5 minute read

Preserving Humanity’s Past in Our Oceans

Preserving Humanity’s Past in Our Oceans

by Jason Griffin R.P.A.

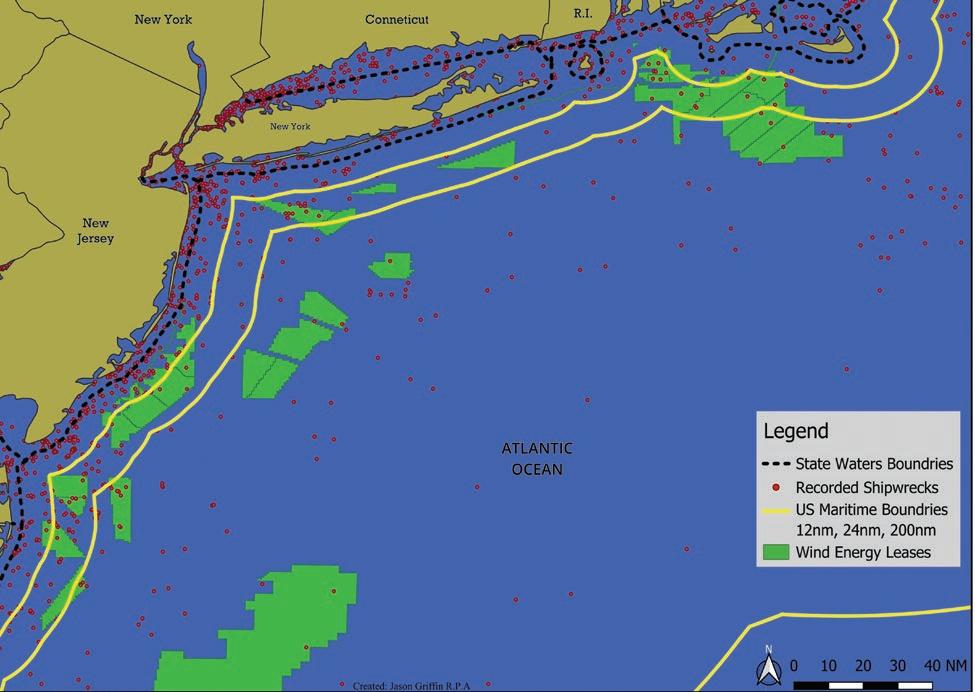

As technological advancements occur through new developments in the offshore wind energy industry, there will be times where these large projects may impact the cultural heritage of humanity's past in our waters. Federal, State, and Tribal government agencies in the United States have regulations in place to protect archaeological cultural resources within and outside their territorial boundaries. The success of offshore projects relies on building positive community engagement and being diligent in following these regulations.

The study and conservation of humanity’s past is an undertaking that stretches back far into the human timeline. Thutmose IV (~15th-14th century B.C.E.) recorded his excavation of the Great Sphinx of Gaza, nearly completely covered by sand, on the Dream Stele. Herodotus of Halicarnassus (550-479 B.C.E) traveled the Mediterranean collecting myths and stories to create his detailed retelling of the Greco-Persian War, The Histories. This endeavor was to preserve human achievements through the annals of time. The Renaissance saw the rise of antiquarians that searched for easily obtained and excavated relics and monuments of the past. These efforts continued into the 18th century C.E., with scholars studying human culture through Anthropology and Archaeology. The study of human culture remained a primarily academic profession until the late 20th century.

In the United States, the first law passed to protect archaeological cultural resources was the Antiquities Act of 1906. This legislation provides general legal protection of archaeological and natural resources on federal lands. Sixty years later, the United States passed the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA). The NHPA established a national program that now requires identifying and protecting historic and archaeological resources. The role of the professional archaeologist expanded to include government and private sector experts to ensure that all measures of the act are followed.

Since its signing on October 15, 1966, amendments made to the NHPA, as well as creation of supplementary legislation, expand upon the protection of archaeological resources. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE), and the Office of Renewable Energy Programs (OREP) are involved in the enforcement of the

NHPA for offshore wind energy projects. The BOEM requires that a wind energy applicant provide detailed information regarding the nature and location of historic properties that may be affected by the proposed development site, as part of the Renewable Energy on the Outer Continental Shelf (30 CFR Part 585). Depending on the scope of the project, the proposal could include a site assessment plan, construction and operations plan, general activities plan, or other submissions that are deemed necessary. Additionally, a wind energy applicant should also contact the State Historical Preservation Officer (SHPO) and Tribal Historic Preservation Officer (THPO) to understand their guidelines in identifying and reporting cultural resources. State governments and Native American Tribes may have additional requirements to what is required by the NHPA. Once these are met and the leases are secured, the survey of the proposed wind project may begin. The archaeological survey is most often conducted in tandem with a geological survey. The data collected is sent to an archaeological firm for review, or, if there is an archaeologist on site, reviewed in real-time.

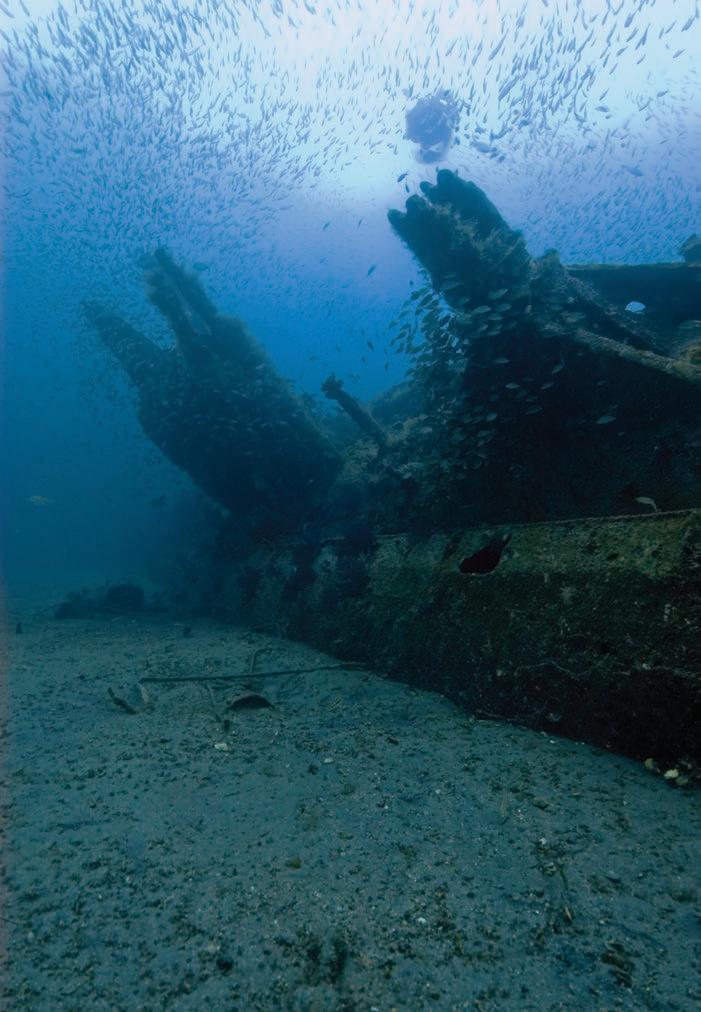

There is no doubt that shipwrecks are the ‘rock stars’ of the maritime archaeology field. The discovery of a shipwreck brings a lot of excitement to both the surveyors and the public, but they certainly are not the only culturally significant sites that maritime archaeologists investigate during a wind energy survey. There is potential for debris fields surrounding any ships, anchors, or anchorages. Also, sites and structures that were docks, World War II radar stations, aircraft, and even spacecraft (that date over 50 years) could be culturally significant.

During a wind energy project, the potential for much older discoveries should not be overlooked. For example, there is a submerged landmass in the North Sea, referred to as Doggerland, that once connected Britain to continental Europe during the late Pleistocene and Holocene. Stone and wooden artifacts have been recovered from coring activities in ancient peat layers in this location. Pre-Contact Native American artifacts have similarly been discovered not far offshore of North American coastlines and waterways.

In the United States, if culturally significant material is found that was not previously noted in a report or database, the archaeologist will document this in their final report with avoidance distance and other recommendations. This information is then used by BOEM in their review, per the requirements of the NHPA in Section 106 and in the Protection of Historic Properties (36 CFR Part 800). The BOEM will also use the information provided to make sure any projects meet obligations under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

Oceans and rivers have always been a valuable resource, and contain much of our human past. They continue to provide the means of transportation, commerce, innovation, exploration, sustenance, and art. Regulations can have the connotation of delaying project timelines, but the NHPA, and similar legislation were created to protect important archaeological cultural resources. Close adherence and cooperation with governing agencies will help build positive community engagement and make wind energy projects successful for all involved.

Jason Griffin R.P.A is Maritime Archaeologist at Berger Geosciences, which provides services to the wind industry with subject matter experts to support the realm of geosciences in a responsible manner.