16 minute read

NMEAC at 40

NMEAC AT 40 As the environmental nonprofit celebrates a milestone, they’ve got a lot of successes to look back on, but not a lot of young people signing up to take over.

By Patrick Sullivan

Sally Van Vleck remembers the day, 40 years ago, when she and three other women sat around a kitchen table in Traverse City and decided to become environmental activists.

They were concerned about the storage of spent fuel rods at the Big Rock Point Nuclear Power Plant located just off the shore of Lake Michigan in Charlevoix.

They’d started out thinking they were anti-nuke activists but realized that this new threat to the region demanded they expand their scope and think about dangers to the environment as a whole.

“It was the proximity to the lake that brought it to our attention,” Van Vleck said. “It was really because my husband at the time was involved in environmental issues and he was reading all this stuff.”

Her husband then, well-known-Traverse City-based environmental attorney Jim Olson, eventually persuaded the women that they should organize a nonprofit in order to be taken more seriously and to raise funds. He also suggested the name: Northern Michigan Environmental Action Council, modeled after other nascent environmental groups across the state.

“He wanted an environmental advocacy organization up here,” Van Vleck said. “It was his idea, and we were like, ‘OK.’”

That name, shortened to NMEAC, might sound clunky and dated today, but in 1980 it contained the energy and enthusiasm of an environmental movement that was new and eager. Its four female founding members wanted a seat at the table. And if they didn’t get one, they were ready to litigate.

FROM NUCLEAR WASTE TO A MALL

As NMEAC celebrates its 40th anniversary (actual celebratory events have been put off until next year, due to the pandemic), the nonprofit has a long list of accomplishments, near accomplishments, and even noble failures to celebrate, but the group also looks a lot different.

The four women who launched NMEAC in 1980 were, at the time, in their late 20s or early 30s, as was Olson, who was in his 30s. Today, despite a clear increase in environmental awareness across all of society — from school kids to senior citizens — the average age of a NMEAC board member is about 70 years old, and its longest-serving board member recently turned 90.

Van Vleck remains a NMEAC supporter, but in many ways, even she’s moved on after those energized early days, which started with the fight against Big Rock (after a protracted battle, NMEAC was not able to influence how nuclear waste was stored at the site, but the nonprofit did outlive the plant, which shut down operations in 1997); gained steam with well-intentioned though somewhat awkward hazardous household waste disposal effort (the group partnered with Dow Chemical, which used incineration to get rid of hazardous waste, which NMEAC opposed); and made an indelible impression into the fabric of Traverse City by 1986, when it fought and stopped the development of what was to be Bayview Mall.

Van Vleck recalls NMEAC’s foray into hazardous waste disposal with humor and believes that although the program didn’t last, the effort was worthwhile because it caused people to think more about the products they buy and what happens to them after.

“We were just dumb and young, and we didn’t realize the extent of the problem,” she said. “We didn’t expect to be inundated with toxic materials, and we didn’t know what they were. … I think it raised awareness more than anything.”

The Bayview Mall, on the other hand, presented NMEAC with its first chance to stop a development in Traverse City.

“The biggest one by far was stopping the Bayview Mall from being built downtown,” she said. “It was a very big issue that split the community. … That’s what put NMEAC totally on the map.”

Many downtown business owners believed the mall would bring people downtown and, as a result, into their doors, too. The young environmentalists saw the proposed six- or seven-story structure as a potential blemish on the beauty of the quaint downtown.

NMEAC recruited young attorneys Grant Parsons and Michael Dettmer to take on their case, and they discovered that part of the area where the mall was supposed to be built, in the parking lots between Front Street and Grandview Parkway, was deeded city parkland; to sell it to a developer, the city had to get approval through a public vote. Bayview Mall lost the election.

“It was going to literally block the bay. It was called the Bayview Mall, but nobody would be able to see the bay from downtown,”

Van Vleck said. THE 17-YEAR FORE!

NMEAC’s next big fight would take place over a proposed golf course in Leelanau County, near Glen Arbor on the shores of the Crystal River.

By now, Van Vleck said, they’d had learned to partner with other like-minded groups to leverage their influence. In this case, NMEAC partnered with the grassroots group Friends of the Crystal River, which had sprung up specifically to oppose the proposed golf course, and this time, they went to court with Olson arguing their case.

Despite the fact that no golf course exists today on the shore of Crystal River, Van Vleck is reluctant to call that one a victory. The legal proceedings took 17 years.

“It was brutal,” Van Vleck said.

Around that time, Van Vleck and Olson separated, and Van Vleck took a step back from NMEAC and partnered with Bob Russell, another long-time NMEAC supporter. Together, the couple decided to focus on peace and justice issues in addition to environmental issues, and to further that goal, they started the Neahtawanta Center on the Old Mission Peninsula.

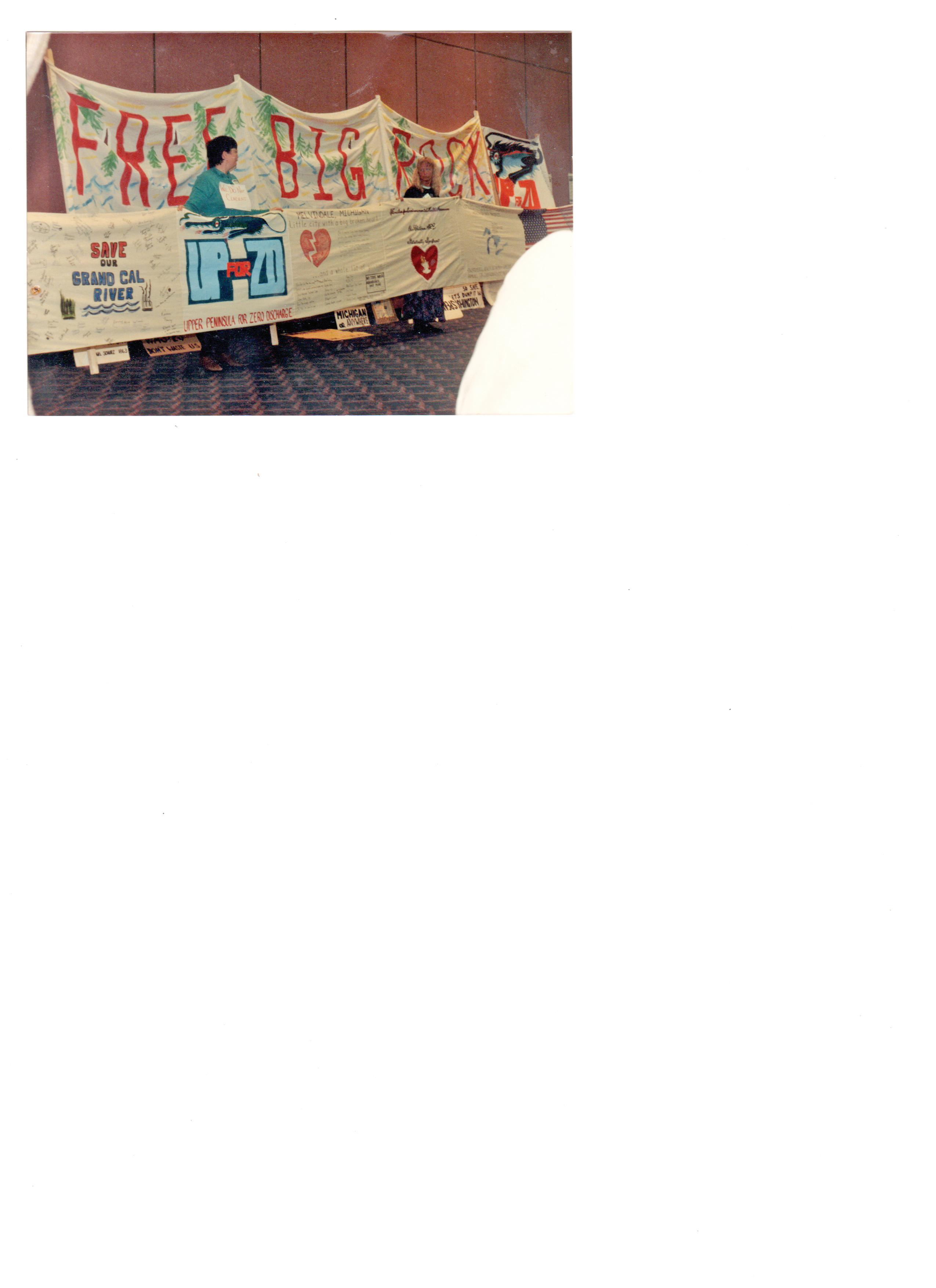

From left: Sally Van Vleck at a rally at the Open Space back in the ’80’s. “I believe it was a rally about chemical contamination of Lake Michigan,” Van Vleck tells Northern Express.

Ann Hunt, an activist from the Citizens for Alternatives to Chemical Contamination, at a water protection event with NMEAC, protesting the potential contamination of Lake Michigan by Big Rock Nuclear Plant.

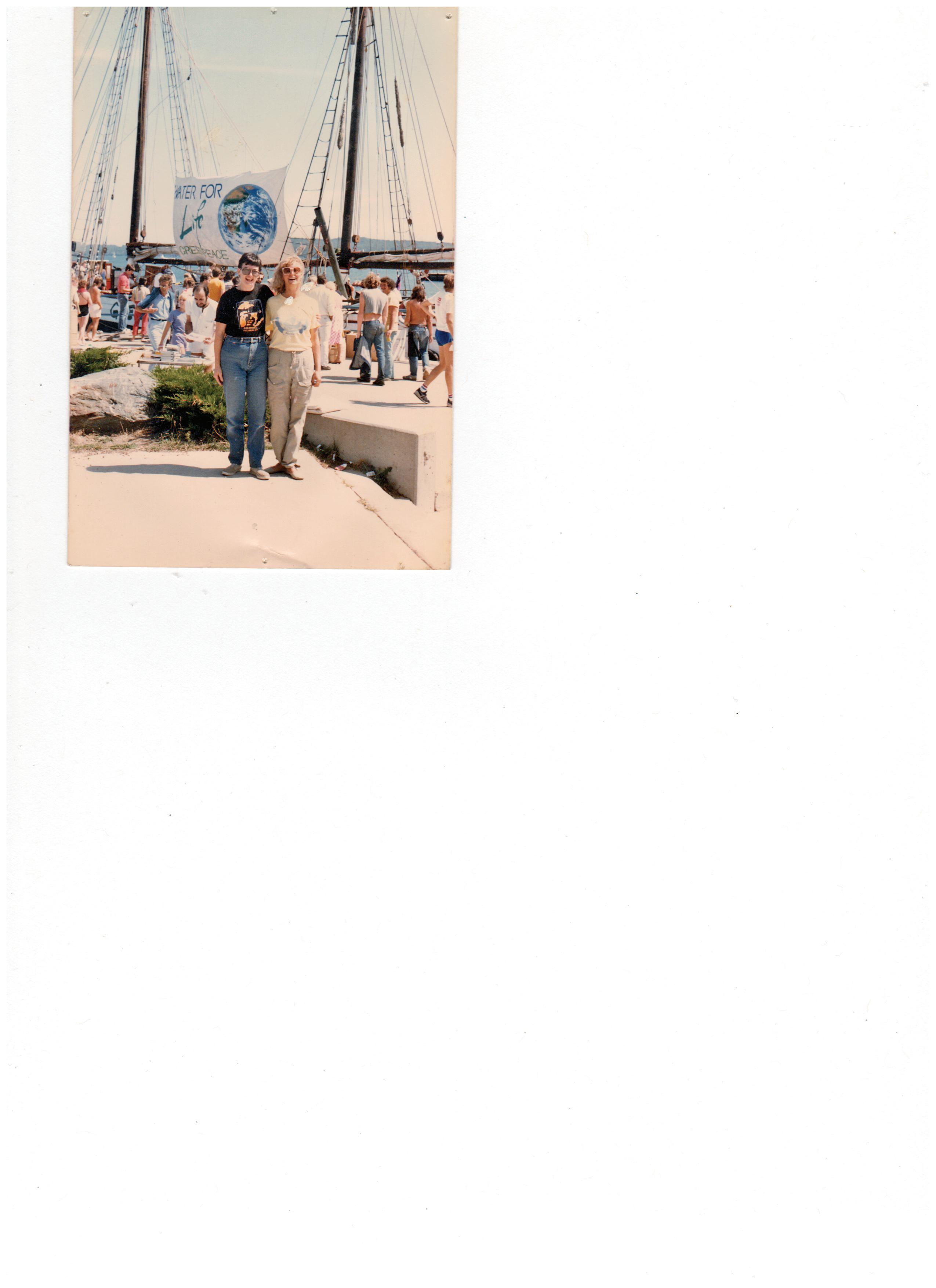

Friends and enviro-fighters Ann Hunt and Sally Van Vleck join forces again when Greenpeace brought a ship into Grand Traverse Bay as part of its Zero Discharge Campaign.

Ann Rogers, the longest-serving board member, who recently turned 90, said she was too busy with her teaching career in the 1980s and early ’90s to get too involved beyond donating money, but that all changed when the Michigan Department of Transportation and Traverse City officials proposed widening Peninsula Drive — where she lived — from two lanes to four lanes. The move would have wiped out gardens, a stone fence, and lots of lawn space separating houses from traffic.

Rogers said she was particularly upset that the change, proposed to take place between Bryant Park and the intersection of Center Road, would mean 70 or 80 trees would fall.

Rogers, who was later elected to the city commission, said she got active in NMEAC once she realized that MDOT needed to get official approval from Traverse City to go ahead with the project.

Rogers doesn’t exactly look back in fondness at that period in her life, but she said she is satisfied that NMEAC prevailed in the end.

“We fought it for several years. Those were rather anxious times,” Rogers said. “There were a couple of people on the road who said, ‘Oh, you can’t fight City Hall.’ But we did. And we won. We organized the neighborhood and worked very hard to get the city to say no to it, and it took a lot of work.”

The nonprofit’s next big fight would be to question what was going on with the thenpolluted Boardman Lake.

A Traverse City business, Cone Drive, had inherited a problem: Helicopter blades had been manufactured at the factory it inhabited, and pits, dug decades earlier to store used oil, was leaching into the lake.

Rogers said she doesn’t blame Cone Drive or even the original polluters — people simply didn’t grasp how watersheds worked in the early 20th Century — but she said NMEAC had to force the state to ensure

the landowner mitigated the pollution. In this case, NMEAC prevailed. “They are still monitoring over there. It isn’t in the water anymore — at least you can’t see it. Now it’s contained and monitored,” she said.

MALLS, MALLS, MALLS

Ken Smith hooked up with NMEAC after an early leader noticed that his passion for land use aligned with the nonprofit’s goals.

“I wrote letters to the editor [to the Traverse City Record-Eagle] that caught the attention of Phil Theil, the executive director [OF NMEAC] at the time,” Smith recalled. “He called me up and said ‘It’s time for you to get involved in NMEAC.’”

It was 1987, and Smith, like most of the members of NMEAC, was in his mid-30s.

He was upset that a landowner in Garfield Township wanted to rezone some land for industrial use, an auto wrecking yard.

The business would have been located on Keystone Road, at the base of the hills below the J.H. Rogers Observatory, where there are soccer fields today. For the first time in his life, Smith said, he found himself at a government meeting, speaking out against a proposal. It was an activity that he would eventually warm to, although even today he says he was “roped in” to becoming the group’s executive director.

The zoning change request was ultimately granted, but the scrap yard never materialized, so Smith counts that as a partial victory. The bigger win though, was that the experience taught him something valuable about how Garfield Township’s government operated then, and subsequently, NMEAC began looking closer at the development proposals in the township.

Of the township board that approved the rezoning, he said: “They heard all the public comment with arms folded and lips sealed shut, and then they went ahead and approved the zoning change despite what the public wanted.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, given how the initial battle panned out, it didn’t take long before Smith found himself mixed up in another Garfield Township fight. In the late 1980s, the Horizon Outlet Mall was proposed for an area that was then undeveloped farmland.

Although the outlet mall (now home to Oryana West, Hobby Lobby, the AMC Cherry Blossom 14 movie theater, and more) won out in the end, NMEAC was able to force some design changes. At the onset, there was supposed to be an access road that would have connected US-31 with Silver Lake Road to the west. That got scrapped. NMEAC was also able to force the developer to include some stormwater runoff mitigation to protect Kid’s Creek and to create a small buffer between the development and US-31.

“We did achieve some sort of a victory there, by shaping what ended up being built and acquiring some natural space there between the mall and the highway,” Smith said.

Next, around 1990, came the proposal for yet another shopping center, the Grand Traverse Mall. Like the Horizon Outlet Mall, it, too, would rise up on what was then rural farmland.

NMEAC obviously lost that battle, too, but again, Smith said he and others learned a lot in the fight to stop it.

Smith said the experience shaped him as a pragmatic environmentalist. He said it was his decision that NMEAC partner with the owners of the Cherryland Mall; those owners chipped in tens of thousands of dollars that enabled NMEAC to launch lawsuits against the proposed Grand Traverse Mall, hire expert witnesses, and conduct hydrologic studies.

“I am a very pragmatic person. That’s probably my main touchstone as an environmentalist,” Smith said from his home in rural Oregon, where he moved to from Traverse City several years ago. “Do what you have to do to get the most that you can.”

NMEAC was able to get some concessions and affect the design. Smith acknowledges that NMEAC sued the developers using environmental law related to how the large development could affect the watershed, but that the group was primarily motivated to stop sprawl.

“We won a lot,” Smith said. “It doesn’t seem like much when you consider that the mall was built and all the development that we had predicted took place, but it would have been a lot worse.”

THE HARTMAN-HAMMOND ZOMBIE

Some of the concessions NMEAC won in their litigation against the Grand Traverse Mall developers: were that the developer had to construct stormwater retention ponds and the township ultimately revamped some of its environmental planning rules) — two factors that changed the playing field just in time for the next proposed development: Grand Traverse Crossing, a retail complex across South Airport Road from the Grand Traverse Mall.

In that case, the developer took NMEAC’s concerns to heart and crafted a proposal that, despite exacerbating Traverse City’s sprawl, didn’t represent an environmental threat so compelling that NMEAC would feel the need to attack — a good thing, because NMEAC’s attention was quickly directed elsewhere.

Around the late 1990s, the Grand Traverse County Road Commission announced the construction of the Hartman-Hammond bridge, about a mile south of the two malls, a proposal that NMEAC members considered reckless and a sign of further sprawl.

“It was supposed to be built in 1998, and everybody told me ‘Why are you fighting this? It’s a done deal,” Smith said.

NMEAC teamed up with the Michigan Land Use Institute (today known as the Groundwork Center for Resilient Communities) and came up with an alternative plan called the “smart roads plan,” which was developed through a series of community meetings to find different solutions to the eastwest traffic flow south of Traverse City.

“That was a very successful effort,” Smith said. “Having an alternative to point to made it easier to oppose the project.”

Several of the recommendations in that alternative plan are a reality today, including the improved bridge on Cass Road near Keystone road.

Smith said that NMEAC and other partners were able to delay the project long enough for a recession that hindered its progress to come — and for changes in state and federal government to make it impossible. At least for a while.

Traverse City native John Nelson got involved with NMEAC not long after he moved back to his hometown from Maine in 1997.

It was the Hartman-Hammond bridge proposal that drew him in. He’d been attending meetings and speaking out and eventually, he was recruited.

“I found it very troubling what was going on,” Nelson said. “One thing led to another, and they said, “Why don’t you join our board?’ So, I did.”

Two things about the proposed bridge bothered Nelson — the intrusion into the Boardman River valley, and the potential that the bridge would create a new corridor even further south, which could be consumed by even more sprawl.

Nelson said he thought the road commission meetings were led in a “dictatorial fashion” and that, initially, the process was going to be a rubber stamp.

The dramatic tale of the fight against the Hartman-Hammond bridge isn’t over, perhaps proving that despite solutions being enacted, the pressures of sprawl and development never go away. Today’s Grand Traverse County Road Commission is moving forward yet again with plans to build a Hartman-Hammond bridge.

“It’s reared its head again,” said Nelson. “They’ve committed up to $2.5 million now to moving ahead with the project. Here it is again. It’s like a zombie — it keeps coming back.”

“THE WORLD IS CHANGING”

Today, the face of NMEAC is Greg Reisig, a Chicagoan with roots in Northern Michigan. He’s lived in Elk Rapids since around 1990.

Throughout the 1990s, Reisig published an independent newspaper called the Lake Country Gazette. The paper focused on environmental issues and local history. Smith asked Reisig to volunteer for NMEAC enough times that he finally agreed.

Just prior to joining NMEAC, in the early 2000s, Reisig got involved in a battle over wetlands that would shape his tenure on the NMEAC board.

“The way I originally got involved is I started seeing dump trucks drive by my house here in Elk Rapids, all the time, and I followed them,” Reisig recalled. “I saw that they were over in this real low area inside the village of Elk Rapids, and then I realized that they were basically filling these wetlands for a development.”

Reisig took it upon himself to challenge the developer, and he discovered that the wetlands in question were close enough to Lake Michigan to be regulated by the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers. Reisig not only stopped the development, he said, “[The developer] had to restore some of the wetlands, and he had to sign an agreement with the Corp of Engineers that he wouldn’t develop that area.”

Reisig would go on to be known as the “wetlands guy,” a moniker that would serve him well when he learned about a project by the same developer in East Bay Township.

The developer was using an agricultural exemption to avoid a law prohibiting the filling in of wetlands on a wide swath of land just north of Hammond Road and south of Traverse City’s airport.

NMEAC challenged the wetlands destruction — near the basin of Mitchell Creek, which flows into East Bay — and after a protracted legal fight, prevented the land from being developed.

NMEAC’s penchant for opposing development also brought division in later years.

When NMEAC campaigned against a tall building proposal in 2016, for example, many young people who identify as environmentalists complained that NMEAC was neglecting smart, centralized growth and the need for affordable housing.

With an aging board of directors and a lack of young faces coming into the group, the chasm between the age of the average NMEAC member today and the age of the average environmentalist could be a problem for NMEAC going into the future.

Reisig said that NMEAC has been able to be so bold for so long because they are a scrappy volunteer organization that runs on small donations from supporters. They don’t owe anyone anything. But that also means that unlike many other nonprofits, they are unable to pay employees, and they’ve had trouble recruiting young volunteers.

Van Vleck said she thinks many would-be activists in their 20s or 30s simply don’t have time to get involved.

“I think it’s harder economically to make it, and I think people need to pay attention to that,” she said. “There’s definitely less free time.”

Rogers, the board member who recently turned 90, agreed. She said that, as a teacher, she didn’t have time to become active until she retired.

“I do know that a lot of the young people are very concerned. They’re tuned in, they are knowledgeable, but they just don’t have the time,” she said. “I feel for these young folks because their world is changing.”