Tami Ailster

Isabelle Alegria

Dominique Boyer

Yvonne

Mercedes

Monique Espinosa

Tiana Fontejon

CONTRIBUTORS

Tami Ailster

Isabelle Alegria

Dominique Boyer

Yvonne

Mercedes

Monique Espinosa

Tiana Fontejon

Volume 19, No. 1 Spring 2021

Niceville, Florida

Blackwater Review aims to encourage student writing, student art, and intellectual and creative life at Northwest Florida State College by providing a showcase for meritorious work.

Managing Editor:

Dr. Vickie Hunt

Prose Editor:

Dr. Jon W. Brooks

Poetry Editor: Amy Riddell, MFA

Art Direction, Graphic Design, and Photography:

Benjamin Gillham, MFA

Editorial Advisory Board:

Dr. Beverly Holmes, Dr. Christopher Snellgrove, Dr. Anne Southard

April Leake, Dr. David Simmons, and Dr. Jill White

Art Advisory Board:

Yvonne Christine, MFA, Benjamin Gillham, MFA, J. Wren Supak, MFA, MA, Leigh Westman, MFA

Blackwater Review is published annually at Northwest Florida State College and is funded by the college. All selections published in this issue are the work of students; they do not necessarily reflect the views of members of the administration, faculty, staff, District Board of Trustees, or Foundation Board of Northwest Florida State College.

©2021 Northwest Florida State College. All rights are owned by the authors of the selections. Front cover artwork: Dark Café, Hannah Schloemp

The editors and staff extend their sincere appreciation to Northwest Florida State College President Dr. Devin Stephenson, Dr. Deidre Price, and Dr. Robyn Strickland for their support of Blackwater Review.

We are also grateful to Frederic LaRoche, sponsor of the James and Christian LaRoche Distinguished Endowed Teaching Chair in Poetry and Literature, which funds the annual James and Christian LaRoche Memorial Poetry Contest, whose winner is included in this issue.

We would also like to acknowledge the gift from the estate of James P. Chitwood, whose generosity helps fund prizes for select student writers.

Fiona Morris

Weren’t always sunny, but I preferred the fearful sky as it was an excuse to sit inside with you. I remember the stormy days most. You’d tell your best stories when the wind howled louder than your own thoughts. I’m surprised you heard them.

The rain continued to tap dance on the tin roof as you made ice cubes out of Coca Cola and I sipped on my orange soda while checking on your tomato vines. They never grew after you passed. And the summers in the screen room are as dull as your aged shed tools.

First Place, James and Christian LaRoche Memorial Poetry Contest, 2021

Shane McLeese

My heart is a sea, Deep and sometimes Unforgiving. Dark Waters bottomless. The sandy beaches, My friendly and warm Outer edges welcome You, gifting you joy and Peace and a palatable Torrent of waves in Which you can play. But to see my real and Vast beauty you must Learn to keep your Stomach in check. Seasickness will not do. And you will Learn to keep upright And steady in the storms That sometimes rage, Otherwise I will swallow You whole. Your ship Must be built on Fortitude And patience and You need to Understand the charts Written in the Stars to truly Manifest your Destiny with me. But under the

Surface and far from Land I contain Multitudes. My truths Are kelp forests My fears, the great White sharks that Ceaselessly hunt. My love for you is Water that swirls And crashes And provides A home for the Itch you feel in Your feet And adventure Drumming in Your heart.

Ella Joslin

i

He was on the cusp of life as light as lemon meringue blonde sunshine cupped the gleaming ball He made the bat sing

ii

we’d’ve rechristened apple pie mt. rushmore and the boston sox howled no way, columbus day our boy deserves your holiday

hallowe’en would’ve seen twenty-odd sprouts in their green got up like David of the Game going at Goliath

hero, hero! holy rollers head and shoulders like the wind winner, winner chicken dinner demigod in dusty skin

like a tiger burning bright He made the stands glow gold all night what a wonder under eighteen up and at em, fight—fight

our summers passed by on parade like lost and drifting kites

He was It, All, Everything in photographs of Him mid-swing with perfect poise and concentration coronation of the Baseball King

Ella Joslin

Frenzy Grace you spent your days hazily grazing on dud conversational cuds dull eyelashes

flapping over intelligent pupils

vapid dreck drizzled on your bedcover wet your feet froze your toes but all the while thrashed a rose through the itching rash

twitching worms of housewifery swarmed in your ear warming their wings in your hollow head drum like moths of fear but mingling in the murk nibbling at the needlework was something queer he dumbly couldn’t figure or finger

until one day you snapped

grasped the hatchet—hacked through the im—mac—u—late morass he mired you in one chop for each day you stayed in the den paid admission into plays of opinion or stood pinioned as he pissed toxicity down your drain in the name of justice

Frenzy Grace you didn’t flounder fall with a splat! on your face or splutter like a fish before it’s gutted your soul flew through your new prison

like a butterfly in an invisible prism

Wallace McCarty

She drifts, as she likes to do sometimes, soaring down the dim, endless corridors, past loose wires, mazes of pipes, and sealed-off hatches and doors behind which she will never know what lies. Her hair curls upwards, or whatever direction that is, and too often she has to brush it out of her face every time she changes direction. At the end of the dark hall is a sterile light acting as a beacon so she doesn’t get lost like she used to. Darting through the final stretch, she gracefully lands on the door, the porthole revealing the glorious beacon inside, and she punches in the code without taking her eyes off it.

The last functioning console, a flickering white void, illuminates the dead space along with the light of dying stars outside the windshield. Binary beeps from computers and the ever-present buzz from the life-support systems keep the room from being desolate, along with the occasional creaking from the ship’s hull, which at this point seems entirely normal.

With the pull of a lever, she lands back on her feet, disoriented, and stumbles into the chair in front of the heavenly light. The screen turns to black as she logs on, and a daunting white circle slowly rotates as she tries to stop herself from impatiently fidgeting with the array of buttons and switches spanning the board.

RSS Almayer - Console 4

The white circle seems to chase itself around slower than ever. It’s the same looping pixelated animation, over and over again.

Running Server Diagnosis…

She bounces her elbow on her knee, cracking her knuckles on her chin.

Connecting to Almayer Server…

Piercing through the chest of her jumpsuit, it’s as if her heart is trying to punch its way out, thumping louder than the trembling heels of her boots on the metal floor panels.

It almost bursts out. She sinks her face in-between her knees, curling up into the fetal position as the screen blinks a too familiar message.

No Connection for:

45 Days

A lonely weep joins the symphony of rumbling and chirping machines, and they quickly begin to die down and click off as the console screen dims.

Possible Solution(s):

She ignores the final prompt and jams the red button on the side of the console, leaving the room dark. Wiping the streaks from her face, she takes a longing stare out the window at what she must face. Amongst it all is a pale blue dot, which she knows where to find in the array of constellations by heart now, drifting with several other faint reminders of home. It looks almost the same as it did from when she’d go camping, the peaking Appalachians guiding the eye up to a vast heaven. Back when she was surrounded by friends, heck, back when she was surrounded by anybody. Nights huddled around a flickering orange fire, illuminating the shadowed pine trees and laughing faces. She loved to point out all the figures in the sky, return to her notes, and assign her friends’ readings about their day and future trajectories. The only faces she can still see from those affectionate nights now are Aries and Leo. Those adventurous late-night hikes with beloved familiar faces could sometimes turn treacherous when there was no moon and their flashlights had all died, and as she did whenever the universe came to tell her she had failed, she would curl into a ball and look up, waiting for something that’d catch her eye. The sky those nights was a splash of cosmic glitter, dazzling in the brilliant streaks of the galaxy’s spiral arms. A beacon that could lead her back home, she would draw a line between the Big Dipper and connect it to Polaris, finding almost true north, much to the amazement of her friends who never took her weird fascination with zodiacs and star signs seriously. It’s no surprise she’s still looking at the stars, just never thought it

would be this close, for this long. They’re everything she loves, and have become so much of what she fears. And now, without standing on that pale blue dot for reference, her trajectory is completely vague.

“Antennae realignment” are haunting words in the books of star sailors. For the first time, she puts the glass bubble over her head and feels it click with the magnetic ring around her neck, and just as she had practiced every day since she was set adrift, she succumbs to the forces of gravity, or lack thereof, and jets out into the abyss. There’s complete silence except for the heavy breathing of a fledgling space-walker. She had not seen the exterior of her vessel since beginning her voyage, and now it sits there unanchored, dark and astray.

Nervously throttling bursts of gas from her backpack, she attempts to maneuver herself above the satellite dish, which is facing away from home as it had been for 45 days and counting. Her heart is once again trying to escape, and every inch she gets closer to her target it threatens to leap out of her pressurized suit and into the unforgiving vacuum.

She aims for the circular port on the back of the dish, the connecting plug outreached in her hand, all the while juggling with the sensitive throttle. An aerial ballet of precision; her numb limbs and trembling hands don’t make it any easier. Doesn’t even realize she’s forgetting to breathe, something that’s not taken for granted out here. She lets out a final exasperated gasp once the jack clicks into its place, and she anxiously tries to keep herself from drifting off, which could potentially rip the plug out of the socket. A beep followed by radio static comes over her coms as she realizes an absence of a live frequency with any signs of voices she had long forgotten.

She looks to the stars, and amongst the familiar constellations and friends, she finds it: that pale, barely blue, speck of dust suspended in a sunbeam. Home. Grabbing the dish, which spans the entire length of her arms, she thrusts it to face the beacon and scans the radio one last time. Something begins to echo under the static, and trying not to scream herself, she hears a voice.

Carter Hyde

This isn’t your story to tell–It’s mine–

But like the shape shifter, I’ll take your name, face, and place anyways.

And so, for the sake of this not-so-brief introduction, you are the Protagonist, as untrue as this may be–

For, indeed, you will be untrue.

You will read this poem with one eye covered. Go on. Do it. It’s how you really see the world.

Direct your attention (direct your perception) so that this poem encompasses your line of vision. Nothing else exists, and I am a God.

You may as well be too.

The others do not exist. The space around you does not exist. The person behind you does not exist–

But don’t look, for looking truly will ruin the illusion and break the spell; is your hand still covering your eye?

Put it back.

Perspective, dearest Audience, is everything.

Circumstance and Coincidence make up everything–

cannot be trusted to tell any tale that isn’t tall– and so the story you protagonise (/antagonise)(/agonise)(you don’t recognise it but) it’s told by them.

You are insecure.

Paranoid. Resourceful, yes, but what do you use them for? To idolise another? A lover?

You are the Protagonist, but your motive is weak, your conflict is all in your head. It’ll be your downfall someday.

You are the Narrator, but like your virtues, your vices, my literary devices we are unreliable.

Tiana Fontejon

The bell suddenly rang as I was startled awake. While I packed up my binder and pencils, I rubbed my eyes and tried to remember what we had talked about in class. My ninth grade English teacher had just droned on and on for an hour about To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee. She was spouting something about the overarching theme of prejudice, and she had unknowingly put me to sleep. As I walked out of the classroom toward biology, I started to question why I thought the class was so boring. Most of the other kids participated in the discussion, so it was not just my teacher’s fault. Why was I lacking in enthusiasm? Did I hate To Kill A Mockingbird, or did I hate reading in general? I only knew that I had stopped reading entirely.

In the fourth grade, my teacher held a read-at-lunch program, where someone’s mom would come to lunch and read to a small group of students. My read-at-lunch day was Wednesday, which just so happened to be Mrs. French. Coined by all the kids, she was the energetic “cool mom,” with bright red hair and a wide smile. She chose to read her favorite book, The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster. Every week I was on the edge of my seat when I listened to her read the book. I loved the world building of the different kingdoms, and I wished that I could travel inside the book and see the story firsthand. At the time, this response was the case for almost every book I read. Even if it was nonfiction, I loved to soak in all the words in the book. As a freshman in high school, however, books lost their novelty.

After my junior high years, books did not seem interesting or exciting anymore. They were just assignments I had in English class. I avoided the library because it was too quiet, and I ignored my mom’s book recommendations. I had somehow lost my love of reading. I thought that I had grown out of it, not

unlike a pair of socks or eyeglasses. I rarely saw many adults reading books, so I took it as a sign of maturity. This conclusion ruled my mind for two years until the coronavirus hit.

The virus took the world by storm. Restaurants, schools, and businesses closed. I was forced to stay home and avoid contact with other people. My volleyball tournaments, academic team practices, and test deadlines suddenly disappeared. I had nothing to do at home besides staring at the wall. In order to cure my boredom, I picked up a book and started to read. Suddenly, I had an interest in the storyline and characters. After I finished a book, I would excitedly tell my mom, “Then there was a plot twist! I would’ve never guessed!” I began to read more and more books. I even started to check out books on my Kindle and read e-books. I cried when my favorite characters died, and I cheered when the main couple in the book started to date. I realized that I had stopped reading because I had no time on my hands. I could not focus on the storyline of a book if I was in the middle of a loud volleyball tournament, and I rarely picked up a book because I had more important assignments to do. Because my life got busier, I stopped focusing on books.

Now that the quarantine has ended, my life is filled with schoolwork and volleyball games again. However, unlike previous years, I focus on my reading alongside my other work. Even if I have a big volleyball game or a history essay due the next day, I take some time to get a few pages in. Reading is important to me because it makes me happy, and it gives me a way to escape from my stressful life. Although I read more advanced books than The Phantom Tollbooth, I now carry the same excitement I had in fourth grade. Recently, I reread To Kill a Mockingbird, and now I understand why my teacher was so enthusiastic.

Wallace McCarty

It’s a five-legged desk that I carved From a fair but simple slab of soft Wood, which I bought at that eerie Lumberyard hidden off the main road.

The wry man there, whose stench hinted at a life Encompassed by circular saws and cigarettes, Sneered as I fumbled and jostled the plank Into the back of my dainty little car.

Just as I crafted it to do, it sits there, Its shape like the clean curve between Your pointer finger and thumb when You make a neat little arrow or pistol, Settling nice and flush with the wall In my corner by the window.

The natural, earthy brown tones And warm, woody scent complements The timber shelves of books and records, Black and white cult movie posters, Some weeding plants I forgot to water, And candid photos of friends on film Pinned up on a cluttered cork board.

Fiona Morris

Dad’s half of the summer was spent stuffed in the back of his pickup truck. I don’t remember the exact model, but it sort of looked like a 1995 Ford F-150, all white with a blue stripe down the side. The inside was completely gray. It had some kind of uncomfortable fabric that I won’t even begin to describe. The ceiling of the vehicle was falling apart because my dad would put his cigarettes out against it. I always used to see if I could stick all my little fingers through the burnt spots with one hand. There were too many holes, and I couldn’t stretch my fingers out far enough, so I never won my own game.

No matter how long we’d dust off our feet, sand always somehow managed to cling to the floorboards. We were cautious about this because we hated his lectures about the sandy floorboards and despised having to vacuum out his truck after such fun trips to the springs and whatnot. I remember paying extra attention before I’d enter the truck, always showing dad just how clean my feet were before I got in. I wanted him to see I cared about him, that I cared about his feelings and his truck, too. No little girl ever wants to upset her father; that’s a no brainer.

Though he’d strive for a clean interior, it was usually the outside of his truck that was the messiest. Orange dirt coated the sides of it as he’d fly down those muddy roads, speeding from his thoughts and concerns for the children he was supposedly watching over. Dead bugs joined our every adventure as they stuck to the grill of the truck. I guess he liked that because he never asked us to clean them off. Dad collected more bugs as we continued to drive down these unnamed paths. I’d argue we grew up on these lonely grounds more than at our trailer house, knees bouncing against each other involuntarily on the sweaty Sundays before dad had to go back to work.

Trip after trip, the seating arrangement never changed.

Elias, who is two years older than I, always sat up front with Dad, dreamily looking out the window. He was tall for twelve years old and had a full head of soft brown hair that was hardly brushed but never tangled. I sat behind him and would poke him whenever I missed his smile. I always loved the way his wired frames would rise against his freckled nose when he’d crinkle his face up at me. Laiken sat beside me on my left, and sometimes she’d poke him, too. We were similar in height despite her being three years younger, but we were easily distinguishable. As opposed to my dark hair and brown eyes, she had crazy blonde curls and bright blue jewels on each side of her face. I loved her like she was related to me by blood, but Laiken and the boy next to her, Jaden, were my step siblings. Jaden had dark curly hair like me and was a chubby kid, an easy target for assholes to pick on because he wasn’t the most confident kid either.

My dad was one of those assholes. His excuse was that he was an ex-Marine, but last time I checked, not all ex-Marines bullied their kids for the hell of it. Dad is probably around 6’3”. He usually has a scowl on his face, and it doesn’t compliment his bald head or the tattoos that litter his body. He has always been a big, scary, and intimidating man my whole life. Dad really still was that high school bully that loved having people fear and obey him. It’s always been like that, and I know he will never change.

The road was extra bumpy that day, so Laiken and I smashed our shoulders together repeatedly. Dad was taking me and my siblings out to Niceville. We were excited to spend another summer day in the cold water, though anxious because of his quiet disposition. We didn’t question it when he lit another cigarette and turned down an unfamiliar road. I thought we were going to Turkey Creek, as we usually did if we didn’t go to the springs, but this was not that route. So I asked where we were going.

“Just a different side of it. All leads to the same place,” he replied, taking a drag and pushing it back out the cracked window.

It all leads to the same place.

When we arrived, there were no other cars in the gravel parking lot. Just dark, overgrown trees and with vinery displayed on the bushes surrounding the entrance to the water. I watched as mosquitos flew around the green and listened carefully to the flowing water and singing birds. I was already comfortable, even in this unfamiliar place. Laiken, who was seven at the time, rushed out of the car with excitement. Jaden and I had to be around ten, and we weren’t far behind her. Dad tossed his smoke to the ground, not even bothering to stomp it out as he trailed at his own pace down to the water.

I danced to the end of the dock, light footsteps searching for any bit of shade on the wood. Elias was bringing down the cooler, and Jaden had the bag with the towels in it. I walked to the end of the long stretch and placed my hands on my hips before digging out a wedgie. The sun slapped across my face the longer I stood there, unmoving. It really was a warm day. One of those days where if there was water in front of you, you were in it, no matter how scary it might’ve looked. And I remember vividly how fast that stream was. Constantly rushing, pulling forward random pieces of wood; it was far from inviting. The water was a dirty brown, and you couldn’t see how deep it was from a first glance. My adolescent mind told me there were thousands of snakes beneath my feet, and a handful of gators was also somehow in this creek water. I still lived with no fear at this time, and I held onto the hope that my dad would help me if something were to happen.

Jaden, Elias, and I were already great at swimming, so we’d jump in to cool off our tanned skin. We all focused against the current and reached for the metal handles against the dock, pulling ourselves up only to do it all over again. It must’ve been over an hour we were out there before I realized Laiken hadn’t touched the water once. She was sitting at the top corner of the dock, mindlessly chewing on the plastic cap to a Kool-Aid Jammers. If Laiken was scared of something, there was no use in trying to convince her otherwise because she’d pinch her ears shut until you stopped talking. This is only expected from a

seven year old. She said the water looked moldy, and we laughed. If she didn’t want to go in because she was uncomfortable, she shouldn’t have to, right?

Wrong.

“That’s ridiculous,” he said, marching toward her. “It’s fine, c’mon.” With outstretched arms, my dad towered above her, commanding her to get up. Her only reaction was to wrap her tiny arms around the wooden fence, shaking her head. It was a “blink and you miss” scenario. One second she’s cradling the dock, and the next she’s in his strong arms, wiggling aggressively as he brings her to the end of the pier. He shouted, “Shut up and stop squirming,” somehow smirking at her struggling. And with one easy toss, Laiken was submerged into the cold water of the creek.

I think we were all laughing at her, following Dad’s words and repeating, “See? It isn’t too bad! See?” She was laughing with us at first, even with her baby teeth clattering from the temperature now surrounding her. Laiken was holding a steady spot in the water, keeping her legs kicking back and forth as fast as she could, maybe trying to prove that she could do it. But the instant she tried to swim against the current to climb back up was the moment she lost trust in herself. The water grabbed onto her ankles and easily dragged her weightless body along the creek, unexpectedly taking her out of our field of vision. I stopped laughing as soon as I heard her cry out for help. Quickly whipping my head back at my dad, I pointed to her and noticed he was still chuckling into his hand. How could he laugh?

“Daddy, are you gonna go help her?” I hate to admit that there was already fear in my voice as well. I had no idea how far the stream had taken Laiken, but I heard her crying out for someone to get her. And since Dad was too busy giggling to answer me or help my sister, I did the only thing I could think of: jump in and save her.

The second I saw Laiken’s tiny hand gripping a protruding tree and her horrified face, I began crying as well. It was too deep for her to touch, and her anxieties were yanking her

head down into murk repeatedly. I’d watch her cry above the water, then feel the vibrations of her screams when her head was dunked in it. I wanted to say something to relax her, to keep her from thrashing around so much. But the moment I reached her, frantic Laiken was climbing on top of me like a monkey and accidentally pushing me under the water, too. While underwater with the child on my head, I tried fighting the current. I really swam as hard as I could, kicking my legs like this was the last day I’d ever have them. I knew I had to stay calm for her; I had to be the big sister and pull her back to the dock. Despite my best efforts, I became just a buoy for her to cling to, and my crying was only heard by the snakes and gators looming beneath my purple painted toes.

Above the water, dad was belittling Laiken as I held onto a slimy stick that was poking from the ground. “Let go! Don’t be so damn stupid; just let the current take you. Let go already! You’re just makin’ it worse!” Her fingernails only dug into my scalp harder, and her chest weighed my torso down. I heard her sobbing that she was going to die, and that set a whole new panic in me. If Laiken was going to die even with me as a lifesaver, then I would surely die first. I couldn’t see anything when my eyes shot open--only bits of sand and dirt were entering my vision now. This was too much. My lungs felt like they were wringing out any bit of air like a wet towel. It was too hard to breathe. One hand slipped off the slimey stick and wrapped around my throat. I squeezed my skin, flailing my legs and digging my nails into the wood even tighter. I didn’t want to do this, but I had to let go of the stick completely and pull my poor little Laiken off me.

I heard her resilient screams. Those were what hurt me the most.

“N-N-NO! NO, F-FI-FIFI, S-S-S-ST-STOP!”

I needed air. I had to.

“PUH-LEEZ, ONA! D-DON’T!”

I had to climb on top of her. Just for a second. One second was all I needed!

“FIFI-”

So I submerged Laiken, using my hands to shove her back down forcefully so I could boost myself to the sky. I started choking instantly, sniffling and taking the loudest gasps for air I knew I ever had. I was so relieved to breathe, and the first time I tried to scream for my dad, no sound came out.

“DAD-EE!” I remember sobbing. It was so pathetic. So fucking pathetic. “H-H-HELP ME!”

“Just swim, Fiona! Shut up and stop crying; you’re fine.” His words were becoming meaningless to me, and I suddenly couldn’t hear. Everything looked blurry, but I figured it was from the shit in my eye. Why hadn’t he jumped in? What happened to my dad being my hero? How could he sit there and watch his two little girls scream, cry, and drown one another? We were terrified, and it was funny. We were being dramatic, but this was life threatening. We were his little girls. Why hadn’t he jumped in?

“It all leads to the same place. Let the current take you!” No matter what he said, I felt no hope. I didn’t trust his words. I learned not to after ten years. My body was so exhausted that my eyes slid shut easily, slamming like garage doors once I allowed them to. It was even becoming difficult to keep Laiken below me; she was still moving so much. Oh my god, Laiken! I awoke from my daze to feel her squirming. I was going to kill her, my own sister. I was the only one trying to help her, but I was about to drown her. I released Laiken and yanked her back up by her armpits. She coughed all over my face, and I wished I had enough energy to tell her I was sorry. I gasped for air once more, understanding that it was my turn to hold my breath again. And as she dunked me this time, I felt something else enter the water with me.

I felt his fingers wrap around my wrist and tug. I knew my dad wouldn’t let me drown; I really did. Laiken had fallen off

me and was holding onto my free hand as tightly as she could, flailing her legs like crazy again as we were being saved. I didn’t know if she was boosting us or not, but the moment my head came back out of the water and my eyes adjusted, I was greeted by a surprise. My dad wasn’t the one who saved me; he was still on the dock, hands on hips. It was Elias who was pulling us with all his might. My bubba. And he had a stern expression, mouth sewn shut and minimal grunts being made as he swung us hard enough to reach the metal handles on the dock’s side. I had never seen him make that face before, and I might not ever see it again. Lifelessly, we climbed up with noodle-like arms, helping one another back to the burning platform.

I remember collapsing, smushing my face against the wood. It was scalding my body, but to be on stable ground felt so good. I figured Laiken would have been lying beside me, but she coughed, cried, and crawled all the way back up the ramp to her corner. Jaden was there, sitting with a heavy heart and his arm locked around the fence. He didn’t want to be thrown in like she had, but he immediately comforted his sister after she had arrived. Jaden made sure to lock her in the corner, and I watched as he put a protective arm around her and hid her from my father.

I was paralyzed, silently shivering and hiccupping as my wet and boney shoulders bumped against Laiken’s on the ride home. She held onto Jaden’s hand, and I held onto my own, pretending it was bubba’s. It was silent, and I don’t remember if I was grateful for that or not. Elias stared out the window. Dad lit another cigarette. As I looked down, my lips trembled once I noticed the amount of grime and dirt I had just brought into the truck. I knew better. My feet were coated still, and my toes curled against my bruised rubber flip flops. I shut my eyes and started to cry, unable to hold back the stinging tears. I didn’t brush the sand off my feet that day, and I never have since.

Turn a Blind Eye

Photograph

Ella Joslin

July killed my hot fudge urge

Emperor Sherbet, shape some shining dirge

Of maraschino words plus milk curds

To shimmy off the heat

I want a deadbeat

Dreamboat float

Bananas foster sugarboat to fight the cloistered coat

That foists its hot self on me

Whip cream

To seem like a swirly sunbeam

How nice

To whirl in a vanilla-ice vortex

Curl my tongue in slurps and sips

As silky as pink ladies’ slips

Studded nutty silly putty

Push off that bitch heat pushup pops

Carter Hyde

The old gods of the South called together a meeting in a steakhouse parking lot. (I know this sounds like the beginning of a bad joke. The worst part is it doesn’t end.)

Humidity cried summer rain onto the pavement. Humility patted her shoulder and said, “Bless your heart.” The Heat glared at all of them. Over her sunglasses, the Church glared at a couple passing by. The fireworks started then, and the one we don’t name pulled up in a Ford truck. Everyone paused and turned. The one we don’t name, as much the land as the land is his, fills our silence with a war cry, pulls out a flag and a gun. Bless our hearts indeed.

Jason Knaebel

A stoic man, my father has been deployed to combat six times, suffered a broken back, and endured more emotional agony than any man I know (from which I will spare you the details). Growing up, my older brother Jon and I made sure to steer clear of our dad unless we needed permission to open a box of Zebra Cakes or to go play with the neighbors. However, when we were stationed in State Center, Iowa, from 2003 to 2005, Jon and I were almost bursting at the seams every weekend that Dad would say, “Better get some sleep; we’re waking up early to head to the Drop Zone.”

The Dropzone, or DZ, is “the term [skydivers] use to describe a skydiving center”(“How”). At a minimum, it consists of a large open field dissected by a runway, adorned with a few airplane hangars where jumpers don their parachutes, load into airplanes, and climb to 14,000 feet to parachute back down to the ground. The reason Jon and I were always so happy to come here was the fact that the Drop Zone was the only place that my mother, my brother, and I could see dad relaxed, cheerful, and smiling. When we would visit, it was a weekend trip. Every day, Jon and I would ride our bikes or jump on the trampoline until our mom would shout to us, “Boys, get over here; your dad’s about to jump!”

After that we would all crane our necks to the sky and watch his black, pink, and blue striped canopy twirl and turn amongst the other jumpers, descending to the DZ. Once his feet met the ground followed by his canopy, he would walk back to us with a devilish grin from ear to ear and hug all three of us. That would happen on repeat for the majority of the weekend, and once the weekend was through, the merriment would die down again and leave me pondering a question that I was always too timid to ask. Why does he only seem happy when he skydives?

I never received an answer to that question until July 10, 2020, fifteen years later in Fort Bragg, North Carolina. I had been in the Army for four years at this point and was only one month from separating and becoming a civilian. Meanwhile, my brother Jon had been skydiving for six years and was urging me to get my skydiving certification. I was apprehensive about spending $3,400 for the course, but I weighed my options and bit the bullet. Once the money was out of my pocket and the lessons began, my apprehension disappeared. I spent one day in a wind tunnel, where I learned how to maneuver in 120 mileper-hour winds by arching, or putting my “pelvis forward while arching my back with [my] chin high”(“Skydiving”). I spent the next day in a classroom learning the mechanics of a parachute, how to operate my equipment, and how to correct every type of malfunction. The third day I was ready for my first solo qualification jump.

I arrived early that morning so I could be the first student to jump. I ensured my equipment was operational, donned it, and began rehearsals with my instructor, Dusty. Once the plane was ready, we loaded into it and climbed to 13,500 feet. I planted myself in the small door, gave Dusty a nod, took one step to the left, and fell.

During my freefall, amongst the roaring wind and my adrenaline overload, all I could focus on was how safe my altitude was, corrections to maintain my stability, and when I needed to pull my parachute. There was no time for anything else. Once I reached back and threw the spherical ripcord connected to my parachute, the canopy unraveled and transformed my rapid descent into a blissful, weightless float above a landscape so vast I could see the curvature of the Earth.

While I basked in the glory of the moment, I had an epiphany. My father, like most adrenaline junkies, doesn’t skydive for the sole purpose of adrenaline. He jumps for what the adrenaline provides. Freefall provides him, and now myself, with an experience of life and death that is so extreme and exciting that it leaves us no time to dwell on the past or stress about the present. Afterwards, once we are afloat under

the canopy, the release of oxytocin floods our body from the adrenaline and provides a high that can only be described as heavenly. We don’t just skydive for fun; we skydive to escape the world and have our heads in the clouds for a little while. An experience like that will put a smile on even my dad’s face.

Works Cited

“How to Research a Dropzone.” Skydive Paraclete XP Raeford, NC. skydiveparacletexp.com. Accessed 10 Sept. 2020.

“Skydiving Tips for Beginners: The Arch.” Skydive! Carolina. skydivecarolina.com. Accessed 10 Sept. 2020.

Knaebel • 59

Fiona Morris

“I’ll be there, I’ll be there.”

With a heavy heart and an even heavier foot, Miguel repeated these words like a mantra. The steering wheel felt foreign in his brown, cracked hands. He rolled his tongue over the roof of his mouth, tasting the blood that he stole from his chewed fingertips. It was a familiar taste. Nail fragments were edged between the crooks of his teeth, and he had given up trying to remove them. He swallowed the saliva that pooled in his mouth, and his throat stung from vomiting earlier. Miguel’s vision was blurred--from the tears, from the rain, from the alcohol. From the imaginative visions that she would be okay.

He was driving the 2000 Oldsmobile Bravada, and it smelled like her, his mother, who was currently in bed, smothered in white sheets, surrounded by people in white, and secured in the white room. That was no way to die, without your son by your side, kissing your cheek, squeezing your fragile palm.

“I’ll be there, I’ll be there.”

The hospital was still twenty-two minutes away, but Miguel was determined to make it there in three. His whole life, Mamá was there for him; not once could he recall waiting on her. And now twenty-nine years later, she’s waiting for him at her most precious time. His father would say, “hijo típico,” typical son. Miguel could hear his father now, moaning from the grave. Spitting out of his busted lips, the young man found himself repeating, “t-typical Miguel, typical Miguel…” He said this until it lost its meaning, and he ignored that his voice sounded just like his father’s.

Swerving through the eleven p.m. traffic, Miguel rolled down both windows and screamed at the noisy world. Nobody heard, but the Earth still responded with bullets of rain punching his sorrow-ridden face. The rain replaced the tears

as he shut his tired eyes, fingers still gripping around the leather wheel like they were trying to break something, maybe themselves.

As the water sprayed against his face, Miguel pictured his mother teaching him how to drive in this car. He listened to the rattling of his unbuckled belt against the door, recalling all the missed turns and curbs he’d ridden over. There was something about that memory and the tempo of the belt that forced him to shut his eyes with a sigh, and he allowed it.

The second of darkness displayed when he closed them felt peaceful. Somehow, this wiped his worries for an instant, and the void of his mind felt more comforting than the black of the road ahead. He shuddered in the silence, letting it coat his body and weigh him down into the cracked leather seat like a thick tar might. His sudden humming matched the noise of his mother’s old car, and his fingers loosened for a moment as he leaned to the right. The disheveled young man almost fell asleep, but it was all brutally interrupted by another driver slamming on her horn, alerting Miguel that he was drifting into her lane. Típico.

A sharp breath was pulled from his trembling lips, and he shot up immediately, taking a few heartbeats to remember where he was, what he was doing. The tires made a disgusting screech as he pulled back to his side of the road, blinking at the other driver before pressing on the gas harder. The bottle rattled in the cup holder; it was half empty. Miguel didn’t want to be seen, but he halted at the illuminating red light ahead, coming neck and neck with the one who had honked at him.

“You okay, man? You need to get off the road?” The stranger shouted. She waited for a reply that never came before hollering, “You alright, man? Ay, I’m talkin’ to you! You been all over the road tonight!” The woman chuckled as if it were funny, and that laugh was sickeningly sweet.

Before Miguel could consider replying, his eyes and ears were pulled to the floorboard of the passenger seat. His phone began to dance against the stained rug, the generic Samsung ringtone singing obnoxiously loud. At this moment, he paid no

mind to the woman wanting to help, and in a rush he unbuckled and lunged for the device. His fragile fingers fumbled with the phone as it was dressed from the fresh rain that snuck in through the window. The man’s breathing was already labored, fear and pure regret filling his soul as the car behind him flashed its brights and beeped the horn. Miguel shared a final look with the woman to his right before answering the call, pounding his foot against the gas as quickly as possible.

A voice boomed from the speaker. “Miguel! Where are you!? We’ve been-”

“I’ll be there; I’ll be there!” He knew his brother’s voice anywhere. That harsh bite that every word had. That unsettling tone that had become all too familiar.

“-and I bet you’re still at that damn bar! No, don’t make any fucking excuses this time! You knew! You KNEW!”

With each word he screamed, Miguel found himself driving faster. The windshield wipers’ rhythmic thumping against the glass matched the beat of his frantic heart. It seemed to never slow down, and the rain kept up with the pace.

“I’m trying, mi hermano!” He sobbed, lifting a hand to dig his knuckles into his dead eyes. He was ready to wake up from this nightmare, ready to be a good son for his mother. “I-I’m- II’ll be th-”

“Miguel, you shouldn’t come- just- you just shouldn’t fucking come. Do you really want mamá’s last memory to be of you like this?”

Miguel made a sharp turn, whining out for his mother, but losing sight of the road. Suddenly, he completely lost handling on the wheel. The heavy vehicle lost its traction on the flooded roads the moment his cracked phone slipped from his shaking hands. His brother was still shouting as the car hopped a curb and collided with a tree. The crash was abrupt. Miguel was flung aggressively through the glass, shutting his eyes as his beaten body tumbled roughly down the ditch. His heartbeat finally learned to slow.

When Miguel opened his eyes, it was an older man who brought him off the ground. As the familiar calloused hand wrapped around his, the man mumbled hijo típico and pressed

a kiss against his temple. Miguel couldn’t look at him; his eyes were stuck on his mother, standing beautifully, still in white. Fearfully, he blinked and stepped forward, a pitiful sob breaking from his smiling lips, “Mamá, mi amor, did I make it?”

Carter Hyde

The butterfly struggles in the spider’s web, wings fluttering like manic arms, scales flooding the ground in nine-lives clumps

You, unsuspecting you, wield a stick as a pocket-knife, and you, with two-dimensional eyes, cut it free from its restraints.

It flies off none the wiser, lazily, injured, better for it. You waltz off none the wiser and get ready for work.

Somewhere, a spider is furious. Venom seeps from its maw like a river’s torrent-it runs to the earth and spreads like a plague. The outer crust shudders and groans, in Red Sea waves, mud is displaced,

and somewhere, silently, a world crashes and burns.

Forgive me, Father, a sinner am I: my shirt is of two fabrics and at my unclean time shelter did not find me.

My apologies, Father: my weak and bloody knees did not fall into the sticky, elitist pews of your House. Call it unacceptable, but in the bright white room, her gentle hand stroked the sweaty hair from my pale face.

Mea Culpa, Father: the silk lays immodestly upon my skin, rainbows oozing grotesquely from every pore.

Forgive me, Father: I know her lips drip with honey, and in the cold, her cheeks are as red as the blood spilled over these rules about the pureness of our clothes and whom we can love.

Ella Joslin

my sapphic sunday was in close contrast to those you checked acceptable in starched frocks standup collars and clean-cut buttoned-up lips

in odgay’s gold dog bowl puke up crewcut dollars cuz old pro Piety demands your soul plus tax (in coins) uplift in righteous harmony the loins of every member quick a green buck fans the embers of your prim shoepolish flame

but your colorless chorus of christian excuses which oozes over hallelujahs cringing under smiles on fake faces poked into place by samaritan syringes does not compare to the silent song of my loving lips

i came from the island far from your studebakers serial sockhops and ice cream socials where woMan worshippers fear to steer off the path of plain vanilla

while you inserted gingerly gloved fingers in the inanimate folds of a hollow tome, i loved a living thrush flush and hallowed by the prayers of my tongue

Aaron Halbrook

To cast blame on you was like blacking the sun out with my thumb. It was pointless, temporary, and though my eyes stopped hurting, I still saw the luminescent glow on the outer reaches of my fingernail.

As I lay in the lawn, I think of all the tennis games we’d play

On blood-splattered clay courts with my heart as the ball, Still beating with each strike from our racquets. Your hits were hard and mine were feeble, And I scolded you for your blows

But soon realized I provided means for the game.

This was a gentleman’s sport, but you carried no gentleness. Your shots were aces and mine were double faults, Or at least that’s what you’d convince yourself of.

When I’d win our rallies, your face burned white hot, Like embers on a dying hearth, Eager for retaliation and desperate to regain jurisdiction Over the points awarded justly to me.

By the end of each match, I stood behind the baseline, Watching as you waved to nonexistent crowds, Screaming your own name in pleasure and Adjusting the collar of your polo to flash the bit of Chest hair that hadn’t left with your age or arrogance.

As I stood on the green blue of the court, I reasoned that I wouldn’t be level there

If I hadn’t served myself to you first.

Though I’d started this game, I was elated to finish it.

Even in your self-proclaimed victory, I was still the better player.

Wallace McCarty

A romanticized legacy Hides his true character.

Leathery skin, cigarette hanging From his steady, chapped lips, Stoic and silent, probably because There’s no one out here he can talk to.

Or maybe it’s that he lacks the vocabulary To tell you what’s really on his mind. In that regard he truly is a “man’s man.”

Hiding how fragile he is, And taking all the day’s hits, Never complaining.

What he yearns for is someone Who’ll wait for his return.

Someone who’ll stay up all night

Just to talk, to help guide him through The emotions he’s never expressed, Or even knew he had.

It’s their compassionate touch, Not an outlaw’s punch to his face, That would shatter him to pieces.

So he rides alone into the sunset, Maybe with a partner in crime Or some tied-up bounty, But never with a friend or a lover.

Carter Hyde

Man is born in an unmade bed and christened in refrigerator lights. He is created by morning commutes and peanut butter jelly sandwiches.

Humanity is found at man’s lowest. Humanity is found looking bloated and basking in a television screen heavy headed and dormant, domestic.

It is found in a nose scrunched, offended at the smell of sulfur at a bus stop. It is found frustrated in a lover’s dispute, an argument over nothing.

Oh, we would love to be mighty and bright, would love to be the Milky Way’s center. We would love to be the force around which the planets revolve, roaring like the sun.

Can you not see those stars from the gutter?

Fiona Morris

The sky is filled with raging clouds that I can’t ignore and their smokey effect will hypnotize my tired eyes. I wish to be inside, but the storm’s strong scent, mixed with the field’s ripe strawberries, will beg me to begin my day. So the raindrops kiss my skin as I march to the vast field, picking buckets cradled safely in my arms like newborns.

Although it’s four in the morning, my brown, stained knees will smooch the moist muck and I’ll get to work. This daunting task consumes me. Filling one bucket, then four, then six, then eleven. Only three hours have passed and yet my body aches for a break. Until my eyes land on my uncle, with over forty years between us, he works harder than anyone I know.

Suddenly, I find my motivation lies in one man. It was he who planted these seeds, which grew and I picked. From his hands, to mine, to the truck, to your dish.

Carter Hyde

i.

Dearest Dionysus, lord of the beer keg, adorned with a wreath of plastic grapes, show me a way through these sweat-drenched rooms and the endless maze of emptied, hallowed halls.

O blooming one, let me get laid, man or woman, it matters not for I have Dionysian sums of love to give, and I am sick of my cold, empty mattress.

ii.

O Dionysus, patron saint of the speaker the ones who sing (sting) of many a party before, you, the thunder beneath her platform boots, the woozy backlash of an awful dance,

show me a way, God, show me away. Show me, host of the volatile bacchanal, out of the bender–o please, goat-killer.

To you I offer this half-empty bottle and the burn in my throat when I puke up my guts. O Dionysus, let me go.

Joshua Vaughn

It was a fittingly cold and damp night. Seattle had never given anyone much cause to expect something different this late in the fall, but the bitterness of the cold sat particularly deep in me that night. From across the street, I stood and watched for a moment. Sgt. Pepper’s is one of about a dozen gay bars near Cal Anderson Park. Perfectly innocuous for this meetup, and perfectly quiet for my own peace of mind. Something sat low in my stomach as I made my way across the street. A feeling that is almost always identified too late.

The building looked more like a pub than a bar if that makes sense. It was housed in an old storefront with a bay window with the entrance recessed beside it. I crossed the street, j-walked in fact, straight up to the door. When I opened it, what first hit me was the warmth. It penetrated my coat almost instantly and made me forget the ache in my bones from the cold. There were tables stretching on the left side back towards the bathrooms, and the bar itself occupied the right wall. There was a microphone setup in the bay of the window, no doubt for the livelier nights at Sgt. Pepper’s. The only thing separating this bar from most others was the small TV mounted above the microphone playing reruns of Full House instead of the Seahawks game. That, and the fact that the bartender was a burly leather-clad gentleman with black sunglasses and a black patent-leather peaked cap. I made eye contact with the other patron of the establishment, a middle-aged man sitting at one of the tables towards the back. He nodded with a small smirk and lifted his drink.

I found my feet firmly planted in the doorway, until the gravelly voice of the bartender beckoned me in. “What are you waiting for,” he said, “a formal invitation?”

“No, I-” I paused as I walked towards the stool on the front end of the bar. “I was just looking around. I guess you’re

the sergeant?” I sat, noticing the medicinal boozy and fruity smell of the bar, like a liquor store. More pleasant than the stale smell of sticky beer in most other bars I had been to.

“I only bust out the uniform on Sundays. Lord’s day and all.” He smiled, polishing a rocks glass. I gave a small laugh, not really thinking about what he said. “Can I get you anything?” He asked with a warm tenor.

“Screwdriver?” I squinted my eyes and lifted the word, as if he might not know what I was talking about. One move after another, I felt more and more awkward. He must not have noticed, since he put down the glass he just dried so thoroughly and got to work.

“Some occasion or are we just starting the night right?” he asked.

“I’m just waiting on someone.”

“Sounds like fun.” He finished the drink with a splash of grenadine, so it sat like a film on top, and set it in front of me.

“Have I seen you in here before?”

“No, first time in here.” I looked at the neon sign above the back of the bar, one of three supplying the light in the establishment. A red thigh high boot about four feet across, laying sideways above the top shelf liquors. “But I like your décor.”

“Thanks, we got Stella from a drag bar’s liquidation auction. Ms. Hunny B. comes in sometimes and tells people a story about when that boot fell on her during karaoke performance and she didn’t skip a beat.”

“Sounds like fun.” I said, maybe too dryly.

“It’s funnier when she’s here to tell it.”

I sat and sipped on my drink, watching Full House in silence as the bartender wiped off the clean counter. It was the one where DJ is trying to lose weight before a pool party, so she starves herself and works out neurotically.

“What time is he supposed to meet you?” The bartender asked out of nowhere.

“What makes you think I’m meeting a guy?” I said, and that is where I really showed my ass. The man at the table,

Vaughn • 73

whom I had forgotten about completely, had an audible chuckle at my response.

“If I thought you were meeting a girl, I’d be asking ‘why here’ not ‘what time?’”

“Well. it’s supposed to be nine.”

“She cute?” he asked, already knowing the answer.

“He is,” I said between sips.

“Must be if you’re willing to show up twenty minutes early to meet him.” No small amount of satisfaction in his voice.

“Do you talk to everyone who comes through here like this?” I asked defensively.

“Only when it’s slow,” he said, “and only when it looks like someone could use good conversation.” I am still unsure what exactly about my demeanor signaled I could use a good conversation, but I assume he saw something in my face that was instantly recognizable to him and few others.

“Well I appreciate it, but I’ve got plenty on my mind,” I said.

“Care to share? I’ve got nothing but time right now.” I did not usually appreciate prying, but he was right. We had time. What was one consequence free, completely honest chat with a stranger who has doubtlessly seen more desperate cases than I was?

“A little slow for a Sunday night, isn’t it?” Changing the subject.

“Give it time. Not many real adults frequent the night life around here, and not many young adults come out before nine.” There was a breath in the conversation, finally, so I took another sip and noticed the first half of my drink seemed to have disappeared.

My eyes were drawn to the neon sign hanging in the window, facing the street. It was a bright yellow rose with blue leaves. Even though it was facing away, the coldest range of its light spilled backwards into the bar. The last light in the bar, apart from the ceiling lights that would not come on until close, was a rainbow running horizontally along the back wall above the bathroom door.

“Aesthetics in here are a little confusing, but people don’t generally care,” said the sergeant. I looked at him, and I said what he seemed to have guessed.

“I have a girlfriend. Fiancée, actually,” I said, with regret.

“I had a wife once upon a time,” he said, and I looked at him with raised eyebrows, but the nonplus nature of my expression was not new to him. “How do you feel about this fiancée?”

“I’d rather not talk about her.” The feeling in my stomach made its presence known again. I drank and drank again.

“Clearly. Would you rather hear about my problems, then? Get the feeling you could learn from them.” He said this like I did not know the nature and gravity of my situation, and he was right.

I finished my drink and slid the empty glass forward. “Can I get a Long Island?” He turned, working the magic of a booze therapist. At this point, I knew I would not be entirely lucid by the time my meetup got there, and that was probably for the best. He turned around with a short-stemmed glass and set it in front of me. He dropped a pink paper umbrella in my drink with a straw and a lemon wedge.

“Delicious.” I said after my first eager sip. “So, you had a wife?”

“I did. Loved her too. And our kid,” he said, one hand mindlessly wiping his side of the bar. “She’s a great woman, and she deserved better than me. Truth be told I always knew I wasn’t straight, but I came up in the ’80s. In suburban Ohio. It seemed a lot easier for me to couple up with a girl I liked, fake my way through everything and just not talk about how hot I found Uncle Joey.” He paused, looking up at John Stamos’s character on the television.

“He has a lot going for him,” I said.

“Hm, yeah. So did Margery. We were friends in high school, and then when it was so critical that I explore who I am, I just ignored it. We dated, had awful sex, and got married after college. Being young and busy, the first several years of our relationship were easy. We didn’t focus on each other that much. Then she got pregnant, and I was genuinely happy.

Having a kid would have me committed to something, keep me grounded. Plus I thought it would be good for me and her to have something real between us.” I thought about my fiancée, thought about our future kids, the same ones I thought about when I proposed. I drank.

“Take it that didn’t work out?” I ask stupid questions when I drink.

He chuckled and said, “It did for about six years after George, our son, was born. We were happy to talk about him, his future, and not so much the distance we found between us. We were still plenty busy; we were successful in our own careers. She was a real estate and travel agent, while I was a corporate accountant, believe it or not. We had our own two story 4 bed 3½ bath house and a puppy to boot. Plenty to do instead of talk. Never went far from the suburbs of Cincinnati, except for the odd family wedding or weekend getaway.”

It sounded like the dream life, normalcy, and he guessed my thoughts. “I’m sure it sounds picturesque, but every meal, every car ride, every time we were together, it was just awkward. There was a wedge; it was growing, and we were both hurting from it. And I was the one putting us through it, by not being honest with myself and her. Mags was my best friend, but she needed me to be a husband, and I couldn’t be available like that as long as my sexuality was gnawing at me.”

“She’s my best friend too, my fiancée.” I said, noticing as I blinked slow and staggered, that I was a bit drunk. So, I drank more.

“Things only get worse if you keep sneaking around, meeting guys at dead bars. You might think she doesn’t know you cheat, but they always do, or she at least feels something’s not right,” he said. I wanted to defend myself, having just been called a cheater, but we both knew I could not. “Things were at their worst for me when I acted on my repressed self because then in secret I thought I could have both worlds. I thought I could be with men I’m attracted to and spare a woman I really loved.” He paused for a minute as he leaned back against the bench behind him and folded his arms across his chest. “There

was this guy. His name was Danny; he worked in IT at my company, and we started hanging out at lunch first. Then he made one move, and I jumped on it. I liked the guy, liked how he made me feel, except for the guilt.” That is what it was; the feeling hanging low in my guts was guilt.

“Did Danny know you were married?” I asked, glad to still be the one doing the prying.

“I never hid my ring from him, but we never talked about it. He only brought it up once, towards the end. Just a sec.” The bartender walked down the bar and tapped another beer for the guy at the table. He washed out the old glass and set it upside down on the rack of glasses above the bar. He walked back towards me tentatively, just as a small group of people walked in and down the bar. He went over and made three different cocktails I did not recognize. I looked up at the clock above the door, 8:50. I could have left and cancelled on the guy, but instead I cancelled on the guy by text and stayed, hoping he would not show up anyway.

As the bartender walked back over, he smiled at me and grabbed a rocks glass. He poured himself straight whiskey, the nice kind, and had a sip before saying, “Figure if we’re going to keep talking like this I’d better catch up.” I laughed, a little too loud, and the guys at the other end of the bar looked at me for a second too long.

“Ah don’t worry about them, a few regulars that always start their crawl here,” he said reassuringly.

I shifted a bit in my stool and straightened up to take a semi-sobering deep breath in. A lot of good it did. “Can I please get some water?”

“Coming right up.”

“Where was I?” he asked as he put the dewy glass of water in front of me, “Right. After I’d been seeing Danny for about eight months, Margery took notice. Late worknights, being really defensive, no libido… she knew. She just assumed I was with a woman. Our office administrator was a helpful, kind, plain ditsy girl who met my wife at all the parties. My wife, apparently, first took notice when in conversation about our

Vaughn • 77

anniversary plans she said, ‘All the good ones are gay or taken,’ or something to that effect. I swore up and down that nothing was wrong; I wasn’t fooling around, and I didn’t love another woman. I wanted to take her away somewhere, just us. We were going to go on a trip to a couple’s resort in Bermuda. We both liked the brochure, but Mags agreed without expression. She knew I was just placating her or attempting to. Band-Aids on bullet holes.

“We were already packed, getting ready to leave the next day, when we had our last fight. We yelled at each other until she just cried and said, ‘Just take your whore; I don’t want to go anywhere with you.’ I was hurt, even though I had no right to be, but I felt hurt, and I left with my luggage and proved her right. I changed the names on the reservation and brought the tickets to Danny, who was ecstatic for the surprise trip. I felt so scummy at that moment.” The bartender took a drink. “But not too scummy to quit.”

I drank down the iced tea, ignoring the water. He drank again, nearly half finished with the four-ounce pour, and I said, “Does the owner know you drink while you work?”

“Hahaha, that’s a good one. I happen to own the place. Besides, night is young, this’ll wear off by the time the real crowds roll in.” He rolled the amber liquid around in the glass and put it down. “Anyhow, Danny and I had a lovely time in paradise. Well, I tried to match his enthusiasm, but over the course of four days I realized I had made a huge mistake. He was alright with dating a married man, and I didn’t love him. Also that I was a real piece of shit for how this was unfolding, and especially for my audacity in trying to fly away and forget about the extreme hurt I’d just inflicted on my wife and child.” At the same time, the episode of Full House got to the part where DJ passes out at the gym after starving herself and making her friend keep her secret. It was ironic to both of us, and funny as hell from the booze.

“When I got back home,” he continued, “after trying to call from the airport, I realized she’d done what I feared and what I can’t blame her for doing. She left with George, to her

mother’s house an hour away. I called her for days until she finally answered. All she said was, ‘I don’t care what you have to say; we haven’t been in love in a long time, and you’ve made your priorities clear.’ All I could say to her was ‘I’m sorry,’ and she hung up. I didn’t see her again without a lawyer around, which made the coming out part really awkward. After she said in deposition I was with another woman, I felt the uncontrollable urge to say ‘I’m gay.’ She was stunned as the lawyers scribbled furiously. Things were more amicable after that, thankfully, not that I deserved it from her. She was really classy about the whole ‘identity crisis’ aspect of my infidelity. It made custody sharing with George considerably more pleasant that Margery always had a determination to be the bigger person.”

I got the feeling he knew what I wanted to ask, but the man sitting at the table walked up to the bar and called the owner over to close him out. He dropped some bills in the tip jar and left, nodding to me and saying, “Hope things turn out upright for you, kid.” Me too, I thought, but that depended on me, and I knew it.

“What happened wi-”

“Danny wasn’t very happy with me when I told him I was ‘grateful for the time we had, but I feel differently about myself now, and I need work and time to grow before I’m deserving of someone like you.’ You know the speech.” He cringed at the recollection of his own words. “Been basically single ever since, ‘working on myself.’”

“That’s not reassuring,” I said, leaning over my drink.

“That was my choice, to stay in the ‘dating phase’ permanently. You might not find that you’re better for yourself than you are for someone else. But you won’t know until you’re honest with yourself, and your best friend.” I had a different feeling in my stomach when he said that, like butterflies. I was hopeful that I could have what he was talking about. As deep as I was into my bullshit, that I could have a ‘come to Jesus’ and live a fulfilling life afterwards was just too sweet.

“Hey, it’s five past; your guy should be here by now,” he said looking at the clock.

“Don’t think he’s coming,” I said looking at my drink.

“Think he’s standing you up?”

“I think I called it off,” I said.

“Glad to know my conversation alone can keep you seated,” he said, smirking.

“More like your drinks keeping me seated,” I said, “but the conversation’s been really grounding, too.”

“Thought it’d do you good to hear it.”

“I hope so,” I said, sipping at the water. “Can I get the bill?”

“Sure thing,” he said, “come back and see us sometime.”

He slid the ticket across the bar, and it was blank.

I assured him with a silent nod and smile that I would be back, dropped a 20 note at my spot, and walked out in a slight stupor. The door opened faster than I intended, and all at once the warmth of Sgt. Pepper’s was washed off me in a sudden biting cold wind. My next breath brought both clarity and dread as the dead chill filled my lungs, and I knew that the next conversation with my girlfriend would be a difficult one.

Kathryn Leaver

I am from milkshakes on hot days, The cold condensation dripping down the glass onto my hand, Chilling my skin leaving its freezing trail behind. I am from castles upon hills and winding roads. I am from the tall oak tree in the backyard, The rusted swing set under its boughs. I am from music playing through my earbuds Drowning out the daily fights.

I am born from love turned hatred through the years, A phoenix rising from the ashes

Of leftover words spilt out from their piercing tongues, Lost happiness between role models. I am from tears running down my face Leaving its hot tracks on my cheeks.

That day was the day I never really thought would happen. My clothes were laid out over my bed, limp and flat, waiting for me to put them on and in doing so, admit that he had died. I stood in front of my bedroom mirror in my black pants and my pretty shirt, the shirt with pale pink silk covered by black lace, a single black cloth button at the nape of my neck. Later I would cut my pretty shirt into pieces with an anger I didn’t understand, stuffing the jagged, shredded lace and silk scraps into the kitchen trash can, but I would keep the black button for years to come.

On the car ride to the church, there was no conversation, just heaviness. It was a cold November day, and bleak grey light came from the sun, which hung in the sky hidden by wispy clouds. The cream-colored leather of my mom’s back seat was smooth, but I sat hunched against the window, my breath creating fog clouds on the cold glass. Glancing over to the driver’s seat, I saw my father’s big hands on the steering wheel. My father, who stood six foot two, was a man whom I had seen cry for the second time in my life a few months ago, when my parents told my brother and me that our uncle had been diagnosed with cancer. There are certain things from my childhood I’ll never forget, and seeing my father cry is one of them. I twisted the strand of pearls around my neck, the pearls I had been saving for my wedding day. The world was shaping into a strange place.

The church was old and plain, nestled in the heart of a neighborhood. The surrounding houses were small and old, with brown lawns wrapped in bent wire fencing, with BEWARE OF DOG signs hanging from most of them. The broad, cracked cement steps of the church were cold, a satisfying grey that added to the greyness of the day. People congregated outside the doors, shaking hands, hugging, and talking about his

widow, about his children, about the fact that Thanksgiving would be next week and there would be an empty chair at the table. None of them had faces. They spoke with the same voice, and they were all smudges of black in the dull church scene. There was a single black bird perched on a power line all alone, and he cocked his head at me silently. He understood that grief takes all your air.

My aunt was inside talking with the pastor, her black dress hung on her frail shoulders showing the toll the stress had taken. Her young, pretty face now the face of a single mother, the face of a widow. People began to take their seats in the long wood pews with worn red cushioning. The inside of the church was covered in bright red carpeting that showed its age with stains and bald spots, matching the cushions. At the back of the church there were red carpeted steps that opened to a sort of stage, with a podium for the Bible and a black piano. Today there was a table with a fancy cloth and clusters of arranged soft yellow roses and an urn. Pamphlets were handed out with my uncle’s face on the front, young and handsome, his name printed in bold important letters, and the words Celebration of Life. The year he was born and the year he died were also printed, separated by a small dash and only forty years. I would go home later and stuff the pamphlet in a dresser drawer, and I wouldn’t be able to look at it for a few years.

I sat in a wooden chair at the corner of the elevated stage, and my aunt stood behind the podium. She held pieces of printed paper in her hands, the eulogy she had written. My hands tightened around the arms of my chair until my fingertips turned white. My own eulogy, a couple of handwritten pieces of paper, rested in my lap. I looked out into the crowded pews. I saw my uncle’s parents who sat close together, his mother was crying, his father was still. For years after, at family functions I would see my uncle’s father, and the way he walked would catch my breath. He walked like my uncle, and like my uncle used to, he stood quietly with his hands in his pockets, in his face I could see my uncle’s face and see how my uncle should have aged. I saw my uncle’s three children, my little cousins,

small and beautiful in their tiny suits and black dress. They looked back at me with his eyes. They spoke with his voice. The youngest was only four years old, a coloring book and a couple crayons in his lap. They didn’t have a father anymore. When my aunt started to speak, my attention blurred, zoning in and out. Not like it did in geometry class, but in a sense of survival. I heard her when she laughed softly and told happy stories of my uncle, so I laughed too. I also heard her when her voice cracked, and although I could only see the back of her blonde head, I knew there were tears in her eyes. Tilting my head back, I looked up at the brown beams arching against the stark white ceiling, keeping my eyes up and the tears back. This was the ugliest church I’d ever seen, I thought, and I almost laughed. There was some ugly pale green imitation stone on the wall behind me that must have been nice in the 1970s. In front of me was a huge triangle shaped stained glass window. Waves of rich jewel toned glass, royal purple, emerald green, and deep blue gave the effect of sea tides, small fish clustered in the bottom corners. At the top was a golden crown with a ruby red cross through its center. Above the cross was a dove and a six-pointed star shining gold light. The dove stood out to me; it was alive somehow, and I got the feeling I was meant to see it, meant to feel the golden light like peace, shining through the emptiness of the grey day.

When my turn to speak came, my hands shook. I smoothed out my pieces of paper against the wood podium. My throat was tight. I was afraid to speak in public, but I was even more afraid to talk about my uncle, the pain that would come with it. I reminded myself why I wanted to do this, why this was important, and told myself that I was solid as stone, imagining my face sculpted in granite. My voice was soft at first, but as I read, I was carried back in time. Back to building Lego sets, unwrapping Christmas gifts. Back to cherry red snow cones vibrant against the soft ocean blues, a salty breeze mixed with childhood laughter. How my uncle played with us always, throwing my brother and cousins and me high in the air so we would splash into the pool water loudly. Building campfires that

flickered as sticky marshmallows roasted on cool fall nights, “This is what nights like this are made for’’ he would say. There was pain, but not the crushing kind. It was the kind of pain that comes with a doctor rebreaking a bone, hard and necessary. As I spoke, I cried, and people cried, too; they felt the sting of the pain in the joy of remembering, the joy that felt at first like salt in the wound, reminding us of what we had lost, and yet, how lucky we were to ever have had it.

After I spoke, I sat down in a pew with my parents and my little brother. A nervous looking pastor stood up and rambled on and on behind the podium. He kept adjusting his collar, and I got the impression he hadn’t done this before. He looked young. He kept reading random Bible verses Genesis to Revelation, all disjointed and disconnected. He was trying to fill the allotted time with other people’s words. I felt a strange surge of frustration at the injustice of all the things that should’ve been said and would not be.

Finally, the time came to stand; well, music played. I only remember one song. It was my aunt and uncle’s wedding song, “Wild Horses” by the Rolling Stones. It was soft, gentle, “wild, wild horses couldn’t drag me away…” I looked over and saw my aunt standing, holding tightly to the back of the pew in front of her, bent and fragile like a wilted flower. Her youngest child stood next to her. He looked up into her face, and his brow wrinkled as his eyes filled with the understanding of a man. He placed his hand on top of hers.

When the service ended, we mingled for a little while, hugging and squeezing hands with knowing eyes. My grandma gave me a handkerchief, soft white cotton embroidered with a delicate pink rose in the bottom corner. It was my great aunt’s. It would go home with me and live with the pamphlet, the button, and a dried yellow rose in the bottom of a dresser drawer. I hugged my aunt tightly; I could wrap my arms completely around her.

“He loved you so much,” she whispered.

“I love you,” I whispered back.

We filed out of the church doors and congregated again

on the grey steps. A sharp wind blew through, shaking the bare branches of the trees, stinging my eyes and cheeks. I held my Mom’s hand. I looked around and saw all the people I loved, people that loved me. Their faces, their voices, all gave me strength. I looked up and saw the black bird, still all alone on his power line. He spread his dark feathery wings, soft and silent like the wings of death, and flew away.

Ella Joslin

i

Alice looked like christmas when I saw her last

ii the boys used to be crazy ’bout Alice – “dig that girl” all week dug their heels in til she’d blitzspritz like a looong cool frisko flavored drink across the gym floor now-a-days louts lounge by on sundays capture her lonelys in butterfly nets if onlys don’t do you much good if you’re dragging in places you used to be tight as a drum

iii dum dum

Aliceidiot looked like a fool claimed kosher but no teetotaler – rover; life was over ’cause she totaled the t-bird whew – when He heard beat her blackblue

iv blanc et noir on le silver screen

Alice liked seeing them on the big thing – no Gable on cable “it just ain’t the same” – no sweat drips the size of buicks on tv

tinfoil lightning, soupcan thunder Alice wants an evening in Hollywould and when Doris starts singing, you betta letta she hums in her head “what will be” will be

v see Alice’s empty floor “where’s that girl gone to” maybe the isle of innisfree

Tami Ailster retired at age 48 and returned to college in 2018. She is seeking a bachelor’s degree in graphic arts.

Isabelle Alegria believes literature can provide a powerful message of strength and survival after devastating heartbreak.

Dominique Boyer plans to major in marine biology or zoology and hopes to tie her artistic skills to this future profession.

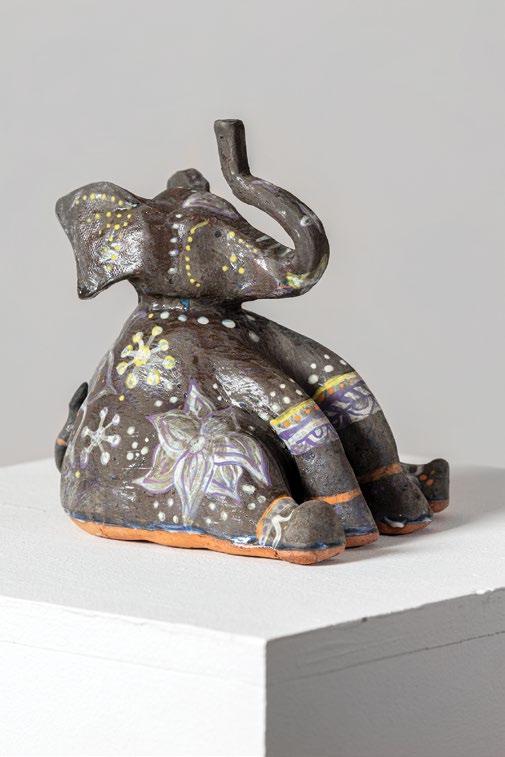

Yvonne Cabrera is a self-taught artist, who is finally pursuing an art degree at Northwest Florida State College. Her work consists of acrylic, sculptures, and mixed media.

Mercedes Damon is dual enrolled through Seacoast Collegiate High School.

Monique Espinosa is retired and pursuing a second career in graphic design, following a lifetime desire to work in the arts.