VOLUME 16.1

Davide Barnes General Manager

Davide Barnes General Manager

In this edition of Halekulani Living, we celebrate artists, makers, and stewards of nature and culture who source materials, meaning, and purpose from the world around them.

At his studio in rural Hau‘ula, sculptor Jerry Vasconcellos carves native woods and stones into enigmatic sculptures. Artist Ruthadell Anderson’s vibrant textiles, featuring colors and fibers inspired by Hawai‘i, evoke a sense of place. Photographer Michelle Mishina chases light to create enchanting and captivating images of her island home.

Others have made an art of stewarding the abundance that surrounds them. As an alternative to the petroleum-heavy boards that dominate the industry, Bizia Surf is transforming invasive albizia trees into high-performance surfboards. In Waialua, a young farmer is supporting the movement for food security at Sweet Land Farm, Hawai‘i’s only certified commercial goat dairy. And at Lyon Arboretum, a public botanical garden in Mānoa, a seed lab is working to save Hawai‘i’s most critically endangered native plants.

In a place so steeped in culture, we also celebrate those dedicated to perpetuating the traditions, aesthetics, and values that have shaped these islands. Hear how the performing arts troupe Ukwanshin Kabudan is connecting members of Hawai‘i’s Okinawan diaspora with their culture through music and dance. Also ahead, learn the origins of The Waitiki 7, a band of conservatorytrained musicians dedicated to keeping the sounds of mid-century exotica alive, and who delighted audiences during their sold-out shows at House Without A Key this past fall.

Please enjoy this issue of Living—we hope that it sparks creativity within you.

ハウウラの田園地帯にあるアトリエでは、彫刻家のジェリー・ヴ ァスコンセロスがハワイの原生林や石を彫り、謎めいた彫刻を制作。ま た、アーティストのルサデル・アンダーソンは、ハワイにインスパイアされ た色や繊維を使った鮮やかなテキスタイルで、場所の感覚を呼び起こし ています。フォトグラファーのミシェル・ミシナは、光を追い求め、島の故 郷の魅惑的で魅惑的なイメージを創り出しています。

また、自分たちを取り囲む豊かな自然を管理することを芸術とす る人たちもいます。業界の主流である石油を多用したボードに代わるも のとして、ビジア・サーフは侵略的なアルビジアの木を高性能のサーフ ボードに変えています。ワイアルアでは、ハワイで唯一の認定ヤギ酪農 場であるスウィート・ランド・ファームで、若い農家が食料安全保障の運 動を支援しています。そしてマノアにある公立植物園、リヨン植物園で は、絶滅の危機に瀕しているハワイの原生植物を救うため、シードラボ が活動しています。

文化が色濃く残るハワイでは、この島々を形作ってきた伝統、美 学、価値観を永続させるために尽力している人々も祝福しています。舞 台芸術集団「ウクヮンシン・カブダン」が、音楽とダンスを通してハワイの 沖縄系ディアスポラ(ディアスポラ=琉球人)の人々と自分たちの文化 をどのように結びつけているのかを聞いています。さらに、ミッドセンチ ュリーのエキゾチカ・サウンドを生かすことに専心し、この秋、ハウス ウ ィズアウト ア キーの公演でソールドアウトとなった観客を喜ばせた、 音楽院で訓練を受けたミュージシャンのバンド、ザ・ワイティキ・セブン の成り立ちも紹介します。

今号のLivingをどうぞお楽しみください。あなたの中に創造性が 芽生えることを願っています。

2

WELCOME

JEWELS THAT TELL TIME © 2023 Harry Winston SA. HARRY WINSTON OCEAN DATE MOON PHASE AUTOMATIC ALA MOANA CENTER 808 791 4000 ROYAL HAWAIIAN CENTER 808 931 6900 HARRYWINSTON.COM

HALEKULANI CORPORATION

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER

PETER SHAINDLIN

CHIEF EXECUTIVE ADVISOR

PATRICIA TAM

GENERAL MANAGER, HALEKULANI

DAVIDE BARNES

DIRECTOR OF SALES & MARKETING

LISA MATSUDA

HALEKULANI.COM

1-808-923-2311

2199 KALIA RD. HONOLULU, HI 96815

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER

JASON CUTINELLA

GENERAL MANAGER, HAWAI‘I

JOE V. BOCK

JOE@NMGNETWORK.COM

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

LAUREN MCNALLY

MANAGING DESIGNER

TAYLOR NIIMOTO

PUBLISHED BY

NMG NETWORK

41 N. HOTEL ST. HONOLULU, HI 96817

NMGNETWORK.COM

© 2024 by NMG Network, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted without the written consent of the publisher. Opinions are solely those of the contributors and are not necessarily endorsed by NMG Network.

14 MASTHEAD

Opening May 2024 – Ala Moana Center 1 (877) 726-3724

Step into this dreamy fashion editorial shot among the Florentine architecture of La Pietra.

ラ・ピエトラのフィレンツェ建築 の中で撮影された夢のようなフ ァッション・エディトリアルに足

を踏み入れてみよう。

目次

ABOUT THE COVER:

Largesse of the Loom

Against the Grain

Cream of the Crop

Seeding Sustainability

Chasing Light

A Diasporic Dialogue

Rhythms of Reverie

Photographer Michelle Mishina captures mesmerizing images of her island home.

写真家ミシェル・ミシナは、彼女の島の 家の魅惑的な写真を撮影している。

This shot of model Misty Ma‘a was captured by photographer Mark Kushimi at La Pietra, a college preparatory school whose campus was inspired by an Italian villa. Find the editorial on page 98 and see it come to life on Living TV.

16

24

32

CUISINE 44 A

54

64

74

ARTS

Fluid Forms

Sweet Heritage

CULTURE

86

DESIGN 98

112

WELLNESS

A Beautiful Mind EXPLORE

122

98

122

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The late artist Ruthadell Anderson infused spaces with a sense of place.

アーティストの故ルサデル・ アンダーソンは、空間に場 所の感覚を吹き込んだ。

TABLE OF CONTENTS

目次

ARTS 24

器の大きな織機 32

流動的なフォルム

CUISINE 44

甘い遺産 54

クリーム・オブ・ザ・クロップ

CULTURE 64

ディアスポリック・ダイアログ 74

幻想のリズム

Ukwanshin Kabudan is reconnecting Hawai‘i’s Okinawan community with their culture.

ウークワンシン・カブダンは、 ハワイの沖縄コミュニティと 彼らの文化を再び結びつけよ うとしている。

WELLNESS 86

アゲインスト・ザ・グレイン DESIGN 98

美しい心 EXPLORE 112

持続可能性の種まき 122

光を追いかけて

ABOUT THE COVER: 表紙について:

このモデルのミスティ・マアのショットは、フォトグラファーのマーク・クシミが、イタリアの別荘をイメージしたキャンパスを 持つ大学進学準備校、ラ・ピエトラで撮影した。この記事は本誌98ページとリビングTVでご覧いただけます。

18

24 64

RoyalHawaiianCenter.com • Waikīkī • Open Daily • 808.922.2299

Fendi | Harry Winston | Hermès | Tiffany & Co. | Jimmy Choo | Stüssy | Rimowa | Saint Laurent | Ferragamo

P.F.

|

|

|

| Partial

FROM SUN UP TO SUN DOWN, THERE’S MAGIC AROUND EVERY CORNER. Fashion.

Culture. from day to night

Ka Pō Me Ke Ao

KITH | Tory Burch | Valentino | Tim Ho Wan | Doraku Sushi

|

Island Vintage Wine Bar | Restaurant Suntory

Chang’s

The Cheesecake Factory

TsuruTonTan Udon | Wolfgang’s Steakhouse

Noi Thai

Listing

Dining.

I

Living TV is produced to complement the Halekulani experience, with videos that focus on the art of living well. Featuring cinematic imagery and compelling storytelling, Living TV connects guests with the arts, culture, and people of Hawai‘i. To view all programs, tune in to channel 2 or watch online at living.halekulani.com.

客室内でご視聴いただけるリビング TVは、ハレクラニならではの上質なひ とときをお過ごしいただくため、豊か で健康的なライフスタイルをテーマに したオリジナル番組をお届けしていま す。臨場感あふれる映像と興味をかき たてるストーリーで、ハワイの芸術や 文化、人々の暮らしぶりをご紹介しま す。すべての番組はチャンネル2または living.halekulani.comからご視聴い ただけます。

watch online at: living.halekulani.com

FLUID FORMS

流動的なフォルム

Jerry Vasconcellos has carved out a lifelong career as a sculptor of scavenged native woods and stone.

ジェリー・ヴァスコンセロスは、拾い集めた原生林や石を使った 彫刻家として生涯のキャリアを切り開いてきた。

A SWEET HERITAGE

甘い遺産

Local confection makers share their heritage through culturally rooted sweets.

地元の菓子職人は、文化に根ざしたお菓子を通して自分たちの 伝統を分かち合う。

A DIASPORIC DIALOGUE

ディアスポリック・ダイアログ

A performing arts troupe connects Hawai‘i’s Okinawan community to their homeland through music and dance.

ハワイの沖縄コミュニティと故郷を音楽とダンスでつなぐ芸能 団体。

A BEAUTIFUL MIND

美しい心

On the elegant grounds of La Pietra, ethereal fashions and bookish pursuits conjure an air of charm and whimsy.

ラ・ピエトラのエレガントな敷地内では、エスプリの効いたファ ッションや本好きの人たちが、魅力的で気まぐれな雰囲気を醸 し出している。

AGAINST THE GRAIN

アゲインスト・ザ・グレイン

Invasive albizia trees gain new life as an alternative to the petroleum-based surfboards that dominate the industry.

業界を支配する石油ベースのサーフボードに代わるものとして、 侵略的なアルビジアの木が新たな命を得ている。

WHAT TO WATCH

WINDSWEPT CURLS & SHIMMERING PEARLS BLOOMINGDALE’S | CARTIER | MAISON MARGIELA | MAUI DIVERS JEWELRY | SHABUYA | UNIQLO | YETI 350+ STORES & RESTAURANTS AT THE HEART OF THE PACIFIC ALAMOANACENTER.COM

IMAGE BY

JOHN HOOK

ARTS

TEXT BY ANNA HARMON

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK & CHRIS ROHRER

文=アナ・ハーモン

写真=ジョン・フック、

クリス・ローラー

LARGESSE OF THE LOOM

器の大きな織機

Ruthadell Anderson’s monumental public works infused spaces with a sense of place while nurturing a creative community.

ルサデル・アンダーソンの堂々たる作品群は、展示された公共の施設をハワイらしさで満たすと同時に、クリエイティブなコミュニティを育んできました。

Textile artist Ruthadell Anderson made her mark by pushing the boundaries of the craft.

テキスタイル・アーティス トのルサデル・アンダーソ

ンは、工芸の限界を押し 広げることでその名を知 らしめた。

For Ruthadell Anderson, there was something special about working with fibers, about creating on a loom. Perhaps it was the detailed planning, the delayed gratification. Maybe it was the tactile play of texture and color, or the ritual labor of weaving weft through warp. She had practiced ceramics and tried her hand at metalwork, but weaving was the art form that kept her interest for decades, during which she pushed the limits of ancient tapestries and modern murals with an aesthetic both abstract and reflective of Hawai‘i’s environment.

One of Anderson’s compelling traits was her ability to make work sized to the architectural spaces

ルサデル・アンダーソンにとって、糸と向き合い、機織り機で作品を創り 上げる作業は特別だった。綿密にデザインを練るのが好きだったのか もしれないし、長い作業の果てに味わえる達成感がよかったのかもしれ ない。繊維の触感や色彩とたわむれる喜びもあっただろうし、黙々と横 糸と縦糸を組んでいく作業が気に入っていたのかもしれない。とにかく、 陶芸も手がけ、金属細工にも挑戦した彼女が数十年にわたって情熱を 注いだのは織物で、ハワイという環境を抽象的に描いた作品の数々で、 伝統的なタペストリーや現代壁画の限界を打ち破ってきた。

アンダーソンの特徴のひとつとして、展示される建物の大きさに 合った作品を生み出す才能が挙げられる。1966年、彼女を一躍有名に

24 ARTS

within which they would live. Her 1966 breakout creation, a 15-by-8-and-a-half-foot tapestry inspired by the Hawaiian legend of Maui ensnaring the sun, exemplified this place-based sensibility. It was created for the Bank of Hawai‘i Waikīkī building, now the Waikīkī Galleria Tower. The piece was a textural geometric interpretation of a sun, with colors and fibers inspired by Hawai‘i and featuring local materials like banyan roots and hau fibers. Made in five pieces, it took 400 hours and two assistants to complete.

The Bank of Hawai‘i tapestry was not Anderson’s first time working with local materials, or with other weavers. By 1966, she had spent 20 years exploring the craft and growing her circle of local makers and artists. Born and raised in San Jose, California, she moved to Hawai‘i in 1947 at 25 years old with her first husband, Claude Horan. He had been invited to start the ceramics program for the University of Hawai‘i by Hester Robinson, a professor who began teaching its first fiber arts classes a year earlier. At the time, Anderson’s focus was on ceramics, but her background in weaving naturally drew her to Robinson.

By 1951, Anderson and Robinson were working together to demonstrate weaving’s commercial potential on behalf of the Industrial Research Advisory Council, a government committee exploring promising industries for the Territory of Hawai‘i. They wove local materials like palm midribs and haole koa into table mats and lamp shades for public display. Throughout the decade, Anderson immersed herself in the Hawai‘i crafts scene, among other things working as a weaver for a local studio and developing the Hawaiian Craft Association. She was one of the founding members of Hui Mea Hana, which was spearheaded by Robinson and was the precursor to Hawai‘i Handweavers’ Hui, one of the largest fiber arts groups in the state today.

In 1963, Anderson returned to UH for her MFA in weaving with the goal of opening her own studio. She saw a growing demand for original weavings “both for residential use and for public buildings,” she said in her entry for Francis Haar’s compendium Artists of Hawai‘i: Volume II. Post-World War II, the growing real estate market and tourist economy created a demand for custom textiles.

She graduated in 1964 and opened a studio and shop in a little house in Waikīkī with ceramist

したのは太陽を捕える半神マウイのハワイ伝説をモチーフにした約4.5 x 2.6メートルのタペストリーで、ハワイの土地柄をみごとに表現してい る。ハワイ銀行のワイキキビル、現在のワイキキ・ギャラリア・タワーのた めに制作され、ハワイらしい色彩と素材を用いて太陽を図形的に表現 したもので、バニアンの木の根やハウの繊維など身近な素材も織り込ん でいる。5つのピースで構成されるこの作品を、アンダーソンは助手2人 とともに400時間かけて完成させた。

彼女がハワイならではの素材を用い、共同作業で作り上げた作 品は、ハワイ銀行のこのタペストリーが最初ではない。1966年当時の アンダーソンは、すでに20年にわたるタペストリー制作の経験を持ち、 ハワイ在住の織物作家やアーティストの知り合いも多かった。カリフォ ルニア州サンノゼの出身のアンダーソンが、最初の夫クロウド・ホーラン とともにハワイに移住したのは1947年、25歳のときだった。その前年 にハワイ大学で織物を教えはじめたヘスター・ロビンソン教授が陶芸 の授業もはじめることになり、ホーランが招聘されたのだ。当初、アンダ ーソンの活動の中心は陶芸だったが、織物の経験もあったことから自 然にロビンソン教授の活動に惹かれていく。

1951年、アンダーソンとロビンソン教授は、当時まだ準州だっ たハワイの将来を支えうる産業を模索しようと準州政府が組織した産 業調査諮問委員会で、織物産業の可能性を示すデモンストレーション を行っている。ヤシの葉の中肋やハオレコアといった素材を用いてテー ブルマットやランプの傘を作り、一般にも公開した。1950年代のアン ダーソンは地元のスタジオで織り手として働きながらハワイの手工芸 の世界にどっぷり身を投じ、〈ハワイアン・クラフト・アソシエーション〉 という団体も発足させる。現在では布アート関連のハワイ最大の団体 のひとつである〈ハワイ手織り作家のフイ(クラブ)〉の前身、ロビンソン 教授が中心になって発足した〈フイ・メア・ハナ〉の創設メンバーにも加 わっていた。

1963年、アンダーソンはいずれ自分のスタジオを開こうと決意 し、芸術学の修士号を取得するためにハワイ大学に戻る。フランシス・ ハールによる概論『ハワイのアーティストたち 第2巻』のなかで彼女 自身が述べているように、”個人住宅、公共施設を問わず”、タペストリ ーの需要は高まっていた。第二次世界大戦が終わり、不動産市場も観 光市場も活況を見せていた時期で、カスタムメイドのタペストリーは人 気だったのだ。

26 ARTS

Upon moving to Hawai‘i in 1947, Anderson immersed herself in the local crafts scene and sourced inspiration and materials from the world around her.

1947年にハワイに移住したアンダーソンは、地元の工芸シーンに没頭し、 インスピレーションと素材を世界中から集めた。

27

Louise C. Guntzer. Swiftly, Anderson garnered commissions that balanced art and function, including wall hangings for Sheraton Kauai, Royal Aloha Hotel, and Kauai Surf Hotel and blinds for Woolworth’s Ala Moana and the Hawaiian Airlines Waikīkī office.

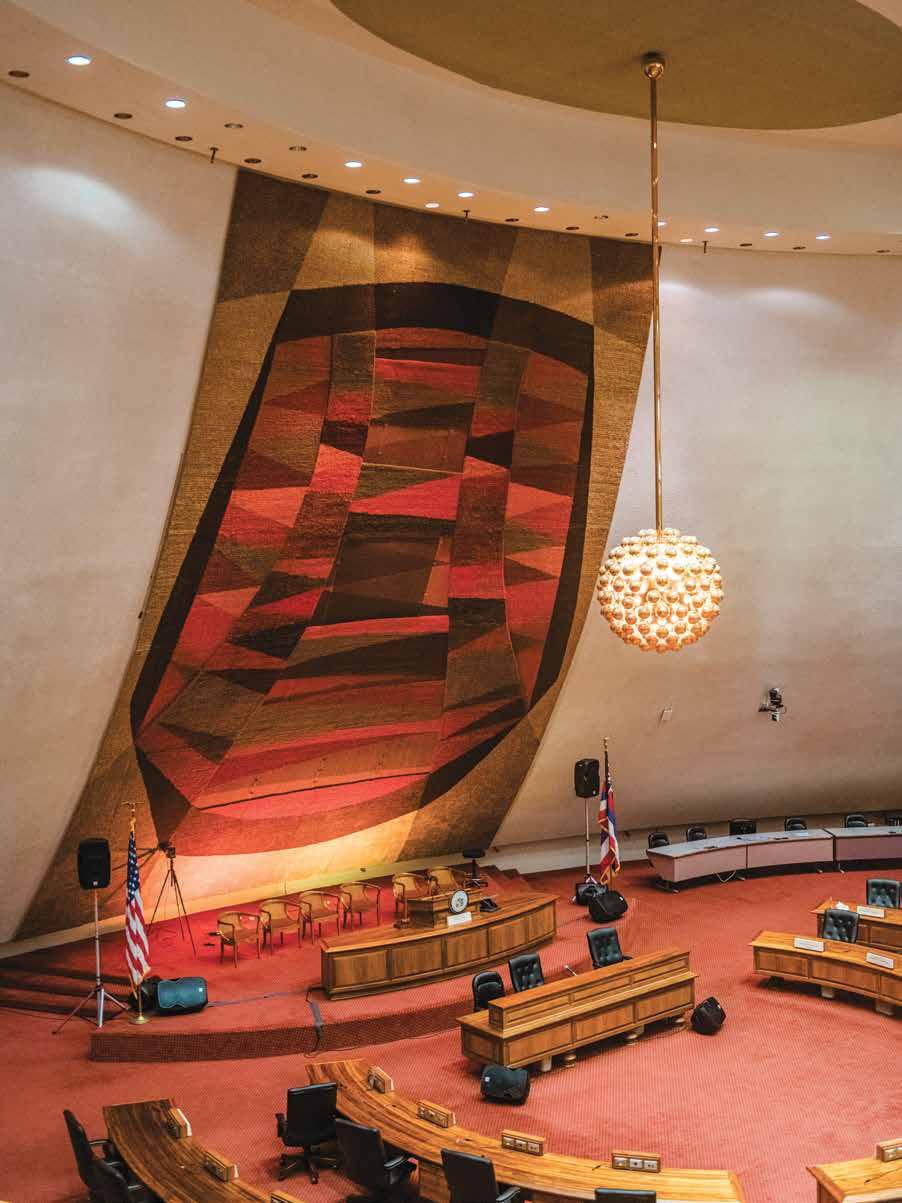

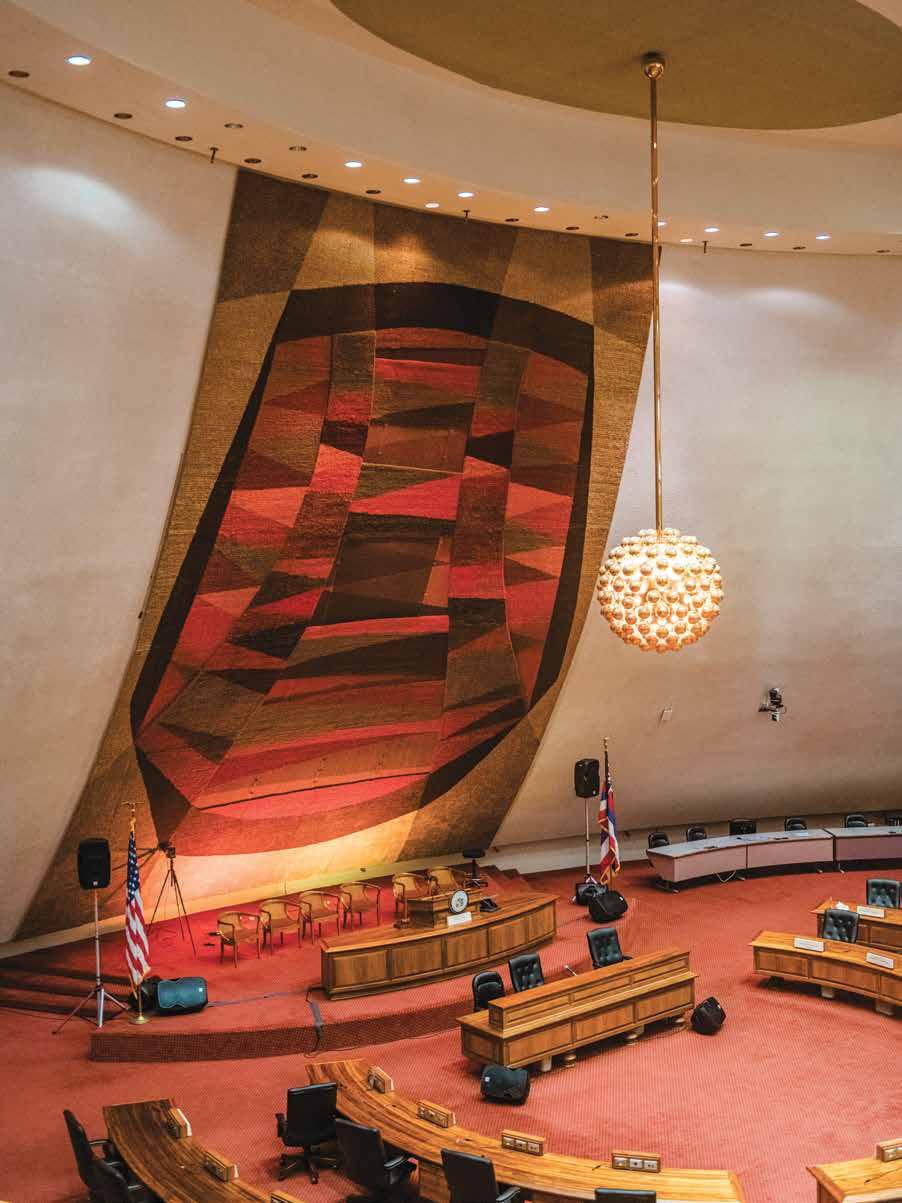

By the time the State of Hawai‘i Fine Arts Committee announced they were commissioning artworks for the new State Capitol building in 1967, including wall hangings behind the rostrums of both legislative chambers, Anderson had established her reputation in the art form. Anderson was selected for the House wall hanging. It would be the largest project she would ever undertake.

The work took several years to plan, make, and install and required more than a dozen weavers to produce. After seeing her House wall hanging, the Senate chose Anderson for their installation as well. The final creations, each 39 feet high, hug the concave walls of the Senate and House chambers. Abstract in nature, each features an interplay of geometric shapes in hues of Hawai‘i—one of the earth in deep reds, oranges, and browns; the other of sky, water, and sand, blue hues surrounded by tans.

Anderson went on to make murals as far flung as Tahiti. She created a series of 11 fiber sculptures for the Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalaniana‘ole Federal Building that hung from the ceiling of the first-floor lobby. She wove a series of large wall hangings for architect Vladimir Ossipoff’s 1970 remodel of the International Terminal Building at the Honolulu International Airport, leaning into a simplistic aesthetic of bright colors, lines, and geometric shapes. Her 6-by-13-foot wall hanging for Kaua‘i Community College titled “Wailele,” meaning “leaping water,” is a lush geometric abstraction of a waterfall: blues and purples flowing through blocks of browns and greens reminiscent of both lo‘i and Midwest agriculture. Over her career, her aesthetic morphed to match the demands of her clients and her own experimentation in fiber and form. Throughout, she played with abstract shapes, lush colors and texture, Polynesian inspiration, and the sculptural qualities of the craft.

Anderson’s large-scale installations often required more than one weaver to produce. Her success in

1964年、修士号を取得したアンダーソンは陶芸家ルイース・C・ ガンツァーとともにワイキキの小さな住宅でスタジオ兼店を開く。美し さと機能を兼ね備えた彼女の作品への依頼は次々に舞い込んだ。シェ ラトン・カウアイ・ホテルやロイヤル・アロハ・ホテル、カウアイ・サーフ・ホ テルの壁を飾るタペストリー、アラモアナの〈ウールワース〉やハワイア ン航空ワイキキオフィスのブラインドも彼女が手がけたものだ。

1967年、ハワイ州芸術委員会が、新しいハワイ州議事堂の上院 と下院の演壇後ろの壁も含め、建物を飾る作品の制作を依頼すると 発表した時、この分野でのアンダーソンの名声はすでに揺るぎないも のになっていた。そして、下院の壁を飾る作品は彼女に任されることに なるのだが、それはかつて引き受けたことのない大がかりなプロジェク トだった。

構想から制作、そして実際の設置までに数年の歳月と十数人の 織り手を要した。下院に取り付けられた作品を見て、上院もアンダーソ ンに作品を依頼。完成した作品はそれぞれ高さ約12メートルにおよ び、上院と下院の議会場の傾斜した壁にぴたりと貼りつくように設置さ れた。真紅とオレンジ、茶色を基調に大地を表現した作品と、さまざまな 青を黄土色で囲み、空と海、砂を表現した作品。いずれも自然がモチー フで、ハワイらしい色彩と幾何学模様が織りなす抽象的な図柄だ。

アンダーソンの創作活動はさらに続き、遠くタヒチのミューラル なども手がけた。プリンス・ジョナ・クヒオ・カラニアナオレ連邦ビル1階 の天井から下がる布を使った11の彫刻的連作も彼女によるものだ。 建築家ウラジミール・オシポフが1970年に改修したホノルル国際空港 (訳注:現ダニエル・K・イノウエ国際空港)の国際線ターミナルでも、 明るい色彩で線と図形をシンプルかつ美しく描いた彼女の作品群が 壁を飾った。カウアイ・コミュニティ・カレッジの壁を飾る約2 x 4メート ルのタペストリーのタイトルは《ワイレレ》。ハワイ語で”跳ねる水”とい う意味だ。豊かな水流を幾何学的かつ抽象的に描いたこの作品。茶色 と緑の四角のあいだを青と紫が流れるさまは、ロイ(訳注:タロ芋の水 田)や米国ミッドウエストの農業地帯を思わせる。長い創作期間を通し て、アンダーソンの作風は依頼主の要望や糸や素材の試行錯誤の結果 に合わせてさまざまな変化を遂げたが、抽象的なデザイン、色と素材 の多彩さ、ポリネシア文化の影響、そして彫刻的という特徴は終始変 わらなかった。

28 ARTS

Anderson’s large-scale works, which include a set of highprofile commissions for the House and Senate chambers, often required many weavers to produce.

アンダーソンの大規模な作品には、上下両院の議場のための一連 の有名な依頼も含まれ、制作には多くの織り手を必要とすることが 多かった。

29

pulling off such projects locally speaks volumes about her connections in the Hawai‘i artistic community. In fact, while weaving seems like a solitary act, Anderson nearly always made her commissions with an apprentice or collaborator. “I really enjoy the stimulation of working with others,” she said in Artists of Hawai‘i: Volume II. “The creative act gives me the most satisfaction.”

In her lifetime, Anderson mentored dozens of weavers. “She was so important to the fiber scene here,” said Barbara Okamoto, who met Anderson through Robinson when studying weaving at UH and later worked at Anderson’s Loom Originals store in Kaimukī. Back when weaving was still largely deemed a craft rather than an art form, Okamoto recalls that there was never any doubt that Anderson was an artist.

But, according to Okamoto, recognition as an artist wasn’t something Anderson prized. Rather, she remembers Anderson encouraging fellow weavers and fretting over the pricing of materials, wanting them to be accessible to the community. Cathy Levinson, who frequented Anderson’s store to shop and talk story, recalls that “Ruthadell created a warm atmosphere of artistic creation and support for weavers.”

One of Anderson’s later works, which is now among the collection of the Hawai‘i State Foundation on Culture and the Arts, is a rectangular weaving of black yarn about three feet long, with white fibers projecting along its center. Titled “803 Whiskers” and made with whiskers shed by her cats, the piece is stark and masterful yet also tender and humorous. It leaves an impression similar to that of Anderson herself, who came across as serious and direct at first but was generous and funny, according to those who knew her.

For decades, Anderson dedicated her life to the work of weaving—an act of care and intention, of improvisation and reflection. Even now, after her passing in 2018, Anderson’s archives are in the company of the Hawai‘i Handweavers’ Hui on the second floor of a building in Chinatown, where looms clatter and click and weavers honor what came before, working together to shape what comes next.

彼女の大がかりな作品は複数の織り手を必要とすることが多か った。こうした大プロジェクトをハワイ在住の織り手の力だけで完成さ せられたのは、ひとえにハワイの芸術家コミュニティとアンダーソンのつ ながりの深さによるものだろう。一見、孤独な作業に思える機織の世界 で、彼女はほぼ必ず助手またはほかのアーティストと共同作業で作品 を作り上げてきた。”人と作業をするのは刺激があって好きなんです” 『ハワイのアーティストたち 第2巻』のなかで彼女は供べている。”作 品を創造することで、何より深い満足感を得られるのです”

アンダーソンは生涯を通じ、多くの織物作家に影響を与えてきた。 「ハワイの織物界で、彼女はとてつもなく重要な存在でした」そう語る のはバーバラ・オカモトさん。ハワイ大学でロビンソン教授を通じてアン ダーソンの知己を得て、のちにカイムキにあったアンダーソンの店〈ルー ム・オリジナルズ〉でも働いた人だ。織物が一般的にまだ芸術ではなく、 ただの手芸と考えられていた当時でも、アンダーソンはまぎれもなく芸 術家だった、とオカモトさんは振り返る。

だが、オカモトさんによれば、アンダーソン自身は芸術家としての 自分の評価などあまり気にしていなかったそうだ。オカモトさんにとっ ては、織物仲間を励ましたり、材料費の高さを嘆き、もっと手頃に手に 入ればいいのにとこぼすアンダーソンの姿のほうが印象的だ。アンダー ソンの店を頻繁に訪れて材料を買い求め、おしゃべりを楽しんだという キャシー・レヴィンソンさんは回想する。「ルサデルの店はわたしたち織 物作家を温かく迎え、支えてくれるムードに包まれていました」

アンダーソンの後期の作品で、現在はハワイ州文化芸術財団の コレクションとして所蔵されているもののなかに、黒い毛糸で織られ、中 央に白い毛が立ち上がった長さ1メートルほどの長方形の作品がある。 《803本のひげ》と題されたその作品には、彼女の飼い猫たちのひげ が織り込まれている。簡潔で力強く、同時に繊細かつユーモラス。第一 印象は生真面目でぶっきらぼうだが、身近な人は器が大きくて愉快な 人だったというアンダーソン自身の印象にそっくりだ。

アンダーソンは愛情の深さと意志の強さ、思いつきと深い洞察 を映すタペストリーの制作に数十年にわたって身を投じた。2018年の 他界後も、彼女の作品群はチャイナタウンのとあるビルの2階、ぱたん ぱたんと織機の音が響く〈ハワイ手織り作家のフイ〉のスタジオで、先 人を偲びつつ、力を合わせて織物の未来を切り拓いていく作家たちを 見守っている。

30 ARTS

TEXT BY JACK TRUESDALE

IMAGES BY CHRIS ROHRER FLUID FORMS

TEXT BY JACK TRUESDALE

IMAGES BY CHRIS ROHRER FLUID FORMS

流動的なフォルム

文=ジャック・トゥルーズデール

写真=クリス・ローラー

Inspired by themes of the natural world, Jerry Vasconcellos has carved out a lifelong career as a sculptor of scavenged native woods and stone.

自然界からインスピレーションを得たジェリー・ヴァスコンセロスは、廃材や石を使った彫刻家として生涯のキャリアを築いてきた。

32 ARTS

There are still some things sculptor Jerry Vasconcellos doesn’t know at 75: what he’s making when he sets out to carve the many wood and stone figures perched throughout his carport studio; what sometimes slows him to a halt, forcing him to go start something new; what will happen to all his unfinished works when he dies.

On a rainy winter day, Vasconcellos fishes out a black stone from a pile of uncut shapes on his desk. “It’s more fun for me to try and figure out what the story of a piece is as I’m doing it,” he says. He plugs in a Dremel power tool, flicks on an old fan, and gets to work, dust blowing as he grinds a small valley between two knobs in the rock. “Hopefully the visual will be powerful enough that someone else can see that same thing,” he says, “or they see what they want to see.”

Blue-eyed and clean-shaven but for a stout gray mustache, he’s wearing an aloha shirt and board shorts, elbows resting on his knees as he sits and carves. “What I’m trying to do is to work towards a reason for doing it,” he says. Vasconcellos has been what he calls an “instinctual” sculptor most of his life. His works draw out the natural curves of the materials he forages from the beach and in the woods.

He spent most of his life in Honolulu before moving north several years ago to the tiny town of Hau‘ula, where he lives a short walk from the shore.

“This just swallowed me. I don’t need anything else,” Vasconcellos says, content just to sell enough work to afford a nice dinner with his wife now and again. “So much of what I’m doing is for myself.”

Vasconcellos grew up in the storied Wailele artist colony, built alongside a waterfall deep in verdant Kalihi Valley. Soon after his family moved in, the top floor of the house burned down, so they moved into the gallery, living among the art of former residents Lillie Hart Gay and George Burroughs Torrey. As a teenager, he plunged to the bottom of the river by his home and emerged with a dark, porous rock. At the time, he’d been taking in the quasi-abstract figures of Henry Moore and Jean Arp, so he took a hammer to the rock and pounded out a donut shape. Afterward, he asked himself: “Did it look like more than a rock with a hole in it?” He carved another rock, then another. The aim: “Create that which wasn’t before.”

After college at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Vasconcellos found a job that allowed him

彫刻家ジェリー・ヴァスコンセロスには、75歳になった今でもわからな いことがある。それは、カーポートのアトリエのあちこちに置かれたたく さんの木や石の彫刻を彫り始めるとき、自分が何を作っているのか、と きどき何が原因で作業が中断し、新しいことを始めなければならないの か、自分が死んだら未完成の作品はどうなるのか…。

冬のある雨の日、ヴァスコンセロスは机の上に積まれた切りっぱ なしの形から黒い石を取り出す。「作品を作りながら、その作品のストー リーを考えていく方が楽しいんだ」と彼は言う。彼はドレメルの電動工 具を差し込み、古い扇風機のスイッチを入れると、岩の2つのツマミの 間の小さな谷を削り、ほこりを吹き飛ばしながら作業に取りかかる。"願 わくば、そのビジュアルが他の誰かにも同じものを見てもらえるような 力強いものになればいいのだが...... "と彼は言う。

青い目、口髭だけを残してきれいに刈られた髭、アロハシャツにボ ードショーツを履き、膝に肘をついて座って彫刻をしている。「僕がやろ うとしているのは、それをやる理由に向かって努力することなんだ」と彼 は言う。ヴァスコンセロスは、彼が「本能的」と呼ぶ彫刻家である。彼の 作品は、ビーチや森で採取した素材の自然な曲線を引き出している。

人生の大半をホノルルで過ごした彼は、数年前にオアフ島の北 に位置する小さな町ハウウラに移り、海岸から歩いてすぐのところに住 んでいる。「これが僕を飲み込んだんだ。他に何もいらないんだ」とヴァ スコンセロスは言う。妻との素敵なディナーをたまに楽しめるだけの仕 事を売るだけで満足なのだ。「私がしていることの多くは、自分自身の ためなんだ」。

ヴァスコンセロスは、緑豊かなカリヒ渓谷の奥深く、滝のそばに建 てられた木と石造りの家、ワイレレのアーティスト・コロニーで育った。 彼の家族が引っ越して間もなく、家の最上階が全焼したため、ギャラリ ーに移り住み、かつての住人リリー・ハート・ゲイやジョージ・バロウズ・ トーリーのアートに囲まれて暮らした。ティーンエイジャーの頃、彼は家 のそばの川の底に飛び込み、真っ黒な多孔質の岩を持って出てきた。当 時、彼はヘンリー・ムーアやジャン・アルプの準抽象的な人物を見ていた ので、ハンマーで岩を叩いてドーナツの形を作った。その後、彼は自問し た「穴の開いた岩以上のものに見えただろうか?彼はまた別の岩を彫 り、そしてまた別の岩を彫った。その目的は、"以前にはなかったものを 創り出す "ことだった。

ハワイ大学マノア校を卒業後、ヴァスコンセロスはアートに時間 を割ける仕事に就いた。ホノルル市の海洋レクリエーション・スペシャリ ストとして、ボディ・サーフィン・コンテストやその他の海洋プログラムを

34 ARTS

アーティスト、ジェリー・ヴァスコンセロスは、ハワイからタヒチへの処女 航海でホクレア号を操縦したミクロネシアの航海士、マウ・ピアイルグか ら彫刻の手ほどきを受けたという。

35

Artist Jerry Vasconcellos credits Mau Piailug, the Micronesian navigator who piloted the Hōkūle‘a on her maiden voyage from Hawai‘i to Tahiti, with teaching him how to carve.

After spending most of his life in Honolulu, Vasconcellos now lives and works in rural Hau‘ula.

人生の大半をホノルルで過 ごしたヴァスコンセロスは、 現在はハウウラの田舎に住 み、仕事をしている。

time for art. As an ocean recreation specialist for the City and County of Honolulu, he ran bodysurfing contests and other ocean-going programs while honing his artistic eye for foraged materials. He scrutinized beaches for stones, looking for “a quality rock” with an “appropriate shape.” He’s found rarities like feather-like lava rock and dense red lava rock conjoined by a crystalline layer. The material’s consistency is key, he says: “You need to know that you can carve it.” He used to hike up into the mountains looming over Honolulu to look for wood that needed to “be released.” He’d start carving a piece on site before carrying it down from the woods to complete it. Finding materials in the wild was both cost effective and enlightening. He grew to notice certain details as he carved, like “the response to your impositions” in the wood. Vasconcellos doesn’t force the material to bend to his will, instead allowing subtle forms to reveal themselves: an almost-head, an almost-face, an almost-dancer.

In the late 1970s, Vasconcellos went to an art show by Rocky Jensen, who ushered in the contemporary maoli fine arts movement and founded the group

運営するかたわら、採取した素材に対する芸術的な目を磨いた。彼は浜 辺で石を探し、"適切な形 "をした "質の良い石 "を探した。彼は、羽のよ うな溶岩や、より結晶性の高い層で結合された緻密な赤い溶岩のよう な珍しいものを見つけた。素材の一貫性が鍵だと彼は言う。彼はよくホ ノルルに迫る山々をハイキングして、"解放 "される必要のある木を探し た。その場で彫り始めてから、森から運んで完成させるのだ。自然の中で 材料を探すのは、費用対効果も高く、勉強にもなった。彼は木を彫りな がら、「自分の押しつけに対する反応」のような細部に気づくようになっ た。ヴァスコンセロスは、素材を自分の意のままに曲げようとはせず、微 妙なフォルムが姿を現すようにする。

1970年代後半、ヴァスコンセロスはロッキー・ジェンセンのアー トショーを見に行った。彼はコンテンポラリー・マオリ・ファインアート・ ムーブメントの先駆者であり、ハワイ文化を広めるためにハレ・ナウアー IIIというグループを設立した。「私はそのすべてに魅了されました」とヴ ァスコンセロスは言う。「非ハワイアンの私を参加させてくれたんです」。 ヴァスコンセロスはグループでアートを発表するようになり、ジェンセン はハワイ文化の知識を彼に伝えた。「地元での私の知識は不足していま した」と彼は言う。

38

ARTS

Vasconcellos doesn’t force the material to bend to his will, instead allowing subtle forms to reveal themselves.

ヴァスコンセロスは、素材を自分の意のままに曲げることを強要せず、 微妙なフォルムが姿を現すのを待つ。

39

Hale Nauā III to promote Hawaiian culture. “I was just taken by the whole thing,” Vasconcellos says. “He let me join as a non-Hawaiian.” Vasconcellos started showing his art with the group, and Jensen passed some of his knowledge of Hawaiian culture to him. “My knowledge of things, locally, was missing,” he says.

Vasconcellos credits Mau Piailug, the Micronesian navigator who piloted the Hōkūle‘a on her maiden voyage from Hawai‘i to Tahiti, with teaching him how to carve. He was working his county job at Kualoa Park in 1976 when Piailug showed up there to put the canoe together. Vasconcellos made himself a devoted acolyte. “As far as I was concerned, it was a total apprenticeship, and as far as he was concerned, I was there helping him,” he says. Piailug taught him to understand his materials, use an adze, and always work with the grain. Vasconcellos’ tools of choice are still chisels and adzes he made himself, which he packs in two canvas bags and takes to a park near his home to work on pieces.

Vasconcellos demurs about his success as an artist. Decades ago, his first solo show, Who Would Have Thought a Dead Tree Could Talk?, sold just two pieces. “It was all very slow. I’m not even clear on what renown I have,” he says. “I’d get mentioned in the newspaper when I was doing shows with other groups, and that was always nice.” Today he sells pieces at Nā Mea Hawai‘i and Cedar Street Galleries in Honolulu. His past public commissions include a congregation of stone figures outside the Keahuolū Courthouse in Kailua-Kona and, flanking the pedestrian path at the University of Hawai‘i Cancer Center, a pair of totemic sculptures with carvings that resemble watchful eyes.

In his studio, Vasconcellos continues grinding away, undisturbed by all the dust flying from the stone he’s working on as he turns it over in his bare hands. Out in the yard, dozens of stones sit untouched “because I like ’em so much,” Vasconcellos says, admitting he may never carve them into sculptures. Others have been shaped into graceful, undulating forms. Tall ones stand along the wall with an almost human presence. One stout wooden figure vaguely resembles a tiki statue. And on one rough and knobby hunk of wood, he’s penciled out possible contour lines. “As something starts to develop, you pursue that and deal with it however you have to,” he says. “It’s nice: The more you do it, the more you feel you can do it.”

ヴァスコンセロスは、ハワイからタヒチへの処女航海でホクレア号 を操縦したミクロネシアの航海士、マウ・ピアイルグから彫刻の手ほど きを受けたという。1976年、ピアイルグがカヌーを組み立てるためにク アロア・パークに現れたとき、彼は郡で仕事をしていた。ヴァスコンセロ スはピアイルグの熱心な信奉者となった。「私はそこで彼を手伝いまし たが、その仕事は私にとっては勉強でした」と彼は言う。ピアイルグは彼 に、材料を理解すること、斧を使うこと、常に木目に沿って作業すること を教えた。ヴァスコンセロスの道具は、今でも自分で作ったノミと斧であ り、それらを2つのキャンバスバッグに詰めて、自宅近くの公園に持って 行き、作品作りに励んでいる。

ヴァスコンセロスは、アーティストとしての成功については否定 的だ。数十年前、彼の最初の個展『Who Would Have Thought a Dead Tree Could Talk?』を開いた際、売れたのは2ピースのみだった。 「すべてが遅々として進まなかった。自分がどんな名声を持っているの かさえよくわからない。他のグループと一緒にショーをやっているとき は、新聞に紹介されることもあった」と彼は言う。現在、彼はホノルルの Nā Mea HawaiʻiとCedar Street Galleriesで作品を販売している。 過去にはカイルア·コナのケアウオル裁判所前にある石像の集合体や、 ハワイ大学がんセンターの歩道脇にある、監視の目を思わせる彫刻が 施されたトーテムの彫刻など、公共の場での依頼も多い。

アトリエでヴァスコンセロスは、作業中の石を素手でひっくり返し ながら、粉塵が舞うのも気にせず削り続けている。庭に出ると、何十個 もの石が手つかずのまま置かれている。ヴァスコンセロスは「とても気に 入っているから」と言い、彫刻に彫ることはないかもしれないと認めてい る。他の石は、優美で起伏のある形に成形されている。背の高いものは、 ほとんど人間のような存在感で壁に沿って立っている。あるがっしりと した木像は、どことなくティキ像に似ている。また、ある木の塊には、輪 郭線が鉛筆で描かれている。「何かが発展し始めたら、それを追求し、ど のようにでも対処するんだ。「いいことだよ、やればやるほど、できる気 がしてくる」と彼は言う。

40 ARTS

Turn a moment of fate into a lifetime of purpose.

OluKai.com/AnywhereAloha

MIKE COOTS / Kaua‘i, HI

IMAGE BY CHRIS ROHRER

IMAGE BY CHRIS ROHRER

CUISINE

TEXT BY MARTHA CHENG

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK & CHRIS ROHRER

文=マーサ・チェン

写真=クリス・ローラー、

ジョン・フック

A SWEET HERITAGE

甘い遺産

Local confection makers are finding delicious inspiration in the traditional desserts of their heritage.

地元の菓子職人たちは、伝統的なデザートに美味しいインスピレーションを見出している。

44 CUISINE

In the landscape of sweets, European-style confections and pastries have long been considered the pinnacle of refinement, the height of aspiration. But in recent years, in the islands and across the country, a new generation is reclaiming their heritage and blending it with Hawai‘i and American culture to create sweets that are simultaneously familiar and novel. Ranging from the rustic to the refined, the resulting confections—Okinawan doughnuts from Aloha Andagi, Korean rice cakes from Rice Blossoms, and Filipino jams from Palaman Purveyors—are all born out of each maker’s personal memories of another time and country. Here’s a sweet taste of their efforts.

ALOHA ANDAGI

Every time Junko Bise makes andagi, some 1,000 to 2,000 at each of her monthly pop-ups, she thinks about her grandmother. “Actually, she didn’t teach me how to do because dangerous by the fire,” Bise says. But she remembers watching her grandmother dropping dough into the hot oil—formed from a stiffer batter than what we know in Hawai‘i, and in much larger portions—producing Okinawan doughnuts almost 10 times the size of andagi in Hawai‘i.

It wasn’t until Bise came to Hawai‘i that she learned how to make andagi by helping her senpai, or mentor, at fundraisers. In 2012, encouraged by Hidejiro Matsu, the owner of Marukai at the time, she started Aloha Andagi. “Hawai‘i is very famous for making andagi for all kinds of occasions like bon dance, birthday party,” Bise says. But with her business, she wanted to meld the culture of Okinawa and Hawai‘i. “So mine is not Okinawan Okinawan—it’s OkinawanHawai‘i andagi,” she clarifies, sometimes expanding upon traditional andagi by incorporating flavors like strawberry, matcha, and, during the holidays, pumpkin spice and ginger cinnamon.

About once a month at Marukai, Bise sets up her three woks with hot oil and methodically shapes dough balls by hand. Dropping them into the wok, she waits until they are golden brown before removing them and lightly squeezing out the excess oil from each one. The result? An andagi with a crunchy exterior—craggy and crisp—served

お菓子の世界では、ヨーロッパ風のお菓子やペストリーが洗練の頂点、 憧れの高みと考えられてきた。しかし近年、ハワイ諸島やアメリカ全土 で、新しい世代がその伝統を取り戻し、ハワイやアメリカの文化と融合 させて、親しみやすさと新しさを同時に感じさせるスイーツを生み出し ている。アロハ・アンダギーの沖縄風ドーナツ、ライス・ブロッサムズの 韓国風餅、パラマン・パーベイヤーズのフィリピン風ジャムなど、素朴な ものから洗練されたものまで、出来上がったお菓子はすべて、作り手そ れぞれの別の時代や国の思い出から生まれたものだ。ここでは、その甘 い味を紹介しよう。

アロハアンダギー

ジュンコ・ビセさんは、毎月のポップアップで1,000〜2,000個のアン ダギーを作るたびに、祖母のことを思い出す。「実は、火を使うのは危 険なので、祖母は私に作り方を教えてくれなかったんです」とビセさん は言う。ハワイのドーナツの10倍近い大きさの沖縄のドーナツができ るのだ

ハワイに来て初めて、彼女は先輩の資金集めの手伝いからアンダ ギーの作り方を学んだ。2012年、当時マルカイのオーナーだった松 秀 二郎氏の勧めもあり、アロハアンダギーを始めた。「ハワイは盆踊りや誕 生日パーティーなど、あらゆる場面でアンダギーを作ることでとても有 名です」とビセさんは言う。しかし、彼女は沖縄とハワイの文化を融合さ せたかったのだ。「だから、私のは沖縄のオキナワンではなく、沖縄のハ ワイのアンダギーなんです」と彼女は明言する。伝統的なアンダギーを ベースに、ストロベリーや抹茶、ホリデーシーズンにはパンプキンスパイ スやジンジャーシナモンなどのフレーバーを取り入れることもある。

マルカイでは月に一度、ビセさんは3つの中華鍋に熱した油を敷 き、手作業で生地を成形する。それを中華鍋に落とし、きつね色になる まで待ってから取り出し、余分な油を軽く絞る。出来上がりは?という と、外はカリカリ、中はサクサクで、できたてのアツアツが食べられる。

46

CUISINE

Junko Bise learned to make Okinawan doughnuts in Hawai‘i but cherishes memories of her grandmother’s andagi back home.

ジュンコ・ビセはハワイで沖縄のドーナツ作りを学んだが、故郷の祖母 が作るアンダギーの思い出を大切にしている。

47

fresh and hot. While other venues have offered her pop-up spaces, Bise refuses, preferring to sell almost exclusively at Marukai, out of loyalty to Matsu. She cites him as the reason why, more than 10 years since its inception, Aloha Andagi still exists, ensuring that people in Hawai‘i have classic Okinawan andagi—as well as new flavor twists—to return to.

RICE BLOSSOMS

Five years ago, when Shana Lee tasted baekseolgi, a fluffy and chewy steamed Korean rice cake, for the first time, she was struck by its ephemerality—her Korean mother-in-law instructed her to eat it within 12 hours. A few years later, when she was looking online for Korean dessert recipes to make for her father-inlaw, she came across Rice Blossoms, a New Jerseybased company making modern Korean sweets in pretty pastels. During the pandemic, Lee further delved into the Korean dessert world and took Rice Blossom’s online workshops to learn how to make treats such as song-pyeon, steamed rice flour dumplings filled with sesame seeds sweetened with brown sugar and honey. She was smitten. After six months of intensive training and with the blessing of Rice Blossoms founder Jennifer Ban, Lee brought these confections to Honolulu through pop-ups and special orders.

For Ban, who is of Korean heritage, the traditional sweets were a part of her childhood. “Mom loved rice cakes,” Ban says, recalling her mother’s affinity for injeolmi, soft and chewy like mochi, coated with soybean powder or rewarmed in the microwave and dipped in sugar or honey. “Our after-school snack would be rice cakes instead of cupcakes,” she says. During a vacation in Korea as an adult, Ban took a dessert class and fell in love with the simplicity of the ingredients and the beauty of the Korean desserts she had eaten growing up. Although Korean culture has increased in popularity stateside—everything from K-pop to Korean tasting menus—Ban noticed a void in sweets. In 2017, she started Rice Blossoms “to play a role in sharing modern Korean desserts.”

New mothers seeking a connection to their heritage often reach out to Rice Blossoms for a baeksolgi tteok, a white rice flour cake, symbolizing purity and

他の店からポップアップ・スペースを提供されることもあるが、ビセさん は松への忠誠心から、ほとんどマルカイでの販売に限定している。創業 から10年以上経った今でもアロハアンダギーが存在し、ハワイの人々 が定番の沖縄アンダギーだけでなく、新しい味にアレンジされたアンダ ギーをリピートしてくれるのは、彼のおかげだと彼女は言う。

ライス・ブロッサムズ

5年前、シャナ・リーは初めてペクソルギというふわふわモチモチの蒸し 餅を食べた時、その儚さに衝撃を受けた。数年後、義父に作ってあげよ うと韓国風デザートのレシピをネットで探していたとき、彼女はニュー ジャージー州を拠点に、かわいらしいパステルカラーのモダンな韓国 菓子を作っているライス・ブロッサムズに出会った。パンデミックの間、 リーは韓国デザートの世界をさらに掘り下げ、ライス・ブロッサムのオン ライン・ワークショップを受講し、ソンピョン(黒砂糖と蜂蜜で甘く味付 けした胡麻入り米粉蒸し団子)などの作り方を学んだ。彼女は夢中にな った。6か月の厳しいトレーニングとライス・ブロッサムを最初に作った ジェニファー・バンに認められ、リーはポップアップや特別注文を通じて ホノルルにこのお菓子を持ち込んだ。

韓国の血を引くバンにとって、伝統的なお菓子は子供時代の一 部だった。「お母さんはお餅が大好きでした」とバンは言う。インジョル ミはお餅のように柔らかくモチモチしていて、きな粉をまぶしたり、電子 レンジで温めて砂糖や蜂蜜をつけたりして食べる。「放課後のおやつは カップケーキの代わりにお餅でした」と彼女は言う。大人になってから 休暇で韓国を訪れた際、デザート教室に参加したバンは、素材のシンプ ルさと、幼い頃に食べた韓国のデザートの美しさに惚れ込んだ。K-POP から韓国のテイスティングメニューまで、韓国文化の人気は全米で高 まっているが、バンはスイーツの空白に気づいた。2017年、彼女は "モ ダンな韓国デザートを共有する役割を果たすため "にライスブロッサ ムを始めた。

48

CUISINE

innocence, that’s customary at a child’s 100th day or first birthday. It’s often an austere cake, but Ban adorns her baeksolgi tteok with delicate peonies, roses, cherry blossoms, and other flowers piped from bean paste.

Rice cakes are deeply rooted in Korean culture: “Koreans traditionally used to share them as a symbol of love and care,” Ban says, whether it was coming together to make song-pyeon during the mid-autumn harvest festival or bringing new neighbors pat sirutteok, a rice cake layered with red beans. While the ritual of occasion-specific rice cakes may have faded, Ban still sees the younger generations trying to connect with their culture, saying they “mix and match with the new and old these days.” And in Hawai‘i, Lee sees modern Korean sweets easily embraced in local culture, which is already familiar with similar desserts like Japanese mochi and yokan. Lee says, “I always try to make those references to local people so that they can have some kind of connection and understanding as well.”

PALAMAN PURVEYORS

Palaman Purveyors began with jam. First, a pandan flavor, its steamed rice notes rounded out with coconut; and then ube halaya, a jam made with Filipino purple yam; and then mais con queso, a sweet corn spread sharpened with cheddar—all nostalgic flavors to Randy Cortez and Arlyn Ramos. The pair had initially connected on Instagram over a shared love of food during the pandemic and learned that they had both moved to Hawai‘i from the Philippines when they were children. Together, they created Palaman (which means “filling” or “stuffing” in Tagalog) Purveyors to celebrate the Filipino food culture of their memories, even down to the soda commonly served in plastic bags.

“Coming here, you had to assimilate, and the language and culture gets left behind,” Cortez says. He would look forward to when his mom would cook dinner: eating the food of his childhood “was reclaiming my identity and also remembering what I left behind.”

But while Palaman Purveyors’ signature jams are anchored in nostalgia, Cortez and Ramos aren’t afraid to innovate: pop-up menu items have included

自分たちの伝統とのつながりを求める新米ママたちは、子供の百 日目や1歳の誕生日に食べる習慣のある、純潔と無垢を象徴する白い 米粉のケーキ、ペクソルギ・トックを求めてライス・ブロッサムズを訪れ ることが多い。渋いケーキになりがちだが、バンは牡丹や薔薇、桜など の繊細な花を餡で包んだペクソルギを作る。

餅は韓国文化に深く根ざしている: 韓国人は伝統的に、愛と気 遣いの象徴として餅を分け合っていました」とバンは言う。中秋節にみ んなで集まってソンピョンを作ったり、新しいご近所さんに小豆入りの餅 「シルトク」をごちそうしたり。餅つきの儀式は薄れたかもしれないが、 若い世代は自分たちの文化とつながろうとしている。またハワイでは、日 本の餅や羊羹のようなデザートに慣れ親しんでいる地元の文化に、韓 国のモダンなスイーツが受け入れられやすいとリーは見ている。リーは 言う、"私はいつも、地元の人々が何らかのつながりや理解を持てるよう に、それらを参考にするようにしています"。

パラマン・パーベイヤーズ

パラマン・パーベイヤーズはジャムから始まった。まず、蒸し米の香りを ココナッツで丸めたパンダンフレーバー、次にフィリピンの紫ヤムイモ を使ったジャム、ウベ・ハラヤ、そしてチェダーチーズでシャープに仕上 げたスイートコーンスプレッド、マイス・コン・ケソ。2人はパンデミックの 最中に、食への共通の愛情からインスタグラムで知り合い、子供の頃に 2人ともフィリピンからハワイに移住したことを知った。そして二人は一 緒にPalaman Purveyors(パラマンはタガログ語で「詰め物」の意)を 設立し、ビニール袋に入れて飲むソーダなど、懐かしいフィリピンの食 文化を讃えています。

「ここに来ると、同化しなければならず、言葉も文化も置き去り にされてしまう」とコルテスは言う。彼は母親が夕食を作ってくれるのを 楽しみにしていた。子供の頃の料理を食べることは、"自分のアイデンテ ィティを取り戻すことであると同時に、置き去りにしたものを思い出す ことでもあった"。

ポップアップメニューには、ピーナッツバター・バナナトーストのよ うな味の黒ゴマとアップルバナナのルンピア、メキシカンチョコレート・ チャンポラード(甘いお粥)、パンダンシロップで甘くしたアイスコーヒ ーなどがある。

50

CUISINE

The Philippine-born confectioners behind Palaman Purveyors bonded over their shared childhood sweets.

パラマンパーベイヤーズを支えるフィリピン生まれの菓子職人たちは、幼 少期に食べたお菓子をきっかけに意気投合した。

51

In celebration of their unique cultures, Hawai‘i confection makers offer a taste of sweet memories from their past.

ハワイの菓子職人たちは、 それぞれのユニークな文化 に敬意を表し、過去の甘い

思い出を味わう。

a black sesame and apple banana lumpia that tastes like peanut butter banana toast; a Mexican chocolate champorado, or sweet rice porridge; and iced coffee sweetened with pandan syrup.

Though Hawai‘i has the largest percentage of Filpinx residents of any state in the country, Filipino cuisine in the islands is largely confined to casual and old-school turo turo spots. On the U.S. mainland however, Filipino chefs are bringing Filipino American flavors to the forefront of the dining scene in cities from Seattle to Los Angeles to Chicago. “That’s what we’re trying to do,” Ramos says. “To be a little part of the Filipino food movement would be awesome.”

ハワイは全米で最もフィリピン系住民の割合が多い州だが、島々 のフィリピン料理はカジュアルで昔ながらのスポットに限られている。し かし、アメリカ本土では、シアトル、ロサンゼルス、シカゴなどの都市で、 フィリピン人シェフがフィリピン系アメリカ人の味をダイニングシーンの 最前線に押し上げている。「それが私たちがやろうとしていることです」 とラモスは言う。「フィリピン料理のムーブメントのほんの一部になれた ら最高です」とラモスは言う。

52

CUISINE

TEXT BY SARAH BURCHARD

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK CREAM OF THE CROP

TEXT BY SARAH BURCHARD

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK CREAM OF THE CROP

文=サラ・バーチャー

写真=ジョン・フック

Sweet Land Farm is O‘ahu’s only certified goat dairy.

スウィート・ランド・ファ

ームはオアフ島で唯一の 認定ヤギ酪農場。

クリーム・オブ・ザ・クロップ

On an island that imports the vast majority of its food, every farm counts—especially when that farm is the only one of its kind.

食料の大部分を輸入しているこの島では、すべての農場が重要である。

On a sunny morning at Sweet Land Farm, a group of 15 are gathered outside of a four-car garage that has been converted into a farm shop and cheese-making room. They are surrounded by rolling green pastures, blue skies, and red barns that house the farm’s roughly 300 goats.

After a primer on goat dairy operations from Emma Bello, the 34-year-old owner of the farm, guests meander from barn to barn, feeding, petting, and learning to milk the goats. The animals are playful, snuggling up when guests reach out their hands. “They’re a lot like dogs,” Bello says. “They make you laugh. They make you mad. At the end of the day, they’re very lovable.”

ある晴れた日の朝、スウィート・ランド・ファームの15人のグループが、 ファーム・ショップとチーズ製造室に改装された4台分のガレージの外 に集まっていた。なだらかな緑の牧草地、青い空、そして約300頭のヤ ギを飼う赤い納屋に囲まれている。

34歳の農場主、エマ・ベロからヤギの酪農作業について入門的 な説明を受けた後、ゲストは納屋から納屋へと移動し、ヤギに餌をやっ たり、撫でたり、乳しぼりを習ったりする。動物たちは遊び好きで、客が 手を伸ばすと寄り添ってくる。「ヤギは犬に似ています。彼らはあなたを 笑わせたり、怒らせたりします。結局のところ、彼らはとても愛すべき存 在なのです」。

54

CUISINE

何年も前に人から「なぜそのようなことをしているのですか?」と訊かれたことがあります。私は答えました。「私は人々に食を 与えようとしているのです。」私たちはただそれだけのためにあるもうひとつの農場です。-エマ・ベロ、農場主 “

I was once asked many years ago, ‘Why do you do what you do?’ I responded, ‘I feed people.’ We are one more farm striving to do just that.”

Emma Bello, farmer

At the local industry’s peak in 1955, when it was valued at more than $33 million, there were over 80 dairies on O‘ahu. That number declined dramatically as lower-cost imports priced out local farms. Hawai‘i now imports 80 to 90 percent of its food—a major cause for concern for food security in the islands. According to David Lopez, executive officer at the Hawai‘i Emergency Management Agency, if there is a natural disaster and cargo ships can’t reach O‘ahu, there is only enough food on the island to support the resident and visitor population for about four days.

To address this alarming dependence on imported food, the state government created a plan in 2005 to double local food production by 2030. As the only option for milk and cheese produced commercially on O‘ahu, Sweet Land Farm is not just an attraction for visitors, schools, and families, it represents a crucial step forward in meeting Hawai‘i’s sustainability goals. “Because we are the only dairy on O‘ahu, it’s essential, you know?” Bello says. “We need this farm going for the community.”

Originally a culinary student, Bello intended to pursue a career as a pastry chef. But as the daughter of two poultry farmers, she was also curious about farming. After interning at Alan Wong’s in Honolulu, Bello took on a summer internship at Surfing Goat Dairy on Maui. She was bottle-feeding a baby goat one day, laughing at how he was grunting and sticking his tongue out, when she knew she was meant for goat farming. “I stayed there for a whole year instead of just the summer,” Bello says. Before she left Maui, her family purchased 86 acres outside of Wahiawā, where Bello grew up and where her family has lived since the 1800s. While they prepped the land, Bello continued her training on a goat farm in California, returning to open Sweet Land Farm in 2010.

Today the farm makes four varieties of goat cheese—soft and spreadable chevre; salty, crumbly feta; gouda, ready to be sliced and melted; and tomme, a hard cheese similar to parmesan—in addition to soaps, lotions, and desserts, all made from scratch with goat milk produced on site. After the tour, the day’s visitors pile into the farm shop and emerge with treats to enjoy outside on picnic tables at the center

最盛期を迎えた1955年、地場産業は3,300万ドル以上の価 値があり、オアフ島には80以上の酪農場がありました。しかし、低価格 の輸入品に押され、その数は激減した。現在、ハワイでは食料の80% から90%を輸入しており、ハワイ諸島の食料安全保障にとって大きな 懸念材料となっている。ハワイ緊急事態管理局のデビッド・ロペス執行 役員によると、自然災害が発生し、貨物船がオアフ島に到着できない 場合、島には住民と観光客の人口を約4日間支えるだけの食料しかな いという。

この憂慮すべき輸入食品依存に対処するため、州政府は2005 年に、2030年までに地元での食料生産を倍増させるという計画を策 定した。オアフ島で商業的に牛乳とチーズを生産する唯一の選択肢で あるスウィート・ランド・ファームは、観光客や学校、家族連れにとって 魅力的であるだけでなく、ハワイの持続可能な目標を達成するための 重要な一歩なのだ。「オアフ島で唯一の酪農場ですから、必要不可欠 なんです。地域のためにこの農場を維持する必要があるのです」とベロ は言う。

もともと調理師を専攻していたベロは、パティシエとしてのキャ リアを追求するつもりだった。しかし、養鶏農家2軒の娘である彼女は、 農業にも興味があった。ホノルルのアラン・ウォンズでインターンをした 後、ベロはマウイ島のサーフィン・ゴート・デイリーで夏季インターンを した。ある日、子ヤギに哺乳瓶でミルクを与えていた彼女は、うなりなが ら舌を出す子ヤギを見て笑い、自分がヤギの飼育に向いていることを悟 った。「夏だけでなく、1年間そこにいました」とベロは言う。マウイ島を 離れる前に、彼女の家族はベロが育ち、彼女の家族が1800年代から 住んでいるワヒアワー郊外に86エーカーの土地を購入した。土地の下 準備をする間、ベロはカリフォルニアのヤギ農場で修業を続け、2010 年にスウィート・ランド・ファームをオープンするために戻ってきた。

現在農場では、ソフトなシェーブルチーズ、塩味で砕けやすいフェ タチーズ、スライスして溶かすだけのゴーダチーズ、パルメザンに似たハ ードチーズのトムメチーズの4種類のヤギのチーズのほか、石鹸、ローシ ョン、デザートを製造している。ツアーが終わると、その日の訪問者はフ ァーム・ショップに集まり、ファームの中央にあるピクニック・テーブルで 食事を楽しむ。その中には、家族連れ、シェフ、ブロガー、食通などが混 じっているが、この農場は、食べ物を愛し、その産地を気にかける人な ら誰でも惹きつけられる。

58

CUISINE

“They’re very lovable,” says farm owner Emma Bello, who discovered her passion for goat farming while interning at a goat dairy on Maui.

「ヤギはとても愛くるしいんです」と語るのは、農場主のエマ・ベロさん。 マウイ島のヤギ酪農場でインターンをしていたときに、ヤギ飼育への情 熱を見出したという。

59

Bello and her family live and work at the farm, which occupies 86 acres in Waialua.

ベロと彼女の家族は、ワイ アルアにある86エーカーの

農場に住み、働いている。

of the farm. Among them are a mix of families, chefs, bloggers, and foodies, but the farm is a draw to anyone who loves food and cares about where it comes from.

Customers help dictate the farm shop’s growing offerings, which can also be found at Whole Foods, Foodland Farms, and select boutique wine shops on the island. To serve its expanding fan base, the company will begin taking online orders and shipping country wide beginning in spring 2024. Also this year, Sweet Land Farm will start selling bottled goat milk, a product in high demand among guests to the farm.

Bello doesn’t just raise goats—she helps them give birth, talks to them, makes them feel safe. “They think of me as their mommy,” she says. And Bello is just as dedicated to educating the community and being part of a more resilient local food system as she is to her beloved goats. “I was once asked many years ago, ‘Why do you do what you do?’” Bello says. “I responded, ‘I feed people.’ We are one more farm striving to do just that.”

顧客は、このファーム・ショップが提供する商品の成長を決定する のに役立っている、ファームのアイテムは、ホールフーズ、フードランド・ ファーム、島内の厳選されたブティック・ワインショップでも購入でき る。拡大するファン層にサービスを提供するため、同社は2024年春か らオンライン注文の受付と全国への発送を開始する。また今年、スウィ ート・ランド・ファームは、牧場を訪れるゲストの間で需要の高いボトル 入りヤギ乳の販売を開始する。

ベロはヤギを育てるだけでなく、出産を手伝い、話しかけ、安心感 を与える。「ヤギたちは私のことをママだと思っています」と彼女は言う。 そしてベロは、愛するヤギたちと同じように、地域社会を教育し、より弾 力的な地域食料システムの一部となることに献身している。「何年も前 に”なぜそんなことをするのか?”と訊かれたことがあります」ベロは振り 返った。「私は答えました。”私は人が食べるものを作っているんです”っ てね。わたしたちの農場は人が食べるべきものを作ろうと努力している だけなんですよ」

60

CUISINE

The story of aloha wear is a story of Hawai‘i

ON VIEW STARTING APRIL 12 900 S Beretania St honolulumuseum.org

IMAGE BY IJFKE RIDGLEY

CULTURE

TEXT BY TINA GRANDINETTI

IMAGES BY IJFKE RIDGLEY

文=ティナ・グランディネッティ 写真=アイフク・リッジリー

A DIASPORIC DIALOGUE

ディアスポリック・ダイアログ

Ukwanshin Kabudan reconnects

Hawai‘i’s Okinawan community with their homeland through music, dance, and cultural education.

音楽、ダンス、文化教育を通じて、ハワイの沖縄コミュニティと故郷を再び結びつけるウクヮンシン・カブダン。

Ukwanshin Kabudan uses dance and music to ignite conversations about Ryūkyūan sovereignty.

ウクワンシンカブダンは、ダ ンスと音楽で琉球の主権に ついて語り合う。

In Uchināguchi, one of the Indigenous languages of Okinawa, there is a saying: Ichariba chōdē. Once we meet, we are chōdē—brothers and sisters. For many in the diaspora, including myself, the saying reassures us that when we return to our homeland, we are welcomed as family. Yet, on a rainy winter night in Kalihi, my understanding of the saying is challenged by Eric Wada and Norman Kaneshiro, Hawai‘i-born Uchinānchu and co-founders of Ukwanshin Kabudan, a performing arts troupe dedicated to perpetuating Okinawan arts and culture in Hawai‘i.

“It’s a powerful phrase, right?” Kaneshiro says. “But if you’re coming from a take-take-take perspective—a colonizer perspective—what it means is that you’re entitled to everybody’s friendship and love without doing anything in return.”

In January 1900, 26 Okinawan contract laborers arrived in Hawai‘i to work on the plantations, launching a wave of emigration that sent thousands of Okinawans into the diaspora. In the years since, Okinawans in the homeland have endured a brutal battle between two empires, fractured to this day by ongoing Japanese colonization and American military occupation. Meanwhile, those in diaspora have faced discrimination while making home in a foreign land. Today, roughly 100,000 Okinawans live in Hawai‘i.

In this context, what does it mean to meet as chōdē who, though connected by family genealogies and ancestral villages, are also separated by five generations of emigration, an ocean, a language barrier, and vastly different experiences of war and colonization?

沖縄の先住民族の言語のひとつであるウチナーグチには、「 いちゃり ばちょーでー」ということわざがある。一度会えば、私たちは「兄弟」で あり「姉妹」なのだ。私を含む多くのディアスポラにとって、このことわ ざは、祖国に帰れば家族として迎えられるという安心感を与えてくれ る。しかし、カリヒの雨の降る冬の夜、ハワイ生まれのウチナーンチュ であり、ハワイで沖縄の芸術と文化を永続させることを目的とした舞 台芸術集団「ウークヮンシン・カブダン」の共同創設者であるエリック・ ワダとノーマン・カネシロによって、このことわざに対する私の理解は 覆された。

「力強い言葉でしょう?」とカネシロは言う。「でも、もしあなたが テイク・テイク・テイクの視点、つまり植民地支配の視点から来たとした ら、この言葉の意味は、見返りを求めることなく、皆の友情と愛を受ける 権利があるということなのです」。

1900年1月、26人の沖縄人契約労働者がプランテーションで働 くためにハワイに到着し、何千人もの沖縄県民をディアスポラ(海外移 住)に追いやる移民の波が始まった。それ以来、祖国の沖縄県民は2つ の帝国間の残酷な戦いに耐え、現在も続く日本の植民地化とアメリカ の軍事占領によって分断されている。一方、ディアスポラの人々は、異国 の地で故郷を作りながら、差別と同化に直面してきた。現在、ハワイに はおよそ10万人の沖縄県民が暮らしている。

64 CULTURE

When Wada and Kaneshiro founded Ukwanshin Kabudan in 2007, it was with the aim to nurture connections between Hawai‘i and Okinawa through traditional music and dance. More deeply, it was to instill in Hawai‘i’s Okinawan community a sense of reciprocal responsibility, both to the islands of our ancestors and the islands that raised us.

“It’s a strong kuleana (responsibility),” Wada says as we sit on the floor of the dance studio he built in his Kalihi home. He wears a blue T-shirt emblazoned with the Hawaiian adage, “ola i ka wai,” meaning “water is life.” Above him, portraits of masters of the Tamagusuku style of Okinawan classical arts hang in the manner of respected uyafāfuji, or ancestors. He continues, “In Uchināguchi we call it fichi-ukīn.” The verb pulls together two roots, fichun, to pull or inherit, and ukīn, to accept or embrace. Combined, it signifies our accountability to the responsibilities we inherit from our ancestors.

As young boys yearning for more of a connection to their Okinawan ancestry and Uchinānchu identities, Wada and Kaneshiro both took up dance and sanshin, an Okinawan stringed instrument. Kaneshiro was 16 when he met Wada, ten years his senior, but they quickly bonded over a shared passion for the arts, not just as a practice but also as a kind of compass on their journey to make sense of themselves.

Together, they worked their way through the hierarchies of Okinawan classical arts, studying in Okinawa and deepening their commitment to cultural practice as a way of life. Wada reached the level of shihan, or grandmaster, in dance. Kaneshiro reached the same pinnacle in music. They learned both Japanese and Uchināguchi and became wellversed in cultural protocol.

“In a five-minute song, there’s this whole history, this whole world behind it,” Kaneshiro marvels. As he and Wada explored those worlds, they increasingly understood cultural practice as a political act. “Even speaking your language is a form of activism,” Wada says.

Before it was annexed by Japan in 1879, Okinawa was an independent nation known as the Ryūkyū Kingdom. Much like in Hawai‘i, annexation brought the systematic suppression of language and culture, such that today, Okinawa’s Indigenous languages

このような状況の中で、一族の系譜や先祖代々の村落でつなが りながらも、5世代にわたる移住、海、言葉の壁、そして戦争や植民地化 という大きく異なる経験によって隔てられている者同士が、長者として 出会うとはどういうことなのだろうか。

ワダとカネシロが2007年にウークヮンシンカブダンを設立した のは、伝統音楽と舞踊を通してハワイと沖縄のつながりを育むためだっ た。より深く言えば、ハワイの沖縄コミュニティーに、祖先の島と私たち を育ててくれた島に対する相互責任の感覚を植え付けるためだった

「強いクレアナ(責任)です」と、カリヒの自宅に作ったダンススタ ジオの床に座りながらワダは言う。ハワイの格言 "ola i ka wai"、つま り "水は命 "と書かれた青いTシャツを着ている。彼の頭上には、沖縄 古典芸能の玉城流の師匠たちの肖像画が、尊敬するウヤファーフジ(先 祖)のように飾られている。ウチナーグチでは "フィチウキーン "と呼ん でいます。この動詞は2つの語根、fichun(引っ張る、受け継ぐ)とukīn (受け入れる、抱きしめる)を引っ張り合わせたものだ。この動詞は、祖 先から受け継いだ責任に対する私たちの説明責任を意味する。

ワダとカネシロは、沖縄の祖先やウチナーンチュとしてのアイデン ティティとのつながりを求めていた少年時代、ダンスと三線を始めた。 カネシロが10歳年上のワダと出会ったのは16歳の時だったが、二人は すぐに芸術に対する共通の情熱で結ばれた。

ふたりは沖縄で学び、生き方としての文化的実践へのコミットメ ントを深めながら、沖縄古典芸能の階層を共に歩んできた。ワダは舞 踊で師範の域に達した。カネシロは音楽で同じ頂点を極めた。彼らは 日本語とウチナーグチの両方を学び、文化的な儀礼にも精通するよう になった。

「5分の曲の中に、その背後にある歴史や世界があるんだ」とカ ネシロは感嘆する。カネシロとワダはそうした世界を探求するうちに、 文化的実践を政治的行為として理解するようになった。「母国語を話す ことさえ、活動の一形態なのです」とワダは言う。

1879年に日本に併合される前、沖縄は琉球王国として知られて いた独立国家だった。ハワイと同様、併合は言語と文化の組織的な弾 圧をもたらし、今日、沖縄の固有言語は深刻な絶滅の危機に瀕してい ると考えられている。多くの文化的慣習も失われている。ワダとカネシ ロが彼らのパフォーマンス一座につけた「冠神兜団」という名前自体、

68

CULTURE

The troupe aims to instill in Hawai‘i’s Okinawan community a sense of reciprocal responsibility, both to the islands of their ancestors and the islands that raised them.

この一座は、ハワイの沖縄コミュニティに、先祖の島と自分たちを育てて くれた島に対する相互責任の感覚を植え付けることを目的としている。

69

are considered severely endangered. Many cultural practices have been lost. The name that Wada and Kaneshiro gave their performance troupe, Ukwanshin Kabudan, is itself a reminder of this sovereign history, referring to the ukwanshin, or “crown ships,” that carried large envoys from China to Ryūkyū for the coronation of a monarch. Upon their arrival, elaborate music and dance programs known as ukwanshin udui (crown ship dances) were offered to entertain the Chinese delegation. These would become the foundation for Okinawan classical arts.

Heavily influenced by the work of Hawaiian nationalists like Haunani-Kay Trask and Lilikalā Kame‘eleihiwa, Ukwanshin Kabudan looked to dance and music as a way to ignite conversations about Ryūkyūan sovereignty and reclaim a culture and history that colonization and occupation tried to erase. In Hawai‘i, that meant not just performing for the Okinawan community, but also educating people about the rich history of Okinawa—and confronting the role of Okinawans as settlers on Hawaiian lands. “We started bringing up the words ‘colonized, assimilated, settler, discrimination,’ and especially the older generation didn’t take to it,” Wada recalls. “It was something they couldn’t talk about.” Gradually, the conversation changed, often by making connections between the desecration of sacred lands in both Okinawa and Hawai‘i—particularly by the United States military, which currently operates 32 bases in Okinawa.

In Okinawa, Wada and Kaneshiro found that their outside-insider identities—Uchinānchu born in Hawai‘i but also certified shihan—granted them a unique kinship with those in their homeland. As musicians, they could create intimate spaces for difficult conversations about Okinawa’s history. And as visitors from the diaspora, they were slightly removed from the familial and intergenerational trauma that arose from those discussions. Eventually, they found themselves tending to wounds that had long been hidden. “We got to this other level where elders could talk to us,” Kaneshiro says. “Things they had a hard time sharing with their own children but wanted to tell us, because it needed to be passed down to the next generation.” This deep trust demonstrated for them the importance of a reciprocal relationship between Hawai‘i and Okinawa. Where once they

このような宗主国の歴史を思い起こさせるものであり、君主の戴冠式 のために中国から琉球に大使を運んだ「冠神(冠船)」にちなんでいる。 到着すると、中国からの使節団をもてなすために「冠船舞」と呼ばれる 趣向を凝らした音楽と舞踊が披露された。これが沖縄の古典芸能の基 礎となった。

ハウナニ・ケイ・トラスクやリリカラー・カメエレイヒワといったハ ワイのナショナリストの活動に多大な影響を受けたウクヮンシン・カブ ダンは、琉球の主権について語り合い、植民地化と占領が消し去ろう とした文化と歴史を取り戻す方法として、舞踊と音楽に注目した。ハワ イでは、沖縄のコミュニティのために演奏するだけでなく、沖縄の豊か な歴史について人々を教育し、ハワイの土地に入植した沖縄の人々の 役割と向き合うことを意味した。「植民地化された、同化された、入植し た、差別された......という言葉を持ち出し始めたのですが、特に年配の 人たちには受け入れられませんでした」とワダは振り返る。「彼らはその ことを口に出せなかったのです」。沖縄とハワイの聖地が冒涜されてい ること、特に沖縄に現在32の基地を置いている米軍によるものである ことを関連づけることで、会話は徐々に変わっていった。

ワダとカネシロは沖縄で、ハワイ生まれでありながら師範の資格 を持つウチナーンチュという、外から内からのアイデンティティーが、故 郷の人々とのユニークな親近感を生んでいることに気づいた。音楽家と して、彼らは沖縄の歴史について難しい話をするための親密な空間を 作ることができた。また、ディアスポラからの訪問者として、彼らはその ような話し合いから生じる家族間や世代間のトラウマから少し離れて いた。やがて彼らは、長い間隠れていた傷に手を当てていることに気づ いた。「年長者が私たちと話すことができる、別のレベルに到達したの です」とカネシロは言う。「次の世代に受け継がれる必要があるからで す」。この深い信頼関係は、彼らにハワイと沖縄の相互関係の重要性を 示した。かつて沖縄に信頼と権威を求めていたワダとカネシロは、ハワ イで沖縄の人々と先住民族のアイデンティティを取り戻し、共同創造す る機会を得たのだ。

70

CULTURE

Japanese annexation brought the systematic suppression of Okinawa’s Indigenous languages and culture, an enduring loss felt by generations of Okinawans today.

日本による沖縄併合は、沖縄固有の言語と文化を組織的に弾圧するこ とをもたらした。

71

looked to Okinawa for a sense of authenticity and authority, Wada and Kaneshiro saw an opportunity to reclaim and co-create an Indigenous identity with Okinawans in the homeland.

Over the years, Wada, Kaneshiro, and others at Ukwanshin Kabudan have expanded the organization’s activities dramatically, offering uta-sanshin classes from co-director Keith Nakaganeku, Uchināguchi language classes from board member Brandon Ing, monthly workshops on Okinawan culture and politics, and an annual LooChoo Identity Summit that invites Okinawans from around the world to Hawai‘i to spark dialogue about who we are as a people.

It has also become increasingly focused on the kuleana that Okinawans have to Hawai‘i and Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians). In 2019, during the stand for Mauna Kea, members of Ukwanshin Kabudan led a delegation of Okinawans to offer ho‘okupu (gifts) in solidarity with those protecting the sacred mountain at Pu‘uhonua o Pu‘uhuluhulu, and in the aftermath of the Red Hill jet fuel leak in 2021, Ukwanshin Kabudan hosted panel discussions to draw vital connections between the U.S. military’s contamination of both Hawai‘i and Okinawa’s aquifers. Most recently, the group has become involved with efforts to repatriate the remains of Okinawan ancestors and return them to their rightful resting places.

Reflecting on the ways Ukwanshin Kabudan has grown over the years, Wada says, “Going back to fichi-ukīn, because that word is connected to so much—to who we are, and who we’re supposed to be—it just grows.” That is, perhaps, the burden and privilege of living in diaspora: You inherit responsibility for two different kinds of home.

Kaneshiro adds, “Because when you’re family, you don’t just show up to the house to eat and drink. You clean up after, you take care of the house. You come back and show up for the hard times. That is what it means to be chōdē.”

ワダ、カネシロをはじめとするウークヮンシン・カブダンのメンバ ーは、この数年の間に活動を飛躍的に拡大し、共同ディレクターのキー ス・ナカガネクによる歌三線のクラス、理事のブランドン・イングによる ウチナーグチ語のクラス、沖縄の文化や政治に関する月1回のワークシ ョップ、そして世界中の沖縄県民をハワイに招き、私たちがどのような民 族であるかについて対話を促す年1回のルーチュー・アイデンティティ・ サミットなどを開催している。

また、沖縄県民がハワイとカーナカ・マオリ(ネイティブ・ハワイ アン)に対して持つクレアナにますます焦点を当てるようになってい る。2019年、マウナケア山への抗議行動中、ウクヮンシン・カブダンのメ ンバーは沖縄県民の代表団を率いて、プウホヌア・オ・プウルフルの聖な る山を守る人々と連帯してホオクプ(贈り物)を捧げ、2021年のレッド ヒル・ジェット燃料漏えい事件後、ウクヮンシン・カブダンはパネルディ スカッションを開催し、米軍によるハワイと沖縄の帯水層汚染との重要 なつながりを明らかにした。最近では、沖縄の先祖の遺骨を送還し、本 来の安住の地に戻す取り組みにも参加している。

この言葉は、私たちが何者であるか、そして何者であるべきか、多 くのことにつながっているからです。それこそが、ディアスポラに生きる ことの重荷であり特権なのかもしれない。

カネシロはこう付け加える。「家族である以上、ただ家に来て飲 み食いするだけではありません。後片付けをして、家の世話をする。辛 いことがあっても、また戻ってくる。それが "chōdē "であるということ なのです」。

72

CULTURE

Today roughly 100,000 Okinawans live in Hawai‘i, many of whom have faced discrimination while making home in a foreign land.

現在、およそ10万人の沖縄県民がハワイに住んでいるが、その多くは 異国の地で故郷を築きながら差別に直面している。

73

CULTURE

TEXT BY MITCHELL KUGA

IMAGES BY GERARD ELMORE & LAURA LA MONACA

文=ミッチェル・クガ

写真=ジェラルド・エルモア、

ローラ・ラモナカ

The Waitiki 7 share in their devotion to an oftenmisunderstood genre.

ワイティキ7は、誤解され

がちなこのジャンルへの 献身を共有している。

RHYTHMS OF REVERIE

幻想のリズム

On a mission to legitimize exotica as an art form, The Waitiki 7 make a case for fantasy.

エキゾチカという音楽ジャンルをアートとして確立することを使命に、ワイティキ・セブンはファンタジーを追求しています。

In 2003, when Randy Wong and Abe Lagrimas Jr. established their musical partnership, they were motivated by a feeling familiar to many far-flung transplants: homesickness. The two friends were studying in Boston at the time—Lagrimas at the Berklee College of Music and Wong at the New England Conservatory—“experimenting as musicians with different concepts for being local boys away from home,” says Wong, who plays bass.

Two projects formed out of that experimentation, an ukulele-forward trio called Akamai Brain Collective, and Waitiki, an exotica quartet inspired by Arthur Lyman, Les Baxter, and other forefathers of the genre. They launched the two acts on the college lū‘au circuit, performing

2003年、ランディ・ウォングさんとエイブ・ラグリマス・ジュニアさんが 音楽家としてコンビを組んだとき、ふたりは故郷から遠く離れた場所で 暮らす多くの人々におなじみの心情、つまりはホームシックに駆られて いた。ラグリマスさんはバークリー音楽大学、ウォングさんはニューイ ングランド音楽院。それぞれボストンの学校に在学中で、ベース奏者で あるウォングさんの弁によれば、”故郷を離れたハワイのローカルボー イという素材を音楽的にさまざまなコンセプトで表現しようと試みて いた”そうだ。

こうした試みから生まれたふたつのプロジェクトが、アカマイ・ブ レイン・コレクティブの名で活動したウクレレ中心のトリオ、そしてワイ ティキだ。ワイティキはアーサー・ライマンやレス・バクスターなどこのジ ャンルの生みの親と呼ぶべきミュージシャンたちに影響されたエキゾチ

74

Waitiki’s music is a living time capsule of the cultural landscape in post-war Hawai‘i, a tapestry of influences set against the alluring backdrop of the golden age of travel.

ワイティキの音楽は、戦後のハワイの文化的景観の生きたタイムカプセ ルであり、旅の黄金時代という魅力的な背景のもと、様々な影響を受け たタペストリーである。

75

at Hawai‘i Club events at Boston University and Harvard, then observed which was more popular. “Waitiki is the concept that won,” Wong says.

Over the next two decades, Waitiki emerged as one of the preeminent acts in the revival of exotica, a form of tropical lounge music that emerged postWorld War II in the U.S. and peaked in popularity leading up to Hawai‘i’s statehood. “Exotica music became so popular in the ’60s that it became cliché,” Wong says, adding that genres like surf rock came to replace exotica in appeal. Today, it’s music you’re most likely to hear in a tiki bar.

Part of Waitiki’s mission is to legitimize exotica—often considered a fringe genre—as an art form. In 2008, the group expanded to a septet, The Waitiki 7, and has since released seven records and performed internationally, in Germany and Mexico. Highlights include playing with a 25-piece big band honoring the work of legendary Mexican composer Juan García Esquivel and being accompanied by the Hawaii Youth Symphony to a gala that helped raise over $150,000 for music education programs statewide. More recently, in November 2023, Waitiki played two sold-out shows at Halekulani’s House Without a Key—a long way from the group’s more idiosyncratic beginnings.

“When I got involved with Waitiki, my second gig [with the band] was a bar mitzvah at the aquarium,” says Tim Meyer, who joined on woodwinds in 2005 and flew in from Mexico for the performances at Halekulani.

“With pop-and-lock dancers,” Wong adds.

“And my third gig was The Hukilau,” Meyer says, “which is a tiki festival in Florida.”

Wong smirks. “Don’t forget the Hot Rod Hula Hop in Columbus, Ohio, with the barnyard burlesque dancers.”

Growing up in Honolulu, Wong was exposed to exotica without really realizing it. His grandfather was friends with Arthur Lyman, considered one of the exotica greats alongside Martin Denny and Les Baxter. As a kid, Wong would accompany his grandfather to Waialae Country Club on the weekends to watch Lyman perform his signature vibraphone. “It was just really cool music,” Wong recalls of his early introduction to exotica’s unique style and sound.

カのカルテット。彼らは一連の大学のルーアウ、ボストン大学やハーバ ード大学のハワイクラブのイベントなどでそれぞれ別のグループとして 演奏し、どちらが人気を集めるか見守った。「コンセプトとして、ワイティ キに軍配が上がったんです」とウォングさん。

それからの20年、ワイティキはエキゾチカのリバイバルブームに 乗り、卓越したパフォーマンスでその名を博した。そもそもエキゾチカ とは戦後の米国で生まれた南国風のラウンジミュージックで、その人 気はハワイが米国の州になった頃(1959年)にピークを迎える。「人気 が高まりすぎて、’60年代に入ると次第に飽きられてしまうんです」そ して、人々の関心はサーフロックなどのジャンルに移っていったそうだ。 今日、エキゾチカといえば、南国をテーマにしたティキバーなどで耳に する音楽だ。

ワイティキの使命のひとつは、しばし傍流として扱われがちなエ キゾチカという音楽ジャンルを芸術として確立することだ。2008年、7 人組に成長したグループはワイティキ・セブンと名乗りはじめた。すで に7枚のアルバムをリリースし、ドイツやメキシコなど海外でも演奏して いる。なかでも特筆すべきは、伝説的なメキシコの作曲家フアン・ガルシ ア・エスキベルの偉業を讃え、25人のビッグバンドで演奏したことや、ハ ワイの音楽教育プログラムのために15万ドル以上の募金を集めた催し でハワイ・ユース・シンフォニーと共演したことなど。最近では2023年 11月、ハレクラニのハウス ウィズアウト ア キーで行われたショーで、2 回ともチケットは完売となった。むしろ特異ともいえる彼らのスタートを 思えば、ずいぶん成長した感がある。

「ワイティキに参加して二度目のギグは、水族館で行われた バルミツバー(訳注:ユダヤ教の男子の成人のお祝い)だったんです よ」2005年に木管奏者として加入し、ハレクラニでの演奏のためにメ キシコから来布したティム・メイヤーさんは振り返る。

「ポップ・アンド・ロックのダンサーも一緒でした」ウォングさん がつけ加えた。

「で、三度目のギグはザ・フキラウですよ」とメイヤーさん。「フキ ラウというのは、フロリダで行われるティキ・フェステバルのことです」 ウォングさんがにやりと笑う。「オハイオ州コロンビアのホット・ロ ッド・フラ・ホップも忘れちゃいけない。お笑いのストリップダンサーたち との共演だったじゃないか」

ホノルル出身のウォングさんは、いつの間にかエキゾチカという音 楽に触れていた。彼の祖父は、マーティン・デニーやレス・バクスターと並 んでエキゾチカの大家とされるアーサー・ライマンの友人で、ウォングさ

76

CULTURE

It’s a genre that Wong feels is often misunderstood as an ironic, kitschy province of musical hobbyists, not professionals—minimized for being more about the fantasy of the South Seas than the actual place. In 2004, a Waitiki show in Boston was picketed by a small group of law students from Hawai‘i, who argued that exotica isn’t Native Hawaiian music. “But no one’s saying it’s Native Hawaiian music,” Wong explains, noting that a conversation with the picketers helped clarify where Waitiki was coming from. For Wong, Waitiki’s music is a living time capsule of the cultural landscape in post-war Hawai‘i, a tapestry of Polynesian, Asian, hapa haole, and Latin elements, set against the alluring backdrop of the golden age of travel.

Echoing Martin Denny’s sentiment, “it’s pure fantasy,” and to further emphasize that element of escapism, the group created a fictional island from which they claimed to originate—Okonkuluku—and a complicated handshake that Okonkuluku “natives” use to greet one another.

According to Wong, what distinguishes Waitiki from most modern neo-exotica acts is the group’s musicianship. Waitiki’s rotating cast of members are all virtuosos, some with deep connections to the genre, like percussionist August Lopaka Colón Jr., whose father was a founding member of Martin Denny’s band. It’s what allows the group to reproduce the sounds of the genre as they were played mid-century, during exotica’s heyday.

“It’s upright bass, not electric bass,” explains Wong, who also serves as president and CEO of the Hawaii Youth Symphony. “It’s piano and vibraphone, not synthesizer. It’s bird and animal sounds made by people, not by samples.”

At the House Without A Key show, the mood was relaxed and festive. Wearing matching aloha wear, the group riffed, jammed, improvised, and swayed their way through a setlist of covers and originals. Within a single song, Colón Jr. worked through a hodgepodge of percussive instruments—he had over 30 with him on stage—but the most striking sounds were the ones emanating from his throat. His assortment of bird calls soared above the lanterns hanging from the hotel’s iconic kiawe tree, piercing the night sky.

んは毎週末祖父のおともでワイアラエ・カントリー・クラブを訪れ、トレー ドマークのヴィブラフォンを演奏するライマンのパフォーマンスを目の当 たりにしてきた。「とにかくかっこいい音楽でした」ウォングさんは幼い頃 に触れたエキゾチカ特有のユニークなスタイルと音を振り返る。

キッチュで風刺的で、一部の音楽マニア向け。プロの芸術家は見 向きもしない。実在の場所でもなく、ただの空想上の南の海の音楽と見 下されている。エキゾチカというジャンルはそんなふうに誤解されがち だとウォングさんは言う。2004年、ボストンで行われたワイティキのシ ョーでは、ハワイ出身の法学部の学生たち数人が、エキゾチカはハワイ 固有の音楽ではないと主張してピケを張った。「そもそもハワイ固有の 音楽だなんて誰も言っていないんですよ」だが、ピケを張った学生たちと の対話のおかげでワイティキの源がはっきりしたそうだ。ウォングさん にとってワイティキの音楽は、戦後のハワイ文化全般を今によみがえら せる生きるタイムカプセル。魅惑あふれる旅行の黄金時代を背景に、ポ リネシア、アジア、ハパ・ハオレ、ラテンなどのエッセンスが紡ぎ出す文化 のタペストリーなのだ。エキゾチカは”純粋なる空想の世界”というマー ティン・デニーの言葉を反映しつつ、現実逃避という側面をますます強 調するために、ワイティキのメンバーは”オコンクルク”という架空の島か らやってきたことにしている。そして、”オコンクルク人”の挨拶として複 雑な握手を交わすのだ。

ウォングさんによれば、もっと最近のほかのネオエキゾチカのバ ンドからワイティキが一線を画しているのは、演奏技術の高さだという。 ワイティキの準メンバーたちはいずれもその楽器の達人で、マーティン・ デニー・バンドの創設メンバーを父に持つパーカッショニストのオーガ スト・ロパカ・コロン・ジュニアさんのようにエキゾチカというジャンルへ の造詣も深いメンバーもいる。だからこそエキゾチカ全盛期、20世紀中 頃の音楽性をそのまま再現することができるのだ。「ベースはコントラバ ス。エレクトリックのベースギターは使いません」ハワイ・ユース・シンフ ォニーの団長兼CEOも務めるウォングさんは説明する。「シンセサイザ ーではなく、ピアノやヴィブラフォンも使います。鳥や動物の鳴き声も、サ ンプリングではなく人が実際に真似ているのです」

ハウス ウィズアウト ア キーのショーは、陽気でくつろいだムード に包まれていた。おそろいのアロハシャツに身を包み、彼らは心のおも むくままにリフを重ねて演奏を楽しみ、リズムに乗って、音に身をゆだね ながら、カバー曲とオリジナル曲が入り混じるセットリストの演奏を終 えた。1曲のなかでもコロン・ジュニアさんはステージに持ち込んだ30

78

CULTURE

The band’s percussionist, August Lopaka Colón Jr., makes a point of incorporating bird calls that are native to Hawai‘i.

79 バンドのパーカッショニスト、オーガスト・ロパカ・コロン・ジュニアは、ハ ワイ固有の鳥の鳴き声を取り入れることを大切にしている。

The group’s rotating members are all virtuosos, some with deep connections to the genre.

グループのメンバーは入れ 替わり立ち替わり、このジャ ンルと深い関わりを持つ名 手ばかりだ。

Later in the evening, Harold Chang, the last remaining member of the Martin Denny and Arthur Lyman group, was invited on stage. The crowd erupted into spirited applause as the 95-year-old drummer accompanied the group in playing “Quiet Village,” a lush exotica staple from Denny’s album Ritual of the Savage. A week later, Wong was still pinching himself.

For Wong, Chang’s presence and participation lent credence to Waitiki’s passion and purpose. “Some say exotica isn’t a culturally authentic art form because it’s not native,” Wong says. “But it has its own world and its own presence, and to have Harold there playing with us, it’s like he’s telling us what we’re doing is the right thing to do.”

以上の打楽器を巧みに演奏し分けるのだが、圧巻は彼の喉から出てく る声だ。彼が真似をするさまざまな鳥の声は、提灯が下がるホテルの シンボル的なキアヴェの木の上に舞い上がり、夜空を突き抜けるよう に響き渡った。

夜もふけ、マーティン・デニーとアーサー・ライマン・バンドの最後 の生き残りであるハロルド・チャングさんがステージに招かれた。デニ ーのアルバム『未開人の儀式』に収録されているゴージャスなエキゾチ カの定番『静かな村』の演奏に95歳のチャングさんがドラムで加わる と、会場は猛烈な拍手喝采で沸き返った。それから一週間たった今も まだ夢のような気がして、ウォングさんは頬をつねらずにはいられない。

チャングさんがそこにいたこと、そして共演してくれたことで、ワイ ティキというグループの情熱と使命が裏付けられたように思えた、とウ ォングさん。「エキゾチカはハワイ固有の音楽ではないから本物の芸術 ではないという意見もありますが、エキゾチカにはエキゾチカ独自の世 界とあり方があるんです。ハロルドさんが共演してくれたことで、おまえ たちのやっていることは正しいよと言われたような気がします」

80

CULTURE

Introducing Ward Village’s Newest Residential Offering

The Launiu Ward Village residences are an artful blend of inspired design and timeless sophistication. Expansive views extend the interiors and a host of amenities provide abundant space to gather with family and friends.

The Launiu Ward Village は、芸術性あふれるタイムレスな洗練をまとったレジデンス。 広がる眺望は室内に広がりをもたらし、素晴らしいアメニティの数々では家族や友人たちとの かけがえのない時間を紡ぐ。

Studio, One, Two, and Three Bedroom Honolulu Residences ホノルルのスタジオ、1ベッドルーム、2ベッドルーム、3ベッドルームレジデンス

INQUIRE

thelauniuwardvillageliving.com | 808 470 6740 Offered by Ward Village Properties, LLC RB-21701

THE PROJECT IS LOCATED IN WARD VILLAGE, A MASTER PLANNED DEVELOPMENT IN HONOLULU, HAWAII, WHICH IS STILL BEING CONSTRUCTED. ANY VISUAL REPRESENTATIONS OF WARD VILLAGE, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION, RETAIL ESTABLISHMENTS, PARKS, AMENITIES, OTHER FACILITIES AND THE CONDOMINIUM PROJECTS THEREIN, INCLUDING THEIR LOCATION, UNITS, VIEWS, FURNISHINGS, DESIGN, COMMON ELEMENTS AND AMENITIES, DO NOT ACCURATELY PORTRAY THE CONDOMINIUM PROJECTS OR THE MASTER PLANNED DEVELOPMENT. ALL VISUAL DEPICTIONS AND DESCRIPTIONS IN THIS ADVERTISEMENT ARE FOR ILLUSTRATIVE PURPOSES ONLY. THE DEVELOPER MAKES NO GUARANTEE, REPRESENTATION OR WARRANTY WHATSOEVER THAT THE DEVELOPMENTS, FACILITIES OR IMPROVEMENTS OR FURNISHINGS AND APPLIANCES DEPICTED WILL ULTIMATELY APPEAR AS SHOWN OR EVEN BE INCLUDED AS A PART OF WARD VILLAGE OR ANY CONDOMINIUM PROJECT THEREIN. WARD VILLAGE PROPERTIES, LLC, RB-21701. COPYRIGHT ©2024. EQUAL HOUSING OPPORTUNITY.

WARNING: THE CALIFORNIA BOARD OF REAL ESTATE HAS NOT INSPECTED, EXAMINED OR QUALIFIED THIS OFFERING.

THIS IS NOT INTENDED TO BE AN OFFERING OR SOLICITATION OF SALE IN ANY JURISDICTION WHERE THE PROJECT IS NOT REGISTERED IN ACCORDANCE WITH APPLICABLE LAW OR WHERE SUCH OFFERING OR SOLICITATION WOULD OTHERWISE BE PROHIBITED BY LAW. NOTICE TO NEW YORK RESIDENTS: THE DEVELOPER OF THE LAUNIU WARD VILLAGE AND ITS PRINCIPALS ARE NOT INCORPORATED IN, LOCATED IN, OR RESIDENT IN THE STATE OF NEW YORK. NO OFFERING IS BEING MADE IN OR DIRECTED TO ANY PERSON OR ENTITY IN THE STATE OF NEW YORK OR TO NEW YORK RESIDENTS BY OR ON BEHALF OF THE DEVELOPER/OFFEROR OR ANYONE ACTING WITH THE DEVELOPER/OFFEROR’S KNOWLEDGE. NO SUCH OFFERING, OR PURCHASE OR SALE OF REAL ESTATE BY OR TO RESIDENTS OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK, SHALL TAKE PLACE UNTIL ALL REGISTRATION AND FILING REQUIREMENTS UNDER THE MARTIN ACT AND THE ATTORNEY GENERAL’S REGULATIONS ARE COMPLIED WITH, A WRITTEN EXEMPTION IS OBTAINED PURSUANT TO AN APPLICATION IS GRANTED PURSUANT TO AND IN ACCORDANCE WITH COOPERATIVE POLICY STATEMENTS #1 OR #7, OR A “NO-ACTION” REQUEST IS GRANTED.

THE LAUNIU WARD VILLAGE AMENITY LOBBY

THE LAUNIU WARD VILLAGE AMENITY LOBBY

IMAGE BY JOSIAH PATTERSON

IMAGE BY JOSIAH PATTERSON

WELLNESS

TEXT BY MARTHA CHENG

IMAGES BY MCKENNA CONFORTI, JOSIAH PATTERSON & BRENT RAND

文=マーサ・チェン

写真=マッケンナ・コンフォルティ、

ジョサイア・パターソン、ブレント・ ランド

AGAINST THE GRAIN

Bizia Surf transforms one of Hawai‘i’s most destructive trees into a sustainable alternative for the surfboard industry.

Bizia Surfは、ハワイで最も破壊力の強い樹木のひとつを、サーフボード業界のための持続可能な代替品へと変身させた。

WELLNESS

86

アゲインスト・ザ・グレイン

What’s first striking about the surfboards is how beautiful they are. Made with lengths of invasive albizia, they feature striations of blonde and light brown, like the highlights in a surfer’s hair. Then, upon picking them up, what’s most noticeable is how light they are— the fish model weighs the same as a standard twin fin, the 9-foot longboard is barely heavier than a typical noserider. In the water, too, they are surprisingly lively—buoyant, even.

Made by Bizia Surf, these surfboards take one problem—the environmentally toxic production process and materials of modern-day boards—and addresses it with another: invasive albizia, one of Hawai‘i’s most destructive trees. Introduced to the islands in 1917 from Indonesia as a reforestation effort, Hawai‘i’s albizia are among the fastest-growing trees in the world, crowding out native ecosystems as they gain more than 15 feet a year. In 2004, heavy rains and albizia debris caused the flooding of Mānoa stream and an estimated $85 million in damage. In 2014, albizia became known as “the tree that ate Puna” when thousands of them fell during Hurricane Iselle, destroying houses, downing power lines, and blocking roads.

Because of how quickly albizia grows, it was commonly assumed that the wood was weak. Still, in 2015, Joey Valenti, then an architecture graduate student, lamented when he saw huge albizia trees, some 150 feet tall, cut down during a removal project at Lyon Arboretum and learned that the logs—free potential lumber—were just being dumped. With the help of a structural engineer, Valenti found that the wood was just as strong as Douglas fir, a common lumber, and set out to prove that you could build with albizia.

In the process, he went to visit master woodworker Eric Bello at his millwork shop in Wahiawā. In that first meeting, he spotted an albizia surfboard behind Bello. “I felt like I was in the right place,” Valenti says. For years, though, his attention was diverted by his architecture thesis project, and with Bello’s help, he set to work on Lika, a proof of concept for albizia as a building material. When the arched wooden structure resembling the Waikīkī Shell was completed in 2018 and displayed on the front lawn of UH Mānoa, demand for Valenti’s work immediately grew. High-profile clients like the Patagonia store at

サーフボードでまず目を引くのは、その美しさだ。破壊力の強いねむの 木の長さで作られたサーフボードは、サーファーの髪のハイライトのよ うなブロンドとライトブラウンの縞模様が特徴だ。フィッシュモデルの重 さは標準的なツインフィンと同じで、9フィートのロングボードは一般的 なノーズライダーよりもほとんど重くない。水中でも、驚くほど生き生き としていて、浮力さえある。

Bizia Surfが製造するこのサーフボードは、環境に有害な製造工 程や素材といった現代のボードの問題を、ハワイで最も破壊力の強い 樹木のひとつである特定外来生物のねむの木という別の問題で解決し ている。1917年、森林再生のためにインドネシアからハワイに持ち込 まれたねむの木は、世界で最も急速に成長する樹木のひとつであり、1 年に15フィート以上も成長するため、ハワイ固有の生態系を混雑させ ている。2004年、豪雨とアルビジアの破片がマノアの小川を氾濫させ、 推定8500万ドルの被害が出た。2014年、ねむの木はハリケーン「イゼ ル」の際に数千本が倒れ、家屋を破壊し、電線を切断し、道路を封鎖し たことから、「プナを食べた木」として知られるようになった。

ねむの木は成長が早いため、一般的に木材は弱いと思われてい た。それでも2015年、当時建築学科の大学院生だったジョーイ・ヴァレ ンティは、リヨン樹木園の除伐プロジェクトで伐採された高さ約150フ ィートのアルビジアの巨木を見て嘆いた。ヴァレンティは構造エンジニ アの協力を得て、この木が一般的な木材であるダグラス・ファーと同等 の強度を持つことを突き止め、ねむの木を使った建築が可能であること を証明しようとした。

その過程で彼は、ワヒアワにある木工所の巨匠エリック・ベロを 訪ねた。その最初のミーティングで、彼はベロの後ろにねむの木のサー フボードを見つけた。「ここだ、と思った」とヴァレンティは言う。しかし、 何年もの間、彼の関心は建築学の論文プロジェクトに注がれていた。ベ ロの助けを借りて、彼は建築材料としてのねむの木のコンセプトを証明 する「リカ」の制作に取りかかった。2018年にワイキキ・シェルに似たア ーチ型の木造構造物が完成し、ハワイ大学マノア校の前庭に展示され ると、ヴァレンティの作品に対する需要はすぐに高まった。ワードにある パタゴニアストアやプリンスヴィルにあるいちホテルのような知名度の 高いクライアントが、ねむの木のエレメントをデザインするために彼を 指名したのだ。「そして、ある時期から、サーフボードのアイデアを密かに 片付け始めたんだ」と彼は言う。

88

WELLNESS

Bizia Surfは地元ハワイのシェイパーと提携し、侵略的なねむの木の 木から作られたボードのラインナップを増やしている。

89

Bizia Surf partners with local shapers to produce its growing lineup of boards made from invasive albizia trees.

Ward and 1 Hotel in Princeville tapped him to design albizia elements for their properties. “And then, at some point,” he says, “I just started chipping away at the surfboard idea on the side, very covertly.”

For the next four years, he developed prototypes for surfboards made entirely out of albizia and, in 2021, won a $250,000 USDA Wood Innovations Grant to build the boards. In 2023, he debuted the boards in a storefront in Wahiawā across from Bello’s mill. At the hybrid coffee shop and surf store, the various surfboard models line the walls like artwork.

The wood is scavenged from around the island when utility companies, land owners, and community members are looking to clear out albizia. Valenti calls it a “resource misplaced.” And while he uses a high-tech process at Bello’s shop to manufacture the surfboards, the philosophy underlying them is an old one. Native Hawaiians made the first surfboards out of koa and other local wood. “Obviously they figured out the properties of the different woods, what worked best— buoyancy and all that,” Valenti says.