BRINGING THE OCEANS BACK

Oceana Philippines looks back on 10 years of milestones

HEALTHY WATERS, HEALTHY LIVES

Oceana scores marine habitat protection victories in some of the archipelago’s richest ecosystems

CHAMPIONING TRANSPARENT, SCIENTIFIC FISHERIES

Monitoring and knowledge are paving the way for more sustainable practices

A BIG ‘NO’ TO PLASTIC

Taking a stand against the scourge of marine pollution

PUBLISHER: OCEANA PHILIPPINES INTERNATIONAL

VICE PRESIDENT: Atty. Gloria Estenzo Ramos

EDITOR: Alya B. Honasan

MANAGING EDITOR: Joy Rojas

ART DIRECTOR: Noel Avendaño

WRITERS: Alya B. Honasan, Joy Rojas

4 Messages

Oceana Chief Executive Officer

Jim Simon

Oceana Vice President

Atty. Gloria Estenzo Ramos

An Oceana in the Philippines

Looking back on Oceana’s dynamic decade

Oceana’s victories—and continuing work—across the Philippine archipelago

Why this insidious pollution problem must be stopped

Championing transparent, science-based fisheries

Monitoring and management will save the seas

Fish on every Filipino’s table

It’s about food and nutrition security for all, especially the poorest fisherfolk

How the Philippines plays a pivotal role in Oceana’s vision

TEN years ago, Oceana launched a campaign team in the Philippines, where our data showed overfishing was rampant, species were dwindling, and small-scale fishers dependent on their catches were suffering economically and nutritionally.

We recognized that the Philippines, as the 12th largest fishing nation in the world, plays a pivotal role in our vision of creating a more sustainable source of seafood to feed the world by supporting the needs of local fishers.

We knew that with small-scale fishers by our side, we could fight back against illegal and destructive fishing that threatened to wreak havoc on the Philippines’ abundant and biodiverse waters and the more than 100 million people that rely on them for food and jobs.

I have been proud of our team, who have accomplished much. We helped local fishers, many of whom we know by name, demand a seat at the table and have their voices heard by their government. It has been gratifying to see them beginning to benefit from their own catches. We know that they can sustain their livelihoods when we help them protect areas where fish populations can rebound.

With the help of supporters like you, the Philippine government has cracked down on illegal fishing, increased transparency of commercial fishing activity, and began measures to rebuild overfished populations. Together, we have boosted enforcement of marine protected areas and helped to create new ones like Benham Bank. And we have protected sensitive marine habitats from destructive bottom trawling and helped safeguard ecosystems from harmful coastal development projects.

We can all take pride from the victories achieved in the Philippines. And there is much more to do.

That’s why Oceana recently launched a campaign to work with local fishers in the local government unit in Samar—a region in the Philippines that faces some of the highest levels of malnutrition and poverty in the nation—where fish loss is currently at over 40 percent. In many cases, this is because the fishers lack the supplies and facilities needed to keep fish fresh longer, including ice, landing centers, and facilities for fish to be dried and stored. If you know Oceana’s team in the Philippines, you know that they won’t stop until they’ve reduced this loss to 10 percent.

I always enjoy meeting with our team in the Philippines. They are a dedicated, smart, and effective group of professionals who support one another and keep their eye on getting results. Their leader, Golly Ramos, is both a visionary and a skilled practitioner who has shown the way on how to improve the oceans, not only for her team but also for her Oceana colleagues around the world.

Of course, none of these accomplishments would be possible without the partnership of our allies in the Philippines and our generous funders. We send all of you our sincere thanks.

With your help, I know we can ensure that local seafood continues to support local communities in the Philippines for years to come.

With deep appreciation,

JAMES F. SIMON Chief Executive Officer Oceana

We are excited to embark on a new campaign integrating food and livelihood, and reducing post-harvest fish loss

I REMEMBER the two-day launch for Oceana in the Philippines on the theme “The road to sustainable fisheries governance” on November 3-4, 2014. Excitement filled the air as Oceana’s then Chief Scientist and Strategic Officer, now Senior Advisor, Dr. Mike Hirshfield, introduced Oceana to the 100 stakeholders from the government and fisheries sectors, academe, and nongovernment organizations (NGOs) and people’s organizations (POs) that attended the first day of the symposium. Our keynote speaker, the world-renowned fisheries scientist and Oceana Board member Dr. Daniel Pauly, presented the results of a global study that indicated world fisheries catch is much higher than previously thought, and declining much faster than data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) suggests. As then newly minted Oceana Vice President for the Philippines, I emphasized that overfishing and illegal fishing are threats that should be taken seriously, and I was honored to take on the role for Oceana to make a difference in the country and the lives of our people.

The year 2014 was also eventful, as the European Union issued a warning to the government through a yellow card fisheries rating, which then moved the Aquino administration to adopt strong measures to fight illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. Congress swiftly passed the bill which lapsed into law as Republic Act 10654, amending the Fisheries Code in February 2015. In April 2015, EU lifted the yellow card.

Ten years after, has much changed?

RA 10654 paved the way for genuine reforms to take place, with political will from key decision-makers, backed by strong multi-stakeholder engagement. There is a science-based and participatory Fishery Management Area system in place. Vessel monitoring devices are installed in almost 90 percent of commercial fishing vessels in the country. There is a management plan for sardines, which is among the most important sources of nutrient-packed food for our people, especially those in remote areas, and livelihood for many of our artisanal fisherfolk. But, it has to be implemented by the ultimate decision-makers: our local governments and constituents.

We are excited to embark on a new campaign integrating food and livelihood, and reducing postharvest fish loss, piloting the same in Daram, Samar, for replication nationwide in due time. We are looking at the day government finally bans singleuse plastics from being manufactured and traded, and enacts new laws to protect Panaon Island in Southern Leyte and other ecologically significant areas, and to establish coastal greenbelts in the country.

There is still a lot of work to be done, however. Transparency and obtaining data and information from government remain a challenge. Accountability measures have to be instituted by government and more of our citizens, for our laws to be fully implemented.

I must say that 10 years in Oceana have been among the best years of my life. I got to know the most caring, determined, brilliant, supportive and compassionate people from all over— Oceana’s Board members, our CEO Jim and former CEO Andy, my Executive Committee colleagues and Oceana teams in the country and various offices worldwide, and of course our partners and friends, who are our real heroes who put primacy on safeguarding our marine wealth and our people amid the immense challenges. We also thank our families for supporting us unconditionally in our collective goal to restore our wild fish population, and for our people to thrive amid the climate and biodiversity crises we face.

Leading Oceana in the Philippines in its fight to stem humaninduced pressures on our marine environment has been a journey I will cherish. I got to understand the importance of patience and vigilance. Hearing our artisanal fisherfolk expressing a newfound faith in the law, and taking action to effect changes in their lives, give additional meaning to what we have been doing.

The journey has just begun, however, as it is a continuing fight beyond us and the current generation. Ipatuloy ang laban!

For the oceans,

GLORIA “GOLLY” ESTENZO RAMOS Vice President Oceana

Oceana Philippines looks back on 10 years of milestones and collaborations

IT was a critical revelation for several prestigious foundations.

A study commissioned by the Pew Charitable Trusts, Oak Foundation, Marisla Foundation (formerly Homeland Foundation), Sandler Foundation, and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund reported that less than 0.5 percent of spendings by environmental nonprofit groups in the United States was focused on ocean advocacy. No group was working

exclusively to protect and restore the world’s oceans.

That was the catalyst for the establishment of Oceana, an international organization focused only on oceans, working to effect measurable change through science-based policy campaigns. Since its founding, Oceana has won more than 300 victories and protected nearly 4 million square miles of ocean.

Oceana already had offices in some

countries when it sought a venue for its work in Asia. The Philippines is considered the center of marine biodiversity, scattered across its 7,641 islands, and as one of the top 12 fishing nations in the world, has fisheries that sustain and feed millions of people. For Filipinos, fish accounts for 56 percent of animal protein intake and 12 percent of all the food they eat.

It was Bloomberg Philanthropies that

Since its founding, Oceana has won more than 300 victories and protected nearly 4 million square miles of ocean

pushed for the opening of a Philippine office, as it was also supporting the environmental organization Rare, which worked on climate change, biodiversity, food systems, and conservation, and which already had programs in the Philippines, reveals Dr. Mike Hirshfield, Oceana Senior Advisor and former chief scientist and strategy officer. “We saw a country that caught a lot of fish, which was one of our important criteria for where we wanted

to open a new office. It was in Asia. It had a lot of people who were dependent on fish. And we were imagining that we could work with Rare to support the small-scale fisherfolk by trying to regulate better the commercial fishermen who everybody told us were fishing illegally in municipal waters, and stealing the fish from the small-scale fishermen.”

“We evaluate whether campaigns can be run,” says Dr. Daniel Pauly, member of

Oceana’s Board of Directors. “We attempt to translate them into legislation that can be applied nationally; we assess whether the government is sufficiently responsive. And we found in Golly (Ramos) a person who was aware of what could and could not be done.”

“The Philippines is a high priority for Oceana for multiple reasons,” says Oceana CEO Jim Simon. “Because the Philippines is the 12th largest fishing nation in the world,

we can help increase food abundance by helping the country to manage fisheries sustainably. Further, because the Philippines is a nation of islands, by increasing fish abundance, we can help support the livelihoods of many fishers, their families, and their communities. The country is also the home of some of the richest biodiversity in the world, which we can help protect.”

It was also an established fact that 75 percent of the fishing grounds in the Philippines were already overfished, and reef fish catch had declined between 70 and 90 percent over the years. Plus, illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing remained a big problem,

Atty. Gloria Estenzo Ramos was running the Philippine Earth Justice Center (PEJC) in Cebu and teaching at the University of Cebu School of Law when Oceana reached out to her, just as Bloomberg Philanthropies had launched its Vibrant Oceans Initiative (now called the Bloomberg Oceans Initiative). “It was such a big funding for the Philippines,” Ramos recalls thinking. “I said, wow, this will really make a big difference in effecting reforms.”

know that what works in the United States doesn’t necessarily work in every country around the world,” says Hirshfield, who set up the Oceana office in the Philippines with Ramos and the initial team. “We’ve learned over the years how important it is to pay attention to local cultural differences.”

“The key point in Oceana’s success in various countries where we are is that we don’t parachute instant experts who don’t know what the hell is happening,” says Pauly. “Golly implemented the general guideline, that is, that we should tackle things that are solvable in principle. But she did that on her own, without somebody elsewhere telling her whom she should hire.”

It was an established fact that 75 percent of the shing grounds in the Philippines were already over shed, and reef sh catch had declined between 70 and 90 percent over the years

It was a bonus that Oceana was sensitive to and respectful of the local culture. Ramos recalls how Hirshfield would sometimes say, “Okay, I’ll be very American about this.” Her reply: “Don’t worry, Mike! I can take it!” It was all about equity, justice, and no discrimination. “We were smart enough to

Was there apprehension over yet another non-government organization (NGO) adding to the many already working in the Philippines, and one focused only on marine conservation, at that? “Not everybody loves NGOs, as we’re always pushing government to do their jobs and do better,” agrees Hirshfield. “It’s very, very important here to have an ocean-focused NGO like Oceana, because Palawan is an island,” says Gerthie Mayo-Anda, executive director of the Palawan-based Environmental Legal Assistance Center, talking about the advantage of having an organization like Oceana on their side. “We are actually a dynamite and cyanide hotspot in the Philippines. Because of their research, Oceana was able to present to the provincial government the results of their studies that proved that it really is a hotspot. Informing our local officials about

this very disturbing data is important.”

“There are other organizations that are also involved in fisheries and governance, but it’s okay, because there’s a lot of work that needs to be done,” affirms Dr. Wilfredo Campos, fisheries expert from the University of the Philippines Visayas. “And I think organizations like Oceana really have a role, because there are only certain things that the government can attend to effectively. So it’s a good complementation.”

Oceana Senior Director for Campaigns, Legal, and Policy Atty. Liza Osorio says it is “advantageous” to be focused on marine conservation, “because we’re surrounded by water. We’re an archipelago. We recognize the importance of oceans and the fisheries for food, for livelihoods, so we need the integrated coastal management principles that we have in the country.”

‘Not everybody loves NGOs, as we’re always pushing government to do their jobs and do better’

It was during the time of Dr. Mundita Lim, now executive director of the Asean Centre for Biodiversity, who first worked with Oceana as then director of the Biodiversity Management Bureau of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), that the Coastal and Marine Division was created to tackle marine biodiversity. This was at a time when the department “was focused on terrestrial. So, for me, it was a welcome partnership with Oceana. It was very effective, because there were certain policies that needed to be advocated in the legislative department. We were limited by bureaucratic processes, but with our partnership with Oceana, they could easily approach Congress, explain the priorities. It was easier for them to identify champions in the legislature and follow through. Oceana could facilitate things for us, and it helped expand our sphere of influence.”

“I’m always a believer in engaging with NGOs or the private sector in general, because the government has no monopoly,” says former Agriculture Secretary William Dar, who worked closely with Oceana on authorizing the use of vessel monitoring to combat IUU fishing. “It should really be the private sector and commercial and municipal fishers taking the lead in supporting the environment and the mechanisms provided by both government and NGOs. If Oceana continues to have

good programs, of course, there will always be challenges along the way. But I think working with government will always be a good platform to enhance the understanding of leaders in government.”

Oceana opened its office in the Philippines in 2014, just when the European Union, one of the biggest importers of Philippine fish and fish products, had issued the country a yellow card warning for failure to stop IUU fishing. The same year, the Amended Fisheries Code, RA 10654, became law, and by the following year, Oceana had already participated in consultations leading to the adoption of the code’s implementing rules and regulations, including the use of vessel monitoring measures (VMM) and electronic reporting systems (ERS).

Department of Agriculture-Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (DABFAR) Undersecretary for Fisheries Drusila Bayate welcomed the amendments,

‘Oceana became the way’

Pablo Rosales President, Pangisda-Pilipinas

Sa pagtutulungan ng Pangisda at Oceana, maraming mga lider ang natuto, lalo na usapin ng mga batas na magagamit sa gawaing pag-oorganisa, at nakatulong ng malaki sa pagtataas ng kaalaman na naging dahilan upang lumitaw ang mga lider na aktibong nagpapalakas ng aming organisasyon. Ang Oceana ay naging daan upang mapagkaisa sa isang banda ang mangingisda, habang nagkaroon ng lakas ng loob ang mga mangingisda na ipahayag ang kalagayan at mga kahilingan.

Ang Pangisda-Pilipinas, sa pangunguna ng lider at kasapian, ay bumabati ng isang makabuluhang paggunita na inyong ika-10 taong anibersaryo ng paglilingkod sa ating pangisdaan at walang pagdadalawang isip na suportahan ang pakikipaglaban ng sektor para sa isang malusog at masaganang pangisdaan.

(With the cooperation of Pangisda and Oceana, many leaders learned, especially about the laws that can be used in organizing work, which helped a lot in raising knowledge that led to the emergence of leaders who actively strengthen our organization. Oceana became the way to unite the fishermen on one hand, while the fishermen had the courage to express their situation and demands.

Pangisda-Pilipinas, led by the leadership and membership, wishes you a meaningful commemoration of your 10-year anniversary of service to our fisheries, and your support, with no hesitation, of the sector’s fight for a healthy and prosperous fishery.)

and Oceana’s role in nudging them along. “That is the beauty in the law. It needs to be reviewed every five years, which is ample time to implement and see the weaknesses or gray areas of the law that give us operational or implementation concerns. Because if you don’t implement it correctly, it becomes contentious among the stakeholders.”

More milestones followed in support of important marine habitats as well as fisheries all over the country. “The biggest shift I’ve observed at Oceana following the launch of this office is how deeply engaged we became with small-scale fisheries,” says Jim Simon. “It really changed our take on how to rebuild fisheries, and we have applied these learnings around the world. The Philippines is special because it is both a top fish-catching and fish-consuming nation, so this really became our bedrock in the Philippines.”

Oceana joined a team of experts on an expedition to the Benham Rise in 2016; the Philippines’ claim on the territory had been adopted by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) Commission in 2012. Monitoring was required for all commercial fishing vessels by the Protective Area Management Board (PAMB) of the country’s largest marine protected area, the Tañon Strait Protected Seascape Protected Area Management Board (PAMB), in 2017. “The Philippines should recognize that Tañon Strait is a very important area for marine biodiversity, and

ergo, also important for other services like fisheries and tourism,” says Dr. Mundita Lim. “But it is necessary to balance that because we still want the communities to benefit from Tañon Strait, so that they can also help us protect the biodiversity.”

In 2018, Benham, renamed the Philippine Rise, was declared a marine resource reserve. Trawling was banned in all municipal waters by the Fisheries Code, with implementing guidelines for the ban released in 2018 through a Joint Memorandum Circular of the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) and the DA-BFAR.

‘IN

“The municipal waters belong to them,” states BFAR Regional Director for Region VI Remia Aparri on involving fisherfolk in policymaking that ultimately benefits them. “We involve them directly in the process, so we not only create awareness, but they can see our sincerity. They feel the support or the commitment of the government. We have to show them that we are here because we want the sustainability of the resource, and we develop their sense of ownership. And what we always emphasize is, it’s not only for today, but it’s their obligation to the future generations. That’s in their heart.”

implementing as many strategies as you can to help you get to your goal,” says Osorio. “You’re utilizing tools like legal action, writing letters, petitioning; at Oceana, we can go as far as filing cases against our supposed partners.”

“Policy is supposed to institutionalize the changes you want,” Anda says. “There’s guidance. They will constantly go back to it; that’s the importance of having something written. Because it’s also for the future. It’s an important legacy, like the Amended Fisheries Code, which has a lot of good provisions. But there has to be political will to implement it.”

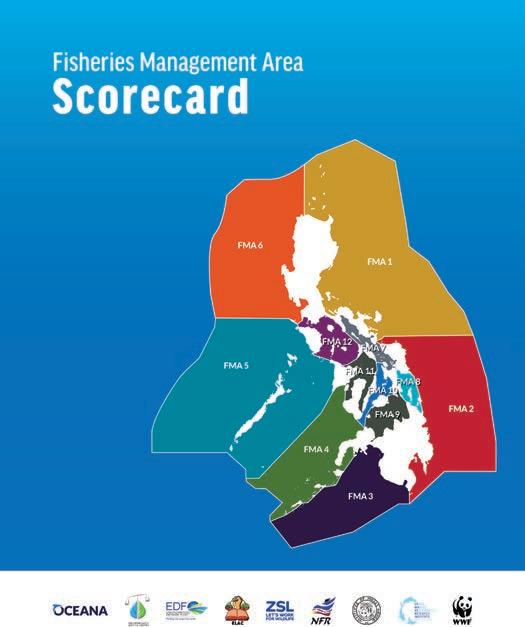

“The National Sardine Management Plan (NSMP) is part of policy,” Campos says of the plan approved in May 2020 by DA-BFAR. “The policy frameworks are for different fishing grounds to lay down specific rules and actually implement them. The management plan just has general guidelines, but the different Fisheries Management Areas (FMAs) have to have detailed measures and actions.”

‘Our laws are good, and we have a world-class legal framework, but we’re very weak in implementation’

“You start with a premise that’s built upon people’s hearts,” echoes Hirshfield. “We identify the things that we believe people value—that the small-scale fishermen have a viable livelihood catching fish, that the coral reefs stay bright and colorful and have lots of fish. Of all the countries that we work in, the Philippines is the most engaged, where people care the most about oceans.”

There is a solid rationale behind Oceana’s thrust of effecting change through policy-making. “Our laws are good, and we have a world-class legal framework,” says Ramos. “But we’re very weak in implementation. And the government can’t get away with it. That’s why the challenge is to make them implement a clear mandate.” Otherwise, the organization sends interrogatory letters or goes through the Office of the President or the Anti-Red Tape Act Authority—“all avenues to reveal data.”

“You’re effecting change when you’re committing to getting policy changed, and

“In that way, they are clever,” Bayate adds. “Why? If you don’t start with policy, you won’t know the acceptable limits when you work, because the policy will give you the limits.” The best approach, she says, is to engage all of the stakeholders. “Then you can have different perspectives. And sometimes, you can calibrate your point of view.”

The previous year, 2019, Fisheries Administrative Order (FAO) 263 had called for the establishment of the aforementioned 12 FMAs all over the Philippines, each one with its own management body and scientific advisory group. “That’s the beauty of the FMA,” says Aparri, who leads the first of the FMAs to be established, FMA 11. “We use the concept and principles of FMA, of converging, of partnership, and tapping other relevant concerned agencies, including Oceana, to work with us, because we cannot do this alone. There’s continuous capacity building. And for that milestone, of course, I would like to acknowledge Oceana as our initial partner. We were implementing the concept of an FMA even before the FMAs, in 2017.”

Also in 2019, Oceana and several partner civil organizations developed the FMA Scorecard to monitor the implementation of FAO 263, and together with the League of Municipalities of the Philippines, launched the first online

platform for reporting illegal commercial fishing in municipal waters in the Philippines, Karagatan Patrol.

The DA would approve the implementation of the NSMP in all FMAs in 2020. “The average layman doesn’t think there’s a problem with sardine fisheries management,” notes Ramos of this species that makes up 15 percent of all the catch in the country. “And the industry’s resistance to the plan is intense. But you cannot be more powerful than the law.” Three years later, BFAR issued the implementing guidelines to integrate the concepts of reference points and harvest control rules, used in FMAs, under the NSMP. In the future, the plan would be implemented through local legislation in some municipalities and provinces; by 2024, it would be put in place by 29 local governments in Samar and Northern Samar.

Also in 2020, Oceana would lead an expedition to Panaon Island in Southern Leyte, home of some of the most resilient coral reefs in the world, as identified by the 50 Reefs Initiative, with Bloomberg Philanthropies among the initial funders. Bills would be filed in Congress to declare Panaon Island a protected area under RA 11038, the Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System Act. The House of Representatives passed the bill in December 2023.

Then Agriculture Secretary William Dar would issue FAO 266 in 2020, calling for the immediate implementation of vessel monitoring to deter any illegal intrusion of commercial fishing boats in municipal waters. It would, however, take another three years, constant campaigning by Oceana and fisherfolk groups, and even an attempt to suspend FAO 266, before President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. directed the full implementation of vessel monitoring to track the location, speed, and catch of all commercial fishing vessels bigger than 3 gross tons in the country.

“The crafting of implementing regulations on vessel monitoring really became one of our clear policy wins,” says Ramos. “It’s been a long fight. And now almost 90 percent of the vessels have transponders.” “To me, that’s the biggest system change,” seconds Hirshfield. “The fisheries management system in the Philippines is different now. There’s a level of professionalism, a level of science that’s permeating some of the decisions, that would not have been there without Oceana.”

In 2022, Oceana would be involved

in campaigns to protect mangroves, supported by legislation pushing for coastal greenbelts. In 2024, on its 10th year, Oceana would be working with PAMBs nationwide to ban single-use plastics in protected areas such as the Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park, Apo Reef Natural Park, Palaui Island Protected Landscape and Seascape, Siargao Island Protected Landscape and Seascape, Magapit Protected Landscape, and the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, the country’s largest protected area. This year, 2024, the National Coastal Greenbelt Bill is also under deliberation in the Senate, after having been passed in the House of Representatives. To date, 91 local governments have passed resolutions or executive orders establishing coastal greenbelts.

Oceana has collaborated with many allies over the decade—”like friends you make along the way,” Ramos says. “You’ll realize who’s genuine and who would stand by you, or whose visions align with yours.” The organization has found one such champion in Senator Cynthia Villar, Chair of the Senate Committee on Environment, Natural Resources, and Climate Change, as a staunch defender against reclamation and illegal commercial fishing, and as an author of the Amended Fisheries Code, Republic Act 10654. It is such alliances that Oceana is banking on to propel it into the next 10 years, as the organization focuses further on ensuring that fish continues to sustainably feed Filipinos, especially fisherfolk.

“Oceana is getting stronger as a team, and I’m amazed at the passion,” says Ramos. “It’s important, because not only do you have campaign goals, but the staff themselves have that sense of determination that we can fix this. We are in a privileged position because we have the resources to help effect that change.”

“These people are fighters,” says Hirshfield, who still visits Manila to guide the team as its self-confessed “godfather.” “They’re smart, they’re committed, they’re passionate, and they’re getting things done.”

“I think the 10 years that Oceana has worked in the Philippines should continue, because the next decade will probably be more challenging,” says Anda. “The combination of law, science, advocacy, and enforcement is to me a perfect recipe for sustaining the advocacy of Oceana. There is a confluence of expertise there—law, science, communications. Environmental lawyers are important, but they cannot swim alone.”

‘We can be heard’

Martha Cadano Woman fisher and member of the Victoria Municipal Entrepreneurs Multipurpose Cooperative, Northern Samar

I sang mainit na pagbati at pagbibigay ng pasasalamat sa Oceana sa inyong ika-10 anibersaryo.

Ako po ay personal at taos-pusong bumabati at nagpapasalamat sa pagbibigay ng pagpapahalaga sa aming sector. Malaki po ang naitulong ninyo para kami ay marinig at mapakinggan na dati ay hindi namin naramdaman.

Malaki po ang nagawang impluwensya sa pagpapalakas ng aming partisipasyon sa ating lipunan sa ngayon. Ikinagagalak kong sabihin na ramdam po namin ang inyong tulong, lalo na sa pagpapatupad ng mga batas.

Maraming salamat po. Sana po ay magpatuloy pa ang inyong mga gawain upang sa huli ay makamtan din po namin ang aming inaasam na tagumpay. Napakaraming issue na kami po ay nakakilos dahil nandyan po kayo. Kung wala pong nag-guide sa amin, marahil po ay hindi namin nagawa yun.

(A warm greeting and thanksgiving to Oceana on your 10th anniversary.

I personally and sincerely congratulate and thank you for giving appreciation to our sector. You have helped us a lot so that we can be heard and listened to in a way that we did not feel before.

It has had a great influence on strengthening our participation in our society today. I am happy to say that we appreciate your help, especially in the enforcement of laws.

Thank you very much. I hope that your work will continue so that we can finally achieve our desired success. There are so many issues that we have acted on because you are there. If no one guided us, maybe we wouldn’t have done it.)

Oceana scores marine habitat protection victories, but continues the ght to safeguard even more

A valuable ecosystem officially becomes Philippine territory—and is legally protected

Imagine a vast, unexplored area with 100 percent hard and soft coral cover— trees and terraces of coral descending like underwater staircases into unknown depths, one scientist commented, as far as the eye could see. There were algae, sponges, and some 200 or more fish species at any given time, from dainty damselfish, to bluefin tuna, and among

the elasmobranchs and apex predators patroling the untouched landscape, large tiger sharks—all in a pristine mesophotic or deep-sea reef ecosystem.

Such was the sight that greeted the team of explorers, composed of experts from the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR), the University of the Philippines (UP) Marine Science Institute, the UP Los Baños School of Environmental Science and Management, the Philippine Navy and Philippine Coast Guard, and the marine conservation organization Oceana, who had headed out to explore the Benham Rise on an expedition funded by the Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic, and Natural Resources Research and Development (PCAARRD) of the Department of Science and Technology. The team sailed to the site on board the

government research vessel M/V DA-BFAR from May 23 to 31, 2016—and findings from the journey would provide the impetus for Oceana to campaign fervently for the protection of this important marine ecosystem and fish source.

Located some 250 kilometers east of the coastline of Isabela, the Benham Rise is a massive seamount—an extinct underwater volcano—with an original area of some 13 million hectares, reaching estimated depths of 5,000 meters. The most shallow portion, which the expedition focused on, the Benham Bank, has an area of about 17,000 hectares, with depths of up to 70 meters. Believed to have been named after an American admiral and surveyor from the 18th century, Benham Rise first came to public consciousness when the Philippines claimed the area as part of its territorial

waters in 2008, a claim hastened by threats of incursion from other countries, and ultimately recognized in 2012 by the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. The recognition expanded the territory in question by another 11.4 million hectares, bringing the new total to 24.4 million—almost as big as the size of the entire Philippine archipelago itself.

Little had previously been known about the area when an initial expedition headed out on May 3, 2014, to check out the Philippines’ newest territory, also on board the M/V DA-BFAR. Oceanographers, fish larvae experts, and marine biologists from UP Diliman, Los Baños, and Baguio, along with representatives from Xavier

Rise rst came to public consciousness when the Philippines claimed the area as part of its territorial waters in 2008

University and Ateneo de Manila, dove to 50 meters for about 25 minutes, already discovering and recording a wealth of underwater life. “The landscape at the bottom was a coral reef that was in very good condition, something rarely encountered now anywhere in the country,” wrote Romeo Dizon, assistant professor of biology and a coral ecology expert from UP Baguio, in an article in the Philippine

Star published in September 2014. “This was a world that had remained practically untouched by man, at least until we came.”

Oceana brought out more “big guns” for documentation for the 2016 expedition, along with technical divers and videographers. A remotely operated vehicle (ROV) took video and photographs for two hours at a time, giving researchers more time to study and examine the marine life. Baited remote underwater systems (BRUVS) made use of two cameras to “capture” fish with bait within a frame, recording for as long as five hours at a time, and allowing scientists to study individual fish as well as biomass. “We made sure that the pictures taken with the sophisticated technology that Oceana was able to bring

(Clockwise from above) A team of technical divers ascending from the bank and making a safety stop, very important in dives deeper than 30 meters (100 feet) to prevent decompression sickness; branching corals contribute to the complexity of the reef, sheltering reef fishes; a hawkfish (Cirrhitichthys falco), a solitary species usually spotted at dropoffs; oriental wrasse (Oxycheilinus rhodochrous) are known to inhabit coral reefs with abundant invertebrates, which they feed on. OCEANA/UPLB

in really showed it,” said Oceana Vice President Atty. Gloria Estenzo Ramos. “That helped it become a national issue.” Technical divers also collected samples from the sea bed for further study.

Oceana scientists on the expedition documented their day-to-day activities in their online “Benham Diaries”: “While the BRUVS were luring species into the camera sight in the depths, the ROV team expertly navigated the camera/robot setup over Benham Bank’s live terrain,” they recounted on May 25. “The ROV shows real-time footage on board, so our team watched excitedly as the ROV glided over a slope covered with all manner of marine life, including corals, soft sponges, algae, and fish. It was quite a sight to see this array of marine life at Benham Rise in real time, and know that it was all living and breathing right below us.” Meanwhile, the technical divers went down “to a miraculous 60 meters (197 feet) below the surface and captured some incredible images of the life on Benham Rise…It really is stunning to see the type of life the ocean can support at such depths.”

Nearing the end of the expedition, on May 29, the scientists concluded, “Collectively, among the decades of

experience studying the ocean that we have aboard the ship, no one has ever seen reefs like this. Benham is indeed a special place, and we feel truly privileged to be here.”

Deep sea reefs such as those found in Benham Rise provide shelter to fish that end up heading deeper because of the increasingly warm surface temperatures resulting from climate change, providing a habitat for important species that both enrich the ecosystem and provide food for the Philippines’ estimated one million fishers.

Why then is Benham Rise a veritable economic treasure and a valuable addition to Philippine territory? Oceana estimates that a mere one square kilometer of wellmanaged, relatively healthy coral reefs can have an annual yield of 15 tons of seafood, which is life-changing for fishers and coastal communities for whom fish is the main protein source. Healthy waters mean healthy fisheries, and consequently, healthy lives because of better nutrition and food security.

conducted from 2014 to 2017 and led by Dr. Wilfredo Licuanan, director of the De La Salle University-Br. Alfred Shields Ocean Research (SHORE) Center Marine Station, it’s not a pretty picture. Of 166 reefs sampled, and based on the parameter of live coral cover (LCC, combining hard and soft corals), more than 90 percent of the areas were in the poor and fair categories, with none being classified as “excellent,” defined as having 75 percent cover and higher. Only an average of 22 percent had structurally essential hard coral cover (HCC).

Over 26,000 Filipinos signed an online petition initiated by Oceana and other conservation groups to protect the site

Throw in constant threats such as unsustainable fishing practices, ocean pollution, climate change, coastal development, and other manmade pressures, and it becomes evident that better management and more marine protected areas (MPAs) are needed, along with the laws required to protect them.

The statistics on coral conditions have been grim, however. Based on the landmark study of the National Assessment of Coral Reef Environment (NACRE) Program

“Benham Bank holds tremendous potential for discovering more unique species and outstanding samples of marine resources,” Ramos stated after the exploration. “Based on the huge success of this expedition, and the inspiring

collaboration among the partners, we foresee government and stakeholders working together to protect and sustainably manage this extraordinary natural heritage, which is now part of our territory.”

After the expedition, Oceana immediately began work on the campaign to legally protect Benham Rise, recognizing its importance to biodiversity conservation, managing the effects of climate change, and ensuring food security for Filipinos. Over 26,000 Filipinos signed an online petition initiated by Oceana and other conservation groups to protect the site. In March 2017, when the Department of National Defense detected a Chinese vessel surveying the area, Oceana pushed for urgent action, with Ramos urging the administration to “expedite the formulation of the management framework for Benham Rise to protect and sustainably manage it…We need to prioritize its protection, including the pristine Benham Bank as a no-take zone.”

Such a plan would include details on law and monitoring, biodiversity conservation, fisheries, and commercial and economic activities in the area, as well as ensuring that poaching and illegal commercial fishing will be subject to punishment. Sectoral consultations had already been held by the Department of Environment

The Philippine Rise is backed by the United Nations, an executive order, and a proclamation to boot

When President Rodrigo Duterte issued Executive Order No. 25, renaming Benham Rise to the Philippines Rise, on May 6, 2017, it was the culmination of years of research to lay claim to the underwater plateau east of Luzon measuring a mindboggling 13 million hectares and boasting a rich biodiversity of coral, natural gases, fish, and other marine species.

Pushed as a possible extended continental shelf area by representatives of the University of the Philippines Institute of International Legal Studies to facilitate the Department of Foreign Affairs and the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority in implementing the Law of the Sea in 2001, Benham Rise was the subject of a formal claim filed by the Philippines before the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) in 2009. The claim was approved in April 2012.

According to EO 25, the term “Philippine Rise” shall be used in official maps, charts, and documents. “The Philippines is the sole claimant of the Philippine Rise,” stated an explanatory note authored by Senator Francis Tolentino. “Under international law, no other state may exploit or undertake exploration activities in the Philippine Rise without express consent of the Philippines.”

About a year later, on May 15, 2018, after continuing campaigns from conservation

organizations and other stakeholders, President Duterte signed Proclamation No. 489, “declaring a portion of the Philippine Rise situated within the exclusive economic zone of the Philippine Sea, north eastern coast of Luzon Island, as protected area under the category of Resource Reserve as defined under RA No. 7586, to be known as the Philippine Rise Marine Resource Reserve (PRMRR).”

A mammoth 352,390 hectares, PRMRR has a Strict Protection Zone of 49,684 hectares, and a Special Fisheries Management Area under the Amended Fisheries Management Code of 1998, “for the sustainable development and regulated utilization of the resources thereat pursuant to relevant laws, rules and regulations, and to address the social, equitable and economic needs of the Filipino people without causing adverse impact on the environment.”

The Department of Environment and Natural Resources has administrative jurisdiction and control over these areas. As such, it can conduct “assessment of the area and develop the management plan, including its research framework, in consultation and coordination with the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources of the Department of Agriculture, Department of Energy, and other concerned agencies.”

Disturb, or worse, destroy Philippine Rise’s vast marine ecosystem and you face hefty fines and imprisonment as prescribed in RA No. 7586, RA No. 9147 or the Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act, RA No. 8550, as amended, and other applicable laws, rules and regulations.

(RA 10654, 2014), and their implementing rules and regulations. Among other specifics, the code bans the use of active fishing gears in FMAs, to discourage Illegal fishing as well as overfishing.

and Natural Resources–Biodiversity and Management Bureau (DENR-BMB) for this management framework, while the Senate held a public hearing on a planned Benham Rise Development Authority.

President Rodrigo Duterte took the first step on May 16, 2017, with Executive Order (EO) No. 25, “Changing the Name of ‘Benham Rise’ To ‘Philippine Rise’ and for Other Purposes.” “In the exercise of its sovereign rights and jurisdiction,” the EO declares, “the Philippines has the power to designate its submarine areas with appropriate nomenclature for purposes of the national mapping system.”

Naming it did not immediately equate to protecting it, however, and many groups continued their campaign. An umbrella organization called Pangisda Natin Gawing Tama (PANAGAT), composed of conservation groups Oceana, Greenpeace, the World Wide Fund for Nature, Tambuyog, NGOs for Fisheries Reform, the Institute for Social Order, Pangisda, and others marked the 3rd International Year of the Reef (IYOR) with Benham Bank as its flagship effort, even sending then Secretary of the Environment Roy Cimatu a Valentine’s card in February 2018 to persuade him that legal protection was critical.

The persuasion apparently worked on the national leadership, because three months later, in a widely acclaimed move, President Duterte declared the Philippine Rise a marine resource reserve. He signed Presidential Proclamation 489, “Declaring a Portion of the Philippine Rise Situated Within the Exclusive Economic Zone of the Philippine Sea, North Eastern Coast of Luzon Island, as Marine Resource Reserve Pursuant to Republic Act (RA) No. 7586, or the National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 1992, to be Known as the Philippine Rise Marine Resource Reserve,” on May 15, 2018 on board the ship BRP Davao del Sur while docked off Casiguran, Aurora.

The 17,000 hectares of Benham Bank were declared a no-take zone, with no human activities other than scientific research allowed. Under the aforementioned NIPAS Act, what would be known as the Philippine Rise Marine Resource Reserve (PRMRR) would cover 352,390 hectares, with a Strict Protection Zone, also as defined by the NIPAS Act, covering 49,684 hectares. The remaining sections were declared a Special Fisheries Management Area (FMA), as defined under the Philippine Fisheries Code (RA 8550, 1998) and the Amended Fisheries Code

The proclamation further mandated that the DENR should assess the area and formulate the management plan, in collaboration with BFAR and other government agencies. It also ordered the punishment of any “destruction or disturbance” of the Philippine Rise, as mandated by law. In a press release by Oceana, President Duterte also made provisions for “the continuous assessment of coral reef and fish species…vital for the management of the Philippine Rise and its resources.” He further highlighted the work awaiting Filipino scientists to study and document the Philippine Rise.

In what Senator Loren Legarda described in the same Oceana press statement as “a remarkable event, especially for the protection of our oceans and ensuring seafood security for future generations,” the Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System (ENIPAS) Act or RA 11038, “An Act Declaring Protected Areas and Providing for Their Management, Amending for This Purpose Republic Act No. 7586, Otherwise Known as the ‘National Integrated Protected Areas System (NIPAS) Act of 1992’ and for Other Purposes,” which sought to increase the number of Congress-declared protected areas in the archipelago, was also expected to be passed. It was approved on June 22, 2018— just over a month after the Philippine Rise was officially declared protected.

“We can say we’re proud of this campaign, because we were the ones that helped make people aware about this special place we have that needs to be protected,” said Atty. Liza Osorio, then a consultant of Oceana, now the organization’s Senior Director for Campaigns, Legal, and Policy.

Mike Hirshfield, Senior Advisor and member of Oceana’s Executive Committee who provided guidance to Oceana from the organization’s establishment, calls the Benham victory “a wonderful, wonderful thing. It helped raise Oceana’s visibility. Having an excuse to put pretty pictures on the front of the newspaper is great for both the issue and for the organization. And getting Benham to happen took a lot people, and a lot of time.”

The work continues to declare this island of excellent reefs a protected seascape

It was in 2014 that Bloomberg Philanthropies, a charitable foundation based in New York City, with global projects in the arts, education, the environment, government innovation, and public health, launched the Vibrant Oceans Initiative, now known as the Bloomberg Ocean Initiative (BOI). “Coral reef ecosystems around the globe are likely to disappear by 2050 if the goals of the Paris Agreement are not met,” stated Bloomberg Philanthropies on its website. “Even with drastic emission reductions to ensure we keep warming within 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, 70-90 percent of the world’s corals could still vanish by mid-century, leaving only remnants of the reefs we see today.”

With the overarching goal of ocean sustainability, the initiative zoomed in on efforts to identify the world’s most

climate change-resistant coral reefs, the planet’s best bets and “insurance plans” for replenishing the rest of the world’s reefs in the future. The goal is to protect 50 of these ultra-resilient reefs, which would represent 75 percent of global coral species—and which could most likely create more reefs in the future. This meant working in areas with important coral reef ecosystems, in predominantly fishing nations, where fish is a main and important food.

“Climate resilient corals have been found around the world,” said the Bloomberg Philanthropies website.

“Reducing emissions in line with the Paris Agreement, and managing local pressures on resilient reefs, allow these reefs to thrive and replenish neighboring reefs— ensuring the long-term survival of our world’s coral reefs.”

Based on five major scientific indicators—a history of warming, predicted future warming, exposure to typhoons, how waters in the area transport larvae, and environmental stress, such as coral bleaching or constant pollution—regions were identified where such coral reefs still existed, or even remained abundant. Known as bioclimatic units (BCUs), such regions spanned the globe, with three of them located in the Philippines.

The strip on the map known as BCU

34 has an area of 1.5 million hectares— including 71,000 hectares of coral reefs—and is home to coastal populations exceeding 3.5 million people. Stretching from the island of Mindanao to Cebu, BCU 34 includes a 30-kilometer chunk of land in Southern Leyte surrounded by beaches and reefs, known as Panaon Island.

Flush from the 2018 victory of the legal protection of the Philippine Rise, Oceana lost no time in finding a new project site. Oceana’s initial feasibility studies in Panaon in 2019, and the groundwork done by the organization Coral Cay Conservation, which determined the area to have high coral cover, made Panaon a natural choice.

“We were overjoyed by our victory in the Philippine Rise, and started looking for other areas we could protect,” said Oceana Vice President Atty. Gloria Estenzo Ramos in an interview for the 2022 Oceana publication The Champions of Panaon. “Panaon used to be a place where dynamite fishing was rampant, but it recovered. It had a very inspiring story from the very beginning, where you see the relationships, the legal framework, the

ordinances crafted by local government. It was the perfect place for us to undertake another coral reef campaign.” When the region was recognized by the BOI, “It gave us a stronger sense of responsibility that this pristine place should be protected… The coral reefs in this region remain some of the least disturbed habitats in the Philippines.”

An initial survey conducted among residents of Panaon’s four municipalities— Liloan, Pintuyan, San Francisco, and San Ricardo—revealed that 35 percent of the fishers are subsistence fishermen, keeping between 81 and 100 percent of what they catch for consumption. Fortyseven percent of total respondents and 59 percent of fishers identified illegal fishing as the main threat to their natural resources, along with marine pollution and

59 percent of Panaon shers identi ed illegal shing as the main threat to their natural resources

climate change. Fifty-nine percent also revealed that the fish catch had definitely decreased over the years. Panaon was also the site of 19 marine protected areas, which, surprisingly, accounted for only 21 percent of the reefs being protected by local government ordinances.

In 2022, the Philippine Statistics Authority revealed that about 3.14 million hectares of the country’s waters are designated as marine protected areas (MPAs), defined by the International

Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as “a clearly defined geographical space, recognized, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values.” The aforementioned national figure, however, adds up to only 1.42 percent of the Philippines’ total marine areas—a disheartening number, considering that the country is an archipelago surrounded by kilometers of coastline. Since Panaon scored high in terms of coastal development and a growing population, focusing on its protection has become even more urgent. Oceana’s landmark Panaon Expedition took place on October 15 to November 5, 2020, smack in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines,

which made the already complex endeavor an even bigger challenge. Southern Leyte Provincial Governor Damian Mercado had to endorse the voyage to the InterAgency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases Resolutions (IATF), the governing body in the country for all movement during the pandemic, which required that team members never set foot on land during their trip .

Two days of COVID testing and isolation were also factored in before the trip on board the M/Y Discovery Palawan, a commercial dive boat which comfortably accommodated the 32-member team led by Oceana scientists and campaign managers, including consultants Dr. Badi Samaniego, assistant professor at the University of the Philippines Los Ba ños (UPLB) and a reef fish specialist, and Dr. Victor Ticzon, UPLB associate professor and head of the university’s Aquatic Zoology Research Lab and a coral reef specialist, as well their respective teams, photographers and videographers, and dive guides.

The immediate goal was to check out the island’s MPAs and neighboring reefs. The bigger agenda was to gather evidence to back up the campaign for Panaon Island to be covered by the Expanded National Integrated Protected Area Systems (ENIPAS) Act of 2018, “which would give it more stability in terms of accessing financial resources, which is important for the sustainable management of the protected area,” said Ramos.

“The ENIPAS Act will highlight Panaon on a national scale, giving it national coverage, attention, funding, and effort, whereas now it’s just on the local government unit and barangay level,” added Dr. Samaniego in an interview for The Champions of Panaon. “If we could rally all those resources and that intensity so that potential ‘destroyers’ will know it’s backed up, that would help.”

The team logged 34 dives over 12 days, including a day spent docked close to land to avoid one of the four typhoons they encountered during the expedition. Dr. Ticzon talked in an interview about how he experienced a “reset” after Panaon, after years of “writing obituaries” for dead or dying coral reefs. “It’s very rare to encounter an area in the Philippines with that much hard coral cover.”

Such coral cover does much more than shelter fish populations, Ticzon noted; along with mangroves, they are more effective at protecting coastlines against frequent storms. “If you have healthy reefs, they will do a better job, at a lower cost.”

The

expedition’s bigger agenda was to back up the campaign for Panaon Island to be covered by the ENIPAS Act of 2018

Government officials who backed the move to protect Panaon dovetailed their efforts after the expedition. In August 2022, Southern Leyte 1st District Rep. Luz Mercado and Southern Leyte 2nd District Rep. Christopherson “Coco” Yap filed House Bills 3743 and 4095 respectively, both declaring Panaon and its surrounding waters a protected seascape, pursuant to the ENIPAS Act. Four months later, on December 14, Rep. Yap would follow up with House Bill 6677, “An Act Declaring the Waters Surrounding Panaon Island, in the Province of Southern Leyte, a Protected Area with the Category of Protected Seascape under the National Integrated Protected Areas System (NIPAS), to be Referred to as the Panaon Island Protected Seascape, Providing for its Management, and Appropriating Funds Thereof.”

On January 18, 2023, Senator

Cynthia Villar, chair of the Committee on Environment and Natural Resources, filed a counterpart bill at the same Congress, Senate Bill 1690. “This bill seeks to declare the Panaon Island as a Protected Seascape to regulate utilization of marine resources and ensure the conservation and continuity of critical, endangered, threatened coral reefs, seagrasses, and mangrove forests, as well as the endemic and threatened species therein,” the bill stated. “It seeks the conservation, protection, and preservation of a protected seascape in accordance with the provisions of Republic Act No. 7586, otherwise known as the National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 1992, as amended by Republic Act No. 11038, or the Expanded National Integrated Protected Area System (ENIPAS) Act of 2018.”

Provincial Governor Damian Mercado took his own step with a local government unit (LGU) Executive Order signed May 16, 2023, declaring the whole of Panaon Island a protected seascape, and ordering the Provincial Environment and Natural Resources Office (PENRO) to come up with implementing rules and regulations.

Also in May 2023, to push their cause, Rep. Yap and Oceana collaborated on a

photo exhibit on Panaon at the House of Representatives, featuring images of coral reefs, mangroves, and other habitats, as well as the rich wildlife. “For a coastal area like my district, food, economic, and job security are deeply tied to nature,” Rep. Yap said in a message during the exhibit opening. “This is why it is crucial for us to do what is necessary to protect our seas, which allows us to continue to thrive.”

The images hit home, as on November 29, 2023, 247 members of Congress approved the consolidated bill, principally authored by Reps. Mercado and Yap, and declaring over 60,000 hectares of waters surrounding Panaon Island a Protected Seascape under the ENIPAS Act. The proposed Protected Seascape will cover the municipalities of Liloan, San Francisco, Pintuyan, and San Ricardo, helping to preserve the island’s estimated 60 percent coral cover, and safeguarding endangered species identified by the IUCN, including whale sharks and sea turtles.

In a statement after the approval of the bill, Oceana hailed this first step towards creating a law to ensure

‘It is especially important that the coral reefs in the waters of Panaon Island are granted national protection before they are exposed to pervasive threats’

comprehensive protection for Panaon’s precious ecosystems. “The declaration of Panaon Island Protected Seascape sets the framework that will ensure sustainable ecotourism and livelihood activities that balance socio-economic development with conservation efforts,” the statement read.

“Oceana is very proud of the concerted efforts to move for the national protection of Panaon Island’s magnificent coral reefs,” said Atty. Liza Osorio, Oceana’s Senior Director for Campaigns, Legal, and Policy. Meanwhile, Ramos lauded how many different sectors, from government agencies and NGOs to community leaders and even artisanal fisherfolk, had rallied behind the proposed protection.

“The passage of the bill at the House of Representatives is a testament that through collaborative efforts, we can achieve more in protecting our vital marine

ecosystems for the present and future generations. We are looking forward to the passage of the counterpart bill on Panaon Island in the Senate.”

In an interview in The Champions of Panaon, former Oceana Chief Executive

Officer Andrew Sharpless stated, “While we often hear that coral reefs in the Philippines and around the world are in dire condition from the impact of climate change, Panaon Island offers some hope… And it is especially important that the coral reefs in the waters of Panaon Island are granted national protection before they are exposed to pervasive threats.”

So what will happen when Panaon does become legally protected? The next steps would be formulating a management plan, in light of what would be a clear official mandate to combat overfishing, illegal fishing, habitat destruction, and other threats to the marine environment. Such a law would

preserve biodiversity, maintain ecosystem balance, conserve natural resources, and defend important habitats in this natural wonder. Ultimately, legal protection would also allow Panaon to build greater resilience to climate change, and enable sustainable livelihood for its residents.

“Oceana’s expedition in 2020 unveiled the marine treasures of Panaon, from untouched coral reefs to diverse marine life,” Sen. Villar said in a message during the Panaon Exhibit opening in Congress, speaking for everyone with a stake in seeing this place thrive. “We are hopeful for the passage of the proposed Panaon Island Seascape Act.”

It’s time these defenders of the coastline got their due

Could this mark the beginning of the proper, long-delayed acknowledgement of the value of Philippine mangroves?

In May 2023, the Philippine House of Representatives unanimously passed House Bill (HB) No. 7677, “An Act Adopting Integrated Coastal Management as a National Strategy for the Holistic and Sustainable Management of Coastal and Related Ecosystems and the Resources Therein From Ridge to Reef, Establishing the National Coastal Greenbelt Action Plan, Other Supporting Mechanisms for Implementation, and Providing Funds Therefor,” otherwise known as the Integrated Coastal Management (ICM) Act. The bill mandated for ICM to be carried out by all local government units (LGUs), utilizing all necessary national and local infrastructure and systems, “in consultation

and partnership with all stakeholders through participatory governance.”

Senate Bills No. 591 and 113 had already been filed in July 2022 by Senators Risa Hontiveros and Nancy Binay, with Senators Cynthia Villar and Loren Legarda also filing Senate Bills No. 1237 and 1117 the following month, all collectively known as the National Coastal Greenbelt Act of 2002—and all identifying responsible government agencies and specifying funding and general guidelines for management that is both scientific and cost-effective.

In a statement released after the HB approval, Oceana’s Senior Director for Campaigns, Legal, and Policy Atty. Liza Osorio, expressed hope that if the Senate counterpart bills were likewise passed soon, “Our coastal communities will not only gain immense benefits from mangrove forest areas as shield and protection from the impact of storm surges and strong waves during extreme weather events, such as super typhoons. Their food and livelihood will also be secured because mangroves are the spawning ground of fish and the habitat of crabs, shrimps and other shellfish.” A centralized bill would also bring together different mangrove conservation policies through the years, leading to more streamlined management and protection. It seems incongruous that in an

archipelago like the Philippines, with an estimated 18,000 kilometers of coastline, mangrove forests remain hugely undervalued. Oceana defines mangroves as “trees that live along tropical coastlines, rooted in salty sediments, often underwater.” The trees grow complex root networks in the water that become critical habitats and nurseries for the juveniles of various species, including fish that will eventually move to coral reefs and become part of life-supporting fisheries. “When you support fish communities, it’s essential to protect these habitats as part of their life cycle,” said Panaon Expedition consultant and fish expert Dr. Badi Samaniego in an interview for the magazine The Champions of Panaon. “Otherwise, if seagrass beds are buried and eroded, and mangroves cut and reclaimed, developmental habitats are lost. Marine conservation must be approached holistically.”

ECOSYSTEM ENGINEERS

“Like reef-building corals, mangroves are ecosystem engineers,” stated the Oceana website. Mangrove forests also protect coastlines from erosion due to wave action, playing the role of buffers for coastal communities, while also being sources of livelihood and subsistence. For the bigger picture, mangroves are also remarkable carbon sinks, with even greater

absorption capacities than tropical forests, providing yet another barrier, this time to the deadly effects of climate change. Accounts published in the Philippine Daily Inquirer have told of how communities in Del Carmen, Siargao Island and Giporlos, Eastern Samar were saved from the ravages of typhoons Odette and Yolanda, respectively, because of their proximity to mangrove stands.

Still, such mangrove benefits remain largely unknown to many Filipinos. Over the last 50 years or so, almost half of the country’s mangrove growth has been lost to deforestation and firewood extraction, reclamation and human development, pollution, fishpond conversion, and more natural occurrences like stronger typhoons, sea level rise, and inadequate conservation efforts.

The draft for the Senate Bill establishing coastal greenbelt zones cites how, according to Global Mangrove Watch, mangrove habitats in the Philippines covered a total of 2,675.27 square kilometers in 2016, but had decreased by 144.01 square kilometers between 1996 and 2016. Aquaculture was

also cited as a major reason for mangrove loss, to make way for fishponds. When such fishponds are abandoned, undeveloped, and underutilized (AUU), however, they could be converted back into mangroves—but no government agency has taken on the responsibility for this task.

“We live in an archipelago with one of the longest coastlines that is also the pathway of typhoons and storm surges,” noted Oceana Vice President Atty. Gloria Estenzo Ramos, “yet the government favored the so-called development projects in exchange for coastal defense provided by mangroves and beach forest areas, which have been decimated as a result of reclamation and dump-and-fill projects,”

Oceana officially launched its campaign for the restoration of mangrove forest areas in 2022, with the goal of making such efforts and regulations a national law. Since March of that year, the organization has been working with government agencies and stakeholders. Significantly, Oceana has also been helping local government units create their own coastal greenbelt zones, to protect existing mangroves and to

include even small communities in overall conservation efforts.

In October, for example, Negros Occidental Governor Eugenio Jose Lacson issued Provincial Executive Order (EO) 22-50, declaring a network of coastal greenbelt zones and allocating resources for the initiative. Other municipalities that have declared local coastal greenbelt areas protected by ordinances are Sta. Fe in Cebu Province, Bais City in Negros Oriental, Calbiga and Sta. Rita in the Province of Samar, and the entire Province of Southern Leyte. Oceana now counts some 92 municipalities nationwide with mandated coastal greenbelt areas.

In the draft for a municipal ordinance for establishing a coastal greenbelt, Republic Act 10121, otherwise known as the Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act of 2010, is cited, as it requires LGUs to “identify and implement cost-effective risk reduction measures and strategies.” Quoted about the Senate Bill she authored in an Oceana press statement, Senator Risa Hontiveros noted how the cost of establishing coastal greenbelts would

only be a fraction of the damages caused annually by typhoons and storm surges.

Further, the draft municipal ordinance states that it is the city or municipality’s responsibility to uphold its residents’ right to “a balanced and healthful ecology” by designating coastal greenbelt zones. This also entails formulating a local coastal greenbelt management action plan employing precautionary principles, ecosystem-based adaptation and mitigation, and a science-based approach; engaging civil society organizations (CSOs), the private sector, the youth, and academe volunteers in the local coastal greenbelt action plan; and providing logistics and resources for the protection, maintenance, administration, and regulation of the coastal greenbelt zone.

In the draft of the Senate Bill, a “coastal greenbelt” is defined as “a strip of natural or artificially created coastal vegetation including mangroves, beach forest, phytoplankton, and seagrasses…designed to prevent coastal erosion, and mitigate the adverse impacts of natural coastal hazards on human lives and property and mitigate the impacts of climate change.”

The cost of establishing coastal greenbelts would only be a fraction of the damage caused annually by typhoons and storm surges

In a position paper released February 24, 2024, to maintain awareness and push once more for an informed Integrated Coastal Management Act to become law, Ramos further shared the definition of a coastal greenbelt suggested by Dr. Jurgenne Primavera, Chief Mangrove Scientific Advisor for the Zoological Society of London, an internationally acknowledged mangrove expert, and one of the scientists pushing for government action on the law:

“Coastal greenbelt refers to a 100-meterwide strip of natural or planted coastal vegetation extending from the seaward edge of mangroves (middle intertidal zone) towards land, or extending from the seaward edge of beach forest (high tide line) towards land, in cases where mangroves are absent,” Primavera stated. “Its function is to absorb wave energy during storms, thereby reducing wave damage, preventing coastal erosion, and protecting human lives and property.” It is a scientific and experiencebased definition, noted Ramos, citing how, based on a 2012 study by McIvor et al, such a belt could reduce destructive wave energy by as much as 60 percent.

In the position paper, Ramos further cited the importance of separate but complementary sections on National

Coastal Greenbelt Action Plans (NGCAP) and Local Coastal Greenbelt Action Plans (LCGAP). Implementing a national plan would mean bringing it to the communities via local plans, sending much-needed support to localities that have already established such greenbelts. Meanwhile, local plans would reflect the bigger principles of a national plan at the grassroots level, and would entitle them to “the necessary support and technical assistance from national agencies and supervising local governments.”

In the interest of facilitating further action, the position paper also brought forward the importance of integrating the LCGAP with the Local Climate Change Action Plan, the Comprehensive Land Use Plan, and other local development plans. The paper further discussed designated areas for coastal greenbelts, incentives for best practices in local government, the role of national agencies and local government, the need for a scientific advisory group, prohibited activities, and a provision for monitoring, evaluation, and reporting on the implementation of the law. Thus, a National Coastal Greenbelt law would directly tackle the paramount concerns of food security and increasingly dangerous natural disasters.

In July 2024, a photo exhibit on “Our Coastal Greenbelts, Our National Treasure” was held at the National Museum of Natural History, organized by Oceana and scientifically curated by Dr. Primavera.

In the meantime, stakeholders and even civic groups continue to campaign for legislation that will clearly and unequivocally protect these guardians of Philippine coastlines.

Businesswoman Mona Lacanlale, president of the Sigma Delta Phi Sorority Alumni Association, recounts how the association teamed up with Oceana to help fund the restoration of mangroves in San Enrique, Negros Occidental. The group is also planning information campaigns to spread awareness among more Filipinos.

“Each one of us should be involved, as earthlings living on this planet,” she says. “You don’t get to complain about floods and things like that if you’re not a contributor to what is good for the environment. And organizations like Oceana are the vehicles that can put us on the right track.”

Taking a stand against the scourge of marine pollution

It is a global recognition for the Philippines, but certainly a dubious one.

In a statement for its campaign against single-use plastic, Oceana confirmed that the country is indeed one of the world’s worst offenders when it comes to marine plastic pollution, as one of the five countries responsible for half of the world’s plastic waste, based on a 2020 study by the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA), a nongovernment organization working to fight plastic pollution. In terms of waste mismanagement, despite a significantly smaller population, the Philippines has a bigger proportion of mismanaged plastic waste (MPW) than the United States, India,

and Brazil combined, at 5.91 percent. A 2021 study by Lourens J. J. Meijer, et al, further revealed that this amount of MPW adds up to 4 billion tons per year.

In 2017, the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) had already brought up the scourge of microplastics: “Plastic debris is found in the environment in a very wide range of sizes. Researchers first reported finding tiny beads and fragments of plastic, especially polystyrene, in the ocean in the early 1970s. The term ‘microplastics’ was introduced in the mid-2000s. Today, it is used extensively to describe plastic particles with an upper size limit of 5 mm.”

“…Once ingested by fish, birds

or sea mammals, the compounds (in microplastics)—which penetrate the structure of the plastic—may start to leach out…Organisms become continuously contaminated by contact with their environment and by ingestion of contaminated food.” Microplastics are found in many consumer items, from clothing to cosmetics. The clincher: “Many products labelled ‘biodegradable’ (that is, they allegedly break down over time) are not.”

In 2019, the report “Plastic & Health: The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet” by the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) also determined that some of the chemicals used in plastic may have links to diseases such

as cancer, neurological, reproductive, and developmental problems, and compromised immunity. More recently, in March 2023, in a study by experts from the Mindanao State University, the Iligan Institute of Technology, and Ateneo de Cagayan, published on the website of the US National Institutes of Health’s National Library of Medicine, it was revealed that one can actually breathe in microplastics; the presence of microplastics in the atmosphere was seen in ambient air in Manila—the first study to record such a phenomenon. All the 16 cities and one municipality in Metro Manila tested were confirmed to have suspended atmospheric particles (SAMPs), almost certainly

The Philippines is one of the world’s worst o enders— one of the ve countries responsible for half of the world’s plastic waste

affecting residents’ health.

IN

“Microplastics are in the air we breathe, in the soil, freshwater, and our seas,” said Atty. Liza Osorio, Senior Director for Campaigns, Legal, and Policy of Oceana, which is advocating the ban of single-use plastics at the source, namely the manufacturers. “Plastic is an escalating crisis for the environment, health, and climate. If we don’t act now to mitigate its impacts, when will the government move?”

A video produced by Oceana listed additional alarming data. As leading consumers of products in sachets— shampoo, toothpaste—Filipinos go through a staggering 6 billion sachets a year, not counting other culprits like plastic bags and bottles; 3 million disposable diapers are thrown into the sea annually, as well, along with 48 million shopping bags. The fact is, only 9 percent of all plastic all over the world is recycled; 12 percent is burned and 70 percent thrown, with 8 million tons heading to the oceans annually— the equivalent of a large garbage truck unloading its insidious contents every single minute.

No wonder then that birds, turtles, fish and other wildlife are killed by plastic; in fact, the video stressed, if Filipinos enjoy their seafood, they are highly likely to be

eating the microplastics consumed by fish, as well: “Sarap, ano? (Delicious, right?)”

In a statement on “Plastic Pollution 101” in July 2021, Oceana had backed this data: “Forty percent of the plastic currently produced is for packaging and single-use plastic, and the amount of plastic entering the ocean, is expected to triple by 2040.” A year earlier, a study published in July on the website Science (science.org) and funded by the Pew Charitable Trusts estimated that 710 million metric tons of plastic waste would still end up in the environment by 2040, despite efforts to curb consumption. Thus, it must boil down to drastically reducing the production of single-use plastic—companies have to stop making them, and offer consumers plasticfree alternatives for their products.

The video discussed how this material, created in 1907 from fossil fuels, first became popular in the 1950s as an alternative to glass because it was light, durable, and cost-efficient, achieving new levels of packaging convenience. Unfortunately, the convenience has cost us, noted the Oceana statement: “The problem is simple. Single-use plastics are profoundly flawed by design. They use a material made to last for centuries—but used only for a few moments…While we’ve been spoonfed by the plastic industry the idea that if everyone recycled, our oceans would not be in its current predicament, the reality is recycling alone can’t solve this crisis.” In fact, the UNEP also estimated that at the current rate, there will actually be more plastic than fish in the oceans by 2050.

Also in July 2021, Oceana hosted a webinar with the International Pollutants Elimination Network and Ecowaste Coalition, where Australian fisheries expert and veterinarian Dr. Matt Landos,