Up Front: Information on the Ground

This year, Ground published its “Democracy” issue. This year also saw multiple landscape architects in public office in Ontario: some incumbents, and some for the first time. And they have lessons about the synergy of landscape and democracy.

Designs by landscape architects can also be described as “democratic,” as the process seeks to obtain answers to a number of questions about the users and the public. As a landscape architect, you have a unique skill set that can make a real

01/ Mississauga, Ontario

03 Up Front .64

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Canva

PROGRESS elected officials 01

impact in your community, especially if you’re an elected official. By leveraging your training and experience, you can help to give your community a voice, and shape it in a variety of meaningful ways.

One of the more important things you can do is to advocate for green infrastructure and sustainable design practice. This could mean advocating for parks, green spaces, and other public spaces that promote healthy living and community engagement.

It could also mean supporting policies that incentivize building owners to maximize building efficiency, manage stormwater, and reduce the urban heat island effect.

“At the municipal level, it’s about being a quality service provider and being creative to get things done,” says Ken Yee Chew, councillor for Ward 6 in the City of Guelph, and one of three newlyelected municipal councillors who are members of OALA.

and realized he was able to facilitate meaningful conversations through some of his training in landscape architecture and urban design.

“That week there was a council meeting and my neighbours encouraged me to delegate on their behalf. At the meeting, I shared a presentation that showcased techniques from my landscape architecture training, such as inventory and context analysis,” says Chew, who is also an urban designer and landscape architectural intern.

“By putting together some visual markups for that application, it led to a meeting between the neighbours, myself, and the developers. It was very empowering to use my professional expertise to facilitate the conversation.”

Town of Cobourg Councillor Miriam Mutton has been involved in municipal politics since 2006. She was re-elected in 2022.

She says landscape architects are problemsolvers because their training helps them appreciate natural and built environments. This has become increasingly important, especially with today’s climate concerns.

“We play a vital role in the public. Specific to Cobourg, we feel development pressures as we’re at the outer and ever-expanding edge of the Greater Toronto Area and seeing growth eastward, including younger families,” says Mutton, who is also the sole proprietor of a landscape architecture business.

“The way of living has changed dramatically, and with the business at council, I am in dialogue with various groups discussing different points of view. I understand development and how to read plans and how the pieces could go together. I undertake to ask the important questions.”

Councillor Chew chose to get involved in municipal politics when he learned the neighbours in his area were unhappy about a development application,

As an elected official, you also have an opportunity to bring a unique perspective to the decision-making process. Your training and experience in design and planning can help ensure public initiatives are thoughtfully crafted and consider the needs of all stakeholders. You can help advocate for designs that are not only functional but beautiful, promoting quality of life and community pride.

02 04 Up Front .64 03 04

Another area where landscape architects can make a real impact democratically is in transportation planning. By working with other elected officials and community organizations, you can help create bike lanes, pedestrian-friendly streets, and other infrastructure that supports active transportation and recreation, which reduces congestion. This not only benefits individual health and mobility, but also creates more liveable and vibrant communities.

“The interesting thing about being a landscape architect and a politician is that it’s almost the same thing,” says Center Wellington Mayor Shawn Watters, a veteran Landscape Architect.

“Politicians do the same kind of thinking as landscape architects [when it comes to] big community building. The two may not necessarily seem connected, but both roles have a vision. It’s how you pull all these elements together and work with your staff to build the community.”

Anecdotally, the general feeling in our profession is that we tend to be more reserved, but we really are the storytellers in the design industry. That’s why it is increasingly

important to speak up when conversations go differently, and becoming more proactive in the democratic process is key.

“Get involved in activities that you and your family are interested in,” says Mutton.

understand it initially, but, while we must be open to understanding different views, as professionals we have a duty to demonstrate new ways of seeing. As well, for the younger landscape architects who are now entering the profession, they are going to have an even bigger impact on our future. It would be a good idea to keep an eye on how your local government is functioning because that’s where important decisions by the local government will affect your everyday.”

“When we work together with different stakeholders—and even amongst design professionals, there will always be friction and tension—it’s almost like different puzzle pieces not quite falling into place when you initially try to piece them together,” says Chew.

“Eventually, however, with persistence and discernment on the placement of the puzzles, they come together like a mosaic. That is, in one essence, our democracy.”

“Keep an open mind, and volunteer on advisory committees, as they have different themes and mandates. Many municipalities are facing issues such as resilient communities, safer communities for all ages, and climate change. Get involved in task forces and participate in public forums.”

Landscape architects who are elected officials can also help to promote a greater understanding and appreciation of the profession. By educating other officials and the public about the value of good design, you can help to raise awareness and support for landscape architecture as a critical component of building healthy, sustainable, and equitable communities.

“I believe one has to practice what they preach,” says Mutton.

“I have a natural garden at my home which is now all the rage. People didn’t

Landscape architects who are elected officials have a unique opportunity to make a real impact in their municipalities. The countless ways your knowledge and skills can impact your communities, from advocating for sustainable design practices to shaping transportation planning initiatives, can help create more liveable, vibrant, accessible, and equitable communities for all.

02/ Ken Yee Chew

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Ken Yee Chew

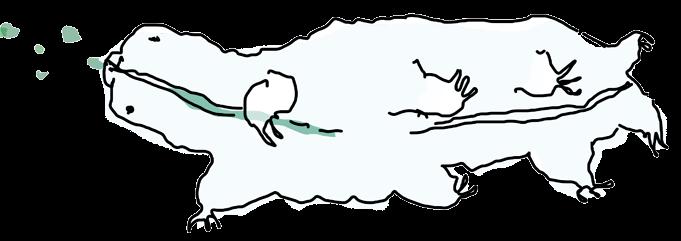

03/ Kingston, Ontario

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Canva

04/ Ottawa, Ontario

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Canva

05/ On the campaign for Miriam Mutton.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Miriam Mutton

TEXT/ ROB NORMAN, OALA EMERITUS, HAS SERVED AS AN ELECTED PRESIDENT FOR BOTH THE CSLA AND THE OALA. ROB CURRENTLY IS THE CHAIR OF THE OALA’S MUNICIPAL OUTREACH COMMITTEE, A BOARD MEMBER FOR THE ROYAL BOTANICAL GARDENS AND IS THE GOVERNANCE CHAIR FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH’S LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION.

05 Up Front .64

05

06 Tiny Terraformers .64

TEXT BY HEATHER SCHIBLI, OALA

TEXT BY HEATHER SCHIBLI, OALA

01/ A Peeudacharutes species eating a slime mould/myxomycete fruiting body. From Cape Tribulation, Australia, April 2016, from regrowth rainforest.

IMAGE/ Andy Murray, website: chaosofdelight.org

02/ A Forcipomyia larva.

IMAGE/ Andy Murray, website: chaosofdelight.org

Soil is not dirt. Dirt, on the other hand, may have once been part of soil, but has since lost its place. Dirt is displaced soil. Like shattered glass to what was once a window into a home, dirt is the residue of disruption. Dirt is the dismembered fragments of a soil ecosystem that have borne witness to a traumatic event.

02 07 Tiny Terraformers .64

CHARLES E. KELLOGG, USDA YEARBOOK OF AGRICULTURE, 1938.

01

To understand the significance of soil versus dirt, we must first explore what soil really is. Beneath our feet and holding us up is a world both infinitesimally small and profoundly expansive. Soils, collectively named the pedosphere, contain no less than fifty per cent of our world’s species. Soils are scaffolded worlds housing thriving, proliferating, and decaying multiplicities of creatures. The pedosphere is the unique milieu where atmosphere, biosphere, lithosphere, and hydrosphere collide and interact, forming the foundation of terrestrial life. Healthy soils have structure, meaning they include spaces between the mineral and biological solids for gases, liquids, and creatures to shift, spill, and spread. In fact, healthy soils are composed of 50 per cent air, 25 per cent water, and only 25 per cent solids.

There would be no soil without life. Soils are created by weathered rock fragments and decayed and petrified bodies. Early colonizers like lichens and mosses secrete acids that unlock minerals from solid bedrock, which are then absorbed and combined into their bodies. These same fragments enter and exit bodies again and again, joining once airborne and waterborne minerals dropped by rain or deposited by wind. Slowly, these fragments accumulate and possibly chemically bind, but only once living organisms shape, mold, and glue do these same fragments aggregate. You see, the soil’s micro-, meso-, and macro-biomes constitute myriad creatures that threedimensionally terraform their environments. Microbial secretions bond particles together, much like how we cement liquids, solids, and gases together to form our buildings.

Here is where scale matters. Like Ray and Charles Eames’ Powers of Ten film, envisioning different scales yields repeating patterns. Our cities are larger versions of the soil environments where air, water, and solids mingle. The pedosphere, imagined at human scale, might look like an M.C. Escher print where stairways and hallways run in every direction and residents grip various surfaces irrespective of gravity. Our cities, like soils, appear firm and unyielding until an earthquake, hurricane, or a bomb puncture and collapse the built environment into rubble. Into dirt. When we till the earth, when we drive equipment, or strip the earth of its roots, we collapse the air spaces, the habitats within, which kills many of the creatures that maintain soil’s crucial structure. Without structure, it is no longer living and is, in fact, mere dirt.

Soil, and the microbiome within, is sometimes referred to as the skin of the Earth. This is an appropriate description for biocrusts, whereby mosses, lichens, and algae form a sheath with arid soils, serving a similar role to our skin as a protective barrier. A more fitting corporal analogy for the pedosphere, however, would be that of our digestive system, and primarily of our gut. Many of the same processes unfold within soils as in our intestines: microbes

digest nutrients from organic matter and recirculate those same nutrients within the larger system. Instead of this process being folded, tucked, and coiled into a body, digestion on a planetary scale happens out in the open. Like our own digestive tracts, the biosphere’s nutrient cycling is both functionally and physically central. Nestled between air and bedrock and combined with water, these processes make available the very building blocks of life. In fact, we share many of the same bacterial species in our bodies as are found in the soil. Geophagy, the practice of ingesting soil, is common among many birds and mammals, including humans. Though not part of western culture, consuming clay soils has proven beneficial for absorbing certain nutrients, binding toxins such as phenols, and as treatment for gastrointestinal ailments. The similarities between these two biomes doesn’t end there. In recent years, links between biodiversity, invasion biology, and system health have been explored in both the health sciences (e.g. autoimmune diseases, mental health) and ecology. Culturally, our collective gut microbiomes have dropped in biodiversity since we have moved into cities and away from the soil. Stripped of access to biodiversity, like tilled and pesticide-laden farm fields, our microbial biodiversity has waned.

Who are these critters in our soils? And what do they need to thrive? Soil ecology is immensely diverse and also sitespecific. Adjacent soils hosting different plant communities unsurprisingly boast different soil fauna and flora. Microbiota, consisting of both microorganisms and microfauna, are the smallest soil residents, ranging from 20 to 200 μm (micrometres) in length. Microorganisms are by far the most abundant and include algae, bacteria, cyanobacteria, fungi, yeasts,

08 Tiny Terraformers .64

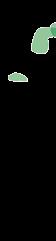

03/ Slime mould fruiting body. IMAGE/ Illustration by Heather Schibli 04-06/ Tardigrades IMAGES/ Illustration by Heather Schibli 03 04 05

myxomycetes, and actinomycetes. These are the main decomposers who can transform virtually any organic matter into nutrients. Microfauna—small mites, springtails, nematodes, and protozoa— feed on these microorganisms, along with plant roots, and other microfauna. They connect microbes to the rest of the soil food web and release nutrients bound up within microorganisms. Mesofauna is a collection of creatures measuring 200 μm to 10 mm. Collembola, tardigrades, pseudoscorpions, protura, diplura, mites, small myriapods, and enchytraeids live within soil pores, in leaf litter, and mosses. They decompose organic material and feed on microflora, microfauna, and invertebrates. Larger still are the macrofauna. These we can easily see without instrumentation and are thus the most familiar. Earthworms, ants, and termites considerably impact the soil structure by ingesting, tunneling, binding, and moving soil particles. In their native ranges, these macrofauna are recognized as integral keystone species that shape and create habitats that enrich biodiversity. Since the last ice age, Canada’s native soil engineers include mites, nematodes, millipedes, and fungi; not earthworms. As earthworms have spread across North America, since being introduced by European settlers, they expedite decomposition rates, thereby altering the very soil fabric that our ecosystems have evolved with. Many of Canada’s native tree species and spring ephemerals rely on thick layers of slowly decaying leaf litter. This layer, known as the ‘O’ layer for organic, is composed of duff, litter, and humus, and can reach depths of 65 centimetres in Canada’s boreal forests. Many soil organisms live in this layer where moisture and nutrients are readily available. Some of my favourite soil dwellers live within the organic soil horizon, and the following are just a couple.

07/ Fungus on a fallen log.

IMAGE/ Jennifer Wan

08/ A eurypauropod

IMAGE/ Andy Murray, website: chaosofdelight.org

09 Tiny Terraformers .64

06 07 08

09/ Land planarian, Burrington Combe, Somerset, UK.

IMAGE/ Andy Murray, website: chaosofdelight.org

10/ Acanthanura species,Collembola/ springtail Lamington National Park, May 2016.

IMAGE/ Andy Murray, website: chaosofdelight.org

11/ Dicyrtomina minuta-Collembola/ springtail, standing on snail eggs East Pennard March 2015.

IMAGE/ Andy Murray, website: chaosofdelight.org

The ever resilient tardigrade is a phylum of minute, eight-legged, lumbering creatures whose appearance has inspired their common names: water bears and moss piglets. In recent years they have entered popular culture with cameos on Star Trek, Ant-Man, South Park, and Family Guy. Although many of the thousand or so identified species of tardigrade are considered terrestrial, they live within thin films of water on moss, lichens, plants, leaf litter, sands, and soil. These films may not be visible to us but they are the tardigrades’ entire universe. When these films evaporate

with the midday sun, tardigrades enter into a state of cryptobiosis, whereby their metabolism drops to less than 0.01 per cent the normal rate. Within this state, they can live decades waiting for better conditions to return. Moss samples stored in a museum for 120 years wielded live tardigrades once reintroduced to water. Researchers have found that tardigrades can contain nearly 1/6th foreign DNA within their genome, acquired primarily from bacteria, but also from plants, fungi, and archaea, through horizontal gene transfer. This bends our understanding of species and evolution.

10 Tiny Terraformers .64

09 10 11

Photos don’t do justice to these waddling creatures, you have to see them move to fall in love, and I encourage you to seek out videos online.

Before I listened to Lucy Jones’ exquisite essay for Emergence Magazine on slime molds, my only encounter with myxomycetes was with the ubiquitous dog vomit slime mold (Fuligo septica) that gathered upon my garden bed. This creature, like other slime mold, begins life as an amoeba-like single-celled microscopic eukaryote that resides within soils consuming bacteria. When these single celled creatures experience adverse environmental conditions, they may congregate and fuse with one another to emerge as a multinucleate mass with a singular cell membrane, also known as a plasmodium, which can move and produce spores. It is during this stage that we humans might take note, however they can still be easily overlooked. Macrophotographers Andy Murray, Alison Pollack, and Barry Webb reveal the surreal Dr. Seussian worlds of slime molds: perfect glistening metallic spheres sit upon threadlike stalks; glass-like coral structures sprout from decaying wood; and yellow cotton candy-filled cones spiral toward the sky. Slime molds defy our attempts to categorize; they are shape shifters that can have more than 700 sexes. With no brain, they can still solve math problems and navigate terrain. They suspend reality and force us to question our assumptions about this world.

As landscape architects, what can we do to support life in the soil? Given their fragility, we should try to avoid moving, tilling, scraping, and trampling soils. We can prescribe soil rehabilitation and care within our drawings and specifications. We can opt for biodegradable mulches instead of petroleum-based landscape cloth. We can avoid loading soils with synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, insecticides, and salts. We kill the life within soil when we apply such inputs. Instead, we can work with soil, feed the soil with compost, leafmold, bio-char, and other healthy foods. We can leave the leaves and not even mulch them. We can just leave them to feed the soil, to protect roots, and to house insects. Remember, our world evolved with these cycles, and when we disrupt them, we dampen that shimmer of life.

12/ W. bicornis from behind.

IMAGE/ Andy Murray, website: chaosofdelight.org

13/ Cepheus dentatus and micro snail.

IMAGE/ Andy Murray, website: chaosofdelight.org

14/ Holacanthella spinosa mature adult.

IMAGE/ Andy Murray, website: chaosofdelight.org

BIOS/ HEATHER SCHIBLI, OALA, IS A LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT, ECOLOGIST, AND ARBORIST, WHO DRAWS UPON HER DEEP AFFINITY FOR THE NATURAL WORLD TO GUIDE HER DESIGN PRACTICE AND CONSULTING WORK FOR DOUGAN & ASSOCIATES, A GUELPH-BASED TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY FIRM. SINCE 2019, SHE HAS BEEN AN ADMINISTRATOR FOR THE NETWORK OF NATURE (FORMALLY CANPLANT), WHICH IS A PARTNERSHIP WITH CANADIAN GEOGRAPHIC THAT IS DEDICATED TO SUPPORTING AND RESTORING CANADA’S UNIQUE BIODIVERSITY AGAINST THE STRESSES OF DEVELOPMENT, EXTRACTION, AND CLIMATE CHANGE.

11 Tiny Terraformers .64

12 13 14

the seen and unseen value of landscape

01

12 Round Table .64

BIOS/

EHA NAYLOR, OALA, HAS OVER 40 YEARS OF EXPERIENCE IN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE, BEGINNING WITH HER WORK AT HOUGH STANSBURY. SHE HAS SERVED AS CHAIR OF THE OALA PRACTICE LEGISLATION ACT COMMITTEE, A PARTNER AT DILLON CONSULTING, AND IS PRESIDENT OF THE LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE CANADA FOUNDATION. SHE HOLDS A BACHELOR’S DEGREE IN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO, AND A BUSINESS DEGREE FROM SCHULICH SCHOOL OF BUSINESS.

JOHN ZVONAR, OALA, GRADUATED WITH A MASTER’S DEGREE IN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA IN 1988. HE RECENTLY COMPLETED A 30-YEAR RUN AT THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT’S CENTRE OF EXPERTISE IN HERITAGE CONSERVATION, PROTECTING NATIONALLY SIGNIFICANT CULTURAL LANDSCAPES, NOTABLY FOR PARKS CANADA, MULTIPLE FEDERAL DEPARTMENTS, AND OFTEN THE PARLIAMENTARY AND JUDICIAL PRECINCTS. HE IS ALSO INVOLVED WITH THE ALLIANCE FOR HISTORIC LANDSCAPE PRESERVATION, AND SERVES AS THE CANADIAN VOTING MEMBER WITH THE ICOMOS-IFLA INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE FOR CULTURAL LANDSCAPES. JOHN WAS HONOURED WITH HIS ELECTION TO THE CANADIAN SOCIETY OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE’S COLLEGE OF FELLOWS IN 2014.

ALEX BOZIKOVIC IS THE ARCHITECTURE CRITIC FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL. HE IS AN AUTHOR OR EDITOR OF THREE BOOKS: TORONTO ARCHITECTURE: A CITY GUIDE; HOUSE DIVIDED; AND THE BESTSELLER 305 LOST BUILDINGS OF CANADA. HE WON THE 2019 PRESIDENT’S MEDAL FOR MEDIA IN ARCHITECTURE FROM THE ROYAL ARCHITECTURAL INSTITUTE OF CANADA FOR HIS JOURNALISM.

GLYN BOWERMAN IS THE EDITOR OF GROUND MAGAZINE. HE IS ALSO A TORONTO-BASED JOURNALIST WHO WRITES ABOUT URBAN AFFAIRS, AND HOST THE MONTHLY SPACING RADIO PODCAST.

Glyn Bowerman: What designed landscapes are typically acknowledged for having value, beauty, utility or cultural significance?

John Zvonar: When I was in school at the University of Manitoba, Cornelia Oberlander’s work with Arthur Erickson on the Vancouver law courts building was all the rage. I really wanted to see Cornelia’s work there, and ultimately did, and appreciated it as a truly welldesigned, bold effort. There are others across the country, but that’s the one I would start with.

Eha Naylor: I started my career with Hough Stansbury & Associates, they were the landscape architects for Ontario Place, and that’s a timely topic regarding what people value in landscape. When I was growing up in Toronto, I loved Ontario Place. It was exciting, it was on the water, it was kind of a magical place that was accessible and available

02 03

01/

Park, Vancouver. IMAGE/ John Zvonar 02-03/ Ontario Place, Toronto. IMAGES/ Jennifer Wan 13 Round Table .64

MODERATED BY GLYN BOWERMAN

Stanley

04-06/ Ontario Place/Trillium Park, Toronto.

IMAGES/ Jennifer Wan

07/ Aerial view of Stanley Park.

IMAGE/ John Zvonar

08/ Stanley Park, Vancouver.

IMAGE/ John Zvonar

to everybody. And it had a cultural side too: it had a beautiful architectural ethic to it, and it was just a fun place to be. It had this indelible impact on us all. And now that changes that are occurring, there’s no surprise there’s such a strong sentiment about whether you think the new provincial government plan for it is right or wrong, good or bad. It’s really exciting when landscapes do that for you.

Alex Bozikovic: I’ve written a lot in the last year or two about Ontario Place and, like Eha, feel very passionately about it. Specifically, the importance of that place as a landscape, not just a park in a more utilitarian sense, but a work of landscape architecture.

In my upbringing, the most formative of landscape projects was the Toronto Islands Park, which I visited as a kid from a very early age and grew to appreciate, again, as a piece of landscape architecture. Both are really good examples of a certain brand of public space in which landscape architecture was, over a 20-year period, at its high point of cultural influence. That was the moment so many great cultural projects were being designed and built across the country. And, while you could argue landscape today is in some ways more influential, or the range of landscape architecture is larger, the projects of that era were formative for so many people.

It’s a useful point that we’ve already established that these landscapes have a strong set of ideas shaping them, and also a strong social value. They’re important to everyone.

GB: Do we appreciate the value of these landscapes because of the quality of their design? Is it because of the need they fulfill? What is it people can intrinsically appreciate, or is it a combination of multiple things?

JZ: For me, it’s what Frederick Law Olmsted said about Central Park in New York as being the lungs of the city. If you’re in Downtown Vancouver, referring back to the Law Courts, you want a place

where you can unwind, because it’s a busy, happening place. It’s probably good planning, design, execution, and decent, long-lasting materials. It’s extremely important that they don’t fall apart and have barriers up all the time.

Also in Vancouver is Stanley Park, Winnipeg has Assiniboine Park, Mount Royal Park in Montreal—these are great places that are where they are needed and what they were intended to be to benefit the local community.

EN: It’s the emotional conditions they evoke: whether it’s because it’s a beautiful natural space or a nicely crafted urban space, you have a visceral reaction. And that’s what makes landscapes, whether they’re institutional landscapes, public parks, gardens, or national parks, really memorable.

AB: It’s interesting that, with the places we’ve talked about here, we often go straight to thinking about landscapes as involving an experience of nature, and that Olmstedian function of the park or the green space as a necessary, almost therapeutic service. But the other thing that parks do is serve as gathering places. Even outside of the pandemic, that function is just as, or perhaps even more, important. In our mostly suburban country, which in many cases doesn’t

04 07 08 05 06

14 Round Table .64

11/

IMAGE/ Susan Coles

really have a strong history of public space outside of some very specific places, this has been a really important job that landscapes have done over the past century, but especially over the last two generations. Providing focal points and gathering places for community. A big part of why we use public places is to actually be with other people. Those two functions can sometimes be in contention, but I think most of us want both.

GB: When does the value of designed landscapes typically go unseen or maybe even underappreciated?

JZ: It matters whether they’re going to be used and used well. One place that comes to mind is Boston City Hall. One of the complaints about the adjacent plaza was it was windswept, there weren’t enough trees. It looked really good in plan and perspective, but, in terms of the winter environment, it was particularly harsh. The established micro-climate in the area can determine whether people will want to use a place in all seasons.

EN: There’s another layer to this. If a landscape is poorly executed, it won’t be appreciated or enjoyed. But sometimes a landscape goes unseen or unappreciated as a consequence of it not being understood as a cultural place. There are historic, intrinsic

qualities to a place that, unless you help people appreciate and understand the history and why it’s so special, and there’s no interpretation or education about it, then it’s underappreciated. People won’t get why that place is so significant. And, somehow, that has to come into the practice of landscape architecture: to help people understand why some landscapes that may not seem spectacular are important to our country, our community, or the place we live.

JZ: Charles Birnbaum from The Cultural Landscape Foundation was decrying the fact there were a number of modernist landscape masterpieces from the ‘60s and ‘70s under threat because nobody was advocating on their behalf. If you’re not talking about them as a professional, who else is going to do that? Some time ago, I’d been involved in an exercise within and around the Judicial Precinct (Supreme Court) in Ottawa, looking at landscapes that were important. This included the Garden of the Provinces and Territories. That was an iconic example of modernist design by Donald Graham in the ‘60s. At one point, I had the opportunity to stand on the site with him. How many opportunities do you get to stand with the actual designer of a place all those years later to talk about and understand it? But if landscape architects are not advocating for these places, why should others?

AB: I’m one of very few people in the country outside of the design professions whose role it is to advocate for those places. Preservation of modernist buildings remains very difficult in Canada and modernist landscapes even more so for a variety of reasons. One is that there hasn’t been enough of a generational shift in terms of the people who are leading and overseeing projects, such that there are a lot of people who remember the ‘60s and ‘70s and can’t really frame those works as historic. Even though that period was the most important in the history of the design professions in Canada. But there are also a lot of people, particularly older people, who find it difficult to do the kind of intellectual

09/ Assiniboine Park, Winnipeg.

IMAGE/ John Zvonar

10/ Great Lakes Fountain, Garden of the Provinces and Territories, Ottawa.

IMAGE/ John Zvonar

Garden of the Provinces and Territories, Ottawa.

09 10 11 15 Round Table .64

work needed to appreciate modernist landscape projects as cultural projects.

We lack a cultural landscape foundation here. Even so, there’s just not a lot of reverence among ordinary people for these landscapes in the same way there is for other kinds of cultural production. And part of how I see my job is attempting to remedy that. But it’s tricky. We’re at a point in history where a lot of things made two generations ago now really require maintenance and new investment and need to be understood and framed intellectually as significant. And we don’t talk about design enough generally in this country.

JZ: I’ve already mentioned Don Graham’s name and Michael Hough has come up. I live five miles west of downtown Ottawa. Don Graham in the mid-1960s laid out the what was then called the Ottawa River Parkway—today called the Kichi Zıbı Mıkan. Speaking of unseen landscapes, I would say 99 per cent of people that use that parkway don’t have a clue that it was actually designed. That was probably ever thus. I mention Michael Hough because he, about 25 years ago, was trying to naturalize the acres and acres of turf grass that is part of that parkway. And people got really angry that it looked messy, but these days, naturalization rules!

EN: The National Capital Commission charged Michael with naturalizing the Transitway. I was fresh out of school and working with Michael at the time. He would be thrilled to see what it looks like today.

GB: Are there landscapes right now that you feel are jeopardized by a lack of appreciation or acknowledgement for the role they play in the fabric of a community? We mentioned Ontario Place, but do other ones come to mind?

JZ: We have a group within the CSLA, the Cultural Landscapes Legacy Group. To the question of how to get people interested or excited? Well, part of it is actually getting your own profession to remember what came before. And so, in anticipation of this May when the CSLA will meet in Winnipeg to celebrate 90 years as a society, one of the things that will be launched is a collection we have been working on to acknowledge great

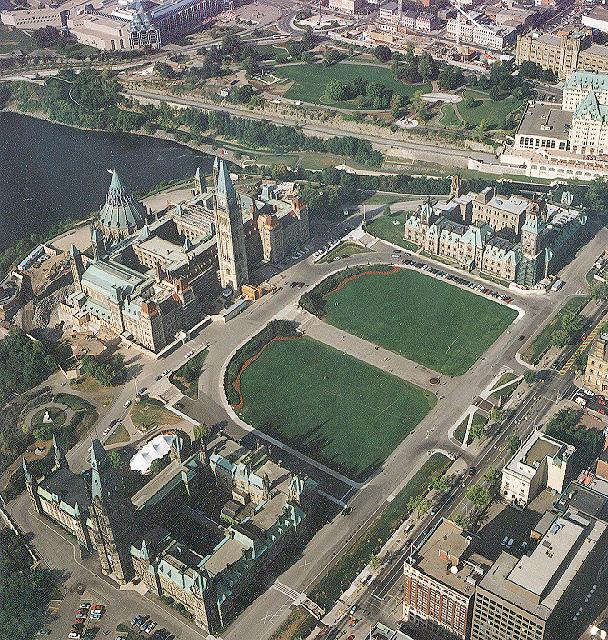

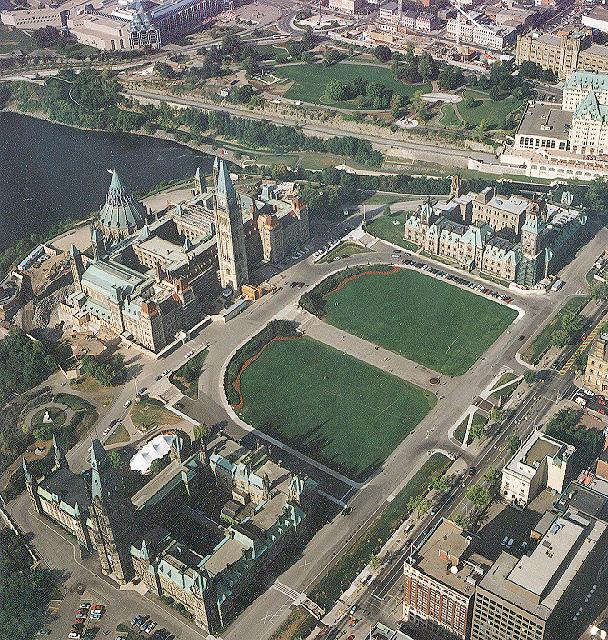

works of landscape architecture across the country. For example, Ontario Place is part of that, Mount Royal Park in Montreal, and Parliament Hill here in Ottawa.

What is it that a given community values, and what are you going to protect, moving forward, while adding in things the community wants today? That’s the ongoing discussion. When I first started my career, people would say, ‘You heritage people don’t want us to do anything.’ But that’s not true. A landscape isn’t a museum. These are evolving, changing places. And the community can make a decision about what it wants to change, for better or worse. And, some point down the road, someone will have to change it again. But that’s natural.

12-13/ Kichi Zibi Mikan, Ottawa IMAGES/ John Zvonar

12 13 14 16 Round Table .64

14/ Mount Royal Park, Montreal. IMAGE/ John Zvonar

15/ Parliament Hill, Ottawa.

IMAGE/ Caise Chandler

16/ Aerial View of Parliament Hill.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the National Air Photo Library

17/ C Block, Parliament Hill, Ottawa.

John Zvonar

EN: The loss of an important landscape is not usually premeditated, ‘Let’s wipe it out and do something totally different.’ It’s a death by a thousand cuts. And I look at Parliament Hill which has the bones to be one of the most beautiful and celebrated places in Canada. It’s been decimated by one parking lot after another. And that’s happened not because landscape architects haven’t tried to protect it, but because, for whatever reason, parking has become prioritized over the public realm.

Sometimes landscape architects aren’t empowered to be able to turn the table and say, ‘This is not the right thing to do in this particular place.’ And it’s a real-time problem. But it happens in a lot of places where the intended use is subverted by convenience and lack of imagination or poor policies, as opposed to poor landscape architecture.

AB: Another threatened landscape in Ottawa is the one within the atrium of the Bank of Canada building—another Oberlander project with Erickson—which was effectively privatized for the most preposterous, spurious security reasons. And consultants went along with that. The architects from Perkins & Will Toronto told me very seriously that, of course, this was a reasonable idea that terrorists might choose to strike the reception

area of the Bank of Canada. But there is a tendency in any large organization to regard public spaces as challenging, difficult, or a drain on resources. And that kind of self-privatization is common.

GB: Is part of the problem a lack of continuity of stewardship, or even confusion on who the steward should be for a designed landscape?

EN: In my experience it is. Good stewardship requires a mandate, and the mandate has to come from somewhere, it can’t just be assumed. It needs to come from a position of authority that allows stewardship to be grounded. Without that, it’s very tricky because no one’s in charge, or everyone’s in charge. There needs to be clarity around the role of who the steward is, and then the steward should be including others.

JZ: In Washington D.C., they have an office called the Architect of the Capitol. And I’m guessing other major G8 cities across the globe have something similar. I’ve been closely connected to Parliament Hill for most of my career, consulting or providing advice, and once in a while someone from the Architect of the Capitol would come to visit. We’d have an opportunity to cross paths and I’d think, “Why can’t we do that here?”

IMAGE/

15 16 17 17 Round Table .64

You talk about continuity, that would be it: there would be an office, and that person or persons can change, but at least the mandate would be consistent and continuous.

AB: Anything that can be done to elevate the conversation and remind people that what we have exists and is important. This summer I visited what I think is one of the most important parks in what is now the City of Toronto— mostly designed by architects, actually— Shim-Sutcliffe Architects’ Ledbury Park, which they did together with NAK Design Strategies, for the former City of North York in the ‘90s. It’s a very beautiful, mannered ensemble of landscape and buildings. And it has been absolutely destroyed by the City itself in a renovation in the last year or two. It had a multi-layered fountain with a bridge over it. It was a landscape that required a certain degree of maintenance, but had a very specific character. And, in 25 years, that has been absolutely lost, to the point that the people working there had absolutely no idea why I would be interested in it. Within governments themselves, there’s no consistency, there’s no chief architect. But you need that internal champion of quality, of history.

EN: There are a lot of disciplines that understand design, what’s involved in it, and how it can be a problem solver, a conduit for creativity, it’s a really important component in city planning. I’m sad to say, I think the planning community doesn’t understand design. As a consequence, it gets relegated to something that is not considered an important part of planning. Design culture, as Alex said, is not foundational to Canadian culture as it is in some other countries. Design is not well understood here, and it’s part of our responsibility to promote its importance.

JZ: My hometown is Thunder Bay. In 2011, I was at a CSLA Congress and a representative of Brook McIlroy was presenting a project for the redevelopment of the waterfront there. Since it’s been done, when I visit, I love it! But I have friends back home and all they can talk about is how much it cost to build that.

AB: Yeah, that drift towards austerity is the subtext to all of this. There was a moment when designers could get away with stuff, when there was more money and there were a lot more projects getting built, and when an Ontario Conservative premier would build Ontario Place—this weird set of Metabolist buildings, floating over an incredible landscape with a rotating stage concert venue. It’s wild to think about that today.

But I’d like to talk about how landscape intersects with the urbanist project which in many ways seemed, until COVID, to be very successful: the effort to re-energize and reassert the value of central cities. We’ve seen fantastic examples where landscape has been an important part of that and intersects with that effort by creating public spaces that people really love. I feel it’s very important that we do better creating gathering places within cities. High-quality public space that serves other functions, including ecological ones, but most of all provides places for people to hang out. We need more public squares—which is not a tradition here, but

18 Round Table .64

18

18/ Berczy Park, Toronto. IMAGE/ Sean Marshall, Flickr, creative commons license

19/ Love Park, Toronto.

IMAGE/ wyliepoon, Flickr, creative commons license

20/ Sugar Beach, Toronto: “Icicles.”

IMAGE/ Rene_Beignet, Flickr, creative commons license

a few people know how to do it. Claude Cormier, rest in peace, knew how to do it. And those very urban, distinctly not naturalized or quasi-natural landscapes can also be really powerful. Everybody loves a square.

EN: Everybody loves the square and everybody loves a beautiful streetscape or promenade, as well. You can walk and shop, while visiting a friend. And that’s part of what we do.

GB: We’ve seen recent landscape highlights like new parks opening, and then lowlights like the threat to Ontario Place. Both have, at least, got people talking about landscapes in the public sphere, even organizing around landscapes and their importance. What needs to happen, politically, professionally, culturally, to bring appreciation for designed landscapes to the forefront?

EN: It is incumbent on our profession and allied professionals to champion good design and good public space making and to be brave about it. Because it’s really hard at times: with Ontario Place, for example, the political context is so unfriendly and misguided. And there’s a need to be outspoken and to take up the challenge. Do it, because it’s important for everybody and it will be very important for future generations.

JZ: People are getting the word out in the media that okay is not good enough and we should be doing much better. We have enough professionals that we should be taking advantage of, particularly in Ottawa. When people come here, they should feel a sense of awe, as a world capital city. That intent is starting to grow. An interdisciplinary chorus should help to a great degree.

AB: All design professions need to be more political, and show more solidarity between themselves. One of the fundamental problems I keep coming back to in writing about public work, both architecture and landscape, is designers are undercutting each other. Some of the best designers in this country won’t even touch public work because they understand the pay and working conditions are not going to be adequate, and that is a real problem.

This is also one of the richest countries in the world. We have a lot of good designers. We have a lot of building happening. We really should aspire to deliver the absolute best. And designers need to get better at making the case for why quality design makes people’s lives better, generates better social outcomes, generates financial returns, generates economic development. I knew nothing about landscape architecture until a few years into my career, and I was increasingly fascinated to learn just how powerful and efficacious landscape work can be, and how relatively inexpensive it is. Landscape architects, with the right resources and effort, can do remarkable things. I don’t think that is appreciated, and I don’t think that capacity is being put to use well enough in our society, and it should be.

19 20 THANKS TO TERENCE LEE, JENIFER WAN, AND HELENE IARDAS FOR COORDINATING THIS ROUND TABLE.

19 Round Table .64

01 20 Healthy Roots, Healthy Trees .64

02

TEXT BY TODD IRVINE

When trying to determine why an urban tree is stressed or dying, I first look down, not up, for answers. That’s because damage to roots, and the soil they grow in, is one of the most frequent causes of tree mortality in cities.

I’ve worked for nearly 25 years as an arborist, a decade of which was spent consulting on development projects, from backyard decks to the construction of new transit lines. Early on, I lost track of the number of times construction contractors assured me the roots of the large tree they were working near wouldn’t be damaged because the concrete walkway they were installing was only going down 30 centimetres below the existing grade. Or the landscape drawings I reviewed with notes saying no trees were to be disturbed, yet showed a new swale adjacent an existing row of trees. Or the number of homeowners who would call me a couple years after a redesign of their backyard was completed so I could help them figure out why their mature trees were looking unhealthy, only to find new in-ground irrigation from fence line

to fence line, and the trunks of their trees surrounded on all sides by elaborate stonework.

Towering mature trees are beloved features of urban landscapes because of their imposing beauty and the many ecological benefits they provide, yet the need to protect the soil and roots of existing trees on landscape projects is frequently overlooked. Architects, landscape architects, engineers, and construction contractors understand the need to protect the aboveground parts of the tree—the part we can see. Any damage there would be obvious and its consequence easily understood. But the tree’s vast network of delicate, easily damaged roots are out of sight, and therefore often not adequately considered. Neglecting to afford them necessary protection often results in the tree’s slow, irreversible demise.

A tree is a giant pump, with roots absorbing water and nutrients from the cool ground. The tree draws this water through its vascular system and into its leaves, in the process

01/ Roots of mature silver maple in Coronation Park, Toronto, exposed using air spade technology, prior to new walkway install.

IMAGE/ Todd Irvine

02/ Close up of extensive silver maple roots near soil surface in Coronation Park, Toronto.

IMAGE/ Todd Irvine

03/ Roots of mature sugar maple, cleanly pruned to allow for construction of new house foundation. All roots are located in top metre of soil.

IMAGE/ Todd Irvine

04/ Roots of Norway maple exposed using hydrovac technology, prior to installation of new communication lines.

IMAGE/ Todd Irvine

03 21 Healthy Roots, Healthy Trees .64

04

of evapotranspiration that enables photosynthesis. A large tree can absorb and pump hundreds of litres a day. As the water in the leaves is warmed by the sun, it becomes a vapour that exits through tiny holes called stomata on the undersides of leaves, creating a suction that continues the upward pull of water. When roots are damaged, or the soil is compacted, the tree is unable to pull water from the ground and the pump breaks down, causing the leaves and branches in the top of the tree’s crown to wilt and die.

Given their importance, the obvious goal on landscape projects should be leaving the roots of existing trees undisturbed. Unfortunately, we tend to greatly underestimate their size and location, and how easily their growing environment can be adversely altered.

The majority of a tree’s roots, especially those responsible for water and nutrient absorption, are in the top 30 centimetres of soil, which makes sense considering the water they’re trying to absorb comes from rainfall and the top layer of soil is where decomposition occurs, providing nutrientrich organic matter. It’s also more aerated than the denser soil horizons below.

Larger transport roots that grow outward horizontally from the trunk support a vast network of fine feeder roots that tend to grow upward into the desirable soil near the surface. These extensive feeder roots grow by developing cells at their threadlike tips, which force their way through the pore spaces between soil particles in search of water and nutrients, which they absorb through tiny hairs. As such, they grow best in well-aerated soil, with a diversity of particle sizes, adequate water, rich with fungi and organisms that decompose organic matter.

In healthy soil, a tree’s roots can extend out three times as wide as its crown, with more than 60 per cent of the absorbing roots extending beyond the dripline (edge of the foliated crown). This enables the roots to take up water during short summer rainfalls, while the ground

closer to the tree under the leafy crown stays dry. (Of course, the size, extent, and configuration of roots are greatly influenced by the soil conditions, growing environment, and species of tree.)

Ideal soil conditions that may have allowed a beloved tree to reach 200 years of age can be altered permanently in a day, without a single shovel entering the soil. The culprit is soil compaction, often caused by equipment or trucks. Compaction alters the structure of the soil, forcing out the pore spaces roots require for gas exchange and water infiltration. The resulting increase in density greatly limits the ability of the delicate feeder roots to force their way through the soil. Once soil is compacted, it is very difficult to reverse the damage.

And it doesn’t take long, or much, for soil to become compacted. I’ve had many projects where we protected the trees on a development site for years during construction, only to have the tree protection fencing come down in the final week and landscape contractors bring in a skid-steerer to scrape off the existing

05/ Roots of white mulberry damaged by backhoe during digging for a house foundation.

IMAGE/ Todd Irvine

06/ Pressurized water and suction hose of hydrovac technology exposing silver maple roots, prior to construction of Ontario Veterans Memorial.

IMAGE/ Todd Irvine

22 Healthy Roots, Healthy Trees .64

05 06

patchy grass under the trees. They then drive back and forth for hours bringing in new topsoil, as specified by the landscape drawings. The repeated passes by such equipment can compact bare soil to the density of concrete, making it completely inhospitable to roots.

Root damage can also have serious consequences for a tree’s structural integrity. The large, spreading network of criss-crossing roots anchors the tree in the ground. Not just the large structural roots, but the thousands of smaller feeder roots stitched into the particles of soil, creating a dense mat, held down by the weight of the soil. So damaging roots not only affects the health of a tree, it can make it unstable and more likely to fall during a windstorm.

Recognizing these impacts, many municipalities in Ontario have enacted bylaws to protect trees. Toronto, for instance, has a bylaw that protects all trees on private property with a trunk greater than 30 centimetres diameter, measured at 1.4 metres from the ground. Trees regulated by the bylaw must have barriers erected around them prior to construction to protect the crown, trunk, and root system of the tree. The size of the tree protection zone (TPZ) is dependent on the size of the tree’s trunk, with a 30 cm diameter tree requiring a TPZ of 2.4 metres radius. A 100 cm diameter tree would require a TPZ of 6 metres radius. However, these are minimum requirements, and they rarely end up being as wide as the tree’s crown. Considering that the roots of a tree can extend out three times as wide as the crown, these tree protection requirements should be treated only as a starting point. Whenever possible, trees should be provided TPZs as wide as their crown, and even wider when the opportunity presents itself. Efforts should also be made to erect protection around groupings of trees to allow them to share larger areas of undisturbed soil. Do away with the circular TPZs, they are hard to build and provide less protection. Instead, show them square on drawings.

07

Landscape architects have an invaluable role to play in tree protection. Your designs, plans, and approach to project management contribute greatly to our urban forest. From the outset, identify the valuable mature trees, visualize the extent of their root systems, and plan your designs around them. Develop designs that minimize excavation and avoid soil compaction. If you do have to install hard surfaces where roots exist, minimize their depth, use porous materials that don’t alter the soil’s pH, and use paving products designed to disperse loads. Ensure the soil under mature trees and areas where new trees will be planted stays undisturbed throughout the project. Top dress these areas with lots of compost, mulch, and leaves. Work with an arborist, and remember that even when building permits are not required, you are still responsible for adhering to tree protection bylaws.

By ensuring mature trees survive, and your newly-planted trees thrive, your landscapes will be green, lush, and sustaining for future generations to enjoy.

08

07/ The author using an air spade to conduct an exploratory excavation of a white spruce root system, prior to a new house construction.

IMAGE/ Todd Irvine

08/ The root system of a Norway maple exposed using hydrovac technology for a research project conducted by the Town of Oakville.

IMAGE/ Todd Irvine

HOMEOWNERS AND PROFESSIONALS ABOUT PROPER TREE CARE.

23 Healthy Roots, Healthy Trees .64

BIOS/ TODD IRVINE IS AN ISA CERTIFIED ARBORIST AND HOLDS A MASTER OF FOREST CONSERVATION FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO. HE WORKED FOR 20 YEARS AS AN ARBORIST AND CONSULTANT AT BRUCE TREE AND IS NOW THE OWNER OF HIS OWN COMPANY CITY FOREST, WHICH IS FOCUSED ON EDUCATING

The project to naturalize the mouth of the Don River is unique because, although it is a major infrastructure project, the prime consultant is not a large engineering firm but a landscape architecture firm, Michael Van Valkenburg Associates (MVVA), with engineers, architects, and ecologists working as subconsultants. Landscape architectural leadership means that all design, construction, and cost decisions are guided by a landscape-scale vision of the site, and informed by considerations about the human experience of the landscape, as well as the viability of the ecosystems that will thrive in this extraordinary place.

24 Above and Below the New Surface of the Don River .64

TEXT BY NETAMI STUART, OALA

Impossible to see after it’s constructed, yet one of the most sophisticated design elements of the Port Lands Flood Protection Project (PLFP) is the landscape below ground. To create a naturalized river out of a contaminated brownfield, the designers had to design layers that, once constructed and inundated, will mimic a river valley in ecological function. Not only must the soil profiles behave like the natural strata below a natural river valley and support plant and aquatic life, they must also be affordable and constructible. Built in the dry excavation of the river valley and made from locally available materials that can be placed by machine,

01/ Fabric-encapsulated soil (FES) lifts form the banks of the river and will be seeded and planted.

IMAGE/ Vid Ingelevics / Ryan Walker

02/ Placement of the impermeable membrane portion of the liner system that protects the river valley from potential groundwater contaminants.

IMAGE/ Vid Ingelevics / Ryan Walker

03/ A small portion of excavated material from the site.

IMAGE/ Vid Ingelevics / Ryan Walker

04/ A view of the Commissioners Street bridge and construction of the river valley, taken from the middle of the future river bed. Streambed aggregate has been placed.

IMAGE/ Vid Ingelevics / Ryan Walker

25 Above and Below the New Surface of the Don River .64

02 03 04 01

the construction process must accomplish in years what geological processes take millennia to deposit.

Deep below the 1,500 millimetre-depth surface profiles of soil and stream bed aggregates or stone, below the subgrade fill used to shape the valley, the lowest of the constructed layers must act as a barrier to contaminated groundwater. Designed like an inside-out landfill liner, this specialized sandwich of sand, geomembrane, bentonite, and activated carbon will keep any remaining byproducts of the former industrial land uses in the area from seeping into the river, the harbour, and the parks where people, fish, and plants might be impacted.

Design of the underground landscape starts with an understanding of the deepest history and foundation of the valley, and moves up through time and the soil horizons to the present day and to the experience of the place as it will be in the coming years.

Until the late 1800s, the mouth of the Don River flowed into Ashbridges Bay, one of the largest freshwater marshes in the Great Lakes until it was filled to create Toronto’s Port Lands. The PLFP site is a former marsh with very deep organic and alluvial soils, covered over during the early 1900s with up to eight metres of unconsolidated and mixed urban fill and rubble, and then used for half a century as a heavy industrial area. For the project design, this meant not only was the environmental quality of the site a concern, but the geotechnical quality of the land meant any new construction would require geotechnical improvements in order to prevent differential settlement of pipes and surface features following construction. To prepare the parks for construction, material excavated from the river valley was placed over and above the final design grades for durations of up to a year, then removed prior to rough and fine grading. In the river valley, where differential settlement has less impact on the function of landscape features, the landscape was constructed without ground improvements with the understanding that greater settlement was acceptable.

The design team hoped that during the excavation of the former marsh, some materials would be encountered that would be of suitable quality to use as substrates for the wetland and riverine habitats being designed in the wetlands. As the excavation of the valley and the construction of the wetlands progressed, the characteristics of the soils within the excavation were revealed. Ultimately, there was far less unimpacted soil than was predicted by borehole data, but the excavated peat material that was clean enough to re-use as planting soil was an ideal material to use as a wetland substrate. This peat material that once lay below the Ashbridges Bay marsh was created in the ancient wetlands at the mouth of the Don and buried for over 100 years below eight metres of fill. In one of the most delightful surprises of the project, this peat has maintained a viable seed bank of wetland plants that can now germinate in the new valley. The presence of ancient soils and ancient plants that will live as part of a new ecosystem ties this manufactured landscape to its ancient roots and creates a functional connection to the historic wetlands that once thrived here.

Around three million years ago, long before the last ice age, channels of water were forming that would eventually become the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River. The area where the Don River currently runs was the site of one of the ancient tributaries to this system, which cut a channel into the bedrock that lies immediately underneath the current mouth of the Don River. While the water of the contemporary Don River of Toronto is only a metre or two deep during most of the year, the bedrock channel cut by the ancient river lies up to 40 metres below ground level. Even a couple of city blocks east or west of the site, bedrock is less than five metres below the ground. The Don is among the most ancient of rivers, existing long before humans existed on earth, and long before Lake Ontario was formed.

This depth to bedrock is an important factor in the design of the river valley, since critical structural features of the site rely heavily on a bedrock foundation. One that is very deep and expensive to reach from the surface.

In the river valley, the drawing set issued for construction included nine soil profiles, eight stream bed aggregate profiles, and seven stone profiles, each describing a different configuration of soil horizons. The profiles are applied across the site based on the relationship of the profile to water and the type of plant communities that grow in relationship to water. Lake levels (elevation), water flow, and ice impacts expected at any location within the valley were factors in where the soil profiles were located around the site. In wetlands, the lowest (wettest) soil profiles include a shallower top layer of sandy soil, underlaid by absorptive clay soils; whereas layers higher in elevation that will only be seasonally or rarely underwater included a loamier, deeper top layer to support forbs and meadow marsh plant communities. In areas of the site that will be permanently underwater, aggregates of various gradations are placed to provide fish habitat for spawning and to provide stability where river forces would otherwise erode the channel.

The design and construction teams worked closely to develop alternate soil profiles that would maintain their function, while responding to the availability of site soils and local sources of sandy and clay materials from off site. By the time most of the soils were placed at the end of 2023, the original nine soil profiles had grown to eleven to allow the contractors flexibility to build with the available materials.

Raw materials for the construction of the soil profiles were sourced as supply contracts separate from the installation. This allows consistent quality of soils across the 90-hectare site, despite numerous different installation contractors. There is one projectwide contract for stone and aggregates, one for topsoil, and others for clean clay excavated from local GTA infrastructure projects to create impermeable levees in the river valley. All the horticultural topsoil for the project was sourced from a former farm site near Barrie that is being developed as

26 Above and Below the New Surface of the Don River .64

housing. The soils on the source site met all the environmental and horticultural criteria for the project, with a naturally occurring sandy loam that was within reasonable trucking distance. Because it was a direct transfer of topsoil from a source site to the project site with no mixing prior to placement, the testing requirements were less frequent than if the soil had been a mixed or manufactured product. Additionally, the single source site and years-long contract allowed for organic matter to be added at the source site by growing cover crops and tilling them into the soil before it was harvested. Great care has been taken to maintain the soil biology at every step of the supply, from harvesting and placing separate horizons to on-time harvesting and delivery with as little stockpiling as possible.

Knowledgeable people will visit the site and recognize the success and resilience of the plant communities, the diversity of the plant palette, and the beauty and complexity of the plan as it relates to water levels and human activity. What will remain unseen is the extraordinary complexity of the landscape underground that supports the river that we have built and the fish and plants within it.

05/ Several months before image 04, landforms in the valley below the bridge are not yet shaped, and the streambed aggregate yet to be placed.

IMAGE/ Vid Ingelevics / Ryan Walker

06/ Scirpus spp. growing from seed in an Ashbridges Bay wetland 100+-year old seedbank exposed during excavation in late summer 2021.

IMAGE/ Vid Ingelevics / Ryan Walker

07/ A volume of soil to fill the SkyDome was excavated from the site. 70 80% was reused following rigorous testing and management.

IMAGE/ Vid Ingelevics / Ryan Walker

PROFESSIONALLY AND AS A VOLUNTEER NETAMI HAS MADE URBAN ECOLOGY AND TORONTO’S PUBLIC PARKS HER PASSION FOR OVER TWENTY YEARS. AS A LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT AND ARBORIST, NETAMI WEAVES LIVING SYSTEMS, DESIGN THINKING, AND DELIGHT INTO HER WORK IN TORONTO’S PUBLIC SECTOR. PREVIOUS TO WATERFRONT TORONTO, NETAMI WORKED FOR CITY OF TORONTO, PMA LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS, ECOPLANS, EVERGREEN AND URBAN FOREST ASSOCIATES. SUPPORTING THE INTEGRATION OF DESIGN AND STEWARDSHIP, NETAMI REPRESENTS THE ONTARIO ASSOCIATION OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS ON THE BOARD OF THE ONTARIO PARKS ASSOCIATION.

27 Above and Below the New Surface of the Don River .64

BIO/ NETAMI STUART, OALA, IS SENIOR PROJECT MANAGER, PARKS FOR THE PORT LANDS FLOOD PROTECTION PROJECT AT WATERFRONT TORONTO. BOTH

05 06 07

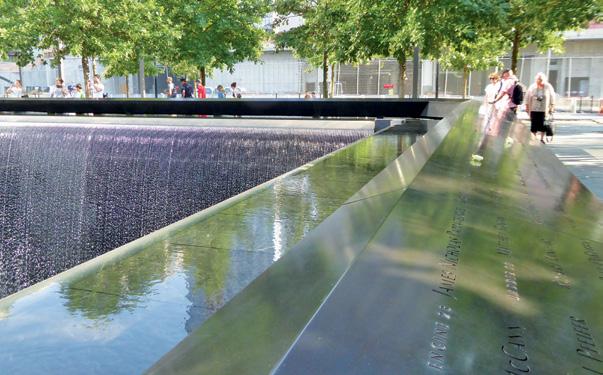

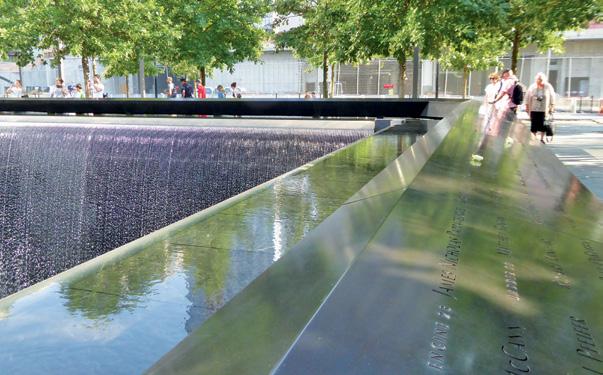

03/ National September 11 Memorial

Terence Lee

04/ University of Cincinnati

Terence Lee

05/ National September 11 Memorial

Terence Lee

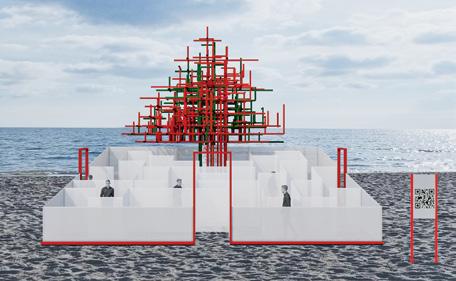

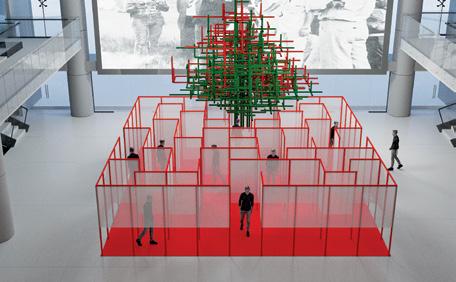

On March 22, 2023, a group of technologists, called the Future of Life Institute, along with other technology elites like Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak and Tesla CEO Elon Musk, signed an open letter expressing their concerns for the extraordinarily rapid growth of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Concerns are founded, given AI’s ability to imitate humanity’s every move, and the sum total of our knowledge readily available on the internet, it’s no wonder they called for a six-month hiatus on the training of AI systems. AI is no doubt an exciting new technology that holds tremendous promise for automation. Some even refer to it as the extension of humanity. While clearly fraught with dire implications that magnify dangers of misinformation and false-realities in our public discourse, AI is quickly becoming the new frontier.

However, what AI cannot do is to create. More specifically, AI cannot create with creativity and truly invent or innovate. That will always require imagination, a singularly human trait that cannot be replicated, especially when we consider the human condition of emotion, desire, and fear. We are in that moment now: most of us are suspicious and fearful of where AI can

28 The Brave New Landscape in a World of Artificial Intelligence .64

01 02 04 03

07

TEXT BY TERENCE LEE, OALA

IMAGE/

01/ Miller House and Garden IMAGE/ Terence Lee

02/

University of Cincinnati

Terence Lee

IMAGE/

IMAGE/

05

IMAGE/

go. It is certainly taking the machine to a whole new level. Let’s not forget that machine, computers, and automation have always been part of our destiny and detriment. Advancement in the industrial age led to new and inventive machinery. The production line once tended by human labour has been replaced largely with machines and robots. Then machines became more powerful, coming to be known as computers. If there is any solace in this, it is that we’ve been here before. But, like those generations that came before us, we humans found other more important things to do. We put our human ingenuity to work and invented more technologies to enrich our lives, found cures for diseases, and even vaccines to manage a global pandemic. We’ve been here before and there is yet plenty of space for humans to create.

Regarding landscape architecture, I know of a few moments of true ingenious creative thought: moments that led to new paradigms that are the very foundations of our field today. To think of these examples as beautiful works of landscape architecture is not enough. We must put these into the historical context of what we know today as modern landscape architecture, that in one moment in time, a few individuals invented a new way of thinking, a new approach to the design of our outdoor spaces, all without technology, without AI. My perspective on these brilliant moments are summarized in here.

06/ View of horse chestnut allee (today Ohio buckeye) at the Miller House and Garden, Columbus, Indiana, by Dan Kiley.

IMAGE/ Terence Lee

When Dan Kiley visited the French gardens of Le Notre towards the end of the Second World War, he was taken aback by the beauty and clarity. He discovered how landscapes can be expressed in powerful compositions of “lines, allées and orchards/bosques of trees, tapis verts and clipped hedges, canals, pools and fountains could be tools to build landscapes of clarity and infinity, just like a walk in the woods.” With his fortunate association with the likes of architects Louis Kahn and Eero Saarinen, and a keen eye for modern architecture, his brilliant moment came when he realized the aesthetics of French gardens were complimentary to modern architecture. Lines of clarity in architecture became clarity of landscape expression. Vast, low ground covers and clipped hedges gave

07/ View of crab apple grove (originally redbud) at the Miller House and Garden, Columbus, Indiana, by Dan Kiley.

IMAGE/ Terence Lee

08/ View of interior of family room and landscape beyond at the Miller House and Garden, Columbus, Indiana, by architect Eero Saarinen and landscape architect Dan Kiley.

IMAGE/ Terence Lee

09/ View of the honey locust allee at the Miller House and Garden, Columbus, Indiana, by Dan Kiley.

IMAGE/ Terence Lee

10-11/ Views of St. Louis Gateway Arch at the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial from the north pond, by architect Eero Saarinen and landscape architect Dan Kiley.

IMAGES/ Terence Lee

29 The Brave New Landscape in a World of Artificial Intelligence .64

06 09 10 11 07 08

way to panoramic views of the landscape beyond. Kiley’s design for the garden at the Miller House in Columbus, Indiana, is punctuated with trees and allées, so that the sunken family room enjoys an impressive view of an open lawn and the Flatrock River valley beyond. Instead of using the allées in a traditional sense, the trunks of honey locust trees were used as columns to create a loggia along the westerly frontage of the house. Each room in the house has unique views of the landscape, which is, in turn, designed to compliment each room. These landscape rooms are subdivided by ground covers and hedges. Kiley continued his use of the formal composition of trees and gardens throughout his career, citing frequently that a walk through a bosque of trees is like a walk in the woods. The association of the clarity of French gardens with nature and architecture was employed to astounding effect, and became one of Kiley’s unique signatures.

Unlike the way Kiley brought the clarity of French gardens into modern landscape architecture, Peter Walker introduced the sensibility and discipline of modern art into

his craft. Minimalism in art requires a high sense of attention to detail. Every detail in a piece of minimalist art counts. The execution is an integral part of the expression of the art itself. Throughout his decades of practice, Peter Walker brought this discipline into landscape architecture and focused on execution as the key component in expressing his landscape creations. From the IBM Solana office builiding, to a series of projects in Japan in the ‘90s like Marugame Station Plaza, the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, and ”Sky Forest” at Saitama-Shintoshin Station. And nowhere else has any one project brought together the culmination

12-14/ Views of reflective pool and fountain at Cleveland Clinic Main Campus, by PWP Landscape Architecture.

IMAGES/ Terence Lee

15-17/ Views of the waterfalls, stone benches and the Glade at National September 11 Memorial, by PWP Landscape Architecture.

IMAGES/ Terence Lee

18-20/ Views of landform, path, earthwork, water feature and landform at the University Commons, University of Cincinnati, by Hargreaves Jones.

IMAGES/ Terence Lee

21/ View of intertwined braided paths at Campus Green, University of Cincinnati, by Hargreaves Jones.

IMAGE/ Terence Lee

of a design practice’s ultimate search for expression and execution excellence than the National September 11 Memorial in New York. There, you will find the reoccurring themes and motifs in Walker’s firm PWP Landscape Architecture’s work expressed in its fullest intent. Lines of trees and paving create a banded pattern that envelopes the site, resulting in a wholistic vision for the project. While uncharacteristic for PWP, tree spacing along each row of trees differs due to conflicts with the myriad of proposed and existing utilities. The clarity of space was created by Walker’s endeavour for a clean and flat site. This was done by frequent rows of slot drains designed into the banded pattern to minimize the rise over run distance for positive drainage. With the incredible amount of project complications, from client stakeholders to site design issues, not to mention an immaculate waterfall feature designed by Dan Euser, OALA, (Canadian landscape architect and water feature designer), the site is executed with rigour and precision, not uncommon for PWP.

30 The Brave New Landscape in a World of Artificial Intelligence .64

13 12 14 15 16 17

From the finite to the expansive, George Hargreaves sought the answer for largescale landscape interventions in the works of land art. Like Michael Heizer and Robert Smithson, Hargreaves approached his early work with unencumbered enthusiasm for working with the earth. Pushing and sculpting the land, Hargreaves drew inspiration from land art for an approach to create large scale landscape interventions that were both functional, as park spaces, and practical, as large infrastructural-scale construction projects. Against the norm, Hargreaves Associates (now Hargreaves Jones) worked in close collaboration with engineers to create a sculpted riverfront park system, known as the Guadalupe River Park, that became an accessible and enjoyable place for people, as well functioning flood mitigation for downtown San Jose. While many of Hargreaves works do not resemble

the typical aesthetic of the classic Olmstedian landscape architecture of New York’s Central Park, the intent and ambition is comparable. Earth mounds that resemble naturecreated landforms at the William J. Clinton Presidential Library offer respite and open space to be enjoyed, or the intricate braidedlandscape resembling the fluvial movements of a once active creek functions as paths and resting spaces at University of Cincinnati are all examples of Hargreaves’ ambitious, large scale landscape interventions.

These examples are only a snippet of brilliant and unique moments in the history of design in landscape architecture. They are singular moments, created by designers who found their own and unique voice, and cannot be synthesized or generated by a machine. If we focus on design that is human, socially conscious, empathetic to society, machines and AI will become irrelevant. After all, behind all machines are the humans who create them. Behind all AI, there are humans inputting prompts. AI can be a powerful tool, but concerns about it taking over society simply puts the focus back on humanity and the importance of unique designs and designers, as humanity continues its move towards the brave new world.

BIO/ TERENCE LEE, OALA, IS A SENIOR ASSOCIATE LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT AT NAK DESIGN STRATEGIES. WITH OVER 25 YEARS OF EXPERIENCE THAT INCLUDE A WIDE RANGE OF PROJECT TYPES, HE HAS WORKED FOR THE PROFESSION’S MOST CELEBRATED PRACTITIONERS SUCH AS DAN KILEY, GEORGE HARGREAVES, PETER WALKER, AND THE MULTI DISCIPLINARY FIRM AECOM (FORMERLY EDAW). FROM URBAN INFILL DEVELOPMENTS TO INSTITUTIONAL CAMPUSES AND REGIONAL PUBLIC PARKS, TERENCE HAS LED THE DESIGN PROCESS FROM INITIAL CONCEPT TO FINAL BUILT PROJECTS. HIS WORK FOCUSES ON MEANINGFUL NARRATIVES THAT INTEGRATE THE CONTEXT OF PLACE, SITE PROGRAMMING, AND NATURAL SYSTEMS. HIS WORK SPANS THROUGHOUT CANADA, USA, AND ABROAD. HE IS A GROUND MAGAZINE EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBER.

31 The Brave New Landscape in a World of Artificial Intelligence .64

22/ View of intertwined braided paths at Campus Green, University of Cincinnati, by Hargreaves Jones.

IMAGE/ Terence Lee

23/ View of Main Street, University of Cincinnati, by Hargreaves Jones.

23 22 18 19 21 20

IMAGE/ Terence Lee

TEXT BY HEATHER SCHIBLI, OALA

TEXT BY HEATHER SCHIBLI, OALA