is the co-founder and CEO. The ‘Ōiwi TV documentarians provided live updates and web streaming, and shot, edited, and cut materials for international news pieces. The documentarians worked through perilous conditions, the type familiar to readers of Hemingway and Melville. The film includes several scenes of waves breaking over

Hōkūle‘a ’s twin hulls as midshipmen brace through intemperate seas.

“In the first voyages of Hōkūle‘a , everything was on film,” Anthony says of the canoe’s earliest outings in the 1970s. “In 2014, when we started this documentary, we spent most of our time figuring out what they did in the film days, how to keep things dry.”

The Polynesian Voyaging Society was founded in Honolulu in 1973. It was created, in part, to test legends of deep-sea Pacific voyages recounted by story, chant, and legend and taught by specialized sects of the community, as well as competing theories of transoceanic voyages made by Polynesians prior to Western contact. In the intervening centuries since Western contact, many traditional forms of canoe-building and navigation had been lost. The Polynesian Voyaging Society spawned a cultural resurgence of Pacific identity. Deep-sea voyaging canoes have been built throughout the Pacific and on all the major Hawaiian islands since Hōkūle‘a , and thousands of sailors and navigators have since learned to guide them on perpetual voyages of discovery.

Those who participated in Mālama Honua have been forever changed. “After the world premiere screening I noticed that the orchestra pit, the one in front of the stage, that’s the same size as the deck of Hōkūle‘a ,” Anthony says, of its 62 feet by 10 feet space. “That’s all the room we had. As filmmakers, we had to get new angles, new shots. When we started, we were somewhat novices at this.”

As a Pacific odyssey, the Mālama Honua journey was the first of its kind. Ports presented range of experiences to the crew members. Some were sparsely populated anchorages in which the crew readied the canoe and connected with a host to get something to eat. Other ports were global cities in which elaborate cultural festivals were attended by thousands, replete with offerings, speeches, dignitaries, and the presentation of gifts.

ュメンタリーを撮り始めて直面した課題は、フィルムを使用していた時 代に彼らはどうやって機材を濡らさずに撮影できたのか、を解明するこ とでした」と語る。

1973年にホノルルで結成したポリネシア航海協会は、物語やチ ャント、伝説を通じて語り継がれ、コミュニティの一部の人々の間で受 け継がれてきた伝統的なカヌーによる太平洋航海術や、西洋文化の影 響を受ける以前のポリネシア人による大西洋横断についての相反する 理論の実証を目的に設立された。ハワイでは西洋の影響を受けてから 何世紀もの間、伝統的なカヌー製法や航海技術は失われてしまってい た。ポリネシア航海協会による太平洋独自の文化復興運動によって、 ホクレア号が誕生して以来、太平洋全域やハワイ諸島全島で多くの遠 洋航海カヌーが作られるようになり、何千人もの航海士やナビゲータ ーが未知の発見の旅へと続く航海術を習得している。

マラマホヌアでの経験は、参加者たちに多くの影響を与え、彼ら の人生を永遠に変えるものとなった。アンソニーさんは、「ワールドプレ ミアの上映会のあと、ステージ前にあるオーケストラのピットの広さが ホクレア号の甲板と同じだと気づきました。限られた空間で角度やフ レームを変えて撮影するのに最初は苦労しましたね」と幅3m奥行き 18mのカヌーの上での撮影を振り返る。

マラマホヌアは、太平洋を旅する航海としては世界初の規模で あった。寄港先では多くの貴重な体験が乗組員を待っていた。人口の 少ない停泊地ではクルーたちが自らカヌーを整備し、ホストと連絡を 取って食べ物を入手することもあった。一方、国際的な都市では要人 のスピーチや沢山の供え物やギフト贈呈が用意され、数千人もの人々 が参加してカヌーの到着を祝う盛大なイベントが行われた。

複数の区間を総勢245名体制で帆走するホクレア号の航海中 には、ニュージーランドと南アフリカで乾ドックに入り、何ヶ月もわたっ てカヌーの修理が行われた。この映画は、教師と生徒たちが海での凝 縮された時間をどのように過ごしたか、そしてクルー達が訪れた先々で 体験した感動的な文化交流を捉えている。その中でも主役的な存在と

Director Nā‘ālehu Anthony, pictured opposite, dedicated at least three years to capturing the emotions and lessons that the sea offered to those aboard the canoe.

監督のナアレフ・アンソニー氏は海上で過ごすカヌーの乗組員たちの 感情や旅から学んだ経験を捉えるのに少なくとも3年を費やした。

The film Moananuiākea recounts the worldwide voyage of Hōkūle‘a. It’s a story of oceanic adventure, indigenous resilience, and environmental activism.

映画『モアナヌイアケア』は、 ホクレア号の世界一周航海 の記録である。オセアニア

航海の冒険や先住民の逞し さ、環境保護活動について のストーリーを伝えている。

Two-hundred-forty-five sailors manned Hōkūle‘a on various legs of the journey. Hōkūle‘a needed to be repaired several times during the voyage, and was dry-docked for months in New Zealand and South Africa. The film shows what happens in intimate moments at sea between teachers and students, and the emotional cultural exchange that happened everywhere the crew went. Women star in most of these scenes. Apprentice Navigator Jenna Ishii and Captain Ka‘iulani Murphy, who are both educators on land, first appear in the film training in classrooms and off of Honolulu Harbor as men speak platitudes of oceanic navigation. After nearly half a decade at sea, they are transformed into seasoned, capable navigators and community leaders, and they are running the meetings.

“This isn’t just a film for canoe lovers, this is a film for everyone in Hawai‘i,” Anthony says. “This is an opportunity for us to come together. We see it as an extension of the voyage. We hope to screen the film at the ports that supported us, to go everywhere the voyage went.”

して登場するのが、地上ではともに教育者の資格を持つ二人の女性、 航海士見習いのジェナ・イシイさんと船長のカイウラニ・マーフィーさ んだ。教室とホノルル港沖で長時間にわたる航海術のトレーニングを 受けて航海に挑んだ二人は、海で約5年間という歳月を過ごし、今で は豊富な経験とスキルを持つベテラン航海士として、また地域のリー ダーとして活躍している。

「この作品はカヌー好きのためだけの映画ではなく、ハワイに住 む人はもちろん、全ての人に捧げるものです。私たちが同じ地球人とし て互いに協力し合える機会を与えてくれます。それがホクレア号の世界 一周の旅の目的でもあるのです。私たちを応援してくれた国や港の人 たちがこの映画を見てカヌーとともに世界を旅することができることを 願っています」とアンソニーさんは語った。

TEXT BY JADE SNOW

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

TEXT BY JADE SNOW

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

文=ジェイド・スノー

写真=ジョン・フック

ART OF THE STITCH

針と糸の芸術

Hawaiian quilts embody treasured memories from Hawai‘i’s storied history and remind us of the value of craftsmanship.

職人が一針一針手で縫い上げる美しいハワイアンキルトは豊かな物語に満ちたハワイの歴史を今に伝えている

A single quilt requires thousands of intricate stitches fastened by hand and often takes years to complete.

一枚のキルトには何千

本もの繊細なステッチ

が手で縫い込まれるた

め、完成するのに何年も かかる。

Intention and mindfulness are essential to the successful creation of a Hawaiian quilt. When completed, a quilt is given a name to bring its purpose to life. For master quilter Patricia Lei Murray, this process is just as important as the product. “Once a pattern has been decided and dedicated, the meditation begins,” says Lei Murray, who has been quilting for more than 40 years. “There is a quiet prayer at the cutting and deep breaths supporting the progress. Once the pattern is cut and laid folded at the piko (center), the quilt is born.” These projects often take years. Even a small quilt requires thousands of intricate stitches done by hand. During the process, an intimate relationship is formed, and the individual’s mana becomes imbued in the quilt.

ハワイアンキルト作りで何より大切なのは、思いを込めて一針一針丁寧 に縫うことだ。完成したキルトには全て、作り手の意図が込められた名 前が付けられる。キルト職人のパトリシア・レイマレーさんは、キルトの 命名には作る作業と同じくらい重要な意味があるという。40年以上に わたってキルト製作を続けているレイマレーさんは、「図案が決まると、 まずは瞑想から始めるの。静かに祈りを捧げて深呼吸しながら生地を 裁断し、切ったパターンを折ったまま布のピコ(中央)に置く。その瞬間、 キルトに命が宿るのよ」と説明する。キルト製作には何年もの歳月がか かる。小さな作品でも、何千本もの複雑なステッチを全て手で縫うため だ。その過程で、作り手とキルトの間に絆が生まれ、一針ごとに作り手の マナがキルトに縫い込まれていく。

Hawaiians were already fluent in the language of textile art when missionaries introduced the technique of quilting to Hawai‘i at the end of the 19th century. Kapa was the traditional Hawaiian barkcloth fabric made by pounding wauke (paper mulberry) into a pliable cloth and stamping it with inked patterns using ‘ohe kāpala, or hand-carved bamboo stamps. These delicate tapestries were used for everything from clothing to bed coverings to burial wrappings. As native attire gave way to Victorian-style fashion, traditional kapa moe (bed coverings) transformed into heavier Hawaiian quilts adorned with patterns featuring native foliage.

“I believe Hawaiian women were interested in bringing nature into their homes in a larger way and instinctively figured out a way to do this,” Lei Murray says. She recalls a beloved origin story about a woman laying her sheets in the sun under an ‘ulu (breadfruit) tree, detailing how the leaves and fruit cast shadows upon sheets. This inspired the woman to create the first Hawaiian quilt pattern, the ‘ulu. This plant is not only significant as a staple food throughout Polynesia, but also symbolic: the Hawaiian word ‘ulu means “abundance and growth.”

Though quilting is often solitary, connections among practitioners are nurtured. Lei Murray began her journey in the craft as a young mother when she connected with quilting via continued education courses at Kamehameha Schools Kapālama. “Every quilt has a story,” she says. “I learned from the early kūpuna that each quilt receives mana, or power from the quilter, with thoughts of aloha quietly stitched into the echoes of the pattern.” Lei Murray’s natural talent for quilting blossomed and soon she was creating her own pieces, like a treasured quilt in honor of Hawaiian women during the Overthrow when the Hawaiian flag was lowered from ‘Iolani Palace. She named it “Ku‘u Hae Aloha Mau” (“My Beloved Flag Forever”). The quilt is displayed proudly at the Office of Hawaiian Affairs as a reminder of the strength and unity of the Hawaiian Kingdom and all it has endured.

宣教師がハワイにキルティングの技術を持ち込んだ19世紀の終 わり頃、ハワイアンはすでにテキスタイルアートを楽しんでいた。ハワイ 伝統の布は、ワウケ(桑の木の一種)の樹皮を打って柔らかくなめし、オ ヘ・カパラと呼ばれる手彫りの竹製スタンプを使って捺染したもので、 「カパ」と呼ばれる。こうやって作られた繊細なタペストリーは、衣服から ベッドカバー、死装束まであらゆるものに使われていた。先住民の服装 がビクトリア様式のファッションに取って代わられるようになると、伝統 的なカパ・モエ(ベッドカバー)は、ハワイ固有の植物の葉をモチーフに した厚手のハワイアンキルトに姿を変えていった。

「ハワイアンの女性たちは、自然をより大きなスケールで家に取 り入れたいと考え、きっと本能的にその方法を知っていたのね」。レイマ レーさんは、ある女性が太陽の光が注ぐ中、ウル(ブレッドフルーツ)の 木の下にシーツを広げた際に、葉と果実がシーツに落とした影の美し さに魅了され、ハワイアンキルトの最初のパターンの「ウル」が生まれた、 という彼女のお気に入りのハワイアンキルトの成り立ちのストーリーを 教えてくれた。この植物はポリネシア全体の主食として重要であるだけ でなく、ハワイ語の単語「ʻulu」は、豊かさと成長を意味するハワイ文化 にとって象徴的なものである。

キルト作りは時にして孤独な作業であるが、作り手同士の間に 育まれる絆も楽しみの一つだ。当時、若い母親だったレイマレーさんは、 カメハメハスクールズのカパラマ校で受講したキルティングコースがき っかけでハワイアンキルトの世界に入った。「すべてのキルトには物語が あってね。初代キルターのクプナから、キルトの一枚一枚には作り手の マナ(力)が込められ、パターンを繰り返すごとにアロハの心が少しずつ 刻み込まれていくのだと教わったものよ」。レイマレーさんは天性の才 能が開花し、まもなくキルト製作の注文を受けるようになった。ハワイ 王朝の転覆によって降ろされたイオラニ宮殿のハワイ王国旗を象徴す る「クウ・ハエ・アロハ・マウ(私の最愛の旗よ永遠に)」と名付けられた 作品もその一つだ。当時を生きたハワイアンの女性を称えるこの貴重な キルトは、ハワイ王朝が歩んだ激動の歴史とハワイの人々の強さや団結 の象徴としてハワイ人問題事務局(OHA)に飾られている。

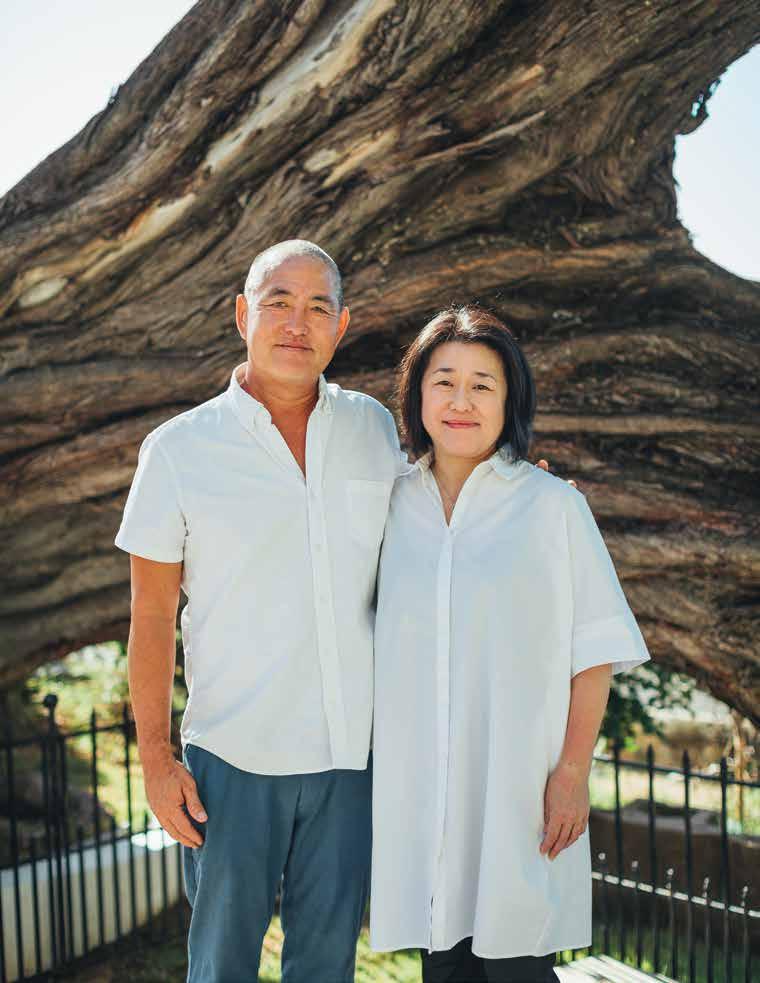

Quilting not only connects fragments of fabric, but a tight-knit community of practitioners. Above, Pat Gorelangton and Patricia Lei Murray.

キルト作りは生地を繋ぎ合わせるだけでなく、作り手同士の親密な絆 をも繋いでいる。上:パット・ゴアラングトンさんとパトリシア・レイマレ ーさん

An author of multiple books about sewing and the culture of Hawai‘i, Patricia Lei

Murray considers quilting to be a meditative experience.

裁縫やハワイ文化についての本 を何冊も書いている著者のパト リシア・レイマレーさんにとって キルト作りは瞑想のようなもの だという。

In 2013, Lei Murray began teaching courses at the Honolulu Museum of Art School, where she met quilter Kanani Reppun, one of her earliest students. “It is definitely meditative, in that I’m very focused,” Reppun explains. “I can sit in a room and quietly quilt for hours, or I can do so in the presence of my quilting sisters where we express aloha to our quilts.”

Thirty-year-old quilter Pat Gorelangton is a member of The Poakalani and Co. Hawai‘i Quilting Guild led by the late master quilters Althea Poakalani Serrao and husband John Serrao. Gorelangton quilts an estimated 10 hours a day at home and looks forward to sharing her pieces at the weekly Poakalani gatherings. “It has certainly taught me creativity,” she says. “I’m so happy with myself when I can come up with a design that is pleasing to me as well as pleasing to others, because I often try to put a more modern twist.”

Though the quilters are purists when it comes to technique, their love for the artform welcomes modern applications and opportunities. Lei Murray was approached by Amber Thibaut, owner of keiki clothing company Coco Moon, to design a pattern for a baby blanket that would pay homage to the artform but be printed atop buttery-soft bamboo fabric. “I didn’t want to just mimic the style of a Hawaiian quilt,” Thibaut says. “I wanted to truly bring it to life by working with a master quilter who could infuse it with love, tradition, and care.” Lei Murray employed

2013年、レイマレーさんは、ホノルル美術館でキルトのコースを 教え始めた。そこで最初の教え子となったキルターのカナニ・レップンさ んと出会った。「精神を集中する作業のキルト作りは、瞑想と同じような 効果があります。キルトを作るときは、部屋の中で何時間も座ったまま 静かに一人で作業することもあれば、姉妹のようなキルター仲間たちと 一緒に縫いながらアロハを分かち合うこともあります」とレップンさん。 キルターのパット・ゴアラングトンさん(30歳)は、キルト職人のアルテ ア・ポアカラニ・セラオさんと夫のジョン・セラオさんが運営する「ザ・ポ アカラニ&カンパニー・ハワイ・キルティング・ギルド」のメンバーだ。ゴ アラングトンさんは、自宅で毎日キルト作りに10時間ほど費やし、毎週 開催されるポアカラニの集まりで仲間と作品を共有することを楽しみ にしている。「キルトのおかげで創造力が豊かになりました。モダンな要 素をデザインに取り入れて楽しんでいます。自分が気に入り、他の人に も喜んでもらえるデザインに仕上がった時は何より幸せです」と彼女は 言う。

キルティング技術においては伝統に忠実なキルターたちも、その 芸術表現は実に様々で、近代的な用途や新しいアイディアを柔軟に取 り入れて楽しんでいる。レイマレーさんは、ココムーンという子供服ブラ ンドのオーナーのアンバー・チバウトさんに依頼され、竹製の布ででき た優しい肌触りのベビー毛布にプリントするキルトのデザインを考案し た。「ハワイアンキルトの型だけを真似するのではなく、ベテランのキル ト職人の力を借りて、愛や伝統、思いやりを感じさせる本物のハワイア ンキルトをデザインしたかったのです」とチバウトさんは話す。レイマレ

“I

l earned from the early kūpuna that each quilt receives mana, or power from the quilter, with thoughts of aloha quietly stitched into the echoes of the pattern.”

— Patricia Lei Murray, master quilter

「初期のキルターのクプナから、キルトの一枚一枚には作り手のマナ(力)が込められ、パターンを繰り返すごとに アロハの心が少しずつ刻み込まれていくのだと教わったものよ」とキルト職人のレイマレーさんは語る。

The ‘ulu (breadfruit) is one of the earliest Hawaiian quilt patterns.

ウル(ブレッドフルーツ)は、

初期のハワイアンキルトの パターンの一つだ。

the same handcrafted approach to the process. The resulting print is thoughtfully detailed, down to its graphically rendered stitches, and is a heartwarming nod to tradition, with the patterned ‘ulu symbolizing the nurturing of growing babies and families.

“The secret to success in Hawaiian quilting is to love the process,” Lei Murray says. She and her fellow quilters seek to share this process, including the tradition of Hawaiian quilting and the values the discipline has imparted. Gorelangton embraces modern platforms such as Poakalani and Co.’s website and her personal Instagram page (@hawaiianquiltsbypat) to display her work and connect with others. “The practice of quilting has given me a true appreciation for this art,” Gorelangton says. “I love the tactile process, the stories and the connections that I’ve made. It’s amazing and very fulfilling.”

ーさんのおかげで、丁寧に愛情を込めて作られたキルトと同じようにス テッチの一本一本まで詳細に再現された手作り感溢れるプリントが生 まれた。成長していく赤ちゃんや家族を象徴するウルのデザインは、心 温まるハワイアンキルトの伝統そのものだ。

「ハワイアンキルトを上手に作る秘訣は、その過程を楽しむこと なの」。レイマレーさんはキルト作りを通して、ハワイアンキルトの伝統、 そして丹念な仕事から生まれる芸術と絆をキルト仲間と共有できるこ とに喜びを感じている。一方、ポカラニ・アンド・カンパニーのウェブサ イトやインスタグラムページ(@hawaiianquiltsbypat)で作品を紹介 することで交流を図っているゴアラングトンさんは、「キルト作りを実践 するようになってハワイアンキルトへの深い感謝の気持ちが生まれまし た。キルトの感触、それに込められた物語、キルト作りを通して生まれた 人との繋がりはどれも素晴らしいものです。それは私の人生を満たして くれています」と語る。

TEXT BY SONNY GANADEN

TEXT BY SONNY GANADEN

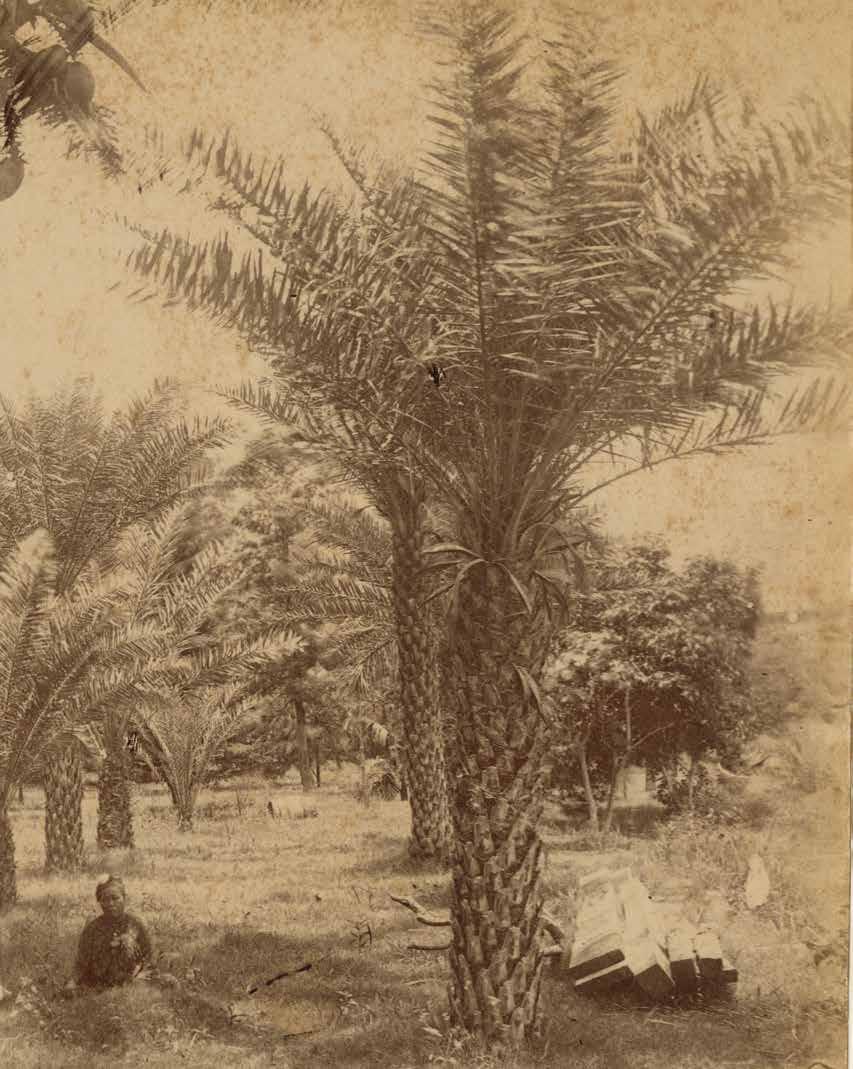

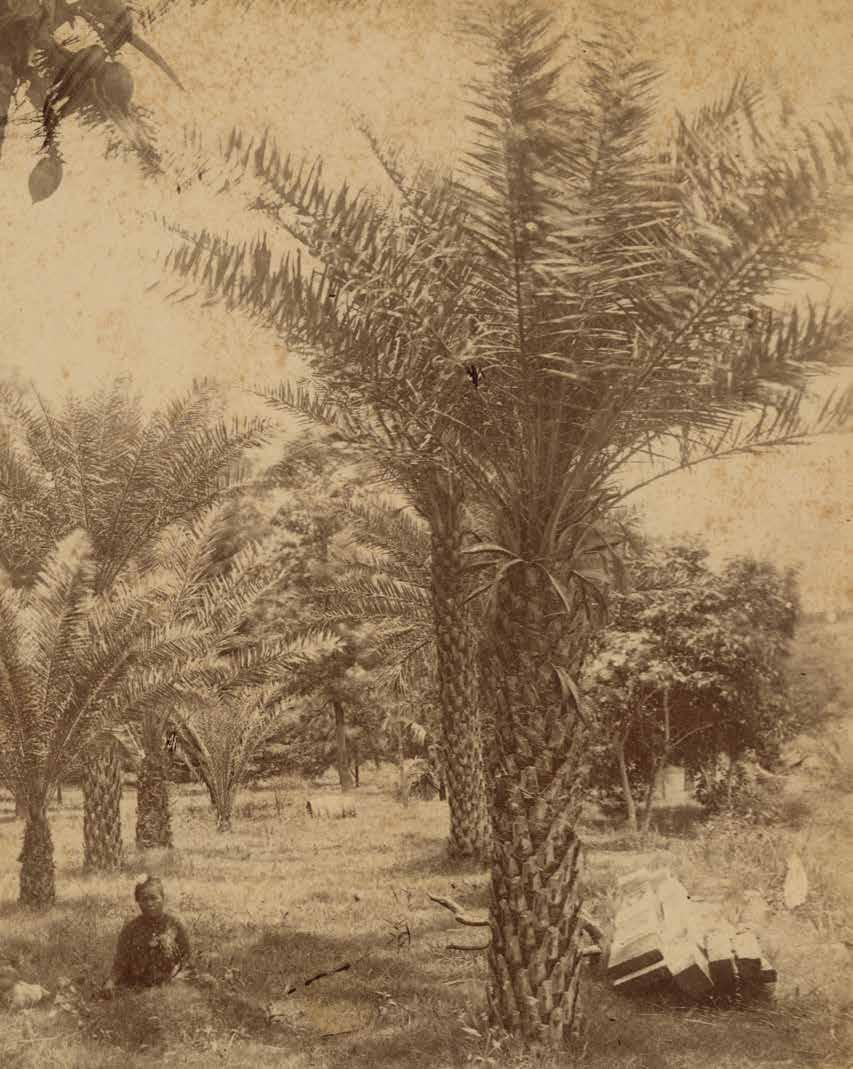

IMAGES FROM HAWAI‘I STATE ARCHIVES

文=ソニー・ガナデン

写真=ハワイ公文書館提供

ALONG THE COCONUT BELT

ココナッツベルト

The islands’ robust coconut industry of the turn of the century may be only a memory to many, but its flavors live on in Hawaiian cuisine.

ハワイの産業としては定着しなかったココナッツの栽培。その味わいはハワイの料理に今も生き続けている。

The populated islands of the Hawaiian-Emperor seamount chain lie at the northern border of the Coconut Belt, where the palm tree Cocos nucifera prefers to grow, thriving in the sandy soil and salty wind of the tropics. It is the historic tree of life for the peoples of the Pacific and Indian oceans.

A coconut tree’s usefulness is extraordinary: Its massive leaves provide thatching and bedding, its timber is both sturdy and seaworthy, it is a source of sweet water, and its pulp can produce fatty milk or be dried and pressed to make oil. Coconut husk can be woven or braided to create rope, and the polished coconut itself makes an excellent vessel for storing fine jewelry or drinking ‘awa.

The niu—the Hawaiian word for coconut— is a “canoe plant,” brought to Hawai‘i as cargo aboard the double-hulled sailing canoes of intrepid Polynesian voyagers, and later planted inland. Some coastal groves are the result of drupes that have been carried by wind and current, capable of surviving for up to four months at sea. Hawai‘i’s coastlines bear remnants of hundreds of cultivated coconut groves planted over generations as part of the endogenous economy that developed over centuries. Within the last several years, some groves have also been planted in an attempt to build a coconut industry. Coconut-based foods are staples of a traditional and contemporary Polynesian diet. Coconut milk can be stewed for hours with squid and taro leaves to make squid lū‘au, or it can be prepared quickly with a thickener (starch or gelatin) and sugar to create the universally beloved haupia.

For tourists craving the traditional experience, coconut harvesting is still performed at lū‘au across the islands. As part of the display, men crack jokes while tree climbing, husking, grating, and straining coconut milk, and occasionally starting a fire. The jokes, like the uses of the coconut itself, have become ubiquitous, best delivered in Hawaiian Pidgin or a Samoan accent: Eh, you guys get dry skin? Coconut oil. Split ends? Coconut oil. Divorcing? Coconut oil. Never gets old.

The coconut is resilient to climate change and has become en vogue for its water and oil over the last decade. These days, the coconut-based goods business is worth more than $2 billion worldwide. While the notion of becoming rich off a nearly indestructible tropical tree is nothing new, it never stuck in Hawai‘i. Even when the Honolulu Star

ハワイ諸島をはじめとするハワイ海山群と天皇海山群の人口のある島 々は、「ココナッツベルト」の北端にある。ココナッツベルトとは、南国独 特の砂質の土壌と潮風のおかげでココヤシの木がよく育つ地域のこと だ。椰子の実がなるヤシ科のココヤシは、昔から太平洋とインド洋の島 々に住む人たちの生活に欠かせない「命の木」である。ココヤシの木に は驚くほど多くの用途があるのを知っているだろうか。大きな葉は茅葺 き屋根や寝具となり、木材は頑丈で耐航性がある。椰子の実は飲料に 適した水分を蓄えているだけでなく、果肉からは脂肪分を豊富に含んだ ココナッツミルクを、乾燥させればココナッツオイルも抽出することがで きる。椰子の殻は織ったり編んでロープを作ることができるし、椰子の 実を磨けばココナッツミルクを飲む器や容器、美しい宝石にもなる。 椰子の木を表すハワイ語の「niu」には、カヌーの植物という意味 がある。それはポリネシアの航海者たちがカヌーに乗ってハワイに運び 込んだ貴重な荷物の1つであったことに由来する。椰子の実は4ヶ月は 海水に浸かっていても枯れず、発芽することができるため、他の島から 流れ着いて自生するものもあった。ハワイの海岸線には、何世代にもわ たって植えられた何百本もの椰子の林が残っている。これらは何世紀 にもわたって発展した内生的経済の名残である。ここ数年の間にも、コ コナッツ産業を築くために椰子の林を植える試みがあった。

ココナッツからできた料理は、伝統的でかつ現在も食べられてい るポリネシアの食生活に欠かせない食べ物だ。ココナッツミルクは、イ カとタロイモの葉と一緒に長時間煮込んだシチューの「スクイッド・ルア ウ」にしたり、増粘剤(デンプンまたはゼラチン)と砂糖を加え、加熱して 固めたハワイの人たちが大好きなデザート「ハウピア」を作るのに使わ れる。

伝統的な体験を求める観光客のため、椰子の実の収穫は、島の 各地で開催されるルアウで今も行われている。このようなルアウのショ ーでは、男性が椰子の木に登り、椰子の殻を剥ぎ、中の実を削ってココ ナッツミルクを絞り、時には火を起こして見せてくれる。このようなショ ーでは、ハワイの方言ピジンやサモアのアクセントで、ココナッツオイル がいかに万能であるかというジョークを飛ばすのが定番となっている。 乾燥肌?ココナッツオイルがいいよ。枝毛?ココナッツオイルが効くよ。 離婚?それにもココナッツオイルが一番。年を取らないからね。笑 椰子は気候の変化に強い植物で、ここ10年間ではココナッツウ ォーターとオイルが大流行した。最近では、ココナッツを原料にした商 品のビジネスは、世界中で20億ドル規模におよぶという。この丈夫な熱 帯の木を使ってビジネスをしようと思いついた人はこれまでに数知れ ない。だが実際のところハワイではこれまでに産業として定着したこと はない。1913年にハワイの新聞、ホノルル・スター・ブレティンの一面に

Coconut-based foods are staples of a Polynesian diet.

ココナッツでできた食べ物は ポリネシア人たちの食生活に 欠かせない。

Bulletin’s front page exclaimed “Very Enthusiastic Over Coconut Industry” in 1913, the sugar and pineapple industries dominated the economy of the Territorial Era, and coconuts were relegated to the ubiquitous groves of the islands. Harvesting coconuts remains dangerous and labor intensive, and most farmers have better luck with produce nearer to the ground.

If your favorite coconut product has ties to Hawai‘i, that doesn’t mean the coconuts necessarily come from the islands. Indonesia, the Philippines, and India dominate the international coconut trade, with Caribbean and African countries increasing production to meet demand. But the coconuts seen at Hawai‘i’s roadside kiosks and small restaurants are mostly from local landowners who supply their own small bounty with their community, family, and those passing through.

「ココナッツ産業が熱い」という見出しの記事が掲載されたこともあっ たが、その後も領土時代の経済を支配し続けたのは砂糖とパイナップ ル産業であり、椰子の木は島のどこにでもある木として忘れ去られてい った。なぜなら椰子の実の収穫は今でも危険な作業で、多くの労働力 に頼らなくてはならず、多くの農家は畑で栽培できる農産物を好むか らだ。

ハワイに関連したココナッツ製品であっても、必ずしもハワイ産 の椰子の実が原料であるとは限らない。世界のココナッツ貿易を支配 しているのはインドネシア、フィリピン、インドであり、カリブ海やアフリ カ諸国も増加傾向にある需要に合わせて生産量を増やしている。ハワ イの路傍の売店や地元のレストランで目にする椰子の実は、地主の敷 地内で採れたものを地元のマーケットで売ったり、家族に分けてくれた りするものがほとんどであろう。

文=カイリー・ヤマウチ 写真=クリス・ローラー

The creatives in the following pages find inspiration in their mother’s teachings and character. Right, Mihana and Nāpali Souza; below, Mālia Ka‘aihue and Micah and Keānuenue DeSoto.

MOTHER KNOWS BEST

母親が一番よく知っている

Living visits the homes of six wāhine and their children to converse on motherhood, childhood, and creativity.

母親と子供の関係や創造性について、6人の女性とその子供たちをインタビューした。

続くページは母からの教えや 人格をテーマにしたもの。上:マ ヒナさんとナパリ・スーザさん、

下:マリア・カアイフエさん、マイ カ・デソトさんとケアヌエヌエ・ デソトさん

In Hawai‘i, we typically honor our mākuahine (mothers) with lei and brunch. Keeping her favorite flower in mind (for my mother, pīkake and pakalana), we buy or make a lei and hope it complements whichever Manuheali‘i dress she decides to wear. Then, arriving arm-in-arm with her, we treat her to a meal in honor of all the times she made our school bentos and financed our crackseed-store visits. As we sip our mimosas, we give the final gift—the gift of “talking story,” so mom can reminisce about the days before and after she raised us, and relive all the cherished moments in between.

ハワイ語で母親は「マクアヒネ」。ハワイでは通常、レイを贈ったり、家族 でブランチに出かけたりして母の日を祝う。母の好きな花を選び(私の 母のお気に入りはピカケとパカラナだ)、母が着るドレスに合うレイを買 うか作って、母と仲良く腕を組んでレストランに向かう。弁当を作ってく れたり、お小遣いをくれたり、母がこれまで私たちにしてくれたこと全て に感謝の気持ちを込めて、特別な食事をご馳走するのだ。ミモザを飲み ながら会話を楽しみながら、何よりも家族の思い出話に花を咲かせる のが、母にとっては一番の贈り物だろう。私たちが生まれた頃の貴重な 瞬間や私たちを育てれくれた頃の懐かしい記憶が蘇り、幸せなノスタル ジーに浸ることができるのだから。

Beadie and Donne Dawson

Deep in the lush recesses of Nu‘uanu Valley is the Dawson residence. Here, words like kuleana (responsibility), ha‘aha‘a (humility), and mālama ‘āina (take care of the land) have been passed down through generations, spreading like educational roots that connect one Dawson to another. The late Annie Kanahele, her daughter Beadie Dawson, and her granddaughter Donne Dawson have lived by these values. This is shown in their activism, conservation endeavors, and efforts to educate others on Hawaiian rights.

Kanahele had witnessed and mourned the deterioration of ‘Iolani palace since the Overthrow, which began in 1893, three years before she was born. In 1965, her daughter Beadie proposed that the Junior League of Honolulu’s next project be the restoration of the historic building and the reclaiming of its original furnishings. Beadie’s fellow league members agreed to undertake the large project, primarily relying on word-of-mouth to track down the original décor. Today, the palace nearly resembles its past self, and it continues to be restored by The Friends of ‘Iolani Palace.

Beadie’s protection of Hawaiian rights did not end there. In 1997, she volunteered to legally represent Na Pua a Ke Ali‘i Pauahi—the student, teacher, alumni, and parent beneficiaries of Princess Pauahi’s trust—as they fought to reform the trustees’ actions. For years, the Bishop Estate’s trustees had been accused of using trust funds to benefit themselves over the school’s beneficiaries. As Na Pua’s lawyer, Beadie ensured that the investigation into the trustees’ actions was objectively conducted. When the report became public, it confirmed years of misdeeds by the trustees and garnered more public support for the beneficiaries.

Today, Donne Dawson has found her own form of activism. As the Hawai‘i State Film Commissioner, Donne ensures that Hawai‘i’s lands and oceans are protected and Hawaiian culture is accurately portrayed during filming. She also decides which film projects are allowed to be produced in the state, taking into consideration her culture when doing so. “There are times when I’ve come under attack for feeling strongly about my culture and environment,” Donne says. “But I do not waiver. It’s in my DNA, I think.”

ビーディーとドン・ドーソン

緑豊かなヌウアヌ渓谷の奥深くにドーソン一家は住んでいる。彼らの家 庭ではクレアナ(責任)やハアハア(謙虚さ)やマラマ・アイナ(土地や環 境を守る)といった言葉が、教育の柱として世代から世代へと受け継が れている。故アニー・カナヘレさんとその娘のビーディー・ドーソンさん、 そして孫娘のドン・ドーソンさんが代々大切に守ってきたこれらの価値 観は全て、環境保護への取り組みやハワイアンの権利に関する知識の 普及活動といった彼らの行動の指針となっている。

1893年のハワイ王国の転覆。その3年後に生まれたカナヘレさ んは、その後も荒廃の一途を辿るイオラニ宮殿の行く末を憂いていた。 娘のビーディーさんは1965年、女性のコミュニティリーダーで構成さ れるボランティア団体「ジュニア・リーグ・オブ・ホノルル」の次期プロジ ェクトとして、この歴史的建造物の修復と家具の復元を提案した。この 大規模なプロジェクトに賛同した仲間のメンバーたちは、まずは人づて を頼りに、オリジナルの家具の在りかかを調査し始めた。今日のイオラ ニ宮殿は、非営利団体「フレンズ・オブ・イオラニパレス」によって今も修 復作業が続けられ、ほぼ元の姿に戻りつつある。

その後もビーディーさんはハワイアンの権利保護活動を続けて いる。1997年には、ハワイアンの子孫の教育のために多くの遺産を残 したパウアヒ王女の遺言信託を管理する受託者のあり方を見直すため に訴訟を起こしていた受益者の学生や教師、卒業生や保護者たちで構 成される「ナ・プア・ア・ケ・アリイ・パウアヒ」を無償で弁護した。ビショッ プ・エステートの受託者たちは、本来の受益者である学校はなく受託者 自らの利益を優先するため、信託財産を長年にわたり利用してきたと 非難されていた。ナ・プアの弁護士であるビーディーさんの働きにより、 受託者の行動に関してより客観的な外部調査が行われるようになっ た。この結果が報道されたことで、受託者による長年の不正行為が暴か れ、信託受益者に対する一般市民からの支持も得ることができた。 孫のドン・ドーソンさんも彼女自身の分野で普及活動を続けてい る。ハワイ州への映画撮影の誘致や支援を行う映画コミッショナーとし て活躍するドンさんは、映画の製作過程におけるハワイの環境と海洋 保護や作品中でのハワイ文化の描写の妥当性を監督し、作品の内容を ハワイ独自の文化的視点で吟味した上で、ハワイ州内での撮影を許可 すべきかを決定する。「自分の文化や環境に対して強い意識を持ってい ることで、個人的な攻撃を受けることもあります」とドンさんは言う。「そ れでも揺らぐことはありません。きっとそれが私のDNAなのです」。

Always fight for what is just and pono.” – Beadie Dawson, to her daughter Donne “

Be clear in what you believe in and advocate for those things.

ビーディー・ドーソンさんから娘のドン・ドーソンさんへの言葉:「常に明 確な信念を持ち、そのために主張しなさい。正義やポノ(善良や健康、 調和のとれた状態)のために戦いなさい)」

Mālia Ka ‘ aihue and Micah and Keānuenue DeSoto

At the beginning of the year, the Ka‘aihue and DeSoto ‘ohana set personal goals and then share them among their growing family of 10. (The youngest child, Wailana, was born on December 30, 2018.) These include practical goals like paying rent and getting a 4.0 GPA. But Mālia Ka‘aihue, the 39-year-old mother of this family, also pushes her husband and children to focus on building character. Her 21-yearold son, Micah, is working on being more present and grateful. His 15-year-old sister, Keānuenue, wants to be more patient. Mālia, an entrepreneur and community leader, is determined to be more engaging and mindful in her day-to-day life.

When she was a freshman at the University of Hawai ‘ i at Mānoa, Mālia became pregnant with Micah. For the next decade, as she pursued four degrees, she was both a mother and a student. While studying for her PhD, Mālia would start her day at 6 a.m., preparing her children for school, attending class at 9 a.m., and then making time to write her dissertation. After attaining her doctorate in political science, Mālia taught in higher education and then joined the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Then, in 2013, she founded DTL Hawaii, a Hawaiian strategy studio committed to asking this question: How can DTL provide the highest level of inclusion of culture and community into Hawai‘i’s big projects that will shape Hawai‘i for the next 10 generations?

Meanwhile, her children have followed her advice to be “the designers of their own lives.” When Micah was a junior in high school, he walked his first fashion show for local designer Manaola. The following year, he signed with Nomad Mgmt, a modeling agency based in New York and Miami, which gave him the opportunity to model in Thailand and walk at New York Fashion Week twice. Today, Micah continues to model locally and abroad. Keānuenue, a sophomore at Kamehameha Schools, is also an entrepreneur. In 2015, she founded Anu Hawai‘i, a swimwear brand. In October 2018, she held a fashion show for the Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement. Now she is working with a factory in Bali to mass-produce her line.

Micah admits that the DeSoto children don’t always follow their New Year’s resolutions. But creating yearly goals echoes an important lesson from their mother: “Don’t wait for things to happen, make them happen.”

マリア・カアイフエとマイカ&ケアヌエヌエ・デソト カアイフエさんとデソトさんの一家では、毎年年初めに10人家族 (2018年12月30日に末っ子のワイラナ君が生まれたばかり)の各自 が新年の抱負を設定し、全員で話し合うのが恒例だ。中には優秀な成 績を取ることや家賃を滞納せず支払うといった現実的なものもあるが、 母親のマリア・カアイフエさん(39歳)は、夫と子供たちにそれぞれの人 間性を磨くことを求める。21歳になる息子のマイカさんは、明確な意識 と感謝の気持ちを持つこと、マイカさんの妹の15歳のケアヌエヌエさん は、忍耐強くなることをそれぞれ目標に掲げている。起業家でコミュニ ティリーダーでもあるマリアさん自身もまた、日々の生活において多くの ことに関心を持ち、周りに気を配れるよう意識して毎日を過ごしている。 マリアさんはハワイ大学マノア校に入学して間もない大学一年の 時、マイカさんを妊娠した。その後彼女は、10年間かけて母親業と学 業を両立しながら4つの学位を取得した。博士課程の勉強をしていた 頃は、毎朝6時に起き、子供たちの学校の支度を済ませ、午前9時から の授業に出席、睡眠時間を削って論文を書く日々を送った。政治学で博 士号を取得した後、マリアさんは高等教育の教職をとり、しばらくしてハ ワイ人問題事務所(OHA)に入った。その後、2013年に今後10世代先 の未来を担う子供達にとって有益なハワイを形作るために、大規模プ ロジェクトとハワイの文化や地元社会とのより密接な関与を提案する 戦略的組織「「DTLハワイ」を設立した。

その間、子供たちは「自分の人生は自分で設計するもの」という 母親のアドバイスに忠実に従っていった。マイカさんは高校3年生のと き、ローカルデザーナー「マナロア」のファッションショーでモデルとし てデビューを果たした。翌年、彼はニューヨークとマイアミに拠点を置く モデル事務所のノーマッドマネジメントと契約し、これまでにタイでの 仕事を受けたり、ニューヨークのファッションウィークのショーにも2回 出演した。マイカさんは今も地元ハワイや海外でモデルを続けている。 カメハメハスクールズの高校2年生のケアヌエヌエさんも一端 の起業家である。2015年に、水着ブランドの「アヌ・ハワイ」を立ち上 げ、2018年10月にはハワイの文化経済振興を支援する非営利団体の 「カウンシル・オブ・ネイティブ・ハワイアン・アドバンスメント」のための ファッションショーを開催。現在、彼女はバリにある工場で彼女の水着 ブランドの大量生産に取り組んでいる。デソト家の子供たちは、たとえ 新年の抱負が実現できなくても、毎年新たな目標を設定することで、「 物事は起きるのを待つのではなく、自分で起こすもの」という母からの 大切な教えを実行することができるのだと教えてくれた。

Be mindful of your culture. Never be shame of who you are.”

– Mālia Ka‘aihue, to her children Micah and Keānuenue

マリア・カアイフエさんから息子のマイカ・デソトさんへの言葉: 「自分の持つ文化を意識して。自分を決して恥じることのないように」

The

most precious gift for a mother is “talking story,” so we can reminisce about the days before and after she raised us, and relive all the cherished moments in between.

思い出話を楽しむことが、母にとっては一番の贈り物だろう。私たちが生まれた頃の貴重な瞬間や育 ててくれた母の懐かしい記憶に家族で浸ることができるからだ。

Mari Matsuda and Kimiko Matsuda-Lawrence

Most children don’t learn about intersectionality, patriarchy, or systemic racism until they’ve reached college. But Kimiko Matsuda-Lawrence is an exception, having been raised by Mari Matsuda and Charles Lawrence III, both professors of law at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. In Kimiko’s childhood home, critical race theory and feminist theory were discussed around the dining table. Renowned scholars and theorists like Catharine MacKinnon are among her parents’ good friends. Mari, the first female tenured Asian American law professor, took her children to protests in between sewing Halloween costumes and chaperoning school field trips.

Making a home in Washington D.C. and then Honolulu, Mari immersed her children in both political climates. Whether they joined her in the law classroom or at national conferences, Kimiko and her brother, Paul, glimpsed a world that awaited them. While Kimiko was attending Harvard for her undergraduate degree, the daily campus newspaper, The Harvard Crimson, published an anti-affirmative action story questioning the qualifications of its black students. In response, Kimiko created “I, Too, Am Harvard,” a photo campaign featuring 60 black students and their experiences at the university. In the campaign, black students held up whiteboards displaying racist statements others had said to them. Since its debut in 2014, “I, Too, Am Harvard” has inspired similar projects at universities from Yale University and University of Iowa.

Today, Kimiko lives in New York, where she is a writer and playwright, and Mari teaches law at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Both mother and daughter continue to make community activism an integral part of their relationship. In December 2018, Kimiko visited Hawai‘i to partake in the usual holiday festivities. While she was home, she also joined her mother in protesting U.S. militarism and reef destruction in Okinawa.

マリ・マツダとキミコ・マツダ・ローレンス

大抵の子供たちは、大学に通うまで地域格差問題や家父長制度、組織 的人種差別について学ぶことはないだろう。ともにハワイ大学マノア校 の法学部教授のマリ・マツダさんとチャールズ・ローレンス3世に育て られたキミコ・マツダ・ローレンスさんは例外だ。キミコさんが育った家 庭では、批判的人種理論やフェミニスト理論が食卓を囲んで日常的に 議論された。両親は著名な学者で理論家のキャサリン・マッキノンさん とも親しい交友関係にあった。アジア系アメリカ人女性としては初の 終身職の法学部教授であったマリさんは、ハロウィーンの衣装作りや 修学旅行に同行する合間を縫っては、子供たちを連れて抗議行動に 参加した。

マリさんは、ワシントンDCとのちにホノルルにも家を持ち、異な る政治情勢に子供たちを積極的に触れさせた。それにより母親に同行 して法学の授業や全国会議に出席することもあったキミコさんと弟の ポールさんは、子供の頃から彼らを待ち受ける現実の世界を垣間見る ことができた。キミコさんがハーバード大学の学士課程に在学中、キャ ンパスの日刊新聞『ハーバードクリムゾン』に黒人学生の資格を問う反 アファーマティブアクションを容認する記事が発表された。それを受け て、キミコさんは60人の黒人学生をフィーチャーし、彼らの大学での経 験を綴った写真キャンペーン『アイ・トゥー・アム・ハーバード』を展開し た。黒人の学生たちが大学の他の人種の学生から受けた差別的な発言 をホワイトボードに書いて掲げたこの『アイ・トゥー・アム・ハーバード』 キャンペーンは、2014年に始まって以来、エール大学やアイオワ大学と いった他の大学にも波及ている。

今日、キミコさんは作家と劇作家としてニューヨークに住み、マリ さんは現在もハワイ大学マノア校で法律を教えている。この母娘にとっ て、地域社会活動は二人の関係に今も欠かせないものとなっている。

2018年12月、キミコさんは例年通りホリデーを楽しむためにハワイを 訪れた。彼女は実家に滞在中も、沖縄での米軍駐留とサンゴ礁の破壊 に反対する母の抗議運動に加わっている。

your

Joyce Okano and Kenna Reed

In 1984, while she was still in college, Joyce Okano left her job at Gucci to manage the first independent Chanel shop in the United States. She did so to be able to make her own rules. The store drew customers from Japan who were already familiar with the brand, and Okano found ways to attract Hawai‘i residents as well, choosing merchandise with a local flare and even turning the top floor of her shop into a local art gallery. Because of her wise management of this first shop, Okano was asked to help open Chanel stores across Hawai‘i and then the U.S. West Coast.

Okano’s 28-year-old daughter Kenna Reed has also chosen to be her own boss. Growing up, Reed didn’t realize attending fashion weeks in Paris and New York were atypical experiences for kids her age. While immersing her three daughters in the fashion world, Okano made sure to dissuade them from following the toxic messages of runway. “I told my daughters, those models up there on the runway are freaks of nature,” she says. “No one is naturally that skinny.”

But early in Reed’s photography career, she found herself in a local scene similar to her mother’s, shooting thin models and then having her images Photoshopped to achieve unnatural beauty standards. So Reed turned her lens to subjects she was personally drawn to, both human and inanimate, and the resulting aesthetic got her recurring photoshoots with Kaka‘ako flower shop Paiko. Today, the freelance photographer enjoys pursuing and refining the craft she loves. Reed hopes that her professional journey will one day inspire her two daughters, who are 1 and 5 years old, to be relentless in pursuing their own creative passions.

As Reed’s creative ventures were growing, Okano retired from Chanel. Now she is president of the nonprofit Friends of the Hawaii State Art Museum. Over the years, she has converted her Kahala home into her own private gallery. The paintings and sculptures within harken back to family excursions to the Louvre and MoMA. Of all the memories from fashion-week trips, Okano and Reed recall these museum visits most fondly.

ジョイス・オカノとケナ・リード

1984年、まだ大学生だったジョイス・オカノさんは米国初の独立店舗 となるシャネルの経営を任されることとなり、グッチでの職を離れた。ル ールは自分で作りたかったという彼女。このブティックには、シャネルの ブランドにすでに親しんでいた日本人顧客が集まり、オカノさんはハワ イ市場に合う商品を選び、店の最上階を地元のアートギャラリーに改 造して、ローカル顧客を取り込むことにも成功した。初店舗でのこの功 績が認められ、オカノさんはハワイやアメリカ西海岸でのシャネルの新 店舗開拓のサポートを依頼されるようになった。

オカノさんの28歳の娘、ケナ・リードさんもまた起業家になる道 を選んだ。子供の頃からパリやニューヨークでのファッションウィーク に出席していた経験がいかに特別なものであるかを当時は知る由もな かったと話す。オカノさんは、幼い頃からファッション界に身を置いてい た3人の娘がランウェイから発信される有害なイメージに感化されるこ とがないよう、敢えて「『ランウェイを歩くモデルたちは異常よ。あんなに 痩せているのは自然ではないわ』と娘たちに教えていました」という。 リードさんはハワイで写真家としてのキャリアを歩みだした当初、 母親と同じようなことを経験した。痩せた体型のモデルを撮影し、さら にその写真をフォトショップで加工して、不自然なまでの美しさを作り 上げる。そんな美の世界に疑問を抱いたリードさんは、人間であれ物で あれ個人的に魅力を感じるものにレンズを向けることにした。以来、彼 女はカカアコにあるフラワーショップのパイコでの撮影の仕事を受ける ようになり、フリーランスの写真家として自らが愛する美の世界を追求 し、腕を磨くことを日々楽しんでいる。リードさんは、彼女の仕事での経 験が、いつの日か1歳と5歳の2人の娘にとって、彼ら自身の創造力をど こまでも追求するインスピレーションとなることを願っている。

リードさんのクリエイティブなキャリアが開花し始めた頃、オカノ さんはシャネルを退職した。現在、彼女はハワイ州立美術館の非営利 団体「フレンズ・オブ・ザ・ハワイ・ステート・アート・ミュージアム」の会長 を務める。長年にわたってカハラにある自宅をプライベートギャラリー に作り変えてきたオカノさん。これらの絵画や彫刻はルーヴル美術館や MoMAに家族で訪れた時の思い出に満ちている。これまでに経験した ファッションウィークの旅の中でも親子で訪れたミュージアムがオカノ さんとリードさんにとっては一番の思い出だという。

“

I feel like the best advice has always been way more about her leading by example.” – Kenna, of her mother, Joyce Okano

ケナさんは母親のジョイス・オカノさんについて 「母の生き方そのものが私にとっては何よりの アドバイスでした」と語る。

Mihana and Nāpali Souza

Nāpali Souza remembers hiding under his mother’s mu ‘ umu ‘ u as a child while she played music. The flowery folds of Mihana Souza’s dress draped over him, but he was still able to hear the sounds of the bass she cradled and the Hawaiian melodies she sang. Today Nāpali isn’t sure if the memory is real or a dream, but the imagery is nevertheless telling of how his life turned out.

Nāpali, who is 36 years old, is enveloped in fashion as a cofounder of Salvage Public, a Hawaiianinspired clothing company based on O ‘ ahu. Some of Salvage Public’s designs draw from Nāpali’s musical upbringing with Mihana, who is a member of Puamana, an all-female family trio. Mihana played the upright bass against her stomach when she was pregnant with Nāpali. Once he was born, Nāpali entered into what he jokingly calls “the brown version of the Von Trapp family.” With the famous Hawaiian composer Irmgard Aluli as his grandmother and a handful of cousins and siblings who had also been taught to harmonize and dance hula, music is the core of his family.

When Mihana had late-night performances young Nāpali could not attend, he would wait patiently on the front steps for her to come home. Now, sitting in the backyard of this same Kailua home, Nāpali sings a lyric from a song by Auntie Irmgard that inspired an early Salvage Public T-shirt design. “Pau ka hana, time to play,” he gently croons, and Mihana chimes in, finishing the lyric with her son.

ミハナとナパリ・スーザ

子供の頃、母親が音楽を演奏している間、ムームーの下に隠れていたの を記憶しているという ナパリ・スーザさん。ミハナ・スーザさんの花柄 のたよやかなドレスに覆われながら、彼は母親の奏でるベースの音と彼 女の歌うハワイアンメロディーを聞いて育った。ナパリさんは、その記憶 が現実であったのか夢だったのか今や定かではないというが、その情 景はその後の彼の人生がどうなったのか物語っている。

36歳のナパリさんは、オアフにあるハワイアンデザインのアパレル ブランド、「サルベージ・パブリック」の共同創業者である。サルベージ・ パブリックのデザインには、ナパリさんの幼少時代、女性3人組のバンド 「プアマナ」のメンバーのミハナさんから受けた音楽的影響が反映され ている。ナパリさんを妊娠中、ミハナさんはベースをお腹に当てて演奏 し、自ら「『サウンドオブミュージック』のトラップ一家のハワイ版」と呼ぶ ほどの音楽一家に育った。著名なハワイアン作曲家のイルムガード・ア ルリさんを祖母に持ち、従兄弟や兄弟姉妹全員が歌やフラを習ってい た彼にとって、音楽は常に家族の中心にあった。

ミハナさんの公演からの帰宅が深夜になると、幼いナパリさんは 決まって家の玄関で母の帰りを辛抱強く待っていたという。今、同じカ イルアの家の裏庭に座って、ナパリさんはサルベージ・パブリックのTシ ャツのデザインのインスピレーションにもなっているアンティ・イルムガ ードの歌の歌詞をつぶやく。「パウ・カ・ハナ、タイム・トゥー・プレイ」。そ こにミハナさんが加わり二人で優しく歌い上げる。

「何事でも為せば成る」と息子のナパリ・スーザさ んに語りかけるミハナ・スーザさん。

TEXT BY MATTHEW DEKNEEF

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

TEXT BY MATTHEW DEKNEEF

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

文=マシュー・デニーフ 写真=ジョン・フック

CREATION OF KAPA

カパ作り

Through deep research and a passion for the practice, kapamakers continue to untangle, demystify, and reclaim the nearly forgotten artform of kapa.

長年の研究と鍛錬によって失われつつあるカパの神秘を紐解き、復活させたカパ職人たち

If you happen to encounter a piece of kapa (barkcloth), and you are wondering if it’s authentically Hawaiian, hold it up to the light. Examine it closely, at a slight angle, and behind its kaleidoscopic patterns and earthen colors a hidden texture should appear. This impression undulating across the fabric is a detailed watermark, and it is distinctive to Hawai‘i’s kapa tradition.

Iterations of kapa, also known as tapa elsewhere, can be found throughout the Pacific’s island societies. In Hawai‘i, this paper-thin textile, made by hand-pounding the inner bark of the mulberry tree, dressed chiefs and commoners for centuries. Around the oceanic region, kapa was donned for all sorts of occasions, utilized in ritual ceremonies, and provided comfort as pillows, blankets, and bedspreads. From checkerboard to zig-zags, the designs on kapa come in a dizzying range, drawing on motifs found in nature or possessing sacred meanings known only by the kapa-master who fashioned them.

Dalani Tanahy is one of these modern-day masters. There are a handful of kapamakers scattered across the islands, and of them, she’s the only one who produces kapa full-time as a business enterprise. In 2007, when she started Kapa Hawaii, a self-run, one-woman atelier based on a dusty plot of land fronting her Mākaha home, she had already spent more than 25 years studying and experimenting with the material. Before kapa practices were revitalized in the 1970s during the Hawaiian Renaissance, most notedly by late practitioner and kahuna Puanani Van Dorpe, kapa was considered a lost art. There were no direct lineal descendants of kapamakers left in Hawai‘i to draw on for direct knowledge, unlike those who maintained tapa legacies in Samoa, Tonga, and Fiji. But through recorded oral histories, archived materials, Bishop Museum collections, and trial and error, practitioners have revived the artform. Tanahy is a product of that renaissance. Today, kapamakers continue to pass down, untangle, demystify, and reclaim this nearly forgotten practice.

“Kapamaking is so much more than people realize,” Tanahy says. “You have to be a botanist, a carver, a graphic designer.” The fabric begins as a tall, spindly tree with scruffy leaves larger than the palm of someone’s hand. The trunk is so thin, it’s incredible to think it could yield enough yards of

ハワイアンのカパを目にしたことがあるだろうか。何世紀にもわたって 島の酋長や島民たちが身につけていたカパは、桑の木の内側の樹皮を 木の棒で叩いて薄く伸ばして作られた布だ。光にかざせばそれが本物 のカパであるかが分かる。土色をした万華鏡のような模様のある布を 斜めにしてよく見ると、一面に独特の質感のあるパターンが広がってい る。これが「アハ」と呼ばれるハワイの伝統的なカパ特有の細かい透か し模様である。

太平洋の他の島々では「タパ」とも呼ばれるカパは、この地域の島 の社会全体で見られる。この布は、ハワイ以外の島でも人々が身につけ る衣服として、または伝統儀式に使う装飾や、枕や毛布、ベッドカバーな ど、日常生活のあらゆる用途や場面で使用された。格子模様からジグザ グ模様まで、そのデザインには膨大な数があり、自然をモチーフにした ものや、中には作り手のカパ職人にしか分からない神聖な意味を持っ たものもある。

ダラニ・タナヒーさんは、ハワイで現在もカパを製作する数少な い職人の一人であり、カパ作りをフルタイムの仕事とする唯一の職人 だ。カパの研究と製作を25年以上にわたって続けてきた彼女は、2007 年にマカハにある自宅に面した空き地に女性一人で経営するアトリエ 「カパ・ハワイ」をオープン。ハワイで指折りのカパ職人のカフナ・プアナ ニ・ファン・ドルペさんがこの世を去って以来、1970年代に盛んになっ たハワイ文化復興運動によってカパ作りが復活を遂げるまでカパは失 われた芸術と見なされていた。カパの伝統を現代に伝える職人が今も 健在なサモアやトンガやフィジーとは異なり、ハワイにはカパ職人の直 系の子孫が残っていなかったためだ。だがハワイの文化従事者たちは、 口頭伝承によって残された記録や歴史資料、ビショップ博物館の民族 学コレクションをもとに研究し、試行錯誤を繰り返すことによって、忘 れ去れかけていたカパという芸術を復活させ、その神秘を今も解明し 続けている。

カパ作りは手間のかかる孤独な作業であるだけでなく、高度な 専門性と多くの研究時間を要する。「カパ職人になるということは、想像 以上に大変です。植物学者と彫刻家とグラフィックデザイナーの素質を 兼ね備えていなければならないのですから」とタナヒーさん。

Kapa, known as tapa elsewhere in Polynesia, are hand-printed with designs and techniques unique to its island cultures.

ポリネシアの他の場所ではタパとも呼ばれるカパは、それぞれの島の文 化独自のデザインや技術によって手で染められている。

From checkerboard to zig-zags, their amazing range of designs draw on motifs found in nature, while others possess unknown sacred meanings except to the kapa-master who fashioned them.

碁盤目からジグザグ模様まで、自然にあるモチーフのバラエティに富んだデザインが施されているカパ。中には 作り手のカパ職人にしか分からない神聖な意味が込められているものもある。

At the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, its ethnology collection preserves ancient kapa piece.

バーニース・パウアヒ・ビショッ プ博物館にある民族学のコレク ションには古代のカパが保存さ れている。

fabric to eventually drape across a person’s body. But, that’s where the physical labor comes in, of a seated kapa practitioner hunched over a cut tree that’s steadied on a flat stone and hand-pounded for hours upon hours.

On her Mākaha acreage, Tanahy tends to a dense and towering grove of wauke she planted nearly a decade ago. Wauke, or the paper mulberry tree, was clearly treasured by the first waves of Hawai‘i’s settlers, who brought the plant with them in the hulls of their canoes. “To understand kapa, you have to understand wood,” Tanahy says.

The ways of wood must also be considered for kapa’s central implement, the i‘e kuku, which is a four-sided anvil carved of native wood that is robust enough to physically beat the bark into shape. Tanahy makes every i‘e kuku herself, shaping them and then etching each side of the beater with grooved patterns that will ultimately become the watermark of her kapa works.

Appreciating a finished piece can be a cerebral affair. The various patterns, which she often makes with ‘ohe kapala (bamboo stamps) and plant dyes, inspire questions about the significance and application of geometry and colors. Tanahy’s works have an unmatched vibrancy and range: On one end of her kapa portfolio are understated and

カパの原料は、手の平より大きな葉をつける細長く背の高い木か ら取れる。タナヒーさんは「カパを知るにはまず元になる木について知 らなければなりません」と言う。マカハにある彼女の敷地には、彼女が 10年ほど前に植えた背の高いワウケの木の林が密集して生えている。 ワウケは桑の木の一種で、その樹皮が新しい島での生活に欠かせない 貴重な資源となることを知っていたハワイの初期の入植者たちが、カヌ ーに乗せて持ち込んだ植物だ。天然木でできた頑丈で四角い棒の「イ エ・クク」はカパ作りに欠かせない道具で、樹皮を叩いて平らにするのに 使用する。この棒を作るのには彫刻の技術も必要とされる。タナヒーさ んはこれらの木材を自ら調達し(性質の似ているもので外来種の木材 を使用することもある)、全てのイエ・ククを手作りしている。出来上がっ た棒の側面には、完成したカパの表面に透かし模様として浮かび上が るデザインが一本一本彫り込まれる。

カパの作品にはそれぞれ深い意味が込められている。詳しい人 が見れば一枚のカパから多くを読み取ることができるだろう。幾何学模 様や色で表現される多様なパターンは、様々な植物から取れる染料と 「オヘ・カパラ」と呼ばれる竹製のスタンプを使って刻印されたものだ。 タナヒーさんの作るカパは、活き活きとした多彩なデザインが特徴だ。 彼女の作品群には、ジェットコースターのレールのようなねじれ模様が 躍動感を感じさせるカパもあれば、控えめでエレガントな真っ白なカパ まで幅広いデザインのものがある。

The i‘e kuku is a four-sided anvil traditionally carved of native woods.

カパを打ち付けるのに使う 四角い棒のイエククは本来、

天然木を削って作られる。

elegant all-white cloth pieces, while on the other are energetic kapa canvases with twisting patterns that resemble rollercoaster tracks. Her kapa are on display in diverse contemporary spaces, from hotels throughout Hawai‘i to art galleries to private collections abroad. She also perpetuates the art, consulting for hula hālau who want to dance in kapa during the Merrie Monarch Festival and occasionally holding educational workshops at the Honolulu Musuem of Art School.

Recently, Tanahy finished two kapa pieces for display at the bases of kahili markers flanked over Queen Kapi‘olani’s bedframe. She has also made kapa for funereal rites (Native Hawaiians would customarily wrap their loved ones’ bones in the barkcloth), which she considers a priceless honor. At work in the shade of her wauke trees, Tanahy uses techniques rooted in the same disciplined and repetitive motions women have been fine-tuning since they first set foot in the islands. She uses an ‘opihi shell to strip the bark. She colors a bamboo stamp with inks. She presses it with purpose against the weathered cloth. She leaves her mark.

今日、タナヒーさんの作品は、ハワイ中のホテルやリゾートなど、 数多くの現代アートスペースに飾られ、海外のアートギャラリーやアー トコレクターによって収集されている。タナヒーさんは、メリー・モナー ク・フェスティバルに出場するフラハラウから伝統的なカパを身につけ たいという相談を受けることもあれば、ホノルル美術館でカパ作りのワ ークショップを開くこともある。

最近では、カピオラニ女王のベッドフレームの上に並ぶ2本のカ ヒリの土台を飾るカパを2枚完成させた。伝統的な葬儀に使用する神 聖なカパ(ハワイ先住民の間では昔から愛する人の骨をカパで包む慣 習がある)を作ることも、彼女にとっては光栄なことだという。ワウケの 木陰で丹念な手作業を繰り返すタナヒーさんの技術は、先住民の女性 たちがこの島に入植して以来、腕を磨き、受け継いできたカパ作りの伝 統に根付いている。オピヒ貝の殻で樹皮を剥ぎ、竹のスタンプにインク をつけ、カパへの思いを込めて押しつける。そこにまた一つ彼女のマー クが刻まれていく。

A Sculpture Rising From a Garden

IMAGES BY

MARK KUSHIMI

STYLED BY

ARA LAYLO

HAIR + MAKEUP BY

HMB SALON

MODELED BY

IMAGES BY

MARK KUSHIMI

STYLED BY

ARA LAYLO

HAIR + MAKEUP BY

HMB SALON

MODELED BY

Bills Hawaii

Earrings, M33MS Designs, from We Are Iconic Coat, Burberry; Dress, Tory Burch; Beret, Eric Javits; all from Neiman Marcus

Bills Hawaii

Earrings, M33MS Designs, from We Are Iconic Coat, Burberry; Dress, Tory Burch; Beret, Eric Javits; all from Neiman Marcus

Bean About Town Top, Simone Rocha; Pants, Brunello Cucinelli; Bag, Tory Burch; all from Neiman Marcus

Bean About Town Top, Simone Rocha; Pants, Brunello Cucinelli; Bag, Tory Burch; all from Neiman Marcus

ARS Cafe Bag, Cult Gaia; Jacket, Co Clothing

Top and pants, Brunello Cucinelli; Earrings, Ippolita; Shoes, Chloé; all from Neiman Marcus

ARS Cafe Bag, Cult Gaia; Jacket, Co Clothing

Top and pants, Brunello Cucinelli; Earrings, Ippolita; Shoes, Chloé; all from Neiman Marcus