There is a sense of ease that comes with life in Hawai‘i. Like returning home after a long time spent away, Hawai‘i offers its residents a source of familiarity and respite that is reminiscent of being swaddled in a warm blanket on a chilly night.

This welcoming environment is exemplified in the residences developed by The MacNaughton Group and Kobayashi Group, as well as in this edition of PALM. In its pages, we invite you to rediscover some of O‘ahu’s most familiar sights. Walk the streets of urban Honolulu. Explore the resort center of Waikīkī. Discover its old breezeways and balustrades, the familiar sounds of waves lapping at the shore, and decades’ worth of architectural and design history.

Hawai‘i’s ever-present natural beauty is a source of constant inspiration and innovation for those who live here. In artist Taiji Terasaki’s work, the northwest corner of O‘ahu helped convey fragile ecosystems in danger of disappearing. The ocean provided scientist Alan Friedlander the backdrop for pioneering work on declining populations of reef fish. The islands’ pristine weather set the stage for Hawai‘i to become a national leader in sustainable energy.

Stories like these encourage closer looks at places we may pass by every day. For it is in these intricate nooks of island life that we find the comforts of home.

ハワイでの暮らしには、心地良い軽やかさがあります。ちょうど、 長い間留守にしていた家に帰って来た時に感じるような、ほっと する心持ちです。肌寒い夜に温かな毛布に包まれる時の気持ち にも似ているかもしれません。

この快い環境は、ザ・マクノートン・グループとコバヤシ・グ ループの作るレジデンスにも、そして今号のPALMマガジンにも 表現されています。今号では皆様をオアフ島のもっとも見慣れ た風景を再発見する旅へご案内します。ホノルルの街角を歩き、 リゾートの中心地、ワイキキを新しい視点で探検してみてくださ い。古いポーチや手すりのある建物、打ち寄せる波の音、そして 何十年もの間にさまざまに移り変わってきた建築とデザインの 歴史をお楽しみください。

どの時代にも常に、ハワイの豊かな自然美がここに住む 人々のインスピレーションの源となってきました。アーティスト、 タイジ・テラサキさんの作品には、危機に直面している繊細な生 態系がオアフ島北西部の風景の中に表現されています。科学者 のアラン・フリードランダーさんにとっては、ハワイの海はサンゴ 礁の魚たちの生息環境を研究する貴重な場所です。また、この 地の恵まれた天候が、ハワイをサステイナブルなエネルギー推 進のリーダーにしています。

こうしたストーリーを知ると、毎日何気なく通り過ぎてい る場所もより注意深いまなざしで見たくなります。この島のあち こちに散らばる繊細で入り組んだ小さな断片が、私たちの心地 良いホームを作り出しているのですから。

10 LETTER From the Developer

CEO & PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER & EDITOR

Lisa Yamada-Son lisa@nellamediagroup.com

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Ara Feducia

MANAGING EDITOR

Matthew Dekneef

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Anna Harmon

PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR

John Hook

TRANSLATIONS Japanese Yuzuwords

Korean AT Marketing

COPY EDITOR

Andy Beth Miller

MEDIA

Gerard Elmore

Lead Producer

Kyle Kosaki

Video Editor

Shaneika Aguilar

Junior Video Editor

Aja Toscano

Network Marketing Coordinator

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley

Group Publisher

mike@nellamediagroup.com

Francine Naoko Beppu

Network Strategy Director Francine

Chelsea Tsuchida Marketing & Advertising Executive

Kylee Takata Advertising Coordinator

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock Chief Revenue Officer

Gary Payne VP Accounting

Courtney Miyashiro

Operations Administrator

PUBLISHED BY:

Nella Media Group

36 N. Hotel St. Ste. A Honolulu, HI 96817

PALM is published exclusively for:

The MacNaughton Group & Kobayashi Group © 2018 by Nella Media Group, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted without the written consent of the publisher. Opinions are solely those of the contributors and are not necessarily endorsed by Nella Media Group.

12

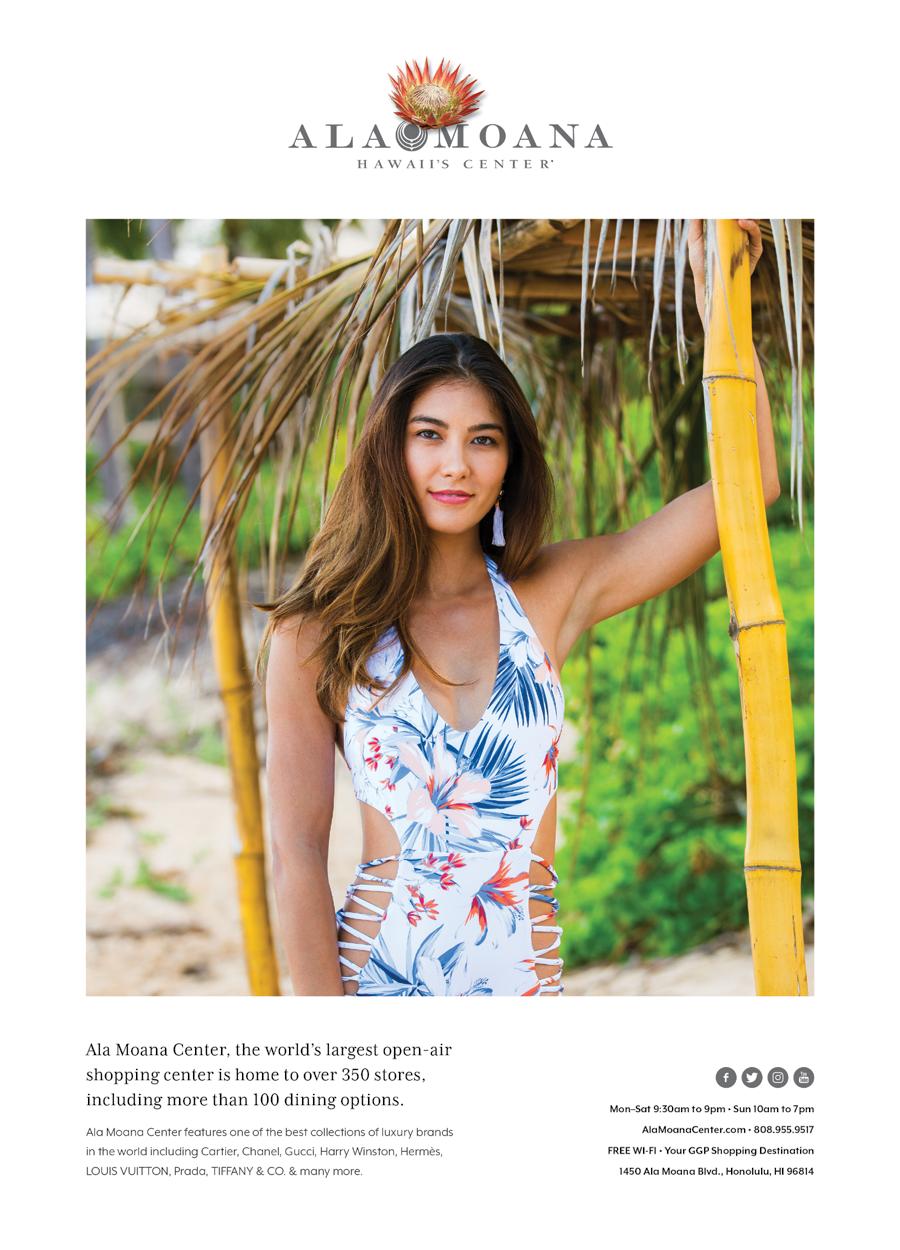

The cover image, photographed by Mark Kushimi, features model Tejas Tevari wearing a vintage silk handkerchief, wool jacket, Italian collar dress shirt, and high waisted chelsea pants, all from Hermès.

14 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTS 20 Through the Mist BUSINESS 32 Winds of Change 40 Real to Reel CULTURE 52 Cultural Kīpuka DESIGN 66 Weird, Wacky, Waikīkī 82 A Checkered Past 96 Fashion: It’s a Breeze ESCAPES 116 Island of a Thousand Rituals: Bali 126 Escaping East of Town FARE 140

and

96 126 ON

COVER

Tradition

Bounty

THE

表紙:

(表紙)写真:マーク・クシミ、モ デル:テイジャス・テヴァリ。シルク 地ハンカチーフ、ウール地ジャケッ ト、イタリアンカラーのドレスシャ ツ、ハイウェストのチェルシーパン ツ:すべてエルメス)。

アート 20

靄の向こうに ビジネス 32

変化の風 40

ハワイで映画を

文化 52

文化のキプカ デザイン

66

奇妙でレトロなワイキキ

82

格子縞の物語 96

ファッション エスケープ

116

千の儀式が生きる島

126

楽園の東 食 140

海と山の幸

16 目次 96 66

Visual that amplify

notions

AR TS

A PALM アート

CUL TU RE

of place that A sense fosters the human spirit

the soul of the city

PALM PALM A

19

Through the Mist

靄の向こうに

Text by Martha Cheng

文 = マーサ・チェン

Images by AJ Feducia

写真 = AJ・フェデュシャ

Artwork images courtesy of Taiji Terasaki

作品画像 = タイジ・テラサキ氏提供

20 A ARTS Taiji Terasaki PALM

Taiji Terasaki’s work reflects the fragility of life, both real and imagined.

タイジ・テラサキさんの作品は、現実の世界でも夢幻の世界でも出会う生命のはかなさを表現しています。

On a quiet street off Kalaniana‘ole Highway in ‘Āina Haina, Taiji Terasaki’s studio rises above the surrounding low-slung homes. From the sidewalk, all that is visible of it are tall panes of glass capped by a roof with one end angled toward the sky and the other end tethered by cables, as if it was a sail lashed to a boat. The structure is like the artist’s installations: rich in details yet spare in aesthetic. It is also a physical manifestation of conservation and agriculture, the topics Terasaki has been turning over in his mind lately. At the entrance of Terasaki’s studio grow breadfruit and sugarcane with stalks so dark purple they are almost black. A bee nestled in the crack of the gate flaps its wings unceasingly, as if excited to tell that there is more behind the door. And there is. The liliko‘i vine-wrapped cables stretching from the roof are revealed to be part of Terasaki’s aquaponics system, in which taro, water spinach, liliko‘i, and other plants feed directly on the waste of tilapia raised in a pond below the plant beds.

PALM

カラニナオレ・ハイウェイを外れたアイナハイナの静かな住宅街に建つタイジ・ テラサキさんのスタジオは、まわりの家々の屋根の上にひときわ高く聳え立って います。歩道から見えるのは、背の高いガラス張りの壁と、一方を空に向け、片方 はケーブルで地面に繋がれた、まるでヨットに張られた帆のような屋根だけで す。この建物も、テラサキさんのアートと同じく、行き届いた豊かなディテールを 持ちながらもゆったりとした空間を感じさせます。またこの建物は、テラサキさ んが近年熱心に取り組んでいる、環境保護と農業というテーマを体現するもの でもあります。

スタジオの入り口にはブレッドフルーツの木と、ほとんど黒に見えるほど濃 い紫色の茎を持つサトウキビが植えられています。門扉のひび割れの中にミツバ チが1匹せわしなく羽ばたいていました。まるで扉の後ろにあるものを見せたくて たまらないというかのよう。たしかに見るべきものが隠れていました。屋根から伸 び、リリコイのつるが絡みついているケーブルは、テラサキさんが設置した水耕 栽培システムの一部だったのです。このシステムで、タロ、水菜、リリコイ、その他 の作物が育てられています。水はその下にあるティラピアの養殖池から直接取り

22 A ARTS Taiji Terasaki

Surrounding the studio are food crops that grow well in Hawai‘i, such as māmaki and moringa. The landscaping is based on principles of agroforestry, and edible plants are grown in layers and canopies.

While his studio’s precise angles manifest in glass, smooth concrete, and pale wood, the works Terasaki creates in the space have a softer quality, which is lent to them by mist. Recently, he has been playing with what he calls “mist-based photography.” In his studio, he uses a water vaporizer to create a thin screen of mist onto which he projects an image. He manipulates the image by running his hand through or blowing on the vapor to create different patterns, and then he photographs the results. The recursive process results in hazy images, like the recollection of a dream within a dream.

Terasaki has always been drawn to this suspended element in his artwork. His first art project while pursuing an MFA at Hunter College in New York City was an installation of large sticks and clear plastic in a swamp. “The main thing was that it became part of the mist and the landscape that was there,” says Terasaki, who graduated from Hunter College in 1985. He took a photograph of it, and this became the art piece.

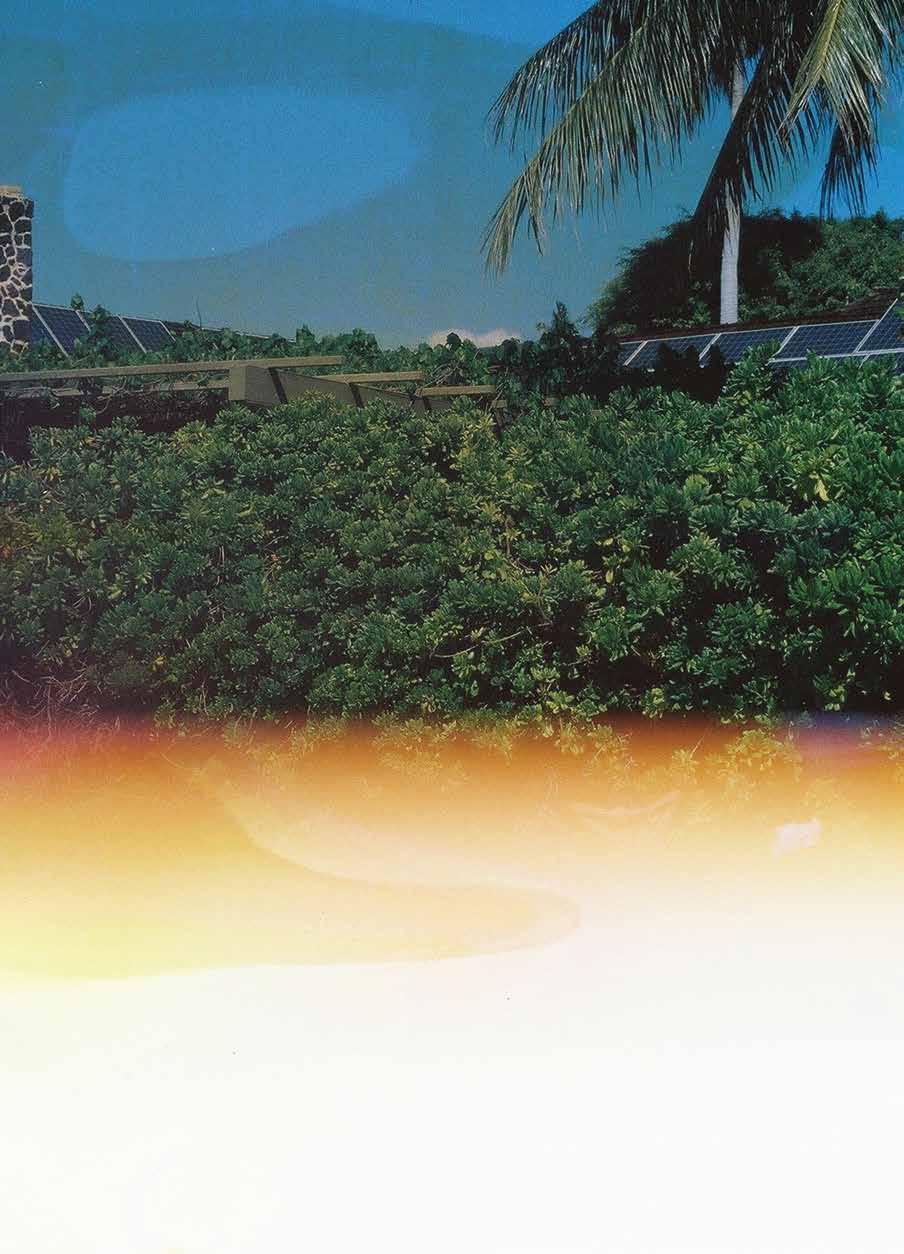

In his latest installation, Mist Over Kaena Point, which was showcased at T Galleria in Waikīkī in April 2018, Terasaki captured gauzy images of the coastline that juts sharply out of the northwestern corner of O‘ahu. He did so, he says, “to convey the state of our environment in many places that are in danger of disappearing.”

When he started the project, the artist knew he wanted to depict the fragility of places like Hawai‘i in the face of climate change. He visited sites around the state and decided on Ka‘ena Point when confronted with its physical and cultural richness. “As a nature preserve, there’s plenty of wildlife, both animal and plant, that you just don’t normally see,” Terasaki says. “And it has a lot of Hawaiian history there. … There are so many myths and legends in that area. All the culture, all the ideas that are in that piece of land, that was really important to me.”

Prior to Mist Over Kaena Point, Terasaki created an exhibition called Feeding the Immortals to honor his father, a pioneer in organ transplant medicine who died in 2016. It included mist-based photographs as well as structures resembling butsudan, shrines where the living would leave food offerings for the dead. With the death of his father, he realized, “There isn’t really a culture of grieving. I haven’t been so much for organized religion, so in a crisis like parents dying, how do you deal with it? I don’t want to believe that life just stops.”

Feeding the Immortals became a ritual that helped Terasaki through the grief. He also invited anyone to bring a food reminiscent of a deceased loved one and

込まれています。スタジオの周りには、ハワイの気候でよく育つママキやモリンガ といった作物が植えられています。ランドスケープは自然と共生する農業「アグロ フォレストリー」の原理に従って構成され、食用植物がいくつもの層をなして栽 培されています。

スタジオの建物はガラス、なめらかなコンクリート、明るい色合いの木材 を使い、精緻な角度を作り出していますが、テラサキさんがここで制作するのは 柔らかな風合いを持つ作品。それは靄の中から生まれてきます。このところ、テラ サキさんは「ミスト(靄)ベースの写真」と名づけた作品作りに取り組んでいます。 まず、スタジオ内に設置したミストの発生装置を使い、薄い水蒸気の幕を作りま す。そしてその水蒸気に映像を投射し、さらに息や手の動きでその蒸気の幕をか き乱して異なるパターンを作り、それを写真におさめていきます。この再帰的な 手法によって、もわっと霞んだ、夢の中で思い出そうとしている夢を描いたかのよ うな不思議なイメージが出来上がります。

テラサキさんは、これまでの作品の中でも常にこうした霧のような要素に 惹かれていました。ニューヨークのハンターカレッジで美術修士取得に向けて学 んでいた時の最初のアートプロジェクトは、沼地に設置した大きな杭と透明なプ ラスチックのインスタレーション作品でした。「作品のポイントは、それが沼地の 霧と風景の一部になるということでした」とテラサキさんは説明します。そのイン スタレーションのようすを収めた写真も、アート作品となりました。

最新のインスタレーション「Mist Over Kaena Point(カエナ岬の靄)」で

は、オアフ島の北西端の海に鋭く突き出ている海岸線を柔らかに包む靄の風景 を捉えています。この写真は2018年4月、ワイキキのTギャラリアに展示されまし た。テラサキさんはこれらの作品で「消滅の危機に瀕しているさまざまな場所で 環境がどのような状態に置かれているのかを伝えたいのです」と語っています。

このプロジェクトに着手した時、テラサキさんは、ハワイのような場所が気 候変動の前にどれほど影響を被りやすいかを描きたいと考えていました。州内の さまざまな場所を訪ねた後、その景観と文化上の豊かな意義から、カエナ岬を 題材とすることに決めました。「自然保護区域ですから、ほかではあまり見ること のない野生の動物も植物も豊富です。そして、たくさんのハワイの物語がある場 所でもあります。実に多くの伝説を持つ場所なのです。そういった文化のすべて、 そしてその土地の一部となっているあらゆる事柄が、私にとってはとても重要だ ったのです」とテラサキさんは説明します。

「カエナ岬の靄」に先がけて、テラサキさんは「Feeding the Immortals (不滅の者たちへの供え)」と題した展覧会を構成しました。この展示は、2016 年に亡くなった彼の父(臓器移植手術のパイオニアでした)を讃える意味が込め られていました。展覧会には、ミストをベースとした写真と、仏壇に似た立体作品 が展示されました。仏壇は、生きている者が死者のために食べものを供える場 所でもあります。父の死に直面したテラサキさんには気づいたことがありました。 「嘆くための文化というものを私たちは持たないのです。私は組織的な宗教と はほとんど無縁でした。肉親の死といった危機に直面して、どのように対処した ら良いのでしょうか。人の生命が単に終わってしまうとは信じたくないのです」と テラサキさんは語ります。「不滅の者たちへの供え」を制作することは、テラサキ さんにとって父を失った後の悲嘆を切り抜けるための儀式となりました。また、こ の展示では、希望する人は誰でも、亡くなった身近な人のためにそこに供え物を 捧げ、その人たちについて語るようにすすめていました。「それは、私のためだけの ものではなくて、コミュニティのものになったのです。同じような状況に直面して いる人が多いようですから」。

24 A ARTS Taiji Terasaki PALM

"세계에

대한 나의 경험은 매우 육체적이다,"

라고 삶과 죽음뿐만 아니라 종종 보존의

주제를 다루는 작품인 타이지 테라사키가

말했다. 테라사키의 실수를 담은 사진은

꿈 속의 꿈의 기억과 같은 흐릿한 이미지를

만들어 낸다.

Like the themes found in his art, Taiji Terasaki’s home and studio space are meditations on conservation and agriculture.

speak about that person. “It became not only for myself but for the community because it seems like many people are in that same kind of situation,” he says.

For two decades, Terasaki had stayed away from studio art. He only returned to it a year after his father died. While he sometimes frames himself as the black sheep in a family of scientists, perhaps the disciplines of science and art are humanity’s way of making sense of the world, of exploring and assigning tangibility to that we have yet to understand.

“I think I’m always yearning for something more spiritual,” Terasaki says. “My experience of the world is very physical. I think that in reality, there is another reality that’s not like that. The mists help me imagine something different.”

テラサキさんは20年ほど制作からは遠ざかっていましたが、 父の死を契機に再び制作を開始しました。テラサキさんは、科学者 ばかりの家系で自分は異端児だったと振り返りますが、おそらくは 科学も芸術も、人間が世界を認識しようとし、まだ私たちが理解で きないでいる事柄に形を与えようと模索する方法なのでしょう。

自分は特に宗教的な人間ではないといいますが、「スピリチ ュアルな存在には常に心を惹かれていたのだと思います」とテラ サキさんは語ります。「私は、常に世界を形ある、触れられるものと して体験してきました。でも、そうではない現実というのもあるの だと思います。靄(ミスト)が、目に見えないものを想像するのを助 けてくれたのです」

28 A ARTS Taiji Terasaki PALM

Trends that drive

BU SIN ESS

B PALM ビジネス

of place that A sense fosters the human spirit

CUL TU RE

the economy

PALM PALM B

31

Winds of Change

変化の風

Once the most oil-dependent state in the nation, Hawai‘i is surging toward energy independence.

かつて米国で最も石油依存度が高い州だったハワイが、エネルギー自立に向 けて大きく前進しています。

Text by Kate Mykleseth

文 = ケイト・マイクルセス

Infographics by Michelle Ganeku

On almost any given morning at Ala Moana Beach Park, the sun’s rays illuminate waves rolling through a surf spot. Meanwhile, the northeast tradewinds lift the leaves of the trees along the park’s walkway in light gusts. The potential for Hawai‘i to be 100 percent self-sustaining is evident: The renewable ingredients for O‘ahu’s energy independence warm my skin and tangle my hair. Already, renewable resources—the sun, the wind, fuel from organic and waste materials—supply 20.8 percent of O‘ahu’s electricity.

アラモアナの海岸では、沖合いのサーフスポットを超えて打ち寄 せる波をほとんど毎朝のように陽光が輝かせています。一方で、 北東から吹いてくる貿易風が軽い突風となって公園の歩道に沿 って並ぶ木々の葉を揺らしています。この光景を見ただけでも、ハ ワイにエネルギー自給率100%を実現できる可能性があるのは 明らかです。オアフ島をエネルギー自立へと導く二つの自然資源 が私の肌を温め、髪を乱していきます。実際、オアフ島の電力の 20.8%は、すでに太陽光、風力、バイオマス燃料といった再生可 能資源で賄われています。

2015년에는 국가에서 석유 의존도가 가장 높은 하와이가 재생

에너지의 100%를 2045년까지 활용하겠다는 야심찬 목표를 세웠다. 이 법은 하와이를 100 퍼센트 재생 가능한 에너지원으로

발전하려는 국가 최초의 주가 되게 했다. "우리는 기후 변화라는 거대한 도전에 맞서기 위해 사람들을 하나의 큰 목표 주위에 동원하는 것이 중요하다고 생각했습니다,"라고 푸른 행성 재단의 멜리사 미야시로 정책 국장이 말했습니다.

BUSINESS Renewable Energy 32 B

PALM

O‘ahu’s existing and proposed renewable energy sources in 2017

O‘ahu’s map to 100% renewable energy

Renewable energy percentage across Hawai‘i in 2017

Solar Wind Biomass Biofuel

100% 70% 30% 26.8% 2045 2040 2020 2017

56.6% 42% 34.2% 20.8%

Big Island Kaua‘i

Maui

O‘ahu

“What we’re doing here in Hawai‘i is truly showing the rest of the world it is possible,” says Chris Lee, House representative and chairman of Hawai‘i’s House Committee on Energy and Environmental Protection. “Hawai‘i is leading the world in a very real way, and it is going to benefit our local residents in the long term.”

Roughly a decade ago, Hawai‘i’s lawmakers began the path toward harnessing renewable power supplies. In 2009, the state passed a law that required 40 percent of the state’s electricity come from renewable resources by 2030. At the time, Hawai‘i was the most oil-dependent state in the nation. It spent more than $2 billion on oil to meet 75 percent of its electricity needs in 2009.

Once the 2009 law passed, a ripple effect spread throughout the state and its energy industry. The passing of the law was the first drop that would later expand into a question about the business model of Hawaiian Electric Company, Hawai‘i’s utility that supplies electricity to 95 percent of Hawai‘i’s residents, and all of the residents on O‘ahu. The utility has been responsible for generating all of the island’s power and distributing it, a business model it had been using since its inception in 1891. The ripple began expanding, with everyone’s sights on transitioning off oil.

“Everyone was seeing the impact of high electricity prices,” says Scott Seu, senior vice president of public affairs at HECO. “From a business perspective, not only for us but for our customers, it makes sense to transition off of this really volatile oil, just in terms of predictability.”

Six years later, a convergence of young minds, advocacy groups, and lawmakers picked up the pace, adding momentum to the ripple effect created by the 40 percent renewable energy law, and turning it into a wave. In 2015, Hawai‘i set a more ambitious goal to be 100 percent renewable by 2045. The law made Hawai‘i the first state in the country seeking to be powered by 100 percent renewable energy sources. “We thought it was important to mobilize people around one big goal to combat the enormous challenge that is climate change,” says Melissa Miyashiro, policy director at Blue Planet Foundation, the lead advocacy group for the 100 percent renewable law. “What has happened since the law has been passed proves that that theory works.”

ハワイ州下院議員でエネルギー・環境保護委員会の議長も務めるクリ ス・リーさんはこう語っています。「ここハワイでの我々の取り組みは、再生可能 資源によるエネルギー自給が可能であることを世界に示しています。ハワイは 再生可能エネルギー利用の面では真に現実的な形で世界に先駆けており、長 期にわたって地域住民に恩恵をもたらすことになります」。

ハワイの議員たちが再生可能エネルギー源の活用に向けて歩み始めたの は、10年ほど前のことでした。州議会は2009年に、2030年までに州の再生可 能資源による発電率を40%に引き上げることを義務づける法案を可決しまし た。当時、ハワイは米国で最も石油依存度が高い州でした。2009年、ハワイ州の 需要電力の75%は石油が頼りで、その購入費用は20億ドルを超えていました。

2009年に法案が可決されると、州にもそのエネルギー産業全体にも波 及効果が起こり始めました。法案成立が最初の一石となり、やがて電力会社の ビジネスモデルを問いなおす動きへと拡大していきました。ハワイアン・エレク トリック・カンパニーは、ハワイ州住民の95%とオアフ島の全住民に電力を供 給しています。同社は、1891年の設立以来用いてきたビジネスモデルに基づ き、オアフ島で使われる全電力の発電と供給を担ってきました。法案成立の波 及的影響が広がり始め、誰もが石油から再生可能エネルギーへの移行に視点 を据えるようになりました。

ハワイアン・エレクトリック・カンパニーで広報担当シニアバイスプレジデ ントを務めるスコット・スーさんは、「誰もが電気料金高騰の影響を認識してい ました。「ビジネスの観点から見て、当社だけでなくお客様のためにも、供給の 予測可能性という点だけ見ても非常に不安定な石油から離脱することは理に かなっています」と語ります。

法案成立から6年たち、若者たちのアイデア、支持団体の活動、議員らの 取り組みが結集され、再生可能エネルギー利用率40%を目指す法律により生 じた波及効果にさらなる弾みがついて、勢いのある変化の波へと変わっていき ました。そして2015年、ハワイ州は2045年までに総発電量の100%を再生 可能エネルギーで賄うというさらに野心的な目標を定めました。この法律によ り、ハワイは再エネ比率100%を目指す米国で最初の州となりました。再エネ 比率100%法の最大の支持団体であるブルー・プラネット・ファンデーション のポリシー・ディレクター、メリッサ・ミヤシロさんは、「気候変動という巨大な 問題に立ち向かうには、この州に住む人たちを一つの大きな目標に向かって動 員することが重要と考えたのです。法案可決後の展開が、この理論が有効であ

34 B BUSINESS Renewable Energy PALM

One megawatt of solar energy can power 164 homes when the sun is shining and a solar energy system is sending out energy at its full potential, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association.

50,268

The number of customer solar systems on the rooftops of O‘ahu businesses and residents as of 2017.

HECO has seven solar projects across the island that generate a total of 64.4 megawatts when the sun is out. They have the potential to power roughly 10,561 homes. There are also some additional military projects that aren’t considered part of the public electric grid.

Waianae Solar 27.6 MW

Waipio Solar 14.3 MW

Waihonu Solar 6.5 MW

Aloha Solar Fund 1 5 MW

Kalaeloa Solar Two 5 MW

Kalaeloa Renewable Energy Park 5 MW

Kapolei Sustainable Energy Park 1 MW

WAI‘ANAE SOLAR

These customer’s homes have the potential to provide 502 megawatts of power to the island’s grid. This amount of power has the potential to keep the lights on at 82,328 homes on the island.

BIOMASS

Biomass is plant or animal matter burned to create electricity. This matter can include wood, grasses, algae, vegetable oils, as well as trash or processed sewage.

H-POWER , the waste-to-energy facility on O‘ahu, provides 68.5 megawatts of energy to the island’s grid. Unlike wind or solar, which can be variable, biomass provides a firm power source.

In early 2017, the largest solar installation in the state, the Waianae Solar project, began operation on O‘ahu. Waianae Solar has the capacity to meet the energy needs of 4,526 homes.

BIOFUELS

Biofuels are fuels created from plant or animal matter, such as wood, grasses, algae, vegetable oils, or animal waste. TerViva—a California-based business with pilot projects in Florida and Hawai‘i that include an orchard near Hale‘iwa— aims to use the seeds from its pongamia trees to create a fuel that can be used at power plants in place of or mixed with petroleum. (It can also be used for fertilizer and feed.)

CAMPBELL

INDUSTRIAL PARK

Biofuel use: 120 MW

WIND

There are two wind farms on

KAHUKU WIND

30 MW enough to power 7,700 homes

KAWAILOA WIND

69 MW enough to power 17,710 homes

OFFSHORE WIND

HECO has said that to reach 100 percent renewable by 2045, O‘ahu needs resources beyond those available on the island. Multiple companies have submitted proposals to build wind farms off the north and south coasts of O‘ahu.

BATTERIES

Because solar facilities and wind turbines only send power to the grid when the sun is shining and the trades are blowing, HECO and the renewable energy industry are working to integrate battery technology into O‘ahu’s grid. Connecting energy storage technology to O‘ahu’s power system would absorb the extra renewable energy when there is more power being generated by the sun and wind than is needed at the time, to be used during times when there is none at all.

One Tesla powerwall has the capacity to store 13.5 kilowatt-hours of usable electricity.

1 powerwall = 17.25 hours

The number of hours one fully charged Powerwall will sustain an average home’s energy needs (not including air conditioning).

of Renewable

Types

Energy

O‘ahu.

SOLAR

1MW solar = 164 homes

The law was signed June 8, 2015. Soon after, companies from Norway, Denmark, and Oregon inquired about building offshore wind farms, each vying to construct roughly 50 floating wind turbines off O‘ahu’s north and south shores.

Interest in building solar projects in Hawai‘i has also grown. In March 2017, Tesla, Inc. announced the completion of a large solar-plus-battery system on Kaua‘i that can store enough power to service 4,500 homes during evening hours when energy use is at its highest. O‘ahu has three large-scale solar projects set to be operational in March and June of 2019.

While one of the law’s effects set Hawai‘i on the global stage, the crux of the change came from within. The monopoly utility began to change its tune. Initially, HECO combatted the 2015 law’s deadline of 2045, pushing for a 2050 goal instead. Then, after the 100-percent goal by 2045 was set in stone, the utility pledged to hit 100 percent renewable by 2040, five years ahead of schedule.

While the laws drew interest from companies outside of the isles and focused the utility’s plans, residents had already been taking energy independence into their own hands by installing rooftop solar on their homes. That grassroots momentum has led to more than 50,000 solar systems on businesses’ and residents’ rooftops on O‘ahu alone in 2017. These customers are now some of the electric utility’s most notable suppliers of energy. In its most recent plans, HECO said it expects 42 percent of the homes in its territories to have rooftop solar by 2030.

Because of this, the utility is changing the business model it used for more than 100 years. “It’s not just about running a business anymore,” Seu says. “It’s not about selling things. It’s not about making money. … We need to converge. We need to bring ourselves together. We need to operate outside of our normal lanes and put ourselves toward this broader, higher-level purpose.”

Just as the sets push surfers offshore of Ala Moana Beach Park, the decade-long progress of laws and grassroots campaigns guide the island on its own wave barrelling toward energy independence.

ることを証明しています」と話してくれました。 この法律は2015年6月8日に成立しました。それから間もなく、ノルウェ イ、デンマークやオレゴン州の企業からオアフ島沖の洋上風力発電所建設につ いての問い合わせが舞い込み、オアフ島の北岸と南岸沖に建設する約50基の 浮体式風力タービンの受注をめぐって各社が争っています。

また、ハワイに太陽光発電施設を建設するプロジェクトへの関心も高ま っています。2017年3月には、テスラ・インクが、太陽光発電設備と蓄電装置か らなる大規模施設をカウアイ島に完成したと発表しました。この施設には夜間 の電力需要が最も高い時間でも住宅4,500世帯に供給するのに十分な電力 を蓄える能力があります。オアフ島では現在3つの大規模太陽光発電施設建 設プロジェクトが進行中で、2019年3月と6月に運転を開始する予定です。

再エネ比率100%法のおかげでハワイは世界から注目されることになり ましたが、変化の根幹は内部から生まれました。電力事業を独占していた電力 会社がその姿勢を変え始めたのです。当初、ハワイアン・エレクトリック・カンパ ニーは、2015年に成立した法が定める期限に抵抗し、2045年を2050年に 延長するよう求めていました。しかし、2045年までの再エネ比率100%の達 成目標が確定すると、同社は姿勢を一変させ、期限よりも5年早い2040年ま でに100%を達成することを誓約したのです。

この法律は主に電力会社の計画を対象とし、州外の企業の関心を引い ていますが、ハワイの住民は自宅の屋根に太陽光発電設備を設置するなど、す でにエネルギー自立に向けて自主的に動いています。そうした草の根的レベル の取り組みで、2017年だけでも5万基を超える太陽光発電設備が商業施設 や住宅の屋根に新しく設置されました。こうした顧客のいくつかが、今では電 力会社にとって最も特筆すべき電力供給者となっているケースもあります。ハ ワイアン・エレクトリック・カンパニーは、同社の最新の事業計画の中で、2030 年までに供給エリア内の住宅の42%が太陽光発電設備を屋根に設置するよ うになると予測しています。

このため、同社は、過去100年間続いてきたビジネスモデルを変えようと しています。スーさんはこう語りました。「これはもはや、事業運営だけの問題で はなくなっています。大切なのは商品を売ることでもなく、利益を上げることで もありません。…力の結集が必要になったのです。皆で力を合わせる必要があ ります。慣れ親しんだ事業の外に踏み出して、これまでよりも幅広く高い目標に 向かって努力していかねばなりません」。

セットの波がアラモアナ・ビーチパークの沖でサーファーたちを乗せて運 ぶように、10年かけて前進してきた法律と草の根運動がオアフ島を変化の波 へと導き、今、エネルギー自立へと突き進ませているのです。

PALM 38 B BUSINESS Renewable Energy

Real to Reel

ハワイで映画を

In her role as state film commissioner, Donne Dawson serves as an economic and cultural liaison between Hawai‘i and Hollywood.

ハワイ州のフィルムコミッショナー、ドン・ドーソンさんは、ハワイとハリウッドの橋渡し役と して、ハワイの環境と文化への理解を広める活動をしています。

Text by Matthew Dekneef

文 =マシュー・デクニーフ

Images by Michelle Mishina 写真 =マイケル・ミーシナ

Donne Dawson finally has an hour. Somewhere between securing location permits for a Disney film feature and a weekend volunteer trip to Kaho‘olawe, Hawai‘i’s state film commissioner has found a free moment at approximately 3:30 p.m. on a Friday—in other words, the absolute tail end of another hectic week at the Hawai‘i Film Office.

ようやく、ドン・ドーソンさんに会うことができました。インタビュ ーを申し込もうと1か月にわたって電話やテキストでやり取りを した後で、やっと時間を取ってもらうことができたのです。約束は 金曜日の午後3時半。ハワイ州のフィルムコミッショナーとして 「ハワイ・フィルム・オフィス」を率いる彼女にとって、いつものよ うに目まぐるしい1週間の最後に空いた時間でした。

주 영화 위원으로서 그녀의 역할을 하고 있는 돈 도슨은 하와이와 할리우드 사이에서

섬의 환경과 다문화적 경관이 필요로 하는 연락 담당자이다. 그녀의 관리 하에, 그녀는 로스트, 하와이 파이브-0, 그리고 다가오는 MagnumP.I.의 재부팅을 포함한 주요 영화와 텔레비전 제작을 통해 하와이에 연간 약 3억 5천만달러의 수입을 가져다.

BUSINESS Donne Dawson 40 B

PALM

“This is not a normal 9-to-5 job by any means,” Dawson says in her brightly lit office on the fifth floor of the No. 1 Capitol District Building in downtown Honolulu. “Most people don’t understand what a film commissioner does, so just imagine me wearing a firefighter’s helmet all day, every day.” This allusion to Murphy’s Law—that if anything can go wrong, it will—is warranted. With five major film and television productions shooting concurrently across the islands, including a reboot of Magnum, P.I. that is loaded with car and helicopter chases and a hotly anticipated Netflix show starring Ben Affleck and Oscar Isaac, what could possibly go awry? “Let’s just say it’s problem solving, 24/7,” she reiterates.

When the Hawai‘i Film Office was created in 1978, it was set up to centralize and streamline the administration of permits for film production companies. Forty years later, its function has far exceeded its original ambitions. In addition to simplifying the permitting process for state and county jurisdictions, the office also spearheads economic development for Hawai‘i’s film and TV industry, manages the Hawai‘i Film Studio at Diamond Head (a cavernous set where Hawaii Five-0 shoots), markets the islands to production companies, and upholds the state’s reputation as a film-friendly environment. Dawson, who became state film commissioner in 2001, runs the entire show.

She does so with a measurable success record. In 2001, Hawai‘i’s film industry contributed less than $100 million a year to the state economy; today, it brings in an estimated $350 million a year. According to Dawson, there are a few factors to spotlight here: the concentration of diverse geological settings in the island chain, a well-established and relevant workforce, and the passage of a refundable production tax credit program in 2006 that keeps Hawai‘i competitive with top filming destinations around the world. All these work in concert, Dawson says, to “[solidify] Hawai‘i’s global reputation as a mature filming destination in a fiercely competitive film and TV climate.”

In this behind-the-scenes world of moviemaking, Dawson’s role is less referee and more diplomat. Because of this, she is who Hollywood producers call after they fall in love with a particular locale and want access to film there. Negotiations between production companies and government agencies like the Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources or the Department of Transportation over permission to shoot on Hawai‘i’s public lands do get sticky. These agencies can be protective and territorial, and understandably so, contends Dawson, who acts as a liaison in conversations about permitting.

This was famously the case when J.J. Abrams and Damon Lindelof, the early co-creators of Lost, laid

「この仕事は、朝9時から夕方5時までの標準的な勤務時間にはまるで 収まらないんです」。ハワイ・フィルム・オフィスの明るいオフィスで、ドーソンさ んはそう語ります。オフィスはハワイ州立美術館があるNo. 1キャピトル・ディス トリクト・ビルディングの5階に位置しています。「ほとんどの人はフィルムコミ ッショナーがどんな仕事をしているのか知らないと思いますが、四六時中消防 士のヘルメットをかぶって火消しに走り回ってると思ってもらえばいいんじゃ ないかしら」。おなじみのマーフィーの法則(「まずい事が起こる可能性がある なら、それは必ず起こる」)をほのめかしてドーソンさんは説明します。ハワイ州 では現在、長編映画とテレビ番組が5件も撮影中。この中には、80年代に大ヒ ットした『私立探偵マグナム』のリブート版や、ベン・アフレックとオスカー・アイ ザックの共演で熱い注目が集まっているネットフリックスのオリジナル作品も 含まれています。そんな中で一体、どんなまずいことが起こる可能性があるので しょう?「私の仕事は問題の解決なんですよ。それも年中無休、24時間稼働の ね」とドーソンさん。

映画製作という舞台裏の世界にあって、州のフィルムコミッショナーとし てのドーソンさんの役割は、審判というよりも外交官のようなものだそうです。 ハワイの公共の場所での撮影許可取得をめぐって映画の制作会社と土地天 然資源局(DLNR)や交通局といった政府の機関の間で行われる交渉は、しば しば困難で秘密性の高いやり取りになります。そこでドーソンさんがリエゾンと して登場し、交渉をスムーズにすすめられるよう、両者の間のクッションとなっ て働くのです。ハリウッドのプロデューサーたちは、ハワイのある特定の場所が 気に入り、そこでロケをするための足がかりが必要になるとドーソンさんに電 話をかけてきます。有名なケースには、J・J・エイブラムスとデイモン・リンデロフ (『LOST』のショーランナー)が目をつけたモクレイア・ビーチがあります。オア フ島のノースショアに位置するこのビーチの景観は、『LOST』の設定になくて はならないものだったとドーソンさんは説明します。「あのビーチは、真っ青な 明るい海の横に白い砂のビーチがあり、さらに緑の山々がすぐ隣り合っていて、 すべてが一つのフレームにきれいに収まる場所だったのです」。しかし、その白 い砂の上に墜落した航空機の機体が散乱するという設定に、DLNRは難色を 示しました。ハワイ州ではどのビーチも公共のものとして、すべての人にアクセ スが保証されています。これは訪れる人にも住人にとってもハワイを特別な場 所にしている公共の権利ですが、DLNRは許可を出すことでこのアクセス権が 侵害されたという苦情が殺到するのを恐れたのです。

「ロケ撮影に許可を出すことに対して神経質になっている役所の人た ちを安心させてあげることが肝心なのです」とドーソンさんは語ります。「ある プロダクションのために代弁するときは、私は彼らの手腕を全面的に保証しま す。あの時は、(『LOST』とABCの)スタッフは経験を積んだベテランであるとい う事実と、彼らが土地にも、海にも、それを取り巻くコミュニティにとっても「ポ ノ」な、つまり正しいやり方で仕事をするということを説明しました」。そしてド

42 B BUSINESS Donne Dawson

PALM

their eyes on Mokulē‘ia Beach. “It was the bright blue ocean next to the white sandy beach next to the green mountains, and it was within one frame where they could get all of that,” explains Dawson of the North Shore visage that the writer-director team considered crucial to the pilot. But the show’s premise that a commercial airliner has crashed on a deserted island required the sands to be strewn with aircraft wreckage, a cause of reservation for DLNR. The department didn’t want to be bombarded with complaints about the beach’s accessibility to the public, one of the core right-of-ways that makes Hawai‘i so special to its citizens and visitors.

“It’s all about providing comfort to these agencies that are nervous to let people shoot there,” Dawson says. “When I advocate for a certain production, I’m vouching for it. I explained the fact that these guys [with Lost and ABC] are seasoned veterans, and they’re going to do this the right the way, in a way that’s pono to the land, ocean, and the community around it.”

Ultimately, Dawson was able to convince the regulating departments to grant permission at the final hour. Had she not been successful, Lost may have moved its series to Australia. “Pulling that off was really monumental,” Dawson says. “I’m very proud of the fact that we made that happen.” Lost proved to be a global Emmy-winning success that garnered acclaim among audiences and television critics and bolstered Hawai‘i’s repute with Hollywood creatives. Throughout the series’ six seasons, which were shot at locations around O‘ahu, the island convincingly stood in for assorted locales including Japan, Iraq, Australia, France, and the U.S. Midwest. “Lost became our new calling card,” Dawson says. “[That series] proved that with creativity we could film about anything here.”

Dawson’s facilities, however, aren’t to be confused with blind appeasement. She shut down a Chris Brown music video when its producer attempted to set up a fullblown dance stage on Ahu o Laka, the Kāne‘ohe sandbar that’s considered a fragile cultural and ecological site. When the title of writer-director Cameron Crowe’s film Aloha was criticized as an eye-rolling display of cultural appropriation by local audiences, she told the Hollywood Reporter that had she known the name, she would have advised against it. (The film was still called “The untitled Cameron Crowe project” during shooting.) After a producer approached her with a cringe-worthy pitch for a Dancing with the Stars-style reality TV competition that traded ballroom dancing for hula, she talked him down from trying to get it made. “If I know a production is walking right into a landmine, whether it’s putting themselves at risk of being shut down, of being picketed by the public, of receiving terrible press, it’s my job to try and mitigate that,” Dawson says. “We’re living in a time where audiences are more demanding and savvy. They want authenticity, not the stereotypical view of Hawai‘i.”

ーソンさんは最終的に当局を説得し、撮影許可を得ることに成功しました。こ の許可が下りていなければ、『LOST』全シリーズはオーストラリアで撮影され ていたかもしれません。「あのロケ撮影の成功は、本当に大きかったですね。皆 で実現できたことをとても誇りに思っています」とドーソンさん。

『LOST』は国際的に大ヒットし、エミー賞も獲得しましたが、視聴者や 批評家の支持を得ただけでなく、ハワイとハリウッドのクリエイターたちとの間 に信頼関係を築くことにもつながりました。6シーズンにわたった『LOST』はオ アフ島の各所で撮影され、島のあちこちが日本、イラク、オーストラリア、フラン ス、アメリカ中西部といった遠くの場所に扮し、説得力をもって画面に登場しま した。これ以降、映画業界にハワイを売り込むにあたって、「『LOST』が新しい 名刺代わりになったのです。(『LOST』の成功は、)ハワイでどんな映画でも撮 影できることを、クリエイティビティをもって示してくれました」とドーソンさん は語ります。

映画業界の成長は収益の伸びに見て取れます。2001年、ハワイの映画 産業の収益は年間1億ドル未満でした。それから約20年後の現在、ドーソンさ んの指揮下でその数字は3倍以上に伸び、推定年間3億5,000万ドルに達し ています。これは、大型のプロジェクトが増えたことと、アトランタやカナダとい った国際的なライバルに対してロケ地としての競争力をつけるため2006年に 可決された映画製作を対象とする税控除プログラム「Act 88」の効果による もの。ハワイ・フィルム・オフィスは、1978年、映画制作会社のために撮影許可 の申請と受領を一括して支援する州の窓口機関として創設されました。40年 後の今、同事務所の業務は当初の目標を大きく超えるものとなりました。現在 の業務には、撮影許可のプロセスを簡素化することに始まり、ハワイの映画産 業のための経済開発、ダイヤモンドヘッドにある「ハワイ・フィルム・スタジオ」 (『Hawaii Five-0』はここで撮影されています)の管理、制作会社に対するマ ーケティング、さらには映画業界人たちの間にハワイ州は仕事をしやすい場所 だという評価を保つことも含まれます。ドーソンさんは2001年にフィルムコミ ッショナーの職に就いて以来、すべてを取り仕切ってきました。

とはいえ、ドーソンさんの手腕は、やみくもな懐柔策によるものではあり ません。ドーソンさんはしばしば、自分がハリウッドのエグゼクティブたちと業 界のネイティブハワイアンたちの間で、異文化交流の最初の接点として働いて いることに気づくそうです。たとえば、ドーソンさんは、クリス・ブラウンのミュー ジックビデオのプロダクションがカネオへのアフ・オ・ラカと呼ばれるサンドバー (砂州)にダンス用ステージを設置しようとしていたのを知って撮影を止めさ せました。このサンドバーは繊細な生態系を持つ環境であるうえ、文化的にも 重要な意味を持つ場所で、撮影許可には含まれていなかったためです。また、 とあるプロデューサーが『ダンス・ウィズ・ザ・スター』風の、社交ダンスをフラ に変えたコンペティションで構成するリアリティ番組の企画を嬉しそうに語っ ていた時にも、そのアイデアは良くないと説得しなければなりませんでした。ま た、キャメロン・クロウの監督・脚本による映画『アロハ』が、このタイトルは文化 の盗用だとハワイの観客から抗議された時には、ドーソンさんは『ハリウッド・

46 B BUSINESS Donne Dawson PALM

Episodes like these reveal a need for more education about Hawai‘i’s unique culture, believes Dawson, who is of Native Hawaiian descent. Her own cultural knowledge and personal relationships with Hawaiian practitioners and experts have made her something of a kia‘i (guardian) of cinema. Since late 2017, Dawson has been earnestly working on a digital manual called The Hawaiian Handbook with the University of Hawai‘i at West O‘ahu, modeling the document after The Brown Book: Māori in Screen Production, a similar cultural call to arms tailored to New Zealand’s film industry. She imagines it as a “user-friendly navigation tool to successful mediamaking in Hawai‘i” that covers everything from sacred and archeological sites to value systems like mālama ‘āina (to care for the land). Dawson intends for it to help visiting production teams better understand the nuances of shooting in Hawai‘i and the dos-and-don’ts of conducting business here.

“Producers just don’t know what they don’t know,” Dawson says. But when Hollywood flies in swarms of crew members throughout the year for designated amounts of time, she insists there is a need for them to have a baseline awareness of Hawai‘i’s history, peoples, and sensitivities about the environment. “We’re not the censor police,” she says. “What we’re doing is educating them about our native culture and ensuring that whatever creative project they want to bring to fruition has a chance of surviving.”

The following afternoon I get a sense of Dawson’s openness when a photographer and I arrive at Polihiwahiwa, her historic Mediterranean-style twostory family home in Nu‘uanu, to take portaits of her. The house is surrounded by manicured hāpu‘u ferns and has a Hawaiian flag waving majestically over the carport. As I take in its stone walls, high ceilings, and Hart Wood architecture, I can’t help but imagine it as a film set artdirected to reveal some of Dawson’s character. Binders fanned out on an ottoman are labeled “Genealogy.”

Shelved in a nearby bookcase are tomes dedicated to legislative law through the decades next to well-worn hardcovers from preeminent Hawaiian scholars; here, State of Hawai‘i documents are at home next to works by Hawaiian historian Samuel Kamakau. Upon sighting a banana grove beside the brick-lined swimming pool, the photographer suggests we set up there, but first Dawson fetches a machete so we can hack off a bundle of browning leaves. The home has portals and archways that allow for gorgeous natural light that clearly inspires the photographer. What is supposed to be an hour of Dawson’s time somehow transforms into three, but she doesn’t seem to mind. She just wants to help us get the shot.

レポーター』の取材に応え、もし知っていたらほかのタイトルにするようにアド バイスしただろうと語りました(撮影中は映画のタイトルは明らかにされておら ず、「キャメロン・クロウの名称未定プロジェクト」とされていました)。「もし、制 作中の作品がまっすぐ地雷原に踏み入ってしまったら、そのダメージを何とか 軽減しようと努めるのが私の仕事です。それが制作中止のリスクであっても、デ モで抗議されることであっても、または悪夢のような広報上の失敗であっても です」とドーソンさんは説明します。「今の時代の観客は、以前よりも要求が高 く、賢くなっています。ステレオタイプなハワイ像ではなく、本物のハワイが求め られているのです」。

こうした逸話を見るにつけても、ハワイのユニークな文化についてもっ と知ってもらうことが必要、とドーソンさんは考えています。ネイティブハワイ アンとしてのアイデンティティとハワイ文化についての知識を持つドーソンさ んはシネマの「キアイ(守り人)」の役割を果たしているといえるでしょう。ハワ イアンの血を引くドーソンさんは、カホオラウェ島の保護団体「プロテクト・カ ホオラウェ・オハナ」や「ザ・ドーターズ・オブ・ハワイ」など、ハワイアンのための 活動や非営利団体にボランティアとして長らくかかわり、映像作品の中でも外 でも、ハワイ文化と環境がそのままの形で守られ、保存されていくように力を 尽くしてきました。現在は、ハワイ大学ウエストオアフ校との協力により「The

Hawaiian Handbook(ザ・ハワイアン・ハンドブック)」というデジタルマニュ アルを制作中。これは2019年に完成予定で、外部から訪れる映画制作プロ ダクションのチームに、ハワイで撮影を行うにあたって知っておくべき文化の ニュアンスを伝え、この土地でビジネスを行う上で押さえておくべきこととやっ てはいけないことについて理解を深めてもらうのが狙いです。アオテアロア(ニ ュージーランド)の映画産業が発行している「The Brown Book: Māori in Screen Production(ザ・ブラウン・ブック:映画の中のマオリ)」を参考とした このハンドブックは「ハワイで映像制作をする際のユーザーフレンドリーなナビ ゲーションツール」として使ってほしいと考えているそうで、神聖な場所や考古 学的遺跡についての情報から「マラマ・アイナ(土地への敬意)」という価値観 に至るまで、さまざまな要素を網羅したものになるそうです。映像制作者たちは 「ハワイが置かれているコンテクスト、歴史、文化、そして環境に対してハワイ の人々が抱いているずば抜けて繊細な感覚を理解しなければなりません」とド ーソンさんは語り、こうつけ加えました。「私たちは検閲をしているのではありま せん。制作チームが成功させようと取り組んでいるクリエイティブなプロジェク トが生き残れるように、私たちのネイティブ文化について学んでもらおうとして いるのです」。

48 B BUSINESS Donne Dawson PALM

A sense

CUL TU RE

of place that

C PALM 文化

fosters the human spirit

PALM C 51

Cultural Kīpuka

文化のキプカ

Text by Al Town

文 = アラン・タウン

Images courtesy of NOAA Fisheries and by Wayne Levin & Mike Coots

写真 = アメリカ海洋大気庁海洋漁業局とアンドリュー・グレイさん提供

Golden sweeper in Timor Leste; image courtesy of NOAA Fisheries/Kevin Lino.

52 C CULTURE Hawai‘i Fisheries PALM

When Hawai‘i’s fish need nurseries, the state looks to traditional local communities to serves as cribs.

伝統漁法を継承する地元のコミュニティに、ハワイの漁業資源回復の希望が 託されています。

2017년 가을, 하와이 대학의 과학자 앨런 프리들랜더는 하와이 주변의 식용 산호초 물고기의

감소하는 개체 수를 설명하기 위한 획기적인 연구를

발표했다. Friedlander는 어획이 전통적인 방법에

의해 행해지는 지역 사회에서 수확 제한과 산란 주기를

존중하는 수확기를 가진 수확 가능한 산호초 물고기의

개체 수가 번성합니다. 이 연구는 하와이의 해양

생태계를 되살리는 길을 닦는 데 도움이 된다.

Alan Friedlander’s eyes do wild things to the light that hits them. His irises look like deep layers of shattered glass, and a tiny fleck extends over the aperture of the left pupil—something difficult to ignore when speaking to him. The more than 10,000 hours he has spent underwater all over the world, subject to pressure changes and saltwater, may account for these anomalies. The ocean has changed him.

In the fall of 2017, Friedlander, who is the chief scientist of the National Geographic Pristine Seas Project and director of the Fisheries Ecology Research Lab at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, released a groundbreaking study that sought to explain declining

アラン・フリードランダーさんの眼は、光が当たると独特の様相を呈します。虹 彩はひびの入ったガラスが厚い層をなしているように見え、左眼には瞳孔から 伸びる小さな斑点があります。向かい合って話すと無視するのが難しい特徴で す。世界各地の海での潜水時間が1万時間を超え、繰り返し圧力の変化と海水 にさらされてきたことが原因でこうした変化が起きたのかもしれません。まさ に、海がフリードランダーさんを変えたのです。

ナショナル・ジオグラフィック協会の「原始の海プロジェクト」主任研究 員であり、ハワイ大学マノア校の漁業資源生態学研究所所長も務めているフリ ードランダーさんは、2017年秋に画期的な研究成果を発表しました。この研 究は、ハワイの主要諸島全域でウルア(ロウニンアジ)、マニニ(シマハギ)、ウク

54 C CULTURE Hawai‘i Fisheries

PALM

This page, left: A rainbow runner and gray reef shark offshore of Kaho‘olawe; image courtesy NOAA Fisheries/Andrew Gray. Middle: healthy plate and finger coral in Kealakekua on Hawai‘i Island; image by Wayne Levin. Right: Threadfin butterfly fish in the Pacific Remote Islands, Kingman Reef; image courtesy of NOAA Fisheries/Kevin Lino. Opposite page: reef fish off Kaho‘olawe; image by Wayne Levin.

This page, left: A rainbow runner and gray reef shark offshore of Kaho‘olawe; image courtesy NOAA Fisheries/Andrew Gray. Middle: healthy plate and finger coral in Kealakekua on Hawai‘i Island; image by Wayne Levin. Right: Threadfin butterfly fish in the Pacific Remote Islands, Kingman Reef; image courtesy of NOAA Fisheries/Kevin Lino. Opposite page: reef fish off Kaho‘olawe; image by Wayne Levin.

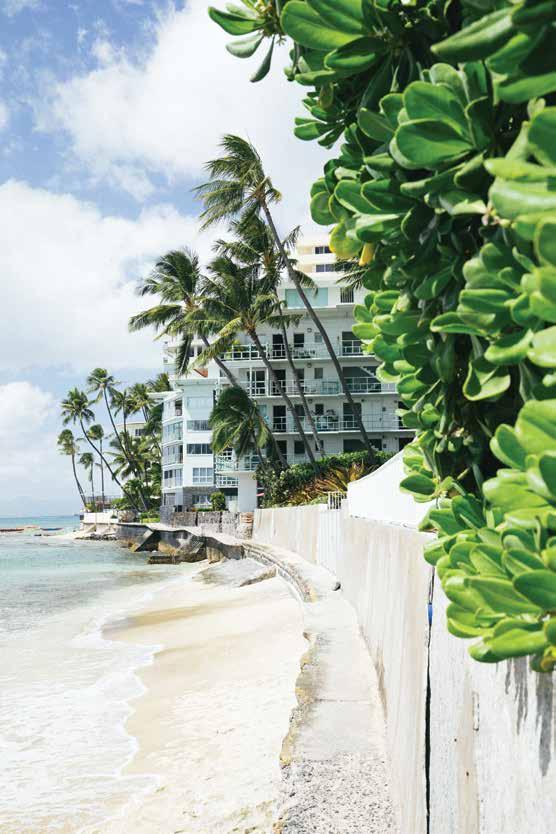

Coastline of Hā‘ena on Kaua‘i’s north shore, which became the state’s first community-based subsistence fishing area in 2015; image by Mike Coots.

Coastline of Hā‘ena on Kaua‘i’s north shore, which became the state’s first community-based subsistence fishing area in 2015; image by Mike Coots.

populations of edible reef fish such as ulua (giant trevally), manini (convict tang), and uku (grey snapper) across the main Hawaiian Islands. By aggregating more than 25,000 studies conducted since 2000—the largest collection of data ever compiled in Hawai‘i—he identified overfishing as the primary cause of decline, which sent commercial fishers clambering to defend themselves. The silver lining: Friedlander discovered that in communities where fishing is done by traditional methods, with harvesters respecting catch limits and spawn cycles, edible reef fish populations are flourishing. These customary methods are not only admirable, they are instructive. With the help of state support and hightechnology monitoring by scientists like Friedlander, communities proposing these traditions as new laws are leading the way to an ocean revival.

In places with small populations, like the Hāmākua coast on Hawai‘i Island, Kīpahulu on Maui, and the island of Ni‘ihau, the reefs are nearly pristine. “We still have some great places left,” Friedlander says. “Kaho‘olawe looks more like the northwest Hawaiian Islands than it does the rest of the state.” And these fish havens are not just healthy in their little bubbles. They act as fisheries, promoting the spawning that helps restore the surrounding areas. Following the moon cycle, fishermen in these parts know which fish to avoid at certain times, and to leave the biggest ones to lay the most eggs. In such areas, including the Hawai‘i Island community of Miloli‘i, fishers refer to the ocean by the same name as another food source that needs constant replenishment: the icebox.

In 2015, Hā‘ena on Kaua‘i’s north shore became the state’s first community-based subsistence fishing area. Decades in the making, the landmark approval reaffirmed traditional Hawaiian fishing practices by creating a protected fishing area, setting bag limits on catches, and prohibiting practices including fish feeding,

(ネズミフエダイ)といったサンゴ礁に棲息する食用魚の数が減少している原 因の究明を試みるものでした。2000年以降に実施された25,000件を超える 研究結果を統合するという、ハワイ州でも史上最大規模のデータ集積作業の 末に、魚の減少の主な原因が乱獲であることを突き止めたのです。この結果を 受けて、商業漁業者たちは苦しい防御に回ることになりました。しかし一方で、 希望の光ともいえる事実も明らかになりました。フリードランダーさんは、伝統 漁法を用い、漁獲制限を守って魚の産卵周期に配慮しているコミュニティで は、サンゴ礁の食用魚の魚群が豊かであることを発見したのです。こうした昔 ながらの漁法は賞賛に値するだけでなく、大切な知恵を伝えるものでもありま す。伝統漁法の法制化を提案するコミュニティが、州政府の支援とフリードラ ンダーさんのような科学者による最新技術を駆使したモニタリングに助けられ ながら、海洋環境再生への道を先導しています。

ハワイ島のハマクア海岸、マウイ島のキパフル、ニイハウ島といった人口 が少ない地域では、サンゴ礁はほとんど手つかずの状態を保っています。フリー ドランダーさんは「素晴らしい魚の棲息地がまだいくつか残っているのですよ。

カホオラヴェ島は、ハワイの他の地域よりも北西ハワイ諸島の島々に近い状態 です」と語ります。こうした魚群豊かな海域は、隔離された狭い生態系の中だけ で健康を維持しているわけではありません。海域全体がいわば養殖場のよう に働き、周辺の魚群回復にもつながる魚の産卵を促進しているのです。こうし

た地域の漁師たちは、月の周期に従い、特定の時期に特定の魚を獲るのを避 け、産卵量が多い大きな魚たちは獲らずに保護しています。ハワイ島ミロリイの コミュニティをはじめとするそうした地域の漁師たちは、海を「冷蔵庫」と呼ん でいます。常に補充を必要とする食料の保存庫と考えているのです。

カウアイ島ノースショアに位置するハエナは、2015年に州で初のコミュ ニティ管理型生活権漁業水域に指定されました。実現までに数十年を要した この画期的な施策は、ハワイの伝統漁法の長所を改めて認め、保護漁業区域 を設定し、漁獲量を制限したうえ、餌付け、水中銃や刺し網の使用、夜間のスピ アフィッシングなどを禁止しています。コミュニティが、地元の資源を利用した い人たちを教育し監視することによって、資源を保護する力を得たのです。

PALM 58 C CULTURE Hawai‘i Fisheries

Dolphins over healthy coral reef in Keauhou on Hawai‘i Island; image by Wayne Levin.

Dolphins over healthy coral reef in Keauhou on Hawai‘i Island; image by Wayne Levin.

the use of spear guns and lay nets, and spearfishing at night. The result is a community empowered to protect its resources by educating and monitoring those who wish to use them.

Hā‘ena remains the state’s sole regulated zone of this kind, though at least 19 other communities are interested in the designation. One of these initiatives, to protect the 27-mile stretch of coastline on Moloka‘i known as the Mo‘omomi fishery, is inching closer to approval. This effort dates back to 1993, when University of Hawai‘i ethnic studies professor Davianna Pōmaika‘i McGregor was asked by the Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources to work with the Moloka‘i community on a subsistence study. She and local group Hui Mālama o Mo‘omomi proposed that the fishery become a protected fishing area. But when working with the state proved to involve too many procedural and legal hurdles and conflicting commercial interests, they decided to continue on their own.

Mac Poepoe, the Hui Mālama o Mo‘omomi’s cofounder and a master fisherman, led the grassroots effort with McGregor’s help. “They were all about pono practices, proper times of fishing and farming so as not to disrupt natural processes,” Friedlander says. “They were the first to really institute the Hawaiian moon calendar, in the sense that they made a physical copy of it and started disseminating it as an education tool.”

Twenty-five years later, seeing Hā‘ena’s success and that its kūpuna are aging, Hui Mālama o Mo‘omomi is again pushing for a state-sanctioned community-based subsistence fishing area on Moloka‘i. “Mostly because the next generation doesn’t have the respect and authority that the kūpuna do,” explains McGregor, “they’ll need the backing of something like rules to help them take on that kuleana (responsibility) of managing the resources.”

In her book Nā Kua‘āina: Living Hawaiian Culture, McGregor writes of cultural kīpuka. In nature, kīpuka are areas of land that are spared by lava flows that act as oases of growth and habitat. Native Hawaiian communities, providing their extant knowledge and customary practices, mimic this phenomenon. They are cultural kīpuka. There are few with the understanding possessed by fishers like Poepoe, his arcana gained through years of experience with earlier practitioners. But as more traditional fishing centers are given state distinction with the help of those

ハエナは、この種の規制区域としてはまだ州で唯一の例ですが、このよう な指定取得に関心を抱いているコミュニティは少なくとも19に上ります。そう したイニシアチブの一つはモロカイ島の43kmの海岸線。「モオモミ漁場」とし て知られるこの海岸線を保護区域に指定する提案も、少しずつ実現に近づい ています。この試みは、1993年、ハワイ大学で民族学を教えていたダヴィアナ・ ポマイカイ・マクレガー教授が、モロカイ島のコミュニティと協力して自給自足 研究を行うようにハワイ州土地天然資源局(DLNR)から依頼を受けたことか ら始まりました。マクレガー教授と地元団体フイ・マラマ・オ・モオモミ(モオモ ミ保全組合)は、この漁場を保護漁業水域に指定することを提案しました。し かし、州政府に働きかけるにはおびただしい手続き上と法律上の難関があり、 商業的な利害の対立も伴ったため、自分たちで活動を継続することにしたので す。

フイ(組合)の共同設立者であり熟練した漁師でもあるマック・ポエポエ さんは、マクレガー教授の助力を得ながらこの草の根運動を主導してきました。 「フイの人たちが目指してきたのは、ポノ(道義的に正しい)な慣行、つまり天 然資源を破壊しないように適切な漁期と農期を守ることでした。ハワイ式月齢 カレンダーを真に利用し始めたのは彼らが初めてといえます。彼らはカレンダ ーを印刷して教育のために配布し始めたのです」とフリードランダーさんは語 ります。

それから25年後の今、ハエナの成功例を目の当たりにし、フイのクプナ (長老)たちも高齢となったため、フイ・マラマ・オ・モオモミは再びモロカイ島 にコミュニティ管理型生活権漁場を設定しようと州に働きかけています。マク レガー教授は、「次世代の人たちにはクプナが得ていたほどの尊敬や権威がな いというのが主な理由で、彼らが資源管理のクレアナ(責任)を担うのを後押し する規則のようなものが必要なのです」と説明します。

自著『Nā Kua‘āina: Living Hawaiian Culture(ナ・クア・アイナ:生き ているハワイ文化)』の中で、マクレガー教授は文化的な「キプカ」について書い ています。キプカとは、溶岩流に埋もれるのを免れ、そこだけ植物が茂り生物が 棲む、オアシスのような役割を果たしている場所を指します。今も失われずに 残っている知識と慣行を提供するネイティブハワイアンのコミュニティは、この 自然現象に似ています。そうしたコミュニティはいわば、文化のキプカだといえ ます。ポエポエさんの深い知識は先人の漁師たちと共に長年培った経験によ って得られたものであり、彼のような知見を持つ人はもうほとんどいません。で

CULTURE Hawai‘i Fisheries 62 C PALM

Multi banned butterfly fish off the coast of Kaho‘olawe; image by Wayne Levin.

like him, the avenues to learn such practices will become faster, spawning newly devised ways of bringing urban centers up to speed with tradition.

The proposal for Mo‘omomi to become a communitybased subsistence fishing area awaits a hearing with the Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources. In the meantime, Poepoe has been working with the community of Miloli‘i, according to McGregor, conferring his experience to help them develop a proposal of their own. Kīpahulu may be next. Thanks to Governor David Ige’s 2016 Sustainable Hawai‘i Initiative, the state is already committed to protecting and managing 30 percent of its nearshore marine areas by 2030. A recently passed bill—the first of its kind in the world—bans harmful reef-bleaching sunscreen, showing promise.

“Hopefully, people have just lost the knowledge,” McGregor says from her home a few miles from Mo‘omomi, “and these community-based subsistence areas can popularize the knowledge.”

も、ポエポエさんのような人たちの助けによって州の認定を受ける伝統漁法継 承漁場が増えれば、そうした漁法を短期間で学べるようになり、やがては都市 部にも漁の伝統を広めていく新しい方法が考案されていくことでしょう。

モオモミのミュニティ管理型生活権漁場の認定に向けた申請は、DLNR の審理を待っているところです。マクレガー教授によれば、ポエポエさんはその 間もミロリイのコミュニティと共に働き、コミュニティが独自の提案を練り上げ られるよう、自らの経験を共有して助言しているそうです。その次に認定申請 へ名乗りを上げるのはキパフルかもしれません。イゲ知事による2016年の「サ スティナブル・ハワイ・イニシアティブ」により、ハワイ州ではすでに、2030年ま でに沿岸海域の30パーセントを保護・管理することにコミットしています。つい 最近では、サンゴ礁白化の原因の一つともなる環境に有害な成分を含む日焼 け止めを禁止する、世界で最初の法律が可決されました。こうした動きが確か な希望をもたらしています。マクレガー教授は、モオモミから数キロの所にある 自宅でこう語りました。「古来からの知恵はまだ失われてから時間が浅く、こう したコミュニティ管理型の自給漁場を通してその知識がまた広められていくと いいのですが」。

64 C CULTURE Hawai‘i Fisheries PALM

flourishing The of creative facilities

PALM D 65 デザイン PALM 65

DE SI GN

Weird, Wacky, Waikīkī

奇妙でレトロなワイキキ

Text by Timothy A. Schuler 文 = ティモシー・A・シュラー

Images by John Hook & Mark Kushimi 写真 = ジョン・フック &マーク・クシミ

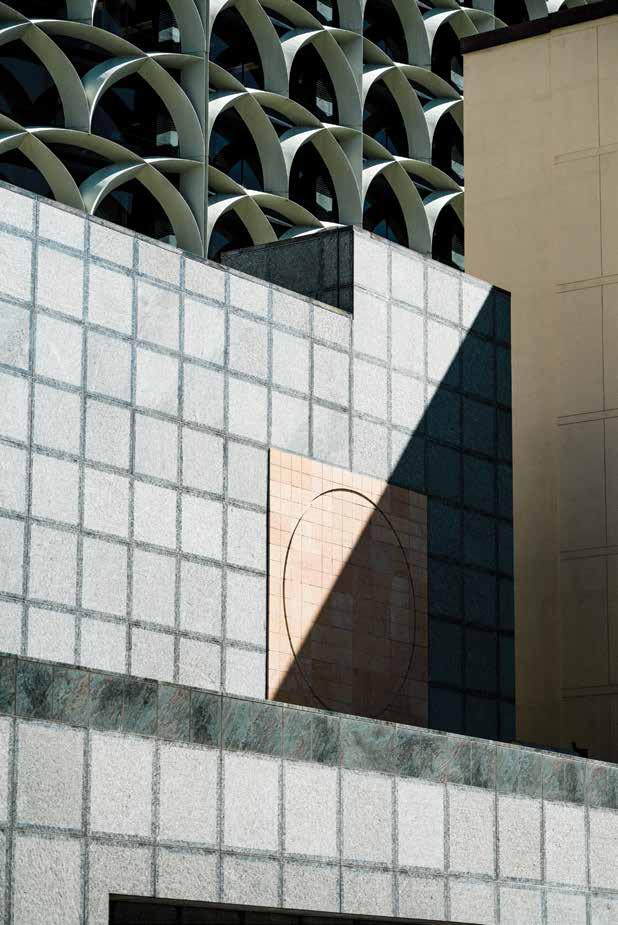

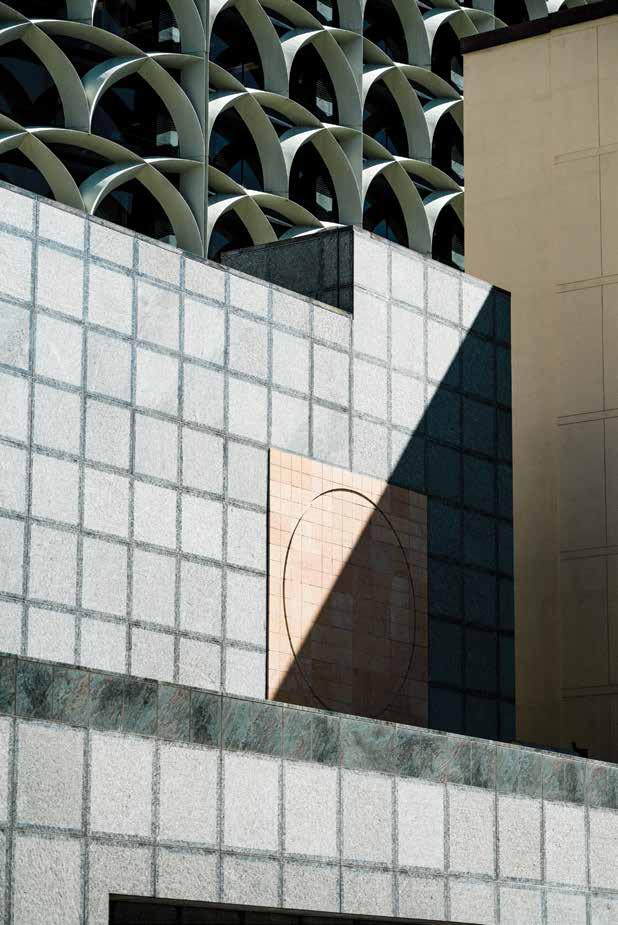

St. Augustine Church by the Sea and Waikīkī’s colorful banisters and balustrades are physical markers of its layered history.

66 D DESIGN Architecture PALM

A stroll through the infamous tourist trap is actually an endless walk through time.

観光地としてあまりにも有名なワイキキ。でも目をこらせば時を超えた散歩が 楽しめます。

팜 스프링스나 마이애미 비치와 같은 일부

관광지와는 달리, 와이키 코크는 건축으로

알려져 있지 않다. 하지만 옛날 옛적에, 그

지역은 건축의 선구자의 놀이터였습니다.

유명한 관광객 트랩을 지나다 보면 알게 될

것입니다. Waikiki는 실제로 시간을 통해

끝없는 산책을 제공합니다.

The sun is up, but it hasn’t yet reached the cluttered back streets of Waikīkī. Here, everything is bathed in a cool blue light. Seen from a distance, Honolulu’s famous beachfront strip appears as a homogenous blob of blocky beige towers, as if extruded from the sand, the overall effect one of bland repetition. But like most places, Waikīkī reveals itself slowly, haltingly. A stroll through its streets is a walk through time, though not a linear one. With every step, it seems, you encounter a different era: the 1920s with its grand, ornamental architecture, or the 1950s with its tiki modernism.

太陽はもう顔を出しましたが、ワイキキのごちゃごちゃとした裏通りには朝の最 初の光はまだ届いていません。そこはまだ、冷たく青い色彩の中です。遠くから 眺めただけでは、この名高いビーチフロントの通りは、似たようなベージュ色の 四角いビルが砂から突き出したかのように延々と並ぶ面白味のない繰り返しの 風景に見えます。でも、多くの場所がそうであるように、ワイキキもじっくりと見 る人の前にはその本質を少しずつ、断続的に露わします。ワイキキの町を歩くの は、時間をさかのぼる旅でもあります。とはいえ、時代を順序良く追えるわけでは なく、一足歩くごとに違う時代が現れるのです。たとえば、1920年代の華やかな 装飾に飾られた建築の隣りに1950年代の「ティキ・モダニズム」のビルがある

68 D DESIGN Architecture

PALM

Waikīkī is and always has been many things. Its name means “spouting waters” and refers not to the ocean but to the stream-fed wetlands that made the area an agricultural hub even as members of the royal family built residences there. The wetlands disappeared with the construction of the Ala Wai Canal in the 1920s, creating acres of prime beachfront property that soon were populated with hotels and taverns. Since the late 1800s, Waikīkī has also been a place people have called home, slowly evolving into an urban neighborhood with a population of some 20,000 people and a tireless energy.

Not long ago a friend of mine, an architectural historian who lived in Hawai‘i for several years, sent me a note unbidden. “People often clap back at Waikīkī as an inauthentic place, but I’ve never felt that way,” she wrote. “It’s walkable, and it’s dense, and personally, the combination of tall buildings and mountains gets to me.” Some of her favorite buildings, like the Waikīkī Theater, have been demolished in recent years, she said, “but I’m pleased to see that most of the low-rise apartments still have character. Waikīkī should be a landmark district.”

Unlike some tourist destinations, such as Palm Springs or Miami Beach, Waikīkī isn’t known for its architecture. And yet once upon a time, the area was the playground of the architectural vanguard. In 1957, Buckminster Fuller built one of his famous geodesic domes on the grounds of what is now Hilton Hawaiian Village. The year before, George “Pete” Wimberly, who went on to design the Sheraton Waikiki—which, in 1971, was the largest resort in the world—had given Waikīkī its most iconic structure to date: the hyper-modern, tiki-flavored Waikikian Hotel, whose lobby featured a dramatic, hyperbolic paraboloid roof that curved in two directions and dipped nearly to the ground.

It was as bold as Waikīkī ever got, an outgrowth of post-World War II optimism and Hawai‘i’s increasing prominence in the American imagination. In the 1960s, advancements in commercial air travel shortened the flight time from the West Coast to Hawai‘i from nine hours to less than five, making the islands more accessible than ever. Between 1960 and 1970, visitors increased sixfold and began staying for shorter periods. If this glut resulted in more utilitarian architecture, it also changed what a hotel was. Large suites with full kitchens, once de rigeur, were no longer needed. Hotel rooms shrank accordingly and were perched higher and higher in the sky.

Many of Waikīkī’s iconic structures were torn down to make way for ever-larger resorts. The Waikikian closed in 1996, its fantastical lobby and restaurants demolished.

といったように。

ワイキキは、常に多面的な存在でした。「ワイキキ」は「湧き出る水」という 意味ですが、それは海の水ではありません。この場所は川が注ぎ込む湿地帯で、 農業の中心地であり、王族の住居もここにありました。1920年代にアラワイ運 河が建設されると湿地はなくなり、ビーチフロントの一等地に間もなくホテルや レストランが立ち並ぶようになりました。19世紀後半からワイキキに住む人も少 しずつ増えはじめ、やがて疲れを知らないエネルギーに満ちた人口2万人の都 会的な街へと成長していきました。

少し前、建築史家であり、数年間ハワイに住んでいたことのある友人が、ふ とこんなメッセージを送ってきたことがありました。「人はよくワイキキをニセモノ くさい場所だと馬鹿にするけれど、私はそう感じたことは一度もないな。歩いて 移動できるし、密度が濃くて、それに個人的に、山と高いビルの取り合わせにグッ とくる」と彼女は書いていました。「ワイキキ・シアター」はじめ、彼女のお気に入り のビルのいくつかはもう取り壊されてしまったものの、「低層アパート群のほとん どが今でも個性を保っているのは嬉しいし、ワイキキはランドマーク地区に指定 されるべきだと思う」と考えているそうです。

パームスプリングスやマイアミビーチといった観光地とは違い、ワイキキの 建築は世に知られていません。でも、その昔、ここは先進的な建築家たちが腕を競 う場所だったのです。1957年には、現在ヒルトン・ハワイアンビレッジになってい る一画に、バックミンスター・フラーが有名なジオデシック・ドームを建てました。 その前年、ジョージ・「ピート」・ウィンバリー(彼は1971年、当時世界最大のリゾ ートだったシェラトン・ワイキキも設計した建築家です)が、ワイキキでもっともア イコニックな建物だった「ザ・ワイキキアン・ホテル」を設計。これはティキ風の趣 きを加味したきわめてモダンな建物で、ロビーの屋根は放物面を描いて2方向に カーブし、その一端は地面すれすれまで届いていました。

それは、第2次大戦直後の楽観的な空気の中、ハワイがアメリカ人の想像 力の中で特別な位置を築きつつあった時代に生まれた、ワイキキで最も大胆な 建物でした。1960年代には旅客機の進化により、米国西海岸からハワイへの飛 行時間が9時間から5時間未満に短縮され、ハワイへの旅がますます身近になり ました。1960年から1970年の間にハワイへの観光客数は6倍に増加し、同時 に滞在日数も短くなり始めます。この過剰なまでの需要増で実用的な建築が増 える一方、ホテルのあり方も変化しました。それまでなくてはならなかったゆった りとしたスイートやフルサイズのキッチンは不要になり、客室はますます小さくな り、ますます空高くそびえるホテルが増えていきました。

ワイキキのアイコニックな建築群は、より大きなホテルに場所を空けるた め次々と取り壊されていったのです。「ザ・ワイキキアン」は1996年にその扉を閉 ざし、目を奪われるようなロビーとレストランは取り壊されました。フラーのドー ムはドン・ホーなどのパフォーマーが出演するナイトクラブとして使われていまし

70 D DESIGN Architecture PALM

The Kaiulani Court Apartments’ breadfruitpatterned railings are characteristic of the tropical embellishments that make Waikīkī’s architecture one of a kind.

Fuller’s dome, which had served as a nightclub and venue for performers like Don Ho, came down three years later. Beachfront property reached such a premium that even tiny parcels were sold off for development. On the sliver of land in front of St. Augustine Church By the Sea, a relic of atomicage architecture, were built a Burger King and an ABC Store, severing the church from the street and beachfront. Still, a surprising amount of significant works remains. On Kalākaua Avenue, Wimberly’s Waikiki Galleria Tower from 1966, with its arching, tessellated, Escher-like façade, sits next to Hart Wood’s Asianinfluenced G. Gump Building built 40 years earlier in 1927, now a store for Louis Vuitton. Some of the seemingly unremarkable walk-up apartment buildings have architectural pedigrees of their own, like the uber-retro Darlani Apartments, designed by the architects who would later help realize the Hawai‘i State Capitol building.

たが、その3年後に取り壊しとなりました。稀少なビ ーチフロントの土地はどんなに小さな区画も残らず 売りに出され、開発されました。セント・オーガスティ ン・バイ・ザ・シー教会の建築もアトミック・エイジの 遺産ですが、この教会の前の区画も開発されて、教 会とビーチの間にバーガー・キングとABCストアが 建ちました。

大きな変貌を遂げたものの、ワイキキにはま だ重要な建築物が驚くほどたくさん残っています。 カラカウア通りには、隙間なくアーチを連ねた、エッ シャーの絵を思わせるデザインの外壁を持つワイキ キ・ギャラリア・タワーがあります。これはウィンバリ ーが1966年に設計したもの。その隣りは、ハート・ ウッドによる設計で1927年に建てられたG.ガンプ・ ビル。アジアの影響濃いこの建物は、現在はルイ・ヴ ィトンのブティックになっています。一見して何の変 哲もない外階段式の低層アパートメントも、建築史 上重要な血筋をひいています。たとえば、見るからに レトロな「ダーラニ・アパートメント」は、後にハワイ

74 D DESIGN Architecture PALM

The neighborhood’s railings alone could fill a coffee table book. They come in every material (wood, steel, iron, concrete) and pattern (leaves, sails, surfboards) imaginable. They bend and wave and zig and zag. They are black, white, aquamarine. Like its ubiquitous breezeblocks or characteristic copper signage, Waikīkī’s banisters and balustrades are functional yet serve as stylistic flourishes.

At the Kaiulani Court Apartments on the corner of Ka‘iulani Avenue and Kūhiō Avenue, a breadfruit motif is rendered in black wrought iron. Down the road, on Lau‘ula Street, a two-story building is adorned with subtle wood panels depicting banana leaves in relief. Along with lava rock walls and cantilevered lānai—hallmarks of Hawai‘i’s tropical modernism—the railings are symbolic of the designer’s wish to represent the beauty of the islands in the built environment. They give Waikīkī a sense of self.

Today, the old Waikīkī is seeing something of a revival. Building on a worldwide interest in midcentury modern design, hotels like the Laylow and the Surfjack Hotel and Swim Club have rehabed buildings from the 1950s and 1960s, filling their lobbies with mod-inspired furniture and generating a newfound appreciation for Waikīkī’s midcentury modern architecture.

Last year, the Surfjack partnered with Docomomo, a preservation group devoted to midcentury modern design, to create a self-guided walking tour of some of Waikīkī’s most significant buildings, including the low-rise Beachside

州庁舎の設計にも関わった建築家たちが手がけたものです。

この界隈のビルの手すりを集めただけでも、見ごたえのある写真集を作れ ることでしょう。素材(木材、スチール、ロートアイアン、コンクリートなど)にもパ ターン(葉、船の帆、サーフボードなど)にも、ありとあらゆる工夫が凝らされてい るのです。曲線を描くもの、波型やジグザグのもの、カラーも黒、白、アクアマリン とさまざまです。いたるところで使われている穴あきブロックや、個性が際立つ銅 素材の看板と同じく、ワイキキのビルの手すりにも実用的でありながらスタイリ ッシュなデザインが花開いています。カイウラニ・アベニューとクヒオ・アベニュー の角にある「カイウラニ・コート」アパートメントの手すりは、ブレッドフルーツを モチーフにした黒いロートアイアン素材のもの。ラウルア・ストリートの角の2階 建てビルは、バナナの葉を浮き彫りにした木製のパネルで飾られています。

溶岩素材の壁やカンチレバー式のラナイといったハワイのトロピカル・モ ダニズム建築の特徴に加えて、こうした手すりにもハワイの美を表現したいとい う設計者の願いがこもっているのです。こういったディテールが、ワイキキに独特 の感覚をもたらしています。

今日、そういった昔ながらのワイキキ的センスがリバイバルを見せていま す。世界各地でミッドセンチュリーモダンのデザインが注目されている中、「ザ・ レイロウ」「ザ・サーフジャック・ホテル&スイムクラブ」といった新しいホテルが 1950年代や60年代の建築を再利用し、モダンな家具でロビーを飾って、ワイキ キのミッドセンチュリーモダン建築に新たな注目を集めています。

昨年、サーフジャック・ホテルは、モダン建築の調査と保存に尽力する組織

76 D DESIGN Architecture PALM

Apartments, designed in 1959 by pioneering local architect Ernest Hara. Last fall, the Queen Emma Land Co. announced its plans to restore the Beachside Apartments, along with two other midcentury walk-ups on Kānekapolei Street.

Like a song full of samples, Waikīkī defies easy categorization, serving up continually surprising textures and juxtapositions. It is at its best when it embraces this multifaceted aspect of itself, its disparate worlds and clashing styles. The old Waikīkī is not gone. It exists, in pockets alongside every other Waikīkī that has come before and after it, and each future Waikīkī that is yet to come.

「ドコモモ」との提携で、ワイキキの最も重要な建築を巡る セルフガイドのウォーキングツアーを作成しました。ツアー で訪ねる中には、1959年に地元の先進的な建築家アーネ スト・ハラが設計した低層アパート「ビーチサイド・アパート メンツ」などがあります。昨秋、地主であるクイーン・エマ・ラ ンド・カンパニーは、このアパートを含む3軒のカネカポレイ 通りにあるミッドセンチュリー低層アパートを修復し、もと の姿に復元する計画を発表しました。

さまざまなビートやサウンドを取り入れた曲のよう に、ワイキキは一つのカテゴリーに縛られることなく、意外 な風合いや取り合わせで私たちの目を驚かせ続けてくれま す。ワイキキは、その多面的な要素を謳歌し、まったく異なる 世界観やぶつかり合うスタイルを包み込んでみせるときに 最高の個性を発揮します。オールド・ワイキキは消えてしま ったわけではありません。移り変わる街角のあちこちにひっ そりと息づいています。そして、これからやってくる新しいビ ルの間でも生き続けていくことでしょう。

80 D DESIGN Architecture PALM

A

Checkered Past

格子縞の物語

Text by Alexis Cheung

文 = アレクシス・チュン

Images by Josiah Patterson

写真 = ジョサイア・パターソン

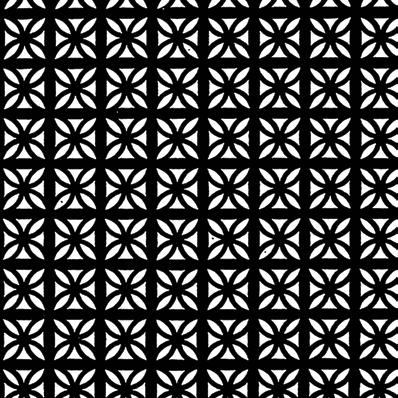

The opening image features a palaka dress by Bete Mu‘u from Nā Mea Hawai‘i.

Photographed at Hawaii’s Plantation Village

82 D DESIGN Palaka PALM

From the sugar cane fields to retail boutiques, this homegrown checked shirt migrated beyond the plantations and into Hawai‘i’s social scene.

サトウキビ畑からセレクトショップへ。プランテーションで誕生したハワイ生まれの格子 柄のシャツがファッションシーンに登場するまでの歴史を振り返ります。

그것은 알파 셔츠보다 더 지역적인 것으로

여겨집니다:체크 무늬 파란 색과 흰색으로

짠 단추가 팔라카라고 알려져 있습니다.

사탕수수 밭에서 소매점에 이르기까지, 이

국내산 체크 셔츠는 전통적인 "제도의 패턴"

으로 알려진 농장을 넘어 하와이의 사회적

환경으로 이주했습니다.

It’s believed to be more local than the aloha shirt: the checked blue-and-white woven button-up known as the palaka. Plantation workers first embraced the garment for its sturdiness in the fields. Later, it was donned for its reputation as “the traditional ‘Pattern of the Islands,’” as explained by scholar Alfons L. Korn.

While the garment’s name refers to its inimitable pattern, the word palaka is actually a Hawaiian transliteration of the English word “frock.” It comes from the loose-fitting, long-sleeved work shirts that Western sailors wore when they first appeared in the islands, starting with Captain Cook in 1778. Apparently, when the Hawaiians asked about the shirt’s fabric, sailors told them about the style of shirt, and the name stuck.

青と白の格子柄に織られた布で作られたボタンつきシャツ「パラカ」は、アロハ シャツよりもハワイらしいシャツと考えられています。畑での過酷な作業に耐え る丈夫なこの服を最初に愛用したのは、プランテーション労働者たちでした。文 学者アルフォンス・L・コーンは、パラカがその後、「伝統的な『ハワイの柄』」であ るために好まれるようになったと解説しています。

その独特の柄を指す「パラカ」という名称は、実はもともと英語の「frock」 (仕事着)をハワイ語に音訳したものでした。1778年のクック船長の上陸を皮 切りに、西洋の水夫たちがハワイ諸島に初めて現れた時期に着ていた、ゆったり とした長袖の作業シャツがその起源です。どうやら、ハワイアンたちがシャツの布 地について尋ねた時に水夫たちはシャツの型を答え、その名前が定着してしまっ たようです。

84 D DESIGN Palaka

PALM

Palaka was introduced to Hawai‘i more than a century ago. It served as a durable de facto uniform for the islands’ plantation workers. Pictured above and previous are vintage palaka garments from Barrio Vintage.

Simple in silhouette, the palaka stands out for its pattern. The fabric hails from Germany, where it was first imported from in the 1800s to create hardy clothing for plantation workers. According to Barbara Kawakami, author of Japanese Immigrant Clothing in Hawaii, 18851941, “During the 1920s and 1930s, palaka was woven of 100 percent cotton and was very thick, very strong, and rough in texture.”

The sturdy twill was occasionally called “Hawaiian denim.” Japanese immigrants who worked the fields referred to the print as gobanji (the Japanese term for plaid, or checkered, design). “[They] were particularly fond of the palaka because it reminded them of the plaid prints in the yukata (unlined kimono made of printed cotton) they had worn in the summer months in their villages back home,” Kawakami wrote.

シンプルなシルエットを持つパラカの特徴 は、ひと目でそれとわかる柄。布地はドイツ製 で、1800年代にプランテーション労働者たちが 着る丈夫な服を作るために初めて輸入されました。

『Japanese Immigrant Clothing in Hawaii, 1885-1941(ハワイ日系移民の衣服:1885年 ~1941年)』の著者バーバラ・カワカミさんによる と、1920年代から1930年代にかけてのパラカは 100%綿で織られ、非常に厚くて丈夫で、布目が粗 かった」そうです。

この丈夫な綾織の布は「ハワイアン・デニム」 と呼ばれたこともありました。畑で働いていた日本 からの移民たちは、このプリント地を「碁盤地」と呼 んでいました。日本人移民たちは「故郷の村で夏に 着ていた浴衣の絣(かすり)を思い出させることか ら、パラカを特に好んでいた」とカワカミさんは書 いています。

86 D DESIGN Palaka PALM

In the 1930s, palaka garments were adopted by the islands’ stylish social set. Pictured on the model is a vintage three-quarter sleeve palaka shirt from Barrio Vintage.

Most commonly recognized today as a shirt, the palaka began as a jacket. Its long-sleeved style became popular in the 1920s with plantation workers in the pineapple and sugarcane fields. The only color choice available was navy, likely because the material was imported. Plantation workers appreciated that the durable fabric protected them in the fields, dried quickly in the rain, and was easy to mend; stevedores and paniolo (Hawaiian cowboys) adopted the palaka for laboring under the hot Hawaiian sun. Workers wore the palaka with denim trousers, creating a signature Hawai‘i ensemble.

The palaka’s popularity spurred a cottage industry, particularly for Okinawan immigrant Zempan Arakawa. In 1904, Arakawa came to Hawai‘i to work, becoming a water boy on a sugar plantation in Waipahu. After obtaining a foot-

パラカは今では一般にシャツとして知られて いますが、当初は上着として作られていました。長 袖スタイルのパラカはパイナップル畑やサトウキビ 畑で働くプランテーション労働者たちの身体を守る のに役立ったので、1920年代に流行しました。輸 入生地だったためか、種類は濃紺色のものだけでし た。プランテーション労働者たちは、畑で身体を守っ てくれ、雨に濡れても素早く乾き、繕いやすい丈夫な 布地を重宝し、やがて、港湾労働者やパニオロ(ハワ イのカウボーイ)たちも照りつけるハワイの太陽の 下でパラカを着て働くようになりました。労働者た ちはパラカにデニムのズボンを合わせて履くように なり、ハワイ独自のアンサンブルが誕生しました。 パラカの人気は、このシャツを作る家内産業が誕 生するきっかけにもなりました。特に、沖縄から移 住してきたゼンパン・アラカワがその先駆者でし た。1904年にハワイで働くためにやってきたアラカ ワは、ワイパフにあるサトウキビ農園でウォーター ボーイ(飲水配給係)となりました。足踏み式ミシン

88 D DESIGN Palaka PALM

pedal sewing machine, he started a makeshift tailor shop. Alongside kau kau bags (made for carrying food) and tabi (Japanese split-toe socks), he sold palaka work shirts for 75 cents each. This venture grew into Hawai‘i’s largest rural department store, Arakawa’s of Waipahu, which lasted from 1909 to 1995.

By the late 1930s, the palaka had been adopted by the social set. As a result, apparel manufacturers “started cutting off the sleeves and using a lighter-weight fabric,” explains Linda Arthur Bradley, professor emerita at Washington State University and author of Aloha Attire: Hawaiian Dress in the Twentieth Century. “The shirt went from being a kind of jacket to what we recognize today as an aloha shirt.”

Eventually, the palaka pattern was used for other attire: bikinis, board shorts, table linens. Young people had palaka garments made for play clothes, according to Bishop Museum historian DeSoto Brown. He even recalls an image of a Kahala home draped in palaka curtains and table cloths. Everyone wore these short-sleeve palaka shirts, and the classic pattern expanded into more colorful hues, ranging from red and pink to green and orange.

While the palaka had its moment with tourists, the shirt mostly resonated with the local crowd. “It really was the kama‘āina shirt,” says Dale Hope, author of The Aloha Shirt: Spirit of the Islands. He remembers how Goro Arakawa (Zempan’s son who took over Arakawa’s with his five siblings) told him that wearing the palaka “was more aloha than the aloha shirt, with its history and all those years it has been worn by so many diverse people.” Goro even claimed, “It was the most important shirt that Hawai‘i’s ever had.”

By the 1950s and 1960s, Bradley explains, “The palaka shirt became a badge of local identity.” From the 1960s through the 1980s, while O‘ahu underwent rapid

を1台手に入れたアラカワは、即席の仕立て屋を始めます。食料を運ぶための カウカウバッグと足袋に加えて、パラカの作業シャツも1枚75セントで売りまし た。この事業はやがて、アラカワズ・オブ・ワイパフという名のハワイ最大の地方 百貨店に成長し、店は1909年から1995年まで存続しました。

1930年末までには、上流社会の人々もパラカを着るようになっていまし た。その結果、縫製業者たちは「袖を短くし、軽い布地を使い始めたのです」と語 るのは、『Aloha Attire: Hawaiian Dress in the Twentieth Century(アロ ハの装い:20世紀のハワイの服装)』の著者、ワシントン州立大学のリンダー・ア ーサー・ブラッドリー名誉教授。「パラカシャツは、一種の上着から今日アロハシ ャツと見なされているものへと変遷していきました」。

やがて、パラカの柄は、ビキニやボードショーツといった他の衣服やテー ブルリネンなどにも使われるようになりました。ビショップ博物館の歴史学者、 デソト・ブラウンさんによれば、若者たちはパラカ生地で作られた遊び着を持っ ていたそうで、ブラウンさんはカハラのある家でパラカ生地のカーテンやテーブ ルクロスがかかっていたのを見た記憶もあるといいます。男性も女性も半袖の パラカシャツを着るようになり、従来の色だけでなく赤やピンク、グリーンやオレ ンジといったよりカラフルな色彩が使われるようになりました。

観光客の間で一時人気を博したこともありましたが、パラカシャツはもっ ぱら地元の人たちに親しまれてきました。「あくまでもカマアイナ(ハワイ住民) のシャツだったのです」『The Aloha Shirt: Spirit of the Islands(アロハシャ ツ:ハワイの心)』の著者、デイル・ホープさんは言います。ゼンパンの息子で5人 の兄と姉とともにアラカワズを継いだゴロー・アラカワが、パラカは「歴史があ り、実に多様な人々が長年愛用してきたことから、アロハシャツよりもアロハな 服装だった」と語り、パラカが「ハワイ史上で最も大事なシャツだった」とさえ言 っていたことを憶えているそうです。

ブラッドリーさんは、1950年代と1960代には「パラカシャツは地元民で あることを示すしるしとなった」と説明します。1960年代から1980年代にかけ

PALM 92 D DESIGN Palaka

urbanization, palaka emerged as a sartorial symbol in local politics. But unlike the aloha shirt, the palaka’s popularity has waned, especially since the original reason for the palaka’s existence—the plantations—are gone. Yet glimmers of resurgence exist. Patagonia created palaka board shorts in 2008, and local designer Kini Zamora created a collection around the fabric. Today, brands including the Hawai‘i Island-based Western Aloha and Los Angeles-based Gordon create palaka-patterned garments. Given the palaka’s storied past, the pattern inherently communicates a special connection to Hawai‘i. According to Hope, wearing palaka demonstrated that you were rooted to the islands, “and that you appreciated this wonderful Hawaiian, kama‘āina lifestyle,” he says. “It was probably the loudest print Hawai‘i’s ever done.”

ては、オアフ島が急速に都市化を遂げる一方で、パ ラカは地域の政治運動を象徴するファッションに なりました。しかし、アロハシャツと違って、特にパラ カの当初の存在理由であったプランテーションが なくなってしまったため、今日ではパラカはあまり 知られていません。

でも、復活の兆しも見えています。アウトドアス ポーツウェアメーカーのパタゴニアが2008年にパ ラカのボードショーツを発売し、ハワイのデザイナ ー、キニ・ザモラもこの布地を主役にしたコレクショ ンを発表しました。現在では、ハワイ島を本拠とす るウエスタン・アロハやロサンゼルスを本拠とする ゴードンなどのブランドがパラカ柄の服をデザイン して販売しています。豊かな歴史に彩られたパラカ の柄は、ハワイという場所との特別なつながりをお のずから表現しています。ホープさんによれば、パラ カを着ることは、その人がハワイに根を下ろし「ハワ イならではの素晴らしいカマアイナ的ライフスタイ ルを愛していること」を示しているといいます。「おそ らく、ハワイが生んだ最も自己主張の強い柄といえ るでしょう」とホープさんは語っています。

94 D DESIGN Palaka PALM

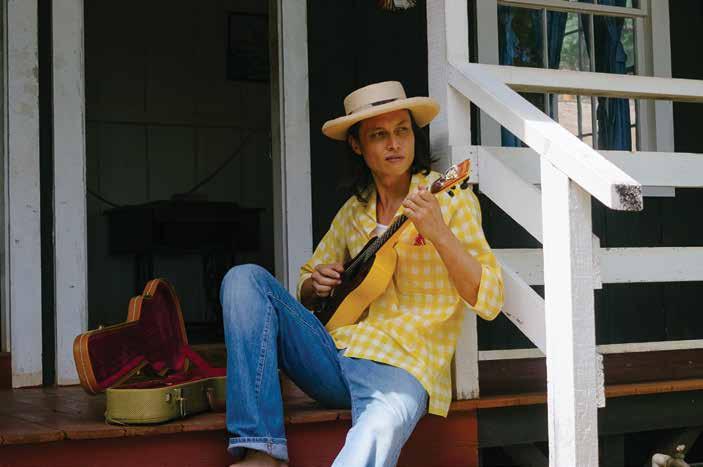

It’s a Breeze

Taking to the streets of Honolulu and Waik ī k ī

Images by Mark Kushimi

Styled by Ara Feducia

Hair

Modeled by Tejas Tevari & Jasmyn Polombo

Dries Van Noten knit top and drawstring pajama pants, both from Saks Fifth Avenue.

and makeup by Bailee Naka‘ahiki, Holly Tomita, Jarrod Shinn, & Jonah Dela Cruz, HMB Studios

Off-White silk shirt, Neiman Marcus; Off-White jeans, Saks Fifth Avenue. Akris blazer and Off-White sheer lace top, both from Neiman Marcus.

Off-White silk shirt, Neiman Marcus; Off-White jeans, Saks Fifth Avenue. Akris blazer and Off-White sheer lace top, both from Neiman Marcus.

Akris hidden zip coat and Mansur Gavriel satchel, both from Neiman Marcus.

Vintage silk handkerchief, wool jacket, Italian collar dress shirt, and high waisted chelsea pants, all from Hermès.

Akris hidden zip coat and Mansur Gavriel satchel, both from Neiman Marcus.

Vintage silk handkerchief, wool jacket, Italian collar dress shirt, and high waisted chelsea pants, all from Hermès.

Karen Walker round sunglasses, Neiman Marcus; Proenza Schouler striped long sleeve and wool pants, both from Saks Fifth Avenue

Karen Walker round sunglasses, Neiman Marcus; Proenza Schouler striped long sleeve and wool pants, both from Saks Fifth Avenue

Issey Miyake forest taffeta and pants, Imperia Trading Inc. crew neck, and Bally driving shoe, all from Saks Fifth Avenue.

Karen Walker round sunglasses, Neiman Marcus; Proenza Schouler striped long sleeve, Saks Fifth Avenue.

Brunello Cucinelli tee and linen trousers, and Nicholas Kirkwood loafers, all from Saks Fifth Avenue; Proenza Schouler crossbody bag, Neiman Marcus.

Akris hidden zip coat, Neiman Marcus.

Brunello Cucinelli tee and linen trousers, and Nicholas Kirkwood loafers, all from Saks Fifth Avenue; Proenza Schouler crossbody bag, Neiman Marcus.

Akris hidden zip coat, Neiman Marcus.

Akris hidden zip coat and cropped chino pants, and Mansur Gavriel satchel, all from Neiman Marcus; Alexander McQueen leather slides, Saks Fifth Avenue.

Akris hidden zip coat and cropped chino pants, and Mansur Gavriel satchel, all from Neiman Marcus; Alexander McQueen leather slides, Saks Fifth Avenue.

Thom Browne wool jacket, Issey Miyake pants, and Bally leather loafers, all from Saks Fifth Avenue.

Thom Browne wool jacket, Issey Miyake pants, and Bally leather loafers, all from Saks Fifth Avenue.

Thom Browne wool jacket and button-down shirt, both from Saks Fifth Avenue.

Fendi cat-eye sunglasses and Off-White asymmetric top, both from Neiman Marcus.

Fendi cat-eye sunglasses and Off-White asymmetric top, both from Neiman Marcus.

Kenzo colorblock cotton parka, Neiman Marcus; Thom Browne cotton button-down, Saks Fifth Avenue; sunglasses, stylist’s own.

Marc Jacobs sweater and cotton printed skirt, and Stuart Weitzman leather sandals, all from Saks Fifth Avenue; Mansur Gavriel leather backpack, and Céline aviator sunglasses, both from Neiman Marcus.

Kenzo colorblock cotton parka, Neiman Marcus; Thom Browne cotton button-down, Saks Fifth Avenue; sunglasses, stylist’s own.

Marc Jacobs sweater and cotton printed skirt, and Stuart Weitzman leather sandals, all from Saks Fifth Avenue; Mansur Gavriel leather backpack, and Céline aviator sunglasses, both from Neiman Marcus.

Travel

ES CA PES

experiences

both

E PALM エスケープ

CUL TU RE

of place that A sense fosters the human spirit 115 115 faraway and familiar

PALM PALM E

Island of a Thousand Rituals

千の儀式が生きる島

Text by Lynne Hong

文 = リン・ホン

Images by Yosuke Zen Moriya

写真 = ヨウスケ・ゼン・モリヤ

116 E ESCAPES Bali PALM

The sights and sounds of sacred chants, ancient healing rituals, and temple gongs in Bali reflect a welcoming rhythm of life that follows celebrations and rituals of near magical proportions.

神聖な詠唱、古代から伝わる癒やしの儀式、寺院に響く銅鑼の音は、心 地良い生命のリズムを反映しています。日常がお祭りや儀式で溢れたバ リ島は、魔法の島のよう。

발리의 신성한 찬송가, 고대의 치유 의식, 사찰

징의 광경과 소리는 거의 마법 같은 비율의 축하와

의식을 따르는 삶의 환영 리듬을 반영한다.

The country of Indonesia has the world’s largest Muslim population, but on the island of Bali, a distinctive Hindu culture is worn like a badge of honor. Animism, the belief that all things possess a spiritual essence, is a cornerstone of Balinese Hinduism, and a corresponding reverence for nature abounds. There are temples in seemingly every house and village, on mountains and beaches, in rice fields, trees, caves, and rivers. This culture is vibrant and accessible, which makes a trip to Bali unlike that to any other destination.

PALM

インドネシアは世界で最もイスラム教徒の数が多い国ですが、バリ島の人々は 独自のヒンドゥー文化を勲章のように尊び、誇りとしています。バリ島のヒンド ゥーはアニミズムを基本とし、豊かな自然の森羅万象への崇拝に通じます。ど の家にもどの村にも、山の上にも海辺にも、稲田の中、樹々の上、洞窟や川にも 寺院があります。活気に溢れ、親しみやすい文化が、バリ島への旅をどんな場 所への旅とも違う体験にしてくれます。

118 E ESCAPES Bali

The Trance

The Kecak and Fire Dance is one of Bali’s most iconic performances. The best place to witness it is at the Uluwatu Temple amphitheater, which sits at the edge of a cliff overlooking the turquoise water of the Indian Ocean. The striking silhouette of the Uluwatu Temple just to the south adds to the spectacular view. When the sun begins to dip below the horizon and the water is bathed in its golden glow, the dance begins on the amphitheater floor. Roughly 100 bare-chested Balinese men sit in concentric circles, swaying and chanting in hypnotic rhythm as the story unfolds. The haunting sounds leave nearly everyone in the arena mesmerized. The Kecak is also known as the Ramayana Monkey Chant and was developed in Gianyar as a trance ritual. It was later adapted into a storytelling dance by a visiting German artist in the 1930s, Walter Spies, intended for performance before Western tourist audiences. The drama depicts a battle from the Sanskrit epic poem Ramayana. The story retells Prince Rama’s attempt to rescue his wife, Princess Sita, from the demon king Rahwana.

The Silence

While most of the world celebrates New Year’s Eve on December 31, Bali celebrates it in March, welcoming the new year with a day of silence called Nyepi. For three days leading up to Nyepi, the streets fill with boisterous crowds and excitement hangs in the air. In the villages, locals parade gigantic ogoh-ogoh, which are papier-mâché effigies, through the streets accompanied by gamelan, the traditional music ensemble made up of percussive instruments. The ogoh-ogoh are often grotesque, with bulging eyes, fangs, and hairy backs to represent evil spirits. After their display, the effigies are torched with jubilation, symbolizing the burning away of one’s demons. On Nyepi, everything shuts down for 24 hours— including the airport. No flights arrive in or leave Bali. Visitors are expected to remain in their accommodations to observe the silence. On this night, the sky is blanketed with stars, free from light pollution as nature takes a break from human activities.

The Triumph

The holiday of Galungan enlivens the entire island for more than 10 days. A celebration of the triumph of good over evil and the creation of the universe, Galungan marks a period when the gods come down to Earth

陶酔

ケチャと火の踊りは、バリ島で最も有名な舞踏の一つです。ケチャを見るなら ウルワツ寺院の屋外円形劇場がベスト。ここは崖の上にあり、ターコイズ色の インド洋が眺められるうえ、すぐ南側にあるウルワツ寺院のシルエットが壮大 な景観をさらに印象強いものにします。水平線の彼方に太陽が沈み始めると

海は黄金色に輝き、劇場ではケチャの舞踏劇が始まります。100人ほどの半裸 の男性が円陣を組んで座り、身体を揺らしながらまるで催眠術のようなリズム で合唱する中で、舞踏の物語が進行していきます。合唱の声が紡ぐ忘れがたい 響きには劇場にいる誰もがいやおうなしに引き込まれずにいられません。「モン キーチャント」と呼ばれることもあるケチャは、ギャニャール地方で行われてい たトランス状態で踊る儀式をもとに発展してきました。そうした儀式が1930 年代にドイツ人画家ワルター・シュピースによって舞踏劇として脚色され、西洋 からの観光客向けの伝統として根づいたのです。舞踏劇は、ヒンドゥー教の叙 事詩「ラーマヤナ」の中から、ラーマ王子が魔王ラーヴァナのもとから妻のシー タ姫を救い出す戦いの物語を語っています。

沈黙

世界のほとんどの場所では1年の終わりを12月31日に祝いますが、バリ島で は3月が新年。「ニュピ」と呼ばれる元日は、沈黙の1日です。ニュピの前の3日間 は、通りは陽気な群衆で埋め尽くされ、国中がお祭り気分に包まれます。村々 では「オゴオゴ」という巨大な張り子の像をかついで行列が練り歩き、さまざま なパーカッションで構成された伝統のガムラン音楽が鳴り響きます。オゴオゴ は多くの場合とてもグロテスクで、ぎょろりとした巨大な目玉、牙、毛むくじゃら の背中などを持つ、悪霊の化身として描かれています。通りを練り歩いた後、オ ゴオゴの像には火がつけられ、悪霊を追放する象徴として、人々の歓声の中で 燃えていきます。翌日のニュピの間は丸24時間にわたって島中のすべてが閉鎖 されます。これには空港も含まれ、この日にバリ島を発着する飛行機は1機もあ りません。観光客もホテルの部屋にこもり、沈黙の1日を過ごすことになります。 その日の夜空は一切の光害がなくなるため、満天の星が輝きます。人々の暮ら しの中に、自然が1日だけ戻ってくるのです。

勝利 ガルンガンの祭日は、10日間にわたって島中が活気づきます。ガルンガンは悪 に対する善の勝利と世界創造をお祝いする祭礼で、この期間には神々が地上 に降り立ち、先祖の霊がこの世に戻って来るとされています。バリ島の人々は

120 E ESCAPES Bali PALM

and the souls of ancestors visit. Locals are more than happy to have tourists involved in preparations for Galungan such as making cakes (a job done by women only) or constructing penjor, which are tall, curved bamboo poles decorated with coconut leaves, cassava, fruits, and 11 Chinese coins. The penjor symbolizes the mountain and is synonymous with Mount Agung, the holiest mountain in Bali. Kuningan marks the end of the festivities, celebrating purification. On this day, the ancestors’ souls leave the family temple. With its centuries-old temples, romantic old charm, and fascinating rituals, Bali, the “Island of Gods,” offers visitors more than just a slice of Hindu heaven. It is in such sacred rituals that the essence of Balinese culture lies.