8 minute read

Personal Narratives

Nicole Greal

I have lifelong experiences with both environmental and food allergies. I received allergy shots for my allergies that are environmentally based for a few years during middle school and early high school, which helped with maintenance and overall symptoms. My food allergies are more prominent in my everyday life as far as exercising preventative measures. I am allergic to tree nuts, which are a fairly common ingredient in a lot of health foods, desserts, and snack-type foods. Being that I am a vegetarian, I have to be considerate of the fact that many vegetarian products include tree nuts as a source of protein. I also learned from a young age—I became aware of my tree nut allergy around 11 years of age—that it is important to ask for confirmation of ingredients before consuming any food given to me by someone else. In the early years of being aware of my tree nut allergy, I accidentally consumed tree nuts on a few occasions and learned that it is better to be safe and politely decline food if someone is unsure of all of the ingredients. I have also made a habit of carrying an Epi-Pen with me at all times since becoming aware of my food allergy. While I am fortunate that I have never had a severe allergic reaction thus far, I am aware that preventative care and having a line of defense in the form of my Epi-Pen is important to maintaining my health and wellness. While my allergies do not have a significant impact on my everyday life, they are something I am aware of on a daily basis and give consideration to around meal times, especially if I am eating something I didn’t cook. In my eyes, these small preventative efforts help to mitigate the potential for a greater health crisis as a result of my allergies.

Advertisement

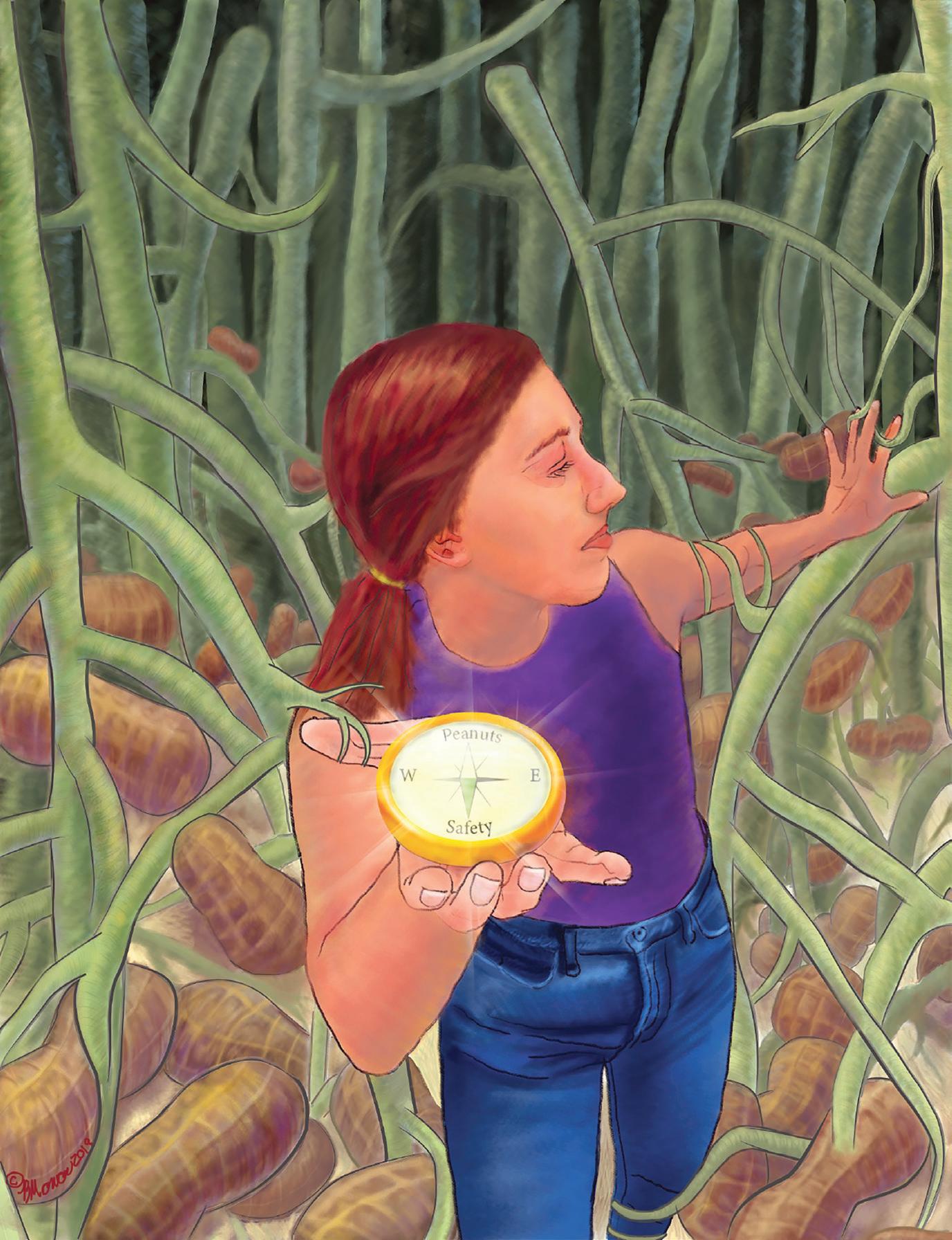

Illustration by Brianna Monroe

About the Artist

Brianna Monroe is a Chicago-based medical illustrator. She received her Bachelor of Arts at Iowa State University in biological/pre-medical illustration (BPMI) with minors in anthropology and biology in 2018. She is currently completing her Master of Science degree in Biomedical Visualization at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Attending the BPMI 30th anniversary her freshman year at Iowa State opened her eyes to all of the possibilities this career has to offer in the medical, veterinary, and natural sciences. Brianna aims to use her passion to educate others through visually communicating complex scientific topics to a broad range of audiences.

Luke Nordman

In my experience, people have recently become very conscious of food allergies and the fact that, for many people, an allergic reaction can be life-threatening. When I explain that the reason I’m not eating any of the home-made pastries brought into work is because of a food allergy, I’m nearly always asked, “what are you allergic to?” and, “is it okay to have this food around you?” I am rarely asked, “what does that mean?” As someone with a peanut/tree nut food allergy that results in anaphylaxis (swelling of the throat) when I consume –not inhale –food containing my allergen, I usually reply, “It’s fine to have it around here! So long as I don’t eat it, I should be fine, and I carry several Epi-Pens in case of an emergency.” The fact that the majority of people are aware of food allergies and only need to be informed of what I’m allergic to and how sensitive I am to my allergen makes communicating my allergy very simple on my end.

The biggest challenge to managing my allergy is simply the uncertainty of what foods could contain peanuts or tree nuts. If it is a store-bought dessert, for example, there may be allergy information listed—but the most common phrase I see on labels is “processed in a facility that handles peanuts or tree nuts.” There is a level of uncertainty that exists when such food is being made and processed alongside desserts that do contain peanuts or tree nuts. If it is a homemade good, it depends on the circumstance. If the person who made the food is present and able to remember the ingredients, it can be fairly easy to determine whether or not the food is safe to eat. However, if they are not available, I have to default to not eating whatever tasty treat has been brought into work or a classroom. Ultimately, the uncertainty with what can be safe to eat, typically with homemade and store-bought desserts, means I often have to do without, or eat something I personally brought. However, when I compare my dietary restrictions with someone who has a gluten intolerance or allergy, not being able to eat desserts frequently seems far less difficult to deal with on a day-to-day basis than giving up things like bread entirely!

Kreena Patel

When I tell people that I’m allergic to nuts, their first response is something like “Oh, that’s so sad! You can’t eat any nuts? I love almonds, I wouldn’t be able to live without them!” But I’m not actually sad that I can’t eat nuts. I’ve never been able to eat them, so I don’t know what I’m missing. What is more taxing about having a food allergy is the constant vigilance it takes to avoid having a reaction. As a kid, I would have to turn down free sweets and snacks at school parties because I didn’t know what was in them. The occasional temptations to try something sometimes ended fine, but other times sent me into a terrifying reaction. Even knowing the consequences, it took me a long time to become comfortable with advocating for myself at restaurants by letting the server know about my allergies. I felt embarrassed, like I was burdening the nice restaurant with a pesky food restriction, rather than a life-threatening allergy. I often adopted the “it probably doesn’t have nuts in it,” mentality, because I didn’t want to ask. Having food allergies can make you feel like a burden, and for some of us, it takes a while to be confident about advocating for ourselves. For me, it took a recent trip to the emergency room for anaphylaxis and the accompanying several-thousand dollar bill to finally push me to always ask at restaurants. So when you meet someone with a food allergy, instead of saying how sad it is, be a friend and make sure they feel supported enough to ask about their allergens in any setting.

Nikita Salovich

It’s a strange feeling being told that something the size of your fingernail can kill you. It’s an even worse feeling knowing that the only way to stop it is something that you cannot do yourself. When I was twelve years old I was mowing the lawn –– one of my household chores –– when I accidentally ran over a wasp nest in the ground. I was stung several times on my arms and legs and within minutes I was struggling to breathe. I remember being more confused than anything; I cried, but I couldn’t gasp enough air to sob. I don’t remember the paramedics injecting the Epi-Pen, just that there was a hole in my favorite jeans after. The next day was my first day of sixth grade. I spent it in the hospital.

From then on I had to make room in my pencil case for my Epi-Pen. Testing determined that I had a life-threatening allergy to bees, wasps, yellow jackets, and hornets (basically anything that stings). “Look on the bright side,” my doctor joked. “At least you don’t have to worry about telling them apart.” Having an allergy may seem trivial, but it quickly became part of my daily life and identity: I carried my Epi-Pen and oral steroids with me everywhere I went; I took a bus to my doctor’s office every Wednesday after soccer practice to get a shot as part of my allergy immunotherapy so I could be cleared by my doctor to study abroad; one year my mom had to choose between buying my family Christmas presents and buying me a new set of Epi-Pens; and, of course, I memorized the steps I needed to take if I ever got stung again. I did everything I could to prepare and protect myself, but when the day came when I was stung again, all of my preparation wasn’t enough to save my own life.

I was walking home from class in college when I felt the all too familiar burn of a bee sting radiate from my arm. I calmly sat down on the curb and pulled out my Epi-Pen from my backpack, ready to carry out the rehearsed steps: pull out the blue safety cap, angle it above my thigh, press for 10 seconds. Instead, my hands began to shake thinking about the needle inside the pen and the pain that would follow; I felt nauseous and horrified realizing that I couldn’t do it. I couldn't save myself.

I looked up to see another college student walking down the street and waved my hands to get his attention. When he pulled off his headphones I asked him without pause, “excuse me, do you think you could save my life?” At first he looked startled, as most people would being beckoned by a half-hysterical stranger sitting on the side of the road. But after I explained my situation he accepted and kneeled down next to me on the grass. As I coached him through how to use my Epi-Pen (he had never seen one before) I could feel my throat starting to itch. My arms wrapped tight around my backpack, he counted down from three and pushed the Epi-Pen into my leg. We waited together for an ambulance (after I politely declined his offer to call an Uber or borrow his roommate’s moped). He was confused but courteous, and, above all else, he was calm. In a cloud of delirium, I thanked him, vaguely remember saying goodbye, and never saw the man who saved my life again.

Six years later, I often think of how fortunate I was to be able to catch a stranger’s attention, and that the person I asked was willing to stop and offer me help. There could have been an incredible amount of barriers: timing, language, location, fear. So many people are affected by severe and deathly allergies, and although they may be equipped with the knowledge and tools to save themselves, the awareness, patience, and initiative of strangers to support them in that process can be extremely valuable. Even if you feel like you may not know what to do, you can always ask how you can help. As was my case, you could even save a life.