3 minute read

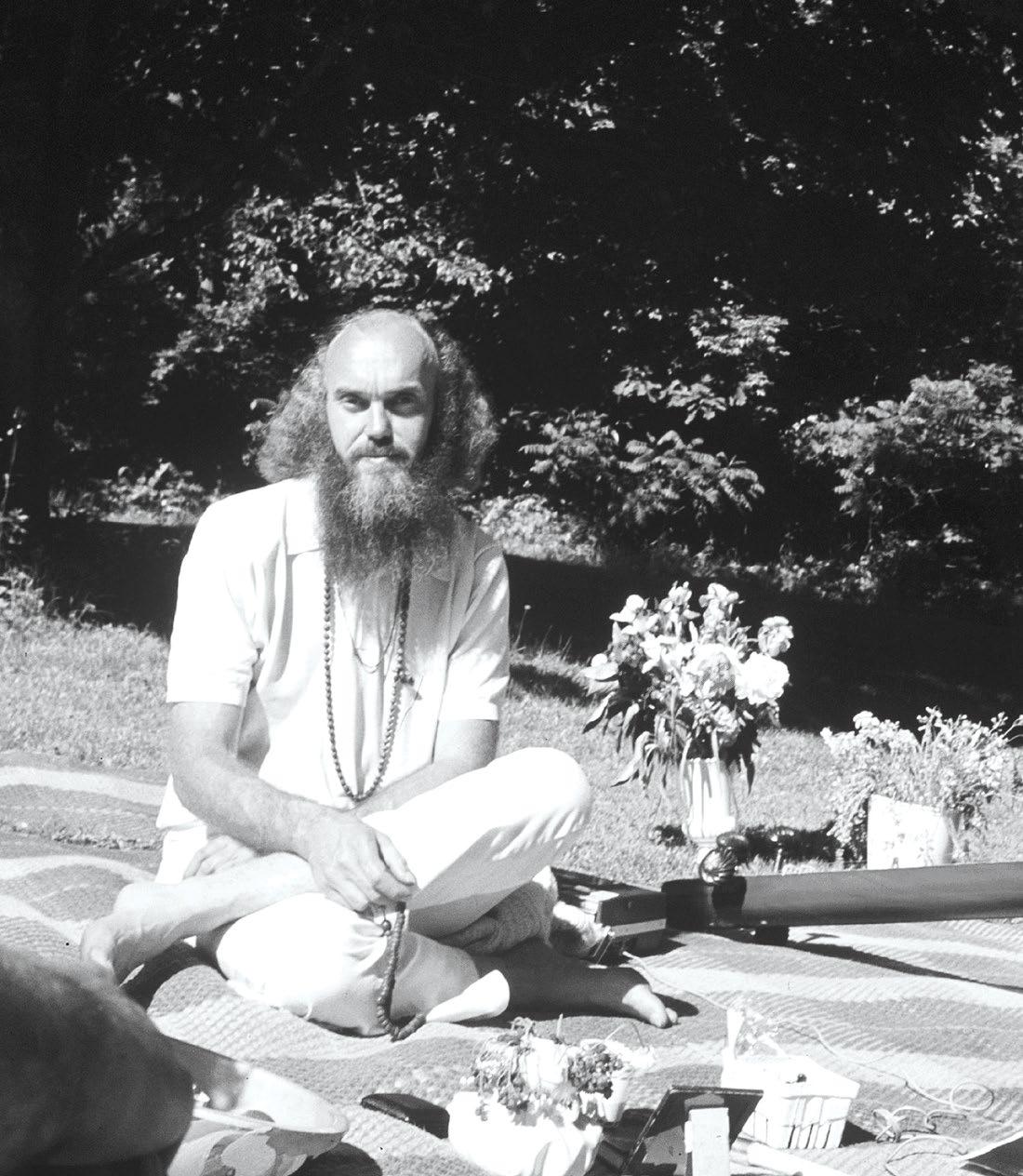

HIGHLY LIKELY RAM DASS

RAM DASS

WHEN RAM DASS passed away in December of last year, a collective wave of grief moved across spiritual communities around the world.

hat’s because Dass was revered throughout many of the world’s spiritual traditions. But how did he come to spirituality? The answer lies in the molecules that make up the compound known as lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD.

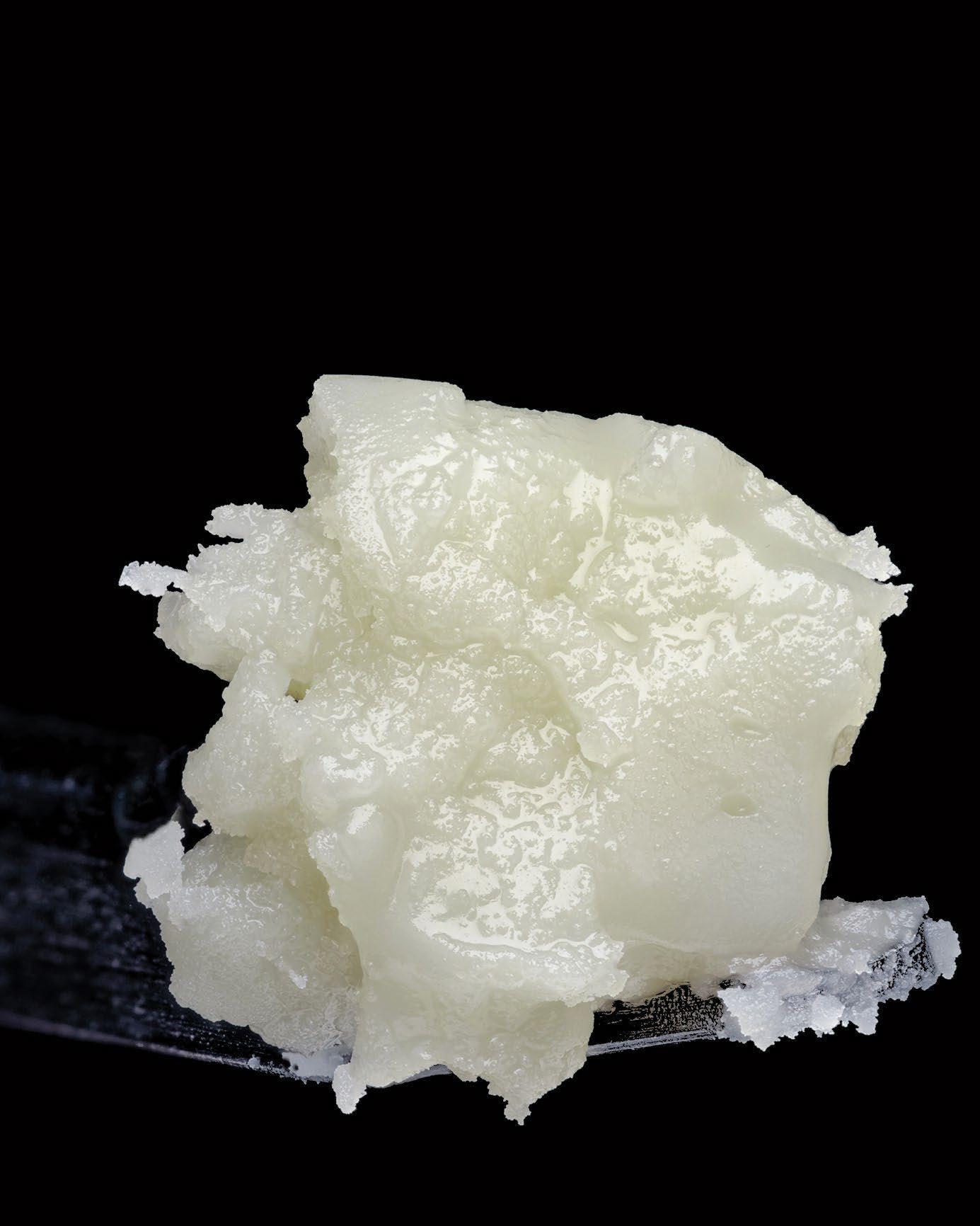

Dass was born Richard Alpert in 1931, raised in a Jewish family in Boston, and said that he felt that his religious upbringing was hollow. Dass said he “didn’t have one whiff of God until taking psychedelics.” In college, he studied psychology – eventually earning his Doctorate in 1957 from Stanford University. A year later, he was an assistant professor at Harvard, teaching clinical psychology. In 1961, he met fellow Harvard professor Timothy Leary, devoting himself to the study of the therapeutic effects of psilocybin (found in mushrooms) and LSD.

One of the most notorious trials of hallucinogenic compounds on individuals at Harvard took place in 1962. Dubbed the ‘Good Friday Experiment’ Leary and Alpert (along with graduate student Walter Pahnke) conducted a T

double-blind experiment that administered psilocybin to theology students prior to the Good Friday mass. Almost every member of the group that received the hallucinogenic dose reported having a profound religious or mystical experience.

While this experiment was revelatory, it also had the effect of getting both Leary and Alpert dismissed from Harvard. From there, the two founded the International Federation for Internal Freedom (IFIF) in upstate New York. In this location, known as Millbrook, Leary and Alpert set up a sort of communal setting for “seeking the divinity within each person” and rapidly changed the substance for seeking from psilocybin to LSD.

In the late 60s, Alpert journeyed to India where he met the person who would change his life and name forever. It was Neem Karoli Baba - whom Alpert referred to as ‘Maharaji’ - who gave Alpert the name ‘Ram Dass’ meaning ‘servant of God,’ and set him on the spiritual path that would define the second half of his life.

Dass told a poignant story of one of his first meetings with Maharaji, where the guru asked Dass, “Have you got any of that yogi medicine?” Dass figured out that what he was asking for was, indeed, LSD. From there he gave the Maharaji capsules that were 300 micrograms each (the guru asked for 3, which in Dass’s opinion was a massive dose).

From there, Dass recalled, “Well this will probably be very interesting, but then – absolutely nothing happened.” Dass went back to the United States and told the foundation members the story of the LSD having no effect on the guru. He started to believe that the wise sage had fooled him and done a slightof-hand, not actually consuming the LSD.

Upon returning to India two years later, the Maharaji asked, “Did you give me some medicine last time you were here?” Dass replied, “Yes, I did.” The guru then asked, “Do you have any more?”

He then proceeded to take 400 more micrograms from Dass, carefully placing each dose on his tongue so that he would observe that he did, indeed, eat the acid. After about an hour, the Maharaji (still seemingly unaffected) looked back at Dass and said, “These were known about thousands of years ago,” but went on to explain that yogis don’t do the proper preparation anymore to prepare for the experience. Dass asked if he should continue the experiments with LSD and the yogi replied, “Yes, but only if your mind is turned toward God.” After these experiences, Ram Dass began work on what would become his most famous work, “Be Here Now” - the 416-page illustrated book and manual for conscious being that is still in print today.

This is but a simple overview of the life of a very important human being who spent time on this planet. Dass’s contributions to society are far greater than his work with psychedelic drugs. For example, his work with end-of-life care is some of the most inspiring - but we only have so much time and space in this article.

The reader is encouraged to go and explore more of his ideas in independent study.