NUBIANMESSAGE

Hey, hey, hey, Hello and Happy Black History Month!

We wrote about everything from historical editorials to fashion opinions to structural racism. Whether you celebrate Black History Month by uplifting Black voices, educating yourself about Black history or by simply relaxing: we have something for you.

In our playlist and media reviews we highlight Black musicians, authors and more. Stop by our photo spreads to see our staff capture Black joy and creativity . And don’t forget the back cover and its beautiful illustration.

I hope you enjoy reading La Vie en Noir.

With love, -Jaz

4 BLACK WRITERS THROUGHOUT HISTORY

A Look at Important Black Authors

10 TO THE BALLROOM

Going over the importance of ball culture

12 BLACK HISTORY MONTH EDITORIAL How Nubian is embracing Black History Month

15 A LOOK AT AFRICAN PROVERBS Translation and meaning. Do you know the difference?

The Sentinel of the African-American Community at N.C. State Since 1992.

314 Witherspoon Student Center, NCSU Campus Box 7318, Raleigh, NC 27695 office 919-515-1468 advertising 919-515-2411 online thenubianmessage.com

Editor-in-Chief Managing Editor

Jaz Bryant nubian-editor@ncsu.edu

Ugonna Ezuma-Igwe nubian-managingeditor@ncsu.edu

Social Media

Alianna Kendell-Brooks

Milan Hall

Copy Editor

Milan Hall

Jeanine Ikekhua

Jo Miller

CoMM. Lead Layout designers

Isaac Davis Ugonna Ezuma-Igwe

Abigal Harris

Milan Hall

Staff writers

Austin Modlin

Nadia Hargett

Jeanine Ikekhua

Micah Oliphant

Eleanor Saunders

Only with the permission of our elders do we proudly produce each edition of Nubian Message:

Dr. Yosef ben-Yochannan, Dr. John Henrik Clark, Dr. Leonard Jeffries, The Black Panther Party, Mumia A. Jamal, Geronimo Pratt, Tony Williamson, Dr. Lawrence Clark, Dr. Augustus McIver Witherspoon, Dr. Wandra P. Hill, Mr. Kyran Anderson, Dr. Lathan Turner, Dr. M. Iyailu Moses, Dokta Toni Thorpe and all those who accompany us as we are still on the journey to true consciousness.

“Never be limited by other people’s imaginations.”- Dr. Mae

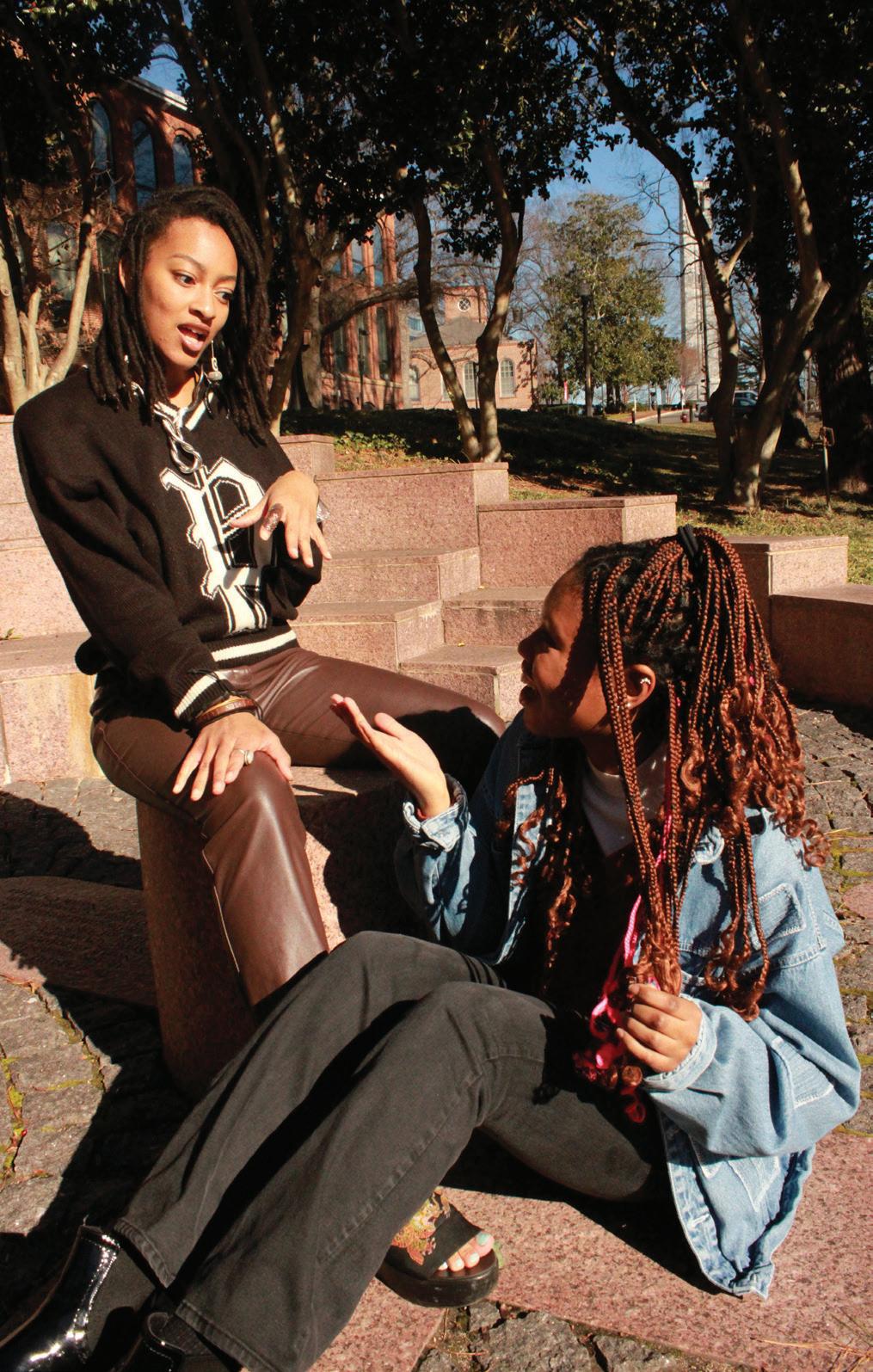

Johnsoncover photo BY micah oliphant / Photo Corespondent On Saturday. Feb. 18, Nubian Message staff had a Black Joy themed photoshoot.

Generational wealth has eluded the Black community for decades. Centuries of enslavement, prejudice and consequent trauma have largely kept Black families from experiencing the same comforts that the average American family enjoys. According to the Federal Reserve Board of Consumer Finances, the median wealth of Black households in the United States is $24,100, compared to the staggering $188,200 for white households. The reparations effort will not fully close the racial wealth gap, but many hope it will at least help the younger generation.

In hopes of closing the racial disparity, Governor Gavin Newsom of California implemented a Reparations Task Force of nine members in 2020. Five of these members were handpicked by the Governor, two by the President pro-tempore of the Senate and two by the Speaker of the Assembly. This Task Force is to produce a report for lawmakers on their recommendations for state-level reparations. These recommendations must be agreed upon by Sacramento lawmakers to be written into state legislation.

California is historically known for gaining its wealth through the Gold Rush in the late 1840s. White settlers brought enslaved African Americans to work in the gold mines as well as performing housework, farmwork and other hard labor, mostly for free. Decades later, Black Californians were again taken advantage of by the unfair redlining of the largest Californian cities, leaving them with little to no political power during the 1950s and ‘60s. California (and all other states) owes its Black residents for its present wealth and power.

The job of the Reparations Task Force is to propose recommendations to effectively compensate Black residents in a way that will satisfy Californian lawmakers. About 2.5 million Californians identify as Black or African American, and those who are descendants of enslaved African Americans or of a “free Black person living in the United States prior to the end of the 19th century” will be eligible for reparations. There's a possibility that the eligibility requirement is worded in a way that would allow white descendants with ancestors who fit this description to be eligible for reparations meant for Black residents. Conversations are being held about how to best distribute compensation for those that are eligible. Many have proposed to distribute compensation through cash payments, tuition and housing grants. It is possible to distribute

compensation between five areas: property seizures, Black business and healthcare, housing accommodations and unfair mass incarcerations. The price tag of this proposal could reach hundreds of billions of dollars, which is a major cause of opposition among many Californian taxpayers.

The talks of reparations are not likely to eliminate the racial wealth gap completely, though it is a small step in reaching racial equity in the United States if other state and federal legislations become motivated to propose large-scale reparations. By no means would this be the first time reparations have been considered legislatively in the United States. In recent years, $10 million in reparations have been distributed in the form of housing grants in Evanston, Illinois, a suburb in Chicago. In local news, Asheville, North Carolina, has also proposed $2.1 million in reparations.

The destruction of Black communities in California has been a big issue since the first settlement of slave owners in the West especially during the 1950s to 1970s redlining era. A great example is the 1960s destruction of Russell City, California, a thriving music scene where famous musicians such as Etta James and Ray Charles would come to play for the Black community. Residents were

forcefully moved out of their homes to make space for an industrial park. The displacement of Black families due to gentrification is prevalent in most major American cities; and within cities, poverty plagues Black communities in the forms of food deserts and mass incarcerations, among other things.

Many Black leaders and activists have voiced their opinions on the implementation of reparations in the United States. The displacement and stolen opportunities of acquiring wealth has empowered many Black Americans to seek reparations for what they were generationally robbed of. This proposal will hopefully fan the demands of addressing racial inequity across the nation.

Rebecca HernÁndez CorrespondentOne genre in American music, rock ‘n’ roll, is considered one of, if not, the most influential 20th century genre in the United States. When talking about these influential artists we hear names such as The Rolling Stones, Guns N Roses, David Bowie, Queen, Led Zeppelin – but rarely do we ever hear of the ones who built and catapulted the genre into what it is today.

Rock music, originally called “rock ‘n’ roll,” originates from rhythm and blues, as well as using riffs from the electric guitar prevalent in country music, the heavy and powerful vocals. Originating in the Southern United States, rock became a fusion of multiple genres. Black artists, such as Sister Rosetta Thorpe and Big Mama Thorten, blended the two genres together along with gospel to create the foundation for what we know as rock today. Chuck Berry, nicknamed the forefather of rock, may not have been behind as much of the creation of the genre as Thorpe, but he developed the “attitude” part of being a rockstar. Both Thorpe and Berry had heavy usage of electric guitar and elements of storytelling in their songs, two things that are distinct and paramount to rock music.

Although legends in creating the genre, neither of the two are remembered as well as their white counterparts. White audiences paid no attention until the likes of Elvis Presley, the so-called “King of rock and roll,” emerged. Many of Presely’s songs are “inspired” by Thorpe and other artists. And that famous Elvis personality, well, that was also very “inspired” by Berry. Though Elvis was the first artist in the genre to take such heavy “inspirations” from Black artists, he would not be the last.

In the 1960s, rock began to take on the sound that we know and love today. All of this is thanks to the legendary Jimi Hendrix, an experimental guitarist who focused mostly on psychedelic rock. Hendrix’s rendition of the star spangled banner at Woodstock is probably his most notable performance ever. Hendrix was known for his unique sound and spontaneity, as he never played any of his songs the same, because he never learned how to read music.

Hendrix started this trend, within the rock scene, of creating a distinctive

new sound with each performance. Hands-down Hendrix is one of, if not the most talented guitarist of all time. He took inspiration from Berry and Thorpe, creating those early rock sounds and completely changed them forever.

We heard the build up of rock in the 1950s, the classic and experimental sound of the 1960s and 1970s, the 1980s was the introduction of some of the most famous rockstars of all time — Tina and Ike Turner, Lenny Kravitz, Prince and Rick James among others. What sets each and everyone of this new generation of rockers apart from previous generations is the distinct sound that each of them have, whilst also staying true to their rock roots.

The 1990s saw a renaissance-like era for rock as a whole. Though it had never gone away, there was a large return to the classic rock of the 1970s, as well as the hard rock movement. This movement like all other subgenres of rock was started by Black artists – Living Colour, Fishbone and 24-7 Spyz to name a few. Hard rock, unlike other subgenres, focused mostly on vocals as the majority of these bands had frontmen with very powerful voices. This stemmed from Big Mama Thorten, who originally gave rock its voice back in the 1950s.

Many argue that rock died in the 21st century. Others say that it's still alive and well, pointing to bands such as Green Day, Red Hot Chilli Peppers and Greta Van Fleet. All white groups/artists. Greta Van Fleet has been receiving praise especially for bringing back the classic rock sound, but not nearly as many have given this same praise to Brittany Howard and her work towards bringing back blues, the original original rock sound.

As we see a resurgence of more classic and original rock sounds, we are also once again witnessing the emergence of new sound. Artists and bands, like NoMBe and BLACKSTARKIDS, have been playing around with alternative and indie sounds within rock music.

Rock is one of the most American genres of music to exist. Something that’s exemplified with the majority of these huge rockstars being American and all, but it still has a largely white audience despite its Black roots. Without these artists, we never would have the insane range that is rock music.

“ During the ‘60s, the residents were forcefully moved out of their homes to make space for an industrial park. ”

Rice is a staple part of Black people's diets, including single-pot tomato-based dishes Jollof Rice and Jambalaya. We can trace these dishes' similarities back to slavery. Because rice was not native to the Americas, colonists had no idea how to cultivate and maintain it. Given their vast expertise in rice farming, colonists deliberately abducted Africans from the "West African Rice Coast." "West African Rice Coast" refers to the West African region from the lower Casamance River in present-day Senegal to Sierra Leone. They carried West African cuisine with them and with time, they evolved.

Àkàrà. Kosai. Acarajé. All of these are names for a fritter made from fried beans or cowpeas. Several variations of these fritters can be found throughout Africa, the Caribbean and Brazil. In Nigeria, Akara is made from peeled black-eyed peas, typically eaten with bread or akamu ogi. While in Brazil, Acarajé is a stuffed fritter made from a blend of black-eyed peas stuffed with fried beef, mutton, dried shrimp, pigweed, fufu osun sauce or coconut.

The name Cola is derived from kola nuts, seeds of Cola trees in the tropical rainforests of Africa. Cola originally sourced caffeine from the kola nut. The introduction of kola nut to the Americas can be traced back to its use during the slave trade. As Europeans explored Africa they found that Africans used kola nuts to relieve thirst, improve the taste of water by chewing on it, strengthen the stomach and combat liver disease. Slavers used this knowledge on slave ships to enhance the taste of water, as enslaved Africans were given poor-quality water.

Okra is a vegetable that appears throughout Diasporic foods. Okra is derived from the Igbo word "ókùrù" Through the years, the word was modified and eventually became okra. Okra made its way to the Americas by way of enslaved Africans. In North America, Okra is seen in Gumbo, a popular soup that originated in Louisiana. Okra is used as a thickener in gumbo soup to get its notable thick, almost viscous consistency. In Bahia, Brazil, okra is known as quiabo and is used to prepare caruru, a dish of cultural and religious importance.

Diaspora wars are counterproductive cross-cultural arguments amongst those in the African diaspora where they express their differences. While there is nothing wrong with having cross-cultural discussions, these conversations have become a way to spread the anti-Black ideologies that many have sadly internalized. The Black diaspora spans six continents and despite all of our differences, we all have a history of colonial oppression. This is shown through similarities in music, food, dances and traditions preserved despite the disconnect from Africa.

Throughout history, art has been used as a form of resistance and a symbol of hope. In Black history, literature and poetry have been utilized by writers to illustrate their thoughts, form identities and promote unity throughout the Black community. Literature and poetry also have provided Black people with an escape from their everyday struggles.

Writers sometimes go overlooked when examining Black history. We at Nubian wanted to take the time to highlight a few iconic Black writers.

in which she criticizes the students of Cambridge University for protesting being served stale butter when people like her could only dream of having an education. Another is “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral” a collection of 39 poems that were published in America and Great Britain. The collection received praise from readers and critics and she was offered the honor of being presented to King George III of England, however, she was unable to attend.

Phillis Wheatley’s work had heavy religious themes. The intent of the language she used is debated today as people question if she was using religion in her poems to represent slavery and the treatment of Black people. One thing however is for certain, Wheatley broke many glass ceilings.

writing often explored the psychological effects of racism on the oppressed and the oppressor. His writing style was often praised for how observant yet personal it was. Baldwin's novels and plays take a realistic yet exploratory approach to racism and human nature. His novel “Go Tell It on the Mountain'' represents this aspect of his writing well. The novel centers around the 14 year old John Grimes and his relationship with his family, his identity and his religion.

Despite being enslaved, Philis Wheatly was one of the most prolific poets pre-19th century. She was the first African American to publish her poetry internationally, gaining acclaim in England and New England. Upper class Bostonians would even invite her to come read her poetry for them.

Wheatley was taught how to read and write by Mary Wheatley, the daughter of those who enslaved her. Wheatley went on to study astronomy, geography, history and British literature. She wrote her first poem “On Being Brought from Africa to America” at age 13. Wheatley’s work was an example of how Black people could be intelligent and creative.

Some of Wheatley’s most famous works are “To the University of Cambridge”

James Baldwin was a novelist, essayist and playwright. Baldwin’s works focused on race and would have themes of religion and sexuality. Many of his works drew from his own experience as a gay man who grew up in the Church. A few years after graduating from high school, Baldwin went to live in Paris for eight years. While in Paris, Baldwin wrote “Giovanni's Room” (1956) a novel about an American man living in Paris struggling with his sexuality.

Once Baldwin returned to America in 1957, his fame as a writer grew alongside the civil rights movement. Baldwin’s

Zora Neale Hurston was a writer and folklorist during the Harlem Renaissance. Hurston attended Howard University from 1921 to 1924. She attended Barnard College from 1925 to 1928, studying anthropology. After graduating from Barnard she pursued graduate studies in anthropology at Columbia University. Hurston was heavily interested in Folklore which can be seen in many of her works. She published her study of folklore “Mules and Men” in 1936. Hurston's most popular work is “Their Eyes Were Watching God” (1937) a novel about the biracial Janie Crawford and her somewhat tragic story of trying to find love. Although known and respected, after her death she was mostly forgotten. Houston's fame came years after her death when writer Alice Walker wrote the essay

Octiva Butler is known for her works and contributions to the science fiction genre. Her works combined science, mysticism and African American spiritualism. Butler was the first Black woman science fiction writer to gain national recognition and the only writer of her genre to receive a MacArthur Fellowship. She also won two each of the Nebula and Hugo awards, two awards very prestigious in the science fiction community.

Butler was the victim of cruelty at school and in her home life all she knew was working, for her, writing was an escape. Butler’s works would explore the “what-if” questions and present the reader with many moral issues. One of her most famous novels is “Kindred” (1979) in which Dana, a young black woman, is teleported between her home in 1979’s California and a pre-civil war Maryland. Another one of her famous novels is “Parable of the Sower,'' (1993) a story set in the future that follows Lauren Olamina who can feel the pain of others.

These Black writers and many others tell the story that don't get discussed in the classroom. Take the time to look into some of these writers or feel free to do your own exploration.

From the folks here at Nubian to you, Happy Black History month! One of the greatest expressions of revolution is embracing Black love and joy in every form. Take time to breathe, stroll through the park and play a game of chess.

Micah

Oliphant / CorrespondentOriginal Album

Cover

“Negro Swan,” is the fourth studio album by the band Blood Orange, led by Devonté “Dev” Hynes. It is an Alternative R&B, Neo-Soul and Experimental Jazz album that takes you through the struggles and common experiences of a Black person within majority white spaces. In songs like "Minetta Creek" and "Charcoal Baby," Hynes accurately depicts being Black in America. He even references times in his adolescence when he was attacked because of his skin tone, in other songs like "Dagenham Dream" and ‘Orlando." “Negro Swan” is easily one of the most compelling bodies of work by Hynes to date and is worth the listen.

Isaac Davis / Correspondent

Isaac Davis / Correspondent

playlist by Nubian Message Staff

Songs from some of our favorite Black Artist that motivate us.

bag lady Erykah badu ft. roy ayres movin. kiana ledÉ

Original Book Cover

"Son of the Storm" is a captivating African fantasy novel set in the bustling city of Bassa. The story follows Danso, a young scholar, on his journey of self-discovery. After discovering dangerous secrets about his city, Danso must choose between uncovering family secrets and his cushy life in Bassa. With the help of Lilong, a mysterious warrior from the Nameless Islands, Danso and his guardian, Zac, must navigate the treacherous political landscape of Bassa while coming to terms with their new lives. This engaging tale is full of adventure, mystery and magic, making it a must-read for fantasy lovers.

Jaz Bryant / Editor-in-Chief

Jaz Bryant / Editor-in-Chief

charcoal baby blood orange get munny erykah badu akaraka the cavemen.

ubi ego Otigba Agulu ft. flavour

round here (part one) tobe nwigwe

Original Book Cover

“The Naked Truth: Young, Beautiful, and (HIV) Positive,” is about the journey of a young teenage girl diagnosed with HIV in the early 2000s. The memoir starts with a tale as old as time: an older man preying on a young woman. After deciding to take their relationship to the next level, Brown, a former track and basketball athlete, finds herself lying sick in a hospital bed. This narrative displays the different ways Brown’s loved ones responded to her illness, highlighting the misinformation and stigma around HIV in the Black community. This compelling book is definitely worth the read.

Hernández / Correspondent

Hernández / Correspondent

rise solange knowles

spice girl aminÉ you gotta be des'ree feeling good nina simone protect my energy little simz

Original Album

Cover

“Bad Girls” is Donna Summer’s seventh studio album. It is a disco album with aspects of pop and takes you out for a night on the town. Summer was a disco icon throughout the 70s, closing out the even more iconic decade with this album. Unlike her previous albums, the Queen of Disco decided to move away from the glimmer of that disco dance floor and into other genres such as soul, pop and rock. Bad Girls tells a story through the perspective of a streetwalker portrayed by Summer. This came after her very public return to Christianity, further displaying the multifaceted and iconic Donna Summer.

jealousy fka twigs ft. rema

Everywhere Chloe x Halle

bmo ari lennox

Fear, lies and White supremacy. What do these words have in common? The unsolicited destruction of innocent Black families, Black businesses, Black schools, Black churches and whole Black communities. What remained from this destruction? Generational trauma, governments that purposefully underestimate the destruction and intentional undercoverage in our news and educational systems.

The destruction of Black communities was not a one-time event. Communities in Oklahoma, North Carolina, New York, Illinois, Washington, D.C., Georgia, Florida and Tennessee were all terrorized by angry, uncontrollable white mobs. Many communities were burned down, ran-off, and most importantly, killed. Angry yet?

According to CNBC, Black Wall Street in Tulsa, Oklahoma was, at one point, one of the wealthiest Black communities in the United States. All that ended in a matter of 48 hours.

Between May 31 and June 1, 1921, white residents crossed the railroad tracks that separated the prosperous Black community from the neighboring white community. What they did next was horrifying. “Thirty-five blocks were systematically looted and burned, destroying 190 businesses and leaving 10,000 people homeless.” There was over $31 million dollars in damages.

The aftermath of this massacre is almost as bad, if not worse. The two white newspapers in Tulsa, Oklahoma purposefully did not cover the tragic event for decades. Those who wanted to research the massacre lives and careers were threatened. Tulsa’s police department ordered all photographs of the massacre to be confiscated. Newspapers deemed the event as a “riot,” and blamed the Black community for it.

The massacre was kept quiet within the Black community for decades. Families were scared that if they spoke up, their lives would be destroyed all over again.

“The historical trauma is real and that trauma lingers, especially because there is no justice, no accountability and no reparation or monetary compensation,” said Alicia Odewale, an archaeologist at the University of Tulsa.

According to Duke Chronicle, the Black Wall Street in Durham, North Carolina was a “vibrant and successful variety of Black-owned businesses.” The city was nationally known for promoting entrepreneurship within the Black community. Because of its’ successes, Durham was known as the “capital of the Black middle class in America.”

The destruction of Black Wall Street in Durham, North Carolina was not as violent as the destruction of the original Black Wall Street in Tulsa, Oklahoma rather it was a calculated move. At the beginning of desegregation, Black owned businesses had difficulty competing with their white counterparts. The government took advantage of this situation.

A federal government initiative, called Urban Renewal, was set on redeveloping the “‘blighted' or ‘slum’ neighborhoods”. This resulted in the construction of the Durham Freeway 147. This highway ran right through the Black Wall Street community in Durham. It destroyed the Black business district and harmed “more than 100 Black businesses and displaced hundreds of Black families.” The area where Black Wall Street once was and now harbors hotels and apartments.

The only coup d’état on American soil, the Wilmington Massacre was prompted by exaggerated journalism and White supremacists who were afraid of “Negro domination.” Before the massacre, according to the Zinn Education Project, three out of the ten aldermen were African American. Black people were seen working in the police force, as firemen and even magistrates.

White supremacists did not like such an integrated society and sought to end it. Former Confederate Col. Alfred Waddell

gave a speech where he encouraged lynching to white supremacists as a method “to protect [the white] woman’s dearest possesion from the ravening human beast.” In response. Alex Manly, an African American and editor of Wilmington's Black newspaper, the Daily Record, wrote an article opposing the white supremacists. Manly spoke out against the lynching and the hypocrisy of the speech. He pointed out the white man describing Black men as “big burly, black brutes” when in all actuality, white men were the ones who regularly raped Black women. He added that “some relations between races were consensual.” This led to a mob of 2000 armed white men burning the Daily Record to the ground on Nov. 10, 1898.

Soon after, an altercation took place in a saloon between Black and white men that resulted in gunfire. The Wilmington Light Infantry, the White Government Union and the Red Shirts (part of the KKK) stormed into Black neighborhoods. They killed and destroyed the community.

While shots were being fired, supremacists democrats used this time to overthrow the local government. They then placed a white supremacist sympathizer in the republican alderman’s seat. Afterwards, thousands of Black citizens fled.

In 1916 and 1917, the Black Migration brought thousands of African Americans from the South to East St. Louis, Illinois. White residents and the city’s political leaders tried to stop this by “prohibiting the railroads from transporting Black people to the region.”

When these efforts failed, white residents resorted to violence. Between July 2 and July 5, 1917, 200 African Americans were “shot, hanged, beaten to death or burned alive after being driven into burning buildings.” Afterwards, 6000 African Americans fled the city, and only 20 members of the white mob went to prison for their actions.

Rosewood was a thriving Black community in Levy County, Florida. The destruction of this community started with

a very common lie of the time: a white woman accusing a Black man of assaulting her.

What resulted caused trauma in the Black generations to come. In Jan. 1923, an angry white mob stormed into the Black community and burned it to the ground. Black families lost their land and their possessions. Some hid in a nearby swamp or took refuge in the only white household in the town. Families were pushed into poverty after they lost their family wealth.

The story of the Rosewood Massacre did not surface until the 1990s. Stephen Hanlon, a lawyer, was tasked with taking on tough cases that would have gone untried for years. What he uncovered, along with the massacre, were years of generational trauma.

Black families kept what happened to them all those years ago a secret, intentionally choosing to not tell their children. But with the help of Stephen Hanlon, seventy years after the massacre, the case was brought before the Florida Legislature in 1993…and won.

The families of the victims were paid in reparations. This was the first time in American history that Black people were paid reparations for racial violence. However, the survivors did not care for the reparations. They just wanted their story and history told.

These were not the only communities that were destroyed out of fear and white supremacy. However, even after all this pain and destruction, six Black communities and families persevered.

Established 100 years after the destruction of Black Wall Street in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the New Black Wall Street Market opened in Georgia in Oct. 2021. Their mission is to “increase the size and number of minority and women-owned businesses throughout the United States and Globally.” NBWSM contains over 100 shops and restaurants where visitors can expect “family fun, entertainment, retail, gourmet grocery shopping and fine dining.” It is now a major tourist destination.

After all the killings and burnings, Black people still found a way to persevere. We will not stop until we achieve what we know we deserve.

Ballroom culture is such an important creation, and I’m not referring to the fancy dance parties with banquets and waltzing.

I’m referring to the illustrious subculture that popularized iconic dance moves, such as voguing and dipping.

Popular television shows such as “Pose,” “Legendary,” “Rupaul’s Drag Race” and major music artists featuring drag queens in their music videos are amongst the many things that have pushed the ballroom and drag scene into the spotlight. Behind all of these sparkling details, however, is a deep and rich history that emphasizes the importance of the ballroom scene and how it served as a safe haven for LGBTQ+ Black and Brown individuals. To me, ballroom culture is far more influential and historically essential than it gets credit for.

Ballroom culture dates all the way back to the late 19th century. William Dorsey Swann, one of the first people to adopt the identity of a drag queen, was also the first person in the United States to lead a queer resistance group. In fact, he led a series of drag balls in Washington, D.C. during the 1880s and 1890s, with formerly enslaved men making up most of the attending population. As a formerly enslaved man himself, Swann paved the way for LGBTQ+ individuals in the Black community to have an outlet to express themselves freely.

Ballroom truly arose during the Harlem Renaissance, specifically in response to the Black churches advocating for the expulsion of LGBTQ+ residents in New York City. Ball events back then were so diverse and vibrant that they even garnered the attention of African American poet and activist Langston Hughes, who notably wrote of his experience at the annual Hamilton Club Lodge Ball in his essay, "Spectacles of Colors.”

Hughes wrote, “It is the ball where men dress as women and women dress as men. During the height of the New Negro era and the tourist invasion of Harlem, it was fashionable for the intelligentsia and social leaders of both Harlem and the downtown area to occupy boxes at this ball and look down from above at the queerly assorted throng on the dancing floor, males in flowing gowns and feathered

headdresses and females in tuxedoes and box-back suits."

The first ball held by the Hamilton Lodge was integrated despite the presence of racial segregation in the U.S., although racism and prejudice still occurred within it. With no Black judges and a very little number of Black prize winners, it became a common belief that the judging was rigged in favor of white participants. It was even famously implied by drag icon Crystal LaBeija in the documentary “The Queen,” created by Frank Simon in 1968, that Black queens had to make themselves look white to win any prizes at drag beauty contests.

Racial tensions eventually pushed Black members of the ball community to find their own safe haven to express themselves. Crystal LaBeija, along with a fellow drag queen Lottie LaBeija, decided to do something in response to the racially oppressive drag system. So, in 1972, they established the first ballroom house and hosted their own annual event "Crystal & Lottie LaBeija presents the first annual House of Labeija Ball at Up the Downstairs Case on West 115th Street & 5th Avenue in Harlem, NY."

This formation is thought to be the “birth” of houses as it created a trend of more iconic house formations, such as

the House of Xtravaganza and the House of Ebony. Houses served and continue to serve as a place of security for Black and Brown queer people. Houses began to take on a family structure, with a “mother” or “father” acting as a mentor for their “children.”

With more and more houses on the rise, they began to compete with each other in order to outdo one another, with each competition having different categories. The most notable categories include face, body, runway and performance amongst various, more nuanced others.

Drag balls reached mainstream audiences in Jennie Livington’s award winning 1990 documentary,“Paris is Burning.” It truly offered an excellent exploration of queer culture, class and race in America, and specifically highlighted the ball culture of New York City and the communities within it. With this came the emphasis of the hardships the community faced.

Prominent members of the ballroom scene such as Venus Xtravaganza, Angie Xtravaganza, Pepper LaBeija and Willi Ninja were featured in the film. Each of them were nterviewed about issues such as the HIV/AIDS epidemic, racism, transphobia, homophobia, poverty and violence. Several interviewees expressed

they would be disowned by transphobic or homophobic parents and were left homeless, with some even having to resort to sex work to support themselves. Some said that they would shoplift just to have clothes to walk in ballrooms.

One of the prominent subjects in the film, Venus, was murdered before filming finished, suspected to have been strangled by a speculated “disgruntled customer” during a sexual exchange. Her house mother, Angie, reacted to her death on camera, making for a display of the raw, tragic reality of existing as a racial and sexual minority.

With more people knowing and understanding the struggles that the ballroom community faced, people became inspired by it, including popular celebrities such as Madonna and Beyonce. Even Beyonce’s most recent album, “Renaissance,” takes clear inspiration from ballroom culture and house music; she directly thanked the queer community for “their love and inventing the genre,” at the Grammys earlier this year.

Ballroom culture has offered so much light and love for the LGBT+ community and people of color. It has influenced so many aspects of modern popular culture, along with inspiring so many LGBT+ people today such as Laverne Cox and Billy Porter. The way it was created truly shows how minorities will rise in the face of adversity, to truly express themselves and reject conformity. Born from tragic discrimination, the ball scene is a hopeful reminder that even the most shunned individuals will always have a place to go and vogue the house down!

“ Born from tragic discrimination, the ball scene is a hopeful reminder that even the most shunned individuals will always have a place to go and vogue the house down! ”

From the poisonous lead-contaminated water supplied to residents of Flint, Michigan, to the industrial corridor dubbed “Cancer alley” in Baton Rouge, Mississippi, Black communities in the United States have been long subjected to environmental injustices.

According to a 2017 study done by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (N.A.A.C.P.) and the Clean Air Task Force, African-Americans are 75 percent more likely than other Americans to live near facilities that produce toxic waste. Furthermore, the highest rates of asthma and deaths from cardiovascular disease are found among communities of color – all of which are linked to disproportionate exposures to pollution. To fully understand the intersectionality of anti-Blackness and environmental injustice, we must recontextualize environmentalism in American society.

Environmentalism wasn’t meant for Black people. In the 1970s, environmentalism began as a political movement aimed at protecting the quality of the environment and has long been composed of predominantly middle-class white Americans. More concerned with saving the turtles, national parks and themselves, white America pays little to no attention to the environmental crises that disproportionately affect Black communities.

Then and now, Black and Brown people are seen as forms of pollution. This is apparent in historically racist practices such as redlining. The concentration of African Americans into disinvested, “redlined” neighborhoods by banks and insurers. The segregation of BIPOC communities into slums and urban housing projects is a recurring theme throughout U.S. history. So, why are Black people easily blamed and accused of being the creators of the unjust environments they endure?

We are currently witnessing first hand the gentrification of minority neighborhoods to make room for cleaner, whiter spaces. Kicked to the outskirts of their neighborhoods and the environmental movement, environmentalism has long been underscored by the oppression, extraction and pollution of marginalized life. Thus, we cannot depend on the Environmental Movement to address the

unique social and physical environments of Black life. Instead, we turn to the emergence of the Environmental Justice Movement (EJM) and Black ecology.

The EJM began in North Carolina in 1979, when the state began dumping toxic soil laced with carcinogenic chemicals in Warren County, a population that was 67 percent Black. Over the next four years, hundreds of the county’s residents and civil rights activists would be arrested for protesting the disposal of 60,000 tons of contaminated soil. Although their efforts were unsuccessful in preventing the dumping, the NAACP and other organizations took notice and began pressuring the government for environmental justice.

The EPA defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” Despite increased efforts, their so-called “fair” environmental laws have continually neglected minority environments and infrastructures. Thus we see cases such as Flint, Michigan, one of many instances where cries for environmental justice are ignored in predominantly Black “sacrifice zones.”

The Environmental Movement lacks the nuance to change the lives of those directly affected and is historically in favor of white Americans. The Environmental Justice Movement (EJM) lacks the scope to fully encapsulate the ecological concerns of Black and Brown communities.

To properly address Black environmental concerns, the EJM and the government must turn towards Black ecology and recognize the history of environmental racism in the U.S. sociologist Dr. Michael Warren Murphy defines Black ecology as “the ongoing reality of black and African diasporic vulnerability to dangerous environmental conditions.”

If climate change, pollution and toxic waste dumps predominantly affect Black communities, why is the government focused on white ecological concerns?

The lack of green spaces, urban decay and impending gentrification of Black communities must be addressed through the lens of Black ecology. Through which, environmental injustices can be understood and Black people can be liberated from polluted environments. But even with the rise of Black ecology and environmental justice, mainstream environmentalism continues to neglect marginalized life.

Vigil Abloh was born Sept. 30, 1980, in Rockford, Illinois, to Ghanaian immigrant parents. Abloh is the founder of the famous streetwear brand, Off-White, and is one of the most notable creative directors behind the Louis Vuitton Menswear Collection.

Abloh's work within the fashion industry was revolutionary. He was coined by the New York Times as a “barrier-breaking Black designer whose ascent to the heights of the traditional luxury industry changed what was possible in fashion.” He passed November 28, 2021 after silently battling with a rare terminal form of cancer, cardiac angiosarcoma.

In honor of him and Black History Month, let’s take a look at some of Abloh’s most notable projects within the industry.

Virgil Abloh and rapper/ fashion designer, Kanye West, were very close friends, meeting each other in 2002, and soon after taking the fashion industry by storm. West appointed Abloh as the creative director of Donda, West’s creative agency. Soon after, Abloh earned a Grammy nomination for his artistic direction on West’s and another rapper, Jay-Z’s, collaborated album, “Watch the Throne.” Some of Abloh’s most memorable work includes designing album covers. He did covers for “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy” and “Yeezus” by Kanye West, “Luv is Rage 2” by Lil Uzi Vert, “WZRD” by Kid Cudi and many more. You can read more about Abloh’s other covers in Complex.

In 2013, Abloh released his first brand, Pyrex. The first garments under the brand name being ‘deadstock’ Ralph Lauren plaid flannels with screen prints of the name ‘Pyrex’ on the back. They sold for $550. Abloh then went on to rebrand Pyrex and turn it into the notable, luxury, hype beast/streetwear brand we know and love today, Off-White. According to Vogue, Abloh described the meaning of the brand, Off-White, as “the gray area between black and white.”

Some of Off-White’s most notable works include their partnerships with Nike and Jordan, which produced items such as ‘The

Ten,’ ‘Jordan’ 1 and ‘Sail’ Jordan 4s. Other defining Off-White projects include the Mona Lisa Hoodie, the OffWhite Industrial Belt and the Arc'teryx x Off-White Dress. Read more about Virgil and Off-White's work at HighSnobiety.

Off-White’s signature hovering quotations were inspired by how fashion adjectives are often used within writing. “It's a place where fashion is a cultural conversation, much more than just expensive clothes” according to HighSnobiety. On Virgil’s work, 032c’s Thom Brettridge said “quotation marks are one of the many tools that Abloh uses to operate in a mode of ironic detachment. Abloh rejects the who-did-it-first mentality of previous generations in favor of the copy-paste logic of the Internet and its inhabitants. His new order is protected by a fortress of irony.”

In 2018, Abloh was appointed creative director of the Louis Vuitton Menswear Collection. Abloh is the first person of African descent to be head of a European fashion brand. Abloh’s first collection at Louis Vuitton in Spring/Summer 2019 in his newly appointed position was definitely one to remember. His collections had many odes to his predecessor Kim Jones, but also added hints of his own creative vision. There were lots of twists on how men dressed at that time and a play on men’s silhouettes, bright colors, fabrics and experimenting with repurposed accessories. You can read more about Abloh’s work throughout Louis Vuitton here.

Virgil Abloh is an icon and a huge inspiration. His creative mind, artistic vision, inspiration and outstanding work throughout the industry is compacted into a legacy that will never be forgotten. Rest in Power Virgil Abloh.

To learn more about Virgil Abloh and his work throughout his career, check out these links: Vogue, Sneaker Jagers, and Time Magazine.

'I’ve embraced Black History Month by pushing forward in my studies. I am one of the few Black Graphic Design majors in my studio class, so I make it known through my designs that I deserve to hold a place in the design community. I don’t see many Black designers, so I continue to learn and push myself in the field."

- Abigail Harris"Black History Month is always a good time to reflect not only on the historical growth of Black people worldwide but also a reminder to remember the hardships and struggles that Black people go through daily. It is both a time to celebrate Black excellency and mourn Black struggle, and as a nonBlack POC, uplift the voices of my Black peers."

- Billie Vicente"The way that I have embraced this Black History Month is through my writing. My article for this issue centered around unpacking the misrepresented history of the Black experience within the film industry."

- Leila Ganim"I embrace Black History Month every month by living as my ancestor’s wildest dreams. I take the blessings they fought so hard to provide me with and work every day to ensure they do not go to waste."

- Isaac Davis"I have embraced Black History Month by consistently seeking more knowledge about Black people and how we have developed our cultures. Instead of looking at the negative things, I’ve aimed for the positive, like how ball culture was formed, the different types of traditional meals Black people make and why we began making them. I’ve sought Black joy while also understanding our pain, and it’s helped me garner an even deeper passion for my people."

- Nadia Hargett"I’ve embraced Black History month by creating a presentation on Black and marginalized Autistic traits and their embodiment. Black neurodiversity is under-researched, under-represented and scarcely talked about in Black communities; so I want to help me, my family, friends and peers learn, uplift and destigmatize and uplift Black neurodiversity."

- jelina-Jo Miller"I have embraced Black History Month by furthering my knowledge of famous Black women in history, like Dorothy Dandridge, Josephine Baker and Ida B. Wells-Barnett."

-

Shaere DelgiudiceBy being Black.

- Milan Hall"Black History Month highlights the importance of Black culture, Black queerness, Black art, Black music and well Black History. This month, I’ve furthered my knowledge on Queer Afro-Latinx icons within my community such as Coleman Domingo, MJ Rodriguez and Ariana DeBose among others. It is important to take this month to listen to, learn from and uplift the Black voices of your community, and not just this month."

- Rebecca Hernández"I have embraced Black History Month by learning more about Black History. For instance, did you know that Garret Morgan, an African American, in 1922 invented the traffic light? Or the fact that the feminist movement gained momentum because white women were upset that black men were able to vote before them?"

- Eleanor Saunders"I allowed myself to rest and reflect. I gave myself the space to slow down. I stopped and smelled the roses. I sometimes take for granted that I am in a position to live rather than simply survive. I embraced Black History Month by remembering that fact."

-

Jaz Bryant"By embracing every part of who I am and standing proud in every aspect."

- Ugonna Ezuma-IgweI'Yari Wade, a first-year in exploratory studies and Tuccoae McDowell, a fourth-year studying computer engineering, work on their paintings while (from left to right) Zania Sanders, a first-year studying biological sciences and Richard McNeill, a third-year studying psychology, look over the others' work at the Black History Month Pass and Paint event in the Washington Sankofa Room on Friday, Feb. 17, 2023. The Black History Month Pass and Paint event had participants passing their art around for everyone to work on.

Sahmad Moore (left), a second-year studying computer engineering, laughes with I'Yari Wade (right), a first-year in exploratory studies, at the Black History Month Chat & Chew in the African American Cultural Center on Wednesday, Feb. 15, 2023. The Black History Month Chat & Chew presented multiple poems for the attendees to discuss.

‘The ocean is an alien world right here on earth that is as rich and exotic as anything that I could imagine myself.’

James CameronVersacePrew/StaffPhotographer

The Disney film "Song of the South,” had its theatrical release in 1946, during a renaissance in animation creation. In March, 1948, the 20th Academy Awards gave the actor James Baskett, who played Uncle Remus, an Oscar for his performance in “Song of the South.” The film won numerous Oscars and awards, due to its groundbreaking use of new animation techniques. Flash forward to 1986, the film was rereleased, reviving its faded popularity. This rerelease led to the idea of constructing a ride based on the film's animated sequence. The ride first opened in the original Disneyland park located in Orlando, Florida. Splash Mountain officially cut the grand-opening ribbon on July 17, 1989. By 1992, two more Splash Mountain rides opened in Walt Disneyland and Tokyo Disneyland.

Since 2020 there has been a plan to revamp Disney’s historically racist popular ride known as Splash Mountain. In the summer of that year, a petition went around through the platform Change.org. The petition called upon the leaders of Disney to address the ignorance of maintaining the theme of the previous ride. By 2022 there were many rumors in circulation describing future changes to the park, but no formal plans were set in stone. Then in an interview on "LIVE with Kelly and Ryan Show," Anika Noni Rose, who voices Princess Tiana, confirmed the ride will be completed by 2024.

African American representation within cinema history contains numerous examples of offensive and outwardly wrong images of stereotyping. In an article titled “Toms, C**ns, Mul*ttoes, Mammies, and Bucks. An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films” the author and American film historian, Donald Bogle, describes the top five most commonly portrayed character types. The use of these tropes laid foundations for continual distortions of the Black image in cinema.

To preface the latter portion of the article Bogle explains the history of misrepresentation within Black cinema. He begins with unpacking the fact that many times in its earliest renditions the actors themselves weren’t even Black. They were normally white males in blackface, giving their interpretations of deeply socialized

racial stereotypes of the time.

This led to the first character type known as Uncle Tom. “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” directed by Edwin S. Porter, was a twelve-minute long motion picture film depicting a middle-aged Black man, however the actor was clearly a middle-aged burly white man in blackface. Poorly executed, Bogle explains “None of the types was meant to do great harm, although at various times individual ones did. All were merely film reproductions of Black stereotypes that had existed since the days of slavery and were already popularized in American life and arts.” and continues “The movies, which catered to public tastes, borrowed profusely from all the other popular art forms. Whenever dealing with Black characters, they simply adapted the old familiar stereotypes, often further distorting them.”

Reflecting an internalized racism that becomes visible and tangible in the media created during that period. The function of the Uncle Tom figure in cinema was to limit autonomy and promote subservience. Bogel describes “Always as toms are chased, harassed, hounded, flogged, enslaved, and insulted, they keep the faith, n'er turn against their white massas, and remain hearty, submissive, stoic, generous, selfless, and oh-so-very kind. Thus they endear themselves to white audiences and emerge as heroes of sorts.”

The Uncle Tom character codifies a passive personality in the face of institutionally organized racism. After the creation of the Uncle Tom figure came the

c**n figure. This is normally a character designed for comedic relief. However, the comedy often circulates around the complexion of the character, rather than any display of intellectual humor. The character type of the c**n served as a foil to Uncle Tom; the unrealized punching bag of the white audiences across the United States.

Bogle explains the popularization of two distinct versions of the c**n figure. The first figure was a pickan*nny. Bogel describes this character type as “a harmless, little screwball-creation whose eyes popped, whose hair stood on end with the least excitement, and whose antics were pleasant and diverting,” using descriptions that would fit other subhuman species of beings. The drastic dramatization of the physicalities again emphasize the racial othering by white producers and consumers.

The second c**n figure was Uncle Remus. Bogel describes this figure as “Harmless and congenial, he is a first cousin to the tom, yet he distinguishes himself by his quaint, naïve, and comic philosophiz-ing,” serving a demeaning description of the Black experience. Again, a poorly executed image that promotes African Americans as intellectually inferior to their white counterparts.

Bogel furthers, “He [the c**n figure] did not come into full flower until the 1930s and 1940s with films such as "The Green Pastures" (1936) and "Song of the South" (1946). Remus's mirth, like tom's contentment and the c**n's antics, has

always been used to indicate the Black man's satisfaction with the system and his place in it.” This represents an individual who stands for a community of people taken advantage of by an institutionalized racist system; essentially, a symbol created to prevent a sense of desire to change. The film industry lays its foundation on this tendency towards projecting white superiority over other racial groups. The creation of these character types are the manifestations of these tendencies.

As Bogel explains, “Song of the South,” was a pivotal film within African American cinematic history because it birthed the Uncle Remus trope. Evidence of racist implications come to light while examining the dynamics between the white and Black characters within the film. There is no direct statement of the time period, but a definite implication of the reconstruction period. Within the film, those presenting as Black are of the lower socioeconomic class and their white counterparts of a higher socioeconomic class. This detail of the film points to an insinuation of a masterslave relationship. The film additionally uses incredibly racist nomenclature, and presents the audience with yet another flawed trope known as the "magical minority figure."

Currently, it feels like the moment in the film where Tiana, not yet a princess, sang one of the most iconically motivational songs Disney has ever produced. In “I’m Almost There,” she belts as she sweeps the dust off the vacant remains of a forgotten popular night club. Working diligently to rebuild a new restaurant both metaphorically and literally pioneering a new dawn of representation for African Americans within cinema. Tiana’s character gives the audience a portrayal of a vivaciously young African-American woman capable of making something of herself.

Princess Tiana gives the audience a narrative that is monumentally different from her historical predecessors. As revolutionary as her character is in the representation of the Black experience, is it enough? Are we in fact almost there in equal and fair representation or are we just grazing the surface in a seemingly never ending struggle for change? Disney must proceed with caution as they continue to make content for a global audience and practice mindfulness when creating their next generation of African American representations within film.

Growing up, I was often the only kid who looked like me in any of my classes. My features were always different from most of my peers and I would get a lot of comments and questions about my hair in particular.

Every school year, I wished for another girl that looked like me to join my classes, but it rarely happened.

Outside the classroom, I hardly saw girls with my features in shows, movies or commercials. Not on book covers, billboards or the front of magazines.

So, when I went to the Scholastic Book Fair and saw the book “Purple Princess Wins The Prize” by Alyssa Crowne, I loved it instantly. My love for this book went beyond it featuring my favorite color, purple, though that was a bonus; the thing that made this book so special for me was the main character herself, a girl named Isabel. Right there, front and center on the cover, was an illustration of a girl that looked just like me. Isabel had my same complexion, big, dark eyes and big, dark curly hair. It is the only book I can remember coming across in my childhood where I saw a character vaguely similar to me inside of its pages. Even this tiny sliver of representation was immensely important to me. As I got older, thankfully, women with my features started to receive more of a spotlight.

In 2019, for example, the winners of Miss USA, Miss Teen USA, Miss America, Miss World and Miss Universe were all Black or, like myself, mixed-race women. I remember my mom telling me to look at the tv because the new Miss USA, Cheslie Kryst, had hair just like mine, something that even just a few years ago, I rarely saw.

It took me a long time to truly and completely love my features the way they are. Seeing actresses and models embrace the hair I often wished wasn't "so big" and the eye color I always wished was "more interesting" helped

me realize the beauty of my own look. If I had even half of the examples I do now growing up, it would have made a world of difference. I doubt I would've been as insecure as I was in my teenage years.

I never saw anyone that looked like an older version of me so I could never actually picture myself outside of how I looked in the present. Seeing more women who looked like me, like model Imaan Hammam, actresses Yara Shahidi and Sofia Wylie and sustainable fashion creator Jazmine Rogers, would've given me a way to see my future self. Something that, despite having an active imagination as a kid, I often found myself incapable of seeing.

The experience of not seeing myself represented in the media isn't unique to just me. PBSs’ Student Reporting Labs asked students around the country how the lack of representation in popular culture and media makes them feel. They reported that students said they needed people like themselves on the screen to have something to identify with. Also, that representation of people that look and sound like them serves as an inspiration.

The lack of Black representation in popular culture media, in particular, is especially harmful, considering studies show that Black children “consume more media” than other racial groups.

In addition, a study by the University of Michigan found that simply watching tv in general “predicted a decrease in self-esteem for all children except White boys.”

While representation has been showing some signs of improvement in recent years, most racial and ethnic groups are still heavily underrepresented when looking at media as a whole, according to a UCLA study.

It’s true that media has made strides across various sectors since I was a kid. However, there's still plenty of work left to do to ensure the confidence and reassurance I feel now is enjoyed by young women like me from the start.

I recently walked into Target and stumbled upon a book about African proverbs. Immediately, I rolled my eyes and said, "What have they done now?" My friend insisted I look at the book and see what was in it. And to my surprise, the book was even worse than I could have imagined.

"Where are these from?" This question was all I could ask as I flipped through, hoping that the answer was within the pages as I turned. My heart sank, as it was evident that they had completely removed the beauty of African proverbs. As I looked at a book filled with "African proverbs," all I could see was English. There were no indications of their language or country of origin. It became evident that they only included the proverbs' meanings rather than their translations.

Translation and meaning. Two words used interchangeably, though vastly different in their intent. Translation defined by Peter Newmark, a renowned professor of translation, as "rendering the meaning of a text into another language in the way that the author intended the text." In contrast, meaning is intended to communicate something that is not directly expressed.

A linguistic difference that these authors needed to understand. African proverbs advise and display wisdom through illustration and visualization of an idea, concept or belief for centuries. They have a rich culture and are displays of heritage. Many African proverbs still widely used in everyday speech have been passed down from generation to generation. The beauty of African proverbs is their ability to provoke thought, and guide you to an answer instead of stating what's to be discerned.

You're probably asking, "What was wrong with the book?" The book removed the reader's journey to understanding by providing them with a vision instead of allowing them to craft their own. To show what I'm describing, I analyzed two of Ìgbò proverbs. I will provide the proverb in Ìgbò, the English translation, the popular meaning and its significance.

Nwaanyi muta esi ofe mmiri mmiri, di ya amuta ipi utara áká suru ofe

Translation: If a woman learns to make soup watery, her husband will learn to press the swallow to dip and scoop the soup.

Meaning: When presented with situations/obstacles, one must be able to adapt.

Significance: Swallow is a term used in Nigeria to describe a dough-like substance that accompanies native stews and soups. You pinch it to create a dent, so when you dip it into your soup, the soup sits in the dent and then you swallow it whole. You are only able to do that if the soup has a thick viscosity. In this proverb, the wife presented her husband with an obstacle: Either he figured out how to eat the soup, or he would go hungry. Forced to think outside of the box, he figured out that if he dented the swallow more than usual, it would allow him to eat the watery soup.

Onye ji mbe n’ala ji onwe ya

Translation: He who holds the turtle on the ground, holds himself

Meaning: You’re delaying your own success by trying to hinder others

Significance: For Ìgbò people, folktales are a revered practice used to educate and pass on the wisdom of their elders to younger generations. Throughout those folktales, turtles make a continuous appearance. In these tales, turtles are depicted as wise and cunning creatures. In this proverb, the use of a turtle was intentional. Since turtles are seen as wise and the person was holding the turtle down, it allowed the reader to literally envision themselves holding down their own wisdom.

While the Target book's authors may have had good intentions, their actions were quite harmful. These authors eradicated each of those proverbs' histories through their actions. Exemplifying that when speaking about different cultures, it is important not to tell their story for your enjoyment but instead tell the story of their reality.

There is an Ìgbò adage that says, "Onye na-amaghị ihe onwere, ọ gaghị ama uru o bara." Translating to he who does not know what he has, does not know its value or worth. I encourage you to find your own meaning in that story.

Graphic by Abby Harris

Graphic by Abby Harris