assembly

is the art journal of the School of Fine and Preforming Arts at the State University of New York at New Paltz

is the art journal of the School of Fine and Preforming Arts at the State University of New York at New Paltz

Welcome to the second issue of assembly, an art journal published to celebrate the work and accomplishments of students from the art program at SUNY New Paltz. Our first issue emerged out of a pandemic need to provide a culminating experience for the Spring 2020 cohort of graduating BFA students. But even at that time, there was an intention for the journal to evolve into an annuallypublished, student-curated and produced, online publication featuring artwork and writings from our MFA, BFA, BS, and BA students. We made great strides toward this goal in producing the current issue.

Elizabeth Hunt (MFA Printmaking) and Jessica Judith Beckwith (BFA Sculpture) embraced this massive project as the curators, designers, and producers of the second issue. Together, they established the theme, coordinated the call for submissions, vetted the applications, interviewed featured artists, structured the content, arranged the pages, and published the finished journal. They did all of this in one semester. Along the way, they expanded assembly to include alumnx as a vital aspect of our New Paltz community. I congratulate them on this incredible achievement and thank them for their critical and pioneering roles in this burgeoning project.

I am enthusiastic to bridge the first and second issues of this journal through the work of Paige O’Toole, our cover artist for the first issue. She carried the momentum of her senior work into an artist’s residency this year, refining and strengthening it—even through the continued challenges of a pandemic world. Liz, Jessica, and I chose an image of her new sculpture to kick off this second issue of assembly. In doing so, we honor Paige’s resilience and that of all the artists featured in these pages.

Asbill, Faculty Advisor and Visiting Lecturer in Sculpture Michael

Michael

Artists have a practice of returning to the unknown. They continually live in the space of creation, death, and rebirth—a cycle that is inherent and essential, yet often feels untenable and cruel while passing through it.

The necessity for the enduring power of the arts in culture is so often underestimated. It is a space of loving reflection, education, community, and confrontation. The arts hold, push, and question. assembly was created to support and empower our community of creators.

As time and space shift around us, and outdated social structures are challenged, we stand in uncharted territory—new ways of understanding ourselves, our relationships and our communities, local and global, are being called for.

The definable, that which could be standardized and reproduced efficiently, has informed our educational systems, our economy, our industries, our governments. The divergent, celebrated on the fringe, has been quietly suppressed. Here, in our second issue of assembly, we hear the call of powerful individual voices who are crossing into these new territories and defining fresh possibilities.

It has been an honor to review the thoughtful, stunning work of the artists of our SUNY New Paltz art community, both current and alumnx. We were struck by the unique voices resounding through the many proposals we received. It became clear, in walking through the process of each of these artists, that it is in the truth of our individual experiences that we find our places of connection. It is in discovering and expressing our voices that we heal, reveal, discover, and reclaim. Through the fear of loss we find love. Through transparency, a new way of seeing is discovered, and worlds are revealed. Through recognition comes the possibility of change; and through absence, presence and healing become possible. It is in our many facets, colors, cultures, genders, ages, perspectives that our community thrives.

Welcome to the second issue of assembly.

Jessica Beckwith, BFA Sculpture Elizabeth Hunt, MFA PrintmakingSanFord richardSon FelS in Conversation with JessiC

Jessica Beckwith: The element of play in your work seems to be an act of empowerment and agency. Do you experience that?

Sanford Richardson Fels: Absolutely! Part of it stems from this worry I always had as a kid that there wouldn’t be any room for fun in what I did, whatever profession I ended up in as an adult. I was determined to make sure that wouldn’t happen, but I was still worried it would. When I started studying art, and making what I made, I realized that I did it, I was having goofy good fun professionally. When I hold these swords, it feels like wielding my life in my own hands, or taking the reins of fate—whatever expression you prefer for taking control of your life and your fate. I have always known that there are so many different ways to see and go about life, and the swords help me to carve out my own way of doing things.

JB: In what ways do you think play could aid a broader cultural collective sense of empowerment and agency?

SRF: I think sort of in the same vein I just talked about, it has the power to disrupt and give agency, but collaboratively it also adds an understanding of empathy and care. As an adult, or really as any person in a structured society, we look and live through the perspective we learned, through school or parenting or what-have-you. In Western society, and most societies, play isn’t a part of that structure—but it is something that we all know, and is familiar. Playing and having fun is an instinct! So when you introduce play to an adult or an “adult” system, after a little coxing anyone can pick it up—and then this playing disrupts the given structure and perspective, and can lead to new thoughts and ideas for the individual and collective. If people were to embrace play as a group, playing together, they would quickly realize that their goals are the same: to have fun. This connection can create empathy and spark collaboration in play. Plus, everyone knows that eventually, it is more fun to play with others than alone. I guess what I am trying to say is that when you understand that everyone is just trying to have fun, enjoy life in all of its beauty, and you indulge in that sense of fun, then it’s easier to see things from others’ perspectives, and to think outside of your own. I think a larger sense of play in society could very much aid a sense

Sanford Richardson Fels

of empowerment, but acting on that empowerment

JB: Has play had a role in how you’ve come free of a culturally-projected gender binary? relate, and how you develop relationships that

SRF: To be honest, I have never thought terms of “play” or “playing,” beyond the or cultural norms. But I do think it connects norms for something more enjoyable—that fate into your own hands that I just talked two things, gender and relationships, are two to give you joy—joy through expression, I suppose it is a sort of playing. But where sudden moment of realizing “Oh, just because can’t play with this sculpture.” Just because woman, doesn’t mean you can’t be something this is actually really funny, I am realizing this can play in a gallery—I have such a distinct time realizing “Oh wait, we can be in our intimate relationships, making us more happy.” taboo thing, but when we just thought about of what would make sense culturally, it became have been able to understand so many different or platonic or things that don’t fit in those relationship and gender is all fun and especially when there is not just a lack framework actively working against you.

I always try to understand each new relationship and unique thing, but that is hard when down. It is also just worth noting that go about ethical polyamory is to “just have communicate what makes each person

empowerment is a whole other fish fry.

to know yourself and discover your identity, binary? Has play informed and shifted how you that are free of cultural role play?

thought about my gender and relationships in phrasing “playing around” with gender connects in the way of disregarding cultural enjoyable—that shift of perspective or taking your talked about. It certainly can be fun! These two vastly personal things that are meant and joy through connection. In that way where it really connects for me is the same because I am in a gallery doesn’t mean I because someone says you are a man or a something else. In terms of relationships— this was a similar feeling to realizing you distinct memory of me and my partner at the our relationship, while also being in other happy.” Ethical polyamory is still such a about what would make us happy instead became an obvious option. From there I different types of relationships, romantic those categories. But that’s not to say that games. It’s hard, emotional, and messy, lack of cultural framework, but a cultural relationship with a friend as a truly new my vocabulary is so specific, so shaved in no way think that the best way to have fun.” It’s to have fun in mind, and happy. When you play with others you

must communicate and consider their feelings.

JB: By claiming this phallic war symbol of power and suppression and co-opting it for symbolic social play, you’re able to re-write the use of this power tool as a way of capturing someone’s essence and the truth of their self-expression. You’re also claiming a new way of relating to others and re-writing what community can mean. Traditionally it feels like we’ve operated in a tribal sense where community is associated with committing to your tribe and following to legitimize and give that tribe worth and power. Does that resonate for you? Can you talk about your process in deciding to use the sword as a symbol, and who you chose to come to play and rediscover through play and dress in this communal event?

SRF: First off: you said it better than I ever could have, and while those connotations were not meant when I first started making the swords, the meanings evolved perfectly into what you just described.

When I started making them (although it was not that much an active decision as an act of playing around with materials), I realized that I was making them with the idea of wielding narrative. They held the power to wield a story, and to propel a story further, solely because whenever someone would pick one up, suddenly a narrative was formed in their mind about why they had that sword, what their quest was. To add to this, within the loose context of the tales of King Arthur and the Sword in the Stone, a sword tends to be a symbol of empowerment, as we’ve been talking about.

My dream, of course, was to create communal empowerment, where you tell a narrative together. I think there was a sort of side effect in telling a collective narrative, where the playing out of this story highlighted each specific relationship between those who were telling it.

At least, I think that makes sense within the photos here, with the people I asked to pose and play with the swords. These models are three dear friends of mine, all of whom are in a relationship together that ranges from romantic to platonic, so there is already quite a nuanced communal relationship which I honestly

wasn’t trying to show, but I think it was expressed regardless. They are a family of sorts, a family that I know shares my enthusiasm and ability to play without regard to what might be expected of them. Plus, it doesn’t hurt that they all play an absurd amount of Dungeons and Dragons, which I knew would make them easy to get into the state of mind for the photoshoot.

JB: What were your preparations like? Did you prepare everyone you invited with a backstory, or was it all improvisation? Were you each exploring specific aspects of connection, community, and play, or was it discovered in the moment?

SRF: It was a very spontaneous thing. The only planning was that of a date and time that worked for everyone, and the rest was improv. So, yes, it was all discovered in the moment. There was a little stagnation at the beginning, where they asked me if they should be portraying something specific, but the only direction aside from how to angle the swords and where to be was to just play around, and they did exactly that. It was really lovely watching them develop a sort of narrative of protecting and betrayal, and uniting.

JB: Did everyone select their own outfits? Were they exploring through dress or were their outfits their everyday wear?

SRF: Oh, the outfits! I was a little surprised and delighted when everyone showed up in costumes of a sort, when I didn’t specify to do so. I say “of a sort” because these outfits are not that far off from what these friends would normally wear, but they were a little exaggerated. The most “costume-like” item was the cape on my friend Gil, and maybe his fish earring which spurred an entire narrative of pirates coming to take a fair maiden—but aside from that they were pretty similar to their everyday wear. They are a particularly spectacular and creative bunch, which is why I asked them to be my models.

Swords

2019–2021. Spruce, pine, and cherry wood

anna KruSe in Conversation with JessiC a BeCkwith

Jessica Beckwith: How do you see the role of play in personal and social/collective empowerment and agency?

Anna Kruse: I am not sure if I see play in social empowerment. I suppose in relation to a sense of freedom, but overall I think of play as a meandering, while I would say that empowerment and agency are quite rooted in a direction of advancement. True play though has no real beginning or end.

JB: Is play a part of your creative process?

AK: Yes, of course, I would say play is an integral part of the process.

JB: Culturally there is a lot of interest and exploration around rewriting narratives that have been binding and damaging. Is this something that you're exploring in your work?

AK: I wouldn’t say my work explores this on a cultural level. I would say my work explores my personal narrative, and that everyone has experienced damage to some degree, but I do not feel I am rewriting narratives.

JB: Have you found personal freedom in the process of play and/or in the rewriting of a narrative that you no longer find valuable? Can you tell us a little bit about that narrative and the ways in which your process has opened up your voice and personal empowerment?

AK: I have found freedom in the process of play. Much of my practice is intuitive, responding to the work as it progresses, with little to no prescribed expectations or outcomes. Of course I know what I want to convey, but I try to respond to outcomes not with it being the end but rather being a moment to meander. At the root of this is play. I think having a more fluid approach to making lends itself to surprises and combinations that one may not have been able to find if only working within strict boundaries.

Clearing the Wax

2020. Ceramic, 28 x 17 x 20 in. (left)

How Are You?

2020. Ceramic, 46 x 35 x 59 in. (right)

Anna Kruse

MFA Ceramics

Anna Kruse

MFA Ceramics

BUBBL3GUM_BiiTCH

2020. Steel, silver, spray paint, stickers, glitter 6.2 x 6.4 x 2.3 in. (left)

G00$HY_CL00T

2020. Brass, spray paint, stickers, glitter 7.4 x 7.5 x 7 in. (center)

$P4C3_C4STL3

2021. Brass, steel, fine silver spray paint, glitter 10 x 10.3 x 10.1 in. (right)

Disconnecting from the here and now, I create work that unapologetically challenges social order. As a form of escapism and emotional avoidance, I investigate ways to exist in a constant state of disassociation and derealization. As a means to address my sense of identity and gender, I reconceptualize normalcy and my perception of the world through my alternate reality.

Mando Bee MFA Metals

thoughtS From a 1975 alumnx — elisa d’arrigo

What happened once you left school? How has your work changed over time, since your graduation from New Paltz to now?

Since I left school in 1975, a lot has obviously happened, but the constant is I kept making work, and by virtue of that, connecting with art and artists.

In retrospect, I can see that my body of work has built upon things I’ve found so compelling since childhood: drawing, and the magic of creating a line, whether through traditional drawing materials, a hand-sewn stitch, or a clunky cloth-covered wire. The search for form, especially three dimensional form, and how abstract form can communicate meaning and emotion. A love of dance, and how movement and position can be incredibly expressive, and even convey humor.

After graduating in 1975 with a BFA in Ceramics, I moved back to NYC ( I grew up in the Bronx), and continued working in clay until approximately 1981, when I found myself needing a different challenge. I felt drawn to work with materials that were not as responsive as clay, had different properties, or perhaps most importantly, were less familiar to me. That began a decades-long investigation into making sculpture that used or combined materials such as paper, cloth, thread, wire, wax, wood, paper-maché, and unfired clay, all the while incorporating various craft processes in their construction. The resultant abstract forms, which were wrapped, woven, torqued, hand-sewn, or accreted, conveyed the innate psychological qualities of those processes.

Elisa D’Arrigo

From the 1990s until 2010, desiring a flexible tactility for my work, I constructed pieces by hand-sewing flat or hollow elements, formed from layers of cloth or paper, and stained with acrylic paint and dry pigments, which imparted an often intense coloration. These densely stitched, undulating forms had no understructure and were held together by thread alone. Seams defined contours; stitches created lines, marks and surface. Each piece unfolded differently depending upon chance and whim. Categories—sculpture, drawing, and painting were dissolved, recalling my work in ceramics, a medium in which these categories are already conflated. This is what first attracted me to ceramics and what intrigues me still. My growing impulse at around this time to introduce humor and a more fluid gesture was uniquely compatible with clay’s immediacy.

Following that impulse, in 2010 I began working with ceramics once again. The vase form, with its necessary orifice, has become my muse. Functionality implies use, whether real or imagined, and suggests an intimate involvement with the viewer, inviting touch, whether real or imagined, and even domesticity.

The pieces begin as hollow, hand-built elements that I manipulate and combine in a period of intense improvisation. The “postures” that result allude to the body in a gestural and even visceral manner. Their hollowness evokes the notion of interiority, and animation from within. Surfaces are activated and even transformed by the alchemical process of glazing.While non-representational, my work alludes to the body from the inside out, and seeks to project a physicality that also embodies states of mind.

So I’ve come full circle in a way. One reason I chose SUNY New Paltz was because I heard there was a good ceramics department. I wanted to learn ceramics. I was following my childhood dream to make free-form, wildly patterned ceramic vases. I somehow never quite did that then, but am now.

One of the things we would love to hear from you are your thoughts on what you would say to the young artists that are just graduating now.

I’d say, hang in there, keep working, find ways of keeping on working. Develop relationships with other artists of all disciplines. Look at everything. Be open. The pandemic has shown us (as if we did not already know this), that even a kitchen table can be a studio. Stay excited, follow what is compelling to you.

What role has the community played in your work as an artist?

The community has been almost everything. Source of friendships. Mutual support and encouragement. A reservoir of information and opportunities. The most important audience.

What are artists to For me, Without 1. Show it is, even work, and events of performances, 2. Follow Follow up contacts are doing. 3. Pay attention the “failures”. 4. Wait hate. It may

are the two or three most important things that you suggest to sustain their careers?

the work comes first. the work, no career is possible.

up: that means work in the studio consistently, wherever even if only a sketchbook or a phone app. For me, work begets and working creates inspiration. It also means attend the of other artists/writers/curators: shows, talks, studio visits, performances, readings, presentations.

Follow up: apply for things, there are so many opportunities now. up on invitations. Say yes when possible. Stay in touch with you’ve made. Be truly interested in others, and what they doing.

attention in the studio to the unexpected, the unplanned, “failures”.

at least a year before throwing out a piece you think you may be you’re just not ready for it yet.

Spotificationization

2020. Glazed ceramic, 7 x 5 x 6 in.

My art practice, based in intuitive drawing, deals with ideas of permeable boundaries, overgrowth, and disrupted narrative. I attempt to portray moments in which something hasn’t quite emerged or is rapidly disappearing from view. My drawings and paintings often take the form of abstract comics; I employ a graphic narrative vocabulary to make anti-narrative images. I am compelled by the idea of what exists along the borders of language and fact.

Eileen Townsend MFA Painting and Drawing

courtney haeicK in Conversation with JessiC a

Jessica Beckwith: I’m curious about the materials themselves that you use and your process of finding yourself in or through those materials. Absence and presence—how does that dichotomy play into your work?

Courtney Haieck: Metal is a major component to my body imprint series. I can alter the color and quality of metal with natural processes such as fire and a water-based solution. I find the body to be considered an important material in any practice as well. My practice comes from a place of adornment, growth, and body acceptance. The action of being nude in a private setting and coating my body in coconut oil and then pressing myself against the bare steel is uncomfortable but gratifying in the impression of the gesture. The interaction I have with the material makes the work seem more personal. I gain an attachment to the work as though it is another part of me. Yet I feel protected by having an absent presence. I am displaying my most vulnerable side from the start and slowly covering up my body image or letting the natural elements of the materials take charge to obliterate my figure to protect myself from the gaze of others.

JB: There is a phenomenological presence in the material that you pick and even in the conversation that takes place between your hands and body in the making of your work with that material. Are you aware of that silent dialog? Is there a thread that connects to a broader cultural dialog there or is there a more personal healing process taking place in the making?

CH: Both processes in creating my metal and performance works have been self-gratifying in the realization of who I truly am. I am a technically trained dancer and have been a perfectionist in everything I do. I was worried about having flaws in myself and my work, but as years have gone by, I have learned that having more freedom and letting go of my self-consciousness is the most rewarding experience. My work is meant to reach out to others that struggle with their body

image and bring people together struggles of vulnerability.

JB: It seems that by removing down and access an essence representing the individual presence. that? I’m curious if in eliminating to something universal?

CH: I want my work to be Although the work is personal vulnerability, and the gaze, I am who feel connected to similar so I think about how we grow to my work. Having an unfixed more because of the stages the time, memory, entropy, and the

JB: Through erasure of the image what another sees of you? Shattering

CH: I question my own power artist that works with my body gaze by obstructing it and seeing is for the viewer and myself. identity with a silhouette of myself. am other than a female artist. through the representation of

Apart, Steel sheet, 4 x 5 ft. Courtney Haeick MFA Sculpturetogether to have a conversation about the

the presence of individual identity you distill that resonates with greater power than presence. What were you exploring by doing eliminating the individual you were seeking to connect seen as a universal image of a woman. personal to me with the concepts of growth, am making connections to other women similar concepts. My pieces are also ephemeral, grow and change throughout time in relation unfixed image makes me appreciate my work the material goes through. I am exploring the beauty of life’s transitory nature.

image of self are you claiming your power over Shattering the cultural projection and the gaze?

power over the viewer’s gaze since I am an body directly in my work. I am dismantling the seeing what the outcome of the experience In my work I erase the gaze by hiding my myself. No one knows or can judge who I artist. The only way a viewer can identify me is of the occurring movement.

This is an ode to hair that has been shunned, dismissed, chemically burned and hidden for centuries. This series is an effort to come to terms with conflicting feelings I have borne the moment I realised the significance of the crown that was placed upon my head from birth. I invite the viewer into my space, to experience my daily rituals and the intimate and complex relationship with my hair.

Brushing, shedding, cutting, detangling … discard

These hairs from my head, light as a feather

Yet heavy with the weight of history

These fallen hairs are gathered for a new purpose, a drawing of sorts. They are truly dead, but the moment they make contact with hot fused glass, they come back to life—crackling and dancing on the surface. Each hair takes its last breath and fizzles into the air.

Leaving its scent, an intense mark, stronger even—than when it was a part of me.

Funlola Coker

Funlola coKer in Conversation with JessiC a BeCkwith

Jessica Beckwith: You spoke about your hair as a crown, and your work uses a form that has its references in Imperial royalty. In the act of making this piece were you claiming your own power, grandeur, and sovereignty?

Funlola Coker: I suppose you could say that by making this piece I was reclaiming some sort of power that was stripped away by the British Empire. I think for me, if I was actively trying to reclaim anything it was just my desire to exist despite the impact of the British Empire on my Nigeria (where I am from).

JB: I love the image of you wearing this symbol on your chest that holds your hair which, as you describe, has been given a new life and risen from its death through the heat of the glass, rich with a scent made stronger through this metamorphosis. It’s a powerful image. Did you experience a similar metamorphosis in the making of this piece?

FC: I chose the format of the brooch because it is historically recognised as a symbol of identity. In making it a little larger than normal size, it is unapologetically displayed close to the heart. Wearing it has an impact on me as much as it has on the viewer. If I experienced a metamorphosis, it was in taking the steps to be able to speak about these very internalized

My Honour | My Shame

Enamel on copper, mild steel, sterling silver, artist’s hair, stainless steel, 4.75 x 3.5 in.

In a future where the oppressed sex will no longer repress, a new kind of imagery is born. Hysterical fiber paintings scream in a language that comes before any language. The woman’s body is reimagined and reinstated as the primal source of power and creation, a home of its own. Hysteria in this context is not seen as a weakness anymore; women are not stigmatized because of it. Hysteria is instead understood as a feminine, visceral manifestation of one’s unconscious, once repressed and consequently expressed through involuntary bodily reactions such as numbness, fainting, and stuttering.

In this effort to reclaim the past, I create the future. And in doing so, I release goddesses and entities of the unseen from the depths of my (and maybe your) unconscious.

In this feminist sci-fi reality, trauma accumulated through centuries is invited into the visual world, and it is angry. It brings, now voluntarily, symptoms in the form of visual elements: stuttering as repetitive stitching, colors that yell, numbness turned into an explosion.What does trauma look like? What can anger be transformed into? Through obsessively, compulsively stabbing a fabric with a yarn gun, the unseen takes shape.

Farina

histérica #1 (hysterical #1), 2020.

Upcycled fibers on monk’s cloth, 34.5 x 27.5 in.

Anahistérica #4 (hysterical #4), 2020.

Upcycled fibers on monk’s cloth, 52.5 x 29 in.

histérica #7, Baubo (hysterical #7, Baubo), 2020.

Upcycled fibers on monk’s cloth, 50.5 x 29.5 in.

histérica #5 (hysterical #5), 2020. Upcycled fibers on monk’s cloth, 30 x 40 in.

histérica #2 (hysterical #2), 2020.

Upcycled fibers on monk’s cloth, 29 x 35.5 in.

histérica #3 (hysterical #3), 2020.

Upcycled fibers on monk’s cloth, 25 x 34 in.

histérica #8, Jardim Secreto (hysterical #7, Secret Garden), 2021. Upcycled fibers on monk’s cloth, 40.5 x 63.5 in.

emily downes interviews

Emily Downes: Basically, more or less what is that you find an image or a reference that the image, not by leaving things in or taking taking the meaning away from an image and necessarily physically.

John McCabe: I was just kind of thinking, something, putting my perception of reality different, like that one sort of weird family juggalo…

ED: That honestly, that was the image that [both laugh] because I want to hear so much

JM: So that was just like a tongue in cheek, absurd. I guess tongue in cheek is underplaying is this weird, fun image where people look What is going on here?” But it was that what’s going on in the world and at the feels like it was so long ago. There were talking about, once again, because I was Kong stuff, they were talking about how is with facial recognition and cameras these news stories of, I’m sure it’s here and I don’t want to get too tin-foil-hat conspiracy using facial recognition software on their whatever to unlock their phone or their took this to the next level where you can

Why Can’t we Find You? 2019. Oil on canvas, 24 x 30” nterviews John mccabewhat I understand about your process that has content and you break down taking things out and changing them, but and appropriating it conceptually, not

thinking, when I am decontextualizing reality into it, I’ll talk about something family portrait where everyone’s a that made me want to interview you much more about this!

cheek, or maybe it’s just completely underplaying it but basically, that image look at it like, “Whoa, what is this? that same process I was reacting to time, and still am, but Jesus, 2019 were a lot of news stories that were was always up to date on the Hong authoritarian their whole society everywhere. I was seeing all of here to a certain capacity in the US conspiracy person but with people their cell phones, their iPhones or their computer and in China, they can literally use your face as your

currency because your face is tied to your ID and they just cut out the middleman, like “Oh yeah, we read your face and know how much social credit you have” to go to the vending machine to get your soda. Just imagine, you don’t even need your wallet and just walk up and do that whole thing.

But I was seeing these articles that were like scaring me because I was seeing the CIA or the FBI or whoever is in charge of that here was like “Yeah we can definitely do this and have this up and running like sooner than you think” and I’m like, “Jesus, please no” and then I saw this hilarious article that said juggalo face paint made it so whatever facial mapping process it goes through to recognize faces, the juggalo paint made it so the cameras couldn’t read faces because the stark white and black made it so it can’t decipher the landmarks on the face; where the tops of the cheeks are and the chin, and where everything is. So I was sort of imagining this funny, utopian society where everybody had juggalo face paint on to stick it to the man in a sense.

ED: That would be so funny.

JM: [laughs] Like everybody’s got their juggalo paint on so the Big Brother authoritarian regime would leave them alone. So I picked the funniest, family stock photo that I could find which was this super generic, white bread, white people family. And everybody in the picture, like the kids were clearly not related but I don’t know, I guess it was just this layer upon layer of inside jokes but it all kind of culminated into this fuckin’ family photo with juggalo paint on. I don’t know if that helps answer the question.

ED: Yeah, I think it does because I think what I was trying to get at was just how do you apply these broader themes in a different way than how they are originally preconceived? And it’s really funny, when you were first talking about the thought of this painting, my initial reaction was “Aw, you’re protecting them from the government with this juggalo face paint” and I don’t know, that kind of, in a paranoid, pandemic brain way, it kind brought me to the whole mask thing. Just in terms of thinking about blocking out areas of the face. And with the politics and the freedom behind the whole anti-masker movement saying that wearing masks is “anti-freedom” when the freedom is the protection of you and others. I’m assuming that this was painted before that and everything. But the thing that’s really cool about your work, but also just art in general is that you can look at something in twenty different ways and can be like “this makes sense in this context” or “this makes sense in that context” and that this imagery is just so powerful, just because of the connotations we have.

JM : That’s a fun parallel you drew. The 2019 juggalo is the 2020 medical mask, you know? That’s funny.

Jessica Beckwith: Once the violence of governments has made its mark, the people are left to make a life within these new circumstances. How do you feel that the presence of these different cultures, and violence, suppression, as well as cohabitation, have affected the Taino people and culture?

Joseph Kattou: The tricky thing about these sorts of generational traumas is that they never go away. The colonization by Spain nearly destroyed the Taino people, and once they destroyed their population the Colonists began to bring in enslaved Africans to continue the forced labor. This displacement lead us to a very thorough creolization that is very apparent in the modern day. The masks of Puerto Rico take artistic and cultural cues from not only the indigenous Taino, but the descendants of enslaved Africans as well, all fit within a Spanish-dominated cultural industry.

JB: How has this history affected you and your family? Did those personal experiences inform and inspire this series of masks?

The history of Spain’s occupation is still very apparent in the culture, language, architecture and just about every facet of life in Puerto Rico. The later conquest by the United States, who have historically enacted violence against the people, means that no living Puerto Rican has known an island that was not under Colonial rule from an outside force. It leads to a certain adaptability and composite cultural identity that Puerto Ricans actively shape.

The Careta masks are created as a part of carnival in Puerto Rico, right?

JK: Many of the masks, like the famous horned mask called the Vejigante are typically used in street festivals and dance. The masks in this series take direct inspiration from that contemporary practice as well as remnants of Taino masks and surviving petroglyphs of the Cemi, or ancestor spirits.

Joseph Kattou

BFA Sculpture, Alumnx 2019

JoSeph Kattou in Conversation with JessiC a BeCkwith

BFA Sculpture, Alumnx 2019

JoSeph Kattou in Conversation with JessiC a BeCkwith

JB: What do the Careta masks represent to you? Are they an aspect of erasure, or a claiming of your culture?

JK: They walk the line of both to me. They represent a kind of endurance and adaptability that the people can always preserve their heritage, even as they enter the diaspora.

JB: What is your experience when you wear these masks? Do they act as a thread connecting you to your cultural identity or are they an element of erasure of self and culture to you?

JK: They are, to me, both a caricature and a statement of resistance. There are many preconceived notions of what a Puerto Rican is. These masks are not immediately recognizable as Puerto Rican to many unaware of the culture, but they do immediately read as ‘other’, ‘foreign’ or ‘native’ to those same unaware people. As those in the series condense their identity into this mask they also assert a fragment of their own personality via the way they dress, the props they hold, and how they carry themselves.

JB: I know you explore the ongoing damage of colonization and othering. Do you think art has the power to rewrite this history of erasure in a way that can empower future generations?

JK: I believe that rather than rewriting history, projects like these reveal the historical truths. History is already heavily redacted and rewritten in the favor of the colonizers. With a series like Orgulloso I work to assert two truths: we did not forget where we came from, and we won’t let anyone take that from us again. I hope that other Puertorriqueños feel seen and empowered and everyone else can begin to educate themselves on who we are, because we are not leaving anytime soon.

Orgulloso Series - Self Portrait in a Sun Mask

Digital photograph, resin, paint, gold (left & right)

My work provides the opportunity for viewers to consider their relationship with the ‘others’ of society. I create wearable, metal forms that discuss the psychological effects of Post Traumatic Stress Injury (PTS) found among displaced persons due to their flight and temporary living conditions. I recognize my position of privilege, and utilize the resources I have to highlight the lack of resources and oppression these individuals face. My pieces challenge those with economic privilege to recognize the pain of others, while simultaneously validating the refugees’ experiences of suffering. The literary descriptions I pair with my jewelry are a call to action: rousing individuals to take responsibility for their role in social transformation. I translate the inequalities of our society into tactile, wearable jewelry that offers insight into the harsh realities of physical and psychological survival in exile.

I delight in constructing intricate works of metal with various movable hinged and swiveling mechanisms that capture the intrigue of the wearer. As one is drawn to interact with these pieces, they become engaged in the conceptual matter that relays the traumas of refugees. I integrate mixed media with the metal fabrications, incorporating transparent resin casts of common blue tarpaulin within the jewelry to reference the temporary building materials often used to construct refugee camps. My metal works are displayed upon ceramic forms that mimic the texture of shredded tarpaulin sheets to present a united body of work. By altering the refined metal surfaces with textures, patinas, and alternative materials, the object resides in a worn, accessible context that invites the wearer’s intimate connection rather than reverent distance.

Rachel Brainerd

BS in Visual Arts, Metals

Inescapable Past - Intrusive Memory

2020. Copper, brass, liver of sulfur, resin, tarpaulin, laser print ink, 4 x 4 x 2 in. (left)

Catching Dreams of Refugees - Sleep Disturbance

2020. Copper, tarpaulin, magnet filament, resin, fire 16 x 4 x 1 in. (center)

Ruptured Shelter

2020. Copper, liver of sulfur, WD40 18 x 3 x 3 in. (right)

Ferris Ramirez

BFA Photography

BFA Photography

Waiting (left) The Ephemeral Exchange (middle) Omphalos (right)

Waiting (left) The Ephemeral Exchange (middle) Omphalos (right)

Jiyu An

Windows 1, Porcelain, wooden shim, 10 x 10 x 9 in. (left) Cities, Porcelain, 11 x 9 x 10 in. and 7 x 7 x 10 in. (right)

William Koenig-Vinicombe

BFA Photography, Alumnx 2020 Click here to view William’s video Initate

William Koenig-Vinicombe

BFA Photography, Alumnx 2020 Click here to view William’s video Initate

Karen Rothdeutsch

Untitled (Pat in the kitchen) Untitled (John Canor)

BFA Photography

Untitled (Pat in the kitchen) Untitled (John Canor)

BFA Photography

Swarm Paper lithography on kitakata dipped in wax 7” diameter

Lost Marble City, Acrylic and pastel on paper, 38 x 50 in. (left)

Breakfast Techno At the River House, Oil, acrylic and pastel on canvas, 42 x 36 in. (right)

Emma Hines

BFA Painting and Drawing

By under-firing enamel, I am able to describe the true texture and color of the natural surface. Rocks or sand can be melted to make glass, which is the main ingredient of enamel. Conversely, I melt enamel to make rocks. Natural rocks absorb heat slowly and dissipate slowly; these qualities of warmth and resonance are embedded into wearable objects that quietly evoke difficult subjects. By bearing these objects on the body, I urge the wearer and audience to consider the new lightness of these burdens, and propose new ways to move forward.

Splitting Rock Necklace

2019. Enamel, copper, silver, photograph, tickets, letters 3.5 x 4.5 x 12 in.

Peeling Rock Brooch

2020. Enamel, copper, sterling silver, steel 5 x 2.2 x 1.5 in.

Circle of Life Necklace

2020. Enamel, copper, sterling silver

4 x 10 x 12 in.

dirt: inSide landScapeS

— Clara Pierson and anna Conlan in Conversation with

Emilie Houssart is redefining the museum gallery space, transforming into an interactive and earth-related project that serves to challenge people look at dirt. The SUNY New Paltz MFA student has served Artist-in-Residence at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, where the interactive exhibition DIRT: Inside Landscapes. By examining between communities and dirt, Houssart hopes to bring awareness view, treat, and interact with the earth. This relationship is acknowledged interactive elements, where guests are encouraged to share their on the matter, while also employing the art of local creators from permanent collection, from Thomas Cole to Peter Iannarelli. Using works, Houssart examines people’s views on dirt, while also noting interpretations have evolved over time and place.

This is a conversation that occurred between Emilie, Anna Conlan, Director, and myself, where we explored the role of DIRT in the museum the exhibition has expanded beyond the gallery’s walls.

Clara Pierson: So, why did you choose dirt for the theme of this

Emilie Houssart: It really came out of immigrating to the States that people use the word ‘dirt’ for the earth over here. As grew up in England, I found that really shocking, because negative word for us, and I never quite managed to forget my work at the moment I’m looking at things like industrial food practices, and a dissociation from nature coming from this vision of America where everything exists to serve humans. to all of that, so it was really exciting to focus in and try to relationships with dirt further, especially in the very clean the museum.

CP: How do you think this exhibition fits into the Dorsky as a museum

EH: The Dorsky doesn’t feel to me like a physically very welcoming

The architecture is quite hard to be around as a human. I’m really in the geometry of our built environments, and how that unilateral ways of thinking. In theory, the museum is built but it doesn’t always feel that way. With this exhibition, I wanted

with emilie houssart

transforming its walls challenge the way served as the Spring she has curated examining the relationship awareness to how we acknowledged through their own feelings from The Dorsky’s Using these artists’ noting how these Conlan, the Dorsky’s museum and how exhibition?

States and noticing someone who “dirt” is a very forget about that. In industrial farming, toxic this postcolonial humans. Dirt is the key think about our environment of museum space?

welcoming space. really interested that represents for the public, wanted to try to

make the barriers between the community, the museum, and the landscape more porous; and to connect typical museum associations with landscapes to the land under our feet right now. Seeing people respond so warmly to the dirt of Peter Iannarelli’s piece in an air conditioned museum room with no windows is really exciting—even before they’ve engaged with it as an artwork. And it feels good to have this growing community organism of thoughts—a contemporary, public landscape—occupying the same space as Thomas Cole and Sharon Core.

Anna Conlan: In terms of the museum not being accessible, that’s something that we really want to change.We want the community to know that this is a space for them, we are here to serve them, and the Artist-in-Residence program is also part of that. The goal of the program is to have a contemporary artist use the museum, interact with the Museum’s collection, our audiences, and the space, and create a project as a result. Emilie really ran with that! She took art and interpreted it with labels that tell a new story while also connecting with her wider practice as well. That’s a wonderful thing about working with artists because they think in different ways and look from different angles.

EH: If I had to summarize my goal with the residency, it’s to make people realize that their relationship with the ground in the future is a choice. And of course, that choice is completely up to them. But I would like them to come in and have an experience, so that when they leave, they’re no longer able to say that they’ve never thought about that relationship. Also, I’m a Dutch Huguenot immigrant from England, so this is an amazing opportunity to think about the relatively recent history of my predecessors coming here and destroying a multiple thousand-year-old culture; one that is now becoming a model for us again of how we might exist collaboratively with the land around us. This model of Eurocentric land domination has become normalized but it’s not sustainable, and it’s not ok, in so many ways.

AC: I’m curious if your ecological consciousness has been something that you’ve been interested in for a long time, or is it something that you’ve developed and grown? I remember seeing your paintings early on and noticing the incredible classical training that you received, and how sophisticated they were. Then I saw your prints and they were so abstract and different, and now the work that I’m seeing you do involves sculpture and performances with potatoes. I’m interested in

DIRT: Inside Landscapes, at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, 2021. Photo: Bob Wagner/Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art (left)

Wall writing from DIRT: Inside Landscapes at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, 2021. Photo: Emilie Houssart/Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art (above)

the stylistic and formal journey that you’ve been on in your practice, and whether it is a departure, or part of a continuous timeline of ecological consciousness and activism.

EH: I understand those works much better now. They all came out of a general dissatisfaction with humans—with what I now understand to be European colonial culture. The dead birds were an absurdist thing about dignity and value. It was like, let’s take this Dutch Old Masters tradition and do it on bits of trash I’ve found on the ground, of something that manages to be at the same time tragic and slapstick; beautiful and really revolting. And that was the only place I felt comfortable—in the murky, grey area between those two axes. Then I started making these little prints where you would take a geometric element and smash it, pushing delicate artisanal paper to its absolute extreme limits. At some point, I realized that when you crush a piece of paper you’re not creating chaos, but an interdependent system, an ecology, that’s unique and far too complex for humans to understand. So in an abstract way, I was getting there; I was fed up with an anthropocentric culture and was breaking down geometry with these systems, with handmade and natural elements colliding violently with mechanical ones. And that makes total sense with what I’m making now! It was a sort of sketching process. But it’s hard to make those giant transitions in isolation, and I’m really grateful for the set of forward-thinking faculty who opened the door for that to get to where it was going. There’s also some really exciting sustainability work going on at SUNY that I’ve had access to as a Graduate Faculty member.

CP: I’m curious if there is any person in particular that has informed your practice? I think there are some really interesting connections between your work and works of minimalism and I was wondering if that has any influence on what you create.

EH: Absolutely—so many! The professors I’ve worked with in the sculpture department have been hugely influential in the way that they think about the world, and Linda Weintraub, who is a force of nature herself. But also something like that piece by Agnes Denes where she planted a wheat field in New York City—just an incredibly simple but huge, beautiful statement, you know? You can’t unsee that kind of thing. Also, imagine the experience of that in the 1970s, and then to think about what that land looks like now... It’s pretty staggering. I’m also enjoying reacting against artists. Using these geometric forms is definitely in conversation with minimalism, with male-centric, white cube gallery pieces. And I love many of those works! But this is taking that and flipping it upside down. Putting those shapes in the forest, for example, exposes them as jarringly simple against the trees—which, again, are just too complex for us to understand, so we assume they are chaotic, but it’s not at all the case. Hopefully it also makes people think about what kind of spaces art is for, and why we think that these forms are normal.

Wall writing from DIRT: Inside Landscapes at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, 2021. Photo: Emilie Houssart/Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art

AC: Do you have any goals, or ambitions, or dreams of how your work or DIRT can be shared with audiences?

EH: It’s been very exciting to do workshops, and I think that has become part of my practice now. I’m just at the beginning of this journey, trying to figure this out for the first time, but that feels like some of the most meaningful stuff that has happened. As a privileged white person, I think that educating polluters, people like me, is in my scope. And I think education with school kids is a really important way of engagement. Not in a didactic way, but by showing that the dirt, or the earth, or the soil—whatever you call it—is a living thing; so what does that mean in terms of our relationship to it? Can you own something that’s alive? Is the dirt near you safe, and is that fair? This whole residency is a learning project for me, learning what works, what I should be doing more of, and what didn’t really work... how I can be helpful in different spaces going forward. My current project for Owning Earth at Unison Arts Center needs to be made in the forest, but can then be disseminated online, and as a publication. And, increasingly, the audiences are part of the work. I’m learning to embrace performance as a key part of these projects.

CP: I was curious if you think your use of social media for this exhibition has changed how you view accessibility or informed other aspects of your practice.

EH: Yeah! It’s not something that I was drawn to beforehand, but it’s actually a more democratizing way of disseminating work. I had hoped to have a Dorsky kiosk in the supermarket, getting people to come and draw something—maybe an industrially farmed potato—while we talked about the health of the ‘wild’, and just see where that led. That wasn’t possible during COVID. The call for people to participate in DIRT started very locally, just trying to get people to come into the museum, but that didn’t feel satisfying at all because only a very small segment of the population would actually come. So that call has now been extended through Instagram, and through Nextdoor and Facebook community pages for Poughkeepsie and New Paltz. People have such varied experiences of dirt, both recreationally and professionally, and I’ve had some amazing feedback through social media. This project is just beginning, and I intend to keep it growing beyond the life of the residency. It feels like something that’s simple and important that I haven’t fully understood yet. This kind of socially engaged work is messy, and that’s great! It just needs to get bigger and continue to open up, regardless of my expectations of where it might go.

DIRT: Inside Landscapes is on view thru July 11, 2021

All Hudson Valley residents are welcome to participate. Follow along on instagram @dirt.scapes

DIRT Dinner Party Workshop, in conjunction with DIRT: Inside Landscapes at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, 2021. Photo: Emilie Houssart/Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art

DIRT Dinner Party Workshop, in conjunction with DIRT: Inside Landscapes at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, 2021. Photo: Emilie Houssart/Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art

Jessica Beckwith: Light dissolves materiality and seems to act as a vehicle for sentience or consciousness in your works, creating a sense of presence and transparency, which creates a rich multi-dimensional reality. I wanted to ask you about the ways in which transparency and light offer a window into the interiority of place in your work. Do you feel a connection between the interiority of these spaces and the outer world or collective space?

Kristina Pray: I definitely feel there’s a connection. The spaces I create are a mosaic of places I consume and inhabit, either consciously or subconsciously. The light and transparencies act as layered transitional spaces between the several dimensions of reality I’m depicting.

JB: How do you see this informing the way you see the world? You talk about using a combination of digital media and photography in the process of creating your paintings. I’m curious about how that layering influences your work? Is it purely visual or are you drawing from a phenomenological presence within the images that you’re using to inform your paintings?

KP: Digital imagery has helped me think about depth and color of spaces in an expansive way. I find myself paying selective attention to parts of spaces in the real world the same way I might select a fragment of a found image when I create digital collages. I’m often thinking about how things like a digital texture might translate to a physical texture and vice versa. That visual difference I would say is really important in my creative process. Many of the digital textures in my work have inspired a greater variation in the physical marks I make with paint. It feels instinctual to me now to fluctuate between thinking about elements of a space in a digital and physical form.

JB: You’ve spoken about consciousness and/or emotion and ‘liminal spaces of the psyche’ within the environments you create. Light seems to be the fabric that knits your environments together and carries the psyche of the environment with it. Can you speak a little more about that interconnectivity?

KP: I don’t usually start a painting thinking about where the light will be coming from. I feel like that element reveals itself to me later on in the process of piecing together a space. Once that happens I’ll build off of what the painting shows me it needs. I like the idea of certain architectural elements giving off their own light as if the space is a living conscious thing itself.

KriStina pray in Conversation with JessiC a BeCkwith Kristina Pray

pamela ellicK in Conversation with JessiC a BeCkwith

Jessica Beckwith: Light dissolves materiality and seems to act as a vehicle for sentience or consciousness in your works, creating a sense of presence and transparency, which creates a rich multi-dimensional reality. I wanted to ask you about the ways in which transparency and light offer a window into the interiority of place in your work. Do you feel a connection between the interiority of these spaces and the outer world or collective space?

Pamela Ellick: I think I'm in denial about who some of the figures in my work are, because my whole life I've been terrified by the idea of paranormal things, yet I am fascinated by light beings and spiritual bodies. I suppose it is just semantics. I use light and transparency as a means to suggest a spirit of something, be it emotions or physical places and beings, rather than someone specific and fleshy (so yes, dissolving materiality). Embedded into all the glitter, my images often have a psychological narrative based in isolation and the desire for community.

Light and transparency allow me to create an alternate dimension of beings and their environment while still being relatively relatable. Suggesting auras and energy fields through these transparencies and inner-glow environments activates the space, and even ‘lifeless’ environments prove to have energy and aura. The physical, tangible textures of nature versus the invisible ~stuff~ that you might see in an altered state of consciousness (such as meditation or purposeful lucid dreaming) provides a grounding effect that still feels a bit floaty. Concentrating on specific things in my environment such as textures, colors, and the way that transparent things interact with light (i.e., water, glass, smoke, sheer cloth) encourages me to be more aware of my surroundings and more mentally present when possible.

JB: How do you see this informing the way you see the world? You talk about using a combination of digital media and photography in the process of creating your paintings. I’m curious about how that layering influences your work? Is it purely visual or are you drawing from a phenomenological presence within the images that you’re using to inform your paintings?

PE: I use digital media as a means to extend the capabilities of oil paint, such as using manipulated photo references and making videos of layered and collected footage to create moving imagery that communicates the energy I envision. My paintings are detailed snapshots; my videos are intended as virtual manifestations of realities that can only be conceived in dreamlike/altered mental states, as far as I know! I layer images and videos to create a delay and glow affect that reads as less physical and more airy, more illuminated. It helps communicate that there is this ~other~ world somewhere/ somehow that we can’t quite understand all the way.

Pamela Ellick

BFA Painting and Drawing, Alumnx 2020

BFA Painting and Drawing, Alumnx 2020

Are You Leaving

2020. Oil and acrylic, 18 x 24 in. (left)

Bubble Bath, 2020. Oil, 10 x12 in. (right)

Fake wood, toxic vegetables, ads for lavender-flavored bleach: symptoms of human disassociation from the ecology of our own planet pervade our language, our culture, and our physical and virtual environments. In an age of climate awareness, our celebrated conscious intelligence has proved devastatingly basic in relation to the sophisticated interdependent systems surrounding us. In a variety of commercial and ‘wild’ settings, I hope to disrupt socially normalized constructs that contribute to our numbness to nature, while highlighting the role of inherited European colonial anthropocentrism in this disconnection. I try to create space for exploratory conversations, on the premise that our future relationships with the ground are a choice; while fostering renewed respect for all life forms on earth and presenting alternative models of success.

Drawing on absurdist theater, I design provocative interventions for public spaces that aim to actively reconnect people both physically and psychically with the land surrounding them.

Earthrisings, maquette 2020. Vines, branches, earth (including approx. 1 billion microorganisms), suburban hedge clippings trimmed in performance, forest floor matter, 4 x 2 x 2 ft. (left)

Rupture iv 2019. Kozo wall sculpture, 14 x 10 in.

Emilie Houssart

MFA SculpturerethinKing materialS: John Stowe in Conversation with liz hunt

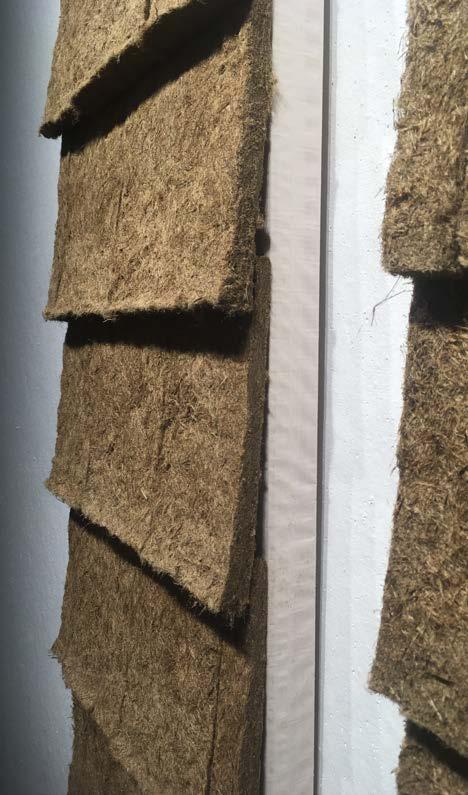

John and I met via WebEx to discuss his thesis explorations into substantial building materials with papermaking techniques using wild-harvested plants from the local area and his home in Florida. He has been collecting Sable Palm and Stiltgrass, breaking the fibers down into pulp to cast in molds and reform into siding.

John is completing his second year as an MFA candidate in printmaking at SUNY New Paltz.

Liz Hunt: We both came back to school in our early thirties. Do you find that that has given you a different perspective returning to school now?

John Stowe: They say the thirties are the new twenties.There is something to taking time off between the undergraduate and graduate level, coming into that next degree with a different mindset.

LH: It’s like you are excited to go back.

JS: The gratitude you have being in that space and doing what you are doing is greater. You feel it more – you want to be there.When you are working in the real world, you’re thinking that being in the studio is so much cooler than working nine to five. I was doing contract work, construction, full time, seven days a week. Working for myself, dealing with clients, doing the entire job from start to finish, sacrificing personal time to get more and more work, with the goal to eventually reach a place where you don’t need to work so hard. I was kind of happy when I was able to stop doing that. Now the energy I was putting into that, I’m able to put into my art practice. And that’s hard to teach, and it’s one of those extra things you bring with you. You know what you are capable of, and that work ethic you bring to the studio is different.

LH: My impression of you is that you fit well into the culture of

New Paltz. It feels like a community where everyone wants to be outside and do things together and is in a great location.

JS: Yeah, but COVID threw a wrench into all of that. I’ve spent the majority of my time here on my own. I can imagine that if I were living in the town of New Paltz, this year would have been different for me. I wouldn’t have felt so fulfilled in my graduate studies. I wouldn’t have been able to cook fiber in a four-foot pit in my backyard. The stars aligned.

LH: Do you feel that the location of your graduate program at New Paltz, here in New York State, framed your thesis?

JS: Growing up in Florida, the ecosystems are different –the pine scrub, the oaks, and palmettos. Wild Florida looks very different from wild New York. Everything was so new; my eyes were wide open. I saw many things I wanted to talk about, like soil degradation and nutrient pollutants getting into the waterways. As my work developed, I was making prints and drawings of potential solutions. How could we reimagine infrastructure or record that these things are happening so that the pathways became visible to us?

I got to a point in the fall where I just wanted to move away from speculative solutions and try to create something that could be a physical solution. A manifestation of it in the real world, moving beyond print into three-dimensional reality.

LH: Was there a reason your focus landed on home structures and building materials?

JS: Maybe it ties to where I moved from; Jacksonville is one of the largest cities spatially in the United States. The urban sprawl is noticeable. Large areas of land are clear-cut for townhomes or apartment complexes. I thought about the residential buildings—how we build our homes, there is

so much room for improvement. There they are trying to control the land – to keep things out. Here in New Paltz, there is a blurry edge. We are in the best-case scenario where we can change that thinking. So close to the preserves, the Catskills, we are on the edge where those boundaries can start moving into more suburban areas.

I hate saying this is the solution. I like to remind myself that environmental issues are so complex. The answers to specific problems are going to look very different depending on where you live. The stiltgrass is a particular problem to New Paltz. Let’s start by using this first, and if it doesn’t work, let’s move onto the next thing instead of using trees. Trees are living organisms that take longer to grow than I’ve been alive, and then they are just cut down to be turned into lumber.Why not use other plants that grow faster for similar purposes?

LH: So instead of using standard materials for home building, you are looking at what resources are local and plentiful around you and exploring what you can do with them – Japanese stiltgrass here in New York and Sabal Palm in Florida?

JS: The potential is great for many different things. I’ve been looking at Shigeru Ban’s work building architectural structures using recycled cardboard tubes. His load-bearing structures are built from paper fiber, and I’m only using fiber as a surface application. It’s interesting to see people being so skeptical of this when humans have such a long history of using plants to create shelter. It’s wild to think that people believe this won’t work – it has been working. It’s only been decided over the past hundred years or so that there is a set range of materials you can choose from in commercial homebuilding. They are convenient and easy; the modes of production are already in place, and to try anything else is to go against the system.

LH: In looking for a more sustainable solution for building materials, what got you to explore using sabal palm, stiltgrass, and papermaking techniques to create the siding boards?

JS: The underlying thing I’m most interested in is my connection to the land. It’s something I’ve enjoyed most since I’ve been here and something I would hope to communicate if I continue doing this work. To keep being out in the field, understanding the relationships between particular organisms, specifically plants. It’s been great living where I live – I can spend so much time outside. I can easily observe what is happening, see how plants move around, how they propagate, where the seeds are moving, and understand the system and forces at work that move these things around. They are not stationary, not stagnant.

Invasive species like stiltgrass that came from overseas have negative effects on biodiversity. But still, it’s just a plant, that’s good at what it does, quickly propagating and spreading itself. The stiltgrass grows quickly, tall and fast. In the winter, it falls over and forms a blanket, and it does this at the same time it is seeding. It creates a mat that blocks the sun; everything underneath it dies. I think we are too quick to hate it for that. Instead, I’m making something positive from stiltgrass, using its rapid growth as a way to transform it into building materials.

I’ve come to an understanding where papermaking is a piece of ecological knowledge. We can find these processes in nature, all you need is water and time. People in the past have harnessed that process. It’s a process of decomposition— breaking down the lignin in the fiber and reforming it. If you look at the grand scale of time, papermaking is a moment on that timeline where we pause that decay. In the grand scheme of things, everything is going to fall apart eventually

and decompose. I’m pausing the plant fiber at that point to form these boards.

It’s been great to see that happening in nature. Being outside has informed my understanding of the ecosystems that I’m living in. As someone who is not an ecologist—I’ve taken a few classes, but it’s far from a deep scientific understanding of biology and botany—it’s sort of like, I’m hoping that if I pay attention, listen closely enough, look closely enough, I can start learning these things. Then supplement that with my own research to inform myself and understand the processes and systems at work in nature. If people realized that if they go out and spend some time in nature, they could also learn and apply those lessons to something.

LH: Your talk about observing and learning from nature is similar to renaissance naturalists—going out and observing the whole system rather than an isolated part of it in a lab. You are seeing the complete picture and looking at nature as a community.

JS: That’s what’s so great about being an artist. I’m not beholden to the lab and data necessarily. Many ecologists will tell you the best part of their job is the time they spend in the field. That’s what it’s about. The scientific conclusions you get from the research are the life’s work of many of them. As far as the balance of time spent in the lab vs. outside—I don’t have to do that. I get to make up whatever comes up in this crazy head of mine.

I have more flexibility to apply the knowledge in unscientific ways—I have the freedom to dream up crazy applications that may be totally outside of scientific goals. I’m making siding from plant materials!

In the end, I’m making an art object—I’m not in the business of making siding. I don’t plan on starting a company and make

a living on it. I’m more interested in seeing if we can have a closer relationship with other organisms around us. I am reestablishing my connection to the land.

What can I do to make my relationship with the land more sustainable? A part that drives me that sends me outside is that I can do more than current institutional methods to promote change. I am making a personal choice to find other alternatives in my artwork. At the moment, I’m just scratching the surface. I’m making very literal connections to building materials right now. I needed to add visual components like vapor barrier and framing timber to have my artwork seen as building materials and structures. To create the visual language of the components of a house, you can live within. However, in the future, I won’t need to add those extra visual elements. This is just a step I have to do, especially seeing so much skepticism of using plants as building materials. It’s so silly.

It makes me think there is a sort of a myth in the American psyche, like the story of the three little pigs—homes of straw, sticks, and brick. In the story, we tell it as if we are the pigs and we need to make a home that will withstand the big bad wolf. But, in that story, we are the big bad wolf—there is nothing out there to eat us. Top of the food chain, do we need homes that last so long? ... Other than the weather anyway—I am from Florida, after all.

Sabal Palm Lap Siding

Sabal palm, vapor barrier, wood, 36 x 96” in.

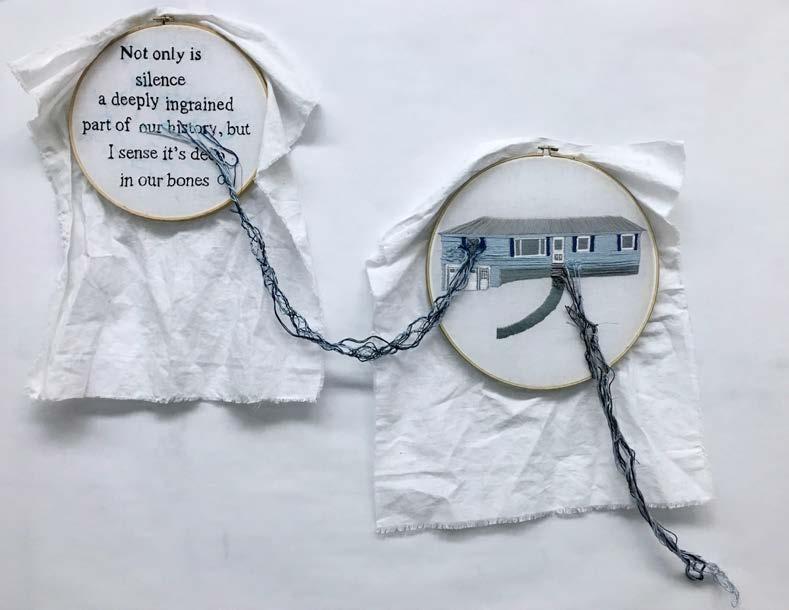

Using photographic imagery and handwritten text, I investigate my fallible memory after suffering a traumatic brain injury. Lithographic printed imagery and text become visual elements to artist books, haptic wall hangings, and installations. Recalled fragmented and distorted memories of significant experiences, feelings, and actions become components to a collective memory. A tangible memory requires the intimate experience of touch to be understood.

Julia McBride

When Am I Gonna Lose You

2021. Die-cut paper lithography onto handmade recycled paper, beeswax, 8 x 4 ft.

Snowbank in a Shop Window, Poughkeepsie, Feb 21 (left) St. Francis, Poughkeepsie, April 21 (middle) Discarded Clothing Beneath a Telephone Pole, Poughkeepsie, March 21 (right)

Snowbank in a Shop Window, Poughkeepsie, Feb 21 (left) St. Francis, Poughkeepsie, April 21 (middle) Discarded Clothing Beneath a Telephone Pole, Poughkeepsie, March 21 (right)

The following took place on an evening zoom call under lamp lighting. Afterward, Renee went to work in her studio and Kristina watched A Space Odyssey.

Kristina Pray: I’m curious about how you consider your interactions with the objects you create and collect. In Bill Brown’s Thing Theory he mentions “[confronting] the thingness of objects when they stop working for us”. Is this confrontation something you think about?

Renee Ricci:Yeah, I find that idea very interesting because I’ve just started to delve into non-functional tool objects. Something I’ve also started thinking about recently is the second life of objects. I take a lot of things that have been thrown away. I hate buying stuff to use for making. I’ll call myself the scavenger of the room and go around and take everything. I’ll also pick up rocks outside and think ‘this’ll work!’.

KP: Do you consider these objects precious to you? What emotions come to mind during your creative process?

RR: It’s kind of a euphoria, honestly, making something that is finely crafted and beautiful and has the grace of a tool where you look at it and you think ‘this is a functional object. It has beauty and functionality’. That brings me a lot of joy, but to push an object to a place where it actually doesn’t work, it sort of teases you with functionality. It gives me mischievous happiness. It’s like playing a prank on whoever is viewing my objects (laughs). It’s fun. I think the idea of working through a material and the intentions I have creates preciousness and brings value because I care so much.

KP: Does working with the intention of creating ineffectual objects sometimes cause complications in your metalworking process? Or does it feel more freeing?

RR: It’s a mixture. Everything has to go together really smoothly and I have to make things very precise. Sometimes at the end I’m a little disappointed because I can’t use the thing. I sort of prank

myself that way. I have a respect for functional tools, but I think I have a sort of reverence for the nonfunctional ones. They aren’t usable and they don’t have a purpose besides being what they are.

KP: Bill Brown also writes about “the suddenness with which things seem to assert their presence and power. For example, when you cut your finger on a sheet of paper” it “teaches you that the body is a thing among things”. Are there ever times where you feel like your experience transcends being the maker of these objects and you become part of the work?

RR: Definitely. I see everything I make as a self-portrait. It definitely reflects how I feel a lot of the time. My thesis is sort of a combination of memoir and self-portrait. It’s my life history and where I’m trying to bring myself into the future. I really like the idea of experiencing the thingness of your body and I feel like metalworking allows that.You work with your hands so much and they get horribly beat up. These are my tools (holds up hands to camera). I’m constantly like ‘oh, my hand is bleeding again’ and I’ll glue my finger back together. Band aids don’t even work anymore, I have to glue myself back together (laughs).

KP: Sounds like an intense process.

RR: It is, it’s a learning experience of respecting my body which then, in turn, reflects onto respecting my tools and my work. I kind of see the body as a machine through which we experience life and create things.

KP: Do certain materials or processes of manipulating materials relate to certain emotions or memories from your past? Susan Stewart in On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection writes about “imagining the self as place [and object and how the memory of the body is replaced by the memory of the object]”. She goes on to say this object’s “functionality is to envelop the present within the past”. Is this something you’ve thought about?

RR: That ties right into my work. I grew up in the country working with knives a lot of the time. If the power went out, which it frequently did, I would just light a bunch of candles and practice tying knots. I’m trying to pay homage to the things I did as a kid that were so important to me. It was all very based in physicality; connecting with my body and the outdoors.

KP: Are there any processes in metalworking that you feel are critical to your work?

RR: I feel like metalworking is sort of what I was meant to do because it ties in all of my favorite things I’ve been practicing my whole life. Fire, for example, I’ve always been fascinated by fire.There’s a picture of me on my first birthday sitting on my dad’s lap and I’m mesmerized by the candle on my cupcake. I used to have fantasies as a kid that I would be able to touch fire and it wouldn’t hurt me. Growing up and being able to work with fire and growing up with my dad being a mechanic has made metal very important to me. I think the process of using fire in my everyday work and having such an intimate relationship with it is great. Also the process of riveting. I love it. It’s the simplest way of putting two things together and it’s really sturdy; It’ll last forever.

KP: Tracey Bensen in The Museum of the Personal: Souvenirs and Nostalgia speaks about how “[objects are transformed from the moments they embody] becoming a pathway for the owner to create stories and narratives around their experiences of the past”.Would you say the objects you create represent this kind of transformation for you? Do certain materials and processes represent specific parts of your identity?

RR: I take the past and future and sort of meld them into my objects. I feel like a lot of my things go back to my relationship with my parents. Metalworking in general and toolmaking strongly connects me to my father. He was the one who taught me how to use tools. I would watch him work on cars as a kid and I’ll still rummage through his toolbox whenever I see him. The last time I saw him he gave me an

old screwdriver which I’m actually basing a new piece on. Making things helps me process parts of my past. I can think about how it has affected me with that single minded focus while I’m making.