Isabelle

Isabelle

Volume 20, No. 1 Spring 2022

Niceville, Florida

Blackwater Review aims to encourage student writing, student art, and intellectual and creative life at Northwest Florida State College by providing a showcase for meritorious work.

Managing Editor: Dr. Vickie Hunt

Prose Editor:

Dr. Christopher Snellgrove

Poetry Editor:

Dr. Jessica Temple

Art Direction, Graphic Design, and Photography:

Benjamin Gillham, MFA

Editorial Advisory Board:

Dr. Beverly Holmes, Dr. Anne Southard, Dr. Robyn Strickland

April Leake, Dr. David Simmons, and Dr. Jill White

Art Advisory Board:

Benjamin Gillham, MFA, Lesha Porché, M.Arch, J. Wren Supak, MFA, MA

Blackwater Review is published annually at Northwest Florida State College and is funded by the college. All selections published in this issue are the work of students; they do not necessarily reflect the views of members of the administration, faculty, staff, District Board of Trustees, or Foundation Board of Northwest Florida State College.

©2022 Northwest Florida State College. All rights are owned by the authors of the selections.

The editors and staff extend their sincere appreciation to Northwest Florida State College President Dr. Devin Stephenson, Dr. Deidre Price, Dr. Dana Bigham Stephens, and Dr. Robyn Strickland for their support of Blackwater Review.

We are also grateful to Frederic LaRoche, sponsor of the James and Christian LaRoche Distinguished Endowed Teaching Chair in Poetry and Literature, which funds the annual James and Christian LaRoche Memorial Poetry Contest, whose winners are included in this issue.

We also would like to thank the estate of James P. Chitwood for funding the Editors’ Prizes, which the editorial staff awards for writing excellence.

This issue is dedicated to Dr. Jon Brooks and Professor Amy Riddell, whose dedication to quality and love of writing made them two of the finest editors Blackwater Review could ever hope for.

This year we celebrate the 20th issue of Blackwater Review by featuring cover art from our previous issues. We hope you enjoy this look back!

Isabelle Alegria

It’s the color of tombstones, of last words, of untimely goodbyes.

The color of spreading your ashes into steely sea waves, The regret of all the things I wanted to tell you but didn’t know how to say.

It’s the color of memories warped by time,

The injustice of feeling crisp details fading away.

It’s the color of the miracle that was supposed to save you, But never came.

First Place, James and Christian LaRoche Memorial Poetry Contest, 2022

Jared Smith

He won’t settle for a single costume. Today: Peter Pan, a ninja, and Hawkeye. He laughs like Ernie from Sesame Street, Less coarse, more bubbly, a gargled guffaw. His voice an innocent falsetto, singing Elton John; He’s obsessed with the artist because I am. He knocks endlessly, I hear quite clearly through my door, “Can you come play with me?” I do, at 7 a.m.

He’s enraptured by cemeteries and the deceased, This year he celebrates Año de los Muertos. He reads now, which I detest. He liked when I did voices.

No more will I pass out in that bottom bunk, His cold hand on my face, baby skin not shed yet. He laid in that crib, miniature and motionless, A vivid memory, I still hear “The Well-Tempered Clavier.”

I have loved him since I saw him first, I have not let go of that baby boy. Now, Exaggerated smiles, just two teeth missing, Show that he loves me back.

Second Place, James and Christian LaRoche Memorial Poetry Contest, 2022

McCaid Paul

“What can I do? She’s in so much pain.”

“We can help with that, but you’ll have to make the decision to sign the Do Not Resuscitate form. You’ve been hesitant to do that.”

When my dad didn’t reply, the man went on. “Her liver has failed, her kidneys have shut down, and she’s currently in congestive heart failure. There’s nothing else we can do but make her comfortable.”

I sat in the corner of the dim-lit hospital room, gripping the arms of my chair. The conversation between the man in scrubs and Dad had taken a turn for the worse. But so had the diminutive woman lying back in the large hospital bed, an IV attached to one of her purple-veined, arthritic hands. Her eyes were closed. She was asleep, for now, but I knew it wouldn’t be long before she tossed awake, wincing and mumbling about the pain.

I’d never seen a person die before, only heard about it. How a room hums with silence after, death so eerily quiet, until the body begins to make gurgling noises, trapped air releasing through the mouth and nose. I imagined it’d be the same for her, and, selfishly, I didn’t want to experience that; didn’t want to watch the woman who’d given out bone-crushing hugs to me through the years like candy succumb to nothing but a frail carcass of skin and bone.

It just didn’t seem fair. But watching my grandma writhe in bed day after day, not even capable of sitting up straight— the same woman who mastered the toughest Sudoku puzzles and liked her tea sweet enough to kill fruit flies—was proof enough that nothing about life is fair.

She was an American woman, the typical Grandma and KFC connoisseur all rolled into one. The woman who survived the Great Depression, World War II, rode to town in a wagon

as a young girl, and yet never owned a cellphone. The woman who talked about characters in Hallmark Christmas movies like they were real people. The woman whose grocery lists took Mom, Dad, and me combined to try and decipher, made mostly of items suitable for a teenage pothead: donuts, Snickers ice cream bars, Cheetos, Club Crackers, Oatmeal Creme Pies, Golden Grahams, and Dr. Pepper (by God, she was the poster granny for Dr. Pepper).

The woman who cheered for the Atlanta Braves every season. (They won the National League pennant the other day. I know she would’ve been proud.)

The woman who received the first copy of my book when it came out.

The woman who read said book with a magnifying glass held within a millimeter of her face, mumbling the words aloud to herself. Even though she could only read a chapter at a time due to her dry eyes, it was an honor knowing she cared enough to try.

A day or so after the conversation between Dad and Grandma’s doctor, we all gathered together in her little hospital room for one of the last times. My mother pulled me to the side and whispered, “Go tell your Grandma goodbye.”

And so, as my legs trembled and my throat tightened like it would close up, I crept to the edge of her bed and looked down at her. Her body trembled every few moments as she sucked down air, but her eyes were closed and her skin had yellowed. Carefully, I leaned down and kissed her snow-white hair, which felt as soft as cotton against my lips. At the touch, she didn’t stir like I expected; didn’t reach for my head to kiss me back.

It just didn’t seem fair.

The unconscious form in the bed was nothing like the spunky woman I used to know. In a way—though I felt great shame for thinking it—it was as if she were already gone. I remembered something I’d read once, how cancer patients are dead long before they die, and although she’d been fortunate enough to never experience such a thing, I knew the same applied for her.

I wasn’t there when she called out the names of her sisters and late husband in her sleep, dreaming of better days.

I wasn’t there when Dad gripped her hand and whispered, “Momma, when you wake up, you’ll be with Jesus.”

I wasn’t there when she died, but I heard it was silent and peaceful, though I’ve never thought of death that way.

I wasn’t there enough, and that’s something I’ll always regret.

But the other day, I stopped by her house and looked inside. It’s been two years since she passed, but I still expect to see her, smiling back at me from her dingy-red recliner, a sweaty can of Dr. Pepper in hand. I still expect her to ask how I’ve been doing and to please replace her half-empty soda can with a cold one from the fridge.

The other day, when I stepped across the threshold, I noticed both of my books propped atop the mantel. I opened them up, read the message I’d written inside nearly four years ago, and smiled to myself. One of the pages was still creased from where she left off. It almost made me cry.

Before I left, I grabbed a can of Dr. Pepper from the fridge, retraced my steps back to the living room, and stared at the books on the mantel far longer than I’d care to admit.

I remember thinking: That’s the greatest memorial you left me, right there on that shelf.

And there they’ll stay.

McCaid Paul

Oh, river, how I’ve missed you. Today, as I drove over Harrison Bridge, you were there, shining just below, gurgling and burbling and murmuring against the sandy-white banks.

I closed my eyes, just for a moment, and I could feel the sun’s warmth and the cool breeze kissing my skin, almost like I was there again.

Back in my father’s boat, a bream pole gripped in hand, anticipating the first nibble, that first chance of fate.

Even then, the weight on the end of the line felt like a promise, a secret both father and son shared, as you gave up your fish like an unselfish merchant.

This morning, peering down at your still surface, glistening like fish scales in the sun, I remembered your murky depths, your vastness, your tangled terrain, like a separate world, or some undiscovered domain.

And I remembered— the fingers of fog sneaking through leafy foliage, hovering like damp breath; the sweet and smoky scent of cypress; the whisper of wind, shedding yellow dust; fishing lines swishing over your rusty-brown surface— until you slipped from sight, forever in my rearview, replaced with the blur of the pines.

Elan Camaret

His time was running low. The sky began to shed its blues in favor of bloody shades of orange and pastel violets–signaling to Rob that his mother would be mad if he didn’t head home soon. She’d given him until sundown to enjoy the surf before requiring him to return home. Tomorrow would be his first day at his new school, and Rob’s subpar performance at his last three high schools awakened a strictness he’d never seen from his mom before. Rob had been helping his mom unpack boxes all day, and still, he’d had to argue hard for the chance to get in the water for just a couple of hours before preparing for school the next day.

Rob sat there in the frigid water on his 6-foot-10 Bear Designs he’d brought with him from California, wind rustling his wet, salty hair and ripping through the tattered wetsuit he had gotten for his 13th birthday. The lineup was vacant compared to where he’d come from, but there was still a handful of surfers around. His calloused fingers and chewed-down nails throbbed with every gust of the bitter, offshore wind. But to Rob, every second of discomfort was worth it to surf these waves. He’d never seen nor surfed East Coast waves before, but the tales he’d heard of the fast, thumping swells at the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse held up handsomely. Rob paddled for a small left that peeled off the jetty. He popped up and rode it mildly, just trying to scrub the extra speed he wasn’t familiar with, and then paddled back out next to the jetty.

Rob, his mother, and his stepdad had arrived at their new rental house just yesterday, and the only thing Rob could think of was the surf. He’d called it: The nor’easter that was set to blow through town in a few days was sucking the wind offshore so that it made its way over the shrubby dunes, glassing up the surface of each perfect curl before exiting over the top and sweeping the salty spray off the backs to cloud his vision.

Again, Rob dropped into a fair left. He tried to tuck into the pocket when it hollowed out, but there was more power than he was used to—the waves came from deeper, wilder water— so he dug his rail and got sucked over the falls. He used the jetty again to paddle back out.

He was no stranger to this setting. Only he had always experienced it on the other side of the country—2800 miles away in Encinitas, California. His stepdad, Ron, was a traveling salesman, though Rob never knew why anyone would buy something from him. His gaze beamed from his beady black eyes perched awkwardly above his big nose and sharp chin, and his tall, thin frame could’ve scared away a thousand crows. But he could talk circles until his victim didn’t know up from down—maybe that’s why Rob’s mother had fallen for him. Rob was beginning to understand the water around him better. He tried this time for a slightly bigger peak but stayed ahead of the pocket roaring behind him. Instead, he played on the shoulder with a few easy backside carves up and down until it faded out. He received a friendly greeting from a local who was also using the jetty to make his way out.

Rob faltered before responding, which seemed to give away that he came from the West Coast. No one ever spoke to each other out there. Rob smiled to himself as he finished paddling back out but caught himself before he got carried away. Encinitas was the longest he’d ever been in one place and, after a year, he’d played the dangerous game of making friends. Of course, it was a game he lost. They moved too much, and Rob knew that making new friends would only lead to new pain when they left. So he kept his eyes strictly on the horizon and stayed further from the pack as he waited for the next one. Still, he couldn’t keep his ears from taking in the playful laughter echoing from the small group of surfers.

Rob let an entire set roll under him as the others took their picks and tore the waves apart. No one from California surfed the way they did. Every wave in the Pacific was the same as the last, meaning if you could ride one, you could ride a hundred more without any surprises. It was different on the East Coast.

Each wave carried its own unique personality all the way to the sand. These surfers knew how to embrace these differences: Their styles were aggressive and fast and nothing caught them off guard. Rob was instantly in awe of their mastery. He knew that every second of his free time here would be spent striving for such proficiency.

The sun was so low now that the dunes were backlit from the west and the waves had been cast into shadow, and, somehow, it got colder. This didn’t seem to phase the others as their banter continued while they returned to their place in the lineup. Rob knew he’d have hell to face when he got home, but that didn’t hinder his decision to disobey his mother and keep surfing. He knew that his mom’s anger would fade eventually— just like he knew they would move again, he would lose any friends he made, and the cycle would begin again. Everything always changed for him. Surfing seemed to be the only constant in Rob’s life. The undeniable truth that the waves would be there long after he was gone was his only comfort and the only thing Rob cared for as he paddled for another one.

Megan Gardner

today the moon is just a low sliver the edge of a plate dipped in sunlight i think about the other side how bright and full it must be from a different perspective the light of the sun so far away yet we still see its effects even at night a finger tracing the sky i think about the old times how easy it must have been then to believe in a creator each day a new phase with no knowledge of why or how all in calendar motion, never pausing or changing how easy it must have been then to believe in the smallness of earth when all that you know is all that is there the sun rising and setting new every morning the moon’s dance changing face for show even now i still can’t help but imagine the night and day sky revolving us as if we truly were the center of the universe

Dear Lily,

Megan Gardner

I broke your necklace the other day.

Transparent turquoise with white and green swirls

The feel of it like glossy ocean waves

On a frigid day at the rarely calm sea, Found shattered into three uneven pieces

Under a park bench in the dusty gravel.

You gave it to me after Italy. You’d only moved there a year ago, But with every homesick glance, hidden By a daylight smile, I knew the truth. It had already become your home. Fourth-grade friends ‘til the end Or until fifth grade.

You came bearing gifts,

As if you owed us for leaving, Hand-taken photos of clotheslines

Draped across mustard and pink buildings, Bicycles strolling down cobblestone streets, And of course, that seafoam and teal necklace, With “Made In Italy” etched in gold on the back.

I didn’t break it on purpose, of course. No, never on purpose… It was never my intention To leave it there, in pieces

Abandoned on the ground. In fact, it was quite the contrary.

I saved it for seven circuitous years Before I decided to even risk exposing That shiny coating that gave way to blue. A real mistake, I guess.

Seven years, I seldom had a thought To the fourth-grade friend that I lost To a child’s inability to stay in touch.

Dear Lily, I wore your necklace the other day, And somehow, that aquamarine teal Unattached itself from the glass Between each cloudy spiral. The crystal cracked, Leaving me standing here With blood on my hands, Staring down in terror At the fragments of colorful glass.

It took all of me not to fall apart with it.

Abby Brodzeller

I read the time on the clock in my mom’s Nissan Murano at around 7 o’clock. It was a school night, and I had unfinished homework, but that was not unusual for me. I trusted I would be able to finish it just in time. Time seemed to have slowed to a near stop. After what seemed like hours of tapping my feet and rubbing my thumbs together, I finally arrived. I was nervous but excited. I walked up to the front door, and a familiar face turned the knob to invite me in.

Once inside, I was greeted by the sloppy kisses of a dog I was unfamiliar with. He didn’t know me either, but he didn’t seem to mind.

My friend led me into the living room to greet his parents. “Nice to meet you,” I exhaled, attempting to look as polite as possible. We carried on down the stairs to the basement. The area was beautifully finished and spacious. A large TV accompanied by an even larger leather couch took up just a small portion of the room. Behind the couch was a green felted pool table. It was recently used; the sticks were sprawled across the table with chalk remnants as evidence. Behind the table was a small bar. Bright ceiling lights encompassed the entire area, but the bar remained untouched from any light. The basement was a comforting space, or so I believed.

I took a seat upon the leather couch. The cushions were cold against my skin but warmed up eventually. They molded to my touch, slowly bouncing back to their original shape once left alone. Next to me sat the boy’s friend whom I had just met. We all talked for hours. The time seemed to have picked up speed. Around 9’ o’clock, it was time for the boy’s friend to go home. He mentioned homework he needed to get done and said his goodbyes before leaving me and the boy to ourselves.

“Wanna play darts?” The boy got up from the leather couch, leaving a perfect imprint of his body behind. It was faded by the time I decided to answer his question by getting up and joining him. As we took turns throwing, we tried to distract each other from our

throws in various ways. My go-to tactic was a little shove, harmless but effective. I never realized something so innocent could be laced with bad intentions so quickly. His next attempts to distract me quickly became less innocent as our turns went by. As I felt his unwanted hands on my body, I immediately went flush.

I tried to laugh it off. How could someone I thought I knew so well violate me with no concern for how it made me feel? How could I put myself into this situation? His parents were just upstairs. Did they know what was happening? I felt so stupid. So many thoughts ran through my mind, a new one forming before the previous was even complete. In an attempt to change the subject, I told him I did not want to throw darts anymore. We instead sat on the couch, molding ourselves into our previous spots. I felt another hand. The same hand I felt while throwing darts. The same hand that made my heart jump into my throat and become lodged, unable to move up or down. Swallowing became more and more difficult. My reflexes shot me out of my sitting position, and I walked over by the wall next to the pool table.

“What’s wrong?” he asked.

“Nothing.” I refused to make eye contact. He came up next to me. I felt the same hands again, this time roaming farther than before. They were warm, but they were not comforting. “Stop.” I felt so little. The things I really wanted to say would not come out.

“Why?” he said so calmly, as if he couldn’t see how uncomfortable he was making me. As if what he was doing was okay.

“Because.”

“Because why?”

“Because.” My answer was not good enough for him. He pried and pried in hopes I would give in. Time was slowing down again, even slower than my drive there. I could’ve sworn the clock stopped a few times.

Eventually, I got the text that my mom had arrived. I felt my frozen body slowly defrost. I quickly gathered my things and began my walk up the stairs. I turned around, taking one last glimpse of my surroundings. I looked back at the leather couch. Though the couch in that basement may be able to reshape itself after molding to my touch, I knew I would never be able to reshape myself from the feeling of his touch.

Fiona Morris

The portrait of a handsome family of four greeted those who stepped foot into the church on the corner of St. Martin street. Javier Estrada stands inside with his hands tucked tightly underneath his armpits, wincing each time the door is pulled open to reveal the loving sunlight that is desperately trying to intrude. He watches with his judgmental eyes as couples tightly walk along the clean floor, clutching candles and flowers they bought twenty minutes before their arrival. Very few people acknowledged him, nodding with tight lips as they make their way to the main event. The others simply walk past Javier as if he were a ghost. Maybe they were too nervous to speak, or too embarrassed to admit they never cared about his family. Did they even notice he is one of the four grinning in that family portrait?

The air is thinning as the room overflows with mysterious faces and, personally, too much chatter for Javier’s taste. It’s only been a few nights since, but everyone in the town seems to have heard. It is easy to hone in on those conversations that begin, “Mother and son on the same night, can you believe it?”

His nose crinkles as he observes the crowd more, catching the brief, “I heard the son was speeding to get to his mom before she passed; it’s so tragic. But, you know, the weather has been so bad these past few nights. He just lost sight of the road.”

No, he didn’t, Javier yearns to interrupt, he was drunk. He finds himself avoiding the two caskets that are adorned by the altar as he purposefully moves to a cluster by the pews.

“I heard about the accident from the news. Javier is the only living member of the Estrada family. He’s over there.”

Perfectly in command, their heads slowly turn to face the older gentlemen whose suit is a bit more formal than how they’re dressed. Javier glares at them before they huddle back up to continue murmuring.

“Here—I pulled up an article. Vivianna Estrada passed comfortably in her sleep, says here she was 64. And her youngest son, oh, hold on, there’s an ad—yeah, her youngest son was Miguel Estrada. Apparently, he was on his way to comfort her in the hospital when he got into an accident that resulted in his immediate death.”

It is so unbearably stiff in the room. His fingers curl into a fist as he bites back the words he wishes to scream, We are not your tourist attraction. This is my family. And hearing people mourn for Miguel, his drunk, idiot of a brother, lights another pit of anger. He wants to shout again, He was never there for Mamá ! He did nothing but worry her!

Oh, how Javi did nothing but worry for her… His heavy feet glide towards her stilled body as if she had beckoned him. Javier can barely stand as he is against his mother’s painted corpse. How she looks as alive as she was four months ago before she was stationed at the hospital full time. It is almost frightening to see her without that tangle of tubes that hugged her every day. Javier feels ridiculous for his belated realization that she’d no longer needed them, or him.

He avoids that thought and focuses on the sounds of the room. Behind her busy casket stands a collection of three elderly women, rosaries clutched in their hands as they repeat another Hail Mary under the rowdy air vent. He can’t help but wonder if they’re saying it for his mother or for him.

Peering down at her glossed fingertips that encompass her own aged rosary, Javier suddenly notices how much attention her dead body received. He flinches. Where was this attention when she was alive? Where was it when there was still time to save her? He continues waiting for her chest to fall as he watches her now, hating how perfect she looks and resisting the urge to pull her gentle bangs out from behind her ears. No one in this room will ever look at her with as much love as Javier does now.

Smoldering next to his mother’s casket is that of Miguel Estrada, the boy everyone has come to see. He takes long steps over, almost hesitating before peering into the box that sheltered Miguel’s body better than the vehicle he crashed in.

Javier’s dark face hangs high above his younger brother’s, confused and mournful eyes scanning every detail as if to memorize him in this new way. For the first time in years, he looks sober. Miguel’s rebuilt face mocks Javier for his lack of empathy throughout his short life, and he can see Miguel’s lips move as he whispers, “If only you had been there for me when I needed you. If only you hadn’t yelled so much...”

“They’re here for you,” Javier starts with a straight face, a single fist resting against the wood, “You’ve got the image of a hero now.” His eyes sting as he leans in lower, “Because it’s so heroic to steal money from our family to feed your pathetic addiction. The money that could have gone to keep our Mamá alive a little longer. But you always needed your fix, didn’t you?”

His spiteful words slap against Miguel’s blushing lips. Javier prays that it stings him. “This should have been our mother’s day, yet your selfishness stole that from her, too. If you hadn’t died the other night, Miguel, I’m sure you’d show up to this wasted just like you did when Pa died.”

Javier waits for another slimy excuse but this time, Miguel’s mouth stays sewn shut. His tears swim against Miguel’s cold skin, falling upon the lips that could no longer breathe. Only then did he realize his brother was truly gone. He breaks, “I want to be mad at you, mi hermano, but there is no you to be mad at anymore.”

Fiona Morris

Weren’t always sunny, but I preferred the fearful sky as it was an excuse to sit inside with you. I remember the stormy days most. You’d tell your best stories when the wind howled louder than your own thoughts. I’m surprised you heard them.

The rain continued to tap dance on the tin roof as you made ice cubes out of Coca Cola and I sipped on my orange soda while checking on your tomato vines. They never grew after you passed. And the summers in the screen room are as dull as your aged shed tools.

It’s fall in the screen room now and there’s an empty recliner next to me. I stare at it, patiently waiting for you to walk through that broken screen door to join me, Coke in hand. I know you won’t, but the rain lies and tells me you’re up there, working on the roof.

McCaid Paul

My wheels tremble with every rut along the tired road. A Mellow Yellow rattles in the cup holder, dog tags swinging and clinking from the rearview mirror. It’s their first trip back home.

In the distance, barbed wire fences circle arid pastures, heat waves shimmering above sun-scorched earth. Tucked beneath spindly oak branches, Mr. Fountain’s farmhouse sags on its foundation, tin roof now a speckled rusty-brown. In my wake, a thick red cloud of dust drifts like a contrail from an airplane.

Today, there are no other cars, station wagons, or tractors hugging the one-lane road. Better yet, there is no one around for miles. Not Elton, Mr. Fountain, or Miss Judy, whose bodies now rest beneath faded white marble.

Ahead, a brindle hound feasts on a slab of red meat, its bones trembling with every bite as flecks of drool string from its snout. The dog reminds me of Sally, my old Blue Heeler, who’d listen to me read aloud from my tattered Old Yeller paperback every Saturday beneath the limbs of a towering sycamore in Elton’s front yard. Every day after elementary school,

I swung on a rope tire attached to that tree, until Mama’s voice beckoned me inside for supper. At thirteen, I drank bourbon for the first time under the safety of the sycamore’s canopy, until Dad found the empty bottles in the watering hole behind our house.

Now, as I pass Elton’s yard, choked with weeds, wild grass, and briar patches, I notice that sycamore is now only a stump. My tires crawl to a halt, Mellow Yellow quietening in its holder, dog tags growing still, as the truck lever shifts to park.

I close my eyes, just for a moment, imagining bark digging into my back, the breeze tousling my hair, the smell of pine and honeysuckle, and Sally panting at my feet. In the span of a thought, I’m twelve years old again.

If only I could tell that boy to stop, rest, and think things through. If only I could tell him that this will be as good as it gets; please don’t ruin it so soon. If only I could tell him that things don’t have to change, that he doesn’t have to leave to be content.

I want to tell him, yet I know he won’t believe me, until he’s driving down these roads in thirty years, a few more wrinkles added to his once boyish face, sprouts of gray in his hair, his beard, searching for the things that disappeared during those years he left them behind.

Wallace McCarty

Standing on the stern of the ferry, he gazed back at the skyline he’d seen countless times before, the glittering shore seeming to mirror itself endlessly in the reflection of glass skyscrapers. The lower deck was astonishingly vacant, as was actually the usual case per his account, aside from the few cars that were hitching a ride to the Staten Island suburbs.

“This. This is how we do it in the city, my guy,” he murmured in his deep, raspy—yet still quite easy, good for radio—Brooklyn accent. “You don’ wanna be up there with the other tourists and guys in suits, down here you get the view. You really get to see the city.”

Water splashed up on my face from the waves left in the ferry’s wake; it felt nice on that balmy day in June. Seeing the statue in the harbor with the breeze in our faces created this liberating sensation—even he had to admit it. He took off his Yankees cap to reveal a receding hairline and proceeded to wipe off his forehead and glasses with the waist of his collared shirt, exposing pale bones underneath.

“It’s a beautiful day; we really never get enough of these— the tourists have been behaving themselves.” He turned back to the group, “When we went down to Strawberry Fields, it was like we weren’t even in the city. Usually, it’s fifty guys with guitars doin’ John Lennon tributes and some dozen-odd outof-towners stompin’ all over the mosaic.”

The ferry reached the other end of the Upper Bay and we got off at the classy Staten Island terminal, which was another great spot to view the city through the glass atrium. As we went up the escalators, all the security guards smiled, and would occasionally yell, “Chicken Man!” which seemed to be a constant for most places we went.

We’d be walking down Wall Street and guys in suits would come up and give him fist bumps. “Jimmy!—Chicken Man!”

A group of touring school children in Chinatown. “Chicken Man! Chicken Man!” Heck, cops would tip their hats at him outside the 9/11 memorial out of all places. “Chicken Man!—

How’s Reggie?”

He’d look back at us with slight distaste and back to Reggie. “My guy, I think they’re onto us!”

If they didn’t recognize his face, many could point out the small plush chicken he always carried with him. They nicknamed it Reggie. Beaten, torn up by dogs, thrown off the Empire State Building and into a murky puddle during rush hour. It was fading from white to a soiled black in spots, and the crest on its head was held together by stitches. A New Yorker. He had kinda become an urban legend of sorts—Jimmy the Chicken Man.

“Alright guys, we made it to Staten Island,” we got to the top of the escalator and looked around, “and can anyone tell me the best thing we can do in Staten Island?” Jimmy proceeded to turn around and hop on the escalator going back down. “Leave.”

We got back on the same bright orange ferry heading Manhattan-bound.

Jimmy leaned against the railing, the chicken still grasped in his fist, and took a moment of silence to look at the small group of about ten or so. “Well, guys, it appears I’m out of things to talk about on the ride back. So…where are you all from?”

They went around in a circle. “New Jersey.” “Philly.”

“We just got off the plane from Manches’tuh.”

“I’m from California.”

He got to the end of the line and raised an eyebrow at me. “And you, my guy?”

“Florida,” I said sheepishly.

Jimmy nodded slowly with swagger, in sync with the sway of the boat. “As I mentioned earlier, I’m from Brooklyn, which is right over there.” He pointed towards the east side of the bay, past a large island that looked like an old castle or fort. He quietly stared at the island as it got closer and then turned

McCarty • 23

back around to look down at his phone. When he typed, he didn’t use two thumbs but instead swiped the keyboard with the slide of his finger, a feature I thought no one actually used. It was a peculiar detail, but for some reason it stood out to me. Impatient yet precise.

Someone spoke up in the back of the group; it was the gentleman from England. “Have you lived in the city your whole life?” he asked in his native Mancunian dialect.

He shrugged and smiled, “Pretty much. I’m one of those poor New Yorkers who can’t figure out where to go, but only knows they don’t want to die here.”

The gentleman’s wife followed up, “You don’t want to stay in New York?”

“Don’t get me wrong, I love the city, but I think everyone who’s been here more than half their life, y’know, real New Yorkers, feel the need to get out eventually. They either get out or get consumed.” He looked back at the island, now floating past on the starboard side—that was the right side, as Jimmy had taught us all earlier (‘P-O-R-T equals L-E-F-T. Remember that and starboard is what you have left, but not L-E-F-T, that’s port—just don’t make me say it again.’). After a final longing stare, he turned back to face us.

“My dad was a pro animal trapper, and one summer he took me out to the abandoned mental hospital on Governors Island to take care of feral cats.” He gestured towards the small group of buildings on the island, all with a distinct old fashion style of stone architecture. “Used to drive around in an old 1968 Cadillac ambulance, like the Ghostbusters one, doin’ ‘nuisance wildlife patrol.’ We’d roll through stoplights, throw on that old siren, woooo. Everywhere we go, people on the corner would be yellin’ ‘Ghostbusters!’

“Dad was a New Yorker by every sense of the word. You know what I mean. Born down in Brooklyn, raised in the ole’ city, ‘fuhgeddaboudit,’ all that. He remembers the nightmare years of New York you’d see in the movies. The one the old men act like they’re nostalgic for, but no one really misses.

“So anyway, he’d catch, for example, a squirrel in Brooklyn,

release it in Manhattan, because, y’know, squirrels can’t swim, that sorta deal. Possums in the attic. One time he had to get a fighting rooster out of someone’s backyard, the ones with the sharpened talons. Another time, apparently, he had taken a job where there was a chimpanzee in someone’s apartment. Fullgrown chimpanzee and he tried to tackle the thing, and it bit him on the hand—he had a chimpanzee scar—and it threw him into the wall. Then he decided to just tranquilize some bananas, so he ate some bananas and came in and just tied up the ape after that. There was also a mountain lion. Both the chimp and the mountain lion were abandoned, more than likely trophy pets of a drug lord or something like that.

“This city is crazy, and a job like that in a place like this can really make you go insane, and frankly, he did.

“So, here I am, living in the city my whole life, and I’m only in my thirties thinking, ‘I’ve seen it all!’—but my old man… fuhgeddaboudit.

“Gentrification has changed the city quite a bit. You guys might feel scared about visiting New York, I think. The things you see in movies and things like that. You get the idea. It’s a wild time in the city.

“When I was a kid, growing up in Park Slope, you got to go to Manhattan, the Big City New York, on the weekends, y’know? I thought it would be really cool to go to Manhattan for school—like in most places, you have to apply for college, but here you have to apply for high school and everything, too—so I would actually commute to go to school, cross-county, interborough, I would take the subway and then a bus and I would go to school on the Lower East Side.

“They’d have ‘no-captive ’ lunches, they called it, where they used to let you go around the neighborhood and buy food from the local bodegas and ‘le établisse-ments.’ So one day we’re going out, and we look under a car, and what do we see under a car? Low and behold: dead body.

“ Well, we thought it was a guy sleeping at first, and then our skills of New York intuition think about it and we’re like, ‘yeah, nobody sleeps under a car, even homeless people don’t

sleep under a car.’ It reminded me of, like, when an animal will crawl into a small hole to die.

“So we looked down, and I definitely did the Stand By Me. Don’t even remember where I got a stick in the city—we found something to poke him with, probably like a piece of metal because we don’t have many sticks—we poked it, and you know, nothin’. So we go down to one of these red boxes on the corner—one of them’s police and the other is fire—and we called the fire department and we’re like, ‘uh, there’s like a body under a car,’ and of course, we wanted to watch them get it out. Entertainment value, baby!

“So we go get some food. Get it, bring it back, post up, stoop up. Get up on the stoop, eating the slice, drinking the Coke, lookin’ down, watchin’ them, y’know, peel this body from under the car.

“It was not as entertaining as we thought it would be. They used a little jack to get the thing up. It was too fresh— that’s the story. We should’ve waited on it. Told nobody. In a couple of days, come back, see what’s what. Decomposes. Huh?

“So anyway we left. And that was the story.

“ Traumatic, right? Is this am I the only one who thinks this is not… normal? I don’t know, but that’s what it was like growing up in the New York, the Big City. We’re kinda… trapped in the city. I mean, I don’t even know how to drive, my guy. Fuhgeddaboudit.”

The gentleman from Manchester stared blankly into Jimmy’s eyes. The breeze blew into all of our faces, perturbed as the Manhattan terminal came into view; the gates opened and the boarding ramp was lowered. We were just another batch of tourists.

Jimmy held the chicken high as he marched the group off the boat. “This place we’re going for lunch on Fulton, you’re really gonna love it. It’s not a buffet, though; you should never call it that. If you say that to their face, gee, fuhgeddaboudit…”

Dallas Le

The lull of thunder rolled through as the announcer welcomed the Choctawhatchee band into the stadium. We didn’t know what would happen then. We only gripped our flags, sabres, and rifles close to our chests and kept our expressions stern as we walked into our sets.

Each flag was placed down carefully. I glared at my own flag, the red and black silk of the flag slightly dampened from an earlier rain shower. I furrowed my brows to it, playing it off to the spectators as if I’m just more focused and passionate about the show. But I mentally gave my flag a flimsy ultimatum. “You drop, you die.”

Any good guard girl knew not to point blame on the flag and not herself being out of practice. But it made my lips quirk into a smile at the thought of throttling an inanimate object after it humiliated me in front of a hundred people.

I heard one of the more notorious vets, Cheyanne, quietly whining about the wet sod on the ground. She was near the front. She and I were part of the thirteen members of the just-flag line. Anna, one of the cockier rookies, hissed at her to be quiet.

We were sitting in a circle around a black stage, eyes dancing between our more flexible peers on the circular platform. They’d dance between the drumline before leaping off the structure to mingle back with the flag line.

Our legs were spread wide, one hand resting on a knee while the other held by our ear, cupping our face. The sound of our drum major calling for attention and a recording of some elderly man preaching about the need for chaos and calmness began.

A droplet fell on my hand.

“Five…” Cheyanne began. Our coaches hated that we counted the rookies off. They’ve been in guard for about four

months now. But we had gotten the bad habit of coddling our rookies too much to offset how much two of our four coaches hated them.

“Six.” Chastity, one of my friends, murmured behind me as the drumline began to kick off. Her eyes were downcast.

“Five, six, seven, eight.” I finished, in sync with the flags as we suddenly began our own dance.

We pretended our heads were cracking under the stress, that our bodies were pulled taut with the clash of cymbals and the second roar of thunder. As we mocked birds, leaping over others’ flags, a couple of rookies began to panic, hesitating on their leaps as we still chanted our counts.

The trumpets and tubas circled us as the sky began to sprinkle gentle droplets of rain on the field. I didn’t register the sudden cold feeling on my neck, mistaking it for sweat. After all, we had just gotten to our flags, and the fun was about to begin.

The band sparked to life; pandemonium turned into a melody. My flag was no longer a lifeless pole but now an excited mustang as it sprung into the air. It swung to my hips with a desperate fervor. A smile cracked through my facade of stress.

The rookies were still counting out loud, eyes caked in eyeliner locked with mine. I wished that there was a way for me to console them with eyes alone, but I wouldn’t have time to before I’d turn my back to them, leaping into the next set.

I’d have to run through two tuba players. One of them had the bad habit of walking towards me. However, my glasses were starting to fog up with condensation just as a rogue trumpet blared between me and the tuba player. The trumpet and I made direct eye contact. Her sky-blue eyes whispered one word, “sorry,” as she crossed my lane to her next spot in the show.

I faked the toss. The trumpet was too close for me to get the full rotation. My eyes scanned the sea of band kids to find Anna landing her toss.

Together, we’d run to our next set, preparing for the ballad.

By now, the shivers running down my back weren’t from adrenaline, no. They were from the downpour of rain sticking to me and my flag. I wouldn’t have long before my flag lost its spark.

Every drop of rain painfully added another gram of weight to my flag. The drumline masked the rage of the storm but I knew that the rain wouldn’t be easing up as I volleyed my flag into the air.

It was then I finally cast my gaze to the audience. Something was askew. One of my fellow flags wasn’t performing like she was supposed to. Bleached blond hair, tied into a fake ponytail. Cheyanne.

She was going through the motions. Not because she had forgotten the choreography. Not because her heart wasn’t in it. But because her flag itself wasn’t even in her hands. My eyes glanced around. Why didn’t she have a flag in her hands?

Cheyanne was supposed to always have a flag in hand. She’s supposed to be the epitome of a flag member. What is this?

The rain is pouring now. I can’t see any of my tosses. Instead of a vibrant red silk and black taped pole, it’s merely a blob of the aforementioned colors, flying into the air and back down in my hands. If I could force the dying air in my lungs to speak, I would have been screaming my counts. Cheyanne didn’t have a pole, the rookies were more like frenzied farm animals in the midst of a wolf attack, and the rain wouldn’t stop.

I caught the last double of the phase, heaving as my body forced itself to not collapse too hard into it. My head was bowed, just as my coaches wanted, but my expression was shameful as I knew I was a count off. The pit started off, another recording of that same elderly man discussing the calmness now.

We got through the first part of the ballad without a hitch. It was when I crouched down to pick up my yard-long swing flag that I realized yet another thing, other than Cheyanne missing a flag, the rookies panicking, and the rainstorm, was wrong. See, the coach in charge of assigning our makeup was a

professional dancer. He taught at the Fred Astaire Dance School in Fort Walton Beach. But, on that day, he had made a severe lapse in judgment.

He had ordered every guard member to go to Walmart and buy eyeliner gel. Then instead of working on a wing that would win a drag show, he had us cake it onto our eyes. The Choctawhatchee Colorguard looked like the backup dancers for Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” music video.

And now? The makeup was trying to come off.

Makayla, the girl three yard lines away from me, was a mess. I could see her desperate attempts to clear her eyes, but it was a futile attempt. She wasn’t an uncredited extra in the back anymore. She looked like she belonged as the lead singer for KISS.

She wasn’t the only girl suffering from the rain’s harassment of the Walmart brand makeup. Nonetheless, she was the worst off.

The rest of the ballad was rough. Our swing flags were heavy enough to begin with, but with the added weight of being saturated with water, they wouldn’t move the way we wanted them to.

My flag stuck to my body at all the wrong angles. The end of the silk would be coiled around one leg, making hiding my flaws all the more troublesome as every movement was accentuated by the black to golden orange ombre flag on a green unitard.

As the ballad finally came to an end, I ran to my next place, moving to grab the oversized swing flag. I must’ve yanked too hard because instead of it dazzling the audience with my dainty movements, the flag shrieked as it began to tear at the pole.

The finale had finally come. Makayla went from being three yard lines to being right next to me, crouching by the stage, away from the view of the audience. I could hear Cheyanne’s panicked cries as she still reeled from abandoning her flag at the initial set.

We didn’t have any more time. This was it. Our final act. We had to finish strong. We were wet and could barely see, but we couldn’t falter now.

With a few words of condolences and comfort to my peers, I lifted my flag, preparing my most happy smile. The audience didn’t need to know we were living through our show’s theme, dedicated to chaos. No, instead, they would believe we were calm and collected at our cores.

My flag was soaking wet. A simple drop spin was pushing not only against the wind but the dripping water in the silk of it. Next was a double. It wasn’t a full rotation, barely getting enough for me to fake that I succeeded. But I continued with the bravado of a master and the boldness of a phony.

I heard the last crescendo of the band, letting the flag soar through the air, weighted silk and all. And I caught it and hoisted my flag in the air like a proud mother.

The crowd burst into applause. They were all safe, hurdled under bright umbrellas and clear ponchos while we stood in our poses, shivering but not daring to move a muscle. The rain shower finally came to an end as we cleaned up our flags, as if satisfied with the torture it spat upon us.

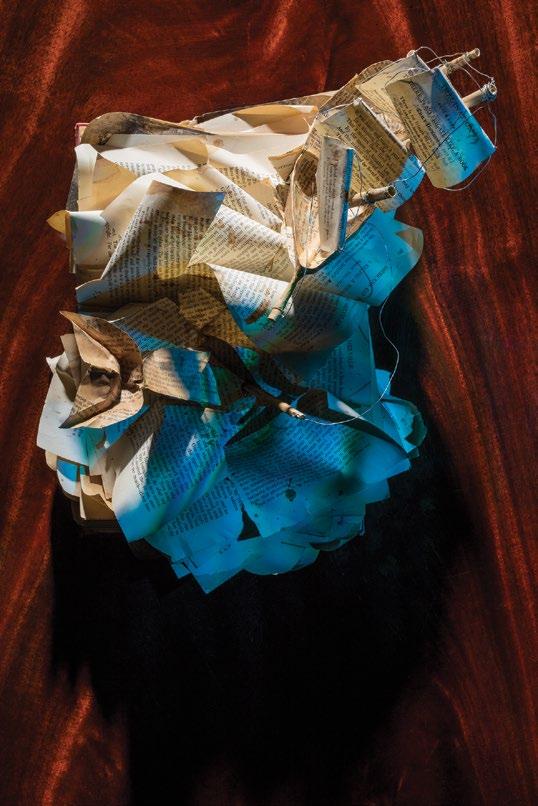

Isabelle Alegria

The photos pile up in boxes, Awkward and unwanted after the divorce. These memories belong to no one now, They drift helplessly in dark seawater, Haunted and silent like shipwreck debris.

They are photos of the beginning, My father and my mother before me, before my brother. They are young, happy, innocent and arrogant. They have nothing and share everything, Birthday cakes with glittering candles, Plastic table cloths, and crooked smiles.

It’s their first Christmas together, Her blonde bangs frame blue eyes, She’s wearing a black dress and tights, Red lipstick she doesn’t like anymore, And a pair of gold hoop earrings that now Live alone in a vanity drawer. His eyes are bright and dark, Glittering with ambition instead of greed. A wide smile of silver braces, tall, lean, eager to impress. There was laughter and dancing, Noses touching, spinning slowly, A perfect pair, the sun and the moon. A love that was legend for twenty-four tumultuous years, Friendship and unity, no bitterness, nothing broken, no betrayal.

They grew up, they grew apart, Chasing each other in circles with empty promises and threats, Everything came slowly collapsing down, She called in all his debts, a failed attempt to keep him, He fought his way out of our home, Teeth barred and claws bloody, A lion makes no apologies.

Lost love frozen in photos, Pictures that belong to the past. Before he stepped on her ribs like ladder rungs.

Ethan Howard

This earthly coil grows weary and brittle, Blows away like chaff in an angry gale; And yet, Every day greets us with a newborn sun. My wood may rot, bricks crumble, My plaster chip, and cement fade into dust; And yet My memories will never be washed away, Lovingly carved By the ever-roiling ebb and flow of time.

I’ve been here through a score of multicolored years, Each one creating its own mosaic of laughter and sorrows. Stains and cracks adorn me like fine jewelry, Tresses of ivy belie my years.

My doormat grows heavy from the dirt and dust Deposited by soles of homebound footwear. I welcome them in, from dawn till tangerine dusk.

I’m friend to human and animal alike; The lizards and geckos appoint me as their reptilian paradise, I provide a sun-baked vacation to the occasional frog. Spiders and insects call my crooks and crannies home, Snails grace my bowing vinyl siding, Leaving their slime-trail regards.

Still, I leave a place for you among my multitude of guests, You who take refuge behind my sturdy wooden doorframe, Painted white as the fluffy marshmallow skies. My wizened concrete foundation Remains vacant for you.

Ethan Howard

Wet grass crunched underneath Jedediah’s grimy leather boots. He trudged through the rain with brawny resolve, fighting against the suction of mud grasping at his soles. With a grunt, he adjusted the weight of the musty burlap potato sack slung over his shoulder. A towering 6’ 7” giant of a man, Jed dwarfed the squatty bulldog chasing his heels. She nipped playfully at his ankles.

“Not n-n-now, Rosie.”

A bolt of lighting cracked open the roiling sky, briefly illuminating the Pickett farmstead. Jed continued his solemn slog past the rickety back porch of the main farmhouse; the awning sagged under years of disrepair, forming a divot in the shingles that funneled rainwater into a miniature waterfall. He glanced up the moldy, rotting stairs to look at the wicker chair Momma always sat in while he played outside. Echoes of her screeching still played in his memory:

“Jedediah Pickett, you get the hell out of that mud before I come over there and beat you!”

“If you track that inside, there’ll be no supper for you tonight! I won’t be the one answering to your father, you hear me!?”

His 5-year-old brain paid her no heed. He liked feeling the gooey earth squish between his toes.

“Jedediah!”

He stared quizzically at the ground, focused on a blob of brown that stood out against its muddy surroundings. Plunging his tubby fist into the warm muck, he grasped his fingers around the squishy, warty object. He crouched to peer at it. Two black, beady eyes peered back. The creature croaked meekly, as Jed held it gingerly

and watched its gullet pulse with breath.

“F-f-f fr- froggie-”

Just then, an iron vise-grip clamped around his throat. Jedediah gave out a strangled cry, hands shooting up to his neck in an attempt to free himself from the oxygen-denying chokehold. The frog, dropped in the ensuing struggle, bounded away in a fright.

“Did you not hear me, boy?” Momma hissed through brandywashed teeth.

Jedediah replied by gulping down air in panic, in an attempt to cool the stinging in his throat.

Momma continued, “Get yourself inside. I hope you’re looking forward to Pa’s belt…”

Shoving the memories from his mind, Jedediah refocused his gaze upon his goal. Two red tail lights shone like an eerie glare through the hazy rainfall, marking the bed of his beloved pickup truck. They pierced through him, as if they were silently judging the black deeds that stained his being. He glared back at them in defiance.

It only took a few more strides of his lumbering gait to reach the truck bed. Wiping the condensation from his eyes, Jed rolled the sack off of his goliath shoulders, clenching the fabric tightly with both hands. Rosie jumped up in excitement, biting and tearing at the burlap. Jed nudged her gently with his boot.

“Git down girl! You can have s-some’n in a minute.”

Without hesitating, he swung the potato sack with the full weight of his body, sending it over his head and into the truck bed with a meaty squelch. It bounced limply off of the metal frame then settled in place next to an identical burlap bag.

Jed heard an expectant yip from the ground beneath his feet. Looking down, he saw Rosie’s rain-drenched face, her drooping jowls flapping to the rhythm of her panting. His gaze moved to the red-and-purple shoeprint branded into her white coat. It struck him with visions of that morning.

Jed had awoken to his father’s smoker-lung voice screaming at him from downstairs.

“I thought I told you to keep your bitch dog out of my kitchen!”

There were the muffled noises of a bulldog barking and snarling.

“Mangy mutt, let go a’ my steak!”

A flurry of sounds echoed from the floor below: leather striking flesh, the frightened whimpers of a wounded animal, claws clattering across wooden floorboards.

Jed’s muscles moved before he knew what he was doing. His footfalls descended down the Pickett house’s neglected staircase, echoing like a war drum off of the oak panels.

He reached the final step, pivoting off the banister to face the wretches he called his parents. They turned slowly to stare at him; Momma looking up from her pot of barely-edible grits, Pa still scraping blood from his shoe with a crusty, crumpled napkin. Reflected in their eyes was an emotion Jedediah had never seen them express before: blood-chilling terror.

“You shouldn’ta done that, Pa.”

The pitter-pattering of raindrops wrenched Jed back to the present. Rosie still gazed up at him, fur matted with blood and rainwater. He sighed, turning back to the truck bed.

“It’s a-alright girl.”

He shoved his hand deep into a potato sack, fishing around with his fingers until they brushed against smooth bone. Haphazardly yanking out the prize, he tossed it to the begging bulldog. Rosie snapped at the treat with delight. Her teeth clamped excitedly around the femur as it arced towards the earth, digging into the still-moist meat in a frenzy. Jed crouched down, supporting himself with his tree-trunk thighs, and carefully caressed her head as she devoured her meal.

“Don’ w-worry old girl. We w-won’ have to think about Momma and Pa ever again.”

McCaid Paul

Amber light crawls through the blinds in Dad’s room, revealing the epitome of despair: a dusty alarm clock, a laundry basket overflowing with sweaty clothes, an unmade bed with ruffled white sheets skirting the stained linoleum floor.

On the nightstand, a woman smiles behind fingerprint-smudged glass, forever frozen. Her almond eyes, cherry-red lips, and hair the color of honey spur a memory in my mind— one which involves a Blue Moon crate balanced on my mother’s hip, as she gazes over at me like I’m nothing more than a piece of lint on a new shirt.

Look at me, son, she whispers. Instead, my eyes bore into her black stiletto shoes. I love you, but I have to go. Now, staring at her photo, I hear the click-clack of those heels mixing with Dad’s damn yous and a slamming screen door. All over again, I feel the pain of digging my nails into my fleshy palms,

and the tight knot in my throat, like a jagged thorn lodged there, stabbing me every time I dare cry, Don’t go. Please don’t go.

Staring at her photo, I remember the Friday nights bundled in her lap in the back of Dad’s Chevy Silverado; her face, swathed in golden streetlight as she sang about those lyin’ eyes and hands as cold as ice. I remember when the sky would rage and the room would tremble and she would hold me tighter, whispering, I’ve got you. I’m right here. I remember towering cakes and dripping candles and my mother’s voice: Another year older, but you’ll always be my little boy. I remember pitch-dark seconds after the nightlight would burn out, and I would call for her and she would come.

Staring at her photo, I see those lyin’ eyes she used to sing about, like a crack in her picture-perfect façade; smile a thin disguise, as if she contemplated leaving all along. Staring at her photo, I see a prophecy, set in place long before I ever considered that one day even I wouldn’t be enough to make her stay.

ReAnne Harrison

English is my mother’s third language

And the only one I speak. When she stutters in her speech, “Can you put on the…” Hand reaching at a blank TV. “Filipino news channel?”

The screen resumes its normal programming Of people gossiping in that familiar foreign tongue. I watch for their movements and tone, Listening for the words they don’t say.

My mother never boasted about her chores. Laundry always clean and spotless Freshly stacked on my mattress.

Never knowing how the stains disappeared, I learned to keep away from paints and dirt. Sometimes buying clothes

Just to avoid the growing pile.

My mother deftly vacuumed every Monday morning, While my sister and I were gone. The neat lines carved in the cream carpet Was her activities’ only evidence. We would always give thanks on our return, And should we miss that visual cue of tousled floor, I learned to say “thank you” even without clues. A faith sometimes misplaced

On task avoidant coworkers

And despondent boyfriends.

My mother always had food ready in the kitchen. A mouthwatering mixture of spiced meat and rice, Thoughtfully made to each of our tastes.

Each element was expertly made without explanation. So as soon as my hands failed to mimic her movements, She’d salvage my meal before it could crumble. Never having a chance to taste a flopped meal, I learned to simply stay out of that domain. That world of unknown delicacies Are better left to the skilled hands of a chef Over my own fumbling.

My mother made sure we were properly packed for family vacations To visit her family a day away by plane and jeepney. The water park we all went to was a cool getaway From tropical fields and torrid pastures. Hours went by as I enjoyed the vast pools, Until she handed me the large tshirt She had prepared in her beach bag. Realizing her gentle questions were not suggestions, I learned that modesty was in fashion. Even in a sea of family, It’s better to pick clothes and mannerisms That compliment their view.

Without the vocabulary, These were lessons my mother tried to teach And lessons my mother didn’t mean to. She still wishes she spoke her mother tongue To us while we were young. If I had learned those jokes that made my mother laugh While on Skype with her sisters, Or could understand exactly what my mother meant When she pointed to a faded family photo, Maybe these lessons wouldn’t have been so hard to hear. I can’t help but wonder if silence Wouldn’t be so loud.

Fiona Morris

The polished court smiles at me, inviting my timid toes to skip along the fresh pine-scented wood. Though this court belongs to you, I recklessly intrude. It’s my home, too. If it’s clean, don’t dirty it. I repeat those rules as I climb the abandoned bleachers, entering a new atmosphere that smells more like a lost loved one than the Carmex yellow of the court.

As the bleachers fill with the game’s crowd, I mimic that sitting sculpture outside the public library: the stone-faced immaculate, warily eyeing the jersey that is desperately seeking me out. My fear gives me away, and the beast inside you can smell dread mixing with the estranged scent of a lost loved one. You associate me with both.

I was clean, but you never much liked the rules. Don’t dirty me, yet you drag me along the playing field, forcibly folding me into whatever you desired. Your hand weighs down my head, dribbling around the court where your sneakers squeak and I dance between your feet, careful to slip past you and your long, egotistical strides. You always caught me though, and you’d dribble me longer, exhausting me, anticipating the crowd’s cheer before taking a shot. You missed it.

My cheer is of a thrown-up, littered deposit of sandpaper. No itch is satisfied on my pimpled back as you claw at me, aggressively still wanting more from my tired shell. I ache the same innocent pain of the day when you lied your way

to steal my freedom, reporting to the judge that you’ve never missed a shot. As you hold me up, I see the teeth of the court beaming at me— how could they all smile? When the buzzer screams, your beloved audience leaves and I’m left searching for your approval. Daddy, did I give a good enough show?

If it’s clean, don’t dirty it. If it’s dirty, clean it up. If it’s broken, then fix it. If it’s Fiona, throw it out. You heard the rules, so deflate me, I beg! Release me to the floor and I will cling to it, kissing it graciously, thanking it for holding me. Throw me out, I plead! I dream of smelling like a lost loved one, so go on. Make it happen, you coward.

Kendra Belton

Once upon a time…no, wait. This isn’t a fairy tale. It’s a true story, so it should begin in a believable way.

How about this: A little while ago, sometime at the beginning of this century, two children were making mud pies together. Their faces were speckled with dirt and their hair stood up on end. Impulsively, the little boy kissed his friend on the cheek. In return, she screeched, “Kay!” and slung her pie into his face.

Through a mouthful of mud, Kay sincerely declared, “Gertie, I’m going to marry you one day.”

The little girl just giggled in her adorably high-pitched way and got back to work, making another pie out of the earth. Years passed, and Kay watched Gertie grow from a chubby toddler with lopsided pigtails and a crooked grin to a petite young lady with a not-quite-curvy body (but in the best way), shiny black hair, and soft brown eyes. He listened as her voice matured from that of a screechy kid’s to one that stopped everyone in their tracks when she sang. He teased her for being half a foot shorter than him. He listened when she told him her secrets, and he willingly told her his. He relished their deep conversations and how they could disagree without hard feelings.

To be sure, Gertie did not ignore the way Kay grew taller and stronger and more charismatic. She didn’t mind his floppy blonde bangs or his superb performance in class, and she even liked his storm-grey eyes that occasionally flashed with passionate lightning. She figured he was an all-around good guy, and, of course, they were best friends. But why in the world were so many of their classmates convinced that the two of them were dating? She could not imagine. Yet sometimes, she let her mind wander in that direction…just the tiniest bit. The morning after they’d had an intense study session in

the local library, Gertie couldn’t believe that Kay hadn’t shown up for first-semester finals. There was snow on the ground, she reasoned. Perhaps he couldn’t back out of his driveway. Still, as the day went on, she became incredulous that Kay hadn’t come to school after their hard work. Gertie tried very hard to forget the argument they’d had before Kay had gone home – it was quite minor, really. She tried to forget how they had whisperscreamed at each other amid the piles of books, blaming one another for getting them stuck in the library when it started to blizzard (both of them knew that it was for another reason entirely: Kay didn’t like it when Gertie flirted with the guy at the desk, but neither of them would come out and say so since they were both so miffed). Finally, Kay had thrown his hands up in disgust and charged out into the storm. Gertie also tried quite hard to ignore the dark silhouette of a slender woman she’d seen in the snowy dusk. The image haunted the back of her mind as she texted Kay throughout the day and into the night, but to no avail. She didn’t know how to explain she’d only been trying to see if Kay would get jealous; they could talk about anything at all besides their own possibility of romance. He never responded. Eventually, Gertie even called Kay’s mother, but she was clueless as to where Kay was. During the conversation, Gertie swore that the older woman sounded choked up, as if she’d been sobbing.

A week passed. A month. Two months. Still, Kay did not reappear. Shortly after Kay’s absence, Gertie took up running. While she ran, she daydreamed of his return. What if she kissed him on the cheek when he came back? What if she kissed his lips?

Every morning she ran past a bakery where an ashen, crippled old lady sat: a beggar on the streets. Sometimes, when she had the money, Gertie offered to buy the lady a pastry. The beggar always accepted the offer and told Gertie stories while they ate. The eldery woman’s favorite story to tell was about a little boy named Kay and a little girl named Gerda who were playmates. One day, Kay went sledding and disappeared. Gerda went on an adventure and rescued him from the court

of the Snow Queen. When they grew up, they got married and lived happily ever after. The entire story was punctuated with knowing chuckles and unnecessary comments.

Gertie humored the lady, never wishing to impolitely interrupt, even though the story and apparent insanity was always the same. One day, Gertie asked who wrote the story. To this, the crone said, “Well, you ought to know, dontcha think?” With that, she hobbled away to find a new spot to ask passersby for food.

The thought of Kay’s disappearance was forever on Gertie’s mind. She missed his laugh, his hair flips, and the way his eyes never ceased to shock her. She forgot to eat, even when she bought food for her “friend” on the streets. She ran longer routes weekly. Her hair thinned and her clothes no longer fit around her body the same as they had before. Her fingers decided to entangle themselves with each other, her toes took up the habit of tapping, and her soft, green eyes hardened.

Gertie’s encounters with others grew shorter and more constrained; her daydreams grew longer and she wallowed more deeply in memories of Kay. One day in late spring, Gertie passed by the lady near the bakery on her run, but did not stop to talk with her. She couldn’t bear to plaster a smile on her face for one more second. As if reading her mind, the lady screeched out in her screechy, crazy, third-person syntax, “Of course you’ll run, you idiot! You’ll always run! But Mrs. Raven knows where Kay is! Yes, she does!”

Gertie skidded to a halt and turned around to face Mrs. Raven. She was cackling uproariously and beckoned to the girl with a crooked finger: “Come here, girl. Mrs. Raven will help you find your love. She knows all about him. Yes, she does. She does!”

When Gertie was close enough to the woman to smell her foul breath (she did not correct her when she called Kay Gertie’s “love”), Mrs. Raven snatched Gertie’s phone from her hand and ran with it, faster than any old woman, crippled or not, should. Gertie chased after Mrs. Raven in hot pursuit, but the lady raced at a steady pace out of the town and into the meadows.

Abruptly, she came to a pause. Gertie had been so busy running that she had not noticed the changes that overtook the lady: instead of bent-over, she was tall. Instead of crippled, she was strong. Instead of ashen and weary, she looked tanned and rejuvenated. Her sparse white hair was now thick and dark, and her wrinkles had faded into her skin.

Gertie, gasping for breath, stared at Mrs. Raven in amazement.

“Whatcha lookin’ at, girl?” the transformed woman demanded.

“You…you…but—” Gertie spluttered.

“Meet the Robber Girl,” Mrs. Raven—the Robber Girl— gestured to herself, before handing the phone back to Gertie.

“The…the Robber Girl? Like in the story?” Gertie questioned.

“Of course. I had to play it a bit crazy to get to know you, but I know how to help you, ya know.”

“I… I know.” Gertie decided to believe the homeless, crazy lady-turned-Robber-Girl.

“Alright. Sorry, I don’t got a reindeer for you, but my husband’s got a horse.”

As if on cue, a majestic chestnut mare came charging out of the setting sun, like in a movie. A tall man sat atop it, dressed from another time, like Robin Hood. He pulled the mare to a stop and looked down at the Robber Girl.

“This the kid who’s got a fella in the Wasteland?”

A “fella”? Gertie thought, confused, yet secretly pleased that someone had possibly confirmed her feelings for Kay. Despite her evergrowing daydreams, she’d been unable to fully admit that perhaps she thought of Kay as more than a friend.

“Yup,” the Robber Girl replied, shoving Gertie towards the horse. “Love ya. Don’t die.”

With that, the man swept Gertie up onto his horse and galloped away. They rode for hours and hours, but Gertie never got bored, for “Robin Hood” entertained her with stories of him, his wife, and their raven.

The sun set, the moon rose, and the stars twinkled in

Belton • 47

the wide expanse of the sky. A bitter wind began to blow, and the traveling party approached an icy wasteland. A dilapidated castle that must have once been grand stood in the distance. A frozen expanse of lake separated the living beings from the palace and in the middle of the lake, a hunched figure sat upon a flattened spire of ice.

“This is where I leave ya,” the man briefly grunted. “You know what to do—just like in the stories Robber Girl told ya. I’ll know when you save ‘im. I’ll be back. Don’t freeze, okay?”

As Gertie nodded, he and his horse disappeared in a gust of snow.

“‘Don’t freeze,’ huh?” Gertie murmured as she started to make her way across the lake. “Easier said than done.”

The wind ripped through her thin running attire and bit her fingers and cheeks. Her meatless bones quaked in the frigid environment, and her stringy hair blew into her face.

After what seemed like hours, Gertie finally made it to the spire and recognized that the figure on top was Kay. She saw spikes jutting out the entire length of the structure, so she took a deep breath and started to climb. Gertie hoisted herself up on each spike, consciously denying her numbing fingers and appendages bleeding from the jagged points of ice. After what felt like many more hours, Gertie reached the flattened surface and stumbled towards Kay, exhausted.

She fell short when she saw his face: lips purple, ice hanging from his scraggly hair, and his eyes. And… holy crap, his eyes! They were frozen wide, glowing an icy blue instead of the stormy grey color that Gertie had begun to romanticize in her dreams. He did not move.

All of a sudden, Gertie rushed towards Kay, sobbing and reaching out to hug him. She held him to her bony figure, with tears freezing the moment they left her eyes. She whispered, “I love you, I love you, I love you,” over and over again. She didn’t care how cliché it sounded; it was true, and she knew it.

In her arms, Kay stirred. He saw her for the first time in months and took in her tears and skinniness and sadness and joy, and his eyes thawed out to their beautiful grey as he hugged

her back. Despite her being a deathly ghost of her former self, he’d never thought she could be so beautiful. He was so happy to see her again after the terror he’d been through.

Slowly, very slowly, Kay got up, walked to her, and promptly passed out. Gertie sighed, shook her head, and dragged him down the spire and across the lake to the shore with newfound strength. “Robin Hood” met them there, and rode with them all the way to the city limits.

When Kay came to his senses, he was lying in a warm bath in what he recognized as Gertie’s bathroom.

“So,” she said. “When are we getting married?”

“Huh?”

“Hm,” she grinned. “Have you ever heard the story of the Snow Queen?”

Megan Gardner

sage green

it’s the steam coming off of a warm mug of chamomile tea the lingering smell of incense burned long ago old hardwood floors against bare feet condensation in the evening grass foggy seaglass, just a little warm from being held too long or just long enough the almost-crunch of wet leaves on the forest floor before daylight it’s a hidden smile, a resolving piano chord a purring kitten, a mother’s song a fresh sprig of rosemary, hung out to dry a weighted blanket pretending to be a hug worn out converse, worn out for another day, it’s sugar cookies in the oven raindrops on a windowpane muffled laughter the downstairs neighbor’s piano softened by the floor/ceiling in between both of us classical vibrations through carpet and cement as I lay there, close to its heartbeat

Carly Veach

As the seasons change their tune

I revel in their gifts

The cacophony of new sights

The sound of nature shifts

The sun is wont to rise in the morning

The air is wrought with light

I ought to be enjoying its company

But I prefer the night

With the seasons comes change

And moving time heals my pain

September showers bring autumn flowers

But I prefer the rain

The weather dips to two extremes

The heat won’t go away

With the sun, the leaves gain color

But I prefer the gray

And as the season changes tune

I revel in the past

I can’t keep up with the time

The world moves too fast

I can’t keep up with you

Your world moves too fast

Kendra Belton

I love it, I hate it— with its foreign words and magical endings, its hours of practice and breathtaking applause. Its rubbed-raw skin beneath my chin and dexterous fingers delicately balanced on smooth wood. I hate that I’m never enough when I feel like I should be, but am perfectly lovely when I feel the exact reverse. I love the black dress—perfect, uniform, moving in unison with my fellows. Except when we’re not, and we’re in a back room— yelling, scrambling, hurting, preparing for the brilliant yellow light and a thousand pairs of eyes, and, more importantly, a thousand pairs of ears, waiting to behold us. There’s clapping, of course, regardless of any presented prestige; always congratulations, especially when it’s just me, up on stage, alone in black. They tell me I’m the best, but I know better. (Truth be told, I long to be the worst, or barely just mediocre, so that no one expects anything of me.) Why, then, do I devote myself, a groveling slave to this piece of wood, synthetic string, and horsehair? The long, long sessions of grueling thought, the frustrating repetitions of patterns and endless clicking? I hate it, I say! I want nothing to do with it! And yet, I love its beauty, profound. It expresses what I cannot write.

(I cannot speak, regardless.) It brings smiles to many, tears to some. I love it, I love it. I hate it, I hate it. I love it, I hate it... I love it.

Finn Harris

oh no!

the goldfish floats, dead in its cramped plastic bag. its soft belly faces the veiled sky, presenting its most vulnerable parts in submission towards God. it didn’t reach home, pitiful thing. maybe the bumping of the ride did it in, bike wheels harshly jumping on crooked sidewalk and cancer-coated gravel. the bagged fish thumped against the frame of the bike as you clutched it and the handle together in one nail-bitten hand. or maybe the wicked fumes of the city, composed of car exhaust and cigarette smoke, were what killed it. who knows what kind of poison could have crept into the bag, malicious tendrils of carbon monoxide worming invisibly through the seal? or maybe it was the sun, furiously heating the small bag of water with the wrath of a pinprick star that doesn’t have much else to do. always vain and self-conscious, the sun tries anything to feel important. or perhaps its death was of illness from before you even left the pet shop, completely unrelated to the inconveniences of being a fish in a plastic bag in a vicious city. maybe the whole affair was doomed from before you left your apartment. whatever the case, you are holding a scrap of plastic with a wet fish corpse wrapped inside. how strange it is that things ended up this way. you dig a hole in the earth, drop your dead inside, and cover it up again. you rest on the ground, belly up, and submit to God for a little while.

Finn Harris