I Ka Pō Me Ke Ao

私たちはダンスを通して私たちのことを伝える。私たちの手がイメージを創り出す。そして、私たちが身につけるものは、私たち の島の故郷の美しさを分かち合うものです。ワイキキの集いの場、ロイヤル・ハワイアン・センターが建つヘルモアへようこそ。 無料カルチャー・レッスンに参加して、ハワイを共有しましょう。ヘ・マイ!

センター&レストランの営業時間とカルチャースケジュールは、jp.RoyalHawaiianCenter.comをご参照ください・ 年中無休・カラカウア通りとシーサイド・ワイキキ・808.922.2299

目 次

アート 16

青の中へ 28

機能性を超越した フォルム

文化 42 静かなる力 52

ある夜の ディアスポラ的対話 64

動きが意味すること

ウェルネス 76

珊瑚礁の守護者たち

新しい何かを探して 90

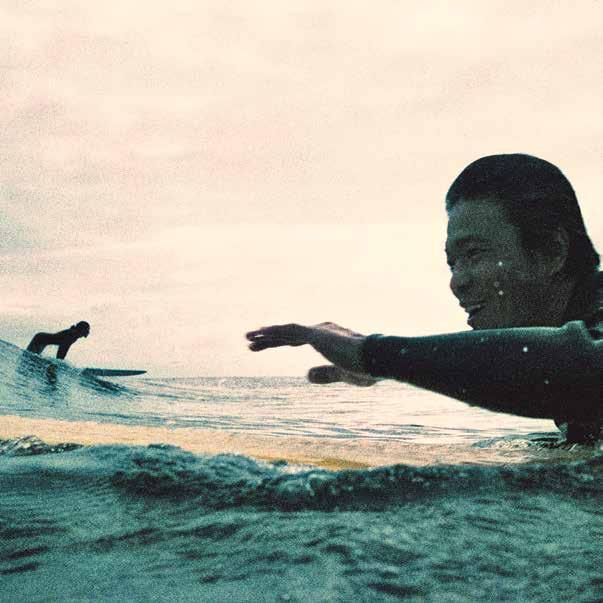

波のある⾵景

102

アナログの島

写真家の千田拓真がとらえた

サーフセッション前の ボードシェイパー中村俊之。

Photographer Takuma Chida captures board shaper Toshiyuki Nakamura before a surf session.

表紙について

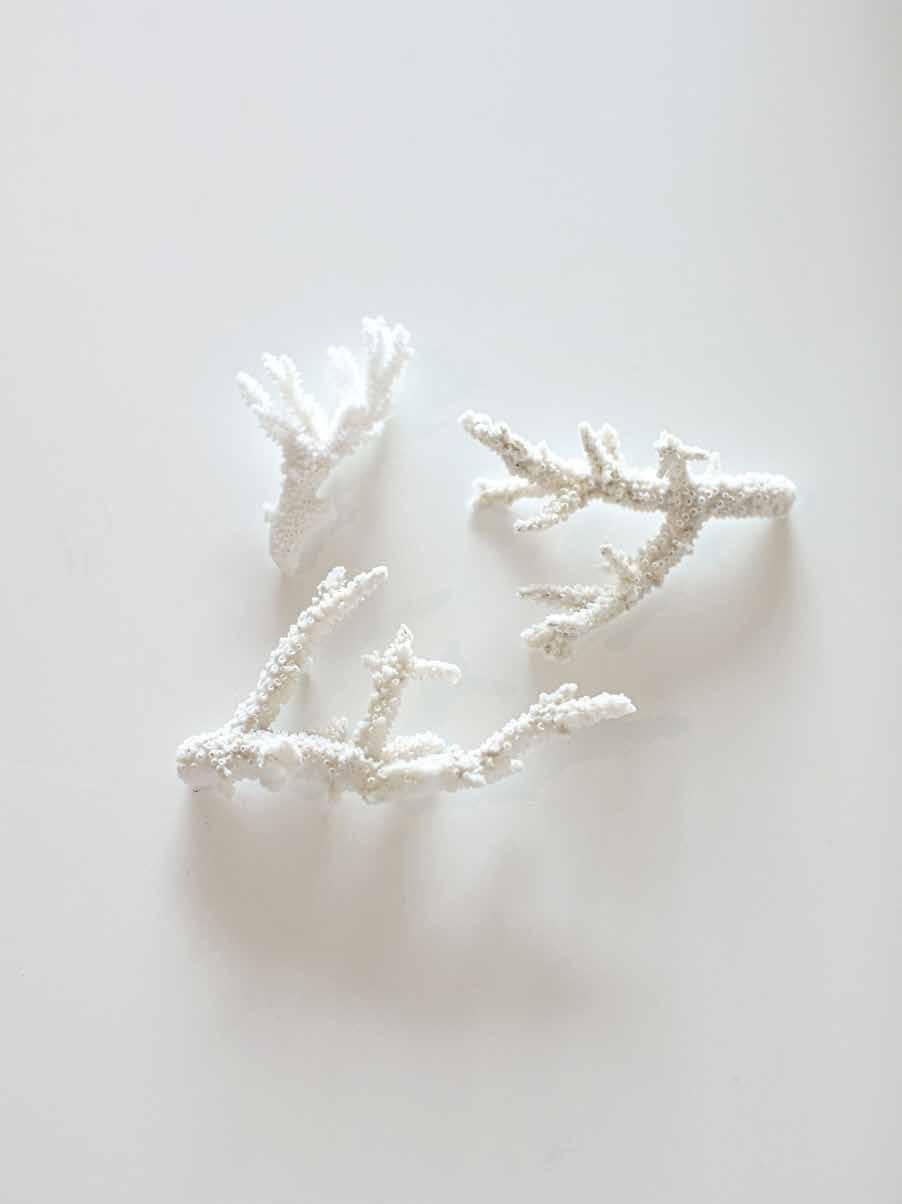

サキシマスオウノキの⾼い隆起根を描写した写真家キャローラ・メッチの青写真。

ハレクラニ沖縄 Living

Turn a moment of fate into a lifetime of purpose.

MIKE COOTS / Kaua‘i, HI

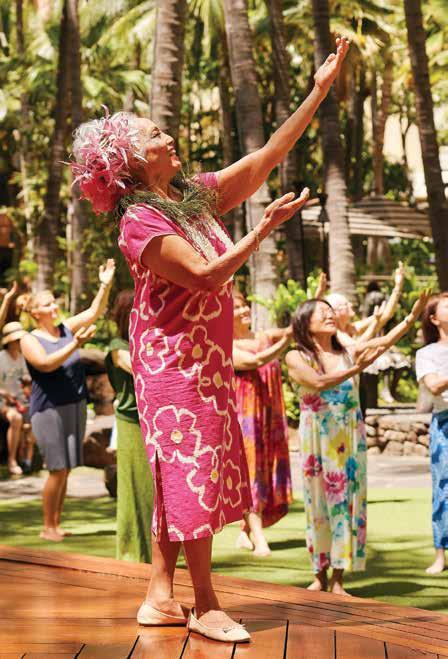

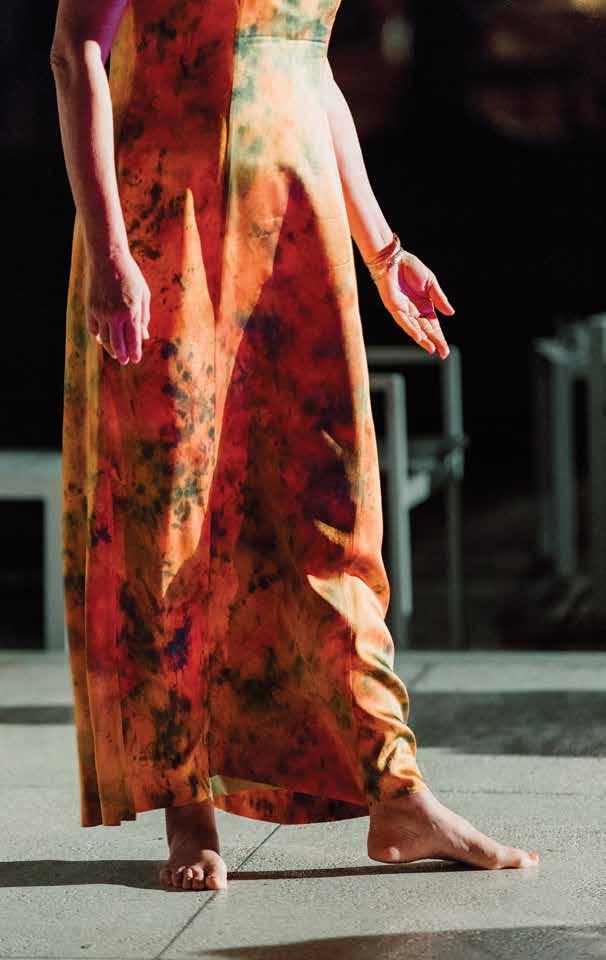

ダンサーのカノエ·ミラーは、小さく 繊細な動きこそがフラに意味を与え ていると信じている。

Dancer Kanoe Miller believes it’s the small, subtle movements that give hula its meaning.

This cyanotype by photographer Karola Mech depicts the tall buttress roots of the Sakishima-suōnoki tree.

テ レ ビ 番 組

客室内でご視聴いただけるリビン グ沖縄TVは、ハレクラニ沖縄なら ではの上質なひとときをお過ごしい ただくため、豊かで健康的なライフ スタイルをテーマにしたオリジナル 番組をお届けしています。臨場感あ ふれる映像と興味をかきたてるスト ーリーで、沖縄とハワイの芸術や 文化、⼈々の暮らしぶりをご紹介し ます。すべての番組は客室TVまたは living.okinawa.halekulani.com からご視聴いただけます。

Living Okinawa TV is produced to complement the Halekulani Okinawa experience, with videos that focus on the art of living well. Featuring cinematic imagery and compelling storytelling, Living Okinawa TV connects guests with the arts, culture, and people of Okinawa and Hawai‘i. All programs can be viewed on the guest room TV and online at living.okinawa.halekulani.com.

動きが意味すること

MEANINGINMOVEMENT

ワイキキのフラダンサーが海を越え、沖縄のハウス・ウィズ アウト・ア・キーで踊る。

A Waikīkī hula dancer crosses the Pacific to perform at House Without A Key in Okinawa.

watch online at: living.okinawa.halekulani.com

青の中へ INTOTHEBLUE

困難を乗り越え、家業を守り抜く三代目染色職⼈を紹介。

Meet a third-generation senshoku artisan who overcame obstacles to keep his family legacy alive.

静かなる力 PEACEFULPOWER

剛柔流の理念と伝説的な創始者の教えを大切にする空手 家たち。

Karate practitioners uphold the principles of Gōjū-ryū and those of its legendary founder.

美味しい沖縄 ‘ONOOKINAWA

ハワイのオアフ島で美味しい沖縄料理を楽しめるレストラ ンを探訪。

Explore the eateries that bring delicious Okinawan fare to the Hawaiian island of O‘ahu.

茶の道 THEWAYOFTEA

ハワイに移住してから茶道の世界へ飛び込み、⼈生が変わ った女性のストーリー。

Following her move to Hawai‘i, a woman journeys into the life-changing world of chado.

ハレクラニ沖縄

IMAGE

BY TAKUMA CHIDA

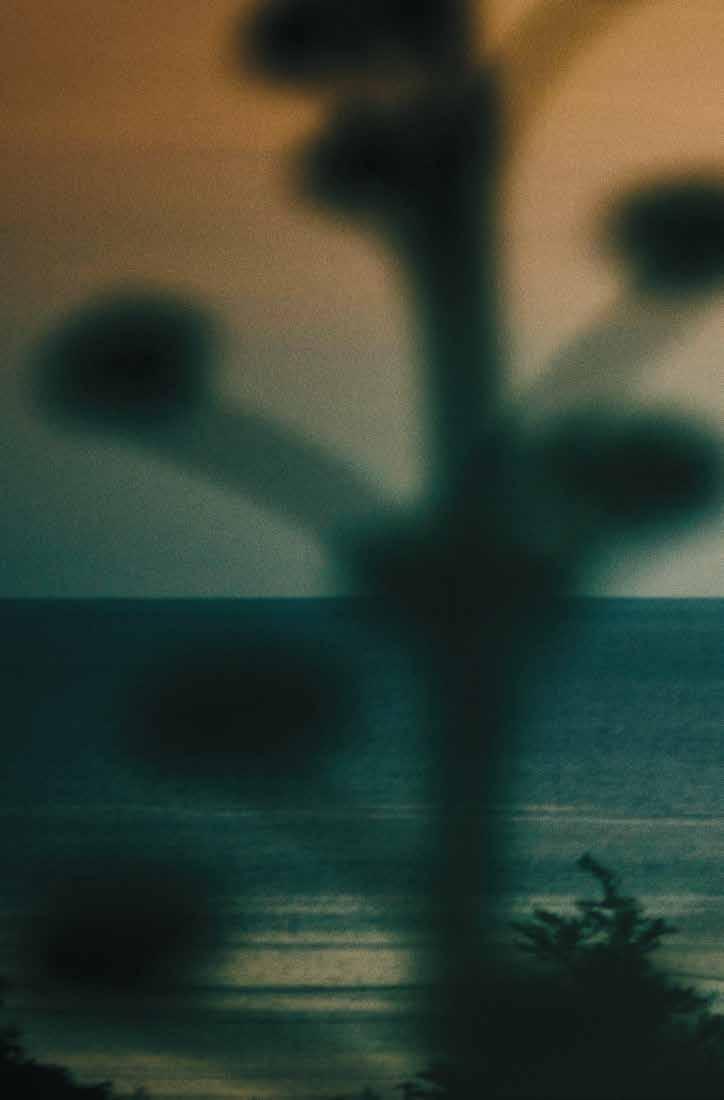

青の中へ

INTO THE BLUE

TEXT BY DARREN GORE

IMAGES BY TAKUMA CHIDA & GERARD ELMORE

TRANSLATION BY AKIKO MORI CHING

過去を敬い新しいものを生み出す 3代目染色職⼈が守る家族の伝統

A third-generation senshoku artisan upholds a family legacy of honoring the past while creating anew.

Okikazu Maeshiro is stationed at a loom in his family’s atelier in Motobu, a district overlooking the East China Sea on the western coast of Okinawa’s main island. The region’s notably humid climate is favored by the indigo plants used in Ryūkyū-ai dyeing, and Motobu, dotted with fields where these species thrive, is Okinawa’s indigo heartland.

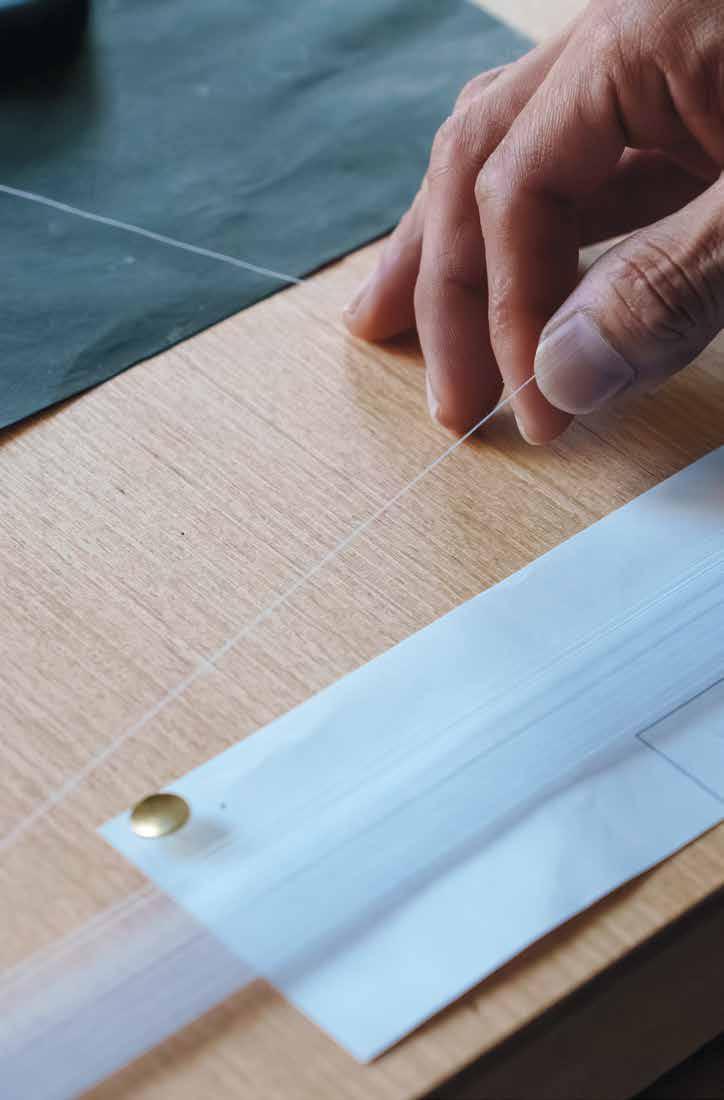

With a deft precision honed over his years of devotion to the art of kasuri weaving, Maeshiro finesses the threads that he has painstakingly colored with Ryūkyū-ai indigo through resist-dyeing, a technique that leaves adjacent sections uncolored.

沖縄本島の西海岸、東シナ海を臨む本部町にある家族のアトリ エで、真栄城興和は織機に向かっていた。とりわけ湿度が⾼いこ とで知られる本部町地区は、琉球藍染の原料となる藍の産地で ある。

真栄城は長年絣織りに打ち込み、緻密な技術を培ってきた。隣 り合う部分を着色しない防染技法によって、琉球藍で丹念に染め た繊細な糸を使って精緻に仕上げていく。その糸を手動の織機に 通すと、縞模様や幾何学的な形、自然から着想を得たモチーフな どが、布に浮かび上がってくる。それらはすべて、沖縄の青い海と 空への賛歌だ。

発酵の力により、琉球藍の

色鮮やかな青の色調が生み 出される。

Through the power of fermentation, Ryūkyū indigo produces a vibrant shade of blue dye.

Passing these threads through the manually operated loom, patterns emerge in the resulting cloth: stripes, geometric shapes, and motifs inspired by the natural world. Together they are a paean to the blue seas and skies around Okinawa.

Maeshiro’s family ties to the craft run deep— post-World War II, his paternal grandfather, Kōsei Maeshiro, was an important figure in the revival of Ryūkyū indigo dyeing and kasuri weaving, together known as senshoku. In addition to honoring traditional Ryūkyūan patterns, Maeshiro’s grandfather devised his own original designs, referring to them as “Ryūkyū bigasuri” to distinguish his creations from the kasuri weavings of others.

Yet the intricacies of the form were a mystery to Maeshiro as he was growing up. “From the moment I became aware of my surroundings, my father would be indigo dyeing while my mother was weaving,” he says. “But as a child, I wasn’t permitted to

真栄城の家族は、工芸とのつながりが深い。第二次世界大戦 後、父方の祖父である真栄城興盛は、琉球藍染と絣織り(あわせて 「染織」として知られる)を復興させた重要な⼈物だった。彼は伝 統的な琉球文様を大切にしながらも、独自のデザインを考案し、 他の絣と区別するために「琉球美絣」と名付けた。

その複雑な表現形式の工芸は、幼少期の真栄城にとっては不 思議なものだった。「周囲の環境に気づいた当初から、父は藍染め をしていて、母は機織りをしていました。しかしながら、子どもの頃 は、吊るされている糸がとても繊細なものだったため、アトリエに 入ることは許されず、家業を十分に理解することはできていません でした」と言う。

真栄城が、家族の下で追求している天職にあらためて思いを馳 せるようになったのは、家を遠く離れてからのことだった。城西国 際大学で学生時代を過ごした真栄城は、当時を思い出しながら 「大学時代は千葉の海岸で過ごしました。地元だけではなく全

真栄城興和にとっての藍染めとは、自然のリズムと調和する 作業だ。

For Okikazu Maeshiro, indigo dyeing is about working in harmony with the rhythms of nature.

琉球美絣

車椅子生活を余儀なくされた

が真栄城は家業を受け継ぐこ

とを決心していた。

Even after he became reliant on a wheelchair, Maeshiro was determined to carry on the family business.

enter the atelier due to the delicacy of the threads hanging there, so I didn’t fully understand our household’s work.”

It took travel far from home for Maeshiro’s imagination to be captured by the activity pursued under the family’s roof. “I spent my university years living on the Chiba coast,” he says, recalling his time at Josai International University, east of Tokyo. “There I became immersed in surfing both locally and all over the country, where I encountered aspects of nature, including the colors of sundown and the blue ocean. The blues of surfing and the blues of Ryūkyū-ai came to overlap in my mind.” With the encouragement of his thesis advisor—a fellow native of Okinawa—Maeshiro nurtured his growing interest in his family’s Ryūkyū bigasuri practice, and following graduation he began working in the family atelier alongside his father, Okishige Maeshiro.

国各地でサーフィンに没頭し、日没の色や青い海など、自然の表 情に出会いました。私の心の中で、サーフィンの青と琉球藍の青 が交錯し重なり合ったのです」と話す。同じ沖縄出身の卒業論文 の指導教官の勧めもあり、家業の琉球美絣への真栄城の関心は ⾼まり、卒業後は家族のアトリエで、父親の真栄城興茂と共に働 き始めた。

2011年、職⼈として独立した30歳の真栄城は、先天性の脊椎 疾患を発症し、車いすでの生活を送ることになる。染色や織物の 作業からも離れざるを得なくなったが、琉球美絣と皮革を融合さ せたブランド「BIGASURI」を立ち上げ、今まで沖縄の絣文化を 知らなかった⼈にその文化を紹介することを目指した。 しかし、染織物に戻りたいという真栄城の思いは決して色褪せ なかった。結局、6年もの長い期間の後、車いすで操作できる織機 の製作を木工職⼈に依頼することとなった。「新しい織機での作 業に慣れるにはたくさんの困難がありました。ところが、(絣の)糸

Maeshiro had established himself as an independent artisan when, in 2011, at age 30, he developed a congenital spinal disease that left him reliant upon a wheelchair for mobility. Forced to step away from dyeing and weaving work, he focused on developing a brand named “Bigasuri,” which combines Ryūkyū bigasuri and leather, with the aim of introducing Okinawa’s kasuri culture to new audiences.

But Maeshiro’s desire to get back to senshoku never waned. Eventually, after six long years, he enlisted a woodworker to build a loom that he could operate from his wheelchair. “There were other difficulties as I got myself used to working at this new loom,” he says. “But as I handled the threads [of kasuri], my determination to overcome these challenges was strengthened.”

Maeshiro marked his return to the loom with a lofty ambition. “I felt I should give myself some big new objective,” he remembers, “so I set myself the challenge of exhibiting in the art world’s number one city, New York.” Four years later, in 2021, Maeshiro put on a solo show, “Okinawa Blues,” at Tenri Gallery in Manhattan.

For the exhibition, he produced a kasuri stole that takes elements of traditional Ryūkyū kasuri and imbues them with a contemporary spirit. Titled Three Little Birds, the stole depicts an avian trio flying above stripes rendered in a gradient of indigo hues. “This bird motif, called the ‘tuigwa’ in local dialect, is a traditional Okinawan design,” Maeshiro explains. “In homage to the Bob Marley song the piece is named for, I used three of these birds. True to the Ryūkyū bigasuri created by my father and grandfather, I feel my mission is to develop patterns that are unique and also suit the times.”

While he is no longer riding the indigo waves that captivated him as a surfer, Maeshiro continues to find inspiration in surf culture and the ocean, riffing on traditional Ryūkyūan designs to conjure visuals inspired by surfboard fins and surging swell. “Though I’m presently unable to go surfing, it’s as if the hues of the ocean and sky, which change throughout the day, become my color samples as I dye threads for my kasuri,” he says. “It’s these colors that I want to express in cloth.”

を扱ううちに、その困難に立ち向かうための決意が強まっていっ たのです」と話す。

真栄城は⾼い志と共に織機のもとに戻った。「何か新しい目標 が必要でした。そこで、アートの世界でナンバーワンの都市、ニ ューヨークでの作品展示を目標にしました」。それから4年後の 2021年、マンハッタンのニューヨーク天理ギャラリーで「沖縄ブ ルース」と題した個展を開いた。

この個展のために、彼は伝統的な琉球絣の要素に現代的な解 釈を加えた絣ストールを制作した。「ThreeLittleBirds」と題 されたこのストールは、藍色のグラデーションで描かれた縞模様 の上を三羽の鳥が飛んでいる。「方言でトゥイグヮーと呼ばれるこ のモチーフは、沖縄の伝統的なデザインです。作品名の由来とな ったボブ・マーリーの曲へのオマージュとして、この3羽の鳥を使 いました。父や祖父が創り出した琉球美絣を忠実に再現しながら も、他では⾒ることのできない、時代に合った柄を開発することが 私の使命だと思っています」

サーファーとして魅了された藍色の波に乗ることはもうないもの の、真栄城は今もサーフカルチャーや海からインスピレーションを 受け続けている。そして、サーフボードのフィンやうねりといったビ ジュアルを用いて、伝統的な琉球文様に新しい息吹を吹き込む。 「今はサーフィンには行けませんが、絣の糸を染めていると、一日 を通して変化する海や空の色合いが、自分の色⾒本になっている ように思います。私が布で表現したいのは、まさにこういった色な のです」と語る。

機能性を超越したフォルム

FORMS OVER FUNCTION

TEXT BY ALEXIS CHEUNG

IMAGES BY ARCHIVES OF AMERICAN ART, BROWNGROTTA ARTS, & TOSHIKO TAKAEZU FOUNDATION

TRANSLATION BY MUTSUMI MATSUDA 文

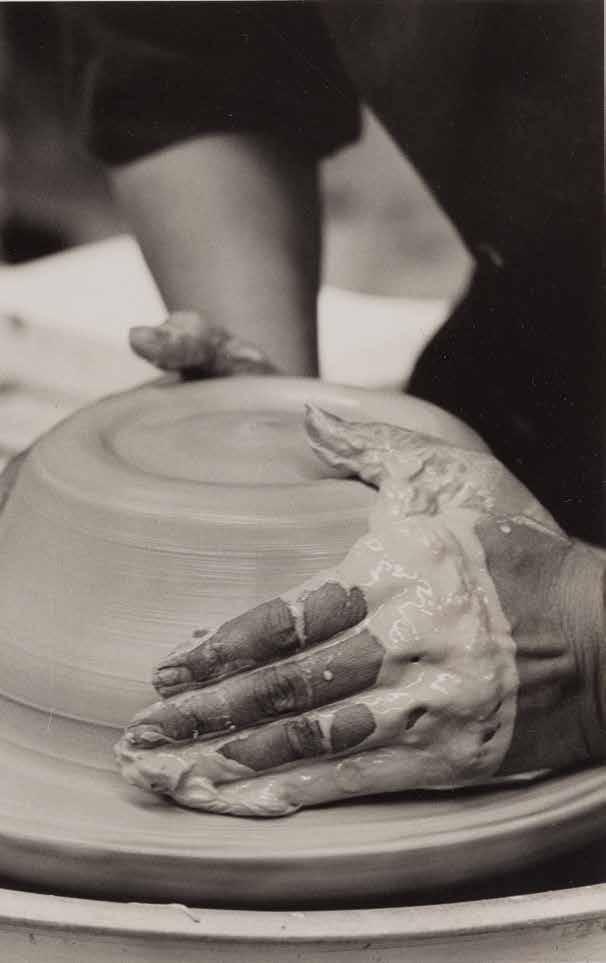

陶芸の限界に挑み、実用性重視の工芸品を 芸術作品へと進化させたトシコ・タカエズ

Pushing the boundaries of pottery, Toshiko Takaezu elevated functional craft into fine art.

It’s called Devastation Trail in Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park because lava swallowed the forest and charred the ground from green to black. In 1959, Kīlauea Iki erupted on Hawai‘i Island, and for 37 days, it spewed ash and sputtered fountains of lava, turning the hollow crater into a burning, molten lake.

Almost nothing survived, save for a handful of trees that were damaged but not destroyed, their trunks stripped of branches and leaves by falling cinder and spatter. They stand like skeletons, stark against the volcanic nothingness, white as bone. Other trees that were engulfed but not immediately burned left behind “lava trees”: upright, hollow trace fossils that resemble stone sculptures.

「荒廃した道」という意味のハワイ火山国立公園内にある「デバ ステーション・トレイル」は、溶岩流が森を飲み込み、緑の大地を 黒一色に染め上げた⾵景から名付けられた。1959年に噴火した ハワイ島のキラウエア・イキ火口は、37日間にわたり火山灰を吐 き続け、一帯に溶岩を撒き散らし、空洞だった火口はドロドロに溶 けた灼熱の湖に変貌したという。

噴火活動が収まると、そこにはほとんど何も残されていなかっ た。かろうじて倒壊を免れた数本の木も、噴石や飛散物によって 枝や葉が剥ぎ取られている。荒涼とした景色の中、それはまるで 骸骨のように白く浮かび上がって⾒える。幹に含まれる水分によ

ハレクラニ沖縄

Starting in the 1970s, the ceramicist Toshiko Takaezu created her own Devastation Trail. Inspired by the roughly one-mile path of destruction, she began molding thick clay slabs into tall, hollow cylinders of up to eight or more feet tall. In Homage to Devastation Forest (Tree Man Forest) , seven tree-like forms are clustered on a field of crushed rocks, glazed in striated tones of moon white, obsidian black, and soil brown. Another work, entitled Lava Forest , stands among the plant life in the front courtyard of Hilo International Airport, their phallic forms stained in inky black and ochre hues.

“It must be true that where you were born influences you,” Takaezu, born to Okinawan immigrant parents in 1922 in Pepe‘ekeo, Hawai‘i, told the Princeton Alumni Weekly in 1982. The impact that the islands had on Takaezu’s work is apparent throughout her oeuvre—either explicitly, as with her Makaha Blue works, which capture the vibrant color of the ocean on the west side of O‘ahu, or implicitly, in glazes of golden orange and soft pink that mimic the sunrise from the summit of Haleakalā on Maui.

At 18, she moved from Maui (her family relocated there in 1931) to O‘ahu and found work as a housekeeper for Hugh and Lita Gantt of the Hawaiian Potters’ Guild. It was there that she met her lifelong mentor, Lieutenant Carl Massa, and honed pottery skills that later led her to the ceramics program at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Takaezu would go on to enroll in drawing classes at the Honolulu School of Art; study ceramics, design, art history, and weaving at the university; and eventually leave Hawai‘i to study under renowned Finnish-American artist Maija Grotell at the prestigious Cranbrook Academy of Arts in Michigan.

“Hawai‘i was where I learned technique; Cranbrook was where I found myself,” Takaezu has said of her studies there. Grotell encouraged her self-discovery, stirring her to experiment with multi-spouted tea vessels and early iterations of the closed forms for which Takaezu would ultimately become known.

Despite her growing sense of individuality, Takaezu had long felt divided by her Okinawan heritage and American identity. According to Darlene Fukuji, Takaezu’s great-niece and president of the Toshiko Takaezu Foundation, there was a constant pressure to cast off one identity in favor of another: Okinawan for Japanese after the Ryūkyū archipelago

り、溶岩流に飲み込まれてもすぐに焼け落ちなかった木々は、「溶 岩樹」と呼ばれる中が空洞で直立した石の彫刻のような奇岩を 遺した。

陶芸家のトシコ・タカエズが、独自のデバステーション・トレイル の制作を開始したのは1970年代のことだった。荒れ果てた道か らインスピレーションを得たタカエズは、厚い粘土板を成形して、 最大約2.4メートル以上にもなる、中が空洞の巨大な円筒を創り 始めた。《オーメージ・トゥ・デバステーション・フォレスト:ツリー・ マン・フォレスト(荒廃した森へのオマージュ:樹⼈の森)》は、釉 薬をかけて月の白、黒曜石の黒、土の茶の色合いを縞状に表現し た7本の木のようなフォルムが、砕石を敷いた土台の上に集合し ている作品だ。また、《ラヴァ・フォレスト(溶岩の森)》と題された 別の作品は、黒色および黄土色に染められた男根のようなフォル ムが、ヒロ国際空港のコートヤードの植栽の中に並べられている。

1922年にハワイ島のペペエケオで、沖縄移民の両親のもとに 生まれたタカエズは、「自分が生まれた場所の影響を受けるとい うのは、真実だと思います」と、1982年に『プリンストン・アルムナ イ・ウィークリー(プリンストン大学同窓会週報)』に語っている。

オアフ島西部の鮮やかな海の色を明瞭に捉えた《マカハ・ブルー》、 ゴールデンオレンジとソフトピンクの釉薬をかけて、マウイ島のハ レアカラ山頂から昇る朝日をさりげなく表現した作品など、ハワイ の島々がタカエズの作品に与えた影響が⾒てとれる。

タカエズは1931年に家族と共にマウイ島に移住した。18歳で オアフ島に移り、ハワイ陶芸家組合のヒュー・ガント氏とその妻リ タのもとで家政婦として働き始める。そこで彼女は生涯の師とな るカール・マッサ中尉に出会い、陶芸の技術を磨いた。後にハワイ 大学マノア校の陶芸科に進学し、さらにホノルル・スクール・オブ・ アートでデッサンのクラスを受講、大学では陶芸、デザイン、美術 史、織物を学んだ。その後ハワイを離れ、米国を代表する美術大 学院であるミシガン州のクランブルック芸術学院で、著名なフィン ランド系アメリカ⼈芸術家のマイヤ・グロテル氏に師事した。 「ハワイでは技術を身につけ、クランブルックでは自分自身を ⾒つけました」とタカエズはそれぞれの場所での学びについて語 っている。師であるグロテル氏から、自分自身の個性を⾒つける ように勧められたタカエズは、注ぎ口がいくつもある茶器や、のち に彼女の名を世に知らしめることになるクローズド・フォーム(閉 じたフォルム)の初期作品をはじめ、数々の実験的な試みをおこ なった。

タカエズは、自身の作品の特徴であるクローズド・フォルムによっ て、色彩と抽象性を探求するためのより大きなキャンバスを得た。

Takaezu’s signature closed forms afforded her a wider canvas on which to explore color and abstraction.

1998年の展覧会「トシ コ・タカエズ:アット・ホー ム・アット・ザ・ハンタード ン・アート・ミュージアム」 展示⾵景。

Installation view from the 1998 exhibition

“ Toshiko Takaezu: At Home at the Hunterdon Art Museum.”

was annexed in 1879; Japanese for American during World War II. “It’s so complicated and also comes out really beautifully in her work, those dualities,” Fukuji says.

In 1959, Takaezu traveled to mainland Japan and Okinawa for eight months to commune with her origins and other ceramicists about the medium. There she met potter Tōyō Kaneshige, who reintroduced her to Shōji Hamada, Sōetsu Yanagi, and other leaders of the mingei, or folk craft, movement, which focused on elevating ordinary forms like bowls into a higher art.

Takaezu was more drawn, however, to the work of Kazuo Yagi, the head of the avant-garde clay group Sōdeisha, or the “Crawling through Mud Association,” which was formed in opposition to the dominant ceramic style of mingei. Their work emphasized the sculptural over the functional, and their pieces lacked

着実に自分の個性を確立してきたタカエズだが、長い間、自身の 沖縄の血とアメリカ⼈としてのアイデンティティの間で葛藤を感じ ていた。タカエズの曾姪でトシコ・タカエズ財団理事長のダーリー ン・フクジさんは、タカエズには一つのアイデンティティを手に入 れるためには、別のアイデンティティを手放さなければならないと いうプレッシャーが常に付きまとっていたと話す。1879年に琉球 列島が日本に併合されると沖縄⼈は日本⼈として扱われるように なり、第二次世界大戦中はアメリカ⼈として扱われた。「とても複 雑な問題ですが、彼女の作品にはそういった二面性が顕著に表 現されています」とフクジさんは語る。

1959年、タカエズは日本の本州と沖縄に8か月間滞在し、自身 の原点を振り返ると同時に、媒体としての陶芸について他の陶芸 家たちと意⾒を交わした。そこで彼女は陶芸家の金重陶陽と出会 い、あらためて濱田庄司や柳宗悦をはじめとする民藝運動の指導

Takaezu leads a workshop at California State University in Hayward, California, in

「自分が生まれた場所の影響を受けるというのは、 真実だと思います。けれども、それは後からついてく るものであって、一つのものから直接別のものが作 り出されるわけではありません。」

トシコ・タカエズ、陶芸家、ハワイ州出身

“It must be true that where you were born influences you. But it comes later. It’s not like taking directly from one thing to make another.”

—Toshiko

Takaezu,

Hawai‘i-born ceramic artist

the holes or “mouths” that defined quotidian vases and pots.

Under the aesthetic influence of Sōdeisha, Takaezu returned to the states and created some of her most distinctive work, which continued to evolve beyond utilitarian cups, plates, and bowls to include ball-shaped “moon” pots and sculptural closed vessels that narrow into nipple-like points and contain ceramic “rattles”—bits of clay she would drop inside before closing the shape and kiln firing.

The closed form afforded Takaezu a wider canvas on which to explore color and play with glazes in an abstract-expressionist manner, giving her pieces their signature “paintings-in-the-round” quality. “I was able successfully to merge the glaze as painting to the form, so that the two—painting and form— became one total and complete piece,” the artist once said, according to the Toshiko Takaezu Foundation. “In some ways this form, and the painting on it, have returned me to sculpture and painting on canvas.”

Regarded by art-world figures of the time as the “Madonna of Clay” and “the most important female ceramicist in America,” Takaezu was pivotal in transforming the traditionally functional medium into fine art in the United States. She was named a Living Treasure of Hawai‘i in 1987 and received the Konjuhosho Award in 2010 by the emperor of Japan as someone who has made significant contributions to Japanese society—in part because she fully integrated herself into her art. “I felt like a ping-pong, back and forth,” Takaezu told interviewer Daniel Belgrad in 1993 in reference to her upbringing. “But then, when I got older, I realized that it isn’t East or West, really, it’s yourself. You take the best of both.”

者たちを紹介される。民藝運動は、たとえば丼鉢のような普段使 いの工芸品に至⾼の美を⾒いだそうとする生活文化運動だった。 だが、タカエズが強く心を惹かれたのは、実用性を大前提とす る民藝の陶磁器とは対極にある前衛的な陶芸を創作する作家集 団「走泥社」の代表である八木一夫の作品だった。機能性よりも 彫刻的な芸術性を重視した彼らの作品には、日常的な花瓶や鉢 に⾒られる穴や「口(開口部)」が存在しなかった。

走泥社から美学的影響を受けて帰国したタカエズは、実用的な カップや皿、鉢をさらに進化させたボール状の「月」ポットや、形を 整え窯で焼成する前に作品の中に陶製の「ガラガラ(粘土のかけ ら)」を仕込み、天辺に乳首のような突起がついた開口部のない 器など、彼女の最も代表的な作品をいくつか創作した。

クローズド・フォルムによって、抽象表現主義的な色彩の探求や 釉薬を活用するためのより大きなキャンバスを得たタカエズは、 彼女の作品の特徴の一つである「円形に描かれた絵画」を生み出 した。トシコ・タカエズ財団によると、かつてタカエズは、「釉薬を 絵の具にして、うまくフォルムに融合させることに成功したおかげ で、絵画とフォルムの2つが一体となった作品ができあがりまし た」と話していたという。「このフォルム、そしてそこに絵を描くこと で、ある意味、私は彫刻と絵画の世界の一員に戻れたのです」 当時の美術界で、「粘土のマドンナ」「アメリカで最も力量ある女 性陶芸家」と称されていたタカエズは、それまでアメリカでは実用 性のみ重視されていた陶磁器を、芸術作品へと昇華させた先駆者 となった。1987年にハワイの「生きている宝」に選ばれたタカエ ズは、2010年には日本社会に多大な貢献をした⼈物に与えられ る紺綬褒章を天皇陛下から授与された。表彰の理由の一つには、 彼女が自身の芸術に完全に溶け込んでいたことが挙げられるだろ う。1993年、自身の生い立ちについてタカエズは、「行ったり来た り、まるでピンポン玉になったような気分でした」とインタビュア ーのダニエル・ベルグラッド氏に語っている。「でも、歳を取るにつ れ、東洋か西洋かは関係なく、要は自分次第なのだと気づきまし た。両方の良いところを取り入れればいいのです」

ハワイ生まれのアーティストは、30年以上にわたりニュージャー ジー州クエーカータウンの田舎町に居を構え、庭づくりに励み、 さらに大規模な作品を制作した。

For more than 30 years, the Hawai‘i-born artist lived, gardened, and made increasingly large-scale work in the rural hamlet of Quakertown, New Jersey.

静かなる力

PEACEFUL POWER

TEXT BY CHRIS WILLSON

IMAGES BY GERARD ELMORE & CHRIS WILLSON

TRANSLATION BY AKIKO MORI CHING

剛柔流の理念と伝説的な創始者の教えを 今に伝える空手家の姿

Generations of karate practitioners uphold the principles of Gōjū-ryū and those of its legendary founder.

On a hot summer evening in Naha’s Kume village, the drone of cicadas is punctuated by the cracks of fists against wooden boards. The synchronized pounding of feet and spirited yells echo around the neighborhood. It is here at Meibukan Hombu Dōjō, and at other karate schools throughout the islands, that Okinawa’s unique culture is preserved.

Seated in a corner is Meitetsu Yagi, a master of a style of karate known as Gōjū-ryū. He began his training from the age of 6 years old and earned his first dan (rank) in both karate and judo at age 16. Like many Okinawan karate masters, he went on to hold a day job alongside his martial arts practice, but his true passion and calling was karate. Working as a high school English teacher until he retired at age 60, he considered the two parts of his life—teaching and karate training—connected. “The goal of education and budō (the way of the warrior) is the same,” he says. “To become a nice person who can contribute to the world.”

His son, Ippei Yagi, a barrel of a man, stands at the front of the room. Gripping the wooden floor with his toes, Ippei twists his hips and powers his arm and fist into an invisible target. As an All Okinawa Karate Champion of kumite, or sparring, Ippei wasn’t known for flashy kicks or rapid strikes but powerful, welltimed blows. Today he is the next successor in line after his father to oversee many of the dōjōs affiliated with the Meibukan branch of Gōjū-ryū karate founded by his grandfather, the late Meitoku Yagi. In 1997, Meitoku became a holder of the Intangible Cultural Property title for Okinawa karate and kobudō. He is said to have learned all 12 core Gōjū-ryū kata (forms) from Miyagi Chōjun, the legendary forefather of Gōjū-ryū.

Meibukan Hombu Dōjō is situated in an apt location: Just a short distance away is Fukushūen, a traditional Chinese garden that celebrates Naha’s connection to its sister city of Fuzhou in China’s Fujian province, where Miyagi honed his skills. On his return to Okinawa, Miyagi blended what he had learned in China with his knowledge of Naha-te—a regional style of combat that combined Chinese martial arts and local fighting methods—to create Gōjū-ryū, meaning “hard-soft school.”

Japanese statesmen had taken an interest in Okinawan martial arts after the Ryūkyū Kingdom was annexed and became Japan’s Okinawa Prefecture, believing that their rigorous conditioning and discipline

暑い夏の夜、那覇の久米地区には、セミの鳴き声に交じって板に 拳を打ち付ける音が響いていた。揃って踏み込む力強い足音や威 勢のいい掛け声が近隣に響く。ここは明武館本部道場。沖縄の各 地にある他の空手道場と同様に、沖縄独自の文化が守り伝えられ ている場所だ。

道場の片隅に座っているのは八木明哲、剛柔流空手の師範であ る。6歳から空手を学び、16歳で空手と柔道の初段を取得する。

明哲も他の沖縄空手の師範たちと同じように、日々の仕事に就き ながら、空手の修行を続けてきた。しかしながら、彼の真の情熱は 空手に注がれ、空手こそが天職だった。60歳で定年退職するまで ⾼校の英語教師を務めた明哲は、自分の⼈生を占める2つの側面 である教育と空手の修行は密接に結びついていると感じている。 「教育と武道の目指すところは同じです。それは、世の中に貢献で きるような素晴らしい⼈物になることなのです」と言う。

息子の八木一平は、力強くたくましい男だ。部屋の前方に立ち、 つま先で木の床をとらえ、腰をひねり、腕と拳に力を込め、⾒えな い敵と対峙する。全沖縄空手道選手権大会の組手部門のチャン ピオンだった一平は、派手な蹴りや素早い一撃ではなく、パワフル でタイミングのよい打撃を得意としていた。現在は、祖父の故八 木明徳が創設した剛柔流空手明武館に加盟する多くの道場を統 括する父の後継者として、忙しい日々を送っている。1997年に沖 縄県指定無形文化財「沖縄の空手・古武術」保持者となった明徳 は、伝説的な剛柔流の祖と呼ばれる宮城長順より、すべての基本 的な12の型を学んだといわれている。

宮城は中国福建省福州市で腕を磨いた後、沖縄に戻り、中国で 学んだ武術を那覇手の知識に加え、剛と柔を併せ持つという意味 を込めた剛柔流を創設した。明武館本部道場は、姉妹都市である 福州市と那覇とのつながりを称える伝統的な中国庭園スタイル の福州園のすぐ近くにある。

琉球王国が日本に併合されて沖縄県となった後、日本の政治 家たちは、沖縄の武術に目をつけた。そして、教育制度にその厳し い鍛錬と規律を組み込めば、社会に役立つものと考えたのだ。空 手はもともと中国の手を意味する「唐手」と表記されていた。しか し、沖縄の空手家たちは、空手が中国を越えて進化を遂げたこと を讃え、その武器を使わない(空の手という)特質を振興するため に、1936年から「空手」と表記するようになった。

沖縄空手案内センターのミゲール・ダルーズ代表は、「剛柔流の

2016年の「空手の日」には、ギネス記録樹立のために、那覇の 国際通りに約4000⼈の参加者が集まり型を演じた。

On Karate Day in 2016, nearly 4,000 participants gathered on Kokusai Street in Naha to set a new Guinness World Record for the most people performing a kata.

「非暴力と他者への尊重という姿勢、それが空手の 真髄なのです。」

ミゲール・ダルーズ、沖縄空手案内センター

“It’s an attitude of non-violence, of respect toward others, That’s what karate is really about.”

—Miguel Da Luz, Okinawa Karate Information Center

would benefit society, particularly if integrated into the education system. The term “karate,” as it came to be known, was originally written with kanji characters meaning “Chinese hand,” but in 1936, Okinawan karate masters changed its writing to mean “empty hand,” both to honor karate’s evolution beyond China and to promote its weaponless nature.

Gōjū-ryū, a distinct style of karate that combines hard, linear striking techniques with soft, circular movements, is “like yin and yang,” says Miguel Da Luz, a representative of the Okinawa Karate Information Center. “You need both aspects. When needed, you have to adjust between the two.”

As Ippei leads the evening’s class, guiding his young students with a tender discipline, it’s clear there is a deeper meaning to Gōjū-ryū’s duality of hard and soft. “The stronger you become, the gentler your heart should be, the more kind and humble,” Ippei says. “Karate is like a weapon. Instead of just giving students the weapon, you have to teach them the mindset. It’s dangerous to only give them the technique and not teach them the philosophy behind it.”

When he was approached by Halekulani Okinawa to offer karate lessons to hotel guests, Ippei was pleased to learn that the resort was more interested in promoting the philosophy behind the form than teaching the mechanics of combat. “The important thing is to train the body, hone the technique, and nurture the mind, [not] beat people up,” he says. “Halekulani is the only hotel that asked me to focus on the philosophy.”

As Da Luz puts it, karate is more than a martial art; it’s a way of life. “It’s an attitude of non-violence, of respect toward others,” he says. “That’s what karate is really about.”

Ryuhei Yagi, Ippei’s eldest son, stands at the center of the dojo surrounded by his peers. Moving with unwavering intensity, he performs a kata, his kiai (battle cries) piercing the thick heat of the room. Like his siblings and cousins, Ryuhei began his training at a young age, and the fruits of his labor are apparent in his fierce precision and commanding gaze. It is his spirit, however, that Ippei is most interested in strengthening. “I’m most happy when someone tells me that my students are good people,” Ippei says. “This is the philosophy at our dojo.”

空手は、陰と陽のように、直線的な打撃技と柔らかく円を描く動き を組み合わせた独特の様式です。どちらも欠かせないものであり、 必要に応じて、その各々を調整してバランスを取らねばなりませ ん」と語る。

一平が夜のクラスで、若い生徒たちを柔和ながらも厳格な規律 のもと、指導している。そこには、明らかに剛柔流の剛と柔のより 深い意味が込められている。「⼈は強くなればなるほど、その心は より優しく、思いやりがあり、謙虚であるべきです。空手は武器の ようなものです。しかしながら、生徒たちには、単に武器を与える のではなく、正しい心の持ち方を教えなければなりません。技術だ けを教えて、その背後にある哲学を教えないのは危険なことです」 と一平は言う。

ハレクラニ沖縄から宿泊客に空手のクラスを教えて欲しいと打 診されたとき、一平は喜んだ。なぜなら、同ホテルが戦いの技術を 教えることよりも、空手の背景にある哲学を広めることに関心を 持っていると知ったからだ。「大切なのは、体を鍛え、技を磨き、心 を育成すること。相手を打ちのめすことではありません。私に、空 手の哲学に焦点を当てるように求めた唯一のホテルがハレクラニ だったのです」

ダルーズが言うように、空手は単なる武道ではなく、生き方その ものなのだ。「非暴力と他者への尊重という姿勢が、空手の真髄 です」と彼は言う。「本当の空手とは、まさにそれなのです。」 一平の長男である八木竜平が、同年代の仲間と一緒に道場の 中央に立っている。一糸乱れず動きながら型を演じ、その気合は 熱気を突きぬけていく。兄弟や従兄弟と同じくして、竜平も幼い頃 から稽古を積み重ねた。鋭く正確な動き、凛としたまなざしは鍛 錬の成果だ。しかし、一平が最も鍛えたいのは自身の精神だとい う。「一番嬉しいのは、私の生徒が立派な⼈間であると⼈から言わ れることです。それこそが私たちの道場の哲学ですから」と語る。

TEXT BY TINA GRANDINETTI

A DIASPORIC DIALOGUE

音楽と舞踊でハワイのオキナワン・コミュニティと 故郷を再び繋ぐ御冠船歌舞団 ある夜のディアスポラ的対話

TRANSLATION BY AKIKO MORI CHING

In Uchināguchi, one of the Indigenous languages of Okinawa, there is a saying: Ichariba chōdē. Once we meet, we are chōdē—brothers and sisters. For many in the diaspora, including myself, the saying reassures us that when we return to our homeland, we are welcomed as family. Yet, on a rainy winter night in Kalihi Valley on the Hawaiian island of O‘ahu, my understanding of the saying is challenged by Eric Wada and Norman Kaneshiro, Hawai‘i-born Uchinānchu and co-founders of Ukwanshin Kabudan, a performing arts troupe dedicated to perpetuating Okinawan arts and culture in Hawai‘i.

“It’s a powerful phrase, right?” Kaneshiro says. “But if you’re coming from a take-take-take perspective—a colonizer perspective—what it means is that you’re entitled to everybody’s friendship and love without doing anything in return.”

In January 1900, 26 Okinawan contract laborers arrived in Hawai‘i to work on the plantations, launching a wave of emigration that sent thousands of Okinawans into the diaspora. In the years since, Okinawans in the homeland have endured a brutal battle between two empires, fractured to this day by ongoing Japanese colonization and American military occupation. Meanwhile, those in diaspora have faced discrimination and assimilation while making a home in a foreign land. Today, roughly 100,000 Okinawans live in Hawai‘i.

In this context, what does it mean to meet as chōdē who, though connected by family genealogies and ancestral villages, are also separated by five generations of emigration, an ocean, a language barrier, and vastly different experiences of war and colonization?

When Wada and Kaneshiro founded Ukwanshin Kabudan in 2007, it was with the aim to nurture

ウチナーグチ(沖縄の伝統的方言)には、「行き逢りば兄弟(イチ ャリバチョーデー)」という言葉がある。「ひとたび出会えば皆兄 弟や姉妹になる」という意味だ。祖国に帰れば、家族として迎えて もらえる。私を含め、ディアスポラ(「故郷を離れた⼈々」)にとっ ては、なんとも頼もしく安心感を与えてくれる言葉だ。しかし、ある 雨のふる冬の夜、ハワイのオアフ島にあるカリヒバレーで、2⼈の ウチナーンチュ、エリック・ワダとノーマン・カネシロに出会ったと き、私はこの言葉の本当の意味を理解していなかったことを悟っ た。ハワイ生まれの彼らは、ハワイに沖縄の芸術文化を永続させ るために活動する舞台芸術集団「御冠船歌舞団(ウクゥワンシン カブダン)」の共同創設者だ。

「それって力強い言葉だよね? でも、ただ奪い取っていくだ けの植民地的視点からこの言葉を考えると、何のお返しをするこ ともなく、皆の友情や愛を得る権利があると主張していることに なるんだよ」と、カネシロは言う。

1900年1月、26⼈の沖縄⼈(「オキナワン」)の契約労働者が、 プランテーションで働くためにハワイに到着した。それがきっかけ となり、何千⼈ものオキナワンが故郷を離れ、波のように続々と海 外へ移住することになった。その後、祖国沖縄の⼈々は2つの帝国 間の残酷な戦いに巻き込まれ、日本による植民地化とアメリカの 軍事占領による爪痕は今日まで残っている。一方、故郷を離れた オキナワンたちは、異国の地に居場所を築きつつも、差別や同化 への圧力に直面しながら暮らしてきた。現在、ハワイには約10万 ⼈のオキナワンがいる。

このような状況の中、たとえ親戚だったり、祖先が同じ村の出身 だったりしても、5世代も前の移民、祖国を隔てる広い海、言葉の 壁、戦争や植民地化といった大きく異なる経験などにより隔てら れてきた⼈々が、「チョーデー」として出会うことに、どのような意 味があるのだろうか?

Ukwanshin Kabudan reconnects Hawai‘i’s Okinawan community with their homeland through music and dance.

IMAGES BY IJFKE RIDGLEY

御冠船歌舞団はハワイのオキナワン・コミュニティに、先祖の島と 自分たちを育ててくれた島の相互責任の意識を植え付けることを 目的としている。

Ukwanshin Kabudan aims to instill in Hawai‘i’s Okinawan community a sense of reciprocal responsibility, both to the islands of their ancestors and the islands that raised them.

connections between Hawai‘i and Okinawa through traditional music and dance. More deeply, it was to instill in Hawai‘i’s Okinawan community a sense of reciprocal responsibility, both to the islands of our ancestors and the islands that raised us.

“It’s a strong kuleana (responsibility),” Wada says as we sit on the floor of the dance studio he built in his home. He wears a blue T-shirt emblazoned with the Hawaiian adage, “ola i ka wai,” meaning “water is life.” Above him, portraits of masters of the Tamagusuku style of Okinawan classical arts hang in the manner of respected uyafāfuji, or ancestors. He continues, “In Uchināguchi we call it fichi-ukīn.” The verb pulls together two roots, fichun, to pull or inherit, and ukīn, to accept or embrace. Combined, it signifies our accountability to the responsibilities we inherit from our ancestors.

As young boys yearning for more of a connection to their Okinawan ancestry and Uchinānchu identities, Wada and Kaneshiro both took up dance and sanshin, an Okinawan stringed instrument. Kaneshiro was 16 when he met Wada, ten years his senior, but they quickly bonded over a shared passion for the arts, not just as a practice but also a kind of compass on their journey to make sense of themselves. Together, they worked their way through the hierarchies of Okinawan classical arts, studying in Okinawa and deepening their commitment to cultural practice as a way of life. Wada reached the level of shihan, or grandmaster, in dance. Kaneshiro reached the same pinnacle in music. They learned both Japanese and Uchināguchi and became wellversed in cultural protocol.

“In a five-minute song, there’s this whole history, this whole world behind it,” Kaneshiro marvels. As he and Wada explored those worlds, they increasingly understood cultural practice as a political act. “Even speaking your language is a form of activism,” Wada says.

Before it was annexed by Japan in 1879, Okinawa was an independent nation known as the Ryūkyū Kingdom. Much like in Hawai‘i, annexation brought the systematic suppression of language and culture, such that today, Okinawa’s Indigenous languages are considered severely endangered. Many cultural practices have been lost. The name that Wada and

ワダとカネシロは2007年、音楽と舞踊を通じてハワイと沖縄 のつながりを育むべく、御冠船歌舞団を創設する。実は、その創設 には、さらに深い目的があった。それは、ハワイのオキナワン・コミ ュニティに、祖先の島と自分たちを育ててくれた島には相互的に 責任がある、という理念を植え付けることだった。 「そこにあるのは、強いクレアナ(ハワイ語で「責任」の意)なん だ」。自宅に設えたダンススタジオの床に座り、ワダは語る。身に 着けた青いTシャツには、「olaikawai(水は命)」というハワイ 語の格言が刻まれていた。頭上には、沖縄古典芸能の玉城流の師 範たちの肖像画が、尊敬するウヤファーフジ(「ご先祖様」)のよう に掲げられている。「ウチナーグチではそれをフィチウキーンとい うんだ」。この言葉は、「引っ張る」「受け継ぐ」という意味の「フィチ ュン」と、「受け入れる」「大切にする」という意味の「ウキーン」とい う2つの語根を合わせたもので、祖先から受け継いだ義務に対す る責任感を表している。

沖縄の祖先とのつながりやウチナーンチュとしてのアイデンティ ティを強く求めていたワダとカネシロは、共に少年時代から舞踊 と三線を学んでいた。カネシロがワダと出会ったのは16歳のとき だった。ワダはカネシロより10歳年長だったが、芸術への熱い情 熱を抱く二⼈はすぐに意気投合する。彼らにとって芸術とは、練習 するだけのものではなく、自らを理解するための羅針盤のような ものだったのだ。

二⼈は沖縄で学び、生きる術としての文化活動に専心しなが ら、沖縄古典芸能界の階段を昇っていった。ワダは沖縄舞踊の師 範となり、カネシロは音楽の世界で同じく頂点を極めた。共に日 本語とウチナーグチを学び、文化や礼儀にも通じている。

「たった5分の歌の裏には、それぞれの歴史や世界があるん だ」と、カネシロは感嘆して言う。自ら飛び込んだ世界を探求する うちに、彼らは文化活動を政治的なものとしても捉えるようにな った。「自分自身の言語で話すことだって、一種の(政治的な)活動 なんだよ」と、ワダは言う。

1879年に日本に併合される前、沖縄は琉球王国と呼ばれる 独立国家だった。ハワイ同様、併合は言語や文化を組織的に抑圧 し、それにより今日、沖縄の伝統的な言語は絶滅の危機に瀕して いる。多くの文化的な慣習も失われてしまった。ワダとカネシロが 彼らのグループに名付けた「御冠船歌舞団」という名前は、この王 国の歴史に由来するもので、「冠船」は中国から琉球に向けて、国

Kaneshiro gave their performance troupe, Ukwanshin Kabudan, is itself a reminder of this sovereign history, referring to the ukwanshin or “crown ships” that carried large envoys from China to Ryūkyū for the coronation of a monarch. Upon their arrival, elaborate music and dance programs known as ukwanshin udui (crown ship dances) were offered to entertain the Chinese delegation. These would become the foundation for Okinawan classical arts.

Heavily influenced by the work of Hawaiian nationalists like Haunani-Kay Trask and Lilikalā Kame‘eleihiwa, Ukwanshin Kabudan looked to dance and music as a way to ignite conversations about Ryūkyūan sovereignty and reclaim a culture and history that colonization and occupation tried to erase.

In Hawai‘i, that meant not just performing for the Okinawan community, but also educating people about the rich history of Okinawa—and confronting the role of Okinawans as settlers on Hawaiian lands. “We started bringing up the words ‘colonized, assimilated, settler, discrimination,’ and especially the older generation didn’t take to it,” Wada recalls. “It was something they couldn’t talk about.” Gradually, the conversation changed, often by making connections between the desecration of sacred lands in both Okinawa and Hawai‘i—particularly by the United States military, which currently operates 32 bases in Okinawa.

In Okinawa, Wada and Kaneshiro found that their outside-insider identities—Uchinānchu born in Hawai‘i but also certified shihan—granted them a unique kinship with those in their homeland. As musicians, they could create intimate spaces for difficult conversations about Okinawa’s history. And as visitors from the diaspora, they were slightly removed from the familial and intergenerational trauma that arose from those discussions. Eventually, they found themselves tending to wounds that had long been hidden. “We got to this other level where elders could talk to us,” Kaneshiro says. “Things they had a hard time sharing with their own children but wanted to tell us, because it needed to be passed down to the next generation.” This deep trust demonstrated for them the importance of a reciprocal relationship between Hawai‘i and Okinawa.

御冠船歌舞団

王の戴冠式に参加するための大規模な使節団を乗せて航海した 船にちなんでいる。冠船が到着すると、中国使節団をもてなすた めに、ウクヮンシンウドゥイ(御冠船踊り)と呼ばれる趣向を凝ら した音楽と舞踊が披露され、これが沖縄の古典芸能の基礎とな ったのだという。

御冠船歌舞団は、ハウナニケイ・トラスクやリリカラー・カメエ レイヒヴァといった、ハワイの民族独立活動家から大きな影響を 受けた。そして、琉球⼈の主権回復と植民地支配や占領が消し去 ろうと試みた民族の文化と歴史を取り戻す術として、舞踊や音楽 に着目したのだ。

それは、ハワイにおいてはオキナワン・コミュニティのために演 奏することだけでなく、沖縄の豊かな歴史をハワイの⼈々に広め、 ハワイの土地に入植したオキナワンとしての役割と向き合うこと を意味していた。「僕たちは植民地化、同化、入植者、差別などと いう言葉を使って話をしたんだけど、最初はみんな、とくに年配の ⼈々は受け入れようとしなかったんだ。そのあたりは、彼らにとっ て、すごく話したくない部分だったからね」とワダは言う。しかし、 沖縄とハワイの聖地が冒涜されていること、中でもそれが沖縄に 現在32の基地を置いている米軍によるものであることと関連づ けることで、会話は徐々に変わっていった。

ハワイ生まれのウチナーンチュでありながら師範の資格を持つ ワダとカネシロは、沖縄ではアウトサイド・インサイダー(外からの 仲間)としてのアイデンティティが、故郷の⼈々と特異な親近感を 生むことに気付いた。音楽家だからこそ、親密な雰囲気の中で沖 縄の歴史についての奥の深い話ができた。また、海外からの訪問 者だからこそ、このような議論によって生じた家族間や世代間の トラウマから少し距離をおける。やがて彼らは、自らが長い間隠さ れていた傷の手当てをしていることに気付いた。「僕たちは新たな レベルに到達したんだね。長老たちは、自分の子どもたちに伝え るのが難しいことでも、僕たちには話してくれた。いずれ次の世代 には伝えないといけないことだから。」この深い信頼関係は、彼ら にとってハワイと沖縄の相互理解の重要性を示すものだった。か つて沖縄に「本物であること」と「力強さ」を求めたワダとカネシロ は、祖国のオキナワンたちとともに先住民族としてのアイデンティ ティを取り戻し、共に歩んでいくという機会を得たのだ。

ワダとカネシロそして御冠船歌舞団のメンバーたちは、何年も かけてその活動を大幅に拡大してきた。共同ディレクターのキー

Where once they looked to Okinawa for a sense of authenticity and authority, Wada and Kaneshiro saw an opportunity to reclaim and co-create an Indigenous identity with Okinawans in the homeland.

Over the years, Wada, Kaneshiro, and others at Ukwanshin Kabudan have expanded the organization’s activities dramatically, offering uta-sanshin classes from co-director Keith Nakaganeku, Uchināguchi language classes from board member Brandon Ing, monthly workshops on Okinawan culture and politics, and an annual LooChoo Identity Summit that invites Okinawans from around the world to Hawai‘i to spark dialogue about who we are as a people.

It has also become increasingly focused on the kuleana that Okinawans have to Hawai‘i and Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians). In 2019, during the stand for Mauna Kea, members of Ukwanshin Kabudan led a delegation of Okinawans to offer ho‘okupu (gifts) in solidarity with those protecting the sacred mountain at Pu‘uhonua o Pu‘uhuluhulu, and in the aftermath of the Red Hill jet fuel leak in 2021, Ukwanshin Kabudan hosted panel discussions to draw vital connections between the U.S. military’s contamination of both Hawai‘i and Okinawa’s aquifers. Most recently, the group has become involved with efforts to repatriate the remains of Okinawan ancestors and return them to their rightful resting places.

Reflecting on the ways Ukwanshin Kabudan has grown over the years, Wada says, “Going back to fichi-ukīn, because that word is connected to so much—to who we are, and who we’re supposed to be—it just grows.” That is, perhaps, the burden and privilege of living in diaspora: you inherit responsibility for two different kinds of home.

Kaneshiro adds, “Because when you’re family, you don’t just show up to the house to eat and drink. You clean up after, you take care of the house. You come back and show up for the hard times. That is what it means to be chōdē.”

ス・ナカガネクによる歌三線教室、理事のブランドン・イングによ るウチナーグチ教室、沖縄の文化や政治に関する月1回のワーク ショップ、そして毎年世界中からオキナワンをハワイに招き、自分 たちがどのような民族であるかについて意⾒交換を促す「ルーチ ュー・アイデンティティ・サミット」などを開催してきた。 そして、ハワイおよびカナカマオリ(先住ハワイアン)に対して抱 くクレアナに、オキナワンはさらに焦点を当てるようになる。2019 年、ハワイ島マウナケアの天体望遠鏡建設反対運動が巻き起こっ た際には、御冠船歌舞団はオキナワンの代表者を率いて、この先 住ハワイアンの聖なる山を守る⼈々と連帯し、ホオクプ(ハワイ語 で「贈り物」の意)を捧げた。2021年に発生したオアフ島のレッド ヒルにおけるジェット燃料流出事故後には、米軍によるハワイと 沖縄の帯水層汚染の重要な関連性を示すパネルディスカッショ ンを開催した。最近では、オキナワンの先祖の遺骨を本来の安住 の地に送り還す取り組みにも携わっている。

御冠船歌舞団が長年にわたり成長してきた過程を思い出しな がら、ワダはこう言った。「フィチウキーンに立ち返るんだ。この言 葉は、すごくたくさんのものとつながっているから。自分たちが誰 であるか、自分たちはどうあるべきかということに」つまり、それは 海を渡ったディアスポラとして生きることの重荷であり、特権なの だ。2つの異なる故郷に対する責任を受け継ぐのだから。

「家族である以上、ただ家に立ち寄って、食べたり飲んだりする だけではすまない。後片付けをし、家を大事にする。大変なときに も、戻ってきて顔を出す。それがチョーデーであるということなん だよ」と、カネシロは付け加えた。

Introducing The Launiu Ward Village

The Launiu Ward Village residences are an artful blend of inspired design and timeless sophistication. Expansive views extend the interiors and a host of amenities provide abundant space to gather with family and friends.

The Launiu Ward Village は、芸術性あふれるタイムレスな洗練をまとったレジデンス。 広がる眺望は室内に広がりをもたらし、素晴らしいアメニティの数々では家族や友人たちとの かけがえのない時間を紡ぐ。

Studio, One, Two, and Three Bedroom Honolulu Residences ホノルルのスタジオ、1ベッドルーム、2ベッドルーム、3ベッドルームレジデンス

INQUIRE

thelauniuliving.com | +1 808 470 8022 Offered by Ward Village Properties, LLC RB-21701

THE PROJECT IS LOCATED IN WARD VILLAGE, A MASTER PLANNED DEVELOPMENT IN HONOLULU, HAWAII, WHICH IS STILL BEING CONSTRUCTED. ANY VISUAL REPRESENTATIONS OF WARD VILLAGE, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION, RETAIL ESTABLISHMENTS, PARKS, AMENITIES, OTHER FACILITIES AND THE CONDOMINIUM PROJECTS THEREIN, INCLUDING THEIR LOCATION, UNITS, VIEWS, FURNISHINGS, DESIGN, COMMON ELEMENTS AND AMENITIES, DO NOT ACCURATELY PORTRAY THE CONDOMINIUM PROJECTS OR THE MASTER PLANNED DEVELOPMENT. ALL VISUAL DEPICTIONS AND DESCRIPTIONS IN THIS ADVERTISEMENT ARE FOR ILLUSTRATIVE PURPOSES ONLY. THE DEVELOPER MAKES NO GUARANTEE, REPRESENTATION OR WARRANTY WHATSOEVER THAT THE DEVELOPMENTS, FACILITIES OR IMPROVEMENTS OR FURNISHINGS AND APPLIANCES DEPICTED WILL ULTIMATELY APPEAR AS SHOWN OR EVEN BE INCLUDED AS A PART OF WARD VILLAGE OR ANY CONDOMINIUM PROJECT THEREIN. WARD VILLAGE PROPERTIES, LLC, RB-21701. COPYRIGHT ©2024. EQUAL HOUSING OPPORTUNITY.

WARNING: THE CALIFORNIA BOARD OF REAL ESTATE HAS NOT INSPECTED, EXAMINED OR QUALIFIED THIS OFFERING.

THE LAUNIU WARD VILLAGE AMENITY LOBBY

動きが意味すること

MEANING IN MOVEMENT

TEXT BY LAUREN MCNALLY

IMAGES BY MICHELLE MISHINA & CHRIS RUDZ

名フラダンサーが分かち合う フラという芸術

A renowned hula dancer shares the art of hula with audiences near and far.

It’s show time at House Without A Key, but instead of taking the stage on Halekulani’s beachfront lawn like she’s done countless times over the past 46 years, Kanoe Miller is taking shelter from a typhoon. Tonight, the hotel’s resident hula dancer is on the opposite end of the Pacific from her typical post in Waikīkī, and her performance at House Without A Key at Halekulani’s sister property in Okinawa has been moved indoors due to the approaching storm.

In the more intimate setting of Halekulani Okinawa’s upstairs banquet room, the former Miss Hawai‘i has decided to improvise. “Let’s call people up out of the audience,” she says, turning to her band. “We’re going to have them dance.”

It felt like they were at home, Miller shares the following day over Zoom, during a few hours of downtime in her hotel room overlooking the azure waters of Nago Bay. “That’s the way you would do it,” she continues. “You talk to people, make them laugh, have fun. You share your hula with the audience as if they’re sitting in your living room.”

Despite her long tenure as a hula performer, Miller didn’t always consider herself an authority on the art form. When Kapi‘olani Community College approached her about teaching a series of hula seminars in 2009, more than 30 years into her career as a professional dancer, she initially declined. I’m no hula teacher , Miller thought. With so many worthy, credentialed kumu hula (hula teachers) on the island, she wondered, Why me ?

As it turns out, the school was looking for an instructor unaffiliated with any of Hawai‘i’s established hālau hula (hula groups)—someone “neutral” who could serve as an ambassador of the dance for the seminar’s Japanese attendees. Reluctantly, Miller agreed to lead the class, on one condition: “I’m going to have to do it my way.”

ハウス・ウィズアウト・ア・キーで、今まさにショーが始まろうとして いる。フラダンサーのカノエ・ミラーは、過去47年にわたり、ワイ キキの海を目の前にしたハレクラニの芝生に設えられたステージ で繰り広げられる、数えきれないほどのショーで⼈々を魅了してき た。だが、今宵彼女は、ワイキキからは太平洋を隔てた遥か彼方、 台⾵が近づきつつあるハレクラニ沖縄にいた。

ショーが行われるハレクラニ沖縄の3階にある宴会場は、屋外 よりも観客との距離がより近い空間だ。それを⾒た元ミス・ハワ イのミラーは、いつもと違うショーにすることにした。「お客様に ステージに上がってもらい、踊ってもらいましょう」と、バンドに声 をかけた。

「お客様たちは、寛いでいらっしゃったわ。それが大切なことな の。⼈々と語らい、笑い、一緒に楽しむ。まるで誰かの家のリビングル ームにいるかのように、お客様とフラを分かち合うのよ」。ショー の翌日、名護湾の紺碧の海を⾒下ろすホテルの部屋で休憩中のミ ラーが、Zoom越しに話してくれた。

プロのフラダンサーとして、30年以上の長いキャリアを積んで きてはいたが、ミラーは自分がフラの権威だとはまったく思ってい ない。2009年にカピオラニ・コミュニティ・カレッジから、フラセミ ナーの講師の職を打診されたときも、最初は断った。「私はフラの 講師ではないし、島には資格のある立派なクム・フラ(フラの指導 者)がたくさんいるのに、なぜ私が?」

実のところ同校は、ハワイのどのフラ・ハーラウ(フラ・グループ) にも属していないインストラクターを探していた。セミナーに参加 する日本⼈のために、「中立的」な立場で、フラのアンバサダーとし ての役割を果たせる⼈物を探していたのだ。「それでは、私のやり 方で行う」ことを条件に、しぶしぶながら、ミラーはクラスを担当す ることに同意した。

彼女はそれから数か月を費やし、フラの技術だけでなく、手の動

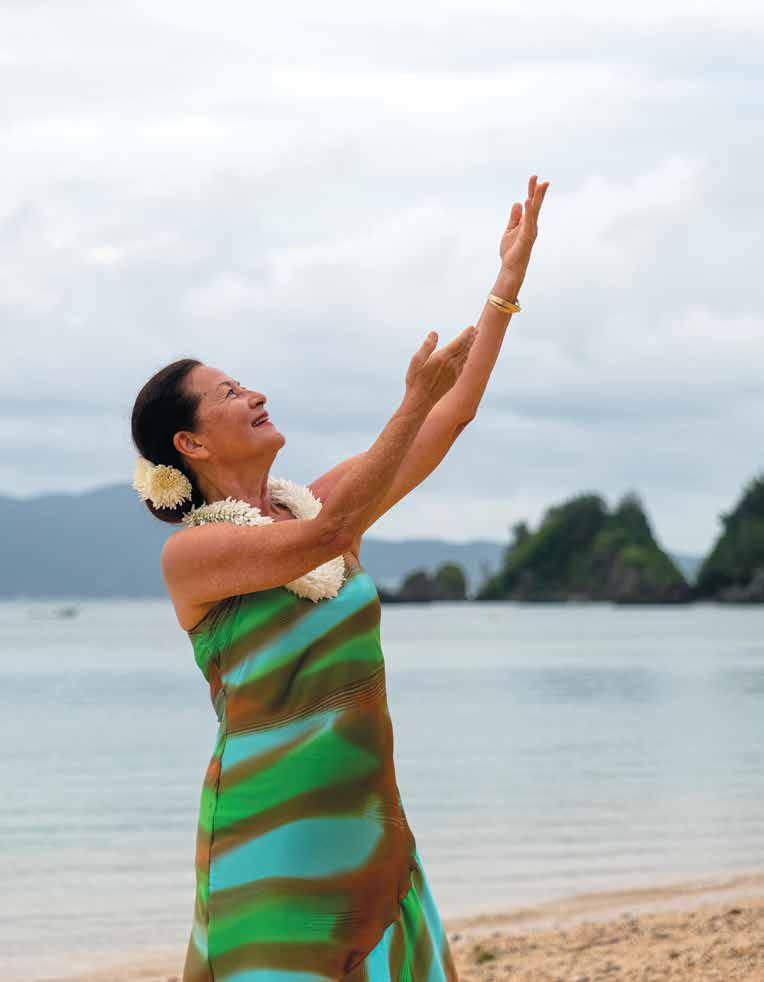

Longtime Waikīkī performer Kanoe Miller dances hula on the beach in Okinawa.

She spent the next couple of months developing a curriculum to teach not only the mechanics of hula, but the nuances that give the dance its significance and meaning: a gesture of the hand, a glint in the eye, a subtle tilt of the head. “Hula is storytelling,” Miller says. “You have to come to it with an open heart, that way, you can tell the story from your own experience.”

Over the ensuing decade, Miller made frequent trips to host workshops for her growing following in Japan, traveling back and forth to maintain her schedule of weekly hula shows at Halekulani. After the pandemic hit, putting an end to her usual pipeline of performing and teaching engagements, Miller and her husband, John, outfitted the living room of their Kāne‘ohe home with everything she’d need to bring her classes into the virtual realm: recording equipment, a sound system, studio lights, a 70-inch TV.

But when the time came for Miller to host her first Zoom class, she was met with a screen full of dancers moving to music streamed over unsynchronized internet connections around the globe. At the end of the session, Miller said goodbye to her students, shut off the screen, and wept, convinced that all the money and effort they’d invested in the endeavor had gone to waste.

In the absence of other revenue streams, however, the couple had no choice but to make it work. Miller took to dancing with her back to the camera so that students could follow along from behind, then learned to dance in reverse so she could turn around and mirror their movements. Most of all, she says, “I stopped expecting them to be synchronized and learned to see them as individual dancers.”

Focusing on one student at a time, Miller could offer pointers if she noticed a girl’s fingers were out of place, or if another wasn’t moving her hips correctly or flexing her knees enough. In calling out one student, she realized, others were quick to selfcorrect. She’d ask the class to turn off their screens while a select few performed, making clear that she was attuned to each and every dancer in attendance. From her days as a young entertainer, Miller was already in the habit of fixing her gaze on the camera when she spoke, and so she addressed her students the same way—as if she were looking them right in the eyes.

き、目の輝き、頭の微妙な傾きといった、踊りに意味と意義を与え るニュアンスを盛り込んだカリキュラムを作り上げた。「フラとはス トーリー・テリングなの。心を開いてフラに向き合えば、自分自身 の経験から物語を紡げるようになるわ」という。

それからの10年間、増え続けるファンのために、毎週のハレク ラニでのショーの合間を縫って、ミラーは何度も来日し、ワークシ ョップを開催した。しかし、コロナウイルス感染症の世界的流行 を受け、フラショーやワークショップの場は失われてしまう。なら ばと、ミラーは夫のジョンとともに、自宅のリビングルームにレコー ディング機材、音響システム、スタジオ照明、70インチのテレビ などを持ち込み、バーチャルな世界でのクラス開催に乗り出すこ とにした。

ミラーの第1回目のZoomクラスが始まった。ところが、スク リーンに映し出されたのは、送受信や通信がスムーズに行われな い不安定なインターネット接続を介しストリーミングされる音楽 に合わせて踊る世界各地のダンサー達の姿だった。セッションを 終え、生徒たちに別れを告げたミラーはスクリーンを閉じ、せっか く彼らが投資してくれたお金と努力を無駄にしてしまったと感じて 涙を流した。

しかし、他に収入源もない夫婦はこの方法で何とかやっていく しかなかった。生徒たちが背後から彼女を観察し、動きについて いけるようにとの配慮から、まずはカメラに背を向けて立つことに した。そして何よりも、「皆の動きがシンクロするのを期待するの ではなく、一⼈ひとりを個々のダンサーとして⾒ることを学んだ」 のだという。

一度に一⼈ずつの生徒に集中することで、指の位置がずれてい たり、腰の動きが正しくなかったり、膝が十分に曲がっていない 生徒がいれば、それを指摘する。だが、そうして一⼈の生徒に声を かけると、他の生徒たちも自らそれを正そうとすることに気づい た。そこで、個別に指導しているときは、他の生徒にはスクリーン を消すように指示し、出席しているすべてのダンサーへ気を配っ ていることを伝えた。若いエンターテイナーだった頃から、ミラー は話すときにしっかりとカメラを⾒据える癖がある。そして生徒た ちにも同じように向き合った、まるで彼らの目を直接⾒つめてい るかのように。

約2年間のロックダウン期間中、彼女のパフォーマーとしての生 活は、まるで記憶の彼方に押しやられたようだった。ミラーは新た な方法でフラに打ち込み、探求に没頭した。そして新しい振付を

文 化

2019年のグランドオープン から4年後、ミラーは再び

ハレクラニ沖縄に招待され、 フラを踊った。

Four years after dancing at the hotel’s grand opening in 2019, Miller was invited back for a repeat performance at Halekulani Okinawa.

文 化

2年ものロックダウンを

終えてのステージ復帰は、 ミラーにとって感動的な ものだった。

Returning to the stage after nearly two years of lockdown was an emotional experience for Miller.

After nearly two years in lockdown, her life as a performer felt like a distant memory. The period of forced isolation enabled Miller to devote herself to the craft of hula in a new way, granting her the time to dive into research, document new choreography, and build up an archive of recorded classes. “I went down to Waikīkī twice, just to drive through,” Miller says. “I didn’t miss it at all.”

That is, until Halekulani reopened and she felt the familiar thrill of being on stage. “When the music started and I heard the live harmonies, I wanted to cry,” Miller says. “It all came rushing in: This is who I am. This is where I belong.”

An entertainer at heart, Miller is back to performing every Saturday and every other Friday in Waikīkī, though she’s far from abandoning her second love of teaching. Hula classes continue to occupy the majority of her time—and they’re all still virtual, as she’s long embraced the opportunity to share hula with audiences both near and far. “Teaching hula, you have to study the words and teach your students to express them, so you’re sharing the stories of Hawai‘i in that way too,” Miller says before signing off, ending our Zoom call to get ready for the evening’s show.

文書化し、録画したクラスのアーカイブを構築しながら過ごした。 「車で2回ほどワイキキを通り過ぎることがあったけれど、ワイキ キを恋しく思うことはなかったわ」と話す。

しかし、それはハレクラニが営業を再開し、ステージに立つとい う、あの慣れ親しんだスリルを感じるまでのことに過ぎなかった。 「音楽が始まり、生のハーモニーを耳にしたとき、泣きそうになっ たわ。すべてが押し寄せてきたの。これが私なんだ。ここが私の居 場所なのだって」

根っからのエンターテイナーであるミラー、現在は毎週土曜日 と隔週金曜日にワイキキでフラを踊っている。そして、パフォーマ ンスの次に大切にしているフラのクラスも続けている。彼女は今で もクラスに多大な時間を割いているが、長きにわたり、各地の生 徒たちとフラを分かち合う機会を育んできたので、今でもクラスは すべてバーチャルで行われているという。「フラを教えるというこ とは、言葉を勉強し、それを表現する方法を生徒に教えるという こと、そしてその取り組みを通じてハワイの物語を分かち合うこ となの」と、彼女はZOOM通話を締めくくり、今夜のショーの準備 に入るのだった。

珊瑚礁の守護者たち

GUARDIANS OF THE REEF

TEXT BY ANDY GAYLER

IMAGES BY DANIEL DENDLER & YOSHITAKA KINJO

TRANSLATION BY MUTSUMI MATSUNOBU

気候変動をはじめとする様々な脅威に直面する

沖縄の海と珊瑚を護る地元の環境保護活動家たち

In the face of climate change and other threats, local environmentalists are turning the tide to protect Okinawa’s coral-rich waters.

Growing up in Okinawa, Yukino Kinjo had always thought of herself as an ocean lover. But as with many casual beachgoers, the sea was mostly a picturesque backdrop for barbecues, sunsets, and the occasional dip in the water. Then, at age 18, she took a diving course that changed everything.

Descending below the waves, she was astonished to discover a breathtaking seascape of corals teeming with fish, crustaceans, and mollusks. The experience made her a proselytizer of the reef, eager to instill in others the same sense of wonder she felt upon encountering its vibrant splendor for the first time. “When people would tell me how beautiful it is,” she says, “it was as though they were also complimenting me.”

So it came as a shock some years later when, on a snorkeling trip to a neighboring island, a fellow diver told her the sunscreen she was applying was toxic to coral reefs. “His words haunted me,” Yukino recalls. “I love the ocean—I thought I was one of the good ones.”

She dedicated herself to researching everything she could on the subject, learning that chemicals commonly found in sunscreen—oxybenzone and octinoxate, among others—are indeed detrimental to coral health. She also found that, despite an abundance of commercially available alternatives in the West, there was relatively little awareness of the problem in Japan. Eventually, she was able to leverage her growing expertise to develop her own reef-safe sunscreen formula, launching the product Coral-friendly Sunscreen in 2017. Two years later, she followed it up with another project, Manatii,

沖縄で育った金城由希乃は、それまで自分のことを海好きな⼈間 だと思っていた。だが実のところは、一般の海水浴客となんら違わ なかったのだ。海は、バーベキューを楽しんだり、夕日を眺めたり、 たまに水に浸かるときの美しい背景でしかなかった。そのような 彼女の認識は、18歳のときに初めて受けたダイビングの講習です べて覆される。

波の下に潜ると、色とりどりの魚や甲殻類、軟体動物が生息す る美しい珊瑚の世界が広がっていた。この経験で珊瑚礁の素晴ら しさに目覚めた由希乃は、鮮やかで生命力に満ちた珊瑚礁に初め て出会ったときの感動を、多くの⼈に伝えたいと強く願うようにな る。「誰かが珊瑚礁の美しさを褒めると、まるで自分が褒められて いるかのような気持ちになるんです」と彼女は語る。

そのような由希乃だったが、数年後にシュノーケリングのため に近隣の島を訪れた際、使っていた日焼け止めが珊瑚礁に有毒で あることを仲間のダイバーから知らされ、大きなショックを受ける。 「彼の言葉が頭から離れませんでした」と由希乃は振り返る。「私 は海が大好きです。自分は海を愛する⼈間の一⼈だと思っていま した」

この問題についてできる限り調べた由希乃は、日焼け止めによ く使われる紫外線吸収剤のオキシベンゾンやオクチノキサートと いった化学物質が、実際には珊瑚の健康に有害であることを知 る。それと同時に、欧米諸国には珊瑚に優しい市販の日焼け止め 製品が豊富にあるのに対し、日本ではこの問題に対する認識自体 が相当に低いことにも気づかされた。最終的に、それまで積み上 げた専門知識を活かし、珊瑚礁に安全な独自の日焼け止め処方 を開発した由希乃は、2017年から「サンゴに優しい日焼け止め」 の製品販売を開始する。その2年後には、地元組織の協力のもと、

金城由希乃は、日焼け止めの 多くが珊瑚に有害であることを 知り、珊瑚礁の保護活動に参加 する決意を固めた。

Upon learning that many sunscreens are harmful to coral, Yukino Kinjo became a steward of the reef.

partnering with local organizations to offer beach clean-ups as an ecotourism activity for residents and visitors.

Yukino is not alone in taking a stand for Okinawa’s coral reefs. Midway up Okinawa Honto’s west coast, the mayor of Onna village declared Onna a “Village of Coral” in 2018 in a pledge to protect its famed reefs. Home to some of the island’s finest snorkeling and diving sites, Onna became the first tourist destination in Japan to adopt sustainable tourism guidelines set forth by Green Fins, an initiative of the UN Environment Programme and The Reef-World Foundation, a U.K.-based charity.

Two years after Halekulani Okinawa opened its doors in Onna village in 2019, it joined the community’s efforts to uphold Onna’s designation as a “Future City” in support of the United Nation’s Sustainable

住民や旅行者が参加できるエコツーリズム活動として、ビーチの 清掃活動を行うプロジェクト「マナティ」を始動させた。

沖縄の珊瑚礁のために立ち上がったのは、由希乃だけではな い。2018年、沖縄本島の中央部西海岸に位置する恩納村の村長 は、村の有名な珊瑚礁を保護するという誓約を立て、恩納村を「サ ンゴの村」とすることを宣言。沖縄有数のシュノーケリングやダイ ビングのスポットが点在する恩納村は、国連環境計画と英国に本 拠を置く慈善団体「リーフ・ワールド財団」が定めたサステナブル・ ツーリズム(持続可能な観光)のガイドラインを、日本の観光地と しては初めて採用した。

ハレクラニ沖縄は「SDGs未来都市」に指定された恩納村の地 域の取り組みに参加している。「珊瑚礁は海全体の面積のわずか 0.2%にすぎませんが、海洋生物の4分の1は珊瑚礁に依存してい るのです」と語るのは、ハレクラニ沖縄でサンゴや海の環境保全

「珊瑚礁は海全体の面積のわずか0.2%にすぎませんが、

海洋生物の4分の1は珊瑚礁に依存しているのです。」

国仲英純、ハレクラニ沖縄

“Only 0.2 percent of the sea is coral reef, but a quarter of all marine life depends on it.”

—Eijun Kuninaka, Halekulani Okinawa

Development Goals (SDGs) for the area, including contributing to coral reef and marine environmental conservation around the hotel. “Only 0.2 percent of the sea is coral reef, but a quarter of all marine life depends on it,” says Eijun Kuninaka, who leads the hotel’s SDG initiatives. “Coral provides nutrition to small creatures, such as shrimps and small fish, and these are food for the bigger fish, and so on up the food chain.” Unless meaningful action is taken, Kuninaka believes the world’s corals will be gone within this century—a potentially devastating blow to coastal communities that rely on coral reefs for sustenance, income, and protection, and to the countless others who benefit from the vital ecosystem services they provide.

Though experts agree that a variety of strategies are necessary to address threats to the world’s reefs, environmentally sustainable coral cultivation is one of growing interest among those in the field. Kuninaka is restructuring the program based on research by the Tropical Biosphere Research Center at the University of the Ryukyus to enhance the environmental adaptability of corals, aiming to increase the survival rate after coral transplantation. “Even if we can’t change anything in this generation, the next generation can continue [this work],” he says.

When it comes to protecting the island’s reefs for future generations, conversations often lead to one man—Koji Kinjo, who Yukino describes as “the face of coral preservation in Okinawa.” Research on Okinawa’s diverse coral reefs dates back to the mid20th century, but it was thrust to the forefront in 1998, when a severe El Niño event led to the unprecedented mass bleaching of as much as 90 percent of Okinawa’s corals and the loss of 15 percent of corals worldwide. Koji, a restaurant and shop owner at the time, was deeply disturbed at the grim sight. “I grew up with the ocean, and so I knew it when the coral was full of color, in Hi-Vision,” he recalls. “But it was like we had switched back to black and white.”

After many discouraging years of experimentation as an amateur coral farmer, Koji was successful in propagating, transplanting, and spawning coral in the wild. At Sango Batake, the coral breeding facility he went on to build on the coast of Yomitan village, Koji now educates visitors about reef ecology and has grown nearly 200,000 corals from 120 species.

に取り組んでいる国仲英純だ。「サンゴから栄養を得た海老や小 魚が、より大きな魚の餌となり、食物連鎖が続いていきます。今こ こで有意義な対策をとらなければ、世界のサンゴは今世紀中に消 滅するのではと言われている」と、国仲は懸念する。傍観している だけでは、珊瑚礁を食物源や収入源、または天然の防波堤として 頼りにしている地域社会のみならず、珊瑚礁から産み出される重 要な生態系の恩恵を受けている多くの⼈々が、壊滅的な打撃を受 ける恐れがある。

世界中の珊瑚礁への脅威に対処するには、さまざまな戦略が必 要であることに、専門家らも同意している。なかでも、この分野に 携わる⼈々の間で関心が⾼まっていることの一つが、環境に適合 したサンゴの養殖だ。国仲は、サンゴ移植後の生存率を⾼めるた めに琉球大学熱帯生物圏研究センターによるサンゴの環境適応 能力を向上させる研究をベースにプログラムの再構築を行ってい る。「たとえ私たちの世代で何も変えられなくても、次世代の⼈々に (この仕事を)引き継いでもらえます」 次世代のために沖縄の珊瑚礁を護っていこうという話題になる と、たいていある⼈物の名前があがる。由希乃が「沖縄の珊瑚保 護活動の第一⼈者」と呼ぶ金城浩二だ。多種多様な沖縄の珊瑚 礁に関する研究は20世紀半ばにまで遡るが、この研究が世界か ら注目を浴びるようになったのは、1998年の深刻なエルニーニ ョ現象により、前例のないほど大規模な珊瑚の白化現象が発生 し、沖縄の珊瑚の90%(世界中の珊瑚の15%)が失われたときだ った。当時、レストランとショップを経営していた浩二は、その悲惨 な光景を⾒て愕然とした。「私はこの海で育ったので、珊瑚がハイ ビジョンで⾒るように、とてもカラフルだった頃を知っています。 でも、それがまるで白黒テレビに戻ったかのような有様だったの です」

素⼈の珊瑚養殖家として実験を繰り返し、何年も失敗を重ねた 後、浩二はついに野生の珊瑚の繁殖、移植、産卵に成功した。浩 二は現在、読谷村の海岸に建設した珊瑚の養殖場「さんご畑」を 訪れる⼈々に珊瑚礁の生態について教育する傍ら、120種におよ ぶ20万株近くもの珊瑚を育てている。自分の養殖場を「供給セン ター」と冗談めかして呼ぶが、そこは珊瑚の実験室でもある。そし て、近年、温暖な海水域にも耐性のある珊瑚の育種において、革 新的な成果を上げている。「珊瑚は地球上で⼈間よりも長い年月 を生き延びてきました」と浩二は語る。「珊瑚には適応力があるの です」

「さんご畑」の⼈工池で再生力 の強い珊瑚を繁殖させるために 試行錯誤を重ねる金城浩二と 彼のチーム。

Koji Kinjo and his team work to breed resilient corals in Sango Batake’s artificial pond.

He jokingly calls his farm a “supply center,” but it’s also something of a laboratory—in recent years, Koji and his team have made groundbreaking headway in breeding coral resistant to warmer waters.

“Corals have a longer history than humans,” he says. “They are adapting.”

But it’s not only the corals that need to adapt, Koji says. “Our generation came to believe it’s not our fault—it’s someone else’s, so we don’t have to take responsibility or do anything about it,” he says. “If we keep that kind of attitude and do nothing, the next generation will say, ‘Our parents’ generation just experienced the good things and didn’t leave anything.’”

だが、適応力が問われるのは珊瑚だけではない、と浩二は語る。 「私たちの世代は、こうなった責任は自分たちではなく他の誰か にあるのだから、私たちが責任をとったり、何か働きかけたりする 必要はないと考えがちです」と続ける。「でも、そんな考え方のまま で何もせずにいたら、次の世代から『親の世代は自分たちだけい い思いをして、私たちには何も残してくれなかった』と言われてし まうでしょう」

珊瑚礁

波のある⾵景

SCENES OF SURF

喜びと畏敬の念と献身、地元写真家たちのレンズを 通して描き出される沖縄のサーフィン・コミュニティ

Moments of joy, reverence, and devotion within Okinawa’s surfing community come into focus through the lens of local photographers.

IMAGES BY TAKUMA CHIDA & HIDEKI ITO

沖縄にある他の多くのサー フスポットとは違い、ここ本 部は遠浅で、まるでビーチブ レイクのようなうねりが発 生する。

Unlike the vast majority of surf spots in Okinawa, the shallow waters of this one in Motobu offers up swell like a beach break.

左から反時計回り:山原のサ ーフボード・シェイパー中村 俊之が出来上がったボード の試乗へ。波に乗る息子の太 音。名護のサーフボードファク トリーG-Factoryで制作中 のボード。

前の⾒開きページ:今帰仁村 の木工職⼈の藤城徹也は、沖 縄に自生するセンダンの木か らサーフボードのフィンを彫 り上げる。

Counterclockwise from left, Yanbaru surfboard shaper Toshiyuki Nakamura takes a board out for a test ride; his son, Tao, rides a wave; a work in progress at G-Factory, a surfboard factory in Nago. On the previous spread, woodworker Tetsuya Fujishiro of Nakijin village carves a surfboard fin from Okinawa’s native sendan (chinaberry) tree.

「私のサーフィンの写真は技術よりも感情や気持ち が先にきます。何も考えずにただ波に乗るんです。」

伊藤秀樹、写真家

“ My surf photography is more about emotion and mood than technique. I just ride the wave without thinking.” —Hideki Ito, photographer

アナログの島

ISLAND IN ANALOG

TEXT BY LANCE HENDERSTEIN

IMAGES BY LANCE HENDERSTEIN & KAROLA MECH

伝統的な西表島の生活に魅入られ、写真家が⾒つけた

インスピレーション

Immersed in the island’s traditional way of life, a photographer finds a muse in Iriomote.

It's hard to deny the inexplicable energy that exists on Iriomote. Part of the island’s magnetism lies in its mesmerizing landscape of mountainous jungle and dense mangroves, its miles of sandy coastline, meandering inlets, and pristine coral reefs. With such undeveloped wilderness throughout the region, it’s no surprise that nature is an inextricable part of Ryūkyūan culture, which remains deeply rooted on Iriomote despite an aging population of elders and a long history of weathering cultural hegemony of China, the United States, and Japan.

And with access limited to boat or ferry from Ishigaki island, there is also Iriomote’s profound sense of seclusion. In my limited visits to Iriomote as a writer and photographer, once in 2017 and again in 2023, I tried to evoke the palpable feeling of isolation that permeated my experience as a visitor there, but it’s a

西表島には不思議なエネルギーが流れている。巨大な密林や鬱 蒼としたマングローブの林、何キロメートルも続く砂浜の海岸線、 曲がりくねった入り江、手つかずの珊瑚礁といった⾵光明媚な自 然景観には、⼈を惹きつけてやまない魅力がある。このような未開 発の土地が島全域に広がっていることを考えれば、琉球文化と自 然が切っても切れない関係にあるのは当然のことと納得できる。

住民の⾼齢化や、中国やアメリカそして日本による文化的支配を 乗り越えてきた長い歴史にも⾵化されることなく、西表島にはい まも琉球文化が深く根付いている。

島へのアクセスが石垣島からの船かフェリーに限られるのも、 秘境感を⾼めている。私は2017年と2023年に文筆家兼写真家 としてこの島を訪れ、限られた経験ながらも、実際に訪れた者の みが肌で感じることのできる隔絶感を呼び覚まそうと試みたが、

西表島

place that requires much more than a few visits to fully grasp. Polish-born photographer Karola Mech felt that power and an immediate connection to Iriomote during her first visit to Okinawa in 2016 and stayed, making it her home and the subject of her photographic practice.

“I loved Iriomote instantly. I felt like, this is it, this is my place,” Mech recalls. “On the last day, I found out about WWOOF-ing (Worldwide Opportunities on Organic Farms) and thought, ‘This is perfect. I can stay for three months, live with the locals, and in my free time I can take photos.’”

Mech returned for good in 2019 and now lives in the small Iriomote village of Hoshidate, where she works as a cultural guide for visitors to the island. She has made treasured memories through attempts at a more traditional lifestyle on Iriomote—once sharing rice-farming duties with her Hokkaido-born husband. “My husband borrowed the field from our next-door neighbor, Ojīchan (Grandfather),” Mech says. “Rice is a big part of the culture here. There is some machinery to thresh the rice afterward, but it’s all grown by hand.”

When she’s not guiding guests for her tour experience, Cultural Walk Iriomote, Mech is busy building an impressive body of work documenting the culture, traditions, and people of Iriomote. Her time invested in the community as a local resident has allowed her to gain access to private Ryūkyūan rituals and ceremonies on Iriomote and the surrounding Yaeyama and Miyako islands.

It’s an ongoing project that continues to evolve the longer she lives on the island. Her desire to explore the essence of Ryūkyūan beliefs first led her to photographing religious rites on Iriomote, but she has since taken to examining other aspects of life on the island through various mediums, including capturing audio recordings of interviews, songs, and sounds in nature.

“I had some concept in the beginning about the role of women in society because Okinawan religion is matriarchal and led by women. I wanted to investigate that, but the project has grown to include more aspects, like the Ryūkyūan languages and the Iriomote dialect, which are disappearing,” Mech says. “But I’m still fascinated by the Ryūkyūan religion, which is ancient and beautiful. It’s all intuitive—I’m following my interests here.”

Long-term documentary photography is inherently an exercise in delayed gratification, but even more so as Mech practices it: using a Rolleiflex camera and

この島のことを完全に把握するには数回訪れただけでは足りない ようだ。ポーランド生まれの写真家、キャローラ・メッチが初めて 沖縄を訪れたのは2016年。西表島のもつエネルギーに自分との 直接的な繋がりを感じたメッチは、そのまま西表島に住み着き、 島をテーマにした写真を撮り続けている。

「訪れてすぐに西表島が大好きになりました。ここだ!この島 が私の居場所だ、と感じたのです」とメッチは振り返る。「滞在最 終日に、WWOOF(世界中の有機農場に無償で滞在しながら農 場を手伝いたい⼈と農家を繋ぐサイト)について知り、『これは完 璧だ』と思いました。3か月間島に滞在して、地元の⼈々と一緒に 暮らし、自由時間には写真を撮れるのですから」

結婚を機に2019年に日本に戻ったメッチは、現在は西表島の 星立という小さな集落に住み、島を訪れる旅行者のための文化ガ イドとして働いている。より伝統的な島の生活を送ることで、大切 な思い出をいくつも作れたと話す。北海道生まれの夫と共に、稲 作に挑戦したこともあった。「夫が隣家のおじいちゃんから田んぼ を借りたのです」とメッチ。「島の文化では、米が重要な地位を占 めています。稲を脱穀する機械はありますが、耕作はすべて手作 業です」

自身がガイドを務める体験ツアー「カルチュラル・ウォーク・イリ オモテ」で旅行者を案内していないとき、メッチは西表島の文化 や伝統そして⼈々を記録するために、島中を飛び回っている。地 元住民として地域社会に貢献している彼女は、西表島や周囲の八 重山諸島そして宮古島で行われている琉球古来の民間儀式や祭 典に参加することを許されている。

この記録プロジェクトは現在も進行中で、その内容は彼女が島 に長く住むにつれ充実し続けている。琉球における信仰の本質を 探求したいという願望から、初めのうちは西表島の宗教儀式をカ メラに収めていたメッチだが、徐々にインタビューや歌そして自然 界の音の録音など、さまざまな媒体を使って、宗教以外の島の生 活についても調査するようになった。「沖縄の宗教は女性主導の 母系制のため、最初のコンセプトは沖縄社会における女性の役割 についてでした。けれども調査を続けるうちに、このプロジェクト は失われつつある琉球語や西表方言など、より多くの様相を含む ようになりました」とメッチは語る。「とはいえ、いまでも私は古く て美しい琉球の宗教に魅了されています。すべてにおいて直感的 に、自分が興味をそそられることに素直に従うようにしています」

写真家のキャローラ・メッチが撮影したスディナのディテールシ ョット。スディナは西表島をはじめ八重山諸島の女性が祭りで着 る伝統衣装。

Photographer Karola Mech composes a detail shot of a sudina, a traditional garment worn on festive occasions by the women of Iriomote and other Yaeyama islands.

西表島行きフェリーでの静かなひとときを 文筆家兼写真家のランス・ヘンダーステイン が撮影。

Writer and photographer Lance Henderstein documents a quiet moment on the ferry ride to Iriomote.

analog film. “I will always remember the first time I entered a darkroom—the red light, the dripping water. It was silent, dark, and smelled of chemicals,” Mech says. “To see a complex photograph appearing in the tray was magical.”

Each photograph is an investment of great effort and expense—an act of faith in one’s artistic vision, and in the value of light and instinct as a conduit for interpreting fleeting moments. “I have the same feeling [as that first time in the darkroom] when doing cyanotypes now,” Mech says, referring to the 19th-century printing process that employs light-sensitive chemicals to produce monochrome images in a distinctive blue hue. “After exposing the paper with the blueprint chemicals, the photo appears while it is immersed in water. The magic of a blueprint is that every single one is different, and I never know how it will come out.”

But the thrill of analog photography comes at a price, especially in a place like Iriomote, where Mech must contend with the possibility of losing precious images of local rituals and religious ceremonies— rare windows into a world she has spent years seeking to immortalize in images. “Analog photography

長期的なドキュメンタリー写真の撮影は、本質的に成果を得ら れるまでに時間がかかるものだが、ローライフレックスという昔の 二眼レフカメラとアナログフィルムを使用するメッチの場合は、さ らに手間がかかる。「初めて暗室に入ったときの、赤い光と滴る水 のことをいまも覚えています。静かで暗くて、化学薬品の匂いが漂 っていました」とメッチは語る。「現像液のトレイに浸した印画紙 から、複雑な写真が浮き出てくるさまは魔法のようでした」 彼女の写真の一枚一枚には、多大な労力と時間が投じられてい る。それは、写真家が自身の芸術的ビジョンを信じ、光と勘を頼り に、ある瞬間を表現しようとする行為にほかならない。「いまはシ アノタイプ(青写真)を制作するときに、(初めて暗室に入ったとき と)同じような気持ちになります」とメッチは語る。青写真は、感光 性の化学薬品を使用して独特の青い色合いのモノクロ画像を作 り出す19世紀の印画技術だ。「青写真用の薬品で感光紙を露光 した後、水に浸すと画像が現れます。青写真の魅力は、一枚一枚が 異なり、出来上がりがどのようになるか予想がつかないことです」 とくに西表島のような場所ではそうだが、アナログ写真の制作 には、しばしば代償が伴う。彼女が何年もかけて記録し、永遠に残

(左ページ)織物作家兼染色家の石垣昭子の青写真。

(右ページ)西表島の祖内という集落で行われる節祭(しち)に 登場するフダチミという全身黒装束を纏った女性の青写真。

Pictured above and on the opposite page are cyanotypes of master weaver and dyer Akiko Ishigaki and a disguise inspired by fudachimi, a figure unique to the Shichi festival held in the Iriomote village of Sonai.

新 し い 何 か を 探 し て

メッチは、西表島に住む

⼈々の内なる世界を深く

掘り下げる。

Mech seeks a deep understanding of the inner worlds of those living on the island.

is much more hazardous than digital,” Mech says. “Negatives can get light leaks during loading and unloading, storing and developing. They can be damaged in transport or in the fridge if the power is off during a typhoon. Making mistakes during development creates irreversible damage.”

Despite the inherent challenges of such an unpredictable medium, there are moments that have reaffirmed her creative path on Iriomote, making it that much more rewarding when all the elements come together. The first time Mech exhibited her cyanotype photographs at a craft market on Iriomote, an Okinawan elder began to weep at the sight of one of the images. The print, rendered in cyan blue, depicted a tsukasa (Okinawan priestess) in prayer, just as the elder’s own mother, who had also been a priestess, had done when she was alive. “Her tears were the best praise I could have received,” Mech says. “They let me know that what I am doing here makes sense.”

そうとしている島の祭式や宗教的儀式への入り口となる貴重な画 像は、決して失いたくないものだ。だが、「アナログ写真はデジタル 写真よりもはるかに厄介なのです」とメッチは語る。「ネガフィルム は、カメラに装填するときや取り出すとき、保管時、現像時にも感 光してしまう恐れがあります。また、空港のX線検査や、台⾵でフ ィルムを保管していた冷蔵庫が停電して駄目になることもありま す。現像中にミスをすると、それこそ取り返しのつかないダメージ を被ります」

このように予測のつかない媒体特有の課題はあるものの、西表 島での創作活動の方向性を再認識する瞬間もあり、すべての要素 が形になると、さらにやりがいを強く感じられるという。メッチが 西表島のクラフトマーケットで初めて青写真を展示したとき、一 枚の写真を⾒た沖縄の老⼈が泣き始めた。シアンブルーのその写 真には、司(沖縄の巫女)が祈りを捧げる姿が写っていたが、その 老⼈の母親も生前そうやって祭祀をとり行っていたのだという。「 彼女の涙は、私にとって最⾼の賞賛でした」とメッチは語る。「ここ で私がやっていることは、意味があるのだと気づかせてくれたので すから」

ハレクラニ沖縄 Living

沖縄・恩納村の美しい海辺に開業した ハレクラニ沖縄はこの神秘の楽園アイランドがもつ 自然のエネルギーと、最⾼峰のラグジュアリーを 融合させた唯無二のリゾートです。

Located along the beautiful coastline of Onna Village in Okinawa, Halekulani Okinawa is an unrivaled resort that seamlessly combines the natural energy of this mystical paradise with the pinnacle of luxury.

ダイニング

DINING

最先端の美食を堪能できるガストロノミーダイニング から、プールサイドで気軽に美味を味わえるプールバー まで、4つのシグネチャーレストランとバーを擁します。

We offer four signature restaurants and bars, ranging from gastronomic dining that serves cutting-edge cuisine to a poolside bar where you can casually enjoy delicious food.

Innovative “SHIROUX” is helmed by Chef Hiroyasu Kawate, one of the leading chefs in the Japanese culinary scene, serving as a consulting chef. As the owner-chef of Michelin two-star restaurant Florilège in Tokyo, which ranked 27th on the list of the World’s 50 Best Restaurants in 2023, Chef Kawate brings a culinary expertise that has captivated food enthusiasts worldwide. The dining experience at Innovative “SHIROUX” continues to evolve through collaborations with local Okinawan producers.

イノベーティブ「SHIROUX/シルー」は、日本の美食界を牽 引するシェフのひとりである川手寛康がコンサルティングシェフ を務めます。東京のミシュラン2つ星レストラン「フロリレージ ュ」のオーナーシェフであり、2023年「世界のベストレストラン 50」において27位に選ばれるなど、世界の食通たちを魅了して いる川手氏の料理の世界観が、地元沖縄の生産者とのコラボレ ーションにより進化をし続けているダイニングです。

イノベーティブ「シルー」

INNOVATIVE “SHIROUX”

ハレクラニ沖縄で味わうイノベーティブな食体験

Experience innovative culinary delights at Halekulani Okinawa.

White sandy beaches, white waves breaking onto the shore, and white clouds billowing in the sky— Shiroux, meaning “white” in the Okinawan language, is where the delicate culinary world of Chef Hiroyasu Kawate meets the food culture of Okinawa.

The innovative French cuisine adds a fresh interpretation to local ingredients while maintaining a menu structure that is sustainable and minimizes food waste. We offer a luxurious wine pairing featuring meticulously selected fine wines and mixology cocktails to perfectly match your meal. Enjoy a one-of-a-kind dining experience that combines innovative cuisine with seasonal tasting menus and paired cocktails to add an elegant touch.

白砂のビーチ、打ち寄せる白波、湧き立つ白雲、沖縄の言葉で 「白」を意味する「シルー」。ミシュラン二つ星、東京「フロリレー ジュ」のオーナーシェフ川手寛康氏がコンサルティングシェフを 務めるダイニングは、シェフの繊細な料理の世界感と沖縄の食 文化が出会う場所です。

沖縄の食材に新たな解釈を加えるフレンチをベースとしたイノ ベーティブな料理は、食材を無駄にしないサステナビリティを意 識したメニュー構成です。料理に合わせたミクソロジーカクテル や、上質なワインをセレクトした贅沢なペアリングドリンクをご 用意しています。季節ごとに変わるコースメニューに華を添える ペアリングカクテルと、イノベーティブな料理が融合したここで しか味わうことのできない食体験をご用意しています。

HALEKULANI OKINAWA ESCAPES

沖縄独自の生活を体験「長寿の知恵」

Experience the unique lifestyle of Okinawa and its “Secrets of Longevity.”

The hotel offers five “Halekulani Okinawa Escapes” programs in which guests can experience “the island of longevity,” which has gained attention worldwide for its traditional lifestyle and dietary habits.

“Discover the Island’s Umui (Spirit)” and “Discover the Island’s Mabui (Soul)” are two programs where guests can experience the secrets of longevity, developed by Halekulani Okinawa in partnership with Dr. Masashi Arakawa, Ph.D., at the University of the Ryukyus.

To “Discover the Island’s Umui (Spirit),” guests engage in the practice of mindful wellness, reflecting on their past and present, and savor meals deeply rooted in the concept of “food as medicine,” derived from our local culinary traditions.

To “Discover the Island’s Mabui (Soul),” guests enjoy a wellness experience that teaches the fundamental “kata” of karate, a martial art with a rich history dating back to the Ryūkyū Kingdom era, which is also integrated as a health practice in daily life. Wrap up your day with a healthy meal and a spa treatment infused with traditional Okinawan ingredients.

ハレクラニ沖縄では、伝統的な生活や食習慣などの理由が解明 されつつある、ブルーゾーンの一つとして世界的に注目されてい る“長寿の島”である沖縄を体感いただける「ハレクラニ沖縄エ スケープ」として5つのプログラムをご用意しています。

ウェルネス研究の第一⼈者、琉球大学の荒川雅志医学博士 監修による、沖縄の「長寿の知恵」の秘密を体験することができ る「この島の想い(うむい)に触れる」「この島の魂(マブイ)に触 れる」のふたつのプログラムがあります。

「この島の想い(うむい)に触れる」では、ご滞在中にホテル外 で自身の過去・現在を⾒つめ、未来を創造するマインド・ウェルネ スの実践と医食同源に根付いたお食事をご堪能いただけます。

「この島の魂(マブイ)に触れる」では、琉球王国時代から盛ん な空手の歴史と日常生活で健康法として取り入れることができ る基本の”型”を学び、ヘルシーなお食事や沖縄の食物を取り込 んだスパトリートメントで一日を締めくくるウェルネス体験をお 楽しみいただけます。

HALEKULANI OKINAWA ESCAPES

神秘的な沖縄の美しさを体験

Experience the mystical beauty of Okinawa.

“Discover the Island’s Glow” and two new programs, “Connect with Nature in Yanbaru” and “Wade Through the Waters of Yanbaru,” are three precious experiences, sure to delight even the most discerning travelers.

Guided by a local naturalist, guests “Discover the Island’s Glow” with an excursion into the Yanbaru National Park shortly before sunset. After climbing in a kayak and paddling through mangrove trees, guests will witness a dazzling display of twinkling fireflies, creating a truly enchanting ambiance and unforgettable experience. This program is available from July through September, making the excursion even more unique and exclusive.

Available exclusively to guests of Halekulani Okinawa, “Connect with Nature in Yanbaru” and “Wade Through the Waters of Yanbaru” are unique private excursions that encourage travelers to harness the healing power of nature while exploring Yanbaru, one of Japan’s newly recognized UNESCO World Natural Heritage Sites.

神秘的な沖縄の美しさを堪能する「この島の自然の輝きに触れ る」、最新プログラム「やんばるの自然の息吹(いぶき)に触れる」 と「やんばるの清らかな水界に触れる」は、エリートトラベラーた ちをも満足させる珠玉のウェルネス体験プログラムです。 沖縄の北部は“山原(やんばる)”と呼ばれ、多様で固有性の⾼ い生態系を有し、絶滅危惧種の生息地として世界的に重要であ ることが評価され、2021年にユネスコ世界自然遺産へ登録され ました。

7月~9月の期間限定で体験できる「この島の輝きに触れる」 では、日没前にやんばる国立公園からカヤックに乗り、蛍が多く 生息する秘密のスポットを訪れて自然に触れていただけます。

「やんばるの自然の息吹(いぶき)に触れる」と「やんばるの清 らかな水界に触れる」では、“やんばる(山原)”を舞台に、豊かな 沖縄の大自然に抱かれながら心と身体を開放し、素晴らしい“癒 し”を体験していただける特別なプログラムです。ここ「ハレクラ ニ沖縄」でしか体験できないこの魅力的なプログラムの数々をご 堪能ください。

ワイキキビーチに建つハレクラニの旗艦ホテルは、 1883年、最初のオーナーであるロバート・ルワーズが 現在の本館がある場所に二階建ての家を建てたとき

から多くの⼈々を迎えてきました。

Halekulani’s flagship location on Waikīkī Beach has welcomed people since 1883, when the original owner, Robert Lewers, built a two-story house on the site of what is now the main building.

The fishermen of the area would bring their canoes onto the beach in front of the property to rest. So welcomed were they by the Lewers family that the locals named the location “house befitting heaven,” or Halekulani.

In 1917, Juliet and Clifford Kimball purchased the hotel, expanded it, and established it as a stylish resort for vacationers, giving it the name the locals originally bestowed on it, Halekulani. The hotel was sold following the passing of the Kimballs in 1962. Almost 20 years later, it was purchased by what is now the Honolulu-based Halekulani Corporation. The hotel was closed and rebuilt as the existing 453-room property.

Today, Halekulani’s staff, location, and hospitality reflect the original Hawaiian welcome that defined the property.

ルワーズ一家が、邸宅前のビーチにカヌーを引き揚げて休憩する ワイキキの漁師たちを歓迎したことから、地元の⼈たちはこの場 所を「天国にふさわしい館」という意味のハレクラニと呼ぶように なりました。

1917年にジュリエット&クリフォード・キンバル夫妻によって 購入、拡張されたこのホテルは、旅行者のための洗練されたリゾー トとして生まれ変わり、地元の⼈たちによってつけられた「ハレク ラニ」と命名されました。1962年、キンバル夫妻の死去を機に売 却されたホテルは、ほぼ20年後、現在ホノルルに拠点のあるハレ クラニ・コーポレーションによって購入され、一時閉館すると、改 築工事を経て、現在の453室あるハレクラニに生まれ変わりまし た。

ハレクラニでは、歴史あるワイキキのビーチフロントで、現在も 昔と変わらないハワイならではのおもてなしの心で、スタッフ一同 お客様をお迎えいたします。

HALEKULANI BOUTIQUE

ご自宅でもハレクラニ沖縄をお楽しみください

Feel Halekulani at home.

Discover a diverse array of curated items that encapsulate the spirit of Halekulani Okinawa. From the moment you wake up with a delightful breakfast that lifts your spirits to the luxurious comfort of a good night’s sleep, we deliver the enchanting moments of Halekulani Okinawa to your home.

ハレクラニ沖縄のこだわりがたっぷり詰まったアイテムを豊富にセレクト。 気分が華やぐ朝食のひとときから、上質な肌ざわりに包まれる眠りの瞬 間まで、ハレクラニ沖縄での心ときめく時間をご自宅にお届けいたします。