A Colorful Universe

Comfort is king for this queen of design

Join us! Become a Member today.

nordicmuseum.org/membership

Comfort is king for this queen of design

Join us! Become a Member today.

nordicmuseum.org/membership

The Magazine of the National Nordic Museum

EDITORIAL BOARD AND MAGAZINE STAFF

Eric Nelson Chief Executive Officer

Leslie Anne Anderson Director of Collections, Exhibitions, and Programs

Jenny Iverson Development Manager

Erik Pihl Community Engagement

Rosemary Jones Publisher / Marketing Director

Devon Kelley Editor / Marketing Manager

Ani Rucki Design and Layout / Art Director

CONTRIBUTORS

Leslie Anne Anderson | Paul Bannick | Kirby Gilbert | Jenny Iverson | Rosemary Jones

Dakota Keene | Devon Kelley | Michelle Koutnik | Timothy Krumland | John Lundin

Lauren Messenger | Caroline Parry | Fred F. Poyner IV | Lindsay Ravensong

BOARD OF TRUSTEES Trustees

Thomas Malone (President) | Hans Aarhus (Vice President) | Valinda Morse (Secretary)

Earl Ecklund (Treasurer) | Electa Anderson | Lars Anderson | Steven Barker | Anne-Lise Berger

Jann Blackbourn | Ray Brandstrom | Jay Bruns III | Ulf Edwaldsson | Ann-Charlotte Gavel Adams

Mike Hlastala | Tapio Holma | Jane Klausen | Monica Langfeldt | Kurt Manchester | Kurt Ness

Aaron Overland | Tuula Rytilä | Maria Jones Staaf | Birger Steen | Henrik Strabo | Johan Erik Strand Heli Suokko | Nina Svino Svasand | Lisa Toftemark | Tor Tollessen | Margaret Wright Consuls

Mark T. Schleck, Honorary Consul, Denmark | Matti Suokko, Honorary Consul, Finland

Jon Marvin Jonsson, Consul General, Iceland | Geir Jonsson, Honorary Vice Consul, Iceland

Kristiina Hiukka, Honorary Consul, Finland | Viggo Forde, Honorary Consul, Norway

Petra Hilleberg, Honorary Consul, Sweden Honorary Trustees

Senator Reuven Carlyle | Leif Eie | Senator Mary Margaret Haugen | Irma Goertzen | Sven Kalve

King County Council Member Jeanne Kohl-Welles | Senator Marko Liias | Mayor Ray Stephanson

Representative Gael Tarleton

MUSEUM STAFF

Executive

Eric Nelson Chief Executive Officer

Kirstine Bendix Knudson Special Project Coordinator

Lisa-Marie MacKenzie Executive Assistant

Sandra Nestorovic Chief of Staff

Erik Pihl Community Engagement Curatorial

Leslie Anne Anderson Director of Collections, Exhibitions, and Programs

Stina Cowan Educational and Cultural Programs Manager

Fred F. Poyner IV Collections Manager

Jonathan Sajda Exhibitions Manager

Alison Church Children’s Education Coordinator

Alison DeRiemer Archivist and Oral History Specialist

Kaia Wahmanholm Registrar

Development

Jenny Iverson Development Manager

Rachel Ballister Membership and Database Coordinator

Anna Craddock Development Events Coordinator

Lauren Messenger Donor Services Representative

Caroline Parry Grants and Giving Coordinator

Finance and Human Resources

Pamela Brooks Director of Finance & Human Resources

Carolyn Carlstrom Bookkeeper

Drue Chatfield Human Resources Generalist

Timothy Krumland Volunteer Coordinator

Marketing and Communications

Rosemary Jones Marketing Director

Devon Kelley Marketing Manager

Ani Rucki Graphic Designer

Sheila Stickel External Relations

Mark Murray Nordic Innovation Summit Consultant Operations

Adam Lee Allan-Spencer Director of Operations and Facilities

Donna Antonucci Guest Services and Event Associate

Caroline Beston Guest Services Associate

Roberta Chen Guest Services Associate

William Ekstrom Venue Services Coordinator

Becky Forsberg Guest Services Manager

Joni Hughes Store and Purchasing Manager

Daniel Jones Facilities Associate

Evan Miller Facilities Coordinator

Lindsay Ravensong Guest Services Associate

Welcome to Nordic Kultur, the magazine of the National Nordic Museum! In 1980, the original Nordic Heritage Museum opened its doors to the public, and what a wonderful adventure the last four decades have been. As we enter the third year in our new space, the awards continue to pour in. Not only did we add “National” to our name through an Act of Congress in 2019, we journeyed to the Building Museums Symposium in Chicago, Illinois, to accept a Buildy Award. In the words of the selection committee, this award recognizes the “high level of achievement in planning, implementation, and sustainability” achieved by our design team, as well as key staff, volunteers, donors, and Board members here at the Museum. We are incredibly proud of these accolades and look forward to what 2020 brings.

Speaking of looking forward, we are excited to introduce our new Director of Collections, Exhibitions, and Programs, Leslie Anderson. Leslie, who joined us in September 2019, is leading insightful new approaches to our visiting exhibitions and programs, expanding our interpretive efforts and reach. Make sure to read her overview of what’s coming for the next year and how we are incorporating our Fjord Hall Alcove to present a broader view of Nordic culture and its impact around the world. Our 2020 temporary exhibitions, including works by Danish photojournalist Jacob Riis, Swedish fashion designer Gudrun Sjödén, and legendary Norwegian artist Edvard Munch, are sure to inspire you.

In this issue, we take a closer look at a few pieces in our permanent collection. We dive into the history of the East Garden’s runestone and the significant contributions of Gordon Ekvall Tracie. We also share with you a recent acquisition that links Ben Franklin to our collection—but you’ll have to read the article to find out how!

Looking ahead to the Nordic and global future, this edition has several articles that explore current issues, and how the modern generation is reacting to them. We introduce you to a number of young people who are using Nordic traditions, crafts, and community to launch new businesses in Seattle. You can explore how six generations have grown their family farm toward a model of sustainability. And we discuss how climate change impacts the flora, fauna, and landscape of the Nordic arctic and sub-arctic regions. You will find that exploration of the Nordic connection to nature echoed in our summer celebration as well.

We continue the important work of sharing Nordic innovations that are helping to literally save the planet at our third annual Nordic Innovation Summit. This fall we are pleased to bring our first genealogy conference to the National Nordic Museum. Our work in recording oral histories and assisting with genealogical research has been an important and popular part of our Cultural Research Center, and we are glad to highlight both through the conference.

In 2020, we look back at the past forty years of achievements, while looking ahead to a future inspired by Nordic culture, values, and innovations. May this issue of Nordic Kultur inspire you.

Eric Nelson Executive Director/CEO

In this exhibition presented by the Danish Immigration Museum, thirteen individuals who were deported from Denmark in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are chronicled via material from the archives of the Copenhagen and Helsingør police. The Deported consists of portraits and accompanying texts, revealing stories that form a narrative of Danish immigration laws of the era.

Feb 1–Mar 15

A pioneer of photojournalism, Jacob Riis’s camera lens captured the unbearable conditions of New York City tenements in the late nineteenth century. Here, his personal correspondence, handwritten journals, and photographs exposes the Danish-American reporter’s efforts to effect change in European immigrants’ living and working conditions. Jacob A. Riis: How the Other Half Lives was adapted from the exhibition Jacob A. Riis: Revealing New York’s Other Half, organized by the Museum of the City of New York and made possible by the National Endowment for the Humanities. It is curated by Dr. Bonnie Yochelson and co-presented by the Library of Congress.

Feb 1–Mar 15

Three Danish photographers spotlight social justice issues in Legacy Selections from Lasse Bak Mejlvang’s Air Like Poison series reflect the public consequences of cities plagued by air pollution. Sofie Amalie Klougart’s awardReaching Europe chronicles the plight of African migrants who have made it to the shores of Europe, only to be detained indefinitely in a Sicilian reception center. Former social worker Magnus Cederlund’s Skin Close documents homelessness in Copenhagen over a twentyyear span.

Mar 5–Jul 19

The National Nordic Museum boasts a permanent collection of over 80,000 objects, a number that grows thanks to the generosity of our donors. However, all potential acquisitions must meet a rigid set of criteria and answer the following questions in the affirmative: Is it a candidate for display and research? Is it in exemplary condition? Is it relevant to the Museum’s mission and core values? This exhibition poses this last question and illustrates possible responses through recently acquired objects. The exhibition includes fine and decorative artworks, archival materials, and archaeological finds.

6

As a designer, Gudrun Sjödén derives ideas for feminine fashions from folk motifs both near and far. As an entrepreneur, Sjödén’s brand follows sustainable practices and utilizes eco-friendly materials. This Swedish artist’s design ethos proves immensely popular with women around the globe, and it is now the subject of this major exhibition, which was originally produced by the American Swedish Institute, in collaboration with Gudrun Sjödén Design. Learn about Sjödén’s inspiration, process, and practice through her watercolors, clothing, textiles, and archival materials.

23–Sep 27

In 1974, Sweden became the first country to offer parental leave, and it continues to develop generous policies that promote gender equality. Photographer Johan Bävman studies the everyday lives and activities of contemporary fathers who have elected to stay home with their children for more than six months. Bävman’s work further explores how this decision informs family dynamics and society at large. Swedish Dads is an exhibition excerpted from Bävman’s photo essay of the same name.

Sep 19, 2020–Jan 31, 2021

Edvard Munch’s paintings and prints need no introduction: they are cultural icons of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But the Norwegian artist also experimented with photography. Munch delighted in the distortive and blurred effects and unconventional camera angles afforded by the medium. The resulting photographs are deeply personal, investigational images of himself and his immediate environment. Organized by the American-Scandinavian Foundation | Scandinavia House in partnership with the Munch Museum in Oslo, this exhibition explores his photographic experiments. Curated by Wellesley College professor Dr. Patricia Berman, The Experimental Self casts new light on a familiar face.

Oct 8, 2020–Jan 3, 2021

Based in the Virgin Islands (formerly the Danish West Indies), artist La Vaughn Belle explores the material culture of Danish colonialism. Belle’s Chaney series of paintings evokes the fine china imported to her home region as a result of its former plantation economy. Through her works, viewers are encouraged to ponder past and present—how do historic European ceramics, typically experienced as shards in the Virgin Islands, inform understanding of contemporary Caribbean societies? Curated by the National Nordic Museum, this is the first exhibition of Belle’s work in the Pacific Northwest.

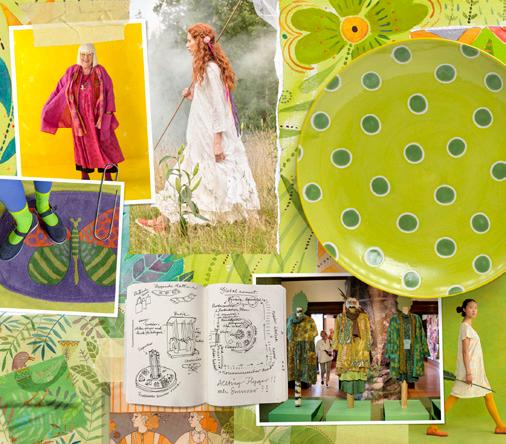

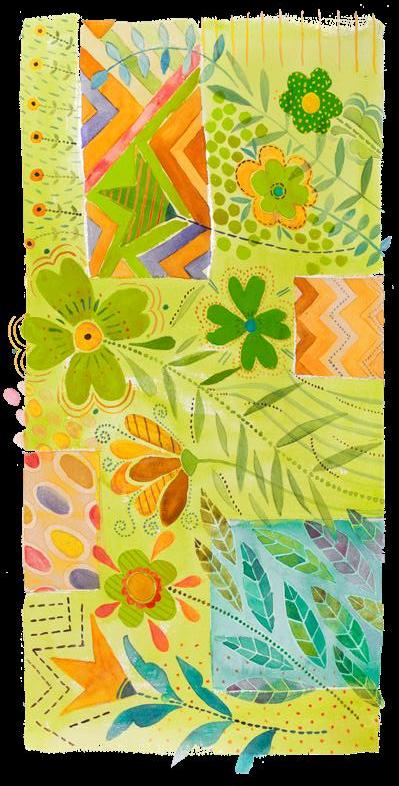

The technicolored story of an inspired, knowledgeable, and principled creator of fashion for women worldwide is brought to vivid life in Gudrun Sjödén—A Colourful Universe. This career retrospective of Swedish fashion designer Gudrun Sjödén (b. 1941) will examine her philosophy, process, and practice through watercolors, clothing, textiles, and archival materials. The exhibition title references a guiding consideration in her designs—color. Sjödén cites French artist Henri Matisse’s bright, brilliant canvases and Mexican painter Frida Kahlo’s eclectic, vibrant personal style as influences. From Sweden, the artistic influence of the Sámi captured Sjödén’s attention early in her career, and she has since discovered that her own maternal line may be traced to the indigenous inhabitants of Sápmi, more specifically the Kola Peninsula. Each of her collections

examines a region of the world, and she collaborates with designers who have firsthand understanding of these aesthetics and their significance. In 2019, Sjödén partnered with the mother-and-daughter design team of Delina White and Lavender Hunt, founders of IamAnishinaabe, members of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, Anishinaabe Nation, and residents of the Leech Lake Reservation in Northern Minnesota. The floral patterns of Delina’s cross-body bag are unique to the Anishinaabe Nation, and they align with Sjödén’s interest in nature.

Fascinated by folk motifs and flowers, Sjödén has explored the visual culture of Europe, North and South America, and Asia. Recurring motifs are abstracted sunflowers, tulips, and roses—the last being her signature shape.

Sjödén’s work begins as a painting in watercolor, which she then translates into

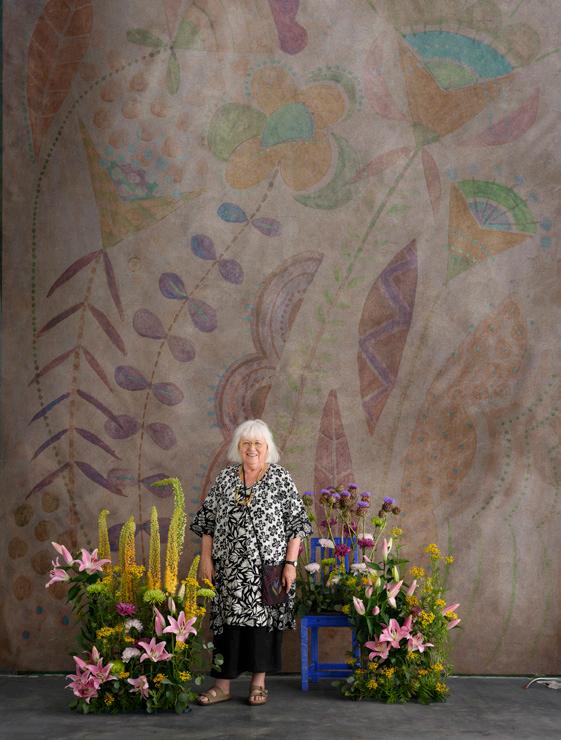

Bold, beautiful botanicals—floral motifs feature heavily in Sjödén’s work. Here the designer is pictured next to colorful blossoms and in front of a backdrop based on one of her watercolors.

*Note: The European title spelling is intentional, reflecting the artist’s origins.

textile design. She received her artistic training in regional textile traditions at Stockholm’s Konstfack University of Arts, Crafts and Design (1958–1963) and draws from this foundational educational experience in each year’s collection. In 1974, she registered her trademark—Gudrun Sjödén AB—which led to Sjödén opening a storefront from which to sell her textiles two years later.

Sjödén creates clothes for environmentally conscious consumers. In the mid-to-late 1970s, her collection of sports casuals featured neutral shades. In the 1990s, advancements in organic cotton production led to the increasing use of vegetable dyes, fueling her passion for color and eco-friendly practices. Her 2015 “Green Winter” line, for example, alluded

to nature both in its predominately green palette and in its materials. She made use of dyed organic cotton and recycled down in winter weather outerwear. Sjödén’s labeling system signals to buyers the garment’s certified organic production, firmly proclaiming her brand’s ethos.

Committed to a sustainable and organic method of farming and processing, Sjödén seeks suppliers who source their cotton from Central and South Asia. The contemporary professionalization of organic farming makes achieving these environmental goals possible. Sjödén is keenly aware of the conditions in each growing region and seeks to philanthropically enrich these areas. One year, she donated proceeds from her collection to the Swedish Aral Sea Society, which raises awareness of the

Aral Sea’s desertification due to ineffective irrigation channels.

Since her line’s inception, Sjödén has designed for all ages and body types, encouraging women of every stripe to dress colorfully, boldly, and with style. The lines of her clothes remain largely unaltered over her forty-year career, unifying her brand across the decades and enhancing the timeless quality of her garments. Sjödén has described her collections as including “loose-fitting pants [that] taper at the ankle, while a-line skirts hug the hips and widen at the hem,”—

classic silhouettes flattering to an array of body types. The universality of Sjödén’s designs account for their broad appeal among women.

From her first brick and mortar location on Stockholm’s Regeringsgatan to today’s online marketplace, Gudrun Sjödén— A Colourful Universe traces the trajectory of her life as a fashion designer and entrepreneur.

Gudrun Sjödén—A Colourful Universe is on view at the National Nordic Museum March 28 through September 6, 2020.

Sjödén’s patterns have been adapted for a line of housewares, like the plate seen above, which echo the colors and patterns of her textile wares.

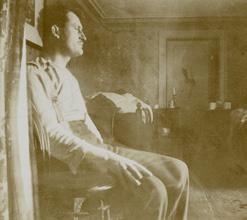

Internationally celebrated for his paintings, prints, and watercolors, and the creator of the globally iconic work “The Scream,” Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863–1944) also experimented with photography. The Experimental Self: Edvard Munch’s Photography brings the photographic work of the master painter to the Pacific Northwest for the first time. This exhibition of photographs, prints, and films by Munch emphasizes the artist’s experimentalism, examining his exploration of the camera as an expressive medium. By probing and exploiting the dynamics of “faulty” practice—such as distortion, blurred motion— eccentric camera angles, and other photographic “mistakes,” Munch photographed himself and his immediate environment in ways that rendered them poetic. In both still images and in his few forays with a hand-held moving-picture camera, Munch not only archived images, but invented them.

Similar to the ways in which the artist invented techniques and approaches to painting and graphic art, Munch’s informal photography both honored the material before his lens and transformed it into unusual images.

On special loan from the Munch Museum in Norway, the forty-six reproductions and selection of prints in this exhibition highlight a curious experimentation and deep introspection by the artist. A continuous screening of Munch’s films and contextualizing panels further examine Munch’s photographic exploration.

Edvard Munch seems to have been one of the first artists in history to take “selfies.” Like his paintings, prints, and writings, the most consistent theme in Munch’s photography was self-portraiture. In his self-images, produced in a variety of media, Munch assumed a range of intimate, as well as performative, personae. As an amateur photographer, Munch exploited the expressive potential of long exposure times that resulted in the ghosting of his own body through movement. Such challenges to the camera’s capacity—to record an aspect of reality—were replicated and shared by Munch in other media. However, he did not exhibit his photographs.

Munch’s photographs have been dated to two periods—1902 to 1910, and 1927 to the mid1930s. Munch took up photography in 1902, the year in which he and his lover Tulla Larsen ended their long-term relationship, following a confrontation with a pistol shot that mutilated one of the artist’s fingers. This event, and Munch’s accelerating career, triggered a period of increasing emotional turmoil that

A selection of the portraits that will be on view. Blurred motion and imperfect focus are two hallmarks of Munch’s photographic self portraits. Double exposures and longer shutter speeds could both result in ghost-like figures, while unfocused figures add an element of tension.

Original was a gelatin silver contact print

Self-Portrait wearing Glasses and Seated with two Watercolors at Ekely c. 1930

Original was a gelatin silver print

Edvard Munch and Rosa Meissner in Warnemünde

1907

Original was a collodion contact print

culminated in a rest cure in the private Copenhagen clinic of Dr. Daniel Jacobson from 1908 to 1909. The second period of activity, from 1927 into the mid-1930s, was bracketed by triumphant retrospective exhibitions in Berlin and Oslo and by a hemorrhage in Munch’s right eye, which temporarily impaired his vision. This was also the time that Munch tried his hand at home movies.

Exploring the dynamics of layered imagery, undefined form, and shadows that replace living bodies, Munch pursued photography as an experimental medium and himself as an experimental subject.

of myself, often with amazing results,” Edvard Munch stated in 1930. “Some day when I am old, and I have nothing better to do than write my autobiography, all my self-portraits will see the light of day again.”

The exhibition was organized by New York City’s Scandinavia House and Oslo’s Munch Museum and curated by Dr. Patricia Berman of Wellesley College, an expert on the artist and a scholar of Scandinavian art.

The Experimental Self: Edvard Munch’s Photography is on view at the National Nordic Museum September 19, 2020 through January 31, 2021.

“I have an old camera with which I have taken countless pictures THE EXPERIMENTAL SELF: EDVARD MUNCH’S

With one of the most generous parental leave systems in the world, Sweden has made strides in gender equality among stay-at-home parents, but many fathers still don’t take full advantage of the system. Photographer Johan Bävman has turned his lens on Swedish dads in hopes of sharing and encouraging both Swedish fathers and the global community to examine the father/child bond.

Unlike American fathers (or mothers, for that matter,) whose government does not mandate that companies give their employees paid parental leave, Swedish fathers are in a unique position: the Swedish government provides benefits that make being a stay-at-home dad both societally and financially feasible. In fact, because the government gives extra support to those families where the father and the mother take equal time off, it is a financial benefit for Swedish fathers to take their full allotted parental leave. However, many fathers do not, and the bulk of parental leave is still taken by mothers. When Bävman took his own family leave time, he found depictions of fathers and young children were either “Instagram pretty” or simply missing.

In the exhibition and photo essay of the same name, Swedish Dads focuses on the men who have chosen to stay home with their children for more than six months. Bävman has captured the moments— intimate, domestic, mundane, sweet, chaotic—that form the days for parents

of young children. Through a selection of portraits and quotes from the fathers themselves, Swedish Dads shares an unusual domestic snapshot while simultaneously questioning why this scene is still surprising in the twenty-first century.

Says photographer Bävman “There are two aims to this project. The first is to describe the background to Sweden’s unique parental allowance. The second is to inspire other fathers—in Sweden, and further afield—to consider the positive benefits of such a system.”

Swedish Dads is on view at the National Nordic Museum July 23 through September 27, 2020.

Despite the financial incentive to do so, only fourteen percent of parents share the leave time equally.

“I love the way nature interacts with the city of Seattle. It reminds me of growing up in Copenhagen. You are never far from the water, and that means space, where you can feel the elements and the changes of light. As the new Music Director of the Seattle Symphony, it is my joy to share music that can inspire you, that can move you — and that can open you to the magic of possibility. I look forward to seeing you at Benaroya Hall.”

The legacy of Gordon Ekvall Tracie, Ove Gullin, and The Skandia Folkdance Society

by Fred F. Poyner IV

A large granite runestone rises from the Museum’s East Garden lawn, part of the landscape but clearly intentionally placed. A bronze plaque set into the turf at its base describes the legacy of two individuals who have made lasting contributions to Nordicinspired art and the cultural history of the Pacific Northwest. Its raised letters read:

This great stone, patterned after ancient Runestones, was carved by Ove Gullin. It was placed here to commemorate the work done by Gordon Ekvall Tracie in promoting Scandinavian folk music, dance and culture.

This four-foot high picture stone is titled Music and Dance, and was designed and hand-carved by Ove Gullin, a Swedish immigrant artist from Seattle. Centered on the front of the stone is an intricately carved design: a dragon and a serpent intertwine and form a treble clef musical note.

The design is one of symbolism and significance. The serpent character serves as an allegorical symbol of control, its coils twisting around the dragon’s body. The dragon’s head curls around and points down to form the curve of the clef. The figures from the design are reminiscent of the Old Norse mythical Jörmungandr, often portrayed as a sea serpent and referred to as the Midgard World Serpent. Gullin once explained that the carving is a tribute to Tracie and his lifetime of devotion of sharing Scandinavian music and dance, both here in Washington State and in the Nordic countries.

For Gordon Ekvall Tracie, the creation of the picture stone commemorated his identity

as teacher, musician, and advocate for Scandinavian folk dance and music. Gullin had first met Tracie in 1963, at a dance held at the YMCA’s Eagleson Hall (a local dance hall for the Skandia Folk Dance Society— a group Tracie helped to start in 1948 as the Skandia Folkdance Club), and the two quickly became friends.

Born in 1920, Tracie was originally from Seattle, and had an early career as a newspaper man and served in the US Coast Guard during the Second World War. Later, he studied and travelled throughout Europe, with a special desire to learn about folk music and dance from the Nordic countries. His travels abroad included a year at the Institute for Folklife Research in Sweden. These experiences led Tracie to focus on sharing what he had learned with others in the Pacific Northwest who had a similar passion for Scandinavian music and culture.

Upon his return to America, Tracie wasted no time in doing so. In addition to helping found the Skandia Folkdance

Club, he organized Nordiska Folkdancers, a dance team whose members performed locally at both regular public events and festivals.

In an oral history interview from 2014, Gullin described Tracie’s interest in how festivals in Sweden were done; cultural practices which both men would later help

The Pioneer Trio, pictured here in 1982, began playing together in 1956. From left to right, they are Gordon Ekvall Tracie, Art Nation, and “Fiddlin’” John Sears.

Ove Gullin, pictured wearing a leather apron.

The picturestone in the Museum’s East Garden.

instill into the festivals here in the Pacific Northwest:

[Tracie] always asked me about the rituals we had for Midsummer festivals. I used to raise the pole in Sweden. We had a pole with a bar, you know, with the garlands around it and so forth, and one “tupp” on top. And we used to raise it the 21st of June. That’s the shortest night of the year. So, I used to do that one, and then I knew a lot of game dances for kids. I used to dance around the pole, and I used to teach them a few little things, so we all kind of danced around.1

During this time, Tracie was building his reputation as an authority on Scandinavian folk dance and music. This work included arranging recording sessions with musicians and singers during his many visits to Scandinavia, and then making these and other recordings available to audiences in the United States. He wrote essays and instructional courses for dance classes and workshops, recorded the history and practice of folk dance, and performed with Skandia and other groups for live audiences across the country. But always he returned to the Pacific Northwest. Much of his free time was spent at his Samish Island home, where he and Gullin discussed their creative ideas and developed a close friendship.

Another longtime friend, Richard Sacksteder, recalled in an oral history interview Tracie’s immense knowledge of musical instruments, and his natural ability to teach others in this regard:

who served on the boards of several music organizations, has described how the Swedish Consulate in San Francisco once conveyed to him the importance of Tracie’s work abroad:

You go down to Stockholm and they say: ‘All those old fogies up there with that music. Who cares?’ Well he went up there and met Knis Karl. He started at the top. Knis Karl was number one, and got things going. He brought the fiddlers down and, with Gunnar Hahn, they started producing records with these fiddlers. And pretty soon it started to spread. And now there’s a lot of that going on in Sweden. But when he [Tracie] got up there in 1947, there wasn’t much happening . . . he was a kind of catalyst for getting that stuff going, and they recognized that.3

By the 1960s, Tracie was well-versed on the world’s stage, comfortable in a variety of roles that served his passion to promote Scandinavian culture. The Swedish Broadcasting Company commissioned him to write The Folk Music of Sweden, published in 1961. In recognition of his role as an ambassador and facilitator of Nordic folk culture for more than two decades, Tracie was awarded the Order of Vasa for cultural endeavor by King Gustaf VI of Sweden in 1962. This was followed by the Gold Medal of Merit from King Carl Gustaf XVI of Sweden in 1978. He served as the Folklore Consultant from 1973 to 1976 at the invitation of the Smithsonian Institution for its Folklife Festival.

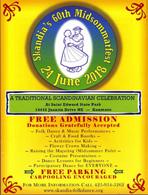

A poster for the sixtieth annual Midsommarfest, at which Tracie’s group Nordiska Folkdancers regularly performed.

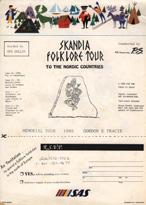

A poster for the 1990 Skandi Folklore Tour organized by Gullin in memory of Tracie.

He introduced the Swedish fiddle to probably fifty or sixty people playing it around here now [2001]. He brought them in. The music was all in his head, and he played the mandolin, which is fingered just like a fiddle.2

Tracie’s efforts not only benefited those in the United States: he was a bridge for cultural exchange, dating back to his earliest visits to Sweden in 1947. Sacksteder,

By this time, Gullin was determined to make a lasting tribute to his friend. He shared his idea with another local artist, Bud Allan Johnson. For Gullin—himself a professional artist—the concept of creating a modern picture stone to honor his friend held a deep personal meaning, and was akin to practices dating back to the Viking Age:

So, then I said to Bud, “You know, I’d like to make it very simple for Gordon. I feel like I’m second in command for

Gordon.” I was thinking about the old Vikings. In the early days, when the head man goes out to war, or does something and he gets killed, there was always the second man in command that either found a stonemason or did it himself. They carved the stone they called the runestone, and they carved on the stone exactly what happened at that place on that day.4

The carved picture stone was finished in 1980, and subsequently found a home at the Nordic Heritage Museum which opened to the public that same year. It became one of the defining pieces of art that reflects the identity of Gordon Ekvall Tracie, whose estate provided the Museum a basis for an ethnomusicology library in his name in 1988. Today, the Gordon Tracie Music Collection numbers approximately 16,000 total items, including musical recordings, sheet music, books, photographs, and ephemera both produced and collected by Tracie and associations he made with the Skandia Folk Dance Society over the years of his life. The collection is archived today at the National Nordic Museum’s Cultural Resource Center, with many examples available online through the Museum’s online collections portal.

From its place in the Museum’s East Garden, it is fitting that Music and Dance continues to present visitors with a means to honor the efforts of not one, but two individuals and their efforts to promote Nordic art and culture for everyone. The contributions of Ove Gullin and Gordon Ekvall Tracie to the Museum and our region’s Nordic community live on through this piece and the Gordon Tracie Music Collection to inspire musicians for generations to come.

1 Ove Gullin interview, 2014.

2 Richard Sacksteder interview, 2001.

3 Ibid.

4 Gullin interview.

by Fred F. Poyner IV

The summer of 2019 witnessed the completion of several projects in the National Nordic Museum’s East Garden.

Among these, the sauna (originally built in 1914) once again became functional—able to reach temperatures up to 180 degrees Fahrenheit— accommodating up to six saunagoers at a time. The restoration effort ensures that the sauna will last well into the next century while earning the Museum a world record: this sauna is now among the oldest working saunas in North America.

Many individuals and several private companies donated time, materials, and other in-kind support for the sauna project. Among those Timo Lehtola, the “Saunaman” from Colorado, made several trips to Seattle and to Finland at his own expense to research the authentic design for a sauna of this type and period. Timo also helped to coordinate partners to supply equipment and materials. The red cedar wood for the new floor, benches, and trim were made possible through the support of the sauna company TyloHelo Inc. of Cokato, Minnesota. The new electric sauv (sauna heater), lights, and thermostat were donated by Finlandia Sauna of Portland, Oregon. Volunteers who donated their labor and talent contributed more than 100 hours of work over eight months.

In addition, two new flagstone pathways were added to the garden over the summer: one leading from the main walkway to the sauna entrance; with the other along the garden’s donor wall on the north fence. The fence displays over 800 plaques bearing the names of donors who have contributed to the new $52 million museum facility. New signage for the sauna, Music and Dance picture stone, and Nordic Spirit longboat were installed to provide interpretative history for the enhancement of these displays.

The East Garden serves as both an exhibition and program space, as well as a place for all visitors to relax in an outdoor environment. Plantings of birch trees, evergreens, and other native plants found both in the Pacific Northwest and the Nordic countries grow throughout the grounds, underscoring the Museum’s connection to nature—a Nordic ideal shared with the global community.

Northwest Trio Looks to Nordic Culture for Inspiration

by Rosemary Jones

Afashion designer, a restaurateur, and a woodcarver all walk into a mead hall. What do they have in common? An interest in Nordic culture and a willingness to start a business based on it.

This trio of Northwest entrepreneurs—Madison Leiren, Adam McQueen, and Brian Takeuchi—each took Nordic traditions and created something special with a handcrafted feel.

For fashion designer Madison Leiren, her Norwegian heritage informs her recent projects. “My uncle, Professor Leiren (Terje Leiren, who teaches at University of Washington), was a big influence. There was that fascination with Vikings and folklore. He has so much passion and knowledge of those topics,” Leiren said.

After studying design in California, she moved to Seattle to be “closer to my family, culture, and heritage. As I got more entwined with my roots, it elevated [my design business] to what it is now.” Today, Leiren creates custom bridal wear and is working on a series of couture pieces inspired by Norwegian folk tales. As her website proclaims, “designing is more than fabric and thread, it is the art of telling stories.”

“Goddesses like Freya, who represent love, beauty, and magic, what would they wear?” mused Leiren. “Would there be silver and gold, that sort of ornamentation? I’m taking those archetypes

and working backwards from what they represent. The dramatic beauty of nature that is so Scandinavian—Norway’s fjords, Iceland glaciers—that definitely plays a role. Nature can be so magical and transformative. Being an artist and not giving those elements a nod would be disrespectful.”

Working with photographer Becca Bjorke, Leiren creates scenes where models draped in her dresses bring old Scandinavian folktales to life. She’s also pairing with authors of Nordic descent to combine her photographs with modern retellings, creating twenty-first century versions of the old myths. “I grew up with troll books with illustrations from the late nineteenth century. I’m hoping this book will be done in 2020. We’re planning a few gallery showings with a full poster made from the photograph and the dress on display next to it. When people see this, they will fall in love with the stories.”

Each dress represents a labor of love for Leiren. “I do all the sewing myself. Some of these dresses take hundreds of hours. The payoff comes at the end—seeing the finished product after Becca has edited the photographs,” she said.

For Adam McQueen, owner and creator of Skål Beer Hall, inspiration came from the food traditions of his Swedish and Norwegian ancestors who emigrated to the United States more

than 100 years ago. “I had a lot of encouragement from my family,” said McQueen, when he decided to create a Nordic-themed bar in Ballard. “I do remember a lot of traditional Scandinavian meals growing up.”

Noting how many people in America have Scandinavian heritage, he began to wonder why you could go into any city in the country and find an Irish bar, but not so many Viking mead halls. In 2017 he started searching for the perfect site for his Nordic vision. Not surprisingly, he found it in the Ballard neighborhood of Seattle. In what was once the historic Vasa Sea Grill, he helped demolish nearly eighty years of drywall and plywood to open up a long, light-dappled hall of seasoned timber, industrial brick walls, and windows that frame Ballard’s still-gritty working waterfront.

“It’s not a historically authentic mead hall,” he said, pointing out his Viking figurehead with a horned helmet discovered in a Poulsbo antique shop. “It’s a neighborhood gathering place. I’m always most pleased when we have people in their 20s and people in their 80s sitting at the community tables.”

One of those older patrons told McQueen that he’d first come to the Vasa Sea Grill as a sixteen-year-old immigrant. It was a place that immediately felt like home to him because of the older sailors and waterfront workers gathered there. It still feels homey to the patrons today, even the ones with no Viking heritage.

For Brian Takeuchi, there are no Nordic ancestors in his lineage as far as he knows, but patrons of the National Nordic Museum’s Julefest flock to Brian and his mother Dawn’s table to snatch up his hand-carved ornaments just the same. Woodworking has been in their family for more than four generations. Dawn recalled that her son started carving around age five. She had wanted to learn as a child herself, but older relatives kept telling her that she was too young to handle the knives. She did pick up woodcarving as an adult, however. “I tried a lot of things, but I kept coming back to wood,” she said.

Takeuchi, with his mother’s encouragement, kept looking around for classes to improve his skills. “I took four years with Erik Holt at the Museum,” he said. Then, on Holt’s recommendation, he went to Norway for two years to study at Hjerleid—the same school where Holt trained.

“I love the feeling of preserving the culture,” said Takeuchi. His pieces are generally made from wood that he sources himself, as was traditional with Scandinavian carvers. “If I can cut down my own tree, I will. When I’m at Julefest, I really like to answer questions on how something is made.”

Next Takeuchi would like to go to Sweden and take classes on how to build a Viking boat. “When I was seventeen, I carved my own dugout canoe. I’ve always wanted to learn more about how the Vikings made their boats.”

Images, top to bottom

Friends enjoy a

a

A photo from Leiren’s collection of modern retellings of ancient myths.

Photographer: Bekka Björke; Wardrobe Leiren Designs; Model, HMUA, Styling: Madison Leiren

A selection of Takeuchi’s carvings and tools.

For all three young entrepreneurs, the National Nordic Museum is both a fun place to visit and a source of inspiration for their own work. McQueen volunteered to pour shots at the 2019 Julefest bar as well as hosted the after-hours Julefest gathering at Skål. Takeuchi and his mother are regulars every year at various events. Leiren also volunteers when she can and her designs have been shown at donor events.

“I love our museum,” said Leiren. “I’m really honored when I can be a part of that legacy.”

Poulsbo History / Maritime Museums

Poulsbo History / Maritime Museums

Daily 10 - 4 pm,

Daily 10 - 4 PM

Norwegian Lunch Buffet

Norwegian Lunch Buffet

Wednesdays 11 -2, Sons of Norway

Wednesdays 11 -2, Sons of Norway

2nd Saturday Art Walks

2nd Saturday Art Walks

Each Month, Year Round

Each Month, Year Round

SEA Discovery Center

SEA Discovery Center

Thursday - Sunday, 11 - 4 PM

Viking Fest

Thursday - Sunday, 11 - 4 PM

Viking Fest

3rd Weekend in May

3rd Weekend in May

Fireworks on the Fjord

Fireworks on the Fjord

July 3, Liberty Bay waerfront park, Dusk

Nights by the Bay

July 3, Liberty Bay waterfront park, Dusk

Free Concerts July & August, waterfront park

Nights by the Bay

Free Concerts July & August, waterfront park

Viking City Classic Car & Boat Show

September 12, 2020

Viking City Classic Car & Boat Show

September 12, 2020

Sons of Norway Jule Fest

1st Saturday in December

Sons of Norway Jule Fest

Nordic Holiday Wonderland in December

1st Saturday in December

Free Nordic Santa visits & Carriage Rides

Nordic Holiday Wonderland in December

Free Nordic Santa visits & Carriage Rides

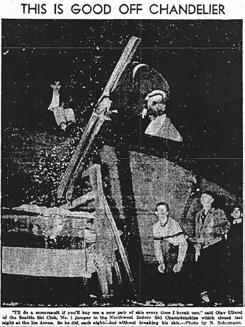

Olav Ulland and Hjalmar Hvam entertain the crowd at the 1938 Silver Skis race on Mount Rainier by doing a side-by-side flip. The race was postponed due to bad weather.

Bottom: This red sweater was worn by Ragnar Ulland during his skiing career. He donated it along with several other important items to the Museum’s collection.

by John W. Lundin

By 1930, over one million people living in the United States were born in Norway or had Norwegian parents. “The Norwegians brought to their new country a passion for skiing” said Harold Anson in Jumping Through Time. “They organized ski competitions to strengthen their ethnic ties, showcase their abilities, and generate a new sense of belonging to their new country.”

From the teens through the 1940s, ski jumping was a very popular form of winter sport in the Northwest, thanks to the region’s many Nordic immigrants. Our first jumping event occurred in February 1916, when Norwegian businessmen built a ski jump on Queen Anne Avenue to demonstrate the “popular Scandinavian sport” of ski jumping. Between 1917 and 1924, “genuine Norwegian ski jumping tournaments” were held over the July 4th holiday at Mount Rainier’s Paradise Valley.

From 1924 to 1933, the Cle Elum Ski Club held ski jumping tournaments that attracted competitors from all over the Northwest, watched by 3,000 to 5,000 spectators. In 1931, the club built a giant new ski jump, said by the Seattle Times to be “one of the most hazardous in the world, six percent steeper than any in Norway.” The Seattle Ski Club, organized by Norwegian immigrants in 1929, built a jump on Beaver Lake Hill at Snoqualmie Summit with “one of the steepest landings in the world, a hill three of four degrees steeper than the famous Holmenkollen Hill in Norway.” The Leavenworth Winter Sports Club formed in 1928, and built its giant ski jump in 1932 on what was later named Bokke Hill. Not to be outdone, Portland’s Cascade Ski Club formed in 1929, and built a ski jump on Mount Hood.

Ski jumpers competed in a circuit of tournaments, traveling between Cle Elum, Snoqualmie Summit, Leavenworth, and Mount Hood—often on successive weekends. Tournaments attracted

Anyone who has been close to a ski jumping hill is likely to know Ragnar Ulland and the Kongsberg jumping tradition. During the golden age of ski jumping, Kongsberg, Norway, was known for its incredible and daring jumpers, who flew through the chilly air in bright red sweaters emblazoned with white

Ks. These men were renowned throughout Europe and the United States in the 1930s and ‘40s: three of the four Olympic gold and silver medals awarded at ski jumping events during this period were won by Kongsberg skiers. Ragnar Ulland was born into an extended family of ski jumpers in Kongsberg. The Ulland family had seven brothers who grew up jumping in Kongsberg. The first to come to America was Sigurd, who in 1928 set hill jumping records at Lake Placid and Mount Shasta. After notable wins in Europe, younger brother Olav came to Seattle in 1938 to coach aspiring

thousands of hardy spectators—mostly Scandinavians— who traveled long distances, hiked up steep hills to reach the jumping sites, and stood outdoors for hours, often in snowstorms, to watch Norwegians fly off the jumps, fighting for distance records. In December 1937, Olav Ulland from Kongsberg, Norway, moved to Seattle to coach ski jumping, after his brother Sigurd immigrated in 1928. Olav, the first to jump beyond 100 meters, was a mainstay of ski jumping in the Northwest for decades.

In 1938, the famous Ruud brothers from Kongsberg—Birger and Sigmund—entered the Seattle Ski Club’s tournament at Snoqualmie Summit. Sigmund won an Olympic silver medal in 1928, and Birger won gold medals in 1932 and 1936. Seven of the sixteen jumpers at the tournament were from Kongsberg: Birger and Sigmund Ruud, Olav and Sigurd Ulland, Rolf Syverrtsen, Tom Mobraaten, and Hjalmar Hvam. Birger Ruud won the tournament with a near perfect score, somersaulting to a stop at the bottom.

Sigurd Ulland won the 1938 US National Championships in Vermont, then won the 1938 Leavenworth tournament, beating Birger Ruud, his brother Olav, and two members of the 1936 US Olympic team. Sigurd won the 1939 Leavenworth tournament, setting a new national distance record that lasted only a few hours, as Alf Engen jumped further at Big Pines, California.

In anticipation of the National Four-Way Championships in spring, 1940, Milwaukee Railroad built a world class ski jump at its Milwaukee Ski Bowl on Snoqualmie Pass. In addition to Alf Engen, the jumping event featured Torger Tokle, a recent Norwegian immigrant and rising star, whom Engen had beaten to win the 1940 National Jumping Championship. Tokle had the longest jump, but Engen won the Ski Bowl’s jumping event on form points. Showing he was a master of both Alpine and Nordic

skiing, Alf Engen won the Four-Way Competition, followed by his brother Sverre, Seattle’s Sigurd Hall, and Portland’s Hjalmar Hvan. Alf Engen won Leavenworth’s 1940 tournament, beating Sigurd Hall and nearly setting a new national distance record.

In February 1941, Alf Engen set a new North American distance record at Iron Mountain, Michigan, only to have it broken later in the month by Torger Tokle at Leavenworth. At the National Jumping Championships at the Milwaukee Ski Bowl in March 1941, Tokle set his second distance record in a month, beating Engen. Tokle set another distance record in 1942, but was killed in Italy in May 1945, as a member of the Tenth Mountain Division. During his short career, Tokle had broken twenty-four jumping records and won forty-two of the forty-eight tournaments in which he competed.

The US jumping team for the 1948 Olympic Games was selected after a tournament at the Milwaukee Ski Bowl. The

by Kirby Gilbert

young ski jumpers—and eventually the 1956 US Olympic ski jumping team. They were joined by their brother Reidar in 1947, who brought his fourteen-year-old son, Ragnar, to Seattle in 1951.

During the 1952–53 season, Ragnar notched five first-place finishes in the Northwest. The following year he began

jumping in Class A events—consistently taking second in tournaments and even beating his legendary Uncle Olav. In 1955 he won the National Junior Ski Jumping Championships at Leavenworth, where he tied the hill record with a standing leap of 284 feet. With a fourthplace win at the tryouts

for the US Olympic ski jumping team, he landed a coveted spot on the team.

His Olympic hopes were not to be, however —Ragnar badly hurt his back during practice in Cortana, Italy. He came home, being unable to compete further. Ragnar rallied, however; back in the US, he took third in

the Northwest Championships in 1958, and set a hill jumping record of 224 feet at Multorpor Hill the following year.

Today, Ragnar is retired and lives in Washington State, although he still skis and makes annual trips to Norway to visit Kongsberg relatives and friends. He has donated several items from his

skiing celebrity days to the National Nordic Museum—including the iconic red sweater— where they are valued parts of the collection. Ragnar Ulland’s existing Multorpor ski hill record of 224 feet still stands.

team was coached by Alf Engen and Walter Prager. Gustav Raaum, who had won Norway’s junior Holmenkollen tournament, stayed to attend the University of Washington and lead its jumping team, becoming a mainstay of Northwest ski jumping. Raaum listed fifty-six Norwegian students who competed for Northwest schools, forty-one in Washington alone. “The Milwaukee Ski Bowl hosted the National Jumping Championships in 1948, and a new distance record was set there in 1949, by a Norwegian exchange student.”

A major blow to Northwest skiing came in December 1949, when fire destroyed the lodge and train depot at the Milwaukee Ski Bowl, and the Milwaukee Road decided not to rebuild in fall 1950. The loss of the Ski Bowl’s Olympic caliber jumps was a major blow to Northwest ski jumping, although the sport continued at Leavenworth, Snoqualmie Pass, and elsewhere. Leavenworth hosted four National Jumping Championships through 1978, and three distance records were set there. In 1972, Leavenworth native Ron Steele became the second Washingtonian to be selected to the US Olympic jumping team, joining Ragnar Ulland (Olav’s nephew) in 1956.

In 1954, “a hardy group of Norwegian ski jumpers,” led by Olav Ulland, Gustav Raaum, and others, formed the Kongsberger Ski Club. The club built a ski jump at Cabin Creek east of Snoqualmie Pass, held competitions, gave jumping instructions, and assisted with jumping competitions at Olympic Games and international competitions.

Interest in ski jumping in North America diminished in the 1960s, and dropped further in the 1970s. The last Leavenworth tournament took place in 1978, which was a National Championship. In 1982, the New York Times published an article, “Ski Jumping Faces a Long Decline,” saying the popularity of ski jumping had nosedived and the sport was struggling.

Despite the ebbs and flows in popularity, Nordic ski jumping had a positive impact in the Northwest, serving as a way to continue Nordic traditions and values while sharing them with a broader community. National pride in American athletes of Nordic descent grew. Alf Engen was named skier of the century in 1950, and together with Torger Tokle, was inducted into the US Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame in 1959. Northwesterners

Ulland does a somersault during the Northwest Indoor Ski Championships. The skiers descended the jumping hill outside before coming through a window into the Ice Arena in front of the audience. Article clipped from The Seattle Times, November 12, 1939.

inducted into the US Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame include Seattle’s Gustaav Raaum and Olav Ulland; Leavenworth’s Hermod Bakke, Magnus Bakke, and Earl Little; and Portland’s Hjalmar Hvam and John Elvrum.

The Washington State Ski and Snowboard Museum on Snoqualmie Pass preserves and shares the history of ski jumping in Washington through a multi-media exhibition showcasing film clips, memorabilia, and other collections pieces. Learn more at www.wsssm.org.

“(The) breath-taking pastime of risking life and limbs on skis” is how a 1937 Seattle Times article described ski jumping.

Filmmaker Warren Miller agreed. “Jumping takes great courage, or a low IQ,” he said. “The agony of climbing, the shak-

iness of the scaffolds built out of scrounged lumber, and the lack of safety bindings kept most people from ever becoming ski jumpers. They were smart.”

Many Nordic ski jumpers were much more blasé about the risks involved. This casual attitude of jumpers toward their

sport was described by Norwegian Olympian Torbjorn Yggeseth in an interview in the Seattle Times of February 28, 1960. He scoffed at the idea of being afraid while flying the length of a football field over frozen terrain. “It’s not really as dangerous as downhill skiing,” he said. “You’re only going about

60 miles an hour at top speed. As you follow the curve of the hill, you’re never more than 20 feet high. And there are no trees to wrap yourself around. You land at 40 miles an hour. Some skiers land so gently they don’t even leave a mark in the snow.”

When Norway’s Petter Hugsted won the

John W. Lundin

Olympic gold medal in jumping in 1948, he was asked which was harder: winning an Olympic Gold or winning the Holmenkollen?

The Holmenkollen, he said. “In the Olympics you jump against four Norwegians, in the Holmenkollen you face fifty.”

July 24–26, 2020

November 21 & 22, 2020

by Rosemary Jones

Throughout the Nordic countries, Christmas shopping means bundling up and taking the family to an outdoor market. With more fresh air than your average mall, Jack Frost is likely to nip at your nose and toes. Fortunately, the markets also have a cure: glogg. No market is complete without at least one place where you can warm yourself from the inside out with the local version of glogg.

Although Christmas markets originated in the Germanic countries—one of the earliest is thought to be the “December Market” held in Vienna in 1298—the tradition is now found in almost all the European countries. The Nordics have certainly embraced this festive fête, with Christmas markets—complete with mulled wine—making merry in almost all the Nordic countries.

The Swedish amusement park Liseberg claims to hold the largest Christmas market in Scandinavia. From November through December, it features multiple live shows, spectacular nighttime light displays, and food specialties such as döner kebab made from reindeer meat. If the glitz of Liseberg sounds a bit too much like Disneyland at Christmas, smaller and more traditional markets can be found throughout the country. But whether you’re at a major city market or out in the countryside, you’ll be sure to find glögg, the traditional Swedish spiced wine drink. While Liseberg sells a family-friendly non-alcoholic version in the amusement park, traditional glögg contains spices, raisins, almonds, red wine, port, and brandy. Every market—and each country—seems to have its own variation.

Norway’s open-air museum Maihaugen in Lillehammer and the Norsk Folkemuseum in Oslo both hold open-air Christmas markets, featuring decorated houses and rooms sharing Christmas traditions from the Middle Ages to the 1950s, with

Christmas workshops, gingerbread cookies, puppet shows, and more. And, of course, you can find gløgg, which adds the country’s national spirit—aquavit— to the mix.

In Denmark, the Christmas market in Odense plays up nineteenth century fairy tale atmosphere for the fans of Hans Christian Anderson. Meanwhile, Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen offers properly sugar-dusted æbleskiver with fresh jam at their market. Danish gløgg—which a number of foodies argue can be called “liquid hygge”—often adds such ingredients as honey, orange rind, cinnamon sticks, raisins, almonds, cardamom seeds, and cloves to the red wine base.

The Finnish Christmas markets begin around pikkujoulu or “Little Christmas” in early December. Aleksanterinkatu is Helsinki’s official Christmas street, with a bright tradition of lighted windows that began in 1949 as a symbol of hope after the darkness of the war years. Christmas markets in Finland offer hot glögi, similar to the gløgg of Norway and Denmark. Some Finnish food blogs suggest spiking store-bought or homemade glögi with nontraditional ingredients such as blood orange or grapefruit juice, cherries, or almond liqueur. Even less traditional? New Nordic cuisine fans can find “blonde glögi” that substitutes white wine for red.

As Iceland grows as a tourist destination, so do the jólamarkaður, but Christmas markets are still a relatively new idea in the “land of fire and ice.” (Iceland’s longest running Christmas market didn’t start until 2002, but locals and tourists alike are still embracing the open-air holiday market tradition.) Held in Hafnarfjörður—known for being the town of elves and lava—visitors see lots of references to Iceland’s famous thirteen Yule Lads and their troll mama, Grýla. According to legend, the Yule Lads come to town to cause mischief while Grýla tries to grab naughty children for her cauldron. And don’t forget Grýla’s kitty, the Yule Cat, who will eat any children who did not receive a gift of clothing for Christmas. Fortunately, there’s something for those looking for something other than naughty kids to eat. The Hlemmur Mathöll Food Hall opened in August 2017 in Reykjavík’s main bus station and offers a “new foodie” Christmas market, where revelers can find a version of gløgg even though the drink is not a tradition in Iceland yet.

The National Nordic Museum’s own holiday market and Christmas celebration, Julefest, features a heady glögg with an intoxicating blend of cardamom, star anise, and cloves. And if that’s not traditional enough, the festival is slated to become an authentic outdoor Nordic Christmas market in 2020. God Jul!

but the exact recipe varies by region and personal taste.

One of the Museum’s longest-standing traditions may also be its most delicious. Volunteer run and led since its inception, Goodies2Go is a beloved part of the Museum’s Christmas tradition. Under the direction of Gail Blaine (left) and Sharon Lucas (right), dozens of volunteer bakers spend weeks beating together untold amounts of butter and sugar, rolling yards of dough, and anxiously peeking into ovens to make thousands of favorite holiday baked goods like krumkake, rosettes, and princess gems. Highly anticipated by Julefest attendees, the Goodies2Go selection regularly sells out each year. “We could have made $10,000 (in 2018) if we didn’t run out of cookies,” said Gail. In 2019, the bakers exceeded that goal.

by Timothy Krumland Volunteer Coordinator

Simply put, Goodies2Go is a bake sale, but Gail and Sharon—who have overseen the endeavor for several years—would say otherwise. “It is a fundraiser,” Sharon acknowledges. But more than that, Gail and Sharon both feel food is an important way to hold strong to the traditions of the Nordic community in this area. They influence both—continued heritage and the bottom line—thanks to their careful stewardship of this program.

That success may be owed to the women’s striking differences. Gail is a musician and avid baker; Sharon has a history working in non-profits, even serving as the Nordic Heritage Museum’s interim director in 2007. But those different skills and backgrounds have only strengthened

Goodies2Go over the years. The two have found a perfect division of labor, with Sharon handling the administrative side and Gail more of the creative tasks. Together, they have streamlined the Goodies2Go process and produced an ever-growing list of committed bakers.

Gail grew up in Ballard, and even attended Webster Elementary, the former home of the Museum. She explains that a huge part of her upbringing was centered around food, which was the main tradition her family brought with them from Scandinavia. This tradition of food is something Gail wants to share with others and has found willing pupils. “People are becoming more and more interested in learning about their culture,” says Gail, “and through baking traditional recipes it creates a tie to that culture.”

Though Sharon had never been to the

Museum prior, her strong experience in non-profits lead her to interview for the interim executive director position in 2007.

After her tenure, Sharon stayed involved with the Museum by volunteering at special events. It wasn’t long before she was asked to take on the Goodies2Go project. Though she describes herself as a mediocre baker, she is highly organized and detail oriented. Sharon’s organizational skills combined with Gail’s baking acumen made the duo an instant success.

Sharon says she and Gail have one big similarity: they get things done. Their follow through and stick-toitiveness has allowed for exponential growth in Goodies2Go. They’ve expanded the number and variety of goodies offered each year, as well as recently began hosting baking classes for potential Goodies2Go bakers. Not only will the classes contribute even more treats for Julefest, Gail and Sharon hope that these classes will bring in a new generation of bakers. Thanks to these expansions, Goodies2Go now has almost 130 bakers, who range in age from 12 to 96. Despite the work Gail and Sharon do to make Goodies2Go happen, they are quick to say that equal credit should go to all the bakers. Like all the Museum’s achievements, Goodies2Go is the result of teamwork, collaboration, and the tireless dedication of our volunteers. Thank you to Gail Blaine, Sharon Lucas, all our past Goodies2Go leaders, and the hundreds of bakers who make this tradition a success.

by

by Leslie Anne Anderson, Director of Collections, Exhibitions, and Programs

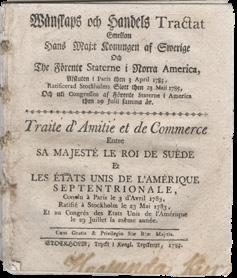

Americans regard 1783 as a watershed in the history of the United States. Famously, the American Revolution concluded with the Peace of Paris, signed on September 3. The United States’ consular relations with Sweden commenced that year, as well. Several months prior to the Peace of Paris, Benjamin Franklin negotiated with Sweden for formal recognition of the United States. The Treaty of Amity and Commerce (Svenskamerikanska vänskaps-och handelstraktaten) was the first such agreement the country made with a foreign power not yet an ally in its fight for independence. On behalf of King Gustavus III (r. 1771–1792), the Swedish ambassador to the French court,

Gustaf Philip, Comte de Creutz (1731–1785), initiated talks with Ben Franklin. King Gustavus III’s goal was for Sweden to be recorded as the first European country to extend an unsolicited offer of friendship. Congress responded by empowering Franklin—the newly-minted Minister Plenipotentiary to Sweden—to broker the deal on its behalf.

The twenty-seven articles of the bilingual treaty—written in Swedish and French— were intended to facilitate navigation and commerce between the countries. The treaty also made provisions in the event of war and granted reciprocal rights for residents of both countries, such as freedom of worship, suitable burial locations, and

distribution of property. The terms of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce Between Sweden and the United States, which was signed in Paris on March 5 and postdated April 3, 1783, remained in effect for fifteen years, yet the “true and sincere friendship” between the two continues to this day.

Thanks to Dr. Maria Albin, who first acquired this item, and the generosity of Dr. Lotta Gavel Adams, who donated it to the Museum, the treaty entered the National Nordic Museum’s collection in 2019. Visitors will be able to see the document in the exhibition Why We Collect: New Acquisitions from the National Nordic Museum on view from March 5 through July 19, 2020.

Seattle, Washington, northern Utah, and most of Minnesota are wellknown Nordic epicenters. But there are Nordic gems throughout the US— areas where Nordic immigrants made their mark on the local landscape in historic, artistic, and sometimes downright fun ways. Here is a sampling of Scandi sights to see on your next American road trip!*

1 La Crosse, Washington

Selbu Lutheran Church

Operating since 1903, the church was founded by Norwegian immigrants who had come to farm. Fun fact: the church was named for the Selbu district near Trondheim, Norway, from where the majority of its congregation hailed.

Bethany Lutheran Church

Norwegian immigrants to Toole County formed a congregation in 1911, and completed construction on their church house in 1925.

Though a staple of Nordic diets for millennia, lingonberries also grow wild and commercially in the Pacific Northwest. There are approximately 17 acres of commercial lingonberry production here, representing one-quarter of the commercial acreage worldwide.

4 Kingsburg, California

Swedish Coffee Pot Water Tower

“Central California’s Swedish Village,” Kingsburg, honored their Swedish heritage by designing one of their water towers to look like a Swedish coffee pot. Unfortunately, there’s only water in the 122-foot structure, not the 1.28 million cups of coffee it could hold.

Red Clog

Solvang puts its roots on display, with public art throughout the city paying homage to Denmark. Tourist favorites include the Little Mermaid Fountain, a replica Rundetaarn (Round Tower), and a big red clog outside of the Solvang Shoe Store.

Balto Creek

Samuel Johannesen Balto was a NorwegianSami explorer who skied across Greenland with Fridtjof Nansen in the 1880s. He moved to Alaska and was hired by the US government as a reindeer herdsman. This creek is named after him, as was Balto the sled dog.

Spanish Fork represents the oldest Icelandic settlement in the US, marked by a lighthouse statue. The first settler, Gudmundur Gud- mundsson, was a goldsmith and Mormon missionary who traveled to Utah in the 1850s.

The Rock Church

Constructed of limestone blocks by Nor- wegian immigrants in 1886, St. Olaf Kirke Church, also known as “The Rock Church,” still holds services.

Icelandic State Park

Icelandic homesteader G. D. Gunlogson donated 200 acres upon his death to create a protected nature preserve, which today includes restored historic buildings and a heritage center.

Wild Dala Herd Lindsborg, or “Little Sweden,” was settled in 1869 and has the “Nation’s only wild herd of Dala horses.” Thirty-one painted horses make up the herd in a city-wide community art project. Visitors can find the horses around the town if they “fala the Dala Horse Road.”

Nelsen’s Hall Bitters Pub & Restaurant Opened in 1899, Nelsen’s holds the title of Wisconsin’s oldest continuously operating tavern. When prohibition shut down alcohol sales, Nelsen applied for a pharmacist license to dispense bitters (90 proof).

Washington Island is also home to a fullsized replica of the 1150 Borgund Stave Church in Norway. Built in 1995, Stavkirke includes hand-carved dragon heads, a model schooner hanging from the ceiling, and twelve masts.

Finlandia University (Suomi College)

Finnish immigrant Juho Kustaa Nikander founded this school in 1896 to preserve Finnish culture and train Lutheran pastors. Today, the university hosts the Finnish American Heritage Center.

*What’s your favorite Nordic gem in America?

Let us know at marketing@nordicmuseum.org for possible inclusion in 2021’s map!

Statue of Saint Urho

March 16 celebrates Urho, the Patron Saint of Finland. Saint Patrick’s counterpart, Saint Urho is said to have driven the grasshoppers from Finland, saving the nation’s grapes.

America’s Largest Dala Horse

Twenty-five feet tall and seventeen feet long, this 3,000 pound fiberglass replica Dalecarlian horse is the largest in the US.

Danish

This 1848 smock windmill hales from Norre Snede, Denmark, and was brought to Elk Horn by a local farmer in 1976. It required hundreds of volunteer hours to assemble and is the only authentic, working Danish windmill in America.

Scandinavian

Founded and funded by the Norwegian Government, the church served as a place for Norwegian sailors to gather and worship while in Louisiana. The church blended with the local culture, adopting jazz as part of its Sunday service. The building stands, but the Norwegian government cut funding in 2016 and the church closed its doors.

Midnight

Lake Worth and Lantana have the largest permanent Finnish population outside of Scandinavia, so it’s no surprise they started Finlandia Days in 1983. Now christened the Midnight Sun Festival, the party includes music, food, drinks, and the Florida State Wife Carrying Championship.

One of the oldest log cabins in America, this log house was constructed by Finnish settlers in 1685! This 16- by 22-foot house is made of oak and ironware from the 1590s, as well as bricks brought to America by ship.

This 1997 working replica of the 1625 tall ship serves as a classroom and maritime experience. The original ship together with Fogel Grip brought Swedish and Finnish colonists to America in the 1600s. They helped found Fort Christina, New Sweden Colony in 1638—the first permanent European settlement in Delaware.

by Lauren Messenger

At Kristoferson Farm, environmental stewardship and sustainability combine the smell of lavender and hay, the happiness of friends and family coming together over a dinner table, and the joyful adrenaline rush of wind whipping past as you zipline through the trees. Located on Camano Island, Washington, this family-owned farm has operated for six generations and joins innovation and tradition in a very Nordic way.

Mona Campbell, the Director of Marketing at Canopy Tours Northwest and Kristoferson Farm, says that the history of the family and their commitment to sustainable land management informs their work today: “Our mission at Kristoferson Farm celebrates family, honors heritage, and respects the land. Our generation spent time developing our mission and it comprises our top priorities—our family, longstanding activities at the farm (forestry and agriculture), and environmental stewardship.”

Swedish immigrants Alfred and Bertie Kristoferson established the Kristoferson Dairy in 1897, starting their business with ten acres of land on Mercer Island. The business grew as Seattle did, introducing the delivery of milk in glass bottles and pasteurized milk to Seattle families. In 1912, Alfred Kristoferson purchased 1,400 acres of farmland on Camano Island that had been stripped of old growth forest by the timber industry. Alfred, his son August, Sr., and his grandson, August, Jr. established a farm there. Today, the now 231-acre farm cultivates crops of organic hay, lavender, pumpkins, and apples—while carrying on

the family tradition of sustainable growth. Once-vanished trees have reappeared, thanks to a century of careful stewardship by the family.

Sustainability and environmental stewardship come naturally to a family with strong Nordic heritage, and modern food and farming trends support that approach. The New Nordic food movement, for example, embraces precision farming, zerowaste production and transport models, resource conservation, and environmental education. Agritourism, which provides supplemental income to smaller farms and farming communities, allows visitors to reconnect to agricultural practices and landscapes. People come out of the experience with a greater understanding of where their food comes from, and a deepened appreciation for natural resources and farming communities.

Kristoferson Farm opens the landscape and history of Camano Island to visitors, in the hope that they will have a fun, transformative experience that will lead to a greater desire for change. “We hope that the larger community learns, understands, and values the precious natural resources of the land. Sustainability over the long term requires that we preserve and protect our water, wildlife, and habitats,” Mona Campbell explained. “We have learned a lot about forest stewardship and organic farming. We try to share that information in the activities at the farm as well as a bit about our family history. Our platform displays, our zipline guides, and displays in our barn feature how we manage our forest in a

90-year rotation and our farming activities utilizing organic practices. At our Dinner in the Barn series, we have historic photos and highlight the history of our 1914 barn.” For visitors, Kristoferson Farm offers exciting and meaningful experiences, as well as outstanding agricultural produce and artisanal foods and crafts. You can sit down to a delicious farm-to-table dinner, take a zipline tour through the lush tree canopy, work as a team to navigate the unique challenges and obstacles of the Terra Teams course, learn how to make your own lavender wands and wreaths, or celebrate a festival with dancing, music, food, and family activities. Mona Campbell’s favorite activity at the Farm is the zipline tour. “It brings families and friends together in a unique way as they experience an adventure that may be challenging as well

as fun. It is a joy to see guests return from a zipline tour and be elated and laughing, and also to know that they have experienced time in the forest enhanced by interpretation from our guides and platform displays. Developing the zipline tour was an innovative approach that fit our mission beautifully as it is a low impact activity, shares this amazing location with the public, and provides insight into environmental stewardship. At first glance, it sounded like a crazy idea, but further investigation proved it to be a good fit!”

While setting an example of what can be accomplished on the larger scale, the farm remains deeply tied to its local community on Camano Island. “As our generation became more active at the farm and in the community,” Mona Campbell said, “we learned how important the farm is to the local community. Its beauty is treasured by the Camano Island residents that pass it daily; and now with our businesses at the farm (Canopy Tours Northwest and Terra Teams), we have provided jobs to the local community as well. For the last three years, we have been host to a fall festival that brings the community together and supports local charitable organizations.”

The Kristoferson family, who have acted as stewards to the farm for over 100 years, continues to consider the importance of making decisions with the long-term impact in mind, with projects such as a timber harvest rotation that allows most trees to reach 90 years old, reestablishment of native plants on the farmland, and improving fish habitat through riparian planting along Kristoferson Creek. Kristoferson Farm is and will continue to be a leader in both conservation efforts and exciting new agriculture ventures.

This photo was taken shortly after the dairy and hay barns were completed in 1914. Both are still standing with the original fir structure and siding intact.

Sheep were among the first animals kept on the farm.

Zip lining is one of the new activities available to visitors.

by Paul Bannick

No one feels ambivalence toward owls. Throughout human history, encounters with owls have elicited strong feelings, firmly embedding them in cultures throughout the world. We have immortalized owls in both our art and our lore, describing them with real or imagined powers. Their natural mystery combined with our mythicization help to make every encounter with an owl memorable.

Six owl species live in both Nordic and North American landscapes, and serve as a natural and cultural link between these lands and the cultures that live upon them, inspiring us and reminding us of our responsibility for the conservation of our natural world.

The owls we share are spread irregularly across the northern part of the globe. In some cases, they breed in our areas and at other times they visit us during the winter. Owls of the North are dependent upon particular habitats, including Arctic tundra, boreal forests, mixed conifer forests, steppe, and grasslands. The owls that live in these areas are indicator species: their relative abundance helps us measure the health of and assess the threats to these ecosystems.

The owls that share North American and the Nordic environments also face common threats, chief among them climate change, which is already eliminating habitat and reducing populations of their essential

prey animals. Each of these owl species requires our immediate attention if they are to continue gliding through our landscapes and stories.

The Snowy Owl, the most easily recognized owl in the world, nests directly on the ground on promontories in the tree-less Arctic of North America and Eurasia. Snowy Owls have historically nested in parts of Greenland, Sweden, Finland, and Norway, and very occasionally in Iceland. During migration season, Snowy Owls move into southern Canada and the northern United States—including Washington State—as well as into parts of Eurasia, including Norway, Sweden, Finland, and occasionally Denmark. During “irruption” winters when great numbers show up in unusual places, they venture much further south. Irruptions are driven by either scarcity of prey or a bounty of young owls, but in both cases great numbers of owls must travel to survive.

The warming climate is shrinking Snowy Owl habitat from both the north and the south. Wintering Snowy Owls often live on the sea-ice, where they capture birds concentrated at the openings, but as ice melts the birds disperse, making it more difficult for the owls to find food.

Ominously, the frozen layer of earth under-laying the tundra is also melting. Without this permafrost, water soaks through the soil, eliminating the moist habitat needed by lemmings—the Snowy Owl’s primary food. The melting permafrost is allowing trees and shrubs to spread north, thereby eliminating Snowy Owl and lemming habitat from the south.

In addition, resource extraction, such as proposed drilling in Alaska’s National Petroleum Reserve, is threatening Snowy Owl habitat in an area that is also important to denning polar bears and many species of nesting birds.

In light of new research and findings, the International Union for Conservation of Nature changed the Snowy Owl’s status to “vulnerable” on its Red List of Threatened Species in December, 2017.

The Boreal Owl—known as Tengmalm’s Owl in Europe and Pearl Owl in Finland— is found in a latitudinal boreal band across North America and Eurasia, and south into the adjacent subalpine forest habitats. The Boreal Owl is found in the spruce forests from Alaska and Canada and into a few of the northern and western states including Washington. Across the Atlantic, it is found in the forested parts of Eurasia, including

Sweden, Norway, and Finland.