12 minute read

Advances

Advances in our understanding of allergic reactions have led to exciting discoveries and new treatments. With earlier and better treatments, we may begin to dampen the impact of allergies on public health. However, as with all new treatments and information, we must consider the safety and larger public health impact of new discoveries and treatments. Below, we have highlighted a few of the many exciting advances as well as some of the potential public health implications.

Allergy Research in the News

Advertisement

What is Eosinophilic Esophagitis?

You may be familiar with the burning sensation associated with gastric acid reflux, commonly known as heartburn. As acid backs up into the esophagus (your food pipe) from the stomach, it causes inflammation and irritation, or esophagitis. This clinical condition may be common, but its lesser known cousin, eosinophilic esophagitis (EE), first described in the mid-1990s, is starting to gain press [1].

Eosinophilic esophagitis has little to do with gastric acid and is, instead, a reaction to commonly ingested allergenic foods. While this is not a classic anaphylactic-type reaction, it is a specific food-related reaction akin to an allergy. Those living with EE commonly experience food getting “stuck” in their chest and learn to eat small bites and drink excess water to “wash food down.” On the cellular level, tissue biopsies of these patients’ esophagi display an excess number of eosinophils (a specialized immune cell). The current proposed mechanism of disease suggests that food allergens trigger specific IgE independent immune reactions in the esophagus which result in recruitment of eosinophils to the esophagus wall (for more information on IgE dependent allergies, see the article “What is an Allergy?”). Continued inflammation and immune activation in the esophagus leads to chronic inflammation and a breakdown in the esophagus wall barrier leading to the symptoms described above [1].

Interestingly, these patients’ symptoms improve with specialized diets. When individuals eliminated the six most commonly allergenic foods (wheat, milk, soy, nuts, eggs, and seafood) from their diet, a large number of patients felt better, and their biopsies contain fewer eosinophils. If the patients resume eating trigger foods, however, they will relapse [1]. Approximately 56 out of 100,000 U.S. citizens are currently living with EE [2]. Some theorize that a change in our environmental exposures - cleaner environments, less population crowding, and more C-sections - have led to an increase in prevalence [1]. That said, it is unclear if the true prevalence of EE is rising or if we are now more equipped to recognize the condition thus more people are being diagnosed. Whatever the root cause may be, EE is a newly-described entity rooted in the concept of allergic reactions with a unique biochemical mechanism.

Illustration by Jennie Chen

References [1] Noel, Richard J., Philip E. Putnam, and Marc E. Rothenberg. "Eosinophilic esophagitis." New England Journal of Medicine351, no. 9 (2004): 940-941. [2] Dellon, Evan S., Elizabeth T. Jensen, Christopher F. Martin, Nicholas J. Shaheen, and Michael D. Kappelman. "Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in the United States." Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 12, no. 4 (2014): 589-596.

Sleep and Allergies

Is your nose keeping you up at night? It may seem obvious, but when you’re dealing with allergies it can be hard to get a good night’s rest. Allergic rhinitis, better known as “hay fever,” is a major culprit. Individuals with hay fever often struggle to breathe through their nose when their symptoms are acting up, and that’s frequently just when the sun has gone down and people are getting ready for bed. Add in the challenge of keeping the body’s airways open while lying down, and you lose quality sleep. Individuals with allergies may experience snoring, sleep apnea, and even difficulty using the machines that help with sleep apnea. Researchers found that the worse an individual’s hay fever symptoms, the harder it was to get quality sleep. Some studies also noted that treatments dedicated to fixing allergy, sinus, and nasal issues don’t always improve sleep quality. However, there is still hope! Researchers recommend medically or surgically reducing obstructions in the nose to find sound sleep and ultimately achieve a better quality of life.

Artwork by Morgan Marshall

About the Artist

Morgan Marshall is a Chicago-born artist who has dabbled in many different medias of illustrations and visualization. She obtained her Bachelor of Science from Lake Forest College in 2016. After graduating, Morgan worked at Northwestern Medicine as a research technologist and mouse colony manager for two years. In 2018, she was accepted in various Master of Science programs for Medical Illustrations, for a prospective graduation date of 2020. She is currently completing her Master of Science in Biomedical Visualization at the University of Illinois at Chicago, under rigorous training.

References [1] Kent, D. T., & Soose, R. J. (2014). Environmental Factors That Can Affect Sleep and Breathing. Clinics in Chest Medicine, 35(3), 589–601. doi: 10.1016/j. ccm.2014.06.013 Accessed from https:// www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/ pii/S0272523114000513

Allergies and C-Sections

Could the reason why you can’t eat shellfish be linked to how you came into the world? To find some answers, researchers investigated the association between different types of birth and the development of wheeze and allergies. Previously, scientists hypothesized that children born via C-section missed receiving vital bacteria from their mothers’ birth canals that, if they had been born vaginally, would have served as a foundation for their microbiome. Without these protective bacteria, according to the hypothesis, the children were more likely to develop food allergies or wheeze.

To test the theory, researchers examined longitudinal data from more than 5,000 children from the Upstate KIDS cohort. They tracked kids’ allergies and wheeze and compared reports from children born via C-section, both planned and emergency, to children born vaginally. Interestingly, after controlling for several factors such as prepregnancy BMI, the researchers found that children born via emergency C-section were more likely to also develop wheeze and food allergies compared to children born vaginally. Those born via a planned C-section were not more likely to develop a food allergy. The findings seem to diverge from the theory that receiving the mother’s bacteria seeds the infant’s microbiome and protects the infant from developing allergies or wheeze. In many situations leading

to an emergency C-section, the fetal membranes may break, allowing some bacteria from the mother’s vagina to reach the fetus. This spread of bacteria would not be as common in a planned C-section. If the proposed hypothesis was correct, children born through emergency C-sections should be less likely to develop allergies or wheeze, given that they would be more likely to receive some of their mothers’ bacteria compared to those born through planned C-sections. The researchers suggested that the findings may disagree with the theory because the data could include incorrectly labeled emergency or planned C-sections and because the study included twins— which are typically delivered via planned C-section. Another important finding from this study: breastfeeding mediated the association between emergency C-section delivery and wheeze. So, regardless of how you were born, whether or not your mother breastfed you may play an important role in whether you can safely eat that plate of shellfish or not.

References [1] Adeyeye, T. E., Yeung, E. H., Mclain, A. C., Lin, S., Lawrence, D. A., & Bell, E. M. (2018). Wheeze and Food Allergies in Children Born via Cesarean Delivery. American Journal of Epidemiology, 188(2), 355–362. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy257. Accessed from: https://academic.oup.com/ aje/article/188/2/355/5210258?casa_ token=_DX7VihLu7YAAAAA:gbyEoNFPdOCXvImhSV-6O_ T3P1vbNcGvY_Fuj2eVDp8J3u5pIOgcufwXNlSv731Wh_aY1pF0edew

Advances in Allergy Treatment

Summarizing Popular Media

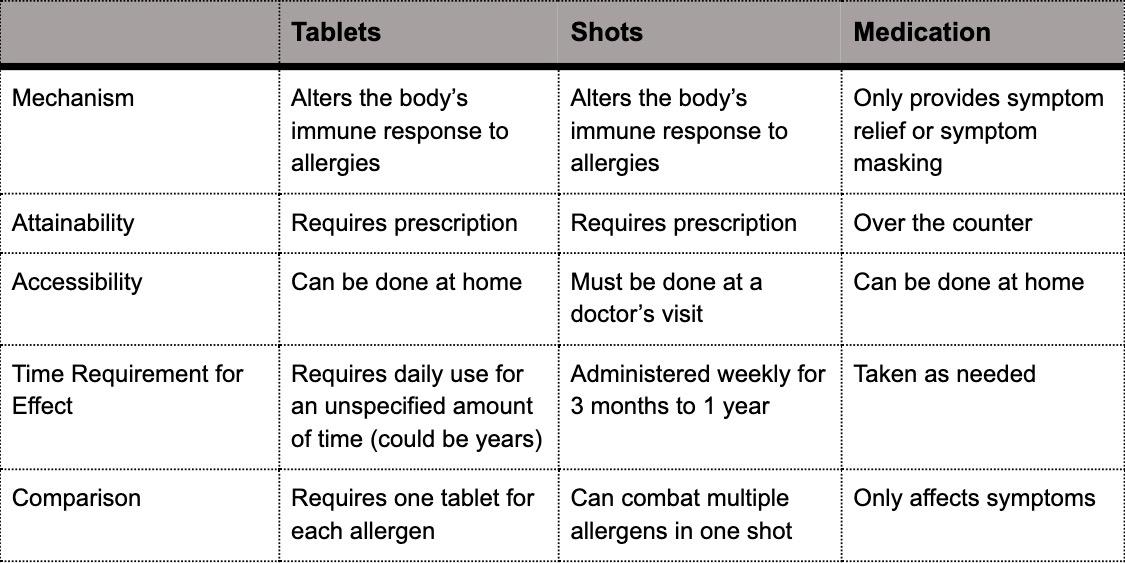

Will new immunotherapy tablets fight off allergies? More than 50 million people in the United States suffer from allergies making them the sixth leading cause of chronic illness in the country. There are two traditional allergy treatment options: medication to reduce or block symptoms, or immunotherapy to change the body’s immune response to an allergen. Immunotherapy allergy treatment is conducted through shots that occur during scheduled visits to a doctor’s office, typically once a week for up to 12 months. These shots alter the body’s immune response by providing increasing doses of a specific allergen to build up immunotolerance to that allergen.

Now, a new form of allergy immunotherapy has emerged in the form of a tablet that allergy victims can take at home. The tablets are seen as a breakthrough treatment that can change the body’s response to allergens without a weekly visit to the doctor. While the at-home availability of allergy tablets offers increased convenience, the tablets require strict adherence to a prescribed dosage plan which could include daily use for a number of years. If the dosage schedule is not properly followed, a visit to a physician is required to reset the schedule. An exact timeline for how long an individual would need to continue allergy tablet treatment to receive desired effects has yet to be established. While safe for most individuals to use from home, allergy tablets are not safe for home-use by those with severe asthma. Unlike allergy shots that can be used to combat multiple allergens simultaneously, each allergy tablet is only capable of combating one allergen at a time. To affect the body’s response to multiple allergens, multiple allergy tablets are required. Accompanying table is shown below...

References [1] Thorbecke, Catherine. “What to know about the new immunotherapy allergy tablets treatment.” Good Morning America, Navjot Sobti (ABC News Medical Unit). April 11, 2019. Retrieved from https:// www.goodmorningamerica.com/wellness/ story/immunotherapy-allergy-tabletstreatment-62315324 [2] “Allergy Tablets (Sublingual Immunotherapy).” American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. December 28, 2017. Retrieved from https://acaai. org/allergies/allergy-treatment/sublingualimmunotherapy-slit/allergy-tabletssublingual-immunotherapy

American Academy of Pediatrics Endorses Early Introduction to Peanuts

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) released research suggesting early introduction to peanuts may reduce an infant’s risk of developing a peanut allergy. In its 2019 clinical report communicating updates of infant and child atopic disease prevention, the AAP details infant safe methods of introducing peanuts to high risk children 4 months or older. However, the AAP also cautions that the data for early introduction to eggs remains ambiguous. The report also reaffirms the lack of evidence for delaying the introduction of common allergenic foods to prevent atopic diseases such as food allergies.

The 2019 report further addresses other maternal and early infant dietary strategies for preventing atopic diseases such as asthma, dermatitis, and food allergies in infants and children. Of note, the report reinforces the lack of evidence to suggest prenatal and lactation period maternal dietary restriction or any breastfeeding duration prevents or delays atopic disease, including food allergies. Additionally, the AAP rescinds the position that hydrolyzed formulas prevent atopic disease in infants fed formula for 3 to 4 months, indicating that research in the years since the previous 2008 report shows no compelling evidence of atopic disease prevention even in high risk infants.

References [1] Greer, F. R., Sicherer, S. H., & Burks, A. W. (2008). Effects of Early Nutritional Interventions on the Development of Atopic Disease in Infants and Children: The Role of Maternal Dietary Restriction, Breastfeeding, Timing of Introduction of Complementary Foods, and Hydrolyzed Formulas. Pediatrics, 121(1), 183–191. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007- 3022. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/pubmed/30886111

OIT for Peanut Allergies - A Cost-Benefit Decision

Peanut allergy is one of the most common food allergies, affecting a seemingly increasing number of children worldwide [1]. Subcutaneous immunotherapy, colloquially known as allergy shots, used to manage inhaled allergen and insect sting sensitivities are unavailable for food allergies. Traditionally, those suffering from peanut allergies avoid contact with peanuts, and in more recent years, carry auto-injector epinephrine in case of emergencies. These precautions are effective when peanut allergy sufferers and their caregivers are strict in monitoring and preventing potential peanut exposure. With this vigilance comes daily stress and unease of an accidental exposure. Especially when the peanut allergy sufferer is a small child, caregivers can feel helpless and as though this “avoid and react when necessary” method of managing the peanut allergy is analogous to “doing nothing” and simply waiting for an anaphylactic reaction to occur.

Oral immunotherapy (OIT) is an active form of food allergy therapy which has received growing attention and investigation over the past decade. OIT aims to desensitize the immune system with small and increasing doses of the allergen in question until the subject can tolerate low dose exposure to the allergen. The concept is familiar: similar to allergy shots, expose the immune system to the allergen in a controlled environment so as to ease the immune system into an attenuated response to the allergen. This desensitization requires daily maintenance doses of the allergen and is not an all out cure for peanut allergy. Patients who successfully complete the build up phase of OIT, that is increasing doses until a benchmark “accidental exposure” threshold is tolerated, are still affected by large exposures to peanuts. The effect is simply moderated to be manageable at low dose with the tools peanut allergy sufferers are already familiar: albuterol, diphenhydramine, and epinephrine [2].

OIT has shown to be effective in achieving the desired peanut desensitization in clinical trials over the past decade, with OIT participants 12.42 times more likely to pass a food challenge, designed to mock an out-of-clinic accidental exposure, without anaphylactic incident [3]. However, those who participated in OIT were at a 3.12 times greater risk to experience an anaphylactic reaction than those who avoided peanuts altogether. Additionally, evidence of an increase in quality of life for those participating in OIT was lacking [3]

With the potential FDA approval of Aimmune Therapeutic “peanut capsules” arriving in 2020, OIT for peanut allergy may garner even more attention [4]. Physicians and insurance companies largely considered OIT to be investigational and not medically necessary for peanut allergy [5]. However, these peanut capsules have the potential to make OIT at home easier and an FDA approval may give credence to the therapy. As OIT becomes more familiar among the community of peanut allergy sufferers, individuals and their physicians will have to weigh the risks and benefits in attemptingOIT.

References [1] Prescott, S. L., Pawankar, R., Allen, K. J., Campbell, D. E., Sinn, J., Fiocchi, A., … Lee, B. W. (2013). A global survey of changing patterns of food allergy burden in children. The World Allergy Organization journal, 6(1), 21. doi:10.1186/1939-4551-6-21 [2] Jones, S. M., Pons, L., Roberts, J. L., Scurlock, A. M., Perry, T. T., Kulis, M., … Burks, A. W. (2009). Clinical efficacy and immune regulation with peanut oral immunotherapy. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology, 124(2), 292–300.e3097. doi:10.1016/j. jaci.2009.05.022 [3] Chu, D., Wood, R., French, S., Fiocchi, A., Jordana, M., Waserman, S., . . . Schünemann, H. (2019). Oral immunotherapy for peanut allergy (PACE): A systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacyandsafety. The Lancet, 393(10187), 2222-2232. [4] Aimmune Therapeutics to Present AR101, OIT and Peanut Allergy Data at 2019 AAAAI Annual Meeting. (2019, February 4). Retrieved from http://ir.aimmune.com/news-releases/news-releasedetails/aimmune-therapeutics-present-ar101-oit-and-peanut-allergydata. [5] Landhuis, E., Roberts, J., & Roberts, J. (2019, September 30). Why Parents Are Turning to a Controversial Treatment for Food Allergies. Retrieved September 9, 2019, from https://undark. org/2019/08/05/oral-immunotherapy-food-allergies/.