Up Front: Information on the Ground

In the relentless march toward urbanization, cities face the challenge of balancing rapid growth with sustainability. As concrete sprawls across landscapes, there’s an increasing call to reclaim forgotten spaces and repurpose them for greener, more community-centric purposes. Enter alleyway agriculture: an innovative and under-explored approach within landscape architecture that holds the promise of transforming overlooked urban corridors into thriving hubs of sustainable food production and community engagement.

01/ People gather at the Blue-Green Alley Project in Montreal.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Alliance Ruelles bleues-vertes

ALLEYWAY AGRICULTURE sustainable

Every day, hundreds of thousands of people walk past alleyways without taking any notice, they’re simply a shadow in the corner of our eyes. They have always seemed to represent a city’s dark and forgotten aspects, where the unknown lies and darkness dwells. However, around the globe, many have taken the initiative to repurpose these afterthoughts into vibrant community gardens that not only feed but also nurture our communities.

As of 2019, a staggering 50 per cent of the Earth’s habitable land has been dedicated to agriculture. Yet, nearly 10 per cent of the global population grapples with food insecurity. With cities expanding and available arable land diminishing rapidly, the need for innovative solutions to address food insecurity is more urgent than ever. Alleyway agriculture’s key advantage lies in its ability to maximize small, limited urban spaces. With some care and attention, alleys, often dismissed as unusable, can be transformed into thriving micro-farms, providing fresh produce to urban residents.

Using various techniques including plant pots, hanging structures, vertical gardening, hydroponics, and tiered systems, locals are embracing alleyway agriculture and turning neglected spaces into flourishing gardens that sustainably feed the community. The versatility of the initiative allows agricultural growth in all types of conditions. While sunnier sites may improve overall yield, using low-light crops such as beets, carrots, radishes, potatoes, and garlic allows for success in even the darkest of spaces. This decentralized approach to agriculture reduces dependence on distant farms, promotes diverse crops, enhances local food security, and minimizes the environmental impact associated with long-distance food transportation.

Alongside the obvious space-maximizing benefits, alleyway agriculture offers a range of environmental advantages. A remarkable example of these benefits is the Montreal Blue-Green Alley project. In 2016, Montreal initiated over 300 green alley projects aimed at harnessing unused urban space to mitigate the negative impacts of increased precipitation and rapid urbanization. The project involved redesigning alleyways to incorporate green infrastructure, including permeable surfaces, rain gardens, vegetable gardens, and native plantings. Driven by passionate community members, the project bloomed into a transformative effort that reduced runoff, ameliorated urban heat island effects and poor air quality, increased biodiversity, and showcased the incredible potential of community-driven environmental initiatives.

In addition to providing fresh produce and resilience, alleyway agriculture brings a multitude of community and social benefits to urban areas. These community gardens serve as gathering points where neighbours come together, forging connections, sharing knowledge, and cultivating a stronger sense of community cohesion. Community members who actively participate in their upkeep and cultivation receive a sense of ownership and pride. Moreover, these green oases offer educational

opportunities for children and adults alike, teaching valuable lessons about sustainability, food production, and environmental stewardship.

In 2019, the Green Alley Initiative, spearheaded by Arts on the Ave and driven by the Edmonton community, embarked on a journey to revitalize neglected alleyways into welcoming community spaces. At the core of this initiative was a collaborative effort aimed at celebrating the community and its people. By incorporating raised flower and vegetable beds, unique lighting installations, and colourful murals, Edmonton succeeded in beautifying its alleyways and creating safe and beautiful community spaces where children could play freely and residents could come together to socialize, connect, and celebrate.

Supportive policies and urban planning initiatives are essential to unlock the full potential of alleyway agriculture. Local governments and city planners must recognize the value of these spaces and create regulatory frameworks that encourage and facilitate their transformation into productive green zones. Advocacy from environmental groups, community organizations, and urban agriculture enthusiasts can play a pivotal role in garnering support for such initiatives.

No longer do alleyways have to hide in the shadows; by pulling back the curtain and cutting away the concrete, these stark spaces can thrive and flourish into bustling hubs of growth and productivity that benefit our communities. Through the use of alleyways, we are not only transforming physical spaces but also dismantling barriers to access and sustainability. Alleyway agriculture champions a vision where fresh, locally-sourced produce is not a luxury but a shared resource. These once-overlooked corridors, now teeming with life, serve as a testament to the idea that, even in the most urbanized environments, nature and community can reclaim their place in the sun.

mural in Edmonton, AB. of Arts on the Ave. Arts on the Ave. event Edmonton. of Arts on the Ave planters in Edmonton. of Arts on the Ave the Ave. crew. of Arts on the Ave

CULTIVATION

seeds & soup

Each plant we add to a drawing or stick in the ground represents a staggering investment of time, energy, and resources. Often, designers and community members are disconnected from the propagation process, leaving an under-appreciation for these plants and the value they bring to the landscape. Notably, plant production initiatives such the Toronto Seed Orchard have been an exception. It’s turned into a social nexus for people from all backgrounds interested in native plants.

The Toronto Seed Orchard, hosted by NVK Nurseries in Dundas, ON, was developed from cross-sector discussions of the Toronto Seed Strategy Working Group. Now entering its third season of production, the successful harvests of the first two years were only made possible by hundreds of hours of planning, wild seed harvest, processing, propagation, planting, maintenance, orchard collection, and subsequent

10

07/ Coreopsis tripteris (tall tickseed).

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

08/ Desmodium canadense (showy tick-trefoil). Hand model: Liam Doyle.

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

processing. This project has become a large collaborative effort between many stakeholders and volunteers. Seed collectors, nursery operators, landscape architects, contractors, academics, landscape architecture students, and other community volunteers are instrumental throughout this process. The orchard has become a social hub for plant propagation.

The job of collecting and preparing seed for the following year doesn’t end once it’s bagged in the field. When seeds are collected, either from wild populations or managed production areas, a lot of other plant parts come with them. It is important to separate this material and the process can be time-consuming. For many species, the seed processing takes more effort than

the field collection itself, and each species requires different processing techniques.

On November 25th, 2023 and January 13th, 2024, the Toronto Plant Market hosted a Seeds and Soup event. Here, a group of enthusiastic community members helped process seed and, as a reward for their work, enjoyed some delicious soup. It was estimated that volunteers helped process 60 pounds of seed from 42 plant species. That’s tens of millions of seeds and, potentially, tens of millions of genetically diverse, locally adapted plants that can be used for Southern Ontario landscape projects. Thankfully, ecologist and seed specialist Stefan Weber generously shared his knowledge with workshop participants, helping them to learn efficient, species-specific seed cleaning protocols. Without the good will and participation of so many plant enthusiasts,

this scale of impact would be difficult to achieve. However, these workshops represent just one piece of a much larger process. The hard work led to camaraderie while enjoying soup and talking about plants.

These seeds came from the Toronto Seed Orchard, one of a series of seed production areas funded by WWF Canada with the aim of increasing availability of source-identified native plants. Locally sourced plants can be well adapted to local environmental conditions, which translates to lower maintenance requirements and better survival in the absence of maintenance. These plants may also have evolved relationships with local pollinators and other animals. Plants grown from seed also have greater genetic diversity and adaptive capacity than asexually propagated plants. The importance of a plant community’s ability to adapt to rapid environmental change becomes more obvious with each passing season.

Producing these plants takes a tremendous amount of coordination and collective labour. Making locally sourced plants available for landscape projects is a huge challenge and, in the absence of meaningful government support, requires this style of cross-sector collaboration. The Toronto Seed Orchard has been wildly successful in that respect.

However, its ultimate success will lie in the degree to which designers adopt and enforce more stringent plant sourcing requirements in their projects. Through efforts like the Toronto Seed Orchard, and the community of people involved with the

09/ Desmodium canadense (showy tick-trefoil) being harvested. University of Guelph Landscape Architecture students Kelsey Moore and Alex Feenstra harvesting seed.

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

project, locally sourced plants are becoming more available to landscape architects. But we and our other-than-human kin only benefit if those plants make it into the ground. Each plant also carries ecological implications for its planting site and the broader landscape. As ethical practitioners, we have a responsibility to make well informed plant selection decisions at every step in the plant production process.

Unique efforts like the Soup and Seeds event are an example of how our landscapes can be transformed through community action. Through this process, people are brought closer to the propagation process, improving appreciation of native plants. Along with millions of plant seed that will soon add colour and ecological value to the landscape, the seeds have helped spread social connections throughout the landscape. Some good will, a bit of seed, and sips of soup can do a lot.

10/ Verbena hastata (blue vervain). Ecoman Owner and Operator Jonas Spring harvesting seed.

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

11/ Lobelia inflata (Indian tobacco). University of Guelph Landscape Architecture students Carol Pietka and Victoria Lau harvesting seed.

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

12/ Verbena hastata (blue vervain).

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

13/ Vernonia missurica (Missouri ironweed). University of Guelph Landscape Architecture student Carol Pietka sorting seed.

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

14/ Stefan Weber instructing how to clean seed.

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

15/ Solidago ptarmicoides (upland white goldenrod).

IMAGE/ Ryan De Jong

TEXT/ LIAM DOYLE IS A MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE STUDENT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH, RESEARCHING THE EFFECT OF SEED SOURCE ON PLANT-POLLINATOR INTERACTIONS.

RYAN DE JONG IS A DESIGNER FOR REEP GREEN SOLUTIONS AND GROUND EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBER.

TEXT BY MARYAM SABZEVARI, BRANDY GLOVKA, AND ADAM VANDERMEIJ

Landscape architects, contract and City arborists, and urban designers all find themselves today in the middle of the conflict between a housing shortage crisis and the need for intensification, and a climate crisis and the need for tree preservation.

It’s not hard to make a case for trees. Toronto’s trees have always been an integral part of its character: the self-described ”city within a park.” And while we’re not likely to simply plant our way out of the climate crisis, it’s well understood that increasing canopy cover in the urban environment will be essential for both the mitigation of climate change and adaptation to its inevitable impacts, such as extreme heat events.

the time when such benefits should dictate the protection of trees, pressure from development, in part due to the housing crisis, is resulting in the loss of mature trees that are ecologically and economically simply not replaceable.

01/ The Tolman sweet apple at Yonge and Sheppard Ave. in Toronto is the last tree from David Gibson’s orchard.

IMAGE/ Edith George

02/ A street tree that has died due to poor site conditions and incorrect planting practices.

IMAGE/ Brandy Glovka

03/ A protected tree on Roehampton Ave.

IMAGE/ Adam Vandermeij

The myriad benefits of trees in the urban environment are well understood; these assets—in every sense of the word— provide crucial ecosystem services, including greenhouse gas reduction through carbon sequestration and removing air pollution, improving air quality. Beyond simply providing shade, trees literally cool the air through evapotranspiration, mitigating the urban heat island effect, all while reducing stormwater runoff and benefiting biodiversity. From an economic standpoint, the energy savings of a reduced urban heat island effect and avoided runoff, alone, is worth an estimated $55 million annually (according to the 2018 Toronto Tree Canopy Study). There is also a growing body of evidence that trees, by their very presence, have a direct and measurable impact on both mental and physical health. Yet, at precisely

In 2013, the City of Toronto adopted a 10-year road map, through the Strategic Forest Management Plan, to increase the tree canopy from 26 per cent to 40 per cent. The city achieved a 5 per cent increase in tree canopy over the span of 10 years, and is now set to achieve the 40 per cent target by 2050. While the planting of new trees is essential to achieving this goal, it is highly unlikely that 40 per cent coverage can be reached by 2050 without the preservation of existing trees. This is highlighted by the findings of the Toronto Tree Canopy Study which found that, while between 2008 and 2018 the total tree canopy coverage increased, the total leaf area for trees decreased by 11 per cent. According to those findings, only 8.8 per cent of street trees and 6.9 per cent of private trees in Toronto are large, mature trees between 45.8 centimetres to 61 centimetres DBH (diameter at breast height). Preserving mature trees has greater benefits than planting trees, given the larger leaf area. The average tree diameter in Toronto is 16.3 centimetres. Only 14 per cent of Toronto’s trees are greater than 30.6 centimetres in diameter. A 75-centimetre tree in Toronto intercepts ten times more air pollution, can store up to 90 times more carbon and contributes up to 100 times more leaf area to the City’s tree canopy than a 15-centimetre tree (according to Every Tree Counts: A

04/ Tree planting in public streets providing thermal comfort for pedestrians.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Maryam Sabzevari

05/ Incorrect tree planting practices: buried root crown, insufficient space.

IMAGE/ Brandy Glovka

06/ Incorrect tree planting practices: buried root flare/volcano mulch, nursery wrap left in place, staking used.

IMAGE/ Brandy Glovka

07/ A child hugging a tree in a public street – trees are an important asset for the future generation to combat climate change.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Maryam Sabzevari

Portrait of Toronto’s Urban Forest, 2013). The loss in canopy cover must also be viewed through an equity lens. Nature Canada’s report on urban forests (Tree Equity: Bringing the Canopy to All, 2022) demonstrates that “tree canopy tends to be much lower in lower income and racialized communities,” and that larger trees with higher biodiversity are more abundant in wealthier neighbourhoods. Areas with lower tree equity scores are often more accessible to racialized communities that experience socioeconomic inequity, and it is the same neighbourhoods that are often most susceptible to change and intensification, making these communities even more vulnerable in terms of tree canopy preservation. In a single application for an infill development in Flemingdon Park, there are 99 existing mature trees as large as 150 centimetres DBH being proposed to be removed.

The development process presents many challenges to tree preservation. Whether from pressures to maximize Ground Floor Area (GFA), or due to conflicts with utilities or transportation, all too often trees are being lost where they are most needed. Development pressure resulting from Toronto’s housing crisis is often used as the justification to remove trees that conflict with new developments. Even though the OALA

Code of Ethics and Standards of Professional Practice includes stewardship and duties to the environment, it can be extremely challenging for landscape architects to make a case to developers for preserving trees if they are in conflict with a proposed building or underground parking footprint and have a direct impact on pro-forma. Arborist reports often identify these trees and recommend removal, regardless of the health and size of the tree in question. Arborists also often highlight the negative aspects of trees, leaving out the botanical health and structure characteristics of a tree that is in good condition. They also do not make suggestions for how a tree could be preserved through changes to the development, especially those that may be considered less impactful on GFA and parking supply.

Adding to this, a new vision of a site— envisaged by both civil and private landscape architects and urban designers—often comes at the cost of existing trees. Further conflicts are revealed through the development review process, such as paths of travel, fences, and new landscape features. Through the previous iterative process of development review, solutions could have been found to mitigate these conflicts, without necessarily resulting in the loss of trees. Ontario’s Bill 109, however, has significantly reduced the timelines of the approval process, reducing opportunities for such solutions through the resubmission of the plans. Most design decisions are now being made at the preapplication stage, which often does not yet include existing or proposed trees, further limiting the ability to make any meaningful changes to tree protection or planting due to the reduced timelines for approval.

Moreover, even with the most stringent tree protection policies, municipalities still have limited authority when a tree is in conflict with the development proposal that is approved through the approval process or as-of-right permissions; this puts the onus on landscape architects and arborists to prioritize tree preservation at the outset. The location of the existing mature trees should be an organizing element, influencing the site organization from its conception.

Reliance on cars and underground parking structures, even when the intensification is justified due to its proximity to transit, resulted in many of the newly planted trees being proposed in encumbered areas. This means the tree’s lifetime is bound by the lifespan of the underground slab and its necessary maintenance over time.

While it is true that, when trees are removed, there is often a requirement for the planting of new trees, this also presents its own host of challenges; just because a tree is planted, there is no guarantee it will survive. The causes of failure in newly planted trees are numerous and complex, but planting practices are unquestionably a significant factor affecting tree mortality and one in which landscape architects play a pivotal role. Tree planting details based on the current best practices are crucial. Without this, there is little hope that newly planted trees will be planted appropriately, giving them the best chance at long-term survival. All too often, outdated tree planting details that do not comply with current best practices have the potential to undermine the establishment of newly planted trees. The removal of wire baskets and burlap, the treatment of the root ball, the grade at which a tree is planted, soil specifications, and mulch application, all impact the establishment of new trees. Tree staking alone represents a significant issue; many nurseries require the use of tree stakes for the purposes of their warranty, however, in most applications, tree staking is inappropriate and detrimental to the health of the tree.

Equally important to the use of appropriate details and specifications, however, is the role of the landscape architect and contract arborist in oversight and supervision of actual tree planting on-site. This, and the City’s oversight, even though limited, are the most effective ways to prevent incorrect planting practices that can lead to decline and failure.

Education emerges as a crucial aspect of this, highlighting the importance that newly graduated landscape architects work closely with and are mentored by experienced landscape architects and their contracted arborists, providing these new professionals

08/ Trees provide visual interest in public realm.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Maryam Sabzevari

09/ Incorrect tree planting practices: buried root crown.

IMAGE/ Brandy Glovka

10/ Fatal girdling wound on tree due to staking material not being removed.

IMAGE/ Brandy Glovka

with the knowledge they require to uphold such OALA standards of professional practices such as duties to the environment.

Never has the need for interdisciplinary collaboration amongst landscape architects, arborists, urban designers, and planners been more important. There is not only a professional obligation, but also a moral and ethical imperative to prioritize the preservation of mature trees. These disciplines need to work, not only with each other, but also with landscape contractors, developers, and all stakeholders to ensure efficiency without sacrificing some of Toronto’s most valuable assets, its trees.

BIOS/ MARYAM SABZEVARI IS A SENIOR URBAN DESIGNER

WITH THE CITY OF TORONTO.

BRANDY GLOVKA IS A LANDSCAPE DESIGNER AND

SITE PLAN TECHNICIAN WITH THE CITY OF TORONTO. ADAM VANDERMEIJ IS AN ARBORIST AND PLANNER

WITH THE CITY OF TORONTO, URBAN FORESTRY.

MODERATED BY GLYN BOWERMAN

BIOS/ ALLI NEUHAUSER IS CURRENTLY A LANDSCAPE DESIGNER AT SEFERIAN DESIGN GROUP, A LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE FIRM BASED OUT OF BURLINGTON, ONTARIO. SHE IS A GRADUATE OF THE MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE (MLA) PROGRAM AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH AND, IN ADDITION, HOLDS AN HONOURS BACHELOR OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT (HBEM) FROM LAKEHEAD UNIVERSITY.

PAMELA CONRAD, PLA, ASLA, LEED AP, IS AN INTERNATIONALLY RECOGNIZED LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT FOCUSED ON SCALING NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS TO THE CLIMATE AND BIODIVERSITY CRISES. SHE IS THE FOUNDER OF CLIMATE POSITIVE DESIGN AND FACULTY AT HARVARD’S GRADUATE SCHOOL OF DESIGN.

SCOTT TORRANCE, OALA, CSLA, IS THE SENIOR DIRECTOR OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE AT FORREC. HIS WORK HAS BEEN RECOGNIZED WITH LOCAL AND NATIONAL AWARDS FOR DESIGN EXCELLENCE IN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE.

ROBERT WRIGHT, OALA, FCSLA, AN ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR AT THE DANIELS FACULTY OF ARCHITECTURE, LANDSCAPE AND DESIGN, HE IS ALSO THE ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF THE CENTRE FOR LANDSCAPE RESEARCH WHERE HE IS HEAD OF SPECIAL PROJECTS. HE IS ALSO AN ASSOCIATE OF THE CITIES CENTRE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO AND IS CROSS-APPOINTED WITH THE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO.

GLYN BOWERMAN IS A TORONTO-BASED JOURNALIST AND EDITOR OF GROUND HE ALSO HOSTS THE MONTHLY SPACING RADIO PODCAST ABOUT CANADIAN CITY ISSUES.

Glyn Bowerman: What is the biggest challenge that has forced you to adapt in your professional work and practice?

Pamela Conrad: I’ve been practicing for about 20 years. In the last 10, I’ve focused on adaptation projects. About seven years ago, I was working on what I thought were very innovative, sustainable projects, adapting to sea level rise, and I realized I had no idea about the carbon footprint of these projects. We didn’t have a tool to measure, improve, and understand those impacts. So I developed the Pathfinder landscape carbon calculator app, which is a free, web-based tool for landscape architects to use to measure and improve their project’s carbon footprint.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Climate Positive Design

Robert Wright: We’re seeing a transformation of all the professions right now, primarily technological. I have an ecological background, so my challenge has always been thinking about landscape as ecosystems and the kind of relationships around performance and how we predict things. Landscape architecture is well anchored in the 19th century and the picturesque, and the challenges we’re facing now—climate change, carbon (especially biogenic)—are transforming the way we think and teach students.

So my biggest challenge as a practitioner and educator is training students for the next 10 years, given what we’re facing right now. This is why I’ve spent a lot of time in the artificial intelligence (AI) and generative

01/ Slide from Pamela Conrad’s Climate Positive Design presentation.

design space. I work with people that do deep models and things like that, and we’ve been looking at things like evolutionary theory and how it affects cities in the University of Toronto’s Urban Genome Project. There’s a lot of transformation coming and we need to start thinking about how it’s actually going to affect practice.

Alli Neuhauser: Just coming into the profession, we focused a lot on stormwater management and how to design for 100-year storm systems that are turning into 50-year storms—they’re happening more frequently. That’s always in the back of my head when I’m working on projects. I come from a forestry and ecological background so I think a lot about plants that have adapted to certain areas, and what the best plant is for a given space. It might be something that isn’t native to here but is native just a couple zones south and starting to migrate up this way.

Scott Torrance: I’ve only ever worked in private practice and I feel like staffing is always difficult. Finding people with a solid foundation of landscape architectural skills who are enthusiastic, willing to try different things, study multiple options, and not too focused on the big picture or trying to analyze the thing to death to find

some kind of connection. I’ve actually been returning to projects I would call the “nuts and bolts” of landscape architecture, many from the 1970s and ‘80s, and seeing how well some of that material is holding up. My perspective is from the urban perspective— mainly the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area. We’re trying to create landscapes that change over time, particularly with plant material that’s resilient to all the things we throw at it—people, pets, salt, vibrations, and soil compaction—and looking, not only to tried-and-true standards of design, but also proven planting methods for an urban environment.

Central Park, for example, is always filled with people, in one of the biggest cities in the world, and it’s still standing up so well.

GB: How is landscape architecture changing to meet current challenges?

RW: What Alli mentioned about climate change and what’s called the “assisted migration” of plants. I always try to keep my hand in the practice, just to remind myself how difficult it is to get anything done. I did planning work in Sudbury based on assisted migration—because the edge of the boreal forest is highly impacted by climate change. We’re seeing oaks move into that area that are normally where bogs, black spruce, white pine, and fir should be. The biggest threat to trees are fire and invasive species. So these are things that are challenging us.

To Scott’s point, understanding soil in the urban environment is critical. How much soil do we need? How do we make this material live for long periods of time?

AN: I’m working on projects built in the ‘90s and 2000s that now need to be fixed because the plants selected at the time failed. And the people on, say, a condo board would just plant something else because they like how it looks, but it fails. So, trying to figure out what’s going to work in a certain spot, long term, is a challenge.

PC: I’ve been working on the San Francisco Waterfront Resilience Program, which was looking to adapt about seven and a half miles of shoreline for flood and earthquake risks. An interesting shift that happened over time is people recognized we can’t just build a bunch of concrete sea walls along the shoreline. There are lowercarbon ways to do that and incorporate Nature-based Solutions (NbS) the public actually want to see. Hearing that come from the public and knowing all the other performance benefits that come with (NbS) is a major shift.

Also recognizing the significant embodied carbon emissions in projects from the materials and construction over time, and the desire to figure out how to improve those is important. For example, the Atlanta Belt Line is a multimodal loop around the City of Atlanta, and a good majority of that project had been already completed. But the client (the City) said, “We know we’re

putting down a lot of concrete, what can we do to improve this?” So we worked with them to change the codes and standards and find cement substitutions to lower the embodied carbon and apply that to future projects going forward. So that was a shift.

The third shift I’ve seen is the transformation of places and existing landscapes that have a desire to lower their operational emissions and their maintenance over time, while increasing biodiversity. I just finished working with a project with Stimson Landscape Architects on Penn State’s campus. The students on their Eco Action Club there wanted to improve the sustainability of their campus. We realized through the process that most of their emissions were coming from highmaintenance lawns requiring constant mowing. There are greenhouse emissions that, when blades of grass decompose, are released back into the atmosphere. We learned we should be using more electric maintenance equipment and less fertilizers, chemicals, and pesticides to reduce emissions. Now they’re planning on transitioning half the lawns on campus to new plantings to increase biodiversity, reduce water needs and energy use, and increase carbon sequestration.

GB: How will landscape architects’ baseline skillset need to evolve to effectively deal with the environmental, technological, and societal challenges of today? And does there need to be more of a back-and-forth collaboration and mutual understanding between emerging and senior professionals?

RW: There’s always been a tension between the junior and senior levels, especially when there are skill changes. When AutoCAD came into offices, none of the principals knew what it was and all the young students picked it up right away. Also, the type of things students are required to know now are changing significantly, particularly around performance. Clients are becoming more interested in what the performance of landscapes are doing in terms of the value they have over a long period of time. So maintenance becomes a crucial issue.

AN: As an emerging professional, I also came into my MLA with different skills and viewpoints than someone more established. I’m a drone pilot, and my thesis used drones to look at visual impact assessments, particularly in the Niagara escarpment area. You can

05/ Map of the San Francisco waterfront. IMAGE/ Courtesy of Port of San Francisco, CMG Landscape Architecture

06/ Rendering of the Atlanta Beltline project. IMAGE/ Courtesy of Atlanta Beltline Inc., Alta Planning & Design

07/ Discussion for the Penn State sustainable landscape plan.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Penn State University, Stimson Landscape Architects, Climate Positive Design

see more of the topography with a drone, and in real time, versus contours on a screen which can be hard to read. From my experiences with senior staff, they’ve been willing to invest in someone like me because of this other skillset, and/or other emerging professionals with different ways of doing things, and giving it a try on a certain projects. Is there something there to explore, and can we use that in the future on new projects? And is there a willingness to learn? I know some people can get set in their ways after a couple years in any field. But when there’s a willingness to see across the generational divide, there can be mutual trust in different experiences.

PC: I agree with Robert about the need to develop performance-based metrics for carbon, biodiversity, and water. There’s a demand for it. And there’s a need between the generations for openness to new tools. In my own experience, I don’t

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Seferian Design Group

09/ Waterloo Park in Waterloo, Ontario. Guelph.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Seferian Design Group

10/ Appleby College in Oakville, Ontario.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Seferian Design Group

have a tech background at all, but I see the value of apps and new tools. I think that encourages others to see where the gaps are and jump in. We don’t want to overdo it, but we should recognize we have a lot of challenges and wherever we can utilize technology to help us we should.

ST: We can’t ignore how the pandemic completely changed the way we work. I hired somebody out of University of Toronto who I absolutely loved, and I didn’t even meet him in person. We actually went out to a site around eight months later and it was like, ‘Oh, hey, nice to actually meet you!’ I asked him if it was a challenge working for months with someone he hadn’t met in

08/ Casablanca Waterfront Park in Grimsby, Ontario.

person. But he started working late 2020, his last semester was completely virtual, so he said he found the transition seamless.

But, as far as the need to evolve skills, I think it will become all about AI, because it’s in everything, but we still need to be critical of it. You’ve got to be able to check your sources. I still keep Michael A. Dirr’s Manual of Woody Landscape Plants out. I need to have a resource I can trust. And I still want people I’m working with to check those references.

RW: The one thing ChatGPT is good for, depending on which model you’re using, is I can scrape the Dutch masters’ catalogue and have it perform an analysis and create a spreadsheet of all of its plant material and what’s available at what sizes in half a day. So there are certain ways these new tools will begin to help us. You do need an expert who actually checks it, but I find it very effective in certain areas. It’s going to transform a lot of day-to-day tasks. It will also shift labour practices. People wonder if AI will take their jobs. It won’t, but it will take your services, because certain services are easier to do and deliver in a very short period of time with AI. We’re going to have to adapt to that, for sure.

PC: We do need to adapt to new tools and use them well. But there are places where personal relationships are critical, like community engagement. When you are building trust and working with a community, especially one facing risks from climate change, you still have to be there physically to understand those people and build relationships. There are some benefits to doing community engagement virtually, because maybe more people can attend, but you still need human connection in certain aspects. There’s going to be constant tension between being open to change and recognizing we’re still humans who need to be with each other.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Port of San Francisco, CMG Landscape Architecture

12/ Graphic showing unsustainable green maintenance practices.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Penn State University, Stimson Landscape Architects, Climate Positive Design

13/ Outdoor discussion for the Penn State sustainable landscape plan.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Penn State University, Stimson Landscape Architects, Climate Positive Design

11/ Pamela Conrad at the Port of San Francisco Waterfront Resilience event.

14/ Mature trees are integrated into a rain garden that manages site stormwater at Stanley Green Park, Toronto.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of FORREC

15/ Forbs, grasses, and woody shrubs support pollinators in planters that are managed by the condominium at Aquabella condo on Lake Ontario, Toronto.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of FORREC

16/ Limestone benches and a capstone retaining wall create a natural amphitheatre-like setting for users of the York University Student Centre, Toronto.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of FORREC

17/ A play and learning garden of local plants, rock, and wood for children at the Mount Dennis Child and Family Centre, Toronto.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of FORREC

18/ Plants selected for colour, scent, texture and movement support the youth wellness programs offered by the North York General Hospital at Maddie’s Healing Garden, Toronto.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of FORREC

RW: I will say, when you have a group of students sitting around their table in studio, they learn at twice the speed together than when they are alone. When I was a dean, one of the saddest things was seeing students who had moved to Toronto in the pandemic, never met their classmates, never saw anybody else’s work and didn’t know whether their work was good or not, and couldn’t ask a peer for help. We are social beings. There is something about studio environments and working as groups that cannot be replicated.

If you talk to engineering companies, their productivity went up 35 per cent, because they do mostly analytical stuff, they work mathematically. They were asking themselves, ‘Why are we paying $20,000 a month for an office in downtown Toronto when we could all could be in our houses in the suburbs and be just as productive?’ But it’s really important for younger people to have in-person connections. That’s something we’re struggling to figure out: what is the balance? There’s no singular model anymore.

AN: I agree. The first year of my MLA was all online and it was tough. You can’t just nudge someone and say, ‘How’d you draw that polyline in AutoCAD? I’m lost!’ Or we didn’t see each other’s work as organically. We did office-style sessions in Microsoft Teams, sharing screens and all that, but it didn’t feel the same. Once we moved more in-person in 2021, that just happened more organically. You don’t see the fine nuances of someone’s scanned drawings. For me, I work from home about once a week, and those days I usually just do things like drawing a base plan in AutoCAD. I can do that without having to talk to anyone. Then there’ll be days when I’m in the office: I’m sketching, and one of our seniors stops by and gives their own two cents and that works well.

GB: When basic human needs like housing, food opportunity, or even human rights are not available to everyone, landscape architecture may be perceived by some as a frill. What can the profession do to promote itself as a problem-solving discipline for these broad, systemic issues?

RW: We have to differentiate between marketing and what you would call “social justice” that we do in these projects. We know from the pandemic, for example, that access to open space became a real issue for people, because being outside was the mediating factor in most people’s social lives. We have to look at and understand different impacts.

For me, it’s all about operationalizing your definition of what that means for landscape architects. Because climate change, sea level rise, these are great challenges which will

not be the purview of any single discipline. We’re going into a trans-disciplinary world. Even if you’re in a firm, I tell students, normally you have ten sub-consultants. These are complicated problems, they’re not going to solve themselves. And there’s a politicization of everything we do today. So, where are we politically? That’s something everyone’s going to have to figure out and take a position on. We’re not going to solve housing unless we increase taxes and subsidize rents. You can only build a building so cheap. My kids all have good jobs and can’t save fast enough to get a down payment on a house in Toronto, let alone carry the mortgage if the interest rates change. So this is now a social issue for all of us. Housing should be a right. Good, safe shelter: we’ll pay way less in the long run if we provide those things than if we don’t. Saul Alinsky, the socialist radical, used to say, “If things keep going the way they are, the poor won’t be able to afford to eat, but the rich won’t be able to afford to sleep.”

AN: In my firm, we like to think every project has a story to tell, no matter how small it may be. A lot of times, the award-winning projects are the larger parks, or a newly-built condo in a downtown, with ridiculously high fees so only a few could afford to live there. But we like to focus the same amount of energy into a small park, for example, in a neighbourhood that might not have a lot of green space in it. If we can improve that and the lives of people in that area, that’s a little win in a complex issue.

We also work on affordable housing projects with architects, where landscapes are a very small aspect, but we want to have a nice space for the people who are going to live there. We don’t want to just throw in Japanese forest grass or something else hardy and call it a day. We still have to work within budgets. The money has to come from somewhere. But treating every project with the same attention to detail, no matter the scale or demographic, is important.

ST: In terms of not being a “frill,” we were always told when studying that landscape architects brought a holistic skill to projects, and I still really see we do. The one thing that makes us stand apart is understanding how important living things are. Plants and the skill

PC: I can’t agree more, and I reject the “frill” idea. The challenges we’re facing are so great these days, and the fact our skill sets are so well-suited to help address them means our relevance can’t be ignored. Personally, I’ve made a conscious effort to focus solely on mission-driven work, with climate-positive design where the focus is to have a positive impact on the climate and biodiversity crises through education, advocacy, and design. To me, that means questioning the systems we’ve inherited and coming up with new models for our practice: embarking on a nonprofit approach and looking at opportunities like working remote to lower costs, to be more flexible and adaptive, to help the cities with changing their building standards, or teaching parttime and consulting on projects. I don’t have all the answers, but I really believe in how important our profession is to the challenges we face today. And I encourage others to think differently about how we practice.

0000: Exhilarating and intimidating Today is an extra ordinary junction of design and technology that is both exhilarating and, to some extent, intimidating. Last year, Google CEO Sundar Pichai said, “Today, the scale of the largest AI computations is doubling every six months, far outpacing the Moore’s Law. At the same time, advanced generative AI and Large Language Models (LLM) are capturing the imagination of the people around the world.” The pace of change is undeniably exponential, raising the ubiquitous question: will robots and AI take over our jobs? I believe answering this question necessitates reflecting on the Bauhaus movement, a testament to technology’s profound impact on architecture and art in 20th century and exploring a new definition of it in 21st century.

0001: Bauhaus: art and technology a new unity.

Originating from the Bauhaus school, this movement stands as one of the most influential modernist art schools of the 20th century. Its emphasis on the interplay between art, society, and technology reverberated across Europe and the United States. In 1923, Walter Gropius, the school’s founder, issued a new motto: art and technology—a new unity. “Technology” specifically refers to the industrialization, mass production, and machinery that emerged during the early 20th century after industrial revolution. Today, technology should not be solely viewed as machines and tools, but as the integration of computational logic and intelligence into the very fabric of industries and, of course, the design fields. As we grapple with the rapid growth of technology in recent years, society once again finds itself in a debate over the balance between technology and humanity.

TEXT BY AFSHIN ASHARI

This dialogue is far more intricate today, encompassing issues from employment to social media dynamics, and from truth to AI ethics. Addressing these concerns require embracing technological advancement and adapting ourselves accordingly.

movement championed the unity of art and technology, this new definition urges us to merge architectural creativity with computational intellect.

0011: The Artist’s Palette: XR, AI, ML, NL... as creative tools

0010: New Bauhaus: art and technology — an intellectual unity

The symbiosis of humans and technology has long fascinated me, beginning with my undergraduate studies in computer science and continuing through my studies in Master of Landscape Architecture. My journey integrating the digital realm with landscape architecture began during my second year at the University of Toronto’s MLA program in 2014. It was a time when the parametric design movement, coined by Michael Schumacher in 2008, was rapidly evolving within the field of architecture, although not yet fully embraced in the profession.

We are currently transitioning from the parametric design era to the computational design era, which encompasses a broader scope. Computational Design represents more than just digital tool usage and advanced machinery; it’s a paradigm shift in the design process. It leverages algorithms, artificial intelligence, and data analysis to challenge traditional design approaches, guiding us toward crafting intelligent, adaptable, and sustainable solutions grounded in our complex world. This is what I propose as the ‘New Bauhaus’ era in the 21st century. Much like the Bauhaus

Augmented reality, artificial intelligence, machine learning, natural language processing, and similar terms are no longer distant concepts confined to science fiction; they are vibrant tools in the design palette, offering fresh avenues for creativity. These tools and methods unlock insights and unveil potentials previously unseen, fostering a new era of innovation in landscape architecture. Currently, I see three primary approaches to integrating the computational methods into the design process.

Firstly, one can utilize open-source and readily available software programs or platforms such as Midjourney, Dall-E, and Stable diffusion, which are capable of image generation (LLM). This approach does not require an in-depth understanding of the underlying technologies.

Secondly, using parametric or computational modelling plugins such as Grasshopper in Rhino and Dynamo in Revit demands a basic level of algorithmic thinking and data management.

Lastly, one can create algorithms and write programs for specific goals. In this scenario, the landscape architect takes on

the role of a toolmaker, crafting custom solutions to address unique challenges or opportunities within a project. This requires a deep understanding of the underlying computational approaches and skillsets in the field of computer science.

0100: The We[AR] Project: a canvas of collaboration

After spending a few years in practice and academia, I finally had the opportunity to develop and experiment with a custom tool or “platform.” WE[AR], a temporary installation located at Woodbine Beaches in Toronto, served as a small-scale pilot study, exploring the integration of Augmented Reality and data processing in an interactive environment. Responding to the theme of “Radiance,” it became the first-ever interactive AR art installation for the Winter Stations competition in 2023. Symbolizing a global movement of solidarity and unity, WE[AR] urges individuals to illuminate critical societal challenges. Visitors are encouraged to explore the installation at their own pace, fostering conversations with other users and forging alliances with communities. Users can download the WE[AR] app developed by the team, in Apple Store and Google Play, and start the experience. As more individuals engage with the installation on their devices, it evolves and completes its form, allowing visitors to co-create their environment.

WE[AR] app homepage.

Users choose the social issue they would like to learn about.

Augmented reality will be projected and interact with users.

Visitors can freely walk around the interactive installation and observe the changes they are making to the installation.

As visitors walk towards the middle of the installation, hashtags supporting the social issue will appear.

The assigned sphere to each visitor will travel up into the point cloud and celebrate the completion of experience.

DATA/FEEDBACK COLLECTION

PROJECTION IN AUGMENTED REALITY

This platform provides instant, real-time feedback as users interact with the installation. This data is processed in a cloud through an algorithm designed by the designer for a specific goal. The outcome provides insights into the user experience, potential design changes, and informs decision-making. The workflow utilizes Unity for AR, Grasshopper for creating algorithms for form-finding, a linear regression machine learning method using Python and C# programming and AWS (amazon cloud processing). Currently, we are exploring new potentials with AI and image processing to explore more potentials in spatial computing.

This project was a collaboration between a student team, including University of Guelph BLA and MLA students, and a tech team, consisting of a tech solution architect and an interactive media developer. I truly enjoyed leading both teams and it was a unique experience, as they approached the project from different angles: one from an engineering and binary perspective and the other from an artistic perspective.

There are many potentials in terms of community engagement, participatory design, predicting vegetation growth, showcasing ecological behaviour, public behaviour, illustrating real time analysis on site, and preconstruction evaluation for landacape architecture projects using the similar workflow.

0101: Landscape Architects With Technology Today

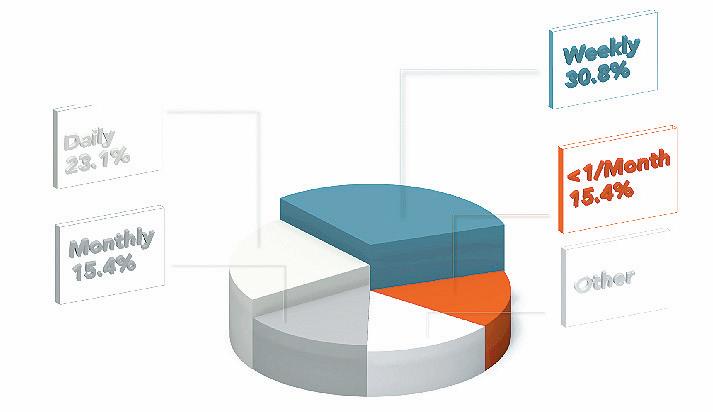

It is still surprising to me why computational technology has not been well-integrated into landscape architectural practice compared to architecture. It leaves me pondering the need for more effort and skillsets to adapt our industry to new technological changes. In 2022, we conducted a survey with Catherine Yan (BLA student), to investigate the utilization of parametric design in landscape architecture in both practice and academia. We reached out to 76 practices and 50 academic institutions in North America and Europe, achieving a response rate of about 50 per cent. Our findings revealed a clear gap in both pedagogy of landscape architecture programs and firms in terms of integrating advanced computational design in curriculum and office processes. This was in 2022, when AI and AR were not being used very often.

03/ The evolving process of the WE[AR] project.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Afshin Ashari

04/ Another close-up of WE[AR] at work.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Afshin Ashari

Users start the experience on a smartphone or smart glasses.

Each user provides feedback and input according to the prompts.

The AWS DynamoDB collects the users inputs to be analyzed and starts the process.

The API Gateway will send the processed data back to users and update the projection.

The experience will become an interactive augmented reality projection.

The experience is globally accessible and helps to raise awareness of a series of social issues.

DATA CLOUD

& PRACTICE

Do you use any parametric design tools in your project/research?

How often do you use PD in your research?

PRACTICE

How often do you use PD in your projects, including research, design, analysis, and construction?

05-06/ The pedagogy gap in landscape architecture programs and firms for integrating advanced computational design. IMAGES/ Courtesy of Afshin Ashari

0110: Breaking Boundaries: rethinking the designer’s role

The architecture field introduced the role of “computational designer” years ago, and we are witnessing growing interest in this role. The role encompasses skillsets like data-driven design, generative algorithms, machine learning and artificial intelligence, immersive environments, robotic fabrication, agent-based modelling, energy modelling, and simulation. Embracing these advancements challenges landscape architects to rethink their roles and embrace new methodologies and collaborations. Without practitioners and educators exploring the possibilities and validating the importance of this role, the landscape architecture field will continue to struggle with integrating technology into the design process, much like what occurred with parametric design about 20 years ago.

The new technological era clearly highlights the necessity for collaboration beyond the current partnerships with civil engineers, structural engineers, architects, ecologists, and others. Traditional perceptions of designers as solitary creators are evolving towards a more collaborative model, where interdisciplinary partnerships with computer scientists should become increasingly prevalent. This allows landscape architects to leverage technology to push the boundaries of what is possible in design.

0111: Navigating Uncertainty: embracing the creative journey

Of course, embracing new technologies and roles is not without its challenges. Uncertainty looms large on the horizon, and designers must navigate uncharted waters with courage and creativity. Yet, it is precisely in these moments of uncertainty that the most profound innovations often emerge. By embracing the creative journey, landscape architects can turn challenges into opportunities for growth and innovation. Innovation requires a willingness to take risks, experiment, and learn from failure.

1000: A Call to Action

Bauhaus emerged as a reaction to the ‘soulless’ manufacturing and the relentless pursuit of economic growth during the 19th century. Unlike many anti-modernity movements like Dadaism, Bauhaus refrained from viewing technology as an adversary. Instead, it saw technology as a means to enrich human lives and society as a whole, both materially and artistically.

A century ago, society fell into the trap of framing society in binary dystopian/utopian terms, and today, innovations such as AI are perpetuating a similar pattern. As we stand on the brink of paradigm shift in landscape architecture, the call to action is clear. There are currently researchers in the profession such as Bradley Cantrell (University of Virginia) and Pia Fricker (University of Alto, Finland), Jillian Walliss (University of Melbourn) and practitioners such as Fletcher studio exploring advanced computational methods and the possibilities they present.

The question of whether robots and AI will take over our jobs is nuanced. While AI has the potential to significantly reshape the

nature of our work, the extent of its impact will depend on a complex interplay of technological, economic, and social factors.

AI, in general, holds vast potential, and landscape architects should not limit their perspective to open-source programs such as Midjourney alone. We need to recognize the necessity of computational designers in our field to understand the full capacity of AI computing and computational methods. By embracing the intellectual unity, we can work towards a future where humans and technology collaborate synergistically to create a more productive, inclusive, and sustainable society. Let’s adapt ourselves in the new Bauhaus era and get ahead of the “robots” before they can get ahead of us, and take over our jobs.

PRACTICE

Are you interested in incorporating PD into your firm design process?

Are you interested in incorporating PD/CD course into your LA curriculum?

Does parametric software inhibit the traditional design approaches?

Yes

BIO/ AFSHIN ASHARI IS AN ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE AT THE SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT (SEDRD) AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH. PRIOR TO JOINING SEDRD, HE WAS INVOLVED IN A RANGE OF ARCHITECTURAL AND LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURAL PROJECTS IN BOTH THE PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SECTORS, MOST RECENTLY WORKING WITH BROOK MCILROY INC. HE IS CURRENTLY THE PRINCIPAL OF ASHARI ARCHITECTS.

ACADEMIA

ACADEMIA

ACADEMIA

ACADEMIA

PRACTICE

TEXT BY REKA SIVARAJAH

As urban landscapes evolve, so too must the outdoor spaces that weave through them. Change is intrinsic to city-building, driven by shifts in development, infrastructure, and population dynamics. Since the pandemic, the significance and the value of outdoor spaces have tremendously increased.

Change to outdoor spaces could mean placemaking projects (or abandonment, but that is not the focus of this article). Revitalization of outdoor spaces could be temporary, permanent, or a transition from temporary to permanent. Nevertheless, the common denominators are re-vision, re-vitalization, and re-engagement of diverse stakeholders. Grounded in these common factors were the inception of downtown placemaking projects in the City of Brampton and Kitchener—while involving different people and places.

In 2022, a 23-week activation project at Vivian Lane in Downtown Brampton transformed the space with an eye-catching ground mural by a local artist with assistance from over 40 community volunteers. As a pedestrian-only laneway connection to Garden Square, Vivian Lane became more inviting and welcoming to visit and pass

01/

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the City of Brampton

02/ A view of Gaukel Block in Kitchener, ON.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Habila Mazawaje / City of Kitchener

through, with the pop-up trees, flexible seating, sandboxes, lighting, and decorative yarn bombing. With a wide range of familyfriendly programs and events such as live music, night markets, chess lessons, story time, yoga, drumming, crafts and bingo, it was inclusive to all age groups.

While the Vivian Lane activation project has wrapped up, about a five-minute walk from there is the currently active Nelson Square Pocket Park, another temporary activation project. Artificial turf, rubber accessible pathway, salvaged tree logs as seating, and greenery animated a few parking spaces in August 2023 in downtown Brampton. Located within the Nelson Street Parking Lot at the corner of Diplock Lane and George Street North, the Nelson Pocket Park is a temporary placemaking project that will be active until August 2024.

These activations and other interactive installations at under-utilized laneways and public gathering spaces in downtown

Brampton were part of Active Downtown Brampton, an interim strategy to address local business and community challenges induced by the pandemic and major construction. Supported by the pillars of partnership, funding, and community engagement, these urban spaces transformed into temporary vibrant destinations. 8 80 Cities, The City of Brampton, and the Downtown Brampton Business Improvement Area partnered together on these placemaking projects. Funding through the My Main Street Community Activator Program (operated by the Canadian Urban Institute and funded by the Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario), enabled these interventions to be realized. As the ultimate users of these spaces, the community’s feedback was paramount to the re-envisioning process.

Furthering the evolution of urban landscapes, the City of Kitchener views streets, not only as conduits for transportation, but also as potential canvases for vibrant public spaces.

A prime example of this transformation is Gaukel Block, a former two-lane thoroughfare nestled between Joseph and Charles Streets in downtown Kitchener. In 2020, what started as ‘lighter, quicker, cheaper’ (borrowing Eric Reynold’s terms) with picnic tables and other experimental elements during off-peak days and hours, turned into a bold placemaking endeavour in 2023. The City reimagined Gaukel Street as a pedestrian-only street, repurposing it from a car-centric thoroughfare to a bustling hub for passive and programmed community gatherings. Located between the north part of Victoria Park, a large City park, and Carl Zehr Square, a public square in front of the Kitchener City Hall, Gaukel Block connects existing public spaces as well as other built forms.

As vehicular traffic gave way to pedestrian activity, the dynamics of the space underwent a fundamental shift. Communityled events surged, surpassing expectations and underscoring the newfound demand for vibrant public spaces. Gaukel Block was animated with art murals, including Indigenous art, horticulture, and places to sit,

Vivian Lane in Brampton, ON.

and programmed with artist performances and markets. Between May and September 2023, Gaukel Block welcomed approximately 40,000 visitors, further solidifying its role as a focal point of community interaction.

The reason for this transformation was multifaceted. The shift was catalyzed by Kitchener’s long-term city planning (a high-level vision) for a pedestrian-oriented Gaukel Street, which aligned with the permanent closure of the Charles Street Bus Terminal (due to LRT plans) that Gaukel Street was primarily serving (at least from a traffic point of view). This vision was further defined and expedited by community advocacy and municipal support when a condo development (called Charlie West) closed a portion of Gaukel Street for approximately three years, highlighting the feasibility of repurposing Gaukel as a pedestrian-only street.

The project was bolstered by strategic funding initiatives. The City’s Economic Development Department secured a $500,000 grant from the Government of Canada through the Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario; this provided essential resources for the physical transformation of the Street.

Transitioning a traditional street into a pedestrian-centric space necessitates meticulous planning and coordination. New maintenance and operational protocols such as garbage collection, graffiti removal, and security surveillance require diligent oversight and sustained investment to uphold the integrity of the public realm. The dedication to quality upkeep ensures Gaukel Block continues to leave a positive impression on the community and visitors to the City.

Gaukel Block exemplifies the transformative potential of streets as catalysts for placemaking. By embracing change, reimagining urban spaces as dynamic, inclusive environments, embedding the new vision into planning policies, and collaborating with diverse internal and external stakeholders with different priorities

and interests, staff at the City of Kitchener set a positive example out of Gaukel Block—not only does it offer a new public space to the City’s public realm, it also demonstrates the potential of streets as public spaces. As cities grow, their streets should be viewed not merely as thoroughfares, but as integral components of the urban landscape puzzle, essential to fostering connectivity, vitality, and a sense of belonging.

There is no single formula for successful public space revitalization projects; shared learning is the best approach because people and places—the two main elements of any placemaking project—are unique. Here are a few shared learnings from staff at the City of Kitchener and City of Brampton to city-builders who may endeavour similar projects:

• integrate strategic partnership and/or collaboration into placemaking projects

• identify operational/maintenance needs early on and establish necessary protocols

• be creative and flexible with the design and programming

• engage the community, potential partners, and the Council early in the process

• embrace temporary activations, and utilize existing materials.

03/ Gaukel Block at Charles Street, Kitchener.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Habila Mazawaje / City of Kitchener

04/ Night time at Gaukel Block.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the City of Brampton

05/ People of all ages enjoying Nelson Square Pocket Park in Brampton.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of the City of Brampton

06/ An arial view of Gaukel Block.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Habila Mazawaje / City of Kitchener

THANK YOU, CITY OF BRAMPTON AND CITY OF KITCHENER FOR PROVIDING ADDITIONAL INFORMATION FOR THIS ARTICLE.

BIO/ REKA SIVARAJAH, MES (PL), IS A SEASONED COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT PRACTITIONER WITH EXPERIENCE IN BOTH THE PRIVATE AND PUBLIC SECTORS OF CITY-BUILDING. IN HER VOLUNTEER CAPACITY AS AN EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBER FOR GROUND, SHE CHANNELS HER ENTHUSIASM FOR PUBLIC SPACES INTO CURATING CONTENT IDEAS FOR THE MAGAZINE. AS AN ADVOCATE FOR GENDER EQUITY IN THE BUILDING AND DEVELOPMENT INDUSTRY, REKA TAKES AN ACTIVE ROLE IN THE WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP INITIATIVE TORONTO, SPEARHEADING IMPACTFUL INITIATIVES THAT SPOTLIGHT WOMEN’S CONTRIBUTIONS.

01/ Rooftop collection.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Wausau Tile

02/ Marriott El Paso.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Wausau Tile

03-04/ Fowler Rooftop.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Virginia Burt Designs, Inc.

05/ Hello Apartments.

IMAGE/ Courtesy of Wausau Tile

Expanding services and increasing revenue for landscape architects through rooftop amenity designs can be a highly lucrative venture, especially in today’s urban landscape where outdoor space is a premium commodity. The growth of high-rise living has created a demand for outdoor retreats and social spaces, leading developers to invest in rooftop amenities as a means to attract tenants and enhance property value.

Rooftop amenities have evolved from being perceived as novel features to becoming essential components of modern urban living. In recent years, they have become increasingly common in new, high-end apartment and condo buildings, catering to the needs and desires of tenants who seek access to outdoor spaces that their apartments often lack. Rooftop decks not only provide a connection to nature but also offer breathtaking views of the surrounding skyline, serving as an escape from the hustle and bustle of city life.

TEXT BY CHRISTOPHER DUNCAN

For landscape architects, rooftop amenity designs present a unique opportunity to showcase their creativity and expertise. By offering innovative and functional designs, landscape architects can help developers differentiate their properties in a competitive market while maximizing the return on investment. From conceptualization to execution, landscape architects play a crucial role in transforming rooftop spaces into vibrant and inviting environments that enhance the overall quality of life for residents.

One of the key factors driving the demand for rooftop amenities is their ability to increase property value and attract tenants willing to pay a premium for enhanced living experiences. Research has shown that luxury rooftop amenities, such as top chef cooking stations, hidden gardens, fire pits, and sculptural water features, can significantly boost the desirability and perceived value of a property. Buyers and tenants are increasingly drawn to properties that offer unique and upscale amenities that promote social interaction and outdoor recreation.

In addition to providing aesthetic appeal, rooftop amenities also contribute to the overall well-being of residents. Rooftop fitness areas, for example, offer residents the opportunity to stay active while enjoying panoramic views of the city. Kidfriendly spaces and court games provide opportunities for families to bond and engage in recreational activities, fostering a sense of community within the building.

As the demand for rooftop amenities continues to grow, landscape architects have an opportunity to expand their services and increase their revenues by offering comprehensive design solutions tailored to the needs of developers and property owners. By staying abreast of the latest trends and innovations in rooftop design, landscape architects can position themselves as industry leaders and trusted advisors to their clients.

Collaboration is key in delivering successful rooftop amenity projects. Landscape architects must work closely with developers, architects, engineers,

and other design professionals to ensure that rooftop spaces are not only aesthetically pleasing, but also functional, safe, and compliant with building codes and regulations. By leveraging their expertise and that of other professionals, landscape architects can deliver holistic design solutions that exceed client expectations.

When it comes to designing rooftop amenities, there are endless possibilities for creativity and innovation. Whether it’s creating lush rooftop gardens, designing state-of-theart fitness facilities, or incorporating unique water features, landscape architects have

the opportunity to push the boundaries of traditional design and create truly iconic spaces that leave a lasting impression.

Moreover, rooftop amenity projects offer landscape architects the chance to showcase their commitment to sustainability and environmental stewardship. Green roofs, for example, not only provide valuable green space in urban environments but also offer numerous environmental benefits, such as reducing heat island effect, improving air quality, and mitigating stormwater runoff. By integrating sustainable design principles into rooftop amenity projects, landscape architects can help create healthier and more resilient communities while also reducing the environmental impact of urban development.

Rooftop amenity designs present an exciting opportunity for landscape architects in a rapidly growing market. By offering innovative, functional, and sustainable design solutions, landscape architects can help developers create vibrant and inviting rooftop spaces that enhance the overall quality of life for residents while maximizing the value of their properties. Collaboration, creativity, and a commitment to excellence are essential ingredients for success in this dynamic and evolving field.

TEXT BY TERENCE LEE, OALA

I received one of the best ever pieces of advice from someone while I was at University. I was contemplating whether to go to Europe for my fourth-year fall term and struggled to decide whether I could really afford it. I was told, “Just go! You won’t regret it!” They were right. From that moment on, I have loved travelling, and whenever possible, I would give the same advice to anyone thinking about travelling. Whether it was the nerve-wracking experience of making sure I was on the right part of the train while travelling overnight from Paris to Florence, or the right part of the train from Florence to Barcelona (both times, no, I had to jump out in the middle of the night with my bags and run to the opposite end of the train), or going somewhere totally foreign (Japan) where I managed to get around with limited English signs, or being sent out on a plane to Singapore (for the first time) as my first day working for Peter Walker, I found it all invigorating (if a little daunting). At the end of the day, that was good for me. Not only should we remain vigilant when travelling (try not to look like easy targets for professional pick-pocketers), staying alert also means turning on my design brain—soaking in all the great, or not so great spaces and architecture in every city I visit.

IMAGE/ Terence Lee

02/

IMAGE/ Terence Lee

03/

IMAGE/ Terence Lee

04/

IMAGE/ Terence Lee

01/ Interstate 64 East, Leavenworth, Indiana.

Accidentally discovering MOCA Cleveland, architect Farshid Moussavi.

Golden hour at the harbour, Louisville Waterfront Park, by Hargreaves Jones.

First Christian Church by Eero Saarinen (landscape by Dan Kiley).

05/ Hands-on at the decomposed-granite ground plane of Honey Locust allée, Miller House, by Dan Kiley.

IMAGE/ Terence Lee

06/ Honey Locust allée, looking north from south end at Miller House, by Dan Kiley.

IMAGE/ Terence Lee

07/ Crabapple Bosque in front lawn of Miller House, by Dan Kiley. View from Mr. Miller’s private office.

IMAGE/ Terence Lee

08/ View of Honey Locust allée and Flatrock River valley beyond at Miller House, by Dan Kiley.

IMAGE/ Terence Lee

For one long weekend last summer, I finally heeded my own advice. I planned a road trip from Toronto to Columbus, Indiana, via Detroit, then St. Louis, Louisville, Cincinnati, Cleveland, then finally home via Buffalo. I travelled through a vast array of landscapes. While nature was everywhere, so was Americana, with highway billboards preaching either religion or guns. An eclectic tapestry of agricultural, suburban, and City-scapes, I found driving through middle America fascinating (with a tinge of anxiety). With Obama’s A Promised Land audio book blasting, the irony was not lost on me as I search for the roots of my landscape design heroes and their work.

In Columbus, I finally visited Dan Kiley’s masterpiece, Miller House. But, prior to my arrival, I was able to arrange for myself a very special guided tour. Ben Wever has been the grounds manager at Miller House since 2010. While his grandmother was the personal assistant to the Miller family, Ben literally grew up at the Miller House. His large, line-backer figure cannot be more understated by his humble, friendly demeanour. As we walked through the grounds together in the August heat, he talked excitedly about all the triumphs and challenges in maintaining one of the most iconic symbols of American modernism, like replanting the horse chestnut allée at the end of their lifespan with the more local, climate-appropriate buckeye flavour, or the recent replanting of a cedar hedge at the swimming pool which adorned the restored ornate fence and gate, to the recent planting of the crab apple bosque at the front of the house. All of which came along with stories of challenging management of timing and funding on the appropriate planting material, while maintaining a living museum that receives visitors throughout the summer months. Entrusted by the Miller family and the Newfields, formerly Indianapolis Museum of Art, Ben is the de facto custodian of Dan’s legacy.

While at the house, I looked and took pictures—I’m sure from all the same spots the likes of Alan Ward have done for the past several decades. But, even though I recognized everything I saw from multiple books, there’s nothing like physically visiting a place you’ve studied for many years. There, while walking through each landscape room, I was finally able to take in the scale and details of the place: the height of the clipped hedge beneath today’s buckeyes, the very unique paver at the driveway and vehicular court imported from Switzerland at the request of the Millers, subtle differences in grasses

delineating different spaces, and, finally, the grandest feature of the garden. The Honey Locust allée was more than just an allée. In classic Dan style, he took a traditional landscape element and turned it on its head. For those who are familiar with the garden, we all know that this allée is not traditional in the sense that it leads one from one significant point to another, typically from house to a specific garden feature, but rather it was turned 90 degrees and used as a transitional space, creating more of a landscape ‘loggia’ to provide shade and comfort to the house. However, when you’re there in person, you’ll understand the power of a carefully considered landscape space. The scale, the ground material, and the plant material cannot be understood until you’re actually standing in that space—in my case, I wanted to lie down and roll around on it, but Ben would not allow it. So, as I sat on the curb edge near the family room patio and placed my hand on the soft, warm, decomposed granite (gravel) bed, I took in a quiet moment, reflecting on landscape architecture, this place, the man who designed it, the man who I knew so well after having worked for him for more than two years in his Vermont studio, and my place in this universe. I came to another level of appreciation for

landscape architecture: one that has the power to move people’s emotions, and heighten their sense of nature, design, space, and time.

Ben was kind enough to take me to another Dan Kiley site he manages, the North Christian Church. Since the congregation no longer meets there, the building remains unused and locked. The incredible building and its interior design by Eero Saarinen remains impeccable, frozen in time, a living, three-dimensional representation of the history book images I have at home. Columbus, Indiana is filled with fine examples of American modernist works by the likes of the Saarinens, Father Eliel and son, Eero, as well as Harry Weese, I.M. Pei, Kevin Roche, Myron Goldsmith, and Edward Charles Bassett. While several names of modernist architects come to mind, only one landscape architect can truly be called modernist: Dan Kiley.

My road trip continued west, then south and east, as I made my long loop around Lake Erie. Physically inhabiting a place cannot be replaced by staring at a computer monitor screen, no matter how fantastic the image might be. To live and breath the same air as the trees and flowers, to hear the birds chirping