BEST OF DUBLIN

A GUIDE TO CITY & COUNTY JOHN GIBNEY

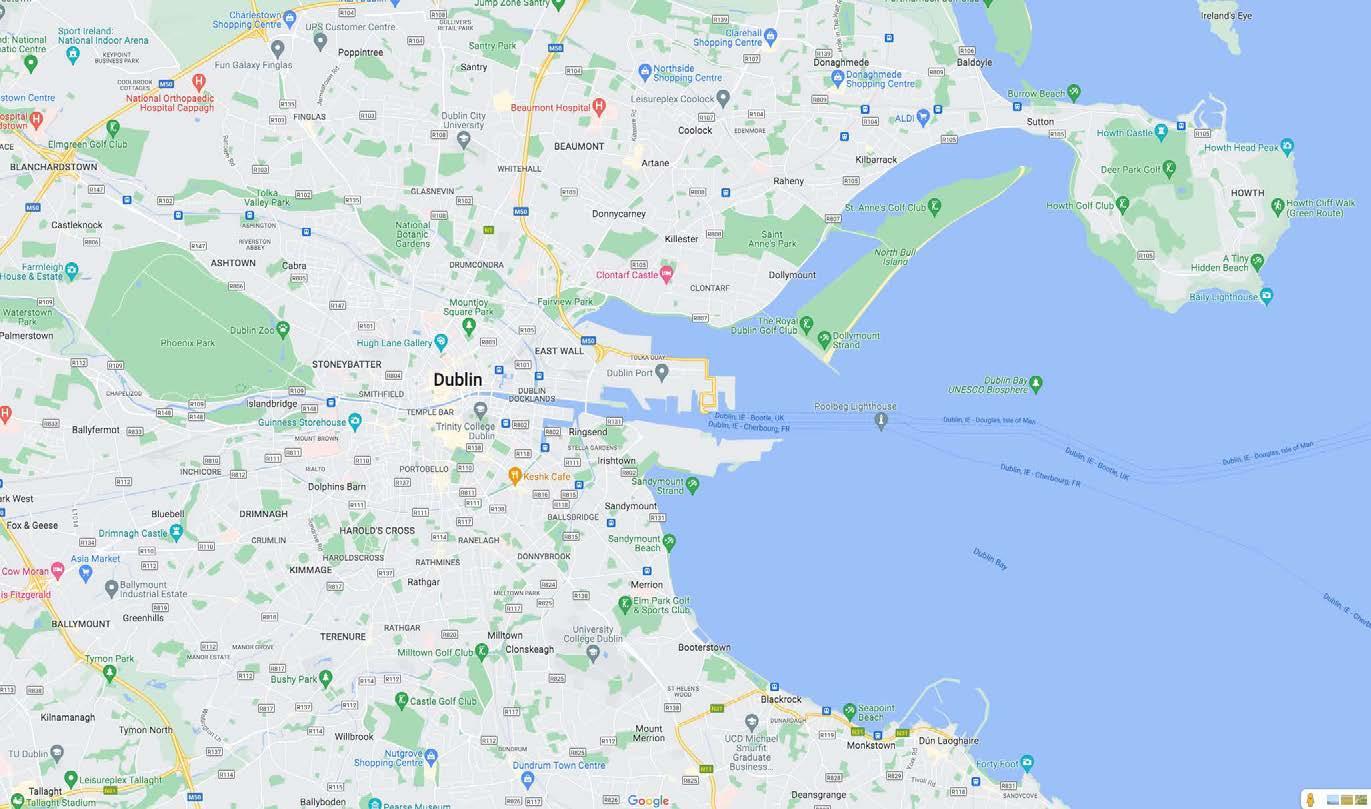

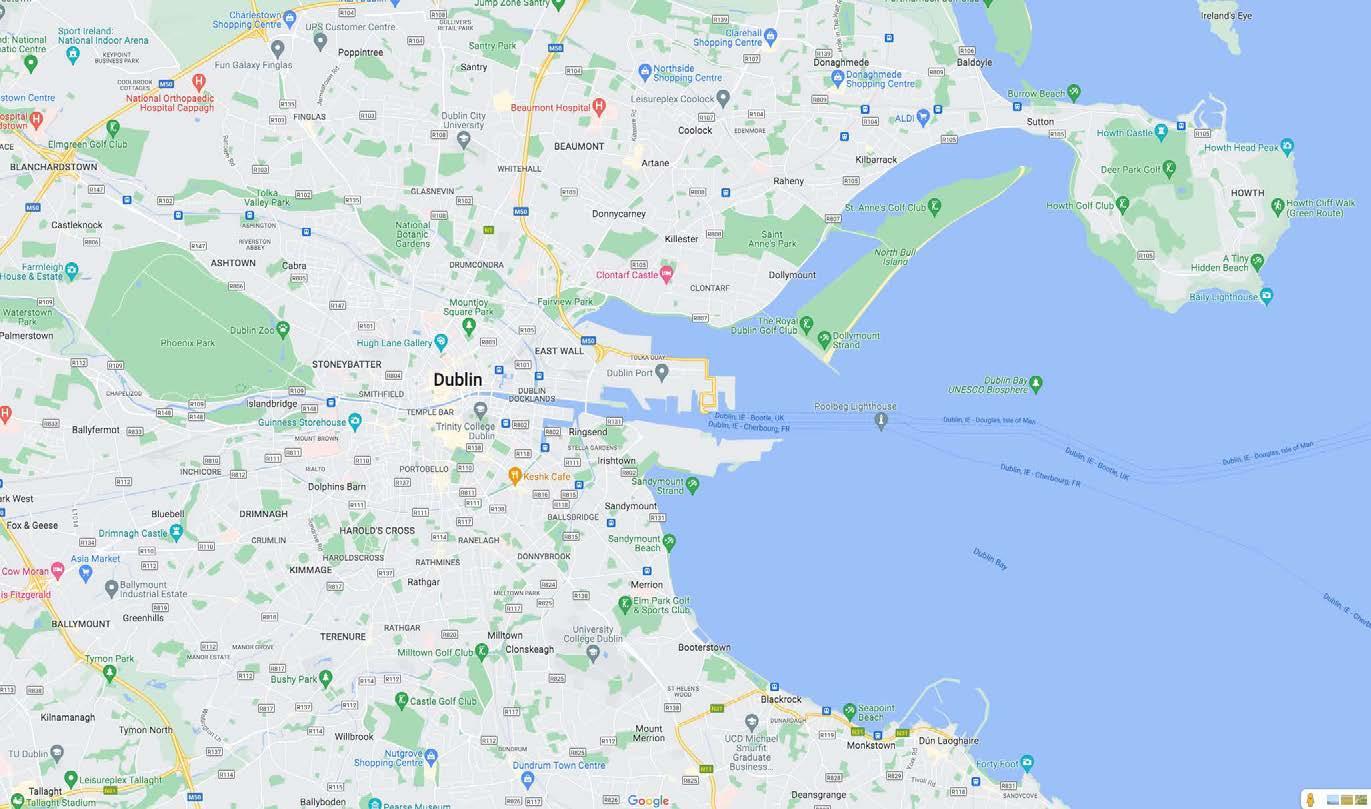

Dublin viewed from the mouth of the River Liffey, with the Poolbeg Lighthouse in the foreground.

Dublin viewed from the mouth of the River Liffey, with the Poolbeg Lighthouse in the foreground.

John Gibney is a historian with the Royal Irish Academy’s Documents on Irish Foreign Policy project. Prior to this he finished a PhD at Trinity College Dublin and worked in heritage tourism in Dublin for over fifteen years. His books include Dublin: A New Illustrated History (2017) and A Short History of Ireland, 1500–2000 (2017).

A Georgian doorway on Merrion Square, with the distinctive fanlight above the door.

A Georgian doorway on Merrion Square, with the distinctive fanlight above the door.

4. Georgian Dublin: College Green to Parnell & Mountjoy Squares

College Dublin and College Green

Street and the General Post Office (GPO)

and Dublin City Gallery the Hugh Lane

5. St Stephen’s Green to Merrion Square: Georgian and Victorian Dublin Grafton Street and St Stephen’s Green Leinster House, the National Museum and the National Library of Ireland

6. South Dublin beyond the Grand Canal

and Sandycove

7. North Dublin beyond the Royal Canal

and the Botanic Gardens

Photos on p. 4 (clockwise from top left): Temple Bar; the Campanile in Trinity College; Grattan Bridge; deer in the Phoenix Park.

Photos on p. 6 (clockwise from top left): Grand Canal; Fusilier’s Arch, St Stephen’s Green; Fairy Castle on Ticknock Hill; Howth Harbour.

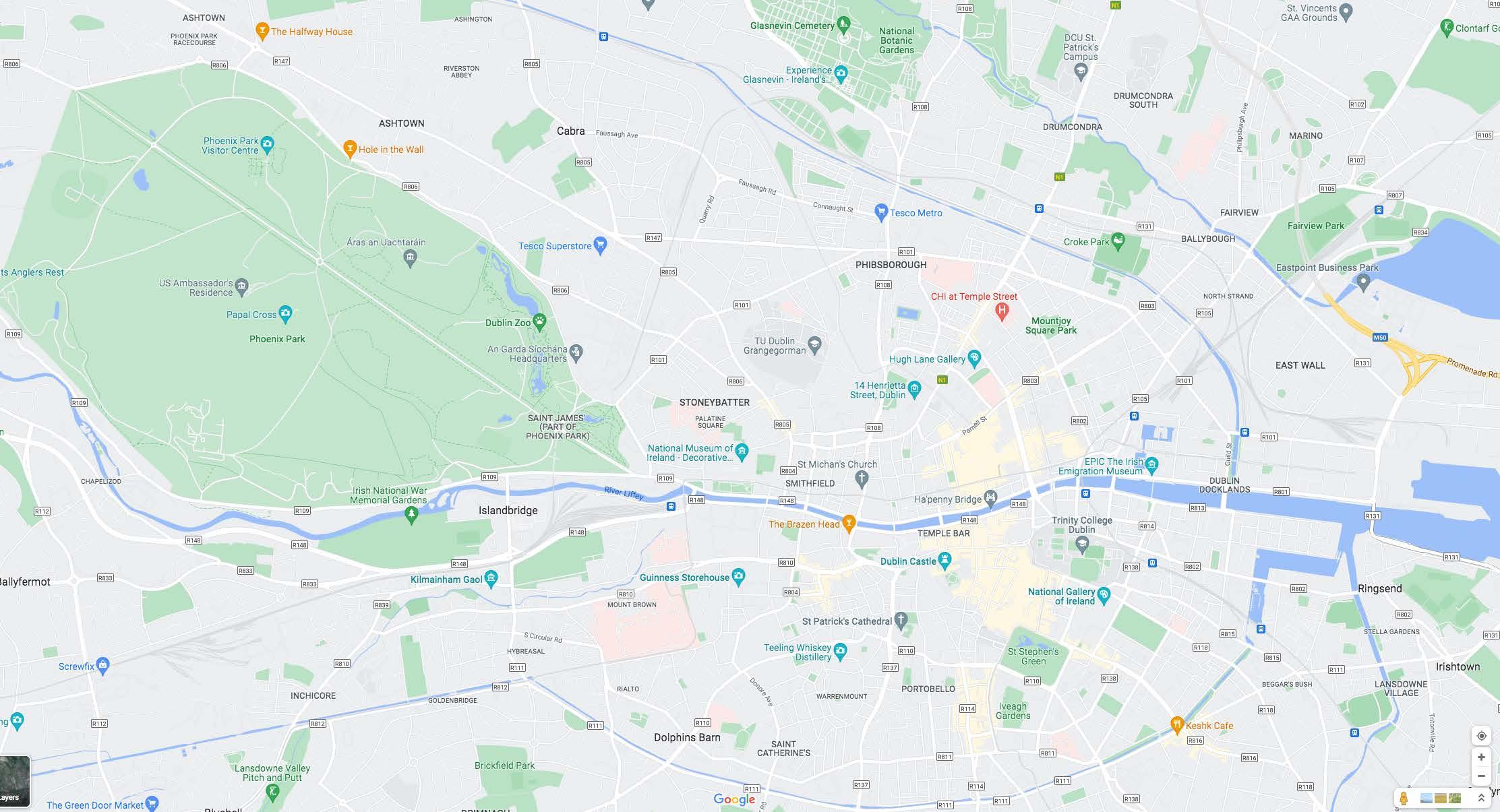

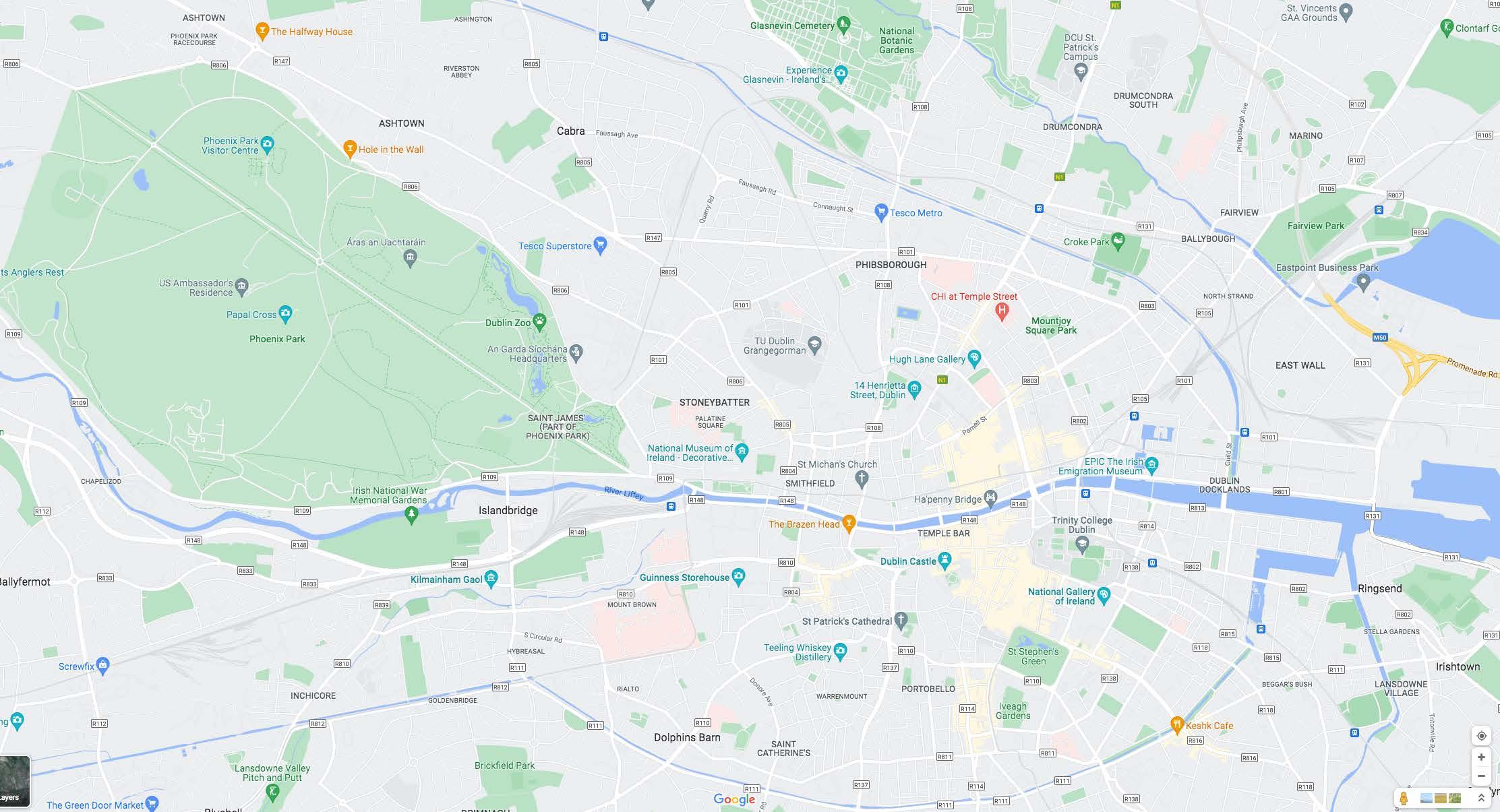

DUBLIN DOCKLANDS

GUINNESS STOREHOUSE

SMITHFIELD

TEMPLE BAR TRINITY COLLEGE DUBLIN

BOTANIC GARDENS Glasnevin Cemetery DUBLIN ZOO PHOENIX PARK PEARSE MUSEUM HUGH LANE GALLERY

IRISH NATIONAL WAR MEMORIAL GARDENS

HEUSTON STATION

ROYAL HOSPITAL KILMAINHAIM IRISH MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

PHOENIX PARK KILMAINHAM GAOL GUINNESS STOREHOUSE L I B E R T I E S COLLINS BARRACKS STONEYBATTER ARBOUR HILL SMITHFIELDBROADSTONE BUS ÉIREANN DEPOT

HUGH LANE GALLERY

MOUNTJOY SQUARE PARK

CROKE PARK

14 HENRIETTA STREET

ST MICHAN’S CHURCH

FOUR COURTS

WOOD QUAY

GRATTAN BRIDGE

TEMPLE BAR

CHRIST CHURCH CATHEDRAL

DUBLIN CASTLE

GPO

O’CONNELL STREET

O’CONNELL BRIDGE

CUSTOM HOUSE

CONNOLLY STATION

HA’PENNY BRIDGE

COLLEGE GREEN

DAME STREET

CITY HALL

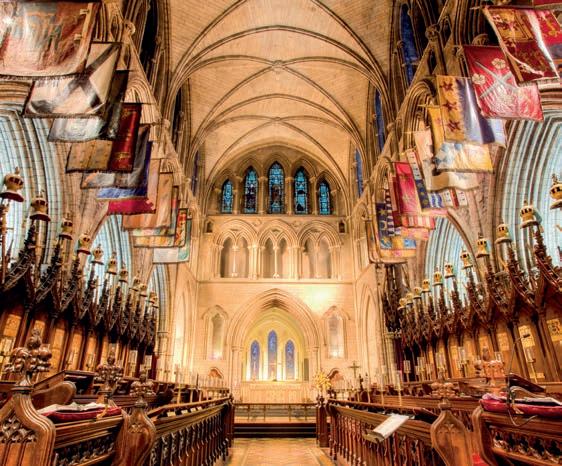

CHESTER BEATTY LIBRARY ST PATRICK’S CATHEDRAL

MARSH’S LIBRARY

GRAFTON STREET

CHQ& EPIC

FAMINE MEMORIAL

TRINITY COLLEGE DUBLIN

NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF IRELAND LEINSTER HOUSE

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF IRELAND

ST STEPHEN’S GREEN

IVEAGH GARDENS

MERRION SQUARE

DUBLIN DOCKLANDS

Welcome to Dublin! In this short guide we are going to take you on a journey, in words and images, through the history of Ireland’s capital city from its origins to the twenty-first century. The city that became the Irish capital grew out of settlements established by Vikings over a thousand years ago, and much of the streetscape and street plan that exist today are a legacy of the eighteenth-century, when Dublin was one of the most important cities in western Europe. For most of its history, Dublin has been the largest urban area on the island of Ireland, and in the twentieth century it expanded dramatically into suburbia. The pages that follow explore the city through its architecture, buildings and unique sites, along with its history and culture, and expand to include Dublin’s hinterland and suburbia. But, as with everything, we need to begin at the beginning.

Dublin was founded by the Scandinavian raiders known as Vikings, but virtually nothing of their city remains, at least not above ground. The modern city of Dublin evolved from settlements founded by the Vikings from the 840s onwards (though the area in and around what became Dublin was inhabited long before they arrived). Originally raiders attacking the Irish coast, mostly from Denmark, the Vikings soon established more permanent bases around the coast in order to strike farther inland.

The Dublin region was an obvious location: it was on the east coast, at the mouth of a river sheltered in a bay. The Vikings settled at the junction of two rivers, the Liffey and the Poddle, which formed a natural harbour; here, they established their maritime base, or longphort. The Irish term for this geographical feature – Dubh Linn, a dark or black pool – gave the city its traditional anglicised name, and it was located on or beside the site of the circular garden outside the Chester Beatty, within the grounds of Dublin Castle. It can take a leap of the imagination to visualise the Viking city but Dublin, as it exists today, would not have come into being without it.

Viking Dublin lay on the southern banks of the River Liffey, in and around the modern location of Wood Quay, which houses the main offices of Dublin City Council (the municipal authority). When the council offices’ foundations were dug in the 1970s, layers of the modern city were stripped away to reveal the Viking city that lay beneath. What followed was one of the largest excavations of a Viking archaeological site undertaken anywhere; the fact that the excavations were eventually built over was a source of enduring controversy. A fragment of the old city wall can be seen in the middle of the office complex, with the most substantial sections of the medieval city wall surviving on nearby Cook Street.

What can also be seen along the pavements in this area are monuments and replicas of what was found: Báite, the

sculpture of a Viking longboat by artist Betty Newman Maguire on Essex Quay, the outlines of Viking houses embedded on the pavements at the northwest corner of Christ Church, and the bronze replicas of Viking artefacts scattered along the pavements around Wood Quay. The most eye-catching of these include a piece of Viking graffiti carved onto a plank, and a slave collar. Viking Dublin was eventually part of a trading empire that stretched from Iceland to Asia, and the trade in slaves was part of this. The history of Viking and medieval Dublin can be explored in more detail at Dublinia, the dedicated interactive museum located in the former Synod Hall directly across from Christ Church Cathedral.

dublinia.ie

Prior to the 1600s, Dublin’s buildings were mostly made of wood, which is one reason why so little of the original city has survived. An exception, however, is Christ Church Cathedral. Built on a ridge in the 1170s by the English and Welsh adventurers of Norman ancestry who invaded Ireland after 1169, Christ Church lay at the heart of medieval Dublin. It is on the site of an earlier church built by Sitric Silkbeard, a Viking king of Dublin who converted to Christianity. Christ Church has been heavily renovated over the centuries: much of the exterior was rebuilt in the nineteenth century, and the adjoining Synod Hall, which now houses Dublinia (a ‘living history’ museum) and which is connected to the cathedral building by an archway across Winetavern Street, dates from 1875. But the spire of Christ Church as it stands today can be recognised in a sixteenthcentury woodcut, and the interior of

the cathedral retains much its medieval fabric. Like its counterpart, St Patrick’s, it is a cathedral of the Church of Ireland, the episcopal church founded during the Reformation, which was Ireland’s official state religion until 1869. The crypt explores the history of the cathedral through a wide range of displays and artefacts, including, famously, the mummified bodies of a cat and mouse which got stuck in an organ pipe.

At the eastern end of Christ Church is Fishamble Street, which runs down to the River Liffey and which took its name from the fish market located here during the Middle Ages. It has a small but important role in musical history: on 13 April 1742, the first performance of Messiah, written by the German composer George Frideric Handel, received its premiere in a music hall (long gone) on the street. The anniversary is usually marked by a public performance of extracts from Messiah on the street.

At the junction of Parliament Street and Dame Street, just east of Christ Church, stands Dublin City Hall, originally opened in 1782 as the Royal Exchange. The beautiful rotunda is usually open to the public, and a close look at the exterior will reveal the marks of small-arms fire: City Hall is a veteran of the Easter Rising of 1916, when it was briefly occupied by insurgents seeking Irish independence from Britain. It was seized because it lay beside Dublin Castle, which housed the British governments that ruled Ireland until 1922.

Dublin Castle is best entered through the gate to the Upper Castle Yard, beside City Hall. At first glance it may not look like a traditional castle. It was built from 1204 onwards, with the River Poddle serving

as a natural moat to the south and east. It never had a central keep, though some of the medieval corner towers survive today. The foundations of the older structures can be seen beneath the more modern buildings (but are accessible only by tours). By the seventeenth century, it had fallen into disrepair and much of the existing complex was rebuilt after a fire in 1684. The Upper Castle Yard consists of terraces of offices and administrative buildings, including the ornate state apartments.

Notable buildings in the complex include the elaborate Gothic Chapel Royal in the Lower Castle Yard, completed in 1814, while the castle is also home to the Chester Beatty, which contains the extraordinarily rich collections of artefacts, books and manuscripts acquired by the Irish-American mining

magnate Alfred Chester Beatty, who donated his collections to the Irish state after settling here in 1950. They have been housed here since 2000. In front of the library is the garden located on the approximate site of the original Dubh Linn, while behind it, on Ship Street, are the old barrack quarters, which housed British troops until 1922.

dublincastle.ie

chesterbeatty.ie

From top: The Chester Beatty; A display in the Chester Beatty; An interior view of the rotunda of Dublin City Hall.

Facing page: The Bedford Tower, located in the Upper Castle Yard of Dublin Castle and completed in 1761.

St Patrick’s is the national cathedral of the Church of Ireland and is the second of Dublin’s two cathedrals. The current building was constructed from the 1220s onwards and, like many other locations in Ireland, was associated with the fifth-century Welsh missionary Patrick, who reputedly baptised converts to Christianity at a nearby well. Like Christ Church, St Patrick’s was built on the site of an earlier church but, unlike its counterpart, it was outside the city walls. The spire dominates the skyline in this part of the city. The cathedral tower (known as Minot’s Tower, after one of the archbishops) dates from the fourteenth century and the spire itself was added in 1749.

St Patrick’s is most famously associated with Jonathan Swift, author of the classic satire Gulliver’s Travels (1726), who spent most of his career as dean of the cathedral, and who is buried inside. A more obvious but lesser-known association is with the Guinness brewing dynasty. St Patrick’s was extensively renovated in the late nineteenth century, and the work was paid for by the Guinness family. They also funded the construction of St Patrick’s Park beside the cathedral and the distinctive red-brick Iveagh Trust buildings on the northern side of the park.

stpatrickscathedral.ie

Beside St Patrick’s is the modest but elegant structure of Marsh’s Library, named after the archbishop of Dublin, Narcissus Marsh, who oversaw its foundation. Established in 1707, it was opened for the use of ‘graduates and gentlemen’ and has the distinction of being the first public library in Ireland. While small, its collections are extremely rich and are showcased in rolling exhibitions curated by the library staff. The original collections belonged to Marsh himself and reflected his interests in science and languages.

His collection was added to by the first librarian, the French Huguenot Elié Bouhéreau. Readers over the centuries have included Bram Stoker (author of Dracula) and James Joyce (author of Ulysses). The interior of the library was modelled on that of Oxford’s Bodleian Library, and has one very distinctive security feature: a set of three cages into which readers were locked to peruse the books, which had to be returned before they were let out.

marshlibrary.ie

The area west of St Patrick’s Cathedral is traditionally known as the Liberties. The name itself goes back to the Middle Ages, when distinct jurisdictions – ‘Liberties’ –outside Dublin’s walls were administered by various noblemen and churchmen. Over time, the name was applied to the entire district. Traditionally, the Liberties was associated with artisan trades. It was on the edge of the city with a number of rivers and watercourses running through it. Textiles, brewing and distilling became important industries in the area. Many of these declined in the nineteenth century, undermined by competition from Britain, and poverty became increasingly widespread throughout the area. Many of the distinctive red-brick houses in the Liberties were built towards the end of the 1800s to replace tenements and slums. The Liberties, centred in and around Francis Street and Meath Street, remains one of the most famous districts of Dublin’s inner city.

libertiesdublin.ie

The Liberties is often associated with Huguenots: French Protestants who fled religious persecution in their homeland at the end of the seventeenth century. Many were highly skilled, and so were often encouraged to settle in Britain and Ireland. Some certainly settled in the Liberties, working in textiles, but Huguenots were found throughout the city, and there were perhaps 3,600 members of the community in Dublin by 1720 (a dedicated Huguenot cemetery can still be seen on Merrion Row, to the east of St Stephen’s Green). Many were prominent in the gold and silver trades as craftsmen. One of the chapels in St Patrick’s Cathedral, the Lady Chapel, regularly hosted services in French for Huguenots, and Dublin had a lively French-speaking community for much of the eighteenth century.

The Liberties was very well supplied with water, so it is no surprise that brewing and distilling were prominent here. Traditionally, Dublin had relatively little heavy industry, and some of the city’s biggest employers in the modern era were producers of food and drink. Brewing and distilling made the Liberties into one of Dublin’s only real industrial quarters. There were dozens of breweries across the city in the eighteenth century but, by the nineteenth century, distilling had become more prominent, and the drinks industry employed thousands in the Liberties.

A notable landmark is the old windmill of the original Roe’s distillery on the

northern side of James Street, completed in its current form in 1805 and topped with a distinctive tapered copper dome. Many breweries and distilleries in the area went out of business over time –the National College of Art and Design, on Thomas Street, is located in what was once the Powers Distillery. Legally, whiskey can only be called whiskey if it has been matured for three years, and the twenty-first century has seen a resurgence of distilling in the area. There is a dedicated Irish Whiskey Museum on Grafton Street, beside College Green.

irishwhiskeymuseum.ie

The Guinness Storehouse is one of the most substantial Victorian industrial buildings in Dublin. Arthur Guinness established a brewery near St James’s Gate in 1759. With the growth of rail networks in the nineteenth century, Guinness expanded its market outside Dublin, and left a huge imprint on the city as it grew. It also squeezed out many of its competitors in the Liberties, often incorporating their premises into its own. The imposing buildings that line the west end of James Street are reminders that

Guinness was the largest brewery in Ireland from the 1830s onward and by the end of the century it was the largest in the world. The Storehouse was completed in 1905 and now houses the enormously successful visitor centre. It is located on a distinctive semicircular crescent that was originally a dedicated harbour for the brewery, located on a spur of the Grand Canal that has since been filled in: another sign that the Guinness brewery has been a very large operation for a very long time.

guinness-storehouse.com