A Finnish Touch

150 years of Finnish landscapes

Leading by Example

Nordic innovation, global reach

Artistic Inheritance

Emil and Dines Carlsen

M(other) Tongues

Weaving family and art

The Magazine of the National Nordic Museum

NORDIC KULTUR 2021–22

See what’s in store…

Nordic housewares, artisan jewelry, small-batch candies, best-selling books, Scandinavian toys, and more in the Museum Store

nordicmuseum.org/museumstore

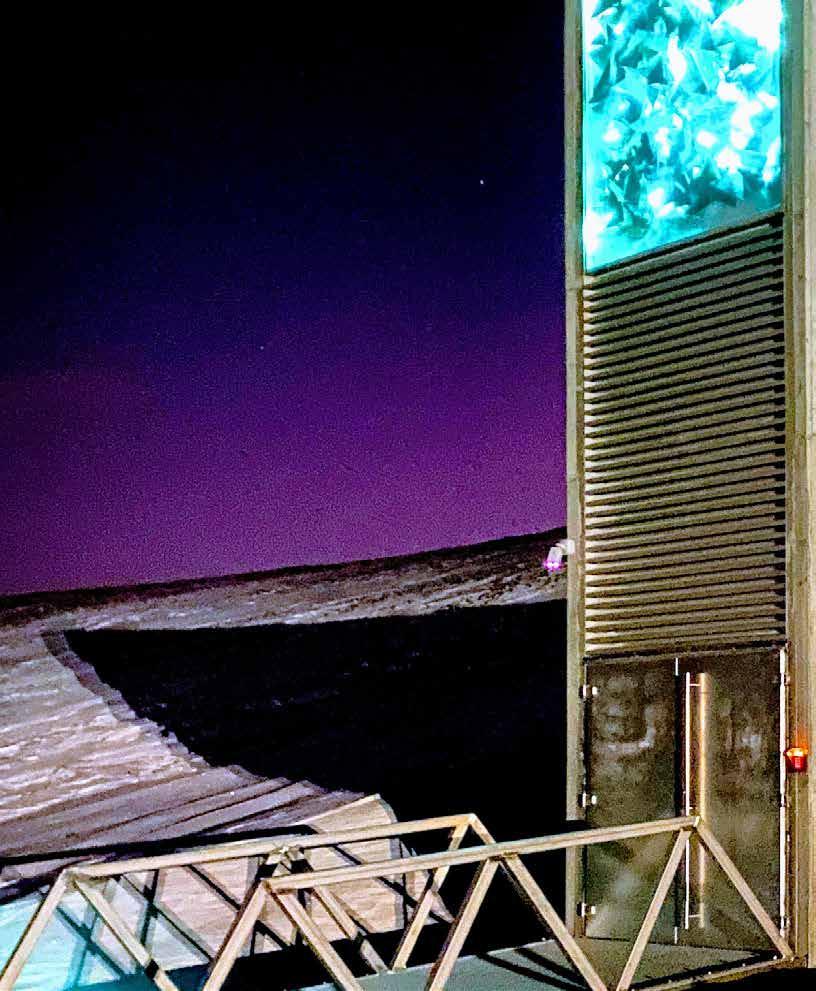

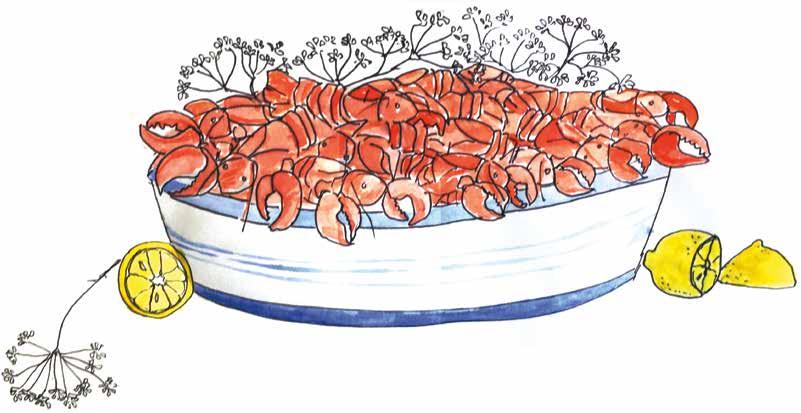

CONTENTS 3 FROM THE CEO 4 EXHIBITIONS 2021–22 An overview of art 6 AMONG FORESTS AND LAKES Finnish National Gallery Masterpieces 11 A ROYAL WEAVING New tapestry acquisition 12 M(OTHER) TONGUES Three generations making art together 16 PAPER DIALOGUES A papercut conversation 18 A PANDEMIC PRESERVED Oral history in the time of COVID 22 IN THE CARLSENS’ STUDIO A father/son artist duo 26 LEADING BY EXAMPLE Why the world needs Nordic innovation 29 VOLUNTEER SPOTLIGHT Q & A times three 30 DRESSING A NATION The Nasjonaldrakt 35 A STITCHED SAGA A crowd-sourced embroidery project 36 NORDIC AMERICA National Nordic hotspots 38 SAVING FOR THE FUTURE Norway’s seed vault 41 SCAN DESIGN An important partnership 42 A TOUCH OF NATURE Friluftsliv and you 44 WEAR IT AGAIN, SAM Creating a closed-loop fashion industry 46 SILVER SCREEN, GOLDEN GOAL A Nordic commitment to equality in film 48 HERE COMES THE BRÚÐR Nordic wedding traditions 51 A BIG DILL Host your own crayfish feast 54 HIP HIP HOORAY Happy birthday, Moomin and Pippi 58 BEER SOUP A new twist on a classic

Join the National Nordic Museum— become a Member today.

Free Museum admission, early access to event tickets, discounted program prices, savings in the Museum Store, and more.

nordicmuseum.org/membership

NORDIC KULTUR 2021–22

The Magazine of the National Nordic Museum

EDITORIAL BOARD AND MAGAZINE STAFF

Eric Nelson Executive Director/CEO

Leslie Anne Anderson Director of Collections, Exhibitions, and Programs

Jenny Iverson Development Manager

Erik Pihl Director of Development

Rosemary Jones Publisher / Director of Marketing

Devon Kelley Editor / Marketing Manager

Ani Rucki Design and Layout / Graphic Designer

CONTRIBUTORS

Leslie Anne Anderson | Rachel Ballister | Stina Cowan | Alison DeRiemer | Judith H. Dern

Kate Dugdale | Becky Forsberg | Lotta Gavel Adams, PhD | Carrie Hertz, PhD | Jenny Iverson | Rosemary Jones

Devon Kelley | Timothy Krumland | Caroline Parry | Erik Pihl | Robert Strand, PhD

BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Trustees

Thomas Malone (President) | Hans Aarhus (Vice President) | Earl Ecklund (Treasurer) | Monica Langfeldt (Secretary)

Electa Johnson Anderson | Lars Anderson | Anne-Lise Berger | Jann Blackbourn | Ray Brandstrom | Jay L. Bruns, III

Ulf Edwaldsson | Ann-Charlotte Gavel Adams | Mike Hlastala | Tapio Holma | Jane Klausen | Kurt Manchester

Jens Molback | Kurt Ness | Per Norén | Aaron Overland | Tuula Rytilä | Maria Jones Staaf | Birger Steen

Henrik Strabo | Johan Erik Strand | Heli Suokko | Nina Svino Svasand | Lisa Toftemark

Consuls

Mark T. Schleck, Honorary Consul, Denmark

Matti Suokko, Honorary Consul, Finland | Kristiina Hiukka, Honorary Vice Consul, Finland

Geir Jonsson, Honorary Consul, Iceland

Viggo Forde, Honorary Consul, Norway

Petra Hilleberg, Honorary Consul, Sweden

Honorary Trustees

Senator Reuven Carlyle | Leif Eie | Irma Goertzen | Senator Mary Margaret Haugen

Lars Jonsson | Sven Kalve | Council Member Jeanne Kohl-Welles | Senator Marko Liias

Fidelma McGinn | Representative Gael Tarleton

MUSEUM STAFF

Executive

Eric Nelson Executive Director/CEO

Sandra Nestorovic Chief of Staff

Curatorial

Leslie Anne Anderson Director of Collections, Exhibitions, and Programs

Stina Cowan Educational and Cultural Programs Manager

Alison DeRiemer Archivist and Oral History Specialist

Kate Dugdale Education and Interpretation Coordinator

Pete Fleming Exhibition Designer and Preparator

Kaia Wahmanholm Registrar and Collections Specialist

Development

Erik Pihl Director of Development

Jenny Iverson Development Manager

Rachel Ballister Membership and Database Coordinator

Caroline Parry Grants and Giving Coordinator

William Ekstrom Development Events Coordinator

Marketing & Communications

Rosemary Jones Director of Marketing

Devon Kelley Marketing Manager

Finance & Human Resources

Pamela Brooks Director of Finance and Human Resources

Carolyn Carlstrom Bookkeeper Drue Chatfield Human Resources Generalist

Timothy Krumland Volunteer Coordinator

Operations

Adam Lee Allan-Spencer Director of Operations and Facilities

Donna Antonucci Guest Services and Event Associate

Roberta Chen Guest Services and Store Associate

Becky Forsberg Guest Services Manager

Joni Hughes Store and Purchasing Manager

David Leers Facilities Coordinator

NATIONAL NORDIC MUSEUM 2655 NW MARKET STREET, SEATTLE, WA 98107 | 206.789.5707 | NORDICMUSEUM.ORG

Welcome to Nordic Kultur, the magazine of the National Nordic Museum!

Like many cultural attractions, the Museum faced a challenging year in 2020. Our doors were closed to the public for nearly eight months; we were unable to welcome visitors to the Museum to view our exhibitions or participate in our programs, special events, and festivals. Those quiet hallways and empty galleries spurred us to find new ways to engage with you and steered us to a year of experimentation and innovation. We shifted our programming to a virtual format to share content, highlighting national and international artists, noteworthy academics, and global thought leaders to explore a host of compelling subjects. The new virtual approach enabled us to build an international online community, dramatically expanding our reach.

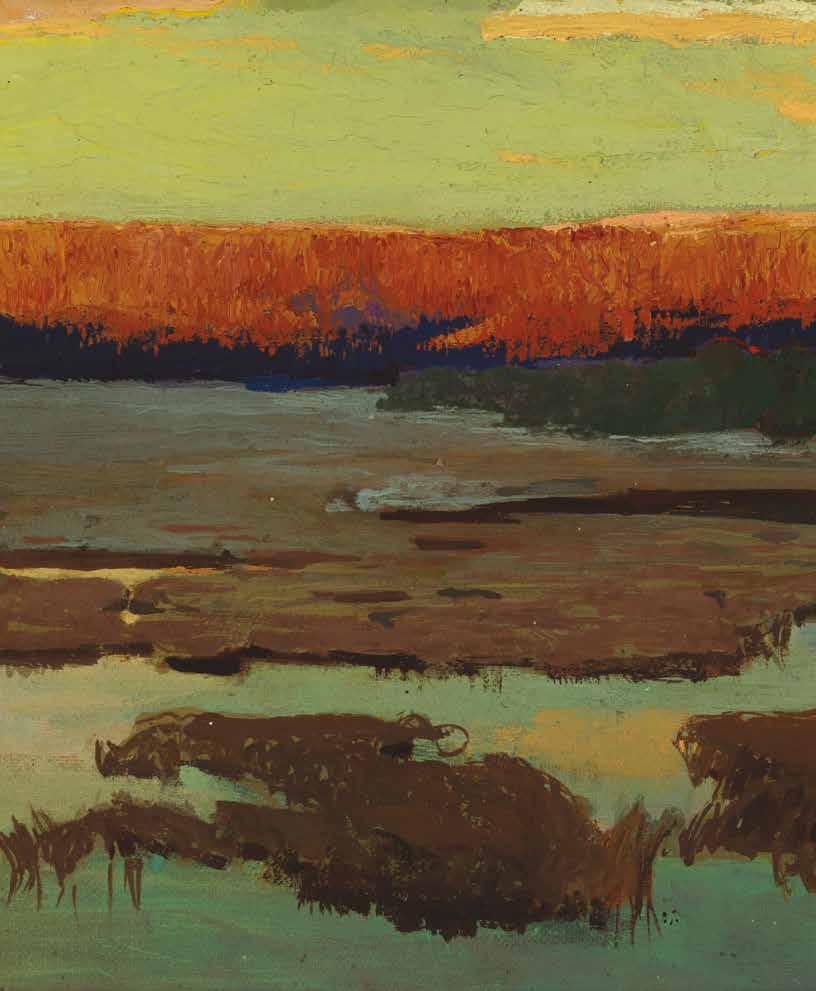

As we look to 2021 and beyond, I am pleased to welcome you back to our galleries to enjoy incredible new exhibitions. In May, we host Among Forests and Lakes: Landscape Masterpieces from the Finnish National Gallery which examines how Finnish artists have depicted the landscape of their native country from the 1850s until the present day. Curated by the Finnish National Gallery, the exhibition explores the sophistication of the Finnish art establishment and the concurrent development of the landscape genre through more than fifty paintings, prints, and video art. Additional 2021 exhibitions explore the history of Nordic ski jumping in the Pacific Northwest, a cross-cultural papercut dialogue,

the multi-generational work of a very artistic Dominican-Norwegian family, and the works of Danish-American artist Dines Carlsen.

Also featured in this issue are articles about our recent acquisition of a royal Swedish tapestry, our new pandemicrelated oral history initiative, a piece on Nordic innovation by Dr. Robert Strand, as well as ruminations on the new Nordic “it” word, friluftsliv. Additionally, UW professor Ann-Charlotte Gavel Adams shares perspectives on Nordic children’s icons, and our own Stina Cowan talks about Nordic cinema. All of these and more articles await you in this issue of Nordic Kultur. I hope you enjoy these stories and articles, and that they inspire you to come visit your Museum.

Eric Nelson Executive Director/CEO

3

Exhibitions 2021–22

Sublime Sights: Ski Jumping and Nordic America

April 17, 2021–July 18, 2021

“To see how an expert ski jumper executes a jump is one of the most sublime sights the earth can offer us.”

—Fridtjof Nansen, polar explorer

Organized by the National Nordic Museum and the Washington State Ski & Snowboard Museum, this exhibition examines how early Nordic-American athletes connected to their adopted land through the sport of ski jumping. It features ski equipment and memorabilia, photographs, film clips, and oral history interviews to show the sport’s development and demonstrate its cultural significance. THIS EXHIBITION IS SUPPORTED BY PEOPLES BANK .

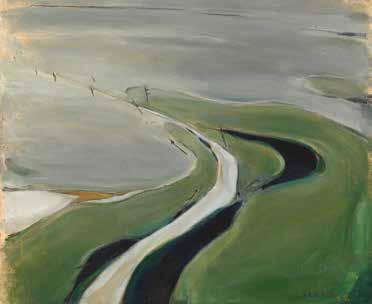

Among Forests and Lakes: Landscape Masterpieces from the Finnish National Gallery

May 6, 2021–October 17, 2021

Drawn from the Ateneum Art Museum/Finnish National Gallery’s collection, this exhibition considers how Finnish artists have depicted the landscape of their native country since the mid-nineteenth century. Over 50 paintings, works on paper, and video art cover more than 150 years and 800 miles from the coast and archipelago in the south to the Arctic Ocean in the north. Among Forests and Lakes is organized into four themes and includes well-known Finnish and Sámi artists such as Akseli Gallen-Kallela and Marja Helander. THIS EXHIBITION IS SUPPORTED BY ANN-CHARLOTTE GAVEL ADAMS, THE BARBRO OSHER PRO SUECIA FOUNDATION, AND THE ROBERT LEHMAN FOUNDATION

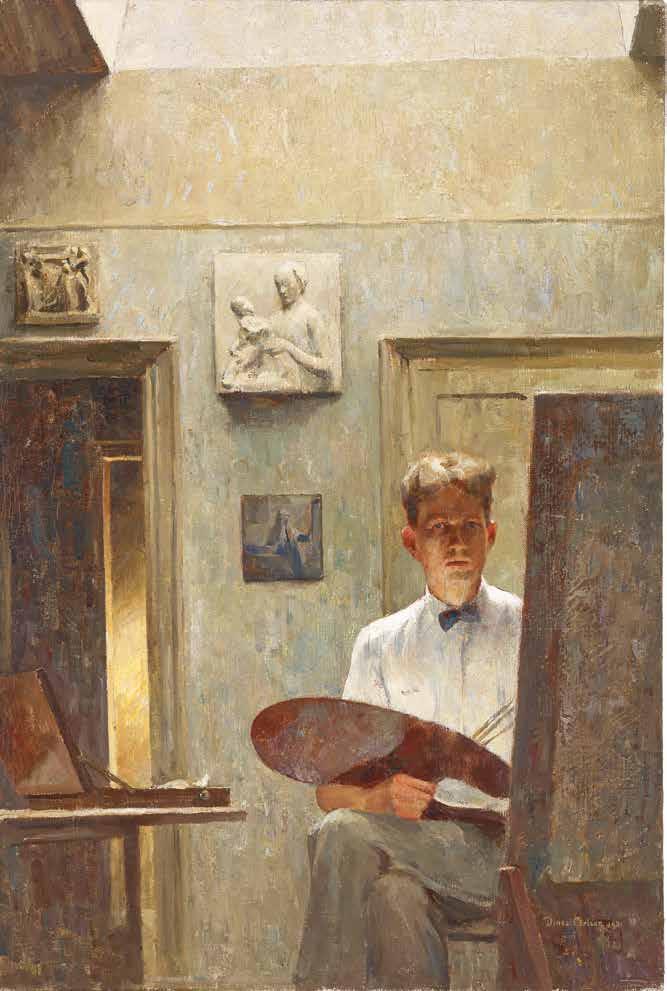

Dines Carlsen: In His Own Manner

July 22, 2021–October 24, 2021

In 1916, American artist William Merritt Chase saw the work of fifteen-year-old Dines Carlsen exhibited at the National Academy of Design, and he predicted “a future of great brilliancy” for the teenaged artist. Dines’s father, Danish-born artist (Søren) Emil Carlsen, had risen to prominence as a skilled painter of still lifes, seascapes, landscapes, and portraits. Because the Carlsens shared a studio and the spotlight, reviews focused on their familial bond. Upon the death of his father in 1932, Dines relocated permanently to northwestern Connecticut, where he developed a style distinct from his famous father. In this dynamic exhibition, visitors will enjoy a rotating selection from the collection of the National Nordic Museum, which received a gift of more than 900 works by the artist in 2020. THIS EXHIBITION IS SUPPORTED BY THE SCAN DESIGN FOUNDATION.

4

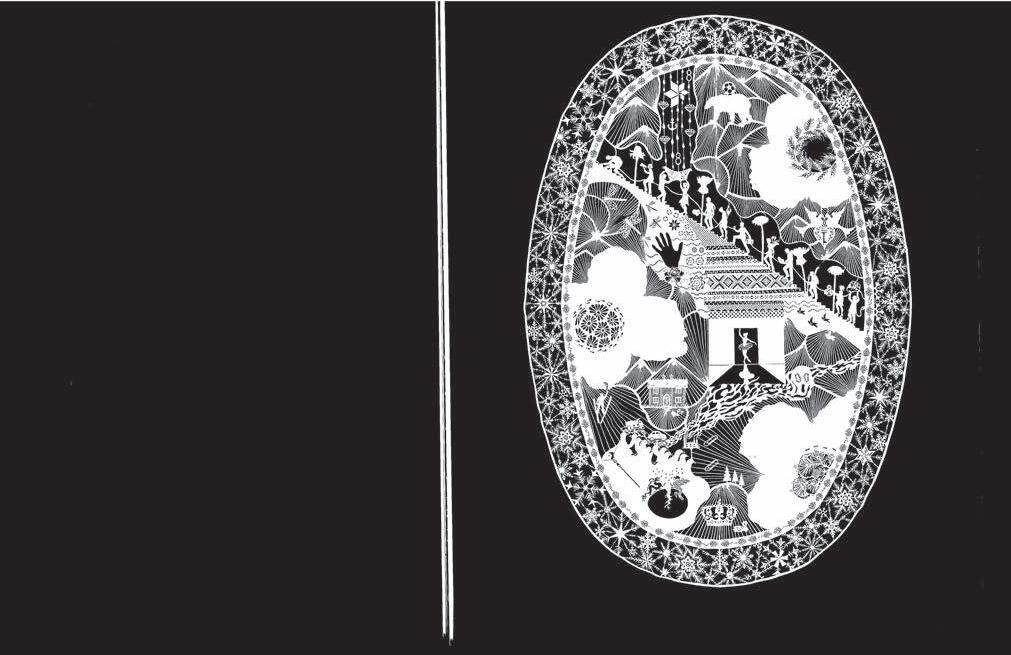

Paper Dialogues: The Dragon and Our Stories

October 28, 2021–January 31, 2022

Paper Dialogues pairs the work of contemporary paper-cutting artists Karen Bit Vejle, Layla May Arthur, Emma Reid, and Qiao Xiaoguang. The mythical dragon motif figures prominently in British, Chinese, and Nordic visual culture. Through shared subject matter and medium, Arthur, Reid, Qiao, and Vejle initiate a cross-cultural conversation that offers personal interpretations of the histories and traditions of their home regions. THIS EXHIBITION IS SUPPORTED BY 4CULTURE, ARTSFUND (GUENDOLEN CARKEEK PLESTCHEEFF GRANT), AND THE SCAN DESIGN FOUNDATION.

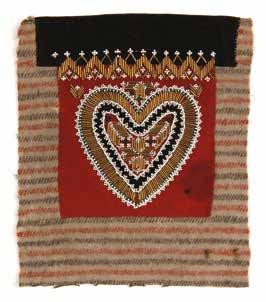

M(other) Tongues: Bodhild and Las Hermanas Iglesias

October 28, 2021–January 31, 2022

This exhibition examines the Iglesias family’s artistic collaborations. The fiber art of Norwegian-born Bodhild Iglesias is displayed alongside the works on paper of her daughters Janelle and Lisa Iglesias. The family considers artistic traditions of Norwegian and Dominican cultures passed down from each generation. Inspired by the “mother of modern textiles” Anni Albers (1899–1994), the three artists translate abstract motifs from one medium into another. Interpretation of the exhibition is offered by Bowie, Bodhild’s grandson, who leads visitors on an audio-guided tour. The artists will also participate in the biennial Nordic Knitting Conference in November 2021. THIS EXHIBITION IS SUPPORTED BY 4CULTURE AND ARTSFUND (GUENDOLEN CARKEEK PLESTCHEEFF GRANT).

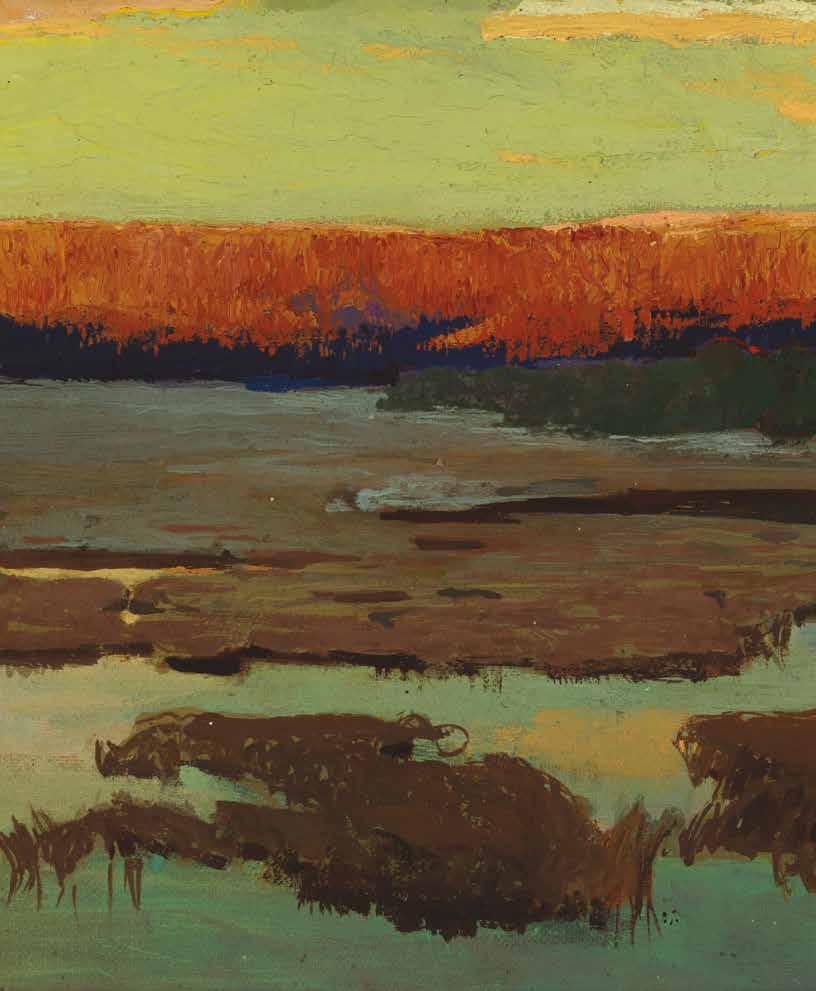

COVER IMAGE

Hugo Simberg, Spring Evening, Ice Break, 1897, oil, Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum.

Photo: Finnish National Gallery / Hannu Aaltonen

EXHIBITIONS 2021–22 | 5

6 | NORDIC KULTUR Exhibitions 6 | NORDIC KULTUR Finnish National

/

Gallery

Hannu Pakarinen

Among Forests and Lakes: A conversation with the curators

by Leslie Anne Anderson, Director of Collections, Exhibitions, and Progams

In preparation for our summer 2021 temporary exhibition, Among Forests and Lakes: Landscape Masterpieces from the Finnish National Gallery, the Museum spoke with curators ANU UTRIAINEN and HANNE SELKOKARI to gain deeper insight and context on this superlative show of work by some of Finland’s most famous artists.

LESLIE ANNE ANDERSON: Why has landscape been a significant genre in Finnish art?

ANU UTRIAINEN: Landscape themes emerged as a category of European art during the nineteenth century. Previously, they had generally served as backdrops for other types of works, such as paintings with historical, mythological, or religious subject matter. As such, landscapes were not often explored as an independent genre by artists.

The rise of landscape painting has its roots in the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Along with its spread emerged the ideal of nationalism, national self-rule, and the need to create unified national culture. In Finland, the era of building a national identity is linked to the birth of the concept of “Finnishness.” This concept took form mainly in literature and poetry in the first decades of the nineteenth century—at that time, Finland was a Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire. The idea of an independent nation created a strong need to depict the country and its people in visual form. One of the most significant landscape painters of the first half of the century was Werner Holmberg (1830–1860), who studied in Düsseldorf, Germany. Holmberg adapted the themes and ideas of Romantic landscape painting to the Finnish environment.

AMONG FORESTS AND LAKES | 7

This was a pioneering project as there were no professional Finnish artists or public art museums in Finland until the Finnish Art Society (established 1846) began to collect artworks through donations, commissions, and purchases, and established the Drawing School in the mid-nineteenth century. The aim was to amass a collection of Finnish art for public display. This momentous campaign culminated in the inauguration of the Ateneum building in 1887, consisting of two art schools, the Art Society’s offices, and an art museum for the collections. By that time, landscape painting had achieved a key role in the newly established art scene.

Even today, landscapes are greatly loved by Finnish museum visitors; and landscape painting as a genre and means of artistic expression is popular among contemporary visual artists.

LAA: This exhibition shares 150 years of artwork. How has the depiction of the Finnish landscape changed in the 150 years represented in the exhibition?

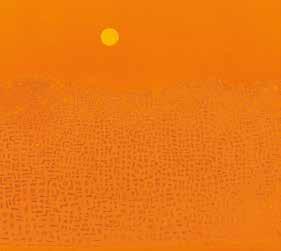

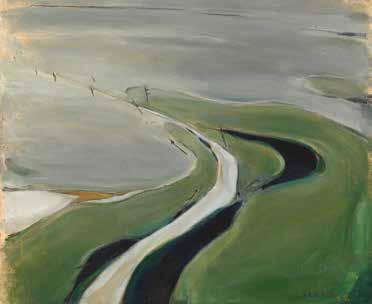

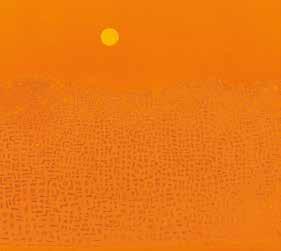

HANNE SELKOKARI: The ways to experience and express the landscape and nature varies in methods, but many ideas conveyed through it remain the same. Evoking the sublime in the viewer, which was the aim of the early artist, progressed into showing details of nature through careful studies executed in nature like in Holmberg’s sketches; or depicting snow and ice in a variety of ways with different techniques from Fanny Churberg to Väinö Blomstedt and H. Ahtela. Lea Ignatius and Aimo Kanerva are both masters of expressing the warm sun and heat in their works (Heat and Hot Day) by using just one radiant color.

An untouched lake landscape seen from a bird’s eye view was, for a long time, an ideal type of Finnish landscape. Symbolist landscape painting began in the 1890s, and as a style, is still strongly present in contemporary art. The Finnish landscape is not just countryside and pure nature. It is present in built environments or cities. The idea [that manufactured environments could be landscapes] originally came from the writer and historian Zachris Topelius, according to whom nature, people, and culture are a single entity. An opposite view was held by the poet J. L. Runeberg, whose romantic idea was that untamed nature and pristine wilderness represent the very opposite of culture and were important for that very reason.

LAA: The exhibition is divided into four themes—Seasons, Inside the Landscape, Symbolist Landscape, and Sápmi. Why did you decide to organize this exhibition thematically versus chronologically? How did you identify these four themes?

AU: There are certain recurring types and forms of landscapes, out of which the most canonical one is a view over a lake seen from a high vantage point. Another common feature are depictions of the four seasons, out of which winter landscapes can be mentioned as typically Finnish, especially at the turn of the twentieth century. At the same time, Symbolism in general—and Symbolist landscape painting in particular—were significant stylistic and philosophical movements and genres in Finnish art, so it was obvious they would play a role in this show as well.

PREVIOUS SPREAD

Gabriel Engberg, Landscape from Sápmi, Summer Night, 1898, oil, Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum, Hoving Collection.

FACING PAGE

LEFT TO RIGHT FROM UPPER LEFT

Anton Lindforss, Autumn, 1941, oil, Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum, Hoving Collection.

H. Ahtela, Winter Road, 1952, oil, Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum, Ester and Jalo Sihtola Fine Arts Foundation Donation.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Winter, study for the Juselius Mausoleum frescoes, 1902, tempera, Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum, Antell Collections.

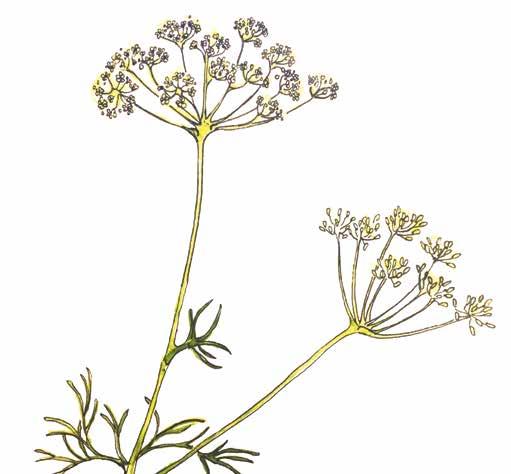

Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Wild Angelica, 1889, oil, Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum, August and Lydia Keirkner Fine Arts Collection.

Lea Ignatius, Heat, 1974, etching, relief printing, Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum

Werner Holmberg, Landscape from Kuru in Morning Light, 1858, oil, Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum.

Sápmi in the north, on the other hand, is both a geographical and cultural region (the latter is referred to as Sápmi), and has enthralled artists ever since the 1920s when it became more accessible by car and train. The “magic” of north was thus an evident theme we could not ignore, and which has since become a very current topic in the discourse of decolonization and the rights of indigenous people.

In terms of motifs, forests, open fields, and lakes occur over and over again. After World War II, Finnish society changed radically. Urbanization and industrialization were rapid and sweeping. Finland turned from an agrarian country into a modern industrial society in a couple of decades. This had an effect in art and landscape painting as well, and cityscapes became a popular motif.

The curatorial process and organization of the show under these themes was actually pretty easy when we realized that the above mentioned are the most common motifs and topics, supplemented with urban landscapes from the modern era. Interestingly enough, the core concept of the “Finnish landscape,” created in the mid-nineteenth century, has survived over time. It has transformed many times in terms of style, technique, and form, but the initial idea of a pristine and intact landscape, or an image of it with a hint of human intervention, has never disappeared.

LAA: Many of the works included in the exhibition were created by canonical artists, while others are by less well-known artists. What was the process for selecting works of art for the show?

AU: The Ateneum is the biggest and most well-known art museum in Finland. The permanent collection exhibition, “The Stories of Finnish Art,” shows many of the most significant works from the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries. In recent years, the collection’s timeline has been extended until 1970. Today, the Ateneum is not only a museum of older art, it also holds the biggest collection of modern art in Finland. We have been working on this part of the collection more

8 | NORDIC KULTUR

AMONG FORESTS AND LAKES | 9

Finnish National Gallery / Jenni Nurminen

Finnish

National Gallery / Ainur Nasretdin

Finnish National Gallery / Hannu Pakarinen

Finnish National Gallery / Jenni Nurminen Finnish National Gallery / Hannu Aaltonen

Finnish National Gallery / Hannu Pakarinen

intensely, making the modern collection more accessible to our visitors, at home and abroad.

Another important factor is emerging areas in art historical research. This has had a ground-breaking effect in the way we analyze and study those parts of the collection that may have fallen off our radar in recent decades. The concepts of good taste or style have changed and, for example, climate change, rising interest in environmental issues, and processes and concepts like decolonization or posthumanism are examples of new ways of seeing. Landscapes and cityscapes are at the very center of these issues.

You can’t talk about Finnish art and not mention the role of Finnish women artists. They have always played a central and significant role in the Finnish art scene. Women artists have embraced new trends and ideologies in a pioneering way, and shaped the way modernism and modernistic styles were adopted in Finnish art at the turn of the twentieth century and after. They also have an essential role in this display as well. Women might not yet be as canonical and acknowledged internationally as they are in Finland, but we are putting lots of effort toward making a change here. As an example, our Modern Woman project, with four modern women artists, has been shown in New York City, Tokyo, Stockholm, and it just opened in Copenhagen. Helene Schjerfbeck (1862–1946), one of the most well-known Finnish artists, was on display at London’s Royal Academy of Arts last year.

These are just examples of how art history, general opinions, and objects of interest are changing as the world is rapidly changing around us. We think museums and curators have an essential role in addressing these issues.

LAA: Can you explain the collecting history of the Ateneum, and the efforts made in this exhibition to include works by Sámi artists from the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma (part of the Finnish National Gallery)?

HS: The Ateneums’s collection started in the mid-nineteenth century with acquisitions by the Finnish Art Society. Landscape painting in its different phases and themes was and is one of the mayor interests in the collection, not least because Finnish artists have always been keen to study and paint nature.

Works by both Sámi artists and contemporary artists are fairly new acquisitions for the Finnish National Galleryand are part of Kiasma’s collection. Our aim as curators was to show work by artists from all parts of Finland. We wanted to represent landscapes from all over the country by as wide a range of artists as possible.

LAA: This is a major exhibition and the National Nordic Museum is the exclusive North American venue. How often do works like Hugo Simberg’s Spring Evening, Ice Break travel to institutions outside Helsinki, Finland, or Europe?

HS: Actually, Simberg’s painting has been on the move for the last twenty years and in at least eighteen exhibitions! Ateneum Art Museum arranged an extensive exhibition on Hugo Simberg with several publications in 2000. Before this solo exhibition,

Simberg was known and loved in Finland, but over the last twenty years, his paintings (and sometimes also drawings) have played an important role when depicting turn-of-the-century Finnish art abroad. Spring Evening, Ice Break is one of the small treasures of the Symbolist period in Finnish landscape art. The last time this piece was shown in North America was in 2007 in Minnesota.

LAA: What have you discovered in researching this exhibition that surprised, challenged, or expanded your understanding of Finnish art?

AU: I find myself in continuous state of awe and astonishment when working with our marvelous collection. I really enjoy studying it and trying to find new ways of putting our works of art in a context that gives museum visitors new perspectives, experiences, and ways of thought. Because I have worked with the collection for many years, the most interesting part is the modern collection. It has not been studied or shown as much as the older part, and it gives me great joy to make discoveries.

Women artists are one of my special interests—painters, printmakers, and sculptors—and how they were able to build their careers as professional artists.

It was not a surprise to find that there are lots of images of lakes, forests, and fields, but it was a bit of a surprise that there are so few seascapes and images of the archipelago, even though they are an essential and huge part of the Finnish landscape. One answer to this is political—artists were interested in the more unknown and untouched hinterlands, the original “Finnish” inland, as they were commissioned to give it a visual form as a national landscape. Seashore was considered to be more civilized. Language was an important factor—the coastline was more inhabited by the Swedish-speaking population, including most of the artists themselves who came from the Swedish-speaking upper classes until the early decades of the twentieth century, and therefore, it might not have been considered as a genuine Finnish landscape.

In general, this project has only strengthened my presumption of the landscape as one of the most essential and widespread themes in Finnish art of all times.

Among Forests and Lakes: Landscape Masterpieces from the Finnish National Gallery features over fifty works of art that span over 150 years of history, from the 1850s to the present day. Among Forests and Lakes is on view at the National Nordic Museum May 6, 2021 through October 17, 2021.

For more information on the Ateneum’s collecting history, visit ateneum.fi/ en/the-story-of-ateneum/

View the Ateneum’s entire digital collection at kansallisgalleria.fi/en/search

Leslie Anne Anderson is Director of Collections, Exhibitions, and Programs at the National Nordic Museum. A former Fulbright grantee to Denmark and American-Scandinavian Foundation Fellow, Leslie specializes in 19th-century Nordic art. Her curatorial work has received the Award for Excellence from the international Association of Art Museum Curators. She has published articles in numerous scholarly journals, and she serves on the editorial board for the peer-reviewed journal Arts. Born to a Cuban mother and a Danish-American father, her current curatorial interests lie in contemporary cross-cultural artistic conversations.

10 | NORDIC KULTUR

The National Nordic Museum Acquires a Swedish Royal Tapestry

by Leslie Anne Anderson, Director of Collections, Exhibitions, and Programs

by Leslie Anne Anderson, Director of Collections, Exhibitions, and Programs

Museum Officially Names The Barbro Osher Gallery

In 2021, the Museum’s large temporary exhibition gallery will be renamed The Barbro Osher Gallery in recognition of the philanthropist’s generous support for the Museum’s capital campaign. The first exhibition to be held in the newly-renamed gallery will be the landmark exhibition Among Forests and Lakes: Landscape Masterpieces from the Finnish National Gallery. The 3,700 squarefoot gallery is among the Museum’s most frequented spaces and the site of at least three major special exhibitions each year. Built to Smithsonian standards, this state-of-the-art gallery allows the Museum to display loaned works from world-class institutions.

On December 1, 1928, Swedish Count Folke Bernadotte of Wisborg (1895–1948), son of Prince Oscar Bernadotte and nephew of King Gustaf V, wed the daughter of an American industrialist, Estelle Romaine Manville (1904–1984), at Saint John’s Episcopal Church in Pleasantville, New York. Theirs is believed to be the first European royal wedding officiated in the United States.

To commemorate their union, the Count and Countess Folke Bernadotte commissioned from Swedish artist, author, and ethnologist Ossian Elgström (1883–1950) a tapestry depicting the arrival of Norse explorer Leif Eriksson on the shores of North America around the year 1000 CE. The subject matter references the couple’s roots and the shared history of the Nordic countries and North America. It was woven between 1929 and 1930 by the studio at Sankta Birgittaskolan, operated by Swedish textile artist Emy Fick.

Elgström’s design evokes the period it depicts. At upper center, the work’s title Leif Eriksson upptäcker Vinland (Leif Eriksson Discovers Vinland) is written in what resembles a runic script. In the upper right corner, a personified easterly wind propels the stylized Viking ships and their crews toward the Western Hemisphere. The aurora borealis and constellations of stars illuminate the ships’ route. In the foreground, several Vikings reach the shore to find fertile ground. The growth of grapes alludes to the name Eriksson bestowed on the region—Vinland (Land of Wine).

Several publications, including Ord och Bild (Word and Image) in 1929 and The American-Scandinavian Review in 1936, featured the tapestry. The tapestry was shown in the 1930 Stockholm Exhibition and the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. Nearly ninety years later, plans for its preservation and future display are currently underway. This important textile entered the National Nordic Museum’s permanent collection in 2020 thanks to a generous gift from Barbro Osher.

(608) 687-4299

LefseTime.com

For all your Scandinavian Cookware & Gift Needs, it’s.... Lefse Time!

SWEDISH ROYAL TAPESTRY | 11 Collections

12 | NORDIC KULTUR Exhibitions

Janelle, Bodhild, and Lisa Iglesias. FACING PAGE Bodhild, Janelle, and Lisa Iglesias, Knit painting (2019), quilted acrylic yarn, stretched over metal frame.

Image Credit: Christine Sloan Stoddard

IN FALL 2021, the National Nordic Museum hosts an exhibition of works titled M(other) Tongues: Bodhild and Las Hermanas Iglesias by a family of women artists—Bodhild, Janelle, and Lisa Iglesias—with roots in Norway and the Dominican Republic. Though currently located on opposite coasts, sisters Janelle and Lisa often create project-based work as a pair under the name “Las Hermanas Iglesias” (Spanish for “The Iglesias Sisters”), a reference to the Spanish surname of their Dominican father Bienvenido. They have individual artistic practices and careers: Janelle is Assistant Professor of Studio Art at University of California San Diego and creates objects and installations that are three-dimensional, while Lisa is Associate Professor of Art at Mount Holyoke College and prefers the two-dimensional mediums of drawing and painting. They impart their expertise as educators, nurturing aspiring artists. However, when partnering on a project, their work considers their roles as sisters, mothers, and daughters. For the show M(other) Tongues: Bodhild and Las Hermanas Iglesias, they enlist the textile talents of their Norwegian-born mother Bodhild, a fiber artist, to expand the conversation across mediums. In preparation for their first exhibition in the Pacific Northwest, I sat down with Janelle and Lisa to discuss the importance of identity and heritage in their contemporary collaborative practice.

LESLIE ANNE ANDERSON: Lisa and Janelle, you collaborate with each other as Las Hermanas Iglesias. How does the work of this artistic collaboration differ from or extend your individual practices?

LAS HERMANAS IGESIAS: At the very beginning of our collaborations in 2005, we thought of our working-together as something very separate from what we did in our individual studios. The flexibility to experiment, break our own rules, and try

new things has always been woven into our collaboration, so our philosophy about the structures of our relationship has naturally shifted over time. . . . We think of Las Hermanas Iglesias now as a separate enti-

M(OTHER) TONGUES: BODHILD AND LAS HERMANAS IGLESIAS

LAA: Explain the genesis of your artistic collaboration with each other and with Bodhild. When did you decide to include the artistic perspectives of Lisa’s son Bowery (Bowie Gerlitz) Iglesias and Janelle’s baby August Som-Iglesias?

By Leslie Anne Anderson, Director of Collections, Exhibitions, and Programs

ty from our individual practices, yes—but binaries and borders don’t apply here—our work as Las Hermanas Iglesias has fluidly evolved to intermingle with, borrow from, and thread through our individual studios and frequently extends to other makers, communities, and family members. Perhaps a difference between this collaboration and our individual practices might be that a certain kind of multiplicity—a relational identity, our familial connection—is foregrounded as central to the premise of our collective work.

LHI: We celebrate and acknowledge that we’ve been collaborating with our mother in various ways since gestation—the connections that have physically and emotionally bound us to each other have affected every detail, every gesture in our lives. The first time we worked with our mother to create a deliberate and collaborative artwork object involved our invitation for her to knit a conjoined dress for us. We wanted a garment that would visualize this physical binding, a dress we could wear together while performing tasks like creating artworks or attempting to walk in opposite directions. As our collaboration as Las Hermanas Iglesias gradually became more complicated in terms of relationships and structures for working together, so too our desire to work more directly and intimately with our mother grew, adapting to her increased availability after retirement from teaching in the elementary public school system, our father’s death, and mirroring our own instincts towards incorporating more of the familial, maternal, and textile. In extending our respect for how knowledge is passed between generations, it just follows organically that we invite Bowie’s contributions and honor this child’s interpretations of these practices.

LAA: As Las Hermanas and Familien Iglesias, you have examined transnational identity. Your mother Bodhild was born in Norway, and your father Bienvenido was Dominican. What aspects of Norwegian and Dominican cultures inform your work?

LHI: Our work reflects the mashups and hybridic qualities we experience through

AN INTERVIEW WITH ARTIST DUO LAS HERMANAS IGLESIAS | 13

our autobiographies. There are unique relationships and constellation points between our parents’ home countries, including the cod fish—an important export in Norway (klippfisk) and one of the national dishes in the Dominican Republic (bacalao). We grew up within a variety of colliding cultural traditions, expectations, and motifs. We are shaped by and interested in the static and the ways that these qualities counteract and intersect each other, and we also experience many parallel values that Latinx and Scandinavian cultures share. Some of the shared values inherited from our parents that actively inform our work include a persistent transformation of materials, an intense respect for mending, an assumption of re-use and collection, a re-consideration or re-activation of ideas and objects, a love and reverence for the hand made, and an appreciation for using things at hand to problem solve.

LAA : Did you travel frequently to Norway in your youth? What were your impressions of your mother’s native country?

LHI: We grew up in Queens, very geographically distant from our relatives in the Dominican Republic and in Norway. We didn’t go to Norway very often at all in our youth— our mother took us with her to visit family

as infants, and we went again with her for a week to the small mountain farming town when we were sixteen and seventeen years old. One of the most striking impressions of our mother’s native country was the presence of a large family—and the feeling that we were deeply loved by a group of people outside of our home in Hollis. The stories and imaginations of her upbringing that had always been close at hand now gathered the tangibility of the touched and witnessed—the proximity of school to home for commute by skis, the grass grown on the roof to at times be mowed by goats, the impossibly-dated year of her home’s construction chiseled into rafters. These layers of the home and farm where she is from exist alongside her children’s own bridge and tunnel experience in Queens.

LAA: Your story resonates deeply with me, as a second-generation American and as a person who is both Hispanic and Nordic American, as well as with others who have had multicultural upbringings. Did you initially seek to bridge cultures and communities through your collaborative work?

LHI: Our identities as daughters and sisters, our parents’ experiences as immigrants, our upbringing as marked by the colliding and

overlapping of the cultures and knowledges of our parents—these layers and more are in the DNA of the work, and we hope that these layers translate in some way to the communities with which we engage. Unpacking our own identity—a feeling during childhood that we occupied an in-between space as we navigated our own definition of ourselves— has impacted our ways of working. The translation of ideas and patterns between participants and across mediums is inspired by the presence of multiple languages in the house. Our installations and object choices usually include references to the cultural traditions of our parents. We consider our work to be interdisciplinary and we resist a signature aesthetic or category for production, preferring to think of our practice as porous, ever-growing, and un-fixed.

LAA: The exhibition at the National Nordic Museum is multigenerational, and it celebrates motherhood in your own family. You also reference artistic motherhood with Anni Albers (1899–1994), who is considered to be the mother of modern textiles. Are there other creative maternal figures who have inspired you?

LHI: We’re influenced by the energies and contributions of so many artists who feel like

14 | NORDIC KULTUR

maternal figures—people who have generated paths we continue to walk. Anni Albers is a major inspiration as well as Mary Kelly, Lygia Clark, Lorna Simpson, Yoko Ono, Ruth Asawa, and Louise Bourgeois. . . . and inspired by how contemporary artists interweave their practices of family care and making as Wendy Red Star, Carmen Winant, Sheilah and Dani ReStack, Rachel Hayes, Lenka Clayton, and Andrea Chung do.

LAA: You are both professors who foster the development of artists at Mount Holyoke College and the University of California San Diego. How do your respective artistic philosophies inform your educational philosophies?

LH: Our artistic philosophies and politics regarding collaboration, experimentation, challenges to traditional hierarchies, and acknowledgements of privilege and power dynamics inform our pedagogy—resulting in syllabi and classroom cultures that value lateral learning environments, education, and thinking through materials and critical analysis of our actions. We’ve been deeply influenced by Paolo Freire, bell hooks, Audre Lorde, James Baldwin, Rebecca Solnit, and Sister Corita Kent in the studio and the classroom.

M(other) Tongues: Bodhild and Las Hermanas Iglesias is on display at the National Nordic Museum October 28, 2021 through January 31, 2022.

November 6–7 & 13–14

Classes, demos, talks, vendors, and special guests

nordicmuseum.org/knitting

15

Nordic Knitting Conference 2021

Photo by Solen Feyissa on Unsplash.

FACING PAGE Las Hermanas Iglesias in collaboration with Bodhild Iglesias, “ma is as selfless as i am” (grid) series, gouache and flashe on paper, acrylic and wool yarn, stretcher bars, 24x18 inches (knit paintings) 14x11 inches (works on paper).

Paper Dialogues: The Dragon and Our Stories

by Leslie Anne Anderson, Director of Collections, Exhibitions, and Programs

The artistic collaboration between Karen Bit Vejle and Qiao Xiaoguang was born in fire. In 2010, Sino-Norwegian diplomatic relations were strained when the Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded the annual Peace Prize to Chinese human rights activist Liu Xiaobo. Although bilateral relations normalized six years later, it was under these strained conditions that Vejle and Qiao’s cross-cultural conversation began.

With the support of the Norwegian government, Danish papercutting artist Karen Bit Vejle traveled to China in order to exhibit her work there. As an artist, Vejle draws inspiration from Norway’s medieval wood carvings and the nineteenth century papercuts of Danish Golden Age author Hans Christian Andersen. She is also knowledgeable about other cultures that have fostered the art of papercutting, including China. China witnessed the birth of the art form over 1,500 years ago: papercutting became a craft that thrived amongst women artists in rural areas who used it as a form of expression.

When Vejle visited this cradle of papercutting, she sought out a colleague with whom to collaborate on a project. Together, Vejle hoped, they could explore how their two cultures approach the same artistic medium. In April 2013, she met Professor Qiao Xiaoguang at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, and they selected a common motif in Nordic and Chinese art—the dragon—to depict alongside each other. The dragon figures prominently in

Chinese culture throughout time and is an auspicious symbol (called “long”), while the Norse dragon is most often associated with the Viking period and the Middle Ages as an apotropaic (evil-repelling) symbol.

Though the artists spoke different languages and relied on translators for verbal communication, Vejle feels that she and Qiao are “like-minded” in their artistic philosophies, even while their styles and methods of display differ. For example, Vejle’s mounts sizeable papercuts between glass plates and relies on lighting the papercuts in such a way as to cast shadows, giving the two-dimensional works a three-dimensional, or sculptural, presence. These methods were new to Qiao. The artists’ works informed each other, as previous cultural encounters had on artists of earlier eras. One of Vejle’s papercuts produced during this collaboration alludes to earlier exchanges. One piece in the exhibition features a knitting pattern popularized by Norwegian women in World War II. The pattern became a cryptic symbol of camaraderie among compatriots, yet its origins are Asian.

Their cross-cultural approach lent itself to an exhibition that travels the world. Hosted by the ArtHouse Jersey in the Channel Islands in 2016, the exhibition Paper Dialogues expanded to include two new artists, Layla May Arthur and Emma Reid. It is this iteration of the exhibition that will travel to the National Nordic Museum in the fall 2021, encouraging American practitioners in the art of psaligraphy to join in the conversation.

16 | NORDIC KULTUR

Exhibitions

Paper Dialogues is on view at the National Nordic Museum October 28, 2021 through January 31, 2022.

FACING PAGE Karen Bit Vejle, Dragon Egg 2, 2014, paper, 31.5x39.3 inches.

PAPER DIALOGUES: THE DRAGON AND OUR STORIES | 17

History in the Making: Collecting Oral Histories in the Midst of a Global Pandemic

by Alison DeRiemer, Archivist and Oral History Specialist

IN SPRING 2020, as the COVID-19 health crisis cast a shadow of uncertainty upon nearly all aspects of global life, the National Nordic Museum embarked on a mission to document these remarkable times in the form of a new oral history initiative. A Pandemic Preserved: The COVID-19 Crisis in the Nordic Countries and the Pacific Northwest was launched.

A Pandemic Preserved expands on the impressive body of interviews already gathered by the Museum. These recordings supplement ongoing oral history initiatives at the Museum, which, to date, include nearly 1,000 oral histories of Pacific Northwesterners with ties to the Nordic countries.

Part of the Museum’s longstanding and uninterrupted tradition of collecting oral histories, Nordic American Voices (NAV) was started by Museum volunteers in 2009 and is still coordinated by this dedicated core group of supporters over a decade later. As of February 2020, NAV has collected a remarkable 750-plus interviews, focusing on stories from Nordic immi-

“When we disembarked, there was a whole line of CDC personnel. They all had black uniforms, and they all had masks, and some of them had eye shields. They were all lined up. It was just disconcerting. Then, I think we were screened initially before we went through customs. So, we lined up. We were supposed to stay six feet apart, you know, the usual, but of course, it doesn’t always happen that way, because people are anxious.”

—Marjorie Graf, Seattle, May 18, 2020

grants and their descendants in the Pacific Northwest. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, NAV kept a busy schedule, conducting eight interviews nearly every month since its inception. Hundreds of these interviews are available on the Museum’s website; many more are scheduled for inclusion in the future. Additionally, NAV has produced two documentaries related to oral histories from the Second World War as well as a book, copies of which are available for sale in the Museum Store.

Launched in 2016, Interwoven is Museum’s project dedicated to collecting oral histories that examine culture and identity from individuals with blended heritage. The first phase of this project focuses on individuals of Nordic and Native American descent. Interwoven was the subject of two symposia in recent years in partnership with the Tulalip Tribes’ Hibulb Cultural Center.

As NAV and Interwoven paused their work for health and safety reasons in early 2020, the Museum shifted its focus to collecting oral histories related to the current global crisis. The

18 | NORDIC KULTUR

Collections

All photos by Laura Cooper.

“We have other crises around the corner. We have the climate crisis. Even though we try to shut our eyes as hard as we can to not recognize this, we keep on living like we don’t have a climate crisis. My hope is that maybe we’ll realize when we’re in the middle of this [pandemic] what is important in our lives. Is it to be able to buy more stuff, junk, gadgets, whatever? Or is it to have a healthy family and friends that you can be with?”

—Goran Andersson, Köping, Sweden, May 19, 2020

“The first two flights—one from Seattle to Detroit, and then from Detroit to Amsterdam, went fine. It became a very eerie feeling, because the plane was onethird full, which was great, because we kept our distances. And we had to wear masks. At that time, they had started to require masks. But arriving in Amsterdam, it was a totally different thing. There, people were milling around. Most people did not wear masks. The plane to Copenhagen was absolutely filled, and that was quite scary, actually.”

—Marianne Forssblad, Halland, Sweden, June 18, 2020

“It wasn’t meant to, but the upper side of my hand touched the upper side of his hand for like half a second, and then I realized, this is the only human touch contact I’ve had in three, four, five weeks, and that’s depressing.”

—Kristin Stoltz Thomassen, Oslo, Norway, June 24, 2020

National Nordic Museum is not alone in this pursuit; many other museums, universities, cultural institutions, and individuals are documenting the pandemic as well. When determining how this oral history project could best represent the pandemic, the Museum felt it was important to take advantage of the institution’s role as an internationally-focused museum. This makes A Pandemic Preserved the Museum’s first oral history project to collect stories internationally. Participants represent both the Pacific Northwest—the first United States epicenter of the disease—as well as all five Nordic countries. Through this broad lens, life during a global pandemic is being preserved and shared.

As of August 2020, eighteen interviews (with twenty-two narrators) have been completed for this ongoing oral history project. Interviews are conducted remotely via the video conferencing software, Zoom. The project’s participants represent a wide array of backgrounds and job sectors, including education, healthcare, and the arts, among several others. Discussions have centered

on the numerous ways in which the pandemic has affected lives, work, and outlooks on the future. Many narrators have relayed personal stories and candid perspectives, adding an intimacy and depth to these discussions.

This project is just beginning. Throughout 2020 and these next several critical years, the Museum will continue to collect these personal experiences as the global story unfolds. Each of the stories collected will be preserved for future generations, which will undoubtedly find oral histories to be an invaluable resource in studying our era.

Full interviews, videos, and transcripts can be found at nordicmuseum.org/collections

Copies of the NAV documentaries and book can be purchased at nordicmuseum.org/museumstore

More of the Museum’s oral histories can be heard at nordicmuseum.org/ collections

HISTORY IN THE MAKING | 19

PAGES 18–20 Seattle artists painted murals on shuttered Ballard businesses during the height of the pandemic.

“Right away, after [I was diagnosed with COVID-19], the Icelandic health system took over, so to speak. We got phone calls every day. It was a very nice kind of secure feeling. You were not alone, somehow.”

—Jón Ársæll Þórðarson, Reykjavík, Iceland, May 14, 2020

Alison DeRiemer is the Archivist and Oral History Specialist for the National Nordic Museum. In her spare time, you might find her wandering the beaches and forests of the beautiful Pacific Northwest. The next Nordic country she plans to visit is Finland.

“We had three layovers. On the first flight, there were four people—four passengers, and four flight attendants on the whole plane. So, they were joking about it, being like a private flight. They gave us lots of stuff for free, like food and stuff. It was a really bizarre feeling. But the other flights were pretty normal, [but] people were very worried. It was kind of a tense feeling.”

—Love Karlsson, Stockholm, Sweden, May 16, 2020

“For my son, I think what’s hard for him, when you’re eight, you’re not texting with your friends. Zoom is awkward. For him, we’re really his only social outlet. What’s been incredibly hard is that he sees us all day long, and he hears us all day long, but we’re unavailable to him. And when you’re eight years old, that feels like a rejection: to see your parents, to hear them talking, to have them 20 feet away, but have them saying, ‘You need to do something else right now; I can’t play with you; I can’t watch a video with you.’ You know, I think for him, it feels extra lonely.”

—Julie Lowe, Seattle, May 4, 2020

June 19–26

Virtual Northern Lights Auktion 2021

A benefit for the National Nordic Museum

nordicmuseum.org/auktion

20 | NORDIC

KULTUR

All photos by Laura Cooper.

Nordic Women in Leadership Series

BRINGING TOGETHER TOP FEMALE EXECUTIVES from the Nordic countries and the Pacific Northwest, the Nordic Women in Leadership series will host three lively, interactive discussions in 2021. These leaders will join the Museum virtually to discuss the challenges and successes they have experienced as principals in their respective fields.

“Female-Founded Startups and the Investing Journey,” scheduled for May, will examine entrepreneurship in the Nordic countries and in the United States. The second panel in the series, “Nordic Women in the Cultural and Creative Sectors,” premieres in July. This panel will convene directors of major art and cultural history museums as well as heads of philanthropic organizations in the Nordic countries and be moderated by an American arts leader. “Making a Mark on the West Coast” is the final panel of 2021, scheduled in September. This talk will include three Nordic and Nordic-American women leaders in different industries—information and communication technology, food, and service industries—all based on the Pacific Coast of the United States.

Discussions center on a comparative look at opportunities for women in both the Nordic region and the United States, and the panels will offer actionable steps for aspiring women leaders to achieve success in business. The 2021 panels follow on the success of the first Nordic Women in Leadership event at the Museum, held virtually in August 2020. The conversation between two Swedish-born CEOs, fashion designer Gudrun Sjödén and head of the outdoor recreation company Hilleberg the Tentmaker and Honorary Swedish Consul Petra Hilleberg, attracted over 450 participants and continues to capture new views on YouTube.

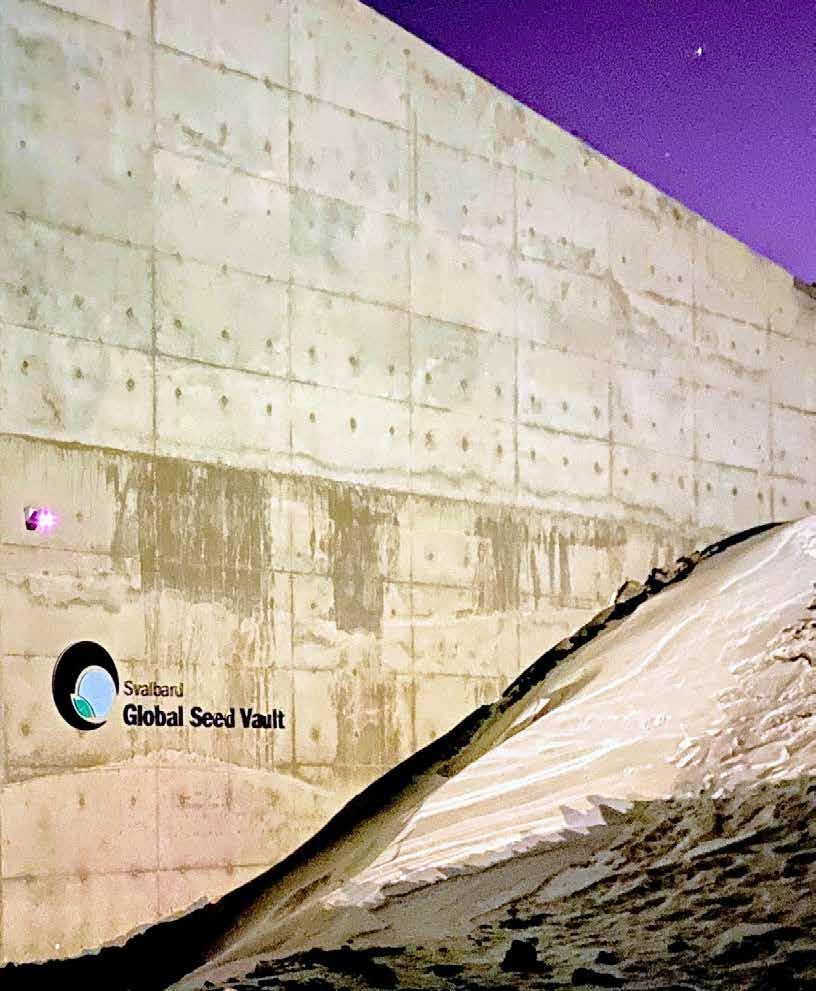

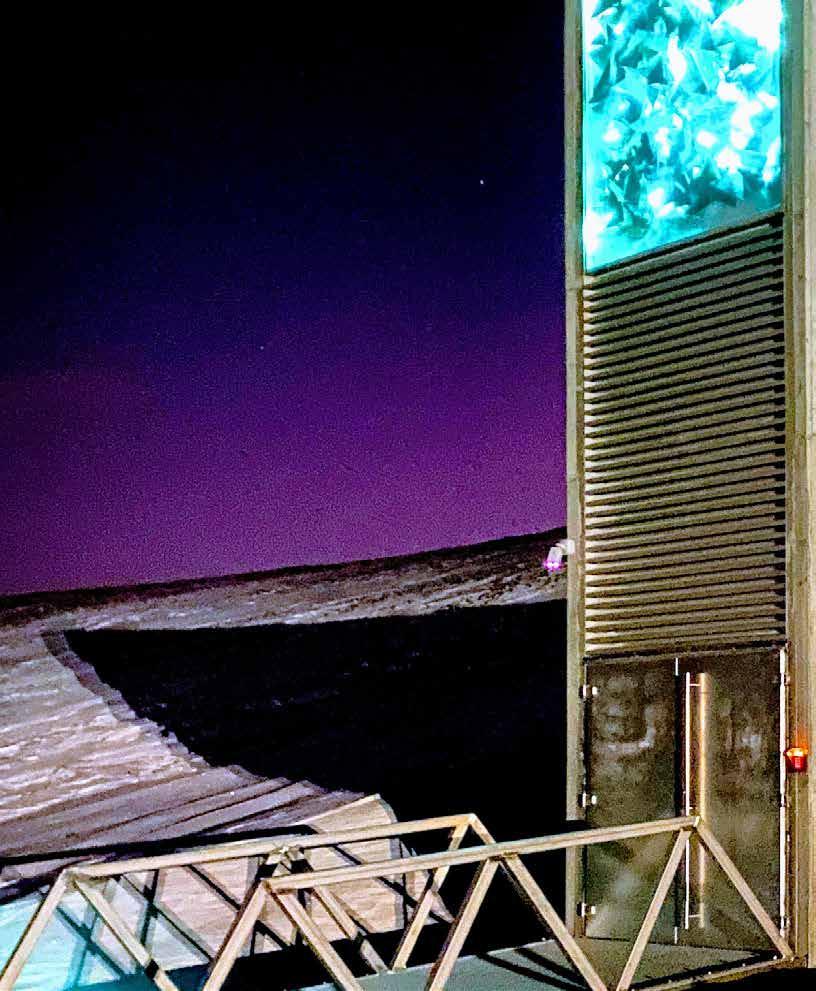

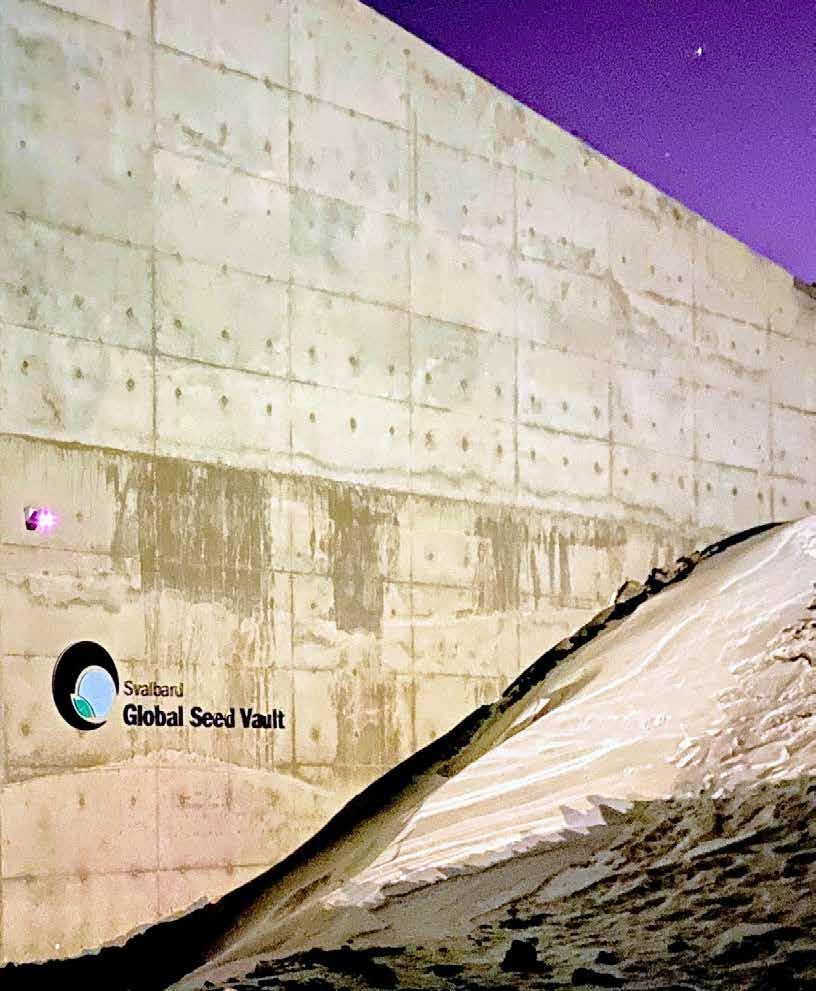

Food Security and Sustainability Series

IN THIS TIMELY NEW SERIES OF TALKS , the National Nordic Museum brings together leading innovators and advocates for sustainable food practices and conservation who will discuss solutions to contemporary issues in the areas of fine dining, food processing, and agriculture. These leaders from the Nordic region and Washington State increase awareness and inspire positive actions for a more secure and sustainable world.

Beginning in May 2021, these talks will share the latest industry news and sustainable practices. The first panel, “Fine Dining for All: How Chefs Fed Communities during COVID-19,” explores how fine dining pivoted during the COVID-19 pandemic to instead serve food-insecure households or adopt new business models. “Tastemakers: Effecting Change in Food Processing and Packaging” investigates how companies in the Nordic countries and the United States demonstrate their commitment to sustainable strategies to minimize waste. The third panel, “Preventing the Collapse of Colonies: Saving Bees and the Global Food Supply” gives the latest buzz on the cultivation of plant-based foods plus efforts to combat declining populations of the world’s most important pollinator. And finally, “Finding Solutions to Food Waste” shares creative ways to make food waste a thing of the past.

May 2021

June 2021

July 2021

August 2021

Fine Dining for All: How Chefs Fed Communities During COVID-19

Tastemakers: Effecting Change in Food Processing and Packaging

Preventing the Collapse of Colonies: Saving Bees and the Global Food Supply

Finding Solutions to Food Waste

May 2021

July 2021

Female-Founded Startups and the Investing Journey

Nordic Women in the Cultural and Creative Sectors

September 2021 Making a Mark on the West Coast

21

Photo by Karl Magnuson on Unsplash. Photo by Jakub Kapusnak on Unsplash.

Innovation

22 | NORDIC KULTUR Exhibitions

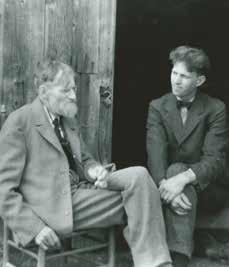

In the Studio of DanishAmerican Artists Emil and Dines Carlsen

by Leslie Anne Anderson, Director of Collections, Exhibitions, and Programs

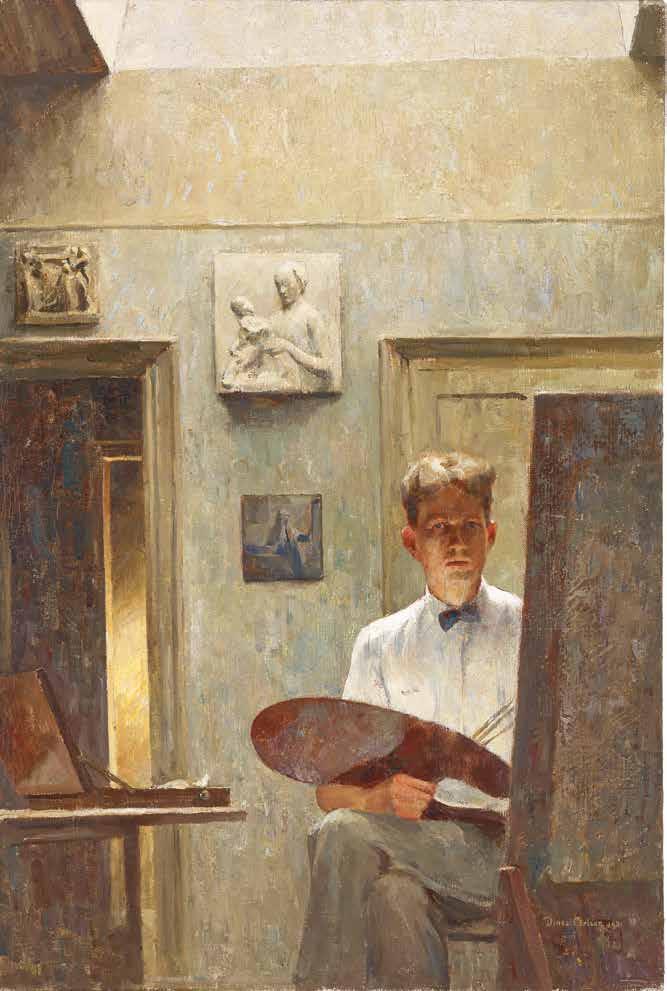

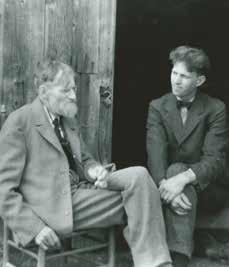

THE MUSEUM’S LARGEST acquisition of art occurred in 2020. The Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields gifted nearly one thousand works by artist Dines Carlsen (1901–66), son of famed Danish-born American painter (Søren) Emil Carlsen (1848–1932), to the National Nordic Museum. Along with the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, the Museum has become the primary repository for materials related to the artistic family. The new collection had long been familiar to this article’s author, who researched the works extensively at Indianapolis from 2014 until 2015. While the senior Carlsen was well known at the time, it soon became apparent through this research that the accomplished and prolific junior Carlsen merits more attention than scholars previously paid him.

In spring 1916, fifteen-year-old artist Dines Carlsen exhibited a still life painting at the National Academy of Design, a New York City institution committed to the instruction and exhibition of its members. There, the painting caught the eye of American artist and tastemaker William Merritt Chase (1849–1916), who purchased it. After Chase acquired the painting, The American Magazine of Art predicted that “a

future of great brilliancy” awaited the teenage painter. In 1920, Dines’s painting The Jade Bowl (1919; fig. 1) received the Academy’s prestigious Hallgarten Prize. The Friends of American Art for the collection of the John Herron Art Institute (now the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields) acquired the painting shortly thereafter. At the age of twenty-one, Dines became the youngest Associate inducted into the National Academy of Design, a record that remains unbroken in 2021. Another Hallgarten Prize followed for a painting titled The Flemish Tapestry (1923) Yet, despite this early success, Dines’s star would soon fade in the absence of his mentor.

Dines’s father, Emil Carlsen (fig. 2), rose to prominence as a skilled painter of still lifes, seascapes, landscapes, and portraits. Emil provided his precocious son with private instruction, and later the opportunity to exhibit their paintings together. In 1929, for example, the Macbeth Gallery in New York City organized a show of the pair’s works. Because they shared the spotlight, critics rightly focused on their relationship with each other. They cited pictorial evidence of the Carlsens’ familial bond in the similarity of their styles and their selection of subject matter. The artistic identities of father and son blurred in subsequent, but scant scholarship. A deeper, more nuanced examination of their shared artistic phi-

losophy can be found by exploring a single work: Studio

Dines painted Studio in 1931 (fig. 3). This painting, held in the collection of the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields since 1981, reveals much about Dines’s ideology at the pivotal time of its execution. Studio, which was finished shortly before Emil’s death on January 2, 1932, may be understood as a tribute to the artist’s father and instructor, a modern Freundschaftsbild (the German term for a “friendship picture,” which memorializes shared beliefs). Careful of analysis of the painting and a trove of material—including letters exchanged between the Carlsens and fellow artist Helen Elizabeth Keep (1868–1959) from 1930 until 1957—support this interpretation.

Dines displayed Studio at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia in 1932 and at the National Academy of Design in 1934. Confirmed by exhibition records, the title—Studio—suggests that the painting was an interior scene first and a self-portrait second. This follows the instructions Emil had given to colleague Helen Elizabeth Keep, who had solicited the senior artist’s advice. On July 3, 1930, Emil offered the following opinion: in the most celebrated interiors . . . a figure or two were generally the telling center, as you know . . . A still life should not have life in it, a landscape does not need life, but

IN THE STUDIO | 23

FACING PAGE

FIGURE 3 Dines Carlsen, Studio, 1931, oil on canvas, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields.

an Interior, I think, needs life in some form dogs or cats might do. This is an individual opinion, might be wrong.

Taking his father’s direction, Dines selected himself as Studio’s central figure. However, the true subject of the painting is the artistic work conducted in the space. Dines includes a sampling of the artists’ tools—paintbox, palette, brushes, and canvas resting on an easel—to underscore the room’s important function.

Emil and Dines shared two studios; one was in an urban setting at 43 East 59th Street in Manhattan and the other in rural Falls Village, Connecticut. The contents of the Manhattan studio shown here reveal their shared artistic practice in several ways. For example, two Florentine plaques installed above the doorway and underneath the skylight also appear in other still life paintings executed by father and son. Tacked on the wall is a source of mutual artistic inspiration, a small reproduction of seventeenth century Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer’s Young Woman with a Water Pitcher (ca. 1662; fig. 4). Vermeer’s original painting has been a highlight of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection since 1889 and hung on its walls only twenty-three blocks north of the Carlsens’ studio. After the death of Emil, Dines described the influence of Vermeer’s

paintings on his father and by implication himself in a 1932 letter to Keep.

Another lesson from the senior Carlsen reveals itself in Studio if we consider the painting as a self-portrait. Dines depicts himself with a painting currently underway. Though he denies the audience access to its imagery, we can speculate that it is the very painting we are studying. The artist’s self-surveillance in a mirror located beyond the easel is obvious. The artist’s gaze does not meet the viewer’s because he is examining his own reflection. Moreover, the right-handed Dines appears to be a lefty. He holds his palette and brushes in his right, while his left composes the scene. Further evidence is found in the intimately-scaled Vermeer print, which has been reversed. We can assume this painting is a faithful representation: in an April 1935 letter to Keep, Dines shared Emil’s adherence to nature, remaining faithful to subject matter depicted. He agreed with his late father stating, “the pure abstractions evolved by thought without any relation to visual phenomena are entirely beyond my grasp and I must keep my hands off.”

Deviating from his father’s lessons, the canvas of Studio itself, called the “support,” may reveal the younger Carlsen’s intentions for the painting. He executed Studio on a coarsely-woven canvas. The Depression-era date of the work may

suggest financial hardship; however, the Carlsens’ letters reveal no need to economize. Emil had encouraged the use of fine materials in works for public display. In a letter to Keep dated July 3, 1930, Emil offered the following appraisal and recommendation: “your picture[s] have quality, your color is deep and rich, —but in color on a well-made canvas would carry your works further.” Studio may have been conceived initially as an intimate gift, a “friendship picture” for Emil, and perhaps had not been intended for public display.

Studio represents the culmination of Dines’s artistic mentorship with the proposed recipient. When Emil passed away in 1932, Dines submitted the recentlycompleted work for display, paying tribute to his father’s legacy.

Research for this article was conducted at the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, where the author studied paintings and drawings by Dines Carlsen in 2014 and 2015, as well as the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art in Washington, DC, the National Academy of Design in New York, and the Falls Village—Canaan Historical Society in Connecticut. Findings were subsequently presented at the annual meeting of the Society for the Advancement of Scandinavian Study in May 2015.

24 | NORDIC KULTUR

LEFT TO RIGHT

Spire of Vor Frelsers Kirke, Copenhagen, 1928–1966, conte crayon on bond paper, 11x8.5 inches. Still Life, Featuring Plate, 1928–1966, conte crayon on bond paper, 11x8.5 inches.

IN THE STUDIO | 25

CLOCKWISE FROM ABOVE

FIGURE 1 Dines Carlsen, The Jade Bowl, circa 1919, oil on canvas, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields.

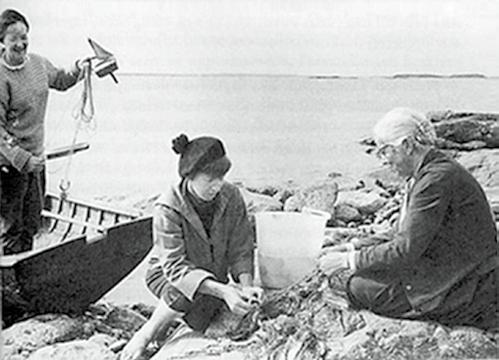

FIGURE 2 Emil and Dines Carlsen, 1931, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Archives of American Art, Emil Carlsen Family Photographs.

FIGURE 4 Johannes Vermeer, Young Woman with a Water Pitcher, circa 1662, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

RIGHT Self Portrait; Pen in Hand, 1928–1966, pen and black ink on bond paper, 11x8.5 inches.

26 | NORDIC KULTUR

Innovation

Photo by Nikita Kachanovsky on Unsplash.

FACING PAGE

Robert Strand and Birger Steen record clips for the 2020 Virtual Nordic Innovation Summit. Norwegian Consul General Jo Sletbak takes a selfie while Robert Strand records.

THE WORLD NEEDS NORDIC INNOVATION

by Robert Strand, PhD, Executive Director of the Center for Responsible Business

WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF INNOVATION? I asked myself this question a lot in advance of 2020’s Nordic Innovation Summit last May. I’ll return to this question.

I have dedicated my professional life to understanding Nordic global leadership in sustainability and building resilient societies—and what lessons America can draw from these Nordic experiences. Barbro Osher, the Swedish Consul General in San Francisco, gave me the nickname “Mr. Nordic,” so when I was invited to emcee 2020’s annual Nordic Innovation Summit alongside Birger Steen, Mr. Nordic happily accepted.

Though held virtually due to COVID-19, the Nordic Innovation Summit 2020 presented by Ericsson successfully brought together innovation leaders from the Nordic region, the Pacific Northwest and beyond

to share insights, build new relationships, explore opportunities for collaboration, and inspire new ways of thinking. Founded in 2018 –by the Museum with the support of Steen, a principal at Summit Equity and Museum Trustee, the summit has flourished since.

Built around four core Nordic values of openness, social justice, connection to nature, and innovation, the National Nordic Museum is the natural home for the Nordic Innovation Summit. The Nordic value of innovation is of course a focus for the summit: but when we talk about Nordic innovation, we are inherently also talking about innovation with the other values. Nordic innovation is about making the world a more just and sustainable place. Nordic innovation is about tackling the world’s most pressing challenges.

So back to that question: WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF INNOVATION? As we entered the 2020 Nordic Innovation Summit amidst a global pandemic, heightened social unrest, and rising global temperatures, it became clear to me that the purpose of innovation is to meet real needs of the world. It simply has to be. Anything else would be a colossal waste of precious time and talent.

And this is precisely what Nordic innovation does. Nordic innovation meets real needs of the world.

As we kicked off the summit, I shared a story about Nordic innovation meeting real needs that is most relevant in these challenging times. Just before the summit, The Atlantic ran an article titled “The Doc-

tor Who Had to Innovate or Else.” That doctor was Danish physician Bjørn Ibsen. Bjørn Ibsen’s innovation—a new way to use positive pressure to save polio patients in the 1950s—was born out of a real need. At that time, negative pressure ventilation was used for polio patients to breathe—a procedure which required use of the iron lung, a device invented in the 1920s. In the 1950s, when polio was one of the most serious communicable childhood diseases, the entire country of Denmark had only a single iron lung. Without iron lungs at his disposal, Ibsen innovated a new practice, involving hand pumping ventilators and using positive pressure, that would come to save hundreds of lives in Denmark.

Drawing from Ibsen’s learnings, the Swedish company Engström invented a machine that pumped ventilations mechanically the following year. That machine is the basis for the modern ventilator. Ventilators used around the world to save lives today—from COVID-19 and other diseases—are built upon this Nordic innovation. A real need driving innovation. That’s Nordic innovation.

When we talk about the real needs of the world, we are also inherently talking about the increasingly urgent need to address our world’s greatest sustainability challenges. This brings us back to the Nordics, as the very definition of sustainability has deep Nordic roots. Former Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland chaired the Brundtland Commission, which generated the timeless definition

THE WORLD NEEDS NORDIC INNOVATION | 27

of sustainable development that we know and still use today: sustainable development is “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

Launched in 2015, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals—or SDGs—serve as a globally-recognized framework that brings together the world’s most pressing challenges. Reduced Inequalities, Good Health and Well-Being, No Poverty, Climate Action, Clean Water and Sanitation, Zero Hunger, Gender Equality, Quality Education, and Affordable and Clean Energy are a few of the seventeen SDGs.

Nordic innovation tackles SDGs head on. It’s therefore unsurprising that the Nordics are global SDG leaders who regularly dominate the annual SDG Index. Sweden, Denmark, and Finland topped the

most recent 2020 index, and Nordic countries have routinely taken the top three places since the index’s inception in 2015.

This is not to say that Nordic work is done. The young Swedish activist Greta Thunberg reminds us that when it comes to urgent challenges like climate change and overconsumption, the whole world needs rapid improvement, including the Nordics. But a Nordic approach rooted in the Nordic values of openness, social justice, connection to nature, and innovation to meet real needs of the world represents our best hope to effectively address our greatest global challenges.

In my upcoming book, Sustainable Vikings: What the Nordics Can Teach Us about Reimagining American Capitalism, I begin with the bold statement “I believe the Nordics can save the world.” I truly believe this. But this is not meant as convenient praise: I offer this as a call to duty.

The world needs leadership. The world needs inspiration. The world needs hope and proof that societal, environmental, and economic well-being can go hand in hand.

The world needs Nordic innovation. And, fortunately, the annual Nordic Innovation Summit brings Nordic innovation to the world.

Dr. Robert Strand is Executive Director of the Center for Responsible Business and member of the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley, Haas School of Business. He also holds the title of Associate Professor with the Copenhagen Business School in Denmark and is a former US Fulbright Scholar to Norway. His upcoming book Sustainable Vikings: What the Nordics Can Teach Us about Reimagining American Capitalism will be published in 2022. Care to help with his efforts to launch a Nordic Center at the University of California, Berkeley? He can be reached at MrNordic@berkeley.edu (yes, that is his actual email address).

September 8–10

nordicmuseum.org/innovation

28 | NORDIC KULTUR

Photo by Oakie on Unsplash.

VOLUNTEER SPOTLIGHT

by Timothy Krumland, Volunteer Coordinator

The National Nordic Museum is privileged to rely on a wide range of volunteers for their support, time, and expertise. For this issue of Nordic Kultur, a few of our volunteers shared their thoughts and experiences on volunteering with us.

JACK HARMON-DAVIS , 17 years old, volunteer since mid-2018

What sparked your interest in volunteering with the National Nordic Museum?

My family had recently begun to talk more about our homeland (Finland and Sweden.) It made me naturally curious about my heritage, and it was the original inspiration to work for the Museum.

What is your favorite way to volunteer?

I work front desk normally, but to me my favorite work was done in the offices. Upstairs I would handle mail and outgoing volunteer forms, raffle and auction papers, et cetera. Also, working with the volunteer database had me rapidly get used to technology I had very little previous experience with.

What advice would you give to a new volunteer?

Engage with staff, get to know everyone. Everybody at the Museum has something to offer to your work experience.

KIM RUSSELL, 35 years old, volunteer since mid-2018 (visitor since 2016)

What sparked your interest in volunteering with the National Nordic Museum?

After moving to Seattle from Los Angeles where I completed an MA in Scandinavian Studies, I knew I wanted to stay connected to Nordic culture in some way. I also wanted to make connections with people and find community. I had one small kid at the time and wasn’t quite ready to start looking for work so I decided to volunteer my time when I could. I had previously worked at the American Swedish Historical Museum in Philadelphia and knew how much fun a cultural museum can be.

What is your favorite way to volunteer?

I love to volunteer in the Museum Store. I get to talk with visitors from all over the world about great Nordic design and culture. I had a fantastic time volunteering at the flower crown table during Nordic Sól in 2019. Visitors were excited to try their hand at making a flower crown, a typical Swedish Midsummer experience. It was a great example of a Scandinavian

custom that anyone can participate in, regardless of heritage. There is no one perfect way to make a flower crown!

What advice would you give to a new volunteer?

Have fun and dig in! Immerse yourself in the experience and make the museum your third place. It may be world class, but it is also a warm community! Volunteer during regular hours but also volunteer for events and lectures to see a different side of the Museum. Talk to visitors and tell them what you love about the Museum and about Seattle.

BRANDON BENSON ,

62 years old, volunteer since about 2005 (Member since late 1990s)

What sparked your interest in volunteering with the National Nordic Museum?

I found the Museum had many events and activities, and volunteering was an opportunity to be more involved with the organization.

What is your favorite way to volunteer?

I have taken on a wide variety of volunteer roles at the museum, though I find volunteering with the Nordic American Voices project to be very interesting and rewarding. A memorable volunteer experience would be an interview that Gordon Strand and I conducted for the Nordic American Voices project. Gordon and I interviewed Dane Jensen and focused on Dane’s experience designing and creating Danish furniture. The interview took place at the former Museum location, and at the time of the interview, the Museum had an exhibit that featured Danish furniture. Because the interview took place on a Monday, when the Museum was closed, we held the interview in the exhibit.

What advice would you give to a new volunteer?

I suggest that volunteers try new volunteer opportunities. I do not knit, but I volunteer at the registration table for the Knitting Conference that is held every two years.

Thank you to Jack, Kim, and Brandon for sharing your volunteer memories with us, and thank you to the thousands of wonderful volunteers we have been fortunate to work with over the past 41 years. If you are interested in volunteering for the Museum, please contact Timothy Krumland at timothyk@nordicmuseum.org

VOLUNTEER SPOTLIGHT | 29

Volunteer Spotlight

Timothy Krumland has worked for the National Nordic Museum in several capacities, most recently as the Volunteer Coordinator. He loves all things Swedish and soccer.

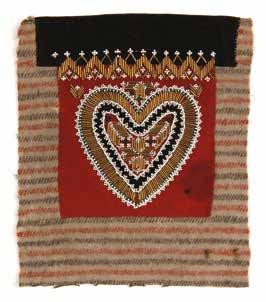

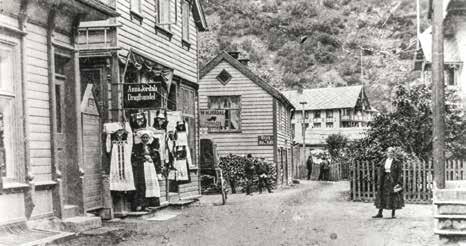

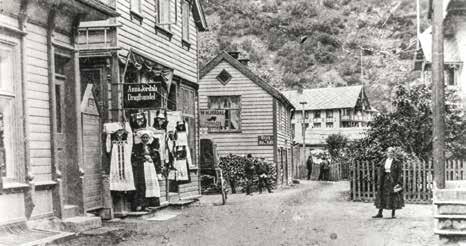

The Legacy of Norway’s First Bunad, The Nasjonaldrakt

by Carrie Hertz, PhD, Curator of Textiles and Dress at the Museum of International Folk Art

FOR RITES OF PASSAGE, public celebrations, and national holidays, a growing number of Norwegians wear bunader in a dazzling array of styles. This contemporary clothing is made in the likeness of preindustrial regional festive dress and worn as a marker of local and national identity. Proponents of the early twentieth-century bunad movement prioritized clothing’s symbolic potential to evoke the notions of place and a shared past.¹ Before the bunad, however, there was the Nasjonaldrakt (literally “National Costume”), a standardized form of clothing inspired by the dress of Hardanger, a district nestled around the Hardangerfjord in Hordaland county (now part of Vestland county). Of all the districts of Norway with characteristic folk costume, Hardanger became especially meaningful to how the nation was perceived at the end of the nineteenth century.

Between 1814 and 1905, Norway freed itself from Denmark, ratified a democratic constitution, and quickly lost its nascent independence to Sweden. Held in unequal union, Norwegians rallied around symbols of national resilience and distinction. To revolutionaries, the dramatic vistas of the western fjords and the beautiful dress of its proud farmers represented everything unspoiled and indomitable about Norway. Patriots championed the folkways of Hardanger as pure survivals heroically resisting modernization and foreign dominance. Farmers and their characteristic dress be-

came both symbols of the mythic past and the recipe for progress as quintessential Norwegian rebels.

At the turn of the twentieth century, women still wore locally-distinct styles of dress in Hardanger. In paintings, sketches, and photographs, European artists depicted the region’s resplendent folk dress against a backdrop of sparkling waterfalls, towering mountains, forests, and glaciers. Enticed by these thrilling images, tourists (both foreign and domestic) flocked to Hardanger.²

Tourism altered daily life throughout Hardanger, but nowhere more so than Odda, a tiny village perfectly situated at the end of the Sørfjord branch of the Hardangerfjord. By the 1890s, multiple cruise lines terminated at Odda, supporting new entrepreneurs who ferried visitors to nearby waterfalls, guided hikes and salmon fishing expeditions, sold handicrafts, and opened hotels, cafés, and souvenir shops.

Beyond the magnificent scenery, tourists hoped to see exotically-dressed women like the bride depicted in Hans Gude and Adolph Tidemand’s 1848 Brudeferd i Hardanger (Bridal Procession in Hardanger), perhaps the most famous painting to emerge from the era. The idealized and widely-shared images of Hardanger brides in their bejeweled crowns and red beaded bodices epitomized a glorious past and its innocence from worldly modern corruption. From his souvenir shop in Odda, Ole Theresius O. Ohm sold hand-painted

portraits of young women dressed as Hardanger brides.