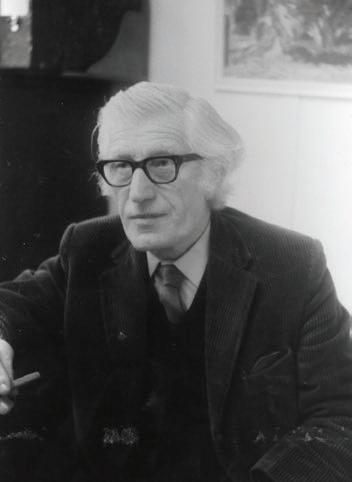

MICHAEL O’BRIEN

4 July 1941 – 31 July 2022

First published 2024 by The O’Brien Press Ltd, 12 Terenure Road East, Rathgar, Dublin 6, D06 HD27, Ireland.

Tel: +353 1 4923333; Fax: +353 1 4922777

E-mail: books@obrien.ie. Website: obrien.ie

The O’Brien Press is a member of Publishing Ireland.

ISBN: 978-1-78849-527-1

Text © Michael O’Brien and The O’Brien Press 2024

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

Editing, typesetting, layout, design © The O’Brien Press Ltd

Cover and inside design by Emma Byrne.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including for text and data mining, training arti cial intelligence systems, photocopying, recording or in any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 28 27 26 25 24

The author and publisher thank the following for permission to use photographs and illustrative material:

Photographs: The majority of photographs are reproduced from The O’Brien Press archives and the O’Brien family archives. Other images are credited to: p.43 Stephen Conlin; p.54 (bottom) Ian Broad; p.203 (top) Richard Mills. If any involuntary infringement of copyright has occurred, sincere apologies are o ered, and the owners of such copyright are requested to contact the publisher.

Printed and bound in Ireland by Sprint Books.

The paper in this book is produced using pulp from managed forests.

A Note on Fragmented Memories page 7

Why is Book? 9

Chapter 1: Family Background, Childhood, Youth12

Chapter 2: An Accidental Publisher 41

Chapter 3: e Early Years of e O’Brien Press51

Chapter 4: Changing Technology 68

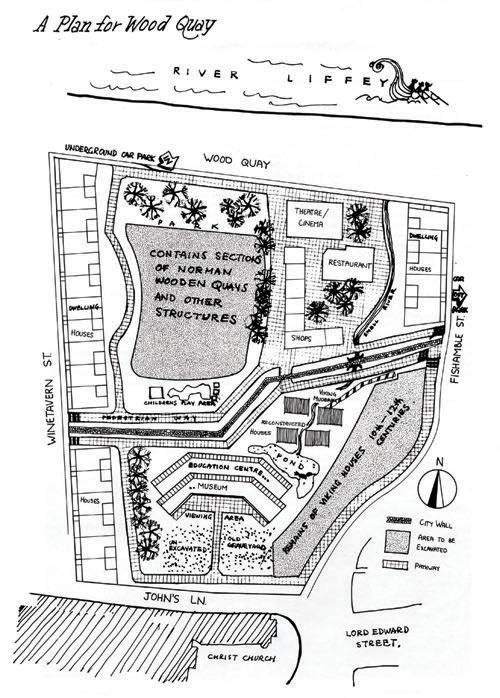

Chapter 5: Wood Quay 76

Chapter 6: In Search of an International Market99

Chapter 7: Children’s Books – A New Direction117

Chapter 8: Personal Favourites and Landmark Books 140

A Few Final Words – Un nished oughts190

Afterword – Ivan O’Brien 192

This book marks the ftieth anniversary of the founding of e O’Brien Press in November 1974. e book was originally conceived as a memoir to be written by Michael O’Brien, joint founder of the company with his father, Tom. Michael asked me to work with him on it as I had been involved as editor at the company from 1982 to 2007 and subsequently worked on a daily basis with Michael for many years.

Michael began the book and dictated a good deal of material. He was helped at di erent times by several people to get the project underway. However, his sudden death in July 2022 meant that there was now no longer the possibility of a complete memoir. It existed in fragments in many places. Sadly, we had only just begun the task of getting the nal book assembled and written.

e O’Brien Press directors Ivan O’Brien and Kunak McGann and I came to the conclusion that though these fragments regrettably could not be a full exploration of all the themes, events and issues of Michael’s life and work, there were still interesting

memories and musings already recorded that could represent many of his core beliefs and could tell the story of the birth and development of an independent Irish publishing house at a signi cant historical moment in Irish publishing. Despite the fact that the project had been cut short far too early in its development, and that there were huge gaps, we felt this book might be a tting celebratory publication for the ftieth anniversary of the company.

e fragments we have here are very much in Michael’s own words, words he would no doubt have honed and expanded (and in some cases double-checked), had time allowed.

ey are primarily memories of the early years of the press and thoughts on favourite or signi cant projects. ey re ect on Michael’s family background, his formative years, his core values, his business approach, and his experience as founder of e O’Brien Press in 1974.

Ide ní Laoghaire

Editorial Director, e O’Brien Press

1982–2007

Quite a few years ago I was asked by another publisher to write my memoirs. I wondered why. Why would anyone be interested? It was pointed out to me that my life was interwoven with the emergence of the publishing industry in Ireland, and that I was one person who had actually lived that experience and knew all the details involved. So, I gave it some thought. I tried to write it – but I am not a writer and prefer to spend my personal time painting or gardening or reading art books. is activity didn’t suit me at all, so I gave up. I cancelled the contract. e project then sat there, abandoned.

Until one day a group of O’Brien Press sta were talking about our forthcoming ftieth anniversary in 2024 – the company had been set up in 1974 – and someone said: what about those memoirs? Would they be tting at that time? I gave the suggestion some further thought.

In the end, I persuaded a few people to come on board to assist in the writing. It would not really be a personal memoir as I don’t believe that that is relevant to anyone apart from me and my family; it would be more an account of my life as a publisher – what that was about and how it all evolved, and how I saw it and experienced

it. Some family details would help shape an approach to publishing, so I would include them.

e O’Brien Press has published over 2,000 books in its fty years, and currently has nearly 700 on its list. You could not possibly tell the story of all those books, interesting though some of those stories are. I had to select. As I began to write, I tried to pick out those books that represent stages in our development – as a country and as an industry, as well as a company – and I managed to squeeze in a few of my own personal favourites too. Personal favourites are what keep a publisher going, after all.

e year 1974 is roughly fty years after Ireland’s independence. I thought how tting to look back now, another fty years later, and recall how the indigenous Irish book publishing industry came about. Publishing seems to be a late developer in a postcolonial situation; in the 1970s, the market was still dominated by products from the original empire, though ironically many interesting, groundbreaking and successful authors often come from dominated countries. Perhaps a dominated people has more to say than those who are comfortable with the status quo.

In the decades just before the birth of e O’Brien Press, the Catholic Church continued to dominate moral and welfare issues in Ireland, in particular matters such as marriage, divorce, abortion and the school system. As the twentieth century progressed, the power of the Church began to fall away, and a freer, more democratic society emerged; this was to prove a fertile publishing environment.

I rmly believe it is important for every country to have its own publishing industry. ere are events that are of huge importance to that country but to nobody else; there is the question of the ‘take’ on many situations – the voice of a people expressed on

major and minor issues. It is important that smaller countries have their say and that colonised countries make space for their own point of view and do not continue to rely on the opinion of the former dominant country. All of this means that a healthy publishing industry is vital, providing an independent platform for a nation. Creating this possibility, with all its challenges, has been an interesting journey. It feels like a hectic fty years.

Four large multinational publishing groups have o ered to buy e O’Brien Press. I have always said no. I feel that the main motivation of such companies is to get rid of the competition. I expect and hope that my family and team will continue with this independence.

Michael O’Brien

Icome from an unusual mix of backgrounds for Ireland of the 1940s: my father was a communist, from a Catholic family, and my mother was Jewish, from an immigrant Russian-Jewish family. ey met at Dublin’s New eatre Group, set up as a workers’ theatre in 1937 to explore radical political views. eir plays were put on at the Peacock eatre and in various trade-union halls. My parents’ shared interests at the time were theatre, literature and opposition to the rise of fascism. ey wanted to help bring about a fair and democratic socialist society.

My father, Tom, was born on 21 April 1914. e family had a ne house in Phibsboro and a shop at 14a Phibsboro Road. He was one of seven children – two boys, who both became left-wing radical

activists, and ve sisters, all conservative Catholics. e family circumstances are a bit of a mystery. When the last two sisters, Mona and Lucy, died, they left behind a strange mix of squalor and elegance: a beautiful clavichord, handmade chairs, tables and mirrors, alongside junk, disorder and a plethora of holy pictures. It appeared as if the family had come down in the world.

My father had the usual Irish Catholic childhood of that era until his older brother Jamesbecame interested in left-wing politics and Tom then went on to follow in his older brother’s footsteps. ese interests led to my father becoming a communist. In 1938 he joined the International Brigades and went with them to the Spanish Civil War, to do his bit to try to prevent the fascists, especially Hitler, taking over Europe. However, he never talked much about his earlier life, and most of what I know comes from

discoveries after his death – often from documents found literally ‘under the bed’. I knew that he had left school at fourteen, as did many at that time, and that his political views had led to him joining the IRA in the early 1930s.

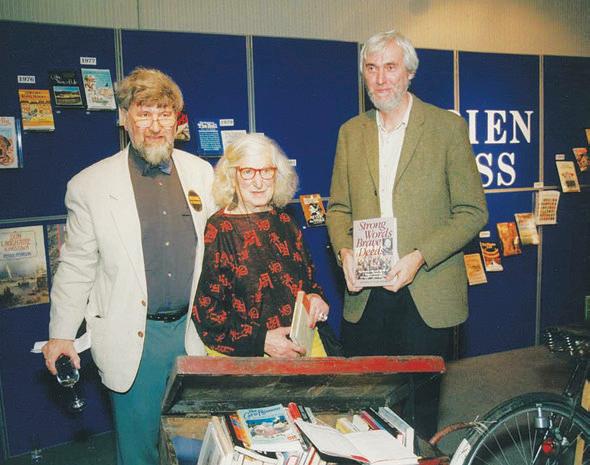

Many years later, in 1994, I was to discover more about my father when H. Gustav Klaus, a German academic, contacted me out of the blue from former East Germany, asking if I knew a poet called Tom O’Brien. He was researching socialist activities in 1930s Ireland and he was amazed when my mother showed him a case containing letters to my father in Spain, a collection of his poetry in progress, and a cowboy book and plays that he had written. A book about his life, Strong Words, Brave Deeds: e Poetry, Life and Times of omas O’Brien, Volunteer in the Spanish Civil War, was conceived, and was published by e O’Brien Press to mark the twentieth anniversary of the founding of the press and of his death. is biography of my father includes an account of his activities in Spain, extracts from correspondence during those years, articles for left-wing publications such as Workers’ Republic, along with some of his poetry (some of which had originally been published in anthologies in the 1930s); it also reproduces New eatre Group plays, and essays by socialist activists of the period.

My father was one of the Irish volunteers who went to Spain with the International Brigades. eir journey took them rst to London, then Paris, where they were lodged in small hotels by the French Communist Party, then by train to Languedoc, where they stayed in isolated farmhouses, then over the Pyrenees by foot, walking in the cold and the dark along smugglers’ pathways and

mountain ridges. A number of volunteers who had come earlier had already died in the con ict. Tom and his colleagues waited in villages near the river Ebro, which marked the front line. ‘Waiting, waiting, waiting’ was a strong theme in my father’s poetry about Spain. In 1994, I interviewed Eugene Downing, a fellow volunteer of my father in Spain. Downing was wounded during the war and had a foot amputated. He remembered:

‘Your father and I crossed the river together. We both had hung from our belts strings of hand grenades, a ri e and ammunition. If we fell over, we would drown, as the weight would keep us below water. Franco’s troops were ring across the river – colleagues and friends were struck and drowned. We both crossed successfully.’

I believe that my father was injured during this period because I remember asking him about a scar above his temple. He said it was a bullet from Spain.

I rely a lot on his poems to show me what he thought and felt. Here is a small taste of what he wrote about the Spanish Civil War:

I have written poems in words Now I shall write one in action I shall go and do the things I wrote and thought about.

From Strong Words, Brave Deeds

After ghting in Spain, he wrote many poems, including the following:

I will sing of men who died

In a land of black and white.

O, the white sun, the white still standing sun

And the black still standing shadow

And the split dry mouth of earth

All hot and panting hot

All panting hot and all unblinking.

Sun faced the earth unblinking

Unblinking earth faced back,

Heat stilled, heat held, heat spelled,

Man and the beetle moved

From crack of earth to crack

And under leaf, man moved …

A lonely student in a silent room

Quits his lagging pen to dream

Of thundering mountains;

From Strong Words, Brave Deeds

Crouches, tight-faced, where the vine-stump

Spreads its silent singing leaves,

Still eyes where the lifting dust

Speaks of death;

Leaps from vine to covering vine

To the mound of safety;

Dies, as fancy has it,

Gladly on the sun’s bright theatre …

From Strong Words, Brave Deeds

Both before and after his period in Spain, my father struggled with stretches of unemployment. In his earlier years he had unusual ways of earning money. One of his enterprises was O’Brien’s Library, which I only became aware of after his death when my mother o ered me a gift from my father’s book collection. Looking through the bookcases, I noticed that a few books were neatly covered in brown paper. I pulled down three of them and was amazed to see them stamped inside with: O’Brien’s Best Book Library –Books at your Doorstep, 14a Phibsboro, Dublin. is was the address of the shop where my aunts, my father’s sisters, lived at this stage in their lives. It was the original family home, a ne Victorian

brick and granite house, but by the time my extended family and I inherited it, it was in a dreadfully run-down condition and couldn’t be rescued so we were forced to sell it to a builder.

I remember asking my mother, ‘What is this O’Brien’s Library?’ and she answered in an o hand way, ‘Oh your dad ran a little library, it wasn’t much.’ She looked embarrassed, but I decided to nd out more. e books I had pulled from the shelves were a Graham Greene novel and My Struggle by Adolf Hitler – a 1939 English translation of Mein Kampf (1933). I learned later that my father believed it was important for readers to know the evil plans of Hitler. ere was also Tess of the D’Urbervilles by omas Hardy.

Around the same time, on a visit to the Phibsboro house to meet up with my aunts Mona and Lucy, I noticed a wooden trailer with

pram wheels and asked, ‘What is this?’ ‘Oh, nothing much,’ I was told. ‘Your father had a library.’ It transpired that this trailer was my father’s travelling library and he attached it to his bicycle to travel around making deliveries and collections. ‘What’s it used for now?’ I asked my aunts. ‘Collecting coal,’ they told me. So I asked if I could take it and I have it still.

While discovering more about my father’s interests and endeavours, I also found a small archive of the New eatre Group in the attic of one of the group’s founders. e papers were destined to be thrown out, so I had them digitised and the archive is now in my possession. It is a valuable archive of a small group of activists from the 1930s – with information about their aims, what they did, who else was in the group, and so on. ( is archive was donated to Maynooth University in 2023.)

e 1940s saw my father back in Ireland, where he turned his attention to the printing industry.

e printing company

E&T O’Brien, where our publishing activities later began, was set up around 1948 by him and Elinor O’Brien. She was not related to our family but came from a wealthy O’Brien family

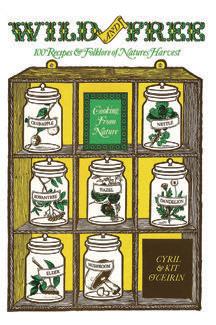

An example of an E&T O’Brien calendar. Calendars were key administrative tools for business during this era.

from the Shannon estuary area in Limerick and was descended from William Smith O’Brien, leader of the Young Irelanders, a political movement in the 1840s seeking independence. A talented photographer, botanist and an artist, her work is to be found in the National Library’s Photographic Archive and in the Irish Museum of Modern Art; she was also involved in a broad range of leftist activities, both cultural and political. At a time when the establishment was Catholic-led and conservative, Elinor was dedicated to promoting the cause of socialism and challenging that establishment. She invested in E&T O’Brien and also worked in Tom’s printing enterprise as the two were united in their political leanings.

e company imported a small litho printing machine from America – it was one of the rst of its kind in Dublin and considered advanced at the time. As a business, E&T still needed to earn money alongside printing propaganda to promote socialist views. ey printed legal documents (Articles of Association), o ered general trade printing, and printed Second oughts: e inking Competitors’ Weekly, a weekly national crossword solver written by my father – another unusual money-making idea of his. At the time, two major Sunday newspapers o ered substantial prize money to crossword fans, so there was a good market for the solver. e company was located at 13 Parliament Street in the heart of Dublin, then moved to Clare Street, also in central Dublin, in the 1970s.

I was very close to my mother, Ann. As an ex-Jew, she was not part of any religious community. Her main interests were in ne art

and culture, and Crumlin where we lived in the 1950s was, for her, devoid of social activities. She was a young mother with a growing family. Gardening was the only activity open to her.

My mother was a strong character, as she demonstrated even a few months before her death. She suffered a stroke in her house in Crumlin in the late 1990s. I was at work in Terenure when I got an overwhelming feeling that my mother was trying to contact me. I jumped into my car and drove the fteen-minute journey to her home. I had a key to the house and knocked on the door while removing the key from my pocket at the same time. I went upstairs. My mother was holding a phone. ‘Michael! You have come,’ she said, with a slur. I knew straight away something was radically wrong. ‘I think something has happened,’ she said.

She had a Jewish doctor, the same doctor for much of her life, who lived up the road, and he came and said, ‘We have to get Ann into a hospital immediately.’ When the ambulance came, Ann was nding it di cult to talk, but managed to say, ‘I am not going to a hospital!’

Two paramedics entered the house and o ered to assist Ann down the stairs into the ambulance. ‘I am not going to hospital,’ she insisted. One paramedic turned to me and said they had a legal obligation to ensure Ann was taken to hospital. I acknowledged that that might well be the case but that I would not be accountable for what could happen if they tried to force Ann into the ambulance. ‘When my mother says she’s not doing something, she will not do it,’ I informed them. ‘Sure, we understand, Michael,’ they said, ‘but we deal with cases like this every day. If you wouldn’t mind just stepping back …’ As one orderly approached my mother to remove her to a stretcher, she punched him with full force in the face. ‘I am not going to hospital,’ she reiterated. e crew retreated in haste, assuring me that they had done everything they could, but could assist no more under the circumstances.

Ann remained living in her home for some months until she died. e family established a roster to ensure she had family support for the last months of her life until she eventually had to be taken to hospital. I was at her bedside in her nal hours, holding her hand. Her last words were: ‘Michael, was I a good mother?’ ‘You were the best mother in the whole world,’ I replied. And I meant it. A moment later, she quietly slipped away. ‘My dad chose well,’ I often thought in later life when I remembered my mother. * * *

My mother’s parents came from Crimea and Ukraine in the southern Russian Empire. ey were Jews, and were originally called Zhevitovsky, which my grandfather, Abram (later known as Abraham), changed to Sevitt. As a teenager, my grandfather was

conscripted into the Tsarist army, but he escaped; he was captured and spent three months in jail, then escaped again with another Jewish friend. He went to an uncle who put him in touch with an illegal unit that was helping Jews get out of Russia. He then left Russia, aged eighteen, with a cousin, and they crossed Europe on foot, as so many others did at that time. ey eventually arrived in Hamburg, and there they were told that a particular boat would take them to America. But it didn’t – my grandfather and his companion had been conned. is was very common at the time as there was a huge racket going on with ships. ey ended

up in East London, where there was a large Jewish community, and Grandfather worked in a garment shop as a salesman. He eventually moved to Liverpool, where he met his future wife, Elizabeth Armider, and they got married there. She had been born in Khmilnyk, Ukraine.

My uncle Simon recalled:

‘My mother’s family lived in the southern part of Ukraine – she lived in a town, called a shtetl, which literally means a small town in Yiddish. But more than that, it meant a place where Jews were allowed to live and have a certain amount of freedom. ey were not allowed to own land; they couldn’t be farmers; thus they were restricted to certain occupations – such as shopkeeping, tailoring or any trade using the new technical developments like electricity or gas. ey were the people who helped the Russian peasantry to change the shtetls into the beginnings of modern civilised towns. ey supplied the essential social needs of these places; they made it possible for these ultra-backward places to reach at least the beginnings of modernisation. ey knew about trading.

‘She was a more skilled worker than my father. She was a tailor, a dressmaker and a ladies’ suit-maker. Before arriving in England, she worked for a Jewish rm in Khmilnyk, earned a pittance and worked umpteen hours a week. e only rest day was the Sabbath.

‘ e Jews were victims of Tsarist pogroms … they were mowed down, attacked and their houses burnt. My mother got to Liverpool. She had an older brother there already. My mother was only about seventeen when she left Ukraine.’

My grandfather Abraham (as he was now spelling his name) and my grandmother Elizabeth married in Liverpool in 1903 and had one son, who died soon after. Eventually, they moved to Dublin, where Abraham had a brother, Solomon. ey considered themselves lucky to be there as Ireland was then considered one of the safest countries for Jews. Seven children were born, including my mother, Ann.

certi cate for

eir mother did not work in tailoring at this time as she had a large family to look after.

For several years, they lived at 17 Martin Street, Portobello, but this was not their rst home in Dublin. e family’s location is unclear at times. ey may initially have lived on Capel Street, in the city’s inner north side, where there was an old abbey, St Mary’s Abbey; the crypt remains there to this day. Beside it is a building which used to be a synagogue and the family may have lived beside this before moving to Martin Street.

Abraham was working as a tailor by this time and had opened a shop in Harcourt Row. He was also involved in founding the Tailors’ Trade Guild. In 1938 he brought the rst dry-cleaning service to Dublin, taking ideas and methods from the USA. Over the years, family members were involved in various businesses, and also in left-wing politics.

My mother worked as the manager in the family tailoring and dry-cleaning business in the 1930s. Her sister Julie ran what we believed to be Dublin’s rst fashion boutique, ‘Julie’s’, in Harcourt Row. Another sister, Jay, was involved in the Tailors’ Union, and later went to the USA and later again to Australia. Celia, an excellent artist, went to London and married Jim Prendergast, a trade unionist and communist. She was also involved in running London’s Left Book Club, set up by publisher Victor Gollancz and others in 1936; Victor Gollancz was a Jewish refugee and had fought against Franco in the Spanish Civil War. Celia’s prints and etchings were selected for major collections, including a collection at the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Russia. Scholarship as well as business ran in the family, as it often did in Jewish families. My mother’s brother, Simon, received various scholarships and studied physics and medicine simultaneously at Trinity College Dublin. Later, he became head of the Birmingham Burns Hospital and a world leader in injury and burns research. e area around Portobello where they lived was largely a Jewish part of Dublin at the time, and everybody knew everybody. e Sevitt family knew and loved Chaim Herzog, who was later to become the sixth President of Israel. In time, they moved to Donore Avenue to a bigger house with a garden.

True to their own beliefs, my parents married in Liverpool, in a civil marriage, which was not an option in Ireland at that time.

Tragically, when my mother, Ann, married my father, a gentile, her strict Jewish father, Abraham, disowned her. He did this despite my mother being a kingpin in his business – she did the accounts, she met the customers. Abraham scored a massive own

goal. His business su ered after she left, and he saw his dream of an extended Jewish family all around him fall apart. His eldest daughter, Julie, had no children; and most of his children went abroad, including his daughter Celia to London, and his son Simon to Birmingham; and his son Benny had no children. Ann’s family were the only ones around, but her father couldn’t accept us. When the eldest, my sister Sonya, was born in Dublin’s Rotunda Hospital in 1940, my mother took a risky gamble and presented the rst Sevitt grandchild to her mother by arriving on her doorstep and saying, ‘ is is your rst grandchild.’ Grandma Sevitt said, ‘Give me my grandchild!’ and invited my mother inside. Abraham died three months after I was born, in 1941.

My uncle Simon remembered my father from those early days:

‘Tom – your father, Michael – was a great man, both personally and politically. One of the best. One of the rare breeds of true Irishmen, who were not only good in themselves and to their families, but also clear-headed, political and brave.’

When my parents had their children, my mother named the girls and my father named the boys, hence the oddity of very Irish boys’ names (Michael, Dermot, Brendan) and Jewish girls’ names, though my eldest sister is called Sonya, which is not a Jewish name, but it is a common Russian name. My mother was obviously trying to hold on to a little bit of her heritage through naming her girls (Ruth, Deborah, Miriam). My name, Michael – I was the second-born – crosses the boundaries, being both Jewish and Christian, and very common in Ireland. ere was little Jewish in uence in our household. We didn’t celebrate any of the Jewish

festivals. My mother had walked away from her heritage. Instead, she became deeply involved in the cultural community; she was a member of the New eatre Group, and regularly attended concerts and visited exhibitions.

A member of the New eatre Group, Paddy Byrne, remembered:

‘ e New eatre Group was a most interesting development and one of the nest things that I remember coming out of that period [1930s]. At that time, there were a number of plays with a left leaning coming on the market, mainly from America and Britain … In Dublin at the Abbey, the stagegoing public were being o ered the old peasant rubbish … there was only one play critical of Irish society – ey Shall Be Remembered Forever by Bernard (Barney) McGinn. To ll this vacuum, the New eatre was formed … We put on progressive, anti-fascist plays that no other theatre would touch.’

One way my mother’s Jewish inheritance lived on was in the context of food. She sometimes made borscht, Ukrainian/Russian beetroot soup, unknown in our neighbours’ households. My father loved it, but the rest of the family hated it! If my mother made borscht, there would be a general strike in the house. Of course, the food she made was quite simple – she had seven children and very little money. When she had some money, she would shop in Magill’s food store, which specialised in Jewish and Mediterranean food. So, in this context her Jewish upbringing still had some in uence on us as children growing up. One event I recall is that when our uncle Benny died, all us boys had to wear a Jewish skull cap on our heads for the funeral. We were told too that the co n must be modest, made to a simple standard form, regardless of the status of the deceased. My uncle Simon told us: ‘ ere is no heaven – you do your best for the one life you have on this earth.’ Looking back, I feel the main in uence I had from my mother was: follow your dream, develop creative skills, aim high and let the world be your studio.

At one stage in her later life, my mother was invited back to the Jewish community. e community had a meeting place called the Maccabi, a big sports ground and recreational centre o Kimmage Road (Irish businessman Ben Dunne later bought it and turned it into a sports complex). I recall being approached by an elderly Jewish woman who said that Ann would be welcome to come back into the Maccabi, meaning into the community. I dutifully asked my mother if she would like to go there. She said she would give it some consideration. Eventually she said, ‘No, I simply don’t want to go back into that small community. I have my own life now.’

She was quite political. My father was very political too. Together, they had lived a wide-ranging cultural life, which encompassed art, theatre, travel and left-wing politics, all of which my mother continued after my father died.

Initially, as a family we lived in Bray. e house there was a small, timber bungalow – it was actually a holiday home. It had three large rooms and a large garden, where my mother grew vegetables and fruit. It was in a well-to-do area of the then largely Protestant Sidmonton Road. At the end of the garden was a boundary wall and the woman in the neighbouring house put broken glass on the top of the wall to stop us children climbing it. My mother went out with a hammer and, piece by piece, smashed the glass to a ne powder, much to the approval of my father; she took direct action! I remember seeing the woman several weeks later over the low boundary wall and asking her: ‘Why did you put glass on the wall?’ e woman stared, speechless, at this audacious small boy who asked such an impertinent question.

ere was great excitement at home for storytime with Dad. He invented a series of magical worlds: one I recall was a home with ten windows, and each story began with characters popping out of the windows to act out the latest story. Years later, when a journalist researching a Christmas article phoned me at e O’Brien Press, he asked me, ‘What were your favourite books as a child?’ I was struck dumb! I couldn’t remember any books, only Dad’s stories.

My father kept himself informed about the Second World War and the Nazi fascist murder machine that had been forecast by his Spanish Civil War colleagues. He also told us children about it, even though we were very small, but he was to go on to repeat

the information over the years. He told us that when Hitler was coming into power, he had people placed all over Europe who could make a list of all the Jews so they could be exterminated. He believed that the head of the Irish National Museum and others were Nazi sympathisers, and that they had made a list of all the Irish Jews (including us) and sent it back to Berlin. I checked this out many years later with one of our authors, Tomi Reichenthal (I Was a Boy in Belsen), and he told me he saw the list in the Berlin Jewish Museum. ere were four thousand Jews listed in Ireland at the time of the Second World War.

During the war my father had a map of the world stuck up in

the kitchen – a large map – where he marked out the expansion of the Germans and the Japanese. I am told he would declare: ‘If the Germans win the war our whole family will be exterminated.’ He was well aware of what a German win would mean for Jews living in Ireland. As a result of his steadfast belief, I have always been acutely aware of the dangers of political extremism and the rise of Nazism.

We all loved Bray as young children. I recall walking Bray Head with my sister Sonya and going to the coal harbour to watch coal being unloaded by crane, and persuading shermen to let us on their boats. ere were also Dawson’s Amusements, candy oss and ice cream when our ‘wealthy’ Aunt Julie came to visit. I remember playing in Bray with our cousins visiting from London. Bray was a great place for a child.

To save the train fare from Bray to Dublin, my father would often cycle from Bray to his printing works on Parliament Street in Dublin, a round trip of around 50 km. en a wonderful opportunity arose for our family. Dublin Corporation o ered my parents a site to build a house on St Teresa’s Road, Crumlin, just o Kimmage Road West. is arrangement was common enough at the time. My father had been alerted to the scheme by a friend, Joe Deasy, who as a councillor in Dublin Corporation had lobbied for social housing. ere was 2.5 per cent interest on a twenty- veyear Corporation loan. e development consisted of about twenty semi-detached privately owned houses built to a standard design and joined onto the excellent Corporation houses on Stannaway Avenue. is was the 1950s, with a huge amount of unemployment. Much of the male population was working in England. Many

became builders. Some came back to help build their own houses.

Moving to our own house in Crumlin was a signi cant step up in the world and o ered more space for the family. I was ten years old when we moved. Opposite our new house, 42 St Teresa’s Road, was a large, unkempt and wild area that was designated to become a park. e houses were built, the roads were there, but there were no footpaths, just humps of gravel and soil. e park didn’t materialise at that time, but we played there anyway. ere is a large, beautiful park there now. I remember building a wind-powered trolley – a trolley with a sail on it. It was common in Dublin at that time for young boys to make trolleys. Most were simply a piece of wood with wheels, but I wanted to take it to the next level, harnessing the power of the wind. I wanted to be an inventor. I found an actual steering wheel from a car and a rack-and-pinion steering mechanism. My route was downhill – down the road to a sharp right turn, but I hadn’t factored in the wind at the end of the road which would catch the sail and blow the whole cart over. Lesson learned!

On St Teresa’s Road, my mother’s background and my father’s experience and political education distinguished them somewhat from most of the neighbours, who had all had a traditional Catholic upbringing, with little international contact or experience. Very few of them had an education beyond fourteen years of age as it cost real money in those days to attend secondary school or university. Many were more familiar with the Catholic catechism than with any other book, as it was drummed into them at school by the brothers and nuns. We were often made aware that the neighbourhood children, and many of the adults, were afraid of going to

Hell – and we were frequently informed by other children that that was where we were heading. In the O’Brien household, Hell simply didn’t exist. Heaven didn’t exist either, as my father and mother were both atheists.

As a child and young person, I was hyperactive – always making things and drawing. One great memory I have is of being in the scouts. e scouts had a really positive and lasting in uence on me. I was in the 23rd Donore company on Donore Avenue o the South Circular Road. Meetings were held in a Presbyterian hall next to the church. Going away to camp was a wonderful experience for me at the time, and trips to camps in Wicklow were very adventurous. Lord Powerscourt, who owned vast estates in Wicklow, let the scouts have campsites all over the Powerscourt estate. Some of the more well-to-do scout groups, like Zion and Rathgar, even built wooden cabins there.

Camp res, songs and cooking on the re on the Powerscourt estate near the waterfall were a wonderful part of childhood for me. I would cycle out through Kimmage, all the way to Powerscourt in Wicklow on a bicycle without gears. As I cycled up the hills, scouts from Zion or Rathgar would pass by in their father’s car (women hardly ever drove in those days), an interesting class di erence and a formative and educational experience for me. Rope-work and knot-making, common scouting activities, would prove useful in later life when I took up sailing.

e highlight of my youth was when I went as junior scout leader to an international jamboree in Sweden. I also went to jamborees in Wales and the Isle of Man. is was a time when very few people travelled for anything other than work, and they usually

went to building sites or factories in London. Big jamborees would have fty countries represented. I loved meeting people from exotic regions of the world.

I became close to a neighbouring family called Rosenberg – the children, Peter and Heddi, attended my national school, St Mary’s National, a Protestant school. ey were the only other ‘unusual’ family in our area so it was not surprising we would link up. e parents were Estonian and they lived on Armagh Road, not far from my family home. Later, Peter and I were in the Clogher Road Technical School, known as e Tech, together and he was interested in cars. Mr Rosenberg was the chief engineer of a ship. During the war the Irish Government had purchased a few ships –they were renamed Irish Elm and Irish Oak. But Ireland had hardly any marine skills then, so these skills had to be imported. Mr Rosenberg was o ered a job on one of the ships. He was away quite a bit. At Christmas time, I remember that they had beautiful Estonian handmade glass ornaments, handed down from generation

to generation. I often helped to put up the Christmas tree in the Rosenberg household, though Heddi, the daughter, was very protective of the ornaments and wouldn’t let me touch some of them. I recall that Mrs Rosenberg and my mother got together to see if they could make a match between me and Heddi! We were about seventeen years old at the time. I have to say that I was oblivious to the prospective match being hatched, and getting married was far from my mind: I was interested in drawing, making things, scouting, and was not well versed in matters of romance. Heddi was a wonderful and adventurous cook, distinguishing her from her typical Irish peers, and she invited me to dinner. We ate in the dining room, where Heddi laid the table beautifully, carefully arranging the family’s nest silverware. When Heddi served the food, I asked for salt, but Heddi declared: ‘Michael! e way I cook, you do not need salt.’ Much as I admired Heddi, I knew I was no match for her, or her mother, and was unschooled in the ways of the world.

When I left Clogher Road Technical School, the possibility of joining my father’s printing works was not an option as it was small and struggling to pay a salary even for my father. So I joined Edmonds’ Sign Makers and Screen Printers. My father knew the Edmonds and used his contacts to get me a job there. I worked in an attic on Exchequer Street, making signs by hand. While working in Edmonds by day, I was also studying by night in the National College of Art, located in the old stables at Leinster House (Dáil Éireann). I had very little social life for a number of years, but for me, art college was not work; it was recreation and inspiration. I studied life drawing, sketching, painting, calligraphy, commercial art and commercial design. I loved it there and encountered great teachers.

Seán Keating, the well-known painter, was one of those inspiring teachers. He was boisterous, active, lively and t. Life painting and life drawing under his guidance were a revelation to me. We had very small classes and Keating always had a live model for a life-drawing class. I was a bit taken aback: a naked woman stood in the centre of a circle of students, and we were to draw her! I was very tentative and timid, but Keating grabbed my brush and attacked the canvas, shouting, ‘No, no, no! You must go for it, Michael.’ He thrust the brush back into my st: ‘Now! Go for it!

e brush is its own master. You never know what the result is going to be. Do it with energy.’ It was a lesson that would remain with me for life. From Keating I learned courage.

Another teacher I had there was Maurice McGonigal. He was more academic, drawing on the history of Western painting. From him I learned perspective and how to mix colours. I also developed an appreciation of beauty. en there was Brian King, who taught commercial art and design.

I had a talent for calligraphy but was somewhat weaker at designing posters. Both my strengths and weaknesses would be spotted. Not everything was positive there. Professor Romaigne, remarking on my weakness at designing posters, said to Brian King: ‘Tell Michael he is not going to make it.’ But I took the knock-back with a pinch of salt. What does he know? I thought. Why tell me that? It ran counter to everything I was learning from Keating: be bold, be brave, attack it! So I ignored everything else.

I spent four years in total at the College of Art, four nights a week, and I didn’t miss a lesson. en I went to the College of Commerce in Rathmines, where I did two years at night studying commercial

art. Again, with most of the students doing day jobs, there was little social life or activity. We were too busy working and studying.

Meanwhile, my parents were involved in education too. e People’s College was founded in 1948 by the Irish Trade Union Congress (ITUC), and my father was one of the founders. ey had a beautiful period building in Ballsbridge, headquarters of ITUC. ey taught public speaking, music appreciation, art appreciation, astronomy, painting and more. e idea was to provide education for working-class workers and trade-union members. At the time, universities were for the elite and rich only. I attended classes at the People’s College that were partially educational and partially recreational.

One class I remember, in particular, was public speaking. I had the feeling it might come in handy in later life. Unfortunately, the tutor was a religious fanatic, using the classes as an opportunity to preach the gospel to left-leaning workers. Most of the people in the room were ill-equipped to respond in front of the large gathering. When the tutor invited a member of the class to give their thoughts, I raised my hand and stood up in the middle of the room. I had something to say and also an opportunity to practise my public-speaking skills. ‘How dare you come here with your rightwing Catholic propaganda,’ I said. ‘We came here to learn public speaking, not to be brainwashed.’ I got a round of applause from the students and assembled union members! is emboldened some students to make a formal complaint to the college authorities, a committee well known to my parents. After an inquiry into the experience of the other students, action was taken. e public-speaking tutor was not heard of in the college again. And

from then on, I was cultivated as a potential board member!

My parents also started a painting group in the People’s College, and my father made his printing works on Clare Street available at night-time as a community studio. Both my mother and father painted in the evenings and left behind truly beautiful paintings: still lifes, vibrant landscapes and portraits.

* * *

e printing company of E&T O’Brien eventually began to make some real money in the 1960s. I was working in Taylor’s Signs at the time as a sign designer and salesman. I was well paid, with a company car. en I was asked by my brother Dermot to join E&T. ere were eight sta at the time – all very talented people, but not with any particular business experience or inclination. My sister Ruth, brother Dermot and father, Tom, all worked there. ey were printing Articles of Association of companies, but it could take some months before Articles of Association were nally approved or rati ed by the relevant body or board. is delay often left E&T with cash ow problems for the period between printing and nal payment. At any one time, there could be over a hundred long-term payments outstanding, often for several years. When I started work at the company, I decided to introduce a 90-day payment period, resulting in more prompt payment, or sometimes staged payments for work already done. It had a signi cant and important positive e ect on the company. My father had great ideas but a laissez-faire approach to business, with little natural instinct for accumulating pro t.

My brother Dermot had been working in the business for over

twenty years, and he didn’t actually have a share in the business, just a weekly wage. He and I approached our father requesting 20 per cent of the company each and a pay rise. My father initially disagreed, but he nally agreed to the shares, leaving himself with 60 per cent holding, but held out on the pay rise.

After I had helped to turn the company around, E&T started to make proper money, and my parents began taking foreign holidays, often visiting art galleries in France, Italy and other parts of Europe. When the dictator Franco died in 1975, they went to Spain and visited the sites of the Spanish Civil War.

Dermot and I were still young men, with young and growing families. By the early 1970s, the printing rm was making signicant pro ts that were not being shared su ciently. I gave my father an ultimatum. I felt it was a matter of justice: we needed to be paid more. But I also began to feel a growing dissatisfaction and unease as I had never really wanted to be a printer. ‘If you don’t agree to more pay, Dad,’ I told him, ‘I would like to sell you my shares and I will walk away.’ When it came to the deadline for the pay rise, he said ‘No!’ So, I sold him my 20 per cent stake in the company for £3,500, a sizable sum of money then. I had bought a semi-detached house in Dundrum with my wife Valerie for a similar sum just a few years earlier. With the money from the shares, I bought a summer house in Wexford, at auction. It was an old schoolhouse built in 1808, with a large garden. I was taken with it on rst sight.

While still working for my father in E&T O’Brien, in the early 1970s, I had become involved with a number of enlightened activists campaigning to save what was left of the built environment of Dublin city and prevent further destruction. ese included Ian Broad, Deirdre Kelly, Peter Pearson, Bride Rosney and members of An Taisce. Extensive areas of Georgian Dublin were falling down and large chunks of Li ey-side central Dublin were also disintegrating –much of which was being bought by speculative ‘developers’.

In these early years of the 1970s, I put together an outline for a book to be called something like ‘Dublin Under reat’, proposing an illustrated book showing the destruction of Dublin due to neglect as well as corrupt and ignorant planning. I wrote the text and illustrated it myself. I was sure a publisher would jump at it. I sent it to Gill publishers and they rejected it. e only way

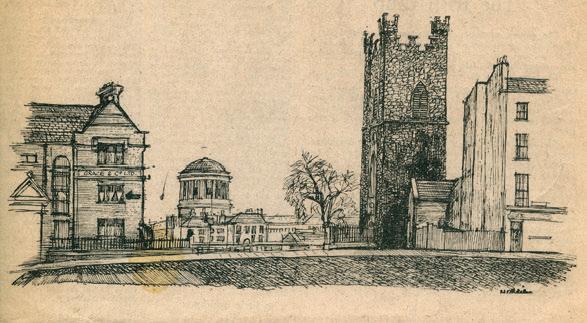

forward was to publish it myself, which I did in 1973, using as an imprint my father Tom’s printing company E&T O’Brien. is was to be the beginning of my publishing activity. Fifteen of my own drawings of Dublin were published as a portfolio-booklet, called Changing Dublin. I selected buildings of Medieval, Georgian and Victorian vintage that were of great value or were under threat of demolition. At the time, I had spent many hours drawing Dublin’s buildings and streetscapes, and the work had appeared in an occasional column in the Irish Times.

‘I have tried to show through my drawings that there is beauty, history and tradition all around us, in the old laneways and back streets as well as the familiar buildings and places.’

From Changing Dublin

I was also active in the Dublin Arts Festival, a large, voluntary annual event that focused on historic areas of Dublin. We worked to save Tailors’ Hall, a beautiful Queen Anne period guildhall for tailors on Back Lane facing Christ Church Cathedral. We put

on eighty events – music, drama, lectures and walks focusing on Dublin history – in order to promote the building as an arts centre and make people aware of the history and culture of Dublin’s Medieval quarter. e festival-organising committee decided to clean up the building, and in the process discovered some hidden treasures. We got wheelbarrows and removed the rubbish from inside the building into a pile outside, and in the process we uncovered an extraordinary replace. e walls were then stripped of plaster, revealing vintage stone and mortar walls. e hall became our festival headquarters. Ian Broad, one of my fellow organisers, suggested that we have an exhibition of my drawings. I also published a catalogue of the festival, illustrated with my drawings. is morphed into a widely publicised exhibition, which was opened by Garret FitzGerald, then a Fine Gael TD.

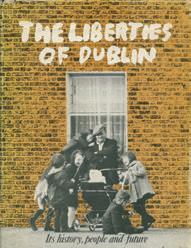

On foot of this activity, Elgy Gillespie, an Irish Times journalist, proposed a book to me: e Liberties of Dublin. I explained

Tailors’ Hall in its heyday. Reconstructed drawing by Stephen Conlin, from Dublin: e Story of a City

St Audoen’s (top) and Marsh’s Library (above), examples of artwork by Michael O’Brien, exhibited during the 1974 Dublin Arts Festival and reproduced in the Irish Times.

that E&T O’Brien were not actually publishers and recommended that she go to book publishers, and I supplied her with a list. She was rejected by six publishers. Her book was a collection of essays by di erent authors on old Dublin, illustrated with photographs, maps and drawings of buildings. I thought it was hugely important and relevant. I said to my father, ‘We have to publish this book,

Dad.’ ‘No problem, Michael,’ he replied. ‘Do it.’

e Liberties of Dublin was published in 1973 by E&T O’Brien. It was edited by Elgy and designed, marketed and distributed by me. In the story of the development of e O’Brien Press publishing house this book can be regarded as a landmark publication. ough E&T O’Brien was actually a printing company, we were now also publishing books!

A short time after these rst forays into publishing, I left the printing world to become a full-time artist. I was keen to develop

Top left: e cover of e Liberties of Dublin

Top right and above left: Pages from the landmark publication, e Liberties of Dublin.

Above right: e Liberties of Dublin title page signed by the contributors.

my urban-drawing career asI enjoyed it immensely and nancially was doing quite well. e media had taken a strong interest in my exhibition of Medieval Dublin – the Evening Press visited frequently to report on which drawings had been sold. e Head Librarian for Dublin City bought about ten drawings for the Dublin City Council Archives. Many of the buildings were knocked down in the years following the exhibition, so the work was to prove a valuable record of old Dublin. Fortunately, I kept bromide (photographic paper print) copies of the drawings sold.

My second exhibition was held in St Mary’s Abbey’s crypt on Capel Street in the north inner city, also as part of the Dublin Arts Festival, and was opened by Conor Cruise O’Brien, then a Labour TD.

My third was in Cork. e well-known sculptor Séamus Murphy invited me down to Cork to draw the buildings of the city. I had met him through his daughter as she had been involved in the Dublin Arts Festival, and she introduced me to her family. Her mother agreed to run an exhibition of my drawings in the Cork Arts Society gallery on Lavitt’s Quay. Séamus Murphy took me on a memorable tour of Cork, pointing out the heritage buildings and telling me their histories. I did thirty drawings and they were put up for sale – and they sold quite well.

I was busy as an artist, and work was rolling in. After the Cork exhibition, I was approached by the Cork Examiner newspaper and asked to do a weekly column on historic Cork, illustrated by one drawing each week. Séamus Murphy helped me with the history. Cork had not experienced the same level of urban development as Dublin and there was quite an abundance of ne historic buildings throughout the city.

Examples of Michael O’Brien’s drawings of Cork, Grand Parade and the Roundy on Castle Street.

So I had a collection of drawings of Dublin and Cork, in a newspaper series in the Irish Times called ‘Villages of Dublin’. Also, with the writer JB Malone, an environmentalist who developed the Wicklow Way, I had a series in the Evening Herald called ‘Vanishing Dublin’. I felt that things were looking good for me in this sphere.

I was invited by Dublin Tourism, before it became part of Fáilte Ireland, to go out and draw pictures of my own choosing, and they would buy them for marketing purposes. I made my way to Howth to draw the famous Abbey Tavern. At the same time, I was approached by several auctioneers to draw the historical buildings on their books, as they felt a drawing could be far more appealing to prospective buyers than a photograph. I received occasional commissions from the O ce of Public Works to draw classical Georgian buildings threatened with ‘redevelopment’ or demolition – the aim was to present the buildings sympathetically and in their best light as the political attitude to Georgian buildings in Dublin at the time often approached something akin to contempt.

en a critical moment came for me and for E&T. One of the Liberties authors, Éamonn Mac omáis suggested a book to be called Dear Old Dirty Dublin, celebrating the culture and history of Dublin. I felt this book held great promise and also that it should be published to promote pride in Dublin’s history. Éamonn was a great storyteller and knew a lot about Dublin’s history and folklore; in fact, he later became well known as a most popular and entertaining guide around Dublin. Would E&T O’Brien become an actual publisher? And would I leave my career in art too and set up as that publisher? I phoned my father asking would he be willing to start a publishing company with me, and if it could be 50/50 ownership. He agreed. I suggested the name ‘O’Brien Press’, but he suggested ‘ e O’Brien Press’, saying, ‘Always put your name over your shop as the one and only.’ I prepared the legal documents. As it happens, my father was also working on a number of books: a collection of poems by the Scottish poet Tom Leonard (who was married to my sister Sonya), e Riddle of Erskine Childers by Andrew Boyle, and Peadar O’Donnell: Irish Social Rebel written by Michael McInerney, political journalist at the Irish Times. McInerney was an old socialist friend of my father’s. is book was intended to be the lead title in a proposed series of books on overlooked socialist leaders in Irish history, a topic that was very close to my father’s heart. Tom also knew Peadar O’Donnell, the subject of the book, from Republican Congress days in the 1930s. O’Donnell was a socialist activist from Donegal and the author of many novels; he was ninety years of age at this time. My father and I decided to go ahead with our publishing idea, and we set up e O’Brien Press in the summer of 1974.

I was working on Me Jewel and Darlin’ Dublin (Mac omáis’s book previously called Dear Old Dirty Dublin). is was to be the rst book carrying the imprint of e O’Brien Press. It was published in November 1974 and was followed shortly by Irish Social Rebel. Together, these books expressed both my father’s and my personal passions, which was very satisfying.

We held two successful launches: Me Jewel was launched at e Stag’s Head pub, Dublin, in November 1974. e author was in Mountjoy Prison at the time for republican activities. I’d had to go to the prison occasionally to work with him. Two weeks after the launch of Me Jewel and Darlin’ Dublin, we launched Peadar O’Donnell: Irish Social Rebel in Kilmainham Gaol, where my father had been involved in the Kilmainham Restoration Committee in the 1950s (the state eventually renovated it). e event was featured on the front page of the Irish Times. With these two books, e O’Brien Press came into being.

However, that year, on 6 December, just a month after the second book launch, and before e O’Brien Press had even been o cially registered as a company, I was to receive a devastating phone call: ‘Your father collapsed in Baggot Street and you will be happy to know that he got the last rites.’ As it happens, I was not happy to hear of the last rites, but such were the assumptions of religious belief in those days. At Sir Patrick Dun’s Hospital, where my brothers and sisters had all gathered, I remember the feeling of deep shock as I was handed a bag of my father’s things: watch, pipe, coins. e burial took place in Mount Jerome cemetery. ere was an oration by a Spanish Civil War comrade, the Waterford teacher Frank Edwards. My sister Miriam, then a trainee teacher, was accompanied to the funeral by the Mother Superior of her school –but afterwards Miriam was not allowed to continue her career there because her father had been a communist! Fellow teacher Bride Rosney supported her. Later, Rosney became a real force in Irish education, working with the City of Dublin Vocational Education Committee in Trinity College, and she was also central to the Dublin Arts Festival and a pillar of Mary Robinson’s presidency.

Publishing was a very small industry in Ireland in the 1970s. I was later to discover that this situation was common in all formerly colonised countries as it took many years for an independent publishing industry to grow. At bookfairs when we compared our situation with that of other post-colonial countries, they were very similar indeed. Irish publishing, and even more so Irish bookselling, was totally dominated by books from English publishers. It was generally perceived as simply impossible to compete, and certainly not to make a business out of it. ‘Gentleman’ publishing might be ne … but if you needed to make money consistently, it was deemed impossible. Writers, especially ction writers, all wanted to be published in London. It was almost the same in Scotland

as we discovered when we linked up with publishers there – and in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, India and so on. is was a challenging arena for any edgling Irish publishing venture. But by now I seemed to be driven and was determined to try to make my publishing a success.

e di culties of being an Irish publisher had made themselves clear to me when E&T O’Brien published e Liberties of Dublin by Elgy Gillespie in 1973, but these problems became more serious when I became a full-time professional publisher. With e O’Brien Press’s rst two o cial publications in 1974, Me Jewel and Darlin’ Dublin by Éamonn Mac omáis and Peadar O’Donnell: Irish Social Rebel by Michael MacInerney, I visited all the bookshops in an attempt to sell the books. I was mostly made welcome, but sometimes I got a very frosty reception.

‘We do not stock books from Irish publishers,’ I was informed by Mr Sibley, in his West Brit accent. He was one of the owners of Combridge’s ne art shop on Grafton Street. is was one of the best-located bookshops in Dublin. When I stood my ground, he repeated: ‘Did you not hear, Mr O’Brien? We do not stock books from Irish publishers. Now leave my bookshop.’ Before I left, I said, ‘Your bookshop will not survive.’ And ultimately it didn’t.

Cover of Peadar O’Donnell:Irish Social Rebel by Michael MacInerney.

I had been warned about this anti-Irish publisher attitude by a friendly sales agent for UK books. Still, I was shocked, and had to experience it myself to understand the scale of this policy. I was amazed that such a thing could happen to an Irish publisher in his own city. I found it hard to believe. I wondered, ‘What were these booksellers afraid of?’

Robin Montgomery of the Paperback Centre, Su olk Street, explained that the people in the book trade often came from the ‘Big House’ tradition and that even being in business was looked down on by them. His own family shared that view: ‘My parents were shocked when I went into business.’ He believed in the development of Irish publishing and was very supportive of our new enterprise, stocking all e O’Brien Press books.

Allen Figgis of Hodges Figgis in Dawson Street, who had two bookshops and was also an occasional publisher, was always committed to Irish writers but did not hold back on his criticism of our publishing e orts, ‘It’s a pity, Mr O’Brien, you did not use real cloth.’ (He was referring to e Liberties, and yes, a cloth binding would have been lovely but very pricey indeed). However, we were also showing the book to Marion Murnane, his manager, and she was excited about e O’Brien Press and was to support our endeavours over the years. ‘You don’t have to take it if you don’t want it,’ I told them. ‘We’ll take fty,’ they said. at was a big order.

Eason’s was the biggest outlet in Ireland. eir wholesale company supplied all their own shops around the country as well as lots of smaller independent bookshops. e manager at the wholesaler’s was Harold Clarke. Harold informed me: ‘Mr O’Brien, Eason’s

Above: View of O’Connell Street and long-standing bookshop Eason’s. Below: e iconic sign that hung outside Greene’s Bookshop on Nassau Street, Dublin, for many years.

have decided not to order Me Jewel and Darlin’ Dublin.’ is was a body blow. He didn’t give a reason, but I guessed correctly that it was because the author, Éamonn Mac omáis, was a well-known republican. But when I decided to call directly to the large Eason shop on O’Connell Street, the manager there, Maura Hastings, said, ‘Give me ve hundred copies and I’ll put them at the front of the shop.’ at was a huge order at the time. But she knew her market – they sold – and she ordered more. It strikes me that the women in the trade largely supported what we were doing, but some of the male managers were more hesitant, and there were far more of them around; I wonder now were they more stuck in the past and conscious of their status? Some time later, Harold Clarke phoned me to say that Eason Wholesale were now going to stock

Me Jewel. It was supposed to be like a kind of gift to me, but in a t of pique I made a most unbusinesslike decision and refused! I told him, no, he was not getting it as he had blocked it when I needed his support. We were later to become friends, and he helped e O’Brien Press to grow, particularly in Northern Ireland. ere were many bookshops in Dublin at the time, each with its own personality and avour. Celsus Brennan had a beautiful bookshop at the top of Grafton Street, and he was also a library supplier. Hugely knowledgeable about books and the trade, he was always full of ideas. Years later, when rents on Grafton Street increased, he was forced to close the shop. APCK was on Dawson Street, and though born to promote Protestant Biblical values, developed into a magni cent – and liberal – bookshop, but years later it crashed, leaving behind a legacy of debts. Greene’s antiquarian bookshop, run by generations of the Pembrey family, was located opposite E&T O’Brien printers on Clare Street. It was a warren of joy –with antiquarian, new books and the classics. In 2007 it moved to Sandyford as an online business, then disappeared. Hanna’s was on Nassau Street facing Trinity College Dublin. It was overseen by Fred Hanna, a brilliant, lovable and knowledgeable bookseller, with three generations of his family working there. Eventually, he sold out to Eason’s who turned it into a mass-market shop. It was tragic for Dublin to lose such a broad and varied shop, stocked with so many interesting books. Gill on O’Connell Street represented generations of bookselling and publishing experience. Upstairs they stocked Catholic relics and items such as bishops’ clothing, rosary beads and so on. ey were also an excellent bookseller, with a republican ethos. ey eventually closed the shop and moved

Bookseller Fred Hanna (right) receiving e O’Brien Press sponsored Bookseller of the Year Award, 1995.

their publishing activity to a business park. Michael Gill was very helpful to us as new publishers. ere were a few other Christian bookshops in Dublin.

Outside Dublin it was di erent. ere were very few shops in the midlands, although there were some great ones scattered around the country, such as O’Mahony’s in Limerick, Mercier and a few more in Cork, and others in Galway and Kilkenny. Northern Ireland presented a special challenge. Eason had a separate distribution operation in Belfast and, uniquely for Northern Ireland outlets, they made a habit of buying Dublin-published books. ey also had a chain of shops, though none in Catholic towns like Derry and Newry, but they eventually, through acquisitions, rectied this. However, in 2020 during Covid they closed all their six

retail shops in that part of the country and never reopened them, a big blow for Irish publishing and bookselling.

Down through the years, e O’Brien Press sometimes developed publishing ideas with booksellers, which proved fruitful for all parties concerned.

Of course, there was also censorship of books by successive Irish governments working with the sex-obsessed Irish Catholic Church.

Many of the best writers ed to Britain, Europe or America, depriving Ireland of a normal, buoyant book-publishing industry. When book censorship ceased largely to be implemented, it opened the literary doors to freedom of expression and opportunities to publish.

Publishing was not going to be easy within this atmosphere of rejection in the book trade of Irish businesses and local publishing. I rmly believed this attitude was a hangover from colonialism. It was time to tackle the status quo head on.

CLÉ

I was advised to join the Irish Publishers’ Association (CLÉ) and to make contact with the magazine of the book trade, Books Ireland, edited by Jeremy Addis. I went along to a building on Merrion Square in search of Jeremy. My welcome was memorable:

‘You will nd Jeremy up a ladder in the library,’ I was informed. Me (to the ladder): ‘I wish to join CLÉ.’

Jeremy (shouting down): ‘Who are you?’

Me: ‘Michael O’Brien of e O’Brien Press. I’m new.’

Jeremy: ‘Consider yourself a member.’

And that was it! I was delighted.

In the 1960s and 1970s there was one large publishing company based in Dublin, the Irish University Press, but that closed in 1974. A hundred jobs were lost. Seamus Cashman had worked there as a senior editor, and in 1974 he too set up his own publishing house, called Wolfhound Press, the same year as e O’Brien Press. I met him one day in an antiquarian bookshop as we both had a strong interest in antiquarian books. He told me how he had lost his job and was setting up Wolfhound Press. He became a lifelong friend and colleague.

At the beginning of our publishing enterprise, we had problems nding sta and skilled people as there was no formal industry training available. Also, very few illustrators worked in Dublin. Where would we nd people who could do the job? And how did publishers themselves learn their trade? Publishing is a complex activity involving selection of scripts, editing, planning the layout and look of the book, illustration, covers, contracts, marketing, sales and so on. ere are also a lot of technical dimensions, e.g. using photography, and the whole process of printing. ere were no computers in those early days, so everything was done by hand. It was a tough, raw beginning and often you just worked by the seat of your pants and followed your gut instincts. e new companies were small. e O’Brien Press worked from two rooms in my family house ( rst Dundrum, then Rathgar) with family life going on around us. is was typical of that era. Wolfhound also functioned initially from Seamus’s home.

Beginning in 1974 with just myself, by the end of the 1970s the company had two full-time employees: myself (Publisher) and Catherine Boland (Production). e part-time people were: Sharon Gmelch (Non-Fiction Editor), Peter Fallon (Fiction Editor), Valerie O’Brien (Accounts). Occasionally others worked on a particular job. Sharon was an American scholar in the eld of anthropology, and she was in Ireland to work on her PhD. We published her book based on her PhD studies: Tinkers and Travellers. She left Ireland in 1981 to return to academic work in the USA. Peter Fallon left to pursue his own poetry publishing with the Gallery Press. Shortly after, Íde ní Laoghaire joined us as editor.

Our rst catalogue was produced in 1974. It consisted of a single sheet of pink paper, folded in four.

e O’Brien Press 1974 ‘catalogue’ was a simple printed sheet. e titles we listed were: Me Jewel and Darlin’ Dublin (1974) by Éamonn Mac omáis, £4.20; e Liberties of Dublin by Elgy Gillespie (paperback 1974), £2.25; Peadar O’Donnell: Irish Social Rebel (1975) by Michael McInerney, £3.50; Drawings of Cork Portfolio (1974) by Michael O’Brien, £3.00. It also included two books published by Tom O’Brien before e O’Brien Press existed: e Riddle of Erskine Childers by Andrew Boyle (paperback), 70p; Poems by Tom Leonard (paperback), 60p.

Front page of the 1976 O’Brien Press ‘catalogue’. By 1976 e O’Brien Press catalogue had added these titles: Skellig, Island Outpost of Europe (1976) by Des Lavelle; Hands o Dublin (1976) by Deirdre Kelly; Tinkers and Travellers (1975) by Sharon Gmelch, with photographs by Pat Langan; e Irish Town – An Approach to Survival (1975) by Patrick Sha rey, architect and judge of Tidy Towns competition.

Early publishing highlights serve to illustrate the focus and developing scope of e O’Brien Press.

In 1976 we published a book by Patrick Sha rey called e Irish Town: An Approach to Survival. is was the rst-ever general trade

Cover of e Irish Town: An Approach to Survival

book about town planning in Ireland. A leading and well-known architect, Patrick Sha rey was the nal adjudicator in the Tidy Towns Competition. He was an idealistic and highly sophisticated man who had studied towns and villages all over Europe. I decided to do the book because I felt it was important. But who was going to buy it? I wondered. ‘Every councillor and every local authority, that’s who,’ Paddy told me. And he was right. Planning o cers with very little training or background were being appointed to various planning departments, and they had no idea what to do! Towns were being destroyed. ey needed guidance. When we published the book, we got bulk orders from county councils all over the country. e book had a lasting a ect and a big impact on our built environment. Patrick Sha rey had huge knowledge and high regard for the beauty of good urban landscape. I myself had been drawing the urban landscape for many years, and Paddy and I connected over an appreciation of good urban design, so I really wanted to publish this book and I am very glad it worked out commercially too. Paddy and I continued our association with two other books: Buildings of Irish Towns (1983) and Irish Countryside Buildings (1988). e Irish Architectural Archive describes these two books as ‘extraordinary records of ordinary buildings’. ey were both beautifully iIllustrated by Paddy’s wife, Maura.

Another key book in the development of the press from this time is Hands o Dublin by Deirdre Kelly. An environmental activist living in Ranelagh, Deirdre, along with a group of students, had occupied wonderful Georgian structures in the 1970s in an attempt to stop

them being knocked down and replaced with ugly o ce buildings. e impact of her book can be seen today in Ranelagh, where there is a thriving, modern community that still retains its Georgian avour. Pat Langan, one of the nest photographers of that time, took the photographs for Hands o Dublin. He gave his time free of charge, as did everyone working on the book. We created the book in a few weeks because there was an urgency as precious buildings were under immediate threat of illegal demolition. Deirdre hired a bus and persuaded about twenty-seven journalists from all the major papers and RTÉ to come on board and they drove around, stopping at various locations where Deirdre took a microphone and talked about why this site or building was important. It was an active and e ective protest. Everyone involved was focused and passionate in their beliefs and desire to preserve our built heritage.

We published a second book with Deirdre Kelly in the late 1980s, Four Roads to Dublin: A History of Rathmines, Ranelagh and Leeson Street, going right back to medieval times.

Tinkers and Travellers by Sharon Gmelch

Another groundbreaking book we published in 1976 was Tinkers and Travellers by Sharon Gmelch. is was the rst book published in Ireland to be devoted exclusively to Travellers. It explored their lifestyle and lore, including their tradition of tin-smithing, from

which the word ‘tinker’ originated. For centuries, these people made useful things and were a viable part of the economy.

Sharon and her husband, George, were American anthropologists. For six months they lived in a caravan alongside the Travellers. As a result, they wrote a signi cant report.

I have always taken a great interest in minorities and the disenfranchised and I was fascinated to read this study of the Traveller community. Photographer Pat Langan had introduced me to Sharon and her husband. At this time, Travellers still had covered, horse-drawn wagons. In the 1970s, there was an o cial programme underway to integrate Travellers into the settled community, but the people organising the programme seemed not to understand that some Travellers still wanted to travel for part of the year – being on the move was in their blood. Some of these families had been travelling for hundreds of years. ere was very little empathy or anthropological understanding of the Travellers

as a people. Over the years, much of the Travellers’ livelihood died out, and a small section of their community was forced to turn to a life that involved crime and, for some, violence.

In 1976 we set up O’Brien Educational, a sister company to e O’Brien Press, in partnership with Seamus Cashman of Wolfhound Press. Attempts were being made by forward-looking teachers to alter the staid and xed second-level curriculum. ey had set up a Curriculum Development Unit at Trinity College with the involvement of the City of Dublin Vocational Education Committee and the Department of Education. It included inspiring and creative teachers and academics, including Anton Trant, Tony Crooks, Bride Rosney, Peter MacMenamin and Agnes McMahon. e aim was to make the curriculum more relevant and more approachable for students. Textbooks were needed to accompany this change, and this was where we came in: a new educational publishing house was created with the Curriculum Development Unit.

We hit on the idea of turning school books into ordinary trade books too, and, uniquely, these books were sold both to schools as schoolbooks and on the open market as general books. is was revolutionary in Ireland at the time and the approach of straddling the two markets meant that O’Brien Educational became commercially viable.

Between 1976 and 1990, O’Brien Educational published about thirty titles on economics, Irish language, history, humanities, science, social studies and media studies – resulting in books for the evolving curriculum for vocational and other schools. Some titles, such as A World of Stone (about the Aran Islands), Celtic Way of

Life and Divided City: Portrait of Dublin 1913 (detailing the 1913 Lockout, currently titled: Dublin 1913: Lockout and Legacy) are still in print on the general market, having been carefully revised and updated down through the years.

Original and today’s covers of A World of Stone (now entitled e Aran Islands), Celtic Way of Life and Divided City: Portrait of Dublin 1913 (now entitled Dublin 1913: Lockout and Legacy) – three books that have stood the test of time.

One of the stranger items at an O’Brien Press book launch – the preserved arm of boxer Dan Donnelly, with (from left) unknown, Michael O’Brien and Patrick Myler, at the launch for Patrick Myler’s Regency Rogue (1976).

In the early days of my publishing life, we worked on paper; there were no computers. Even the printing machines were very di erent from those used nowadays.

When my father founded E&T O’Brien printers in 1948, he imported two small litho machines from the USA. ey could print using paper or metal plates on a rotating drum. It was possible to type or draw on the paper plates and to transfer images to the metal plates by a photographic method, in a kind of ‘oiland-water’ system where chemicals blocked o those parts which were not to be printed. You could print at high speed onto paper. Litho replaced the classic letterpress technology, which involved metal type of varying sizes. I was familiar with the old system as my

father had retained a small rotary letterpress machine. When I was a child, he let me compose type, picking individual characters from the font trays and sliding them onto a ‘stick’ to make lines of type. Large letterpress machines continued to be used up to the 1970s by newspapers and trade printers.