HEAVENLY AND TERRESTRIAL APHRODITE: FROM PRE-SOCRATIC TO VICTORIAN TIMES

HEAVENLY AND TERRESTRIAL APHRODITE: FROM PRE-SOCRATIC TO VICTORIAN TIMES

TiTle

HEAVENLY AND TERRESTRIAL APHRODITE: FROM PRE-SOCRATIC TO VICTORIAN TIMES

AuThor

Achilleas A. Stamatiadis

lAyouT - Design

Myrtilo, Lena Pantopoulou

CopyrighT©

Achilleas A. Stamatiadis

MAPH Graduate Student

All rights reserved 2023

FirsT eDiTion

Athens, February 2023

Cover photo: Gustave Moreau, Aphrodite, 1871, Fogg Art Museum

Vatatzi 55, 114 73 Athens

ΤEL.: +30210 6431108

E-MAIL: ocelotos@ocelotos.gr www.ocelotos.eu

ISBN 978-618-205-401-7 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of the author.

HEAVENLY AND TERRESTRIAL APHRODITE: FROM PRE-SOCRATIC TO VICTORIAN TIMES

‘AND THE END {…} WILL BE TO ARRIVE WHERE WE STARTED AND KNOW THE PLACE FOR THE FIRST TIME.’

T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets

Foreword to the first edition

I met Mr Stamatiadis for the first time in August 2012 in Boston in the halls of Northeastern University: I was given the opportunity to teach Ancient Greek History as an Adjunct Lecturer in NU’s History Department while finishing my doctoral dissertation at Harvard on ethnicity in Homer’s Iliad and the Trojan War. At the end of my first lecture, one of my students informed me, after I let him know that I shared his interest in Greek myth and had even done quite a bit of research on the mythical figure of Achilles, that another student in the class was in fact Greek and named Achilles! The next minute we met was the beginning of what would become a perennial friendship, not unlike that of Achilles and Cheiron, for quite some time at least.

Heavenly and Terrestrial Aphrodite: from Pre-Socratic Philosophy to Victorian Times will not only satisfy the exoteric curiosity of mythology enthusiasts, as it deals with a goddess first presented to undergraduate students when they are introduced to the birth of Aphrodite in Hesiod’s Theogony, it will also undoubtedly appeal to advanced researchers in philosophy, literature, and the history of ideas. The present work breaks new ground in a variety of ways, not least of which is tracing the origins of Aphrodite’s dual nature to pre-Platonic models, reaching all the way to Empedocles and Prodicus; Empedocles, who equates Aphrodite with the abstract concept eros ‘love’ (as opposed to eris ‘strife’), is thought to have influenced the author of the Derveni papyrus, who speaks of a celestial Aphrodite (Ἀφροδίτη Οὐρανία), like Plato in the Sym-

posium.; Prodicus, as Achilleas points out, may have directly inspired Plato with his twin Venuses: Socrates’ most famous pupil makes a passing reference to Prodicus’ choice of Heracles in the Seasons: the hero must choose between the female personifications of Vice (Κακία) and Virtue (Ἀρετή); these are potential forerunners or approximations of Plato’s celestial and earthly Aphrodites. I would add that the notion of a skyborn Aphrodite is reflected in the Homeric genealogy of the goddess: at Iliad 5.370 and and 38.1, Aphrodite is the daughter of Dione, clearly a feminine cognate of the day sky god Zeus (*Dyews) whose female consort was Di-wi-ya in Linear B.

Fast-forwarding to the end of the Roman Republic, Lucretius too engages with the dual nature of the goddess. Mr Stamatiadis draws attention to a ring compositional structure uniting the start and end of De Rerum Natura: whereas a vernal Venus ushers in light and life in the proem, the cosmic plague that engulfs the universe unveils the deleterious power of Venus Vulgivaga; whereas the one heals and dissipates anxieties, the other one brings on disease, uncontrolled desires and the wages of ignorance. The contrasting and complementary aspects of Venus are clearly subsumed under the idea of coincidentia oppositorum or unity of opposites, which extends to other deities as well. Apollo, for instance, a god of light, as emblematized by his epithet Phoibos “Pure and Radiant,” is also a healer god, as when he helps Hector recover consciousness in Iliad 15.262. And yet, in Book I, the very same healer is also the god who sends the plague upon the Achaeans: instead of radiating light, this other Apollo “came like the night” (1.47).

Further fast-forwarding to the 19th century, Alfred Tennyson found in Lucretius a kindred spirit. Tennyson, like Lucretius, looked askance at passionate desire, which he likens

to a disease. In one of his poems, the English poet ascribes to Lucretius’ wife Lucilla the suspicion that her husband’s frigidity is imputable to some unknown rival: little did Lucilla know that her husband’s mysterious love interest that kept him away from her were the the extant writings of Epicurus and his disciples. Tragically, Lucilla obtains a philtre from a witch and gives it to Lucretius. The solution backfires spectacularly as Lucretius starts dreaming of “the breasts of Helen,” a feature of the earthly Aphrodite or Aphrodite Pandemos. Ridden with guilt, Tennyson’s Lucretius commits suicide. Mr Stamatiadis painstakingly documents the probable origins of Lucretius’ alleged suicide, as narrated by Tennyson: Jerome is not so much the source, as some have claimed: rather, they can be imputed to “minsterpretations of the Eusebius-Jerome source by Lucretius’ biographers from the 1490s through the end of the sixteenth century.”

Returning back to antiquity, the book probes the world of ancient Greek and Roman novels for evidence of the goddess. Mr. Stamatiadis has identified numerous references to Aphrodite Urania in the 1st century CE novel Callirhoe by Chariton of –none other–Aphrodisias. The city of the eponymous goddess in inland Caria was founded five thousand years or so before the novelist’s lifetime: it is generally agreed that the worship of Aphrodite in and around the city is the Hellenization of an indigenous deity, just as the Aphrodite of continental Greece herself is also thought to have arisen through syncretism of different goddesses, an Indo-European dawn goddess and a Levantine goddess of love.

Be that as it may, Mr Stamatiadis observes that the shrine of Aphrodite described by Chariton in 2.2-2-5 is reminiscent of the shrine of Aphrodite Urania in Elis near Olympia (Pau-

sanias, Description of Greece). He further posits, persuasively, that the novel’s protagonist Callirhoe displays features that are characteristics of the celestial Aphrodite. Such parallels between mortals and gods are truly fascinating and inadequately explored by modern scholars. Whereas some of the relations between such mortals and gods may be benevolent, as in the case of Apollo and Paris in the Iliad, others may entail antagonism, as in the case of Achilles and Apollo. In Callirhoe, the eponym’s relation to the goddess evolves from antagonistic to benevolent.

I read with great interest Achilleas’ section on the 12th-century Byzantine scholar Tzetzes, with whom I was previously acquainted through his valuable, yet oft-ignored Homeric commentaries. In book 3 (25-26) of his Allegories of the Iliad, Hector characterizes Paris’s beauty as ‘gifts of Aphrodite’, which Tzetzes construes as either ‘desire’ or ‘the star’, I’ll note in passing that the much-maligned Paris never lets down throughout his life the goddess whom he chose on Mount Ida. Mr Stamatiadis perceives in this distribution Aphrodite Pandemos and Aphrodite Urania. In his Prolegomenon, Tzetzes tellingly defines Aphrodite as ‘the harmonious mixture of all the bonded elements’: this aligns with the features of Aphrodite Urania.

Renaissance art and literature were not left unexamined in Mr. Stamatiadis’s scholarly investigation. Though not a specialist of this period of history, I was not surprised that thinkers steeped in Christianity like Marsilio Ficino or Antonio degli Agli were attracted to Plato’s twin Venuses and further availed themselves of Plotinian partitions of the universe, such as the One, Mind, Soul, Body/matter, and Form/formless matter. Inspired by the figure of Diotima in the Symposium, Ficino

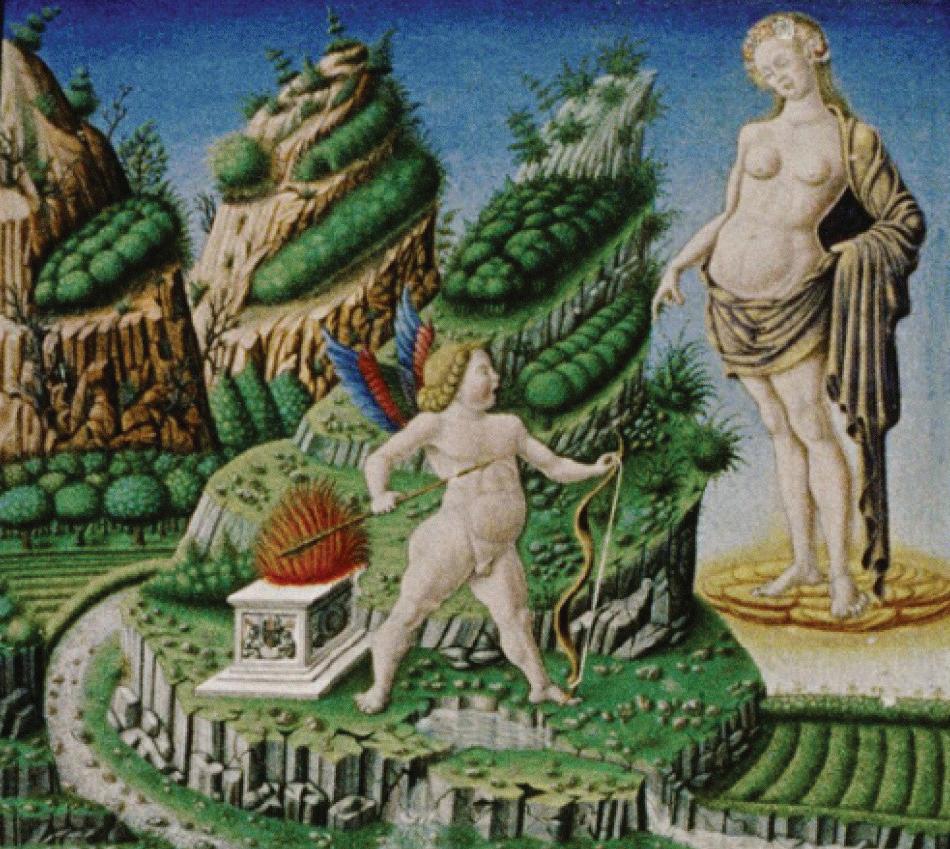

held that contemplation of the non-bodily form of beauty is the springboard for beautiful actions in the real world, positively impacting politics, lawmaking and philosophy. In the realm of art, the reader will appreciate Achilleas’ discussion of a remarkable depiction of Venus by Christoforo de Predis on a 15th century manuscript of the astrological treatise De Sphaerad’Este. The two contrasting and complementary aspects of the goddess are arguably discernible: whereas the rose and couples underneath the goddess stand for the terrestrial / carnal aspect, the mirror resonates with the heavenly aspect and Plato’s Phaedrus in which the lover is conceptualized as the beloved beholding himself.

Heavenly and Terrestrial Aphrodite is an important contribution to one of the most universally relatable dichotomies embedded and repeated in the human experience. There is little doubt in my mind that the polarization of ‘good love’ and ‘bad love’ is also attested in other cultures at different times in history with no palpable ties to ancient Greece. The basket of goods in this scholarly endeavour will placate the hunger of readers with heterogeneous backgrounds and disparate levels of expertise ranging from undergraduate students to advanced researchers in the Humanities.

Guy P. Smoot (PhD) Honorary LecturerThe Australian National University

Canberra, 30. October 2021