12 minute read

A Scramble for the Arctic? How Melting Ice is Shifting the Focus of International Shipping and Geopolitics

WINNER GAINSBOROUGH PRIZE

A SCRAMBLE FOR THE ARCTIC? HOW MELTING ICE IS SHIFTING THE FOCUS OF INTERNATIONAL SHIPPING AND GEOPOLITICS

Advertisement

By Luke McWatters

Climate change is melting the Arctic sea-ice. This has been going on for a long time, but it is happening much faster than previously thought. Since the 1980s the polar ice caps have receded by about 30%. This trend is expected to continue. The receding ice brings governments and firms new environmental worries, but also new economic opportunities. Beneath the Arctic there are massive deposits of natural resources.

Meanwhile, on the surface melting ice means waters are increasingly navigable, potentially allowing for shorter Europe-Asia transports across northern waters. The expansion of economic activity in the Arctic is fraught with environmental and geopolitical risk. The Arctic is home to a wide array of unexplored biodiversity which could be under threat from increased human activity. There are also numerous indigenous communities living in the region whose way of life might be threatened.

Furthermore, the borders are poorly defined, which has left governments scrambling for influence over a new economic frontier.

FIGURE 1: Map of Arctic ice melting. (Humpert and Raspotnik, 2012, The Arctic Institute)

For the moment, global shipping remains focused on southern routes through the Suez and Panama Canals. However, routes through the Arctic are generally 40% shorter and could result in fuel savings and journey times (Astrasheuskaya & Foy, 2019). This could mean an average cost saving of 10% (Bekkers et al, 2015). So if the routes are navigable and reliable then it would make economic sense for shipping companies to reroute. There has already been an increase in traffic along the two main Arctic Routes, with ships making use of the waters now open in summer. In 2017 the first ship sailed the Russian Northern Sea Route without help from icebreakers. Then, in 2018, Danish shipping firm Maersk Line sent a newly developed “ice-class” ship along the route (BBC, 2018). However, these voyages were exploratory and not cost-effective because of higher insurance costs from higher safety risks.

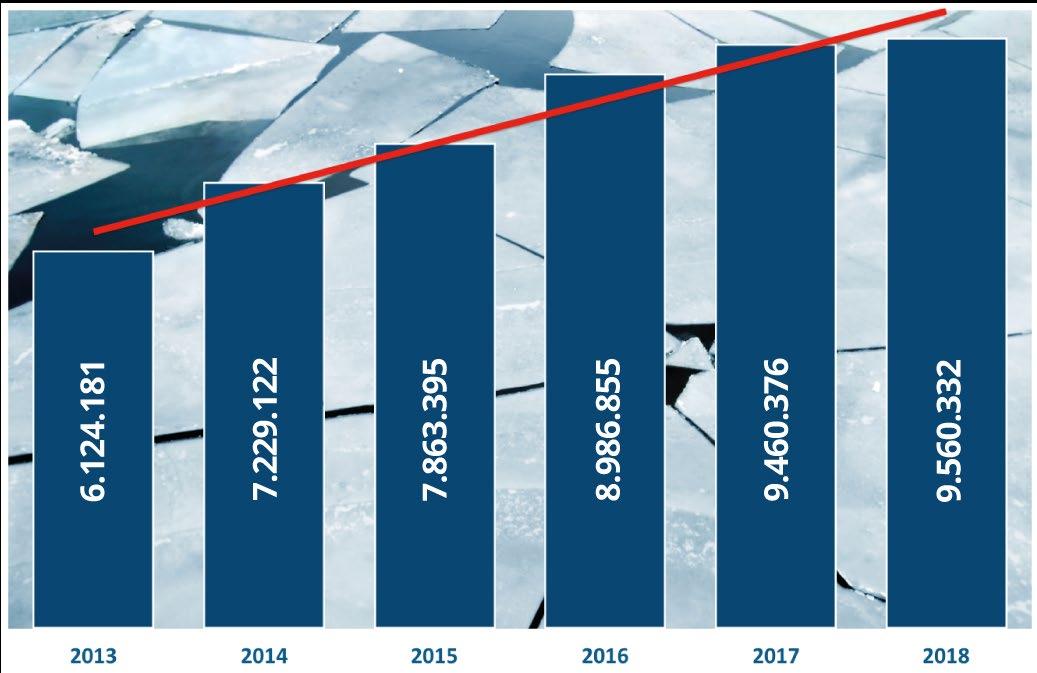

FIGURE 2: Distance travelled by ships in the Arctic 2013-2018. (Arcgis Storymaps, 2019)

For the route to be commercially viable it needs to become much more predictable, both to lower insurance costs and allow for reliable shipping schedules. To achieve this predictability, a large amount of investment is needed. At the moment, communication systems in the Arctic regularly fail and satellite signals can be faulty. The weather forecasting along Arctic routes is poor compared to other competing shipping routes. This is particularly important since the weather is so extreme and variable. There is some disagreement on the extent to which these problems will be overcome. Many studies predict that the Northern Sea Route – which goes along Russia’s northern coast – will be commercially viable soon and that it is only a matter of time before economic incentives spur on the investment needed (Yumashev, van Hussen, Gille et al., 2017, Bekkers et al., 2015). A report by the Copenhagen Business School claims that, assuming the Arctic continues to melt, it will compete with the Suez and Panama Canals by 2040. Some go even further and say that route could be navigable year-round by 2030, leading to two thirds of Suez traffic being rerouted to the Arctic and 5.5% of all trade (Bekker et al., 2015). Many disagree with this exuberant analysis. Some climate scientist say that the unpredictable nature of the ice means that even when ice coverage is low, crucial straits can be closed off. (Melia, Haines & Hawkins, 2017). They believe the prediction that the arctic could be navigable year-round to be unrealistic. Instead they think that the Arctic will see more short journeys than Europe-Asia shipping, brought by people travelling between the region’s massive oil, gas, minerals and fish supplies. The resources that are extracted will also need to be shipped. Furthering the need for short-hop shipping is the fact that permafrost and onshore ice is also melting, making land travel less reliable as much of the existing Arctic road infrastructure is built on ice. This need for smaller-scale shipping and investment may allow for the slow build-up

of expertise and technology to tackle technical problems standing in the way of larger-scale trans-Arctic shipping.

Whether or not year-round trans-Arctic shipping becomes a reality, some level of increased economic activity in the region is expected. This is incredibly difficult to reliably forecast, since it is impossible to know what technologies might be developed in the future or whether there will be a change in global trade patterns. While it is by no means definite that Arctic shipping routes will be a major artery of future trade, this is a real possibility. If it does not materialise, there will still be an increased international focus on the region.

In spite of the uncertainty, Russia appears convinced by predictions of the Arctic rivalling the Suez and Panama Canals. President Putin announced that one-tenth of all Russian economic investments are now in the Arctic (Astrasheuskaya & Foy, 2019). Russia is building new fleets of icebreakers to assist ships. Putin says that the Russian Arctic fleet will have at least 13 heavy-duty icebreakers by 2035, nine of which will be nuclear powered (Vasilyev, 2019). Even if there is still some ice, the government plans to use these ships to break it and create safe passages. Furthermore, new ports will be built and old ones expanded on both ends of the route. At the start of this year, the Kremlin announced $300bn of incentives for new oil and gas projects in the region (Turner, 2020). Then in March it published a document outlining its 15-year plan to increase use of the Northern Sea Route, increasing the Arctic regional population and protect its territorial sovereignty, which it sees as compromised by increasing foreign interest.

Under the Soviet Union the Arctic was seen as a priority for Moscow’s national security, since the country was isolated from much of the world. Stalin began prioritising the region with his “Red Arctic” propaganda in the 1930s (Melino & Conley, 2020). Throughout the Soviet era many airstrips and military bases were built. Arctic exploration was encouraged, with the first icebreaker reaching the North Pole in 1977 on the anniversary of the October Revolution. At the end of the Soviet Union in 1991 many of these bases were shut down. But 50 have now been refurbished. Many military analysts believe that Russia is trying to develop the Arctic to project power over its “avenues of approach” to the United States – territories between Russia and America – thus tilting the geopolitical scales in its favour. The military developments do not stop short at nostalgic rebuilding of Soviet-era bases. They are also testing new technologies such as hypersonic cruise missiles and undersea drones. The Russian message is simple: the Arctic is ours and if it becomes a crucial waterway you will abide by our rules.

The reason this is so concerning is that the borders in the Arctic are not clearly defined. Countries are normally given exclusive economic control over waters 200 nautical miles from their borders. Since the Arctic is so vast, there is a large amount of territory left unclaimed. Countries can claim this territory on the basis of their continental shelf extending from their borders into the unclaimed areas. The trouble is that Canada, Denmark (through Greenland) and Russia all have overlapping claims. Russia claims that it has a right to control waters extending to the North Pole. The way these disputes are dealt with is through the United Nations (UN). Countries should submit their claims to a scientific committee. Russia’s initial claim was rejected for lack of evidence, but it submitted a new one in 2015 (Oliphant, 2015). With Russia building up its military power in the region, many wonder if it would accept an unfavourable UN ruling on its territorial claims. Are we to believe that Putin’s government would just let Canada or even Greenland gain control over the territory?

It is not just Russia that is being proactive about its position in a future Arctic economy. The Chinese government has declared itself to be an “important stakeholder in Arctic affairs” since it is a “Near Arctic State” (The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, 2018). Like Russia, China plans on extending its military capabilities and extracting natural resources in the area. Beijing is encouraging the development of the Northern Sea Route, with the first Chinese ship making the crossing in 2012. In 2013 the country gained “observer status” on the UN’s Arctic Council. President Xi Jingping also wants to extend China’s already massive Belt and Road Initiative to include a Polar Silk Road. This venture is in partnership with the Russian government, reflecting China’s pledge to work “jointly with Arctic states” (Wen, 2018). The diplomatic circuit speculates that part of this partnership might involve a deal where Russia recognises Chinese sovereignty in the South China Sea, where China has artificially built islands to extend its economic exclusive zone. This Chinese plan is far more longterm than the Russian plans. Beijing sees the Arctic as one of many areas where it can increase its global influence, while Russia sees the Arctic as part of its national identity.

While these two major powers have been jointly planning how to project power in the Arctic, the obvious question is where are their geopolitical rivals? The other Arctic nations (Norway, Denmark/Greenland, Canada and the United States) are all members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), set up during the Cold War to oppose Soviet influence. A generation after the Soviet Union collapsed, NATO and Russia continue to have frosty relations, with NATO members imposing sanctions on Russia for its annexation of Crimea. However, in the Arctic these countries have been rather slow to act. The United States ordered its first icebreaker in two decades last year (Astrasheuskaya & Foy, 2019). This late start means that it is well behind Russia in terms of icebreaking capabilities and military presence. Perhaps one reason for the slow start is the greater commitment to environmental standards of NATO members, at least until Trump’s 2016 election. The Canadian government says that its primary goal in Arctic policy is to protect its indigenous peoples and its second priority is to preserve the environment. This has meant that, along Canada’s vast Arctic coastline, investment has been limited when compared to Russia. Putin wields far more domestic power than his Western counterparts and using this power he has been able to waive regulations and taxation for companies operating in the Arctic. Both Putin and Xi are able to plan much further into the future than most Western governments. Their grasp on power is much safer than those of most Western heads of state. As a result, they can spend more on longer-term projects.

Regardless of why NATO members have been so slow to act, they are beginning to act now. In 2018 NATO conducted its largest military exercise since the Cold War, with 50,000 troops taking part on Norway’s northern coast. Recently the US withdrew from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Missiles (INF) Treaty and reportedly, in a move reminiscent of 19th century Alaska purchase, offered to buy Greenland from Denmark. Some defence analyst say this may mean that this is part of a “broader US strategy to enhance nuclear deterrence, which could envisage the installation of a network of missile defense and post-INF Treaty offensive missile systems in the Arctic to counter both China and Russia.”(Koh, 2020) With the United States and its NATO allies awakening to the geopolitical importance of the Arctic, it seems that the region is set to become a hotspot for great power competition. The danger is that such competition could reduce the importance of environmental protection and the preservation of indigenous communities in the eyes of governments. If tension gets out of hand, then geopolitical risks might create so much uncertainty that companies will not want to invest in the region. The geopolitical struggles for economic opportunity may well diminish the very opportunities being fought over.

References

Astrasheuskaya, Nastassia, and Henry Foy. 2019. “Polar Powers: Russia’s Bid For Supremacy In The Arctic Ocean”. Ft.Com. https://www.ft.com/content/2fa82760- 5c4a-11e9-939a-341f5ada9d40.Bekkers, Eddy, Joseph F. Francois, and Hugo Rojas-Romagosa. 2017. “Melting Ice Caps And The Economic Impact Of Opening The Northern Sea Route”. The Economic Journal 128 (610): 1095-1127. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12460.“China’s Arctic Policy”. 2018. English.Gov.Cn. http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/ white_paper/2018/01/26/content_281476026660336.htm.“Container Ship Takes On Arctic Sea Route”. 2018. BBC News. https://www.bbc. co.uk/news/business-45271766.“IBRU: Centre For Borders Research : Arctic Maps - Durham University”. 2020. Dur.Ac.Uk. https://www.dur.ac.uk/ibru/resources/arctic/.Koh, Swee. 2020. “China’s Strategic Interest In The Arctic Goes Beyond Economics”. Defense News. https://www.defensenews.com/opinion/ commentary/2020/05/11/chinas-strategic-interest-in-the-arctic-goes-beyondeconomics/.Melia, Nathanael, Keith Haines, and Ed Hawkins. 2017. “Future Of The Sea: Implications From Opening Arctic Sea Routes”. Assets.Publishing.Service.Gov.Uk. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/ attachment_data/file/634437/Future_of_the_sea_-_implications_from_opening_ arctic_sea_routes_final.pdf.Melino, Matthew, and Heather Conley. 2019. “The Ice Curtain: Russia’s Arctic Military Presence”. Csis.Org. https://www.csis.org/features/ice-curtain-russiasarctic-military-presence.Oliphant, Roland. 2015. “Russia Claims Resource-Rich Swathe Of Arctic Territory”. Telegraph.Co.Uk. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/ europe/russia/11782413/Russia-claims-resource-rich-swathe-of-Arctic-territory. html#:~:text=Russia%20submits%20claim%20to%20large,tons%20of%20oil%20 and%20gas&text=Russian%20officials%20on%20Tuesday%20submitted,far%20 as%20the%20North%20Pole.Raspotnik, Andreas, and Malte Humper. 2012. “The Future Of Arctic Shipping Along The Transpolar Sea Route”. Arcticyearbook.Com. https://arcticyearbook. com/arctic-yearbook/2012/2012-scholarly-papers/20-the-future-of-arcticshipping-along-the-transpolar-sea-route.“THE INCREASE OF ARCTIC SHIPPING”. 2019. Arcgis Storymaps. https://storymaps. arcgis.com/stories/322f7ec35d8f46a6a4a26f3fe1aa8a17.Turner, Julian. 2020. “The Cold Thaw: Inside Russia’S $300Bn Arctic Oil And Gas Investment”. Offshore Technology | Oil And Gas News And Market Analysis. https://www.offshore-technology.com/features/the-cold-thaw-inside-russias- 300bn-arctic-oil-and-gas-investment/.Vasilyev, Dmitry. 2019. “Russia, Eyeing Arctic Future, Launches Nuclear Icebreaker”. U.S.. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-arctic-icebreaker/ russia-eyeing-arctic-future-launches-nuclear-icebreaker-idUSKCN1SV0E4.Wen, Philip. 2018. “China Unveils Vision For ‘Polar Silk Road’ Across Arctic”. U.K.. https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-china-arctic/china-unveils-vision-for-polar-silkroad-across-arctic-idUKKBN1FF0JC.Yumashev, Dmitry, Karel van Hussen, Johan Gille, and Gail Whiteman. 2017. “Towards A Balanced View Of Arctic Shipping: Estimating Economic Impacts Of Emissions From Increased Traffic On The Northern Sea Route”. Climatic Change 143 (1-2): 143-155. doi:10.1007/s10584-017-1980-6.