Making Waves with David Montalba

As a child, David Montalba’s favorite pastime was rearranging his bedroom. He thrilled at the seemingly endless configurations of furniture, the latent potential of unlocking the novel in a room that just before felt stale in its familiarity: changing the orientation of the bed to open up the space or moving the desk from the shadowy entryway to face the windows instead, so that natural light can spill unencumbered onto its surface.

Growing up, I too enjoyed the act of transforming my childhood bedroom. After all, commanding sovereignty over one’s personal space is a natural symptom of coming of age; an expression of one’s fledgling independence.

For Montalba, though, the act transcended that typical adolescent itch for autonomy. Because even from a young age, he knew a room wasn’t just a room. That the spaces we inhabit are more than places to eat or sleep or congregate. Our relationship to our built environment isn’t unilateral, it’s reciprocal: as we change our surroundings, so too do our surroundings change us.

“Something as silly as reorganizing the furniture in my room when I was 10 years old and realizing how much that affected

me emotionally—that quickly gave me an awareness of the power of design,” says Montalba, from Santa Monica, where he currently lives and works. In true Los Angeles fashion, he dials into our virtual meeting from his car as he drives from one appointment to the next. It’s symbolic of that famous facet of L.A., its residents’ so used to life on the go.

And yet, it’s also indicative of the cadence of Montalba’s own life. As the founding principal of the award-winning Santa Monica-based firm Montalba Architects, he is undoubtedly always in demand. His daily itinerary is filled with business meetings and client consultations, not to mention helping to oversee the numerous multidisciplinary projects his firm handles. Theirs is a portfolio that encompasses breathtaking residential homes and mindful office spaces, sleek airport terminals and immersive resort properties—spanning the urban streets of New York and Los Angeles to the bucolic landscapes of Switzerland and Wyoming.

He founded Montalba Architects in 2004, a firm rooted in a design philosophy that Montalba describes as a humanistic approach to architecture. “Ultimately, we’re designing a building or a space that’s really

20

text by Eunica Escalante images by Kevin Scott Sense of Place

Montalba Architects’ LR2 House

focused on how one experiences it,” he says. “Whether it’s crafting a large-scale building that acts as a public space or a home, it’s really about trying to craft and improve the day-to-day experience.”

It’s a philosophy Montalba traces back to those childhood days rearranging his bedroom, influencing his formative understanding of design’s visceral effects. For the past 26 years as an architect, 15 of which includes his career as a principal founder of his own company, he has honed this humanistic approach into an ideology of thoughtful design. “We bring an experiencefocused and humanistic approach to all aspects of the architect process,” Montalba has said in the past. “We focus on how we experience space and how the building will affect our lives.”

One can see this ideology manifest across Montalba Architects’ dossier of projects, which features works for the likes of Sony Music, The Row, and his own home. Though the firm has cultivated a signature style over the years—exemplified by pared down aesthetics in favor of elegant functionality and a championing of material integrity—no two buildings ever look or feel the same. Each one is alive with its own

character, its personality manifesting in its carefully curated materials or its distinctive expressions of technique.

This structural sui generis is a result of the firm’s approach to design, wherein a building’s context—its location, history, and landscape—is among the primary drivers of its look, feel, and flow. “You have to be contextual and really think about your surroundings,” Montalba explains. “For us, being thoughtful participants in the built environment, knowing what is around us and really responding to it, that is really important.”

Take the Headspace Santa Monica Campus as an example. When the popular meditation app’s success led to quickly outgrowing their original offices, the company turned to Montalba Architects to design a spacious multipurpose headquarters. It would be located in Bergamot Station, the nearly 5-acre swath in eastern Santa Monica that over the years has transformed from its original industrial roots, historically home to railroad stations and factories, to what is today a sprawling artistic complex.

Working within the context of Bergamot Station’s distinctive history, Montalba

24

Architects chose to preserve two of the site’s existing steel structures, lending the headquarters’ buildings an industrialized feel. Materials like the corrugated metal exterior and concrete floors, and design choices like an exposed truss ceiling and the bi-fold garage door opening onto a sprawling courtyard, converted from an erstwhile parking lot, served to heighten the aesthetic. Repurposing the extant buildings wasn’t just for appearances, though. It meant a spacious floor plan, purposely kept open by the firm’s design team to facilitate the organic ebb and flow of productivity and communion—a key tenet of Headspace’s company values.

In contrast, Montalba’s own family home, dubbed the Vertical Courtyard House, takes inspiration from a surrounding neighborhood of single-family residential homes. Hoping to blend seamlessly with their Santa Monica Canyon neighbors, Montalba chose to limit the property’s vertical footprint. “We were allowed to build a taller home,” he says. “We intentionally built it smaller because we wanted to fit into the neighborhood.”

Whereas others would have turned to the surrounding environment for views of natural landscapes, Montalba chose to look inward. The house’s nickname is drawn

from its three-story courtyard and atrium, ensconced at the heart of the property. In centering the courtyard, the home’s design blurs the divide between the internal and the outdoors. Expansive, operable glass walls eliminate the traditional physical and visual barriers, and the home’s interior spaces become a natural extension of the greenspace beyond. “Every outdoor space in that property is an extension of the indoors—that was really intentional,” Montalba says. Beyond inviting the outdoors in, the fluidity of its boundaries delivers ample natural light and air into the space, making its rooms and corridors feel even more expansive. A Japanese Zen aesthetic brings a certain tranquility onto the space, compared to the innovative energy felt within Headspace SM’s industrial walls.

“They’re a little like children, right?” Montalba says, explaining the firm’s contextual approach. “You can’t force a personality on your children. Yes, you can influence them a little, but at the end you have to listen to them. For us, projects are about listening to the client and the site conditions. Sure, we want to guide that, but ultimately it needs to reflect a little bit of the client’s personality and the site’s personality.”

36

Boeing 747-400 Nose Loader service and Ad Hoc charters on demand. Connecting LAX and HNL For more information, a free quote or to book online visit pacificaircargo.com or call 213.568.1977 AIR FREIGHT SPECIALISTS EXCEEDING ALL EXPECTATIONS daily with daily connections to Neighbor Islands and weekly service to Pago Pago and Guam.

It can be more difficult, and riskier, to make natural wine, the goal of which is to produce a true expression of the natural environment where the grape was grown, or the region’s terroir, rather than one that reflects a chemically engineered flavor profile.

California has long been known as America’s wine country, with its agreeable climate, varied geography and long history of grape growing. But as wine has become a commercial product, it’s also become mass produced, engineered with modern farming methods to meet demand.

Over the last few decades, some winemakers have been operating on the fringes of that norm, making wine through minimal intervention, now more commonly known as natural wine. While there’s no official definition or certification, natural wine is generally understood to be wine made with organically or biodynamically farmed grapes, grown without synthetic pesticides, fungicides or fertilizers. Once harvested, those grapes ferment only with the native yeast that already exists on the skins, and without any commercial additives to help control or propel the process, aside from occasionally a small amount of added sulfur dioxide to stabilize and preserve the wine. While it can be more difficult, and riskier, to

make wine this way, the goal is to produce a true expression of the natural environment where the grape was grown, or the region’s terroir, rather than one that reflects a chemically engineered flavor profile.

James Jelks, the producer behind Florèz Wines in Santa Cruz, says generally wines become diminished “because people are trying to do things to them; They’re trying to get them to be a way.” As a natural winemaker and wine drinker, he says, “I want as authentic, as honest a product as possible.”

This means natural wines can vary in color—from soft and golden yellows, to orange and salmon pinks, light reds and deep, dark purples—and suggested serving temperatures (chilled reds are popular in hotter months). Some can have a very traditional palate, while others are often described as “funky,” to note a kombucha-like taste, or “effervescent,” to express a hint of fizz. Depending on the winemaker’s filtration methods, they can appear clear or slightly

38

text by Lauren

images by Andrew

illustrations by Yoko

A Good Wine, Naturally

Martha Souman poses with product. On the next, she overlooks her haul.

Messman

Thomas Lee

and

Tyler Tronson

Baumberger

cloudy, with harmless leftover sediment occasionally dusting the bottom of the bottle.

The Los Angeles-based natural winemaker Rachel DeAscentiis, who runs the label Say When with her husband Michel, has current and upcoming releases within that diverse spectrum. On the less conventional end, she has a piquette, which is a light and refreshing wine-like beverage made by rehydrating grape skins that have already been pressed. The drink is becoming more popular in the natural wine world because it’s another way to utilize discarded grape skins, seeds and stems.

On the more refined side, DeAscentiis, 33, is also about to release a syrah sourced from 50-year-old vines in Los Olivos, CA, which she believes could be one of the “most pure, elegant tasting wines I’ve ever made.”

“Even if you don’t like orange wines or don’t like wines that kind of taste like kombucha,” she says, “there are very serious, elegant red wines that are made naturally that I think just aren’t what people associate with natural wine.”

For some consumers, the range of natural wine’s characteristics is redefining what wine can be, how it can taste and its impact on the environment, all of which are contributing to natural wine’s recent surge in popularity. Across the country—but especially in the coastal hubs of New York

City, San Francisco and Los Angeles—there are wine bars, restaurants, wine stores and even zines dedicated to natural wine.

But despite its rise in trendiness, natural wine isn’t new. The recent movement is instead revitalizing traditional methods that winemakers around the world have been practicing and handing down for centuries, long before modern farming and production practices made their way into our stemware.

Both Jelks, 31, of Florèz Wines, and Martha Stoumen, 38, are graduates of UC Davis’s Viticulture and Enology program, but they also spent time working in vineyards to learn low-intervention techniques first-hand. For Stoumen, who spent eight years learning from winemakers across Europe and in New Zealand, the cultural preservation of their methods was part of what inspired her to return to California and make her own wine.

Stoumen now runs her own label from her hometown of Sebastopol, CA, in Sonoma County. She sources organic grapes from longtime California growers, and also leases vineyard land where her grapes are dry farmed, a method that relies only on natural rainwater, rather than irrigation. These farming parameters lead Stoumen to seek out the freshest and most expressive varietals in a given year, instead of pursuing a specific grape. Her approach is more about assessing “what are the grapes telling us to make?”

42

“We’re not going to adjust the flavors,” she says. “We’re not going to add a bunch of things once we get back to the winery. We’re not going to add tannin and acid. You can basically buy bags of wine flavoring if you want to, but we’re not going to do any of that.” For Jelks, being forced to be resourceful, both in the vineyard and in the winery, is a challenge that’s paid off. At one point, he was fermenting picpoul, a white grape that was picked slightly early and emitting what he called an “intense kind of fruitiness.” At the same time, he had a portion of pinot noir that he felt was “too jammy” to release on its own. To salvage them, he tried blending the two fermentations together, creating Florèz’s Poilu’s Pinard.

“Together they complemented each other perfectly, and that wine was probably one of the most popular wines on that release,” Jelks says. “I don’t know if I want to call it a mistake, but it didn’t go according to plan.”

The approachability of the natural wine movement is also attracting people outside of the traditional food and beverage world. Not long ago, James Murphy, of the band LCD Soundsystem, opened the Four Horseman in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, which New York Magazine has called “perhaps the premiere New York destination for natural wine.” And consumers have been enamored with Las Jaras Wines, a label of low-intervention offerings from comedian Eric Warheim and winemaker Joel Burt.

Before coming together to create Good Boy Wine in Los Angeles, Eric Bach, 38, and David Bourke, 36, had no formal winemaking knowledge. Instead, they did their own research and reached out to natural wine producers within two hours of L.A. who offered guidance and encouraged them to continue.

Bach then spent time training with winemakers in France and, by harnessing French old-world techniques, he says he aims to make wine “for the California palette, where it’s always hot, and you’re having a good time, and you’re maybe drinking a little bit more quickly than you should.”

Good Boy’s grenache, called Warm Breeze, he deems a perfect representation of that. On the label’s website, tasting notes include: “campari spiked strawberry Koolaid” and “summer vacation in Mallorca.”

Good Boy Wine is also dedicated to fostering collaboration among like-minded producers and consumers, an attempt, Bach says, to “pay it forward” after being welcomed into the natural wine community as newcomers.

“We’re always supporting each other. Inviting each other to our different events. Doing collaborative wines, whatever it may be,” Bach said. “It feels like we’re in it together.”

Recently, Bach and Bourke hosted Good Boy & Friends, a tasting event at a local bar

“We’re not going to adjust the flavors.”

44

that brought together representatives from 12 natural wineries and wine shops around Southern California. As a DJ spun disco records and a spray-paint artist created custom T-shirts, the gathering was stylishly unfussy, celebrating collaboration, rather than competition—without the pretension or snobbishness that’s plagued the wine world in the past. Before coming together to create Good Boy Wine in Los Angeles, Eric Bach, 38, and David Bourke, 36, had no formal winemaking knowledge. Instead, they did their own research and reached out to natural wine producers within two hours of L.A. who offered guidance and encouraged them to continue.

Bach then spent time training with winemakers in France and, by harnessing French old-world techniques, he says he aims to make wine “for the California palette, where it’s always hot, and you’re having a good time, and you’re maybe drinking a little bit more quickly than you should.”

Good Boy’s grenache, called Warm Breeze, he deems a perfect representation of that.

On the label’s website, tasting notes include: “campari spiked strawberry Koolaid” and “summer vacation in Mallorca.”

Good Boy Wine is also dedicated to fostering collaboration among like-minded producers and consumers, an attempt, Bach says, to “pay it forward” after being welcomed into the natural wine community as newcomers. “We’re always supporting each other. Inviting each other to our different events. Doing collaborative wines, whatever it may be,” Bach said. “It feels like we’re in it together.”

Recently, Bach and Bourke hosted Good Boy & Friends, a tasting event at a local bar that brought together representatives from 12 natural wineries and wine shops around Southern California. As a DJ spun disco records and a spray-paint artist created custom T-shirts, the gathering was stylishly unfussy, celebrating collaboration, rather than competition—without the pretension or snobbishness that’s plagued the wine world in the past.

46

A bottle of Good Boy.

Photo by Tyler Tronson.

A CULINARY ADVENTURE

IS ON THE HORIZON

Resting directly on the sand in Santa Monica, Shutters on the Beach and Hotel Casa del Mar are home to six memorable culinary destinations. Endless ocean views complemented by seasonal menus, craft cocktails, and live music nightly.

A luxuriant day-to-night space serving morning coffee, light meals, afternoon tea, or a night cap. Linger by the fireplace or enjoy breathtaking Santa Monica sunsets from the best seat in town.

One of Southern California’s premier beachfront dining destinations. Experience Coastal California Cuisine at its finest when you dine under the stars in the 1 Pico Courtyard.

Relax and enjoy California inspired dishes from Chef Vittorio Lucariello at Coast, a family friendly, casual environment to enjoy great food and picturesque views of the Pacific.

Get your ciao on at this charming trattoria celebrating Italian inspired coastal cuisine. Enjoy a chilled sparkling Prosecco and signature dishes from Chef Gemma Gray.

The hottest luxe meeting space in Silicon Beach serving after-work cocktails and a selection of Chef’s canapés. Reserve a cabana for a day of work or a creative retreat.

Taking a front row beachside seat at the foot of the iconic Hotel Casa del Mar is our new al fresco bistro, Patio del Mar. Steps from the strand, it is the perfect place for a summer lunch or sunset dinner with friends.

image

by Nancy Pastor

WELLSPRING

Through its deliberate pacing, and gradual progression, this cuisine works to quiet the mind.

—Victor Ramsey

We asked a guy obsessed with omakase sushi to explain how it got its hooks into him so deeply.

I scrutinized the product—a sliver of fish atop an oblong ball of rice—with the intensity and focus of an F1 driver at the starting line. Chef Moriyuki, placing the nigiri sushi on the earthenware dish before me, gave the fish its name: “baby snapper”— or kasugodai in Japanese. Its pearlescent skin, left on, was flecked with green from a dusting of zested yuzu. Its unblemished flesh, which ran in gradient from warm translucence to sunset-pink, testified to the keen knife work that had separated it from the filet in a single unwavering stroke.

I watched, admiringly, as the ball of rice, touching down on the ceramic plate, settled ever-so-slightly into itself, easing gently downward under its own weight, as if releasing a gentle sigh. This almost imperceptible movement was a promising sign, indicating that the latticework of rice had not been overly compressed in the hands of the chef (which would mark a critical lapse), and so retained an airiness between the grains that would lead to a pleasing dispersal upon their happy arrival to my mouth.

For moments like this—poignant, expectant—I had (yet again) reshuffled my monthly budget, borrowing from the already anemic gas and grocery line items to reallocate to the overtopped sushi category, offering myself the token reassurance that a budget represented an ideal to aspire to,

not an ironclad diktat to be slavishly obeyed. And anyways, to not let things get out of hand, I pledged to abstain from sake with the meal and to stoically forego any extra orders at its conclusion. All this bargaining and equivocation, just to get my lunch time fix at the newest entrant to Santa Monica’s high end sushi scene: The Brothers Sushi, a Woodland Hills institution that had recently planted its second flag on the other side of the mountain, among the posh and breezy shops and eateries of Montana Avenue.

An hour later, as I waited for my add-on orders of dashi-marinated salmon eggs (magical orbs that burst rich salinity), giant clam (with its oceanic crunchiness), and penshell scallop (a sweeter, denser version of its more common cousin) to arrive, and as the waiter offered up a generous pour of my third sake—this one a honjozo fittingly named “Endless Summer”—I wondered vaguely how I had found myself, yet again, blowing budgets and breaking pledges for the sake of raw fish on rice.

My obsessive descent into edomae (Tokyostyle) sushi began with a trip to Japan in my early thirties. There, a fateful bite of raw sardine—of all things—draped over a pillow of vinegared rice provided me my first experience of sushi-induced bliss. I returned to Los Angeles desperate to find a local joint that could replicate that high. I set money aside—dedicated to sushi, and sushi alone—

52 text by Victor Ramsey images by Nancy Pastor To Entrust

Right, Chef Mark Okuda of The Brothers Sushi in Santa Monica.

and ventured from Pasadena to Simi Valley, Torrance to the San Gabriel Valley, following leads gathered from food forums, Instagram accounts and magazines, in search of that perfect bite, that next fix.

The search has led me to every corner of Los Angeles and beyond. I’ve gone over budget several times. It may be time to admit I have a problem.

That’s what’s brought me here to one of my favorites, The Brothers Sushi, enjoying a late afternoon meal while trying my best to not consider its financial consequences. I found some degree of solace for my shortcomings in commiserating with the woman sitting next to me at the counter who, after her previous visit, had resolved to wait a respectable month before returning for her next meal. Yet here she was, three weeks later (so close!), biting contentedly into orange lobes of Hokkaido uni that had been enfolded, tacolike, into a strip of crispy nori that crackled audibly as it shattered while she chewed. Her ensuing groan of satisfaction seemed to indicate she had forgiven herself.

Pleasant satiety, intermingling with the warmth of the sake, fostered in me a general sense of wellbeing. I wondered how such a seemingly simple food as nigiri sushi, consisting of no more than a topping (neta in Japanese, usually fish) on seasoned sushi rice (shari), had come to captivate appetites of so many Angelenos. Specifically, the format

of this cuisine known as omakase—wherein the customer leaves it to the chef to decide the substance and sequence of the meal (translated from the Japanese, it means “to entrust” or, more loosely, “I will leave it up to you”)—seems to have worked its magic on not only my palate, but the collective. What special power resided in this style of cuisine that its appeal drove scores of foodie pilgrims to seek it out across Los Angeles, eager to pay expensive tribute at these temples of rice and fish?

The aughts had seen a remarkable profusion of omakase-focused sushi-yas weave themselves into the fabric of the city. With minimal seats (often counter only) and maximal prices (the going rate at the ultrahigh end establishments can now run well over $250 for food alone), they had found their place in the most unassuming of locations; buried in the basement of office buildings (like Sushi Kaneyoshi in DTLA), or behind boarded-up exteriors (see Mori Sushi in West LA), or, most commonly, tucked into discrete corners of generic strip malls (Matsumoto in West Hollywood, Kogane in Alhambra, Takeda in Little Tokyo).

As quickly as they multiplied, so too did their customers, whose insatiability was matched only by their seemingly unlimited funds. As the late great sage of the Los Angeles food scene Jonathan Gold rightly noted, Angelenos had proven themselves far more willing to expend their fine dining

56

budgets on processions of raw fish at humble sushi-yas than on more buttonedup and extravagant prix-fixe, multi-course meals at a New American or Frenchinflected restaurants. But why?

Answers to these questions were put on momentary pause by the arrival of my check upon the birch wood bar. At $200 dollars for lunch—$90 for the omakase, plus $30 for the inadvertent add-ons, the rest on drinks and tax—the meal, truth be told, proved a relative bargain considering its superb quality and reasonable portions. And with multiple bottles of sake on the menu clocking in at over $700, not to mention a bottle of Napa red for $1400, I knew things could have been much, much worse.

As I settled up, the genial waiter provided a complimentary pour of plum wine. Fuchsiatoned and velvet-textured, the wine’s happy interplay of sweet and sour was the perfect send off.

I realized then that perhaps the mystery of omakase’s ascendance was not so mysterious after all. In a world that scatters our attentions across a thousand and one distractions, here is a cuisine that, through its deliberate pacing and gradual progression, through its austere technique and limited ingredients, works to quiet the mind and channel its focus. I watch, rapt, as the mackerel is sliced, the rice sculpted, the wasabi dabbed, the neta pressed and molded

into the shari, until the nigiri achieves its final, quintessential form. I admire the chef’s economy of movement, poised and purposeful and devoid of undue expenditure, honed through countless repetitions.

I remind myself of the long chain of hidden labors that made this perfect bite possible— the fishermen in Boston, Hokkaido, and the Canary Islands who stake their livelihoods on the fickle sea; the distributors and fish mongers who assess, sort and send the choicest specimens to their most deserving customers, with whom they have built reciprocal trust over many years. I think of the chef’s early rise each morning, day after day, to break down the fish, debone it, age, cure, and marinate it, to prepare the rice to the most exacting of specifications. I marvel at the years of training required to learn to do this properly. We, the omakase obsessives, behold these diverse efforts concentrated into the edible object before us, rice and fish, a study in simplicity borne of monumental efforts.

Perhaps seeking out this style of eating is not so much an addiction as a brief reprieve from them, from the phone’s insistent notifications, a job’s incessant demands, from the regrets of the past and concerns for the future. Here was a space devoted to fashioning perfect simplicity from untold complexity, and that asks nothing but to pay attention, to appreciate, and, of course, to pay up.

THREE OTHER HIGHEND SUSHI OMAKASE RESTAURANTS WORTH BLOWING YOUR BUDGET FOR...

MORI SUSHI

11500 W. Pico Blvd.

West LA

Chef Maru puts on a oneman show at this West Los Angeles stalwart. Hosting only a few small groups of private diners an evening, Mori Sushi maintains its focus on serving the most understatedly exceptional edomae cuisine in the city. $250 - $300. morisushila.com

SHUNJI

3003 Ocean Park Blvd

Santa Monica

Firmly established in its new counter-only Santa Monica digs, eponymous chef Shunji Nakao continues his Michelenstarred tradition of creatively-composed small plates and red-vinegared nigiri, crafting perfect bites for the discerning diner. $250.

shunji-ns.com

MATSUMOTO

8385 Beverly Blvd

Beverly Grove

Offering an unmatched variety of fish from a discrete West Hollywood strip mall, Matsumoto pairs neighborhood comfort with broad ambition, plating some of the finest sushi to be found on the Westside. $130 - $250 matsumoto-restaurant.com

62

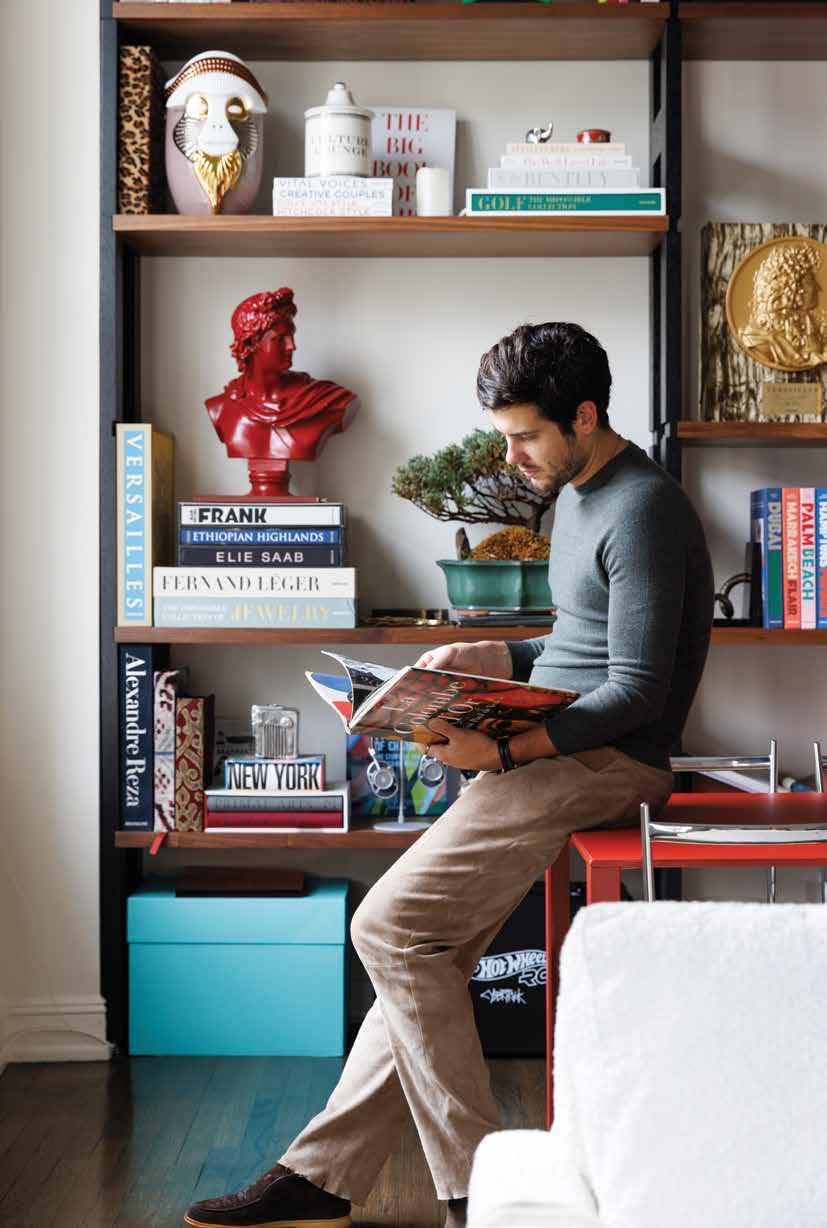

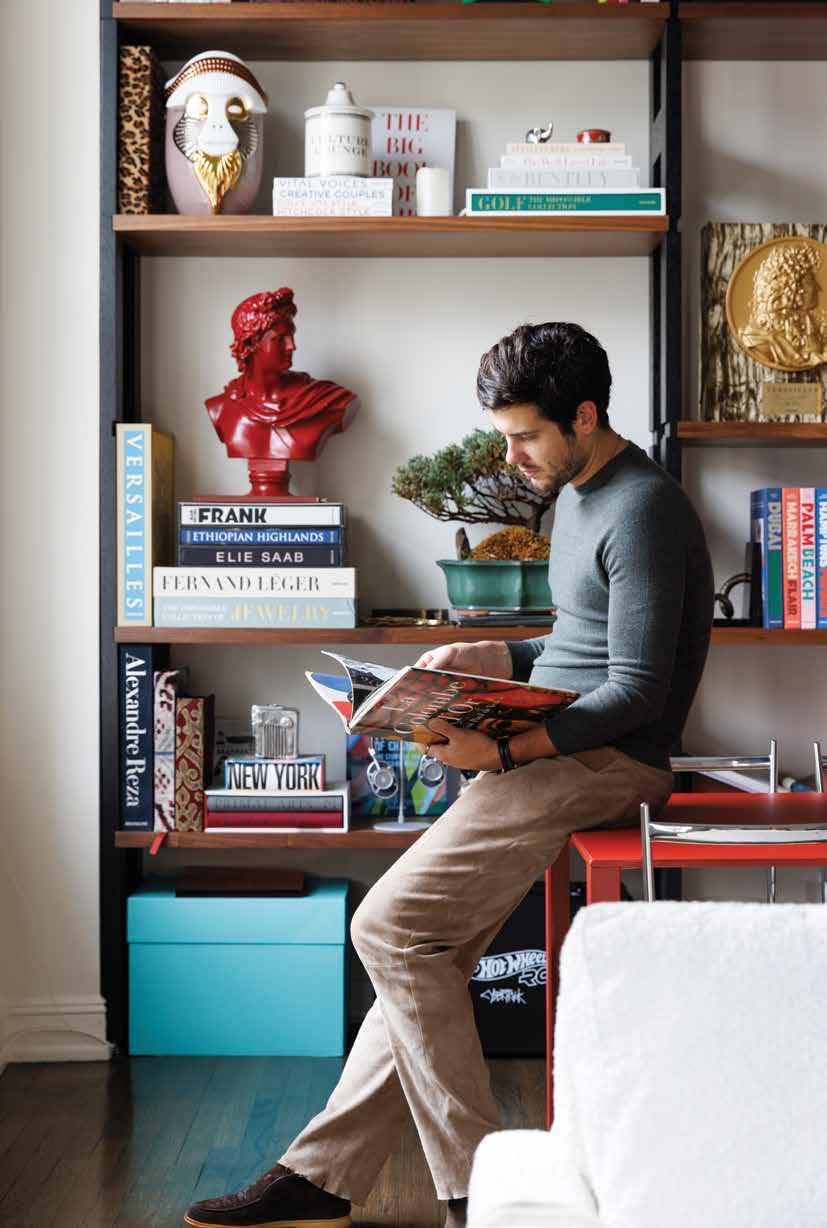

Designing a home library is the perfect way to display your passion. These three publishing world experts will show you how.

As children, we read books in part to escape ourselves. Pirates don’t have bedtimes, and astronauts can have dehydrated ice cream for dinner, if they want. But as we grow, our books tend to become more than an escape, they’re also a reflection of who we are, of what we care about, and who we want to be. Naturally, at some point we want to display this accumulated desire and knowledge, although the task can seem daunting. Thankfully, there’s help. Combining the knowledge of a librarian or a publisher with the touch of a luxury stylist, private library curators help create collections and enclaves that feel unique to the individual.

“You’re trying to find the books that have resonated with them in their life,” says Philip Blackwell, the CEO and founder of Ultimate Library, “whether it’s childhood, their degree, their line of work or pleasure, interests, and pursuits.”

There are, in a way, two sides to creating a home library: design and collection. Both

share a similar genesis, a central question to be answered: What do you want out of your reading sanctuary?

“The library should feel alive,” Alex Assouline says. The son of the couple behind the Assouline publishing house, he started offering curation and design services for both home and professional libraries after being commissioned to do so by a friend in 2017. “It should always be there to provide the right moment for escape and to inspire.”

To find that inspiration, curators start with the clients drawing out motivations, ideas, themes, and goals for their libraries. These could be cherished books from childhood, deep dives on areas of passion, or even a mood; a collection that invokes a feeling of Zen, perhaps, or energizes.

“It should really be an engaging and fun exercise for both parties,” says Blackwell, “to understand what people are looking for, and then take your encyclopedic knowledge

THE CENTERPIECE It’s the book that draws everyone’s eyes. It’s the book that your friends can’t stop flipping through when they visit.

“You always need a centerpiece,” says Assouline. Whether displayed on their eponymous fixtures, cover out on a shelf, or even on a custommade bookstand, these are the titles that will grab your visitor’s attention. If you’re looking for the pièce de résistance of your collection, this is a sampling of publishers who specialize in the books that will “wow” friends before they even read a word.

64

text by Robert Spuhler images courtesy of Assouline Shelf Expression

of the four million books available, drilling down to the 300 that are going to press the hot buttons in these people.”

This may sound like some sort of shortcut, a way to buy an image of culture and erudition. But there’s more to a library than its brainy aesthetic.

“I expected more people to want to hire me to look smart,” says Christy Smirl, the owner of Foxtail Books & Literary Services in Jackson Hole, WY. “And that’s not what they’re looking to do. They’re book people and they want their guests to see the things that make them interesting.”

“We talk about them internally as books that people have lied about reading,” Blackwell says of those stereotypical collections of the great works of literature that make for a beautiful, but bland, backdrop. “We say we’re happy to make all the books red as long as they’re well-read.”

In many cases, these library collections help add a sense of place to a home. Working in Jackson Hole means that Smirl often works on the libraries of either newcomers or those with well-established second homes. Reflecting that location in clients’ book choices separates that particular shelf from one in another residence.

“If you live somewhere like Jackson, or L.A., San Francisco, [or] New York, you’re there because you’re really excited about that place,” she says. “And whether you’re into the nature, history, great restaurants, I think having books on your shelf, similar to having local art or something else visual, reminds you where you are.”

When the collection’s main idea is decided upon, curators (and their teams) get to work. In some cases, that may mean choosing between different editions of the same book for aesthetic purposes, but it could also be tracking down, through networks of dealers and specialists around the world, first editions, autographed copies, or even copies with alternate cover art.

All of the effort, no matter what form it takes, serves to create a library that can double as a representation of a person’s DNA, one that engenders the sort of ineffable passion that only art can create.

“I’ve had clients that hold a book to their chest, because it means so much [to them],” Smirl says. “There’s something about books… some people might want a home that gives them a spiritual vibe, or some might want a party atmosphere, and literature can, in a special way, provide that.”

ASSOULINE

If you’re looking for a reminder of that mindexpanding trip, Assouline might be able to help. Alongside the publisher’s art and culture titles, its city-specific books bring destinations to life, with gorgeous photography and great writing. It can even help you display that travelogue; the company has branched out into library furniture, as well. assouline.com

TASCHEN

Perhaps the largest and most famous of the “centerpiece” brands, Taschen has stores around the world that attract browsers looking for largeformat artist retrospectives and deep dives into culture (or counter-culture). Taschen has two stores in Los Angeles, one in Beverly Hills, and the other in Hollywood. taschen.com

GESTALTEN

For a contemporary twist, this German publisher stays on the cutting edge of trends in design, architecture, and adventure (think backpacking, hiking, and even #vanlife). It is consistently updating its Monocle series of practical travel books with advice for off-the-beatenpath gems. us.gestalten.com

68

70 image by Thula Creative

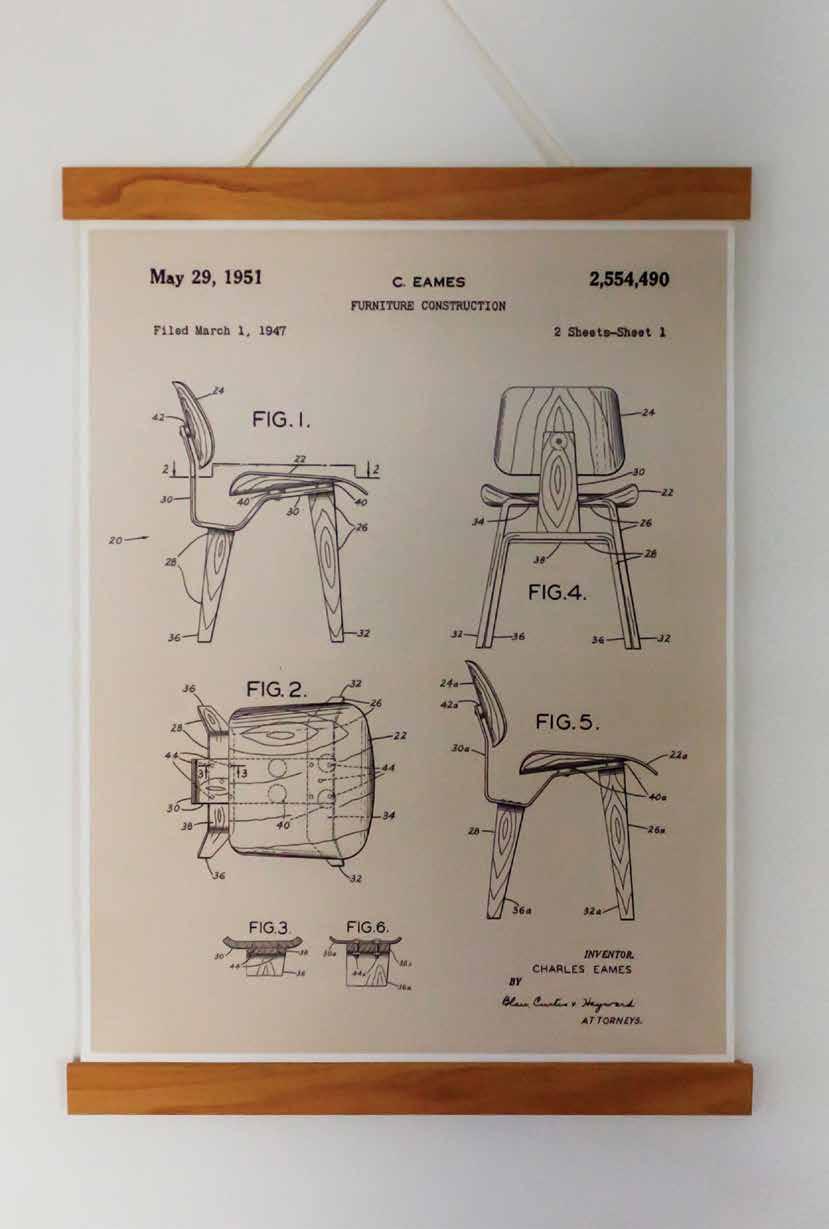

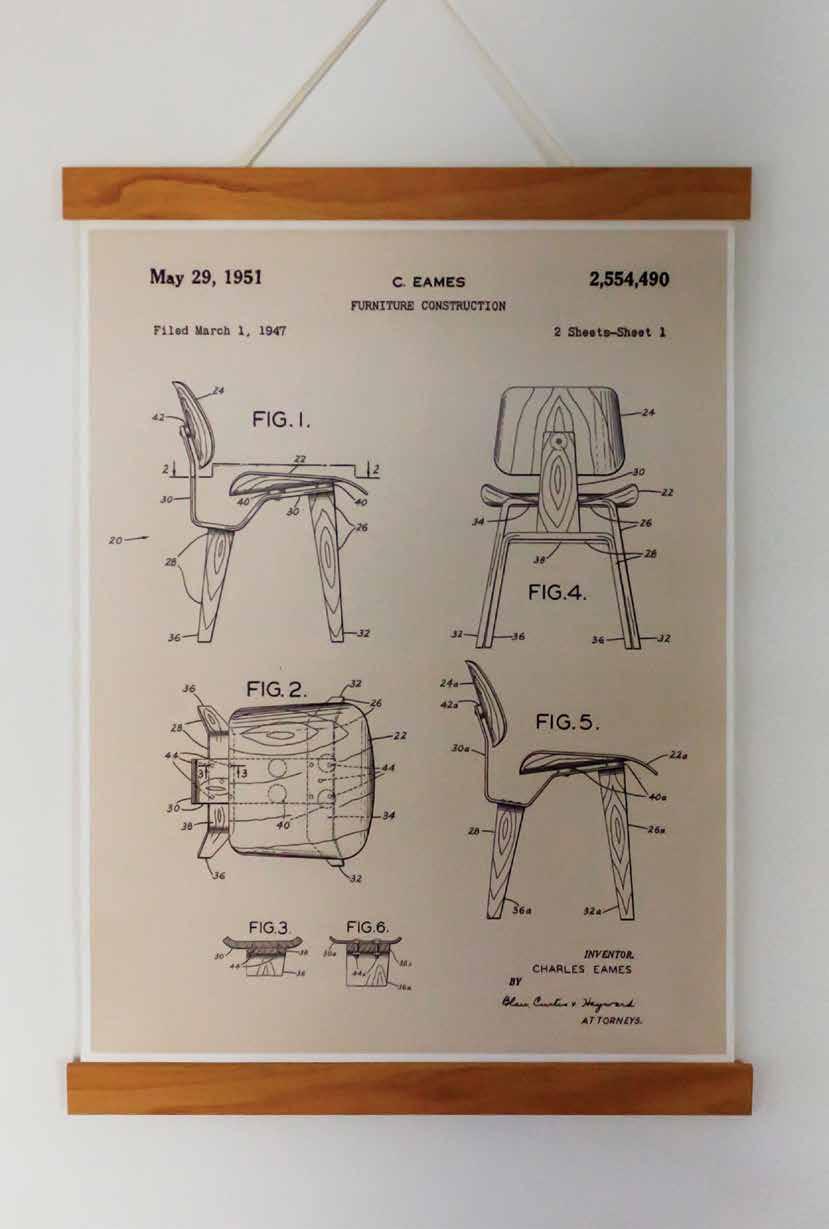

I always compare the Eames Lounge Chair to a Rolex watch.

—Ryan Hobbs

PEOPLE

The home of the legendary couple, in Pacific Palisades, has become something of a mecca for lovers of modern design.

The Eames House, located in the Pacific Palisades neighborhood of Los Angeles and often heralded as a landmark of mid-20th century modern architecture, rests atop a bluff that’s high enough to see the ocean in the distance. Charles and Ray Eames, a married pair of American industrial designers, moved in on Christmas Eve 1949 and stayed until the end of their lives. (Charles died in 1978; Ray in 1988.) The home, which they built as part of a program meant to encourage affordable modern housing, features exposed steel and a number of sliding glass doors that open to the outside, where wildlife teems around fresh-smelling eucalyptus trees.

It also, on a limited basis, fills with people. The place has become something of a mecca for appeciaters and lovers of modern design, as the younger generations of Eames have kept it maintained for the public.

The structure now stands as a National Historic Landmark and museum, offering a number of tours throughout the year. Guests, who should certainly plan ahead if

they cared to visit, pay $30 for an exterior showing of the grounds and an occasional peek into a window, where they can view the couple’s meticulously curated art. If you choose, you can also schedule an interior tour, running at $275, or $225 for members, for one to two adults and $450, or $400 for members, for three to four adults.

The Eames House is, in no small part, tantamount to the legacy of Charles and Ray, the former of whom said the role of a designer as “a very good, thoughtful host anticipating the needs of his guests.”

Based largely in Los Angeles, Charles, an architect, and Ray, a painter, had polymathic careers, where for decades they complimented each other, allowing their respective creative aspects to shine through, and made significant contributions not only to furniture designs, but to communications, filmmaking, art, and photography. They had the confidence, emphasized Pat Kirkham, a professor emerita at Bard Graduate Center and the author of Charles and Ray Eames: Designers of the Twentieth Century, “to follow

72

Right, a classic fiberglass molded Eames armchair.

The Eames Era

text by Alex Norcia images by Thula Creative, Dennis Scherdt, and Juan Miguel Agudo

their own interests and seemed to only take on work that they really wanted to do.” It’s a luxury, perhaps, that’s not afforded to every designer.

“Their legacy has always been changing,” she says. “A lot of the questions I get from students now are much less technical than when I was teaching in, say, the 70s. Today, I think much more the legacy is around ethical use and integrity. It’s about quality at the end of the day. Like the notion of truth to materials and honesty to construction—doing something very well in the appropriate manner.”

Beyond that, they developed a reputation as the good “hosts” Charles once described. Quite literally: They constantly entertained friends and family and took a real joy in their labor and creation, in a way expanding an arts-and-crafts theory from the midto-late 1800s popularized by the textile designer William Morris. “They took your pleasure seriously,” Kirkham says. “Maybe a better way to put it is that they took pleasure in the serious parts of their lives.

They had the ability to make everyday occasions very special.”

For them, designing—and the pleasure they derived from it—didn’t stop. “The design process for Chales and Ray never ended in manufacturing,” Eames Demetrios, a grandson of Charles and Ray and the current director of the Eames Office, said during a TED Talk. “It continued. They were always trying to make things better and better.”

“They didn’t obsess about style for style’s sake,” he later added. “They didn’t say our style is curves; let’s make the house curvy. They didn’t say our style is grids; let’s make the chair gridy. They focused on the need. They tried to follow the design problem.”

As mid-century furniture has had a kind of revival in the past few years, so too has consumers’ fascination with Charles and Ray’s work, particularly the series of Eames Lounge Chairs and Ottomans they constructed during their lives. Certain versions of chairs, which the couple fussed with over the decades, can fetch thousands

74

Six figure design Charles Eames Furniture Construction Schematic.

and thousands of dollars in the secondary market. (Some of them are even exhibited in New York’s Museum of Modern Art.)

The demand for the Eames Lounge Chair became so high that Ryan Hobbs, a former high school teacher, quit his job to restore them and other mid-century modern furniture full-time. Hobbs, the owner with his wife Nicole of Hobbs Modern, a mid-century modern furniture dealer and restorer in San Diego, had no formal training in furniture restoration. But an admirer of Charles and Ray, especially their eye for precision, sparked a passion that turned into his vocation. Eventually, he approached a local furniture restorer in San Diego who, on the brink of retirement, agreed to teach Hobbs the trade. He never looked back.

“Every component of the Eames chair was just built really, really well,” Hobbs says. “The Eames bases were all sawed aluminum, so we sometimes polish the aluminum to factory

chrome shine. The wood shells can take a day to sand. And then putting shock mounts on the chair, which are super precisely put in.” Hobbs searches for his own chairs to buy and restore, and he also has clients who approach him for custom restorations. He’s constantly on the lookout for Eames chairs, scouring Facebook Marketplace, Offer Up, auction houses, and estate sales.

“I always compare the Eames Lounge Chair to a Rolex watch,” Hobbs says. “It’s an item that, once you’ve made it in life, you’re like, ‘I want one of those.’ Today, I can probably get $4,000 more for an Eames Lounge Chair than I could only a few years ago.”

Hobbs spends more than 30 hours restoring a given chair, and estimates he has already restored more than 100 with no likelihood of slowing down. He has never enjoyed working more in his life. The whole process, he says, is a joyful one. It’s a pleasure taking other people’s pleasure seriously.

76

The Rolex of lounge chairs

“It’s an item that, once you’ve made it in life, you’re like, ‘I want one of those,’” says Ryan Hobbs, pictured right.

mount tamalpais image by Simone Anne

There are two things chefs want: to cook at The James Beard House and Outstanding in the Field.

—Jim Denevan

After two decades of staging al fresco dining adventures, Outstanding in the Field founder Jim Denevan has no plans to come inside.

Twenty years ago, Jim Denevan had a simple idea. A burnt-out restaurant chef from northern California, Denevan wondered if there might not be a better way to deliver food to people than through the pressurefilled aperture of a restaurant. “I had just read Anthony Bourdain’s ‘Kitchen Confidential,’” he tells me, “and I was fed up with the idea of chefs as swashbuckling, drug-taking a–holes.” What he wanted was more joy, more space, more connection. His solution was a roving dinner party composed of (mostly) strangers in exquisite locations (often fields) called Outstanding in the Field. (One of his first events was for a hundred diners in a sea-side cave in Half Moon Bay, CA.) Each dinner was a virtuosic feat of logistical bravado and culinary bravura. Twenty years on, both are on display, though the field has gotten much larger.

“It’s become a little bit more stable,” Denevan says. Instead of three or four events a year, this season consists of hundreds, and most unfurl not upon topologically suspect perches but in actual farmer’s fields. They stretch literally around the globe from the rolling hills of Blue Moon Community Farm in Stoughton, WI, to the small organic farm Tenuta San Carlo in Grosseto, Tuscany to a field kitchen in Accra, Ghana. “We have a schedule of 25,000 tickets,” Denevan says proudly. Most sell out.

A typical Outstanding in the Field evening finds an extremely long, impressively long, Dr. Seussian-long table, fully set with wine glasses that gleam in the sunlight and plates in precise order atop a hemp and linen tablecloth. Sometimes the table is in a straight line, as it was on a pier in Malibu.

80 text by

images by

Joshua

David Stein

Emily Hagen, Brighton

Field Guide

Denevan, and Ilana Freddye

84

Previous page, dining on Stinson Beach. Left, an Outstanding event in Big Sur. Images by Emily Hagen; Right, dinner on the Malibu Pier. Image by Brighton Denevan.

Sometimes it snakes to mimic the contours of the landscape, as it did at a secret sea cove in San Mateo, CA. (Denevan, apart from running Outstanding in the Field, is a land artist in the vein of Andrew Goldsworthy or Maya Lin.) Guests arrive—events usually max out at 160 people and cost around $385 per person—in the afternoon, glowing with anticipation, exuding good health. Women wear flowing floral dresses and wide hats. Men wear various pastel shades and light slacks. There are shoes but rarely socks. It’s a vibe. “I want the guests to be overwhelmed by the magic and beauty of the circumstance and put their phone down and concentrate on the menu, the surroundings and the story telling,” says Denevan of the guests, “they can’t help but soak it up. “

In the early years, it was Denevan himself lugging tables into the field. Now, although he still attends about 60 percent of the events, he says there’s a team of close to 100 people who help. His mission remains undimmed. “The table is both a driver of culture and a portrait of contemporary culture,” he says. “It feels good that finally the cultural moment is recognizing what we’ve been doing since 1999.” And that moment has in turn allowed Outstanding in the Field to

increase its breadth and scope in terms of both chefs and locations. This season features chefs like Fatmata Binta from Ghana’s Fulani Test kitchen cooking in a field kitchen in Accra on November 11.

But what has given Outstanding in the Field longevity isn’t simply Denevan’s penchant for location selection. The caliber of chefs and farmers on whom he is able to draw include some of the best in the world. In past seasons, for instance, chefs included Francis Ang, of San Francisco’s Filipino restaurant Abacawho, who cooked at the 50,000 acre Richardson Ranch; and Julien Hawkins of Austin’s live-fire hotspot Hestia. Both restaurants recently won spots on Esquire’s “Best New Restaurants” list. Denevan’s own background as a chef, as well as his close partnership with the farmers in whose fields his events unfold, helps in recruiting the talent. What attracts the chef willing, as he puts it, “to endure all the hassles” of lugging equipment around into a makeshift kitchen is a feeling of bonhomie. “There are two things chefs want,” Denevan says,“ they want to cook at the James Beard House and Outstanding in the Field. The James Beard House is a temple among chefs. But Outstanding in the Field is a sense that, now, I’m among my people.

OTHER NOMADIC DINING CLUBS

Although Outstanding in the Field is one of the first of its kind, now that fine dining has been liberated from the four walls of restaurants, other companies have popped up curating once-in-a-lifetime experiences around the world. Here are three of our favorites:

SECRET SUPPER

A smaller outfit founded in 2015, Secret Supper adds to the surprise by keeping the location of the supper… secret until just 24 hours before the event. (It is within two hours drive from the listed city.) Events are on the smaller side, about 50 to 60 people, and cost $249 per person. A recent supper, in partnership with Peroni, offered at “Taste of Italy” over five courses from chefs Mia Castro, Ashley Rodriguez, and Jodi Moreno in Miami, Los Angeles, and New York, respectively.

DINING IMPOSSIBLE

The brainchild of culinary ambassador Kristian Brask Thomsen, Dining Impossible started as an exclusive dinner party and has since morphed into DI:JET, a four day global tour aboard a private jet to some of the world’s best restaurants. Price is available upon request.

LAST SUPPER SOCIETY

Sacramento-based Last Supper Society was founded by Byron Hughes and Ryan Royster and celebrates the intersection of art and food in various locales in northern California like an intimate artist dinner at Casino Mine Ranch, a vineyard in Plymouth, CA.

88

Luxury watches have become their own asset class, but even before the boon their value was timeless.

At the beginning of September, Jon Carter learned that Grönefeld, a small, wellrespected watchmaker in the Netherlands, would be releasing its first sports watch. He knew Bart and Tim Grönefeld—known affectionately in the industry as the “Horological Brothers”—would probably only be selling a few dozen a year. The small team at Grönefeld make each one by hand, and many collectors fervently seek them out. Carter, a lawyer based in New York City, signed up to purchase one. Within a week, he received an email asking for a 30 percent deposit and informing him that his new 1969 Deltaworks—which retails at around $50,000—would not be available until the second half of 2026. At the earliest.

“This is for a brand that the average person has not heard of,” Carter says. “That was nowhere near the case when I first started collecting.”

As Carter’s anecdote serves to illustrate, interest in collecting high-end, luxury watches has skyrocketed over the past decade—what many collectors and industry

insiders contribute to the advent of the internet, especially Instagram. “Things that were not available outside of Los Angeles or Chicago or New York, now they are much more known and much more visible,” Carter says. “Because of that, I think they’re gaining traction in what you might call these secondary and tertiary markets.”

“That’s one of the things that has really fascinated me is how much this hobby and passion extends beyond major metropolitan areas,” he continues. “I travel a fair amount for work, and I have people stop to comment on a piece I’m wearing, or vice versa, and I’ll see something unique in a place that I would never expect to see it. Like I’m talking about watches I know for fact wouldn’t be sold in that particular city or even state.”

Carter’s observation is backed up by data. Swiss watch exports have hit record highs in recent years, and many experts have attributed the phenomenon to consumers spending their stimulus checks and freshly obtained crypto wealth on vintage watches they might be looking at as long-term

“It would not be an overstatement to say that at least three-quarters of the people who I know think about market and resale value when buying new watches.”

90

text by

images by

Time Is Money

Alex Norcia

Hunters Race, Alex Perez and Lola Rose

investments. Retail prices have naturally soared, as have prices in the secondary market, which can sometimes fetch up to five times the retail value. Perhaps the most coveted watch in the world, a Patek Philippe Nautilus 5711 has been reported to be for sale for more than 1,300 percent above its retail price.

Of course, it takes eye-popping amounts of money to fetch these watches at retail too, especially when talking about limited edition rarities like Carter’s Grönefeld. The Audemars Piguet platinum and titanium Royal Oak with turquoise dial, for instance, can run over a million dollars. Patek Phillipe’s Grand Complications in 18K rose gold and black index dial is over 30-percent more expensive than that. Both can resell for even higher.

“It would not be an overstatement to say that at least three-quarters of the people who I know think about market and resale value when buying new watches,” Carter says, explaining he’s only sold watches when he (rarely) grew tired of them or wanted to fund another acquisition. “They really have turned into an asset class in a very material way. Again, it’s not hyperbole to say that there are certain watches, if you can get them at retail

price, you are instantly going to turn a large profit if you were to sell it the next day.”

However, with the so-called “crypto collapse” crippling would-be buyers in mid-May 2022, some industry observers have noted that the frenzy is certain to cool soon, as supply might finally be starting to outstrip demand. Others, like Kathleen McGivney, who cofounded a social group called RedBar for watch collectors and enthusiasts across the globe, have long suspected that would be the case, and emphasizes there’s “a big difference between who the industry thinks it’s selling to and who is actually buying.”

“The vast majority of collectors I interact with are not thinking of collecting in that way,” says McGivney, who estimates she currently has about 40 watches in her collection. “They are thinking about it as an asset, in the sense that they insure their watches, but not as, like, their retirement fund or anything. They’re looking at them as items of value that they will protect just as they would their house or their car.”

For Carter, who has been obsessed with watches since childhood, he now tries to have pieces that “are all interesting and unique in their own way, whether

92

that’s the story behind them or how they were designed.” At the moment, he has a little more than 20 watches total in his collection. “I try not to have a lot of stuff that looks the same either,” he says. “I see them, too, as accessories for an outfit— something that can accentuate what I’m wearing or blend in with it.”

“A lot of people might seem to think that expensive watches are expensive just because they can be,” he continues. “They don’t necessarily connect the cost with anything other than the prestige or status, and they fail to recognize how much work and engineering and precision goes into these things.”

Both McGivney and Carter stress, while news stories tend to paint collecting as a kind of investing bonanza, that framing is often antithetical to a lot of watch collectors who—no doubt aware of the resale value—are typically more concerned with their own idiosyncratic philosophies. This approach, in turn, has created a varied

and diverse community, McGivney says, as the captivation around collecting has only continued to grow. A niche, hobbyist pursuit has become relatively mainstream. Two prominent musicians, Ed Sheeran and John Mayer, have extensive watch collections, and even they speak about watches less as luxury items than as objects with which they’ve developed personal relationships.

“What keeps me really glued to the whole thing is the community—the people who come together and end up becoming great friends over this shared passion for these, quite frankly, obsolete objects, those connections are priceless,” McGivney says.

“Everyone has their own approach,” she adds. “I have one friend who mostly just collects highly complicated watches, and others who only collect vintage or dive watches. Learning why—and hearing their stories— that’s so much more interesting to me than, like, showing up somewhere and saying, ‘Look at my shiny, gold thing.’ For me, that’s what makes collecting fascinating.”

94

Reserve a front-row seat beachside at Santa Monica’s newest al fresco bistro, Patio del Mar. Perched just a few steps off the beach at the iconic Casa del Mar, this beautiful ocean facing terrace is perfect for relaxing over lunch under California’s blue skies or enjoying the sunset with friends over a refreshing summer spritz.

Menu highlights include local seafood from California and the Baja Peninsula, with favorite dishes sourced from sustainable local purveyors and farms, and wine selections from vineyards up and down the coast. Fresh from the market favorites will include gazpacho, heirloom tomato, melon and burrata salad, grilled stone fruit salad, and a kale chicken Caesar salad. Land and sea options range from a daily selection of east and west coast oysters, shrimp ceviche, salmon tartare, Dungeness crab avocado toast, a Maine lobster roll, beef carpaccio, and more.

Patio del Mar is open Thursday through Monday from noon to 8:00pm.

96

Santa Monica’s newest al fresco bistro has arrived.

images courtesy of ETC Hotels

A Picture Perfect Patio

Constantly searching the world for the farmers, anglers, and ranchers who cultivate and harvest the finest ingredients is at the core of 1 Pico Restaurant’s philosophy.

Once discovered, those raw ingredients are delicately seasoned and prepared over flame to bring out their inherent flavors.

“We call our concept ‘simply grilled,’ but it is everything but simple,” says 1 Pico Chef Sean Runyon.

1 Pico’s Amberjack is imported from the Japanese island of Shikoku, famous for its warm waters and dedicated fish farmers who reportedly even have conversations with their finned friends daily to promote their development. The result is an enticing, meaty filet that is a slightly sweet and mellow umami of buri (yellowtail) crossed with saba (mackerel).

Also sought after by world-class chefs, including Thomas Keller and Daniel Boulud, is the Elysian Farms lamb. Reared in Pennsylvania’s Allegheny Mountains, the lamb graze free with year-round access to

these fertile fields. The result is a product with the most exquisite taste and texture.

For produce, there is little reason to look outside of sunny California. One colorful 1 Pico find are the Candy Stripe Beets. These striking heirlooms, also called Chioggias—for the Italian town where they originated—are now a favorite of California beet growers. Resembling candy canes with their red and white stripes, they are the perfect complement in the restaurant’s sweet and savory gazpacho with organic California strawberries, John Givens organic tomatoes (harvested just up the Pacific Coast Highway) and blended with a crisp champagne vinegar.

“Los Angeles is an international gateway and a city of foodies, we are passionate about impressing those who we have the pleasure to serve,” explains Chef Runyon.

Paired with stunning ocean views and exemplary service, the restaurant’s new menu is simply a feast for the senses and not to be missed.

“We call our concept ‘simply grilled,’ but it is everything but simple.”

Culinary Quest

images courtesy of ETC Hotels

100