In this issue, we celebrate the things that make people and places unique. The connections that strengthen us when we’re together—and the influences that feed us when we’re apart—are all the more important as we adjust to a new normal as individuals and as a community.

We’re offered a glimpse into the creative universes of artist Kahi Ching and classical pianist Grace Nikae, prodigies who parlayed their gifts into fruitful, lifelong careers in the arts. We follow learning ecologist Daniel Kinzer in his search for the “genius” of place, evident in the resilience of communities and habitats and in the patterns of nature that reveal themselves when we slow down long enough to notice their extraordinary forms. We celebrate the singular charms of destinations near and far, from the mythical vistas along Iceland’s Ring Road to the eccentricities of Wailuku, Maui, a town in the midst of a cultural resurgence.

In recognizing what’s exceptional about the world around us, we’re reminded of our capacity for overcoming adversity, creating beauty, striving for excellence, and evolving always. We invite you to seek inspiration in the pages that follow as we reimagine, move forward, and build a better tomorrow.

今号では、人や場所を豊かにする独自性について紹介しています。共 に過ごすことで強まる絆と離れていることの影響。それらは私たちが 個人やコミュニティとしてニューノーマルに適応していく上でますま

す重要になっています。

芸術に才能を惜しみなく注ぎ込み、生涯にわたるキャリアで成功 を収めている奇才アーティストのカヒ・チンさんとクラシックピアニ ストのグレース・ニカエさんのクリエイティブな世界を覗いてみまし ょう。心にゆとりを持って自然界の驚異的な姿を観察すれば見えて くるコミュニティや生息環境の耐性と自然の法則のような自然界の 「天才」に学ぶ方法を、エコロジストのダニエル・キンザーさんとと もに探究します。さらにアイスランドのリングロードの神秘的な絶景 から文化復興の真っ只中にあるマウイ島ワイルクの風変わりな景色 まで、世界のデスティネーションのユニークな魅力を紹介します。 世界中の素晴らしいものを賛美することは、私たちの中に潜在 する能力に気づかせてくれます。それは逆境を克服し、美しさを創造 し、卓越性を目指して努力し、常に進化し続けることのできる力です。 続くページが私たちの考えを深め、前向きに生き、より良い明日を築 いていくためのインスピレーションとなることを願っています。

12 LETTER From the Developer

CEO & PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

VP BRAND DEVELOPMENT

Ara Laylo

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Lauren McNally

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Matthew Dekneef

NATIONAL EDITOR

Anna Harmon

SENIOR EDITOR

Rae Sojot

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Eunica Escalante

SENIOR PHOTOGRAPHER

John Hook

DESIGNER

Mai Lan Tran

PUBLISHED BY:

NMG Network

36 N. Hotel St. Ste. A Honolulu, HI 96817

PALM is published exclusively for:

MACNAUGHTON &

CREATIVE SERVICES

Marc Graser VP Global Content

Shannon Fujimoto

Creative Services Director

Gerard Elmore VP Film

Blake Abes

Romeo Lapitan Filmmakers

Kaitlyn Ledzian Brand & Production Manager

Taylor Kondo

Brand Production Coordinator

TRANSLATIONS

Japanese

Akiko Shima

Yuzuwords

Korean AT Marketing

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley VP Sales mike@nmgnetwork.com

Chris Kelly Partnerships & Media Executive

Courtney Asato Marketing & Advertising Executive

Codey Mita Sales & Marketing Coordinator

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock Partner / General Manager - Hawai‘i

Rob Mora VP Special Operations

Francine Naoko Beppu VP Network Strategy

Gary Payne VP Accounting

Courtney Miyashiro Operations Administrator

GROUP © 2021 by Nella Media Group, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted without the written consent of the publisher. Opinions are solely those of the contributors and are not necessarily endorsed by NMG Network.

14

KOBAYASHI

74 16 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTS 22 State of the Art 30 Growing Up Gifted CULTURE 44 A Big Deal 52 The Genius of Place 66 Electric Light Orchestra DESIGN 74 A Nautical Niche 82 Diamond in the Rough ESCAPES 96 Light and Landscapes 108 Wailuku’s Renaissance FARE 120 Raising the Bar 82 ON THE COVER

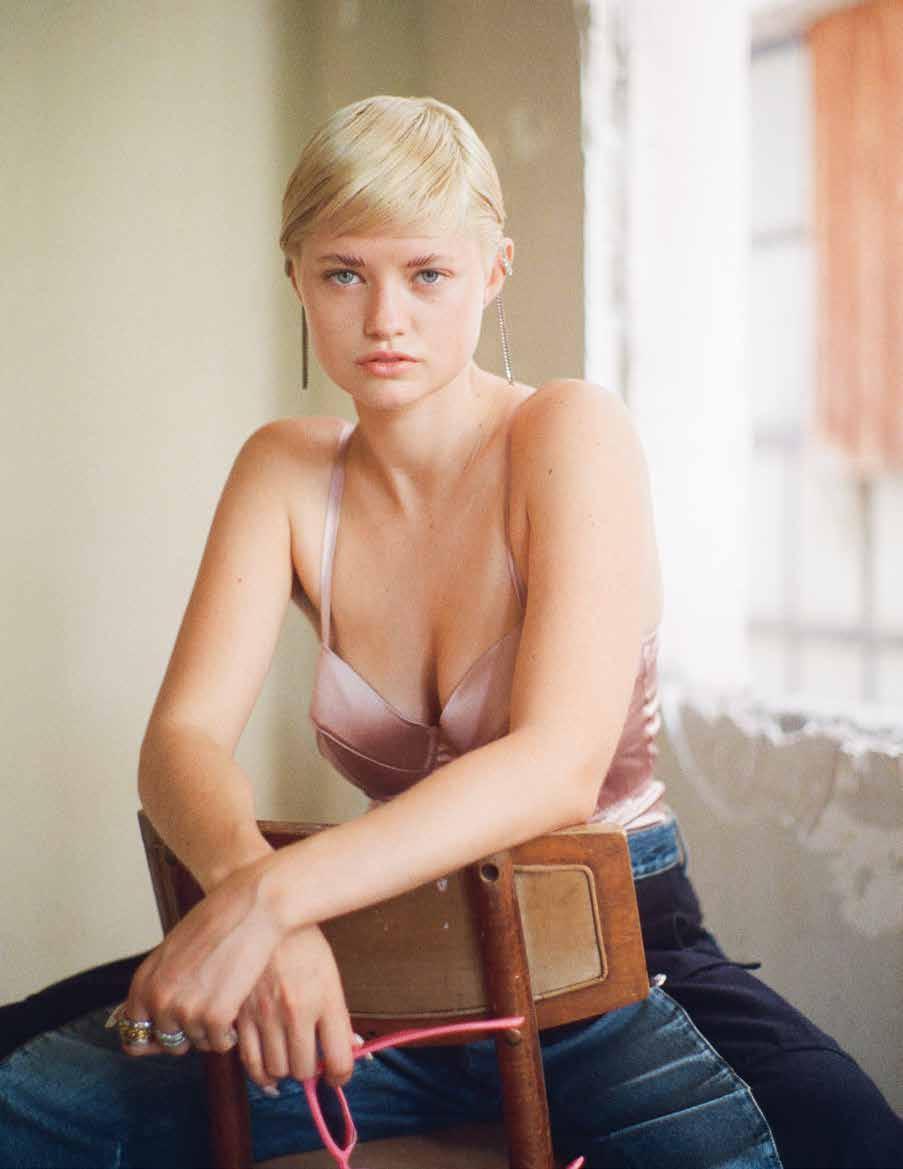

Brooke Wood is photographed by Mark Kushimi inside the historic Wo Fat Building in Honolulu’s Chinatown.

表紙

写真:マーク・クシミ

モデル:ブルック・ウッド

撮影場所:ウォーファッ トビルディング

天性の才能を伸ばす

小さな一歩、大きな変化

海の上のニッチ

ダイヤモンドの原石 エスケープ

ワイルク・ルネッサンス 食

新世代の居酒屋

18 82 96 目次 アート 22 ステート・オブ・ザ・アート 30

文化 44

52

66 エレクトリックライト・オーケストラ

74

自然界の天才に学ぶ

デザイン

82

96

108

アイスランドの光

120

notions

AR TS

that amplify

A PALM アート

Visual

the soul of the city

21

PALM A

PALM

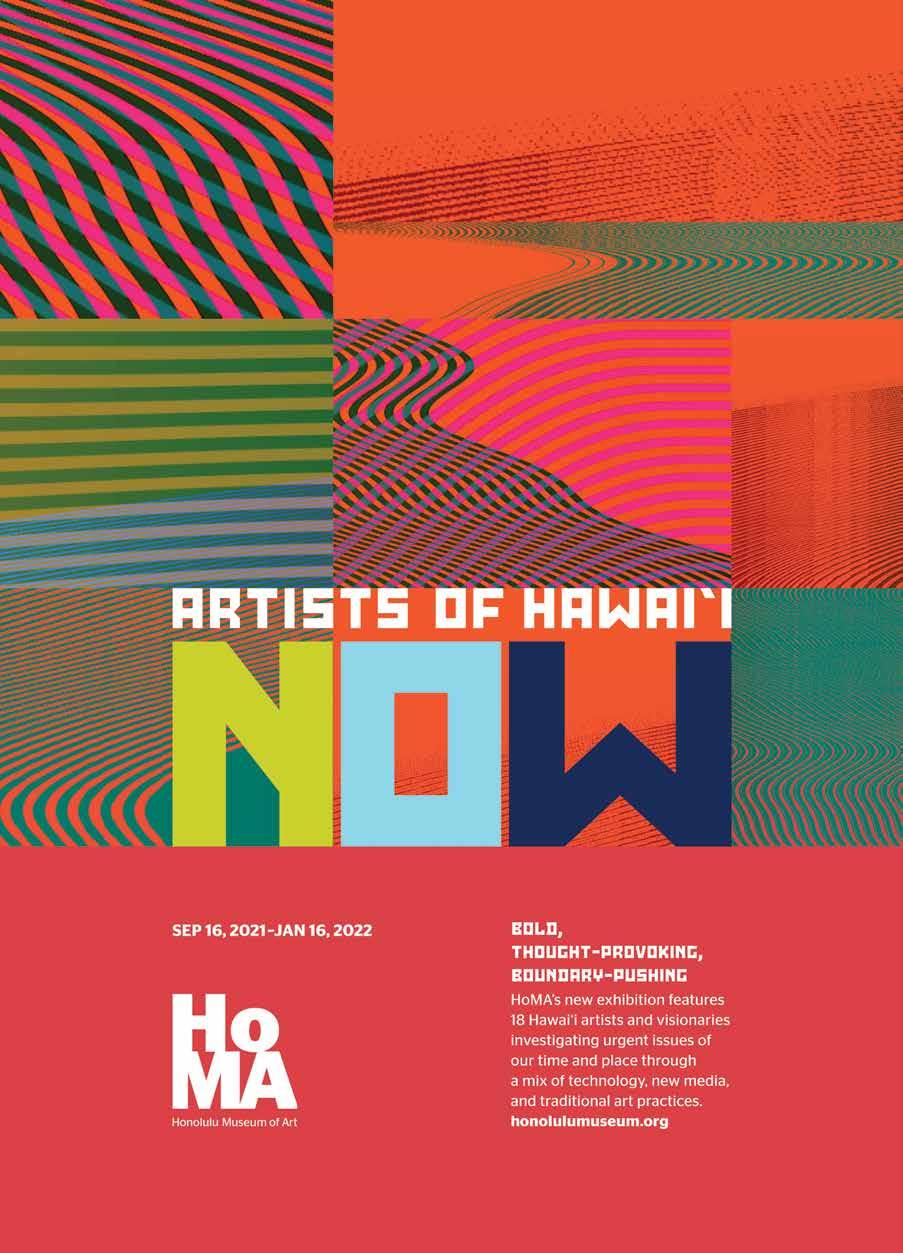

State of the Art

Text by Josh Tengan

Images courtesy of the artists and Hawai‘i Contemporary 文

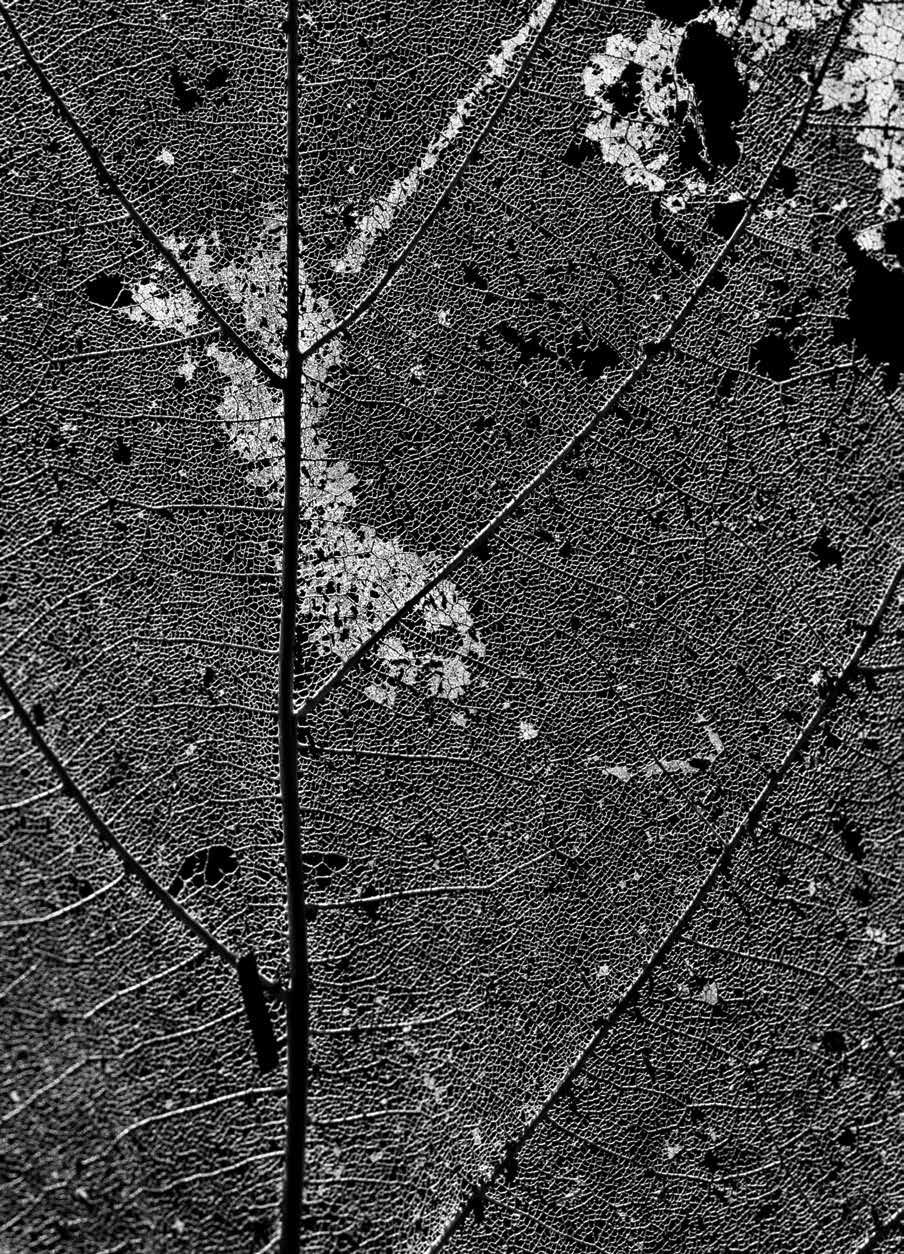

Details of Paul Pfeiffer’s Poltergeist for Honolulu Biennial 2019 and Drew Kahu‘āina Broderick’s Billboard I (The sovereignty of the land is perpetuated in righteousness) at Honolulu Biennial 2017.

22 PALM A ARTS Curators

ステート・オブ・ザ・アート

= ジョシュ・テンガン 写真 = アーティストとハワイコンテンポラリー提供

In anticipation of the Hawai‘i Triennial 2022, two curators affiliated with the international art exhibition discuss the role of biennials and triennials in shaping dialogues about place.

国際美術展「ハワイ・トリエンナーレ2022」を前に、コミュニティとは、パンデミ ックが地元の美術館に与える影響、地域性を語る上でのビエンナーレとトリエ ンナーレの役割について、過去と現在2人のキュレーターに聞きました。

Translation by Akiko Shima

翻訳 = 島有希子

2022년의 하와이 트리엔날레에 기대를 가지고 국제 미술 전시

회의 전 큐레이터와 현재 큐레이터가 장소에 대한 대화를 나누

며 비엔날레와 트리엔날레의 역할에 대해 논의합니다.

Honolulu’s contemporary art ecosystem is relatively small and underdeveloped for a city of its size. Its Indigenous art community is an even smaller subsection of that. Everyone knows everyone.

I was reintroduced to artist, gallerist, curator, and educator Drew Broderick in 2014 after moving home to Hawai‘i from England. He was running SPF Projects, the only independent artist-run initiative at the time, whose mission was to support art with a critical focus on Hawai‘i. Not long after, I began working for his mother, Maile Meyer, founder of Native Books/Nā Mea Hawai‘i and executive director of the arts nonprofit Pu‘uhonua Society.

ホノルルの現代アートのエコシステムは、このサイズの都市にしては小規模で 発展途上である。その中でも先住民のアートコミュニティはさらに小さく、誰も が顔見知りだ。

私がドリュー・ブロデリックさんと再会したのは2014年。イギリスからハ ワイに帰国した後のことだった。アーティスト、ギャラリスト、キュレーター、教 育者と多くの顔を持つ彼は、当時唯一の独立アーティストによる「SPFプロジ ェクト」を運営し、ハワイにフォーカスしたアートをサポートしていた。再会から 間もなくして、私は彼の母親のマイレ・メイヤーさんの元で働き出すことになっ た。マイレさんは「ネイティブブックス/ナ・メア・ハワイ」の創設者で、アート関

24 A PALM ARTS Curators

Above, an installation view of Ei Arakawa’s Surrounded by Biennials (Sharjah Biennial) during Honolulu Biennial 2019. At left, Hawai‘i Triennial 2022 curators Dr. Miwako Tezuka, Dr. Melissa Chiu, and Drew Kahu‘āina Broderick at the Honolulu Museum of Art.

Above, an installation view of Ei Arakawa’s Surrounded by Biennials (Sharjah Biennial) during Honolulu Biennial 2019. At left, Hawai‘i Triennial 2022 curators Dr. Miwako Tezuka, Dr. Melissa Chiu, and Drew Kahu‘āina Broderick at the Honolulu Museum of Art.

Their ‘ohana has supported artists and creatives in Hawai‘i for generations. After six years of working collectively on various efforts, I am a part of this extended network of continuity and care.

In 2018, I was appointed assistant curator, alongside curator Nina Tonga, of Honolulu Biennial 2019, a multisite public exhibition of art and ideas from Hawai‘i and the Pacific. Broderick was a participating artist in the first edition of the biennial in 2017, curated by Ngahiraka Mason. He returns as an associate curator for the exhibition’s third iteration, Hawai‘i Triennial 2022, themed Pacific Century: E Ho‘omau no Moananuiākea. Since its inception, Hawai‘i Contemporary (the nonprofit formerly known as the Honolulu Biennial Foundation, which organizes the periodic exhibition) has overcome skepticism from the local community and leadership change. Today it faces all of the strains that come with a global pandemic. Perhaps now more than ever is a momentous occasion to reflect on the relevance of international art festivals in a cultural moment characterized by isolation and ideological difference. At the core of our conversation is the underlying question: “How do internationally oriented contemporary art events like biennials and triennials impact local communities?”

JT: What communities do you belong to? As one of the curators of the upcoming Hawai‘i Triennial, who do you see as your audience?

I’m from Mōkapu, a peninsula between the bays of Kāne‘ohe and Kailua, on the windward side of the island of O‘ahu in the occupied archipelagic nation of Hawai‘i. It’s from this place that my sense of belonging comes.

“Community” is a loaded word, full of relationships, fraught with contradictions, as alienating as it is empowering. Sometimes we claim, and sometimes we are claimed. Either way, the context from which we live, work, make, and care shapes us, as do the communities we belong to and the audiences that our collective efforts serve.

Knowing this, I try not to assume a particular audience, as there are often many more than we initially imagine. That said, I believe that biennials and triennials, no matter where they happen, should begin from where they are. Without Hawai‘i, there is no Hawai‘i Triennial. This understanding is fundamental. Regardless of who the upcoming triennial is for, those involved must embody a deep sense of responsibility to the forms and flows, both animate and inanimate, that comprise this place— Hawai‘i nei.

連の非営利団体「プウホヌア・ソサエティ」の事務局長を務める。彼らの家族( オハナ)は何世代にもわたってハワイのアーティストやクリエイターたちを支援 してきた。様々なプロジェクトで彼らとコラボレートして6年が経った今、私はこ の文化保護の継続的な取り組みの一端を担うオハナの一員となっている。 2018年、私はキュレーターのニーナ・トンガさんとともにホノルル・ビ エンナーレ2019のアシスタントキュレーターに任命された。ホノルル・ビエ ンナーレは太平洋地域とハワイの現代アートを通して人々に芸術やアイデ ィアのグローバルな交流の場を提供する国際美術展だ。2017年にナヒラ カ・メイソン氏がキュレーションを手掛けた初回ビエンナーレにアーティスト として参加していたドリューさんは、再び「太平洋の世紀:E Hoʻomau no Moananuiākea」をテーマにした3回目のハワイ・トリエンナーレ2022にアソ シエイトキュレーターとして戻ってくる。

ハワイコンテンポラリー(定期的にアート展を主催する非営利団体、旧 ホノルル・ビエンナーレ財団)は設立以来、地元社会からの懐疑的な視線やリ ーダーシップの交代という難局を乗り切って今に至る。そして現在はパンデミ ックに起因する様々な試練に直面している。孤立やイデオロギーの違いといっ た文化的に試されるこの時こそ、国際アートフェスティバルのあり方について 見直す大切な機会なのかもしれない。今回追求するテーマは、「ビエンナーレ やトリエンナーレのような海外へ向けた現代アート展が地元社会に与える影 響とは?」というものだ。

JT: あなたはどのコミュニティに属していますか?次回ハワイ・トリエンナー レのキュレーターのあなたにとって、対象のオーディエンスは誰ですか? 私はモカプの出身です。モカプはかつて違法に占領された群島国家ハワ イのオアフ島ウィンドワード側のカネオヘ湾とカイルア湾の間にある半島です。 私の帰属意識はこの場所から来ています。

コミュニティという言葉にはたくさんの意味があって、それは人間関係や 矛盾に満ち、力を与えてくれることもあれば疎外感を与えることもあります。自 分たちで主張することもあれば、奪われることもあるのです。私たちが住み、働 き、作り、大切にするものが私たちを形作るのと同じで、国際芸術祭を形成す るのは私たちが属するコミュニティとアートを発信する対象のオーディエンス なのです。

その上で私はあえて特定のオーディエンスに特化しないようにしていま す。なぜなら実際には私たちが想定するよりはるかに多くのオーディエンスが いるからです。それでもビエンナーレとトリエンナーレは開催場所にかかわら ず、アートが生まれた場所からスタートすべきだと私は考えます。ハワイ抜き にハワイ・トリエンナーレは存在しません。れが根底にある考え方です。次のト リエンナーレのオーディエンスが誰であれ開催側の私たちはこの場所「ハワ イネイ」を作り上げるあらゆるアートに対する使命感を具現化する必要があ ります。

26 PALM A ARTS Curators

Installation view of Demian DinéYazhi’s my ancestors will not let me forget this at Honolulu Biennial 2019.

Installation view of Demian DinéYazhi’s my ancestors will not let me forget this at Honolulu Biennial 2019.

Some of the major arguments in favor of launching the inaugural Honolulu Biennial (now the Hawai‘i Triennial) were that most major cosmopolitan cities around the world host large-scale international art exhibitions, and that Hawai‘i provides a unique exhibition context as a crossroads of the Pacific, where East, West, and Indigenous culture collide. How do you understand this framing of the place you call home?

From my perspective, the second point you mention is perhaps more significant to the work that has been done and continues to be done locally within communities. If something is happening elsewhere in the world, that doesn’t necessarily mean it should take place here. We are well aware that biennials and triennials originated in a European context during the late 19th century.

Indeed, Hawai‘i has a lot to offer global conversations. Our unique position at a piko of Moananui, a center of the Pacific, is not to be taken for granted. With time and practice, however, I have realized that internationally oriented art events often take more from Indigenous and local communities than they give. This asymmetry is commonplace throughout the global circuit and deserves to be considered carefully and challenged intentionally wherever and whenever possible. Hawai‘i’s contested histories and the ongoing acts of refusal and affirmation that define daily life allow us to do just that. As Native Hawaiian nationalist, educator, political scientist, author, and poet Haunani-Kay Trask has written, “Resistance is its own reward.”

We are in a moment when local museums and institutions have shifted their programming to center on local artists— Bishop Museum recently did a ten-year survey of Pow! Wow!, Honolulu Museum of Art is commissioning Hawai‘i artists in a series of site-specific installations activating their courtyards. Is this a trend that we can expect for Hawai‘i Triennial 2022?

The unevenly distributed Covid-19 pandemic has placed local institutions and organizations in an even more precarious position than before. With the rise in international shipping costs and restrictions on travel, artists and audiences of Hawai‘i have become more crucial than ever. The irony is that it took a deadly virus for some to recognize and acknowledge the value of Hawai‘i. Another way to look at it is that our museums are simply appropriating the grassroots efforts of communities because their relevance depends on it. Regardless, if supporting Native and local artists is a current trend— long overdue—then yes, the upcoming Hawai‘i Triennial 2022 will continue in this direction.

ホノルル・ビエンナーレ(現在のハワイ・トリエンナーレ)を開催すべき理由と してサポーターの多くは、世界の国際都市のほとんどで大規模な国際美術展 が開催されていること、そしてハワイが東と西と先住民文化の交わる太平洋 の中心にあってユニークな展示を可能にする点を挙げていました。あなたの 故郷であるハワイについてのこの捉え方をどう思いますか?

後者のポイントは地元コミュニティの中で作られ、作り続けられているア ートにとっては特に重要な意味があるかと思います。世界の他の都市で開催さ れているからといって、必ずしもハワイにもなければとは思いません。ビエンナ ーレやトリエンナーレは19世紀後半のヨーロッパに起源がありますね。

実際、ハワイには世界に向けて発信できることがたくさんあります。私た ちが「モアナヌイのピコ」と呼ぶ太平洋の中心にあるハワイのユニークな地理 的環境はとても特別なものです。ところが時間と経験を重ねるうちに、国際芸 術祭の多くは先住民や地元のコミュニティに与えるものより奪うもののほうが 多いことに気づいたのです。この不均衡はグローバル社会で一般的に広く見ら れる問題で、慎重に配慮し、できるだけ多くの場面で意図的に意義を唱えてい く必要があります。それはハワイの争いの歴史と日常生活における否定と肯定 の繰り返しが私たちにさせてくれた唯一のことです。ネイティブハワイアンの民 族主義者、教育者、政治学者、作家、詩人のハウナニ・ケイ・トラスクさんが書い ているように「抵抗はまさにそれ自体が見返りなのです」。

今地元の美術館や機関は、地元のアーティストに焦点を当てたプログラムに シフトしつつあります。ビショップ博物館では最近、Pow! Wow!の10年の 歴史を振り返る展示を行い、ホノルル美術館では複数の地元アーティストに よるハワイにフォーカスしたアートシリーズを中庭に製作中です。ハワイ・ト リエンナーレ2022でもこのトレンドが見られるのでしょうか? 地元の芸術施設や団体は不均衡な新型コロナウイルスのパンデミック によって、以前にも増して不安定な状況に置かれています。海外配送コストの 増加と旅行制限の影響でハワイのアーティストとオーディエンスがこれまで以 上に重要となっています。致命的なウイルスのおかげで以前にも増してハワイ の価値が認知されるようになったのは皮肉なことです。そしてハワイの美術館 は、人々の関心を集めるコミュニティの草の根的なアート活動に注目するよう になりました。ネイティブハワイアンと地元のアーティストをサポートすること が現在のトレンドであるとすれば、それは本当にありがたいことです。それはま さに次回ハワイ・トリエンナーレ2022が目指しているものです。

28 A PALM ARTS Curators

Growing Up Gifted

天性の才能を伸ばす

文 = リンゼイ・ケセル

写真 = クリス・ローラー

30 PALM A ARTS Prodigies

Text by Lindsey Kesel

Images by Chris Rohrer

A pair of former child prodigies talk inspiration, art as language, and the evolution of their craft.

かつて天才児と呼ばれた二人が、インスピレーショ ンの源、表現手段としての芸術、そしてそれぞれの才 能をいかに昇華させてきたかを語ってくれました。

GRACE NIKAE Classical Pianist

Atrue-to-form prodigy, Grace Nikae took her first piano lesson at nine months old. Two years later, she was playing complex concertos and reading Mark Twain novels. “You don’t realize what you’re doing is not like everyone else. It’s the most natural thing in the world,” she says. “But our way of perceiving patterns is different. It doesn’t simply apply to musical notes but also math, language, reading words on a page.”

典型的な天才少女だったグレイス・ニカエさんは、 生後9か月で最初のピアノのレッスンを受けてい る。その2年後には複雑なピアノ協奏曲を弾きこな し、マーク・トウェインの小説を読んでいた。「自分 がほかの子とは違うことをしているなんて知りませ んでした。ごく自然にピアノを弾き、小説を読んでい たんです」とニカエさんは振り返る。「ただ、私たち がパターンを理解する方法は普通とは違っていま す。音符だけではなく、数学や語学、書かれた文字 を読むときもそうなのです」

두명의 비범한 어린이가 영감, 언어로서의 예술, 기술의 발전에 대해 이야기합니다.

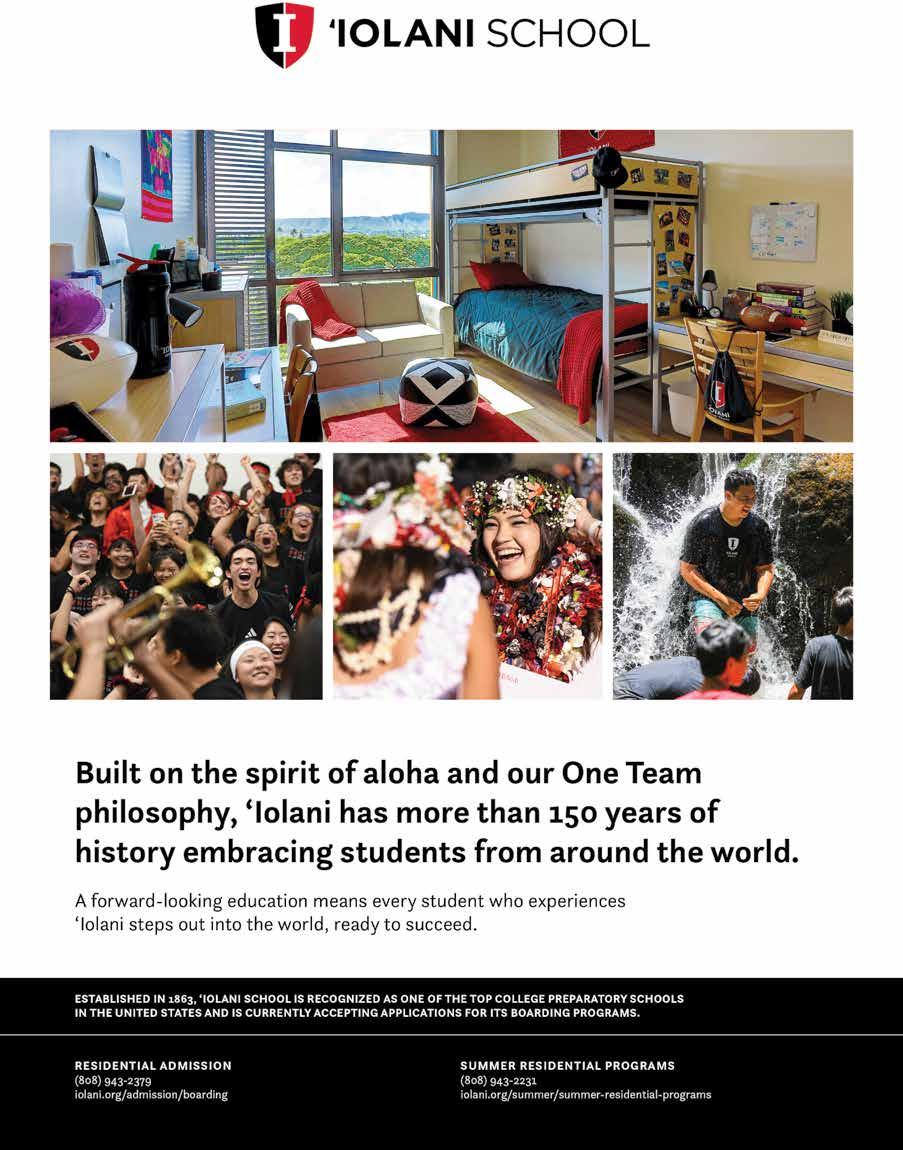

Nikae made her professional debut with the Honolulu Symphony Orchestra at 8 years old. At 14 years old, she was offered early university acceptance but chose instead to continue her education at ‘Iolani School. She played Carnegie Hall before her 18th birthday and, at 21 years old, began studying under renowned Ukrainian pianist Alexander Slobodyanik, “a profound influence who helped me transition from child to adult artist.” Then Nikae embarked on an international concert career that spanned two decades and showcased her music in elite concert halls from London to Tokyo.

Playing piano has always been a journey of self-discovery for Nikae: “Music gave me a voice to say things I couldn’t say with my real voice, to explore the great themes of existence—what does it mean to be an individual, to love, to grieve, to search for something more?” She found inspiration in the many

ニカエさんがプロとしてデビューを飾った のは8歳のとき。ホノルル交響楽団との共演だっ た。14歳で大学への早期入学を認められるが、 イオラニ校(ホノルルにある幼稚園から高校まで の私立一貫校)で学び続ける道を選んだ。18歳 の誕生日を迎える前にカーネギー・ホールで演奏 し、21歳でウクライナ出身の著名なピアニスト、ア レクサンドル・スロボジャニクに師事。「子どもから 大人のアーティストへと移行するときに、多大な影 響を受けました」。それから20年にわたり、ニカエ さんは国際的なプロの演奏家として、ロンドンから 東京まで一流のコンサートホールでその音楽的才 能を披露してきた。

ニカエさんにとって、ピアノの演奏は常に自 分を発見する旅でもあった。「音楽は、自分の声で は伝えられないことを表現する手段と、自分の存 在を支える大きなテーマを探る手段を与えてくれ ました。私が個人として存在することにどんな意 味があるのか。愛すること、嘆き悲しむこと、さらに もっと深く何かを探求することの意味を知りたか

Translation by Eri Toyama Lau 翻訳 = ラウ外山恵理

32 A ARTS Prodigies

クラシック・ピアニスト

グレイス・ニカエ(二替具麗子)さん

“You don’t realize what you’re doing is not like everyone else,” says piano prodigy Grace Nikae, who made her professional debut with the Honolulu Symphony Orchestra at 8 years old.

artists and intellectuals in her family, including a mathematician uncle who solved a theorem he’d been working on for 25 years. “I remember when he finally solved it, it was so beyond my understanding,” Nikae says. “I was so struck by the amount of concentration and the amount of passion. Even when he couldn’t see a result, he continued to believe and search.”

Seeking a way to connect with others more directly through music, she served as a cultural ambassador for the U.S. Department of State and as an artistic ambassador for UNICEF Spain, helping children in impoverished areas in India, Nepal, and Ghana develop their artistic voices. In 2014, she renounced the rigors of touring to forge a new path, one she hoped would bring her greater fulfillment. “This art belongs to you, but very often, the world makes the artist feel like they have an obligation to give that art to everyone else,” she says. “I wanted to be able to find out who I was when I walked away from the piano.”

Since then, Nikae has published nine novels under a pen name and founded Gracefully Live, an organization that helps business executives develop leadership skills and shift their companies’ internal culture toward empowerment. “I went from being a young girl who led an entire orchestra to going headto-head with executives to get them to lead hundreds of people in the right way,” she says. “I’m working with people so they can realize their truths and become their fullest self. In many ways, that’s what I had done with myself through my art all those years.”

Nikae still plays piano every day, and she enjoys the perpetual challenge of performing her favorite pieces for benefit concerts and other charitable causes that have personal meaning to her. Now, making music is about building relationships with her listeners, where both artist and audience are united and enriched. “Every time you play, you discover another layer, another nuance, new ways you want to express it that you couldn’t fathom before,” she says. “There’s always, to the very last breath of life, an opportunity to grow.”

ったのです」。ニカエさんは、25年間研究を続けた末に定理を実証した数 学者である伯父をはじめとして、親族のなかにいる多くのアーティストや 知識人からインスピレーションを得てきた。「伯父がようやく定理を証明し たときのことを覚えていますが、あれは私の理解をはるかに超えていまし た」と、ニカエさんは振り返る。「伯父の集中力と情熱のすさまじさは衝撃 的でした。結果を見ることができないのに、伯父はひたすら信じ、研究を続 けたのです」

音楽を通じてより直接的に他者とつながる方法を求めて、ニカエさ んは米国国務省の文化大使やユニセフスペイン支部の芸術大使として、イ ンドやネパール、ガーナなどの貧困地域の子どもたちの芸術的活動を応援 してきた。2014年、より大きなやりがいを求めて、ニカエさんは過酷なツア ー活動から引退した。「芸術はその人自身のものです。それなのに、アーティ ストは往々にしてその芸術をほかの人々に捧げなければいけないという義 務感を背負わされてしまうのです」ニカエさんは語った。「ピアノをとったら 自分は何者なのか。私はそれを知りたかったのです」

以来、ニカエさんはペンネームを使って9編の小説を発表する一方 で、企業のトップを対象にした団体「グレイスフリー・リブ(優雅に生きる」 を立ち上げた。彼らがリーダーシップをとる企業の文化を、人々にさらなる 力を与える方向へと導くための団体だ。「少女時代に楽団全体をリードし たことのある私が、企業のトップと直接話し合って、何百人もの人々を正 しい方向へ導くための手助けをするようになりました。人々が本当の自分 を見つけて、自分の可能性を最大限に活かせるように応援したいのです。 それこそが、いろいろな意味で私が昔から芸術を通してしてきたことだか らです」

ニカエさんは今も毎日ピアノを弾いている。個人的に思い入れのあ る慈善事業のためのコンサートで得意の曲目を披露し、大好きな音楽が もたらす尽きることのない挑戦を楽しんでいる。最近のニカエさんにとっ て、演奏とは聴衆との絆を築くこと。聴衆とひとつになり、お互いに心豊か になる。ニカエさんは語る。「演奏するたびに、その曲の新しい側面、新しい ニュアンス、以前は理解できなかった新しい表現方法を発見します。人は いつだって成長し続けることができるのです。それこそ息を引きとる最後の 瞬間までも」

36 A PALM ARTS Prodigies

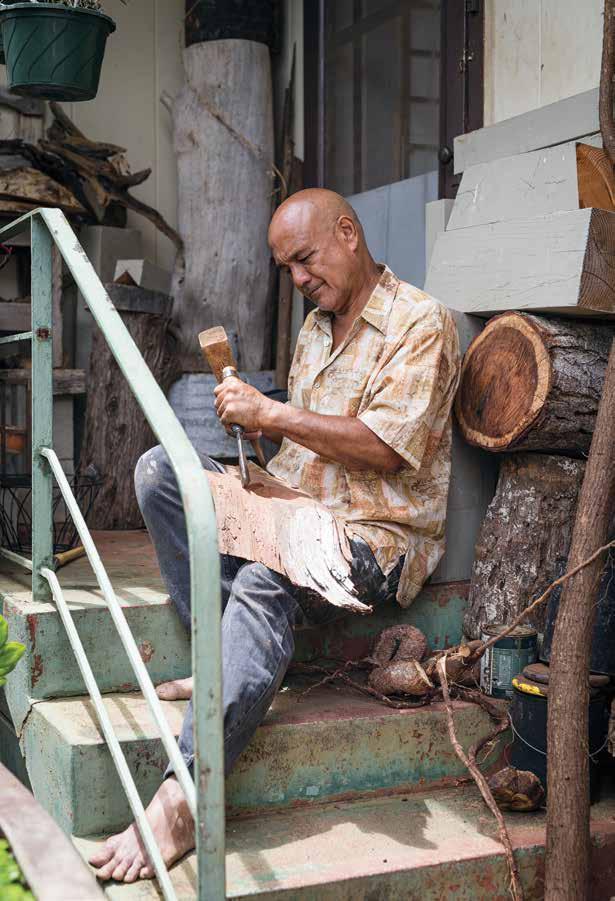

KAHI CHING Artist

KAHI CHING Artist

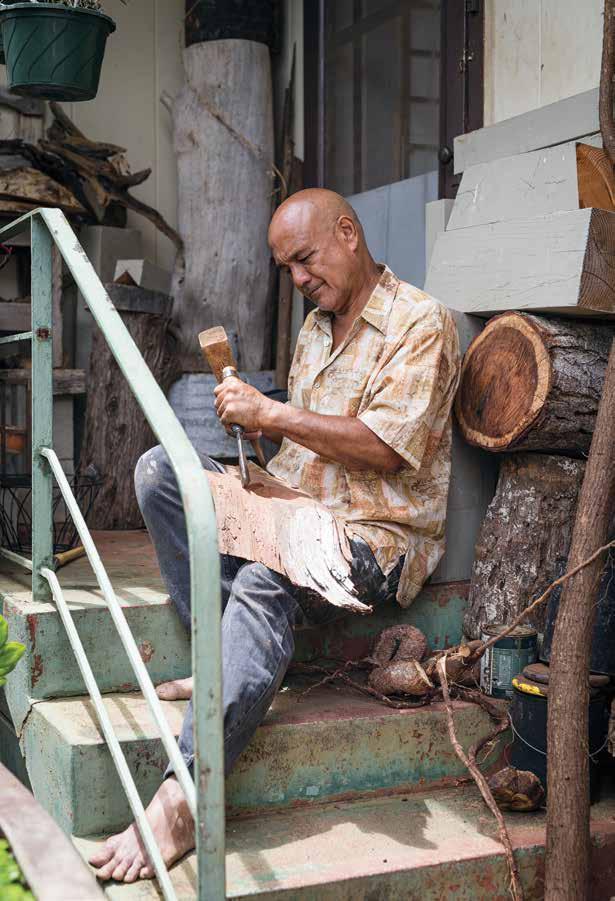

Before he was old enough to wield a pencil or paintbrush, Kahi Ching was interpreting the world around him with an artist’s eye. “I was drawing things in the sand. I would draw with burnt wood or carve into a potato with my fingernails,” he says. At 5 years old, he began to collect treasures from the beach fronting his Kāne‘ohe home—sea glass, driftwood, glass bottles, rocks, and wood scraps— arranging them neatly and sketching what he saw.

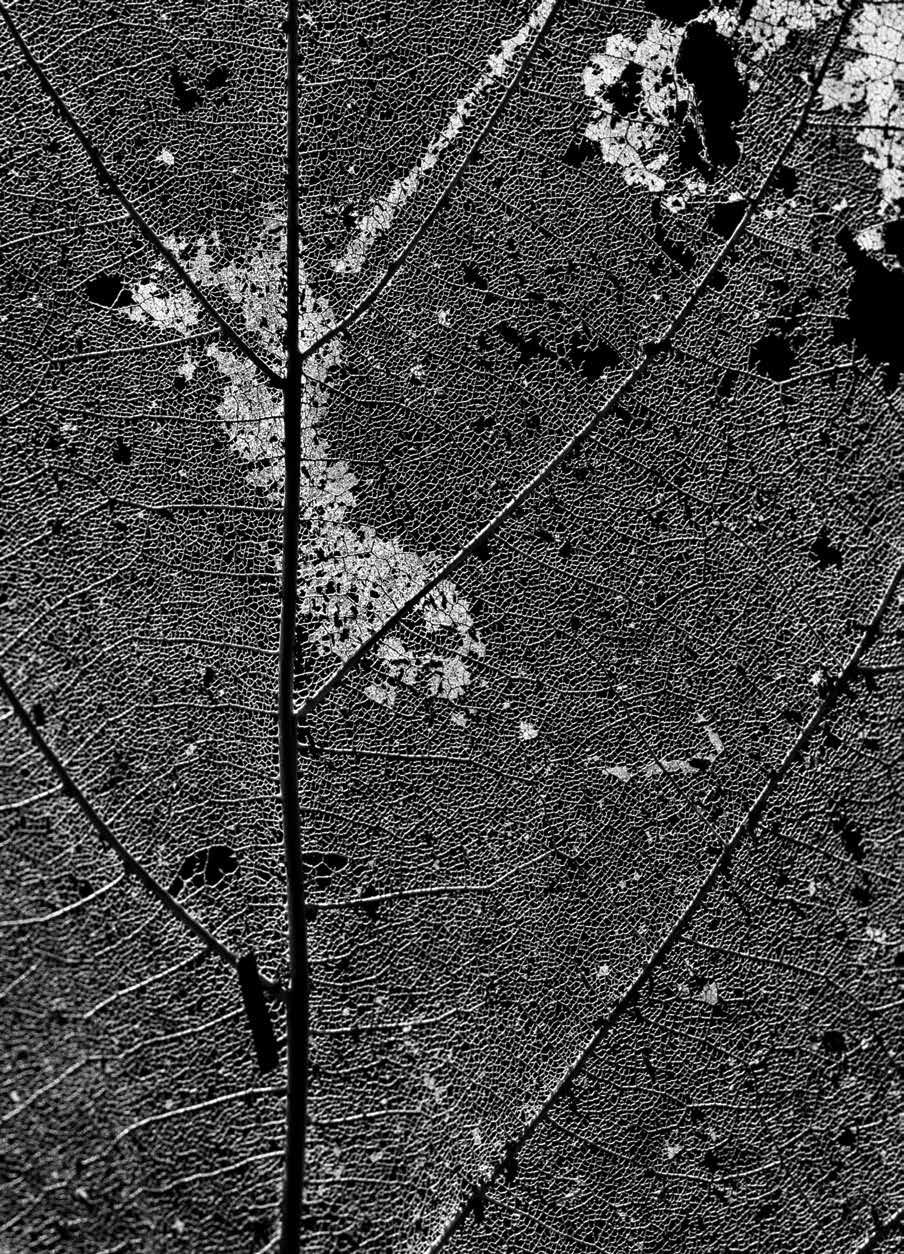

As he grew, Ching’s drawings became more intricate. In grade school, he struggled with dyslexia, and making art allowed him to express what words could not. “Drawing and painting, that was my language, and that is still my language today,” he says. He would sit on the beach and study the sky, the ocean currents, and the texture of sand. He spent hours contemplating the journey taken by a piece of wood or sea glass in order to translate every detail into his art, to tell the story of the object through the grain of the weathered wood or the shininess of the glass. “I pay attention to everything,” he says. “Curiosity is the best inspiration for finding the truth and the beauty of the cosmos.”

At 11 years old, Ching created his first oil painting, a seascape, which became his first piece to sell. A breakout student of the gifted art program at Castle High School, he was painting sets for the theater department and putting up murals on the school’s walls. At 18 years old, he won a national arts contest with his pencil drawing, Curios. The prize included a scholarship to the Rudolph Schaeffer School of Design in San Francisco, where he says, “The experiences of talking story and riding the BART did as much to expand my thinking as art school.”

カヒ・チンさん アーティスト

まだ鉛筆や絵筆を握る前から、カヒ・チンさんは芸術家のまなざしでまわり の世界を見ていた。「砂の上にいろんな絵を描いていました。木の燃えさし で絵を描いたり、じゃがいもの表面を爪で彫ったりもしていたそうです」。5 歳の頃にはカネオヘの自宅前のビーチで宝探しをはじめていた。シーグラス (波に洗われたガラスのかけら)、流木、空き瓶、石、木片などをきれいに並 べたり、目に映るものをスケッチしていた。

成長するにつれ、チンさんの絵は精細になっていった。小学校では失 読症で苦労しながら、言葉では表現できないものをアートとしてかたちに した。「描くことが僕の言葉でした。今でもそうです」と、チンさんは語る。砂 浜に腰を下ろして、空のようす、海の潮の流れ、砂の粒子を観察する。流木 やシーグラスがどんな旅を経てそこにたどり着いたのか、何時間も思いを 巡らせる。そして、日や波にさらされて乾いた木片やぼんやりと輝くガラスの かけらが、その風合いを通して伝える物語のすべてをアートとして表現する のだ。「僕はどんな細かいことも注意して見ます。好奇心こそが、宇宙の真実 と美しさを見つける鍵なのです」

11歳のとき、チンさんは最初の油彩画を手がけた。海の風景を描い たその作品は、彼が最初に売った作品になった。キャッスル高校の英才美 術プログラムのなかでも抜きん出た存在だったチンさんは、演劇部のため の舞台背景や、学校の壁の壁画を描いた。18歳のときには、『Curios(骨 董品・風変わりな人)』と題した鉛筆画で全国的なアートコンテストに優 勝する。賞品にはサンフランシスコにあるルドルフ・シェイファー・スクー ル・オブ・デザインの奨学金も含まれていた。そこで「人々と語り合ったこ と、BART(サンフランシスコの鉄道)に乗り下りして見聞したことも、美術 学校で学んだことと同じくらいに僕の視野を広げてくれました」

PALM 38 A ARTS Prodigies

As a child, artist Kahi Ching would spend hours contemplating the journey taken by a piece of wood or sea glass in order to translate every detail into his art.

As a child, artist Kahi Ching would spend hours contemplating the journey taken by a piece of wood or sea glass in order to translate every detail into his art.

Today, Ching’s many artistic pursuits include mastering the art of bonsai in his home garden in Honolulu.

Over the course of his life, Ching’s art practice has taken many forms, each an extension of his ongoing quest to capture “the beautiful lines all around us,” he says. He has experimented with sign painting, ceramics, wood sculpture, concrete furniture, and public art, and for a time he ran his own gallery. His latest endeavors include creating a 12-foot-tall glass, metal, and stone sculpture for Hilo Union School, mastering the Japanese art of bonsai in his home garden, and experimenting with music. After he finished designing and painting a mural at Turtle Bay Resort in 2020, Ching was asked if he played guitar. Always up for a challenge, he wrote his first song on the spot and played it for a small audience.

On the cusp of turning 60, Ching regards getting older as an opportunity to see more of what he calls “the linework or heartbeat of life” and to mentor other aspiring artists. “Now I’m learning how to be an elder, so I can share the wonder of what is—look at that color, listen to that song, smell that fragrance!” he says. “I’m talking story with my children and my neighbors and learning about other cultures. All of this is in the linework of my art.”

チンさんは、「僕らを取り巻く美しい線たち」 をとらえるために、さまざまな表現方法を試みてき た。看板、陶芸、彫刻、コンクリート製家具、そして パブリック・アートなどに挑戦し、自分のギャラリー を持っていた時期もある。最新作のひとつは、ヒロ・ ユニオン・スクールのために制作したガラスと金 属、石を素材とする高さ4メートル近い彫刻だ。自 宅の庭では盆栽を手がけ、実験的に音楽とのコラ ボレーションも行っている。2020年、タートル・ベ イ・リゾートのミューラルを完成させたチンさんは、 ギターを弾くかと尋ねられた。挑戦は受けて立たず にいられないチンさんは、その場で最初の曲をつく り、数人の観客の前で演奏したそうだ。

まもなく60歳の誕生日を迎えるチンさんは、 歳を重ねていくことを、彼が「生命の描く線画、ま たは鼓動」と呼ぶものをさらにたくさん間近で見 つめる機会、そして、野心あふれるほかのアーティ ストたちを応援していくための機会だと受けとめ ている。「この世のすばらしさを伝えられる長老に なれるように、学んでいるところです。この色やあの 音楽、この香りのすばらしさ! その驚異を分かち 合いたいのです」とチンさんは続けた。「子どもたち や近所の人々と語らい、知らない文化を学んでい ます。そのすべてが、僕のアートの線画に映し出さ れるのです」

PALM 40 A

ARTS Prodigies

CUL TU RE of

place that A sense

C 文化 PALM

fosters the human spirit

43

A Big Deal

44 PALM C CULTURE Big Trees 写真 = メーガン・スズキ 小さな一歩、大きな変化 文 = ミシェル・ブローダー・ヴァン・ダイクン・ダイク

Text by Michelle Broder Van Dyke

Images by Meagan Suzuki

Local and national conservation initiatives work in tandem to protect the native ecosystem along Mānoa Cliff Trail.

マノアの森のエコシステムを守るため、地元のボランティアたちと全国的な環 境保全イニシアティブが力を合わせて活動しています。

Translation by Mikiko Shirakura

翻訳 = 白倉三紀子

지역 및 국가 보전 특정한 문제 해결가들은 중 요한 산림 생태계의 발전을 지원하기 위해 협 력합니다.

Hiking Mānoa Cliff Trail on Pu‘u ‘Ōhi‘a, commonly known as Mount Tantalus, I am on a mission this summer morning to see a 33-foot-tall koki‘o ke‘oke‘o, an endemic white hibiscus tree. While hibiscuses are often bushes, this type of hibiscus grows to be a big tree, and the biggest one ever identified grows along this trail.

I walk through a thicket of invasive bamboo before entering a wet tropical forest populated by native ‘ōhi‘a ‘āhihi and smaller koki‘o ke‘oke‘o as well as alien ginger flowers and palm grass. After 45 minutes, I reach the fence and gate at the edge of a restoration

夏の朝、私はある目的のためにプウオヒア山(通称「タンタラスの丘」)のマノア クリフ・トレイルを歩いていた。その目的とは、高さ33フィート(約10メートル) にもなるコキオ・ケオケオというハワイ固有のホワイト・ハイビスカスの木を見 ることである。ハイビスカスの多くは低木だが、この希少なハイビスカスは巨樹 に成長する。そして、これまでに確認された中で最大の個体が、このトレイル沿 いに生育しているのだ。

外来種の竹の茂みを抜け、湿潤な熱帯林に入っていく。そこには、ハワイ の花木オーヒア・アーヒヒをはじめ、やや背の低いコキオ・ケオケオ、外来種の ジンジャーフラワーやパームグラスなどが生育している。さらに45分ほど歩く

46 PALM C CULTURE Big Trees

The Mānoa Cliff Restoration Project was launched in 2005 after Mashuri Waite, a botanist who earned his doctorate from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, received a state permit to work on restoring a six-acre portion of the native forest at the juncture of Mānoa Cliff Trail, Pu‘u ‘Ōhi‘a Trail, and Pauoa Flats Trail. Waite, who is hiking barefoot in the mud when we meet at the restoration site, says he picked this spot because of the native plants still surviving here and because of its proximity to urban Honolulu. Every Sunday, at least a dozen volunteers gather on the mountain to pull alien weeds and cut down invasive trees in order to help the slower growing native plants flourish.

Walking through the area, there are dozens of koki‘o ke‘oke‘o, but Waite and Sebastian Marquez, a horticulturist who has been volunteering here since 2010, lead me directly to the biggest one of all. This tree was nominated by a Hawai‘i resident and submitted to the National Register of Champion Trees, a competition started in 1940 by the nonprofit American Forests to locate the biggest tree—based on height, circumference, and crown spread—of each tree species in the United States. Hawai‘i has been competing since 2011, and champions have been crowned for 18 of the state’s 21 eligible trees. Locals are encouraged to keep looking for champion trees among the elusive a‘e, wauke, and koki‘o ‘ula, a red hibiscus.

と、「マノアクリフ復元プロジェクト」のボランティアが管理する区域に着いた。

境界にはフェンスがあり、ゲートから中に入ると、そこはまさに在来植物の宝 庫。ここに生育する植物の多くは、世界でここにしかない固有種だ。まるで別の 時代の、どこか違う場所に迷い込んだかのようだった。

マノアクリフ復元プロジェクトは、ハワイ大学マノア校で博士号を取得し た植物学者のマシュリ・ウェイトさんが、州から活動の許可を得て2005年に 立ち上げたもので、マノアクリフ・トレイル、プウオヒア・トレイル、パウオア・フラ ッツ・トレイルという3つのトレイルがぶつかる地点に広がる原生林の一部、6 エーカー(約2.4ヘクタール)ほどの区画の植生復元に取り組んでいる。ウェイ トさんは、裸足でぬかるみを歩きながら、この場所を選んだ理由は、まだ在来 種が自生していることと、ホノルルの市街地に近いためだと語ってくれた。毎週 日曜日、少なくとも十数人のボランティアが山に集まり、外来種の草を抜いた り、生態系に影響を及ぼす外来の木々を伐採したりして、外来種よりも成長の 遅い在来植物が繁茂するのを助けている。

区画内を歩くと、ハワイ原生の白いハイビスカス、コキオ・ケオを何十本 も見ることができた。そして、最大の個体が生育している場所までは、2010年 からここでボランティア活動をしている園芸家のセバスチャン・マルケスさんと ウェイトさんが直接案内してくれた。このハイビスカスの巨木は、ハワイ住民の 推薦で「全米巨樹登録(National Register of Champion Trees)」という プログラムに国内最大の樹木標本として登録されている。このプログラムは、 非営利団体アメリカン・フォレストが、樹種別に米国最大の巨樹を特定するた めに1940年に開始したもので、樹高、周長、樹冠の広がりを評価基準としてい る。ハワイは2011年からこのプログラムに参加しており、対象となる21の樹 種のうち18種でチャンピオンを獲得している。アエやワウケ、赤いハイビスカス area maintained by volunteers with the Mānoa Cliff Restoration Project. Stepping inside, native plants abound; I feel like I’m entering a different time and place, as many of these plants are found nowhere else in the world.

48 PALM C CULTURE Big Trees

Along with protecting the area’s native hibiscus trees, the conservation work of the Mānoa Cliff Restoration Project ultimately helps all the native plants and animals in the forest.

The white hibiscus tree looming before me has a thick, gnarly trunk brimming with endemic ferns, mosses, lichens, and bugs. It’s so large that it’s impossible to take it all in from one view. I find myself trying to delicately walk around it, as there are other native species planted in the understory. Its many outstretched branches spread up into the sky and blend into several adjacent hibiscus trees, forming a canopy 27 feet wide. Like a temple, the tree invites us to gather beneath its high ceilings. According to Waite, records that were kept of the area starting in the 1950s show that this hibiscus is at least 70 years old. The flowers have delicate white petals and pink stamens, and they omit a subtle and sweet fragrance.

Sixteen years ago, when volunteers first started working in the area, the forest understory was thick with invasive plants, choking out much of the native flora, including these hibiscuses. “In those early days, it was just a matter of weeding, weeding, and then coming across a native plant,” Marquez says. The fence was installed in 2009 to keep feral pigs from digging up native ferns and hibiscus seedlings before they have a chance to grow strong. “Once you get some protection and some work, the plants will come back,” Marquez says. “You can make a difference.”

The hibiscus grows from seed, but to help it flourish, the volunteers also propagate hibiscus from the branches of older plants. While the hibiscus blooms year round, Waite says there is usually a “big pulse of flowers” that starts at the end of August. “When they are in full flower, the canopies are just covered with white flowers. It’s dramatically different,” Marquez says of this late summer display. “If you had a drone and flew up a couple hundred feet, you’d see this green forest full of white dots, and all of the white dots are hibiscus trees.”

Along with helping the hibiscus and the plethora of plants and bugs it hosts, the conservation work of the Mānoa Cliff Restoration Project ultimately helps all the native plants and animals in the forest. “Once we get the canopy and ferns established, we’ll see more native plants coming up,” Marquez says. Using historical records, volunteers have also identified and planted native flora that had vanished from the area, like the koki‘o ‘ula. Today the reserve is home to as many as 125 native plant species.

Every Sunday, volunteers are encouraged by rare endemic honeycreeper birds, like the crimson ‘apapane and yellow-green ‘amakihi, singing in the trees. “We’ve seen how our actions have made a benefit for these plants, so it’s nice to think maybe that’s why ‘amakihi and ‘apapane are here,” Marquez says. “We hear them all the time.”

の一種コキオ・ウラなどは見つけにくい種であるため、今後もチャンピオン 樹木を探し続けるよう地元の人々に協力を求めている。

私の目の前にそびえ立つホワイト・ハイビスカスの太い節くれ立った 幹は、ハワイ固有種のシダやコケ、地衣類で覆われ、虫たちの住処となって いる。ひと目では全貌がつかめないほどの大きさだ。下層部にはほかの在 来種が植えられているため、それらを踏まないように気をつけながらこの 木の周りを歩いてみた。たくさんの枝が空に向かって広がり、周りのほかの ハイビスカスと互いに枝を重ね合い、幅27フィート(8メートル)ほどの林 冠を形成している。この巨木は、まるで礼拝堂のように、高い天井で覆われ た空間へと私たちを招き入れる。1950年代から始まるこの地域の記録に よれば、このハイビスカスは少なくとも樹齢70年になるという。花は繊細な 白い花弁とピンクの雄しべを持ち、ほのかに甘い香りを漂わせる。

16年前、ボランティアがこの地域で活動を始めた当時、森の下層部 には侵略的な外来種が生い茂り、このハイビスカスを含む在来植物の多 くは姿を消してしまっていた。「その頃は、草むしりが主な仕事でした。えん えんと外来種を抜いていって、ようやく、ぽつりと自生する在来種に出会え る、という感じでした」とマルケスさん。2009年には、在来のシダやハイビ スカスの苗木がしっかり成長する前に野生の豚が掘り起こしてしまうのを 防ぐため、フェンスが設置された。マルケスさんは言う。「ある程度の保護と 手入れを行えば、植物は戻ってきます。私たちが変化を生み出すことがで きるんです」。

ハイビスカスは種から育つが、繁殖を促すために、ボランティアの手 で古い株の枝から増やす取り組みも進めている。ハイビスカスは一年中花 を咲かせるが、ウェイトさんによると、通常8月の終わり頃から「開花の大 きな波」が来るのだという。晩夏の最盛期についてマルケスさんはこう語 ってくれた。「満開になると、林冠は白い花で埋めつくされます。普段とはぜ んぜん違いますよ。ドローンで数十メートル上空から撮影すれば、緑の森 にたくさんの白い点が見えるでしょう。その点がすべて、ハイビスカスの木 なんです」

マノアクリフ復元プロジェクトの保護活動は、ハイビスカスとそこに 宿る多種多様な植物や虫たちを守るだけでなく、結果として、森に生息す るすべての在来の動植物を保護することにもつながっている。「林冠がしっ かりと形成され、シダが繁殖すれば、さらに多くの在来植物が見られるよ うになるでしょう」とマルケスさん。ボランティアたちは過去の記録を頼り に、コキオ・ウラをはじめとするこの地域から消えてしまった在来種の特定 と植えつけを行っており、現時点でこの保護区には125種もの在来植物が 生育している。

深紅色のアパパネや黄緑色のアマキヒなど、木々の枝の上から歌声 を聞かせてくれるハワイ固有の希少なミツドリたちの姿は、毎週日曜日にこ こを訪れるボランティアたちの励みになっている。マルケスさんは言う。「私 たちの活動がこの地の植物にどのような利益をもたらしているのかが、目 に見える形で現れてきました。アマキヒやアパパネが集まってくるようにな ったのも、おそらく私たちの活動の成果でしょう。そう思うと嬉しいですね。 今では、ミツドリたちのさえずりが絶えず聞こえてきますよ」

50 PALM C CULTURE Big Trees

The Genius of Place

自然界の天才に学ぶ

Text by Martha Cheng

文 = マーサ・チェン

Images by John Hook

写真 = ジョン・フック

Learning ecologist Daniel Kinzer takes cues from nature’s elegant rhythms, patterns, and interconnections.

52 PALM C CULTURE Biomimicry

A biomimicry professional’s annual walk around the perimeter of O‘ahu reveals clues on how humanity can live in harmony with nature.

生体模倣の研究家が毎年恒例の歩くオアフ島調査で探る自然と調和 して生きるために人類にできること

Translation by Akiko Shima

翻訳 = 島有希子

생체모방기술 전문가가 오아후 섬 주변을 돌아다니

며 섬 주변의 "천재성"을 찾아봅니다.

By 2019, Daniel Kinzer had been to more than 70 countries. In the year prior, he spent two weeks in Antarctica as part of a National Geographic teaching fellowship, and then for a week, he studied island ecology at Isla Espíritu Santo, just off the coast of Baja California Sur. He decided he wanted to explore O‘ahu next, his home since 2016. “I wanted to really appreciate home in the ways that I was being invited to appreciate these

2019年までにダニエル・キンザーさんが訪れた国は70か国以上にのぼる。昨 年は、ナショナルジオグラフィックの教育フェローシップの一環で南極で2週 間を過ごした後、バハカリフォルニア・スル州の沖合にあるエスピリトゥサント 島で1週間、島の生態系を調査した。キンザーさんが次に調査しようと決めた のは彼が2016年から住んでいるオアフ島だ。キンザーさんは「依頼された先 々での調査と同じように、僕の住む島の魅力を掘り下げてみたかったんです」 という。そして彼は歩き出した。マキキの自宅を出発して西へ向かい、オアフ島

PALM 54 C CULTURE Biomimicry

other places,” he says. So he walked. He walked 140 miles around the perimeter of O‘ahu for two weeks, setting off from his home in Makiki and heading west. He chose to walk during the Thanksgiving and Makahiki season, a Hawaiian festival honoring Lono, the god of agriculture, fertility, and peace. During ancient times, ali‘i had circumnavigated the islands collecting offerings for Lono and assessing the health of the land and people.

Gratitude wasn’t Kinzer’s only motivation. He also wanted to uncover what he calls the genius of places on O‘ahu. “The genius of a place is in its ability to hold the tension between resilience and transformation in a way that is typically inclusive and generous,” he says. “The way everything is interconnected and fits together so elegantly, and how it adapts and evolves.”

Kinzer, previously the director at Punahou’s Luke Center for Public Service, had just finished a degree in biomimicry, the design of materials, structures, and systems that are modeled on biological entities and processes. He had also started working with Purple Mai‘a, an organization dedicated to youth educational programs that combine modern technology and Hawaiian cultural values. He learned about ‘ike kūpuna, ancestral Hawaiian knowledge, and was beginning to “think about culture and community as a technology,” or how past traditions could provide solutions for the present.

There are many ways to explore an island, but Kinzer chose to stick to the shoreline.

“There’s a lot of magic that happens in that intertidal zone,” he says. “This is a place where life is going to be born. It’s a nursery for sustaining our whole ocean.” But what surprised him was the way the urban environment met the natural world along the shore. On the southern side of the island, he saw ‘ae‘o, the endangered Hawaiian stilt, in Paikō Lagoon in Kuli‘ou‘ou, and even along Pu‘uloa, or Pearl Harbor, and in small pockets of wetland right next to the power plant in Waipahu. On the leeward coast, he spotted monk seals huddled next to a houseless encampment at Mā‘ili Point, and near Wai‘anae Coast Comprehensive Health Center, he saw numerous hawksbill and green sea turtles where a few streams feed into the ocean.

の周りを2週間かけて歩いた。その距離225キロ。そのためにキンザーさん は感謝祭とハワイでマカヒキと呼ばれる時期を選んだ。マカヒキは農耕、 豊饒、平和の神「ロノ」を祀る古代ハワイのお祭りシーズンで、この時期に アリイ(王族)が島を一周してロノへの供物を集め、土地と人々の健康状態 を評価していた。

キンザーさんがこの島の調査を思い立った理由は礼を尽くすこと以 外にもあった。彼が「ジーニアス・オブ・プレイス」と呼ぶ自然や生態系から 学び、模倣するバイオミミクリー(生体模倣)の概念をオアフ島に見い出し たいと考えたのだった。「ジーニアス・オブ・プレイスは耐性と変革の間の 緊張関係を保つことができます。それは一般的には包括的かつ寛容なもの で、環境の全てが相互に繋がっていて見事に補完し合い、それがどのよう に適応し進化しているかという自然に倣った考え方です」と彼は言う。

以前プナホウスクールのルークセンター・フォー・パブリックサー ビスの所長を務めたキンザーさんはその頃、バイオミミクリーの学位を取 得したばかりだった。生物の優れた機能や自然の仕組みを学び、材料や構 造、システムの設計に生かす学問だ。同時に現代のテクノロジーとハワイア ンの文化的価値観を生かした青少年教育プログラム「パープルマイア」の 仕事を始めた彼は、そこでハワイアンの先祖の知識「イケクプナ」について 学んだ。以来、文化とコミュニティを一つのテクノロジーとして捉え、過去 の伝統を現在の問題の解決にどう役立てることができるかについて考え るようになった。

島を調査するさまざまな方法がある中で、キンザーさんは海岸沿い を歩くことを選んだ。彼は「磯ではたくさんの不思議な現象が起きます。こ こは生命が生まれる場所です。ここで育まれたいのちが海の豊かな生態系 を支えています」と語る。キンザーさんにとって驚きの発見は、都市環境と 自然界が海岸線で交わる光景だった。島の南岸では、絶滅の危機に瀕して いるハワイ固有のクロエリセイタカシギ「アエオ」の姿をクリオウオウのパイ コラグーンやワイパフの発電所のすぐ隣にあるプウロア(真珠湾)沿いの湿 地の入江で目にした。オアフ島西海岸リーワードのマイリポイントにはホー ムレスのテント村の脇に群がっているモンクアザラシの姿があり、ワイアナ エコースト総合保健センター横の支流が海に流れ込む河口付近には多く のタイマイとアオウミガメが生息していた。

彼は野生生物の行動リズムや月の満ち欠けや潮の干満を観察した。

夜はビーチに寝袋を敷いて寝たため、潮の満ち引きに注意しないと濡れて 目を覚めることもあったという。「自然の流れやリズムの多くが乱れ無視さ れて、人間の日常生活との関わりが 失われてしまったのです」とキンザー さんは言う。「私たちのライフスタイルを見直し、より自然と調和した文化を 作り出すことはできないでしょうか?」

56 C CULTURE Biomimicry PALM

He observed the rhythms of wildlife, the moon phases, and the tides. Laying down his sleeping bag on the beach at night, he had to consider tidal cycles to avoid waking up soaked by the incoming sea. “So many of nature’s flows and rhythms have been disrupted or ignored that they’ve become irrelevant to people’s daily lives,” Kinzer says. “What if we could design our lifestyle and create a culture that was more in tune with them?”

As an example, he points to muliwai, where streams meet the sea and where salt water and fresh water mix, which were a central component in the design of loko i‘a (fishponds). Hawaiians built them on the shoreline and created ‘auwai kai (channels) to draw fish into the ponds. It’s these sort of ancient technologies that Kinzer hopes to bring into the modern world. He draws on the idea of an urban ahupua‘a, “the idea that the human-built environment can serve ecological function and purpose, that it can be regenerative to both people and place, like the more land-based architecture of the Native Hawaiians.”

Just before he set out on his first walk in 2019, he founded Pacific Blue Studios, which folds this philosophy and biomimicry principles into youth education as well as project design. Currently, he’s working with a team of youth to design, build, and install a sustainable moorings network in Hawai‘i, a project inspired by ECOncrete, an Israeli company that creates coastal infrastructure that works in concert with the sea. The company’s recent pilot project at the Port of San Diego features concrete structures that mimic natural tide pools, offering protection against flooding while encouraging marine life.

ここで彼はムリワイの例を挙げる。ムリワイは小川が海に流れ込み、 塩水と淡水の混ざり合う河口のことで、それは昔からハワイのロコイア(養 魚池)の設計に欠かせないものであった。ハワイアンの人々はロコイアを海 岸に建設し、池に魚を引き込むためのアウワイカイと呼ばれる水路を作っ た。キンザーさんが現代社会で採用したいのは、このような古代のテクノロ ジーだ。彼は現代都市における「アフプアア」の構想を掲げる。人間が構築 した環境が生態学的な機能と役目を果たし、人と自然環境の両方にとって 負荷を少なくする。それはまさに土地の環境に配慮したネイティブハワイア ンの建築に対する考え方でもある。

2019年の調査に出る少し前に、彼はパシフィックブルースタジオを 立ち上げた。このスタジオではこの思想と生体模倣の原理を青少年教育と プロジェクト設計に取り込んでいる。

現在、彼は若者のチームと協力してハワイでサステイナブルな係留ネ ットワークの設計、構築、設置を行っている。このプロジェクトは、海洋生態 学的フットプリントを削減した港やマリーナなどの沿岸インフラストラクチ ャーを手掛けるイスラエル企業のECOncreteからヒントを得ている。同社 が最近手掛けたパイロットプロジェクトではサンディエゴ港に自然の潮溜 まりを模倣したコンクリート構造物を採用し、海洋生物の生態系を維持し ながら沿岸を洪水から守っている。

今やキンザーさんのオアフ島を歩く調査は毎年恒例の行事となって いる。自然と文明が出会う場所の観察を通して現代の問題のソリューショ ンを見出せることを期待する彼はこう語る。「私たちはすべてをコントロー ルしたい欲求に駆られますが、人生をコントロールすることはできません。

気候変動をとっても、私たちは制御不能な環境で生きる準備をしなくては なりません。未知のものや絶え間ない変化や変動に対応するために、そし て海の生態系のためにはどのような設計をすればいいか考え始めなくては ならない時がきているのです」。

60 C CULTURE Biomimicry

PALM

Kinzer has now made the around-theisland walk an annual ritual, hoping to find answers to modern-day problems by observing places where wilderness and civilization meet. “We want to control everything, and yet life is uncontrollable,” Kinzer says. “Especially with climate change, we have to be ready to live an uncontrollable existence. We have to start thinking about how we design for the unknown. How do we design for constant change and fluctuations, how do we design for the ocean?”

“We used to think there was a separation between the old way of doing things and the new way of doing things,” Kinzer says. “But I think what we’re seeing emerge is an effective practice of looking at the so-called old way of doing things and translating it for today.” And Kinzer is one of the translators—the past and present technologies mixing within him, like fresh water and salt water on the shoreline.

「以前は昔のやり方と新しいやり方に隔たりを感じていました。でも 最近では少しずついわゆる先人の知恵の解釈を深め、効果的に今に活か す動きが出てきている気がします」と語るキンザーさん。それを解釈するの がキンザーさんの仕事だ。彼の頭の中に混在する過去と現在のテクノロジ ーはまるで海岸で入り混じる淡水と塩水のようだ。

62 C CULTURE Biomimicry

PALM

DE SI GN

The

D PALM デザイン

flourishing of

facilities creative 65 PALM D

Electric Light Orchestra

Text by Natalie Schack

66 PALM D DESIGN Jen Lewin 文 = ナタリー・シャック エレクトリックライト・オーケストラ 写真 = ジェン・ルウィン・スタジオ提供

Images courtesy of Jen Lewin Studio

Artist Jen Lewin’s luminous,

interactive public sculptures merge art, science, and play.

芸術と科学と遊びを融合させた芸術家 ジェン・ルウィンの光るインタラクティブ なパブリックアート

At 3,000 feet above the ocean on the volcanic slopes of Haleakalā, the clouds are at eye level and the ocean stretches out in a vast blue sheet of apparent tranquility. When the sun sinks below the cloud line, it sends its rays through the cumulus and stratus and cumulonimbus in glowing golden threads of brilliance, a stunning light show that’s both earthly and unearthly. “It was glorious,” says artist Jen Lewin of the spectacle visible from her childhood home in the pastoral upcountry of Kula, Maui. “And it happened every day.”

Returning as an adult to this quiet, powerful scene and witnessing the same explosions of light that captivated her in childhood, Lewin had a revelation. “Of course I make light art,” she laughs. “I spent my childhood looking at these beautiful, glowing, colorful displays.”

“Light art” is a loose term for what Lewin creates. Her technical sculptures combine engineering, digital technology, and illumination, often in the form of public installations that encourage viewer participation and community engagement. The large-scale works combine Lewin’s passion for performance art as well as disciplines like construction and computer programming, a dichotomy she’s been navigating her whole life.

海抜914メートルのハレアカラ火山の斜面から見 る雲は目の高さにあり、海は広大な青いシーツを 広げたように穏やかだ。太陽が雲の下へと沈むと き、積雲と層雲と積乱雲の隙間からきらめく黄金 の糸のような光線を放ち、天のものと地のものとも つかない見事な光のショーを繰り広げる。「とても 神々しい景色だったわ」とマウイ島のクラという牧 歌的な田舎町で過ごした幼少期の家から見えた光 景について芸術家のジェン・ルウィンさんは語る。 「それが毎日見れたのよ」。

大人になってこの静かでパワフルなスポット に戻ったルウィンさんは、子供の頃に心を奪われた この光の爆発をふたたび目にし、啓示を受けたと いう。「私がライトアートを作るようになったのはご く自然なことね」と彼女は笑う。「子供の頃からこん なにカラフルで美しい光のショーを見て過ごして いたのだから」。

ルウィンさんの作品はライトアートという一 言では表現しきれない。技巧を凝らした彼女の作 品にはエンジニアリングやデジタルテクノロジー、 照明技術が活かされていて、その多くがコミュニテ ィに根差したインタラクティブアートとして公共空 間を飾る。大型の作品には幼い頃からルウィンさ んの関心を二分し続けているパフォーマンスアー トへの情熱と理数系の建築やコンピュータープロ グラミングの領域が混在する。

医師の父親と振付師の母親に育てられたル ウィンさんは、父親の診察器具で遊ぶのも踊るの も同じくらい好きだったという。彼女は幼い頃から

아티스트 Jen Lewin의 밝고 인터랙티브한

조각품은 예술, 과학 및 놀이의 결합된

작품입니다.

Translation by Akiko Shima 翻訳 = 島有希子

68 D DESIGN Jen Lewin

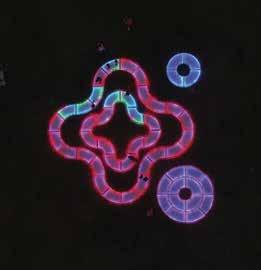

Above, The Pool photographed by Ben Hicks in 2020 at the Asia Culture Center in Gwangju, South Korea. At top right and on opposite page, Andante and Helix photographed by Oriol Tarridas in 2021 in Doral, Florida.

Above, The Pool photographed by Ben Hicks in 2020 at the Asia Culture Center in Gwangju, South Korea. At top right and on opposite page, Andante and Helix photographed by Oriol Tarridas in 2021 in Doral, Florida.

Growing up with a physician father and a choreographer mother, Lewin was equally likely to be found dancing or fiddling with her father’s tools. She fell in love with theater from an early age, drawn to both performance and the technical aspects of backstage. As a university student, she sought a true liberal arts education, one that combined both art and science, and landed in the architecture department at the University of Colorado Boulder. During the technology boom of the ’90s, she moved to Silicon Valley, where she found work as a creative director at a tech company. It was an amazing job, Lewin says, but it didn’t nurture her skills and interests equally. “I realized I had kind of only achieved half of what I had set out to do,” she says.

Lewin is now based in New York City, where she creates highly technical public sculptures that have taken her all over the world. Recently, though, she’s come full circle, beckoned back to the islands where her fascination with light and nature began. First, she brought her traveling, interactive artwork Aqueous to Kapolei Commons in West O‘ahu as a temporary installation in the winter of 2018. Conceived as a sitespecific work for Burning Man 2017, the sculpture’s reflective, serpentine pathways mirror the sky during the day and light up at night, changing color as participants navigate its glowing contours after dark.

Then, ‘Iolani School commissioned Lewin’s first permanent installation in Hawai‘i: Flow, a graceful, playful sculpture installed on the wall of the school’s Kosasa Performance Studios building in 2020. The sculpture looks like a wave made from the pipes of some futuristic organ, frozen in mid-undulation until it comes alive with the intervention of passersby. Place your hand beneath one of the sculpture’s 24 polycarbonate tubes and a sensor triggers a musical note and fills the tube with colored light. Hold your hand beneath another and you get a different color and tone. Move your hand back and forth beneath multiple pipes to activate a brilliant and ethereal orchestra of light and sound.

The more participants engage, the more tones and lights are triggered, and the more complex the show becomes. “It’s purposeful—how you move through it, how it responds to you,” Lewin says. “It’s not telling you what to do, it’s allowing you to have a relationship with it.”

演劇に夢中になり、パフォーマンスと舞台技術の両方に惹かれた。大学で は芸術と科学を両立するためにリベラルアーツ学科を選び、コロラド大学 ボルダー校の建築学部に進学した。90年代のテクノロジーブームの頃、彼 女はシリコンバレーに移り、テクノロジー会社のクリエイティブディレクタ ーの仕事に就いた。それはやりがいのある仕事だったが、スキルは磨けて も、彼女の興味を満たしてくれるものではなかった。ルウィンさんは「やりた いと思っていたことの半分しか達成できていなかったことに気づいたの」 と振り返る。

ルウィンさんは現在ニューヨークを拠点に高度な技術を使ったパブ リックアートの制作をしながら世界中を飛び回っている。だが最近は原点 に立ち返り、彼女が初めて光と自然に魅せられたハワイに戻ってきた。まず 2018年の冬に、移動式のインタラクティブアート『Aqueous』を西オアフ のカポレイコモンズに仮設のインスタレーションとして持ち帰った。もとも とネバダ州のブラックロック砂漠で開催される実験都市型アートイベント「 バーニングマン2017」のために作られた作品だ。反射性のある曲がりくね った小道のようなディスプレイは昼間には空を映し出し、夜にはライトアッ プしてその上を人が歩くと色が変わる。

その後、2020年にはハワイの私立校のイオラニスクールから初の 常設作品の委託を受けた。校内にあるコササ・パフォーマンス・スタジオの 建物の壁に設置された優美で遊び心のあるインタラクティブアートには『 フロー』というタイトルが付けられている。波状にうねって光る未来のパイ プオルガンのような作品である。静止したかと思うと、次の人が通って生き 返ったようにふたたび美しい音色が響く。24本あるポリカーボネート製の チューブの下に手をかざすとセンサーが反応して音を奏で、チューブが様 々な色に光る仕組みだ。色と音階はチューブによって異なり、パイプの下に 次から次へと手をかざしながら移動すれば、カラフルで極めて優美な光と 音のオーケストラを楽しむことができる。

多くの人が参加すればするほど、たくさんの音とイルミネーションが 重なってより複雑なショーを織りなす。「あなたの動きによって反応が変わ る。そこに意味があるの」とルウィンさん。「どうすればいいか教えてはくれ ない。だからアートとあなただけの関係を築くことができるの」。

70 PALM D DESIGN Jen Lewin

Jen Lewin, new media and interactive light sculptor, photographed by Chip Kalback.

Jen Lewin, new media and interactive light sculptor, photographed by Chip Kalback.

The installation is the first time Lewin has employed both sound and light at quite this level of interplay and interaction. Other elements of the work—collaboration, community, engagement, and, always, light— are themes she’s been exploring throughout her life and career, beginning with her days basking in the dazzling sunbeams above Haleakalā, Hawaiian for “house of the sun.”

“A lot of what I make comes from this desire to recreate what I see in nature, the way light is on a pool of water, how it streams through a cloud,” Lewin says. “That magical experience of awe.”

ルウィンさんが手がけるアートの中でも音と光がここま で見事に相互作用するインタラクティブな作品はこれが初めて だ。彼女の作品のテーマとなっているコラボレーション、コミュニ ティ、エンゲージメント、そして常にある「光」の要素は、彼女が生 涯とキャリアを通じて探求してきたテーマだ。その探求はハワイ 語で「太陽の家」という意味を持つハレアカラの上から降るまば ゆい太陽の光線を浴びていた日々から始まっている。

「私の作品の多くは、私が自然界で目にしたものを再現 したいという思いから生まれているの。それは水たまりに当たっ ている光だったり、雲の中を流れる光だったり。うっとりするほど 感動的な体験よ」とルウィンさんは語る。

72 D DESIGN Jen Lewin PALM

A Nautical Niche

海の上のニッチ

Text by Mara Pyzel

文 = マラ・パイゼル

Images by John Hook

写真 = ジョン・フック

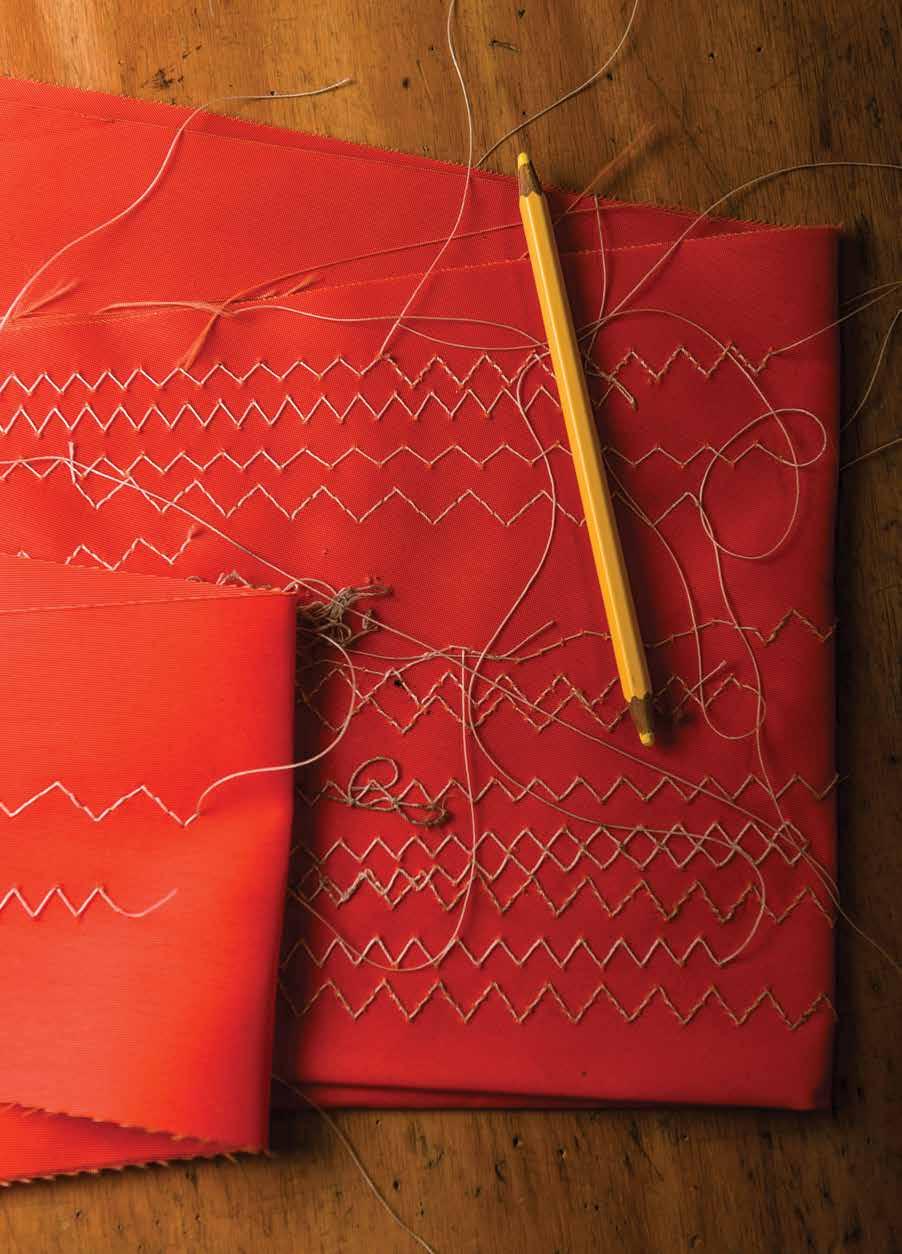

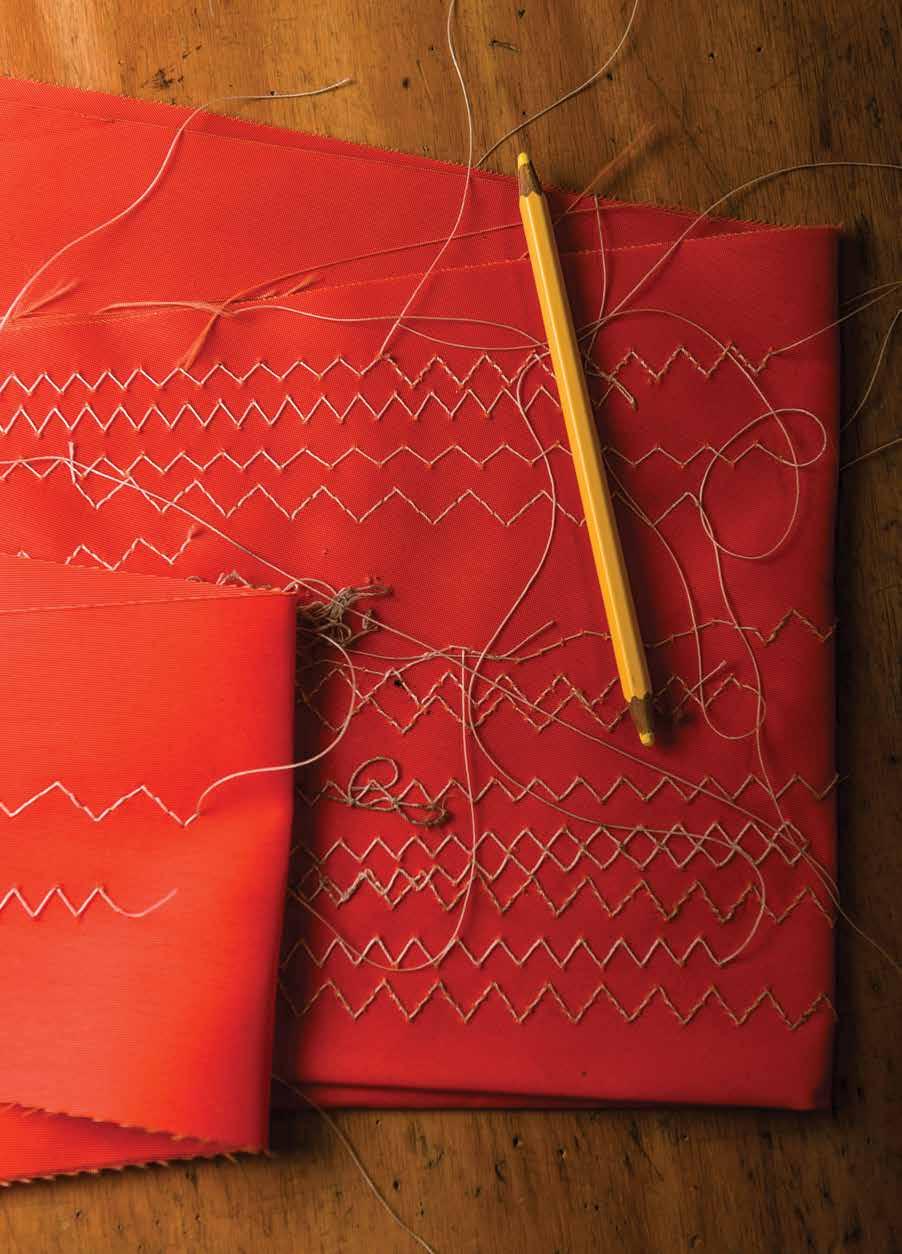

The niche craft of sailmaking requires diligence, practice, and, often, a personal bond between sailor and sailmaker.

74 PALM D

DESIGN Sailmakers

Sailmaking is an age-old craft, but it’s far from a dying art.

セイルメイキングは、古くから伝わり、今なお 生き続けている技術です。

Translation by Tamara Usono 翻訳 = 鷽野珠良

항해술은 오래된 기술이지만 쇠퇴

하는 예술과는 거리가 멉니다.

In the sailmaking and rigging industry, business is often conducted outside the confines of a traditional office setting. For Larry Stenek and Marc Barra of Ullman Sails Hawai‘i and Art Nelson Sailmaker, this holds true: work meetings are anything but traditional. They take place as casual, dockside chats and run-ins at the harbor, or on afternoon sails with a client’s crew. Armed with valuable feedback from out in the field, the master sailmakers return to their factory in Kalihi, where they craft custom rigging and sails tailored to Hawai‘i’s unique clientele and weather.

ヨットのセイルや索具制作の業界では、仕事の多くはオフィスの外で行われる。

「ウルマン・セイルズ・ハワイ&アート・ネルソン・セイルメーカー」のラリー・ス テネックさんとマーク・バラさんにとっても同様で、商談や会議は屋内ではな く、埠頭でのなにげない会話や港でのやりとり、あるいは顧客のクルーと出か ける午後のセーリングといった場で進む。熟練のセイルメーカーである二人 は、そういった場で得た貴重なフィードバックをホノルルのカリヒ地区にある 工房に持ち帰り、ハワイ独特の気候と顧客たちのニーズに合わせたカスタムの 索具やセイル制作に活かしている。

PALM 76 D DESIGN Sailmakers

Sailmakers rely on their in-depth understanding of materials, regional weather patterns, and the sport of sailing itself to craft the best sail possible for clients.

The best sailmakers are perfectionists who rely on this hands-on experience and meticulous observation. Stitching the right sail to optimize a boat’s performance requires diligence, practice, and ample communication— the kind that can only come from establishing trust and a personal bond between sailor and sailmaker. “It’s that personal aspect,” Barra says. “The sailing community is a little old school in that way.”

Barra and Stenek know this because they are both sailors too, having inherited their seafaring enthusiasm while growing up in California. As a kid, Barra’s grandfather would set him loose on a small boat in North San Diego Bay, tethered to the safety of the dock by a 50-foot line. His interest in sail cuts and rigging set-ups grew while crewing with older sailors, including worldrenowned sailors and sailmakers Mark Reynolds and George Szabo. They all became his mentors, teaching him to cut, craft, and stitch. “We would store scraps of material and tools in the old refrigerators at the bar, which still had the labels for gin and vodka and rum,” Barra says with a laugh, recalling the makeshift storage spaces at the restaurant-turned-sail loft where he cut his first canvas.

For Stenek, too, sailmaking was part of his natural progression as a sailor. Early on in his sailing career, he was faced with a hard truth: “If you wanted to keep sailing in the ’60s and ’70s and were not independently wealthy, you had to work in the industry,” he says. In 1972, Stenek moved to Hawai‘i and began learning from legendary local riggers and sailmakers Laurie Dowsett and Sonny Nelson. Along the way he met Barra, who moved to Hawai‘i in 2001 to continue carving out a career in sailmaking, and the two craftsmen joined forces.

With roots stretching back more than a century in Hawai‘i, Ullman Sails Hawai‘i and Art Nelson Sailmaker’s legacy remains an impressive one. Stenek and Barra maintain their company’s competitive edge with an emphasis on adapting. When Stenek first moved to the islands, he remembers studying the weather patterns specific to Hawaiian waters. That in-depth understanding continues to inform his designs today. “The conditions are much windier around Hawai‘i,” Stenek says. “Our sails have rounder forwards and flatter leeches and tend to be much stronger to withstand these conditions.”

As high-tech materials made their way into sail manufacturing and mending lofts around the world, techniques have evolved as well, presenting new challenges for Barra, who serves as the company’s head sailmaker. Modern-day sails come in a wide range of materials—from Kevlar and laminates to Mylar and plastics—but now even casual sailors request the black carbon sails once

最高のセイルメーカーとは、そういった実地で得た経験と精緻な観察に もとづいて仕事をする完璧主義者たちのことだ。ヨットの性能を最大に引き出 すセイル作りには、不断の努力、実践、そして十分なコミュニケーションが不可 欠で、そのためには、顧客とセイルメーカーの間にしっかりとした個人的な信 頼関係が築かれていなければならない。「個人的な要素が大きいのです。そう いう面では、セイリングのコミュニティには古風なところがあるんですよ」とバ ラさんは語る。

バラさんもステネックさんも自らヨットに乗るので、それをよく心得てい る。二人ともカリフォルニアで船に親しんで育った。バラさんが子どもの頃、祖 父は、ノースサンディエゴ湾の埠頭に約15メートルのロープでもやった小さな ボートをバラさん一人で操らせてくれた。その後、年上のクルーたちとともにヨ ットに乗り組むようになり、セイルの形や索具の装備に対するバラさんの興味 はますます深まっていく。そのなかには世界的に有名なセーリング選手であり セイルメーカーでもあるマーク・レイノルズやジョージ・スザボなどもいた。彼 らはバラさんのメンターとなり、帆布のカットや縫製のやり方を教えてくれた。 バラさんが初めて帆布をカットしたのはレストランを改装した工房だった。「素 材や道具は、バーの古い冷蔵庫に収納していました。冷蔵庫には『ジン』『ウォ ッカ』『ラム』なんてラベルが貼られたままでしたよ」と、当時を思い出してバラ さんは笑う。

ステネックさんも、セーリングから自然にセイルメイキングへの道に入 った。セーリングを始めた頃、ステネックさんは厳しい現実に直面していた。 「1960年代から70年代には、よほどのお金持ちでない限り、セーリングを続 けるためにはこの業界で働く必要があったのです」。ステネックさんは1972年 にハワイに移住して、地元の伝説的なセイルメーカーであったローリー・ドーセ ットとソニー・ネルソンの下で学び始め、その過程でベラさんに出会った。ベラ さんも、セイルメイキングのキャリアをさらに伸ばそうと2001年にハワイに移 住していた。こうして二人のクラフツマンは、力を合わせていくことになった。 ハワイで1世紀以上にわたる歴史を持つウルマン・セイルズ・ハワイ&ア ート・ネルソン・セイルメーカーのレガシーには目をみはるものがあるが、ステネ ックさんとバラさんは、現況に適応しつづけることで同社の競争力を保ってい る。ステネックさんは、ハワイに移住した当初、ハワイの海独特の気候パターン を研究した。その深い理解は現在でもデザインに役立っている。「ハワイ周辺は とても風が強いのです。うちのセイルは、フロント部分に丸みがあり、リーチ(後 縁)がよりフラットで、そういうコンディションに耐えられるよう、かなり強靭に できています」とステネックさんは説明する。

セイルメイキングやメンテナンスの工房にも世界的にハイテク素材や新 技術が登場し、セイルメイキング部門の責任者であるバラさんにとって新しい 課題となっている。ケブラー、ラミネート、マイラー、プラスチックなど、さまざま

78 PALM D DESIGN Sailmakers

reserved for competitive racing. “If it’s a white Dacron sail, you can tell the manufacturer by the color stitching or the shape of the patches,” Barra says. “But nowadays, all the sails are made of black carbon fiber, so it’s made me learn a new stitching pattern for that type of material.”

Sailmaking may be an age-old craft, but it’s not a dying art. With the rapid rise of extreme sports like kitesurfing, a new generation of tradesmen, including Barra’s teenage son, Cameron, are being called to the task. “He wants to learn to use the sewing machine to build things for kite foiling,” Barra says. And along with breeding creativity and innovation, sailmaking may hold deeper insights and timeless lessons too. “When you start sewing things yourself, you see how much of the world is actually made from being sewn together,” Barra says. “You look at something and think, ‘I could build that.’”

な素材がセイルに使われるようになり、今ではヨッ トを始めたばかりの人までが、レーシング用の黒 いカーボン繊維のセイルを所望するようになった。

「白いダクロン(ポリエステル素材)のセイルなら、 縫い糸の色やパッチの形でどこで作ったものかわ かりますが、今じゃ、どのセイルも黒いカーボン繊 維製ですから。新しい素材に合わせた縫製を学ば なければならないのです」とバラさん。

セイルメイキングは歴史ある技だが、けっし て消えつつあるわけではない。カイトサーフィンの ようなエクストリームスポーツの興隆によって、新 世代が参入してもいる。バラさんの10代の息子、 キャメロン君もその一人だ。「カイトフォイリングの ギアを作るために、ミシンの使い方を覚えたいん だそうです」。創造性と革新の波が寄せるなか、セ イルメイキングには深い見識と、時を超えた学び がある。バラさんは言う。「自分の手でミシンを使っ て何かを縫い始めると、世の中の多くのものが縫 い合わせて造られていることに気づくのです。何か を見て、『これなら自分にも作れる』と思うようにな るんですよ」

80 D PALM DESIGN Sailmakers

Diamond in the Rough

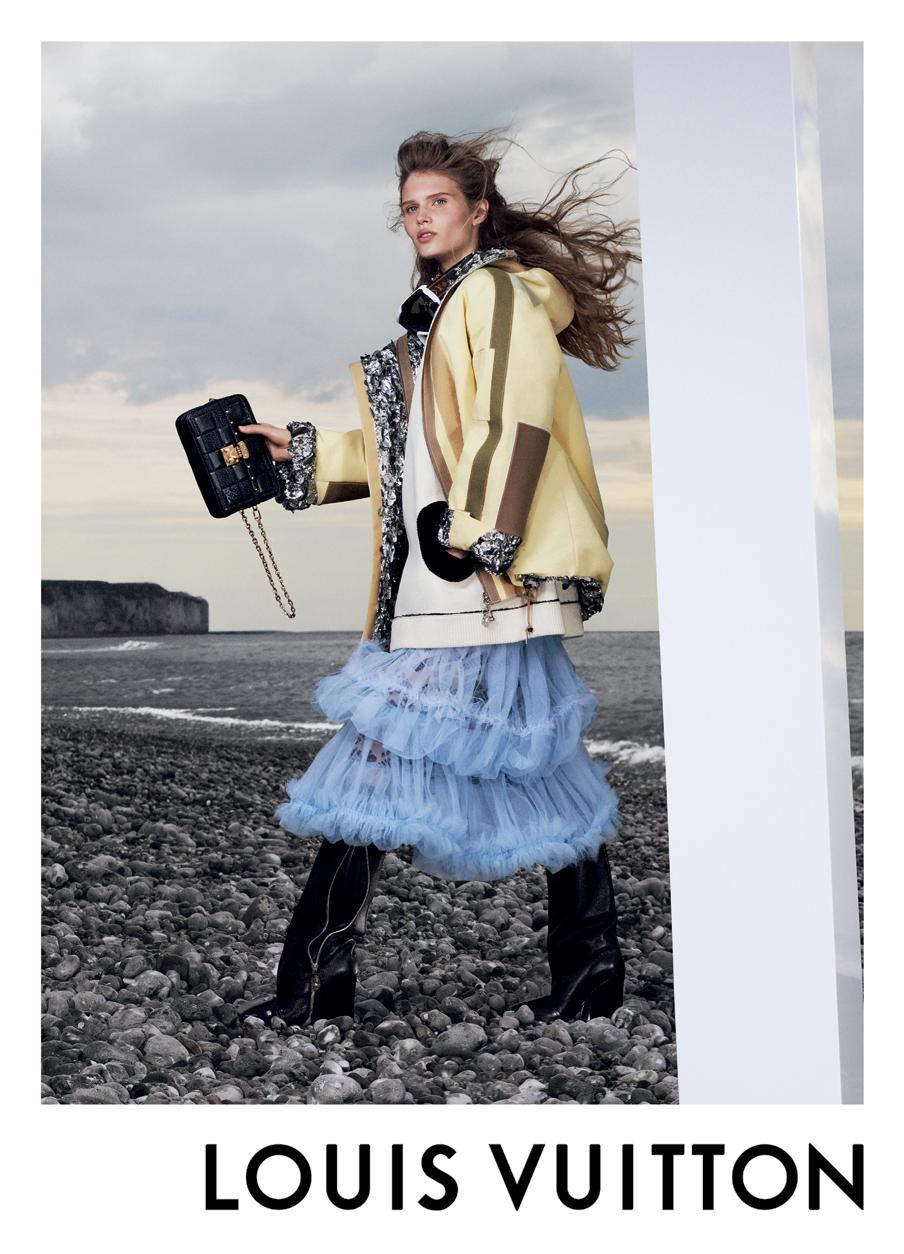

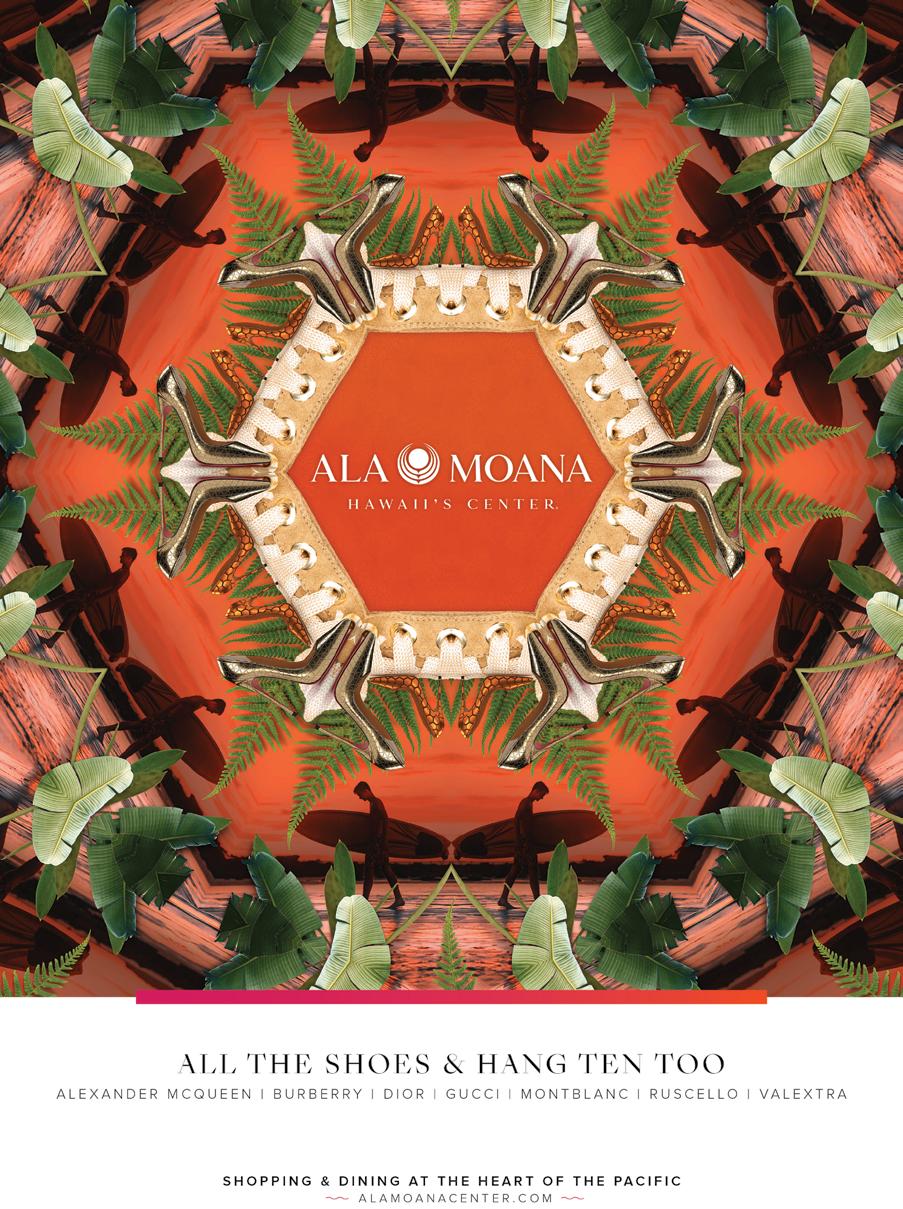

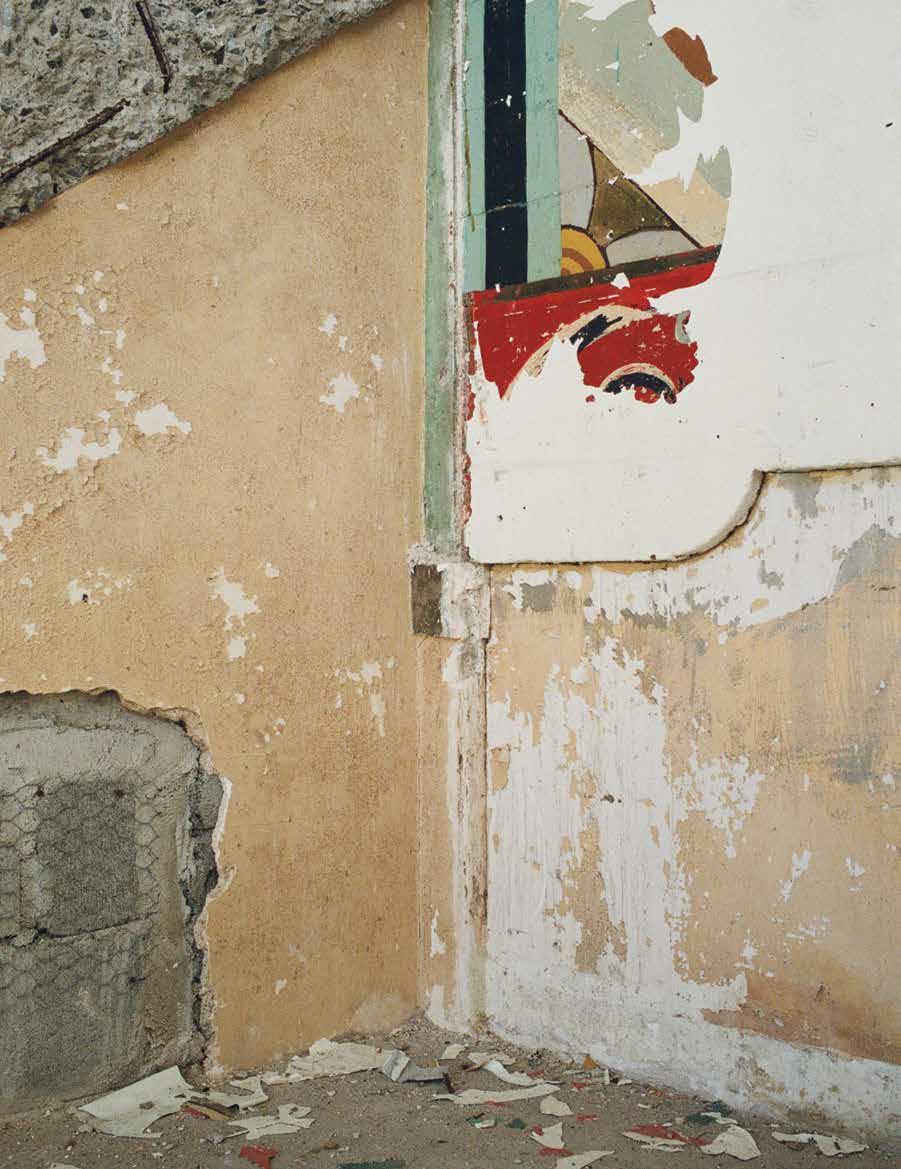

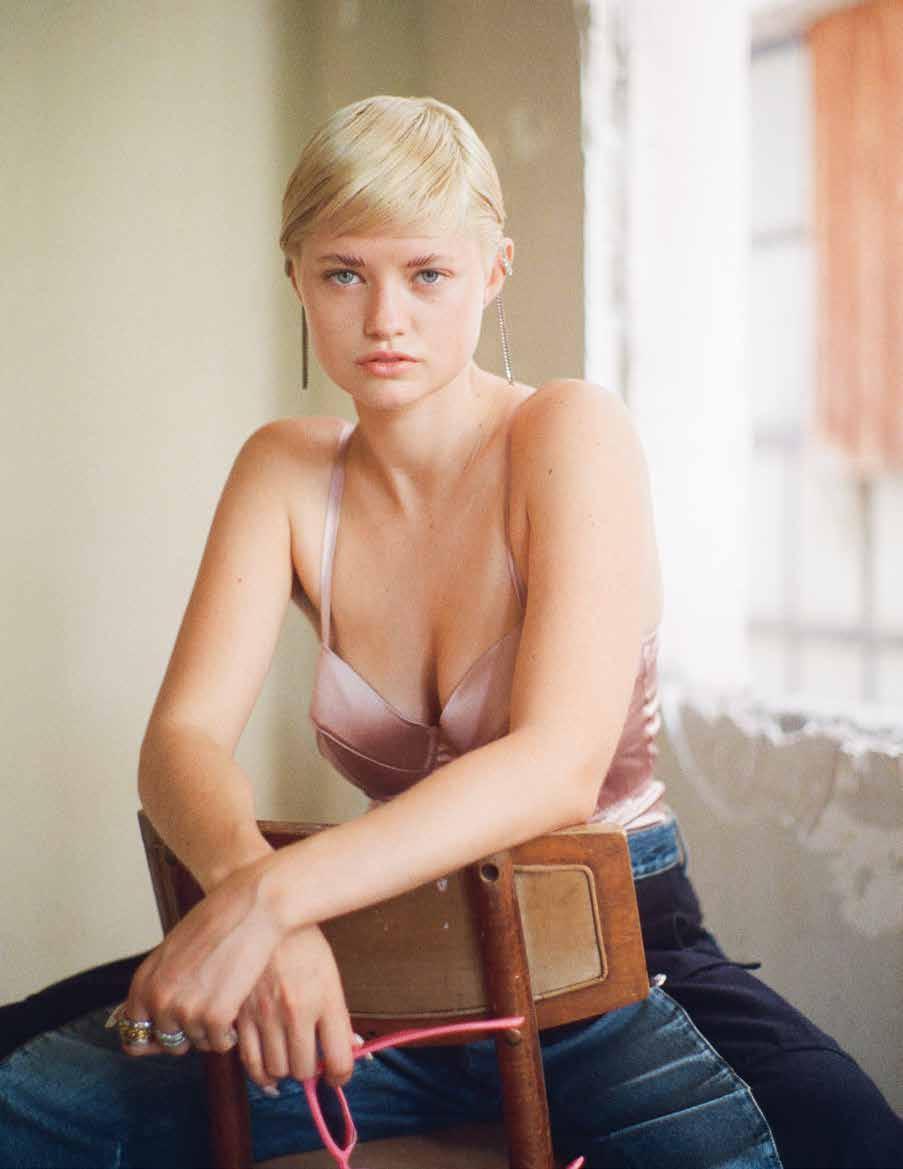

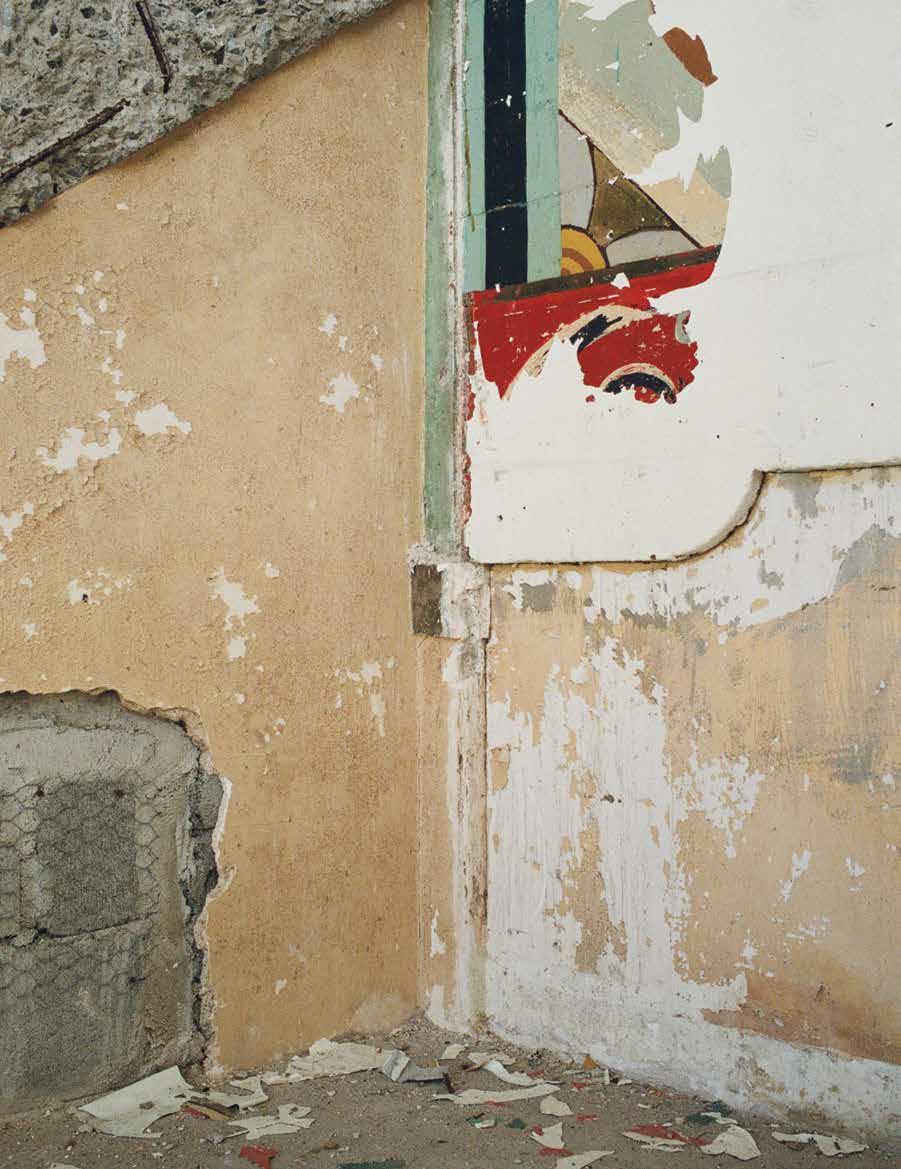

Structured garments and flashes of metal hardware are at home among the ornate, hand-painted details and rough edges of Chinatown’s Wo Fat Building, a historic landmark soon to be transformed into a restaurant and boutique hotel.

82 PALM

Images by Mark Kushimi

Styled by Ara Laylo

Hair & Makeup by Risa Hoshino

Modeled by Brooke Wood

ダイヤモンドの原石

Alexander McQueen peacoat and skull mask sunglasses. Black dress, black leather mini crossbody bag, and black platform boots from Tod’s.

Tiffany HardWear double long link earrings in 18K gold from Tiffany & Co.

Alexander McQueen peacoat and skull mask sunglasses. Black dress, black leather mini crossbody bag, and black platform boots from Tod’s.

Tiffany HardWear double long link earrings in 18K gold from Tiffany & Co.

Virgin wool, cashmere, and silk link stitch sweater with dazzling mohair stripes from Brunello Cucinelli.

Tiffany HardWear graduated link necklace and triple drop earrings in 18K gold from Tiffany & Co. Hat, stylist’s own.

Virgin wool, cashmere, and silk link stitch sweater with dazzling mohair stripes from Brunello Cucinelli.

Tiffany HardWear graduated link necklace and triple drop earrings in 18K gold from Tiffany & Co. Hat, stylist’s own.

Alexander McQueen obsession asymmetric lace top, tall story bag, punk chain and stud double ring, antique silver pavé earpiece, antique silver pavé double ring, and punk chain ear cuff. Black pants and DiorClub V1U DiorOblique visor from Saks Fifth Avenue.

Alexander McQueen obsession asymmetric lace top, tall story bag, punk chain and stud double ring, antique silver pavé earpiece, antique silver pavé double ring, and punk chain ear cuff. Black pants and DiorClub V1U DiorOblique visor from Saks Fifth Avenue.

Alexander McQueen trousers, graffiti oval sunglasses, punk chain and stud double ring, antique silver pavé earpiece, and antique silver pavé double ring. Fleur du Mal satin bullet bodysuit from Saks Fifth Avenue.

Trench dress, Shirley bag, and Tom Ford 50MM blue block square optical glasses from Saks Fifth Avenue. Tiffany HardWear graduated link necklace, Tiffany T T1 narrow diamond hinged bangle, T1 narrow diamond ring, and T1 wide ring in 18K gold from Tiffany & Co. Alexander McQueen tread heeled Chelsea boot.

Alexander McQueen midi dress, antique silver pavé earpiece, punk chain ear cuff, and tread heeled Chelsea boot.

Alexander McQueen midi dress, antique silver pavé earpiece, punk chain ear cuff, and tread heeled Chelsea boot.

experiences

ES CA PES

both

Travel

E エスケープ PALM

faraway and familiar

95

Light and Landscapes

Text by Wailana Kalama

文 = ワイラナ・カラマ

Images by Erica Davidge

写真 = エリカ・ダヴィッジ

96 E PALM ESCAPES Iceland アイスランドの光

Myths and drama permeate Iceland’s otherworldly terrain.

伝説に彩られたアイスランドの、異世界のような目をみはる風景を巡る旅。

Translation by Tomoko Shirota

翻訳 = 城田 朋子

신화와 드라마는 아이슬란드의 비세속적인 지 형에 스며 있습니다.

The first thing I noticed in Iceland was the light. How it pierced through my jetlag, cut through the brisk air, full of promise. How, even in early winter, it tucked itself away for all but four breathtaking hours of the day.

One October, three friends and I decided to tour the Ring Road, the single highway that encircles Iceland, and take in the glaciers, lagoons, waterfalls, and other natural wonders the country is famous for. The island’s

アイスランドに着いてまず目についたのは、光だった。時差ぼけの目に、ぴりっ と澄んだ空気をつらぬいて降り注ぐ日差しが眩しい。飛び切り素晴らしい旅を 約束するかのようだ。まだほんの初冬でも、アイスランドが目を見張るようなそ の光に包まれる時間はわずか4時間。残りは静かな休息の中だ。

とある10月、私は友人3人とともにアイスランドを一周する唯一の道路「 リングロード」を巡り、氷河、ラグーン、滝、そのほか、この島を世界的に有名に している自然の造形美を訪ねる旅に出た。とても同じ地球上とは思えないよう

PALM 98 E ESCAPES Iceland

Though it’s dubbed a highway, Iceland’s Ring Road is just two lanes, which wind past glaciers, lagoons, waterfalls, and other natural wonders.

otherworldly landscapes have long been muses for artists, photographers, and filmmakers; we were curious if the myriad depictions of this place did it justice.

It was early morning when we climbed into our rental car, an essential when wandering Iceland’s lonely roads, where you can go hours without seeing a single sign of civilization. We stopped at a small café in Reykjavik for a breakfast of fermented shark, dense rye bread, and dried cod with butter. Across the street loomed Hallgrímskirkja, a landmark church that dominates the capital’s skyline. An homage to the hexagonal basalt columns of Svartifoss waterfall to the east, Hallgrímskirkja rises from the earth like a gigantic, angelic organ waiting to be played.

In Iceland, the landscape permeates everything— religion, myth, art, literature. There is a heightened awareness of the earth, the water, the magma beneath your feet. Iceland is similar to Hawai‘i in that way, especially Hawai‘i Island, where I’m from. Both are geologically young, with dramatic mountains, sandy beaches, and active volcanoes. The land in both places is precious because there is so little of it. In Reykjavik, you’re constantly reminded of that fact. To the north, ships bob in the bay; to the south lies Nauthólsvík geothermal beach; and to the west, the Atlantic Ocean seems to stretch on endlessly. If you get lost, look to the waves to know where you are.

なこの島の景色は、昔からアーティストや写真家、映像作家たちにインスピレ ーションを与え続けている。そうした無数の作品がどれほど真に迫っているの かを、ぜひこの目で確かめてみたかったのだ。

私たちは早朝からレンタカーに乗り込んだ。アイスランドの寂しい道を気 ままに旅するにはレンタカーが不可欠だ。なにしろ文明の片鱗も見あたらない 荒野が何時間もえんえんと続くのだから。まずはレイキャビクの小さなカフェ に立ち寄って、発酵させたサメ肉、どっしりしたライ麦パン、干した鱈とバター の朝食をとる。カフェの向かい側には、レイキャビク有数のランドマークである ハットルグリムス教会がそびえ立っている。島の東岸にあるスバルティフォスの 滝。その後ろの崖に並ぶ六角形の柱状玄武岩をイメージして設計されたという 教会は、まるで演奏されるのを待つ巨大な天国のオルガンのように、堂々とあ たりを睥睨している。

宗教、伝説、アート、そして文学。アイスランドでは、あらゆるもののなかに 自然の景観が浸透している。大地と水、そして地面の下を流れる溶岩にも、意 識が向けられ、研ぎ澄まされている。アイスランドはある意味でハワイに、特に 私の故郷であるハワイ島に似ている。どちらの島も地質学的にまだ若く、壮麗 な山々、砂浜、そして活発に活動中の火山を持つ。そして、どちらの島でも土地 は限られていて貴重だ。レイキャビクでは常にそれを意識させられる。街の北側 は船舶が停泊する湾で、南側には地熱ビーチのノイトホゥルスヴィークがあり、 西側には果てしない大西洋が広がっている。道に迷ったら、海を見れば自分が どこにいるかがわかる。

100 PALM E

ESCAPES Iceland

After Reykjavik we continued on Route 1, as the Ring Road is also known. As it was autumn, much of the lowlands were brown, their grasses like fine troll hair. Before following the road south, we detoured inland to Þingvellir Valley. This wide rift valley lies at the meeting point of the north American and Eurasian tectonic plates and is one of the three main landmarks along the Golden Circle, a scenic loop that takes you from Reykjavik to central Iceland and back. During the Viking Age, Icelanders gathered at Þingvellir to make laws and settle grievances, using its craggy cliffs as a natural amphitheatre. From there, it was a short drive to the two other nonpareils on the Golden Circle: Gullfoss, a waterfall that drops in two tiers into a mist-sprayed canyon, and Haukadalur valley, an area of shooting geysers, bubbling hot springs, mud pots, and fumaroles.

Back on the Ring Road and continuing south, the landscape changes from grassy lowlands to mountainous highlands. Plains and lonely peaks give way to mosscovered lava fields and ice-capped volcanoes. Though it’s dubbed a highway, the Ring Road is just two lanes, which wind past waterfalls with names that read like ancient secrets: Seljalandsfoss, Skógafoss, Aegissidufoss, Gluggafoss. Legend has it that a Viking settler buried treasure in a cave behind Skógafoss.

Myths pepper the coast, giving the landscapes flavor and life. At Reynisfjara beach—a stretch of black sand, ghostly surf, and basalt cliffs—two legendary sea stacks stand just offshore. As the story goes, the ancient monoliths are the remains of two trolls who lost track of time and were caught in the rays of the rising sun, which petrified them into stone. Gazing out at them in the draining light, it’s hard not to believe.

Iceland is drama, a barren, black landscape interrupted by tufts of pale yellow grass. Iceland is a long glacier tongue tumbling into a lagoon, thawing into icebergs of luminous blue, soot black, milky white. At Jökulsárlón, I spotted a lone seal gliding from the black waters of the lagoon out to the Atlantic, past the shore of glassy ice known as Diamond Beach.

In the Highlands, all pretense of villages or farms fades away into canyons and volcanic landscapes. Here, nature takes supremacy. Ravens test their wingspans from atop derelict cairns. The waterfalls are more powerful than those to the south, unrivaled in strength or roar. In the cliffs of Vopnafjörður, we spied the skeleton of an Arctic fox, pecked or weathered clean.

The region of Mývatn lake is a geologist’s dream, alive with pseudocraters, calderas, thermal springs, and lava fields. Iceland has not one Santa but 13, and they all live here, in Dimmuborgir, a field of malformed and ostentatious lava rocks. For souvenirs, a lapidary there sold us some obsidian, called hrafntinna in Icelandic. Raven-flint. When I tilted a piece in my hand, splinters of light jumped eagerly off its glassy edges.

レイキャビクを後にして、「ルート1」とも呼ばれるリングロードを走る。 秋のことで、低地のほとんどは茶色く枯れて、枯れ草はトロルの髪のように細く 柔らかだ。南に向かう前に、シンクヴェトリルの谷へ寄り道をした。北米とユー ラシア、二つの大陸プレートの境目に位置するこの広い谷は、レイキャビクから アイスランド中央部を回るルート「ゴールデンサークル」の三大名所の一つ。ヴ ァイキングの時代、アイスランドの人々はこのシンクヴェトリルに集まり、岩の 切り立った崖を自然の野外舞台に使って、法を制定したり対立を解決したりし た。そこからは、ゴールデンサークルのほかの二つの景勝地(水しぶきに包ま れた峡谷に二段に水が落ちていくグトルフォスの滝、そして、間欠泉やボコボコ と湧き出す温泉、泥火山、蒸気を噴き出す噴気孔などがあるホイカダールルの 谷)も車ですぐの距離だ。

リングロードに戻って島の南へ向かう。草の生い茂る低地から、山地へ と景色が変わる。寂しげな丘陵がまばらにある平原に変わって、苔に覆われた 溶岩原と、氷を頂いた火山が見えてくる。「ハイウェイ」とはいっても、リングロ ードはたった2車線の道路だ。セリャラントスフォス、スコゥガフォス、アエギシ デュホス、グルガフォス……まるで古代の魔法の呪文のような名前の滝をいく つも過ぎる。スコゥガフォスの滝の後ろの洞窟には、ヴァイキングが財宝を隠し たという伝説も残されている。

海岸沿いには伝説が多く、自然の景観にさらなる風味と人の息吹を添え る。レイニスフィヤラはおぼろに白い波が打ち寄せる黒砂のビーチで、玄武岩 の崖に面し、岸から少し離れた海中に二つの巨岩がある。伝説によれば、この 岩は、時が経つのを忘れて朝日を浴びてしまい、石になったトロルたちなのだ という。暗くなりはじめた光の中で眺めていると、その伝説を信じないわけにい かない気がしてくる。

アイスランドは、黒々とした不毛の大地を薄黄色の草地が彩るドラマチ ックな土地だ。氷河の長い舌がラグーンに届き、そこから溶け出した氷塊は、透 き通った青や炭のような黒を帯びた乳白色に輝く。ヨークルスアゥルロゥン氷 河湖では、アザラシが1頭、ラグーンの黒い水のなかから現れ、「ダイヤモンドビ ーチ」と呼ばれるなめらかな氷塊群を越えて大西洋に泳ぎだすのが見えた。 高地では村や農地はすっかり姿を消し、峡谷と火山が続く。ここでは自 然がすべての上に君臨する。見捨てられた積石の上でワタリガラスが羽を広げ ている。高地の滝は南側の滝よりもパワフルで、圧倒的な力強さで轟音を響か せる。ヴォプナフィヨルズルの崖の上に、私たちはホッキョクギツネのきれいな 白骨を見つけた。猛禽類に食べられたか風雨にさらされたのだろう。

ミーヴァトン湖付近は、偽火口、カルデラ、温泉、溶岩原など、多彩な地 形が見られる、地質学者にとっては夢のような場所だ。アイスランドにはサンタ クロースはひとりではなく13人もいて、その全員が、奇妙な形の溶岩が立ち並 ぶディムボルギルという荒野に住んでいるのだという。そこの細工物の店で、私 たちはアイスランド語で「ラプンティナ」つまり「カラスの火打石」と呼ばれる黒 曜石をいくつか買った。手のひらの中で角度を変えると、なめらかな縁から一 筋の光が飛び出した。

104 PALM E ESCAPES Iceland

Wailuku’s Renaissance

文 = レヒア・アパナ

写真 = ジャナ・ディロン

108 E PALM

ワイルク・ルネッサンス

ESCAPES Wailuku

Text by Lehia Apana

Images by Jana Dillon

Amid an ongoing cultural resurgence, the historic town of Wailuku, Maui, retains its local accent.

マウイ島の歴史ある町、ワイルクは、新しいエネルギーを迎え入れ ながら、独特の個性を保っています。

Translation by Eri Toyama Lau 翻訳 = ラウ外山恵理

지속적인 문화 부활 속에서 마우이의 유서

깊은 마을인 와일루쿠는 현지 하와이 억양을

유지하고 있습니다.

Igrew up with conflicting perceptions of my hometown.

There were the stories from old-timers, who reminisced about a lively Main Street, at times bustling with people shoulder to shoulder. And then there was the reality of my youth: other than law offices and sleepy storefronts, the streets were mostly empty.

Now, three decades later, Wailuku looks much like it did when I was a little girl. Driving into the town center from Ka‘ahumanu Avenue is like rolling into a painting. The concrete bridge built in 1936—known simply as “Wailuku Bridge” among locals—still stands as the gateway into town. It’s unremarkable by today’s standards, but a

小さい頃から、私は故郷の町ワイルクについて、矛盾するイメージを抱いてき た。一つは、昔からの住人たちの思い出話の中の町。その昔はメインストリート が人であふれていて、肩をぶつけ合うようにして歩いたものだ、とお年寄りたち は懐かしそうに語ったけれど、子どもだった私の目に映る実際の町は違った。 町の中心にはいくつかの弁護士事務所と寝ぼけたような商店が並んでいるだ けで、歩く人の姿もほとんどなかった。

それから30年の月日が流れたが、ワイルクの町は今も、私が少女だった 頃とあまり変わらない。カアフマヌ・アヴェニューから町の中心へと車を走らせ ると、まるで絵のなかに溶け込んでいくような錯覚に襲われる。地元の人たち

110 PALM E ESCAPES Wailuku

By the mid 1800s, the booming sugar industry brought thousands of laborers to Wailuku, and the area quickly became the center of work and play for the generations that followed.

closer look reveals a craft that lives mostly in nostalgia. Framing the bridge are thousands of hand-chiseled stones fixed with such rugged precision as to elevate the structure into a work of art.

I glance mauka (toward the mountains) to the wildly lush ‘Īao Valley—or, as Mark Twain dubbed it, the “Yosemite of the Pacific.” More than just a scenic landscape, this area is steeped in Hawaiian history. In 1790, Kamehameha I, chief of Hawai‘i Island, defeated Maui ruler Kalanikūpule in a battle so bloody that warriors’ bodies dammed the river. By the mid 1800s, the booming sugar industry brought thousands of laborers to Wailuku, and the area quickly became the center of work and play for the generations that followed.

From storied battleground to the current seat of Maui County government, Wailuku has long influenced the politics of the rest of the island. The area is in the midst of a resurgence, and today you’ll find a diversity of culture that reflects the people and eras that have shaped this island.

Double lanes merge into one as I approach, gently coaxing my foot off the pedal and slowing the car to a relaxed 20 miles per hour. Wailuku often appears as a rolling time-lapse in the car window. But today I’m navigating the town the old-fashioned way: one step at a time.

I slide into a parking spot near the intersection of Main and Market streets. Quiet compared to tourist-laden Lahaina and Pā‘ia, Wailuku has retained its local accent. Outsiders are welcome, but storefronts cater to locals. The clues are everywhere. A sign advertises “fresh lei,” potted ti plants color storefront windows, and tanned 20-somethings carry gear purchased from the neighborhood outrigger paddling shop. Even vandals are guided by a sense of place. On a crosswalk sign in the town’s center, a graffitied stick figure wears a malo and traditional headdress.

I begin at Wailuku Coffee Company, a coffee shop that doubles as an unofficial town center. Girls in trucker hats wait for their orders beside a businessman in a pressed suit clutching important-looking papers. I nab an outdoor table, adjusting my seat for some of Maui’s finest people watching. Spandex-clad cyclists trade stories and swallow their final gulps of caffeine before rolling down Market Street. A group of old guys stroll past with their tiny dogs, and it’s unclear who is walking who.

がシンプルに「ワイルクの橋」と呼ぶ、1936年に建造されたコンクリートの陸 橋。それが今も町の入り口だ。現代の基準からすればなんの変哲もない橋だ が、目を凝らせば今はもうめったに見られない匠の技が生きている。人の手で 刻まれ、しっかりと正確に積み上げられた何千もの石たちが、橋を芸術的な存 在にしている。

マウカ(山側)の方角、マーク・トウェインが「太平洋のヨセミテ」と呼んだ という緑あふれるイアオ峡谷に目を向ける。美しい景色というだけでなく、この 一帯はハワイの歴史の上でも重要な場所なのだ。1790年、ハワイ島を支配し ていたカメハメハ一世が、マウイの支配者カラニクプレをこのあたりで打ち負 かした。それはそれは壮絶な戦いで、戦士たちの死体が川の流れを止めたと言 い伝えられている。19世紀なかばには急成長するサトウキビ産業を支えるた め、何千人もの労働者がワイルクに押し寄せた。それから数世代にわたり、ワイ ルクは仕事と娯楽の中心地として栄えたのだ。

かつては歴史を彩る戦場として、現在ではマウイ郡庁所在地として、ワイ ルクはマウイ島の政治に大きな影響をおよぼしてきた。そのワイルクが今、活 気を取り戻しつつあり、マウイ島をかたちづくってきたさまざまな人や時代を 映す多様な文化が見てとれる。

2車線だった車線はやがて1車線になり、私はアクセルペダルを踏んでい た足をゆるめ、スピードを時速20マイル(約32キロ)に落とした。ふだん車の窓 から眺めるワイルクは、タイムラプスの動画のようにあっという間に過ぎてしま う。でも今日は、昔ふうのやり方で、ワイルクの町を丁寧に訪ねてみたい。

メインストリートとマーケットストリートの交差点に近い駐車場に車を 乗り入れた。観光客であふれかえるラハイナやパイアに比べるとずっと静かな ワイルクは、独特の個性を保っている。この町の店はどれも、外からの来訪者を 歓迎しながらも、基本は地元の人々向けだ。その証はいたるところで目につく。

「新鮮なレイ」の看板。ショウウィンドウを彩るティリーフ。よく日に灼けた20 代の若者たちが、近所のアウトリガー・パドリング店で購入したらしいギアを 抱えて歩いている。落書きさえもワイルクらしい。町の中心にある横断歩道の 標識では、渡ろうとしている人物にマロと呼ばれる腰みのと伝統的な冠がつけ 加えられていた。

まずは「ワイルク・コーヒー・カンパニー」を訪れてみた。非公式ながら町 の中心的存在と目されているコーヒーショップだ。ぱりっとしたスーツ姿の、重 要そうな書類をかかえたビジネスマンの横で、トラッカーハットをかぶった女 の子たちが自分たちの飲み物を待っている。外のテーブルに陣取り、椅子の角 度を調節したら、そこはマウイ島でも最高のピープルウォッチング用特等席だ。 スパンデックスで身をかためたサイクリストたち。マーケットストリートに漕ぎ 出す前に、カフェインの最後のひとくちを飲み干しながら情報交換に忙しい。

小型犬を散歩させている年配のグループ。人が犬を散歩させているのやら、犬 が人を散歩させているのやら。

112 PALM E ESCAPES Wailuku

From

storied battleground to the current seat of Maui County government, Wailuku has long influenced the culture and politics of the rest of the island.

In the distance, I spot David Sandell, an artist who came to Maui in the ’70s and never left. Canvas under his arm, he’s a sight as unmistakable as the frenetic paintings he creates, looking every bit the starving artist in his trademark cutoff aloha shirt and worn-in slippahs. His shop is a remnant from a bygone era, one that somehow blends seamlessly with the new wave of Wailuku creatives around him.

Brick-lined walkways lead to Wailuku’s grande dame, the Historic ‘Iao Theater. Opened in 1928, the theater is a time capsule that continues to host some of the hottest acts in town. Bob Hope and Frank Sinatra entertained under this roof; today it’s home to community theater troupe Maui OnStage.

From the outside, the town appears stuck in time— and not just one time but several. Art deco wings embellish one building’s façade, as if ready to lift it into flight. The 1950s National Dollar Store, now home to a performing arts academy, still sports the dollar-sign logo at its entryway. Plantation-era touches, like corrugated metal and wood-framed windows, remain.

It’s the kind of local authenticity that other Maui towns lost years ago, and that some Wailuku residents fear will be eclipsed by a new generation of entrepreneurs. This quiet transformation is heralded by the sounds of concrete trucks and jackhammers, a signal of what’s to come: a four-story parking structure that will double as a site for farmers markets and festivals, promising not just more parking spaces but renewed energy.

Though it’s still a relaxed town, Wailuku has its frills. There’s Esters Fair Prospect, which serves farm-to-table fare on tiny plates and pours a cocktail named after a Pink Floyd song. Around the corner, Wai Bar hosts trivia nights and DJs with monikers like Sandy Cheeks and Boomshot. Throughout the town, previously bare walls are colored by the imaginations of local muralists, many with deep ties to Wailuku. Thoughtful island motifs—no dolphins or coconut bras here—are based on ‘ōlelo no‘eau, or traditional Hawaiian proverbs.

少し離れたところにデイヴィッド・サンデルさんを見つけた。70年代にマ ウイ島にやってきて、そのままいついてしまったアーティストだ。小脇にキャンヴ ァスを抱えた姿は、彼の作品と同じように奔放でエネルギーにあふれ、見間違 えようもない。切りっぱなしのアロハシャツに履き古したビーチサンダルがトレ ードマークで、いかにも食うや食わずのアーティスト然とした格好だ。過ぎ去っ た時代の名残りでいっぱいの彼の店は、今ワイルクの町に押し寄せているクリ エイティブな新しい波とまったく違和感なく調和している。

煉瓦敷きの歩道は、歴史に彩られたワイルクの貴婦人「イアオ・シアタ ー」へと続く。1928年にオープンしたこの劇場は、昔から町いちばんのホット なショーが連綿とくり広げられてきたタイムカプセルだ。ボブ・ホープやフラン ク・シナトラもこの屋根の下で観客を魅了した。現在は、地域の劇団マウイ・オ ンステージの拠点となっている。

一見すると、町は時代に取り残されたように見える。ひとつの時代だけで はなく、いくつもの時代の中にとどめられているかのようだ。ビルの壁を飾る、 今にも飛び立っていきそうなアールデコ様式の翼。今は舞台芸術の学校として 使われている1950年代建造の「ナショナル・ダラー・ストア」の建物には、入り 口にドルマークのロゴが残る。プランテーション時代の名残である波型トタン と木枠の窓も健在だ。

ほかの町からはとっくの昔に失われてしまった「マウイ島らしさ」が、今も ワイルクの町には残っている。町の人のなかには、新しい世代の起業家たちの 台頭でそれが消えてしまうのではと恐れる人もある。セメントトラックや削岩機 の轟音は、静かに進行していく変化の予兆なのかもしれない。現在建設されて いるのは四階建ての駐車場だ。ただ駐車スペースを増やすだけではなく、ファ ーマーズマーケットやフェスティバルの会場にもなる予定で、新たなエネルギ ーの創造をも約束しているというわけだ。

相変わらずのんびりした町ながらも、ワイルクの町はおしゃれな一面も 持ち合わせている。「エスターズ・フェア・プロスペクト」では、小皿で供される農 家直送の食材を使った料理と、ピンク・フロイドの曲から名前をとったカクテル を楽しめる。少し先の角にある「ワイ・バー」ではトリビア・ナイトが開催され、サ ンディ・チークスとかブームショットといったニックネームを持つDJたちが選曲 している。町のあちこちのむき出しだった壁に、その多くがワイルクと深い結び つきを持つミューラルアーティストたちが想像力を駆使して彩りを加えている。 ここではイルカの群れや、ココナツ製の水着を身につけたダンサーといった通

114 PALM E ESCAPES Wailuku

Wailuku’s diversity of culture reflects the people and eras that have the shaped the island of Maui.

The dining scene retains its island flavor but is seasoned by an inventive new generation of chefs. Sushi takes a playful turn at Umi, where you can order a spicy tuna roll topped with potato chips and salmon garnished with furikake Chex mix.

Beyond these signs of life is a vantage that remains unchanged. Some of the shops from my youth are still around, as are the lawyers and old-timers. New businesses have moved in, mingling with their aging neighbors. Though technically not “mom and pop,” there’s still a good chance you’ll be greeted by the owner.

Walking these streets, Wailuku feels both familiar and brand new. Wailuku isn’t changing, I tell myself. It’s waking from a nap.

俗的なテーマは見当たらず、オレロ・ノエアウ(伝統 的なハワイのことわざ)をもとにした、ハワイならで はの深い意味を持つモチーフが描かれている。

町のレストランでは、地元らしさを残しなが らも、新しい世代のシェフたちが独創的な新たな スパイスを散りばめている。たとえば、遊び心にあ ふれる寿司の店「ウミ」では、ポテトチップスがかか ったスパイシーなツナロールや、チェックスミック スのふりかけを添えたサーモンなどが楽しめる。

新たな生命の息吹の奥には、変わることの ない特質が息づいている。町の弁護士たちや古く からの住人たちと同様、私が子どもの頃から親し んできた店のいくつかはまだ健在だ。新しいビジネ スも、年配の隣人たちとうまく馴染んでいる。家族 経営のいわゆる「パパママ・ストア」ではないにして も、店主が出迎えてくれる店もまだたくさんある。町 を歩けば、懐かしさと新鮮さが同時に胸に広がる。 私は自分に言い聞かせる。ワイルクは変わっていな い。ただ、昼寝から目覚めただけなのだ、と。

116 PALM E ESCAPES Wailuku

FA RE

Culinary delights and F PALM 食

delectable hidden gems

119

F PALM

Raising the Bar

新世代の居酒屋

Text by Rae Sojot

文 = レイ・ソジョト

Images by John Hook

写真 = ジョン・フック

120 PALM F FARE Izakaya

Three Honolulu eateries offer unique twists on the traditional izakaya concept.

伝統を受け継ぎながらも新しい感 覚で個性を発揮するホノルルの居 酒屋3軒をご紹介します。

Opening a restaurant demands practicality and passion. For Kin Lui, chef and owner of Tane Vegan Izakaya, it involved a bit of kismet too. One afternoon, while working as a sushi chef in San Francisco years ago, Lui came across an article about bycatch and declining fishing populations. A few months later came a chance introduction to Casson Trenor, a sustainable seafood advocate. Lui, on the brink of opening his own sushi restaurant, was curious to know how his tentative menu looked through a lens of sustainability and asked Trenor to review it. Trenor agreed, and then proceeded to strike through nearly every fish offering on the menu. Lui sat back, gobsmacked. If his sushi restaurant offered at-risk fish, then other sushi restaurants did too. Something clicked, Lui recalls: Why not do something different?

Over the last decade, Lui has doubled down on being different, leading to a series of successful restaurants that reflect his pioneering spirit, including San Francisco’s Tataki, which offers solely responsibly sourced seafood, and Shizen, a vegetarian sushi spot. Tane, located in an unassuming corner of urban Honolulu, is Lui’s latest venture and his first in Hawai‘i: an entirely vegan sushi izakaya.

Since opening in 2019, Tane remains a daily labor of love for Lui and his team. Each morning, Lui checks his to-do list before spiriting around town for items like tofu and noodles. Then, instead of heading to the fish auction house for choice