9 minute read

Out of the Blue

By Tyler Francke, Veterans News Magazine

Blue Water Navy Act brings compensation, recognition to thousands of veterans who have borne the scars of war through toxic exposure decades ago

Among Blue Water Navy veterans — who were often exposed to toxic herbicides like Agent Orange and other carcinogens, despite not serving directly in the fields and forests of Vietnam — the stories are often frustratingly similar.

“I went to doctors for years, because I would just feel bad,” says Vern, a Vietnam-era Boiler Technician for the United States Navy who asked Oregon Veterans News Magazine to use only his first name. “I would always hurt. But they would run tests and say, ‘There’s nothing wrong with you.’”

Those who knew or served with Vern know he’s far from the type that you might question his toughness. He was a first-rate service member, earning the rank of Petty Officer Second Class (the equivalent of sergeant in the Army and Marines) in just a couple of years.

“I was an excellent sailor,” Vern says. “I followed orders and did exactly what I was told. I wasn’t a drinker. I wasn’t a druggie. I just did my job.”

Outside of the military, Vern was a timber faller — a physically demanding and dangerous job that involves felling large trees for lumber milling, and which he worked for 48 years, retiring just this past year at the age of 70.

So, when Vern said he felt like there was something wrong with him inside — it was not because he was unaccustomed to hard labor or pain.

Those years before his illness was finally diagnosed were full of frustration.

“You just get that empty feeling with all of the denials,” Vern says. “I’d come home after seeing my doctors and my wife would say ‘How’d it go?’ And I’d just be like, ‘I feel like I wasted my time today.’”

In 2007, Vern paid $800 out of pocket for a slate of blood tests at the Mayo Clinic, which resulted in a “ticker tape about five feet long” that was inconclusive.

Two years later, Vern finally got a new doctor in Medford — an oncology specialist experienced in newer methods of diagnosis. A bone marrow test confirmed what his new doctor suspected: Vern had chronic lymphocytic leukemia, also called CLL, a form of cancer that affects the body’s ability to produce white blood cells.

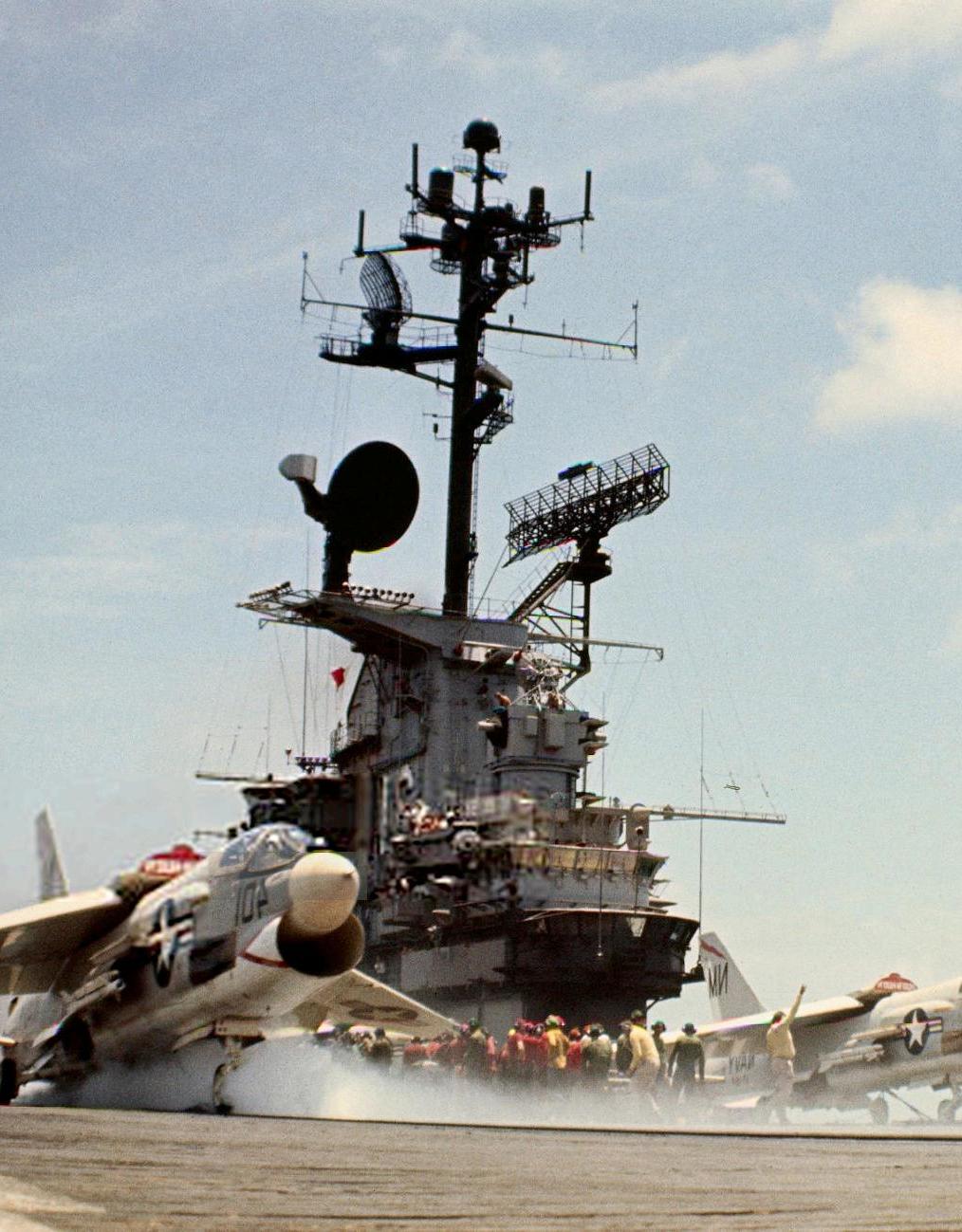

Two Vought F-8E Crusader fighters of VF-194 Red Lightnings squadron take off from the American aircraft carrier USS Bon Homme Richard (CV-31), during operations off the coast of Vietnam in August 1965.

Creative Commons photo by Manh Hai.

For Vern, the feeling was bittersweet.

“It was kind of a relief because I knew what I have now,” he explains. “But it still knocks the heck out of you. I’d wake up in the middle of the night thinking, ‘Man, I have cancer.’ It kind of haunts you.”

Though the risk factors for CLL are not fully understood, it’s strongly linked to exposure to certain chemicals, including Agent Orange. Vern doesn’t claim any exposure to the herbicide, but he regularly worked with a number of caustic chemicals that are now known to be carcinogenic, including benzene, which was used as a cleaning agent in the boiler room.

“I remember several times where we’d just be soaking in the stuff,” he recalls. “When you can taste it in your mouth, you know it’s in your system. But I did what I was told. I left the service never knowing I had damaged myself.”

He remembers having to throw out his dungarees because they were so soaked with benzene and fuel oil that it wouldn’t wash out. He also remembers spending several days painting the boiler air casing with high-heat aluminum paint — without ventilation or breathing protection.

“Now, you probably have to have a full-face mask and oxygen assistance to work with that stuff,” he says. “But back in those days, they didn’t know.”

Used ubiquitously by the U.S. military to clear forested areas in Vietnam, the toxic contaminant dioxin in Agent Orange has been linked to a slew of health problems, including leukemia, lymphoma, throat cancer, and many other diseases.

In a landmark consent decree, the U.S. Veterans Administration in 1991 agreed to assume all veterans who “served in the Republic of Vietnam” from 1962 to 1975 were exposed to Agent Orange.

This decision meant the VA would also presumptively grant service-connected disability claims for certain conditions and diseases that have known links to Agent Orange, such as Type 2 diabetes, Hodgkin’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, neuropathy, prostate and respiratory cancer, and soft tissue sarcomas.

However, this act left out many sailors and other veterans (like Vern) who served offshore and had exposure to many of the same toxins — but never actually set foot on Vietnam.

That finally changed in 2019 with the Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans Act, which extended the same benefits and list of Agent Orange presumptives to any veterans who served on a vessel that came within 12 nautical miles of Vietnam and Cambodia during the Vietnam War.

“When this law passed, we set out to identify every Vietnam veteran that walked through our doors so we could review their file to see if they may be eligible to reopen a claim based on conditions related to exposure,” says Josephine County Veteran Service Officer Lisa Pickart — one of the VSOs who assisted with Vern’s claim. “We identified almost 650 in our county who may be eligible based on their service. We are still contacting these veterans.”

Vern filed his first claim for disability compensation in 2009 — the same year his CLL was diagnosed. Because Blue Water Navy veterans were not recognized at the time, his claim was denied.

But when the law changed a decade later, it entitled him to retroactive pay — a lump sum of the monthly compensation owed to Vern dating back to the date of his first claim.

It amounted to $336,771.87 — the largest retro payment to a Blue Water Navy veteran in the state of Oregon. He also received an ongoing monthly payment of $3,649.83, and free medical coverage for his spouse from a program called CHAMPVA.

“I remember going to the Veteran Service Office the day we found out, and everyone there was just in tears,” he says. “They were so happy for me. I didn’t know what was going on.”

Vern received notice of the payment on Feb. 11, and the funds were transferred to his account two days later.

After all the years of denial, it was a shock to his system how quickly his claim came together.

“It was like the easiest thing I had ever done in my life,” he says. “I had given up on my claim back in 2009 because nothing ever came of it.”

When the Blue Water Navy Act passed, ODVA and the statewide network of local Veteran Service Officers swung into action, reaching out to the estimated 1,400 veterans who had previously filed claims that were newly eligible.

Most of those claims have been processed, so now the mission shifts to reaching out to veterans who may be eligible for compensation but never filed claims. Surviving spouses of veterans who meet the criteria may also be eligible, Pickart says.

“Claims such as these can be especially life-changing to a widow who may have relied on her husband’s income,” she says. “We estimate that tens of thousands of veterans or surviving spouses meet the legal requirements to claim these benefits but do not know how or what to do.”

If you are uncertain about eligibility, contact your local Veteran Service Office. Visit www.oregon.gov/odva/services/ pages/county-services.aspx or call 1-800-692-9666 to find services closest to you.

Josephine County Veteran Service Officer Lisa Pickart works with a veteran at her Grants Pass office in October 2020.

Working with a local veteran service officer

Filing a claim for service-connected disability benefits through the federal VA is actually a legal process. In order to receive benefits and compensation, you must file a claim against the United States proving eligibility through legal, military and medical evidence.

Though it is possible to file a claim yourself (just as you may represent yourself in a court of law), it is highly recommended that you seek the free and confidential assistance of an accredited Veteran Service Officer (VSO).

Step 1: Meet with Your Local VSO. Discuss the details of your current ongoing disability, and how it relates to your military service. Your VSO will be able to advise you on the merits of your claim, and help develop a path to your success. A VSO can file an Intent to File form, which provides up to 365 days to provide time to obtain evidence.

Step 2: Obtain Evidence. You must submit evidence to support your disability claim. The type of evidence required will depend on the case, but generally, you will need to prove that you served in the U.S. armed forces, that you have a disability and that your disability resulted from or was aggravated by your service. This evidence may include service records, medical records or lay testimony from individuals (also known as “buddy statements”).

Step 3 : File a Claim through Your VSO. The disability claim process begins the moment you formalize a claim. To file your claim through a VSO, you must sign a representation form, which authorizes the VSO to act on your behalf in preparing, presenting and pursuing your claim for any and all benefits from the federal VA.

Step 4: Complete your Compensation and Pension Exam. If the VA determines that your claim is supported by the evidence in your file, they will schedule you a one-time exam called a Compensation and Pension Exam (commonly referred to as a C&P exam). This is necessary to successfully complete your claims process. This exam will determine if the medical provider believes that your disability is related to your military service. Afterward, a report will be prepared and sent to the VA for review.

Step 5: VA Rater Completes Record. A VA rater will decide your claim based on the evidence submitted and in your military records. You will be informed of the decision via mail. If your claim is approved, a rating will be decided based on the severity of your conditions.

Step 6 : Meet Back with Your VSO. After a decision has been made, your VSO will inform you about all applicable next steps. This can include filing for newly obtained state and local benefits, or filing an appeal.