Volume 5, No. 1 Spring 2007

Okaloosa-Walton College

Niceville, Florida

Blackwater Review aims to encourage student writing, student art, and intellectual and creative life at Okaloosa-Walton College by providing a showcase for meritorious work. The BWR is published annually at Okaloosa-Walton College and is funded by the college.

Editors:

Julie Nichols, Fiction

Amy Riddell, Poetry

Art Director: Benjamin Gillham

Editorial Advisory Board:

Jack Gill, Vickie Hunt, Delores Merrill, Charles Myers, Deidre Price

Art Advisory Board:

J.B. Cobbs, Benjamin Gillham, Stephen Phillips

Lyn Rackley, Karen Valdes, Ann Waters

Graphic Design and Photography: Candice Joslin, James Melvin

All selections published in this issue are the work of students; they do not necessarily reflect the views of members of the administration, faculty, staff, District Board of Trustees, or Foundation Board of Okaloosa-Walton College.

©2007 Okaloosa-Walton College. All rights are owned by the authors of the selections

Front Cover Photograph: Window, Michael McLeish

The editors and staff extend their sincere appreciation to Dr. James R. Richburg, President, and Dr. Jill White, Senior Vice President, Okaloosa-Walton College, for their support of the Blackwater Review.

We are also grateful to Frederic LaRoche, sponsor of the James and Christian LaRoche Distinguished Endowed Teaching Chair in Poetry and Literature, which funds the annual James and Christian LaRoche Memorial Poetry Contest, whose winner is included in this issue.

Sidney Speer

Clasped hands before his waist

Wrists bound by the white rim of starched sleeve

Graced by antique moonstone cufflinks, He is still as stone.

An Easter Island monument

Staring at his own likeness

Hereafter.

Mozart preludes prepare attendant hearts. A heralding of angel.

Set jaw above his shoulders

Noosed by Hermès silk, A double knot.

He is pressed to perfection.

Utility and breeding, packaged, Waiting delivery from his life Into another.

Bach fugues freeze the mother’s fears. A seducing of her precious.

His hair parted as if split

By the arrow of that vile temptress, Leaving no blood, No visible wound

But a stolen heart

And his organ of love

Dangling from Cupid’s sheath.

Handel processionals position the mourners Standing for the end of the start. The beginning of the beginning.

Speer / 1

Reid Tucker

The windows were rolled down partly to cool us off in lieu of air conditioning, partly so that I could command a dominating presence over the length of hood, and partly so that it would be loud inside the car, so loud I could pretend I didn’t hear what I wish she would say, would have to holler over at her, momentarily avert my gaze from the blacktop, and let me watch her mouth and eyes so that I could be sure what I heard was real. But she never said anything, just propped her head on her arm, and rested it in the open window while we flew past the rows of barren cotton stalks in the fields on either side. Her other hand was on the faded black vinyl of the seat beside my fist while it choked the life out of fourth gear, the speedometer held steady at 70. It was Saturday afternoon in the early autumn, and the weather was fine for driving with the windows down, despite how much I hated it.

I glanced, just a movement of the eyes, imperceptibly, over her litheness and the afternoon’s melancholy and the burning orange daylight that lingered on her neck, her opaque brown hair that curled just before her shoulders, and the white shirt she wore, the sun bathing them in molten radiance. I looked back at the road when I saw her hand start to move across the partially cracked seat cover, a sort of shudder, with the little finger reaching to pull the rest of the hand over; the nails that were never painted around me glistened a little in the light. I just gripped the wheel and squeezed down the gas, the roar from the headers blasting away the immediacy, and the four-barrel opened up and I turned down the dirt road to our right, off of the highway.

I looked over again: she was staring at the floorboard, and the diamonds I gave her caught the sun in their prisms and shot a chameleon of fiery light across the plastic dashboard. The air was cooler now, out of the direct sun, and I frowned when the car bounced on its thirty-six-year-old frame as it moved

across a well worn rut in the road and we were lifted for a fraction of a moment and she still didn’t look over, and more so, that she pressed her palm against the seat and it didn’t move, not even involuntarily toward me. I slowed the car down when I had passed several houses and the fields that their residents worked, filled with the huge tight-packed, tarpaulin-topped modular bales of cotton yet to be taken to the gin. The road widened out and I pulled off to the side, half slashed by an oak tree’s shadow as the Chevelle came to rest out of the way. A cloud of our dust blew past and, caught in the rays of the sun, dueled down the light to disappear in the armrest she leaned on, the tops of her legs together and smooth and their fairness glowed against the car’s hard black interior. Finally she looked at me. I didn’t release the wheel, but stared straight ahead, through the distant trees at the setting sun, a pinprick of light above the empty fields.

I could feel the air reverberate with the glacial coldness of the blue in her eyes and still I could not look towards her. I could read the names of all the others before this most recent one in that space between her gaze and my face, transient and shifting as the dust that still hovered in the air. He was another in the list of whom she would leave and go back to and cry over on the phone for hours; the ones I hated, unfairly, when I saw her walking with them through the halls of school, the ones I resented when she would smile knowingly, sadly, beautifully at me, seeing me looking at the two of them. I loathed myself, hiding behind a V8 and the memories of the times when we were alone and she would look, and finally see me, and those moments when she kissed me and was someone else’s, always someone else’s, and never enough her own; how, instead of initiative I had a conscience and her friendship, and that, I reasoned, was better than nothing.

When I didn’t look at her she slowly reached her hand out and touched mine, still gripping the shifter, and my heart drowned out the pipes, bought for her to hear. Tucker / 3

Amber Stokes

Today. I will wear my bones outside my skin, to remember the Ones before me. Mothers, standing on street corners. And those, who rallied with bleeding signs in the rain, proudly proclaiming the soft pink lilies between their legs.

Lace me up, Until my breasts turn violet. Those fully ripened plums, pinned to my chest send the flies vomiting in delight. Those thieves of Hera’s milk, sucking the sweet honey from my heart.

I will hold my hot breath of conviction, until I have coughed out Adam’s rib. While a wet silence streams rivers from tired eyes, to salty cheeks and into mouths calling for Patience.

But he is pinned down and forced to confess, I am a woman.

Squeeze a vase of fertile lilies from voluptuous fervent flesh. Hidden between mended lace, an Aphroditian apostle waits. An

A-line statue with plagiarized hips, conforming to a fashionably flawed vision, while the heads of men perspire, erect with content disillusion.

I will stare confused once more, at the cold cloth cadavers hanging in my closet. A sigh, for the sad witches of MALEdiction, whose fortune left them swinging from branches so tall, their feet no longer touch the ground.

Lace me up,

I wear the neon vertical v’s, signaling towards the hope of an era, when hearts will be humbled. From reminders of what is, and never was a sacred flower of moon drops and baby hair. The scented perfumes of life.

So, today.

I will wear my bones outside my skin, vicariously. So that our daughters may dance naked behind their bedroom doors and like children, marvel at new found body parts, while they make love to mirrors with the lights on, still trying to unravel the knots their mothers tied behind their backs.

Stokes / 5

Deborah R. Majors

I smell like old people when I visit him in this place corralling the sick and dying, like a musty attic wiped with a single cotton ball, alcohol heavied. The pungent promise evaporates, leaving behind the returning worn odor of time, dust, and use mingled with suspenders, shawls, slippers, and sticks for walking.

I disdain this aroma that clings to my frame like knit pants to knee highs, revealing illusion as I step back, tricked, offended and brazen, gloating in my newness, daring Death to spritz my squared shoulders with its signature cologne

6 / Blackwater Review

Sidney Speer

The debate all summer revolved around arrival dates–mine and the baby’s. Lexy wanted me in Frankfurt two weeks after the baby came so I could take over kitchen patrol when Stefan returned to work. I agreed, but during the summer months I heard fear in my daughter’s voice, so I opted to fly just when the baby was due. As my flight departed Atlanta, I received word that Lexy and Stefan were driving to the Burgher Birth Center near the Alfred-Brehm-Pfingst-Platz in Frankfurt. She was having contractions. Somewhere above the Atlantic I would become Omi, or so I thought.

Instinct had guided my timing of the flight, but it was uncomfortable. Five seats across the middle and I was dead center, Mr. Bigpig on my left, Mr. Sniff on my right. The snot poured out of his nose like Karo syrup, and he declined my offers of Kleenex as if I would infect him with bird flu. I could feel my glands swell while I tried to sleep. Stuck in the on position, the overhead light spotlighted my forehead as if I were being interrogated for the entire nine-hour flight.

Arrival was 9:00 AM Frankfurt time, but my body knew it was just before dawn, and I was the walking dead. Crowds bustled past me getting tickets, clearing customs, rushing for trains, but it seemed the terminal was ghostly quiet. No laughter, no children screaming, no cacophony of conversations; travelers stood waiting in silence for family and baggage. This was Germany. I heard my name spoken softly and controlled my excitement as Stefan hurried toward me.

“Tell me,” I spoke after our hugs, “are you a father yet?”

“Actually,” he answered in perfect but rather formal English, “our beautiful Lexy was admitted last night, but no little one has yet arrived. Things are progressing slowly. Shall I take you to the hotel, or will you return to delivery with me?”

Driving across the Main River into Frankfurt, Stefan pointed out the ruins of the Roman aqueduct and described how the empire was defeated by his ancestors. His polished Speer / 7

manner and diction matched his Arian fine features, but I knew he was anxious because he drove extremely fast, even for a German. I marveled that my daughter had vowed to marry this man after their first meeting, and in eighteen months had adopted a new country, learned a new language, and created a new life form.

“Will she get the epidural, what you call the PDA?” I asked.

“She has certainly been demanding it, but the Hebammes--those are the midwives--support natural childbirth. They run the birthing center and can inhibit the doctors from using drugs. This baby is large, and Lexy is scared they will make her deliver naturally.” He downshifted out of the roundabout and drove even faster.

We rushed up four flights of stairs, and I stifled a heart attack as we entered the birthing room. Lexy had likened it to a torture chamber, and I could see her point. The bed was round, with curved sections that moved or tilted, increasing the size or changing the shape of the bed. From large hooks screwed into the ceiling, a hammock-shaped piece of greasy green fabric with several large knots hung directly over the bed. Beneath the knotted fabric on the circular birth bed was my Lexy. She was big as a whale. She looked tired, scared, and embarrassed, especially when I couldn’t quite get my arms around her for a hug.

“I’ve missed you so much.” I held her for a long time, inhaling the smell of her hair.

She cried softly when she saw me. “Oh, Ma, do I look terrible? Don’t answer.”

At that moment her doctor appeared and told Stefan and me to wait outside. She had already been induced; now he would break Lexy’s water and return to his practice.

“Things happen fast once the water breaks,” I said. “Might there be a Starbucks nearby?”

If he heard me, Stefan didn’t reply. He was so thin I was embarrassed to mention my hunger. “Lexy has been here all night,” he said. “Maybe it’s just a false alarm.”

“No chance of that, not once the water breaks,” I smiled, hoping to see a Coke machine, but I already knew there would be no such convenience.

When we re-entered the birth room, there was vomit on the floor. Lexy was alone and she was pleading for help. I sent Stefan to find someone. He discovered the birth center was full; every room was in use; every employee was attending. Hair raising screams came from behind closed doorways. Soon a young girl entered and sat in a chair. She was the receptionist, she explained. Everyone else was busy.

Lexy contorted with pain. “Mom, what do I do?”

“What did they teach you in classes?” I said helplessly.

“I didn’t take classes because Stefan was always working and couldn’t go.”

“Well, what about books?” I said. “What books did you read?”

“The books here are all in German.” Lexy was groaning.

“So,” I said.

“Mom, I barely speak German. I can’t read it.”

“But, honey, you work in a German law firm.”

“They pay me to fix their English, not read German,” she hissed.

“How about take the shot and call me in the morning,” I chided, but Lexy wasn’t listening. She was screaming bloody hell. Stefan was sitting on the platform facing her, braced as she bore down against him. I applied a cool cloth to Lexy’s neck and fast-forwarded every episode of medical TV I could recall: Dr. Kildare, Marcus Welby M.D., ER, Grey’s Anatomy. My two children were born over thirty years ago, and all I did was show up. I was draped for privacy, had the benefit of shots, surgical kit, and forceps, and had someone at my shoulder telling me what to do every minute that passed. And it had all been in English.

“Breathe,” I spoke with conviction. She started to parrot my breathing. Then a pause. I told Stephan to check the time to make him feel useful. Before long Lexy yelled again, and I got her panting like a professional athlete. Another pause. The young girl fled and during the next spasm, an older Hebamme entered and stood aloof in the corner. Lexy spoke in German. I heard the consonant sounds for p, d and short vowel a , and the word bitte . The woman looked negative.

“Bitch,” Lexy spoke in English. Then as the next wave

Speer / 9

of pain twisted her, she let out an amazing flurry of German, interlaced with a purely American expletive. I heard bark bark bark fuck bark bark ph dh ah bark bark. Whatever Lexy was saying, it was not making the Hebamme sympathetic for her. I had seen Lexy speak French before, which was a lovely picture, but hearing her hack out these guttural syllables hardened my feeling that this was a house of horrors.

The baby’s position changed, and Lexy needed to push. The Hebamme remained indifferent. “Lexy,” I said. “Why are they not helping you?”

“They dislike Americans. They say we always want drugs, which of course we do. I should have told them I was from Canada.”

“I suggest you try the hanging device,” I said, not having a clue what to do.

“Shit,” she said. “If you’re in the torture chamber, might as well use the toys.”

She grabbed the knot, trying to climb to the ceiling to escape the pain.

When she lay still again, I walked to the foot of the bed. Lexy was almost completely unclothed, her bare legs were bent and spread wide. I could see the baby’s skull which was more than I wanted to see. It appeared about the size of a tennis ball, so I told her to keep pushing. Stefan shifted his weight to come stand beside me when Lexy grabbed him by the collar.

“Don’t you even look in that direction,” her jaw tightened as if she were giving birth to the words.

The tennis ball flowered into a softball, and Lexy weakened. A slim, dark complexioned man entered the room. I thought perhaps he was an orderly, to clean the floor, but he was impeccably dressed in white shirt and pants with sharp creases. He watched with a detached air of authority.

“Doctor?” I inquired. He nodde affirmative.

“Omi?” He inquired.

I nodded, and stood straighter. I was Grandma.

The softball had expanded to the size of a tea saucer, but with each push event it failed to emerged as Lexy became more exhausted and less able to strain. We were stuck.

10 / Blackwater Review

I looked at Doctor and said in my best faux language, “Episiotomy?” He lifted his shoulders and looked bored.

Panic nipped me. Lexy was softly weeping on Stefan’s chest; her tears darkened a design on his cable knit vest. He stroked her hair, whispering how wonderful it would be when they were a family. How improbable, I thought. This man who keeps his neckties coiled in rows in the bureau loves Lexy who drops her dirty underwear in front of the toilet seat. He didn’t appear concerned, but he couldn’t see what I was looking at. This baby was going to be the size of a small house, and I was afraid it would injure Lexy, or the baby, or both, to linger in this state.

I spoke to the Doctor and Hebamme. They heard yip yip yee yee malpractice yip yip yee, but neither showed any signs of taking action. After Lexy gave one more heartless and hapless push, I walked up to the doctor, if he really was one, violently slapped my right fist into my left hand, and did my best to communicate via eye contact that if anyone was going to die today, it would be him.

Slowly, and without expression, he turned and opened a drawer, pulling out a felt wrapped bundle of instruments. It looked just like the tool packet that came in my neighbor’s first BMW. He sauntered across the room and took something off a hook. It was a long apron, the kind a meat butcher wears, only it was sewn of clear plastic. The straps went around his neck and tied behind his waist, and it hung to the floor. Stefan looked at me and we both swallowed. The butcher drew a scalpel from the packet and then put on some gloves. He crossed the room and sat beside Lexy on the wide part of the platform across from Stefan and, sterile gloves on, patted her on the leg. He said nothing to Lexy or Stefan.

She tried to muster another push, but she was spent. Stefan and I weren’t sure it was the right thing to do, but we encouraged her to keep pushing. As she pushed as hard as she could, sweat dropping into her eyes, the butcher casually reached over and, with the same motion you would use to cut the twine on a Christmas package, sliced her at the opening, making a minute nick on the crown of the baby’s head.

Speer / 11

Lexy screamed. Blood gushed. The baby came. I had to steady my heartbeat, but Stefan was calling me to get the camera. The Hebamme sprang into action when the baby emerged, and when she handed Stefan his swaddled baby, I snapped it, their first introduction, father and daughter eye-to-eye. The digital camera was the most high tech instrument used during the delivery.

Lexy lay there in a pool of her blood for at least forty minutes. The butcher leaned back against the wall. I half expected him to smoke a cigarette. Then another doctor came in, and they argued about something, I learned later it was about anesthesia for the stitches, but Lexy never got any. Stephan didn’t notice; he was lost in fatherhood, his head and the baby’s resting on Lexy’s heart. Then the butcher just sewed her up, Lexy crying out, but not as loud as before. He wrapped the bloody sheet into a ball and threw it across the room into the sink, splattering blood against the mirror behind the faucet.

“Stefan,” I said. “I thought Germans were clean freaks.” He shrugged, not taking his eyes off his beautiful daughter.

The clock showed six in the evening, twenty-four hours since I had departed Atlanta. I embraced the idea everyone would rest now, but they helped Lexy walk to a charming private room with a balcony overlooking a garden. Before Lexy even lay down, Stefan’s brother and girlfriend ran in, brimming with excitement, presents and food. Lexy, high on post partum adrenaline, babbled in German about her delivery.

In Germany no one cares what babies weigh. A ninepound one-ounce baby is of no consequence to a German. For them it is all about the skull size. Lexy had bragging rights. Her friends realized her little cherub was the size of a three-monthold, and when they read 37 centimeters on the ID card, Lexy got some respect, and moreover, she felt respect for her own labors. She had survived a German rite of passage. More friends arrived, a family of five with wine and gifts. Lexy walked to the bathroom, blood trickling down her leg, unnoticed by everyone except the two small children. I relaxed behind the language barrier, too ignorant to converse in German, too tired to try.

By nine the guests were gone, although more were re-

12 / Blackwater Review

ported on the way. A nurse pushed Stefan outside and barked something at Lexy, who clearly did not understand. The tall nurse was dressed in white, had a thin straight nose and blond hair tied in a bob atop her head. She looked like a duck. She spoke again. I heard quack, quack . . . quack quack, ice condom, quack, bark bark, quack. Lexy looked completely confused, but she nodded in agreement. The nurse left the room, then returned with the biggest frozen member you could imagine. I raised my eyebrows, to which she retorted, quack quack, ice condom episiotomy, quack bark quack. Lexy laughed so hard she would have split herself open, if she wasn’t already. I wrapped the frozen thing in a wash towel and she set it between Lexy’s legs to calm the swelling.

I kissed my sleepy daughter, her husband, and their beautiful infant, took a nice bottle of the gift wine and left before the next onslaught of Germans arrived, stopping briefly at the nurses’ station to speak to the duck lady. A cab drove me into Sachenhausen, the old section of the city left intact after WWII, and stopped just two blocks from Lexy’s house at a dimly lit sign, Hotel Kautz. Herr Kautz apologized that the kitchen was closed as he gave me my fifth floor room key and pointed to the stairway. I considered sleeping on the third floor landing, but managed to struggle up to my room, dropping everything except the wine bottle just inside the door. I opened the wine. The hotel was too European to provide refrigerants, but there was an ice condom in my purse. I smashed it in the sink, dropping a big ice chunk into a plastic drinking glass. From the open window I heard patrons of the Apfelwein garden below. They sat outside drinking and singing at long bench tables, swaying together as one. I emptied my glass and poured another, listening to the revelers. Maybe the next night I would drink and sing with them.

Speer / 13

Daniel Baker

While my strings have been strummed, plucked, and picked lightly, intensely made to sing and sigh, to moan when bowed, to purr the instant urged, at present, silence is their sound.

I grasp my strings in stillness. They gasp for music, they shall have none. For when played their pitch pains, and pricks at lacerations left by those who have found satisfaction, beating with their bow.

And though I will not hear my strings joined in joy, neither will I be agonized with torturous tones.

Now I will never speak.

I’ve been played like fire in the forest, Like the frenzied winds of the storm. Forced to voice words not mine, To spew them, to shriek them, To whisper these lies. I shall not be played. Baker / 15

Kyra Candell

Can you hand her something real

Something tangible

Not just thoughts that collect on dusty, aged shelving

Can you hand her something raw and unfinished

Something textured

Frayed denim fabric with weathered seams

No pristine cloth with a pressed, stainless body

Can you show her a glimpse of warmth

Or just unaltered emotion

Be it poignant or plain

She does not crave stoic ideas

Or black and white truths with sharp corners

Let her see the wrinkles in your smile

The imperfections that sleep beneath

Show her that gift

The veracity of your heart

And when she sees those worn corners, the sincere hues

That is the honesty she once thought absent

Matt Haemmerle

I step out into the fresh air and watch the vibrant leaves seared with fiery hues twitter in the breeze. A memory from my youth that I had relived in my head many times before is suddenly evoked. At age eleven I went apple picking, and many times in autumn when the crisp wind brushes by me, I relapse into an earlier stage of my life, amongst the ripening apple trees in the rustic field.

I tugged my red fleece down to my waist to ease the numbness from the chilly air. Rows and rows of stubby apple trees were lined like soldiers. Searching for a tree to climb, I ran down the gap of two rows with my wooden bucket dangling from my clenched hands. The many ripe apples flushed out an aura of fragrant smells that was so thick it had to be pushed out of the way. I grasped the outstretched arm of a tree and pulled myself up. The bark of the coarse trunk gave me the grip I needed to boost up onto a limb and rest in the solace of my childhood.

On a branch I paused briefly to catch my breath. The sun peered through the tree limbs, splashing light on the frosthardened ground, the unmerciful world below. Up high in the tree of my youth, I felt completely guileless. The warm sun thawed my back, and I felt free from troubles and complications. For now I would not eat the forbidden apples as Adam and Eve once did. I was fortified with my innocence up in the branches of my Eden, which wasn’t to perish just yet. Standing from up in the tree I saw a field, apple trees, and mangled leaves; everything was still.

That is what I saw then, but today I see the broader image that I hadn’t understood before. Today I recall that beyond the pumpkin patch tall strands of tawny grass were waving in the wind. The limbs on the apple trees swayed gently. Fallen leaves, much like people who’ve fallen from their childhood tree, surged to life, springing off the ground and anticipating Haemmerle / 17

the tumble that they were to eventually take back onto the hard, stodgy earth littered with obstacles like twigs and rocks. Everything was in constant motion, and everything would eventually succumb to the ground--even people. For those brief moments in the tree I thought I was stagnant in time; today I only wish that were so. I jumped down from the tree, out of my youth, and into a world full of obstacles in such a hurry, and now all I want to do is climb back up. This is impossible, though, and now I eat apples and tumble with everybody else on the hard, stodgy earth.

Dareen Mohamad

I am not Zarathustra, but I shall speak. Nor am I Tolstoy, but no less do I feel the Kingdom of God within me.

Castles and castles and castles of dust.

Fungus in the government, extremism in the brush. We are a Christian nation living on Prozac pills. Unyielding to our temptations, we’re drowning in McFlurry fills. The administration? People educated and learned. What are we getting in return?

Blank sensations and patriotic rug burns. What are we standing for?

1984 is waiting in the corridor.

We are the era of the automatons.

Idiotic blue skies and polluted black swans. We’ll kill our fellow man! We’ll blow him into shards!

Fancy black suits and phony business cards!

How well you smell, Mr. X!

You quell with your artillery shells, embedded in survival’s chest. Won’t you ask “What is worse than the man who kills because of religious conviction?”

I promise to reply with “The masses who have been convinced by this politician.”

“What luck for rulers that men do not think.” - How right you are, Monsieur Adolf.

Reduced to this, oblivious and distracted by the circus, we shall blindly waltz to the sound of Strauss. We are waltzing, waltzing into the damnation of us.

Mohamad / 19

Sidney Speer

In the cool salty air, steam from her morning coffee lifted like fog. A crazy seabird cavorting near the reef caught her attention. She watched it lift from the surf then plunge into a swell, saw it gambol like a pinball bouncing off a fuchsia sunrise, alighting on her dock winging off, then losing lift as if crashing an invisible window, screaming into the waves.

A familiar ring tone moved her from the veranda. “Three o’clock is fine,” she said, “the house will smell of fresh baked brownies.”

Soft shell crab undulated on a hook. The line invisible snapped the gull from flight, flinging the bird out of trajectory after it stole its prize, the barb digging deep as the unforgiving tensile jerked the tethered bird back to the sea. Dazed, the creature rose again to be yanked, landing where the sinister twine wrapped itself on pier and pile, tangling, tearing, ensnaring wings in a translucent web of filamental death.

It was not quick. By midday fifty feet of unseen string adorned the dock, until the bird at last dangled from the edge, head down, like a trussed squab slowly turning on an invisible spit in the gentle midday breeze.

In the warm salty air the salesman urged expectant buyers to appreciate the seascape, noticed a web wrapped like yellow tape at a crime scene. Diverting their attention, he found the pitiful bird of twine suspended barely above its reflection. “Lets go see the house,” he escorted them to land. “The owner made some brownies, and there’s a nursery.” Speer / 21

Kyle Webb

They bleat, A mass of mannequins.

Mindless meat— Fish without fins.

Oblivious to life, Mechanical monotony. Blind under the knife, Megalomaniacal society.

Like cows to the slaughter, Pigs on the wing.

Anarchical Big Brother, Pharisees, let us sing.

Vanity, lust, Vacuous minds.

Arrogant power just, Egg timers wind.

Grazing in the pasture, Like sides of beef.

Complacent master, Sheep.

22 / Blackwater Review

Denise Harrigan

Sparks flying through the air catch a hollow of drought, igniting lusty devotion.

A ruby glow kindles in the arid twilight air. Flames saunter across the forest floor, tickling the roots of sturdy oaks, the thirsty bark combusting into an inferno.

Fiery locks caress chiseled hickory trunks. Tendrils of flame licking each branch fondling, stroking, devouring each limb in an embrace of greedy, insatiable hunger.

Whispering leaves of longing dance through torrid currents, rushing to be consumed in waves of crimson and amber rapture, roaring with pleasure in crackling laughter.

Billowing clouds of smoke rise to drown out the moonlight. A canvas of shadows surrounds the hard woods as they succumb to the molten blaze.

The sun rises on a soft hush of satisfaction, as smoldering embers eternally bind fire and forest in ashy gray cinders.

Harrigan / 23

Sidney Speer

My desk is small, standing at the side wall beside a fire that rarely burns. The old swivel envelops me, and kitty too, posing a soft curl beneath the warmth from the green lampshade. My throat constricts, I sort and shove papers into piles around the floor until I feel burl walnut waxy like my old man’s skin, cigarette burns at the edge still smell of fingertips wiping my tear, telling me I can.

Molly Mosher

Henry was a toddler, Mister, and he loved his blanket. He loved it so much that he carried it with him everywhere. It had a hole in the middle, and Henry wore it as if it were a picture frame. The satin edges were worn by love.

His father, General Stevens, hated this blanket; he thought it made his son look like a sissy. He had never had a blanket.

One Tuesday, the General told Henry a story.

“Son, you know the garbage man who stops by here every Monday and Wednesday?”

“Yes, sir.”

“He is so poor that he sleeps outside on the ground, and he has a daughter who does the same. They don’t even have a blanket.”

Henry looked at the General, knowing what was asked of him.

“Good talk, son.”

A week passed and Henry continued to love his blanket, more than ever, perhaps. He knew he couldn’t keep it forever. The next day was Wednesday, and Henry knew the garbage man would be coming.

When trash day finally came, Henry saw the garbage man pull up. He walked outside and walked his four-year-old self up to the man who was removing their refuse.

“This is for your daughter,” Henry said, placing the blanket into the garbage man’s filthy gloved hand.

The garbage man gave it one look, and tossed it into the back with the other trash.

Mosher / 25

Adam Duckworth

The bags of plastic in one hand, the bottle in the other refracting the light in an amber brown tint, promising doses of smiles in ten milligrams as the chemicals crash in the bloodstream like a cymbal in a symphony. He puts the pill in his jittery palm, praying to a god regulated by the endorphins that it evens out as he swallows, as he gulps as he takes it in like the scent of perfume during a kiss.

Meagan Dahl

Dad’s beloved, rusted red jeep charges up the canyon road. Bracing against the cold, I roll down the passenger window to drive away the smell of stale cigarettes. The bitter wind threatens my carefully curled ponytail tied up with a baby blue gingham ribbon, so I jerk the handle and roll the mud streaked window up again. I get to see dad only a couple of times a year; I don’t understand why he can’t stop smoking for a measly three days so that I can breathe. The jeep pulls up to a spacious home perched high above the river. Dad puts out his cigarette and turns on a smile.

“Here we go, Sweetie.”

We are greeted at the front door by a bunch of smiling, unfamiliar people and the smells of Thanksgiving dinner. Dad rests his hand on the back of my neck, an intimate gesture that suddenly seems inappropriate. I know that these people invited us because they know dad can’t cook and that he wants to impress me. The other kids are watching a Disney movie in the den, but I wander aimlessly around the house to wait for dinner and avoid uncomfortable conversations. There are photos everywhere of posed family portraits, vacations to Mazatlan, and awkward prom couples. Everything in the house reminds me of what Dad and I don’t have. I pass by a window and can see his broad shoulders hunched against the cold. Dad towers at 6’6” but never stands up straight, like people won’t notice his size if he slumps down and hides in corners. He’s out there, all alone on the deck, smoking and hating this as much as I do. Dinner is announced, and by some miracle I am allowed to leave the kiddy table and sit with the adults. These people remind me of my mom and step-dad, talking all at once about books, art, traveling to Europe, politics, and tragedies in Africa. I watch dad stare at his food and slouch even farther down in his chair. I finish my pumpkin pie and long to have this dinner with my own family, who are not these nice strangers. We Dahl / 27

are all feeling the effects of a turkey coma when dad pulls out a carefully wrapped box. He sets it in front of me with hope shining in his eyes.

“Happy Thanksgiving!”

I tear open the box with an illustration of a deer in the crosshairs on the lid. A Remington 22 rifle lies in a pile of paper on the table. I want to run for cover, as if this gun will stand up on its own and shoot me between the eyes like that innocent deer. All of the dirty little boys crowd around me like seagulls begging for a crust of bread. What dad notices is that I never once touch the cold black steel.

“Hey, Sweetie, we can get some cans and target practice out on the deck.”

“Dad, it’s too cold out there and I’m too full…maybe some other time.”

The boys play tug-o-war with the gun while I watch Dad go out on the deck alone to smoke another cigarette. I want to run out there and scream at him for humiliating me in front of another family, but instead, I fold the blanket of tissue over the gun and hold back tears as I shut the lid.

Ashley Schreckengast

(a sip of hospital coffee and newspaper ads)

Somewhere is a road of red dirt and dust. A place where sidewalks narrow to an end and the grass curls like fringe along the edges. No signs here, no blinking lights or busy noises. (a lively man, stiff in his death bed) Blah, this ancient speaks to me.

“What’s that?

Did you actually speak for once?”

It’s just senseless drool. “Why do you care to try?”

I’m baffled, By this spewing nothingness. He speaks, struggling with that heavy tongue. Nodded remarks are made for Those words too tough to say. He bites back pain, And I am tired Of hollow sounds on pinch-y notes. (discovering the discomfort of falling asleep beside the patient)

Suffering. He’s here with The beeping machines, the cool metal bed frames, he must be frightened. Yet he tries so hard,

Schrechengast / 29

To keep the act alive. Why didn’t he tell me?

Wheezing machines.

( the will is left intact)

Back and below is a mountain of ecru smokes and undertones. A scene where ledges crumble to granulated salt and rocks stand like tawny ancients preserving the sands. No life here, no roaming spirits or hindering obstacles.

(Alive, but not well)

He twitches in his sleep.

“Am I seeing things or can that skeleton move?”

He blinks back pain, Swaging a finger like it Consoles.

Simple illusions to unreliable gestures. He squeezes my hand.

“Why attempt? How can you think this eases?”

He has a begging stare, straining to encourage.

I’m Exasperated. With dampened spirits denying the truth. (there is no way to ease this)

Anguish.

I’m here.

The rigid body, the fragile health, it horrifies me. I want to hold on to him.

Why don’t we have answers to cancers? These screens flash death.

30 / Blackwater Review

(there are flaws in contentment) Ahead and above is a river of perse currents and trout. A world where leaves embrace tense surface and stones glint like brassy gems along the bottom. No buildings here, no manmade chemicals or human consequences. (the sheets were left undone) Such things he questioned.

“Is there a reason To keep the play going Once the curtain has fallen?”

A life has an end And he finished his last act Without grace.

I breathe his past Like a hospital bill lived his nightstand. “Leukemia was it? Or some other illness? I forget. I buried his death seed in the red mud, I wandered the cliff of unknown legends, and I cast aside a waterway to oncoming oblivion like I deserved no rest or peace for mourning. I saw the play end, Breathing like those tubes That feed his arm, One last heavy sigh. Schrekengast / 31

Reid Tucker

How red is the heat Inside this unwritten arm of mine, Erect on the tile of the kitchen bar? My skin is paraffin Against the tile, against him.

He looks at my face, My bare eyes cut deep down With the cold of his youth, gone now and brown Like his own eyes and arms: His parchment of dust and the sun. He made me for himself, And the palm in his clutch Is like his own, my body his crop Grown from the earth he plowed. I am the fruit of his blood.

Like Moses in Sinai I strain against him, the rock of his will, Disobeying even in the act of striving; And I see him split wide, The water in his knit eyebrows.

For with a dull crack The hollow back of his hand Is mired in the valley of tile grout, And I can hardly be proud Because what I’ve done to him-

Was for me, myselfAnd through my own strength, the heat In my ice-cut eyes, through the unwritten life, Of my flesh, I have beaten him. And he did not let me win.

Lily Bruns

We both know it’s a bad idea, we both know nothing good can come of this, we both know we’re going to feel terrible in the morning. But we both know what selfish and selfdestructive moods we’re in, and we both know we just want to do something stupid and willful.

There are certain guys in this world that I am undeniably attracted to. It doesn’t matter what, when, where or why, but if the situation arises, I won’t be able to resist him. Even when I know it’s a bad idea. Even though I know I’ll regret it by morning.

He falls under that category. It’s all well and fine when he’s safely coupled off. Then I can resist because of the sheer fact that he’s off limits--I respect that. But what happens when he’s all of a sudden single again?

I was startled when he announced his bitter toast to being single again. I had to chug that beer to cover up my ridiculous reaction. The thing is, I know he noticed my reaction and purposefully took note.

I thought I was fine, I was so over him, but when the possibility arises I can’t help but reconsider. Especially when he said it right in front of me. I can see past the little games and charades. We’re both loosened up, not drunk, but one couldn’t say sober, and out of the blue he suggests going over to my house. Pretend as we might that it’s all innocent, everybody knows otherwise. Even if I deny it and I won’t acknowledge to anyone, not even myself

Once we’re home, he’s safely in bed upstairs. I’m nestled under my own covers. But I know we’re both thinking the same thing. Is this really it? Are we really not going to do anything about it? We’re still in denial even when I tell him to go ahead and come downstairs, that bed is gross and uncomfortable. We’re still in denial when he’s there lying next to me. We’re still in denial even when he takes his shirt off because it’s Bruns / 33

too warm in my room. I’m still in denial as we’re “keeping each other warm.” I’m still in denial when I’m nestled into his shoulders. And then our lips meet. How? I don’t know, but after that I can’t deny.

I stop and ask what’s going on. We both know it’s a bad idea, we both know nothing good can come of this, we both know we’re going to feel terrible in the morning. But we both know what selfish and self-destructive moods we’re in, and we both know we just want to do something stupid and willful.

Donovan Murdorf

leaves falling lives spent tossed aside down to dirt to mulch to the roaches from glorious heights and brilliant green to the ground below in brownest rot they fall in grace yes but sadly they descend let go and brought by the coldest wind to lie, still withered forgotten

Denise Harrigan

I spent the night with Poseidon calling back the last ten years. I carved my story in the shore, raking my fingers through silt and sand. I made my stand on a slipping sandy foundation, hoping the tide would conquer me. Pain washed over each image with every wave he crashed on the beach. I cried to him “There’s no escape from these memories I can’t let go.”

With each surge and swell he challenged me to relinquish my rage, leaving my fury on the shore. Each recollection that surfaced before me drowned by salty kisses stinging tear-spent eyes. His foamy white tendrils and silky cool fingers soothed me through the night. On the crisp wind he whispered, “Balance, my dear, With every ebb there is a flow.”

Alisa Self

Tear up these old photographs

The people smiling back are strangers now

I can almost find the humor in it all

But it’s no laughing matter, not right now

And for the first time

You get creative, drawling me in

With well rehearsed, beautiful lines

This time through, I have prepared mine

And I can break you like you’ve broken me

You’re eyes get wide, like it wasn’t evident

We’ve been slowly losing pieces of ourselves

You seem to forget everything

While my head keeps spinning

All the colors bleed—it’s just black and white

Just like difference between us

And you were never right

And you were never honest

So just do what you do,

Just turn your head away

Maegan Hartley

Up through the trees in the mountains

Boredom causing the curious to wander

Out past the boundaries, where no other child plays

Like a bee, marking the way to its next flower

Finding a deserted home

Rise in the rubble, art and peace

Find their way to each other in this one place

The heart knows that inspiration flows

Only in those curious enough to find it

Dirt gathering on the floor

Dust crawling up the arms

Still she dances,

Swirling about her as she twirls through the thick humid air

With the smell of lilacs and mildew hovering about her

Energy flows through her arms, through the room

So silent, so loud her actions speak to her soul

She internalizes the beauty of strength, inspiration

No one to watch her but her shadow on the wall

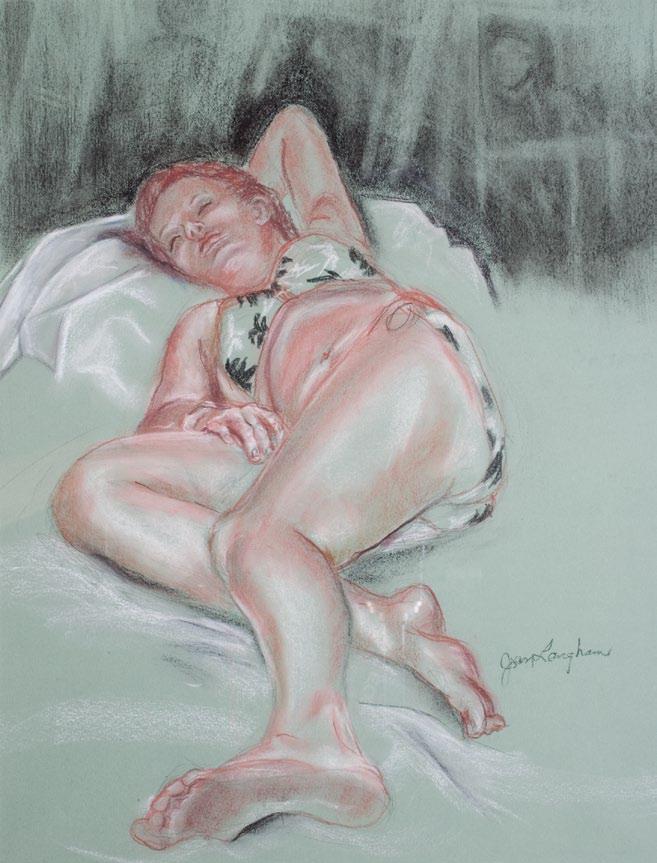

Shelf photograph

Joan Langham

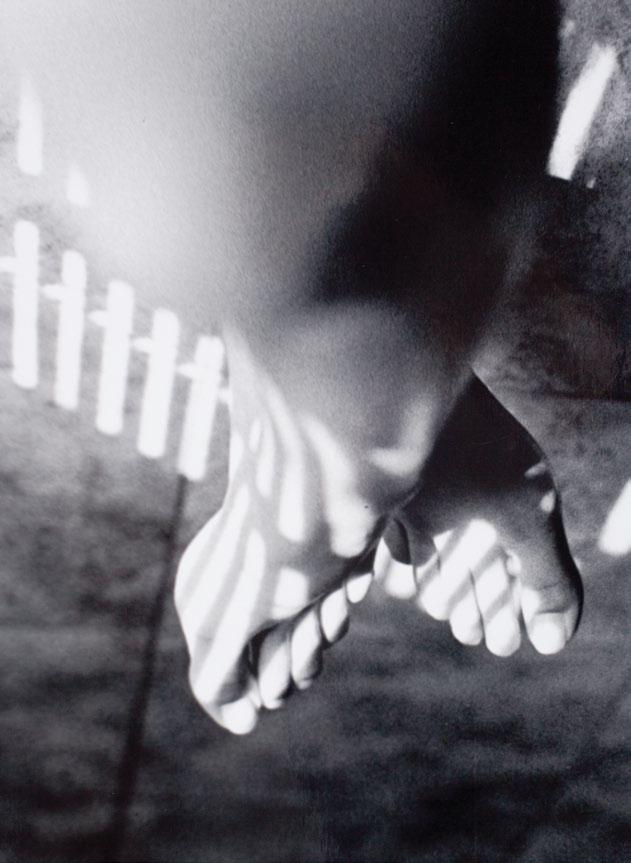

Maria B. Morekis

The Pool digital image

Maurice L. Price

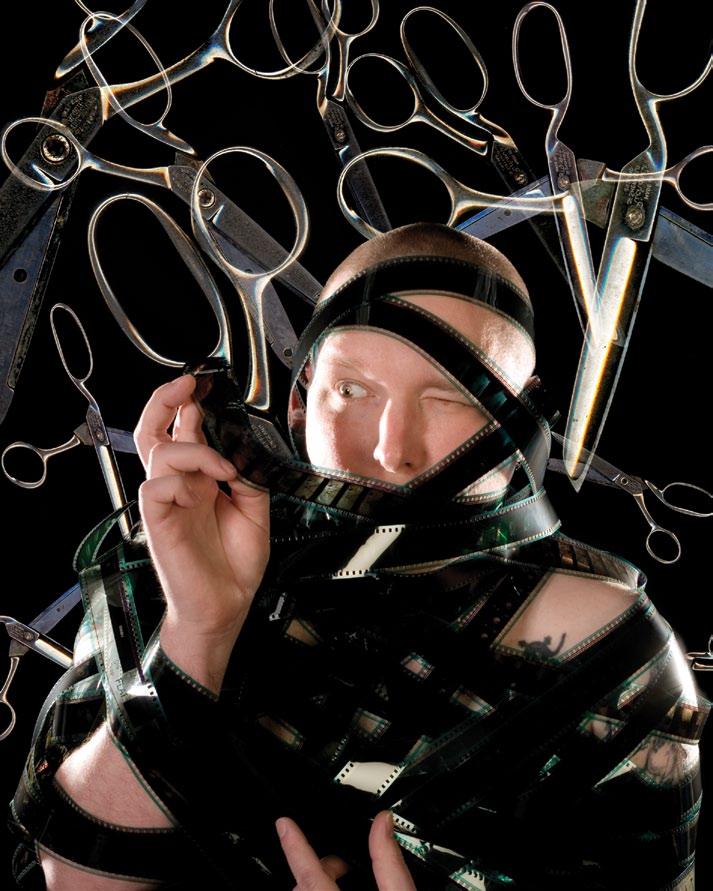

Stacy Davis-Tsui

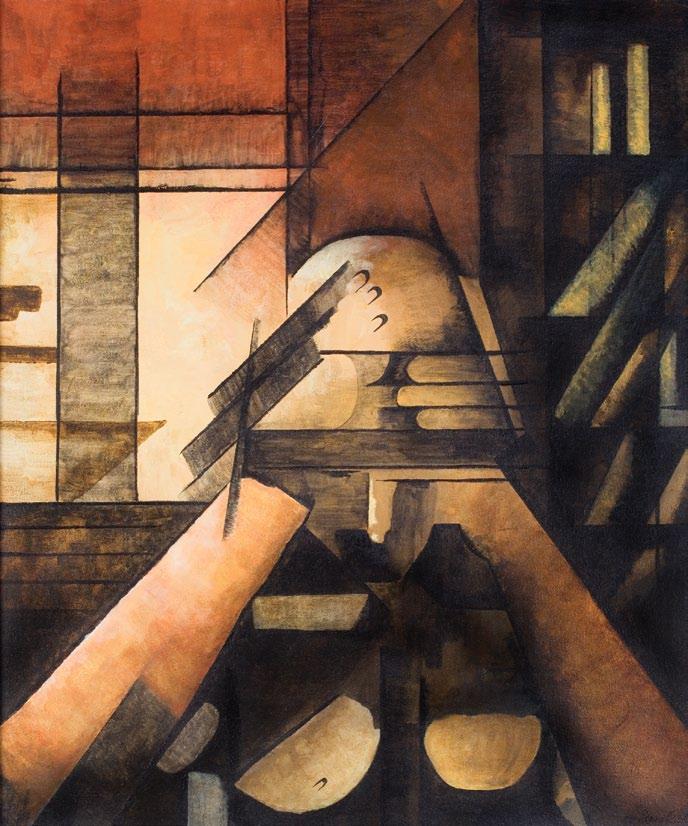

Daniel Baker

Iries awoke at 3:30 a.m. with phonetic C, crows and bells, clanging in his mind’s ear in concert. His eyes unclenched abruptly; there in the black was a crane, its reed-like neck curved into the shape of the sound. A cat’s tail dangled from the crane’s beak, and a crown made of frogs croaked atop its head. The crane unfolded its wings and began to writhe, and Iries heard the same ringing strings of the tokos, the shakuhachi’s soft shrill, and the great pounding of the odaiko that stirred the bird. Bewitched by the music, he leaped from the bed to the center of the room, joining in dance with the crane. Over book and chair they went, bounding round and round. Then they were upon the old, oaken dresser, dashing it beneath their feet.

As spontaneously as the music had happened, it ended; and there, from the lithe throat of the crane came an ethereal voice in song; it sounded like rain, and laughter, and mourning in unison. Iries felt as if he would cry, as if he would shriek, but he lay on the floor where he had fallen after the music had ceased, timid and huddled, like a toad when touched. After what Iries thought so little time, the crane closed its beak, doubled its wings, and bent its noble, narrow head downward toward Iries’ own. It then pecked at his mouth, kissing him, he thought. It rose and flew through his eastward window, though it was not open, leaving the cat’s tail on his pillow in the curve of C.

He was roused in the morning by the alarm clock he regularly set but never meant to wake by. He found himself perched, like a pigeon on a wire, upon the edge of the chair in front of his secretary, his legs tucked tightly under the rest of him. The computer was still on, and the research he would need that day unfinished. He snatched his only good pen and drove it into one of the many stacks of sheet-paper on the desk, fracturing the end of the pen. It was then he observed the slender sketch, on that same sheet, of an extraordinary crane, circled with a C. The escapade of the previous night swirled in his skull. Baker / 55

Iries collected himself. It was another dream. His head ached severely; it always did after a dream.

Professor Helix would not be pleased. This would make the second time Iries had been late that week. He had typed a bit more on the paper that was expected that day and printed it off. Things would be much worse if he did not bring something; Professor Helix required it. He had then gone out to the drive only to find someone had unplugged his car. Iries took Thom’s bicycle. Thom and Iries shared the same toilet; their dormitories were adjacent to it on either side. Thom’s major was art history. Ireis knew he wouldn’t be attending class; he was certain. Though Thom did not need drink to encourage an absence, it did take him a day of nursing to recover from a night when he had been. Unfortunately for Thom, his nurse had left him some weeks before, and he was intent on displaying his grief, caught deeply in an alcoholic stupor.

Iries looked at his watch as he propped the bicycle against the tree nearest the entrance to Dobbins’ Hall. Dobbins’ Hall was home to all classical interest here at the University of Massachusetts. It was 8:20, and he was 20 minutes late. This meant of course that he was 30 to 35 minutes overdue, according to Professor Helix. Iries paced rapidly through the main corridor. He arrived at the small office that Professor Helix gave him a corner of while assisting with research, grading, and the like. He did not knock but quickly opened the door with the gaudy, gold lettering above it, which declared, DR. HELIX, PROFESSOR OF EASTERN RELIGION AND FOLKLORE.

“Mr. Ethein, you are late.” Professor Helix was sure to give gravity to every word.

“Yes, Sir, I know. I’ve tried to…”

“It is not like you to be late, Ethein, but never mind. Don’t let it happen again, though. There were many other candidates capable of serving as my assistant, but I chose you. Please do not disappoint me.”

Iries inwardly scoffed at the idea of there being a line

56 / Blackwater Review

of applicants for such a position. “I’m sorry, Sir. I wasn’t able to quite fin…” A second time Iries was interrupted. He had grown used to such treatment, however.

“I expect you completed the work I gave you yesterday.” As if to prompt an answer, he crooked his head forward, his eyes protruding behind his glasses and below his brow.

“There’s a little that still needs going over,” Iries said hurriedly, making his way to the small desk in the corner of the office.

“As long as it’s finished by the scheduled time. You know it must be submitted today,” Professor Helix said austerely. “Ah, Ethein, there’s nothing the matter, is there?” Helix was hesitant. “You have not seemed yourself this week.”

“What does the crane symbolize, in folklore, I mean?”

“Well,” his head tilted upward and his eyes rolled, probing his thoughts, “the crane can be a harbinger of good fortune, increased fertility, and in some cultures even death. Why do you ask?”

“Oh, I’ve been dreaming.” Once more, the images of the previous night liberated Iries’ thoughts.

“Having nightmares involving cranes?” Professor Helix’s expression was mocking.

“No, not nightmares, only dreams,” Iries said. “I apologize for interrupting your work, Doctor. I’d best get back to mine as well if you want this on time.” He tapped the document on his desk with his pencil. Iries was sure to keep his eyes on his research. He wished he had not said anything; Helix’s interest was now aroused. Helix fancied himself something of an astrologer. Iries was not alone in knowing this unfortunate fact. Iries could sense Helix’s intent gaze, knowing he wanted nothing at that moment but for Iries to look up and ask him to presage the fate which Iries would be soon to meet.

Iries pretended to be hard at writing the final page of his research, entitled “Emblems of Superstition and their Influence on Folk-cultures.” His head was beginning to ache again, and he felt strangely nauseated. The visions of the crane began to assail his mind; the pain became worse. Violating the stillness of the room was a faint thump. It started to form Baker / 57

“Iries, you look very red, and you appear to be perspiring.” Iries stared at Professor Helix; his glasses were assuming the shape of the letter A. Iries continued to gaze as Helix’s ears drew upward and his chin jutted into an acute angle. His mouthed stretched to either side of his face. His features resembled, flawlessly, a capital A, turned on its axis. He looked like a carnival demon. Iries stood up swiftly, knocking his chair aside.

“Is something bothering you, Ethein?” he asked, as the teeth before the anxious voice began to alter, morphing into statuettes of renowned avatars. One slipped loose, tumbling across the desk, and down to the floor.

“I have to leave.” Iries advanced toward the door, stopping only to acquire the diminutive Buddha ahead of Professor Helix’s desk.

“Ethain, Mr. Ethian, wait!” Iries rushed to the hall’s main access, suppressing the urge to dance to the active air, ringing in his ears. He mounted his borrowed bicycle, rode for his dormitory, and thought on A.

Iries arrived at his abode in little more than fifteen minutes. He threw the bicycle aside on the rack near the door to the flight of stairs. He entered the passageway on the second floor, counting the 36 steps to the third door on the right, Room 111. He was calmer now. Thom was sitting on a stool that braced the door to Room 113. The only sound in the habitually commotion-filled foyer was the ring of Thom’s guitar; he was playing “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” Thom was devoted towards few things; the guitar was one of those things.

“You take my bike, man?” He continued to play, not looking up.

“Yeah, sorry I didn’t ask. Somebody unplugged my car again; I had to go to work.”

“It’s cool, man. That’s the price you pay for savin’ the

58 / Blackwater Review a rhythm, mounting in volume and intensity. Iries glanced at Professor Helix, but he did not seem to hear the great drums growing louder. Iries began to sweat, and as a bead spotted the paper on his desk, he heard all the music of the night the crane came.

environment, probably some Republican prick, goin’ round unpluggin’ electric-cars. As if suckin’ and fuckin’ the earth wasn’t enough.” Thom looked up now, and the tendrils of his hair tumbled down his face.

“No, I don’t think so, Thom. It’s likely it was an accident. There are a few drunks that sleep in that parking-garage.” Iries enjoyed these conversations with Thom, always extraneous. They comforted him somehow, making him feel like he was hidden, like a duck must feel before it is flushed by a dog from the brush. Everything was upset now, though. The sensation of ambiguity was no longer there. He was flying clear of the bush, and the dog was howling.

“I wasn’t down there last night, man. I was up here.” Thom stopped playing now. “Why don’t they pronounce it ‘car,’ you know, with a long A but the same hard C sound. That way they could have electric-‘car,’ like to show the owners care for the world around him.” Thom bore the same, awed expression whenever he thought he was being particularly profound.

“I’m not sure, Thom. Perhaps you should ask them sometime.” Thom laughed.

“Listen, Thom, I have to go lie down. I’m not feeling well. The day’s been really weird.” Iries touched Thom’s shoulder. Thom nodded in farewell. Stalin, Thom’s cat, ran through the door’s partial opening and under Thom’s chair. He was tailless. Iries walked through the entry to his room and left, unfastening the door he had always locked.

Iries turned on his computer and sat down before it after deciding he could not sleep. He opened a poem he had started a week ago. The title was “By Bit and Peace.” He had been compiling a short book of antiwar-themed poems for some time now, since 2002. The tingling of inspiration began to re-ignite. He wrote, but after moment it faded. He kept a booklet of crossword-puzzles for just such times, in a drawer of his study. They were listed in order of difficulty. There was one left that had “novice” above it. He started the puzzle.

Thirty-three minutes had passed and Iries was still occupied with the crossword. He had less than half of it completed. Baker / 59

His thoughts were assembling once more; he felt he could write now. He wanted to fill in one last blank, 14, down. The cue read, “The inverse of the twenty-first.” Even though he was not good at crossword-puzzles, it irritated him every time he was baffled. He went to the bookcase alongside his study, returned, and sat back down.

There was nothing about “the inverse of the twenty-first” in his Comprehensive Dictionary to all Crossword-puzzles. He released his grip, letting the book fall to the floor. He picked the booklet of puzzles back up. All of his inserted letters had been extracted from their allotted words, creating a large N in the puzzle’s box. Iries rapidly shut the booklet and his eyes, holding both clamped for several seconds. He reopened them together, the N was there. He ripped out the page, walked to his bed and collapsed. The music had started for a third time. He pulled something from under his head; it was the rigid cat’s tail. He put it on his nightstand, next to the page and the statuette. Iries fell asleep to beautiful music.

Iries awoke at 6:59 a.m. He sensed a slight pressure on his chest, and it was difficult to breath. He tilted his head up and saw a stuffed, pink rabbit sitting on top of him. It was the same rabbit he had as child; he had taken it with him to college to remind him of his mother. It stayed in the closet from the first day.

The rabbit’s ears had been torn off, the fibrous padding puffed out. It looked like it had earmuffs on. The ears themselves were bound together in the shape of a cross. The rabbit bore these on its shoulder, holding the cross-ear steady with one bulging arm. It also had a crown on its head, thumbtacks fixed together with ribbon and tape.

“You’re Jesus?” he asked earnestly. Iries was willing to believe anything at this point. The rabbit tottered forward tenderly, and offered the cross to Iries. He took it. The rabbit directed Iries’ gaze to the nightstand. All of the objects had been structured. The cat’s tail first, the image of the avatar, and then the page. Iries placed the cross at the end. “Cant,” he said questioningly. The rabbit nodded in affirmation. It tripped off the bed and returned to the closet.

Iries wearily slumped to the restroom, the same affecting music rumbling in his ear. He put on the water, letting it run until it warmed. As his wet hands slid over his face, he thought that he must be insane, but he was not frightened. He stared at himself in the mirror. His straight auburn hair hung about his ears, his 5’7 frame looked fatigued, but his usually sullen eyes shone with a gray illumination, and the tattoo on his left arm of a girl he had wish for, more vibrant. He had seen that girl so many times, in the library, on the way to a class.

Iries had never gotten a tattoo on his arm, or anywhere else. He watched his reflection as that same tattooed arm guided his hand’s likeness to his corduroy’s pocket, pulling out a pack of cigarettes, removing one, and then replacing the pack. His likeness lighted the cigarette with a lighter it had gotten from the other pocket, put it to its lips and drew in deeply. Iries had not moved the entire time. The water was still running. He filled his cupped hands, dousing his face another time. He looked up; his reflection was not bent over as he was. He noticed the same music playing in his head.

“Are you crazy?” The likeness spoke with a strong Brooklyn accent. “Why do you keep lookin’ at me like that?”

“I believe I am, yes. Have you come to give me another letter?” Iries’ voice trembled. He knew only someone truly mad could see themselves while talking to themselves.

“Good tune, huh?” His image bobbed his head and snapped his fingers. Iries did not respond. His image was no longer keeping the rhythm. It was very still and frowning. “Look, I’m just s’ppose to tell you, ok. ‘Re,’ that’s all you need, got it. Oh, and get some rest, you look like hell.”

“‘Re’? Cant-re?”

“No, you moron, recant. As in ‘re’-cant, all right? Say it.”

“Recant,” Iries whispered. He could not refuse the smile that swelled over his face.

“Recant what, exactly?” Iries felt somehow elated. He was bewildered too, like a fish must feel when its mouth engulfs a daggling, defenseless cut of flesh, puzzling at the prick in its cheek as its towed to the surface.

Baker / 61

“You an’t happy Iries. Look at me. Do I look happy?” The image pulled down its left eyelid, better revealing a bloodshot eye. “Things an’t goin’ good for us. You got to leave it, all of it.”

Today had been the first day Iries had been happy in a very long time. He had not realized how much he missed it until now. He nodded, and whispered, “Everything.” He packed two sets of clothes and what money he had into a small duffle and walked out into the hall. He left a note onThom’s door, saying he’d caught a train for Maine, and intended to remain. He knew Thom would like it. He’d probably write a song about it.

Jzolandria Williams

What is black love? What is self love? I see the black persuasion, the edifying factor of my existence dwindling away to satisfy a world that encompasses no more respect for our presence, our legacy, our cause, our contributions.

They tell us that our boys should not stand so broad, with their hats turned backwards, with their pants baggy and their shoes unlaced. They tell us that our black men should exemplify an English sophistication in their dialect and abandon “slang.” They tell us that braids, twist, dreads, plaits, and afros are not a professional outlook on what capitalism defines as being professionally marketable.

If our women’s rumps are not full, and her hair is not kinked up then she is not the true representation of being black. This stereotype is a misconception of black love. They move so boldly away from our obvious reality, to define what they think our reality is.

She will go bald and showcase that globe of knowledge and legacy

Her hair may stand free and natural to give us a time portal back to our beginning

She may wear her hair straight and long flowing to intensify the beauty that is overlooked

Her hair may be atheistically twist, braided, corn rolled, dreaded to intertwine and clasp onto our true identity

Our black man may wear his pants low with a rim of underwear Does this state whether or not he has great character? What is truly being gangster, thuggish, gutter, or ghetto?

Williams / 63

Are not all black people raised in different settings that profile a smoother or rougher brilliance?

If a man chooses to say “dat” rather than “that,” does this mean he is less intelligent than you are I?

If he decides to wear a Malcolm X shirt down a city street rather than Hollister, is he truly acting like a communist or “homebased terrorist?”

People let us grab onto the light. Some shall say that God granted us daylight. Some say some scientific reasoning, Buddha, or maybe Prometheus? Wherever you stand in your beliefs, which possibly stand in the black arena, let us find self love through self awareness.

Ashley Schreckengast

The walls all take on the same tone anymore. Some stiff sort of white, sterile and soaked in such a sullen aftertaste.

Uncertain of my barriers, these limbs have often longed to break out. Stretch. Stretch these lines drawn around me so I bleed… a blotch of color I’m suspended as. Somewhere, my breath lingers longing to hug air and blend into the wind among the other words of knowledge we’ve long forgotten. But speech is but a bubble trapped in the fluid of my present lifespan. Childhood is but a shell. The solid that makes surviving obtainable. It curtained off a window to the violence that resulted in me. I am but a captured chaos. Cells multiplying, combining, and forming to spread the branches of society. The society of oculars has formed mentally.

Schreckengast / 65

And my physical blindness is but a peak to my sight. Somewhere, my hand pushes against a sanity that incubates me. A door handle shakes, the wood splinters around the hinges somehow crudely opening a door as the hard exterior cracks. A woman stands before me and with an electric flash produces my identity. Gute morgen.

Achtzehn Jahre und schließlich lebend.*

*Good morning. Eighteen years and finally living.

Daniel Baker

I think the slain care little whether they sleep or rise again —Aeschylus

They sleep in hills and holes, in earthen cells, in capsules of stone. Captives, detained in deterioration by those they once walked with, those they loved. There are some, with fetid flesh that teems with worms, fed by their rotting corpse; these are the newly dead, and the reek of their afterbirth still is draped about them. There are others, whose parched and brittle frame has lain so long within the soil that there is little left but a forlorn echo of remembrance in the hollow of their skull, consoled wholly by warmth like winter’s breath.

The deceased are caught in a perpetual dream; when I dream I hear their murmurs on the storm, frail yet unyielding, like many minor waters mounting a flood. The words are unintelligible; they worry me, reverberating with remorse and misery. They are moaned laments for love, for loathe, for lives unfulfilled. A shrill plea shocks the ear above the many whispers; it can be heard in the roll of the waves, in the beat of the rain, in the rustle of the forest, insistently in urges, “do not forget.”

Baker / 67

In truth, the dead do not beseech the living. Numbed from drinking the waters of Lethe, they now drift on tides of oblivion, not troubled by hopes, doubts and divinities. This hushed, voiceless speech is mine, and it reaches a scream with the death of every day. I think, too soon, I may be number among them: nameless shadows. It is brevity…do not forget.

*First place, James and Christian LaRoche Memorial Poetry Contest, 2007

Shannon E. Horning

He ran his hand through his short, fuzzy black hair. He wasn’t sure if she would like his new hair-do. The “Fasten Seatbelt” sign flickered off as the airplane jerked to a stop at the gate. He could feel the sweat pool forming between the pectoral muscles of his chest dribble down to his navel as he shifted in his seat. He straightened his light brown tie, just a nervous gesture because he knew it was perfectly in place. He twirled the colorful pins on his uniform out of nervousness. He fished for his Chapstick and applied some to his cracked, sun burnt lips. He hoped she wouldn’t mind too much when they kissed again.

“Fifteen months, four days, eleven hours, and twenty…” he glanced at his watch, “…six minutes since I had to watch her silhouette walk down that terminal, through those gates and out of sight,” he thought to himself heatedly, as he remembered the final boarding call reluctantly pulling him towards the attendant who accepted his ticket and shooed him down the corridor.

She was the bulk of all his thoughts during his miserable stay in Iraq. When he tried to escape from his life as a marine, alone at night in that desert with the sounds of patrolling vehicles and endless rioting filling the streets, migrating towards his room like cannon balls into the hollow cells of an abandoned beehive, it was she who soothed his anxieties enough to catch a few hours’ rest so to be able to succumb to another day beneath the merciless, penetrating sun.

As he slept, he dreamt of their one bedroom apartment with her silly daisy stickers on the front door. Inside, he saw the endless piles of knick-knacks stacked high on every level surface she could find. Pictures of her original photography hung in their living room, along with his ridiculous Rocky posters hanging proudly right next to them.

“Everything of yours matters to me, and everything is equally beautiful in our home, sweet babe,” she had told him

Horning / 69

He would follow the hazy dream images as she worked on overdue papers and make-up exams, playing her favorite Ryan Adams album loud enough to fill up the empty, unoccupied space he had created when he left her. He saw her fiddling with his dog tag that she wore around her long, elegant neck as she eyed the simple stone that rested on top of her ring finger amorously.

He savored these images. She kept him focused and centered and she sincerely saved him from many nights of threatening terrors and raging anxieties. He had maintained his sanity and was now coming home to prove it to her.

He gathered his things as the other travelers made their way out of the stuffy plane and out towards their own destinations. He straightened his brown tie again and popped an orange-flavored Tic-Tac between his teeth. He hoped she would like his new haircut. He knew she would.

/ Blackwater Review when he asked if he could tack them up. And he knew she truly believed that.

Rob Morada

I have her. She doesn’t know it yet, but she’s mine. I can tell from the way she runs her finger along the lip of her drink; game over.

The club is one of those generic pre-packaged clubs that women seem to go nuts over. They have a second rate band playing second rate cover songs, trading out every hour with what has to be the most unoriginal DJ in the history of clubs. I guess that’s something; at least something about the place is A-list. The place is just now starting to empty. They should be calling last call any minute now, and not a moment too soon because if I have to hear “I‘m In Love With A Stripper” one more time, I think I‘m gonna be in love with playing in traffic.

The girl’s name is Emily. She’s pretty, in an I-want-tosleep-with-her kind of way. Shoulder length hair the color of the cherry wood bar top in front of us, tight little body covered in an outfit that looks like it was painted on, and a dash of freckles across a perfect face is definitely a recipe to catch my attention.

We’ve been here a good three hours now, drinking and dancing. Guys get drinking, but dancing; dancing is one of those things that most guys just don’t get, and I don’t get what’s so hard to understand. It’s the quickest route from point A, the club, to point B, her bed. It‘s not even hard. For the most part you just have to stand there like a statue while the girl dances around you.

“One more,” she says in a light voice. The kind of voice that says she doesn’t have a care in the world.

“I don’t know. I mean you‘re already putty in my hands,” I answer, letting my most disarming smile play across my lips.

“Come on. Please,” she says, letting an exaggerated sad puppy dog look take over her face.

“All right.” I lean over to whisper in her ear. The light perfume she’s wearing is now tinged with a hint of Crown Royal.

“You know if you were a booger, I’d pick you first.”

Morada / 71

This causes her to lean back and erupt in the biggest surge of giggles yet. The movement is almost too much for her, and she has to grab the bar to regain her balance. Watching her is almost enough to make the whole thing feel less than sporting. I mean, I could have gotten her into bed dead sober; this just makes it too easy.

“What?” she asks when she notices me smiling at her.

“Nothing.”

“No what?” She lays her hand on mine.

“Just thinking that we’ve been here for a few hours now, and between the band and the DJ, we must have heard a few dozen songs. And not a single one has been anywhere near as perfect or pretty as you laughing.”

Her smile gets a little bigger, and she turns a little red. Her other hand moves down to rest on my knee.

“It’s a little late. You wanna get out of here?” she says.

As we walk out to my car, she’s leaning on me with her head on my shoulder; her two hands intertwined with one of mine. My car stands out pretty well in the parking lot; it’s a bright yellow Corvette, just washed and waxed this morning. To be honest the only time I ever bother washing it is before a date.

I lead her around to the passenger side to open her door, and she stops to kiss me. I have this steadfast belief that at some point in high school girls are required to take Sloppy Drunk Kissing 101; they sit around in class, probably sometime between gym and lunch, get all hammered and make out. Emily does nothing to dissuade me of it.

The drive back to her place is filled with the sound of her skimming through my MP3 player prattling on about who she loves and who she hates. Her hand is attached to mine as if by Super Glue.

We get to her building, and I walk her up to her doorperfect gentlemen. I even have the good taste to act surprised when she invites me in.

A funny thought flits across my mind as she works to unlock the door. It’s about that old wise tale of how monsters can hurt you only if you invite them into your home.

I met Emily at the supermarket where I do most of my

shopping. She was in line behind me. I had a basket full of Chef Boyardee Raviolis. I love the damn things, have since I was a kid. Growing up, they were dinner almost every night. Mom always made sure that there was something in the house I could make for myself.

“So is that like from Atkins or something?” she said to me. Confidence attracts me to women more than anything else. Not just any confidence either, but the confidence that can come only from the beautiful, from those who have always had everything handed to them. Nothing makes me go all gooey more than banging a hottie who thinks she can get whatever she wants.

“What? Pre-processed beef and fake meat sauce. Atkins has nothing on the Chef.”

Now one thing that I know more than anything else in this world is that a first conversation with a girl is like a Kung Fu showdown. There are kicks, blocks, dodges, and punches. You always have to stay one step ahead and not let them outmaneuver you.

“Oh, I see. Thus the incredible shape he’s in.” She throws a jab from the left.

“Hey, round. Best shape there is. Anything good is round– donuts, cakes, pies.” Block with my right, throw a left of my own.

“Well, aren’t you the hypocrite. I mean,”– She looks me up and down –“you don’t exactly look like you subscribe to that theory.” Interesting. She decides to duck and surprise me with a leg sweep.

“Don’t be fooled. Underneath is a fat man just crying to get out.” I almost get knocked down but manage to recover.

“I’m Emily,” she says, kicking high, looking for a weakness.

I shake her hand. It’s smooth and cool to the touch, no ring.

“Josh.” We slowly circle each other, our battle far from over. “So you critique your boyfriend’s diet like this.” I must be getting rusty. She saw that kick from a mile away.

“No boyfriend.” She just swats it away.

“So then you’ll go out with me Friday night,” I say, com-

Morada / 73

pletely surprising her with a roundhouse kick to the head. From the look of surprise on her face, I can tell it’s a hit, and I know the answer before she even says it.

It may seem very strange to ask a girl out within a minute of meeting her, but that’s why it worked. You see, most men believe there is some grand mystique to women. Women are actually painfully simple to figure out. They’re crazy. I know it may seem complicated, but really, there’s a simplicity to it that’s beautiful. They don’t know what they want, only that whatever it is, they have to have it. All you have to do is pick up certain clues and become something that they think they want. Because to get it, they’ll accept any amount of strangeness.

Emily was even worse. Just from the way she struck up a conversation with me, I could tell she was used to getting her way. Not many people flirt with a complete stranger out of nowhere--too high a fear of rejection. Girls like Emily don’t know rejection, so there was nothing to fear.

Friday night came and I was surprised to find myself in a part of town that wasn’t exactly home to the pillars of the community. Broken glass on the ground and a few abandoned buildings, the background of my childhood and memories of busted knuckles and bloody noses. What was a girl like Emily doing living here? A place like this beats you down pretty quick. No way the confident girl I met at the grocery store was from here. Emily answered the door on the first knock, and from the quick view of the interior of her place, I had my answer. Nice furniture, neat; it seemed little Emily was a poor little rich girl slumming it up, maybe so that years from now she could tell herself she knew how the other half lived for a few months. She was all smiles as we walked down to my car. As I leaned over to open her door for her, it was easy to see why. It seemed she had started the party a little early. She was scented with a slight touch a Crown; anyone else would never had noticed. Maybe she just felt the need to loosen up a little bit before a date, or then again maybe my first instinct of her being a party girl was dead on. I didn’t give it much thought because the smell of it, like the apartment building, sent me

74 / Blackwater Review

back a few years, back to thoughts of Mom.

I come from a small town. One just big enough to have a poor part, and just small enough where everyone knew the more colorful characters in the town. My mother was one of these colorful characters. I must have been seven or eight when I found out just how colorful.

My whole life up until that point was normal, well, at least normal to me. Looking back it’s kind of funny how I used to think everyone’s mom got visited by the same men from town every week. I don’t know what was going through my head every time Mr. Sam, Casey, Jim, Jake, Larry, Bob, and “insert name here” came over to visit for an hour or so; I had grown up with it, so to me it was normal. Then came the day I got sent home from school early. A few of the older kids decided to give me a little higher education.

Mom picked me up from school in the only car we ever had, a beat up, rust colored Beetle. Her eyes were red and that smell clung to the car, Crown Royal. We got home and walked up the steps to our small apartment, and as soon as we got in, she started weeping. I didn’t know what I did that made her so upset, so I said the only thing that came to mind.

“Sorry, Mom.”

“For what, baby?” she said, wiping her eyes.

“I don’t know….fighting?”

“No, sweetheart,” she said, wrapping her arms around me. The red wool of her sweater was rough, and I could feel it scratching my cheek. “You didn’t do nothing wrong.”

I could feel her warm tears running down the side of my face.

“So what did those kids say to you today?” She didn’t say those little shits or fuckers, like most would say in that situation; she said kids. My entire life I can’t remember a single time my mom cussed in front of me.