Capturing No Fidelity in words has always been a challenge. NoFi is KRLX and The Cave, yet it is not quite either. NoFi is music and writing and art all at once, yet it feels like something more. NoFi is raw and unfiltered student creativity, somehow directed and poised. Serious and silly. Truly, the reigns that lead NoFi have always lied within the passionate and chaotic hands of our dedicated members. I am continually grateful for the faith of this group in this ongoing experiment that is our club. Issue to issue, release to release, this group has reinvented what No Fidelity means as an idea and has kept this group fresh with possibility and ambition.

If this is your first exchange with us, welcome. NoFi is open to all students interested in or passionate about music, art, and pop culture and welcomes all varieties of submissions. Email nofi@ krlx.org or dm us on Instagram @no.fidel with inquiries, questions, etc.

In other news, KRLX 88.1FM is hosting a mutual aid radiothon on Nov 16th-17th to benefit Carleton Mutual Aid. We encourage you to consider a donation to the cause!

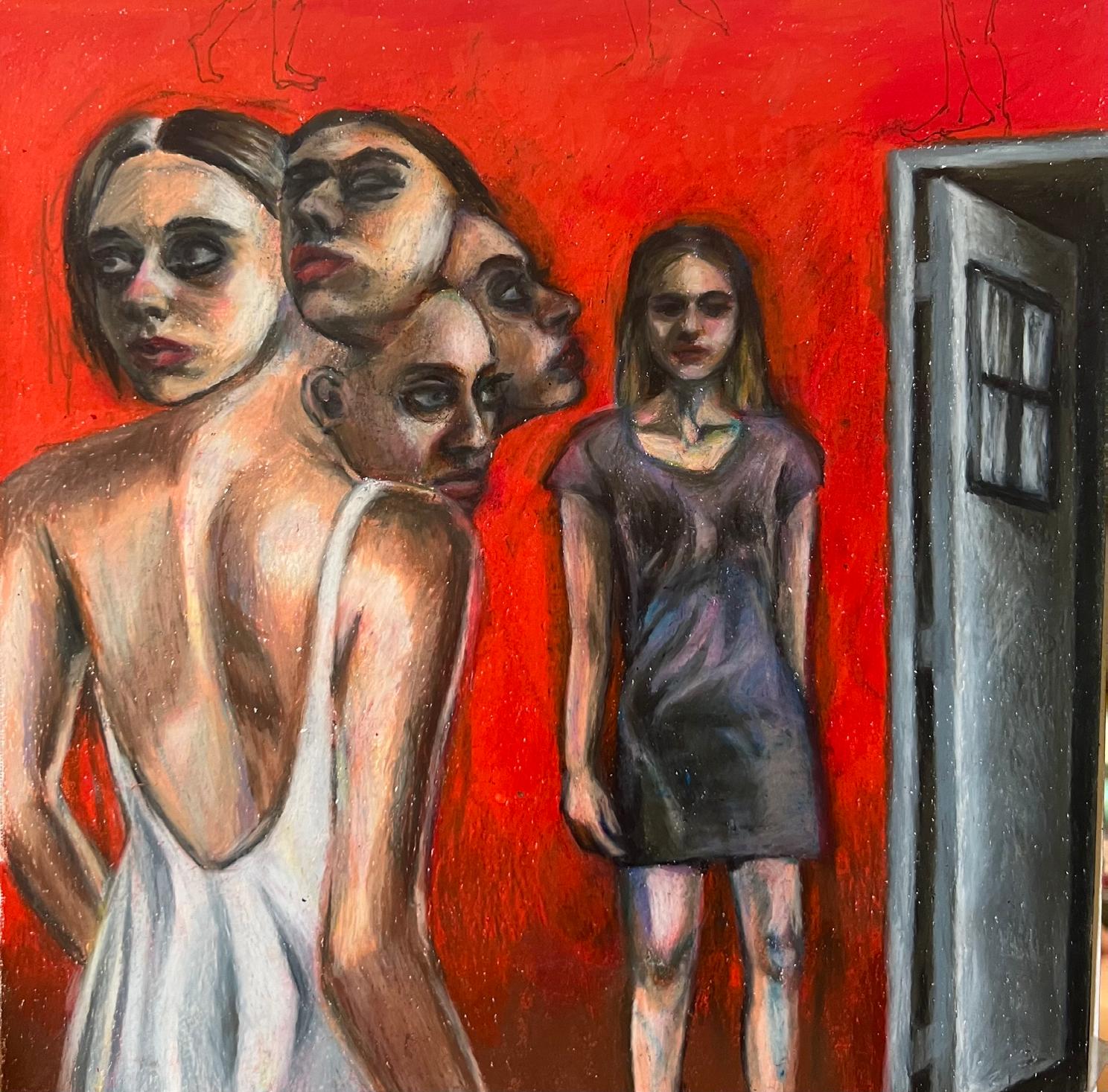

This term we have seen numerous developments across areas in our group. With the publication, we continue to recover and republish the lost works of NoFi’s first era on our Issuu site: https:// issuu.com/nofidel. We’ve seen an expansion this Fall of wonderful artistic contributions to our publication and the piloting of the NoFi Notebook in the KRLX studio for DJs to create the plethora of doodles that spot this issue. With our Imprint, we are stoked to see the presence of several new student bands and artists accompanying this term’s student music release. It will be released on Spotify and can be found via our Instagram. We are also so excited to see the return of live music at Carleton’s music venue, The Cave for the first time since the pandemic. With its reopening, The Cave has reminded us of the important place that live music has on Carleton’s campus for entertainment and the community at large.

Until Winter Term, Henry Holcomb ‘23

Etta Marcus: 20-year-old Etta Marcus is a newcomer to the sad girl indie scene, and she has the potential to go far. Even though she has only released seven songs, five of which are on her EP, her music is definitely worth a listen. Marcus’ voice is beautiful and rich –like a more emotionally expressive Lana del Rey. Her song composition is also noteworthy: each track has some solid chord progressions and stunningly haunting har monies that scratch an itch in my brain. She plays her guitar in her songs, which is an added plus (yay female guitarists). I’m excited to see what she comes out with, but to start out, I recommend “View from the Bridge,” “Hide & Seek,” and “Pro vider.”

joe p: This indie/alt singer hails from Asbury Park, New Jersey, where he records his coming-of-age type music in his base ment. His voice is expressive and his songs have a lot of texture to them, often involving big crescendos throughout. While people tend to know “Off my Mind,” his other songs deserve much more recognition than they get, especially “Leaves” on his debut EP Emily Can’t Sing. This month, he released his new EP, French Blonde, which includes bangers such as “Color TV” and “All Day I Dream About,” among a fitting homage to Asbury’s Bruce Springsteen with an acoustic cover of “I’m on Fire.”

Sudan Archives: I saved my personal favorite for last. Sudan Archives may be one of the most unique artists I have listened to in a while. She is a mostly self-produced singer, songwriter, and violinist whose sound has been described as avant-garde, experimental, and psychedelic. Her songs bend many genres, combining elements from R&B, jazz, soul, electronic, West African fiddle tradition, and house. Each track is incredibly layered, and her airy voice compliments that texture. What makes her music unmistak able is her violin, which appears in most of her songs. It’s hard to be bored with her music because her tracks always have multiple components to focus on. Take that from someone who has the attention span of a squirrel. Because her discography can be overwhelming, here are some tracks that really encompass her sound: “Loyal (EDD),” “TDLY,” “Icelandic Moss,” “Yellow Brick Road,” “Green Eyes,” “Black Vivaldi Sonata- A COLORS ENCORE,” “Confessions,” “Come meh Way,” and “Glorious.”

Soren Eversoll

Soren Eversoll

The Beach Boys’ Smile is perhaps the most legendary album never made. Meant to be the grand slam to follow Pet Sounds, which elevated the band from twee California surf rock into baroque pop glory, Smile was never released and marked the beginning of the end for the band—The Beach Boys would release eighteen more albums, though none would reach the level of artistry they’d achieved in the sixties. Exacerbated by inter-band tensions, fame, drugs, and the pressure facing frontman Brian Wilson to follow up on what had already been declared a perfect album, the Beach Boys never fully escaped the album’s specter. It would not be until 2004 that demands from fans prompted Wilson to re-record the album with original collaborator Van Dyke Parks and release Brian Wilson Presents Smile; archived sessions from the original studio recordings would be released in 2011. Never before has an unreleased pop album become the subject of two retrospective albums, of rabid obsession, of such total rock fetishism. Why?

Much of The Beach Boys’ action in the early to mid-sixties was inexorably linked to the orbit of The Beatles. The band ushered the new British Invasion into America that paved the way for The Who and The Rolling Stones and, with the release of Rubber Soul in 1965, transformed the studio album from what was meant to be a faithful reproduction of the live act into an art form all its own. Music journalist Steve Turner described it as starting “the pop equivalent of an arms race’. Upon hearing Rubber Soul Wil son became determined for his group to release their own work that relied less upon the success of singles than the strength of the album as a cohesive whole, telling his wife Marilyn that he was going to make “the greatest rock album ever made’.

Beatles or not, Wilson’s desire to musically transcend the surf rock cliches The Beach Boys had ridden to popularity on were, by 1965, long-stewing. It had soon become apparent that Brian, brother to Beach Boys Dennis and Carl Wilson, cousin Mike Love, and childhood friend David Marks, had a special attunement to music that his bandmates lacked. As a child, Wilson demon strated an exceptional talent for learning by ear, able to recite verses as a baby that his father had sung for the first time only moments before. Wilson also had perfect pitch and a voracious appetite for learning new instruments, even though he was com pletely deaf in his right ear due to a childhood blow to the ear from a lead pipe held by a neighborhood boy.

Recording sessions for Pet Sounds began on July 12, 1965, and ended on April 13, 1966. During this time Wilson took full creative control of the studio, often demanding endless takes from the studio musicians to achieve the sound he wanted, relegating his bandmates to the backseat. No sonic possi bility was off limits—at one point, Wilson asked the producer if it would be possible to bring a horse into Sunset Boulevard’s Western Studio to record the coda to “I Know There’s An Answer’. Harpsi-

chords, string quartets, French horns, the Theremin, soda cans, and found sounds all found their way into the album’s final mix. Tensions over Brian’s sole leadership arose, particularly between Wilson and Mike Love, who felt the band was moving in an unsellable, overtly-hippie direction.

While it did not commercially sweep upon its American release, Pet Sounds was quickly labeled an artistic triumph. This was particularly noticeable in British media—one advertisement labeled it: “The most progressive pop album ever!” This sort of hype was accentuated by an aggressive market ing campaign spearheaded by the former press officer to none other than The Beatles themselves, Derek Taylor. In an effort to brand The Beach Boys as legitimate artists alongside John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and Bob Dylan, Taylor frequently circulated the phrase “Brian Wilson is a genius’, when interviewed by the press. In a 1966 article for the British magazine Melody Maker titled “Brian, Pop Genius!” Taylor depicted Wilson as a musical marvel, drawing comparisons to Bach, Mozart, and Bee thoven: “This is Brian Wilson. He is a Beach Boy. Some say he is more. Some say he is a Beach Boy and a genius. This twenty-three year-old powerhouse not only sings with the famous group, he writes the words and music he then arranges, engineers, and produces…. Even the packaging and design on the record jacket is controlled by the talented Mr. Wilson. He has often been called ‘genius’, and it’s a burden’. Pet Sounds sales soared in the U.K., and by the end of 1966 London-based magazine, New Music Express’ reader’s poll ranked Wilson as number four in its list of world music personalities.

gan in Pet Sounds’ Western Studio with demos for the song “Wind Chimes’. No longer touring with the rest of the band, Wilson had developed a posse of talent execs, publicists, singers, and reporters who became fixtures at his home and in studio sessions. Drugs, particularly the amphetamine Des butal, were ever present—to prepare for the album Wilson had bought about two thousand dollars worth of cannabis and hashish, equivalent today to about $17,000. One article reported that he had constructed a hotboxing tent in what was once the dining room and a sandbox under the grand piano in his living room. The fixture of the press’ depiction of Wilson was centered around his identity as a reclusive genius, as America’s homegrown response to McCartney and Lennon. Smile became one of the most discussed albums in the rock press, projected for a release in December of 1966. Derek Taylor continued to give interviews and anonymously submit articles to publications—in one, Los Angeles Times West Magazine described Wilson as “the seeming leader of a potentially revolutionary movement in pop music’.

In October The Beach Boys released the single “Good Vibrations’, first for the upcoming album. The

recording of the song was a microcosm of the experimental approaches Wilson was adopting for Smile. Pop music in the sixties was commonly recorded in a single take—in “Good Vibrations’, Wilson took sections from different recording sessions and forced them together into a single song, a method later known as tape splicing. This is evident in the song’s dramatic switches in mood and key. Dubbed a “pocket symphony” by Taylor, “Good Vibrations” boasted propulsive cellos, the Electro-Theremin, and the jaw harp. It was emblematic of the studio as the principal instrument, of editing becoming more important if not equal to recording. Wilson produced over ninety hours of tape to get “Vibra tions” the way he wanted it, costing Capitol Records tens of thousands of dollars in the process. Upon its release, it became the band’s third number-one American hit and the first in Great Britain. In De cember, Capitol ran an ad in Billboard: “Good Vibrations. Number One in England. Coming soon with . The Beach Boys’. Another ad in TeenSet ordered: “Look! Listen! Vibrate! SMILE!….other new and fantastic Beach Boys songs…and…an exciting full color sketch-book inside the world of Brian Wilson!” In an interview following the single’s release, Beach Boy Dennis stink. That’s how good it is’. , Wilson wanted to produce a response to what he saw as the increasingly-anglicized state of popular music. By 1966 the British Invasion had fully come to dominate the popular consciousness. In response, Wilson and Parks wanted to create songs that were distinctly American, that embodied a sort of early American ethos and slang, and that drew their inspiration from doo-wop, ragtime, gospel, and cowboy movies. This necessitated the incorporation of traditional American instruments like the tack piano, harmonica, fiddle, banjo, and steel guitar. Wilson simultaneously viewed the album as a “return to the pre-grammatical, non-linear, and analogical thinking of early childhood— they are the artefacts of play’. Songs were intentionally made to be silly. In response to this Wilson to be a totally American article of faith…it seemed the best way to do that was to be counter-counter-cultural’. Wilson constantly took in new inspirations, ranging from astrology to the occult to the book The Act of Creation by Arthur Koestler. Material for Smile visions and rearrangements; stantly shifting nature of the tensive use of tape splicing, where some songs ended and content of the songs varied and Villains’, which devoted days and cost an estimated son scrapped all recordings, Old West. “Cabin Essence” Union Pacific in an abstract, Mike Love objected to many believing them to be thin es to drug culture. “Do You cerned the colonization of nent. Worms are mentioned nowhere in its lyr ics. One stanza goes: “Bicy cle Rider, just see what you’ve done, Done to the church of the American Indian!” “Bicycle Rider” refers to Bicycle Rider Back playing cards printed in the 19th century. This stanza is followed by lyrics in Hawaiian delivered in near-demonic chants, translated to: “Thank you, thank you very much, it’s so late’. This was meant to repre sent a sarcastic response to

colonists, having already expanded and conquered America far beyond repair. At one point Wilson conceptualized a four-part movement titled “The Elements’, with each song representing air, fire, earth, and water. To record “Fire”, Wilson brought fire helmets and a bucket of burning wood into the studio, filling the room with smoke. A few days after the initial session a building across the street from the studio burned down. Convinced his music had caused the fire, Wilson discarded the song.

The scrapping of “Fire” marked the beginning of Smile’s recording issues. The Beach Boys had en tered into a lawsuit with Capitol Records over payment disputes. This dragged on for months and frayed relations with the label—at one point, a Beach Boys single was released by EMI without the band’s consent. Wilson was heavily under the influence of Desbutal, which caused paranoia, en hanced-ego, and horrible crashes. Wilson would later be diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and while his bandmates would attest that his symptoms were almost totally absent while recording Smile, some delusional traits and fixations began to show themselves. The Beach Boys were growing frustrated with their frontman’s eccentricities and the seemingly endless nature of the project, leading to intense confrontations in the studio that gave Wilson severe anxiety attacks. This was only exacerbated by the near-constant coverage in the press following Pet Sounds. Wilson had already been a perfectionist, but declarations of the project’s genius prompted him to become even more uncompromising in the studio, burning through money and frustrating his musicians and collaborators. He was also loaded. Dennis Wilson recalled: “Drugs played a great role in our evolution but as a result we were frightened that people would no longer understand us, musically’. Bandmates like Mike Love believed that the bi zarre Americanized concept album had gotten too weird, too avant-garde. The excesses of the studio that had once seemed like freedom were now pits of inactivity. Capitol pressured for a new single to replace “Good Vibrations:” “Heroes and Villains” became the object of Brian’s obsession, leaving other tracks on the back burner. In February, Wilson and Parks began to clash over lyrical content—tired of being stuck in the middle of family feuds that he thought were of no concern to him and constantly subservient to Brian’s creative veto, Parks left the Smile project on March 2, 1966.

Wilson continued to fall into drug-addled delusion. In one episode he became convinced that a portrait a friend showed him had captured his soul. In another, after attending a screening of the movie Seconds, Wilson became paranoid that the film contained coded messages sent to him from idol Phil Spector. Wilson was preoccupied with what he perceived as competition with The Beatles—upon hearing “Strawberry Fields Forever’, under the influence of the barbiturate Seconal, he reportedly pulled his car to the side of the road and told a friend: “They did it already—what I wanted to do with Smile. Maybe it’s too late’.

Parks’ departure marked the true end of Smile. With out him, Wilson was lost in the woods of his own cre ation. Public expectation, which had initially heightened with the album’s ever-increasing delays, grew impatient. This marked the beginning of a shift in public opinion towards Wilson, from eccentric genius to troubled recluse; the image of Wilson that Derek

Taylor and Capitol Records had so meticulously constructed was beginning to eat its subject alive. On May 6 Wilson fully scrapped the album. The release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in June only exacerbated his feelings of insecurity. He later said: “Time can be spent in the studio to the point where you get so next to it, you don’t know where you are with it’. Wilson announced to his bandmates that all the material on Smile was now off-limits.

From June to July the Beach Boys met in Wilson’s makeshift home studio on Bellagio Road to record Smiley Smile, the official follow-up to Pet Sounds. While now considered a revolutionary work in the genres of lo-fi and bedroom pop, Smiley Smile was nowhere near as technically advanced as Smile. All vocals with echo were naturally created using Wil son’s emptied-out swimming pool; recordings were carried out with radio broadcasting equipment. To create a feeling of comradery, Wilson ceded many of his production ideas to his bandmates. When it was released on September 18, 1967, Smiley Smile peaked at 41 on the Billboard charts, making it The Beach Boys’ lowest charting album yet. “Undoubt edly the worst album ever released by The Beach Boys’, said Melody Maker. “Prestige has been seriously damaged’. NME wrote: “By all the standards which this group has set itself, it’s more than a grade disappointing’. In February 1968, a Rolling Stone article announced the album as a “disaster” and an “abortive attempt to match the talents of Lennon and McCartney’.

The trauma surrounding the production of Smile would cause Wilson to block all talk of the album until the early 2000s when it was finally revisited and partially recreated.

Today, it’s easier to see that the mystique swirling around Smile is less about any of the songs themselves but the potential of what they could have been. Smile has come to represent the frenzied way that members of the press and fans construct mythologies that are impossible to ever realize, that become self-sustaining in their own right, and that cease to be concerned with the music or hu manity of the artist at all. When Wilson was asked in 2002 about the universally acclaimed, totemic status of Pet Sounds, even he was mystified: “It keeps going back to Pet Sounds here in my life, and I’m going, ‘What about this Pet Sounds? Is it really that good an album?’ It’s stood the test of time, of course, but is it really that great an album to listen to? I don’t know”. Wilson should know better than anyone that in the cultural consciousness music always falls short of the myth, the hype, the transformation of the artist into the genius, the album into the opus. Every human on the planet knows that the Mona Lisa is great, as is Ulysses, Citizen Kane, and Kind of Blue, without ever needing to go to the Louvre, crack open the book, or attend a screening, or play the record. These things are simply great. It is not an opinion so much as a fact. Ironically, it is this very belief that killed Smile. Wilson became so consumed with the idea of creating something great that he was prevented from finishing anything at all, paralyzed by the attention and the hundreds of thousands proclaiming that they were in the presence of a genius. The hype consumed itself.

Nonetheless, if you listen to the session recordings released in 2011, which have been remastered to be an almost impossible recreation of one of Smile’s potential final forms, it’s possible to briefly understand just how great of a pop album Smile could have been. Freed from the burdens of genius and able to flourish on its own, perhaps the music could have survived.

Comic: Esmé Bessor-Foreman

October 2nd was a very special day, one of the greatest Midwest emo albums of all time (in my pro fessional opinion) was finally available on streaming services. Curious enough, the band who made it, Inválido, is not from Minnesota, Nebraska, Illinois, or any midwestern state. In fact, this band is not even from The United States, and this record is not in English.

Regreso a Córdoba was released in 2005, as Inválido’s first LP. After debuting with a messy but beautiful EP, Afónico Inefable, the band has consolidated its sound in an eight-track album that spans an hour and three minutes on a beautiful take on the typical Midwest emo, riff-heavy sound. One of the great things about Regreso a Córdoba is its more “ethereal” approach to the genre, with its guitars sounding more similar to what a 90s post-rock band might sound like.

However, I’m not here to get into the style, or how similar it might be to Mineral, or how the riffs are technical, or how the lyrics “put you back in high school,” when nerds would talk about any popular album in the genre. Different from the typical Midwest emo album, there is no sign of joy in this record. The guitars and lyrics lack the sweet in the sweet and sour, a description usually given to any record of this kind. This album has two outstanding characteristics (and that makes me love it): 1. The repetition (something that personally fascinates me, but I’ll talk about it another time) and 2. It’s very cryptic, to the point that the lyrics, which generally drown in the instrumen tals, make no sense. I don’t see this as a bad thing, but I rather like it a lot although it’s not some thing that attracts music lovers or people in general.

I’m getting off-topic. How repetitive and ambiguous this project can be, I think it reflects your own personality and its imperfections. Humans tend to avoid leaving our comfort zone, and we seek tranquility in the same behaviors that we always repeat. And ambiguity represents how abstract our thoughts can be, –especially when we are vulnerable– looking for answers in something that

, I liked it, but I left it at that. A very short time later, I made a mistake with someone close to me, I revisited the album as this record was in my “just added” on my phone. I fell not only in love with the album, but also identified with it because I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. I was doing the very thing I wanted to avoid, always falling for the same thing, and there was this album to relate to.

As always, time passed and things were resolved, but I was still listening to that album. That’s when I started noticing everything I have written above.

The long pauses the singer makes mixed with the very ambiguous and repetitive lyrics made the album seem like an album from Tumblr. I thought this was pretty funny, but in a good way, I still appreciated the record. It is something so basic and redundant but it made me feel different emo

It’s like loving someone with their flaws, which makes them perfect, highlighting what makes you feel and enjoy as much as possible with that person. This contradictory feeling is what compensates for the obvious lack of traditional musicianship here.

Sports Arena Stadium, forever cemented in my memory as the monolithic monster whose con cert-goers caused many traffic-filled afternoons of driving home from school, was about as devoid of windows as I had remembered. I can’t imagine that the 15,000-seat arena has changed much since its construction: the faded red and mustard stripes on the wall, obscured by a perpetual yet unidentifiable smokey haze, teleported me straight into 1960s San Diego.

Somehow, it seems to me that a venue like Sports Arena that stands somewhat outside of time is the perfect place to see The Killers. The general admission crowd at the late-August show shared the same excitement almost bursting from my sister and me as we waited in line. From our vantage point on the arena floor, surrounded by now-vintage Killers t-shirts and stories of past shows, we could tell that this was not a show for casual listeners or half-interested fans.

This was a show of a band in their golden years, where every listener knows every song, old and new, and shares a dedication only strengthened by time.

The depth of my almost-frenzied elatedness from being at this show is difficult to imagine. The concert was—and I cannot stress this enough—a transformative experience, filled with a variety of emotion: I sobbed about being “On the corner of Main Street/Just tryna keep it in line,” as “Read My Mind” rung through the stadium, and my sister and I gripped each other with the panic of uncharacteristic hero-worship each time Brandon Flowers waltzed onto our side of the stage.

The culmination of my joy came right at the encore, as the sleazy, opulent glamor of The Killer’s modern aesthetic was driven home by rotating images of Adonis during “The Man” (a personal fa vorite glitzy ode to masculinity and manliness off of 2017’s Wonderful Wonderful).

The show ended as the crowd was pelted by dollar bills decorated with the bands’ faces. As we drove home, emotionally numb with ears ringing, my sister’s friend summed the experience up precisely:

“Well, he doesn’t look a thing like Jesus.”

I spent the majority of my elementary school years memorizing every lyric of each Killers’ song, Christmas special, and B-side—jealously watching as my sisters and mom jaunted off to concerts and returned with a deep analysis of the quality of Brandon Flowers’ hair or the trajectory of Ron nie Vannucci’s drum sticks.

Because of my basically lifelong attachment, I tend to think of The Killers as my band, with a pos sessiveness completely unjustified for a group so popular and well-known. I can’t help but associate The Killers with my family and the place where I grew up. And, in a way that’s become more bitter sweet and pertinent as I’ve left home, with how I conceptualize the Southwest—the sullen desert land that remains indescribably detached from the rest of the West.

The Killers originated in Las Vegas, perhaps the most culturally potent city of the Southwest. The glitz and hopeless artifice of the oasis-like Strip has made its mark across their discography—in no

clearer place than throughout the much-reviled (but personally beloved) Sam’s Town, released in 2006 following Hot Fuss.

Titled after a Vegas casino of the same name, the powerfully Americana-infused album took in much criticism during its time. To be sure, the nostalgic references to “The good old days, the honest man / The restless heart, the Promised Land,” among rebellious descriptions of “Red, white and blue upon a birthday cake,” and towns “meant for passing through,” feel so powerfully and artificially American that they can leave a sickly-sweet taste in the mouth. With their glamorization of patriotism (“Running through my veins / an American masquerade”), it can feel like The Killers Vegas’d being American.

Yet for an album that was created in a land as placeless, eclectic, and new as the Southwestern section of the United States, it just seems to make sense. Somehow, throughout their entire discography, The Killers have managed to capture the variable faces of the spirit of the Southwest.

This is not an easy task. Despite having grown up on the edges of the same dusty desert that shaped The Killers, I don’t understand the Southwest. It’s far too many things.

It’s cowboys and colonialism—otherworldly and alien to those who didn’t grow up among the blooming cacti and towering Joshua Trees. It’s the land of opportunity and where dreams go to die. It’s the desolated desert highways on the way to my grandparent’s house in Yerington, Nevada—and it’s the cracked Southern Californian asphalt upon which I burn my feet each summer. It’s where the Santa Ana winds blow in every fall, stopping planes and drying skin and making way for an end less fire season. It’s where the only season is fire season. It’s a place where small towns are defined by their public lands and libertarianism, and where big developers with shady pasts pop out of the dust like a mirage to irrigate the desert and replace it with gleaming (and eerie) green grass.

Other regions of America seem to be able to claim artists and genres as their own—the East coast calls to mind the dignified Sinatra-types, whereas the South lays claim to its complex interwoven web of blues, jazz, and the origins of rock. In the Midwest (laying aside Midwestern Emo as the obvious choice) originated Chicago blues and folk singers like Bob Dylan. Even the Pacific Northwest has its 90s grunge (and whatever’s going on in Portland). But the Southwest seems to lack the musical identity of the other parts of the United States—ex cept for The Killers.

There is no artist as Southwestern as The Killers, and none who’ve embraced the region so whole heartedly. Their most recent concept album, Pressure Machine, is a tribute to the small town of Nephi, Utah, where Flowers was raised. The album is tender toward the harsh desert landscape of its cover: it includes Flowers’ own meditations on a train wreck which killed a teenage couple, and cites influences from authors John Steinbeck and Sherwin Anderson.

In watching them perform again, right after the release of Pressure Machine, I was struck by The Killers’ wholehearted embrace of such an incomprehensible and hard-to-understand region. Yet The Killers are also somewhat of an incomprehensible band—so perhaps the mutually baffling relationship between The Killers and their home allows us to gain an understanding of both.

Through The Killers, we see the heart of the Southwest—and it’s only by looking at the Southwest can we truly see The Killers.

Following the 90s, mainstream metal was choking on its own figurative vomit. Pantera was soon to release their final album, Metallica had run the course of their odd hard rock phase and had nowhere left to go but down, the golden age of thrash metal was long since gone, and nu metal was running out of ideas to recycle. Many groups would help to fill the void, yes (Tool was yet to reach their peak, Slipknot had just taken off, and the “core” genres were still in a pioneering phase, to name a few), but there is arguably no metal band more synonymous with the early 2000s than System of a Down. Few groups in history have combined brutal heaviness with goosebump-in ducing melodic sensibility and political awareness with to tal absurdity in such a complete, satisfying musical whole as SoaD have in their five albums, and probably none with the same level of commercial success. They also happen to be one of my favorite bands of all time.

This term, I decided to make a list of every System of a Down song ever, ranked (theoretically) from best to worst. This decision came with a mixed bag of feelings and opinions for me. Before I embarked on this challenge, I was of the firm opinion that SoaD was a band with few er bad songs than the top speed in miles per hour of a naked mole rat (like 5, or something). I saw legitimate and unique artistic value in everything they wrote, and frequently found that my favorite song of theirs was

whichever I had most recently listened to. At the same time, however, I was always interested in flexing the amount of time I had spent listening to and thinking about SoaD on everyone around me. Therefore, when it came to deciding what to write about this term, I was left with only one choice. In order to impress my enormous erudition surrounding System of a Down’s discography upon the waiting world, I would have to go against my own beliefs and place every one of their songs in a strict hierarchical relationship to one another based on raw musical quality, as perceived by yours truly.

However, despite the overwhelming power of intellect and determination I put into my song-ranking efforts, I found it difficult to be consistent in my judgements. I decided from the outset that this would be a purely qualitative list, essentially based on a loose sense of relative goodness which depends heavily on context and which is always changing, and that led to some contradictions. I would hear one song, and then hear anoth

best snort 29.A.D.D 30.Sugar *most overrated 31.Ego Brain 32.Soldier Side *most sad

33.Suggestions 34.ATWA 35.Forest 36.Revenga *moody award 37.Roulette 38.Psycho 39.Kill Rock N’ Roll 40.Radio/Video 41.U-Fig 42.Cigaro 43.Stealing Society 44.Tentative 45.Bubbles 46.Nüguns 47.Lonely Day *awful taste, great execution 48.Genocidal Humanoidz *best guitar-as-gun imitation 49.Boom! 50.Shimmy 51.Pictures 52.Protect the Land 53.Thetawaves 54.Science 55.Bounce *obnoxious award 56.Jet Pilot 57.This Cocaine Makes Me Feel Like I’m On This Song *best song title 58.Chic N’ Stu *best song about pizza 59.Vicinity of Obscenity 60.Peephole *best trombone 61.X 62.She’s Like Heroin 63.F**k the System 64.Arto

65.CUBErt *best dolphin impression

66.36 *how does Serj even do that

67.Old School Hollywood *I like to think of this song as a mistake

68.Darts

er, and decide which of the two seemed to be the more interesting, satisfying, or beautiful piece of music; later a third song would enter the discussion whose own musical qualities would seem to invalidate all that. The only solution was to keep ranking anyway. What came out of it all is a list which makes sense (to me) when com paring any two songs on it, but which has very limited consistency when it comes to the entire ranking. If I were to review this list, I would probably make a lot of chang es, and that’s not to mention other peoples’ opinions. I think that anyone capable of making their own SoaD song ranking would, and should, take objection to a large portion of my decisions here (though they would of course be wrong). SoaD is a band who applied a similarly intense degree of creativity and energy to every one of their albums and almost all their songs in my humble opinion, and so any listener, even if they are trying to avoid ranking songs simply based on which they like and listen to the most (as I did), will have a different sense of which songs are stronger or weaker.

Finally, a disclaimer: this list contains only songs listenable through Apple Music, so none of the songs from the Japanese release of the self-titled album, and none of the random covers. With that out of the way, here are the rankings!

So there you have it! All five albums plus the 2020 EP split into 68 pieces and scattered over the page in an order that theoretically reflects their relative musical quality, whatever that happened to mean to me as I was listening to them. Oh man, this did take a long time. As you can see, I also decided to spice things up with some awards for songs that stand out in special ways, of which there are many, more than I chose to acknowledge. As for how the albums compare to each other, they are remarkably even. Even though some stand out as having a higher con centration of songs in certain areas on the ranking (looking at you, Toxicity), every album has songs all over the list, with only Steal This Album! having a much lower ranking on average (38) than the other albums (which would probably change if the flow of the album were considered). The highest average ranking just barely goes to the self-titled, surprisingly enough, with 29, probably because of how experimental and provocative the songs are. With that, I got no more thoughts, so go forth, ask your people what is right, let your mother pray, don’t ever try to fly, don’t ever get stuck in the sky, don’t eat the fish, but do eat all the grass that you want, and live at your own pace.

Henry Holcomb

Henry Holcomb

Putting on DJ Sabrina The Teenage DJ for the first time trans ports you across time. Blending disco and synth with the sounds of soundtracks that dominated pop culture in early 2000s me dia, DJ Sabrina takes house music in a new direction. Often stretching past the 7-minute mark, DJSTTDJ’s music feels as though she is opening up space for the listener to ruminate on times long past, patiently building her tracks sonically and emotionally as they progress. It is clear she is building a world for herself too, filling her discography with an interpretation of figures from the television show Sabrina the Teenage Witch.

DJSTTDJ teases out feelings from forgotten memories of child hood; the excitement of turning on your favorite show, the snippets of conversation overheard in passing, or as the radio switches -almost moments more than memories, allowing the listener to try to grasp and recall more. Put together, DJ Sabri na’s music stands out, giving the experience of reading a bedtime story that you want to dance and scream and cry to all at once. I had the pleasure of interviewing the elusive witch as summer drew to a close; check out the conversation below!

Your tracks are soaked in early 2000s nostalgia and carry themes of the highest highs and lowest lows. Do you wish you had your own music to listen to through your teenage years and are you making music for your younger self? How did your teenage years shape your musical inter ests?

I definitely make music for myself, I often think I listen to my own music more than anyone else haha! I think that’s why I make the albums the length that I’d want to hear or I spend so long trying to get everything “perfect” (or as close to perfect as possible) since I always feel like I’m the only one who’ll be listening to it! I definitely feel grateful that the sort of music that influences me has existed, it would have been cool for my younger self to have my music to listen to, but then I’d have nothing to make now! XD

In your Charmed novelization you constructed a series of characters in the DJSTTDJ universe, how did the book expand the persona you are trying to create and the world you are trying to build? What is your inspiration for these characters besides what is established from Sabrina the Teenage Witch?

The albums are always part of a bigger story that’s being told, and I felt with Charmed it was the right time to try and expand on the meanings of the individual songs, as well as the album and pentalogy as a whole. It also had canonical relevance with the following albums, so I wanted to

make it so you’d have an idea of where the story was following on. I think the characters are a mixture of me and the songs, they’re the vehicles for getting across what I was trying to say, but with the pre-established style of the sitcom characters they’re a little easier to visualize in many ways.

On a related note, you write in the novel about “creating art with a crease,” how do you see your creases form within your music and how do they change its meaning?

I think a lot of the songs (and albums) have an almost Möbius strip quality, the seam is actually just the flip-side. I always think something that is beautiful but unconventionally is a hundred times more beautiful, if it’s a little unexpected or comical it can come across even more emotional and heartbreaking if done correctly, the juxtaposition can be so overwhelming it makes you feel a lot more of it.

How was writing the novel different from making music; did you find that written work allowed you the flexibility to tell your story in a different way? Can we expect to see more novels in the future?

Not a whole lot, I think it all comes from a similar place and I kinda pace all of my “work” in a similar way, it just allows me to communicate a little more explicitly. If I’d done it again, I’d probably have preferred to write a screenplay as writing is always very visual to me, but the novella format is really nice for being able to almost create a movie as a self-contained piece, and allow the reader to experience it in their own way.

Your audience has expanded significantly since Charmed, what do you feel you have been the most motivated to produce as your base has grown?

Honestly, having an audience at all is pure motivation for me! It’s truly unbelievable to me that anyone likes what I do, I never imagine anyone else in the world is going to like any thing I’m working on, but to have an audience is an unbeliev ably motivating thing. You eradicate all personal questions of whether making anything is worthwhile, a waste of time, good enough, etc, all those un-creative and dissuasive ways of thinking. It’s just an absolute joy to me, and as I keep quoting, “not really seeking to talk to any of them…” (isolation, reclusive), “at this rate I’d be surprised if anyone’s still listen ing…”

Between your music, books, and iconic presence online it is clear that you approach the DJSTTDJ persona holistically, what motivates you to engage your audience in so many different ways?

I’ve never thought of myself as a musician or songwriter or producer or whatever, more like a multimedia maker or something, so while the music is probably the main focus for most people (and obviously myself), I don’t think of the other aspects as being less important to building the persona. I’ve always thought of the mixes as being almost mini-albums as I approach them in similar ways, and the album artwork, merchandise, books, etc all have equally similar amounts of consideration put into them. I really have a personal disdain for artists who don’t connect with their supporters or act as if their more important than the people listening to them, so for me it’s very important to do my best to engage with each and every person who’s taken to the time to talk to me, say something nice to me or even just listen in the first place!

You have released an incredible library of music so far, how do you get into the headspace to create on a given day?

What journeys do your songs go on be fore they are released publicly?

I work pretty much every single day, I don’t wait until the muses find me, I just show up at the same place and they’ll be there (was that Ebert or King who said that?) and I try to make sure every single thing I start gets finished at some point; I think that was a Beatles concept, use every scrap of an idea, never throw anything away. The songs have so many, many, many hours of mixing, remixing and mastering to try and achieve some kind of perfection (which of course, you never reach) but since I’ll be listening to the music in future (to learn from) I need it to be as perfect as I can get… which is usually pretty far off the mark imo, unfortunately :(

What you have released with Call You / Under Your Spell has seen significant interest already, as the Fall approaches, what can we expect to come from DJSTTDJ in the future?

Well, originally I wanted to release 3 albums at the same time, but the heatwave was just so in tense (42c or whatever it was) I became so exhausted from working all summer and I realized that Bewitched had shaped up really tidily. I didn’t want to spend another 4-6 months mixing the other two albums first, and I thought it would be nice to have something for people to listen to during the end of the summer. Bewitched and Beyond (which contains songs from the other two albums) was originally meant to be released on its own, but it actually turned out to be a nice accompani ment release with the album. To be honest, I’ve still got too many songs for even these next two albums, including some recent pieces I’ve been working on, so there’s just genuinely no shortage of

plans for future music… I just wish I had more time to get it all mixed!

Finally, is there anything else you would like to add?

I really hope I never come across as egocentric, to me I think music is best when the personality is detached from the creation and you can just enjoy what you’re listening to without any preconcep tion of who’s behind it. I like to experience music (particularly production-oriented music) in a kind of omnipresent, ego-less way… you know it was made, but you don’t really know who or how or why, and it can open up the listening experience a lot more… or at least hopefully that’s the way it comes across!

Thank you again, it has been really exciting to get into contact with you! No problem, absolutely anytime! :D

Punk, az a movement, iz an anti-culture. It iz an urban folk movement sounding out the restless, disillusioned energy of a generation growing up in an alienated society. It iz a generation of pinheads who will shout proudly about their autolobotomization amid a culture of consumptive objectification. Punks gloriously fall into a sort of chaotic acquiescence az the world iz swal lowed by self-interested nihilism.

lyrics, but the same cannot be said for the Butthole Surfers or the Circle Jerks. In order for folk to devolve into such aut, it had to shed a few skins of selfsignificance.

American folk waz resuscitated when public schools invited communists to sing songs to American schoolkids, songs that happened to preach antifascism and serial trespassing. And when those kids grew up some of them sang those songs in what can be understood as a cultural revival after a consumptive depression attempting, repressively, to soothe the wounds of a hundred years of an exodus.

However, punk iz a communal act. A punk con cert––a punk song––iz good or bad based on how it channels the listeners’ energy, whether it can satisfy the manic spirit within a collective. But it iz a disorganized collective, anarchic and lib erated from shame.

Technically, the music of punk iz not very skill ful. Anyone can play it. Three strings, power chords, indiscernible lyrics distorted by volume, and overextended voices. Endurance iz more important than virtuosity. That iz the beauty of it. Anyone can play it, anyone can participate.

The democratizing ethic of punk finds roots in the solidarityminded origins of folk music. In perfect Pete Seeger fashion, the singer/song writer iz a medium to channel the voice of the community, to tell the news, preach the truth, and cool the spirit. Their test iz whether they can weave together a common experience, and create a sense of collective identity that will stand firm in a picket line, throughout a 190-day strike. In this sense, the music iz performed az the voice of the working class. Punk iz a work ing-class musical tradition revived by stolen guitars and simple chords.

Strummer may have studied Guthrie for hiz

Soon enough those schoolkids dropped acid, just another chemical in the average person’s diet rewiring the brain. Except they took acid, and where Hudie and Houston preached solidarity, Kesey and Leary proclaimed intersubjectivity. When, truly, everybody must getstoned, someone needs to improvise a lick in order to sustain the vibes, for between us there iz a tremen dous power of sig nificance, creativity, freedom, and love. The free association of acid rock dislodged any pretensions of meaningful lyrics.

Folk channels political economic militancy in ritualizing collective identity of common folks working various jobs from cowboys to cotton spinners. By the time the dropout ethic of psy chedelia took hold, the music had instilled faith that, by refusing to participate, by deliberately stepping into the absurd, by being intentional ly and unashamedly outside society, the bodies dancing within its sphere would be liberated from the capitalist machine. An efficient and productive free market system lowers its prices to appease the consumers by reducing the work ers’ pay and increasing their hours, so anti-cap italist music stirs the illogical, the expressive,

and the emotional within multitudes to pleas antly awaken them into dialectical conflict and concrete socioeconomic changes.

In the redundant apocalypse years of the 1970s, punk shouted through the repressive boredom, drawing upon the mystical otherworldliness of psychedelia to produce the dynamic corporeal unit known as the mosh pit. This tumultuous embodiment of nihilistic anarchy iz a miracle in unifying divergent consciousnesses. So many bodiez moving separately, all pushing against each other but gleefully embracing the collective motion. All of these people, hopelessly thrown about in a sea of everchanging others, let their agency be stripped––or lean into the chaotic force that they possess. With an ampli fied wall of sound coursing through the moshers, punk fosters a collectivity based on no qualification.