LUCID

fever

mundane

utopia

02

Abby Falzone

ART DIRECTOR

Renee Pearce

EDITORS IN CHIEF

Jessica Brite

Lily Elwood

Husein Esufally

Farrah Haytham

FASHION EDITOR Hill Mak

BEAUTY EDITOR Antonia Sousa

LIFESTYLE EDITOR Elena Plumb

WRITERS

Alex Trotto, Soomin Yang, Meghna Iyer, Sophia Naumovski, Lily Elwood, Lauren Violette, Nyree Christianian, Wraven Wantanabe, Rachel Erwin, Valeria Martinez, Sarah Gordon,

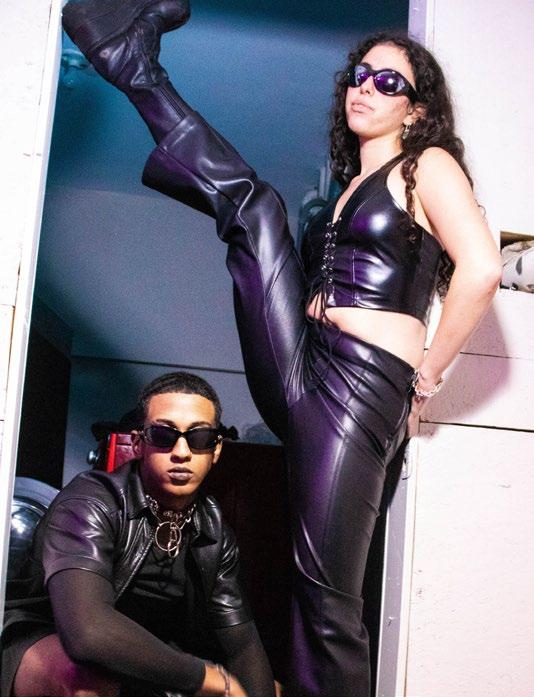

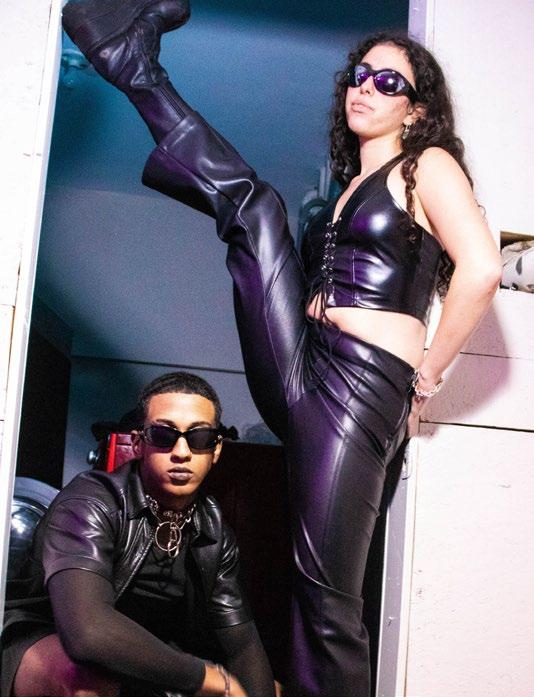

MODELS

Sasha Lewis, Anthony Peters, Ax Balione, Tanya Verma, Sam Levis, Samantha Diaz, Rachel Solomon, Yue Chen, Miles Stevenson, Bhavana Sinha, Annika Geiben Lynn, Jason Harris, Kat Tse, Elana Lane, Bita Adel-Zadeh, Lazaria Harris, Marisa Munoz, Andrew Barnett, Lina Petronino, Wraven Watanabe, Halima Duarte, Andrea Gertrudis, Ty Orlando, Lazaria Harris, Ronnie Efremov, Jacyn Daniels, Harrison Freiman, Yene Usua, Srishti Gummaraju, Luna Bruss, Amelia Ball, Aidan Sevier, Hannah Hartsough, Sasha Shrestha, Chloe Cowan, Schekinath Biaou, Jennifer Uyanga, jack deutsch, Chris Parker, Lynne Khouri, Ken Yin,Cassie Stanely, Cassidy Chamillard, Hill Mak

STYLISTS

Gigi Gillen, Adriana Alvarez, Solomon Canada, Woody Lindor

MAKEUP ARTISTS

Clarisa Zalles, Sofia Urrutia, Celine Plaisir

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

MANAGING EDITORS

PROJECTS EDITOR David Donoian ASSOCIATE CREATIVE DIRECTOR Sasha Lewis ASSOCIATE ART DIRECTOR

Jacyn Daniels PHOTO DIRECTORS

Angelina Chau Lynne Khouri ASSOCIATE PHOTO DIRECTOR Mia Rapella VIDEO DIRECTOR Sara Akhtar VIDEOGRAPHER Cali Cardenas VIDEO EDITORS Emanuele Dokyi Katie Ma

Gray Timberlake, Isabella Bernstein, Ebube Onwusika, Logan Roberts, Kat Tse, Adriana Alvarez

Azra Schorr, Peyton Pollard, Kathleen Ma, Shirley Wang, Izzy Bernstein, Serena Buscarello, Sydney Singh, Jenna Ory, Lauren Violette, Mukki Gill, Olivia Leon, Emma Lawson, Amanda Kerr, Cali Cardenas, Alex Chang, Kira Briggs, Isabella Pozzi DESIGNERS Daisy Tuller, Sydney Singh, Vanessa Peng, Sharon Chen, Emlyn Griffiths, Sophie Fiks DESIGN DIRECTOR Claire Higgins ASSOCIATE DESIGN DIRECTOR Rachel Osborne DIGITAL DESIGN DIRECTOR Tanya Kler HEAD STYLIST Yeani Kwon MAKEUP DIRECTOR Melanie Barest UX/UI DESIGNERS Jason Harris Titamah Simpson Jade Khatib SOCIAL MEDIA DESIGN Elana Lane WEB DEVELOPER Ania Misiorek COMMUNICATIONS DIRECTOR Azra Schorr COMMUNICATIONS ASSOCIATE Elana Keller OUTREACH COORDINATOR Rachel Mann PRODUCTION ASSISTANT Hannah Shapiro PRESIDENT Isabelle Roberts VICE PRESIDENT Tommy Bell TREASURER Paige Keeler SECRETARY Phoebe Kahn

PHOTOGRAPHERS

04

AN EXPLORATION OF HOW OUR FANTASIES JUXTAPOSE REALITY TO CREATE A CLEARER LENS THROUGH WHICH WE VIEW THE WORLD.

LUCID:

LETTER FROM

THE EDITORS

06

This semester we entered a new era of The Avenue, with a brand new leadership team, ushering in quite a bit of nerves with the fear that we didn’t know what we were doing. To be honest, most of the time it very much felt like we were making it up as we went — who knew we would spend hours on Zoom with the Creative and Art Directors just to plan out a calendar. Nevertheless, here we are, and we couldn’t be prouder to present this issue. Both of us have been with the magazine since our first year at Northeastern as writers, columnists, and section editors, so taking on the EIC position has been an incredible and humbling experience.

This issue, we really wanted to keep the writers in mind for our magazine theme. Something that spoke to them, that evoked creativity — and we arrived at a theme that would allow our writers to explore aspects of fantasy-based storytelling in media and dive deeper into how our culture is shaped. LUCID is exactly that. It perfectly encapsulates the line between reality and fantasy; how we as people interact with the world through different lenses of thinking; how media interacts with fantastical elements to create something tangible for our consumption. It is both sanity and insanity, the concept of control over yourself and your environment, it is theatricality, it is over-thetopness. Lucidity is about hyper-awareness, understanding that you are a product of your environment, at its mercy, while simultaneously knowing that change is possible.

The articles that came out of our brainstorming process are both outrageous and muted, both fantastical and realistic, both light and dark. The comparison of opposite aesthetics became a staple for us as we sent our writers to begin their processes. Keeping in mind a light or dark theme allowed them to go full throttle in their specific direction and has given this issue an air of juxtaposition that The Avenue has not had in the past.

With this issue, the editorial team worked on overdrive for weeks concepting and perfecting this semester’s slew of articles. We were able to connect with the creative process as well, striving to make the magazine cohesive across the board, all in the hopes of giving our readers the best immersive experience.

LUCID is the product of hours and hours of hard, collaborative work between the creative and editorial teams. It is so inspiring to work with like-minded, talented, creative individuals who deeply care about the finished product. There truly is nothing like being a part of something every step of the way from its inception to its final form. Overseeing the process has ultimately been such a joy for the both of us and it absolutely represents everything we believe The Avenue to be — innovative, beautiful, and of course, extremely fashionable. Thank you so much for taking the time to read LUCID; we hope you enjoy it.

JESSICA BRITE AND LILY ELWOOD EDITORS IN CHIEF

LETTER FROM THE CREATIVE DIRECTOR

08

THE FANTASTICAL, THE PERFECT, THE TERRIFYING

LUCID has pushed the boundaries of what The Avenue is, what we can produce, and how far we can experiment as a collective before we get lost in it all. With all of the new talent added to our team this semester, our creative collaboration has never hit a high this amazing and I can’t help but believe that this is a turning point for The Avenue as a whole. Always pushing each other to question if we’re “doing too much,” I am extremely proud and grateful for everyone involved in making this issue what it is.

One of our biggest goals as we moved into this semester was connecting to our audience, showing our readers that this is not just an exclusive, high-fashion magazine. We aimed to connect and evoke emotion and excitement out of everyone who lays eyes on our spreads and articles. LUCID represents the fantastical, the perfect, the terrifying, the real in our everyday lives and society. We hope that we’ve created a world in this issue that you can not only see, but touch, feel, and get lost in.

This being my first issue as creative director, I hope to have started a new chapter and push what it means to be a part of The Avenue and its production. From styling to design to photo to direction and everything in between, I am so, so proud of this issue and how far we’ve come since we sat down in May and started building our creative team. With all of the (literal) blood, sweat, and tears we have spent on making LUCID what it is, I can whole-heartedly say that it was worth it.

I hope you can feel the passion we’ve put into making this issue what it is, and that The Avenue continues to push what is possible as a publication at Northeastern, Boston, in the industry, and in our lives. Thank you to everyone who was a part of this beautiful creation process, enjoy.

ABBY FALZONE CREATIVE DIRECTOR

10

UTOPIA 60s Fashion: A Conduit for Social Change Iris Van Herpen: Fashion in Flux Romanticizing Your Life The Sweet Escape Psychedelics: In Pursuit of Change Young and Beautiful Healing through Mindfulness All That Glitters Finding Answers in the Stars 012 024 030 036 042 046 050 056 060 066 072 084 090 094 098 102 108 112 116 122 MUNDANE I Am Not a Sin Fashioning the Mad Hatter Dissecting the 90s 'Heroin Chic' Look Not So Clean After All Victoria's Dark Secret The Nihilist Generation Dreams: Fantasy

Reality? Couture

the Dark FEVER TABLE OF CONTENTS

or

from

12

creativedirection ABBY FALZONE artdirection RENEE PEARCE photography MIA RAPELLA design CLAIRE HIGGINS contributingartdirection JACYN DANIELS modeling SCHEKINATH (KIKI) BIAOU & CHLOE COWAN styling YEANI KWON & GIGI GILLEN & ADRIANA ALVAREZ makeup&hair MELANIE BAREST & GIGI GILLEN & JACYN DANIELS & ELANA LANE

creativedirection ABBY FALZONE artdirection RENEE PEARCE photography MIA RAPELLA design CLAIRE HIGGINS contributingartdirection JACYN DANIELS modeling SCHEKINATH (KIKI) BIAOU & CHLOE COWAN styling YEANI KWON & GIGI GILLEN & ADRIANA ALVAREZ makeup&hair MELANIE BAREST & GIGI GILLEN & JACYN DANIELS & ELANA LANE

14

16

an imagined world

18

pearls modular necklace by foreign resource

u p dress ri g h t d i r ce t i o n u p right direct i o n pu

u p ihw t e

right d i re c t i o n pu thgir noitceid

noitcerid

up

dress by right d i r e c t noi pu

white dress b y thgir noitcerid

ta i lored 20

tailored dress yb rengised thgir

white

22

24

60S 60S 60S

60S FASHION: a conduit for social change

In times of struggle, people often turn to fashion to express their emotions. They look to it to spark the cultural changes they crave but aren’t ready to speak aloud. As such, fashion becomes the conduit for social change and the beginnings of a revolution.

We do this on a small scale every day as individuals. However, when a community of people join together in the movement, it can push the boundaries of shared cultural values. This cultural phenomenon was exemplified during the war-filled 1960s. As the Vietnam War and the Cold War unfolded, people felt a range of emotions — from fear, to rage, to a desire to escape from the chaotic world around them. Women stepped up to fill nontraditional roles, and style trends evolved to suit their changing needs. As people attempted to find direction in the midst of social turmoil, fashion and style became dictated by each individual. In this era, fashion ceased to begin in the hands of designers, but instead grew from people and the way they chose to live.

In the midst of war, optimism is a necessity. There was a common wish to escape and a sought-after remedy at the time was psychedelics. They grew to be popular because they provided a means of freedom from reality, and through this escapism, people were able to access a semblance of hope. This social movement found its way into the patterns and colors of clothing. The bright designs evoke a sense of confusion, resisting reason or order. Men’s clothing in particular drew influence from psychedelics and music. The novel prints found in their clothes grew to be known as “A Peacock Revolution for Men.” The bright prints were used most prominently by musicians like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, whose lyrics frequently explored the use of psychedelics.

writing MEGHNA IYER modeling RONNIE EFREMOV & JACYN DANIELS & HARRISON FREIMAN photography MUKKI GILL design DAISY TULLER styling ADRIANA ALVAREZ makeup CELINE PLAISIR

CREATION AND ROLE DISRUPTION

26

Similarly, music has the power to subdue and transport an individual to another world — one that, at times, is easier to live in than the real world. When a person wears the chaos and immerses themselves in it, they let go of the pressure to process the chaos around them, which opens the door toward acceptance of one’s circumstances. This mindset helped people to cope with the effects of war and made room to hope that better days were ahead. Men’s clothing had never been colorful or bold before, but these new trends enabled them

to explore their feelings regarding the traditional features of masculinity in greater depth and ultimately confront them.

For women, the ‘60s was a time of creation and role disruption. With the threat of death and violence looming in the background, many young women used their time to live life to the fullest and without regrets, which included embodying non-traditional roles for the first time. From that youthful, rebellious spirit came the miniskirt. After seeing how women

28

were shortening their own skirts, French fashion designer Andre Courrèges and Mary Quant, an English designer, were the first to pioneer the miniskirt. They were made in every color and pattern, including “Space Age” themed skirts, which reflected the future-friendly sentiments inspired by the ongoing Space Race. The trend of futuristic fashion fueled the Mod, or Modernist, clothing movement, an era characterized by more rulebreaking. Women did not have to follow the age-old rules of what to wear or who they should be — they could be anyone they wanted.

As women made their way into positions of power within the workplace and the wider world, the first pantsuit for women was designed. In 1966, Yves Saint Laurent debuted the “Le Smoking” tuxedo for women. Previously, the tuxedo had been a clothing item reserved for men, and with the advent of this suit, it became more socially acceptable for women to don them as well. As women gained social agency, so too were they able to better control what they wore and how they were perceived — a kind of power that, until the 60s, had been unheard of.

The ‘60s were about creative dissent and challenging norms amidst dwindling support for the ongoing war. The fashion trends of the decade represented a time of dissonance and redefining what it means to be ourselves. People dressed to be free and to express their passions, a pivot made possible through communities finding common ground. Clothes do not magically inherit the power to break boundaries on their own. Individuality is its own culture, but the community is a counterculture with the potential to restructure the ordinary.

REDEFINING WHAT IT MEANS TO BE OURSELVES

30

FASHION IN FLUX

Is human evolution ever complete? Are our physical bodies reflections of our souls or impediments to humanity’s next stage of development? Ethereal fashion designer Iris Van Herpen’s latest collection, “Meta Morphism,” suggests that the human form is an ever-evolving concept. Our current state is not the end of Darwin’s thesis, but simply a point on the map of the human continuum.

Rarely does fashion send its audience spiraling into existential crises. However, toeing the line between fantasy and reality has become somewhat of a trademark of Van Herpen’s career — and “Meta Morphism” is no exception. Van Herpen explores humanity’s relationship with nature by delving into the lore of Ovid’s “Metamorphoses,” deconstructing the poem’s transformative themes to comment on humanity’s increasing reliance on technology. Through sustainable materials, a manipulation of shape and form, and celestial designs, the forwardthinking fashion designer is writing her own mythos of transhumanism, leaving the audience wondering how the next stage of humanity will emerge.

It is no secret that Iris Van Herpen is the fashion industry's unrivaled paragon of biomimicry. Even as a student at ArtEZ University of the Arts, her unconventional ingenuity was evident. What other student constructs designs from umbrella boning and metal boat paneling? Her designs are evocative of both a dreamscape and the future of fashion, combining whimsy and methodical modernity in an unprecedented manner.

Drawing influence from the beauty and chaos of nature, the shape of the human body, and the flow of movement itself, Van Herpen has defined her label with her surreal designs for the past 15 years. She hopes to elevate fashion beyond limiting labels such as a “garment” or “commercial product.” Instead, she operates under the more abstract definition of fashion: an art that explores its interactions with its surroundings. Even for Van Herpen, “Meta Morphism” is her most ambitious project to date; it posits that such otherworldliness is now fast approaching our lived reality.

writing SOPHIA NAUMOVSKI illustrations IAN NICASTRO design VANESSA PENG

Meta Morphism” reinforces that the human form is in constant flux. Its unique manipulation of form distorts models’ bodies along with our sense of reality, muddling our understanding of where the human form ends and art begins. The flowing silhouettes and exoskeleton bodices become an extension of the models, transforming them beyond the constraints of their natural figures. The draping of white tulle in the “Ananda-Maya” gown frames its model in a shroud of smoke, rebirthing her as a celestial goddess emerging from the heavenly clouds of Olympus. The billowing, copper sleeves of the “Singularity” jumpsuit become fluid appendages of the model, gliding with her as if they are one entity. These transcendental, mystic shapes elevate the models into supernatural beings.

As Arachne becomes the spider and Daphne becomes the Laurel tree, Van Herpen fabricates her own definition of a utopian reality through humannature symbiosis, an evolution sought after since Ovid’s time. The “Mano-Maya” and “Arachne” gowns breathe beauty into the woman-spider mythos, with the former enhancing the model with claw-like limbs and the latter entwining her in the of the collection materializes the myth of Daphne. the boundaries between clothing and body. Such through Ovid’s dream, where humanity and nature

The Maison's insistence on the sanctity of nature is further realized through its creative process. Van Herpen utilizes some of the most environmentallyconscious materials and tools to spawn her designs. In this collection alone, she employed biodegradable banana leaf fabric blended with raw silk, cocoa shell beans, and up-cycled and overstocked organza. Such eco-friendly inventions are made possible through Van Herpen’s use of cutting-edge technologies like 3D printing, laser cutting, and electroplating. Even as nature remains the essential player in her designs, Van Herpen embraces human technology as a tool for modernizing fashion. She realizes its potential as an asset to facilitate sustainability, rather than a threat to the natural world.

In this collection, technology is not only a means of production but a central theme in her work. “Meta Morphism” is more than a reflection on ancient mythology and the literal objectification of women’s bodies — it is a metaphor for humanity’s next leap in reality: virtual reality.

Where the metamorphic transformations of Daphne and Arachne are fantastical fables, transhumanism is a near reality, where humans seek to enhance their bodies and cognitive faculties beyond their natural capabilities. Though cyborgs are still science fiction, the advent of the Metaverse has made the virtual universe a concrete possibility. The Metaverse is opening a new dawn of humanity

32

34

where socialization, work, and play may take place on a completely different plane, where humanity and technology converge as one. Reality is now being redefined, begging the question if such an “enhancement” is a blessing or a curse.

Will a virtual lifestyle threaten to dissolve our sense of self? What happens to the “real world” if life exists exclusively online? Just as Van Herpen finds the beauty in Daphne’s metamorphosis, she also finds it in the transhuman transition. The “Glitched Growth” dress allows the model to embody a futuristic cyborg form without sacrificing Van Herpen’s signature, ethereal style. The dress’s robotic, exoskeleton bodice is embossed in a reflective, silver coating and embellished with loose threads looping from the shoulders to the hem, reminiscent of tangled wires. The dress seems to imply that our bodies are still evolving; this is simply a stage in the negotiation of boundaries between human form, natural evolution, and technology.

As Van Herpen embraces these changes, she also warns of the hazards of transformation. Taking inspiration once again from Ovid’s genius, her “Narcissus” gown layers the model’s face against an embroidered white profile on a black organza panel. The model’s face blends with the dress and is swarmed by distinct, yet similar reflections of white faces throughout the dress, materializing the danger of both narcissistic self-obsession and a loose grasp on self-identity. The Metaverse provides an opportunity for people to redefine themselves, which can both promote self-expression and muddle our sense of identity. Assuming different identities between the physical and virtual may create a confusing and complex split reality.

evolution of form.

“Meta Morphism” is more than simply another haute couture collection festooning Paris Fashion Week’s runways. Van Herpen seized the opportunity to remind us that new technology is not a threat because it challenges conventions of humanity. In fact, she welcomes it as a tool for transformation. This collection is a supernatural experience, ushering in a new wave of reality at the nexus of nature, humanity, and technology. If anyone is guiding us on this intimidating journey of hyperreality, it's going to be Iris Van Herpen.

36

When the future is undefined, limitless, and unknown, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed. I often feel like I am sailing through choppy waters, with waves crashing in every direction. Uncertainty and instability are at the forefront of my mind, clouding any ability to remain present or optimistic.

Our generation has witnessed seemingly endless hardship. We were born right around 9/11, making fear an emotion ingrained from birth. We were taught how to hide silently underneath desks as news channels flashed headlines of the latest school shooting. We saw natural disasters that ravaged communities and took hundreds of lives.

I used to be the type of person who trusted that things would work out. I trusted that my life would fall into place and that I would become everything

I wanted to become. As my adulthood quickly approaches, I’ve found it difficult to maintain that optimism. When reality feels overwhelming, there’s comfort in an escape. I, like many others, will scroll through social media to find entertainment and reassurance in curated snippets of other people’s lives — ones that seem significantly more enjoyable by comparison. They appear more regulated, more beautiful, and more predictable, like a movie montage. I envied them and wanted to recreate this feeling in my own life. I needed to know if it was possible to regain the hopeful mentality of my youth through romanticizing life, and in turn regain the magic that it used to hold.

writing NYREE CHRISTIANIAN

modeling SRISHTI GUMMARAJU photography KIRA BRIGGS design EMLYN GRIFFITHS styling YEANI KWON makeup MELANIE BAREST

writing NYREE CHRISTIANIAN

modeling SRISHTI GUMMARAJU photography KIRA BRIGGS design EMLYN GRIFFITHS styling YEANI KWON makeup MELANIE BAREST

To test whether romanticizing my life would actually make me feel better, I gave romanticism a threeday trial run. Three days where anything that didn’t make me feel fulfilled fell to the back burner. Three days of movie-montage soundtracks. Three days of loving myself and the people around me, hard and unabashedly. Three days of conscious effort to remain present, and trust that the life I want is coming my way.

The first day was a challenge — I couldn’t quite grasp how to remain present. I was so overloaded with deadlines that it felt nearly impossible to focus on myself. I spent the morning feeling anxious, and the afternoon feeling disappointed in myself for not checking off every item on my to-do list. To move past the feelings that would have previously demotivated me, I decided to look at my life as a story, categorizing this moment as a growth period; the rising action part of my story. I was able to gain perspective by journaling, engaging in my EFT tapping routine, and listening to the countless Spotify playlists built to inject a little more sunshine into my life.

The following morning, I was uncertain of the efficacy of my three-day trial but cautiously optimistic that it would be better than yesterday. My boyfriend and I were scheduled to fly out for my cousin’s wedding: we woke up before the sun and played music while we made the bed, grabbed our luggage, and eventually headed out the door to Mike’s Donuts. We sat in that tiny restaurant where we were regulars, and watched the sunrise through the café windows. I felt so full of love and so full of hope. I couldn’t wait to celebrate love with my love.

There’s no doubt that travel days can be tough for most people. My checked bags were not initially recorded in the airline’s system, but after a minor panic attack and a laugh with the lady standing next to me in line, my baggage tags were printed and we were ready for take-off. The remainder of the flight was easy, and my mani-pedi was waiting for me when we landed. I sank into the massage chair and pictured my ideal life, careless and worry-free. Spending a day on self-care is not something I usually prioritize, but I immediately felt grounded, in touch with myself, and able to take on the day.

38

the excitement and pure joy in the groom's eyes. A beautiful moment was made even more beautiful because I was present — my phone was buried in my bag, and my self-consciousness seemed to melt away when I danced. I felt like I was in a movie, watching the speedy exit of wedding crashers, overhearing two brothers reconnect, and slowdancing with my boyfriend.

I really wasn’t sure whether romanticizing my life would change how I felt, especially because it is such an abstract mentality. However, I felt real physical and mental changes. I have struggled with anxiety ever since I can remember, but at this event, which would have previously sent me into sensory overload, I felt in control of my emotions. I was reminded of all the strategies I had accumulated throughout my years in therapy and was able to

Even though I am still filled with uncertainty, romanticizing my life rewarded me with a smile that widened each time I reminded myself that I am in control. I get to decide what city I move to next and which career I choose to pursue; who I let into my life and who I let go. Who I am, and who I will become. I am the author of my own story. This time, I’m sailing toward the horizon, no matter the storm.

40

the sweet

We are obsessed with escape — the luminous, magical, the distant — obsessed with diverting from the dull monotony of our day-to-day lives and into better realities.path to healing.

Escapism is the desire to disengage from reality and escape into a world of wonder and fantasy. Designers draw inspiration from the fantastical and imagined to help wearers and audiences to break free from normalcy. Escapist fashion has been interpreted by designers both established and emerging, utilizing elements from science fiction, fantasy, and more. They seek to transport viewers of their collection to a new reality, one perhaps more bearable than the one we currently exist in. The imaginative nature of escapist fashion allows designers freedom from the constraints of modern, on-trend collections that may fall victim to blending in with the crowd. From ready-to-wear accessories to haute couture, designers of wearable art transport their subjects and audiences into their imaginations with their extraordinary creations.

Embroidery designer kaMILA of Mila Textiles enhances the human form with hand-embroidered bags and balaclavas. The one-of-a-kind accessories are like their own miniature worlds, which are exploding with vibrance and color. kaMILA’s stitch work is embellished with beads and sequins and, according to their website, is “inspired by natural surroundings with a touch of surrealism.” Their designs look like colonies of coral polyps from afar, but a closer look reveals dense patches of hand-stitched embroidery thread, clusters of tiny beads arranged in spikes like sea urchins, sequins, pearls and iridescent beads that sparkle and shine, and the occasional grinning critter. kaMILA posts photos modeling the playful, saturated balaclavas and nothing of their face shows except for the expression they wear on their eyebrows and dark eyes. Instead of being lost in the explosion of color and life of the piece, the juxtaposition of reality and the surreal makes the mask wearer’s eyes become even more entrancing and somber, as if they are yearning for the imagined world the mask comes from.

Wearable art is not only a means for escape, but a tool to enhance the escapist visions of their wearer’s imaginations. As such, these extraordinary pieces are often worn by performers and music artists onstage or in music videos to heightenthe illusion of fantasy. Fashion has always been entwined with the music industry, and has become a way for performers to both assert their individual brand to their audience and create a memorable experience at concerts, in their music videos, and walking red carpets.

42

escape

writing GRAY TIMBERLAKE modeling YENE USUA photography SERENA BUSCARELLO design SOPHIE FIKS makeup SOFIA URRUTIA styling WOODY LINDOR

writing GRAY TIMBERLAKE modeling YENE USUA photography SERENA BUSCARELLO design SOPHIE FIKS makeup SOFIA URRUTIA styling WOODY LINDOR

Rapper and singer Doja Cat takes us to the world of “Planet Her” in her “Need to Know” music video, a space-travel themed number full of holograms featuring a star-studded clique of aliens — including an elf-eared Grimes. Doja Cat’s skimpy space outfit contrasts massive, out-of-this-world Windowsen FW21 Athletic Platform Thigh High Boots. Windowsen’s Creative Director, Sensen Lii, combines exaggerated costumewear and sportswear in their dramatic, genderless designs. Inspired by science-fiction media like the TV series Black Mirror, Windowsen’s futuristic wearable art effortlessly enhances Doja’s otherworldly allure.

Like Doja Cat, futuristic dance-pop artist Grimes’ music videos also break viewers free from reality, and she uses otherworldly art and fashion to enhance the imagined worlds that exist in her videos. Grimes’ “Shinigami Eyes” music video brings us into a world that bears no resemblance to our own. “Shinigami Eyes” evokes a glitchy, trippy, futuristic escape, exploding with holograms, color and fantasy, where cyborg women duel with shiny metal swords and laser beams. This world is electric and techy, but a closer look reveals much of it is influenced by the natural world. The abstract, spiky metal mask Grimes wears enriches these biopunk aesthetics that are the core of the video.

The mask was created by Lance Victor Moore, a self-described mask-artist, face jewelry creator, and avant-garde fashion designer who has created fantastical pieces for the likes of Grimes, Machine Gun Kelly, Iris van Herpen, and Lady Gaga. Moore gives animal products like horns, bones, and leather a second life by resurrecting them into nature-inspired face masks. He uses parts of animal carcasses as the base of his pieces, but he transforms them into wearable art with a metal and punk style — giving bear-fanged skulls metal grills and embellishing leathered pony skin with large studs. His masks cover most of the wearer’s face, but he says his pieces make people feel more free, as they can be anyone in any world while wearing them.

Escapism is meant to take us out of our world, but it often brings us right back to it with inspiration from its natural elements. At the same time, escapist art and fashion can truly take those who experience it out of their world, as artists are creating surreal, fantasy worlds to escape to, with wearable art functioning as the conduit.

44

take us of our world out

PSYCH- EDELICS

46

What does the word “psychedelic” bring to mind? One might imagine the Beatles tripping out with tangerine trees and kaleidoscope eyes, or Alice discovering Wonderland. Aside from fanciful lyricism and surrealist literature, the term “psychedelic” is used to describe the class of hallucinogenic drugs that run the gamut of LSD, psilocybin mushrooms, ayahuasca, and peyote.

Throughout history, psychedelic drugs have served countless functions and become important cultural phenomena. Some use psychedelics for religious and spiritual experiences, while others use them socially at parties or festivals. Many people try them out of pure curiosity. Beyond making one hallucinate, many believe psychedelics grant us the ability to see life through a different lens.

Psychedelic drugs have long been associated with escapism. LSD, for example, is known for its crazy, colorful psychedelic properties and its ability to trigger transformative, mind-altering experiences, or “trips.” What better escape than to enter a seemingly alternate reality filled with bright colors and eccentric hallucinations?

But for many, using psychedelics isn’t necessarily about escape. Although LSD is a hallucinogen, having an “acid trip” probably won’t make one see things that aren’t there. LSD does cause visual distortions like swirling patterns and movements among still objects but is best known for its effects on your mindset. Researchers don't fully understand the effects of LSD and other psychedelics on the brain, but previous studies have revealed that they depress certain parts while stimulating others. A series of brain scans conducted by experts at the University of Sussex and Imperial College, London found the drugs to induce a “heightened state of consciousness” overall.

LSD may trigger euphoric feelings and intense empathy. People on psilocybin mushrooms might experience similar excitement and giggles. However, these drugs can just as easily induce a state of intense paranoia and anxiety, also known as having a “bad trip.” Whether one has a good or bad experience depends on their mood and surroundings, signaling that the psychedelic experience greatly amplifies what the user is already experiencing.

writing WRAVEN WANTANABE modeling LINA PETRONINO & WRAVEN WANTANABE photography AMANDA KERR design RACHEL OSBORNE styling WOODY LINDOR

OF

Aside from altering emotions, psychedelics are characterized by their ability to elicit a deep preoccupation with their present surroundings. Someone on LSD might become fascinated with an element of their environment, fixating on it for long periods of time. Such preoccupation might also come in the form of emotionally connecting with someone else or reflecting upon oneself. Since the drug can inspire intense contemplation or soul-searching, many describe their experiences as profound mental or emotional journeys. Rather than providing an escapist reality, psychedelics can allow people to very deeply connect with themselves and their environment.

The “psychedelic experience” contrasts with much of what younger generations like Generation Z experience. From cell phones to social media, we exist in a hyperconnected era. We’ve grappled with a global pandemic, climate disasters, and a mental health epidemic, so one might think escapism would be in high demand. However, it’s not everyone’s cup of tea. Some, left listless by the pandemic or weary about the future, might gravitate towards psychedelics in the search for an entirely new lease on life, or at least a different lens through which to view the world. Some may only try them once, whereas others will have countless psychedelic experiences over their lifetime.

Regardless, more and more people are interested in psychedelic drugs, and the social and cultural trends of our generation are a hint as to why their popularity is increasing.

Today’s rise in psychedelics draws parallels with the popularity of LSD during the 1960s. At the time, a counterculture movement was taking place, born from the anti-war sentiments of young people — LSD was partially a symbol of that movement. The culture that arose culminated in the “Summer of Love” in 1967, a social phenomenon that drew roughly 75,000 young people to the streets of San Francisco to usher in a new era of liberation by way of fashion, ecstasy, and Utopianism. While Gen-Z isn’t gathering in the thousands to do psychedelics together, we are seeing the undercurrents of a new social revolution. The Black Lives Matter movement (BLM), the anti-work movement, and global support for Ukraine are examples of the shifts we are seeing. So, while psychedelics don’t represent our generation in the same way they represented the free-spirited folks of the 60s, their popularity and usage are representative of young people seeking change.

Ultimately, psychedelics are just a small category of the countless recreational drugs that humans use. Their popularity is rising, but they aren’t used as widely as alcohol and marijuana. Regardless of the numbers psychedelics are extremely culturally significant. From our ancient ancestors first discovering plants with hallucinogenic properties to hippies doing LSD at Woodstock, they have played an important role in our collective social development. Although everyone has different experiences with psychedelics, it’s clear that the most important thing they can do is allow us to see things from a unique perspective.

48

WHAT BETTER ESCAPE THAN TO ENTER A SEEMINGLY ALTERNATE REALITY FILLED WITH BRIGHT COLORS AND ECCENTRIC HALLUCINATIONS?

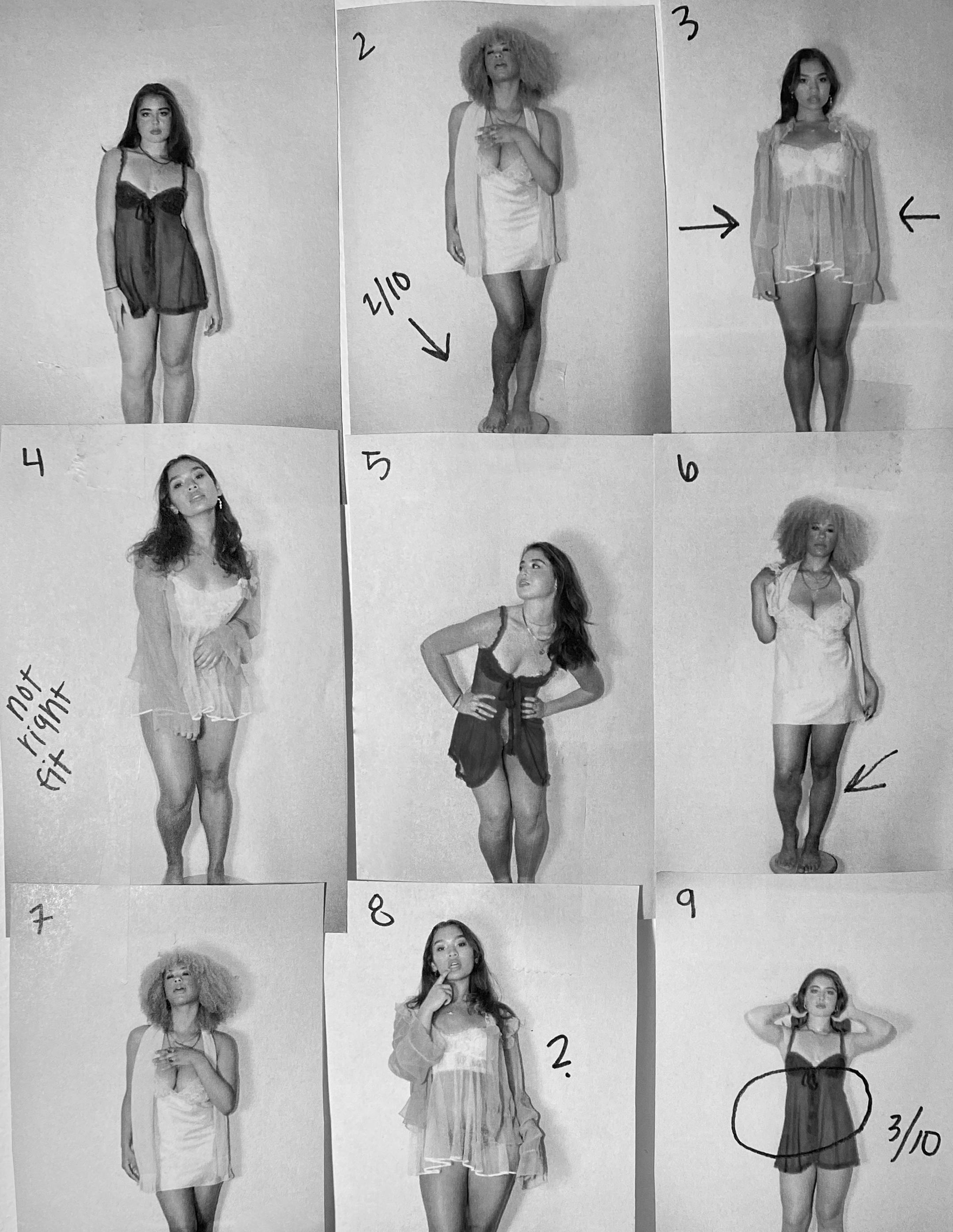

& BEAUTIFUL COQUETTE REFERS TO A FASHION STYLE CONSISTING OF A CLASSIC, ROMANTIC, AND HYPER-FEMININE APPAREL 50

YOUNG

writing ISABELLA BERNSTEIN modeling BITA ADEL-ZADEH & SOFIA FRANCHESCHINI & MARISSA MUNOZ photography OLIVIA LEON design SYDNEY SINGH styling ADRIANA ALVAREZ makeup CLARISA ZALLES

writing ISABELLA BERNSTEIN modeling BITA ADEL-ZADEH & SOFIA FRANCHESCHINI & MARISSA MUNOZ photography OLIVIA LEON design SYDNEY SINGH styling ADRIANA ALVAREZ makeup CLARISA ZALLES

From the minute her first album, “Born To Die,” was released, Lana Del Rey has been a fashion and cultural inspiration. She burst onto the music scene in 2012, quickly becoming a prominent icon on social media app Tumblr in the early 2010s, and has been idolized across platforms such as Instagram, Pinterest and TikTok for the entirety of her career. Often labeled as “sad-girl” pop, Del Rey’s raw, personal lyricism and dreamy musical style serenades listeners directly. Her accessibility — particularly in these online spaces — has made her extremely influential. Del Rey’s 1950s and 60s Americana-inspired aesthetic pairs flawlessly with her emotional and glamorous lyrics, making for a perfect source of inspiration for style-inspo videos, movie edits, and photo captions.

A common tag on posts utilizing Lana Del Rey’s media is “#coquette,” a word defined by the dictionary as a flirtatious woman. Recently, the idea of a coquette refers to a fashion style consisting of classic, romantic and hyper-feminine apparel. Coquette style contrasts girlish charm and luxurious sex appeal, and is dominated by dainty patterns, lace and frills, bows, natural makeup and light neutral colors, punctuated by deep reds. The expansion of coquette’s dictionary definition to a complex subculture can be credited to Del Rey’s lyrics, which are arguably the most interesting and influential aspect of her artistry.

Famous for dialogue about taboo topics such as drug use, violence, naivety and unrequited love, Lana Del Rey is a master at mixing sad motifs with romanticism and opulence. Her risqué lyrics have garnered controversy over the years, but these illicit

52

topics are most likely the biggest appeal to her music — their shocking nature and raw humanity are what make them influential and powerful.

Del Rey’s lyrics glimmer with vintage romantics, melancholia, and luxury. Songs referring to luxury items, like “The Other Woman” and “Off To The Races” have inspired listeners to love high-end designers including Chanel, Dior, and Vivienne Westwood. But this is just the tip of the iceberg. Del Rey often alludes to youthfulness and adolescence, as seen in songs such as “Lolita” and “Carmen,” and unreleased songs such as “Put Me In A Movie.” These allusions parallel the girly, bashful and seemingly innocent essence of the coquette, explaining the bows, frills, lace, and ballet attire that is seen throughout the style.

Lana Del Rey often references clothing and makeup in her songs. She mentions heart-shaped sunglasses in “Diet Mountain Dew,” a 50s babydoll dress in “Yayo,” and says “I keep my lips red” in “Black Beauty.” These references have direct influences on her listeners. The stylistic philosophy Del Rey is known for has quickly become a staple of coquette fashion. When Del Rey makes explicit references to pieces in her wardrobe, her listeners are able to purchase their own versions. This is part of what makes Del Rey so magnetic — anyone can wear what she sings about and recreate her air of glamor.

Lana Del Rey’s lyrics are not her only influence over the rise of the coquette trend. Soft vocals, effervescent melodies, and classical and jazz influences have characterized Del Rey’s music across her many albums. She often utilizes

euphonic instruments such as the piano, violin, and harp, seen most prominently in her 2019 album, “Norman F****** Rockwell.” This accentuates the sense of classic, romantic and victorian lusciousness in her music, coupling her work further with the ornate nostalgia of the coquette style. Del Rey’s vocals — soft, high, and whispery — have a feminine, flirty and innocent charm like no other. The mixture of these dream-like harmonies and mature lyrics are embodied in the coquette style, as it combines both elements with its contradictory youthful girlishness and quiet sex appeal.

Lana Del Rey’s music videos — perhaps closer to short films or video art — are equally as significant as her lyrics. Del Rey masterfully pairs her retro-chic visuals and personal style with her music, furthering her influence on the way her listeners dress. Her natural makeup is often paired with a graphic 1960s liner, as seen in “National Anthem.” White, lacy dresses, heart-shaped sunglasses, and pearls have become staples of the coquette style for their lovely, elegant, slightly provocative and — most importantly — nostalgic flavor.

Lana Del Rey’s visual iconography and recurring motifs also contribute to the style as a whole. Her use of flower and water imagery coincides with the florals and flowy materials that dominate coquette clothing. Most of Del Rey’s videos are filmed on old,

grainy cameras, or in black and white, making her work look like it is straight out of a time capsule. This presentation matches her evocative, retro lyrics and melodies, and is yet another tie to the vintage look of coquette.

The coquette style of clothing is not isolated to internet and commercial fashion trends. Recently, high-fashion designers have been inspired by the modern day coquette, elevating the style on runways around the world. Australian fashion house Ozlana showed a stunning collection — each look complete with bows, pastels, hearts and pom-poms — in Winter of 2021 at Shanghai Fashion Week. Sandy Liang’s Spring 2023 collection incorporates coquette’s classic girlish pleated skirts, flowy fabrics, bows and braids. In October of 2021, Marc Jacobs dropped a collection inspired by Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides, a staple of the coquette subculture.

Not a soul captures lovely nostalgia as effortlessly as Lana Del Rey. She has truly brought the past back to life with great technicolor and her own modern twist. Coquette holds an innocent, feminine beauty that has been ever present throughout the ages – it is centered around the concept of love. Everything Lana Del Rey creates embodies this. What could be more “classically feminine” than love, the desire to love, and the desire to be loved?

54

IT COMBINES BOTH ELEMENTS WITH ITS CONTRADICTORY YOUTHFUL GIRLISHNESS AND QUIET SEX APPEAL

HEALING THROUGH

MINDFULNESS

56

I still remember the very first time I entered the orange room and met my meditation instructor: Berna. The room was strikingly large and enclosed by warm orange lights. I placed my backpack on the ice cold floor and my attention immediately turned to the aromatic smell that came from the incense on her table side.

“Gently close your eyes and take a breath in,” Berna said, as I caught myself fidgeting with the pillow she gave me to sit on.

Since I was 14, I had struggled with anxiety on a day-to-day basis. Some days were better than others, but overall, it was a challenge for me to get through just three full days without breaking down or feeling drained.

On the harder days, I felt like I only had the energy to be upset. It was like I was sinking underwater — into the deep, blue ocean, where the darkness seemed to have taken over my sense of self, future and identity. I wished I could swim back to the shore, but the waves kept dragging me back out.

It had come to a point where I knew I had to ask for help. After many different trials of several different practices, I finally decided to enter the world of mindfulness: the practice of seeking comfort from my breathing and from within.

As Berna instructed, I took a breath in, but my mind was racing with thoughts. I was bored and didn’t feel comfortable, but I became patient with the practice and began to feel calm.

“Place your hand over your heart, and start taking care of your inner child,” Berna said. “The one that feels abandoned, the Kat that needs love and care. Don’t leave her alone, because you are truly loved.”

Tears started trickling down my face and a wave of emotion rushed through me. I was confused by how I felt — I thought meditation was supposed to make me feel more calm and centered, so why was I crying? Was the practice itself a trigger, or was I finally confronting all of my suppressed emotions?

Over the next few months, Berna and I continued uncovering these hidden emotions. It took some time for me to sit still and be at peace with my heart, but once I slowed down and observed the way my body moved, everything gradually began to piece together.

writing KAT TSE modeling KAT TSE photography KATHLEEN MA design SOPHIE FIKS styling GIGI GILLEN

Six months later, I bought a notebook and began to write. I wrote all of my thoughts, worries and fears down onto the pages of my notebook. From the test I had to take at school next week to the things I hated about my body, every single thought that appeared in my brain was written.

It was through this practice that I started to distinguish what I do and don’t have control over.

A few weeks later, Berna and I burned these pages. We watched all my most destructive thoughts go up in flames. The “unrealistic expectations” were now specks of ash in a fireplace. Over time, I realized that I shouldn’t have to worry or beat myself up over situations that were beyond my control. It’s nice to reminisce about the past every now and then, but I must be careful to not sink back into that hole.

For me, the most helpful meditation practice was thinking about the past, then bringing my breath and my mind back to the present. It was a mind technique that I had to slowly master from within.

I realized that the uncertain feelings of guilt stemmed from my childhood traumas, and fresh betrayals, such as my recent breakup, triggered a constant battle between my mind and heart. Once I started to become more aware of my triggers and emotional patterns, I could start to feel a sense of ease and comfort with my own company.

Over time, I learned my boundaries — what I liked and disliked. I learned how to give myself space and time to reflect instead of jumping to conclusions. It was these breathing and mindfulness exercises that brought me this level of clarity. It was taking a small pause from the busy hustle culture to reconnect with myself and my inner child. With these new tools in my arsenal, I slowly started to heal from my past traumas.

Today, I can use this technique anywhere I want — not just in the orange room. I could go for a walk around the park and truly take in my surroundings. I could admire how the trees swayed side by side, how the birds chirped and how the rays of sunshine felt as they brushed past my face. I began truly appreciating the small wins that life could offer me, and became grateful for the little things that I might’ve previously taken for granted.

58

AT THE END OF THE DAY, IT ALL CAME BACK TO MY BREATH, MY BODY, AND ME

60

writing RACHEL ERWIN modeling SAMANTHA DIAZ & SAM LEVIS & TANYA VERMA photography SYDNEY SINGH design SYDNEY SINGH styling GIGI GILLEN makeup CLARISA ZALLES

GLITTERS ALL THAT

This year, I struggled to come up with a theme for my birthday party. I wanted it to be something fun, flashy and affordable for my friends.

It had to be glitter.

Glitter is everywhere: it’s in Sephora, Party City, Target and most likely your favorite corner store. It usually comes cheap, priced below $5 per offering. You can find a glittery version of almost anything, ranging from edible sparkles to a dazzling cowboy hat.

Glitter has been a part of my life for as long as I can remember, and it’s been a lasting presence on Earth since 40,000 B.C. Mica, a glittery mineral found in rocks, can be found in cave drawings and on Mayan temples. Later on, Egyptians, including Cleopatra herself, used crushed beetles to adorn their faces with glitter.

The glitter we use today originated in 1934 when Henry Ruschmann discovered a way to use plastics and other landfill materials to make packaged glitter. Decades later, glitter has become a beauty staple. Notable brands like Revlon and Estée Lauder were among the first to formally introduce glitter to the beauty industry in the 1960s, an era defined by a “refined shimmer” rather than bold, bright sparkles. The 1970s and 80s saw more daring uses of glitter, from David Bowie’s glittery alter ego, Ziggy Stardust, to the rise of British glam rock. By the

62

1990s, glitter had taken over products marketed to young girls, with sparkly school supplies and fashion accessories filling the shelves at stores like Claire’s and Limited Too.

What was once just an accessory, has become a tool of expression and rebellion used by marginalized groups. Looking beyond the Euphoriathemed parties and the Fenty body sauce, one will see the countless ways feminist and LGBTQ+ activists have made glitter their weapon. In a sense, it is the perfect battle tool for those seeking a nonviolent form of protest.

2011 signaled the start of “Glitter bombing” — the act of showering someone in glitter, first employed by activist Nick Espinosa against right wing presidential candidate Newt Gingrich. At a book signing, Espinosa doused Gingrich in rainbow sparkles, making a statement about Gingrich’s disdain for the LGBTQ+ community. For Gingrich and other right wing politicians, it was perceived as a threat to their masculinity, as a spray of a feminine powder is undoubtedly as dangerous as a nuclear weapon. Additionally, when trying to clean up glitter, it is nearly impossible to find every fleck, which added to the politicians’ frustration.

GLITTER IS USED AS A WAY TO CELEBRATE AND EMPHASIZE

In a statement against body negativity, individuals on social media have started their own rebellion, painting their stretch marks with gold glitter and calling them “tiger stripes.” In this case, glitter is used as a way to celebrate and emphasize a feature that once made someone insecure. It puts the power back into the hands of people who have been badgered and bullied for their natural bodies.

In a few major cities like New York and Chicago, queer-friendly churches are mixing ashes and purple glitter on Ash Wednesday in a movement titled “Glitter+Ash.” Glitter Bombs for Choice, a group of pro-choice activists, mails anti-abortion organizations packages filled with glitter, in a statement that people with uteruses should have control over their reproductive decisions. While the LGBTQ+ community has used glitter as a form of expression for decades, it has also long been associated with women most often perceived as a trivial display of femininity and vanity. Glitter may appear frivolous and soft, but when used as a weapon, it can be a powerful tool of public humiliation and shame.

IT ADAPTS AND EVOLVES, EACH TIME A LITTLE MORE POTENT

Following an alleged sexual assault of two girls by a police officer, feminist activists in Mexico City protested the normalization of violence against women by throwing pink glitter across the streets and at the security minister. This act was intriguing in the way that it paired typical protest violence with the dispersal of glitter, a nonviolent act.

These instances, as well as many more not listed here, reveal glitter’s uses go far beyond an eyeshadow look. It is a symbol of the fight against patriarchal power and oppressive governmental actions.

That is not to say, however, that glitter is the perfect symbolic tool. Activists must consider that glitter, despite its power, can be detrimental to the planet.

Glitter is usually a microplastic, which can take hundreds, if not thousands, of years to break down. It also requires the usage of fossil fuels in order to be produced, which are detrimental to the ozone layer and remain primary drivers of climate change. Glitter pollution is showing up throughout our planet, especially in bodies of water. This is mainly because, when we come home from a club, a protest or party, we wash the glitter off, then allow it to flow down the drain and eventually into these bodies of water.

There is a way to make glitter using cellulose, which can be plant-based. Universal Soul, a beauty company, is using trees to create biodegradable glitter. If other brands were to follow suit, this innovation could soften the impact of glitter on the environment, making it a more ethically-sound protest tool.

Using mica, as cave painters did in the early days, is still an option, but it is frequently mined by child laborers. Though difficult to differentiate between Mica mined by children or not, a few brands to note, including Coty and L’Oréal, have committed to stopping child labor in India as early as this year.

Knowing all this, how do we decide if the impact of glitter in an expressive sense outweighs its environmental consequences?

Those using glitter should be open to new and more ethical alternatives, provided they remain affordable and readily accessible. It is the responsibility of large corporations and manufacturers to take the necessary steps to keep glitter accessible.

So, when using glitter as part of our wardrobes, beauty routines or party plans, we must consider its history, source and impact. Glitter does not have to be consistently exercised as a statement or a protest symbol; it adapts and evolves, each time a little more potent, each time a little more powerful. For me, glitter is my method of standing out. It announces my courageous, unapologetic femininity in a loud way. It is also fun as hell! We all can use glitter to amplify ourselves because the world is always in need of more unwavering shine.

64

ANSWERS

FINDING IN THE STARS 66

There’s something so unsettling about the unknown. The future may hold our wildest dreams or our greatest fears — so how do we come to terms with the things we do not know? Do we learn to accept uncertainty, or do we escalate our search for answers? Many people turn to divination, the practice of seeking knowledge through supernatural means.

Divination can be practiced in many forms, whether it be fortune telling, psychic readings, astrology, or tarot, but each practice serves the same purpose: to answer our questions. As college students with uncertain futures in regards to career paths, relationships and economic stability, there is little sense of security. Sometimes we find comfort in the answers, or the “path” outlined for us in these age-old practices — whether legitimate or not, they provide at the very least an illusion of certainty, and there is comfort in that.

Astrology interprets how stars and planets influence human destiny. It is one of the oldest practices on Earth, originating in the Mesopotamian region and dating back anywhere from 4,000 to 6,000 years.

Until the 17th century, astrology was considered a scholarly tradition. However, as Western science developed, so did skepticism toward astrology.

In recent years, there has been a surge in the popularity of wellness and self-improvement practices, and with it came the reprise of astrology. Today, many identify with the basic attributes of their sun sign and utilize daily horoscope apps such as Co-Star to help focus their day. Astrologer Steve Parson has watched the practice become increasingly popular throughout the 2010s and was not surprised when more people started using astrology for guidance — he had already been guiding himself and others through life with astrology for years.

At the age of 23, Steve Parson received a chart reading by a woman who he now sees as one of the most incisive astrologers he knows. After an eerily accurate reading about his personality, familial relations, and even a prediction of a family member’s health condition, he began studying astrology himself shortly after. Now a practicing astrologist, Parson offers his own reading services to shed some light on some of the mystery.

writing SARAH GORDON modeling LAZARIA HARRIS & TY ORLANDO photography IZZY BERNSTEIN design VANESSA PENG styling GIGI GILLEN

However, Parson never meets his clients face-toface. He knows each of his clients only by their chart and shares his interpretations through a voice recording. He says a birth chart can tell him when someone will move, break up with their significant other, change career paths, or even take their last breath — though he does not disclose theories that would cause excessive disturbance to the client. By providing insight into the future, astrology can offer a sense of reassurance to those who feel discomfort in the unknown.

“For many, the idea that whatever is happening to them is supposed to be happening to them is validating — that it somehow involves a plan,” he said. “Without astrology it feels like chaos…‘When is this going to end?’ or, ‘Is my life always going to be this way?’”

Parson sees many of his clients regarding uncertainty, particularly within their career choices. He claims the “fear of future regret” is always a major motivation for his clients to seek answers. Many people fear devoting their lives to unrewarding, unstimulating work, and Parson believes his services can help prevent that. Through his clients’ birth charts, he can assess their passions and personalities, which in turn helps them better understand themselves and their desires. Ultimately, Parson operates under the philosophy

68

that what is meant to be, must be. He sees no reason for trying to reshape the future, but instead hopes his clients will use these answers to take control of their lives, live more confidently, and unlock their fullest potential.

Similar to how birth charts can offer a glimpse into the future, a deck of tarot cards can do the same. Through a single deck, tarot readers channel an elevated insight to decipher a person’s past, present and future. Tarot decks are similar to playing cards in the sense that they also have four suits, but instead of diamonds, spades, hearts and clubs, tarot cards have wands, swords, cups and pentacles, with each suit representing a specific approach to life. Cards are shuffled and laid out in a personalized manner to ensure that the client’s energy is reflected.

Card reader Kiki Wallace explains that most of her work is in observing the future. When doing a reading, Wallace says she can focus on someone’s career path, healing journey, friends, or family. Although she says 90% of her clients seek information about their future love life, there are many other insights she can reveal from someone’s future.

“Tarot has the incredible ability to tap into the energy you have already been manifesting to help it come true,” she says.

The use of tarot has also seen a rise in more recent years, which comes as no surprise to Wallace. She saw many clients virtually throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, as they were questioning how long the world would be shut down, what the impact of the new vaccine would be, and what their world would look like post-pandemic. Now, many of Wallace’s clients are curious about the future of the economy and the progression of wars. People want to feel as though they have a sense of certainty in times of uncertainty, and tarot can provide that feeling.

Astrology and tarot foster a sense of confirmation in one’s self. Parson believes the work he does is healing for his clients, as it offers an alternative explanation for why they are the way they are. In a sense, people feel like there is something larger in this world keeping them afloat.

While many find comfort in the use of astrology and tarot, others remain skeptical. Without any science or logic to back these practices, how does one trust their reliability? Wallace reveals that even she has questioned her practice before, but is reassured when time after time, her readings provide a sense of direction to those who feel lost.

Parson agrees, as he knows how questionable it may appear to rely on stars to dictate our personalities and our futures. However, he believes that those who question astrology can see the power for themselves if they open their mind to it.

“How do you reconcile that in 2022, we understand 6% of the human brain and perhaps 7% of outer space? How do you reconcile the existence of the church [with science]?” he asks. “Some things are not reconcilable. There is a great deal we don’t know. Have humility.”

70

READINGS PROVIDE A SENSE OF DIRECTION FOR THOSE WHO FEEL LOST

mun

72

dane

mun dane

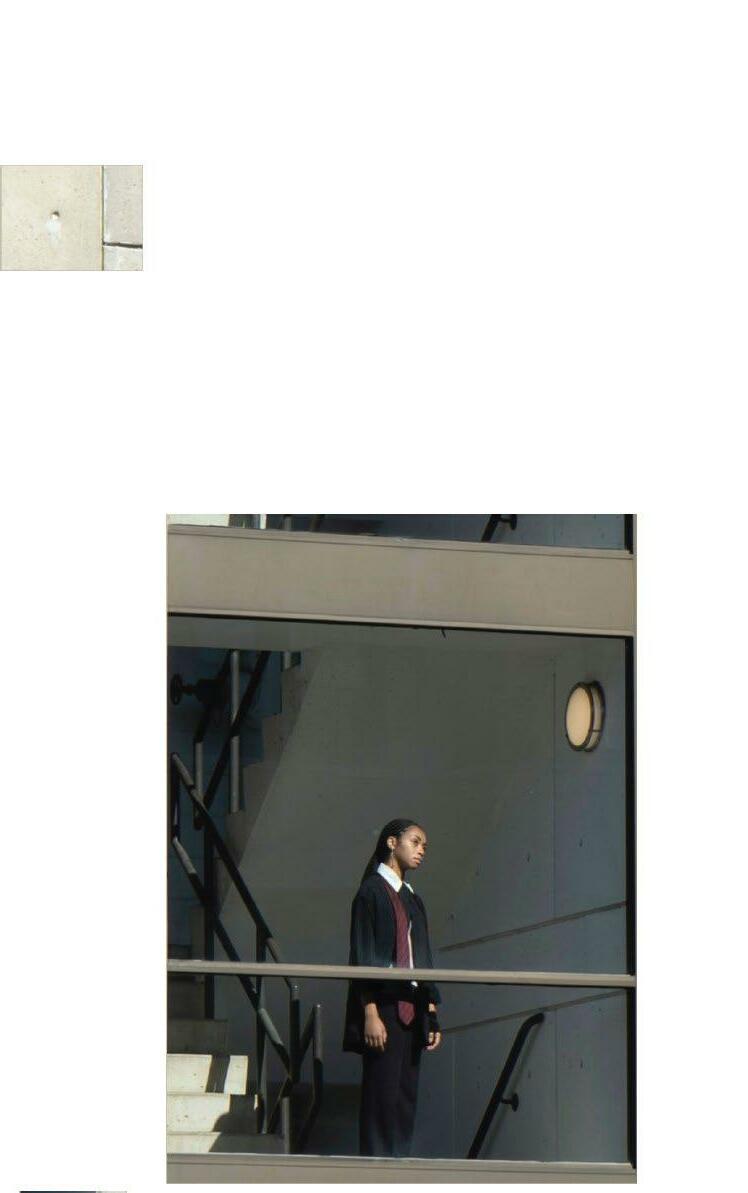

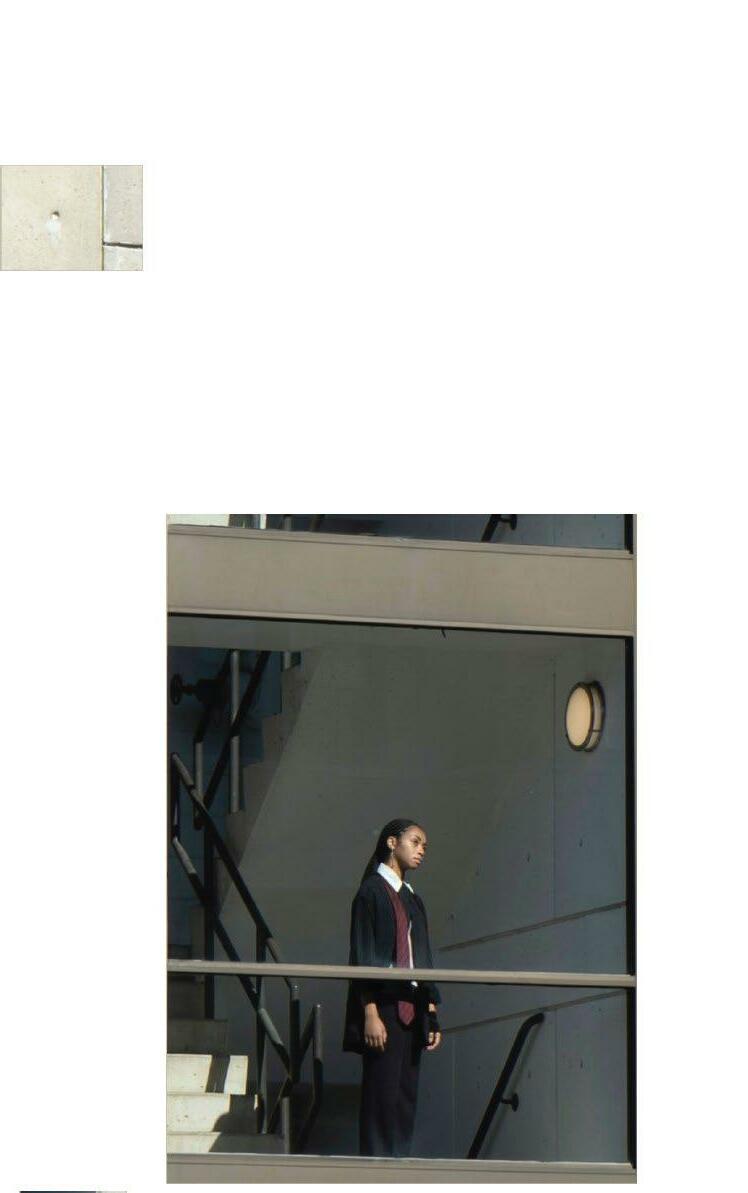

creativedirection ABBY FALZONE artdirection RENEE PEARCE design CLAIRE HIGGINS & RENEE PEARCE photography ANGELINA CHAU contributingcreativedirection SASHA LEWIS makeup MELANIE BAREST styling YEANI KWON & SOLOMON CANADA & GIGI GILLEN & WOODY LINDOR & ADRIANA ALVAREZ modeling JENNIFER UYANGA & CHRIS PARKER & CASSIE STANLEY & JACK DEUTSCH & LYNNE KHOURI & KEN YIN

42.34253 N 71.08636 W 74

76

10/15/22

9:05AM

CAM 02

09:06:04 78

18:45:36

9:30 asdfghjklqwertyuiopzxcvbnm,qwertyuiopasdfg eertgyh" 9:32 “hiashdadhaahdsh haskdhkjsdhd jksahdbe msdcksclkscjn” 9:36 “hiashdadhaahdsh haskdhkjsdhasdf asdf zxcvbnm" 9:42 "sdfghjkl qwertyuisdfgyhjkl; oiuyqawresdfxg" 9:45 "qwertyuhgv cvbnm kjlkjnbgfd hfglhhn rfsgfxkb, ujhvdrd" 9:47 "lkjhgfdw poiuytfdcxvbnjmk "kjghfdxjhgfhsz l.m,ncxdj" 9:49 "asdfghjk erty uhgfv ghjkmvlkhjgashfkdhpowidguwdasukwedgd" 80

9:51 "xcvbgtrfedhjni jkscdasgydw cksjychskcsamndsx" 10:01 “hiashdadh xcvb rtgyhjub vbnjmkjhg ikjh" 9:36 “hiashdadh jsaldhn aslkjdhd iashwdwhq" 9:42 "sdfghjkl qweralskjdj alskjd welej" 10:02 "qwertyuhgv cvblaksjdksjadkljh ajlsk asdjha" 10:04 "lalskdjajsk woieuw ojdsacxj owehwkm" 10:05 "oiuyiuyt 10:08 "kalsdjwueyq dad 10:11 "aospdu jpieuwha akjasjdluy" 10:13 "xcfghikjhb

DAY #2894 CITIZEN #788089049 12/08/22 #16 BEGIN 82

ANOTHER ONE BEGIN AGAIN DAY #2894 CITIZEN #78 ANOTHER ONE BEGIN AGAIN DAY #3208 CITIZEN #788 ANOTHER ONE BEGIN AGAIN BEGIN DAY #3411 DA

I AM NOT A SIN

84

Sunday, 9 a.m.: the bells toll in my small hometown church. Crowds arrive and gather, taking a seat, some speaking Spanish, some speaking English, some speaking both. I sit next to my mother and wait for the pastor. Oblique, beige walls, benches of wood that creak under our weight, stained glass walls that echo the words of the churchgoers, and the inevitably-present cross that stands in the middle of the room. Discomfort? Fear? Anxiety? I wasn’t sure what I felt. But I wasn’t safe.

I never really liked church. I struggled with the idea of praising someone who I couldn’t know existed — and in tandem felt some sort of guilt in that doubt. Yet, here I am, every Sunday. Was it to make my

mother proud? To make myself proud? God proud? To this day, I fail to find the answer. Yet, here I am. Yet, here we all are.

I wasn’t old enough to understand what it meant. I was only 10. But I could see. Small, grim nods. Soft whispers of praise. The small ecstasy of approval for the words, “God loves those who obey, but God shows his anger against all wicked people, and abandonment is all they learn. All they learn, that they turn to abominus, dark and confused worship, worshipping of their shameful desires, sex between each other.” I wasn’t old enough to understand what that meant, but I could see it was wrong. I could feel it was wrong. I was convinced it was wrong.

writing ANONYMOUS modeling ELANA LANE & AX BALIONE photography ALEX CHANG design EMLYN GRIFFITHS styling ADRIANA ALVAREZ

makeup MELANIE BAREST

writing ANONYMOUS modeling ELANA LANE & AX BALIONE photography ALEX CHANG design EMLYN GRIFFITHS styling ADRIANA ALVAREZ

makeup MELANIE BAREST

SO LUST BECAME A THREAT. DESIRE BECAME AN INSECURITY. AND QUEERNESS BECAME MY SIN.

So lust became a threat. Desire became an insecurity. And queerness became my sin. A death sentence to someone I could no longer be, someone I was never given a chance to be.

And who was I to be, so as to defy God? God won’t forgive me. The Catholic Church won’t forgive me. My family won’t forgive me. And at one point, I couldn’t forgive myself. So I did the only thing that was reasonable — I hid.

I couldn’t bear to see who I truly was. I couldn’t bear to know what God thought of me. And I simply could not bear the fact that I could disappoint the person that I had always believed would love me

unconditionally. For 18 years I believed in this truth, and I wanted to make ’Him’ proud. I wasn’t queer, I was just confused. God would only love me if I felt that way. If we felt that way. If we fixed our confused daze, he would give us a chance.

First communion, Sunday mass, Confirmation, Everything was all for you.

For 18 years, everything was for you.

I COULDN’T BEAR TO KNOW WHAT GOD THOUGHT OF ME.

86

Kneeling, praying, and praising became a numbing routine. You became my routine. You became me. And that was all I knew.

Eventually, college began, and I was no longer tied to family or religion. Having the freedom to pursue everything and anything suddenly became an unnecessary, threatening objective for me to chase. A chance that all my work of praise would be crucified if I were to disobey him.

I would lose ‘Him.’

And with him, I would lose myself.

And I couldn’t lose myself at the point in my life when I was supposed to be finding myself. People yearned for it. People feared for it.

It’s the fear of not being enough, coupled with the fear of being too much. The same fear of being you.

Except this time it's different, I was queer. But that was all I knew. That is all we know.

We are queer, but what’s next? Who can we talk to? And why does it feel like we are rushing it? Hiding from it?

A trait of we who are, but a deformity of who we don’t want to be. An endless abyss of straight couples, holding hands, getting married and following the praise of God. But for us, it’s just looks, grim nods of disapproval, and harsh whispers of condemnation. A small ecstasy of castigation that tells us we're not enough, that we'll never have the chance to become something. Anything.

And when we do, it’s rushed. We don’t have time. But we don’t want that time. Because when we have strayed from what we practice, we have the chance to know what has been unfamiliar. And we would rather sit in the uncomfortable silence of that unknown than acknowledge everything we missed, everything that was grasped away from us. Everything that was grasped from me.

88

Our childhood, our life. Our dignity and our identity, just to keep yours alive.

And it only took me 19 years to be sure. Not confident, but sure of who I belonged to. To keep our desires separate from yours. To keep our truths separate from your lies. To keep my community separate from your society. I belong to the LGBTQ community. I am queer. We are queer. We are who you suppressed, who you rushed, who we kept hidden away for your glory. And it’s enough. We have always been enough.

90

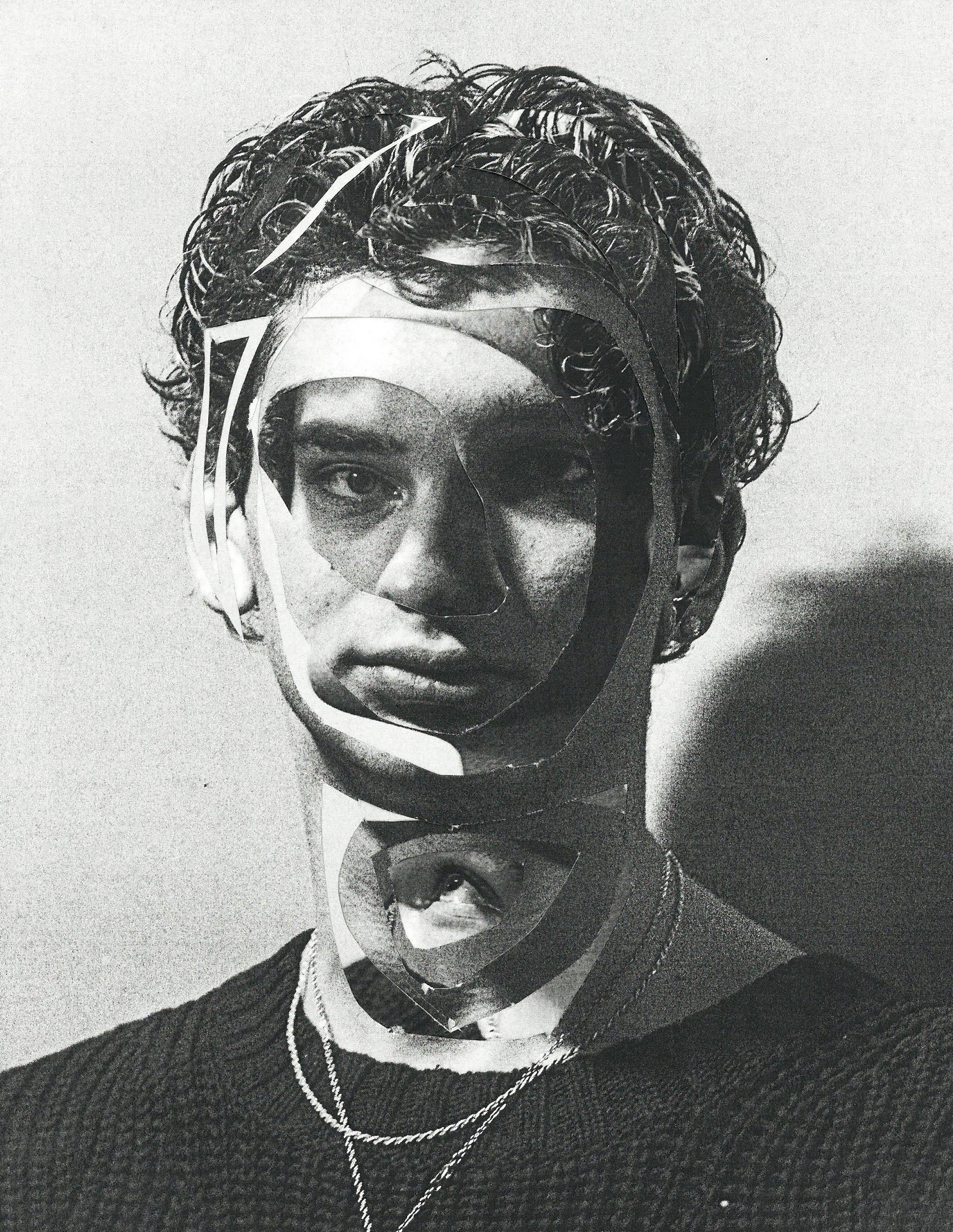

mad

madhatter fashioning the

In 2021, “Alice in Wonderland” was recognized by Vogue Magazine as one of fashion's most enduring muses. It seems we enjoy leaning into the madness and majesty of costumes as a way to soothe the streak of insanity within ourselves.

Fashion is a silent voice, but it’s also a yelling siren, especially when the end goal is to be both mad and magnificent.

Disney’s 2010 “Alice in Wonderland” movie enlisted Colleen Atwood to design its costumes. Tarrant Hightopp, or The Mad Hatter, was usually always in three-quarter culottes that splayed out midshins, wacky socks, a burgundy blazer, distressed tuxedos, and, of course, a hat. His makeup consisted of red eyeliner, bright green and orange contacts, rouge blush that stood out against a pale white foundation, blue eyeshadow, and red gravitydefying eyebrows and hair. When asked about the balance between the bright hues of the costumes and the period piece tailoring, Atwood remarked,

“The Hatter’s look is other-worldly and magical but still somewhat real in a sense. He is in a different head space at the beginning of our story and his costume goes through a journey of trying to help him find his soul.”

While Hatter’s costume is a highly successful extension of his off-kilter personality, contemporary audiences question if he was truly as mad as he appeared. His fashion choices, while unconventional, seem too stylized and calculated to truly be crazy. He is more inspiring where he should perhaps be disconcerting. Rather than scare us away with the loud hues and patterns, it draws us in with the bright colors and enthralling synergy. The costume is almost alive, with an utterly vibrant personality and eye-catching soul.

Audience members, designers, and fashion personas alike still find inspiration in the liveliness and irony of the costume.

writing EBUBE ONWUSIKA

modeling LUCY CHEN & MILES STEVENSON & BAHVANA SINHA photography JENNA ORY design SYDNEY SINGH styling SOLOMON CANADA makeup CELINE PLAISIR

“Mirror Mirror” (2012), a Snow White retelling directed by Tarsem Singh, is also known for its costume storytelling, as the plot of the film was symbolically reflected in the attire of its characters. Designed by Eiko Ishioka, the costumes were described in Fashionista to be so awe-inspiring that they film themselves. The Queen, played by Julia Roberts, wears a red peacock dress with high shoulders, representing the Queen's intimidating nature and her constant efforts to scare away—or, in the case of Snow White, kill—any competition.

Snow White herself was also outfitted with a memorable costume, particularly in the movie’s final scene. She wears a flamboyant orange and blue dress tied back with a gigantic bow. Ishioka wanted the gown to represent Snow White as a gift to the people who lived in the land after bringing an end to the Evil Queen’s reign. Who would expect entire plot lines to be encoded in peacock dresses and giant bows? The costume designers, that’s who — it’s what they do.

We can more clearly see the effects of such costumes when they are juxtaposed with casual clothes in everyday life. This pattern is particularly prominent in 2004’s “Enchanted,” in which Amy Adams plays the bubbly Giselle, a princess magically transported from the fairytale land of Andalasia to New York City. When Giselle first arrives in New York, it is in nothing less than a humongous wedding gown, complete with puffy sleeves and a million layers of hoop skirts — entirely impractical for the cosmopolitan city. As the movie progresses, Giselle starts wearing increasingly smaller dresses, more conservative prints, and smaller sleeves until she reaches her final outfit: a simple, sleek, solid-color evening gown that ditches the sleeves completely. This final gown stands in stark contrast with her initial wedding dress. Costume designer Mona May never explicitly confirmed that this pattern was intentional, but Giselle’s costume changes are an undeniable reflection of her growth during the movie.

92

Though these outlandish outfits may seem removed from our real lives, the costume changes are familiar elements of reality. Not a lot of us can claim that we have the same style now as we did when we were twelve. As our experiences and thoughts change, so does the way we choose to convey ourselves to the world. It’s the exact same thing with costume design in the film: designers aim to reflect characters’ personalities, growth, and even dreams through what they wear — a strategy that is even more remarkable when they come from imaginary worlds.

Inspired costume design draws audiences into the world of fantasy to enrich our real lives. Those of us who are awake in both the whimsical fantasy and cautious reality of our lives most likely find joy in seeing the most erratic and beautiful of finery come to life on the silver screen.w

AWAKE IN BOTH THE WHIMSICAL FANTASY AND CAUTIOUS REALITY OF OUR LIVES

94

90S ‘HEROIN CHIC’

DISSECTING THE LOOK

“Heroin Chic” is an aesthetic that rose to popularity in the early 90s. The term “Heroin Chic” was born from the style’s appropriation of physical features often associated with heroin addiction, including pale skin, a thin figure, dark undereye circles, and mangled hair. The aesthetic took the fashion industry by storm, from photographers to models to producers, and quickly grew from a trend into a cultural movement encompassing glamor, high adrenaline, and partying.

Heroin Chic likely found its advent with supermodel Gia Carangi in the 80s — the New York Times called her “The Model Who Invented Heroin Chic.” However, it did not truly grow to peak popularity

campaign, and remains the face of the aesthetic to this day.

The glamorization of the aesthetic increased with the eye-catchingly raw works of Davide Sorrenti. The famous New York fashion photographer was infatuated with the look, and most of his art was inspired by it. At the peak of 90s, when many in the industry dabbled in drug usage and drug culture, Sorrenti captured the models in a hauntingly beautiful form — though dressed in high-end

writing VALERIA MARTINEZ modeling RACHEL SOLOMON photography AZRA SCHORR design DAISY TULLER styling YEANI KWON makeup MELANIE BAREST

writing VALERIA MARTINEZ modeling RACHEL SOLOMON photography AZRA SCHORR design DAISY TULLER styling YEANI KWON makeup MELANIE BAREST

clothes, he shot their awkward poses and emotion filled eyes. Editors from fashion’s most influential magazines loved the air of naïveté and fragility that came with the uncomfortable posing. The makeup looks the models were photographed in perpetuated these characteristics; a common one being the grunge look, which consisted of pale red eyeshadow, dark liner, and matte lipstick, giving the look a sense of unease and chaos. However, Sorrenti’s success was short-lived, as he died in 1997 at the age of 20 — at the time of a suspected heroin overdose, which his mother later disproved in a 2019 Vogue article.

Despite passing from kidney failure, Sorrenti’s supposed heroin death led to a turning point from admiration to disgust within the industry towards the normalized drug culture and “Heroin Chic” aesthetic. It was a wake-up call to the consequences of the glamorization of addiction in society, and more specifically in the fashion industry.

As depicted by editorial magazines, beautiful fashion shoots, and red carpets, the fashion industry may seem like a glamorous, exhilarating, and vibrant space. As outsiders, all we see are the pretty photos on social media and entertainment outlets. However, the reality is that it’s an overwhelming, stressful, and high-pressure industry where low pay, high hours, and misogyny are common. In a Glossy survey completed by fashion employees, 87% of respondents said they were overworked. The normalization of worker exploitation in the fashion industry led many to unhealthy coping mechanisms, including but not limited to drug abuse. Its prominence within the industry led supermodels like Naomi Campbell and Kate Moss to become victims of substance addiction.

The “Heroin Chic” look the public saw was very different from what models were actually going through. As is often seen in the fashion and beauty industries, extreme thinness was a hallmark of the

Despite its harmful effects, the “Heroin Chic” aesthetic is still seen as an iconic moment to remember in the fashion and beauty industry. It is a mystery the way it is perceived as satisfying, but why is it so chaotic and destructive, yet exquisite and sophisticated at the same time? Perhaps it is due to the constant messaging from multimillion dollar companies pushing imagery that glamorizes and normalizes unhealthy lifestyles to achieve a certain beauty standard. Perhaps it is our culture’s obsession with feminine frailness and weakness, an ideal that was especially prominent during the 90s when looking starved was the new beautiful, especially in editorial and high fashion contexts. Perhaps it just feeds the beast that is the industry as it craves new ways to control women by turning their bodies into trend cycles.

However, over the past two decades, much progress has been made in shining a light on the toxicity of the fashion industry and its lack of inclusivity. Well-known models like Bella Hadid have started to open up about being overworked, the pressure models have to endure, and the importance of prioritizing mental health. The “Heroin Chic” aesthetic’s negative impact on society has in part pushed people to hold brands more accountable for improving their inclusivity and diversity on runways and in campaigns. The hope is that this trend remains in the past and progress continues in pushing the industry to be focused more on acceptance of all bodies and less on glamorizing dangerous lifestyles.

96

naïveté and fragility

98

CLEAN Not So Clean After All