THE WEATHER DIARIES 4

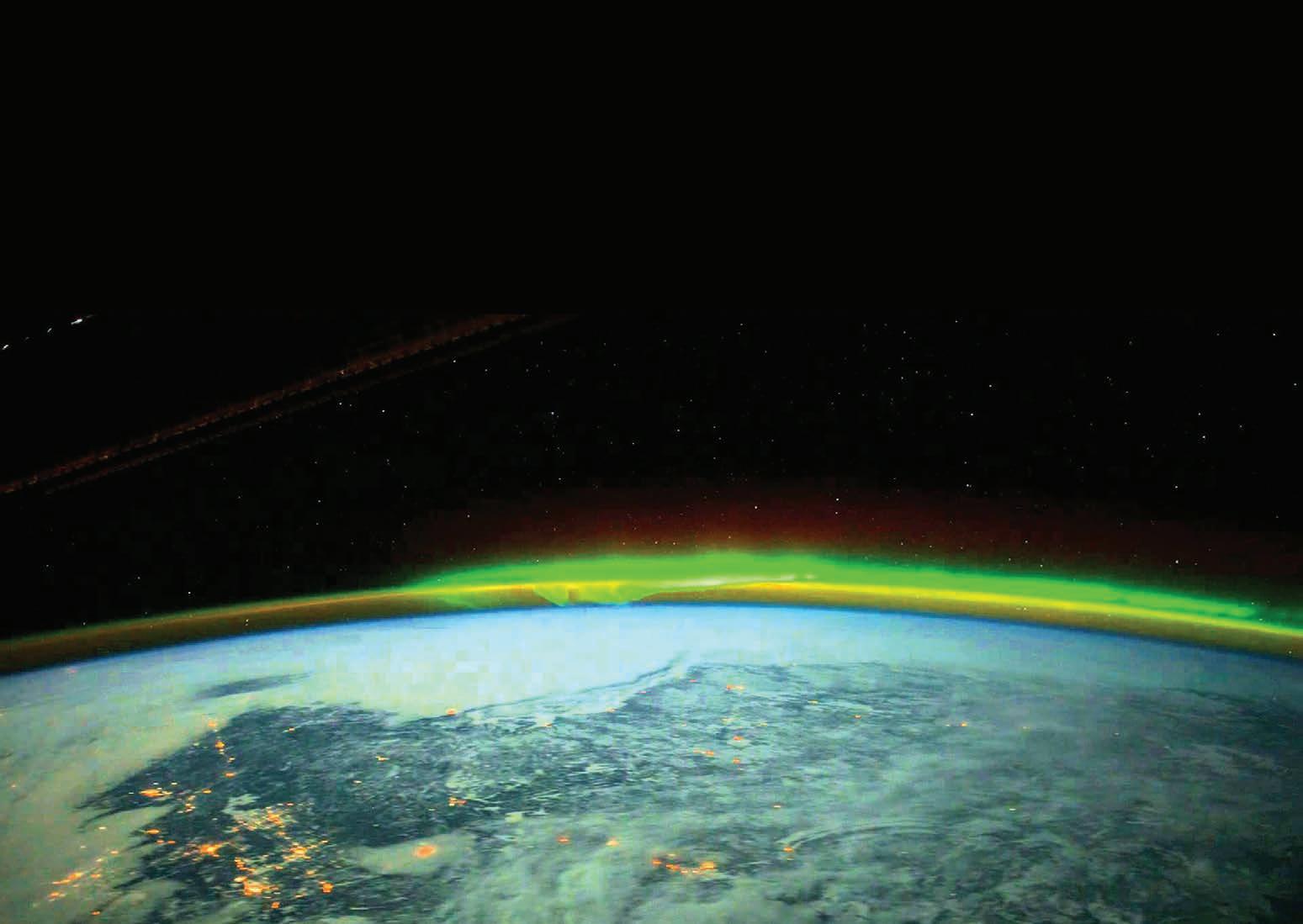

Partners in the Polar Region 9

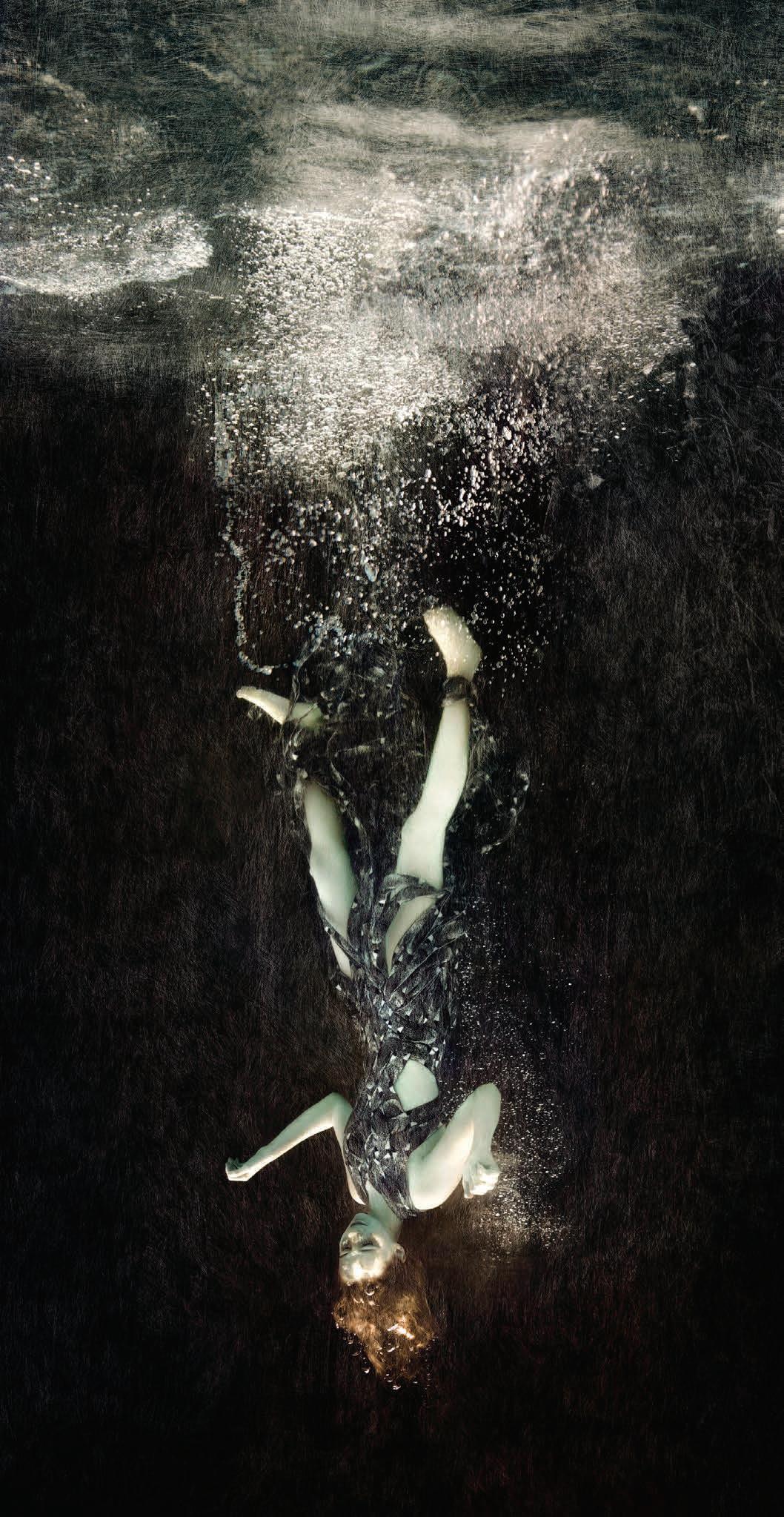

Nathalia Edenmont: Force of Nature 10

Partners in the Polar Region 9

Nathalia Edenmont: Force of Nature 10

The Photography of Anders Beer Wilse 24

Magnus Nilsson 32

August 20 & 21, 2016

November 19 & 20, 2016

Members & Kids under 12 free; General Admission $5

Handcrafted Gifts * Live Music * Nordic Food & Drink * Photos with Santa

nordic KULTUR 2016

Become a Member of Nordic Heritage Museum

Benefits Include:

Membership card allowing unlimited free admission for each Member

10% discount in the Museum Store

Kids’ Corner emails

Subscription to Nordic News and Nordic Kultur

Discounted tickets to educational programs and events

Member-only exhibition previews

Behind-the-Scenes Tour Night (once a year)

Member Appreciation Weeks (20% discount in Museum Store, twice a year)

The magazine of Nordic Heritage Museum

EDITORIAL BOARD

E ric Nelson Chief Executive Officer

Jan Woldseth Colbrese Deputy Director of External Affairs

K irstine Bendix Knudsen Executive Assistant

E lizabeth Martin-Calder Marketing Consultant

S andra Nestorovic Deputy Director of Operations

Fred Poyner IV Collections Manager

A ni Rucki Graphic Designer

Jonathan Sajda Program Manager

BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Trustees

Hans Aarhus | Per Bakken | Steven J. Barker (Treasurer)

Anne-Lise Berger | E arl Ecklund | A rlene Sundquist Empie

Lotte Gavel Adams | I rma Goertzen (President) | Tapio Holma

Christine Ingebritsen | Ken Jacobsen | Sven Kalve | Jane Klausen

Thomas W. Malone (Vice President) | Valinda Morse | Kurt Ness | Allan Osberg

Einar Pedersen | R ick Peterson (Secretary) | Erik Pihl

Vi Jean Reno | M aria Staaf | Birger Steen | Nina Svino Svasand

Tor Tollessen | M argaret Wright (Immediate Past President)

Consuls

Erik D. Laursen, Denmark | Matti Suokko, Finland

Kristiina Hiukka, Honorary Vice Consul, Finland | Jon Marvin Jonsson, Consul General, Iceland

Geir Jonsson, Honorary Vice Consul, Iceland | Kim Nesselquist, Norway | Lars Jonsson, Sweden

Honorary Trustees

Dr. Stig B. Andersen | R epresentative Reuven Carlyle | L eif Eie | Synnøve Fielding

Senator Mary Margaret Haugen | F loyd Jones | S enator Jeanne Kohl-Welles

Bertil Lundh | M ark T. Schleck | R epresentative Helen Sommers

Mayor Ray Stephanson | R epresentative Gael Tarleton

STAFF

E ric Nelson Chief Executive Officer

Jan Woldseth Colbrese Deputy Director of External Affairs

S andra Nestorovic Deputy Director of Operations

K irstine Bendix Knudsen Executive Assistant

Curatorial

Fred Poyner IV Collections Manager

Jonathan Sajda Program Manager

A lison Church Children’s Education Coordinator

Stina Cowan Public Programs Coordinator

S arah Olivo Adult Education Coordinator

K athi Ploeger Music Library Archivist

A riane Westin-McCaw Registrar

C laire Wilbert Registrar

Development

K aty Ahrens Development Associate, Stewardship

Nick DeCicco Grant Writer

Jenny Iverson Events & Sponsorship Coordinator

K elsey Svaren Membership & Database Coordinator

Marketing & Communications

E lizabeth Martin-Calder Marketing Consultant

A ni Rucki Graphic Designer

Operations

Pamela Brooks Finance Manager

D onna Antonucci Caretaker

R ebecca Bolin Weekend Receptionist

C arolyn Carlstrom Bookkeeper

M ichael Ide Volunteer & Staff Resource Coordinator

M ary Ann Namvedt Museum Store Manager

Sune Sandling Facilities Coordinator

NORDIC HERITAGE MUSEUM

3014 NW 67th Street, Seattle, WA 98117

206.789.5707 | nordicmuseum.org

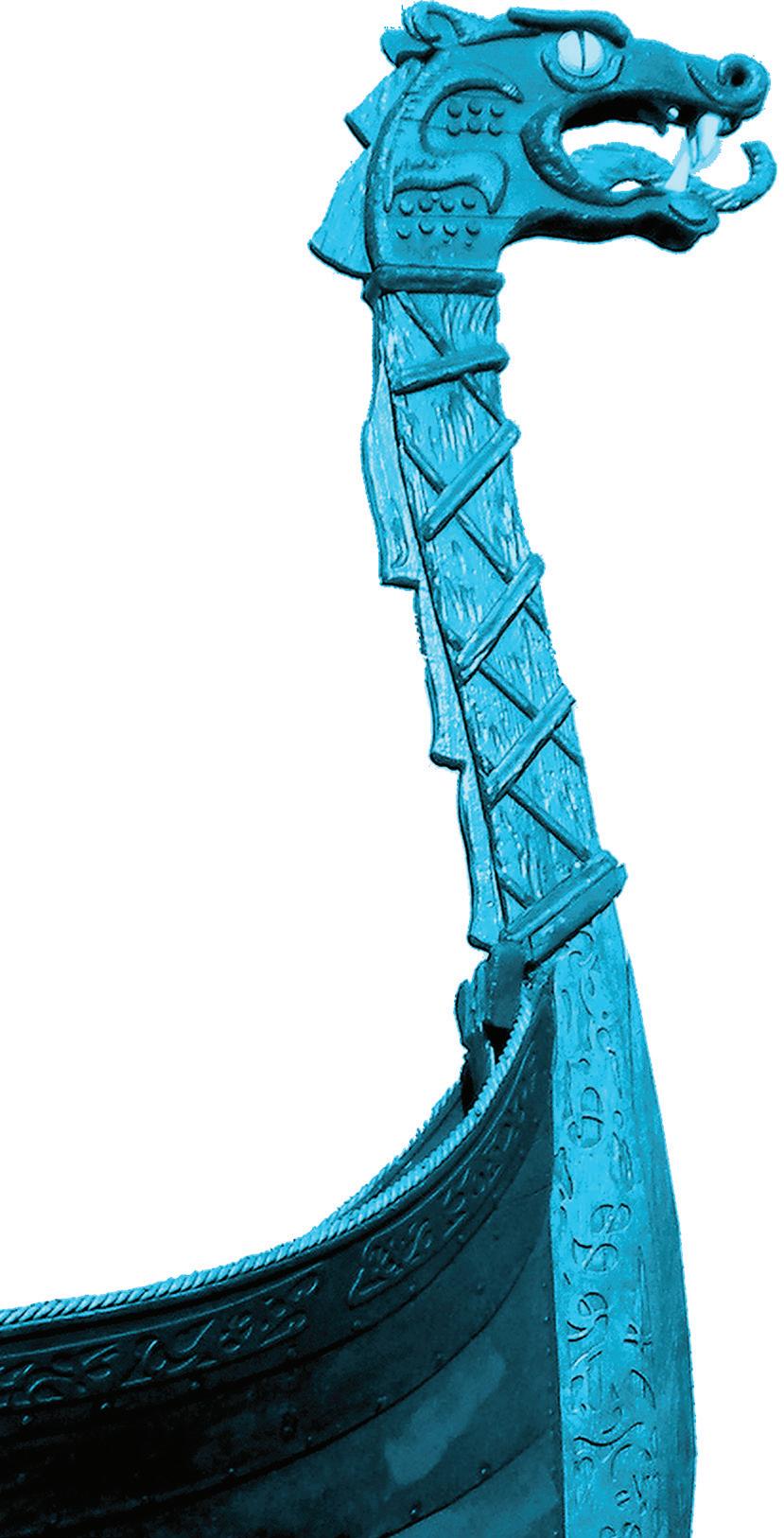

Welcome to Nordic Kultur, the magazine of Nordic Heritage Museum. This edition coincides with a tremendous event: the groundbreaking for our new building in the downtown Ballard neighborhood of Seattle. Years of preparation, planning, and hard work have culminated into a visionary design for the New Nordic Museum. Among a host of new experiences planned for the facility is an expanded core exhibition which will chronicle the parallel histories of Nordic communities in Europe and North America. Nordic sagas will provide a powerful metaphor for the exhibition journey, encouraging us to reach back into the deep past, as well as to explore more recent history, focusing on the values and attributes of the Nordic peoples.

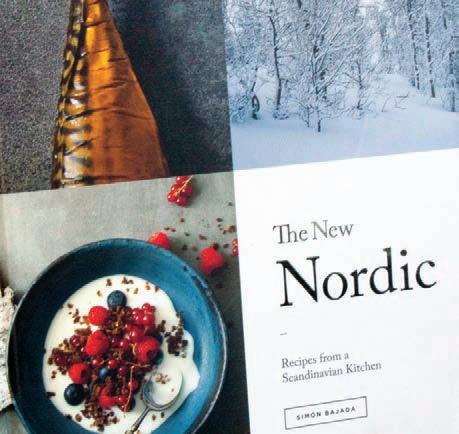

For this fourth issue of Nordic Kultur, several exhibitions and programs are highlighted, starting with The Weather Diaries which showcases West Nordic fashion photography inspired by the dramatic physicality of nature. Stockholm-based artist Nathalia Edenmont captures fantastic dreamscapes with her riveting imagery. And Magnus Nilsson’s Nordic: A Photographic Essay of Landscapes, Food, and People, presents a pictorial essay that reflects connections between the Nordic people and their environment.

Big Jake Bjarnason: The Gentle Giant comes to life with the story of his birth in Iceland to his career as a police officer and sheriff in Ballard over a century ago. His enormous stature and good-natured spirit kept the frontier town safe for a steady influx of Scandinavian immigrants to the area. The highly successful Nordic Lights Film Festival held at the Seattle International Film Festival brought audiences a chance to view The Fencer, a film directed by Klaus Härö, recognized this year as a Golden Globe nominee for Best Foreign Film. We were very fortunate to interview Härö for this issue, and glean his insights into the challenges of making this beautiful film. In addition, a fascinating interview with the founders of the Odin Brewing Company provides a look into the Icelandic origins of this fine craft brewery.

For a look backstage, we describe the journey behind a recent addition to the Museum’s permanent collection: Marita Huurinainen’s “Emo” Dress, and the donation of two important books to our children’s literature archives. Also, you can read about our exciting plans for a Cultural Resource Center in the new museum, serving as a home for our expanding Nordic American Voices library.

When Nordic Heritage Museum opened its doors in 1980, few could have imagined the reality of a spectacular new building. It is to the credit of our members, board, volunteers, and staff that we can truly envision a bright future for the Museum.

Eric Nelson CEO, Nordic Heritage Museum

One-of-a-kind installations from selected designers and large-scale photographic artworks by Sarah Cooper & Nina Gorfer

On assignment from Nordic House Reykjavik, the artist duo Cooper & Gorfer explore the driving forces of creativity behind the fashion of three remote areas of the North Atlantic: Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Greenland. Over two years the artists collected stories from local designers and artisans, whose artistic expression have been shaped by the cultures, traditions, and surroundings of the far western Nordic region. Common to the three islands is their isolation, limited resources, wild nature, and unpredictable weather.

Instead of depicting their findings objectively, Cooper & Gorfer create ambiguous stories, the truth of which are poetic and subjective. They interpret present day North Atlantic identities by effortlessly crossing genres from centuries of visual culture. The resulting body of work is a prolific collaboration between Cooper & Gorfer and some of the most gifted designers and artists from the North Atlantic Islands; a fabulous record from a journey to places where the weather molds the people.

The breathtaking exhibition The Weather Diaries is on view at Nordic Heritage Museum August 12–November 6, 2016.

“The Weather Diaries” is a metaphor for many of the themes addressed in this exhibition. The West Nordic islands, Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands are privy to extreme weather conditions and seasonal periods of total darkness and light. The exhibition explores the roots of West Nordic fashion, and its inimitable creativity and aesthetics, under this umbrella of the strong impact of weather and nature. “Seldom do we see such pleasure for the creative process as we have found in the artists and designers presented here,” explain Cooper & Gorfer.

The exhibition showcases one-of-a-kind installations from select designers alongside large-scale photographic artworks by

Cooper & Gorfer. Below is an excerpt from the accompanying exhibition catalog, produced by Nordic House Reykjavik and distributed by Gestalten. It showcases personal essays, exclusive interviews with the participating designers and artists, and the photographic works by Cooper & Gorfer, as well as other anecdotal references.

No, no, no, we couldn’t find it if our lives depended on it! How could we miss it? It was supposed to be here. We were supposed to drive to the end of the road and continue on up the gravel driveway leading to a gate (which we were to carefully close behind us—the sheep, you see).

“After the gate, drive until the road ends,” Ilmur had told us. “There, up on a little hill, with the forest to the right, you will find it.” But there we were, hiking on a small trail through thorny terrain, and it was nowhere to be found. We had driven as instructed, until the gravel strip had become so narrow we concluded the road must have ended. Maybe we had taken a wrong turn somewhere. But where? It’s not like Iceland has an abundance of roads, after all. In the end, we did not find what we were searching for that blue and windy day in early June 2013. Despite our collective efforts, we could not find the road that would lead us to the abandoned house.

Once they were many. Easy to find, scattered along roadsides, on hill tops, and strewn about empty plains. Many of them witnesses of a time long gone, with their flowery wallpapers and painted wooden floors. In some houses, the cups would still be on the kitchen table, the bed left unmade. People must have just walked out of their house one day, suitcase in hand, never to return. Iceland surely is a place of stories.

A place that, through a paradoxical familiar strangeness, strikes a chord in our imagination. There is of course its mythical nature, young enough to remind us of the forces that shaped the earth. There is also, far more subtly—and hardly noticeable on the first visit—the nature of its people,

who strangely seem to resonate with a more essential, a more primal, part of ourselves.

It was early January 2012, when we were asked to curate the third Nordic Fashion Biennale, scheduled for 2014. As artists, we were initially skeptical of this request. We have never considered ourselves curators, and are far from what one might call fashion experts. But it was hard to hide the excitement this proposal infused into us. After all, it was Iceland that had fostered our first artistic project. It began with a car crash during a blizzard in October 2005, and ended with us creating our first book. The wild Icelandic weather that had scared us into obedience, had also set the seed for our collaboration as artists. More importantly, it had produced the profound friendship we have today. There is an unrelenting magic to a place such as Iceland, so naturally we said yes to the request.

What followed was a two-year-long investigation in the West Nordic Region— Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands —with a focus on fashion. It literally was months of discovery.

Revisiting Iceland had a strong personal meaning for us. But our travels to the Faroe Islands and Greenland opened up new alleyways, raised new questions, and stimulated both our minds and inspiration.

That the first human settlements on the eighteen rather small Faroe Islands have braved the elements, tells of the stubborn and adventurous nature of humanity.

Like the Faroese artist Edward Fuglø put it during our interview at his house in Klaxvik, “It is strange to see when the schoolteacher points to the world map, halfway between Iceland and Scotland, where all you see is blue, saying, ‘We are here, here are the Faroe Islands.…’ It’s odd to grow up on a place that does not even exist on a map.”

Greenland has a story and history all its own. For people outside Denmark it surely must feel peculiar that this vast land of ice could be part of Denmark, part of Europe, part of anything at all other than itself. A rich, majestic, beautiful place. And difficult, in many ways. From our research, it would now be preposterous not to see the effects the long Danish ascendancy had on the Greenlandic Inuit culture, for good and for bad. Foreign domination always leaves its traces. And it is this that we set out to investigate: What impact does cultural heritage and the place you grow up have on your inspiration? How does it influence your creative personality?

In many ways, Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands have their own

idiosyncrasies—each one of them with their own unique identities and stories. But still, we found in all of them a jaunty indomitability, if such a thing could exist, not only toward creativity but toward life at large.

Weather moulds behaviour, and isolation forges a pool of creative bravery. It is a part of the world where market values don’t have to make sense, because the forced freight of commercialism is rarely loaded.

The book in your hands is intended to convey aspects of these northern islands that have enthralled us. In the aftermath of hardship and seasonal darkness and light, reiterative and merciless in its completeness, emerges a relentless creativity. The cultural isolation and the overpowering force of nature spawn the seed of a raw and authentic inspiration.

…They have in common a fearlessness towards creativity, an urge to create for creation’s sake. It was a liberating experience to have had the luck to work with people who are so uncommonly authentic and enchantingly fun, people who remind us of the childlike wonder and indulgence of a mind at play.

Sarah Cooper & Nina Gorfer, Artists Curators of The Weather Diaries

January 29–April 24, 2016

A story of rescue and resistance against Nazi persecution. Approximately 7,200 lives were saved, through the efforts of Danish citizens who ferried Danish Jews by boat to safety in Sweden. This has come to be known as one of the biggest instances of an organized effort against the Nazis during WWII. Exhibition originated by The Museum of Danish Resistance 1940–1945/The National Museum of Denmark, and traveled by The Danish Immigrant Museum in Elk Horn, Iowa.

March 18–May 8, 2016

Heralded as one of the top twenty chefs in the world, Magnus Nilsson is the head chef of Fäviken restaurant in Sweden. Nilsson’s first museum exhibition highlights his original travelogue photography— an illustration and examination of Nordic food culture that unravels the mysteries of Nordic ingredients and introduces the world to Nordic culinary history and cooking techniques. Premiering in the US at Nordic Heritage Museum, the exhibition features Magnus Nilsson’s photography, stories, and recipes from his new book, The Nordic Cookbook (Phaidon, 2015). Exhibition produced by the American Swedish Institute (Minneapolis, MN).

April 29 – July 10, 2016

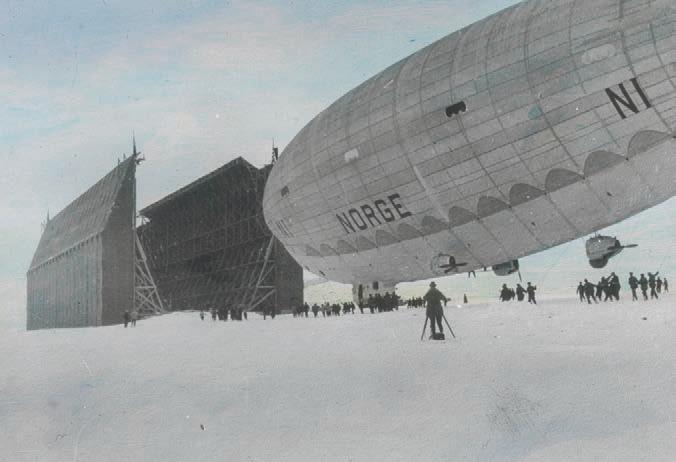

Americans and Norwegians have explored uncharted areas in the Polar Regions for more than a century. Many of the first discoveries in the Arctic and the Antarctic were made by Norwegian or American expeditions, or by Norwegian and American explorers working together. This exhibition is a celebration of their efforts and their contribution to our knowledge of the ends of the Earth. Produced for Nordic Heritage Museum by The Fram Museum (Oslo, Norway).

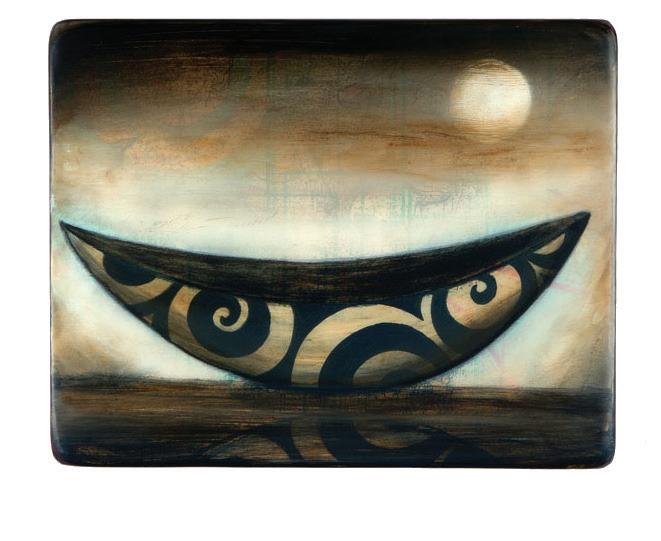

May 20–July 24, 2016

Probing and provocative, Nathalia Edenmont’s photography speaks to life’s inherent truths through a visceral engagement with her own turbulent existence. Rich in symbolism and with clear references to historical genres of art, Edenmont’s frequently beautiful and challenging arrangements can be viewed as a modern expression of traditional iconography. Her autobiographical work explores the darker recesses of her troubled childhood and teenage years in Ukraine, where she resided until moving to Stockholm in 1991. The exhibition features sixteen richly-colored, large-format photographs. Organized by Nordic Heritage Museum with support from Nancy Hoffman Gallery (New York) and Wetterling Gallery (Stockholm).

August 12–November 6, 2016

The Nordic Fashion Biennale (NFB) returns to Nordic Heritage Museum with the latest installment, The Weather Diaries. Photographers Sarah Cooper & Nina Gorfer traveled throughout Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands to explore the roots of West Nordic fashion. This exhibition explores the inspiration of creative minds, probes links to cultural identity, scrutinizes the impact of the inescapable physicality of nature and weather, and showcases one-of-akind installations from the selected designers, alongside large-scale photographic artworks by Cooper & Gorfer. Featured designers include Mundi (IS), JÖR by Guðmundur Jörundsson (IS), Kría (IS), Hrafnhildur Arnardòttir a.k.a. Shoplifter (IS), Guðrun & Guðrun (FO), Barbara Í Gongini (FO), Rammatik (FO), Bibi Chemnitz (GL), Najannguaq Lennert (GL), Nikolaj Kristensen and Jessie Kleemann (GL). Exhibition produced by Nordic House Reykjavik.

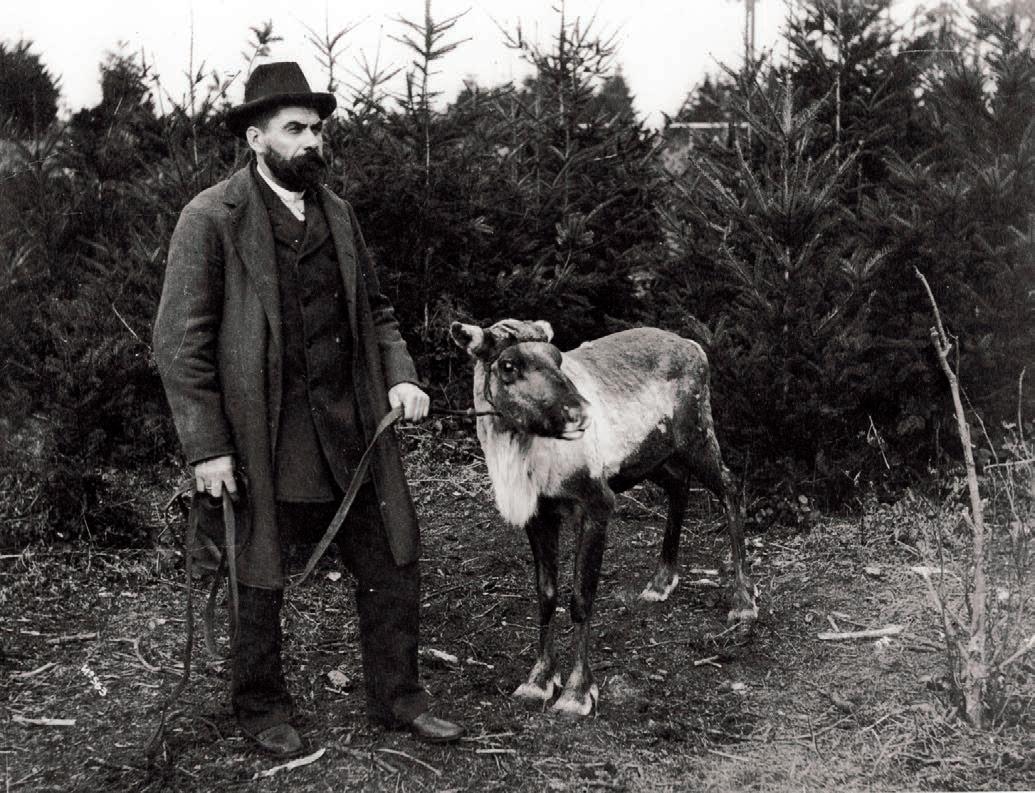

The Photography of Anders Beer Wilse

December 2, 2016–February 28, 2017

Norwegian engineer and self-taught photographer Anders Beer Wilse (1865–1949) lived in Seattle from 1892 to 1900 and left a legacy of early photographs documenting this period of unprecedented growth and change in the city’s history. This exhibition includes Wilse’s photographic images taken both in Washington State and the greater Pacific Northwest region, as well as from select regions in Norway after 1900. Organized by Nordic Heritage Museum and including images from the University of Washington Libraries; the Ballard Historical Society; the Museum of History & Industry (MOHAI); the Norsk Folkemuseum (Oslo, Norway); and the Norsk Teknisk Museum (Oslo, Norway).

Nathalia Edenmont’s world is terrifying and beautiful, sensuous and spartan, fashion-forward and timeless, full of life and brimming with death. Her compositions are straightforward, posing her figures against black seamless backgrounds or white empty spaces. There are no double exposures or blurred reflections, no tricks of the camera, no Photoshop special effects. What you see is what was there, staged before an oversized 8x10 view camera, captured in a single session.

In an age where we have come to doubt the veracity of all photographs—where even documentary photographs are suspect—Edenmont makes images that have not been tampered with in any way. The things we see have actually happened; the image has been built from actual elements. There is no escape hatch or buffer to protect us from these photographs. We cannot say “this cannot happen.” It has happened, as we can clearly see.

Edenmont’s photographs derive their power not from a theoretical framework but from details of her autobiography. Born in Yalta in 1970 when the Ukraine was still part of the USSR, Edenmont had a happy childhood which gave her no reason to question the Soviet propaganda that she learned at school. On an impulse, she asked to go to a children’s art school for her elementary education, a decision her mother supported, and a place where she excelled.

“I think like any other child I liked to draw, but nothing special. When I was nine years old, a neighbor girl, one year older than me, decides she wants to go to art school, so I thought, ‘me too!’ I told my mother and my mother said yes. There we were drawing simple things, like still lifes, but also art history. I remember seeing a picture of a work by Rubens when I was ten years old, I thought all these naked bodies, because in the Soviet Union at the time you never saw anyone naked, I never saw my mother naked, and suddenly I saw all these people naked.”

Nathalia Edenmont is never less than serious when she turns her gaze to Old Master paintings and religious icons. Rather than doubt the power of an image, she is fully invested in their truth. These images first appear to her in her mind, fully formed. Her job is merely to fulfill the vision she has seen by assembling the models, crew, and props necessary to make the dream come true. She has no reason to doubt photographic truth or cast aspersions on the myths surrounding imagemaking. Instead, her goal is solely to bring her reality to a wider public, combining iconoclastic and iconographic impulses.

All was well until young Nathalia’s father died when she was twelve. The following year, she watched her mother suffer slowly in a hospital, an experience captured poignantly in Self-Portrait (Deathbed), in which Edenmont poses as her mother, while her model Cornelia holds her hand. Edenmont recalls that she was home, ironing a dress for her school graduation when a neighbor came to tell her that her mother had died. In shock, she returned to the ironing board, only to find that she had burned the dress. Again, the episode appears repeatedly in her photographs, especially Nostalgia and Devotion in which the clothes on the models are singed and blackened with soot.

“The day I discovered my mother died, I was on my way to get my diploma from school. But when I was handed my diploma, I said to the rector, ‘My mother died.’ He said, ‘What?’ And I said yes. So he gave me my diploma and asked me if I had any relatives. I had no relatives. So he contacted a woman at the Cultural Bureau and told her that he has a student whose mother just died and she has the best diploma. So she contacted an art school in Kiev where I could live. You had to take an examination because many children from the whole country would apply. So three days after my mother died, I made the examination and so I entered the school. I never planned to continue art because my plan was to be a lawyer like my mother but I didn’t have anybody to raise me so I went to this art school where I lived until I was eighteen years old.”

Soon after, at the age of 21, Edenmont moved to Sweden, where she supported herself most often by working as a cleaning woman. Later, under pressure from her second husband to give up painting (Edenmont has been married five times), she attended Forsbergs Skola International School of Design, again hoping for a career as a commercial artist. She was not trained as a photographer, but in graphic design, yet her teachers told her repeatedly that her work did not look commercial. One day, Per Hüttner, a practicing artist and a professor, asked her how she came up with her ideas, because they were by far the most interesting in the class. She said, as she often repeats even now, “I don’t think, I see pictures in my mind.” He asked her to describe a few and immediately responded that that is the work she should be doing. He told her to make an installation that

he could photograph. In seeing the results, he announced, “My God, this is the beginning of your career.”

Edenmont didn’t believe him or want to believe him. In her mind, an artist never had a job and never made enough to support himself. She briefly moved to Australia and married once again, only to move back to Sweden, disappointed. She looked up her old professor and asked his advice. “What am I to do?” she recalls asking him. “I think you are an artist,” Hüttner replied. Since she had no job and no new relationship, she thought she was finally free to pursue an art career. In 2003, at the age of 33, Edenmont had her first solo shows at Mors Mossa Gallery in Goteburg, Sweden and Wetterling Gallery in Stockholm.

Juxtaposing public and private, sacred and sensual, security and discomfort, Edenmont demonstrates a strong relationship to contemporary artists such as Cindy Sherman, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Andres Serrano. These are artists who challenged the superiority of formal concerns—composition, lighting, framing, and camera angle—to address one of the most universal subjects in photography, the body. Each of these artists turned the body—a key symbol and conveyor of eternal beauty since the ancient Greeks—back into a time-based, gender-specific, amalgamation of flesh-and-bone. For Nathalia Edenmont, her tension between high style and intimate content can be disturbing, but it is also the source of undeniably beautiful photographs.

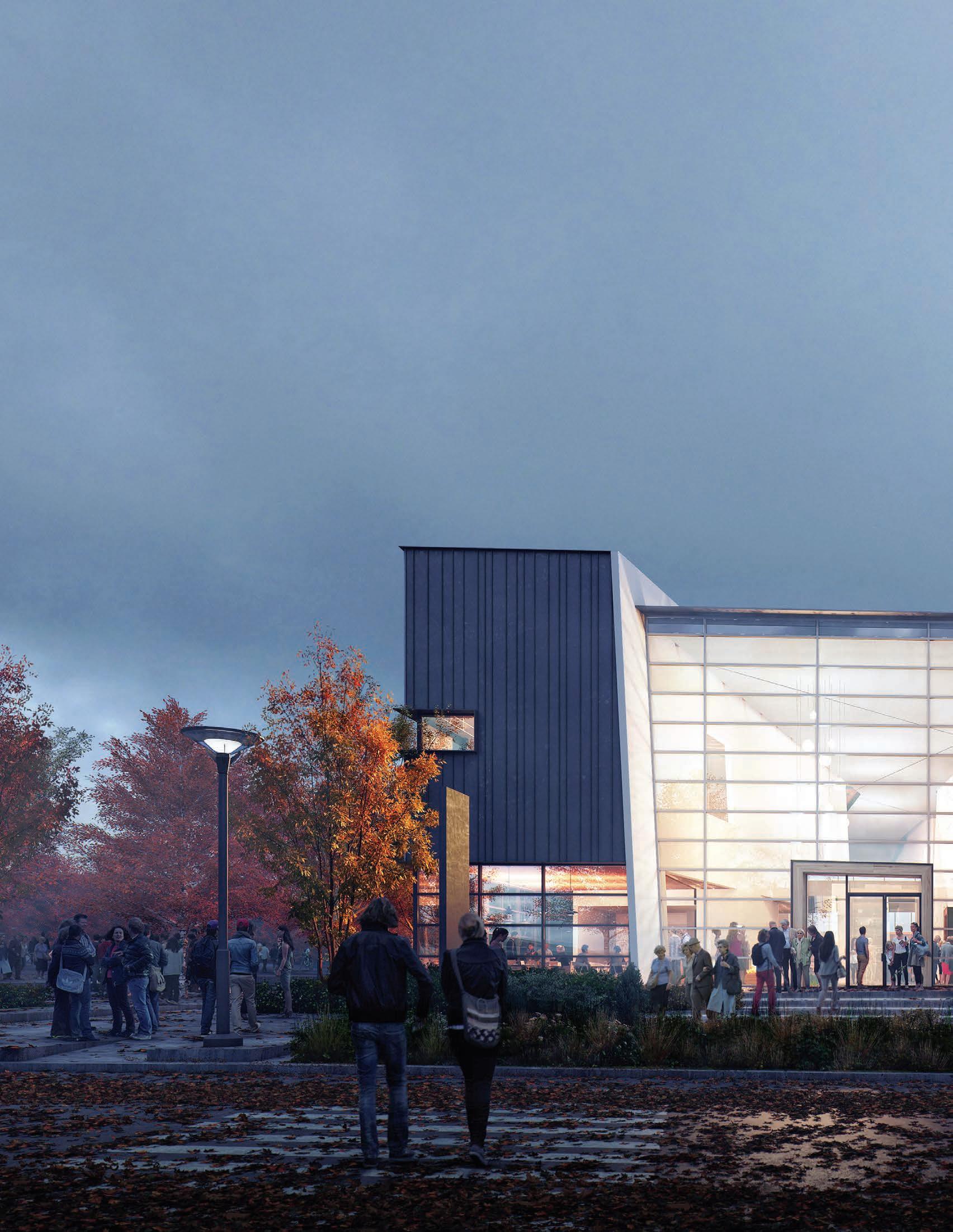

NORDIC HERITAGE MUSEUM is in the final phase of fundraising for a new 57,875-sq. ft. museum and cultural resource center dedicated to the preservation and exploration of Nordic culture. With groundbreaking and a public campaign to begin this summer, opening ceremonies are slated for early 2018.

The new Museum will be located on Ballard’s main artery, Market Street, alongside the vibrant boat docks and the iconic Chittenden Locks—gateway to the Puget Sound, Gulf of Alaska, and Bering Sea.

The newly-designed building includes an auditorium, a museum store, and a café. On the second floor will be a cultural resource center and core exhibition galleries, presenting narratives of both the past and present as a new story emerges—one that explores a continually evolving Nordic culture.

OPENING: Early 2018

NEW MUSEUM LOCATION: 2655 NW Market Street

GROUNDBREAKING: July 30 | 3pm

PUBLIC CAMPAIGN KICKS OFF SUMMER 2016!

Double Your Nordic Spirit with a gift to the capital campaign. Your donation will be matched dollar for dollar. Contact Jan Woldseth Colbrese at 206.789.5707 x39 or janwc@nordicmuseum.org.

Museums rely on the expertise of Collections Specialists and Registrars to care for all types of objects. Dismantling an exhibition can be as involved as the installation process, requiring detailed steps to insure the protection of each piece. Claire Wilbert assisted with the dismantling of the Museum’s 2015 exhibition, Finland: Designed Environments, originating from the Minneapolis Institute of Art. She describes her relationship with the beautiful “Emo” dress, designed by Marita Huurinainen using fabric by Marja Eivola.

was time for the exhibition to end. Now we needed to remove the dress carefully from its display mannequin without damaging the delicate, unbound neckline. I determined the best way would be to remove the mannequin’s arms, so we could lift the dress with extreme caution over the head. Then we positioned the dress in its archival wrappings and crate and sent it back to Minneapolis.

thoughtfully, taking duct tape and an extra protective bag, just to be sure.

I first saw the stunning “Emo” dress at Nordic Heritage Museum when I visited for my interview for the position of Interim Registrar. It stood out because, as a knitter, I could appreciate the amazing amount of time and effort that went into its creation and the delicacy of how it combined wool and peat.

To my delight, I was invited to become the Museum’s Interim Registrar, so my acquaintance with the “Emo” dress was renewed.

I saw it regularly in the course of my daily rounds as a Registrar, when I checked the exhibition thoroughly. Then, all too soon, it

Soon, however, I learned that Fred Poyner IV, the Museum’s Collections Manager, was preparing to secure the dress for our Museum’s permanent collection. To my surprise, I was asked to courier the dress from Minneapolis back to its new home in Seattle. After many emails and phone calls, we received the signed deed of gift from the artist in Finland. Now, once again, I was to be charged with ensuring the safety of the “Emo” dress!

I’d never served as a courier before. I knew my responsibilities as the Museum’s official representative, but all I could think of were the horror stories drilled into me in graduate school…TSA [Transportation Security Agents] agents ripping into crates or customs officials venting their annoyance on unsuspecting registrars. I couldn’t help wondering what was in store. So I packed

I got to Minneapolis without incident and spent time catching up with family— definitely one of the perks of couriering! Then I headed off to the Minneapolis Institute of Art to pick up the dress. For all my mental angst, the transaction was something of a letdown. I went to the security desk, introduced myself, and the MIA’s registrar brought the carefully prepared dress and her set of documents out to me. I signed her documents and she signed mine. Then I headed out of the museum with my precious bundle of bubble wrap.

Soon I was on my way to the airport for the flight back to Seattle. As I unloaded my laptop and took off my shoes in the security line, I mentally checked my list. I was preparing myself to defend the “Emo” dress against the TSA, my fellow travelers, and any other unforeseen threats.

But as I picked up the dress from the conveyor belt and reassembled my carry-ons, I realized the dangers were almost over. I walked happily to my gate with my precious cargo. Soon I would deliver it to the safety of Nordic Heritage Museum, where it will grace the new Nordic Orientation Gallery as a wonderful example of Finnish design.

$5,000,000+

Osberg Family Trust; Allan and Inger Osberg; Osberg Construction Company

$3,000,000–$4,999,999

The A.P. Møller and Chastine Mc-Kinney Møller Foundation

Jane Isakson Lea* and James Lea State of Washington

$1,000,000–$2,999,999 4Culture

Barbro Osher Pro Suecia Foundation

Breivik Family Trust

Floyd and Delores Jones Foundation

Kaare* and Sigrunn Ness

The Family of Einar and Herbjorg Pedersen

Einar and Emma Pedersen

Scan | Design Foundation by Inger and Jens Bruun City of Seattle

Berit and John Sjong

Robert L. and Mary Ann T. Wiley Fund

Anonymous

$500,000–$999,999

Earl and Denise Ecklund

Jon and Susan Hanson

M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust

The Norcliffe Foundation

$100,000–$499,999

Jan and Priscilla Brekke

Svanhild and Russell Castner

Patricia and Robert Charlson

Peter Henning*

Stan and Doris Hovik

Joshua Green Foundation

Koon Family Trust

Karen L. Koon

Nesholm Family Foundation

Donald and Melissa Nielsen

Everett and Andrea Paup

Reimert and Betty Ravenholt

Chris Siddons

Norman Kolbeinn Thordarson and Judy Thordarson

Estate of Leo Utter*

$50,000–$99,999

Pirkko and Brad Borland

D.V. and Ida McEachern Charitable Trust

Estates of Dr. C. Ben Graham and Pearl Relling Graham*

Jon Halgren

Egon and Laina Molbak

Skandia Music Foundation

Arlene Sundquist Empie

Estate of Judith Tjosevig*

$25,000–$49,999

Brandon Benson

Per and Inga* Bolang

Irma and Don Goertzen

Michael and Jill Heijer

Leif Erikson International Foundation

Georgene and Richard Lee

Marilyn and Rodney Madden

Tom and Drexie Malone

Karl Momen

Nordic Council of Ministers

Peach Foundation

Patsy* and Larry Small

Louise Solheim

Maria Staaf and William Jones

Svend and Lois Toftemark

Anonymous

$10,000–$24,999

Karin Ahlstrom Bean

The Boeing Company Gift Match Program

Etienne* and Nancy Debaste

Leif Eie

Francisca Erickson

Asmus Freytag and Laura Wideburg

Gertrude Glad

Estate of Helen K. Hagg*

Sven and Marta Kalve

Olaf Kvamme*

Valinda I. and Lyle S. Morse

Eric and Yvonne Nelson

Alice Ness*

Eldon and Shirley Nysether

Mr. and Mrs. Andrew Price

Börje and Aase Saxberg

Marvin and Barbara Stone*

Nina Svino Svasand and Ernest Svasand

Swedish Finn Historical Society

Donald* and Kay Thoreson

Tor and Ingrid Tollessen

Anonymous (2)

$1,000–$9,999

Hans and Kristine Aarhus

Rick, Marlene, and Derek Akesson

Richard and Constance Albrecht

Myrna Amberson

American Seafoods Company LLC

Bruce and JoAnn Amundson

Stig and Ruth Andersen

Chris and Terrie Rae Anderson

Jan Anderson

B&N Fisheries

Isabella Backman Johnson

Steven and Kathleen Barker

Patti Benson

Keith and Kathy Biever

Anders and Karen Bolang

Herb and Shirley* Bridge

Diana Brooking

Jette and Stephen* Bunch

Ward and Boni Buringrud

Gloria Mae Campbell

Jean K. Carlson

Elaine and Richard Carpenter

Joanne Chase

Jan Woldseth Colbrese and Mike Colbrese

Ragnar Dahl*

Danish Brotherhood Lodge #29

Sandra Egtvet

John and Linda Ellingboe

Embassy of Denmark, USA Embassy of Finland, Washington, D.C.

Embassy of Sweden, Washington

James Feeley

Finn Room Committee

Gunilla and Jerry Finrow

Marianne Forssblad and Roland Wedenström

H. Weston Foss*

Lisa Garbrick

Lotta Gavel-Adams and Birney Adams*

Glacier Fish Co., LLC

John Martin Hansen

Richard and Marilyn Hanson

Harbor Enterprises, Inc.

Fred and Karin Harder

Scott and Lisa Harpster

Peter and Pat Haug

Sandy Haug

Wally and Kristin Haugan

Electa Hendricks* and Electa Anderson

Jeff and Linda Hendricks

Woody and Ilene Hertzog

Kristiina Hiukka

Olavi Hiukka

Ruth and Preben HoeghChristensen*

Roy Holmlund*

Karen Holt

Gunnar Ildhuso, Sr.

Curtis and Shirley* Jacobs

Ernst and Linda Jensen

Stan Jonasson and Linda Jangaard

Steven Jones

Jacob and Ellen Jordal

Mari-Ann Kind Jackson

Ken and Rachel Jacobsen

Kevin and Penny Kaldestad

Jim and Cris Kelley

Arnold Kegel and Martha Fagnastøl Kegel

Lowell and Shirley Knutson

Mina and Raymond Larsen

Leadership Tomorrow Alumni Association

John S. Legg

C. Stephen and Donna Lewis

Elmer and Joan Lindseth

Limback Lumber

Svenn L. Lovlie

Estate of Olav Lunde*

Patricia J. and Richard* Lundgren

Florence Lundquist*

Birgit Lyshol

Jon Magnusson

John and Hanna Liv Mahlum

Josephine* and William Mahon

Leif and Cindy Mannes

Ronda and Brad Miller

Kay Most*

Susan and Russell Ness

Norman Archibald Charitable Foundation

Nysether Family Foundation

Sigurd and Else* Odegaard

Cindy and Ron Olander

Richard and Kay Olsen

Gordon Olson

Carol Oversvee Johnson

Pacific Nordic Council

Barbara Paquette

Kathryn and Jay* Pearson

Walter Pereya

H. Fredrick Peterson

Erik Pihl

Eilert and Virginia Prestegaard

Evan T. Pugh

Megan and Greg Pursell

Gustav and Claire Raaum*

Ed and Marjorie Ringness

Ringstad Enterprises

E. Paul and Gayle Robbins

Dean A. Robbins

Rotary Club of Ballard

Royal Norwegian Embassy in Washington

Vivian Sandaas*

ScanSelect, Inc.; Ozzie Kvithammer and Anne-Lise

Berger

Ralph Schau

Seattle Latvian-American Embroidery Group

Craig and Nancy Shumate

Yara Silva and Lars Matthiesen

Edward Smith

Carol and Norman Sollie

Sons of Norway, Hovedstad

Lodge #94

Harriet Spanel*

William Stafford

Birger Steen

Elaine Stevens

Gordon Strand

Frank and Jennifer Swant

Norman and Phyllis Swenson

Lisa A. Toftemark

Dorothy Trenor

Trident Seafoods Corporation

Susan Laurie Tusa and Dan

W. Durham

Debbi and Larry Vanselow

Raiti Waerness

Colleen White

Karin and Colin Williams

Dale Wright

Margaret and Richard Wright

Anonymous (2)

Up to $999

Chris J. Aaro

Molly Aasten*

Karen Abelsen

Adams Insurance

Diane Adams

Greg Aden

Kay Lynn Alberg

Aven and Shirley Andersen

Dennis Andersen

Margrethe Andersen*

Arlene Anderson

Doug Anderson

Ellen Anderson*

James R. Anderson

Jo Ann and Alan Anderson

Karla Anderson

Marilyn C. Anderson

Roger Anderson and Gene Ampon

Lars Andreasson

Fred Arnason and Family

Curtis and Kimberly Arnesen

Lois M. Arneson

Per A. and Lisa Bakken

J.R. Balison, M.D. and Constance F. Balison

Ballard SeafoodFest Musicians

Bank of America Charitable Foundation

John and Claudia Barnings

Carolyn Basanich

Diane Baxter

Mark and Juliann Beales

Glen and Susan Beebe

Jolie Bergman

Tanya Bevan

Michael Bigney-Russell

Marlene Bissell

Margareta Blix

Sharon Blomlie O’Hara

Shirley Bohannon

Diana Brooking

John and Tonjia Borland

Nickcole Bortz

Robert and Margaret Boyce

Alane and Ralph Boylan

Kathleen Branden

Patricia and Arne Brakke

Olav* and Cynthia Brakstad

David Branch

Dorothy and Chris* Bredal

Eric and Bobbie Bremner

Marilyn Bringedahl

Pamela Brooks

Kari Brothers

Ruth and Richard Brown

Thelma Brown

Gro Buer

Jennie Burwell

Cadence Apartments

Patricia Carey

Dale and Jean Carlson

Nancy Carrs Roach

Katherine and John Casida

Gary and Henryetta Castellano

Jackie Caswell

Hank Chin and Soo Kyung

Chin

Joan Christ and Tom Everill

Kristina Clawson

Anne Coiley

Jo Ann Coney

John and Jodi Coney

Richard and Judith Curley

Clyde Curry

Dan and Andrea Daniels

Laura Cooper and Stuart Mork

Microsoft Matching Gifts Program

Beth Alderman and Edward Boyko

Daughters of Norway, Gina Krog #38

Daughters of Norway, Sigrid

Undset Lodge #32

Jan E. Delismon

Karoline Derse

Patricia Desmond

Cathleen Dickey

Roger and Ruth Diemert

Grete Dixon

Richard and Linda Domholt

Warren Doty

John and Mary Douglas

Marcia R. Douglas

Anna Marie Drexler

Steven and Gail Dzurak

Edna Eckrem

Betty Edwards

Donna Eines

Sharene and Zac Elander

Kathryn Emmenegger

John Enge

Amy Erickson

GeorgeJean Erickson

John Erickson

Kristin Erickson

John and Katherine Evans

Thomas and Willy Evans

Family of Reidar Fammestad

Barbara and Frank Fanger

Mildred Fast

Geoff Ferguson and Joan Valaas Ferguson

Sylvia Field

Elvira and Don Fife

Finnish American Heritage Committee

Joanne Foster

Ryan Franklin

Senator Karen Fraser

Fred Fredrikson

James and Anna Freyberg

Mary O. Fricke

Sharon and Richard* Friel Frihet Lodge #401, VOA

Paul Friis-Mikkelsen and Rita

Hackett

Hansine Frostad

F/V Gene S. Inc.

James and Marilyn Giarde

Ivar Gilje

Shelby Gilje

Bonnie Good

Marjorie J. Graf

Bill Greger

Estate of Elvin B. Gustafson*

Carina Halgren

Betty and Reidar Hammer

Heidi Hansen

Rigmor Hansen

Kermit and Jane Hanson

Bill Harbert

Susan Haris

Kari Hauge Allen

Mary Margaret Haugen

Torgeir and Helen Haugland

Jim and Ann* Hayes

Alice Hedberg

John Heggem

Robert and Donna Hegstrom

Ken and Ruth Helling

Paul Heneghan

Mary Henry

Tom Herche

Inger-Marie Hermann

Jason Herrington

Val and Joe Hillers

Mary and Mark Hillman

Ruth and Gene Hockenberry

Frank Hofmeister

Charlotte Hoiosen

Rolf Hokansson

Tapio and Brend Holma

Ronda and Ray Holmdahl

Fritz Horand

Horgan Associates Inc.

Tore Hoven

Lois Huseby

Icelandic Room Committee

Gail and Roger Ide

Melanie Ito and Charles Wilkinson

Sandi and Joel Ivie

John and Justine Jacobsen

Patricia Jacobsen and Alan Gurevich

Pekka and Mari Jaske

Sally Jepson

Mary and Jim Jessen

Carl and Ellen Johanson

Richard Johnsen*

David Johnson

Jerome and Susannah Johnson

Margaret and Max Johnson

Richard Johnson

Richard and Ingri Johnson

Sigurbjorn Johnson*

James and Dianne Johnston

Paul and Lillian Johnston

Elaine Jorgensen

Ellen Juhl

Camille Kariya

Astrid Karlsen Scott

Christina and Michael Katsaros

Raisa Kaufman

Irwin and Judith Kennedy

T.J. and M.O. Kennedy

Donald Kerr

Ginny Kettunen

Doug Kilgren

Ove and Edith Kilgren*

Sam Kito

Victoria Knoll

Elise Knudsen

Laura Knudson

Jeanne Kohl-Welles and Alex Welles

Jari and Minna Koponen

Glenn and Rosemary Krantz

Ivan Kristjanson

John Kvinge*

Rolf Laderach and Minna Gronlund-Laderach

David and Marlene Lafave

Lang Manufacturing Co.

Dorothea Larsen Adaskin

Ingrid and Lennart Larsson

Kristine Leander

Helen Lee*

Bill and Jody Lemke

Kathleen Lindberg and David

Skar

Joan B. Linde

Rocky and Casey Lindell

List compiled May 2016. Every effort has been made to ensure its accuracy. Please contact Jan Woldseth Colbrese at 206.789.5707 x39 or janwc@nordicmuseum.org for corrections or additions.

Kathleen Lindlan

Brett and Jennifer Liskey

Pat Loftin

Michael and Laura Logan

Lorraine Longo and Frederic

Dahlem

Jette Lord

Richard and Carolyn Luark

Sarah and Arnold Ludvigsen

Stuart and Dorothy Lundahl

Lunde Marine Electronics, Inc.

Laura Lundgren

Edith Maines

Victor and Karen Manarolla

Pat Martin

Richard and Elizabeth Marquardt

Joseph and Charlotte Matsen

Hans and Irina Mauritzen

Paula Maxwell

Art McDonald

Norman and Constance*

McDonell

Robert S. McEwen

Gwen McGrath

Donald McLaren

Eeva and Jeffrey McFeely

Neil McReynolds

Renate McVittie

Joan Melcher

Walter Meredith

Bruce and Carol Meyers

William and Bonnie Meyers

Curtis and Mary Mikkelsen

Kaare Mikkelsen

W. C. Twig Mills and Alison Stamey

Donald and Dolores Mooney

Karoline Morrison and Dennis

Beals

Maureen Munger

Andrew L. and Doris I.* Nelson

Marvin and Sandra Nelson

Ingrid Ness

Sandra Nestorovic

Nona and Robert Nicholson

Stella Nieman

Nordiska Folkdancers

Carl J. Nordstrom III*

Elsie Norman*

Steve and Catherine Numata

Joan Oates

Ted and Jean Oien

Rick Olafson

Shawn Olsen

Shirley Olsen

Steve and Nancy Olsen

Leanne Olson and Jim Bailey

Roselyn M. Olson

Hans and Ingrid Orth

Elisabet Orville

Thomas Ousdale

Christina A. Owens

Dorothy Owens

Alene Patterson

Virginia Paulsen

Jeffrey Payne

Eric and Ingrid Pearson

Ray and Ruth Pennock

Melba Petersen*

Douglas and Sheila Peterson

Mardell and Mark Portin

Virginia Prestegaard

Puget Sound Regional Council

Matt Quint

Marie Ramstead Zobrist

Vija Rauda

Dorothy Raymond, L.T.

Raymond Family, Paul Raymond, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of Lars Brekke

Mollie M. Reeves

Karen Regenauer

Kea Rehn and Douglas Chatfield

R. R. and Hedda Reid

Kay Reinartz and Richard Frith

Kirk Reiten

Steven Reiten

Fred and Alyne* Richard

Julia Ringrose

Roger Rippel

Ann Risvold

Robert and Carmen Robbin

Stanley and Erika A. Rogala

Mabel Rosvold

Claire Sagen

Alice Sagstad

Luis Salazar and Yolanda Leon

John Salenjus

David, Bryn, and Bridget Savage and Laurie Medill

Michael Schick and Katherine Hanson

Steve and Peggy Schmitz

Roy Schonberg

Carleen and Charles See

Roald Severtson and Liz

Gallagher Severtson

Marilyn Sheldon

Shirley Jo Hanna Sigurdson

Jonas Simundson*

C. Elmer and Patricia Skold

Ellen Grude Skugstad

Patricia and Landis Smaaladen

Rosemary Small

Barbara Snoey

Paul and Charlene Snyder

Helen Sommers

Sons of Norway, Grays Harbor Lodge #4

Sons of Norway, Poulsbo Lodge #44

Anker and Ruth Sorensen

Margie Sorlie

Henrik Sortun

Linda and Michael Sprague

Eli Stahlhut

Jim and Sonja Staley

Liv Stangeland*

Monica Stenberg

Judith Anne Stenford

Kirk Gunnar Stensvig

Virginia Stout

Joyce Strand

James and Jenny Strock

Bethany Sugawara

Vesa Suomalainen

Molly Svendsen

Robert and Mary Jo Svendsen

Carl Swenson

Carl E. Swenson* and Jean Eastman Swenson

Alice Swinland

Taku Graphics

Mary Tannehill

Norma Thomasson

Neil and Patricia Thorlakson

Heidi Thorsen and Johnny Stutsman

Robert Thorson and Leone

Murphy

Valerie Thorson

Donald and JoAnn Thuring

Lorna and Ritchie Tilson

Carl and D. Marlene Tingelstad

Daniel and Jean Tolfree

Sandra and Richard Tomlinson

Camille and Alan Torget

Louise Torseth

Joan Tracy

Candace Trautman

Christine Trigg and Doug Hauger

Anne Tstee Aronson

Sonia A. and Richard L. Turner, Jr.

Gordon Tweit

Barbro Carlson Ulbrickson

Sonja Ulvestad Coffman

United Finnish Kaleva Brothers & Sisters Lodge #11

Sylvia Vikingstad

Mark Vinsel

Malfrid Vintertun

Ed and Joyce Waight

Marlys S. Waller

James Warren and Wendy Hutchins Cook

Don K.* and Evelyn K. Weaver

Margit Weingarten*

Ross and Nancy Weinstein

Penny S. Welsh

Norm Werner

West Coast Finnish American Singers Association

Norman* and Benita

Westerberg

Richard and Judith White

James Whiteley

Randal and Kristi Wiant

Dorothy Wicklund

Laurie and George Williams

Lorrin Williams and Lisa Lindstrom

Lynn and Sonny Wirta

Archer Wirth

Elsa Wise

Richard T. Wise

Connie and Roger Wolter

Rosemary Wood

Sonnera Joyce and Edward Wood

Larry T. Yok

Vivian Zagelow

Frank and Shirley Zahner

Sharon Zerr-Peltner

Murlyn Zeske

Anonymous (12)

*Deceased

Contributed by Kirstine Bendix Knudsen

NORDIC HERITAGE MUSEUM, with generous financial support from the Nordic Council of Ministers, had the opportunity to invite forty-five academics, scholars, and museum professionals, from the Nordic countries and from North America, to advise the Museum on the development of the new core exhibition for the future museum. The Nordic Council of Ministers has developed a new strategy for branding the Nordic countries as an aligned unit that supports Nordic Heritage Museum’s vision.

The core of this new approach is described in the opening of the Nordic Council of Ministers Branding Strategy: The Nordic region is appealing. For some time, characteristically Nordic cuisine, design, films, music, and literature have been bringing the Nordic region international recognition. The successes, which come from all the Nordic countries, often share a distinctly Nordic element— a Nordic trademark.

However, the Nordic region first started to distinguish itself internationally in the aftermath of the financial crisis [2008–09]. The Nordic governance and welfare model once again showed it was capable of renewing itself. Countries all over the world began to discuss whether the Nordic model could serve as a possible buffering and stabilizing factor in an increasingly uncertain global economy. The Nordic region is also facing a number of serious challenges and is far from perfect, and it is perhaps this imperfection that makes the region fascinating.

At the same time, the Nordic countries are always at the top of international rankings regarding openness, trust, equality, environment, and happiness. These are the values the Nordic Council of Ministers wants to share with the rest of the world in their strategy for international branding 2015–2018. The objective is not to convey a homogeneous picture of the countries in the Nordic region, nor to give an impression that all Nordic citizens, organizations, and governments think and behave in the same way. Instead of emphasizing the distinctive features of each country, the strategy is to promote what they have in common: the

Nordic perspective, the values, and a culture that has grown out of a common history.1

As a part of their strategy, the Nordic Council of Ministers has hosted a number of events in the US, including the successful Nordic Cool Festival in Washington, D.C. in 2013. From 2016 on, they expect Nordic cooperation to be present on a larger scale in the US with events focusing on climate, culture, and much more.

Nordic Heritage Museum is the only museum in North America that represents the entire Nordic region: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden, as well as the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Åland. The Museum and the Nordic Council of Ministers both share a similar mission: to brand and promote the Nordic Region for an international audience.

In the spring of 2015, Nordic Heritage Museum invited the Nordic Council of Ministers to become a partner and

Openness and a belief in everyone’s right to express their opinions

Compassion, tolerance, and conviction about the equal value of all people

Trust in each other and also, because of proximity to power, trust in leaders in society

New ways of thinking, focusing on creativity and innovations

Sustainable management of the environment and development of natural resources

collaborator in the critical development process for the new Nordic Heritage Museum. It was not only about strengthening the new Nordic Museum’s profile, but also to provide a North American platform for the Nordic Council of Ministers on which to expand, promote, and realize its vision for the Nordic countries. The goals of the project are:

To define the new Nordic Heritage Museum’s core storyline in close collaboration with experts who possess specialized knowledge of Nordic history, culture, and values.

To create partnerships with museums and cultural institutions in the Nordic Region in order to promote the exchange of ideas and artifacts.

To form an alliance with the Nordic Council of Ministers to support the establishment of the new Nordic Museum and contribute to the dual vision of expanding knowledge of the Nordic countries and communicating Nordic values in an American context.

To create an authentic and current Nordic platform in Seattle that will continuously attract cultural stakeholders from the Nordic countries and serve as a showcase for Nordic culture and the promotion of that brand.

A grant from the Nordic Council of Ministers’ program, “Neighbors to the West,” made it possible for the Museum to gather forty-five stakeholders from the Nordic Region and North America in, respectively, Copenhagen and Seattle, for two symposiums. Both meetings were very fruitful. The Museum received valuable feedback from the group and the Nordic Council of Ministers found the project successful: “We are happy to know that our support has given Nordic Heritage Museum an opportunity to work with the storyline for the new museum on a genuine Nordic basis and with support from competent people and professionals from the Nordic countries,” said Dagfinn Høybråten, Secretary General, Nordic Council of Ministers.

THE NORDIC COUNCIL OF MINISTERS is the official intergovernmental body for cooperation in the Nordic Region. There are ten thematic minister councils and an overarching minister council, the Nordic Cooperation Ministers, that coordinate the overall cooperation. The Nordic governments meet at the minister councils to develop and implement policies and strategies, draft Nordic conventions, and much more. In 2014, the Nordic Cooperation Ministers decided on a vision to strengthen the trust-based cooperation by addressing solutions for the challenges and dilemmas within globalization, resource consumption, economic crisis, and climate change through regional and international cooperation.

The Nordic Council of Ministers is a central platform for cultural cooperation. The activities of the Council in the field of culture have positive effects in other areas of Nordic cooperation, both in and outside the Nordic region. norden.org

1Foreword to Strategy for International Branding of the Nordic Region, 2015–2018. Nordic Council of Ministers, 2015.

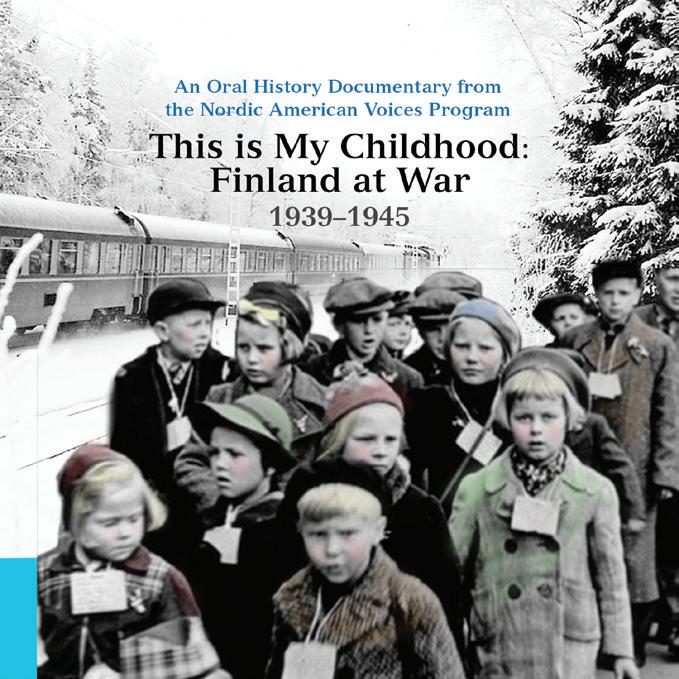

A film documentary based upon oral history interviews conducted by the Nordic American Voices program

A limited numbers of copies are available in the Museum Store.

Featuring Norway’s Arne & Carlos

Nancy Bush

Evelyn Clark

Susanna Hansson

Judith MacKenzie

Laura Ricketts

Susan Strawn

Susan Azadi

OCTOBER 8–10 IN SEATTLE

If you’re looking for something uniquely Nordic, stop in the Museum Store on your next visit!

Members enjoy a 10% discount on all purchases and 20% off twice a year during Member Appreciation Weeks.

ANDERS BEER WILSE (1865–1949) came to America from Norway as a young man, first to Minnesota in 1884 via New York, and then later to Seattle in 1890. Arriving in Washington State, Wilse, who had trained as an engineer, was employed by the Great Northern Railway for two years, building the railroad across Stevens Pass in the

Cascade Mountains. His early photographs from this time document life in the railroad workers’ town, before and after the railway was completed. There are images taken from afar showing workers shoveling snow or laying line on timbered platforms high above the snow pack, as well as more intimate images of daily life, such as workers getting

haircuts. Wilse was an outdoorsman through and through: a primitive hut of slat boards served as his first darkroom during his time in the Cascades. Subsequent travels around the state took him from Spokane to the Olympic coast, north to Kootenay Lake in British Columbia, and to Paradise Valley at the foot of Mount Rainier.

Wilse’s engagement with photography as a profession had a profound shift in focus when, in 1897, he joined travel photographer David Kirk as a business partner in a new photography studio in Seattle. Wilse referred to this as his “do or die” moment in choosing photography as his lifelong pursuit.1 The partnership with Kirk was short-lived—only six

months—and was already over when Wilse left Seattle on a three-month excursion to photograph the landscapes of Montana and Idaho. However, the commercial success of his photographs convinced Wilse to remain in Seattle and to continue documenting subjects such as hotel interiors, the logging industry, Native American encampments, the

Alaskan Gold Rush, and, in 1898, a contingent of visiting Sámi reindeer herders in Seattle’s Woodland Park.

In October 1900, only three years after starting his Seattle studio, Wilse returned to his native Norway, where, on May 1, 1901, he opened a photography studio in Nere Slottsgate in Kristiania.2

Contributed by Fred Poyner IV

Wilse’s 1898 photographs of the Sámi provide an important visual record of Nordic labor of the period. Together with Kirk, Wilse took at least eleven photographs showing a mixed Sámi, Finnish, and Norwegian group of men in March at Woodland Park. The men had been hired by the U.S. Government to escort a shipment of 537 reindeer that arrived in Jersey City on the steamer Manitoban that February, and to shepherd the herd safely to the West Coast, before the animals were to travel north to the Klondike region of Alaska.3

The Seattle herd of 1898 was but one such importation of reindeer for the Northern Territories. There are different versions of why reindeer herds were secured by the U.S. Government for Alaska. In one version, taken from a history of North Kitsap, Washington, the group escorting the Seattle herd was called both “Lapps” and a Norwegian variant, “Samer” (pronounced Sah-mur). The rationale cited was the need to provide reindeer meat to starving “Eskimos” (Inupiaq) located off the Arctic coast of Alaska. Another account, dating from 1906, based the reason for the Seattle reindeer herd on a story that had circulated out of the Yukon in 1897. In this version, American miners “were starving,” and Dr. Sheldon Jackson had persuaded the War Department to release funds for the purchase of the herd from “Lapland.”4 Jackson, who was General Agent of Education in the Alaska Territory, was instrumental in efforts, dating back to as early as 1890, to secure imports of reindeer for native Inupiaq in the Arctic. The intention was to train the Inupiaq as herders and was also part of a broader missionary-led effort to convert them to Christianity.

A third account, published by the Seattle Daily Times the same month the reindeer herd occupied Seattle’s Woodland Park, offered the most insight into the ultimate fate of the herd and the destination of its Nordic handlers:

Although the purpose for which these reindeer were purchased, i.e. the Government relief Klondike expedition, has been abandoned by Secretary Alger, the ultimate destination for the herd is Alaska just the same. The program now is to divide the herd into two parts…the greater number, 337, will leave here for Pyramid Harbor…under the charge of the reindeer expert, W.A. Kjellman [sic]. The remaining 200 reindeer will be sent to Prince William Sound with about fifty herders, under command of Capt. Abercrombie.5

In reviewing the history of the Sámi in Woodland Park, we can look to the photographic record established by Wilse to provide excellent details about the people described in newspaper articles. The aforementioned Mr. Kjellman is shown in Wilse photograph #563, holding the tether to a young, dehorned reindeer calf. He wears a knee-length overcoat, button-down wool jacket, and a square-shaped hat. His personage appears to be one of seriousness, with his gaze focused on something off to the right, and out of view. (The reindeer also looks in this direction.) In the background are a number of young evergreen trees, perhaps recent plantings in the park.

Was Kjellman one of the Sámi, or was he counted among the Finnish or Norwegian members of the Seattle group of herders? He is dressed entirely differently from those individuals seen in other Wilse photographs who can be identified as Sámi by name. This suggests that

Kjellman belonged to either the Norwegian or Finnish contingent of the group of herders. There is a record of Kjellman’s being hired by Dr. Sheldon Jackson in 1893 to be Superintendent of the Teller Reindeer Station in Alaska. In this record, he is identified as a Norwegian from Madison, Wisconsin, who grew up working with reindeer in “Finmark” and is fluent in the Sámi language.6

Wilse’s photograph of Kjellman not only found application in 1898 as a newspaper illustration for the Seattle Daily Times but also serves as a visual commentary in today’s archival record. Digitized copies of the very same photograph have been saved in the University of Washington’s Special Collections and Nordic Heritage Museum’s photograph archive. Moreover, Wilse’s photograph series of the Seattle reindeer herd in Woodland Park offers additional examples of known Sámi individuals and groups. A collection of these will be included in the upcoming exhibition People, Places, Changing Lands: The Photography of Anders Beer Wilse, hosted by Nordic Heritage Museum in December 2016.

1 Anders Beer Wilse, En Emigrants Ungdomserindringer, vol. I, 1936: 50.

2 Ibid, p.121; Roger Erlandsen, Pas paa! Nu tar jeg fra Hullet! Om fotografiens første hundre år I Norge – 1839–1940, 2000: 231.

3 Osborn Spencer, “Ten Thousand Tame Reindeer in Alaska,” Seattle Daily Times, 5 August 1906: 3.

4 “Loaned Deer to Missionaries,” Seattle Daily Times, 2 April 1906: 5.

5 “The Herd of Reindeer,” Seattle Daily Times, 10 March 1898: 5.

6 “Alaska Chronology — 1893,” Báiki: The International Sami Journal, 2001–2015, URL: http:// www.baiki.org/content/alaskachron/1890.htm [accessed: February 25, 2016].

Adapted from the exhibition at the Museum of Danish America

In the early morning of April 9, 1940, German military forces invaded Denmark—a step in Adolf Hitler’s quest to conquer the whole of Europe.

The Danish government and King Christian X knew that fighting Germany was unrealistic: the German army was much stronger and any conflict with them would mean a needless loss of life. So, after a brief battle of a few hours, Denmark surrendered to the aggressor.

An “act of protection” was what the German government called their occupation of Denmark. They saw the Danes as belonging, like themselves, to the Aryan race—the supreme master race that formed the basis of Germany’s Nazi ideology. Because of this, Denmark was allowed keep its own government and authority, and King Christian X could continue to reign as a symbol of national independence. Denmark was permitted a favored-nation status with Germany and, in return, the Danes agreed to export food and industrial goods to Germany.

At this time almost 8,000 Jews lived in Denmark. The Germans were being exceptionally cruel to Jews in other

countries, following Adolf Hitler’s “Final Solution.” But at first, a blind eye was turned toward the Danish Jews. This was in part due to Werner Best, who had been appointed the German Reich’s Commissioner for Denmark. Best knew of Hitler’s plan to exterminate Europe’s Jewish population. He also knew that any attack against Jewish Danes would be seen as an attack against all Danes. To keep the peace, Best reported to Hitler that there was “no Jewish problem” in Denmark.

However, the situation was to change radically in mid-1943 after the Germans suffered major defeats in North Africa and the Soviet Union (Russia) at the hands of the Allies. These victories inspired greater resistance by the Danes toward their German occupiers.

For the previous three years, the Danes had passively resisted the Germans. Now, there were food shortages and other deprivations, and feelings of oppression and hatred toward the Germans grew stronger. Civil unrest soared. The Danish

Resistance Movement led nationwide strikes. Conflict between the Danes and the Germans escalated.

In August 1943, the Danish government refused to accede to new demands from its aggressor. As a consequence, the government of Denmark was dissolved and martial law was instituted by Germany. Now the Jews of Denmark no longer had their government to protect them from the Germans. In fact, the Germans already had a plan for the Jews: they would seize all Danish Jews overnight—between October 1 and 2—and would remove them to Germany in two large boats and a bus. The dates chosen coincided with Rosh Hashanah, one of the holiest times of the Jewish year.

Werner Best told his confidant, German diplomat Georg F. Duckwitz, of the plan to deport the 8,000 Jews. At great risk, Duckwitz traveled to Germany to try to stop the deportation. When that failed, he traveled to Sweden to find refuge for the Danish Jews. Then Duckwitz leaked the information about the

“Something unusual happened to Eichmann and his men: the Jews slipped from their very grasp and disappeared, so to speak, behind a living wall raised by the Danish people in the space of one night.” —Museum of Danish America

pending round-up to Jewish leaders and to Danish Resistance members. He also told them of the sanctuary Danish Jews could find in Sweden. The news spread with lightning speed across the country.

Rabbi Marcus Melchior was among those who learned of the deportation plan. At early morning services, on September 29, the day prior to Rosh Hashanah, Rabbi Melchoir told the 150 Jews in his congregation that the Nazis would invade their homes, seize them, and send them to concentration camps. He warned everybody not to return home, to spread the word, and to go into hiding immediately.

The threat to the Danish Jews was a direct attack on the whole Danish population. It ignited the most impressive and complete rescue mission of World War II.

The citizens of Denmark would not stand for the inhuman round-up of Danish Jews. People from every walk of life came to the Jews’ defense. Ordinary citizens offered hiding places in their homes and on their property. Churches and hospitals became safe havens. Complete strangers offered help to anyone who appeared Jewish or had a Jewish sounding last name. Police officers refused to join in the manhunt.

Most of the Jews looked for safety with Gentile friends or supporters. They also went into hiding in the countryside or

in harbors on the coastline. Because of this unprecedented joint effort, the Nazis found very few Jews when they arrived the next night. Less than 500 individuals, just seven percent of the Danish Jews, were arrested. Most of them were too old, too sick, or unable to flee. A few in hiding were disclosed by Nazi informants. Those arrested were deported to Theresienstadt, the concentration camp in occupied Czechoslovakia. Theresienstadt was not an extermination camp: the Danish Red Cross was permitted to monitor the care of Danish citizens at the camp. Only fiftytwo Danish Jews died at Theresienstadt, because of disease or deprivation.

In the course of just a few weeks, the remaining Jews—close to 7,500 people— were secretly evacuated from Denmark and shuttled across the Oresund to Sweden at night, by any vessel available. The 10-mile journey across the waters of the Sound was cold and rough. There was no question, though, that this was a better option than Nazi concentration camps.

More than 800 trips were made across the Sound. Danish Jews disembarked at their destination to be greeted by Swedes who were awaiting their arrival. Some large ferries carried dozens of refugees at a time. Other refugees found passage in the hulls and storage areas of cramped and smelly fishing boats, or in rowboats or kayaks, where only a few people could be stowed safely.

After Germany’s surrender in 1945, the Danish Jews came back from Sweden. Many found their homes and possessions untouched. They had been protected by their Danish neighbors until their return.

Copenhagen professor Dr. Erik Husfeldt was a renowned surgeon and respected member of the community. He was also a strident oppositionist to the occupying Nazi regime. A leader of the Danish Resistance, his family lived out World War II in hiding, while they aided Danish Jews fleeing Nazi persecution. As the defeated German army marched out of Copenhagen, Husfeldt and his fellow compatriots in defiance wore blue, white, and red armbands—the symbol of the Danish Resistance. This is the armband that Husfeldt proudly wore that very day (above).

Dr. Husfeldt was awarded the American Medal of Freedom with two Bronze Palms by General Eisenhower. He was also one of the signees on the Charter for the United Nations in 1945.

Facing page: Passengers aboard a Danish transport ship, ca. 1943. Museum of Danish America

The Fencer storyline: In the mid-1950s, Endel Nelis arrives in Estonia, having left Leningrad to escape the secret police. He finds work as a physical education teacher and becomes a father figure to his students, as many are orphaned because of the Russian occupation. He teaches them his passion—fencing, and the sport becomes a form of self-expression for the children. The children want to participate in a fencing tournament in Leningrad. Endel must make a choice: risk everything to take his students to Leningrad or put his safety first, and disappoint them.

The Fencer (2015), a film by Klaus Härö, was shown at the 2016 Nordic Lights Film Festival at the Seattle International Film Festival (SIFF). The first-ever Finnish film nominated for a Golden Globe, it was shortlisted for an Oscar in 2016

Härö was interviewed by Nordic Heritage Museum Public Programs Coordinator, Stina Cowan, and Program Manager, Jonathan Sajda.

SC: The Fencer is beautiful! What about Endel Nelis made you want to tell his story?

KH: Actually Anna Heinämaa’s original screenplay attracted me. I had not heard about Endel Nelis, and I made a decision not to find out, either. What I needed to find out were the circumstances of the Estonians during the 1950s Stalin era. I tried to do that research very, very carefully. If I had started to research his life [beforehand] I would have been totally distracted. I’ve been there before: you have a historical subject, and find yourself drowning in all these wonderful stories and interesting facts. You just can’t get them all into an hour and a half or two hours. If I can find a way to capture something of the human condition, which is universal, and about the spirit of the time, then the audience will feel satisfied.

I wanted to go at it through the writer’s central idea—the story of a man in hiding. He has a need for communion with other people, but is forced to be a

loner. This story was very attractive—he finds his life again, finds his way back through the children. I thought that was just a beautiful, beautiful thing.

SC: You directed in Estonian and Russian—two languages you don’t speak? How did that work?

KH: Film is not about dialogue. Movies are about telling stories in pictures. You put one picture to the next, and you add music, you have the audience right there. Everybody is saying, “Oh, I know what’s going on. I know what’s going to happen.” You need a certain amount of dialogue to reveal things, but really what I strive to do is tell the story in a cinematic way. When I read any screenplay, there are two things I’m looking for. One is content: is this something that I really will be interested in a year from now, three years from now? And the other thing, obviously, is a story told in visuals. It doesn’t mean it has to be a very flashy thing. It can be a low-key, intimate thing as well. I felt that this was a story about bringing hope where there is none. And the idea of bringing this beautiful, classical, almost dance-like sport into a world of gloominess…it was an idea to bring beauty into ugliness.

SC: In many of your movies you have child actors, and especially so in The Fencer. How do you work with children to make them such great natural actors?

KH: It is hard work in one respect. Shooting a movie, we might do the last scene first and the first scene last. With children, I need to keep track of what should happen emotionally in every scene. I don’t have to with adult actors. We had to go to schools, sports events, clubs, and look for the kids, and talk to their parents, and ask if they would let them come to a casting. It was a huge undertaking.

JS: We read that The Fencer was the hardest film that you’ve ever made. Could you speak to that a little bit?

KH: As I said, you read a script, you fall in love with it, and then it’s in Estonia, a new culture for me. The language barrier

was pretty hard with the children. We went with very simple instructions in broken English, and I think it went fine. It was a lot of work with all the fencing scenes. [There were] limited resources, so we were really tired in the evenings. But that’s how it should be.

SC: How long did it take you to film the movie?

KH: The shoot took thirty-nine days. Because it was a period piece, we had to build sets for everything; you have to dress everything; you have to prepare everything. You have the sport of fencing, where you have to rehearse before you can

film a single shot. You have to block it very carefully so no one gets hurt. A lot of work!

SC: This is the fourth time one of your movies has been picked to represent Finland as the foreign film at the Oscars. Has this affected your career in any way?

KH: It’s not something you take into account while working on a film. When you choose a project, it’s first and foremost: do I care enough, do I have something to give, do I feel I can go back to the producer and say, honestly, I need to make this film? I resist a story as long as I can, until I cannot, and then I’ll take it on. Being considered for an Oscar, it’s a huge thing. But being selected is not something you get used to. It’s always a gift that makes you very, very humble.

JS: Tell us more about working with actor Märt Avandi. He’s been very successful in comedy before this film, but this is obviously a dramatic role.

KH: When I first saw Märt Avandi, I

thought he would be wonderful as our fencing teacher. He had the look of the old movie actors, [like] Henry Fonda, that kind of beautiful man, with sad eyes…and with a secret. I thought, “Wow, he’s perfect.” In tiny Estonia, he’s a huge star, but I did not know this. I chose him for his acting abilities and his appearance. On YouTube, you’ll see these really silly, absurd sketches he’s done. They’re hilarious in their own way. I’ve worked with comic actors before in dramatic roles. Comedic actors use pain and sadness as inspiration for comedy and are equally able to use those feelings for dramatic roles.

Klaus Härö is one of the most internationallypraised Finnish directors. His films are favorites in both Finland and Sweden. He received the Ingmar Bergman Award at the 2004 Guldbagge Gala, the Swedish equivalent of the Oscars—a first for any non-Swedish director.

SC: American movies are very different from Nordic movies, but it seems that Nordic movies have become increasingly popular here in the US. Why do you think that is?

KH: A good question! Nordic directors are learning from American films. Finnish films have not made that leap into general consciousness the same way Swedish thrillers or Danish dramas have. There’s a reason for that, of course. We just haven’t been at that professional level. I remember growing up watching films by Bille August or Hallstrom, and thinking, they’re so close geographically, but when it comes to quality, they’re light-years away. Today we have a generation of Finnish filmmakers my own age who are very eager to learn and eager to draw on both European and American traditions. There’s a quality, hopefully, that we can give our films that is uniquely Scandinavian—maybe some sort of a fragile feeling, sensitivity, a sort of melancholy.

The mysteries surrounding Nordic food and culture continue to be the topic of exhibitions, articles, and passionate debates amongst critics and members of international culinary circles alike. So what would inspire Magnus Nilsson, one of the pan-Nordic arts and culture’s most critically-acclaimed rising culinary stars, to travel for three years throughout the Nordic region collecting recipes, exploring out-of-the-way kitchens, and curating old family recipes, all while shooting several thousands of photos along the way?

Reality. Not the melodramatic stuff of reality television or the folklore traditions of old, but realism rooted in a genuine curiosity to document the diversity and nuanced techniques of modern-day cooking in the Nordic region. “I wanted to record what people are really cooking, not create a fairytale version of Nordic cooking,” says Nilsson. This same outlook also defines Nilsson’s self-described culinary style, rektún mat, which is Jämtlandic for “real food.” “What really makes food authentic is that it is made by

real people who are doing their best with what is available,” Nilsson explains.

For its North American preview, Nordic Heritage Museum was proud to present Magnus Nilsson’s Nordic: A Photographic Essay of Landscapes, Food, and People, a traveling exhibition produced by the American Swedish Institute in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Nordic features photographs by the celebrity Swedish chef in his international debut as a visual artist, anthropologist, and storyteller.

Nilsson infuses his images with the same passion and personality that permeates his cooking. Nordic highlights original, place-based photographs that Nilsson captured of the people he met and the restaurants, private kitchens, and remote locales he explored during three years researching his acclaimed best-seller, The Nordic Cookbook (Phaidon Press, 2015), while seeking an expanded definition of today’s Nordic cuisine.

Nilsson gathered more than 700 indigenous recipes from home cooks, including his grandmother, throughout Sweden, Denmark, the Faroe Islands, Finland, Greenland, Iceland, and Norway, often sleeping on sofas or in tents to get closer to his subject matter, and ultimately shooting some 8,000 photographs. The exhibition and accompanying catalog showcase selected images and invite viewers to discover

food as a universal touch point sharing heritage across boundaries and time.

Nordic also features images of Nilsson’s restaurant, kitchen, and the workings of a chef as described in essays by Swedish journalist Po Tidhom and documented by Minnesota-based photographer Cameron Wittig.

Nilsson’s growing list of accolades include a 2016 award of two Michelin stars for

his restaurant Faviken, regularly listed among the world’s best restaurants. He was featured in the February 2016 issue of Food and Wine Magazine, and in 2015 he earned the White Guide Global Gastronomy Award. A popular television personality, he is also renowned through appearances in the Emmy Award–winning PBS series The Mind of a Chef and the Netflix docu-series Chef’s Table.

Magnus Nilsson is the head chef of Fäviken Magasinet restaurant in Sweden. After training as a chef and sommelier in Sweden, he worked with Pascal Barbot of L’Astrance in Paris before joining Fäviken as a sommelier. Within a year, he had taken over running of the restaurant. Fäviken recently earned two 2016 Nordic Michelin stars and is ranked in the San Pellegrino World’s 50 Best Restaurants list.

Look for details on our next culinary extravaganza.

Immerse your senses in a series of unique experiences with visionary chefs.

THIRTY-SECOND ANNUAL

BENEFITING NORDIC HERITAGE MUSEUM

Brothers Daniel Lee and Wes Peterson are adding the Nordic touch to some of the finest craft beers available in the Pacific Northwest

Nestled in the abundance of craft- and microbreweries that have peppered the Pacific Northwest landscape over the past few decades, Odin Brewery stands out as one of Washington State’s finest. Odin’s special brands of beers, created by hand with a food pairing orientation, pour through hundreds of taps throughout the Puget Sound region and are carried in most major grocery store chains.