Thank you very much for choosing Halekulani Okinawa from among the many resorts available in the region. In this issue of Living, we bring you stories that delve deep into the rich culture and traditions of Okinawa.

As one of our special features, we introduce a bingata artist who is active in Okinawa. The box of kekkun snacks provided in our welcome amenity is an original design created by Ms. Nawa. She also created Halekulani Okinawa’s distinctive handkerchiefs, which are available for purchase at the Halekulani Boutique and our online shop.

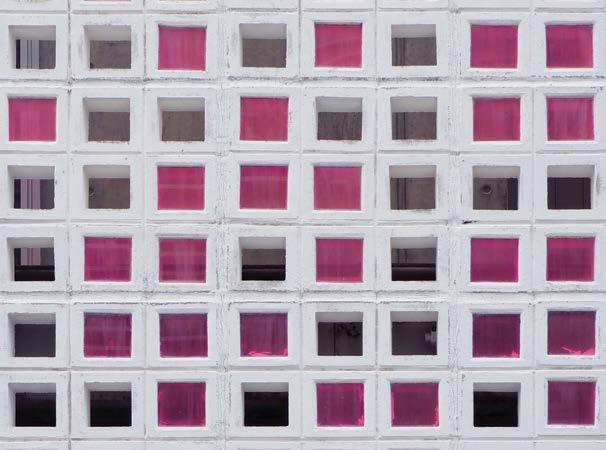

We also offer an introduction to hana blocks, a symbol of Okinawan architecture. The hana blocks used on the exterior walls of Halekulani Okinawa’s Sunset Wing reflect the local climate and culture. Like Hawai‘i’s “breezeblocks,” they combine both practicality and beauty, perfectly suited to the region.

Halekulani, too, cherishes its long history and traditions while continuing to carry on its timeless charm. The story began in 1883 with a small beach house on Waikīkī Beach in Hawai‘i. Its warm hospitality toward local fishermen earned it the name “Halekulani,” meaning “House Befitting Heaven.” Officially opening as a hotel in 1917, it has welcomed countless guests for over 100 years.

Thanks to the ongoing support of our guests, Halekulani Okinawa is celebrating its sixth anniversary in 2025. With the spirit of ‘ohana (family) and Okinawa-style hospitality, we will continue to honor the Halekulani legacy for the next 100 years.

We sincerely hope that your stay at Halekulani Okinawa will be a time filled with peace and relaxation.

この度は、数あるリゾートの中からハレクラニ沖縄をお選びい ただき、誠にありがとうございます。今号のリビングでは、沖縄の 豊かな文化と伝統を深く知ることができる内容をお届けします。 特集の一つとして、沖縄を拠点に活躍する紅型作家、縄トモコ さんをご紹介しています。ウェルカムアメニティの一部として客 室にご用意しているケックン(スナック)の箱は、縄さんが手がけ たホテルオリジナルのデザインです。ハレクラニブティックやオン ラインショップでもお買い求めいただける、ハレクラニ沖縄のオ リジナルのハンカチなどのデザインも彼女が手掛けております。

さらに、沖縄の建築を象徴する花ブロックについてもご紹介 しています。ハレクラニ沖縄のサンセットウイングの外壁に施さ れた花ブロックは、地域の風土を反映したデザインで、ハワイ の“Breezeblocks”同様に地域に適した実用性と美しさを兼ね 備えています。

ハレクラニもまた、長い歴史と伝統を大切にしながら、今もそ の魅力を受け継いでおります。1883年にハワイのワイキキビー チに建てられた小さなビーチハウスから始まった物語が、地元 漁師たちへの温かいおもてなしが評判となり、「ハレクラニ」と 呼ばれるようになりました。1917年に正式にホテルとして誕生 し、100年以上にわたり多くのゲストをお迎えしてきました。ハ レクラニ沖縄も皆さまのご愛顧により、2025年で6年目を迎え ます。「OHANA(家族)」の精神と、沖縄らしいおもてなしの心を 大切に、次なる100年を目指して物語を紡いでまいります。 ハレクラニ沖縄でのご滞在が、安らぎと癒しに満ちたひととき となりますよう、スタッフ一同心より願っております。

Jun Yoshie General Manager Halekulani Okinawa

ハレクラニ沖縄 総支配人 吉江 潤

HALEKULANI CORPORATION

GENERAL MANAGER, HALEKULANI OKINAWA

JUN YOSHIE

DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC RELATIONS

SHOKO MAESHIRO

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER

JASON CUTINELLA

CORPORATE AFFAIRS

JOE V. BOCK JOE@NMGNETWORK.COM

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

LAUREN MCNALLY

MANAGING DESIGNER

TAYLOR NIIMOTO

OKINAWA.HALEKULANI.COM

+81-98-953-8600

1967-1, NAKAMA, ONNA-SON, KUNIGAMI-GUN, OKINAWA, 904-0401, JAPAN

PUBLISHED BY

VP FILM GERARD ELMORE

NMG NETWORK

41 N. HOTEL ST. HONOLULU, HI 96817

NMGNETWORK.COM

© 2025 by NMG Network, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted without the written consent of the publisher. Opinions are solely those of the contributors and are not necessarily endorsed by NMG Network.

Volume 1.2 | December 2024

目 次

アート 18

心の彩り

文化 30

陶芸文化 42

存在を織る糸 52 おおきな木 食 66

沖縄のグルメ

ウェルネス 78

影響力のある球体

新しい何かを探して 88 パターン認識 102

写し出される真実 102

上:ランス・ヘンダーステインさん撮影によるアー ティスト山崎萌子さんのポートレート。反対のペー ジ:宮古島のパリギャラリーでの山崎さんの作品 展示風景。

Above, a portrait of artist Moeco Yamazaki by Lance Henderstein. On opposite page, an installation view of her work at Pali Gallery on Miyako island.

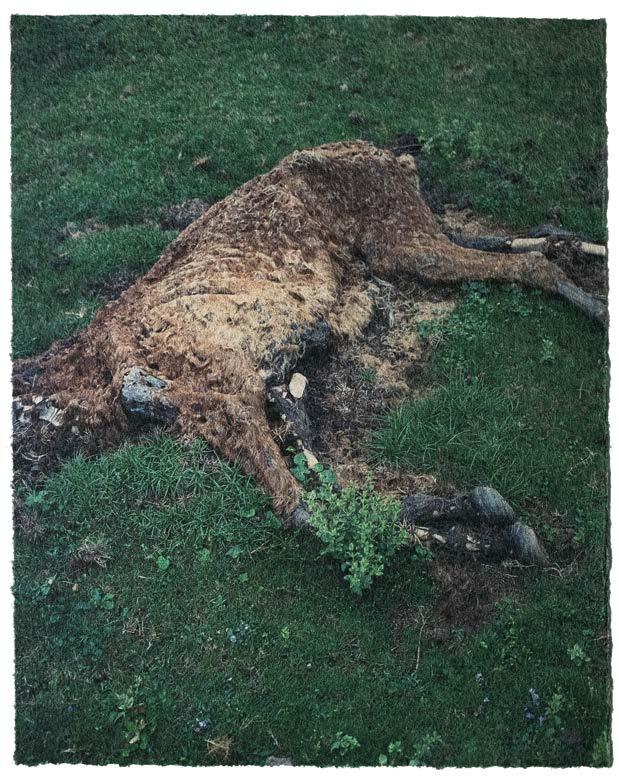

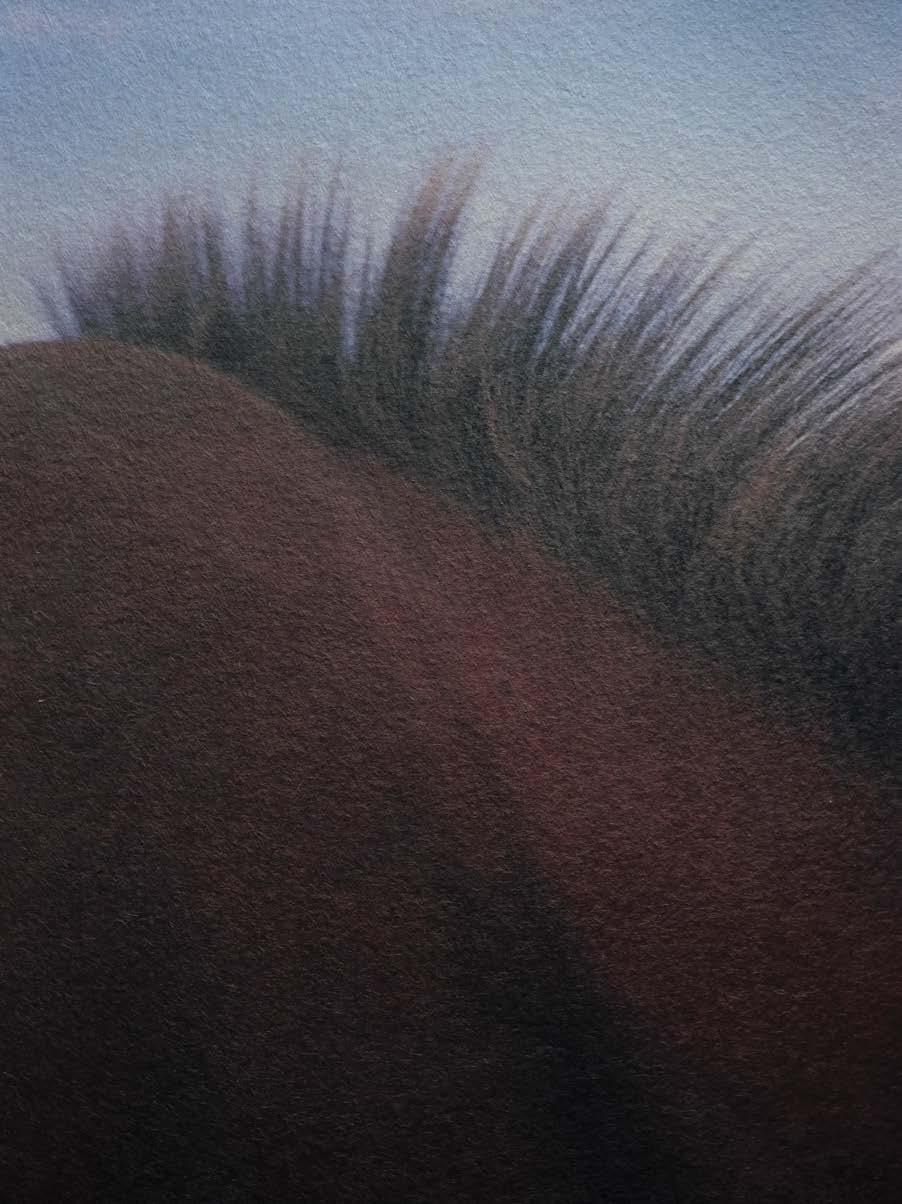

表紙について

アーティスト山崎萌子さんが、与那国島の在来馬から着想を得て制作した数多くの作品のうちの 一点。島に自生する糸芭蕉と馬糞から作られた紙に印刷されている。

ハレクラニ沖縄 Living

The Culture of Clay

of Being

Okinawa WELLNESS

Spheres of Influence

Recognition

Portraits of Place

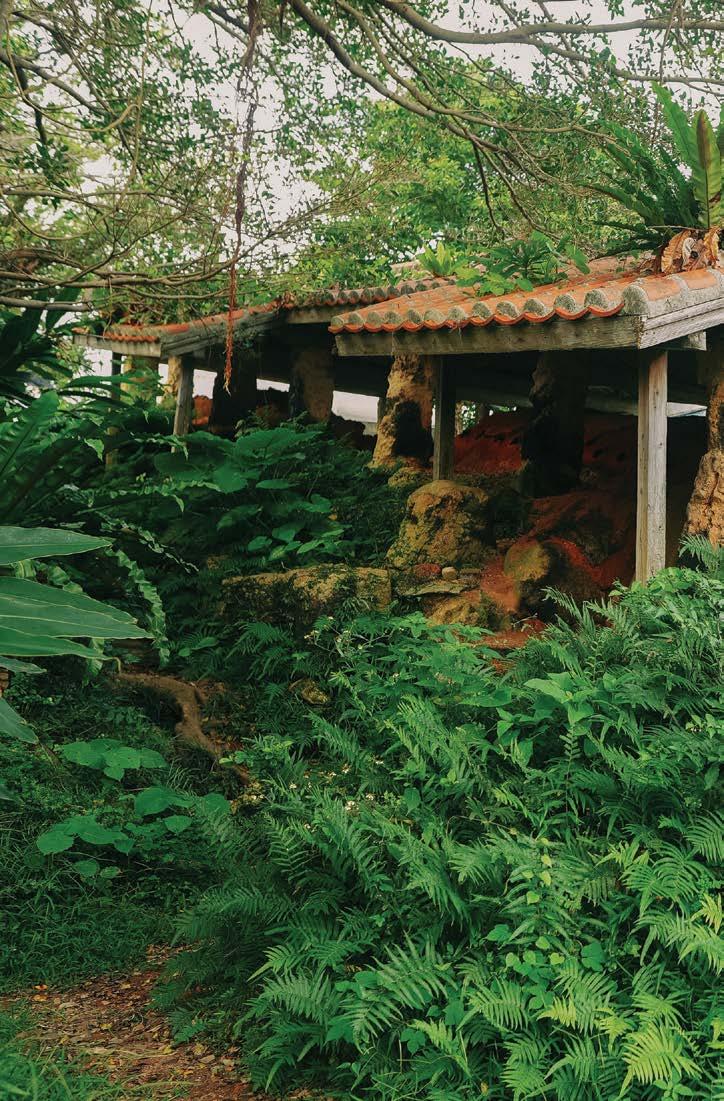

上:那覇市にある緑が生い茂る花 ブロックの壁。右ページ:うるま市の あまわりパーク歴史文化施設館内 にある花ブロックのディテール(写 真:ダーウィン・リンコ)

Above, a wall of overgrown hana blocks in Naha. On opposite page, a detail of the hana blocks at Amawari Park Historical Cultural Institution in Uruma City by photographer Darwin Lingco. ABOUT

THE COVER:

This work by artist Moeco Yamazaki, printed on paper made from ito-bashō and horse manure, is one of many inspired by the native horses of Yonaguni island.

存在を織る糸

FIBERS OF BEING

母と娘が、芭蕉布工芸に貢献し人間国宝となった亡き女家 長の遺志を受け継ぎ、その伝統を守り続けている姿を描く。

A mother and daughter honor the legacy of their late matriarch, named a Living National Treasure for her contributions to the craft of bashōfu.

客室内でご視聴いただけるリビン グ沖縄TVは、ハレクラニ沖縄なら ではの上質なひとときをお過ごしい ただくために、豊かで健康的なライ フスタイルをテーマにしたオリジナ ル番組をお届けしています。臨場感 あふれる映像と興味をかきたてるス トーリーで、沖縄とハワイの芸術や 文化、人々の暮らしぶりをご紹介し ます。すべての番組は客室TVまたは living.okinawa.halekulani.com からご視聴いただけます。

Living Okinawa TV is produced to complement the Halekulani Okinawa experience, with videos that focus on the art of living well. Featuring cinematic imagery and compelling storytelling, Living Okinawa TV connects guests with the arts, culture, and people of Okinawa and Hawai‘i. All programs can be viewed on the guest room TV and online at living.okinawa.halekulani.com.

watch online at: living.okinawa.halekulani.com テ レ ビ 番 組

物語を刻む器 STORIED VESSELS

那覇にある家族経営の工房「角萬漆器」では、熟練した職 人たちが美しく精緻な琉球漆器を作り上げている。

At Kakuman Shikki, a family-run atelier in Naha, a team of skilled artisans create exquisite pieces of Ryūkyūan lacquerware.

心の彩り

COLORS OF THE HEART

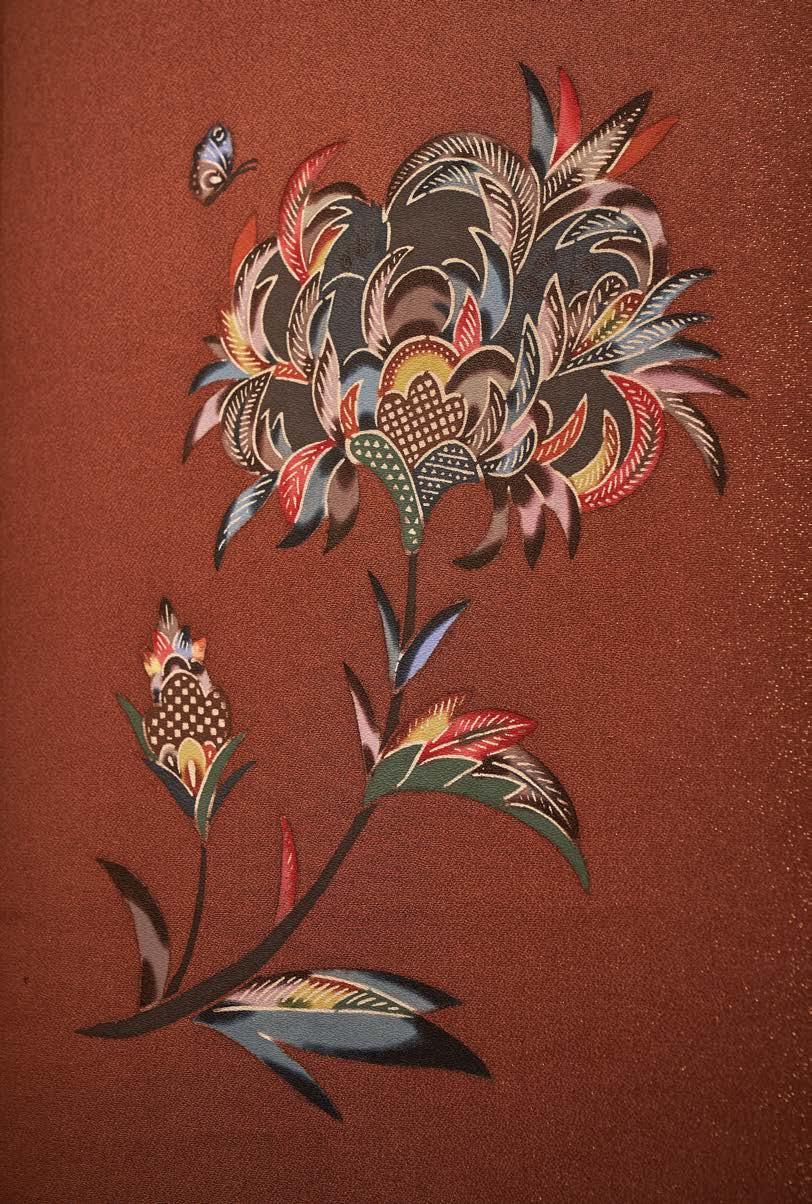

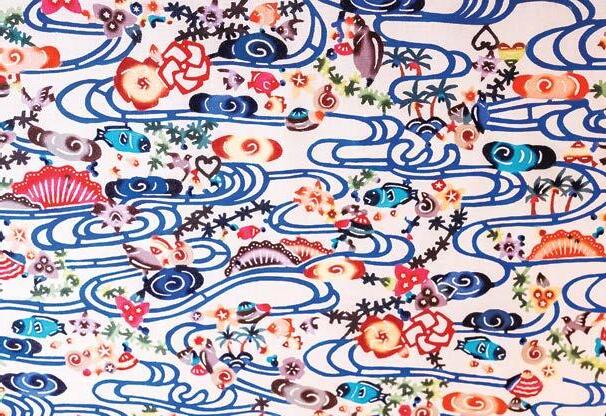

紅型作家の縄トモコさんが、琉球王朝の伝統と名高い歴史 を持つ防染技法である紅型への愛情を語る。

Artist Tomoko Nawa shares her love affair with bingata, a resist-dyeing technique with a royal heritage and storied history.

パターン認識

PATTERN RECOGNITION

那覇とホノルルを巡るこの旅では「花ブロック」として知られる コンクリート建材とハワイ諸島の同種建材との繋がりを探る。

In this jaunt through Naha and Honolulu, learn the connection between the concrete building material known as hana blocks and its counterpart in the Hawaiian Islands.

陶芸文化

THE CULTURE OF CLAY

那覇の高名な壺屋地区を訪ね、現代の職人たちが守り続ける やちむん(陶器)の伝統技法に出会う。

Explore Naha’s famed Tsuboya district, where modern-day makers perpetuate the traditional techniques of yachimun (pottery).

Introducing The Launiu Ward Village

The Launiu Ward Village residences are an artful blend of inspired design and timeless sophistication. Expansive views extend the interiors and a host of amenities provide abundant space to gather with family and friends.

The Launiu Ward Village は、芸術性あふれるタイムレスな洗練をまとったレジデンス。 広がる眺望は室内に広がりをもたらし、素晴らしいアメニティの数々では家族や友人たちとの かけがえのない時間を紡ぐ。

Studio, One, Two, and Three Bedroom Honolulu Residences ホノルルのスタジオ、1ベッドルーム、2ベッドルーム、3ベッドルームレジデンス

INQUIRE

thelauniuliving.com | +1 808 470 8022 Offered by Ward Village Properties, LLC RB-21701

THE PROJECT IS LOCATED IN WARD VILLAGE, A MASTER PLANNED DEVELOPMENT IN HONOLULU, HAWAII, WHICH IS STILL BEING CONSTRUCTED. ANY VISUAL REPRESENTATIONS OF WARD VILLAGE, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION, RETAIL ESTABLISHMENTS, PARKS, AMENITIES, OTHER FACILITIES AND THE CONDOMINIUM PROJECTS THEREIN, INCLUDING THEIR LOCATION, UNITS, VIEWS, FURNISHINGS, DESIGN, COMMON ELEMENTS AND AMENITIES, DO NOT ACCURATELY PORTRAY THE CONDOMINIUM PROJECTS OR THE MASTER PLANNED DEVELOPMENT. ALL VISUAL DEPICTIONS AND DESCRIPTIONS IN THIS ADVERTISEMENT ARE FOR ILLUSTRATIVE PURPOSES ONLY. THE DEVELOPER MAKES NO GUARANTEE, REPRESENTATION OR WARRANTY WHATSOEVER THAT THE DEVELOPMENTS, FACILITIES OR IMPROVEMENTS OR FURNISHINGS AND APPLIANCES DEPICTED WILL ULTIMATELY APPEAR AS SHOWN OR EVEN BE INCLUDED AS A PART OF WARD VILLAGE OR ANY CONDOMINIUM PROJECT THEREIN. WARD VILLAGE PROPERTIES, LLC, RB-21701. COPYRIGHT ©2024. EQUAL HOUSING OPPORTUNITY. WARNING: THE CALIFORNIA BOARD OF REAL ESTATE HAS NOT INSPECTED, EXAMINED OR QUALIFIED THIS OFFERING.

文

心の彩り

COLORS OF THE HEART

TRANSLATION BY MUTSUMI MATSUNOBU

アーティストの創造力が鮮やかな紅型の世界で 羽ばたく

“The delicate petals and buds were blooming in the garden as if singing,” writes bingata artist Tomoko Nawa in a poem entitled “Blooming Like a Song.” “I kept it in my heart, wanting to turn it into a design. I dye it again and again, so that it blooms inside the fabric.” The poem is one of many Nawa has composed over the years as lyrical companions to her bingata creations. Joyful and contemplative, they speak mostly of encounters with nature—rapturous, ephemeral moments in communion with the ocean, sky, and bounty of the seasons.

In one poem, a bashō tree beckons with its giant flowers and lush fruits. In another, Nawa ponders a seashell’s origin. In “Round Flower,” she describes twirling a blossom around in her hands “like a kaleidoscope. The seven different flowers dance and sing. I fell in love, as if being sucked in.”

Nawa was struck by a similar sense of awe upon discovering bingata in 2003. She was living in Japan’s Hyōgo Prefecture at the time, working at a café after graduating from drama and nursing school. Okinawa had been a source of fascination since her late teens, and while flipping through a magazine article on traditional Okinawan crafts, she was stunned to discover bingata’s world of vivid technicolor: maple leaves and plum blossoms bursting in shades of crimson and peony, jade-green forests of bamboo and pine vibrating against fields of cinnabar red and canary yellow. “It was love at first sight,” Nawa recalls.

Historically produced for the ruling class and their imperial counterparts in China, bingata served for centuries as a vibrant symbol of the Ryūkyū Kingdom’s diplomatic prestige and cultural influences from China, Japan, and Southeast Asia. Designs were dictated by the royal court, with larger patterns and brighter colors signifying higher rank.

「謳うように咲く」という詩の中で、紅型作家である縄トモコさ んは「あなたの庭で/謳うように咲いていた/可憐な花弁や蕾 が……」と綴っている。「忘れられず/図柄にしようと心に留める (中略)布の中で咲うように/何度となく、わたしは染める……」 この詩は、縄さんが長年にわたって手がけてきた紅型作品に添え られた詩の一つである。喜びに満ちながらも瞑想的なこれらの詩 は、主に自然との出会いを描き出している。海や空、四季の恵みと 交わる歓喜的で儚い瞬間が、詩の中で美しく表現されている。

ある詩では、芭蕉の木の豊満な実と掌のような花が彼女を 呼び止める。また別の詩では、貝殻がどこから来たのか思いを巡 らせる。「輪舞の花」では、花を手の中でクルリッとまわす様子を 「万華鏡のように」と表現している。「……七変化した花に/わた しは恋をした/吸い込まれるように」

縄さんが紅型に出会ったのは2003年のことだった。その瞬間、 彼女は畏敬の念ともいえる感情を抱いたという。当時、縄さんは兵庫県 に住んでいて、演劇と介護の学校を卒業後、カフェで働いていた。10代 後半から沖縄に惹かれていた彼女が、ある日、沖縄の伝統工芸について の雑誌をめくっていると、紅型の鮮やかな色彩の世界に心を奪われた。 深紅や牡丹色に染まる楓の葉や梅の花、シナ朱色やカナリアイエロー の地に映える翡翠色の竹や松の美しさに衝撃を受けたのだった。「まさ に一目惚れでした」と縄さんは振り返る。

歴史的に琉球の支配階級や中国の皇族のために制作されてきた 紅型は、何世紀にもわたって、琉球王国の外交的威信、そして中国、日 本、東南アジアからの文化的影響を象徴する鮮やかなシンボルとして の役割を果たしてきた。紅型のデザインは宮廷によって決められ、より 大きな模様や鮮やかな色彩は身分の高さを示していたという。「伝統的 な紅型の色彩は、輪郭を縁取る陰影が特徴です」と縄さんは語る。「そ れは、沖縄の強い日差しと濃い影のためだと考えられています」

紅型作家の縄トモコさんがハレクラニ沖縄のために手がけた特注 の紅型には、ホテルならではのモチーフが散りばめられている。敷 地内の曲がりくねった小道に沿って植えられたヤシの木、ホテル 前の海を泳ぐブダイ、恩納村のシンボルであるユウナの花、そして ホテルを象徴するランの花が、美しく描かれている。

Artist Tomoko Nawa’s custom bingata design for Halekulani Okinawa, pictured on previous spread, includes motifs specific to the hotel: the palm trees planted along its winding paths; parrotfish native to the waters fronting the property; the yūna flower, a symbol of Onna Village; and the hotel’s iconic orchid.

鮮やかな色彩に惹かれて紅

型の世界に入った縄さんだ が、彼女の作品は伝統的な 紅型よりも柔らかい色調が特 徴である。

Though she was initially drawn to its vivid colors, Nawa tends to pull from a more muted palette than traditional bingata.

“Traditional bingata patterns are characterized by the shading that outlines the contours,” Nawa says. “People think it was because of Okinawa’s bright sunshine and strong shadows.”

Nawa relocated to Okinawa to devote herself to the craft, spending the next four years in training before embarking on a career as a full-time bingata artist. She’d been exhibiting her tapestries and framed works around the country for some time when, in 2014, she was invited to Hanoi, Vietnam, to take part in a group exhibition with a dozen other female artists from Japan. To represent Japanese culture at the exhibition, the wives of the members of the Japanese embassy who assisted with the show planned to wear kimono to the opening, and they encouraged Nawa and her fellow artists to do the same. Many miles from home, her country’s traditional attire was cast in a new light. “It was then that I realized how wonderful kimonos are,” she says.

紅型の制作に専念するため沖縄に移住した縄さんは、4年の修 行を経て、紅型作家として本格的に活動を始めた。しばらくの間、タペス トリーや額装作品を全国各地で展示する活動を続けていたが、2014 年にはベトナムのハノイに招待され、他の12名の日本人女性アーティ ストと一緒にグループ展に参加した。

展覧会で日本文化を紹介するため、手伝っていた日本大使館員 の夫人らがオープニングで着物を着ることを計画し、縄さんやその他の 参加アーティストたちにも着物を着るように勧めた。日本から遠く離れ た地で、日本の伝統的な装いに新たな光が投げかけられたのだ。「その とき初めて、着物の素晴らしさを実感しました」と縄さんは語る。

現在、縄さんの紅型制作の中心となっているのは、日本の着物 市場向けの帯である。南城市にある彼女の工房では、細長い部屋の端

Today, obi (belts) for the Japanese kimono market are a mainstay of Nawa’s bingata practice. At her studio in Nanjo city, lengths of obi fabric are draped from one end of the long, narrow room to the other, suspended one above another along hanging drying racks like the billowing sails of a ship. It’s here she spends most of her day, leaving for only a few hours at a time to drive the short distance home to prepare meals for her 8-year-old daughter. Fortunately, it’s time she relishes. “Losing track of time while dyeing,” she says, “I feel incredibly happy to do something I truly love.”

Though it was bingata’s lively colors that initially drew her in, Nawa tends to pull from a muted palette, an aesthetic that resonates with her mainland Japanese clientele. “My bingata has a Tottori-San’in filter,” Nawa muses, alluding to Japan’s coastal San’in region and the sparsely populated Tottori Prefecture of her upbringing, with its vast sand dunes, mistcloaked mountains, and serene seascapes. “The colors are a little softer. Gradually I came to realize that I have my own innate sense of color and saturation that comes through in my work. I’ve come to accept that my style is part of my unique expression.”

Her designs, too, reflect the cultural milieu of her native Japan. Along with classic Okinawan bingata patterns, Nawa favors motifs depicting Japanese takarazukushi, or collections of treasures. “My teacher taught me that [the concepts of] denshō and dentō are different things,” Nawa says. “Denshō is about preserving the old as much as possible, just as it is. Dentō is about tradition that changes with the times, incorporating new things. I was taught that both are important. When I thought about which one resonates with me, I realized I’m more aligned with dentō than denshō.”

This approach is one that fueled the revival of many traditional crafts after the fall of the Ryūkyū Kingdom and the periods of political and social turmoil that followed. Eiki Shiroma, a member of a prominent bingata family, is revered as a pioneer of bingata for his efforts to ensure the survival of the craft after World War II, when there was little demand and equally little means for bingata making. Scavenging through the trash at the U.S. military base for materials to use as tools, Shiroma boldly adapted bingata patterns to appeal to new markets,

から端まで広がった長い帯地が乾燥棚に沿って上下に吊り下げられて いる。それはまるで風を受けて膨らむ船の帆のようだ。縄さんは1日の 大半をこの工房で過ごしているが、8歳になる娘の食事を準備するため に、車ですぐ近くの自宅に帰る。それは、彼女にとって大切なひとときだ。 「染色に没頭すると、時間を忘れてしまいます。本当に好きなことをして いるときは、信じられないくらい幸せです」と語る。

最初に縄さんが惹きつけられたのは紅型の鮮やかな色彩だった が、彼女の作品は、より穏やかな色味が特徴で、それが本州の日本人顧 客に支持されているという。広大な砂丘、霧に包まれた山々、穏やかな 海の風景が広がる山陰地方、彼女の故郷であり過疎化の進んだ鳥取に ついて言及しながら「私の紅型には、鳥取や山陰のフィルターがかかっ ているんです」と縄さんは呟く。「色は少し柔らかめです。生まれもった色 彩感覚と彩度の好みがあり、それが作品に表れていることに、だんだん と気づくようになりました。今では、私のスタイルは私独自の表現の一 部なのだと受け入れるようになったのです」

彼女のデザインには、生まれ育った日本の文化的背景も反映さ れている。沖縄の古典的な紅型模様に加え、縄さんは、日本の宝づくし紋 (縁起の良いさまざまな宝物を描いた吉祥文様)を好んで用いる。「伝 承と伝統は違うものだと先生から教わりました」と縄さんは語る。「伝承 とは、古いものをできるだけそのまま保存すること。伝統とは、新しいも のを取り入れながら時代と共に変わっていくものです。どちらも大切だ ということを教わりました。自分にとってどちらがしっくりくるのかを考 えたとき、私は伝承よりも伝統に共感することに気づいたのです」

この観点は、琉球王国が崩壊し、政治的・社会的混乱期を経た 後、多くの伝統工芸が復興する原動力となった。著名な紅型師一族出 身の城間栄喜さんは、第二次世界大戦後の紅型の需要も創作の手段 もほとんどない状況下において、紅型の存続に尽力したことで、紅型の

“I dye it again and again, so that it blooms inside the fabric.”—Tomoko Nawa, bingata artist 「布の中で咲うように 何度となく、わたしは染める」

紅型作家 縄トモコ

縄さんの作品は、日本の着物

市場向けの伝統的な帯として 作られることが多い。

Much of Nawa’s work takes the form of traditional obi for the Japanese kimono market.

expanding upon the classic bingata patterns his family conceived for the ruling dynasties.

It is from this spirit of reinvention that Nawa’s creations blossom, drawing upon the palette of her homeland and the traditions of her home. A custom bingata design she created for Halekulani Okinawa in 2019 conjures the wonders of this exuberant landscape of influences: “Through the palm-lined streets…” she writes in its accompanying poem, “the yūna flower, the flower of Onna village, and the orchid, the symbol of Halekulani Okinawa, beautifully adorn the scene ahead. The endlessly blue sea, the vibrant fish swimming within it, and the radiant coral reefs … I send my wishes to protect and cherish them all.”

先駆者として尊敬されている。米軍基地の廃棄物の中から道具として 使用する素材を探すこともあった。そして、城間さんは、彼の一族が歴 代王朝のために生み出した古典的な紅型模様を基に、新しい市場にア ピールする紅型デザインをさらに繰り広げた。

この再創造の精神から生まれた縄さんの作品は、故郷の色彩や 伝統を取り入れて美しく花開く。2019年にハレクラニ沖縄のために制 作したオリジナル柄は、多彩な影響を受けた風景の魅力を見事に表現 している。「椰子の木の並ぶ道をぬけて……」作品に添えられた詩の中 で縄さんは語る。「恩納村花であるユウナの花と、/ハレクラニ沖縄の 象徴である/ランの花が美しく彩りの先。/どこまでも青い海と、/そ こに泳ぐ鮮やかな魚たち、輝く珊瑚……それらを大事に守っていきたい と願いを込めて制作させていただきました」

TEXT BY LANCE HENDERSTEIN

TRANSLATION BY MUTSUMI MATSUNOBU

THE CULTURE OF CLAY

那覇の名高い壷屋地区で、やちむん(焼き物)の 伝統工芸を受け継ぐ現代の職人たち 陶芸文化

IMAGES BY GERARD ELMORE AND LANCE HENDERSTEIN

Modern-day makers carry on the traditional craft of yachimun in Naha’s famed Tsuboya pottery district.

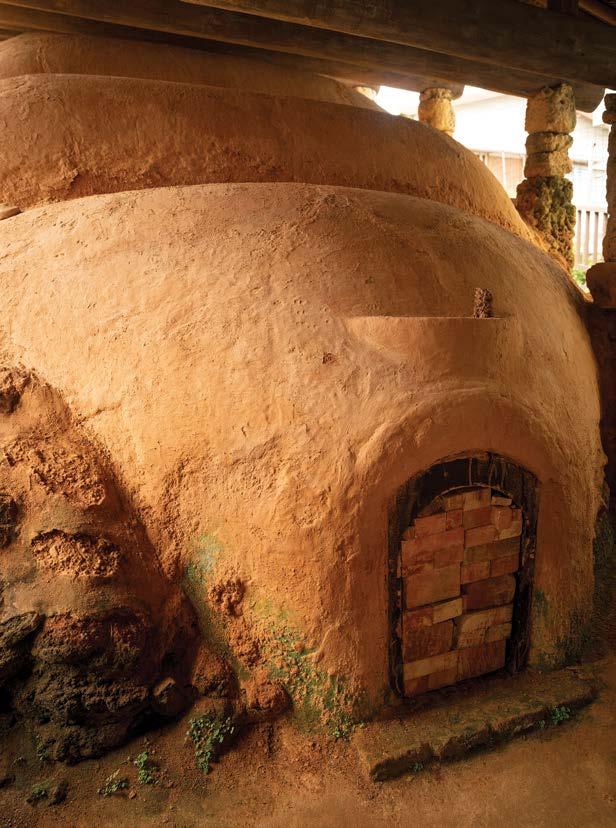

A short walk from the chaos of Naha’s Kokusai-dori (International Street), the asphalt turns to cobbled limestone underfoot, a visual cue that one has entered Tsuboya Yachimun Dori, the main street through Okinawa’s yachimun (pottery) district. Here, pedestrians and window shoppers leisurely mill past decorative tiled walls and along sidewalks embedded with colorful pieces of glazed wares. Along one of the district’s narrow, serpentine alleys, called “sujiguwa” in the Uchinā Yamato-guchi dialect, the climbing kiln of the iconic Arakaki Family Residence, a potter’s house active until 1974, rises like an earthen palace from

那覇の国際通りの喧騒を後にして少し歩くと、足元のアスファル トが琉球石灰岩の石畳に変わり、沖縄のやちむん(焼き物)の街 のメインストリートである壺屋やちむん通りに入ったことを告げ る。通りには装飾タイル張りの壁が続き、色鮮やかな釉薬をかけ た陶器のかけらが埋め込まれた歩道を歩行者やウィンドウショッ ピングを楽しむ人々がのんびりと歩いている。壺屋やちむん通り に向かって緩やかに傾斜した狭くて曲がりくねった路地は、ウチ ナーヤマトグチ(沖縄大和口)の方言で「すーじぐゎー」と呼ばれ る。この路地の途中には、1974年まで活動した陶工が住んでい た新垣家住宅があり、簡素な風景に囲まれた登り窯が土の宮殿

its humble surroundings. Inside, the womb-like kiln has long been sealed shut, but the ceramic tradition it once sustained is very much alive today.

It was by design that the area became a hub of industry, bringing together various ceramic techniques from the region. In 1660, Shuri Castle, the center of politics, diplomacy, and culture of the Ryūkyū Kingdom, burned to the ground, and a vast quantity of roof tiles were needed for the rebuilding effort. The rulers of the kingdom decided to consolidate the island’s pottery industry in 1682, resettling all the potters in Tsuboya near the Asato River to ease the sourcing of clay and other materials and to better facilitate the shipping of finished products.

The surrounding city of Naha was devastated in World War II by heavy American bombing, but miraculously, Tsuboya was spared. Surviving artisans returned immediately to their studios and woodfired kilns to produce the needed objects for daily life. But as the city’s population boomed, the smoke from these traditional kilns made wood-fired yachimun production untenable. By the 1970s, artisans wanting to preserve their traditional methods relocated to the Yomitan area to the north, creating Yachimun no Sato (Yachimun Village), while the remaining workshops in Tsuboya converted to the gas and electric-fired kilns still in use today.

Guide Junichi Takano of Okinawa Slow Tour says that the street and surrounding village, which was thoughtfully planned out using the principles of feng shui, began to take on its current form in 1982. A vibrant center of yachimun culture and technique, the village is now fueled by collectives of multigenerational shokunin (artisan) families committed to preserving and evolving one of Okinawa’s most revered crafts.

About halfway down the meandering mainstreet sits the flagship store of one such pottery family: Ikutoen, a renowned producer of traditional Tsuboyayaki (Tsuboya ware) with a 300-year history and six shops in the area. The keystone of the operation is sixth-generation master potter Tadashi Takaesu, a certified traditional craftsman of Okinawa whose ornately designed creations fill the store’s shelves, their arabesque motifs and imagery of fish and sea creatures bearing his distinctive line-carving techniques. Shisa (lion) figurines, made in the unique style of previous owner and fifth-generation yachi-

のようにそびえ立っている。子宮を思わせる形をした窯の内部は 長い間封印されているが、かつてこの窯が支えた陶磁器の伝統は、 現在も脈々と受け継がれている。

陶芸の中心地として、壺屋に周辺地域のあらゆる陶芸の技術が 集められたのは、意図的な計画によるものだった。1660年、琉球王国 の政治·外交·文化の中心であった首里城が焼失し、再建のために大量 の屋根瓦が必要となった。そこで、1682年に王国の統治者は島の陶器 産業を一か所に集約することを決定し、陶土やその他の材料の調達が 容易で、完成品の輸送をより円滑に行える安里川近くの壺屋に、すべて の陶工を移住させた。

第二次世界大戦中、那覇市は米軍の爆撃により壊滅的な被害に 遭ったが、壺屋は奇跡的に難を免れた。生き残った職人たちは、すぐに 工房や薪窯に戻ると、日常生活に必要な陶器の生産を再開。だが、市 の人口が急増するに伴い、こうした伝統的な窯から立ち上る煙が問題 視されるようになると、薪窯でやちむんを焼くことが困難になっていっ た。1970年代には、伝統的な技法を守りたい職人たちは本島北部の 読谷地区に移住して「やちむんの里」を創設する。一方、壺屋に残った 工房は、薪窯をガス窯や電気窯に切り替えて、現在も使用している。

おきなわスローツアーでガイドをしている高野純一さんによる と、風水の原理に基づいて綿密に計画されたこの通りと周囲の村が現 在の形になり始めたのは1982年のことだという。現在、やちむんの文 化と技術の活気ある中心地であるこの村は、沖縄で最も尊崇されるこ の工芸品の保護と進化に尽力する多世代の職人家族の共同体によっ て支えられている。

曲がりくねったメインストリートの中ほどに、そうした窯元のひと つである育陶園の本店がある。育陶園は伝統的な壺屋焼の有名な製 造元で、300年の歴史があり、この地域に6つの店舗を構えている。ここ の事業の要となるのは、沖縄の認定伝統工芸士である6代目陶主の高 江洲忠さんである。店の棚は、唐草模様のモチーフ、魚や海の生き物の イメージなど、彼の独特の線彫り技法で描かれた緻密なデザインの作 品で埋め尽くされている。先代陶主で5代目やちむんの名工である高江 洲育男さんが独特の作風で制作したシーサーの置物も、棚に静かに鎮 座して、購入される日を待っている。

ハレクラニ沖縄 Living

壷屋焼やちむん道場では、どんなレベルの作り手も 本格的な壷屋焼を体験できる。

At Tsuboya Pottery Yachimun Hands-on Dojo, makers of all skill levels learn to craft authentic Tsuboya ware.

新垣家住宅内の登り窯。1974年まで使用されていた 建物は、素朴な周囲の景観の中にまるで土の宮殿のよ うにそびえ立っている。

The climbing kiln of the Arakaki Family Residence, a potter’s house active until 1974, rises like an earthen palace from its humble surroundings.

mun master Ikuo Takaesu, keep silent watch from the shelves as they, too, await purchase.

“Everyone at Ikutoen has a senmon (specialty),” says Ikutoen’s sales manager, Hikarui Takaesu. “We are divided into three categories: those who manufacture, meaning the shokunin and kiln staff themselves; those who sell; and those who think of new and innovative ways to market and promote our products to the public.”

According to Wakana Takaesu, directing manager of Ikutoen, the days of solitary craftsmanship are in the past. Today, sales and marketing are an essential part of the business. “Shokunin used to be exclusively creators—they didn’t really market themselves,” she says. “Now we know we need to have people here dedicated to communicating the difficulty and wonder of making yachimun to customers. It was a big but necessary change.”

A large part of Ikutoen’s initiative to share the art of yachimun with the public is by way of instruction at its nearby Tsuboya Pottery Yachimun Hands-on Dojo, a red-tiled wooden building nestled amid lush greenery along the yachimun pottery promenade. Inside, fans circulate the humid air as the day’s makers arrive, comprised of a mix of all experience levels, ranging from tourists seeking a do-it-yourself keepsake to aspiring shokunin looking to dedicate themselves to the craft long term. White towels yellowed by clay hang from racks above the many potter’s wheels, where students create everything from simple shisa figurines to more elaborate pieces that are kilned alongside those of the masters.

The yachimun dojo’s supervisor, Sayuri Takayasu, believes that people’s personalities reveal themselves in the things they create. “You can often see it in the face of the first shisa they make or how they carve their lines into the clay,” he says. “Everyone’s style is unique to them.”

The steps involved in creating a vessel are few, but still it’s a craft that takes a lifetime to master. The finicky elements of earth, temperature, humidity, and time make yachimun an exercise in patience and perseverance for even the most skilled practitioner.

The process begins with rokurohiki, or throwing clay on a potter’s wheel. Once the item is shaped as desired, a handmade wooden tool called a tonbō, named for its resemblance to a dragonfly, is used to ensure consistent dimensions. The kezuri shavings

「育陶園の従業員は、それぞれ専門分野を持っています」と話す のは、育陶園の営業部長である高江洲光さん。「私たちの事業は、職人 や窯元のスタッフなど製造を担当する部門、販売担当の部門、さらに製 品を一般に売り込んで宣伝するための新しい革新的な方法を考える部 門の3つに分かれています」

育陶園の代表取締役である高江洲若菜さんによると、職人が一 人で制作に没頭する時代は過去のもので、現在では営業やマーケティ ングが事業に不可欠なのだという。「かつての職人はもっぱら作り手専 門で、自らを売り込むことはほとんどありませんでした」と彼女は話す。 「いまでは、やちむん作りの難しさや素晴らしさを、お客様に伝えること に専念する人材が必要だと理解しています。これは大きな変化でした が、必要な変革でした」

育陶園がやちむんの芸術を一般に広めるために行っている重要 な取り組みのひとつが、近くの「壺屋焼やちむん道場」における陶芸体 験の指導である。このアトリエは、壺屋やちむん道り沿いの豊かな緑に 囲まれた赤瓦の木造建築で、建物の中では扇風機が湿った空気をかき まぜながら、その日の体験者を迎え入れる。体験者の腕前は、自分で作 る記念品を所望する観光客から、将来職人を目指して本格的に取り組 む人まで多岐にわたる。粘土に染まって黄色くなった白いタオルが多く の轆轤(ろくろ)の上の棚からぶら下がっている。簡単なシーサーの置 物から、より精巧な作品まで、この場所で生徒たちが制作した作品は、 匠の作品と一緒に窯で焼き上げられる。

このやちむん道場の指導者である高安彩百合さんは、作り手の 個性は作品に表れると信じている。「最初に作ったシーサーの表情や粘 土に彫る線の描き方から、その人らしさが見えることがよくあります」と 高安さん。「作風はそれぞれ違い、その人だけのものなのです」

陶器作りは工程こそは少ないが、奥義を極めるには一生かかる 奥深い工芸である。土の特性、温度、湿度、時間といった微妙な要素が 絡み合うため、やちむん作りは最も熟練した職人にとっても忍耐と根気 のいる作業だという。

その工程は、轆轤挽き、つまり轆轤を使って粘土を形成する作業か ら始まる。作品が望みどおりの形になると、昆虫のトンボに似ていること から「トンボ」と名付けられた手作りの木製の道具を使って寸法を均一

そこかしこに豊かな伝統陶芸の証しがみられる那覇の壺屋地区。 Naha’s Tsuboya district is filled with signs of its rich pottery traditions.

that pile up on the tools are collected to be formed back into workable clay. Later, members of the studio will gather around the mountain of shavings and rehydrate the ribbons of clay, mixing in water like one might fold an egg into flour to make pasta. They then stomp on the slurry, like wine makers in a vat, marching in a circle to reshape it into usable material.

Perhaps the most consequential step in the process of crafting a piece of yachimun is senbori, carving decorative patterns into the hard clay. One mistake and the piece can’t be sold, in which case it’s used for practice. It is said that these failed pieces thus give more than they take, going on to support tōgeika (ceramicists) in their journey to master the form.

にする。この道具に溜まった削りかすは、成形可能な粘土として再利用 される。作業後、工房のメンバーが削りかすの山の周りに集まり、小麦 粉に卵を混ぜてパスタを作る要領で、リボン状の粘土を水で湿らせ混 ぜていく。そして、桶の中のワイン職人が葡萄を踏むように、円陣を組ん で粘土を踏みつけ、再び使える材料に作り直す。

やちむんの制作過程でおそらく最も重要な工程は、硬くなった粘 土に装飾的な模様を彫る「線彫り」だろう。一か所でも失敗すれば、そ の作品を商品として販売することはできない。失敗したものは、練習用 に使われる。失敗作から得るものは多く、陶芸家がやちむんの技法を習 得する上での支えになっているといわれている。

Stroll along the winding paths near the Ikutoen yachimun dojo and you’ll find an artisan in every other window, hard at work in some stage of the pottery-making process. In the window of the Kobashigawa Seitojou Niougama studio sits 67-year-old Sachio Ikeno, a latebloomer in yachimun pottery, having started training at age 47 after a career as a “salaryman.” “My brother-inlaw was the master tōgeika here,” Ikeno says, recounting the sense of familial commitment that led to his mid-life reinvention as a yachimun tōgeika. “When he was diagnosed with cancer, I decided to try to carry on the practice myself. I swore to him I would try my best, and I have.” He works as he talks, harrowingly moving large trays of cups and bowls onto higher shelves and

育陶園のやちむん道場周辺の曲がりくねった小道を歩くと、職人 が陶器作りの各工程に励んでいるのを窓越しに見られる。小橋川製陶 所・仁王窯の窓辺では、会社員生活を経て47歳で修行を始めた遅咲き のやちむん作家で、現在67歳の池野幸雄さんが座っていた。「義理の兄 がここの名匠陶工でした」と池野さんは言う。中年になってからやちむ んの陶芸家として再出発するきっかけとなった家族への責任感を語っ てくれた。「義兄がガンと診断されたとき、私は自分でこの仕事を引き継 ごうと決心しました。全力を尽くしますと義兄に誓い、それを守っていま す」池野さんは話しをしながら、カップや碗を載せた大きなトレイを慎

名匠陶工だった義兄が癌だと 診断されたことをきっかけに、 池野幸雄さんはやちむん作家 としての道を歩み始めた。

Sachio Ikeno took up the baton of yachimun tōgeika (ceramicist) after his brother-in-law, a master ceramicist, was diagnosed with cancer.

文 化

壺屋地区は、第二次世界大 戦の被害を免れた沖縄唯一

の陶器の産地だったために、 職人たちはすぐに戻って制作 を再開できた。

Tsuboya is the only pottery district in Okinawa that survived World War II, enabling its artisans to return to the area.

transporting the massive head of a shisa sculpture from one end of the studio to the other.

Kobashigawa Seitojou Niougama is best known for resurrecting and recreating the akae technique, a style that uses a traditional red pigment said to have been lost and rediscovered by the Kobashigawa family. This precious material knowledge is what motivates Ikeno to keep going, even on days when he would rather take a break.

“We have this wonderful culture thanks to all those generations who came before us and kept these traditions alive,” Ikeno says. “I feel only kansha (appreciation) each day for the gifts they left, and I hope to pass on what I can to the next generation, as best I can.”

重に高い棚に移したり、巨大なシーサー像の頭部をスタジオの端から 端まで運んだりしていた。

小橋川製陶所・仁王窯は、赤江技法の復活と再現で知られてい る。伝統的な赤色顔料を使用した赤江技法は、かつて失われたとされ ていたが、小橋川家によって再発見されたと伝えられている。この貴重 な素材についての知識こそが、池野さんが休みを返上してでも赤絵の 研究を続ける原動力となっている。

「先人たちがこの伝統を守り続けてくれたおかげで、私たちはこ の素晴らしい文化を享受できるのです」と池野さんは語る。「彼らが残し てくれた贈り物に、毎日感謝するばかりです。そして、私にできる限りの ことを次の世代に伝えていきたいと思っています」

やちむんの精緻な技法を習得するには何年もの修行を要し、奥義 を極めるには一生かかるという。

It requires many years of training to learn the precise techniques of yachimun pottery—and takes a lifetime to master.

存在を織る糸

FIBERS OF BEING

TEXT BY LAUREN MCNALLY

TRANSLATION BY MUTSUMI MATSUNOBU

IMAGES BY GERARD ELMORE AND NARUYASU NABESHIMA

卓越した美しさ、哲学、そして職人技が宿る 伝統工芸を、力を合わせて守る喜如嘉の女性たち

Through their collective effort, the women of Kijōka honor a craft of remarkable beauty, philosophy, and craftsmanship.

Thunder rolls overhead as Nao Taira makes her way to the largest of her family’s bashō (wild plantain) fields in the northern Okinawan village of Ogimi. A shīgu—a small knife used to strip plant stalks— hangs around her neck, and her long sleeves and pant legs shield her from the giant mosquitoes hovering heavy in the air. Arriving at the edge of the field, she heads down a muddy path between walls of bashō plants, their leaves forming a canopy of green above her. A black-and-white butterfly lands on the deep purple inflorescence of a nearby bashō flower. “Obāchan (grandmother),” Nao says, spotting the insect and grinning.

When Nao made the decision to move back home to Ogimi a decade ago, it was to deepen her understanding of bashōfu weaving and of her grandmother, the Living National Treasure Toshiko Taira. Working

頭上で雷鳴が轟く中、平良奈緒さんは沖縄本島北部の大宜味村にあ る、一家が所有する糸芭蕉(芭蕉布の原料になる在来種の野生の芭 蕉)畑の中でも一番大きな畑へと向かっていた。首には「シーグ」と呼ば れる植物の茎を剥ぐための小刀をぶら下げ、激しく飛び回る巨大な蚊 から身を守るため、長袖のシャツとズボンという出で立ちをしている。 畑にたどり着くと、壁のようにそびえる糸芭蕉の間のぬかるんだ小道を 進む。彼女の頭上には、糸芭蕉の葉が緑の天蓋を作り出している。濃い 紫色をした糸芭蕉の花に白黒まだらの蝶がとまった。その蝶を見つけ た奈緒さんは、「おばあちゃん」と呼びかけて笑う。

いまは亡き祖母、人間国宝の平良敏子さんがなぜこれほどまで に芭蕉布に人生を捧げたのかをもっと知りたいと思い、奈緒さんが故 郷の大宜味村に戻る決心をしたのは、いまから10年前のことだった。

大宜味村の喜如嘉地区では、芭蕉布織りは単なる生業ではなく、生き 方そのものだ。

In the Kijoka district of Ogimi, bashōfu weaving is not only a common vocation, it’s a way of life.

文 化

喜如嘉の芭蕉布

喜如嘉の芭蕉布は、1974 年に国の重要無形文化財 に指定された。

Kijoka bashōfu was designated an Important Intangible Cultural Property by the Japanese government in 1974.

with Toshiko in the years before her passing at age 101, Nao witnessed the fierce tenacity that enabled her grandmother to successfully revitalize bashōfu production in the village’s once-thriving Kijoka district, where the craft had nearly died out in the wake of World War II.

Even as a centenarian, when Toshiko could no longer ride her bicycle down the road, she would insist on checking on their bashō fields after the region’s frequent typhoons. “There were other people who could do it, but she wanted to see the fields with her own eyes,” says Nao, who would indulge her grandmother by taking her to patrol the fields by car.

It was only in the last six months of her life that Toshiko scaled back her long hours at the workshop, though she continued to arrive before dawn to prepare the space for the day’s labor. “The mission of a Living National Treasure isn’t about resting at 90,” says Nao’s mother, Mieko Taira, who manages the bashōfu operation that Toshiko left behind upon her death in 2022. “Even after age 100, it’s about self-improvement and nurturing the next generation.”

A native of Fukui Prefecture, Mieko was familiar

敏子さんが101歳でこの世を去るまでの数年間、奈緒さんは敏子さん の薫陶を受け、第二次世界大戦後には途絶えかけていた芭蕉布の生産 を、かつて栄えた喜如嘉地区で見事に復興させた祖母の情熱と粘り強 さを目の当たりにした。

この地域は頻繁に台風の影響を受ける。敏子さんは100歳を過 ぎて自転車に乗れなくなったときでさえ、台風が過ぎ去るたびに必ず 糸芭蕉の畑を見に行っていた。「畑の様子を見に行ける人は他にもい たのですが、祖母は自分の目で確かめたかったのです」と話す奈緒さ ん。敏子さんを乗せて車で畑の見回りに行くと、非常に喜んでくれたと いう。敏子さんが工房での作業時間を減らしたのは人生最後の半年に なってからのことだったが、それでも一日の作業の準備をするために、 毎日夜明け前に工房に姿を見せた。「人間国宝の使命は、90歳になっ たからといって終わるようなものではありません」と、奈緒さんの母であ る平良美恵子さんは語る。美恵子さんは、2022年に亡くなった敏子さ んが残した芭蕉布の制作全般を管理している。「100歳を過ぎても自己 研鑽を重ね、次世代を育てる使命があるのです」

福井県出身の美恵子さんは、芭蕉布職人の家庭に入る以前か ら、義母の仕事をよく知っていた。琉球民芸に興味があった美恵子さん は、1972年に沖縄が日本に返還された後、沖縄へやって来る。一方の

ハレクラニ沖縄 Living

戦後、芭蕉布の生産を復興した平良敏子さん。鮮やかな色を生み 出すために、芭蕉布の糸を木の灰汁で煮てから染色する技法を復 活させた。(写真:鍋島徳恭)

Reviving bashōfu production after the war, Toshiko Taira also resurrected a technique of boiling bashōfu yarn in wood lye before dyeing to produce vivid colors. Image by Naruyasu Nabeshima.

文 化

喜如嘉の芭蕉布

喜如嘉の芭蕉布が今日も

名高い工芸品であり続け

ているのは、平良美恵子

さん(上)や平良奈緒さん

(右 )をはじめとする喜如 嘉の女性たちのたゆまぬ

努力のおかげだ。

It is thanks to the women of Kijoka, including Mieko Taira, above, and Nao Taira, opposite page, that Kijoka bashōfu remains the celebrated craft it is today.

with her mother-in-law’s work well before she and the bashōfu artisan would go on to become family. Mieko’s interest in Ryūkyūan folk crafts brought her to Okinawa after its reversion to Japan in 1972, and by then, Toshiko was renowned for her contributions to the craft, having pursued it in earnest following a formative year of studying dyeing and weaving under Kichinosuke Tonomura, a leader in the mingei (folk art) movement, in Japan’s Kurashiki city shortly after the war.

According to Mieko, Tonomura had once commented, “‘Toshiko-san, your mind isn’t here, is it?’ When you’re lost in thought, the sound of weaving doesn’t flow smoothly—shan-shan-shan-shan. It wasn’t so much about technical teaching but about learning a kind of inner stillness.”

In a video testimony for the Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum, Toshiko recalled of her mentor: “Mr. Tonomura would always tell us, ‘Weaving comes from the heart, and your heart is reflected in

敏子さんは、戦後まもなく倉敷市で民藝運動のリーダーとなった染織 家の外村吉之助さんに師事する。1年間正式に染織を学んだ後、本格 的に芭蕉布織りに取り組み、美恵子さんが沖縄に来た頃には、この工 芸に多大な貢献を果たした人物として知られていた。

美恵子さんによると、かつて外村さんは「敏子さん、心ここにあら ずだね。うわの空だと、機織りの『シャン、シャン、シャン、シャン』というリ ズムが崩れてしまいますよ」と言ったことがあるという。「それは技術的 な指導というより、内なる静寂の学びだったそうです」

沖縄県平和祈念資料館で流れる証言ビデオの中でも、敏子さん は恩師について次のように回想している。「外村先生は日頃から『織物 は心から生まれる、織物には心が表れる』とおっしゃっていました。先生 は技術だけでなく、織物に必要な心構えも教えてくださいました」

倉敷から沖縄に戻った敏子さんは、戦争で村の多くの家が破壊 されたことを目にする。マラリアを媒介する蚊を駆除するため、糸芭蕉 の農園もアメリカ軍に焼き払われていた。織物に対する新たな感性と、

ハレクラニ沖縄 Living

the weave.’ He taught me not only the techniques, but also the necessary mindset for weaving.”

Returning to Okinawa from Kurashiki, Toshiko discovered many homes in her village had been destroyed during the war. The bashō plantations were gone too, burned down by the U.S. military to control the population of malaria-spreading mosquitoes. Galvanized by her new sensibilities for weaving, and by those in Kurashiki who implored her to keep the craft alive upon her return to Okinawa, Toshiko improvised. While she and her family nurtured the bashō fields back to life, they collected thread from the silkworms in their house and unraveled discarded military blankets and tents to repurpose the cotton for weaving.

“Back in the day, bashōfu was a family business,” Mieko says. “The grandfather would take care of the land, the grandmother would produce the thread, and the children would help whatever way they could.” After the war, however, with the village’s imperiled bashōfu industry offering little economic opportunity, many men began leaving to seek carpentry work in urban areas outside of Ogimi.

It was thus the women of the village who Toshiko enlisted to join her in resuming bashōfu production, forming a cooperative dedicated to the preservation of Kijoka’s weaving techniques. Together they developed intricate kasuri (ikat) patterns unique to Kijoka, as well as novel items such as table linens and cushions. The enterprise proved popular among American military families, and once again Kijoka was recognized for the beauty and value of its bashōfu culture.

Today, like so many before it, the air in the weaving room at the Kijoka Bashofu Weaving Studio is thick with a damp heat, primed for the work ahead with humidifiers that keep the delicate bashō fibers supple and resistant to breaking. The gentle whirring of an ūchingibata (spinning wheel) and the humming of fans join the chorus of cicadas buzzing in the trees outside. In an adjacent room, another sound punctuates the quiet: that of porcelain knocking against wood as Mieko rubs an inverted chawan (teacup) along a bolt of fabric in long, firm strokes on the floor, imparting a smooth texture and sheen.

In opening the studio for tours, Toshiko intended for the public to observe the meticulous work of transforming bashō into the distinctive textile known as Kijoka bashōfu, a long and elaborate process requiring deft skill, mathematical precision, and many hands and months of manual labor. “Toward the end, her focus

沖縄に戻っても地元の織物を存続させてほしいという倉敷の人々の 願いに突き動かされ、敏子さんは身の回りにあるもので作品を織り上 げることにした。再び糸芭蕉を栽培しながら、敏子さんと家族は家で蚕 を育てて糸を取り、廃棄処分された軍用毛布やテントを解きほぐして綿 を取り出し、織物に再利用したのである。

「昔は、芭蕉布は家族総出の仕事だったのです」と美恵子さんは 語る。「おじいさんが畑の世話をし、おばあさんが糸を作り、子どもたち はどんな手伝いもしていました」。ところが、戦後になると村の芭蕉布産 業が衰退して経済的な見通しが厳しくなり、男性たちの多くが大工仕 事を求めて、大宜味村を離れ、都市部へ出ていった。

そこで敏子さんは村の女性たちに芭蕉布の生産再開を呼びか け、喜如嘉の織物技術を守るために協同組合を結成する。そして皆で 協力して、喜如嘉独特の複雑な絣(かすり)模様やテーブルリネン、クッ ションなどの新しい製品も開発した。この取り組みは駐留米軍家族の 間で人気を博し、喜如嘉の芭蕉布文化の美しさと価値が再び認められ るようになった。

芭蕉布織物工房の機織り室には、昔と同じように、いまも湿った 熱気が立ち込めている。次の作業に備えて加湿器を使い、デリケートな 芭蕉の繊維をしなやかで切れにくい状態に整えているのだ。

木々で鳴くセミの合唱に、穏やかな糸車の音と扇風機の低い唸りが加 わる。隣の部屋では、別の音が静寂を破って響いている。美恵子さん が、逆さにした湯呑み茶碗を布地に沿わせ、木の床の上で長くしっかり としたストロークで何度も擦りながら布目を整え、布に滑らかな質感と 光沢を与えている音だ。

敏子さんが工房見学ツアーを始めたのは、糸芭蕉が「喜如嘉の芭 蕉布」として知られる名高い織物へと仕上げる緻密な作業を一般の人 々に知ってもらいたいと考えたからだ。それは、巧みな技術や数字的正 確さ、そして何か月にもわたる手作業を要する。恐ろしく気の長く複雑 な工程だ。「晩年の彼女の関心は、芭蕉布が世界の中でしっかりと居場 所を確立することに向いていました」と美恵子さんは語る。敏子さんは、 とくに博物館や美術館の学芸員に働きかけ、彼らのコレクションを通じ て芭蕉布が世界に共有され、永く保存されることを願っていた。

「目的は芸術作品を作ることではありませんでした」と美恵子さ んは即座に明言する。「人々が触りたくなる、着たくなる、そんな生地を 作ることだったのです」。敏子さんはプロデューサーとしての視点を持 ち、労働条件の改善、生産基準の向上、さらに多くの人々がこの工芸技 術を学び洗練させる機会を促進しながら、素材の本質を引き出し、低品 質の繊維でさえもその魅力を引き出す技に長けていた。「布そのものを 変えるというより、布を取り巻く環境を変えるという点で、彼女の功績

芭蕉布職人は皮を剥いだ糸芭蕉の幹のすべてを巧みに利用する が、着物の生地に使用されるのは最高級の内層のみで、一枚の着 物を作るには200〜300本の幹が必要となる。

Though weavers ingeniously utilize all parts of the bashō stalk, only the finest inner layer is used for kimono fabric. It requires some 200 to 300 stalks to produce a single kimono.

was ensuring that bashōfu would find its place in the world,” Mieko says, an effort Toshiko specifically geared toward curators of museums and art institutions in hopes that, through their collections, bashōfu could be shared and preserved in perpetuity.

“But the aim wasn’t to create works of art,” Mieko is quick to clarify. “It was to create fabrics that people would want to touch and wear.” With her producer’s mindset, Toshiko had a keen sense of how to bring out the essence of the material—allowing even lower quality fibers to shine—all the while facilitating better working conditions, higher production standards, and opportunities for others to learn and refine the craft. “Rather than changing the fabric itself,” Mieko says, “I believe her greater impact was in transforming the environment around it.”

With its striking patterns, rich heritage, and hardwon esteem, Nao says there’s no shortage of young people interested in the idea of weaving bashōfu. Few, however, are committed to the reality of the craft. “Good plants are key for good thread,” she says, explaining that a weaver’s work begins in the field, three years before the bashō is ready to be harvested. “There are people who come here to learn about bashōfu but can’t handle the lifestyle. They say, ‘I didn’t come here to do weed-pulling. I didn’t come here to work in the fields,’ and leave.”

This hard truth is what keeps Nao in Kijoka working alongside its aging elders, some of whom have been fixtures in her life since childhood. “If they say they want to keep making thread even when they are 80, 90, or 100 years old, I’ll stay and harvest the fibers to give them,” she says, tears welling in her eyes. “No one is commanding me, and it’s not something I feel I’m obligated to do, but every time I’m asked, I realize I have to do it.”

As if they were a part of the landscape, Nao remembers seeing the women of Kijoka out on their porches every morning on her way to school, tying bashōfu threads under the eaves. To preserve the traditions of Kijoka bashōfu is to preserve the spirit that made it the lifeblood of the village—and to uphold the values of a community that looks after each other like family. “The hearts of the people involved must come together as one,” Mieko says. “United in heart, the bashōfu bears no author’s name. It’s a collective effort.”

は大きかったと思います」と美恵子さんは語る。

特徴的な模様、豊かな伝統、そして苦労の末に勝ち得た名声によ り、芭蕉布を織ることに興味を持つ若者は後を絶たないと奈緒さんは 話す。だが、真剣にこの技術の習得に励む者はほとんどいない。「良い糸 を作るには、良い糸芭蕉が欠かせません」と話す奈緒さん。機織りの仕 事は、糸芭蕉が収穫される3年前から畑で始まると説明する。「芭蕉布 を学びに来ても、ここでの生活に馴染めない人もいます。『草むしりに来 たんじゃない。畑仕事をするために、ここに来たわけではない』と言って 立ち去る人もいます」

この厳しい現実こそが、奈緒さんが喜如嘉に留まり、高齢の職人 とともに働き続けている理由である。職人の中には、幼少期から彼女の 人生に深く関わってきた人もいる。「80歳、90歳、100歳になっても、糸 を作り続けたいと言うなら、私はここに残って彼女たちのために繊維を 収穫してあげたいのです」と語る奈緒さんの目に涙が溢れる。「誰かに 命令されたわけでも、義務感でやっているわけでもありません。ただ、頼 まれるたびに、私がやらなければと思うのです」

奈緒さんは、毎朝学校に向かう途中、喜如嘉の女性たちが縁側 に座り、軒下で芭蕉布の糸を結んでいる姿を目にしたことを覚えてい る。その姿はまるで風景の一部のようだったという。喜如嘉の芭蕉布の 伝統を存続するということは、この工芸を村の命ともいえるその精神を 守ること、そして家族のようにお互いを思いやるコミュニティの価値観 を受け継ぐことにほかならない。「携わる者の心が一つにならなければ なりません」と美恵子さんは語る。「心を一つにするから、芭蕉布には 作者の銘がありません。なぜなら、芭蕉布はみんなの努力の賜だから」

おおきな木

TREE OF LIFE

TEXT BY RAE SOJOT

TRANSLATION BY AKIKO SHIMA 文

IMAGES BY WAYNE LEVIN

ハレクラニのシンボル、130年にわたって豊か な歴史を見守るキアヴェの木

Halekulani’s emblematic kiawe tree has borne witness to 130 years of storied history.

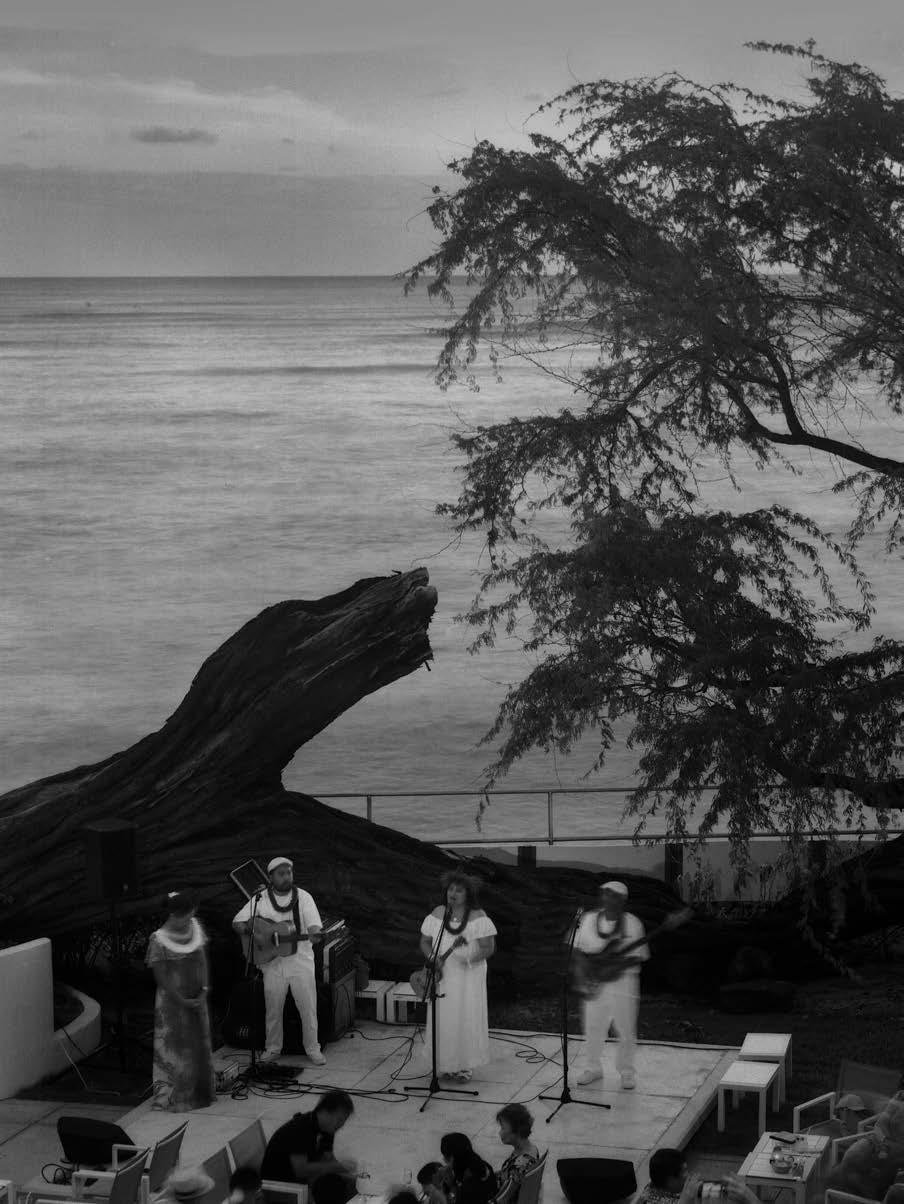

In 1887, 3-year-old Florence Hall, alongside her father, William Hall, planted a small thornless kiawe sapling in the grassy lawn of Halekulani. The simple, seaside ceremony took place just outside of the building where the young Florence had been born. Over the next century, the tree grew, its boughs shaped by the sun and sea breezes, its outstretched canopy a delicate latticework of leaf and stem. Through Hawai‘i’s emergence to statehood, two World Wars, tourism booms, and cultural renaissances, the tree has borne witness to events both grand and minute, holding court over a hundred years’ worth of contemplations, conversations, and celebrations. To this day, paradise is found and memories are made under the silvered boughs of this “grand lady,” as many hotel staff have come to call the arbor.

But in the early, silent hours of August 21, 2016, absent of any monitory wind or rain, the historic tree fell. It pitched over in the most ideal manner, falling between the shore passage railing and the House Without a Key’s stage. No one was hurt and no damage was done. The most unusual aspect of all was that no one witnessed its fall. Surveillance footage revealed the tree upright in one frame, and then moments later, simply lying down.

Following the recommendations of arborists, groundskeepers quickly moved to cover the exposed roots with wet burlap sacks. Some branches were removed, others coppiced. The roots have since reestablished, and tender new shoots now unfurl skyward. Today, the historic kiawe tree continues to be an elegant symbol of the hotel’s grandeur and grace, presiding over the grounds as Halekulani’s living treasure.

1887年、3歳のフローレンス・ホールさんは、父親のウィリアム・ホール さんと、ハレクラニの芝生に刺のない小さなキアヴェの苗を植えた。海 辺でのささやかな植樹のセレモニーは、フローレンスさんが生まれた建 物のすぐ外で行われた。それから一世紀が経ち、苗木は大樹に成長し た。太陽と潮風によって造形された枝と、葉が織りなす繊細で美しい格 子模様の樹冠が、空に向かって大きく手を広げている。この木はハワイ 併合から、2つの世界大戦、観光ブーム、ハワイ文化のルネサンスに至る まで、時代の移り変わりとともにあらゆる出来事を目の当たりにしてき た。100年以上にわたって、この場所を訪れる人々のさまざまな思いや 会話、祝い事をすぐそばで見守ってきたキアヴェの木。ホテルのスタッフ が「グランドレディー(大きな貴婦人)」と呼ぶ、壮厳たる木は今なお、多 くの人々の心に、魅惑の楽園の光景として残っている。

ところが2016年8月21日の早朝、雨も風もない静けさの中、樹 齢129年のキアヴェの木が倒れた。それは海岸沿いの歩道の柵とハウ スウィズアウト ア キーのステージのちょうど間に、誰も傷つけることな く倒れていた。不思議なことに、倒れた瞬間を見た人は一人としておら ず、監視カメラに残された映像には、それまでまっすぐ立っていた木が、 ある瞬間突然、疲れた体を休めるかのように、静かに地面に横たわる 姿が写っていた。

樹木医の勧めにより、作業員たちは露出した根を濡れた麻袋で すばやく覆い、枝を切り落とした。以来、根は再生され、柔らかい新芽が 空に向かって伸びつつある。歴史あるキアヴェの木は、今もハレクラニ の栄光とエレガンスのシンボルであり、生ける宝として、このホテルを見 守り続けている。

文 化

During the 1930s, Chicagoan Annie Irons spent a whirlwind month in the Hawaiian Islands. She chronicled her adventures in a scrapbook filled with a merry assortment of photographs, ticket stubs, and programs, penning detailed captions in meticulous script. The kiawe captured Irons’ attention, meriting an impromptu photograph: “As I sat on the lawn of the Halekulani one day,” she wrote, “I looked up and was so impressed by the lacy pattern overhead that I tilted my camera upward.”

1930年代にハワイ諸島でひと月を過ごしたシカゴ在住のアニー・ア イロンズさんは、その冒険について、写真や切符、冊子などとともに、手 書きの詳細な文章で綴っている。この時、アイロンズさんの目にとまっ たハレクラニのキアヴェの木は、彼女の写真のコレクションに写ってい る。「ある日、ハレクラニの芝生に座って空を見上げたら、レースのよう に美しい模様が広がっていました。それに感動して、おもわずカメラを 向けたのがこの一枚です」

When 16-year-old Tony Good arrived in Hawai‘i on the SS Lurline , he found it to be the stuff of tropical, teenage dreams. Sojourning for months at a time, Good’s family regularly frequented the islands— and Halekulani, where they enjoyed hosted cocktails and graceful hula performances on the seaside lawn. Nearly 60 years later, Good sees the tree as an emblem of his teenage crush. “I used to hide behind that tree and watch Mamo Howell dance hula every day,” Good confesses. “She was the most beautiful woman I had ever laid eyes on.” Years later, Good happened upon a snapshot his father took during one of their stays. In it, an elegant Howell is poised mid-step in dance, and in the background is the profile of a young, love-struck Good, peeking out from behind the kiawe’s trunk.

豪華クルーズ船のSSルーラインに乗船し、ハワイに到着した16歳の トニー・グッドさんにとって、そこは青春と夢の楽園だった。グッドさん の家族は頻繁にハワイを訪れては、数ヶ月単位の滞在を楽しんでい た。ハレクラニの芝生でカクテルパーティを催し、優雅なフラのパフォ ーマンスを堪能したものだった。あれから60年が経った今、この木を 初恋の象徴だというグッドさんは、「この木の後に隠れて、毎日のよう にマモ・ハウエルさんの踊るうっとりするようなフラを眺めていました。 彼女は私が今まで見た中で最も美しい女性でした」と告白する。それ から何年も経って、父親が滞在中に撮ったスナップ写真を見つけた彼 は驚いた。そこにはエレガントなステップを踊るハウエルさんの後方で キアヴェの木の陰から恋する眼差しを向ける一人の若者、グッドさん の姿が映っていた。 文

“In the olden days, it was the men who cleaned the rooms,” says Richard Castillo, who joined Halekulani’s housekeeping staff in 1953. While working the night shift during the late ’50s, Castillo was privy to the evenings’ musical acts, including legendary exotica musician Arthur Lyman, who enthralled crowds with the jungle jazzy sounds of the marimba, xylophone, and wild birdcalls. Castillo often helped Lyman pack up his instruments after the show. “He was a popular guy,” says Castillo, now 86 years old. “He played right there under the tree.”

1953年からハレクラニのハウスキーピングを勤めたリチャー ド・カスティーヨさんは、「以前、客室の掃除は男性の仕事でした」と言 う。50年代の終わり頃、夜のシフトだった彼はホテルで演奏するミュー ジシャンたちの側で仕事をしていた。マリンバや木琴、野鳥の歌声とい った熱帯のジャングルを思わせるアップビートな音楽で群衆を魅了し た伝説のエキゾチカミュージシャンのアーサー・ライマンさんもその一 人であった。カスティーヨさんは、ライマンさんの楽器の片付けを手伝 っていた。「彼はとても人気のあるアーティストでした。あの木のすぐ下 で演奏していました」と当時を思い出して語るのは、今年で86歳のカス ティーヨさん。

ハレクラニ沖縄 Living

The kiawe remains an iconic element of Halekulani’s proud tradition of Hawaiian music, hula, and cocktails—best taken in at the sunset hour, when all is gilded in gold. Famed hula dancer Kanoe Miller feels sweetly sentimental about the tree, having danced under its majestic boughs for nearly 40 years. “It frames the entertainment, the music, dancing. You have Diamond Head and the sunset, the ocean, so that entire picture is in everyone’s head,” Miller says. “The tree created that feeling, that beautiful feeling.”

ハレクラニの歴史とともに歩み、ハワイアン音楽やフラやカクテ ルといった伝統のシンボルであり続けるキアヴェの木。沈みゆく太陽が あたり一面を金色に染める夕暮れ時にはことさら美しい。有名なフラ ダンサーで、40年にわたってこの雄大な木の下でフラを踊っているカノ エ・ミラーさんは、この木に特別な思いを抱いている。「この木はいつの 時代もこの場所に立ち、海辺の音楽やダンスを美しく縁取ってくれまし た。背景にダイアモンドヘッドと夕日、海の広がるこの美しい景色は、誰 もの記憶に残っています。このキアヴェの大樹には、人々を魅了させる 優美さがありました」

When La Mer bartender Henry Kawaiea thinks of the kiawe tree, he invariably thinks of music. For more than three decades, Kawaiea has enjoyed the unique vantage point of his second-story post in the hotel’s historic main building. From it, sweeping views of a moonlit Diamond Head unfold at eye level, and the kiawe’s interior canopy softly glows from the string of lights surrounding the stage. “I’m lucky,” Kawaiea says. “I’ve been able to listen to so many entertainers over the years.” Each evening, the silky notes of Hawaiian music—performed by the likes of the Kahauanu Lake Trio in yesteryear, and Pu‘uhonua Trio today—waft up through the branches, reaching Kawaiea before rising up to the mosaic of stars overhead.

ラ メールのバーテンダーのヘンリー・カヴァイエアさんがキアヴェの 木に想いを馳せる時、真っ先に頭に浮かぶのは音楽だという。カヴァ イエアさんは歴史薫るホテルの本館2階から見えるその特別な景色 を30年以上にわたって楽しんできた。月光に照らされて光るダイアモ ンドヘッドとステージ照明によって内側から柔らかな光りを放つキア ヴェの木の創り出す幻想的な景色だ。「私は幸せ者です。何年もの間、 ここで多くのアーティストの音楽を聴くことができたのですから」とカ ヴァイエアさん。かつてのカハウアヌ・レイク・トリオや、現在のプウホヌ ア・トリオのようなアーティストが毎晩奏でる美しいハワイアン音楽の 音色は、今もカヴァイエアさんのいる本館を抜けて、モザイクのような 満天の星空へと届いている。

Over three days in August, fine-art photographer Wayne Levin photographed Halekulani’s kiawe tree using large-format film. “The fact that [film] slows you down is both a liability and a benefit, it really depends on what you’re photographing,” he says. “For the tree, film was perfect, because it wasn’t something with a lot of motion. It was something that was really static, and it was better to contemplate each picture.” With his work, Levin says, “I hope that I can reach people and make them see things in a little different way, question their sense of what’s real and what’s not.”

この8月、芸術写真家のウェイン・レヴィンさんは3日間にわたり、ハレ クラニのキアヴェの木を大判のフィルムで撮影していた。「フィルム写 真はシャッタースピードが遅いことから、被写体によっては向き不向き があります。この木を撮るのにフィルムは理想的でした。動かずずっと そこにある木は、時間をかけて一枚一枚丁寧に思考プロセスを重ねて 撮影するほうがいいからです」というレヴィンさん。「現実という概念を 疑うような少し異なる視点を持った、心に響く写真を撮りたいと常に 思っています」

TEXT

‘ONO OKINAWA

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK 沖縄のグルメ

BY EUNICA ESCALANTE

沖縄料理が楽しめるハワイのレストランを探訪

Explore the eateries that bring ‘ono (delicious) Okinawan fare to Hawai‘i.

Thick slabs of pork belly marinated in black sugar and soy sauce; delicate cubes of tofu stir-fried into the sharp taste of bitter melon; a broth of fresh mushrooms and thin, tender strips of pork stomach— dishes such as these have been enjoyed in Okinawa for hundreds of years. The fare has bold flavors cultivated from centuries of cross-cultural influence from China and Southeast Asia and has been considered the cause of Okinawans’ longer-than-average lifespans. Yet it is often overshadowed by more familiar Japanese cuisine.

Though Okinawa has been a part of Japan since 1879, the country’s cuisine is distinct from that of mainland Japan. In fact, it more closely resembles Chinese cooking, a result of the islands’ cultural and political connections to China prior to its Japanese annexation. The result is a menu with a heavy emphasis on pork, considered the essence of Okinawan food. Its geographic location also lends a lush subtropical climate where a range of vegetables thrive.

Okinawans immigrated to Hawai‘i at the turn of the 20th century. While restaurants specializing in Okinawan cuisine are still few and far between, the fare of these O‘ahu eateries will satisfy any visitor craving a taste of Okinawa.

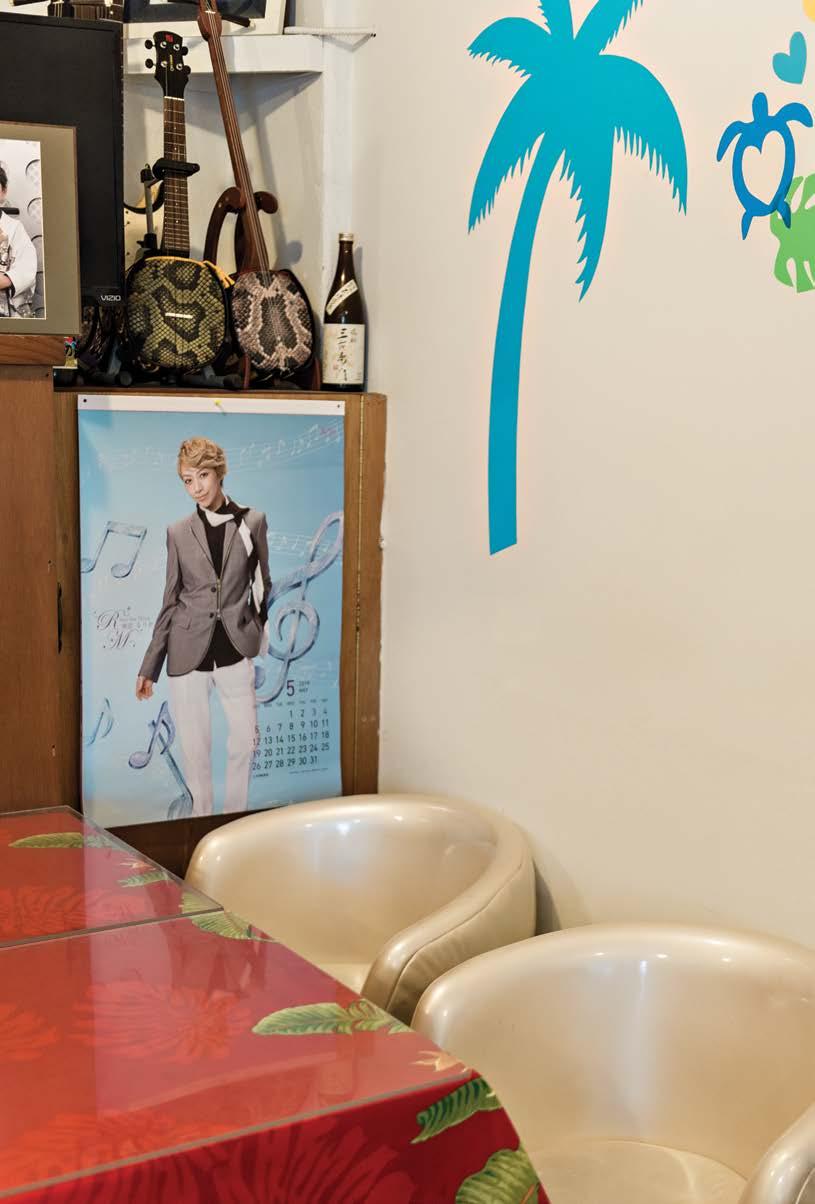

sunrise restaurant

The simple exterior of Sunrise Restaurant looks unassuming among the glowing neon lights that dot Kapahulu Avenue. Situated around the corner from Hawai‘i icons like Rainbow Drive-In and Leonard’s Bakery, it is easy to miss. But owner and chef Chokatsu Tamayose is not interested in drawing in long lines of hungry tourists. His clientele is smaller, more exclusive.

豚バラ肉を黒糖と醤油でとろとろに煮込んだラフテー。苦瓜と豆 腐を炒めたゴーヤチャンプルー。豚モツと椎茸を出汁で煮た中味 汁。どれも伝統的な沖縄の郷土料理だ。長年にわたる中国や東南 アジアといった異文化からの影響によって培われた沖縄料理は、 沖縄の人々の長寿の秘訣とも言われるが、日本料理と比べてあま り知られていない。

1879年に日本に併合された沖縄の料理は、豚肉を中心と したメニューが多く、本土の日本料理とは異なる。併合以前、中国 大陸と文化的や政治的な結びつきの強かった沖縄の食文化は中 国色が濃く、ゆえに豚肉は沖縄料理には欠かせないものとなって いる。地理的にも南にあり、亜熱帯気候の沖縄では、栄養価の高 い野菜が栽培しやすい点も特徴だ。

20世紀初頭、多くの沖縄の人々がハワイへ移住した。オア フ島の沖縄料理レストランは数少ないが、異国情緒を味わえる本 格的な沖縄料理に出会えることだろう。

サンライズ・レストラン

飾り気のない外観のサンライズ・レストランは、派手なネオン看板を掲 げたカパフル通りのレストランに比べると控えめな存在である。レイン ボー・ドライブインやレナーズベーカリーのようなハワイの有名店のす ぐそばにありながら見逃しがちだ。お腹をすかせた観光客が行列を作 る店ではなく、少人数の客に居心地の良い店でゆっくり食事を楽しん でもらいたいというのが、オーナーシェフのチョカツ・タマヨセさんの モットーだ。

中へ入ると、意外にも家庭的な印象に驚かされる。親戚の家の夕 食に呼ばれたような気分にすらなる。店内には、壁に家族の写真や思い

沖縄料理店

食

ホノルルのサンライズ・レ

ストランでは、気取らない

雰囲気の中で家庭的な沖 縄料理を楽しめる。

Sunrise Restaurant serves up home-style Okinawan dishes in a down-to-earth setting in Honolulu.

Stepping inside, I’m struck by how homey the restaurant feels. The atmosphere gives the impression of visiting a relative’s house for dinner. Family pictures and personal memorabilia decorate the walls. Okinawan folk music plays over the speakers. As I pore over the menu, I am engulfed by conversations in Japanese, and I realize that I am the only non-Japanese speaker in the place.

Sunrise was opened in 1999 by Chokatsu and his aunt Kiyo Irei. Today, he runs the restaurant with his wife, Tomoko Tamayose. They serve a pared-down menu of Okinawan dishes similar to those Chokatsu grew up eating. The oxtail soup is lovingly prepared, resulting in tender meat that falls off the bone. Its Okinawan soba, unlike Japanese soba, is made with thick wheat flour noodles that resemble udon and has 出の品が飾られ、沖縄の民俗音楽が流れている。メニューを見ていると 日本語の会話が耳に入ってくる。周りを見回すと外国人客は私だけだ。

1999年にチョカツさんと叔母のキヨ・イレイさんがオープンした サンライズ・レストランは現在、チョカツさんと妻のともこさんが切り盛 りしている。チョカツさんが子供の頃食べて育ったシンプルな沖縄家庭 料理のメニューを提供している。オックステールスープは、肉が骨から落 ちるほど柔らかくなるまで長時間かけて煮込んだ愛情たっぷりの看板 メニューだ。沖縄そばは、そば粉で作るそばとは違い、うどんに似た太 い麺で、ラーメンのような色の薄いスープに、ネギとラフテーの薄切りを トッピングしたシンプルなものだ。

チョカツさんが握る寿司は、どのプレートにも追加して注文でき る。ぶ厚い切り身が並ぶ寿司カウンターで、その日獲れたての魚を慣

ハレクラニ沖縄 Living

沖縄料理には様々な方法

で調理された豚肉がよく 使われる。

Okinawan dishes frequently include pork, cooked and served in a variety of ways.

a light broth garnished simply with green onions and a slice of rafute, or shoyu pork.

Each plate has the option of a side of sushi, which Chokatsu rolls by hand. Thick slabs of the day’s catch line his sushi station, and guests who choose to sit at the bar can watch the chef prepare each piece by hand. Chokatsu makes a limited amount of each dish every day, but there is no need to worry. If one’s first choice runs out, Tomoko has a lineup of other dishes to suggest.

izakaya naru

Izakaya Naru is one of those special eateries you stumble upon while exploring the city, a well-kept secret where a worldly patron brings friends to toast awamori, Okinawa’s version of shochu, and share

れた手つきで捌き、目の前で寿司を握ってくれる。チョカツさんが毎日 手作りする料理は、どれも数が限られているが、希望のメニューが売り 切れたとしても、ともこさんが他のおすすめ料理を作ってくれるので心 配無用だ。

宴レストラン&ラウンジ

店に着くと、店内は多くの常連客や私のような初めての客で賑わってい る。この店を勧めてくれた友人が、平日のランチ時間帯は決まってこう だ、と教えてくれる。

「宴=集う場所」という名前がぴったりの店だ。2001年にオー ナーのジョセリン・コシモトさんがカリヒの中心部にオープンした宴レ

ハレクラニ沖縄

親しみやすい雰囲気と沖縄料理の人気メニューで、常連客が絶え 間なく訪れる居酒屋 成ル。

Izakaya Naru’s convivial intimacy and popular Okinawan-themed menu keep a steady stream of regulars coming through its doors.

platters of grilled beef tongue well into the night. It is a place that leaves guests sated and with maybe too much Orion, the unofficial beer of Okinawa, in the belly.

In the past decade, izakayas have popped up across Honolulu. These restaurants gained popularity in Japan as a casual place to grab drinks and chat over tapas-style dishes after work. Part of a restaurant chain with nine locations across Japan, Izakaya Naru has a rustic aesthetic with an all-wood interior, polished wooden tables, and low stools covered in traditional Japanese-print cloth.

When I arrive, the folk music can hardly be heard over the hum of conversation. The place is intimate, holding no more than 30 guests, which means it often requires reservations. But the experience and fare are certainly worth the wait.

I order one of its specialties, taco rice, which is another example of foreign influence on Okinawan cuisine. With the establishment of American military bases in Okinawa after World War II came an introduction of Western dishes. Soon, the popular American take on tacos featuring heavily seasoned ground meat was adapted by local chefs. At Izakaya Naru, spiced ground meat, raw egg, and taco fixings of shredded cabbage, onions, tomatoes, and cheese are mixed with rice and served sizzling in a stone bowl. Rounding out my meal is a helping of awamori, a distilled, rice-based liquor. Izakaya Naru’s awamori is made in-house in several flavors and can be ordered in flights, a must for first-timers.

utage restaurant and lounge

When I arrive, Utage Restaurant and Lounge is packed, as it often is during the weekday lunch hour. The restaurant is filled with regulars as well as newcomers who, like me, have been ushered in by friends’ recommendations.

「豚に始まり、豚に終わる」と言われるほど、豚肉が食生活の中 心にある沖縄。宴でも多くの豚を使ったメニューを味わえる。豚ばら肉 の厚切りを黒糖と醤油でゆっくり煮込んだ看板メニューのラフテーは、 白米にのせたり炒め物に混ぜる。玉ねぎと砂糖でシンプルな味に煮込 んだ豚モツ薄切りは、炒め料理にしたり、こんにゃくや椎茸とその戻し 汁で煮たスープに入れて食べる。そして沖縄料理を語る上で欠かせな いのが豚足だ。宴では、大根と昆布とからし菜にたっぷりの豚足が入っ たスープを味わえる。

居酒屋成ル

ワイキキからほど近いエリアにある隠れ家的な居酒屋成ルでは、沖縄 焼酎の泡盛、牛タンの塩焼きなど、沖縄を中心とする美味しい居酒屋 料理と沖縄のオリオンビールを深夜まで味わえる。店内は、友人との 楽しい談話や美味しい酒と肴を楽しむ国際色豊かな客層で賑わって いる。

この10年、ホノルルには多くの居酒屋がオープンしている。居酒 屋成ルは、日本国内に9か所の店舗を展開する居酒屋チェーンが海外 にオープンした店だ。店内は、木目のインテリアに磨き上げられた木製 のテーブル、和風のカウンター椅子が置かれた素朴な印象だ。

店に着くと、BGMに流れる歌謡曲が聞こえないくらい会話が賑 やかに行き交っている。こじんまりとした店内には30人も入れば満席 なので、予約をしていない場合には待つ覚悟が必要だが、その価値は 十分にある。

Utage is Japanese for “gathering place.” One of the more popular Okinawan restaurants in Honolulu, it has lived up to its name. Located in the heart of Kalihi, Utage has served Okinawan fare since it was opened by owner Jocelyn Koshimoto in 2001. Pork is the preferred protein in Okinawa. “Every meal begins with pork and ends with pork,” an Okinawan proverb states. In Okinawan fashion, visitors to Utage can choose from a variety of pork-based ストラン&ラウンジは、ホノルルで最も人気のある沖縄レストランの一 つだ。

私は人気メニューの一つであるタコライスを注文した。タコライ スもまた、外国の食文化の影響を取り入れてきた沖縄料理ならではの メニューのひとつだ。第二次世界大戦後、米軍基地が建設された沖縄 では、西洋料理が食べられるようになり、アメリカ人の間で人気のあった 味の濃いひき肉を使ったタコスを地元のシェフたちが作るようになっ

ハワイのオアフ島には、伝統 的な沖縄料理を楽しめる飲 食店が何軒かある。

Several eateries cater to those looking for traditional Okinawan cuisine on the Hawaiian island of O‘ahu.

meals. There is the rafute, or shoyu pork, for which the restaurant is best known. The thick cuts of pork belly are slow-cooked in black sugar and soy sauce before being served on a bed of white rice or in a stirfry. For those wanting lesser-known dishes, there is nakami, thin slices of pig stomach cooked simply with onion and sugar, served in stir-fry or a broth of mushrooms with konyaku, a chewy, gelatinous garnish made from konjac potatoes. Of course, no Okinawan menu would be complete without the signature pig’s feet dish. At Utage, a generous portion of pig’s feet is served in a soup of daikon (winter radish), konbu (kelp), and mustard cabbage.

た。居酒屋成ルのタコライスは、熱々の石焼鍋に入ったご飯に、スパイス の効いたひき肉、生卵、細切りキャベツ、玉ねぎ、トマト、チーズといった タコスのトッピングを混ぜ合わせて食べる。どの料理にも沖縄名物の 泡盛が合う。居酒屋成ルでは、自社製の泡盛も扱っている。初めての人 は、何種類かをテイスティングできるフライトを注文して飲み比べるの もおすすめだ。

文

影響力のある球体

SPHERES OF INFLUENCE

TEXT BY LISA YAMADA-SON

TRANSLATION BY MUTSUMI MATSUNOBU

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

A bioremediation technology from Okinawa offers an answer to Hawai‘i’s polluted waterways. 汚染されたハワイの水路に解決策をもたらす 沖縄発のバイオ修復技術

Tom Honan was walking along the Ala Wai Canal, a two-mile-long waterway near Hawai‘i’s famed Waikīkī Beach, when he saw a large group hurling strange, spherical objects into its murky depths. “Hey, you can’t be doing that!” he recalls shouting at the crowd. Later, upon talking to one of the perpetrators, Fumiko Sato Chun, he learned they were part of a volunteer organization called Genki Ala Wai, united by an ambitious, if not audacious goal: to make the Ala Wai, one of the island’s most notoriously polluted waterways, swimmable and fishable by 2026. Their means for this noble end are what they refer to as “Genki balls,”

誰もが知るワイキキビーチの近くを流れる長さ約3.2キロメートルのア ラワイ運河沿いを歩いていたトム・ホーナンさんは、大勢の人が奇妙な 球状の物体を濁った水に投げ込んでいるのを目撃した。「おい、そんな ことしちゃダメだ!」と彼は集団に向かって叫んだという。それから、そ の中の1人、チュン·佐藤·史子さんと話をしたところ、彼らは「ゲンキア ラワイプロジェクト」というボランティア団体のメンバーであることがわ かった。そして、この団体は島でも汚染が深刻な水路の一つであるアラ ワイ運河を浄化して、2026年までには遊泳や釣りができるようにする という、無謀とはいわないまでも大胆な目標を掲げて活動しているとい

unassuming mudballs made from a mix of beneficial bacteria similar to the kind found in fermented foods like yogurt, kimchi, bread, and beer.

Today, Tom and his wife, Pam, are some of Genki Ala Wai’s most impassioned supporters. At a recent community event, I watch Tom as he demonstrates the surprisingly precise process of Genki ball creation. He starts with sifting mounds of dirt to remove debris, then mixes in rice bran and a liquid teeming with yeast, lactic acid, and phototrophic bacteria until it’s finally time to shape the mixture into tennis ball-sized spheres. I try my hand at making some. Two of my mudballs get rejected, first for being too small, then for being too big. “Quality over quantity,” Tom instructs, before accepting my third attempt. “Just right.”

Volunteers like Tom are the lifeblood of Genki Ala Wai, whose work thus far has relied solely on a homegrown network of private donations, corporate sponsorships, and the very many hands responsible for the more than 146,000 Genki balls (nearly halfway to the group’s goal of 300,000) that have since been released into the canal. This particular event was made possible by ‘Ohana Kōkua Club, a student service organization led by high school sophomore Ellie Chung, after Genki Ala Wai raised the $1,000 necessary to host a workday by selling greeting cards.

“We couldn’t do anything without our volunteers, who just jump right in and do what’s needed,” says Chun, who serves as the group’s community and media liaison. She points to Tom, who uses his walker to wheel around supplies, as evidence of the volunteers’ conviction. Laurie Levi, a retired Lions Club member who lives in Kapolei, makes the 24-mile journey by bus several times a week to help with the community events, Chun adds. Levi also regularly assists in moving supplies from the group’s storage container at Jefferson Elementary School to one of four toss sites along the canal. “We could not run an event without Laurie,” Chun says, her 3-year-old daughter clinging to her as she ferries around aluminum pans of finished mudballs.

The use of effective microorganisms, or EM for short, was first introduced to Hawai‘i in 1997 by Hiromichi Nago, who had learned about the benefit of microbes while in Okinawa under the tutelage of professor Teruo Higa, a professor at the University of the Ryūkyūs. In the early 1980s, after experiencing a bout of pesticide poisoning while researching composting techniques for mandarin oranges, Higa

う。この崇高な目的を達成するための彼らの秘密兵器が「ゲンキボー ル」と呼ばれる地味な泥団子だった。ゲンキボールは、ヨーグルトやキ ムチそしてパンやビールなどの発酵食品に含まれる善玉菌を混ぜて作 られたものだ。

いまでは、トムさんと妻のパムさんは、ゲンキアラワイプロジェク トの熱心な支援者だ。最近開催されたコミュニティイベントでは、トムさ んが驚くほど細かなゲンキボールの作成手順を実演している姿が見ら れた。彼はまず山盛りになった土をふるいにかけてゴミを取り除き、次 に米ぬかや酵母そして乳酸菌や光合成細菌がたっぷり入った液体を土 に混ぜ、最後にその混合物をテニスボールくらいの大きさの球体にまる める。筆者も挑戦してみたが、最初は小さすぎ、次は大きすぎという理 由で、2個の泥団子が不合格となった。3度目の挑戦の前に「量より質が 大事だよ」とトムさんがアドバイスしてくれたおかげで、ようやく「今度は ちょうどいいね」と合格となった。

トムさんのようなボランティアは、ゲンキアラワイプロジェクトの 原動力だ。同団体のこれまでの活動は、民間の寄付や企業スポンサー、 そしてこれまで14万6千個以上のゲンキボール(団体の目標である30 万個のほぼ半分)を運河に放流してきた非常に多くの人々の支援に支 えられてきたのだ。この日のイベントが実現できたのは、高校2年生のエ リー·チャンさんが率いる学生奉仕団体「オハナ·コクア·クラブ」が、ゲン キアラワイプロジェクトのグリーティングカードを販売して千ドルの寄 付金を集められたからだ。

「ボランティアの力がなければ、私たちは何もできなかったでし ょう。みんなが進んで必要なことをしてくれているおかげです」と、同団 体においてコミュニティおよびメディアとの連絡係を務めるチュンさん は語る。歩行器を使って物資を運んでいるトムさんの姿は、まさにボラ ンティアの熱意を表している。そして、カポレイ在住で元ライオンズクラ ブ会員のローリー・レヴィさんは週に数回、同団体のコミュニティイベン トを手伝うため、約39キロメートルの道のりをバスに乗ってやってくる のだとチュンさんは付け加える。レヴィさんは、ジェファーソン小学校に ある同団体の保管用コンテナから、運河沿いにある4か所の投入場所 へ物資を移動させる作業も、定期的に手伝っている。「ローリーさんな しではイベントを開催できませんでした」と、チュンさんは3歳の娘を抱 き抱えながら、完成した泥団子の入ったアルミの鍋を運んでいた。

有用微生物群(略してEM)は、1997年に名護弘道さんによって 初めてハワイに持ち込まれた。名護さんは琉球大学の比嘉照夫教授の 指導のもと、沖縄で微生物の効用について学んでいた。1980年代初

この泥団子は日本では「EM 団子」と呼ばれている。

In Japan, the mudballs are called “EM dango.”

turned his attention to microbes, stumbling upon their beneficial properties by accident. Figuring it a waste to discard the microbe solution down the drain, he poured it over a patch of grass. One week later, he discovered the grass with the microbes had grown significantly better than the grass around it. Tantalized, Higa went on to create EM•1, a trademarked mix of microorganisms that have proved beneficial in a variety of applications, from household cleaner to odor eliminator to landscape fertilizer.

In 2006, heavy rains over Honolulu caused a large wastewater pipe to burst, prompting the city to divert 48 million gallons of raw sewage into the Ala Wai Canal. Nago had a thought: He could put the balls to work at home in Hawai‘i. Although the canal’s developers originally imagined Waikīkī as a “Venice of the Pacific,” the Ala Wai Canal has served as a de-facto waste dump from its inception in 1927, first to drain the wetlands that once made up the area and make way for the infrastructure to support Waikīkī as a burgeoning tourism center; then, to divert dirty rainwater from the golden-hued shores of Waikīkī Beach.

頭、ミカンの堆肥化技術の研究中に農薬中毒を経験した比嘉教授は、 微生物に注目し、その有益な性質を偶然発見する。有用微生物溶液 を排水溝に流すのはもったいないと思った比嘉教授は、その液体を芝 生に撒いた。1週間後、教授は微生物を撒いた芝生が周囲の芝生より もかなりよく育っていることに気づく。この発見に触発された比嘉教授 は、家庭用洗剤から消臭剤そして庭園用肥料まで、さまざまな用途に 効果があることが証明された有用微生物群の混合物であるEM•1を 開発したのだ。

2006年、ホノルルを襲った大雨により大規模の下水管が破損 し、市は1億8,170万リットルもの下水をアラワイ運河に流すことを余 儀なくされる。名護さんは、この泥団子が自分の故郷ハワイで力を発揮 できるのではと考えた。もともと運河の開発業者は、ワイキキを「太平 洋のベニス」にすることを目標としていた。しかし1927年の建設当初か ら、アラワイ運河は事実上の廃棄物投棄場として利用されてきたのだ。 最初は、観光の中心地として急成長するワイキキを支えるインフラ整備 のため、かつて湿地帯であったこの地域の排水を行った。さらに、金色

But despite the going science suggesting the efficacy of using microbes to improve water quality in urban waterways, approval to use Genki balls in the Ala Wai would take 13 years, delayed by a permitting process and the federal Clean Water Act that prohibits the release of unpermitted materials into a waterway. Finally, in 2019, permission to deploy the Genki balls was granted.

Before the group’s inaugural toss, officials from the Hawai‘i State Department of Health squelched out into the canal to take baseline water-quality readings and quickly found themselves mired in murky sludge

に輝くワイキキビーチの海岸に汚れた雨水が流れ込まないように、運河 を利用して迂回させる対策がとられた。

しかし、都市部にある水路の水質改善に微生物を利用すること の有効性が最新の科学研究で示唆されているにもかかわらず、アラワ イ運河でのゲンキボールの使用認可には13年の月日を要する。それ は、許可手続きに時間がかかったり、連邦水質浄化法により無許可の 物質を水路へ投入することが禁止されていたりしたことによるものだ った。ようやくゲンキボールの使用許可が下りたのは、2019年のこと だった。

nearly two feet deep in some spots—the result of decades of runoff pollution and intentional dumping. The pervasiveness of the muck was rivaled only by its odor, a sulfuric stench of rotten eggs that had long beleaguered nearby residents and businesses. The tests further confirmed the high levels of fecal contamination that prompted the city to post signs from as early as the 1970s warning local residents against eating anything from the canal.

The cost of testing remains one of Genki Ala Wai’s biggest obstacles, according to Kouri Nago, Hiromichi’s son, who joined the group’s effort. Federal funds that had been promised to Genki Ala Wai—which was chartered as a nonprofit under the Hawai‘i Exemplary State Foundation, itself tasked with creating a systems-based approach to care for the entire watershed from mountain to ocean—dried up during the pandemic, as did the city’s offer to regularly test water-quality levels. Still, the group remains determined to make the Ala Wai “genki” (meaning “healthy” or “energetic” in Japanese). They are spurred on by ongoing, visible improvements: sandy, rocky bottom where there once was only tarry black sludge; the absence of any fetid stench; the decrease in enterococci bacteria from fecal contamination; the welcomed return of native species, such as weke (a type of goatfish), moi (Pacific threadfin), and Hawaiian monk seals, to parts of the canal once devoid of life. “I know the significance that EM could have here,” says Kouri, who notes that Genki balls have also now been deployed at polluted waterways in the neighborhoods of Salt Lake and Kalihi on O‘ahu, and in the sprawling koi ponds at Hawai‘i Island’s Lili‘uokalani Gardens, said to be the largest Edo-style garden outside of Japan. “I see a vision that this place could be a model for the rest of the world.”

The mudballs, for their part, do much of the heavy lifting once they’re thrown in, dissolving like time-release capsules on the canal floor over the course of a year. “That’s why we love them. They don’t complain, they don’t take vacation,” Chun says, picking up a ball and bowing her head in gratitude. “Now you go and do your good work.”

同団体の記念すべき第1回目のゲンキボール投入にさきがけ、ハ ワイ州保健局の職員が水質基準値を測定するためアラワイ運河に入る と、場所によっては深さ約60センチメートル近くのヘドロに足を取られ てしまった。これが、何十年にもわたる汚れた雨水の流入や意図的に行 われた廃棄物の投棄による汚染の結果だ。汚泥の広がりだけではなく、 腐った卵のような硫黄臭も長い間近隣の住民や企業の悩みの種となっ ていた。ホノルル市では1970年代初頭には、検査によって高濃度の糞 便汚染が確認されたため「運河から採取したものを食べないように」と 地元住民に警告する標識を設置していたのだ。

同団体の活動に参加している弘道さんの息子の洸利さんによる と、水質検査にかかる費用は依然としてゲンキアラワイプロジェクトの 最大の課題の一つだという。ゲンキアラワイプロジェクトは、ハワイ州模 範財団のもと非営利団体として認可され、山から海までの流域全体の 水源保護を目的とする組織基盤のアプローチを構築する任務を担って いるが、連邦政府から約束されていた資金はパンデミック中に枯渇し、 市が定期的に行っていた水質レベルの検査も中止となった。それでも、 同団体はアラワイ運河を「元気」にするという目標に向け、意欲的に活 動している。水質改善が目に見えるようになってくると、彼らの活動にも 拍車がかかる。かつてはタールのような黒いヘドロで覆われていた運河 の水底が、いまでは砂地や岩場になり、悪臭も消えた。糞便汚染による 腸球菌の濃度も低下し、生物の影もなかった運河の一部には、ウェケ (ヒメジの一種)、モイ(ナンヨウアゴナシ)、ハワイアンモンクアザラシ などの在来種も戻ってきた。「ハワイにおけるEM技術が、ここハワイで 果たす意義の大きさを実感しています」と洸利さんは話す。いまでは、ゲ ンキボールはオアフ島のソルトレイクやカリヒ周辺の汚染された水路、 日本国外最大の江戸式庭園といわれているハワイ島のリリウオカラニ 庭園の広大な鯉の池にも導入されているという。「ここが世界の規範と なる場所になる日がきっとくると信じています」

運河に投入された泥団子は、1年かけてゆっくりと運河の底で溶 け出し、徐々にその効果を発揮する。「だからこそ、私たちはゲンキボー ルが大好きなのです。文句も言わないし、彼らには休みも不要です」と 言うと、チュンさんは泥団子を手に取り、感謝を込めて頭を下げた。そし て「さあ、あなたもがんばってね」と優しく送り出した。

PATTERN RECOGNITION

TEXT

BY

TIMOTHY A. SCHULER

IMAGES BY GERARD ELMORE, JOHN HOOK, AND DARWIN LINGCO パターン認識

どこにでもあるような目立たないコンクリートブロ ックが、太平洋を挟んで対峙する2つの島々の風土 や歴史を静かに物語る

Invisible in their omnipresence, these humble concrete blocks speak volumes about the indelible forces that have shaped two island communities on opposite sides of the Pacific.

Ten years ago, when I first began exploring the neighborhoods around my wife’s and my apartment in Hawai‘i’s seaside neighborhood of Waikīkī, I kept noticing the same architectural detail over and over: small, hollow concrete blocks, typically with some sort of shape or pattern in the middle, like a three-dimensional version of the snowflakes children cut out of paper. Entire walls were made of them, and the repetition of dozens, even hundreds, of blocks stacked on top of one another created an even larger, more intricate pattern. The effect was an architecture that felt both solid and porous, sturdy and fragile. I was mesmerized.

I snapped a photo and posted it on Instagram, wondering if there was a technical term for these blocks. It was local curator and community developer Wei Fang who eventually supplied the answer. She wrote one word: #breezeblocks.

Breezeblocks are common to many parts of the world. In Brazil, they are known as cobogós. In Australia, they’re sometimes referred to as Besser blocks, for a prominent manufacturer. In Okinawa, residents often call them hana blocks, or “flower blocks.” Popularized by Nakagusuku-born architect Hisao Nakaza, who took inspiration from hanaui, traditional Ryūkyūan textiles, hana blocks are closely associated with Okinawa’s post-war reconstruction period and are still ubiquitous throughout the prefecture.

10年前、妻と私はハワイのワイキキにあったアパートに住んでい た。そして、アパートの周辺を散策しているときに、ある建築要素 が随所に使われていることに気付いた。それは小さくて中が空洞 のコンクリートブロック。まるで子どもが切り紙細工で作った雪 の結晶の立体版のようなパターンが中央にあしらわれていた。一 つの壁に何十、何百ものブロックが積み重ねられ、さらに大きく 複雑な模様を生み出している。どっしりとした安定感がありつつ も、どこか儚い得も言われぬ魅力が醸し出されている。私は、そ の独特の建築美にすっかり魅了されてしまった。

これはなんと呼ばれるものなのだろう? 写真を撮って、イ ンスタグラムに投稿してみた。答えを教えてくれたのはウェイ・ファ ンさんだった。「#ブリーズブロック」。彼女は一言こう答えた。

ブリーズブロックは世界各地で見られ、ブラジルではコボゴ と呼ばれている。オーストラリアでは、大手メーカーの社名にちな んでベッサー・ブロックと呼ばれることもある。そして、沖縄では 「花ブロック」として親しまれている。中城村出身の建築家である 仲座久雄さんが、琉球の伝統織物「花織(はなうい)」に着想を得 て普及させた花ブロックは、沖縄の戦後復興の象徴としても知ら れ、今でも県内の随所で見られる。

右上から時計回りに:南風原町にある沖縄看護研修センター とオキナワ・デンタルオフィス、那覇市にあるケアハウス てぃん さぐぬ花

Clockwise from top right: Okinawa Nursing Training Center and Okinawa Dental Office, both located in the town of Haebaru; Care House Tinsagunu Hana, located in Naha.

コンクリート製造技術の進歩、人件費および石材や木材などの 従来の建材の高騰もあいまって、日差しを程よく遮りつつ、風通しも よく、費用対効果にも優れている、この装飾的なコンクリートブロッ クは、香港やホノルルそして那覇などの高温多湿地域でとりわけ 人気を博した。

Enabled by advancements in concrete fabrication and rises in the costs of labor and traditional building materials like stone and wood, the decorative concrete blocks were a cost-effective way to screen buildings from excessive sun while also encouraging natural ventilation, making them particularly popular in places with hot and humid climates, like Hong Kong, Honolulu, and Naha.

花ブロックは熱質量が高い。つまり、日中に太陽熱を吸収し、夜間 に放出するという利点があるため、パームスプリングスのような砂 漠地帯にも適している。イスラム建築の格子窓「マシュラビーヤ」 のように、花ブロックは地理的な影響を受けた気候対応型建築の 一例であり、ヨーロッパのブリーズソレイユやインドのジャリのより がっしりとした現代版なのだ。

Hana blocks have the added advantage of high thermal mass, meaning they absorb the sun’s heat during the day and release it at night, making them well-suited to desert locales like Palm Springs. Like Islamic mashrabiya, they are an example of geographically influenced, climate-responsive architecture—a chunkier, more modern version of European brise-soleil or Indian jali.

1950年代から70年代にかけて、世界中で装飾的なコンクリー トブロックの塀や壁が普及した。当時ホノルルは、ちょうど準州か ら州になってすぐの建築ブームの真っ只中だった。ホノルルの建 築家、ジェイソン・セリーさんはいう。「ホノルルでは同じようなデ ザインのプランテーションタイプの家が多く建てられました。だ から、決められたモジュールにおいて、建築家がより自由に創造 性を発揮できた唯一の領域がブリーズブロックのパターンだった のです」と。

Throughout the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, the world saw a proliferation of decorative concrete block screens. In Honolulu, this coincided with the middle of a post-Statehood building boom. “There are a lot of cookie-cutter, plantation-type homes,” says Honolulu architect Jason Selley. “A home’s breezeblock pattern was the “one area where architects could flex some creativity within a standard module.”

沖縄では、推定10万戸の家屋が破壊されたという第二次世界大 戦後の数年間に、コンクリート建築が急速に広まった。そして、今 では各所で見られる花ブロックが誕生したのだ。従来の建築資材 の高騰や米軍の建設技術の導入も、この普及を後押しした。ハワ イと同様に、花ブロックは装飾的でありながら島の亜熱帯気候に 適応し、台風やシロアリといった自然の脅威にも強いという実用 性を備えたものだった。

さらに、コンクリートブロックは安価に製造できた。たった一つの 型から何千ものブロックを作れたのだ。戦後、沖縄各地に米軍基 地が設置されると、コンクリート石工会社が次々に誕生し、建築 家がカタログから選択できるように、標準化した形状やパターン のブロックを製造しはじめた。

In Okinawa, concrete construction exploded in the years after World War II, during which an estimated 100,000 homes were destroyed. Out of this architectural evolution came the now ubiquitous hana block, driven both by the rising cost of traditional building materials and the arrival of U.S. military construction technology. As in Hawai‘i, hana blocks were ornamental but also highly functional, responsive to the island’s subtropical climate and resistant to threats like typhoons and termites.

They were also cheap to produce. Thousands of blocks could be made with a single mold. Concrete masonry companies, which emerged as U.S. military bases were established throughout Okinawa after the war, began offering standard shapes and patterns that architects could select from catalogs.

花ブロックは、仲座さんをはじめ多くの建築家の遊び心をくすぐっ た。一つのブロックを裏返したり、上下を逆さまにしたりすること で、新たなパターンを作り出せたのだ。それは、建物の外観を装 飾するまったく新しい手法でありながら、子ども時代のワクワク するブロック遊びを思い起こさせるような懐かしさも感じさせて くれた。

Hana blocks invited architects like Nakaza to play. A single block could be flipped around or turned upside down to create new patterns. It was a totally new way to decorate façades, and yet there was something timeless about it, almost reminiscent of those early childhood rites of passage of making shapes and stacking blocks.

今日、花ブロックは沖縄の建築には欠かせない「沖縄らしさ」を表 象する要素の一つだが、この装飾的なコンクリートブロックが一 般に受け入れられるには時間がかかった。学者の磯部直樹さんに よると、花ブロックはもともと「異形ブロック」と呼ばれていた。戦 前の沖縄では、石積みの建物は家畜小屋や農具小屋であり、否定 的なイメージがあったのかもしれないという。磯部さんは花ブロッ クの普及と名称の変遷が「石造への拒否反応」を和らげ、その後 のコンクリート建築ルネッサンスの下地を作る役割を果たしたの ではないかと推論している。

While today flower blocks are part of the essential “Okinawaness” of the prefecture’s architectural fabric, it took time for the decorative concrete element to be accepted by the public. As the scholar Naoki Isobe has pointed out, hana blocks were originally referred to as “irregular blocks” and were perhaps negatively associated with stone construction, at the time limited to sheds and outbuildings. Isobe has theorized that flower blocks—and the evolution of their name— may have played a role in loosening the public’s “rejection of stone construction,” laying the groundwork for the concrete architectural renaissance that was to come.

建築の真髄は、その土地らしさを伝えることにある。それは、過去 の世代の人びとがどのように暮らし、何を大切にしてきたのか、 なぜそうしてきたかを示す記録なのだ。沖縄の花ブロックや世界 中の同じようなブロックに囲まれて暮らす人びとにとって、それら ブロック壁はあまりに日常的で、身近にあるので目に留まりにく い存在かもしれない。しかし、この質朴で多様なディテールには、 私たちがどのように建物を作るか、そして作るべきかは、私たち を取り巻く世界に対応し共鳴すべきだ、という思いが秘められて いる。多くのものがそうであるように、このシンプルなブロックに も、先人たちの物語や歴史、こだわりや未来への願いが込められ ているのだ。

At its best, architecture tells us where we are. It is a record of how previous generations lived, what they valued, and why. For those living among the hana blocks of Okinawa and their counterparts across the globe, they are often simply a backdrop, invisible in their omnipresence. But hidden in the many forms of this humble detail is a recognition that how we build can—and should—respond to the world around us. As with so many objects, these simple blocks hold the stories and histories, preoccupations and aspirations, of those who came before us.

PORTRAITS OF PLACE

TEXT BY LANCE HENDERSTEIN

TRANSLATION BY MUTSUMI MATSUNOBU

IMAGES BY LANCE HENDERSTEIN AND COURTESY OF MOECO YAMAZAKI

与那国の野生に満ちた精神を描き出すため、 島の自然を使って新たな表現方法に挑むアーティスト 写し出される真実

Drawing upon the island’s natural elements, an artist ventures into a new medium to conjure the wild spirit of Yonaguni.

A heavy summer rain batters my umbrella as I wait for artist Moeco Yamazaki outside the Koishikawa Botanical Garden in Tokyo’s Bunkyō ward. We’ve decided to meet here, the oldest botanical garden in Japan and one of the oldest in the world, to discuss the journey that brought her from Tokyo’s concrete maze to the pastoral countryside of Okinawa. Despite the hidden splendor of this urban oasis, it is a pale substitute for the wilderness of Yonaguni, the remote Okinawan island where Yamazaki’s artistic practice took root and that continues to act as her muse, studio, and second home.

Yamazaki arrives wearing a knitted black dress and her hair in a long braid. We head into the botanical garden, handing our tickets to the women in the entrance booth, who inform us that we have the entire 160,000 square meters of the garden to ourselves. Benefits of a typhooninduced downpour.