Ulrich Krauer General Manager Halekulani

Ulrich Krauer General Manager Halekulani

Conserving Hawaiian culture is vital for Hawai‘i’s future. In the past, ideas were passed down through spoken word; today, we are able to capture the spirit of the islands through various forms—prose and poetry, photographs, films, and other arts. We are also working to perpetuate this culture with care. Conservation education and groups are necessary for the survival of native plants and animals. The landscape is changing quickly, and we do our best to maintain the place we hold dear.

In this issue of Living, we examine the art of preservation in the islands. These pages feature individuals who ensure that Hawai‘i stays connected to its roots. Kenyatta Kelechi shares his practice of using wet-plate photography to capture the multiculturalism of Hawai‘i’s ‘ohana (family). We take a tour to see some of the most historic architecture in downtown Honolulu, such as the YWCA building, which was designed by San Francisco architect Julia Morgan in the 1920s to create a unique structure adapted to the Hawaiian climate and regional style. In addition, we take a look at ‘Iolani Palace, the official residence of Hawaiian monarchs, and the special autograph book of Princess Ka‘iulani, which helps us reimagine history during the monarchy. We also learn from conservationists about ongoing efforts to save Hawaiian honeycreepers from extinction.

There are many things worth saving in Hawai‘i. They can be as simple as an old family recipe or as pressing as an endangered species. We hope these stories inspire you as well as give you a chance to walk down memory lane and enjoy the present moment.

Warmly,

Ulrich Krauer General Manager Halekulaniハワイの文化を守ることは、ハワイの未来にとって重要なことです。 昔のハワイでは、さまざまな思想が、口述によって伝えられていました。 現在、ハワイの精神は、詩や散文、写真、映画や芸術といったさまざまな 形で表現されています。私たちもまた、その文化を大切にし、継承するこ とに取り組んでいます。在来種の動植物の生存には、それを保護するた めの教育や団体が欠かせません。急速に変化する環境下で、私たちは、 私たちにとって大切な場所を守るために、最善を尽くしています。 今号のリビングでは、ハワイの文化、歴史、自然の保護に焦点を当 て、ハワイのルーツを守るために活動する人々を紹介しています。湿板 写真を用い、ハワイのオハナ(家族)の多文化性を捉えるアーティストの ケニヤッタ・ケレチ氏のストーリーをはじめ、1920年代にサンフランシ スコの建築家ジュリア・モーガン氏がハワイの気候と地域性に合わせ て設計したユニークなYWCAビルなど、ホノルルのダウンタウンにある 最も歴史ある建築を巡ります。さらにハワイ王族の公邸であったイオラ ニ宮殿やカイウラニ王女の貴重なサイン帳を通して、君主制時代の知 られざる歴史を紐解きます。またハワイのミツスイを絶滅から守るため の保護活動家による継続的な取り組みについても触れています。 ハワイには守るべきものがたくさんあります。家族に代々伝わるレシ ピのようなささやかなものから、絶滅危惧種の動植物といった環境全 体の問題まで、その規模は様々です。これらのストーリーが皆様のイン スピレーションとなって、懐かしい思い出を振り返り、今、このひととき を楽しんでいただくきっかけとなることを願っております。

心を込めて ハレクラニ総支配人 ウーリック・クラワー

HALEKULANI CORPORATION

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER

PETER SHAINDLIN

CHIEF EXECUTIVE ADVISOR

PATRICIA TAM

GENERAL MANAGER, HALEKULANI

ULRICH KRAUER

DIRECTOR OF SALES & MARKETING

GEOFF PEARSON

HALEKULANI.COM

1-808-923-2311

2199 KALIA RD. HONOLULU, HI 96815

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER

JASON CUTINELLA

CHIEF RELATIONSHIP OFFICER

JOE V. BOCK

JOE@NMGNETWORK.COM

CREATIVE DIRECTOR ARA LAYLO

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

MATTHEW DEKNEEF

PUBLISHED BY NMG NETWORK

36 N. HOTEL ST., SUITE A HONOLULU, HI 96817 NMGNETWORK.COM

© 2020 by Nella Media Group, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted without the written consent of the publisher. Opinions are solely those of the contributors and are not necessarily endorsed by NMG Network.

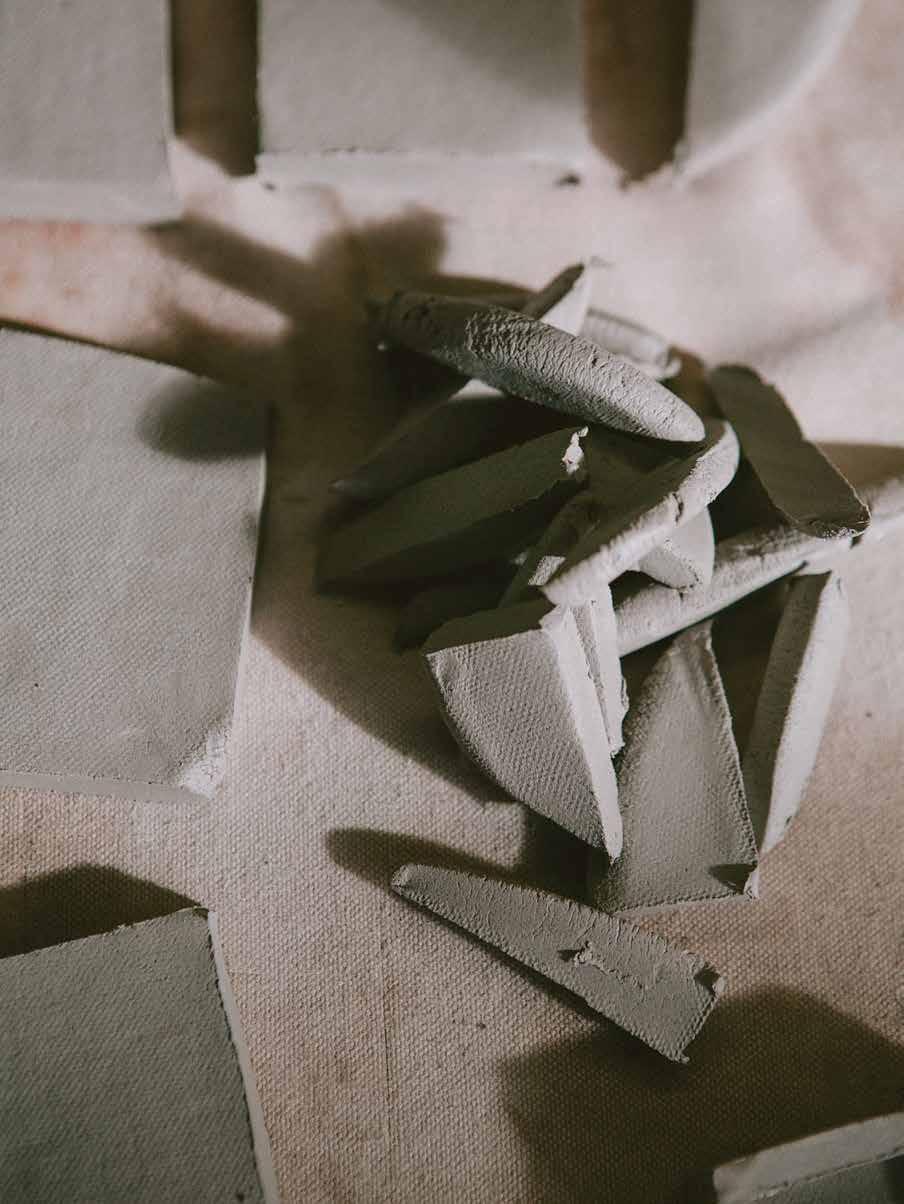

An artist ruminates on making ceramics at the Hawai‘i Potters’ Guild.

ハワイ・ポッターズ・ ギルドでの陶芸について アーティストは語る。

ARTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Julia Morgan’s Enduring Oasis

The Ghost of Manookian

CUISINE 54

Searching for Japan

CULTURE 64

Honoring a Valley 76

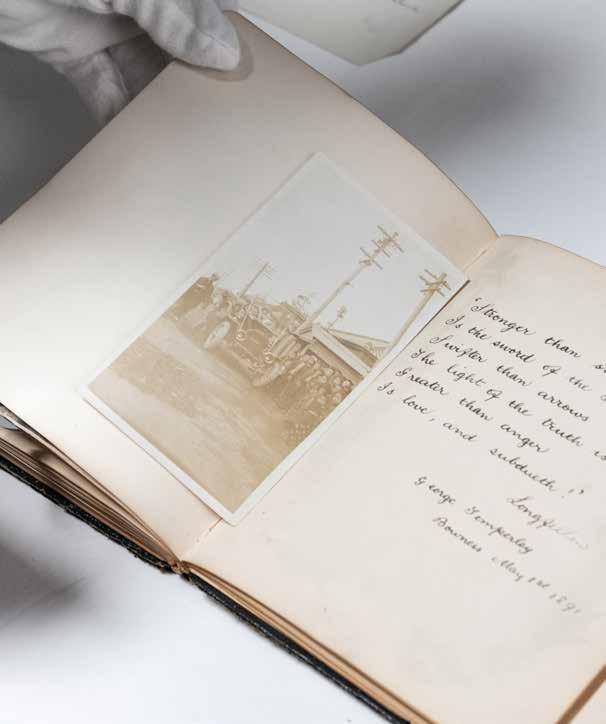

Sovereign Signatures

WELLNESS

Fishing Tales 100

Finding One’s Center

ABOUT THE COVER:

Learn about the lesserknown contributions of Japanese immigrants to historic Chinatown.

歴史あるチャイナタウンの 形成に貢献した日系移民の あまり知られていない歴史 に触れる。

Downtown Express

EXPLORE 126

The Sound of Silence 134

Spotlight: Alexander McQueen

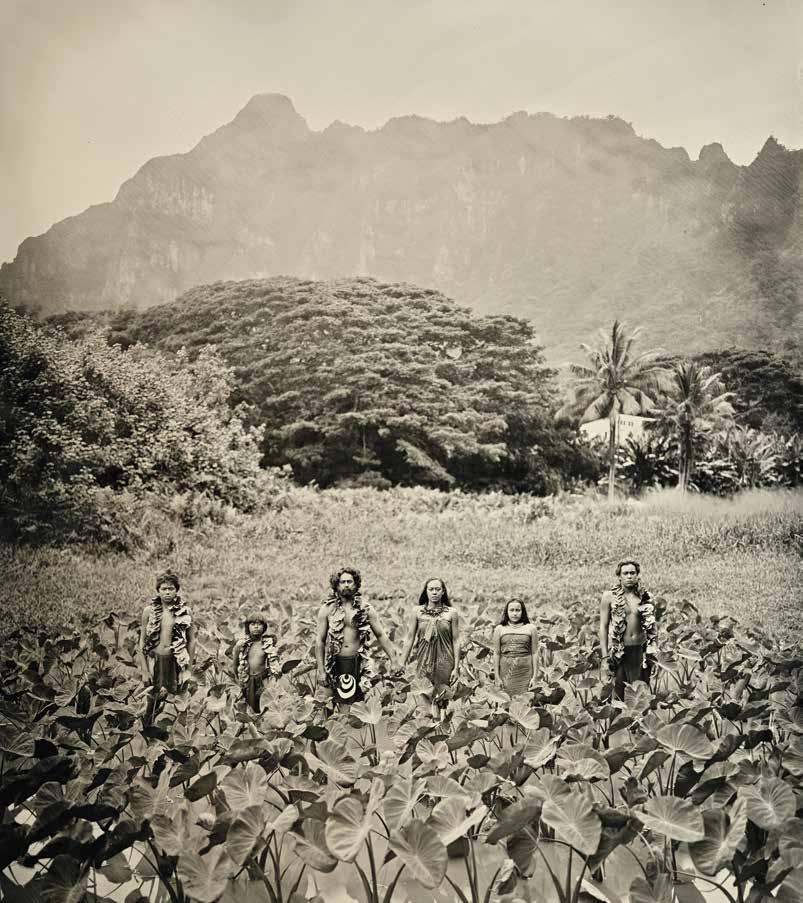

The cover image, photographed by Kenyatta Kelechi, is of the Fukumitsu family in a kalo field on O‘ahu’s windward side. On page 22, read about his studio Manachrome, and watch a feature about his process on Living TV.

Halekulani Living

Discover the charming arts scene around Honolulu.

ホノルルの魅力的なアート シーンを探検しよう。

TABLE OF CONTENTS

目次

ARTS 22

フィルム時代の再来 32

ジュリア・モーガンの 不朽のオアシス 42

マノオキアンの亡霊 CUISINE 54

日本文化探訪 CULTURE 64

渓谷を讃えて 76

君主の署名

Mānoa Heritage Center houses a cultural tradition spanning centuries.

マノア・ヘリテージ・センター には、何世紀にもわたる文化 遺品が残されている。

WELLNESS 90

魚釣りの物語 100

中心を見つける FASHION 114

ダウンタウンエクスプレス

EXPLORE 126

静けさの中の音 134

スポットライト: アレキサンダー・マックイーン

ABOUT THE COVER:

表紙について:

表紙の写真は、ケニヤッタ・ケレチ氏がオアフ島ウィンドワードのタロ畑で撮影したフクミツ一家。彼の写真スタジオ、 マナクロームについては、22ページで紹介しています。ケレチ氏のストーリーは、リビングTVでもご覧いただけます。

Halekulani Living

Living TV is designed to complement the understated elegance enjoyed by Halekulani guests, with programming focused on the art of living well. Featuring cinematic imagery and a luxurious look and feel, Living TV connects guests with the arts, style, and people of Hawai‘i. To watch all programs, tune into channel 2 or online at halekulaniliving.tv.

客室内でご視聴いただけるリビング TVは、ハレクラニならではの上質な寛 ぎのひとときをお過ごしいただくため、 豊かで健康的なライフスタイルをテー マにしたオリジナル番組をお届けして います。臨場感溢れる映像で芸術や ファッション、食文化、ハワイの人々に ついてのストーリーをお楽しみくださ い。すべての番組は、2チャンネルまた はhalekulaniliving.tv からご視聴い ただけます。

ANALOG TIMES

アナログの時代

Through the collodion wet-plate process, Kailuabased photographer Kenyatta Kelechi revives an obscure form of portraiture.

湿板コロジオンを用い、独特のニュアンスのある肖像写真を 撮影するカイルアの写真家、ケニヤッタ・ケレチ氏

VALLEY HERITAGE

渓谷の遺産

In preserving Hawaiian culture, The Mānoa Heritage Center is a love letter to a verdant place.

ハワイの文化遺産を保存する、緑豊かなマノアへの愛と畏敬の 念が込められたマノア・ヘリテージ・センター。

OUT AT SEA

魚突き

Spearfishing in Hawai‘i today runs the gamut from simple set ups to state-of-the-art gear.

シンプルな道具から最先端のギアまで、装備の種類の幅広い ハワイのスピアフィッシング。

watch online at: halekulaniliving.tv

COMMUNAL FORM

Since it was founded in the 1960s, the Hawai‘i Potters’ Guild has become a rock in Honolulu’s arts community.

A LOVE LETTER TO CHINATOWN

チャイナタウンへのラブレター

From museums to marketplaces, Honolulu’s historic charms blaze through.

美術館から市場まで、ホノルルの歴史ある街が放つ多彩な魅力 コミュニティの形 1960年代に設立されて以来、ハワイ・ポッターズ・ギルドは、 ホノルルのアートコミュニティの礎となっている。

PORTRAITS BY

KENYATTA KELECHI IMAGES BY CHRIS ROHRER文=ナズ・カワカミ

肖像写真=ケニヤッタ・ケレチ

写真=クリス・ローラー

MODERN AGE

フィルム時代の再来

The collodion process remains one of photography’s most challenging. Kenyatta Kelechi dips back into time by reviving this tintype style of portraiture.

1930年代に発明された湿板コロジオンは、最も手間のかかる古典的な写真技法のひとつ。 ケニヤッタ・ケレチ氏は、このレトロな技法で肖像写真を撮影する数少ないハワイの写真家だ。

Opposite: The Moniz Family

右ページ:モニース一家

In film photography, the format of a film typically refers to its size. The most common format is 35 millimeter; followed by 120 film (6 centimeter), referred to as medium format; then 4 by 5 inches, known as large format; and finally, 8 by 10 inches, which is also referred to as large format.

The larger the format, the more complicated it is to shoot. Due to the size and potential variables of photographing with large format pieces of film (often referred to as “sheets”), calculating the camera’s settings or even simply focusing your lens can be grueling processes. If you’re the adventurous type, you may even be inclined to try a foundational version of the 8-by-10 format called wet-plate photography, which requires photographers to make the film from scratch, adding even more layers of complication.

Due to the difficulty of attaining an image in this fashion and the time it requires, few photographers shoot on wet plates. One of the only photographers in Honolulu still actively pursuing the elusive 8-by10 wet plate format is Kenyatta Kelechi.

Kelechi undertook the arduous responsibility of keeping wet-plate photography alive in Hawai‘i back in 2015, when his love of film photography drove him to seek even more obscure formats. Since then, he has used Collodion wet plates to photograph friends, family, and those he admires, along with several commercial projects through his company, Manachrome.

写真フィルムの形式は通常、フィルムの大きさを指す。最も一般的な のが、35mm判だ。その次が中判の120フィルム。続いて、4x5イン チの大判フィルム、そして最後が8x10インチで、これも大判と呼ば れている。

フォーマットが大きいほど、撮影の難易度も高くなる。シートと 呼ばれる大判フィルムを使った撮影では、フィルムの大きさと潜在的 な変数の多さにより、カメラ設定の微調整や単にレンズの焦点を合 わせることすら、非常に手間のかかるプロセスとなる。チャレンジ精 神のある人は、フィルムの下準備と複雑な工程が必要な湿板写真と 呼ばれる8x10インチの大判フィルムを使った古典的な撮影技法を 試してみるのもいいだろう。

この技法を使って画像を得るのは難しく、より多くの時間を要 するため、湿板写真を撮影する写真家は極めて少ない。ケニヤッタ・ ケレチ氏は、このレトロな8×10湿板法を追求する、ホノルルで唯一 の写真家だ。

フィルム写真の魅力に惹かれたケレチ氏は、この独特なぼけ感 のある写真を追求するようになり、2015年以来、ハワイの湿板写真 の保存に努めている。以来、彼はコロジオン湿板法で、友人や家族、 彼が尊敬する人物を撮影し、彼の会社のマナクロームでは、この技 法を使ったコマーシャル撮影も行っている。

The process that Kelechi undergoes on each shoot is rigorous and time-sensitive. All the chemicals must be mixed and applied to a surface onsite, as the sensitivity of Collodion—the main ingredient in the process—can decay to the point of being unusable in as little as 20 minutes.

In an onsite darkroom, Kelechi must thoroughly clear his photographic surface—a sheet of glass— to prevent any dust or residue particles from interfering with the final image. Then he covers the glass in a mixture of iodides, bromides, ether, and alcohol before dipping it in silver nitrate, which makes the plate sensitive to light. Finally, he places the plate in a light-tight box.

After Kelechi has determined the proper settings for his camera and considered all variables—ranging from the amount of light on the subject to the amount of water vapor in the air—he attaches the box containing the plate to the camera and fires the camera, exposing the light-sensitive chemistry to the subject. After the exposure is complete, he carries the box back into the darkroom for development. The developer hardens the parts of the chemicals that weren’t exposed to quite as much light, which stick to the plate. When he rinses off the exposed parts, a positive image is revealed. (It’s a bit like drawing a shape on paper with glue, covering the paper with glitter, and then lifting the paper so that only the glitter stuck to the glue remains, revealing your shape.)

Kelechi is devoted to his craft not despite its difficulty but because of it. “With each mistake, I’ve learned,” he says. “By now, when problems come up, I’m able to troubleshoot them, and it’s those challenges that make it worthwhile.” Kelechi has a knack for fixing the problems you might not think of, like when clouds loom and the scene is darker than it’s supposed to be, in which case he adjusts his procedure accordingly.

Kelechi also uses his wet plates as a vessel to better understand and bond with his culture. “The mission of Manachrome is to photograph Native Hawaiians and Hawaiian practitioners,” he explains. “I wanted to do something meaningful in

コロジオン湿板法による撮影では、厳密な作業工程を限られた時 間内に処理する必要がある。感光材料の主成分であるコロジオンの感 度は、時間がたつほどに劣化し、わずか20分で使用できなくなる。その ため、全ての薬品を現場で混ぜ合わせる必要があり、ガラス板に塗った 薬品が乾くまでに撮影を終えなければならない。

現場の暗室で、ケレチ氏はまず、写真にほこりや残留物が映らない よう、ガラス板の表面を綺麗に拭き取る。次に、ヨウ化物、臭化物、エー テル、アルコールを混ぜた溶液をガラス板に塗布し、感光剤の硝酸銀溶 液に浸す。最後に、ネガとなったガラス板を遮光ボックスに入れて準備 完了だ。

次に、カメラの設定を調整し、被写体の光の量や空気中の水蒸気 の量といったあらゆる変数を考慮した上で、湿板の入った箱をカメラに 取り付け、被写体を感光剤に露出させて、撮影に取り掛かる。露光が済 んだ箱は、暗室に戻し、ここからが現像作業となる。光の露出が少ない 部分の薬剤を硬化させてガラス板に付着させ、露出のあった部分を洗 い流すと、ポジ画像が現れる。紙に糊で絵を描き、ラメをふりかけると、 糊のついていない部分の粉が落ちて、絵が現れるのと同じ仕組みだ。 ケレチ氏は、その難易度の高さゆえに この技法に意欲を掻き立て られるという。「間違うたびに、学んでいます。今では、どんなことが起こ っても、ほとんどの問題に対処できるようになりました。そうやって挑戦 し続けることに意味があるんです」という彼は、雲がかかって辺りが暗く なっても、状況に応じて臨機応変に作業の手順を変えるなど、予想外 の問題も解決するコツを心得ている。

自身の文化への理解と繋がりを深めるための手段として、湿板写 真を用いるケレチ氏は、「マナクロームは、ネイティブハワイアンとハワ イ文化の継承者を撮影することを目的に掲げています。20代の間に何 か意義のあることをしたくて、この湿板写真を使って面白いことができ ればと思ったのがきっかけです。ネイティブハワイアンの人々やハワイ文 化の継承者と話をすることで、彼からから学ぶ機会を得られるのと同時 に、彼らのイメージを保護し、保存するという大切な使命を担っていま す」と語る。

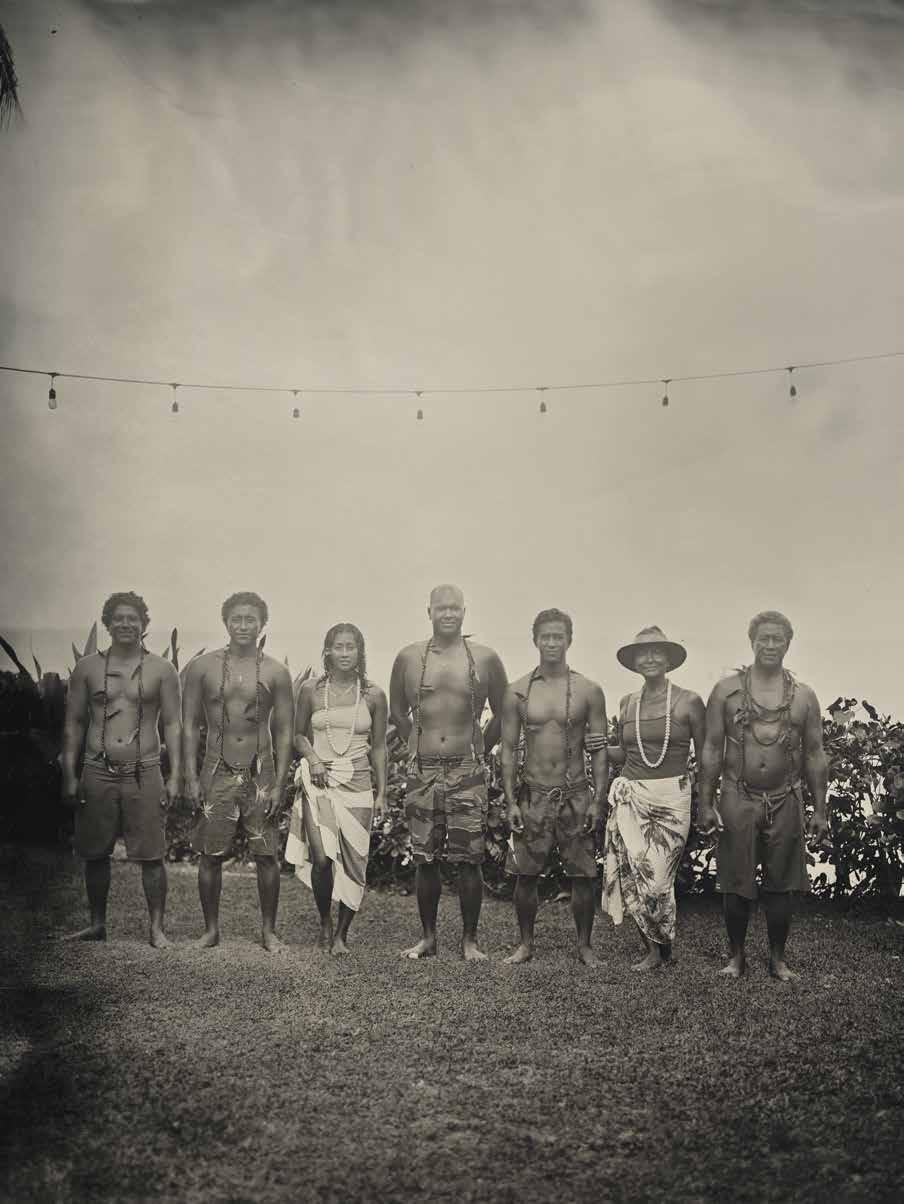

Kenyatta Kelechi, who operates the studio Manachrome, shoots his portraiture on one of the medium’s earliest forms. He is dedicated to capturing Native Hawaiians and cultural practitioners.

写真スタジオのマナクロームを経営するケニヤッタ・ケレチ氏は、レトロ な技法で肖像写真を撮影する写真家だ。ネイティブハワイアンや文化 継承者の撮影を専門とする。

プアマナ Puamana.

プアマナ Puamana.

The wet-plate process is rigorous and technical, involving a variety of chemicals and sensitive handling.

湿板写真は、様々な化 学薬品と厳密な作業を 必要とし、非常に手間の かかる、高度な技術が必 要とされる撮影技法だ。

my 20s, and these plate photographs are something interesting that I can bring to the table; it gives me the opportunity to speak with these Native Hawaiians and practitioners and learn from them, while also protecting and preserving their image, which is important.”

The images Kelechi captures are stunning, irreplaceable, and hard-earned. While his subjects may have seen themselves on phone screens and paper printouts, nothing compares to seeing their images suddenly appear in their hands, according to Kelechi. “They’re never not amazed,” he says. “They’re never not smiling.”

Following a decade of decline that nearly ended with the permanent discontinuation of consumer films, there was a resurgence of emulsion-based photography of all sizes, speeds, and formats, with film producers, like Kodak Alaris and Harmon Technologies, reporting significant yearly growth.

Oddly enough, in addition to older-generation photographers who have remained loyal to film, those responsible for saving film from extinction are overwhelmingly of a younger demographic, ages 15 to 35—not necessarily old enough to remember when

ケレチ氏が撮影する写真は、どれも新鮮で、個性的な苦労の結晶だ。 携帯電話の画面やプリントで自分の写真を見慣れている人も、画像が 目の前で一瞬にして現れる瞬間には、なんとも言えない感動を覚える という。「その瞬間を見て、驚かない人はいません。だれもが笑顔にな るんです」と彼は言う。

ここ10年で衰退の一途をたどり、一時は生産の継続が危ぶま れた一般消費者向けのフィルムも、最近では、あらゆるサイズやスピー ド、フォーマットの乳剤ベースの写真が復活しつつあり、コダックアラ リスやハーモンテクノロジーズといったフィルム製造会社の売り上げ が大きな伸びをみせている。

面白いことに、フィルム写真を救ったのは、フィルムに忠実であり 続けたシニア世代の写真家だけでなく、フィルム時代を必ずしも知ら ない15歳から35歳の若者世代からの圧倒的な支持だった。フィルム

For Kelechi, nothing compares to when his subjects see their images suddenly appear in the developing phase.

ケレチ氏にとって、撮影した人が現像の瞬間を目の当たりにしたとき にみせる感動ほど素晴らしいものはないという。

film was the standard in photography. However, they appreciate film’s distinct look and feel; or perhaps, much like individuals working to keep vinyl factories pressing their favorite records, they recognize the value in preserving and perpetuating endangered artistic mediums. That appreciation for the one-ofa-kind sensation that Kelechi, and all film dabblers, feel—the sensation of the tangible, real image—is what has, and what will, continue to keep film alive.

写真が醸し出す独特のニュアンスを高く評価している彼らは、アナログ レコードの生産をサポートするレコード愛好家と同じように、消滅の 危機にある芸術表現のメディアを保存し、永続させることに価値を見 出しているのだ。ケレチ氏をはじめ、フィルム写真愛好家なら誰もが知 っている唯一無二の作品を生む喜び、そして形のあるリアルな画像が もたらす感動によって、フィルム写真はこれまでも、そしてこれからも生 き続けるであろう。

TEXT BY TIMOTHY A. SCHULER

TEXT BY TIMOTHY A. SCHULER

IMAGES BY CHRIS

ROHRERARCHIVAL IMAGES

COURTESY OF ROBERT E. KENNEDY

LIBRARY

文=ティモシー・A・シュラー 写真=クリス・ローラー 資料写真提供:ロバート・E・ ケネディ図書館

JULIA MORGAN’S ENDURING OASIS

ジュリア・モーガンの不朽のオアシス

In Honolulu, a not-so-hidden gem by one of the most prolific architects of the 20th century.

多くの傑作を残した20世紀を代表する女性建築家によるホノルルの魅力的な建物

The diners in the café sit in twos and threes, chatting over elegantly constructed salads or seared ‘ahi arranged on beds of steamed rice. The tablecloths ripple in a cool breeze, and the midday sun filters through the foliage of palms and plumeria that dance just beyond the large, arched, open windows. The atmosphere is lively yet hushed. There’s such a feeling of serenity that one imagines they are dining at a secluded country estate miles from the nearest city—not inside a Young Women’s Christian Association building in downtown Honolulu.

Tucked off Richards Street, with an elegant landscaped courtyard (designed by Catherine Thompson, Hawai‘i’s first licensed landscape architect), the historic 1920s building and its restaurant, Café Julia, are “like a secret garden,” says Mike Gushard, the former architecture branch chief of the Hawai‘i State Historic Preservation Division. “Everything slows down. Everything is quiet.” Gushard has a more personal connection to the YWCA building as well. He and his partner, Orlando de Lange, were married under its elegant loggia just last year.

That the building maintains the feel of an urban oasis nearly a century after it was built is a testament to the brilliance of its architect and the restaurant’s namesake, Julia Morgan, a 5-foot-tall, 100-pound giant of American architecture who outbuilt Frank Lloyd Wright (completing more than 700 buildings over her career) yet whose name is relatively unknown outside of California and the cluttered offices of architecture scholars.

Born in San Francisco in 1872, Morgan was the first woman admitted to the architecture program at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, then the leading architectural training program in the world, and the first female architect to be licensed in the state of California. She was a prolific architect and a consummate builder, having studied engineering at the University of California, Berkeley prior to her time in Paris.

カフェの店内では、食事中の2人客や3人連れの客が、サラダやアヒの たたきが綺麗に盛り付けされた皿を前に、おしゃべりを楽しんでいる。店 内を吹き抜けるそよ風にテーブルクロスがたなびき、大きなアーチ型の 窓の外に揺れるヤシとプルメリアの木の葉の隙間からは、真昼の太陽が 木漏れ日となって降り注いでいる。ホノルルのダウンタウンにあるキリス ト教女子青年会 (YWCA)の建物の中とは思えない、活気がありながら も穏やかな空気に包まれた静寂さは、都会の喧騒から離れた閑静な別 荘地で食事をしているような気分にさせてくれる。

リチャーズ通りから一本脇道を入ったところにあるレストラン「カ フェジュリア」は、ハワイ州歴史保存課の元建築部門長のマイク・ガシャ ード氏が、“秘密の庭園のようだ”と賞賛するエレガントな中庭(ハワイで 初めてライセンスを受けた造園家のキャサリン・トンプソン氏が設計)の ある1920年代に建てられた歴史的建造物の中にある。「ここはいつでも 静かで、ゆっくりと時間が流れています」と言うガシャード氏自身にとって も、このYWCAビルは、特別な思い入れのある場所だ。彼と彼のパートナ ーのオーランド氏は、昨年、この優雅でエレガントなロッジア(開廊)で式 を挙げたという。

建設されてから約1世紀経った今も、都会のオアシスであり続け るこの建物は、店名の由来となっているアメリカ人建築家の巨匠、ジュリ ア・モーガン氏の優れた才能を物語っている。身長150センチ、45キロと 小柄だった彼女は、生涯を通して、700以上の建物を完成させた。その数 は有名な建築家のフランク・ロイド・ライト氏を上回るが、建築学者を除 いて、カリフォルニア州外で彼女の名はあまり知られていない。

1872年にサンフランシスコで生まれたモーガン氏は、当時、世界 有数の建築訓練プログラムであったパリの国立高等美術学校、エコー ル・デ・ボザールの建築プログラムで学んだ最初の女性で、カリフォルニ ア州でライセンスを取得した初の女性建築家だった。彼女は多くの建物 の設計を手がけた有能な設計士であり建築家で、渡仏以前には、カリフ ォルニア大学バークレー校で工学を学んだ。

Detail of the original blueprint for the YWCA by Julia Morgan, 1925.

ジュリア・モーガン氏が1925年に作成したYWCAのオリジナルの設計図。

Morgan was devoted to women’s empowerment. She designed dozens of buildings for the YWCA over the course of her career—including those at Asilomar, the association’s storied retreat center in Monterey—even as she spent her weekends in San Simeon, California, working with William Randolph Hearst on what would become the sprawling mega-project La Cuesta Encantada, better known as Hearst Castle.

It was Morgan’s work with YWCA that brought her to Hawai‘i. For the association, she designed a women’s residence (now demolished) on the corner of King and Alapa‘i streets in 1921, followed by a headquarters building across from ‘Iolani Palace in 1927 called Laniākea, or “wide skies.” (Morgan’s only other surviving building in Hawai‘i is the Homelani Columbarium in Hilo, a simple, Mediterranean-style building completed in 1937.) Morgan managed the construction of Laniākea from California, relying on daily written reports and film exposures that were sent by boat to San Francisco from her project manager, Edward Hussey.

Although there are touches of the islands in Laniākea’s architecture, such as the Hawaiian flowers carved into the now-weathered teak of the building’s front doors, stylistically, it owes primarily to Morgan’s training at the École des Beaux Arts, with Italian Renaissance columns and the pool area’s Moorish-inflected fountain. Rendered almost entirely in reinforced concrete (a first in Hawai‘i at the time), the architecture is both formal and relaxed, a nod to Morgan’s belief in the dignity of all people and her desire to make them comfortable.

Laniākea’s truest architectural legacy may lie in its functionality and appeal, which persist 93 years after it was built. It’s one of the few Morgan-designed YWCA buildings that hasn’t been substantially altered, so it’s fitting that Morgan be uniquely memorialized here, as a woman who perpetuated the YWCA’s mission of empowerment through architecture.

モーガン氏は、女性の社会的地位向上にも力を注いだ。建築家と してのキャリアを通して、カリフォルニア州モントレーにある歴史的なア ジロマーのレトリートセンターをはじめ、YWCAのための建物の設計を 数多く手がけた。またカリフォルニア州サンシメオンにあるウィリアム・ラ ンドルフ・ハースト氏の「ラ・クエスタ・エンカンターダ」(魅惑の丘)と名付 けられた広大な土地に、のちに“ハーストキャッスル”として知られるハー スト氏の大豪邸を完成させたことでも有名だ。

モーガン氏がハワイに来るきっかけとなったのもやはりYWCAの 仕事だった。1921年には、キング通りとアラパイ通りの角に、この団体の 女性たちのための住まいを設計し(現在は取り壊されている)、その後の 1927年に、イオラニ宮殿の向かいに、“広い空”を意味する「ラニアケア」 という名の本部ビルを建設した。ハワイに現存するモーガン氏による建 物は、このラニアケアと、1937年に建てられたヒロのホメラニ墓地にあ る地中海式の質素な納骨堂の2つのみだ。モーガン氏は、現場監督のエ ドワード・ハッシー氏から毎日船便で届く報告書をもとに、カリフォルニ アからラニアケアの建設工事を指揮した。

ラニアケアの建築は、建物正面のティーク製の扉に刻まれたハワ イの花といった島らしいデザインがさりげなく取り入れられているもの の、イタリアルネサンス調の支柱やプールサイドのムーア風の噴水といっ たモーガン氏がエコール・デ・ボザールで学んだ建築スタイルにあくまで 忠実だ。ほぼ全面を鉄筋コンクリートに覆われたハワイで初の建物は、 格式高くありつつも、心地よいデザインで、人の尊厳を尊重したモーガン 氏らしい、快適に過ごしてほしいという願いが込められている。

ラニアケアの建物が傑作である所以は、建築されてから93年の歳 月にも色あせない、その魅力と機能性だ。それはモーガン氏が設計した YWCAビルの中でも、ほとんど本来の姿のまま残っている数少ない建物 の1つだ。YWCAの建築を通じて、女性の社会地位向上に尽くしたモー ガン氏を偲ぶ場所として、これほどまでにふさわしい場所はあるまい。

ホノルルのダウンタウンにあるYWCAは、都会のオアシスのような1920年代 建築を代表する歴史ある建物だ。現在、ここでは、建築家の名を冠したカフェ ジュリアで食事を楽しむことができる。

Morgan’s education at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris is demonstrated in the Italian Renaissance columns and the pool area’s Moorish-inflected fountain.

パリのエコール・デ・ボザール の建築プログラムで学んだモ ーガン氏の建築スタイルは、イ タリアのルネッサンス様式の 柱とプールサイドのムーア風 の噴水などに現れている。

Gushard says it’s hard to measure just how profound an impact on society an organization like the YWCA has, but the architecture at Laniākea certainly contributes to it. “It’s so perfectly realized, it changes how you feel when you walk into it,” he says. “To have 90 years of a really beautiful space that makes you feel valuable, and that’s accessible to people both by design and manifesto, I can’t imagine the cumulative effect of that.”

ガシャード氏は、YWCAのような団体が社会に与える影響を測 ることは難しいが、ラニアケアの建築が地元社会に果たしている役割は 大きいという。「まさに建築の傑作と言えるでしょう。足を踏み入れるだ けで、気分が変わるんです。90年にわたって私たちを特別な気持ちにさ せ、人々が利用しやすいデザインとマニフェストを併せ持つ美しい空間 が、社会にもたらす影響は計り知れません」。

TEXT BY CHRIS GIBBON

TEXT BY CHRIS GIBBON

ARTWORK COURTESY OF CEDAR

STREETGALLERIES, HONOLULU

MUSEUM OF ART, AND PACIFIC CLUB

文=クリス・ギボン アート提供=シダーストリート

ギャラリー、ホノルル美術館、 パシフィッククラブ

THE GHOST OF MANOOKIAN

マノオキアンの亡霊

The modernist Armenian painter Arman Manookian lived a short and mysterious life. He left a legacy that defies definition yet demands continued interpretation.

謎に包まれた短い生涯を送ったモダニズムのアルメニア人画家、アーマン・マノオキアン氏は、 既存の定義に逆らい、異なる解釈を追求し続けた人物であった。

At the time, the untitled 1930 oil on canvas work, later dubbed “The Mat Weaver,” represented a new direction for artist Arman Tateos Manookian. Its hint of pastel, softer lines, and humanist composition were subtle departures from the bold colors and crisp geometry of his previous works such as “Outrigger and Red Sails,” which portrayed reverent visions of “Old Hawai‘i” as an untouched culture of near mythological beings.

The Turkish-born artist had arrived at Pearl Harbor in 1925 as a 21-year-old clerk for Major Edwin McLellan, a Marine historian who had noticed Manookian’s talent for illustration when he was assigned to his office and tasked the artist with creating drawings to accompany his historical publications. (Manookian’s work also regularly appeared in the Marine Corps magazine Leatherneck.) Manookian had enlisted in the Marines in 1923, after two years of art study at the Rhode Island School of Design. He falsified his U.S. Citizenship to do so; he’d landed at Ellis Island three years prior as a refugee, having fled the Armenian genocide that began in Constantinople in 1915 when he was 10 years old.

After being discharged from the military in 1927, Manookian remained in Honolulu and began to flourish as a painter, his dazzling work quickly gaining public and critical acclaim. A brilliant

当初は無題で、のちに『ザ・マット・ウィーバー』と題された1930年に 製作されたキャンバス画の油絵は、アーマン・マノオキアン氏の芸術 家としての新たなる方向性を示すものであった。パステル色をあしらっ た優しい線使いのヒューマニストな構図は、大胆な色合いと鮮明な幾 何学模様で、神話に出てくるような先住民文化の“古きハワイ”を慎ま しく描いた『アウトリガー』や『レッドセイルズ』といった以前の作品と は、一線を画している。

トルコ生まれのアーティストは、1925年、21歳の時に海兵隊 の歴史家、エドウィン・マクレラン少佐の書記官として、パールハーバ ーに到着し、少佐の部署に在籍中、イラストレーターとしての才能を 買われて歴史書に載せる図面の作成を依頼された。(マノオキアン氏 の作品は、海兵隊雑誌の『Leatherneck』にも定期的に掲載された。 )ロードアイランド・スクール・オブ・デザインで、2年間美術を学んだ マノオキアン氏は、1923年、海兵隊に入隊した。その3年前、10歳の 時、1915年にコンスタンチノープルで始まったアルメニア人虐殺から 逃れ、エリス島に難民として移住した彼は、入隊にあたり、米国籍を偽 らなくてはならなかった。

1927年に除隊後、ホノルルに残ったマノオキアン氏は、画家と して活躍するようになる。才能ある彼の作品は、瞬く間に世間の注目 を集め、批評家の称賛を得ることとなった。色彩センスに長けていた彼 は、感情表現の手段として、鮮やかな赤や青、そして輝くゴールドのシ

Born in Turkey, Manookian arrived in Hawai‘i tasked as a clerk for the Marines.

“Marines of the USS Sir Andrew Hammond at Honolulu” by Arman Manookian. Courtesy of Cedar Street Galleries. Image by Chris Rohrer.

トルコで生まれたマノオキ アン氏は、海兵隊の書記官 としてハワイに到着。アーマ ン・マノオキアン氏による『ホ ノルルに停泊する米海軍船 サーアンドリューハモンド』。

シダー・ストリート・ギャラリ ーズ提供。クリス・ローラー 氏撮影。

colorist, he deployed a simplified yet somehow harmonized palette of electric reds and blues and radiant golds and relied on abstraction for conveying emotion. In a newspaper article, he was quoted as saying, “certain arrangements of abstract forms and colors, quite independent of objective nature, are capable of producing a sensation much more pleasing, satisfying, lasting and profound than any representative painting will ever achieve.”

ンプルでありながら調和のとれた色使いの抽象画を用いた。当時の新

聞記事に彼は、「客観的な性質と関連性のない抽象的な形と色をうま く配置することで、描写的な絵よりも、深い満足感と感銘を与えること ができる」と述べている。

一方で、デイビッド・W・フォーブス氏の著書『楽園との出会い: ハワイとハワイの人々について』(1778-1941)によれば、マノオキア ン氏は、彼の作品が“現代アート”と呼ばれることを拒んだという。この

『無題(ザ・マット・ウィーバー)』アーマン・T・マノオキアン氏作。ホノルル 美術館収蔵。2003年、シェルドン・ジェリンジャー寄贈。

“Untitled (The Mat Weaver)” by Arman Manookian. Honolulu Museum of Art, Gift of Sheldon Geringer, 2003.

アーマン・マノオキアン氏による『無題のカップルと果物」。シダー・ストリ ート・ギャラリーズ提供。クリス・ローラー氏撮影。

“Untitled Couple with Fruit” by Arman Manookian. Courtesy of Cedar Street Galleries. Image by Chris Rohrer.Having rejected the modernist label, Manookian looked to the past for his utopia, in which an unassuming society lives out an idyllic communion with nature.

モダニズムのレッテルを貼られ ることを拒んだマノオキアン氏 は、一般社会が自然と協調して 素朴な生活を送ることのでき るユートピアを過去に見出だ していた。

At the same time, according to David W. Forbes in his book Encounters with Paradise: Views of Hawai‘i and Its People, 1778-1941 , Manookian “rejected attempts to label his work as ‘modern.’” This contradiction was perhaps symptomatic of a deeper internal conflict. Argumentative, temperamental, enigmatic even to those close to him, Manookian was known to have destroyed his work on more than one occasion. He clearly struggled to understand both his personal and professional place in the world.

No one knows what horrors Manookian witnessed as a boy, but art historian John Seed, who is the primary authority on Manookian, has suggested it’s conceivable that his arrival in Hawai‘i inspired him to express a utopian vision of life his own people never had the chance to pursue. While modernism at the turn of the century centered on a rejection of history and a belief in progress, Manookian looked to the past for his utopia, in which an unassuming society lives out an idyllic communion with nature.

Idyllic, and marketable. Before “The Mat Weaver,” Manookian’s pieces more heavily displayed motifs—relative simplicity, planarity, recursion— associated with the art deco movement, which coincided with the Hawai‘i Promotion Committee’s schemes to push the U.S. territory as a world-class travel destination. Art deco has been described as modernism made accessible, and the HPC leveraged this style as the promotional aesthetic of Hawai‘i for the tourism industry for decades to come. Theresa Papanikolas, the curator of an Art Deco Hawai‘i exhibition at the Honolulu Museum of Art in 2014, which featured Manookian prominently, wrote, “artists like Manookian spun the islands’ oft-contested past as an innocent idyll peacefully populated by brave, seafaring men and lovely, accommodating women.”

While Manookian’s portrayals of Hawai‘i may have informed the narrative the HPC was eager to market, there are also clues to a subversive streak. In his 1928 work “The Discovery,” Manookian depicts the arrival of Captain Cook in Hawai‘i: In the foreground, with their backs to us, local chiefs look on, large and proud and rich in color, as the British land ashore as diminutive specters,

明らかな矛盾は、彼の内面的な心の葛藤を示すものだ。論争好きで、神 経質、親しい人にも謎の多かったマノオキアン氏は、自らの作品をたびた び破壊していたことも知られている。明らかに、人としてのあり方とキャリ アの両面において、自らの存在意義に苦悩していたことがうかがえる。 マノオキアン氏が幼少期に体験した恐怖を知る人はいないが、彼 の生い立ちに詳しい美術史家のジョン・シード氏は、ハワイに亡命した彼 は、自国の人々には追求する権利すら与えられなかったユートピア的な 人生観を表現していたのではないかと考える。世紀の変わり目における モダニズムは、過去に対して否定的な進歩主義に基づいていた。その一 方で、マノオキアン氏は、一般社会が自然と協調して素朴な生活を送るこ とのできるユートピアを過去に見出していたのではないか。

牧歌的であり、商業的価値もあったマノオキアン氏の『ザ・マット・ ウィーバー』以前の作品は、アールデコ調のシンプルで平面的な反復す るモチーフが多用されていた。それは、現在のハワイ州観光局にあたるハ ワイ・プロモーション・コミッティー(HPC)が、米国に併合されたハワイ を世界有数の旅行デスティネーションとして、宣伝し始めた時期と重な る。HPCは、何十年もの間、親しみやすいモダニズムとされるアールデコ を、観光業界向けのハワイ観光誘致キャンペーンのデザインに起用して いた。2014年にホノルル美術館で開催され、マノオキアン氏の作品を多 数フィーチャーした「アールデコハワイ展」をキュレートしたテレサ・パパ ニコラス氏は、「マノオキアン氏のようなアーティストは、しばしば論争の 的となるハワイの過去を、勇敢な船乗りたちと優しく美しい女性たちが平 和に暮らす牧歌的な島として描いた」と述べている。

マノオキアン氏のハワイの描写は、HPCの観光誘致の宣伝メッセ ージを伝えた一方、そこには彼の持つ反体制的な思想も潜在していた。

クック船長がハワイに到着した場面を描いた1928年の作品『ザ・ディス カバリー』には、こちらに背を向けて立ち、クック船長たちの船を眺める誇 らしげで体格の良いハワイの酋長たちが、豊かな色彩で前面に描かれて いる。一方、上陸した英国人たちは、ちっぽけで特徴のないグレーの人物 像として描写されている。それは 差し迫りつつある戻ることのできない時 代の変化の前兆を感じさせる。マノオキアン氏は、この絵で、政治的な見 解を示したのであろうか?そうだとすれば、彼の現実逃避的なユートピア と矛盾してしまうのではないか?おそらくそれは、内面的な葛藤だったに 違いない。

“Early Traders of Hawaii,” Alii on the Shore Greeting Tall-Masted Ship by Arman Manookian, c. 1927. Honolulu Museum of Art, gift of the estate of Aneliese Lermann, 1998.

『ハワイ初期の商人たち』。

背の高いマスト船に向かって海 岸から挨拶するハワイのアリイ( 王族)。アーマン・マノオキアン 氏による1927年頃の作品。

ホノルル美術館収蔵。1998年、 アネリーゼ・ラーマン氏寄贈。

grey and featureless, harbingers of impending and irrevocable change. Was Manookian making a political commentary here? If so, how does this reconcile with his escapist utopias? Perhaps this was more internal conflict.

It seems possible, then, that the new direction in “The Mat Weaver” was a response to these dissonances; that Manookian was attempting to embrace the modernism in his work he’d previously denied, and, by presenting a humbler figure going about an everyday task, was pivoting from historical fantasies to more contemporary, social concerns.

Whatever he was searching for in his art, it seems he was unable to find it. In 1931, Manookian took his own life. He was 27. That his career was so short, and yet so seminal and enduring, means that we are compelled to continue to interpret it, even though, like Manookian, we may never find definitive answers.

『ザ・マット・ウィーバー』にみる新たな芸術表現は、これらの不 協和音への彼なりの答えであり、マノオキアン氏は、歴史的な空想か ら、より現代的で社会的な問題に題材を変え、日常生活を営む人物像 を描くことで、以前否定していたモダニズムを作品に取り入れることを 試みていたと考えられる。

芸術を通じて追求していたものが何であったのか。マノオキアン 氏はそれを見つけることができないまま、1931年、わずか27歳で自ら の命を絶ち、独創的で不朽の傑作を残した芸術家として、短かすぎる 生涯を終えた。彼自身がそうだったように、その確固たる答えは永遠 に見つからないのかもしれない。それでも私たちは、いつまでもその意 味を探り続けずにはいられない。

ARCHIVAL IMAGES

COURTESY OF HUNTINGTON LIBRARY

AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

文=カイリー・ヤマウチ

写真=マーク・クシミ

資料写真提供:ハンティントン

図書館と議会図書館

In the early 1900s, Japanese business owners opened shops in a recovering Chinatown, expanding the demographic of consumers in the primarily Chinese district.

1900年代初頭、日系人の事業 主たちは、復興中のチャイナタ ウンに商店を開業し、主に中国 系移民を中心に栄えたエリアの 消費者層を拡大した。

SEARCHING FOR JAPAN

日本文化探訪

A writer uses an old map to trace the earliest Japanese shops in Honolulu’s Chinatown.

古地図をもとに、ホノルルのチャイナタウンにあった初期の日系商店の跡を辿る商店のを探す

A 1906 map of Honolulu’s Chinatown is a daunting puzzle marked by ancient Japanese kanji . Well, daunting at least for a yonsei (fourth-generation) Japanese like myself. Created by Takkei Nekketsu, an early immigrant to Hawai‘i, the map shows Japanese-owned shops and eateries in Chinatown, as well as banks and a custom house, which oversaw imported goods. The map’s red street lines match the present layout of the popular district, but the entirety of the map, including its legend and its bordering advertisements, are entirely in kanji, an extensive writing system of complex characters derived from the Chinese hanji . My seven-year education in Japanese language didn’t enable me to translate more than a handful of words. Even friends fluent in Japanese struggled to identify certain outdated kanji.

1906年当時のホノルルのチャイナタウンの地図には、たくさんの漢字 が並んでいて、私のような日系四世にとっては難解なパズルのようだ。 ハワイへの初期の移民である武居熱血氏によって作成されたこの地図 には、チャイナタウンの日系のショップや飲食店のほか、銀行や輸入品 を扱ったカスタムハウスの場所が記されている。この地図に赤で記され た通りは、活気溢れる現在のチャイナタウンの街並みと一致している が、その凡例や地図を囲む広告に至るまで、地図全体が日本語で書か れ、多くの漢字が使われている。漢字は、古代中国発祥の史上最も文字 数の多い複雑な文字体系だ。7年間日本語教育を受けた私には、ほん の数語しか判読できず、日本語が堪能な友人でさえ、旧字体の漢字を 読むのに苦労したほどだ。

An early immigrant to Hawai‘i, Takkei Neketsu created a map of Chinatown

This illiteracy wouldn’t have been the case more than a century ago. According to historians, copies of the map were distributed to Japanese immigrants as a guide to familiar cultural establishments. Nekketsu, who owned a dry-goods shop, created the map during the peak of Japanese immigration to the islands. The first Japanese laborers were sent to Hawai‘i in 1868, during the reign of King David Kalākaua, to fuel the booming sugar industry. The labor was demanding, consisting of 10-hour shifts harvesting thick stalks under the scorching sun. Nevertheless, Japan was in an economic depression and the plantation work paid. By 1900, Japan and Okinawa were sending laborers by the thousands. But with the arrival of picture brides and the growth of families, Japanese immigrants moved away from the sugarcane fields toward the city to make better wages under fairer conditions.

During this time, Chinatown was recovering from the territorial government’s mismanaged attempt to burn plague-infested buildings, which resulted in a fire that lasted 17 days and left almost all of Chinatown charred and its inhabitants homeless. The addition of Japanese business owners to the primarily Chinese district got the area up and running again and expanded the demographic of consumers. Japanese persons could now buy liquor, eat saimin, watch a movie, or stay at a hotel without being treated as a foreigner or forced to try to speak English.

As I walked the streets of Chinatown one busy Sunday morning, it was difficult to envision this past. The bright-red squares on Nekketsu’s map, which indicate a Japanese-owned business, were now storefronts displaying Chinese last names— Lam, Lao, Sing. I stepped inside the corner store Maunakea Lei and was greeted by an elderly Chinese woman who interrupted a flow of Cantonese to address me in English. Among the buckets of red ginger, I found advertisements for the store’s spine medicine and an old VHS tape of Swiss Family Robinson but no evidence of Japanese influence. I wandered toward a street dotted with grocery stores displaying produce on the sidewalk. The crowd of older Chinese shoppers bustled around

1世紀前には、漢字が読めないなどという心配は無かったはずだ。歴 史家によるとこの地図は、複写され、馴染みのある日本商店の案内図と して、日本人移民に配布されたという。日用雑貨店を営んでいた武居氏 は、日本からハワイへの移民が盛んだった頃、この地図を作成している。 最初の日本人労働者は、1868年、デビッド・カラカウア王の統治時代 に、ハワイに派遣され、活況を呈してた砂糖産業に労働力を供給した。 サトウキビ畑での労働は、焼けるような太陽の下で、太い茎を収穫する 10時間交代制の過酷なものだった。それでも不況だった日本から、賃 金の支払われるプランテーションでの仕事を求めて、多くの人々が移民 した。1900年までに、日本の本州と沖縄から何千人もの人々が労働者 としてハワイにやってきた。だがピクチャーブライド(日本から花嫁をと った写真のみの見合い結婚)の始まりと家族のある世帯が増えるに従 い、日系移民はサトウキビ畑から都市へと移り、より公平な条件で、高 い賃金を得られるようになった。

この頃、チャイナタウンは、ペスト感染者の住む建物を焼き払うため に領土政府が人為的につけた火が広がって起こった大規模な火災か ら復興している最中だった。17日間にわたって燃えた大火災により、チ ャイナタウンのほぼ全域が消失し、住民は家を失った。中国系の移民が 多かった地区に、日本のビジネスオーナーが加わったことで、この地区 は再び活況を取り戻し、幅広い人種が訪れるようになった。ここでは日 本人も、外国人として扱われたり、英語を強いられることなく、酒を買っ たり、サイミンを食べたり、映画を見たり、ホテルに泊まることができた。 日曜の朝、忙しいチャイナタウンの街を歩いていると、そんな昔の街 並みは想像できない。武居氏の地図に鮮やかな赤い四角で記されてい る日系人所有のビジネスがあった場所は、現在、中国系のラムやラオや シンといった名前の店頭に取って代わっている。ルーツが特定しがたい 「マウナケアレイ」という名前の街角にある店に足を踏み入れると、中 国人の年配の女性が迎えてくれ、流暢な広東語の会話を止めて、私に 英語で話しかけてきた。レッドジンジャーの入ったバケツが並ぶ店内の 壁に、この店の脊椎薬の広告と『スイスファミリーロビンソン』の旧式の VHSテープが並んでいるのが見えるが、日本文化の名残は一切感じら れない。歩道に沿って野菜箱が並べられた食料品店が点在する通りに

Chinatown has returned to its pre-1900 origins which catered specifically to Chinese immigrants.

チャイナタウンは中国系移民によって栄えた1900年以前のもとの姿 を取り戻した。

me as I scanned their faces for one that resembled my own. At the end of the day, I found one Japanese business, Maguro Brothers, a hole-in-the-wall poke shop amid tables of fish and vegetables in Kekaulike Market. But it was closed on Sundays.

In a sense, Chinatown has returned to its pre-1900 origins which catered specifically to Chinese immigrants. However, along the margins of Chinatown, newer local businesses have moved in. The Pig and the Lady, Manifest, Olukai, Owens and Co., and others draw younger generations from all backgrounds. At night, Chinatown transforms into a popular bar scene with dancing, deejays, and craft cocktails.

But where did the Japanese culture and cuisine go? By 1920, Japanese persons were 42.7 percent of Hawai‘i’s population, making it impossible for them to reside in one area. Their history in Chinatown is hardly known today, but the assimilation of Japanese culture into local culture is apparent. Five minutes from my childhood home in Kāne‘ohe are two okazuya restaurants, Megumi Restaurant and Masa and Joyce. Behind glass counters, an array of traditional and local Japanese food ranging from cone sushi to chow fun to fried chicken is displayed, ready to be packed in bento boxes and taken to work. As for sit-down Japanese restaurants, none are better than Sekiya’s Restaurant and Delicatessen in Kaimukī. For a reasonable price, I can enjoy steaming green tea, tsukemono , miso soup, a generous bowl of rice, and chicken katsu atop shredded lettuce. And if I’m craving a traditional Japanese treat? Kinako mochi packets are available at Marukai Wholesale Mart and can be made into a snack at home in minutes.

By the end of my Chinatown adventure, I had abandoned Nekketsu’s map completely. Chinatown may never return to the mix of Asian culture that it once was, but that’s fine with me. I can experience Japanese culture everywhere in Hawai‘i—at home, down the street, and in almost every neighborhood if I look hard enough. Just perhaps not on a Sunday in Chinatown.

向かって歩き、通りを行き交う年配の中国人の買い物客の中に、日系人 の面影を探すが見当たらない。1日の終わりに、魚や野菜を扱う生鮮市 場のケカウリケマーケット内に、唯一日本人が営むポケ専門店の「まぐ ろブラザーズ」を見つけたが、あいにく日曜は休業日だった。 ある意味で、今のチャイナタウンは、中国系移民によって栄えた 1900年以前のもとの姿を取り戻したといえる。一方で、チャイナタウン のあちこちに、新しい地元企業も出現している。ピッグ・アンド・ザ・レデ ィ、マニフェスト、オルカイ、オーエンズ・アンド・カンパニーといった店 が、あらゆる人種の若い世代を引き付けている。そして夜になると、チャ イナタウンは、踊りやDJ、カクテルを楽しむ人々で賑わうトレンディなバ ーシーンに一変する。

それにしても日本の文化と料理はどこに行ったのだろう? 1920年 までに、日系人は、ハワイの人口の42.7%を占めるようになり、その居 住区も1つの地域にとどまることはなくなった。チャイナタウンでの日系 人の歴史は、今日ではほとんど知られていないが、日本文化が地元文化 にもたらした影響は計り知れない。私が育ったカネオヘの家から5分の ところにも、メグミレストランとマサ・アンド・ジョイスという2軒のおか ず屋レストランがある。ガラスのカウンターの後ろには、いなり寿司やビ ーフン、フライドチキンといった伝統的な惣菜や地元風の日本料理が並 び、テイクアウトもできる。和食レストランなら、カイムキのせきやレスト ラン&デリカテッセンに勝るものはない。リーズナブルな値段で、お茶、 つけ物、味噌汁、たっぷりのご飯、千切りレタスの上にのったチキンカツ を味わうことができる。和菓子が食べたくなったら、パックに入ったきな こ餅をマルカイホールセールマートで購入し、自宅で手軽に楽しむこと もできるのだ。

チャイナタウンの探索を終えるころには、私は武居熱血氏の地図の ことをすっかり忘れていた。チャイナタウンが、かつてのように様々なア ジア文化が共生する街に戻ることはもうないかもしれないが、それはそ れでいい。今のハワイでは、自宅や通りを歩いていても、ほとんどの場所 に何かしらの日本文化の存在を感じるからだ。日曜のチャイナタウンく らいは、例外であってもいいと思う。

ウル(ブレッドフルーツ)は、

初期のハワイアンキルトの パターンの一つだ。

IMAGE

IMAGE

TEXT BY NATALIE SCHACK

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

TEXT BY NATALIE SCHACK

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

文=ナタリー・シャック

写真=ジョン・フック

HONORING A VALLEY

渓谷を讃えて

In splendid Mānoa, find one couple’s home and homage to the surrounding valley.

美しいマノアをこよなく愛した夫妻の邸宅と渓谷へのオマージュ

Entering the lush paradise that is Mānoa Valley is always, quite literally, like taking a breath of fresh air. Perhaps the sensation comes from the way the urbanity sheds itself before you in favor of charming yesteryear homes and so much green. Or how the light dusting of mist may find occasion to settle suddenly upon your nose. Or maybe it’s the rainbows, those brilliant, proud beauties of legend, which laze and lounge over the valley at all seasons of the year, even they being loathe to leave.

The Mānoa Heritage Center, located in Mānoa Valley, is a love letter to this verdant place. The 3.5acre property is located on Mānoa Road, one of the enclave’s most major of arteries, but you could pass up and down it dozens of times and still not have any idea of the center’s existence. It is perhaps one of the city’s best kept secrets, a privately founded educational space that celebrates all the rich cultural and environmental legacies that the area has hidden in its history. The center has many functions: It’s home to a fully intact and preserved heiau (Hawaiian place of worship) and a garden of native plant species brought to Hawai‘i by the islands’ first settlers, and a space designed to serve cultural practitioners. It’s a place where children can study indigenous technologies (such as ancient heiaubuilding methods used by the earliest Hawaiians), and learn about the many chapters of the history of Hawai‘i, all of which have shaped its current state.

The journey to create Mānoa Heritage Center as it is today started over a century ago, one could say, when Sam Cooke’s relatives arrived as missionaries in 1837 and started the royal school for the children of the royal families. (Among the students who boarded at the school were Kamehameha II, Kamehameha III, and Bernice Pauahi Bishop.) Cooke’s ancestors built the house that was to become the Mānoa Heritage Center in 1911. In 1996, the late Sam Cooke and his

一年中、緑に輝く美しいマノア渓谷は、訪れるたびに思わず深呼吸した くなる場所だ。それは、都会が目の前から姿を消し、豊かな自然に囲ま れた手入れの行き届いた古くからの邸宅の並ぶ景色が広がるマノアな らではの魅力であり、突然舞い降りてくるうっすらとした霧や季節を問 わず一年中渓谷にかかる美しい虹のせいであるかもしれない。 マノア渓谷にあるマノア・ヘリテージ・センターは、この緑豊かな 土地への慈しみに溢れている。広さ3.5エーカーのセンターは、マノア の中心を通るマノアロードに面して建っているが、その前を何度通って も、その存在に気づかない人は多い。この私設の教育スペースは、一般 にはほとんど知られていない自然文化遺産で、この街の豊かな歴史に 触れることができる場所だ。多くの役割を果たすこのセンターには、完 全な状態で保存されているヘイアウと、ハワイ諸島への最初の入植者 によってハワイに持ち込まれた在来植物の庭園、そしてハワイ文化継 承者のために用意されたスペースがある。ここでは子どもたちが、ハワ イを形成する上で欠かせない先住民の伝統技術(初期のハワイ人によ る古代ヘイアウの建築法など)を学び、ハワイの豊かな歴史に触れるこ とができる。

現在のマノア・ヘリテージ・センターが確立されるまで、実に1世 紀以上の歳月がかかった。その歴史は、1837年に宣教師としてこの島 に到着したサム・クック氏の親戚が、王室の子供たちのための王族学 校を設立したことに遡る。この学校に寄宿した生徒の中には、カメハメ ハ2世と3世、バーニス・パウアヒ・ビショップ王女などがいた。1996 年、ともに熱心なアーキビストで収集家であった故サム・クック氏と彼 の妻メアリー氏は、ハワイの貴重品を保存し、人々と共有するために、 このセンターを設立した。「主人と私の夢が形になりました」とメアリ ー・クック氏は語る。

“Hawaiian history and heritage needs to be understood by many more people.”

— Mary Cooke, co-founder of Mānoa Heritage Center 「より多くの人々にハワイの歴史と遺産を知ってもらう必要があります」とマノア・ヘリテー ジ・センター共同設立者のメアリー・クック氏。

Jessica Welch is the executive director at Mānoa Heritage Center, which offers various community programming.

様々なコミュニティプログラム を提供するマノア・ヘリテージ・ センターのエグゼクティブディ レクター、ジェシカ・ウェルチ氏。 CULTURE

wife, Mary Cooke, both passionate archivists and collectors, bought the property from a developer and relatives it had been split among. Then they founded the center as a final joint expression of their care for preserving the treasures of Hawai‘i and sharing those treasures with others. “This is his and my dream come true,” Mary says.

For Mary, the project is very personal; it’s situated right in her backyard. The couple spent years working with experts and the community to preserve Kūka‘ō‘ō, the ancient agricultural heiau, on the grounds, a place where the farmers of old Mānoa used to come to pray for good crops. They reshaped the garden, ridding it of invasive plants and scouring the islands for native and endangered flora to establish there instead. In early 2018, the Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Visitor Hale was completed, a reception and education space for the many school children that visit each year. Today, the space hosts cultural workshops that range from hula dancing to gourd decorating.

メアリー氏にとってこのプロジェクトには、特別な思い入れがあ る。というのも、このセンターは、彼女の住む家の裏庭にあるのだ。夫妻 は、1911年にサム氏の先祖が家を建てて以来、親戚やデベロッパーに 分割されていた土地を買い戻し、マノア・ヘリテージ・センターを立ち上 げた。彼らは、長年かけて専門家や地域社会と共同で、かつてマノアの 農民たちが豊作祈願のために訪れた“クカオオ”と呼ばれる敷地内にあ る農業のためのヘイアウ(古代寺院)の保存に努めた。庭園を作り直し て侵略的外来種の植物を取り除き、島中から集めたハワイの固有種や 絶滅危惧種の植物を植え直した。2018年の初めに「ハリー&ジャネッ ト・ワインバーグ・ビジター・ハレ」が完成し、毎年多くの就学児が訪れ る教育スペースとなった。現在、このスペースでは、フラやひょうたんを 使ったアートといった、文化的なワークショップが開催されている。

クック夫妻は、生涯を通して初期のハワイの絵画を収集している。

The Cookes’ house, known as Kūali‘i, is a beautiful Tudor-style home that is a museum in its own right.

“クアリリ”と呼ばれるクック一 家の邸宅は、それ自体が博物館 のような美しいチューダー様式 の建物だ。

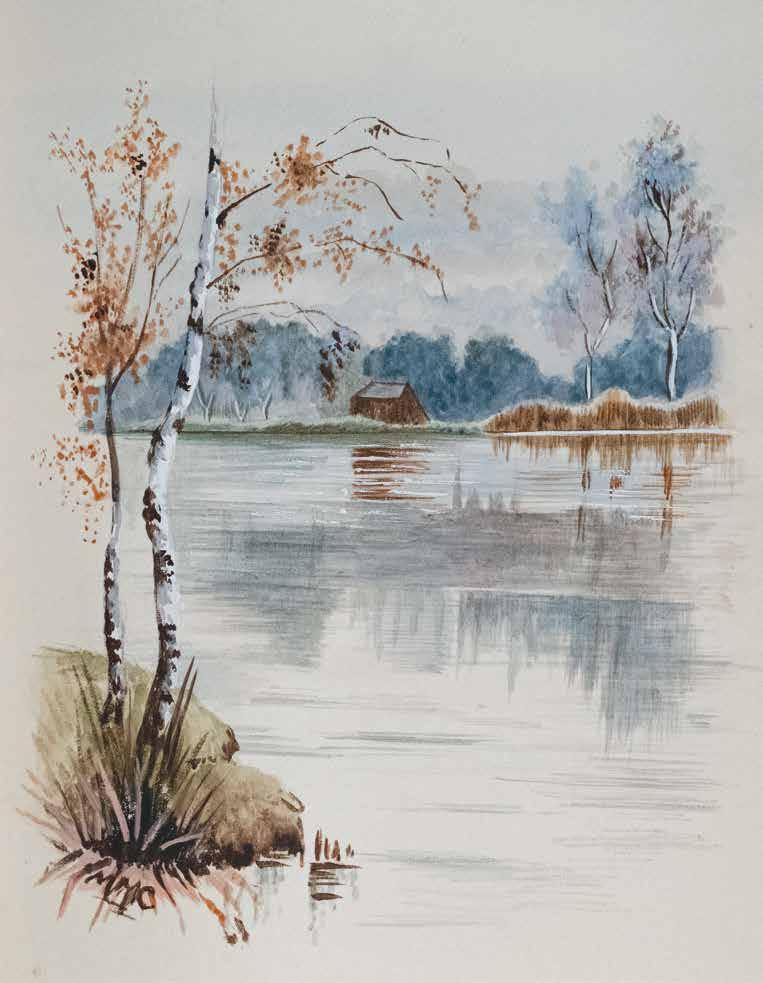

One of the greatest treasures the Cookes will share with the world is their house itself, where Mary still resides. Known as Kūali‘i, the beautiful, Tudor-style home teeters majestically on the edge of a hill. Walk through its halls, though, and you’ll see that it frames so much more than gorgeous vistas of the Mānoa ridgeline. A museum in its own right, Kūali‘i is filled with historic texts and visual art of Hawai‘i which the Cookes spent a lifetime amassing: serene oil landscapes of Kaua‘i taro fields by D. Howard Hitchcock; pinkkissed railways at sunset from a plantation era of yore by Peter Hurd; vintage drawings, now colorized, of an unrecognizable downtown Honolulu by Paul Emmert. “It’s a great history of Hawai‘i through the eyes of the artists that came to Hawai‘i, starting with Captain Cook’s artist,” Mary says.

クック氏が公開している貴重品の中で、もっとも注目に値するの は、メアリー氏が今も住んでいる彼らの家そのものであろう。1911年に 建てられた“クアリイ”という名の歴史ある美しい家は、丘の端に堂々と そびえ立っている。その廊下を歩けば、窓枠に収まったマノア渓谷の美 しい稜線の眺めのほかにも、多くの魅力が詰まった建物であることに気 づくだろう。クック家が生涯を通して収集した、ハワイの歴史的な古書 や写真であふれた家は、まるで建物自体が博物館であるかのようだ。 D. ハワード・ヒッチコック氏によるカウアイのタロ畑を描いた美 しい油絵の風景画や、ピーター・ハード氏によるプランテーション時代 の夕日に染まった昔の鉄道、ピーター・エマート氏によるホノルルダウ ンタウンの風景画に色を塗ったビンテージ作品。「これらの絵は、キャ プテンクックとともに来航した絵描きをはじめ、ハワイを訪れた芸術家 たちの目を通して見たハワイの素晴らしい歴史を綴っています」とメア リー氏。

The Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Visitor Hale hosts school children each year, offering cultural workshops that range from hula dancing to gourd decorating.

ハリー&ジャネット・ワインバー グ・ビジター・ハレでは、毎年、 児童向けのフラやひょうたんを 使ったアートといった様々なカ ルチャーワークショップを開催 している。

To Mary, the center’s primary purpose is to inspire visitors to respect the traditions and histories that exist in the islands. “Hawaiian history and heritage needs to be understood by many more people,” she explains. “And anyone who comes to visit, we want them to carry on their cultural heritage.”

メアリー氏は、このセンターの最大の目的について、ハワイの伝 統と歴史を尊重し、保存することの大切さをハワイを訪れる人々に知 ってもらうことだと語っている。「より多くの人々にハワイの歴史と遺産 を知ってもらう必要があります。そして、ハワイを訪れる全ての人に彼 ら自身の文化遺産も大切にしてほしいと思うのです」。

CULTURE

TEXT BY KYLIE YAMAUCHI IMAGES BY CHRIS ROHRERARCHIVAL IMAGES FROM HAWAI‘I STATE ARCHIVES

文=カイリー・ヤマウチ

写真=クリス・ローラー

資料写真:ハワイステートア ーカイブ

Princess Ka‘iulani, ca.

1897. She was the rightful heir to the throne after Queen Lili‘uokalani.

1897年、カイウラニ王女。

リリウオカラニ女王に続く

王位後継者であった。

SOVEREIGN SIGNATURES

君主の署名

A

Palm Garden Night

Palm Garden Night

TEXT BY RAE SOJOT

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

TEXT BY RAE SOJOT

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

Top by Harlin and Skirt by Ajaie Alaie from Here The Store.

Earrings by Rachel Comey, bag by

Maison Margiela from We Are Iconic

Top by Harlin and Skirt by Ajaie Alaie from Here The Store.

Earrings by Rachel Comey, bag by

Maison Margiela from We Are Iconic

TEXT BY EUNICA ESCALANTE

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK AND ZACH PEZZILLO

TEXT BY EUNICA ESCALANTE

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK AND ZACH PEZZILLO