Front Matter:

Critical Theory & Social Justice

Undergraduate Research Journal

Volume No. 11, 2022

Editorial Board:

Faculty Advisor Malek Moazzam-Doulat

Emily Williams

Ezgi Koc

Gieselle Gatewood

Hunter Isenstein

Isabel Mascuch

Jenna Beales

Lulu Maxfield

Maylene Hughes

Mira Tarabeine

Talia Weinreb

The Critical Theory and Social Justice: Journal of Undergraduate Research offers a transformative space for undergraduate students to engage critical theory in the pursuit of social justice. This journal serves as a peer-reviewed platform for practical interventions that draw upon the various discourses and approaches with which our authors and artists work.

The Journal uniquely publishes original undergraduate articles and artwork in its field. It reflects Occidental College’s Department of Critical Theory & Social Justice (CTSJ), the only undergraduate academic department of its kind.

Since publishing its first volume in 2010, CTSJ’s Undergraduate Research Journal has become a robust and respected institution at its home campus of Occidental College and at peer institutions such as Middlebury College, Brown University, Stanford University, Scripps College, Tufts University, and Yale University. CTSJ is dedicated to providing a forum for undergraduate students to develop and share critical research and writing on the intersections of power dynamics and inequalities as they relate to problems of social justice. The Journal seeks to foster an exchange of ideas across disciplines and to deepen understandings of systems of injustice; in this way, the Journal advances the mission of Occidental College: to develop critical, thoughtful, and active participation in an increasingly pluralistic and conflict-ridden global culture.

Cover: Grayson Cassels, “Digital 2”

Table of Contents:

Writing:

After-Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness: The Zombie’s Declaration of Black Independence

Boatemaa Agyeman-Mensah

“A better, more positive Tumblr”: The Repression of Online Sexuality and the Erasure of a Heterotopian Archive

Lucy Allen

The Transformative Possibility of Canadian Law and Indigenous Rights: Promising in Concept, Improbable in Practice

Aidan Sneyd

Community Land Trusts are the Necessary Future of Black Reparations

Sydni Scott

Foucault on Border and Migration

Robin Ehl

The Means to Match Their Hatred: An Examination of Islamophobic Rhetoric in State of the Union Addresses

Daisy

10.

Media: Top of the List! a film-to-book adaptation of footage from Leslie Cohcran’s 2000 campaign for the Mayor of Austin, TX

48.

56.

74.

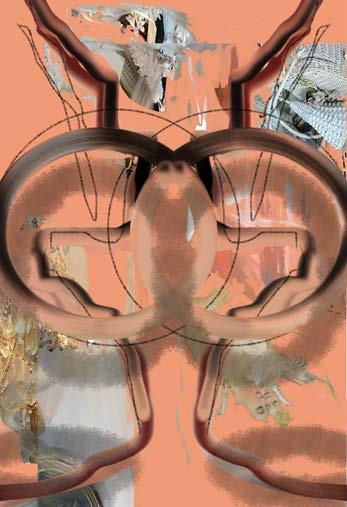

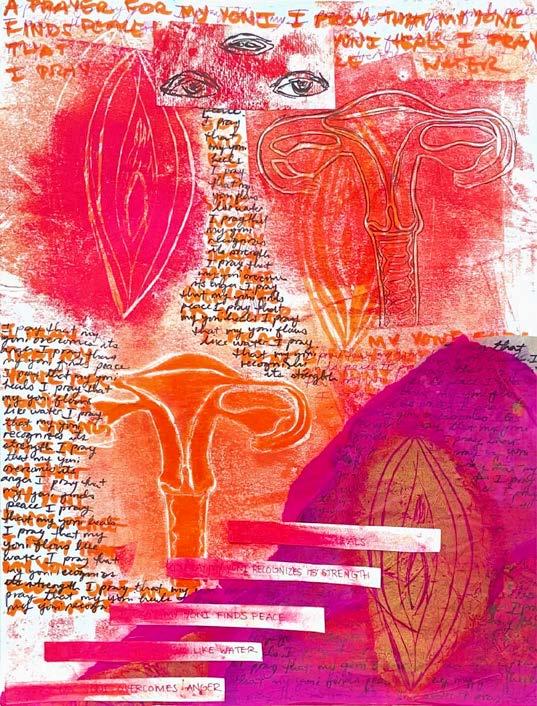

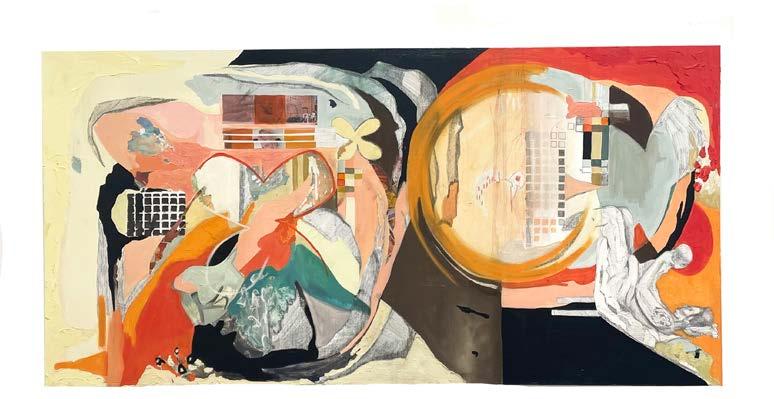

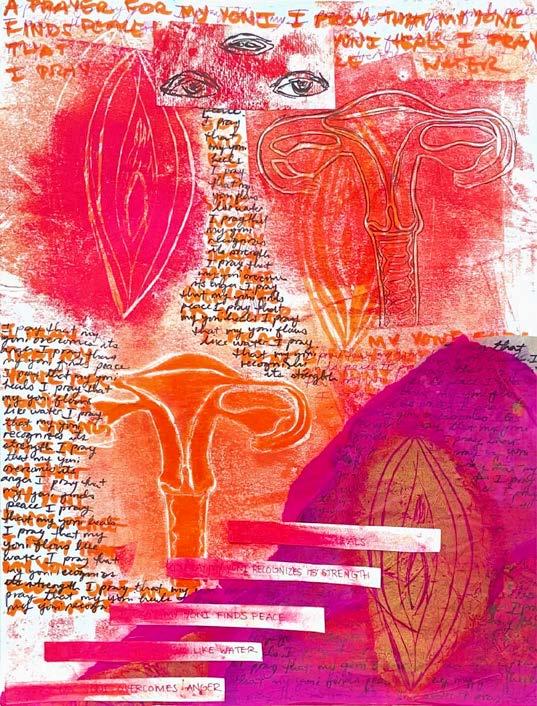

Luis Quintanilla St. Quarantine Crowned with Anxiety Mint Zekoll Altar, Feed, Church Exploring Femininity, Sexuality, and Cyberspace in Painting & Digital Art Grayson Cassels a prayer for my yoni

Esther Karpilow

2 3 CRITICALTHEORY & SOCIALJUSTICE UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL VOLUME 11, 2022

—--

Lupa 4. 40.

88.

50. 62. 76.

After-Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness: The Zombie’s Declaration of Black Independence

Abstract: The archetype of zombies as undead, mindless, flesh-eating monsters is only partially accurate to its historical roots. While it is true that zombies are reanimated corpses, the Western appropriation of the monster has diluted one of the most important factors in its original definition: slavery. The zombies we see in mainstream media today were born from the religious beliefs of enslaved Black peoples on Hispaniola (the 17th century French colony that preceded the creation of Haiti). There, Black spirituality served to reflect horrors of slavery. One way such horrors manifested was in the depiction of the afterlife. Through a process of extricating an individual’s motor functions from their bodily autonomy, a Black corpse could be reanimated for enslavement, even after death. Thus, the word, zonbi, was born to describe these undead, free laborers condemned to eternal servitude. However, if the original zombie is predicated on the fears of slavery, how does zombification occur in a post-racial society? This paper uses Jordan Peele’s 2017 film, Get Out, to explore how iterations of the traditional zombie persist in a post-Obama America. Specifically, it examines how Chris (the main character of Peele’s film) suffers from a loss of bodily autonomy through racial fetishization. However, this paper also explores Chris’ evasion of zombification parallels the 1791 Haitian Revolution— the evasion of racial subjugation and reclamation of bodily autonomy through Black separatism.

I. Introduction

Zombies are beings seemingly frozen in time, unable to transcend residency among the living despite being long deceased. However, the rhetoric that surrounds these creatures is anything but fixed. Depictions of zombies have proven to be fluid throu-

ghout history. One might be surprised to learn that the earliest zombies were devoid of the flesh-eating motivations that typically denote the being. And newer depictions of the creature have selectively abandoned the sluggish, obtuse, and, even, the undead mark of zombification. So, if a universal characterization of the creature is nonexistent, how does a monster come to be classified as a zombie? Examining the social context surrounding portrayals of zombies shows that one pattern may be extracted from the chaos: race. Traditionally, the horror genre has been constructed around society’s “fears of the Other”; conflicts are typically “between the ‘normal,’ mostly represented by… white… heroes and heroines, and the ‘monstrous,’ frequently colored by racial… ideological markers.”1 Therefore, it is unsurprising that variations of zombification on the silver screen have repeatedly paralleled periods of racial conflict within the real world.2 In Jordan Peele’s 2017 breakout film, Get Out, modern zombies can be interpreted as an allegory for the imminent tribulations of Black-white race relations in self-proclaimed post-racial society. And when these fictional monsters are analyzed under a lens of social commentary, the rhetoric surrounding the evasion of zombification proposes Black separatism as the solution to current and forthcoming, real-life racial tensions.

II. The Haitian Origins of the Zombie

Comparing the origins of the term “zombie” to modern usages, it becomes apparent that most zombies in current media have diluted the most important factor in their original definition: slavery. In the 17th century, Black spirituality across the colony of Saint-Domingue3 was dominated by Vodou—a religion born when disparate Central and West Afri-

can peoples conglomerated in bondage on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola.4 Vodou practitioners held that the human body was mere flesh controlled by a soul divided: the ti/petit bon ange was responsible for individuality and consciousness, while the gros bon ange was responsible for physical motor functions.5 Additionally, Vodou believed dying was a multi-day spiritual journey; the progression of the soul during death could be tampered with by external forces during this transitional period. In fact, malicious sorcerers/shamans called bokurs would do just that. During death, bokurs would capture the ti bon ange of a dying person in a bottle, allowing for the gros bon age—and by association, the body—to be exploited for free labor by whomever possessed the ti bon ange container. The Haitian word, zonbi, was born to describe these undead victims.6 When examining the rhetoric surrounding Haitian transformations of man into zombie, the process seems to mimic the conversion of Black Africans into enslaved persons. The phrasing of “capturing” one’s individuality and “exploiting” Black bodies “for free labor,” harkens back to the procedural and dehumanizing terminology of trans-Atlantic chattel slavery. These linguistic parallels suggest that zombies themselves may reflect real-life fears of the very same enslaved Haitians who constructed this monster in the first place. After all, for Black Haitians in the 17th century, what could be worse than slave life? The potential that even death would not provide respite from the torturous conditions of servitude. Therefore, when defining zombies, historical precedent suggests that the designation of “zombie” may be less dependent on an undead quality—which seems to be the central focus of colloquial usage—and more so grounded in a process analogous to bondage: zombification as defined by an institutional loss of bodily autonomy. In recognizing the trans-Atlantic slave trade to be the origin story of zombie lore, it is clear that depictions of these monsters have always been tangential to their racial environment. Thus, it is not only appropriate, 4 Currently known as the nations of Haiti and The Dominican Republic.

but often imperative to read zombies as allegories for Black exploitation unfolding in the real world.

III. Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017) as a “Post-Racial” Zombie Movie

The interpretation of zombies as a proxy for existing race relations is dependent on historical anti-Black sentiments. Therefore, it can be difficult to understand the monster’s applicability as we approach a future that actively attempts to distance itself from racism. However, Jordan Peele’s 2017 debut horror film, Get Out , manages to effectively assuage such doubts by minimizing the gap between past and future. Set in suburban America, the movie centers around the interracial relationship of Chris Washington, a Black man, and his white girlfriend, Rose Armitage. When the two go upstate to spend a few days with Rose’s family, Chris anticipates an icy reception. But he is pleasantly surprised to be met with open (albeit deceptive) arms. However, the flawed nature of this acceptance becomes apparent when Rose’s father, Dean Armitage, attempts to gain Chris’ favor by saying, “I would have voted for Obama for a third term, if I could. Best president in my lifetime, hands down.”7 Although Dean’s reference to the recent Obama administration acknowledges that the movie is set in the present, his sense of normalcy towards the election of a Black president grounds the plot in a pseudo-futuristic reality in which America has become a successfully post-racial society, electing leaders based on merit and merit alone. Yet, Dean’s deep reverence for Barack Obama is baseless. Dean makes the assertion that Obama was the “best president in [his] lifetime” while simultaneously failing to name any outstanding initiatives or distinctive policies during said administration. This passionate favoritism contradicts his attempt to curate a colorblind, blasé attitude towards Blackness as his review of the 44th president is still a reductive assessment of racial caliber, even if it is positive. Thus, Get Out shows how closely acts of

7 Peele.

4 5 CRITICALTHEORY & SOCIALJUSTICE UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL VOLUME 11, 2022

1 Benshoff, 31.

2 Mariani; Moreman and Rushton 1-12, 31-41, 60-73.

3 A French colony in the 17th century. Now known as the country of Haiti..

5

Zarka, “The Origins of the Zombie.” 6 Ibid.

Boatemaa Agyeman-Mensah | University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

racism can align with ostensibly anti-racist rhetoric. Peele asserts that progressive, speculative futures may be indistinguishable from past transgressions if America’s post-racial fantasies are underlined by the same hyper-racial fixations which previously fostered racist ideologies.

Get Out subtly manifests Haitian zombification in futuristic narratives by establishing that losses of bodily autonomy in the future will appear primarily in the form of benevolent racism. Specifically, via racial fetishization.8 When the Armitage family hosts a garden party, Rose parades Chris around the house grounds to meet wealthy white individuals. At one point, a woman named Lisa Deets approaches the couple to comment on Chris’ physical attractiveness. Lisa gropes Chris’ upper body then proceeds to let her gaze drift downwards. In an obvious assessment of his genitals, she asks Rose, “Is it true? Is it better?”9 Here, Lisa’s lustful appraisal evokes the hypersexual stereotype of Black men; particularly, the lore that Black men possess the largest phalli. This monolithic fetishization reduces Chris solely into a corporeal vessel indistinguishable from any other Black man. Chris’ body is treated as if it is devoid of emotion or agency, reducing him to a zombie that exists solely for the sexual pleasure of white women. Furthermore, throughout the entire interaction, Lisa never addresses Chris directly, speaking about him to others as if he is not even present. This blatant disregard of Chris’ consciousness suggests an assumed simplemindedness among Black people; not unlike the mindlessness of zombies deprived of their ti bon ange. Through this darkly humorous scene, Peele highlights the ironic, sycophantic racism that results from white society having almost too much admiration for their Black counterparts. Chris continues to complete his rounds at the party. His interactions culminate in a conversation with Parker Dray, an older white man. Parker proclaims, “Fair skin has been in favor for, what, the past hundreds of years? But now,

the pendulum has swung back. Black is in fashion!”10 While this statement diverges from the hypersexual nature of Lisa’s appraisal, Parker’s assertion still plays into racial fetishization from a capitalistic standpoint. By saying that “Black is in fashion,” Parker suggests how post-racial iterations of Black exploitation may occur via cultural appropriation; for example, Black streetwear, music, hairstyles, and even physical features have been stripped of their cultural value after entering real-world trend cycles. The word “fashion” in reference to Black bodies condenses race into something as wearable and removable as a winter coat—a trivial garment subject to be in-and-outof-style at the whim of white consumers. And with Blackness as nothing more than a mere fashion statement, Chris’ body becomes a material commodity reminiscent of the bondage industry that defined both Haitian zombies and slaves. Furthermore, Parker’s citing of historical white preference suggests that a racist past has been vanquished by an inclusive future. However, Peele refutes this conjecture by establishing time as a “pendulum.” Parker’s declaration that America is on the cusp of anti-racism because “the pendulum has swung back” contradicts the understanding that progress has a forward trajectory; inadvertently he admits the inescapable nature of bigotry across time. In fact, bigotry is made synonymous with time. It, too, is the pendulum. Bigotry is constant behind the superficial iterations by which the same racial subjugation is expressed over the course of history—on one end, the demonization of blackness, and on the other, fetishization. Thus, Get Out diagnoses the issue of modern Black-white tensions to be the benevolent racism that occurs under a presumptuous self-labeling of post-racial life. Much like zombies, anti-Black racism has remained frozen in time, taking on various forms of life to preserve its function (the perpetuation of slavery’s legacy) even after society has hastily pronounced it long dead.

IV. The Haitian Revolution, Black Separatism, and the Zombie’s Demise

When paralleling Vodou zombies to Haitian slavery, history not only imitates corporeal reanimation processes but also proposes the unmaking of such transformations. In 1791, Haitian Blacks began a slave revolt against their colonizers.11 The revolution concluded in 1804, when “black leaders declared national independence… and ordered the massacre of nearly every white man, woman, and child remaining in the territory.”12 Haitian Blacks believed interracial coexistence could never be built on the bedrock of slavery/colonization. Oppression could only be negated in a state devoid of white influence and built on Black self-governance. Just as Vodou demands the soul’s components to be in harmonious separation (only when the gros bon ang e becomes unequally powerful are zombies born), Haitian history similarly suggests the cure to subjugation is Black separatism.

Get Out has also been written into history for a revolutionary act: it is one of few zombie movies that allows the Black protagonist to survive. Or rather, allows him to not just survive, but triumph over white characters via the rhetoric of reclamation comparable to Haitian separatist ideology. In the latter half of the movie, Chris discovers the Armitage family business. In a process analogous to zombification, Rose’s mother uses the sound of a clinking teacup to hypnotize Black characters. She stores their consciousness in the “sunken place” so that they may remain alive and fully aware, yet powerless as the brains of physically impaired white buyers are transplanted into their fully capable bodies. Chris realizes he has been lured into a trap too late. He is bound to a recliner for hypnosis. But Chris claws through the leather upholstery and plugs his ears with cotton stuffing, blocking sounds of the teacup so he can escape the house.13 Given that zombification is a surrogate for Black subjugation, it is notable that Chris uses cotton, the very crop which condemned his ancestors to servitude, to retain bodily autonomy.

Cotton can be symbolic of the forced labor which constructed the economic backbone of America. Therefore, using the crop as a tool for liberation rather than a cause for bondage proposes that the creative repurposing of white assets leads to Black economic reclamation. Furthermore, because Chris proceeds to escape the house following this unique reclamation of cotton, Peele seems to suggest that economic empowerment may be a precursor to racial separatism. In the climactic finale, Chris violently forces his way out of the Armitage house, inadvertently setting it on fire before scrambling onto the road. But he is closely pursued by Rose, the sole Armitage remaining. Rose is fatally wounded with a gunshot to the stomach and Chris uses this opportunity to begin strangling her. At this moment, a police car arrives, and Rose whimpers for help. However, the driver is none other than Rod, a Black TSA worker and Chris’ best friend. The men drive off together as Rose dies.

14The image of Chris mounted atop a helpless Rose evokes the racist narrative of a Black man unable to suppress his barbaric urge to assault an innocent white woman. And Rose is aware of this trope. She pleads to the police for help despite having instigated the ongoing violence because of an understanding of systemic racism and a calculating deployment of her assumed victimhood. However, just as the audience accepts the impending destruction of Chris’ body, Peele subverts expectations of zombification at the hands of law enforcement. The cop car—typically a protective emblem in white society, but a symbol of prejudicial brutality among Black communities—becomes the vehicle of Chris’ salvation. Rod’s position as a member of law enforcement suggests that Black people may further escape institutional zombification (and by extension, systemic racism) by placing organized protection back into the hands of their own community members. Furthermore, by breaking work protocol to drive the police car away from his mundane duties at the airport, Rod suggests that true protection—specifically when considering the protection of Black people—requires the abandoning

14 Peele.

6 7 CRITICALTHEORY & SOCIALJUSTICE UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL VOLUME 11, 2022

8 There is even some anthropological speculation that the Haitian word, zonbi, might have derived from the West African word for “fetish,” zumbi (Moreman and Rushton 3). 9 Peele.

10 Peele.

11 Clavin, 118. 12 Clavin, 118 13 Peele.

of current institutions to serve a greater good. Ultimately, suggesting the creation of a separate society established for the interests of Black people that is upheld by Black people.

One concern to a separatist reading of Get Out is that signs of expatriation only make fleeting appearances towards the end of the film, causing separatism to appear either as a mere afterthought or a wildly outlandish interpretation. But Get Out admits its logical fallacies. Rather than shying away from its burdens of proof, Peele’s work can also be read as embracing the ungroundedness of his separatist claims. In the film’s final image, Chris is shown fleeing a destroyed Armitage home to some unspecified location. The viewer can only guess what steps might be taken next to rectify the atrocities that he has born witness to. Where would Chris find adequate therapy? How could he legally prosecute those surviving perpetrators? What amount of financial compensation could remedy his suffering, and who would deliver it? Peele’s choice to end the film without specific answers acknowledges the pattern to deny survivors of racism support within a society built on the foundation of slavery. Chris’ journey to recovery and attempts at reintegration into white-dominated society would likely feel unrealistic or depressing. By ending without resolve, Peele suggests that running toward any unknown future is superior to remaining near any semblance of the racist past. Moreover, by ending the movie with Chris driving away, Peele asserts that despite little victories like the election of the nation’s first Black president or the triumph of a Black protagonist in the zombie film genre, the quest for racial liberation is ongoing and there is still a long road ahead of us. Peele’s failure to explicitly show Chris reaching his promised land may be considered as a deliberate choice; he does not offer a solution in order to task viewers with the responsibility of writing the next chapter. If Black people are to find safety in real life, a place where they can stop running and call their own, what do we envision such a state of racial respite to look like? And how do we see ourselves getting there?

V. Conclusion

From Haitian history to current social climates, the modern zombie melds past and present to show how slavery’s legacy might persist into post-racial futures. Specifically, zombie rhetoric as presented in Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017) warns of perpetual Black subjugation. His film proposes that the cyclical loss of Black bodily autonomy can only be broken by racial reclamation and separatism. While such interpretations of American race relations may appear extreme, we must consider that zombies appear in a wide range of ways. The exploitation of athletes, rampant police brutality, disproportionate mass incarceration, hyper-sexualization (and subsequent sexual assaults), and extreme maternal/infant mortality rates of Black people are just a few more present-day issues that adhere to the Vodou definition of zombies: the loss of Black bodily autonomy. Zombies ask what it means to not just have a diverse society but an inclusive one. Because if we cannot accomplish the task of peaceful integration, it never hurts to ruminate on a future which distances itself from the monstrosities we have come to accept as normal.

References

Benshoff, Harry M. “Blaxploitation Horror Films: Ge neric Reappropriation or Reinscription?” Ci nema Journal, vol. 39, no. 2, [University of Texas Press, Society for Cinema & Media Studies], 2000, pp. 31–50, http://www.jstor. org/stable/1225551.

Clavin, Matthew. “A Second Haitian Revolution: John Brown, Toussaint Louverture, and the Making of the American Civil War.” Civil War History, vol. 54 no. 2, 2008, p. 117-145. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/cwh.0.0001.

Mariani, Mike. “The Tragic, Forgotten History o f Zombies.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 4 Aug. 2021, www.theatlantic.

com/entertainment/archive/2015/10/how-a merica-erased-the-tragic-history-ofthe-zombie/412264/.

Moreman, Christopher M., and Cory James Ru shton. Race, Oppression and the Zombie: Essays On Cross-Cultural Appropriations of the Caribbean Tradition. McFarland, 2011.

Peele, Jordan, et. al. Get Out. Universal Pictures Home Entertainment, 2017.

Sharf, Zack. “‘Get out’: Jordan Peele Reveals the Rea l Meaning behind the Sunken Place.” In dieWire, IndieWire, 15 Jan. 2019, www. indiewire.com/2017/11/get-out-jordan-pee le-explains-sunken-place-meaning1201902567/).

Zarka, Emily. “Modern Zombies: The Rebirth of the Undead | Monstrum” Youtube, PBS Storied, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=UqPvWdX4ICE.

Zarka, Emily. “The Origins of the Zombie, from Haiti to the U.S. | Monstrum” Youtube, PBS Storied, 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=KIG msxBMnjA.

8 9 CRITICALTHEORY & SOCIALJUSTICE UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL VOLUME 11, 2022

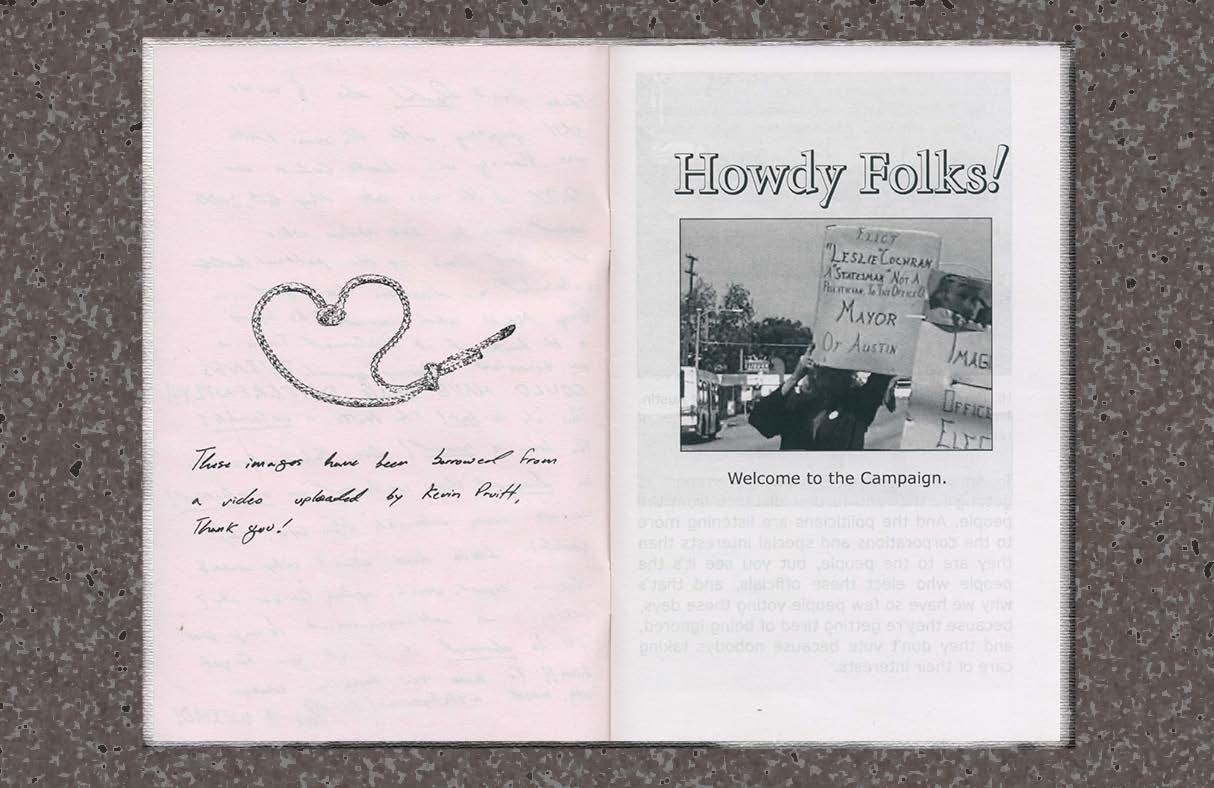

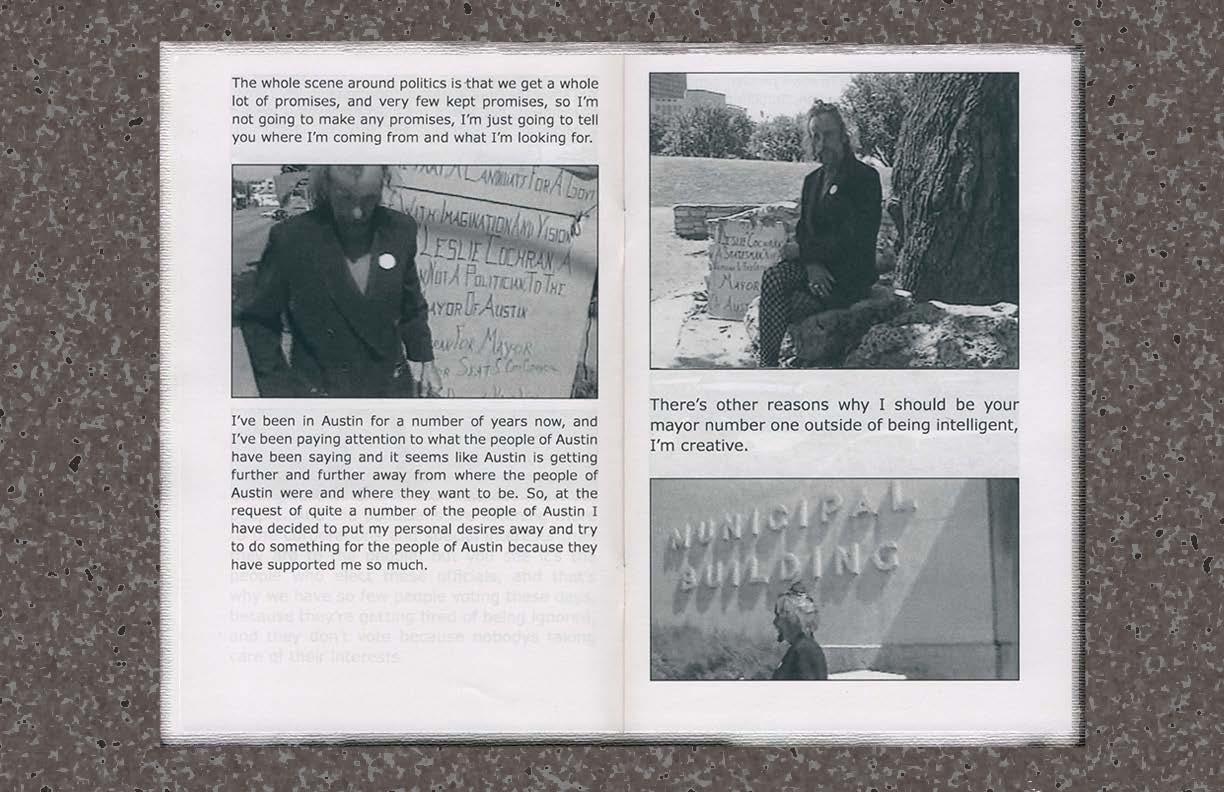

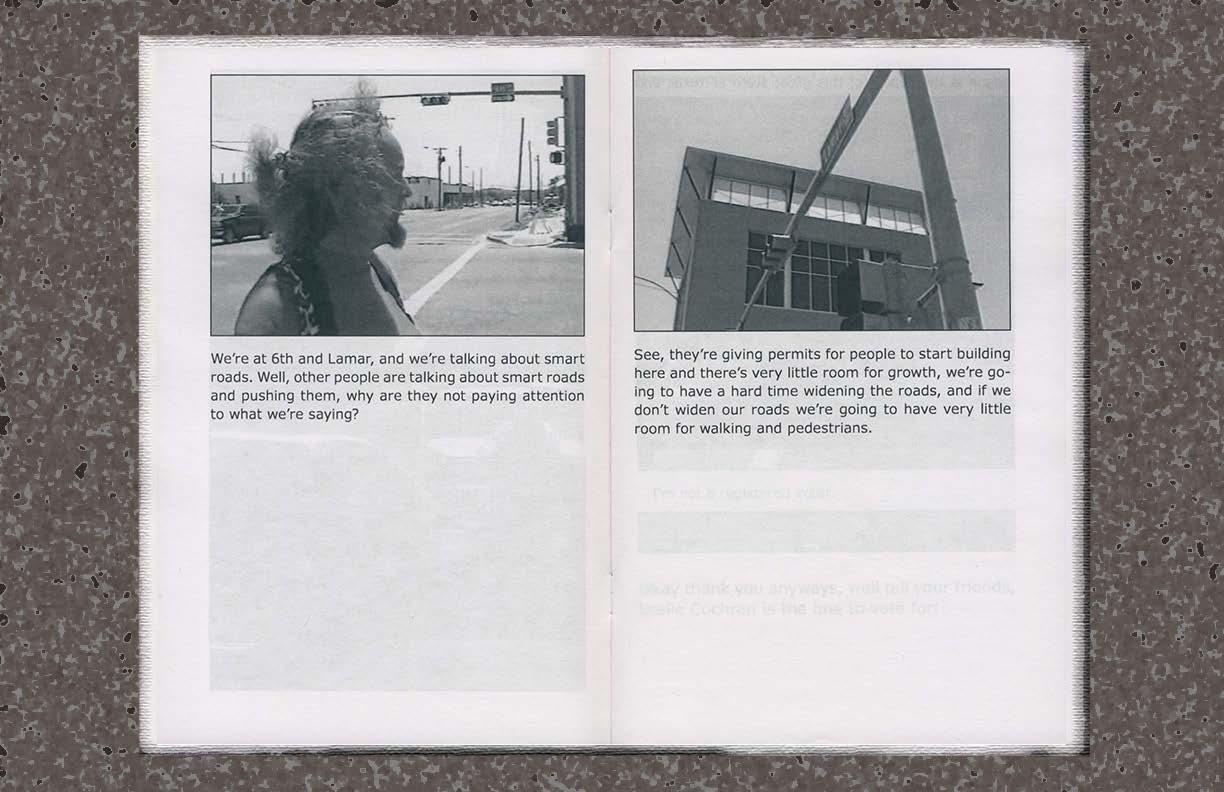

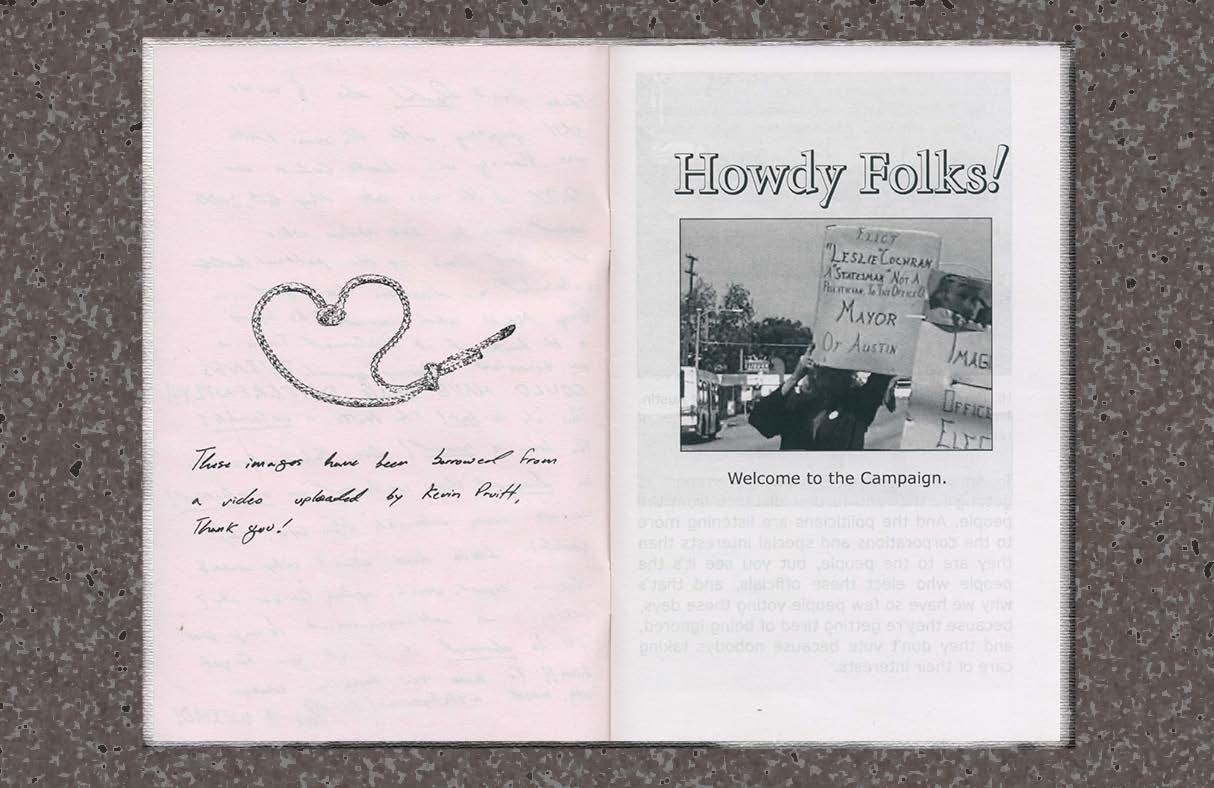

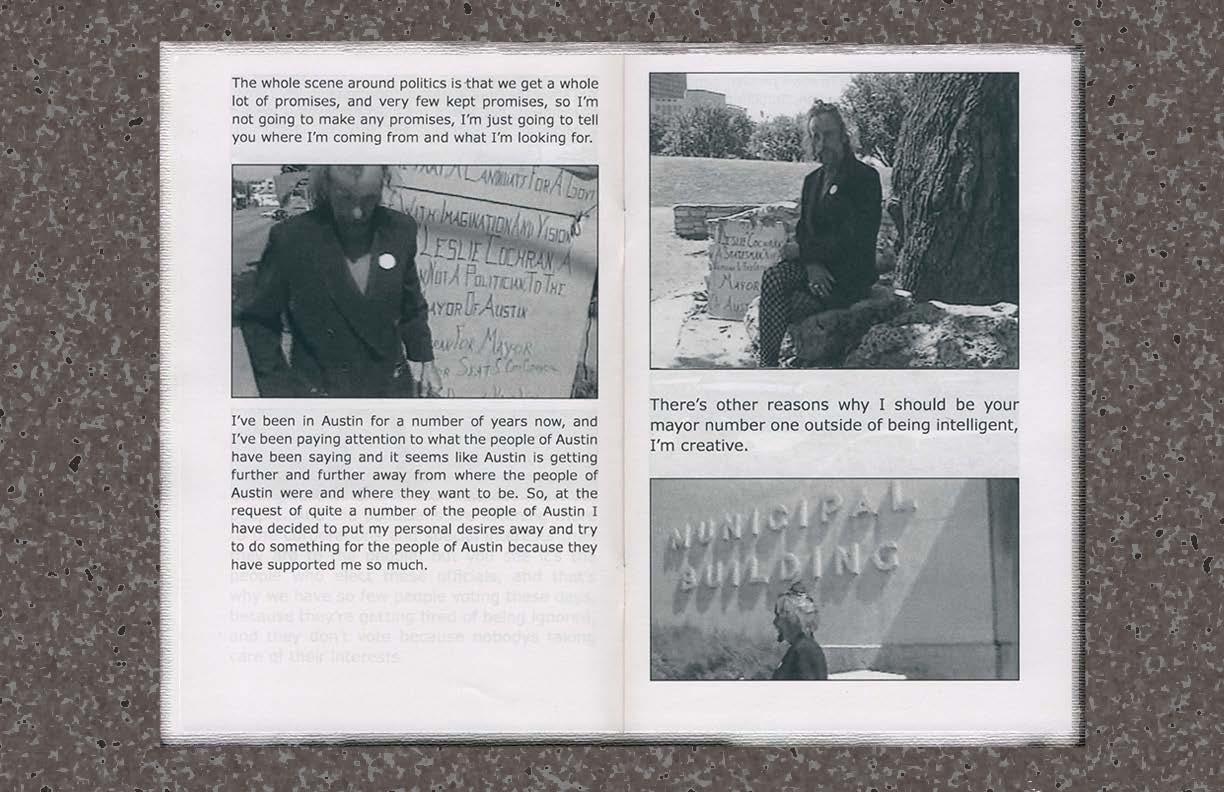

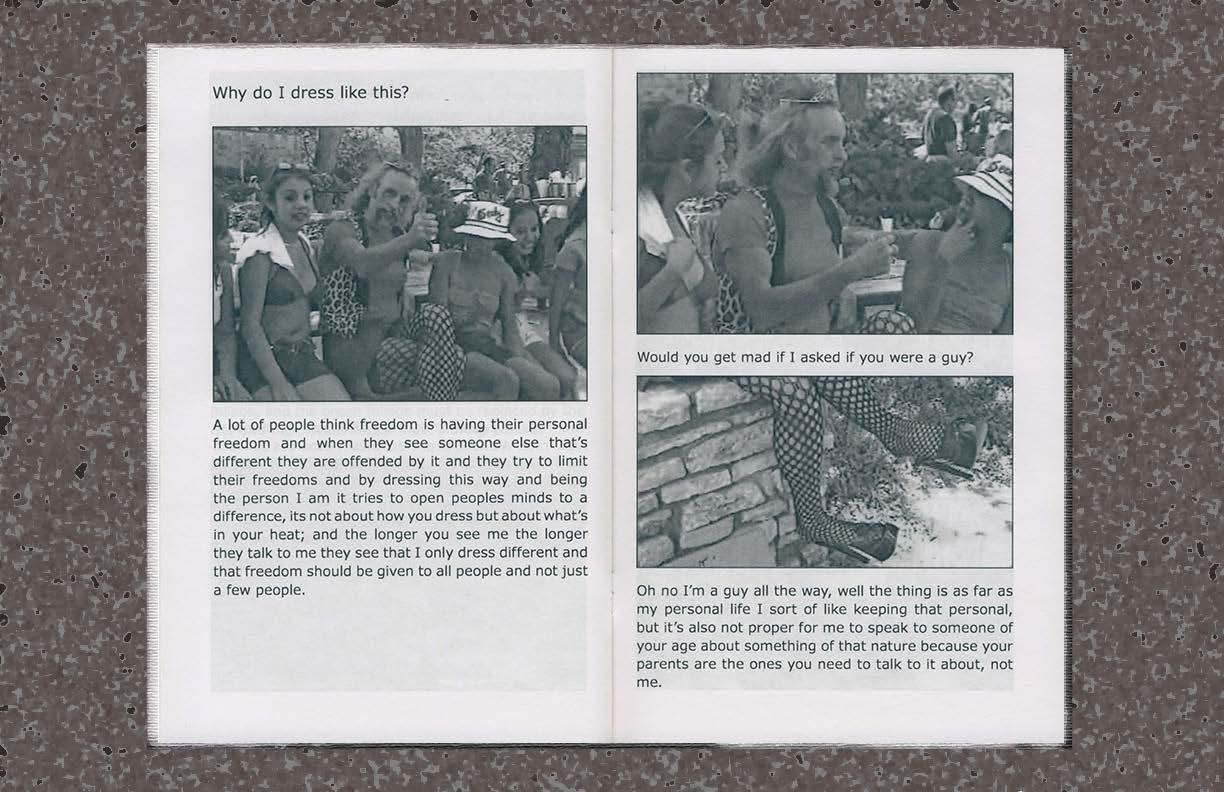

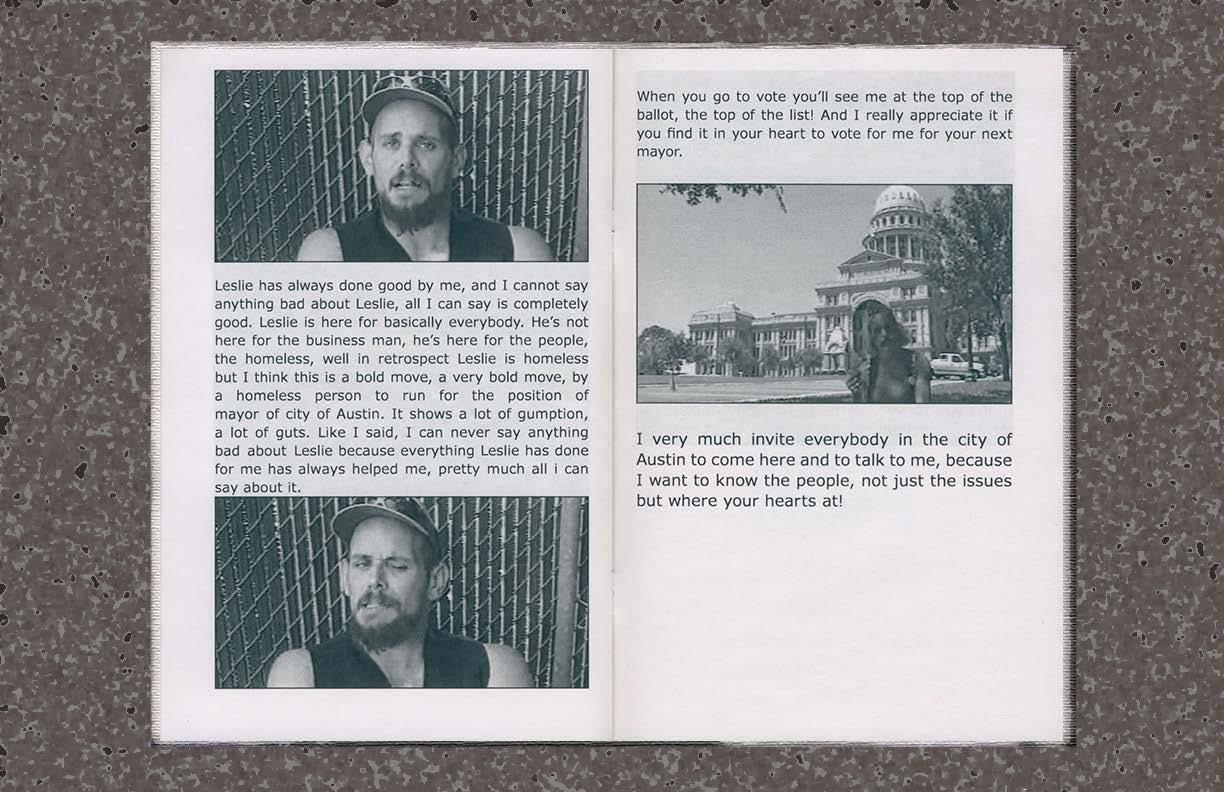

Top of the List!

Luis Quintanilla

Luis Quintanilla

Virginia Commonwealth University

“Top of the List!” is a film-to-book adaptation of a campaign video I found in the ATXN video archives for Leslie Cohcrans loud and DIY run for mayor of the City of Austin, Texas, in May 2000. Leslie Cochran was a homeless cross-dresser, self-proclaimed statesman, city wide heartthrob, and an anti-monument to my past paving the way for radical policy change and queer folks alike. Leslie lost the 2000 mayoral election to Texas state senator Kirk Watson, winning only 7.7% of the city’s vote. In this zine I hybridize early 2000s Sunday comic spreads and television closed captions using subtleties in type treatment and image variations to create compositions highlighting Leslies’ irreverent humor and earnest desire for human-centered change. I vividly remember the conversations Leslie ignited within the larger socio-political landscape of Austin, these were uncomfortable conversations people didn’t want to have surrounding gender and economic heirarchies; everyday citizens didn’t/couldn’t see cross-dressing is a means of gender expression rather than a fetishized sexual act, nor did they see it as entertainment expression like drag. Equally, they didn’t/couldn’t see past Lelie as a person experiencing homelessness, blinding them to the drastically human-centered platform Lelie was running on. In many ways we’re active observants of the echoes of this toxic mindset through legislation that is being passed, and contested, regarding public camping bans (Texas House Bill 1925, LAMC 41.18).

My practice has built itself around publishing as a means to build community and shed light onto our darker societal underbelly. I wouldn’t be interested in muckraking these issues if they weren’t still redeemable at the levels at which they are happening. There are tent cities growing around the nation, the number of individuals experiencing homelessness increases daily, our elected government actively pushes them away from urban centers so as to remain out of sight, and in turn, out of mind. There must be another alternative where capital gain isn’t at the forefront of everyone’s mind. This is where the power of zine multiplicity and dissemination shines brightest, being inexpensive and DIY allows me to circumvent traditional print production constraints and circulate widely. I have printed over 200 copies of “Top of the List!” and distributed them in urban “third place” communal grounds such as coffee shops, libraries, doctors waiting rooms, hair salons, and bodegas to name only a few. Ultimately, it’s my earnest desire that these zines are being digested and conversed over with strangers in third places of gathering to bridge the gaps between us all and act as political catalysts to help heal some of the traumas our world inflicts on our most vulnerable neighbors. I still feverishly believe that small groups of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world.

10 11 CRITICALTHEORY & SOCIALJUSTICE UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL VOLUME 11, 2022

“A better, more positive Tumblr”: The Repression of Online Sexuality and the Erasure of a Heterotopian Archive

Lucy Allen | University of Southern California

Abstract: In late 2018, the social media site and blogging platform Tumblr instated a ban on the erotic and pornographic materials that had once made up a significant portion of the site’s contents. This ban, though framed by Tumblr staff as a move to make the site safer and more welcoming, in fact appeared to be rooted in financial motivation stemming from the passage of the FOSTA-SESTA acts. This paper explores the cultural, political, and economic backdrop of the ban, and its destructive effect on the communities of marginalized subjects that formed on Tumblr. I use Michel Foucault’s theory of the heterotopia, a real space that subverts and reflects the world outside of it, to define Tumblr’s role before the explicit content ban was put in place, and I use critical archival studies to explore Tumblr’s importance in spite of the regulation placed upon it. In examining the dangers of the ban and of its causes, I draw on Gayle Rubin’s pro-sex feminist theory. I argue that Tumblr can be read both as an archive and a former heterotopia, and that the late-2010s sex-driven moral panic serves to erase these important definitions. This paper draws from disparate fields of study to raise questions of relevance to contemporary discourse and to address matters of political urgency.

I. Introduction

When I logged onto my account on the social media and blogging platform Tumblr on December 3rd, 2018, it was as if the whole website were in mourning. That day, the site’s staff had announced, by way of a post on their official blog, that beginning on the 17th of that month users would no longer be permitted to post or share “adult content.” This vague phrase, the staff explicated in a linked post, refers to “photos, videos, or GIFs that show real-life human genitals

or female-presenting nipples, and any content— including photos, videos, GIFs and illustrations— that depicts sex acts.”1 Though the site had an expansive user base with innumerable discrete communities—like particular media objects’ fandoms and groups linked by political affiliation—it was best known for catering to young people, queer people, and those involved in counterculture.2,3 Tumblr was not principally a porn website, but pornographic photos, GIFs, and videos certainly constituted a non-negligible segment of its content. In addition to this porn—much of it portraying queer and kinky sexuality, as well as bodies excluded by normative hegemonic beauty standards—were other sorts of images and materials that would now be proscribed under an explicit content ban: non-sexual nude photography, visuals used in sex education, and any images incorrectly flagged by the imperfect algorithm enforcing the ban.

In elucidating the context of Tumblr’s explicit content ban and its troubling implications for queer and otherwise marginalized communities, I first apply Michel Foucault’s theory of the heterotopia, an “other space” that may both reflect and invert cultural characteristics of the outside world. I connect this heterotopian character to the expansive definitions of the archive proposed by scholars of critical archival studies in order to address Tumblr’s importance as an archival space—while also examining the inherent political and practical limitations of such online archives. I address how and why the ban, rather than stemming solely from the prerogatives of Tumblr’s staff, was instead a move prefigured by a web of governmental and corporate decisions most directly linked to federal anti-sex-trafficking legislation passed in 2018. I use Gayle Rubin’s seminal 1 Staff. “A better, more positive Tumblr.” Tumblr Staff, December 4, 2018. https://staff.tumblr.com/post/180758987165/a-better-more-positive-tumblr.

2 Tiidenberg, Katrin, and Andrew Whelan. “‘Not like that, not for that, not by them’: social media affordances of critique.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 16, no. 2 (2019): 83-102. https://www.tandfonline.com/ doi/full/10.1080/14791420.2019.1624797.

3 Martineau, Paris. “Tumblr’s Porn Ban Reveals Who Controls What We See Online.” Wired, December 4, 2018. https://www.wired.com/story/tumblrs-porn-ban-reveals-controls-we-see-online/.

text “Thinking Sex” as a framework to explicate the connection of this legislation to systemic anxieties around the regulation of sexuality.

II. Tumblr as a Heterotopia

Foucault used the term “heterotopia” in a number of his writings to describe those spaces that are other, meaning they contain ways of life and standards of normalcy that differ from the outside world and at times contradict themselves internally. He defines the term thoroughly in the essay “Of Other Spaces,” itself based on a 1967 lecture given by Foucault. In the essay, he contrasts the heterotopia with the utopia, although he explains that both simultaneously connect with and “contradict” the primary spaces of the outside world.4 While utopias, he acknowledges, are “fundamentally unreal,” many instances of the heterotopia appear in the real world. They are “something like counter-sites…in which…all the other real sites that can be found within the culture are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted.”.5

Heterotopias, Foucault (1986) elaborates, are “capable of juxtaposing in a single real place several spaces, several sites that are in themselves incompatible.”6 Here, he uses the examples of the theater and of the garden—where different identifiable settings or landscapes are artificially constructed in succession or alongsid e one another.”7 This description also characterizes the internet; individual websites may reflect offscreen cultures or places, but their coexistence is enabled only by the architecture of cyberspace. Individual websites may be heterotopias too; Tumblr was and is emblematic among them. As Katrin Tiidenberg and Andrew Whelan observe, “navigating and identifying [Tumblr’s] communities presumes immersion,” as the site’s divisions are delineated by “discursive and psychosocial” means rather than website structure.8 Tumblr was thus heterotopian not only in its cultural difference from broader society but also in its internal divi-

sions and the discourse that formed them. Foucault identifies numerous subcategories of heterotopia and the principles which characterize them. He defines the “crisis heterotopia” as a “privileged or sacred or forbidden place” to which members of a broader society depart to experience a period of crisis, such as sexual maturation, apart from the home.9 There are also “heterotopias of deviation” in which those whose crises are more permanent and definitional must be sequestered.10 Tumblr, in its pre-ban golden age, was characteristic of both of these definitions. As a website most popular among the age group spanning from young adolescence to young adulthood,11 it accommodated, however imperfectly, individuals in the midst of the crises of pubescence and sexual identity formation. Though engagement with materials defined as “adult content” can pose harm to young people navigating the internet—and presumably sometimes did so on Tumblr—the website also served to introduce young people, particularly those who were queer, trans, or questioning, to depictions of sexuality that were not necessarily bound up in the hegemonic constructions of desire and embodiment pervasive in more mainstream pornography.12

III. Tumblr as a Rogue Archive

Foucault begins “Of Other Spaces” with the proclamation, “[t]he great obsession of the nineteenth century was, as we know, history,” and contends that the late twentieth century is much more concerned with space than with time.13 “Heterotopias,” he writes, “are most often linked to slices in time—which is to say that they open onto what might be termed, for the sake of symmetry, heterochronies.”14 Some heterotopias, namely the museum and the library, are characterized by “indefinitely accumulating time…enclos[ing] in one place all times, all epochs, all forms, all tastes.”15

9 Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” 24.

10 Ibid, 25.

11 Smith, Cooper. (2013, December 13). “Tumblr Offers Advertisers A Major Advantage: Young Users, Who Spend Tons Of Time On The Site.” Business Insider, December 13, 2013. https://www.businessinsider.com/ tumblr-and-social-media-demographics-2013-12.

12 Tiidenberg and Whelan, “Not like that, not for that, not by them,” 90.

13 Foucault, Of Other Spaces, 22

7 Ibid.

8 Tiidenberg and Whelan, “Not like that, not for that, not by them,” 90.

14 Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” 26.

15 Ibid.

40 41 CRITICALTHEORY & SOCIALJUSTICE UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL VOLUME 11, 2022

4 Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces,” trans. Jay Miskowiec. Diacritics 16, no. 1 (1986): 24. doi.org/10.2307/464648.

5 Ibid. 6 Ibid, 25.

Given the nineteenth century’s preoccupation with history, Foucault (1986) argues that “the idea of constituting a place of all times that is itself outside of time and inaccessible to its ravages” makes the archival spaces of the museum and library the emblematic heterotopias of the nineteenth century.16

Internet archives are both consistent with that epoch’s heterochrony—in that they accumulate materials from all times alongside one another—and break with it, because they are characteristically ephemeral. In this respect, they echo the heterotopias Foucault describes as “linked… to time in its most flowing, transitory, precarious aspect, to time in the mode of the festival” (26). Where the heterochrony of accumulating time i17s peculiar to the nineteenth century, the heterochrony that characterizes the internet age is the paradoxical simultaneous permanence and precarity of internet archives like Tumblr. Such sites permit an endless amassing of materials in (cyber)space, but do not ensure their preservation or guard against their erasure.

As Tiidenberg and Whelan argue, Tumblr’s format, in conjunction with the cultures that emerged there, enabled particular means of critique and self-presentation that were not available on other sites. This capacity was particularly true within communities where sexual images and writing were created and shared. They write that “regularly and pseudonymously creating, posting, liking, hashtagging, commenting on and reblogging sexual content over an extended period of time” led users to “begin questioning, resisting, and subverting various sets of norms. For this particular community, the norms resisted fall are [sic] under the aegis of hetero-, mono-, and body normativity.”18

The lively, large-scale social justice debates and critical inquiry that unfolded within and without the website’s explicitly sexual corners came to constitute a body of work archived across its pages. Noah Zazanis writes that “the theory developed on that platform—through collaboration, argument, and reflection on personal

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Tiidenberg and Whelan, “Not like that, not for that, not by them,” 83-84.

experience—continues to inform” his and other former users’ work. “The collective knowledge we created there,” he writes, “still remains, even as SESTA/FOSTA and the resulting porn ban have driven much of Tumblr’s membership off for good.”19 The depth of writing and interaction that remain on the website thus constitute something of an archive of the sort Barry Reay, echoing Abigail De Kosnick, calls “the rogue archive.”20 Such archives offer “both quantity and democratization, though not necessarily permanency.”21 Vernacular internet archives have been of particular use to trans communities, for whom institutional memory and memorializing is often sparse. K.J. Rawson argues that “a broad range of online materials, including blogs, videos, and online forums, should be considered historical as long as their purpose is to create a historical record of transgender experience.”22 As Andre Cavalcante argues, social media like Tumblr “serve as easily accessible repositories for collective memory.”23 In lieu of formal archives, “social media provide space for memory making, for archiving non-normative sexual knowledge and history.”24 The classification of such materials as constitutive of an historical archive is an important step toward countering the ephemerality which inheres in much internet culture.

IV. The Tumblr Ban and Internet Sexuality

Tumblr staff framed its decision to ban sexually explicit content as consistent with an ostensible commitment to cultivating a safe and supportive internet space, titling the initial announcement post “A better, more positive Tumblr,” and explaining, “without [adult] content we have the opportunity to create a place where

19 Zazanis, Noah. (2019, December 24). “On Hating Men (And Becoming One Anyway).” The New Inquiry, December 24, 2019. https://thenewinquiry.com/on-hating-men-and-becoming-one-anyway/.

20 Reay, Barry, Sex in the Archives: Writing American Sexual Histories (Manchester University Press, 2019), 9.

21 Ibid.

22 Rawson, K.J. “Transgender Worldmaking in Cyberspace: Historical Activism on the Internet.” QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking 1, no. 2 (2014): 38-60. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.14321/qed.1.issue-2. 39.

23 Cavalcante, Andre. “Tumbling Into Queer Utopias and Vortexes: Experiences of LGBTQ Social Media Users on Tumblr.” Journal of Homosexuality 66, no. 12 (2019): 1715–1735. doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1511131.1

more people feel comfortable expressing themselves.”25 Yet for many Tumblr users, the ban promised to have the opposite effect. As Tiidenberg and Whelan argue, the “rhetorical framing of [this] commercially motivated decision as coming from a desire to be a ‘safe place’ is deeply ironic, given they are effectively erasing, silencing and evicting communities for queer youth, fandoms, art creators, sex workers and NSFW diarists, with limited alternatives.”26 The sexually explicit content housed on Tumblr was an integral aspect defining its status as a queer space absent much of the repressive normativity of the outside world. As Cavalcante argues in an article published just a few months before the ban was announced, Tumblr both created space for queer community formation and “underscore[d] the profound vulnerability of queer individuals and communities in digital, corporatized space.”27 Removing sexuality and nude bodies from Tumblr’s queer communities meant not only imperiling the liberating conditions they seemed to have cultivated, but also revealing the sinister shadow of state and corporate surveillance that had always been present, despite the space’s offer of safety and camaraderie.

As internet use has become more widespread, it has come under greater legal scrutiny. This phenomenon in combination with the already punitive and regulatory relationship of the state to matters of sexuality has ultimately led to a crisis in sexual cyberspace accelerated by the passage of the FOSTA-SESTA anti-sex trafficking bills.28 Cultural discourses like those around sex and sexuality often respond to seemingly unrelated sociopolitical phenomena. In “Thinking Sex,” Rubin argues that fraught conflicts over sexuality tend to emerge at times of disorder and societal fear. These conflicts, she writes, “acquire immense symbolic weight. Disputes over sexual behaviour often become the vehicles for displac-

25

“A better more positive Tumblr.”

26 Tiidenberg and Whelan Not like that, not for that, not by them, 95.

27 Cavalcante, “Tumbling Into Queer Utopias and

1816.

720.

24 Ibid.

ing social anxieties, and discharging their attendant emotional intensity.”29 Furthermore, although “sex is always political…there are also historical periods in which sexuality is more sharply contested and more overtly politicized.”30 The 1980s, the period during which Rubin initially wrote this essay, was such a time, characterized by the consolidation of mounting neoconservative economic and social policy and the beginnings of what would become the AIDS pandemic. The present day, I contend, is another such time. The perhaps incongruous juxtaposition of increasing social liberalism among many civilian communities and reactionary authoritarianism in many of the world’s highest offices has created a global state that both affirms and undermines many of the factors that ostensibly characterized the liberalism of the early 21st century. In the United States, for instance, the hardline right-wing populism of Donald Trump brought fascism to the forefront of American political discourse. 21st century American social liberalism, particularly in the realms of gender and sexuality, is jarringly incompatible with the authoritarian right, and this dissonance results in the sort of friction that—according to Rubin—prompts a collective desire for the regulation of sexuality.31

V. FOSTA-SESTA and Tumblr

This frenzied desire to regulate sexuality has taken shape in the moral panic surrounding an ostensible sex trafficking epidemic, the threat of which is based more in anxiety around public morality than in genuine concern for the well-being of sexual violence survivors. The response to what the anti-trafficking movement characterizes as an epidemic has coalesced into a moral panic because, as Janie A. Chuang argues, the category of “trafficking” has been broadened in the United States to refer to an ever-greater range of forms of exploitative labor arrangements.

32 In a

29 Rubin, Gayle. “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality.” In Culture, Society and Sexuality: A Reader, edited by Richard Parker & Peter Aggleton, 143-178. UCL Press, 1999. 143.

30 Ibid.

31 Rubin, “Thinking Sex.”

32 Chuang, Janie. “Exploitation Creep and the Unmaking of Human Trafficking Law.” The American Journal of International Law 108, no. 4 (2014): 609–649. https://doi.org/10.5305/amerjintelaw.108.4.0609.

42 43 CRITICALTHEORY & SOCIALJUSTICE UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL VOLUME 11, 2022

Staff,

Vortexes,”

28 Musto, Jennifer, Anne E. Fehrenbacher, Heidi Hoefinger, Nicola Mai, P.G. Macioti, Calum Bennachie, Calogero Giametta, and Kate D’Adamo. “Anti-Trafficking in the Time of FOSTA/SESTA: Networked Moral Gentrification and Sexual Humanitarian Creep.”Social Sciences 10, no. 2 (2021): 1-18. doi.org/10.3390/socsci10020058.

phenomenon Chuang refers to as “exploitation creep,” the United States has used this expansive definition to “generate…heightened moral condemnation and commitment to its cause.”33 In an article published in 2014, Valerie Feldman writes that sex worker activists are troubled by the fact that “most scholarly and popular writing on sex work focuses on individuals who are perceived to be the most marginalized: women working in street prostitution…or, more recently, those who have been trafficked for sex.”34 Though these categories encompass a minority of the sex trade—sex worker advocates consistently distinguish their experiences from those of trafficking survivors35,36—legislation nominally aimed exclusively at trafficking tends to affect the sex industry broadly.37

The most recent major legislative results of the sex trafficking panic are the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA) and Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (FOSTA), known collectively as the FOSTA-SESTA package. The package, which passed the Senate with a 97-2 vote, and was signed into law by Trump in April of 2018, established provisions that would allow websites to be held legally responsible for hosting content that could be construed as enabling sex trafficking. The stunning bipartisan unanimity of the Senate’s votes can be attributed to the hysteria that moral panics surrounding illicit sexuality engender. “Sex laws are notoriously easy to pass,” Rubin writes, “as legislators are loath to be soft on vice.”38

Despite the titles of the acts forming FOSTA-SESTA, their effect on the internet has primarily impacted sex workers themselves.39 As Feldman notes, “many workers [have moved] online and indoors due to demographic shifts in urban residency and changing patterns of law

33 Ibid, 611

34 Feldman, Valerie. “Sex Work Politics and the Internet: Carving Out Political Space in the Blogosphere.” In Negotiating Sex Work: Unintended Consequences of Policy and Activism, edited by Carisa R. Showden & Samantha Majic, 243-266. University of Minnesota Press, 2014. https://www. jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt6wr77g.16. 243

35 Musto et. al. “Anti-Trafficking in the Time,” 3.

36 Blunt, Danielle, and Ariel Wolf. “Erased: The impact of FOSTA-SESTA and the removal of Backpage on sex workers.” Anti-Trafficking Review, no. 14 (2020): 117–121. https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201220148. 118.

37 Feldman, “Sex Work Politics and the Internet,” 243. 38 Rubin, “Thinking Sex,” 157.

39 Blunt and Wolf, “Erased: The impact of FOSTA-SESTA,” 117.

enforcement,” so legislation limiting the advertising of sex work on internet platforms disadvantages workers themselves in addition to any would-be traffickers.40 Furthermore, as Danielle Blunt and Ariel Wolf have shown, the limitations imposed on online expression by FOSTA-SESTA have hindered many sex workers’ ability to practice harm reduction in the form of screening clients for “histor[ies] of violence, non-payment, or potential connections to law enforcement.”41 As Rubin explains, “[t]his culture always treats sex with suspicion. It construes and judges almost any sexual practice in terms of its worst possible expression.”42 Thus, the specter of exploitative sex trafficking is made to stand in for all commercial sex in order to secure the harshest legal opprobrium, even as doing so makes sex workers who do not consider themselves trafficked less safe.43 Furthermore, Rubin argues, “[e]very moral panic has consequences on two levels. The target population suffers most, but everyone is affected by the social and legal changes.”44 Not only did sex workers advertising their own services bear the brunt of this legislation, but its reverberations affected individuals not in the sex industry simply by way of their consumption or sharing of sexual and erotic materials online.

In the wake of FOSTA-SESTA’s passage, the administrators of many websites responded with panicked platform and rule changes. The online classifieds page Craigslist took down its personals section, where sex workers had been known to advertise, and the artist support subscription service Patreon halted support for creators of pornographic materials.45 Meanwhile, Tumblr had its own financial concerns linked to its hosting of explicit content. The website’s purchase by Yahoo in 2013 prompted concerns about courting advertisers on a website inundated with porn.46 Furthermore, several months after FOSTA-SESTA was passed, Tumblr had been removed from Apple’s App Store due to

40 Feldman, “Sex Work Politics and the Internet,” 245.

41 Blunt and Wolf, “Erased: The impact of FOSTA-SESTA,” 119.

42 Rubin, “Thinking Sex,” 150.

43 Musto et. al. “Anti-Trafficking in the Time, of FOSTA/SESTA” 8

44 Rubin, “Thinking Sex,” 163.

45 Martineau, “Tumblr’s Porn Ban Reveals Who Controls What We See Online.”

46 Ibid.

reports of child pornography being posted on a Tumblr-hosted blog. Though website staff rapidly removed the content, the App Store, which bars applications “that end up being used primarily for pornographic content,” did not allow the Tumblr app to return.47 These reverberations of corporate anxieties over the impact of pornography on financial gain lend credence to Cavalcante’s observation that the

“[The] potential of Tumblr is limited by its position within a corporate structure that prioritizes profitability…Even as Tumblr’s spokespeople promise an inclusive and progressive platform, the LGBTQ commu nity is nevertheless vulnerable to poten tially adverse corporate paradigms and policies.”48 Though the staff post announcing the adult content ban made no reference to them, the corporate and legal pressures working against the site are clear in the context of corporate responses to FOSTA-SESTA.

Sexual materials on Tumblr were abundant, and thus diverse; like the rest of the site’s content, they presented both queer possibility and the potential to introduce or reinforce harmful depictions or impositions of sexuality on young users.49 The dichotomous nature of Tumblr’s impact that Cavalcante observes further exemplifies the website’s heterotopian status. Contrasting it with Facebook, which requires users to sign up with a single profile under their full, legal names, Cavalcante writes that “Tumblr opened the door for expressing multiple, queer selves. Users can have more than one page.”50 Tumblr, he argues, permits users to construct an identity “that is characteristically patchwork, dynamic, and evolving. Its design permits users to integrate text, photos, links, and video on their pages, allowing for a multimedia expression of self.”51 Like the real-world heterotopias identified by Foucault, Tumblr enables the juxtaposition of diverse materials that together compose a distinct, new space.

VI. Conclusion

The 21st century brought about a new set of heterotopian spaces that appeared at first to be self-contained and outside of the purview of state repression and dominant normative power relations. As a result, communities of the marginalized and others assembled in these spaces with the intent of shielding themselves from the dystopian outside world. The utopias sought online—like all utopias—are definitionally impossible and unreal. As the intervention of FOSTA-SESTA made painfully clear, internet spaces are in fact as intensely surveilled and policed as are geographic spaces, perhaps more so. Tumblr, a heterotopian site which functioned as something of an archive, accumulating the artwork, humor, conflicts, discourses, and tastes of a subset of queer young people, could never truly be “outside of time and inaccessible to its ravages” because it was built under the shadow of digital surveillance.52

Despite this, Tumblr’s vitality and intellectually generative capacity cannot be overlooked. Meaningful cultural production, personal bonds, and sociopolitical debates took place there, phenomena that, outside of the internet realm, would be considered worth preserving. Where the App Store and potential advertisers saw a non-lucrative porn website with the capacity— post-FOSTA-SESTA—to get them in legal trouble, users saw a heterotopia wherein sexuality was a valuable ingredient in the intellectual, artistic, political, and personal discourses taking place.

“Crucially,” Tiidenberg and Whelan write, Tumblr “maintain[ed] its identity as a social media platform, rather than a porn site or a fanfiction forum, thereby maintaining accessibility and the heterogeneity of the userbase.”53 Before, they argue, “Tumblr could have been considered one of the few remaining spaces within the monopolizing, platform-regulated social media ecology that was experienced and used as community-oriented, creative, and safe for non normative or marginalized users.”54 Ephemerality is intrinsic in many human interactions, including those that take place on the internet, but that does not mean that

44 45 CRITICALTHEORY & SOCIALJUSTICE UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL VOLUME 11, 2022

47 Ibid. 48 Cavalcante, “Tumbling Into Queer Utopias and Vortexes,” 1731. 49 Ibid. 50 Ibid, 1721. 51 Ibid.

52 Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” 26.

53 Tiidenberg and Whelan, “Not like that, not for that, not by them,” 96.

54 Ibid.

these interactions should be divorced from history or imagined as outside of the historical record. Deletion of blogs and posts, whether by website algorithms and administration or users themselves, erases documentation of Tumblr’s history, but the absences themselves help to reconstruct it. As Reay writes, “archives are always indeterminate, consisting of the absent as well as the present” (15).55 Rather than mitigating Tumblr’s archival status, ephemerality defines its particular contours. A dialectic of presence and absence defines the sum total of human history; although the venues in which culture is forged look different now, this contradiction persists. And though an age of troubling sexual panic has altered the appearance and capabilities of these online venues, dissent remains in the empty spaces and in the ruins.

References

Blunt, Danielle, and Ariel Wolf. “Erased: The impact of FOS TA-SESTA and the removal of Backpage on sex workers.” Anti-Trafficking Review, no. 14 (2020): 117–121. https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.201220148.

Cavalcante, Andre. “Tumbling Into Queer Utopias and Vortexes: Experiences of LGBTQ Social Media Us ers on Tumblr.” Journal of Homosexuality 66, no. 12 (2019): 1715–1735. doi.org/10.1080/00918369.201

8.1511131.

Chuang, Janie. “Exploitation Creep and the Unmaking of Human Trafficking Law.” The American Journal of International Law 108, no. 4 (2014): 609–649. https://doi.org/10.5305/amerjin telaw.108.4.0609.

Feldman, Valerie. “Sex Work Politics and the Internet: Carving Out Political Space in the Blogosphere.” In Negotiating Sex Work: Unintended Consequenc es of Policy and Activism, edited by Carisa R. Showden & Samantha Majic, 243-266. Universi ty of Minnesota Press, 2014. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/10.5749/j.ctt6wr77g.16.

Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces,” trans. Jay Mis kowiec. Diacritics 16, no. 1 (1986): 22-27. doi.org/10.2307/464648.

Martineau, Paris. “Tumblr’s Porn Ban Reveals Who Controls What We See Online.” Wired, December 4, 2018. https://www.wired.com/story/tumblrs-porn-ban-re veals-controls-we-see-online/.

Musto, Jennifer, Anne E. Fehrenbacher, Heidi Hoefinger, Nicola Mai, P.G. Macioti, Calum Bennachie, Calog ero Giametta, and Kate D’Adamo. “Anti-Trafficking in the Time of FOSTA/SESTA: Networked Moral

55 Reay, Barry, Sex in the Archives, 15.

Gentrification and Sexual Humanitarian Creep.”So cial Sciences 10, no. 2 (2021): 1-18. doi.org/ 10.3390/socsci10020058.

Rawson, K.J. “Transgender Worldmaking in Cyberspace: Historical Activism on the Internet.” QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking 1, no. 2 (2014): 38-60. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.14321/qed.1.is sue-2.

Reay, Barry, Sex in the Archives: Writing American Sexual Histories (Manchester University Press, 2019).

Rubin, Gayle. “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality.” In Culture, Society and Sexuality: A Reader, edited by Richard Parker & Peter Aggleton, 143-178. UCL Press, 1999.

Smith, Cooper. (2013, December 13). “Tumblr Offers Ad vertisers A Major Advantage: Young Users, Who Spend Tons Of Time On The Site.” Business Insider, December 13, 2013. https://www.businessinsider. com/tumblr-and-social-media-demographics2013-12.

Staff. “A better, more positive Tumblr.” Tumblr Staff, Decem ber 4, 2018. https://staff.tumblr.com/post/1 80758987165/a-better-more-positive-tumblr.

Tiidenberg, Katrin, and Andrew Whelan. “‘Not like that, not for that, not by them’: social media affordances of critique.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Stud ies 16, no. 2 (2019): 83-102. https://www.tandfon line.com/doi/full/10.1080/14791420.2019.1624797.

Zazanis, Noah. (2019, December 24). “On Hating Men (And Becoming One Anyway).” The New Inquiry, Decem ber 24, 2019. https://thenewinquiry.com/on-hatingmen-and-becoming-one-anyway/.

46 47 CRITICALTHEORY & SOCIALJUSTICE UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL VOLUME 11, 2022

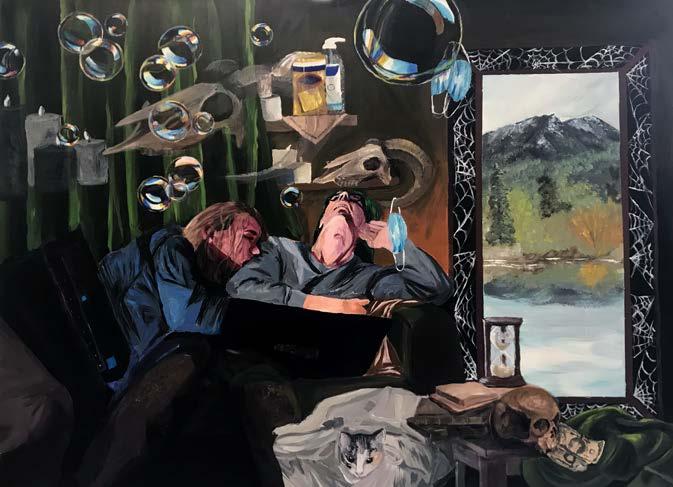

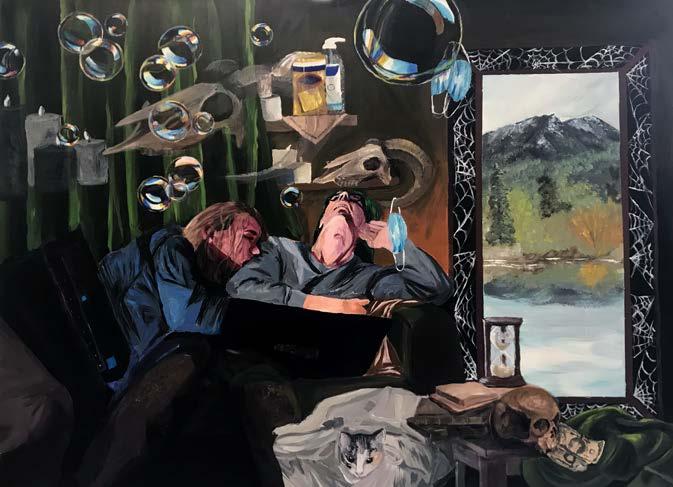

St. Quarantine Crowned with Anxiety

Mint Zecoll | Occidental College

The painting I am submitting for the CTSJ Journal St. Quarantine Crowned with Anxiety is a commentary on the experience of COVID-19 and an exploration of the beauty and fragility of faith and hope when faced with a global catastrophe of such a large scale.

I based my painting off of the European painting Saint Rosalie Crowned with Roses by Two Angels by Van Dyke, from 1624. The painting depicts the historical figure of St. Rosalie - a hermit who devoted her life to catholicism, living in the mountains surrounding Palermo, Italy. She is the patron saint of the city because, allegedly, it was her influence and bones that helped control the plague outburst in the city in 1624 and lead to its cessation in 1625. Her remains, which were found by a hunter after she appeared to him in a vision, were seen as a sign of hope and an intervention to the plague from god.

St. Rosalie is Crowned with Roses by Two Angels, as I interpret it, depicts hope and a longing for healing in the face of a crisis. I’ve taken this message and reapplied it to a crisis that has (literally) plagued us for the past two years - COVID-19.

In my painting, along with the symbols of hope and reprieve, I hoped to represent the sense of anxiety, and the fact that faith alone isn’t enough to cure the world. I decided to create this piece as a statement of my experience with the pandemic, depicting little rays of hope that I experienced over the past two years (i.e. my housemates, my own faith, my cat) and offsetting them with a sense of anxiety that overwhelms the image. In doing so, I wanted to highlight the importance of acknowledging the beauty of small things in a crisis - the lighting, the bubbles, the colors - but I also want to caution myself against overemphasizing beauty over practicality and safety. No one saint can ward off a plague, and no thought or thing can erase the horrors and hardships we have had to endure these past 2 years, but we can choose to see the beauty in them as well, as long as we don’t ignore the fear and anxiety behind them.

48 49 CRITICALTHEORY & SOCIALJUSTICE UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL VOLUME 11, 2022

The Transformative Possibility of Canadian Law and Indigenous Rights: Promising in Concept, Improbable in Practice

Aidan Sneyd | McMaster University

Abstract: In this paper, I will argue that while certain aspects of Canadian law contain theoretical “transformative possibilities” for facilitating Indigenous self-governance and protecting Indigenous rights in general, tangible developments are unfeasible under the approach of the current legal system. To begin, I will briefly explain the concept of transformative possibility. Following this, I will demonstrate that there is a seemingly valid conceptual basis for the idea that Canadian law can help affirm Indigenous authority. Next, I will argue that the mere possibility of progress within the abstract logic of the legal system will not produce meaningful change. On the contrary, problems intrinsic to the current system, such as historical adjudication and jurisprudence and the Canadian government’s general attitude toward Indigenous rights, suggest that material change within the existing power structures of the system is unlikely. In result, this paper will show that, because the hardships that Canada’s current legal system imposes on Indigenous peoples are systemic in nature, the mere changes in attitudes and approaches within the existing system that are submitted by the “transformative possibilities” argument are utterly futile. What is needed, then, are systemic changes; this begins with a recognition of the precise ways in which the current Canadian legal system structurally perpetuates an outdated and onerous framework of Aboriginal rights, one that favors state-interests over genuine amelioration of the relationship between Ca

I. Setting Up the Debate

Patrick Macklem, a Professor of Law at the University of Toronto who has contributed extensive research on Aboriginal Law, has argued that the various forms of law in Canada have failed to accom-

modate Aboriginal needs and interests.1 Instead, the legal system has imposed an unsuitable “Anglo-Canadian” perspective on an Indigenous context that is unique and different from that Anglo-Canadian perspective. 2 The legal system treats Indigenous peoples as both “similar to and different” from non-Indigenous people depending on which position suits state interests, and creates a hierarchical relationship that forces Indigenous people into a position of dependence on the Canadian government.3

In spite of these structural issues, Macklem contends that there is reason to believe that the legal system has the “transformative possibility” to help achieve Indigenous sovereignty and independence.4 In other words, past decisions by the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC), treaty interpretation, and other legal developments show promising possibilities for change.5 If the system’s rigid adherence to Anglo-Canadian legal understandings is reassessed, it can be opened to incorporate Indigenous peoples in important decisions about their “individual and collective destinies.”6

Others, such as Gordon Christie, have argued that the Canadian legal system is structurally opposed to claims of Indigenous authority, as it uses numerous avenues to wear down and defeat any perceived threat to Canadian sovereignty. 7 Christie uses the example of the Yinka-Dene-Alliance’s objection to the Northern-Gateway pipeline based on Indigenous understandings of power and authority, arguing that such a claim would easily be suppressed by the court through various legal mechanisms in

order to protect state sovereignty.8 The law structurally prohibits the success of Indigenous claims of authority by mandating that the claim be tied to an existing legal Aboriginal right, mischaracterizing the right in question, and interpreting the claim as incompatible with historical practice or lacking sufficient continuity in the present day.9 Even if these methods are unsuccessful, rights claims can still be refuted on the grounds that the right in question had been extinguished prior to 1982, or that the Crown acted justifiably in its infringement of the right.10

In sum, Christie submits that the Canadian legal system has multiple channels through which it can shoot down claims of Indigenous authority in order to protect state sovereignty.11 By contrast, what Macklem argues is that the law’s potential to evolve away from these problems makes it a potential instrument of change. Put differently, whatever issues the current approach may have, the possibility of transformation in the law as it applies to Indigenous rights is enough to support continued efforts of improving Indigenous rights within the existing system.

II. The Case for Canadian Law: Transformative Possibility?

This section will examine how “transformative possibilities” provide a background for the claim that such theoretical potentialities are insufficient on their own. As this section will show, even though the current legal approach to Indigenous rights has been historically oppressive, one might reasonably conclude that the course can still be reversed within the current system through diligent jurisprudence and legislation. Though these “transformative possibilities” can be characterized using many different legal categories, two will be addressed here: constitutional interpretation and fundamental legal principles.

that is, it reads those rights based on the original understanding of the words used in the Constitution at the time it was enacted.12 This method is inconsistent with the approach to other provisions of the Canadian Constitution, which are afforded the ability to evolve and adapt over time, while the scope of Aboriginal rights under Section 35 is held static by originalism.13 This interpretive approach discriminates against Indigenous people by denying Aboriginal rights the same benefits granted to the rest of the Constitution.14 Borrows’s argument can be used to support the notion of transformative possibility because it shows that the chosen method of constitutional interpretation impacts the stability of Aboriginal rights.

In other words, Canadian courts could move away from the current method of interpreting Aboriginal rights, which favors originalist reasoning, and instead allow the constitutional reading of those rights to reflect modern-day realities faced by Indigenous people; for instance, by significantly de-emphasizing the focus on pre-contact practices and traditions where it is unnecessary by today’s standards. In short, a revised interpretative approach within the same legal system may help to ameliorate the conditions faced by Indigenous people in Canada. For example, Barsh and Henderson argue that the trilogy of cases sprouting from R. v. Van der Peet changed the law to make it extremely difficult to establish constitutional rights protections for an Aboriginal practice or tradition.15 Yet, Barsh and Henderson note that two later cases, R. v. Adams and R. v. Côté, each ended with rulings in the Aboriginal parties’ favor, in part because the court ignored the “centrality” requirement that was added in Van der Peet.16 While Adams and Côté were not without their own problems, these decisions suggest that the Canadian legal system maintains the internal capability and willingness to overturn decisions that have led to restrictions on Indigenous

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid, 392.

4 Ibid, 392.

6 Ibid, 456.

John Borrows argues that the Canadian state still relies on originalism to interpret Aboriginal rights;

12 John Borrows, Freedom and Indigenous Constitutionalism (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016), 130.

13 Borrows, Freedom and Indigenous Constitutionalism.

14 Ibid.

15

16 Ibid, 1005.

50 51 CRITICALTHEORY & SOCIALJUSTICE UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL VOLUME 11, 2022

1 Patrick Macklem, “First Nations Self-Government and the Borders of the Canadian Legal Imagination,” McGill Law Journal 36 (1991), 391-92.

5 Macklem, “First Nations Self-Government and the Borders of the Canadian Legal Imagination.”

7 Gordon Christie, “Indigenous Authority, Canadian Law, and Pipeline Proposals,” Journal of Environmental Law and Practice 25 (September 1, 2013).

8 Ibid. 9 Ibid. 10 Ibid, 210 11 Ibid.

Russel Lawrence Barsh and James Youngblood Henderson, “The Supreme Court’s Van der Peet Trilogy: Naive Imperialism and Ropes of Sand,” McGill Law Journal 42 (1997).

rights.

Fundamental legal principles may also reveal transformative possibilities. John Borrows’s objection to the comprehensive power of Crown title and sovereignty provides an example. Borrows argues that the “rule of law” is a fundamental element of the Canadian legal system.17 Yet, the imposition of Crown Sovereignty and its denial of pre colonial Aboriginal authority contradicts Canada’s own definition of the rule of law, provided by the SCC, as an injunction against arbitrary power and an abhorrence of legal and political chaos.18 Specifically, by asserting its authority over Indigenous peoples and ignoring their “preexisting” status and authority, the Canadian government has exercised its power arbitrarily.19 This suggests that a properly functioning “rule of law,” a concept fundamental to the Canadian legal system, would prevent the government from neglecting and nullifying Indigenous authority.

In other words, Borrows’s argument can be reversed to support the possibility that the approach towards Indigenous rights may be transformed within the current legal system. However, this point of view would necessitate a shift away from systemic issues like the rigid application of “Anglo-Canadian” norms, problematic interpretive methods, and other applicative problems. These are not simply problems of “bad action” that can be fixed with a change in legal attitude or a revised method of interpretation. Therefore, the mere theoretical possibility of change is inconsequential without a commitment to broader systemic resolution.

III. The Improbable Reality of Transformative Possibility

As introduced in Part III, “transformative possibility” does not naturally entail positive developments for Indigenous self-government and Aboriginal ri-

17 Gordon Christie, “Indigenous Legal Theory: Some Initial Considerations,” in Indigenous Peoples and the Law: Comparative and Critical Perspectives, ed. Shin Imai, Kent McNeil, and Benjamin J. Richardson (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2009), 224.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

ghts. This section will delineate two primary reasons why this is the case: the pervasive issue of “Canadian paternalism,” and the reality that sufficient systemic alterations to the law’s power structures are infeasible.

The Canadian legal system’s approach to Indigenous affairs suffers from the problem of “Canadian paternalism,” whereby the Canadian state has assumed the power to unilaterally define the essence of the uniquely Indigenous experience that is at the heart of Indigenous rights. Similarly, Barsh and Henderson point out that the ruling in Van der Peet “entrenches European paternalism because the courts of the colonizer have assumed the authority to define the nature and meaning of Aboriginal cultures.”20 However, this is a problem for many, if not all existing Aboriginal laws, constitutional interpretations, and other legal categories. Each of these involve non-Indigenous Canadian entities inventing and imposing the criteria for Indigeneity, while also enforcing non-Indigenous norms and values onto an Indigenous context.

For instance, Barsh and Henderson look relatively favorably upon R. v. Sparrow for leaning towards Aboriginal law as the source of Indigenous rights.21 Yet, the decision in Sparrow still suffers from the problem of paternalism by forcing Aboriginal identity into a box created by the “colonial courts.” Particularly, Sparrow still imposes the requirement that an Aboriginal right must be tied to a practice or tradition that existed prior to Canadian sovereignty. Yet, as Barsh and Henderson themselves explain, a characteristic feature of any culture is its ability to adapt and change over time.22 The requirement of preexistence for Aboriginal rights thus plainly ignores the possibility that a given Indigenous practice or tradition may no longer have any clear ties to precolonial society. Thus, the Canadian legal requirement of “preexistence” can deny the validity of a practice or tradition, even if it is genuinely culturally significant to an Indigenous

20 Barsh and Henderson, “The Supreme Court’s Van der Peet Trilogy: Naive Imperialism and Ropes of Sand,” 1002.

21 Ibid, 1008.

22 Ibid, 1001-1002.

group by its own modern standards.

Indeed, the Canadian legal system is intrinsically linked with the problem of paternalism. If non-Indigenous Canadian legal and political bodies maintain the sole right to delineate the borders of Indigeneity, establishing true Indigenous self-government and a full scope of Indigenous rights remains improbable. This is because, by definition, Indigenous communities and individuals are not in control of how their cultural identities and practices are defined. One might argue that, while the problem of paternalism may be inescapable assuming no change to the attitudes and approaches within the current system, the argument for transformative possibility is predicated on such change. In Macklem’s terms, for example, it involves ditching the law’s overreliance on Anglo-Canadian legal understandings. Therefore, this problem is avoidable. Contrarily, I argue that an overhaul to the legal system of the character described here is not realistic.

First, it would simply mark a significant shift from the status quo. The changes proposed here (for instance, to escape the problem of paternalism) would require Canada to relinquish a certain level of control over the ability to adjudicate Indigenous affairs and to determine Aboriginal rights and identity. Importantly, the pursuit of Indigenous self-government and the notion of genuine Indigenous rights are not subject to a single interpretation; different Indigenous nations and individuals may have different understandings of these concepts. Yet, irrespective of one’s understanding of such objectives and outcomes, the changes required would entail a shift in the Canadian government’s current attitudes towards legal and policy decisions surrounding Indigenous peoples. At a minimum, this would involve a revised approach to constitutional interpretation, a larger role for Indigenous knowledge in policy and decision making, and a shift in the way that the common law regulates Aboriginal peoples’ relationship and rights to land. Yet, it will also likely require a more structural change in legislative and federal authority, and a withdrawal of total Crown sovereignty over Indigenous

affairs.

On one hand, it would be incorrect to claim that progress has not been made. For example, constitutional jurisprudence on Section 35 rights has shifted over time from “justifying infringement on Section 35 rights” to “finding that Section 35 recognises[sic], affirms and protects rights.”23 However, despite these positive developments, the courts still do not fully acknowledge Indigenous sovereignty and the independent status of Indigenous law.24 One could argue that this only means that this acknowledgement is the next step in the progression of Canada’s legal approach to Indigenous affairs. However, there is ample evidence to suggest that the government of Canada wishes to avoid this kind of progression.

For one, Canada has long exercised sovereignty over Indigenous peoples, and while historical action is not inherently predictive, expecting radical change from this is a dubious proposition. Furthermore, Canada’s interpretation of the doctrine of discovery “does not recognize the permanent sovereignty of Indigenous Peoples in Canada to land and resources.”25 While Macklem argues that this is an illegitimate interpretation of the doctrine,26 this does not mean the Canadian government itself will eschew this understanding. On the contrary, the state’s continued inclination to stamp out any perceived threat to Indigenous sovereignty, as noted by Christie,27 suggests a continued rejection of the permanence of Indigenous sovereignty that is consistent with the above interpretation of the doctrine of discovery. This issue is a microcosm of the intransigent and uncompromising position that the Canadian legal system has taken towards Indigenous rights.

Most Indigenous groups remain under the con-

23 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Linking Indigenous Communities with Regional Development in Canada. (Paris, France: OECD Publishing, 2020), 43, https://read.oecd-ilibrary. org/urban-rural-and-regional-development/linking-indigenous-communities-with-regional-development-in-canada_fa0f60c6-en#page45.

24 Ibid, 44.

25 Christian Aboriginal Infrastructure Developments (CAID), “Indigenous Sovereignty and Resources,” CAID.ca, Last modified July 28, 2019, http:// caid.ca/Dself_det_resources.html.

26 Macklem, “First Nations Self-Government and the Borders of the Canadian Legal Imagination.”

27 Christie, “Indigenous Authority, Canadian Law, and Pipeline Proposals,” 208.

52 53 CRITICALTHEORY & SOCIALJUSTICE UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL VOLUME 11, 2022