Protecting Peru’s Coastline

Artisanal fishers partner with Oceana to achieve a landmark victory

The impacts of oil spills outlast headlines and some spills aren’t reported at all

FALL 2023

Magazine

OCEANA.ORG

Oil Kills

Oceana honors Morgan Freeman at the 16th annual event

SeaChange Summer Party

Board of Directors

Sam Waterston, Chair

María Eugenia Girón, Vice Chair

Diana Thomson, Treasurer

James Sandler, Secretary

Keith Addis, President

Gaz Alazraki

Herbert M. Bedolfe, III

Ted Danson

Nicholas Davis

Maya Gabeira

César Gaviria

Loic Gouzer

Jena King

Ben Koerner

Sara Lowell

Kristian Parker, Ph.D.

Daniel Pauly, Ph.D.

David Rockefeller, Jr.

Susan Rockefeller

Lex Sant

Simon Sidamon-Eristoff

Rashid Sumaila, Ph.D.

Valarie Van Cleave

Elizabeth Wahler

Jean Weiss

Antha Williams

Ocean Council

Susan Rockefeller, Founder

Kelly Hallman, Vice Chair

Dede McMahon, Vice Chair

Anonymous

Samantha Bass

Violaine and John Bernbach

Rick Burnes

Vin Cipolla

Barbara Cohn

Ann Colley

Edward Dolman

Kay and Frank Fernandez

Carolyn and Chris Groobey

J. Stephen and Angela Kilcullen

Ann Luskey

Peter Neumeier

Carl and Janet Nolet

Ellie Phipps Price

David Rockefeller, Jr.

Andrew Sabin

Elias Sacal

Regina K. and John Scully

Maria Jose Peréz Simón

Sutton Stracke

Mia M. Thompson

David Treadway, Ph.D.

Edgar and Sue Wachenheim, III

Valaree Wahler

David Max Williamson

Raoul Witteveen

Leslie Zemeckis

Editorial Staff

Editor

Sarah Holcomb Designer

Alan Po

Senior Communications Manager

Gillian Spolarich

Creative Director

Patrick Mustain

Oceana Magazine is published by Oceana Inc. For questions or comments about this publication, please call our membership department at +1.202.833.3900 or write to Oceana’s Member Services at 1025 Connecticut Ave. NW, Suite 200, Washington, DC 20036 US.

Oceana’s Privacy Policy: Your right to privacy is important to Oceana, and we are committed to maintaining your trust. Personal information (such as name, address, phone number, email) includes data that you may have provided to us when making a donation or taking action as a Wavemaker on behalf of the oceans. This personal information is stored in a secure location. For our full privacy policy, please visit oceana.org/privacy-policy.

Oceana Staff

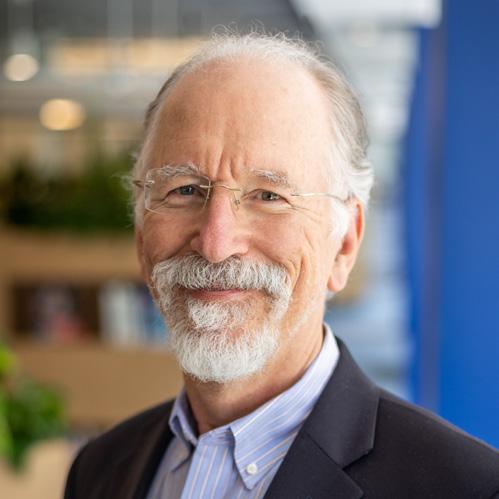

Andrew Sharpless

Chief Executive Officer

Jim Simon President

Jacqueline Savitz

Chief Policy Officer

Kathryn Matthews, Ph.D.

Chief Scientist

Matthew Littlejohn

Senior Vice President, Strategic Initiatives

Joshua Laughren

Senior Vice President, Oceana Canada

Liesbeth van der Meer, DVM

Senior Vice President, Chile

Christopher Sharkey

Chief Financial Officer

Janelle Chanona

Vice President, Belize

Ademilson Zamboni, Ph.D.

Vice President, Brazil

Pascale Moehrle

Executive Director and Vice President, Europe

Renata Terrazas

Vice President, Mexico

Daniel Olivares

Vice President, Peru

Gloria Estenzo Ramos, J.D.

Vice President, Philippines

Hugo Tagholm

Executive Director and Vice President, United Kingdom

Beth Lowell

Vice President, United States

Nancy Golden

Vice President, Global Development

Abbie Gibbs

Vice President, Institutional Giving

Dustin Cranor

Vice President, Global Marketing and Communications

Susan Murray

Deputy Vice President, U.S. Pacific

Vera Coelho

Deputy Vice President, Europe

Kathy Whelpley

Chief of Staff, President’s Office

Michael Hirshfield, Ph.D.

Senior Advisor

Cover Photo: © Ryan Miller Please Recycle.

FSC Logo

Features Contents To help navigate Oceana’s work, look for these six icons representing our major campaigns. Curb Pollution Protect Habitat Increase Transparency Protect Species Stop Overfishing Reduce Bycatch CEO Note Artisanal fishers are Oceana’s key allies in the fight against overfishing 3 | 4 | For the Win Oceana celebrates new victories around the world 6 | News & Notes Oceana partners with DreamWorks for World Oceans Day, premieres documentary in Rio Grande do Sul, and more Q&A Janelle Chanona on The People’s Referendum of Belize 8 | 10 | Protecting Peru’s Coastline Artisanal fishers achieve a victory that will support generations to come 16 | Oil Kills A closer look at how oil spills impact marine life, fishing communities, and the climate 29 | A Glimpse into El Cuyo Photographs captured by members of an artisanal fishing community in Mexico 27 | Supporter Spotlight Christina Ochoa: Storytelling for ocean conservation 22 | Ask Dr. Pauly How does deep-sea mining affect marine life? 26 | Oceana’s Victories Looking back at big wins over the last year 24 | Events Oceana hosts its 16th annual SeaChange Summer Party Parting Shot Striped parrotfish forage along Belize's barrier reef 32 | 1 Protecting Peru’s Coastline Oil Kills 10 16 © Oceana/Sebastián Castañeda © Oceana/Sebastián Castañeda

Call us today at +1.202.833.3900, email us at info@oceana.org, visit Oceana.org/give, or use the envelope provided in this magazine to make a donation. Oceana is a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization and contributions are tax-deductible to the fullest extent of the law. Please Give Generously Today A healthy, fully restored ocean could feed more than 1 billion people each day, forever. Your support makes an ocean of difference

© Oceana/Carlo Suárez

CEO Note

What’s the single biggest reason the oceans are depleted? In a word, overfishing. In two words, industrial overfishing.

Unlike artisanal fishers, whose boats are smaller, less mechanized (in some places, entirely manual), and not heavily powered, industrial fishing vessels can wreak substantial damage on the seafloor and capture and kill large numbers of other creatures who happen to be in the way, like sharks, sea turtles, and marine mammals. In Peru, 50,000 artisanal fishers provide 80% of the fish consumed by Peruvians. These fishers see firsthand the damage that mechanized fishing has done to the coast and their communities.

In June, Peru passed a law reinforcing its ban on industrial fishing in the first five miles offshore. This is a LOT of ocean nearly 25,000 square kilometers (over 15,000 square miles). Turn to page 10 and you’ll learn more about how empowered artisanal fishing communities, supported by

Oceana, used their voices and their stories to accomplish this victory.

Globally, about 60 million people are employed in small-scale fishing, and the United Nations estimates that nearly half a billion people “depend at least partially on engagement in small-scale fishing worldwide.” Artisanal fishers are often very valuable allies in stopping overfishing — which threatens the oceans and their livelihoods — and restoring ocean abundance. We are proud to work closely with these communities to help save the ocean and feed the world. Together, we brought a compelling message to decisionmakers in Lima and we have similarly productive alliances in many countries around the world.

At the end of this issue, you’ll find a special gallery featuring photographs captured by members of an artisanal fishing community in El Cuyo, Mexico. Well aware of the dangers posed by overfishing — which had already collapsed one of their most important

fisheries and hit the local economy years earlier — El Cuyo’s artisanal fishers are working with Oceana. Their photographs will provide you with an intimate and striking portrait of life in El Cuyo and what the ocean means to this community.

If you’re reading this issue of Oceana Magazine, you’re someone who wants an abundant and biodiverse ocean. You count on Oceana, together with our allies, to find ways to win the policies that make that happen. This issue again brings you news of progress. Our advocacy teams can do more if we give them more support. Thank you, as always, for your generosity.

For the Oceans,

Andrew Sharpless CEO Oceana

3 FALL 2023 | Oceana.org

© Oceana/Eduardo Sorensen

For the Win

Oceana and its allies achieved nine new victories to help protect and restore the world’s oceans

Chile Creates New Marine Protected Area, Pisagua Sea

Chile created a new marine protected area (MPA) called “Pisagua Sea” in northern Chile, following four expeditions led by Oceana and the Universidad Arturo Prat, as well as a scientific recommendation to protect this important area. During the expeditions, Oceana documented over 150 species, including large schools of commercially important species like anchovies and jack mackerel. Pisagua Sea, which measures 735 square kilometers (284 square miles) is also home to abundant macroalgae forests and smaller organisms like krill and crustaceans, making it the perfect environment for larger animals like fish, mammals, and birds to reproduce. The new MPA is the first in the country to protect not only marine habitat and species, but also the livelihoods of artisanal fishers, who rely on this richly biodiverse area to support their community and local economy. When Oceana started campaigning in Chile 17 years ago, less than 1% of the country’s ocean was protected. Today, thanks to campaigning by Oceana and its allies, more than 40% of Chile’s waters are now protected.

Four Plastics Victories in 2023

Brazil’s First Plastic-Free Zone

Oceana collaborated with the futuristic science museum, Museum of Tomorrow, to establish a program to eliminate single-use plastics.

New Laws in US States Reduce Plastic Waste

A new law in the U.S. state of Washington increases access to refillable water bottle options, requires hotels to eliminate single-use plastics for personal care products, and reduces pollution from plastic foam-filled floats and docks.

Panama Commits to Reduce Plastic Pollution

Panama’s new measures will stop an estimated 160,000 tons of plastic imported and consumed in the country each year.

Oregon passed two laws: The first prohibits plastic foam and bans PFAS, nicknamed “forever chemicals,” from food packaging. The second enables restaurants to use reusable containers.

4

© Oceana/Eduardo Sorensen

Mexico Addresses Illegal Fishing

Mexico joined the Port State Measures Agreement, a binding international agreement to prevent, deter, and eliminate illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing.

Seafloor Habitats

Protected in US Pacific Waters

Over 1,550 square kilometers (600 square miles) of habitat are now permanently protected, including deepsea corals, off Southern California.

New Protections Against Overfishing

Oceana Defends EU Fisheries Rebuilding Policy from Attack

Despite strong lobbying by the industrial fishing sector, Oceana and its allies successfully fought to keep the European Union’s main fisheries law intact.

Peru Reserves its Coast for Artisanal Fishers

Prohibiting large-scale fishing within the first five nautical miles of Peru’s entire coastline, a new law will benefit over 50,000 artisanal fishers who provide 80% of the fish consumed by Peruvians.

Read more on page 10.

5

FALL 2023 | Oceana.org

© Oceana/Christian Lizarraga

News & Notes

Documentary

shows fish rebounding in Rio Grande do Sul, four years after victory against bottom trawling

In the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul, fish are coming back. Oceana’s documentary, “12 Miles: A Fight Against Bottom Trawling,” shows the return of several fish species four years after the law established a bottom trawling ban along the 12-mile coastline of Rio Grande do Sul. Since the 1980s and 1990s, highly destructive bottom trawling had swept fish schools away from the Rio Grande do Sul coast, threatening fishers’ livelihoods. “The boats would trawl, and the shore would become a carpet of discarded dead fish,” one fisher described. Featuring testimonials from small-scale fishers, scientists, environmentalists, and politicians, the film depicts “before and after” the bottom trawling ban.

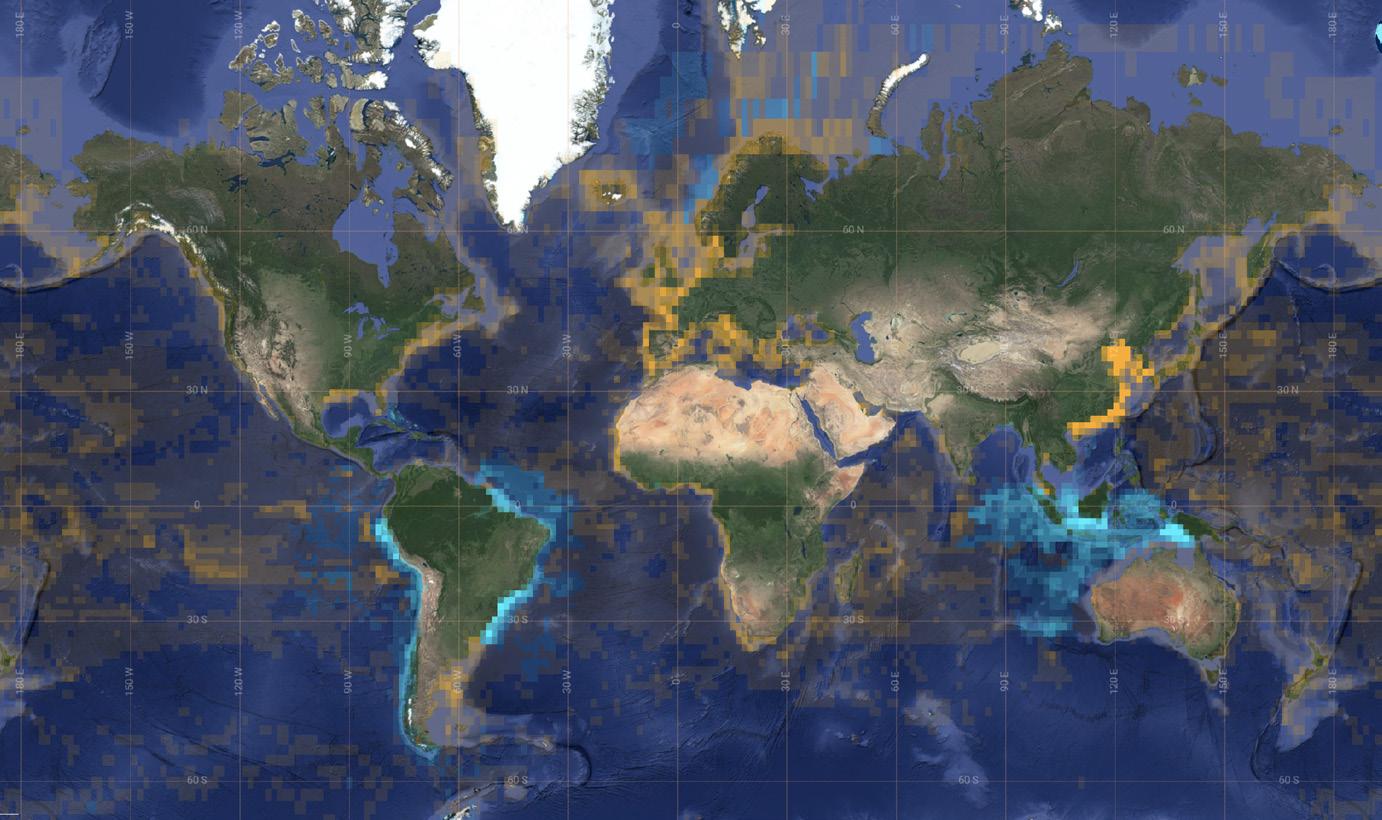

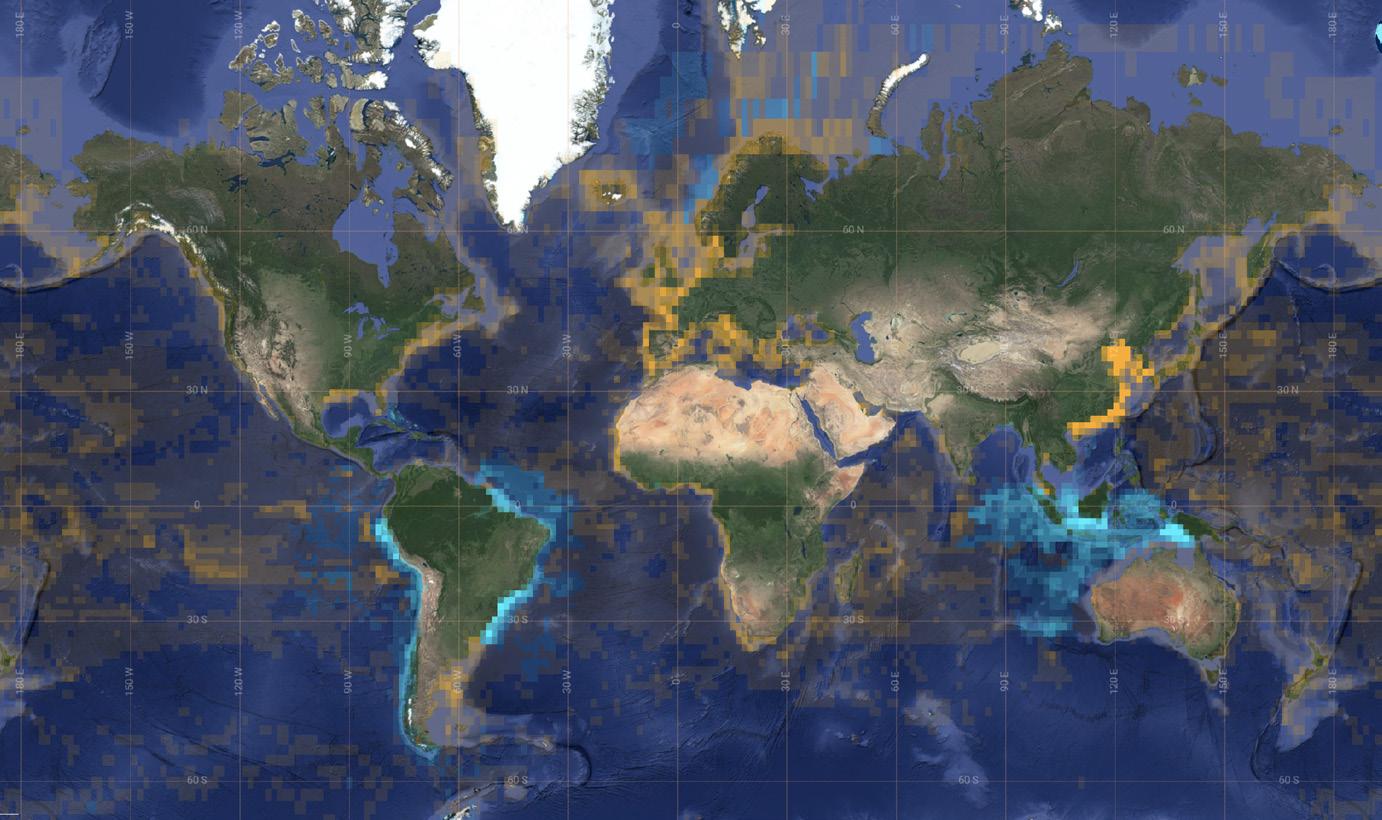

Global Fishing Watch receives TED Audacious grant

Global Fishing Watch has revolutionized our ability to track commercial fishing activity worldwide — and a new grant from the TED Audacious funding initiative will power the next phase for the big data technology platform. Founded by Oceana in partnership with SkyTruth and Google in 2016, Global Fishing Watch has leveraged satellite data to create the firstever global map that tracks fishing activity in near-real time, for free, bringing illicit activity into the light. With its Open Ocean Project, Global Fishing Watch will expand

to cover 100% of industrial fishing vessels, hundreds of thousands of small-scale fishing boats and

non-fishing vessels, and all fixed infrastructure at sea, including aquaculture and oil rigs.

6

Oceana campaigned alongside artisanal fishers to pass a law banning bottom trawling in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul in 2018, which safeguards more than 13,000 square kilometers (over 5,000 square miles) of ocean.

© Oceana/Rodrigo Gorosito

The Global Fishing Watch map is the first open-access platform that visualizes and analyzes vessel activity and marine traffic.

© Global Fishing Watch

Oceana partners with DreamWorks Animation, OUTFRONT Media, for World Oceans Day

To celebrate World Oceans Day on June 8, Oceana teamed up with partners DreamWorks Animation and OUTFRONT Media to drive awareness about its campaigns. Premiering June 30, DreamWorks Animation’s action comedy, “Ruby Gillman, Teenage Kraken,” featured actors Annie Murphy and Lana Condor in a story about a young woman who discovers that she’s a member of the royal family of mythical sea krakens, destined to protect the Seven Seas. A public service announcement featuring both actors supported Oceana and its campaigns. Oceana also partnered with OUTFRONT Media,

one of the largest outdoor media companies, for National Oceans Month in the United States to create an ad campaign featuring whimsical underwater scenes of marine life flanked by messages like

“Protect Our Mysterious World” in high-traffic locations to emphasize the beauty of marine life and our responsibility to protect it.

“Bird flu” affects mammals and marine life

The latest strain of avian influenza, commonly called “bird flu,” has not only affected millions of chickens, geese, and ducks around the world — it has also spread to sea birds and marine mammals. The virus is distributed when wild birds migrate, and seabirds are especially migratory. The virus expanded from North America to Central and South America, including Chile, Ecuador, and Peru, even reaching as far as the Arctic. As of July 21, 2023, 18,000 marine animals had died in an avian flu outbreak on Chile's north coast. Thousands more sea lions died in Peru. Oceana generated increased awareness in Chile and Peru about how the virus transmits, urging the public to reduce contact with birds in order to slow the spread and protect marine life.

FALL 2023 | Oceana.org 7

Humboldt penguins are among the species in Chile impacted by the rapidly spreading “bird flu.”

© Oceana/Lucas Zañartu

Oceana partnered with DreamWorks Animation during World Oceans Day to promote the new film “Ruby Gillman, Teenage Kraken” and to drive awareness around Oceana’s campaigns.

Janelle Chanona joined Oceana as its leader in Belize in 2014. The longtime Belize news anchor and Belmopan native previously ran her own media company and produced documentaries for environmental groups. A dedicated diver, she frequents Belize’s barrier reef and is determined to ensure that the reef, which all Belizeans love and depend on, is protected and made healthier than ever before.

Janelle Chanona on The People’s Referendum of Belize

Growing up in Belize, what experiences shaped your passion for ocean conservation?

JC: My twin and I grew up on the banks of the Sibun River, at the feet of the Sleeping Giant mountain range along the Hummingbird Highway. It’s even more picturesque than it sounds. We learned to swim while learning to walk. At Easter and during summer holidays, we visited relatives on offshore cayes [keys].

Our family turned all those experiences into outdoor classrooms. Our grandfather taught us that trees along the river protected our property from erosion during flooding. Our aunt described seeing crabs wedge themselves into coconut fronds ahead of big storms, a natural warning system. Our cousins helped to point out all the critters hiding in the seagrasses, highlighting the ecosystem’s key habitat role. In that context, you can see why asking questions and stewarding the environment comes naturally to us. And looking back at my professional career, I realize now that I’ve always been an advocate.

Over the last decade, Belizeans have steadily opposed oil drilling in their country’s waters. Tell us about Oceana’s past victories against offshore oil exploration in Belize and how they were achieved.

JC: It’s fair to say that the inherent threats of offshore oil drilling really registered in Belize when we witnessed the BP oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. From that point in April 2010 to achieving Belize’s legislated moratorium on offshore oil almost a decade later in December 2017, it was never lost on Belizeans that offshore oil exploration and exploitation is a dangerous and dirty industry that undermines the cultural and economic value of our fishing, tourism, and way of life.

I’d like to tell you this very clear threat made the campaign “easy,” but it really wasn’t. We pulled out all the stops — science, legal, outreach, everything we could, to ensure Belizeans were empowered with the information they needed to make informed decisions on offshore oil. And to their credit, Belizeans never wavered on this issue. When it came time to

8 Q+A

© Oceana/JC Cuellar

stand up, they jumped! It was a sensational moment to witness and more importantly, it was impossible for leaders to ignore. The citizen-led reaction to offshore oil development — that people power — is why we proudly call the offshore oil moratorium 'The People’s Law.'

Today Belize is up against the threat of offshore oil once more. What changed and what is at stake?

JC: Oil is an overarching threat. That means the Belize we know, love, and need is at stake. Our identity. Our livelihoods. It’s a bread and butter issue: everything is at stake.

Our government leaders changed in November 2020 following national elections. We were very optimistic that the new administration would be interested in strengthening the moratorium. That political will would have been globally significant and we wanted to champion that kind of leadership.

But in November 2022, the government told us they wanted to conduct seismic surveys and to lift the moratorium on offshore oil — and all without public notice, much less approval. Talk about having the wind taken out of your sails. The administration’s position subsequently shifted — the Prime Minister himself wrote as much in a letter to Oceana.

But the scenario underscored the need for clarity and stability moving

forward. That’s why we’ve worked to include a referendum mechanism in the offshore oil moratorium to ensure that any administration who wants to lift the moratorium must first go to the electorate for guidance. Such a major decision needs to be informed, collective, and transparent.

What is Oceana doing to ensure that the people of Belize have their voices heard?

JC: Oceana is committed to sharing science, enhancing community outreach, and advocating for science-based policies and legislation that empower the people of Belize. We’re also amplifying the voices of Belizeans to national and international audiences, which is critical to making sure Belizeans’ agency is recognized and respected, and to counter the mis- and disinformation about the realities of offshore oil.

Before you joined Oceana, you were a well-known television newscaster. What has your career taught you about building powerful connections with the public?

JC: I’m always learning. But one commonality I’ve found between journalism and advocacy is that everyone has a story and something to say, irrespective of age, background, and anything else some might use to create division. My role with Oceana has allowed me to maintain, enhance,

and forge new connections with fellow Belizeans — including family, friends, neighbors, and colleagues. We’re all interconnected. If we don’t speak up and stand beside each other, the bad actors “win.” We must care for one another. It’s as simple as that.

Tell us about your experience leading this charge. What have you come up against, especially as a woman leader working alongside other talented women on your team?

JC: It’s hard to sugarcoat my response here: the patriarchy is real; misogyny is real. I do not think it’s lost on anyone that these types of ideologies undermine a robust democracy and effective policies at a time when everyone’s roles need to be strengthened. But it’s so inspiring to work alongside and to witness younger Belizeans refuse to let these harmful beliefs discourage them from responding to the call to leadership or even just to be honest about their feelings on social media. The next generation does not hold back! Because of them, I have every confidence the future will be more inclusive.

In a few words, what inspires you to keep fighting?

JC: To borrow from John F. Kennedy: If not me, then who? If not now, when?

FALL 2023 | Oceana.org 9

Protecting Peru’s Coastline

By Sarah Holcomb

By Sarah Holcomb

Feature

10

Artisanal fishers achieve a victory that will support generations to come

© Oceana/Sebastián Castañeda

Armando Paiva grew up fishing in Piura, Peru, like his father and grandfather. Full of vibrant marine life and commercially important fish like anchoveta, the first five nautical miles off Peru’s coast cover a vast, biodiverse area important to artisanal fishers, who provide 80% of the fish that feeds Peru’s population. But much can change in a generation.

Fishing vessels now lower weighted nets close to the coast, unselectively scooping up fish and risking damage to the seafloor in the process. While sometimes the catch is destined for Peruvian plates, other times it is bound for processing plants, where the fish are ground into fishmeal and shipped to

foreign countries as feed for livestock and farmed fish.

Now Paiva is a board member of the El Toril Artisanal Fishermen’s Union in Piura, and his career involves not only fishing but advocating on behalf of artisanal fishers in his community and building alliances with others across the country. Their goal: strengthen Peru’s General Fisheries Law to preserve their livelihoods, communities, and the health of the ocean. Their opposition: an industrial fishing industry with deep pockets and equally deep political ties. Yet, thanks to the resolve of Peru’s artisanal fishers and Oceana’s legal support, the tide has finally turned.

FALL 2023 | Oceana.org 11

Fishing vessels dock at Matarani, a port city in Southern Peru.

A purse seine scoops up fish in Peruvian waters.

© Oceana

The sea at stake

Peru’s coastline stretches over 3,000 kilometers (nearly 2,000 miles). And whether you’re at the warm beaches of Piura in northern Peru, or the port of Matarani in the south, the waters closest to the coast are especially vital to the health of ocean ecosystems and local fisheries.

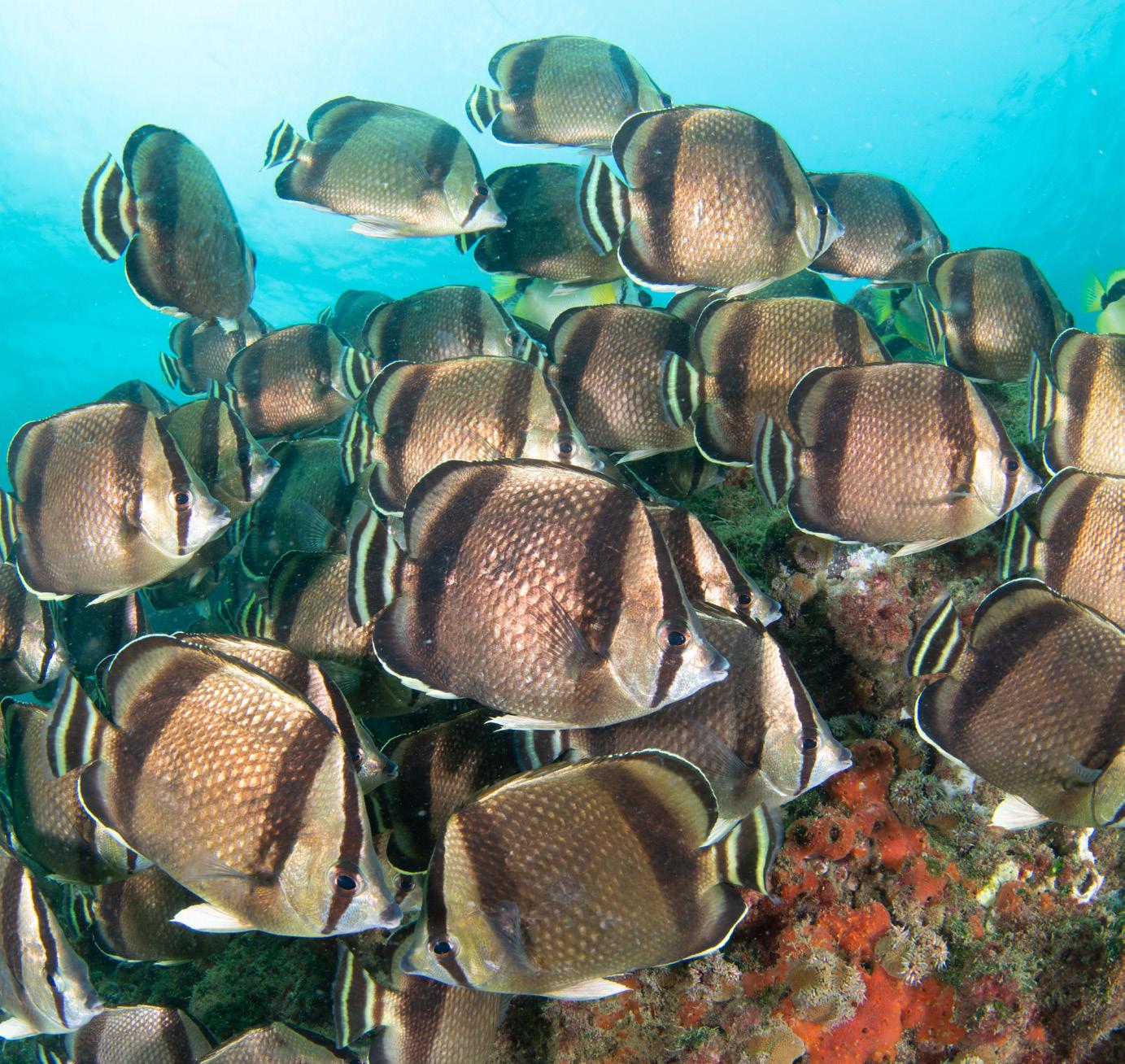

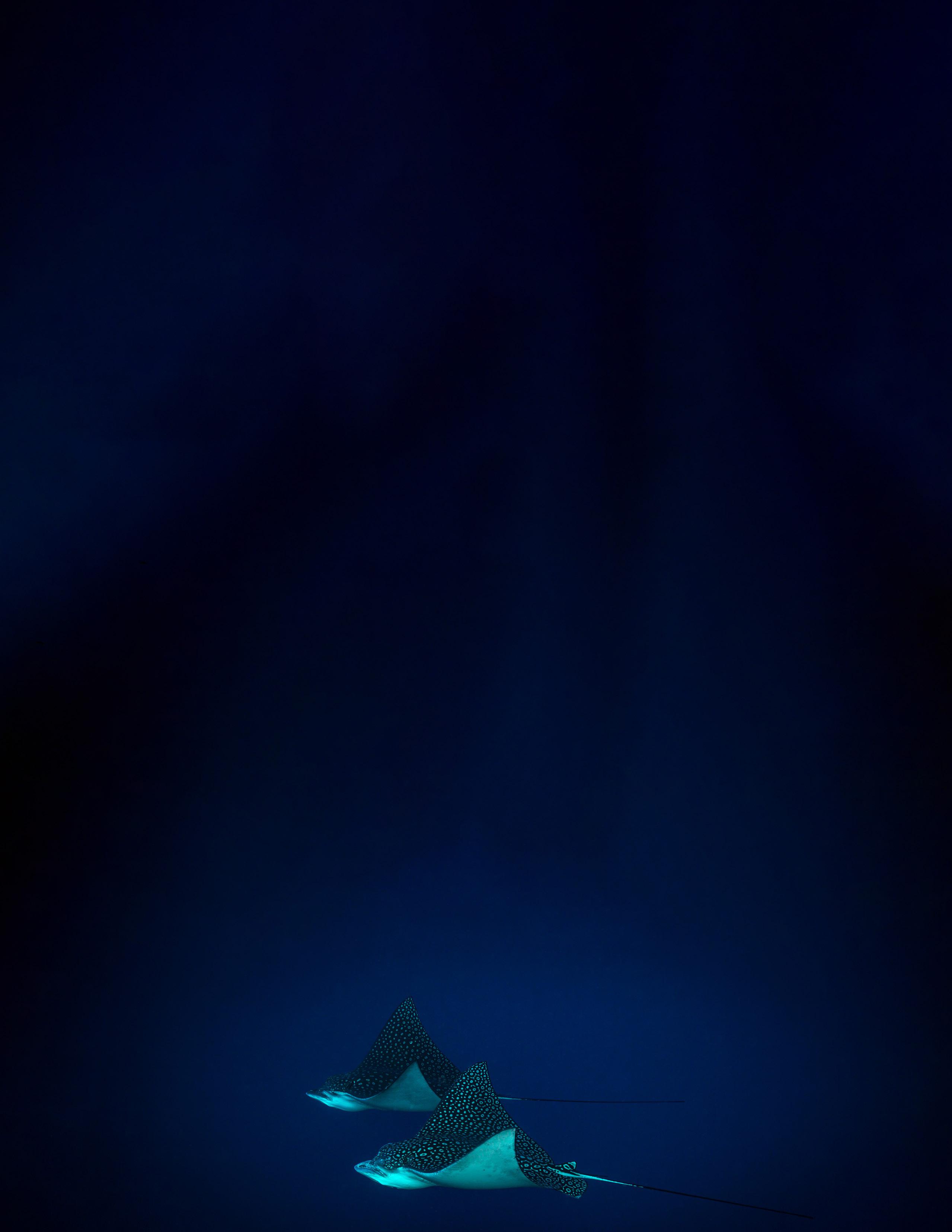

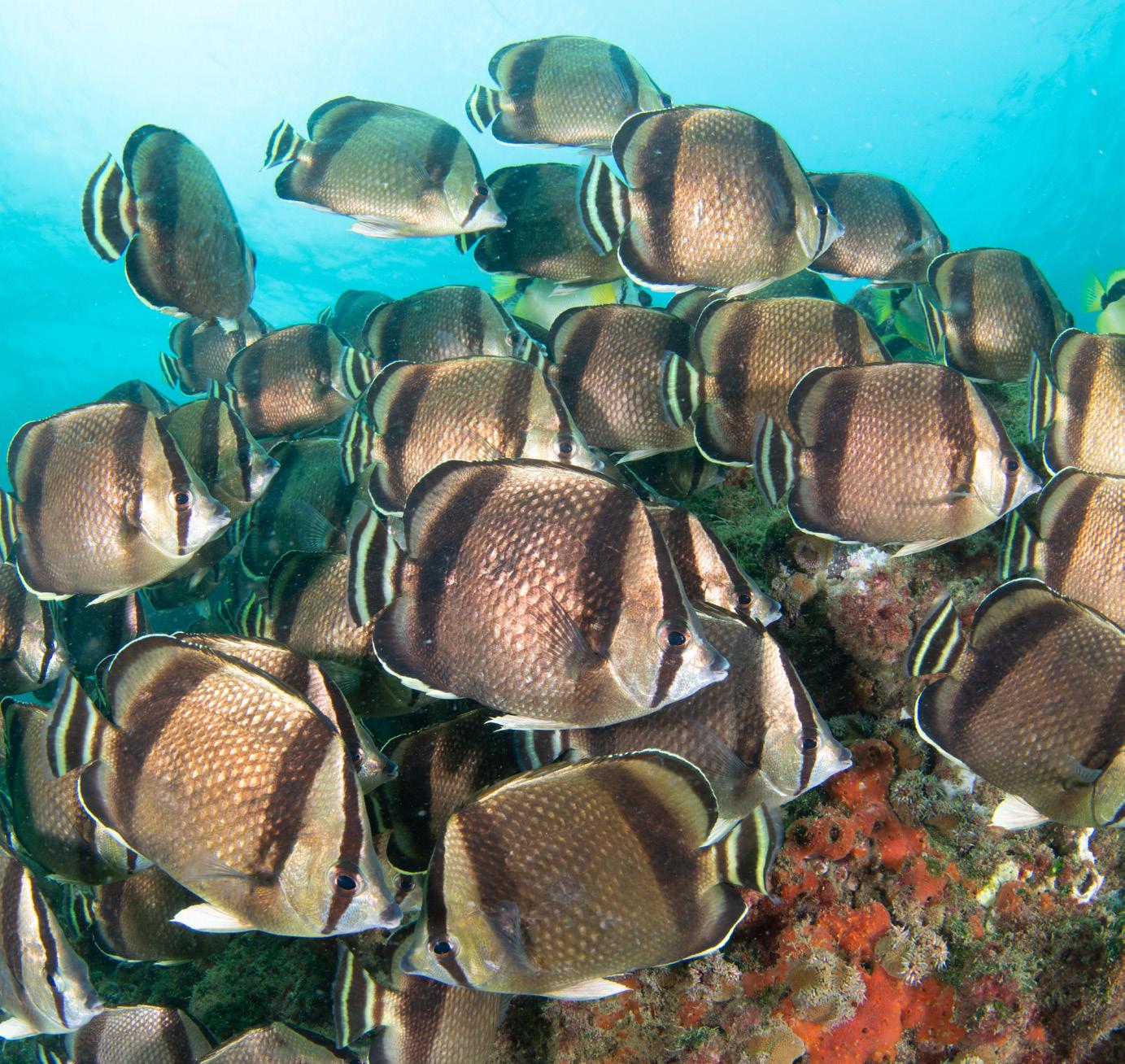

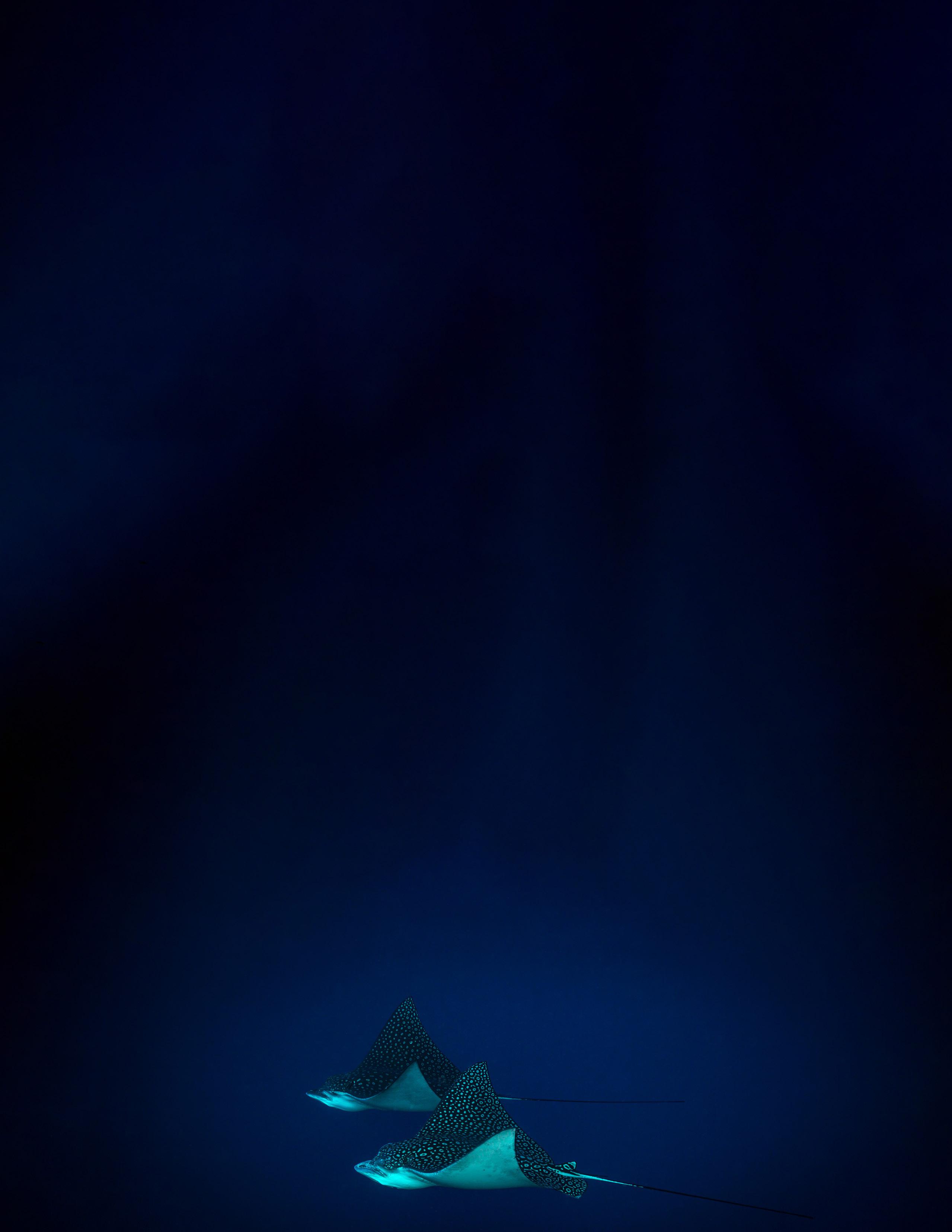

These “first five miles” — shorthand for the massive zone that extends five nautical miles (about 5.8 miles or 9.3 kilometers) from the coast — are as captivating as they are important. Covering about 24,755 square kilometers (9,558 square miles), this coastal zone is home to abundant marine life. Here green sea turtles sail through schools of fish while seahorses cling to seagrass with their tails. Sting rays circle coral reefs, home to octopuses, anemones, and nudibranchs — or sea slugs, as they’re often called — whose soft bodies mirror their vibrant surroundings with designs fit for fine art. Oceana’s science and audiovisual team saw all of this and more during a December 2022 expedition off Peru’s northern coast.

The first five miles “are likely more significant for biodiversity than any other coastal zone,” argues Juan Carlos Riveros, Oceana’s Science Director in Peru. Because the seafloor throughout the first five miles is generally within light’s reach, plants like seaweed and kelp flourish. And these plants provide handy havens for fish to hide or disguise themselves, which is key for young fish to survive and fisheries to stay healthy.

This stretch of sea serves as the reproductive zone for Peruvian anchoveta, the largest singlespecies fishery in the world. Anchoveta is a nutrient-rich protein

source, and despite much of it being used to make fishmeal — which is then used for aquafeed, or in products like fish oil supplements — it’s increasingly being canned or consumed fresh, including in Peru’s artisanal fishing communities.

Most artisanal fishers, Riveros says, sail small boats, no more than 30 feet long, to catch anchoveta and other fish close to the coast. They use gear like hand-held nets and lines. “It’s very selective — you take what you want, and put the others back,” Riveros explains.

Industrial fishers, on the other hand, operate with an unselective, take-all approach that uses mechanized fishing gear called “purse seines” — weighted nets that surround a school of fish, capturing the fish and sometimes other creatures that happen to be in the way. Many small to medium-sized boats claim the name “artisanal,”

but use purse seines instead of artisanal, hand-operated fishing gear, causing harm to both ocean ecosystems and artisanal fishers’ livelihoods as a result.

During dozens of workshops

Oceana hosted along Peru’s coast, artisanal fishers discussed how to update Peru’s General Fisheries Law to shore up protections. Two changes were needed: One, industrial fishers must be prohibited from entering the first five miles, no exceptions. And two: Only artisanal fishers should have access to the three miles closest to the coast. These changes would go an especially long way in Peru’s southern regions, where Peru’s government had repeatedly authorized exceptions for large industrial vessels.

Peru’s Congress would need some persuading. And artisanal fishers would be the ones to do it.

12 Feature

A school of three-banded butterflyfish swim near a coral reef in the first five nautical miles off the coast of Peru.

© Oceana/Eduardo Sorensen

All paths lead to Lima

Legislative change rarely succeeds on the first try. Before artisanal fishers, Oceana, and other allies took their proposal to Peru’s Congress, other attempts had already been made to rewrite or revamp the General Fisheries Law to better protect artisanal fishing communities and the country’s oceans, but this one seemed best timed and positioned for success.

Put to an initial vote, Peru’s Congress voted in favor of the updated protections — but without the supermajority required by Peruvian law. That meant a second, and final, vote.

Up against a powerful industry, Peru’s artisanal fishers were historically overruled or unconsidered. Undeterred, they bussed approximately 18 hours from their coastal hometowns to the capital. Ten fishing leaders from across the country, including Paiva, arrived in Lima to give communities like theirs a fighting chance.

The industrial fishing industry was armed with a formidable public relations guild and a reliable, go-to argument: industrial fishing provides jobs. Technical cases about the damage wrought by fishing gear would not be convincing enough — so the fishers told their stories.

The day of the vote, the fishers “chased congresspeople around the

building,” remembers Carmen Heck Franco, Oceana’s Policy Director in Peru, with a laugh.

Fishers listened to congresspeoples' concerns and refuted industry arguments. They told Congress members how they wanted their grandchildren to be fishers someday, but worried that with few fish in the sea they’d end up hungry. Their arguments were convincing. Even one staunchly opposed congressman came around to their side.

Meanwhile, industry members could tell the fishers were making waves. Their new strategy: postpone the vote.

FALL 2023 | Oceana.org 13

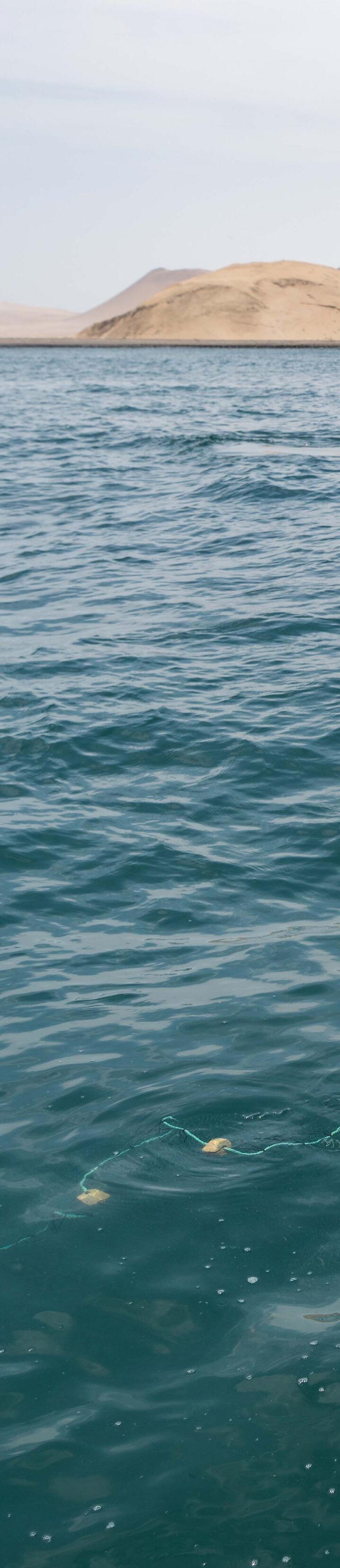

Most artisanal fishers sail small boats, no more than 30 feet long, to catch anchoveta and other fish close to the coast using selective gear like hand-held nets and lines.

© Oceana/Andre Baertschi

© Oceana/Andre Baertschi

Put it to a vote

Not only was the industrial fishing industry’s attempt to delay the vote unsuccessful — officials ushered the artisanal fishing leaders into Congress’ auditorium to witness the final vote. While the fishers sat in the balcony, the president of Congress saluted them for coming. After Congress members debated, the time to vote had come.

The vote was unanimous: The protections passed, with those against abstaining altogether.

For many of the artisanal fishers, this victory seemed too good to be true. For years, their voices had been drowned out.

“For me, the law is important because it vindicates ancestral rights for artisanal fishers. We have regained control of the five miles of the biodiversity of that zone,” says Juan Moina, regional coordinator and former president of an artisanal fishing federation in Peru’s Arequipa region. “The unity of the leaders at a national level has obtained results...and we have managed to achieve better living conditions for artisanal fishers.”

The law supports fishing that is “carried out with respect for nature,” Paiva told reporters, “...and to carry [it] out as an artisan does: with selective nets, respecting the fishing zones, the natural banks, the reproduction seasons of the resources and the closed seasons.”

With the new law in place, any vessel that has more than 32.6 metric tons of whole capacity — that is, an industrial vessel — must fish outside the five miles, no exceptions. Any mechanized purse seiner, no matter the size, is prohibited within three nautical miles.

As directed by the law, Peru’s fishing authority will approve a list of the allowable fishing gear safe for ocean habitat throughout the coastal zone. Partnering with Oceana, artisanal fishing leaders are drafting bylaws so the protections can be practically implemented across the country.

This victory not only marks a milestone for Peru’s fishing communities and seas, but for artisanal fishers around the world who are mobilizing to defend their livelihoods and their oceans from the threats they face every day. In Brazil, 150 artisanal fishing leaders drafted a bill proposal to modernize the country’s fisheries policy. In the Philippines, fisherwomen are building a coalition to speak up to the challenges they face. In Mexico, Oceana is partnering with the fishing community of El Cuyo in Yucatan to create a no-take zone to conserve marine ecosystems and local lobster fishing livelihoods.

As Wilfredo Suárez Morales, the cocoordinator for a sustainable artisanal fishing network in Peru’s provinces of Huacho and Huaral, puts it, “If we, the artisanal fishers, work together, thinking of future generations, I’m sure that we will all win, and we will have marine resources and a stable economy.”

14

Feature

© Oceana/Andre Baertschi

For me, the law is important because it vindicates ancestral rights for artisanal fishermen. We have regained control of the five miles of the biodiversity of that zone... and we have managed to achieve better living conditions for artisanal fishermen.

–Juan Moina

FALL 2023 |

An artisanal fisher uses a handheld “curtain net” as he fishes off the coast of Ica, a city in Southern Peru.

OIL KILLS

Oil spills poison marine life and hurt coastal communities. And they happen more often than you think

By Sarah Holcomb

By Sarah Holcomb

The MT Princess Empress oil spill contaminated the waters and marine life surrounding the Philippine island of Mindoro.

Fishers' boats stay on the coast following the local government's ban on fishing.

16

Feature

© Oceana/Jessie Floren

When a massive oil tanker capsized off the Philippine island of Mindoro in February 2023, spilling over 800,000 liters (over 200,000 gallons) of oil into the sea, hardly anyone or anything — from the smallest mollusk, to seabirds, to local fishing communities, remained unaffected. Even mangroves flanking the island — the “guardians of the coast” that have defended coastlines from typhoons — were not safe from the toxic chemicals unleashed by the sunken MT Princess Empress ship.

Standing in the shifting sediments where land and sea meet between tides, mangrove trees not only buffer the shore from floods and other disasters, but they keep us all afloat in a warming world, absorbing carbon four to five times more effectively than terrestrial forests. In a sad twist, however, they’re especially susceptible to a major source of the climate-changing pollution they protect us from: oil.

As the oil slick spread across 120 kilometers (75 miles) of turquoise waters and white sands turned black on nearby islands, a tragic, but alltoo-familiar story took shape: marine life slathered in sludge, smothered corals, oiled mangroves, closed beaches, oil-wrought illnesses, fishing bans, and lost livelihoods. Beyond the stained shore, oil impacts the marine environment, the climate, and coastal communities. Whether or not they make headlines, oil spills wreak havoc on everything they touch.

FALL 2023 |

Upon closer look Few fish in the sea

Determined to document the MT Princess Empress oil spill’s aftermath firsthand, Oceana’s team in the Philippines saddled onto motorbikes and headed for Mindoro, where oil had been detected near more than 60 coastal villages. There they saw oil coating mangroves along the shoreline, recalls Diovanie De Jesus, Oceana’s Campaign and Science Specialist in the Philippines.

Oceana’s Database Administrator in the Philippines, Jessie Floren, captured photos of a small snail covered in glossy black oil clinging to a mangrove — a snail that locals commonly eat, but, like so much of the local marine life, is now contaminated.

Many birds, fish, and invertebrates die within two weeks of an oil spill. And animals that survive aren’t out of harm’s way. After the infamous BP Deepwater Horizon oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, for example, dolphins suffered lung issues, anemia, and pregnancy problems. Lightly oiled mangrove forests may recover within a couple of decades, while heavily oiled mangroves often defoliate and die within a few months, taking fifty years or more to recover, if they do at all.

As of 2016, the past six decades had seen “at least 238 notable oil spills along mangrove shorelines worldwide,” a study by mangrove ecologist Dr. Norman Duke found. At least 6 billion liters (1.7 billion gallons) of oil had been released into mangrove-lined coastal waters, oiling up to 19,400 square kilometers (nearly 7,500 square miles) of mangrove habitat.

In the water, oil grabs onto seaweed and seagrass, blocking the light the plants need for photosynthesis and jeopardizing their survival. Coral reefs, which

support entire ecosystems, can be “suffocated” by oil, says Dr. Sarah Giltz, Marine Scientist at Oceana. According to scientists at the University of the Philippines, the MT Princess Empress oil spill could threaten 360 square kilometers (140 square miles) of coral reef, mangroves, and seagrass.

Tubig, which translates in English as “living water,” says that in her neighborhood, “families earn by net fishing, others set out to sea to catch fish, some gather shells and seaweed to sell. Now, we cannot do that anymore.”

Months after the spill, fishers still can’t fish due to oil contamination. “Recent fish kills are directly related to the oil spill,” Nikka Oquias, Oceana’s Policy Specialist in the Philippines, emphasizes.

“Eighty percent of families in our community rely on this [ocean] for their livelihood,” explains Edlyn Prado, who is the village chief in Barangay Misong, one of the villages of Pola municipality, ground zero of the oil spill in Mindoro. “While they receive financial assistance, it isn’t enough for the expenses of their children who need to go to school every day.”

Annabell Ferrera Fabula, who lives in the village of Buhay na

The Philippines government paid fishers to help with clean-up — hard work that requires fishers to encounter toxic chemicals. People took short, two-hour shifts. Doctors observed a spike in illnesses, and residents reported dizziness, headaches, and other

18 Feature

© Oceana/Jessie Floren

The oil slick from the Princess Empress oil spill has spread across 120 kilometers (75 miles) of ocean and impacted mangroves flanking the coast.

© Oceana/Jessie Floren

An oil-coated snail clings to a mangrove.

symptoms, as oil continued to contaminate water and fish.

Meanwhile, oil continued pouring from the site of the ship, satellite images showed, reaching the Verde Island Passage known as the "center of the center of marine shore fish biodiversity" in the world. The oil was suctioned off the MT Princess Empress more than three months after the spill.

A lack of public information — including the “fingerprint,” or chemical makeup of the oil — makes responding more difficult, which is why Oceana and others are urging increased transparency from the government. Oceana continues to campaign to protect mangroves and is developing policy recommendations for the Philippine government to help with addressing future oil spills, which the country's Congress invited Oceana to provide during its legislative investigations.

“Oceana’s role is really to help amplify the information on the oil spill, especially the calls from the people affected,” Oceana’s Senior Campaign Manager Danny Ocampo says. “It’s important to keep the issue in the public eye.”

A few months after the spill, media attention already started to wane. And this challenge only becomes greater with time.

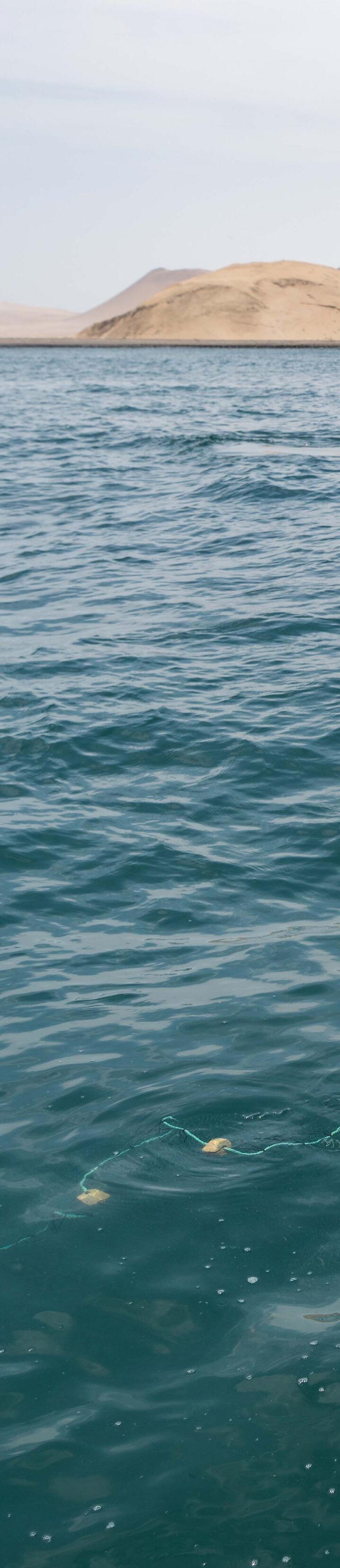

Keep the pressure on

A year and a half has passed since the Repsol spill leaked more than 1,891,500 liters (nearly 500,000 gallons) of crude oil off the central coast of Peru. Still, Oceana has fought to keep the damage and injustice it caused at the fore.

The spill happened close to Peru’s coastline — within the first two miles — essentially wiping away

all signs of life, from crustaceans and mollusks, to sea birds, to Humboldt penguins and seals, says Oceana’s Science Director in Peru, Juan Carlos Riveros. Some species will take years to recover, while others, especially those which migrate within a local area, like sea otters, might never return. The first organization to livestream the oil spill’s aftermath, Oceana used Instagram to bring light to an issue few news outlets had picked up due to the influence of Repsol, the energy company responsible for this disaster (along with others).

Repsol hired Peruvians from the affected areas to help with cleanup. Many did not have access to health services. With no protection except cloth masks leftover from the pandemic and no running water at home to rinse off the oil, they faced heightened risk.

Six months later, Oceana lowered a stunt mannequin into the sea. Surfacing the mannequin, visibly covered in oil, showed that the

waters were still contaminated by the Repsol spill. Instead of scientifically testing fish from these waters, which likely would have revealed oil contamination, government testers used the “smell test” and declared it fit for consumption, Riveros says.

Oceana’s team continues to bring visibility to Repsol’s violations and the spill’s effects on fishing communities. In May 2023, Oceana posted a TikTok revealing that Repsol had offered to send school supplies to fishers’ families, only for the fishers to receive backpacks and notebooks branded with the name of the company responsible for their lost livelihoods.

That’s not all, the video explained: Through an out-ofcourt agreement, Repsol tried to convince the fishers to withdraw their complaints and offered to pay them an amount that, in most cases, did not equal half of what they earned annually before the disaster.

FALL 2023 | Oceana.org 19

© Oceana/Sebastián Castañeda

A volunteer removes oil-covered seabirds from the the Ventanilla Sea following the Repsol oil spill in Peru.

Oceana’s team is helping impacted fishers request their rightful compensation, says Riveros. Oceana served as advisor to a committee in Peru’s congress preparing a report that points out the company’s violations — as well as the Peruvian government’s failings in following through on its rapid response protocols after the spill.

“We are fighting for communities and the ocean,” Riveros says. “This isn’t the classical ‘we are doing good,’ but real action, real response.”

Oil spills don’t stop

Massive oil spills like those in the Philippines and Peru grab headlines, but countless other spills are rarely or barely reported. In the United States, for example, over 6,000 oil spills occurred between 2010 and 2020 — an average of almost two spills every day.

Small, routine oil spills lead to chronic oil pollution. For five decades, United Kingdom oil and gas production in the North Sea has taken place largely out of sight — and out of mind. “In Deep Water,” produced by Oceana and the climate campaign group Uplift, is the first-ever comprehensive review of how the U.K.’s oil and gas industry is damaging the seas.

“I think one of the reasons we don’t hear so much about these everyday oil spills is because oil platforms are given an ‘allowance’ of how much they can legally release into the ocean” says Alyx Elliott, Campaigns Director for Oceana in the U.K. These daily oil spills deposit vast volumes of oil into the ocean over time — and satellites can see some of them from space. This oil seeps into marine protected areas (MPAs), some of which aren’t off-limits to oil drilling in the U.K.

On the international front, the U.K. has helped lead the charge to protect 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030; but when “we look in our own backyard, the government is supporting oil drilling right in the middle of marine protected areas,” Elliott says.

MPAs are among the world’s most important places for safeguarding marine life and habitat. They also help build resilience against the effects of climate change, a team of international scientists found in their 2017 study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Oil pollution here poses a particular danger to the ocean’s resilience.

Stopping the expansion of offshore drilling has the potential to reduce emissions more than any other ocean-based solution, Oceana’s analysis showed in 2022. And it’s not just oil spills that do damage; every step of oil and gas production harms ocean ecosystems, including the noise

pollution it creates — especially seismic airgun surveys. Exploring, drilling, and decommissioning oil and gas infrastructure also releases dangerous chemicals.

In 2020, Oceana and a coalition of groups sued in U.S. federal court and successfully prevented seismic airgun blasting in the Atlantic. Successful campaigns also led East and West Coast governors to oppose offshore drilling off their state's coasts, and even the U.S. president to change course and withdraw four East Coast states’ waters from offshore oil and gas leasing in 2020, effective for 10 years. These victories stop oil spills at the source.

Oil’s impact on marine life can be felt for decades, if not forever. “Everything down to small zooplankton all the way up to dolphins and whales can be really hurt by oil spills,” says Giltz, “and in some cases the environment will be damaged in ways that won’t ever recover.”

20 Feature

© Oceana/Sebastián Castañeda

According to local reports following the Repsol spill in Peru's waters, oil from the disaster was being cleaned up with dustpans, shovels, wheelbarrows, and buckets.

Not over yet

Marine life, including the resilient mangroves and abundant fish of the world, cannot withstand oil’s poisonous effects, nor the climate crisis that oil and gas are fueling. And virtually any coastal community could find itself someday in a tragic headline. “We must protect as much ocean habitat as we can, while working to stop the expansion of offshore drilling,” says Giltz.

In the Philippines, that means campaigning for a protected “greenbelt” that will shield mangroves from the threat of offshore oil. In Peru, it means holding oil companies responsible for the damage they do while

helping fishers achieve justice. In the U.K. and the U.S., it means working to prevent any new oil leases from going forward. In Belize, it means campaigning to ensure people have the power to

protect their waters from oil and gas development.

Oil’s impact cannot be undone, but the future of oil remains in humanity’s hands.

FALL 2023 | Oceana.org 21

© Oceana/Sebastián Castañeda

© Oceana

Oceana staff and supporters attend the “Wave of Resistance” demonstration in London on June 10, 2023 against a new U.K. offshore oil and gas development that would run a gas pipeline directly through the Faroe-Shetland Sponge Belt, a marine protected area.

The Repsol spill leaked more than 1,891,500 liters (nearly 500,000 gallons) of crude oil off the central coast of Peru.

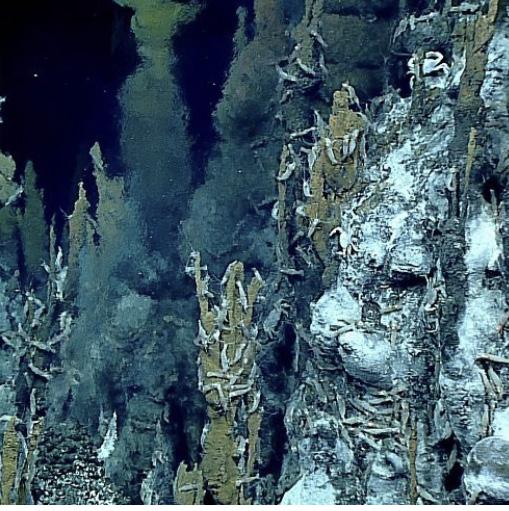

Ask Dr. Pauly

How does

deep-sea mining

affect marine life?

Deep-sea fish can’t cough, which means they’re in danger

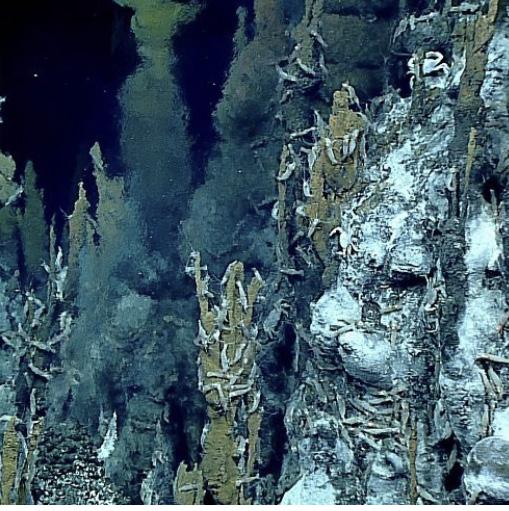

Various companies are interested in mining metals in the deep sea, such as cobalt, nickel, and the like, to be used in the batteries of electric cars and other machines as we transition to renewable energy. Exploitable concentrations of these metals occur in the deep sea on top of seamounts, in deep-sea vents, and in the form of polymetallic nodules on the deep-sea floor.

Mining the tops of seamounts and deep-sea vents cannot mean anything but the destruction of these biodiversity oases.

Polymetallic nodules are associated with less beauty and biodiversity per square meter, though the abyssal seafloor supports some equally incredible life forms. Looking something like dug-up potatoes in a field, these nodules took millions of years to reach their present size but now face an increasingly real risk of exploitation.

How would companies go about collecting these nodules? Since they rest on muddy grounds at immense depths, polymetallic nodules would have to be collected

22 22

Dr. Daniel Pauly is the founder and principal investigator of the Sea Around Us project at the University of British Columbia’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, as well as an Oceana Board Member.

© NOAA

The “Musicians Seamounts” include about 25 underwater mountains in the central Pacific Ocean, which host corals and other marine life.

Three types of deep-sea habitats at risk of mining

Abyssal Plain

The abyssal plain is an immense flat part of the deep seafloor that covers 50% of the Earth’s surface.

Containing cobalt, nickel, copper, and manganese, polymetallic nodules rest on the surface of sediment in vast fields. Animals like sponges, worms, and corals grow on the nodules, while the sediment underneath and surrounding waters host sea stars, sea cucumbers, fish, and more.

by some underwater bulldozers, stirring up the mud they rest in. Then, when they are brought to the surface, the polymetallic nodules would have to be separated from the sediment stuck to them. So, lots of mud — millions of tons of it — would slowly sink from around the vessels collecting the nodules, and immense areas of the ocean would become turbid, like the lower reaches of rivers.

The delicate structure of fish gills, and the thin lamellae that allow oxygen to diffuse from the water into their blood, can be easily clogged. Therefore, fish species that live in turbid environments — like muddy estuaries, shallow seashores, and sediment-filled rivers — have evolved the ability to cough to prevent their gills from clogging by fine particles of silt and other suspended solids.¹,² Just like

Hydrothermal Vents

Hydrothermal vents revealed to humanity how life forms and entire ecosystems can exist in the absence of sunlight.

Hydrothermal venting produces seafloor massive sulfides, which are small, orebearing structures with deposits rich in gold, nickel, copper, and other metals. These ores cannot be mined without destroying the ecosystems hydrothermal vents support.

we humans do when nasty stuff gets into our lungs.

Deep-sea fishes and other organisms have also evolved over millions of years in an ecosystem without turbidity, that is, without gill-clogging particles. Like cavefish that gradually lost the use of their eyes, then their eyes themselves, after they colonized lightless caves, deep-sea fish can be expected to have lost the ability to cough. Coughing requires specialized muscles that are adequately innervated, i.e., an entire system of anatomic and neural adaptations that would cost the fish energy to maintain, yet would be useless in an environment that is never turbid.

Sadly, as a result, deep-sea fishes would almost certainly choke to death in turbid water, along with

Seamounts

Seamounts are underwater mountains that are home to corals and sponges, supporting an abundant food web and providing critical habitat for fish and marine mammals.

Cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts, which accrete on the surfaces of seamounts, are enriched in other metals and rare-earth elements. The same ore that marine life uses for habitat is desired for deep-sea mining, but cannot be mined without destroying the ecosystem.

various other denizens of the deep such as giant amphipods.

Marine areas where polymetallic nodules are exploited would become devoid of non-microbial life. The marine mammals that feed on deep-sea fish would have left long before their prey fish choked to death because of the noise emitted by underwater bulldozers and engines during the mining process.

The statement, “deep-sea fish can’t cough,” expresses a profound insight about deep-sea mining: it is hostile to marine life. I, personally, can only hope that deep-sea exploitation by mining companies will never be allowed.

FALL 2023 | Oceana.org 23 23

1 Carlson, R.W. and Drummond, R.A., 1978. Fish cough response—a method for evaluating quality of treated complex effluents. Water Research, 12(1): 1-6. 2 Hughes, G.M., 1975. Coughing in the rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri) and the influence of pollutants. Revue Suisse de Zoologie, 82(1): 47-64.

© NOAA

© Oceana

© Philweb CC

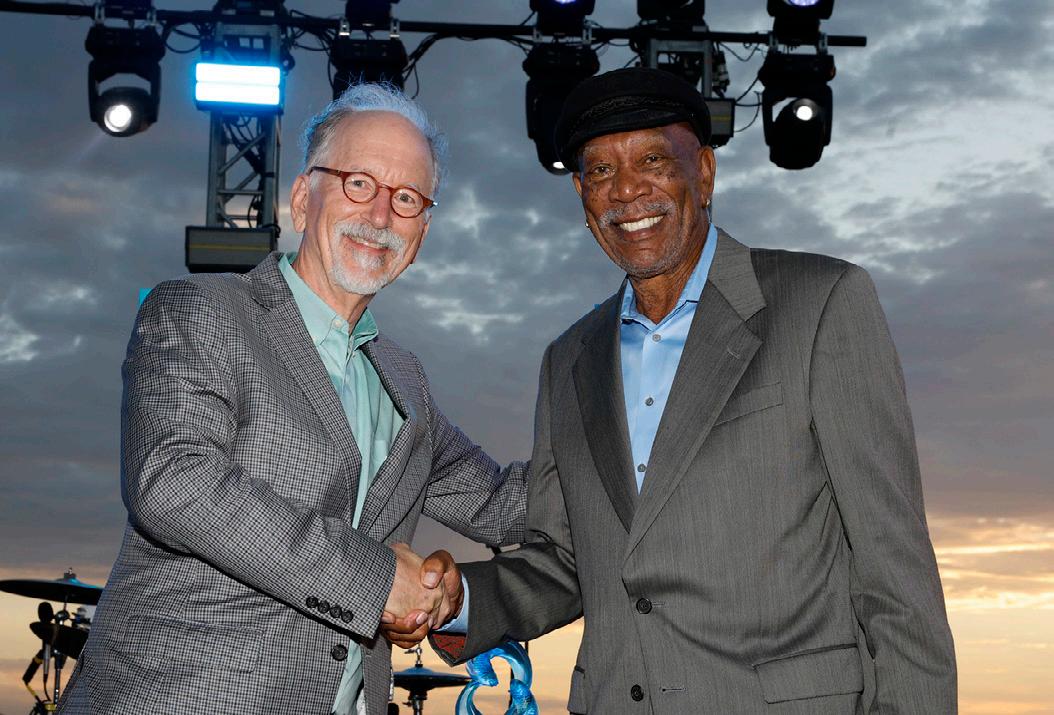

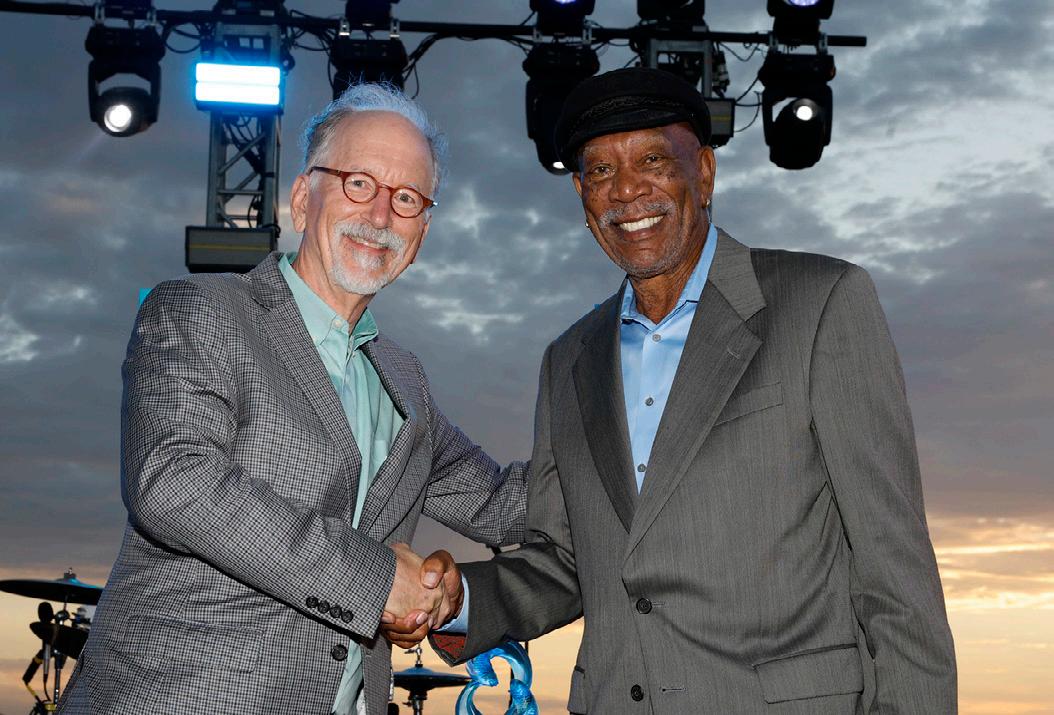

On July 22, Oceana supporters gathered in Dana Point, CA at the 16th annual SeaChange Summer Party to celebrate Oceana’s wave of victories. The event raised more than $1.5 million to protect and restore the oceans in California and around the world. Hosted by activist, comedian, screenwriter, and producer June Diane Raphael, the event honored Academy Award-winning actor Morgan Freeman for his unwavering commitment to ocean conservation. Oceana also recognized ocean champion Paul Naudé, president of the Surf Industry Members Association and CEO of Vissla.

“I’ve worked with Oceana and seen, up close, how effective they are. I’ve seen how they are saving sharks and other ocean creatures, and how they are winning policy victories for our seas,” Freeman told the crowd. “However, much remains to be done here and across the globe. Whales and other marine mammals are under pressure because of fishing and other threats like plastic pollution. But with Oceana’s help, I know that we can protect our oceans from these massive threats.”

“This event is a labor of love… for our oceans, for our SeaChange family, and for the success we are achieving year after year together in support of Oceana,” said event co-chair Karen Cahill. Oceana Board Member and fellow event co-chair Elizabeth Wahler added, “thanks to all of you who help us raise awareness and support for Oceana so that we can bring back the ocean’s bounty for future generations. Because a healthy ocean is every child’s rightful inheritance.”

This year’s SeaChange was made possible by event cochairs Karen Cahill and Oceana Board Member Elizabeth Wahler, along with SeaChange co-founder and Oceana Board Member Valarie Van Cleave as chair emerita and vice chairs Jeff Blasingame and Gabe Serrato. Generous support came from numerous distinguished businesses and philanthropists as well as corporate partners including presenting partner Blancpain and Pacific Coast partners Biossance, BMW and the Orange County BMW Centers, and Northern Trust.

Oceana thanked its additional partners and sponsors including Alec’s Ice Cream; Monique Bär; Michael and Patricia Berns; Bruce and Karen Cahill; CHANEL; Donnie Crevier and Laurie Kraus; Steve and Laurie Duncan; Giorgio Armani; Marisla Foundation; Robert and Britt Meyer; Carl and Janet Nolet; Loro Piana; Gena Reed; Louis and Laura Rohl; South Coast Plaza; Elizabeth Wahler; Valaree Wahler; Uwe Waizenegger and Valarie Van Cleave; and Tim and Jean Weiss. Underwriters included: Brite Ideas; Commerce Printing; Ketel One Botanical; Ketel One Vodka; Nolet’s Gin; Sand Cloud; Signature Party Rentals; and Starborough Wine.

Award-winning American rock band Third Eye Blind provided a powerful soundtrack to end the evening with a selection of their hit songs including “Semi-Charmed Life,” “Jumper,” and “How’s It Going to Be.” In total, the SeaChange community has raised more than $19 million to support Oceana’s ocean conservation campaigns.

24

S U M M E R P A R T Y

SeaChange

Events

Oceana CEO Andrew Sharpless and SeaChange honoree Morgan Freeman

Oceana Board Member Beto Bedolfe and ocean champion Paul Naudé

Reese Witherspoon and Ava Elizabeth Phillippe

© Ryan Miller

© Ryan Miller

© John Watkins

FALL 2023 | Oceana.org 25

© John Watkins

Oceana’s 2023 SeaChange Summer Party was held in Dana Point, CA

Bruce Cahill, event co-chair Karen Cahill, Kira Cahill, and Brent Cahill

SeaChange host and emcee June Diane Raphael

Musical guest Third Eye Blind

© Ryan Miller

© Mariusz Jeglinski

© Kevin Warn

Carl and Janet Nolet

© Kevin Warn

Oscar Nuñez, Ursula Whittaker, Sally Pressman, and Christina Ochoa

Britt Meyer and Oceana CEO Andrew Sharpless

© John Watkins

© Mariusz Jeglinski

© Ryan Miller

Oceana Board Member and event co-chair Elizabeth Wahler and Valaree Wahler

© Movi, Inc

Oceana Board Member and event chair emerita Valarie Van Cleave

Oceana’s victories over the last year

With the help of its allies, Oceana has won 32 victories in the last 12 months

Peru passes a new law to protect its oceans and artisanal fishers

New laws in U.S. state of Oregon prohibit plastic foam and enable refill systems

New law in U.S. state of Washington reduces plastic waste

Mexico joins the Port State Measures Agreement to address illegal fishing

Brazil’s Museum of Tomorrow becomes a plasticfree zone

Panama commits to reduce plastic pollution

Deep-sea corals and seafloor habitats protected in U.S. Pacific waters

Oceana defends EU policy to rebuild fisheries from attack

Chile creates a new marine protected area, Pisagua Sea

Chile rejects Dominga mining project, protects marine life

New York City limits single-use plastic utensils

New Chile law increases transparency in salmon farming and reduces threats to marine life

Amazon publicly reports on plastic packaging footprint for the first time

Canada strengthens emergency measures to protect critically endangered North Atlantic right whales

German and Dutch marine protected areas closed to destructive fishing gear

Shark fin trade banned in the United States

Two largest cities in U.S. state of California ban plastic foam

United States protects whales, dolphins, and sea turtles from deadly drift gillnets

Mediterranean countries agree to mandatory disclosure of vessels allowed to fish in restricted areas

Dow Jones introduces new screening requirements for illegal, unregulated, and unreported fishing vessels

World leader in satellite communications Inmarsat stops services to IUU fishing vessels

New international rule requires countries to investigate and deter companies from engaging with illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing vessels

New rule in the United States requires seafood traceability through the U.S. supply chain

Peru protects sharks and other marine species from illegal trafficking

Brazil’s leading food delivery service, iFood, commits to additional single-use plastic reductions

Spain penalizes fishing vessels for turning off public tracking devices

Over 14,600 square kilometers of deep-sea habitats protected from bottom fishing in the Northeast Atlantic

Marine reserve expanded in Spain’s Balearic Islands

Chilean court orders salmon farming company to release antibiotics data

U.S. state of California enacts boldest plastic pollution reduction policy in the nation

Canada eliminates production, sale, and export of six types of ocean-polluting single-use plastics

U.S. national parks protected from single-use plastics

26 © Shutterstock/Sergemi

Christina Ochoa: Storytelling for ocean conservation

Growing up by the coast in Spain, Christina Ochoa often was left to her own devices. As she wandered the tide pools and beaches along the ocean, they became her “safe place.” Ochoa felt an inherent instinct to love and protect nature — but she doesn’t think her experience is unique. “Aren’t all children instinctually drawn to climbing trees or obsessing over bugs and shells?” she asks. “Maybe I just got lucky because learning about nature was encouraged.”

A scientist by training and an actor by trade, Ochoa is known for her roles in films and shows, including Promised Land, A Million Little Things, Blood Drive, and Animal Kingdom, but does not limit herself to telling stories on screen. She built her career by pursuing challenge and discovery — from studying science to taking up acting in her twenties. It’s no surprise, then, that when she traveled to the Bahamas with Oceana in April 2023, alongside producer and activist Dylan Efron and underwater photographer and filmmaker Andre Musgrove, who share Ochoa’s love for the ocean, her favorite part — aside from the sharks — was seeing the videographers who accompanied them overcome their fears and fall in love with these animals, some even swimming with them for the first time.

Ochoa’s love for sharks, which began at an early age, is one of the reasons she was drawn to ocean conservation. Bringing her passion for cultivating curiosity in kids and adults alike to her role as Oceana ambassador, Ochoa is passionate about many issues

facing our ocean — and the millions who depend on it — including protecting sharks, establishing marine protected areas, fighting single-use plastics, climate change, deep-sea mining, and more. “My goal is always to support organizations who are unrelenting and consistently taking steps towards a better future,” she says. “Joining forces with Oceana was an obvious ‘yes.’”

Since joining Oceana, Ochoa has contributed her skills and platform to address many issues facing the oceans, from recording videos in support of habitat and shark conservation campaigns, to sharing calls-to-action on social media to generate support for campaigns such as Oceana’s efforts to pass plastics reduction legislation in California.

“Together, we can create change on a massive scale,” Ochoa says. “Oceana has the resources, connections, will, and power to have our efforts multiplied, to change legislature, create lasting infrastructures, and shift social awareness.”

Ochoa understands the challenge of advocating for just and worthy causes while “continuously attempting to educate others of why they’re so worthy.” This is why science is most powerful when expressed as stories, she explains. “Not everyone has a favorite peerreviewed paper, but EVERYONE has a favorite movie, show, book, poem... a story. It’s human to connect with a story and then care. Why not use that to our advantage?”

FALL 2023 | Oceana.org 27 Supporter Spotlight

Christina Ochoa (center), activist and producer Dylan Efron (left), and underwater photographer and filmmaker Andre Musgrove (right) traveled to the Bahamas with Oceana, where they swam with sharks.

© Brennen Schuelke

© Michael Dornellas

Make a lasting difference Help protect the oceans for the next generation Join the LegaSea Circle by including a gift for Oceana in your will, trust, or beneficiary designation. You can help protect and restore marine wildlife and habitats for years to come, while enjoying financial benefits for yourself or your loved ones. Visit Oceana.org/legasea for more information. Email plannedgiving@oceana.org or call +1.202.833.3900 to request our LegaSea Circle brochure.

© Oceana/Tim Calver

A Glimpse into El Cuyo

Cuyo, Mexico

By Georgina AIdana and Guillermo Pérez

Reflecting the sea to form two lighthouses, one on land and one on water, this photo symbolizes that for fishers in El Cuyo, home is in both places.

Photographs taken by members of an artisanal fishing community in El

“The Lighthouse”

Photographs taken by members of an artisanal fishing community in El

“The Lighthouse”

29

Photographed by Carlos Hermida

Until 2018, El Cuyo, Mexico, was rich in sea cucumber. The lucrative fishery brought in an influx of people from surrounding towns and villages, unusual for a community of 1,800 inhabitants. Residents of El Cuyo recall how large foreign vessels would park one after another, loading sea cucumbers until, one day, the sea cucumbers were gone. People left, jobs were lost, and earnings disappeared. The impact left the community aware of the dangers of overfishing and determined to protect its biodiversity, says Miguel Rivas, Habitat Campaign

Director

at Oceana in Mexico.

Today, spiny lobster is the main fishery in El Cuyo. But the lobster is becoming more difficult to find. Fishers must go greater distances and dive to deeper depths. Concerned the story of the sea cucumber could repeat itself, the fishers of El Cuyo set out to create a no-take zone, also known as a fisheries refugia — a highly restricted marine protected area that will protect the lobster, the species lobsters depend on, and the seagrass that serves as the lobsters’ habitat.

The fishers organized themselves and looked for allies. In 2021, they reached out to Oceana.

Oceana’s experts facilitated workshops with the community about no-take zones through its habitat protection campaign and brought in scientists to conduct on-site research. El Cuyo has now formally requested that Mexico’s National Fisheries and Aquaculture Commission (CONAPESCA) establish a small no-take zone that will allow them to protect juvenile lobsters’ habitat and ensure the future of local fishing, while also protecting the region from predatory tourist activity.

Instead of telling the story of El Cuyo from an outside perspective,

Oceana’s team in Mexico asked members of the El Cuyo community, who live with the sea, to share their perspectives, explains Rivas. A photography workshop was born, with participants ranging from a woman who owns a small store in town to a 10-year-old who borrowed a cell phone to attend. “Using photography to support their cause, residents of El Cuyo showcase their unique perspectives, reflect on what the ocean means to them, and share it with the world,” Rivas says.

The photographs were displayed in an exhibition in Mexico City in January 2023, attended by media and the public, where they were sold to raise funds to support the no-take zone. Since then, the photos have traveled around the country, reaching more audiences and starting conversations about the importance of collaborations between local communities and organizations, fishers and scientists, to restore the abundance of the oceans.

30

A Glimpse into El Cuyo

“El Cuyo is Yours,” photographed by Edith Martinez

In El Cuyo one can find many mural paintings made by the local artist Carlos Hermida, who also contributed to this exhibit. These murals feature the words, “El Cuyo is yours, take care of it,” reflecting residents’ commitment to look after their community.

FALL 2023 | Oceana.org 31

“Your Hands,” photographed by Guillermo Sosa Nets are made and repaired by the hands of local fishers. With subtle twists and pulls, from turn to turn, knot to knot, the thread takes shape to be used and taken to the sea. With the Virgin Mary in the background, this task becomes a prayer for abundant and productive fishing.

“Glance,” photographed by Iliana Coronel A fisher looks at a sea filled with empty boats on a day when bad weather prevents him from fishing, representing all who must wait to do their work.

“Nets,” photographed by Miguel Rivas Essential for fishing, nets need to be cleaned, repaired, and cared for –tasks that require teamwork.

32

Striped parrotfish forage along a shallow patch of reef off the coast of Placencia, Belize, which Oceana is campaigning to protect from the threat of offshore oil exploration and exploitation.

FALL 2023 | Oceana.org 33

© Henry Brown

1025 Connecticut Ave NW, Suite 200

Washington, DC 20036 USA

phone: +1.202.833.3900

toll-free: 1.877.7.OCEANA

Global Headquarters: Washington, D.C.

Asia: Manila Central America: Belmopan Europe: Brussels | Copenhagen | Madrid | Geneva | London North America: Ft. Lauderdale |

Juneau | Halifax | Mexico City | Monterey | New York | Ottawa | Portland | Toronto South America: Brasilia | Santiago | Lima

Go to Oceana.org and give

A pygmy seahorse (Hippocampus bargibanti) lives on a gorgonian coral 30 meters (98 feet) deep in Philippine waters.

You can help Oceana fight to restore our oceans with your financial contribution. Call today at +1.877.7.OCEANA, go to Oceana.org/give and click on “give today,” or use the envelope provided in this newsletter. You can also invest in the future of the oceans by remembering Oceana in your will. Please contact us to find out how. All contributions to Oceana are tax deductible. Oceana is a 501(c)(3) organization as designated by the Internal Revenue Service.

today.

Oceana’s accomplishments wouldn’t be possible without the support of its members.

© Hussain Aga Khan

By Sarah Holcomb

By Sarah Holcomb

By Sarah Holcomb

By Sarah Holcomb

Photographs taken by members of an artisanal fishing community in El

“The Lighthouse”

Photographs taken by members of an artisanal fishing community in El

“The Lighthouse”